Abdominal wall hernia

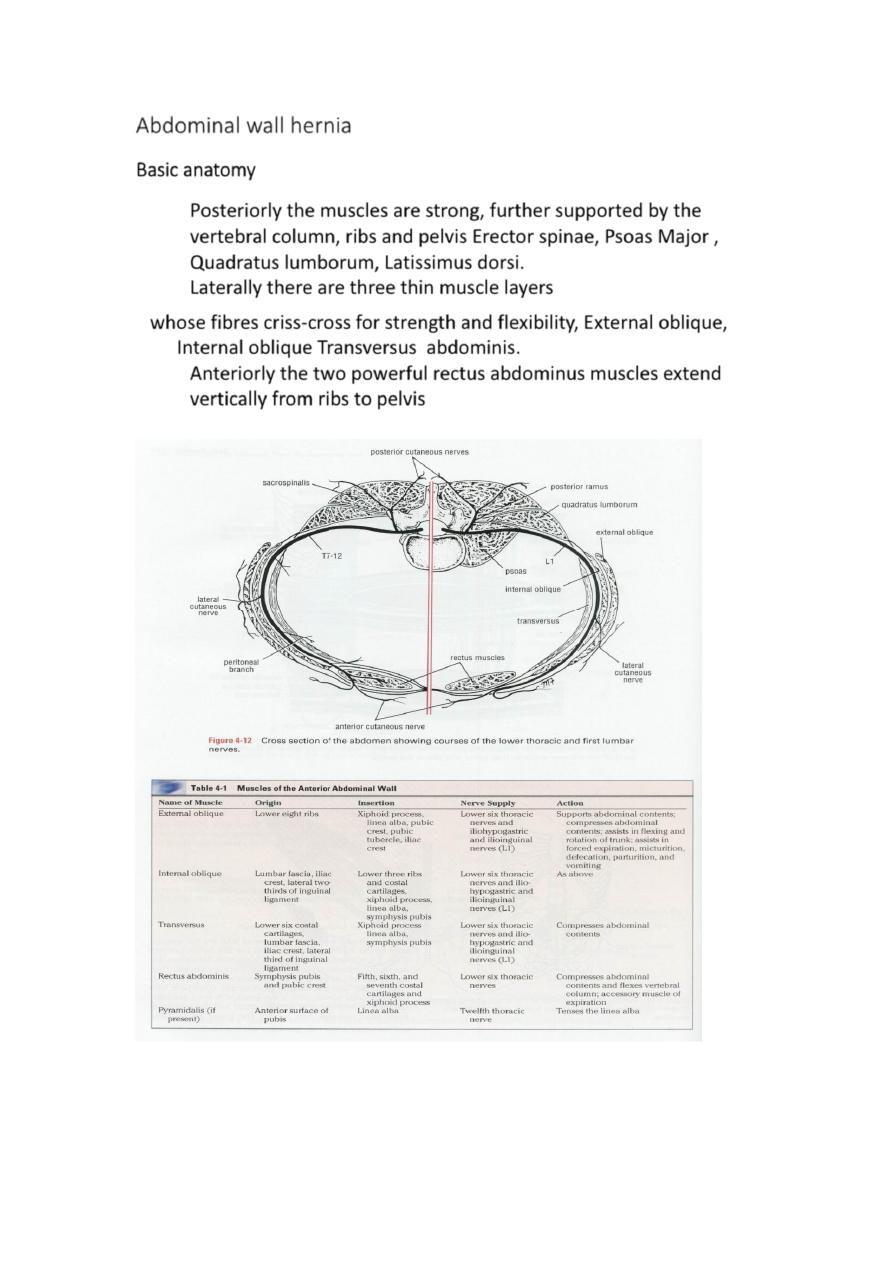

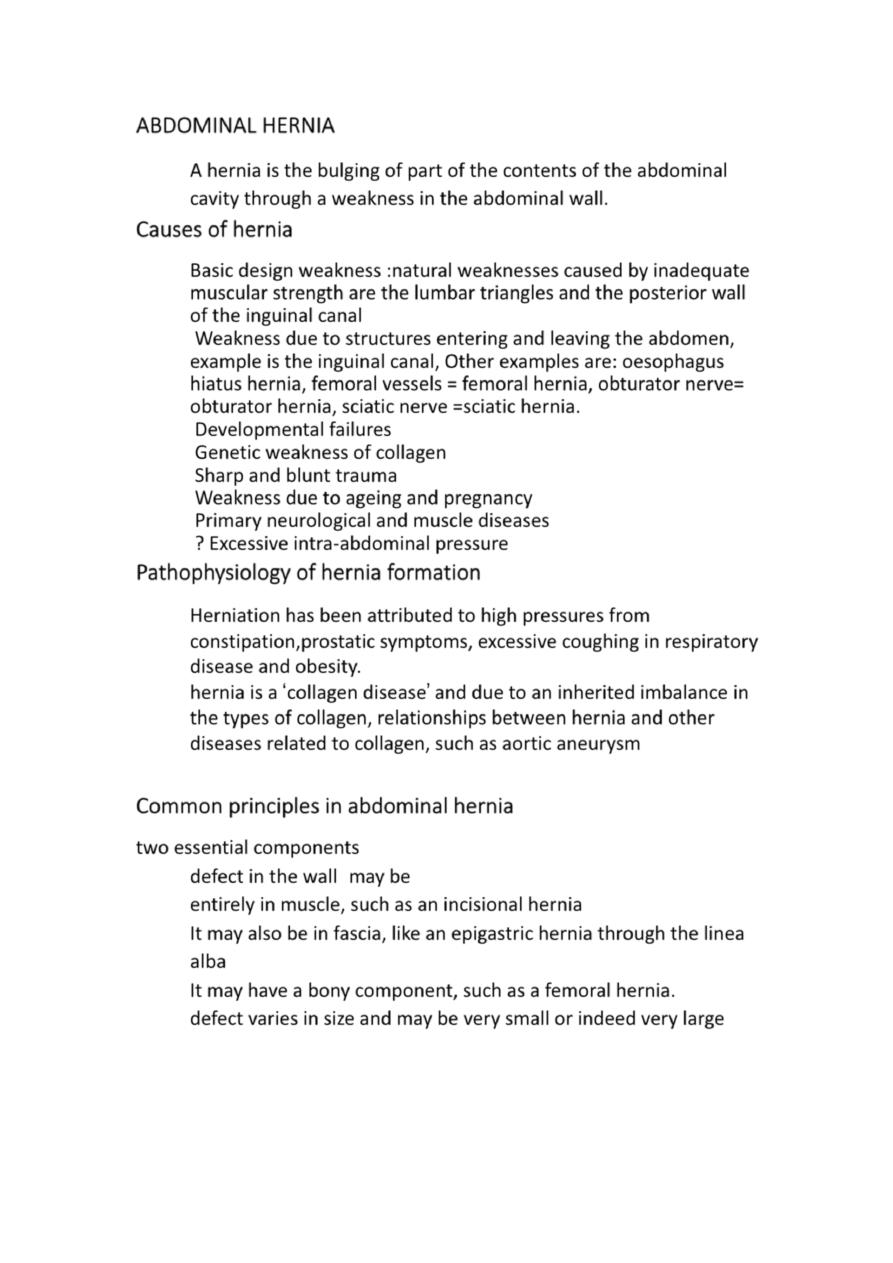

Basic anatomy

Posteriorly the muscles are strong, further supported by the

vertebral column, ribs and pelvis Erector spinae, Psoas Major ,

Quadratus lumborum, Latissimus dorsi.

Laterally there are three thin muscle layers

whose fibres criss-cross for strength and flexibility, External oblique,

Internal oblique Transversus abdominis.

Anteriorly the two powerful rectus abdominus muscles extend

vertically from ribs to pelvis

ABDOMINAL HERNIA

A hernia is the bulging of part of the contents of the abdominal

cavity through a weakness in the abdominal wall.

Causes of hernia

Basic design weakness :natural weaknesses caused by inadequate

muscular strength are the lumbar triangles and the posterior wall

of the inguinal canal

Weakness due to structures entering and leaving the abdomen,

example is the inguinal canal, Other examples are: oesophagus

hiatus hernia, femoral vessels = femoral hernia, obturator nerve=

obturator hernia, sciatic nerve =sciatic hernia.

Developmental failures

Genetic weakness of collagen

Sharp and blunt trauma

Weakness due to ageing and pregnancy

Primary neurological and muscle diseases

? Excessive intra-abdominal pressure

Pathophysiology of hernia formation

Herniation has been attributed to high pressures from

constipation,prostatic symptoms, excessive coughing in respiratory

disease and obesity.

hernia is a ‘collagen disease’ and due to an inherited imbalance in

the types of collagen, relationships between hernia and other

diseases related to collagen, such as aortic aneurysm

Common principles in abdominal hernia

two essential components

1.

defect in the wall may be

entirely in muscle, such as an incisional hernia

It may also be in fascia, like an epigastric hernia through the linea

alba

It may have a bony component, such as a femoral hernia.

defect varies in size and may be very small or indeed very large

2. The content of the hernia

fat within an epigastric hernia

urinary bladder in a direct inguinal hernia

intraperitoneal structures such as bowel or omentum

Types of hernia

the intraperitoneal organs can move freely

in and out of the hernia, a ‘reducible’ hernia

but if adhesions form or the defect is small, bowel can become

trapped and unable to return to the main peritoneal cavity, an

‘irreducible’ hernia

Interstitial hernia occurs when the hernia extends

between the layers of muscle and not directly through

them.This is typical of a Spigelian hernia.

