1

Forth stage

Obstetric

Lec-6

د.أحمد جاسم

16/3/2016

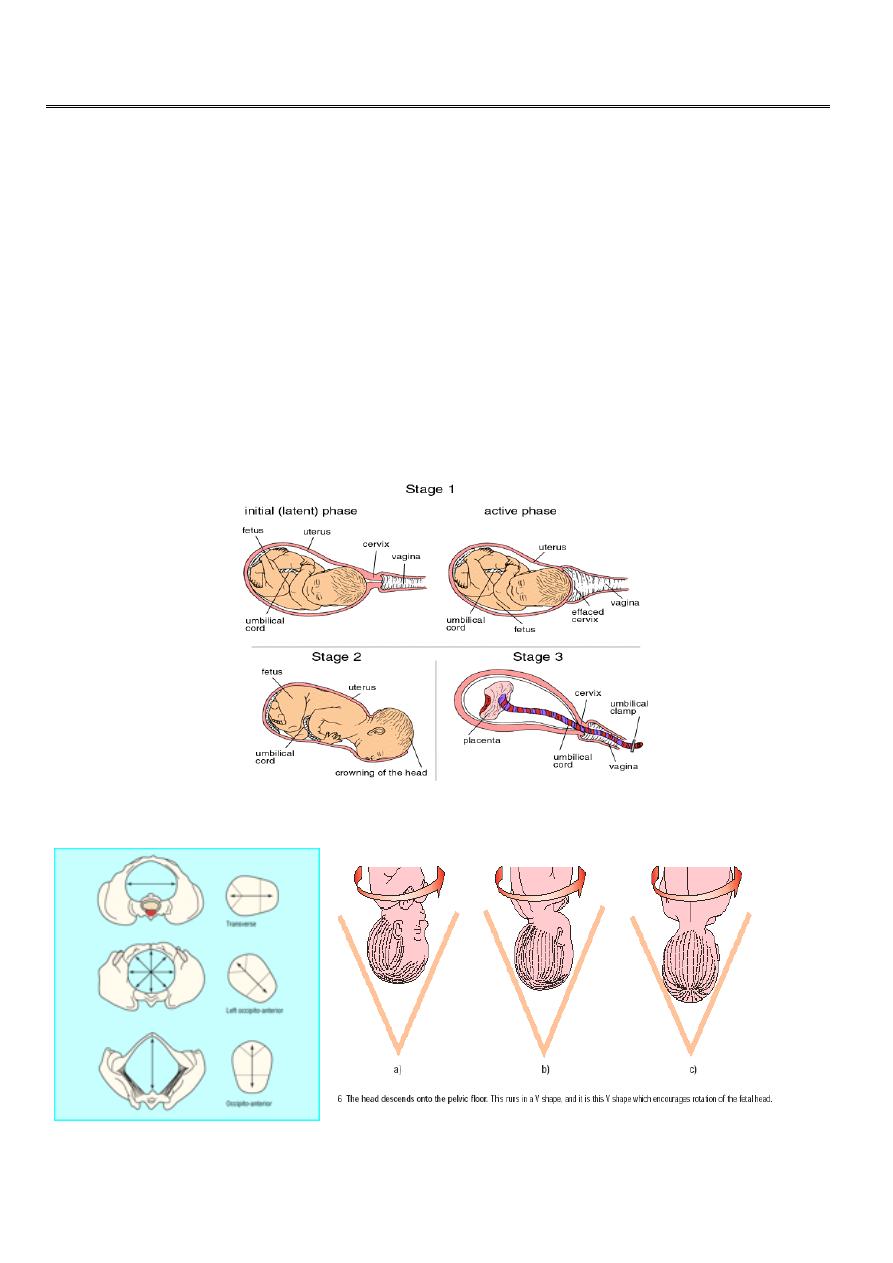

Poor progress in labour

First stage of labour is the time of cervical dilatation and /or effacement and fetal

presenting part descent.

Plotting the finding of serial vaginal examinations on the partogram will help to highlight

poor progress in first stage.

A progressive change in the cervix over a few hours will confirm established labour, and

so a vaginal examination at the time of admission to the labour ward is important to

establish a baseline.

Stages of labour:

2

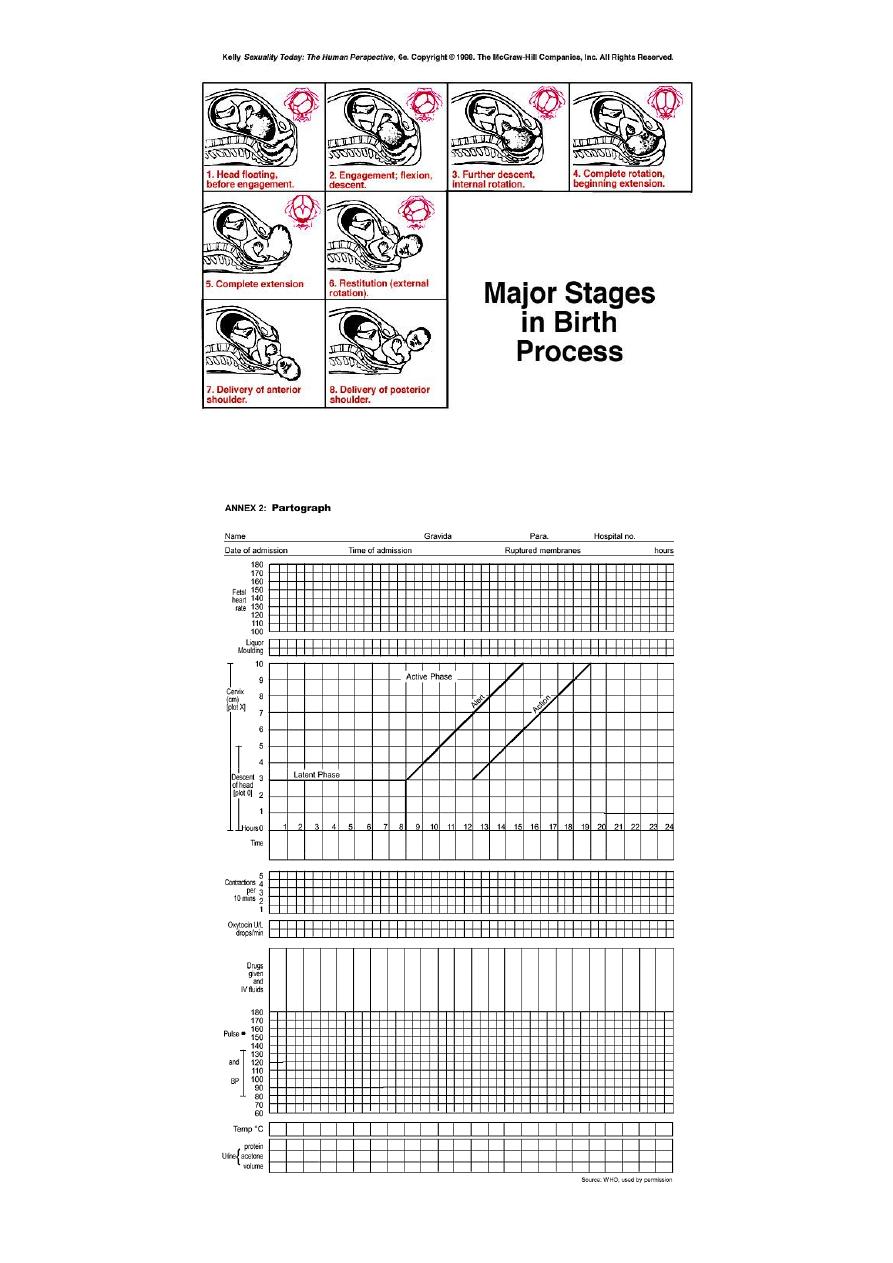

partograph

3

Risk factors

for poor progress in labour:

Small woman.

Big boy.

Malpresentation.

Malposition.

Early membrane rupture.

Soft-tissue / pelvic malformation.

Second stage of labour is the time of descent of presenting part. It is important to diagnose

fully dilated cervix to confirm diagnosis of second stage.

Progress in labour is dependent on three variables:

1. Powers. Efficacy of uterine contractions. frequency of 4-5 contractions per 10 minutes is

considered ideal.

2. Passenger. Fetal size, presentation and position.

3. Passages. Uterus, cervix and bony pelvis.

Abnormalities in one or more of these factors can slow normal progress of labour.

Causes of

poor progress of labour:

Any faults in one or more of these can cause poor progress of labour

Faults in the powers

Inefficient uterine action or incoordinate uterine action (irregular).

It should be considered first.

Assessment of uterine contractions is carried out by clinical examination and by using

External tocography

Internal tocography using an intrauterine pressure sensor may be best but has never

really progressed beyond a research tool.

4

Treatment:

If poor uterine action is suspected steps should be taken to improve it.

A. Maternal rehydration.

B. Artificial rupture of membrane (ARM) if membrane intact.

C. Intravenous oxytocin is the cornerstone of therapy if no contraindication and after

full evaluation. As it increase contraction and treat inco-ordinate uterine

contractions.

Faults in the passages:

May come from distortion in the maternal bony pelvis by disease, damage or

deformity.

There is little that can be done to overcome these, and unless they present only

marginal difficulty, delivery by Caesarean section is usually required.

The soft tissues of the birth canal – cervix, vagina, perineum, may, if rigid, obstruct

progress

.

The passenger:

Fetus may be uncooperative by being excessively large, in the wrong position or

presentation.

If no contraindication, maximize the quality of uterine contractility which may often

overcome minor problems of the passages or the passenger or both. If these

problems persist then Caesarean section is necessary.

5

Patterns of abnormal progress in labour:

Prolonged latent phase (poor progress in active phase of labour).

Primary dysfunctional labour. (<1cm /hour cervical dilatation).

Secondary arrest. When progress in active phase is initially good but then sloes or

stops after 7 cm dilatation.

