Fluid and electrolytes

Blood transfusion

Surgical drains

And Others topics

Anwar Qais Sa'adoon

تمت الطباعة في البصرة

–

ناحية الشهيد عز الدين سليم

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 2

بسم اهلل الرمحن الرحيم

احلمد هلل رب العاملني وصلى اهلل

تعاىل

على

خري خلقه أمج

عني

حممد

األمني

و

على آله

الطيبني الطاهرين

.

ّيسر

ني

أ

ن

أضع

هذا اجلهد امل

وتااضع

بني ايديكم

إخاتي

وأخااتي

والوتمس منكم العذر عن أي

خطأ

أو نقص

ًسائال

اهلل تعاىل ان ي

افقنا

وإياكم اىل ما حيب ويرضى وأ

َّن مين

عليكم و

علينا بالصحة والعافية

ٌانه مسيع

ُجميب

الدعاء

.

أنار قيس سعدون

02

/

8

/

0224

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 3

Contents

Chapter I :

Fluid and electrolytes

Chapter II :

Blood transfusion

Chapter III :

Post operative

complication

Chapter IV :

Surgical drains

Chapter V :

Suture types

Chapter VI :

Shock

Chapter VII :

Wounds, tissue repair

Chapter VIII :

Nutrition in surgery

Chapter IX :

Stomas

Chapter X :

History of common

surgical cases

4

24

33

41

46

51

63

69

75

80

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 4

Chapter I

Fluid and electrolytes

Topics

Body fluid compartments

Water Homeostasis

Effective circulating volume

Daily water requirements

Daily electrolyte requirements

Intravenous fluids

Types of Intravenous fluids

Maintenance fluid

Which Fluid to Choose?

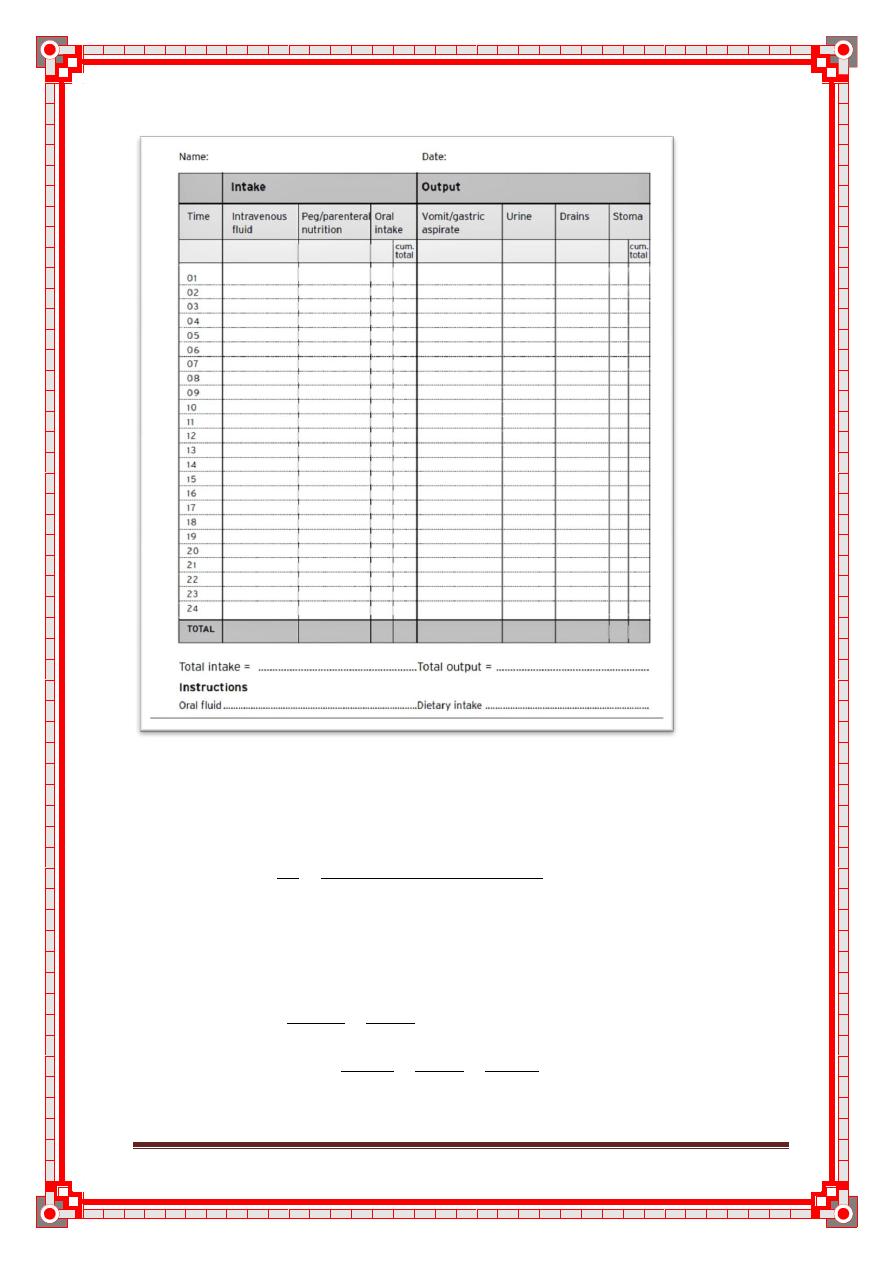

The fluid balance chart

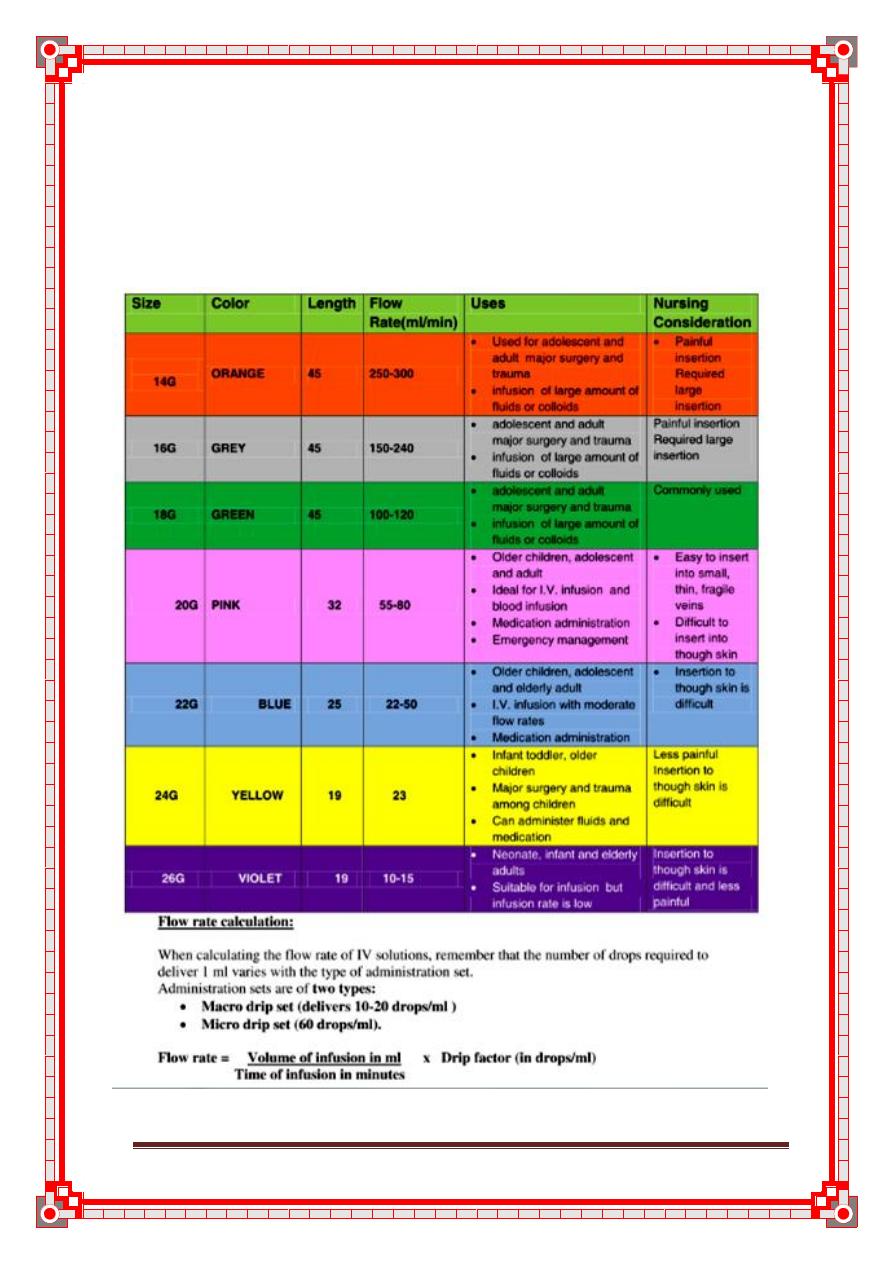

Sizes of the I.V cannulae

Electrolyte balance

Sodium balance

Hyponatremia

Hypernatremia

Potassium balance

Hypokalemia

Hyperkalemia

Calcium balance

Hypocalcemia

hypercalcemia

Acid-Base homeostasis

5

5

5

6

6

7

7

11

11

13

14

15

15

15

17

18

19

20

21

21

22

23

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 5

Body fluid compartments

The TBW is distributed in various locations throughout the body, known as

fluid compartments. These vary somewhat by age, but on average:

Intracellular Fluid Compartment: 2/3 of TBW, 40% of body weight

Extracellular Fluid Compartment: 1/3 of TBW, 20% of body weight

ECF compartment is further divided:

Interstitial Fluid 3/4 of ECF, 15% of body weight

Plasma Water 1/4 of ECF, 5% of body weight

Water Homeostasis

1. Total Body Water ( TBW ) – about 40L

-water intake (food and drink - 2300ml; cell metabolism- 200ml

total- 2500)

-water output (kidneys – 1500ml; skin- 600ml; lungs- 300ml;

GI tract-100ml; total – 2500ml)

2. Disturbances of Water Homeostasis

-hypervolemia (infusion of isotonic i.v. fluid)

-hypovolemia (blood loss)

-overhydration (drinking too much water)

-dehydration (sweating)

3. Four Primary Mechanisms Regulate Fluid Homeostasis

-ADH

-thirst mechanism

-aldosterone

-sympathetic nervous system

Effective circulating volume

That portion of the extracellular vascular space that is perfusing the tissues.

