Saadeldeen majeed

Professor of cardiology and internal medicine

Power point 1

4

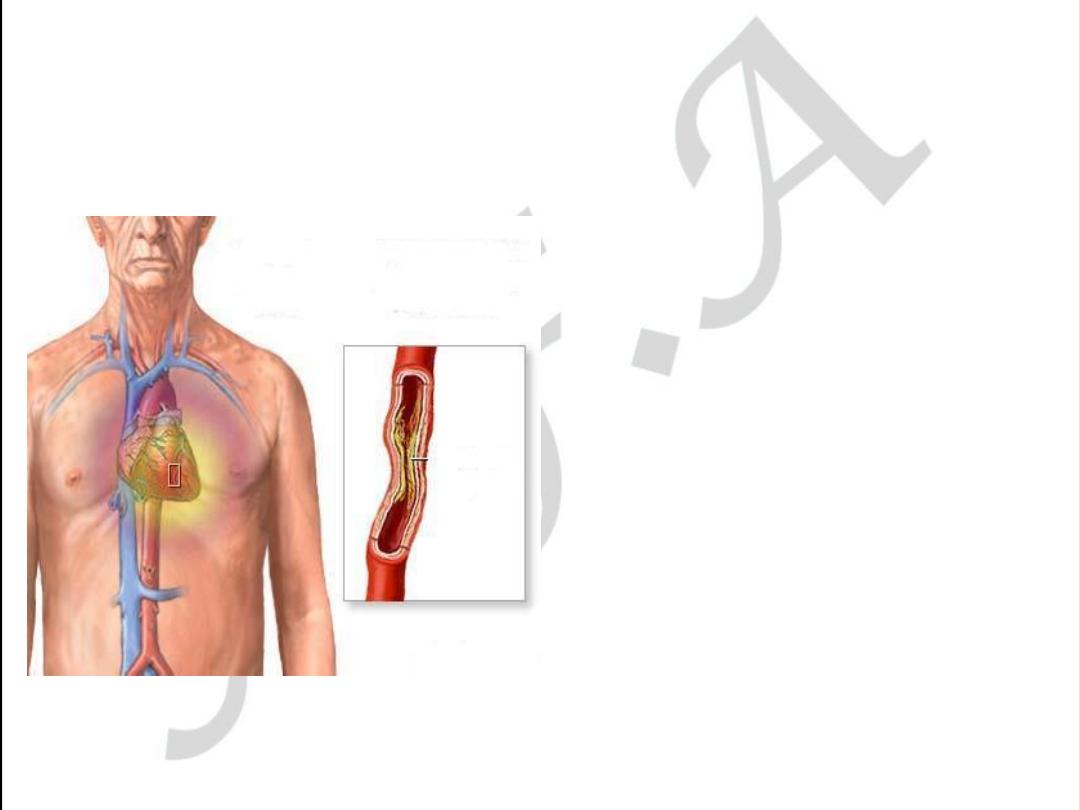

Aortic form of atherosclerosis

Various forms of aorta lesion

What Does It Look Like?

•

The coronary

artery is narrowed

reducing the flow

of oxygen to the

heart.

•

It is easier for

plaque to get

inside a narrower

artery.

6

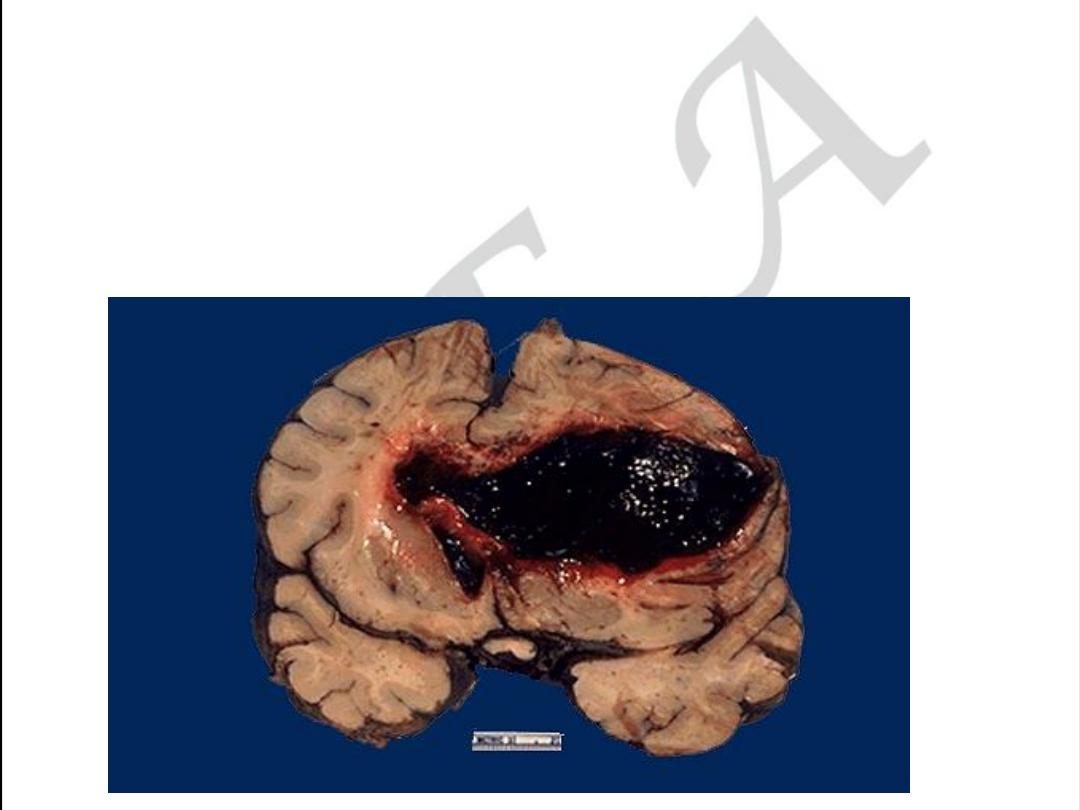

CEREBRAL FORM OF ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Acute form may be as Hemorrhage within

The brain due to rupture

Of atherosclerotic aneurism

7

CEREBRAL FORM OF ATHEROSCLEROSIS

• Chronic form may be as encephalopathy

With cerebral atrophy (decreasing memory)

9

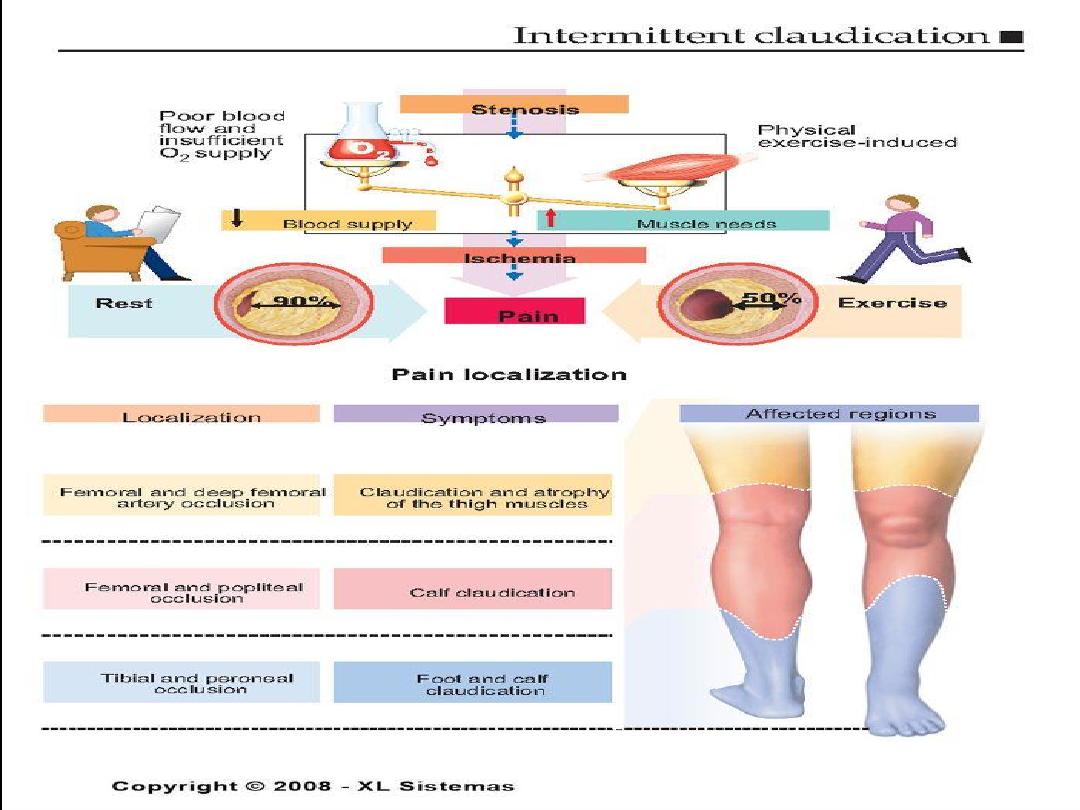

Extremity form of atherosclerosis

• Acute form may be as gangrenous necrosis.

10

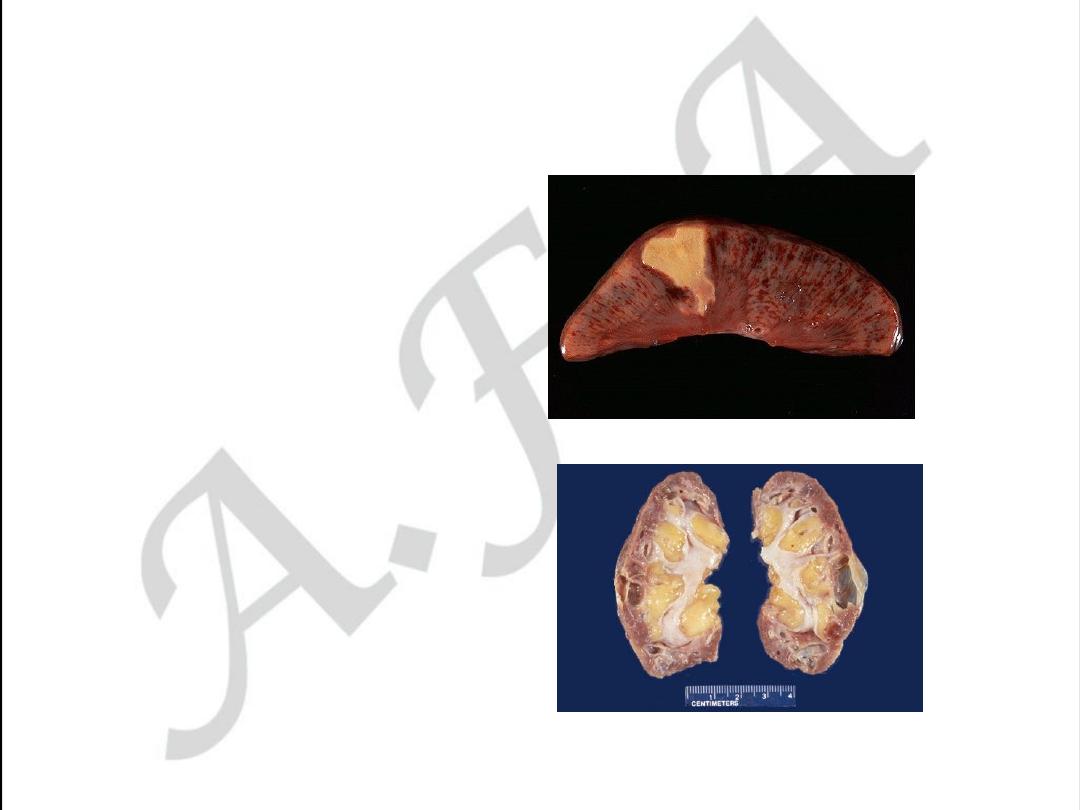

RENAL FORM OF ATHEROSCLEROSIS

• Acute form may be as

infarction

• Chronic form is called

Atherosclerotic

Nephrosclerosis or

Primary contracted

kidney

11

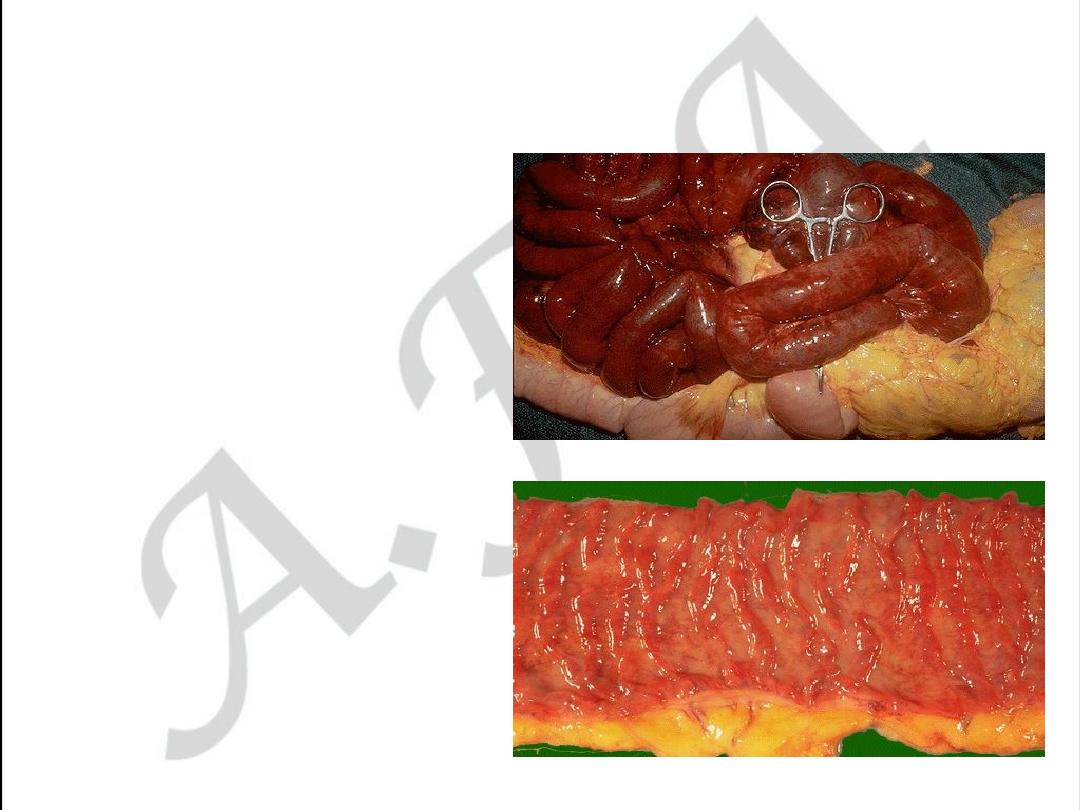

Intestinal form of atherosclerosis

• Acute form may be as

gangrenous necrosis of

the intestine

• Chronic form may be as

ischemic enterocolitis

13

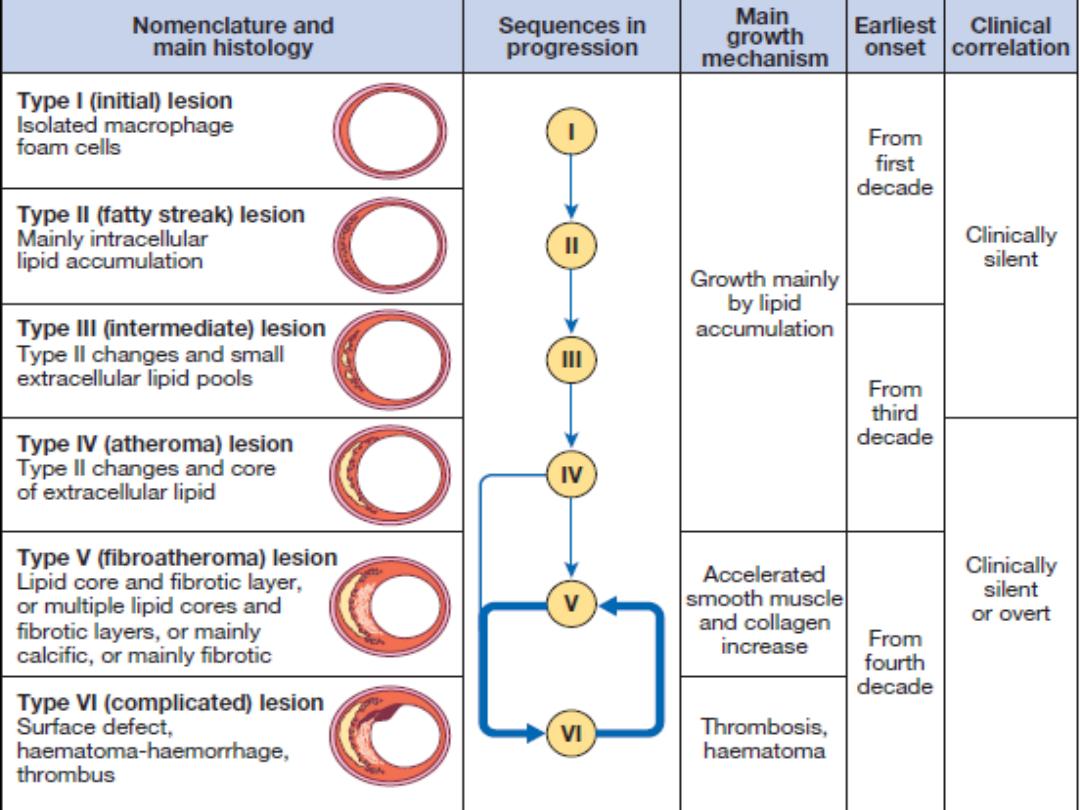

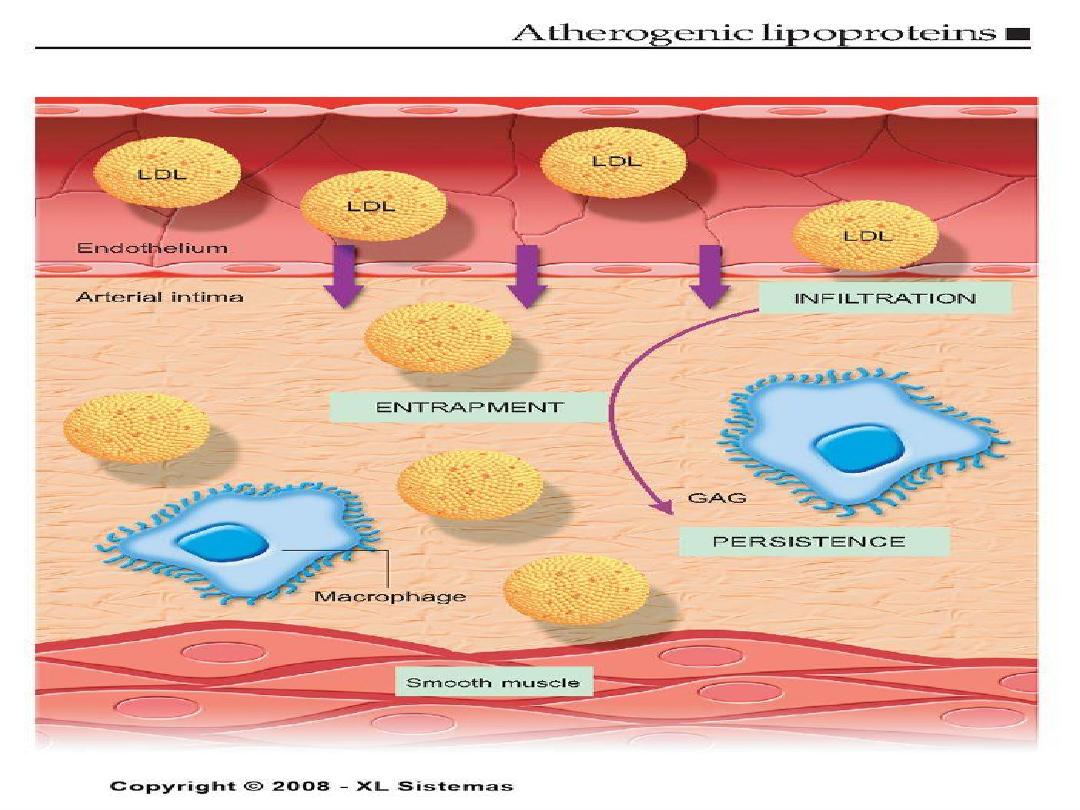

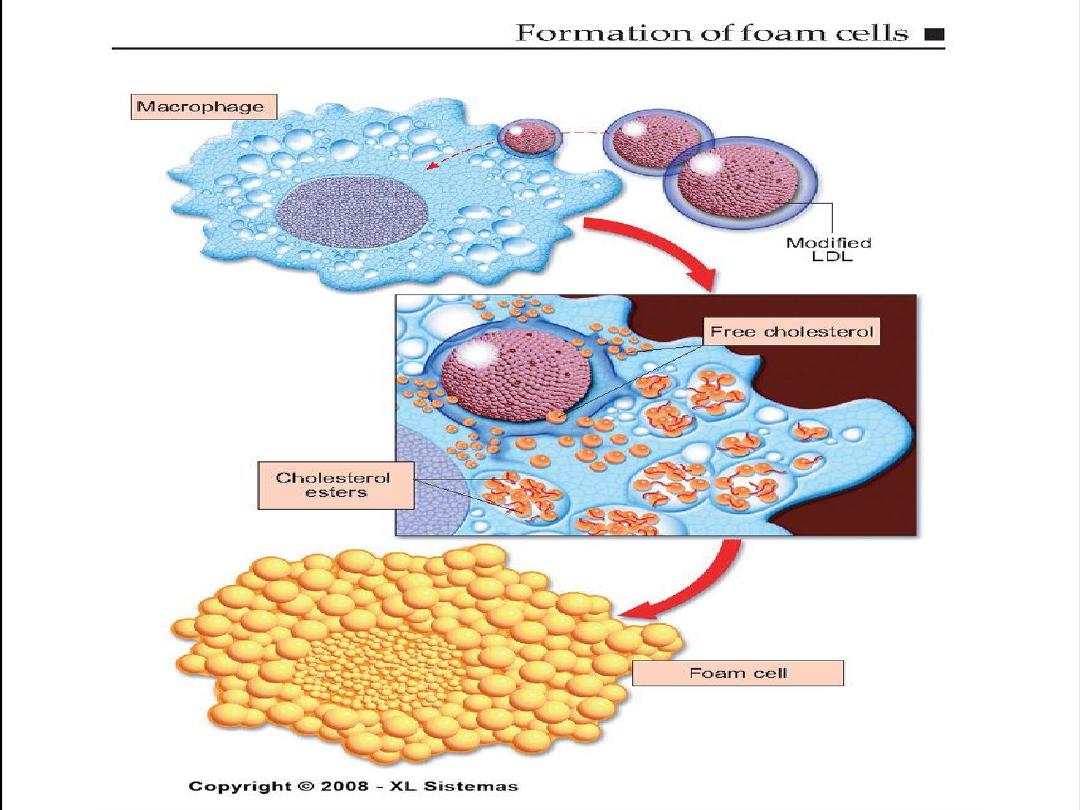

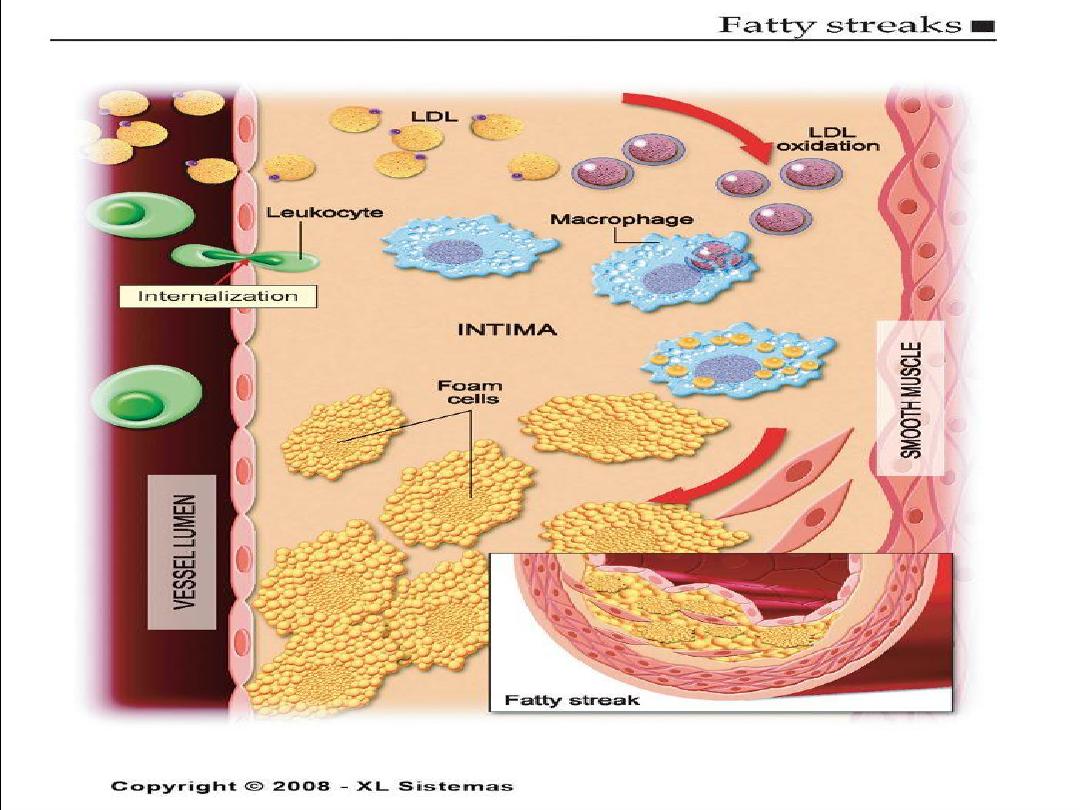

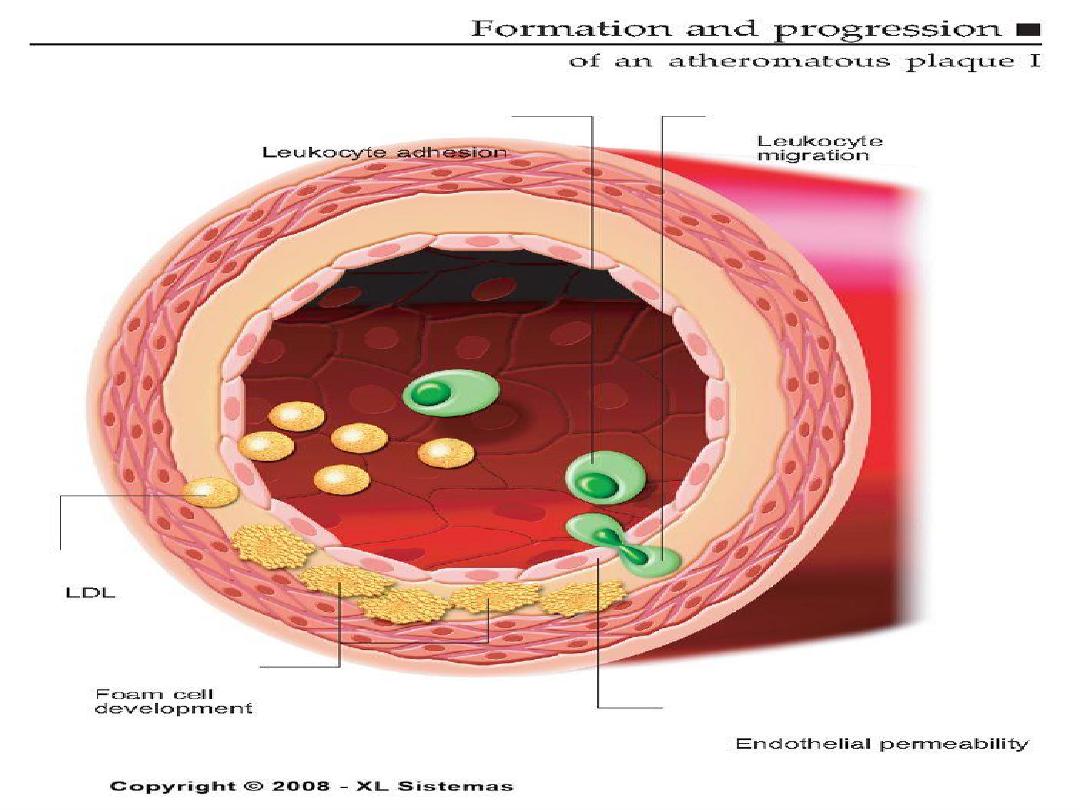

Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis

• According to injury hypothesis

considers atherosclerosis to be a

chronic inflammatory response of the

arterial wall initiated by injury:

