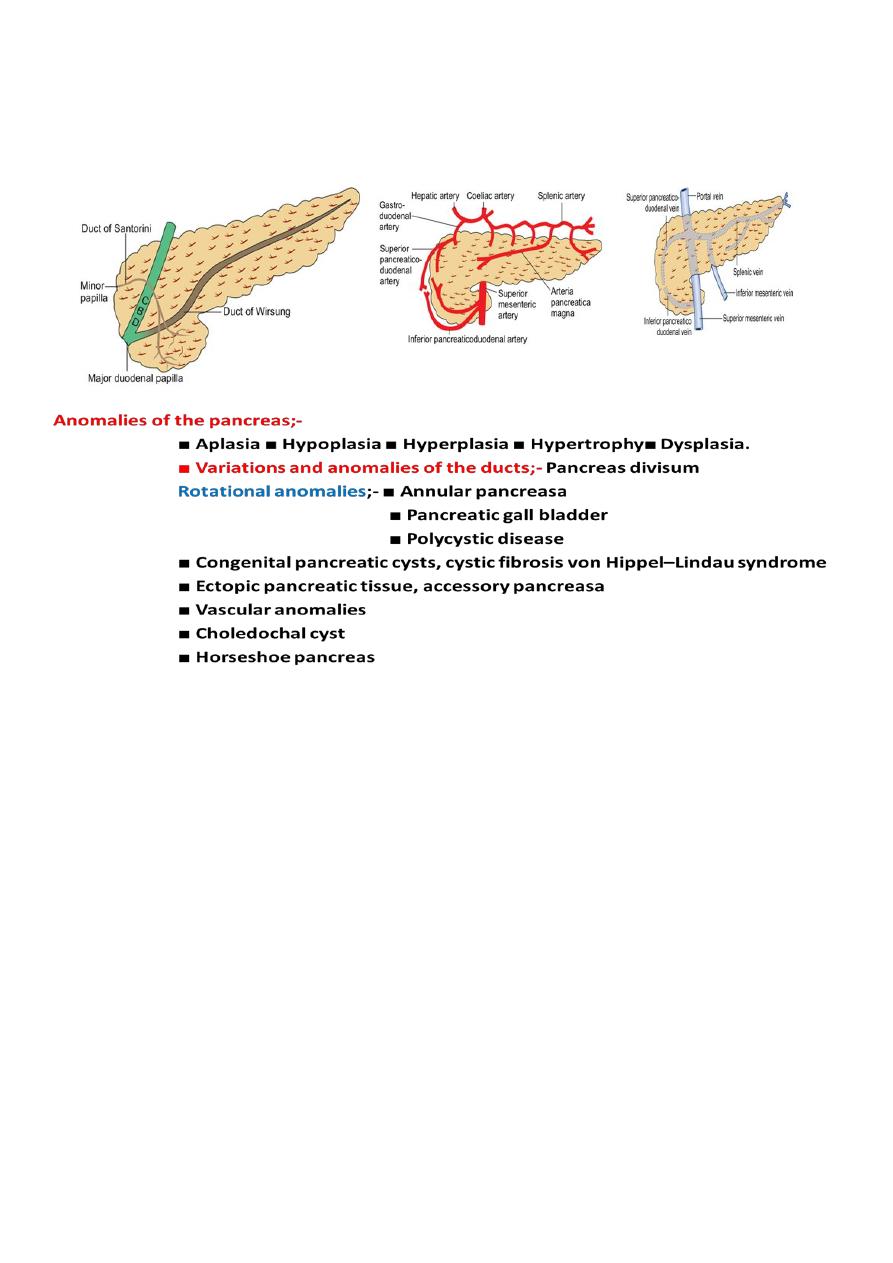

Pancreas

Anatomy and physiology Surgical anatomy

Annular pancreas

This is the result of failure of complete rotation of the ventral pancreatic bud

during development, so that a ring of pancreatic tissue surrounds the second or

third part of the duodenum.

It is most often seen in association with congenital duodenal stenosis or atresia

and is therefore more prevalent in children with Down’s syndrome.

