; therefore

be digested. Also, chewing aids the digestion of food for still another simple

Chewing is important for digestion of all foods, but especially important for

another time; this is repeated again and again.

which inhibits the jaw muscles once again, allowing the jaw to drop and rebound

teeth, but it also compresses the bolus again against the linings of the mouth,

contraction. This automatically raises the jaw to cause closure of the

to drop. The drop in turn initiates a stretch reflex of the jaw muscles that leads

tiates reflex inhibition of the muscles of mastication, which allows the lower jaw

explained as follows: The presence of a bolus of food in the mouth at first ini-

, which may be

chewing reflex

taste and smell can often cause chewing.

thalamus, amygdala, and even the cerebral cortex near the sensory areas for

cause rhythmical chewing movements. Also, stimulation of areas in the hypo-

stem. Stimulation of specific reticular areas in the brain stem taste centers will

fifth cranial nerve, and the chewing process is controlled by nuclei in the brain

as 55 pounds on the incisors and 200 pounds on the molars.

viding a strong cutting action and the posterior teeth (molars), a grinding action.

The teeth are admirably designed for chewing, the anterior teeth (incisors) pro-

swallowing

mechanics of ingestion, especially

tion of the body. The current discussion of food ingestion is confined to the

tional supply for the body; they are discussed in Chapter 71 in relation to nutri-

. These mechanisms in themselves are extremely

. The type of food that a person preferentially seeks

The amount of food that a person ingests is determined principally by intrinsic

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss these movements, especially the auto-

too rapidly, not too slowly.

each of these so that they will occur optimally, not

processing, multiple automatic nervous and hor-

provided. Yet because the requirements for mixing

tract is critical. Also, appropriate mixing must be

tary tract, the time that it remains in each part of the

For food to be processed optimally in the alimen-

Food in the Alimentary Tract

C

H

A

P

T

E

R

6

3

781

Propulsion and Mixing of

and propulsion are quite different at each stage of

monal feedback mechanisms control the timing of

matic mechanisms of this control.

Ingestion of Food

desire for food called hunger

is determined by appetite

important automatic regulatory systems for maintaining an adequate nutri-

mastication and

.

Mastication (Chewing)

All the jaw muscles working together can close the teeth with a force as great

Most of the muscles of chewing are innervated by the motor branch of the

Much of the chewing process is caused by a

to rebound

most fruits and raw vegetables because these have indigestible cellulose mem-

branes around their nutrient portions that must be broken before the food can

reason: Digestive enzymes act only on the surfaces of food particles

,

occurring in less than 2 seconds.

food into the upper esophagus, the entire process

agus is opened, and a fast peristaltic wave initiated by

stage of swallowing: The trachea is closed, the esoph-

To summarize the mechanics of the pharyngeal

by peristalsis into the esophagus.

inferior pharyngeal areas, which propels the food

the entire muscular wall of the pharynx contracts,

5. Once the larynx is raised and the

epiglottis rather than over its surface; this adds

glottis out of the main stream of food flow, so

into the esophagus during respiration. The

contracted, thereby preventing air from going

Between swallows, this sphincter remains strongly

posterior pharynx into the upper esophagus.

) relaxes, thus

of the esophageal muscular wall, called the

At the same time, the upper 3 to 4 centimeters

up and enlarges the opening to the esophagus.

4. The upward movement of the larynx also pulls

cords. Destruction of the vocal cords or of the

of the vocal cords, but the epiglottis helps to

trachea. Most essential is the tight approximation

of the larynx. All these effects acting together

prevent upward movement of the epiglottis, cause

and anteriorly by the neck muscles. These actions,

approximated, and the larynx is pulled upward

3. The vocal cords of the larynx are strongly

the esophagus.

swallowing lasts less than 1 second, any large

sufficiently to pass with ease. Because this stage of

action, allowing food that has been masticated

posterior pharynx. This slit performs a selective

other. In this way, these folds form a sagittal

2. The palatopharyngeal folds on each side of the

nasal cavities.

posterior nares, to prevent reflux of food into the

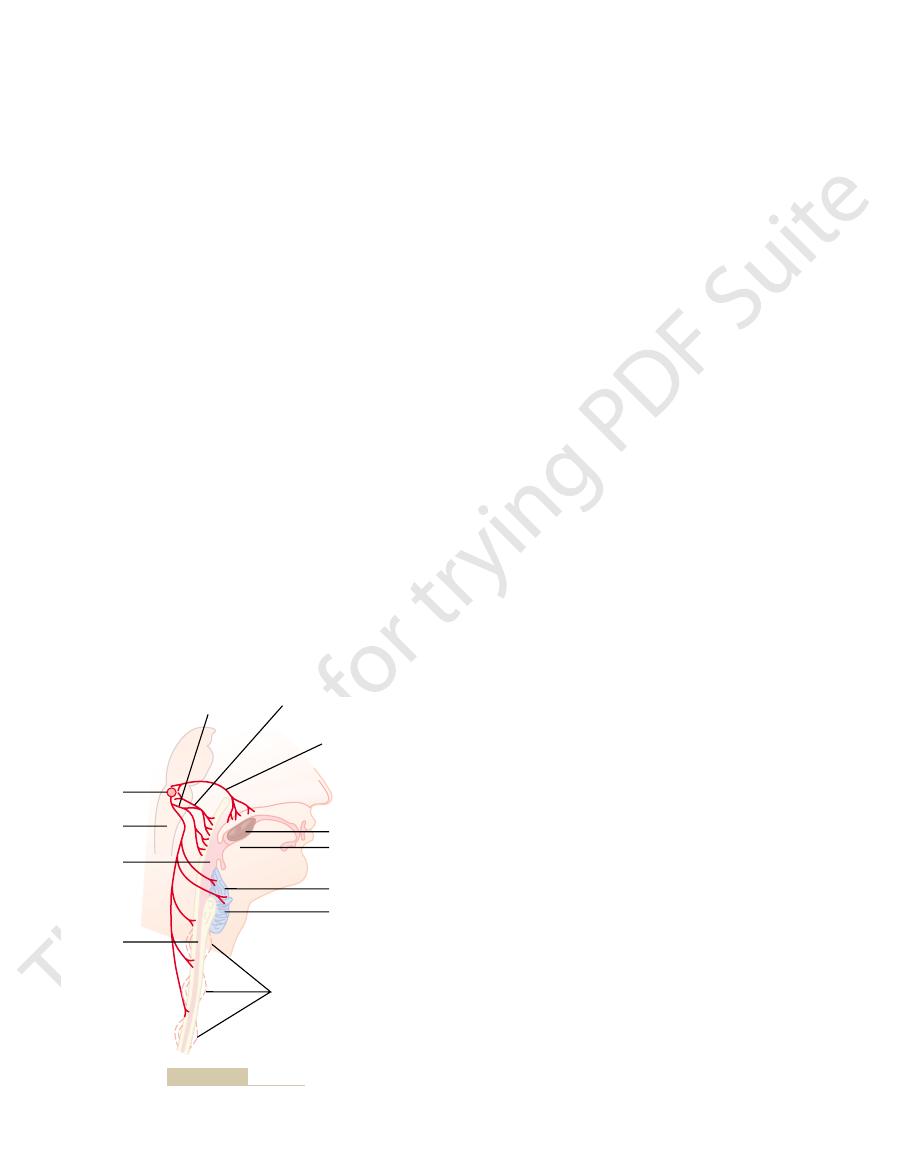

1. The soft palate is pulled upward to close the

pillars, and impulses from these pass to the brain stem

opening of the pharynx, especially on the tonsillar

epithelial swallowing receptor areas

enters the posterior mouth and pharynx, it stimulates

Pharyngeal Stage of Swallowing.

