Pleural Diseases

PLEURISY

Pleurisy is not a diagnosis but a term used to describe pleuritic pain

resulting from any one of a number of disease processes involving

the pleura. Pleurisy is a common feature of pulmonary infection

and infarction; it may also occur in malignancy.

Clinical features

Sharp pain that is aggravated by deep breathing or coughing is

characteristic.

On examination, rib movement is restricted and a pleural rub may

be present. Sometimes this is only audible in deep inspiration or

near the pericardium (pleuro-pericardial rub).

The other clinical features depend on the cause

•Loss of a pleural rub and diminution in the chest pain may

indicate either recovery or the development of a pleural effusion.

•Management

•The primary cause of pleurisy must be treated

PLEURAL EFFUSION

The accumulation of serous fluid within the pleural space is termed

pleural effusion.Accumulations of frank pus (empyema) or blood

(haemothorax).

In general, pleural fluid accumulates as a result of either increased

hydrostatic pressure or decreased osmotic pressure ('transudative

effusion' as seen in cardiac, liver or renal failure), or from increased

microvascular pressure due to disease of the pleural surface itself,

or injury in the adjacent lung ('exudative effusion').

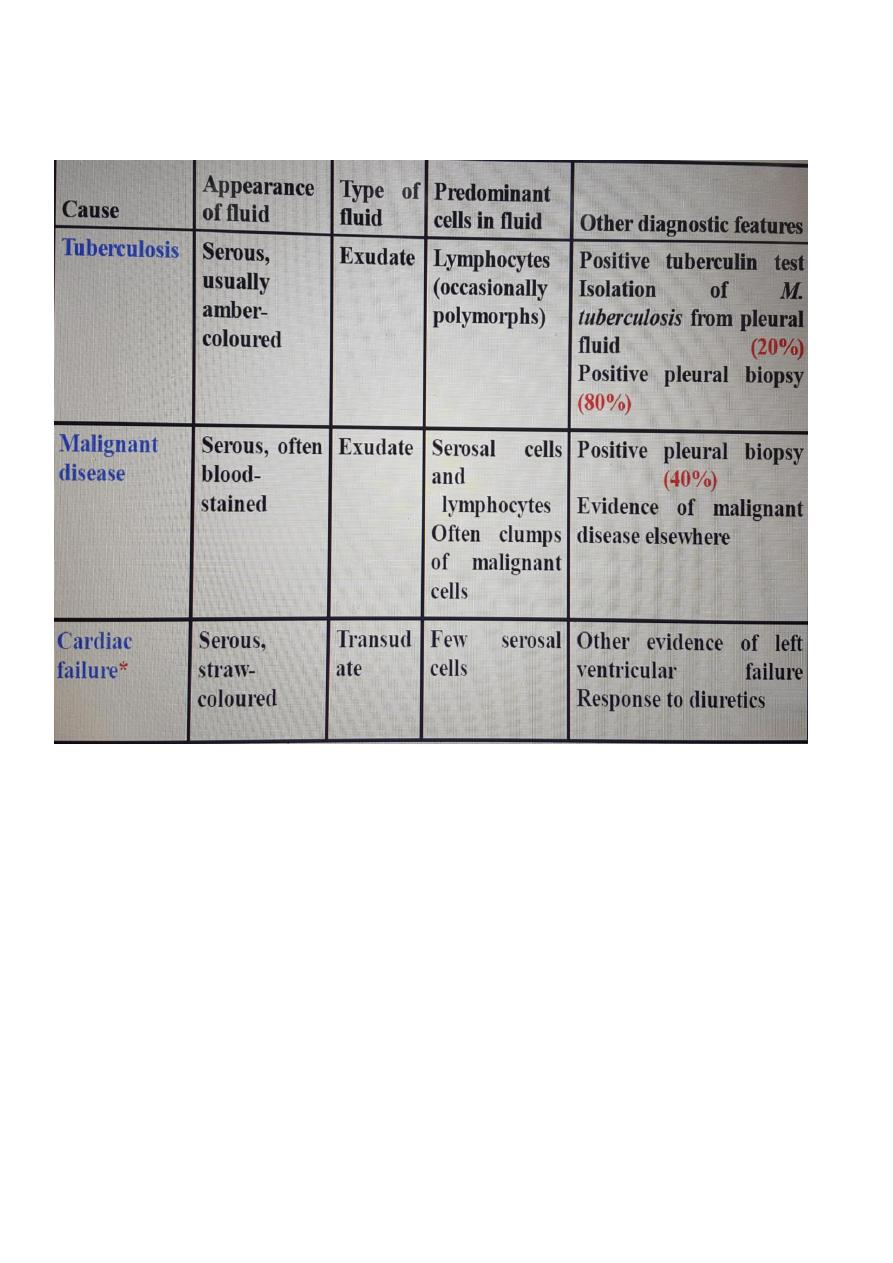

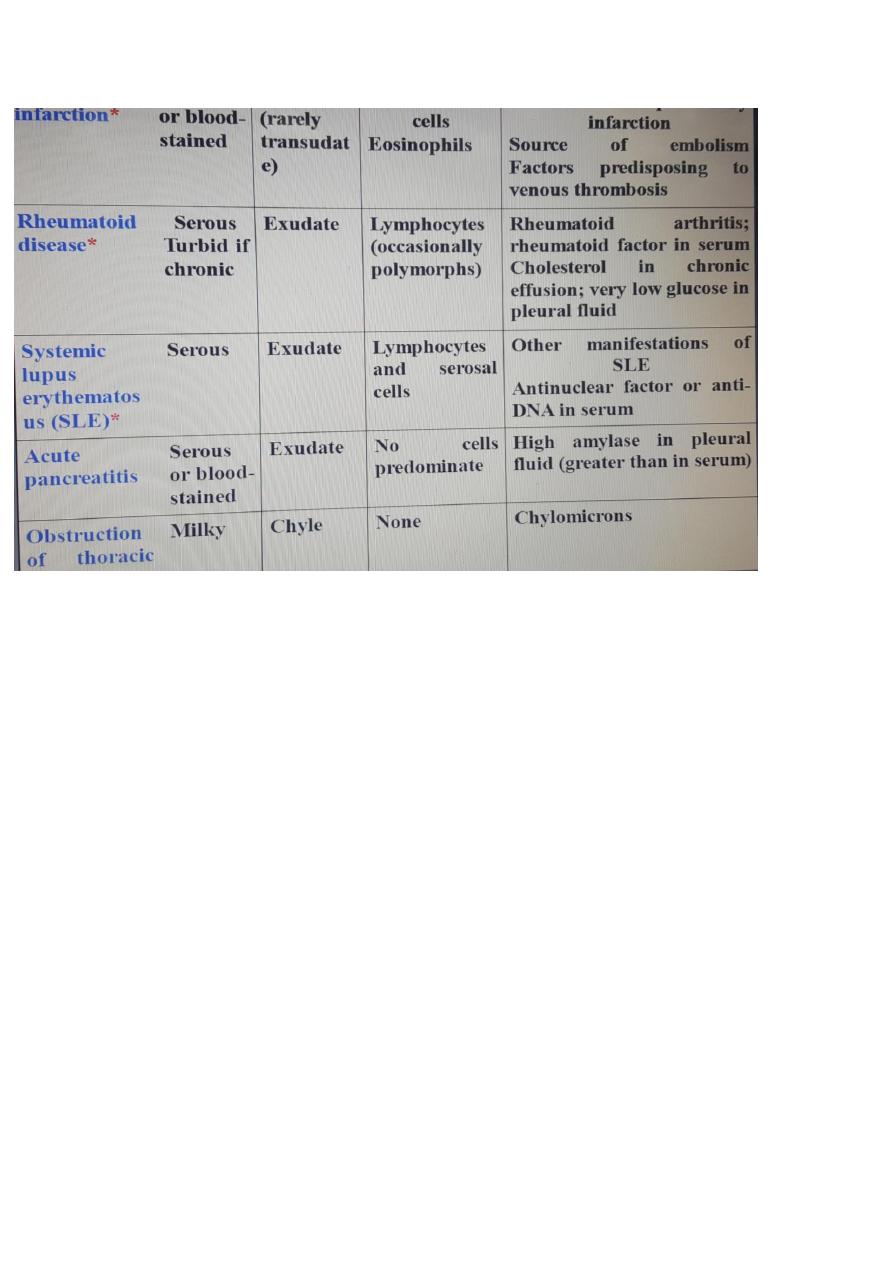

Causes of pleural effusion

Common causes

1.Pneumonia ('para-pneumonic effusion')