Adequate effective circulating

volume MUST be maintained at ALL TIMES. Decreased effective

circulating volume can be seen in:

• Volume loss (vomiting, diarrhea, hemorrhage, burns, surgical drainage)

• Normal or increased volume (cardiac dysfunction, liver disease)

Effective circulating volume is regulated by:

Sympathetic nerves via baroreceptors

Circulating catecholamines

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system ADH

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 6

Daily water requirements

Historically, daily water needs have been estimated based on energy

expenditure:

1 kcal expended/day = 1 ml H2O required

Based on computed energy expenditure of the average hospitalized patient:

First 10 kg = 100ml/kg/day H2O

Second 10 kg = 50 ml/kg/day H2O

Weight over 20 kg = 20 ml/kg/day H2O

Therefore, for a 25kg child, the daily fluid requirement based on this scheme

would

1000ml/day for the first 10kg (10kg X 100ml/kg/day)

500ml/day for the second 10kg (10kg X 50ml/kg/day)

+ 100ml/day for the 5kg over 20kg (5kg X 20ml/kg/day)

TOTAL:1600ml/day for 25kg child

We also can calculate maintance fluid by using “4-2-1” rule and as the

following:

First 10 kg = 4 ml/kg/hr H2O

Second 10 kg = 2 ml/kg/hr H2O

Weight over 20 kg = 1 ml/kg/hr H2O

Therefore, for the same 25kg child used in the example above, IV fluids

based on this method would be:

40ml/hr for the first 10kg (10kg X 4 ml/kg/hr)

20ml/hr for the second 10kg (10kg X 2 ml/kg/hr)

+ 5ml/hr for the 5kg over 20kg (5kg X 1 ml/kg/hr)

TOTAL: 65ml/hr for 25kg child, or

1560ml/day (65ml/hr X 24 hrs/day), pretty close to the 1600ml/day

calculated by the long method, above.

Daily electrolyte requirements

Estimates for daily electrolytes can be based on metabolic demands or, by

extension, on daily water needs:

• Sodium 2 - 3 mEq/100ml H2O /day

• Potassium 1 - 2 mEq/100ml H2O /day

• Chloride 2 - 3 mEq/100ml H2O /day

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 7

Intravenous fluids

Intravenous fluids may be divided into:

1- Crystalloid solutions - clear fluids made up of water and

electrolyte solutions; Will cross a semi-permeable membrane

e.g Normal, hypo and hypertonic saline solutions; Dextrose solutions;

Ringer’s lactate and Hartmann’s solution.

2- Colloid solutions – Gelatinous solutions containing particles

suspended in solution. These particles will not form a sediment

under the influence of gravity and are largely unable to cross a

semi-permeable membrane. e.g. Albumin, Dextrans, Hydroxyethyl

starch [HES]; Haemaccel and Gelofusine

Crystalloid solutions:

A- Saline Solutions

(1) 0.9% Normal Saline – Think of it as ‘Salt and water’

• Principal fluid used for intravascular resuscitation and replacement of

salt loss e.g diarrhoea and vomiting

• Contains: Na+ 154 mmol/l, K+ - Nil, Cl

-

- 154 mmol/l; But K+ is often

added

• IsoOsmolar compared to normal plasma

• Distribution: Stays almost entirely in the Extracellular space

Of 1 litre – 750ml Extra cellular fluid; 250ml

intravacular fluid

• So for 100ml blood loss – need to give 400ml N.saline [only 25%

remains intravascular]

(2) 0.45% Normal saline = ‘Half’ Normal Saline = HYPOtonic saline

• Reserved for severe hyperosmolar states severe dehydration

• Leads to HYPOnatraemia if plasma sodium is normal

• May cause rapid reduction in serum sodium if used in excess or

infused too rapidly. This may lead to cerebral oedema and rarely,

central pontine demyelinosis ; Use with caution!

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 8

(3) 1.8, 3.0, 7.0, 7.5 and 10% Saline = HYPERtonic saline

• Reserved for plasma expansion with colloids

• In practice rarely used in general wards; Reserved for high

dependency, specialist areas

• Distributed almost entirely in the ECF and intravascular space. This

leads to an osmotic gradient between the ECF and ICF, causing

passage of fluid into the EC space. This fluid distributes itself evenly

across the ECF and intravascualr space, in turn leading to intravascular

repletion.

• Large volumes will cause HYPERnatraemia and IC dehydration.

B- Dextrose solutions:

(1) 5% Dextrose (often written D5W) – Think of it as ‘Sugar and

Water’

• Primarily used to maintain water balance in patients who are not able

to take anything by mouth; Commonly used post-operatively in

conjuction with salt retaining fluids ie saline; Often prescribed as 2L

D5W: 1L N.Saline [‘Physiological replacement’ of water and Na+

losses]

• Provides some calories [ approximately 10% of daily requirements]

• Regarded as ‘electrolyte free’ – contains NO Sodium, Potassium,

Chloride or Calcium

• Distribution: <10% Intravascular; > 66% intracellular

• When infused is rapidly redistributed into the intracellular space; Less

than 10% stays in the intravascular space therefore it is of limited use

in fluid resuscitation.

• For every 100ml blood loss – need 1000ml dextrose replacement [10%

retained in intravascular space

• Common cause of iatrogenic hyponatraemia in surgical patient

(2) Dextrose saline – Think of it as ‘a bit of salt and sugar’

• Similar indications to 5% dextrose; Provides Na+ 30mmol/l and Cl

-

30mmol/l Ie a sprinkling of salt and sugar!

• Primarily used to replace water losses post-operatively

• Limited indications outside of post-operative replacement – ‘Neither

really saline or dextrose; Advantage – doesn’t commonly cause water

or salt overload.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 9

Colloid solutions:

• The colloid solutions contain particles which do not readily cross

semi-permeable membranes such as the capillary membrane

• Thus the volume infused stays (initially) almost entirely within the

intravascular space

• Stay intravascular for a prolonged period compared to crystalloids

• However they leak out of the intravascular space when the capillary

permeability significantly changes e.g. Severe trauma or sepsis

• Until recently they were regarded as the gold standard for

intravascular resuscitation

• Because of their gelatinous properties they cause platelet dysfunction

and interfere with fibrinolysis and coagulation factors (factor VIII) –

thus they can cause significant coagulopathy in large volumes.

Questions to ask before prescribing fluid:

1. Is my patient Euvolaemic, Hypovolaemic or

Hypervolaemic?

Assess the patient

Euvolaemic: veins are well flled, extremities are warm,

blood pressure and heart rate are normal (depending on

other pathology).

Hypovolaemic:The patient may have cold hands and feet,

absent veins, hypotension, tachycardia, oliguria and confu-

sion. History of fluid loss or low intake.

Hypervolaemic: Patient is oedematous, may have inspira-

tory crackles; history of poor urine output or fluid overload.

2. Does my patient need IV fluid? Why?

NO:

he may be drinking adequately, may be receiving

adequate fluid via NG feed or TPN, or may be receiving

large volumes with drugs or drug infusions (or a

combination of these). ALLOW PATIENTS TO DRINK IF

AT ALL POSSIBLE.

Hypervolaemic: may need fluid restriction or gentle

diuresis.

YES:

not drinking, has lost, or is losing fluid

So WHY does the patient need fluid?

Maintenance fluid only – patient does not have excess

losses above insensible loss. If no other intake he needs

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 10

approximately 30ml/kg/24hrs. He may only need part of

this if receiving other fluid. Patients having to fast for over

8-12 hours should be started on IV maintenance fluid.

Replacement of losses, either previous or current. If

losses are predicted it is best to replace these later rather

than give extra fluid in anticipation of losses which may not

occur. This fluid is in addition to maintenance fluid. Check

blood gases.

Resuscitation: The patient is hypovolaemic as a result of

dehydration, blood loss or sepsis and requires urgent

correction of intravascular depletion to correct the defcit

3. How much?

a. Obtain weight (estimate if required). Maintenance fluid

requirement approximately 30ml/kg/24hours.

b. Review recent U&Es, other electrolytes and Hb.

c. Recent events – e.g. fasting, intake, losses, sepsis,

operations, fluid overload. Check fluid balance charts.

Calculate how much loss has to be replaced and work

out which type of fluid has been lost: e.g. GI secretions,

blood, infammatory losses.

Note urine does not need to be replaced unless excessive

(diabetes insipidus, recovering renal failure). Post-op: high

urine output may be due to excess fluid;

low urine output is common and may be normal due to anti-

diuretic hormone release.

Assess fully before giving extra fluid.

4. What type(s) of fluid does my patient need?

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 11

Maintenance fluid

IV fluid should be given via volumetric pump if a patient is

on fluids for over 6 hours or if the fluid contains

potassium. Always prescribe as ml/hr not ‘x hourly’

bags.

Never give maintenance fluids at more than 100ml/hour.

Table 1: correct fluid rate according to body weight

Weight kg Fluid Requirement in mls/day Rate in ml/hour

35-44 1200 50

45-54 1500 65

55-64 1800 75

65-74 2100 85

≥75 2400 100 (max)

Preferred maintenance fluids: 0.18%saline/4%dextrose

with or without added potassium (KCl 10/ 20 mmol) in

500ml. 1 litre bags are available. This fluid if given at

the correct rate provides all water and Na

/K requirements until the patient can eat and drink or be

fed. Excess volumes of this fluid (or any) fluid may cause

hyponatraemia.

Alternatively 5% dextrose 500ml and 0.9% NaCl 500ml

may be used in a ratio of 2 bags of 5% dextrose to 1 bag

of 0.9% NaCl. Prescribe each bag with added potassium

(KCl 20mmol) if patient has normal or low potassium.

Which Fluid to Choose?

Hypovolemia: primary goal is volume

expansion.

Use the fluid that will put the most volume into

the intravascular space. NS or LR.

Dehydration (= hyperosmolality): primary

goal is free water replacement. Note that

this is not synonymous with hypovolemia.

Use a hypotonic fluid usually 0.45% saline or

D5W.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 12

Post-operative patients:

Pain and narcotics can be powerful stimulants

of inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH)

Giving hypotonic fluids in this setting can (but

usually does not) cause dangerous

hyponatremia.

This makes 0.9 % saline a safer fluid but

realize that it will also deliver free water in the

setting of SIADH.

Crystalloid Resuscitation - what should you do?

Recommendations:

• Colloid should NOT be used as the sole fluid replacement in

resuscitation; Volumes infused should be limited because of side

effects and lack of evidence for their continued use in the acutely ill.

• In severely ill patients – principally use crystalloid and blood products;

Colloid may be used in limited volume to reduce volume of fluids

required or until blood products are available

• In elective surgical patients – replace fluid loss with ‘physiological

Hartmann’s and Ringer’s solutions; Blood products and colloid may

be needed to replace intravascular volume acutely

• Don’t get in between an anaesthetist and a surgeon when the words

colloid and crystalloid are mentioned!

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 13

Figure 1: The fluid balance chart

To calculate drip rates / transfusion rates:

To calculate the drip rate (drops / minute)

Drip Rate gtt = Volume to be infused (ml) x Drop Factor (gtt/ml)

min Time (minutes)

1 unit of blood is approximately 400ml in volume

E.g. A unit of blood is prescribed to run over 4 hours; The giving set has a

drop factor of 20 gtt /ml. What is the drip rate (drops /min) ?

Drip rate = 400 ml x 20 gtt ; Drip Rate is drops / minute

4 hour 1ml

Thus Drip Rate = 400ml x 20 gtt x 1 hour

4 hour 1 ml 60 minutes

By multidimensional analysis units are correct (drops / minute)

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 14

Drip Rate = 100 / 3 = 33 drops / minute

• Drop rate is rounded up or down to the nearest drop

• In the clinical setting to be able to count drops / minute it is sensible to

have a number divisable by 4 - Thus you would set this drip at 32

drops per minute

Table 2: sizes of the I.V cannula

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 15

Electrolyte balance

Sodium balance

Alterations in sodium balance cause fl uid shifts between compartments. The

clinical picture is most often neurologic, due to fl uid shifts within the brain.

