•

Pneumonia is defined as an acute respiratory illness associated with recently

developed radiological pulmonary shadowing which may be segmental, lobar or

multilobar.

•

The context in which pneumonia develops is highly suggestive of the likely

organism(s) involved; therefore , pneumonias are usually classified as

•

community- or

•

hospital-acquired, or

•

those occurring in immunocompromised hosts.

•

'Lobar pneumonia‘:

•

is a radiological and pathological term referring to homogeneous consolidation

of one or more lung lobes, often with associated pleural inflammation;

•

bronchopneumonia :

•

refers to more patchy alveolar consolidation associated with bronchial and

bronchiolar inflammation often affecting both lower lobes.

Pneumonia

• Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)

• UK figures suggest that an estimated 5-11/1000 adults suffer from CAP each

year, accounting for around 5-12% of all lower respiratory tract infections.

• The incidence varies with age, being much higher in the very young and very

old, in whom the mortality rates are also much higher.

• World-wide, CAP continues to kill more children than any other illness.

• Most cases are spread by droplet infection and occur in previously healthy

individuals but several factors may impair the effectiveness of local defences

and predispose to CAP.

• Strep. pneumoniae remains the most common infecting agent, and thereafter,

the likelihood that other organisms may be involved depends on the age of the

patient and the clinical context.

• Viral infections are an important cause of CAP in children, and their

contribution to adult CAP is increasingly recognised.

• Factors that predispose to pneumonia

• Cigarette smoking

• Upper respiratory tract infections

• Alcohol

• Corticosteroid therapy

• Old age

• Recent influenza infection

• Pre-existing lung disease

• HIV

• Indoor air pollution

• Clinical features

• Pneumonia usually presents as an acute illness in which systemic features such

as fever, rigors, shivering and vomiting predominate.

• The appetite is usually lost and headache is common.

• Pulmonary symptoms include breathlessness and cough, which at first is

characteristically short, painful and dry, but later accompanied by the

expectoration of mucopurulent sputum.

• Rust-coloured sputum may be seen in patients with Strep. pneumoniae

infection, and the occasional patient may report haemoptysis.

• Pleuritic chest pain may be a presenting feature and on occasion may be

referred to the shoulder or anterior abdominal wall.

•

Upper abdominal tenderness is sometimes apparent in patients with lower lobe

pneumonia or if there is associated hepatitis.

•

Less typical presentations may be seen at the extremes of age. Clinical signs

reflect the nature of the inflammatory response.

•

Proteinaceous fluid and inflammatory cells congest the airspaces, leading to

consolidation of lung tissue (which takes on the appearance of liver on a cut

surface: phases of red, then grey hepatisation).

•

This improves the conductivity of sound to the chest wall and the clinician may

hear bronchial breathing and whispering pectoriloquy.

•

Crackles are often also detected.

•

Common clinical features of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)

•

Streptococcus pneumoniae

•

Most common cause. Affects all age groups, particularly young to middle-aged.

Characteristically rapid onset, high fever and pleuritic chest pain; may be

accompanied by herpes labialis and 'rusty' sputum.

Bacteraemia more common in women and those with diabetes or COPD

•

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

•

Children and young adults. Epidemics occur every 3-4 years, usually in autumn.

•

Rare complications include haemolytic anaemia, Stevens-Johnson syndrome,

erythema nodosum, myocarditis, pericarditis, meningoencephalitis, Guillain-

Barré syndrome

•

Legionella pneumophila

•

Middle to old age. Local epidemics around contaminated source, e.g. cooling

systems in hotels, hospitals. Person-to-person spread unusual.

•

Some features more common, e.g. headache, confusion, malaise, myalgia, high

fever and vomiting and diarrhoea.

Laboratory abnormalities include hyponatraemia, elevated liver enzymes,

hypoalbuminaemia and elevated creatine kinase.

Smoking, corticosteroids, diabetes, chronic kidney disease increase risk

•

Chlamydia pneumoniae

•

Young to middle-aged. Large-scale epidemics or sporadic; often mild, self-

limiting disease.

•

Headaches and a longer duration of symptoms before hospital admission.

Usually diagnosed on serology

•

Haemophilus influenzae

•

More common in old age and those with underlying lung disease (COPD,

bronchiectasis)

•

Staphylococcus aureus

•

Associated with debilitating illness and often preceded by influenza.

