Veterinary Clinical Pathology by Prof. Dr. Basima Albadrani

Introduction:

With new technology, in-hospital clinical diagnostic laboratories are becoming

an expected part of every veterinary hospital. Veterinary teams now have the

ability to obtain medical data in complete blood count, chemistry, blood gas,

lactate, urine, and clotting times in minutes—information that would take 1–2 days

to obtain from an outside lab. This allows us to have an excellent medical database

quickly and effectively to help evaluate and treat our patients.

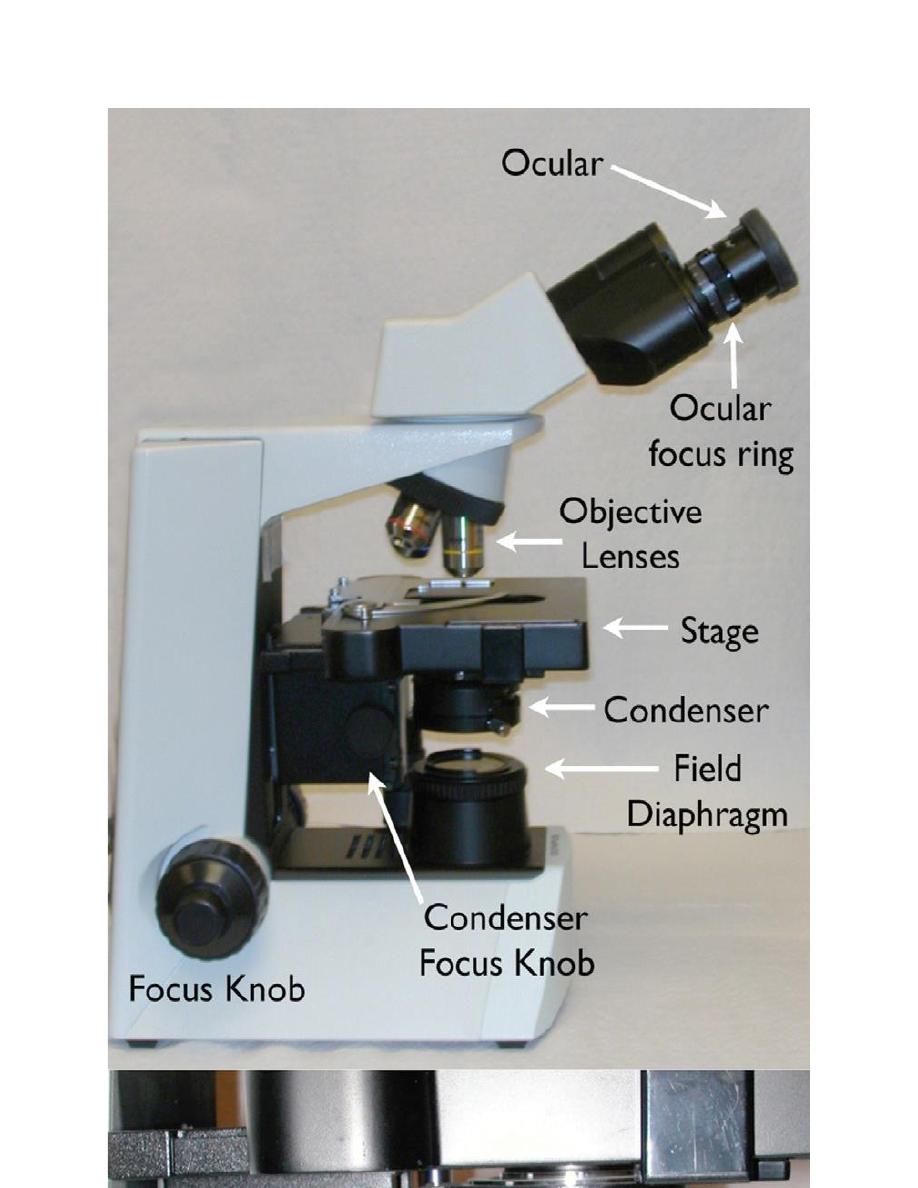

Basic Equipements of clinical pathology laboratory

1. hematology and clinical chemistry instrumentation,

2. a free-arm centrifuge for spinning down serum and urine samples,

3. a microhematocrit centrifuge,

4. a

quality microscope,

5. a refrigerator with a non–frost-free freezer compartment are needed.

The ability to critically examine hematology and cytology specimens depends

upon the clear optics of the microscope. Figure 1.1 identifies the components of a

compound bright field microscope. The standard lenses on most light microscopes

are 10×, 40×, and 100× oil emersion. The addition of a 20× or a 50× oil

emersion lens can facilitate the rapid examination of cytology and hematology

samples. One important note is that the 40× high dry objective requires a cover

slipped slide. The optics of this objective are optimized for viewing histopathology

slides that are always cover slipped. A simple way to use the 40× objective to

view hematology and cytology slides is to use a drop of immersion oil as a

coverslip mounting medium.

Place a drop of oil on the microscope slide and place a coverslip in top of the oil.

This will allow sharp focus of the slide with the 40× objective. It is imperative

that the high dry objective does not get immersed in oil. If this inadvertently

happens, immediate cleaning with a quality lens cleaner (not xylene) and lens

paper is necessary. A good habit is to always rotate the microscope objectives in

one direction, from lowest power to highest power. This will keep the microscopist

from dragging the 40× objective through oil.

Accessory Equipment’s of clinical pathology laboratory:

1. Glasses of different shapes and sizes for carry out the biochemical test and

other measurements, e.g: test tubes, micropipettes, petrei dishes, different

volume flasks, microscopical slides, stains jars…etc.

2. Chemical solutions, Agars and microbiological media….

3. Kits for serology

4. Stains

Laboratory tests are done for a variety of reasons:

Screening tests, such as a complete blood count (CBC), may be done on

clinically normal animals when they are acquired to avoid a financial and/or

emotional commitment to a diseased animal,

to examine geriatric patients for subclinical disease, or to identify a condition

that might make an animal an anesthetic or surgical risk.

Screening tests are often done when an ill animal is first examined, especially if

systemic signs of illness are present and a specific diagnosis is not apparent

from the history and physical examination.

Tests are also done to confirm a presumptive diagnosis. A test may be repeated

or a different test may be done to confirm a test result that was previously

reported to be abnormal.

Tests may be done to assist in the determination of the severity of a disease, to

help formulate a prognosis, and to monitor the response to therapy or

progression of disease

Hematology

is the study of the cellular components of blood. Blood is

composed of both

cells

and

fluid

called

plasma

. The cells are white blood cell

(

leukocytes

), red blood cells

(erythrocytes

), and platelets

(thrombocytes

). The fluid

(plasma) component consists of

water

,

protein

,

electrolytes/

minerals

,

lipids

,

soluble carbohydrates

,

amino acids

, and other non-cellular substances such as

hormones.

Each component of blood has a specific function and can change in

response to disease states.

The

enumeration

and

morphological evaluation of the peripheral blood cells

are

essential parts of the complete blood count (CBC). An understanding of the

formation, function, and peripheral dynamics of white blood cells will allow the

veterinary technician to accurately identify and report changes in the CBC

associated with disease processes.

Components of the Complete Blood count

The

complete blood count (CBC):

is a process by which the cellular components

of the blood are evaluated. The components of the CBC provide data that is used to

determine whether there are abnormalities in

erythrocytes (RBC)

,

leukocytes

(WBC)

, and

platelets (PL)

.

Evaluation of erythrocyte:

The

packed cell volume (PCV

),

hematocrit (Hct

),

hemoglobin concentration

, and

indices

(MCV, MCH, MCHC)

that describe the size of erythrocytes and the

concentration of hemoglobin within the erythrocytes are used to evaluate

erythrocytes.

Evaluation of leukocyte:

The

white blood cell count (WBC)

and

differential leukocyte count

(

DLC

) are

used to evaluate leukocytes.

Evaluation of platelets

Total

number of platelets

and

platelets morphology

are used to evaluate platelets

The blood film evaluation: Is an essential part of the CBC and is used

1. to confirm the

numbers of RBCs, WBCS and platelets

obtained by the

automated or manual CBC

2. To fully

evaluate cell (Erythrocyte, Leukocyte, Platelets) morphology

.

3. For diagnosis and differential diagnosis of anemia.

4. to evaluation of DLC.

5. For diagnosis of some infectious diseases e.g Blood parasite infestation

(microfilariasis), blood protozoa like Babesia, Theileria., Ricketsial infection

like Anaplasmosis, Hemoplasma infection( Hemotrophic mycoplasma).

6. For diagnosis of some infectious diseases as Anthrax (Bacillus anthrasis)

staining blood film by special stain Polychrom Methylen Blue

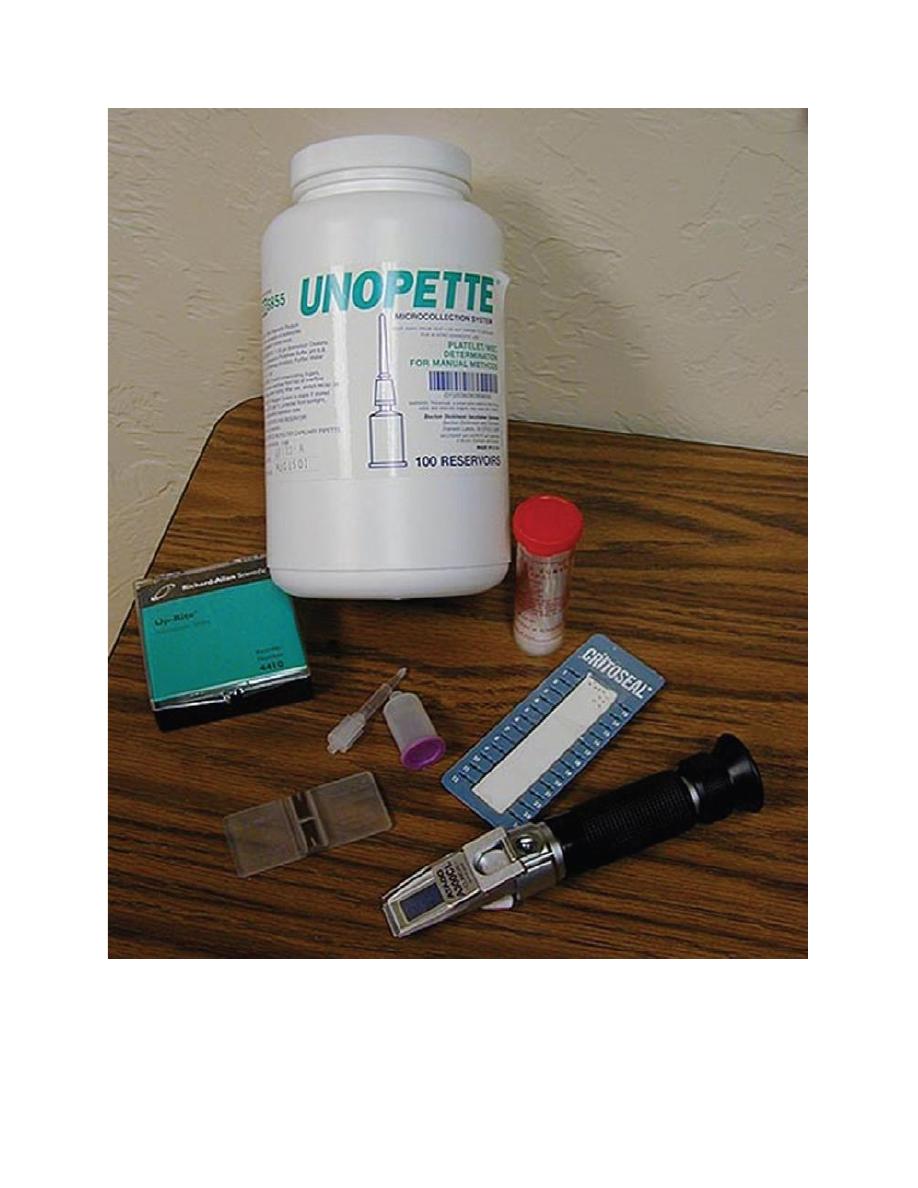

The CBC can be automated or performed manually. The necessary items for a

manual CBC are shown in Figure 2.1. Because it can be difficult to fully

interpret the results of a CBC without a total protein, this measurement should

be included as an important component of the CBC. The total protein can be

measured by refractometer or by an in-house chemistry instrument.

Figure 2.1. (a) Hemocytometer. (b) Refractometer. (c) Microhematocrit tube sealant. (d)

Unopette system diluent reservoir and pipette. (e) Microscope slides. (f) Microhematocrit tubes.

(g) Unopette WBC counting system.

SAMPLE COLLECTION AND HANDLING

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)

is the preferred

anticoagulant

for complete

blood count (CBC) determination in most species, but blood from some

birds, fishes

and

reptiles

hemolyzes when collected into EDTA.

In those species,

heparin

is often used as anticoagulant.

The disadvantage of heparin is that leukocytes do not stain as well (presumably

because heparin binds to leukocytes),24 and platelets generally clump more than

they do in blood collected with EDTA.

However, as discussed later, platelet aggregates and leukocyte aggregates may occur

even in properly collected EDTA-anticoagulated blood

samples.

In those cases, collection of blood using another anticoagulant (e.g.,

citrate

) may prevent the formation of cell aggregates.

Cell aggregation tends to be more pronounced as blood is cooled and

stored; consequently processing samples as rapidly as possible after

collection may minimize the formation of leukocyte and/or platelet

aggregates.

Collection of blood directly into a

vacuum tube

is preferred to collection

of blood by syringe and transfer to a vacuum tube.

This method reduces platelet clumping and clot formation in samples for CBC

determinations, as even small clots render a sample unusable. Platelet counts are

markedly reduced, and a significant reduction can sometimes occur in hematocrit

(HCT) and leukocyte counts as well.

Also, when the tube is allowed to fill based on the vacuum within the tube, the proper

sample-to-anticoagulant ratio will be present.

Inadequate sample size results in decreased HCT due to excessive EDTA solution.

care should be taken to avoid iatrogenic hemolysis, which interferes with plasma

protein, fibrinogen, and various erythrocyte measurements.

Samples should be submitted to the laboratory as

rapidly

as possible, and

blood films

should be made as soon as possible

and rapidly dried

to minimize morphologic

changes.

GROSS EXAMINATION OF BLOOD SAMPLES

Samples are checked for clots and mixed well (gently inverted 20 times)

immediately before removing aliquots for hematology procedures.

