CALCULUS I

Solutions to Practice Problems

Review

Paul Dawkins

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

i

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Table of Contents

Preface ............................................................................................................................................ 1

Review............................................................................................................................................. 1

Review : Functions ..................................................................................................................................... 1

Review : Inverse Functions .......................................................................................................................25

Review : Trig Functions ............................................................................................................................34

Review : Solving Trig Equations ..............................................................................................................51

Review : Solving Trig Equations with Calculators, Part I ........................................................................80

Review : Solving Trig Equations with Calculators, Part II .....................................................................102

Review : Exponential Functions .............................................................................................................118

Review : Logarithm Functions ................................................................................................................122

Review : Exponential and Logarithm Equations .....................................................................................130

Review : Common Graphs ......................................................................................................................148

Preface

Here are the solutions to the practice problems for my Calculus I notes. Some solutions will have

more or less detail than other solutions. The level of detail in each solution will depend up on

several issues. If the section is a review section, this mostly applies to problems in the first

chapter, there will probably not be as much detail to the solutions given that the problems really

should be review. As the difficulty level of the problems increases less detail will go into the

basics of the solution under the assumption that if you’ve reached the level of working the harder

problems then you will probably already understand the basics fairly well and won’t need all the

explanation.

This document was written with presentation on the web in mind. On the web most solutions are

broken down into steps and many of the steps have hints. Each hint on the web is given as a

popup however in this document they are listed prior to each step. Also, on the web each step can

be viewed individually by clicking on links while in this document they are all showing. Also,

there are liable to be some formatting parts in this document intended for help in generating the

web pages that haven’t been removed here. These issues may make the solutions a little difficult

to follow at times, but they should still be readable.

Review

Review : Functions

1. Perform the indicated function evaluations for

( )

2

3 5

2

f x

x

x

= −

−

.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

2

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(a)

( )

4

f

(b)

( )

0

f

(c)

( )

3

f

−

(d)

(

)

6

f

t

−

(e)

(

)

7 4

f

x

−

(f)

(

)

f x h

+

(a)

( )

4

f

[Solution]

( )

( ) ( )

2

4

3 5 4

2 4

49

f

= −

−

= −

(b)

( )

0

f

[Solution]

( )

( ) ( )

2

0

3 5 0

2 0

3

f

= −

−

=

(c)

( )

3

f

−

[Solution]

( )

( ) ( )

2

3

3 5

3

2

3

0

f

− = − − − −

=

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

This works exactly the same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(d)

(

)

6

f

t

−

[Solution]

(

)

(

) (

)

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

2

6

3 5 6

2 6

3 5 6

2 36 12

3 30 5

72 24

2

99 29

2

f

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

− = −

− −

−

= −

− −

−

+

= −

+ −

+

−

= − +

−

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

This works exactly the same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(e)

(

)

7 4

f

x

−

[Solution]

(

)

(

) (

)

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

2

7 4

3 5 7 4

2 7 4

3 5 7 4

2 49 56

16

3 35 20

98 112

32

130 132

32

f

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

−

= −

−

−

−

= −

−

−

−

+

= −

+

−

+

−

= −

+

−

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

Also, don’t get excited about the fact that there is both an x and an h here. This works exactly the

same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(f)

(

)

f x h

+

[Solution]

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

3

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(

)

(

) (

)

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

2

2

3 5

2

3 5

2

2

3 5

5

2

4

2

f x

h

x

h

x

h

x

h

x

xh

h

x

h

x

xh

h

+

= −

+

−

+

= −

+

−

+

+

= −

−

−

−

−

2. Perform the indicated function evaluations for

( )

2

6

t

g t

t

=

+

.

(a)

( )

0

g

(b)

( )

3

g

−

(c)

( )

10

g

(d)

( )

2

g x

(e)

(

)

g t

h

+

(f)

(

)

2

3

1

g t

t

− +

(a)

( )

0

g

[Solution]

( )

( )

0

0

0

0

2 0

6

6

g

=

= =

+

(b)

( )

3

g

−

[Solution]

( )

( )

3

3

3

2

3

6

0

g

−

−

− =

=

− +

The minute we see the division by zero we know that

( )

3

g

−

does not exist.

(c)

( )

10

g

[Solution]

( )

( )

10

10

5

10

2 10

6

26

13

g

=

=

=

+

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

This works exactly the same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(d)

( )

2

g x

[Solution]

( )

2

2

2

2

6

x

g x

x

=

+

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

Also, don’t get excited about the fact that there is both a t and an h here. This works exactly the

same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(e)

(

)

g t

h

+

[Solution]

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

4

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(

)

(

)

2

6

2

2

6

t

h

t

h

g t

h

t

h

t

h

+

+

+

=

=

+

+

+

+

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

This works exactly the same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(f)

(

)

2

3

1

g t

t

− +

[Solution]

(

) (

)

2

2

2

2

2

3

1

3

1

3

1

2

6

8

2

3

1

6

t

t

t

t

g t

t

t

t

t

t

− +

− +

− + =

=

− +

− + +

3. Perform the indicated function evaluations for

( )

2

1

h z

z

=

−

.

(a)

( )

0

h

(b)

( )

1

2

h

−

(c)

( )

1

2

h

(d)

( )

9

h

z

(e)

(

)

2

2

h z

z

−

(f)

(

)

h z

k

+

(a)

( )

0

h

[Solution]

( )

2

0

1 0

1 1

h

=

−

=

=

(b)

( )

1

2

h

−

[Solution]

2

1

1

3

3

1

2

2

4

2

h

−

=

− −

=

=

(c)

( )

1

2

h

[Solution]

2

1

1

3

3

1

2

2

4

2

h

=

−

=

=

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are new variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

This works exactly the same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(d)

( )

9

h

z

[Solution]

( )

( )

2

2

9

1

9

1 81

h

z

z

z

=

−

=

−

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

This works exactly the same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(e)

(

)

2

2

h z

z

−

[Solution]

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

5

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(

)

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

4

3

2

2

3

4

2

1

2

1

4

4

1 4

4

h z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

−

=

−

−

=

−

−

+

=

−

+

−

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

Also, don’t get excited about the fact that there is both a z and a k here. This works exactly the

same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(f)

(

)

h z

k

+

[Solution]

(

)

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

2

1

2

h z

k

z

k

z

zk

k

z

zk

k

+

=

− +

=

−

+

+

=

−

−

−

4. Perform the indicated function evaluations for

( )

4

3

1

R x

x

x

=

+ −

+

.

(a)

( )

0

R

(b)

( )

6

R

(c)

( )

9

R

−

(d)

(

)

1

R x

+

(e)

(

)

4

3

R x

−

(f)

(

)

1

1

x

R

−

(a)

( )

0

R

[Solution]

( )

4

0

3 0

3

4

0 1

R

=

+ −

=

−

+

(b)

( )

6

R

[Solution]

( )

4

4

4

17

6

3 6

9

3

6 1

7

7

7

R

=

+ −

=

− = − =

+

(c)

( )

9

R

−

[Solution]

( )

( )

4

4

9

3

9

6

9 1

8

R

− =

+ − −

= − −

− +

−

In this class we only deal with functions that give real values as answers. Therefore, because we

have the square root of a negative number in the first term this function is not defined.

Note that the fact that the second term is perfectly acceptable has no bearing on the fact that the

function will not be defined here. If any portion of the function is not defined upon evaluation

then the whole function is not defined at that point. Also note that if we allow complex numbers

this function will be defined.

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

This works exactly the same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(d)

(

)

1

R x

+

[Solution]

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

6

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(

)

(

) ( )

4

4

1

3

1

4

1

1

2

R x

x

x

x

x

+ =

+

+ −

=

+ −

+ +

+

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

This works exactly the same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(e)

(

)

4

3

R x

−

[Solution]

(

)

(

) ( )

4

4

4

2

4

4

4

4

4

4

3

3

3

2

2

3

1

R x

x

x

x

x

x

x

− =

+

−

−

=

−

=

−

−

−

− +

Hint : Don’t let the fact that there are now variables here instead of numbers get you confused.

This works exactly the same way as the first three it will just have a little more algebra involved.

(f)

(

)

1

1

x

R

−

[Solution]

(

)

1

1

1

1

4

1

4

1

1

3

1

2

2

4

1

1

x

x

R

x

x

x

x

x

− =

+

− −

=

+ − =

+ −

− +

5. The difference quotient of a function

( )

f x

is defined to be,

(

)

( )

f x

h

f x

h

+

−

compute the difference quotient for

( )

4

9

f x

x

=

−

.

Hint : Compute

(

)

f x h

+

, then compute the numerator and finally compute the difference

quotient.

Step 1

(

) (

)

4

9

4

4

9

f x

h

x

h

x

h

+

=

+ − =

+

−

Step 2

(

)

( )

(

)

4

4

9

4

9

4

f x

h

f x

x

h

x

h

+ −

=

+

− −

− =

Step 3

(

)

( )

4

4

f x

h

f x

h

h

h

+

−

=

=

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

7

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

6. The difference quotient of a function

( )

f x

is defined to be,

(

)

( )

f x

h

f x

h

+

−

compute the difference quotient for

( )

2

6

g x

x

= −

.

Hint : Don’t get excited about the fact that the function is now named

( )

g x

, the difference

quotient still works in the same manner it just has g’s instead of f’s now. So, compute

(

)

g x

h

+

,

then compute the numerator and finally compute the difference quotient.

Step 1

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

6

6

2

g x

h

x

h

x

xh

h

+

= −

+

= −

−

−

Step 2

(

)

( )

(

)

2

2

2

2

6

2

6

2

g x

h

g x

x

xh

h

x

xh

h

+

−

= −

−

−

− −

= −

−

Step 3

(

) ( )

2

2

2

g x

h

g x

xh h

x h

h

h

+

−

−

−

=

= − −

7. The difference quotient of a function

( )

f x

is defined to be,

(

)

( )

f x

h

f x

h

+

−

compute the difference quotient for

( )

2

2

3

9

f t

t

t

=

− +

.

Hint : Don’t get excited about the fact that the function is now

( )

f t

, the difference quotient still

works in the same manner it just has t’s instead of x’s now. So, compute

(

)

f t

h

+

, then compute

the numerator and finally compute the difference quotient.

Step 1

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

9

2

2

3

3

9

2

4

2

3

3

9

f t

h

t

h

t

h

t

th

h

t

h

t

th

h

t

h

+

=

+

−

+

+ =

+

+

− −

+

=

+

+

− −

+

Step 2

(

)

( )

(

)

2

2

2

2

2

4

2

3

3

9

2

3

9

4

2

3

f t

h

f t

t

th

h

t

h

t

t

th

h

h

+

−

=

+

+

− −

+ −

− +

=

+

−

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

8

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Step 3

(

)

( )

2

4

2

3

4

2

3

f t

h

f t

th

h

h

t

h

h

h

+

−

+

−

=

= +

−

8. The difference quotient of a function

( )

f x

is defined to be,

(

)

( )

f x

h

f x

h

+

−

compute the difference quotient for

( )

1

2

y z

z

=

+

.

Hint : Don’t get excited about the fact that the function is now named

( )

y z

, the difference

quotient still works in the same manner it just has y’s and z’s instead of f’s and x’s now. So,

compute

(

)

y z

h

+

, then compute the numerator and finally compute the difference quotient.

Step 1

(

)

1

2

y z

h

z

h

+

=

+ +

Step 2

(

) ( )

(

)

(

)(

) (

)(

)

2

2

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

z

z

h

h

y z

h

y z

z

h

z

z

h

z

z

h

z

+ − + +

−

+

−

=

−

=

=

+ +

+

+ +

+

+ +

+

Note that, when dealing with difference quotients, it will almost always be advisable to combine

rational expressions into a single term in preparation of the next step.

Step 3

(

) ( )

(

) ( )

(

)

(

)(

)

(

)(

)

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

y z

h

y z

h

h z

h

h z

h

h

h

z

h

z

z

h

z

+

−

−

−

=

+

−

=

=

+ +

+

+ +

+

In this step we rewrote the difference quotient a little to make the numerator a little easier to deal

with. All that we’re doing here is using the fact that,

( )

( )

1

1

a

a

a

b

b

b

=

=

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

9

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

9. The difference quotient of a function

( )

f x

is defined to be,

(

)

( )

f x

h

f x

h

+

−

compute the difference quotient for

( )

2

3

t

A t

t

=

−

.

Hint : Don’t get excited about the fact that the function is now named

( )

A t

, the difference

quotient still works in the same manner it just has A’s and t’s instead of f’s and x’s now. So,

compute

(

)

A t

h

+

, then compute the numerator and finally compute the difference quotient.

Step 1

(

)

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

3

3

t

h

t

h

A t

h

t

h

t

h

+

+

+

=

=

− +

− −

Step 2

(

)

( )

(

)(

)

(

)

(

)(

)

(

)

(

)(

)

(

)(

)

2

2

2

2

3

2 3

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

6

2

6

2

6

2

2

6

3

3

3

3

t

h

t

t

t

h

t

h

t

A t

h

A t

t

h

t

t

h

t

t

t

h

ht

t

t

th

h

t

h

t

t

h

t

+

− −

− −

+

+

−

=

−

=

− −

−

− −

−

−

+

−

−

−

−

=

=

− −

−

− −

−

Note that, when dealing with difference quotients, it will almost always be advisable to combine

rational expressions into a single term in preparation of the next step. Also, when doing this

don’t forget to simplify the numerator as much as possible. With most difference quotients you’ll

see a lot of cancelation as we did here.

Step 3

(

)

( )

(

)

( )

(

)

(

)(

)

(

)(

)

1

1

6

6

3

3

3

3

A t

h

A t

h

A t

h

A t

h

h

h

t

h

t

t

h

t

+

−

=

+

−

=

=

− −

−

− −

−

In this step we rewrote the difference quotient a little to make the numerator a little easier to deal

with. All that we’re doing here is using the fact that,

( )

( )

1

1

a

a

a

b

b

b

=

=

10. Determine all the roots of

( )

5

4

3

4

32

f x

x

x

x

=

−

−

.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

10

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

[Solution]

Set the function equal to zero and factor the left side.

