Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

105

“” Presenting problems in cardiovascular disease “”

(Printed by Mostafa Hatim)

- Chest pain - Breathlessness (dyspnoea) - Acute circulatory failure (cardiogenic shock) -

Heart failure - Hypertension - Syncope & presyncope - Palpitation - Cardiac arrest and

sudden cardiac death - Abnormal heart sounds and murmurs

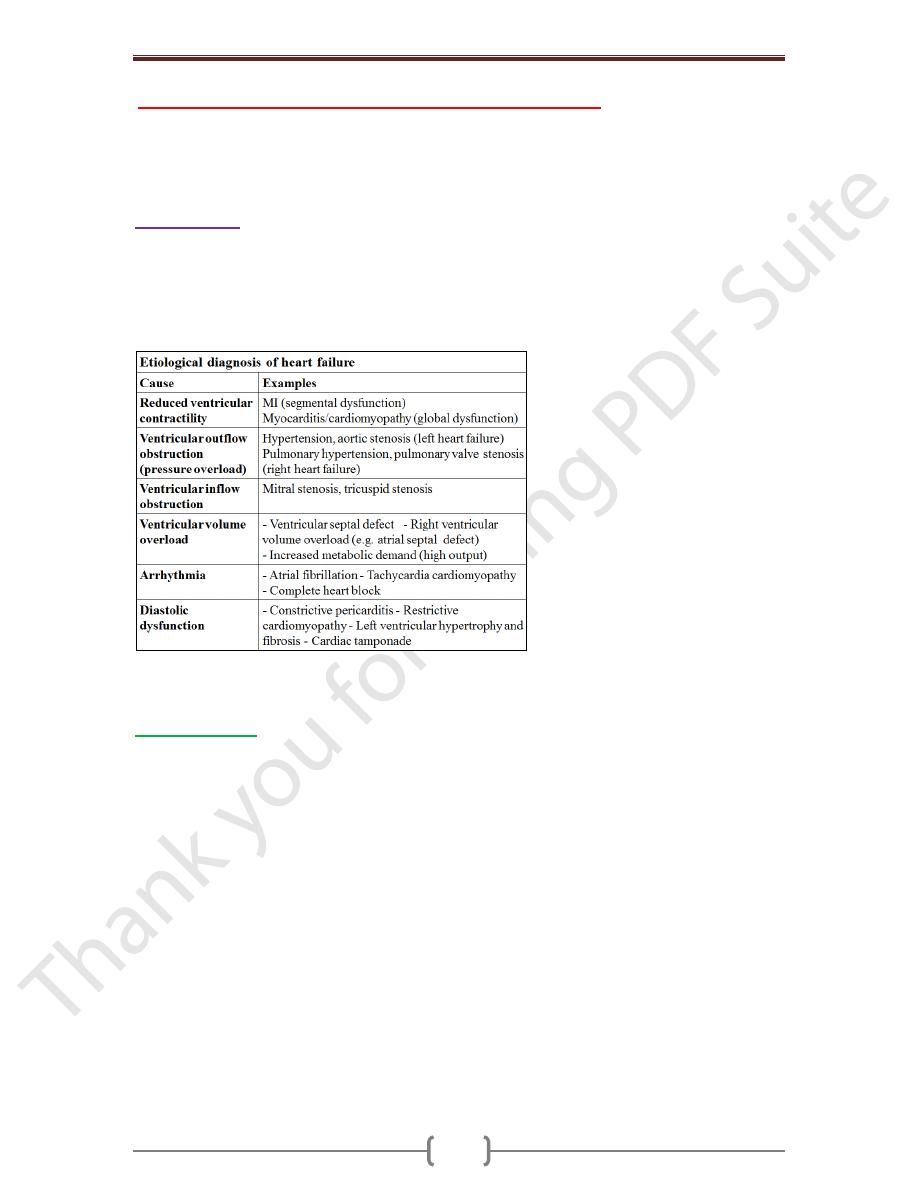

Heart failure

Describes the clinical syndrome that develops when the heart cannot maintain an

adequate cardiac output, or can do so only at the expense of an elevated filling pressure.