2.Tuberculosis

3.Pulmonary infarction

4.Malignant disease

5.Cardiac failure

6.Subdiaphragmatic disorders (subphrenic abscess, pancreatitis

etc.)

Uncommon

causes

1.Hypoproteinemia(nephrotic syndrom,liver failure,malnutrition)

2.Connective tissue diseases (particularly systemic lupus

erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis)

3.Acute rheumatic fever

4.Post-myocardial infarction syndrome

5.Meigs' syndrome (ovarian tumour plus pleural effusion)

6.Myxoedema

7.Uraemia

8.Asbestos-related benign pleural effusion

Clinical assessment:

Symptoms and signs of pleurisy often precede the development of

an effusion, especially in patients with underlying pneumonia,

pulmonary infarction or connective tissue disease. However, the

onset may be insidious. Breathlessness is the only symptom related

to the effusion and its severity depends on the size and rate of

accumulation.

Pleural effusion: main causes and features:

Investigations

Radiological investigations:

The classical appearance of pleural fluid on the erect PA chest film

is of a curved shadow at the lung base, blunting the costophrenic

angle and ascending towards the

axilla.

Fluid appears to track up the lateral chest wall.Around 200 ml of

fluid is required to be detectable on a PA chest X-ray, but smaller

effusions can be identified by ultrasound or CT

scanning.

Previous scarring or adhesions in the pleural space can cause

localised effusions.

•Pleural fluid localised below the lower lobe ('subpulmonary

effusion') simulates an elevated

hemidiaphragm.

•Fluid localised within an oblique fissure may produce a rounded

opacity simulating a tumour.

Ultrasonography:

CT scanning:displays pleural abnormalities more readily than

either plain radiography or ultrasound, and may distinguish

benign from malignant pleural disease.

Pleural aspiration and biopsy:Pleural fluid is an exudate if one or

more of the following criteria are met:

1.Pleural fluid protein:serum protein ratio >

0.5

2.Pleural fluid LDH: serum LDH ratio > 0.6 3.Pleural fluid LDH >

two

3.Pleural fluid LDH > two-thirds of the upper limit of normal serum

LDH

Management:

Therapeutic aspiration may be required to palliate breathlessness

but removing more than 1.5 litres in one episode is inadvisable as

there is a small risk of re-expansion pulmonary oedema.An effusion

should never be drained to dryness before establishing a diagnosis

as further biopsy may be precluded until further fluid

accumulates.

Treatment of the underlying cause-

for example, heart failure,

pneumonia, pulmonary embolism or subphrenic abscess-will often

be followed by resolution of the effusion.

EMPYEMA

This term describes the presence of pus in the pleural space.The pus

may be as thin as serous fluid or so thick that it is impossible to

aspirate even through a wide-bore needle. Microscopically,

neutrophil leucocytes are present in large numbers.The causative

organism may or may not be isolated from the pus.

An empyema may involve the whole pleural space or only part of it

('loculated' or 'encysted' empyema) and is almost invariably

unilateral

Aetiology:

Empyema is always secondary to infection in a neighbouring

structure, usually the lung. The principal infections liable to

produce empyema are the bacterial pneumonias and

TB.

Over 40% of patients with community-acquired pneumonia

develop an associated pleural effusion ('para-pneumonic' effusion)

and about 15% of these become secondarily

infected.

Other causes are infection of a haemothorax and rupture of a

subphrenic abscess through the diaphragm.

Pathology :

Both layers of pleura are covered with a thick, shaggy inflammatory

exudate.The pus in the pleural space is often under considerable

pressure and if the condition is not adequately treated pus may

rupture into a bronchus causing a bronchopleural fistula and

pyopneumothorax, or track through the chest wall with the

formation of a subcutaneous abscess or

sinus.

