Maturation of Red Blood Cells—Requirement for

Vitamin B12 (Cyanocobalamin) and Folic Acid

The erythropoietic cells of the bone marrow are among

the most

rapidly

growing and reproducing cells in the

entire body. Two vitamins, vitamin

B12

and

folic

acid are

important for final maturation of the red blood cells,

Both of these are essential for the synthesis of

DNA

,

Therefore, lack of either vitamin B12 or folic acid causes

abnormal and

diminished

DNA

and, consequently,

failure

of

nuclear

maturation and cell division.

Furthermore, the erythroblastic cells of the bone

marrow, in addition to failing to

proliferate

rapidly,

produce mainly larger than normal red cells called

macrocytes

, and the cell itself is often irregular, large,

and oval instead of the usual biconcave disc.

These poorly formed cells, after entering the circulating

blood, are capable of

carrying

oxygen

normally

, but their

fragility causes them to have a short life, one half to one

third normal. Therefore, it is said that deficiency of

either vitamin B12 or folic acid causes

maturation

failure

in the process of erythropoiesis.

Absorption of Vitamin B12 from the Gastrointestinal

Maturation Failure Caused by Pernicious Anemia.

The basic abnormality is an

atrophic

gastric

mucosa that

fails to produce normal gastric secretions. The

parietal

cells

of the gastric glands secrete a glycoprotein called

intrinsic

factor

, which combines with vitamin B12 in food

and makes the B12 available for absorption by the gut. It

does this in the following way:

(1) Intrinsic factor binds tightly with the vitamin B12. In

this bound state, the B12 is

protected

from digestion by

the gastrointestinal secretions.

(2) Still in the bound state, intrinsic factor

binds

to

specific receptor sites on the brush border membranes of

the mucosal cells in the ileum.

(3) Then, vitamin B12 is

transported

into the blood

during the next few hours by the process of

pinocytosis

,

carrying intrinsic factor and the vitamin together

through the membrane.

Lack

of

intrinsic

factor

, therefore, causes diminished

availability of vitamin B12 because of faulty absorption

of the vitamin.

Once

vitamin

B12

has been absorbed from the

gastrointestinal tract, it is first

stored

in large quantities

in the liver, then released slowly as needed by the bone

marrow. The

minimum

amount

of vitamin B12 required

each day to maintain normal red cell maturation is only

1 to 3 micrograms, and the normal

storage

in the liver

and other body tissues is about 1000 times this amount.

Therefore, 3 to 4 years of defective B12 absorption are

usually required to cause maturation failure anemia.

Failure of Maturation Caused by Deficiency of Folic

Acid(Pteroylglutamic Acid).

Folic acid is a normal constituent of green

vegetables

,

some

fruits

, and

meats

(especially liver). However, it is

easily destroyed during

cooking

.

Also,

people

with

gastrointestinal

absorption

abnormalities

, such as the frequently occurring small

intestinal disease called

sprue

, often have serious

difficulty absorbing both folic acid and vitamin B12.

Therefore, in many instances of maturation failure, the

cause is deficiency of intestinal absorption of both folic

acid and vitamin B12.