In mild to moderate forms of heart failure, cardiac output is adequate at rest & only

becomes inadequate when the metabolic demand increases during exercise or some other

form of stress. Almost all forms of heart disease can lead to heart failure.

HF is a common problem. It is a killing disease, 50% of patients with severe HF will die

within 6 months, 50% of patients with moderate HF will die in 2 years.

Pathophysiology

Cardiac output is a function of the preload (the volume and pressure of blood in the

ventricle at the end of diastole), the afterload (the volume and pressure of blood in the

ventricle during systole) and myocardial contractility; this is the basis of Starling’s Law.

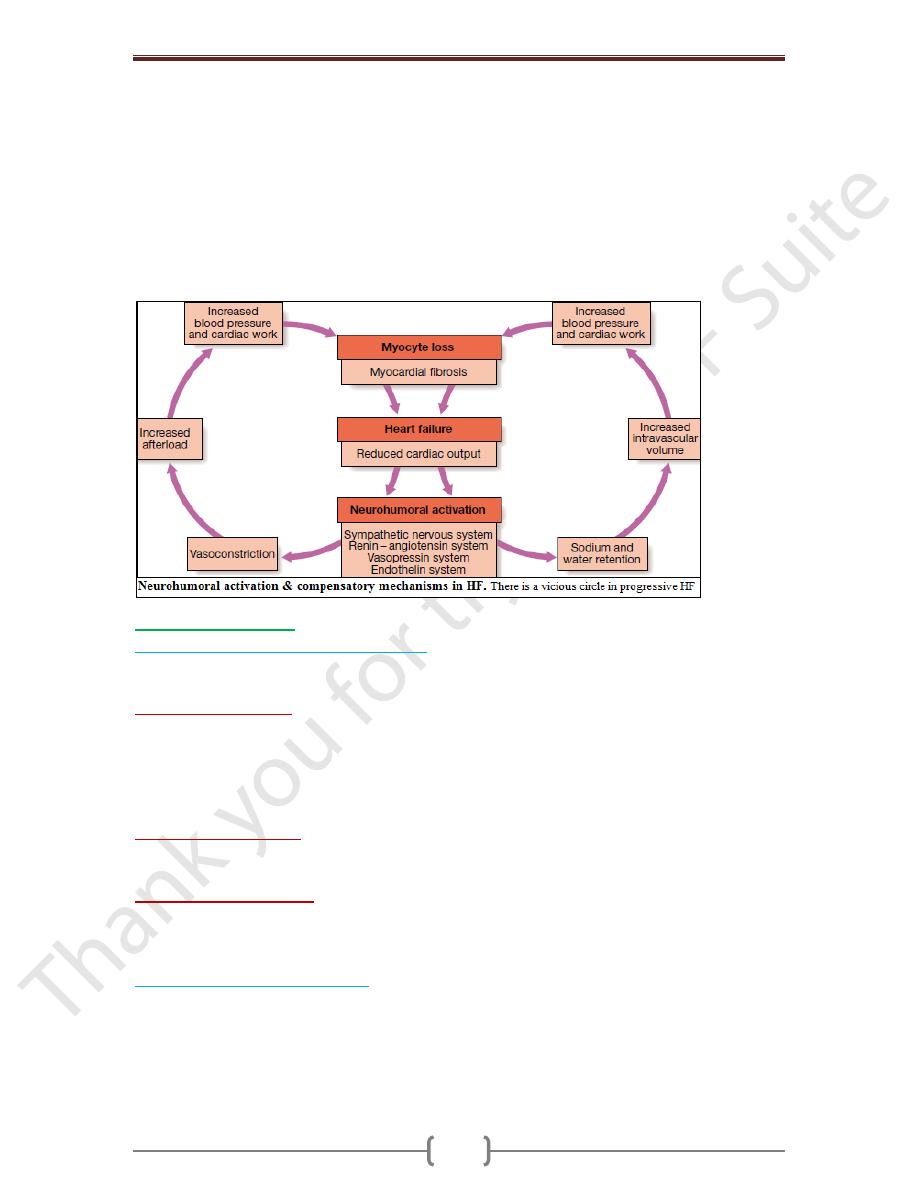

In patients without valvular disease, the primary abnormality is impairment of ventricular

