SYSTEMIC HYPERTENSION

• Hypertension is one of the leading causes of

the global burden of disease.

• Hypertension doubles the risk of

cardiovascular diseases, including coronary

heart disease (CHD), congestive heart

failure (CHF), ischemic and hemorrhagic

stroke, renal failure, and peripheral arterial

disease.

• Although antihypertensive therapy clearly

reduces the risks of cardiovascular and

renal disease, large segments of the

hypertensive population are either untreated

or inadequately treated.

Definition

• Hypertension currently is defined as a

usual BP of 140/90 mm Hg or higher,

for which the benefits of drug treatment

have been definitively established

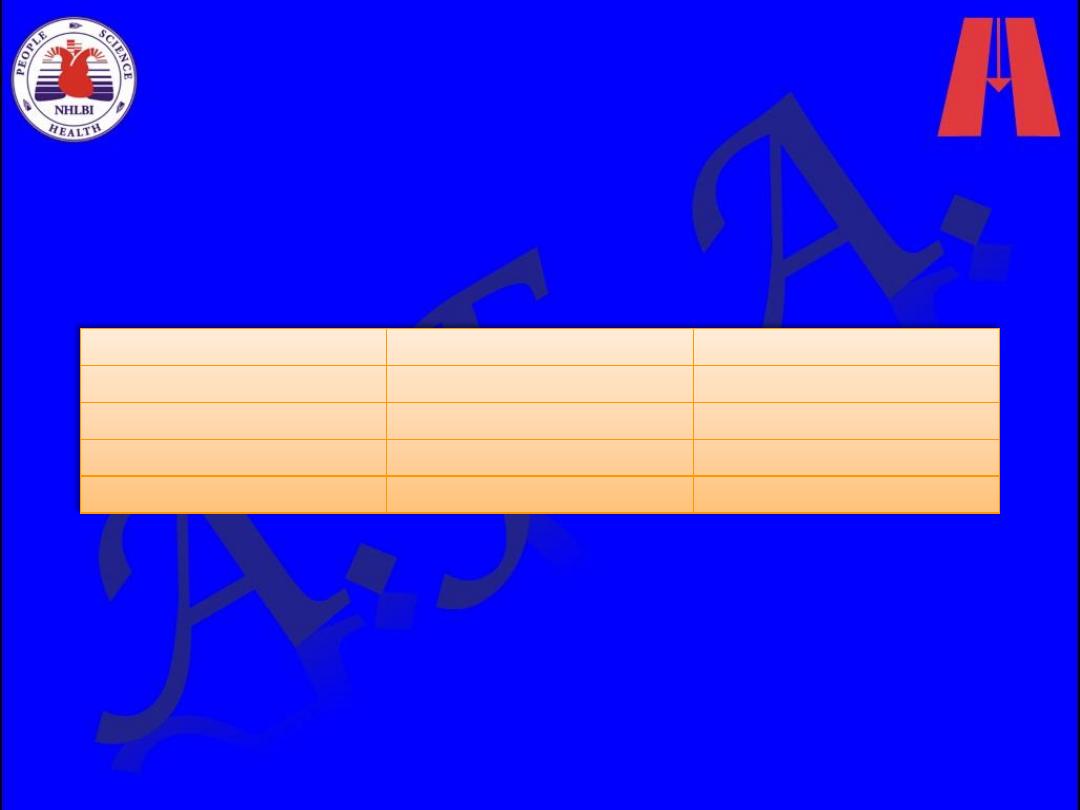

Staging of Office Blood Pressure

BP STAGE

SYSTOLIC BP (mm Hg) DIASTOLIC BP (mm Hg)

Normal

<120

<80

Prehypertension

120-139

80-89

Stage 1 hypertension

140-159

90-99

Stage 2 hypertension

≥160

≥100

Aetiology

1. Primary (Essential) hypertension

– The majority (90–95%) of patients with

hypertension have primary elevation of

blood pressure, i.e. essential hypertension

of unknown cause.

2. Secondary hypertension (5-10%).

Many factors may contribute to

development of essential HT

1. Neural Mechanisms

– Baroreflex control of sinus node function is

abnormal

– Obesity-Related Hypertension

– Obstructive Sleep Apnea

2. Renal Mechanisms

– acquired or inherited defect in the kidneys' ability

to excrete the excessive sodium load

– Low Birth Weight

– Genetic Contributions

3. Vascular Mechanisms

– Endothelial Cell Dysfunction

– Vascular Remodeling: An increase in the medial

thickness relative to lumen diameter (increased

media-to-lumen ratio) is the hallmark of

hypertensive remodeling in small and large arteries.

4. Hormonal Mechanisms

– Activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone

system (RAAS) is one of the most important

mechanisms contributing to endothelial cell

dysfunction, vascular remodeling, and hypertension

Secondary hypertension

1. Renal diseases

These account for over 80% of the cases

of secondary hypertension.

The common causes are:

■ diabetic nephropathy

■ chronic glomerulonephritis

■ adult polycystic disease

■ chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis

■ renovascular disease.

2. Endocrine causes

These include:

– Conn’s syndrome

– Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

– phaeochromocytoma

– Cushing’s syndrome

– acromegaly.

– Hyperparathyroidism

– Primary hypothyroidism

– Thyrotoxicosis

3. Congenital cardiovascular causes

– The major cause is coarctation of the aorta

4. Drugs:

NSAIDs, oral

contraceptives, steroids,

carbenoxolone, liquorice,

sympathomimetics and

vasopressin.

5. Pregnancy (pre-eclampsia)

6. Alcohol

7. Obesity

• All adults should have blood pressure measured

routinely at least every 5 years until the age of 80

years.

