Surgery Dr. Nadim

Esophagus

Congenital anomalies

⦿ Congenital esophageal atrasia and tracheo-esophageal fistula

⦿ Congenital esophageal stenosis

⦿ Duplication cyst

⦿ Congenital achalesia

⦿ Congenital short esophagus

Congenital esophageal atrasia and tracheo-esophageal fistula

1

Surgery Dr. Nadim

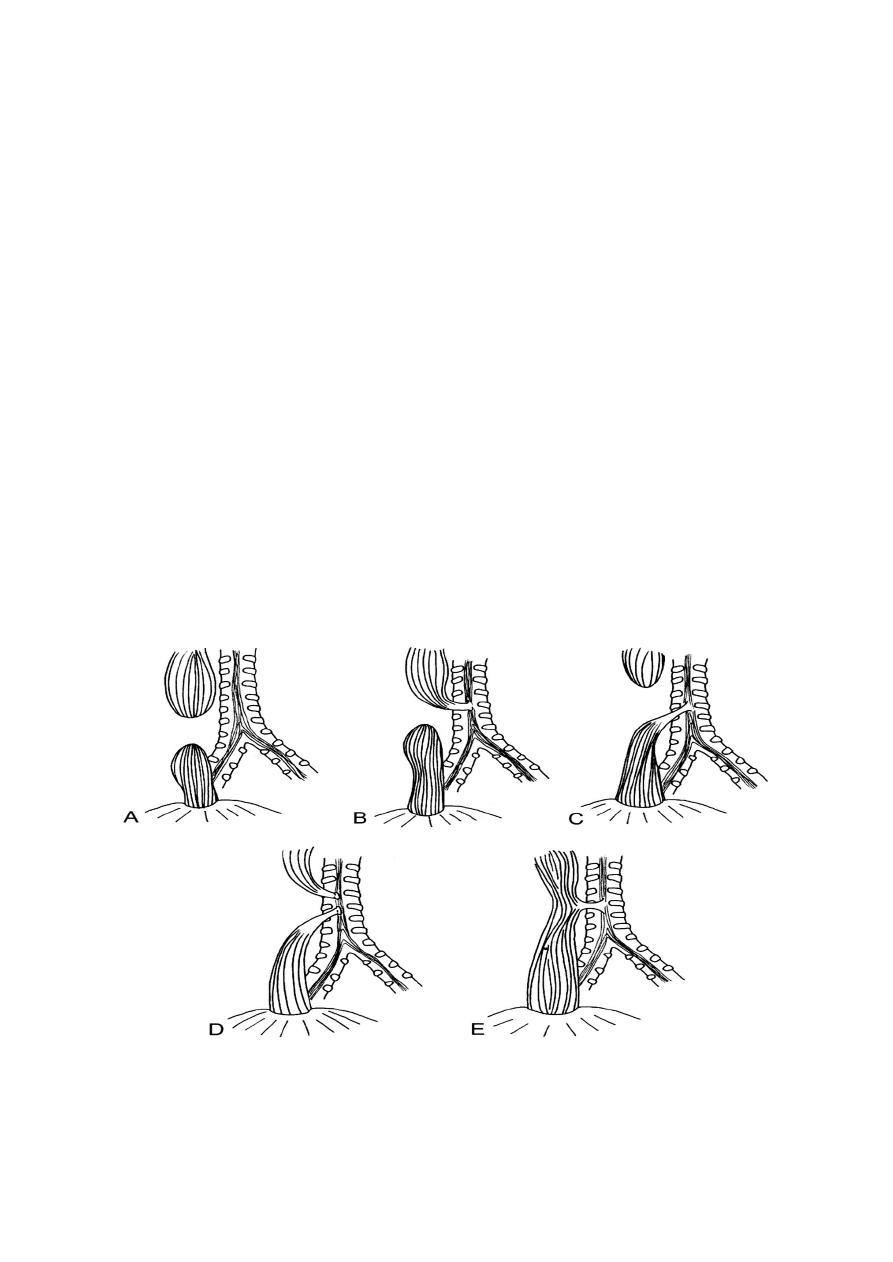

Could be divided into five groups:

Group A:

(8 %) esophageal atrasia without TE fistula, the upper esophagus

ending blindly and the lower esophagus beginning blindly with a

considerable gab between the two segments.

Group B:

(1 %) esophageal atrasia with a fistula between the upper pouch and

the trachea, but the lower esophagus not communicating with the

respiratory tract.

Group C:

(87 %) this is the most common variety, esophageal atrasia, the upper

pouch being blind and the lower esophageal segment communicating

with the trachea.

Group D:

(1 %) esophageal atrasia with both segments communicating with the

trachea by separate fistulae.

Group E:

(4 %) TE fistula but without atrasia (so-called H fistula).

The clinical features of group C (the most common type) is inability of the

infant to swallow saliva. A characteristic fine frothy mucus is continuously

produced in the mouth, while there may be episodes of chocking and cyanosis,

particularly if the diagnosis has not been suspected and a feed is given with

“spell-over” into the larynx. An important clue is the presence of

maternal hydramnios in the antenatal history. Contamination of the

lung is possible not only from inhalation of infected saliva but also

from regurgitation of gastric juice through the distal fistula into the

bronchial tree.

Congenital obstruction of the esophagus is demonstrated by

passage of a 10 Fr plastic radiopaque catheter through the mouth and then into

the esophagus. It will usually be held up, a radiography will demonstrate the

level of the obstruction together with the presence of gas in the stomach and

the intestine.

2

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Preoperatively, the infant should be nursed in a humidified oxygen-enriched

atmosphere in an incubator, the temperature which is usually low on admission

should be restored to normal. The head of the infant should be tilt down 10

degrees, and his position changed from side to side every 30 minutes. The

pharynx must be aspirated repeatedly. Antibiotic therapy is commenced and

vitamin K1 is given by intramuscular injection.

Urgent operation is required, it is usually performed through right

thoracotomy, with separation of the lower esophageal pouch from the trachea,

suturing of the trachea, then primary anastomoses between the upper and the

lower esophageal pouches.

