Tuberculosis (TB), which is one of the oldest diseases known to affect humans ,is a major cause

of death worldwide. This disease is caused by bacteria of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis

complex and usually affects the lungs, although other organs are involved in up to one-third

of cases. If properly treated, TB caused by drug-susceptible strains is curable in virtually all

cases. If untreated, the disease may be fatal within 5 years in 50–65% of cases. Transmission

usually takes place through the airborne spread of droplet nuclei produced by patients with

infectious pulmonary TB.

Epidemiology:

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), which is part

of a complex of organisms including M. bovis (reservoir cattle) and M. africanum (reservoir

human). M. tuberculosis is a rod-shaped, nonspore-forming, thin aerobic bacterium.

Mycobacteria, including M. tuberculosis, are often neutral on Gram's staining. However, once

stained, the bacilli cannot be decolorized by acid alcohol; this characteristic justifies their

classification as acid-fast bacilli. The impact of TB on world health is significant; in 2006, there

were an estimated 9.2 million new cases, 14.4 million prevalent cases and 1.5 million deaths

attributable to TB. Furthermore, it is estimated that around one-third of the world's

population has latent TB. The majority of cases occur in the world's poorest nations, who

struggle to cover the costs associated with management and control programmes. (WHO) in

2009; 95% of cases were reported from developing countries. The resurgence of TB has been

largely driven in Africa by HIV disease, and in the former Soviet Union and Baltic states by lack

of appropriate health care exacerbated by social and political upheaval. the risk of acquiring

M. tuberculosis infection is determined mainly by exogenous factors. Because of delays in

seeking care and in making a diagnosis, it is generally believed that, in high-prevalence

settings, up to 20 contacts may be infected by each AFB-positive case before the index case

is found to have TB.

Reasons for the increasing incidence of TB

• Developed countries

1. Immigration from high-prevalence areas

2. Human immunodeficiency virus( HIV)

3. Social deprivation(homelessness' poverty)

4. Increasing proportion of elderly

5. Drug resistance

• Developing countries

1. Ineffective control programmes

2. Lack of access to health care

3. Poverty, civil unrest

4. HIV

5. Population increase

6. Drug resistance

Factors increasing the risk of TB

1-Patient-related

1. Age (children > young adults < elderly)

2. First-generation immigrants from high-prevalence countries

3. Close contacts of patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB

4. Overcrowding (prisons, collective dormitories); homelessness (doss houses and hostels)

5. Chest radiographic evidence of self-healed TB

6. Primary infection < 1 year previously

7. Smoking: cigarettes

2-Associated diseases

1. Immunosuppression: HIV, anti-TNF therapy, high-dose corticosteroids, cytotoxic agents.

2. Malignancy (especially lymphoma and leukaemia)

3. Type 1 diabetes mellitus

4. Chronic renal failure

5. Silicosis

6. Gastrointestinal disease associated with malnutrition (gastrectomy, jejuno-ileal bypass,

cancer of the pancreas, malabsorption)

7. Deficiency of vitamin D or A

8. Recent measles: increases risk of child contracting TB

Pathology and pathogenesis :

M. bovis infection arises from drinking non-sterilised milk from infected cows. M. tuberculosis

is spread by the inhalation of aerosolised droplet nuclei from other infected patients. Once

inhaled, the organisms lodge in the alveoli and initiate the recruitment of macrophages and

lymphocytes. Macrophages undergo transformation into epithelioid and Langhans cells which

aggregate with the lymphocytes to form the classical tuberculous granuloma. Numerous

granulomas aggregate to form a primary lesion or 'Ghon focus' (a pale yellow, caseous

nodule, usually a few mm to 1-2 cm in diameter), which is characteristically situated in the

periphery of the lung. Spread of organisms to the hilar lymph nodes is followed by a similar

pathological reaction; the combination of a primary lesion and regional lymph nodes is

referred to as the 'primary complex of Ranke'. Reparative processes encase the primary

complex in a fibrous capsule limiting the spread of bacilli: so-called latent TB. If no further

complications ensue, this lesion eventually calcifies and is clearly seen on a chest X-ray.