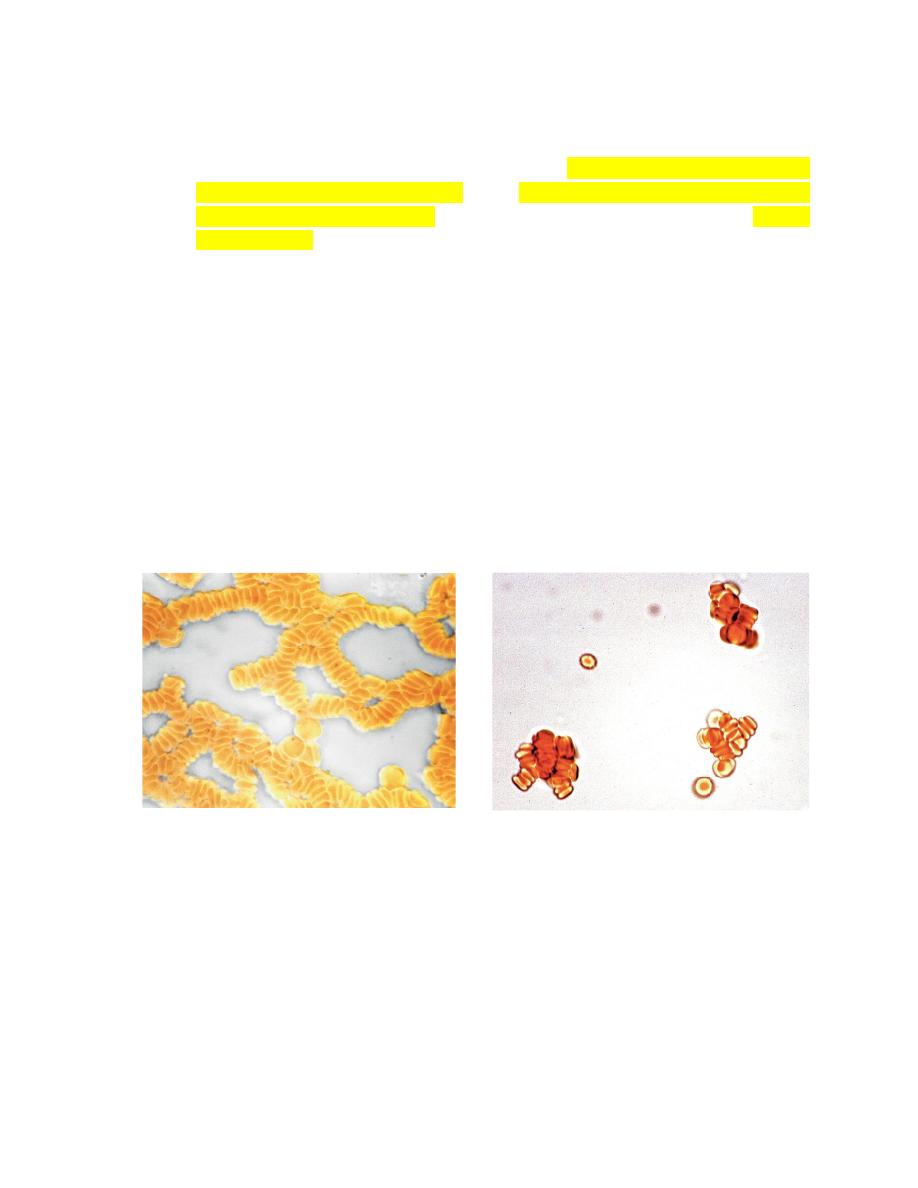

Horse erythrocytes settle especially rapidly because of

rouleaux formation

(adhesion of erythrocytes together like a stack of coins).

Blood should be examined grossly for color and evidence of erythrocyte

agglutination.

The presence of marked lipemia may result in a blood sample with a milky red

color resembling “tomato soup” when oxygenated.

Erythrocyte Agglutination

The appearance of red granules in a well-mixed

blood sample.

However, it is important to differentiate

agglutination (aggregation of

erythrocytes together in clusters

) from

rouleaux (adherence of erythrocytes

together like a stack of coins

), which can be seen in the blood from healthy

horses and cats(Fig. 2-6).

Rouleaux formation is eliminated by

washing erythrocytes in physiologic saline,

but agglutination is not.

This differentiation requires centrifugation of blood, removal of plasma, and

resuspension of erythrocytes in saline.

A rapid way to differentiate rouleaux from agglutination is to mix five drops of

physiologic saline with a drop of anticoagulated blood on a glass slide and

examine it as a wet mount using a microscope. This dilution reduces rouleaux,

but agglutination is not affected.

The microscopic appearance of agglutination in a sample of washed

erythrocytes is shown (Fig. 2-7).

The presence of agglutination indicates that the erythrocytes have increased

surface-bound immunoglobulins.

FIGURE 2-

6: Microscopic rouleaux in an unstained wet mount FIGURE 2-7: Microscopic agglutination in an unstained wet

The Hemogram

The

hemogram

is the collection of

specific measurements

that allow the veterinarian to evaluate

a patient’s erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets. The portion of the hemogram that contains the

parameters that assess erythrocytes is the

erythrogram

and the portion that relates to the

leukocytes is the

leukogram

. Platelet parameters are often reported with the

erythrogram

.

Most

automated cell counters

will provide the following measurements:

Red cell count measured in cells/μL

Hematocrit (Hct) measured in percent (%)

Mean cell volume (MCV) measured in femtoliters (fl)

Hemoglobin (Hgb) measured in g/dL

Mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) measured in g/dL

Mean cell hemoglobin (MCH) measured in pg

Platelets numbers in cells/μL

White blood cell count in cells/μL

Leukocyte differential cell counts (DLC) in percents (%) and absolute numbers in

cells/μL

The Erythrogram

The three erythrocyte parameters in the erythrogram that are directly measured by most

in-clinic hematology instruments are:

Hemoglobin Hb

red cell count TRBC

red cell volume MCV.

The remaining red cell parameters—MCHC, Hct, and MCH—are calculated from the

measured values. As a result, if there are artifactual changes in the measured values, the

calculated values will be erroneous.

Each of these measurements can help identify and characterize the anemic patient.

The definition of

anemia

is decreased circulating erythrocytes. Therefore, an anemic

patient

will have decreased erythrocyte count, decreased Hct, and decreased Hgb

. There

are occasions in which all three of these measurements are not decreased. When this

happens, an investigation into why this discordance is present should be done. To

understand how discordant values occur, the technician must understand how these

measurements are made.

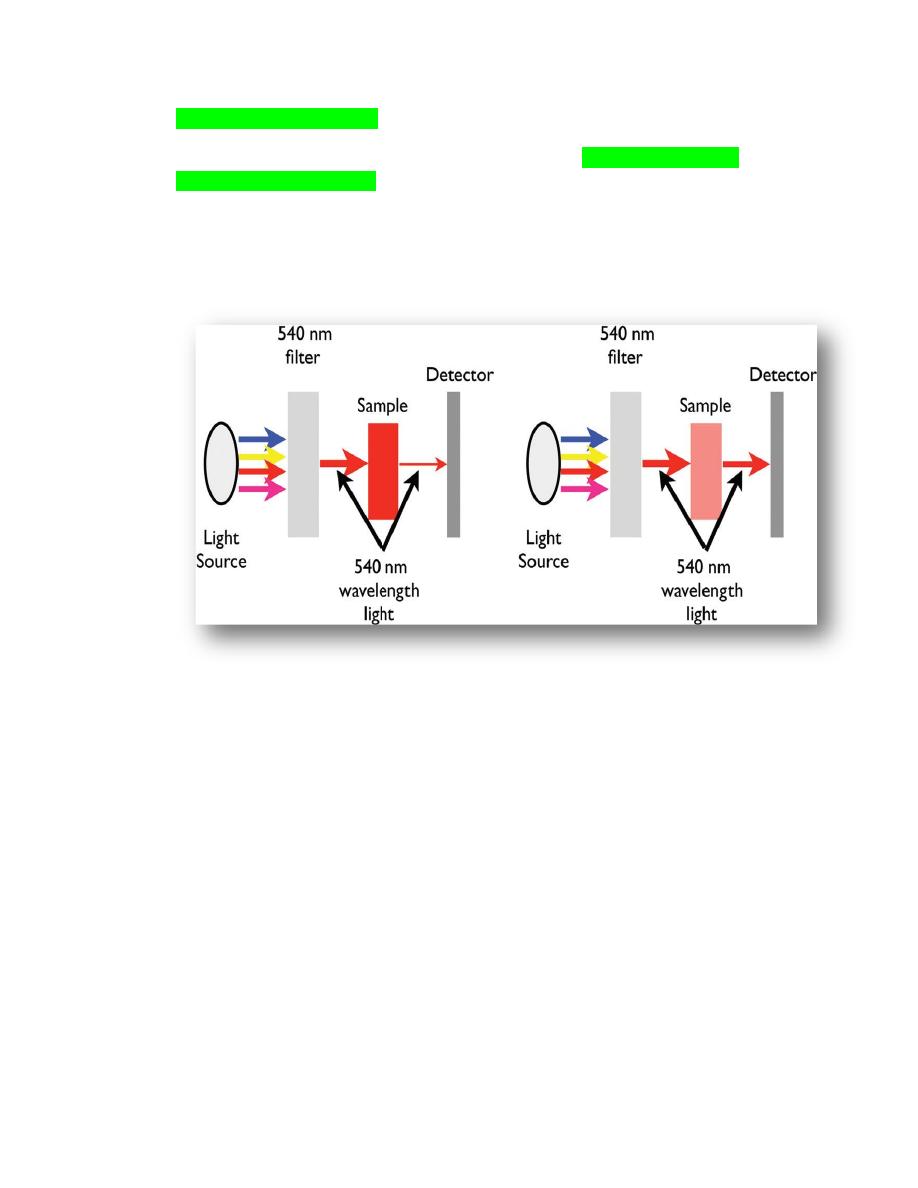

Hemoglobin measurement

The majority of in-house hematology instruments measure hemoglobin using a

spectrophotometric method. When this method is used, a fixed amount of blood is

diluted in

a lysing solution

to release the hemoglobin from the erythrocytes. Then, a

light of a specific

wavelength (540 nanometers)

is passed through the fluid containing

the released hemoglobin, and the amount that is transmitted to the photocell on the side

of the fluid is measured (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2.

The components of a simple

spectrophotometer. The filter allows one wavelength from

the light source to pass through, 540 nm in the case of hemoglobin measurement. The hemoglobin in the

sample will absorb the light in proportion to the amount of hemoglobin. The more hemoglobin in the

sample, the less light will pass through to the detector. Anything that will interfere with light passing

through a solution will erroneously increase the instruments measurement of hemoglobin. (a) The

sample has a high concentration of hemoglobin, absorbs a large amount of the 540 nm wavelength and,

therefore, a small amount of the light passes through the sample for detection. (b) This sample has a low

concentration of hemoglobin and, therefore, a large amount of the light passes through the sample for

detection.

The amount of hemoglobin present is inversely proportional to the amount of light that

is transmitted. The less light that passes through the fluid, the more hemoglobin will be

measured in the fluid. Therefore, anything that will decrease the amount of light that

can pass through the fluid or scatters light as it passes through the fluid will cause an

artifactual increase in the hemoglobin measurement. Artifactual changes in the

measurement of hemoglobin will directly affect the calculation of MCHC and MCH

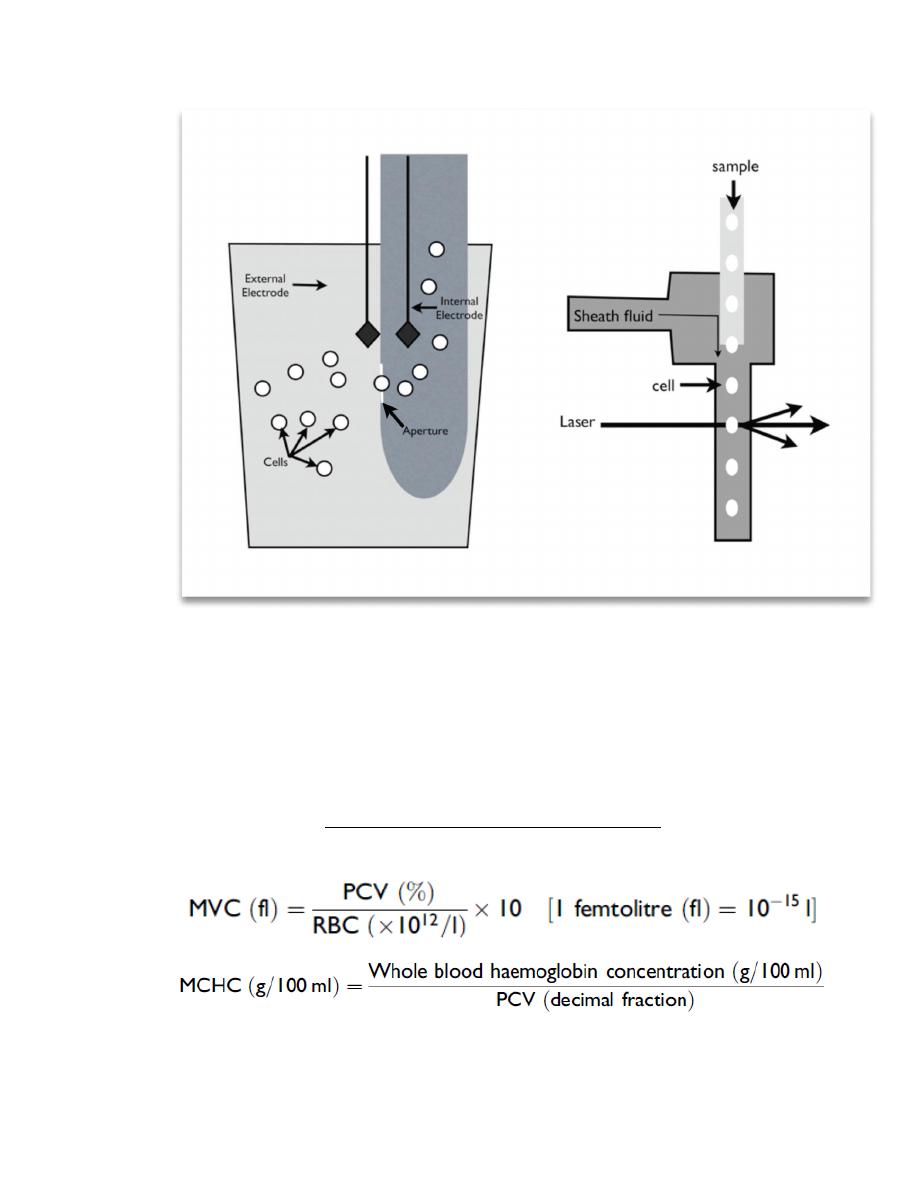

Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3. Schematic of an impedance counter (a) and a laser counter (b). (a) In the impedance counter,

an electrical current is created across a small opening (the aperture) by the external and internal

electrodes. As the cells are aspirated through the aperture, they disrupt the current in proportion to the

size of the cell. As a result, both the number and size of the cells are measured. (b) In the laser counter,

cells flow through a channel in single file and pass through a single beam of focused light. The light is

scattered to a different degree by the different types of cells.

The red cell count is a direct count of individual cells as they pass through an electrical

field (impedance) or a flow cell (laser counters). Erroneous red cell counts will affect

the Hct and MCH. The MCV is a direct measurement of cell size that is related to the

magnitude of the d measurement of theMCVwill affect the Hct and MCHC.

MICROHEMATOCRIT TUBE

EVALUATION (PCV measurement):

A microhematocrit tube is filled to about 90% of capacity with well-mixed blood and

sealed with clay at one end.

The tube is then placed in a microhematocrit centrifuge with the clay plug oriented to

the periphery of the centrifuge head and centrifuged for 5 minutes.

After centrifugation, the blood sample will be separated into three layers based on

density, with

packed erythrocytes

located at the bottom.

A white

“buffy coat”

is located above the erythrocyte layer, and the acellular

plasma

is located above the buffy coat.

When blood is submitted for a CBC, most commercial laboratories determine an

electronic HCT rather than a packed cell volume (PCV) by centrifugation.

This efficiency negates the need to centrifuge a microhematocrit tube filled with blood.

Unfortunately useful information concerning the appearance of plasma is missed unless

a serum or plasma sample is also prepared for clinical chemistry tests.

Packed Cells

The PCV is measured after centrifugation by determining the fraction of total blood

volume in a microhematocrit tube that is occupied by erythrocytes.

Leukocytes and platelets are primarily located within the buffy coat, although certain

leukocyte types may be present in the top portion of the packed erythrocyte column in

some species (e.g., neutrophils in cattle).

The

width of the buffy coat

generally correlates directly with the

total leukocyte count

.

A

large buffy coat

suggests

leukocytosis

(Fig. 2-9, A) or

thrombocytosis

, and a small

buffy coat suggests that low numbers of these cells may be present.

The

buffy coat may appear reddish

owing to the presence of a marked

reticulocytosis.

The Appearance of Plasma

Plasma is normally clear in all species.

It is nearly colorless in small animals, pigs, and sheep but light yellow in horses because

they naturally have higher bilirubin concentrations.

Plasma varies from colorless to light yellow (carotenoid pigments) in cattle, depending

on their diet.

Increased yellow coloration usually indicates increased bilirubin concentration.

This increase often occurs secondarily to anorexia (fasting hyperbilirubinemia) in horses

owing to reduced removal of unconjugated bilirubin by the liver.