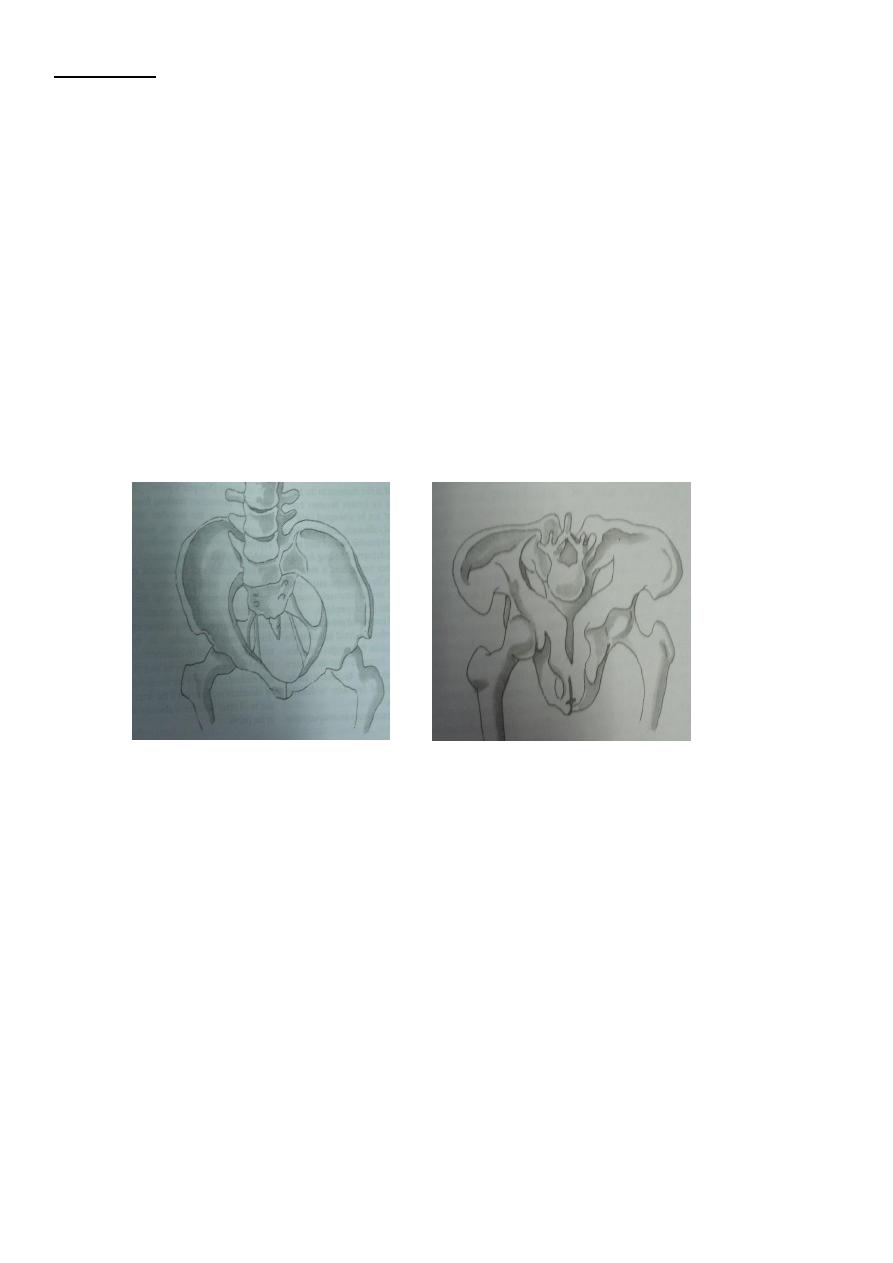

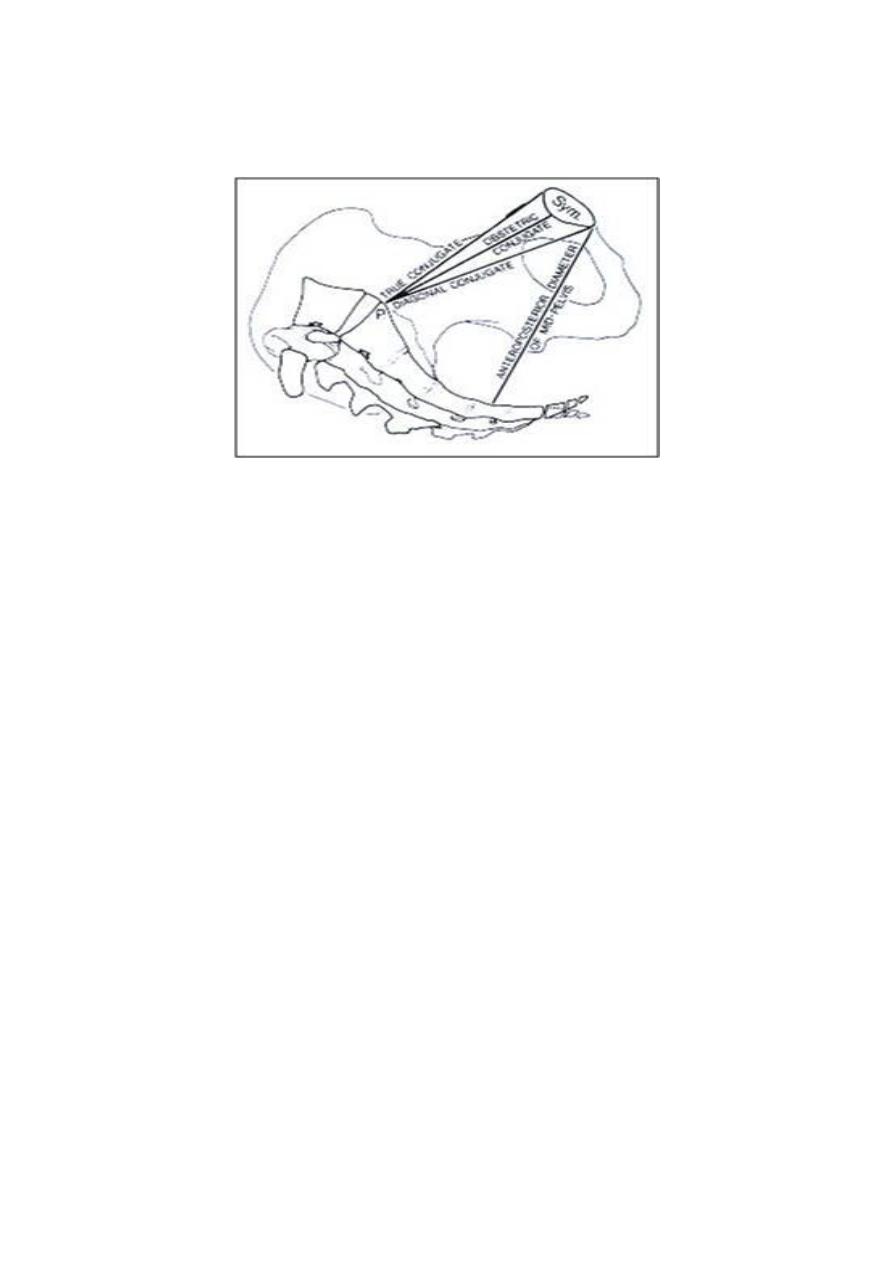

Cephalopelvic disproportion

It implies anatomical disproportion between fetal head and maternal pelvis. It can be

due to a large head, small pelvis or a combination of two.

6

Diagnosis o

f CPD antenatally:

A. Past orthopedic and obstetric history:

B. History of disease or fracture of spine, hips or pelvis should alert about possibility of

pelvic

C. In multipara ask about weight of largest baby previously delivered, details of her

previous labors including duration and mode of delivery outcome, birth weight and

subsequent progress of child.