•

Seated blood pressure

when measured after 5

minutes’ resting with appropriate cuff size and arm

supported is usually sufficient, but

standing blood

pressure

should be measured in diabetic and

elderly subjects to exclude orthostatic

hypotension.

•

The cuff should be deflated at 2 mm/s and the

blood pressure measured to the nearest 2 mmHg.

•

Two consistent blood pressure measurements

are needed to estimate blood pressure, and more

are recommended if there is variation in the

pressure.

• When assessing the cardiovascular risk, the

average blood pressure at separate visits is more

accurate than measurements taken at a single

visit.

Assessment

History

• Family history, lifestyle (exercise, salt intake, smoking

habit) and other risk factors should be recorded.

• The patient with mild hypertension is usually

asymptomatic.

• Higher levels of blood pressure may be associated

with headaches, epistaxis or nocturia.

• Attacks of sweating, headaches and palpitations point

towards the diagnosis of

phaeochromocytoma.

• Breathlessness may be present owing to left

ventricular hypertrophy or cardiac failure,

• symptoms of peripheral arterial vascular disease

suggest the diagnosis of

atheromatous renal artery

stenosis.

Examination

• Findings related to hypertension

Loud A2

S4

Forceful sustained apical impulse

(heaving)

Examination

1. Secondary causes

: Radio-femoral delay (coarctation of

the aorta), enlarged kidneys (polycystic kidney disease),

abdominal bruits (renal artery stenosis) and the

characteristic facies and habitus of Cushing's syndrome are

all examples of physical signs that may help to identify

causes of secondary hypertension.

2. Risk factors

: Examination may also reveal features of

important risk factors such as central obesity and

hyperlipidaemia (tendon xanthomas etc.).

3. Complications:

– The optic fundi are often abnormal

– and there may be evidence of generalised atheroma or

specific complications such as aortic aneurysm or

peripheral vascular disease.

Investigations

investigation of all patients

• Urinalysis for blood, protein and glucose

• Blood urea, electrolytes and creatinine

– N.B. Hypokalaemic alkalosis may indicate

primary hyperaldosteronism but is usually due

to diuretic therapy

• Blood glucose

• Serum total and HDL cholesterol

• 12-lead ECG (left ventricular hypertrophy,

coronary artery disease)

investigation of selected

patients

• Chest X-ray

: to detect cardiomegaly, heart failure,

coarctation of the aorta

• Ambulatory BP recording

: to assess borderline or 'white

coat' hypertension

• Echocardiogram

: to detect or quantify left ventricular

hypertrophy & for the diagnosis ofcoactation of aorta

• Renal ultrasound

: to detect possible renal disease

• Renal angiography

: to detect or confirm presence of renal

artery stenosis

• Urinary catecholamines

: to detect possible

phaeochromocytoma

• Urinary cortisol and dexamethasone suppression test

:

to detect possible Cushing's syndrome

• Plasma renin activity and aldosterone

: to detect

possible primary aldosteronism

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

• Indirect automatic blood pressure measurements

can be made over a 24-hour period using a

measuring device worn by the patient.

• they are used to confirm the diagnosis in those

patients with

‘white-coat’ hypertension

, i.e.

blood pressure is completely normal at all stages

except during a clinical consultation

• These devices may also be used to monitor the

response of patients to drug treatment and, in

particular, can be used to determine the adequacy

of 24-hour control with once-daily medication

• Ambulatory blood pressure recordings

seem to be better predictors of

cardiovascular risk than clinic

measurements.

• Analysis of the diurnal variation in blood

pressure suggests that those

hypertensives with loss of the usual

nocturnal fall in

blood pressure (‘non-

dippers’) have a worse prognosis than

those who retain this pattern.

