Dr.Asaad 2016

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND BIOLOGY OF HIV

The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was first recognized in 1981. It is caused

by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1). HIV-2 causes a similar illness to HIV-1 but

is less aggressive and restricted mainly to western Africa. The viruses almost certainly

originated from closely related African primate viruses, simian immunodeficiency viruses

(SIVs). Sequence analysis has led to the estimate that HIV-1 was introduced into humans in

the early 1930s.

Since 1981 AIDS has grown to be the second leading cause of disease burden world-wide

and the leading cause of death in Africa, where it accounts for over 20% of deaths. Highly

active retroviral therapy (HAART) with three or more drugs has improved life expectancy to

near normal in the majority of patients receiving it, with an 80% reduction of mortality since

its introduction. Immune deficiency is a consequence of continuous high-level HIV

replication leading to virus and immune-mediated destruction of the key immune effector

cell, the CD4 lymphocyte.

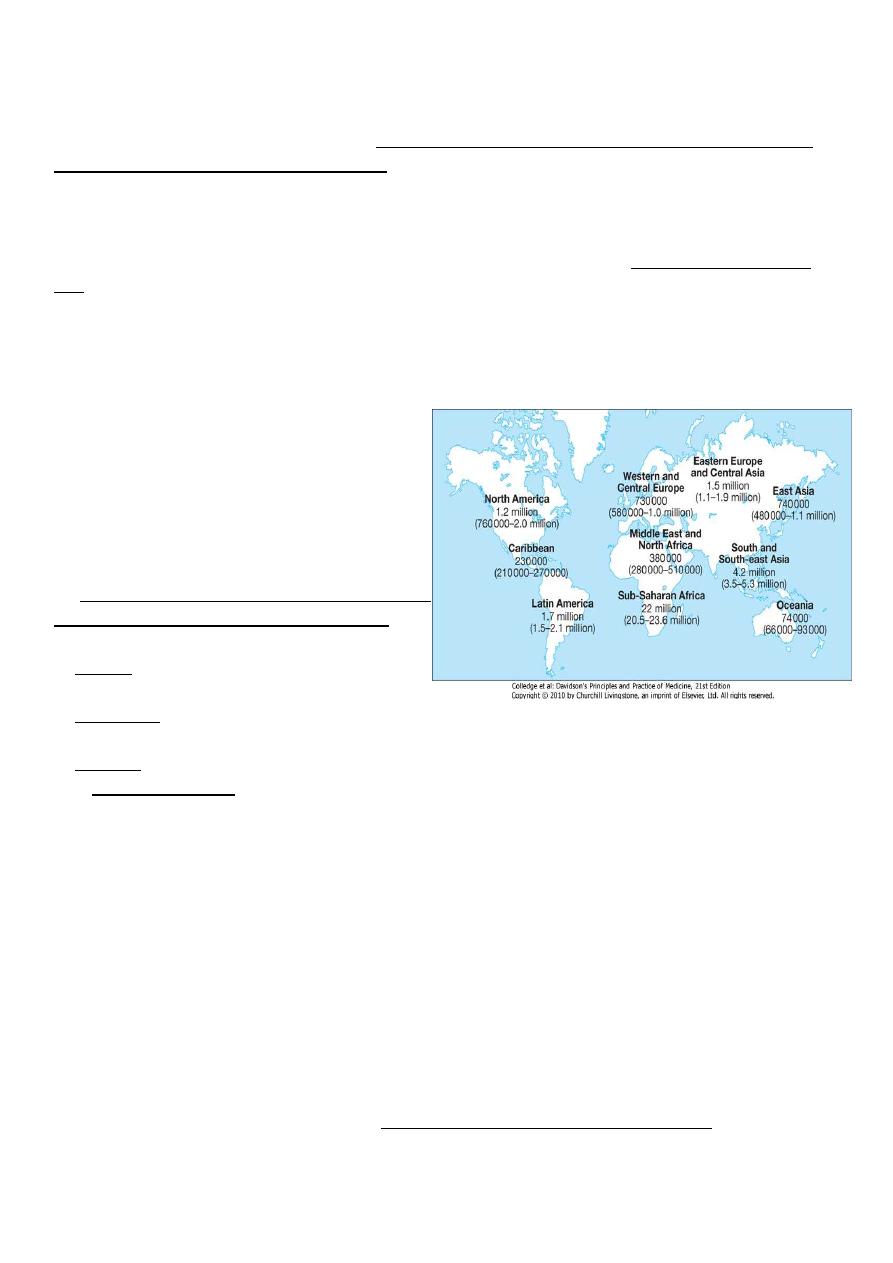

In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that there were 35.3 million

people living with HIV/AIDS, 2.5 million new infections and 2.1 million deaths. The

cumulative death toll since the epidemic began is over 36 million(2012) in 2013 1.4 million

death, the vast majority of cases occurring in sub-Saharan Africa where over 11.4 million

children are now orphaned.

No cure no vaccin

MODES OF TRANSMISSION

HIV is present in blood, semen and other

body fluids such as breast milk and saliva.

Exposure to infected fluid leads to a risk of

contracting infection, which is dependent on

the integrity of the exposed site, the type and

volume of body fluid, and the viral load.

The modes of spread are :

1. Sexual (man to man, heterosexual and

oral).

2. Parenteral (blood or blood product

recipients, injection drug-users and those experiencing occupational injury) and

3. Vertical.

The transmission risk after exposure is over 90% for blood or blood products, 15-40% for

the vertical route, 0.5-1.0% for injection drug use, 0.2-0.5% for genital mucous membrane

spread and under 0.1% for non-genital mucous membrane spread. After >25 years of

scrutiny, there is no evidence that HIV is transmitted by casual contact or that the virus can

be spread by insects, such as by a mosquito bite.

World-wide, the major route of transmission (> 75%) is heterosexual. About 5-10% of new

HIV infections are in children and more than 90% of these are infected during pregnancy,

birth or breastfeeding. The rate of mother-to-child transmission is higher in developing

countries (25-44%) than in industrialised nations (13-25%); postnatal transmission via breast

milk may account for some of this increased risk.

