11/18/2015

Diseases of the heart valves | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%224a6b4f8391bb4f3983c7800b37c50522%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-famil

… 1/9

Rheumatic heart disease

Acute rheumatic fever

Incidence and pathogenesis

Acute rheumatic fever usually affects children (most commonly between 5 and 15 years) or young adults, and has

become very rare in Western Europe and North America. However, it remains endemic in parts of Asia, Africa and

South America, with an annual incidence in some countries of more than 100 per 100 000, and is the most common

cause of acquired heart disease in childhood and adolescence.

The condition is triggered by an immune-mediated delayed response to infection with specific strains of group A

streptococci, which have antigens that may cross-react with cardiac myosin and sarcolemmal membrane protein.

Antibodies produced against the streptococcal antigens cause inflammation in the endocardium, myocardium and

pericardium, as well as the joints and skin. Histologically, fibrinoid degeneration is seen in the collagen of connective

tissues. Aschoff nodules are pathognomonic and occur only in the heart. They are composed of multinucleated giant

cells surrounded by macrophages and T lymphocytes, and are not seen until the subacute or chronic phases of

rheumatic carditis.

Clinical features

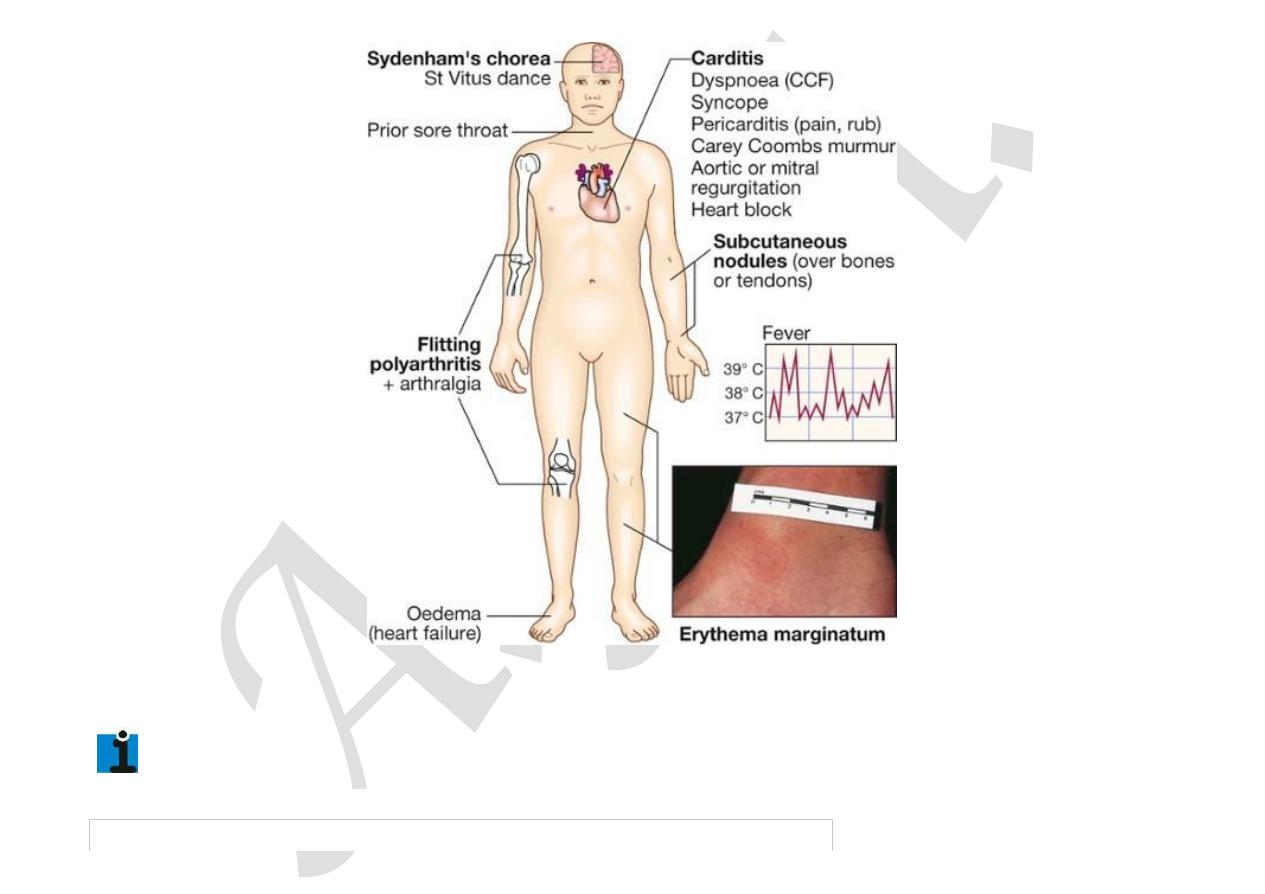

Acute rheumatic fever is a multisystem disorder that usually presents with fever, anorexia, lethargy and joint pain,

2–3 weeks after an episode of streptococcal pharyngitis. There may, however, be no history of sore throat. Arthritis

occurs in approximately 75% of patients. Other features include rashes, carditis and neurological changes (

Fig.