Yellow plasma with a normal HCT suggests hyperbilirubinemia secondary to liver

disease.

Hyperbilirubinemia associated with a marked decrease in the HCT suggests an increased

destruction of erythrocytes; however, the concomitant occurrence of liver disease and a

nonhemolytic anemia could produce a similar finding (Fig. 2-9, B).

Red discoloration of plasma indicates the presence of free hemoglobin. This discoloration

may represent either true hemoglobinemia, resulting from intravascular hemolysis, or

hemolysis occurring after sample collection due to such causes as rough handling, fragile

cells, lipemia, or prolonged storage (Fig. 2-9, C,D).

The HCT value may help differentiate between these two possibilities, with red plasma

and a normal HCT suggesting in vitro hemolysis.

The concomitant occurrence of hemoglobinuria indicates that intravascular hemolysis has

occurred.

Plasma will also appear red following treatment with cross-linked hemoglobin blood

substitute solutions.

Lipemia is recognized as a white opaque appearance in diabetes mellitus, pancreatitis,

hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism, protein-losing nephropathy, cholestasis, obesity,

and starvation may also contribute to the development of lipemia in dogs and cats.

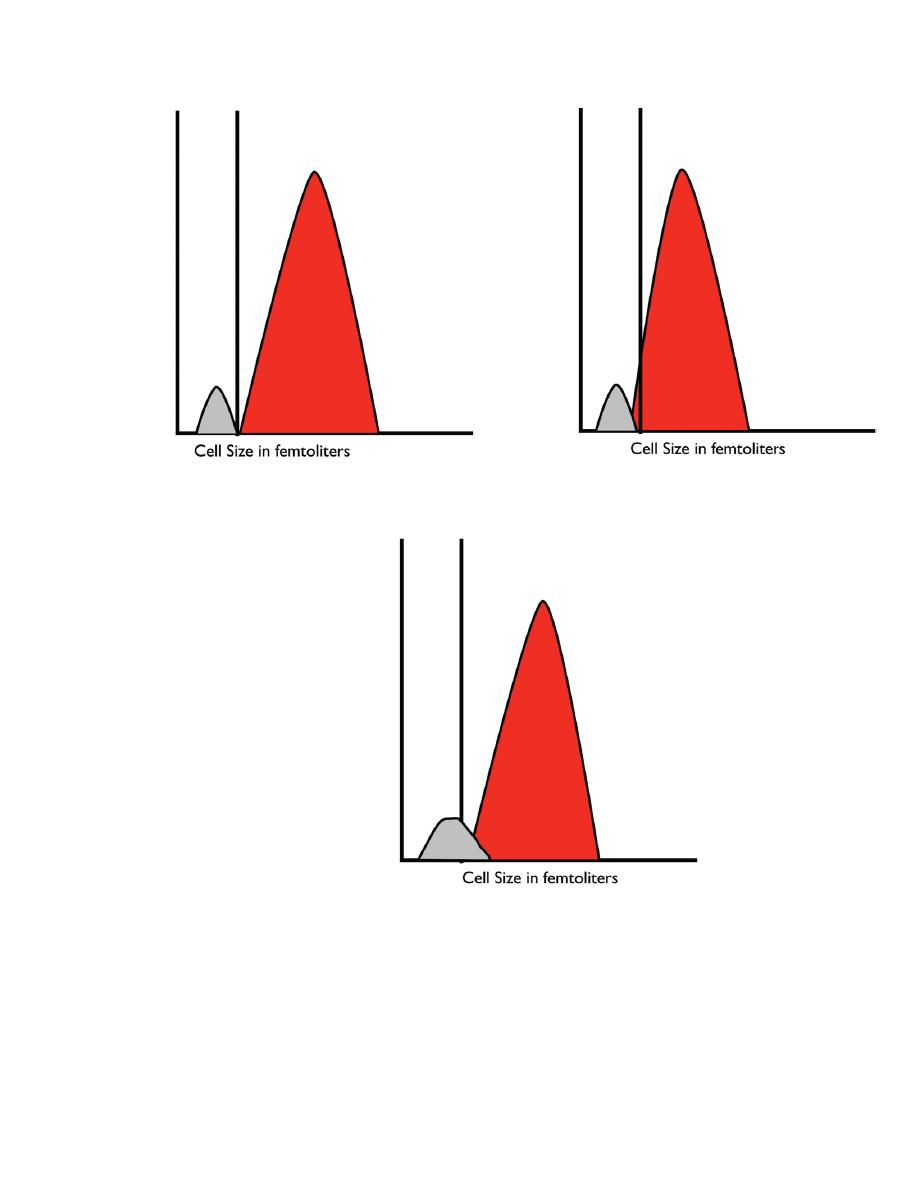

The

platelet count

is usually reported with the erythrogram. Platelets are directly

counted in most instruments. They are counted in the same cycle as the erythrocytes.

The two populations are separated by their size. In those instruments that use

impedance, a histogram (a distribution curve) shows the size difference between the

platelets and erythrocytes. The instrument must be able to identify a valley between (a)

(b) (c) Figure 2.4.

In some cases, large platelets (macroplatelets) may interfere with the count. Large

platelets are produced when platelets are being consumed. . Platelet clumps will also

interfere with the platelet count. Small clusters of platelets are lost in the red cell

population and, therefore, not counted as platelets. The larger clusters are not counted

at all. Evaluation of the blood film is necessary for identification of macroplatelets and

platelet clumps and interpretation of the platelet count.

The Leukogram

components of the leukogram:

The total white blood cell count,

leukocyte differential, absolute leukocyte counts,

Leukocyte morphology abnormalities.

Figure 2.4. Red blood cell and platelet histograms. (a) Normal histogram showing a

well-defined ―valley‖ between the platelets and the red blood cells. (b) Histogram from

an individual with small red blood cells that extend into the platelet size ranges, making

it difficult for the instrument to accurately count the platelets. (c) Histogram from an

individual with large platelets. In this case, the larger platelets will be counted as red

blood cells and an artifactually low platelet count will be reported. The two populations

to produce an accurate platelet count.

The Blood Film

The blood film is an essential part of the complete blood count (CBC). It

can be used as an internal control for the white blood cell count,

differential, and platelet count.

BLOOD-FILM PREPARATION:

Blood films should be prepared within a couple of hours of blood sample

collection to avoid artifactual changes that will distort the morphology of

blood cells.

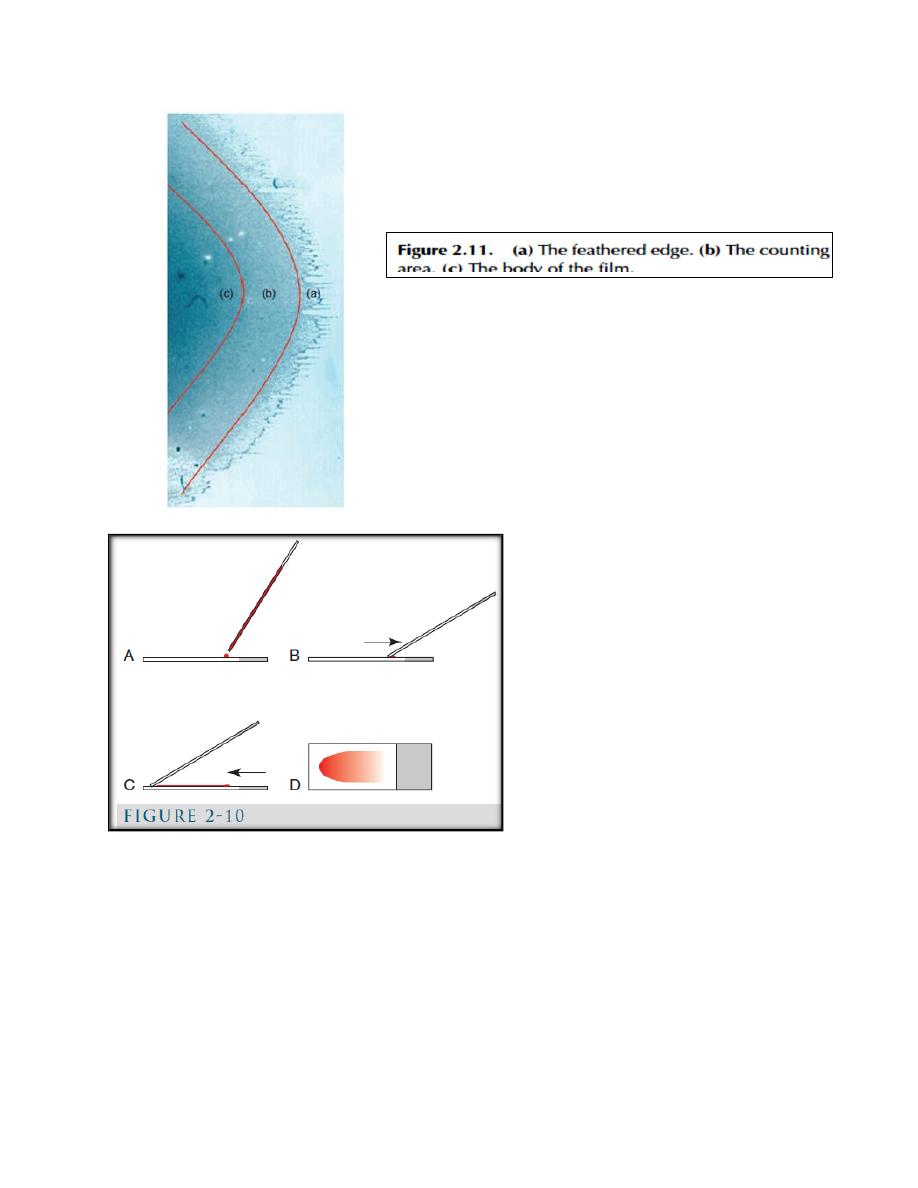

Blood films are prepared in various ways including

a. The Glass-Slide Blood-Film Method (Fig. 2-10).

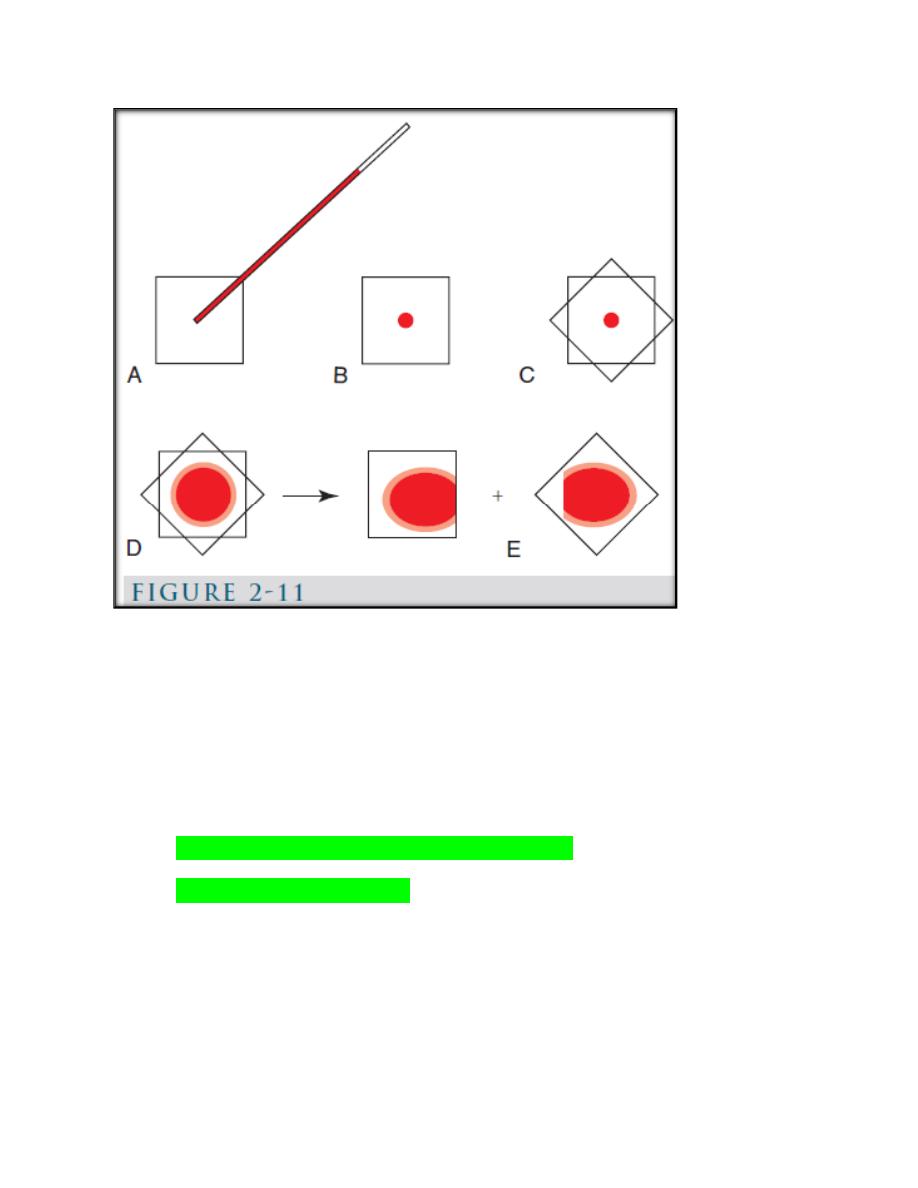

b. Coverslip method (Fig. 2-11).

c. Automated slide spinner method.

It is essential that a monolayer of intact cells is present on the slide

So that

accurate examination

and

differential leukocyte counts

can be

performed.

If blood films are too thick, cells will be shrunken and may be difficult to

identify.

If blood films are too thin, erythrocytes will be flattened and lose their

central pallor and some leukocytes (especially lymphocytes and blast cells)

will be ruptured.

A good uniform blood film is essential to the process of blood film

examination.

There is an

―anatomy‖ to the blood film

, and each part of the blood film is

used for a specific purpose.

(Fig. 2-10): A, a glass slide is placed on a flat surface and a small drop of well-

mixed blood is placed on one end of the slide using a microhematocrit tube. B, a

second glass slide (spreader slide) is placed on the first slide at about a 30-degree

angle in front of the drop of blood. The spreader slide is then backed into the drop

of blood. C, as soon as the blood flows along the back side of the spreader slide,

the spreader slide is rapidly pushed forward. D, the blood film produced is thick at

the back of the slide, where the drop of blood was placed, and thin at the front

(feathered) edge of the slide.

(Fig. 2-11): Coverslip blood film preparation. A, B, One clean coverslip is held

between the thumb and index finger of one hand and a small drop of blood is

placed in the middle of it using a microhematocrit tube. C, A second clean

coverslip is dropped on top of the first in a crosswise position. D, Blood spreads

evenly between the two coverslips and a feathered edge forms at the periphery. E,

the coverslips are rapidly separated by grasping an exposed corner of the top

coverslip with the other hand and pulling apart in a smooth, horizontal manner.

BLOOD-FILM STAINING PROCEDURES

Romanowsky-Type Stains

Blood films are routinely stained with a Romanowsky-type stain (e.g.,

Wright or Wright-Giemsa, Leishman, and Giemsa stain) either

manually or using an automatic slide stainer.

Romanowsky-type stains are composed of a mixture of eosin and

oxidized methylene blue (azure) dyes. The azure dyes stain acids,

resulting in blue to purple colors, and eosin stains bases, resulting in

red coloration.

These staining characteristics depend on the pH of the stains and the

rinse water as well as the nature of the cells present.

Low pH, inadequate staining time, degraded stains, or excessive

washing can result in excessively pink-staining blood films.

High pH, prolonged staining, or insufficient washing can result in

excessively bluestaining blood films.

Blood films should be

fixed in absolute methanol 1-2 minutes

within 4

hours (preferably within 1 hour) of preparation.

If the methanol contains more than 3% water, morphologic artifacts

including loss of cellular detail and vacuolation may be present.

Blood films may have an overall blue tint if stored unfixed for long

periods before staining or if the unfixed blood films are exposed to

formalin vapors, as occurs when blood films are shipped to the

laboratory in a package that also contains formalin-fixed tissue.