The only way in which an empyema can heal is by eradication of the

infection, obliteration of the empyema space and apposition of the

visceral and parietal pleural layers.

This cannot occur unless re-expansion of the compressed lung is

secured at an early stage by removal of all the pus from the pleural

space.

This cannot take place if:

1-the visceral pleura becomes grossly thickened and rigid due to

delayed treatment.

2-inadequate drainage of the infected pleural

fluid

3-the pleural layers are kept apart by air entering the pleura

through a bronchopleural

fistula

4-there is underlying disease in the lung, such as bronchiectasis,

bronchial carcinoma or pulmonary TB preventing re-expansion.In

all these circumstances an empyema tends to become chronic, and

healing is unlikely without surgical intervention.

Clinical features:

An empyema should be suspected in patients with pulmonary

infection if there is persistence or recurrence of pyrexia despite the

administration of a suitable antibiotic. Once an empyema has

developed, two separate groups of clinical features are

found.

1-

Systemic

features

Pyrexia, usually high and remittent Rigors, sweating, malaise and

weight loss Polymorphonuclear leucocytosis, high CRP

2-Local

features

Pleural pain; breathlessness; cough and sputum usually because of

underlying lung disease; copious purulent sputum if empyema

ruptures into a bronchus (bronchopleural fistula) Clinical signs of

fluid in the pleural space

Investigations

Radiological examinationThe appearances are often

indistinguishable from those of pleural effusion.

Ultrasoundshows the position of the fluid, the extent of pleural

thickening and whether fluid is in a single collection or

multiloculated by fibrin and debris. In addition to showing the

pleura,

CT canbe useful in assessing the underlying lung parenchyma and

patency of the major bronchi.

Aspiration of pusThis confirms the presence of an empyema.The

pus is frequently sterile when antibiotics have already been given;

the distinction between tuberculous and non-tuberculous disease

can be difficult and often requires pleural histology and culture.

Management

Treatment of non-tuberculous

empyema

When the patient is acutely ill and the pus is thin an intercostal

tube should be inserted under ultrasound or CT guidance into the

most dependent part of the empyema space and connected to a

water-seal drain system. If the initial aspirate reveals turbid fluid or

frank pus, or if loculations are seen on ultrasound, the tube should

be put on suction (5-10 cm H2O) and flushed regularly with 20 ml

normal saline.

Finally, an antibiotic directed against the organism causing the

empyema should be given for 2-4 weeks.

An empyema can often be aborted if these measures are started

early. If, however, the intercostal tube is not providing adequate

drainage, which can happen when the pus is thick or loculated,

surgical intervention is required. The empyema cavity is cleared of

pus and adhesions, and a wide-bore tube inserted to allow optimal

drainage. Surgical 'decortication' of the lung may also be required if

gross thickening of the visceral pleura has developed and is

preventing re-expansion of the lung.

•Treatment of tuberculous

empyema

•Antituberculosis chemotherapy must be started immediately and

the pus in the pleural space aspirated through a wide-bore needle

until it ceases to

reaccumulate.

•Intercostal tube drainage is often required. In many patients no

other treatment is necessary but surgery is occasionally required to

ablate a residual empyema space.

PNEUMOTHORAX

Classification of pneumothorax:

1-

Spontaneous

PrimaryWithout evidence of overt lung disease. Air escapes from

the lung into the pleural space through rupture of a small

subpleural emphysematous bulla or pleural bleb, or the pulmonary

end of a pleural adhesion It principally affects males aged 15-30 in

whom smoking, tall stature.

SecondaryUnderlying lung disease, most commonly COPD and TB;

also seen in asthma, lung abscess, pulmonary infarcts,

bronchogenic carcinoma, all forms of fibrotic and cystic lung

diseaseis most common in older patients, and is associated with the

highest mortality rates.

2-TraumaticIatrogenic (e.g. following thoracic surgery or biopsy) or

non-iatrogenic.

Clinical features:

The commonest symptoms are sudden-onset unilateral pleuritic

chest pain or breathlessness. In those with underlying chest disease,

breathlessness can be severe and may not resolve spontaneously. In

patients with a small pneumothorax the physical examination may

be normal.