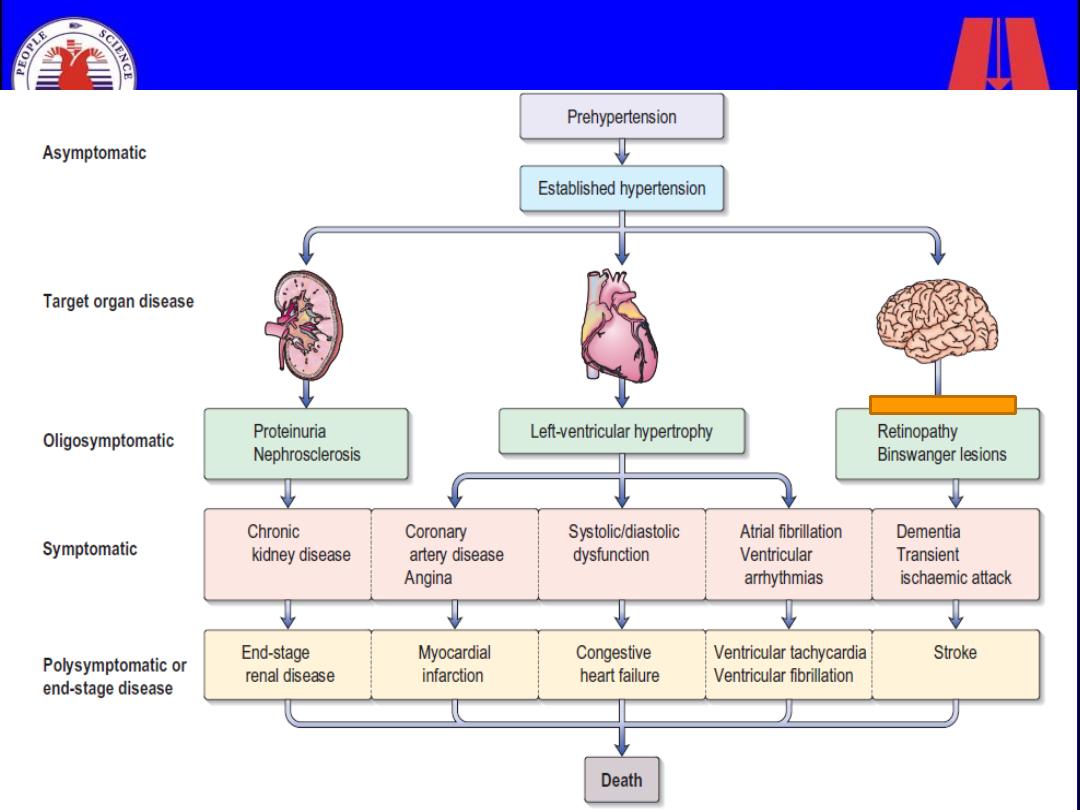

Complications

1. Blood vessels

– In larger arteries (> 1 mm in diameter), the internal

elastic lamina is thickened, smooth muscle is

hypertrophied and fibrous tissue is deposited.

– In smaller arteries (< 1 mm), hyaline arteriosclerosis

– aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection

2. Central nervous system

– Stroke (due to cerebral haemorrhage or infarction).

– Carotid atheroma and transient ischaemic attacks are

more common in hypertensive patients.

– Subarachnoid haemorrhage is also associated with

hypertension.

– Hypertensive encephalopathy is a rare

condition characterised by high BP and

neurological symptoms, including transient

disturbances of speech or vision,

paraesthesiae, disorientation, fits and loss

of consciousness. Papilloedema is

common.

3. Retina

– central retinal vein thrombosis

– Hypertensive retinopathy

Grade I

Arteriolar thickening, tortuosity and increased reflectiveness ('silver wiring')

Grade 2

Grade 1 plus constriction of veins at arterial crossings ('arteriovenous nipping')

Grade 3

Grade 2 plus evidence of retinal ischaemia (flame-shaped or blot haemorrhages and 'cotton

wool' exudates)

Grade 4

papilloedema

4. Heart

– coronary artery disease.

– left ventricular hypertrophy

– Atrial fibrillation

– Diastolic dysfunction

– LV failure.

5. Kidneys

– Long-standing hypertension may cause proteinuria and

progressive renal failure by damaging the renal vasculature.

6. 'Malignant' or 'accelerated' phase hypertension

(Diastole>130 mmgh)

– This rare condition may complicate hypertension of any

aetiology and is characterised by accelerated microvascular

damage and by intravascular thrombosis.

– The diagnosis is based on evidence of high BP and rapidly

progressive end organ damage, such as

retinopathy

(grade 3

or 4),

renal dysfunction

(especially proteinuria) and/or

hypertensive encephalopathy

.

– Left ventricular failure may occur and, if this is untreated, death

occurs within months.

Treatment

Overview

بورد عراقي

)

دكتوراه

(

في الطب الباطني

بورد عربي

)

دكتوراه

(

في الطب الباطني

بورد عراقي

)

دكتوراه

(

اختصاص دقيق في أمراض

وقسطرة القلب والشرايين

Treatment

Overview

Goals of therapy

Lifestyle modification

Pharmacologic treatment

• Algorithm for treatment of hypertension

"The Goal is to Get to Goal!”