VIROLOGY AND IMMUNOLOGY

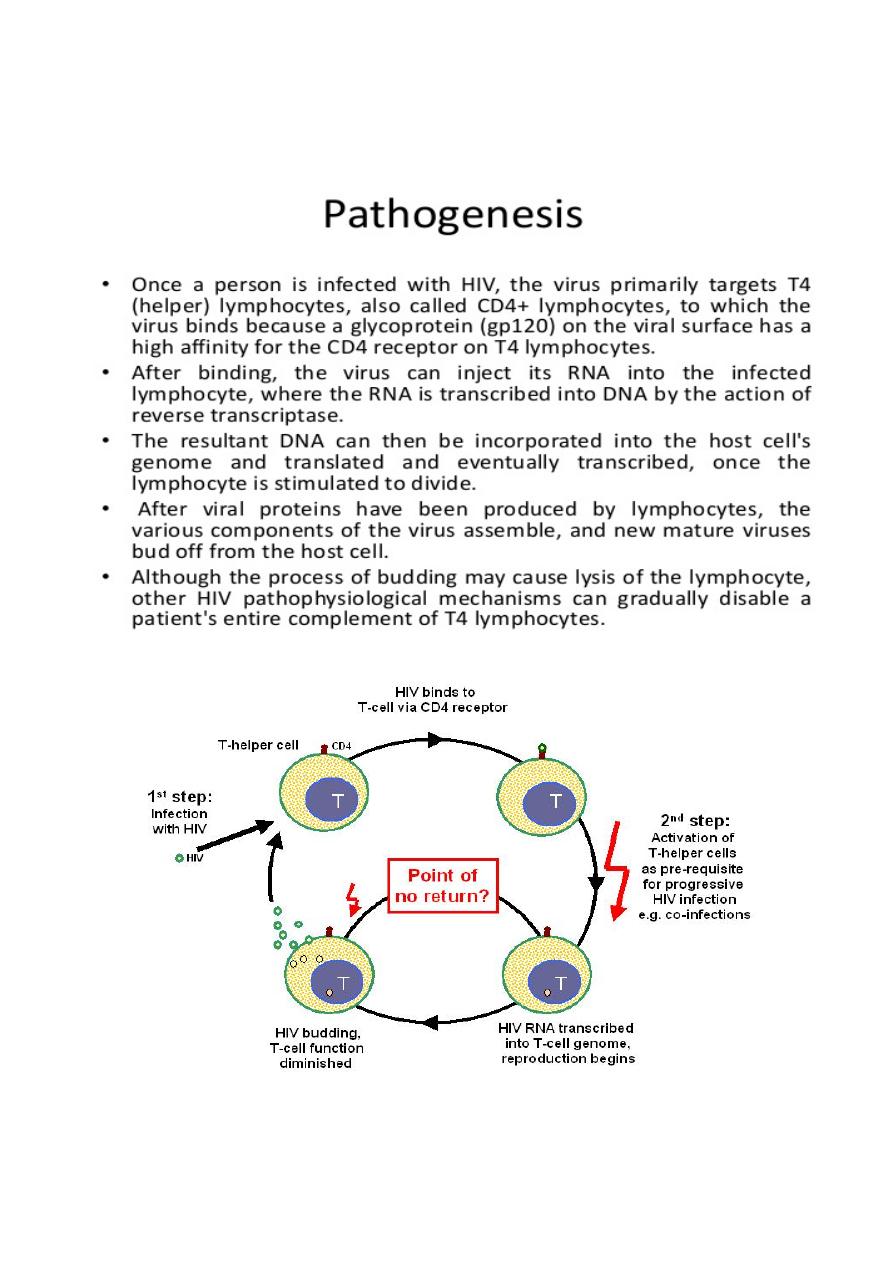

HIV is a single-stranded RNA retrovirus from the Lentivirus family. After mucosal exposure,

HIV is transported to the lymph nodes via dendritic, CD4 or Langerhans cells, where

infection becomes established. Dendritic cells express various receptor that facilitate capture

and transport of HIV-1. Free or cell-associated virus is then disseminated widely through the

blood with seeding of 'sanctuary' sites (e.g. central nervous system) and latent CD4 cell

reservoirs. With time, there is gradual attrition of the CD4 cell population, resulting in

increasing impairment of cell-mediated immunity and susceptibility to opportunistic

infections.

