HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED INFECTIONS

Definition:Hospital-acquired (nosocomial) infections are defined as those not

present or incubating at the time of admission to the hospital. In most cases,

infections appearing after 48 to 72 hours of hospitalization are considered to be

nosocomially acquired. A patient admitted to the hospital in the United States has

a 5 to 10% chance of developing a nosocomial infection

, nosocomial infections have become even more problematic because of:

1. increased numbers of immunocompromised pts.

2.increasing antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria.

3. increased rates of fungal and viral superinfections.

4.increased numbers of invasive procedures and invasive devices.

Infection Control

1. isolation of patients with potentially transmissible diseases (e.g., tuberculosis,

influenza, chickenpox).

2. isolation of patients at increased risk for acquiring infections (e.g., neutropenic cancer

patients).

3. institution of mandatory hand washing.

4. universal precautions" with all patient contact. Universal precautions consider all blood

and certain body fluids (e.g., cerebrospinal, amniotic, peritoneal, seminal, vaginal, and

blood contaminated) as potentially infectious. Gloves must be worn when exposure to

these fluids, nonintact skin, or mucosal surfaces is expected. Additionally, masks and

gowns are worn when splashes are expected.

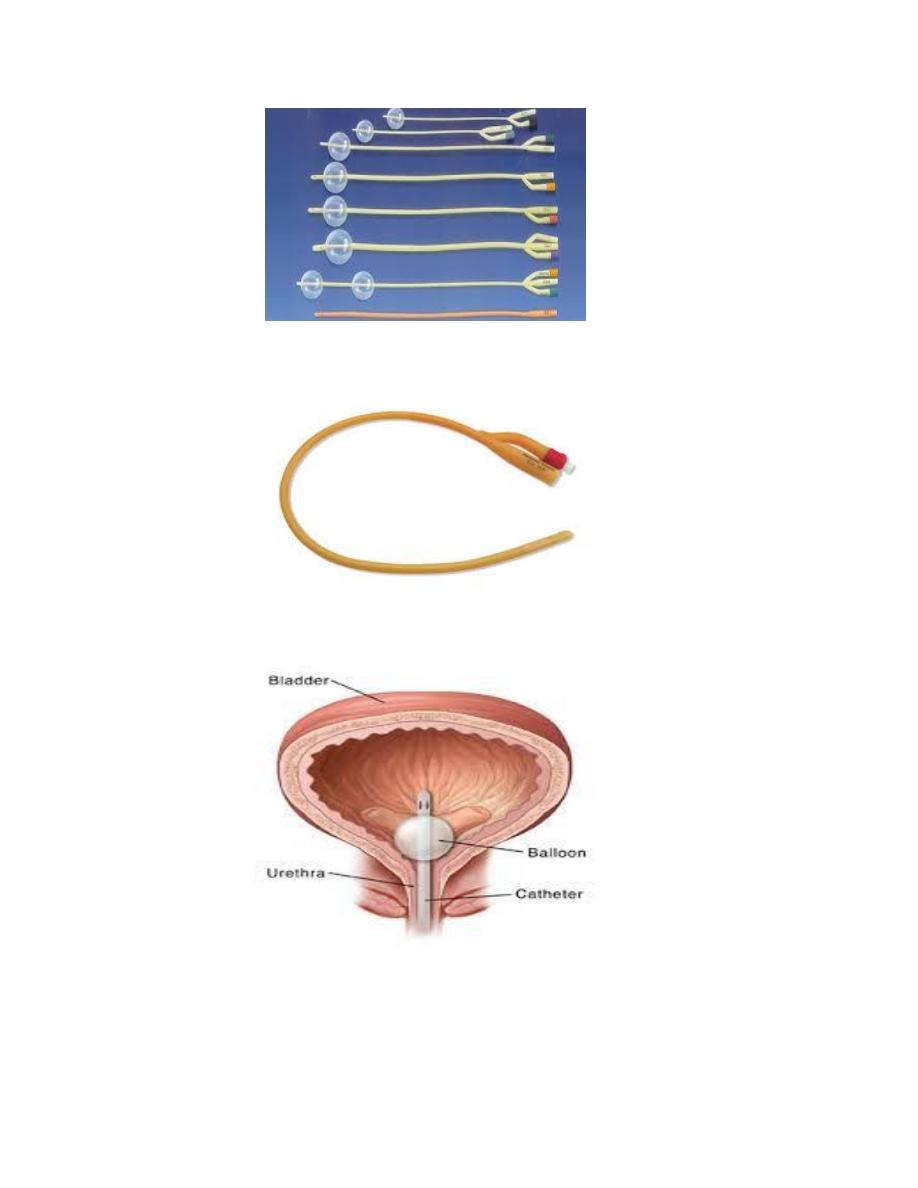

Urinary Tract Infections

Up to 40–45% of nosocomial infections are UTIs. Most nosocomial UTIs are associated

with prior instrumentation or indwelling bladder catheterization. There is a 3–10% risk of

infection for each day a catheter remains in place. Pts become infected with bacteria

ascending from the periurethral area or via intraluminal contamination of the catheter.

The pt should be assessed for symptoms of upper tract disease, such as flank pain, fever,

and leukocytosis. Lower tract symptoms, such as dysuria, are unreliable as markers of

infection in catheterized pts. If infection is suspected, the catheter should be replaced and

a freshly voided urine specimen obtained for culture; Urinary sediment should be

examined for evidence of infection (e.g.,pyuria). Prevention: Catheters should be placed

(by aseptic techniques) only when they are essential, should be manipulated as

infrequently as possible, and should be removed as soon as possible. In men, condom

catheters unless carefully maintained are as strongly associated with infection as

indwelling catheters.