(

)

(

)(

)

5

4

3

3

2

3

4

32

4

32

8

4

0

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

−

−

=

−

−

=

−

+

=

After factoring we can see that the three roots of this function are,

4,

0,

8

x

x

x

= −

=

=

11. Determine all the roots of

( )

2

12

11

5

R y

y

y

=

+

−

.

[Solution]

Set the function equal to zero and factor the left side.

(

)(

)

2

12

11

5

4

5 3

1

0

y

y

y

y

+

− =

+

− =

After factoring we see that the two roots of this function are,

5

1

,

4

3

y

y

= −

=

12. Determine all the roots of

( )

2

18 3

2

h t

t

t

=

− −

.

[Solution]

Set the function equal to zero and because the left side will not factor we’ll need to use the

quadratic formula to find the roots of the function.

2

18 3

2

0

t

t

− −

=

( )

( )( )

( )

( )( )

(

)

2

3

3

4

2 18

3

9 17

3

153

3 3 17

3

1

17

2

2

4

4

4

4

t

±

−

− −

±

±

±

=

=

=

=

= −

±

−

−

−

−

So, the quadratic formula gives the following two roots of the function,

(

)

(

)

3

3

1

17

2.342329

1

17

3.842329

4

4

−

+

=

−

−

= −

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

11

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

13. Determine all the roots of

( )

3

2

7

g x

x

x

x

=

+

−

.

[Solution]

Set the equation equal to zero and factor the left side as much as possible.

(

)

3

2

2

7

7

1

0

x

x

x

x x

x

+

− =

+

− =

So, we can see that one root is

0

x

=

and because the quadratic doesn’t factor we’ll need to use

the quadratic formula on that to get the remaining two roots.

( )

( )( )

( )

4

7

7

4 1

1

7

53

2 1

2

x

− ±

−

−

− ±

=

=

We then have the following three roots of the function,

7

53

7

53

0,

0.140055,

7.140055

2

2

x

− +

− −

=

=

= −

14. Determine all the roots of

( )

4

2

6

27

W x

x

x

=

+

−

.

[Solution]

Set the function equal to zero and factor the left side as much as possible.

(

)(

)

4

2

2

2

6

27

3

9

0

x

x

x

x

+

−

=

−

+

=

Don’t so locked into quadratic equations that the minute you see an equation that is not quadratic

you decide you can’t deal with it. While this function was not a quadratic it still factored in an

obvious manner.

Now, the second term will never be zero (for any real value of x anyway and in this class those

tend to be the only ones we are interested in) and so we can ignore that term. The first will be

zero if,

2

2

3

0

3

3

x

x

x

− =

⇒

=

⇒

= ±

So, we have two real roots of this function. Note that if we allowed complex roots (which again,

we aren’t really interested in for this course) there would also be two complex roots from the

second term as well.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

12

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

15. Determine all the roots of

( )

5

4

3

3

7

8

f t

t

t

t

= −

−

.

[Solution]

Set the function equal to zero and factor the left side as much as possible.

5

4

2

1

1

1

3

3

3

3

3

3

7

8

7

8

8

1

0

t

t

t

t t

t

t t

t

−

− =

−

−

=

−

+ =

Don’t so locked into quadratic equations that the minute you see an equation that is not quadratic

you decide you can’t deal with it. While this function was not a quadratic it still factored, it just

wasn’t as obvious that it did in this case. You could have clearly seen that if factored if it had

been,

(

)

2

7

8

t t

t

− −

but notice that the only real difference is that the exponents are fractions now, but it still has the

same basic form and so can be factored.

Okay, back to the problem. From the factored form we get,

( )

1

1

3

3

3

1

1

3

3

3

0

8

0

8

8

512

1

0

1

1

1

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

=

− =

⇒

=

⇒

=

=

+ =

⇒

= −

⇒

= −

= −

So, the function has three roots,

1,

0,

512

t

t

t

= −

=

=

16. Determine all the roots of

( )

4

5

8

z

h z

z

z

=

−

−

−

.

[Solution]

Set the function equal to zero and clear the denominator by multiplying by the least common

denominator,

(

)(

)

5

8

z

z

−

−

, and then solve the resulting equation.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

13

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(

)(

)

(

) (

)

(

)(

)

2

4

5

8

0

5

8

8

4

5

0

12

20

0

10

2

0

z

z

z

z

z

z z

z

z

z

z

z

−

−

−

=

−

−

− −

−

=

−

+

=

−

−

=

So, it looks like the function has two roots,

2

z

=

and

10

z

=

however recall that because we

started off with a function that contained rational expressions we need to go back to the original

function and make sure that neither of these will create a division by zero problem in the original

function. In this case neither do and so the two roots are,

2

10

z

z

=

=

17. Determine all the roots of

( )

2

4

1

2

3

w

w

g w

w

w

−

=

+

+

−

.

[Solution]

Set the function equal to zero and clear the denominator by multiplying by the least common

denominator,

(

)(

)

1 2

3

w

w

+

−

, and then solve the resulting equation.

(

)(

)

(

) (

)(

)

2

2

4

1 2

3

0

1

2

3

2

2

3

4

1

0

5

9

4

0

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

w

−

+

−

+

=

+

−

− +

−

+ =

−

− =

This quadratic doesn’t factor so we’ll need to use the quadratic formula to get the solution.

( )

( )( )

( )

2

9

9

4 5

4

9

161

2 5

10

w

±

−

−

−

±

=

=

So, it looks like this function has the following two roots,

9

161

9

161

2.168858

0.368858

10

10

+

−

=

= −

Recall that because we started off with a function that contained rational expressions we need to

go back to the original function and make sure that neither of these will create a division by zero

problem in the original function. Neither of these do and so they are the two roots of this

function.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

14

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

18. Find the domain and range of

( )

2

3

2

1

Y t

t

t

=

− +

.

[Solution]

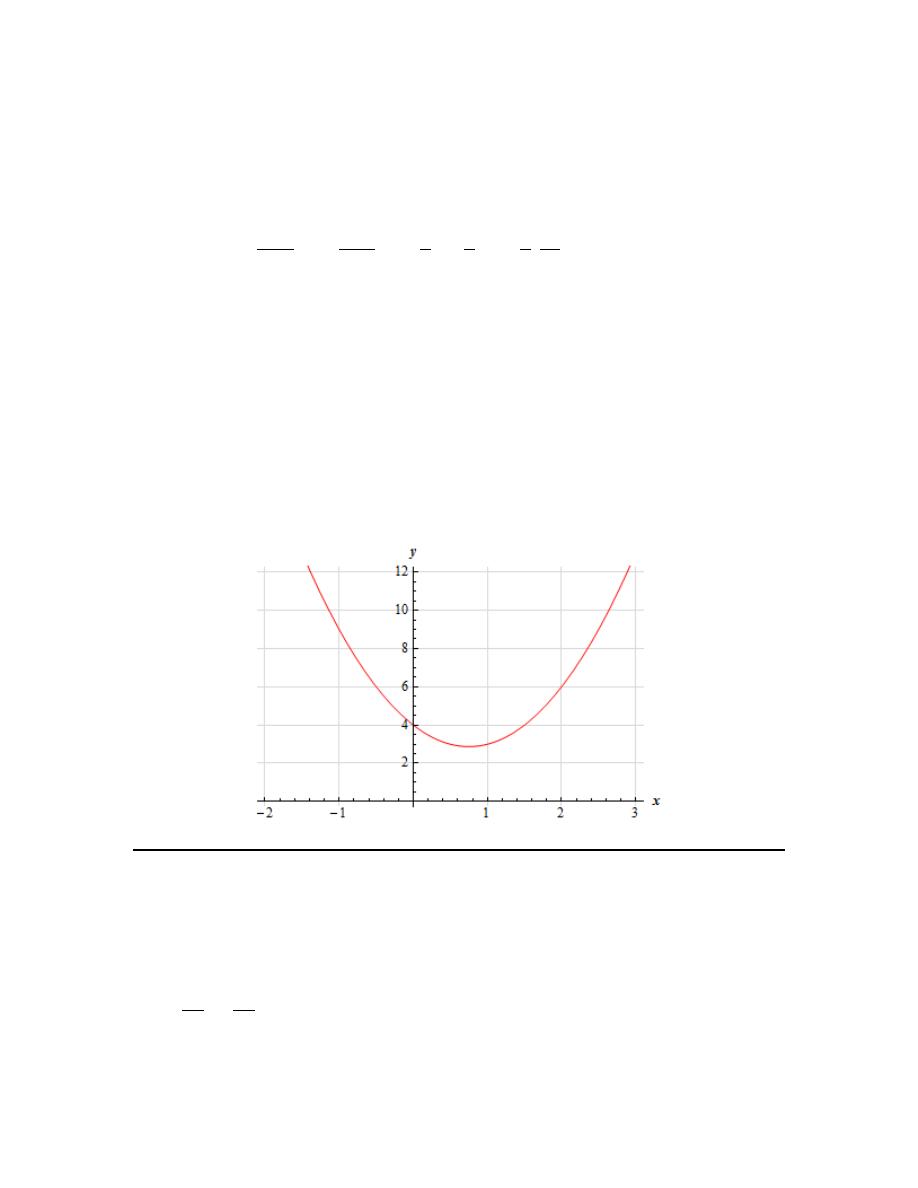

This is a polynomial (a 2

nd

degree polynomial in fact) and so we know that we can plug any value

of t into the function and so the domain is all real numbers or,

(

)

Domain :

or

,

t

− ∞ < < ∞

−∞ ∞

The graph of this 2

nd

degree polynomial (or quadratic) is a

parabola

that opens upwards (because

the coefficient of the

2

t

is positive) and so we know that the vertex will be the lowest point on

the graph. This also means that the function will take on all values greater than or equal to the y-

coordinate of the vertex which will in turn give us the range.

So, we need the vertex of the parabola. The t-coordinate is,

( )

2

1

2 3

3

t

−

= −

=

and the y coordinate is then,

1

2

3

3

Y

=

.

The range is then,

2

Range :

,

3

∞

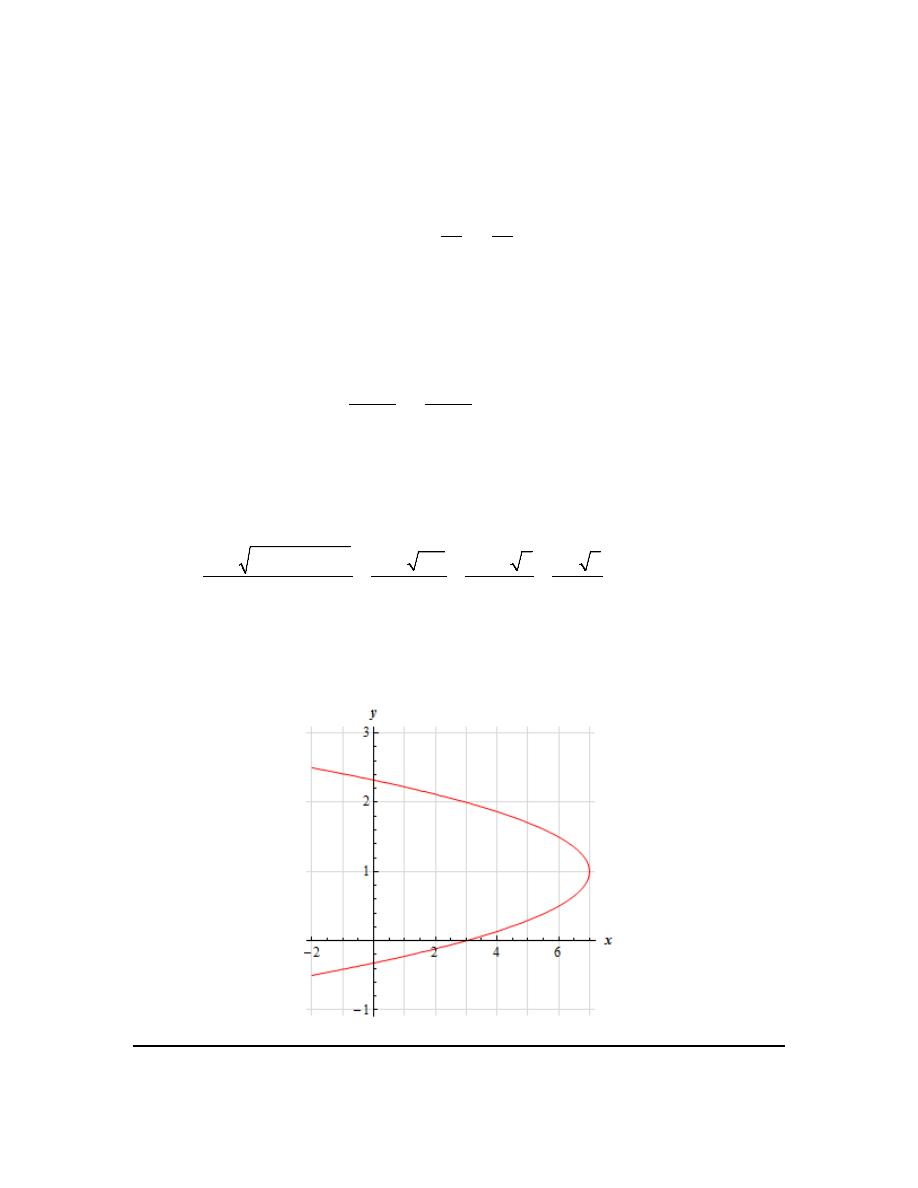

19. Find the domain and range of

( )

2

4

7

g z

z

z

= − −

+

.

[Solution]

This is a polynomial (a 2

nd

degree polynomial in fact) and so we know that we can plug any value

of z into the function and so the domain is all real numbers or,

(

)

Domain :

or

,

z

− ∞ < < ∞

−∞ ∞

The graph of this 2

nd

degree polynomial (or quadratic) is a

parabola

that opens downwards

(because the coefficient of the

2

z

is negative) and so we know that the vertex will be the highest

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

15

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

point on the graph. This also means that the function will take on all values less than or equal to

the y-coordinate of the vertex which will in turn give us the range.

