NEOPLASMS OF THE THYROID

Classification of thyroid neoplasms

-Benign

a) Follicular adenoma

-Malignant

a)Primary b)Secondary

1)Follicular epithelium – differentiated Metastatic

i) Follicular Local infiltration

ii) Papillary

2) Follicular epithelium – undifferentiated ---- Anaplastic

3) Parafollicular cells --------- Medullary

4) Lymphoid cells ---------- Lymphoma

Benign tumours

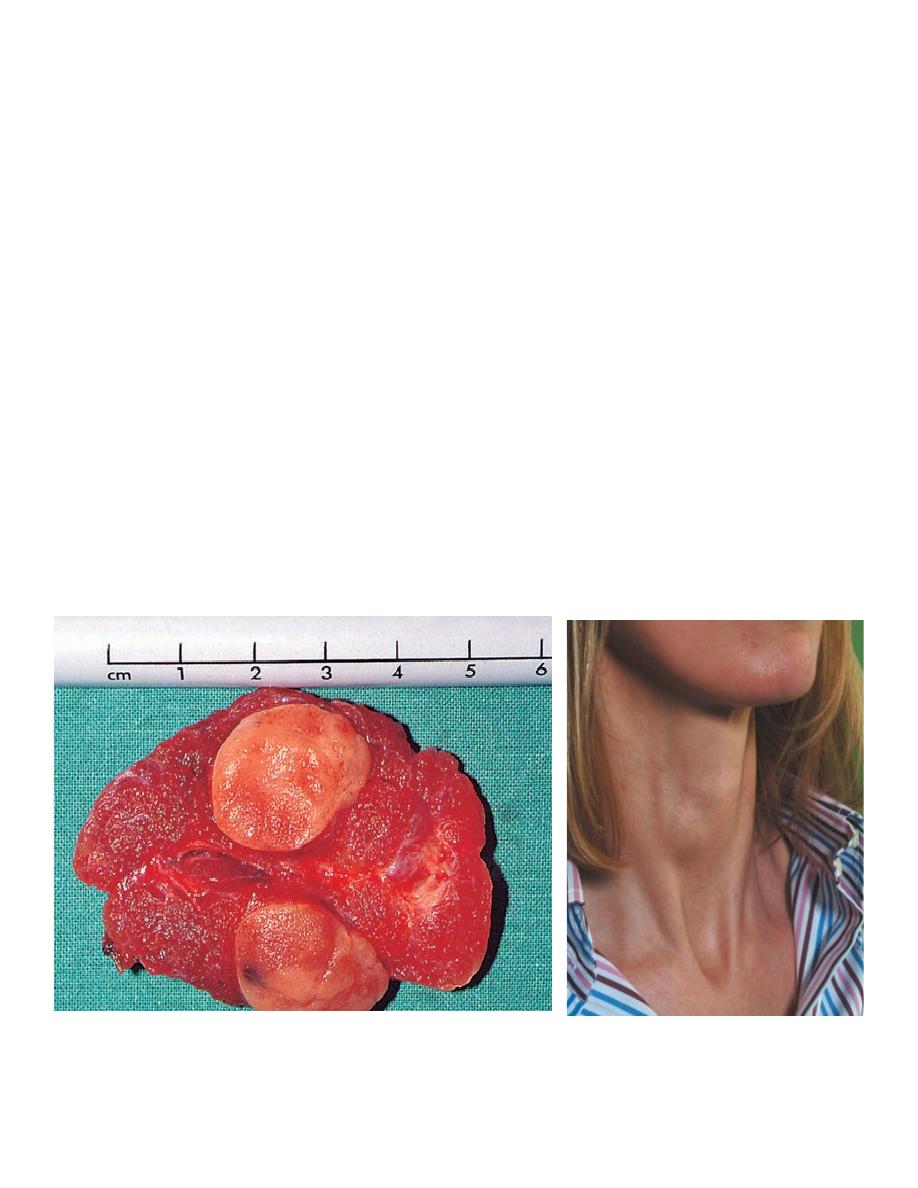

Follicular adenomas present as clinically solitary nodules and the distinction between a follicular

carcinoma and an adenoma can only be made by histological examination; in the adenoma there is no

invasion of the capsule or of pericapsular blood vessels. Treatment is therefore by wide excision, i.e.

lobectomy.