•

Radiographic features include multilobar shadowing, cavitation,

pneumatocoeles and abscesses.

•

Dissemination to other organs may cause osteomyelitis, endocarditis or brain

abscesses. Mortality up to 30%

•

Chlamydia psittaci

•

Consider in those in contact with birds, especially recently imported and

exotic.

•

Malaise, low-grade fever, protracted illness, hepatosplenomegaly and

occasionally headache with meningism

•

Coxiella burnetii (Q fever, 'querry' fever)

•

Consider in workers in dairy farms, abattoirs and hide factories (as amniotic

fluid and placenta carry high risk).

•

Risk of infection increases with age and male sex. Acute illness characterised

by severe headache, high fever, hepatitis, myalgia, conjunctivitis.

•

Chronic disease causes endocarditis, hepatomegaly

•

Klebsiella pneumoniae (Freidländer's bacillus)

•

More common in men, alcoholics, diabetics, elderly, hospitalised patients, and

those with poor dental hygiene.

•

Predilection for upper lobes and particularly liable to suppurate and form

abscesses. May progress to pulmonary gangrene

•

Actinomyces israelii

•

Mouth commensal. Cervicofacial, abdominal or pulmonary infection, empyema,

chest wall sinuses, pus with sulphur granules

•

Primary viral pneumonias

•

Influenza, parainfluenza, measles

•

May cause pneumonia commonly complicated by secondary bacterial infection

•

Herpes simplex

•

May cause tracheobronchitis or pneumonia in the immunosuppressed

•

Varicella

•

May cause severe pneumonia. Heals with small nodules that calcify and become

visible on chest X-ray

•

Adenovirus

•

Pneumonia reported in malnourished children and immunocompromised adults

•

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

•

Pneumonia may be a major problem in transplant recipients (particularly bone

marrow) and those with AIDS

•

Coronavirus (Urbani SARS-associated coronavirus)

•

SARS (severe acute respiratory distress syndrome) should be suspected if a high

fever (> 38°C), malaise, muscle aches, a dry cough and breathlessness follow

within 10 days of travel to an area affected by an epidemic

Investigations

•

The objectives are to:

1. exclude other conditions that mimic pneumonia,

2. assess the severity,

3. and identify the development of complications.