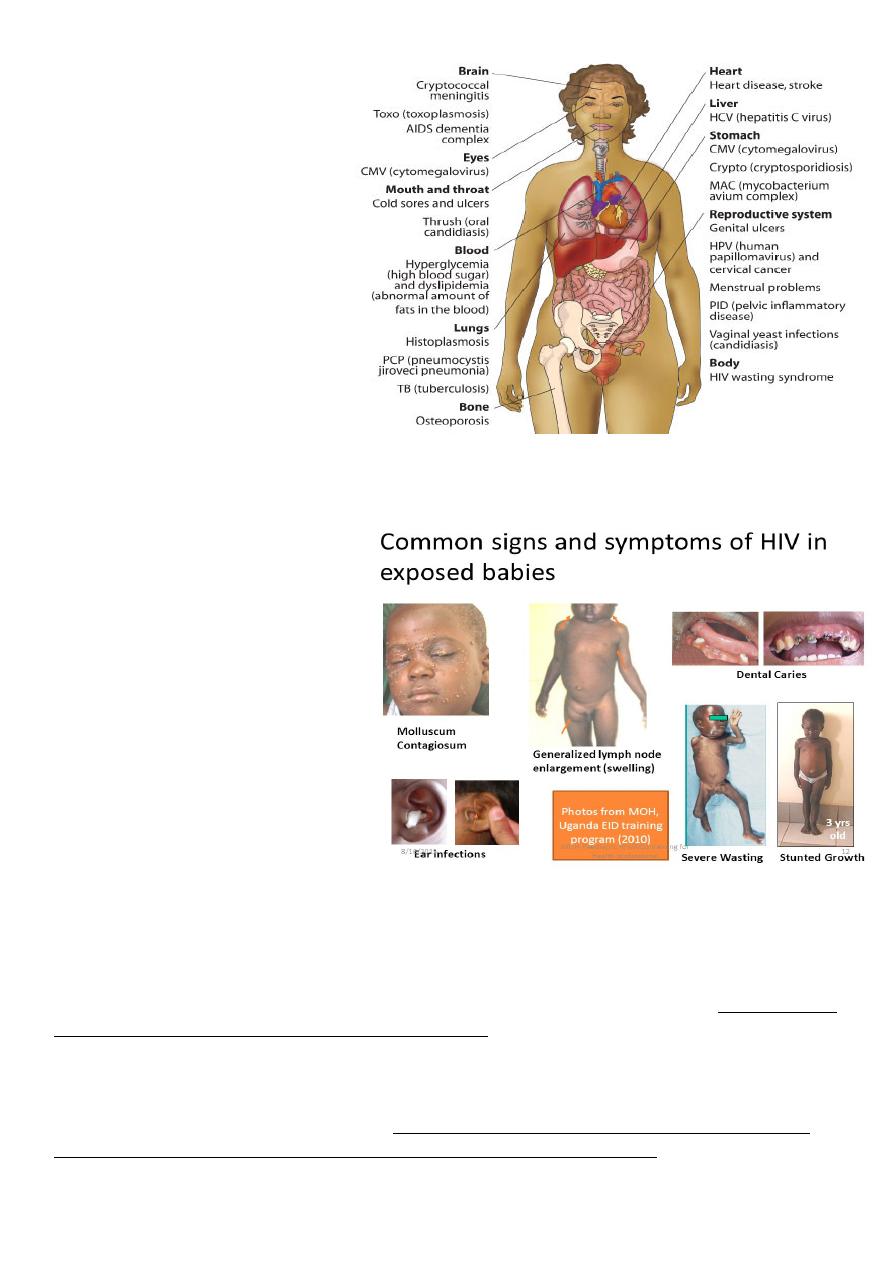

As CD4 cells are pivotal in orchestrating the immune response, any depletion in numbers

renders the body susceptible to opportunistic infections and oncogenic virus-related tumours.

The predominant opportunist infections seen in HIV disease are intracellular parasites(e.g.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis) or pathogens susceptible to cell-mediated rather than

antibody-mediated immune responses. The reduction in the number of CD4 cells circulating

in peripheral blood is tightly correlated with the amount of plasma viral load. Both are

monitored closely in patients and are used as measures of disease progression.