The remaining thyroid tissue is normal so that prolonged follow-up is unnecessary. All papillary

tumours should be considered as malignant, even if encapsulated.

Isolated swelling

Follicular neoplasmas an isolated swelling.

Malignant tumours

The vast majority of primary malignancies are carcinomas derived from follicular cells .

Lymphoma makes up the remainder of primary malignancies.

Metastases to the thyroid account for < 5% of malignancies.

Secondary disease should be considered when there is a history of malignancy, particularly kidney and

breast cancer, and when the cytology of a thyroid swelling is atypical. Direct invasion by upper

aerodigestive squamous cancer is a rare but lethal event. Lymph node and blood-borne metastases to

bone and lung occur and may be the mode of presentation

Aetiology of malignant thyroid tumours

The single most important aetiological factor in differentiated

thyroid carcinoma, particularly papillary carcinoma, is

irradiation of the thyroid under 5 years of age.

Short-latency aggressive papillary cancer is associated with the

ret/PTC3 oncogene and later-developing, possibly less

aggressive, cancers are associated with ret/PTC1. The incidence

of follicular carcinoma is high in endemic goitrous areas,

possibly as a result of TSH stimulation. Malignant lymphomas

sometimes develop in autoimmune thyroiditis, and the

lymphocytic infiltration in the autoimmune process may be an

aetiological factor.

Clinical features of thyroid cancers

The most common presenting symptom is a thyroid swelling

and a 5-year history is not uncommon in differentiated growths.

Enlarged cervical lymph nodes may be the presentation of

papillary carcinoma. Recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis is very

suggestive of locally advanced disease.

Anaplastic growths are usually hard, irregular and infiltrating.

A differentiated carcinoma may be suspiciously firm and

irregular but is often indistinguishable from a benign swelling.

Small papillary tumours may be impalpable, even when

lymphatic metastases are present. Pain, often referred to the ear,

is frequent in infiltrating growths.

Diagnosis of thyroid neoplasms

Diagnosis is obvious on clinical examination in most cases of

anaplastic carcinoma, although Riedel’s thyroiditis is

indistinguishable. The localised forms of granulomatous

thyroiditis and lymphadenoid goitre may simulate carcinoma. It

is not always easy to exclude a carcinoma in a multinodular

goitre, and solitary nodules, particularly in a young male patient,

are always suspect.

