Unit 2: Bacteriology

98

Lecture 7 – Mycobacteria

Tuberculosis Bacteria (TB)

Tuberculosis is unquestionably among the most

intensively studied of all human diseases. In view of the

fact that tuberculosis can infect practically any organ in

the body.

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death

in the world from a bacterial infectious disease. The

disease affects 1.8 billion people/year which is equal to

one-third of the entire world population.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the etiologic agent of

tuberculosis in humans. Humans are the only reservoir

for the bacterium. Mycobacterium bovis is the etiologic

agent of TB in cows and rarely in humans. Both cows

and humans can serve as reservoirs. Humans can also be

infected by the consumption of unpasteurized milk.

This route of transmission can lead to the development of

extrapulmonary TB, exemplified in history by bone

infections that led to hunched backs.

Other human pathogens belonging to the

Mycobacterium genus include

Mycobacterium avium

which causes a TB-like disease especially prevalent in

AIDS patients, and Mycobacterium leprae, the causative

agent of leprosy.

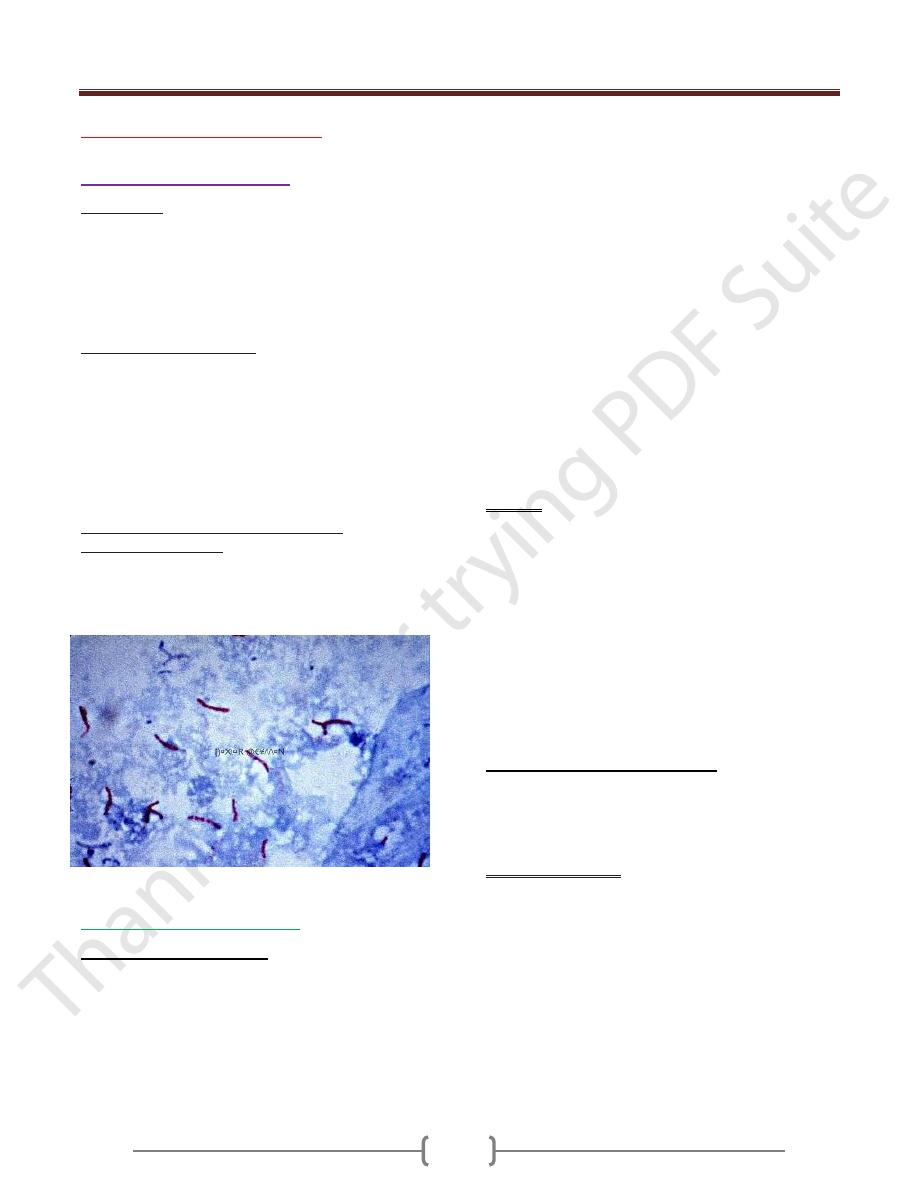

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Ziehl Neilson Stain)

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Morphology and culturing

TB are slender, acid-fast rods, 0.4 µm wide, and 3–4 µm

long, nonsporing and nonmotile. They can be stained with

special agents (Ziehl-Neelsen, Kinyoun, fluorescence).

