12/9/2015

Vascular disease | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of Medicine

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 1/10

)(

pa

ns

i

on

Thromb

u

s

C~'

Diseases of the aorta

Aneurysm, dissection and aortitis are the main pathologies (

Fig. 18.79

).

Diaph

r

agm

E

ABDOM

I

NAL

A

o

rt

i

c

an

e

ury

s

m

A

o

rt

ic

l l

regu

r

gi

t

a

tio

n

D

I

LAT

ED

T

H

OR

A

C

I

C

,

e

.

g

.

Marian

'

s

Aort

ic

d

i

s

s

e

c

tio

n

SACC

U

LAR THORACIC,

e

.

g

.

atheroma

t

o

u

s,

syp

h

ilitic

(

Typ

e

A

)

N

eurolog

i

ca

l

-

•

defici

t

•

(

Ty

pe B

)

11

12/9/2015

Vascular disease | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of Medicine

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 2/10

on

J

I

..,,; I

Aortic

regurgitat

i

Re

n

al

or

m

esent

eric

/

occl

u

s

io

n

"-

c:

---'

----

=

loss o

f

leg

pu

lse

[

B

F I G.

1 8 . 7 9

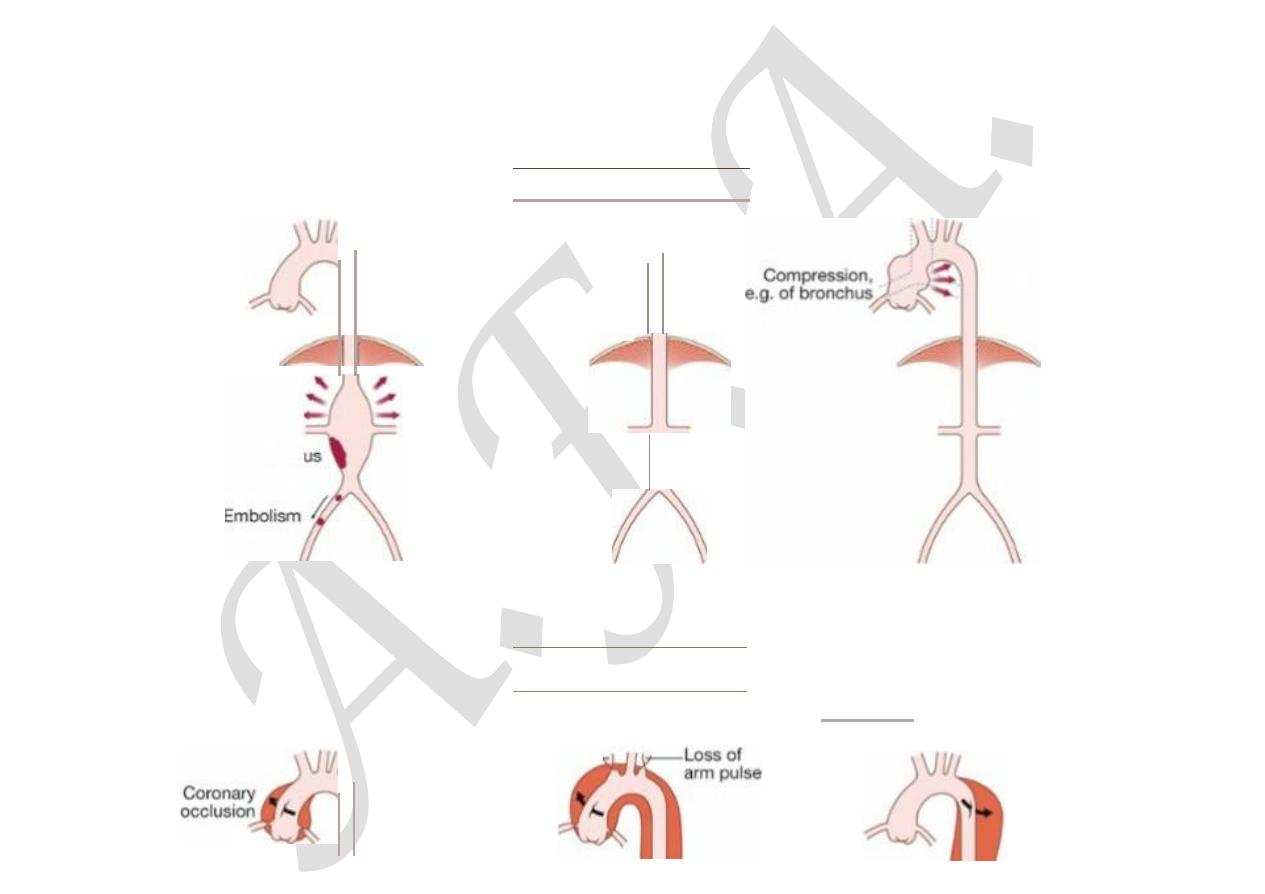

Types of aortic disease and their complications. A Types of aortic aneurysm. B Types of a…

Aortic aneurysm

This is an abnormal dilatation of the aortic lumen; a true aneurysm involves all the layers of the wall, whereas a false aneurysm

does not.

Aetiology and types of aneurysm

Non-specific aneurysms

Why some patients develop occlusive vascular disease, some develop aneurysmal vascular disease and some develop both in

response to atherosclerosis risk factors remains unclear. Unlike occlusive disease, aneurysmal disease tends to run in families and

genetic factors are undoubtedly important. The most common site for ‘non-specific’ aneurysm formation is the infrarenal

abdominal aorta. The suprarenal abdominal aorta and a variable length of the descending thoracic aorta may be affected in 10–

20% of patients but the ascending aorta is usually spared.

Marfan’s syndrome

This disorder of connective tissue is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and is caused by mutations in thefibrillin gene on

chromosome 15. Affected systems include the skeleton (arachnodactyly, joint hypermobility, scoliosis, chest deformity and high

arched palate), the eyes (dislocation of the lens) and the cardiovascular system (aortic disease and mitral regurgitation).