D. General examination: general disease of skeleton or disease of lower limbs or spine

should be noted.

E. Small woman.

FAULTY DEVELOPMENT:

Abdominal examination

In late pregnancy engagement should be examined.

In primigravidae the head normally engaged between 36-38 weeks. In multipara

engagement often does not occur until labour starts.

Although engagement of head after 37 weeks in a primigravida is reassuring, failure to

do so does not necessarily mean the presence of CPD.

Pelvic examination:

Signs suggestive of an inadequate pelvis:

Sacral promontory reached easily in contracted pelvis.

straightness of sacrum.

Convergence of side walls of pelvis.

prominent Ischial spines.

7

Biischial diameter is less than 8 cm.

Distance between ischial tuberosities less than 8 cm.

Distance between ischial tuberosities is less than a closed –hand fist.

Subpubic angle does not admit two fingers comfortably.

Diagnosis of disproportion during labour:

CPD is suspected in labour if:

Progress is slow or arrested despite efficient uterine contractions.

Signs suggestive of CPD during labour are:

Abdominal examination:

Large fetal size.

Fetal head failed to descend.

Pelvic examination:

Cervix shrinking after amniotomy.

appearance of fresh meconium

Edema of cervix.

Head not well applied against the cervix.

Caput formation.

Progressive excessive moulding.

Deflexion of head (easily palpable anterior fontanelle)

Asynclitism (sagital suture not in the middle of pelvis)

8

Others:

Maternal pushing before cervical dilatation.

Early decelerations.

The best diagnosis of CPD is a trial of labour. The diagnosis of cephalopelvic

disproportion is usually retrospective after a well-conducted trial of labour.

Treatment

Failure to progress due to cephalopelvic disproportion in the first stage and in the

second stage when the station is high, delivery is accomplished by caesarean section.