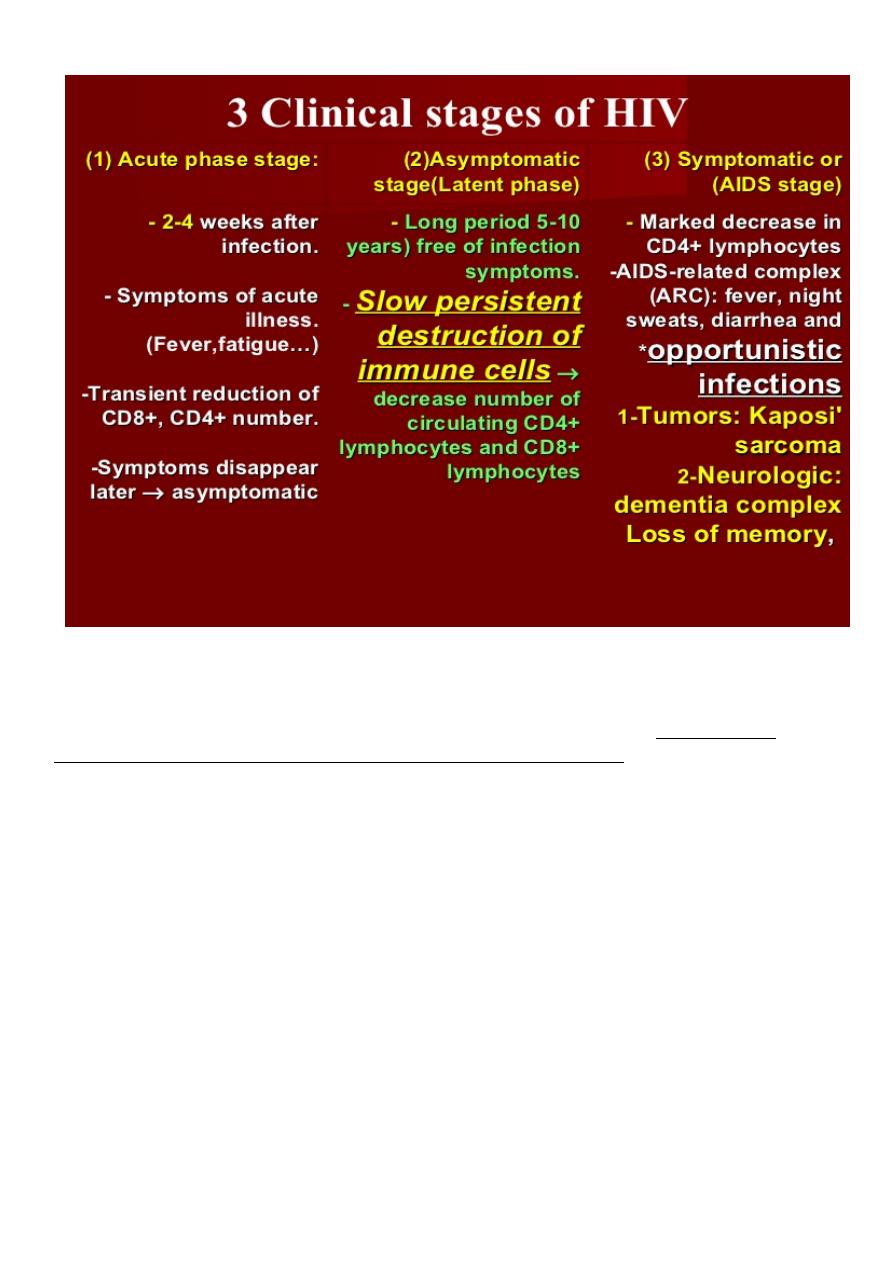

NATURAL HISTORY AND

CLASSIFICATION OF HIV

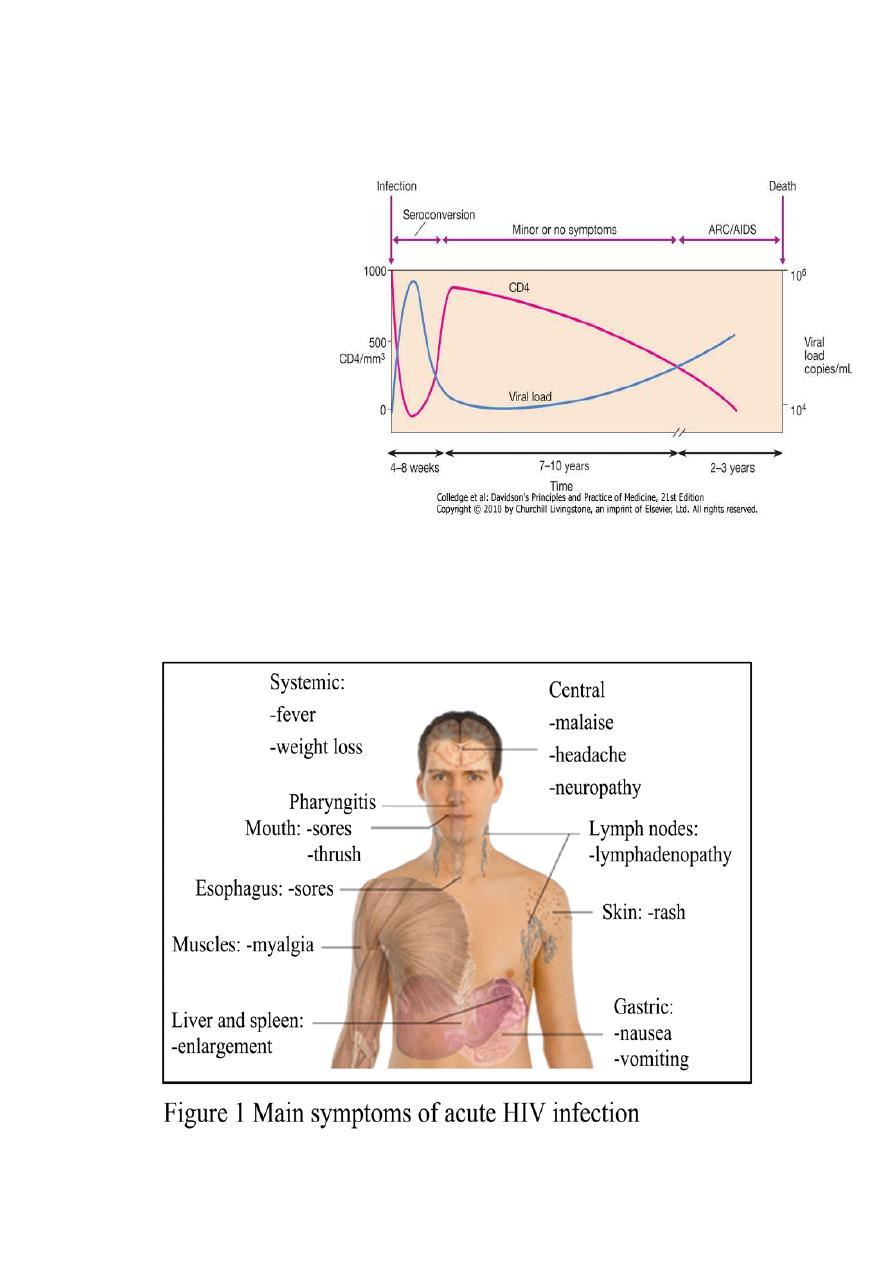

Primary infection is symptomatic

in 70-80% of cases and usually

occurs 2-6 weeks after exposure:

CLINICAL FEATURES OF

PRIMARY INFECTION

Fever with rash

Pharyngitis with cervical

lymphadenopathy

Myalgia/arthralgia

Headache

Mucosal ulceration

Rarely, presentation may be neurological (aseptic meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis,

polyneuritis).

Asymptomatic infection

Asymptomatic infection follows primary infection and lasts for a variable period, during

which the infected individual remains well with no evidence of disease except for the

possible presence of persistent generalised lymphadenopathy (PGL, defined as enlarged

glands at ≥ 2 extra-inguinal sites).

Mildly symptomatic disease

Mildly symptomatic disease then develops in the majority, indicating some impairment of

the cellular immune system. These diseases correspond to AIDS-related complex (ARC)

conditions but by definition are not AIDS-defining. The median interval from infection to the

development of symptoms is around 7-10 years.

HIV SYMPTOMATIC DISEASES

Oral hairy leucoplakia

Recurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis

Recurrent vaginal candidiasis

Severe pelvic inflammatory disease

Bacillary angiomatosis

Cervical dysplasia

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

Weight loss

Chronic diarrhoea

Herpes zoster

Peripheral neuropathy

Low-grade fever/night sweats

Acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome (AIDS)

AIDS is defined by the

development of specified

opportunistic infections, tumours

etc.