However, lymphatic or haematogenous spread may occur before immunity is established,

seeding secondary foci in other organs including lymph nodes, serous membranes, meninges,

bones, liver, kidneys and lungs, which may lie dormant for years. The only clue that infection

has occurred may be the appearance of a cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity

reaction to tuberculin, demonstrated by tuberculin skin testing. If these reparative processes

fail, primary progressive disease ensues. The estimated lifetime risk of developing disease

after primary infection is 10%, with roughly half of this risk occurring in the first 2 years after

infection.

Clinical features:

pulmonary disease:Primary TB refers to the infection of a previously uninfected

(tuberculin-negative) individual. A few patients develop a self-limiting febrile illness but clinical

disease only occurs if there is a hypersensitivity reaction or progressive infection . Progressive

primary disease may appear during the course of the initial illness or after a latent period of

weeks or months

• Clinical presentations of pulmonary TB

1. Chronic cough, often with haemoptysis

2. Pyrexia of unknown origin

3. Unresolved pneumonia

4. Exudative pleural effusion

5. Asymptomatic (diagnosis on chest X-ray)

6. Weight loss, general debility

7. Spontaneous pneumothorax

Post-primary pulmonary TB :Post-primary disease refers to exogenous ('new' infection) or

endogenous (reactivation of a dormant primary lesion) infection in a person who has been

sensitised by earlier exposure. It is most frequently pulmonary and characteristically occurs in

the apex of an upper lobe where the oxygen tension favours survival of the strictly aerobic

organism. The onset is usually insidious, developing slowly over several weeks. Systemic

symptoms include fever, night sweats, malaise, and loss of appetite and weight, and are

accompanied by progressive pulmonary symptoms . Very occasionally, this form of TB may