Internal hernia bowel can enter and become trapped into

abnormal pockets of adhesions form within the peritoneal

cavity

The narrow neck acts as a constriction ring impeding venous

return

If the hernia contains bowel then it may become ‘obstructed’,

partially or totally

If the pressure rises sufficiently, arterial blood is not able to enter

the hernia and the contents become ischaemic and may

infarct ‘strangulated’

(Richter’s hernia) only part of the bowel wall enters the hernia

Clinical history and diagnosis in hernia cases

a lump painless , aching or heavy feeling.

Severe pain should alert the surgeon to a high risk of strangulation

hernia reduces spontaneously or needs to be helped.

primary hernia or whether it is a recurrence after previous surgery

cardiac and respiratory systems are necessary to assess a patient’s

anaesthetic risk

history of prostatic symptoms indicates a high risk of

postoperative urinary retention

Examination for hernia

The patient should be examined lying down initially and

then standing as this will usually increase hernia size

The patient is asked to cough,

If bruising is present this may suggest venous engorgement of the

content

if cellulitis then hernia content is strangulating

cough impulse is felt

In cases where the neck is tight and the hernia irreducible

there may be no cough impulse

Checks

Reducibility

Cough impulse

Tenderness

Overlying skin colour changes

Multiple defects/contralateral side

Signs of previous repair

Scrotal content for groin hernia

Associated pathology

A swelling with a cough impulse is not necessarily a hernia

(saphena varix)

A swelling with no cough impulse may still be a hernia

(femoral hernia)

Investigations for hernia

For most hernias, no specific investigation is required, the

diagnosis being made on clinical examination.

Plain x-ray – of little value

Ultrasound scan – mass or fluid collection, hernia content is in

doubt, haematoma or seroma/early recurrence

CT scan – incisional hernia number and size of muscle

defects, identifying the content

MRI scan – good in sportsman’s groin with pain

Contrast radiology ( herniagram)– especially for inguinal hernia

Laparoscopy – useful to identify occult contra lateral

inguinal hernia

20

%

Management

In reality, most patients with a hernia should be offered repair.

‘watchful waiting’ policy if the hernia is asymptomatic, small in

size,can be reduced easily and is not causing anxiety then

observation alone should be sufficient

Small hernias can be more dangerous than large

Pain, tenderness and skin colour changes imply high risk of

strangulation

Femoral hernia should always be repaired

Operative approaches to hernia

All surgical repairs follow the same basic principles:

1 reduction of the hernia content into the abdominal cavity

with removal of any non-viable tissue and bowel repair if

necessary;

2 excision and closure of a peritoneal sac if present or replac in it deep to

the muscles;

3 reapproximation of the walls of the neck of the hernia if possible;

4 permanent reinforcement of the abdominal wall defect with sutures or

mesh

Mesh in hernia repair

The term ‘mesh’ refers to prosthetic material, either a net or a flat

sheet which is used to strengthen a hernia repair. Mesh can

be used:

• to bridge a defect: the mesh is simply fixed over the defect as a

tension-free patch;

• to plug a defect: a plug of mesh is pushed into the defect;

• to augment a repair: the defect is closed with sutures and the

mesh added for reinforcement.

Mesh types

Woven, knitted or sheet

Synthetic or biological – mainly synthetic (synthetic polymers of

polypropylene, polyester or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE

biological meshes’ which are sheets of sterilised,decellularised,

non-immunogenic connective tissue. They derive from human or

animal dermis, bovine pericardium or porcine intestinal

submucosa.

Light, medium or heavyweight – lightweight becoming more

popular

Large pore, small pore – large pore causes less fibrosis and pain

Intraperitoneal use or not – non-adhesive mesh on one side

Non-absorbable or absorbable – mainly non-absorbable

Positioning the mesh

• just outside of the muscle in the subcutaneous space (onlay);

• within the defect (inlay) – only applies to mesh plugs in small

defects;

between fascial layers in the abdominal wall (intraparietal or

sublay);

• immediately extraperitoneally, against muscle or fascia (also

sublay);

• intraperitoneally.