1

2

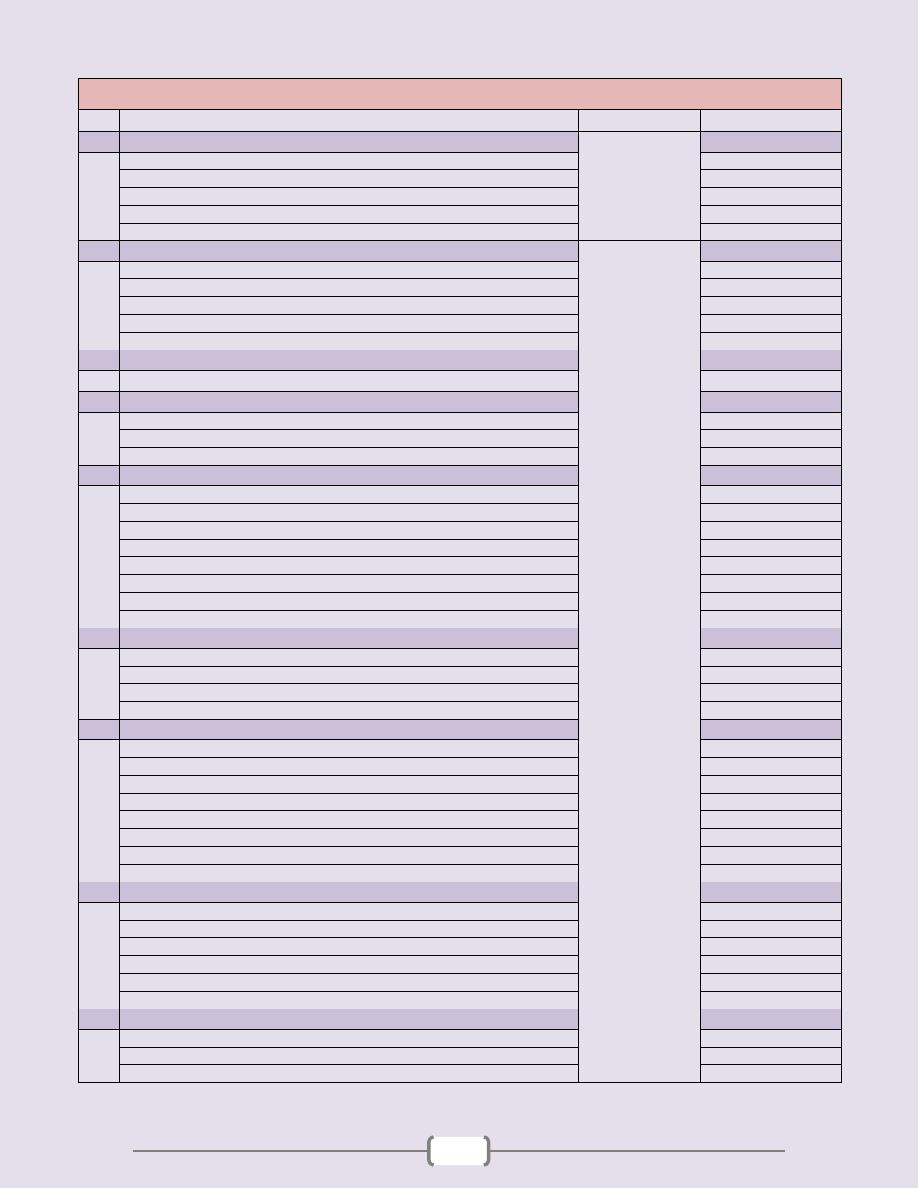

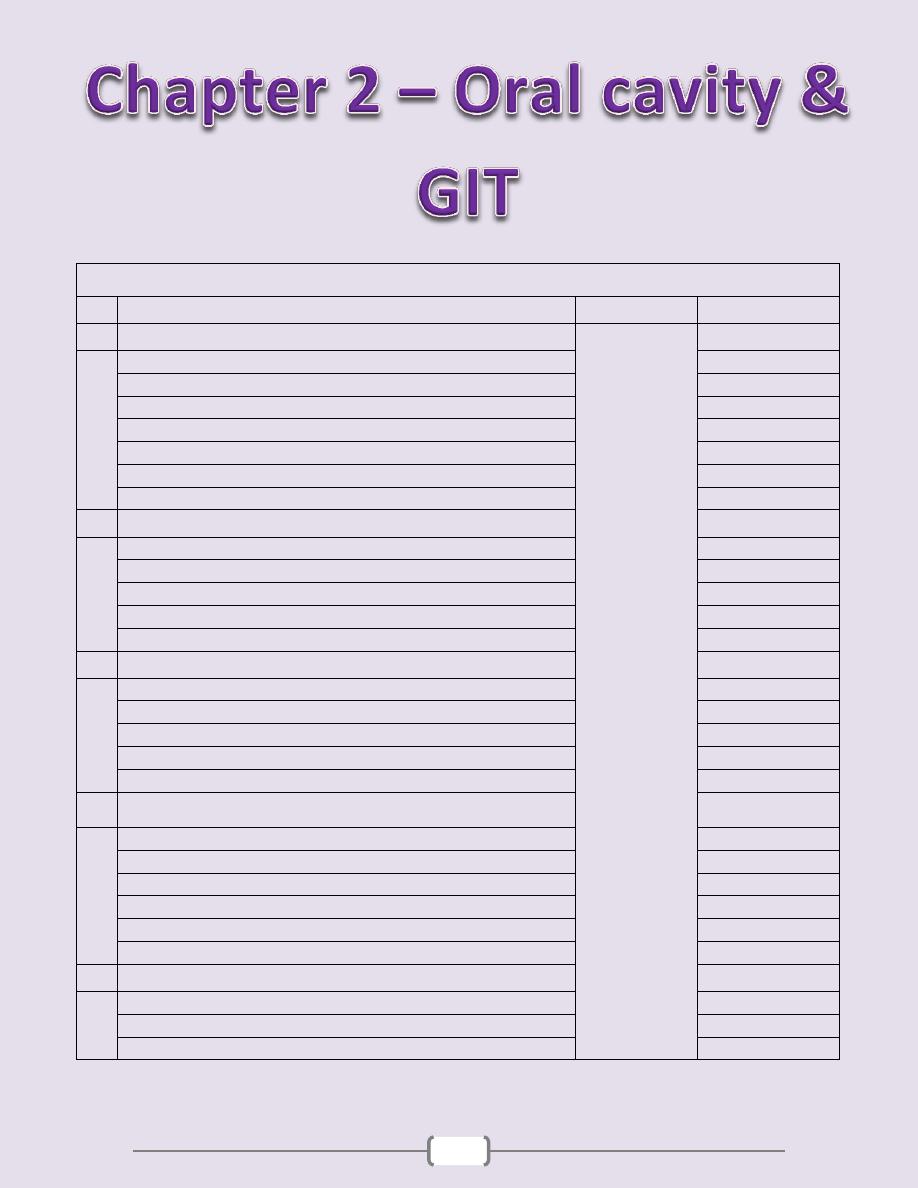

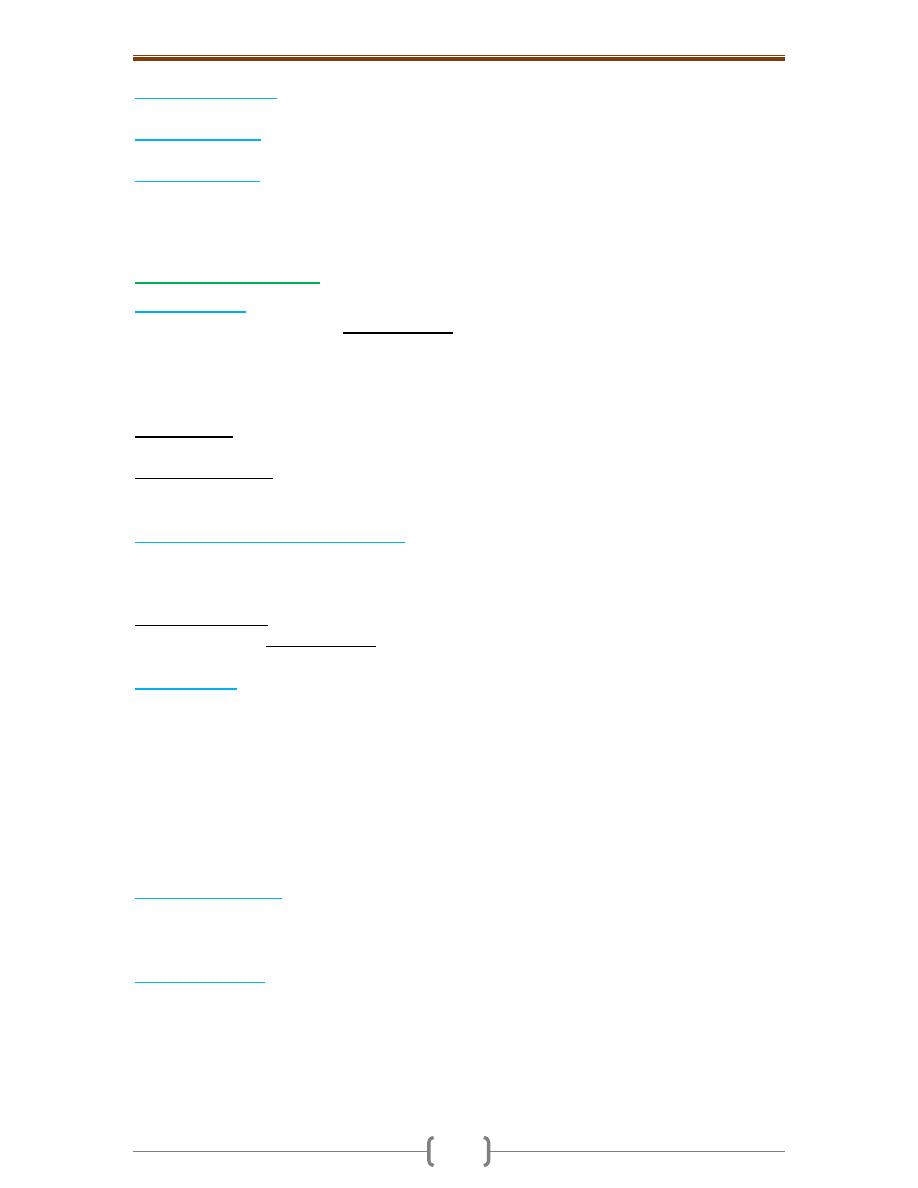

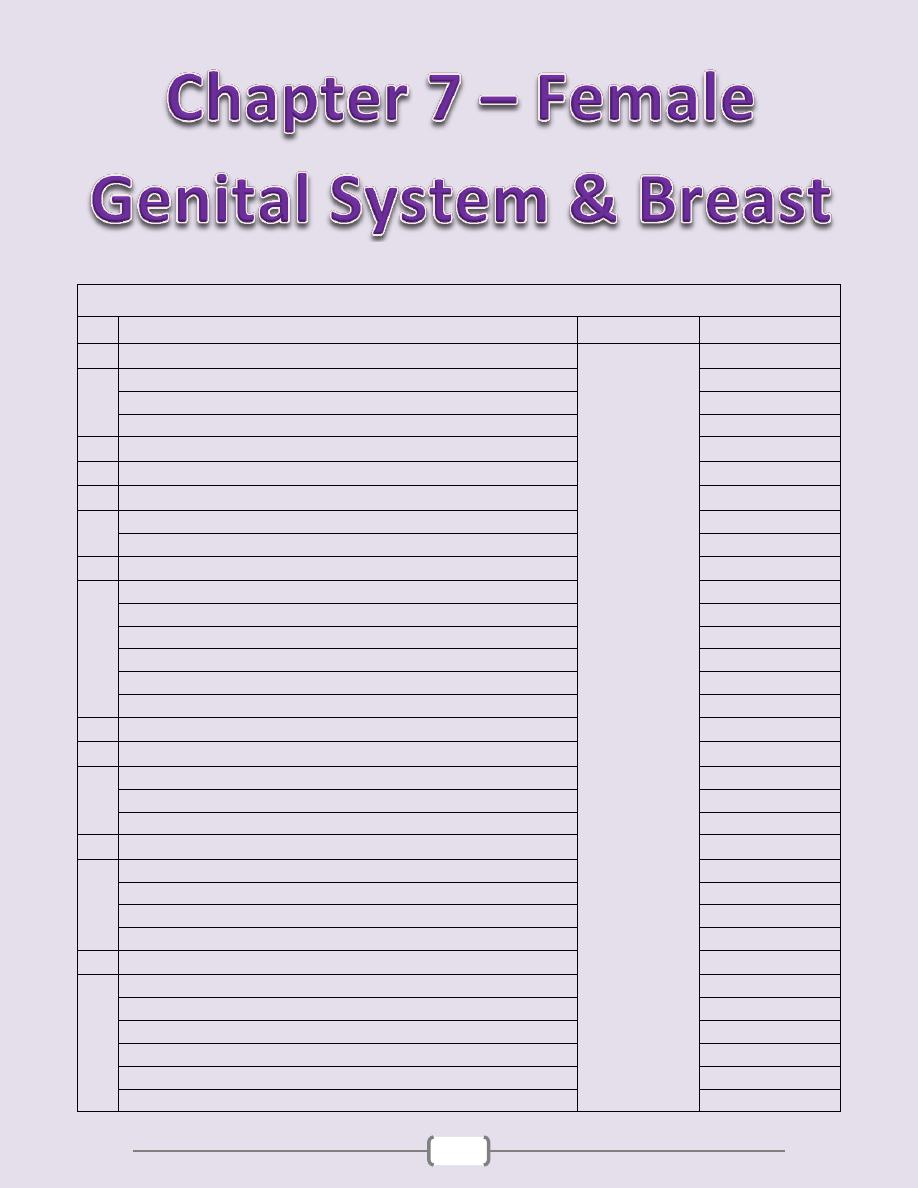

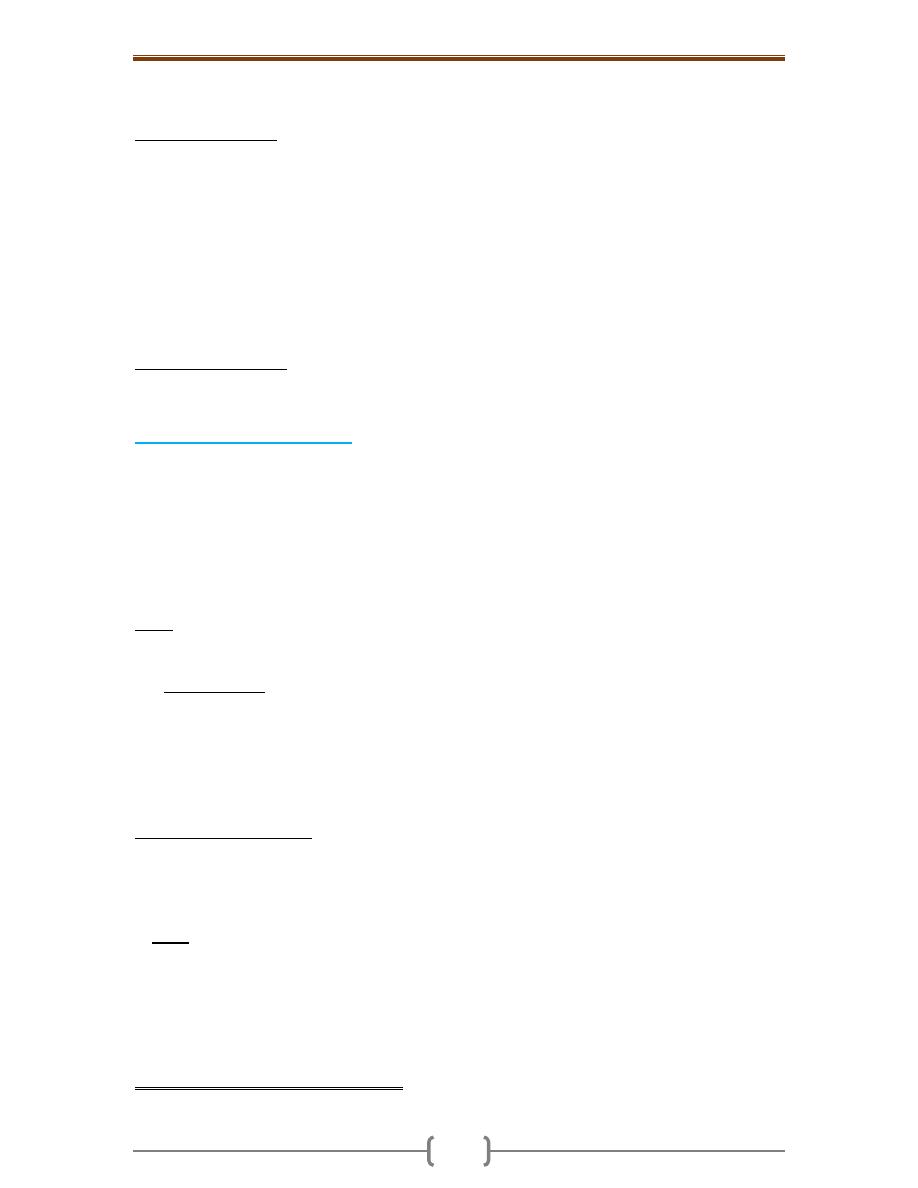

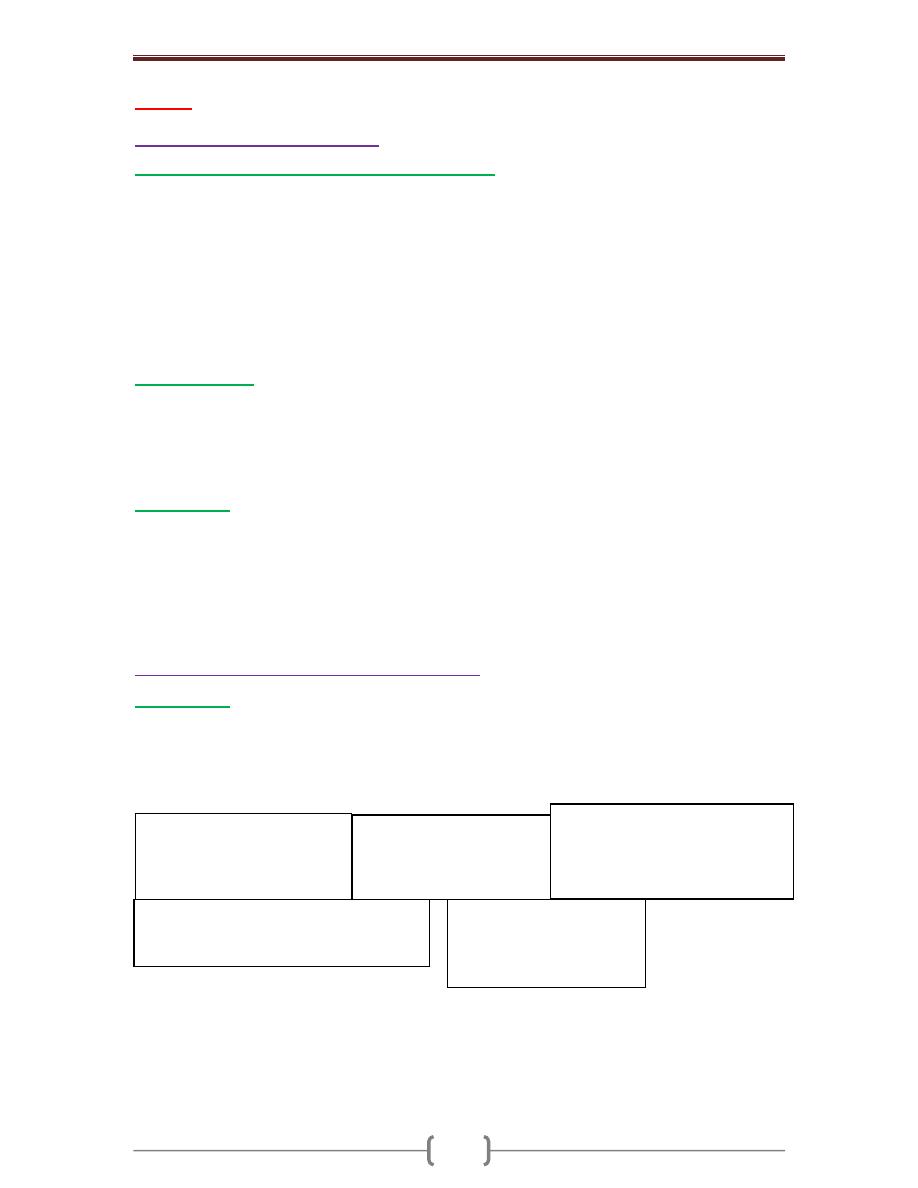

List of contents

Topics

Directed by

Page number

1

Heart

د. مهند

(3

– 14)

Heart Failure

4 - 6

Pericardial disease

7

Valvular heart disease

8 - 10

Cardiomyopathies

11

Congenital heart disease

12 - 14

2

Oral cavity & GIT

د. سالم

(15

– 50)

Oral cavity & Oropharynx

16 - 21

Esophagus

22 - 27

Stomach

28 - 34

Small & Large Intestine

35 - 49

Appendix

50

3

Lymphoid System

(51

– 59)

Lymph Node

52 - 59

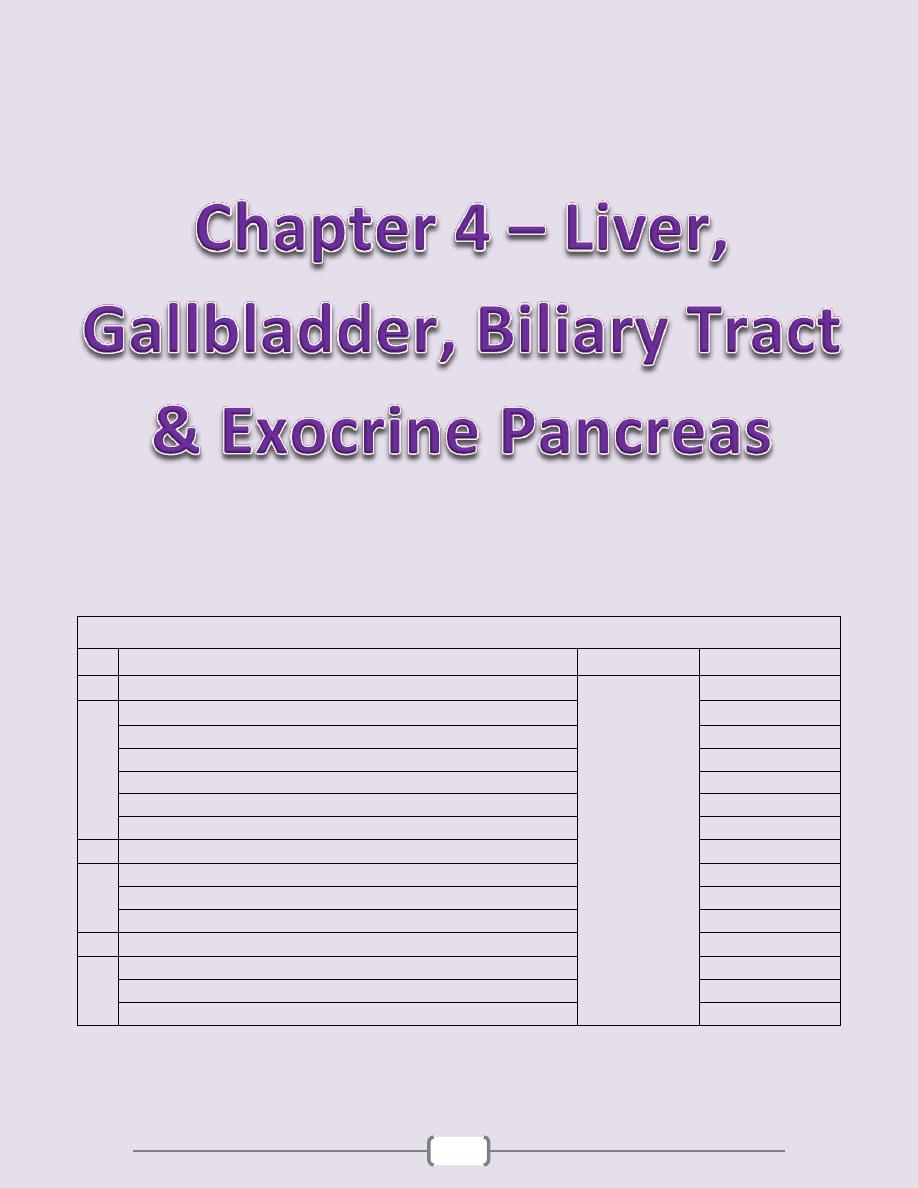

4

Liver, Gallbladder, Biliary Tract & Exocrine Pancreas

(60

– 83)