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) is distantly related

to the Actinomycetes. Many nonpathogenic mycobacteria

are components of the normal flora of humans, found

most often in dry and oily locales. Mycobacterium

tuberculosis is an obligate aerobe. For this reason, in the

classic case of tuberculosis, MTB complexes are always

found in the well-aerated upper lobes of the lungs. The

bacterium is a facultative intracellular parasite, usually

of macrophages, and has a slow generation time, 15-20

hours, a physiological characteristic that may contribute

to its virulence.

Two media are used to grow MTB Middlebrook's

medium which is an agar based medium and

Lowenstein-Jensen medium which is an egg based

medium. MTB colonies are small and buff colored when

grown on either medium. Both types of media contain

inhibitors to keep contaminants from out-growing MT. It

takes 4-6 weeks to get visual colonies on either type of

media. TB are obligate aerobes. Their reproduction is

enhanced by the presence of 5–10% CO2 in the

atmosphere. Cultures must be incubated for three to six or

eight weeks at 37 ºC until proliferation becomes

macroscopically visible.

Cell wall.

Many of the special characteristics of TB are

ascribed to the chemistry of their cell wall, which features

a murein layer as well as numerous lipids, the most

important being the glycolipids (e.g.,

lipoarabinogalactan), the mycolic acids, mycosides, and

wax D . For example

Glycolipids and wax D are

r

esponsible for resistance to chemical and physical

noxae. Also they have adjuvant effect (wax D), i.e.,

enhancement of antigen immunogenicity. Tuberculin is

partially purified tuberculin contains a mixture of small

proteins (10 kDa). Tuberculin is used to test for TB

exposure (Delayed allergic reaction).

Pathogenesis and clinical picture

It is necessary to differentiate between primary and

secondary tuberculosis (reactivation or postprimary

tuberculosis) . The clinical symptoms are based on

reactions of the cellular immune system with TB antigens.

Primary tuberculosis.

In the majority of cases, the pathogens enter the lung in

droplets, where they are phagocytosed by alveolar

macrophages. TB bacteria are able to reproduce in these

macrophages due to their ability to inhibit formation of

the phagolysosome. Within 10–14 days an inflammatory

focus develops the so-called

primary focus

from which

the TB bacteria move into the regional lymph nodes,

where they reproduce and stimulate a cellular immune

response, which in turn results in clonal expansion of

specific T lymphocytes and attendant lymph node

swelling. The primary complex (Ghon’s complex)

Unit 2: Bacteriology

99

develops between six and 14 weeks after infection. At the

same time,

granulomas

form at the primary infection

site and in the affected lymph nodes, and macrophages

are activated by the cytokine

MAF

(

macrophage

activating factor

).

A tuberculin allergy

also develops in

the macroorganism The further course of the disease

depends on the outcome of the battle between the TB and

the specific cellular immune defenses.

Postprimary

dissemination foci

are sometimes observed as well, i.e.,

development of

local tissue defect foci

at

other

localizations

, typically the

apices

of the lungs.

Mycobacteria may also be transported to other organs

via the lymph vessels or bloodstream and produce

dissemination foci there. The host eventually prevails in

over 90% of cases: the granulomas and foci fibrose,

scar, and calcify, and the infection remains clinically

silent.

Secondary tuberculosis.

In about 10% of infected persons the primary

tuberculosis reactivates to become an

organ tuberculosis

,

either within months (5 %) or after a number of years (5

%). Exogenous reinfection is rare in the populations of

developed countries.

Reactivation

begins with a

caseation necrosis

in the center of the granulomas (also

called

tubercles

) that may progress to

cavitation

(formation of caverns). Tissue destruction is caused by

cytokines, among which tumor necrosis factor a (TNFa)

appears to play an important role. This cytokine is also

responsible for the

cachexia

associated with tuberculosis.

Reactivation frequently stems from old foci in the lung

apices.The body’s immune defenses have a hard time

containing necrotic tissue lesions in which large numbers

of TB cells occur (e.g., up to 109 bacteria and more per

cavern); the resulting lymphogenous or hematogenous

dissemination may result in infection foci in other organs.

Virtually all types of organs and tissues are at risk for this

kind of secondary TB infection. Such infection courses

are subsumed under the term

extrapulmonary

tuberculosis

.