Duodenal obstruction typically causes vomiting in the neonate .

Treatment is bypass (duodenoduodenostomy).

The disease may occur in later life as one of the causes of pancreatitis, in which case

resection of the head of the pancreas is preferable to lesser procedures.

Ectopic pancreas

Islands of ectopic pancreatic tissue can be found in the submucosa in parts of

the stomach, duodenum or small intestine (including Meckel’s diverticulum), the

gall bladder, adjoining the pancreas, in the hilum of the spleen and within the

Liver. Ectopic pancreas may also be found in the wall of an alimentary tract

duplication cyst.

Congenital cystic disease of the pancreas

This sometimes accompanies congenital disease of the kidneys and liver, and occurs as part

of the von Hippel–Lindau syndrome.

PANCREATITIS

Pancreatitis is inflammation of the parenchyma of the pancreas.

*Acute pancreatitis is defined as an acute condition presenting with abdominal pain and

is usually associated with

raised pancreatic enzyme levels in the blood or urine as a result of pancreatic

inflammation.

The underlying mechanism of injury in pancreatitis is thought to be premature

activation of pancreatic enzymes within the pancreas, leading to a process of

autodigestion. Acute pancreatitis may recur.

Acute pancreatitis may be categorised as mild or severe.

1-Mild ;- is characterised by interstitial oedema of the gland and minimal organ

dysfunction.

2- Severe ;- is characterised by pancreatic necrosis, a severe systemic inflammatory

response and often multi-organ failure. In those who have a severe attack of

pancreatitis, the mortality varies from 20% to 50%.

Possible causes of acute pancreatitis

■ Gallstones ■ Alcoholism ■ Post ERCP ■ Abdominal trauma

■ Following biliary, upper gastrointestinal or cardiothoracic surgery

■ Ampullary tumour

■ Drugs (corticosteroids, azathioprine, asparaginase, valproic acid, thiazides,

oestrogens)

■ Hyperparathyroidism ■ Hypercalcaemia ■ Pancreas divisum

■ Autoimmune pancreatitis ■ Hereditary pancreatitis

■ Viral infections (mumps, coxsackie B) ■ Malnutrition

■ Scorpion bite ■ Idiopathic

Differential diagnosis

Perforated duodenal ulcer Cholecystitis Mesenteric ischaemia

Ruptured aortic aneurysm Ectopic pregnancy Salpingitis

Intestinal obstruction Diabetic ketoacidosis

Investigations

three to four times above normal is indicative of the disease.

1- A serum amylase level

*A normal serum amylase level does not exclude acute pancreatitis, particularly if the

patient has presented a few days later.

* serum lipase level( it provides a slightly more sensitive and specific test than amylase).

*Serum lipase more specific than amylase.

*Serum trypsin & Trypsinogen activation polypeptide reveals the severity of the acute

pancreatitis.

*CRP (>150 mg/L) is also useful.

2-Liver function tests: Serum bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, alkaline

phosphatase.

3- Blood urea, serum creatinine.

4- Blood glucose (hyperglycaemia is seen).

5- Serum calcium level (hypocalcaemia occurs).

6- Arterial PO2 and PCO2 level to assess pulmonary insufficiency (or ARDS).

7-Total count, haematocrit, platelet count, coagulation profile.

8- Peritoneal tap fluid shows high amylase and protein level (very useful method).

Imaging

are useful in the differential diagnosis.

1-Plain erect chest and abdominal radiographs

(generalized or local ileus (sentinel loop), a colon cut-off sign and a renal halo sign.

Occasionally, calcified gallstones or pancreatic calcification may be seen.

may show a pleural effusion and, in severe cases, a diffuse

2-A chest radiograph

alveolar interstitial shadowing may suggest acute respiratory distress syndrome.

3-Ultrasound does not establish a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

The swollen pancreas may be seen, detect gallstones as a potential cause, rule out acute

cholecystitis and common bile duct dilatation.

indicated in the following situations:

4-Contrast enhanced CT is

• if there is diagnostic uncertainty;

• in patients with severe acute pancreatitis, to distinguish interstitial from necrotising

pancreatitis .

yield similar information to that obtained by CT.