Hypertension

-PLUS-

Diabetes or Renal Disease

< 140/90 mmHg

< 130/80 mmHg

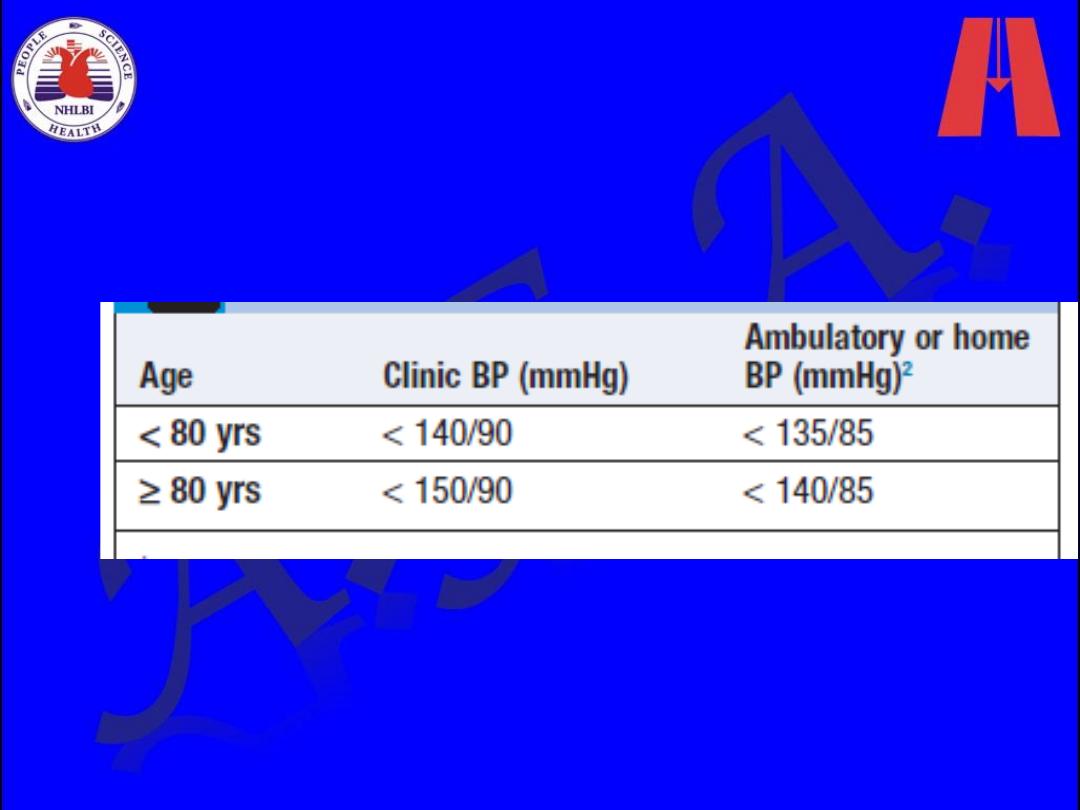

Measurements and goals

should be provided to the

patient verbally and in writing

at each office visit

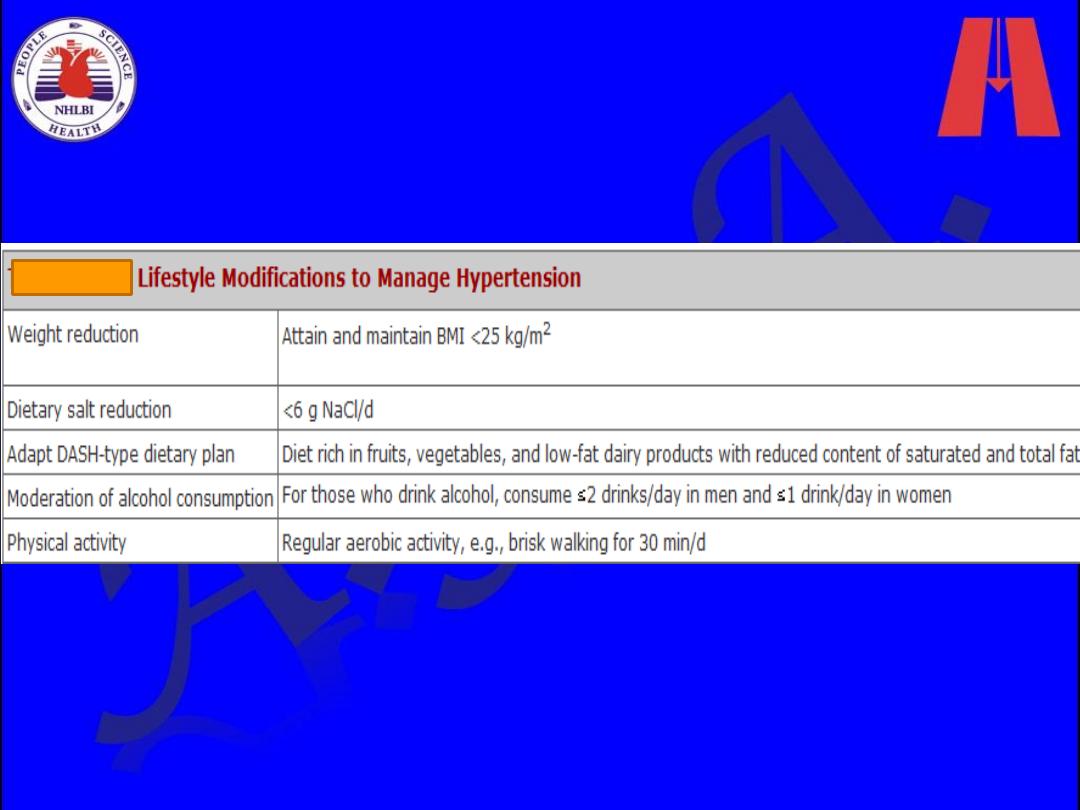

Lifestyle Interventions

• Implementation of lifestyles that

favorably affect blood pressure has

implications for both the prevention and

the treatment of hypertension.

• Health-promoting lifestyle modifications

are recommended for individuals with

prehypertension and as an adjunct to

drug therapy in hypertensive individuals.

Lifestyle Modification

Modification

Approximate SBP reduction

(range)

Weight reduction

5–20 mmHg/10 kg weight loss

Adopt DASH eating plan

8–14 mmHg

Dietary sodium reduction

2–8 mmHg

Physical activity

4–9 mmHg

Moderation of alcohol

consumption

2–4 mmHg

Dietary

Approaches to

Stop

Hypertension

• Lowers systolic BP

– in normotensive

patients by an

average of 3.5 mm

Hg

– In hypertensive

patients by 11.4 mm

Hg

• Copies available

from NHLBI website

http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/hbp/dash/

DASH Eating Plan

• Low in saturated fat, cholesterol, and total fat

• Emphasizes fruits, vegetables, and low fat

diary products

• Reduced red meat, sweets, and sugar

containing beverages

• Rich in magnesium, potassium, calcium,

protein, and fiber

• 3 -1.5 g sodium per day

• Can reduce BP in 2 weeks

Sacks FM. NEJM. 2001; 344:3-10.