The Liver

61 - 76

Disorders of gallbladder and extrahepatic biliary tract

77 - 80

Exocrine Pancreas

81 - 83

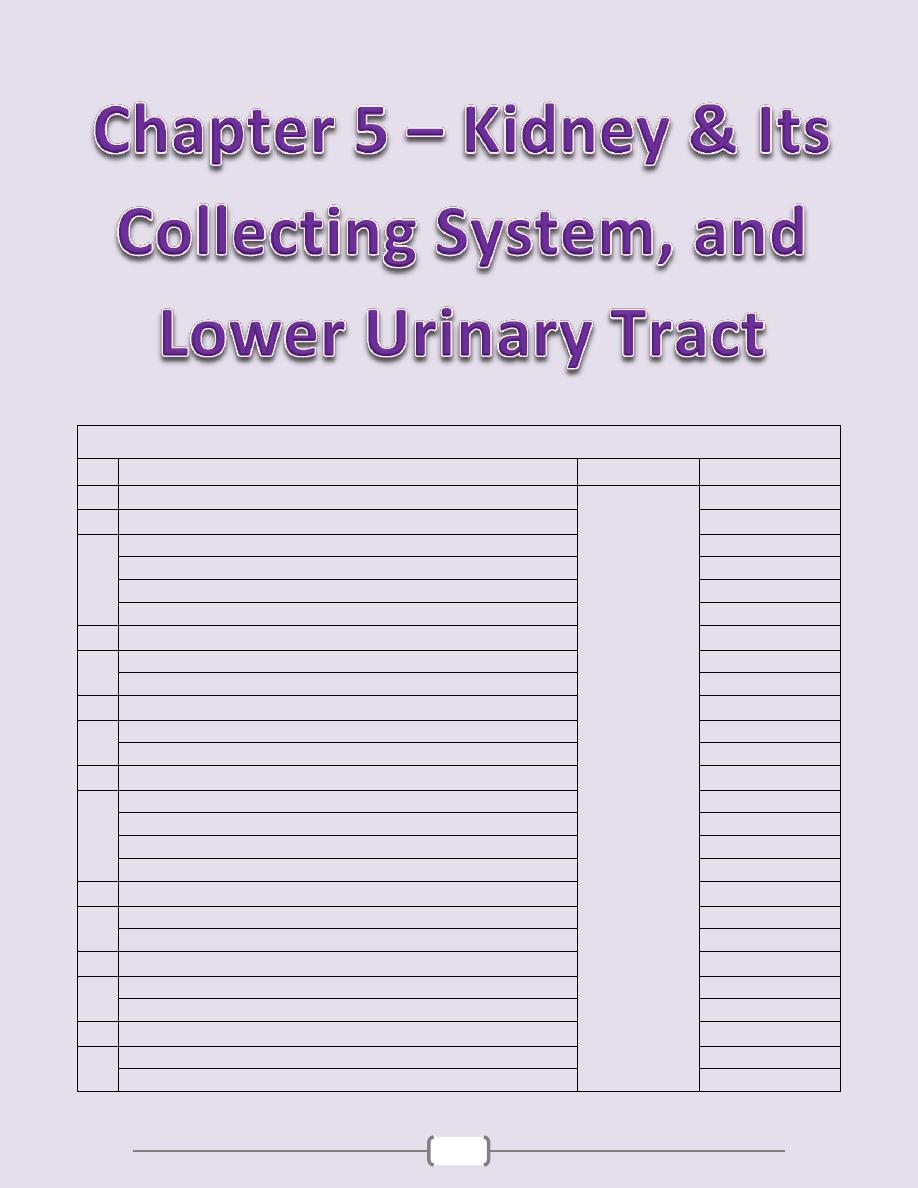

5

Kidney & Its Collecting System, and Lower Urinary Tract

(84 - 106)

Clinical Manifestations of Renal Diseases

86 – 91

Glomerular diseases

86 – 91

Tubulo-interstitial diseases

92 – 95

Diseases of renal blood vessels

96 - 97

Cystic diseases of the kidney

98

Urinary outflow obstruction

99 - 100

Tumors

101 - 102

Renal pelvis, ureter, urinary bladder & urethra

103 - 106

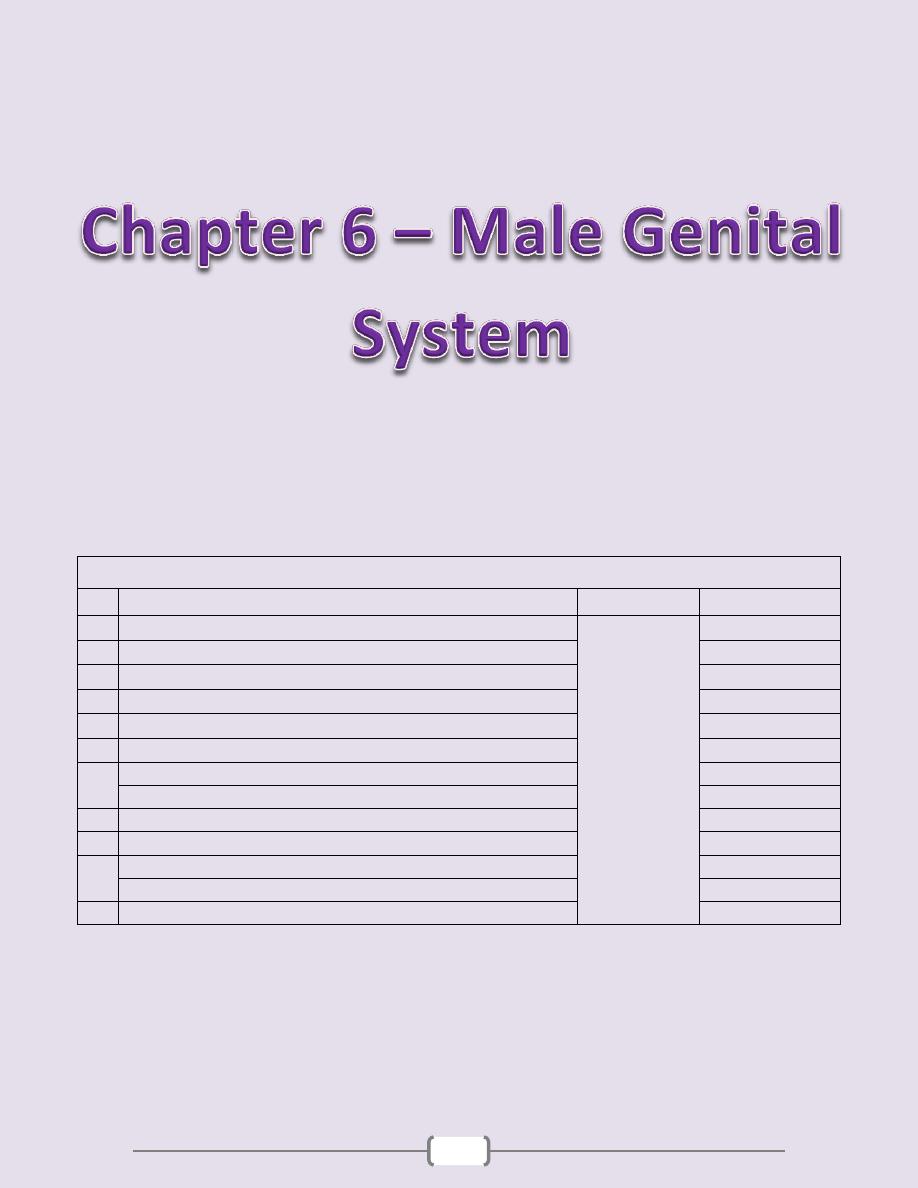

6

Male Genital System

(107

– 117)

The penis

108

Scrotum

109

Testis and Epididymis

110 – 113

The prostate

114 - 117

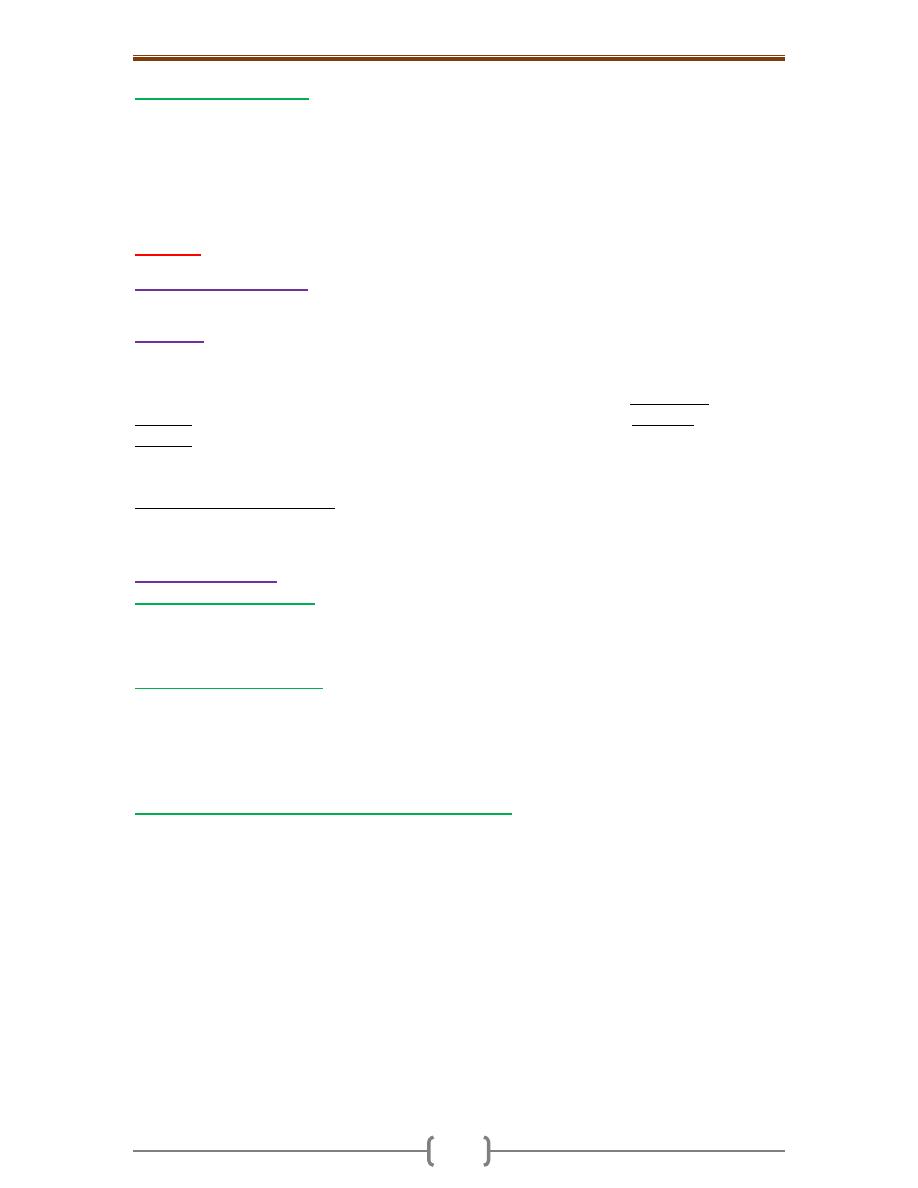

7

Female genital system & Breast

(118

– 144)

