1

Fifth stage

Neurology

Lec-3

.د

بشار

20/10/2015

Epilepsy

Seizures and epilepsy are particularly troublesome for patients because of their

unpredictable occurrence and the associated abrupt loss of competence.

This often results in severe social and personal morbidity with attendant loss of self-

confidence, personal safety, financial and recreational

independence.

Treatment, however, is generally very successful and promising new modalities of treatment

are rapidly being developed or refined

Seizure

From Gk

To be seized from forces without; generally refers to a disturbance of usual neurological

functioning of relatively abrupt onset that is due to transient disturbance of CNS activity.

Other more or less synonymous terms include: attack ,fit ,spell

Epileptic Seizure

A seizure caused by recurrent, sudden, synchronous (paroxysmal) firing of a group of cortical

neurons. In other words, a seizure due to a paroxysmal electrical disturbance of brain

signaling.

Seizures are disorders characterized by excessive or over synchronized discharges of cerebral

neurons.

A seizure is a transient disturbance of cerebral function caused by an abnormal neuronal

discharge.

Epilepsy

A condition in which an individual suffers from recurrent epileptic seizures which is not

temporary.

Epilepsy, a group of disorders characterized by recurrent seizures, is a common cause of

episodic loss of consciousness.

Convulsion

The overt, major motor manifestations of a seizure (rhythmic jerking of the limbs).

Aura

Subjective disturbance of perception that represents the start of certain seizures (actually

represents a focal electrical disturbance at the start of the seizure).

2

Ictus or Ictal phase

The seizure itself; the part of the event where the convulsion occurs or when the brain

activity consists of paroxysmal firing of brain neurons.

Post-ictal phase

The period after the convulsion or actual seizure where the “brain is tired” and the individual

is sleepy, confused, disoriented or experiences temporary neurological dysfunction.

Interictal

Between seizure.

The recurrence rate after a single seizure is about 70 % within the first year, and most

recurrent attacks occur within a month or two of the first.

Furthur seizures are less likely if a trigger factor is definable and avoidable.

Trigger Factors

Sleep deprivation

Alcohol (particularly withdrawal)

Recreational drug misuse

Physical and mental exhaustion

Flickering lights, including TV and computer screens (primary generalized epilepsies

only)

Intercurrent infections and metabolic disturbances

Uncommonly: loud noises, music, reading, hot baths

In some conditions, Epilepsy is the only feature underlying disease, while in others epilepsy

is just one of the manifestation.

The annual incidence of new cases of epilepsy after infancy is 20-70/100000.

The lifetime risk of having a single seizure is about 5 %.while the prevalence of epilepsy in

European countries is about 0.5 %.

The prevalence in developing countries is up to five times higher.

3

Classification of epilepsy

Seizure type

Physiology

Anatomical site

Pathological cause

Seizure type

Partial (simple or complex)

Partial with secondary generalization

Absence

Tonic-clonic

Tonic

Atonic

Myoclonic

Physiology

Focal spikes /sharp waves

Generalized spikes and waves

Anatomical site

Cortex

1. Temporal

2. Frontal

3. Parietal

4. Occipital

Generalized (diencephalon)

Multifocal

Pathological cause

Genetic

Developmental

Tumours

Trauma

Vascular

Infection

Inflammation

Metabolic

Drugs(alcohol or toxins)

Degenerative

4

Primary generalized epilepsy

The primary or idiopathic epilepsy make up 10 % of all epilepsies, including some 40 % of

those with tonic clonic seizures.

Onset is almost always in childhood or adolescence.

No structural abnormality is present and there is often a substantial genetic predisposition.

Some, like childhood absence epilepsy are relatively uncommon, while others like juvenile

myoclonic epilepsy are common (5-10 % of all patients with epilepsy)

Partial Epilepsy

Partial seizures may arise from any disease of the cerebral cortex, congenital or acquired, and

frequently, generalize.

With the exception of few idiopathic partial epilepsies of benign outcome in childhood, the

presence of partial seizures signifies the presence of focal cerebral pathology.

Causes of partial epilepsy ))((لالطالع

Idiopathic

o Benign Rolandic epilepsy of childhood

o Benign occipital epilepsy of childhood

Focal structural lesions

Genetic

o Tuberous sclerosis

o Neurofibromatosis

o Von Hippel-Lindau disease

o Cerebral migration abnormalities

Infantile hemiplegia

Dysembryonic

o Cortical dysgenesis

o Sturge-Weber syndrome

Mesial temporal sclerosis (associated with febrile convulsions

Cerebrovascular disease

o Intracerebral hemorrhage

o Cerebral infarction

o Arteriovenous malformation

o Cavernous haemangioma

Tumors (primary and secondary)

Trauma (including neurosurgery)

Infective

o Cerebral abscess (pyogenic)

o Toxoplasmosis

5

Secondary generalized epilepsy

Generalized epilepsy may arise from spread of partial seizures due to structural disease, or

may be secondary to drugs or metabolic disorders. Epilepsy presenting in adult life is almost

always secondary generalized, even if there is no clear history of a partial seizure before the

onset of the major attack (an aura).

The occurrence of epilepsy in those over the age of 60 is frequently due to CVD.

Causes of secondary generalized epilepsy )) ((لالطالع

Genetic

o Inborn errors of metabolism

o Storage diseases

Cerebral birth injury

Hydrocephalus

Cerebral anoxia

Drugs

o Antibiotics: penicillin, isoniazid, metronidazole

o Antimalarials: chloroquine, mefloquine

o Ciclosporin

o Cardiac anti-arrhythmics: lidocaine; disopyramide

o Psychotropic agents: phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, lithium

o Amphetamines (withdrawal

(

Alcohol (especially withdrawal

(

Toxins

o Heavy metals (lead, tin

(

,

o Organophosphates (sarin

(

Metabolic disease

o Hypocalcaemia, Hyponatraemia, Hypomagnesaemia and Hypoglycaemia

o Renal failure

o Liver failure

Infective

o Meningitis

o Post-infectious encephalopathy

Inflammatory

o Multiple sclerosis (uncommon

(

,

o SLE

Diffuse degenerative diseases

o Alzheimer's disease (uncommonly

(

,

o Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (rarely)