function leading to a fall in cardiac output. This activates counter-regulatory

neurohumoral mechanisms that in normal physiological circumstances would support

cardiac function, but in the setting of impaired ventricular function can lead to a

deleterious increase in both afterload and preload. A vicious circle may be established

because any additional fall in cardiac output will cause further neurohumoral activation

and increasing peripheral vascular resistance.

Stimulation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system leads to vasoconstriction, salt

and water retention, and sympathetic nervous system activation. This is mediated by

angiotensin II, a potent constrictor of arterioles in both the kidney and the systemic

circulation. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system may initially maintain cardiac

output through an increase in myocardial contractility, heart rate & peripheral

vasoconstriction. However, prolonged

sympathetic stimulation leads to cardiac myocyte apoptosis, hypertrophy & focal

myocardial necrosis. Salt & water retention is promoted by release of aldosterone,

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

106

endothelin-1 (a potent vasoconstrictor peptide with marked effects on the renal

vasculature) and, in severe heart failure, antidiuretic hormone (ADH). Natriuretic

peptides are released from the atria in response to atrial stretch, and act as physiological

antagonists to the fluid conserving effect of aldosterone.

After MI, cardiac contractility is impaired & neurohumoral activation causes hypertrophy

of non-infarcted segments, with thinning, dilatation and expansion of the infarcted

segment (remodeling). This leads to further deterioration in ventricular function and

worsening heart failure.

The onset of pulmonary & peripheral oedema is due to high atrial pressures compounded by

salt & water retention caused by impaired renal perfusion & secondary hyperaldosteronism.

Types of heart failure

Left, right and biventricular heart failure

The left side of the heart comprises the functional unit of the LA & LV, together with the

mitral & aortic valves; the right heart comprises the RA, RV, & tricuspid & pulmonary valves.

o

Left-sided heart failure.

There is a reduction in the left ventricular output and an

increase in the left atrial or pulmonary venous pressure. An acute increase in left atrial

pressure causes pulmonary congestion or pulmonary oedema; a more gradual increase in

left atrial pressure, as occurs with mitral stenosis, leads to reflex pulmonary

vasoconstriction, which protects the patient from pulmonary oedema at the cost of

increasing pulmonary hypertension.

o

Right-sided heart failure

. There is a reduction in right ventricular output for any given

right atrial pressure. Causes of isolated right HF include chronic lung disease (cor

pulmonale), multiple pulmonary emboli & pulmonary valvular stenosis.

o

Biventricular heart failure.

Failure of the left and right heart may develop because the

disease process, such as dilated cardiomyopathy or ischaemic heart disease, affects both

ventricles or because disease of the left heart leads to chronic elevation of the left atrial

pressure, pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.

Diastolic and systolic dysfunction

Heart failure may develop as a result of impaired myocardial contraction (systolic

dysfunction) but can also be due to poor ventricular filling and high filling pressures

caused by abnormal ventricular relaxation (diastolic dysfunction). The latter is caused by

a stiff non-compliant ventricle and is commonly found in patients with left ventricular

hypertrophy. Systolic and diastolic dysfunction often coexist, particularly in patients with

coronary artery disease.

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

107

High-output failure

Conditions such as large arteriovenous shunt, beri-beri, severe anaemia or thyrotoxicosis

can occasionally cause heart failure due to an excessively high cardiac output.

