1

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE ABDOMEN FOR LIVER AND BILIARY DISEASE

History and significance of abdominal signs

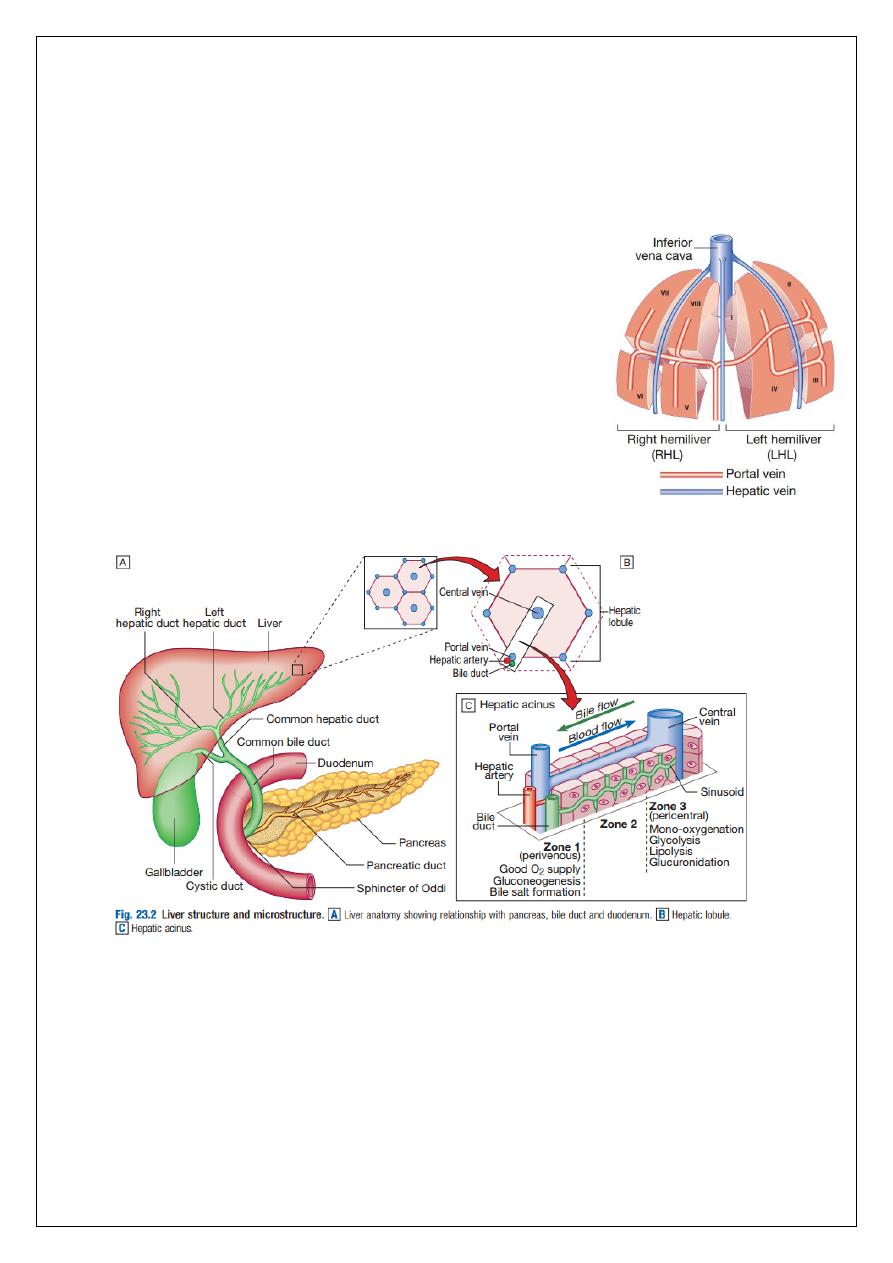

Applied anatomy

Normal liver structure and blood supply: The liver has multiple functions, including key roles

in metabolism, control of infection, elimination of toxins and by-products of metabolism.

2

It is classically divided into left and right lobes by the falciform ligament, but a more useful

functional division is into the right and left hemilivers, based on blood supply. These are

further divided into eight segments according to subdivisions of the hepatic and portal veins.

Each segment has its own branch of the hepatic artery and biliary tree. The segmental

anatomy of the liver has an important influence on imaging and treatment of liver tumours,

given the increasing use of surgical resection.

A liver segment is made up of multiple smaller units known

as lobules, comprised of a central vein, radiating sinusoids

separated from each other by single liver cell (hepatocyte)

plates, and peripheral portal tracts. The functional unit of

the liver is the hepatic acinus. Blood flows into the acinus

via a single branch of the portal vein and hepatic artery

situated centrally in the portal tracts. Blood flows outwards

along the hepatic sinusoids into one of several tributaries of

the hepatic vein at the periphery of the acinus. Bile, formed

by active and passive excretion by hepatocytes into

channels called cholangioles which lie between them, flows

in the opposite direction from the periphery of the acinus.

The cholangioles converge in interlobular bile ducts in the portal tracts.

The hepatocytes in each acinus lie in three zones, depending on their position relative to the

portal tract. Those in zone 1 are closest to the terminal branches of the portal vein and

hepatic artery, and are richly supplied with oxygenated blood, and blood containing the

highest concentration of nutrients and toxins. Conversely, hepatocytes in zone 3 are furthest

from the portal tracts and closest to the hepatic veins, and are therefore relatively hypoxic

and exposed to lower concentrations of nutrients and toxins compared to zone 1. The

different perfusion and toxin exposure patterns, and thus vulnerability, of hepatocytes in the

different zones contribute to the often-patchy nature of liver injury.

3

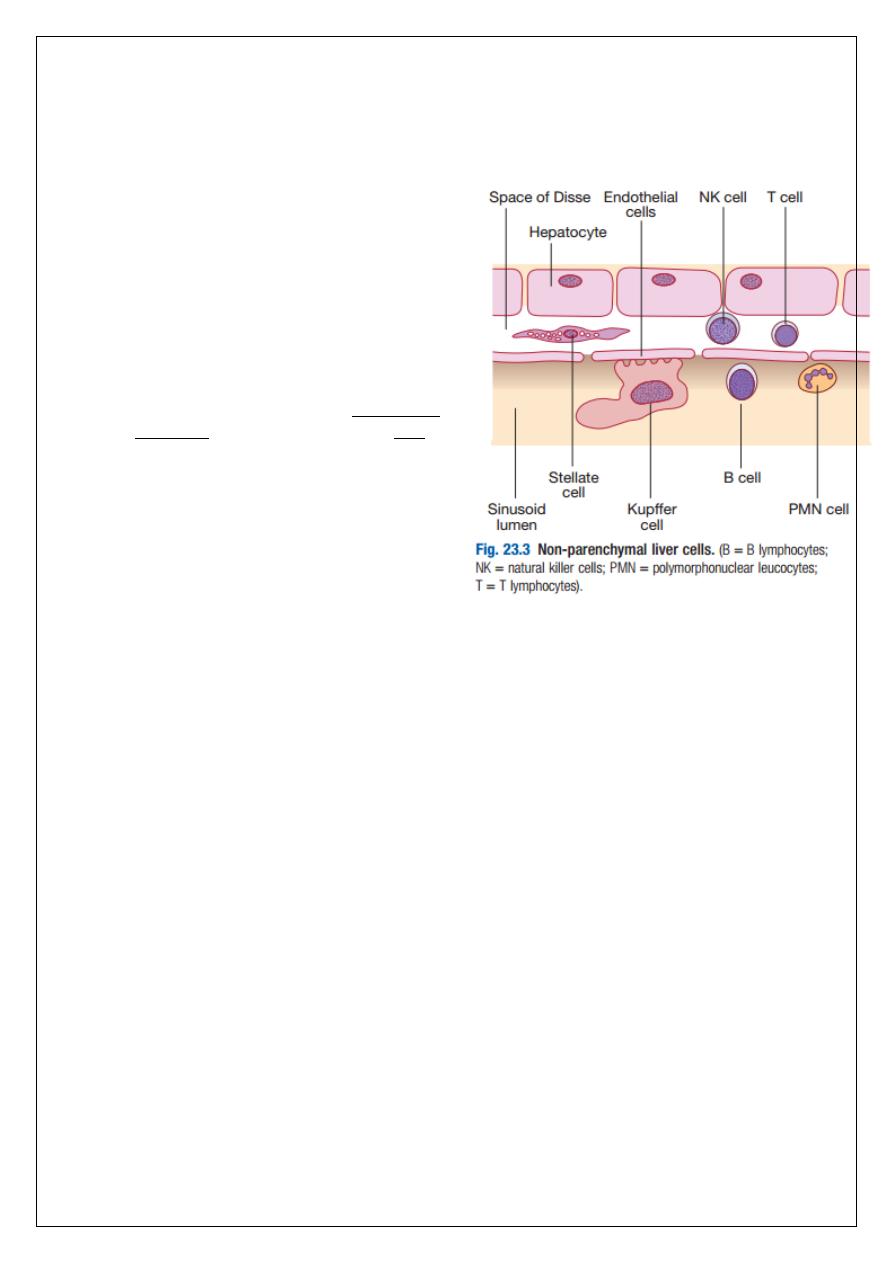

Liver cells:

Hepatocytes comprise 80% of liver cells. The

remaining 20% are the endothelial cells lining

the sinusoids, epithelial cells lining the

intrahepatic bile ducts, cells of the immune

system (including macrophages (Kupffer cells)

and unique populations of atypical

lymphocytes), and a key population of non-

parenchymal cells called stellate or Ito cells.

Endothelial cells line the sinusoids, a network of

capillary vessels that differ from other capillary

beds in the body in that there is no basement

membrane. The endothelial cells have gaps

between them (fenestrae) of about 0.1 micron

in diameter, allowing free flow of fluid and

particulate matter to the hepatocytes.

Individual hepatocytes are separated from the

leaky sinusoids by the space of Disse, which

contains stellate cells that store vitamin A and

play an important part in regulating liver blood

flow. They may also be immunologically active

and play a role in the liver’s contribution to defence against pathogens. The key role of

stellate cells in terms of pathology is in the development of hepatic fibrosis, the precursor of

cirrhosis. They undergo activation in response to cytokines produced following liver injury,

differentiating into myofibroblasts, which are the major producers of the collagen-rich

matrix that forms fibrous tissue.

Blood supply

The liver is unique as an organ as it has dual perfusion, receiving a majority of its supply via

the ❶portal vein, which drains blood from the gut via the splanchnic circulation and is the

principal route for nutrient trafficking to the liver, and a minority from the ❷hepatic artery.

The portal venous contribution is 50–90%. The dual perfusion system, and the variable

contribution from portal vein and hepatic artery, can have important effects on the clinical

expression of liver ischaemia (which typically exhibits a less dramatic pattern than ischaemia

in other organs, a fact that can sometimes lead to it being missed clinically), and can raise

practical challenges in liver transplant surgery.

Biliary system and gallbladder

Hepatocytes provide the driving force for bile flow by creating osmotic gradients of bile

acids, which form micelles in bile (bile acid-dependent bile flow), and of sodium (bile acid-

independent bile flow). Bile is secreted by hepatocytes and flows from cholangioles to the

biliary canaliculi. The canaliculi join to form larger intrahepatic bile ducts, which in turn

merge to form the right and left hepatic ducts. These ducts join as they emerge from the

liver to form the common hepatic duct, which becomes the common bile duct after joining

the cystic duct (see Fig. 23.2). The common bile duct is approximately 5 cm long and 4–6 mm

4

wide. The distal portion of the duct passes through the head of the pancreas and usually

joins the pancreatic duct before entering the duodenum through the ampullary sphincter

(sphincter of Oddi). It should be noted, though, that the anatomy of the lower common bile

duct can vary widely. Common bile duct pressure is maintained by rhythmic contraction and

relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi; this pressure exceeds gallbladder pressure in the fasting

state, so that bile normally flows into the gallbladder, where it is concentrated tenfold by

resorption of water and electrolytes. The gallbladder is a pear-shaped sac typically lying

under the right hemiliver, with its fundus located anteriorly behind the tip of the 9th costal

cartilage. Anatomical variation is common and should be considered when assessing

patients clinically and radiologically. The function of the gallbladder is to concentrate, and

provide a reservoir for, bile. Gallbladder tone is maintained by vagal activity, and

cholecystokinin released from the duodenal mucosa during feeding causes gallbladder

contraction and reduces sphincter pressure, so that bile flows into the duodenum. The body

and neck of the gallbladder pass postero-medially towards the porta hepatis, and the cystic

duct then joins it to the common hepatic duct. The cystic duct mucosa has prominent

crescentic folds (valves of Heister), giving it a beaded appearance on cholangiography.

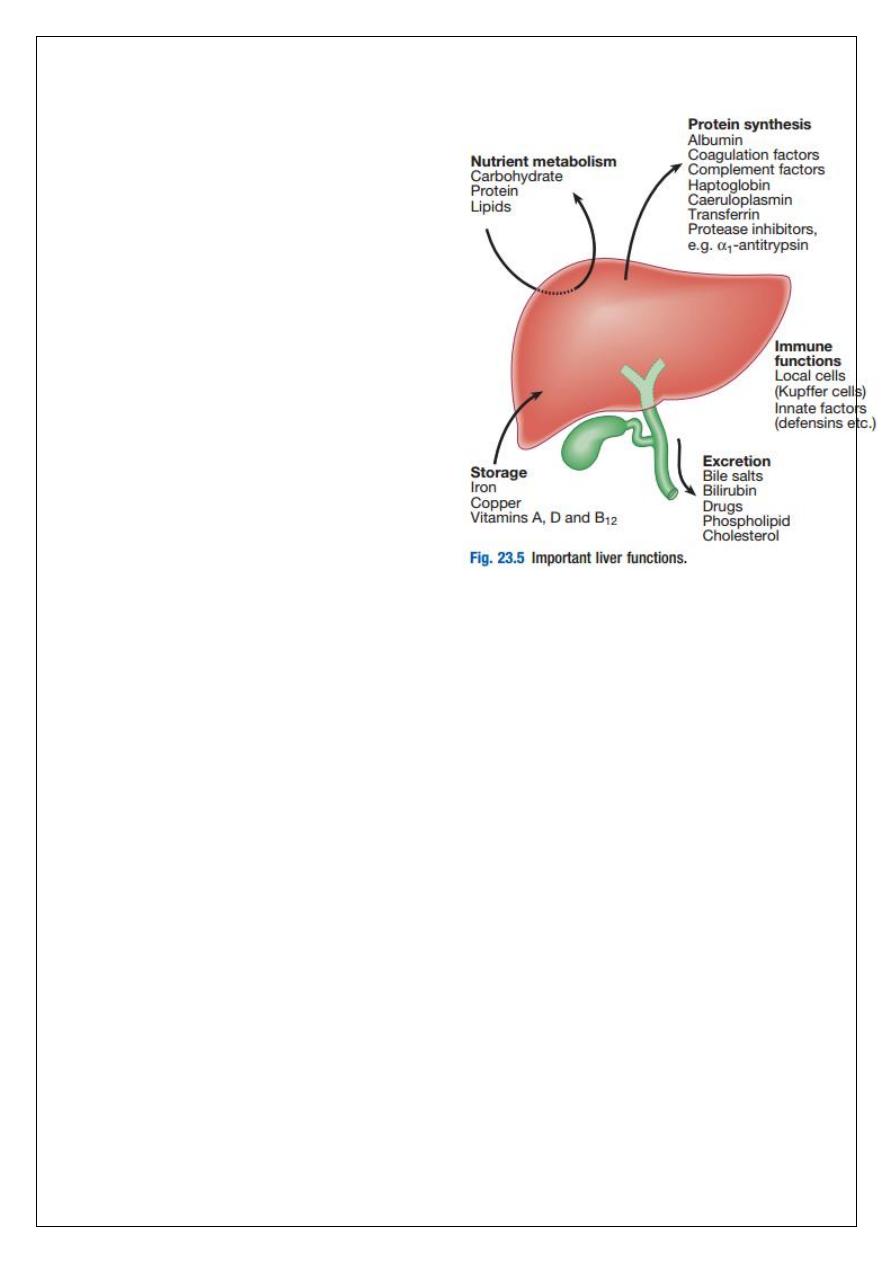

Hepatic function

Carbohydrate, amino acid and lipid metabolism:

The liver plays a central role in carbohydrate, lipid and amino acid metabolism, and is also

involved in metabolising drugs and environmental toxins. An important and increasingly

recognised role for the liver is in the integration of metabolic pathways, regulating the

response of the body to feeding and starvation.

