1

Medicine Dr.Sabah

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME

UNSTABLE ANGINA & MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

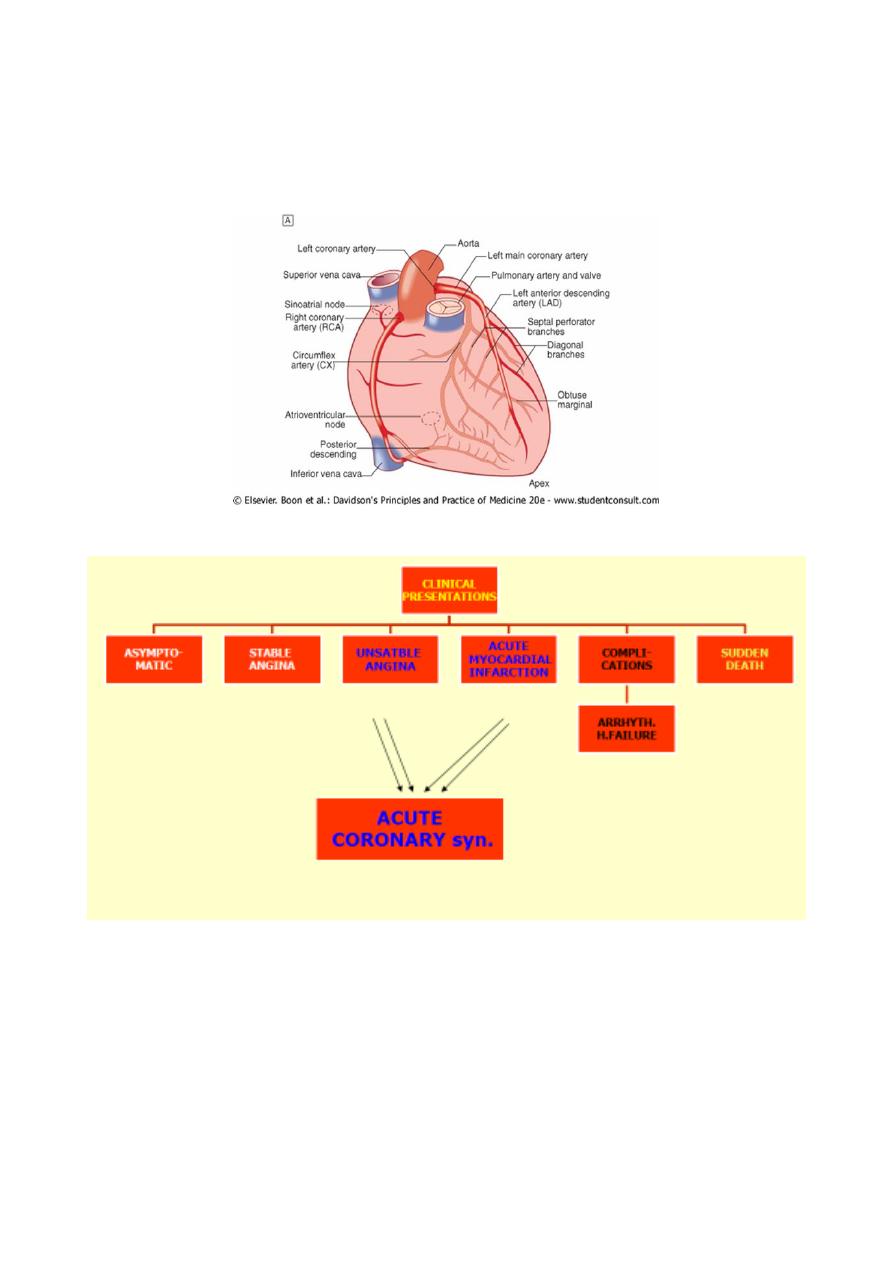

Coronary heart disease:

clinical manifestations and pathology

D Stable angina =Ischaemia = fixed atheromatous stenosis of one or more coronary A

D Unstable angina= Ischaemia = dynamic obstruction of a coronary artery == plaque

rupture or erosion with superimposed thrombosis

2

D Myocardial infarction= Myocardial necrosis = acute occlusion of a coronary artery

=plaque rupture or erosion with superimposed thrombosis

D Heart failure=Myocardial dysfunction =infarction or ischaemia

D Arrhythmia Altered conduction = ischaemia or infarction

D Sudden death Ventricular arrhythmia / asystole or /massive MI

ACS:

c Pathology, clinical manifestations,investigations

c Diagnosis and Risk stratification

c Management

- Early in the first 12-hours

- Late in-hospital management

c Complications and risk stratification

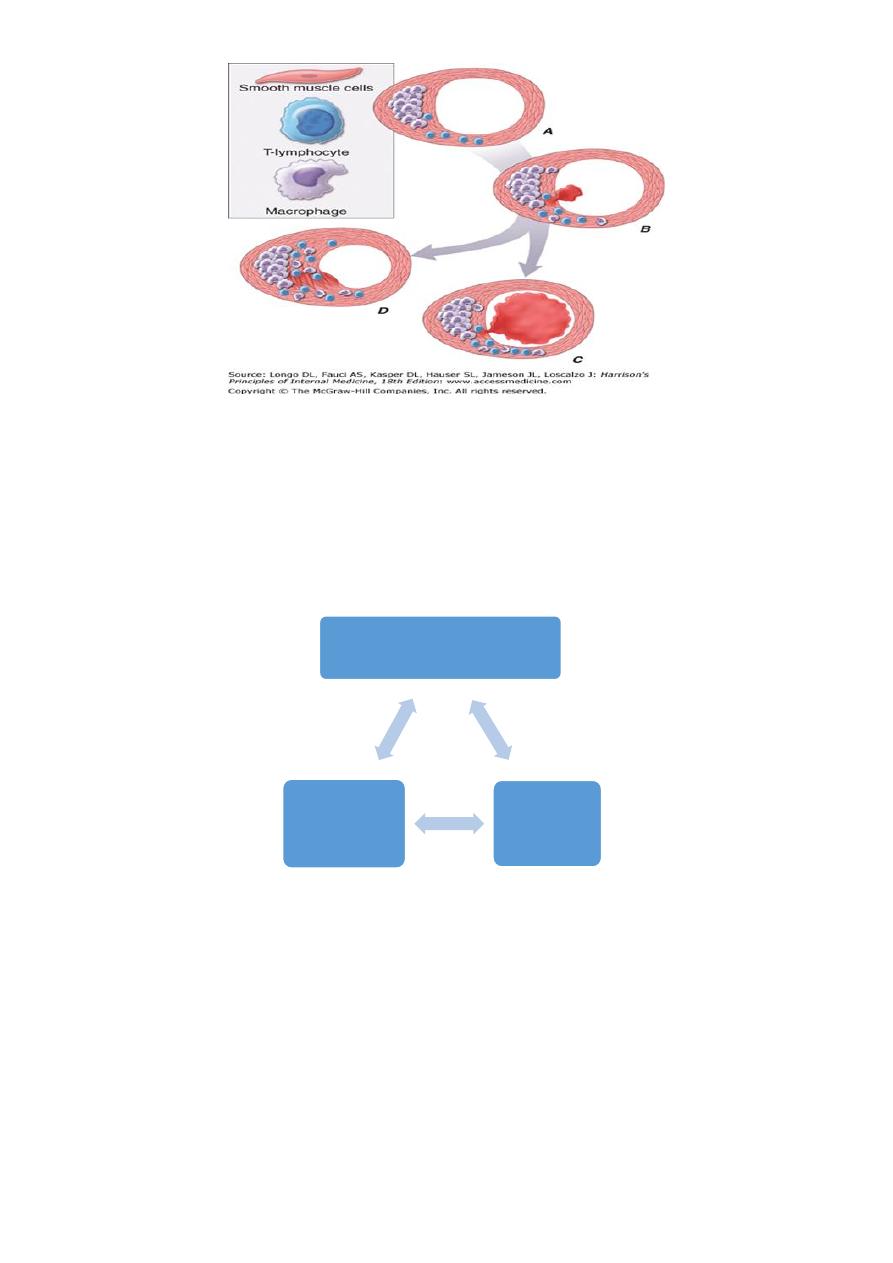

Pathologically

Z Culprit lesion = complex ulcerated or fissured atheromatous plaque + adherent

platelet-rich thrombus + local CA spasm .

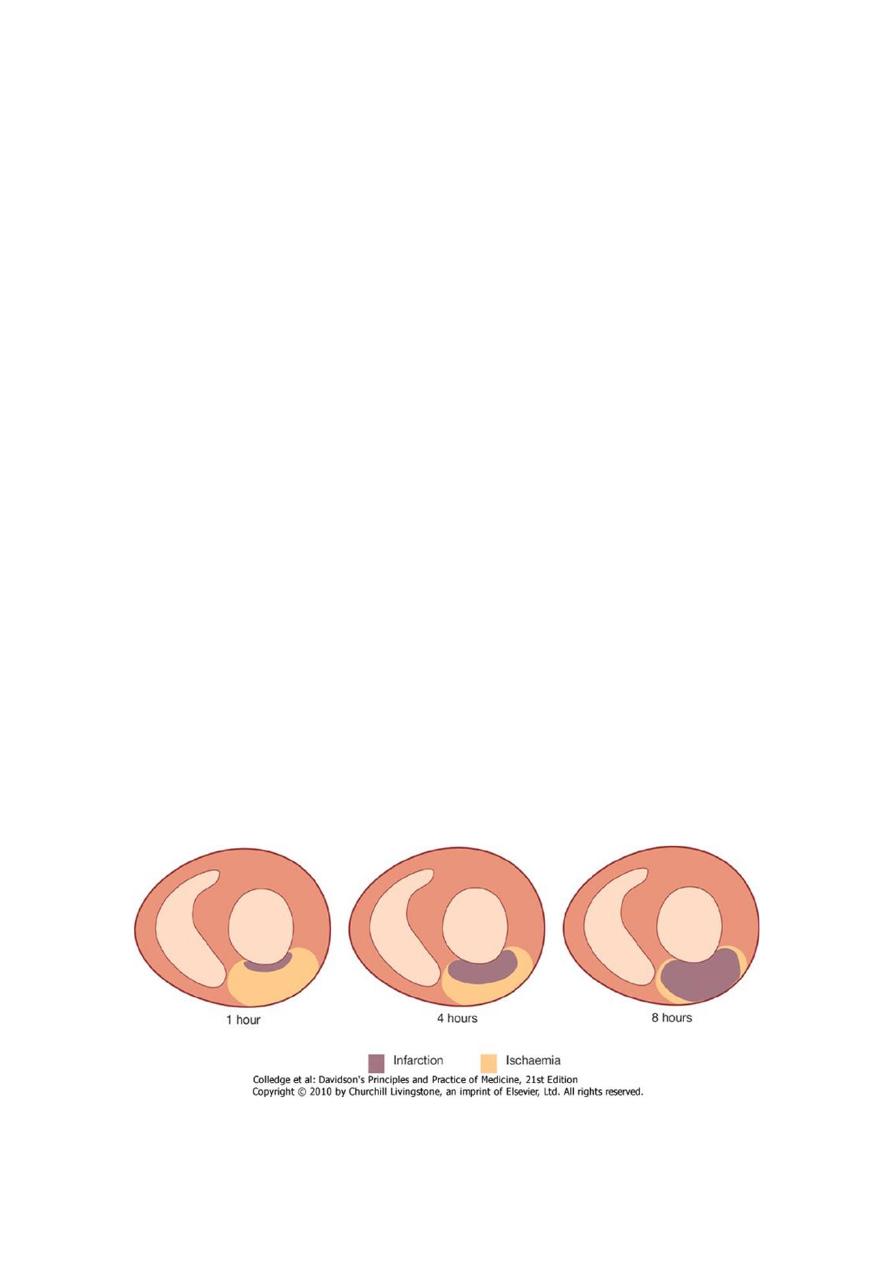

Z Dynamic process =degree of obstruction = increase complete vessel occlusion, or

regress (effects of platelet disaggregation and endogenous fibrinolysis.)

Z Acute MI= occlusive thrombus -at site of rupture or erosion of Ath.plaque

Z thrombus spontaneous lysis over next few days (irreversible myocardial damage

occurred).

Z Without treatment=infarct-related a. permanently occluded in 20-30% process of

infarction progresses over several hours and most p. present -still possible to salvage

myo. and improve outcome

3

Acute coronary syndrome

Both unstable angina and Myocardial infarction

ACS (1) new phenomenon or (2) against background of chronic stable A.