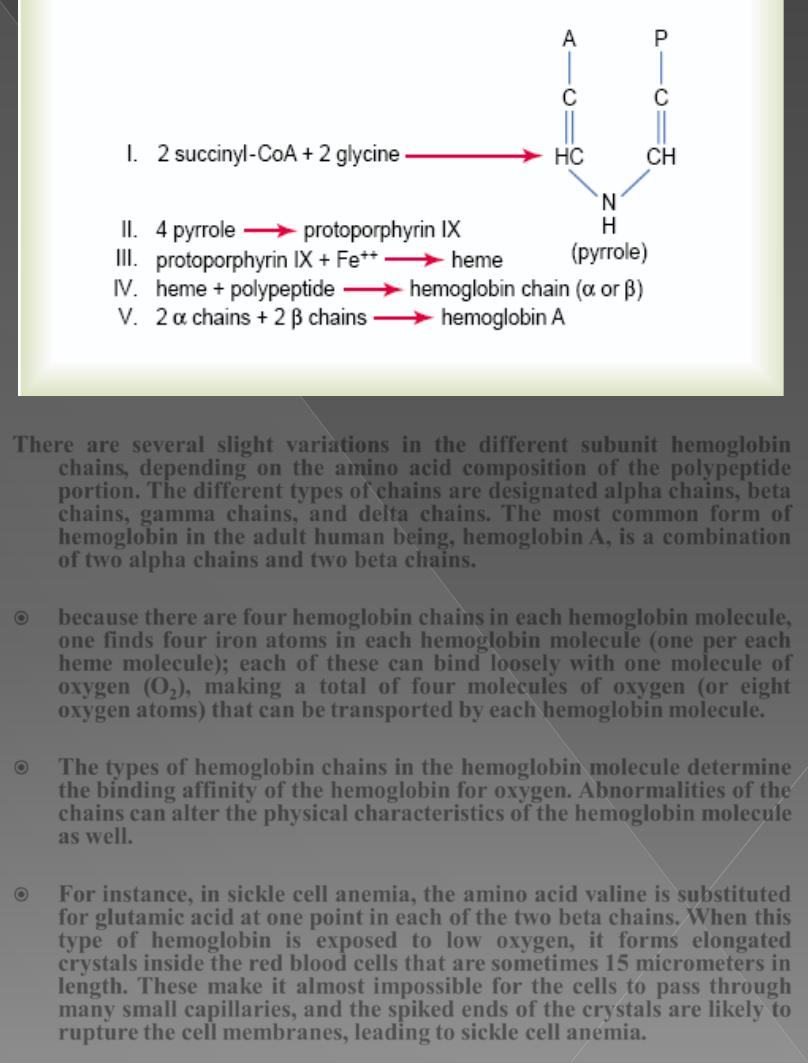

Formation of Hemoglobin

Synthesis of hemoglobin

begins

in the proerythroblasts

and continues even into the reticulocyte stage of the red

blood cells. Therefore, when reticulocytes leave the bone

marrow and pass into the blood stream, they

continue

to

form minute quantities of hemoglobin for another day or

so until they become mature erythrocytes.

succinyl-CoA

, formed in the Krebs metabolic cycle, binds

with

glycine

to form a

pyrrole

molecule. In turn, four

pyrroles combine to form

protoporphyrin

IX, which then

combines with iron to form the

heme

molecule. Finally,

each heme molecule combines with a long polypeptide

chain, a

globin

synthesized by ribosomes, forming a

subunit of hemoglobin called a hemoglobin chain. four of

these in turn bind together loosely to form the whole

hemoglobin molecule.

There are several slight variations in the different subunit hemoglobin

chains

, depending on the amino acid composition of the polypeptide

portion. The different types of chains are designated

alpha

chains

,

beta

chains, gamma chains, and delta chains

.

The most common form of

hemoglobin in the adult human being,

hemoglobin

A,

is a combination

of two alpha chains and two beta chains.

because there are

four

hemoglobin chains in each hemoglobin molecule,

one finds

four iron atoms

in each hemoglobin molecule (one per each

heme molecule); each of these can bind loosely with

one molecule of

oxygen

(

O

2

),

making a total of

four

molecules

of oxygen (or eight

oxygen atoms) that can be transported by each hemoglobin molecule.

The types of hemoglobin chains in the hemoglobin molecule determine

the

binding affinity

of the hemoglobin for oxygen.

Abnormalities

of the

chains can

alter the physical

characteristics of the hemoglobin molecule

as well.

For instance, in

sickle

cell anemia, the amino acid

valine

is substituted

for

glutamic

acid at one point in each of the two beta chains. When this

type of hemoglobin is

exposed to low oxygen

, it forms elongated

crystals inside the red blood cells that are sometimes

15

micrometers in

length. These make it almost impossible for the cells to pass through

many small capillaries, and the spiked ends of the crystals are likely to

rupture the cell membranes, leading to sickle cell anemia.

Combination of Hemoglobin with Oxygen.