Figure 63–1. From here on, swallowing becomes

upward and backward against the palate, as shown in

swallowing, it is “voluntarily” squeezed or rolled pos-

When the food is ready for

Voluntary Stage of Swallowing.

, another invol-

esophagus; and (3) an

, which is involuntary and consti-

, which initiates the swallowing process; (2)

In general, swallowing can be divided into (1) a

promised because of swallowing.

swallowing. The pharynx is converted for only a few

Swallowing is a complicated mechanism, principally

emptied from the stomach into the small intestine,

consistency prevents excoriation of the gastrointesti-

In addition, grinding the food to a very fine particulate

total surface area exposed to the digestive secretions.

782

Unit XII

Gastrointestinal Physiology

the rate of digestion is absolutely dependent on the

nal tract and increases the ease with which food is

then into all succeeding segments of the gut.

Swallowing (Deglutition)

because the pharynx subserves respiration as well as

seconds at a time into a tract for propulsion of food.

It is especially important that respiration not be com-

vol-

untary stage

a pharyngeal stage

tutes passage of food through the pharynx into the

esophageal stage

untary phase that transports food from the pharynx to

the stomach.

teriorly into the pharynx by pressure of the tongue

entirely—or almost entirely—automatic and ordinar-

ily cannot be stopped.

As the bolus of food

all around the

to initiate a series of automatic pharyngeal muscle

contractions as follows:

pharynx are pulled medially to approximate each

slit through which the food must pass into the

object is usually impeded too much to pass into

combined with the presence of ligaments that

the epiglottis to swing backward over the opening

prevent passage of food into the nose and

prevent food from ever getting as far as the vocal

muscles that approximate them can cause

strangulation.

upper esophageal sphincter (also called the

pharyngoesophageal sphincter

allowing food to move easily and freely from the

upward movement of the larynx also lifts the

that the food mainly passes on each side of the

still another protection against entry of food into

the trachea.

pharyngoesophageal sphincter becomes relaxed,

beginning in the superior part of the pharynx,

then spreading downward over the middle and

the nervous system of the pharynx forces the bolus of

Esophagus

Vagus

Glossopharyngeal

nerve

Trigeminal nerve

Bolus of food

Uvula

Epiglottis

Vocal cords

Peristalsis

Pharynx

Medulla

Swallowing

center

Figure 63–1

Swallowing mechanism.

esophagus except under very abnormal conditions.

action of gastric secretions. Fortunately, the tonic con-

agus, is not capable of resisting for long the digestive

mucosa, except in the lower one eighth of the esoph-

contain many proteolytic enzymes. The esophageal

The stomach secretions are highly acidic and

achalasia

satisfactorily, resulting in a condition called

into the stomach. Rarely, the sphincter does not relax

esophageal sphincter ahead of the peristaltic wave,

agus, there is “receptive relaxation” of the lower

the esophagus, which normally remains relaxed. When

of about 30 mm Hg, in contrast to the midportion of

. This

, also called the

lower esophageal sphinc-

juncture with the stomach, the esophageal circular

agus, extending upward about 3 centimeters above its

Function of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter (Gastro-

extent, even the duodenum become relaxed as this

Furthermore, the entire stomach and, to a lesser

myenteric inhibitory neurons, precedes the peristalsis.

stomach, a wave of relaxation, transmitted through

When the

reflex, food fed by tube or in some other way into the

without support from the vagal reflexes. Therefore,

the esophagus are cut, the myenteric nerve plexus of

myenteric nervous system. When the vagus nerves to

, but this portion of

vagus nerves. In the lower two thirds of the esophagus,

. Therefore, the

The musculature of the pharyngeal wall and upper

stomach. The secondary peristaltic waves are initiated

the esophagus itself by the retained food; these waves

stomach all the food that has entered the esophagus,

itself, in about 5 to 8 seconds, because of the additional

Food swallowed by a person who is in the upright posi-

the pharynx to the stomach in about 8 to 10 seconds.

stage of swallowing. This wave passes all the way from

. Primary peristalsis is simply continuation of

The esophagus normally exhibits two types of peri-

the stomach, and its movements are organized specif-

The esophagus functions

Esophageal Stage of Swallowing.

short time that it is hardly noticeable.

is talking, swallowing interrupts respiration for such a

allow swallowing to proceed. Yet, even while a person

this time, halting respiration at any point in its cycle to

piratory cycle. The swallowing center specifically

usually occurs in less than 6 seconds, thereby inter-

The entire pharyngeal stage of swallowing

Effect of the Pharyngeal Stage of Swallowing on Res-

mouth, which in turn excites involuntary pharyngeal

principally a reflex act. It is almost always initiated by

In summary, the pharyngeal stage of swallowing is

cervical nerves.

ing are transmitted successively by the 5th, 9th, 10th,

The motor impulses from the swallowing center to

swallowing center

remains constant from one swallow to the next. The

to the next, and the timing of the entire cycle also

medulla and lower portion of the pons. The sequence

The successive stages of the swallowing process

, which receives essentially all sensory impulses

pillars. Impulses are transmitted from these areas

opening, with greatest sensitivity on the tonsillar

The most sensitive tactile areas of the posterior

Nervous Initiation of the Pharyngeal Stage of Swallow-

Propulsion and Mixing of Food in the Alimentary Tract

Chapter 63

783

ing.

mouth and pharynx for initiating the pharyngeal stage

of swallowing lie in a ring around the pharyngeal

through the sensory portions of the trigeminal and

glossopharyngeal nerves into the medulla oblongata,

either into or closely associated with the tractus soli-

tarius

from the mouth.

are then automatically initiated in orderly sequence

by neuronal areas of the reticular substance of the

of the swallowing reflex is the same from one swallow

areas in the medulla and lower pons that control

swallowing are collectively called the deglutition or

.

the pharynx and upper esophagus that cause swallow-

and 12th cranial nerves and even a few of the superior

voluntary movement of food into the back of the

sensory receptors to elicit the swallowing reflex.

piration.

rupting respiration for only a fraction of a usual res-

inhibits the respiratory center of the medulla during

primarily to conduct food rapidly from the pharynx to

ically for this function.

staltic movements: primary peristalsis and secondary

peristalsis

the peristaltic wave that begins in the pharynx and

spreads into the esophagus during the pharyngeal

tion is usually transmitted to the lower end of the

esophagus even more rapidly than the peristaltic wave

effect of gravity pulling the food downward.

If the primary peristaltic wave fails to move into the

secondary peristaltic waves result from distention of

continue until all the food has emptied into the

partly by intrinsic neural circuits in the myenteric

nervous system and partly by reflexes that begin in the

pharynx and are then transmitted upward through

vagal afferent fibers to the medulla and back again to

the esophagus through glossopharyngeal and vagal

efferent nerve fibers.

third of the esophagus is striated muscle

peristaltic waves in these regions are controlled by

skeletal nerve impulses from the glossopharyngeal and

the musculature is smooth muscle

the esophagus is also strongly controlled by the vagus

nerves acting through connections with the esophageal

the esophagus becomes excitable enough after several

days to cause strong secondary peristaltic waves even

even after paralysis of the brain stem swallowing

esophagus still passes readily into the stomach.

Receptive Relaxation of the Stomach.

esophageal peristaltic wave approaches toward the

wave reaches the lower end of the esophagus and

thus are prepared ahead of time to receive the food

propelled into the esophagus during the swallowing

act.

esophageal Sphincter).