Blood films prepared from blood collected with heparin as the

anticoagulant have an overall magenta tint owing to the

mucopolysaccharides present.

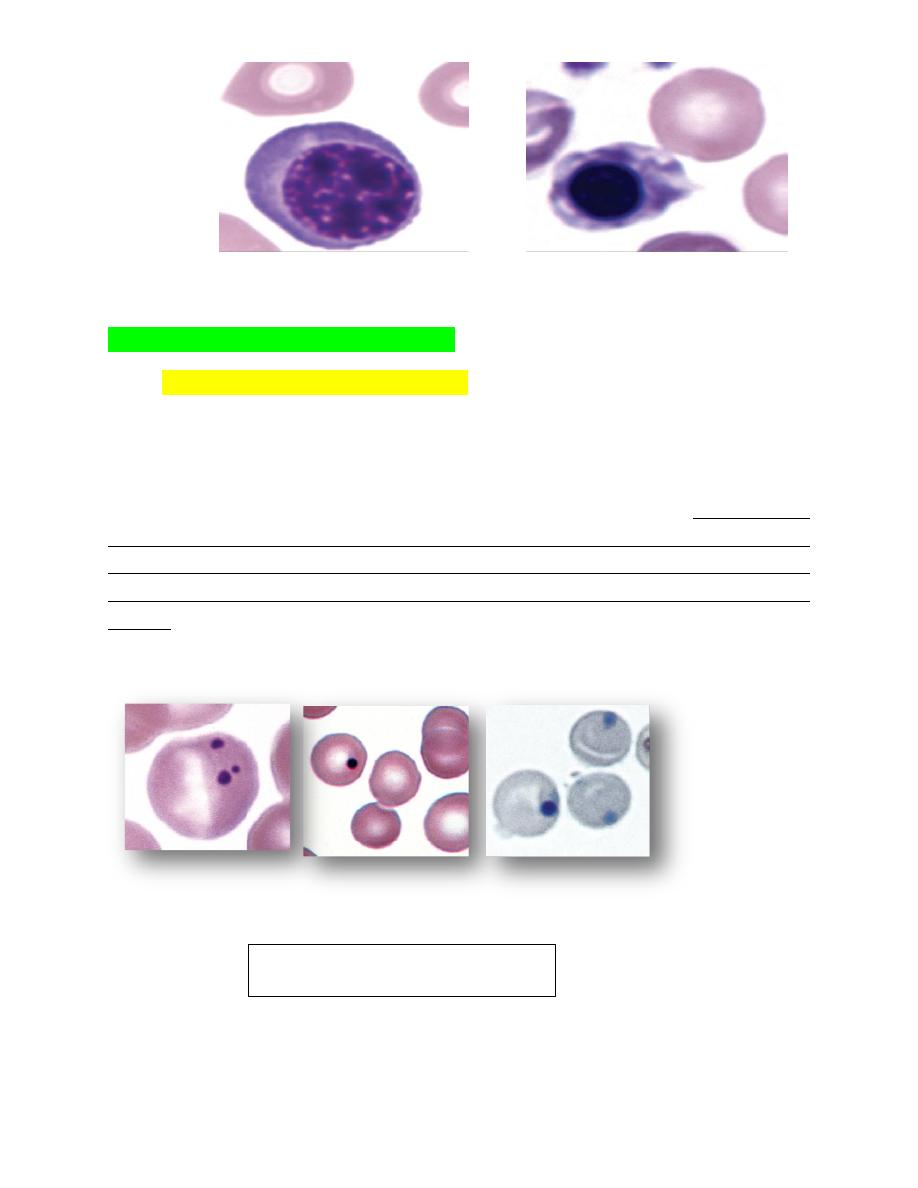

Reticulocyte Stains

Reticulocyte stains are commercially available

stain can do so by dissolving 0.5 g of new methylene blue and 1.6 g of

potassium oxalate in 100 mL of distilled water.

Following filtration, equal volumes of blood and stain are mixed

together in a test tube and incubated at room temperature for 10 to 20

minutes.

After incubation, blood films are made and

reticulocyte counts

performed by examining 1000 erythrocytes and determining the

percentage that are reticulocytes.

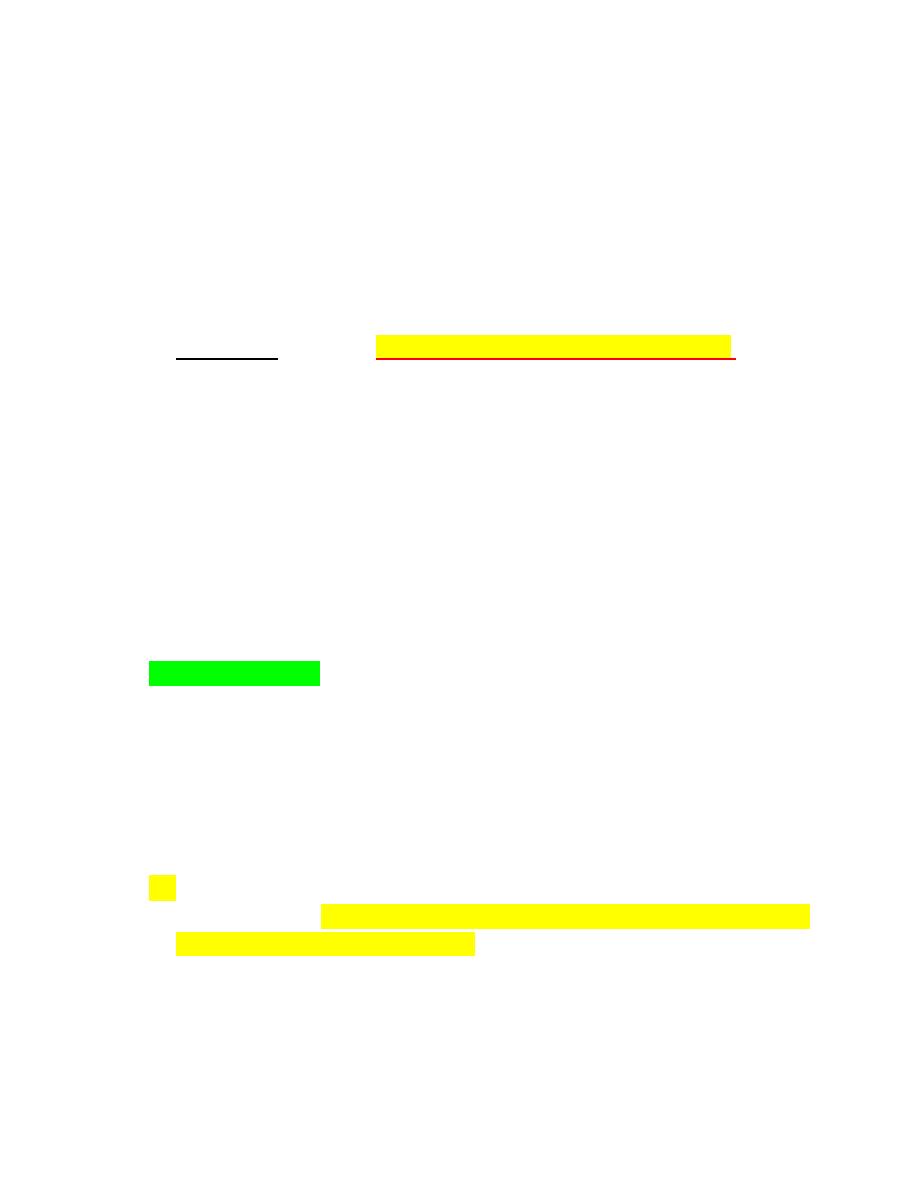

The blue-staining aggregates or “reticulum” seen in reticulocytes (Fig.

2-17) does not occur as such in living cells but results from the

precipitation of ribosomal ribonucleic acid (RNA; the same RNA that

causes the bluish color seen in polychromatophilic erythrocytes) in

immature erythrocytes during the staining process.

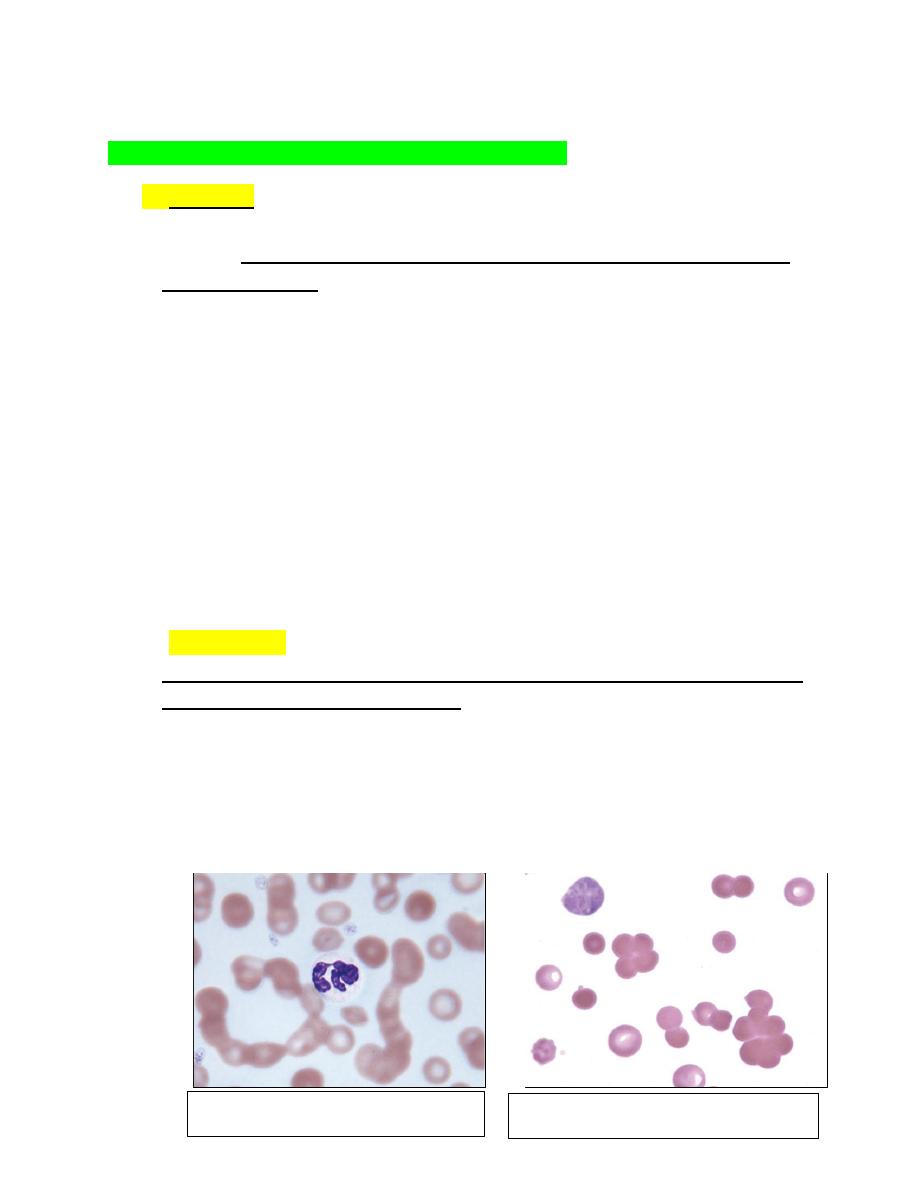

FIGURE 2-17 Reticulocytes in cat blood. with a markedly regenerative FIGURE 2-18 Reticulocytes in the blood of a dog.

Anemia. New methylene blue reticulocyte stain.

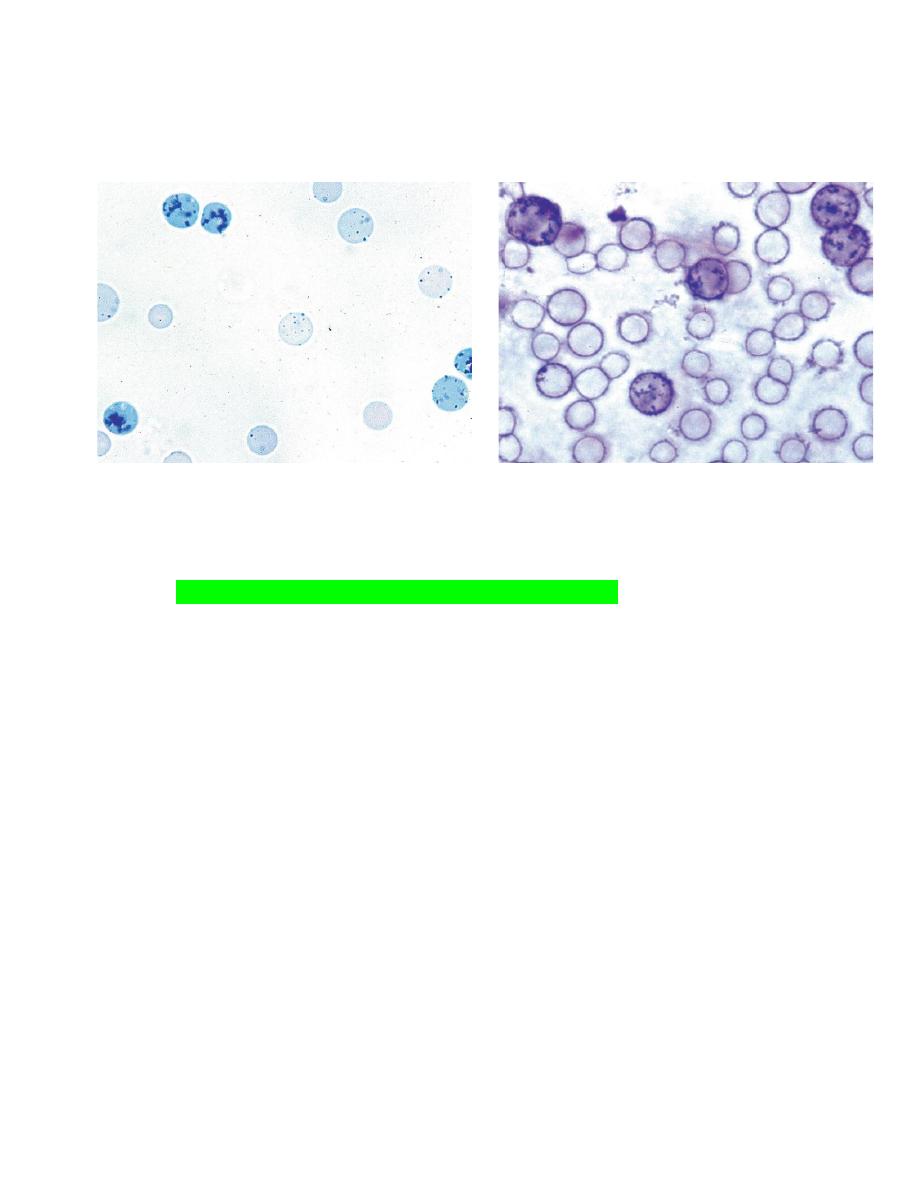

EXAMINATION OF STAINED BLOOD FILMS

Blood films are generally examined following staining with Romanowsky-

type stains such as Wright or Wright-Giemsa.

These stains allow for the examination of erythrocyte, leukocyte, and

platelet morphology.

Blood films should first be scanned using a low power objective to

estimate the total leukocyte count and to look for the presence of

erythrocyte autoagglutination (Fig. 2-21), leukocyte aggregates (Fig. 2-22),

platelet aggregates (Fig. 2-23), microfilaria (Fig. 2-24), and abnormal cells

that might be missed during the differential leukocyte count.

It is particularly important that the feathered end of blood films made on

glass slides be examined.

FIGURE 2-21Autoagglutination of erythrocytes FIGURE 2-22 Leukocyte aggregate in blood

FIGURE 2-23

Platelet aggregate in blood from a cow. FIGURE 2-24 Dirofilaria immitis microfilaria

The total leukocyte count in blood (cells per microliter) may be estimated

by determining the average number of leukocytes present per field and

multiplying by 100 to 150.

