Medicine Dr. Bilal

1

ASTHMA

Asthma is characterised by chronic airway inflammation and increased airway

hyper-responsiveness leading to symptoms of wheeze, cough, chest tightness

and dyspnoea.

It is characterised functionally by the presence of airflow obstruction which is

variable over short periods of time, or is reversible with treatment.

Atopic (extrinsic asthma):

Atopy is the major risk factor for asthma, and nonatopic individuals have a very

low risk of developing asthma.

Patients with asthma commonly suffer from other atopic diseases, particularly

allergic rhinitis, which may be found in over 80% of asthmatic patients, and

atopic dermatitis (eczema).

Atopy may be found in 40–50% of the population in affluent countries, with

only a proportion of atopic individuals becoming asthmatic.

Intrinsic Asthma:

A minority of asthmatic patients (approximately 10%) have negative skin tests to

common inhalant allergens and normal serum concentrations of IgE.

These patients, with nonatopic or intrinsic asthma, usually show later onset of

disease (adult-onset asthma), commonly have concomitant nasal polyps, and

may be aspirin-sensitive.

Medicine Dr. Bilal

2

Epidemiology

The prevalence of asthma increased steadily over the latter part of the last

century in countries with a Western lifestyle and is also increasing in developing

countries. Current estimates suggest that 300 million people world-wide suffer

from asthma and an additional 100 million persons will be diagnosed by 2025.

The socio-economic impact is enormous, particularly when poor control leads to

days lost from school or work, unscheduled health-care visits and hospital

admissions..

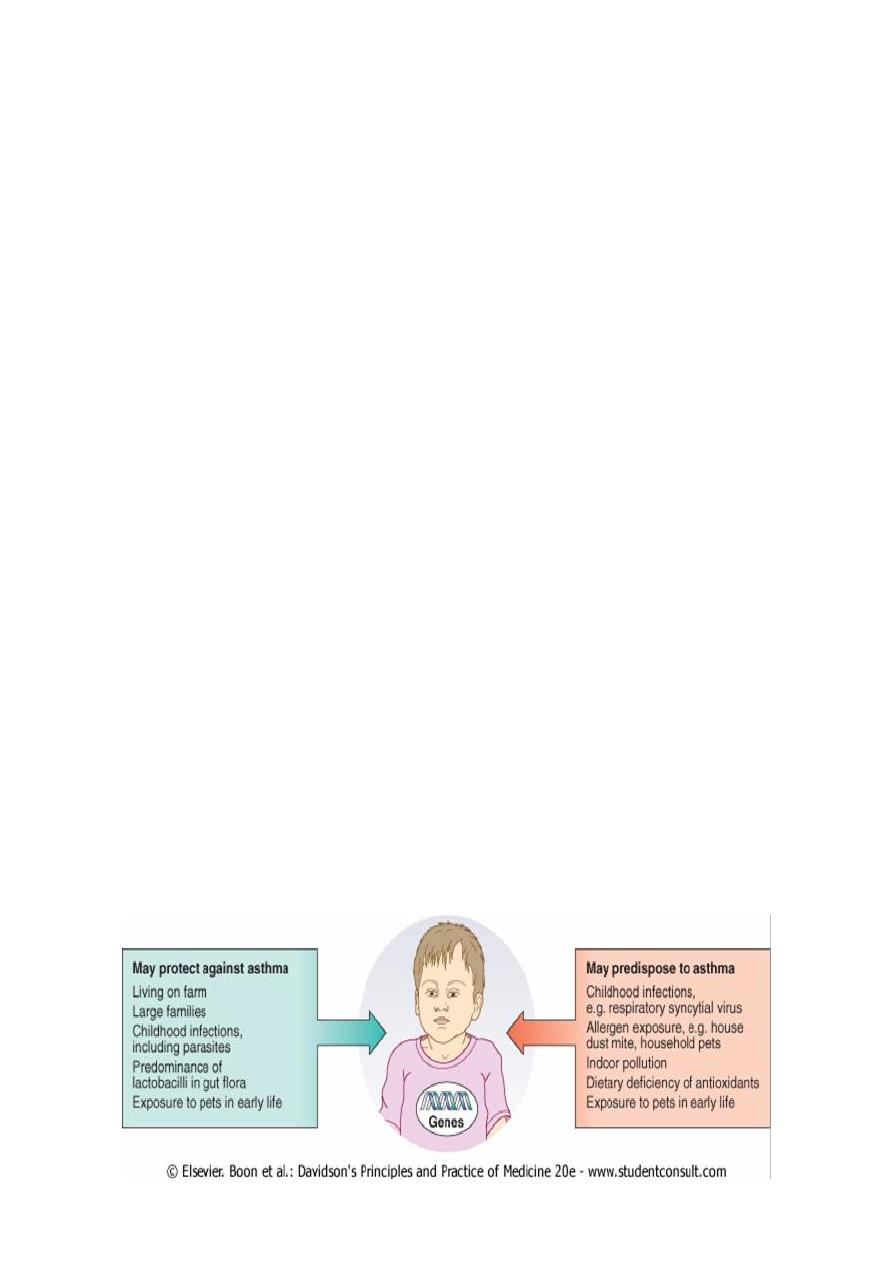

Aetiology:

The aetiology of asthma is complex, and multiple environmental and genetic

determinants are implicated.

The familial association of asthma and a high degree of concordance for asthma

in identical twins indicate a genetic predisposition to the disease .

The hygiene hypothesis proposes that decreased infections in early life bias the

immune system towards an allergic phenotype.

Warm, humid, centrally heated homes favour multiplication of house dust mites

and this may contribute to childhood asthma.

Growing up on a farm appears to be protective for atopy and asthma, but the

mechanism remains uncertain.

Dietary intake may be important. Milk fat and antioxidants such as vitamin E

may protect against the development of asthma in children; however, in other

studies early exposure to cows' milk protein has been linked to the

development of atopy and asthma.