Surgical anatomy of the esophagus

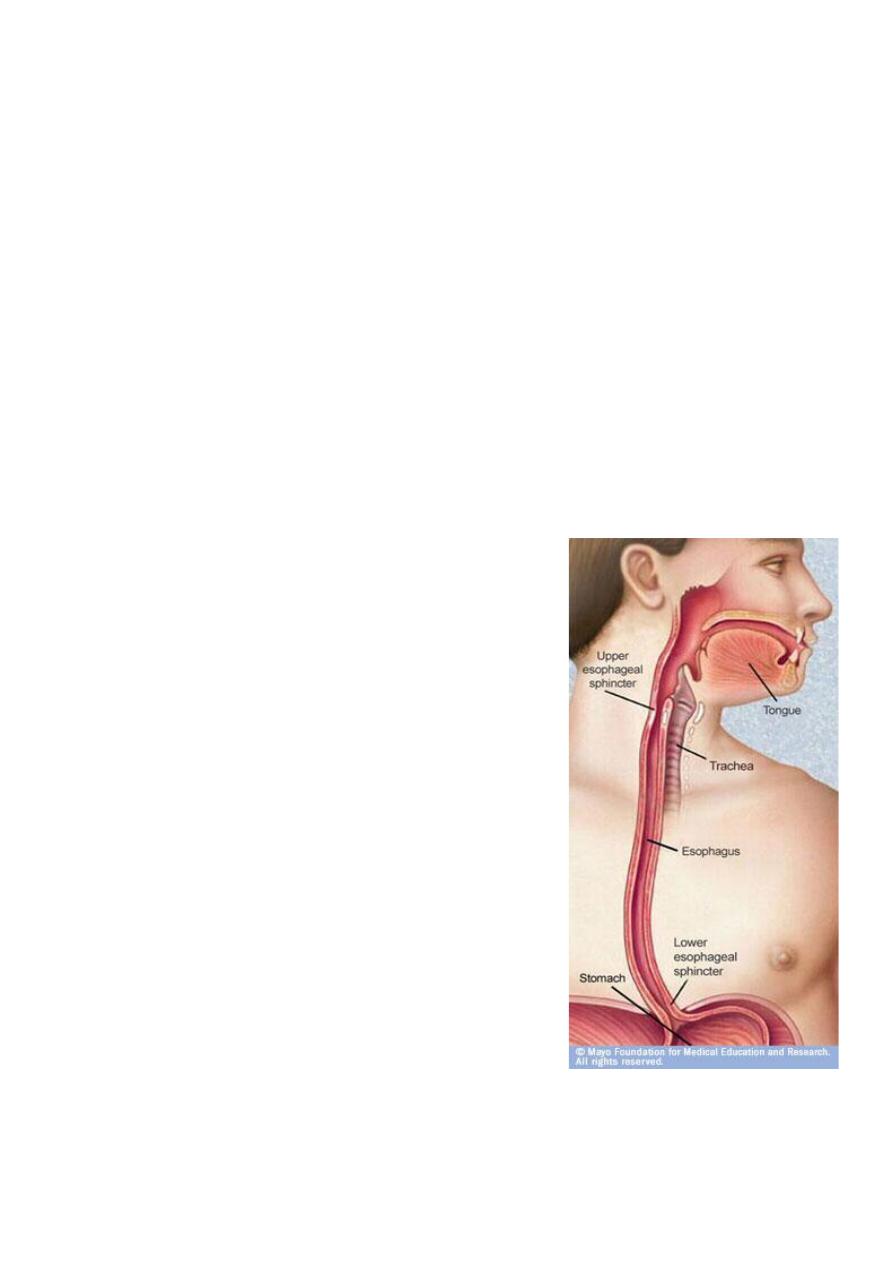

The esophagus is a muscular tube, approximately

25 cm long, extending from the upper esophageal

sphincter in the neck to the junction with the

cardia of the stomach. The musculature of the

upper esophagus is striated, this is followed by

transitional zone.

In the lower half of the esophagus, there is only

smooth muscles. The parasympathetic nerve

supply is mediated by the vagus nerve through the

myenteric (Auerbach’s) plexus.

The upper sphincter consist of powerful striated

muscles. The lower phincter is more subtle, and is

created by asymmetrical arrangement of muscle

fibers in the distal esophageal wall just above the

esophag-ogastric junction. when you perform

endoscopy it is helpful to Remember:

15 cm is the level of upper esophageal sphincter

25 cm is the level of aortic and bronchial

constriction

3

Surgery Dr. Nadim

40 cm is the level of diaphragmatic and sphincter constriction.

Physiology of the esophagus

The main function of the esophagus is to transfer food from the mouth to the

stomach in a coordinated fashion.

➢ The initial movement from the mouth is voluntary.

➢ The pharyngeal phase of swallowing involve sequential contraction of the

oropharyngeal musculature, closure of the nasal and respiratory passages, cessation

of breathing and opening of upper esophageal sphincter.

➢ The body of the esophagus propel the bolus through a relaxed lower esophageal

sphincter (LES) into the stomach, taking air with it. This coordinated esophageal wave

is called primary peristalsis. It is under vagal control (involuntary).

➢ The LES is a zone of relatively high pressure that prevents gastric contents from

refluxing into the lower esophagus. in addition to opening in response to primary

peristaltic wave, the sphincter also relaxes to allow air to escape from the stomach

and at the time of vomiting. The normal LES is 3-4 cm long and has pressure of 10-25

mm Hg

➢ Secondary peristalsis is normal reflux response to a stubborn food bolus or refluxed

materials, designed to clear the esophagus by contraction that is not proceeded by

conscious swallowing.

➢ Tertiary contractions are non-peristaltic waves that are infrequent (<10 %).

Symptoms

Dysphagia

:

Difficulty with swallowing, described as food or fluid sticking, it may occur in

acute or chronic fashion, malignancy must be ruled out.

Odynophagia:

Pain on swallowing, patient with reflux esophagitis often feel retrosternal

discomfort within few seconds of swallowing hot beverages or alcohol.

Regurgitation and reflux (heartburn)

4

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Regurgitation refer to return of esophageal contents from above a functional or

mechanical obstruction. Reflux is the passive return of gastroduodenal contents to

the mouth as part of the symptomatology of gastroesopageal reflux disease (GERD).

Chest pain

Chest pain similar in character to angina pectoris may arise from an

esophageal cause, especially gastroesophageal reflux and motility disorders.

Investigations

Radiography:

1- plain radiography:

will show some foreign bodies.

2- contrast radiography:

useful investigation for demonstrating narrowing,

space-occupying lesion, anatomical distortion or abnormal motility. Video

recording is useful to allow subsequent replay and detailed analysis. Barium

radiography is, however, inaccurate in the diagnosis of GERD.

3- computerised tomography ( CT scan):

is an essential investigation in the

assessment of neoplasms of the esophagus.

Endoscopy:

Endoscopy is necessary for the investigation of most esophageal conditions. It

is required to view the inside of esophagus and the esophagogastric junction, to

obtain a biopsy or cytology specimen, for removal of foreign bodies and to

dilate strictures. There are two types of instruments available, the rigid

esophagoscope and the flexible video endoscope.

Endosonography:

Endoscopic ultrasonography provide high detailed images of the layers of the

esophageal wall and mediastinal structures close to the esophagus.