6

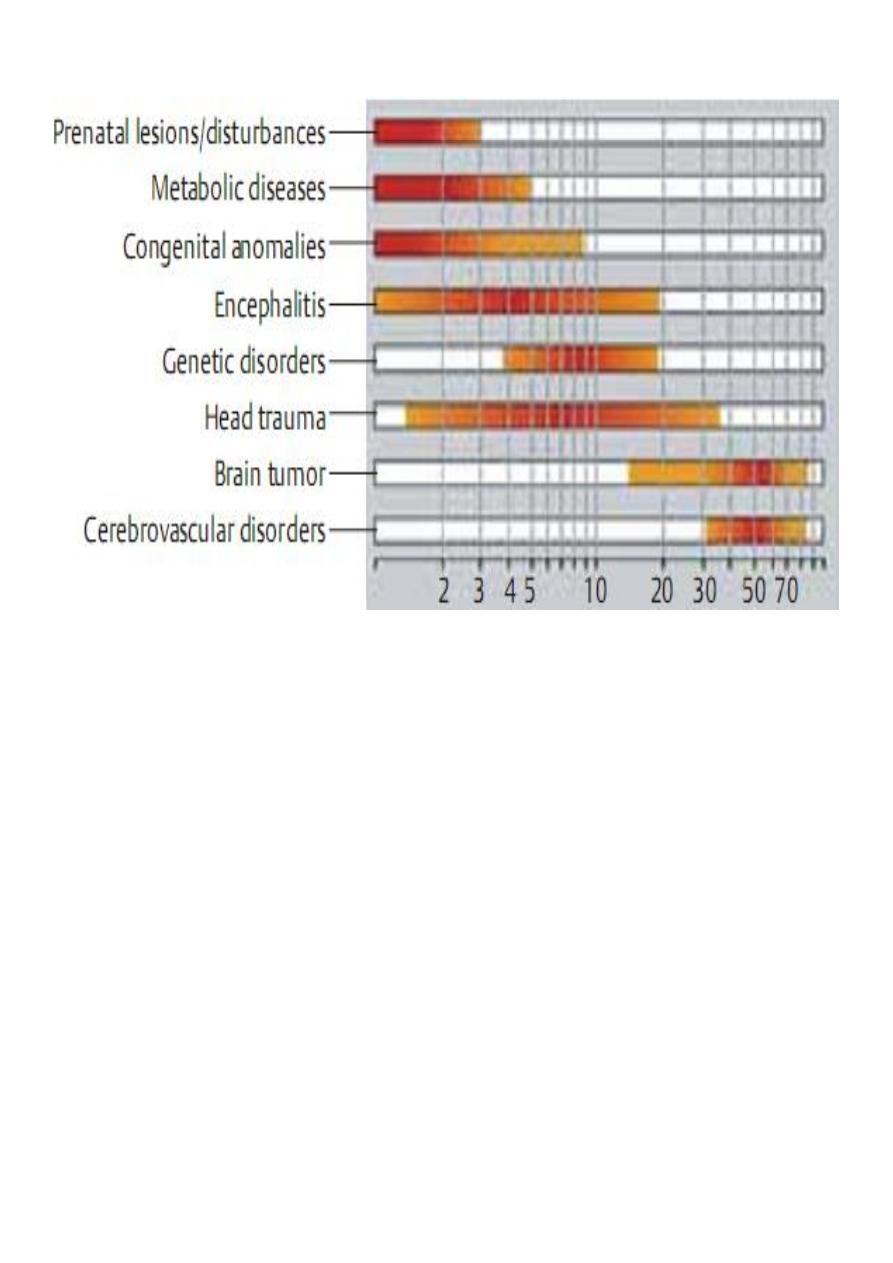

Etiology and age of onset

((مهم

))جدا

Pathophysiology

1- An epileptic seizure represents the abnormal (pathological) paroxysmal, synchronous

firing of a group of (usually) cortical neurons.

This group of neurons is referred to as the seizure focus.

2- Disturbance in the normal balance between inhibition and excitation

a) Neuronal depolarization vs. Repolarization.

b) Propagation vs. limitation of inter-neuronal transmission

c) Glutamate vs. GABA

Examples

1- Pyridoxine is co-factor for synthesis of GABA. Depletion of pyridoxine by isoniazid (drug

for TB) causes uncontrolled seizures. (Too little inhibition!!!).

2- Glycine is co-agonist at NMDA (excitatory) receptor. Non-ketotic hyperglycemia is a

condition in which excess glycine accumulates. It is associated with uncontrolled

epileptic seizures. (Too much excitation!!!) .

7

New developments

In some inherited, familial epileptic syndromes, ion channel defects have been discovered

which are presumably responsible for the disturbance in neuronal excitability.

Example

1- Benign neonatal familial convulsions (BFNC)