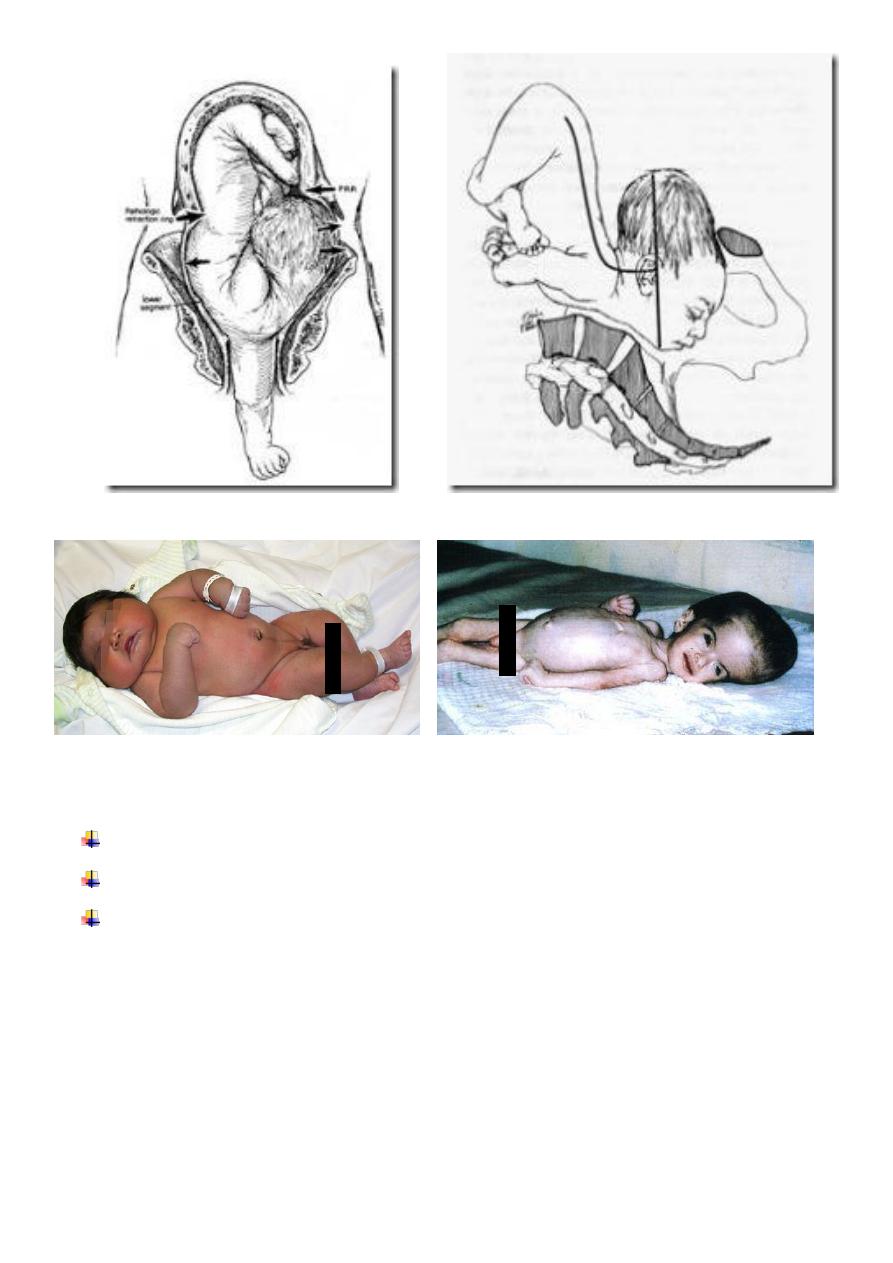

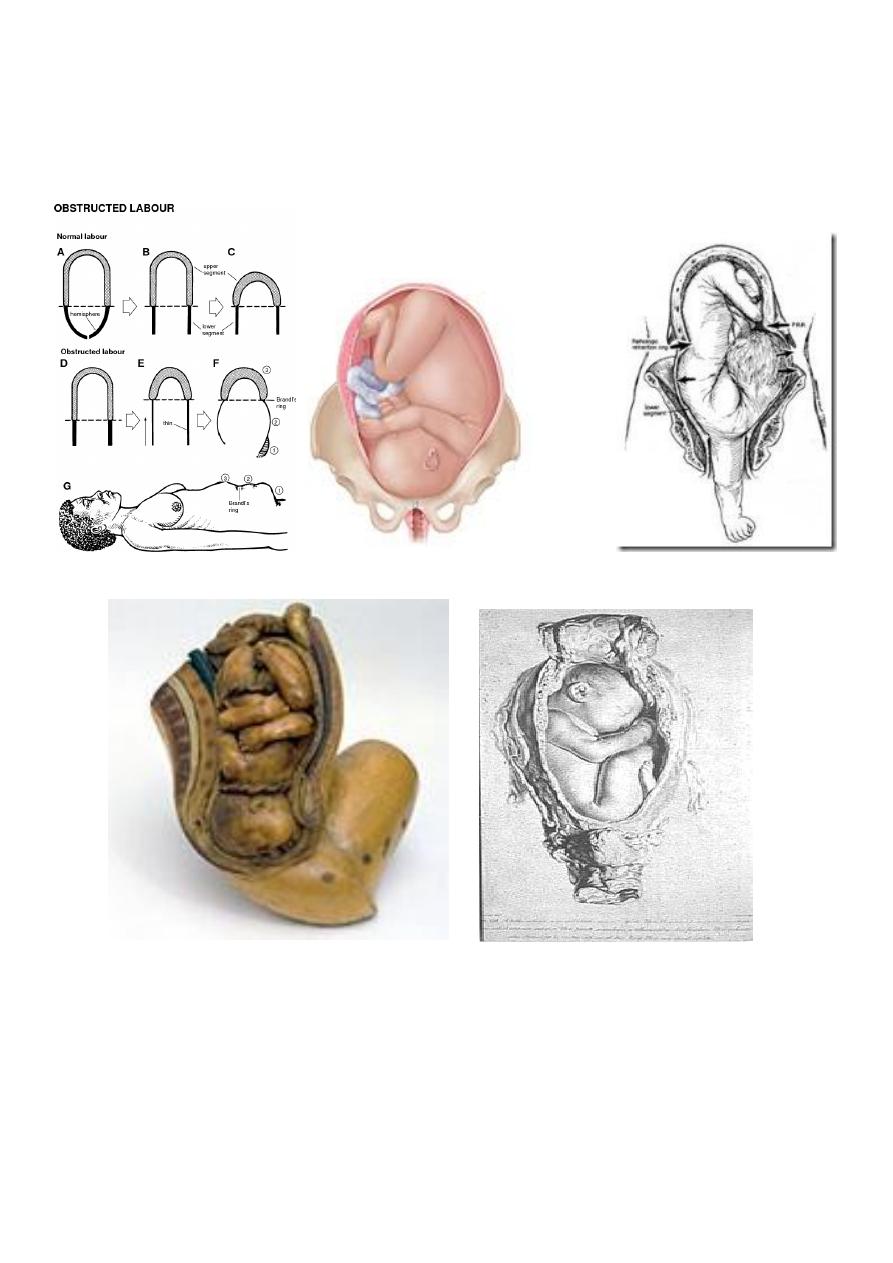

Obstructed Labour

Impending uterine rupture

Labour is said to be obstructed when there is no progress in spite of strong uterine

contractions. It shown by failure of cervix to dilate or failure of presenting part to

descend through birth canal. It is a most dangerous condition if it is untreated and

can be fatal to both mother and fetus.