At the lower end of the esoph-

muscle functions as a broad

ter

gastroesophageal sphincter

sphincter normally remains tonically constricted with

an intraluminal pressure at this point in the esophagus

a peristaltic swallowing wave passes down the esoph-

which allows easy propulsion of the swallowed food

,

which is discussed in Chapter 66.

striction of the lower esophageal sphincter helps to

prevent significant reflux of stomach contents into the

is that of a murky semifluid or paste.

digestion that has occurred. The appearance of chyme

water, and stomach secretions and on the degree of

The degree of fluidity of the chyme leaving the

chyme

oughly mixed with the stomach secretions, the result-

“retropulsion,” is an exceedingly important mixing

combined with this upstream squeezing action, called

pylorus. Thus, the moving peristaltic constrictive ring,

ring toward the body of the stomach, not through the

through the pylorus. Therefore, most of the antral con-

often contracts, which further impedes emptying

wave approaches the pylorus, the pyloric muscle itself

with each peristaltic wave. Also, as each peristaltic

contents in the antrum. Yet the opening of the pylorus

wall toward the pylorus, it digs deeply into the food

These constrictor rings also play an important role

higher pressure toward the pylorus.

stomach into the antrum, they become more intense,

waves” that occur spontaneously in the stomach wall.

cussed in Chapter 62, consisting of electrical “slow

, which was dis-

once every 15 to 20 seconds. These waves are initiated

, begin in the mid- to upper portions of

, called

stomach, weak peristaltic

surface of the stomach. As long as food is in the

strip on the lesser curvature of the stomach. These

, which are present in almost the entire

The digestive juices of the stomach are secreted by

Rhythm of the Stomach Wall

Mixing and Propulsion of Food in the

the completely relaxed stomach of 0.8 to 1.5 liters. The

the wall bulges progressively outward, accommodating

a “vagovagal reflex” from the stomach to the brain

stomach. Normally, when food stretches the stomach,

of the food in the orad portion of the stomach, the

As food enters the stomach, it forms concentric circles

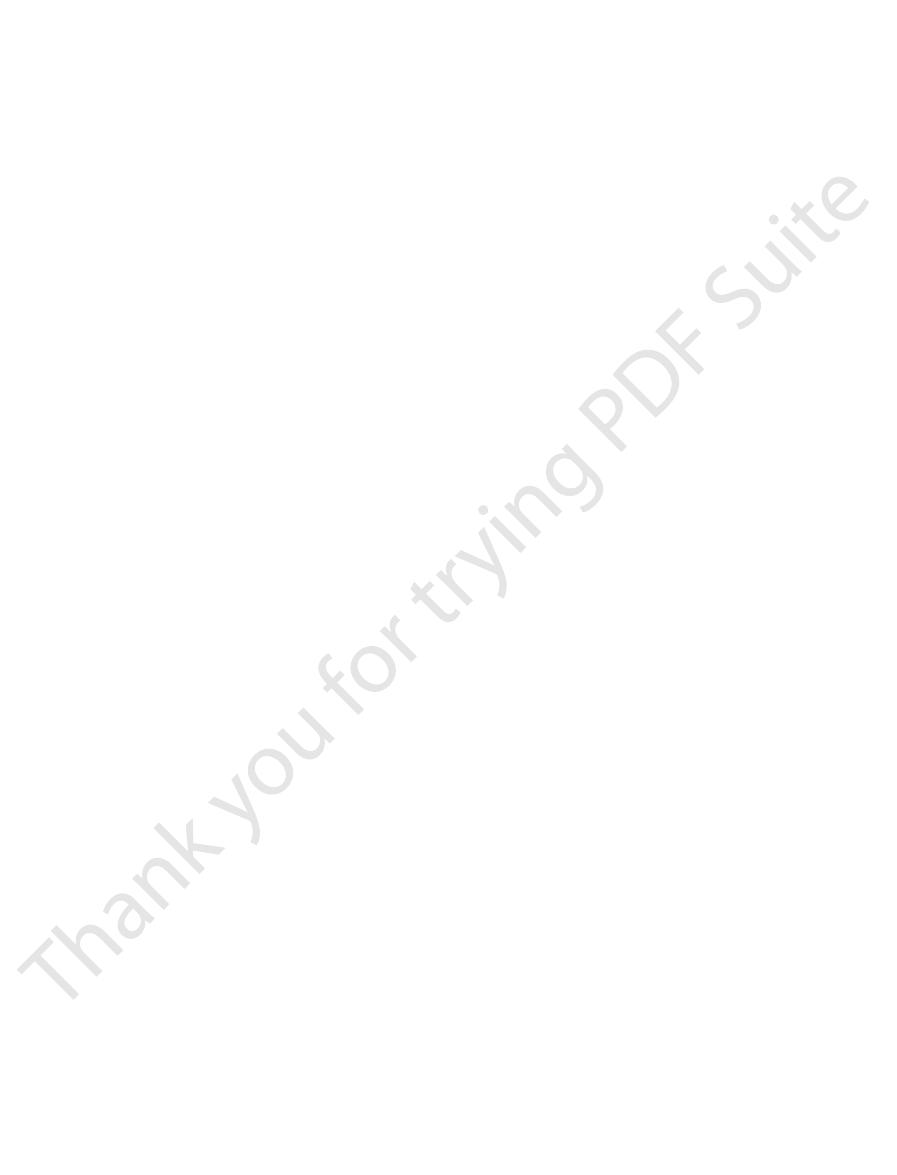

Storage Function of the Stomach

thirds of the body, and (2) the “caudad” portion, com-

(1) the “orad” portion, comprising about the first two

Physiologically, it is more appropriately divided into

into two major parts: (1) the

stomach. Anatomically, the stomach is usually divided

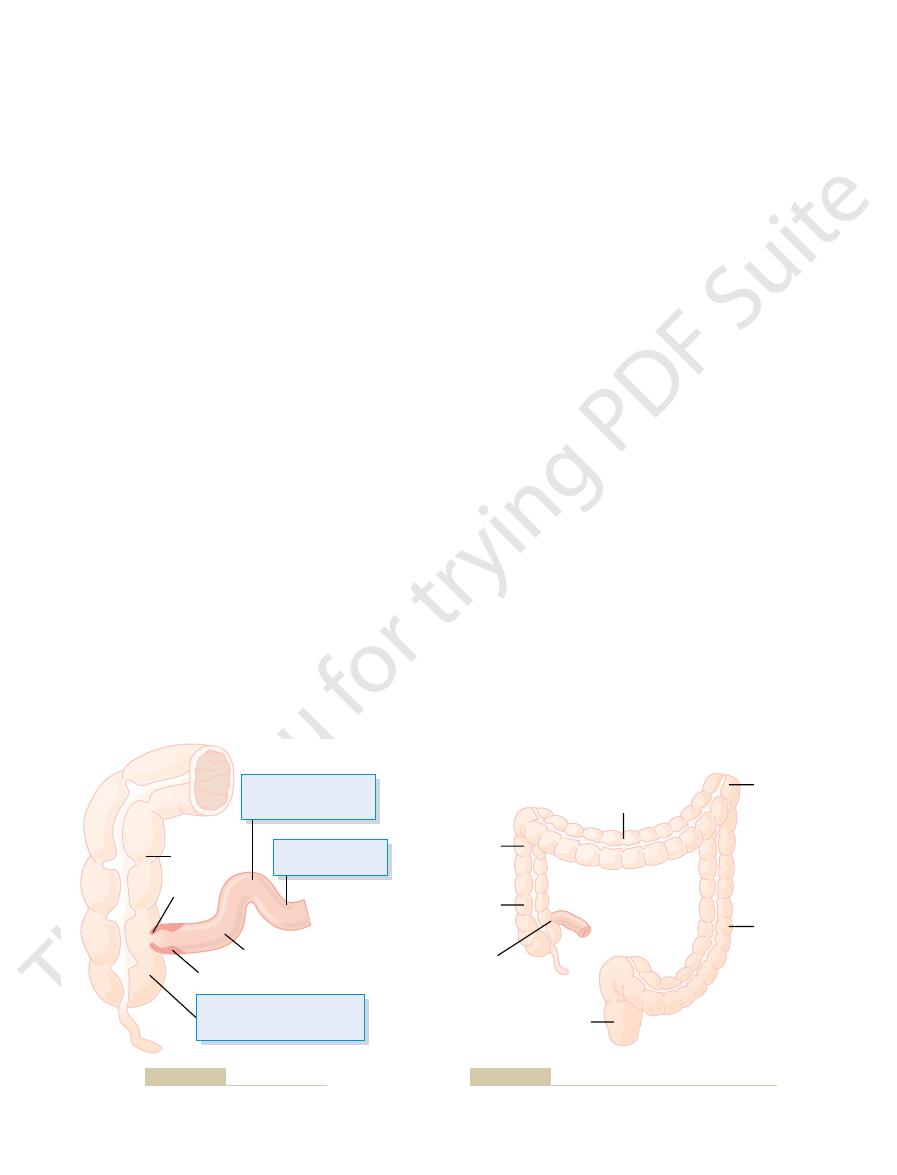

Figure 63–2 shows the basic anatomy of the

proper digestion and absorption by the small intestine.