5-Cross-sectional MRI can

6-EUS and MRCP

can help in detecting stones in the common bile duct and directly

assessing the pancreatic parenchyma, but are not widely available.

allows the identification and removal of stones in the common bile duct in

7-ERCP

gallstone pancreatitis.

In patients with severe acute gallstone pancreatitis and signs of ongoing biliary

obstruction and cholangitis, an urgent ERCP should be sought .

The presentation is so variable that sometimes even an experienced clinician can be

mistaken.

While this is not desirable, occasionally the diagnosis is only made at laparotomy.

The appearances at laparotomy are characteristic.

Clinical Features

1- upper abdominal pain (Sudden onset , severe, agonizing and refractory.

*referred to back.*Pain may be relieved or reduced by Leaning forward.

2-Vomiting and high fever, tachypnoea with cyanosis.

3-Tenderness, rebound tenderness, guarding, rigidity and abdominal distension, severe

illness.

4-Often mild jaundice (due to cholangitis). Jaundice may also be due to bile duct

disease / obstruction or cholestasis.

5- Features of shock and dehydration, Oliguria, hypoxia and acidosis.

6- Grey-Turner’s sign, Cullen’s sign.

7- Haematemesis/malaena due to duodenal necrosis, gastric erosions,

decreased coagulability/DIC.

8- Hiccough when present is refractory.

9- Ascites may be present.

10-Paralytic ileus is common.

11- Pleural effusion, pulmonary oedema, consolidation, features of rapid onset ARDS is

often observed.

12- Neurological derangements due to toxaemia, fat embolism, hypoxia, respiratory

distress can occur. It may be mild psychosis to coma.

Fluid, Metabolic, Haematologic and Biochemical Changes

1- Hypovolemia due to diffuse capillary leak and vomiting causing raised haematocrit,

blood urea, serum creatinine levels.

2- Hypoalbuminaemia which is more revealed after fluid correction.

3- Hypocalcaemia is either due to decreased albumin level or specific loss of ionized

calcium.

4-Total count is raised with neutrophilia. Thrombocytopenia, raised FDP, decreased

fibrinogen,

prolonged partial thromboplastin time and PT—are common. DIC can develop later.

5-Hypochloraemic metabolic alkalosis is common due to repeated vomiting.

6- Reduced insulin secretion, increased glucagon and catecholamine secretion causes

hyperglycaemia, more so in diabetic patients.

7= Hyperbilirubinaemia may be due to biliary stone/obstruction or cholangitis or non-

obstructive cholectasis.

8- Hypertriglyceridaemia is common especially in hyperlipidaemic patients.

9- Methemalbuminemia, when it occurs in acute pancreatitis indicates poor prognosis.

Treatment of acute pancreatitis

* Conservative, 70-90% * Surgical treatment when indicated, 10-30%

, a conservative approach is indicated with intravenous

1- Mild attack of pancreatitis

fluid administration and frequent, but non-invasive, observation.

*A brief period of fasting may be sensible in a patient who is nauseated and in pain, but

there is little physiological justification for keeping patients on a prolonged ‘nil by

mouth’ regimen.

*Antibiotics are not indicated.

*Apart from analgesics and anti-emetics, no drugs or interventions are warranted, and

CT scanning is unnecessary unless there is evidence of deterioration.

to an intensive care or high-dependency

2- Severe attack should be admitted

unit .

*Adequate analgesia should be administered.

*Aggressive fluid resuscitation is important, guided by frequent

measurement of vital signs, urine output and central venous pressure.

* Supplemental oxygen should be administered and serial arterial blood gas

analysis performed.

*The haematocrit, clotting profile, blood glucose and serum levels of calcium

and magnesium should be closely monitored.

*A nasogastric tube is not essential but may be of value in patients with

vomiting.

is felt to be necessary, enteral nutrition (e.g. feeding

If nutritional support

via a nasogastric tube) is should be used.