Vulva

119 - 120

Vagina

120

Cervix

121 – 123

Body of uterus

124 - 127

Fallopian tubes

128

Ovaries

129 – 132

Diseases of pregnancy

133 - 136

Breast

137 – 144

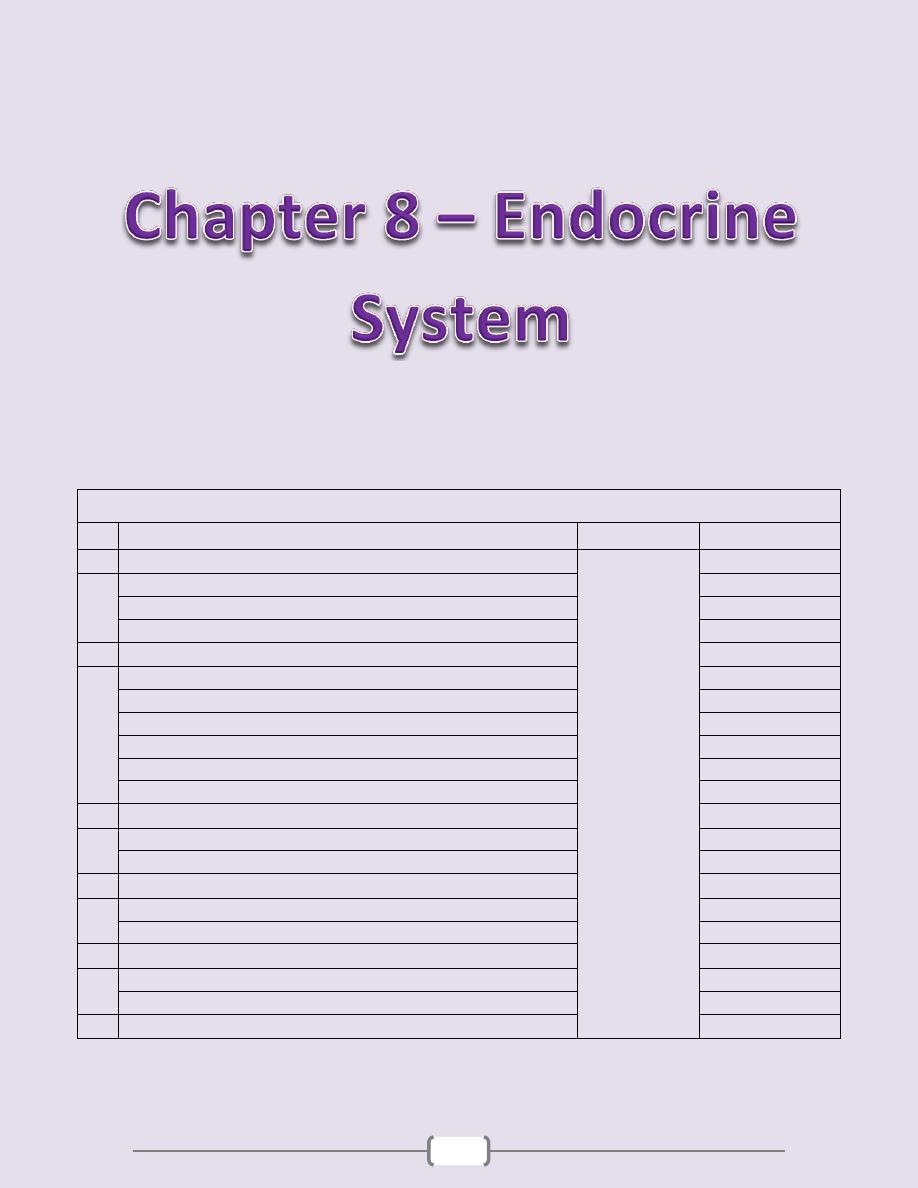

8

Endocrine system

(145

–166)

Pituitary

146 - 148

Thyroid

149 - 155

Parathyroid glands

156 – 157

Endocrine pancreas

158 - 160

Adrenal glands

161 - 165

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Syndromes (MEN)

166

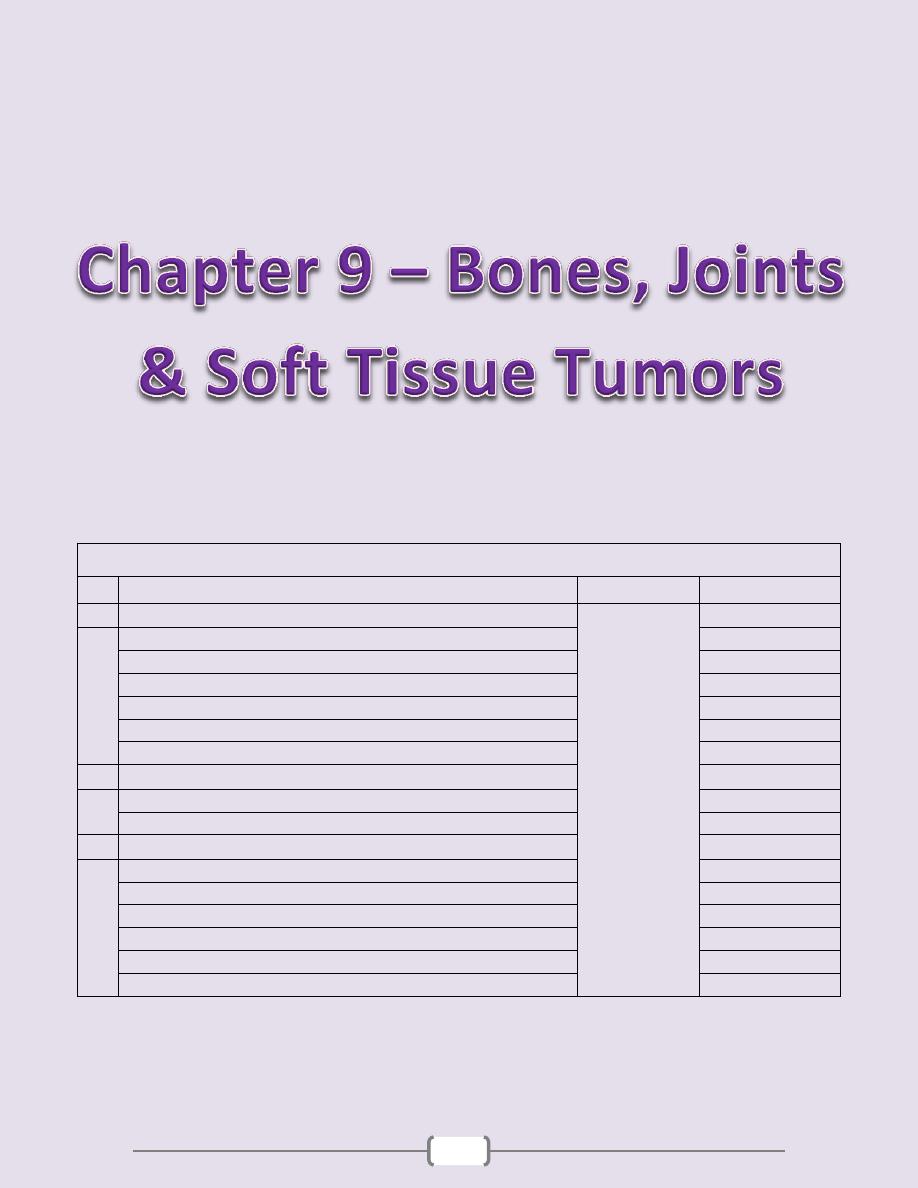

9

Bones, Joints, and Soft Tissue Tumors

(167

–185)