Abnormality in metabolic pathways and their regulation can play an important role both in

liver disease (e.g. non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)) and in diseases that are not

conventionally regarded as diseases of the liver (such as type II diabetes mellitus and inborn

errors of metabolism).

Hepatocytes have specific pathways to handle each of the nutrients absorbed from the gut

and carried to the liver via the portal vein.

5

Amino acids from dietary proteins are

used for synthesis of plasma proteins,

including albumin. This plays a critical

role in maintaining oncotic pressure in

the vascular space and in the

transport of small molecules like

bilirubin, hormones and drugs

throughout the body. Amino acids

that are not required for the

production of new proteins are

broken down, with the amino group

being converted ultimately to urea.

Following a meal, more than half of

the glucose absorbed is taken up by

the liver and stored as glycogen or

converted to glycerol and fatty acids,

thus preventing hyperglycaemia.

During fasting, glycogen is broken

down to release glucose

(gluconeogenesis), thereby preventing

hypoglycaemia.

The liver plays a central role in lipid

metabolism, producing very low-density lipoproteins and further metabolising low-

and high-density lipoproteins. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism is thought to have a

critical role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Lipids are now recognised to play a key

part in the pathogenesis of hepatitis C, facilitating viral entry into hepatocytes.

Clotting factors:

The liver produces key proteins that are involved in the coagulation cascade. Many of these

coagulation factors (II, VII, IX and X) are post-translationally modified by vitamin K-

dependent enzymes, and their synthesis is impaired in vitamin K deficiency. Reduced clotting

factor synthesis is an important and easily accessible biomarker of liver function in the

setting of liver injury. Prothrombin time (PT; or the International Normalised Ratio, INR) is

therefore one of the most important clinical tools available for the assessment of

hepatocyte function.

Note that the deranged PT or INR seen in liver disease may not directly equate to increased

bleeding risk, as these tests do not capture the concurrent reduced synthesis of

anticoagulant factors, including protein C and protein S. In general, therefore, correction of

PT using blood products before minor invasive procedures should be guided by clinical risk

rather than the absolute value of the PT.

6

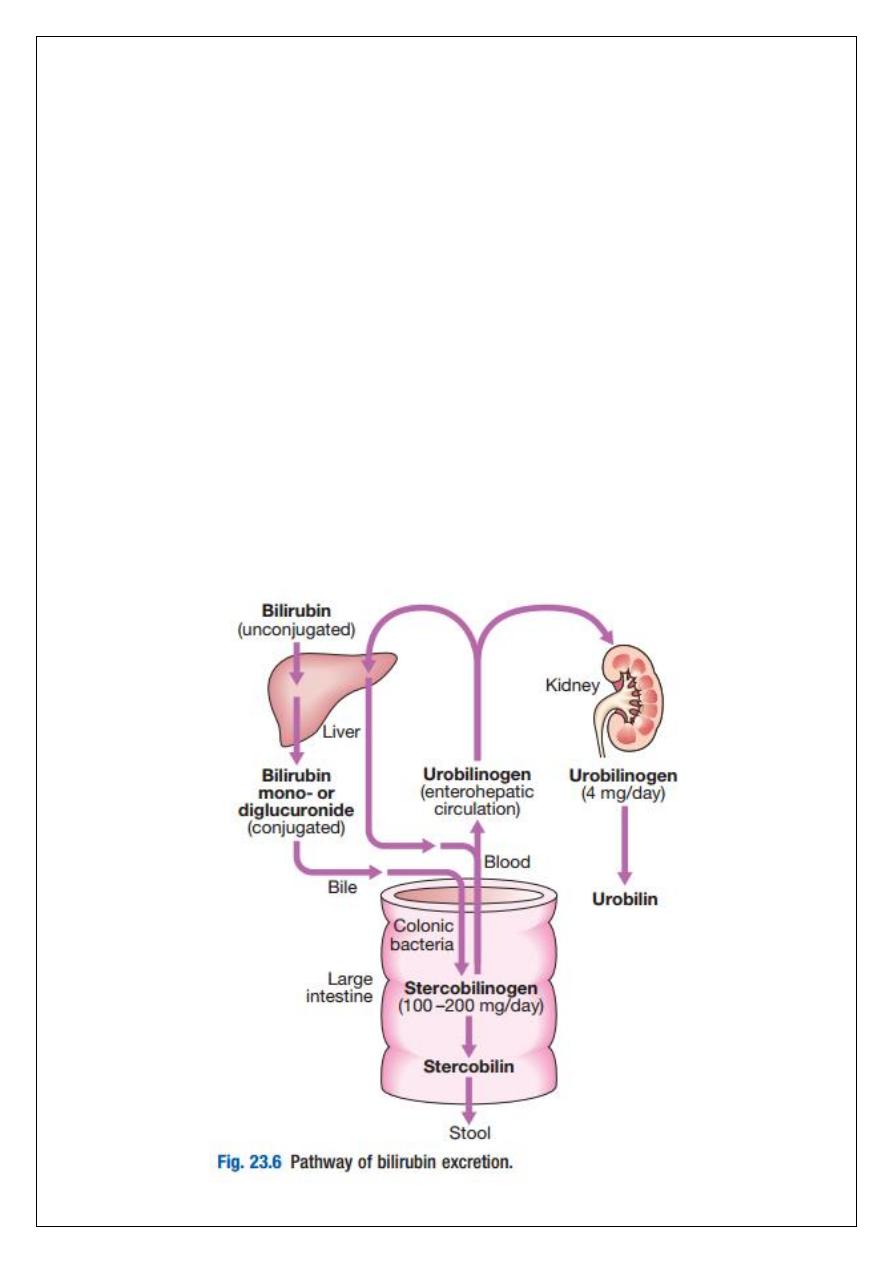

Bilirubin metabolism and bile

The liver plays a central role in the metabolism of bilirubin and is responsible for the

production of bile. Between 250–300 mg of unconjugated bilirubin is produced from the

catabolism of haem daily. Bilirubin in the blood is normally almost all unconjugated and,

because it is not water-soluble, is bound to albumin and does not pass into the urine.

Unconjugated bilirubin is taken up by hepatocytes at the sinusoidal membrane, where it is

conjugated in the endoplasmic reticulum by UDP-glucuronyl transferase, producing bilirubin

mono- and diglucuronide. Impaired conjugation by this enzyme is a cause of inherited

hyperbilirubinaemias. These bilirubin conjugates are water-soluble and are exported into the

bile canaliculi by specific carriers on the hepatocyte membranes. The conjugated bilirubin is

excreted in the bile and passes into the duodenal lumen. Once in the intestine, conjugated

bilirubin is metabolised by colonic bacteria to form stercobilinogen, which may be further

oxidised to stercobilin. Both stercobilinogen and stercobilin are then excreted in the stool,

contributing to its brown colour. Biliary obstruction results in reduced stercobilinogen in the

stool, and the stools become pale. A small amount of stercobilinogen (4 mg/day) is absorbed

from the bowel, passes through the liver, and is excreted in the urine, where it is known as

urobilinogen or, following further oxidisation, urobilin. The liver secretes 1–2 L of bile daily.

Bile contains bile acids (formed from cholesterol), phospholipids, bilirubin and cholesterol.

Several biliary transporter proteins have been identified. Mutations in genes encoding these

proteins have been identified in inherited intrahepatic biliary diseases presenting in

childhood, and in adult-onset disease such as intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and

gallstone formation.

Storage of vitamins and minerals

7

Vitamins A, D and B12 are stored by the liver in large amounts, while others, such as vitamin

K and folate, are stored in smaller amounts and disappear rapidly if dietary intake is

reduced.

The liver is also able to metabolise vitamins to more active compounds, e.g. 7-

dehydrocholesterol to 25(OH) vitamin D. Vitamin K is a fat-soluble vitamin and so the

inability to absorb fat soluble vitamins, as occurs in biliary obstruction, results in a

coagulopathy. The liver also stores minerals such as iron, in ferritin and haemosiderin, and

copper, which is excreted in bile.

Immune regulation

Approximately 9% of the normal liver is composed of immune cells. Cells of the innate

immune system include Kupffer cells derived from blood monocytes, the liver macrophages

and natural killer (NK) cells, as well as ‘classical’ B and T cells of the adaptive immune

response.

Kupffer cells constitute the largest single mass of tissue-resident macrophages in the body

and account for 80% of the phagocytic capacity of this system. They remove aged and

damaged red blood cells, bacteria, viruses, antigen–antibody complexes and endotoxin.

They also produce a wide variety of inflammatory mediators that can act locally or may be

released into the systemic circulation.

INVESTIGATION OF LIVER AND HEPATOBILIARY DISEASE

Investigations play an important role in the management of liver disease in three settings:

identification of the presence of liver disease

establishing the aetiology

understanding disease severity (in particular, identification of cirrhosis with its

complications).

When planning investigations it is important to be clear as to which of these goals is being

addressed. Suspicion of the presence of liver disease is normally based on blood

biochemistry abnormality (‘liver function tests’, or ‘LFTs’), undertaken either as a result of

clinical suspicion or, increasingly, in the setting of health screening. Less commonly,

suspicion arises after a structural abnormality is identified on imaging.

Aetiology is typically established through a combination of history, specific blood tests and,

where appropriate, imaging and liver biopsy. Staging of disease (in essence, the

identification of cirrhosis) is largely histological, although there is increasing interest in non-

invasive approaches, including novel imaging modalities, serum markers of fibrosis and the

use of predictive scoring systems. The aims of investigation in patients with suspected liver

disease are shown below.

8

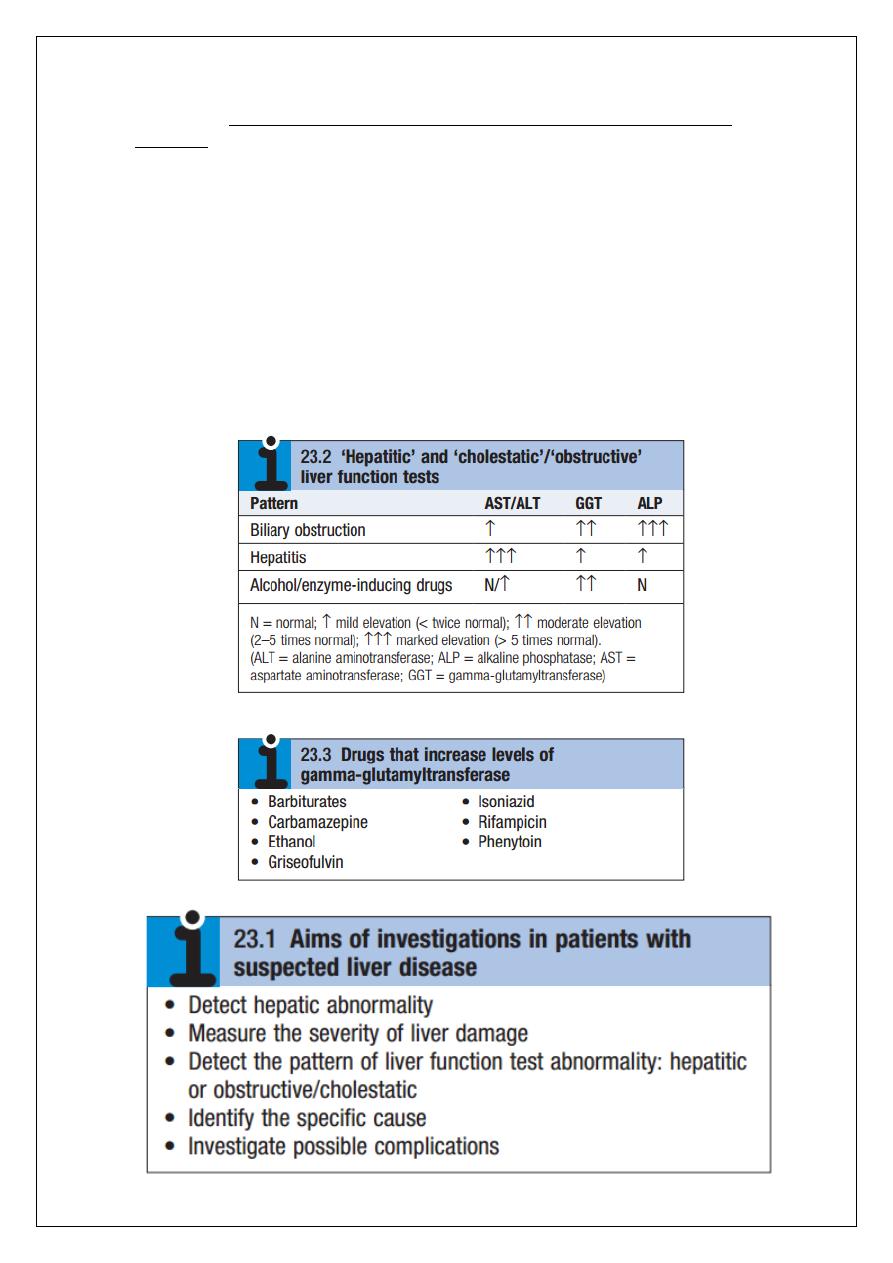

Liver blood biochemistry

Liver blood biochemistry (LFTs) includes the measurement of serum bilirubin,

aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase and albumin.

Most analytes measured by LFTs are not truly ‘function’ tests but, given that they are

released by injured hepatocytes, instead provide biochemical evidence of liver cell damage.

Liver function per se is best assessed by the serum albumin, PT and bilirubin because of the

role played by the liver in synthesis of albumin and clotting factors and in clearance of

bilirubin.

Although LFT abnormalities are often non-specific, the patterns are frequently helpful in

directing further investigations. Also, levels of bilirubin and albumin and the PT are related

to clinical outcome in patients with severe liver disease, reflected by their use in several

prognostic scores: The Child–Pugh and MELD scores in cirrhosis, the Glasgow score in

alcoholic hepatitis and the King’s College Hospital criteria for liver transplantation in acute

liver failure.