If

s are the cause of an attack of predicted or proven severe

gallstone

pancreatitis, or if the patient has jaundice,

cholangitis or a dilated common bile duct, urgent ERCP should be carried

out within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms.

In patients with cholangitis, sphincterotomy should be carried out or a

biliary stent placed to drain the duct.

ERCP is an invasive procedure and carries a small risk of worsening the

pancreatitis.

Surgery;-Indications for Surgical Intervention

1. If condition of patient deteriorates in spite of good conservative treatment.

2. If there is formation of pancreatic abscess, or infected necrosis.

3. When diagnosis is in doubt.

4. In severe necrotising pancreatitis ) very high mortality).

Complications of acute pancreatitis

Systemic;-(

More common in the first week)

Shock/ Arrhythmias

1-Cardiovascular ;

2-

Renal failure

/ ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome /

3-Pulmonary

; DIC disseminated intravascular coagulation

4-Haematological

; Hypocalcaemia/ Hyperglycaemia/ Hyperlipidaemia

5-Metabolic

Ileus

6-Gastrointestinal

Visual disturbances/ Confusion, irritability/ Encephalopathy

7-Neurological;-

Subcutaneous fat necrosis/ Arthralgia

8-Miscellaneous;-

Local

(Usually develop after the first week)

Acute fluid collection Sterile pancreatic necrosis

Infected pancreatic necrosis Pancreatic abscess

Pseudocyst / Pancreatic ascites Pleural effusion

Portal/splenic vein thrombosis Pseudoaneurysm

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

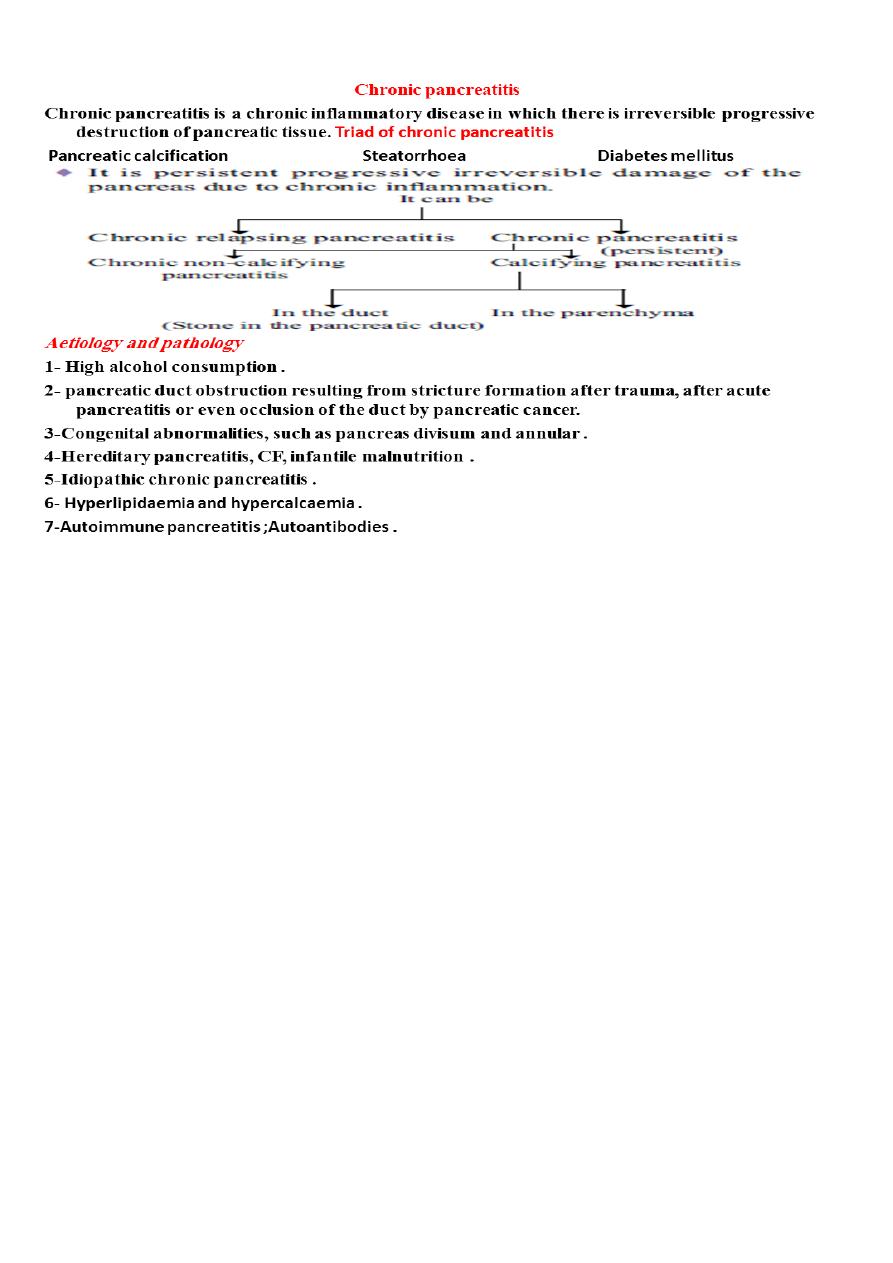

Pseudocyst

A pseudocyst is a collection of amylase-rich fluid enclosed in a wall of fibrous or

granulation tissue.

Pseudocysts typically arise following an attack of acute pancreatitis, but can develop

in chronic pancreatitis or after pancreatic trauma.

Formation of a pseudocyst requires 4 weeks or more from the onset of acute

pancreatitis.

A pseudocyst is usually identified on ultrasound or a CT scan.

EUS and aspiration of the cyst fluid is very useful in such a situation.

The fluid should be sent for measurement of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels,

amylase levels and cytology.

;-Pseudocysts will resolve spontaneously in most instances, but