Hyponatremia

DEFINITION

< 130 mEq/L.

First steps in hyponatremia: Determine volume status clinically, then

determine plasma osmolality!

Step 1: Determine Plasma Osmolality

Normal osmolality—pseudohyponatremia: Lab artifact due to increased

lipids or plasma proteins → next step; check lipid profi le or possible

multiple myeloma.

High osmolality —pseudohyponatremia: Due to increase of osmolality

active molecules—glucose or mannitol.

Low osmolality—true hyponatremia.

Step 2: Assess Volume Status

Hypovolemia

Euvolemia

Hypervolemia

See below for discussion of each.

HYPONATREMIA WITH HIGH PLASMA OSMOLALITY

(PSEUDOHYPONATREMIA)

CAUSES

Hyperglycemia, either physiologic or due to rapid infusion of glucose or

mannitol will cause increased osmotic pressure that shifts fl uid from the ICF

to the ECF. The total body sodium in this case is normal but has become di-

luted due to the fluid shift.

The expected Na concentration can be calculated as follows: For every 100

mg/dL that glucose is increased over 100 mg/dL, the Na concentration falls

1.6 mEq/L. Remember “sweet 16.”

For example, a patient with a glucose concentration of 500 mg/dL is ex-

pected to have a hyponatremia of around 133.6 mEq/L (4 × 1.6 = 6.4, 140 –

6.4 = 133.6).

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 16

HYPONATREMIA WITH HYPOTONICITY (TRUE

HYPONATREMIA)

True hyponatremia refl ects excess ingestion of water that overwhelms the

kidneys (either normal or diseased) or due to increased ADH. Hyponatremia

is not due to increased excretion of sodium.

Hypovolemia (dehydration)

Renal cause: Diuretics.

Extrarenal cause: Vomiting, diarrhea, burns, pancreatitis.

Differentiate using urine Na: Urine Na < 20 mEq/L indicates expected

renal retention in the face of hypovolemia, suspect an extrarenal cause.

Urine Na > 20 mEq/L indicates a renal cause.

Hypervolemia

May be from CHF, cirrhosis, or nephrotic syndrome.

Increased thirst and vasopressin.

Edematous state.

Euvolemia

SIADH: Most common cause of normovolemic hyponatremia.

Increased vasopressin release from posterior pituitary or ectopic source

causes decreased renal free water excretion.

Signs and symptoms:

Hypo-osmotic hyponatremia (hyponatremia with hypotonicity).

Inappropriately concentrated urine (urine osmolality > 100 mOsm/

kg).

Normal renal, adrenal, and thyroid function.

Causes:

Neuropsychiatric disorders, malignancies (especially lung), and head

trauma.

Glucocorticoid defi ciency (Addison’s disease)—cortisol defi ciency

causes hypersecretion of vasopressin.

Hypothyroidism—causes decreased CO and glomerular fi ltration rate

(GFR), which leads to increased vasopressin secretion.

Primary polydipsia—usually seen in psychiatric patients who compulsively

drink massive volumes of water.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 17

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF (TRUE) HYPONATREMIA

Signs: Decreased reflexes, respiratory depression, seizures, coma.

Symptoms: Nausea/vomiting, headache, lethargy, muscle cramps.

Hypovolemic hyponatremia: Give 0.9% NaCl. Na repletion with saline

isotonic to the patient, in order to avoid rapid changes in ICF volume.

Major complication from rapid correction of chronic hyponatremia is central

pontine myelinolysis.

Hypervolemic hyponatremia: Correct underlying disorder—CHF, liver

or renal failure.

Euvolemic hyponatremia: Raise plasma Na (lower ICF volume)—restrict

water intake.

Hypernatremia

DEFINITION

> 145 mEq/L.

Hypernatremia is always associated with hyperosmolarity. (Note that in the

plasma osmolality equation, Na is the major factor).

CAUSES

Loss of water (dehydration!): Diabetes insipidus, diuretics, sweating, GI

loss, burns, fistulas.

Gain of sodium due to excess mineralocorticoid activity: Primary hyper-

aldosteronism, Cushing’s, renal artery stenosis (hyperreninism), congen-

ital adrenal hyperplasia (will cause concomitant hypokalemia).

If thirst mechanism is intact and water is available, hypernatremia will

not persist. Suspect hypernatremia in the young, elderly, and patients

with altered mental status who may not have access to water.

SYMPTOMS

Thirst.

Restlessness, weakness, delirium.

Hypotension and tachycardia.

Decreased saliva and tears.

Red, swollen tongue.

Oliguria.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 18

TREATMENT

Calculate free water defi cit.

If euvolemic: Replace water defi cit with D5W.

If hypovolemic: Use normal saline. Correct one half of water defi cit in

fi rst 24 hours; remaining water defi cit over next 1–2 days.

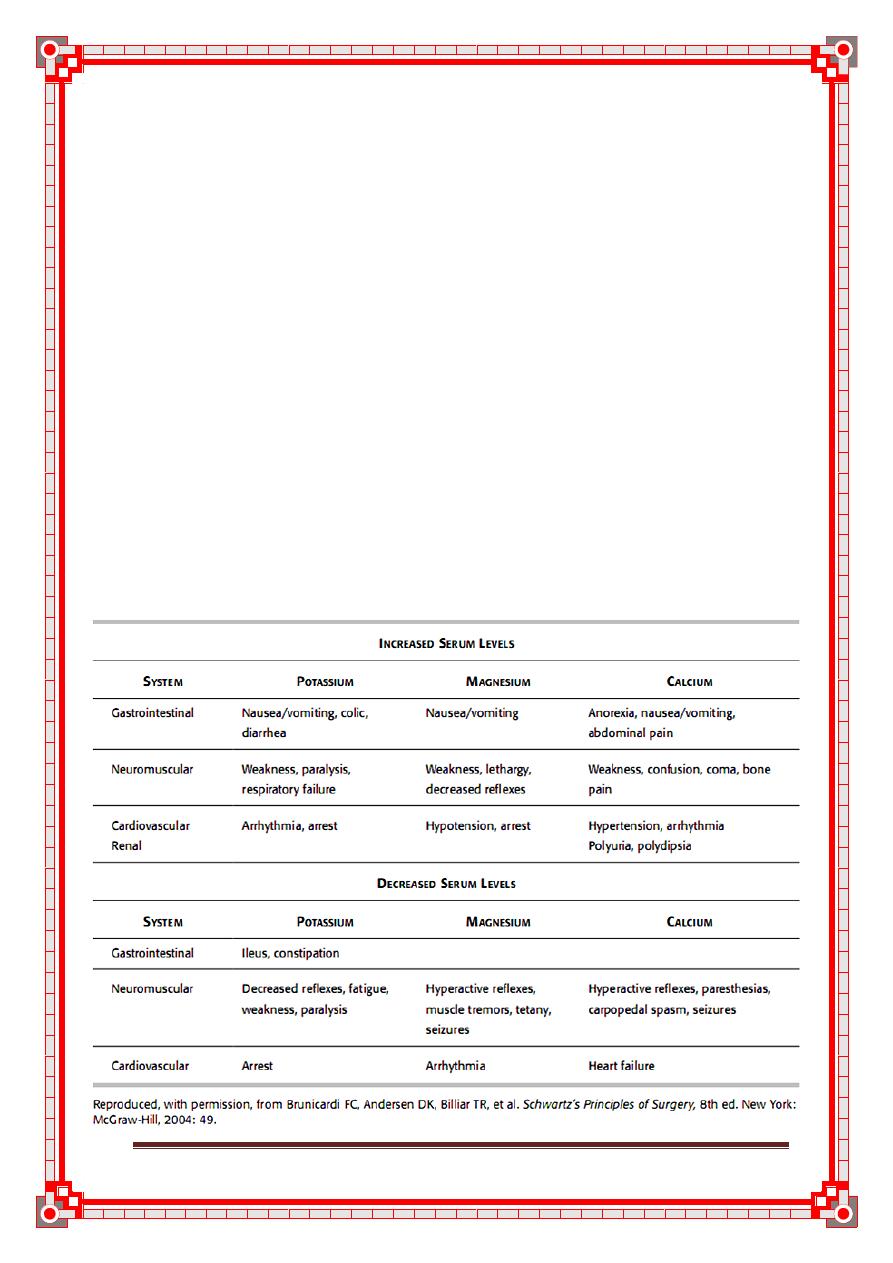

Potassium balance

Ninety-nine percent of K is in ICF. Therefore, small alterations in ex-

tracellular K balance can have signifi cant clinical effects, particularly

impaired electrical signaling in the heart, muscle, and nerve (see Table

3). Proper proportions of K+ and Ca+ must exist for their exchange

across membrane channels that allow electrical conduction to occur.

Cells act as a rapid potassium buffer. Kidney regulates long-term potas-

sium control.

Table 3: Clinical Manifestations of Abnormalities in Potassium, Magnesium,

and Calcium

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 19

Hypokalemia

DEFINITION

< 3.5 mEq/L.

CAUSES

Most commonly due to excessive renal secretion.

Loss of potassium due to excess mineralocorticoid activity: Primary

hyperaldosteronism, Cushing’s, renal artery stenosis (hyperreninism),

congenital adrenal hyperplasia (will cause concomitant

hypernatremia).

Movement of K into cells due to insulin, catecholamines, alkalemia.

Prolonged administration of K-free parenteral fluids.

Total parenteral hyperalimentation with inadequate K replacement.

Loss in excessive lower GI secretions such as diarrhea, colonic fi

stulas,

VIPoma.

Diuretics.

Signs & symptoms

Electrocardiogram (ECG) Flattened T waves, ST depression, U wave.

Arrhythmias, signs of low voltage.

Treatment

Check Mg level first as hypomagnesemia is commonly associated with

hypokalemia and must be corrected before/along with hypokalemia.

Amount of K to be replaced can be conservatively estimated as: (4.0 –

current K) × 100, in mEq.

Example: if current K is 3.1, give 90 mEq (total, not all at once!!!)

In asymptomatic patient with K > 3.0 mEq/L, oral K replacement may

be sufficient.

No more than 40 mEq should be added to a liter of IV fluid since rapid

K administration can cause fatal arrhythmias.

Rate should not exceed 40 mEq/hr.

May cause a burning sensation if given in peripheral IV. Using low

flow rate of 10 mEq/hr or adding a small amount of lidocaine to the

solution can decrease discomfort.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 20

Hyperkalemia

DEFINITION

> 5 mEq/L.

CAUSES

Commonly due to renal failure.

Rarely found when renal function is normal and usually causes a tran-

sient hyperkalemia, due to cellular shifts: Potassium spillage from cells

in severe injury; cells take up hydrogen ions in exchange for intracellu-

lar potassium, acting as a buffer in states of acidosis.

Drugs: Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, potassium-

sparing diuretics.