•

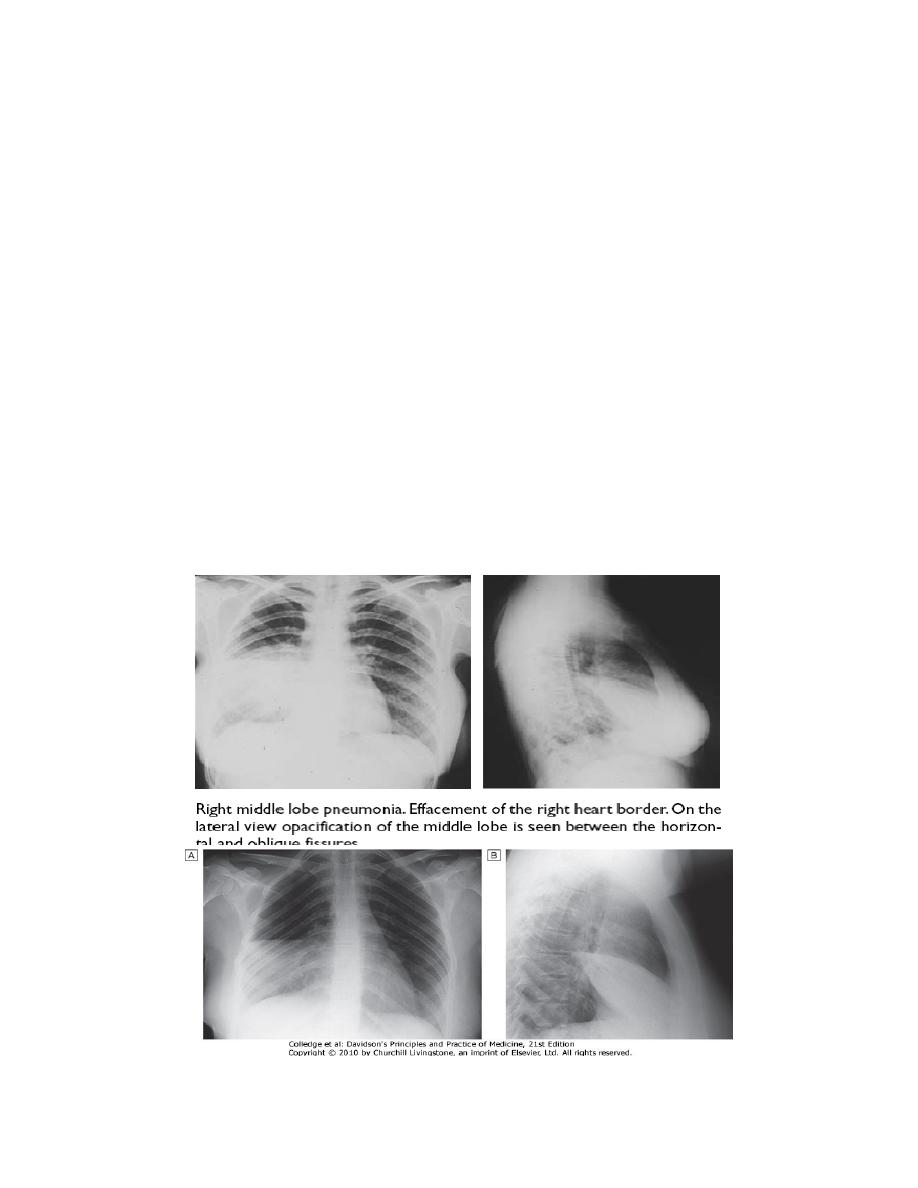

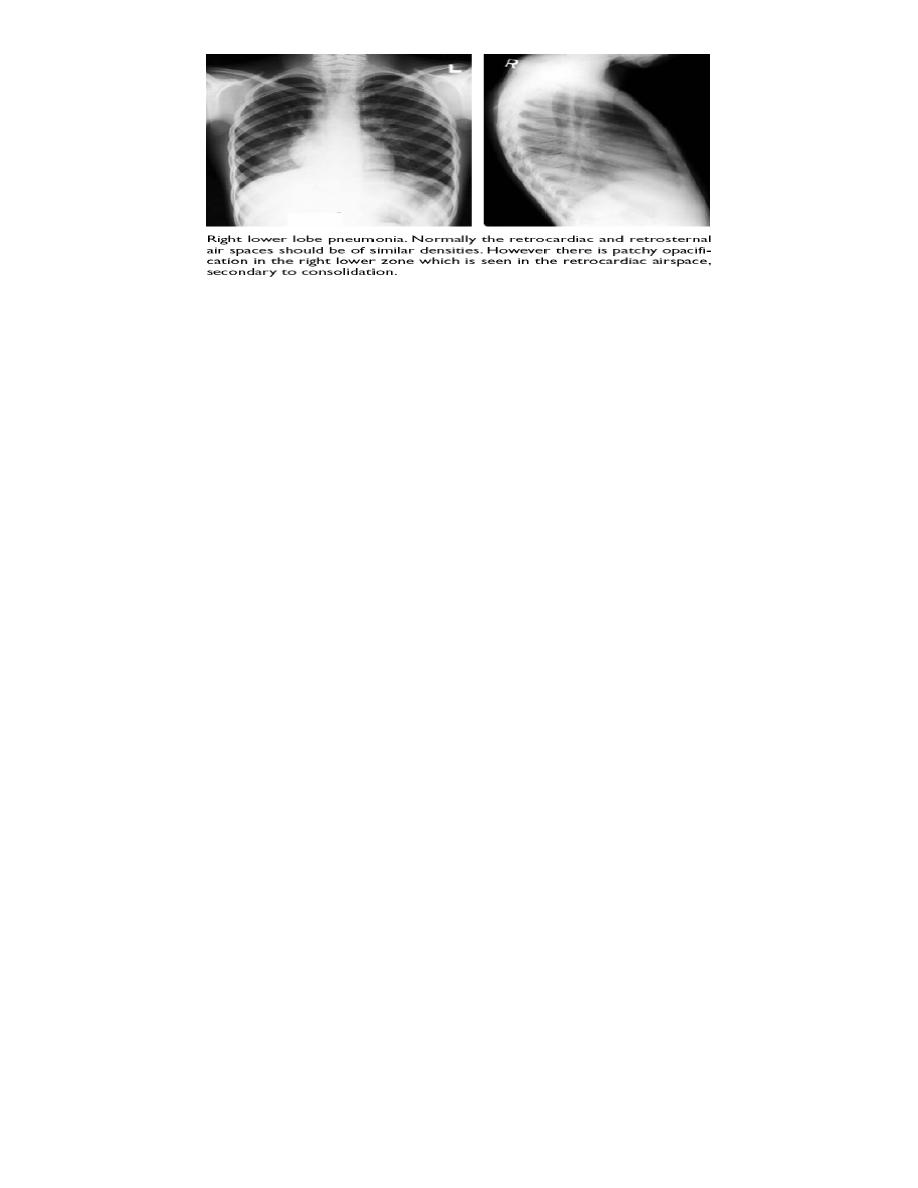

A chest X-ray usually provides confirmation of the diagnosis. In lobar

pneumonia, a homogeneous opacity localised to the affected lobe or segment

usually appears within 12-18 hours of the onset of the illness.

•

Radiological examination is helpful if a complication such as parapneumonic

effusion, intrapulmonary abscess formation or empyema is suspected.

•

Microbiological investigations in patients with CAP

All patients

•

Sputum: direct smear by Gram and Ziehl-Neelsen stains. Culture and

antimicrobial sensitivity testing

•

Blood culture: frequently positive in pneumococcal pneumonia

•

Serology: acute and convalescent titres for Mycoplasma, Chlamydia,

Legionella, and viral infections. Pneumococcal antigen detection in serum or

urine

•

PCR: Mycoplasma can be detected from swab of oropharynx

•

Severe community-acquired pneumonia

•

The above tests plus consider:

•

Tracheal aspirate, induced sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, protected brush

specimen or percutaneous needle aspiration. Direct fluorescent antibody stain

for Legionella and viruses

•

Serology: Legionella antigen in urine. Pneumococcal antigen in sputum and

blood. Immediate IgM for Mycoplasma

•

Cold agglutinins: positive in 50% of patients with Mycoplasma

Selected patients

•

Throat/nasopharyngeal swabs: helpful in children or during influenza epidemic

•

Pleural fluid: should always be sampled when present in more than trivial

amounts, preferably with ultrasound guidance

•