Bones

168 - 178

Joints

179 - 181

Soft Tissue Tumors

182 – 185

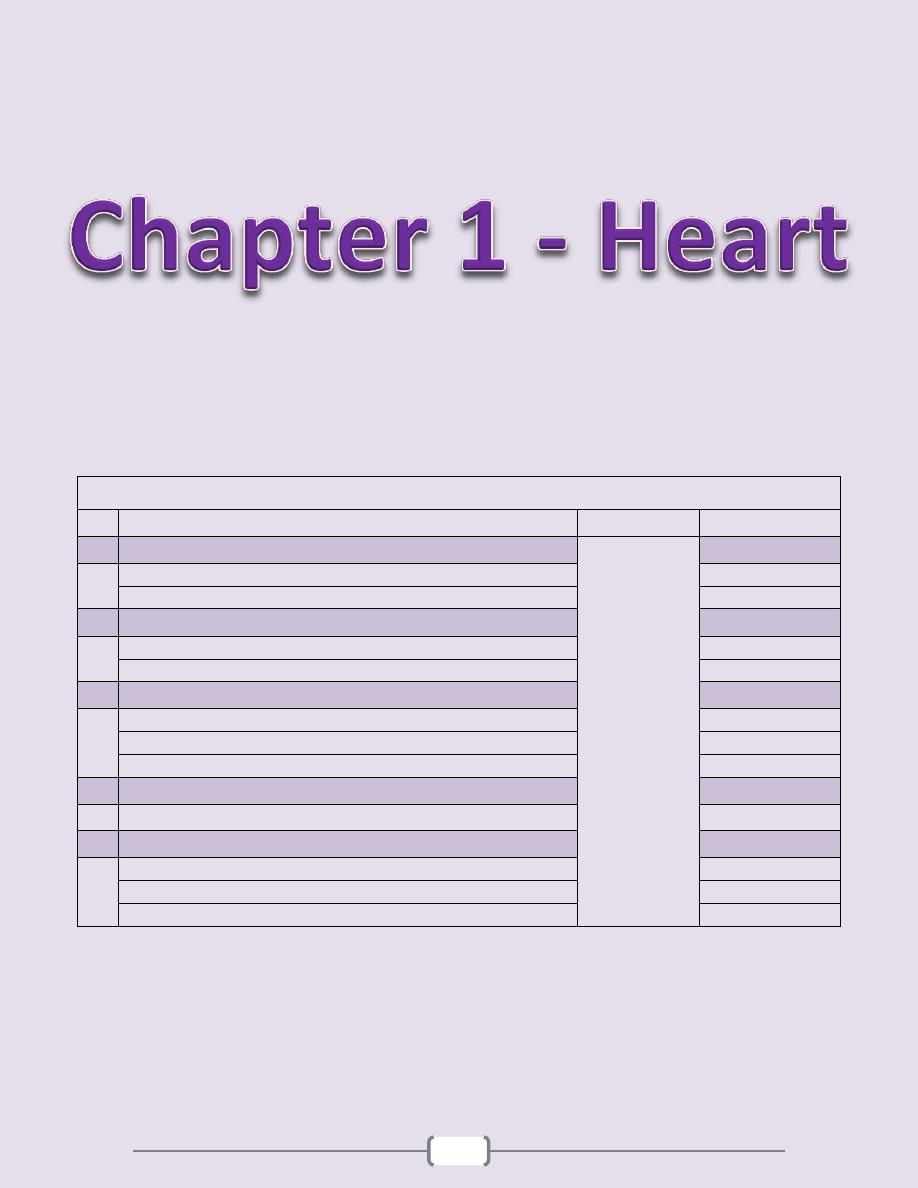

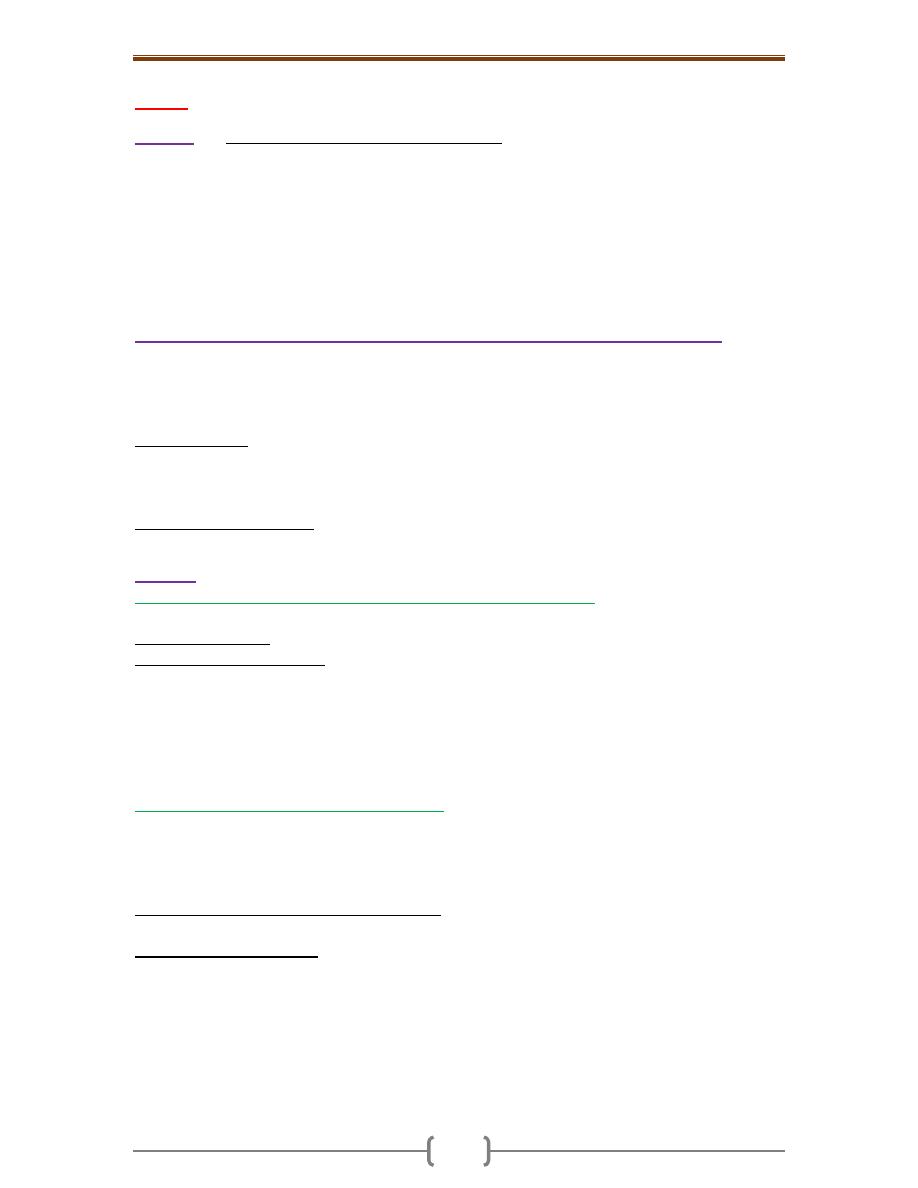

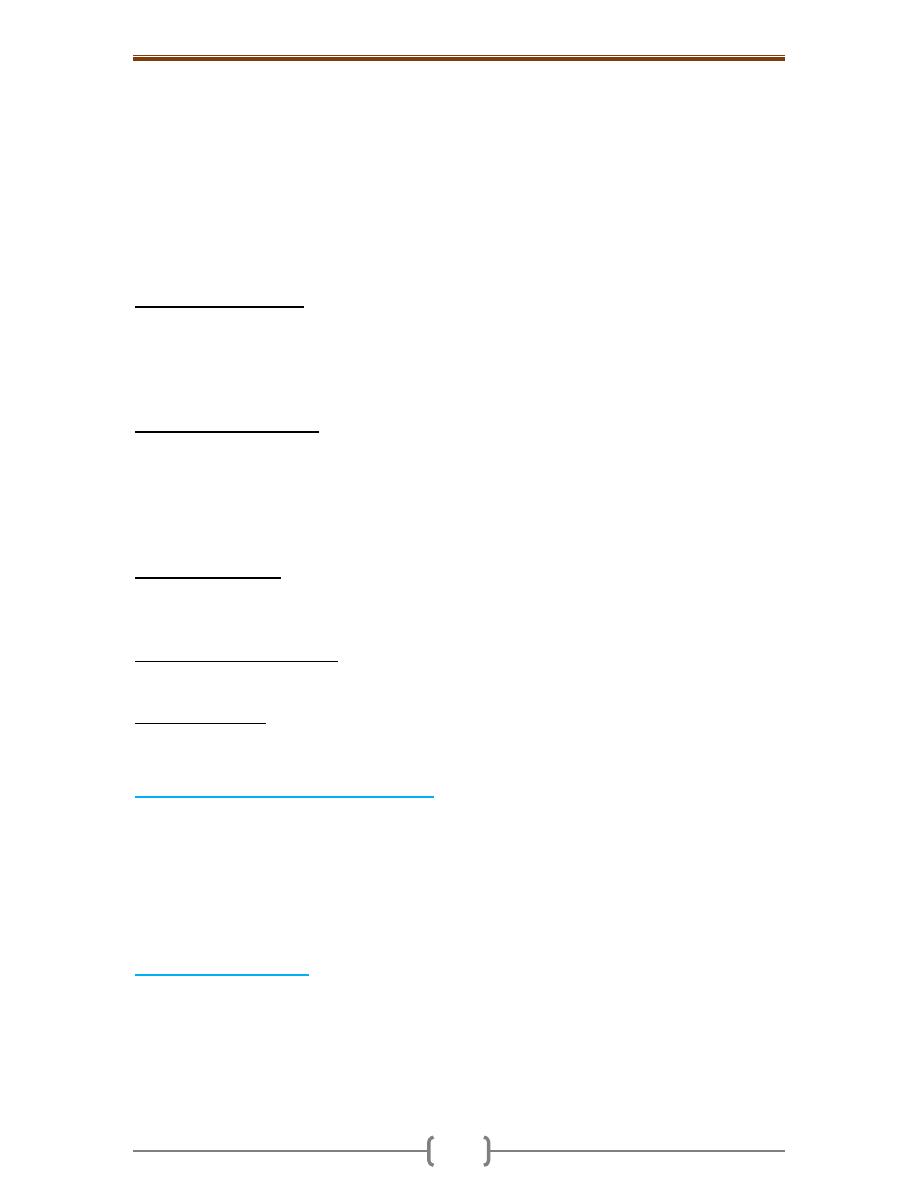

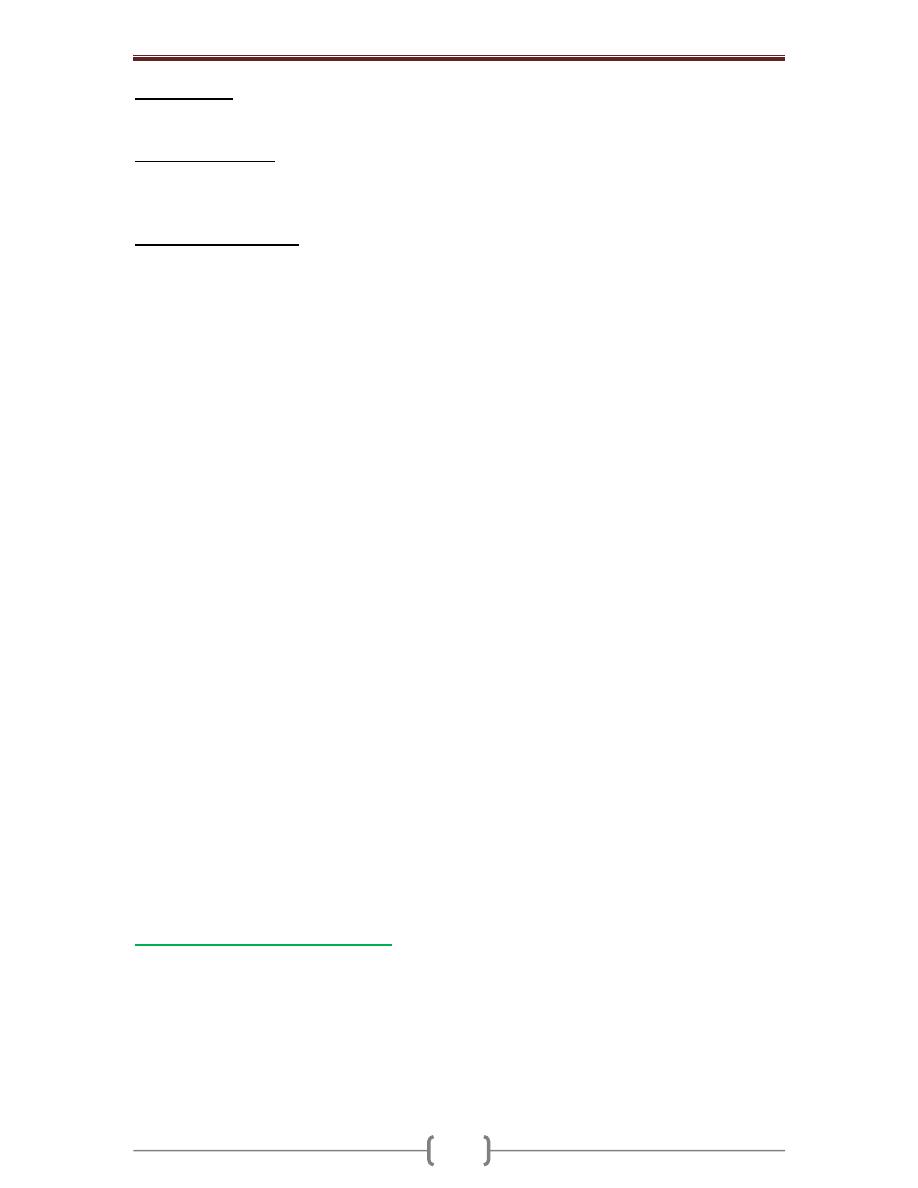

3

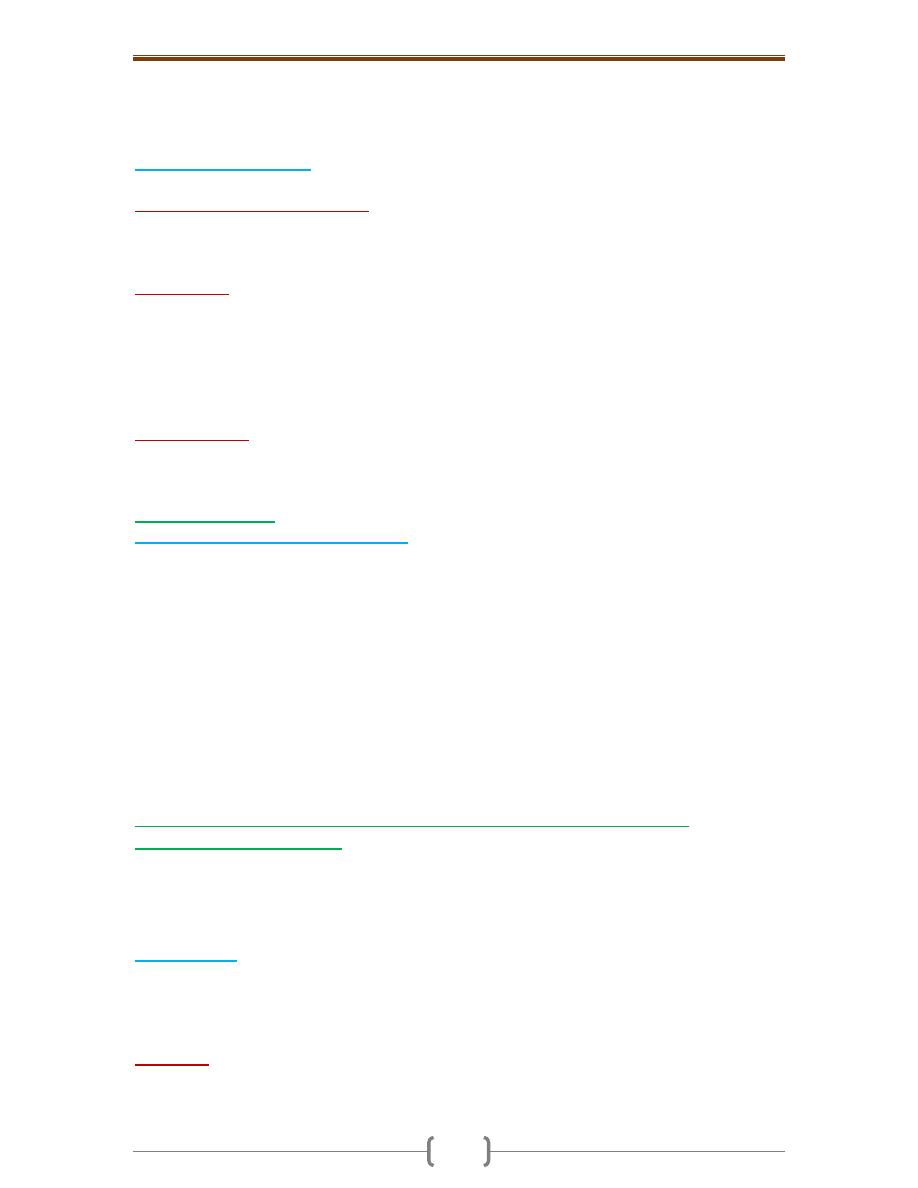

Chapter contents (3 – 14)

Topics

Directed by

Page number

1

Heart Failure

د. مهند

(4 - 6)

Left-Sided Heart Failure

4

Right-Sided Heart Failure

5

2

Pericardial Disease

(7)

Pericarditis

7

Pericardial Effusion

7

3

Valvular Heart Disease

(8 - 10)

Rheumatic Valvular Disease

8

Infective Endocarditis

9

Noninfective Vegetations

10

4

Cardiomyopathies

(11)

Myocarditis

11

5

Congenital heart disease

(12 - 14)

Left-to-Right Shunts

12

Right-to-Left Shunts

13

Obstructive Lesions

13

Chapter 1 - Heart

4

“” Heart Failure “”

Left-Sided Heart Failure

Chapter 1 - Heart

5

Right-Sided Heart Failure

Chapter 1 - Heart

6

Chapter 1 - Heart

7

“” Pericardial disease “”

Pericarditis

Pericardial effusion

Chapter 1 - Heart

8

“” Valvular Heart Disease “”

Rheumatic Valvular Disease

Chapter 1 - Heart

9

Infective Endocarditis

Chapter 1 - Heart

10

Noninfected Vegetations

Nonbacterial Thrombotic Endocarditis

Chapter 1 - Heart

11

“” Cardiomyopathies “”

Myocarditis

Chapter 1 - Heart

12

“” Congenital Heart Disease “”

Left-to-Right Shunts

Atrial septal defect (ASD)

Ventricular septal defect

Chapter 1 - Heart

13

Patent ductus arteriosus

Right-to-Left Shunts

Teratology of fallot

Transposition of great arteries (TGA)