14

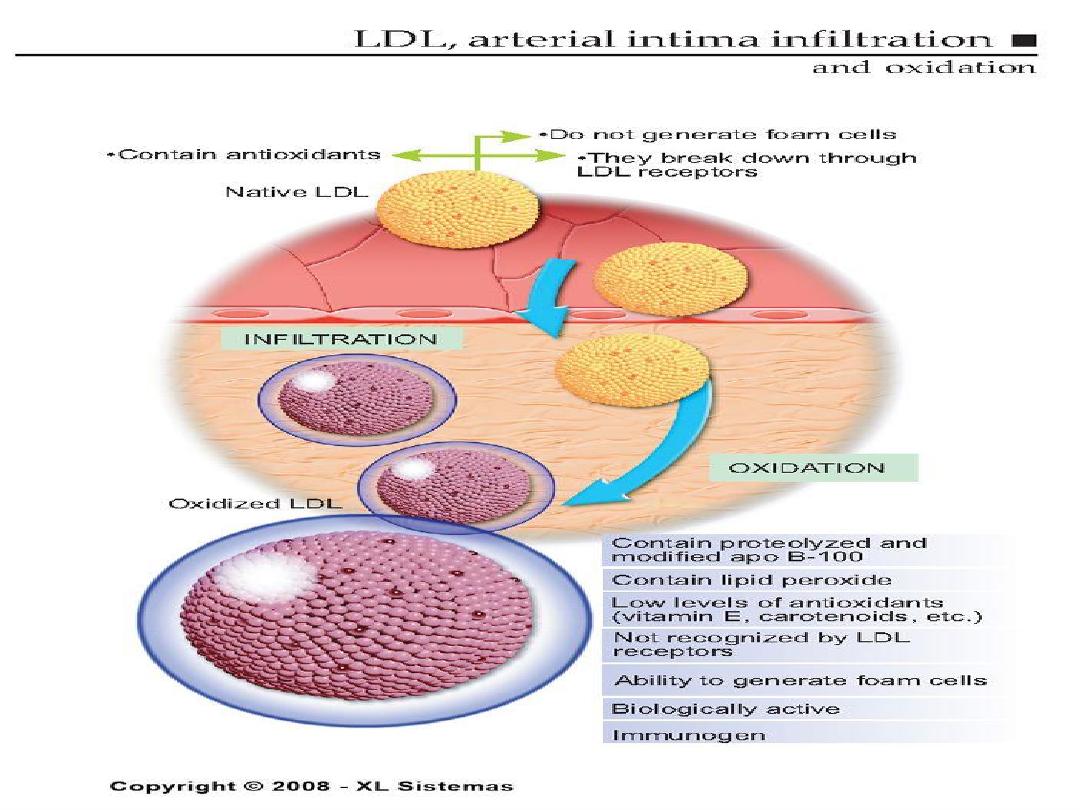

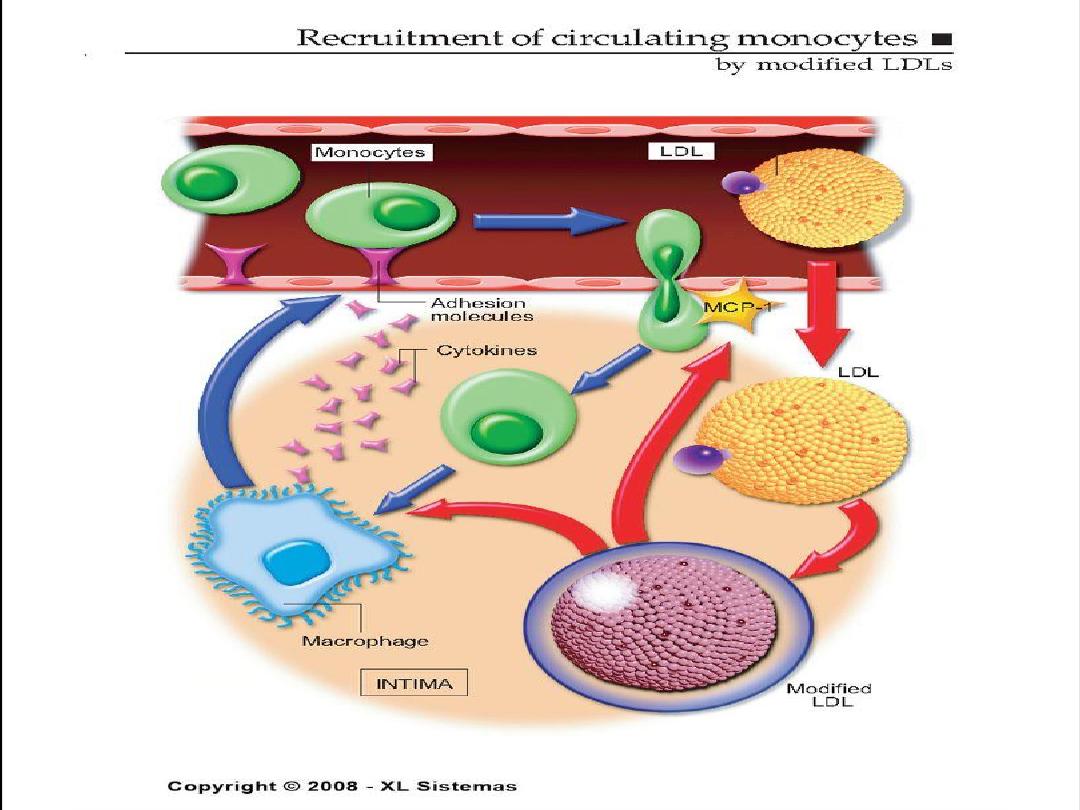

Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis

1.

Chronic endothelial injury.

2 .Insudation of lipoproteins [LDL].

3. Modification of lipoproteins by

oxidation.

4. Adhesion of blood monocytes.

5. Adhesion of platelets.

15

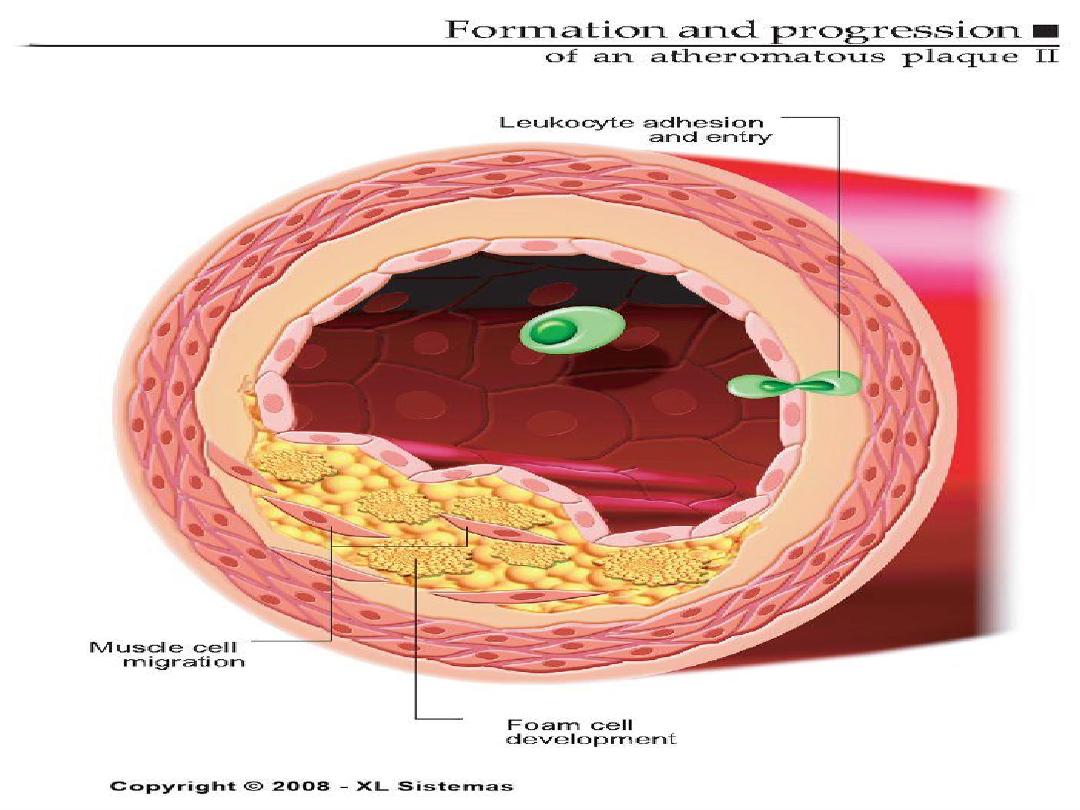

Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis

6. migration of smooth muscle cells

from the media into the intima.

7. proliferation of smooth muscle cells

in the intima.

8. enhanced accumulation of intra and

extra cellular lipids.

16

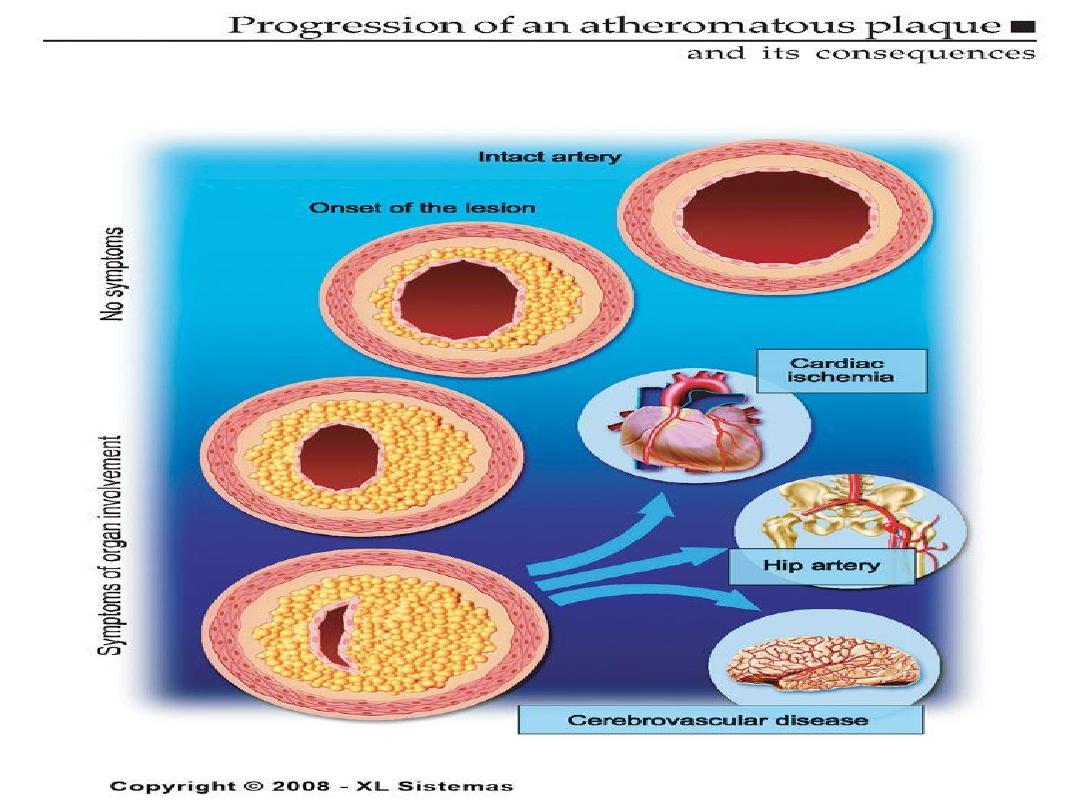

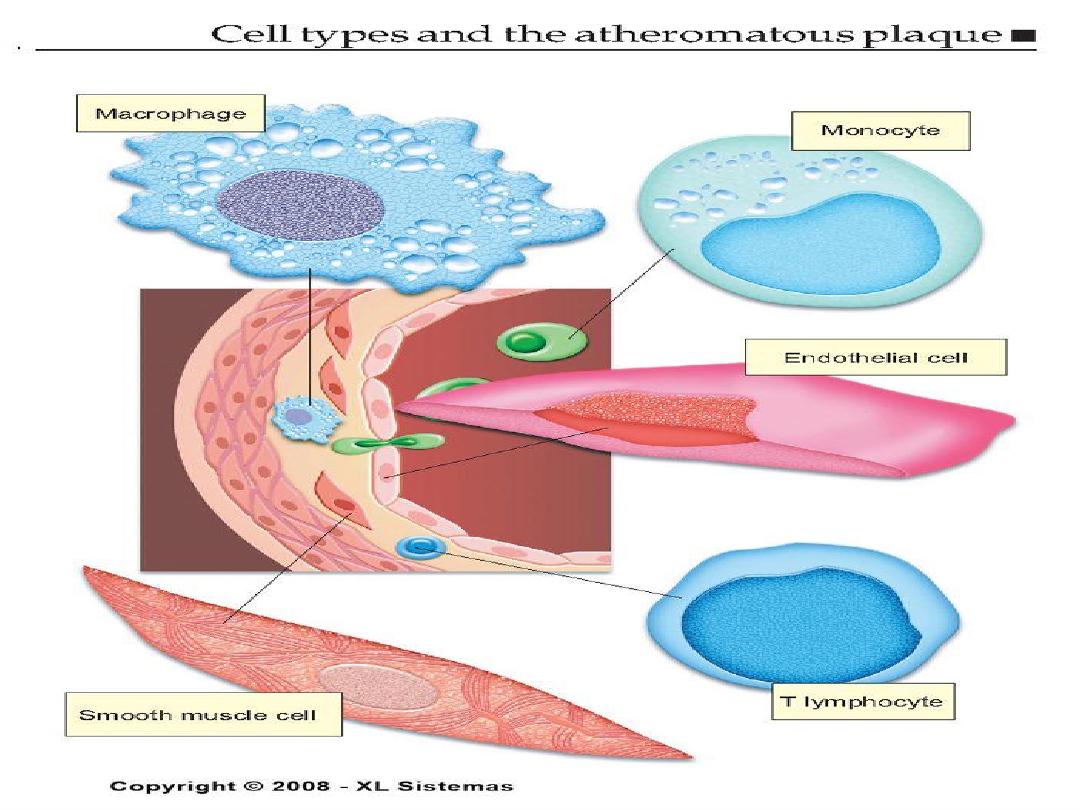

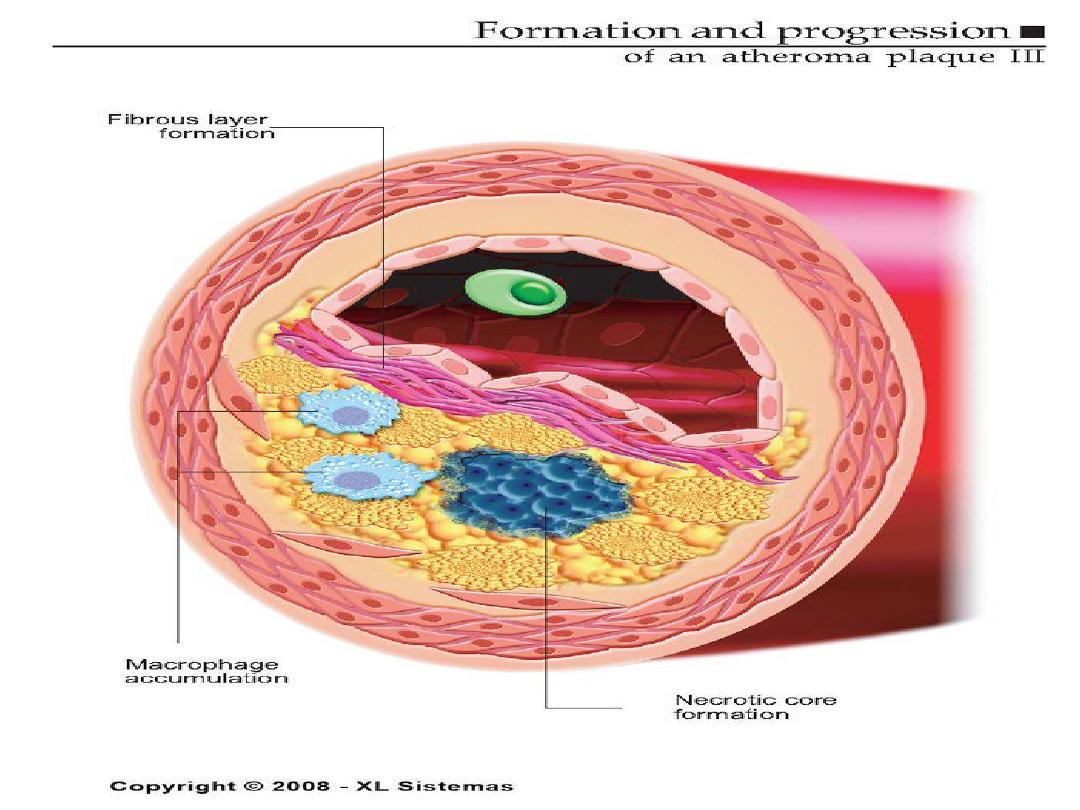

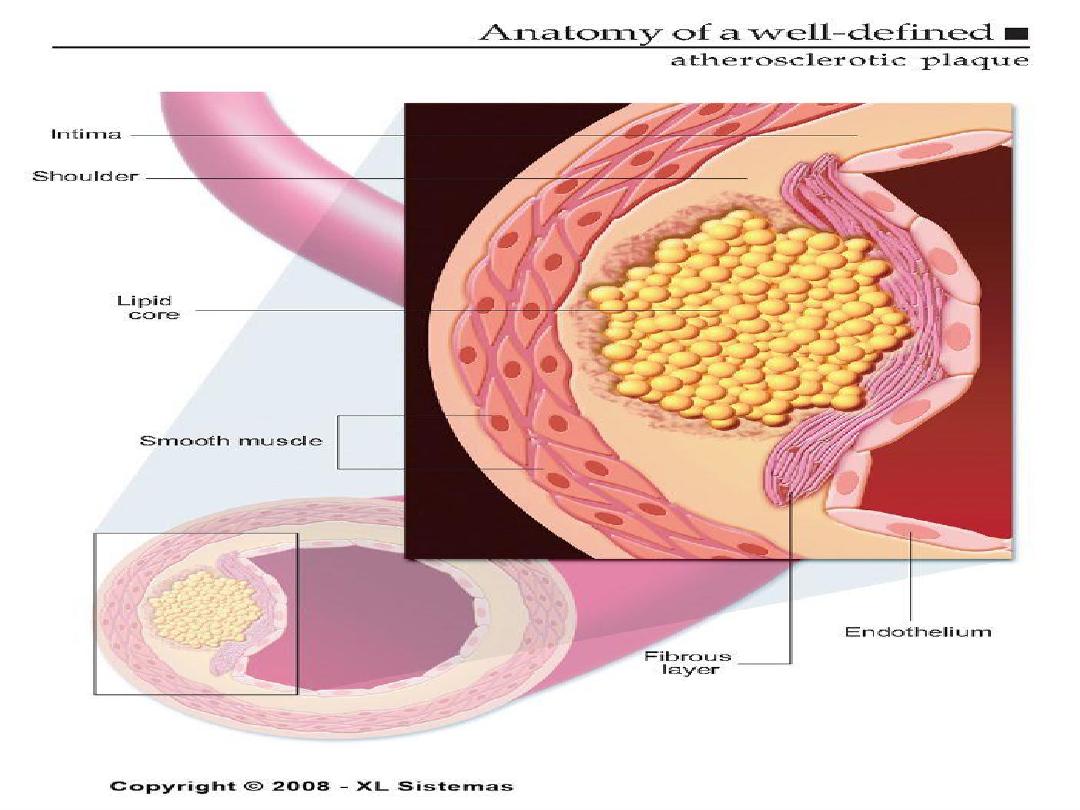

ATHEROSCLEROTIC PLAQUE

• The change of the large arterial intima is

called atherosclerotic plaque or

atheroma

•

atherosclerotic plaque is the intimal

thickening with lipid accumulation

• It consists of fibrous cap, necrotic core and

fibrous basis.

17

Atherosclerotic plaque

•

It has three principle components:

1- cells –smooth muscle cells, macrophages,

other leukocytes.

2 - Extra cellular matrix- collagen, elastic fibers,

and proteoglycans.

3 - Intra cellular and extra cellular lipids.