Iatrogenic causes: Penicillin G contains 1.7 mEq K per one million

units, KCl added to maintenance fl uids, blood transfusion with old

batch of packed red blood cells (RBCs) where K may have leaked out of

cells, overtreatment of hypokalemia.

Digoxin toxicity can cause severe hyperkalemia by blocking the so-

dium–potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) pump.

Hypoaldosteronism.

Pseudohyperkalemia: Can result when RBCs lyse in the test tube and

release potassium. This is a lab error: Repeat test before treating!

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Cardiac effects are most signifi cant. Confirm hyperkalemia and obtain an

ECG.

ECG:

Early: Peaked T waves wide QRS, ST depression.

Late: Disappearance of T waves, heart block, sine wave ominous for

impending fatal arrhythmia, cardiac arrest.

GI: Nausea, vomiting, intermittent intestinal colic, diarrhea.

TREATMENT (IN ORDER OF IMPORTANCE)

Ten percent calcium gluconate 1 g IV—monitor ECG. Calcium tem-

porarily suppresses cardiac arrhythmias by stabilizing the cardiac mem-

brane and should be administered fi rst. Does not affect potassium load.

Lower extracellular K+ (acute treatment): Albuterol, insulin with glu-

cose or sodium bicarbonate promote cellular reuptake of K—transient

relief of hyperkalemia.

Kayexalate—cation exchange resin. As opposed to above measures,

which immediately protect against dangers of high potassium, this actu-

ally removes the potassium from the body.

Dialysis (last resort).

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 21

How does Ca+ help with hyperkalemia?

It stabilizes the membrane potential of cardiac muscle, which would

abnormally fi re in the presence of high potassium. It does not actually have

any effect on the amount of K+ present.

Calcium balance

Normal: 1,000–1,200 mg—most is in the bone in the form of phosphate

and carbonate.

Normal daily intake: 1–3 g.

Most excreted via stool (–200 mg via urine).

Normal serum level: 8.5–10.5 mg/dL (total calcium).

Half of this is nonionized and bound to plasma protein.

If hypocalcemia is seen on laboratory report, fi rst correct for low albumin:

Corrected Calcium = 0.8 (Normal Albumin – Observed Albumin) +

Observed Calcium

If corrected calcium falls within normal range, no action is required.

Ionized calcium is the most accurate measure of calcium, but labs re-

port total calcium.

An additional nonionized fraction (5%) is bound to other substances in

the ECF.

Ratio of ionized to nonionized Ca is related to pH:

Acidosis causes increase in ionized fraction.

Alkalosis causes decrease in ionized fraction.

Hypocalcemia

DEFINITION

< 8 mg/dL.

CAUSES

Acute pancreatitis.

Massive soft-tissue infections (necrotizing fasciitis).

Acute/chronic renal failure.

Pancreatic/small bowel fistulas.

Hypoparathyroidism (common after parathyroid or thyroid surgery).

Hypoproteinemia (often asymptomatic, corrected calcium will fall

within normal range).

Severe depletion of magnesium.

Severe alkalosis may elicit symptoms in patient with normal serum

levels because there is a decrease in the ionized fraction of total serum

calcium.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 22

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Numbness and tingling of fingers, toes, and around mouth.

Increased refl exes.

Chvostek’s sign: Tapping over the facial nerve in front of the tragus of

the ear causes ipsilateral twitching.

Trousseau’s sign: Carpopedal spasm following inflation of

sphygmomanometer cuff to above systolic blood pressure for several

minutes.

Muscle and abdominal cramps.

Convulsions.

ECG—prolonged QT interval.

TREATMENT

IV Ca gluconate or Ca chloride.

Monitor QT interval on ECG.

Hypercalcemia

DEFINITION

> 15 mg/dL.

CAUSES

Hyperparathyroidism.

Cancer (especially breast, multiple myeloma).

Drugs (e.g., thiazides).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Fatigue, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting.

Somnambulism, stupor, coma.

Severe headache, pain in the back and extremities, thirst,

polydipsia, polyuria.

Death.

TREATMENT

Vigorous volume repletion with salt solution—dilutes Ca and

increases urinary Ca excretion:

May be augmented with furosemide.

Definitive treatment of acute hypercalcemic crisis in patients

with hyperparathyroidism is immediate surgery.

Treat underlying cause.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 23

Acid-Base homeostasis

1. pH of body fluids:

-arterial blood- pH 7, 35-7, 45

-venous blood-pH 7, 35

-intracellular fluid-pH 7, 0

-gastric juice- pH 2, 0

-small intestine juice- pH 8, 0

-urine- pH 4, 5-8 ,0 based on diet and metabolic state

2. The body has 3 ways of maintaining a normal pH range:

-chemical buffer system (acts within seconds)

a) carbonic acid / bicarbonate

b) phosphate buffer

c) protein buffer

-respiratory controls

a) acts within minutes

b) important in compensating for metabolic acidosis or alkalosis

c) permits elimination of the volatile acid ( bicarbonate acid )

-renal mechanisms

a) acts within hours or days

b) compensate for respiratory acidosis or alkalosis

c) eliminate fixed acids from the body (metabolic acids generated in

the body that are eliminated only in the urine).

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 24

Chapter II

Blood transfusion and

blood transfusion reaction

Topics

Introduction

Blood and blood products

Whole blood

Packed red cells

Fresh-frozen plasma

Cryoprecipitate

Platelets

Prothrombin complex concentrates

Autologous blood

Indications for blood transfusion

Transfusion trigger

Blood groups and cross-matching

ABO system

Rhesus system

Transfusion reactions

Complications of blood transfusion

Complications from a single transfusion

Complications from massive transfusion

Management of transfusion reactions

Transfusion reactions algorithm

25

25

25

25

26

26

26

26

27

27

27

27

27

28

28

29

29

29

30

32

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 25

Introduction

The transfusion of blood and blood products has become commonplace

since the first successful transfusion in 1829

Although the incidence of severe transfusion reactions and

infections is now very low, in recent years it has become apparent

hat there is an immunological price to be paid for the transfusion

of heterologous blood, which leads to increased morbidity and

decreased survival in certain population groups (trauma, malignancy).

Supplies are also limited and, therefore, the use of blood

and blood products must always be judicious and justifiable in

terms of clinical need.

Blood and blood products

Blood is collected from donors who have been previously

screened to exclude any donor whose blood may have the poten-

tial to harm the patient or to prevent possible harm that donat-

ing a unit of blood may have on the donor. In the UK, up to

450ml of blood is drawn, a maximum of three times a year. Each

unit is tested for evidence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1, HIV-2 and syphilis. Donations

are leucodepleted as a precaution against variant Creutzfeldt–

jakob disease (this may also reduce the immunogenicity of the

transfusion). The ABO and Rhesus D blood group is determined,

as well as the presence of irregular red cell antibodies. The blood

is then processed into sub-components.

Whole blood

Whole blood is now rarely available in civilian practice as it is an

ineffective use of the limited resource; however, whole blood

transfusion has significant advantages over packed cells as it is

coagulation factor rich and, if fresh, more metabolically active

than stored blood.

Packed red cells

Packed red blood cells are cells that are spun down and concentrated.

Each unit is approximately 330ml and has a haematocrit

of 50–70%. Packed cells are stored in a SAG-M solution

(saline–adenine–glucose–mannitol) to increase their shelf-life to

5 weeks at 2–6∞C. (Older storage regimens included storage in

CPD – citrate–phosphate–dextrose solutions – giving cells a

shelf-life of 2–3 weeks).

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 26

Fresh-frozen plasma

Fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) is rich in coagulation factors; it is

removed from fresh blood and stored at –40 to –50∞C with a 2-

year shelf-life. It is the first-line therapy in the treatment of

coagulopathic haemorrhage (see below). Rhesus D-positive FFP

may be given to a Rhesus D-negative woman.

Cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate is a supernatant precipitate of FFP and is rich in

factor VIII and fibrinogen. It is stored at –30∞C with a 2-year

shelf-life. It is given in low-fibrinogen states or in cases of factor

VIII deficiency.

Platelets

Platelets are supplied as a pooled platelet concentrate contain-

ing about 250 × 109

cells per litre. Platelets are stored on a

special agitator at 20–24∞C and have a shelf-life of only 5 days.

Platelet transfusions are given to patients with thrombocyto-

penia or with platelet dysfunction who are bleeding or under-

going surgery.

Patients are increasingly presenting on anti-platelet therapy

such as aspirin or clopidogrel for reduction of cardiovascular risk.

Aspirin therapy rarely poses a problem but control of haemor-

rhage on the more potent platelet inhibitors can be extremely dif-

ficult. Patients on clopidogrel who are actively bleeding and

undergoing major surgery may require almost continuous infusion

of platelets during the course of the procedure. Arginine vaso-

pressin or its analogues [e.g. desmopressin acetate (DDAVP)]

have also been used in this patient group, although with limited

success.

Prothrombin complex concentrates

Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) are highly purified

concentrates prepared from pooled plasma. They contain factors

II, IX and X; factor VII may be included or produced separately.

PCCs are indicated for the emergency reversal of anti-coagulant

(warfarin) therapy in uncontrolled haemorrhage.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 27

Autologous blood

It is possible for patients undergoing elective surgery to pre-

donate their own blood up to 3 weeks before surgery for retrans-

fusion during the operation. Similarly, during surgery blood can

be collected in a cell saver; this washes and collects red blood

cells, which can then be returned to the patient.

Indications for blood transfusion

Blood transfusions should be avoided if possible and many

previous uses of blood and blood products are now no longer

considered appropriate. The indications for blood transfusion are

as follows:

1-

acute blood loss, to replace circulating volume and maintain

oxygen delivery;

2-

perioperative anaemia, to ensure adequate oxygen delivery

during the perioperative phase;

3-

symptomatic chronic anaemia without haemorrhage or

impending surgery.

Transfusion trigger

Historically, patients were transfused to achieve a haemoglobin

level of >10gdl

–1

. This has now been shown to be not only

unnecessary but also associated with increased morbidity and

mortality compared with lower target values. A haemoglobin level of 6gdl

–1

is acceptable in patients who are not bleeding, not about to undergo major

surgery and not symptomatic. There is some controversy as to the optimal

haemoglobin level in some patient groups such as those with cardiovascular

disease, sepsis and traumatic brain injury. Although conceptually a high-

er haemoglobin level improves oxygen delivery, there is little clinical

evidence at this stage to support higher levels in these groups.

Blood groups and cross-matching

Human red blood cells have many different antigens on their cell

surface. Two groups of antigens are of major importance in surgi-

cal practice – the ABO and Rhesus systems.

ABO system

These are strongly antigenic and are associated with naturally

occurring antibodies in the serum. The system consists of three

allelic genes – A, B and O – which control the synthesis of

enzymes that add carbohydrate residues to cell surface glycopro-

teins. Expression of the A and B genes results in specific residues

being added whereas the O gene is an amorph and does not trans-

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 28

form the glycoprotein.

The system allows for six possible genotypes although there

are only four phenotypes . Naturally occurring

antibodies are found in the serum of those lacking the corres-

ponding antigen.Blood group O is the universal donor type as it

contains no antigens to provoke a reaction. Conversely, group AB

individuals are ‘universal recipients’ and can receive any ABO

blood type as they have no circulating antibodies.