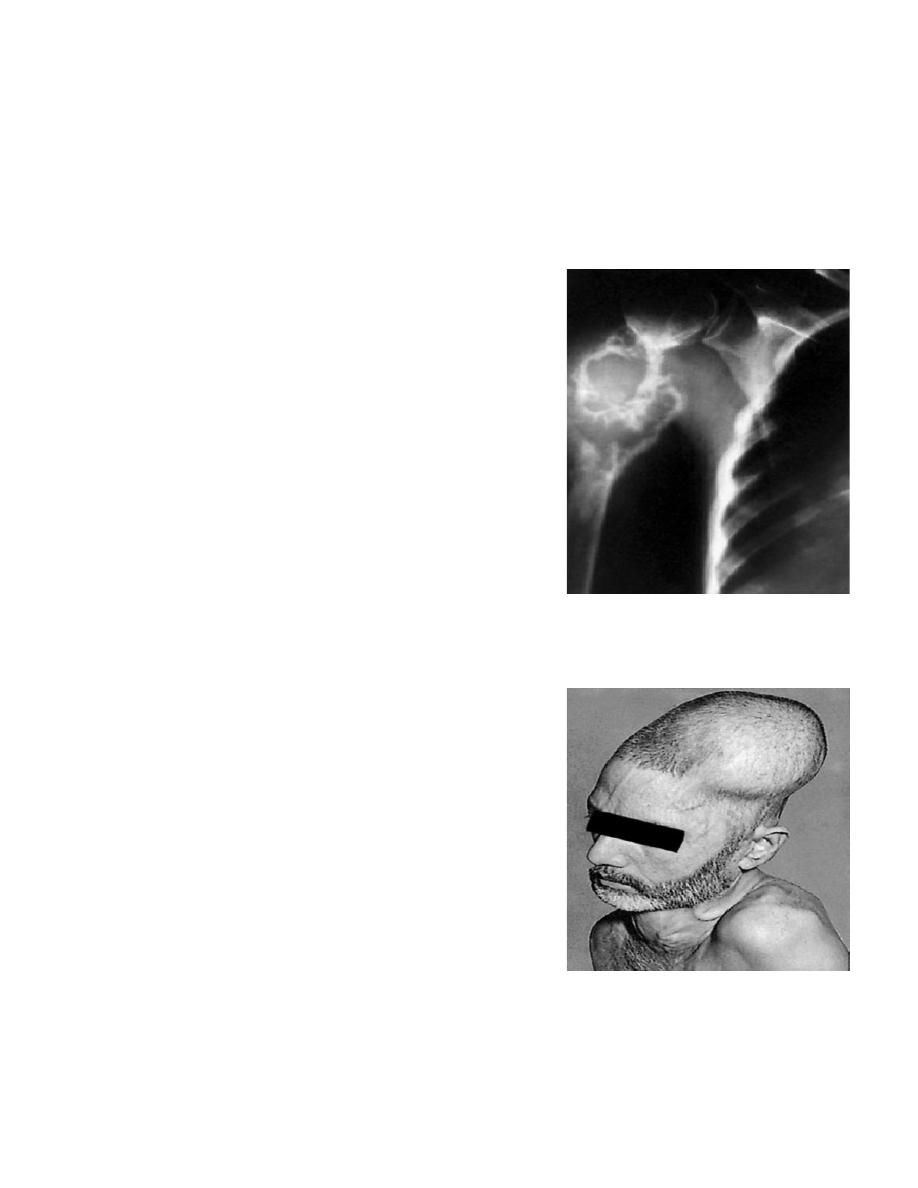

Metastasis in the humerus

from a carcinoma of the

thyroid

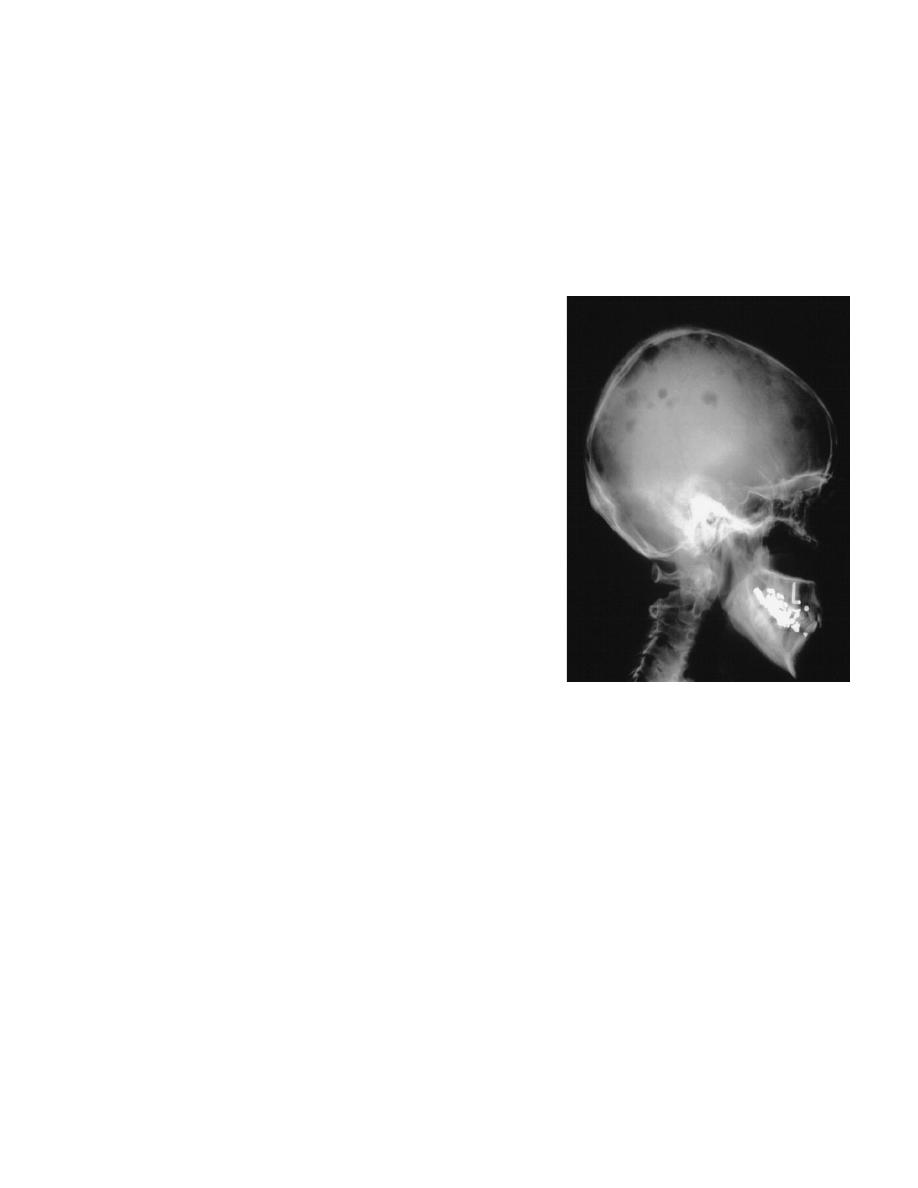

Metastasis in the left

parietal bone from a

carcinoma of

the thyroid

Failure to take up radioiodine is characteristic of almost all thyroid carcinomas [only very rarely will

differentiated carcinoma (primary or secondary) take up 123I in the presence of normal thyroid tissue],

but this also occurs in degenerating nodules and all forms of thyroiditis.

TSH levels are often raised in carcinoma but this may be clouded by simultaneous elevation of anti-

thyroid antibodies. Regarding FNAC there is a false-negative rate with all investigations, and lobectomy

is appropriate when there is a strong clinical suspicion. Incisional biopsy may cause seeding of cells and

local recurrence and is not advised in a resectable carcinoma. In an anaplastic and obviously

irremovable carcinoma, however, incisional or core needle biopsy is justified.