; and (3) slow emptying of the chyme from the

chyme

intestinal tract; (2) mixing of this food with gastric

be processed in the stomach, duodenum, and lower

The motor functions of the stomach are threefold: (1)

esophagus.

or breathed hard, we might expel stomach acid into the

esophagus. Otherwise, every time we walked, coughed,

point. Thus, this valvelike closure of the lower esoph-

that extends slightly into the stomach. Increased intra-

like Closure of the Distal End of the Esophagus.

Additional Prevention of Esophageal Reflux by Valve-

784

Unit XII

Gastrointestinal Physiology

Another factor that helps to prevent reflux is a valve-

like mechanism of a short portion of the esophagus

abdominal pressure caves the esophagus inward at this

agus helps to prevent high intra-abdominal pressure

from forcing stomach contents backward into the

Motor Functions of the

Stomach

storage of large quantities of food until the food can

secretions until it forms a semifluid mixture called

stomach into the small intestine at a rate suitable for

body and (2) the antrum.

prising the remainder of the body plus the antrum.

newest food lying closest to the esophageal opening

and the oldest food lying nearest the outer wall of the

stem and then back to the stomach reduces the tone

in the muscular wall of the body of the stomach so that

greater and greater quantities of food up to a limit in

pressure in the stomach remains low until this limit is

approached.

Stomach—The Basic Electrical

gastric glands

wall of the body of the stomach except along a narrow

secretions come immediately into contact with that

portion of the stored food lying against the mucosal

constrictor waves

mixing waves

the stomach wall and move toward the antrum about

by the gut wall basic electrical rhythm

As the constrictor waves progress from the body of the

some becoming extremely intense and providing pow-

erful peristaltic action potential–driven constrictor

rings that force the antral contents under higher and

in mixing the stomach contents in the following way:

Each time a peristaltic wave passes down the antral

is still small enough that only a few milliliters or less

of antral contents are expelled into the duodenum

tents are squeezed upstream through the peristaltic

mechanism in the stomach.

Chyme.

After food in the stomach has become thor-

ing mixture that passes down the gut is called

.

stomach depends on the relative amounts of food,

Duodenum

Antrum

Fundus

Esophagus

Cardia

Angular

notch

Pyloric

sphincter

Rugae

Body

Pylorus

Figure 63–2

Physiologic anatomy of the stomach.

the vagus nerves all the way to the brain stem, where

stomach, and (3) probably to a slight extent through

in the gut wall, (2) through extrinsic nerves that go to

ated by three routes: (1) directly from the duodenum

denum becomes too much. These reflexes are medi-

When food enters the duodenum, multiple

Inhibitory Effect of Enterogastric Nervous Reflexes from the

Powerful Duodenal Factors That Inhibit

Thus, it, too, probably promotes stomach emptying.

it seems to enhance the activity of the pyloric pump.

functions in the body of the stomach. Most important,

acidic gastric juice by the stomach glands. Gastrin also

This has potent effects to cause secretion of highly

Chapter 64, we shall see that stomach wall stretch and

inhibit the pylorus.

However, stretching of the stomach wall does elicit

in the usual normal range of volume, the increase

stomach that causes the increased emptying because,

tying from the stomach. But this increased emptying

Effect of Gastric Food Volume on Rate of Emptying.

Gastric Factors That Promote Emptying

in the small intestine.

potent of the signals, controlling the emptying of

However, the duodenum provides by far the more

The rate at which the stomach empties is regulated by

Regulation of Stomach Emptying

the duodenum, as discussed shortly.

sistency. The degree of constriction of the pylorus is

duodenum with ease. Conversely, the constriction

sphincter, the pylorus usually is open enough for water

pyloric sphincter

tracted almost all the time. Therefore, the pyloric cir-

stomach antrum, and it remains slightly tonically con-

. Here the

pylorus

The

action called the “pyloric pump.”

causing mixing in the stomach, also provide a pumping

duodenum. Thus, the peristaltic waves, in addition to

When pyloric tone is normal, each strong peristaltic

mixing type of peristaltic waves.

often create 50 to 70 centimeters of water pressure,

the antrum. These intense peristaltic contractions

stomach, gradually pinching off the food in the body

progressively more and more empty, these constric-

can cause stomach emptying. As the stomach becomes

strong peristaltic, very tight ringlike constrictions that

stomach, the contractions become intense, beginning

cause mixing of food and gastric secretions. However,

Most of the time, the rhythmical

to passage of chyme at the pylorus.

contractions in the stomach antrum. At the same time,

succeeding days.

ingestion of food; in starvation, they reach their great-

. Hunger pangs

of the stomach, called

sugar. When hunger contractions occur in the stomach,

person’s having lower than normal levels of blood

testinal tonus; they are also greatly increased by the

Hunger contractions are most intense in young,

contraction that sometimes lasts for 2 to 3 minutes.

strong, they often fuse to cause a continuing tetanic

When the successive contractions become extremely

for several hours or more. They are rhythmical

when the stomach has been

, often occurs

another type of intense contractions, called

Propulsion and Mixing of Food in the Alimentary Tract

Chapter 63

785

Hunger Contractions.

Besides the peristaltic contractions

that occur when food is present in the stomach,

hunger

contractions

empty

peristaltic contractions in the body of the stomach.

healthy people who have high degrees of gastroin-

the person sometimes experiences mild pain in the pit

hunger pangs

usually do not begin until 12 to 24 hours after the last

est intensity in 3 to 4 days and gradually weaken in

Stomach Emptying

Stomach emptying is promoted by intense peristaltic

emptying is opposed by varying degrees of resistance

Intense Antral Peristaltic Contractions During Stomach Empty-

ing—“Pyloric Pump.”

stomach contractions are weak and function mainly to

for about 20 per cent of the time while food is in the

in midstomach and spreading through the caudad

stomach no longer as weak mixing contractions but as

tions begin farther and farther up the body of the

of the stomach and adding this food to the chyme in

which is about six times as powerful as the usual

wave forces up to several milliliters of chyme into the

Role of the Pylorus in Controlling Stomach Emptying.

distal opening of the stomach is the

thickness of the circular wall muscle becomes 50 to 100

per cent greater than in the earlier portions of the

cular muscle is called the

.

Despite normal tonic contraction of the pyloric

and other fluids to empty from the stomach into the

usually prevents passage of food particles until they

have become mixed in the chyme to almost fluid con-

increased or decreased under the influence of nervous

and humoral reflex signals from both the stomach and

signals from both the stomach and the duodenum.

chyme into the duodenum at a rate no greater than the

rate at which the chyme can be digested and absorbed

Increased

food volume in the stomach promotes increased emp-

does not occur for the reasons that one would expect.

It is not increased storage pressure of the food in the

in volume does not increase the pressure much.

local myenteric reflexes in the wall that greatly accen-

tuate activity of the pyloric pump and at the same time

Effect of the Hormone Gastrin on Stomach Emptying.