Medicine Dr. Bilal

3

Pathophysiology:

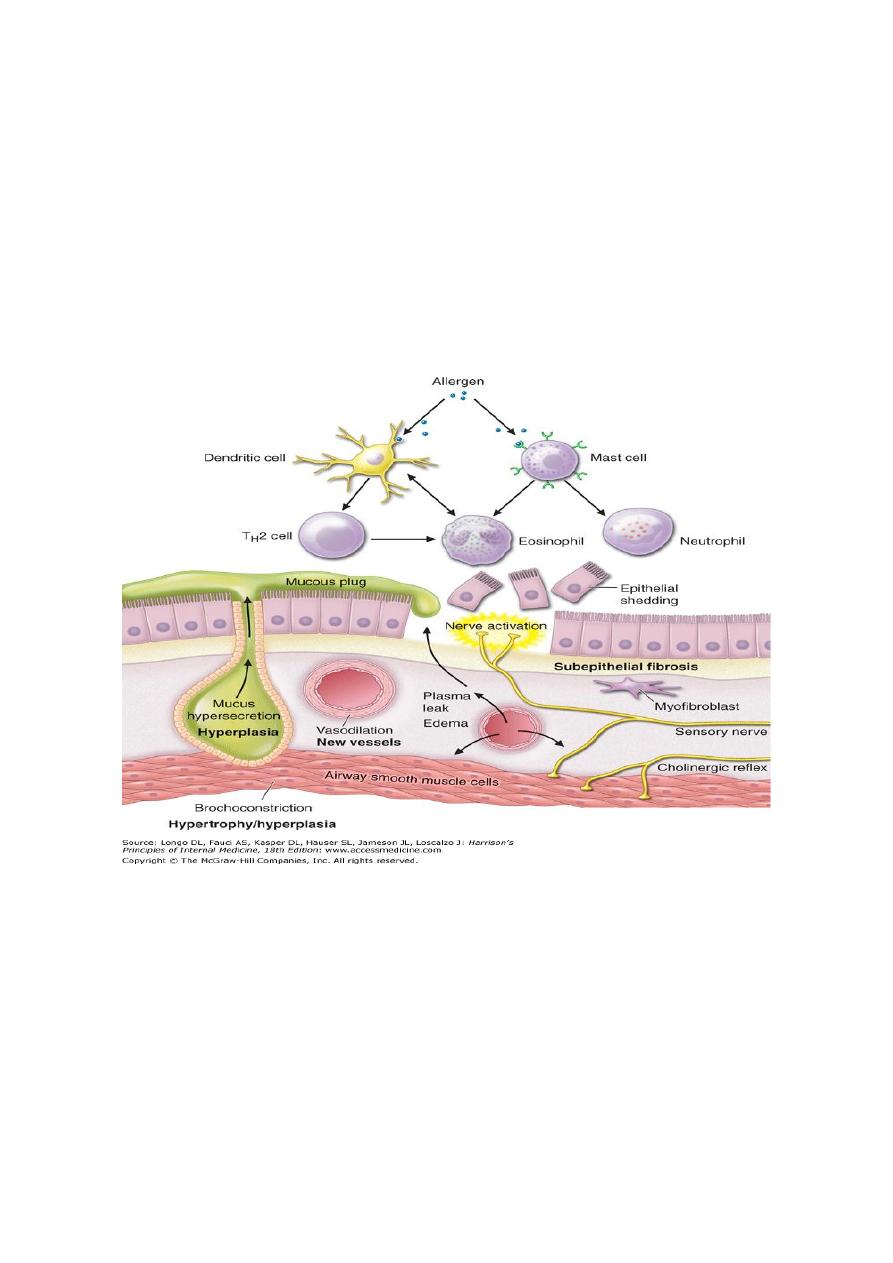

Airway hyper-reactivity (AHR)-the tendency for airways to contract too easily

and too much in response to triggers that have little or no effect in normal

individuals airway inflammation.

Other factors likely to be important include the degree of airway narrowing and

the influence of neurogenic mechanisms.

With increasing severity and chronicity of the disease, remodelling of the airway

occurs, leading to fibrosis of the airway wall, fixed narrowing of the airway and a

reduced response to bronchodilator medication.

The relationship between atopy (a propensity to produce IgE) and asthma is well

established, and in many individuals there is clear relationship between

sensitisation (demonstration of skin prick reactivity or elevated serum specific

IgE) and allergen exposure.

Inhalation of an allergen into the airway is followed by a two-phase

bronchoconstrictor response with both an early and a late-phase response .

In aspirin-sensitive asthma, symptoms follow the ingestion of salicylates. These

inhibit the cyclo-oxygenase, which leads to shunting of arachidonic acid

metabolism through the lipoxygenase pathway, resulting in the production of

the cysteinyl leukotrienes.