Aetiology

A. Maternal conditions:

1. Contraction or deformity of bony pelvis.

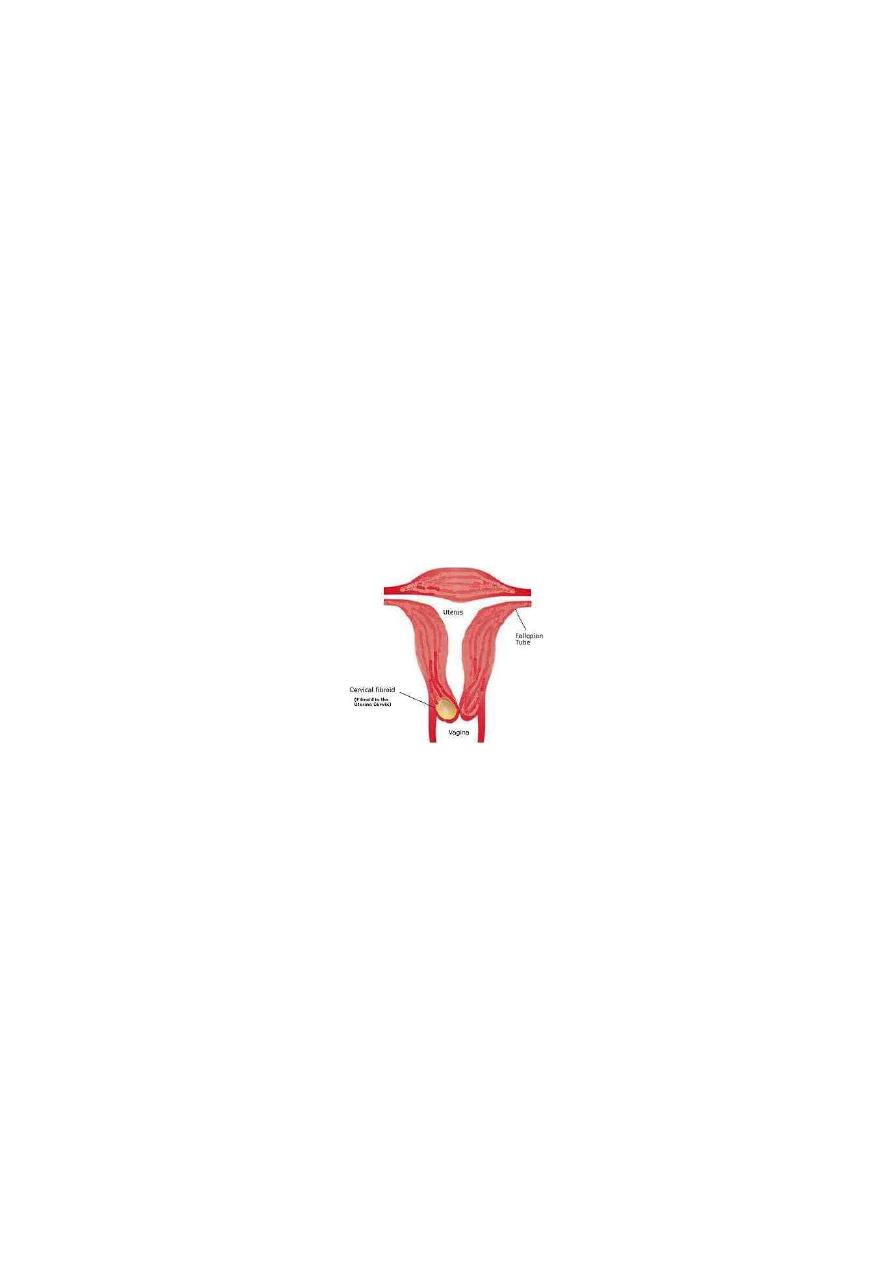

2. Pelvic tumours ( uterine fibroids, ovarian tumours, tumour of rectum. Bladder or

pelvic bones).

3. Pelvic kidney.

4. Abnormality of uterus or vagina:

5. Stenosis of cervix or vagina.

6. Obstruction by one horn of double uterus.

7. Contraction ring of uterus.

B. Fetal condition:

1) Large fetus.

2) Malposition or malpresentation

3) Persistant occiptoposterior or transverse position.

4) Mentoposterior position.

5) Breech presentation.

9

6) Shoulder presentation

7) Compompound presentation

8) Locked twins.

9) congenital abnormalities of fetus

10)

hydrocephalous.

11)

fetal ascitis or abdominal tumours.

12)

hydrops fetalis.

13)

conjoined twins.

Diagnosis

The importance of early detection of possible obstruction is obvious as labour if allowed

to reach point of absolute obstruction will lead to death of fetus and endangered

mother life.

In a primigravida complete obstruction leads within 2-3 days to a state of uterine

exhusation or secondary hypotonia.

In Multigravida, obstruction becomes established much sooner and progressive thinning

of lower segment may lead to uterine rupture in a few hours.

General examination

Deterioration in patient's general condition:

It shows signs of maternal distress and looks tired and anxious, exhausted and loss her

ability to cooperate.

* high temperature (38°C),

* rapid pulse,

* signs of dehydration: dry tongue and cracked lips.

Abdominal examination

The uterus is hard and tender,

Frequent strong uterine contractions with no relaxation in between (tetanic

contractions).

Rising retraction ring is seen and felt as an oblique groove across the abdomen called

retraction ring of Bandle which can be seen and felt in abdominal examination.

In advanced obstructed labour the uterus is found to be molded to shape of fetus

11

Presenting part is often above or at level of pelvic brim.

Fetal parts cannot be felt easily.

Severe fetal distress due to interference with the utero-placental blood flow or

absent fetal heart

.

Vaginal examination

Vulva: is oedematous.

Vagina: is dry and hot.

Cervix: is fully or partially dilated, oedematous.

The membranes: are ruptured.

The presenting part: is high and not engaged or impacted in the pelvis. If it is the head

it shows excessive moulding and large caput.

The cause of obstruction can be detected.