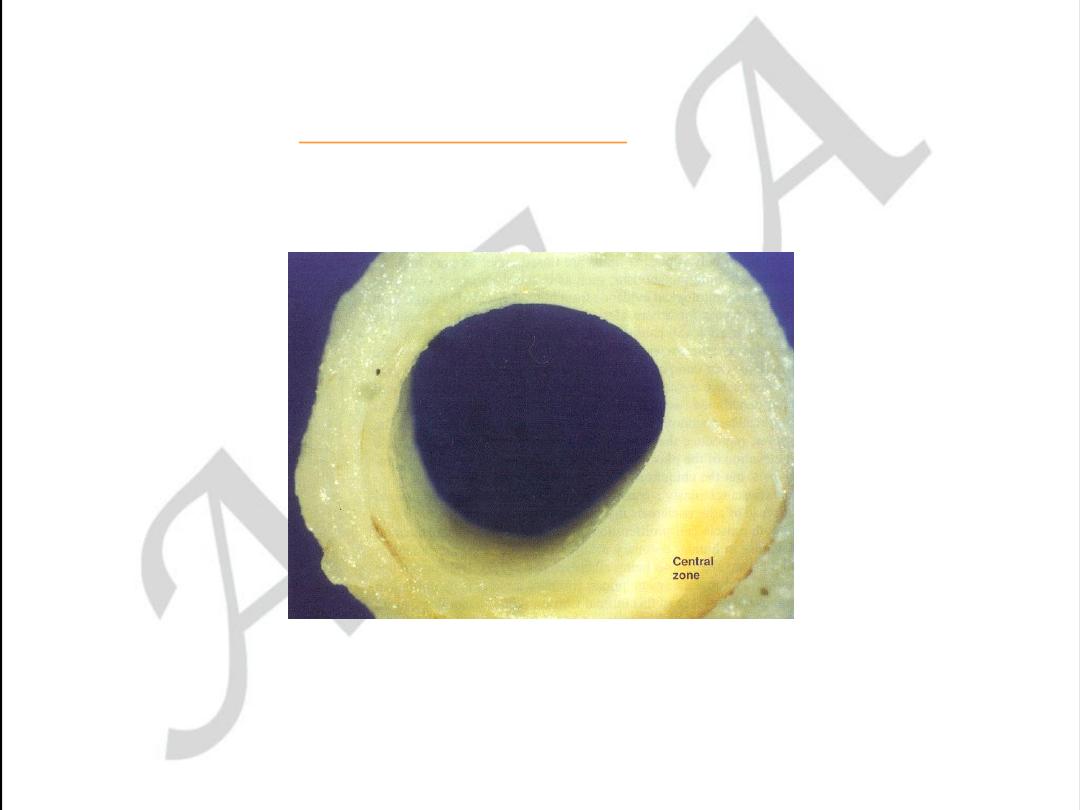

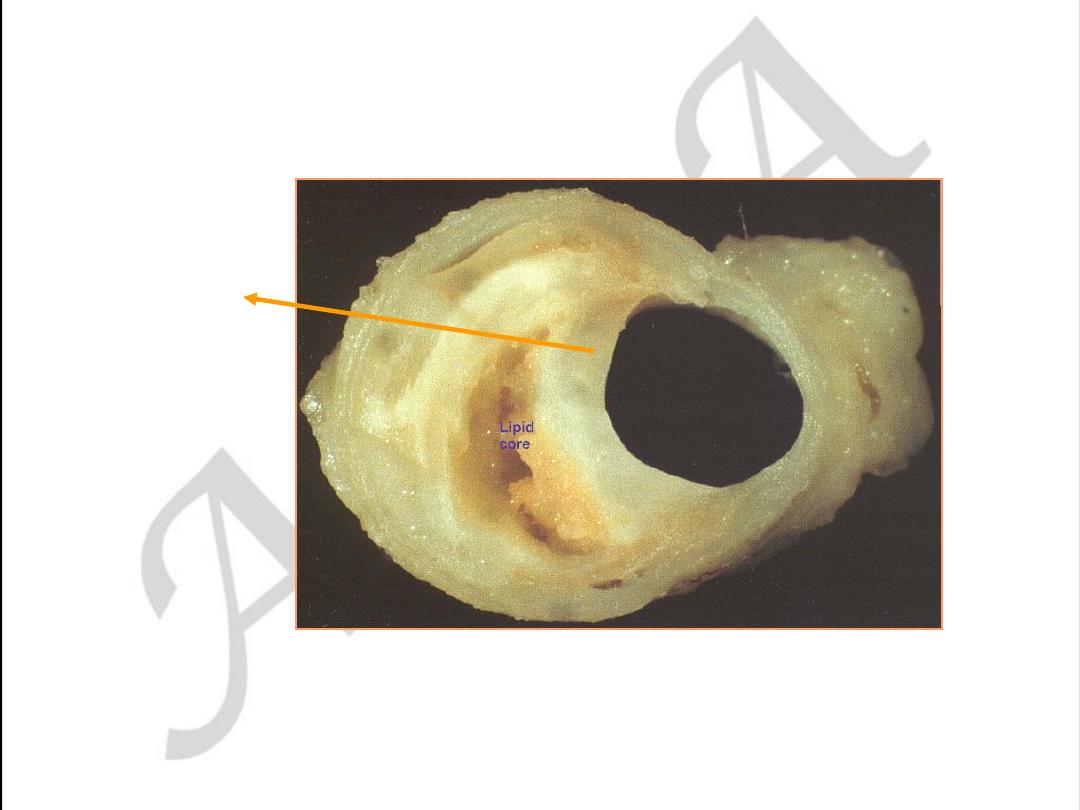

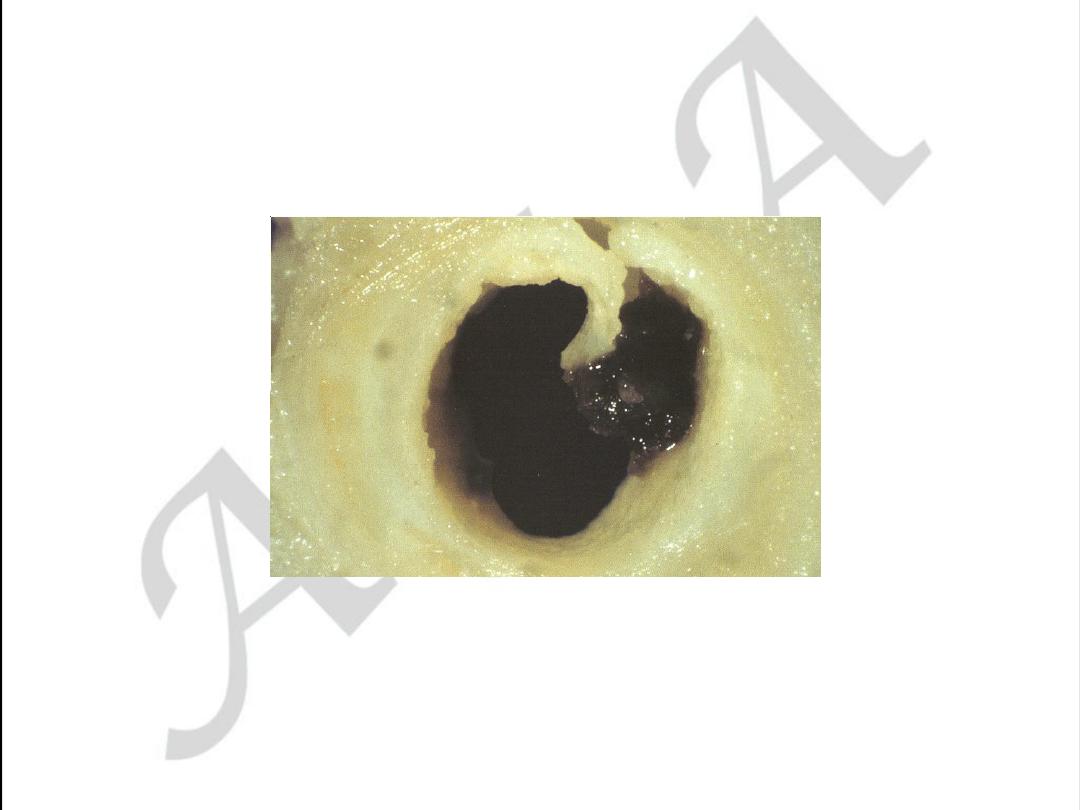

Normal coronary artery

Lumen has been distended at a pressure of 100mmHg

with 10% formal saline

used with permission from

M.J. Davies

Atlas of Coronary Artery Disease 1998

Lippincott-Raven Publishers

used with permission from

M.J. Davies

Atlas of Coronary Artery Disease 1998

Lippincott-Raven Publishers

Early coronary atherosclerosis

Eccentric plaque with a central zone

containing yellow lipid

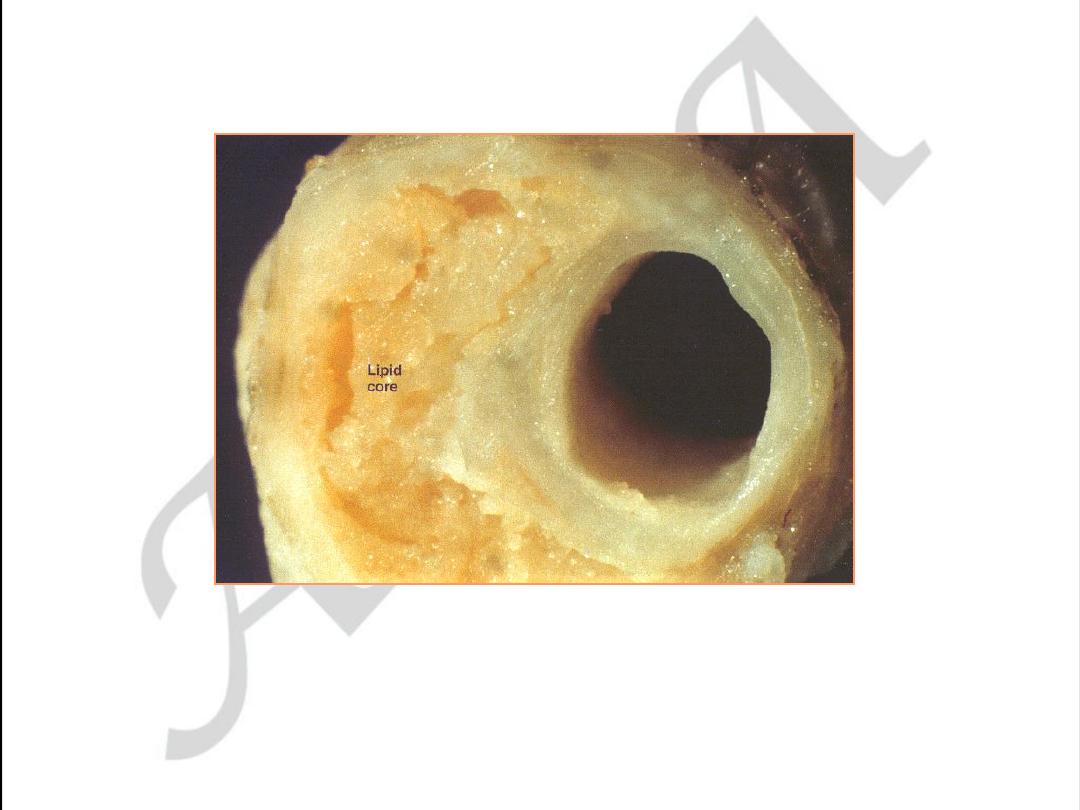

Stable angina. Eccentric coronary stenosis

used with permission from

M.J. Davies

Atlas of Coronary Artery Disease 1998

Lippincott-Raven Publishers

Stable angina. Eccentric coronary stenosis

used with permission from M.J. Davies

Atlas of Coronary Artery Disease 1998

Lippincott-Raven Publishers

thick cap

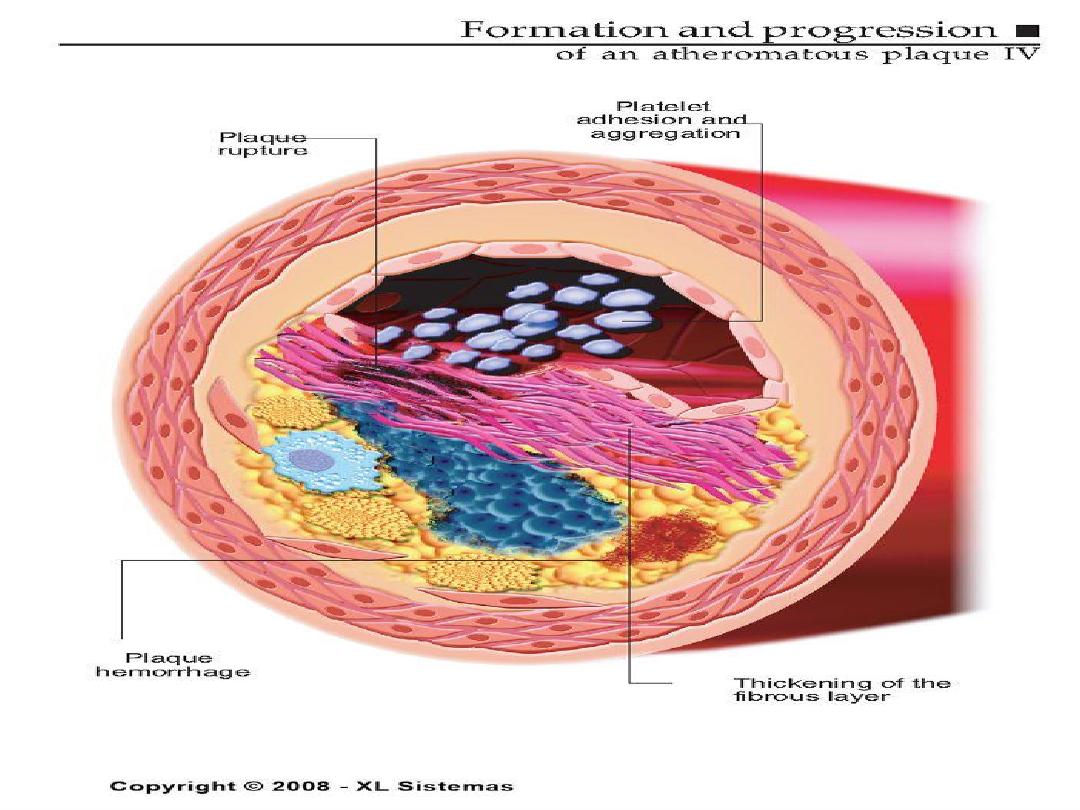

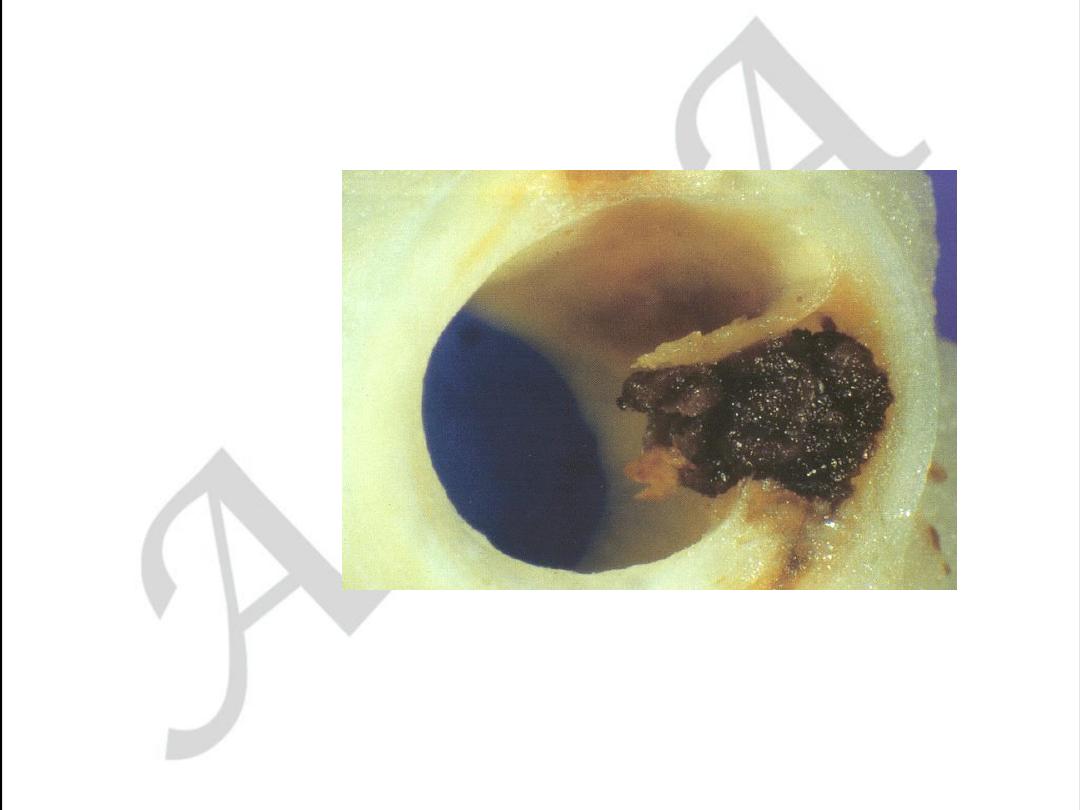

Unstable angina with

plaque disruption

used with permission from M.J. Davies

Atlas of Coronary Artery Disease 1998

Lippincott-Raven Publishers

Unstable angina with plaque disruption

used with permission from

M.J. Davies

Atlas of Coronary Artery Disease 1998

Lippincott-Raven Publishers

The plaque cap is torn,

projects into the

lumen, exposing a

mass of thrombus

filling the lipid core

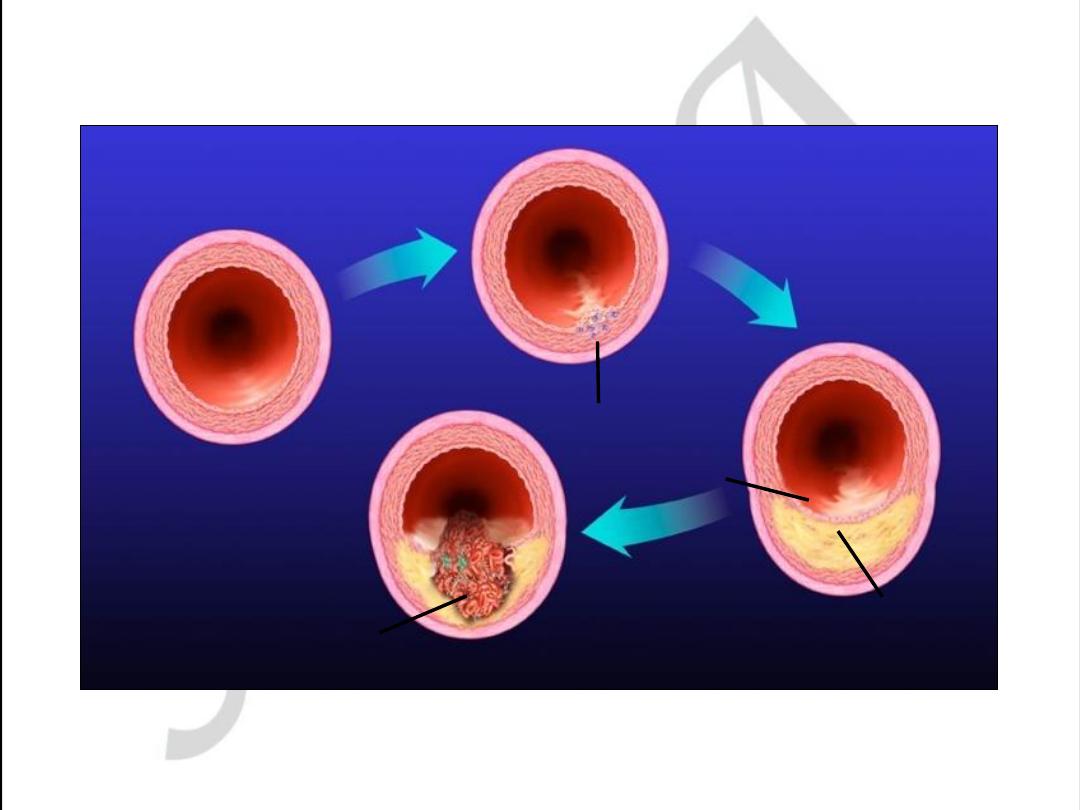

Development of Atherosclerotic Plaques

Normal

Fatty streak

Foam cells

Lipid-rich plaque

Lipid core

Fibrous cap

Thrombus

Ross R.

Nature.

1993;362:801-809.

Libby P.

Circulation.

1995;91:2844-2850.

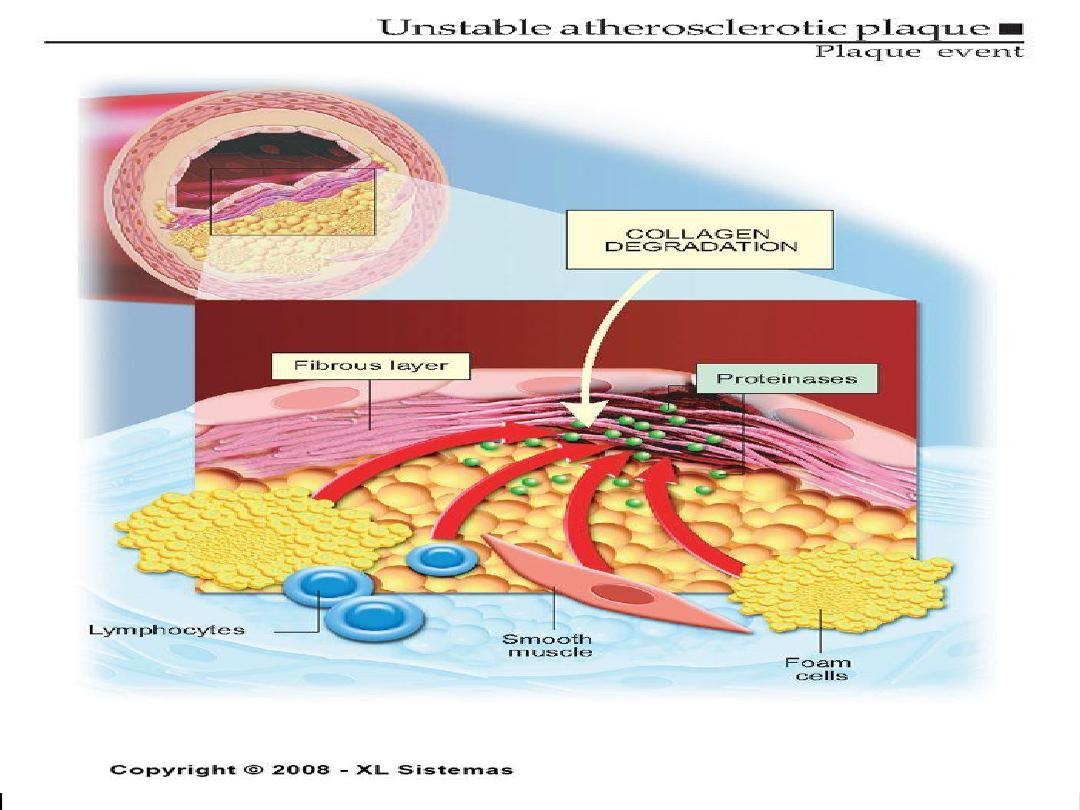

Vulnerable Plaque

• Thin fibrous cap

• Inflammatory cell infiltrates:

proteolytic activity

• Lipid-rich plaque

Lumen

Lipid

Core

Fibrous Cap

• Thick fibrous cap

• Smooth muscle cells:

more extracellular matrix

• Lipid-poor plaque

Stable Plaque

Lumen

Lipid

Core

Fibrous Cap

Vulnerable Versus Stable

Atherosclerotic Plaques

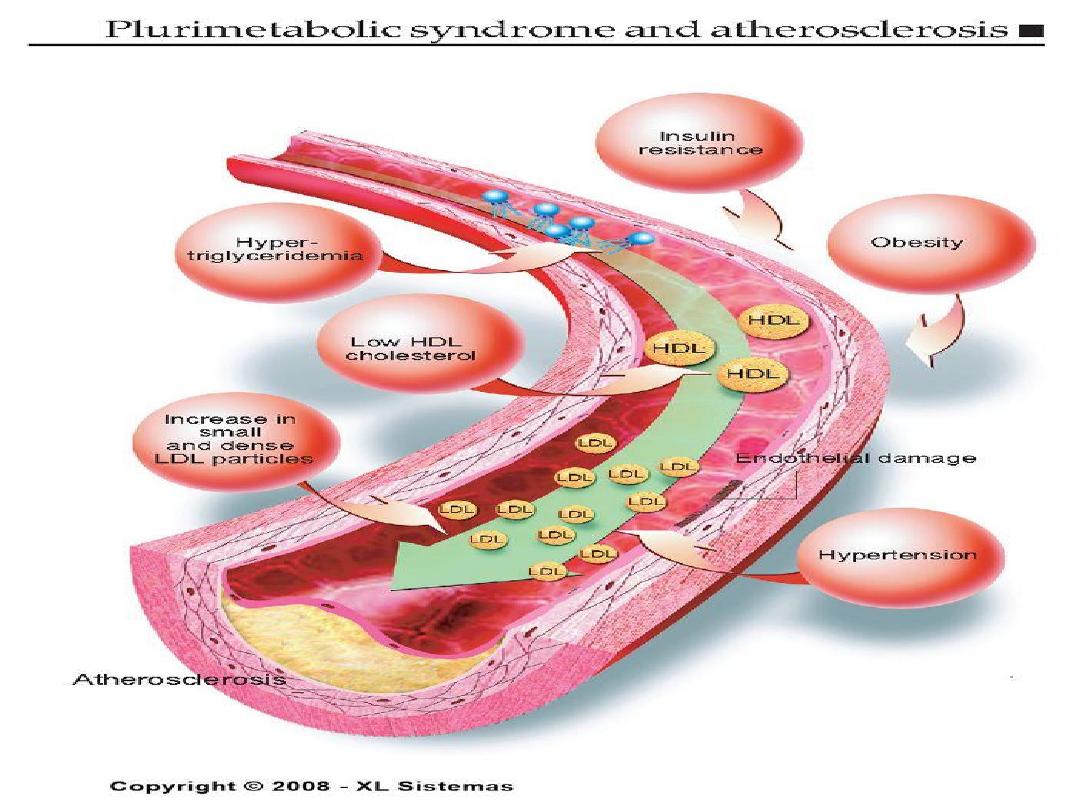

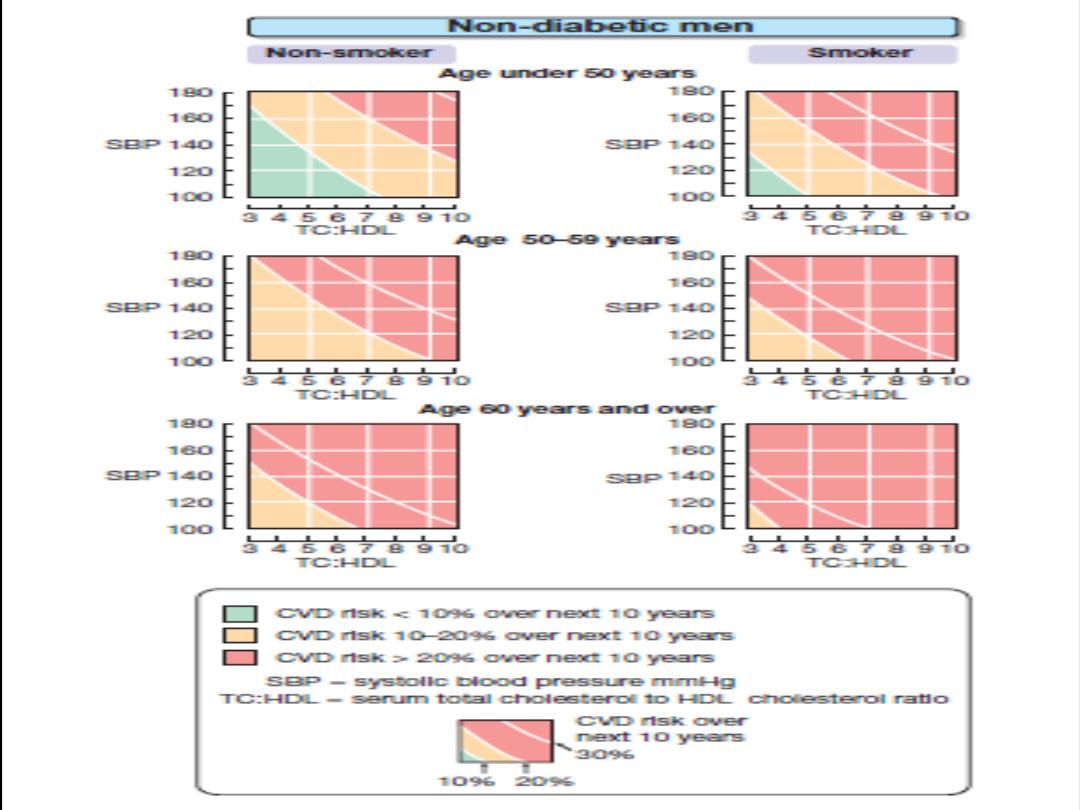

Major modifiable Risk Factors

• Cigarette smoking (passive smoking?)

• Elevated total or LDL-cholesterol

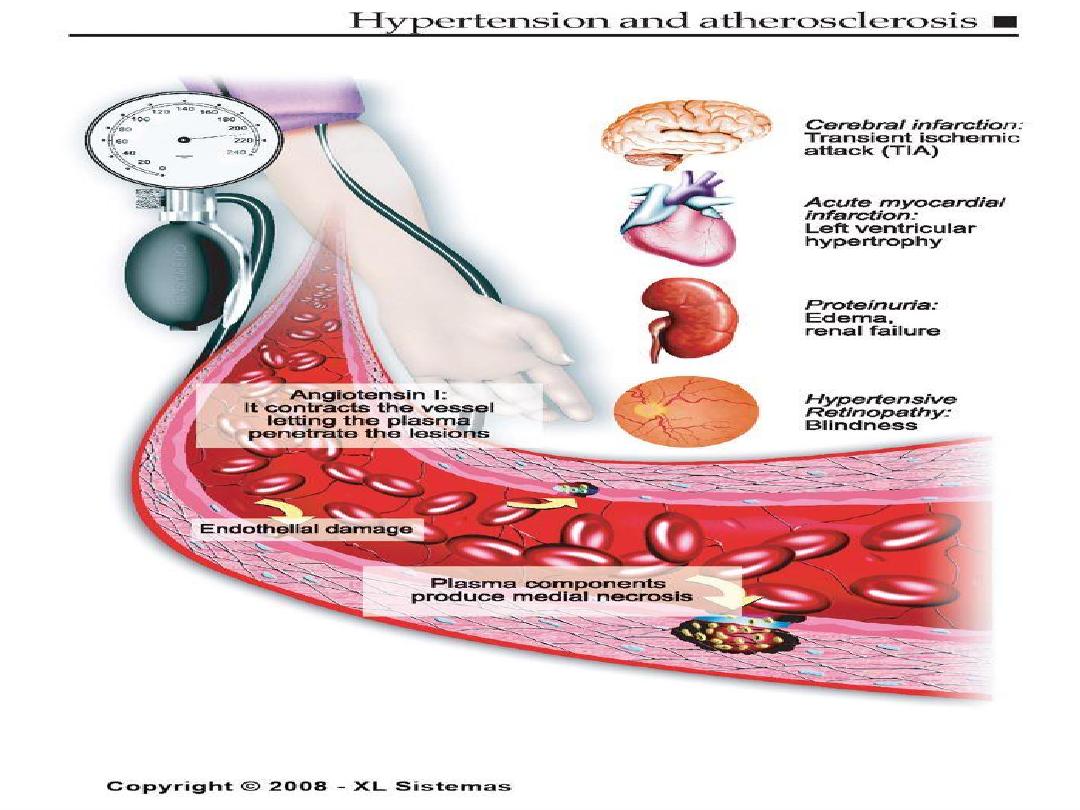

• Hypertension (BP

140/90 mmHg or on

antihypertensive medication)

.. Low HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL)

†

•

Obesity: Body Mass Index (BMI)

– Weight (kg)/height (m

2

)

– Weight (lb)/height (in

2

) x 703

• Obesity BMI >30 kg/m

2

with overweight defined as

25-<30 kg/m

2

• Abdominal obesity involves waist circumference >40

in. in men, >35 in. in women

• Physical inactivity: most experts recommend at least

30 minutes moderate activity at least 4-5 days/week

†

HDL cholesterol

60

mg/dL counts as a “negative” risk factor; its

presence removes one risk factor from the total count.