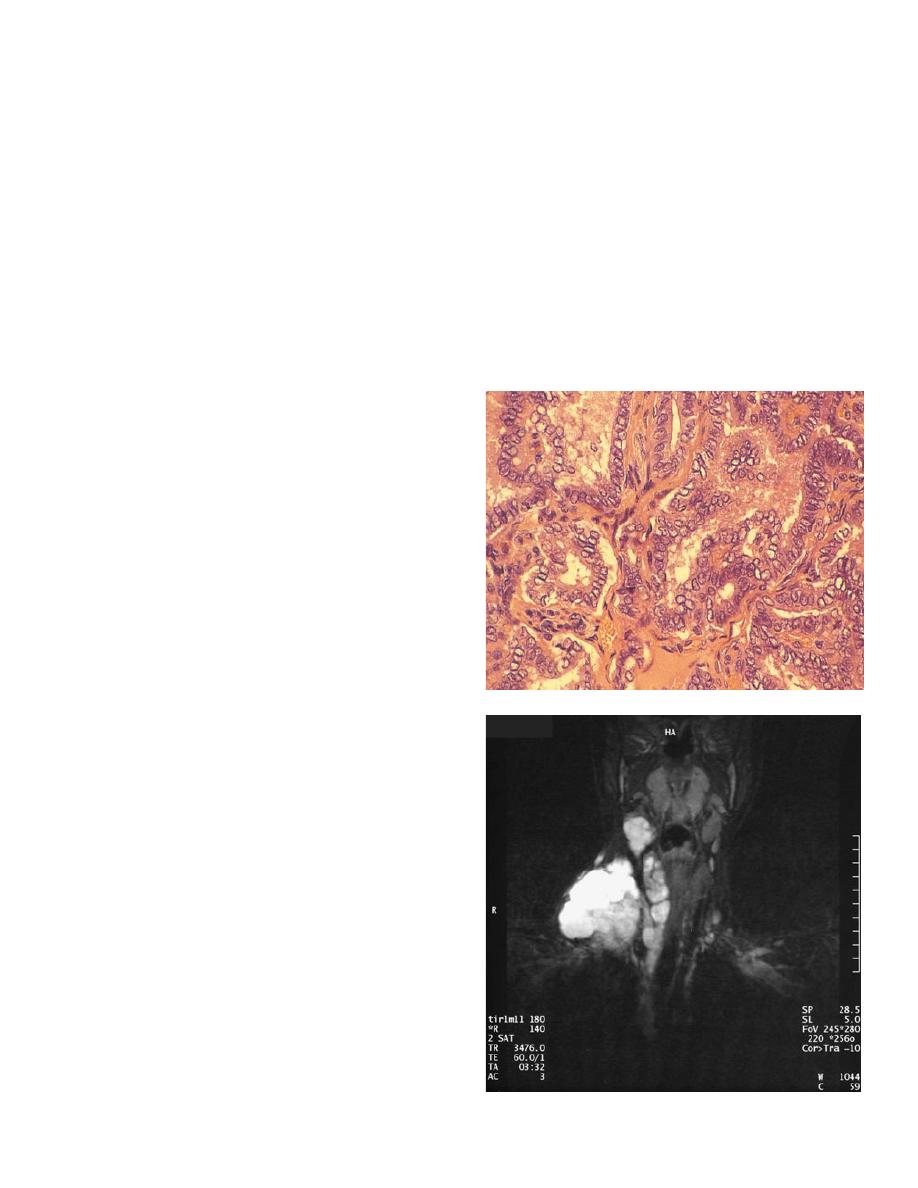

When a preoperative diagnosis is made, imaging with ultrasound, MRI or CT is required. As well as

additional information on the extent of the primary tumour, imaging provides valuable information on

nodal involvement, which permits preoperative planning for nodal dissection.