Differential diagnosis of pneumonia

•

Pulmonary infarction

•

Pulmonary/pleural TB

•

Pulmonary oedema (can be unilateral)

•

Pulmonary eosinophilia

•

Malignancy: bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma

•

Rare disorders: cryptogenic organising pneumonia/bronchiolitis obliterans

organising pneumonia (COP/BOOP)

•

Many cases of CAP can be managed successfully without identification of the

organism, particularly if there are no features indicating severe disease.

•

A full range of microbiological tests should be performed on patients with

severe CAP.

•

The identification of Legionella pneumophila has important public health

implications and requires notification.

•

In patients who do not respond to initial therapy, microbiological results may

allow its appropriate modification.

•

Microbiology also provides useful epidemiological information.

•

Pulse oximetry provides a non-invasive method of measuring arterial oxygen

saturation (SaO

2

) and monitoring response to oxygen therapy.

•

An arterial blood gas is important in those with SaO

2

< 93% or with features of

severe pneumonia, to identify ventilatory failure or acidosis.

•

The white cell count may be normal or only marginally raised in pneumonia

caused by atypical organisms, whereas a neutrophil leucocytosis of more than

15 × 10

9

/L favours a bacterial aetiology.

•

A very high (> 20 × 10

9

/l) or low (< 4 × 10

9

/l) white cell count may be seen in

severe pneumonia.

•

Urea and electrolytes and liver function tests should also be checked.

•

The C-reactive protein (CRP) is typically elevated.