Weakening of the aortic media leads to aortic root dilatation, regurgitation and dissection (see below). Pregnancy is particularly

12/9/2015

Vascular disease | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of Medicine

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 3/10

hazardous. Chest X-ray, echocardiography, MRI or CT may detect aortic dilatation at an early stage and can be used to monitor

the disease.

Treatment with β-blockers reduces the rate of aortic dilatation and the risk of rupture. Elective replacement of the ascending

aorta may be considered in patients with evidence of progressive aortic dilatation but carries a mortality of 5–10%.

Aortitis

Syphilis is a rare cause of aortitis that characteristically produces saccular aneurysms of the ascending aorta containing

calcification. Other rare conditions associated with aortitis include Takayasu’s disease (

p. 1116

), Reiter’s syndrome (

p.

1107

), giant cell arteritis and ankylosing spondylitis (

pp. 1105 and 1117

).

Thoracic aortic aneurysms

These may produce chest pain, aortic regurgitation, compressive symptoms such as stridor (trachea, bronchus) and hoarseness

(recurrent laryngeal nerve), and superior vena cava syndrome (see

Fig. 18.79A

). If they erode into adjacent structures, e.g.

aorto-oesophageal fistula, massive bleeding occurs.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are present in 5% of men aged over 60 years and 80% are confined to the infrarenal

segment. Men are affected three times more commonly than women. AAAs can present in a number of ways (

Box 18.82

). The

usual age at presentation is 65–75 years for elective presentations and 75–85 years for emergency presentations. Ultrasound is

the best way of establishing the diagnosis and of following up patients with asymptomatic aneurysms that are not yet large

enough to warrant surgical repair. CT provides more accurate information about the size and extent of the aneurysm, the

surrounding structures and whether there is any other intra-abdominal pathology. It is the standard pre-operative investigation

but is not suitable for surveillance because of cost and radiation dose.