So, we need the vertex of the parabola. The z-coordinate is,

( )

4

2

2

1

z

−

= −

= −

−

and the y coordinate is then,

( )

2

11

g

− =

.

The range is then,

(

]

Range :

,11

−∞

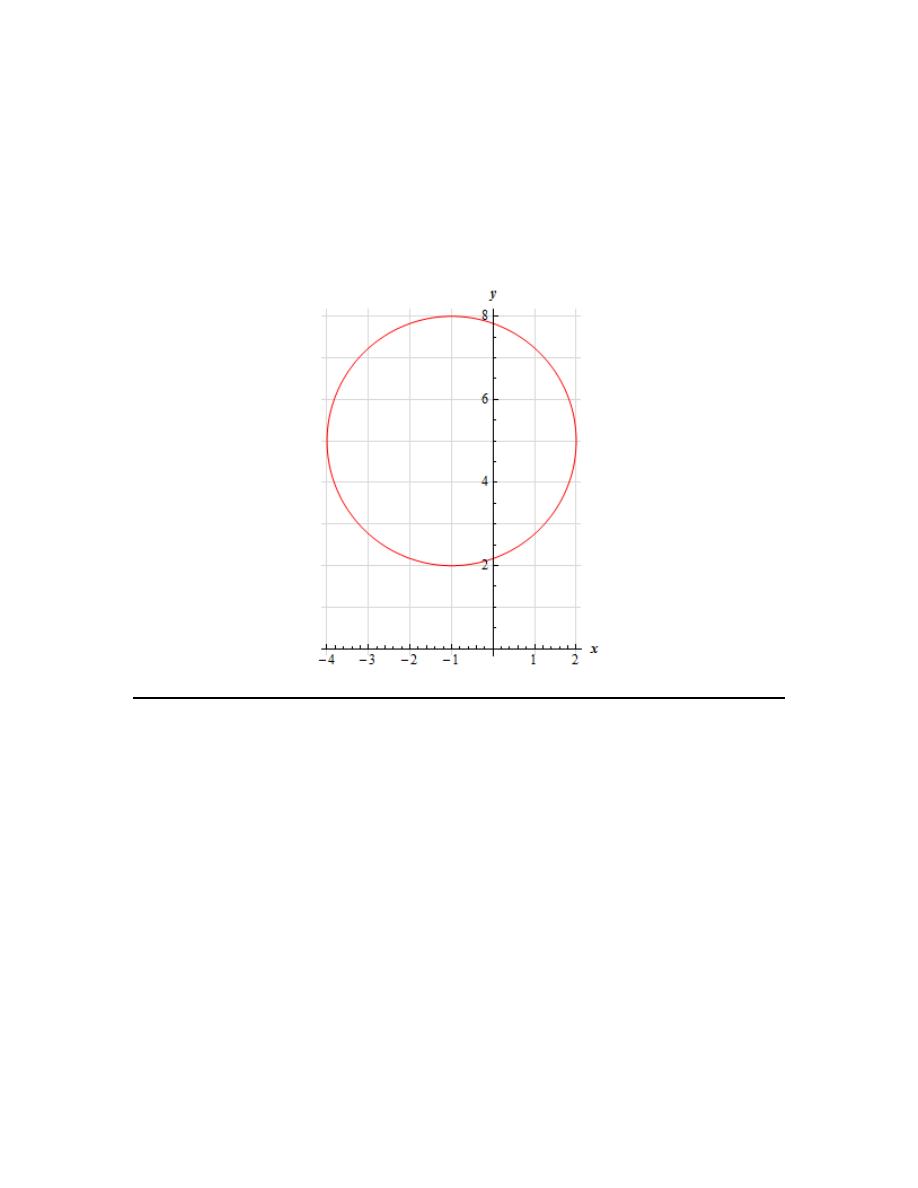

20. Find the domain and range of

( )

2

2

1

f z

z

= +

+

.

[Solution]

We know that when we have square roots that we can’t take the square root of a negative number.

However, because,

2

1 1

z

+ ≥

we will never be taking the square root of a negative number in this case and so the domain is all

real numbers or,

(

)

Domain :

or

,

z

− ∞ < < ∞

−∞ ∞

For the range we need to recall that square roots will only return values that are positive or zero

and in fact the only way we can get zero out of a square root will be if we take the square root of

zero. For our function, as we’ve already noted, the quantity that is under the root is always at

least 1 and so this root will never be zero. Also recall that we have the following fact about

square roots,

If

1 then

1

x

x

≥

≥

So, we now know that,

2

1 1

z

+ ≥

Finally, we are adding 2 onto the root and so we know that the function must always be greater

than or equal to 3 and so the range is,

[

)

Range : 3,

∞

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

16

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

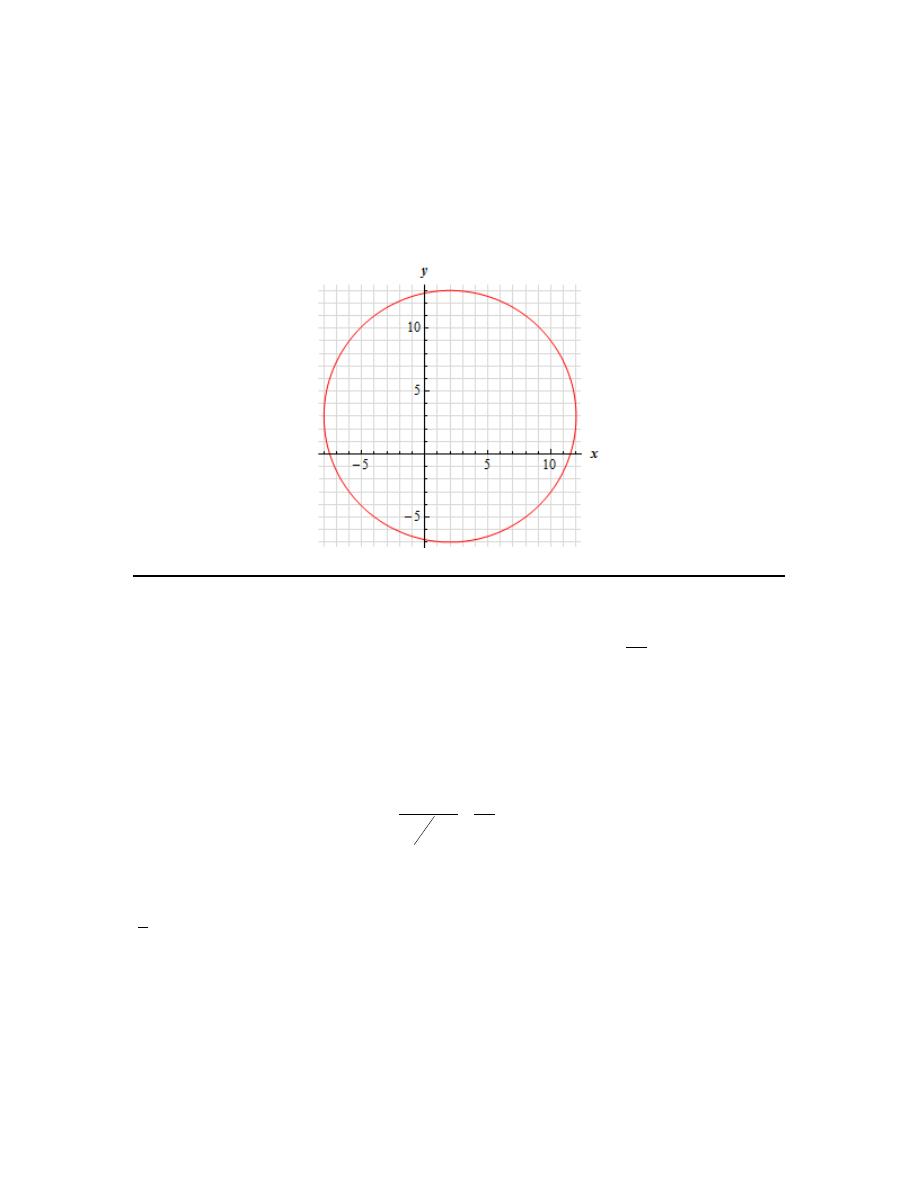

21. Find the domain and range of

( )

3 14 3

h y

y

= −

+

.

[Solution]

In this case we need to require that,

14

14 3

0

3

y

y

+

≥

⇒

≥ −

in order to make sure that we don’t take the square root of negative numbers. The domain is then,

14

14

Domain :

or

,

3

3

y

−

≤ < ∞

−

∞

For the range for this function we can notice that the quantity under the root can be zero (if

14

3

y

= −

). Also note that because the quantity under the root is a line it will take on all positive

values and so the square root will in turn take on all positive value and zero. The square root is

then multiplied by -3. This won’t change the fact that the root can be zero, but the minus sign

will change the sign of the non-zero values from positive to negative. The 3 will only affect the

general size of the square root but it won’t change the fact that the square root will still take on all

positive (or negative after we add in the minus sign) values.

The range is then,

(

]

Range :

, 0

−∞

22. Find the domain and range of

( )

5

8

M x

x

= − +

.

[Solution]

We’re dealing with an absolute value here and the quantity inside is a line, which we can plug all

values of x into, and so the domain is all real numbers or,

(

)

Domain :

or

,

x

− ∞ < < ∞

−∞ ∞

For the range let’s again note that the quantity inside the absolute value is a linear function that

will take on all real values. We also know that absolute value functions will never be negative

and will only be zero if we take the absolute value of zero. So we now know that,

8

0

x

+ ≥

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

17

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

However, we are subtracting this from 5 and so we’ll be subtracting a positive or zero number

from 5 and so the range is,

(

]

Range :

, 5

−∞

23. Find the domain of

( )

3

3

1

12

7

w

w

f w

w

−

+

=

−

.

[Solution]

In this case we need to avoid division by zero issues and so we’ll need to determine where the

denominator is zero. To do this we will solve,

7

12

7

0

12

w

w

− =

⇒

=

We can plug all other values of w into the function without any problems and so the domain is,

7

Domain : All real numbers except

12

w

=

24. Find the domain of

( )

3

2

5

10

9

R z

z

z

z

=

+

+

.

[Solution]

In this case we need to avoid division by zero issues and so we’ll need to determine where the

denominator is zero. To do this we will solve,

(

)

(

)(

)

3

2

2

10

9

10

9

1

9

0

0,

1,

9

z

z

z

z z

z

z z

z

z

z

z

+

+

=

+

+

=

+

+

=

⇒

=

= −

= −

The three values above are the only values of z that we can’t plug into the function. All other

values of z can be plugged into the function and will return real values. The domain is then,

Domain : All real numbers except

0,

1,

9

z

z

z

=

= −

= −

25. Find the domain of

( )

3

2

6

7

4

t

t

g t

t

t

−

=

− −

.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

18

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

[Solution]

In this case we need to avoid division by zero issues and so we’ll need to determine where the

denominator is zero. To do this we will solve,

( )

( )( )

( )

(

)

2

2

1

1

4

4 7

1

7

4

0

1

113

2

4

8

t

t

t

±

−

− −

− −

=

⇒

=

= −

±

−

The two values above are the only values of t that we can’t plug into the function. All other

values of t can be plugged into the function and will return real values. The domain is then,

(

)

1

Domain : All real numbers except

1

113

8

t

= −

±

26. Find the domain of

( )

2

25

g x

x

=

−

.

[Solution]

In this case we need to avoid square roots of negative numbers and so we need to require,

2

25

0

x

−

≥

Note that once we have the original inequality written down we can do a little rewriting of things

as follows to make things a little easier to see.

2

25

5

5

x

x

≤

⇒

− ≤ ≤

At this point it should be pretty easy to find the values of x that will keep the quantity under the

radical positive or zero and so we won’t need to do a numberline or sign table to determine the

range.

The domain is then,

Domain : 5

5

x

− ≤ ≤

27. Find the domain of

( )

4

3

2

20

h x

x

x

x

=

− −

.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

19

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Step 1 Hint : We need to avoid negative numbers under the square root and because the quantity

under the root is a polynomial we know that it can only change sign if it goes through zero and so

we first need to determine where it is zero.

[Show Step One]

In this case we need to avoid square roots of negative numbers and so we need to require,

(

)

(

)(

)

4

3

2

2

2

2

20

20

5

4

0

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

−

−

=

− −

=

−

+

≥

Once we have the polynomial in factored form we can see that the left side will be zero at

0

x

=

,

4

x

= −

and

5

x

=

. Because the quantity under the radical is a polynomial we know that it can

only change sign if it goes through zero and so these are the only points the only places where the

polynomial on the left can change sign.

Step 2 Hint : Because the polynomial can only change sign at these points we know that it will be

the same sign in each region defined by these points and so all we need to know is the value of

the polynomial as a single point in each region.