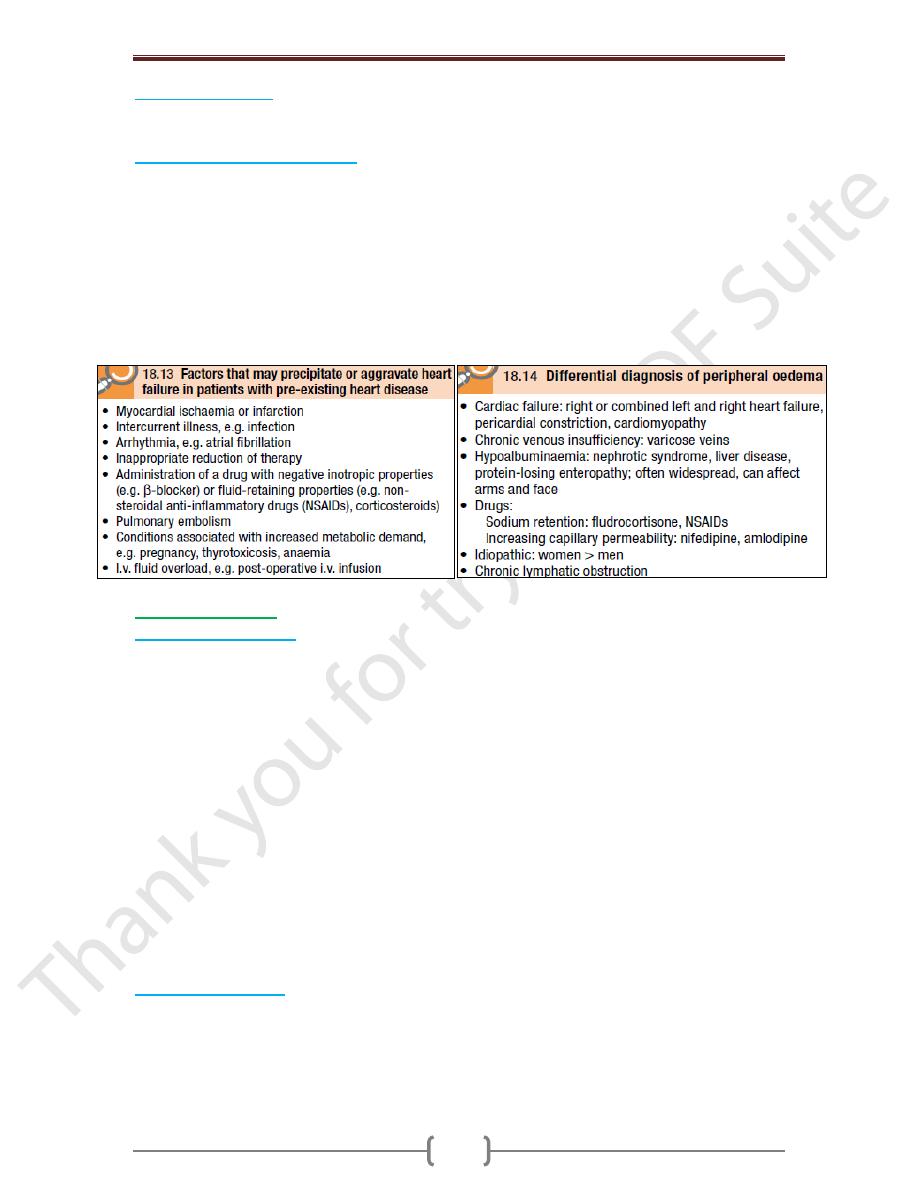

Acute and chronic heart failure

Heart failure may develop suddenly, as in MI, or gradually, as in progressive valvular

heart disease. When there is gradual impairment of cardiac function, a variety of

compensatory changes may take place. The term ‘compensated heart failure’ is

sometimes used to describe those with impaired cardiac function in whom adaptive

changes have prevented the development of overt heart failure. A minor event, such as an

intercurrent infection or development of atrial fibrillation, may precipitate overt or acute

heart failure. Acute left heart failure occurs either de novo or as an acute decompensated

episode on a background of chronic heart failure, so-called acute-on-chronic heart failure.