Obstructive Lesions

Aortic Coarctation

Chapter 1 - Heart

14

15

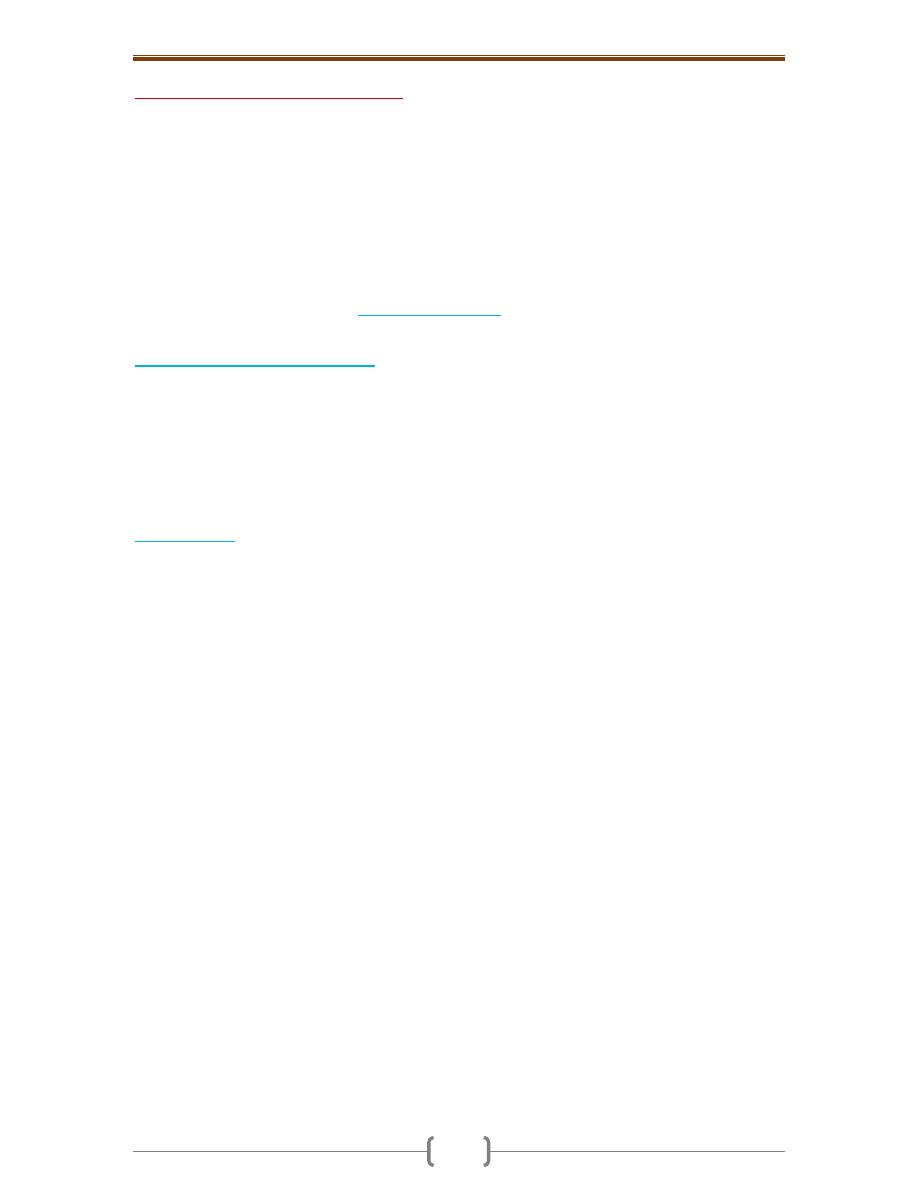

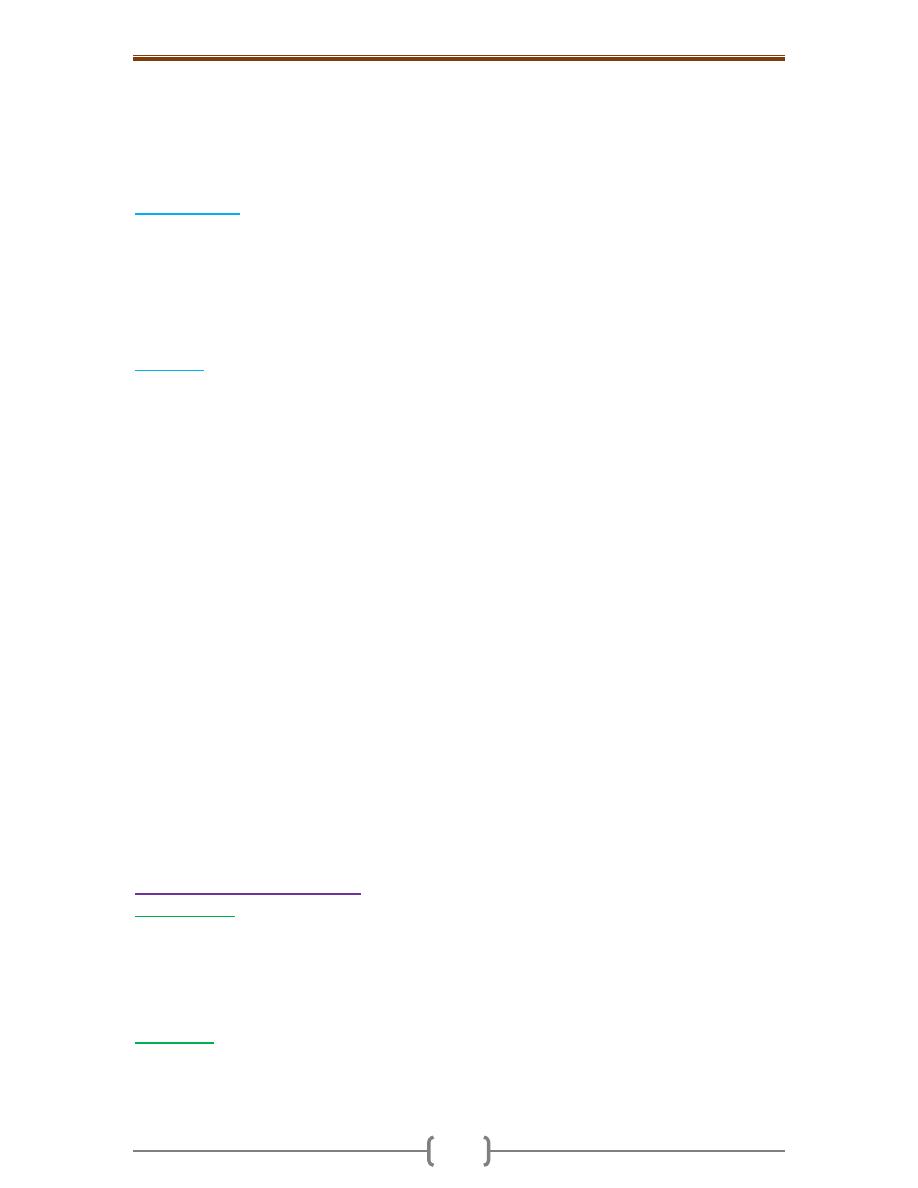

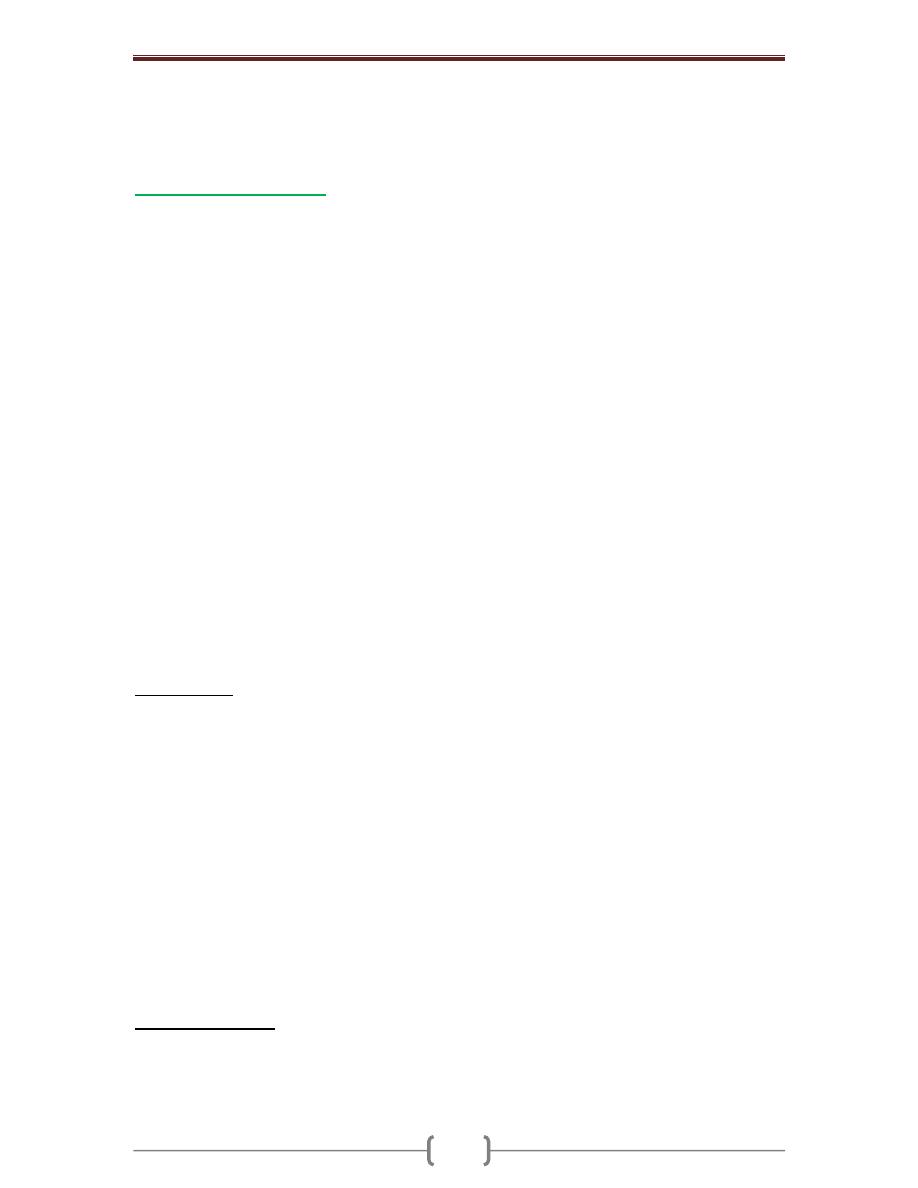

Chapter contents (15 – 50)

Topics

Directed by

Page number

1

Oral cavity & Oropharynx

.د

سالم

(16 - 21)

Gingivitis

16

Proliferative lesions

16

Inflammatory conditions

16

Infections

17

Oral manifestations of systemic diseases

17

Tumors & Precancerous lesions

18

Salivary Glands

19

2

Esophagus

(22 - 27)

Congenital anomalies

22

Lesions associated with motor dysfunction

22

Esophageal varices

23

Esophagitis

24

Tumors of the esophagus

26

3

Stomach

(28 - 34)

Congenital anomalies

28

Gastritis

28

Peptic ulcer

30

Acute gastric ulceration

32

Tumors of the stomach

32

4

Small & Large intestine

(35 - 49)

Congenital anomalies

35

Enterocolitis

35

Vascular diseases

44

Diverticular disease

45

Intestinal obstruction

45

Tumors of the small & large intestine

46

5

Appendix

(50)

Acute appendicitis

50

Tumors of the appendix

50

Mucocele and pseudomyxoma peritonei

50

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

16

“” The oral cavity & oropharynx “”

Many pathological processes can affect the constituents of the oral cavity. The more

important and frequent conditions will covered in this lecture. Diseases involving the

teeth and related structures will not be discussed.

Gingivitis

Gingivitis refers to "inflammation of soft tissues surrounding the teeth (gum)." It is

primarily due to lack of proper oral hygiene that leads to accumulation of dental plaques.

The latter consist of normal flora, proteins of saliva, and desquamated epithelial cells.

Plaques are converted to calculi through mineralization. Continuous and persistent

irritation by these calculi leads to chronic gingivitis. The condition manifests as redness,

edema, and bleeding. Eventually there is loss of soft tissue adaptation to the teeth (loose

tooth). (Fig. 5-1)

Proliferative lesions

The most common proliferative lesions of the oral cavity are

1. Irritation Fibroma and Ossifying fibroma

2. Ossifying fibroma

2. Pyogenic granuloma

3. Peripheral giant cell granuloma

Irritation fibroma

is a nodular mass of fibrous tissue that occurs mainly in the buccal

mucosa along the bite line & gingivo-dental margin. (Fig. 5-2)

Ossifying fibroma

is a common growth of the gingiva. Some may be due to maturation

of a long-standing pyogenic granuloma.

Pyogenic granuloma (granuloma pyogenicum)

is a highly vascular lesion that is

usually seen in the gingiva of children, young adults, and pregnant women (pregnancy

tumor). The lesion is typically ulcerated and bright red in color (due to rich vascularity)

(Fig. 5-3). Microscopically there is vascular proliferation similar to that of granulation

tissue. (Fig. 5-3) They lesion either regresses (particularly after pregnancy), or undergoes

fibrous maturation and may develop into ossifying fibroma.

Peripheral giant cell granuloma (giant cell epulis)

is a relatively common lesion that

characteristically protrudes from the gingiva at sites of chronic inflammation. It is so

named because microscopically there are aggregates of multinucleate giant cells separated

by a fibro-vascular stroma. (Fig. 5-4)

Inflammatory conditions

Inflammatory ulcerations

The most common inflammatory ulcerations of the oral cavity are

1)

Traumatic ulcers

, usually the result of trauma (e.g. fist fighting) or licking a jagged tooth.

2)

Aphthous ulcers

are extremely common, single or multiple, painful, recurrent,

superficial, ulcerations of the oral mucosa. The ulcer is covered by a thin yellow exudate

and rimmed by a narrow zone of erythema. (Fig. 5-5)

3)

Herpetic ulcers

(see under herpes simplex infection)

Glossitis

This is inflammation of the tongue, but sometimes it is also applied to the beefy-red

tongue that occurs in certain deficiency states. The latter is the result of atrophy of the

papillae and thinning of the mucosa, thus exposing the underlying vasculature. (Fig. 5-6)

However, in some instances, the atrophy leads to inflammation (and even shallow

ulcerations). Examples of such deficiency states that include:

1. B12 (pernicious anemia), 2. Riboflavin 3. Niacin 4. Pyridoxine 5.Iron-deficiency anemia

Plummer-Vinson syndrome

is a combination of

1. Iron-deficiency anemia 2. Glossitis 3. Esophageal dysphagia (due to esophageal webs)

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

17

Glossitis (with ulcerations) may also be seen with

* Jagged carious teeth * Ill-fitting dentures

* Exposure to hot fluids or corrosive chemicals

* Inhalation of burn fumes including excessive smoking

* Syphilis

Infections

1) Herpes simplex infections

Most of these are caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 & sometimes 2. Primary

HSV infection typically occurs in children aged 2 to 4 years; is often asymptomatic, but

sometime presents as acute herpetic gingivostomatitis, characterized by vesicles and

ulcerations throughout the oral cavity. The great majority of affected adults harbor latent

HSV-1 (the virus migrates along the regional nerves and eventually becomes dormant in

the local ganglia e.g., the trigeminal). In some individuals, usually young adults, the virus

becomes reactivated to produce the common but usually mild cold sore. (Fig. 5-7)

Factors activating the virus include

1. Trauma 2. Allergies 3. Exposure to ultraviolet light (sunlight)

4. Upper respiratory tract infections 5. Pregnancy 6. Menstruation 7. Immunosuppression

The viral infection is associated with intracellular and intercellular edema, yielding clefts that

may become transformed into vesicles. The vesicles range from a few millimeters to large

ones that eventually rupture to yield extremely painful, red-rimmed, shallow ulcerations.

2) Other Viral Infections

These include

- Herpes zoster - EBV (infectious mononucleosis) - CMV - Enterovirus - Measles

3) Oral Candidiasis (thrush)

This is the most common fungal infection of the oral cavity. The thrush is a grayish white,

superficial, inflammatory psudomembrane composed of the fungus enmeshed in fibrino-

suppurative exudates. (Fig. 5-8) This can be readily scraped off to reveal an underlying

red inflammatory base. The fungus is a normal oral flora but causes troubles only

1) In the setting of immunosuppression (e.g. diabetes mellitus, organ or bone marrow

transplant recipients, neutropenia, cancer chemotherapy, or AIDS) or

2) When broad-spectrum antibiotics are taken; these eliminate or alter the normal

bacterial flora of the mouth.

3) In infants, where the condition is relatively common, presumably due to immaturity of

the immune system in them.

4) Deep Fungal Infections

Some fungal infections may extends deeply to involve the muscles & bones in relation to

oral cavity. These include, among others, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and

aspergillosis. The incidence of such infections has been increasing due to increasing

number of patients with AIDS, therapies for cancer, & organ transplantation

5)

Diphtheria

Characterized grossly by dirty white, fibrino-suppurative, tough, inflammatory

pseudomembrane over tonsils & posterior pharynx. (Fig. 5-9)

Oral manifestations of systemic disease

Many systemic diseases are associated with oral lesions & it is not uncommon for oral

lesions to be the first manifestation of some underlying systemic condition.

1)

Scarlet fever:

strawberry tongue: white coated tongue with hyperemic papillae projecting (Fig. 5-10)

2)

Measles:

Koplik spots: small whitish ulcerations (spots) on a reddened base, about Stensen

duct (Fig. 5-11)

3)

Diphtheria:

Dirty white, fibrinosuppurative, tough pseudomembrane over the tonsils and retropharynx

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

18

4)

AIDS

A. opportunistic oral infections: herpesvirus, Candida, other fungi

b. Kaposi sarcoma (Fig. 5-12)

c. hairy leukoplakia; Approximately 80% of patients with hairy leukoplakia have been

infected with HIV; the remainig 20% are seen in association with other

immunodeficiency states. The condition presents as a white fluffy ("hairy") patches that

are situated on the lateral border of the tongue. (Fig. 5-15) EBV is now accepted as the

cause of the condition. When hairy leukoplakia precedes HIV infection, manifestations of

AIDS generally appear within 2 or 3 years.

5)

AML

(especially monocytic leukemia): enlargement of the gingivae + periodontitis (Fig. 5-13)

6)

Melanotic pigmentation

(Fig. 5-14)

a. Addison disease

b. hemochromatosis

c. fibrous dysplasia of bone

d. Peutz-Jegher syndrome

7)

Pregnancy:

pyogenic granuloma ("pregnancy tumor")

Tumors and precancerous lesions

Many of the oral cavity tumors (e.g., papillomas, hemangiomas, lymphomas) are not

different from their homologous tumors elsewhere in the body. Here we will consider

only oral squamous cell carcinoma and its associated precancerous lesions.

Leukoplakia and Erythroplakia are considered premalignant lesions of squamous cell

carcinoma.

Leukoplakia

(Fig. 5-16) is a white patch that cannot be scraped off and cannot be attributed clinically

or microscopically to any other disease i.e. if a white lesion in the oral cavity can be given

a specific diagnosis it is not a leukoplakia. As such, white patches caused by entities such

as candidiasis are not leukoplakias. All leukoplakias must be considered precancerous

(have the potential to progress to squamous cell carcinoma) until proved otherwise

through histologic evaluation.

Erythroplakias

(Fig. 5-17) are red velvety patches that are much less common, yet much more serious

than leukoplakias. The incidence of dysplasia and thus the risk of complicating squamous

cell carcinoma is much more frequent in erythroplakia compared to leukoplakias.

Both leukoplakia and erythroplakia are usually found between ages of 40 and 70 years,

and are much more common in males than females. The use of tobacco (cigarettes, pipes,

cigars, and chewing tobacco) is the most common incriminated factor.

Squamous cell carcinoma

The vast majority (95%) of cancers of the head and neck are squamous cell carcinomas;

these arise most commonly in the oral cavity. The 5-year survival rate of early-stage oral

cancer is approximately 80%, but this drops to about 20% for late-stage disease. These

figures highlight the importance of early diagnosis & treatment, optimally of the

precancerous lesions.

The pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma is multifactorial.

1) Chronic smoking and alcohol consumption

2) Oncogenic variants of human papilloma virus (HPV). It is now known that at least

50% of oropharyngeal cancers, particularly those of the tonsils and the base of tongue,

harbor oncogenic variants of HPV.

3) Inheritance of genomic instability; a family history of head & neck cancer is a risk factor.

4) Exposure to actinic radiation (sunlight) & pipe smoking are known predisposing

factors for cancer of the lower lip.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

19

Gross features (Fig. 5-18 A)

may arise anywhere in the oral cavity, but the favored locations are

1. The tongue 2. Floor of mouth 3. Lower lip 4. Soft palate 5. Gingiva

In the early stages, cancers of the oral cavity appear as roughened areas of the mucosa. As

the lesion enlarges, it typically appears as either an ulcer or a protruding mass (fungating).

Microscopic features (Fig. 5-18 B)

Early there is full-thickness dysplasia (carcinoma in situ) followed by invasion of the

underlying connective tissue stroma.

The grade varies from from well-differentiated keratinizing to poorly differentiated.

As a group, these tumors tend to infiltrate and extend locally before they eventually

metastasize to cervical lymph nodes and more remotely. The most common sites of

distant metastasis are mediastinal lymph nodes, lung, liver and bones

Salivary glands

There are three major salivary glands—parotid, submandibular, and sublingual.

Additionally, there are numerous minor salivary glands distributed throughout the mucosa

of the oral cavity.

Xerostomia

refers to dry mouth due to a lack of salivary secretion; the causes include

1. Sjögren syndrome: an autoimmune disorder, that is usually also accompanied by

involvement of the lacrimal glands that produces dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca).

2. Radiation therapy

Inflammation (sialadenitis)

Sialadenitis refers to inflammation of a salivary gland; it may be

1) Traumatic

2) Infectious: viral, bacterial

The most common form of viral sialadenitis is mumps, which usually affects the

parotids. The pancreas and testes may also be involved.

Bacterial sialadenitis is seen as a complication of

1. Stones obstructing ducts of a major salivary gland (Sialolithiasis), particularly the

submandibular. (Fig. 5-19)

2. Dehydration with decreased secretory function as is sometimes occurs in

a. patients on long-term phenothiazines that suppress salivary secretion.

b. elderly patients with a recent major thoracic or abdominal surgery.

Unilateral involvement of a single gland is the rule & the inflammation may be suppurative.

The inflammatory involvement causes painful enlargement and sometimes a purulent

ductal discharge.

3) Autoimmune

Sjögren syndrome causes an immunolgically mediated sialadenitis i.e. inflammatory

damage of the salivary tissues.

Mucocele

This is common salivary lesion results from interruption of salivary outflow due to

blockage or rupture of a salivary gland duct. This leads to seepage of saliva into the

surrounding tissues. The lower lip is the most common location due to exposure of this

site to trauma (fist fighting, falling etc.). It presents as fluctuant swelling.

Microscopically, there is accumulation of mucin with inflammatory cells. (Fig. 5-20)

Ranula is a mucocele of the sublingual gland; it may become extremely large.