The most important feature of the hemoglobin molecule

is its ability to combine loosely and

reversibly

with

oxygen.

oxygen does not become ionic oxygen but is carried as

molecular oxygen (composed of two oxygen atoms) to the

tissues, where, because of the loose, readily reversible

combination, it

is released into the tissue fluids still in the

form of molecular oxygen rather than ionic oxygen.

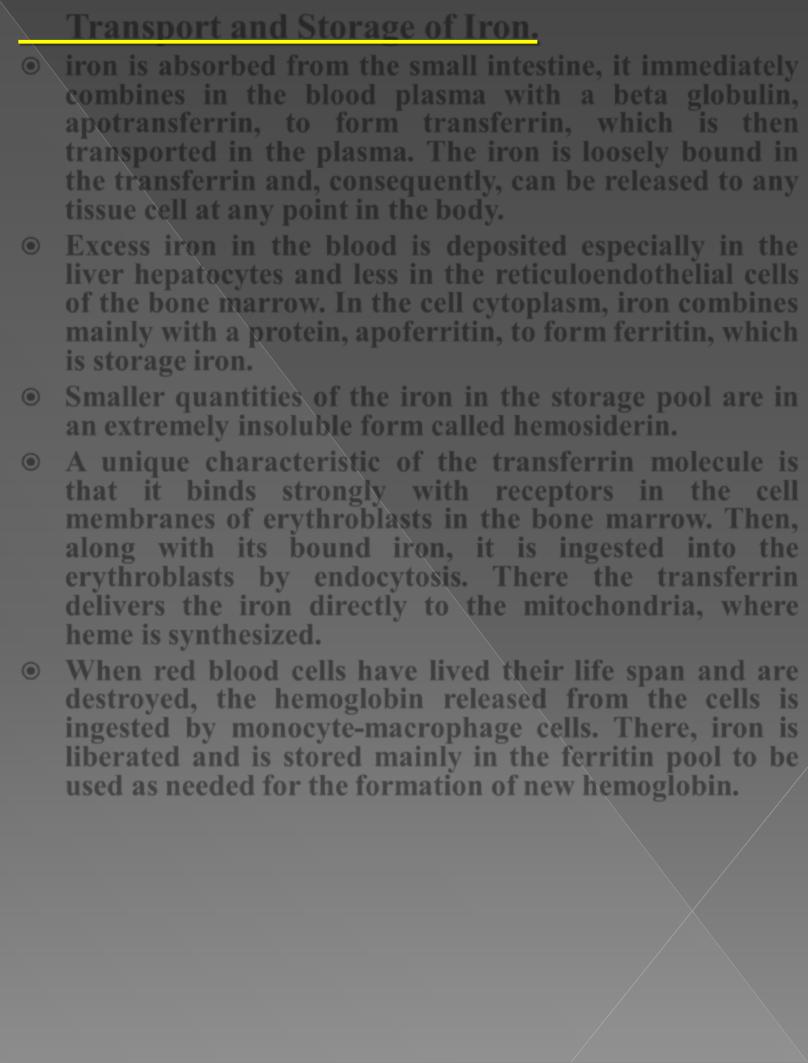

Iron Metabolism

iron is important for the formation not only of

hemoglobin but also of other essential elements in the

body (e.g.,

myoglobin, cytochromes, cytochrome oxidase,

peroxidase, catalase).

The total quantity of iron in the body averages

4 to 5

grams

, about

65

per cent of which is in the form of

hemoglobin. About

4

per cent is in the form of myoglobin

while

15 to 30

per cent is stored for later use, mainly in

the reticuloendothelial system and liver parenchymal

cells, principally in the form of ferritin.