[Show Step Two]

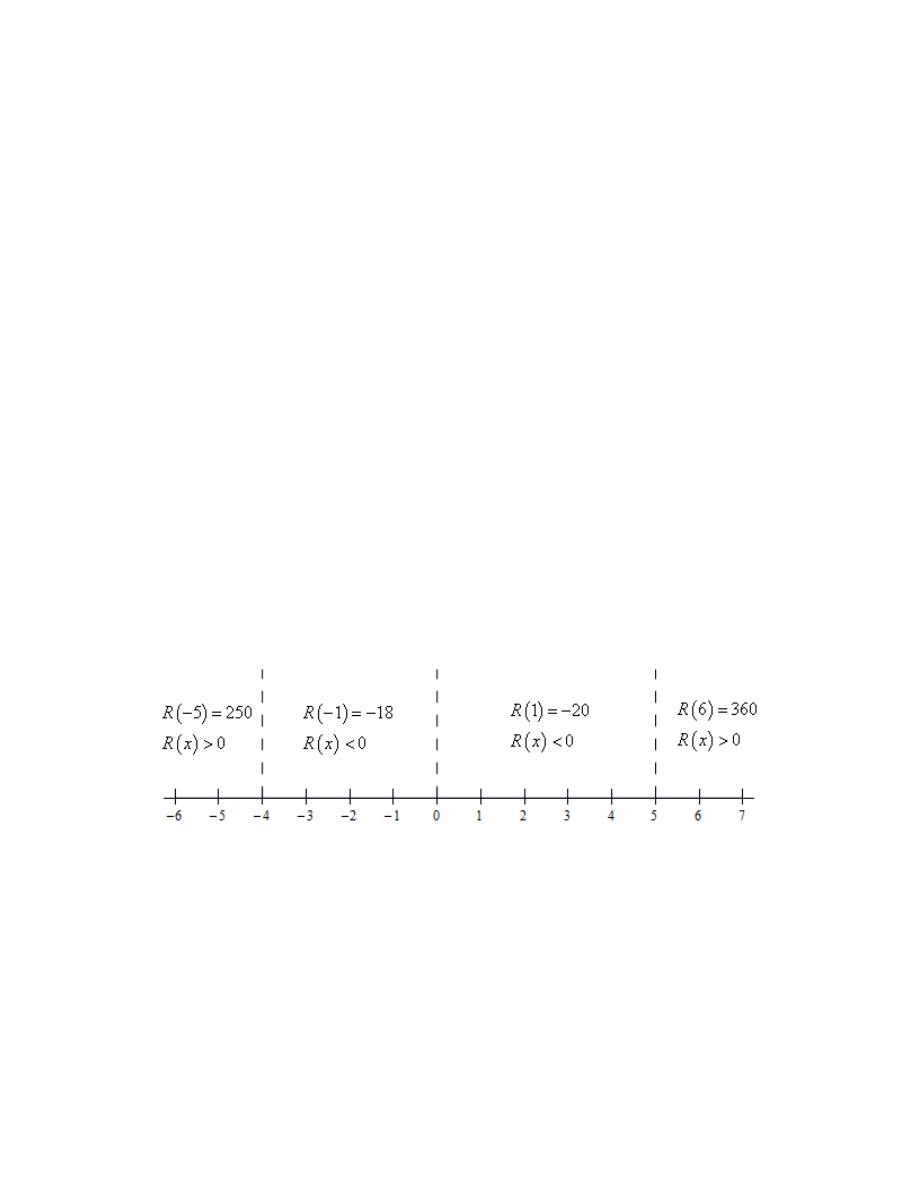

Here is a number line giving the value/sign of the polynomial at a test point in each of the region

defined by these three points. To make it a little easier to read the number line let’s define the

polynomial under the radical to be,

( )

(

)(

)