In

the presence of certain types of foods in the stomach—

particularly digestive products of meat—elicit release

of a hormone called gastrin from the antral mucosa.

has mild to moderate stimulatory effects on motor

Stomach Emptying

Duodenum.

nervous reflexes are initiated from the duodenal wall

that pass back to the stomach to slow or even stop

stomach emptying if the volume of chyme in the duo-

to the stomach through the enteric nervous system

the prevertebral sympathetic ganglia and then back

through inhibitory sympathetic nerve fibers to the

they inhibit the normal excitatory signals transmitted

minute. The contractions cause “segmentation” of the

tended with chyme, stretching of the intestinal wall

When a portion of the small intestine becomes dis-

usual classification of these processes is the following.

least some degree of both mixing and propulsion. The

great extent, this separation is artificial because essen-

. To a

where in the gastrointestinal tract, can be divided into

The movements of the small intestine, like those else-

process.

ing. In this way, the rate of stomach emptying is limited

protein or fat, is hypotonic or hypertonic, or is irritat-

excessively acidic, contains too much unprocessed

back reflexes and hormonal feedback by CCK. These

gastrin on stomach peristalsis. Probably the more

Summary of the Control of Stomach Emptying

especially acidic or fatty chyme, enter the duodenum

gastric emptying when excess quantities of chyme,

In summary, hormones, especially CCK, can inhibit

elsewhere in this text, especially in Chapter 64 in rela-

These hormones are discussed at greater length

stimulate secretion of insulin by the pancreas.

inhibit gastric motility under some conditions, its effect

extent to carbohydrates as well. Although GIP does

response mainly to fat in the chyme, but to a lesser

weak effect of decreasing gastrointestinal motility.

stomach through the pylorus. GIP has a general but

. Secretin is released mainly from the duodenal

response to fatty substances in the chyme. This

cholecystokinin (CCK)

The most potent appears to be

feedback inhibition of the stomach is not fully clear.

other foods.

the pyloric sphincter. These effects are important

stomach, where they inhibit the pyloric pump and at

the epithelial cells or in some other way. In turn, the

epithelium, either by binding with “receptors” on

On entering the duodenum, the fats extract several

degree.

mainly fats entering the duodenum, although other

released from the upper intestine do so as well. The

stomach inhibit stomach emptying, but hormones

tinal contents.

intestine is prevented, thereby also preventing rapid

cially hypertonic) elicit the inhibitory reflexes. Thus,

Finally, either hypotonic or hypertonic fluids (espe-

intestine.

stomach emptying, sufficient time is ensured for ade-

inhibitory enterogastric reflexes; by slowing the rate of

creatic and other secretions.

about 3.5 to 4, the reflexes frequently block further

vated within as little as 30 seconds. For instance, when-

duodenal chyme, and they often become strongly acti-

The enterogastric inhibitory reflexes are especially

the chyme, especially breakdown products of

5. The presence of certain breakdown products in

4. The degree of osmolality of the chyme

3. The degree of acidity of the duodenal chyme

2. The presence of any degree of irritation of the

1. The degree of distention of the duodenum

The types of factors that are continually monitored

pyloric sphincter.

contractions, and second, they increase the tone of the

they strongly inhibit the “pyloric pump” propulsive

reflexes have two effects on stomach emptying: first,

to the stomach through the vagi. All these parallel

786

Unit XII

Gastrointestinal Physiology

in the duodenum and that can initiate enterogastric

inhibitory reflexes include the following:

duodenal mucosa

proteins and perhaps to a lesser extent of fats

sensitive to the presence of irritants and acids in the

ever the pH of the chyme in the duodenum falls below

release of acidic stomach contents into the duodenum

until the duodenal chyme can be neutralized by pan-

Breakdown products of protein digestion also elicit

quate protein digestion in the duodenum and small

too rapid flow of nonisotonic fluids into the small

changes in electrolyte concentrations in the whole-

body extracellular fluid during absorption of the intes-

Hormonal Feedback from the Duodenum Inhibits Gastric Emp-

tying—Role of Fats and the Hormone Cholecystokinin.

Not

only do nervous reflexes from the duodenum to the

stimulus for releasing these inhibitory hormones is

types of foods can increase the hormones to a lesser

different hormones from the duodenal and jejunal

hormones are carried by way of the blood to the

the same time increase the strength of contraction of

because fats are much slower to be digested than most

Precisely which hormones cause the hormonal

,

which is released from the mucosa of the jejunum in

hormone acts as an inhibitor to block increased

stomach motility caused by gastrin.

Other possible inhibitors of stomach emptying are

the hormones secretin and gastric inhibitory peptide

(GIP)

mucosa in response to gastric acid passed from the

GIP is released from the upper small intestine in

at physiologic concentrations is probably mainly to

tion to control of gallbladder emptying and control of

rate of pancreatic secretion.

from the stomach.

Emptying of the stomach is controlled only to a mod-

erate degree by stomach factors such as the degree

of filling in the stomach and the excitatory effect of

important control of stomach emptying resides in

inhibitory feedback signals from the duodenum,

including both enterogastric inhibitory nervous feed-

feedback inhibitory mechanisms work together to

slow the rate of emptying when (1) too much chyme

is already in the small intestine or (2) the chyme is

to that amount of chyme that the small intestine can

Movements of the

Small Intestine

mixing contractions and propulsive contractions

tially all movements of the small intestine cause at

Mixing Contractions (Segmentation

Contractions)

elicits localized concentric contractions spaced at

intervals along the intestine and lasting a fraction of a

folds to appear in the intestinal mucosa. In addition,

The

minutes, sweeping the contents of the intestine into the

the gut wall itself. The powerful peristaltic contractions

. This is initiated

peristalsis, called the

infectious diarrhea, can cause both powerful and rapid

intestinal mucosa, as occurs in some severe cases of

intestine is normally weak, intense irritation of the

these two classifications.

the food down the intestine. The difference between

seconds at a time, often also travel 1 centimeter or so

mentation movements, although lasting for only a few

The seg-

valve into the cecum of the large intestine.

hours until the person eats another meal; at that time,

cal valve, the chyme is sometimes blocked for several

chyme enters the duodenum. On reaching the ileoce-

intestine; and this process intensifies as additional

stalsis, this immediately spreads the chyme along the

chyme along the intestinal mucosa. As the chyme

The function of the peristaltic waves in the small

controlling motility is still questionable.

inhibit small intestinal motility. The physio-

phases of food processing. Conversely,

, all of which enhance

, and

also affect peristalsis. They include

small intestinal peristalsis, several hormonal factors

intestine.

the duodenal wall, but also by a so-called

after a meal. This is caused partly by the beginning

Control of Peristalsis by Nervous and Hormonal Signals.

the ileocecal valve.

averages only 1 cm/min. This means that 3 to 5 hours

movement of the chyme is very slow, so slow in fact

very rarely farther than 10 centimeters, so that forward

usually die out after traveling only 3 to 5 centimeters,

minal intestine. They normally are very weak and

move toward the anus at a velocity of 0.5 to 2.0 cm/sec,

can occur in any part of the small intestine, and they

. These

plexus.

muscle itself that cause the segmentation contractions,

fore, even though it is the slow waves in the smooth

nervous system is blocked by the drug atropine. There-

The segmentation contractions become exceedingly

is usually 8 to 9 contractions per minute.

ulation. In the terminal ileum, the maximum frequency

contractions in these areas is also about 12 per minute,

frequency of the segmentation

jejunum, the

Chapter 62. Because this frequency normally is not

electrical slow waves

frequency of

The maximum frequency of the segmentation con-

intestine.

to three times per minute, in this way promoting pro-

the segmentation contractions “chop” the chyme two

points between the previous contractions. Therefore,

mentation contractions relaxes, a new set often begins,

appearance of a chain of sausages. As one set of seg-

small intestine, as shown in Figure 63–3. That is, they

Propulsion and Mixing of Food in the Alimentary Tract

Chapter 63

787

divide the intestine into spaced segments that have the

but the contractions this time occur mainly at new

gressive mixing of the food with secretions of the small

tractions in the small intestine is determined by the

in the intestinal wall,

which is the basic electrical rhythm described in

over 12 per minute in the duodenum and proximal

maximum

but this occurs only under extreme conditions of stim-

weak when the excitatory activity of the enteric

these contractions are not effective without back-

ground excitation mainly from the myenteric nerve

Propulsive Movements

Peristalsis in the Small Intestine.