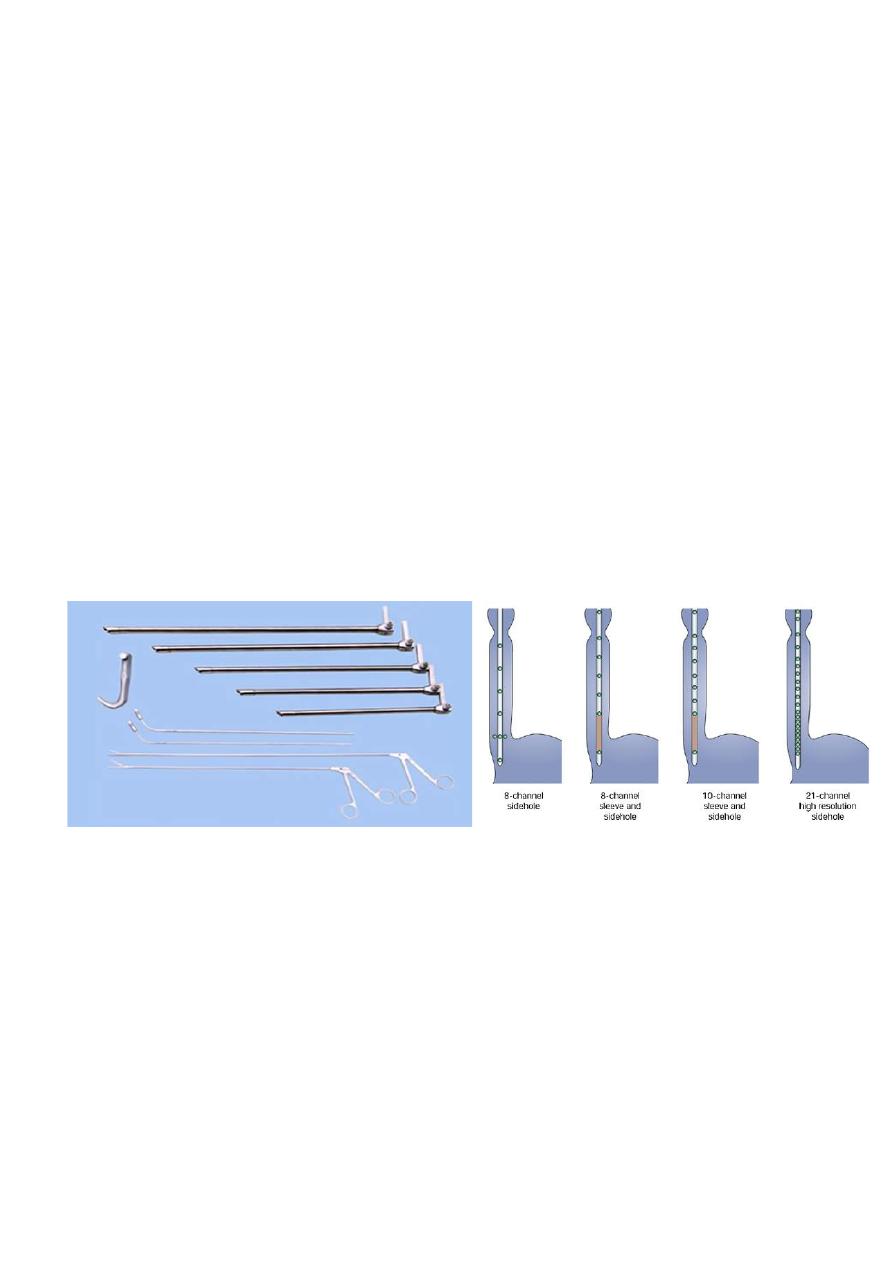

Esophageal manometry:

Manometry is now widely used to diagnose esophageal motility disorders.

Recording are usually made by passing a multilumen catheter with three to

eight recording orifices at different levels down the esophagus and into the

stomach. Electronic microtransducers that are not influenced by change in

5

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Patient position during the test is used. The catheter is withdrawn progressively

up the esophagus,

and recording are taken at intervals of 0.5 – 1 cm to measure the length and the

pressure of LES and assess motility in the body of the esophagus during

swallowing.

24 –hours pH recording

Prolong measurement of pH is now accepted as the most accurate method

for the diagnosis of gastro-esophageal reflux. A small pH probe is passed into

the distal esophagus and positioned 5 cm above the upper margin of the LES.

The probe is connected to miniature digital recorder that is worn on a belt and

allow most normal activities. a 24 hour recording period is usual, and the pH

record is analysed by an automatic computer program.

Foreign body in the esophagus

Different type of materials may become arrested in the esophagus. The most

common impacted material is food. Denture materials also commonly seen,

button batteries is a troublesome problem in children.

plain radiographs are often useful investigation, a contrast examinations is

not usually required.

6

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Foreign bodies that have become stuck in the esophagus could be removed

either with the use of flexible endoscopy using suitable grasping forceps, a snare

or a basket, or with the use of rigid esophagoscope. During endoscopy care

should be taken that foreign body may stuck above a significant pathological

lesion, especially, if the foreign body is food materials.

Perforation of the esophagus

Etiology

1- Barotraumas ( spontaneous perforation, Boerhaave syndrome)

This occur usually when a person vomits against a closed glottis. The pressure

in the esophagus increases rapidly, and the esophagus burst at its weakest point

in the lower third, sending stream of material into the mediastinum and often

the pleural cavity as well.

2- Pathological perforation

Free perforation of ulcers or tumors of the esophagus into the pleural space

is rare. Erosion into adjacent structures with fistula formation is more common.

Fistula into the bronchus is most common and usually encountered in primary

malignant disease of the esophagus or bronchus.

3- Penetrating injury

Penetration by knives and bullets is uncommon, even in wars, as the

esophagus is relatively small target surrounded by other vital organs.

4- Foreign bodies

An object that have been left in the esophagus for several days will erode

through the wall, Perforation during removal of foreign body is more common.

5- Instrumental perforation

7

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Instrumentation is by far the most common cause of perforation, it may

follow biopsy of a malignant tumor. Patients undergoing therapeutic endoscopy

( e.g., graduated dilatation) have a perforation risk that is at least 10 times

greater than those undergoing diagnostic endoscopy.

Symptoms

1- suspicion, in the presence of technical difficulties or interventional

procedures.

2- cervical perforation may result in pain localized to neck, hoarseness, painful

neck movement and subcutaneous emphysema.

3- intrathoracic and intraabdominal perforation, are more common, giving rise

to immediate symptom and signs either during or at the end of the procedure,

including chest pain, haemodynamic instability , oxygen desaturation.

4- within the first 24 hours, there may be evidence of subcutaneous

emphysema, pneumothorax or hydropneumothorax.