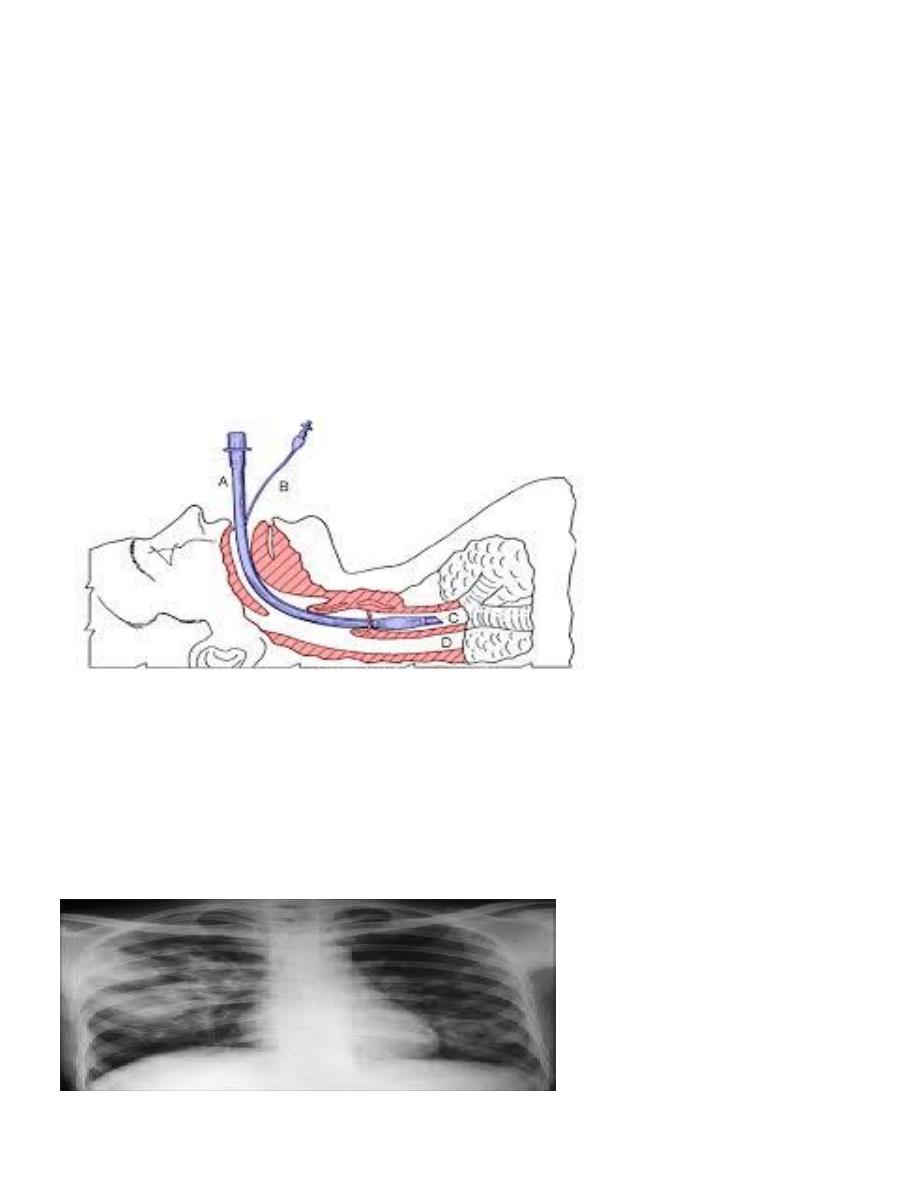

Pneumonia

Accounting for 15–20% of nosocomial infections, pneumonia increases the

duration of hospital stay and costs. Pts aspirate endogenous or hospital-acquired

flora. Risk factors include:

1.events that increase colonization with potential pathogens, such as prior

antibiotic use, contaminated ventilator equipment, or increased gastric pH;

2.events that increase risk of aspiration, such as intubation, decreased levels of

consciousness, or nasogastric or endotracheal tubes.

3.conditions that compromise host defense mechanisms in the lung, such as

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Diagnosis should depend on clinical criteria such as fever, leukocytosis, purulent

secretions, and new or changing pulmonary infiltrates on CXR. An etiology should be

sought by studies of lower respiratory tract samples protected from upper-tract

contamination; quantitative cultures have diagnostic sensitivities in the range of 80%.

Febrile pts with nasogastric tubes should also have sinusitis or otitis media ruled out.

Organisms, particularly in ICU pts, include Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus

influenzae early during hospitalization and Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas

aeruginosa, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Acinetobacter, and other gram-negative bacilli later

in the hospital stay.

Prevention efforts should focus on minimal use of aspiration-prone supine positioning

and meticulous aseptic care of respirator equipment.

Surgical Wound Infections

Making up 20–30% of nosocomial infections, surgical wound infections increase the

length of hospital stay as well as costs. These infections have an average incubation

period of 5–7 days and often become evident after pts have left the hospital; thus it is

difficult to assess the true incidence.

Common risk factors include:

1. deficits in the surgeon’s technical skill.

2. the pt’s underlying conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus or obesity),

3.inappropriate timing of antibiotic prophylaxis.

4. Other factors include the presence of drains, prolonged preoperative hospital stays,

shaving of the operative site the day before surgery, long duration of surgery, and

infection at remote sites.

An area of erythema with a diameter of 2 cm around the wound margin, local pain and

induration, fluctuance, pus, or dehiscence of the wound suggests infection. S. aureus,

coagulase-negative staphylococci, and enteric and anaerobic bacteria are the most

common pathogens. In rapidly progressing postoperative infections, group A

streptococcal or clostridial infections should be considered.

Treatment includes administration of appropriate antibiotics and drainage or excision of

infected or necrotic material.