Chyme is propelled

through the small intestine by peristaltic waves

faster in the proximal intestine and slower in the ter-

that net movement along the small intestine normally

are required for passage of chyme from the pylorus to

Peri-

staltic activity of the small intestine is greatly increased

entry of chyme into the duodenum causing stretch of

gastroenteric

reflex that is initiated by distention of the stomach and

conducted principally through the myenteric plexus

from the stomach down along the wall of the small

In addition to the nervous signals that may affect

gastrin, CCK,

insulin, motilin

serotonin

intestinal motility and are secreted during various

secretin and

glucagon

logic importance of each of these hormonal factors for

intestine is not only to cause progression of chyme

toward the ileocecal valve but also to spread out the

enters the intestines from the stomach and elicits peri-

a gastroileal reflex intensifies peristalsis in the ileum

and forces the remaining chyme through the ileocecal

Propulsive Effect of the Segmentation Movements.

in the anal direction and during that time help propel

the segmentation and the peristaltic movements is not

as great as might be implied by their separation into

Peristaltic Rush.

Although peristalsis in the small

peristaltic rush

partly by nervous reflexes that involve the autonomic

nervous system and brain stem and partly by intrinsic

enhancement of the myenteric plexus reflexes within

travel long distances in the small intestine within

colon and thereby relieving the small intestine of irri-

tative chyme and excessive distention.

Movements Caused by the Muscularis Mucosae and Muscle Fibers

of the Villi.

muscularis mucosae can cause short

Regularly spaced

Isolated

Irregularly spaced

Weak regularly spaced

Figure 63–3

Segmentation movements of the small intestine.

intestine, large circular constrictions occur in the large

ments and propulsive movements.

gish. Yet in a sluggish manner, the movements still

wall movements are not required for these functions,

and the distal half with storage. Because intense colon

Figure 63–5, is concerned principally with absorption,

expelled. The proximal half of the colon, shown in

The principal functions of the colon are (1) absorption

nerves, especially by way of the prevertebral sympa-

emptying of the ileum into the cecum. The reflexes

a person has an inflamed appendix, the irritation of

tant in the cecum delays emptying. For instance, when

chyme into the cecum from the ileum. Also, any irri-

is distended, contraction of the ileocecal sphincter

nificantly by reflexes from the cecum. When the cecum

The degree of

Feedback Control of the Ileocecal Sphincter.

liliters of chyme empty into the cecum each day.

facilitates absorption. Normally, only 1500 to 2000 mil-

cecum proceeds.

in the ileum, and emptying of ileal contents into the

the cecum. However, immediately after a meal, a gas-

. This sphincter normally remains mildly

In addition, the wall of the ileum for several cen-

of water.

backward against the valve lips. The valve usually can

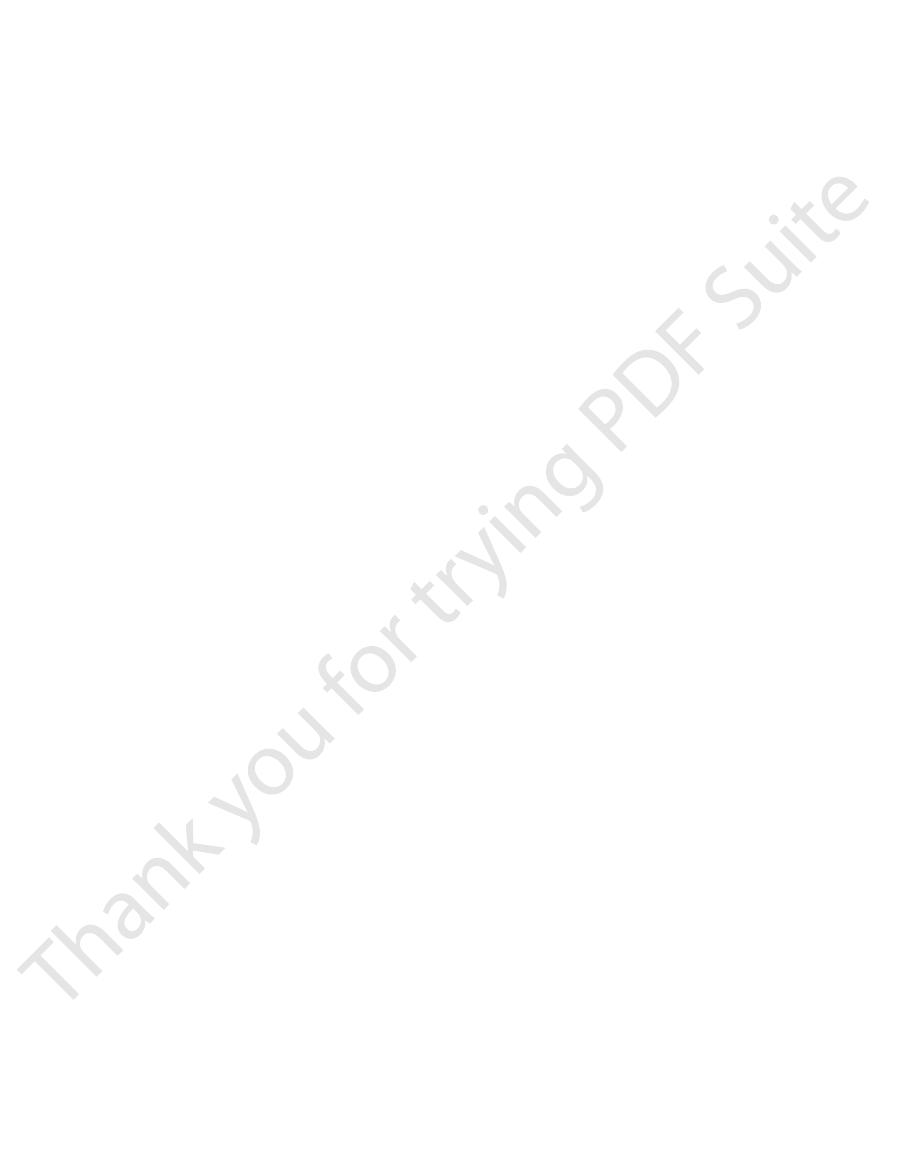

small intestine. As shown in Figure 63–4, the ileocecal

Function of the Ileocecal Valve

the small intestine.

system. These mucosal and villous contractions are ini-

ing again—“milk” the villi, so that lymph flows freely

tions of the villi—shortening, elongating, and shorten-

chyme, thereby increasing absorption. Also, contrac-

tinal villi and cause them to contract intermittently. The

788

Unit XII

Gastrointestinal Physiology

individual fibers from this muscle extend into the intes-

mucosal folds increase the surface area exposed to the

from the central lacteals of the villi into the lymphatic

tiated mainly by local nervous reflexes in the submu-

cosal nerve plexus that occur in response to chyme in

A principal function of the ileocecal valve is to prevent

backflow of fecal contents from the colon into the

valve itself protrudes into the lumen of the cecum and

therefore is forcefully closed when excess pressure

builds up in the cecum and tries to push cecal contents

resist reverse pressure of at least 50 to 60 centimeters

timeters immediately upstream from the ileocecal

valve has a thickened circular muscle called the ileo-

cecal sphincter

constricted and slows emptying of ileal contents into

troileal reflex (described earlier) intensifies peristalsis

Resistance to emptying at the ileocecal valve pro-

longs the stay of chyme in the ileum and thereby

contraction of the ileocecal sphincter and the intensity

of peristalsis in the terminal ileum are controlled sig-

becomes intensified and ileal peristalsis is inhibited,

both of which greatly delay emptying of additional

this vestigial remnant of the cecum can cause such

intense spasm of the ileocecal sphincter and partial

paralysis of the ileum that these effects together block

from the cecum to the ileocecal sphincter and ileum

are mediated both by way of the myenteric plexus in

the gut wall itself and of the extrinsic autonomic

thetic ganglia.