4

3

2

2

20

5

4

R x

x

x

x

x

x

x

=

− −

=

−

+

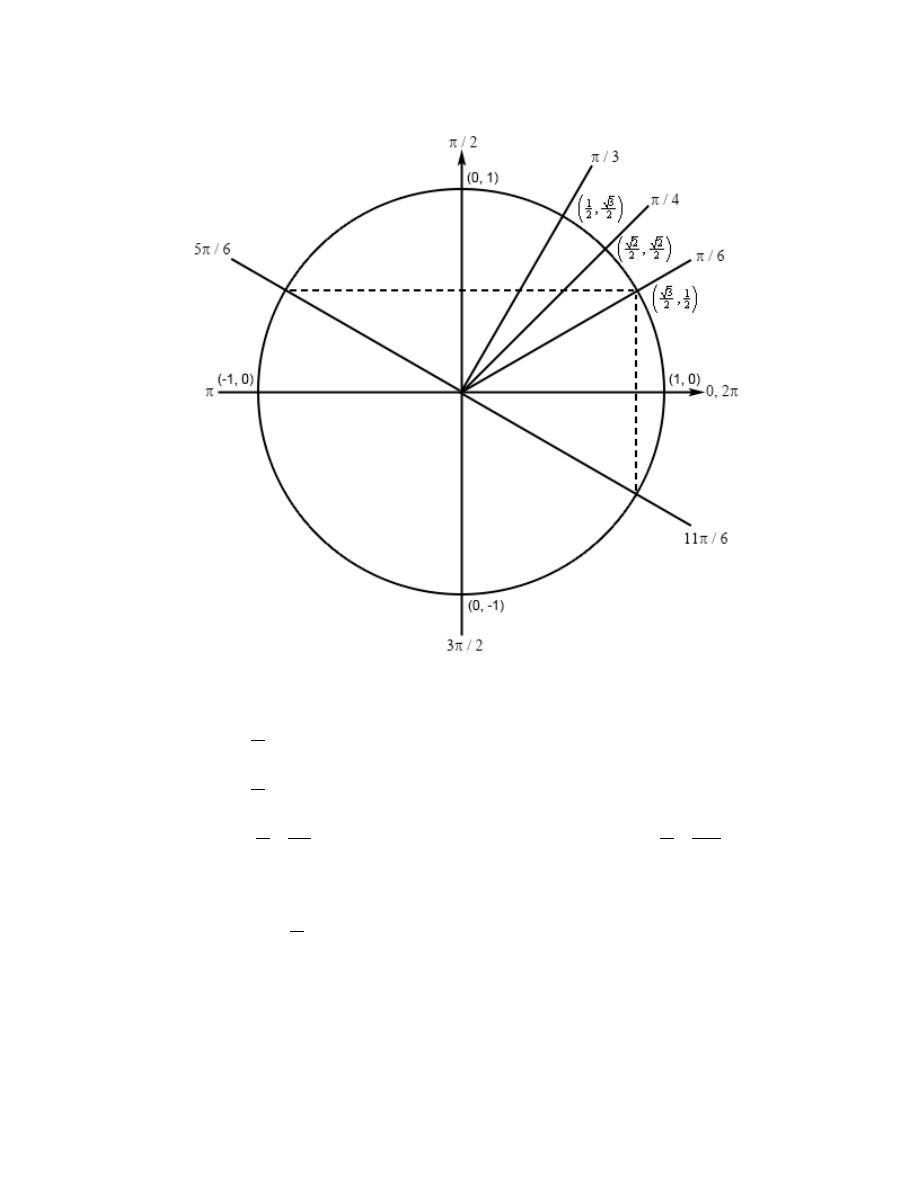

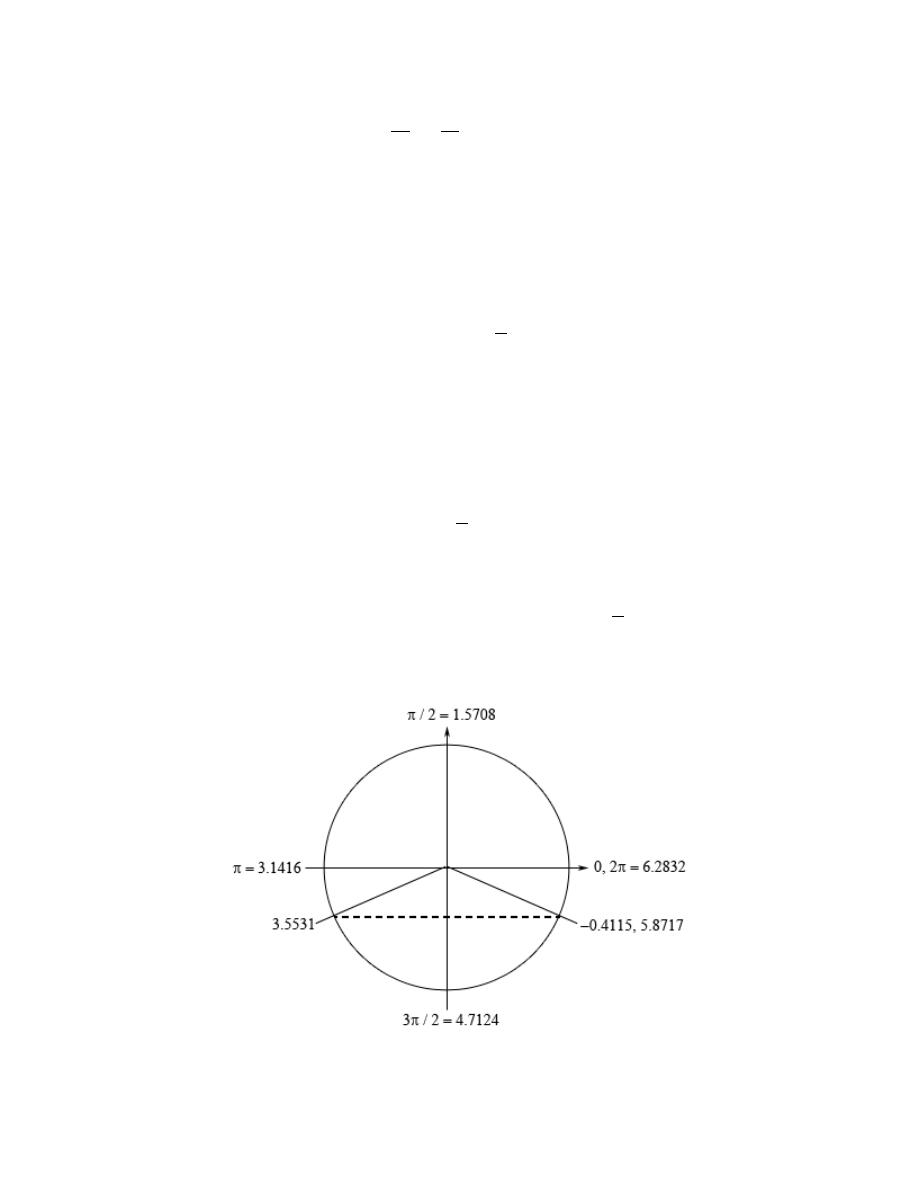

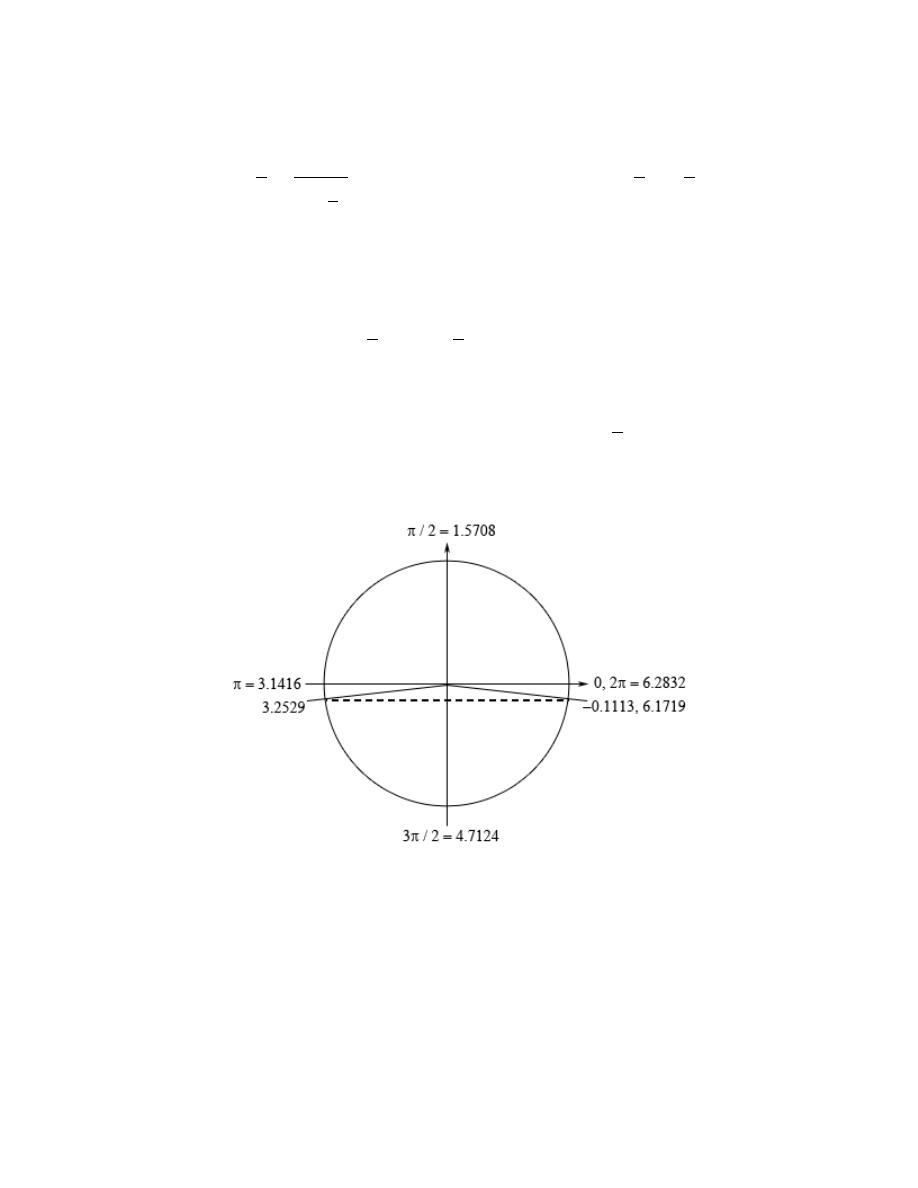

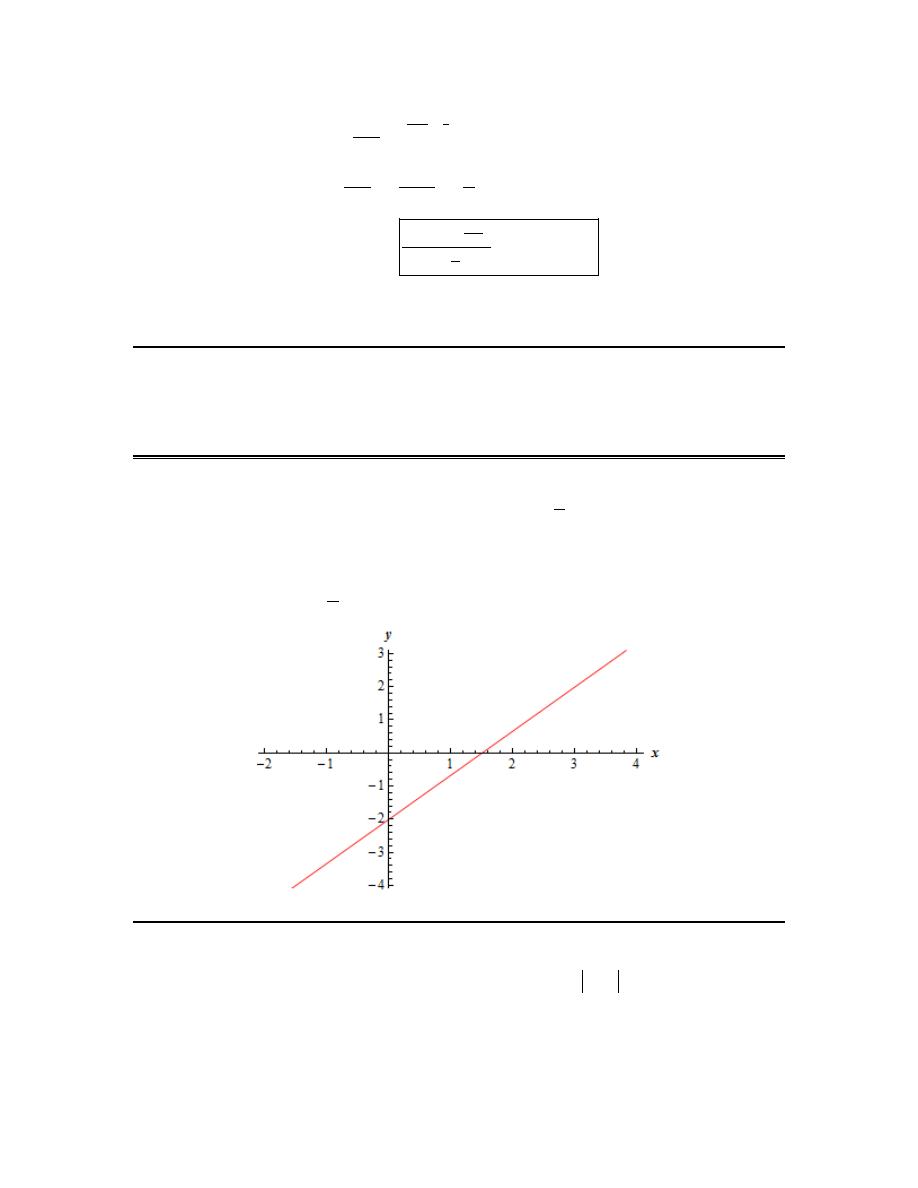

Now, here is the number line,

Step 3 Hint : Now all we need to do is write down the values of x where the polynomial under the

root will be positive or zero and we’ll have the domain. Be careful with the points where the

polynomial is zero.

[Show Step Three]

The domain will then be all the points where the polynomial under the root is positive or zero and

so the domain is,

Domain :

4,

0, 5

x

x

x

− ∞ < ≤ −

=

≤ < ∞

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

20

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

In this case we need to be very careful and not miss

0

x

=

. This is the point separating two

regions which give negative values of the polynomial, but it will give zero and so it also part of

the domain. This point is often very is very easy to miss.

28. Find the domain of

( )

3

2

5

1

8

t

P t

t

t

t

+

=

− −

.

Step 1 Hint : We need to avoid negative numbers under the square root and because the quantity

under the root is a polynomial we know that it can only change sign if it goes through zero and so

we first need to determine where it is zero.

[Show Step One]

In this case we need to avoid square roots of negative numbers and because the square root is in

the denominator we’ll also need to avoid division by zero issues. We can satisfy both needs by

requiring,

(

)

3

2

2

8

8

0

t

t

t

t t

t

− − =

− −

>

Note that there is nothing wrong with the square root of zero, but we know that the square root of

zero is zero and so if we require that the polynomial under the root is strictly positive we’ll know

that we won’t have square roots of negative numbers and we’ll avoid division by zero.

Now, despite the fact that we need to avoid where the polynomial is zero we know that it will

only change signs if it goes through zero and so we’ll next need to determine where the

polynomial is zero.

Clearly one value is

0

t

=

and because the quadratic does not factor we can use the quadratic

formula on it to get the following two additional points.

( )

( )( )

2

1

1

4 1

8

1

33

1

33

3.372281

2

2

2

1

33

2.372281

2

t

t

t

±

−

−

−

±

+

=

=

=

=

−

=

= −

So, these three points (

0

t

=

,

2.372281

t

= −

and

3.372281

t

=

are the only places that the

polynomial under the root can change sign.

Step 2 Hint : Because the polynomial can only change sign at these points we know that it will be

the same sign in each region defined by these points and so all we need to know is the value of

the polynomial as a single point in each region.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

21

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

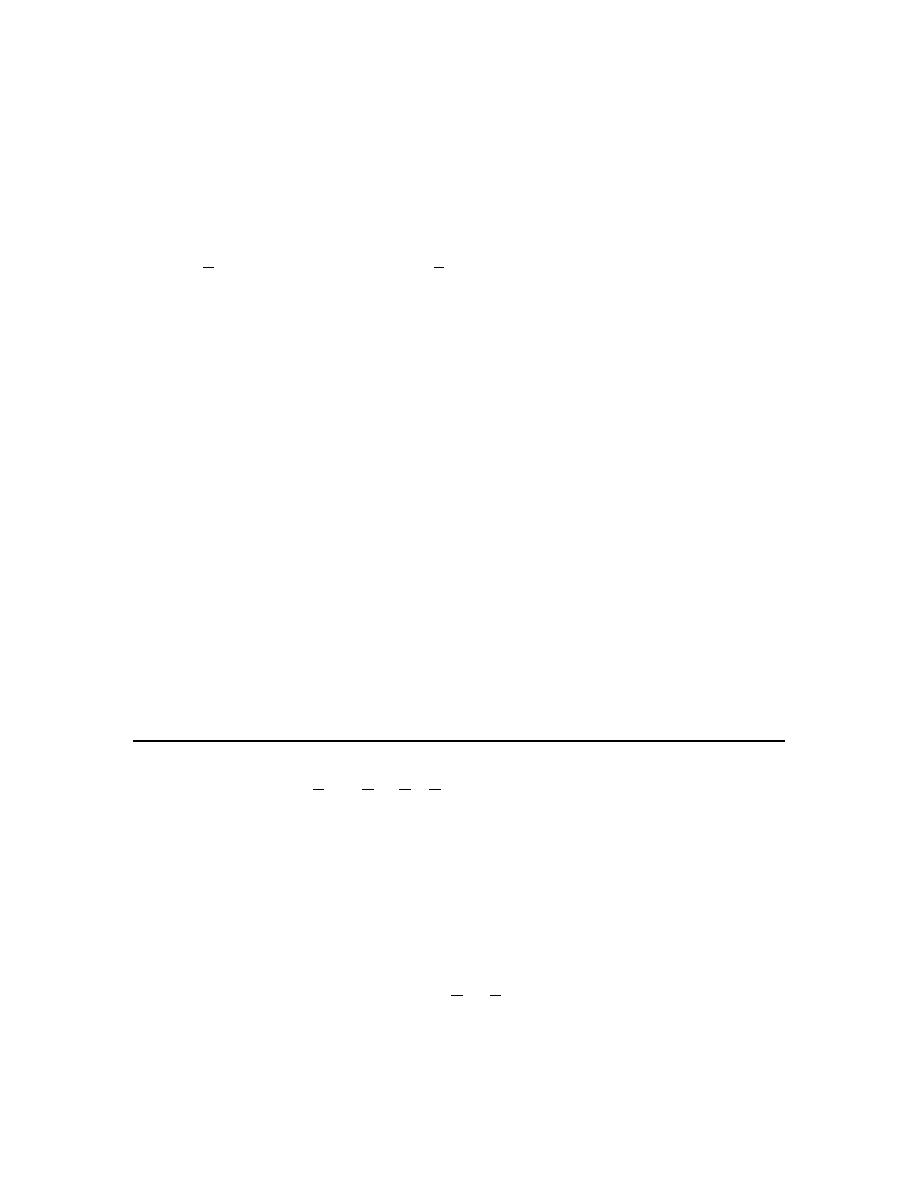

[Show Step Two]

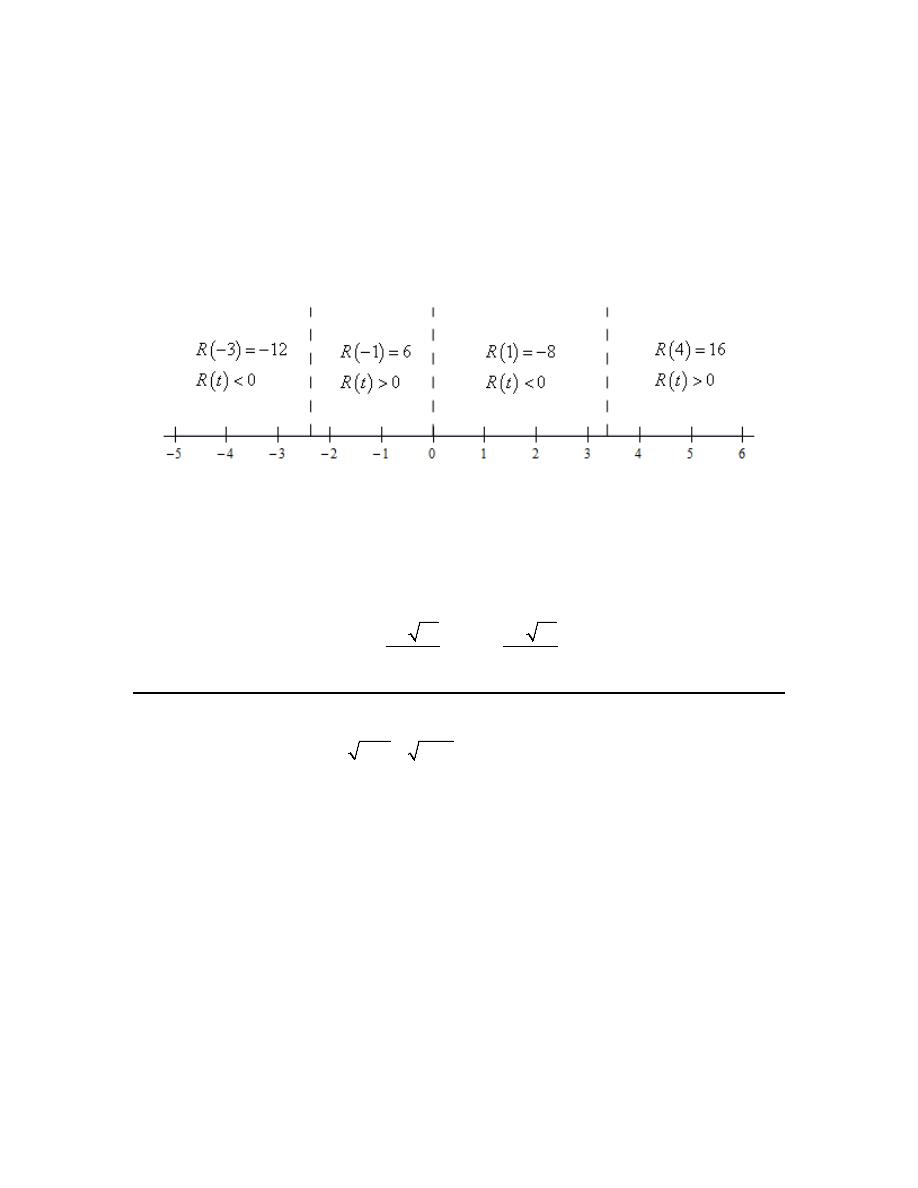

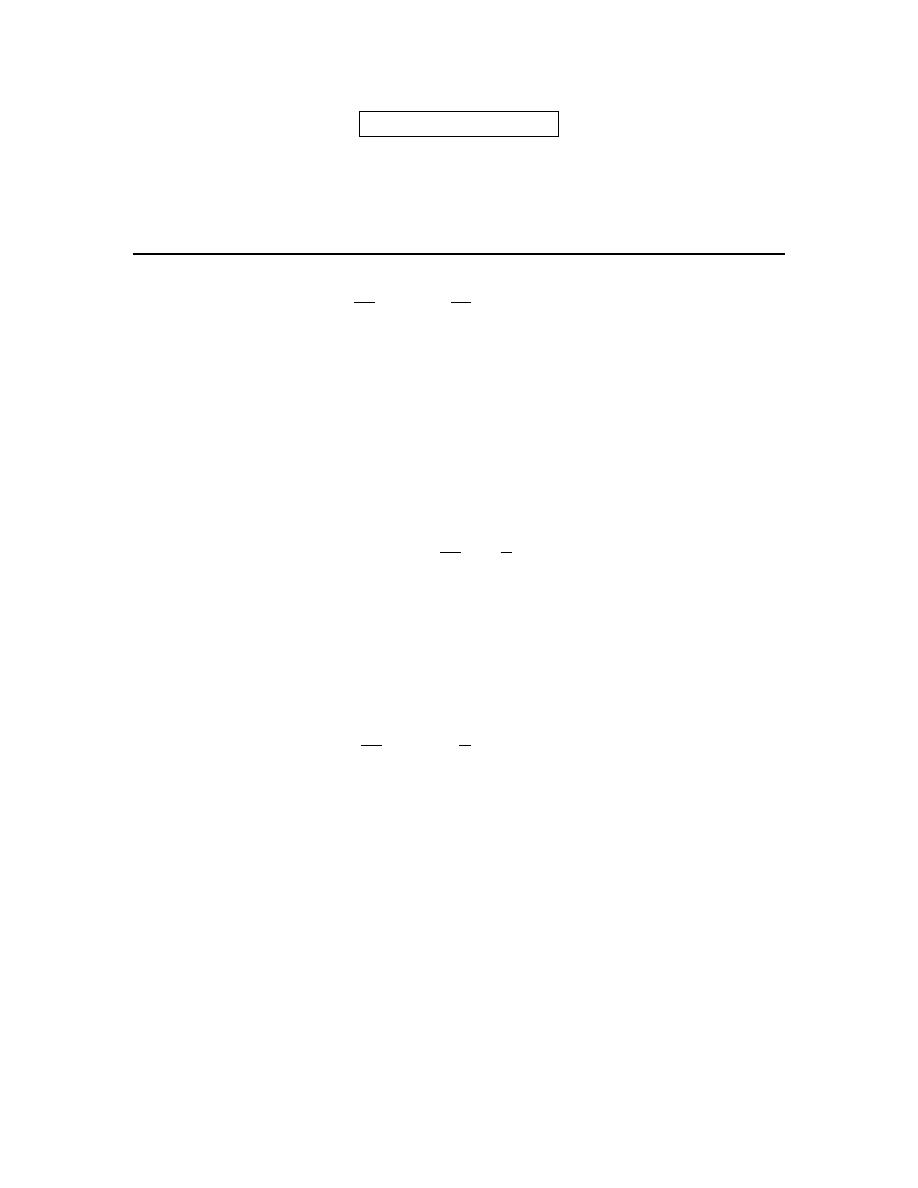

Here is a number line giving the value/sign of the polynomial at a test point in each of the region

defined by these three points. To make it a little easier to read the number line let’s define the

polynomial under the radical to be,

( )

(

)

3

2

2

8

8

0

R t

t

t

t

t t

t

= − − =

− − >

Now, here is the number line,

Step 3 Hint : Now all we need to do is write down the values of x where the polynomial under the

root will be positive (recall we need to avoid division by zero) and we’ll have the domain.