Nonmodifiable Risk Factors

• Age- Age (men

45 years; women

55 years)

the older you get, the greater the chance.

• Sex- males have a greater rate even after women

pass menopause.

• Race- minorities have a greater chance.

• Family history- if family members have had CHD,

there is a greater chance.

Family history of premature CHD

– CHD in male first degree relative <55 years

– CHD in female first degree relative <65 years

Unchangeable Risk Factors: Age, the older you get the greater the chance of heart disease.

Four out of five people who die of congestive heart disease are 65 years of age or older. Sex,

males have a greater rate of congestive heart disease. Race, minorities have a greater chance of

heart disease. African Americans have a greater chance of high blood pressure. The risk is also

higher in Mexican Americans, America Indians, native Hawaiians and Asian Americans. Also

included as unchangeable risk factors is your family history and your own personal medical

history.

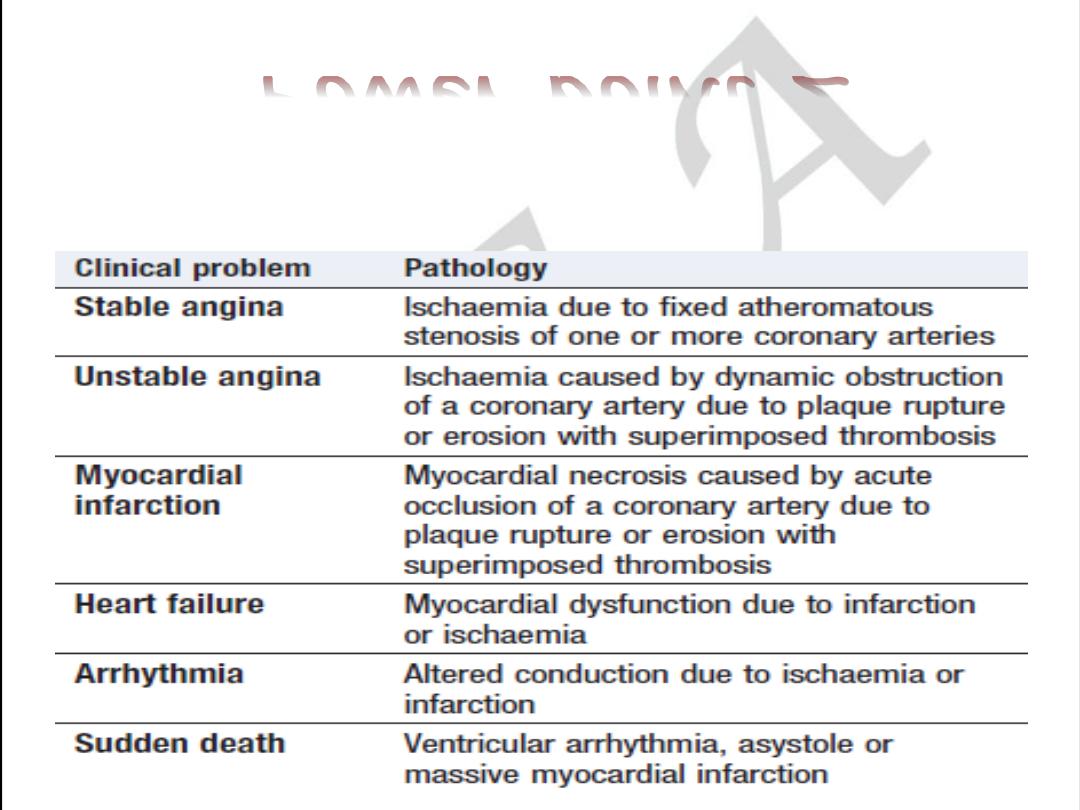

Clinical Manifestations

of Atherosclerosis

• Coronary heart disease

– Stable angina, acute myocardial infarction, sudden death,

unstable angina

• Cerebrovascular disease

– Stroke, TIAs

• Peripheral arterial disease

– Intermittent claudication, increased risk of death from heart

attack and stroke

American Heart Association, 2000.

41

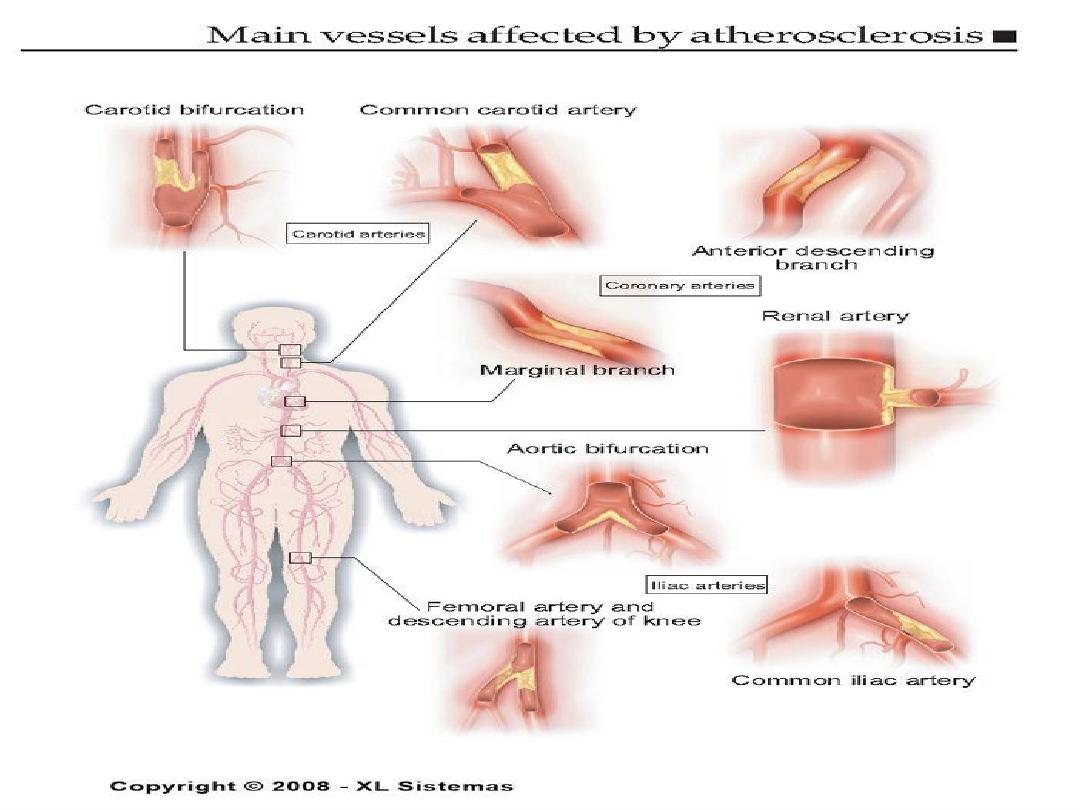

FORMS OF ATHEROSCLEROSIS

• CEREBRAL ARTERIES INJURY

• CARDIAC ARTERIES INJURY

• RENAL ARTERIES INJURY

• AORTA INJURY

• INTESTINAL ARTERIES INJURY

• EXTREMITY ARTERIES INJURY

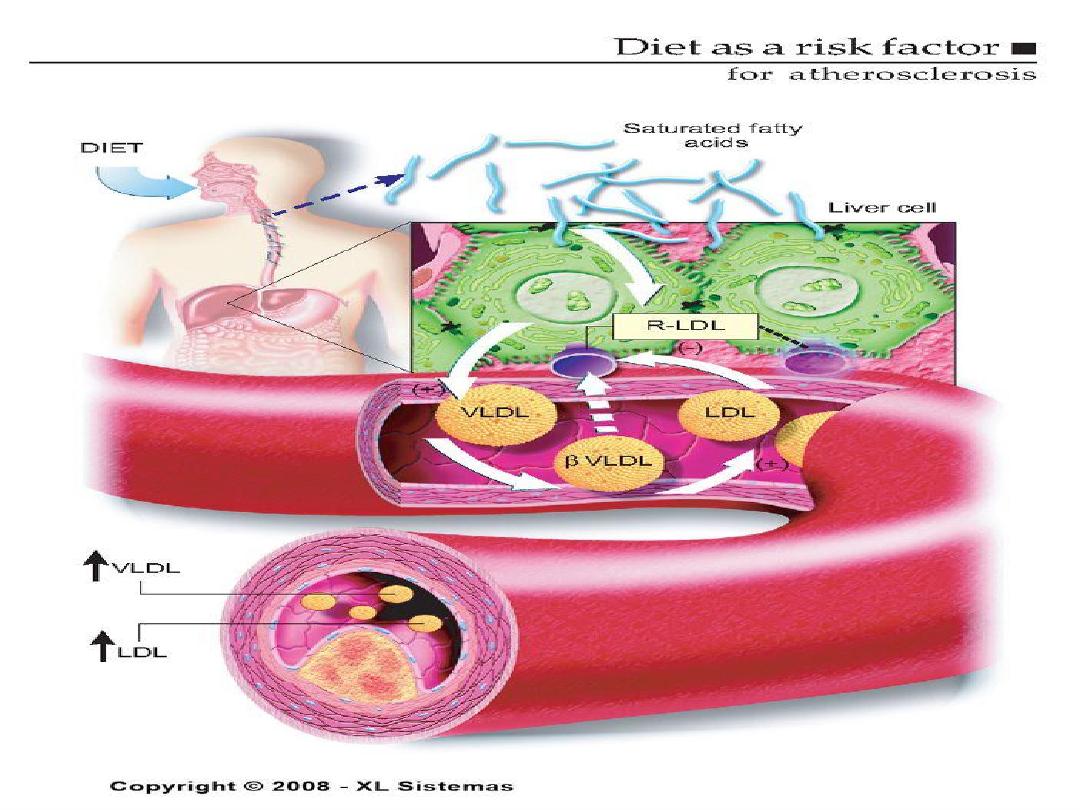

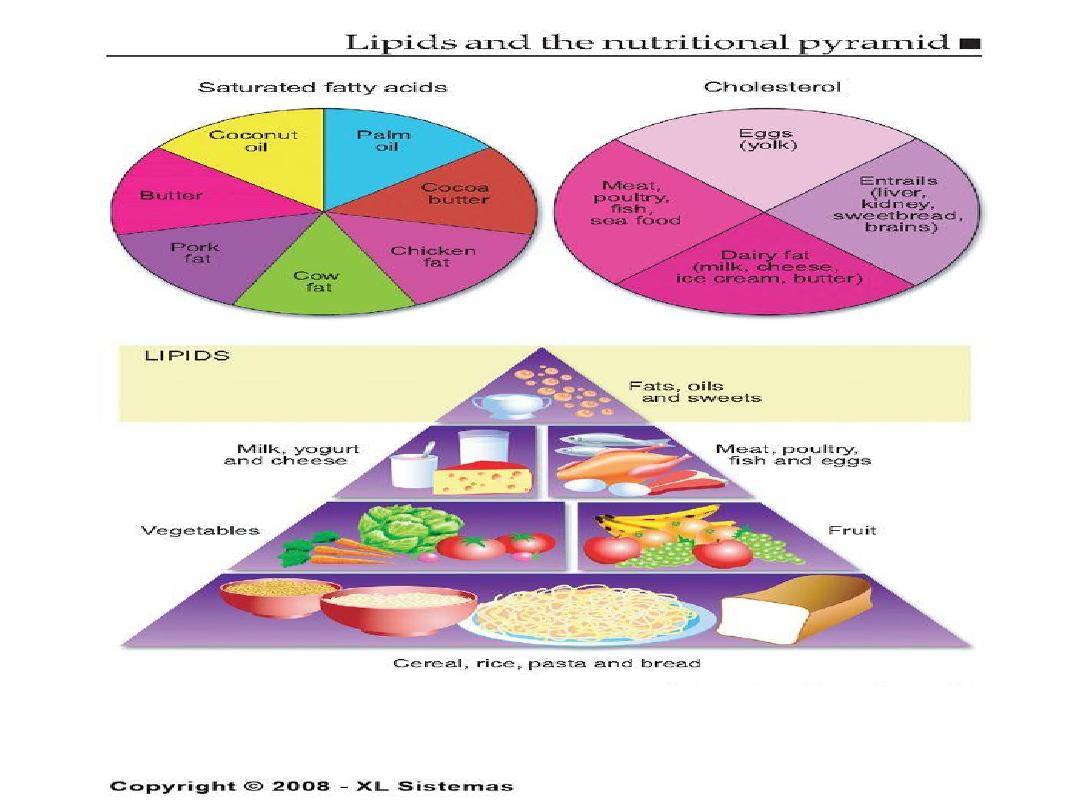

The Skinny on Fat

• Saturated fats- basically means the fat is saturated

with hydrogen, they are solid at room temperature.

Examples are lard and butter.

• Why are they bad for you? They increase levels of

LDL , decrease HDL and increase total cholesterol.

Saturated fats can cause an increase in cholesterol. What is

saturated fat? It is fat that is saturated with hydrogen and is a

solid at room temperature. Examples are lard and butter.

Saturated fats increase levels of LDL, decrease levels of HDL

and increases total cholesterol.

The American Heart

Association recommends you limit saturated fat intake to 7-

10% of your total calories.

The Skinny on Fat

• What are monounsaturated fats?

• They are liquid at room temperature but start

to solidify in the refrigerator.

• Decrease total cholesterol and lower LDL

levels.

Monounsaturated fat includes canola, olive and peanut oils and

avocados.

The Skinny on Fat

• What are trans fatty acids? They are

unsaturated fats but they tend to raise total

and bad cholesterol.

• Where do you find them?

• In fast-food restaurants

• Commercial baked goods. Examples:

doughnuts, potato chips, cupcakes.

Trans fatty acids have hydrogen added to them to give them a

longer shelf life and they also tend to lower HDL levels.

What about Omega 3?

• Type of polyunsaturated fat.

• Consistently lowers serum triglycerides and may

also have an effect on lowering blood pressure.

• Found in oily fish such as salmon, tuna, and herring.

• Is available as a supplement.

The American Heart Association recommends eating fish two

times per week. Mention other fish that contain Omega 3

fatting acids. Omega 3 fatty acids are available as a

supplement but research is till being done to determine the

supplements’ effectiveness.

Physical Inactivity

• Increasing physical activity has been shown to

decrease blood pressure.

• Moderate to intense physical activity for 30-45

minutes on most days of the week is

recommended.

Exercise can help control blood cholesterol,

diabetes and obesity, as well as help lower

blood pressure.

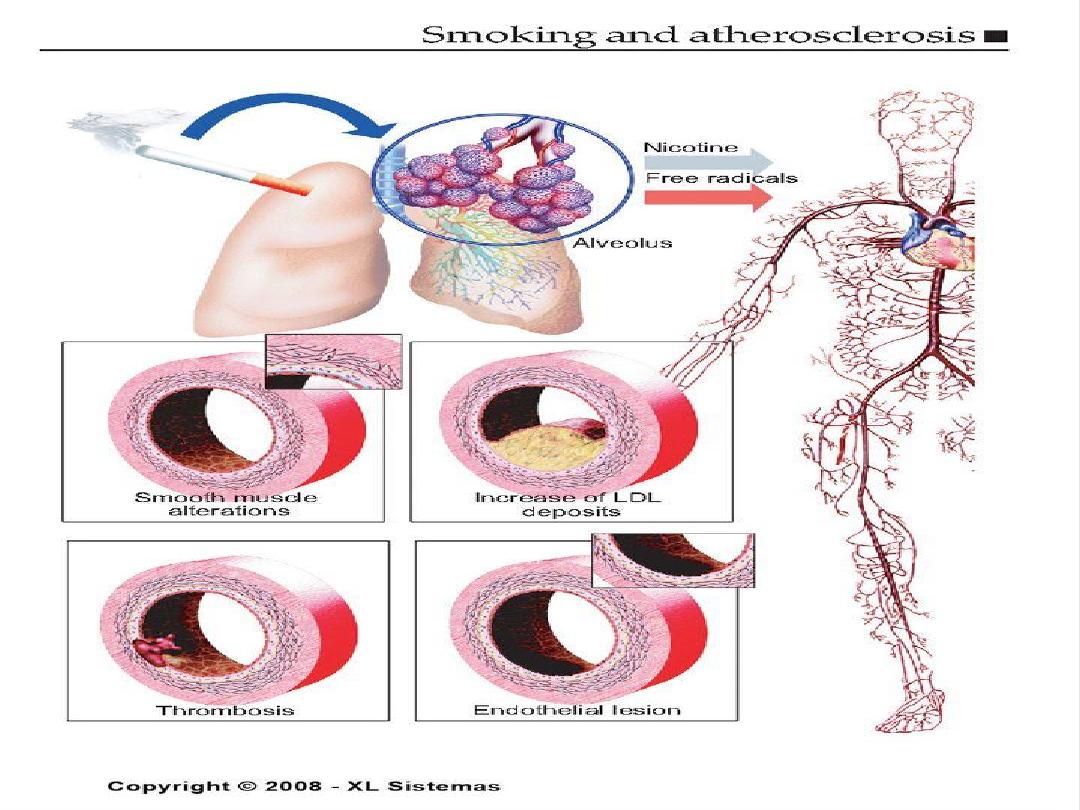

Cigarette Smoking

• Causes an increase in blood pressure

• Usually have lower levels of HDL

• Within 1 year of quitting, CHD risk decreases,

within 2 years it reaches the level of a

nonsmoker.

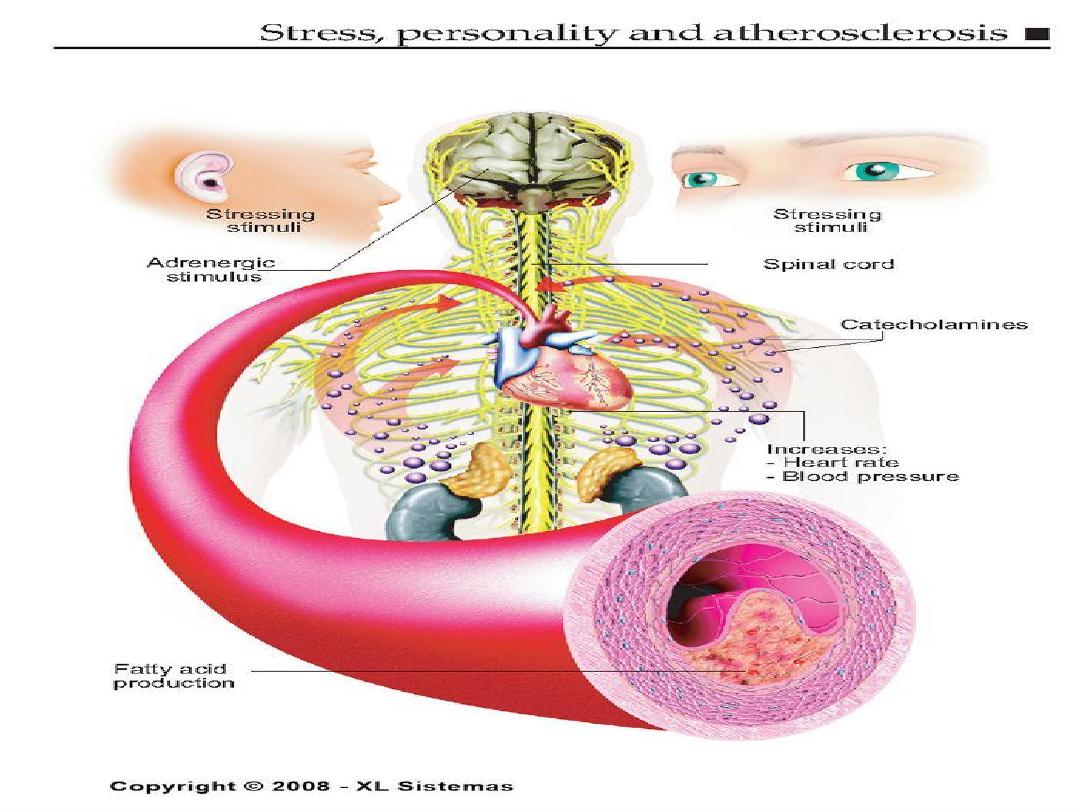

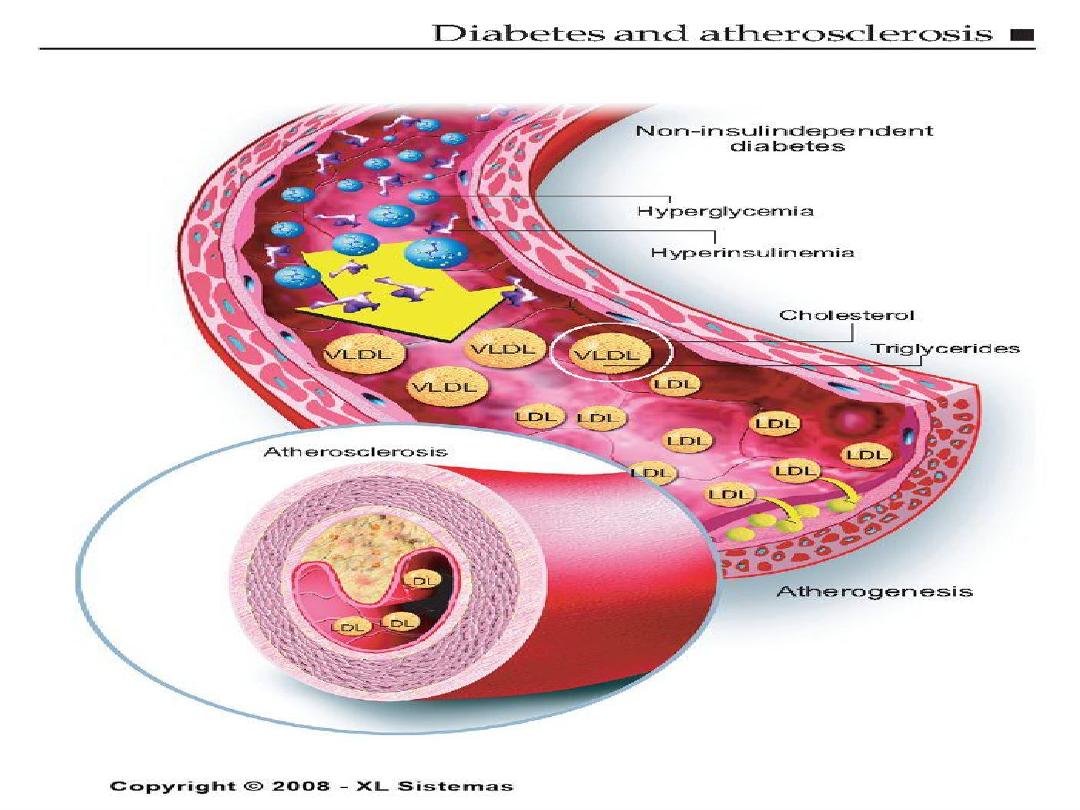

Diabetes Mellitus

• At any given cholesterol level, diabetic persons

have a 2 or 3 x higher risk of atherosclerosis!

• Insulin is required to maintain adequate levels

of lipoprotein lipase, an enzyme needed to

break down bad cholesterols.

About 2/3 of the people with diabetes die of some

type of heart or blood vessel disease.

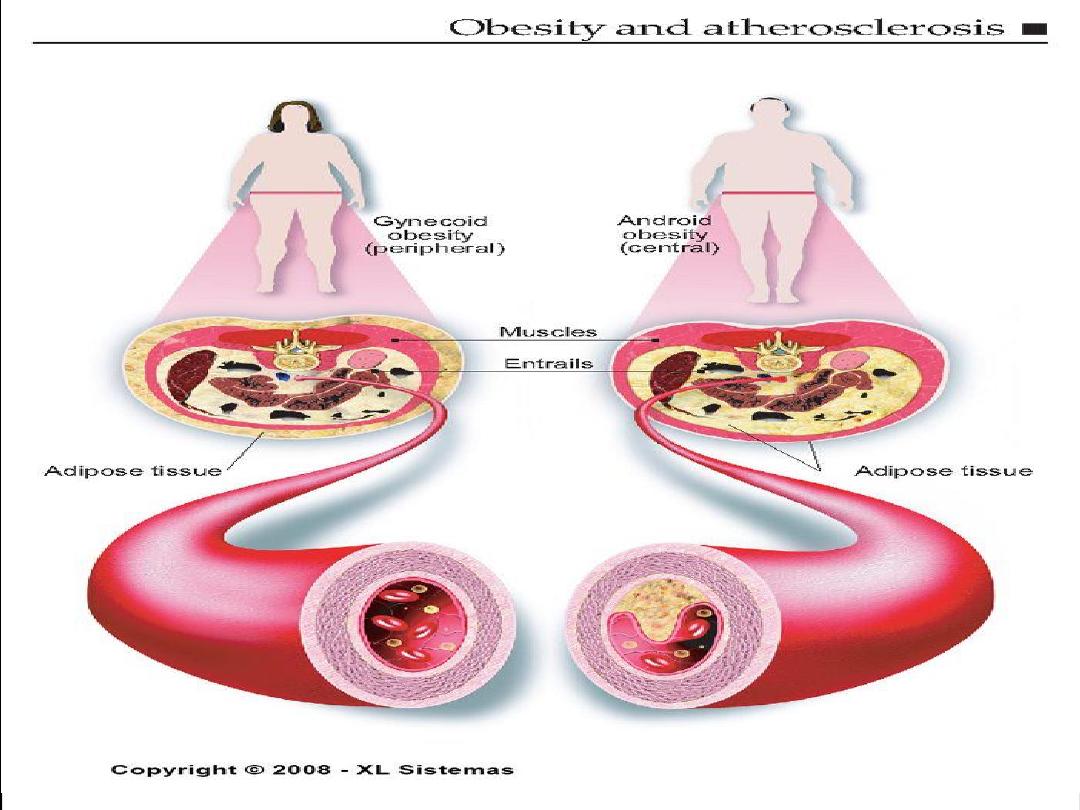

Obesity

• People who are obese have 2 to 6 times the

risk of developing hypertension.

• Location of the body fat is significant.

• Pears of apples?

People who are obese have 2 to 6 times the risk of

developing hypertension even if they have no other risk

factors.