Sample Menu

• Breakfast

– 1 whole-wheat bagel

– 2 tablespoons peanut butter

– 1 medium orange

– 1 cup fat-free milk

– Decaffeinated coffee

• Lunch

– Spinach salad made with 4 cups of fresh spinach leaves, 1 sliced pear,

1/2 cup mandarin orange sections, 1/3 cup unsalted peanuts and 2

tablespoons reduced-fat red wine vinaigrette

– 12 reduced-sodium wheat crackers

– 1 cup fat-free milk

• Dinner

– Herb crusted baked cod

– 1 cup bulgur

– 1/2 cup fresh green beans, steamed

– 1 sourdough roll with 1 teaspoon trans-free margarine

– 1 cup fresh berries with chopped mint

– Herbal iced tea

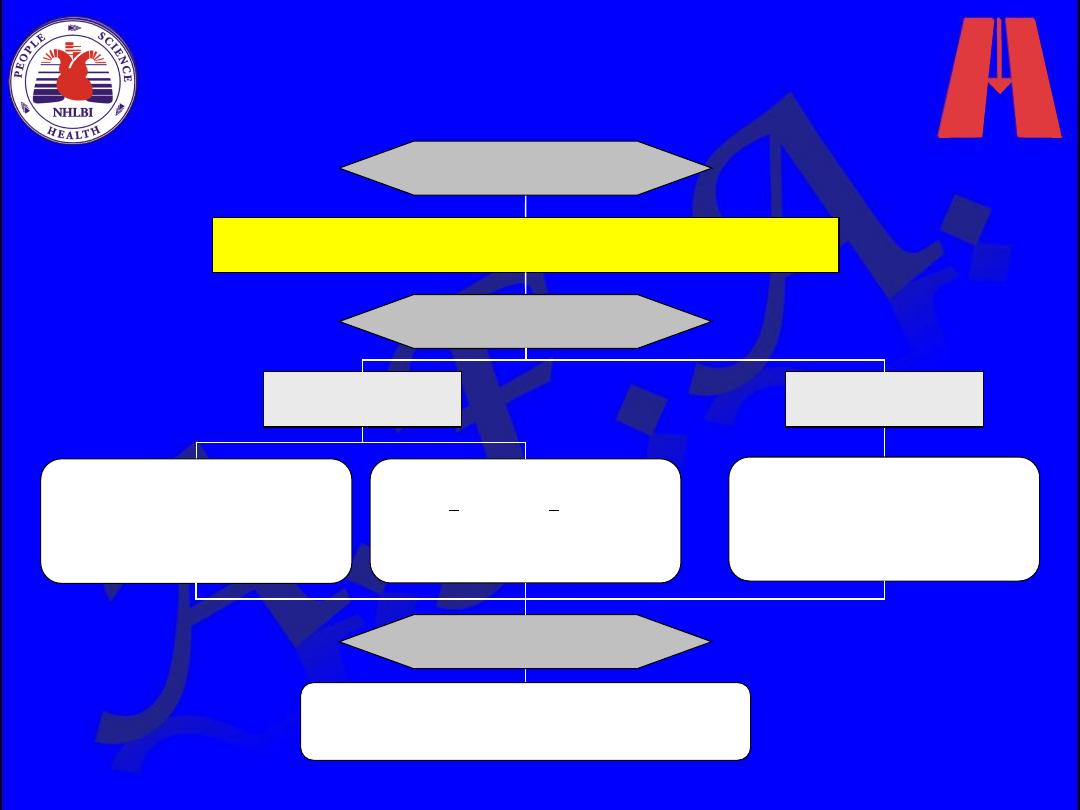

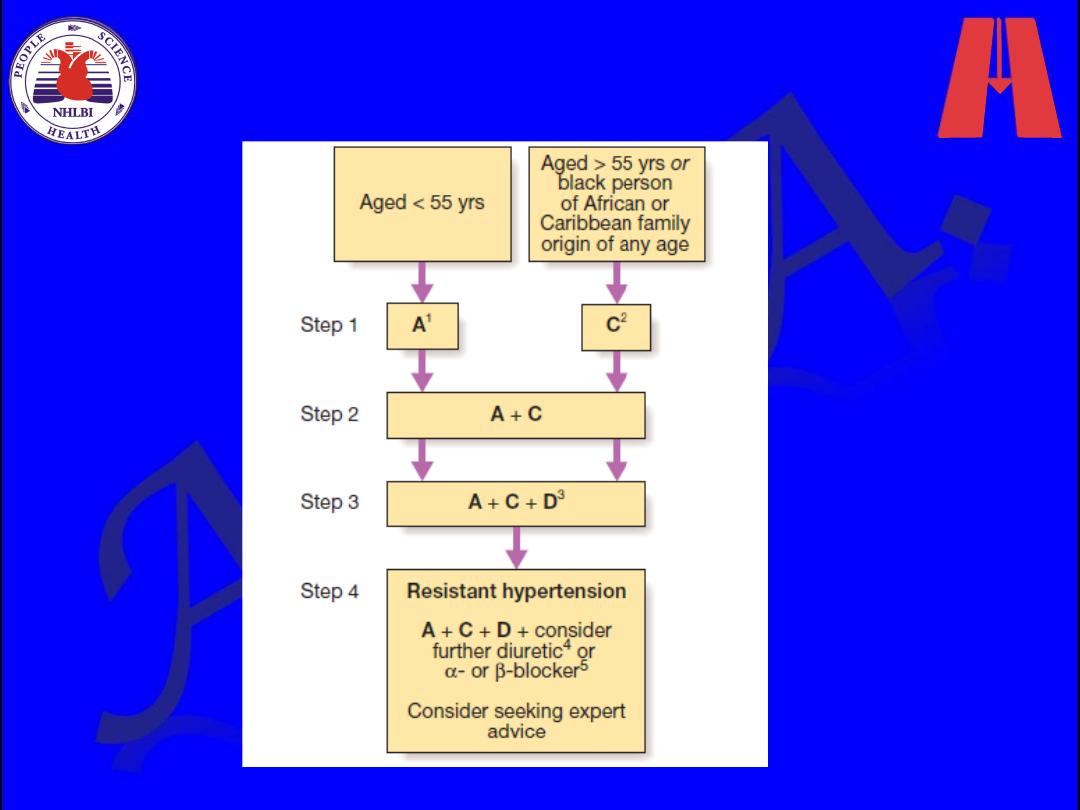

Algorithm for Treatment of Hypertension

Not at Goal Blood Pressure (<140/90 mmHg)

(<130/80 mmHg for those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease)