Medicine Dr. Bilal

4

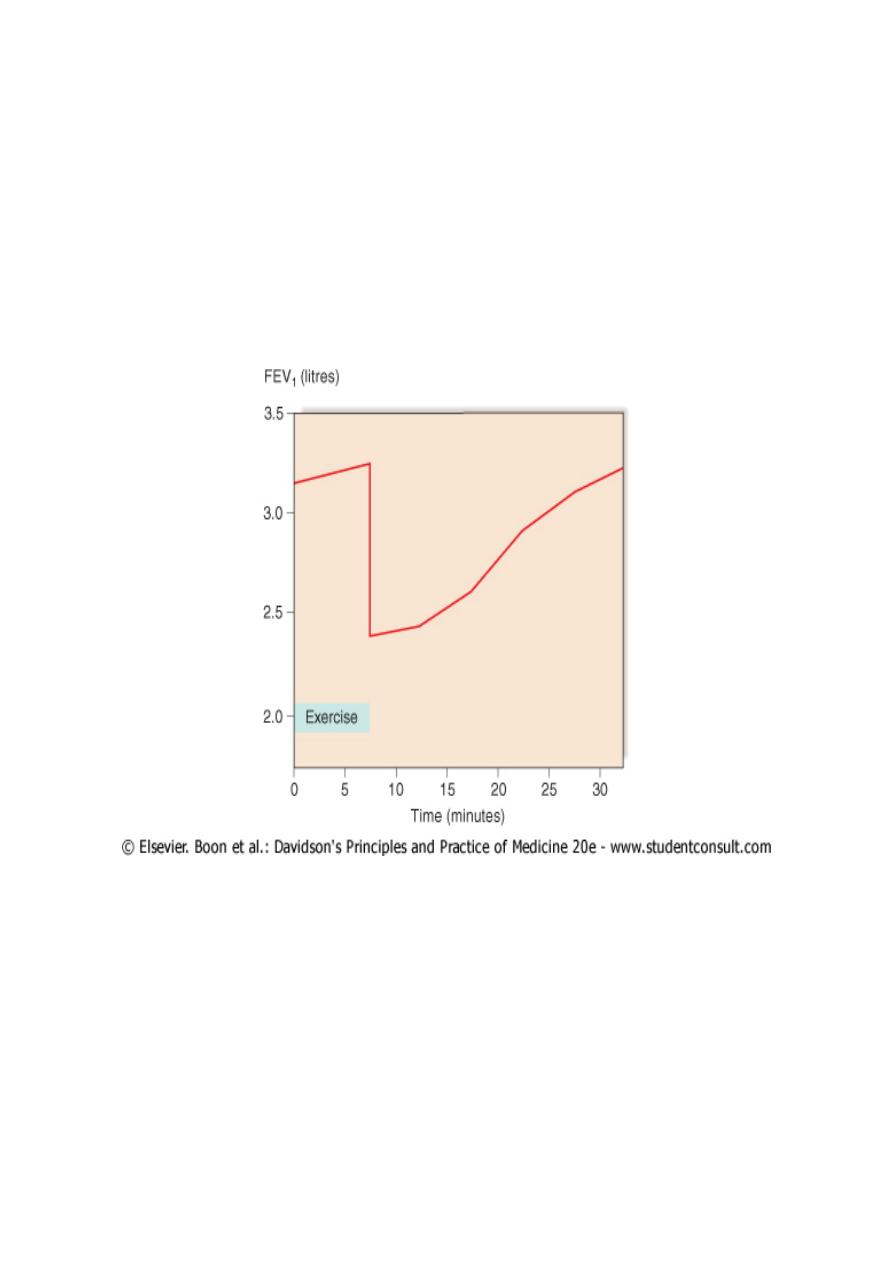

In exercise-induced asthma, hyperventilation results in water loss from the

pericellular lining fluid of the respiratory mucosa, which in turn triggers

mediator release. Heat loss from the respiratory mucosa may also be important.

In persistent asthma, a chronic and complex inflammatory response ensues,

which is characterised by an influx of numerous inflammatory cells, the

transformation and participation of airway structural cells, and the secretion of

an array of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors.

Smooth muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia, thickening of the basement

membrane, mucous plugging and epithelial damage result.

Examination of the inflammatory cell profile in induced sputum samples

demonstrates that, although asthma is predominantly characterised by airway

eosinophilia, in some patients neutrophilic inflammation predominates, and in

others, scant inflammation is observed: so-called 'pauci-granulocytic' asthma.

Cardinal pathophysiological features of asthma

Airflow limitation:

Usually reverses spontaneously or with treatment

Airway hyper-reactivity:

Exaggerated bronchoconstriction to a wide range of non-specific stimuli, e.g.

exercise, cold air

Airway inflammation:

Eosinophils, lymphocytes, mast cells, neutrophils; associated oedema, smooth

muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia, thickening of basement membrane,

mucous plugging and epithelial damage.

Clinical features:

Typical symptoms include recurrent episodes of wheeze, chest tightness,

breathlessness and cough. Not uncommonly, asthma is mistaken for a cold or

chest infection that is failing to resolve (e.g. after more than 10 days).

Medicine Dr. Bilal

5

Classical precipitants include exercise, particularly in cold weather, exposure to

airborne allergens or pollutants, and viral upper respiratory tract infections.

Wheeze apart, there is often little to find on examination.

An inspection for nasal polyps and eczema should be performed. Rarely, a vasculitic

rash may be present in Churg-Strauss syndrome .

Patients with mild intermittent asthma are usually asymptomatic between

exacerbations. Patients with persistent asthma report on-going breathlessness and

wheeze, but variability is usually present with symptoms fluctuating over the course

of one day, from day to day, or from month to month.