Neoplasms of salivary glands

Neoplasms of the salivary glands (benign and malignant) are generally uncommon,

constituting less than 2% of human tumors. We will restrict our discussion on the more

common examples.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

20

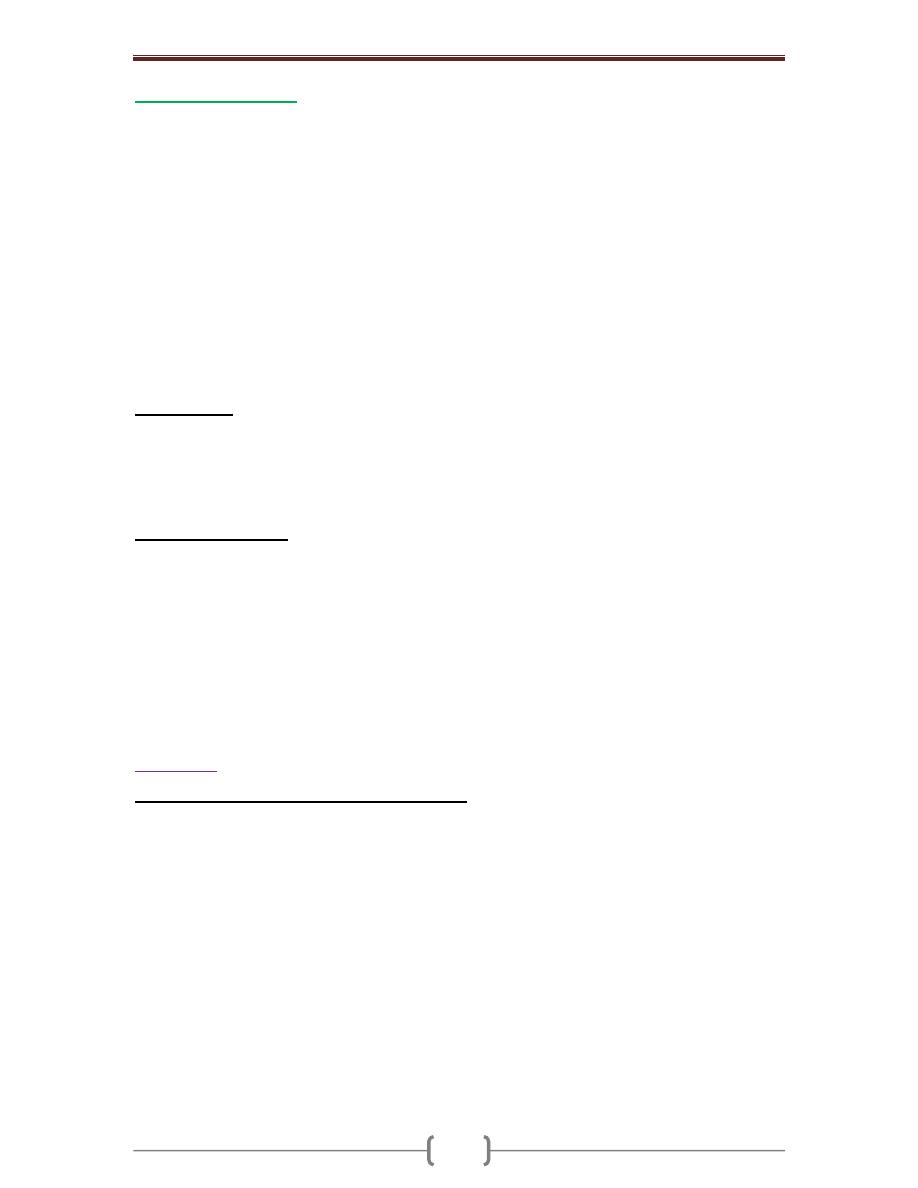

The relative frequency distributions of these tumors in relation to various salivary glands

are as follows

Salivary gland

Relative frequency of tumors (%)

Parotid gland

80%

Submandibular gland

10%

Minor salivary and sublingual glands

10%

The incidence of malignant tumors within the glands is, however, different from the

above

Salivary gland affected

Relative frequency of malignant tumors (%)

Sublingual tumors

80%

Minor salivary glands

50%

Submandibular glands

40%

Parotid glands

25%

These tumors usually occur in adults, with a slight female predominance. Excluded from

this rule is Warthin tumor, which occurs much more frequently in males than in females.

The benign tumors occur most often around the age of 50 to 60 years; the malignant ones

tend to appear in older age groups. Neoplasms of the parotid produce distinctive swellings

in front of, or below the ear. Clinically, there are no reliable criteria to differentiate benign

from the malignant tumors; therefore, pathological evaluation is necessary. (Fig. 5-21)

Pleomorphic Adenomas (Mixed Salivary Gland Tumors)

These benign tumors commonly occur within the parotid gland (constitute 60% of all

parotid tumors).

o Gross features (Fig. 5-22 A)

Most tumors are rounded, encapsulated masses.

The cut surface is gray-white with myxoid and light blue translucent areas of chondroid.

o Microscopic features (Fig. 5-22 B)

The main constituents are a mixture of ductal epithelial and myoepithelial cells, and it is

believed that all the other elements, including mesenchymal, are derived from the above

cells (hence the name adenoma).

The epithelial/myoepithelial components of the neoplasm are arranged as glands, strands,

or sheets. These various epithelial/myoepithelial elements are dispersed within a

background of loose myxoid tissue that may contain islands of cartilage-like islands and,

rarely bone. Sometimes, squamous differentiation is present.

In some instances, the tumor capsule is focally deficient allowing the tumor to extend as

tongue-like protrusions into the surrounding normal tissue.

Enucleation of the tumor is, therefore, not advisable because residual foci (the protrusions)

may be left behind and act as a potential source of multifocal recurrences. (Fig. 5-23)The

incidence of malignant transformation increases with the duration of the tumor.

Warthin Tumor

Is the second most common salivary gland neoplasm. It is benign, arises usually in the

parotid gland and occurs more commonly in males than in females. About 10% are

multifocal and 10% bilateral. Smokers have a higher risk than nonsmokers for developing

these tumors. Grossly, it is round to oval, encapsulated mass & on section display gray

tissue with narrow cystic or cleft-like spaces filled with secretion. Microscopically, these

spaces are lined by a double layer of neoplastic epithelial cells resting on a dense

lymphoid stroma, sometimes with germinal centers. This lympho-epithelial lining

frequently project into the spaces. The epithelial cells are oncoytes as evidenced by their

eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (stuffed with mitochondria). (Fig. 5-24)

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

As the name indicates, these neoplasms are composed of variable mixtures of mucus-

secreting cells (muco), and squamous cells (epidermoid). They are the most common form

of primary malignant tumor of the salivary glands. They occur mainly in the parotids.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

21

Low-grade tumors may invade locally but do not metastasize. By contrast, high-grade

neoplasms metastasize to distant sites in 30% of cases. Grossly, mucoepidermoid

carcinomas are gray-white, infiltrative tumors that frequently show small, mucin-

containing cysts. Microscopically, there are cords, sheets, and cysts of squamous and

mucous-secreting cells. (Fig. 5-25)

Other Salivary Gland Tumors

Two less common neoplasms worth brief description:

o Adenoid cystic carcinoma: half of the cases are found in the minor salivary glands (in

particular the palate). Although slow growing, they have a tendency to invade perineural

spaces and to recur. Eventually, 50% or more disseminate widely to distant sites such as

bone, liver, and brain. Microscopically, they are composed of small cells having dark,

compact nuclei and scant cytoplasm. These cells tend to be disposed in sieve-like

(cribriform) patterns. The spaces between the tumor cells are often filled with a hyaline

material thought to represent excess basement membrane. (Fig. 5-26)

o Acinic cell tumor is composed of cells resembling the normal acinar cells (hence the

name). Most arise in the parotids; the small remainder arises in the submandibular glands.

On histologic examination, they reveal a variable architecture and cell morphology. Most

characteristically, the cells have clear cytoplasm & are disposed in sheets, microcysts,

glands, or papillae. About 10% to 15% of these neoplasms metastasize to lymph nodes.

(Fig. 5-27)

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

22

Esophagus

The main functions of the esophagus are to 1. Conduct food and fluids from the pharynx to

the stomach 2. Prevent reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. These functions

require motor activity coordinated with swallowing, i.e. wave of peristalsis, associated

with relaxation of the LES in anticipation of the peristaltic wave. This is followed by

closure of the LES after the swallowing reflex. Maintenance of sphincter tone (positive

pressure relative to the rest of esophagus) is necessary to prevent reflux of gastric contents.

Congenital anomalies

Several congenital anomalies affect the esophagus including

The presence of

ectopic

gastric mucosa & pancreatic tissues within the esophageal wall,

congenital cysts

&

congenital herniation

of the esophageal wall into the thorax. The

latter is due to impaired formation of the diaphragm.

Atresia and fistulas

are uncommon but must be recognized & corrected early because

they cause immediate regurgitation, suffocation & aspiration pneumontis when feeding is

attempted. In atresia, a segment of the esophagus is represented by only a noncanalized

cord, with the upper pouch connected to the bronchus or the trachea and a lower pouch

leading to the stomach. (Fig. 5-28)

Webs, rings, and stenosis

(Fig. 5-29)

Mucosal webs

are shelf-like, eccentric protrusions of the mucosa into the esophageal

lumen. These are most common in the upper esophagus. The triad of upper esophageal

web, iron-deficiency anemia, and glossitis is referred to as Plummer-Vinson syndrome.

This condition is associated with an increased risk for postcricoid esophageal carcinoma.

Esophageal rings

unlike webs are concentric plates of tissue protruding into the lumen of

the distal esophagus. Esophageal webs and rings are encountered most frequently in

women over age 40. Episodic dysphagia is the main symptom.

Stenosis

consists of fibrous thickening of the esophageal wall. Although it may be

congenital, it is more frequently the result of severe esophageal injury with inflammatory

scarring, as from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), radiation, scleroderma and

caustic injury. Stenosis usually manifests as progressive dysphagia, at first to solid foods

but eventually to fluids as well.

Lesions associated with motor dysfunction (fig. 5-30)

Coordinated motor activity is important for proper function of the esophagus. The major

entities that are caused by motor dysfunction of the esophagus are

1. Achalasia 2. Hiatal hernia 3. Diverticula 4. Mallory-Weiss tear

Achalasia

Achalasia means "failure to relax." It is characterized by three major abnormalities:

1. Aperistalsis (failure of peristalsis)

2. Increased resting tone of the LES

3. Icomplete relaxation of the LES in response to swallowing

In most instances, achalasia is an idiopathic disorder. In this condition there is progressive

dilation of the esophagus above the persistently contracted LES. The wall of the

esophagus may be of normal thickness, thicker than normal owing to hypertrophy of the

muscular wall, or markedly thinned by dilation (when dilatation overruns hypertrophy).

The mucosa just above the LES may show inflammation and ulceration. Young adults are

usually affected and present with progressive dysphagia. (Fig. 5-31)

Complications of achalasia are

1. Aspiration pneumonitis of undigested food 2. Monilial esophagitis

3. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (about 5% of patients)

4. Lower esophageal diverticula

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

23

Hiatal Hernia (Fig. 5-32)

Hiatal hernia is characterized by separation of the diaphragmatic crura leading to

widening of the space around the esophageal wall. Two types of hiatal hernia are

recognized: 1. The sliding type (95%)

2. The paraesophageal type

In the sliding hernia the stomach skates up through the patent hiatus above the diaphragm

creating a bell-shaped dilation. In paraesophageal hernias, a separate portion of the

stomach, usually along the greater curvature, enters the thorax through the widened

foramen. The cause of hiatal hernia is unknown. It is not clear whether it is a congenital

malformation or is acquired during life. Only about 10% of adults with a sliding hernia

suffer from heartburn or regurgitation of gastric juices into the mouth. These are due to

incompetence of the LES and are accentuated by positions favoring reflux (bending

forward, lying supine) and obesity.

Complications of hiatal hernias include

1. Ulceration, bleeding and perforation (both types)

2. Reflux esophagitis (frequent with sliding hernias)

3. Strangulation of paraesophageal hernias

Diverticula

(Fig. 5-33)

By definition a diverticulum is a "focal out pouching of the alimentary tract wall that

contains all or some of its constituents"; they are divided into

1. False diverticulum

is an out pouching of the mucosa and submucosa through weak

points in the muscular wall.

2. True diverticulum

consists of all the layers of the wall and is thought to be due to

motor dysfunction of the esophagus. They may develop in three regions of the esophagus

a. Zenker diverticulum, located immediately above the UES

b. Traction diverticulum near the midpoint of the esophagus

c. Epiphrenic diverticulum immediately above the LES.

Lacerations (Mallory-Weiss Syndrome)

These refer to longitudinal tears at the GEJ or gastric cardia and are the consequence of

severe retching or vomiting. They are encountered most commonly in alcoholics, since

they are susceptible to episodes of excessive vomiting, but have been reported in persons

with no history of vomiting or alcoholism. During episodes of prolonged vomiting, reflex

relaxation of LES fails to occur. The refluxing gastric contents suddenly overcome the

contracted musculature leading to forced, massive dilation of the lower esophagus with

tearing of the stretched wall.

Pathological features

The linear irregular lacerations, which are usually found astride the GEJ or in the gastric

cardia, are oriented along the axis of the esophageal lumen. The tears may involve only

the mucosa or may penetrate deeply to perforate the wall. (Fig. 5-34) Infection of the

mucosal defect may lead to inflammatory ulcer or to mediastinitis. Usually the bleeding is

not profuse and stops without surgical intervention. Healing is the usual outcome. Rarely

esophageal rupture occurs.

Esophageal Varices

Portal hypertension when sufficiently prolonged or severe induces the formation of

collateral bypass veins wherever the portal and caval venous systems communicate.

Esophageal varices refer to the prominent plexus of deep mucosal and submucosal venous

collaterals of the lower esophagus subsequent to the diversion of portal blood through

them through the coronary veins of the stomach. From the varices the blood is diverted

into the azygos veins, and eventually into the systemic veins. Varices develop in 90% of

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

24

cirrhotic patients. Worldwide, after alcoholic cirrhosis, hepatic schistosomiasis is the

second most common cause of variceal bleeding.

Pathological features (Fig. 5-35)

The increased pressure in the esophageal plexus produces dilated tortuous vessels that are

liable to rupture.

Varices appear as tortuous dilated veins lying primarily within the submucosa of the distal

esophagus and proximal stomach.

The net effect is irregular protrusion of the overlying mucosa into the lumen. The mucosa

is often eroded because of its exposed position.

Variceal rupture produces massive hemorrhage into the lumen. In this instance, the

overlying mucosa appears ulcerated and necrotic.

Rupture of esophageal varices usually produces massive hematemesis. Among patients

with advanced liver cirrhosis, such a rupture is responsible for 50% of the deaths. Some

patients die as a direct consequence of the hemorrhage (hypovolemic shock); others of

hepatic coma triggered by the hemorrhage.

Esophagitis

This term refers to inflammation of the esophageal mucosa. It may be caused by a variety

of physical, chemical, or biologic agents.

Reflux Esophagitis (Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease or GERD)

Is the most important cause of esophagitis & signifies esophagitis associated with reflux of

gastric contents into the lower esophagus. Many causative factors are involved, the most

important is decreased efficacy of esophageal antireflux mechanisms, particularly LES tone.

In most instances, no cause is identified. However, the following may be contributatory

a. Central nervous system depressants including alcohol

b. Smoking

c. Pregnancy

d. Nasogastric tube

e. Sliding hiatal hernia

f. hypothyroidism

g. Systemic sclerosis

Any one of the above mechanism may be the primary cause in an individual case, but

more than one is likely to be involved in most instances. The action of gastric juices is

vital to the development of esophageal mucosal injury.

Gross (endoscopic) features (Fig. 5-36 A)

These depend on the causative agent and on the duration and severity of the exposure.

Mild esophagitis may appear grossly as simple hyperemia. In contrast, the mucosa in

severe esophagitis shows confluent erosions or total ulceration into the submucosa.

Microscopic features (Fig. 5-36 B)

Three histologic features are characteristic:

1. Inflammatory cells including eosinophils within the squamous mucosa.

2. Basal cells hyperplasia

3. Extension of lamina propria papillae into the upper third of the mucosa.

The disease mostly affects those over the age of 40 years. The clinical manifestations

consist of dysphagia, heartburn, regurgitation of a sour fluid into the mouth, hematemesis,

or melena. Rarely, there are episodes of severe chest pain that may be mistaken for a

"heart attack."

The potential consequences of severe reflux esophagitis are

1. Bleeding

2. Ulceration

3. Stricture formation

4. Tendency to develop Barrett esophagus

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

25

Barrett Esophagus (BE)

o 10% of patients with long-standing GERD develop this complication. BE is the single

most important risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. BE refers to columnar

metaplasia of the distal squamous mucosa; this occurs in response to prolonged injury

induced by refluxing gastric contents. Two criteria are required for the diagnosis of

Barrett esophagus:

1. Endoscopic evidence of columnar lining above the GEJ

2. Histologic confirmation of the above in biopsy specimens.

The pathogenesis of Barrett esophagus appears to be due to a change in the differentiation

program of stem cells of the esophageal mucosa. Since the most frequent metaplastic

change is the presence of columnar cells admixed with goblet cells, the term "intestinal

metaplasia" is used to describe the histological alteration.

o Gross features

Barrett esophagus is recognized as a red, velvety mucosa located between the smooth,

pale pink esophageal squamous mucosa and the light brown gastric mucosa.