2- Defect in a neuronal K+ channel

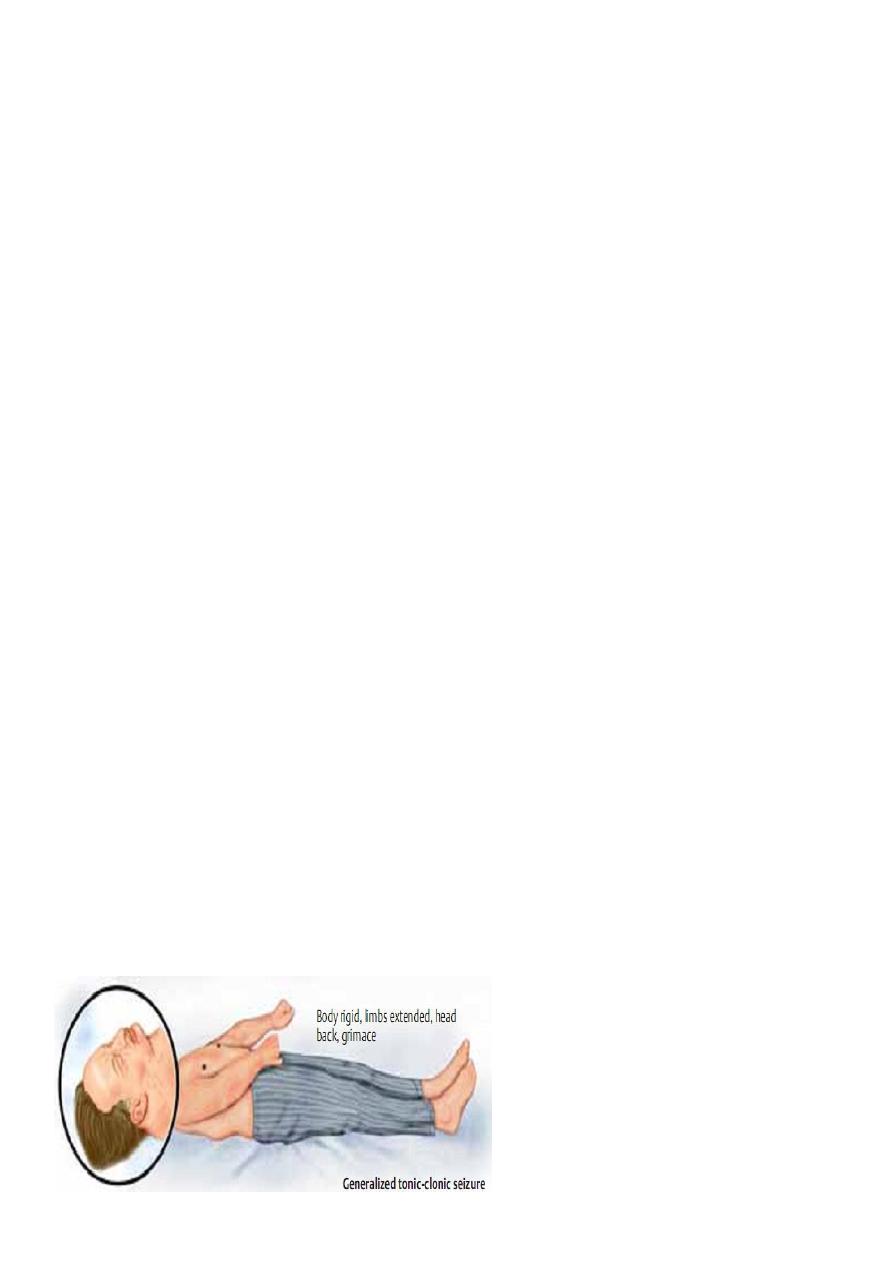

Tonic clonic seizures

A tonic clonic seizure may be preceded by a partial seizure (aura) which can take many forms.

However, a history of such aura is commonly not obtained probably because the subsequent

generalized seizure causes some retrograde amnesia for immediately preceding events.

The patient then goes rigid and becomes unconscious, falling down heavily if standing and

often sustaining injury. During this phase, respiration is arrested and central cyanosis may

occur. After a few moments the rigidity is periodically relaxed, producing clonic jerks. Some

patients don’t have clonic phase and the rigidity is replaced by a flaccid state of deep coma

which can persist for many minutes.

The patient then gradually regains consciousness, but is in a confused and disoriented state

for half an hour or more after regaining consciousness. Full memory functions may not be

recovered for some hours.

During the attack urinary incontinence and tongue biting may occur. A severe bitten bleeding

tongue after an attack of loss of consciousness is pathognomonic of a generalized seizure.

After generalized seizure the patient feels terrible, may have headache and often wants to

sleep.

Witnesses of a seizure are usually frightened by the event often believe the patient to be

dying and may not give a clear account of the episode. This in itself can be a helpful diagnostic

pointer since syncope seldom produce such fear in onlookers. Patients may have no tonic or

clonic phase and may not become cyanosed or bite their tongues.

However, postictal confusion is useful in differentiating seizures from syncope

8

Absence seizure

They always start in childhood. The attacks may be mistaken for complex partial seizures but

are shorter in duration, they occur much more frequently (20 – 30 times per day) and are not

associated with post-ictal confusion. They do not cause loss of posture.

Atonic seizures

Sudden loss of postural tone with a collapse to the ground (“drop attack). If more restricted,

can just involve nuchal and head muscles (head nod).

Can often be intermixed with other seizure types (atypical absence, myoclonic). Often causes

injury.

Tonic & Clonic fits

Tonic seizures are characterized by continuing muscle contraction that can lead to fixation of

the limbs and axial musculature in flexion or extension and are a cause of drop attacks; the

accompanying arrest of ventilatory movements leads to cyanosis. Consciousness is lost, and

there is no clonic phase to these seizures.

Clonic seizures are characterized by repetitive clonic jerking accompanied by loss of

consciousness. There is no initial tonic component.

Myoclonic epilepsy

Sudden, usually generalized, single body jerk, often throwing individual to the ground.

Can affect single body part (in this case, not a generalized seizure).

Soo brief, cannot really know if consciousness is affected.