treatment

complications can develop .

Therapeutic interventions are advised only if;-

1- the pseudocyst causes symptoms,

2-if complications develop or a

3- distinction has to be made between a pseudocyst and a tumour.

There are three possible approaches to draining a pseudocyst:

1- Percutaneous drainage. 2- Endoscopic drainage. 3-Surgical drainage

Pseudocysts that have developed complications are best managed surgically.

Possible complications of a pancreatic pseudocyst

1-Rupture—into bowel or peritoneum. 2- Infection, commonest

3-Bleeding from the splenic vessels.4- Cholangitis. 5- Duodenal obstruction

6-Portal/splenic vein thrombosis and segmental portal hypertension

7- Cholestasis due to CBD block.

Clinical presentations

(recurrent / acute episodic pain with weight loss.)

1-Pain ;-

*The pain prevents sleep and time off work is frequent.

* The number of hospital admissions for acute exacerbations is a pointer towards the

severity of the disease. Analgesic use and abuse is frequent. The patient’s lifestyle is

gradually destroyed by pain, analgesic dependence, weight loss and inability to

work.

attacks, and vomiting may occur.

2-Nausea is common during

, because the patient does not feel like eating.

3-Weight loss is common

.

4- Loss of exocrine function leads to steatorrhoea

bring the patient to the attention of the surgeon.

5-Complications frequently

Severe exocrine /

6-Infection is not infrequent, possibly related to the diabetes mellitus.(

endocrine deficiency, less severe pain, complications like pseudocyst and

obstruction.

Investigations in chronic pancreatitis ;-

1-Only in the early stages of the disease will there be a rise in serum amylase.

2-Tests of pancreatic function= pancreatic insufficiency .

3-Pancreatic calcifications may be seen on abdominal X-ray .

4-CT or MRI scan will show the outline of the gland, and Calcification .

5- ERCP , MRCP will identify the presence of biliary obstruction and the state of the

pancreatic duct .

6-EUS can also be very useful.

Aim of treatment=

Treatment of chronic pancreatitis;-

1- Control of pain.2-Improvement in maldigestion and nutrition . 3- Management of

complications.

Most patients can be managed with medical measures.