Bilirubin and albumin

The degree of elevation of bilirubin can reflect the degree of liver damage. A raised bilirubin

often occurs earlier in the natural history of biliary disease (e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis)

than in disease of the liver parenchyma (e.g. cirrhosis) where the hepatocytes are primarily

involved.

Swelling of the liver within its capsule in inflammation can, however, sometimes impair bile

flow and cause an elevation of bilirubin level that is disproportionate to the degree of liver

injury.

Caution is therefore needed in interpreting the level of liver injury purely on the basis of

bilirubin elevation. Serum albumin levels are often low in patients with liver disease. This is

due to a change in the volume of distribution of albumin, and reduced synthesis. Since the

plasma half-life of albumin is about 2 weeks, albumin levels may be normal in acute liver

failure but are almost always reduced in chronic liver failure.

Alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) are located in the

cytoplasm of the hepatocyte; AST is also located in the hepatocyte mitochondria. Although

both transaminase enzymes are widely distributed, expression of ALT outside the liver is

relatively low and this enzyme is therefore considered more specific for hepatocellular

damage. Large increases of aminotransferase activity favour hepatocellular damage, and this

pattern of LFT abnormality is known as ‘hepatitic’.

Alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is the collective name given to several different enzymes that

hydrolyse phosphate esters at alkaline pH. These enzymes are widely distributed in the

9

body, but the main sites of production are the liver, gastrointestinal tract, bone, placenta

and kidney. ALPs are post-translationally modified, resulting in the production of several

different isoenzymes, which differ in abundance in different tissues. ALP enzymes in the liver

are located in cell membranes of the hepatic sinusoids and the biliary canaliculi. Accordingly,

levels rise with intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary obstruction and with sinusoidal

obstruction, as occurs in infiltrative liver disease.

Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) is a microsomal enzyme found in many cells and tissues

of the body. The highest concentrations are located in the liver, where it is produced by

hepatocytes and by the epithelium lining small bile ducts. The function of GGT is to transfer

glutamyl groups from gamma-glutamyl peptides to other peptides and amino acids. The

pattern of a modest increase in aminotransferase activity and large increases in ALP and GGT

activity favours biliary obstruction and is commonly described as ‘cholestatic’ or

‘obstructive’. Isolated elevation of the serum GGT is relatively common, and may occur

during ingestion of microsomal enzyme-inducing drugs, including alcohol, but also in NAFLD.

10

Other biochemical tests

Other widely available biochemical tests may become altered in patients with liver disease:

• Hyponatraemia occurs in severe liver disease due to increased production of antidiuretic

hormone.

• Serum urea may be reduced in hepatic failure, whereas levels of urea may be increased

following gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

• When high levels of urea are accompanied by raised bilirubin, high serum creatinine and

low urinary sodium, this suggests hepatorenal failure, which carries a grave prognosis.

• Significantly elevated ferritin suggests haemochromatosis. Modest elevations can be seen

in inflammatory disease and alcohol excess.

Haematological tests

Blood count

The peripheral blood count is often abnormal and can give a clue to the underlying

diagnosis:

• A normochromic normocytic anaemia may reflect recent gastrointestinal

haemorrhage, whereas chronic blood loss is characterised by a hypochromic

microcytic anaemia secondary to iron deficiency. A high erythrocyte mean cell

volume (macrocytosis) is associated with alcohol misuse, but target cells in any

jaundiced patient also result in a macrocytosis. Macrocytosis can persist for a long

period of time after alcohol cessation, making it a poor marker of ongoing

consumption.

• Leucopenia may complicate portal hypertension and hypersplenism, whereas

leucocytosis may occur with cholangitis, alcoholic hepatitis and hepatic abscesses.

Atypical lymphocytes are seen in infectious mononucleosis, which may be

complicated by an acute hepatitis.

• Thrombocytopenia is common in cirrhosis and is due to reduced platelet production,

and increased breakdown because of hypersplenism. Thrombopoietin, required for

platelet production, is produced in the liver and levels fall with worsening liver

function. Thus platelet levels are usually more depressed than white cells and

haemoglobin in the presence of hypersplenism in patients with cirrhosis. A low

platelet count is often an indicator of chronic liver disease, particularly in the

context of hepatomegaly. Thrombocytosis is unusual in patients with liver disease

but may occur in those with active gastrointestinal haemorrhage and, rarely, in

hepatocellular carcinoma.

Coagulation tests

11

These are often abnormal in patients with liver disease. The normal half-lives of the vitamin

K-dependent coagulation factors in the blood are short (5–72 hours) and so changes in the

prothrombin time occur relatively quickly following liver damage; these changes provide

valuable prognostic information in patients with both acute and chronic liver failure. An

increased PT is evidence of severe liver damage in chronic liver disease. Vitamin K does not

reverse this deficiency if it is due to liver disease, but will correct the PT if the cause is

vitamin K deficiency, as may occur with biliary obstruction due to non-absorption of fat-

soluble vitamins.

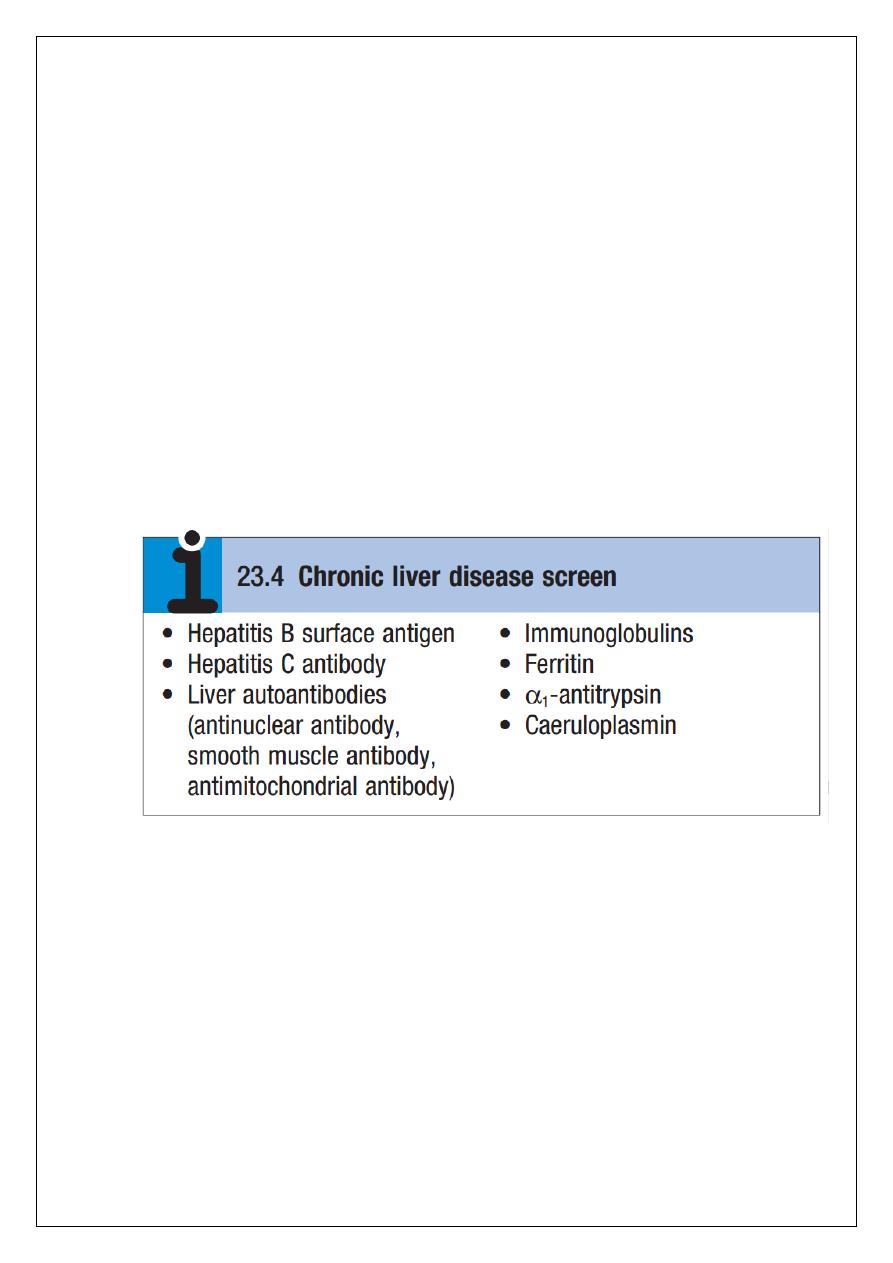

Immunological tests

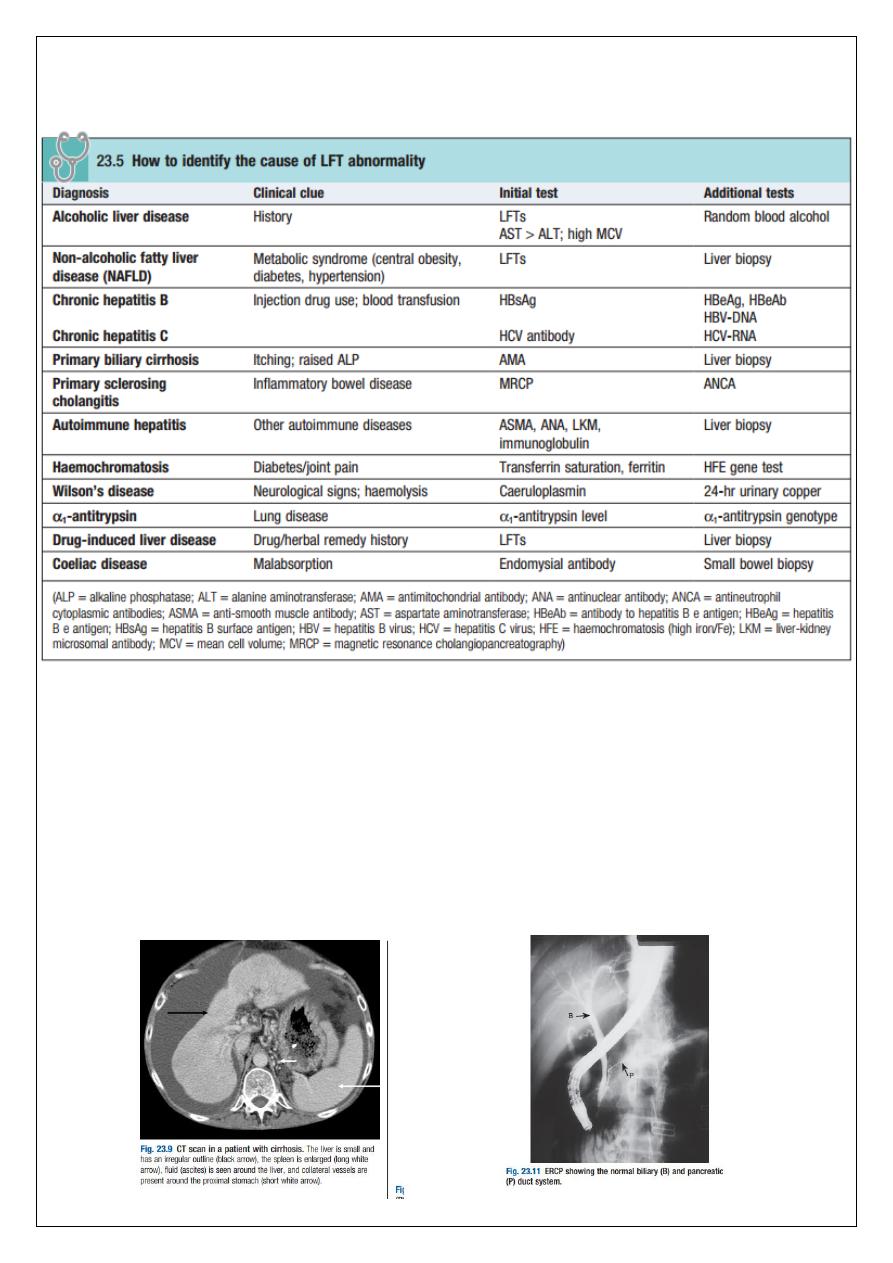

A variety of tests are available to evaluate the aetiology of hepatic disease (Boxes 23.4 and

23.5). The presence of liver-related autoantibodies can be suggestive of the presence of

autoimmune liver disease (although falsepositive results can occur in non-autoimmune

inflammatory disease such as NAFLD). Elevation in overall serum immunoglobulin levels can

also be suggestive of autoimmunity (immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgM). Elevated serum IgA can

be seen, often in more advanced alcoholic liver disease and NAFLD, although the association

is not specifc.

Imaging

Several imaging techniques can be used to determine the site and general nature of

structural lesions in the liver and biliary tree. In general, however, imaging techniques are

unable to identify hepatic inflammation and have poor sensitivity for liver fbrosis unless

advanced cirrhosis with portal hypertension is present. Ultrasound Ultrasound is non-

invasive and most commonly used as a ‘frst-line’ test to identify gallstones, biliary

obstruction or thrombosis in the hepatic vasculature. Ultrasound is good for the

identifcation of splenomegaly and abnormalities in liver texture, but is less effective at

identifying diffuse parenchymal disease. Focal lesions, such as tumours, may not be detected

if they are below 2 cm in diameter and have echogenic characteristics similar to normal liver

tissue. Bubblebased contrast media are now routinely used and can enhance discriminant

12

capability. Doppler ultrasound allows blood flow in the hepatic artery, portal vein and

hepatic veins to be investigated. Endoscopic ultrasound provides high-resolution images of

the pancreas, biliary tree and liver.

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

Computed tomography (CT) detects smaller focal lesions in the liver, especially when

combined with contrast injection. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used to

localise and confrm the aetiology of focal liver lesions, particularly primary and secondary

tumours.

13

Hepatic angiography is seldom used nowadays as a diagnostic tool, since CT and MRI are

both able to provide images of hepatic vasculature, but it still has a therapeutic role in the

embolisation of vascular tumours such as hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatic venography is

now rarely performed.

Cholangiography

Cholangiography can be undertaken by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography,

endoscopy (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, ERCP) or the percutaneous

approach (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, PTC). The latter does not allow the

ampulla of Vater or pancreatic duct to be visualised. MRCP is as good as ERCP at providing

images of the biliary tree but has fewer complications and is the diagnostic test of choice.

Both endoscopic and percutaneous approaches allow therapeutic interventions, such as the

insertion of biliary stents across malignant bile duct strictures. The percutaneous approach is

only used if it is not possible to access the bile duct endoscopically.