(Stable angina =Angina pectoris =symptom complex = transient myocardial ischaemia

1- Unstable angina =characterised by

1. new-onset or rapidly worsening angina (crescendo angina),

2. angina on minimal exertion or angina at rest . No myocardial damage

2- MI :symptoms occur at rest +evidence of myocardial necrosis (elevation in cardiac

troponin or creatine kinase-MB isoenzyme ) myocardial infarction =evidence of m.

necrosis in a clinical setting consistent with m. ischaemia

ACS

MI

UA

4

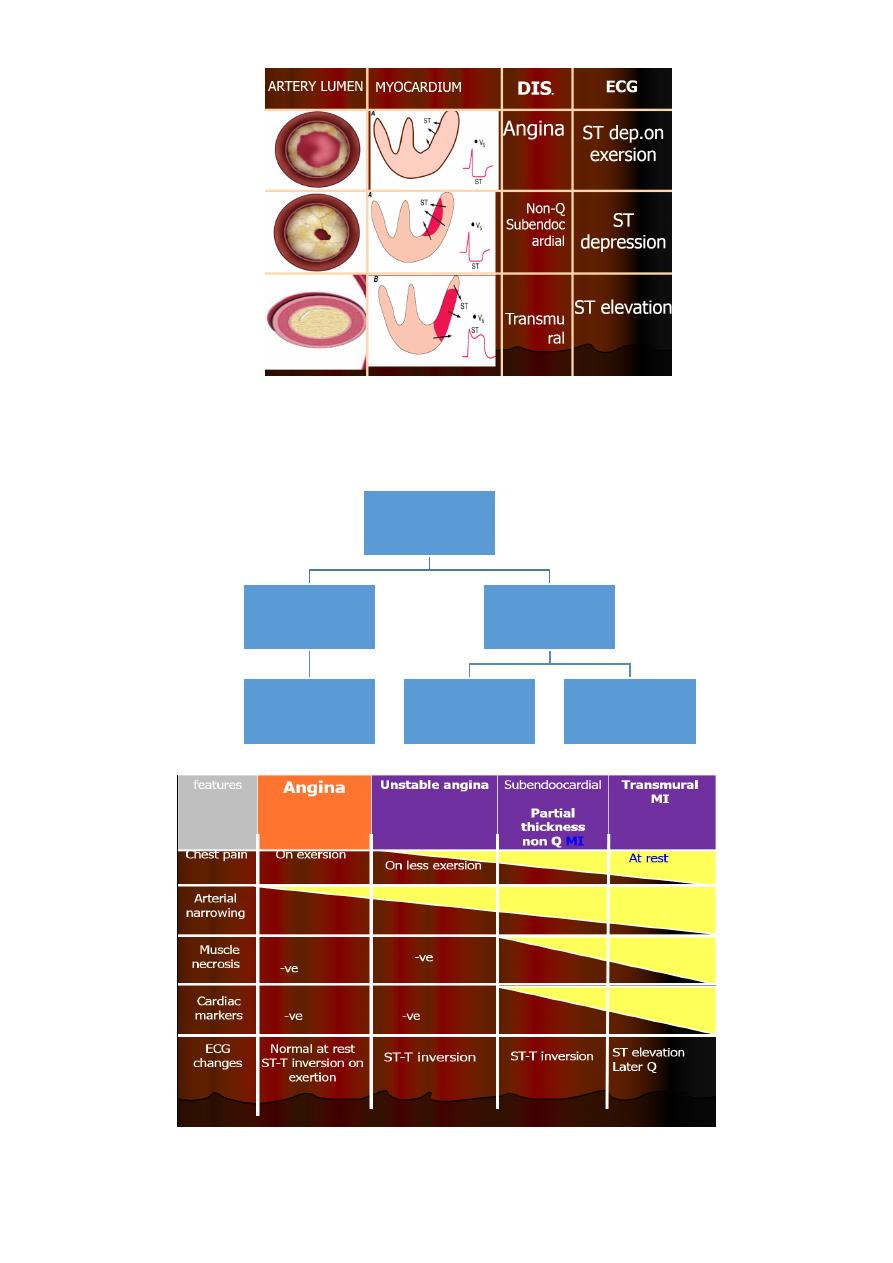

ACS-ECG PRESENTATION

ACUTE

CORONARY

SYNDROME

ST-ELEVATION

MI

TRANMURAL MI

(Q-WAVE MI)

NON-ST

ELEVAT.MI

UNSTABLE

ANGINA

SUB-

ENDOCARD.MI

(NON-Q MI)

5

CLINICAL FEATURES

SYMPTOMS

1. PAIN

2. PAINLESS-SILENT

3. BREATHLESSNESS

4. SYNCOPE

5. SUDDEN DEATH-ARRHYTHMIAS

6. CARDIAC FAILURE

SIGNS

1) GENERAL-SYMPATHETIC AND PARASYMPATHETIC

2) PULSE

3) BP

4) JVP

5) PRECORDIUM

Clinical features

¥ Pain =cardinal symptom, breathlessness, vomiting, and collapse are common features

same sites as angina, more severe , excruciating, and patient's expression and pallor

lasts longer than angina described as a tightness, heaviness or constriction in chest.

- Most patients are breathless (only symptom).

- Painless or 'silent' MI = common in older patients or those with DM.

- MI may pass unrecognised.

¥ syncope =(arrhythmia or profound hypotension).

- Vomiting and sinus bradycardia ( vagal stimulation) -particularly common in

patients with inferior MI.

- Nausea and vomiting(caused or aggravated by opiates given for pain relief).

¥ Sudden death(from VF or asystole) immediately and often within the first hour

- Liability to dangerous arrhythmias remains (If the patient survives this most critical

stage) but diminishes as each hour goes by.

- Development of cardiac failure reflects the extent of myocardial ischaemia major

cause of death in those who survive the first few hours

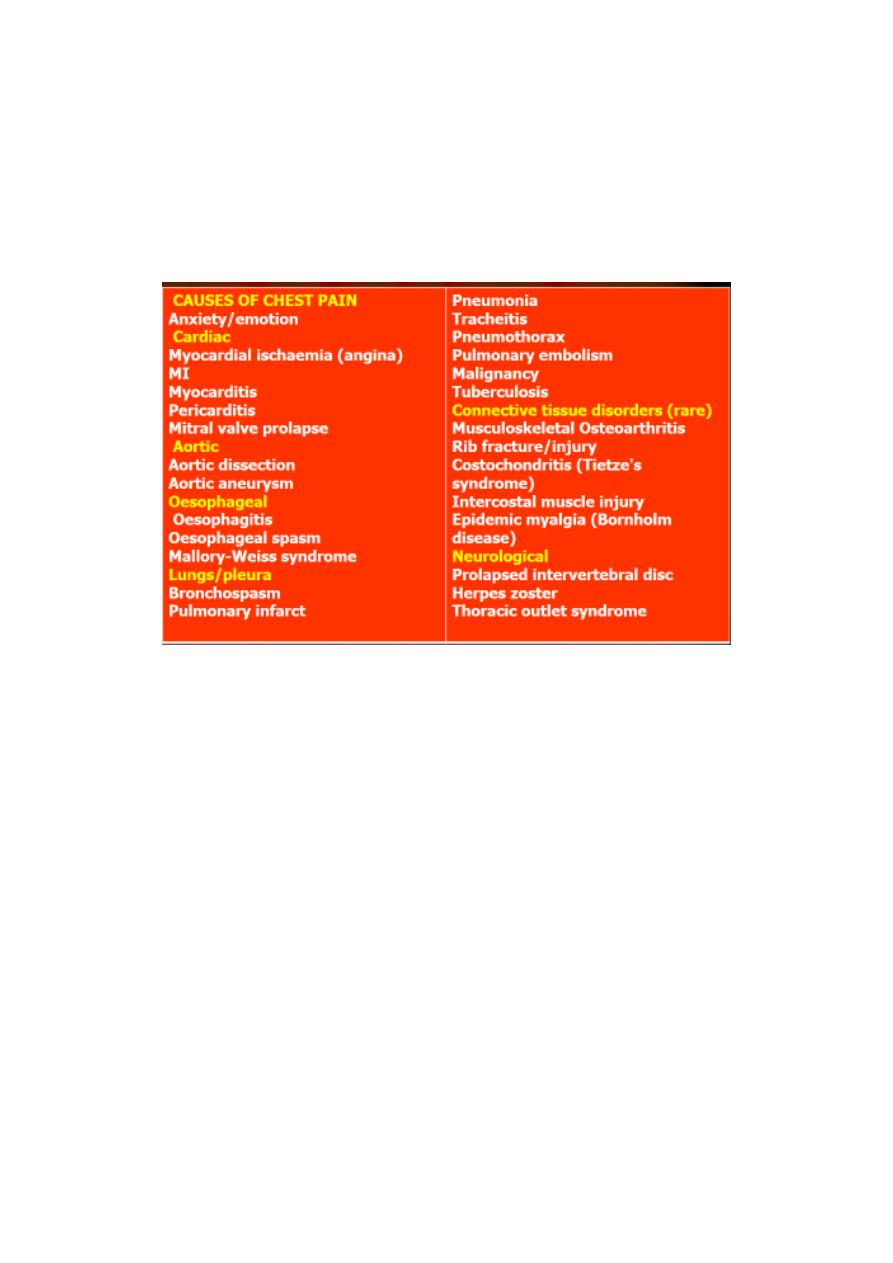

Diagnosis and risk stratification

3 Differential diagnosis includes causes of

1- central chest pain

2- collapse

6

3 Assessment of acute chest pain

3 Risk stratification

3 ECG

3 CARDIAC MARKERS(ENZYMES & PROTEINS)

DIAGNOSIS & DIFFERENTILA DIAGNOSIS

1- central chest pain

2-Shock/collapse:

Causes of circulatory failure or 'shock' -categorised

1) low flow (Low stroke volume )

- Hypovolaemic:

- Cardiogenic:

- Obstructive:

2) low peripheral arteriolar resistance (Vasodilatation )

- Septic/SIRS:

- Anaphylactic:.

- Neurogenic:

3- Syncope and presyncope

Syncope=sudden loss of consciousness =reduced cerebral perfusion.

Presyncope=lightheadedness =.

a. Structural heart disease

b. Neurocardiogenic syncope abnormal autonomic reflexes.

c. Situational syncope identifiable triggers

7

DIAGNOSIS

* CLINICAL

* ECG

* ENZYMES AND PROTIENS(From necrosed muscle)

Universal definition of myocardial infarction

o Detection of rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarkers (preferably troponin), with at least

one value above the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit, together with at

least one of the following:

o Symptoms of ischaemia

o ECG changes indicative of new ischaemia (new ST-T changes or new LBBB)

o Development of pathological Q waves

o Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion

abnormality

o Identification of an intracoronary thrombus by angiography of post-mortem

cardiac death, with symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischaemia, and Presumed new

ischemic ECG changes or new left bundle branch block but death occurring before cardiac

biomarkers were obtained ,or before cardiac biomarkers values would be increased

INVESTIGATIONS

1) Electrocardiography (ECG)