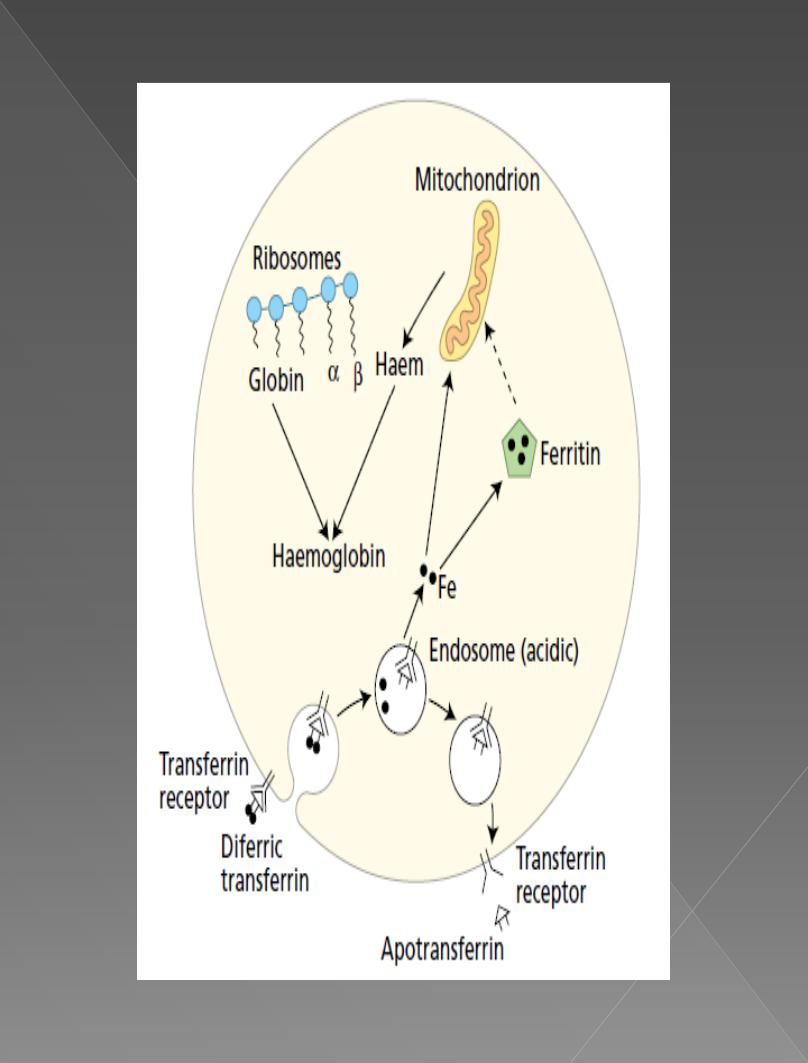

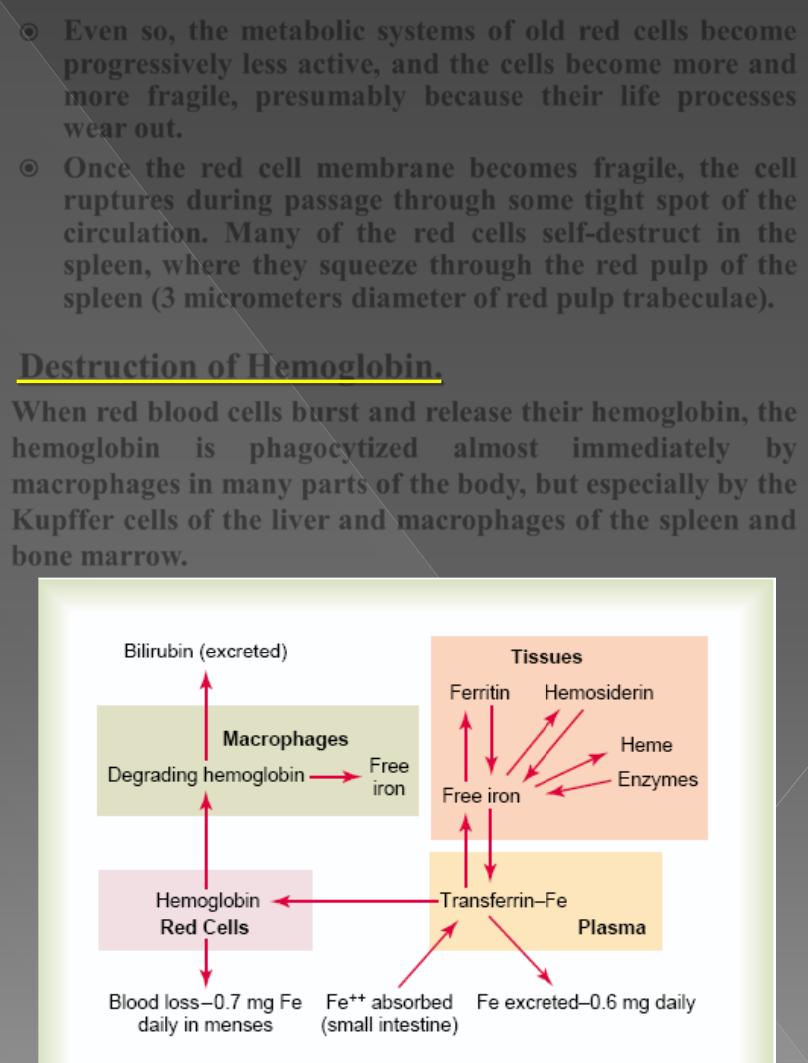

Transport and Storage of Iron.

iron is

absorbed

from the small intestine, it immediately

combines in the blood plasma with a beta globulin,

apotransferrin

, to form

transferrin

, which is then

transported in the plasma. The iron is

loosely

bound

in

the transferrin and, consequently, can be released to any

tissue cell at any point in the body.

Excess

iron

in the blood is

deposited

especially in the

liver

hepatocytes and less in the

reticuloendothelial

cells

of the bone marrow. In the cell cytoplasm, iron combines

mainly with a protein,

apoferritin

, to form

ferritin

, which

is storage iron.

Smaller quantities of the iron in the storage pool are in

an extremely insoluble form called

hemosiderin

.

A unique characteristic of the transferrin molecule is

that it

binds

strongly with

receptors

in the cell

membranes of erythroblasts in the bone marrow. Then,

along with its bound iron, it is ingested into the

erythroblasts by

endocytosis

. There the transferrin

delivers the iron directly to the mitochondria, where

heme is synthesized.

When red blood cells have

lived

their life span and are

destroyed, the hemoglobin released from the cells is

ingested

by

monocyte-macrophage

cells. There, iron is

liberated and is stored mainly in the ferritin pool to be

used as needed for the formation of new hemoglobin.

Daily Loss of Iron.

A

man

excretes about

0.6

milligram of iron each day,

mainly into the feces. Additional quantities of iron are

lost when bleeding occurs. For a

woman

, additional

menstrual loss of blood brings long term iron loss to an

average of about

1.3

mg/day.

Absorption of Iron from the Intestinal Tract

Iron is absorbed from

all