11

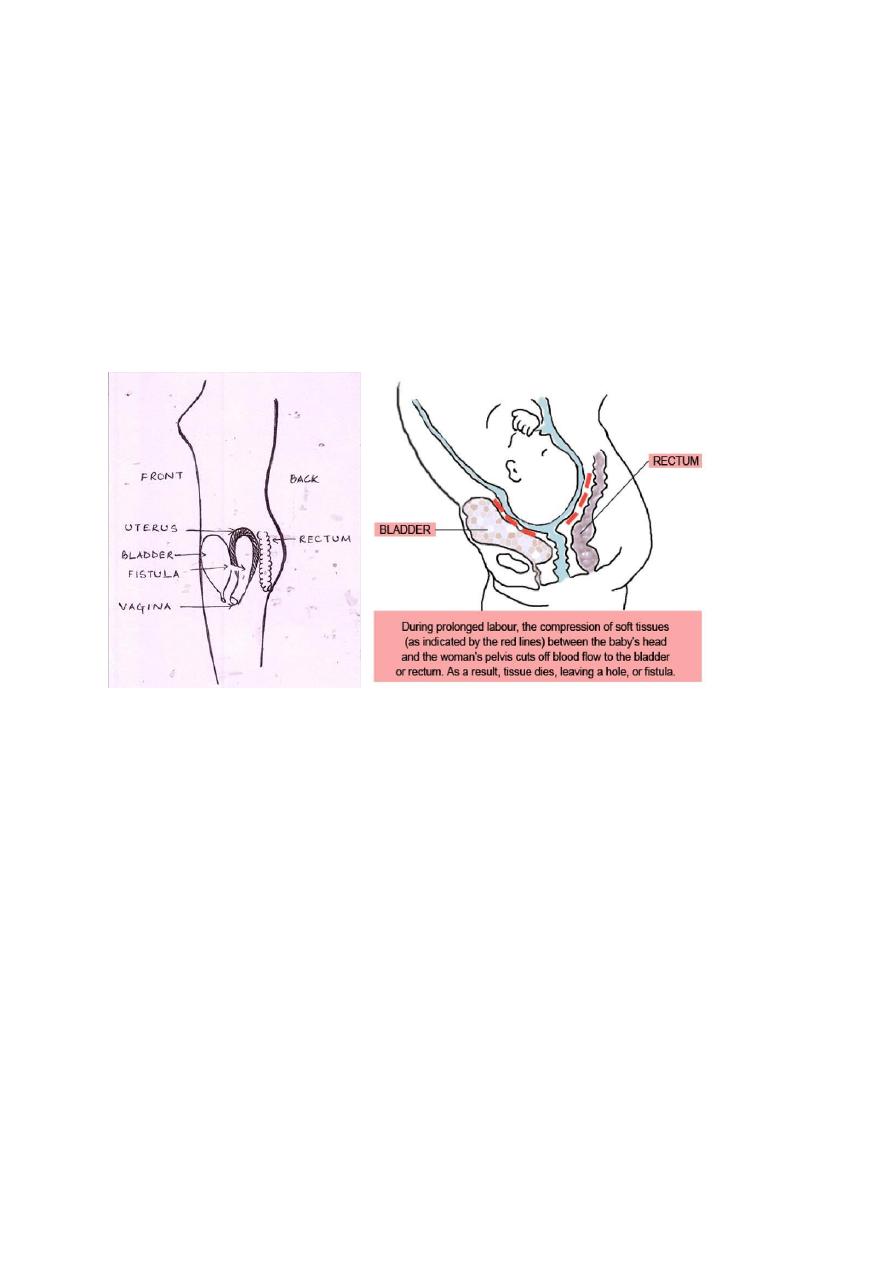

Complications

Maternal complications:

1. Maternal distress and ketoacidosis.

2. Rupture uterus.

3. Necrotic vesico-vaginal fistula.

The fetal presenting part becomes impacted in maternal pelvis and causing ischemia of

maternal soft tissues that lie between presenting part and walls of maternal pelvis which if

neglegted can lead to tissue necrisis and formation of vesicivaginal or rectovaginal fistule.

4. Infections as chorioamnionitis and puerperal sepsis.

5. Postpartum haemorrhage due to injuries or uterine atony.

Fetal complications:

1. Asphyxia.

2. Intracranial haemorrhage from excessive moulding.

3. Birth injuries.

4. Infections

Management

Curative measures:

Caesarean section is the safest method even if the baby is dead as labour must be

immediately terminated and any manipulations may lead to rupture uterus.

There is risk of puerperal sepsis so appropriate antibiotics should be given.

12

Preventive measures:

good antenatal care and plane of action can be made before labour.

Careful observation, proper assessment,using partograph, early detection and

management of the causes of obstruction.

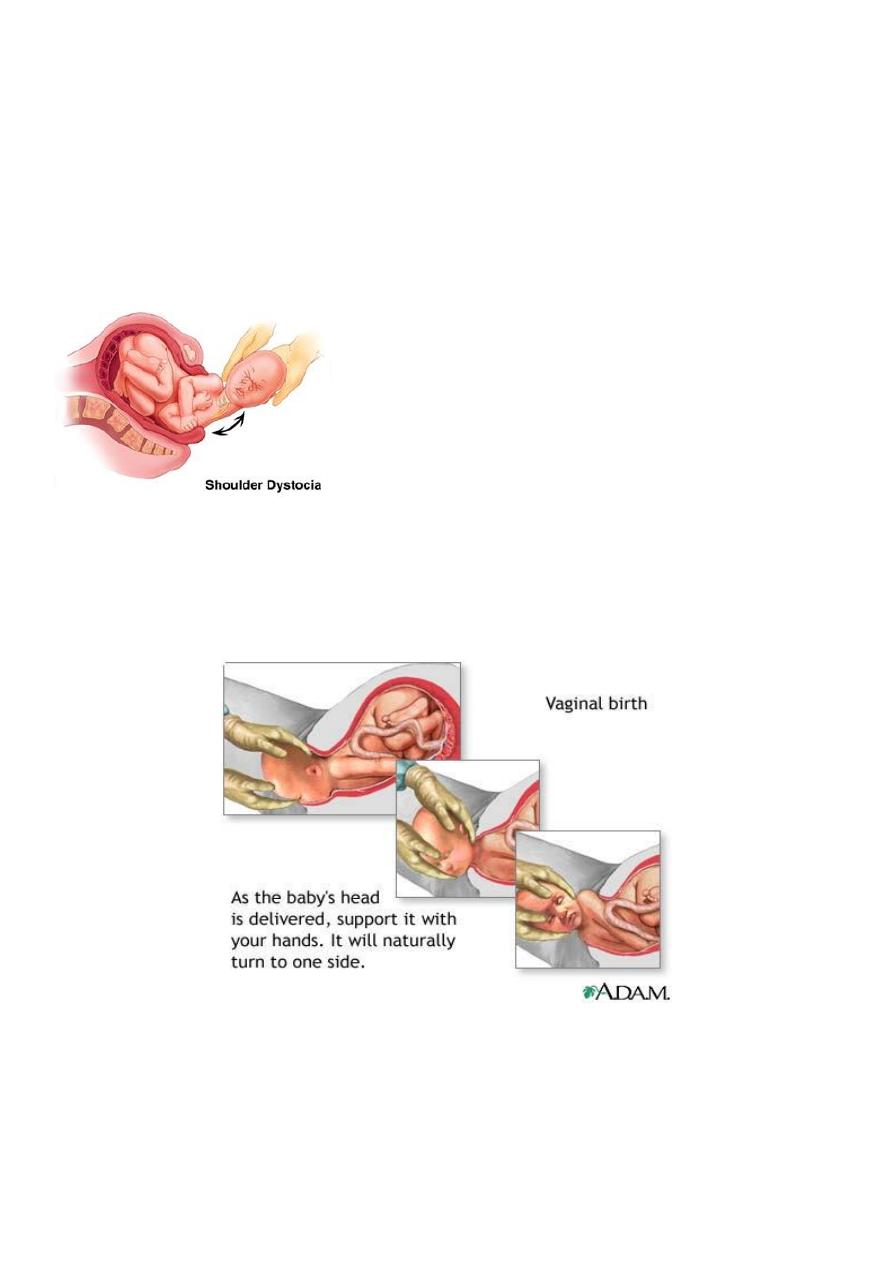

Shoulder dystocia

Difficulty with delivery of fetal shoulder. Occurs in 0.2-1.2 %

.