2) Plasma cardiac markers

3) Other blood tests

4) Chest X-ray

5) Echocardiography

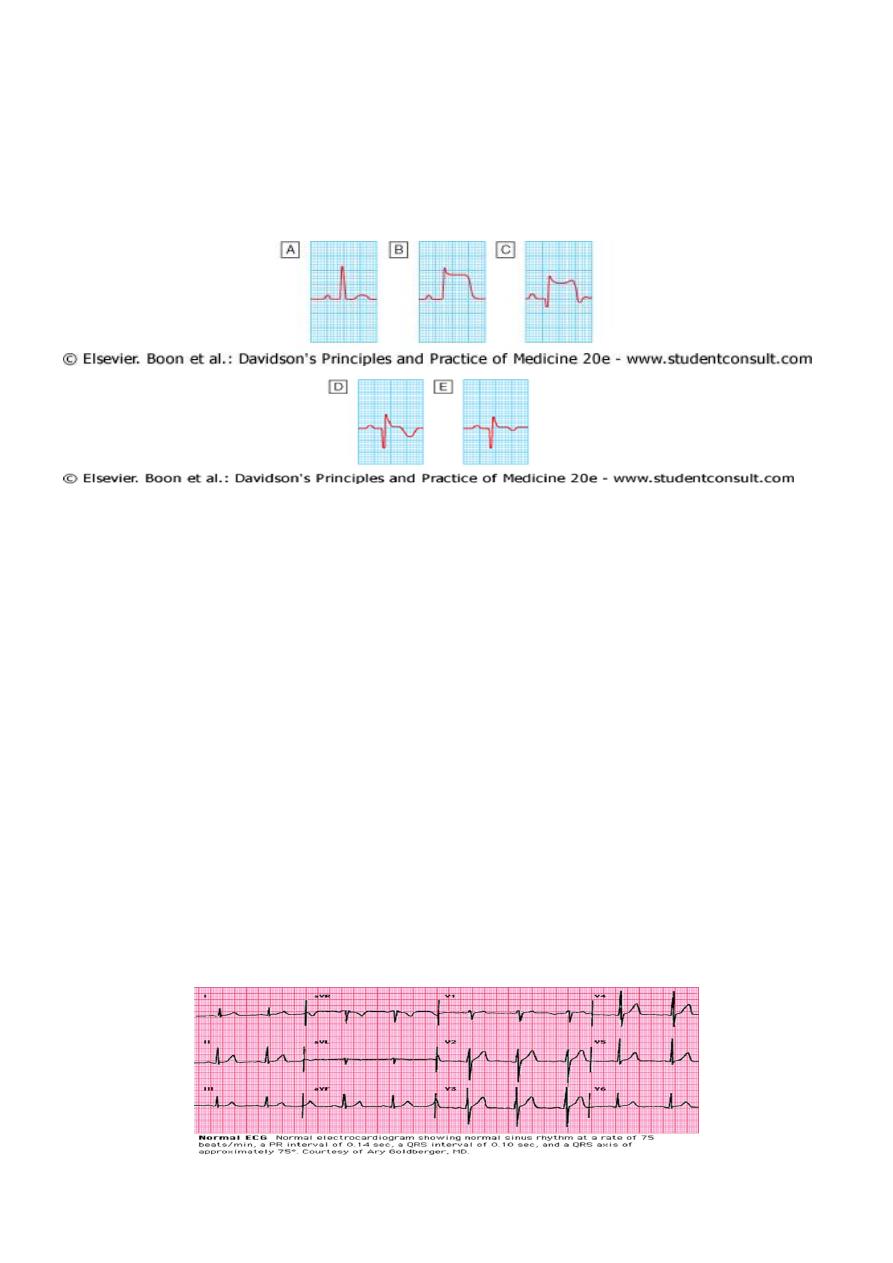

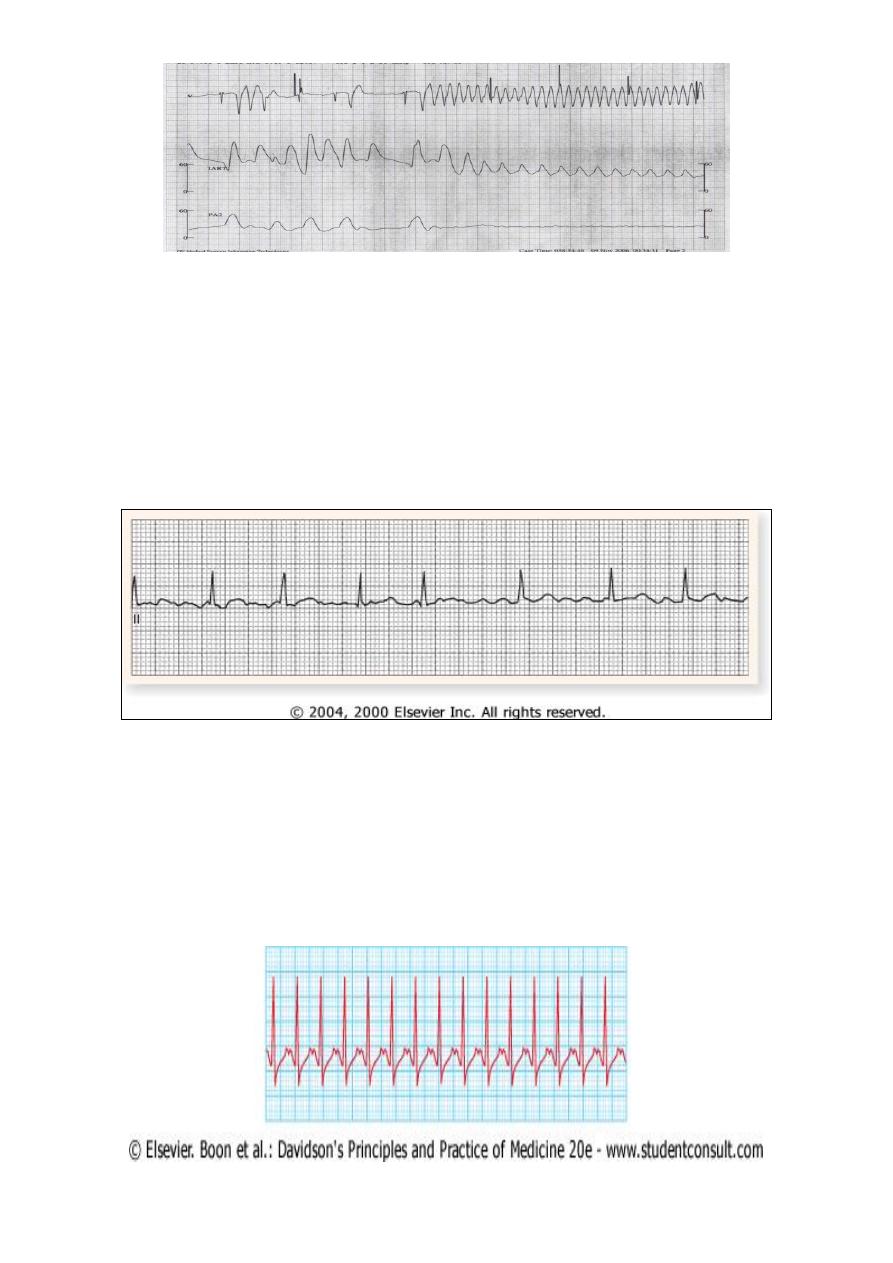

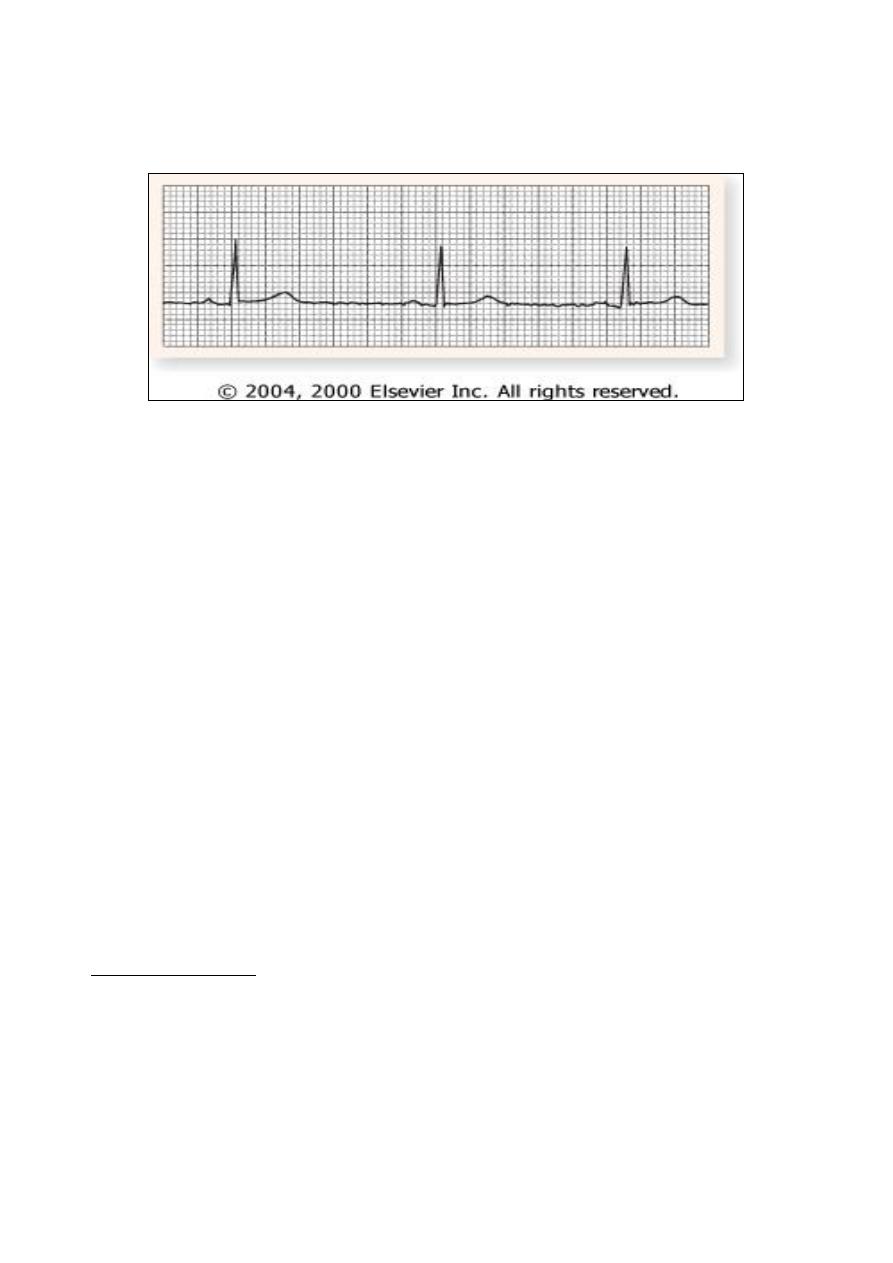

ECG in MI

may be difficult to interpret if there is bundle branch block or previous MI.

Initial ECG may be normal or non-diagnostic in one-third of cases. Repeated ECGs are

important, especially where the diagnosis is uncertain or patient has recurrent or

persistent symptoms

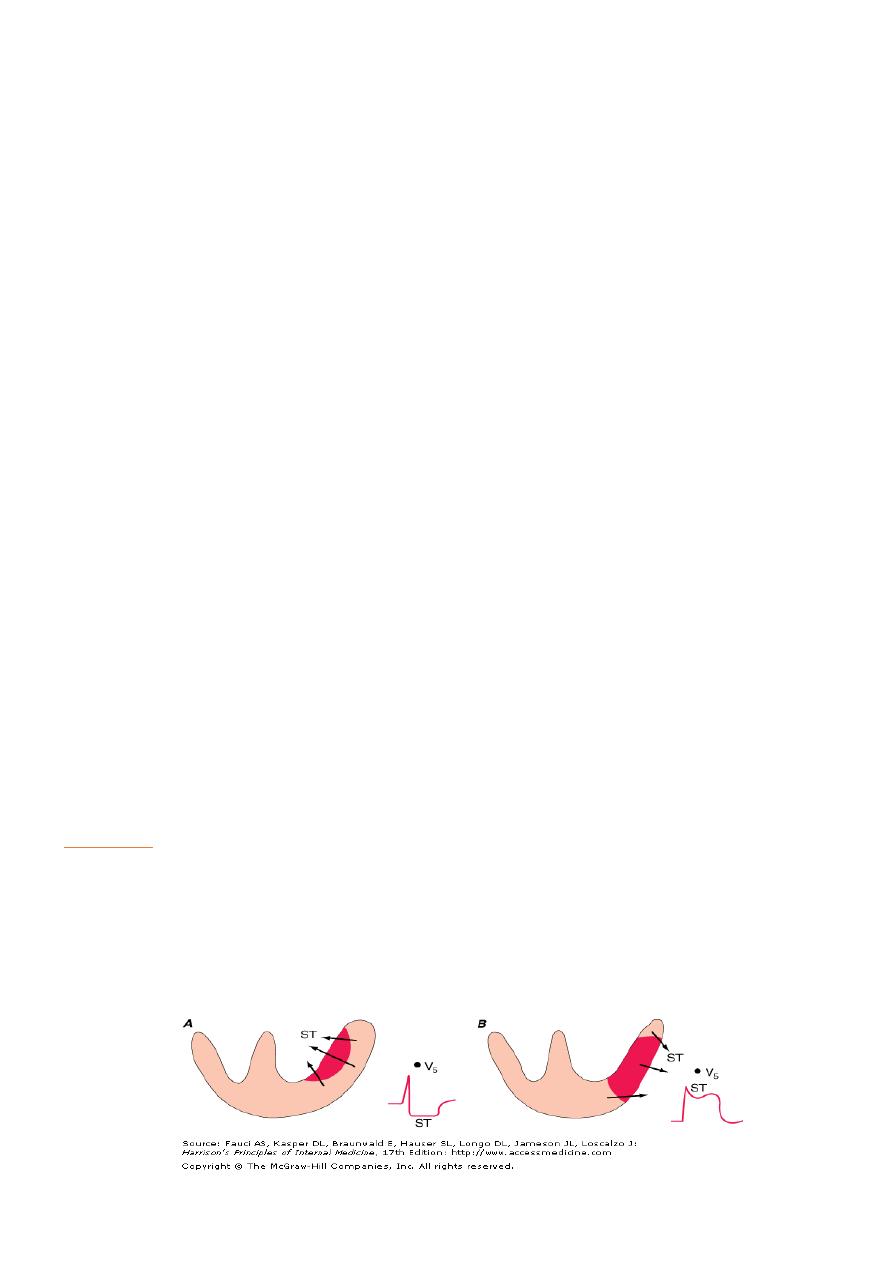

1. ST elevation ACS =proximal occlusion of major coronary a

2. non-ST segment ACS= =partial occlusion of a major vessel or complete occlusion of a

minor vessel

8

1- ST elevation ACS,

` ST-segment elevation (or new bundle branch block) -initially

` later diminution in size of R wave, in transmural (full thickness) infarctionQ wave.