[Show Step Three]

The domain will then be all the points where the polynomial under the root is positive, but not

zero as we also need to avoid division by zero, and so the domain is,

1

33

1

33

Domain :

0,

2

2

t

t

−

+

< <

< < ∞

29. Find the domain of

( )

1

6

f z

z

z

=

− +

+

.

Hint Step 1 : The domain of this function will be the set of all values of z that will work in both

terms of this function.

[Show Step 1]

The domain of this function will be the set of all z’s that we can plug into both terms in this

function and get a real number back as a value. This means that we first need to determine the

domain of each of the two terms.

For the first term we need to require,

1 0

1

z

z

− ≥

⇒

≥

For the second term we need to require,

6

0

6

z

z

+ ≥

⇒

≥ −

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

22

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Hint Step 2 : What values of z are in both of these?

[Show Step 2]

Now, we just need the set of z’s that are in both conditions above. In this case notice that all the z

that satisfy

1

z

≥

will also satisfy

6

z

≥ −

. The reverse is not true however. Any z that is in the

range

6

1

z

− ≤ <

will satisfy

6

z

≥

but will not satisfy

1

z

≥

.

So, in this case, the domain is in fact just the first condition above or,

Domain :

1

z

≥

30. Find the domain of

( )

1

2

9

2

h y

y

y

=

+ −

−

.

Hint Step 1 : The domain of this function will be the set of all values of y that will work in both

terms of this function.

[Show Step 1]

The domain of this function will be the set of all y’s that we can plug into both terms in this

function and get a real number back as a value. This means that we first need to determine the

domain of each of the two terms.

For the first term we need to require,

9

2

9

0

2

y

y

+ ≥

⇒

≥ −

For the second term we need to require,

2

0

2

y

y

− >

⇒

<

Note that we need the second condition to be strictly positive to avoid division by zero as well.

Hint Step 2 : What values of y are in both of these?

[Show Step 2]

Now, we just need the set of y’s that are in both conditions above. In this case we need all the y’s

that will be greater than or equal to

9

2

−

AND less than 2. The domain is then,

9

Domain :

2

2

y

− ≤ <

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

23

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

31. Find the domain of

( )

2

4

36

9

A x

x

x

=

−

−

−

.

Hint Step 1 : The domain of this function will be the set of all values of x that will work in both

terms of this function.

[Show Step 1]

The domain of this function will be the set of all x’s that we can plug into both terms in this

function and get a real number back as a value. This means that we first need to determine the

domain of each of the two terms.

For the first term we need to require,

9

0

9

x

x

− ≠

⇒

≠

For the second term we need to require,

2

2

36

0

36

6 &

6

x

x

x

x

−

≥

→

≥

⇒

≤ −

≥

Hint Step 2 : What values of x are in both of these?

[Show Step 2]

Now, we just need the set of x’s that are in both conditions above. In this case the second

condition gives us most of the domain as it is the most restrictive. The first term is okay as long

as we avoid

9

x

=

and because this point will in fact satisfy the second condition we’ll need to

make sure and exclude it. The domain is then,

Domain :

6 &

6,

9

x

x

x

≤ −

≥

≠

32. Find the domain of

( )

2

3

1

1

Q y

y

y

=

+ −

−

.

[Solution]

The domain of this function will be the set of y’s that will work in both terms of this function.

So, we need the domain of each of the terms.

For the first term let’s note that,

2

1 1

y

+ ≥

and so will always be positive. The domain of the first term is then all real numbers.

For the second term we need to notice that we’re dealing with the cube root in this case and we

can plug all real numbers into a cube root and so the domain of this term is again all real

numbers.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

24

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

So, the domain of both terms is all real numbers and so the domain of the function as a whole

must also be all real numbers or,

Domain :

y

− ∞ < < ∞

33. Compute

(

)( )

f

g

x

and

(

)( )

g

f

x

for

( )

4

1

f x

x

=

−

,

( )

6 7

g x

x

=

+

.

[Solution]

Not much to do here other than to compute each of these.

(

)( )

( )

(

)( )

( )

[

]

(

)

6 7

4 6 7

1

4

1

6 7 4

1

28

1

f

g

x

f g x

f

x

x

g

f

x

g f x

g

x

x

x

=

=

+

=

+

−

=

=

− =

+

− =

−

34. Compute

(

)( )

f

g

x

and

(

)( )

g

f

x

for

( )

5

2

f x

x

=

+

,

( )

2

14

g x

x

x

=

−

.

[Solution]

Not much to do here other than to compute each of these.

(

)( )

( )

(

)

(

)( )

( )

[

]

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

2

2

14

5

14

2

5

70

2

5

2

5

2

14 5

2

25

50

24

f

g

x

f g x

f x

x

x

x

x

x

g

f

x

g f x

g

x

x

x

x

x

=

=

−

=

−

+ =

−

+

=

=

+

=

+

−

+

=

−

−

35. Compute

(

)( )

f

g

x

and

(

)( )

g

f

x

for

( )

2

2

1

f x

x

x

=

−

+

,

( )

2

8 3

g x

x

= −

.

[Solution]

Not much to do here other than to compute each of these.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

25

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(

)( )

( )

(

) (

)

(

)( )

( )

(

)

2

2

2

2

4

2

2

2

2

4

3

2

8 3

8 3

2 8 3

1 9

42

49

2

1

8 3

2

1

3

12

18

12

5

f

g

x

f g x

f

x

x

x

x

x

g

f

x

g f x

g x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

=

=

−

= −

−

−

+ =

−

+

=

=

−

+

= −

−

+

= −

+

−

+

+

36. Compute

(

)( )

f

g

x

and

(

)( )

g

f

x

for

( )

2

3

f x

x

=

+

,

( )

2

5

g x

x

=

+

.

[Solution]

Not much to do here other than to compute each of these.

(

)( )

( )

(

)

(

)( )

( )

(

)

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

4

2

5

5

3

8

3

5

3

6

14

f

g

x

f g x

f

x

x

x

g

f

x

g f x

g x

x

x

x

=

=

−

=

+

+ = +

=

=

+

=

+

+

=

+

+

Review : Inverse Functions

1. Find the inverse for

( )

6

15

f x

x

=

+

. Verify your inverse by computing one or both of the

composition as discussed in this section.

Hint : Remember the process described in this section. Replace the

( )

f x

, interchange the x’s

and y’s, solve for y and the finally replace the y with

( )

1

f

x

−

.

Step 1

6

15

y

x

=

+

Step 2

6

15

x

y

=

+

Step 3

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

26

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(

)

( )

(

)

1

15

6

1

1

15

15

6

6

x

y

y

x

f

x

x

−

−

=

=

−

→

=

−

Finally, compute either

(

)

( )

1

f

f

x

−

or

(

)

( )

1

f

f

x

−

to verify our work.

Step 4

Either composition can be done so let’s do

(

)

( )

1

f

f

x

−

in this case.

(

)

( )

( )

(

)

1

1

1

6

15

15

6

15 15

f

f

x

f

f

x

x

x

x

−

−

=

=

−

+

= − +

=

So, we got x out of the composition and so we know we’ve done our work correctly.

2. Find the inverse for

( )

3 29

h x

x

= −

. Verify your inverse by computing one or both of the

composition as discussed in this section.

Hint : Remember the process described in this section. Replace the

( )

h x

, interchange the x’s

and y’s, solve for y and the finally replace the y with

( )

1

h

x

−

.

Step 1

3 29

y

x

= −

Step 2

3 29

x

y

= −

Step 3

(

)

( )

(

)

1

3

29

1

1

3

3

29

29

x

y

y

x

h

x

x

−

− = −

= −

−

→

=

−

Notice that we multiplied the minus sign into the parenthesis. We did this in order to avoid

potentially losing the minus sign if it had stayed out in front. This does not need to be done in

order to get the inverse.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

27

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Finally, compute either

(

)

( )

1

h h

x

−

or

(

)

( )

1

h

h

x

−

to verify our work.

Step 4

Either composition can be done so let’s do

(

)

( )

1

h h

x

−

in this case.

(

)

( )

( )

(

)

(

)

1

1

1

3 29

3

29

3

3

h h

x

h h

x

x

x

x

−

−

=

= −

−

= − −

=

So, we got x out of the composition and so we know we’ve done our work correctly.

3. Find the inverse for

( )

3

6

R x

x

=

+

. Verify your inverse by computing one or both of the

composition as discussed in this section.

Hint : Remember the process described in this section. Replace the

( )

R x

, interchange the x’s

and y’s, solve for y and the finally replace the y with

( )

1

R

x

−

.

Step 1

3

6

y

x

=

+

Step 2

3

6

x

y

=

+

Step 3

( )

3

1

3

3

6

6

6

x

y

y

x

R

x

x

−

− =

=

−

→

=

−

Finally, compute either

(

)

( )

1

R R

x

−

or

(

)

( )

1

R

R

x

−

to verify our work.

Step 4

Either composition can be done so let’s do

(

)

( )

1

R

R

x

−

in this case.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

28

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(

)

( )

( )

(

)

1

1

3

3

3

3

6

6

R

R

x

R

R x

x

x

x

−

−

=

=

+ −

=

=

So, we got x out of the composition and so we know we’ve done our work correctly.

4. Find the inverse for

( )

(

)

5

4

3

21

g x

x

=

−

+

. Verify your inverse by computing one or both of

the composition as discussed in this section.

Hint : Remember the process described in this section. Replace the

( )

g x

, interchange the x’s

and y’s, solve for y and the finally replace the y with

( )

1

g

x

−

.

Step 1

(

)

5

4

3

21

y

x

=

−

+

Step 2

(

)

5

4

3

21

x

y

=

−

+

Step 3

(

)

(

) (

)

(

)

(

)

( )

(

)

5

5

5

1

5

5

21

4

3

1

21

3

4

1

21

3

4

1

1

3

21

3

21

4

4

x

y

x

y

x

y

y

x

g

x

x

−

−

=

−

−

=

−

−

= −

= +

−

→

= +

−

Finally, compute either

(

)

( )

1

g g

x

−

or

(

)

( )

1

g

g

x

−

to verify our work.

Step 4

Either composition can be done so let’s do

(

)

( )

1

g g

x

−

in this case.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

29

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

(

)

( )

( )

(

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

1

1

5

5

5

5

1

4

3

21

3

21

4

1

4

21

21

4

1

4

21

21

4

21

21

g g

x

g g

x

x

x

x

x

x

−

−

=

=

+

−

−

+

=

−

+

=

−

+

=

−

+

=

So, we got x out of the composition and so we know we’ve done our work correctly.

5. Find the inverse for

( )

5

9 11

W x

x

=

−

. Verify your inverse by computing one or both of the

composition as discussed in this section.

Hint : Remember the process described in this section. Replace the

( )

W x

, interchange the x’s

and y’s, solve for y and the finally replace the y with

( )

1

W

x

−

.

Step 1

5

9 11

y

x

=

−

Step 2

5

9 11

x

y

=

−

Step 3

(

)

( )

(

)

5

5

5

5

1

5

9 11

9 11

9

11

1

1

9

9

11

11

x

y

x

y

x

y

y

x

W

x

x

−

=

−

= −

− = −

= −

−

→

=

−

Notice that we multiplied the minus sign into the parenthesis. We did this in order to avoid

potentially losing the minus sign if it had stayed out in front. This does not need to be done in

order to get the inverse.

Finally, compute either

(

)

( )

1

W W

x

−

or

(

)

( )

1

W

W

x

−

to verify our work.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

30

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Step 4

Either composition can be done so let’s do

(

)

( )

1

W

W

x

−

in this case.

(

)

( )

( )

(

)

[

]

(

)

( )

1

1

5

5

1

9

9 11

11

1

9

9 11

11

1

11

11

W

W

x

W

W x

x

x

x

x

−

−

=

=

−

−

=

− −

=

=

So, we got x out of the composition and so we know we’ve done our work correctly.

6. Find the inverse for

( )

7

5

8

f x

x

=

+

. Verify your inverse by computing one or both of the

composition as discussed in this section.

Hint : Remember the process described in this section. Replace the

( )

f x

, interchange the x’s

and y’s, solve for y and the finally replace the y with

( )

1

f

x

−

.

Step 1

7

5

8

y

x

=

+

Step 2

7

5

8

x

y

=

+

Step 3

(

)

( )

(

)

7

7

7

7

1

7

5

8

5

8

8

5

1

1

8

8

5

5

x

y

x

y

x

y

y

x

f

x

x

−

=

+

=

+

− =

=

−

→

=

−

Finally, compute either

(

)

( )

1

f

f

x

−

or

(

)

( )

1

f

f

x

−

to verify our work.

Step 4

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

31

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Either composition can be done so let’s do

(

)

( )

1

f

f

x

−

in this case.

(

)

( )

( )

(

)

1

1

7

7

7

7

7

7

1

5

8

8

5

8

8

f

f

x

f

f

x

x

x

x

x

−

−

=

=

−

+

=

− +

=

=

So, we got x out of the composition and so we know we’ve done our work correctly.