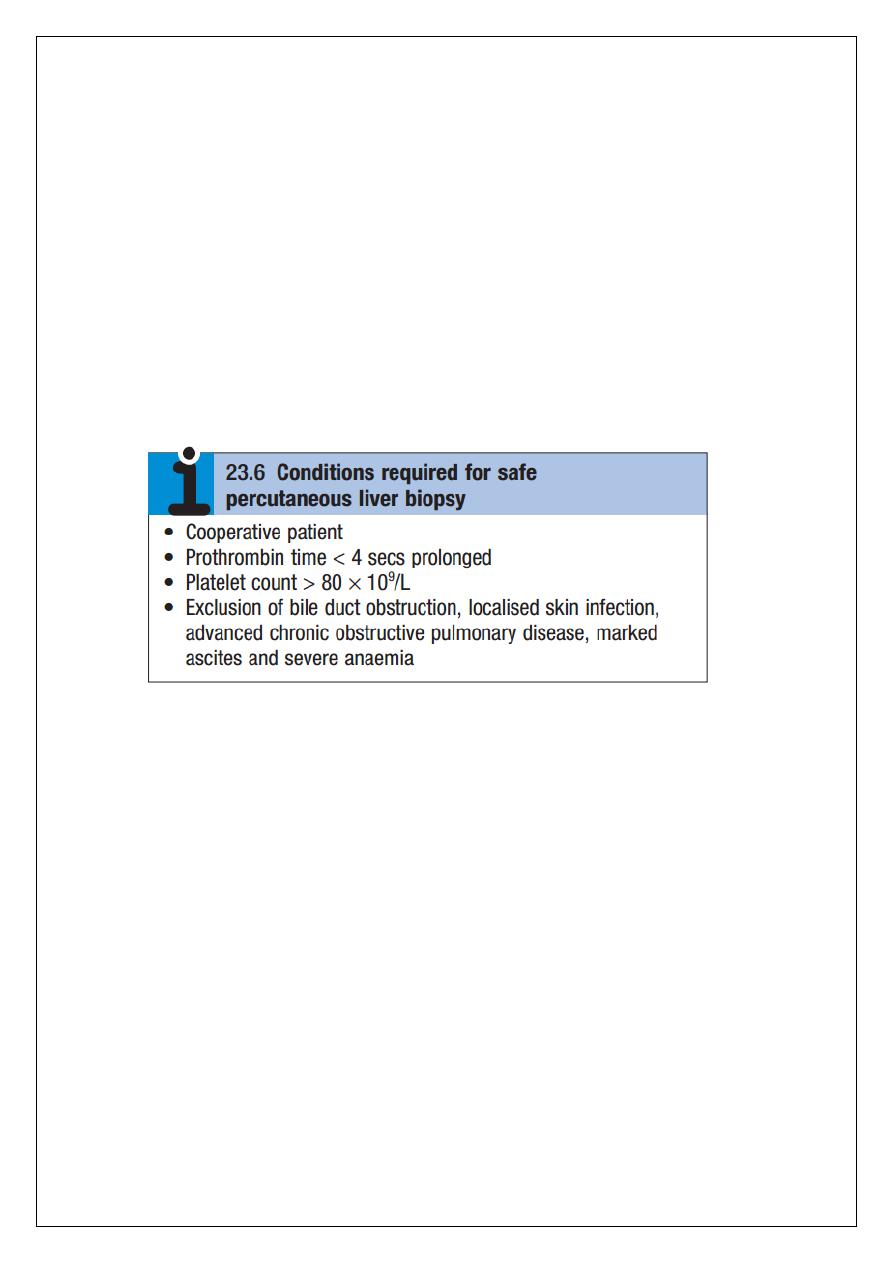

Histological examination

An ultrasound-guided liver biopsy can confrm the severity of liver damage and provide

aetiological information. It is performed percutaneously with a Trucut or Menghini needle,

usually through an intercostal space under local anaesthesia, or radiologically using a

transjugular approach. Percutaneous liver biopsy is a relatively safe procedure but carries a

mortality of about 0.01%. The main complications are abdominal and/or shoulder pain,

bleeding and biliary peritonitis. Biliary peritonitis is rare and usually occurs when a biopsy is

14

performed in a patient with obstruction of a large bile duct. Liver biopsies can be carried out

in patients with defective haemostasis if:

the defect is corrected with fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusion

the biopsy is obtained by the transjugular route, or

the procedure is conducted percutaneously under ultrasound control and the needle

track is then plugged with procoagulant material.

In patients with potentially resectable malignancy, biopsy should be avoided due to the

potential risk of tumour dissemination. Operative or laparoscopic liver biopsy may

sometimes be valuable. Although the pathological features of liver disease are complex, with

several features occurring together, liver disorders can be broadly classifed histologically

into fatty liver (steatosis), hepatitis (inflammation, ‘grade’) and cirrhosis (fbrosis, ‘stage’).

The use of special histological stains can help in determining aetiology. The clinical features

and prognosis of these changes are dependent on the underlying aetiology, and are

discussed in the relevant sections below

Non-invasive markers of hepatic fibrosis

Non-invasive markers of liver fbrosis have been developed and can reduce the need for liver

biopsy to assess the extent of fbrosis in some settings. Serological markers of hepatic fbrosis,

such as α2- macroglobulin, haptoglobin and routine clinical biochemistry tests, are used in

the Fibrotest®. The ELF® (Enhanced Liver Fibrosis) serological assay uses a combination of

hyaluronic acid, procollagen peptide III (PIIINP) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1

(TIMP1). These tests are good at differentiating severe fbrosis from mild scarring, but are

limited in their ability to detect subtle changes. A number of noncommercial scores based on

standard biochemical and anthropometric indices have also been described that provide

similar levels of sensitivity and specifcity (e.g. the FIB4 Score). An alternative to serological

markers is transient elastography in which ultrasound-based shock waves are sent through

the liver to measure liver stiffness as a surrogate for hepatic fibrosis. Once again, this test is

good at differentiating severe fbrosis from mild scarring, but is limited in its ability to detect

subtle changes, and validity may be affected by obesity

15

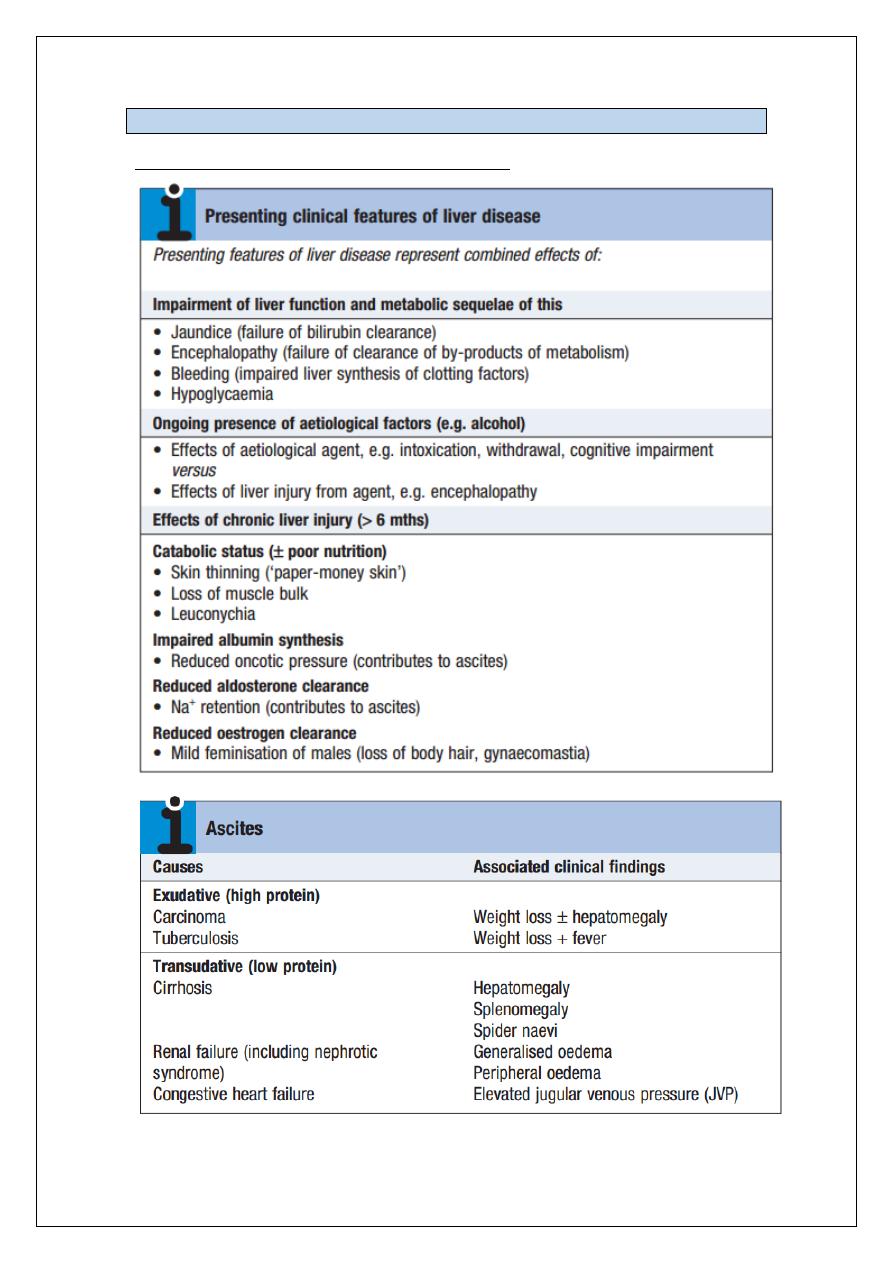

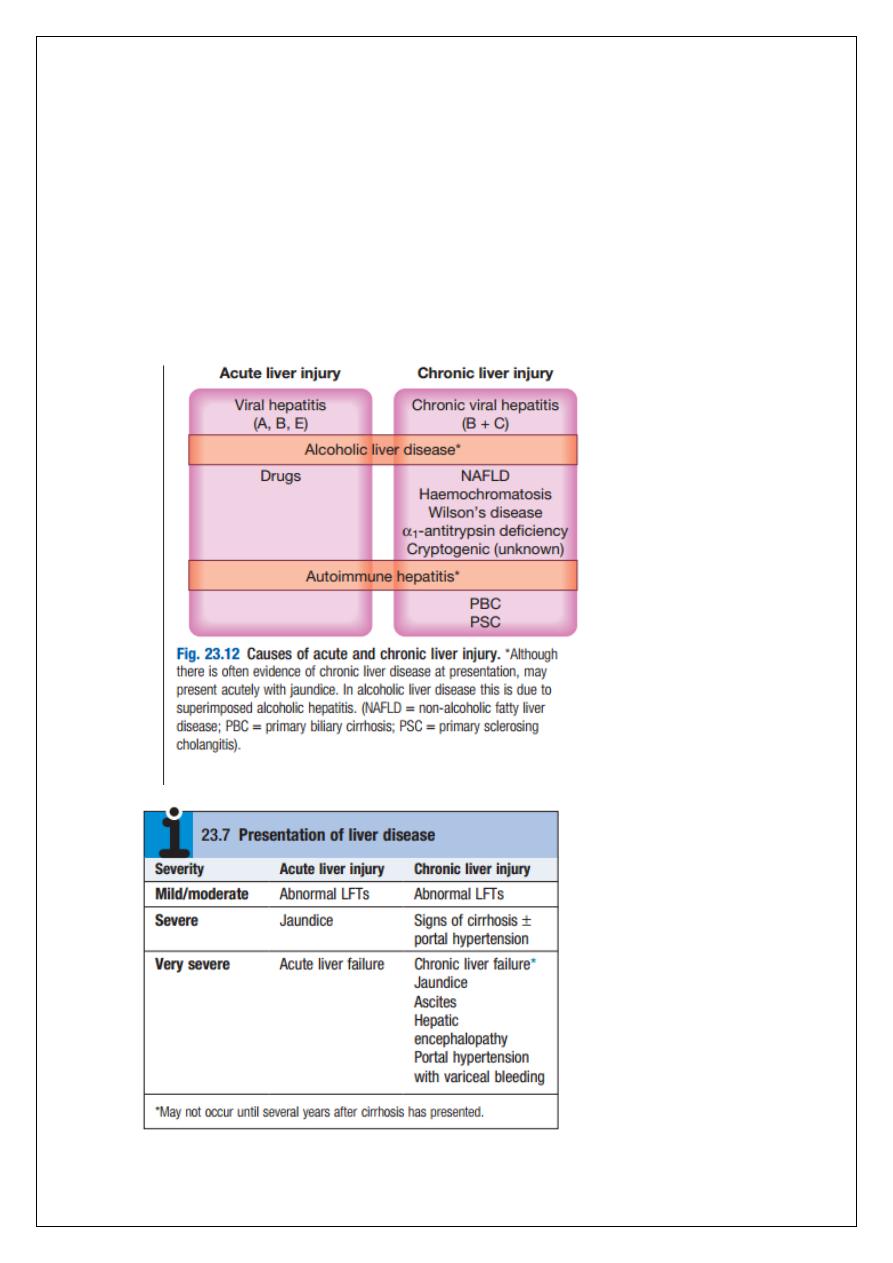

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN LIVER DISEASE

Liver injury may be either acute or chronic.

• Acute liver injury may present with non-specifc symptoms of fatigue and abnormal

LFTs, or with jaundice and acute liver failure.

• Chronic liver injury is defined as hepatic injury, inflammation and/or fibrosis

occurring in the liver for more than 6 months. In the early stages, patients can be

asymptomatic with fluctuating abnormal LFTs. With more severe liver damage,

however, the presentation can be with jaundice, portal hypertension or other signs

of cirrhosis and hepatic decompensation.

16

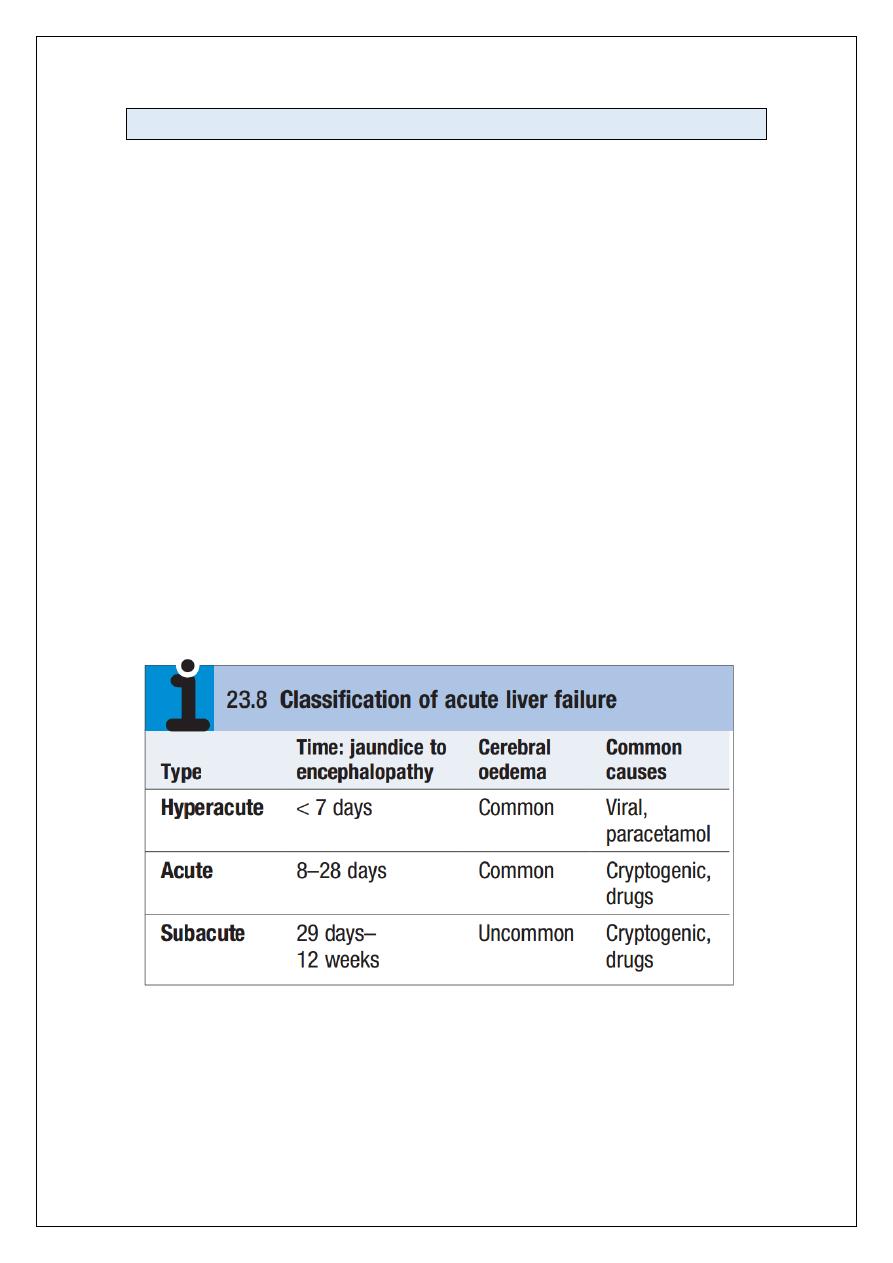

Acute liver failure

Acute liver failure is an uncommon but serious condition.