parts of the small intestine;

mostly by the following mechanism:- The

liver

secretes

moderate amounts of

apotransferrin

into the bile, which

flows through the bile duct into the duodenum.

Here, the apotransferrin

binds

with free

iron

and also

with certain iron compounds, such as

hemoglobin

and

myoglobin

from meat, two of the most important sources

of iron in the diet. This combination is called transferrin.

It, in turn, is attracted to and binds with receptors in the

membranes of the intestinal epithelial cells. Then, by

pinocytosis

, the transferrin molecule, carrying its iron

store, is

absorbed

into the epithelial cells and

later

released

into

the blood capillaries beneath these cells in

the form of plasma transferrin.

even when tremendous quantities of iron are present in

the food, only small proportions can be absorbed.

Regulation of Total Body Iron by Controlling Rate

of Absorption.

When the body has become

saturated

with iron so that

essentially all apoferritin in the iron storage areas is

already combined with iron, the rate of additional iron

absorption from the intestinal tract becomes greatly

decreased.

Conversely

, when the iron stores have become

depleted

, the rate of absorption can accelerate probably

five

or more times normal. Thus, total body iron is

regulated mainly by altering the rate of absorption.

Life Span and Destruction of Red Blood Cells

When red blood cells are delivered from the bone

marrow into the circulatory system, they normally

circulate an average of

120

days before being destroyed.

Even though mature red cells do not have a nucleus,

mitochondria,

or

endoplasmic reticulum, they do have

cytoplasmic

enzymes

that are capable of

metabolizing

glucose

and forming small amounts of adenosine

triphosphate.