18.86

). The diagnosis, made using the revised Jones criteria (

Box 18.96

), is based upon two or

11/18/2015

Diseases of the heart valves | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%224a6b4f8391bb4f3983c7800b37c50522%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-famil

… 2/9

more major manifestations, or one major and two or more minor manifestations, along with evidence of preceding

streptococcal infection. Only about 25% of patients will have a positive culture for group A streptococcus at the

time of diagnosis because there is a latent period between infection and presentation. Serological evidence of

recent infection with a raised antistreptolysin O (ASO) antibody titre is helpful. A presumptive diagnosis of acute

rheumatic fever can be made without evidence of preceding streptococcal infection in cases of isolated chorea or

pancarditis, if other causes for these have been excluded. In cases of established rheumatic heart disease or prior

rheumatic fever, a diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever can be made based only on the presence of multiple minor

criteria and evidence of preceding group A streptococcal pharyngitis.

11/18/2015

Diseases of the heart valves | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%224a6b4f8391bb4f3983c7800b37c50522%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-famil

… 3/9

F I G .

1 8 . 8 6

Clinical features of rheumatic fever. Bold labels indicate Jones major criteria …

18.96 Jones criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever

11/18/2015

Diseases of the heart valves | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%224a6b4f8391bb4f3983c7800b37c50522%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-famil

… 4/9

Major manifestations

•

Carditis

•

Polyarthritis

•

Chorea

•

Erythema marginatum

•

Subcutaneous nodules

Minor manifestations

•

Fever

•

Arthralgia

•

Previous rheumatic fever

•

Raised ESR or CRP

•

Leucocytosis

•

First-degree AV block

Plus

•

Supporting evidence of preceding streptococcal infection: recent

scarlet fever, raised antistreptolysin O or other streptococcal

antibody titre, positive throat culture

N.B. Evidence of recent streptococcal infection is particularly important if there is only one

major manifestation.

Carditis

A ‘pancarditis’ involves the endocardium, myocardium and pericardium to varying degrees. Its incidence declines

with increasing age, ranging from 90% at 3 years to around 30% in adolescence. It may manifest as breathlessness

(due to heart failure or pericardial effusion), palpitations or chest pain (usually due to pericarditis or pancarditis).

Other features include tachycardia, cardiac enlargement and new or changed murmurs. A soft systolic murmur due

to mitral regurgitation is very common. A soft mid-diastolic murmur (the Carey Coombs

11/18/2015

Diseases of the heart valves | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%224a6b4f8391bb4f3983c7800b37c50522%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-famil

… 5/9

murmur) is typically due to valvulitis, with nodules forming on the mitral valve leaflets. Aortic regurgitation occurs

in 50% of cases but the tricuspid and pulmonary valves are rarely involved. Pericarditis may cause chest pain, a

pericardial friction rub and precordial tenderness. Cardiac failure may be due to myocardial dysfunction or valvular

regurgitation. ECG changes commonly include ST and T wave changes. Conduction defects sometimes occur and

may cause syncope.

Arthritis

This is the most common major manifestation and occurs early when streptococcal antibody titres are high. An

acute painful asymmetric and migratory inflammation of the large joints typically affects the knees, ankles,

elbows and wrists. The joints are involved in quick succession and are usually red, swollen and tender for between

a day and 4 weeks. The pain characteristically responds to aspirin; if not, the diagnosis is in doubt.

Skin lesions

Erythema marginatum occurs in less than 5% of patients. The lesions start as red macules that fade in the centre

but remain red at the edges, and occur mainly on the trunk and proximal extremities but not the face. The resulting

red rings or ‘margins’ may coalesce or overlap (see

Fig. 18.86

). Subcutaneous nodules occur in 5–7% of patients.

They are small (0.5–2.0 cm), firm and painless, and are best felt over extensor surfaces of bone or tendons. They

typically appear more than 3 weeks after the onset of other manifestations and therefore help to confirm rather

than make the diagnosis. Other systemic manifestations are rare but include pleurisy, pleural effusion and

pneumonia.

Sydenham’s chorea (St Vitus dance)

This is a late neurological manifestation that appears at least 3 months after the episode of acute rheumatic fever,

when all the other signs may have disappeared. It occurs in up to one-third of cases and is more common in females.

Emotional lability may be the first feature and is typically followed by purposeless, involuntary,

11/18/2015

Diseases of the heart valves | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%224a6b4f8391bb4f3983c7800b37c50522%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-famil

… 6/9

choreiform movements of the hands, feet or face. Speech may be explosive and halting. Spontaneous recovery

usually occurs within a few months. Approximately one-quarter of affected patients will go on to develop chronic

rheumatic valve disease.

Investigations

The ESR and CRP are useful for monitoring progress of the disease (

Box 18.97

). Positive throat swab cultures

are obtained in only 10–25% of cases. ASO titres are normal in one-fifth of adult cases of rheumatic fever and most

cases of chorea. Echocardiography typically shows mitral regurgitation with dilatation of the mitral annulus and

prolapse of the anterior mitral leaflet, and may also show aortic regurgitation and pericardial effusion.