18.82 Abdominal aortic aneurysm: common presentations

Incidental

12/9/2015

Vascular disease | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of Medicine

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 4/10

•

On physical examination, plain X-ray or, most commonly, abdominal ultrasound

•

Even large AAAs can be difficult to feel, so many remain undetected until they rupture

•

Studies are currently under way to determine whether screening will reduce the number of deaths from

rupture (see

Box 18.83

)

Pain

•

In the central abdomen, back, loin, iliac fossa or groin

Thromboembolic complications

•

Thrombus within the aneurysm sac may be a source of emboli to the lower limbs

•

Less commonly, the aorta may undergo thrombotic occlusion

Compression

•

Surrounding structures such as the duodenum (obstruction and vomiting) and the inferior vena cava

(oedema and deep vein thrombosis)

Rupture

•

Into the retroperitoneum, the peritoneal cavity or surrounding structures (most commonly the inferior

vena cava, leading to an aortocaval fistula)

Management.

Until an asymptomatic AAA has reached a maximum of 5.5 cm in diameter, the risks of surgery generally outweigh the risks of

rupture (

Box 18.83

). All symptomatic AAAs should be considered for repair, not only to rid the patient of symptoms but also

because pain often predates rupture. Distal embolisation is a strong indication for repair, regardless of size, because otherwise

limb loss is common. Most patients with a ruptured AAA do not survive to reach hospital, but if they do and surgery is thought to

be appropriate, there must be no delay in getting them to the operating theatre to clamp the aorta.

12/9/2015

Vascular disease | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of Medicine

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 5/10

18.83 Population screening and prevention of ruptured abdominal aortic

aneurysm

‘Ultrasound screening for AAA in men aged 65–75 years, with surgical repair of those AAAs that are bigger

than 5.5 cm, are rapidly growing or become symptomatic, reduces the community incidence of rupture by

approximately 50% and is cost-effective.’

•

MASS Study Group. Lancet 2002; 360:1531–1539.

•

MASS Study Group. BMJ 2002; 352:1135.

For further information:

Open AAA repair has been the treatment of choice in both the elective and the emergency settings, and entails replacing the

aneurysmal segment with a prosthetic (usually Dacron) graft. The 30-day mortality for this procedure is approximately 5–8%

for elective asymptomatic AAA, 10–20% for emergency symptomatic AAA and 50% for ruptured AAA. However, patients who

survive the operation to leave hospital have a long-term survival which approaches that of the normal population. Increasingly,

endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), using a stent-graft introduced via the femoral arteries in the groin, is replacing open

surgery. It is cost-effective and likely to become the treatment of choice for infrarenal AAA. It is possible to treat many

suprarenal and thoraco-abdominal aneurysms by EVAR too.

In the UK, a national screening programme for men over 65 years of age has been introduced using ultrasound scanning. For

every 10 000 men scanned, 65 ruptures are prevented and 52 lives saved.

Aortic dissection

A breach in the integrity of the aortic wall allows arterial blood to enter the media, which is then split into two layers, creating a

‘false lumen’ alongside the existing or ‘true lumen’ (see

Fig. 18.79B

). The aortic valve may be damaged and the branches of

the aorta may be compromised. Typically, the false lumen eventually re-enters the true lumen, creating a double-barrelled

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 5/10

12/9/2015

Vascular disease | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of Medicine

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 6/10

aorta, but it may also rupture into the left pleural space or pericardium with fatal consequences.

The primary event is often a spontaneous or iatrogenic tear in the intima of the aorta; multiple tears or entry points are

common. Other dissections are triggered by primary haemorrhage in the media of the aorta, which then ruptures through the

intima into the true lumen. This form of spontaneous bleeding from the vasa vasorum is sometimes confined to the aortic wall,

when it may present as a painful intramural haematoma.