Approaches to Primary and

Secondary Prevention

• Primary prevention involves prevention of

onset of disease in persons without symptoms.

• Primordial prevention involves the prevention

of risk factors causative o the disease, thereby

reducing the likelihood of development of the

disease.

• Secondary prevention refers to the prevention

of death or recurrence of disease in those who

are already symptomatic

Prevention of atherosclerosis

• Primary prevention:

• Population strategy.

• Targeted strategy.

• Secondary prevention

•

Get regular medical checkups.

•

Control your blood pressure.

•

Check your cholesterol.

•

Don’t smoke.

•

Exercise regularly.

•

Maintain a healthy weight.

•

Eat a heart-healthy diet.

•

Manage stress.

The End

Coronary artery disease

Clinical manifestation and pathology

Power point 2

Angina pectoris

Angina pectoris refers to the

PAIN

caused by

myocardial ischemia

.

Ischemia

is

usually

caused

by

mismatched

oxygen

demand

(tachycardia, anemia, aortic stenosis, left ventricular hypertrophy of

other etiologies)

and delivery in the setting of a hemodynamicaly

significant coronary stenosis due to atheroma

, but it may have other

causes such

as coronary artery spasm

(Prinzmetal’s variant angina).

In more unusual cases the etiology is not completely understood

—

e.g.,

syndrome

X

(chest

pain

with

normal

coronary

arteries).

Alternatively, these conditions may coexist and be exacerbated by

emotional stress.

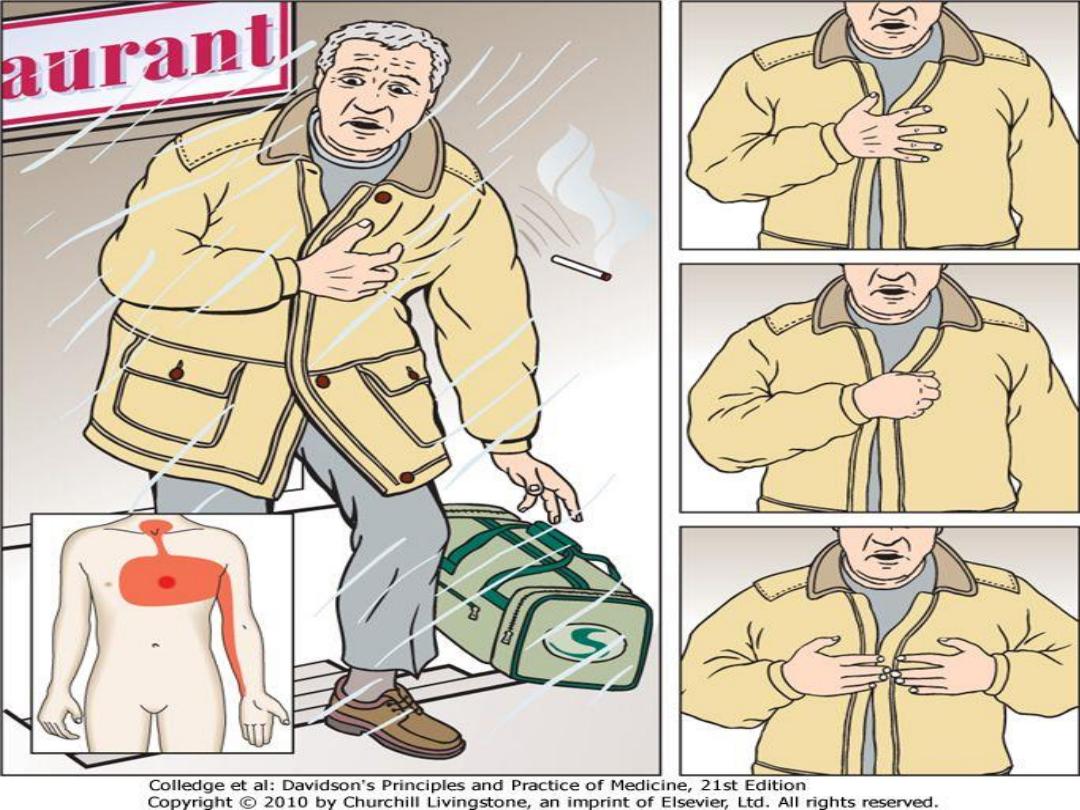

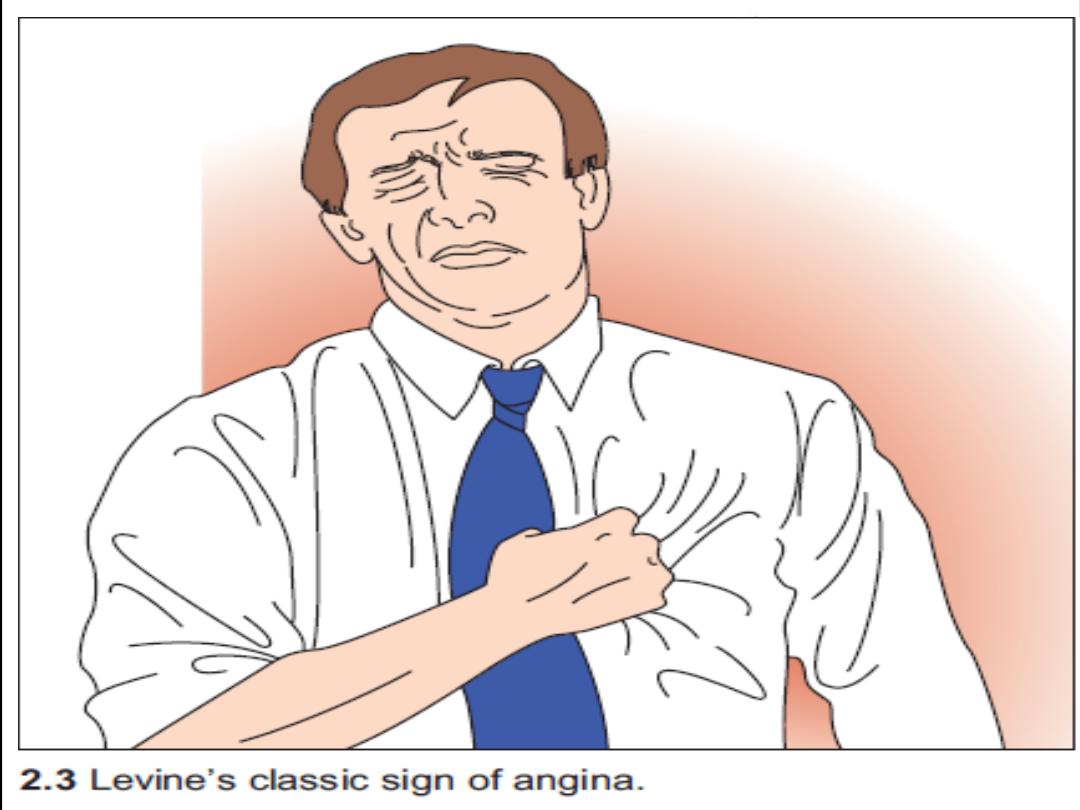

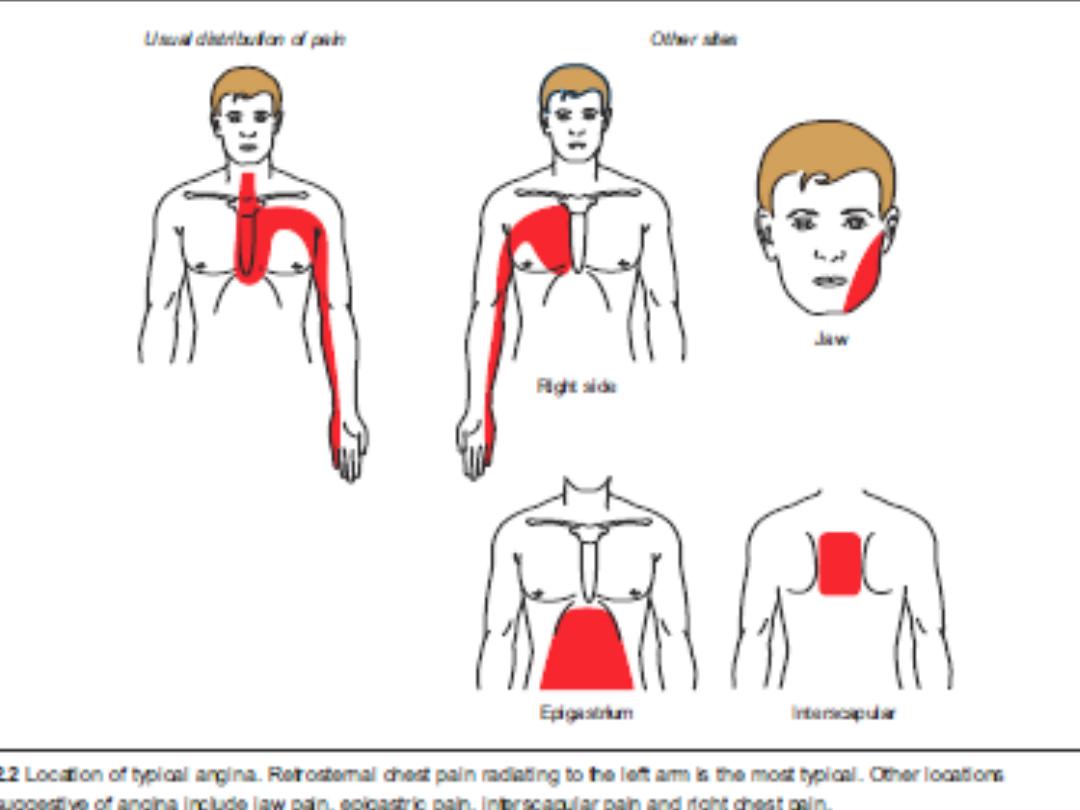

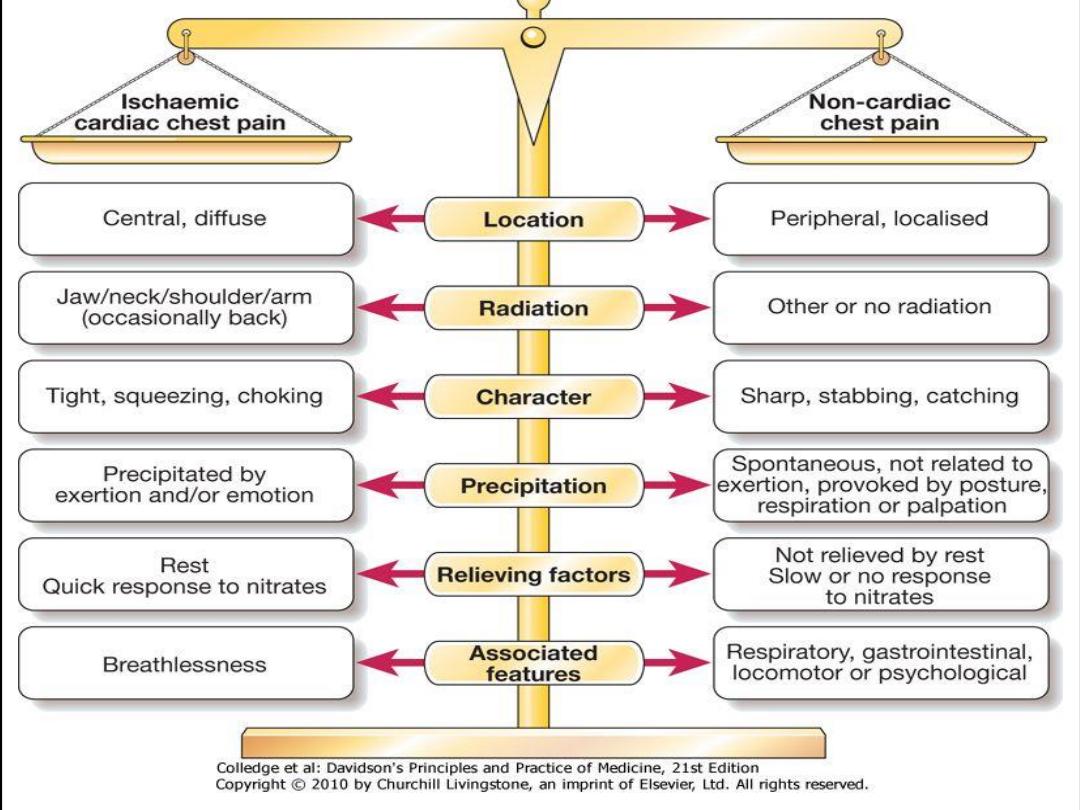

History and examination

Angina pectoris is characterized by a deep and diffusely distributed

central chest

discomfort

. Certain features of pain are of discriminative value.

Patients will not be able to point to where the pain is coming from with

one finger but will use an open palm or fist over the center or left para-

sternal aspect of their chest ( Levin s sign ) .

• The pain is not sharp (some patients confuse “sharp” with “severe”).

• Pain lasts longer than a few seconds and rarely exceeds an hour

without varying in severity. Most episodes will last 1–5 minutes.

• The response to nitroglycerin, if any, will be almost immediate.

Generally, responses taking more than 5 minutes are unlikely to be

related to the drug.

Angina equivalent symptoms -Dyspnea, fatigue, nausea, and recurrent belching may

also represent underlying ischemia and can occur in the absence of the classical

central chest pain. The clue to underlying ischemic heart disease (IHD) lies in their

precipitation by exertion or emotional stress.

•

Chest wall tenderness suggests musculoskeletal pain and does not accompany

angina.

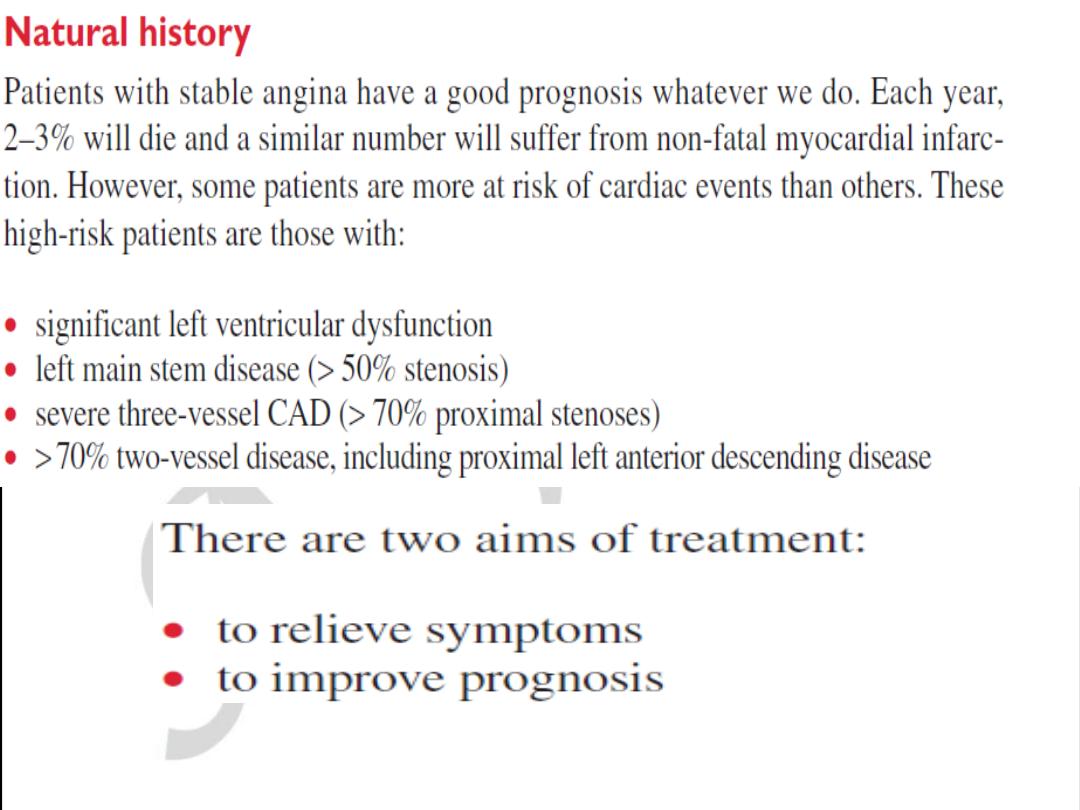

Classification of angina

Angina is often classified according to its temporal pattern and its relation to exertion because

this loosely reflects prognosis.

• Stable angina is characterized by pain occurring after a relatively constant level of exertion.

• Unstable angina is characterized by pain on minor exertion or at rest, which is either new onset

or a dramatic worsening of existing angina.

Also, it can present as pain on ever-diminishing levels of exertion, usually over a period of days.

The Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) system

provides a quantitative means to

describe exertional capacity and is divided into four classes:

I. Minimal limitation of ordinary activity. Angina occurs with strenuous, rapid, or prolonged

exertion at work or recreation.

II. Slight limitation of ordinary activity; angina occurs on walking or climbing stairs rapidly;

walking in cold, in wind, or under emotional stress.

III. Marked limitation of ordinary physical activity; angina occurs on walking 50–100 m on level

ground or climbing 1 flight of stairs at a normal pace in normal conditions.

IV. Inability to perform any physical activity without discomfort; angina symptoms may be

present at rest.

Physical examination

• Measure the pulse rate.

This may be slowed by inferior ischemia due to

atrioventricular (AV) node ischemia. A resting tachycardia, if present, usually

represents activation of the sympathetic nervous system but may be due to

an arrhythmia precipitated by ischemia.

•

Blood pressure measurement

is essential to look for evidence of hypertension

(predisposing to atheroma) or hypotension (may reflect cardiac dysfunction or

overmedication).

• Precordial examination

should include palpation for left ventricular hypertrophy

(LVH), cardiac enlargement, or dyskinesis, and auscultation for added heart

sounds (heart failure or acute ischemia), aortic stenosis, or mitral

regurgitation (due to papillary muscle dysfunction).

• Examine for signs of heart failure

by listening for fine, late-inspiratory crackles

at the lung bases and looking for dependent pitting edema (typically bilateral

ankle ± leg edema, but sacral edema may be the only manifestation if the

patient has been recumbent for some time).

•

Look for evidence of peripheral vascular disease

by palpating for aortic

aneurysm; feeling the carotid and limb pulses; listening for carotid, renal, or

femoral artery bruits; and assessing tissue integrity and capillary refill of the

legs and feet.

• Examine for signs of hypercholesterolemia:

the eyes for xanthelasmata and

corneal arcus, and the skin and tendons (especially the Achilles) for

xanthomata.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of anginal chest pain is wide and includes

• Anxiety and hyperventilation

• Musculoskeletal chest wall pain

• Cervical or thoracic root pain

• Pneumothorax, pneumonia, or pulmonary embolus

• Esophageal problem (inflammation/spasm)

• Other upper gastrointestinal (GI) problem (gastritis, peptic ulcer,

pancreatitis, cholecystitis)

• Pericarditis

• Aortic dissection

• Mitral valve prolapse

• Coronary emboli (LV mural thrombus, atrial myxoma)

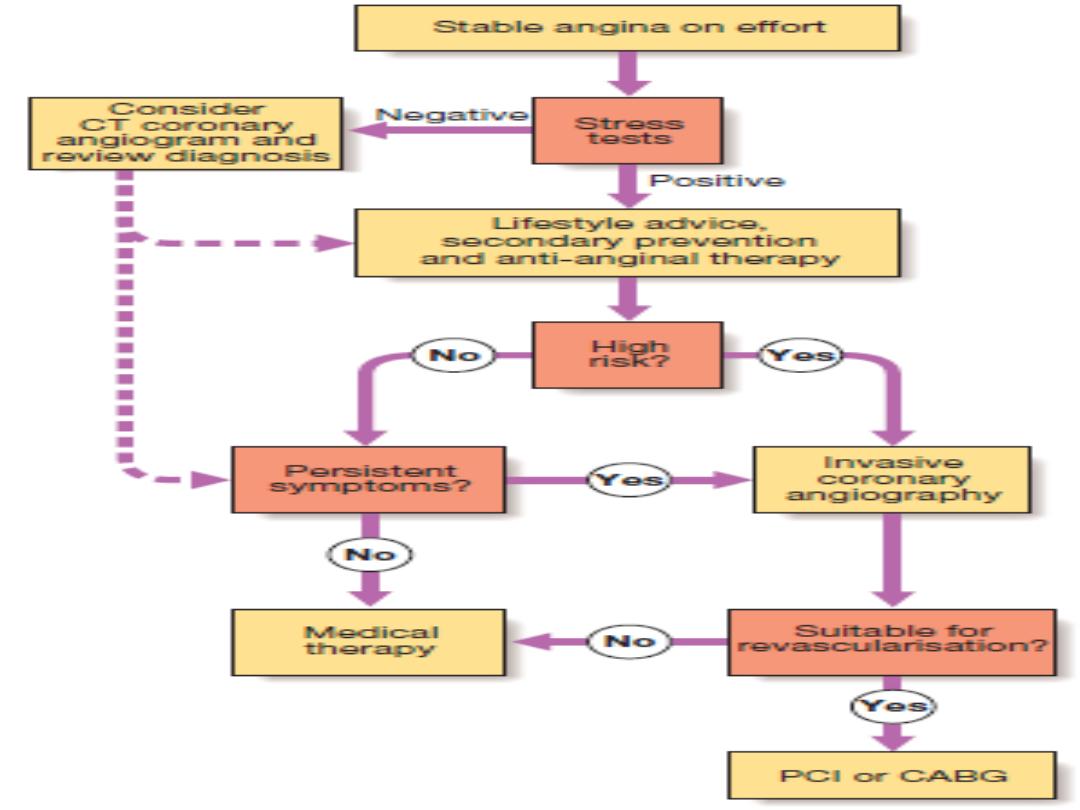

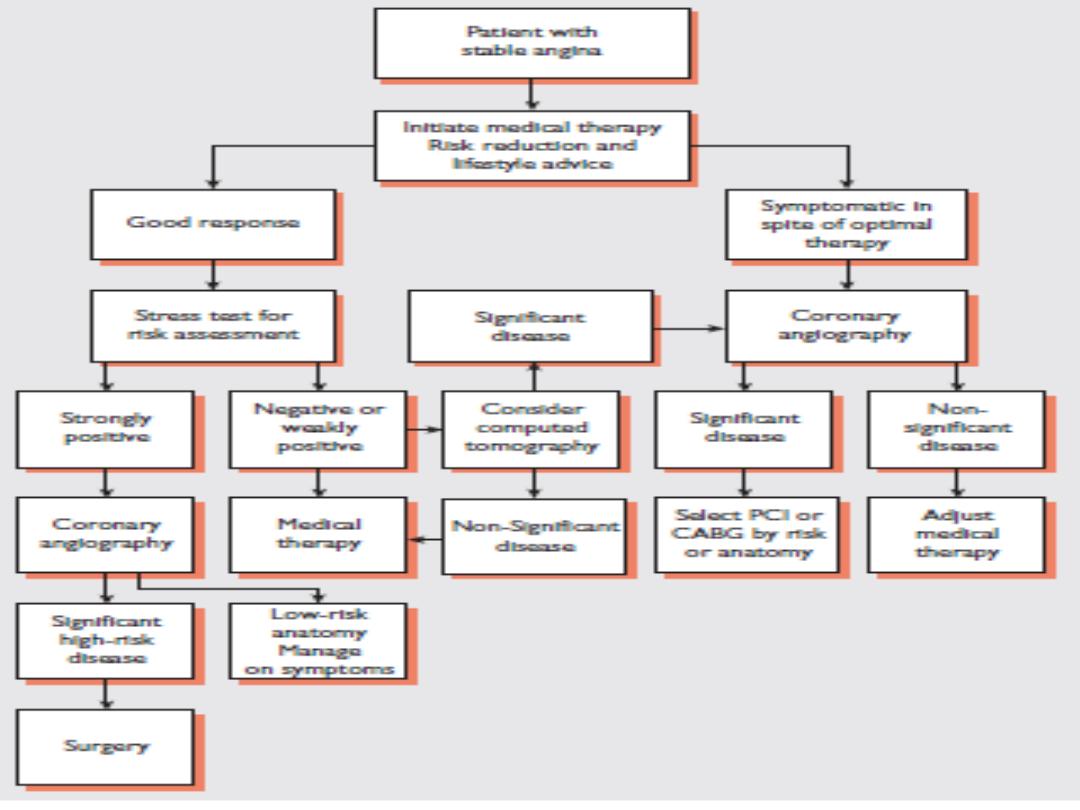

Investigations

Further risk stratification will add to the diagnostic certainty achieved by

history and examination.

Measure complete blood count (CBC), chemistries,

a full fasting lipid profile (total, LDL and HDL cholesterol and triglyceride

levels), and blood glucose.

Chest X-ray (CXR)

is not mandatory but should be performed if there is

suspicion of heart failure, aortic dissection, a pulmonary condition or an

abnormality of the bony structures of the chest wall.

12 Lead ECG

A resting electrocardiogram (ECG) may not confirm the diagnosis but can point

toward ischemic heart disease. The presence of Q waves suggests previous

myocardial injury. The presence of ST depression and, to a lesser extent, T-

wave inversion during pain is a marker of ischemia and patients with these

signs should be further investigated. If ST-segment deviation is observed at

rest, an acute coronary syndrome must be excluded. A 12-lead ECG can

also help identify other causes of chest pain (LVH,arrhythmia, pericarditis).

Tests for inducible ischemia

Tests such as exercise ECG, stress echocardiogram (ECHO), or myocardial

perfusion scanning are useful adjuncts to confirm the diagnosis and aid

management.