Rhesus system

The Rhesus D [Rh(D)] antigen is strongly antigenic and is

present in approximately 85% of the population in the UK.

Antibodies to the D antigen are not naturally present in the

serum of the remaining 15% of individuals but their formation

may be stimulated by the transfusion of Rh-positive red cells or

they may be acquired during delivery of a Rh(D)-positive baby.

Table 4:

Perioperative red blood cell transfusion criteria

Haemoglobin level (gdl

–1

) Indication

<6 Probably will benefit from transfusion

6–8 Transfusion unlikely to be of benefit in the

absence of bleeding or impending surgery

>8 No indication for transfusion

Acquired antibodies are capable of crossing the placenta

during pregnancy and, if present in a Rh(D)-negative mother,

they may cause severe haemolytic anaemia and even death

(hydrops fetalis) in a Rh(D)-positive fetus in utero.

The other minor blood group antigens may be associated with

naturally occurring antibodies or they may stimulate the forma-

tion of antibodies on relatively rare occasions.

Transfusion reactions

If antibodies present in the recipient’s serum are incompatible with

the donor’s cells, a transfusion reaction will result. This usually

takes the form of an acute haemolytic reaction. Severe immune-

related transfusion reactions caused by ABO incompatibility result

in severe and potentially fatal complement-mediated intravascular

haemolysis and multiple organ failure. Transfusion reactions from

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 29

other antigen systems are usually milder and self-limiting.

Febrile transfusion reactions are non-haemolytic and are

usually caused by a graft-versus-host response from leucocytes in

transfused components. There is fever, chills or rigors. The blood

transfusion should be stopped immediately. This form of transfu-

sion reaction is rare with leuco-depleted blood.

Complications of blood transfusion

Complications from blood transfusion can be categorised as those

arising from a single transfusion and those related to massive

transfusion.

Complications from a single transfusion

Complications from a single transfusion include:

1- incompatibility haemolytic transfusion reaction;

2- febrile transfusion reaction

3- allergic reaction;

4- infection:

A- bacterial infection (usually as a result of faulty storage);

B- hepatitis;

C- HIV;

D- malaria;

5- air embolism;

6- thrombophlebitis;

7- transfusion-related acute lung injury (usually from FFP).

Complications from massive transfusion

Complications from massive transfusion include:

1- coagulopathy;

2- hypocalcaemia;

3- hyperkalaemia;

4- hypokalaemia;

5- hypothermia.

Additionally, patients who receive repeated transfusions over

long periods of time (e.g. patients with thalassaemia) may

developiron overload. (Each transfused unit of red blood cells

contains approximately 250mg of elemental iron.)

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 30

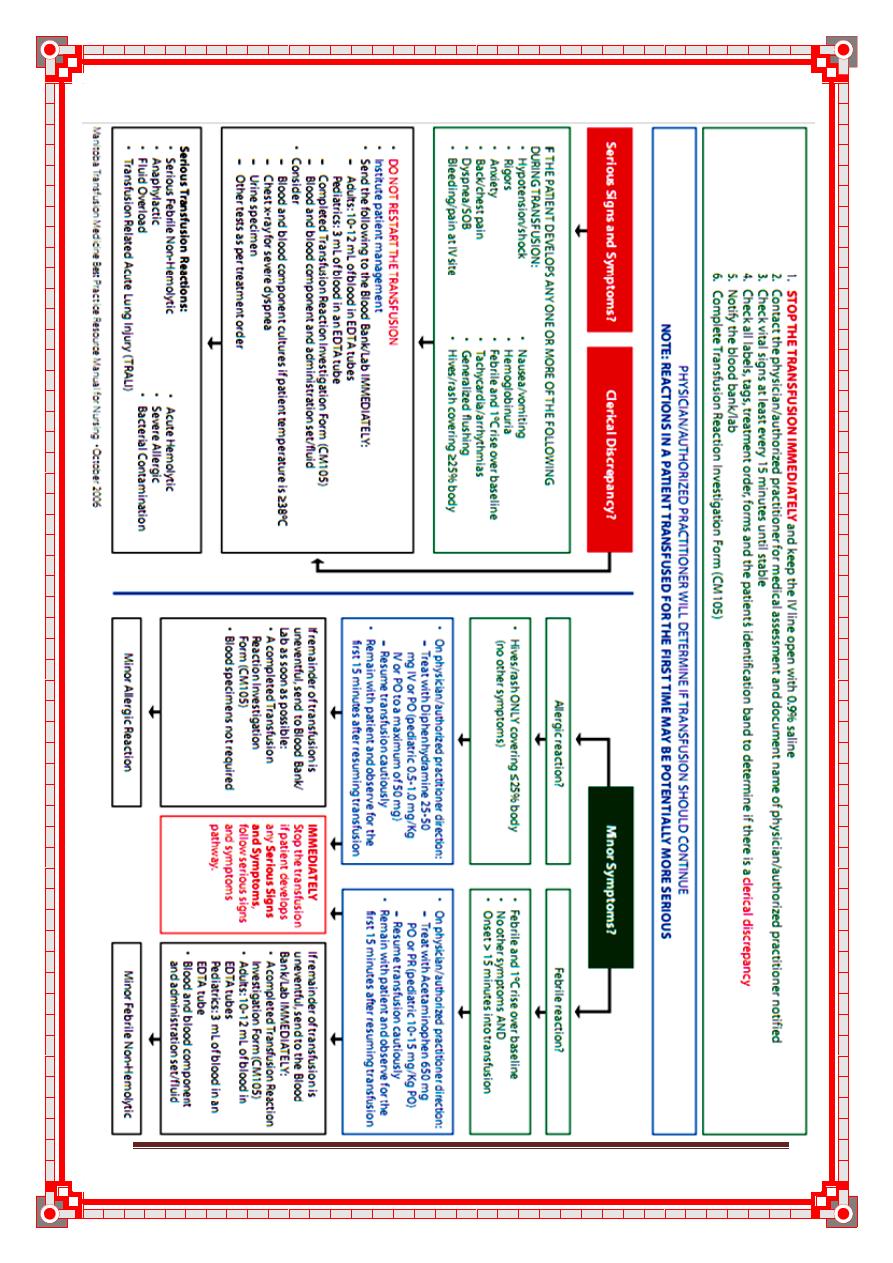

Management of transfusion reactions:

Continuous monitoring of vital signs during generalized anesthesia may

prevent acute circulatory (volume) overload, but it may not detect early signs

of other reactions (eg, acute hemolytic transfusion reactions).

The onset of red-colored urine in a transfused patient should raise the

question of a hemolytic transfusion reaction. When performing checks to

confirm that the correct blood was transfused to the correct patient,

centrifuge a urine sample to determine whether the red color represents

hematuria or hemoglobinuria Rapid test to distinguish hematuria from

hemoglobinuria. The onset of red urine during or shortly after a blood

transfusion may represent hemoglobinuria In addition, the onset of abnormal

bleeding/generalized oozing during surgery in a transfused patient should

raise the question of a hemolytic transfusion reaction with DIC.

Acute hemolytic reactions (antibody mediated)

Immediately discontinue the transfusion while maintaining venous access for

emergency management.

Anticipate hypotension, renal failure, and DIC. Prophylactic measures to

reduce the risk of renal failure may include low-dose dopamine (1-5

mcg/kg/min), vigorous hydration with crystalloid solutions (3000 mL/m2/24

h), and osmotic diuresis with 20% mannitol (100 mL/m2/bolus, followed by

30 mL/m2/h for 12 h). If DIC is documented and bleeding requires

treatment, transfusions of frozen plasma, pooled cryoprecipitates for

fibrinogen, and/or platelet concentrates may be indicated.

Acute hemolytic reactions (nonantibody mediated)

The transfusion of serologically compatible, although damaged, RBCs

usually does not require rigorous management. Diuresis induced by an

infusion of 500 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride per hour, or as tolerated by the

patient, until the intense red color of hemoglobinuria ceases is usually

adequate treatment.

Febrile, nonhemolytic reactions:

Usually, fever resolves in 15-30 minutes without specific treatment. If fever

causes discomfort, oral acetaminophen (325-500 mg) may be administered.

Avoid aspirin because of its prolonged adverse effect on platelet function.

Allergic reactions:

Diphenhydramine is usually effective for relieving pruritus that is associated

with hives or a rash. The route (oral or intravenous) and the dose (25-100

mg) depend on the severity of the reaction and the weight of the patient.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 31

Anaphylactic reactions

A subcutaneous injection of epinephrine (0.3-0.5 mL of a 1:1000 aqueous

solution) is standard treatment. If the patient is sufficiently hypotensive to

raise the question of the efficacy of the subcutaneous route, epinephrine (0.5

mL of a 1:10,000 aqueous solution) may be administered intravenously.

Although no documented evidence exists that intravenous corticosteroids are

beneficial for the management of acute anaphylactic transfusion reactions,

theoretical considerations cause most clinicians to include an infusion of

hydrocortisone or prednisolone if an immediate response to epinephrine does

not occur.

TRALI (Transfusion Related Acute Lung Injury)

Immediately discontinue the transfusion while preserving venous access.

Patients with mild episodes should respond to oxygen administered by nasal

catheter or mask. If shortness of breath persists after oxygen administration,

transfer the patient to an intensive care setting where mechanical ventilation

can be administered. In the absence of signs of acute volume overload or

cardiogenic pulmonary edema, diuretics are not indicated.No evidence exists

that corticosteroids or antihistamines are beneficial.

Treat complications with specific supportive measures.

Circulatory (volume) overload

Move the patient to a sitting position, and administer oxygen to facilitate

breathing.The most specific treatment is discontinuing the transfusion and

removing the excessive fluid.If practical, the unit of blood component being

transfused may be lowered to reverse the flow and to decrease intravascular

volume by a controlled phlebotomy.Less urgent situations may be managed

by a parenteral or oral diuretic (eg, furosemide).If the patient has

symptomatic anemia requiring additional transfusions of RBCs, select

concentrated (ie, CPDA-1-anticoagulated) red cells (hematocrit = 80-85%).

Avoid red cell components diluted with saline additives (ie, AS-1).

Bacterial contamination (sepsis)

Immediately discontinue the transfusion, including all tubing, filters, and

administration sets, and save the transfusion materials for cultures, while

preserving venous access. After appropriate blood cultures have been

obtained, initiate treatment with intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics. If a

microbiologic stain or a culture of the contents of the transfused product

identifies an organism, the initial broad-spectrum antibacterial approach may

be modified accordingly.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 32

Transfusion reactions algorithm

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 33

Chapter III

Post Operative complication

Topics

Common Post-operative Complications

General post -operative complications

Post-operative fever

Haemorrhage

Infection

Disordered wound healing

Surgical injury

Respiratory complication

Common urinary problems

Thrombo-embolism

34

34

35

36

36

37

37

38

39

40

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 34

Common Post-operative Complications

Post-operative complications may either be general or specific to the type of

surgery undertaken.