Predisposing factors for TB infection include:

Close contact with large populations of people, i.e.,

schools, nursing homes, dormitories, prisons, etc.

Poor nutrition

IV drug use

Alcoholism

HIV infection is the number 1 predisposing factor for

MTB infection. 10 percent of all HIV-positive individuals

harbor MTB. This is 400-times the rate associated with

the general public. Only 3-4% of infected individuals will

develop active disease upon initial infection, 5-10%

within one year. These percentages are much higher if the

individual is HIV+.

Immunity

Humans show a considerable degree of genetically

determined resistance to TB. Besides this inherited

faculty, an organism acquires an (incomplete) specific

immunity during initial exposure (first infection). This

acquired immunity is characterized by localization of the

TB at an old or new infection focus with limited

dissemination (Koch’s phenomenon). This immunity is

solely a function of the T lymphocytes. The level of

immunity is high while the body is fending off the

disease, but falls off rapidly afterwards.It is therefore

speculated that resistance lasts only as long as TB or the

immunogens remain in the organism (= infection

immunity).

Tuberculin reaction.

Parallel to this specific immunity,

an organism infected with TB shows an altered reaction

mechanism, the tuberculin allergy, which also develops

in the cellular immune system only. The tuberculin

reaction, positive six to 14 weeks after infection, confirms

the allergy. The tuberculin proteins are isolated as purified

tuberculin (PPD = purified protein derivative). Five

tuberculin units (TU) are applied intracutaneously in the

tuberculin test. If the reaction is negative, the dose is

sequentially increased to 250 TU. A positive reaction

appears within 48 to 72 hours as an inflammatory

reaction (induration) at least 10mm in diameter at the

site of antigen application. A positive reaction means that

the person has either been infected with TB or

vaccinated with BCG. It is important to understand that a

positive test is not an indicator for an active infection or

immune status. While a positive test person can be

assumed to have a certain level of specific immunity, it

will by no means be complete. One-half of the clinically

manifest cases of tuberculosis in the population are

secondary reactivation tuberculoses that develop in

tuberculin positive persons.

Diagnosis

R

equires microscopic and cultural identification of the

pathogen or pathogen-specific DNA.

Traditional method

Workup of test material, for example with N-acetyl-L-

cysteine-NaOH (NALC-NaOH method) to liquefy

viscous mucus and eliminate rapidly proliferating

Unit 2: Bacteriology

100

accompanying flora, followed by centrifugation to enrich

the concentration.

Microscopy. Ziehl-Neelsen and/or auramine fluorescent

staining . This method produces rapid results but has a

low level of sensitivity (>104–105/ml) and specificity

(acid-fast rods only).

Culture on special solid and in special liquid mediums.

Time requirement: four to eight weeks.

Identification. Biochemical tests with pure culture if

necessary. Time requirement: one to three weeks.

Resistance test with pure culture.

Time requirement: three

weeks.

Rapid methods.

A number of different rapid TB diagnostic methods have

been introduced in recent years that require less time than

the traditional methods.

Culture.

Early-stage growth detection in liquid mediums

involving identification of TB metabolic products with

highly sensitive, semi-automated equipment. Time

requirement: one to three weeks. Tentative diagnosis.

Identification.

Analysis of cellular fatty acids by means of

gas chromatography and of mycolic acids by means of

HPLC. Time requirement: 12 days with a pure culture.

DNA probes.

Used to identify M. tuberculosis complex

and other mycobacteria. Time requirement: several hours

with a pure culture.

Resistance test.

Use of semi-automated equipment .

Proliferation/ nonproliferation determination in liquid

mediums containing standard antituberculotic agents.

Time requirement: 7–10 days.

Direct identification in patient material.

Molecular methods used for direct detection of the M.

tuberculosis complex in (uncultured) test material. These

methods involve amplification of the search sequence.

Therapy

The previous method of long-term therapy in sanatoriums

has been replaced by a standardized chemotherapy often

on an outpatient basis.

Epidemiology and prevention

Tuberculosis is endemic worldwide. The disease has

become much less frequent in developed countries in

recent decades. Tuberculosis is still a major medical

problem. It is estimated that every year approximately 15

million persons contract tuberculosis and that three

million die of the disease. The main source of infection is

the human carrier. There are no healthy carriers. Diseased

cattle are not a significant source of infection in the

developed world. Transmission of the disease is generally

direct, in most cases by droplet infection. Indirect

transmission via dust or milk (udder tuberculosis in cattle)

is the exception rather than the rule. The incubation

period is four to 12 weeks.