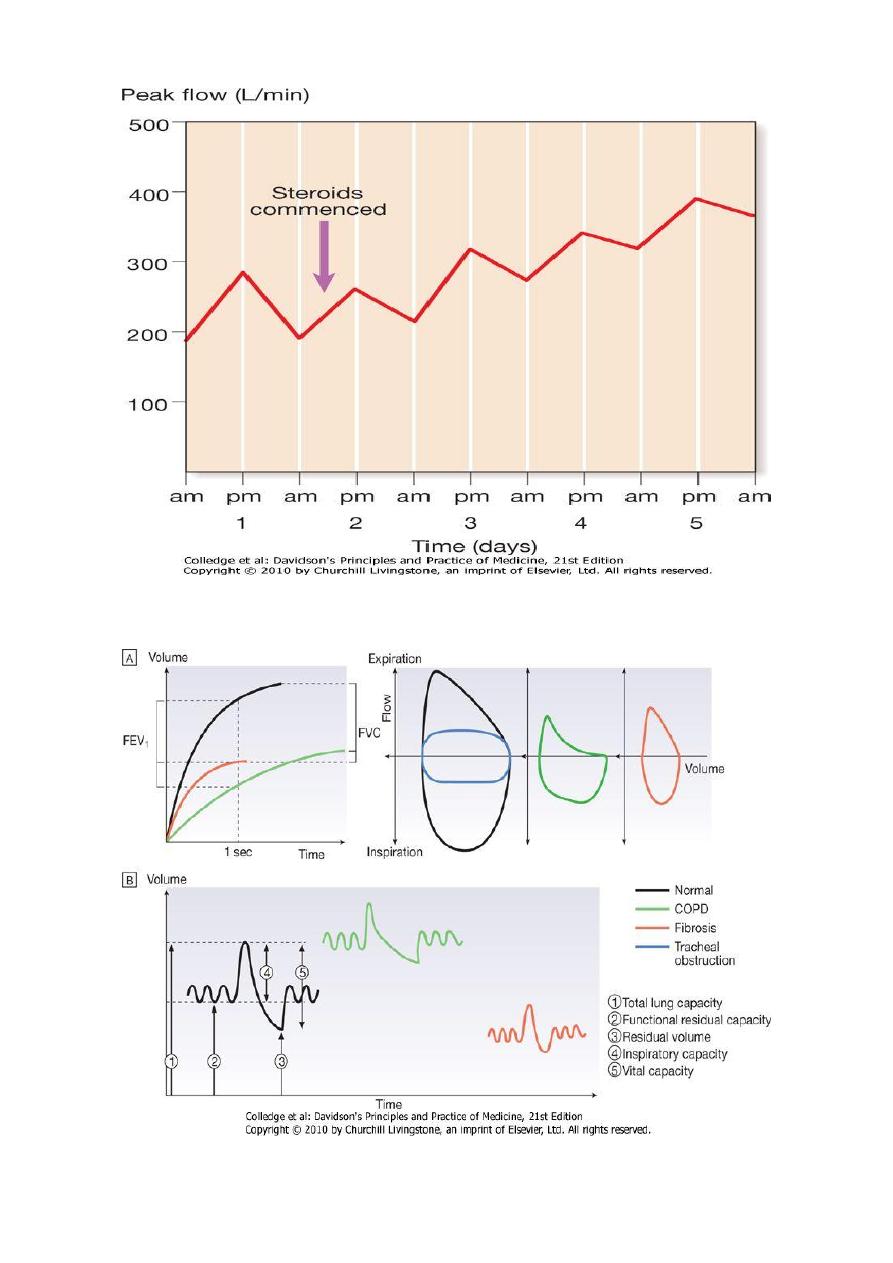

Asthma characteristically displays a diurnal pattern, with symptoms and lung function

being worse in the early morning.

Particularly when poorly controlled, symptoms such as cough and wheeze disturb

sleep and have led to the use of the term 'nocturnal asthma'.

Cough may be the dominant symptom in some patients, and the lack of wheeze or

breathlessness may lead to a delay in reaching the diagnosis of so-called 'cough-

variant asthma'.

Although the aetiology of asthma is often elusive, an attempt should be made to

identify any agents that may contribute to the appearance or aggravation of the

condition.

With regard to potential allergens, particular enquiry should be made into exposure

to a pet cat, guinea pig, rabbit or horse, pest infestation, or mould growth following

water damage to a home or building.

In some circumstances, the appearance of asthma is triggered by medications.

For example, β-adrenoceptor antagonists (β-blockers), even when administered

topically as eye drops, may induce bronchospasm, and aspirin and other non-

steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may also induce wheeze as above.

The classical aspirin-sensitive patient is female and presents in middle age with

asthma, rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps.

Aspirin-sensitive patients may also report symptoms following alcohol (in particular

white wine) and foods containing salicylates.

Other medications implicated include the oral contraceptive pill, cholinergic agents

and prostaglandin F2α.