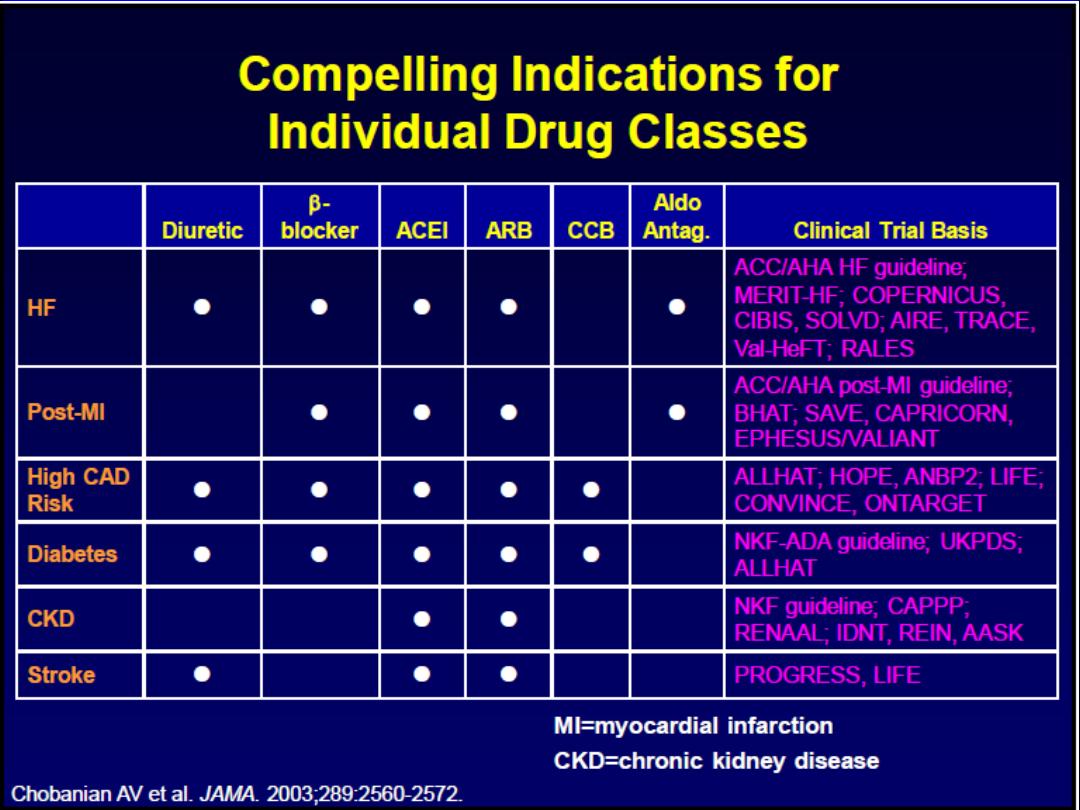

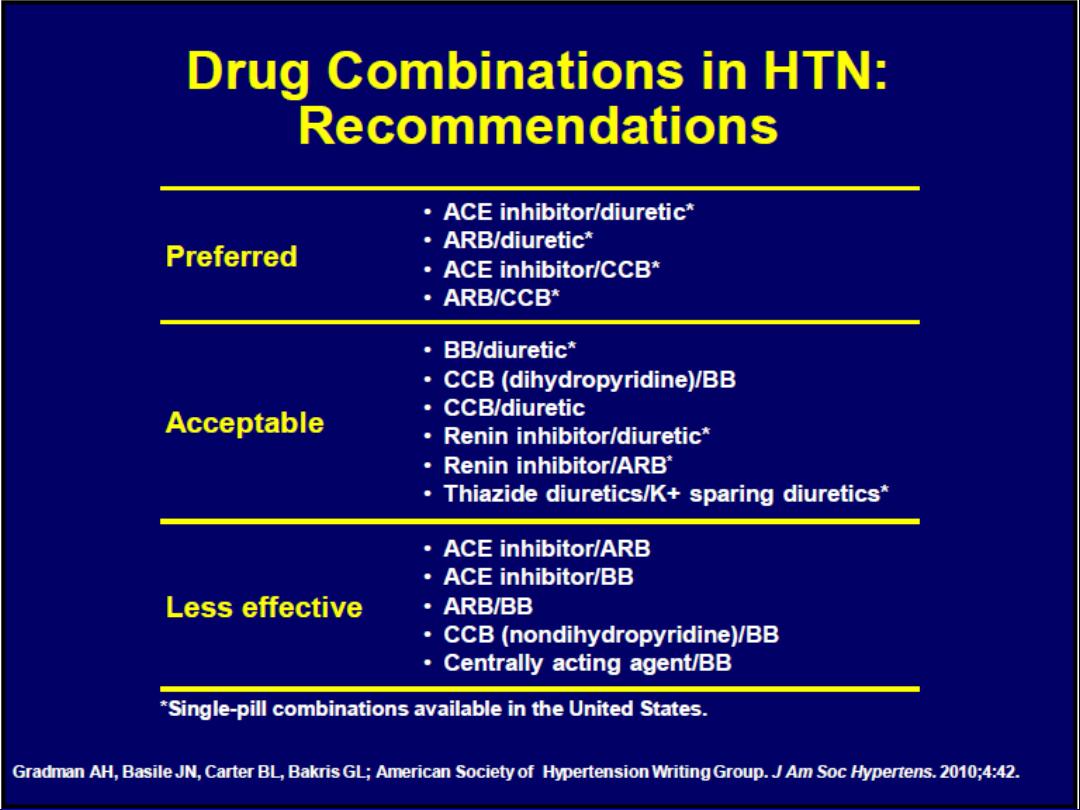

Initial Drug Choices

Drug(s) for the compelling

indications

Other antihypertensive drugs

(diuretics, ACEI, ARB, BB, CCB)

as needed.

With Compelling

Indications

Lifestyle Modifications

Stage 2 Hypertension

(SBP >160 or DBP >100 mmHg)

2-drug combination for most

Stage 1 Hypertension

(SBP 140

–159 or DBP 90–99 mmHg)

Thiazide-type diuretics , ACEI, ARB,

BB, CCB,

or combination.