In HF, CO is about 5L/min & the heart can’t elevate the CO > 5L/min.

Clinical assessment

Acute left heart failure

o Acute de novo left ventricular failure presents with a sudden onset of dyspnoea at rest

that rapidly progresses to acute respiratory distress, orthopnoea & prostration. The

precipitant, such as acute MI, is often apparent from the hx.

o The patient appears agitated, pale and clammy. The peripheries are cool to the touch and

the pulse is rapid. Inappropriate bradycardia or excessive tachycardia should be identified

promptly, as this may be the precipitant for the acute episode of heart failure. The BP is

usually high because of sympathetic nervous system activation, but may be normal or low

if the patient is in cardiogenic shock.

o The jugular venous pressure (JVP) is usually elevated, particularly with associated fluid

overload or right HF. In acute de novo HF, there has been no time for ventricular

dilatation & the apex is not displaced. Auscultation occasionally identifies the murmur of

a catastrophic valvular or septal rupture, or reveals a triple ‘gallop’ rhythm. Crepitations

are heard at the lung bases, consistent with pulmonary oedema.

o Acute-on-chronic heart failure will have additional features of long-standing heart failure

(see below). Potential precipitants, such as an upper respiratory tract infection or

inappropriate cessation of diuretic medication, should be identified.

Chronic heart failure

o Patients with chronic HF commonly follow a relapsing and remitting course, with periods

of stability and episodes of decompensation leading to worsening symptoms that may

necessitate hospitalisation. The clinical picture depends on the nature of the underlying

heart disease, the type of heart failure that it has evoked, and the neurohumoral changes

that have developed.

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

108

o A low CO causes fatigue, listlessness & a poor effort tolerance; the peripheries are cold

& BP is low. To maintain perfusion of vital organs, blood flow is diverted away from

skeletal ms & this may contribute to fatigue & weakness. Poor renal perfusion leads to

oliguria & uraemia.

o Pulmonary oedema due to left heart failure presents as described above and with

inspiratory crepitations over the lung bases. In contrast, right heart failure produces a

high JVP with hepatic congestion and dependent peripheral oedema. In ambulant

patients, the oedema affects the ankles, whereas in bed-bound patients it collects around

the thighs and sacrum. Ascites or pleural effusion occurs in some cases. Heart failure is

not the only cause of oedema.

o Chronic heart failure is sometimes associated with marked weight loss (cardiac cachexia)

caused by a combination of anorexia and impaired absorption due to gastrointestinal

congestion, poor tissue perfusion due to a low cardiac output, and skeletal muscle atrophy

due to immobility.

Complications

In advanced heart failure, the following may occur:

Renal failure

is caused by poor renal perfusion due to a low cardiac output and may be

exacerbated by diuretic therapy, (ACE) inhibitors & angiotensin receptor blockers.

Hypokalaemia

may be the result of treatment with potassium-losing diuretics or

hyperaldosteronism caused by activation of the renin–angiotensin system and impaired

aldosterone metabolism due to hepatic congestion. Most of the body’s potassium is

intracellular and there may be substantial depletion of potassium stores, even when the

plasma potassium concentration is in the normal range.

Hyperkalaemia

may be due to the effects of drug treatment, particularly combination of ACE

inhibitors & spironolactone (which both promote potassium retention) & renal dysfunction.

Hyponatraemia

is a feature of severe heart failure and is a poor prognostic sign. It may

be caused by diuretic therapy, inappropriate water retention due to high ADH secretion,

or failure of the cell membrane ion pump.

Impaired liver function

caused by hepatic venous congestion and poor arterial

perfusion, which frequently cause mild jaundice and abnormal liver function tests;

reduced synthesis of clotting factors can make anticoagulant control difficult.