Aortic disease and hypertension are the most important aetiological factors but other conditions may also be implicated (

Box

18.84

). Chronic dissections may lead to aneurysmal dilatation of the aorta, and thoracic aneurysms may be complicated by

dissection. It can therefore be difficult to identify the primary pathology.

18.84 Factors that may predispose to aortic dissection

•

Hypertension (in 80%)

•

Aortic atherosclerosis

•

Non-specific aortic aneurysm

•

Aortic coarctation (

p. 632

)

•

Collagen disorders (e.g. Marfan’s

syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos

syndrome)

•

Fibromuscular dysplasia

•

Previous aortic surgery (e.g. CABG,

aortic valve replacement)

•

Pregnancy (usually third trimester)

•

Trauma

•

Iatrogenic (e.g. cardiac

catheterisation, intra-aortic balloon

pumping)

(CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting)

The peak incidence is in the sixth and seventh decades but dissection can occur in younger patients, usually in association with

Marfan’s syndrome, pregnancy or trauma; men are twice as frequently affected as women.

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 6/10

12/9/2015

Vascular disease | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of Medicine

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 7/10

Aortic dissection is classified anatomically and for management purposes into type A and type B (see

Fig. 18.79B

), involving

or sparing the ascending aorta, respectively. Type A dissections account for two-thirds of cases and frequently also extend into

the descending aorta.

Clinical features

Involvement of the ascending aorta typically gives rise to anterior chest pain, and involvement of the descending aorta to

intrascapular pain. The pain is typically described as ‘tearing’ and very abrupt in onset; collapse is common. Unless there is

major haemorrhage, the patient is invariably hypertensive. There may be asymmetry of the brachial, carotid or femoral pulses

and signs of aortic regurgitation. Occlusion of aortic branches may cause MI (coronary), stroke (carotid) paraplegia (spinal),

mesenteric infarction with an acute abdomen (coeliac and superior mesenteric), renal failure (renal) and acute limb (usually

leg) ischaemia.

Investigations

The chest X-ray characteristically shows broadening of the upper mediastinum and distortion of the aortic ‘knuckle’, but these

findings are variable and are absent in 10% of cases. A left-sided pleural effusion is common. The ECG may show left ventricular