5- delayed diagnosis beyond 24 hours, the patient will present as unexplained

pyrexia, systemic sepsis or the development of clinical fistula.

Investigations

1- careful endoscopic assessment at the end of the procedure.

2- chest x-ray.

3- contrast swallow, water soluble contrast or a dilute barium swallow.

4- CT scan can be used to replace contrast swallow or as adjunct with it.

Treatment

8

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Perforation of the esophagus usually lead to mediastinitis. The aim of the

treatment is to limit mediastinal contamination and to prevent or deal with the

infection.

Non-operative treatment aim to limit the effect of mediastinitis and provide

an environment in which healing can take place. Indications for non-operative

treatment include:

1- small instrumental perforation of clean esophagus without obstruction.

2- instrumental perforation in the cervical esophagus, which are usually small.

3- thoracoabdominal perforations that are detected early before oral

alimentation.

4-patients who have remained clinically stable despite delay diagnosis.

The principles of non-operative treatment include:

1- hyperalemintations preferably by an enteral rout.

2- nasogastric suction.

3- broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic.

Surgical management is indicated whenever patients:

1- unstable with sepsis and shock.

2- have evidence of heavily contaminated mediastinum, pleural space or

peritoneum.

3- have widespread intrapleural or intraperitoneal extravasations of contrast

media.

Interventions include:

1- placement of self-expanding stent, in frail patient unfit for major surgery with

on-going luminal obstruction (mostly due to malignancy).

9

Surgery Dr. Nadim

2- direct repair if the perforation is recognized early (within 4-6 hours), and the

extent of mediastinal and pleural contamination is small.

3- T-tube into the esophagus along with appropriately located drain and feeding

jejunostomy in the presence of wide spread mediastinitis and pleural

contamination.

10

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Corrosive injury of the esophagus

Accidental ingestion occur in children and when corrosives are stored in bottles

labeled as beverages. Corrosives either alkalis or acids, all can cause damage to

the mouth, pharynx, larynx, esophagus and stomach. The type of the agent, its

concentration and the volume ingested largely determined the extent of

damage.

Alkali cause liquefaction, saponification of fat, dehydration and thrombosis of

blood vessels that usually leads to fibrous scaring. Acids cause coagulative

necrosis with eschar formation, and this coagulant may limit penetration to

deeper layers of the esophageal wall. Acids also cause more gastric damage

than alkalis because of the induction of intense pylorospasm with pooling in the

antrum.

Symptoms and signs are unreliable in predicting the severity of the injury, the

widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and steroids is not supported by

evidence . The key of the management is early endoscopy to inspect the whole

of the esophagus and stomach. Minor injuries with only oedema of mucosa

resolve rapidly with no late sequelae, these patients can safely be fed.

With more sever injuries, a feeding jejunostomy maybe appropriate until the

patient can swallow saliva satisfactory. Regular endoscopic examination are the

best way to assess stricture development.

significant stricture formation occur in about 50 % of the patients with extensive

mucosal damage.

Dilatation may be appropriate for short strictures. Esophageal resection should

be differed for at least 3 months until the fibrotic phase is established.

Esophageal replacement is usually required for very long or multiple strictures.

Because of associated gastric damage, colon may be used as the replacement

conduit.

11

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Gastro-esophageal reflux diseases

Aetiology

Normal competence of gastro-esophageal junction is maintained by LES.

Failure of the LES is caused by inadequate pressure, inadequate overall length,

or abnormal position, i.e., the portion exposed to positive-pressure

environment of the abdomen. In normal circumstances, the LES relaxes

transiently as a coordinated part of swallowing, as a means of allowing vomiting

to occur, and in response to stretching of the gastric fundus, particularly after

meal to allow swallowing air to be vented. Most episodes of physiological reflux

occur during postprandial transient lower esophageal relaxations (TLESRs).

In early stages of GERD, most pathological reflux occur as a result of an

increase number of TLESRs rather than a persistent fall in overall sphincter

pressure. In more sever GERD, LES pressure tends to be generally low, and this

loss of sphincter function seems to be made worse if there is loss of an

adequate length of intra-abdominal esophagus.