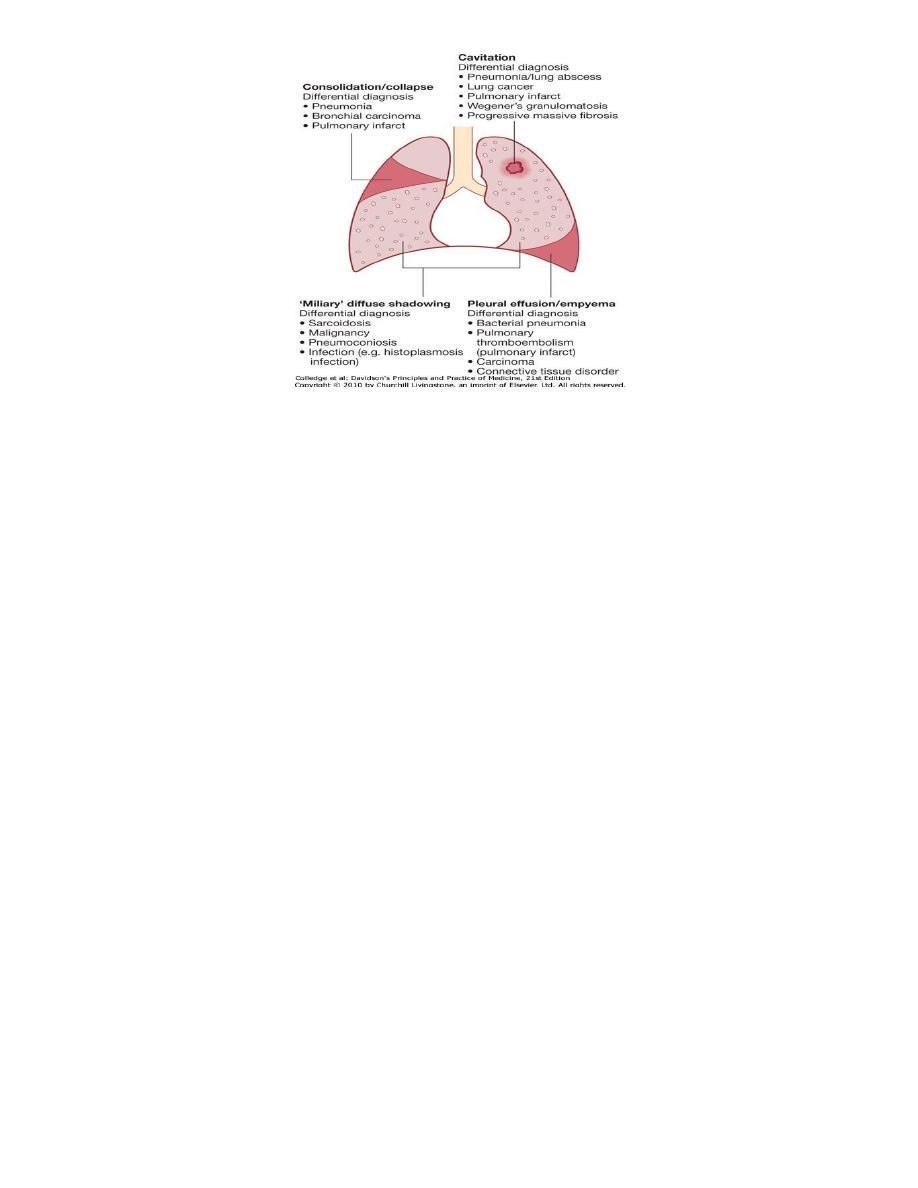

present with one of the complications . Radiological changes include ill-defined opacification

in one or both of the upper lobes, and as progression occurs, consolidation, collapse and

cavitation develop to varying degrees . It is often difficult to distinguish active from quiescent

disease on radiological criteria alone, but the presence of a miliary pattern or cavitation

favours active disease. In extensive disease, collapse may be marked and result in significant

displacement of the trachea and mediastinum. Occasionally, a caseous lymph node may drain

into an adjoining bronchus resulting in tuberculous pneumonia.

• Chest X-ray: major manifestations and differential diagnosis of pulmonary TB.

• Features of primary TB

• Infection (4-8 weeks)

1. Influenza-like illness

2. Skin test conversion

3. Primary complex

• Disease

1. Lymphadenopathy: hilar (often unilateral), paratracheal or mediastinal

2. Collapse (especially right middle lobe)

3. Consolidation (especially right middle lobe)

4. Obstructive emphysema

5. Cavitation (rare)

6. Pleural effusion

7. Endobronchial

8. Miliary

9. Meningitis

10. Pericarditis

• Hypersensitivity

1. Erythema nodosum

2. Phlyctenular conjunctivitis

3. Dactylitis

Cryptic TB

1. Age over 60 years

2. Intermittent low-grade pyrexia of unknown origin

3. Unexplained weight loss, general debility (hepatosplenomegaly in 25-50%)

4. Normal chest X-ray

5. Blood dyscrasias; leukaemoid reaction, pancytopenia

6. Negative tuberculin skin test

7. Confirmation by biopsy (granulomas and/or acid-fast bacilli demonstrated) of liver or

bone marrow

Miliary TB: Blood-borne dissemination gives rise to miliary TB, which may present acutely but

more frequently is characterised by 2-3 weeks of fever, night sweats, anorexia, weight loss and

a dry cough. Hepatosplenomegaly may develop and the presence of a headache may indicate

coexistent tuberculous meningitis. Auscultation of the chest is frequently normal, although

with more advanced disease widespread crackles are evident.Fundoscopy may show choroidal

tubercles. The classical appearances on chest X-ray are of fine 1-2 mm lesions ('millet seed')

distributed throughout the lung fields, although occasionally the appearances are coarser.

Anaemia and leucopenia reflect bone marrow involvement. 'Cryptic' miliary TB is an unusual

presentation sometimes seen in old age.

Clinicalfeatures:

extrapulmonary disease

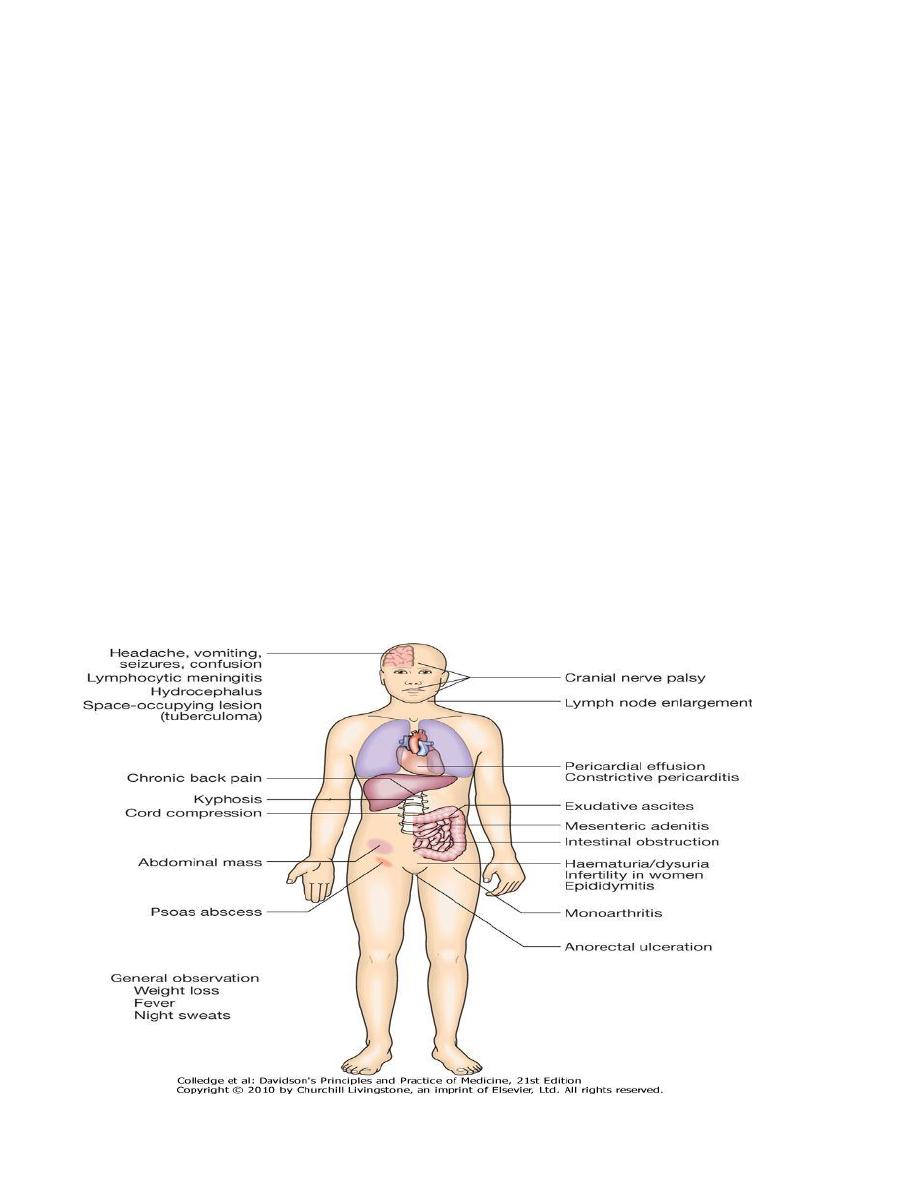

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis accounts for about 20% of cases in those who are HIV-negative

but is more prevalent in HIV-positive individuals. In order of frequency, the extrapulmonary

sites most commonly involved in TB are the lymph nodes, pleura, genitourinary tract, bones

and joints, meninges, peritoneum, and pericardium. However, virtually all organ systems may

be affected.

Systemic presentations of extrapulmonary TB.

Lymphadenitis:

Lymph nodes are the most common extrapulmonary site of disease. Cervical and mediastinal

glands are affected most frequently, followed by axillary and inguinal; more than one region

may be involved. Disease may represent primary infection, spread from contiguous sites or

reactivation. Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy is often the result of spread from mediastinal

disease. The nodes are usually painless and initially mobile but become matted together with

time. When caseation and liquefaction occur, the swelling becomes fluctuant and may

discharge through the skin with the formation of a 'collar-stud' abscess and sinus formation.

Approximately half of cases fail to show any constitutional features such as fevers or night

sweats. The tuberculin test is usually strongly positive. During or after treatment, paradoxical

enlargement, development of new nodes and suppuration may all occur but without evidence

of continued infection; rarely, surgical excision is necessary. In non-immigrant children in the

UK, most mycobacterial lymphadenitis is caused by opportunistic mycobacteria, especially of

the M. avium complex.