` Subsequently, T wave becomes inverted (change in V. repolarisation) this change

persists after ST segment has returned to normal.

` sequential features sufficiently reliable for approximate age of infarct to

2- non-ST segment ACS unstable angina or partial-thickness (subendocardial) MI.

usually associated with ST-segment depression and T-wave changes.

In the presence of infarction=may be accompanied by some loss of R waves in the

absence of Q waves .

SITE (WALLS)

8 ECG changes best seen in leads that 'face' ischaemic or infarcted area.

8 Anteroseptal infarction=abnormalities in one or more leads from V1 to V4

8 Anterolateral infarction = changes from V4 to V6, in aVL and in lead I.

8 Inferior infarction =leads II, III and aVF, at the same time leads I, aVL and anterior

chest leads may show 'reciprocal' changes of ST depression .

8 Infarction of posterior wall of LV does not cause ST elevation or Q waves in the

standard leads can be diagnosed by the presence of reciprocal changes (ST depression

and a tall R wave in leads V1-V4).

8 Right ventricle=Some infarctions (especially inferior) also involve the RV.

8 identified by recording from additional leads placed over Rt.precordium normal ECG.

9

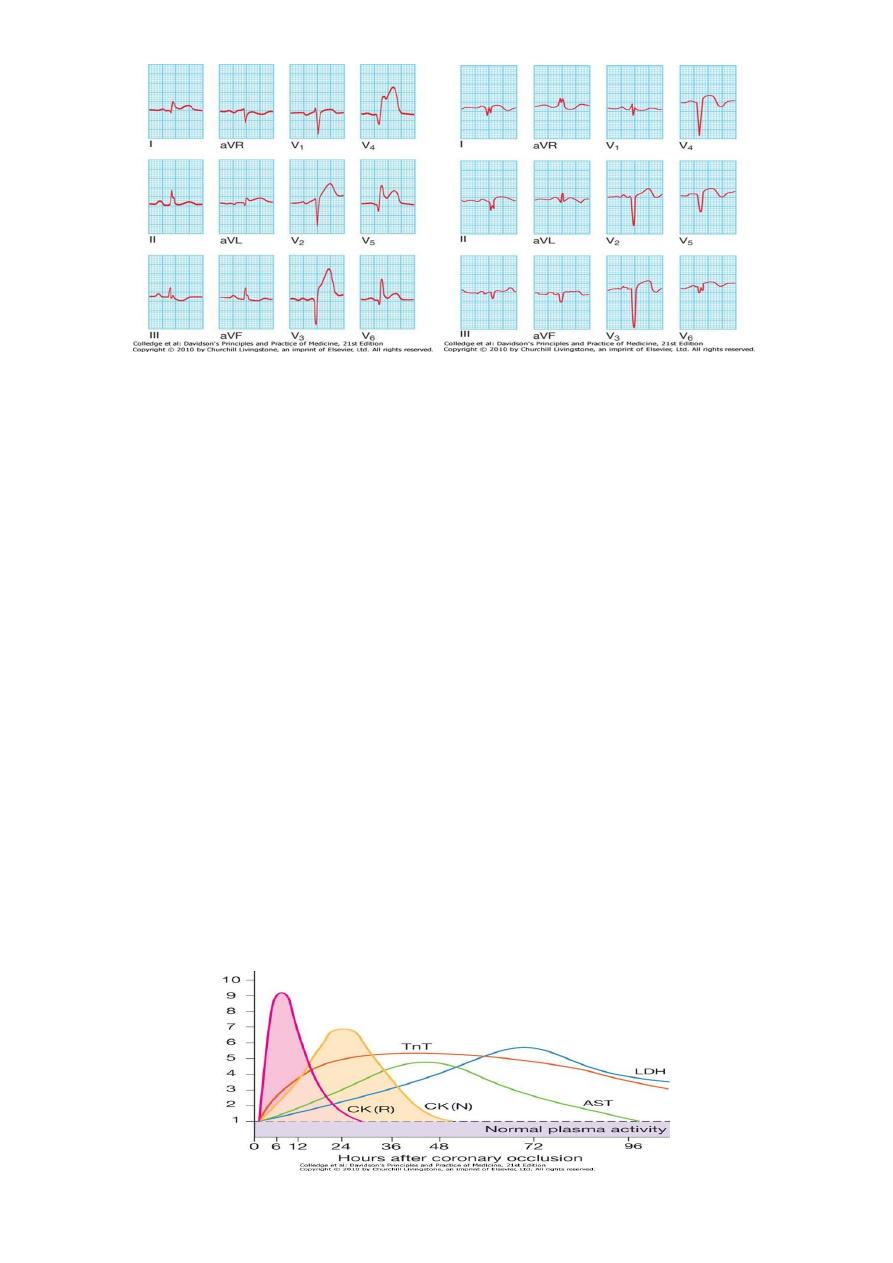

Plasma cardiac markers

E Unstable angina=no detectable rise in cardiac markers or enzymesthe initial diagnosis

is made from the clinical history and ECG only.

E MI = rise in plasma concentration of enzymes and proteins that are normally

concentrated within cardiac cells.

biochemical markers =

1- creatine kinase (CK) more sensitive and cardiospecific isoform of this enzyme (CK-

MB),

2- cardiospecific proteins

- troponins T and I .

- Admission and serial (usually daily) estimations = helpful =change in plasma

concentrations of these markers that confirms the diagnosis of MI .

CK starts to rise at 4-6 hours, peaks at about 12 hours and falls to normal within 48-72

hours. CK is also present in skeletal muscle, and a modest rise in CK (but not CK-MB) may

sometimes be due to an intramuscular injection, vigorous physical exercise or,

particularly in older people, a fall. Defibrillation causes significant release of CK but not

CK-MB or troponins.

Most sensitive markers of myocardial cell damage =cardiac troponins T and I=released

within 4-6 hours and remain elevated for up to 2 weeks

10

Risk stratification

Assessment of acute chest pain depends on

1- analysis of character of the pain and its associated features,

2- evaluation of ECG,

3- serial measurements of biochemical markers of cardiac damage, such as troponin I

and T.

A 12-lead ECG is mandatory and defines initial triage, management and treatment .

1) Patients with ST segment elevation or new bundle branch block require emergency

reperfusion therapy .

2) patients with acute coronary syndrome without ST segment elevation, ECG may show

transient or persistent ST/T wave changes including ST depression and T-wave

inversion.