Movements of the Colon

of water and electrolytes from the chyme to form solid

feces and (2) storage of fecal matter until it can be

the movements of the colon are normally very slug-

have characteristics similar to those of the small intes-

tine and can be divided once again into mixing move-

Mixing Movements—“Haustrations.”

In the same manner

that segmentation movements occur in the small

Pressure or chemical irritation

in cecum inhibits peristalsis

of ileum and excites sphincter

Ileocecal sphincter

Ileum

Valve

Colon

Pressure and chemical

irritation relax sphincter

and excite peristalsis

Fluidity of contents

promotes emptying

Figure 63–4

Emptying at the ileocecal valve.

Mush

Semifluid

Fluid

Ileocecal

valve

Solid

Poor motility causes

greater absorption, and

hard feces in transverse

colon causes

constipation

Semi-

mush

Semi-

solid

Excess motility causes

less absorption and

diarrhea or loose feces

Figure 63–5

Absorptive and storage functions of the large intestine.

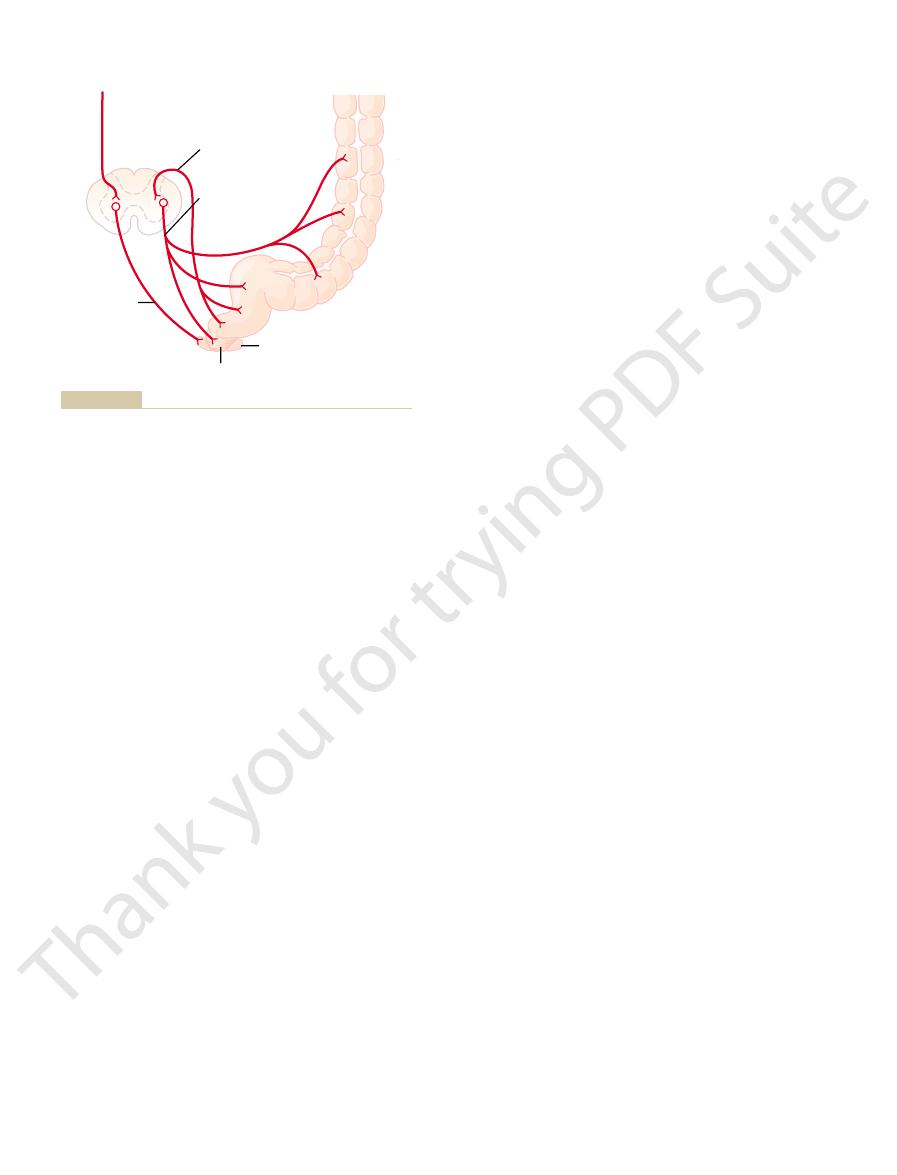

. These parasympathetic signals greatly intensify

to the descending colon, sigmoid, rectum, and anus by

mitted first into the spinal cord and then reflexly back

endings in the rectum are stimulated, signals are trans-

the spinal cord, shown in Figure 63–6. When the nerve

by another type of defecation reflex, a

tive in causing defecation, it usually must be fortified

ing by itself normally is relatively weak. To be effec-

The intrinsic myenteric defecation reflex function-

relaxed at the same time, defecation occurs.

anal sphincter is also consciously, voluntarily

inhibitory signals from the myenteric plexus; if the

the anus, the

toward the anus. As the peristaltic wave approaches

descending colon, sigmoid, and rectum, forcing feces

When feces enter the rectum, distention of the rectal

in the rectal wall. This can be described as follows:

. One of these reflexes is an

defecation reflexes

Ordinarily, defecation is initiated

; subconsciously,

, which is part of the somatic nervous

the internal sphincter and extends distal to it. The

, com-

inside the anus, and (2) an

, a several-centimeters-long thickening

ation of the anal sphincters.

rectum, the desire for defecation occurs immediately,

When a mass movement forces feces into the

rectum. There is also a sharp angulation here that con-

Most of the time, the rectum is empty of feces. This

the time.

movements. For instance, a person who has an ulcer-

to the colon have been removed; therefore, the reflexes

the stomach and duodenum. They occur either not at

. These reflexes result from distention of

colic reflexes

Initiation of Mass Movements by Gastrocolic and Duo-

into the rectum, the desire for defecation is felt.

half day later. When they have forced a mass of feces

to 30 minutes. Then they cease but return perhaps a

mass movement occurs, this time perhaps farther along

occurs during the next 2 to 3 minutes. Then, another

sively more force for about 30 seconds, and relaxation

down the colon. The contraction develops progres-

haustrations and instead contract as a unit, propelling

distal to the constrictive ring

transverse colon. Then, rapidly, the 20 or more cen-

tended or irritated point in the colon, usually in the

First, a

three times each day, in many people especially for

sive role. These movements usually occur only one to

can, for many minutes at a time, take over the propul-

mass movements

From the cecum to the sigmoid,

chyme itself becomes fecal in quality, a semisolid slush

from the ileocecal valve through the colon, while the

from the slow but persistent haustral contractions,

only 80 to 200 milliliters of feces are expelled each day.

the mucosal surface of the large intestine, and fluid and

this way, all the fecal material is gradually exposed to

much the same manner that one spades the earth. In

dug into and rolled over

in other areas nearby. Therefore, the fecal material in

another few minutes, new haustral contractions occur

of forward propulsion of the colonic contents. After

ascending colon, and thereby provide a minor amount

anus during contraction, especially in the cecum and

60 seconds. They also at times move slowly toward the

, contracts. These combined

colon, which is aggregated into three longitudinal

sion. At the same time, the longitudinal muscle of the

timeters of the circular muscle contracts, sometimes

intestine. At each of these constrictions, about 2.5 cen-

Propulsion and Mixing of Food in the Alimentary Tract

Chapter 63

789

constricting the lumen of the colon almost to occlu-

strips called the teniae coli

contractions of the circular and longitudinal strips of

muscle cause the unstimulated portion of the large

intestine to bulge outward into baglike sacs called

haustrations.