Can occur one after another repetitively or in clusters

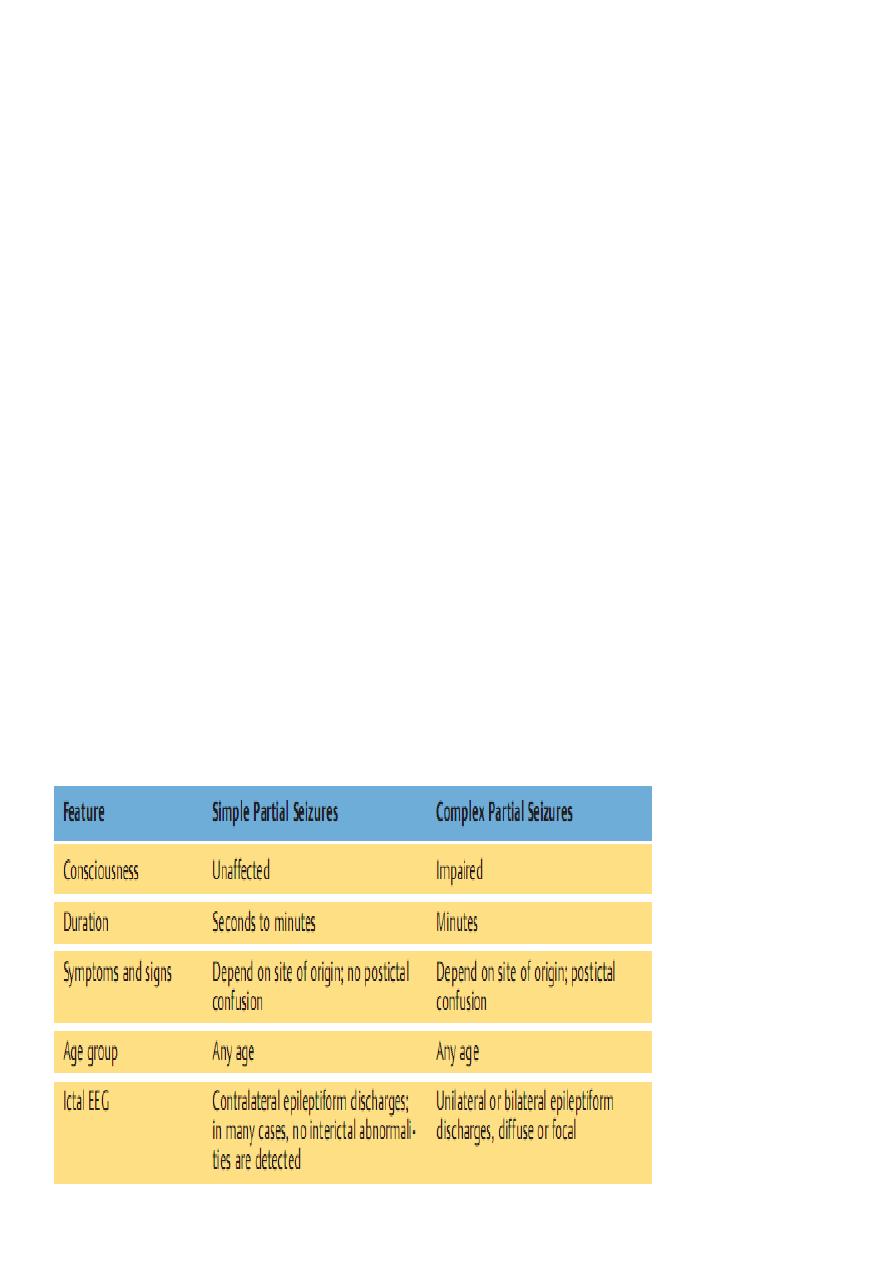

Complex partial seizures

Involve episodes of altered consciousness without the patient collapsing to the ground,

especially if they arise from the temporal and less frequently the frontal lobes.

Patients stop what they are doing and stare blankly, often blinking repetitively , making

smacking movements of the lips, or displaying other automatisms, such as picking at their

clothes.

After a few minutes, consciousness returns but the patient may be muddled and feels drowsy

for a period of up to an hour.

Immediately before such an attack the patient may report alteration of mood, memory or

perception (such as undue familiarity- Déjà vu – or unreality – Jamais vu ) , or complex

hallucinations involving sound , smell , taste , vision , emotion (fear , sexual arousal ) or

visceral sensations (nausea , epigastric discomfort ).

9

If these changes of memory or perception occur without subsequent alteration in awareness,

the seizure is said to be simple partial seizure.

If these seizures arise from the anterior parts of the temporal lobes, they may produce bizarre

behavior patterns including limb posturing, sleep walking, or even ill –directed motor

activities with incoherent screaming.

These can sometimes be very difficult to distinguish from psychogenic attacks. However

abruptness of onset and relative brevity may help point to frontal seizures, as may a tendency

to occur out of sleep.

Partial motor seizures

Epileptic activity arising in the pre central gyrus causes partial motor seizures in the

contralateral face, arm, trunk or legs.

Seizures are characterized by rhythmical jerking or sustained spasm of the affected parts.

They may remain localized to one part or may spread to involve the whole side.

Some attacks begin in one part of the body (e.g. mouth, thumb, great toe) and spread (march)

gradually to other parts of the body; this is known as Jacksonian seizure.

Attacks vary in duration from a few seconds to several hours (epilepsia partialis continua).

More prolonged episodes may be followed by paresis of the involved limb lasting for several

hours after the seizure ceases (Todd palsy).

Partial sensory seizures

Seizures arising in the sensory cortex cause unpleasant tingling or electric sensations in the

contralateral face or limbs. Jacksonian march may also occur.

11

Versive seizures

A frontal epileptic focus may involve the frontal eye field causing forced deviation of the eyes

and sometimes turning of the head to the opposite side.

This type of attack often generalises to become a tonic clonic seizure.

Partial visual seizures

Occipital epileptic foci cause simple visual hallucinations such as balls of light or patterns of

color. Formed visual hallucinations of faces or scenes arise ore anteriorly in the temporal

lobes.

Investigations

After a first seizure, cerebral imaging with CT or MRI is advisable, particularly in patients over

20 years of age, although the yield of structural lesions is low unless there are focal features

to the seizure or there are focal signs. Other investigations for infective, toxic and metabolic

causes may be appropriate.

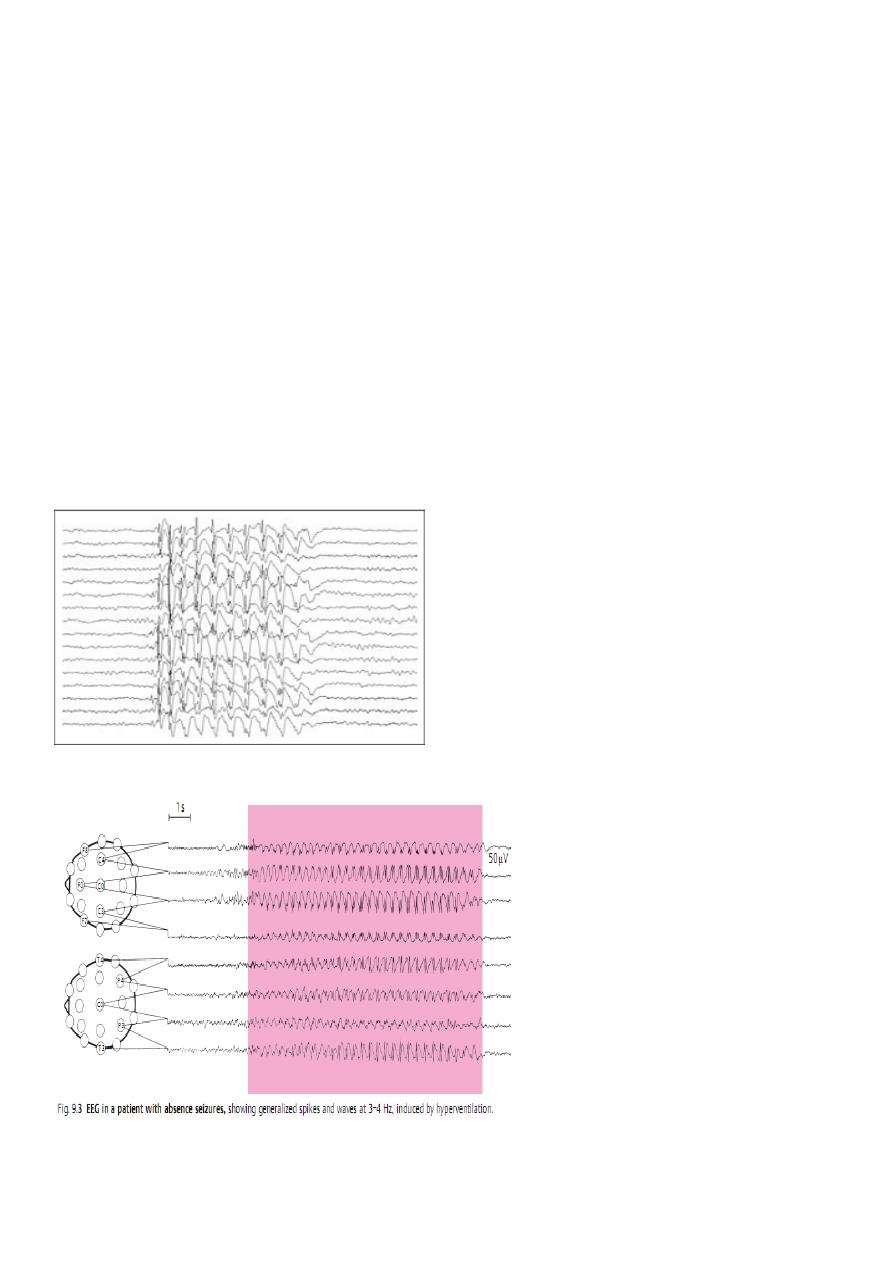

An EEG performed immediately after a seizure may be more helpful in showing focal features

than if performed after a delay. An EEG is often useful when more than one seizure has

occurred, in order to establish the type of epilepsy and guide therapy.