Papillary carcinoma

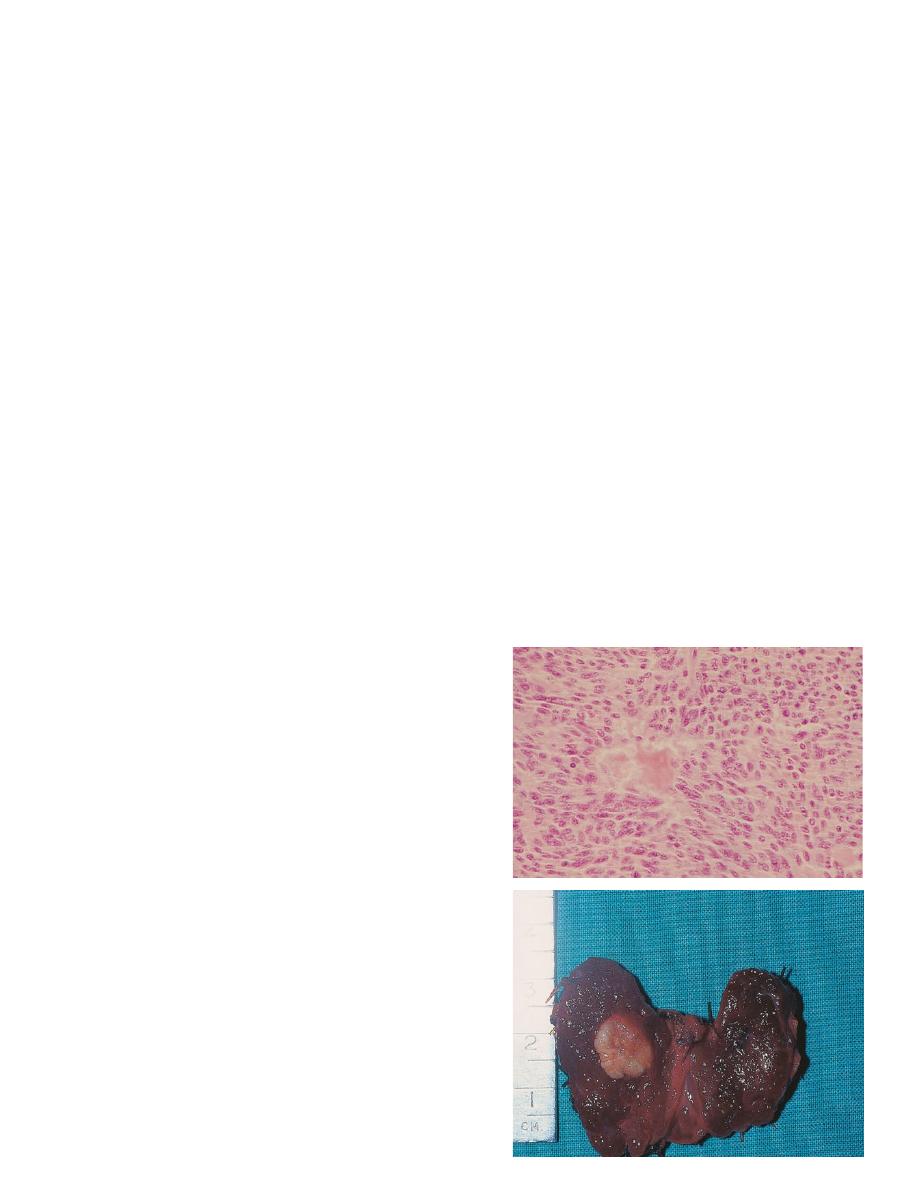

Most papillary tumours contain a mixture of papillary

and colloid- filled follicles and, in some, the follicular

structure predominates. Histologically the tumour

shows papillary projections and characteristic pale

empty nuclei (Orphan Annie-eyed nuclei) . Papillary

carcinomas are very seldom encapsulated.

Multiple foci may occur in the same lobe as the

primary tumour or, less commonly, in both lobes.

They may be due to lymphatic spread in the rich

intrathyroidal lymph plexus or to multicentric growth.

Spread to the lymph nodes is common but blood-

borne metastases are unusual unless the tumour is

extrathyroidal.

Microcarcinoma (occult carcinoma)

Clearly the majority of such tumours never progress

to become a clinically significant entity. A small

percentage of cancers present with enlarged lymph

nodes in the jugular chain or pulmonary metastases

with no palpable abnormality of the thyroid.

The primary tumour may be no more than a few

millimetres in size and is often termed occult. Foci of

papillary carcinoma may also be discovered in thyroid

tissue resected for other reasons, for example Graves’

disease.

Microcarcinoma applied for cancers less than

1 cm in diameter. These have a uniformly excellent

prognosis although those presenting with nodal or

distant metastases justify more aggressive therapy.

Follicular carcinoma

These appear to be macroscopically encapsulated but, microscopically, there is invasion of the capsule

and of the vascular spaces in the capsular region. Multiple foci are seldom seen and lymph node

involvement is much less common than in papillary carcinoma. Blood-borne metastases are more

common and the eventual mortality rate is twice that of papillary cancer.

Hürthle cell tumours are a variant of follicular neoplasm in which oxyphil (Hürthle, Askanazy) cells

predominate histologically. Hürthle cell cancers are associated with a poorer prognosis and some hold

that all Hürthle cell neoplasms are malignant.