A differential leukocyte count is done by identifying 100- 200

consecutive leukocytes using a 40× or 50× objective.

Platelet numbers may be estimated by multiplying the average number

per field by 15,000 to 20,000 to get the approximate number of platelets

per microliter of blood.

After the count is complete,

the percentage of each leukocyte type

present is calculated and

multiplied by the total leukocyte count

to get the

absolute number

of each cell type present per microliter of blood.

It is the absolute number of each leukocyte type that is important. relative

values (percentages) can be misleading when the total leukocyte count is

abnormal.

Let us consider two dogs, one with 7% lymphocytes and a total leukocyte

count of 40,000/μL and the other with 70% lymphocytes and a total

leukocyte count of 4000/μL. The first would be said to have a

―relative

‖

lymphopenia

and the second would be said to have a

―relative

‖

lymphocytosis

, but they would both have the same normal absolute

lymphocyte count (2800/μL).

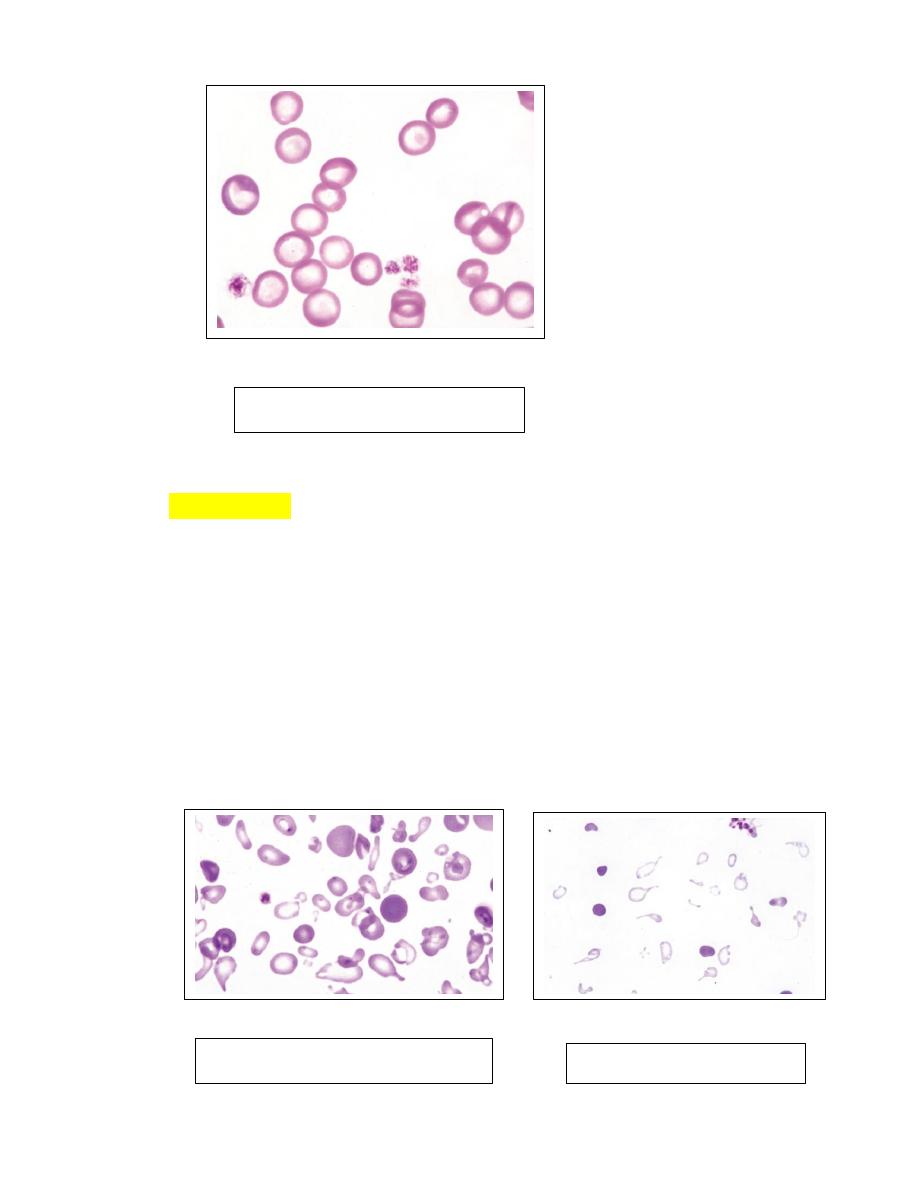

Erythrocyte Morphology

Erythrocyte morphology should be examined and recorded as either

normal or abnormal

.

Erythrocytes on blood films from normal horses, cats, and pigs often

exhibit

rouleaux formation

FIGURE 4-3

; those from normal horses and

cats may contain a low percentage of

small, spherical nuclear remnants

called Howell-Jolly bodies.

Rouleaux and

the

presence of Howell-Jolly bodies should be recorded on

the hematology form when they appear in blood films from species in

which these are not normal findings.

Additional observations regarding erythrocyte morphology, such as the

degree of

polychromasia (presence of polychromatophilic erythrocytes),

anisocytosis (variation in erythrocytes size), and poikilocytosis

(abnormal shape of erythrocytes) should also be made.

Polychromatophilic erythrocytes are reticulocytes that stain bluish-red

because of the combined presence of hemoglobin (red-staining) and

ribosomes (blue-staining).

Abnormal erythrocyte shapes should be classified as specifically as

possible, because specific shape abnormalities can help to determine the

nature of a disorder that may be present.

Examples of

abnormal erythrocyte morphology

include echinocytes,

acanthocytes, schistocytes, keratocytes, dacryocytes, elliptocytes,

eccentrocytes, and spherocytes.

Infectious Agents or Inclusions of Blood Cells

Blood films are examined for the presence of infectious agents or

intracellular inclusions using the 100× objective.

Infectious agents or inclusions that may be seen in blood cells include

Howell-Jolly bodies, Heinz bodies (unstained), basophilic stippling,

canine distemper inclusions, siderotic inclusions, Döhle bodies,

Babesia species, Cytauxzoon felis, hemotrophic Mycoplasma

(formerly Haemobartonella) species, Ehrlichia species, Anaplasma

species, Hepatozoon species, and Theileria species.

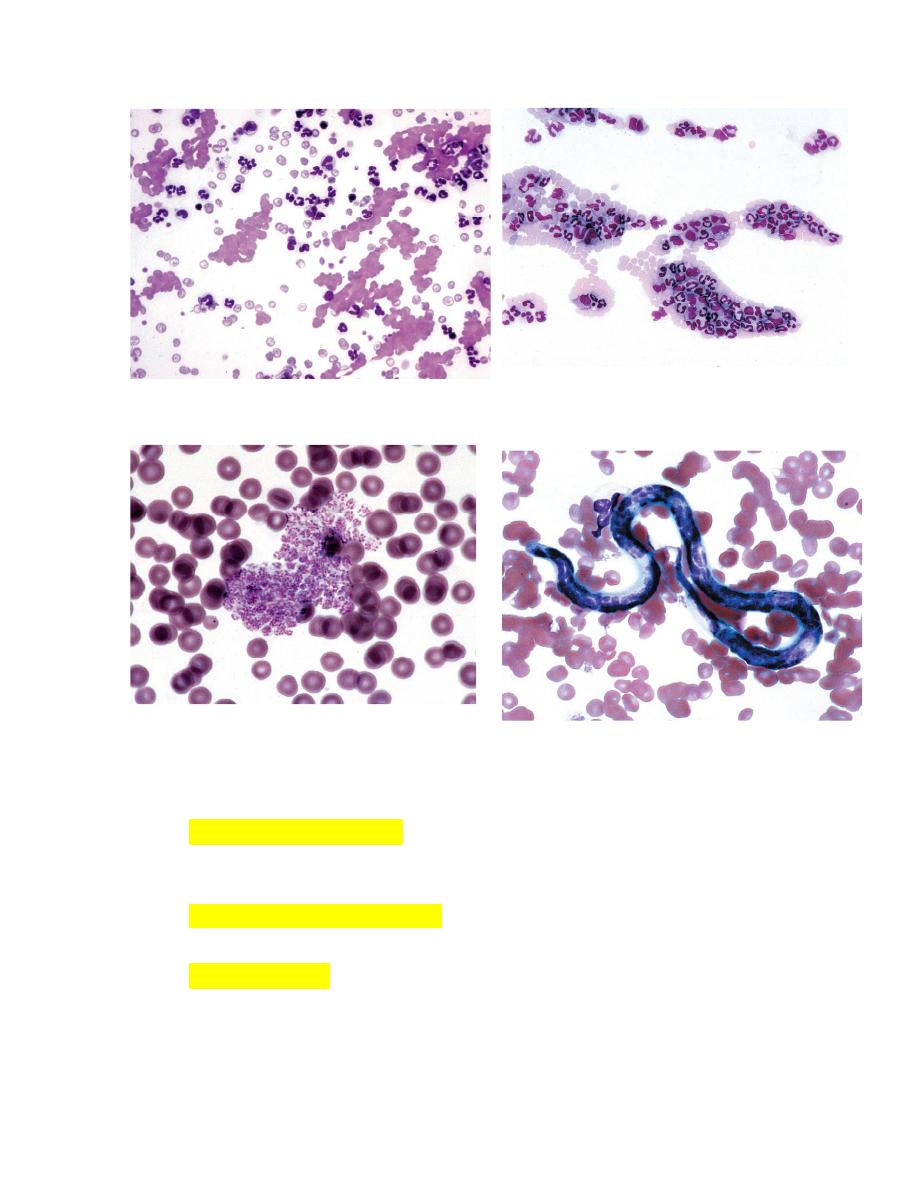

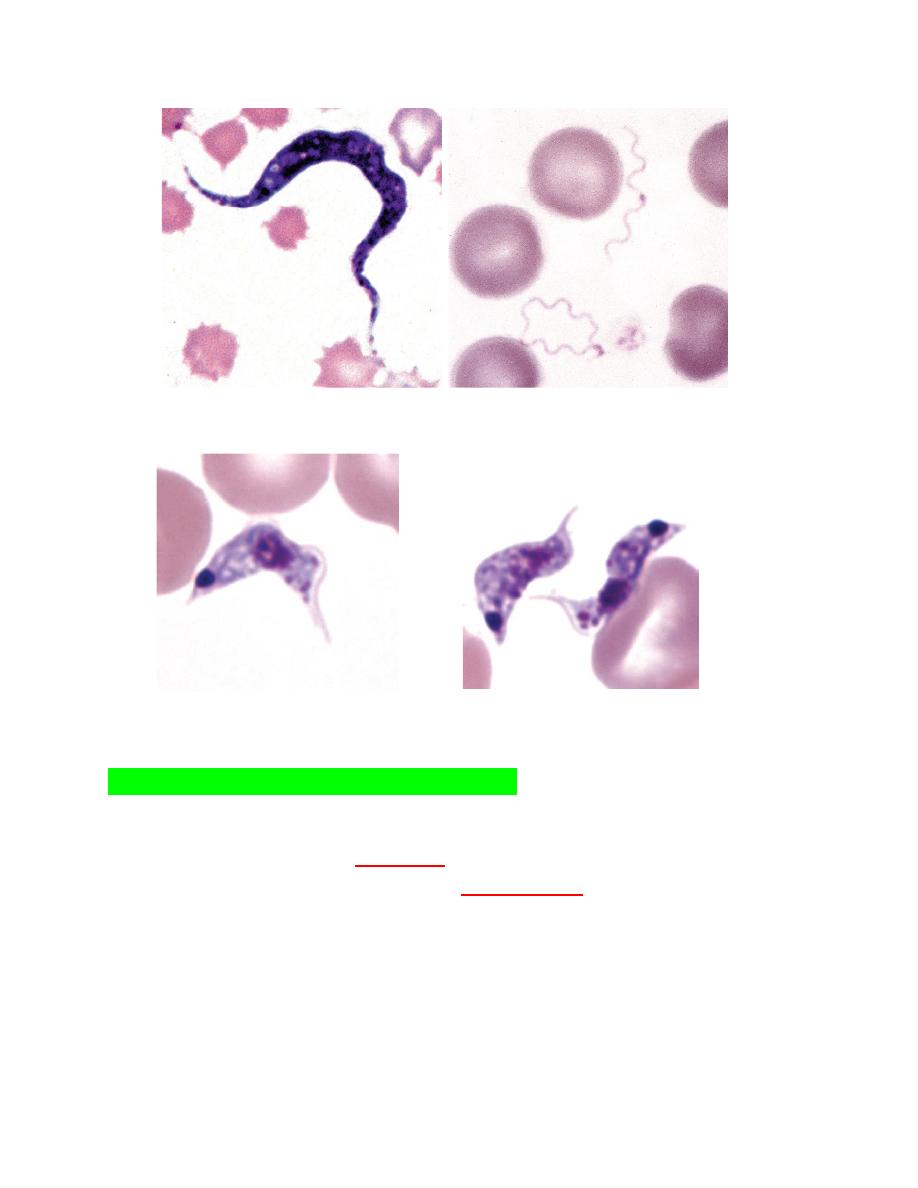

Microfilariae (nematode larvae)

that might be observed include

Dirofilaria immitis (see Fig. 2-24) and Dirofilaria repens in dogs,

cats, and wild canids, Dipetalonema reconditum in dogs, and Setaria

species in cattle and horses.

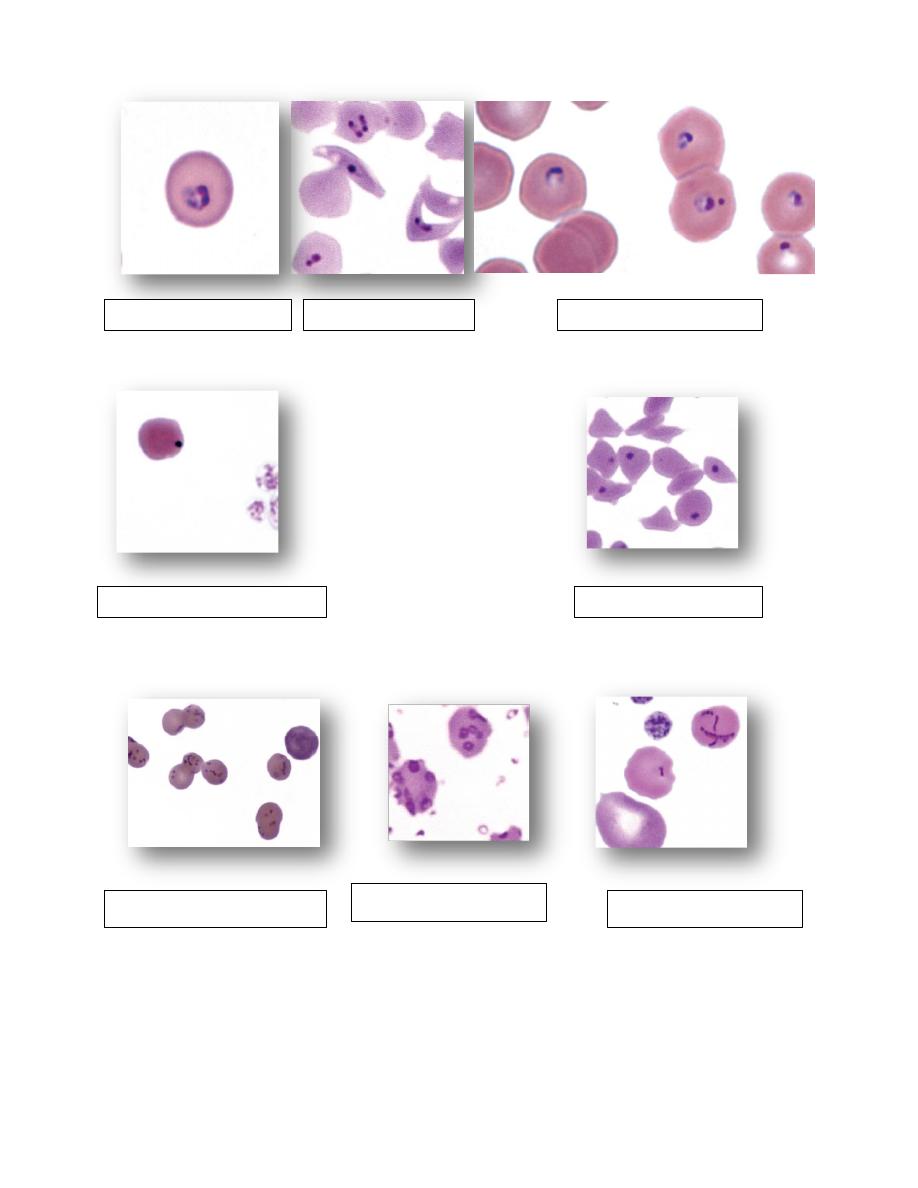

Various

Trypanosoma species

may be seen in blood. These elongated,

flagellated protozoa cause important diseases of livestockbut the

species seen in cattle (T. theileri) (Fig. 2-36). Many dogs are infected

with T. cruzi in the United States, but organisms are rarely seen in

blood and most cases are subclinical (Fig. 2-37). When present,

clinical forms of disease have principally involved heart or neural

dysfunction.