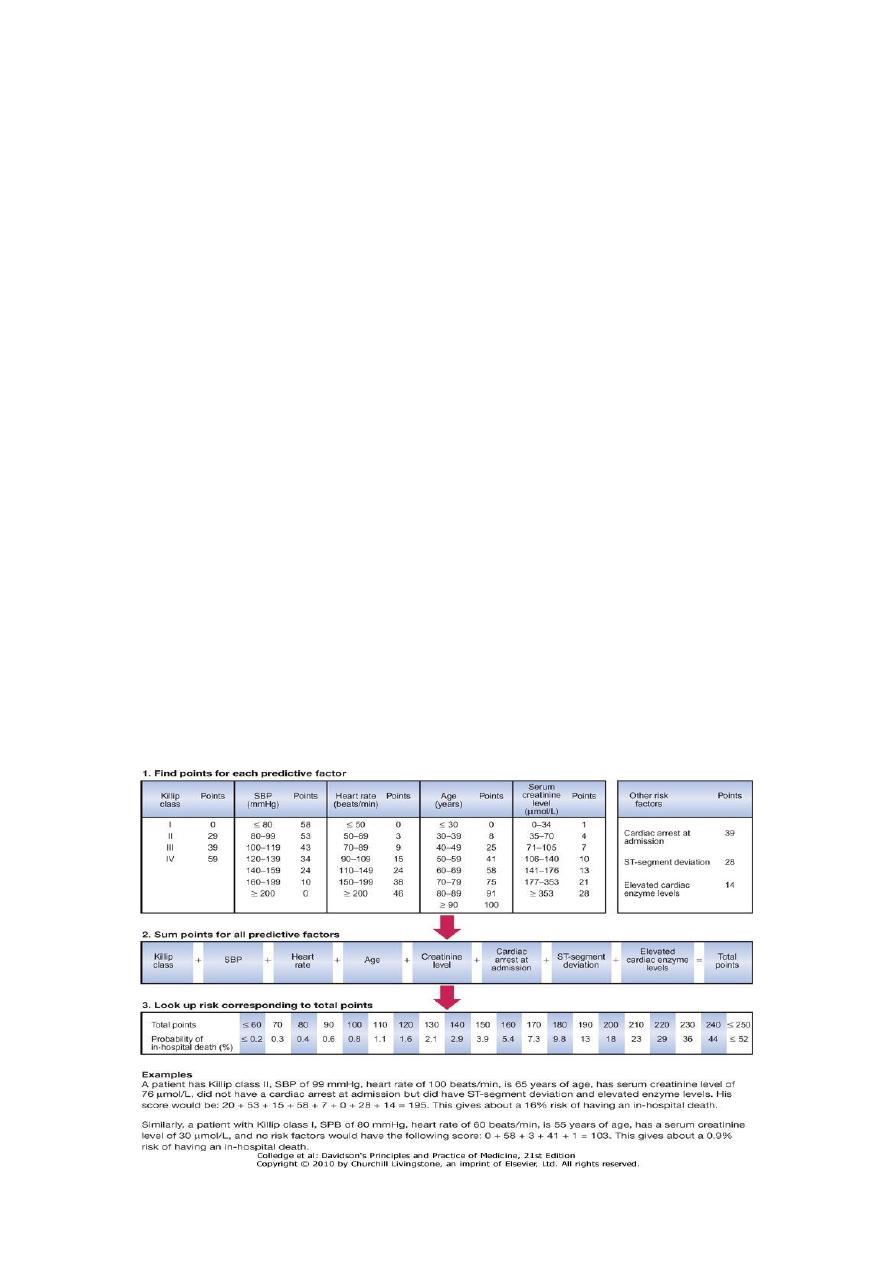

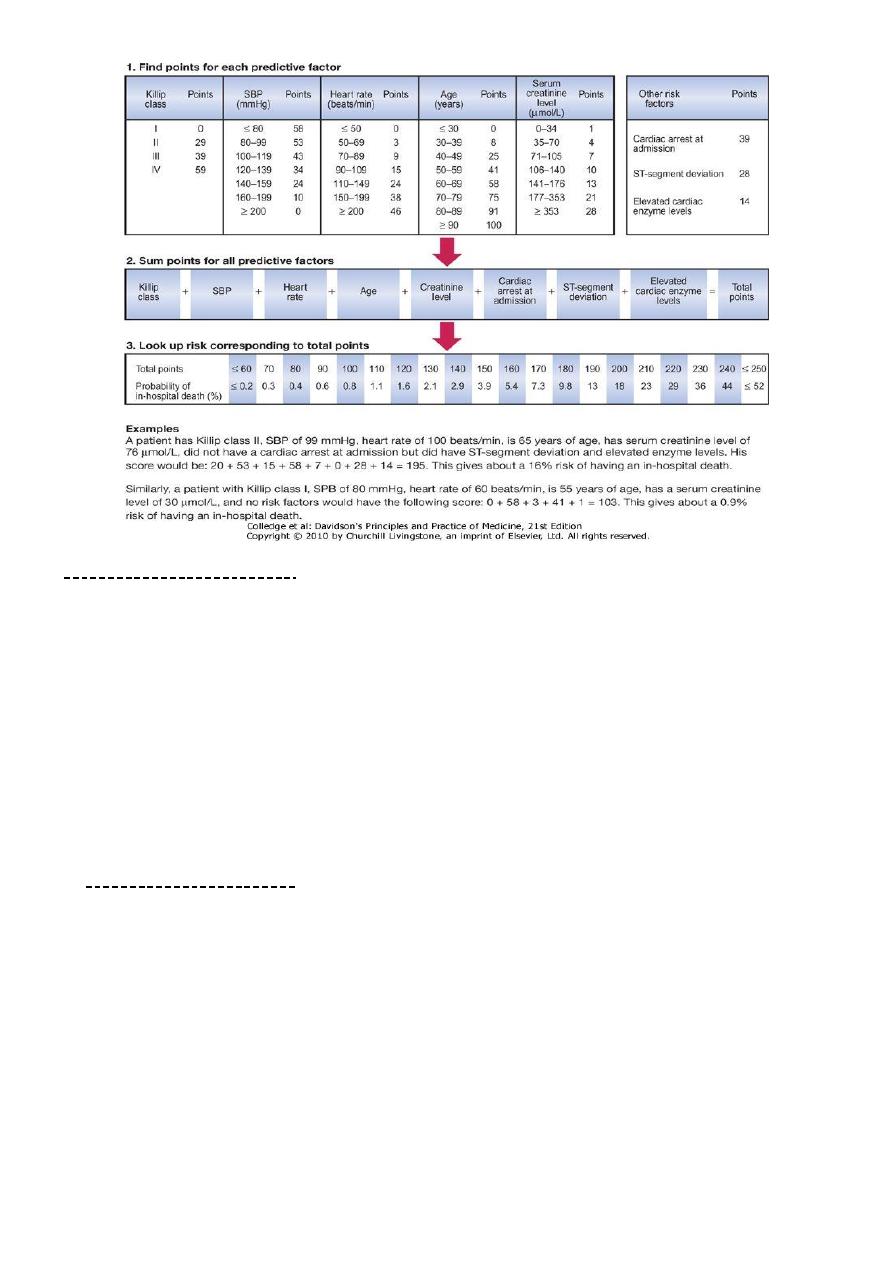

GRACE SCORE

Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events

C Hx of cardiac arrest at admission=39

C Age=0-100(<30->90)

C Dyspnea=killip class(HF)=0-59

C Pulse=0-48(<50->200)

C SBP=0-58(>200-<80)

C ST segment deviation=28

C Enzymes=14

C S.creatinine=1-28(34->353)

11

Risk stratification

Approximately 12% of patients will die within 1 month

fifth within 6 months of the index event.

Risk markers that are indicative of an adverse prognosis

1- recurrent ischaemia,

2- extensive ECG changes at rest or during pain,

3- release of biochemical markers (creatine kinase or troponin),

4- arrhythmias,

5- recurrent ischaemia and

6- haemodynamic complications (e.g. hypotension, mitral regurgitation) during

episodes of ischaemia.

MANAGEMENT OF ACS

IN THE FIRST 12 HR.

O GENERAL ANALGESIA

- ANTI-THROMBOTIC THERAPY

- ANTI-PLATELET

- ANTI-COAGULANT

- ANTI-ANGINAL THERAPY

O SPECIFIC-Reperfusion

TREATMENT OF COMPLICATIONS-

O LATER-AFTER 12 HR :

o risk stratification

o life style change

o mobilization and rehabilitation

o secondary prevention

o device therapy

CAD= CH.STABLE ANGINA

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME(ACS)

UA

NON-ST ELEVATION

SUBENDOCARDIAL

NON-ST ELEVATION MI

TRANSMURAL

ST-ELEVATION MI

12

Immediate management:

first 12 hours

Admission urgently to hospital significant risk of death or recurrent myocardial

ischaemia during the early unstable phase,

Appropriate medical therapy can reduce incidence of these by at least 60%.

Patients are usually managed in a dedicated cardiac unit where the necessary

expertise, monitoring and resuscitation facilities can be concentrated.

If no complications --> mobilize from the 2

nd

. Day discharge from hospital after 3-5

days

13

1- Analgesia

Adequate analgesia = essential to

a. relieve distress

b. lower adrenergic drive -->reduc vascular resistance, BP infarct size susceptibility to

ventricular arrhythmias.

IV opiates

o initially morphine sulphate 5-10 mg or diamorphine 2.5-5 mg + antiemetics (initially

metoclopramide 10 mg) = administered and titrated by giving repeated small aliquots

until the patient is comfortable.

o ( IMr injections -avoided clinical effect may be delayed by poor skeletal muscle

perfusion painful haematoma may form following thrombolytic or anti-thrombotic

therapy

2- Antithrombotic therapy

A) Antiplatelet therapy

1. maintain patency of infarct-related artery,

2. reduce tendency to thrombosis and likelihood of mural thrombus formation or

deep venous thrombosis,

1. Aspirin oral -75-300 mg daily (First tablet (300 mg) 25% relative risk reduction

in mortality. continued indefinitely.

2. Clopidogrel 600 mg

150 mg daily for 1 week

75 mg daily with aspirin-

further reduction in ischaemic events .

14

3. ACS with or without ST-segment elevation, ticagrelor (180 mg followed by 90

mg 12-hourly) more effective than clopidogrel in reducing vascular death, MI

or stroke, and all-cause death without affecting overall major bleeding risk

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists, (tirofiban and abciximab) block final

common pathway of platelet aggregation potent inhibitors of platelet-rich thrombus

formation. ACS who undergo PCI , recurrent ischaemia those at particularly high

risk,(patients with DM or an elevated troponin ) -

B) Anticoagulants

reduces risk of thromboembolic complications

prevents reinfarction

1. in absence of reperfusion therapy or

2. after successful thrombolysis .

achieved using

unfractionated heparin, fractioned (LMW) heparin or pentasaccharide.

pentasaccharides (s.c fondaparinux 2.5 mg daily) best safety and efficacy low

molecular weight heparin (sc enoxaparin 1 mg/kg 12-hr =alternative.

Anticoagulation -continued for 8 days or until discharge from hospital or coronary

revascularisation.

A period of treatment with warfarin -considered if there is

1- persistent atrial fibrillation or

2- evidence of extensive anterior infarction, or

3- if echocardiography-mobile mural thrombus- (systemic thromboembolism)

3-Anti-anginal therapy

NITRATES: Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (300-500 μg) -first-aid measure in unstable

angina or threatened infarction, intravenous nitrates (GTN 0.6-1.2 mg/hr or isosorbide

dinitrate 1-2 mg/hr) =treatment of LV failure and relief of recurrent or persistent

ischaemic pain

B-BLOCKERS

Intravenous β-blockers (atenolol 5-10 mg or metoprolol 5-15 mg -over 5 mins) relieve

pain, reduce arrhythmias, improve short-term mortality in patients who present

within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms .

avoided =heart failure (pulmonary oedema) = hypotension (systolic BP < 105 mmHg)

or bradycardia (HR< 65/min).

CALICIUM CHANNEL BLOCKERS

Dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist (e.g. nifedipine or amlodipine) added to

β-blocker i(persistent chest discomfort )-cause unwanted tachycardia -used alone.

15

Because of their rate-limiting action, verapamil and diltiazem are the calcium channel