Each haustration usually reaches peak intensity in

about 30 seconds and then disappears during the next

the large intestine is slowly

in

dissolved substances are progressively absorbed until

Propulsive Movements—“Mass Movements.”

Much of the

propulsion in the cecum and ascending colon results

requiring as many as 8 to 15 hours to move the chyme

instead of semifluid.

about 15 minutes during the first hour after eating

breakfast.

A mass movement is a modified type of peristalsis

characterized by the following sequence of events:

constrictive ring occurs in response to a dis-

timeters of colon

lose their

the fecal material in this segment en masse further

the colon.

A series of mass movements usually persists for 10

denocolic Reflexes.

Appearance of mass movements

after meals is facilitated by gastrocolic and duodeno-

all or hardly at all when the extrinsic autonomic nerves

almost certainly are transmitted by way of the auto-

nomic nervous system.

Irritation in the colon can also initiate intense mass

ated condition of the colon mucosa (ulcerative colitis)

frequently has mass movements that persist almost all

Defecation

results partly from the fact that a weak functional

sphincter exists about 20 centimeters from the anus

at the juncture between the sigmoid colon and the

tributes additional resistance to filling of the rectum.

including reflex contraction of the rectum and relax-

Continual dribble of fecal matter through the anus

is prevented by tonic constriction of (1) an internal

anal sphincter

of the circular smooth muscle that lies immediately

external anal sphincter

posed of striated voluntary muscle that both surrounds

external sphincter is controlled by nerve fibers in the

pudendal nerve

system and therefore is under voluntary, conscious

or at least subconscious control

the external sphincter is usually kept continuously

constricted unless conscious signals inhibit the

constriction.

Defecation Reflexes.

by

intrin-

sic reflex mediated by the local enteric nervous system

wall initiates afferent signals that spread through the

myenteric plexus to initiate peristaltic waves in the

internal anal sphincter is relaxed by

external

parasympathetic

defecation reflex that involves the sacral segments of

way of parasympathetic nerve fibers in the pelvic

nerves

the peristaltic waves as well as relax the internal anal

options. Am J Gastroenterol 99:739, 2004.

motor abnormalities, sensory dysfunction, and therapeutic

Timmons S, Liston R, Moriarty KJ: Functional dyspepsia:

troenterol 38:421, 2003.

nitric oxide synthase in the gastrointestinal tract. J Gas-

Takahashi T: Pathophysiological significance of neuronal

News Physiol Sci 15:291, 2000.

maker Mechanism Drives Gastrointestinal Rhythmicity.

Sanders KM, Ordog T, Koh SD, Ward SM:A Novel Pace-

troenterology 126(1 Suppl 1):S14, 2004.

Rao SS: Pathophysiology of adult fecal incontinence. Gas-

Physiol 283:G1226, 2002.

motility and aging. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver

IV. Clinical and physiological aspects of gastrointestinal

Orr WC, Chen CL: Aging and neural control of the GI tract:

inflammatory bowel disease. News Physiol Sci 16:272,

tion of intestinal mucosal immunity: implications in

Laroux FS, Pavlick KP, Wolf RE, Grisham MB: Dysregula-

test Liver Physiol 280:G787, 2001.

I. Receptors on visceral afferents. Am J Physiol Gastroin-

mission in the brain-gut axis: potential for novel therapies.

Kirkup AJ, Brunsden AM, Grundy D: Receptors and trans-

Mosby, 2001.

Johnson LR: Gastrointestinal Physiology, 6th ed. St. Louis:

orders. Pharmacol Toxicol 91:333, 2002.

Jensen RT: Involvement of cholecystokinin/gastrin-related

Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285:H1791, 2003.

tion in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease.

Hatoum OA, Miura H, Binion DG: The vascular contribu-

motility. Physiol Res 52:1, 2003.

Hansen MB: Neurohumoral control of gastrointestinal

Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283:G827, 2002.

control of the aging gut: can an old dog learn new tricks?

Hall KE: Aging and neural control of the GI tract. II. Neural

ters. Physiol Rev 67:902, 1987.

Gonella J, Bouvier M, Blanquet F: Extrinsic nervous control

terology 126:1872, 2004.

neuropathies of the enteric nervous system. Gastroen-

De Giorgio R, Guerrini S, Barbara G, et al: Inflammatory

Physiol Sci 18:43, 2003.

you”: ATP in gut mechanosensory transduction. News

Cooke HJ, Wunderlich J, Christofi FL: “The force be with

Neurol 23:453, 2003.

autonomic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. Semin

Chelimsky G, Chelimsky TC: Evaluation and treatment of

Physiol Sci 19:27, 2004.

sonomicrometry and gastrointestinal motility. News

Adelson DW, Million M: Tracking the moveable feast:

vesicointestinal reflexes

ysis, especially in patients with peritonitis. The

of the peritoneum; it strongly inhibits the excitatory

The

renointestinal reflex, and vesicointestinal reflex.

bowel activity. They are the peritoneointestinal reflex,

discussed in this chapter, several other important

enterogastric, and defecation reflexes that have been

Aside from the duodenocolic, gastrocolic, gastroileal,

That Affect Bowel Activity

relaxation of the external anal sphincter.

sected spinal cords, the defecation reflexes cause auto-

tive as those that arise naturally, for which reason

fecal contents into the rectum to cause new reflexes.

increase the pressure in the abdomen, thus forcing

cate, the defecation reflexes can purposely be activated

When it becomes convenient for the person to defe-

evaginate the feces.

the glottis, and contraction of the abdominal wall

other effects, such as taking a deep breath, closure of

flexure of the colon to the anus.

sphincter, thus converting the intrinsic myenteric defe-

790

Unit XII

Gastrointestinal Physiology

cation reflex from a weak effort into a powerful

process of defecation that is sometimes effective in

emptying the large bowel all the way from the splenic

Defecation signals entering the spinal cord initiate

muscles to force the fecal contents of the colon down-

ward and at the same time cause the pelvic floor to

relax downward and pull outward on the anal ring to

by taking a deep breath to move the diaphragm down-

ward and then contracting the abdominal muscles to

Reflexes initiated in this way are almost never as effec-

people who too often inhibit their natural reflexes are

likely to become severely constipated.

In newborn babies and in some people with tran-

matic emptying of the lower bowel at inconvenient

times during the day because of lack of conscious

control exercised through voluntary contraction or

Other Autonomic Reflexes

nervous reflexes also can affect the overall degree of

peritoneointestinal reflex results from irritation

enteric nerves and thereby can cause intestinal paral-

reno-

intestinal and

inhibit intestinal

activity as a result of kidney or bladder irritation.

References

of motility of small and large intestines and related sphinc-

peptides and their receptors in clinical gastrointestinal dis-

2001.

From

conscious

cortex

Afferent

nerve

fibers

Parasympathetic

nerve fibers

(pelvic nerves)

Sigmoid

colon

Rectum

External anal sphincter

Internal anal sphincter

Descending

colon

Skeletal

motor nerve

nism for enhancing the defecation reflex.

Afferent and efferent pathways of the parasympathetic mecha-

Figure 63–6