Thromboembolism.

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism may occur due to

the effects of a low CO & enforced immobility, whereas systemic emboli may be related

to arrhythmias, atrial flutter or fibrillation, or intracardiac

thrombus complicating conditions such as mitral stenosis, MI or left ventricular aneurysm.

Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias

are very common and may be related to

electrolyte changes (e.g. hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia), the underlying structural

heart disease, and the pro-arrhythmic effects of increased circulating catecholamines or

drugs. Sudden death occurs in up to 50% of patients with HF and is often due to a

ventricular arrhythmia. Frequent ventricular ectopic beats and runs of non-sustained

ventricular tachycardia are common findings in patients with heart failure and are

associated with an adverse prognosis.

Investigations

Serum urea & electrolytes, Hb, thyroid function, ECG & chest X-ray may help to establish

the nature & severity of the underlying heart disease & detect any complications.

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is elevated in heart failure and is a marker of risk; it is

useful in the investigation of patients with breathlessness or peripheral oedema.

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

109

Echocardiography

is very useful and should be considered in all patients with heart

failure in order to:

o determine the aetiology

o detect hitherto unsuspected valvular heart disease, such as occult mitral stenosis, and

other conditions that may be amenable to specific remedies

o Identify patients who will benefit from long-term therapy with drugs, such as ACE

inhibitors (see below).