Without Compelling

Indications

Not at Goal

Blood Pressure

Optimize dosages or add additional drugs

until goal blood pressure is achieved.

Consider consultation with hypertension specialist.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Drug therapy is recommended for individuals with blood

pressures 140/90 mmHg. The degree of benefit derived

from antihypertensive agents is related to the

magnitude of the blood pressure reduction.

Benefits of Lowering BP

Average Percent Reduction

Stroke incidence

35–40%

Myocardial infarction

20–25%

Heart failure

50%

Lowering systolic blood pressure by 10–12 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 5–6

mmHg

Diuretics

Low-dose thiazide diuretics often were previously used as first-line agents

alone or in combination with other antihypertensive drugs.

Thiazides inhibit the Na

+

/Cl

–

pump in the distal convoluted tubule and hence

increase sodium excretion.

In the long term, they also may act as vasodilators.

Thiazides are safe, efficacious, inexpensive, and reduce clinical events.

They provide additive blood pressure–lowering effects when combined with

beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), or

angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

In contrast, addition of a diuretic to a calcium channel blocker is less effective.

Drugs recommended

• Indapamide 1.5 mg

• Chlorthalidone 6.25-50 mg/dl

Owing to an increased incidence of metabolic side effects (hypokalemia,

insulin resistance, increased cholesterol), higher doses generally are not

recommended.

Indications:

• HF

• Stroke

Loop diuretics generally are reserved for hypertensive

patients with

• reduced glomerular filtration rates [reflected in

serum creatinine >220 mol/L (>2.5 mg/dL)],

• CHF,

• or sodium retention and edema

Low-dose eplerenone (6.25 to 25 mg/day) or spironolactone

(6.25 to 12.5 mg/day) can be effective in treatment of primary

hypertension, particularly low-renin hypertension in African

Americans.

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

These inhibit the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II and are

usually well tolerated.

They are particularly useful in diabetics with nephropathy, where they

have been shown to slow disease progression, and in those patients

with symptomatic or asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, where

they have been shown to improve survival.

Electrolytes and creatinine should be checked before and 1-2 weeks

after commencing therapy.

Side-effects include first-dose hypotension, cough, rash,

hyperkalaemia and renal dysfunction.

• The most common side effect of ACE inhibitors is a dry

cough. Patients may complain not of a cough but rather of

having to clear the throat or loss of voice later in the day.

These symptoms occur in 3 to 39% of patients, resolve in a

few days after the drug is discontinued, and can be

eliminated by switching the patient to an ARB. The incidence

is higher in African Americans than in whites and is highest in

Asians.

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists

This group of agents selectively block the receptors for

angiotensin II. They share many of the actions of ACE

inhibitors but, since they do not have any effect on

bradykinin, do not cause a cough. They are currently

used for patients who cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors

because of persistent cough.

Angioneurotic oedema and renal dysfunction are

encountered less with these drugs than with ACE

inhibitors.

Indications of both:

• HF

• MI

• Diabetes

• CKD

• Stroke

Beta-adrenoceptor blockers

B-Adrenergic receptor blockers lower blood pressure by

decreasing cardiac output, due to a reduction of heart

rate and contractility.

They are no longer a preferred initial therapy for

hypertension.

Indications:

• Angina

• MI

• HF

• Tachycardia

The major side-effects of this class of agents are

bradycardia, bronchospasm, cold extremities, fatigue,

bad dreams and hallucinations.

Atenolol has been shown to reduce brachial arterial

pressure but not aortic pressure, which is more

significant in causing strokes and heart attacks. Atenolol

is now not a preferred drug for hypertension.

Calcium-channel blockers

These agents effectively reduce blood pressure by

causing arteriolar dilatation, and some also reduce the

force of cardiac contraction. Like the beta-blockers, they

are especially useful in patients with concomitant

ischaemic heart disease.

The major side-effects are particularly seen with the

short-acting agents and include headache, sweating,

swelling of the ankles, palpitations and flushing.

Indications:

• Angina

Alpha-blockers

By blocking the interaction of norepinephrine on

vascular α-adrenergic receptors, these drugs cause

peripheral vasodilation, thereby lowering blood

pressure.

they are effective third- or fourth-line therapy for difficult

hypertension and are particularly useful in older men

with prostatism.

Indications:

• Prostatism

• Phenoxybenzamine remains the drug of choice for preoperative

management of pheochromocytoma

Renin inhibitors

Aliskerin is the first orally active renin inhibitor which

directly inhibits plasma renin activity: it reduces the

negative feedback by which angiotensin II inhibits renin

release.

It has been used in combination with ACE inhibitors and

angiotensin receptor blockers with a significant

reduction in blood pressure. Side-effects are few but

hypokalaemia occurs.

Centrally acting drugs

Reserpine

is used in a low dose of 0.05 mg/day, which

provides almost all its antihypertensive action with fewer

sideeffects than higher doses. It has a slow onset of

action (measured in weeks).

Methyldopa

is still widely used despite central and

potentially serious hepatic and blood side-effects. It acts

on central á2-receptors, usually without slowing the

heart.

Clonidine

provide all the benefits of methyldopa with

none of the rare (but serious) autoimmune reactions.

vasodilators

These include hydralazine (up to 100 mg daily) and

minoxidil (up to 50 mg daily). Both are extremely potent

vasodilators that are reserved for patients resistant to

other forms of treatment.

Hydralazine can be associated with tachycardia, fluid

retention and a systemic lupus erythematosus-like

syndrome.

Minoxidil can cause severe oedema, excessive hair

growth and coarse facial features.

If these agents are used, it is usually in combination

with a beta-blocker.