Exposure prophylaxis. Patients with open tuberculosis

must be isolated during the secretory phase. Secretions

containing TB must be disinfected. Tuberculous cattle

must be eliminated.

Disposition prophylaxis. An active vaccine is available

that reduces the risk of contracting the disease by about

one-half. It contains the live vaccine BCG (lyophilized

bovine TB of the Calmette-Gue´rin type). Vaccination of

tuberculin-negative persons induces allergy &

(incomplete) immunity that persist for about five to 10

years.

Leprosy Bacteria (LB)

Morphology and culture

Mycobacterium leprae (Hansen, 1873) is the causative

pathogen of leprosy. In morphological terms, these acid-

fast rods are identical to tuberculosis bacteria. They differ,

however, in that they cannot be grown on nutrient

mediums or in cell cultures.

Pathogenesis

The pathomechanisms of LB are identical to those of TB.

The host organism attempts to localize and isolate

infection foci by forming granulomas. Leprous

granulomas are histopathologically identical to

tuberculous granulomas. High counts of leprosy bacteria

are often found in the macrophages of the granulomas.

Immunity

The immune defenses mobilized against a leprosy

infection are strictly of the cellular type. The lepromin

skin test can detect a postinfection allergy.

This test is not, however, very specific (i.e., positive

reactions in cases in which no leprosy infection is

present). The clinically differentiated infection course

forms observed are probably due to individual immune

response variants.

Clinical picture

Leprosy is manifested mainly on the skin, mucosa, and

peripheral nerves. A clinical differentiation is made

between tuberculoid leprosy and lepromatous leprosy

(LL). There are many intermediate forms. TL is the

benign, nonprogressive form characterized by spotty

Unit 2: Bacteriology

101

dermal lesions. The LL form, on the other hand, is

characterized by a malignant, progressive course with

nodular skin lesions and cordlike nerve thickenings

that finally lead to neuroparalysis. The inflammatory

foci contain large numbers of leprosy bacteria.

Diagnosis

Detection of the pathogens in skin or nasal mucosa

scrapings under the microscope using Ziehl-Neelsen

staining . Molecular confirmation of DNA sequences

specific to leprosy bacteria in a polymerase chain reaction

is possible.

Therapy

Paucibacillary forms are treated with dapson plus

rifampicin for six months. Multibacillary forms require

treatment with dapson, rifampicin, and clofazimine over a

period of at least two years.

Epidemiology and prevention

Leprosy is now rare in socially developed countries,

although still frequent in developing countries. There are

an estimated 11 million victims worldwide. Infected

humans are the only source of infection. The details of the

transmission pathways are unknown. Discussion of the

topic is considering transmission by direct contact with

skin or mucosa injuries and aerogenic transmission.

The incubation period is 2–5–20 years.

Isolation of patients under treatment is no longer required.

An effective epidemiological reaction requires early

recognition of the disease in contact persons by means of

periodical examinations every six to 12 months up to five

years following contact.

Nontuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM)

Mycobacteria that are neither tuberculosis nor leprosy

bacteria are categorized as atypical mycobacteria (old

designation), nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) or

MOTT (mycobacteria other than tubercle bacilli).

Morphology and culture

In their morphology and staining behavior, NTM are

generally indistinguishable from tuberculosis bacteria.

With the exception of the rapidly growing NTM, their

culturing characteristics are also similar to TB. Some

species proliferate only at 30 °C. NTM are frequent

inhabitants of the natural environment (water, soil) and

also contribute to human and animal mucosal flora. Most

of these species show resistance to the antituberculoid

agents in common use.

Clinical pictures and diagnosis

Some NTM species are apathogenic, others can cause

mycobacterioses in humans that usually follow a chronic

course

NTM infections are generally rare. Their occurrence is

encouraged by compromised cellular immunity. Frequent

occurrence is observed together with certain

malignancies, in immunosuppressed patients and in

AIDS patients, whereby the NTM isolated in 80% of

cases are M. avium or M. intercellulare. As a rule, NTM

infections are indistinguishable from tuberculous lesions

in clinical, radiological, and histological terms. Diagnosis

therefore requires culturing and positive identification.

The clinical significance of a positive result is difficult to

determine due to the ubiquitous occurrence of these

pathogens. They are frequent culture contaminants. Only

about 10% of all persons in whom NTM are detected

actually turn out to have a mycobacteriosis.

Therapy

Surgical removal of the infection focus is often

indicated. Chemotherapy depends on the pathogen

species, for instance a triple combination (e.g., INH,

ethambutol, rifampicin) or, for resistant strains, a

combination of four or five antituberculoid agents.