antagonists of choice if a β-blocker is contraindicated

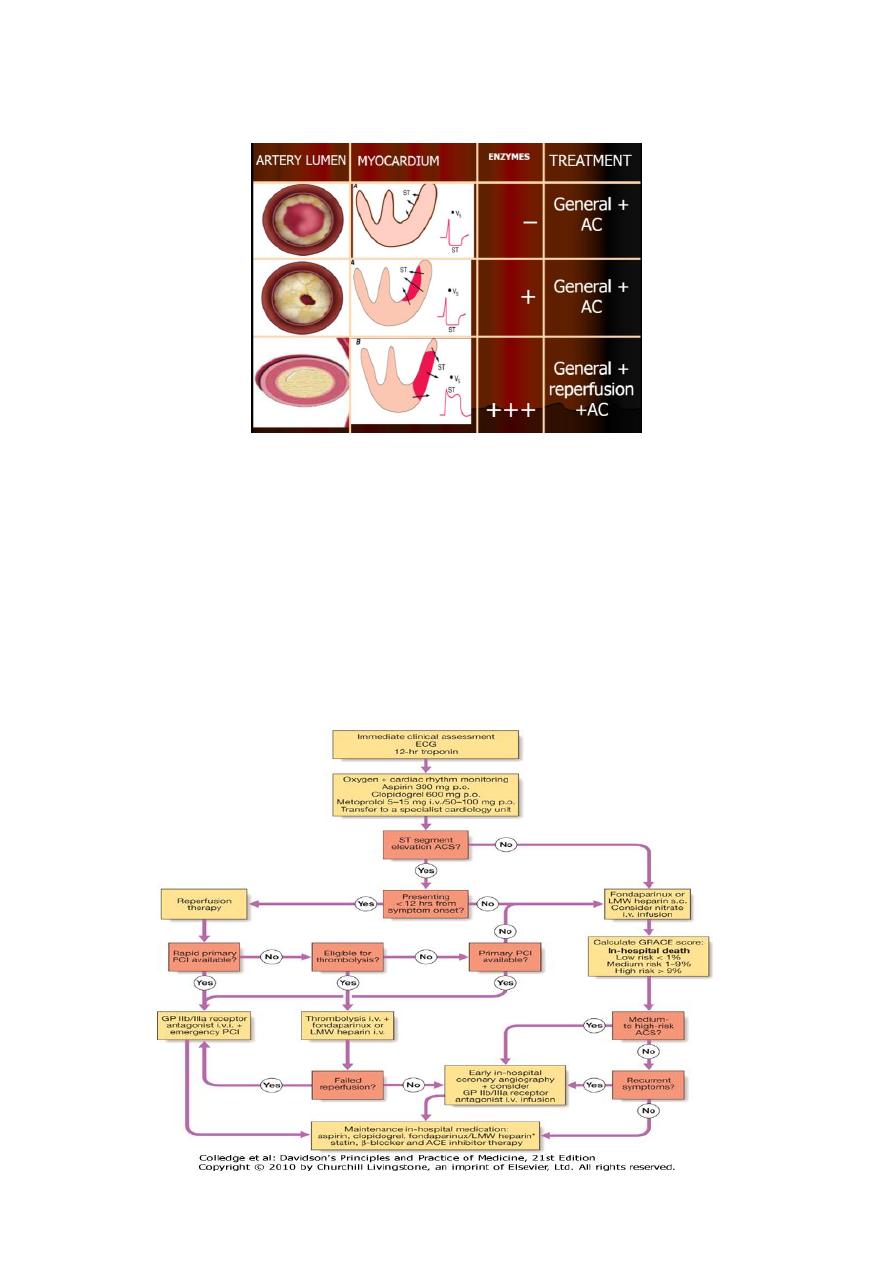

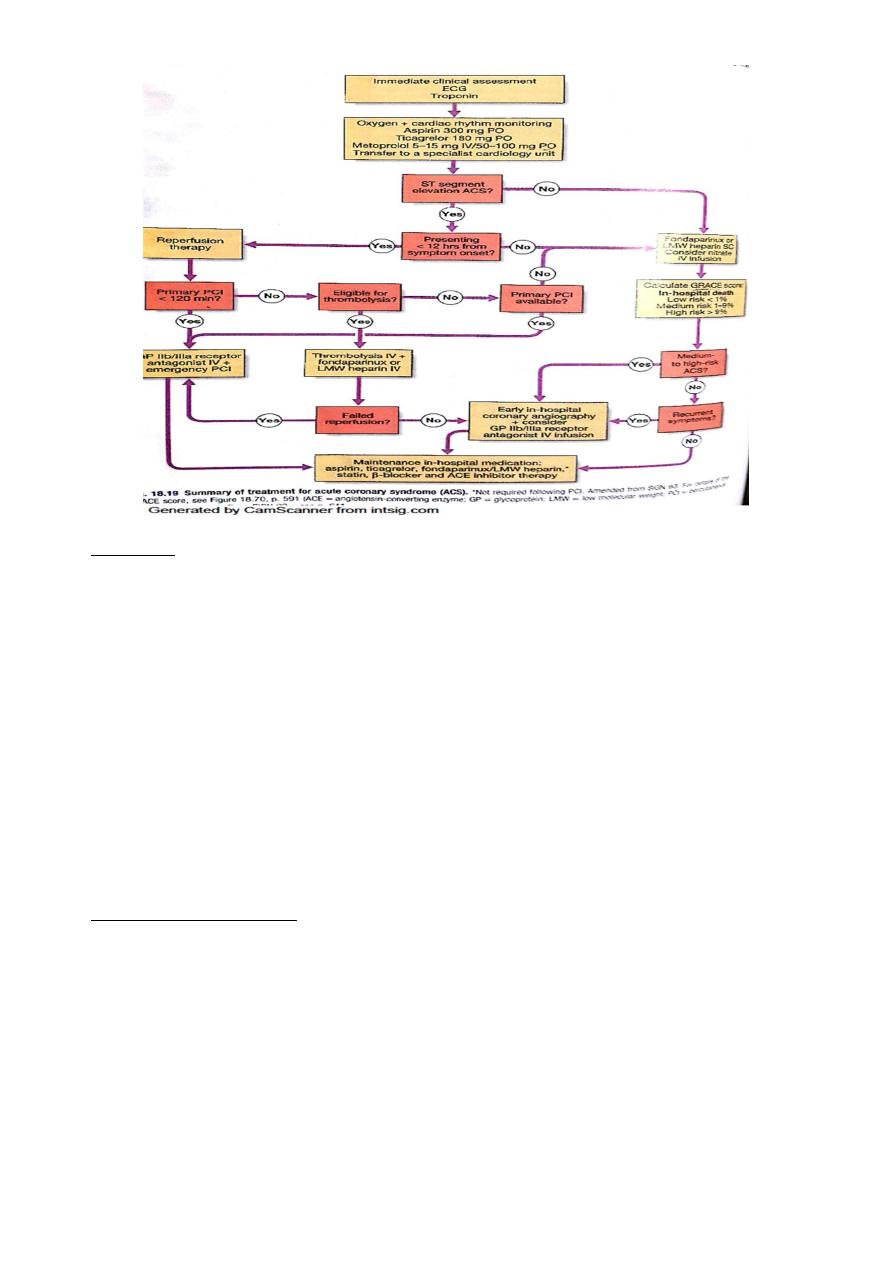

4-Reperfusion therapy

ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Immediate reperfusion therapy

- restores coronary artery patency,

- preserves left ventricular function

- improves survival.

Successful therapy is associated with

- pain relief

- resolution of acute ST elevation

- transient arrhythmias (e.g. idioventricular rhythm

Non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Immediate emergency reperfusion therapy = no demonstrable benefit in patients with

non-ST segment elevation MI

thrombolytic therapy may be harmful.

Selected medium- to high-risk patients do benefit from in-hospital coronary

angiography and coronary revascularisation but this does not need to take place in

the first 12 hours

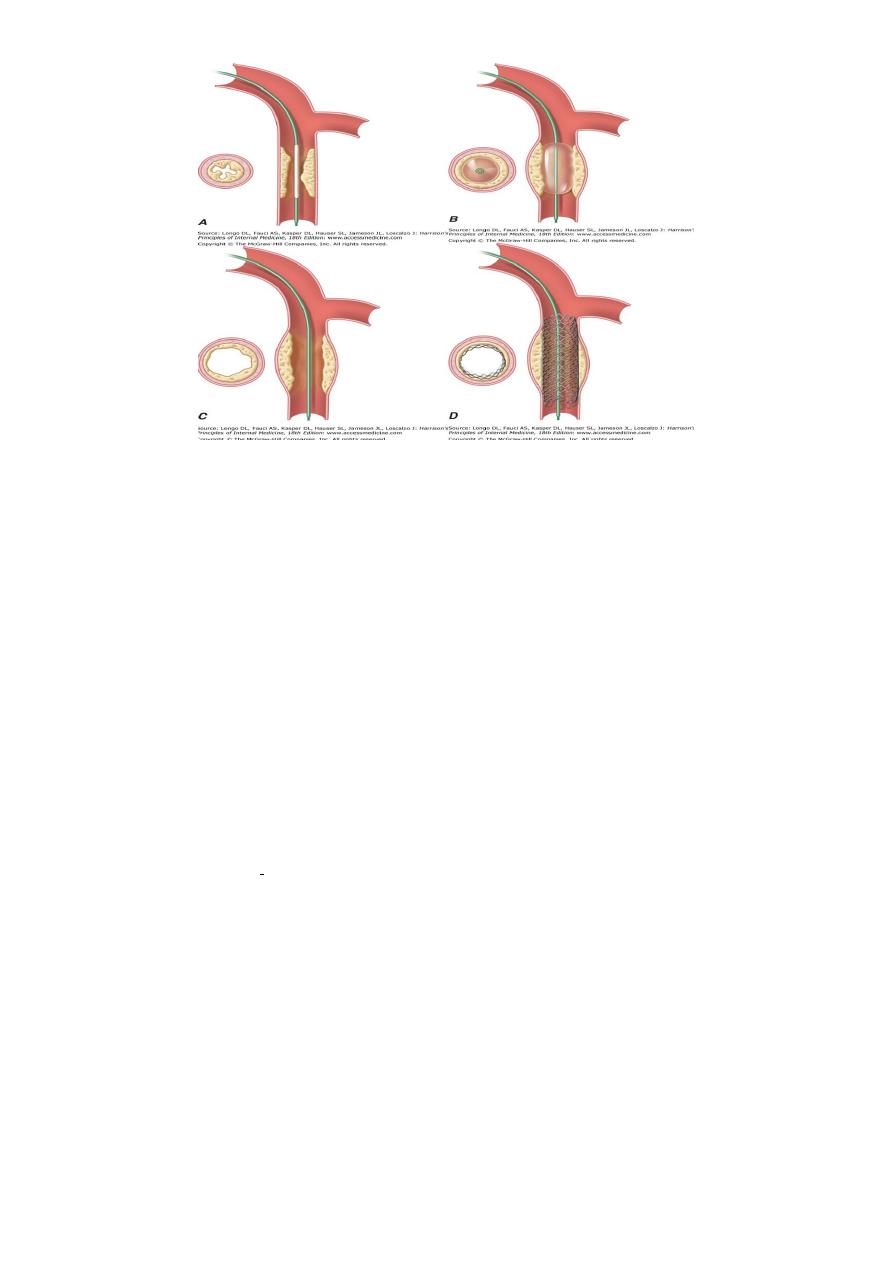

1- Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

treatment of choice for ST segment elevation MI . Outcomes are best when it is used

in combination with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists and intracoronary stent

implantation.

In comparison to thrombolytic therapy, it is associated with a greater reduction in the

risk of death, recurrent MI or stroke

universal use of primary PCI has been limited by availability of the necessary resources

to provide this highly specialised emergency service.

Intravenous thrombolytic therapy =first-line reperfusion treatment in many hospitals,

especially those in rural or remote areas.

When primary PCI cannot be achieved within 2 hours of diagnosis, thrombolytic

therapy should be administered.

16

2-Thrombolysis

Use of thrombolytic therapy = reduce hospital mortality = 25-50% survival

advantage is maintained for at least 10 years .

benefit is greatest in those patients who receive treatment within the first few

hours: 'minutes mean muscle'.

1) Alteplase (human tissue plasminogen activator or tPA) -genetically engineered given

over 90 minutes (bolus dose of 15 mg, -->0.75 mg/kg body wt, but not exceeding 50

mg, over 30 mins and then 0.5 mg/kg body wt, but not exceeding 35 mg, over 60

mins).better survival rates than other thrombolytic agents, such as streptokinase, but

carries a slightly higher risk of intracerebral bleeding (10 per 1000 increased survival,

but 1 per 1000 more non-fatal stroke).

Analogues of tPA, =tenecteplase and reteplase, longer plasma half-life than alteplase

and can be given as IV bolus.

2) Tenecteplase (TNK) is as effective as alteplase major bleeding and transfusion risks

are lower practical advantages of bolus administration may provide opportunities for

prompt treatment in emergency department or in the pre-hospital setting.

3) Reteplase (rPA) is administered as a double bolus and also produces a similar

outcome to that achieved with alteplase, although some of the bleeding risks appear

slightly higher

Thrombolytic therapy

1. reduces short-term mortality in patients with MI if it is given within 12 hours of onset

of symptoms and ECG shows bundle branch block or characteristic ST segment

elevation > 1 mm in the limb leads or 2 mm in the chest leads

17

2. little net benefit and may be harmful in those who present more than 12 hours after

the onset of symptoms in those with a normal ECG or ST depression. benefit greatest

for patients treated within the first 2 hours. major hazard of thrombolytic therapy is

bleeding.

SE

Cerebral haemorrhage causes 4 extra strokes per 1000 patients treated and the

incidence of other major bleeds is between 0.5% and 1%.

treatment withheld if there is a significant risk of serious bleeding .

some patients, thrombolytic therapy is contraindicated or fails to achieve coronary

arterial reperfusion =Early emergency PCI may then be considered, particularly where

there is evidence of cardiogenic shock

RELATIVE CONTRAINDICATIONS TO THROMBOLYTIC THERAPY (POTENTIAL

CANDIDATES FOR PRIMARY ANGIOPLASTY)

Active internal bleeding

Previous subarachnoid or intracerebral haemorrhage

Uncontrolled hypertension

Recent surgery (within 1 month)

Recent trauma (including traumatic resuscitation)

High probability of active peptic ulcer

Pregnancy

COMPLICATIONS OF ACS

Complications of acute coronary syndrome

1. Arrhythmias

2. Ischaemia

3. Heart failure and Acute circulatory

failure

4. Mechanical complications

5. Pericarditis

6. Embolism

7. Impaired ventricular function,

remodelling and V aneurysm

8. Right ventricular infarction

18

Complications of ACS

Functional

1. Left ventricular failure

2. Right ventricular failure

3. Cardiogenic shock

Mechanical

1) Free-wall rupture

2) Ventricular septal defect

3) Papillary muscle rupture with acute mitral regurgitation

Electrical

a) Bradyarrhythmias (first-, second-, and third-degree,atrioventricular blocks)

b) Tachyarrhythmias (supraventricular, ventricular)

c) Conduction abnormalities (bundle branch and fascicular block)

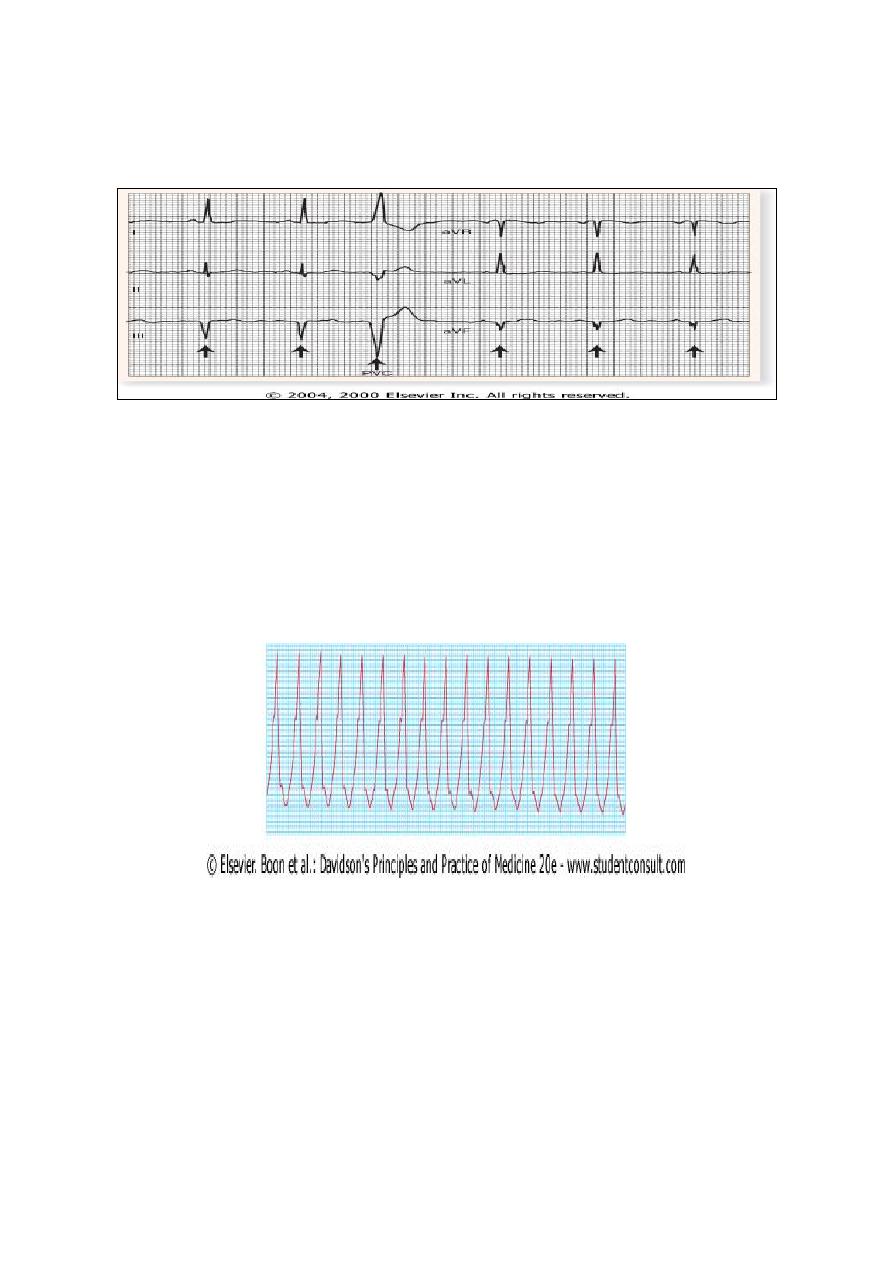

1-Arrhythmias

Common arrythmias complicationg MI

1. Ventricular fibrillation

2. Ventricular tachycardia

3. Accelerated idioventricular rhythm

4. Ventricular ectopics

5. Atrial fibrillation

6. Atrial tachycardia

7. Sinus bradycardia (particularly after inferior MI)

8. Heart block

Nearly all patients with acute MI have some form of arrhythmia; in many cases this is

transient and of no haemodynamic or prognostic significance.