Definition: progressive deterioration in liver function and mental changes progressing

from confusion to coma occurring within 8 weeks of onset of the precipitating illness, in the

absence of evidence of preexisting liver disease.

This distinguishes it from instances in which hepatic encephalopathy represents a

deterioration in chronic liver disease. Liver failure occurs when there is insufficient metabolic

and synthetic function for the needs of the patient. Although the direct cause is usually

acute loss of functional hepatocytes, this can occur in different settings, which have

implications for outcome and treatment.

In a patient whose liver was previously normal (fulminant liver failure), the level of injury

needed to cause liver failure, and thus the patient risk, is very high. In a patient with pre-

existing chronic liver disease, the additional acute insult needed to precipitate liver failure is

much less. It is critical, therefore, to understand whether liver failure is a true acute event or

an acute deterioration on a background of pre-existing injury (which may itself not have

been diagnosed).

Although ultimately liver biopsy may be necessary, it is the presence or absence of the

clinical features suggesting chronicity that guides the clinician. More recently, newer

classifications have been developed to reflect differences in presentation and outcome of

acute liver failure. One such classification divides acute liver failure into hyperacute, acute

and subacute, according to the interval between onset of jaundice and encephalopathy.

Pathophysiology

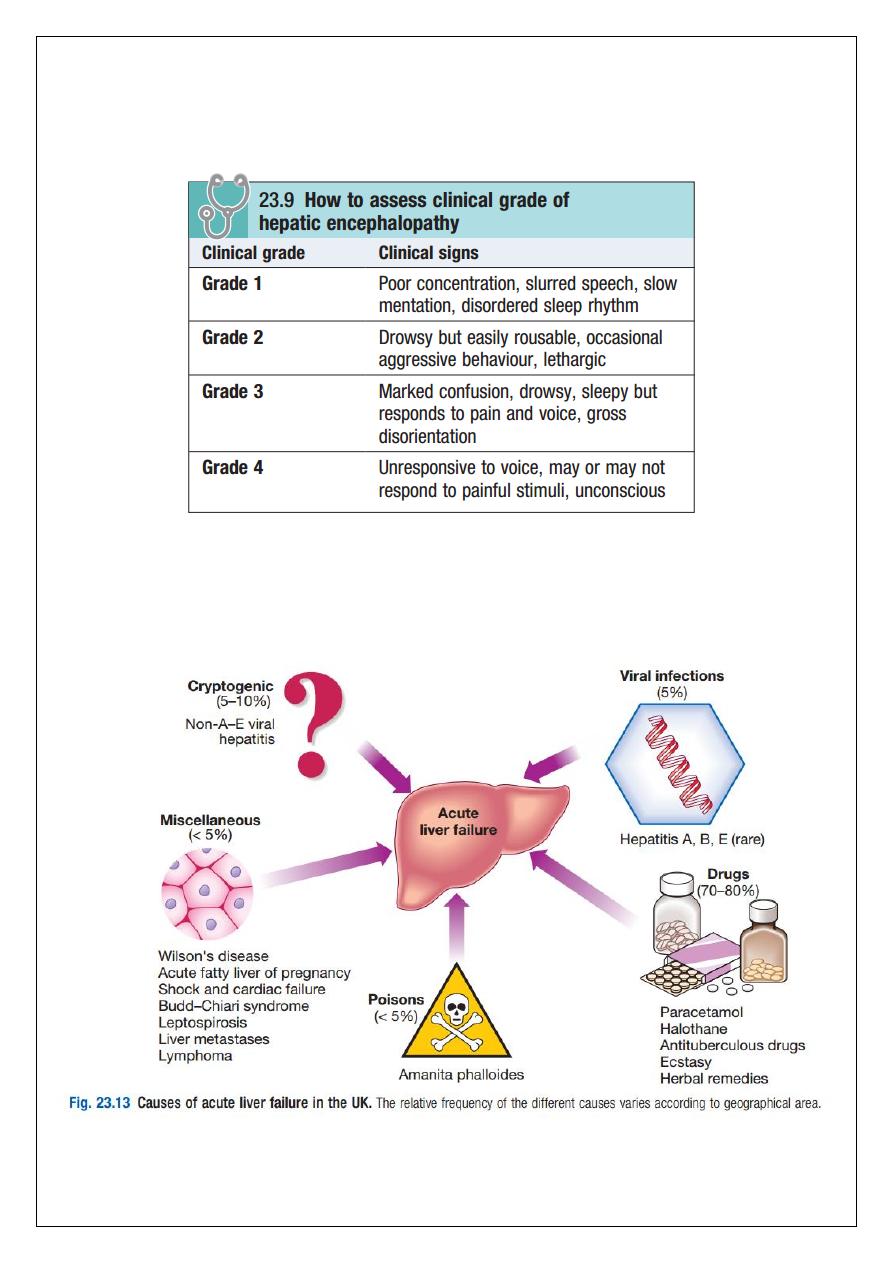

Any cause of liver damage can produce acute liver failure, provided it is sufficiently severe

(Fig. 23.13). Acute viral hepatitis is the most common cause worldwide, whereas

paracetamol toxicity (p. 212) is the most frequent cause in the UK. Acute liver failure occurs

occasionally with other drugs, or from Amanita phalloides (mushroom) poisoning, in

17

pregnancy, in Wilson’s disease, following shock (p. 190) and, rarely, in extensive malignant

disease of the liver. In 10% of cases the cause of acute liver failure remains unknown and

these patients are often labelled as having ‘non-A–E viral hepatitis’ or ‘cryptogenic’ acute

liver failure.

Clinical assessment

Cerebral disturbance (hepatic encephalopathy and/or cerebral oedema) is the cardinal

manifestation of acute liver failure, but in the early stages this can be mild and episodic and

so its absence does not exclude a significant acute liver injury. The initial clinical features are

often subtle and include reduced alertness and poor concentration, progressing through

behavioural abnormalities such as restlessness and aggressive outbursts, to drowsiness and

coma (Box 23.9). Cerebral oedema may occur due to increased intracranial pressure, causing

unequal or abnormally reacting pupils, fixed pupils, hypertensive episodes, bradycardia,

hyperventilation, profuse sweating, local or general myoclonus, focal fits or decerebrate

posturing.

Papilloedema occurs rarely and is a late sign. More general symptoms include weakness,

nausea and vomiting.

Right hypochondrial discomfort is an occasional feature.

The patient may be jaundiced; however, this may not be present at the outset (e.g. in

paracetamol overdose) and there are a number of exceptions, including Reye’s syndrome, in

which jaundice is rare.

Occasionally, death may occur in fulminant cases of acute liver failure before jaundice

develops.

Fetor hepaticus can be present.

The liver is usually of normal size but later becomes smaller. Hepatomegaly is unusual and,

in the presence of a sudden onset of ascites, suggests venous outflow obstruction as the

cause.

Splenomegaly is uncommon and never prominent.

Ascites and oedema are late developments and may be a consequence of fluid therapy.

Other features are related to the development of complications .

18

19

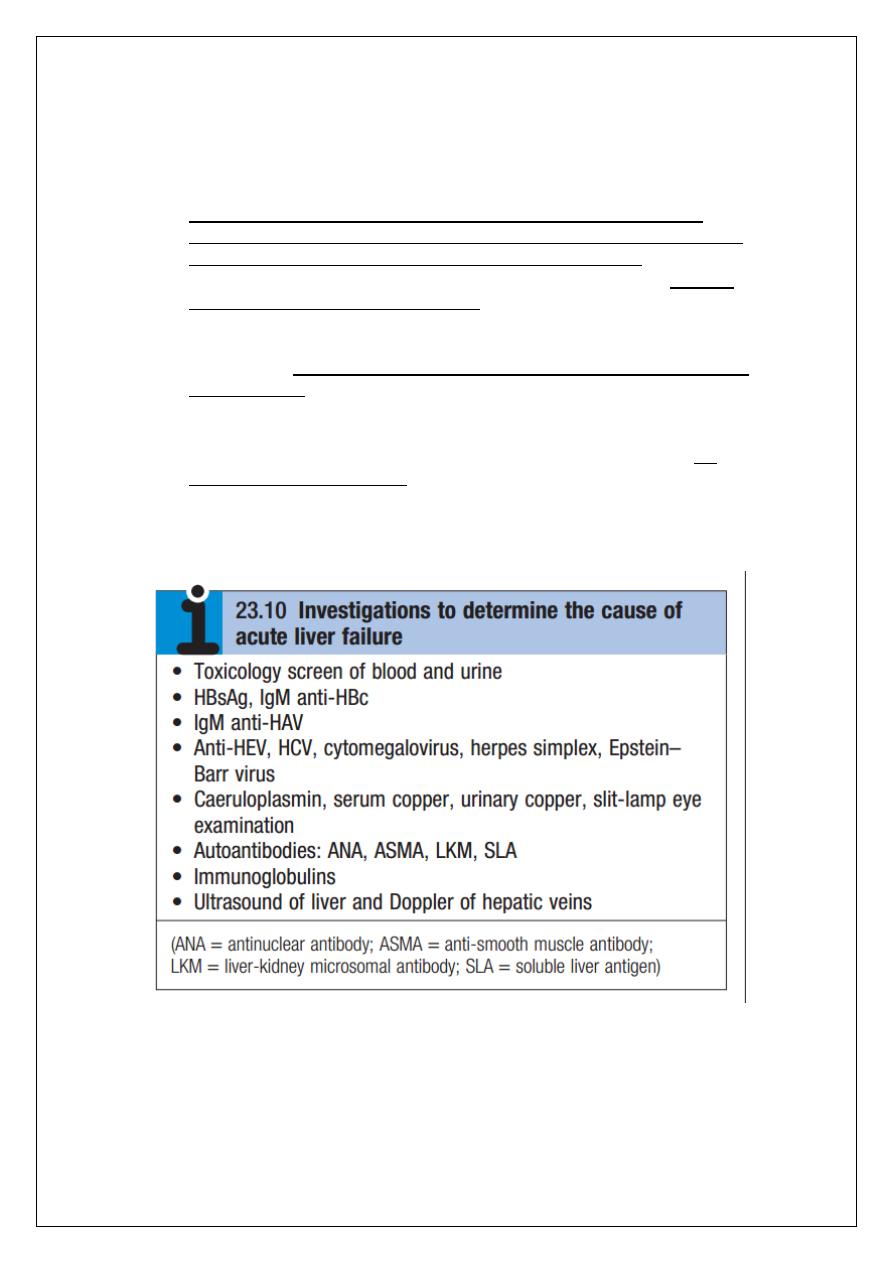

Investigations

The patient should be investigated to determine the cause of the liver failure and the

prognosis (Boxes 23.10 and 23.11).

Hepatitis B core IgM antibody is the best screening test for acute hepatitis B

infection, as liver damage is due to the immunological response to the virus, which

has often been eliminated, and the test for HBsAg may be negative.

The PT rapidly becomes prolonged as coagulation factor synthesis fails; this is the

laboratory test of greatest prognostic value and should be carried out at least twice

daily. Its prognostic importance emphasises the necessity of avoiding the use of

fresh frozen plasma to correct raised PT in acute liver failure, except in the setting of

frank bleeding. Factor V levels can be used instead of the PT to assess the degree of

liver impairment.

The plasma bilirubin reflects the degree of jaundice.

Plasma aminotransferase activity is particularly high after paracetamol overdose,

reaching 100–500 times normal, but falls as liver damage progresses and is not

helpful in determining prognosis.

Plasma albumin remains normal unless the course is prolonged.

Percutaneous liver biopsy is contraindicated because of the severe coagulopathy,

but biopsy can be undertaken using the transjugular route if appropriate.