A larger pneumothorax (> 15% of the hemithorax) results in

decreased or absent breath sounds .

The combination of absent breath sounds and resonant percussion

note is diagnostic of pneumothorax.

If the communication between the airway and the pleura is small, it

can act as a one-way valve allowing air to enter the pleural space

during inspiration but not to escape on expiration.

Large amounts of trapped air accumulate in the pleural space and

the intrapleural pressure may rise to well above atmospheric levels

(a so-called 'tension' pneumothorax).

The pressure causes mediastinal displacement towards the opposite

side, with compression of the opposite normal lung and

impairment of systemic venous return, causing cardiovascular

compromise .

Clinically, the findings are rapidly progressive breathlessness

associated with a marked tachycardia, hypotension, cyanosis and

tracheal displacement away from the side of the silent

hemithorax.

Occasionally, 'tension' pneumothorax may occur without

mediastinal shift if malignant disease or scarring has splinted the

mediastinum. Where the communication between the lung and

pleural space seals off as the lung deflates and does not reopen, the

pneumothorax is referred to as 'closed' .

In such circumstances the mean pleural pressure remains negative,

spontaneous reabsorption of air and re-expansion of the lung occur

over a few days or weeks, and infection is

uncommon.

This contrasts with an 'open' pneumothorax, where the

communication fails to seal and air continues to transfer freely

between the lung and pleural space . An example of the latter is a

bronchopleural fistula which, if large, can also facilitate the

transmission of infection from the air passages into the pleural

space, leading to

empyema.

An open pneumothorax is commonly seen following rupture of an

emphysematous bulla, tuberculous cavity or lung abscess into the

pleural space.

Investigations

The chest X-ray shows the sharply defined edge of the deflated lung

with complete translucency (no lung markings) between this and

the chest wall . Care must be taken to differentiate between a large

pre-existing emphysematous bulla and a pneumothorax to avoid

misdirected attempts at aspiration. Where doubt

exists,CTis useful in distinguishing bullae from pleural air.

X-rays also show the extent of any mediastinal displacement and

give information regarding the presence or absence of pleural fluid

and underlying pulmonary disease.