•

Assessment of disease severity

•

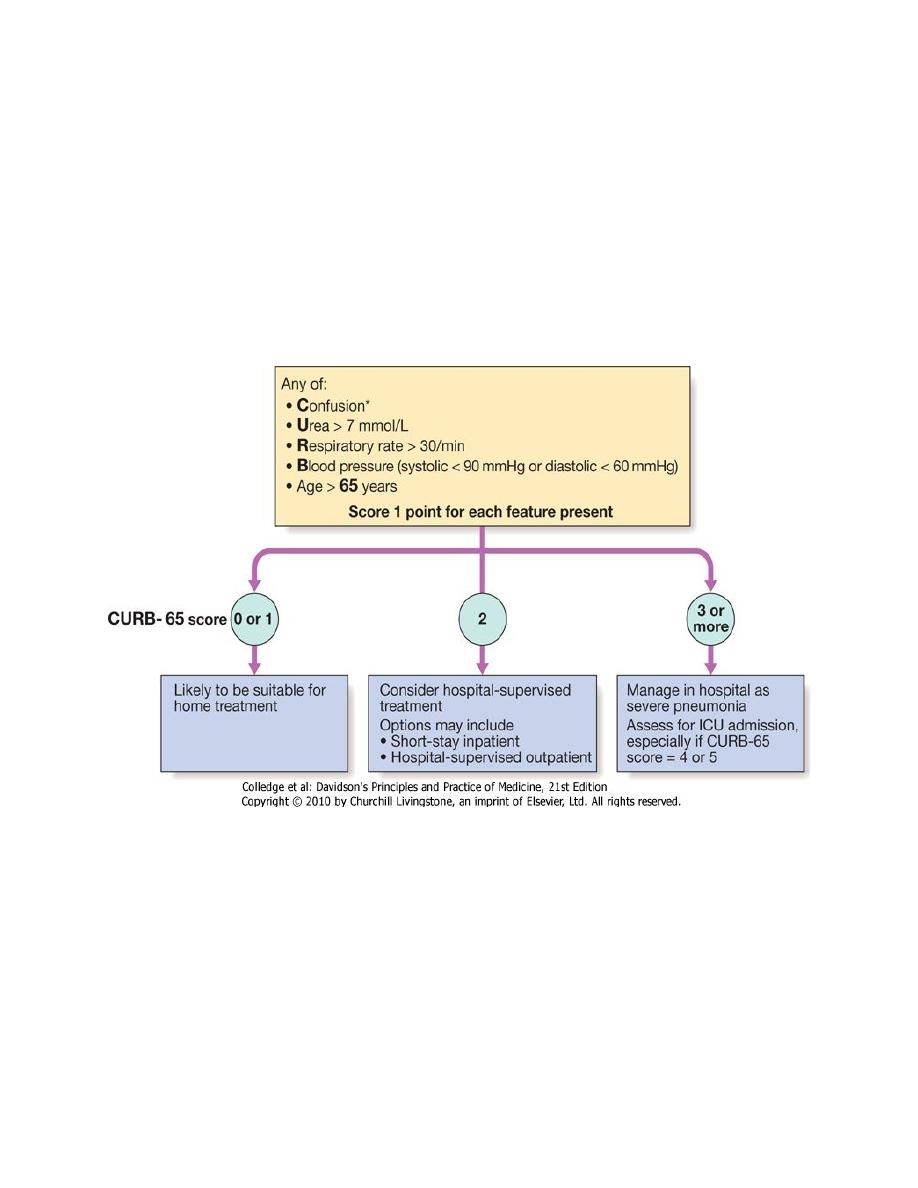

This is best assessed by an experienced clinician; however, the CURB-65 scoring

system helps guide antibiotic and admission policies, and gives useful

prognostic information.

•

Management

•

The most important aspects of management include oxygenation, fluid balance

and antibiotic therapy.

•

In severe or prolonged illness, nutritional support may be required.

•

Oxygen

•

Oxygen should be administered to all patients with tachypnoea, hypoxaemia,

hypotension or acidosis with the aim of maintaining the PaO

2

≥ 8 kPa (60

mmHg) or SaO

2

≥ 92%.

•

High concentrations (≥ 35%), preferably humidified, should be used in all

patients who do not have hypercapnia associated with COPD.

•

Assisted ventilation should be considered at an early stage in those who remain

hypoxaemic despite adequate oxygen therapy.

•

NIV may have a limited role but early recourse to mechanical ventilation is

often more appropriate .