18.97 Investigations in acute rheumatic fever

Evidence of a systemic illness (non-specific)

•

Leucocytosis, raised ESR and CRP

Evidence of preceding streptococcal infection (specific)

•

Throat swab culture: group A β-haemolytic streptococci (also from family members and

contacts)

•

Antistreptolysin O antibodies (ASO titres): rising titres, or levels of > 200 U (adults) or >

300 U (children)

Evidence of carditis

11/18/2015

Diseases of the heart valves | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%224a6b4f8391bb4f3983c7800b37c50522%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-famil

… 7/9

•

Chest X-ray: cardiomegaly; pulmonary congestion

•

ECG: first- and rarely second-degree AV block; features of pericarditis; T-wave inversion;

reduction in QRS voltages

•

Echocardiography: cardiac dilatation and valve abnormalities

Management of the acute attack

A single dose of benzyl penicillin (1.2 million U IM) or oral phenoxymethylpenicillin (250 mg 4 times daily for 10

days) should be given on diagnosis to eliminate any residual streptococcal infection. If the patient is penicillin-

allergic, erythromycin or a cephalosporin can be used. Treatment is then directed towards limiting cardiac damage

and relieving symptoms.

Bed rest and supportive therapy

Bed rest is important, as it lessens joint pain and reduces cardiac workload. The duration should be guided by

symptoms, along with temperature, leucocyte count and ESR, and should be continued until these have settled.

Patients can then return to normal physical activity but strenuous exercise should be avoided in those who have

had carditis.

Cardiac failure should be treated as necessary. Some patients, particularly those in early adolescence, develop a

fulminant form of the disease with severe mitral regurgitation and, sometimes, concomitant aortic regurgitation.

If heart failure in these cases does not respond to medical treatment, valve replacement may be necessary and is

often associated with a dramatic decline in rheumatic activity. AV block is seldom progressive and pacemaker

insertion rarely needed.

Aspirin

11/18/2015

Diseases of the heart valves | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%224a6b4f8391bb4f3983c7800b37c50522%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-famil

… 8/9

This usually relieves the symptoms of arthritis rapidly and a response within 24 hours helps confirm the diagnosis.

A reasonable starting dose is 60 mg/kg body weight/day, divided into six doses. In adults, 100 mg/kg per day may

be needed up to the limits of tolerance or a maximum of 8 g per day. Mild toxicity includes nausea, tinnitus and

deafness; vomiting, tachypnoea and acidosis are more serious. Aspirin should be continued until the ESR has fallen,

and then gradually tailed off.

Corticosteroids

These produce more rapid symptomatic relief than aspirin and are indicated in cases with carditis or severe

arthritis. There is no evidence that long-term steroids are beneficial. Prednisolone (1.0–2.0 mg/kg per day in

divided doses) should be continued until the ESR is normal, and then tailed off.

Secondary prevention

Patients are susceptible to further attacks of rheumatic fever if another streptococcal infection occurs, and long-

term prophylaxis with penicillin should be given as benzathine penicillin (1.2 million U IM monthly), if compliance

is in doubt, or oral phenoxymethylpenicillin (250 mg twice daily). Sulfadiazine or erythromycin may be used if the

patient is allergic to penicillin; sulphonamides prevent infection but are not effective in the eradication of group

A streptococci. Further attacks of rheumatic fever are unusual after the age of 21, when treatment may be stopped.

However, it should be extended if an attack has occurred in the last 5 years, or if the patient lives in an area of

high prevalence or has an occupation (e.g. teaching) with high exposure to streptococcal infection. In those with

residual heart disease, prophylaxis should continue until 10 years after the last episode or 40 years of age,

whichever is later. Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis prevents another attack of acute rheumatic fever but does not

protect against infective endocarditis.

Chronic rheumatic heart disease

Chronic valvular heart disease develops in at least half of those affected by rheumatic fever with carditis. Two-

11/18/2015

Diseases of the heart valves | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%224a6b4f8391bb4f3983c7800b37c50522%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-famil

… 9/9

thirds of cases occur in women. Some episodes of rheumatic fever pass unrecognised and it is only possible to

elicit a history of rheumatic fever or chorea in about half of all patients with chronic rheumatic heart disease.

The mitral valve is affected in more than 90% of cases; the aortic valve is the next most frequently involved,

followed by the tricuspid and then the pulmonary valve. Isolated mitral stenosis accounts for about 25% of all

cases, and an additional 40% have mixed mitral stenosis and regurgitation. Valve disease may be symptomatic

during fulminant forms of acute rheumatic fever but may remain asymptomatic for many years.

Pathology

The main pathological process in chronic rheumatic heart disease is progressive fibrosis. The heart valves are

predominantly affected but involvement of the pericardium and myocardium may contribute to heart failure and

conduction disorders. Fusion of the mitral valve commissures and shortening of the chordae tendineae may lead to

mitral stenosis with or without regurgitation. Similar changes in the aortic and tricuspid valves produce distortion

and rigidity of the cusps, leading to stenosis and regurgitation. Once a valve has been damaged, the

altered haemodynamic stresses perpetuate and extend the damage, even in the absence of a continuing rheumatic

process.