Major differences between papillary and follicular

carcinoma (after Cady)

Papillary (%) Follicular (%)

Male incidence 22 35

Lymph node metastases 35 13

Blood vessel invasion 40 60

Recurrence rate 19 29

Overall mortality rate 11 24

Location of recurrent carcinoma

Distant metastases 45 75

Nodal metastases 34 12

Local recurrence 20 12

Surgical treatment of differentiated thyroid carcinoma

There is agreement that patients with large, locally aggressive or

metastatic DTC require total thyroidectomy, with excision of adjacent involved structures if necessary,

and appropriate nodal surgery followed by radioiodine ablation with long-term TSH suppression.

The conservative approach reserves total thyroidectomy for specific indications (namely those in which

there is a preoperative diagnosis of high-risk cancer, bilateral disease or when there is a clear indication

for postoperative radioiodine therapy). ‘Small’ cancers confined to one lobe can be managed by

lobectomy and TSH suppression.

Additional measures

Thyroxine

Thyroxine (0.1–0.2 mg daily) for all patients after operation for differentiated thyroid carcinoma to

suppress endogenous TSH production Failure of suppression to a level of < 0.1 mU l–1 may indicate an

inadequate dose of thyroxine or, more usually, that the patient is non-compliant..

skull secondaries.

Radioiodine

If metastases take up radioiodine they may be detected by scanning and treated with large doses of

radioiodine. Radioactive iodine is indicated in patients with unresectable disease, local recurrence or

metastatic disease, high-risk patients and in those with a rising serum thyroglobulin level.

Thyroglobulin

The measurement of serum thyroglobulin is of value in the follow-up and detection of metastatic

disease in patients who have undergone surgery for DTC.

Undifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma

Local infiltration is an early feature of these tumours, with spread by lymphatics and by the

bloodstream. They are extremely lethal tumours and survival is calculated in months. Complete

resection is justified if the disease appears confined to the thyroid and possibly the strap muscles and is

only possible in a minority of patients.

Some of these aggressive lesions present in an advanced stage with tracheal obstruction and they

require urgent tracheal decompression. The trachea may be decompressed and tissue obtained for

histology by isthmusectomy. Tracheostomy is best avoided. Radiotherapy should be given in all cases

and may provide a worthwhile period of palliation, but there is little evidence to support the use of

chemotherapy.

Medullary carcinoma

These are tumours of the parafollicular cells (C cells) derived from the neural crest and not of cells of

the thyroid follicle. The cells are not unlike those of a carcinoid tumour and there is a characteristic

amyloid stroma.

High levels of serum calcitonin and carcinoembryonic

antigen are produced by many medullary tumours. Levels

fall after resection and rise again with recurrence making

it a valuable tumour marker in the follow-up of patients

with this disease.

Diarrhoea is a feature in 30% of cases and this may be

due to 5-hydroxytryptamine or prostaglandins produced

by the tumour cells. Some tumours are familial, possibly

accounting for 10–20% of all cases.

Medullary carcinoma may occur in combination with

adrenal phaeochromocytoma and hyperparathyroidism

(HPT) (usually due to hyperplasia) in the syndrome

known as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A (MEN-

2A). The familial form of the disease frequently affects

children and young adults, whereas sporadic cases occur

at any age with no sex predominance.

When the familial form is associated with prominent

mucosal neuromas involving the lips, tongue and inner

aspect of the eyelids, with a marfanoid habitus, the syndrome is referred to as MEN type 2B.

Involvement of lymph nodes occurs in 50–60% of cases of medullary carcinoma and blood-borne

metastases are common.

Treatment

Treatment is by total thyroidectomy and either prophylactic or therapeutic resection of the central and

bilateral cervical lymph nodes.

Malignant lymphoma

The response to irradiation is good and radical surgery is unnecessary once the diagnosis is established

by biopsy. Although the diagnosis may be made or suspected on FNAC, sufficient material is seldom

available for immunocytochemical classification and large-bore needle (Truecut) or open biopsy is

usually necessary.