It is displayed as tongues, patches or broad circumferential bands replacing the

squamocolumnar junction several centimeters. (Fig. 5-37 A)

o Microscopic features

the esophageal squamous epithelium is replaced by metaplastic columnar epithelium,

including interspersed goblet cells, & may show a villous pattern (as that of the small

intestine hence the term intestinal metaplasia). (Fig. 5-37 B)

Critical to the pathologic evaluation of patients with Barrett mucosa is the search for

dysplasia within the metaplastic epithelium. This dysplastic change is the presumed

precursor of malignancy (adenocarcinoma). Dysplasia is recognized by the presence of

cytologic and architectural abnormalities in the columnar epithelium, consisting of

enlarged, crowded, and stratified hyperchromatic nuclei with loss of intervening stroma

between adjacent glandular structures. Depending on the severity of the changes,

dysplasia is classified as low-grade or high-grade.

Approximately 50% of patients with high-grade dysplasia may already have adjacent

adenocarcinoma.

o Most patients with the first diagnosis of Barrett esophagus are between 40 and 60 years.

Barrett esophagus is clinically significant due to

1. The secondary complications of local peptic ulceration with bleeding and stricture.

2. The development of adenocarcinoma, which in patients with long segment disease

(over 3 cm of Barrett mucosa), occurs at a frequency that is 30- to 40 times greater than

that of the general population.

Other causes of esophagitis

In addition to GERD (which is, in fact, a chemical injury), esophageal inflammation may

have many origins. Examples include ingestion of mucosal irritants (such as alcohol,

corrosive acids or alkalis as in suicide attempts), cytotoxic anticancer therapy, bacteremia

or viremia (in immunosuppressed patients), fungal infection (in debilitated or

immunosuppressed patients or during broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy; candidiasis

by far the most common), and uremia.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

26

Tumors

Benign Tumors

Leiomyomas are the most common benign tumors of the esophagus. (Fig. 5-38)

Malignant Tumors

Carcinomas of the esophagus (5% of all cancers of the GIT) have, generally, a poor

prognosis because they are often discovered too late. Worldwide, squamous cell

carcinomas constitute 90% of esophageal cancers, followed by adenocarcinoma.

Other tumors are rare.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

o Most SCCs occur in adults over the age of 50. The disease is more common in males than

females. The regions with high incidence include Iran & China. Blacks throughout the

world are at higher risk than are whites.

o Etiology and Pathogenesis

Factors Associated with the Development of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus

are classified as

1. Dietary

Deficiency of vitamins (A, C, riboflavin, thiamine, and pyridoxine) & trace elements (zinc)

Fungal contamination of foodstuffs

High content of nitrites/nitrosamines

Betel chewing (betel: the leaf of a climbing evergreen shrub, of the pepper family, which

is chewed in the East with a little lime.)

2. Lifestyle

Burning-hot food

Alcohol consumption

Tobacco abuse

3. Esophageal Disorders

Long-standing esophagitis

Achalasia

Plummer-Vinson syndrome

4. Genetic Predisposition

Long-standing celiac disease - Racial disposition

The marked geographical variations in the incidence of the disease strongly implicate

dietary and environmental factors, with a contribution from genetic predisposition. The

majority of cancers in Europe and the United States are attributable to alcohol and

tobacco. Some alcoholic drinks contain significant amounts of such carcinogens as

polycyclic hydrocarbons, nitrosamines, and other mutagenic compounds. Nutritional

deficiencies associated with alcoholism may contribute to the process of carcinogenesis.

Human papillomavirus DNA is found frequently in esophageal squamous cell

carcinomas from high-incidence regions.

o Gross features (Fig. 5-39 A)

Like squamous cell carcinomas arising in other locations, those of the esophagus begin as

in situ lesions.

When they become overt, about 20% of these tumors are located in the upper third, 50%

in the middle third, and 30% in the lower third of the esophagus.

Early lesions appear as small, gray-white, plaque-like thickenings of the mucosa but with

progression, three gross patterns are encountered:

1. Fungating (polypoid) (60%) that protrudes into the lumen

2. Flat (diffusely infiltrative) (15%) that tends to spread within the wall of the esophagus,

causing thickening, rigidity, and narrowing of the lumen

3. Excavated (ulcerated) (25%) that digs deeply into surrounding structures and may

erode into the respiratory tree (with resultant fistula and pneumonia) or aorta (with

catastrophic bleeding) or may permeate the mediastinum and pericardium.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

27

Local extension into adjacent mediastinal structures occurs early, possibly due to the

absence of serosa for most of the esophagus. Tumors located in the upper third of the

esophagus also metastasize to cervical lymph nodes; those in the middle third to the

mediastinal, paratracheal, and tracheobronchial lymph nodes; and those in the lower third

most often spread to the gastric and celiac groups of nodes.

o Microscopic features (Fig. 5-39 B)

Most squamous cell carcinomas are moderately to well-differentiated,

They are invasive tumors that have infiltrated through the wall or beyond.

The rich lymphatic network in the submucosa promotes extensive circumferential and

longitudinal spread.

o Esophageal carcinomas are usually quite large by the time of diagnosis, produces

dysphagia and obstruction gradually. Cachexia is frequent. Hemorrhage and sepsis may

accompany ulceration of the tumor.

The five-year survival rate in patients with superficial esophageal carcinoma is about

75%, compared to 25% in patients who undergo "curative" surgery for more advanced

disease. Local recurrence and distant metastasis following surgery are common. The

presence of lymph node metastases at the time of resection significantly reduces survival.

Adenocarcinoma

With increasing recognition of Barrett mucosa, most adenocarcinomas in the lower third

of the esophagus arise from the Barrett mucosa.

o Etiology and Pathogenesis

These focus on Barrett esophagus. The lifetime risk for cancer development from Barrett

esophagus is approximately 10%. Tobacco exposure and obesity are risk factors.

Helicobacter pylori infection may be a contributing factor.

o Gross features: (Fig. 5-40 A)

Adenocarcinomas arising in the setting of Barrett esophagus are usually located in the

distal esophagus and may invade the adjacent gastric cardia.

As is the case with squamous cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas initially appear as flat

raised patches that may develop into large nodular fungating masses or may exhibit

diffusely infiltrative or deeply ulcerative features.

o Microscopic features (Fig. 5-40 B)

Most tumors are mucin-producing glandular tumors exhibiting intestinal-type features.

Multiple foci of dysplastic mucosa are frequently present adjacent to the tumor.

o Adenocarcinomas arising in Barrett esophagus chiefly occur in patients over the age of 40

years and similar to Barrett esophagus, it is more common in men than in women, and in

whites more than blacks (in contrast to squamous cell carcinomas). As in other forms of

esophageal carcinoma, patients usually present because of difficulty swallowing,

progressive weight loss, bleeding, and chest pain. The prognosis is as poor as that for

other forms of esophageal cancer, with under 20% overall five-year survival.

Identification and resection of early cancers with invasion limited to the mucosa or

submucosa improves five-year survival to over 80%. Regression or surgical removal of

Barrett esophagus has not yet been shown to eliminate the risk for adenocarcinoma.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

28

Stomach

In developed countries, peptic ulcers occur in up to 10% of the general population.

Chronic infection of the gastric mucosa by the bacterium H. pylori is the most common

infection worldwide. Gastric cancer is still a significant cause of death, despite its

decreasing incidence.

Congenital anomalies

These include

Various

heterotopias

(normal tissues in abnormal locations), which are usually

asymptomatic, e.g. pancreatic heterotopia.

Congenital diaphgramatic hernia

, which is due to defective closure of the diaphragm;

this leads to herniation of abdominal contents into the thorax in utero.

Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis

is encountered in male infants four times more

often than females. Persistent, projectile vomiting usually appears in the second or third

week of life. There is visible peristalsis and a firm, ovoid palpable mass in the region of

the pylorus resulting from hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the muscularis propria of the

pylorus. (Fig. 5-41)

Acquired pyloric stenosis in adults may complicate

1. Antral gastritis or peptic ulcers close to the pylorus.

2. Malignancy e.g. carcinomas of the pyloric region or adjacent panceas, or gastric lymphomas

3. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (rare) due to prolonged pyloric spasm

Gastritis

This is by definition, "inflammation of the gastric mucosa". It is a microscopic diagnosis.

The inflammation may be acute, with neutrophilic infiltration, or chronic, with

lymphocytes and/or plasma cells.

Acute gastritis

Is usually transient in nature. The inflammation may be accompanied by hemorrhage into

the mucosa (acute hemorrhagic gastritis) and, sometimes by sloughing (erosions) of the

superficial mucosa (acute erosive gastritis). (Fig. 5-42) The latter is a severe form of the

disease & an important cause of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Although a large number

of cases have no obvious cause (idiopathic), acute gastritis is frequently associated with

1) Heavy use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) particularly aspirin, cancer

chemotherapeutic drugs, or radiation

2) Excessive consumption of alcohol, heavy smoking, and ingestion of strong acids or alkali

as in suicidal attempts

3) Uremia

4) Severe stress (e.g., trauma, burns, surgery)

5) Mechanical trauma (e.g., nasogastric intubation)

6) Distal gastrectomy (reflux of duodenal contents).

Chronic Gastritis

Is defined as "chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa that eventuates in mucosal

atrophy and intestinal metaplasia". The epithelial changes may progress to dysplasia,

which constitute a soil for the development of carcinoma.

Pathogenesis

The major etiologic associations of chronic gastritis are:

1. Chronic infection by H. pylori 2. autoimmune damage

3. Excessive alcohol consumption & heavy cigarette smoking

4. Post-antrectomy (due to reflux of bile-containing duodenal secretions)

5. Outlet obstruction, uremia, and other rare causes

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

29

o Helicobacter pylori Infection and Chronic Gastritis

Infection by H. pylori is the most important etiologic cause of chronic gastritis. Effective

treatment with antibiotics has revolutionized the management of chronic gastritis and

peptic ulcer disease. Those with H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis are at increased

risk for the development of

1. Peptic ulcer disease 2. Gastric carcinoma

3. Gastric lymphoma

H. pylori are curvilinear, gram-negative rods. They have adapted to survive within gastric

mucus, which is lethal to most bacteria. The specialized features that allow these

bacteria to flourish include:

1) Motility (via flagella), allowing them to swim through the viscous mucus

2) Urease production, which releases ammonia and CO

2

from endogenous urea, thereby

buffering the harmful gastric acid in the immediate vicinity of the bacteria

3) Expression of adhesion molecules, which enhances binding of the bacteria to adjacent

foveolar cells

The bacteria appear to cause gastritis by stimulating production of pro-inflammatory

cytokines as well as by directly damaging epithelial cells by the liberation of toxins &

degrading enzymes e.g. vacuolating toxin (VacA), urease, proteases and phospholipases.

After exposure to H. pylori, gastritis occurs in two patterns:

1) Antral-predominant gastritis with high acid production & elevated risk for duodenal ulcer

2) Pan gastritis with low acid secretion and higher risk for adenocarcinoma

IL-1β is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine and a powerful gastric acid inhibitor. Patients

who have higher IL-1β production in response to the infection tend to develop pangastritis,

while patients who have lower IL-1β production exhibit antral-predominant gastritis.

A number of diagnostic tests have been developed for the detection of H. pylori. (Fig. 5-43)

1. Noninvasive tests including

a. Serologic test for antibodies b. Stool culture for bacterial detection

c. Urea breath test: based on the generation of ammonia by bacterial urease.

2. Invasive tests (through gastroscopy): detection of H. pylori in gastric biopsy tissue

samples including

a. visualization of the bacteria in histologic sections with special stains

b. bacterial culture of the biopsy c. bacterial DNA detection by the PCR

o Autoimmune gastritis

About 10% of chronic gastritis are autoimmune in nature. It results from the presence of

autoantibodies to components of parietal cells, including the acid-producing enzyme

H+/K+-ATPase, gastrin receptor, and intrinsic factor. Gland destruction and mucosal

atrophy lead to loss of acid production (hypo- or achlorhydria). (Fig. 5-44) In the most

severe cases, production of intrinsic factor is also impaired, leading to pernicious anemia.

Affected patients have a significant risk for developing gastric carcinoma and endocrine

tumors (carcinoid tumor).

Pathological features of chronic gastritis

Autoimmune gastritis is characterized by diffuse mucosal damage of the body-fundic

mucosa, with sparing of antral rgion (Corpus-predominant gastritis).

Environmental gastritis i.e. due to environmental etiologies (including H. pylori infection) tends

to affect antral mucosa (antral gastritis) or both antral and body-fundic mucosa (pangastritis).

o Gross (endoscopic) features

The mucosa of the affected regions is usually hyperemic & has coarser rugae than normal.

With long-standing disease, the mucosa may become thinned & flattened because of atrophy.

o Microscopic features (Fig. 5-45)

Irrespective of cause or location, the microscopic changes are similar:

The mucosa is infiltrated by lymphocytes & plasma cells.

Frequently the lymphocytes are disposed into aggregates i.e. follicles, some with germinal centers.

Neutrophils may or may not be present.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

30

Several additional histologic features are characteristic; these include

* Intestinal metaplasia: the mucosa may become partially replaced by metaplastic

columnar cells and goblet cells of intestinal morphology; these may display flat or villous

arrangement. If the columnar cells are absorptive (with ciliated border) the metaplasia is

termed complete, otherwise it is incomplete.

* Atrophy as evidecnced by marked loss of the mucosal glands. Parietal cells, in

particular, may be absent in the autoimmune form.

* Dysplasia: with long-standing chronic gastritis, the epithelium develops dysplastic

changes. Dysplastic alterations may become so severe as to constitute in situ carcinoma.

The development of dysplasia is thought to be a precursor lesion of gastric cancer. It

occurs in both autoimmune and H. pylori- associated chronic gastritis.

* In those individuals infected by H. pylori, the organism lies in the superficial mucus

layer on the surface and within the gastric pits. They do not invade the mucosa. These

bacteria are most easily demonstrated with silver or Giemsa (special) stains.

Peptic ulcer disease

An ulcer is defined as "a breach in the mucosa of the alimentary tract that extends into the

submucosa or deeper." Although they may occur anywhere in the alimentary tract, they

are most common in the duodenum and stomach. Ulcers have to be distinguished from

erosions. The latter is limited to the mucosa and does not extend into the submucosa.

Peptic Ulcers are chronic, most often solitary lesions and usually small. They occur in

any portion of the GIT exposed to the aggressive action of acid-peptic juices. They are

located, in descending order of frequency in:

1. Duodenum (first portion) 2. Stomach, (usually antral, along the lesser curve)

3. Gastro-esophageal junction (complicating GERD or Barrett esophagus)

4. Margins of a gastro-jejunostomy

5. Multiple in the duodenum, stomach, and/or jejunum (in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome)

6. Within or adjacent to a Meckel diverticulum (containing ectopic gastric mucosa)

The male-to-female ratio for duodenal ulcers is 3:1, and for gastric ulcers 2:1. Women are

most often affected at or after menopause.

Pathogenesis of peptic ulcers

Peptic ulcers are produced by an imbalance between gastro-duodenal mucosal defenses

and the damaging forces, particularly of gastric acid and pepsin.

Hyperacidity is not necessary; only a minority of patients with duodenal ulcers has

hyperacidity, and it is even less common in those with gastric ulcers.

H. pylori infection is a major factor in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer. It is present in

virtually all patients with duodenal ulcers and in about 70% of those with gastric ulcers;

that is why peptic ulcer disease is now considered infectious in nature. Antibiotic

treatment of the infection promotes healing of ulcers and prevents their recurrence. The

possible mechanisms by which this tiny organism impairs mucosal defenses include:

1) H. pylori induce intense inflammatory and immune responses. As a result there is

increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, most notably, IL-8, by the mucosal

epithelial cells. This recruits and activates neutrophils with their damaging properties.

2) Several bacterial products cause epithelial cell injury; this is mostly caused by a

vacuolating toxin called VacA. H. pylori also secrete urease, proteases and

phospholipases, which also cause direct epithelial damage.

3) H. pylori enhance gastric acid secretion and impair duodenal bicarbonate production, thus

reducing luminal pH in the duodenum with its damaging effects on the duodenal mucosa.

4) Thrombotic occlusion of surface capillaries is provoked by a bacterial platelet-activating

factor. Thus, an additional ischemic element may contribute to the mucosal damage.

Most persons (80-90%) infected with H. pylori do not develop peptic ulcers. Perhaps there are

unknown interactions between H. pylori & the mucosa that occur only in some individuals.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

31

Other factors may act alone or in concert with H. pylori to encourage peptic ulceration:

1) Gastric hyperacidity: this when present, may be strongly ulcerogenic. The classic example

is Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, in which there are multiple peptic ulcerations in the

stomach, duodenum, and even jejunum. This is due to excess gastrin secretion by a

gastrinoma and, hence, excess gastric acid production.

2) Chronic use of NSAIDs: this suppresses mucosal prostaglandin synthesis; aspirin also is a

direct irritant.

3) Cigarette smoking: this impairs mucosal blood flow and healing of the ulcer.

4) Corticosteroids: these in high doses and with repeated use encourage ulcer formation.