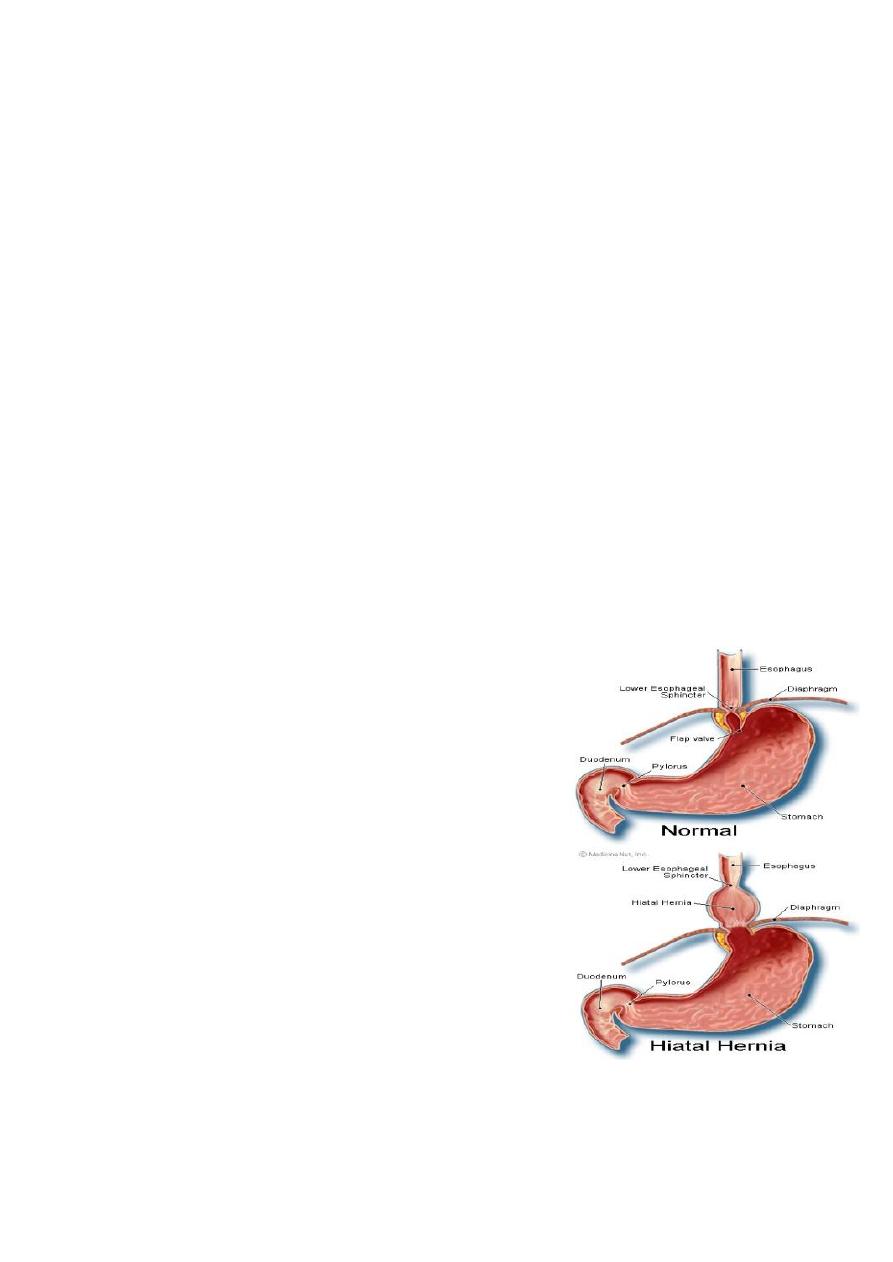

The absence of an intra-abdominal length of the

esophagus result in sliding hiatus hernia. The

normal condensation of peritoneal fasia over the

lower esophagus ( the phreno-esophageal ligament

) is weak, and the crural opening widens allowing

the upper stomach to slide up through the hiatus.

Sliding hiatus hernia is associated With GERD and

make it worse but, as long as the LES remain

competent pathological GERD does not occur.

Many GERD sufferers does not have

hernia, and many of those with hernia do not have

GERD. Reflux esophagitis is a complication of GERD

and occur in a minority of sufferers overall.

12

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Clinical features

The classical triad of symptoms is retrosternal burning pain (heart burn),

epigastric pain (some time radiated through to the back) and regurgitation.

Most patients do not experience all three.

Symptoms are often provoked by food, particularly those that delay gastric

emptying (e.g. fats, spicy foods). As the condition become more sever, gastric

juice may reflux to the mouth and produce an unpleasant taste often described

as “acid’ or “bitter”. A proportion of patients have odynophagia with hot

beverages. Some patients present with less typical symptoms such as

angina-like chest pain,

pulmonary or laryngeal symptoms.

Diagnosis

➢ In most cases, the diagnosis is assumed rather than proven, and treatment

is empirical.

➢ Investigation is only required when: a- the diagnosis is in doubt, b- when

the patient does not response to proton pump inhibitor (PPI), c- if

dysphagia is present.

➢ The most appropriate examination is endoscopy and biopsy. If the typical

appearance of reflux esophagitis, peptic stricture or Barrett’s esophagus is

seen, the diagnosis is clinched, but visible esophagitis is not always present

because the widespread use of PPIs, which cause rapid healing of early

mucosal lesions.

➢ In patients with atypical or persistent symptoms despite therapy,

esophageal manometry and 24-hour esophageal pH recording (gold

standard test) may be justified to establish the diagnosis and to guide

management. These tests are essential in patients being considered for

anti-reflux surgery.

13

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Management

Medical management

• Simple measures include advice about weight loss, smoking, excessive

consumption of alcohol, tea or coffee, the avoidance of large meals late at

night and a modest degree of head-up tilt of the bed.

• PPIs are the most effective drug treatment for GERD. Most patients have

rapid improvement in symptoms within few days, and more that 90 % can

expect full mucosal healing at 8 weeks time.

• If medical management is unsuccessful, these patients should be formally

investigated.

Surgery

The need for surgery should have been reduced as medications has improved

so much. Indication for surgery

➢ “volume” reflux.

➢ “hermit” lifestyle in which the least deviation from life style rules leads to

symptoms.

➢ Poor compliance, this is due to side effects of treatment.

➢ Psychological distress with intolerance of minor symptoms.

Which operation? All the operations must achieve the following:

➢ An intra-abdominal segment of esophagus.

➢ Crural repair.

➢ Some form of wrap of the upper stomach (fundoplication) around the

intra-abdominal esophagus.

Operations that fail to address all the three components have inferior success

rate.

14

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Type of operations:

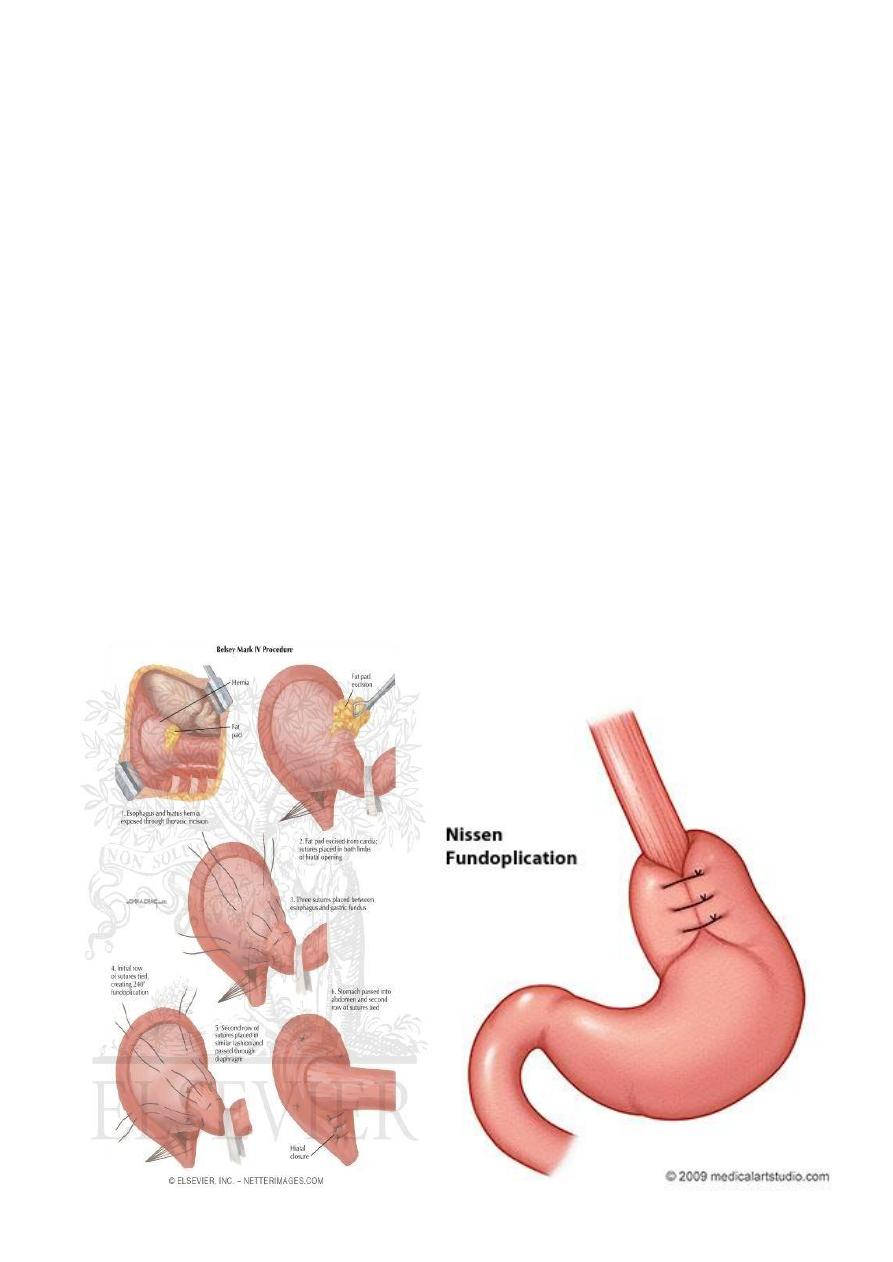

➢ Total fundoplication (Nissen), through the abdomen, the funds of the

stomach is drawn behind the esophagus and then sutured to itself in front

of the esophagus. One of the disadvantage of this surgery is the creation

of overcompetent cardia, resulting in the “gas bloat” syndrome in which

belching impossible.

➢ Partial fundoplication, through the abdomen, whether performed

postreiorly (Toupet) or anteriorly (Dor, watson).

➢ Laparoscopic fundoplication, through the abdomen, by the use of

laparoscope to perform total or partial fundoplication.

➢ Belsey mark IV operation, through the chest, the fundus of the stomach is

warped around the lower esophagus, and the hiatus is narrowed, and

appropriate segment of the esophagus is created inside the abdomen.

15

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Complications of gastro-esophageal reflux diseases

Stricture

Occur mainly in late middle-aged and elderly, it is about 1-2 cm above the

esophago-gastric junction, and should be distinguished from carcinoma. Peptic

strictures generally respond well to dilatation and long term treatment with a PPI.

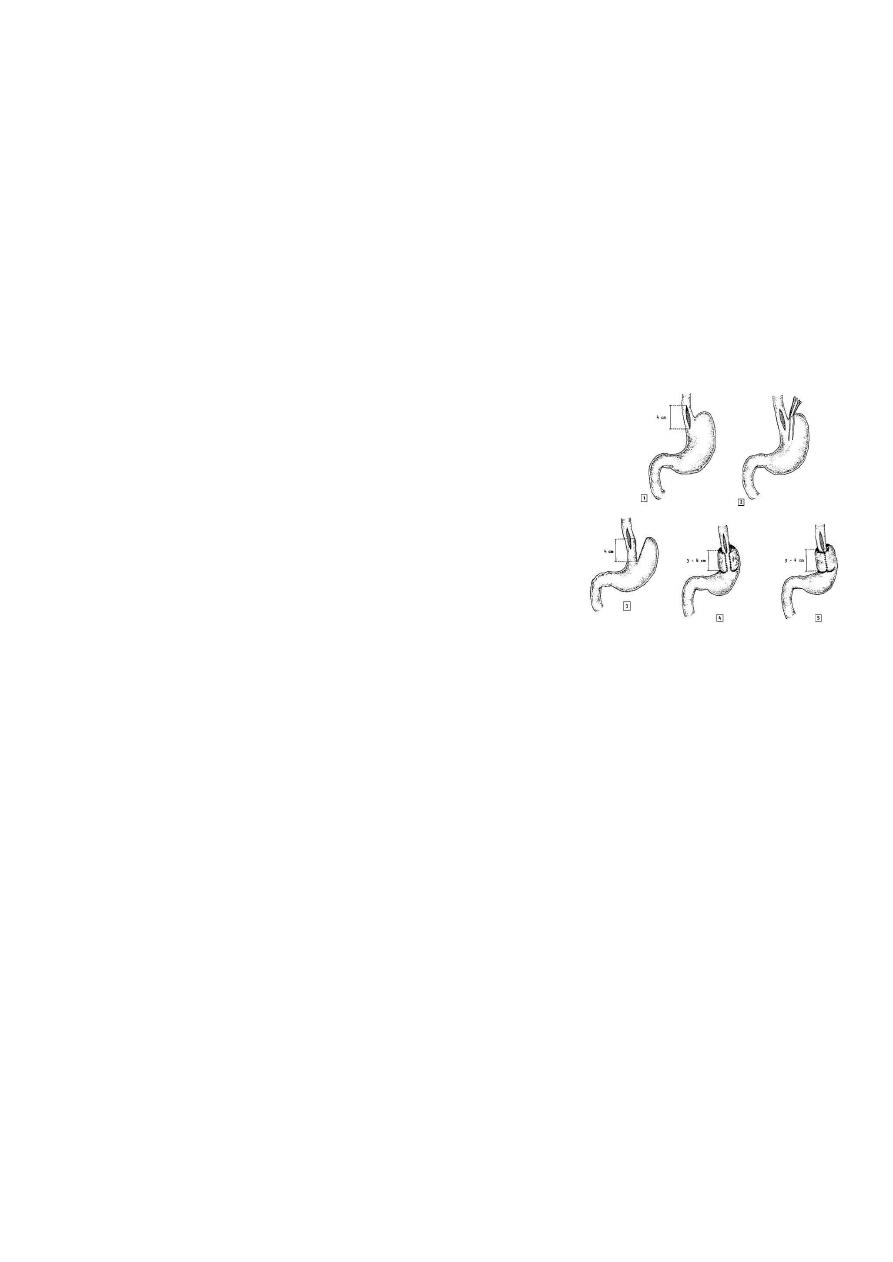

Esophageal shortening

Sever inflammation in the wall of the esophagus

causes fibrosis,and may cause shortening. In the

presence of a large sliding hiatus hernia, the

esophagus is short, but this does not necessarily

mean that, with mobilization from the mediastinum,

it cannot easily be restored to its normal length. If a

good segment of intra-abdominal esophagus cannot

be restored without tension, a Collis gastroplasty

should be performed, usually fundoplication is performed around the

neo-esophagus (Collis-Nissen operation).

Barrett’s esophagus (columnar lined lower esophagus)

Barrett’s esophagus is a metaplastic changes in the lining mucosa of the

esophagus in response to chronic gastro-esophageal reflux. Many of these

patients do not have particularly sever symptoms. The adaptive response to

GERD begins as a simple columnar epithelium that become specialized with

time. The hallmark of specialized Barrett’s epithelium is the presence of mucus

secreting goblet cells (intestinal metaplasia). In Barrett’s esophagus the junction

between sequamous esophageal mucosa and gastric mucosa moves proximally.

When intestinal metaplasia occurs, there is an risk of adenocarcinoma of the

esophagus.