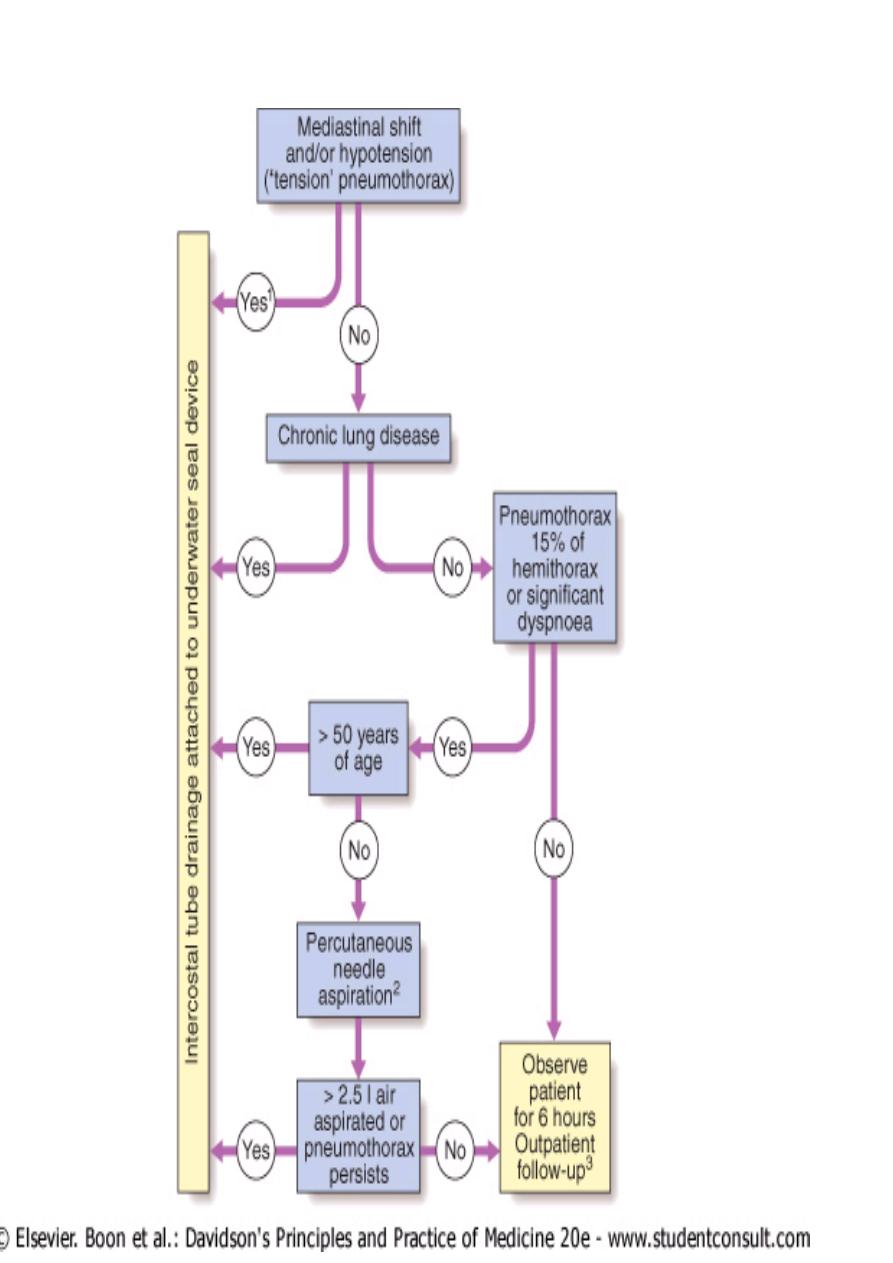

Management

Primary pneumothorax where the lung edge is less than 2 cm from

the chest wall and the patient is not breathless normally resolves

without intervention. In young patients presenting with a

moderate or large spontaneous primary pneumothorax,

percutaneous needle aspiration of air is a simple and well-tolerated

alternative to intercostal tube drainage, with a 60-80% chance of

avoiding the need for a chest drain .

In patients with underlying chronic lung disease, however, even a

small secondary pneumothorax may cause respiratory failure;

hence all such patients require intercostal tube drainage and

inpatient observation.

When needed, intercostal drains should be inserted in the 4th, 5th

or 6th intercostal space in the mid-axillary line following blunt

dissection through to the parietal

pleura.

The tube should be advanced in an apical direction, connected to

an underwater seal or one-way Heimlich valve, and secured firmly

to the chest wall.

Clamping of the drain is potentially dangerous and never

indicated.

The drain should be removed 24 hours after the lung has fully

reinflated and bubbling stopped.

Continued bubbling after 5-7 days is an indication for

surgery.

If bubbling in the underwater bottle stops prior to full reinflation,

the tube is either blocked, kinked or

displaced.

All patients should receive supplemental oxygen as this accelerates

the rate at which air is reabsorbed by the

pleura.

Patients with a closed pneumothorax should not fly as the trapped

gas expands at

altitude.

After complete resolution, there is no clear evidence on how long

patients should avoid flying, although guidelines suggest that a

wait of 1-2 weeks, with confirmation of full inflation prior to flight, is

prudent.

Patients should also be advised to stop smoking and be informed

about the risks of a recurrent

pneumothorax.

Recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax:

After primary

spontaneous pneumothorax, recurrence occurs within a year of

either aspiration or tube drainage in approximately 25% of

patients, and should prompt definitive treatment.

Surgical pleurodesis is recommended in all patients following

a

(1)second pneumothorax (even if

ipsilateral).

(2)first episode of secondary pneumothorax if low respiratory

reserve makes recurrence hazardous.

(3)Patients who plan to continue activities where pneumothorax

would be particularly dangerous (e.g. flying or diving) should also

undergo definitive treatment after the first episode of a primary

spontaneous pneumothorax.

Pleurodesis can be achieved by pleural abrasion or parietal

pleurectomy at thoracotomy or thoracoscopy.