Gastrointestinal disease:

making up 3.5% of extrapulmonary cases in the United States.TB can affect any part of the

bowel and patients may present with a wide range of symptoms and signs . Upper

gastrointestinal tract involvement is rare and is usually an unexpected histological finding in an

endoscopic or laparotomy specimen. Ileocaecal disease accounts for approximately half of

abdominal TB cases. Fever, night sweats, anorexia and weight loss are usually prominent and a

right iliac fossa mass may be palpable. Up to 30% of cases present with an acute abdomen.

Ultrasound or CT may reveal thickened bowel wall, abdominal lymphadenopathy, mesenteric

thickening or ascites. Barium enema and small bowel enema reveal narrowing, shortening and

distortion of the bowel with caecal involvement predominating. Diagnosis rests on obtaining

histology by either colonoscopy or mini-laparotomy. The main differential diagnosis is Crohn's

disease . Tuberculous peritonitis is characterised by abdominal distension, pain and

constitutional symptoms. The ascitic fluid is exudative and cellular with a predominance of

lymphocytes. Laparoscopy reveals multiple white 'tubercles' over the peritoneal and omental

surfaces. Low-grade hepatic dysfunction is common in miliary disease when biopsy reveals

granulomas. Occasionally, patients may be frankly icteric with a mixed hepatic/cholestatic

picture.

Pericardial disease:

Disease occurs in two forms: pericardial effusion and constrictive pericarditis . Fever and

night sweats are rarely prominent and the presentation is usually insidious with breathlessness

and abdominal swelling. Coexistent pulmonary disease is very rare, with the exception of

pleural effusion. Pulsus paradoxus, a raised JVP, hepatomegaly, prominent ascites and

peripheral oedema are common to both types. Pericardial effusion is associated with

increased pericardial dullness and a globular enlarged heart on chest X-ray. Constriction is

associated with a raised JVP, an early third heart sound and, occasionally, atrial fibrillation;

pericardial calcification occurs in around 25% of cases. Diagnosis is on clinical, radiological and

echocardiographic grounds. The effusion is frequently blood-stained. Open pericardial biopsy

can be performed where there is diagnostic uncertainty. The addition of corticosteroids to

antituberculosis treatment has been shown to be beneficial for both forms of pericardial

disease.

Central nervous system disease:

Meningeal disease represents the most important form of central nervous system TB.

Unrecognised and untreated, it is rapidly fatal. Even when appropriate treatment is

prescribed, mortality rates of 30% have been reported and survivors may be left with

neurological sequelae documented in 25% of treated cases.Since meningeal involvement is

pronounced at the base of the brain, paresis of cranial nerves (ocular nerves in particular) is a

frequent finding. The ultimate evolution is toward coma, with hydrocephalus and intracranial

hypertension. AFB are seen on direct smear of CSF sediment in up to one-third of cases, but

repeated lumbar punctures increase the yield. Culture of CSF is diagnostic in up to 80% of

cases and remains the gold standard. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has a sensitivity of up to

80%

Bone and joint disease:

The spine is the most common site for bony TB (Pott's disease), which usually presents with

chronic back pain and typically involves the lower thoracic and lumbar spine . The infection

starts as a discitis and then spreads along the spinal ligaments to involve the adjacent anterior

vertebral bodies, causing angulation of the vertebrae with subsequent kyphosis. Paravertebral

and psoas abscess formation is common and the disease may present with a large (cold)

abscess in the inguinal region. CT and/or MRI are valuable in gauging the extent of disease, the

amount of cord compression, and the site for needle biopsy or open exploration if required.

The major differential diagnosis is malignancy, which tends to affect the vertebral body and

leave the disc intact. Important complications include spinal instability or cord compression.

TB can affect any joint, but most frequently involves the hip or knee. Presentation is usually

insidious with pain and swelling; fever and night sweats are uncommon. Radiological changes

are often non-specific, but as disease progresses, reduction in joint space and erosions appear.

Genitourinary disease:

Fever and night sweats are rare with renal tract TB and patients are often only mildly

symptomatic for many years. Haematuria, frequency and dysuria are often present, with

sterile pyuria found on urine microscopy and culture. In women, infertility from endometritis,

or pelvic pain and swelling from salpingitis or a tubo-ovarian abscess occur occasionally. In

men, genitourinary TB may present as epididymitis or prostatitis.