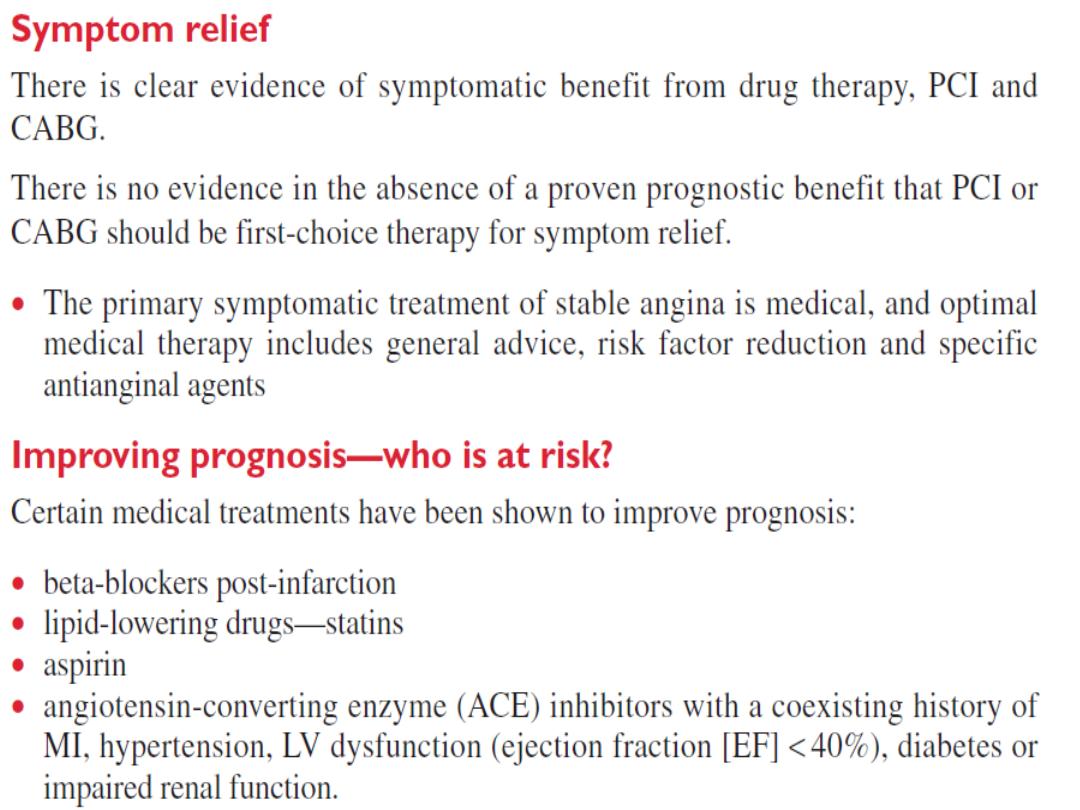

Management

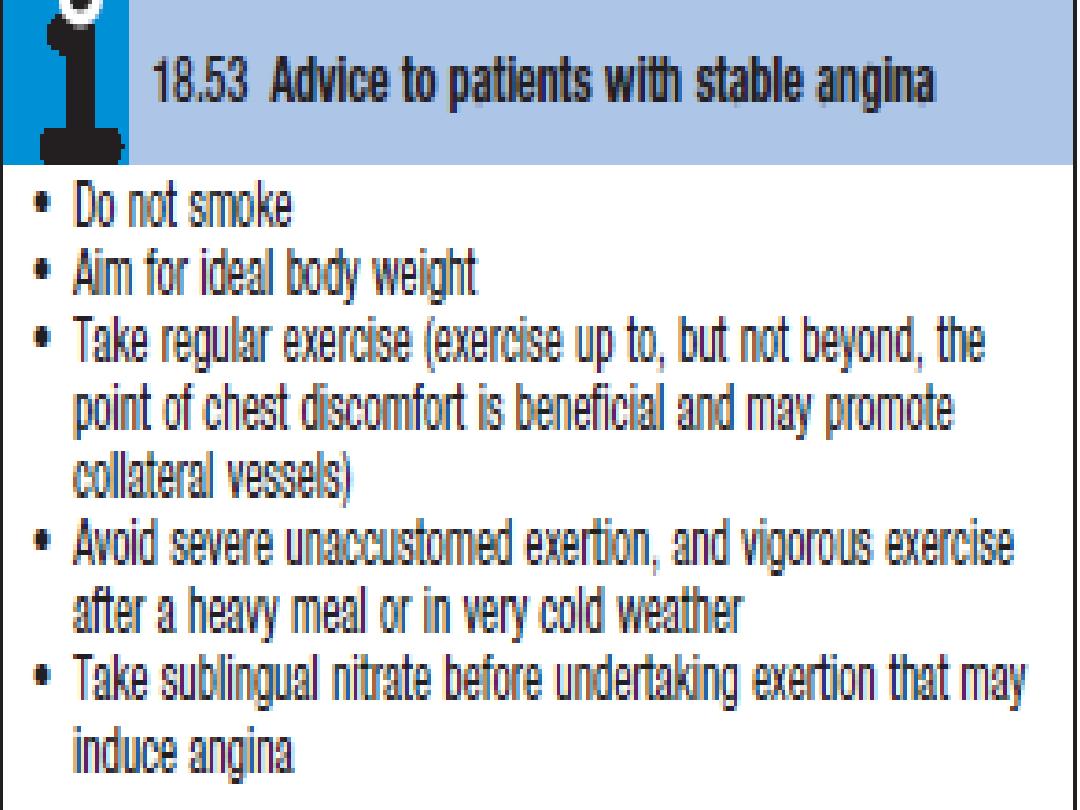

Lifestyle

Smoking cessation is of paramount importance. Encourage daily aerobic exercise within limits of exercise capacity. Look

at the patient’s occupational needs and advise adjustment if symptom level is not compatible. Advise a healthy diet,

collaborating with dieticians if required.

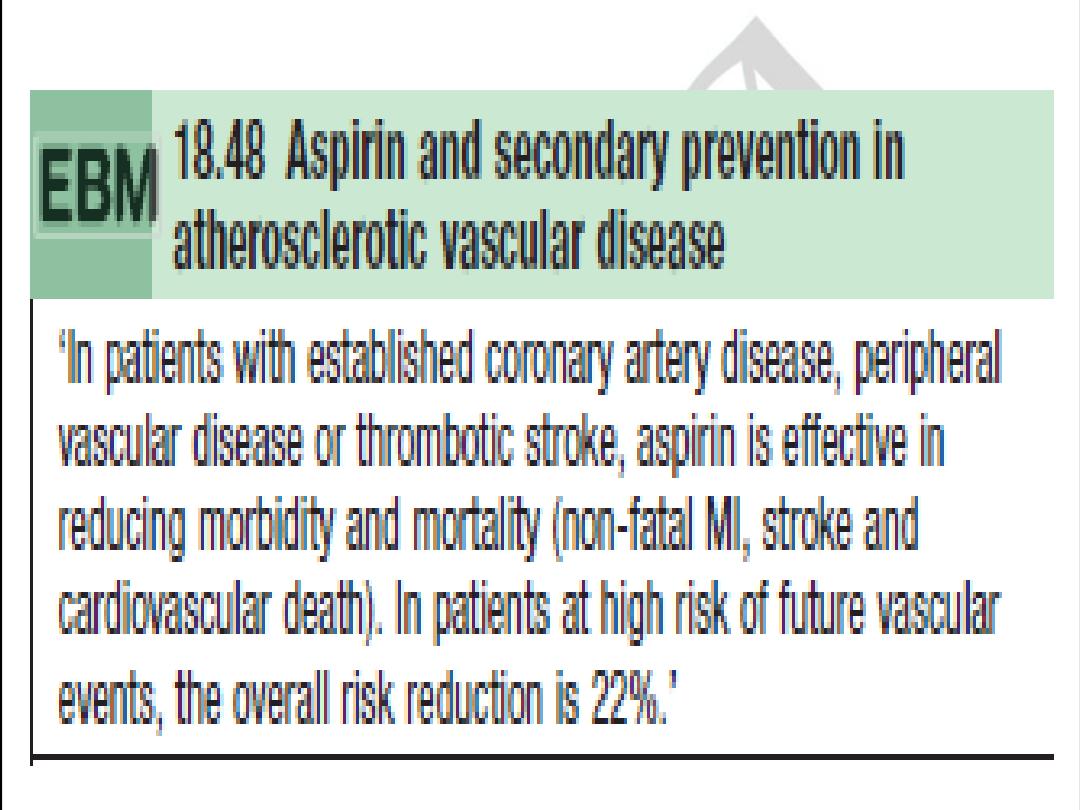

Aspirin

Provide aspirin in all cases unless there is active peptic ulcer disease, allergy (desensitizing may be required), or bleeding

diathesis. Those with past peptic ulcer disease may take a gastro protective agent such as an H2 antagonist or proton

pump inhibitor.

Anti-anginals

• B-Blockers:

First line (e.g., atenolol 25–100 mg qd or metoprolol 25–50 mg bid). Start on suspicion of ischemic heart

disease. Avoid only if contraindicated (asthma with confirmed B-agonist response

(mortality improved in patients with angina and concomitant COPD if they can tolerate bronchospasm), uncontrolled

severe LV dysfunction, bradycardia, coronary artery spasm).

• Calcium antagonists

(e.g., amlodipine or diltiazem): If B-blocker contraindicated or concern for vasospasm, calcium

antagonists become the drug of choice.

• Nitrates

(e.g., nitroglycerin): Used for control of breakthrough angina. Long-acting nitrates (e.g., isosorbide

mononitrate 60–120 mg qd) are a

useful addition to B-blockers for prevention of attacks.

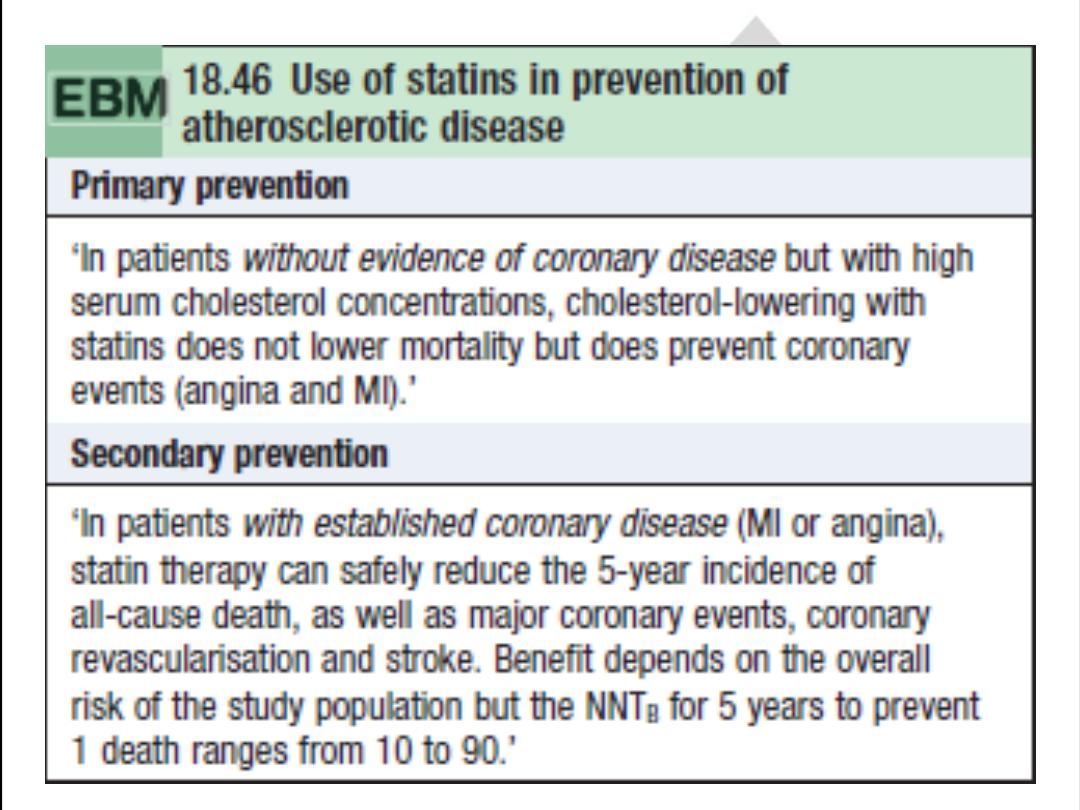

.Statins

Statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors)

reduce mortality by approximately one-third in all risk groups. However, the

underlying risk of events must be taken into account when considering starting the drug, because absolute risk

reduction in young patients with low-risk IHD may be very small, with possible harm of myositis, hepatic failure, and

reduced compliance with other medications

The End

Coronary artery disease

Acute coronary syndromes

Power point 3

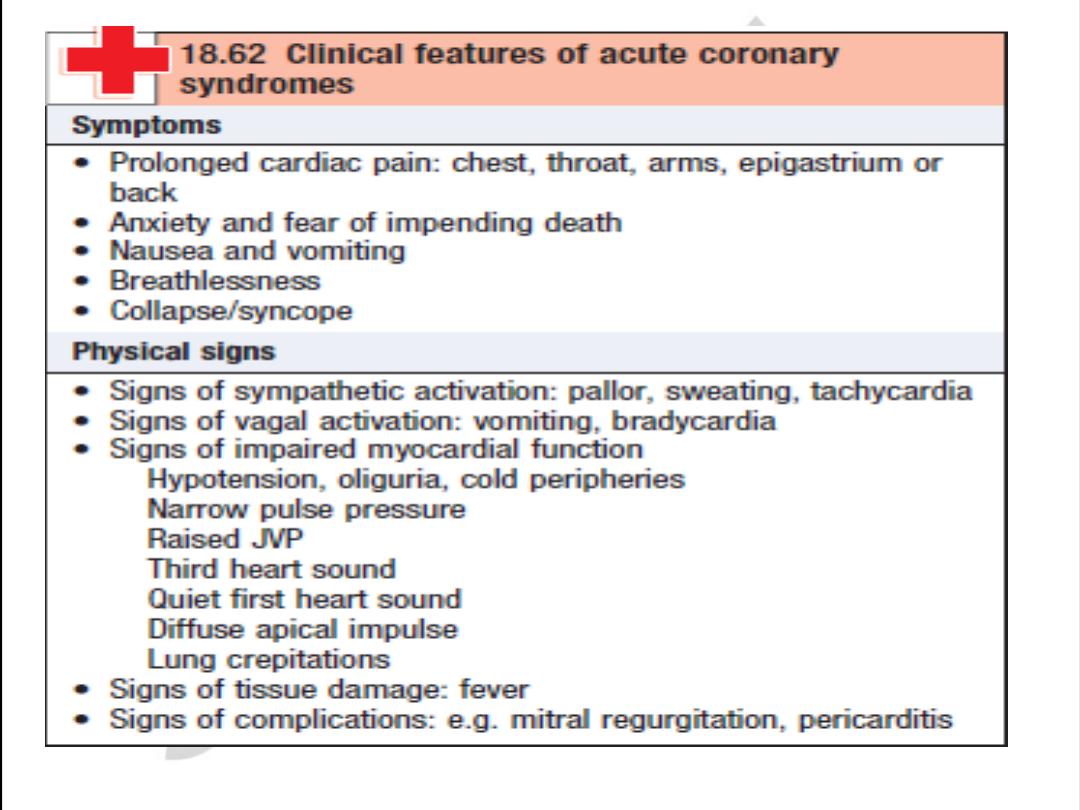

Definition

• Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a term used

to describe a constellation of symptoms

resulting from acute myocardial ischemia.

ACS includes the diagnosis of unstable angina

(UA), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction

(NSTEMI), and ST elevation myocardial

infarction (STEMI).

An ACS resulting in myocardial injury is termed

myocardial infarction (MI).

Acute coronary syndromes

The current nomenclature divides ACS into two major groups on the basis of

delivered treatment modalities :-

1- ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)—

an ACS in which patients

present with chest discomfort and ST-segment elevation on ECG. This group

of patients must undergo reperfusion therapy on

presentation.

2-Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina

(UA)—ACS

in which patients present with ischemic chest discomfort

associated with transient or permanent non-ST-elevation ischemic ECG

changes. If there is biochemical evidence of myocardial injury, the condi-

tion is termed NSTEMI, and in the absence of biochemical myocardial

injury the condition is termed UA. This group of patients is not treated

with thrombolysis.

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

NO ST - elevation

ST - elevation

Unstable angina

NQ w- MI

Q w - MI

NO BIOMARKER RISE

NSTEMI

Conditions mimicking pain in ACS

• Pericarditis

• Dissecting aortic aneurysm

• Pulmonary embolism

• Esophageal reflux, spasm, or rupture

• Biliary tract disease

• Perforated peptic ulcer

• Pancreatitis

Initial management of ACS

• All patients with suspected ACS should have

continuous ECG monitoring and access to a

defibrillator.

• Rapid assessment and stabilization is

imperative.

management of ACS

• Rapid examination to exclude hypotension, note the

presence of murmurs, and identify and treat acute

pulmonary edema.

• Secure IV access.

• 12 Lead ECG should be obtained and reported within 10

minutes of presentation.

• Give the following:

• Oxygen (initially only 28% if history of COPD)

• Morphine 2.5–10 mg IV prn for pain relief

• Aspirin 325 mg po

• Nitroglycerin, unless hypotensive

• Heparin IV and/or Integrilin

• Consider addition of Plavix

• Take blood for the following:

• CBC/chemistries Supplement K+ to keep it at 4–5

mmol/L

• GlucoseMay be i acutely post-MI, even in nondiabetic

reflecting a stress-catecholamine response and may

resolve without treatment

• Biochemical markers of cardiac injury

• Lipid profileTotal cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides

• Serum cholesterol and HDL remain close to baseline for

24–48 hours but fall thereafter and take 8 weeks to

return to baseline.

• Portable CXR to assess cardiac size and pulmonary

edema and to

exclude mediastinal enlargement.

• General examination should include peripheral

pulses, fundoscopy, and

abdominal examination for organomegaly and

aortic aneurysm.

The End

Acute coronary syndrome

Non-ST elevation myocardial

infarction

(NSTEMI)/unstable angina (UA)

Power point 4

UA and NSTEMI

are closely related conditions with similar clinical

presentation, treatment, and pathogenesis but of varying severity. If there

is

biochemical evidence of myocardial damage, the condition is termed

NSTEMI; in the absence of damage it is termed UA.

Unlike patients with a STEMI, in whom diagnosis is generally made on

presentation in the emergency department, diagnosis of NSTEMI/UA may

not be definitive on presentation and evolves over the subsequent hours to

days. Therefore, management of patients with NSTEMI/UA is a progression

through a number of risk strati

fication processes dependent on history,

clinical features, and investigative results. These in turn determine

the

choice and timing of a number of medical and/or invasive treatment

strategies.

Clinical presentation

There are three distinct presentations:

• New-onset angina (in a patient without prior

angina)

• Rest angina (angina when patient is at rest; may

occur in a patient with prior stable, exertional

angina)

• Increasing angina (in a patient with previously

diagnosed angina for whom angina has become

more frequent or longer in duration or requires a

lower threshold to elicit)

NSTEMI/UA: diagnosis

Diagnosis in NSTEMI/UA is an

evolving process

and may not be

clear on presentation. A combination of history, serial changes

in ECG, and biochemical markers of myocardial injury (usually

over a 24- to 48-hourperiod) determine the diagnosis.

Serial ECGs :

Changes can be transient and/or fixed,

especially if a diagnosis of NSTEMI is made.

• ST-segment depression of 0.05 mV is highly specific of

myocardial ischemia (unless isolated in V1–V3, suggesting a

posterior STEMI).

• T-wave inversion is sensitive but nonspecific for acute ischemia

unless very deep ( 0.3 mV).

• Rarely, Q waves may evolve or there may be transient or new

LBBB.

Serial biochemical markers of cardiac injury

These are used to differentiate between NSTEMI and UA, as

well as to determine prognosis. Levels at 0, 6, and 12 hours

after

the last episode of pain. A positive biochemical marker

(CK, CK-MB, or

troponin) in the context of one or more of the

ECG changes listed above

is diagnostic of NSTEMI. If serial

markers over a 24-hour period from the

last episode of chest

pain remain negative, UA is diagnosed

.

Cardiac troponin T and I

Both of these are highly cardiac

speci

fic and sensitive, can detect “micro-

infarction

” in the presence of normal CK-MB, are not affected by skeletal

muscle injury, and convey prognostic information (worse prognosis if posi-

tive)

. Troponins can be raised in nonatherosclerotic myocardial damage

(cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, pericarditis chronic renal failure) and should

thus be interpreted

in the context of the clinical picture.

Both TnT and TnI rise within 3 hours of infarction. TnT may persist up

to 10

–14 days and TnI up to 7–10 days.

•

CK levels do not always reach the diagnostic twice upper-limit of

normal and generally have little value in diagnosis of NSTEMI.

•

CK-MB has low sensitivity and speci

ficity. CK-MB isoforms improve

sensitivity (CK-MB2>1 U/L or CK-MB2/CK-MB1 ratio >1.5), but isoform

assays are not widely available clinically.

•

Myoglobine is non

–cardiac specific, but levels can be detected as early

as 2 hours after onset of symptoms. A negative test is useful in ruling

out myocardial necrosis.

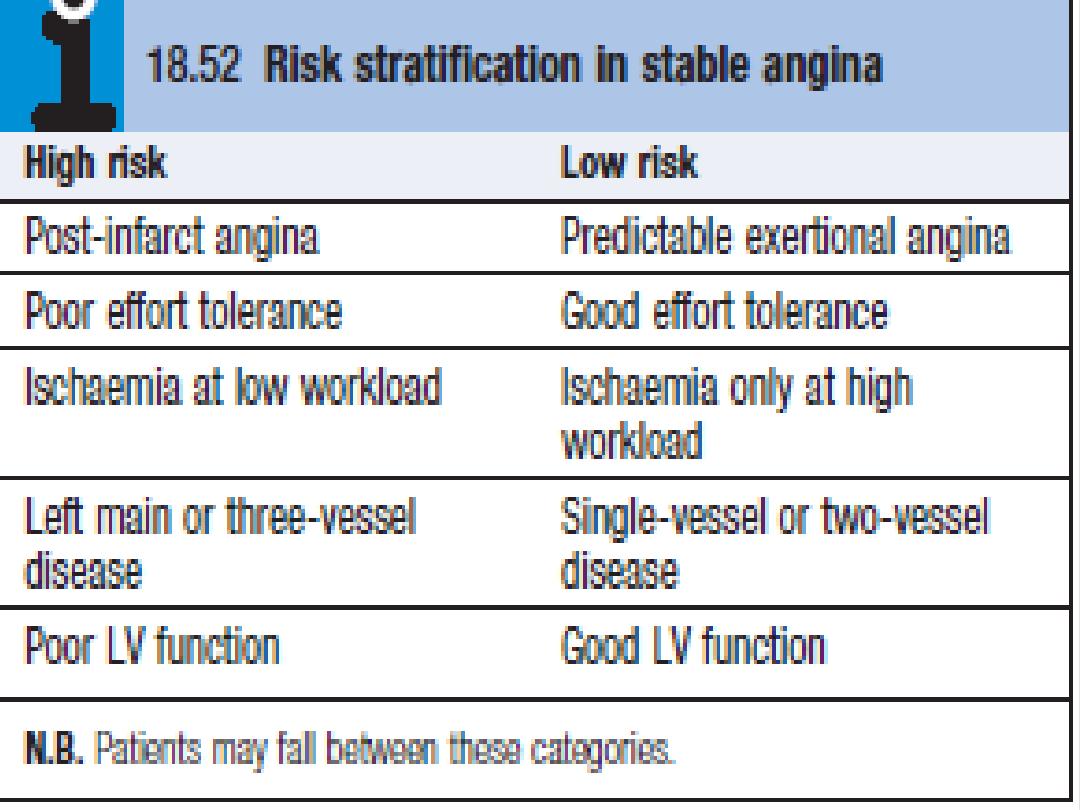

NSTEMI/UA: risk stratification

Early risk stratification

This should take place on presentation and forms part of the initial

assessment used to make a diagnosis. It involves a combination of clinical

features, ECG changes, and biochemical markers of cardiac injury.

Patients are divided into high risk and intermediate/low risk.

• High-risk patients should be admitted to the CCU, follow an early invasive

strategy, and be managed with a combination of :-

. ASA, clopidogrel, LMWH (or UFH), and/or gpIIb/IIIa antagonists

. Anti-ischemic therapy (first-line B-blocker, nitroglycerin)

. Early invasive strategy (inpatient catheterization and PCI within 48 hours

of admission)

• Intermediate- to low-risk patients should be admitted to a monitored

bed on a step-down unit and undergo a second inpatient risk stratification

once their symptoms have settled, to determine timing of invasive

investigations. Initial management should include :-

• ASA, clopidogrel, LMWH (or UFH)

• Anti-ischemic therapy (first-line B-blocker, nitroglycerin)

• Undergo a late risk stratification in 48–72 hours from admission

Late risk strati

fication

This involves a number of noninvasive tests to determine the optimal tim-

ing for invasive investigations in intermediate/low-risk patients. It is gener-

ally performed if there have been no further episodes of pain or ischemia

at 24

–48 hours after admission.

•

Intermediate/low-risk patients who develop recurrent pain and/or

ischemic ECG changes, heart failure, or hemodynamic instability (in

the absence of a noncardiac cause) should be managed as a high-risk

•

. High-risk patients from these assessments should also follow an early

invasive strategy and intermediate/low-risk patients, a more conservative

strategy.

NSTEMI/UA: medical management

1. Analgesia

Morphine 2.5–5 mg IV. Acts as anxiolytic,

reduces pain and systolic blood pressure

through venodilatation and reduction in

sympathetic arteriolar constriction. It can

result in hypotension (responsive to volume

therapy) and respiratory depression (reversal

with naloxone 400 µg to 2 mg IV).

2. Nitrates

•

Nitroglycerin infusion (50 mg in 50 mL normal saline at 1

–10 mL/hr) titrated to pain and keeping SBP >100 mmHg. T

3. B-Blockers

•

These should be started on presentation. Initially use a short-acting agent (e.g., metoprolol 12.5

–100 mg po bid),

which if tolerated, may be converted to a longer acting agent (e.g., atenolol 25

–1000 mg qd).

Rapid B-blockade may be achieved using short-acting IV agents such as metoprolol. Aim for HR of ~50

–60

beats/min.

4. Calcium antagonists

•

Diltiazem 60

–360 mg po, verapamil 40–120 mg po tid. These aim to reduce HR and BP and are a useful adjunct to

treatments 1

–3 above.

Amlodipine/felodipine 5

–10 mg po qd can be used with pulmonary edema and in poor LV function.

5. Statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors)

High-dose statins (e.g., atorvastatin 80 mg qd) have been shown to

re

duce mortality and recurrent MI in the acute

setting. The role of stat

in

s in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events is well

d

ocumented.

Antiplatelet therapy

All patients should be given aspirin and clopidogrel (unless

c

ontraindications)

—gp IIb/IIIa antagonists to high-risk

patients only.

Antithrombotic therapy

They should be used in conjunction with aspirin and clopidogrel in all

p

atients on presentation and continued

for 2

–5 days after the last episode

o

f pain and ischemic ECG changes.

Discharge and secondary prevention

•

Length of hospital stay will be determined by symptoms and the rate of

progression through the NSTEMI/UA pathway. Generally patients are

hospitalized for 3

–7 days.

•

Secondary prevention remains of paramount importance and is similar in

principle to that for STEMI patients.