These enzymes also:-

(1) maintain

pliability

of the cell membrane,

(2) maintain membrane

transport

of

ions

,

(3) keep the iron of the cells’ hemoglobin in the

ferrous

form rather than ferric form, and

(4) prevent

oxidation

of the proteins in the red cells.

Even so, the

metabolic

systems

of old red cells become

progressively

less

active

, and the cells become more and

more

fragile

, presumably because their life processes

wear out.

Once the red cell membrane becomes fragile, the cell

ruptures during passage through some tight spot of the

circulation. Many of the red cells self-destruct in the

spleen, where they squeeze through the red pulp of the

spleen (3 micrometers diameter of

red

pulp

trabeculae).

Destruction of Hemoglobin.

When red blood cells

burst

and release their hemoglobin, the

hemoglobin

is

phagocytized

almost

immediately

by

macrophages

in many parts of the body, but especially by the

Kupffer

cells of the liver and

macrophages

of the spleen and

bone marrow.

During the next few hours to days, the

macrophages

release

iron

from the hemoglobin and pass it back into the blood, to be

carried by transferrin either to the bone marrow for the

production of new red blood cells or to the liver and other

tissues for storage in the form of ferritin.

The

porphyrin portion

of the hemoglobin molecule is converted by

the macrophages, through a series of stages, into the

bile

pigment

bilirubin

, which is released into the blood and later

removed from the body by secretion through the liver into the

bile;

Anemias

Anemia means deficiency of hemoglobin in the blood, which

can be caused by either too

few

red blood cells or too

little

hemoglobin

in the cells. Some types of anemia and their

physiologic causes are the following:-

1. Blood Loss Anemia

.

After rapid hemorrhage, the body replaces the

fluid portion

of

the plasma in

1 to 3 days

,

but this leaves a low concentration of red blood cells.

If a second hemorrhage does not occur, the

red blood cell

concentration

usually returns to normal within

3 to 6 weeks

.

In

chronic blood loss

, a person frequently cannot absorb

enough iron from the intestines to form hemoglobin as rapidly

as it is lost. Red cells are then produced that are much smaller

than normal and have too little hemoglobin inside them, giving

rise to

microcytic, hypochromic anemia

,

2. Aplastic Anemia

.

Bone marrow aplasia

means

lack of functioning bone marrow.

For instance, a person exposed to

gamma

ray

radiation from a

nuclear bomb blast can sustain complete destruction of bone

marrow, followed in a few weeks by lethal anemia. Likewise,

excessive

x-ray

treatment, certain

industrial

chemicals

, and

even

drugs

to which the person might be sensitive can cause the

same effect.

3. Megaloblastic Anemia.

loss

of vitamin B12, folic acid, or intrinsic factor can lead

to

slow

reproduction

of erythroblasts (cannot proliferate

rapidly enough to form normal numbers of red blood

cells, in the bone marrow) As a result, the red cells

grow

too large and have bizarre shapes, and are called

megaloblasts.

Thus,

atrophy

of

the

stomach

mucosa, as occurs in

pernicious anemia, or

loss

of the entire stomach after

surgical total gastrectomy can lead to megaloblastic

anemia. Also, patients who have intestinal

sprue

, in

which folic acid, vitamin B12, and other vitamin B

compounds are poorly absorbed, often develop

megaloblastic anemia.

4. Hemolytic Anemia.

Different abnormalities of the red blood cells, many of

which are hereditarily acquired, make the cells

fragile

,

so that they rupture easily as they go through the

capillaries, especially through the spleen.

a. In hereditary spherocytosis

, the red cells are very

small

and

spherical

rather than being biconcave discs. These

cells

cannot withstand compression forces

because they

do not have the normal

loose,

baglike

cell membrane

structure of the biconcave discs. On passing through the

splenic pulp and some other tight vascular beds, they are

easily ruptured

.

b. In sickle cell anemia

,

which is present in 1.0 per cent of West

African

and

American

blacks, the cells have an abnormal type of

hemoglobin called

hemoglobin

S

, containing faulty beta

chains in the hemoglobin molecule,. When this

hemoglobin is exposed to low concentrations of

oxygen

, it

precipitates into long

crystals

inside the red blood cell.