The fetal head and shoulder rotate to make use widest diameters of pelvis. After

delivery of head, resititution occurs and the shoulders rotate into anterior-posterior (AP)

diameter. This make use of widest AP diameter of pelvic outlet. However if shoulders

have not entered pelvic inlet, the anterior shoulder may become caught above maternal

symphysis pubis. Occasionally both shoulders may remain above pelvic brim.

Risk factors:

Large baby.

Small mother.

Maternal obesity.

Diabetes mellitus.

13

Post-maturity.

Previous shoulder dystocia.

Prolongation of first stage of labour.

Prolonged second stage of labour.

Assisted vaginal delivery.

Prediction and prevention:

Shoulder dystocia can only be completely avoided by caesarean section.

In the majority of cases, recognition of risk factors should lead to an experienced

obstetricans being present at delivery to manage the problem.

As serious traction causing stretching of brachial plexus and nerve damage. Erb's

palsy is a likely consequence. Up to 25% associated with fetal morbidity and

mortality.

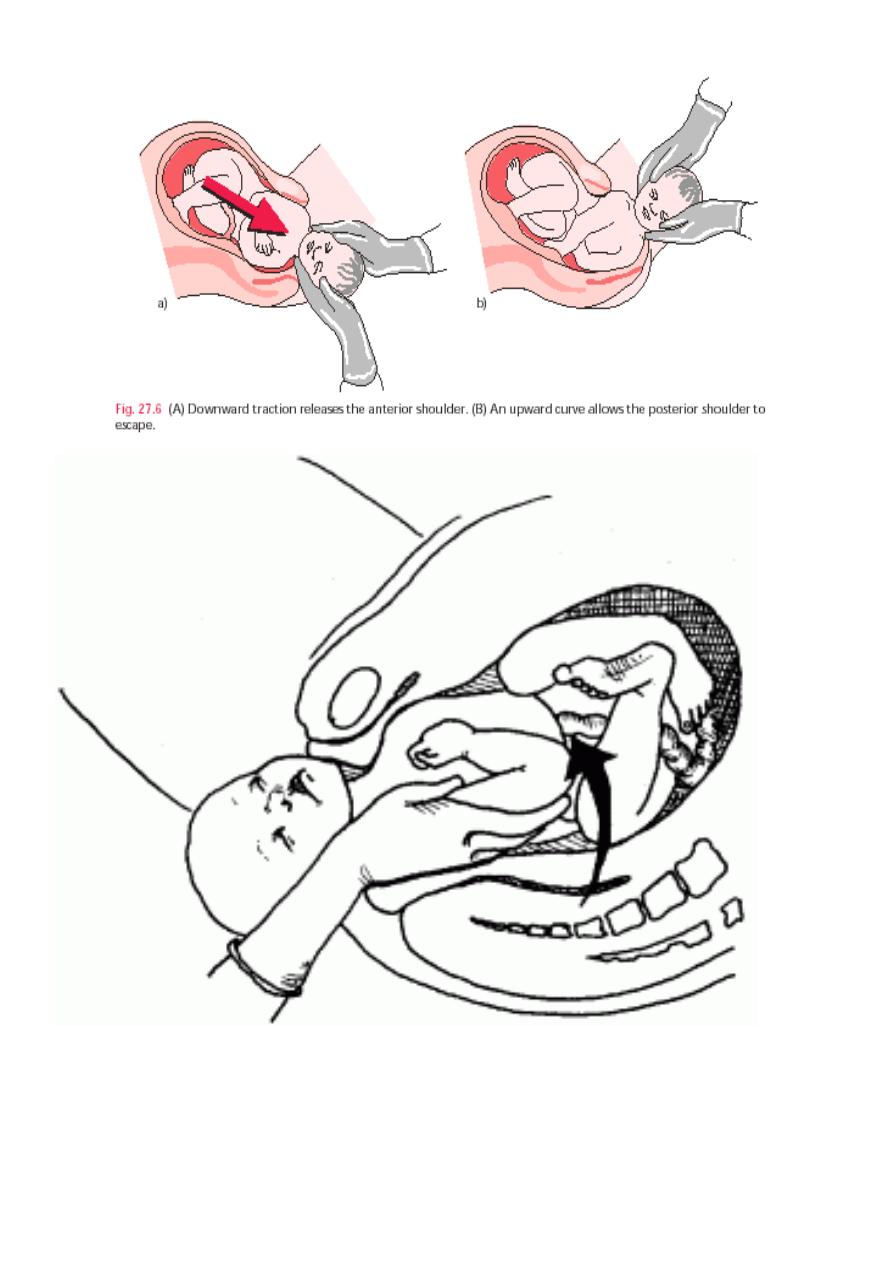

Management:

All in labour ward should have training to treat this.

Reduce interval between time of delivery of head to delivery of body. after 5

minutes, there is risk of cerebral damage.

Shoulder dystocia is managed by a sequence of maneuvers designed to facilitate

delivery without fetal damage.

Large episiotomy

Clear infant's mouth and nose.

Initial gentle attempt at traction, assisted by maternal expulsive efforts is

recommended.

Flex and abduct patient's hips on her abdomen (McRobert's position).

Apply suprapubic pressure pushing on fetal shoulder towards fetal chest.

If above failed, attempt to rotate the shoulders by putting hand into vagina and

pushing on front aspect of posterior shoulder.

Sometimes failed and symphsiotomy, clavicle fracture, caesarean section are tried.

14

A.LY