Various

bacterial species

may be present in blood films. It is

important to verify that these are not contaminants, especially

during the staining procedure. The presence of phagocytized

bacteria

within neutrophils indicates that the bacteria are likely of clinical

significance. Spirochetes have been seen in blood from dogs with

Borrelia infections

.

FIGURE 2-36Trypanosoma theileri FIGURE 2-38 Two Borrelia spirochetes

FIGURE 2-37 A, B, Trypanosoma cruzi

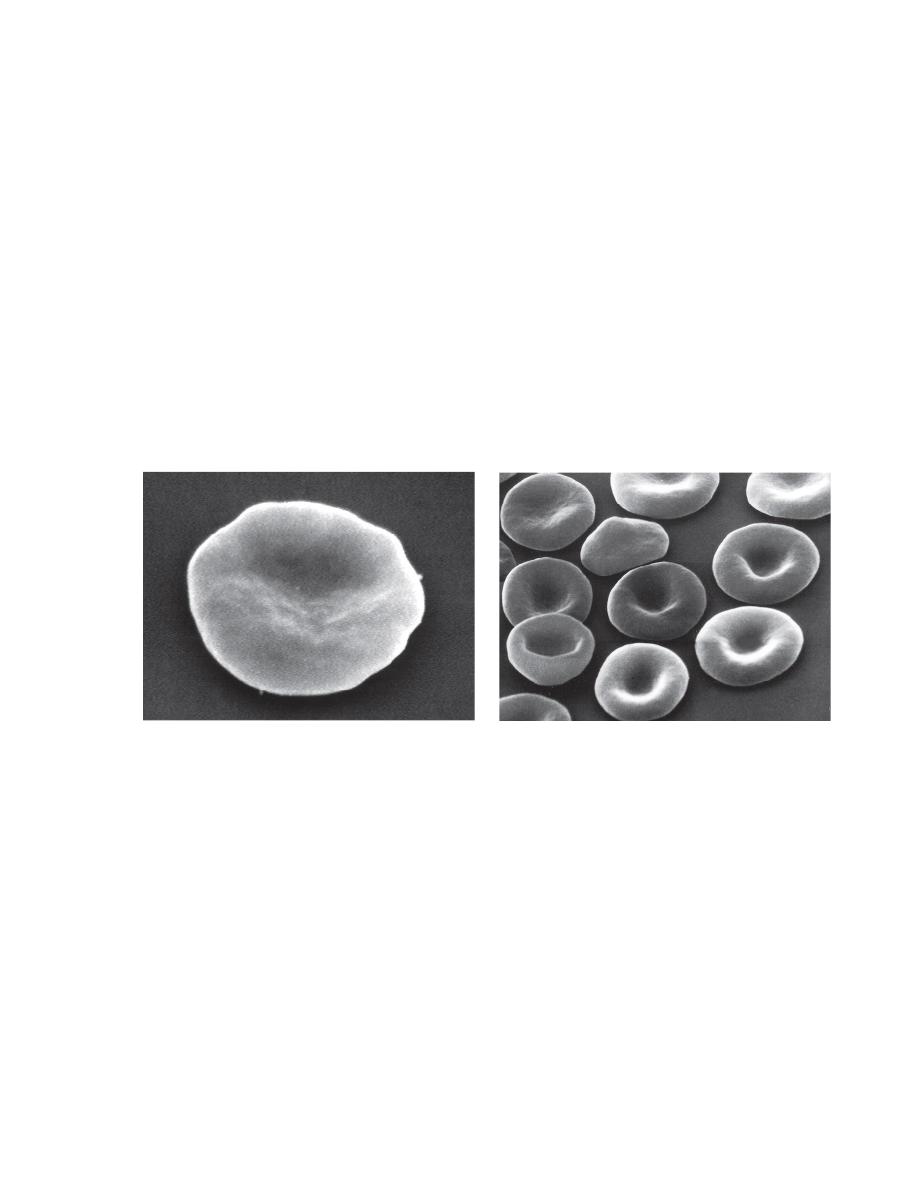

NORMAL ERYTHROCYTES

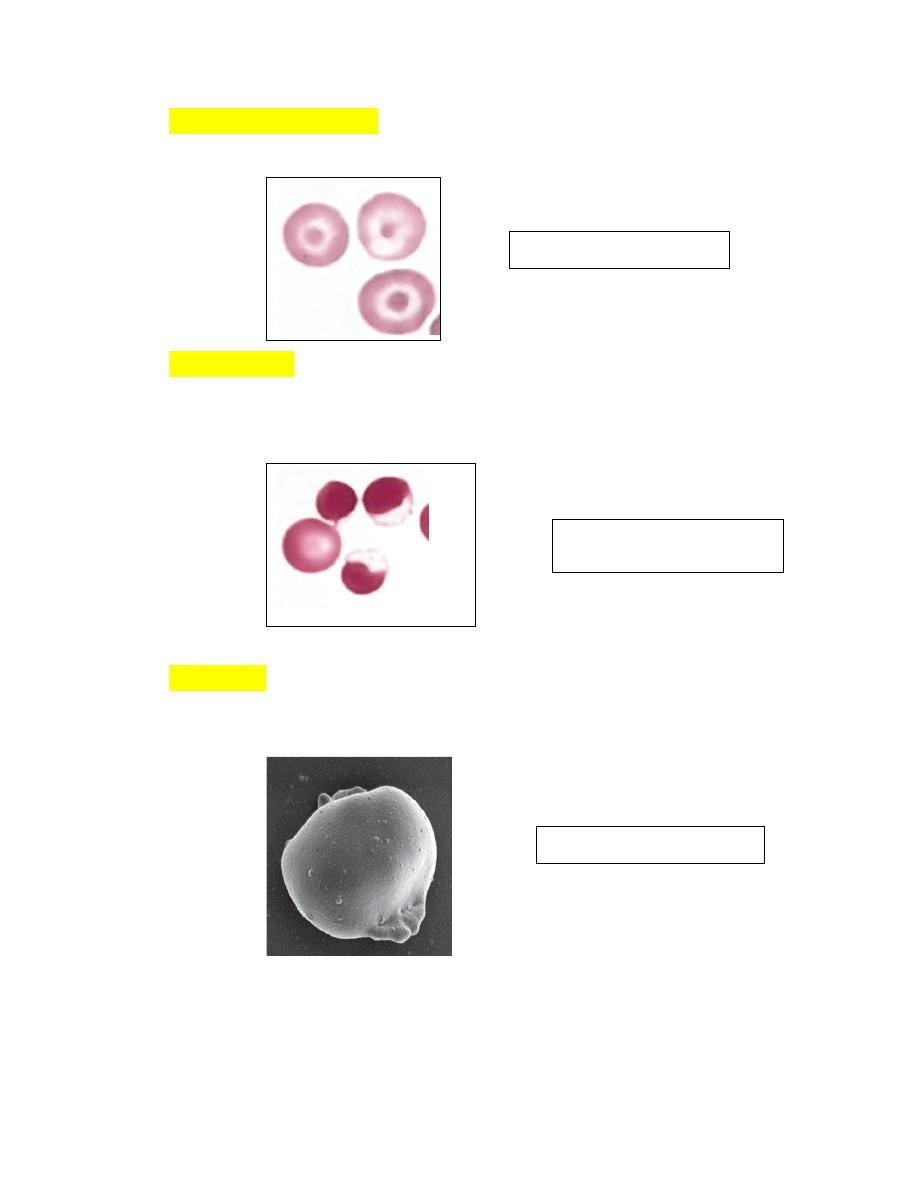

Morphology

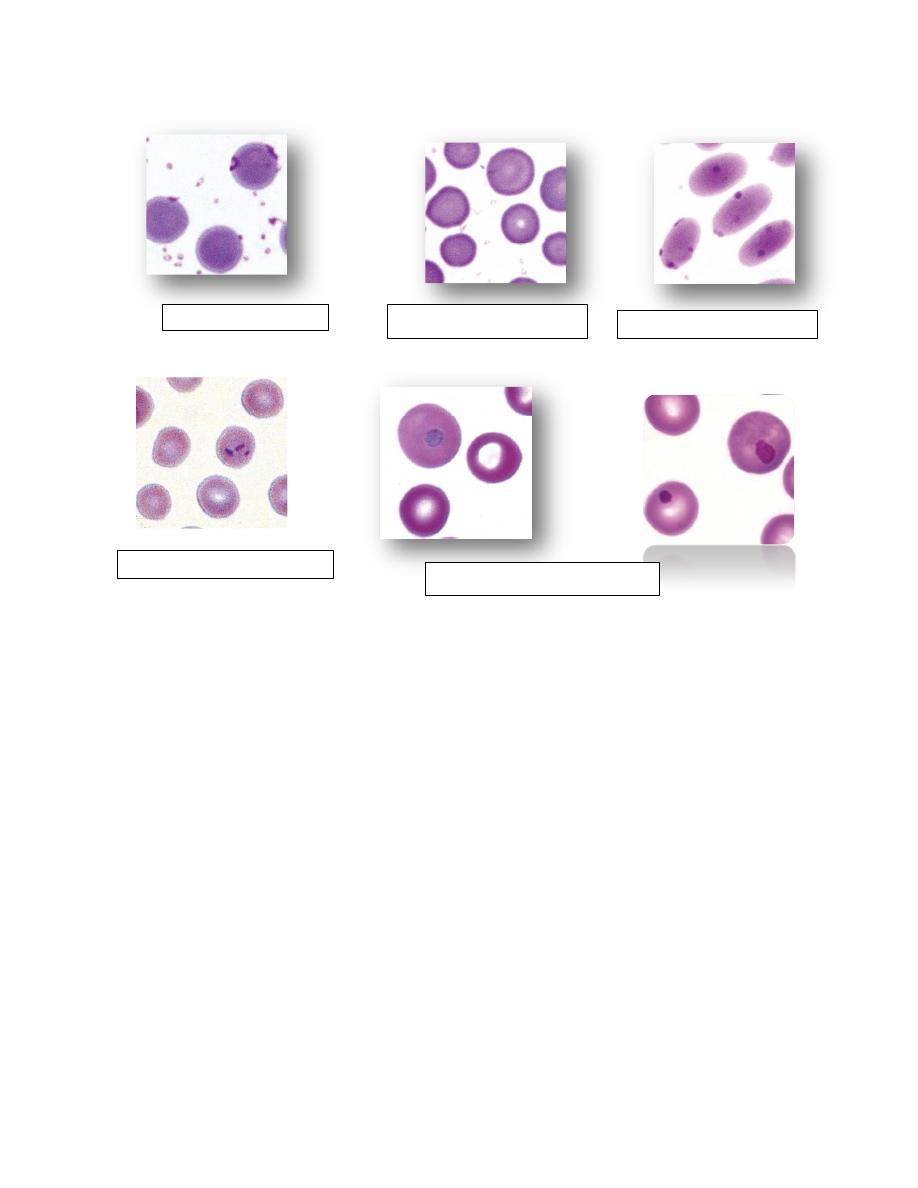

Erythrocytes from all mammals are anucleated, and most are in the shape of

biconcave discs called

discocytes

(Figs. 4-1, 4-2).

The biconcave shape results in the

central pallor

of erythrocytes observed

in stained blood films.

Among common domestic animals, biconcavity and central pallor are most

pronounced in dogs (Figs. 4-5), which also have the largest rythrocytes.

Other species do not consistently exhibit central pallor in erythrocytes on

stained blood films. The apparent benefit of the biconcave shape is that it

gives erythrocytes high surface area volume ratios and allows for

deformations that must take place as they circulate.

Erythrocytes from

goats

generally have a

flat surface

with little surface

depression; a variety of irregularly

shaped erythrocytes (poikilocytes

) may

be present in clinically normal goats (Fig. 4-4).

Erythrocytes from animals in the Camelidae family (camels, llamas, vicuñas,

and alpacas) are anucleated, thin, elliptical cells termed elliptocytes or

valocytes (Fig. 4-6). They are not biconcave in shape and are minimally

deformable.

Erythrocytes from birds (Fig. 4-7), reptiles, and amphibians are also

elliptical in shape, but they contain nuclei and are larger than mammalian

erythrocytes.

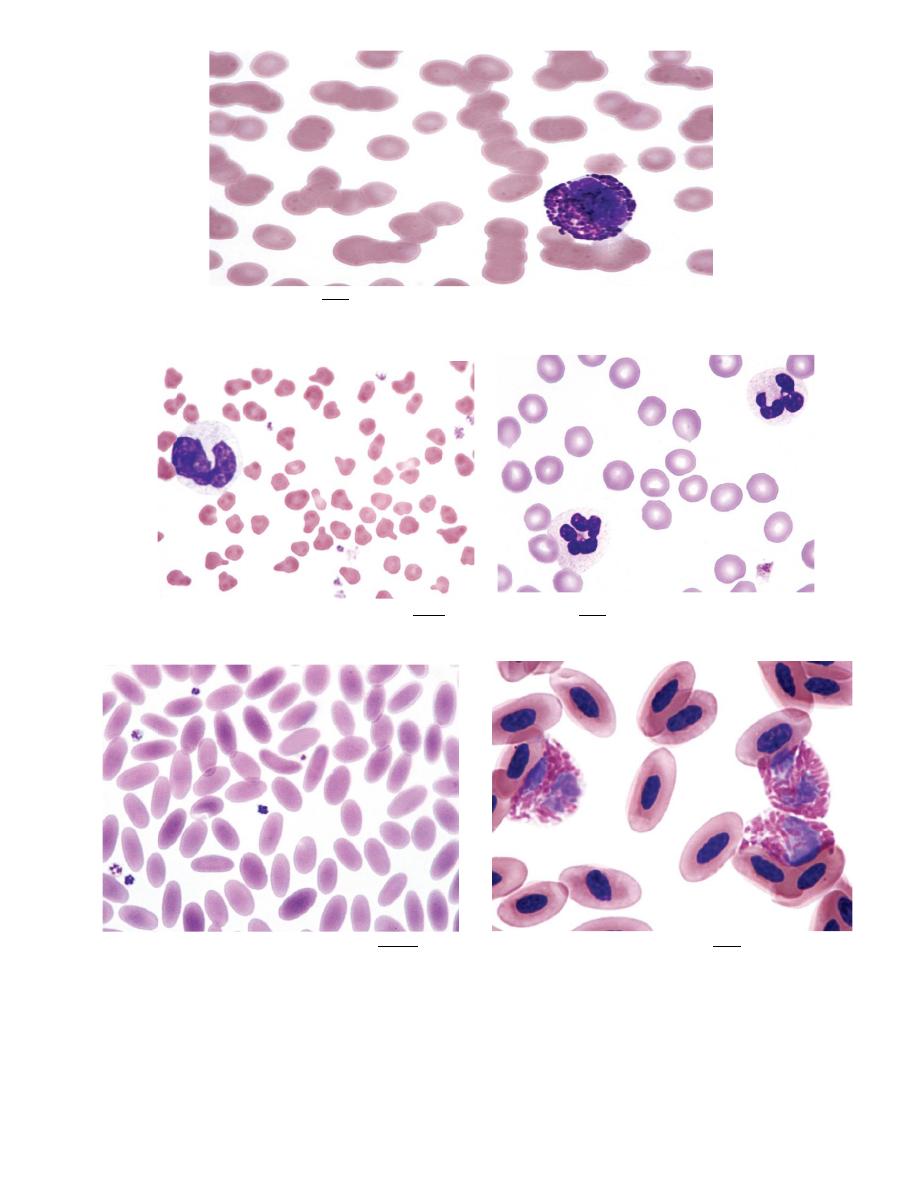

FIGURE 4-1 Scanning electron photomicrograph of a normal FIGURE 4-2 Scanning electron photomicrograph of a

horse erythrocyte called a discocyte normal dog erythrocyte called discocyte.