AIDS-DEFINING DISEASES

Oesophageal candidiasis

Cryptococcal meningitis

Chronic cryptosporidial diarrhoea

CMV retinitis or colitis

Chronic mucocutaneous herpes simplex

Disseminated Mycobacterium avium intracellulare

Pulmonary or extrapulmonary

tuberculosis

Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia

Progressive multifocal

leucoencephalopathy

Recurrent non-typhi Salmonella

septicemia

Cerebral toxoplasmosis

Extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis

Invasive cervical cancer

Extrapulmonary histoplasmosis

Kaposi's sarcoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Primary cerebral lymphoma

HIV-associated wasting

HIV-associated dementia

Diagnosis of HIV Infection

The CDC has recommended that screening for HIV infection be performed as a matter of

routine health care. The diagnosis of HIV infection depends upon the demonstration of

antibodies to HIV and/or the direct detection of HIV or one of its components. Antibodies to

HIV generally appear in the circulation 2–12 weeks following infection. The standard blood

screening test for HIV infection is the ELISA, also referred to as (EIA) an enzyme

immunoassay is an extremely good screening test with a sensitivity of >99.5%. Most

diagnostic laboratories use a commercial EIA kit that contains antigens from both HIV-1 and

HIV-2 and thus are able to detect either. EIA tests are generally scored as positive (highly

reactive), negative (nonreactive), or indeterminate) partially reactive.

)