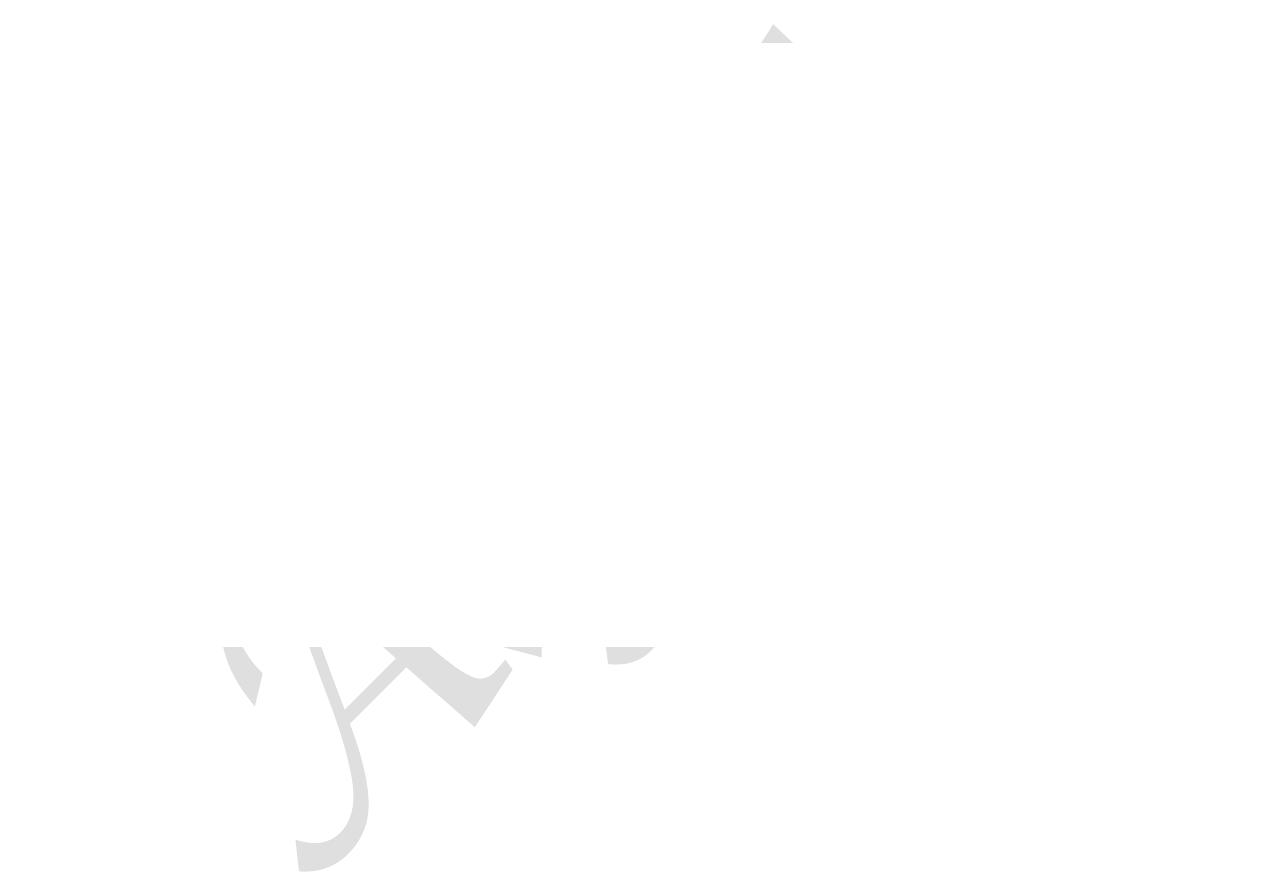

hypertrophy in patients with hypertension, or rarely changes of acute MI (usually inferior). Doppler echocardiography may

show aortic regurgitation, a dilated aortic root and, occasionally, the flap of the dissection. Transoesophageal echocardiography

is particularly helpful because transthoracic echocardiography can only provide images of the first 3–4 cm of the ascending

aorta (

Fig. 18.80

). CT and MRI angiography (

Figs 18.81

and

18.82

) are both highly specific and sensitive.

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 7/10

12/9/2015

Vascular disease | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of Medicine

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 8/10

F I G.

1 8 . 8 0

Echocardiograms from a patient with a chronic aortic dissection. Colour flow Doppler s…