7. Find the inverse for

( )

1 9

4

x

h x

x

+

=

−

. Verify your inverse by computing one or both of the

composition as discussed in this section.

Hint : Remember the process described in this section. Replace the

( )

h x

, interchange the x’s

and y’s, solve for y and the finally replace the y with

( )

1

h

x

−

.

Step 1

1 9

4

x

y

x

+

=

−

Step 2

1 9

4

y

x

y

+

=

−

Step 3

(

)

(

)

( )

1

1 9

4

4

1 9

4

1 9

4

1 9

4

1

9

4

1

4

1

9

9

y

x

y

x

y

y

x

xy

y

x

y

xy

x

x y

x

x

y

h

x

x

x

−

+

=

−

−

= +

−

= +

− =

+

− =

+

−

−

=

→

=

+

+

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

32

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Note that the Algebra in these kinds of problems can often be fairly messy, but don’t let that

make you decide that you can’t do these problems. Messy Algebra will be a fairly common

occurrence in a Calculus class so you’ll need to get used to it!

Finally, compute either

(

)

( )

1

h h

x

−

or

(

)

( )

1

h

h

x

−

to verify our work.

Step 4

Either composition can be done so let’s do

(

)

( )

1

h

h

x

−

in this case. As with the previous step,

the Algebra here is going to be messy and in fact will probably be messier.

(

)

( )

( )

(

) (

)

(

)

1

1

1 9

4

1

4

4

1 9

4

9

4

4 1 9

4

9 4

1 9

4 36

4

36 9

1 9

37

37

h

h

x

h

h x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

−

−

=

+

−

−

−

=

+

−

+

−

+

− −

=

−

+ +

+

− +

=

−

+ +

=

=

In order to do the simplification we multiplied the numerator and denominator of the initial

fraction by

4

x

−

in order to clear out some of the denominators. This in turn allowed a fair

amount of simplification.

So, we got x out of the composition and so we know we’ve done our work correctly.

8. Find the inverse for

( )

6 10

8

7

x

f x

x

−

=

+

. Verify your inverse by computing one or both of the

composition as discussed in this section.

Hint : Remember the process described in this section. Replace the

( )

f x

, interchange the x’s

and y’s, solve for y and the finally replace the y with

( )

1

f

x

−

.

Step 1

6 10

8

7

x

y

x

−

=

+

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

33

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Step 2

6 10

8

7

y

x

y

−

=

+

Step 3

(

)

(

)

( )

1

6 10

8

7

8

7

6 10

8

7

6 10

8

10

6 7

8

10

6 7

6 7

6 7

8

10

8

10

y

x

y

x

y

y

xy

x

y

xy

y

x

x

y

x

x

x

y

f

x

x

x

−

−

=

+

+

= −

+

= −

+

= −

+

= −

−

−

=

→

=

+

+

Note that the Algebra in these kinds of problems can often be fairly messy, but don’t let that

make you decide that you can’t do these problems. Messy Algebra will be a fairly common

occurrence in a Calculus class so you’ll need to get used to it!

Finally, compute either

(

)

( )

1

f

f

x

−

or

(

)

( )

1

f

f

x

−

to verify our work.

Step 4

Either composition can be done so let’s do

(

)

( )

1

f

f

x

−

in this case. As with the previous step,

the Algebra here is going to be messy and in fact will probably be messier.

(

)

( )

( )

(

)

(

)

(

) (

)

1

1

6 7

6 10

8

10

8

10

6 7

8

10

8

7

8

10

6 8

10

10 6 7

8 6 7

7 8

10

48

60 60 70

48 56

56

70

118

118

f

f

x

f

f

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

−

−

=

−

−

+

+

=

−

+

+

+

+

−

−

=

−

+

+

+

−

+

=

−

+

+

=

=

So, we got x out of the composition and so we know we’ve done our work correctly.