Patients who are found to have Barrett’s esophagus may be submitted to

regular surveillance endoscopy with multiple biopsies in the hope of finding

16

Surgery Dr. Nadim

dysplasia or in situ cancer rather than allowing invasive cancer to develop and

cause symptoms. 2-year intervals are probably adequate, provided no dysplasis

has been detected. When Barrett’s esophagus is discovered, the treatment is

that of the underlying GERD.

Neoplasms of the esophagus

Benign tumors

Benign tumors of the esophagus are relatively uncommon. Leiomyomas are

the most common benign esophageal tumors (50 %). The average age at

presentation is 38 years, mostly located in the lower two-third of the

esophagus, usually solitary, vary greatly in shape and size. Typically, leiomyomas

are oval, they grow toward the lumen. Dysphagia and pain are the most

common complaints. Barium swallow is the most useful method to demonstrate

leiomyoma of the esophagus.

Leiomyomas should be removed surgically, the majority can be removed by

simple enucleation.

Other benign tumors: fibromas, myomas, fibromyomas, lipomyomas, myxoma,

firbrolipomas.

Malignant tumors

Non-epithelial primary malignancies are also rare, as in malignant melanoma.

Secondary malignancies rarely involve the esophagus with the exception of

bronchogenic carcinoma by direct invasion of the primary tumor or contagious

lymph node.

Carcinoma of the esophagus

Cancer of the esophagus is the sixth most common cancer in the world. It is a

disease of mid to late adulthood, with a poor survival rate. Only 5-10% of those

diagnosed will survive for 5 years.

Pathology and aetiology

17

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Sequamous cell carcinoma

is the most common type, generally affect the

upper two-thirds of the esophagus.

Adenocarcinoma

is increasing in incidence,

and usually affects the lower one-third. The geographical variation and the

aetiology is as the following:

➢ Sequamous cell cancer is endemic in south Africa and in the Asia “cancer

belt” that extends across the middle of Asia from north Iran to china. The

highest incidence in the world is in Linxian in Henan province in china. The

cause of the disease in the endemic areas in unknown, but it is probably

due to the combination of fungal contamination of food and nutritional

deficiencies.

➢ Tobacco and alcohol are major factors in the occurrence of sequamous cancer.

➢ Obesity and the GERD is likely to be an important factor for the increase

incidence of adenocarcinoma.

Clinical features

Most esophageal neoplasm present with mechanical symptoms, principally

dysphagia. Other symptoms include vomiting, regurgitation, odynophagia and weight

loss. Clinical findings suggestive of advance malignances and surgical cure is unlikely

include:

➢ Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy

➢ Horner’s syndrome

➢ Chronic spinal pain.

➢ Diaphragmatic paralysis.

➢ Cutaneous tumor metastasis.

➢ Enlarged supraclavicular lymph nodes.

Both denocarcinoma and sequamous cell carcinoma tend to disseminate

early. Tumor can spread in three ways:

➢ Direct spread occur both laterally through the esophageal wall layers and

longitudinally within the esophageal wall.

➢ Lymphatic spread, either longitudinally through the submucosal lymphatic

channels, consequently, the length of the esophagus involved by the tumor is

much longer than the macroscopic length of the malignancy at the epithelial

surface. lymph node spread occur commonly, Any regional lymph nodes from

the superior mediastinum to the coeliac axis and lesser curvature of the

18

Surgery Dr. Nadim

stomach may be involved regardless of the location of the primary lesion within

the esophagus.

➢ Haematogenous spread may involve different organs including the liver,

lung, brain and bones.

Investigations

➢ Endoscopy is the first line investigation for most patients, it provides direct

view of the esophageal mucosa and any lesion allowing its site and size to

be documented. Cytology and biopsy specimens taken via the endoscopy

are crucial for accurate diagnosis.

➢ Transcutaneous ultrasound, used mainly to assess spread to the liver.

➢ Chest radiography, to assess spread to the lungs and mediastinum.

➢ Bronchoscopy, may reveal either impingement or invasion of the main

airways in over 30% of patients with cancer in the upper third of the

esophagus.

➢ Laparoscopy, this is useful technique for the diagnosis of intra-abdominal

metastasis. It has the advantage of enabling tissue samples or peritoneal

cytology to be obtained.

➢ Computerised tomography (CT scan), for assessment of the esophagus,

the size and site and the direct invasion of the tumor, lymph nodes

involvement , and haematogenous spread.

➢ Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), it is more accurate than CT scan in determination

the depth of spread of malignant tumor through the esophageal wall, the

invasion of the adjacent organs, and metastasis to lymph nodes.

➢ Positron emission tomography (PET), reduction in PET activity following

chemotherapy might be a way of predicting responders to this approach.

19

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Treatment of malignant tumors

At the time of diagnosis, around two –third of all patients with esophageal

cancer will already have incurable disease and must be offered some form of

palliation. As dysphagia is the predominant symptom in advanced esophageal

cancer, the principle aim of palliation is to restore adequate swallowing. A varity

of methods are available, this include:

➢ Intubations like souttar tube, which made of coiled silver wire, or other

types of rigid plastic or rubber tubes, usually placed under endoscopic

and/or radiological control.

➢ expanding metal stent, more commonly used now in most centers allover

the world, also inserted under radiographic or endoscopic control.

➢ Other methods, like endoscopic laser treatment to core a channel through

the tumor or brachytherapy which include delivering intraluminal

radiation with short penetration distance to a tumor.

Surgery

alone

is best suited to patients with disease confined to the

esophagus without nodal metastasis, with a prospect of cure in between 50%

and 80%. The operative approaches are:

➢ Left thoracoabdominal approach, which opens the abdominal and the

thoracic cavity together, this approach is limited proximally by the aortic

arch and should be avoided when the primary tumor is at or above this

level.

➢ Ivor Lewis operation, the most widely practiced approach in the world,

with an initial laparotomy and construction of gastric tube, followed by

right thoracotomy to excise the tumor and create an esophageogastric

anastomoses.

➢ Transhiatal esophagectomy (without thoracotomy), the stomach is mobilized

through a midline abdominal incision, and the esophagus is mobilized through

20

Surgery Dr. Nadim

an incision in the neck. it may be useful procedure for tumor of lower

esophagus.

➢ Patients with more advanced stages of disease required multimodal

approaches (surgery plus

➢ chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy). In patients who are unfit for

surgery, chemoradiotherapy may

➢ be a useful alternative.

Achalasia

Pathology and aetiology

Achalasia (Greek “failure to relax”) is uncommon. It is due to loss of the

ganglion cells in the myenteric (Auerbach’s) plexus, the cause of which is

unknown. The physiological abnormalities are a non-relaxing LES and absent

peristalsis in the body of the esophagus. In its earliest stages, the esophagus is

of normal caliber and still exhibit contractile (although non-peristaltic) activity.