Various degrees of atrioventricular block are also common.

Pain relief, rest and correction of hypokalaemia can all play a major role in prevention of

arrhythmias

Ventricular Premature Beats

Infrequent, sporadic V premature depolarizations -in almost all patients with STEMI

=do not require therapy.

pharmacologic therapy = for patients with sustained V arrhythmias.

Prophylactic antiarrhythmic therapy = contraindicated for VPB may actually increase

the mortality rate.

19

Beta-adrenoceptor blocking agents are effective in abolishing ventricular ectopic

activity in patients with STEMI and in prevention of ventricular fibrillation.

hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia are risk factors for ventricular fibrillation in

patients with STEMI;

Sustained ventricular tachycardia

A. well tolerated hemodynamically

IV regimen of amiodarone (bolus of 150 mg over

10 min

infusion of 1.0 mg/min for 6 h and then 0.5 mg/min); or Ldocaine may

depress LV function,=hypotension or acute heart failure.

B. if it does not stop or if systolic BP is < 90 mmHg promptly= Synchronised DC

cardioversion (200–300 J VT )hemodynamic deterioration.

Ventricular fibrillation

occurs in about 5-10% of patients who reach hospital, major cause of death in those

who die before receiving medical attention.

Prompt defibrillation usually restore sinus rhythm.

prognosis of patients with early ventricular fibrillation (within the first 48 hours) who

are successfully and promptly resuscitated =identical to the prognosis of patients with

acute MI that is not complicated by VF

Prompt pre-hospital resuscitation and defibrillation have the potential to save many

more lives than thrombolysis

20

Atrial fibrillation

common, frequently transient =may not require treatment.

if causes a rapid ventricular rate with severe hypotension or circulatory collapse=

cardioversion =immediate synchronised DC other situations, digoxin or β-blockers

usually=treatment of choice.

Atrial fibrillation (due to acute atrial stretch) -feature of impending or overt left

ventricular failure,therapy for heart failure.

Anticoagulation may be required if AF persists

Supraventricular tachycardias

j Digoxin -treatment of choice for supraventricular arrhythmias if heart failure .

j Beta blockers, verapamil, or diltiazem= If heart failure is absent=.

j synchronized electroshock (100–200 J monophasic wave form)=

j If the abnormal rhythm persists for >2 h with ventricular rate >120 bpm, or

j if tachycardia induces heart failure, shock, or ischemia =

21

Bradyarrhythmias

Sinus bradycardia does not usually require treatment hypotension or haemodynamic

deterioration atropine (0.6 mg i.v.).

Atrioventricular block

Atrioventricular block complicating inferior infarction = usually temporary

often resolves following thrombolytic therapymay respond to atropine (0.6 mg i.v.

repeated as necessary).

if clinical deterioration =second-degree or complete atrioventricular block=temporary

pacemaker.

Atrioventricular block complicating anterior infarction = more serious (asystole may

suddenly supervene) == prophylactic temporary pacemaker)

2-Ischaemia

MANAGEMENT

1) recurrent angina at rest or on min exertion following ACS - at high risk

- managed as UA=IV nitrates + IV heparin+Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa RA

- considered for prompt coronary angiography (revascularisation).

2) dynamic ECG changes and ongoing pain = IV glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor

antagonists.

3) resistant pain or marked haemodynamic changes

considered for intra-aortic

balloon counterpulsation and emergency coronary revascularisation.

Post-infarct angina occurs in 50% of patients treated with thrombolysis = residual

stenosis in infarct-related vessel ( still viable myocardium downstream). = considered

for early (within the first 6-24 hours) coronary angiography with a view to coronary

revascularisation.

occlusion of a vessel may precipitate angina by disturbing a system of collateral flow

that was compensating for disease in another vessel

22

Early post-MI ischaemia: managed in the same way as patients with high-risk unstable

angina .

1- spontaneous angina=>

2- Patients without spontaneous ischaemia = suitable candidates for revascularisation ==

>exercise tolerance test approximately 4 weeks after the infarct identify individuals

with significant residual myocardial ischaemia

1- exercise test –ve + good effort tolerance,=outlook is good= 1-4% chance of an

adverse event in the next 12 months.

2- exercise test +ve +residual ischaemia = chest pain or ECG changes at low exercise

levels = at high risk

- 15-25% chance of suffering a further ischaemic event in the next 12 months.

- Coronary angiography= angioplasty or bypass grafting

- considered in any patient with spontaneous ischaemia,significant angina on effort,

or a strongly positive exercise tolerance test

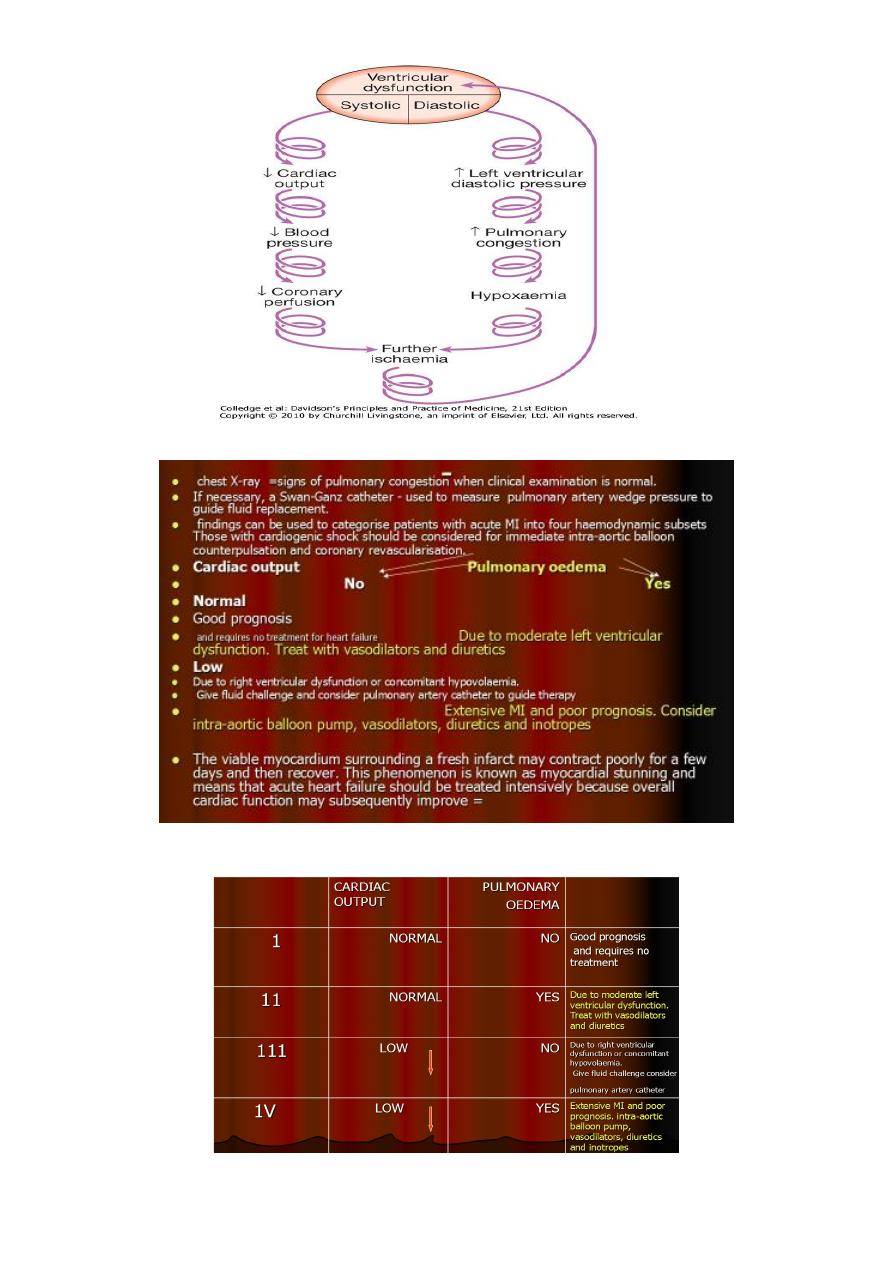

3-Heart failure & Acute circulatory failure

Acute circulatory failure= extensive myocardial damage = bad prognosis.

All other complications of MI = more likely to occur when acute HF is present.

Shock in acute MI

1. left ventricular dysfunction in more than 70% of cases.

2. infarction of the RV

3. a variety of mechanical complications, including tamponade (due to infarction and

rupture of the free wall), an acquired ventricular septal defect (due to infarction and

rupture of the septum) and acute mitral regurgitation (due to infarction or rupture of

the papillary muscles).

Others= pain,arrhythmias,pul.embolism,

Severe myocardial systolic dysfunction = fall in cardiac output, BP and coronary

perfusion pressure.

Diastolic dysfunction = rise in LV end-diastolic pressure, pulmonary congestion and

oedema-->hypoxaemia that worsens myocardial ischaemia=further exacerbated by

peripheral vasoconstriction.

factors combine to create the 'downward spiral' of cardiogenic shock

Hypotension, oliguria, confusion and cold clammy peripheries are the manifestations

of a low cardiac output,breathlessness, hypoxaemia, cyanosis and inspiratory crackles

at the lung bases are typical features of pulmonary oedema.

23

CATEGORIES OF MI+HF

24

Therapy acute MI and resultant LV dysfunction depends on the extent dysfunction.

1. normotensive with symptoms and signs of congestive heart failure (i.e., mild

orthopnea, basilar rales, S3) =Killip class II

- bed rest / salt restriction/ loop diuretic/ low-dose vasodilator ACEI

- digitalis or other inotropic agents invasive hemodynamic monitoring. is not usually

necessary,

2. more severe heart failure (Killip class III or IV)

- hemodynamic assessment.

- Adequate oxygenation.

- urinary catheter,

- IV furosemide = normotensive individual, vasodilator therapy = nitroglycerin and

oral ACE inhibitors

- heart failure and hypotension or an inadequate response to diuretics and

vasodilators = IV inotropic agents (e.g., dopamine or dobutamine)

- mildly hypotensive=dobutamine preferred inotropic agent.

- Dopamine =more severe hypotension

4.Pericarditis

may occur at any stage of the illness particularly common on the second and third

days.

patient recognise that a different pain has developed even though it is at the same

site, and that this pain is positional and tends to be worse or is sometimes only

present on inspiration.

A pericardial rub may be audible.

Non-steroidal and steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided in the early

recovery period as they may increase the risk of aneurysm formation and myocardial

rupture.

Opiate-based analgesia should be used.

Post-myocardial infarction syndrome (Dressler's syndrome)

A. characterised by persistent fever, pericarditis and pleurisy, and is probably due to

autoimmunity.

B. symptoms tend to occur a few weeks or even months after the infarct and often

subside after a few days; prolonged or severe symptoms may require treatment with

high-dose aspirin, an NSAID or even corticosteroids.