Medicine Dr. Bilal

6

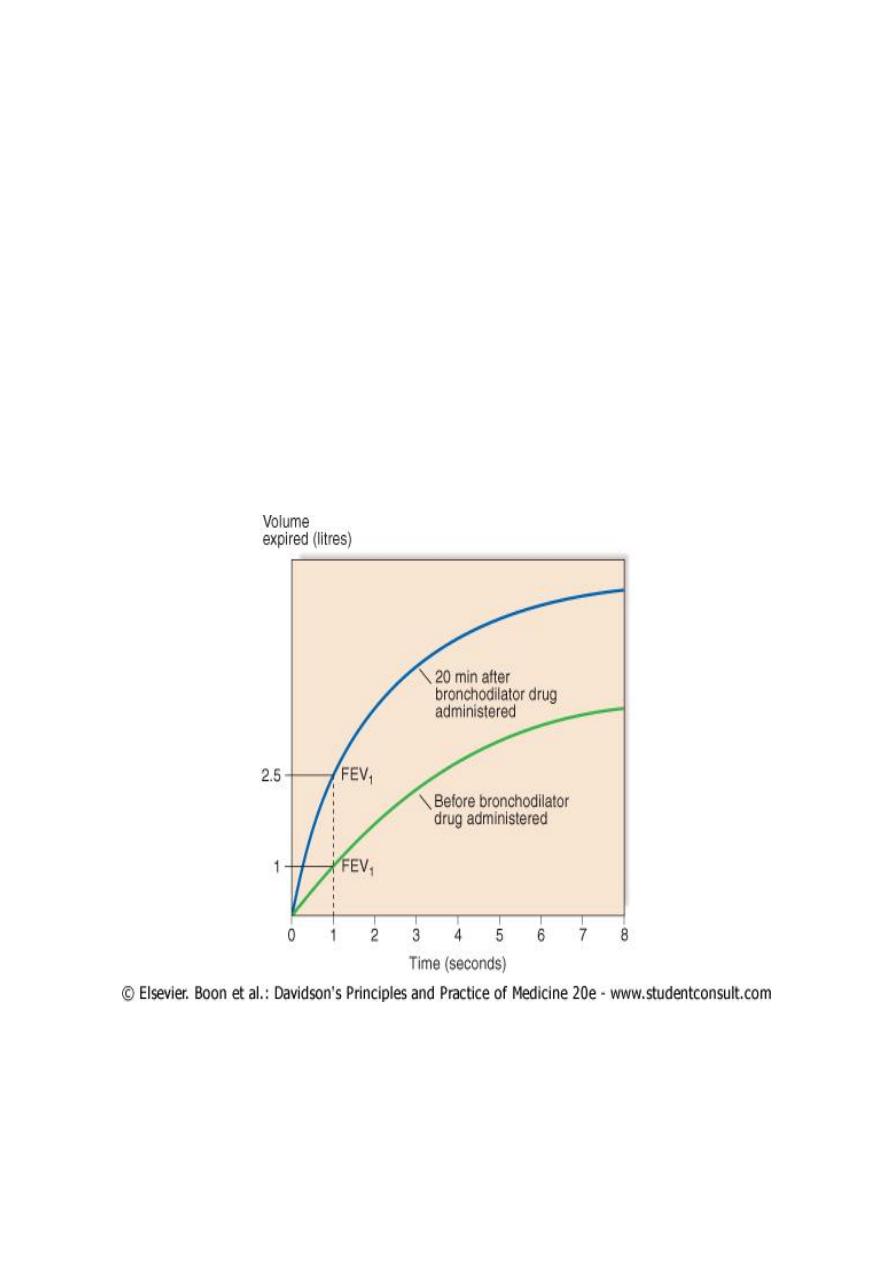

Investigations:

The diagnosis of asthma is made on the basis of a compatible clinical history

combined with the demonstration of variable airflow obstruction

Pulmonary function tests:

Peak flow meters are inexpensive and widely available, and provide a simple

and straightforward method of confirming the diagnosis.

Ideally patients should be instructed to record peak flow readings after rising in

the morning and before retiring in the evening.

A diurnal variation in PEF (the lowest values typically being recorded in the

morning) of more than 20% is considered diagnostic and the magnitude of

variability provides some indication of disease severity.

Medicine Dr. Bilal

7

Medicine Dr. Bilal

8

For patients whose symptoms are prominently related to exercise, an exercise

test may be followed by a drop in PEF or FEV1.

AHR is sensitive but non-specific; it therefore has a high negative predictive

value but positive results may be seen in other conditions such as COPD,

bronchiectasis and CF.

Challenge tests using adenosine may improve specificity. When symptoms are

predominantly related to exercise, an exercise challenge may be followed by a

drop in lung function

Making a diagnosis of asthma

Compatible clinical history plus either/or:

FEV1 ≥ 15% (and 200 ml) increase following administration of a

bronchodilator/trial of corticosteroids

> 20% diurnal variation on ≥ 3 days in a week for 2 weeks on PEF diary

FEV1 ≥ 15% decrease after 6 mins of exercise

Medicine Dr. Bilal

9

Radiological examination:

Radiological examination is generally unhelpful in establishing the diagnosis but

may point to alternative diagnoses.

Chest X-ray appearances are often normal or show hyperinflation of lung fields.

Lobar collapse may be seen if mucus occludes a large bronchus, and if

accompanied by the presence of flitting infiltrates, may suggest that asthma has

been complicated by allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis .

An HRCT scan may be useful to detect bronchiectasis.

Measurement of allergic status:

An elevated sputum or peripheral blood eosinophil count may be observed and

the serum total IgE is typically elevated in atopic asthma.

Skin prick tests are simple and provide a rapid assessment of atopy.

Assessment of eosinophilic airway inflammation. An induced sputum differential

eosinophil count of greater than 2% or exhaled breath nitric oxide concentration

(FE

NO

) may support the diagnosis but is non-specific.

Management

The goals of asthma management:

Achieve and maintain control of symptoms

Prevent asthma exacerbations

Maintain pulmonary function as close to normal as possible

Avoid adverse effects from asthma medications

Prevent development of irreversible airflow limitation

Prevent asthma mortality

Medicine Dr. Bilal

10

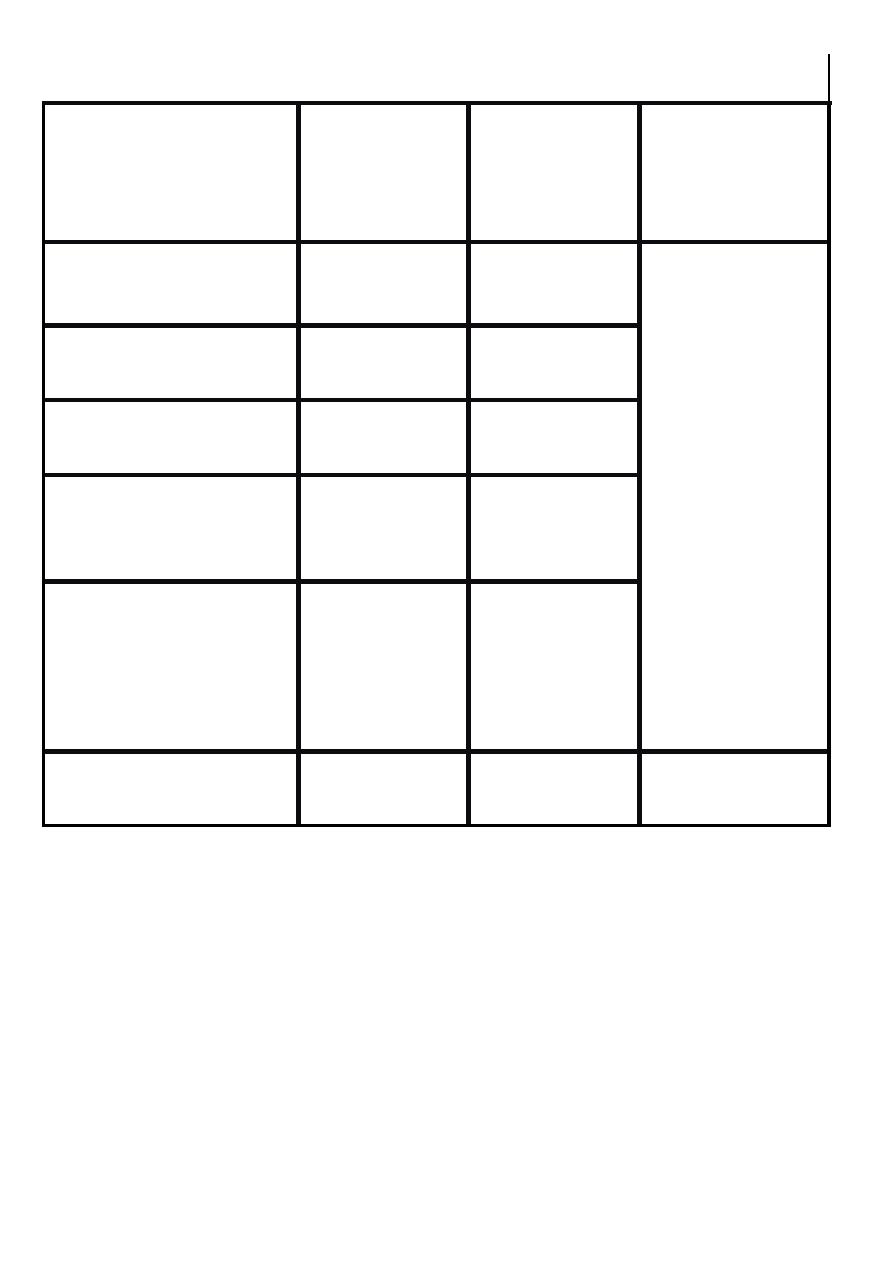

Levels of asthma control

Characteristic

Controlled

Partly

controlled

(any present

in any week)

Uncontrolled

Daytime symptoms

None (2 or

less/week)

More than

twice/week

3 or more

features of

partly

controlled

asthma present

in any week

Limitations of

activities

None

Any

Nocturnal

symptoms/awakening

None

Any

Need for

rescue/'reliever'

treatment

None (2 or

less/week)

More than

twice/week

Lung function (PEF or

FEV

1

)

Normal

< 80%

predicted or

personal best

(if known) on

any day

Exacerbation

None

One or

more/year

1 in any week

Patient education:

Whenever possible, patients should be encouraged to take responsibility for

managing their own disease.

Time should be taken to encourage an understanding of the nature of the

condition, the relationship between symptoms and inflammation, the

importance of key symptoms such as nocturnal waking, the different types of

medication, and, if appropriate, the use of PEF to guide management decisions.

A variety of tools/questionnaires have been validated to assist in assessing

asthma control. Written action plans may be helpful in developing self-

management skills.

Medicine Dr. Bilal

11

Avoidance of aggravating factors:

This is particularly important in the management of occupational asthma, but

may also be relevant to atopic patients where removing or reducing exposure to

relevant antigens, e.g. a pet animal, may effect improvement.

House dust mite exposure may be minimised by replacing carpets with

floorboards and using mite-impermeable bedding, although improvements in

asthma control following such measures have been difficult to demonstrate.

Many patients are sensitised to several ubiquitous aeroallergens, making

avoidance strategies largely impractical.

Smoking cessation is particularly important, as smoking not only encourages

sensitisation but also induces a relative corticosteroid resistance in the airway.