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 8/10

12/9/2015

Vascular disease | Davidson

’s Principles and Practice of Medicine

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-fa

… 9/10

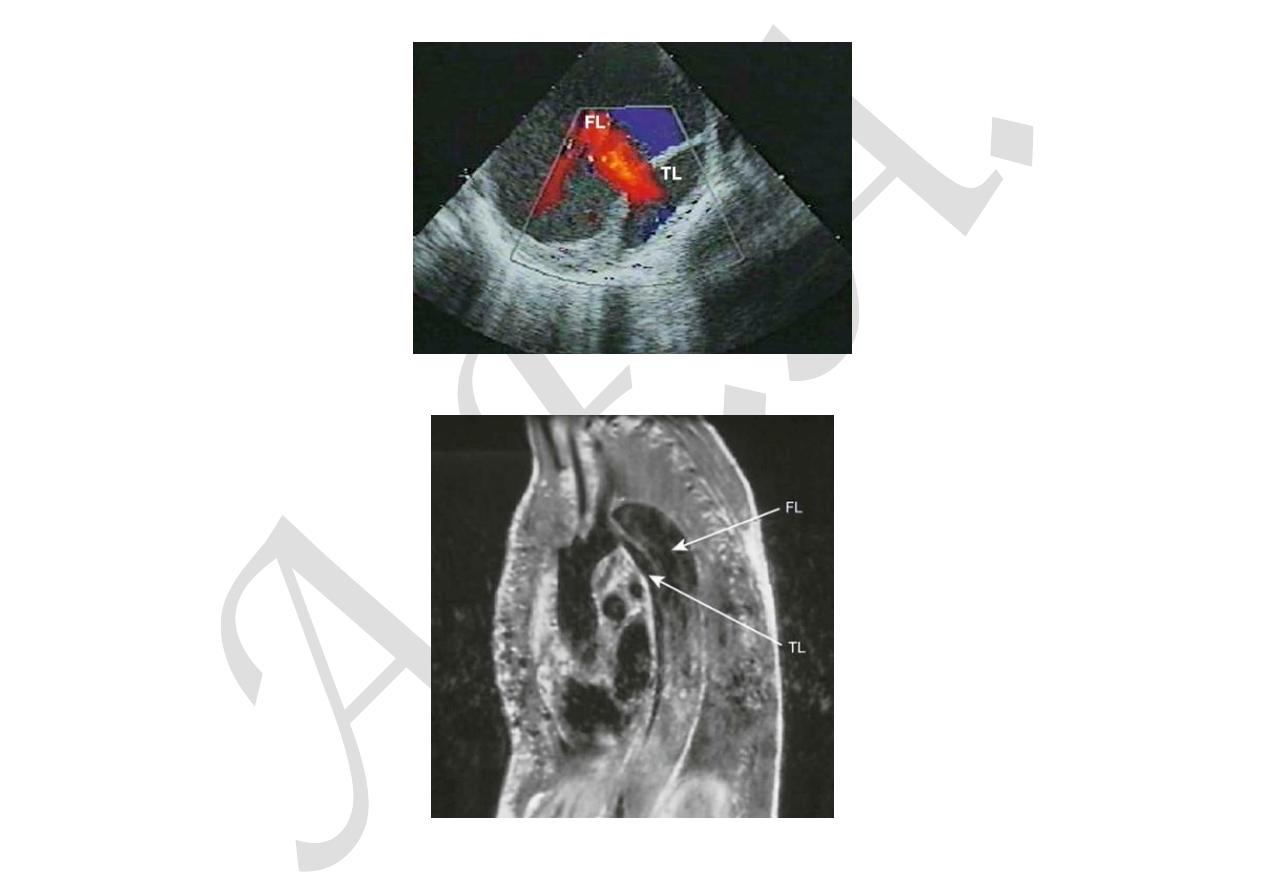

F I G.

1 8 . 8 1

Sagittal view of an MRI scan from a patient with longstanding aortic dissection, illus…