FIGURE 4-3Most horse erythrocytes are adhered together like stacks of coins (rouleaux)

FIGURE 4-4 Poikilocytes in blood from a normal goat. FIGURE 4-5 dog erythrocytes exhibit central pallor

FIGURE 4-6 Elliptocytes in blood from a normal camel FIGURE 4-7 Nucleated erythrocytes of bird blood

ABNORMAL ERYTHROCYTE MORPHOLOGY

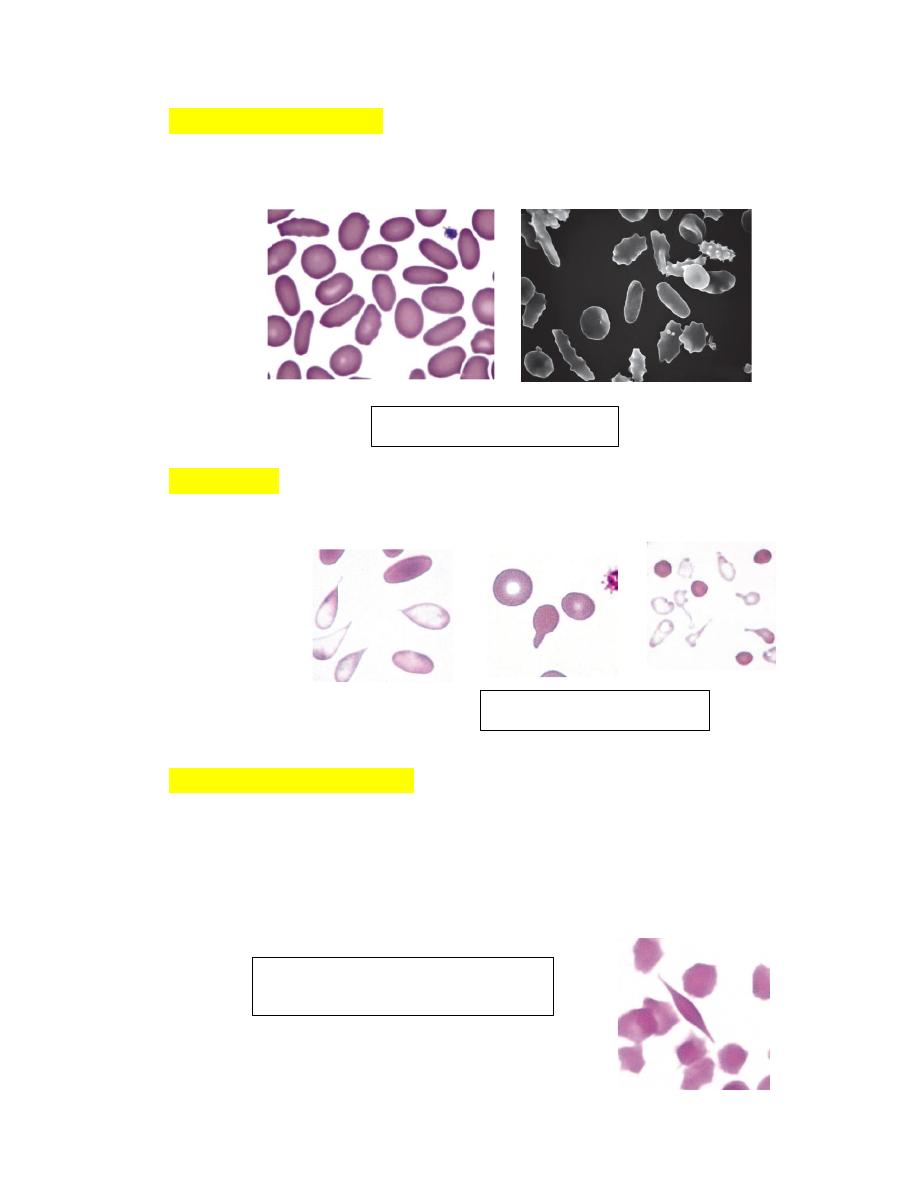

Rouleaux

1. Erythrocytes on blood films from healthy horses, cats, and pigs often exhibit

rouleaux (aggregations of erythrocytes grouped together like a stack of

coins) formations (see Fig. 4-17).

2. Rouleaux formation depends on both the nature of the erythrocytes and the

composition of plasma.

3. Rouleaux formation also depends on the presence of high-molecular weight

proteins in plasma.

4. Increased concentrations of globulin proteins—including fibrinogen,

haptoglobin, and immunoglobulins

5. rouleaux formation in association with inflammatory conditions.

6. Prominent rouleaux formation results in rapid erythrocyte sedimentation

(ESR) in whole blood samples allowed to stand undisturbed.

7. Increased sedimentation rates after 1 hour were suggestive of increased

globulins in plasma, as typically seen with inflammation.

8. Unfortunately the sedimentation rate increases as the hematocrit decreases.

Agglutination

1. Aggregation or clumping of erythrocytes in clusters (not in chains, as in

rouleaux) is termed agglutination (Fig. 4-18).

2. Agglutination is caused by the occurrence of immunoglobulins (IgM) bound

to erythrocyte surfaces.

3. Agglutination did not occur if blood was collected in heparin or citrate.

4. High-dose unfractionated heparin treatment in horses also causes

erythrocyte agglutination by an undefined mechanism.

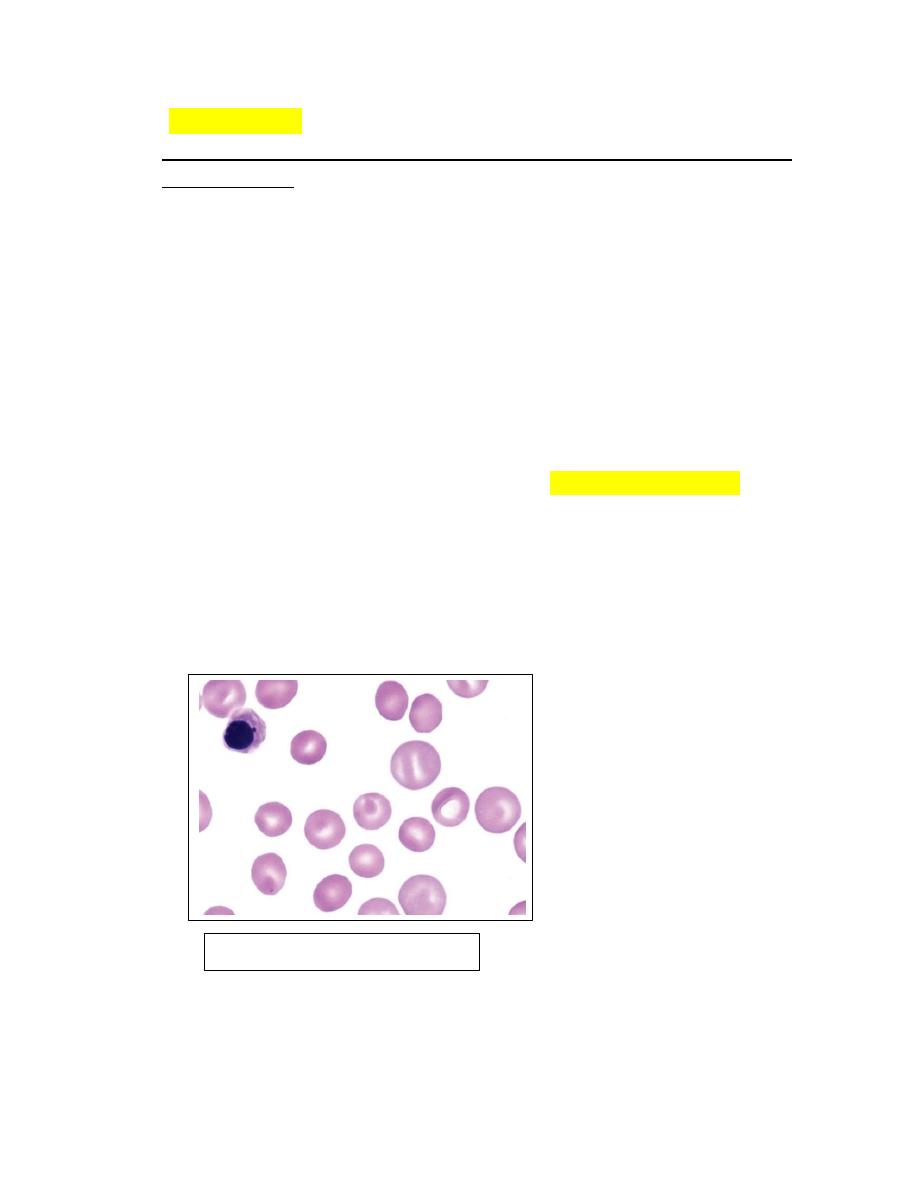

FIGURE 4-17

Rouleaux

FIGURE 4-18

Erythrocyte agglutination

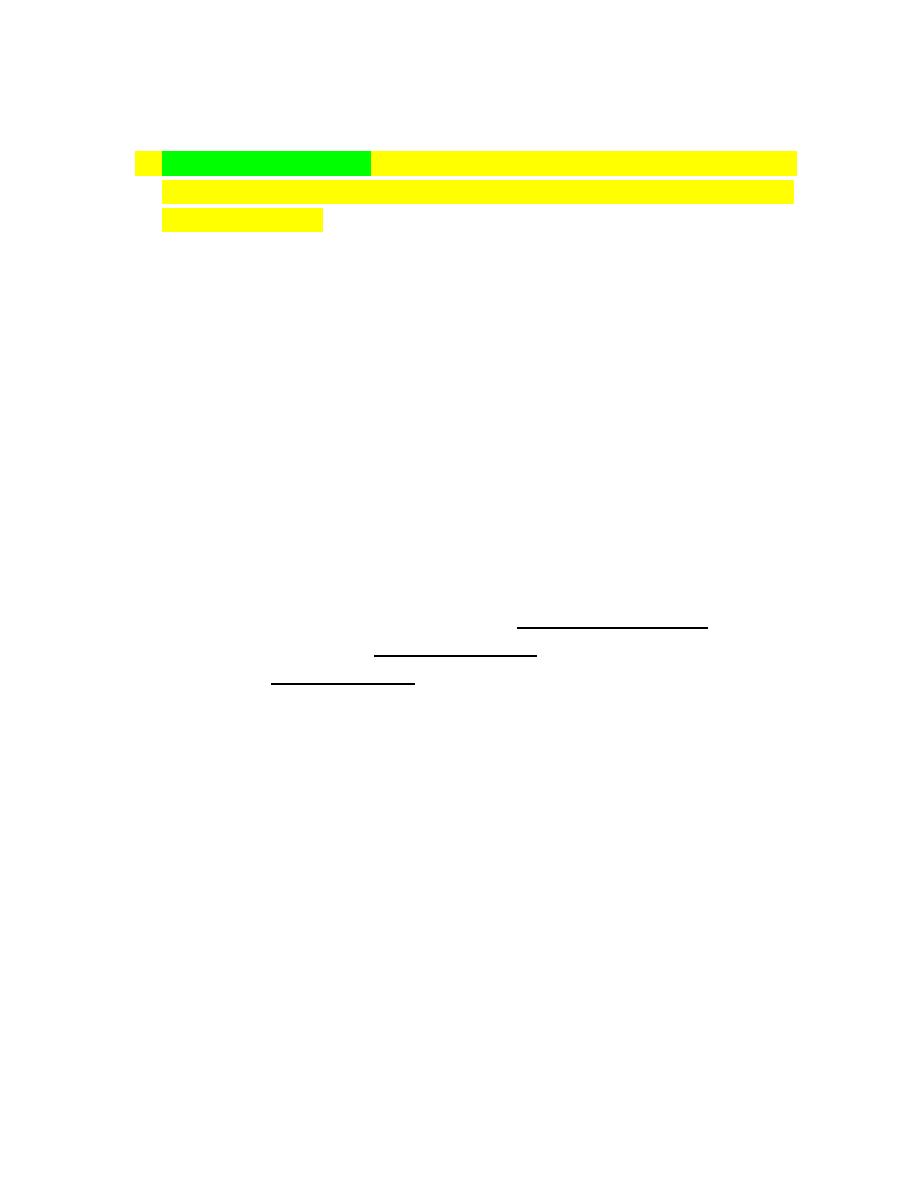

Polychromasia

1. The presence of bluish-red erythrocytes in stained blood films is called

polychromasia (Fig. 4-19).

2. Polychromatophilic erythrocytes are reticulocytes that stain bluish-red owing

to the combined presence of hemoglobin (red staining) and individual

ribosomes and polyribosomes (blue staining).

3. Slight polychromasia may be present in normal cats, but many normal cats

exhibit no polychromasia in stained blood films.

4. Polychromasia is absent in stained blood films from normal cattle, sheep,

goats, and horses because reticulocytes with sufficient RNA to impart a

bluish color are not normally present in the blood in these species.

5. Low numbers of polychromatophilic erythrocytes are usually seen in blood

from normal dogs and pigs.

6. Increased polychromasia is usually present in regenerative anemias

because many reticulocytes stain bluish-red with routine blood stains (see

Fig. 4-19).

7. The presence of a regenerative response suggests that the anemia results

from either increased erythrocyte destruction or hemorrhage.

8. A nonregenerative anemia generally indicates that the anemia is the result of

decreased erythrocyte production.

FIGURE 4-19 Polypolychromasia

Anisocytosis

1. Variation in erythrocyte diameters (size) in stained blood films is called

anisocytosis (see Fig. 4-23, B).

2. It is greater in normal cattle than in other normal domestic animals.

3. Anisocytosis is increased when different populations of cells are present, as

can occur following a transfusion .

4. Anisocytosis may occur when substantial numbers of smaller than normal

cells are produced, as occurs with iron deficiency, or when substantial

numbers of larger than normal cells are produced, as occurs when increased

numbers of reticulocytes are produced.

5. Consequently increased anisocytosis is usually present in regenerative

anemia.

6. Anisocytosis without polychromasia may be seen in horses with intensely

regenerative anemia.

Hypochromasia

1. The presence of erythrocytes with decreased hemoglobin concentration

and increased central pallor is called hypochromasia (Figs. 4-26 )

2. Not only is the center of the cell paler than normal but the diameter of the area

of central pallor is increased relative to the red-staining periphery of the cell.

3. Erythrocytes from dogs, ruminants, and pigs with iron deficiency anemia often

appear hypochromic on stained blood smears.