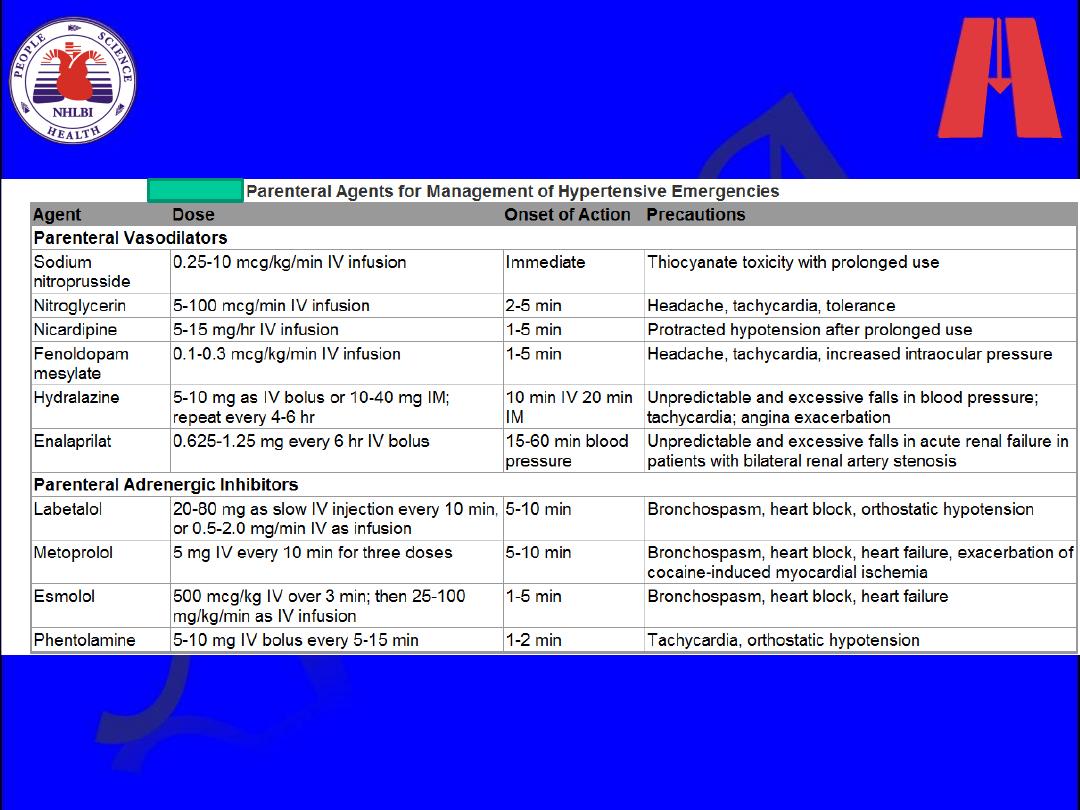

Acute Severe Hypertension

Twenty-five percent of all emergency department patients

present with an elevated blood pressure .

Hypertensive emergencies

are acute, often severe,

elevations in blood pressure, accompanied by acute (or

rapidly progressive) target organ dysfunction, such as

myocardial or cerebral ischemia or infarction, pulmonary

edema, or renal failure.

Hypertensive urgencies

are severe elevations in blood

pressure without severe symptoms and without evidence of

acute or progressive target organ dysfunction. The key

distinction depends on the state of the patient and the

assessment of target organ damage, not just the absolute

level of blood pressure.

The full-blown clinical picture of a hypertensive

emergency is a critically ill patient who presents with a

blood pressure above 220/140 mm Hg, headaches,

confusion, blurred vision, nausea and vomiting,

seizures, pulmonary edema, oliguria, and grade 3 or

grade 4 hypertensive retinopathy .

Hypertensive emergencies require immediate intensive

care unit (ICU) admission for intravenous therapy and

continuous blood pressure monitoring;

In most other hypertensive emergencies, the goal of

parenteral therapy is to achieve a controlled and

gradual lowering of blood pressure.

A good rule of thumb is to lower the initially

elevated arterial pressure by 10% in the first hour

and by an additional 15% during the next 3 to 12

hours to a blood pressure of no less than 160/110

mm Hg. Blood pressure can be reduced further

during the next 48 hours.

hypertensive urgencies often can be managed with oral

medications and appropriate outpatient follow-up in 24

to 72 hours.

Most patients who present to the emergency

department with hypertensive urgencies either are

nonadherent with their medical regimen or are

being treated with an inadequate regimen.

To expedite the necessary changes in medications,

outpatient follow-up should be arranged within 72

hours

Resistant Hypertension

Defined as persistence of usual blood pressure above

140/90 mm Hg despite treatment with full doses of three or

more different classes of medications including a diuretic in

rational combination, resistant hypertension is the most

common reason for referral to a hypertension specialist. In

practice, the problem usually falls into one of four

categories: (1) pseudoresistance, (2) an inadequate medical

regimen, (3) nonadherence or ingestion of pressor

substances, or (4) secondary hypertension.

• Pseudoresistant hypertension is caused by white coat

aggravation

Adjuvant drug therapy

Aspirin.

Antiplatelet therapy is a powerful means of reducing

cardiovascular risk but may cause bleeding, particularly intracerebral

haemorrhage, in a small number of patients. The benefits are thought to

outweigh the risks in hypertensive patients aged 50 or over who have well-

controlled BP and either target organ damage, diabetes or a 10-year

coronary heart disease risk of ≥ 15% (or 10-year cardiovascular disease

risk of ≥ 20%).

Statins.

Treating hyperlipidaemia can produce a substantial reduction in

cardiovascular risk. These drugs are strongly indicated in patients who

have established vascular disease, or hypertension with a high (≥ 20% in

10 years) risk of developing cardiovascular disease