•

Indications for referral to ITU

•

CURB score 4-5 failing to respond rapidly to initial management

•

Persisting hypoxia (PaO

2

< 8 kPa (60 mmHg)) despite high concentrations of

oxygen

•

Progressive hypercapnia

•

Severe acidosis

•

Circulatory shock

•

Reduced conscious level

•

Fluid balance

•

Intravenous fluids should be considered in those with severe illness, in older

patients and in those with vomiting.

•

Otherwise, an adequate oral intake of fluid should be encouraged.

•

Inotropic support may be required in patients with circulatory shock.

•

Antibiotic treatment

•

Prompt administration of antibiotics improves outcome.

•

The initial choice of antibiotic is guided by clinical context, severity

assessment, local knowledge of antibiotic resistance patterns, and at times

epidemiological information, e.g. during a mycoplasma epidemic.

•

In most patients with uncomplicated pneumonia a 7-10-day course is adequate,

although treatment is usually required for longer in patients with Legionella,

staphylococcal or Klebsiella pneumonia.

•

Oral antibiotics are usually adequate unless the patient has severe illness,

impaired consciousness, loss of swallowing reflex or malabsorption.

Treatment of pleural pain

•

It is important to relieve pleural pain, in order to allow the patient to breathe

normally and cough efficiently.

•

For the majority, simple analgesia with paracetamol, co-codamol or NSAIDs is

sufficient.

•

In some patients, opiates may be required but these must be used with

extreme caution in patients with poor respiratory function.

Antibiotic treatment for CAP*

•

Uncomplicated CAP

•

Amoxicillin 500 mg 8-hourly orally

•

If patient is allergic to penicillin

•

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly orally or

Erythromycin 500 mg 6-hourly orally

•

If Staphylococcus is cultured or suspected

•

Flucloxacillin 1-2 g 6-hourly i.v. plus

•

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly i.v.

•

If Mycoplasma or Legionella is suspected

•

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly orally or i.v. or

Erythromycin 500 mg 6-hourly orally or i.v. plus

•

Rifampicin 600 mg 12-hourly i.v. in severe cases

•

Severe CAP

•

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly i.v. or

Erythromycin 500 mg 6-hourly i.v. plus

•

Co-amoxiclav 1.2 g 8-hourly i.v. or

Ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily i.v. or

Cefuroxime 1.5 g 8-hourly i.v. or

Amoxicillin 1 g 6-hourly i.v. plus flucloxacillin 2 g 6-hourly i.v.

•

Complications of pneumonia

•

Para-pneumonic effusion-common

•

Empyema

•

Retention of sputum causing lobar collapse

•

DVT and pulmonary embolism

•

Pneumothorax, particularly with Staph. aureus

•

Suppurative pneumonia/lung abscess

•

ARDS, renal failure, multi-organ failure

•

Ectopic abscess formation (Staph. aureus)

•

Hepatitis, pericarditis, myocarditis, meningoencephalitis

•

Pyrexia due to drug hypersensitivity

•

Physiotherapy

•

Physiotherapy may be helpful to assist expectoration in patients who suppress

cough because of pleural pain or when mucus plugging leads to bronchial

collapse.

•

Prognosis

•

Most patients respond promptly to antibiotic therapy.

•

However, fever may persist for several days and the chest X-ray often takes

several weeks or even months to resolve, especially in old age.

•

Delayed recovery suggests either that a complication has occurred or that the

diagnosis is incorrect.

•

Alternatively, the pneumonia may be secondary to a proximal bronchial

obstruction or recurrent aspiration.

•

The mortality rate in adults managed at home is very low (< 1%); hospital death

rates are typically between 5 and 10%, but may be as high as 50% in severe

illness.

•

Discharge and follow-up

•

The decision to discharge a patient depends on home circumstances and the

likelihood of complications.

•

A chest X-ray need not be repeated before discharge in those making a

satisfactory clinical recovery.

•

Clinical review should be arranged around 6 weeks later and a chest X-ray

obtained if there are persistent symptoms, physical signs or reasons to suspect

underlying malignancy.

Prevention

•

The risk of further pneumonia is increased by smoking, so current smokers

should be advised to stop.

•

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be considered in selected

patients.

•

Because of the mode of spread, Legionella pneumophila has important public

health implications and usually requires notification to the appropriate health

authority.

•

In developing countries, tackling malnourishment and indoor air pollution, and

encouraging immunisation against measles, pertussis and Haemophilus

influenzae type b are particularly important in children