Epileptic nature of attacks?

o Ambulatory EEG

o Videotelemetry

Type of epilepsy?

o Standard EEG

o Sleep EEG

o EEG with special electrodes (foramen ovale, subdural

(

Structural lesion?

o CT

o MRI

Metabolic disorder?

o Urea and electrolytes

o Liver function tests

o Blood glucose

o Serum calcium, magnesium

Inflammatory or infective disorder?

o Full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP)

o Chest X-ray

o Serology for syphilis, HIV, collagen disease

o CSF examination

11

The increasing sophistication of imaging techniques now allows the identification of the

cause of epilepsy in an increasing number of patients, especially those with partial seizures.

Investigations should be pursued more vigorously if the epilepsy is intractable to treatment.

The EEG may help to establish a diagnosis and characterize the type of epilepsy.

Interictal records are abnormal in about 50 % (sharp waves or spikes) of patients with definite

epilepsy so that the EEG cannot be reliably used to exclude epilepsy. However epileptiform

changes on the EEG are fairly specific for epilepsy (falsely positive in 1/1000).

The sensitivity can be increased to about 80 % prolonging recording time or including a period

of natural or drug-induced sleep.

Ambulatory EEG recording or video EEG monitoring may provide helpful information when

attacks are frequent.

Primary Generalized Epilepsy

Absence Seizure

12

Indications for imaging

Epilepsy starts after the age of 20 years

Seizures have focal features clinically

EEG shows a focal seizure source

Control of seizures is difficult or deteriorates

Management

Explain the nature and cause of seizures to patients and their relatives.

Instruct relatives in the first aid management of major seizures.

Epilepsy is common-affects 0.5 – 1%of the population.

Good control of seizures is expected in 80 % of patients

First aid (by relatives and witnesses)

Move person away from danger (fire, water, machinery, furniture)

After convulsions cease, turn into 'recovery' position (semi-prone)

Ensure airway is clear

Do NOT insert anything in mouth (tongue-biting occurs at seizure onset and cannot be

prevented by observers)

If convulsions continue for more than 5 minutes or recur without person regaining

consciousness, summon urgent medical attention

Person may be drowsy and confused for some 30-60 minutes and should not be left

alone until fully recovered

Immediate management of seizures

Ensure airway is patent

Give oxygen to offset cerebral hypoxia

Give intravenous anticonvulsant (e.g. diazepam 10 mg) ONLY IF convulsions are

continuous or repeated (if so, manage as for status epilepticus)

Consider taking blood for anticonvulsant levels (if known epileptic)

Investigate cause

13

Lifestyle modification

Patients should be made aware of the riskiness of any activity where loss of awareness would

be dangerous, until good control of seizures has been established. This includes work or

recreational activities involving exposure to heights, dangerous machinery, open fires or

water. Only shallow baths or showers should be taken, and then with someone else in the

house and with the bathroom door unlocked. Cycling should be discouraged until at least 6

months' freedom from seizures has been achieved. Activities requiring prolonged proximity

to water (e.g. swimming, fishing or boating) should always be in the company of someone

who is aware of the risk of a seizure and able to rescue the patient if necessary. In the UK and

many other countries, legal restrictions regarding vehicle driving apply to patients with

epilepsy, defined as more than one seizure over the age of 5 years. The patient should inform

the licensing authorities about the onset of seizures. It is also wise for patients to notify their

motor insurance company. Certain occupations, such as airline pilot, are not open to anyone

who has ever had an epileptic seizure;

Anticonvulsant therapy

Drug treatment should certainly be considered after more than one seizure has occurred and

the patient agrees that seizure control is worthwhile; a wide range of anti-epilepsy drugs is

available.

The mode of action of these drugs is either to increase inhibitory neurotransmission in the

brain or to alter neuronal sodium channels in a way to prevent abnormally rapid transmission

of impulses.

In 80 % of patients whose epilepsy is controlled, only a single drug is necessary. The

combination of more than 2 drugs is seldom required. Dose regimens should be kept as

simple as possible to promote compliance.

With few exceptions, there is no hard evidence indicating that one drug is superior to

another.

The first choice should be one of the first line drug with the more recently introduced drugs

as second choice.

Phenytoin and carbamazepine are not ideal for a young woman wishing to use oral

contraceptives (inducer drugs).

Carbamazepine, lamotrigene and sodium valproate are preferable to phenytoin because of

the side effect profile of the latter and its complicated pharmacokinetics.