5) Rapid gastric emptying: this is present inn some patients with duodenal ulcers; this

phenomeneon exposes the duodenal mucosa to an excessive acid load & hence ulcerations

6) Patients with the following diseases are more prone to develop duodenal ulcer exposes

a. alcoholic cirrhosis b. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

c. chronic renal failure d. hyperparathyroidism.

Chronic renal failure and hyperparathyroidism are associated with hypercalcemia. The

latter stimulates gastrin production and therefore acid secretion.

7) Personality and psychological stress seems to be important contributing factors.

Gross features (Fig. 5-46)

The vast majority of peptic ulcers are located in the first portion of the duodenum or in the

stomach, in a ratio of about 4:1. Gastric and duodenal ulcers may coexist in up to 20% of

the cases. Gastric ulcers are predominantly located along the lesser curvature.

Although over 50% of peptic ulcers have a diameter less than 2 cm but about 10% are

greater than 4 cm. Ulcerated carcinomas (which tend to be large) may be less than 4 cm in

diameter and may be located anywhere in the stomach. Thus, size and location do not

differentiate a benign from a malignant ulcer.

The classic peptic ulcer is a round to oval with sharply demarcated crater. The margins are

usually level with the surrounding mucosa or only slightly elevated. Heaping-up of these

margins is rare in the benign ulcer but is characteristic of the malignant ones.

Peptic ulcers penetrate the wall to a variable extent. When the entire wall is penetrated,

the base of the ulcer may be formed by adherent pancreas, omental fat, or liver.

The base of a peptic ulcer is smooth and clean, owing to peptic digestion of any exudate

that may form. Sometimes, thrombosed or patent blood vessels (the source of life

threatening hemorrhage) are evident at the base of the ulcer.

Ulcer-related scarring may involve the entire thickness of the gastric wall; puckering of

the surrounding mucosa creates mucosal folds that radiate from the crater in spoke-like

fashion. This is different from malignant ulcers where there is flattening of the mucosal

folds (because of malignant infiltration) in the immediately surrounding of the ulcerative.

Microscopic features (Fig. 5-46 B)

In active ulcers four zones are recognized

1) The base and walls have a superficial thin layer of necrotic fibrinoid necrosis.

2) Beneath this layer is a zone of predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory

infiltrate.

3) Deeper still, there is granulation tissue infiltrated with inflammatory cells. This rests on

4) Fibrous or collagenous scar.

H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis is seen in up to 100% of patients with duodenal ulcers

and in 70% with gastric ulcers. With present-day therapies aimed at inhibition of acid

secretion (H

2

receptor antagonists and parietal cell H

+

/K

+

-ATPase pump inhibitors), and

eradication of H. pylori infection (with antibiotics), most ulcers heal within a few weeks.

The complications of peptic ulcer disease are

1) Bleeding is the most frequent complication (20%). It may be life-threatening; fatal in 25%

of the affected patients. It may be the first warning of an ulcer.

2) Perforation is much less frequent (5% of patients) but much more serious being fatal in

60% of patients.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

32

3) Obstruction (from edema or scarring) occurs in 2%, most often due to pyloric channel ulcers

but may occur with duodenal ulcers. Total obstruction with intractable vomiting is rare.

4) Malignant transformation does not occur with duodenal ulcers and is extremely rare with

gastric ulcers. When it occurs, it is always possible that a seemingly benign gastric ulcer

was, from the outset an ulcerative gastric carcinoma.

Acute Gastric Ulceration

Focal, acutely developing gastric mucosal defects are a well-known complication of

1) Therapy with NSAIDs

2) Severe stress (stress ulcers) as in shock states, extensive burns & severe trauma; they

usually occur in proximal duodenum (Curling ulcers)

3) Sepsis

4) Rraised intracranial pressure or intracranial surgery; these are seen as gastric, duodenal,

and esophageal ulcers & are designated as Cushing ulcers, which carry a high incidence

of perforation.

Generally, acute ulcers are multiple lesions predominantly gastric but sometimes also

duodenal. They range in depth from mere shedding of the superficial epithelium

(erosions) to deeper lesions that involve the entire mucosal thickness and deeper

(ulceration). Acute ulcers are not precursors of chronic peptic ulcers.

Gross features (Fig. 5-47)

Acute ulcers are usually small (less than 1 cm) and circular.

The ulcer base is frequently stained a dark brown by the acid digestion of blood.

They differ from chronic peptic ulcers by the following

1. They are found anywhere in the stomach, and are often multiple

2. The margins and base of the ulcers are not indurated

3. The related mucosal folds (rugae) are normal (cf. chronic peptic ulcer, which show

convergence on the ulcer)

Microscopically

There is focal loss of the mucosa & at least part of the submucosa

Unlike chronic peptic ulcers, there is no chronic gastritis or scarring.

Healing with complete re-epithelialization occurs after the causative factor is removed.

Bleeding from superficial gastric erosions or ulcers sufficient to require transfusion develops

in up to 5% of these patients. If the underlying cause is corrected recovery is complete.

Tumors of the stomach

These can be classified as benign and malignant lesions.

Benign tumors

Gastric polyps

In the alimentary tract, the term polyp is applied to any nodule or mass

that projects above the level of the surrounding mucosa. They are uncommon and

classified as non-neoplastic or neoplastic.

Hyperplastic polyps

(The most frequent; 90%) are small, sessile and multiple in about 25% of cases. There is

hyperplasia of the surface epithelium and cystically dilated glandular tissue. (Fig. 5-48)

Adenomatous polyp (adenoma)

(10% of polypoid lesions) (Fig. 5-49):

They contain proliferative dysplastic epithelium and hence have malignant potential. They

are usually single, and may grow up to 4 cm in size before detection. Up to 40% of gastric

adenomas contain a focus of carcinoma; there may also be an adjacent carcinoma that is

why histologic examination of all gastric polyps is obligatory.

Other specific types of gastric polyps are relatively uncommon and include fundic gland

polyps, hamartomatous Peutz-Jeghers polyps, juvenile polyps, and inflammatory fibroid polyp

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

33

Cancers of the stomach

Carcinoma is the most important and the most common (90%) of malignant tumors of the

stomach. Next in order of frequency are lymphomas (5%); the rest of the tumors are even

rarer e.g. carcinoids, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), leiomyosarcoma, and

schwannoma.

Gastric Carcinoma

Is a quite common tumor in the world. There are, however, marked geographical variations

in its incidence; it is particularly high in countries such as Japan. It is more common in

lower socioeconomic groups. There has been a steady decline in both the incidence and the

mortality of gastric cancer. There are mainly 2 subtypes of carcinoma: intestinal & diffuse.

These sub-types appear to have different pathogenetic mechanisms of evolution.

o Pathogenesis

The major factors thought to affect the genesis of gastric cancer apply more to the

intestinal type, as the risk factors for diffuse gastric cancer are not well defined.

1) Helicobacter pylori Infection: this generally increases the risk five- fold. The bacterial

infection causes chronic gastritis, followed by atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia,

and carcinoma. Long-standing mucosal inflammation is associated with damage of

epithelial cells, which leads to compensatory epithelial cell proliferation, and hence

increased risk of genomic mutation. Since most individuals infected with H. pylori do not

develop cancer, other factors must be involved in carcinogenesis.

2) Adenomatous polyps: 40% of adenomas harbor carcinmatous foci; also adjacent

carcinoma is found in relation to adenomatous polyps in 30% of the cases.

3) Environmental factors: when families migrate from high-risk to low-risk areas (or the

reverse), successive generations acquire the level of risk that prevails in the new

environments. The diet is suspected to be a primary factor. Consumption of preserved and

salted foods; water contamination with nitrates; and lack of fresh fruit and vegetables are

common in high-risk areas. The intake of green, leafy vegetables and citrus fruits, which

contain antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E and beta-carotene, seems to play a

protective role.

4) Autoimmune gastritis, like H. pylori infection, increases the risk of gastric cancer.

o Gross features

The most common location of gastric carcinomas is the pyloric antrum (50%). A favored

location is the lesser curvature. Although less common, an ulcerative lesion on the greater

curvature is more likely to be malignant.

Depth of invasion is the most important determinant of prognosis. Early gastric carcinoma

is defined as "a lesion confined to the mucosa and submucosa." Advanced gastric

carcinoma is a neoplasm extending into the muscular wall.

The three macroscopic growth patterns of gastric carcinoma, which may be evident at

both the early and advanced stages, are: 1. Fungating (exophytic) 2. Flat or depressed 3.

(Fig. 5-50) Ulcerative (excavated). Fungating tumors are readily identified by radiography

and endoscopy in contrast to flat (depressed) malignancy. Ulcerative cancers may closely

mimic chronic peptic ulcers. In advanced cases, there are heaped-up, beaded margins and

necrotic bases. The neoplastic tissue extends into the surrounding mucosa and wall; this

leads to flattening of the mucosa surrounding the ulcer. (Fig. 5-51)

Uncommonly, a broad region of the gastric wall or the entire stomach is extensively

infiltrated by malignancy, creating a rigid, thickened "leather bottle," termed linitis

plastica. (Fig. 5-52)

o Microscopic features

There are two main microscopic type of gastric carcinoma; intestinal and diffuse.

The intestinal variant is composed of neoplastic glands with mucin in their lumina. The

diffuse variant is composed of mucus-containing cells, which do not form glands, but

infiltrate the mucosa and wall as scattered individual and small clusters of cells. In this

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

34

variant, mucin formation expands the malignant cells and pushes the nucleus to the

periphery, creating"signet ring" morphology. (Fig. 5-53)

Sometimes, there is excessive mucin production that generates large mucin lakes

(mucinous carcinoma).

Infiltrative tumors often evoke a strong desmoplastic reaction (fibrosis), in which the

scattered cells are embedded; the fibrosis creates local rigidity of the wall.

Whatever the microscopic type, all gastric carcinomas eventually penetrate the wall to

involve the serosa and spread to regional and more distant lymph nodes.

o For obscure reasons, gastric carcinomas frequently metastasize to the supraclavicular

(Virchow) node as the first clinical manifestation of an occult neoplasm. (Fig. 5-54) The

tumor can also metastasize to the periumbilical region to form a subcutaneous nodule.

This nodule is called a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, after the nun who noted this lesion as a

marker of metastatic carcinoma. (Fig. 5-55) Local extension of gastric carcinoma into the

duodenum, pancreas, and retroperitoneum is also characteristic. At the time of death,

widespread peritoneal seeding and metastases to the liver and lungs are common. A

notable site of visceral metastasis is to one or both ovaries. Although uncommon,

metastatic adenocarcinoma to the ovaries (from stomach, breast, pancreas, and even

gallbladder) is distinctive & designated Krukenberg tumor. (Fig. 5-56)

o Gastric carcinoma is an insidious disease that is generally asymptomatic until late in its course.

The symptoms include weight loss, abdominal pain, anorexia, vomiting, dysphagia,

anemia, and hemorrhage. In Japan, where mass endoscopy screening programs are

employed (because of the high incidence of the disease), early gastric cancer constitutes

about one third of all newly diagnosed gastric cancers. In Europe and the United States,

this figure is only 10% to 15%.

o Prognosis

This depends primarily on

1. The depth of invasion and 2. The extent of nodal and distant metastasis

The histologic type (intestinal or diffuse) has minimal independent prognostic

significance. The five-year survival rate of surgically treated early gastric cancer is 90%;

this drops to below 15% for advanced gastric cancer.

Gastric Lymphomas

Represent 5% of all gastric malignancies. However, the stomach is the most common site

for extra-nodal lymphoma (20%). Nearly all primary gastric lymphomas are B-cell type

and of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphomas). The majority of gastric

lymphomas (>80%) are associated with chronic gastritis and H. pylori infection. The role

of H. pylori infection as an important etiologic factor for gastric lymphoma is supported

by the elimination of about 50% of early gastric lymphomas with antibiotic treatment for

H. pylori. Generally, the prognosis of gastric lymphoma is better than carcinoma.

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GISTs)

These are thought to originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal (normally control

gastrointestinal peristalsis). 95% of GISTs stain with antibodies against c-KIT (CD117).

The tumor can protrude into the lumen or extrude on the serosal side of the gastric wall.

Microscopically, the tumor can exhibit spindle cells, plump "epithelioid" cells, or a

mixture of both. Most of the tumors are quite cellular but mitotic activity is variable.

Gastric Neuroendocrine Cell (Carcinoid) Tumors

Most gastric carcinoid tumors originate from the enterochromaffin-like cells (ECL) cells

in the oxyntic mucosa. The tumor can arise in the setting of chronic atrophic gastritis. The

underlying pathogenesis is probably related to the hypergastrinemia, resulting in ECL-cell

hyperplasia, a presumed pre-neoplastic condition. Gastric carcinoid tumors exhibit similar

histologic features to other carcinoid tumors. The clinical course is quite variable.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

35

Small & large intestine

Several pathological conditions, such as infections, inflammatory diseases, motility

disorders, and tumors, affect both the small and large intestines simultaneously. These

two organs will therefore be considered together.

Congenital anomalies

Anomalies of the intestine are rarely encountered; these include

Duplication

of the small intestine or colon;

Malrotation

of the entire bowel;

Omphalocele

(birth of an infant with herniation of abdominal contents into a ventral

membranous sac related to umbilicus);

Heterotopia

of pancreatic tissue or gastric mucosa;

Atresia and stenosis

;

Imperforate anus

(due to failure of the cloacal diaphragm to rupture).

Meckel diverticulum

(Fig. 5-57)

Results from failure of involution of the vitelline duct, which embryologically connects

the lumen of developing gut to the yolk sac. The small pouch lies on the antimesenteric

side of the bowel, usually 30 cm proximal to the ileo-cecal valve. It consists of mucosa,

submucosa, and muscularis propria. The mucosal lining may be that of normal small

intestine, but heterotopic gastric mucosa or pancreatic tissue are frequently found. Meckel

diverticula are present in 2% of the normal population, but most remain asymptomatic.

When peptic ulceration occurs in the small intestinal mucosa adjacent to the heterotopic

gastric mucosa, intestinal bleeding or symptoms simulating those of an acute appendicitis

may result. Other complications include intussusception, incarceration, or perforation.

Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon (Hirschsprung Disease)

(Fig. 5-58)

This congenital disorder is characterized by the absence of ganglia of the submucosal and

myenteric neural plexuses, within a portion of the intestinal tract. The outcome is

contraction and functional obstruction of the aganglionic segment with secondary

proximal dilation. The rectum is always affected and most cases involve the rectum and

sigmoid colon only (short-segment disease). In some cases longer segments, and rarely

the entire colon may be aganglionic (long-segment disease). Proximal to the aganglionic

segment, the ganglionic colon undergoes progressive dilation and hypertrophy, sometimes

massively (megacolon). When distention overruns hypertrophy, the colonic wall becomes

markedly thinned and may rupture. Diagnosis of Hirschsprung is made histologically by

failure to detect ganglion cells in intestinal biopsy samples of the contracted (agnaglionic)

segment. The disease usually manifests itself in the immediate neonatal period by failure

to pass meconium, followed by obstructive constipation. Abdominal distention may

secondarily develop. The major threats to life are superimposed enterocolitis with fluid

and electrolyte disturbances and perforation with peritonitis.

Enterocolitis

These are divided into three etiological categories

I. Infectious (caused by microbiologic agents)

II. Malabsorption-associated

III. Idiopathic inflammatory bowel diseases

Diarrhea and Dysentery

Diarrhea is present when there is an increase in stool frequency, and/or stool fluidity.

This consists of daily stool production in excess of 250 gm, containing 70% to 95% water.

However, over 6 liters of fluid may be lost per day in severe cases of diarrhea (e.g.

cholera); this is the equivalent of the circulating blood volume.

Chapter 2 - Oral Cavity & Gastrintestinal Tract

36

Dysentery is characterized by low-volume, painful diarrhea with blood.

Malabsorption-associated diarrhea is the result of interference with absorption of

nutrients, which produces bulky stools containig excess fat (steatorrhea).

Infectious enterocolitis

This is the cause of more than 12,000 deaths per day among children in developing

countries & constituting 50% of all deaths before the age of 5 years worldwide. Acute, self-

limited infectious diarrhea is most frequently caused by enteric viruses (such as rotavirus

and adenoviruses). Bacterial infections, such as that caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia

coli, are also common. In up to 50% of cases, the specific agent cannot be isolated.

Viral enterocolitis

The lesions caused by enteric viruses in the intestinal tract are similar. The small intestinal

mucosa shows partial villous atrophy (shortening of the villi) with infiltration of the

lamina propria by lymphocytes. However, in infants, rotavirus and adenoviruses can

produce total villous atrophy (flat mucosa), thus resembling celiac disease (see later).

Bacterial enterocolitis

o Salmonellosis and Typhoid Fever

Salmonellae are gram-negative bacteria that cause either a self-limited food-borne and

water-borne gastroenteritis (S. enteritidis, S. typhimurium, and others) or typhoid fever

(S. typhi) a life-threatening systemic illness. In typhoid fever, Peyer patches in the

terminal ileum become sharply prominent forming flat elevations. Shedding of the

mucosa and the lymphoid tissue creates oval ulcers with their long axes parallel to that of

the ileum. Microscopic examination reveals macrophages containing bacteria & red blood

cells. Intermingled with the phagocytes are lymphocytes and plasma cells; the infiltrate is

characteristically devoid of neutrophils.

o Campylobacter Enterocolitis