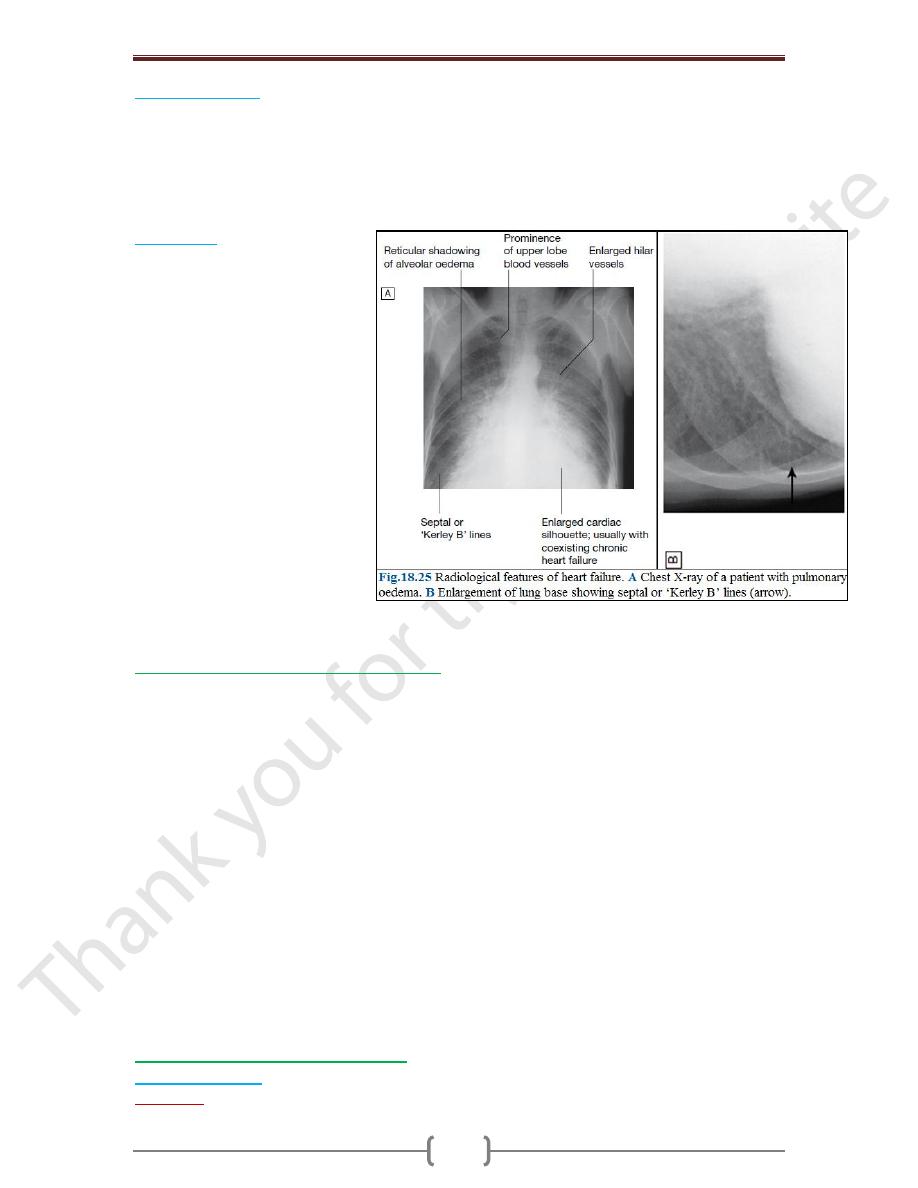

Chest X-ray

A rise in pulmonary venous

pressure from left-sided HF first

shows on the chest X-ray as an

abnormal distension of upper lobe

pulmonary veins (with the patient

in the erect position). The

vascularity of the lung fields

becomes more prominent, and the

right and left pulmonary arteries

dilate. Subsequently, interstitial

oedema causes thickened

interlobular septa and dilated

lymphatics. These are evident as

horizontal lines in the costophrenic

angles (septal or ‘Kerley B’ lines).

More advanced changes due to

alveolar oedema cause a hazy

opacification spreading from the

hilar regions & pleural effusions.

Management of acute pulmonary oedema

This is urgent:

o Sit the patient up in order to reduce pulmonary congestion.

o Give oxygen (high-flow, high-concentration). Noninvasive +ve pressure ventilation

(continuous +ve airways pressure (CPAP) of 5-10 mmHg) by a tight-fitting facemask

results in a more rapid improvement in the patient’s clinical state.

o Administer nitrates, such as i.v. glyceryl trinitrate 10–200 μg/min or buccal glyceryl

trinitrate 2–5 mg, titrated upwards every 10 minutes, until clinical improvement occurs or

systolic BP falls to < 110 mmHg.

o Administer a loop diuretic such as furosemide 50-100mg i.v.

The patient should initially be kept on strict bed rest with continuous monitoring of

cardiac rhythm, BP and pulse oximetry. IV opiates may be cautiously used when patients

are in extremis. They reduce sympathetically mediated peripheral vasoconstriction but

may cause respiratory depression & exacerbation of hypoxaemia & hypercapnia.

If these measures prove ineffective, inotropic agents may be required to augment cardiac

output, particularly in hypotensive patients. Insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump can

be very beneficial in patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, especially when

secondary to myocardial ischaemia.

Management of chronic heart failure

General measures

o Education:

Explanation of nature of disease, treatment and self-help strategies

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

110

o Diet:

Good general nutrition and weight reduction for the obese. Avoidance of high-salt

foods and added salt, especially for patients with severe congestive heart failure

o Alcohol:

Moderation or elimination of alcohol consumption. Alcohol-induced

cardiomyopathy requires abstinence

o Smoking:

Cessation

o Exercise:

Regular moderate aerobic exercise within limits of symptoms

o Vaccination:

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be considered

In patients with coronary heart disease, secondary preventative measures, such as low-

dose aspirin and lipid-lowering therapy, are required. However, statins do not appear to

be effective in patients with severe heart failure.

Drug therapy

o Diuretic therapy

In HF, diuretics produce an increase in urinary sodium & water excretion, leading to a

reduction in blood & plasma volume. Diuretic therapy reduces preload and improves

pulmonary & systemic venous congestion. It may also reduce afterload and ventricular

volume, leading to a fall in wall tension & increased cardiac efficiency.