The highest incidence of post-operative complications is between 1 and 3

days after the operation. However, specific complications occur in the

following distinct temporal patterns: early post-operative, several days

after the operation, throughout the post-operative period, and in the late

post-operative period

General post -operative complications

A- Immediate:

Primary haemorrhage: either starting during surgery or

following post-operative increase in blood pressure - replace

blood loss and may require return to theatre to re-explore

wound.

Basal atelectasis: minor lung collapse.

Shock: blood loss, acute myocardial infarction,

pulmonary embolism or septicaemia.

Low urine output: inadequate fluid replacement intra- and

post-operatively.

B- Early:

Acute confusion: exclude dehydration and sepsis

Nausea and vomiting: analgesia or anaesthetic-related;

paralytic ileus

Fever

Secondary haemorrhage: often as a result of infection

Pneumonia

Wound or anastomosis dehiscence

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

Acute urinary retention

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

Post-operative wound infection

Bowel obstruction due to fibrinous adhesions

Paralytic Ileus

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 35

C- Late:

Bowel obstruction due to fibrous adhesions

Incisional hernia

Persistent sinus

Recurrence of reason for surgery, e.g. malignancy

o Post-operative fever

In total, 40% of patients develop pyrexia after major

surgery; however, in 80% of cases no particular cause is

found. Pyrexia does not necessarily imply sepsis. The

inflammatory response to surgical trauma may manifest as

temperature. In spite of this, a focus of infection must

always be sought if a patient develops anything more than a

slight pyrexia.

Days 0 to 2:

Mild fever (T <38 °C) (Common)

Atelectasis of microalveoli : the collapsed lung may

become secondarily infected

Tissue damage and necrosis at operation site

Haematoma

Persistent fever (T >38 °C)

Specific infections related to the surgery, e.g. biliary

infection post biliary surgery, UTI post-urological surgery

Blood transfusion or drug reaction

Days 3-5:

superficial and deep wound infection

Bronchopneumonia

Sepsis

Drip site infection or phlebitis

Abscess formation, e.g. subphrenic or pelvic, depending on

the surgery involved

DVT

Day 5: chest infection including viral respiratory tract infec-

tion, urinary tract infection and thrombophlebitis;

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 36

After 5 days:

Specific complications related to surgery, e.g. bowel

anastomosis breakdown, fistula formation, wound infection,

, intracavitary collections and abscesses;

• infected intravenous cannula sites, DVTs,

transfusion reactions, wound haematomas, atelectasis and

drug reactions,which may also cause pyrexia of non-

infective origin. Patients with persistent pyrexia need a

thorough review.

Relevant investigations include full blood count, urine

culture if urinary tract infection is suspected, sputum

microscopy, chest radiography if indicated and blood

cultures

After the first week

Wound infection

Distant sites of infection, e.g. UTI

DVT, pulmonary embolus (PE)

o Haemorrhage :

It is classified into :

1-Primary :occurs during surgery or immediately after it .

2-Reactionaly :occurs within 24 hr after surgery .

3-Secondary hemorrhage :occur 7days postoperatively. It is mainly

caused by infection.

o Infection

Infectious complications are the main causes of post-operative

morbidity in abdominal surgery.

Wound infection: most common form is superficial wound infection

occurring within the first week presenting as localised pain, redness and

slight discharge usually caused by skin staphylococci.

Cellulitis and abscesses:

Usually occur after bowel-related surgery

Most present within first week but can be seen as late as

third post-operative week, even after leaving hospital

Present with pyrexia and spreading cellulitis or abscess

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 37

Cellulitis is treated with antibiotics

Abscess requires suture removal and probing of wound but

deeper abscess may require surgical re-exploration. The

wound is left open in both cases to heal by secondary

intention

Gas gangrene is uncommon and life-threatening.

Wound sinus is a late infectious complication from a deep chronic

abscess that can occur after apparently normal healing. Usually needs

re-exploration to remove non-absorbable suture or mesh, which is often

the underlying cause.

o Disordered wound healing

Most wounds heal without complications and healing is not impaired in

the elderly unless there are specific adverse factors or complications.

Factors which may affect healing rate are:

A- Poor blood supply.

B- Excess suture tension.

C- Long term steroids.

D- Immunosuppressive therapy.

E- Radiotherapy.

F- Severe rheumatoid disease.

G- Malnutrition and vitamin deficiency.

D

D

i

i

s

s

o

o

r

r

d

d

e

e

r

r

w

w

o

o

u

u

n

n

d

d

s

s

h

h

e

e

a

a

l

l

i

i

n

n

g

g

i

i

n

n

c

c

l

l

u

u

d

d

e

e

:

:

1- Wound dehiscence and burst abdomen.

2-Incisional hernia

3-Stretched or ragged scar.

4-Hypertrophic scar .

5-Keloid .

o Surgical injury

Unavoidable tissue damage to nerves may occur during many

types of surgery, e.g. facial nerve damage during total

parotidectomy, impotence following prostate surgery or recurrent

laryngeal nerve damage during thyroidectomy.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 38

o Respiratory complications

Occur in up to 15% of general anaesthetic and major surgery and

include:

1- Atelectasis (alveolar collapse):

Caused when airways become obstructed, usually by

bronchial secretions. Most cases are mild and may go

unnoticed

Symptoms are slow recovery from operations, poor colour,

mild tachypnoea, tachycardia and low-grade fever

Prevention is by pre-and post-operative physiotherapy

In severe cases, positive pressure ventilation may be

required

2- Pneumonia:

requires antibiotics, physiotherapy.

3- Aspiration pneumonitis:

Sterile inflammation of the lungs from inhaling gastric

contents

Presents with history of vomiting or regurgitation with rapid

onset of breathlessness and wheezing. Non-starved patient

undergoing emergency surgery is particularly at risk

May help avoid this by crash induction technique and use of

oral antacids or metoclopramide

Mortality is nearly 50% and requires urgent treatment with bronchial

suction, positive pressure ventilation, prophylactic antibiotics and

IV steroids

4- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 39

o Common urinary problems :

A- Urinary retention: common immediate post-operative

complication that can often be dealt with conservatively with

adequate analgesia. If this fails may need catheterisation.

B- UTI: very common, especially in women, and may not present

with typical symptoms. Treat with antibiotics and adequate fluid

intake.

C- Acute renal failure

o Complications of bowel surgery

A- Delayed return of function:

Temporary disruption of peristalsis: may complain of

nausea, anorexia and vomiting and usually appears with the

re-introduction of fluids. Often described as ileus

More prolonged extensive form with vomiting and

intolerance to oral intake called adynamic obstruction and

needs to be distinguished from mechanical obstruction. If

involves large bowel usually described as pseudo-

obstruction. Diagnosed by instant barium enema

B- Early mechanical obstruction: may be caused by twisted or

trapped loop of bowel or adhesions occurring approximately 1

week after surgery. May settle with nasogastric aspiration plus IV

fluids or progress and require surgery.

C- Late mechanical obstruction: adhesions can organise and persist,

commonly causing isolated episodes of small bowel obstruction

months or years after surgery. Treat as for early form.

D- Anastomotic leakage or breakdown:

Small leaks are common causing small localised abscesses with

delayed recovery of bowel function. Usually resolves with IV

fluids and delayed oral intake but may need surgery.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 40

Major breakdown causes generalised peritonitis and progressive

sepsis needing surgery for peritoneal toilet, and antibiotics. Local

abscess can develop into a fistula.

o Thrombo-embolism

Major cause of complications and death after surgery. DVT is very

commonly related to grade of surgery.

Many cases are silent but present as swelling of leg, tenderness of calf

muscle and increased warmth with calf pain on passive dorsiflexion of

foot.

Diagnosis is by venography or Doppler ultrasound.

Pulmonary embolism:

Classically presents with sudden dyspnoea and

cardiovascular collapse with pleuritic chest pain, pleural rub

and haemoptysis. However, smaller PEs are more common

and present with confusion, breathlessness and chest pain

Diagnosis is by ventilation/perfusion scanning and/or

pulmonary angiography or dynamic CT

Management: intravenous heparin or subcutaneous low molecular

weight heparin for 5 days plus oral warfarin.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 41

Chapter IV

Surgical Drains

Topics

Indication of surgical drain

Principles of drains

Complications of surgical drain

Types of drains

Open passive drains

Closed passive drains

Closed active drains

Advantages of the closed drains

General guidance

Removal of surgical drain

42

42

42

43

43

43

44

44

44

45

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 42

Indication of surgical drain

Drains may be used for several reasons:

of fluid, blood, pus, air

(e.g.drainage of a subphrenic abscess, removal of a pneumothorax).

surgery to the bile duct) or potential abnormal fluids or air (e.g. bloody

fluid in the pelvis after rectal surgery).

-

threatening complications (e.g. neck drains after thyroid surgery, chest

drains after chest trauma in patients undergoing general anaesthesia).

Principles of drains

1) Must not be too rigid

2) Must not be too soft

3) Not of irritant material

4) Wide bore enough to function

5) Left for sufficient time so that when drain removed there is minimal

drainage

6) When used prophylactically e.g. duodenal stump or anastomotic

leak, the drain should be left in situ as long as the danger of perforation

exists, i.e. for 10 days, until a fibrous track is formed which will act as

an external fistula (with a safety-valve action).

7) To minimize the infection rate: drain from a separate wound, use

closed system and the shortest duration used.

The complications associated with abdominal drains include:

• trauma during insertion;

• failure to drain because of incorrect placement or blockage;

• complications caused by disconnection;

• sepsis at drain sites;

• drain site metastases;

• erosion by the drain of adjacent tissue and perforation of

abdominal viscera

• Drains do not always drain the substance required as expected and

may give a false sense of security, e.g. failure to drain bleeding after

thyroid surgery or failure to drain faecal fluid after anastomotic leakage

in rectal surgery. There is no place for outline use of drains after surgery

unless there is a clear indication.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 43

The quantity and character of drain fluid can be used to identify

any abdominal complication resulting in fluid leakage (e.g. bile or

pancreatic fluid) or bleeding. The excess loss of body fluids

through the drain should be replaced by additional intravenous

fluids. Blood loss through the drain should be investigated for the

source. Any underlying coagulopathy should be excluded by

checking the coagulation profile and platelet count. Angiography

may be useful to identify the source of blood loss.

The absence of blood in the drain does not exclude heavy

postoperative bleeding. If the patient’s blood pressure and urine

output are lower than expected the wound needs checking for a

collection. Inspection, palpation and ultrasound can all help

identify a developing haematoma.

Types of drains

Materials used include latex rubber (e.g. T tubes), silastic rubber (e.g.

long-term urinary catheters), polypropylene (e.g. abdominal drains),

polyurethane (e.g. nasogastric tubes).

Open passive drains

These provide a conduit around which secretions may flow

Closed passive drains

These drain fluid by gravity (siphon effect) or by capillary flow

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 44

Closed active drains

These generate active suction (low or high pressure)

xudrains®,Redivac drains ®, Minivac ®, Jackson Pratt drains (after

pelvic or breast surgery)

Redivac drains

Advantages of the closed drains

Can calculate the amount.

No risk of infections.

No need for frequent dressing.

General guidance

If active, the drain can be attached to a suction source (and set at a prescribed

pressure).

Ensure the drain is secured (dislodgement is likely to occur when transferring

patients after anaesthesia).