14

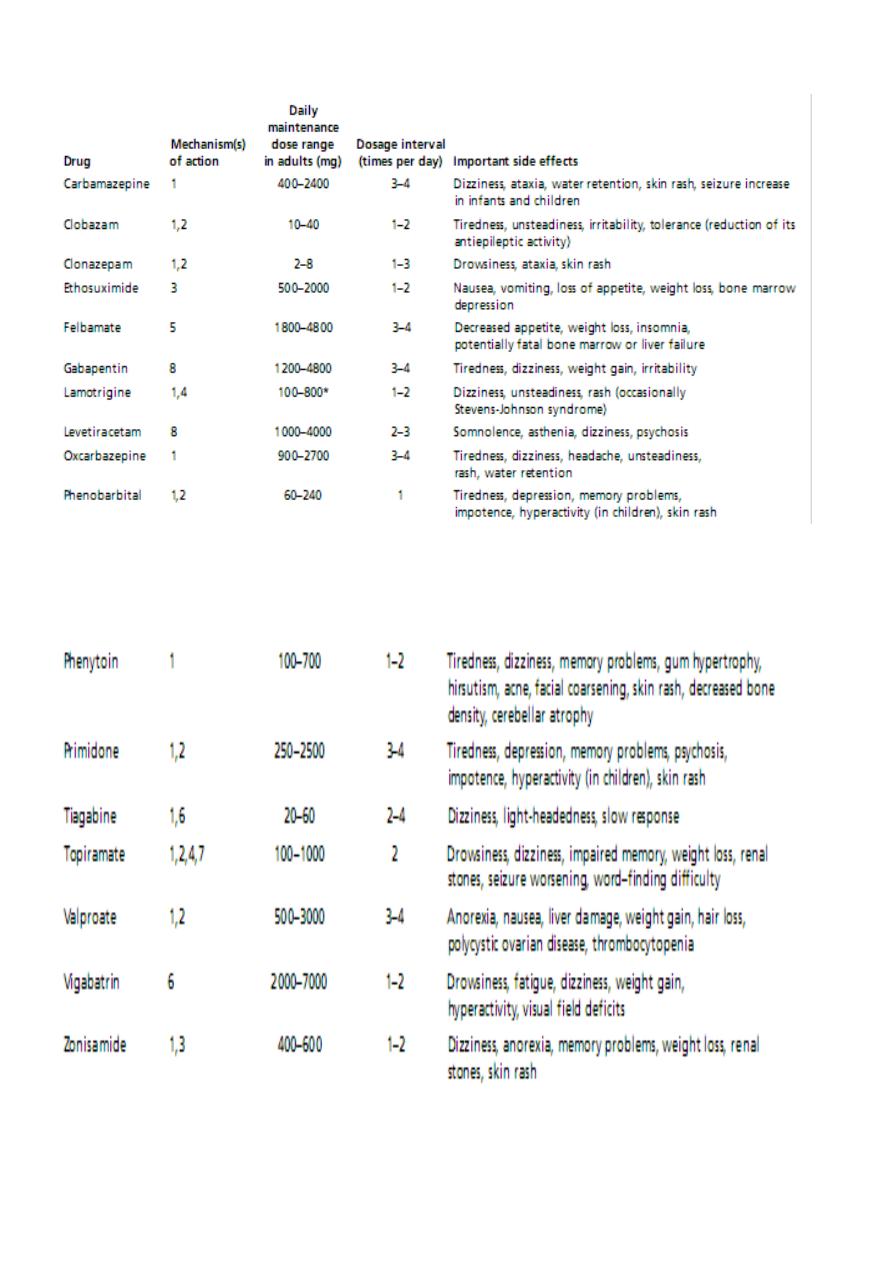

Important Pharmaco-Kinetic features of first and second line of AED

15

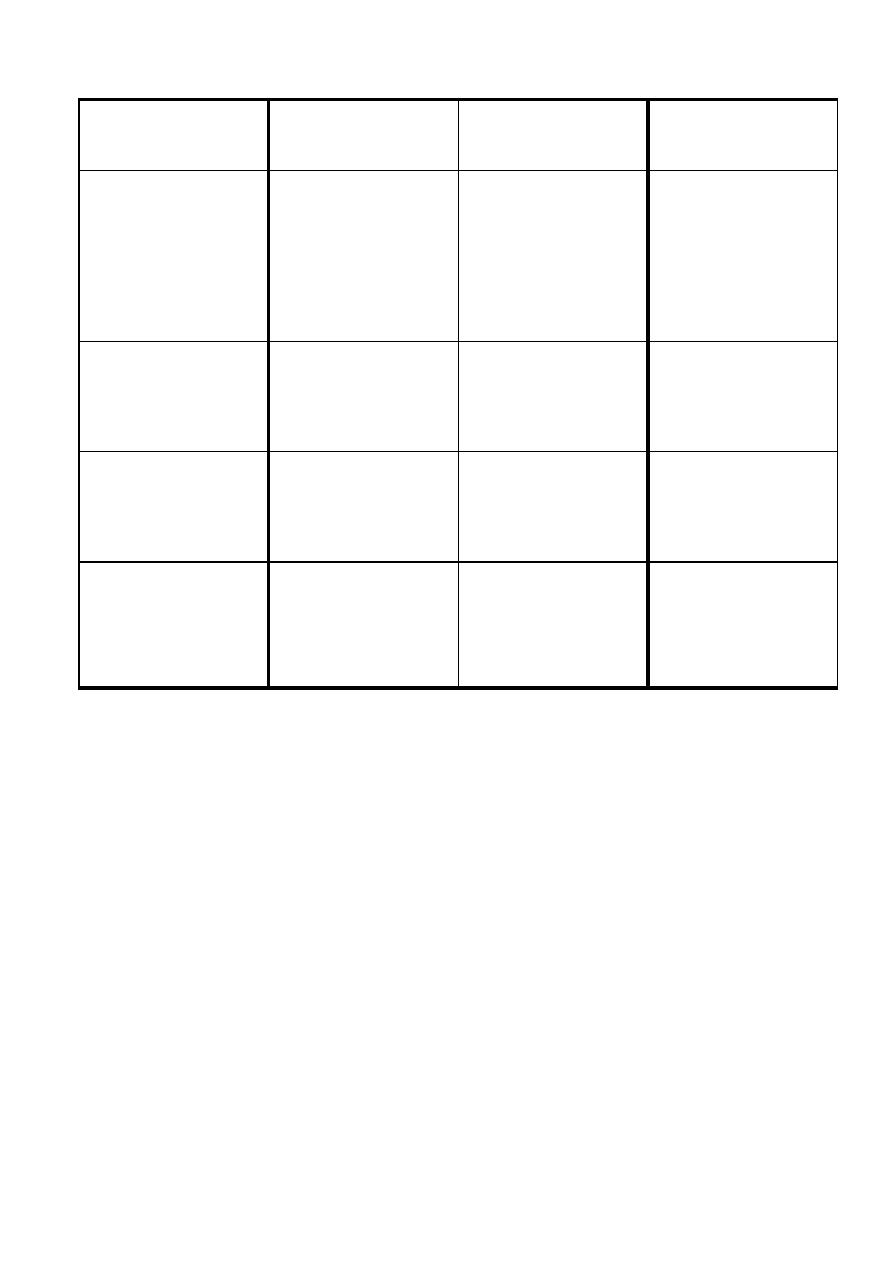

Guidelines for choice of AEDs

Third line

Second line

First-line drug

Epilepsy type

Lamotrigine

Sodium valproate

Levetiracetam

topiramate

carbamazepine

Partial

and/or

secondary GTCS

Lamotrigine

topiramate

Sodium valproate

Primary GTCS

Sodium valproate

ethosuximide

absence

clonazepam

Sodium valproate

myoclonic

Guidelines for anticonvulsant therapy

Start with one first-line drug.

Start at a low dose, increase, dose until effective control of seizures is achieved or side

effects develop (drug level may be helpful).

Optimize compliance (use minimum number of doses per day).

If first drug fails, start second first-line drug while gradually withdrawing first.