20

21

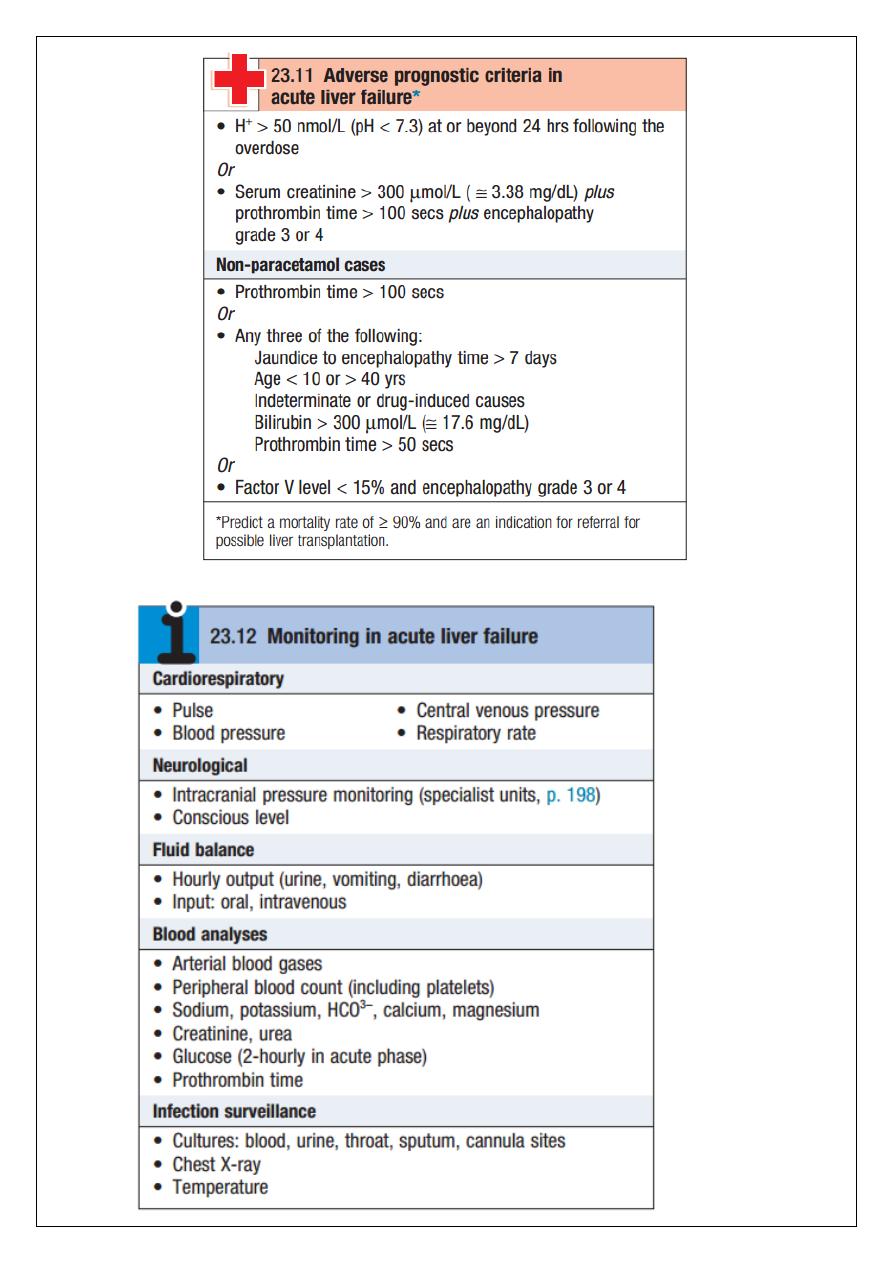

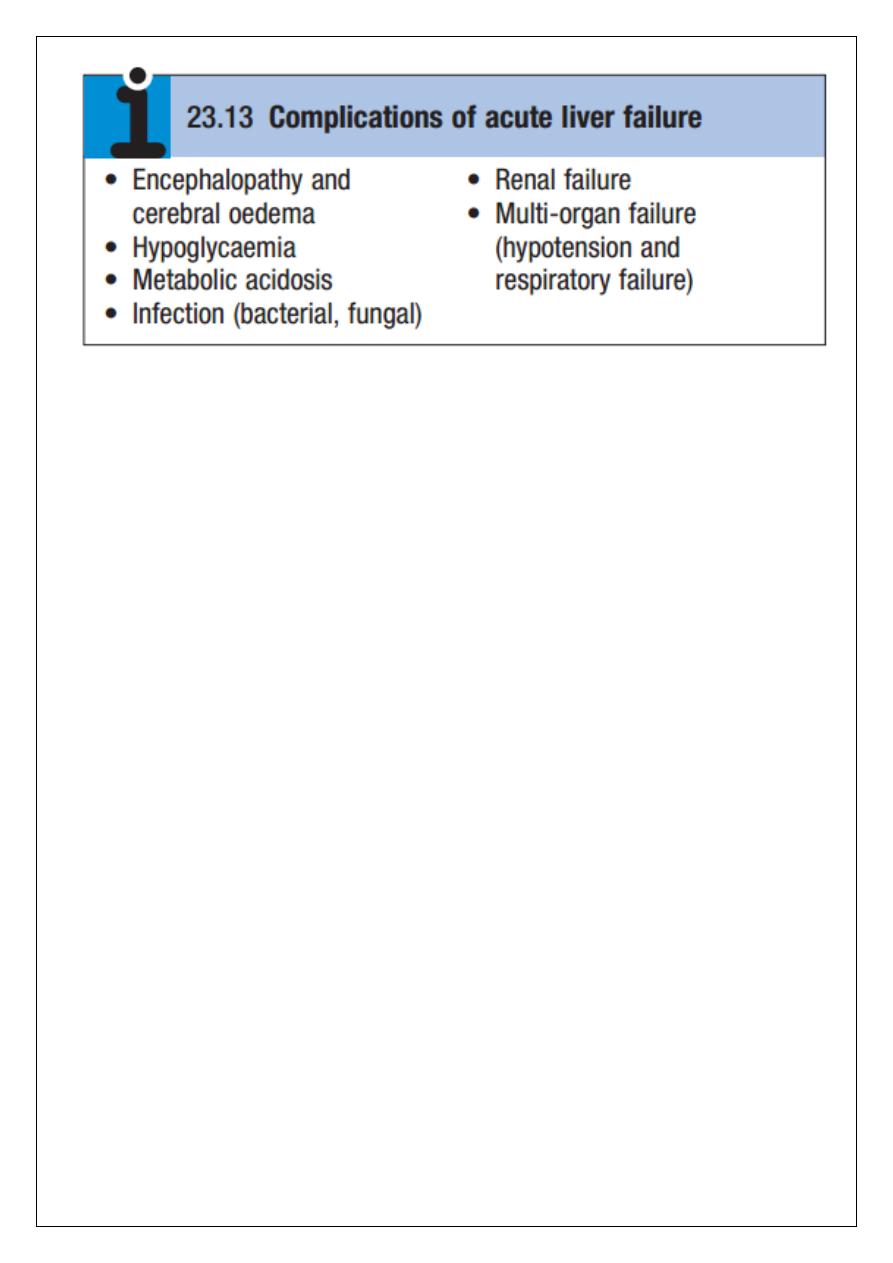

Management

Patients with acute liver failure should be treated in a high-dependency or intensive care

unit as soon as progressive prolongation of the PT occurs or hepatic encephalopathy is

identified (Box 23.12), so that prompt treatment of complications can be initiated (Box

23.13). Conservative treatment aims to maintain life in the hope that hepatic regeneration

will occur, but early transfer to a specialised transplant unit should always be considered.

N-acetylcysteine therapy may improve outcome, particularly in patients with acute

liver failure due to paracetamol poisoning.

Liver transplantation is an increasingly important treatment option for acute liver

failure, and criteria have been developed to identify patients unlikely to survive

without a transplant (see Box 23.11). Patients should, wherever possible, be

transferred to a transplant centre before these criteria are met to allow time for

assessment and to maximise the time for a donor liver to become available. Survival

following liver transplantation for acute liver failure is improving, and 1-year survival

rates of about 60% can be expected.

22

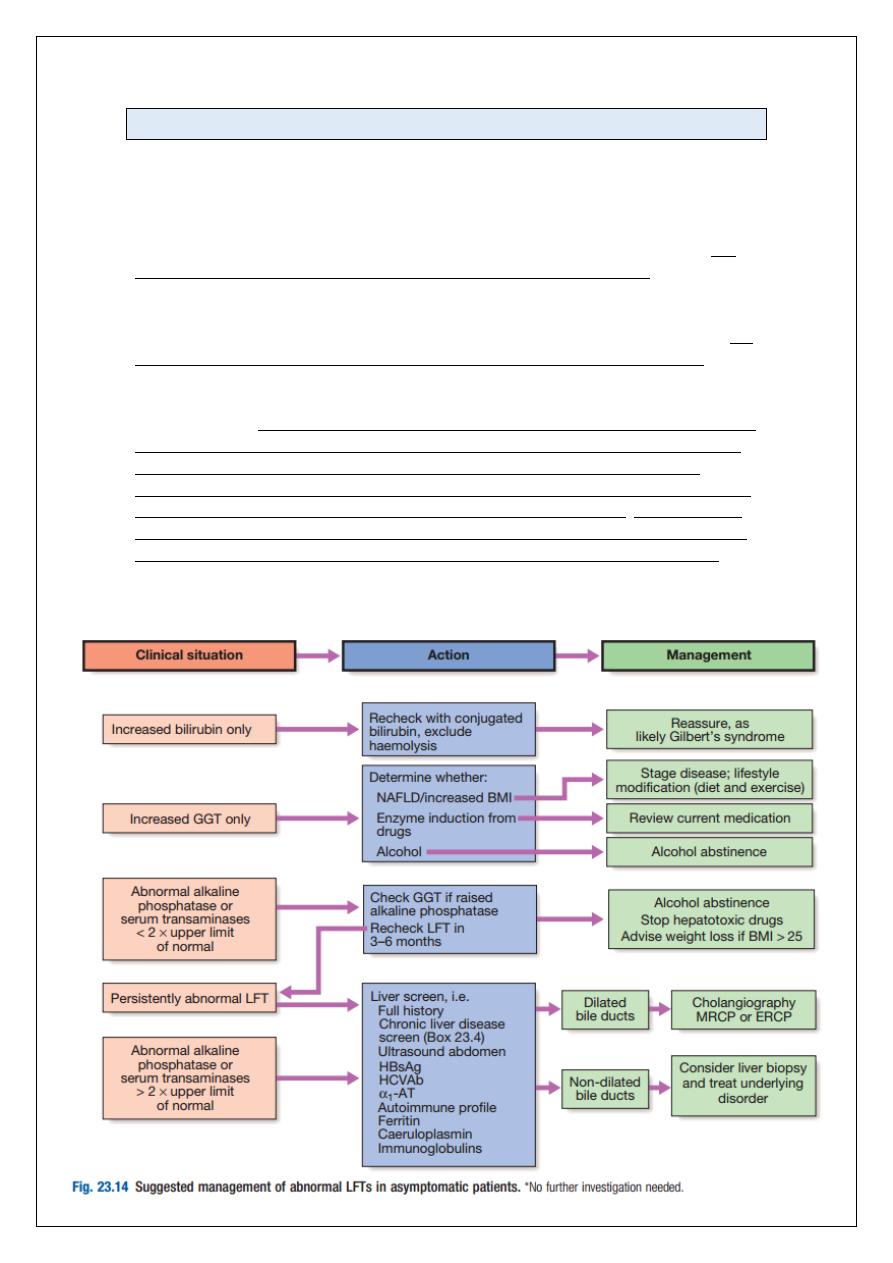

Abnormal liver function tests

Frequently, LFTs are requested in patients who have no symptoms or signs of liver disease,

as part of routine health checks, insurance medicals and drug monitoring. Many patients

with chronic liver disease are asymptomatic or have vague, non-specific symptoms.

Apparently asymptomatic abnormal LFTs are therefore a common occurrence. The

prevalence of abnormal LFTs has been reported to be as high as 10% in some studies. The

most common abnormalities are alcoholic or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Since effective

medical treatments are now available for many types of chronic liver disease, further

evaluation is usually warranted to make sure the patient does not have a treatable

condition. Although transient mild abnormalities in LFTs may not be clinically significant, the

majority of patients with persistently abnormal LFTs do have significant liver disease.

Biochemical abnormalities in chronic liver disease often fluctuate over time, and therefore

even mild abnormalities can indicate significant underlying disease and so warrant follow-up

and investigation. When abnormal LFTs are detected, a thorough history should be compiled

to determine the patient’s alcohol consumption, drug use (prescribed drugs or otherwise),

risk factors for viral hepatitis (e.g. blood transfusion, injecting drug use, tattoos), the

presence of autoimmune diseases, family history, neurological symptoms, and the presence

of features of the metabolic syndrome, including diabetes and/or obesity. The presence or

absence of stigmata of chronic liver disease does not reliably identify those individuals with

significant disease, and investigations are indicated, even in the absence of these signs.

Both the pattern of LFT abnormality, hepatitic or obstructive, and the degree of elevation

are helpful in determining the cause of underlying liver disease.