Dislodgement can increase the risk of infection and irritation to the

surrounding skin.

Accurately measure and record drainage output.

Monitor changes in character or volume of fluid. Identify any complications

resulting in leaking fluid (particularly, for example, bile or pancreatic

secretions) or blood.

Use measurements of fluid loss to assist intravenous replacement of fluids.

Drains are used to drain purulent collections, to prevent accumulation of

blood or to indicate the possibility of leaking surgical anastomoses.

In clean surgery, such as joint replacement, blood

collected in drains can be transfused back into the patient pro-

vided that an adequate volume (>150ml) is collected rapidly

(<12 hours) and that a specifically designed drain and filter

system is used.

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 45

The use of surgical drains has decreased in recent years as the

evidence for their benefits has been questioned. They can result

in complications and so should be used carefully.

Removal of surgical drain:

Generally, drains should be removed once the drainage has stopped or

becomes less than about 25 ml/day. as they are a potential track for

contamination and infection into a wound. Drainage of bile or

faecal matter indicates disruption of a biliary or intestinal anastomosis.

Drains can be 'shortened' by withdrawing them gradually (typically by

2 cm per day) and so, in theory, allowing the site to heal gradually.

Usually drains that protect postoperative sites from leakage form a

tract and are kept in place longer (usually for about a week).

Warn the patient that there may be some discomfort when the drain is

pulled out.

Consider the need for pain relief prior to removal.

Place a dry dressing

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 46

Chapter V

Suture types

Topics

Suture types

Suture sizes

Surgical needles

Surgical instrument

47

49

49

49

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 47

Suture types

Sutures come either as monofilament or braided:

* Monofilament sutures cause less reaction than do braided sutures, but

require more ties to assure an adequate maintenance of the knot compared to

braided suture. Monofilament sutures are usually non- absorbable.

* Braided suture usually incites a greater inflammatory response but,

requires fewer ties to maintain the knot

integrity. These include silk, cotton and Mersilene.

The strength of the sutures varies according to their size, which can be

determined by a uniformly applied number. For example, a 6-0 suture is

more delicate and has less strength than a 4-0 suture.

Sutures come as either absorbable or non absorbable:

Absorbable sutures are made of materials which are broken down in tissue

after a given period of time, which depending on the material can be from ten

days to eight weeks. They are used therefore in many of the internal tissues

of the body. In most cases, three weeks is sufficient for the wound to close

firmly. The suture is not needed any more, and the fact that it disappears is an

advantage, as there is no foreign material left inside the body and no need for

the patient to have the sutures removed.

Absorbable sutures were originally made of the intestines of sheep, the so

called catgut. However, the majority of absorbable sutures are now made of

synthetic polymer fibers, which may be braided or monofilament; these offer

numerous advantages over gut sutures, notably ease of handling, low cost,

low tissue reaction, consistent performance and guaranteed non-toxicity.

Natural Absorbable Sutures

1. Catgut Sutures- Plain catgut and Chromic catgut sutures

Synthetic Absorbable Sutures

2. Polyglycolic Acid Sutures (Vicryl) (PGA sutures)- coated and braided

suture

3. Polyglactin 910 Sutures (PGLA sutures)- coated and braided suture

4. Poliglecaprone Sutures (Monocryl) (PGCL sutures)- monofilament suture

5. Polydioxanone Sutures (PDS)- monofilament suture

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 48

Non absorbable sutures

are made of materials which are not metabolized by the body, and are used

therefore either on skin wound closure, where the sutures can be removed

after a few weeks, or in some inner tissues in which absorbable sutures are

not adequate. This is the case, for example, in the heart and in blood vessels,

whose rhythmic movement requires a suture which stays longer than three

weeks, to give the wound enough time to close. Other organs, like the

bladder, contain fluids which make absorbable sutures disappear in only a

few days, too early for the wound to heal. There are several materials used

for non absorbable sutures. The most common is a natural fiber, silk, which

undergoes a special manufacturing process to make it adequate for its use in

surgery. Other non-absorbable sutures are made of artificial fibers, like

polypropylene, polyester or nylon; these may or may not have coatings to

enhance their performance characteristics. Finally, stainless steel wires are

commonly used in orthopedic surgery and for sternal closure in cardiac

surgery.

Non-Absorbable Sutures:

1. Silk Sutures – Black Braided suture

2. Polypropylene sutures (Prolene)- monofilament suture

3. Nylon suture or Polyamide sutures- monofilament suture

4. Polyester sutures- coated and braided suture

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 49

SUTURE SIZES:

The size of suture material is measured by its width or diameter and is vital

to proper wound closure. As a guide the following are specific areas of their

usage:

1. 1-0 and 2-0: Used for high stress areas requiring strong retention, i.e. deep

fascia repair

2. 3-0: Used in areas requiring good retention, i.e. scalp, torso, and hands

3. 4-0: Used in areas requiring minimal retention, i.e. extremities. Is the

most common size utilized for

superficial wound closure.

4. 5-0: Used for areas involving the face, nose, ears, eyebrows, and eyelids.

5. 6-0: Used on areas requiring little or no retention. Primarily used for

cosmetic effects.

SURGICAL NEEDLES:

There are a variety of needles for wound closure. Curved needles have two

basic configurations; tapered and cutting. For wound and laceration care, the

reverse cutting needle is used almost exclusively. It is made in such a way

that the outer edge is sharp so as to allow for smooth and atraumatic

penetration of tough skin and fascia. Tapered needles are used on soft tissue,

such as bowel and subcutaneous tissue, or when the smallest diameter hole is

desired.

SURGICAL INSTRUMENTS:

It is not necessary to have large numbers of instruments for emergency

wound care. Wounds and lacerations can be managed with the following

instruments:

1.

NEEDLE HOLDERS:

Needle holders come in various sizes and shapes, but

for most lacerations a

standard size 4" will complete the task. For larger, deeper wound closures a

larger needle and needle holder may be required.

2.

FORCEPS:

Grasping and controlling tissue with forceps is essential to

proper suture placement. However, whenever force is applied to skin or other

tissues, inadvertent damage to cells can occur if an improper instrument or

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 50

technique is used. Be gentle when grasping tissue, and never fully close the

jaws on the skin.

3.

SCISSORS:

There are three types of scissors that are useful in minor

wound care.

a.

IRIS SCISSORS

: Iris scissors are predominantly used to assist in wound

debridement and revision. These scissors are very sharp and are appropriate

in situations that require very fine control. They are very delicate and are not

recommended for cutting sutures. However, when very small sutures require

removal they can be use.

b.

DISSECTION SCISSORS

: Used for heavier tissue revision as necessary for

wound undermining.

c.

SUTURE REMOVAL SCISSORS:

Standard 6-inch, single blunt-tip, suture

scissors are most useful for cutting sutures, adhesive tape, and other dressing

materials. Because of their size and bulk, these scissors are very durable and

practical.

4.

HEMOSTATS

: Hemostats have three functions in minor wound care:

clamping small blood vessels for

hemorrhage control, grasping and securing fascia during debridement, and

are an excellent tool for

exposing, exploring and visualizing deeper areas of the wound.

5.

KNIFE HANDLES AND BLADES:

The knife handle holds the blade and is

used in the debridement

and excisions during wound revision. Common blades are the #10 blade

(used for large excisions), #15 blade (small, versatile and well suited for

precise debridement and wound revision), and the #11 blade (ideal for

incision and drainage of superficial abscesses and the removal of very small

sutures).

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 51

Chapter VI

Shock

Topics

Introduction

Classification of shock

Severity of shock

pitfalls

Consequence of shock

Resuscitation of shock

Fluid therapy

Vasopressor and Inotropic support

Monitoring

52

52

54

56

57

58

58

60

60

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 52

Introduction

Shock is a systemic state of low tissue perfusion, which is inade-

quate for normal cellular respiration. With insufficient delivery of

oxygen and glucose, cells switch from aerobic to anaerobic

metabolism. If perfusion is not restored in a timely fashion, cell

death ensues.

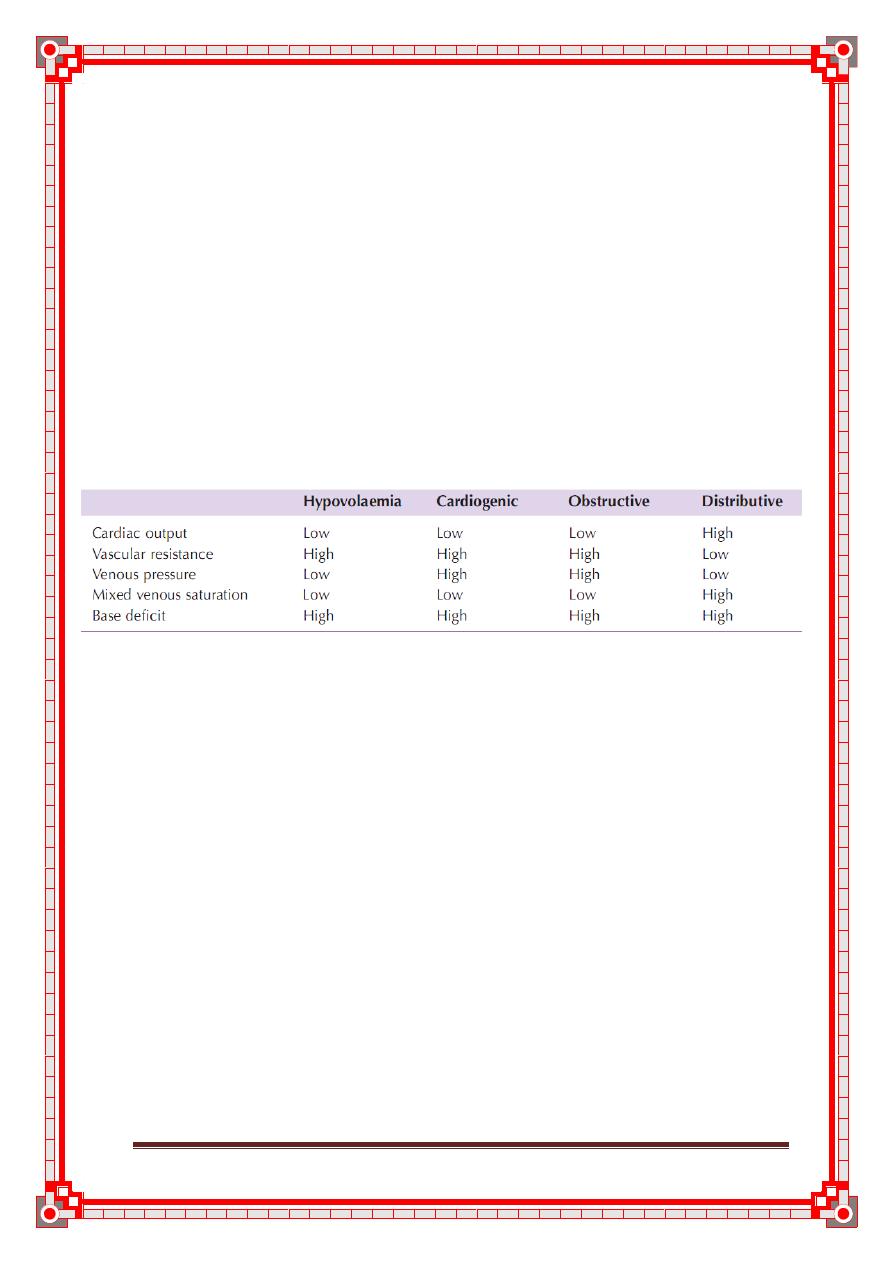

Classification of shock

There are numerous ways to classify shock but the most common

and clinically applicable way is that based on the initiating mechanism .