These crystals elongate the cell and give it the

appearance of a sickle rather than a biconcave disc. The

precipitated

hemoglobin

also

damages

the

cell

membrane, so that the cells become highly fragile,

leading to serious anemia.

Such patients frequently experience a vicious circle of

events called a sickle cell disease “

crisis

,” in which low

oxygen tension in the tissues causes sickling, which leads

to ruptured red cells, which causes a further decrease in

oxygen tension and still more sickling and red cell

destruction.

c. In erythroblastosis fetalis

Rh-positive

red blood cells in the fetus are attacked by

antibodies

from an Rh-negative mother. These antibodies

make

the Rh-positive cells

fragile

, leading to rapid

rupture and causing the child to be born with serious

anemia.

Effects of Anemia on Function of the Circulatory

System

The

viscosity

of the blood

depends

almost entirely on the

blood

concentration

of red blood cells. In severe anemia, the

blood viscosity may fall to as low as

1.5

times that of water

rather than the normal value of about

3

.

This

decreases

the

resistance

to blood flow in the peripheral

blood vessels, so that far greater than normal

quantities

of

blood flow through the tissues and return to the heart,

thereby greatly

increasing

cardiac output.

Moreover,

hypoxia

resulting from diminished transport of

oxygen by the blood causes the peripheral tissue blood

vessels to

dilate

, allowing a further increase in the return of

blood to the heart and increasing the cardiac output to a

still higher level— sometimes three to four times normal.

Thus, one of the major effects of anemia is

greatly increased

cardiac

output, as well as increased pumping workload on

the heart.

The increased cardiac output in anemia partially

offsets

the

reduced oxygen-carrying effect of the anemia, because even

though each unit quantity of blood carries only small

quantities of oxygen, the rate of blood flow may be

increased enough so that almost

normal quantities of

oxygen are actually delivered to the tissues.

However, when a person with anemia begins to

exercise

,

the heart is not capable of pumping much greater quantities

of blood than it is already pumping. Consequently, during

exercise, which greatly increases tissue demand for oxygen,

extreme tissue hypoxia

results, and

acute cardiac failure

ensues.

Polycythemia

Secondary Polycythemia.

Whenever the tissues become hypoxic because of

too

little

oxygen in

the breathed air, such as at high altitudes (called

physiologic

polycythemia), or because of failure of oxygen delivery to the tissues,

such as in

cardiac

failure, the blood-forming organs automatically

produce large quantities of extra red blood cells.

Polycythemia Vera.

In addition to those people who have physiologic polycythemia, others

have a

pathological

condition known as polycythaemia vera, in which

hematocrit may be

60

to

70

per cent instead of the normal 40 to 45 per

cent. Polycythemia vera is caused by a

genetic

aberration in the

hemocytoblastic

cells that produce the blood cells.

In polycythemia vera, not only does the hematocrit increase, but the

total

blood volume

also increases, on some occasions to almost twice

normal. As a result, the entire vascular system becomes intensely

engorged. In addition,

many blood capillaries become plugged

by the

viscous blood; the viscosity of the blood in polycythaemia vera

sometimes increases from the normal of 3 times the viscosity of water

to

10

times that of water.

Effect of Polycythemia on Function of the Circulatory

System

Because of the greatly increased

viscosity

of the blood in polycythemia,

blood flow through the peripheral blood vessels is often very

sluggish

,

decreases

the rate of

venous

return

to the heart. Conversely, the blood

volume

is greatly increased in polycythemia, which tends to increase

venous return. So, the

cardiac output in polycythemia is not far from

normal.

The

arterial pressure

is also normal in most people with polycythemia,

although in about one third of them, the arterial pressure is elevated.

The

color of the skin

depends to a great extent on the quantity of blood

in the skin

subpapillary

venous plexus. In polycythemia vera, the

quantity of blood in this plexus is greatly increased. Further, because

the blood passes

sluggishly

through the skin capillaries before entering

the venous plexus, deoxygenated hemoglobin is elevated. The

blue

color

of all this deoxygenated hemoglobin masks the red color of the

oxygenated hemoglobin givig bluish (cyanotic) tint to the skin.