25

5.Mechanical complications

Part of the necrotic muscle in a fresh infarct may tear or rupture, with devastating

consequences:

1- Papillary muscle damage =acute pulmonary oedema (sudden onset of severe mitral

regurgitation, which presents with a pansystolic murmur and third heart sound).

severe valvular regurgitation=murmur may be quiet or absent. diagnosis =Doppler

echocardiography, and emergency mitral valve replacement may be necessary.

Lesser degrees of mitral regurgitation = papillary muscle dysfunction = common and may

be transient.

2- Rupture of the interventricular septum =left-to-right shunting through a ventricular

septal defect.

sudden haemodynamic deterioration accompanied by a new loud pansystolic murmur

radiating to the right sternal border, may be difficult to distinguish from acute mitral

regurgitation.

acquired ventricular septal defect tend to develop right heart failure rather than

pulmonary oedema.

Doppler echocardiography and right heart catheterisation will confirm the diagnosis.

Without prompt surgery, the condition is usually fatal.

3- Rupture of the ventricle =cardiac tamponade and is usually fatal ,although it may

rarely be possible to support a patient with an incomplete rupture until emergency

surgery is performed

Impaired ventricular function

Remodelling

Acute transmural MI is often followed by thinning and stretching of the infarcted

segment (infarct expansion) ==> increase in wall stress = progressive dilatation and

hypertrophy of the remaining ventricle =ventricular remodelling-.

As the ventricle dilates, it becomes less efficient and HF..

Infarct expansion occurs over a few days and weeks

ventricular remodelling may take years; heart failure =many years after acute MI.

ACE inhibitor = reduces LV remodelling =prevent HF

Left ventricular aneurysm

10%

particularly common -- persistent occlusion of infarct-related vessel.

26

recognised complications

Heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, mural thrombus and systemic embolism.

But not a cause of wall rupture

Other clinical features paradoxical impulse on the chest wall, persistent ST elevation

on the ECG, sometimes unusual bulge from the cardiac silhouette on chest X-ray.

Echocardiography is usually diagnostic.

Surgical removal of a left ventricular aneurysm carries a high morbidity and mortality

but is sometimes necessary.

Right Ventricular Infarction

one-third of patients with inferior infarction demonstrate at least a minor degree of

RV necrosis.

occasional patient with inferoposterior LV infarction = has extensive RV IN

rare patients present with infarction limited primarily to the RV IN

Clinically significant RV infarction

1. causes signs of severe RV failure [jugular venous distention, Kussmaul's sign,

hepatomegaly with or without hypotension.

2. ECG=ST-segment elevations of right-sided precordial ECG leads, particularly lead V

4

R,

are frequently present in the first 24 h in patients with RV infarction.

3. 2D echocardiography =helpful in determining the degree of RV dysfunction.

4. Catheterization of the right side of the heart often reveals a distinctive hemodynamic

pattern resembling constrictive pericarditis (steep right atrial "y" descent and an early

diastolic dip and plateau in RV waveforms) .

5. Therapy =volume expansion to maintain adequate RV preload

6. efforts to improve LV performance with attendant reduction in pulmonary capillary

wedge and pulmonary arterial pressures.

6.Embolism

Thrombus often forms on endocardial surface of freshly infarcted myocardium==>

systemic embolism

stroke or ischaemic limb.

Venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (less common with use of prophylactic

anticoagulants and early mobilisation)

27

LATER IN-HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT

1- Risk stratification and further investigation

2- Lifestyle AND risk factor modification

- Stop smoking

- Regular exercise

- Diet (weight control, lipid-lowering)

3- Mobilisation and Rehabilitation

4- Secondary prevention drug therapy

- Antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and/or clopidogrel)

- β-blocker

- ACE inhibitor

- Statin

Additional therapy for control of diabetes and hypertension

1. Risk stratification and further investigation

Simple clinical tools -used to identify medium- to high-risk patients.

GRACE score =Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events method of calculating

early mortality

help guide which patients should be selected for intensive therapy, and specifically

early inpatient coronary angiograph

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Hx of C. arrest at admission=39 Age=0-100(<30->90)

Dyspnea=killip class(HF)=0-59 Pulse=0-48(<50->200)

SBP=0-58(>200-<80) ST segment deviation=28

Enzymes=14 S.creatinine=1-28(34->353)

Prognosis of pt .who have survived an acute MI is related to

1- degree of myocardial damage,

2- extent of any residual myocardial ischaemia and

3- presence of significant ventricular arrhythmias.

28

1- Left ventricular function

Degree of LV dysfunction –Crude assessment

1) physical findings (tachycardia, third heart sound crackles at the lung bases elevated

venous pressure etc.),

2) ECG changes

3) chest X-ray=size of heart & presence of pulmonary oedema.

Formal measurements

a. echocardiography or

b. radionuclide imaging

2- early post-MI ischaemia managed as high-risk unstable angina .

A) spontaneous angina=>

B) without spontaneous ischaemia (suitable candidates for revascularisation )

- exercise tolerance test

- approximately 4 weeks after the infarct

- individuals with significant residual m. ischaemia

- further investigation

1. exercise test= -ve + good effort tolerance=outlook good 1-4% chance of an

adverse event in the next 12 months.

29

2. exercise test

+ve= residual ischaemia = chest pain or ECG changes at low exercise

levels are at high risk 15-25% chance of suffering a further ischaemic event in next

12 months.

Coronary angiography+angioplasty or bypass grafting spontaneous ischaemia,

significant angina on effort, or a strongly positive exercise tolerance test

3-Arrhythmias

ventricular arrhythmias during convalescent phase of MI = marker of poor ventricular

function may herald sudden death.

empirical anti-arrhythmic treatment == no value and even hazardous

selected patients may benefit from sophisticated electrophysiological testing and

specific anti-arrhythmic therapy (including implantable cardiac defibrillators,

Recurrent ventricular arrhythmias =

1. manifestations of myocardial ischaemia or

2. impaired LV function may respond to appropriate treatment directed at the

underlying problem

2.

Lifestyle and risk factor modification

1- Smoking

5-year mortality =continue smoke cigarettes double that of those who quit

smoking at the time of their infarct.

Giving up smoking single most effective contribution = own future.

success of smoking cessation increased by supportive advice and nicotine

replacement therapy

2-hyperlipedeimia

O Lipids =measured within 24 hours of presentation (transient fall in blood cholesterol

in 3 months following infarction.)

O Dietary advice =given =often ineffective.

O HMG CoA reductase enzyme inhibitors ('statins') = produce marked reductions in

total (and LDL) cholesterol reduce subsequent risk of death reinfarction stroke need

for revascularisation

O Irrespective of serum cholesterol all patients should receive statin therapy after MI

serum LDL cholesterol concentrations greater than 3.2 mmol/l (∼120 mg/dl) benefit

from more intensive lipid-lowering (e.g. atorvastatin 80 mg daily).

3-Maintaining an ideal body weigh taking regular exercise

4- control of hypertension and diabetes

30

3-Mobilization and rehabilitation

histological evidence =necrotic muscle of acute myocardial infarct takes 4-6 weeks

=replaced with fibrous tissue restrict physical activities during this period.

When there are no complications,sit in a chair on second day,walk to the toilet on

third day, return home in 5 days gradually increase activity =returning to work in 4-6

weeks.

majority of patients may resume driving after 4-6 weeks; (most countries, vocational

driving licence holders (e.g. heavy goods and public service vehicle) require special

assessment.

Emotional problems, = denial, anxiety and depression=common, must be recognised

and dealt with accordingly.

Many patients are severely and even permanently incapacitated as a result of

psychological rather than physical effects of MI, all benefit from thoughtful explanation,

counselling and reassurance at every stage of the illness.

Many patients mistakenly believe that 'stress' was the cause of their heart attack and

may restrict their activity inappropriately.

The patient's spouse or partner will also require emotional support, information and

counselling.

Formal rehabilitation programmes based on graded exercise protocols with individual

and group counselling are often very successful, and in some cases have been shown to

improve the long-term outcome

4-Secondary prevention drug therapy

1. Aspirin and clopidogrel : Low-dose aspirin therapy

reduces the risk of further

infarction and other vascular events by approximately 25% continued indefinitely if

there are no unwanted effects.

Clopidogrel : given in combination with aspirin for at least 3 months If patients are

intolerant of aspirin, clopidogrel is a suitable alternative.

2. Beta-blockers : Continuous treatment =reduce long-term mortality by approximately

25% significant minority of patients do not tolerate β-blockers (bradycardia,

atrioventricular block, hypotension or asthma). heart failure irreversible chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease or peripheral vascular disease derive similar if not

greater secondary preventative benefits from β-blocker therapy if they can tolerate it

3. HMG CoA reductase enzyme inhibitors ('statins') : produce marked reductions in

total (and LDL) cholesterol reduce subsequent risk of death, reinfarction, stroke

need for revascularisation .

31

Irrespective of serum cholesterol concentrations all patients should receive statin

therapy after MI. patients with serum LDL cholesterol concentrations greater than 3.2

mmol/l (∼120 mg/dl) benefit from more intensive lipid-lowering (e.g. atorvastatin

80 mg daily).

ACE inhibitors: long-term treatment with an ACE inhibitor (e.g. enalapril 10 mg 12-hourly

or ramipril 2.5-5 mg 12-hourly) can

1) counteract ventricular remodelling,

2) prevent onset of heart failure,

3) improve survival

4) reduce hospitalisation.

- benefit of treatment greatest in those with overt heart failure (clinical or

radiological) extends to patients with asymptomatic LV dysfunction those with

preserved LV function.

- considered in all patients who have sustained a myocardial infarct.

- Caution must be exercised in hypovolaemic or hypotensive patients because the

introduction of an ACE inhibitor may exacerbate hypotension and impair coronary

perfusion.

- In patients intolerant of ACE inhibitor therapy, angiotensin receptor blockers (e.g.

valsartan 40-160 mg daily or candesartan 4-16 mg daily) are suitable alternatives

and are better tolerated.

Aldosterone receptor antagonist: Patients with acute MI complicated by heart failure

and LV dysfunction benefit from additional aldosterone receptor antagonism (e.g.

eplerenone 25-50 mg daily).

Coronary revascularisation AND Device therapy: Coronary revascularisation

Most low-risk patients stabilise with aspirin, clopidogrel, anticoagulation and anti-

anginal therapy, and can be rapidly mobilised.

In the absence of recurrent symptoms, low-risk patients do not benefit from

routine coronary angiography.

Coronary angiography =considered with a view to revascularisation

1- moderate or high risk, including

2- those who fail to settle on medical therapy,

3- those with extensive ECG changes,

4- those with an elevated plasma troponin

5- those with severe pre-existing stable angina.

In these cases coronary revascularisation is associated with short- and long-term

benefits, including reductions in MI and death.

32

Device therapy

Implantable cardiac defibrillators

of benefit in preventing sudden cardiac death in patients who have

severe left ventricular impairment (ejection fraction ≤ 30%) after MI

PROGNOSIS DEATH in MI

$ 25 % of all cases of MI= Die within a few minutes without medical care.

$ 50% deaths from MI occur= Die within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms

$ 40% of all affected patients Die within the first month.

$ prognosis of those who survive to reach hospital much better 28-day survival of

more than 80%.

$ Early death =an arrhythmia

$ later on=outcome determined by extent of myocardial damage.

Unfavourable features =

1- poor left ventricular function,

2- atrioventricular block

3- persistent ventricular arrhythmias.

4- prognosis is worse for anterior than for inferior infarcts.

5- Bundle branch block and high enzyme levels =extensive myocardial damage.

6- Old age, depression and social isolation are also associated with a higher mortality.

Of those who survive an acute attack, more than 80% live for a further year, about 75%

for 5 years, 50% for 10 years 25% for 20 years

MI IN OLD AGE

Atypical presentation: anorexia, fatigue or weakness rather than chest pain.

Case fatality: rises steeply.

Hospital mortality exceeds 25% in those over 75 years old, =five times greater than that

seen in those aged <55 years.

Survival benefit of treatments: not influenced by age. absolute benefit of evidence-

based treatments greatest in older people.

Hazards of treatments: rise with age (e.g. increased risk of intracerebral bleeding after

thrombolysis) and is due partly to increased comorbidity.

Quality of evidence: older patients, particularly those with significant comorbidity, were

under-represented in many of the RCTs that helped to establish the treatment of

myocardial infarction. balance of risk and benefit for many treatments (e.g.

thrombolysis, primary PTCA) in frail older people is therefore uncertain.