In some patients with severe chronic heart failure, particularly in the presence of chronic

renal impairment, oedema may persist despite oral loop diuretics. In such patients an

intravenous infusion of furosemide 10 mg/hr may initiate a diuresis. Combining a loop

diuretic with a thiazide (e.g. bendroflumethiazide 5 mg daily) or a thiazide-like diuretic

(e.g. metolazone 5 mg daily) may prove effective, but this can cause an excessive

diuresis. Aldosterone receptor antagonists, such as spironolactone and eplerenone, are

potassium-sparing diuretics that are of particular benefit in patients with heart failure.

They may cause hyperkalaemia, particularly when used with an ACE inhibitor. They

improve long-term clinical outcome in patients with severe heart failure or heart failure

following acute MI.

o Vasodilator therapy

These drugs are valuable in chronic heart failure. Venodilators, such as nitrates, reduce

preload, & Arterial dilators, such as hydralazine, reduce afterload. Their use is limited by

pharmacological tolerance and hypotension.

o Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition therapy

This interrupts the vicious circle of neurohumoral activation that is characteristic of

moderate and severe heart failure by preventing the conversion of angiotensin I to

angiotensin II, thereby preventing salt and water retention, peripheral arterial and venous

vasoconstriction, & activation of the sympathetic nervous system. These drugs also

prevent the undesirable activation of the renin–angiotensin system caused by diuretic

therapy. Whilst the major benefit of ACE inhibition in heart failure is a reduction in

afterload, it also reduces preload and causes a modest rise in the plasma potassium

concentrations. Treatment with a combination of a loop diuretic and an ACE inhibitor

therefore has many potential advantages.

In moderate and severe HF, ACE inhibitors can produce a substantial improvement in

effort tolerance and in mortality. They can also improve outcome and prevent the onset of

overt heart failure in patients with poor residual left ventricular function following MI.

They can cause symptomatic hypotension & impairment of renal function. Short-acting

ACE inhibitors can cause marked falls in BP, particularly in the elderly or when started in

the presence of hypotension, hypovolaemia or hyponatraemia.

o Angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy

These drugs act by blocking the action of angiotensin II on the heart, peripheral vasculature

& kidney. In HF, they produce beneficial haemodynamic changes that are similar to the

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

111

effects of ACE inhibitors but are generally better tolerated. They have comparable

effects on mortality & are a useful alternative for patients who cannot tolerate ACE

inhibitors. Unfortunately, they share all the more serious adverse effects of ACE inhibitors,

including renal dysfunction & hyperkalaemia. They may be considered in combination

with ACE inhibitors, especially in those with recurrent hospitalisations for HF.

o Beta-adrenoceptor blocker therapy

helps to counteract the deleterious effects of enhanced sympathetic stimulation & reduces

the risk of arrhythmias and sudden death. When initiated in standard doses, they may

precipitate acute-on-chronic HF, but when given in small incremental doses (e.g.

bisoprolol started at a dose of 1.25 mg daily, & increased gradually over a 12-week

period to a target maintenance dose of 10 mg daily), they can increase ejection fraction,

improve symptoms, reduce the frequency of hospitalization and reduce mortality in

patients with chronic HF. Beta-blockers are more effective at reducing mortality than

ACE inhibitors: relative risk reduction of 33% versus 20% respectively.

o Digoxin

can be used to provide rate control in patients with HF & atrial fibrillation. In patients

with severe HF (NYHA class III–IV), digoxin reduces the likelihood of hospitalisation

for heart failure, although it has no effect on long-term survival.

o Amiodarone

This is a potent anti-arrhythmic drug that has little negative inotropic effect and may be

valuable in patients with poor left ventricular function. It is only effective in the treatment

of symptomatic arrhythmias, and should not be used as a preventative agent in

asymptomatic patients.

Implantable cardiac defibrillators and resynchronisation therapy

Coronary revascularisation

Heart transplantation

Ventricular assist devices