• Chronic complications of pulmonary TB

• Pulmonary

1. Massive haemoptysis

2. Cor pulmonale

3. Fibrosis/emphysema

4. Atypical mycobacterial infection

5. Aspergilloma

6. Lung/pleural calcification

7. Obstructive airways disease

8. Bronchiectasis

9. Bronchopleural fistula

• Non-pulmonary

1. Empyema necessitans

2. Laryngitis

3. Enteritis*

4. Anorectal disease*

5. Amyloidosis

6.

Poncet's polyarthritis

Diagnosis:

Specimens required

Pulmonary

Sputum (induced with nebulised hypertonic saline if not expectorating) At least 2 but

preferably 3, including an early morning sample.

Bronchoscopy with washings or BAL

Gastric washing* (mainly used for children)

Extrapulmonary

Fluid examination (cerebrospinal, ascitic, pleural, pericardial, joint): yield classically very

low

Tissue biopsy (from affected site); also bone marrow/liver may be diagnostic in patients

with disseminated disease

Diagnostic tests

Circumstantial (ESR, CRP, anaemia etc.)

Tuberculin skin test (low sensitivity/specificity; useful only in primary or deep-seated

infection)

Stain

Ziehl-Neelsen

Auramine fluorescence

Nucleic acid amplification(These systems permit the diagnosis of TB in as little as several

hours, with high specificity and sensitivity approaching that of culture.)

Culture

Solid media (Löwenstein-Jensen, Middlebrook)

Liquid media (e.g. BACTEC or MGIT = mycobacteria growth indicator tube)

Response to empirical antituberculous drugs

(usually seen after 5-10 days)

Determinations of ADA and IFN-gamma levels in pleural fluid may be useful as adjunct tests in

the diagnosis of pleural TB; the utility of these tests in the diagnosis of other forms of

extrapulmonary TB (e.g., pericardial, peritoneal, and meningeal) is less clear. IGRAs are more

specific than the TST as a result of less cross-reactivity due to BCG vaccination and

sensitization by nontuberculous mycobacteria. The presence of an otherwise unexplained

cough for more than 2-3 weeks, particularly in an area where TB is highly prevalent, or typical

chest X-ray changes should prompt further investigation .

Direct microscopy of sputum is the most important first step. The probability of detecting acid-

fast bacilli is proportional to the bacillary burden in the sputum (typically positive when 5000-

10 000 organisms are present). By virtue of their substantial lipid-rich wall, tuberculous bacilli

are difficult to stain. The most effective techniques are the Ziehl-Neelsen and rhodamine-

auramine stains. A positive smear is sufficient for the presumptive diagnosis of TB but

definitive diagnosis requires culture. Smear-negative sputum should also be cultured, as only

10-100 viable organisms are required for sputum to be culture-positive. A diagnosis of smear-

negative TB may be made in advance of culture if the chest X-ray appearances are typical of TB

and there is no response to a broad-spectrum antibiotic. MTB grows slowly and may take

between 4 and 6 weeks to appear on solid medium such as Löwenstein-Jensen or

Middlebrook. Faster growth (1-3 weeks) occurs in liquid media such as the radioactive BACTEC

system or the non-radiometric mycobacteria growth indicator tube (MGIT). The BACTEC

method is commonly used in developed nations and detects mycobacterial growth by

measuring the liberation of

14

CO

2

, following metabolism of

14

C-labelled substrate present in

the medium. New strategies for the rapid confirmation of TB at low cost are being developed;

these include the nucleic acid amplification test (NAT), designed to amplify nucleic acid regions

specific to MTB,and has the potential to provide a simple, non-invasive test which does not

require a laboratory or highly skilled personnel. The diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB can be

more challenging. There are generally fewer organisms (particularly in meningeal or pleural

fluid), so culture or histopathological examination of tissue is more important. In the presence

of HIV, however, examination of sputum may still be useful, as subclinical pulmonary disease is

common.