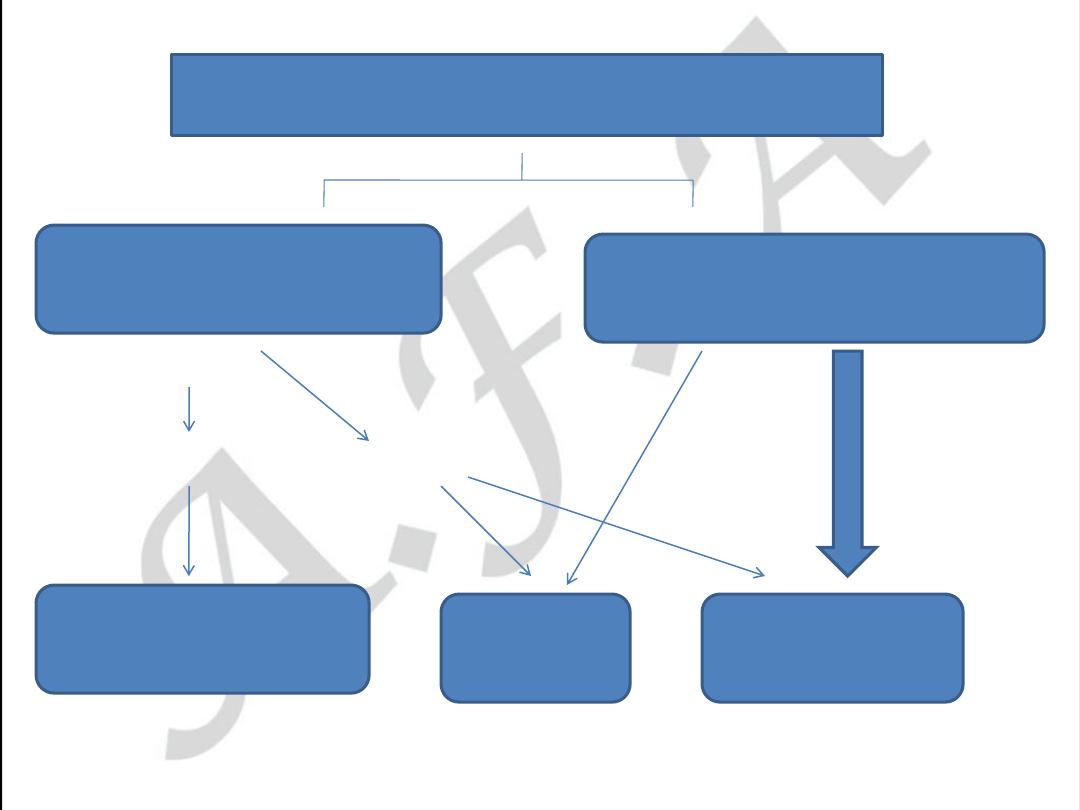

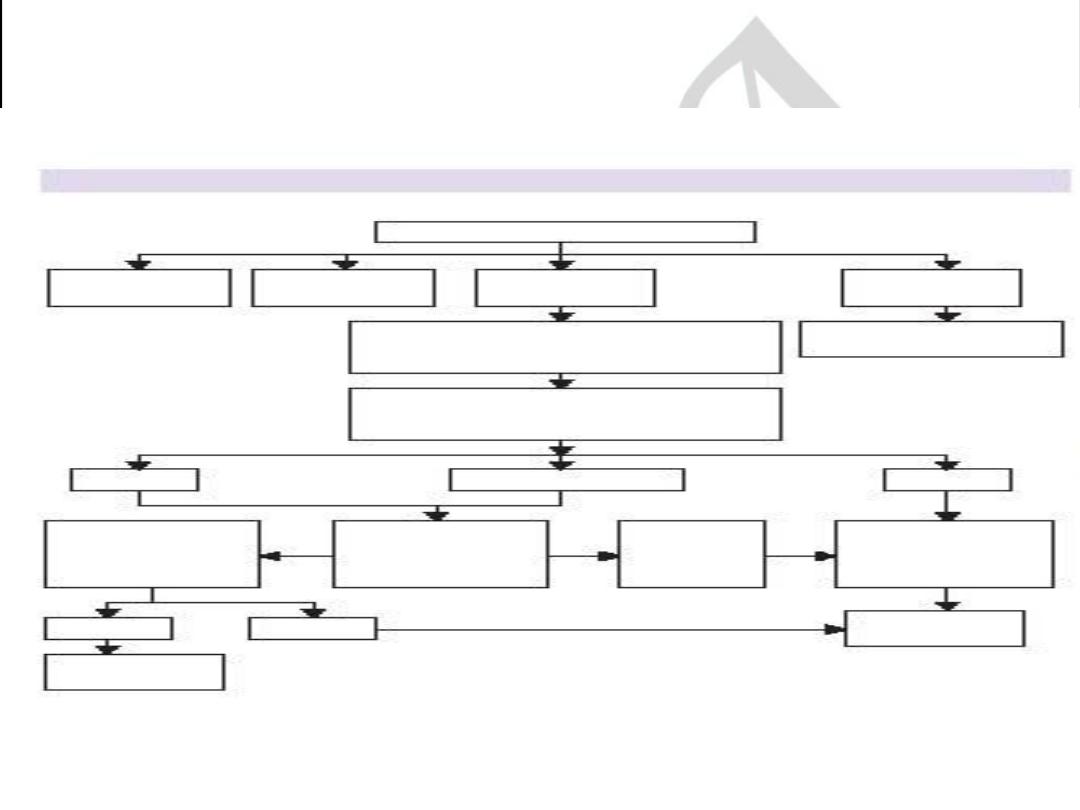

Symptoms suggestive of ACS

Noncardiac

d

iagnosis

Chronic

st

able angina

NSTEMI/UA

STEMI

Admit

,

A

SA, Clopidogrel, LMWH (UFH),

N

TG infusion, B-blocker, statin

Admit to CCU,Reperfusion ther

.

Early risk stratifiction in E.R

Low risk

Intermid. risk

High risk

No,

Late risk stratification

Admit, monitor.

Sympt.cont.?

Yes, treat as

High risk

Admit to CCU

Early invasive strategy

Low risk

High risk

O.P angiography

In patient angiog.

• Mention 3 characteristics of vulnerable

atheromatus plaque.

The End

Acute coronary syndromes

ST elevation myocardial infarction

(STEMI)

Power point 5

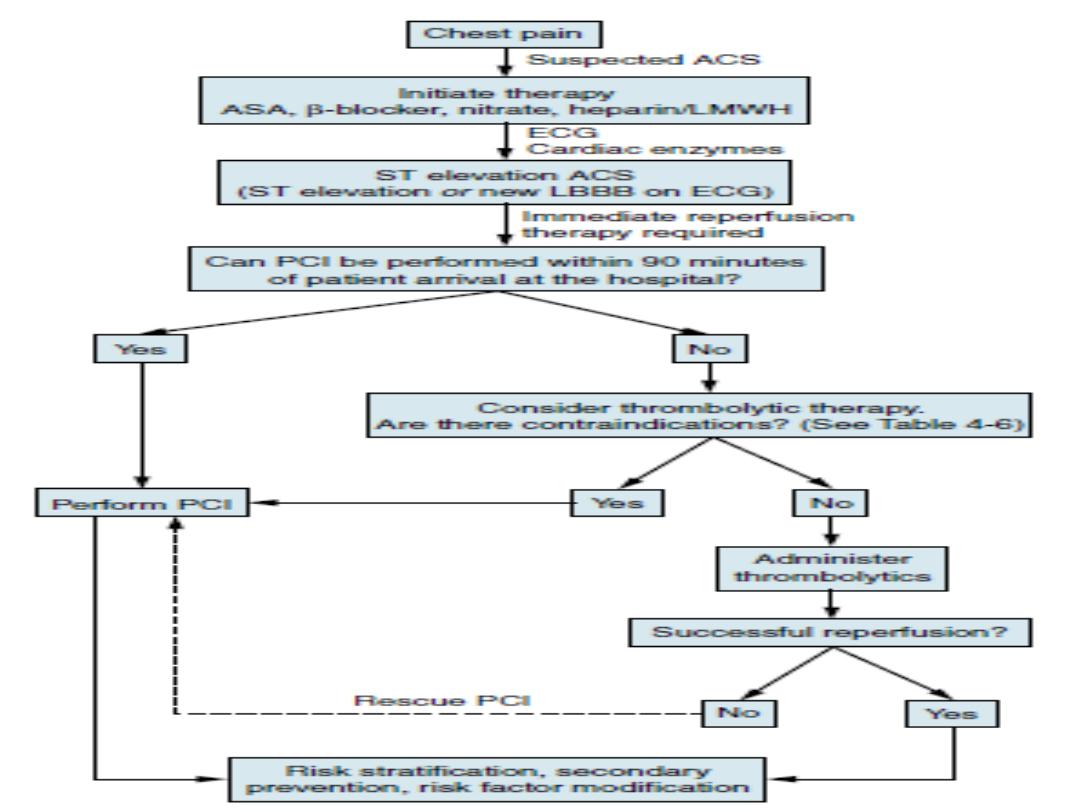

ST elevation myocardial infarction

(STEMI)

Patients with ACS who have ST-segment

elevation or new left bundle branch block

(LBBB) on their presenting ECG benefit

significantly from immediate reperfusion and

are treated as one group under the term ST-

elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

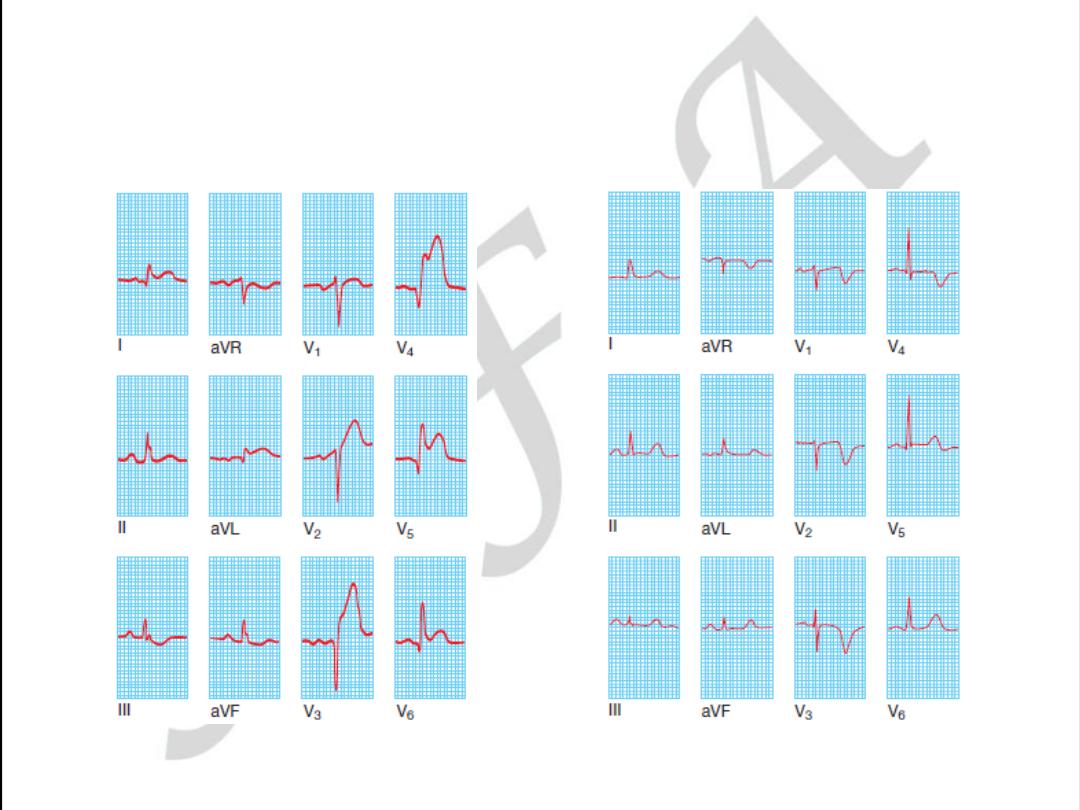

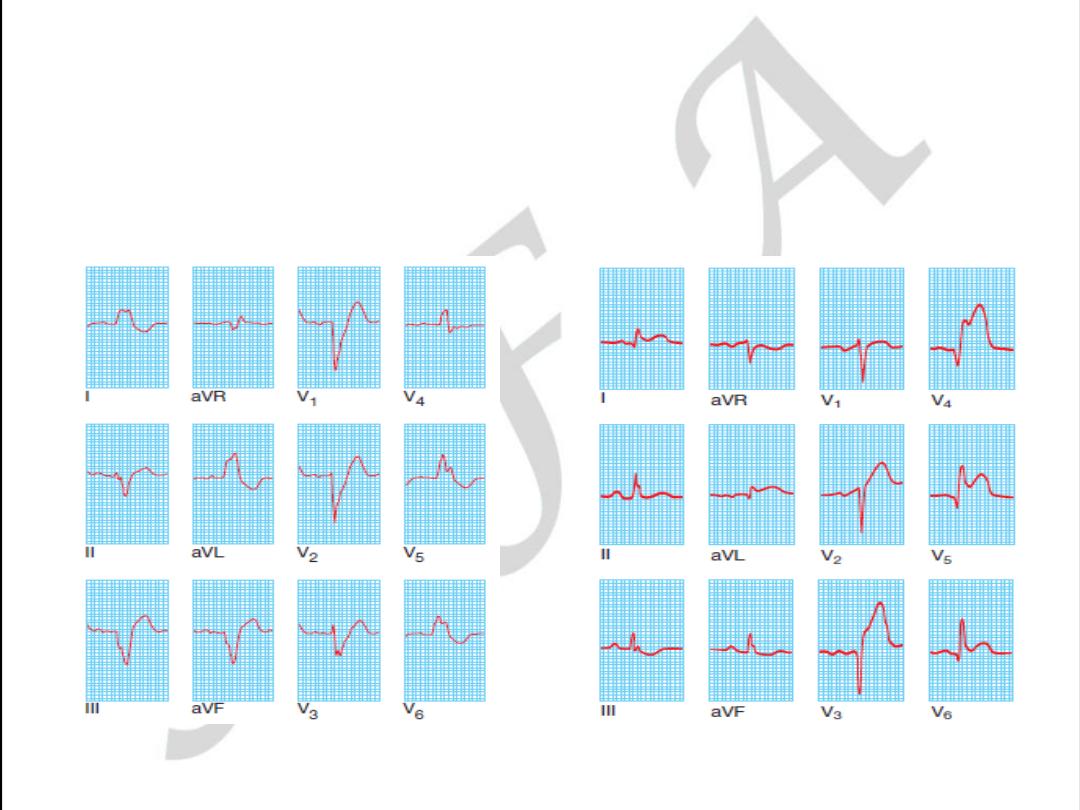

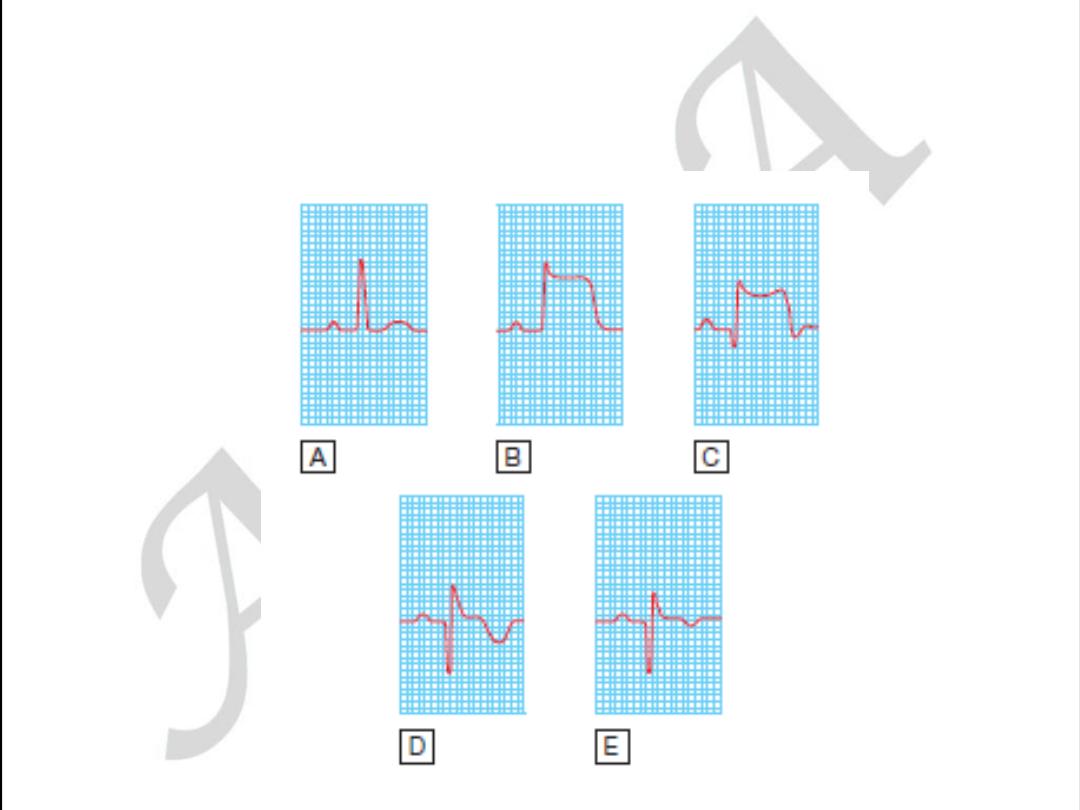

LEFT BANDLE BRANCH BLOCK

ANT.WALL STEMI

Presentation

• Chest pain is usually similar in nature to angina, but of greater severity

and longer duration and is

not

relieved by sublingual (SL) nitroglycerin.

Associated features are nausea and vomiting, sweating, breathlessness,

and extreme distress.

• The pain may be atypical (e.g., epigastric) or radiate to the back.

• Diabetics, elderly, women, or hypertensive patients may suffer painless

(“silent” infarcts) and/or atypical infarction. Presenting features

include breathlessness from acute pulmonary edema, syncope or coma

from arrhythmias, acute confusional states (mania/psychosis), diabetic

hyperglycemic crises, hypotension or cardiogenic shock, central nervous

system (CNS) manifestations resembling stroke secondary to sudden

reduction in cardiac output, and peripheral embolization.

STEMI: diagnosis

• STEMI diagnosis is based on a combination of

history, ECG, and biochemical markers of

cardiac injury.

• In practice, history and ECG changes are

diagnostic.

• Biochemical markers of cardiac injury usually

become available later and help reconfirm the

diagnosis and provide prognostic information

(magnitude of rise).

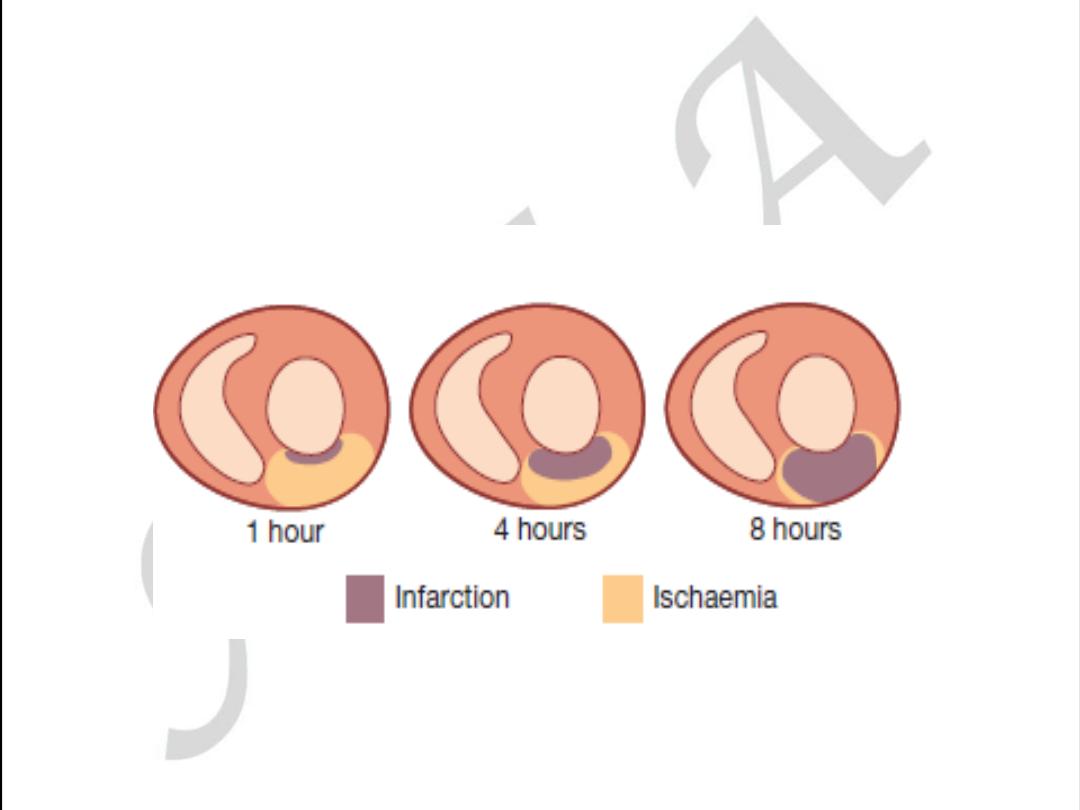

-- Aspects of Diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction by Different Techniques

Pathology

Myocardial cell death

Biochemistry

Markers of myocardial cell death recovered from blood samples

Electrocardiography Evidence of myocardial ischemia (ST and T wave abnormalities)

Evidence of loss of electrically functioning cardiac tissue (Q

waves)

Imaging

Reduction or loss of tissue perfusion

Cardiac wall motion abnormalities

Revised Definition of Myocardial Infarction (MI)

Criteria for Acute, Evolving, or Recent MI

Either of the following criteria satisfies the diagnosis for acute, evolving, or recent MI:

1. Typical rise and/or fall of biochemical markers of myocardial necrosis with at

least one of the following:

a) Ischemic symptoms

b) Development of pathological Q waves in the ECG

c) ECG changes indicative of ischemia (ST segment elevation or

depression)

d) Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional

wall motion abnormality

2. Pathological findings of an acute myocardial infarction

Criteria for Healing or Healed Myocardial Infarction

Any one of the following criteria satisfies the diagnosis for healing or healed myocardial

infarction:

1. Development of new pathological Q waves in serial ECGs. The patient may or

may not remember previous symptoms. Biochemical markers of myocardial

necrosis may have normalized depending on the length of time that has passed

since the infarction developed.

2. Pathological findings of a healed or healing infarction

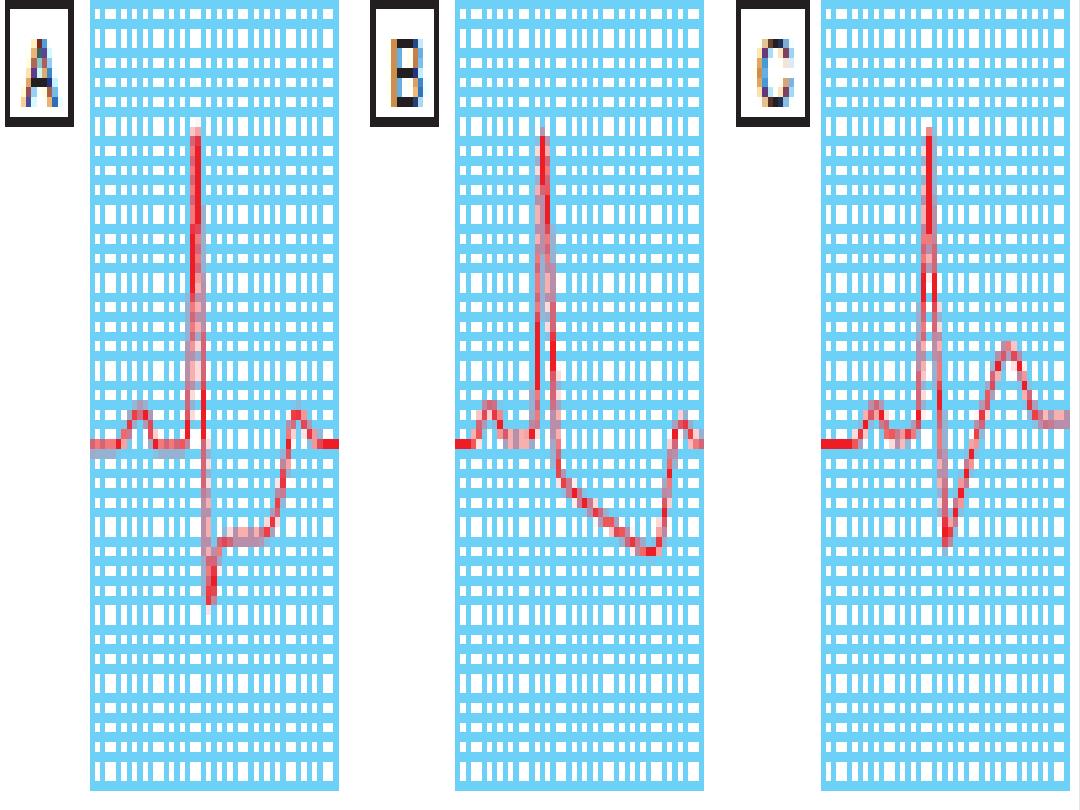

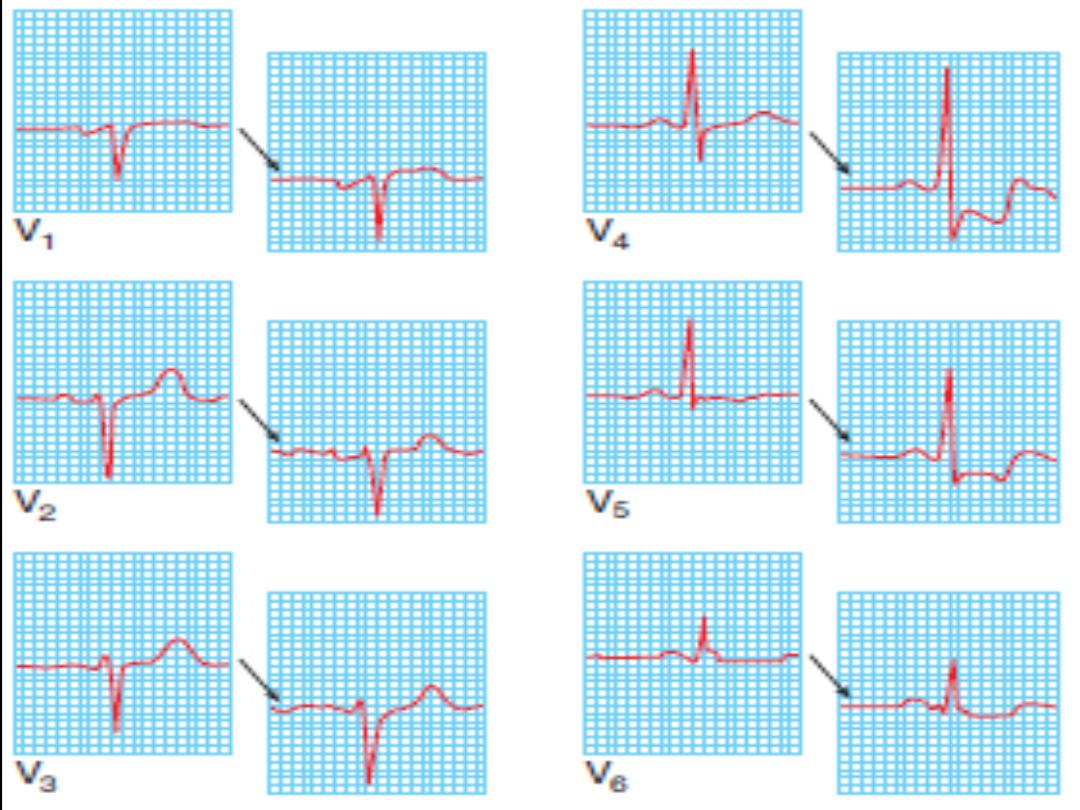

ECG changes

ST-segment elevation

occurs within minutes and may last for up to

2 weeks. ST elevation of 2 mm in adjacent chest leads and 1 mm in

adjacent limb leads is necessary to fulfill thrombolysis criteria. Persisting

ST elevation after 1 month suggests formation of LV aneurysm.