If second drug fails, start second-line drug in combination of preferred first-line drug

at maximum tolerated dose (beware of interaction)

If this combination fails replace second-line drug with alternative second-line drug.

If this combination fails, check compliance and reconsider diagnosis (is there an occult

structural or metabolic lesion or are seizures truly epileptic?).

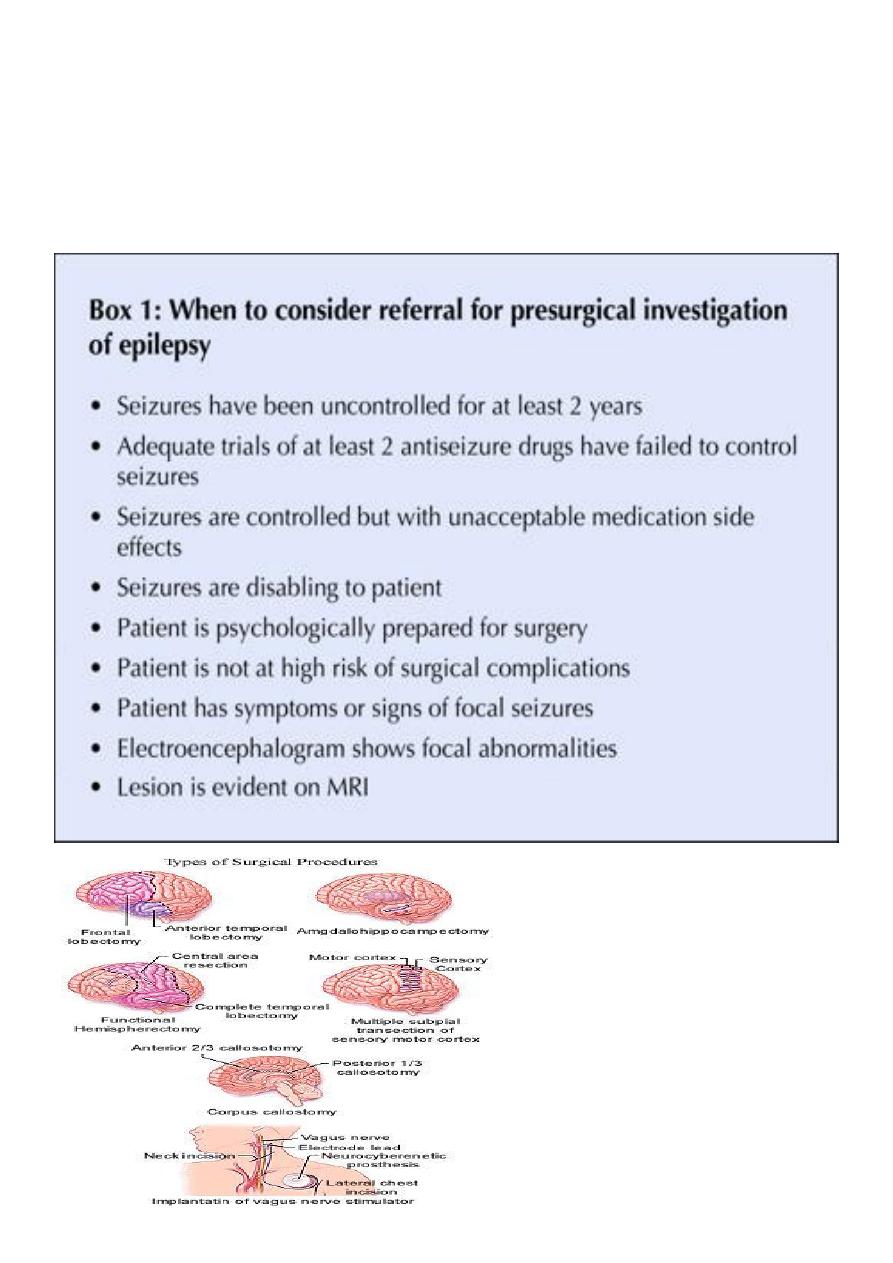

If this combination fails consider alternative non-pharmacological treatment (surgery

or VNS).

Do not use more than 2 drugs in combination at any one time.

16

Monitoring therapy

With some drugs such as phenytoin and carbamazepine, occasional measurement of the

blood level can be a guide whether the patient is on an appropriate dose and is complying

with the medication, but blood levels need to be interpreted carefully.

The dose of AED in an individual patient should primarily be governed by the efficacy of

seizure control and the development of side effects rather than blood levels alone.

With sodium valproate, there is a poor relationship between blood level and anticonvulsant

efficacy and so levels are only useful to assess compliance.

Repeated measurement of blood levels is not generally useful and monitoring is of most

value in dealing with suspected toxicity, the pharmacokinetic effect of pregnancy or in

suspected non-compliance.

Withdrawing AEDs

After complete control of seizures for 2 – 4 years, withdrawal of medication may be

considered.

Childhood – onset epilepsy particularly classical absence seizures carries the best prognosis.

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy have a marked liability to recur after drug withdrawal.

Seizures that begin in adult life particularly those with partial features are likely to recur

especially if there is a structural lesion.

Overall, the overall recurrence rate is about 40 %.

The EEG is generally a poor predictor of recurrence but if the record is still very abnormal,

drug withdrawal is unwise.

Withdrawal should be undertaken slowly, reducing the drug dose gradually over 6-12

months.

VNS Therapy (Vagus Nerve Stimulation)

VNS Therapy consists of electrical signals that are applied to the vagus nerve in the neck for

transmission to the brain.

The vagus nerve has proven to be a good way to communicate with the brain because:

1- There are few if any pain fibers in the vagus nerve.

2- Over 80% of the electrical signals applied to the vagus nerve in the neck are sent

upwards to the brain.

3- The surgical procedure to attach the lead to the vagus nerve does not involve the brain.

It is not brain surgery.

17

The Ketogenic Diet

Very high in fat and low in carbohydrates and protein.

4 grams of fat for each gram of protein and carbohydrate consumed.

Caloric intake is usually 75% of the recommended calorie intake

A minimum of 1 gram of protein per kilogram of body weight per day is provided.

Restricting fluid to 65 mL per kilogram of body weight per day

18

Contraception

Many AEDs, including carbamazepine, phenytoin, barbiturate, induce hepatic enzymes,

accelerate metabolism of estrogen and cause breakthrough bleeding and contraceptive

failure.

Lamotrigine and oxcarbazepine have little interaction.

Sodium valproate has no interaction with oral contraceptives.

The safest policy is to use an alternative contraceptive method, but it is sometimes possible

to overcome the problem by giving higher dose of estrogen.