23

24

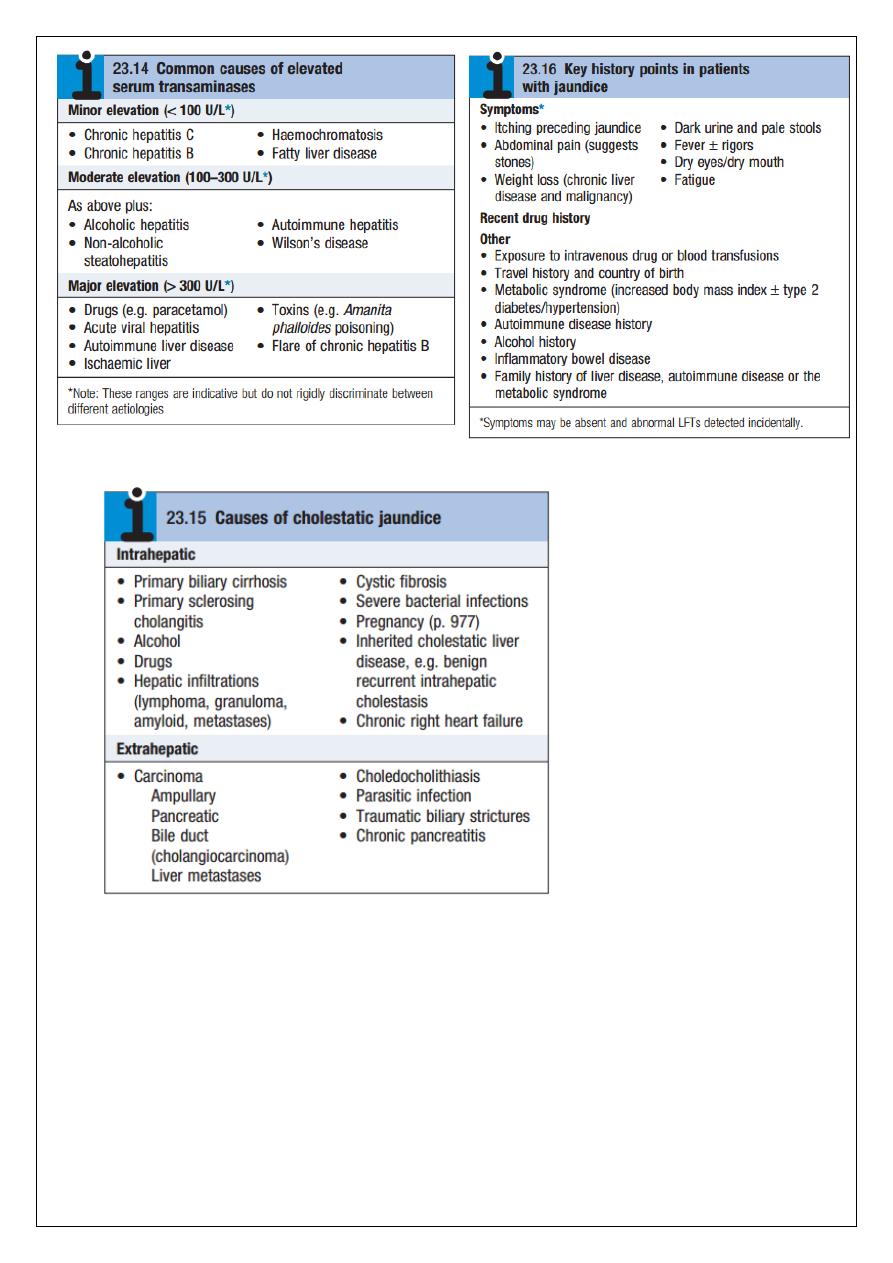

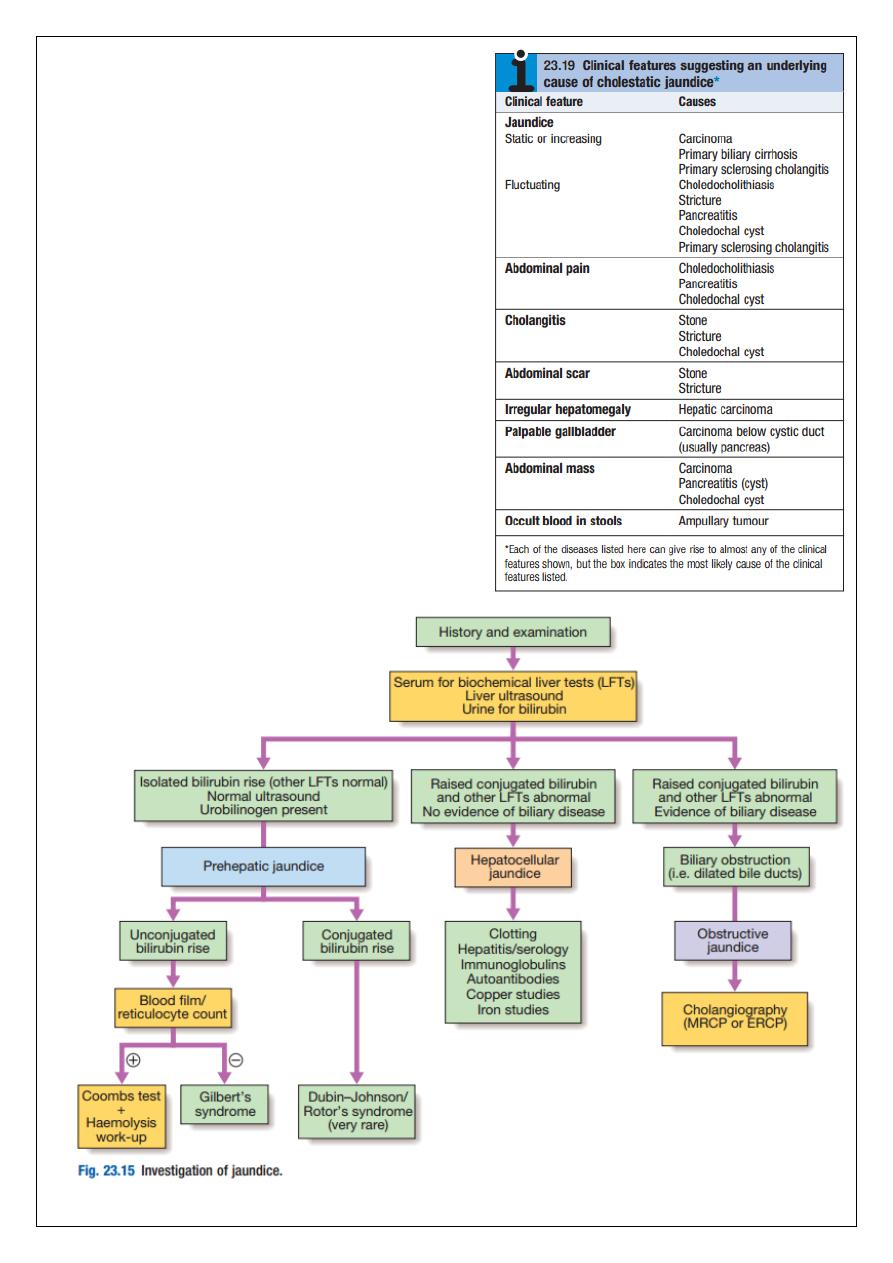

Jaundice

Jaundice is usually detectable clinically when the plasma bilirubin exceeds 2.5 mg/dL. The

causes of jaundice overlap with the causes of abnormal LFTs discussed above. In a patient

with jaundice it is useful to consider whether the cause might be pre-hepatic, hepatic or

post-hepatic and there are often important clues in the history.

Pre-hepatic jaundice

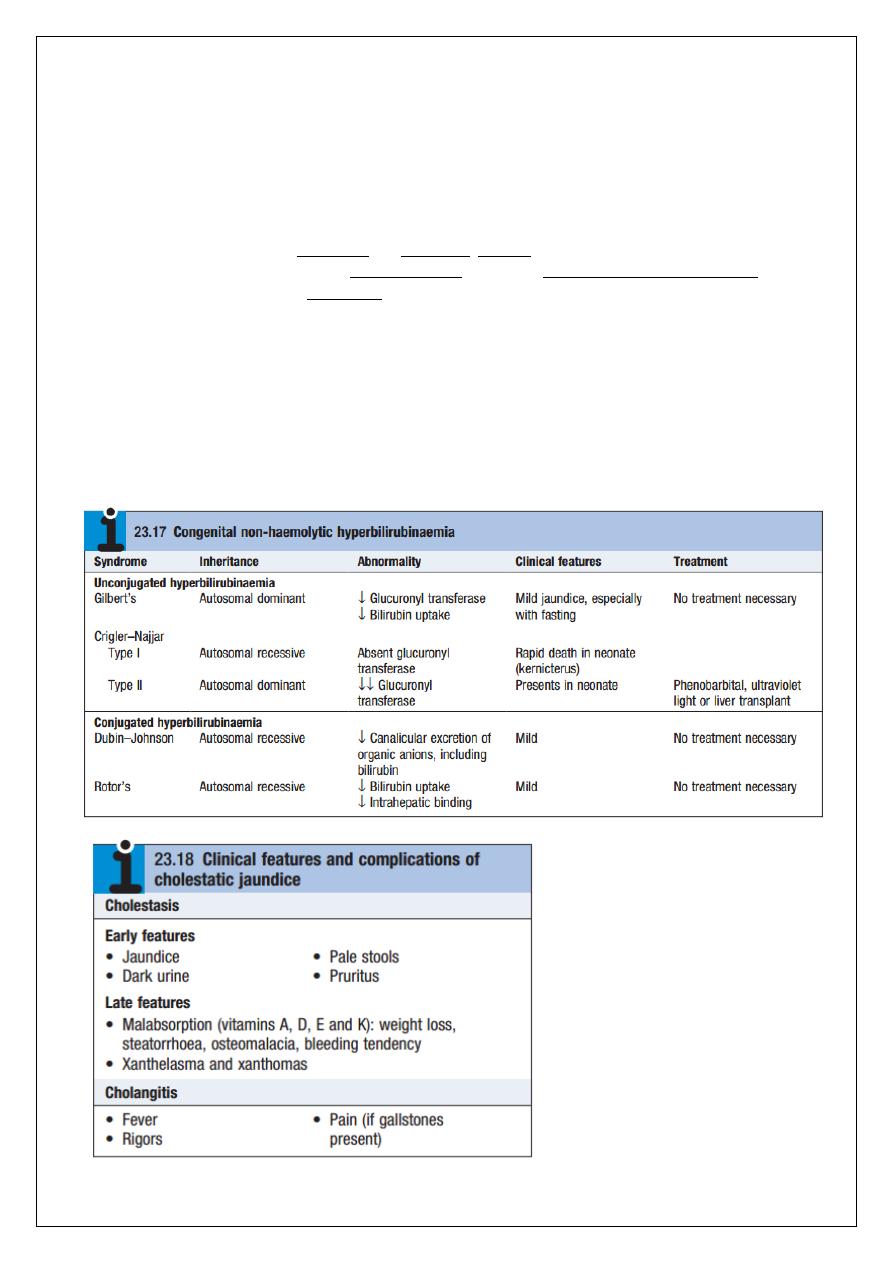

This is caused either by haemolysis or by congenital hyperbilirubinaemia, and is

characterised by an isolated raised bilirubin level.

In haemolysis, destruction of red blood cells or their marrow precursors causes increased

bilirubin production. Jaundice due to haemolysis is usually mild because a healthy liver can

excrete a bilirubin load six times greater than normal before unconjugated bilirubin

accumulates in the plasma. This does not apply to newborns, who have less capacity to

metabolise bilirubin.

The most common form of non-haemolytic hyperbilirubinaemia is Gilbert’s syndrome, an

inherited disorder of bilirubin metabolism. Other inherited disorders of bilirubin metabolism

are very rare.

Hepatocellular jaundice

Hepatocellular jaundice results from an inability of the liver to transport bilirubin into the

bile, occurring as a consequence of parenchymal disease. Bilirubin transport across the

hepatocytes may be impaired at any point between uptake of unconjugated bilirubin into

the cells and transport of conjugated bilirubin into the canaliculi. In addition, swelling of cells

and oedema resulting from the disease itself may cause obstruction of the biliary canaliculi.

In hepatocellular jaundice the concentrations of both unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin

in the blood increase. Hepatocellular jaundice can be due to acute or chronic injury, and

clinical features of acute or chronic liver disease may be detected clinically.

Characteristically, jaundice due to parenchymal liver disease is associated with increases in

transaminases (AST, ALT), but increases in other LFTs, including cholestatic enzymes (GGT,

ALP) may occur, and suggest specific aetiologies. Acute jaundice in the presence of an ALT of

greater than 1000 U/L is highly suggestive of an infectious cause (e.g. hepatitis A, B), drugs

(e.g. paracetamol) or hepatic ischaemia. Imaging is essential, in particular to identify

features suggestive of cirrhosis, to define the patency of the hepatic vasculature, and to

obtain evidence of portal hypertension. Liver biopsy has an important role in defining the

aetiology of hepatocellular jaundice and the extent of liver injury.

Obstructive (cholestatic) jaundice

Cholestatic jaundice may be caused by:

failure of hepatocytes to initiate bile flow

obstruction of the bile ducts or portal tracts

obstruction of bile flow in the extrahepatic bile ducts between the porta hepatis and

the papilla of Vater. In the absence of treatment, cholestatic jaundice tends to

become progressively more severe because conjugated bilirubin is unable to enter

the bile canaliculi and passes back into the blood, and also because there is a failure

25

of clearance of unconjugated bilirubin arriving at the liver cells. Cholestasis may

result from defects at more than one of these levels. Those confined to the

extrahepatic bile ducts may be amenable to surgical or endoscopic correction.

Clinical features comprise those due to cholestasis itself, those due to secondary

infection (cholangitis) and those of the underlying condition. Obstruction of the bile

duct drainage due to blockage of the extrahepatic biliary tree is characteristically

associated with pale stools and dark urine. Pruritus may be a dominant feature and

can be accompanied by skin excoriations. Peripheral stigmata of chronic liver disease

are absent. If the gallbladder is palpable, the jaundice is unlikely to be caused by

biliary obstruction due to gallstones, probably because a chronically inflamed stone-

containing gallbladder cannot readily dilate. This is Courvoisier’s Law, and suggests

that jaundice is due to a malignant biliary obstruction (e.g. pancreatic cancer).

Cholangitis is characterised by ‘Charcot’s triad’ of jaundice, right upper quadrant

pain and fever. Cholestatic jaundice is characterised by a relatively greater elevation

of ALP and GGT than the aminotransferases. Ultrasound is indicated to determine

whether there is evidence of mechanical obstruction and dilatation of the biliary

tree.

26

27

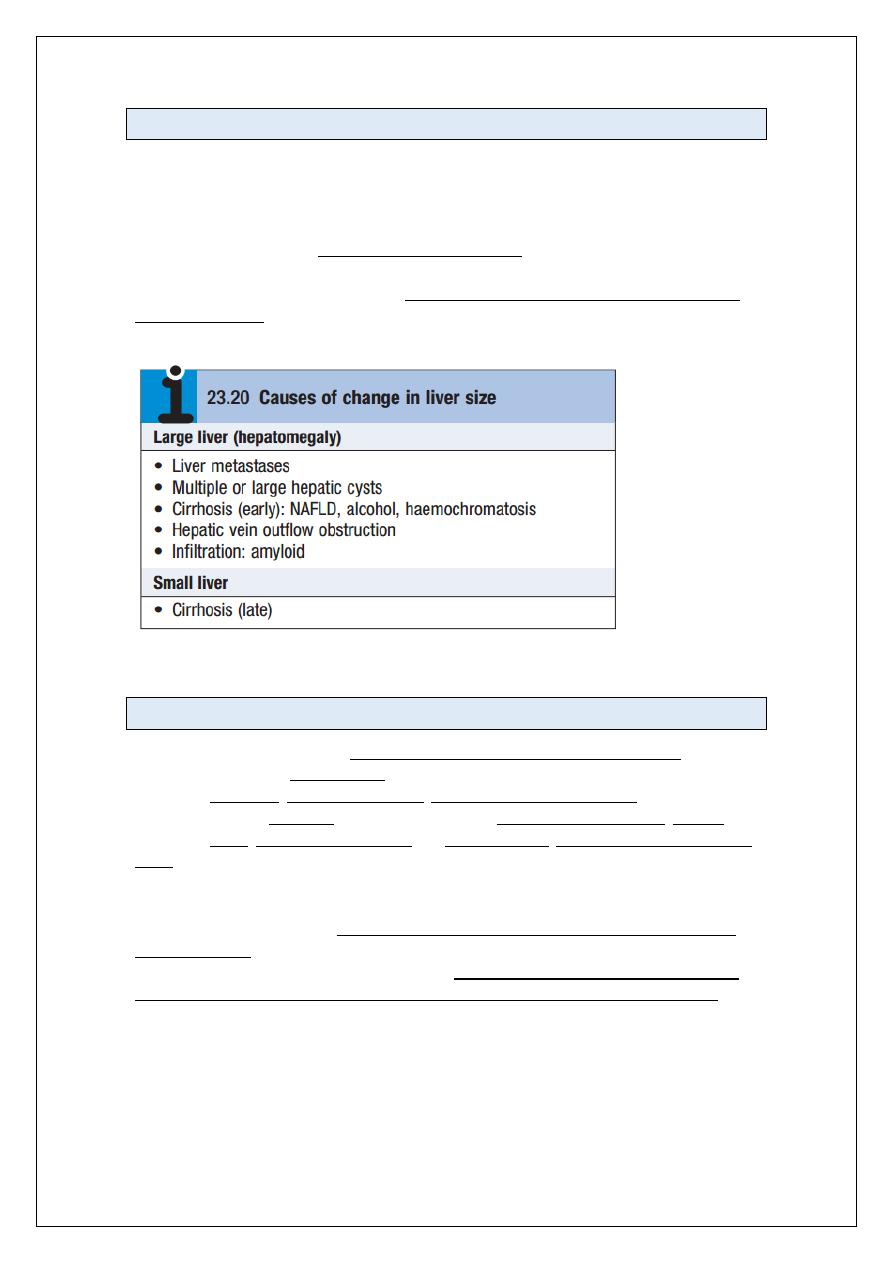

Hepatomegaly

Hepatomegaly may occur as the result of a general enlargement of the liver or because of

primary or secondary liver tumour. The most common liver tumour in Western countries is

liver metastasis, whereas primary liver cancer complicating chronic viral hepatitis is more

common in the Far East. Unlike metastases, neuro-endocrine tumours typically cause

massive hepatomegaly but without significant weight loss. Cirrhosis can be associated with

either hepatomegaly or reduced liver size in advanced disease. Although all causes of

cirrhosis can involve hepatomegaly, it is much more common in alcoholic liver disease and

haemochromatosis. Hepatomegaly may resolve in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis when

they stop drinking.

Ascites

Ascites is present when there is accumulation of free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. Small

amounts of ascites are asymptomatic, but with larger accumulations of fluid (> 1 L) there is

abdominal distension, fullness in the flanks, shifting dullness on percussion and, when the

ascites is marked, a fluid thrill. Other features include eversion of the umbilicus, herniae,

abdominal striae, divarication of the recti and scrotal oedema. Dilated superficial abdominal

veins may be seen if the ascites is due to portal hypertension.