Pathological Q waves

indicate significant abnormal electrical

conduction but are not synonymous with irreversible myocardial

damage. In the context of a “transmural infarction” the Q waves may

take hours or days to develop and usually remain indefinitely. In the

standard leads, the Q wave should be 25% of the R wave, 0.04 s in

duration, with negative T waves. In the precordial leads, Q waves in V4

should be >0.4 mV (4 small sq) and in V6 >0.2 mV (2 small sq), in the

absence of LBBB (QRS width <0.1 s or 3 small sq).

ST-segment depression in a second territory

(in patients with

ST-segment elevation) is secondary to ischemia in a territory other

than the area of infarction (often indicative of multivessel disease) or

reciprocal electrical phenomena. Overall, it implies a poorer prognosis.

T-wave inversion

may be immediate or delayed and generally persists after

the ST elevation has resolved.

Anterior

ST elevation and/or Q waves in V1–V4/V5

Anterseptal

ST elevation and/or Q waves in V1–V3

Lateral

ST elevation and/or Q waves in V5–V6 and T-wave

inversion/ST elevation/Q waves in I and aVL

Inferoseptal

ST elevation and/or Q waves in II, III, aVF, and 5–V6

(sometimes I and aVL)

True posterior

Tall R waves in V1–V2 with ST depression in V1–V3. T

waves remain upright in V1–V2. This can be confirmed with an esophageal

lead if available (method similar to an NG tube). This usually occurs in

conjunction with an inferior or lateral infarct

RV infarction ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads (V3R–

V4R). Usually found in conjunction with inferior infarction. This may only

be present in the early hours of infarction

Localization of infarcts from ECG

changes

Conditions that may mimic ECG

changes of a STEMI

• Left or right ventricular hypertrophy

• LBBB or left anterior fascicular block

• Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome

• Pericarditis or myocarditis

• Cardiomyopathy (hypertrophic or dilated)

• Trauma to myocardium

• Cardiac tumors (primary and metastatic)

• Pulmonary embolus

• Pneumothorax

• Intracranial hemorrhage

• Hyperkalemia

• Cardiac sarcoid or amyloid

• Pancreatitis

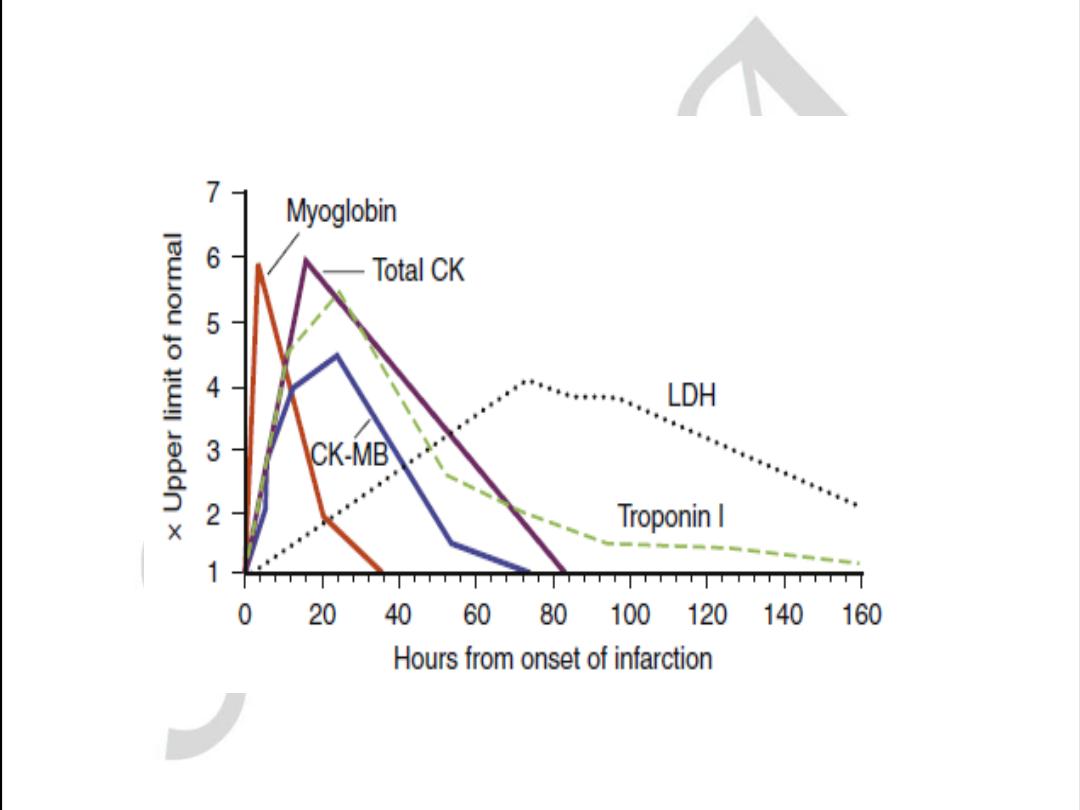

Biochemical markers of cardiac

injury

CK (creatine kinase)

• Levels

twice the upper limit of normal

are considered abnormal.

• Serum levels rise within 4–8 hours post-STEMI and fall to normal within 3–4

days. The peak level occurs at about 24 hours but may be earlier (12 hours)

and higher in patients who have had reperfusion (thrombolysis or

percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]).

• False-positive rates of ~15% occur in patients with alcohol intoxication, muscle

disease or trauma, vigorous exercise, convulsions, IM injections,

hypothyroidism, pulmonary embolism (PE), and thoracic outlet

syndrome.

CK-MB isoenzyme

is more specific for myocardial disease. Levels may be

elevated despite a normal total CK. However, CK-MB is also present in

small quantities in other tissues (skeletal muscle, tongue, diaphragm,

uterus, and prostate) and trauma or surgery may lead to false-positive

results. If there is doubt about myocardial injury with CK-MB levels

obtained, a cardiac troponin must be measured.

Cardiac troponins ( Tn T ,Tn I

)

•

Both TnT and TnI are highly sensitive and speci

fic markers of cardiac injury.

•

Serum levels start to rise by 3 hours post-MI and elevation may persist up to 7

–14 days. This is

advantageous for diagnosis

of late MI.

•

In most STEMI cases, the diagnosis can be made using a combination of the clinical picture

and serial CK/CK-MB levels.

In the event of normal CK-MB levels and suspected noncardiac

sources of CK,

troponins can be used.

•

Troponins can also be elevated

in non ischemic

myocyte damage, such as myocarditis,

cardiomyopathy, and pericarditis

.

Other markers

There are multiple other markers, but with increasing clinical availability of Troponin,

measurements of these markers are not recommended. These include aspartamine

transferase (AST) (rise 18–36 hours post-MI) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (rise 24–36

hours post-MI).

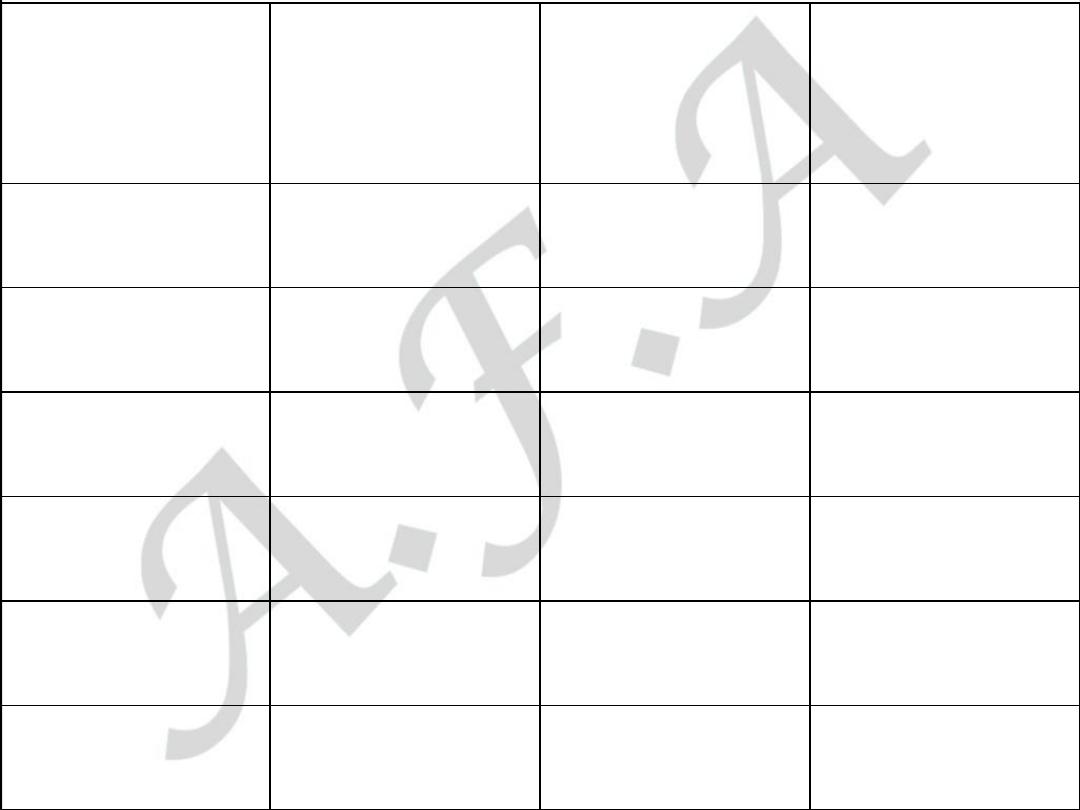

Biomarker

Begins to rise

Peak value

Returns to

normal

Myoglobin

1-2 hours

6-8 hours

1-2 days

CK-MB

2-6 hours

16-20 hours

1-2 days

CK

4-8 hours

16-24 hours

3-4 days

Trop T

4-6 hours

12-24 hours

7-10 days

AST

12-24 hours

36-48 hours

3-4 days

LDH

24-48 hours

72 hours

8-10 days

Factors associated with a poor

prognosis

• Age >70 years

• Previous MI or chronic stable angina

• Anterior MI or right ventricular infarction

• Left ventricular failure at presentation

• Hypotension (and sinus tachycardia) at

presentation

• Diabetes mellitus

• Mitral regurgitation (acute)

• Ventricular septal defect

Mention 3 differences between

unstable angina and myocardial

infarction.

Treatment of STEMI

All patients with STEMI should be admitted to an intensive care unit

(ICU), e.g., coronary ICU (CICU).

Stabilizing measures

are generally similar for all ACS patients.

• All patients with suspected STEMI should have continuous ECG

monitoring in an area with full resuscitation facilities.

• Patients should receive immediate aspirin 325 mg po (if no

contraindications), analgesia, and oxygen. Secure IV access.

• Conduct rapid examination to exclude hypotension, note the

presence of murmurs, and identify and treat acute pulmonary

edema.

Right ventricular failure (RVF) out of proportion to left ventricular

failure (LVF) suggests RV infarction.

Diagnosis

is normally made on presentation (history and ECG changes of ST –

elevation /new LBBBB )followed by

rapid stabilizing measures to

ensure institution

of

reperfusion therapy

without delay.

This is in contrast to NSTEMI/UA, where diagnosis may evolve over a period of

24–72 hours. (Reperfusion must not be delayed to wait for biochemical markers.)

Control of cardiac pain

•

Morphine

2.5

–10 mg IV is the drug of choice and may be repeated

to ensure adequate pain relief, unless there is evidence of emerging

toxicity (hypotension, respiratory depression). Nausea and vomiting

should be treated with metoclopramide (10 mg IV) or a phenothiazine.

•

Oxygen

should be administered at 2

–5 L/min for at least 2–3 hours.

Hypoxemia is frequently seen post-MI due to ventilation

–perfusion

abnormalities secondary to LVF. In patients with refractory pulmonary

edema, endotracheal intubation may be necessary. Beware of CO2

retention in patients with COPD.

•

Nitrates

may lessen pain and can be given (sublingual or IV) provided

that the patient is not hypotensive. These drugs should be used

cautiously in inferior STEMI, especially with right ventricular infarction,

as venodilation may decrease RV

filling and precipitate hypotension.

Nitrate therapy has no demonstrated effect on mortality (ISIS-4).

Correction of electrolytes

Both low potassium and low magnesium may be arrhythmogenic and must

be supplemented, especially in the context of arrhythmias.

Strategies to limit infarct size

B-Blockade

Early B-blockade has been shown to be beneficial by limiting infarct size,

reducing mortality, and decreasing early malignant arrhythmias.

All patients (including primary PCI and thrombolysis patients) should have

early B-blockade.

Patients with the following features may benefit most from B-blocker therapy:

• Hyperdynamic state (sinus tachycardia, hypertensive)

• Ongoing or recurrent pain or reinfarction

• Tachyarrhythmias such as AF

Use a short-acting agent IV initially (metoprolol 5 mg at a time repeated at

5-minute intervals to a maximum dose of 15 mg) under continuous ECG

and BP monitoring. Aim for a HR of 60 beats per minute (bpm) and SBP

100–110 mmHg. If hemodynamic stability continues 15–30 minutes after

the last IV dose, start metoprolol 50 mg po bid. Esmolol is an ultra-short

acting IV B-blocker, which may be tried if there is concern whether the

patient will tolerate B-blockers.

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO THE USE OF B- BLOCKERS

Absolute contraindications:

heart rate (HR) <50, systolic blood

pressure (SBP) <90 mmHg, moderate to severe heart failure, AV

conduction defect, severe airways disease.

Relative contraindications

: asthma, current use of calcium

channel blocker and/or B-blocker, severe peripheral vascular

disease with critical limb ischemia, large inferior MI involving the

right ventricle.

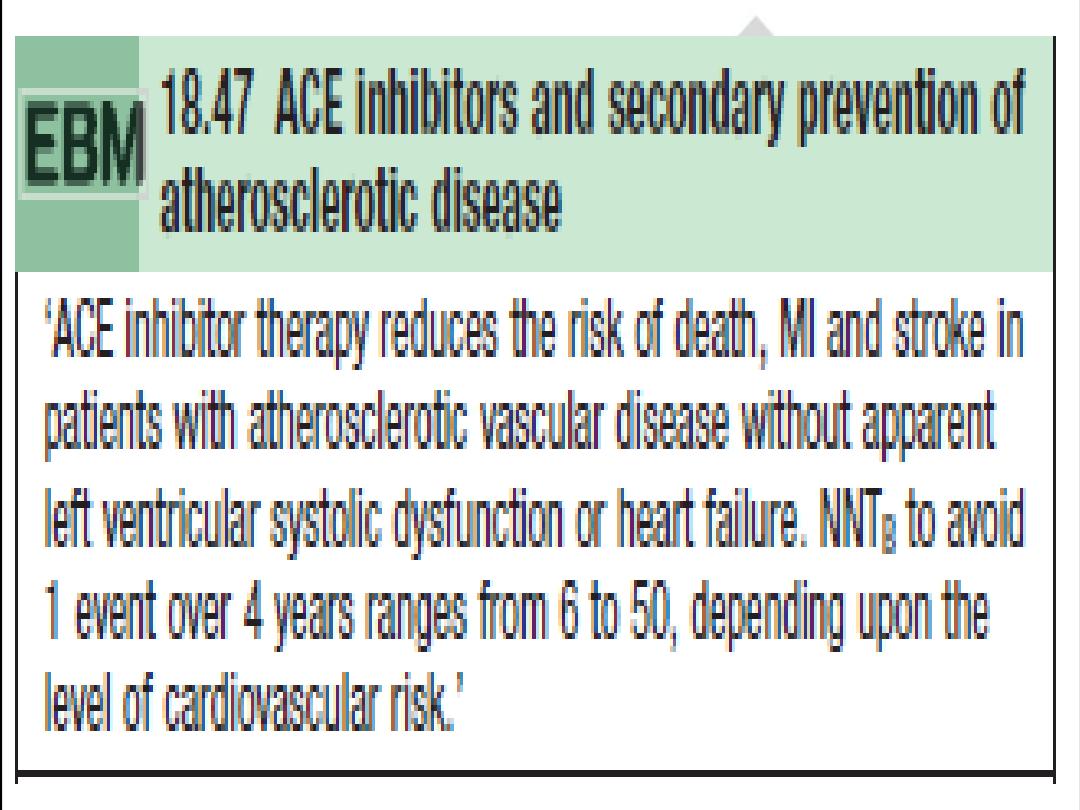

ACE inhibitors

After receiving aspirin, B-blockade (if appropriate), and reperfusion, all

patients with STEMI/LBBB infarction should receive an ACE inhibitor

within the

first 24 hours of presentation.

•

Patients with high risk or large infarcts, particularly with an

anterior STEMI, a previous MI, heart failure, and impaired LV

function on imaging

, will bene

fit most.

•

The effect of ACE inhibitors appears to be a class effect; therefore,

one may use the drug that the physician is familiar with.

Assessment of Reperfusion Options for STEMI Patients

Step 1: Assess time and risk.

• Time since onset of symptoms

• Risk of STEMI

• Risk of fibrinolysis

• Time required for transport to a skilled PCI laboratory

Step 2: Determine if fibrinolysis or invasive strategy is preferred.

• If presentation is <3 hr and there is no delay to an invasive strateg y, there is no

preference for either strategy.

Fibrinolysis is generally preferred if:

• Early presentation (≤3 hr from symptom onset and delay to invasive strategy)

• Invasive strategy is not an option

• Catheterization laboratory occupied or not available

• Vascular access difficulties

• Lack of access to a skilled PCI laboratory

[*][†]

• Delay to invasive strategy

• Prolonged transport

• (Door-to-Balloon)–(Door-to-Needle) more than 1 hr

[‡][§]

• Medical contact-to-balloon or door-to-balloon more than 90 min

Reperfusion therapy (thrombolysis)

Indications for thrombolysis

•

Typical history of cardiac pain within previous 12 hours and ST elevation in two

contiguous ECG leads (>1 mm in limb leads or >2 mm in V1

–V6).

•

Cardiac pain with newly presumed LBBB on ECG.

•

If ECG is equivocal on arrival, repeat at 15- to 30-minute intervals to monitor

progression.

•

Thrombolysis

should not

be given if the ECG is normal or if there is isolated ST

depression (true posterior infarct must be excluded).

Timing of thrombolysis

•

Greatest bene

fit is achieved with early thrombolysis (especially if given within 1

1/2 hours(90min.s) of onset of

first pain.

•

Patients presenting between 12 and 24 hours from onset of pain

should undergo

thrombolysis only with persisting symptoms and ST-segment elevation.

•

Elderly patients (>65 years) presenting within the 12- to 24-hour time period with

symptoms are best managed by primary PCI, as thrombolysis has been

demonstrated to result in increased incidence

of cardiac rupture

.

Choice of thrombolytic agent

•

This is partly determined by each center

’s local thrombolysis strategy.

•

Allergic reactions and episodes of hypotension are greater with streptokinase (SK).

•

Bolus agents are easier and quicker to administer, with a decrease in drug errors in

comparison to

first-generation infusions.

•

Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rtPA) has a greater reperfusion

capacity and a marginally higher 30-day survival bene

fit than that of SK, but this

agent has been associated with an increased risk of

hemorrhage

.

•

More recent rtPA derivatives have demonstrated a higher 90-minute TIMI-III

(coronary reperfusion scale)

flow rate, but have shown similar 30-day mortality

bene

fits to those with rtPA.

•

An rtPA derivative (rather than SK) should be considered for any patient with any of

the following:

• Large anterior MI, especially if within 4 hours of onset

• Previous SK therapy or recent streptococcal infection (as this has been shown to

be a risk factor for allergic reactions to SK)

• Hypotension (systolic BP <100 mmHg)

• Low risk of stroke (age <55 years, systolic BP <144 mmHg)

• Reinfarction during hospitalization where immediate PCI facilities are not

available

Doses and administration of thrombolytic agents

Streptokinase (SK)

•

Give as 1.5 million units in 100 mL normal saline IV over 1 hour.

•

There is no indication for routine heparinization after SK; there is no clear mortality

bene

fit and there is a small increase in risk of hemorrhage.

Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rtPA, alteplase)

•

The GUSTO trial suggested that the

“front-loaded” or accelerated rtPA is the most

effective dosage regimen.

•

Give 15 mg bolus IV then 0.75 mg/kg over 30 minutes (not to exceed 50 mg), then

0.5 mg/kg over 60 minutes (not to exceed 35 mg).

•

This should be followed by IV heparin

.

Reteplase

•

Give two IV bolus doses of 10 units 10 minutes apart.

Tenectaplase

•

Give as injection over 10 seconds at 30

–50 mg according to body weight (500–600

µg/kg). Maximum dose is 50 mg.

APSAC (anistreplase)

•

Give as an IV bolus of 30 mg over 2

–5 minutes.

Complications of thrombolysis

• Bleeding is seen in up to 10% of patients. Most incidents are minor and at

sites of vascular puncture. Local pressure is generally sufficient to stop this

bleeding but occasionally transfusion may be required. In extreme cases,

SK may be reversed by tranexamic acid (10 mg/kg slow

IV infusion).

• Hypotension during the infusion is common with SK. Treatment consists of

placing the patient in a supine position and slowing/stopping infusion

until the blood pressure rises. Treatment with cautious (100–500 mL) fluid

challenges may be required, especially in inferior/ RV infarction.

Hypotension is not necessarily evidence of an allergic reaction and may

not warrant treatment as such.

• Allergic reactions are common with SK and include a low-grade fever, rash,

nausea, headaches, flushing, and, rarely (0.1%), anaphylaxis. Give

hydrocortisone 100 mg IV with chlorpheniramine 10 mg IV.

• Intracranial hemorrhage is seen in ~0.3% of patients treated with SK and in

~0.6% with rtPA.

• Reperfusion arrhythmias (most commonly a short, self-limiting run of

idioventricular rhythm) may occur.

• Systemic embolization may occur from lysis of thrombus within the left

atrium, LV, or aortic aneurysm.

Contraindications to thrombolysis

Absolute contraindications to thrombolysis

Active internal bleeding

Suspected aortic dissection

Recent head trauma and/or intracranial

neoplasm

Previous hemorrhagic stroke at any time

Previous ischemic stroke within the past

1 year

Previous allergic reaction to fibrinolytic

agents

Trauma and/or surgery within past 2

weeks at risk of bleeding

Relative contraindications to thrombolysis

Trauma and/or surgery more than 2

weeks previously

Severe uncontrolled hypertension (BP

>180/110)

Nonhemorrhagic stroke over 1 year ago

Known bleeding diathesis or current use

of anticoagulation within therapeutic

range (INR 2)

Prolonged (>10 minutes)

cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Prior exposure to SK (if planning to give

SK, especially previous 6–9 months)

Pregnancy or postpartum Lumbar

puncture within previous 1 month

Menstrual bleeding or lactation

History of chronic severe hypertension

Non compressible vascular punctures

(e.g., subclavian central venous lines)

Reperfusion by primary PCI

Primary PCI is the current gold-standard reperfusion

strategy for treatment of STEMI.

Indication for primary PCI

• All patients with chest pain and ST-segment elevation or

new LBBB fulfill primary PCI criteria (compare with

indications for thrombolysis).

• This includes a group of patients in whom ST-segment

elevation may not fulfill all criteria for thrombolysis.

• In general, patients in whom thrombolysis is

contraindicated should be managed by primary PCI.

Outcome in primary PCI

• A superior outcome in patients with STEMI who are treated with primary PCI in

comparison to outcomes with thrombolysis.

• There is a significant short-term, as well as long-term, reduction in mortality and

major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (death, nonfatal reinfarction, and nonfatal

stroke) in STEMI patients treated with primary PCI, with better LV function, a higher

vessel patency rate, and less recurrent myocardial ischemia.

• Interhospital transportation for primary PCI (community hospital to invasive center)

is safe, and primary PCI remains superior to thrombolysis despite the time delays

involved.

It is generally accepted that in the acute phase only the “culprit” lesion(s) and vessel(s)

will be treated. The pattern of disease in the remainder of the vessels will determine

whether further revascularization should be performed as an inpatient or an elective

case in the future.

• STEMI patients treated with uncomplicated primary PCI can often be discharged

safely within 72 hours of admission without the need for further risk stratification.

• Primary PCI is more cost-effective in the long term than thrombolysis with significant

savings from fewer days in the hospital, less need for readmission, and less heart

failure.

• Post-discharge care, secondary prevention, and rehabilitation remain identical to

that for other MI cases.

Rescue PCI

Rescue PCI may be performed as an adjunct to thrombolysis but should

be reserved

for patients who remain symptomatic post-thrombolysis

failure to reperfuse) or

develop cardiogenic shock. We recommend

that all patients who continue to have

post-thrombolysis symptoms

and/or ongoing ST-elevation with or without symptoms

be discussed

with the local invasive cardiac center for urgent catheterization and

revascularization.

Surgery for acute STEMI

CABG in the context of an acute STEMI is of value in the following

situations:

•

High-risk coronary anatomy on catheterization (left main stenosis, left anterior

descending [LAD] ostial disease).

•

Complicated STEMI (acute mitral regurgitation, or ventricular rupture)

•

STEMI patients (with or without successful thrombolysis) with additional coronary

lesions whose anatomy is best served by CABG on prior or subsequent

catheterization

STEMI: additional measures

Low-molecular-weight and unfractionated heparin

UFH

•

There is no indication for

“routine” IV heparin following SK.

•

IV heparin (4000 U/max IV bolus followed by 1000 U/hr max adjustedf or an aPTT ratio of 1.5

–2.0 times control)

should be used routinely following rtPA and its derivatives for 24

–48 hours.

LMWH

•

There is clinical trial data supporting the use of LMWH and thrombolysis (e.g., enoxaparin 30 mg IV bolus, then 1

mg/kg SC q12h).

•

As an alternative to UFH, LMWH can be used at a prophylactic dose to prevent thromboembolic events in high-risk

patients.

Clopidogrel

Calcium antagonists

•

This should be administered to all patients undergoing primary PCI (loading dose 300

–600 mg po followed by 75 mg

qd).

•

The length of therapy is determined by the type of stent used. Drug eluting stents require longer term use of

clopidogrel than bare-metal stents (current guidelines for ACS is 1 year of Plavix).

•

These are best avoided, especially in the presence of LV impairment.

•

Diltiazem and verapamil started after day 4

–5 in post-MI patients with normal LV function may have a small

bene

ficial effect.

•

Amlodipine is safe to use in patients with poor LV function post-MI.

•

Nifedipine has been shown to increase mortality and should be avoided.

The End