There is no single therapeutic agent that has been shown to relieve symptoms;

Medical treatment of chronic pancreatitis

1-Treat the addiction

■ Help the patient to stop alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking

■ Eliminate obstructive factors (duodenum, bile duct, pancreatic duct)

■ For intractable pain, consider CT/EUS-guided celiac axis block

2-Nutritional and digestive measures

■ Diet: low in fat and high in protein and carbohydrates

■ Pancreatic enzyme supplementation with meals

■ Correct malabsorption of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and vitamin B12

■ Medium-chain triglycerides in patients with severe fat malabsorption .

■ Reducing gastric secretions may help.

3-Treat diabetes mellitus

Interventions ;-

1- ERCP and pancreatic sphincterotomy might be beneficial in papillary stenosis .

2-Pancreatic duct stones may be extracted at ERCP.

3-Pseudocysts may be drained internally under EUS guidance.

4-Percutaneous or transgastric drainage of pseudocysts under ultrasound or CT

guidance .

The role of surgery is to overcome obstruction and remove mass lesions.

1* mass in the head of the pancreas, for which either a pancreatoduodenectomy or a

Beger procedure (duodenum-preserving resection of the pancreatic head) is

appropriate.

2* If the duct is markedly dilated, then a longitudinal pancreatojejunostomy can be of

value .

Complications of chronic pancreatitis

1- Pseudocyst of pancreas 2-Pancreatic ascites

3-CBD stricture due to edema or inflammation 4-Duodenal stenosis

5-Portal thrombosis—segmental portal hypertension 6-Peptic ulcer

7- Carcinoma 8-Pancreatic pleural effusion, 9-pancreatic

ascites

10- Pancreatic fistula 11-Splenic vein thrombosis 12-Pancreatico-

enteric fistula

PANCREATIC TUMOURS

Classification

A.

Exocrine tumours

Benign cystadenoma. It is rare.

Benign:

Malignant:

in ampulla or periampullary region or head of pancreas.

1. Adenocarcinoma

Periampullary carcinoma ,Occasionally squamous cell carcinoma, or combination of

adeno-squamous can occur.

of pancreas occurs commonly in body and tail of the pancreas,

2. Cystadenocarcinoma

which usually

attains a large size .

B.

Endocrine tumours

1. Insulinoma (β cells) Whipple’s triad

2. Gastrinoma (G cells) Peptic ulcer.

3. Glucagonoma (α cells) Diabetes, necrolytic migratory erythema.

4. Vipoma—Pancreatic Watery diarrhoea, cholera achlorhydria.

5. Somatostatinoma. Diabetes, (S cells)

6- δ cells steatorrhoea, gallstones.

C.

Lymphomas

CARCINOMA OF THE PANCREAS

Pathology

1-More than 85% of pancreatic cancers are ductal adenocarcinomas.

2-Endocrine tumours of the pancreas are rare.

3-Ductal adenocarcinomas arise most commonly in the head of the gland.

4- Cystic tumours of the pancreas may be serous or mucinous.

5-Adenomas of the ampulla of Vater are diagnosed at endoscopy as polypoid

submucosal masses covered by a smooth epithelium.

6-Ampullary adenocarcinomas often present early with biliary obstruction.

Differential diagnosis

1- Retroperitoneal mass/tumour/lymph nodes 2- Advanced adherent carcinoma of

stomach

3- Advanced carcinoma of transverse colon 4- CBD stone 5- Bile duct stricture

6-Lymph node compressing CBD 7- Cholangiocarcinoma of CBD 8- Chronic

pancreatitis

Risk factors for the development of pancreatic cancer

Age (peak incidence 65–75 years)

Male gender/Black ethnicity

Environment/lifestyle/Cigarette smoking

Family history;

/Hereditary pancreatitis ./ Chronic pancreatitis .

Clinical

Presentations

1-

severe, progressive,

Jaundice is of obstructive nature which is of short duration,

associated with

pruritus (due to deposition of bile salts in the skin which releases histamine). Scratch

marks ..