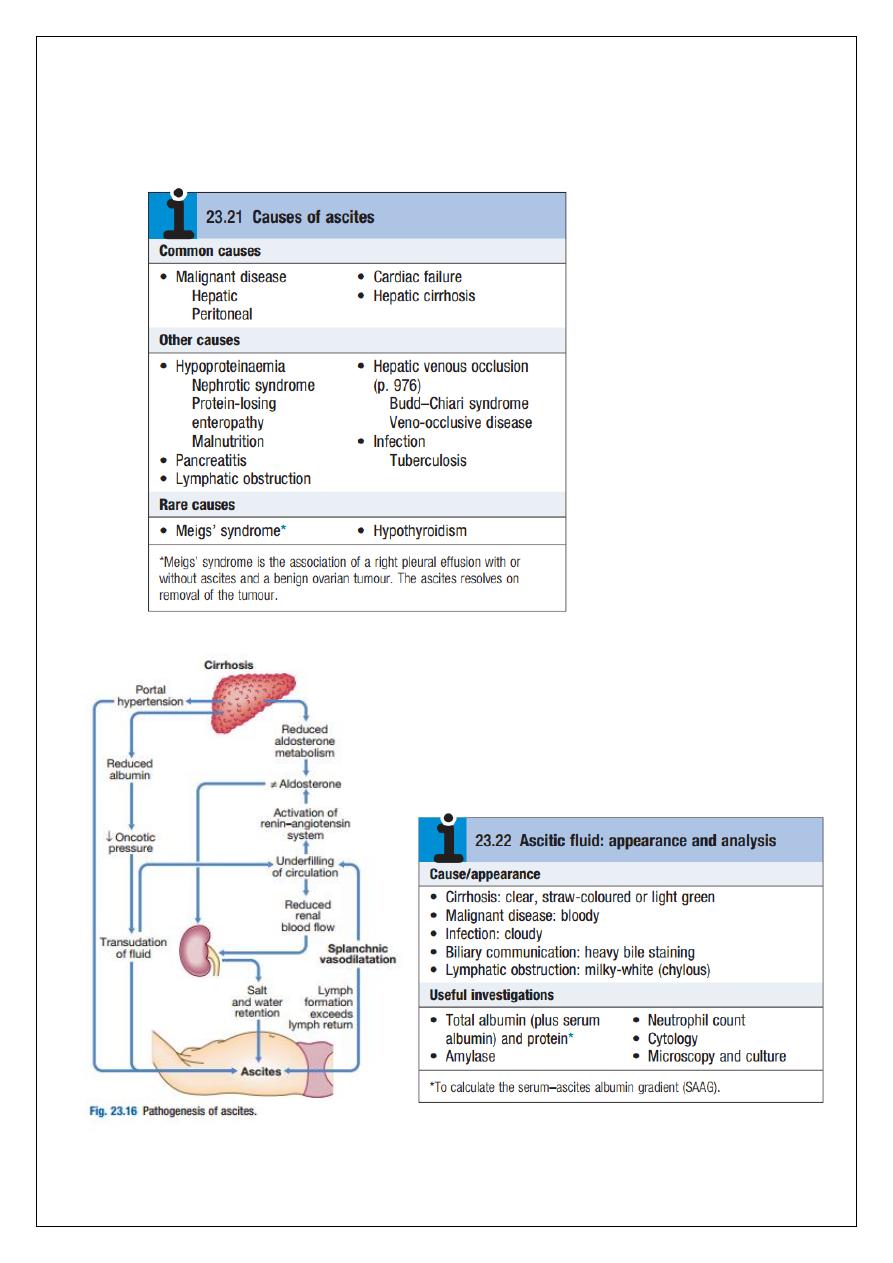

Pathophysiology

Ascites has numerous causes, the most common of which are malignant disease, cirrhosis

and heart failure. Many primary disorders of the peritoneum and visceral organs can also

cause ascites, and these need to be considered even in a patient with chronic liver disease.

Splanchnic vasodilatation is thought to be the main factor leading to ascites in cirrhosis. This

is mediated by vasodilators (mainly nitric oxide) that are released when portal hypertension

causes shunting of blood into the systemic circulation. Systemic arterial pressure falls due to

pronounced splanchnic vasodilatation as cirrhosis advances. This leads to activation of the

renin–angiotensin system with secondary aldosteronism, increased sympathetic nervous

activity, increased atrial natriuretic hormone secretion and altered activity of the kallikrein–

kinin system. These systems tend to normalise arterial pressure but produce salt and water

28

retention. In this setting the combination of splanchnic arterial vasodilatation and portal

hypertension alters intestinal capillary permeability, promoting accumulation of fluid within

the peritoneum.

29

Investigations

Ultrasonography is the best means of detecting ascites, particularly in the obese and those

with small volumes of fluid. Paracentesis (if necessary under ultrasonic guidance) can be

used to obtain ascitic fluid for analysis. The appearance of ascitic fluid may point to the

underlying cause. Pleural effusions are found in about 10% of patients, usually on the right

side (hepatic hydrothorax); most are small and only identified on chest X-ray, but

occasionally a massive hydrothorax occurs. Pleural effusions, particularly those on the left

side, should not be assumed to be due to the ascites. Measurement of the protein

concentration and the serum–ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) are used to distinguish a

transudate from an exudate. Cirrhotic patients typically develop a transudate with a total

protein concentration below 25 g/L and relatively few cells. However, in up to 30% of

patients, the total protein concentration is more than 30 g/L. In these cases, it is useful to

calculate the SAAG by subtracting the concentration of the ascites fluid albumin from the

serum albumin. A gradient of more than 11 g/L is 96% predictive that ascites is due to portal

hypertension. Venous outflow obstruction due to cardiac failure or hepatic venous outflow

obstruction can also cause a transudative ascites, as indicated by an albumin gradient above

11 g/L but, unlike in cirrhosis, the total protein content is usually above 25 g/L.

Exudative ascites (ascites protein concentration > 25 g/L or a SAAG < 11 g/L) raises the

possibility of infection (especially tuberculosis), malignancy, hepatic venous obstruction,

pancreatic ascites or, rarely, hypothyroidism. Ascites amylase activity above 1000 U/L

identifies pancreatic ascites, and low ascites glucose concentrations suggest malignant

disease or tuberculosis. Cytological examination may reveal malignant cells (one-third of

cirrhotic patients with a bloody tap have a hepatocellular carcinoma). Polymorphonuclear

leucocyte counts above 250 × 10

6

/L strongly suggest infection (spontaneous bacterial

peritonitis, see below). Laparoscopy can be valuable in detecting peritoneal disease.

Management

Successful treatment relieves discomfort but does not prolong life; if over-vigorous, it can

produce serious disorders of fluid and electrolyte balance and precipitate hepatic

encephalopathy. Treatment of transudative ascites is based on restricting sodium and water

intake, promoting urine output with diuretics and, if necessary, removing ascites directly by

paracentesis. Exudative ascites due to malignancy is treated with paracentesis, but fluid

replacement is generally not required. During management of ascites, the patient should be

weighed regularly. Diuretics should be titrated to remove no more than 1 L of fluid daily, so

body weight should not fall by more than 1 kg daily to avoid excessive fluid depletion.

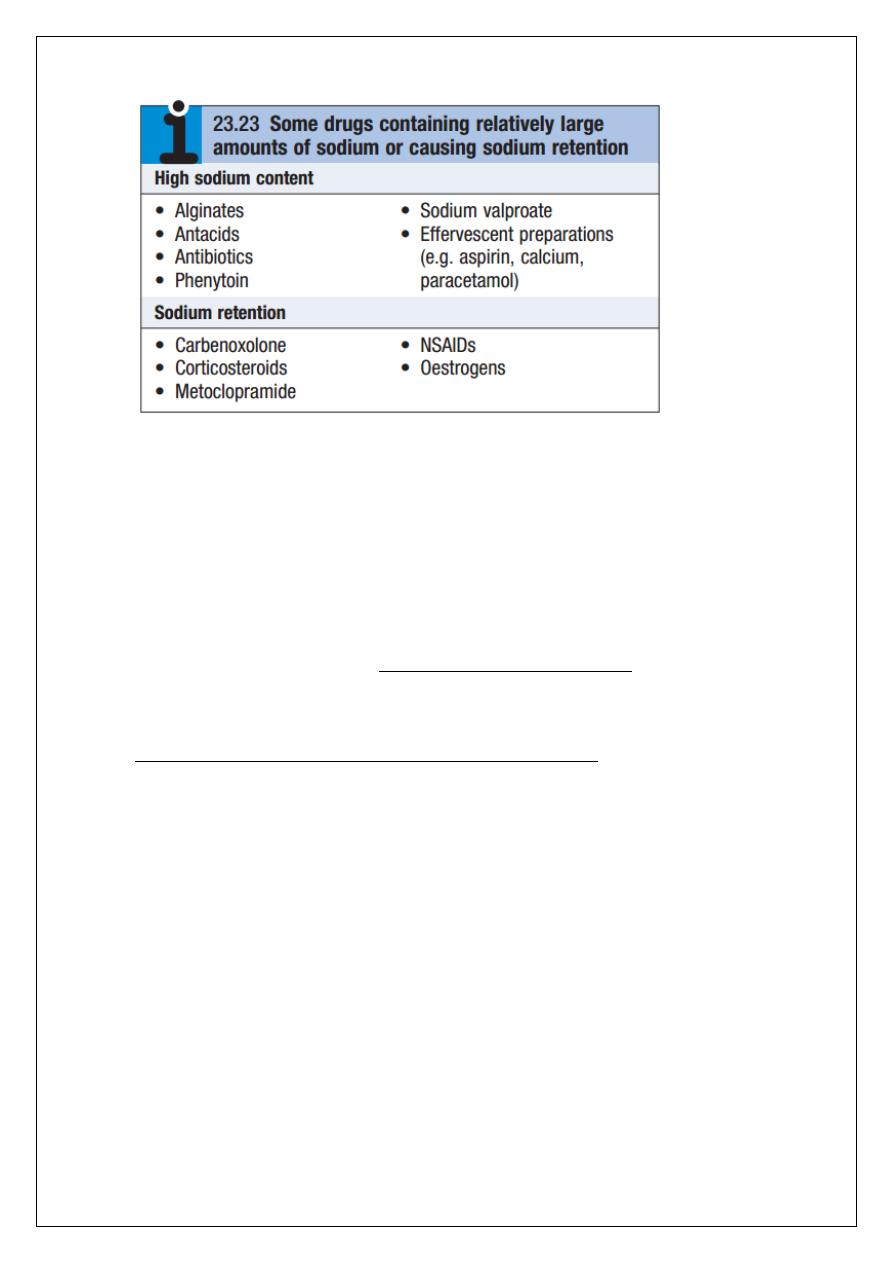

Sodium and water restriction

Restriction of dietary sodium intake is essential to achieve negative sodium balance, and a

few patients can be managed satisfactorily by this alone. Restriction of sodium intake to 100

mmol/day (‘no added salt diet’) is usually adequate. Drugs containing relatively large

amounts of sodium, and those promoting sodium retention such as non-steroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), must be avoided. Restriction of water intake to 1.0–1.5 L/day

is necessary only if the plasma sodium falls below 125 mmol/L.

30

Diuretics

Most patients require diuretics in addition to sodium restriction. Spironolactone (100–400

mg/day) is the first-line drug because it is a powerful aldosterone antagonist; it can cause

painful gynaecomastia and hyperkalaemia, in which case amiloride (5–10 mg/day) can be

substituted. Some patients also require loop diuretics, such as furosemide, but these can

cause fluid and electrolyte imbalance and renal dysfunction. Diuresis may be improved if

patients are rested in bed, perhaps because renal blood flow increases in the horizontal

position. Patients who do not respond to doses of 400 mg spironolactone and 160 mg

furosemide, or who are unable to tolerate these doses due to hyponatraemia or renal

impairment, are considered to have refractory or diuretic-resistant ascites and should be

treated by other measures.

Paracentesis

First-line treatment of refractory ascites is large-volume paracentesis. Paracentesis to

dryness is safe, provided the circulation is supported with an intravenous colloid such as

human albumin (6–8 g per litre of ascites removed, usually as 100 mL of 20% human albumin

solution (HAS) for every 1.5–2 L of ascites drained) or another plasma expander.

Paracentesis can be used as an initial therapy or when other treatments fail.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt

A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS) can relieve resistant ascites but

does not prolong life; it may be an option where the only alternative is frequent, large-

volume paracentesis. It can be used in patients awaiting liver transplantation or in those

with reasonable liver function, but can aggravate encephalopathy in those with poor

function.

Peritoneo-venous shunt

The peritoneo-venous shunt is a long tube with a non-return valve running subcutaneously

from the peritoneum to the internal jugular vein in the neck; it allows ascitic fluid to pass

directly into the systemic circulation. Complications, including infection, superior vena caval

31

thrombosis, pulmonary oedema, bleeding from oesophageal varices and disseminated

intravascular coagulopathy, limit its use and insertion of these shunts is now rare.

Complications

Renal failure

Renal failure can occur in patients with ascites. It can be pre-renal due to vasodilatation

from sepsis and/or diuretic therapy, or due to hepatorenal syndrome.

Hepatorenal syndrome

This occurs in 10% of patients with advanced cirrhosis complicated by ascites. There are two

clinical types; both are mediated by renal vasoconstriction due to underfilling of the arterial

circulation.

Type 1 hepatorenal syndrome is characterised by progressive oliguria, a rapid rise of

the serum creatinine and a very poor prognosis (without treatment, median survival

is less than 1 month). There is usually no proteinuria, a urine sodium excretion of

less than 10 mmol/day and a urine/ plasma osmolarity ratio of more than 1.5. Other

non-functional causes of renal failure must be excluded before the diagnosis is

made. Treatment consists of albumin infusions in combination with terlipressin and

is effective in about two-thirds of patients. Haemodialysis should not be used

routinely because it does not improve the outcome.

Patients who survive should be considered for liver transplantation.

Type 2 hepatorenal syndrome usually occurs in patients with refractory ascites, is

characterised by a moderate and stable increase in serum creatinine, and has a

better prognosis.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) may present with abdominal pain, rebound

tenderness, absent bowel sounds and fever in a patient with obvious features of cirrhosis

and ascites. Abdominal signs are mild or absent in about one-third of patients, and in these

patients hepatic encephalopathy and fever are the main features. Diagnostic paracentesis

may show cloudy fluid, and an ascites neutrophil count above 250 × 10

6

/L almost invariably

indicates infection. The source of infection cannot usually be determined, but most

organisms isolated are of enteric origin and Escherichia coli is most frequently found. Ascitic

culture in blood culture bottles gives the highest yield of organisms. SBP needs to be

differentiated from other intra-abdominal emergencies, and the finding of multiple

organisms on culture should arouse suspicion of a perforated viscus. Treatment should be

started immediately with broadspectrum antibiotics, such as cefotaxime or piperacillin/

tazobactam). Recurrence of SBP is common but may be reduced with prophylactic

quinolones such as norfloxacin or ciprofloxacin.

Prognosis

Only 10–20% of patients survive 5 years from the first appearance of ascites due to cirrhosis.

The outlook is not universally poor, however, and is best in those with well-maintained liver

32

function and a good response to therapy. The prognosis is also better when a treatable

cause for the underlying cirrhosis is present or when a precipitating cause for ascites, such as

excess salt intake, is found. The mortality at 1 year is 50% following the first episode of

bacterial peritonitis.