Management:

Chemotherapy:

A variety of highly effective short-course regimens are available; choice depends on local

health resources and infrastructure . They are based on the principle of an initial intensive

phase (which rapidly reduces the bacterial population), followed by a continuation phase to

destroy any remaining bacteria. Treatment should be commenced immediately in any patient

who is smear-positive, or who is smear-negative but with typical chest X-ray changes and no

response to standard antibiotics. Quadruple therapy has become standard in the UK,

although ethambutol may be omitted under certain circumstances. Fixed-dose tablets

combining two or three drugs are generally favoured: for example, Rifater (rifampicin,

isoniazid and pyrazinamide) daily for 2 months, followed by 4 months of Rifinah (rifampicin

and isoniazid). Streptomycin is rarely used in the UK, but is an important component of short-

course treatment regimens in developing nations. Six months of therapy is appropriate for all

patients with new-onset, uncomplicated pulmonary disease. However, 9-12 months of

therapy should be considered if the patient is HIV-positive, or if drug intolerance occurs and

a second-line agent is substituted. Meningitis should be treated for a minimum of 12 months.

Pyridoxine should be prescribed in pregnant women and malnourished patients to reduce the

risk of peripheral neuropathy with isoniazid. Where drug resistance is not anticipated, patients

can be assumed to be non-infectious after 2 weeks of appropriate therapy.Most patients can

be treated at home. Admission to a hospital unit with appropriate isolation facilities should be

considered where:

1-there is uncertainty about the diagnosis,

2-intolerance of medication,

3-questionable compliance,

4-adverse social conditions or

5-a significant risk of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB: culture-positive after 2 months on

treatment, or contact with known MDR-TB).

In choosing a suitable drug regimen, underlying comorbidity (renal and hepatic dysfunction,

eye disease, peripheral neuropathy and HIV status), as well as the potential for drug

interactions, must be considered .Baseline liver function and regular monitoring are important

for patients treated with standard therapy including rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide,

as all of these agents are potentially hepatotoxic. Mild asymptomatic increases in

transaminases are common but serious liver damage is rare. Patients treated with rifampicin

should be advised that their urine, tears and other secretions will develop a bright orange/red

coloration, and women taking the oral contraceptive pill must be warned that its efficacy will

be reduced and alternative contraception may be necessary. Ethambutol should be used with

caution in patients with renal failure, with appropriate dose reduction and monitoring of drug

levels. Adverse drug reactions occur in about 10% of patients, but are significantly more

common in the presence of HIV co-infection .

Corticosteroids reduce inflammation and limit tissue damage, and are currently recommended

when:

1. treating pericardial or

2. meningeal disease,

3. in children with endobronchial disease.

4. They may confer benefit in TB of the ureter and fallopian tube,

5. pleural effusions

6. extensive pulmonary disease,

7.

can suppress

hypersensitivity drug reactions.

Surgery is still occasionally required (e.g. for massive haemoptysis, loculated empyema,

constrictive pericarditis, lymph node suppuration, spinal disease with cord compression), but

usually only after a full course of antituberculosis treatment. The effectiveness of therapy for

pulmonary TB may be judged by a further sputum smear at 2 months and at 5 months. A

positive sputum smear at 5 months defines treatment failure. Extrapulmonary TB must be

assessed clinically or radiographically as appropriate.

Control and prevention :The WHO is committed to reducing the incidence of TB by 2015.

Important components of this goal include supporting the development of laboratory and

health-care services to improve detection and treatment of active and latent TB.Detection of

latent TB Contact tracing is a legal requirement in many countries. It has the potential to

identify the probable index case, other cases infected by the same index patient (with or

without evidence of disease), and close contacts who should receive BCG vaccination or

chemotherapy. Approximately 10-20% of close contacts of patients with smear-positive

pulmonary TB and 2-5% of those with smear-negative, culture-positive disease have

evidence of TB infection. Cases are commonly identified using the tuberculin skin test . An

otherwise asymptomatic contact with a positive tuberculin skin test but a normal chest X-ray

may be treated with chemoprophylaxis to prevent infection progressing to clinical disease.

Chemoprophylaxis is also recommended for: children aged less than 16 years identified

during contact tracing to have a strongly positive tuberculin test, children aged less than 2

years in close contact with smear-positive pulmonary disease, those in whom recent

tuberculin conversion has been confirmed, and babies of mothers with pulmonary TB.