Painless jaundice is seen in ampullary malignancies.

in the right hypochondrium, epigastrium, or left hypochondrium depending on

2-Pain

location .

Back pain, when present, is due to involvement of retropancreatic nerves, or pancreatic

duct obstruction or stasis, disruption of nerve sheath by tumour.

Pain is more at night, after food and on recumbency; it is relieved by leaning forward.

3- Diarrhoea, steatorrhoea, pale (acholic) stools, tea colored urine.

4-Silvery stool (due to mixing of undigested fat with metabolised blood derived from

the ooze of periampullary growth).

5- Loss of appetite and weight.

is due to release

7-Migratory superficial thrombophlebitis—Trousseau’s sign

of platelet aggregating

factors from the tumour or its necrotic material .

8-Ascites.

9- Left supraclavicular palpable lymph node. 10- Secondaries in rectovesical

pouch (Blumer’s shelf).

11-Gallbladder may be palpable which is nontender, soft, globular, smooth,

moving with respiration,

Mobile horizontally, dull on percussion .

12- Liver is enlarged, smooth, firm, non-tender, due to dilated bile filled

biliary radicles.

Liver can show multiple hard nodules due to secondaries.

13-Splenic vein thrombosis with splenomegaly can occur.

On examination,

1- jaundice, weight loss, a palpable liver and a palpable gall bladder. =

when the common duct is obstructed by a stone,

Courvoisier sign;-

distension of the gall bladder

2- signs of intra-abdominal malignancy should be looked for with care, such

as a;-

palpable mass, ascites, supraclavicular nodes and tumour deposits in the

pelvis.

Investigation

1-In a jaundiced patient, ( blood tests and ultrasound ).

2-contrast-enhanced CT scan.

3-MRI and MR angiography can provide information comparable to CT.

4-ERCP and biliary stenting should be carried out if there is any suggestion of

cholangitis.

It relieves the jaundice and can also provide a brush cytology or biopsy specimen to

confirm the

Diagnosis.

preoperative ERCP and biliary stenting is not mandatory in patients with resectable

disease;

5- The prothrombin time and clotting abnormalities should be corrected with vitamin

K or fresh frozen plasma prior to ERCP.

6-EUS is useful if CT fails to demonstrate a tumour, Transduodenal or transgastric

FNA or Trucut biopsy performed under EUS guidance avoids spillage of tumour

cells into the peritoneal cavity.

7-Percutaneous transperitoneal biopsy of potentially resectable pancreatic tumours

should be avoided as far as possible.

8-Diagnostic laparoscopy combined with laparoscopic ultrasonography.

Management

1-At the time of presentation, more than 85% of patients with ductal

adenocarcinoma are unsuitable for resection because the disease is too advanced.

2- Comorbidities should be carefully taken into account.

3-Tumours of the ampulla have a good prognosis and should, if at all

possible, be resected.

4-Some of the rare tumours and the neuroendocrine lesions should also

Be resected if at all possible.

For those patients who have inoperable disease, palliative treatment

should be offered.

Surgical resection =

Pancreatoduodenectomy

This involves removal of the duodenum and the pancreatic head,

including the distal part of the bile duct.

The clotting should be checked preoperatively and adequate hydration

The operation has three distinct phases:

1- exploration and assessment; 2- resection; 3- reconstruction.

A cholecystectomy is performed

Palliation of pancreatic cancer

Relieve jaundice and treat biliary sepsis

■ Surgical biliary bypass

■ Stent placed at ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography

Improve gastric emptying

■ Surgical gastroenterostomy

■ Duodenal stent

Pain relief

■ Stepwise escalation of analgesia

■ Coeliac plexus block

■ Transthoracic splanchnicectomy

Symptom relief and quality of life

■ Encourage normal activities

■ Enzyme replacement for steatorrhoea

■ Treat diabetes

Consider chemotherapy

INJURIES TO THE PANCREAS

External injury;-

Presentation and management

*The clinical presentation can be quite deceptive; careful serial assessments and a high

index of suspicion are

Required.*The pancreas, is somewhat protected location in the retroperitoneum, is not

frequently damaged in blunt abdominal trauma.