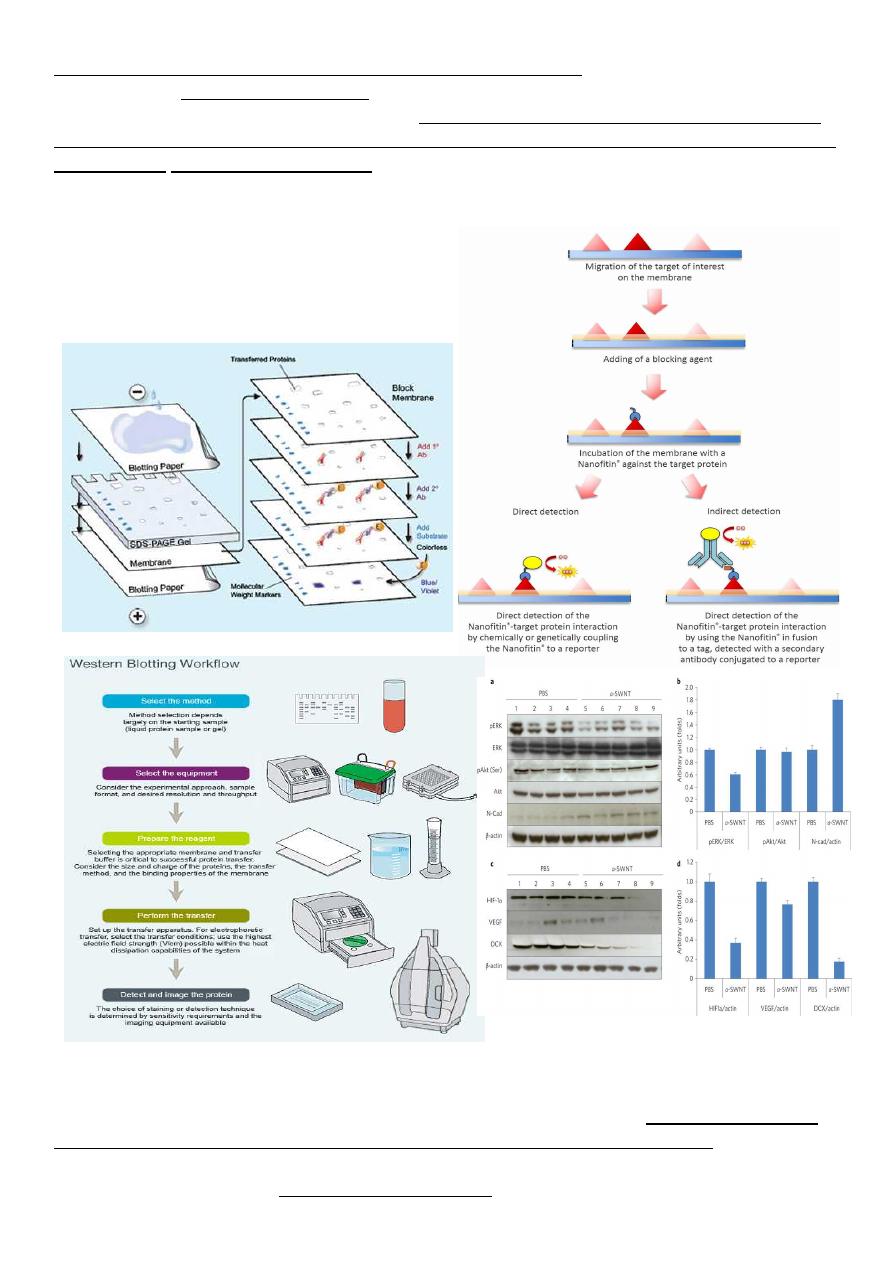

The most commonly used confirmatory test is the Western blot. This assay takes advantage

of the fact that multiple HIV antigens of different, well-characterized molecular weights

elicit the production of specific antibodies. These antigens can be separated on the basis of

molecular weight, and antibodies to each component can be detected as discrete bands on the

Western blot. A negative Western blot is one in which no bands are present at molecular

weights corresponding to HIV gene products. In a patient with a positive or indeterminate

EIA and a negative Western blot, one can conclude with certainty that the EIA reactivity was

a false positive. On the other hand, a Western

blot demonstrating antibodies to products of all

three of the major genes of of HIV (env, pol

&gag) is conclusive evidence of infection with

HIV.

CD4+ T Cell Counts

The CD4+ T cell count is the laboratory test generally accepted as the best indicator of the

immediate state of immunologic competence of the patient with HIV infection. This

measurement has been shown to correlate very well with the level of immunologic

competence. Patients with CD4+ T cell counts <200 are at high risk of disease from P.

jiroveci while patients with CD4+ T cell counts <50 are at high risk of disease from CMV,

mycobacteria of M.avium complex &/0r T.gondi. Patients with HIV infection should have

CD4+ T cell measurements performed at the time of diagnosis and every 3–6 months

thereafter. More frequent measurements should be made if a declining trend is noted.