It should also be considered for HIV-infected close contacts of a patient with smear-positive

disease. Rifampicin plus isoniazid for 3 months or isoniazid for 6 months is effective.

Skin testing in TB:tests using purified protein derivative (PPD) Heaf test Read at 3-7 days

Multipuncture method

Grade 1: 4-6 papules

Grade 2: Confluent papules forming ring

Grade 3: Central induration

Grade 4: > 10 mm induration

• Mantoux test Read at 2-4 days

• Using 10 tuberculin units :Positive when induration 5-14 mm (equivalent to Heaf grade

2) and > 15 mm (Heaf grade 3-4)

False negatives Skin testing :

1. Severe TB (25% of cases negative)

2. Newborn and elderly

3. HIV (if CD4 count < 200 cells/mL)

4. Malnutrition

5. Recent infection (e.g. measles) or immunisation

6. Immunosuppressive drugs

7. Malignancy

8. Sarcoidosis

Tuberculin skin testing may be associated with false-positive reactions in those who have had

a BCG vaccination and in areas where exposure to non-tuberculous mycobacteria is high.

These limitations may be overcome by employing interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs).

These tests measure the release of IFN-γ from sensitised T cells in response to antigens.The

greater specificity of these tests, combined with the logistical convenience of one blood test,

as opposed to two visits for skin testing, suggests that IGRAs will replace the tuberculin skin

test in low-incidence, high-income countries.

Directly observed therapy (DOT): Poor adherence to therapy is a major factor in prolonged

infectious illness, risk of relapse and the emergence of drug resistance. DOT involves the

supervised administration of therapy thrice weekly and improves adherence. It has become an

important control strategy in resource-poor nations. In the UK, it is currently only

recommended for patients thought unlikely to be adherent to therapy: those who are

homeless, alcohol or drug users, drifters, those with serious mental illness and those with a

history of non-compliance. Drug-resistant TB Drug-resistant TB is defined by the presence of

resistance to any first-line agent. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB is defined by resistance to at

least rifampicin and isoniazid, with or without other drug resistance. Extensively drug-

resistant (XDR) TB is defined by resistance to at least rifampicin and isoniazid, in addition to

any quinolone and at least one injectable second-line agent. The prevalence of MDR-TB is

rising, particularly in the former Soviet Union, Central Asia and Africa. It is more common in

those with a prior history of TB, particularly if treatment has been inadequate, and those

with HIV infection .

Diagnosis is challenging, especially in developing countries, and although cure may be possible,

it requires prolonged treatment with less effective, more toxic and more expensive therapies.

Mortality rate from MDR-TB is high and that from XDR-TB higher still.

Factors contributing to emergence of drug-resistant TB:

1. Drug shortages

2. Poor-quality drugs

3. Lack of appropriate supervision

4. Transmission of drug-resistant strains

5. Prior anti-tuberculosis treatment

6. Treatment failure (smear-positive at 5 months)

Vaccines: BCG (the Calmette-Guérin bacillus), a live attenuated vaccine derived from M. bovis,

is the most established TB vaccine. It is administered by intradermal injection and is highly

immunogenic. BCG appears to be effective in preventing disseminated disease, including

tuberculous meningitis, in children, but its efficacy in adults is inconsistent and new vaccines

are urgently needed. Current vaccination policies vary world-wide according to incidence and

health-care resources, but usually target children and other high-risk individuals. BCG is very

safe with the occasional complication of local abscess formation. It should not be administered

to those who are immunocompromised (e.g. by HIV) or pregnant.

Prognosis: Following successful completion of chemotherapy, cure should be anticipated in

the majority of patients. There is a small (< 5%) and unavoidable risk of relapse, which

usually occurs within 5 months and has the same drug susceptibility. In the absence of

treatment, a patient with smear-positive TB will remain infectious for an average of 2 years; in

1 year, 25% of untreated cases will die. Death is more likely in those who are smear-positive

and those who smoke. A few patients die unexpectedly soon after commencing therapy and it

is possible that some have subclinical hypoadrenalism that is unmasked by a rifampicin-

induced increase in steroid metabolism. HIV-positive patients have higher mortality rates and

a modestly increased risk of relapse.

By: Brwa