*If there is damage to the pancreas, it is often concomitant with injuries to other

viscera, especially the liver, the spleen and the duodenum.

* Occasionally, a forceful blow to the epigastrium may crush the body of the pancreas

against the vertebral column.

*Penetrating trauma to the upper abdomen or the back carries a higher chance of

pancreatic injury.

*Pancreatic injuries may range from a contusion or laceration of the parenchyma

without duct

disruption to major parenchymal destruction with duct disruption (sometimes

complete transection) and, rarely, massive destruction of the pancreatic head.

*The most important factor that determines treatment is whether the pancreatic duct

has been disrupted.

*Blunt pancreatic trauma usually presents with epigastric pain, which may be minor at

first, with

the progressive development of more severe pain due to the sequelae of leakage of

pancreatic fluid into the surrounding tissues.

;-*A rise in

occurs in most cases.

Investigation

serum amylase

*A

of the pancreas will delineate the damage that has occurred to

CT scan

the pancreas .

*If there is doubt about duct disruption,

or

should

an urgent ERCP

MRCP

be sought.

Treatment ;-

1-Support with intravenous fluids and a nil by mouth regimen should be

instituted while these investigations are performed.

2-There is no need to rush to a laparotomy if the patient is

haemodynamically stable, without peritonitis.

It is preferable to manage conservatively at first, investigate and, once the

extent of the damage has been ascertained,

undertake appropriate action.

Operation is indicated only if there is disruption of the main pancreatic

duct; in almost all other cases, the patient will recover with conservative

management.

, especially if other organs are injured and the

In penetrating injuries

patient’s condition is unstable, there

is a greater need to perform an urgent surgical exploration.

Assessment of pancreatic damage and duct disruption at the time of surgery

can be difficult, because the bruising associated with the retroperitoneal

damage prevents clear visualisation of the pancreas.

A patient and thorough examination of the gland should be carried out.

** Haemostasis and closed drainage is adequate for minor parenchymal

injuries.

1- If the gland is transected in the body or tail, a distal pancreatectomy

should be performed, with or without splenectomy.

2-If damage is purely confined to the head of the pancreas, haemostasis and

external drainage is normally effective.

In the emergency setting, in an unstable patient with concomitant injuries, a

surgeon unaccustomed to

pancreatic surgery should refrain from trying to ascertain whether the duct

in the pancreatic head is intact or embarking on a major resection.

However, if there is severe injury to the pancreatic head and duodenum,

then a pancreatoduodenectomy may be necessary.

This can occur in several ways:

Iatrogenic injury=

1• Injury to the tail of the pancreas during splenectomy, resulting in a

pancreatic fistula.

2• Injury to the accessory pancreatic duct (Santorini), which is the main

duct during Billroth II gastrectomy.

A pancreatogram performed by cannulating the duct at the time of

discovery of such an injury will

demonstrate whether it is safe to ligate and divide the duct.

If no alternative drainage duct can be demonstrated, then the duct should

be reanastomosed to the duodenum.

3• Enucleation of islet cell tumours of the pancreas can result in fistulae.

4• Duodenal or ampullary bleeding following sphincterotomy.

This injury may require duodenotomy to control the bleeding.

Pancreatic fistula

Pancreatic fistula usually follows operative trauma to the gland or may

occur as a complication of acute or chronic pancreatitis.

It is important to define the site of the fistula and the epithelial structure

with which it communicates (e.g. externally to skin, or internally to

bowel).

Management of pancreatic fistulae

1■ Measure amylase level in fluid

2■ Determine the anatomy of the fistula

3■ Check whether the main pancreatic duct is blocked or disrupted (ERCP )

4■ Correct fluid and electrolyte imbalances

5■ Protect the skin

6■ Drain adequately

7■ Parenteral(TPN total parentral nutrition) or nasojejunal feeding

8■ Octreotide to suppress secretion

9■ Relieve pancreatic duct obstruction if possible (ERCP and stent)

10■ Treat underlying cause

BY:Fatima Ehsan Avci