With time, the esophagus dilates and contractions disappears, so that the

esophagus empties mainly by the hydrostatic pressure of its contents. This is

nearly always incomplete, leaving residual food and fluid.

The gas bubble in the stomach is frequently absent. The esophagus may

becomes huge, and tortuous with persistent retention esophagitis due to

fermentation of food residues “ megaesophagus”.

Clinical features

The disease is most common in middle

life, but can occur at any age. It typically

presents with dysphagia. Patients often

present late, having had relatively mild

symptoms for many years

Regurgitations is frequent, and may be

overspill into the trachea, especially at

night.

Diagnosis

➢ Barium radiography, may show

hold-up in the distal esophagus,

21

Surgery Dr. Nadim

abnormal contractions in the esophageal body, and tapering stricture in

the distal esophagus often describe as a “bird’s beak”. The gastric bubble

usually absent.

➢ Endoscopy, by finding tight cardia and food residue in the esophagus.

➢ Esophageal manometry, give a firm diagnosis.

Treatment

Achalasia respond well to treatment. The two main methods are forceful

dilatation of the cardia and Heller’s myotomy.

Pneumatic dilatation

This involve stretching the cardia with a balloon to disturb the muscle and

render it less competent. The balloon are inserted over a guide wire. Perforation

is the major complication (less than 5%). In the well developed centers forceful

dilatation is curative in 75-85% of cases.

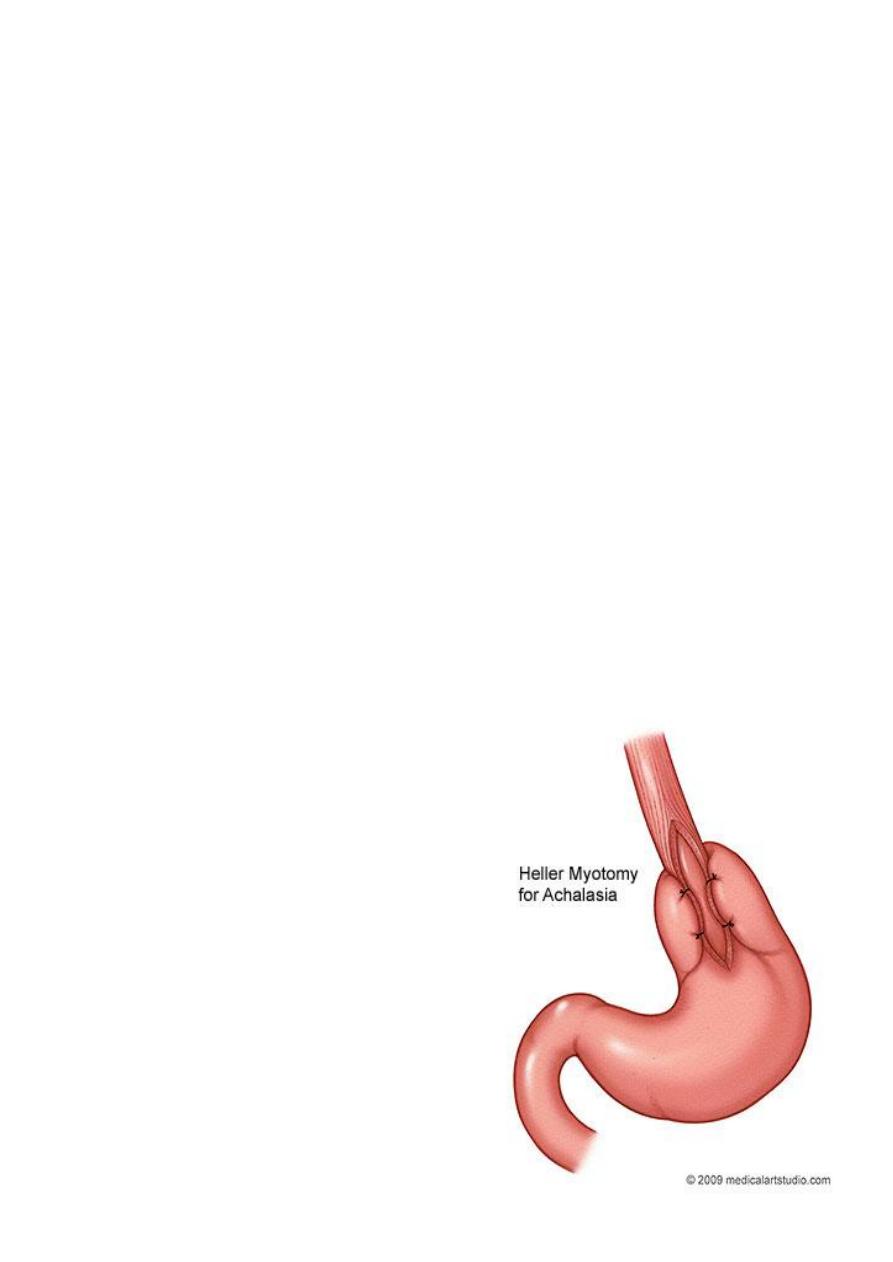

Heller’s myotomy

This involve longitudinal cutting in the muscles of the lower esophagus and

cardia. The major complication is GERD, and many surgeons, therefore, add a

partial anterior fundoplication (Heller’s-Dor’s operation). The operation is

ideally performed through the thoracic approach, but could be done through

abdominal approach, and recently, through minimal access laparoscopic

approach. It is

successful in more than 90% of cases and may be used after failed dilatation.

Botulinum toxin

This is done by endoscopic injection into the LES. It acts by interfering with

cholinergic excitatory neural activity at the LES. The effect is not permanent,

and the injection usually has to be repeated after a few months. For this reason,

its use is restricted to elderly patients with other comorbidities.

Drugs

22

Surgery Dr. Nadim

Drug such as calcium channel antagonists or sublingual nifedipine may be

useful for transient relief of symptoms.

Miscellaneous conditions

Zinker’s diverticulum (pharyngeal pouch)

It protrudes posteriorly above the cricopharyngeal sphincter through the

natural week point (the dehiscence of Killian) between the oblique and the

horizontal fibers of the inferior pharyngeal constrictors.

Epiphrenic diverticulum

Situated in the lower esophagus above the diaphragm, they may be quite

large, but causing few symptoms.

Plummer-Vinson syndrome

Also called Paterson-kelly syndrome, dysphagia occur because of the

presence of a post-cricoid web that is associated with iron deficiency anemia,

glossitis, and Koilonychia.

Schatzki’s ring

Is a circular ring in the distal esophagus, usually at the sequamocolumnar

junction, it may associated with reflux disease. Most are asymptomatic, when

associated with dysphagia, dilatation with anti-reflux drugs must be used.

23