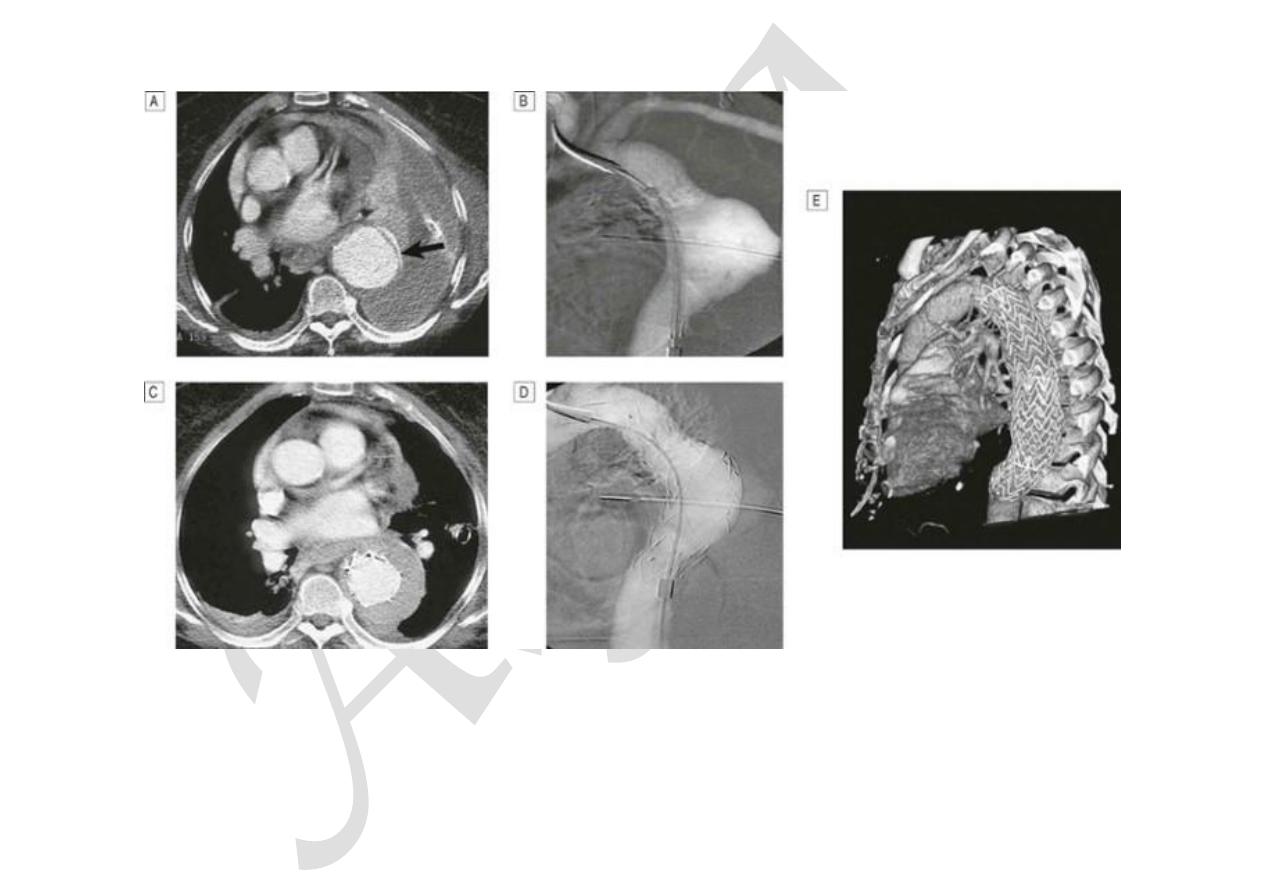

F I G.

1 8 . 8 2

Images from a patient with an acute type B aortic dissection that had ruptured into t…

Management

The early mortality of acute dissection is approximately 1–5% per hour and so treatment is urgently required. Initial

management comprises pain control and antihypertensive treatment. Type A dissections require emergency surgery to replace

the ascending aorta. Type B aneurysms are treated medically unless there is actual or impending external rupture, or vital organ

data:text/html;charset=utf-8,%3Ch2%20id%3D%22cc5a0836d6aa490ca26dd7c15632b559%22%20style%3D%22margin%3A%201.3em%200px%200.5em%3B%20padding%3A%200px%3B%20border%3A%200px%3B%20font-f

… 10/10

(gut, kidneys) or limb ischaemia, as the morbidity and mortality associated with surgery are very high. The aim of medical

management is to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 60–75 mmHg to reduce the force of the ejection of blood from the

LV. First-line therapy is with β-blockers; the additional α-blocking properties of labetalol make it especially useful. Rate-limiting

calcium channel blockers, such as verapamil or diltiazem, are used ifβ-blockers are contraindicated. Sodium nitroprusside may

be considered if these fail to control BP adequately.

Percutaneous or minimal access endoluminal repair is sometimes possible and involves either ‘fenestrating’ (perforating) the

intimal flap so that blood can return from the false to the true lumen (so decompressing the former), or implanting a stent graft

placed from the femoral artery (see

Fig. 18.82

).