Calculus I

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

34

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

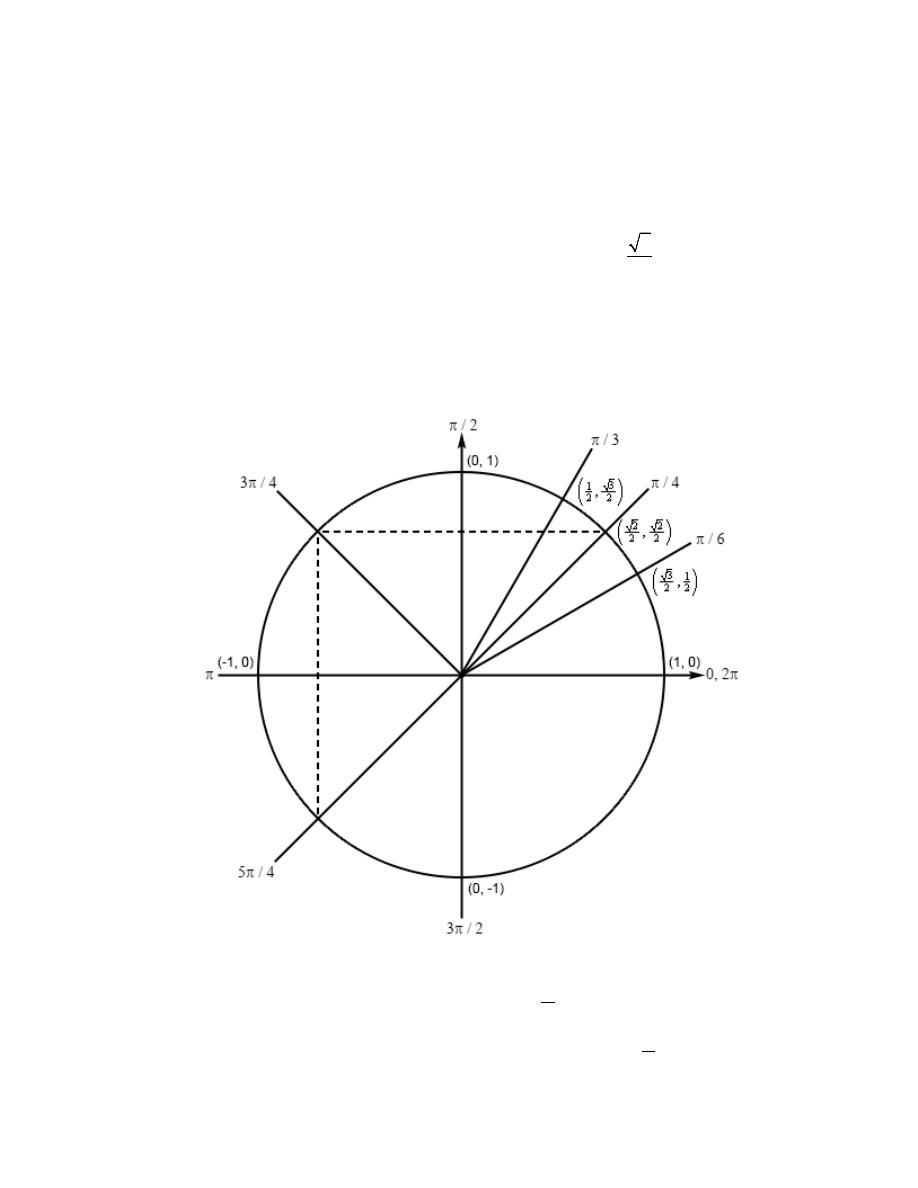

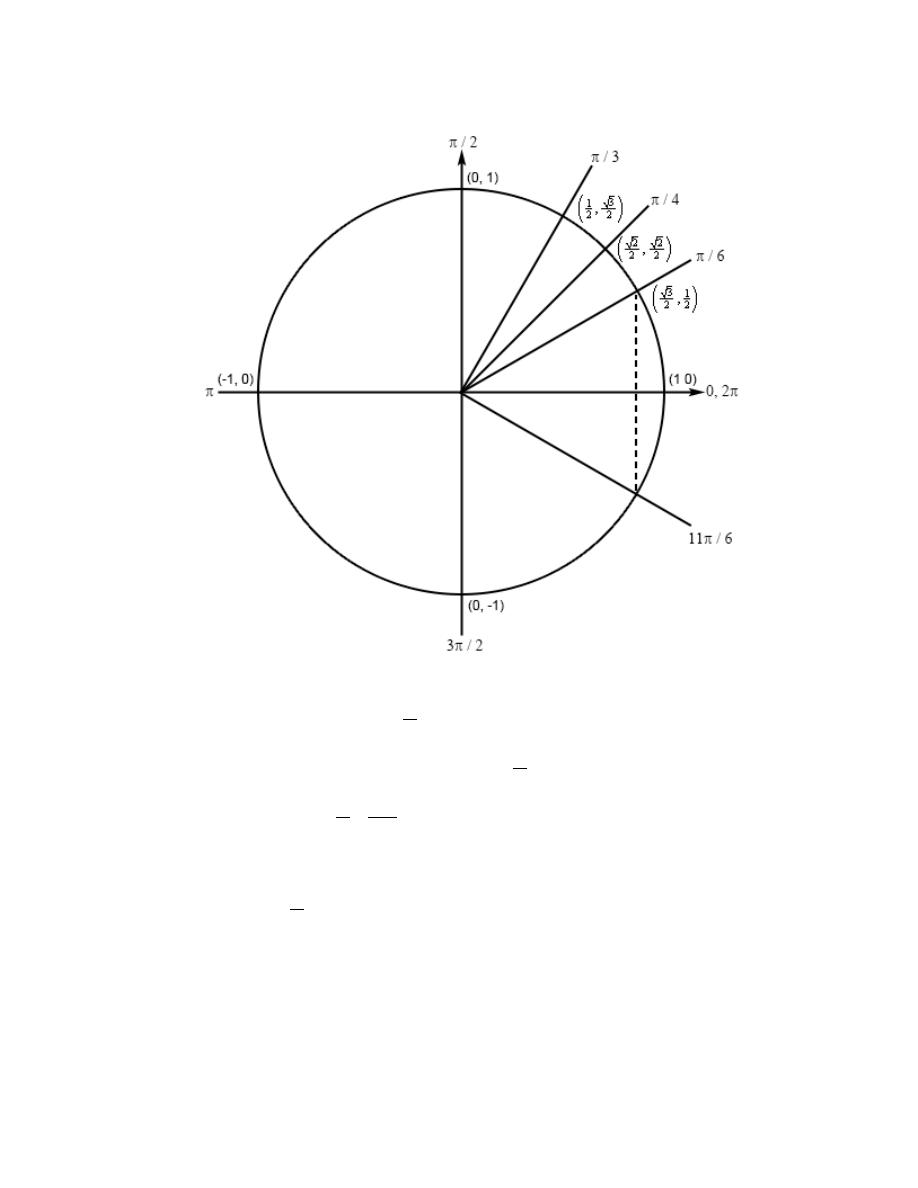

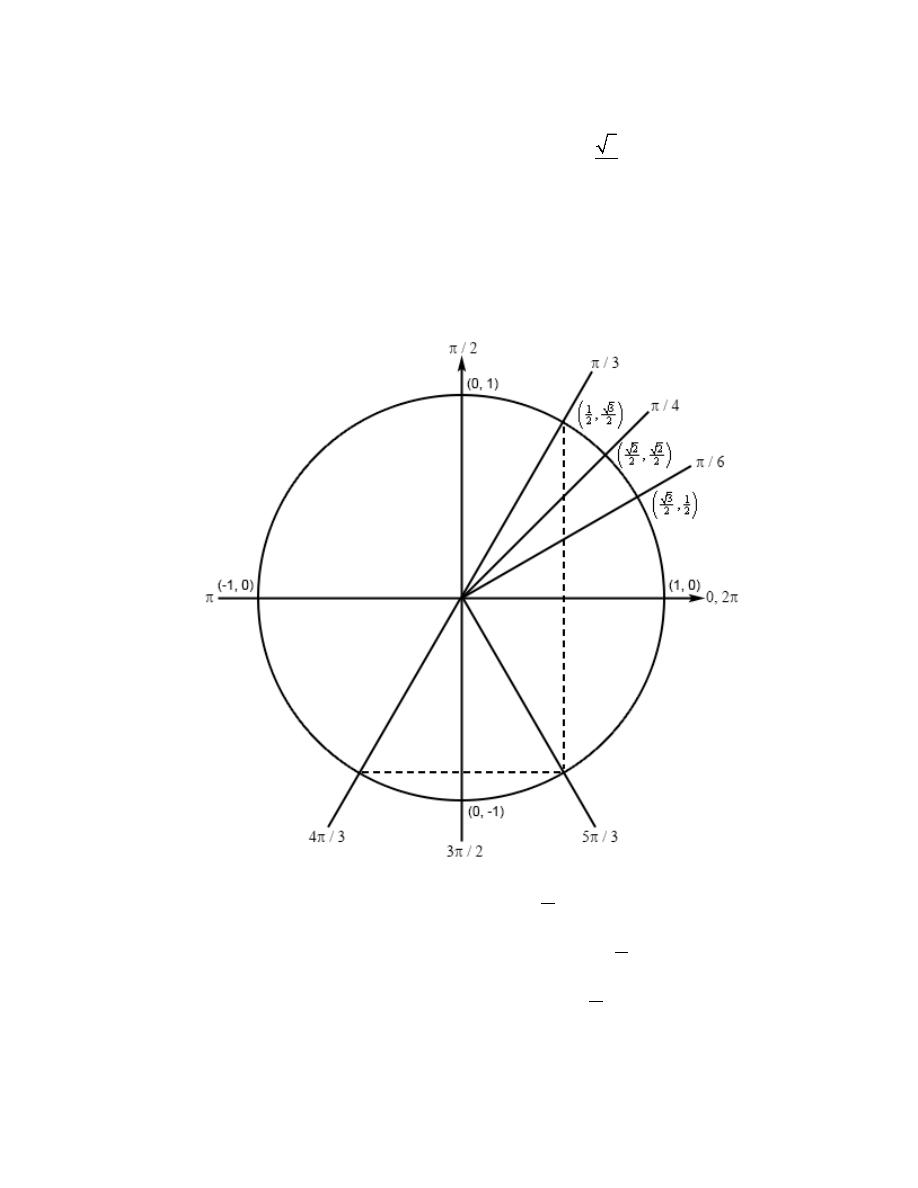

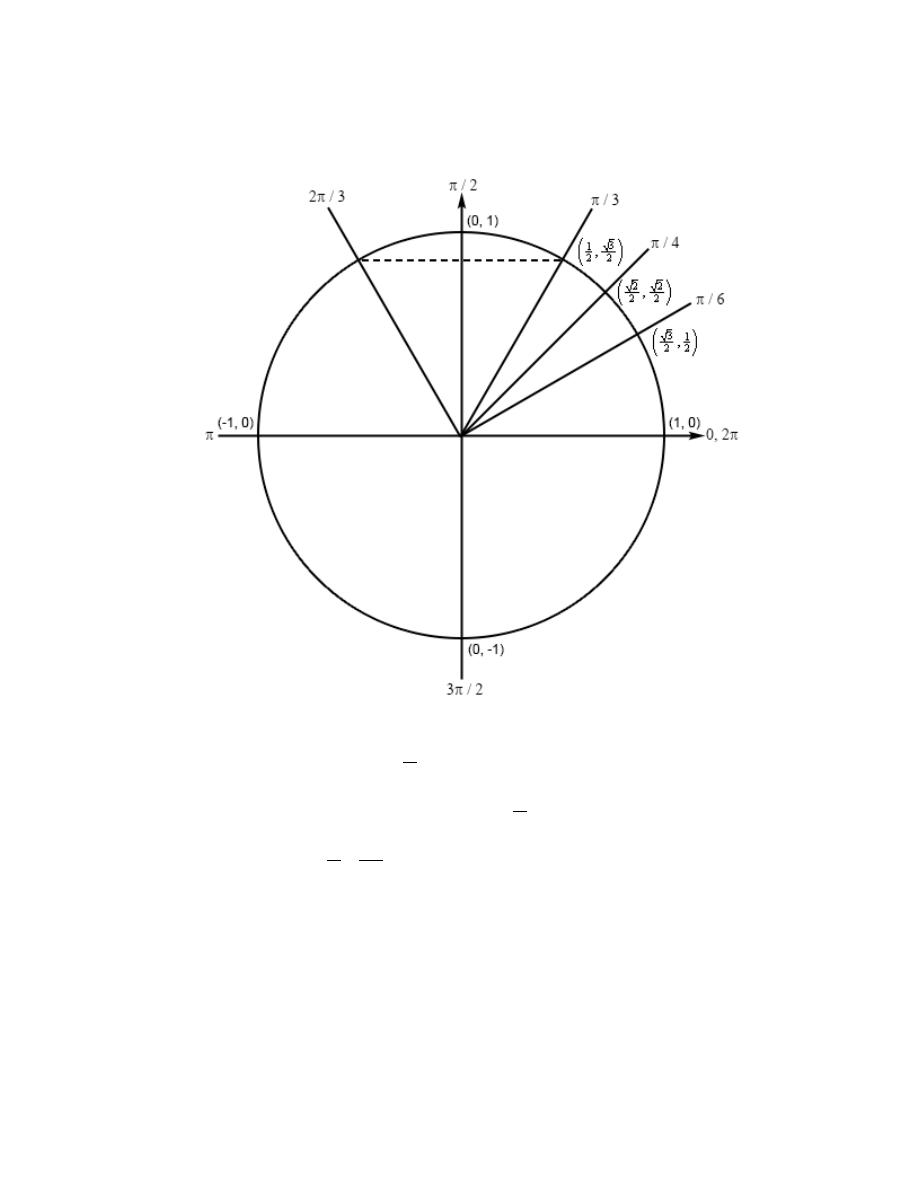

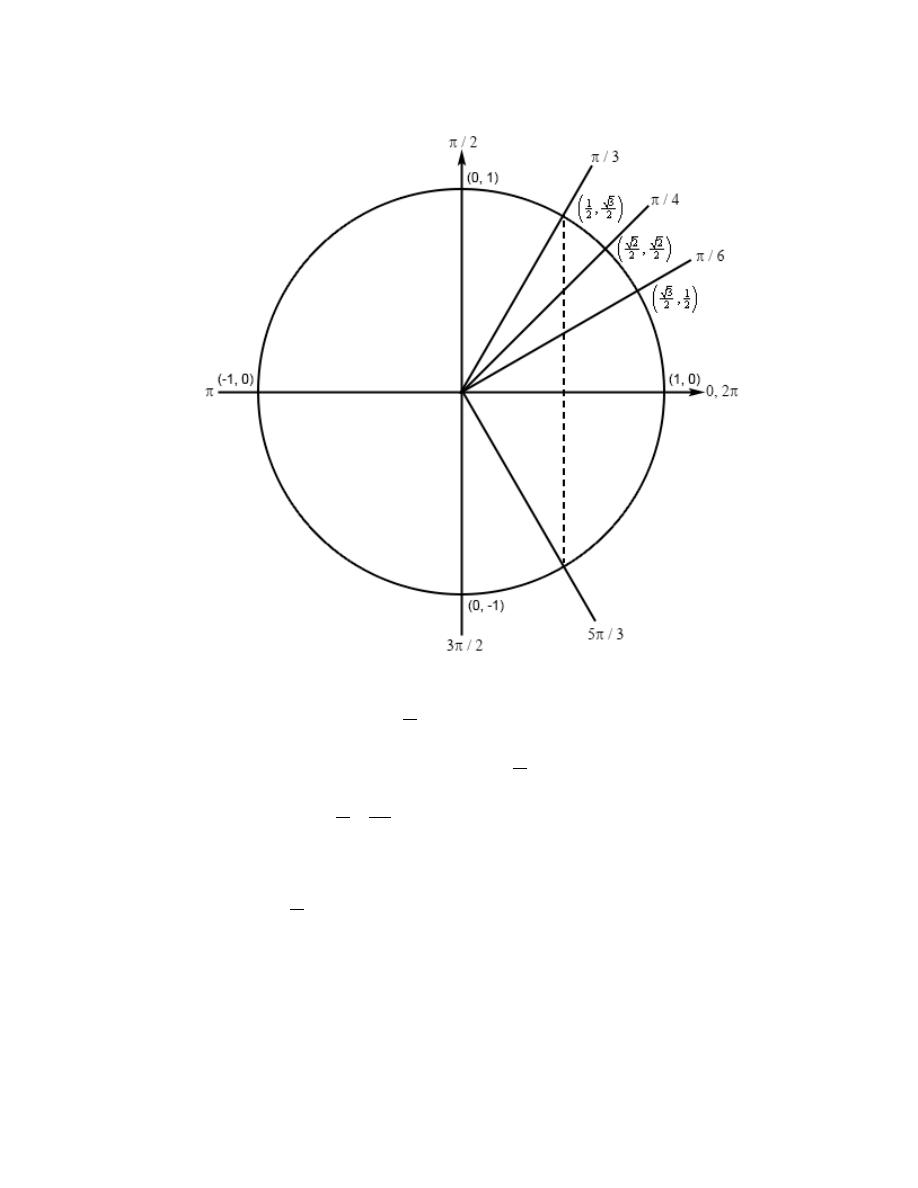

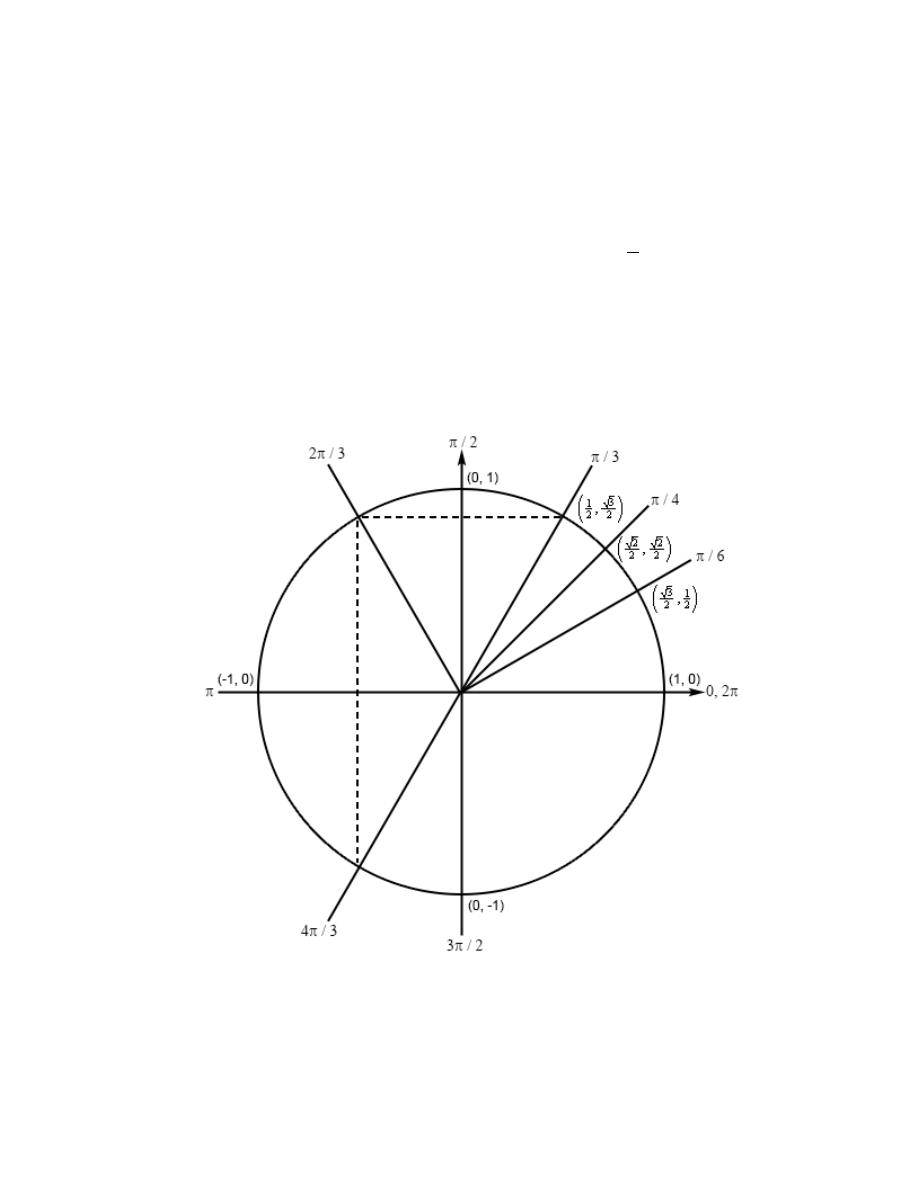

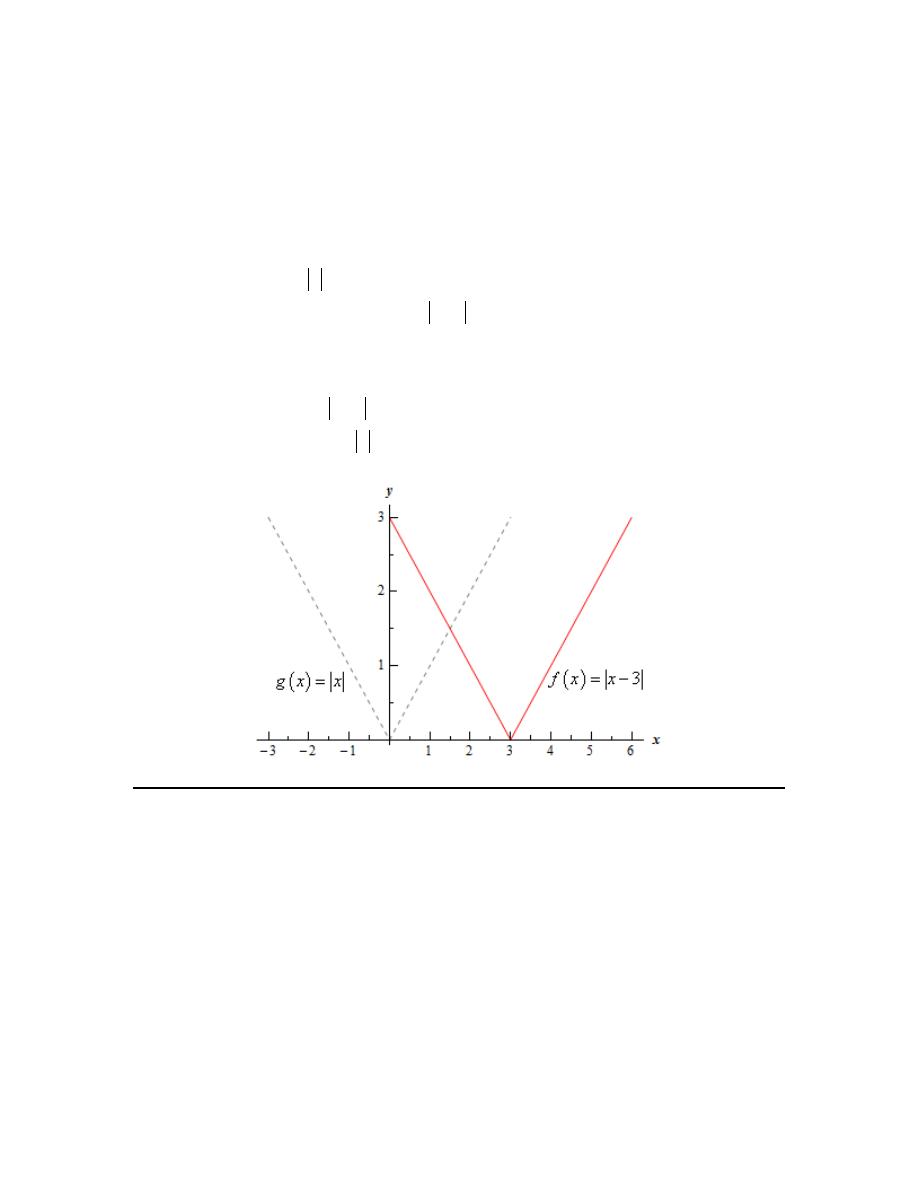

Review : Trig Functions

1. Determine the exact value of