In patients with tracheal compression, isthmusectomy is the most appropriate form of biopsy, although

the response to therapy is so rapid that this should rarely be necessary unless there has been difficulty

in making a histological diagnosis. The prognosis is good if there is no involvement of cervical lymph

nodes. Rarely, the tumour is part of widespread malignant lymphoma disease, and the prognosis in

these cases is worse. Most lymphomas occur against a background of lymphocytic thyroiditis.

THYROIDITIS

Chronic lymphocytic (autoimmune) thyroiditis

This common condition is usually associated with raised titres of thyroid antibodies. Not infrequently

there is a family history of other autoimmune disease. It commonly presents as a goitre, which may be

diffuse or nodular with a characteristic ‘bosselated’ feel, or with established or subclinical thyroid

failure.

The diagnosis often follows investigation of a discrete swelling. Features of chronic lymphocytic (focal)

thyroiditis are commonly present on histological examination in association with other thyroid

diseases, notably toxic goitre. Primary myxoedema without detectable thyroid enlargement represents

the end-stage of the pathological process.

Clinical features

The onset, thyroid status and type of goitre vary profoundly from case to case. The onset may be

insidious and asymptomatic or so sudden and painful that it resembles the acute form of

granulomatous thyroiditis. Mild hyperthyroidism may be present initially, but hypothyroidism is

inevitable and may develop rapidly or extremely slowly.

The goitre is usually lobulated and may be diffuse or localised to one lobe. It may be large or small, and

soft, rubbery or firm in consistency, depending on the cellularity and degree of fibrosis. The disease is

most common in women at the menopause but may occur at any age. Papillary carcinoma and

malignant lymphoma are occasionally associated with autoimmune thyroiditis.

Diagnosis

-Biochemical tests of thyroid function

- Thyroid antibodies

-FNAC is the most appropriate investigation

-Diagnostic lobectomy

Treatment

Full replacement dosage of thyroxine should be given for hypothyroidism and if the goitre is large or

symptomatic because some (under TSH stimulation) may subside with hormone therapy. Occasionally,

the goitre increases in size despite hormone treatment and, in these circumstances, there may be a

favourable response to steroid therapy

Thyroidectomy may be necessary if the goitre is large and causes discomfort. An increase in size of a

longstanding lymphocytic goitre should be assessed urgently because of the possibility of the

development of malignant lymphoma.

Granulomatous thyroiditis (subacute thyroiditis, de Quervain’s

thyroiditis)

Granulomatous thyroiditis is caused by a viral infection. In a typical subacute presentation there is pain

in the neck, fever, malaise and a firm irregular enlargement of one or both thyroid lobes. In 10% of

cases the onset is acute, the goitre is very painful and tender and there may be symptoms of

hyperthyroidism. One-third of cases are asymptomatic but for the presence of the goitre.

There is a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate and absent thyroid antibodies, the serum T4 is high

normal or slightly raised and the 123I uptake of the gland is low. The condition is self-limiting and after

a few months the goitre subsides and there may be a period of months of hypothyroidism before

eventual recovery.

If diagnosis is in doubt it may be confirmed by FNAC, radioactive iodine uptake and a rapid

symptomatic response to prednisone.

The specific treatment for the acute case with severe pain is to give prednisone l0–20 mg daily for 7

days, with the dose gradually reduced over the next month. If thyroid failure is prominent, treatment

with thyroxine may be required until function recovers.

Riedel’s thyroiditis

Riedel’s thyroiditis is very rare, accounting for 0.5% of goitres. Thyroid tissue is replaced by cellular

fibrous tissue, which infiltrates through the capsule into muscles and adjacent structures, including the

parathyroids, recurrent nerves and carotid sheath.

It may occur in association with retroperitoneal and mediastinal fibrosis and is most probably a

collagen disease. The goitre may be unilateral or bilateral and is very hard and fixed. The differential

diagnosis from anaplastic carcinoma can be made with certainty only by biopsy, when a wedge of the

isthmus should also be removed to free the trachea. If the condition is unilateral the other lobe is

usually involved later and subsequent hypothyroidism is common.

Treatment is with high-dose steroids and thyroxine replacement.

BY

Muhammed Shakir Yashar M. Shakir