All states are characterised by systemic tissue hypoperfusion

and different states may coexist within the same patient.

Hypovolaemic shock

Hypovolaemic shock is caused by a reduced circulating volume.

Hypovolaemia may be due to haemorrhagic or non-haemorrhagic causes.

Non-haemorrhagic causes include poor fluid intake (dehydration) and

excessive fluid loss because of vomiting, diarrhoea, urinary loss (e.g.

diabetes), evaporation and ‘third-spacing’,in which fluid is lost into the

gastrointestinal tract and interstitial spaces, as for example in bowel

obstruction or pancreatitis.Hypovolaemia is probably the most common form

of shock and is to some degree a component of all other forms of shock.

Absolute or relative hypovolaemia must be excluded or treated in the

management of the shocked state, regardless of cause.

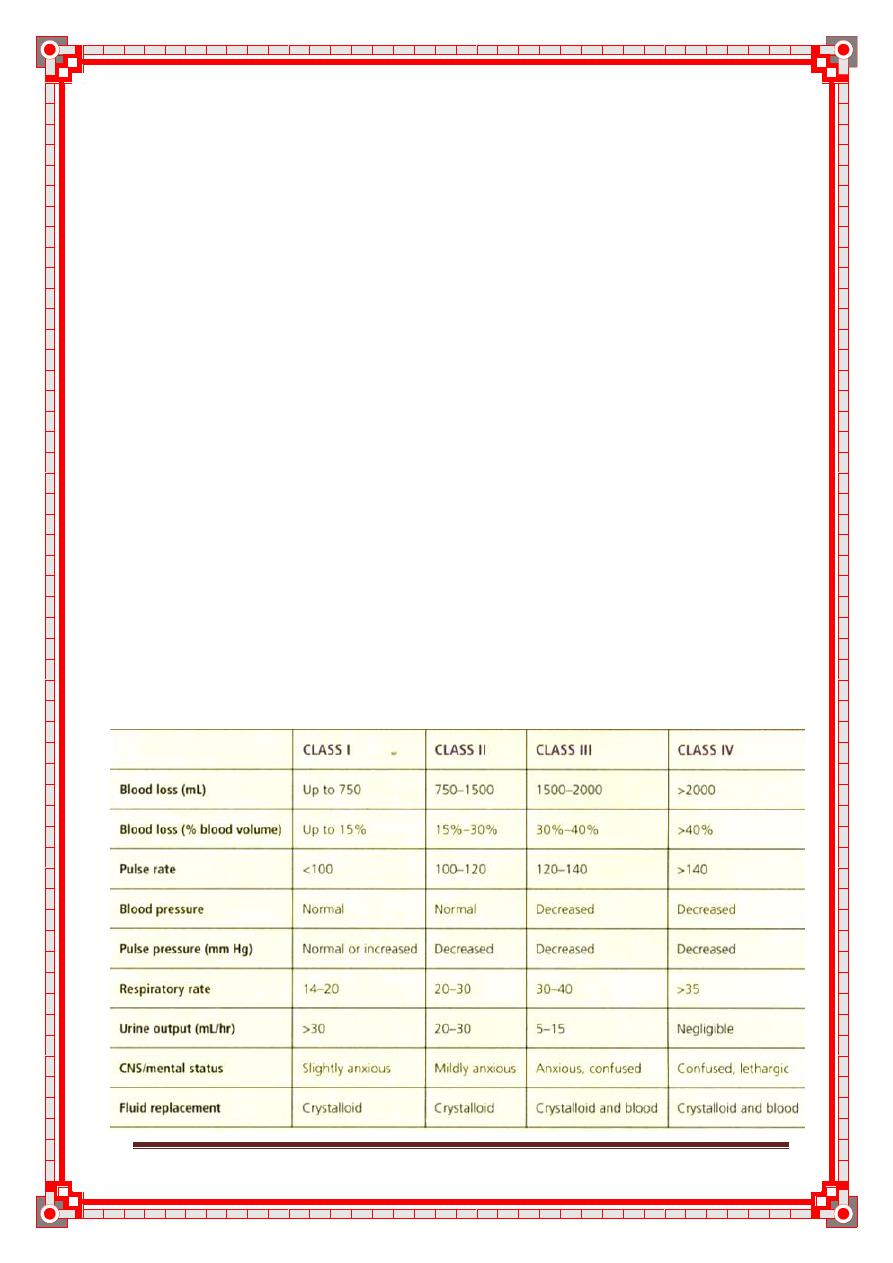

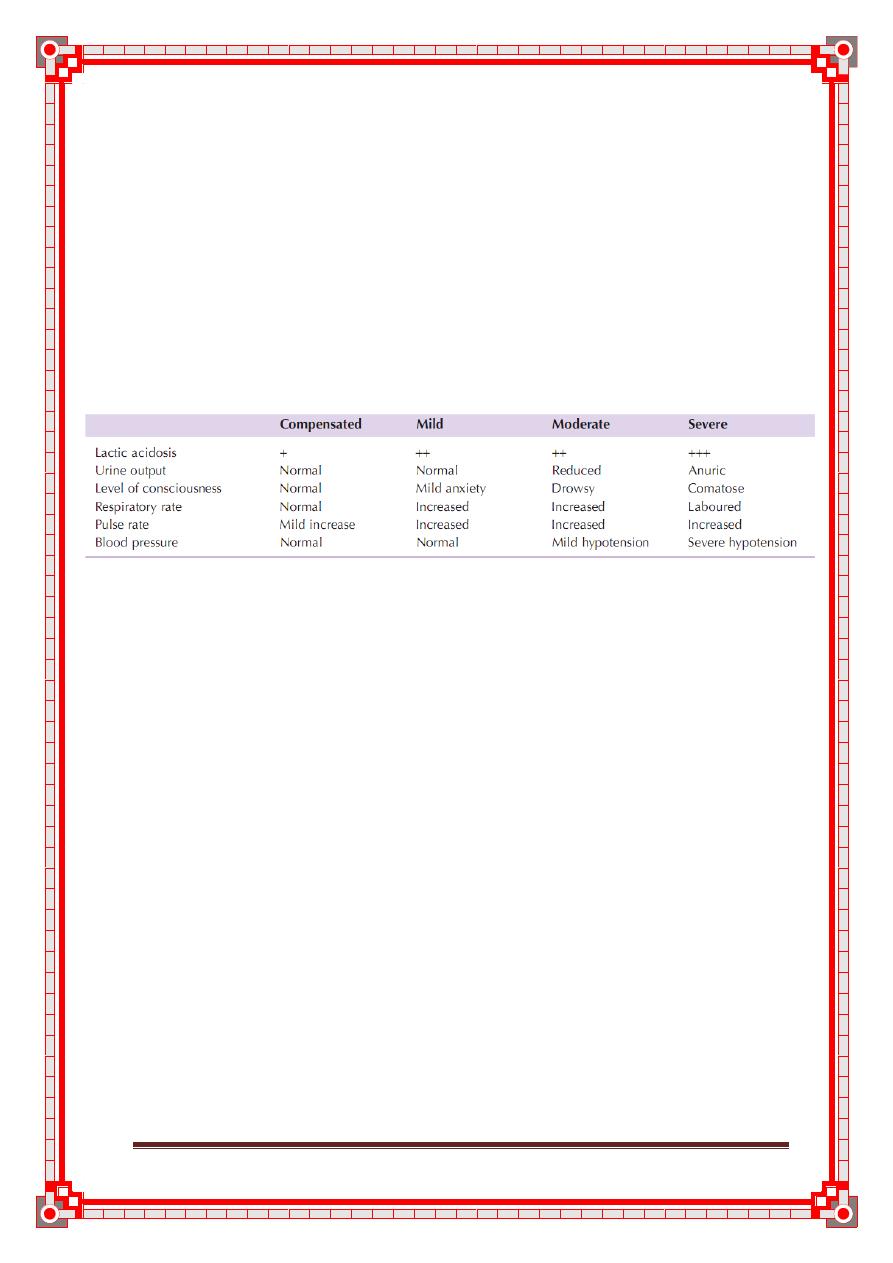

Table 5: Estimated blood loss based on initial patient presentation

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 53

Cardiogenic shock

Cardiogenic shock is due to primary failure of the heart to pump

blood to the tissues. Causes of cardiogenic shock include myocar-

dial infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias, valvular heart disease, blunt

myocardial injury and cardiomyopathy. Cardiac insufficiency may

also be caused by myocardial depression resulting from endogenous factors

(e.g. bacterial and humoral agents released in

sepsis) or exogenous factors, such as pharmaceutical agents or

drug abuse. Evidence of venous hypertension with pulmonary or

systemic oedema may coexist with the classic signs of shock.

Obstructive shock

In obstructive shock there is a reduction in preload because of

mechanical obstruction of cardiac filling. Common causes of

obstructive shock include cardiac tamponade, tension pneu-

mothorax, massive pulmonary embolus and air embolus. In each

case there is reduced filling of the left and/or right sides of the

heart leading to reduced preload and a fall in cardiac output.

Distributive shock

Distributive shock describes the pattern of cardiovascular

responses characterising a variety of conditions including septic

shock, anaphylaxis and spinal cord injury. Inadequate organ per-

fusion is accompanied by vascular dilatation with hypotension,

low systemic vascular resistance, inadequate afterload and a

resulting abnormally high cardiac output.

In anaphylaxis, vasodilatation is caused by histamine release,

whereas in high spinal cord injury there is failure of sympathetic

outflow and adequate vascular tone (neurogenic shock). The

cause in sepsis is less clear but is related to the release of bacterial

products (endotoxins) and the activation of cellular and humoral

components of the immune system. There is maldistribution of

blood flow at a microvascular level with arteriovenous shunting

and dysfunction of the cellular utilisation of oxygen.

In the later phases of septic shock there is hypovolaemia from

fluid loss into the interstitial spaces and there may be concomi-

tant myocardial depression, which complicates the clinical

picture .

New surgical booklet Anwar Qais Saadoon Basrah medical college 54

Endocrine shock

Endocrine shock may present as a combination of hypovolaemic,

cardiogenic and distributive shock. Causes of endocrine shock

include hypo- and hyperthyroidism and adrenal insufficiency.

Hypothyroidism causes a shock state similar to that of neurogenic

shock as a result of disordered vascular and cardiac responsive-

ness to circulating catecholamines. Cardiac output falls because

of low inotropy and bradycardia. There may also be an associated

cardiomyopathy. Thyrotoxicosis may cause a high-output cardiac failure.

Adrenal insufficiency leads to shock as a result of hypo-

volaemia and a poor response to circulating and exogenous cate-