Pregnancy

With the exception of gabapentine, all AEDs is associated with fetal abnormalities such as

cleft lip, spina bifida and cardiac defects.

The risk is greatest when treatment is given in the 1

st

trimester, rising from a background risk

of 2-4% to about 4-8% with one drug and to 15 % with two drugs or more.

Folic acid (5 mg daily) taken 2 months before conception may reduce the risk of some fetal

abnormalities

Seizures often become more frequent during pregnancy, especially during the 3

rd

trimester

when plasma anticonvulsant level tend to fall.

Monitoring of blood levels of anticonvulsants can be helpful with adjustment of drug doses.

Occasionally in a well-controlled patient, AEDs can be withdrawn before conception, but if

major seizures have occurred in the preceding year, this is unwise, since uncontrolled

maternal seizures represent a significant risk to the fetus.

Prognosis

Overall, generalized seizures are more readily controlled than partial seizures.

The presence of structural lesion makes complete control of the epilepsy less likely.

There is a 40 fold increased risk of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP) and

patients may need to be made aware of this in order to help them rearrange their

lifestyle and comply with treatment.

Epilepsy outcome after 20 years

50 % are seizure free, without drugs, for last 5 years.

20 % are seizure free for last 5 years but continue to take medication.

30 %continue to have seizures in spite of AEDs.

19

Status epilepticus

Defined a seizure or a series of seizures lasting 30 minutes without the patient regaining

awareness between attacks. Most commonly, this refers to recurrent tonic clonic seizures

(major status) and is a life-threatening medical emergency. Partial motor status is obvious

clinically, but complex partial status and absence status may be difficult to diagnose because

the patient may merely present in a dazed, confused state. Status is never the presenting

feature of idiopathic epilepsy but may be precipitated by abrupt withdrawal of

anticonvulsant drugs, the presence of a major structural lesion or acute metabolic

disturbance, and tends to be more common with frontal epileptic foci .It should be

remembered that psychogenic or non-epileptic attacks commonly masquerade as 'status

epilepticus', so electrophysiological confirmation of the seizures should be obtained as early

as possible

Management of status epilepticus

Initial:

Ensure airway is patent, give oxygen to prevent cerebral hypoxia and secure intravenous

access. Draw blood for glucose, urea and electrolytes (including Ca and Mg), and liver

function and store a sample for future analysis (e.g. drug misuse). Give diazepam 10 mg i.v.

or rectally or lorazepam 4 mg i.v. –repeat once only after 15 minutes.

Transfer to intensive care area, monitor neurological condition, blood pressure, and

respiration and blood gases. Intubating and ventilating patient if appropriate.

If seizure continue after 30 minutes

Intravenous infusion (with cardiac monitoring) with one of:

1- Phenytoin: i.v. infusion of 15 mg/kg at 50 mg/min

2- Fosphenytoin: i.v. infusion of 15 mg/kg at 100 mg/min

3- Phenobarbital: i.v. infusion of 10 mg/kg at 100 mg/min

If seizures still continue after 30-60 mins

Start treatment for refractory status with intubation and ventilation, and general anesthesia

using propofol or thiopental

Once status controlled

Commence longer-term anticonvulsant medication with one of :

1- Sodium valproate 10 mg/kg i.v. over 3-5 mins, then 800-2000 mg/day

2- Phenytoin: give loading dose (if not already used as above) of 15 mg/kg, infuse at < 50

mg/min, then 300 mg/day

3- Carbamazepine 400 mg by nasogastric tube, then 400-1200 mg/day.

Investigate cause.

21

Non-epileptic attack disorder ('psychogenic attacks', 'pseudo-seizures’)

Patients may present with attacks that superficially resemble epileptic seizures but which are

caused by psychological phenomena and not associated with abnormal epileptic discharges

in the brain. Such patients may present in apparent status epilepticus. People with epilepsy

may have non-epileptic attacks as well, and this diagnosis should be considered if a patient

fails to respond to anti-epileptic therapy, especially in the absence of a structural

abnormality. Non-epileptic attacks may be quite difficult to distinguish from truly epileptic

attacks. Clues pointing towards non-epileptic attacks include elaborate arching of the back in

an attack, pelvic thrusting and/or wild flailing of limbs. Cyanosis and severe biting of the

tongue are rare in non-epileptic attacks, but urinary incontinence can occur. The distinction

between epileptic attacks originating in the frontal lobes and non-epileptic attacks may be

especially difficult, and may require video telemetry with prolonged EEG recordings. Non-

epileptic attacks are three times more common in women than in men and have been

associated with a history of sexual abuse in childhood. They are not necessarily associated

with formal psychiatric illness. Treatment is often difficult and usually requires

psychotherapy and/or counselling rather than drug therapy.

Differential Diagnosis of Seizures

• Syncope

• Vasovagal syncope

• Cardiac arrhythmia

• Valvular heart disease

• Cardiac failure

• Orthostatic hypotension

• Psychological disorders

• Psychogenic seizure

• Hyperventilation

• Panic attack

• Metabolic disturbances

• Alcoholic blackouts

• Delirium tremens

• Hypoglycemia

• Hypoxia

• Psychoactive drugs (e.g.,

• hallucinogens)

• Migraine

• Confusional migraine

• Basilar migraine

• Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

• Basilar artery TIA

• Sleep disorders

• Narcolepsy/cataplexy

• Benign sleep myoclonus

• Movement disorders

• Tics

• Nonepileptic myoclonus

• Paroxysmal choreoathetosis

• Special considerations in children

• Breath-holding spells

• Migraine with recurrent

• abdominal pain and cyclic

• vomiting

• Benign paroxysmal vertigo

• Apnea

• Night terrors

• Sleepwalking

21

Features That Distinguish Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizure from Syncope

Syncope

Seizure

Features

Emotional stress, Valsalva,

orthostatic

hypotension,

cardiac etiologies

Usually none

Immediate

precipitating

factors

Tiredness,

nausea,

diaphoresis, tunneling of

vision

None or aura (e.g., odd

odor)

Premonitorysy mptoms

Usually erect

Variable

Posture at onset

Gradual over seconds

Often immediate

Transition

to

unconsciousness

Seconds

Minutes

Duration

of

unconsciousness

Never more than 15 s

30–60 s

Duration of tonic or clonic

movements

Syncope

Seizure

Features

Pallor

Cyanosis, frothing at mouth

Facial appearance during

event

5 min

Many minutes to hours

Disorientation

and

sleepiness after event

Sometimes

Often

Aching of muscles after

event

Rarely

Sometimes

Biting of tongue

Sometimes

Sometimes

Incontinence

Rarely

Sometimes

Headache

22