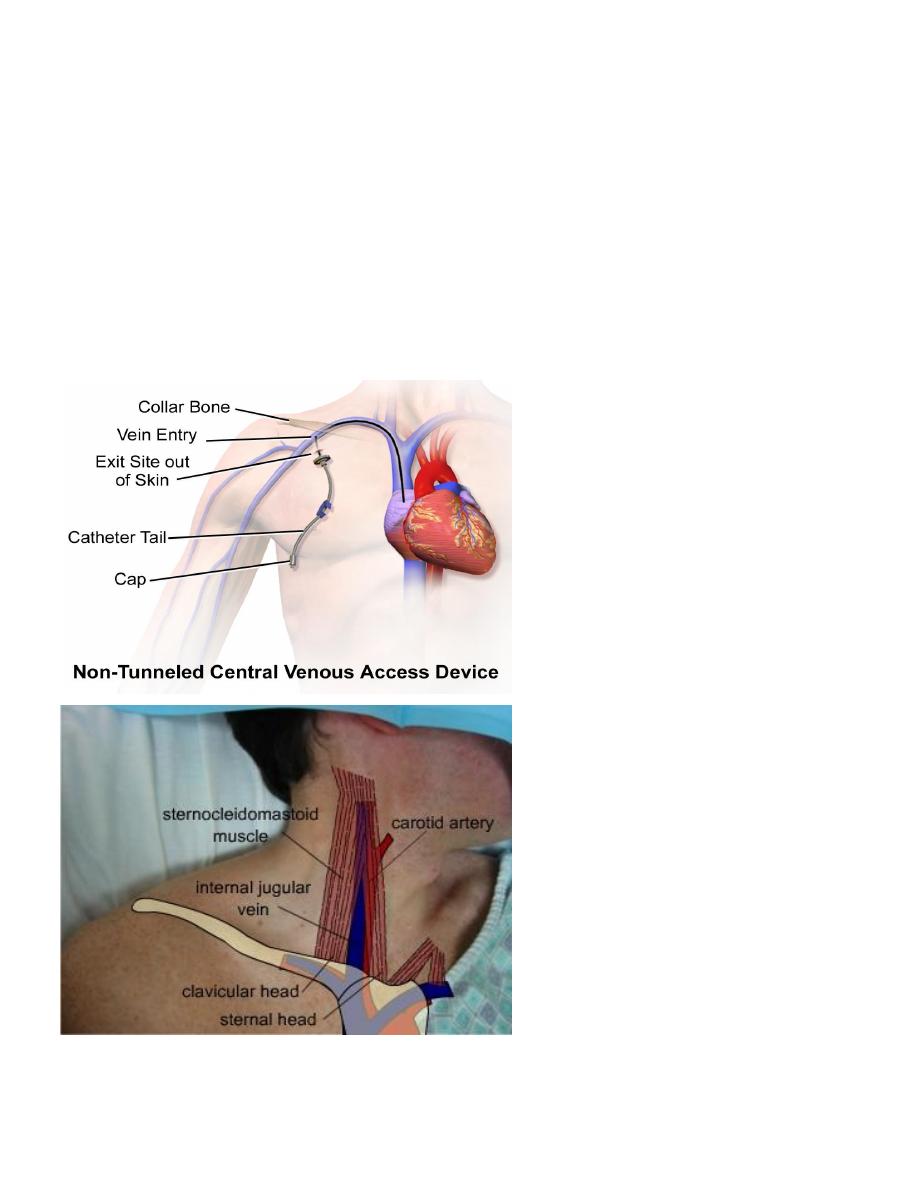

Intravascular Device Infections

Infections of intravascular devices cause up to 50% of nosocomial bacteremias;

central vascular catheters account for 80–90% of these infections. As many as

250,000 bloodstream infections associated with central vascular catheters occur

each year in the United States, with attributable mortality rates of 12–25%.

Pts often present with fever, erythema, purulent drainage, induration, and tenderness at

the exit site. Bacteremia without another source suggests a vascular access infection.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. aureus, enterococci, nosocomial gram-negative

bacilli, and Candida are the pathogens most frequently associated with these bacteremias.

The diagnosis is confirmed by isolation of the same bacteria from peripheral blood

cultures and from semiquantitative or quantitative cultures of samples from the vascular

catheter tip.

In addition to the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment, other considerations

should include the risk for endocarditis (relatively high in pts with S. aureus bacteremia),

whether to use the “antibiotic lock” technique (instillation of concentrated antibiotic

solution into the catheter lumen along with systemic antibiotics), and whether to remove

the catheter (given that its removal is usually necessary to cure infection). If the catheter

is changed over a guide wire and cultures of the removed catheter tip are positive, the

catheter should be moved to a new site.

Prevention: Meticulous aseptic technique during catheter placement and avoidance of

femoral sites minimize the risk of vascular access infection. If a device is expected to

remain in place for 5 days, an antibiotic-impregnated catheter may be useful.