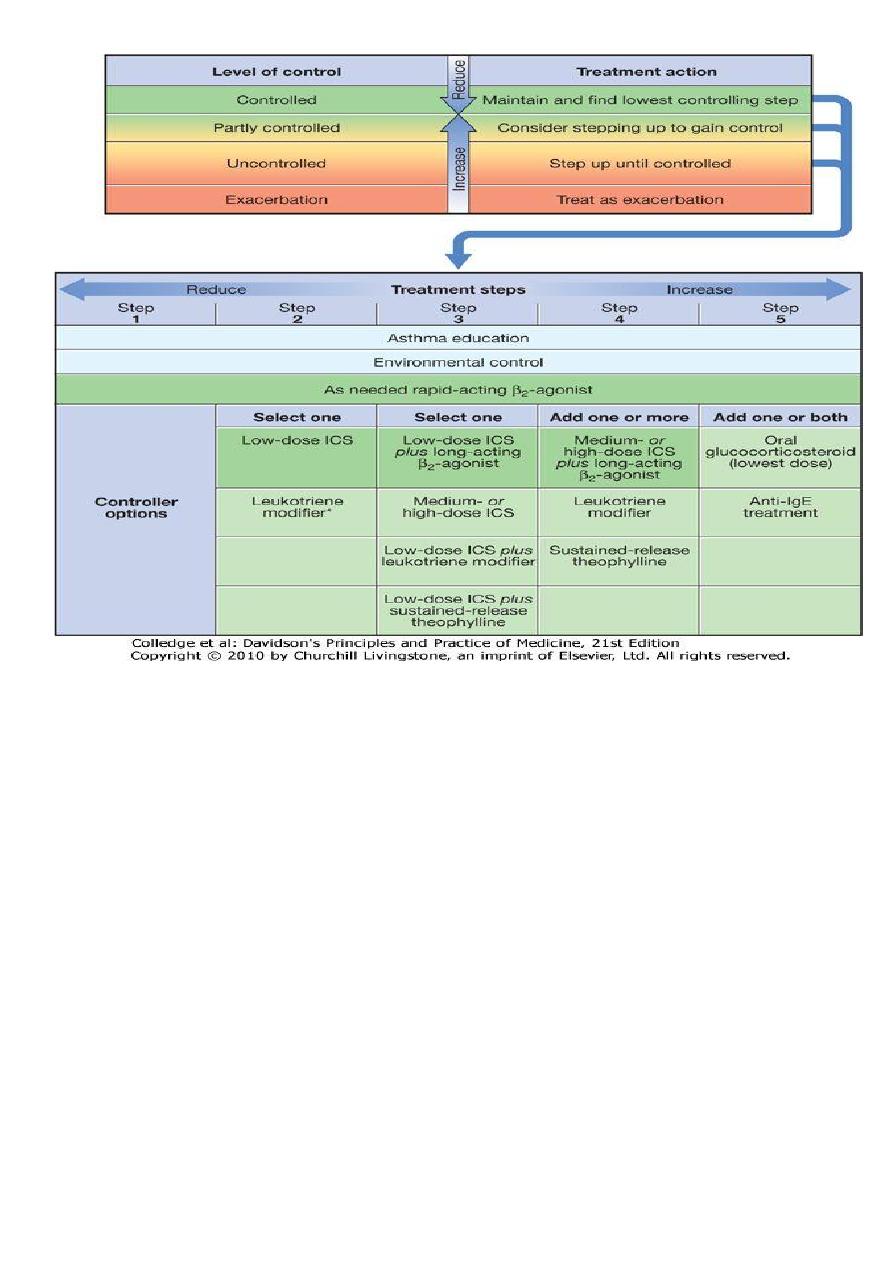

A stepwise approach to the management of asthma

Step 1: Occasional use of inhaled short-acting β2-adrenoreceptor agonist

bronchodilators

Step 2: Introduction of regular preventer therapy

Step 3: Add-on therapy

Step 4: Poor control on moderate dose of inhaled steroid and add-on therapy:

addition of a fourth drug

Step 5: Continuous or frequent use of oral steroids

Medicine Dr. Bilal

12

Step 1: Occasional use of inhaled short-acting β2-adrenoreceptor agonist

bronchodilators

For patients with mild intermittent asthma (symptoms less than once a week for

3 months and fewer than two nocturnal episodes/month), it is usually sufficient

to prescribe an inhaled short-acting β

2

-agonist (salbutamol or terbutaline), to be

used on an as-required basis.

Step 2: Introduction of regular 'preventer' therapy

Regular anti-inflammatory therapy (preferably inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) such

as beclometasone, budesonide, fluticasone or ciclesonide) should be started in

addition to inhaled β

2

-agonists taken on an as-required basis in any patient who:

has experienced an exacerbation of asthma in the last 2 years

uses inhaled β

2

-agonists three times a week or more

reports symptoms three times a week or more

is awakened by asthma one night per week.

Medicine Dr. Bilal

13

For adults, a reasonable starting dose is 400 μg beclometasone dipropionate

(BDP) or equivalent per day, although higher doses may be required in smokers.

Alternative but much less effective preventive agents include chromones,

leukotriene receptor antagonists, and theophyllines.

Step 3: Add-on therapy

If a patient remains poorly controlled despite regular use of ICS, a thorough

review should be undertaken focusing on adherence, inhaler technique and on-

going exposure to modifiable aggravating factors.

A further increase in the dose of ICS may benefit some patients, but in general,

add-on therapy should be considered in adults taking 800 μg/day BDP (or

equivalent).

Long-acting β

2

-agonists (LABAs), such as salmeterol and formoterol, with a

duration of action of at least 12 hours, represent the first choice of add-on

therapy.

They have consistently been demonstrated to improve asthma control and

reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations when compared to

increasing the dose of ICS alone.

Step 4: Poor control on moderate dose of inhaled steroid and add-on therapy:

addition of a fourth drug In adults, the dose of ICS may be increased to 2000 μg

BDP/budesonide (or equivalent) daily.

A nasal corticosteroid preparation should be used in patients with prominent

upper airway symptoms. Oral therapy with leukotriene receptor antagonists,

theophyllines or a slow-release β

2

-agonist may be considered. If the trial of add-

on therapy is ineffective, it should be discontinued.

Oral itraconazole should be contemplated in patients with allergic

bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA).

Step 5: Continuous or frequent use of oral steroids

At this stage prednisolone therapy (usually administered as a single daily dose in

the morning) should be prescribed in the lowest amount necessary to control

symptoms.

Medicine Dr. Bilal

14

Patients on long-term oral corticosteroids (> 3 months) or receiving more than

three or four courses per year will be at risk of systemic side-effects .

Osteoporosis can be prevented in this group of patients by using

bisphosphonates .

Steroid-sparing therapies such as methotrexate, ciclosporin or oral gold may be

considered. New therapies, such as omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody

directed against IgE, may prove helpful in atopic patients.

Step-down therapy: Once asthma control is established, the dose of inhaled (or

oral) corticosteroid should be titrated to the lowest dose at which effective

control of asthma is maintained.

Exacerbations of asthma

The course of asthma may be punctuated by exacerbations characterised by

increased symptoms, deterioration in lung function, and an increase in airway

inflammation.

Exacerbations are most commonly precipitated by viral infections, but moulds

(Alternaria and Cladosporium), pollens (particularly following thunderstorms)

and air pollution are also implicated.

Indications for 'rescue' courses include:

1. symptoms and PEF progressively worsening day by day

2. fall of PEF below 60% of the patient's personal best recording

3. onset or worsening of sleep disturbance by asthma

4. persistence of morning symptoms until midday

5. progressively diminishing response to an inhaled bronchodilator

6. symptoms severe enough to require treatment with nebulised or injected

bronchodilators

Medicine Dr. Bilal

15

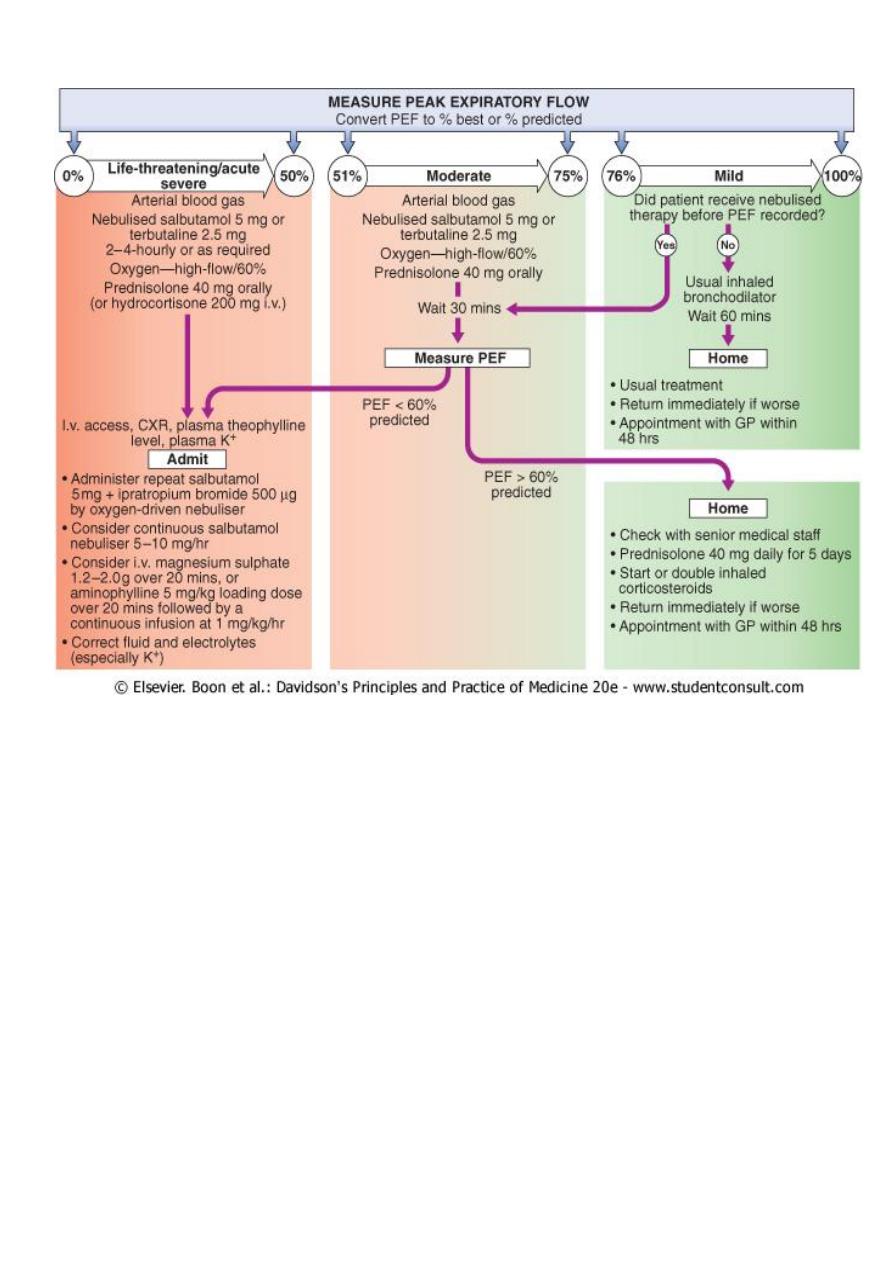

Immediate assessment of acute severe asthma

Acute severe asthma

1. PEF 33-50% predicted (< 200 l/min)

2. Respiratory rate ≥ 25/min

3. Heart rate ≥ 110/min

4. Inability to complete sentences in 1 breath

Life-threatening features

1. PEF 33-50% predicted (< 100 l/min)

2. SpO2 < 92% or PaO2 < 8 kPa (60 mmHg) (especially if being treated with oxygen)

3. Normal PaCO2

4. Silent chest

5. Cyanosis

6. Feeble respiratory effort

7. Bradycardia or arrhythmias

8. Hypotension

9. Exhaustion

10.

Confusion

11.

Coma

Near-fatal asthma

Raised PaCO2 and/or requiring mechanical ventilation with raised inflation

pressures

Indications for assisted ventilation in acute severe asthma

1. Coma

2. Respiratory arrest

3. Deterioration of arterial blood gas tensions despite optimal therapy

a. PaO2 < 8 kPa (60 mmHg) and falling

b. PaCO2 > 6 kPa (45 mmHg) and rising

c. pH low and falling (H+ high and rising)

4. Exhaustion, confusion, drowsiness

Medicine Dr. Bilal

16

Management of acute severe asthma:

1. Initial assessment:

2. Oxygen:

3. High doses of inhaled bronchodilators:

4. Systemic corticosteroids:

5. Intravenous fluids:

6. Subsequent management: If patients fail to improve, a number of further

options may be considered. Intravenous magnesium may provide

additional bronchodilation in patients whose presenting PEF is < 30%

predicted.

Medicine Dr. Bilal

17

Prognosis:

The outcome from acute severe asthma is generally good. Death from asthma is

fortunately rare but a considerable number of deaths occur in young people and

many are preventable.

Prior to discharge patients should be stable on discharge medication (nebulised

therapy should have been discontinued for at least 24 hours) and the PEF

should have reached 75% of predicted or personal best.

Asthma in pregnancy Unpredictable clinical course: one-third worsen, one-

third remain stable and one-third improve.

Labour and delivery: 90% have no symptoms.

Safety data: good for β

2

-agonists, inhaled steroids, theophyllines, oral

prednisolone, and chromones.

Oral leukotriene receptor antagonists: no evidence that these harm the fetus

and they should not be stopped in women who have previously demonstrated

significant improvement in asthma control prior to pregnancy.

Steroids: women on maintenance prednisolone > 7.5 mg/day should receive

hydrocortisone 100 mg 6-8-hourly during labour.

Prostaglandin F2α:

may induce bronchospasm and should be used with extreme caution.

Breastfeeding: use medications as normal.

Uncontrolled asthma represents the greatest danger to the fetus: Associated

with maternal (hyperemesis, hypertension, pre-eclampsia, vaginal

haemorrhage, complicated labour) and fetal (intrauterine growth restriction and

low birth weight, preterm birth, increased perinatal mortality, neonatal hypoxia)

complications.