Treatment slow the course and lead to near normal life expectancy, reduce the risk of death

and complication

Without treat. Avarage survival time from infection is 9-11 year

MANAGEMENT OF HIV

Management of HIV involves both treatment of the virus and prevention of opportunistic

infections. The aims of HIV treatment are to:

1*reduce the viral load to an undetectable level (< 50 copies/ml) for as long as possible

2*improve the CD4 count (above 200 cells/mm significant HIV-related events rarely occur).

3*increase the quantity and improve the quality of life without unacceptable drug-related

side-effects or lifestyle alteration.

4*reduce transmission (mother-to-child and person-to-person).

DRUGS

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)

Zalcitabine (ddc)

Didanosine (ddI)

Lamivudine (3TC)

Zidovudine (ZDV)

Stavudine (d4T)

Abacavir

Emitricitabine (FTC)

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)

Nevirapine

Efavirenz

Delavirdine

Protease inhibitors (PIs)

Indinavir

Ritonavir

Nelfinavir

Lopinavir

Atazanavir

PREVENTION MEASURES FOR HIV TRANSMISSION:

Parenteral

1. Blood product transmission: donor questionnaire, routine screening of donated blood,

blood substitute use.

2. Injection drug use: education, needle/syringe exchange, sharing and support for

methadone maintenance programmes.

Perinatal

1. Routine antenatal HIV antibody testing.

2.Preconception family planning if HIV- seropositive.

3. Measures to reduce vertical transmission.

Occupational

1. Education/training: universal precautions, needle stick avoidance.

2. Post-exposure prophylaxis.

Formatted by Mohammed Musa