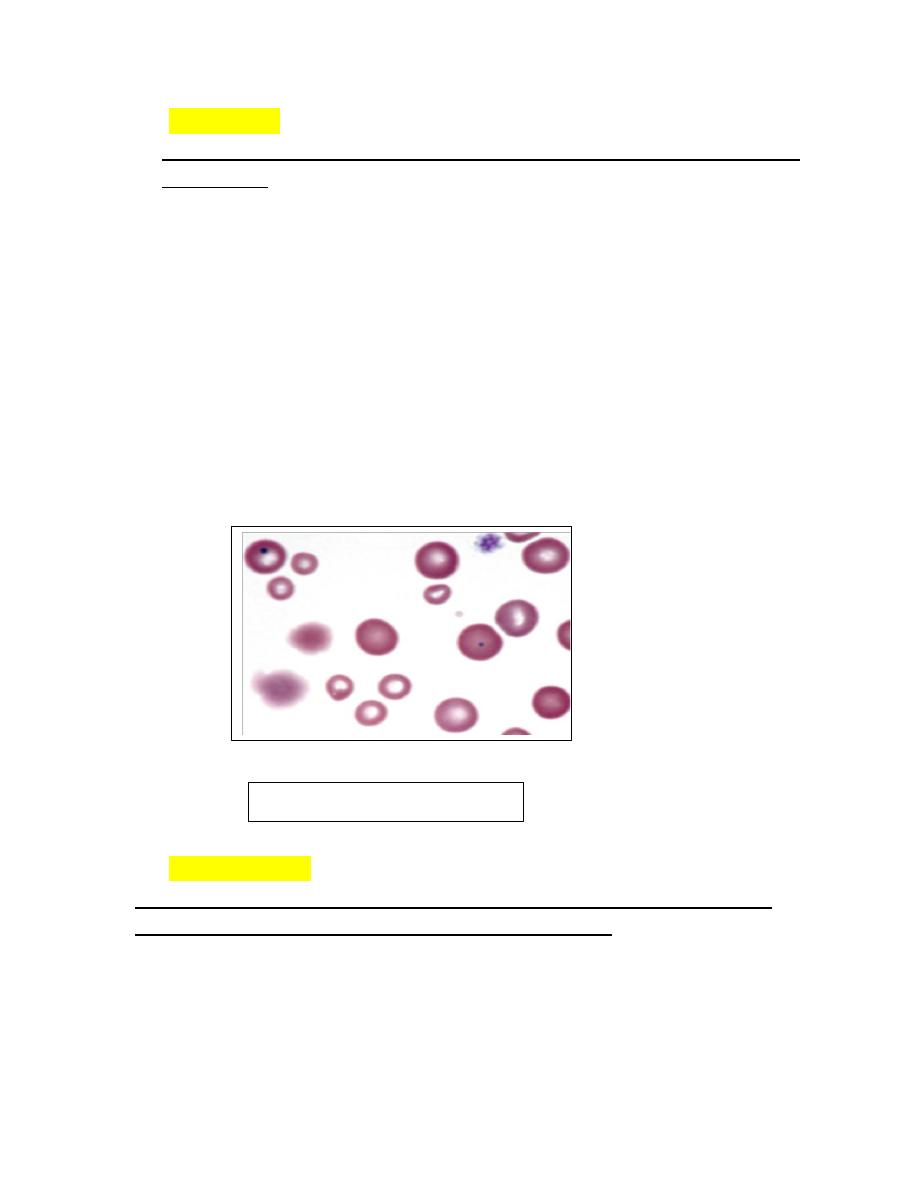

Fig. 4-23, B). Anisocytosis

Poikilocytosis

1.

Erythrocytes can assume a wide variety of shapes. Poikilocytosis is a general

term used to describe the presence of abnormally shaped erythrocytes (

Fig. 28-

29).

2. Poikilocytosis may be present in clinically normal goats and young cattle.

3. In some instances, these shapes appear to be related to the hemoglobin types

present.

4. Poikilocytosis forms in various disorders associated with erythrocyte

fragmentation, including disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), liver

disease, myeloid neoplasms, myelofibrosis, glomerulonephritis, and

hemangiosarcoma (dogs).

FIGURE 4-26

Hypochromic erythrocytes

FIGURE 4-28

poikilocytosis and hypochromasia

FIGURE 4-29

Poikilocytosis

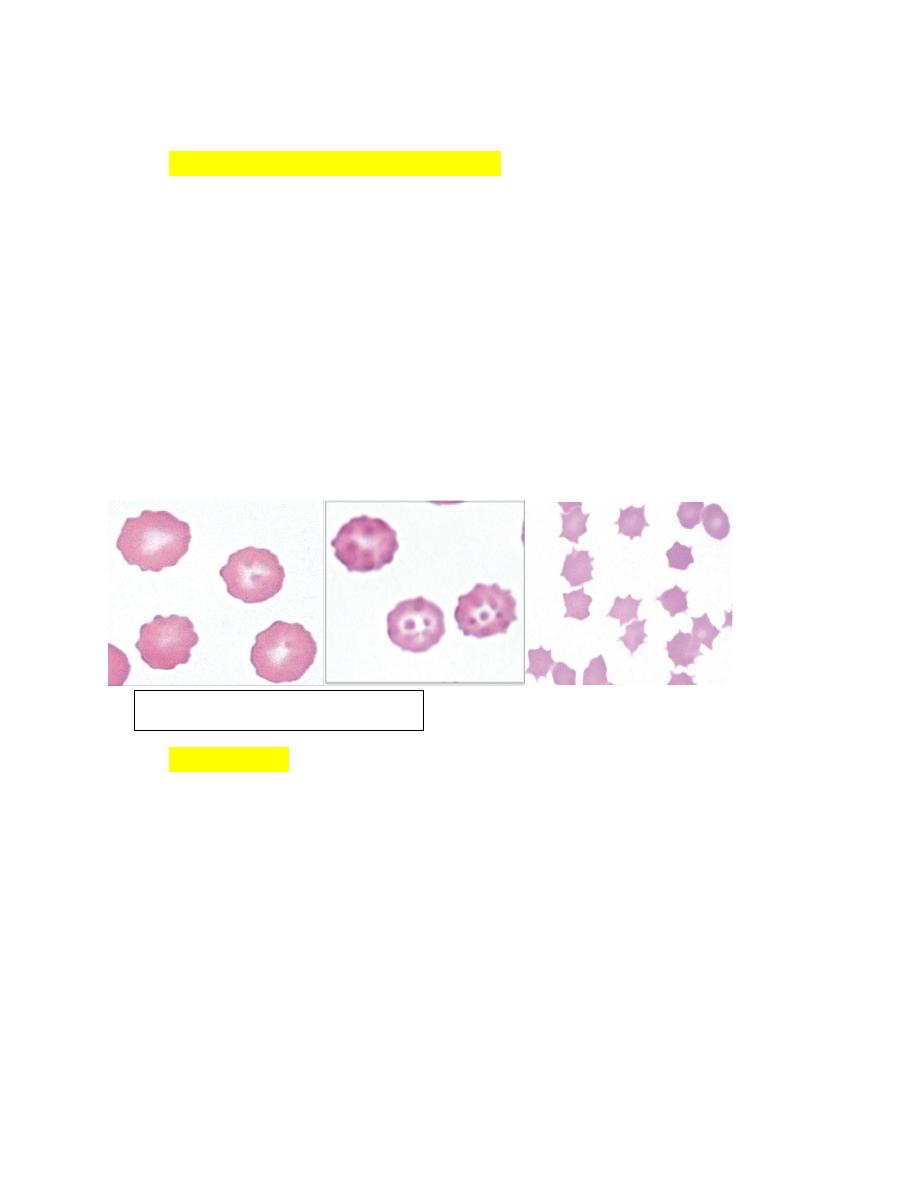

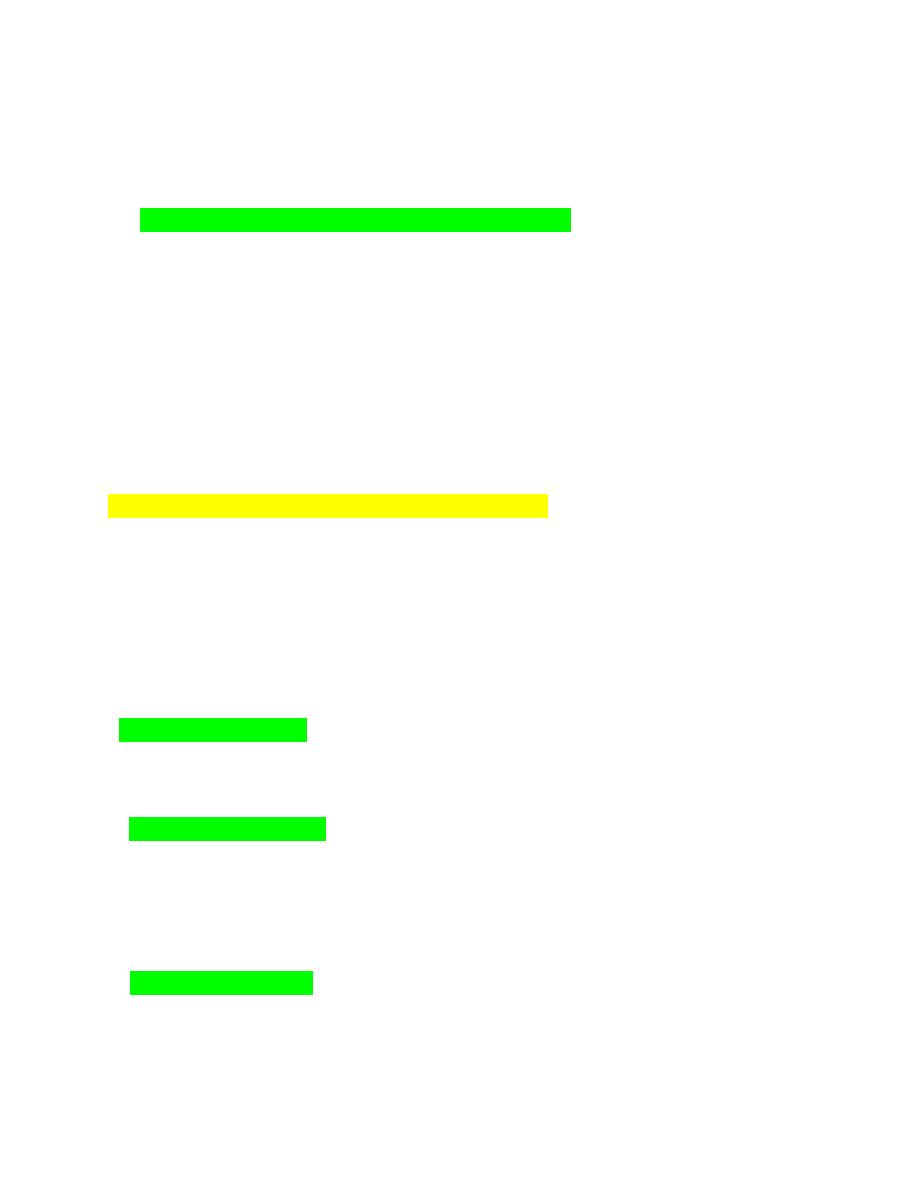

Echinocytes (Crenated Erythrocytes)

1. Echinocytes are spiculated erythrocytes in which the spicules are relatively

evenly spaced and of similar size.

2. Spicules may be sharp or blunt.

3. When observed in stained blood films, echinocytosis is usually an artifact that

results from

a. excess EDTA,

b. improper smear preparation,

c. or prolonged sample storage before blood film preparation.

4. The appearance of the echinocytes can vary depending on the thickness of the

blood film (Fig. 4-37).

5. They are common in normal pig blood smears.

Acanthocytes

1. Erythrocytes with irregularly spaced, variably sized spicules are called

acanthocytes or spur cells (Fig. 4-43).

2. Acanthocytes form when erythrocyte membranes contain excess cholesterol

compared to phospholipids.

3. If cholesterol and phospholipids are increased to a similar degree, codocyte

formation is more likely than acanthocyte formation.

4. Acanthocytes have been recognized in animals with liver disease.

possibly due

to alterations in plasma lipid composition, which can alter erythrocyte lipid

composition.

5. Marked acanthocytosis is reported to occur in young goats and some young

cattle.

FIGURE 4-37

Echinocytes in blood

6. Acanthocytosis of young goats occurs as a result of the presence of

hemoglobin C at this early stage of development.

Keratocytes

1. Erythrocytes containing one or more intact holes are called prekeratocytes,

and erythrocytes with ruptured holes are called keratocytes (Figs. 4-46).

2. the hole results in the formation of one or two projections.

3. Keratocytes have been recognized in various disorders including iron-

deficiency

anemia,

liver

disorders,

doxorubicin

toxicity

in

cats,myelodysplastic syndrome, and in various disorders in dogs having

concomitant echinocytosis or acanthocytosis.

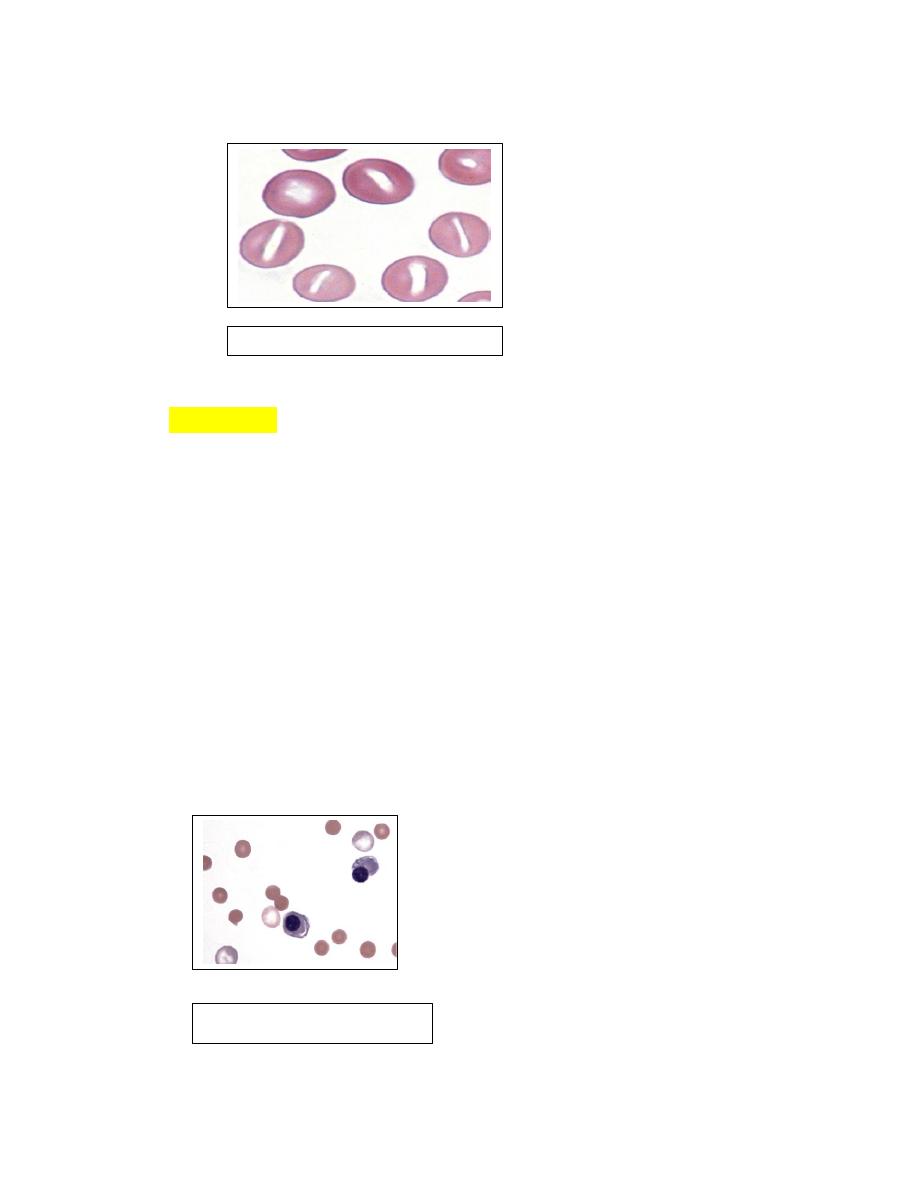

Stomatocytes

1. Mouth like erythrocytes that have oval or elongated areas of central

pallor when viewed in stained blood films are called stomatocytes (Fig.

4-48).

2. They most often occur as artifacts in thick blood film preparations.

FIGURE 4-43 Acanthocytes

FIGURE 4-47 Keratocytes in blood

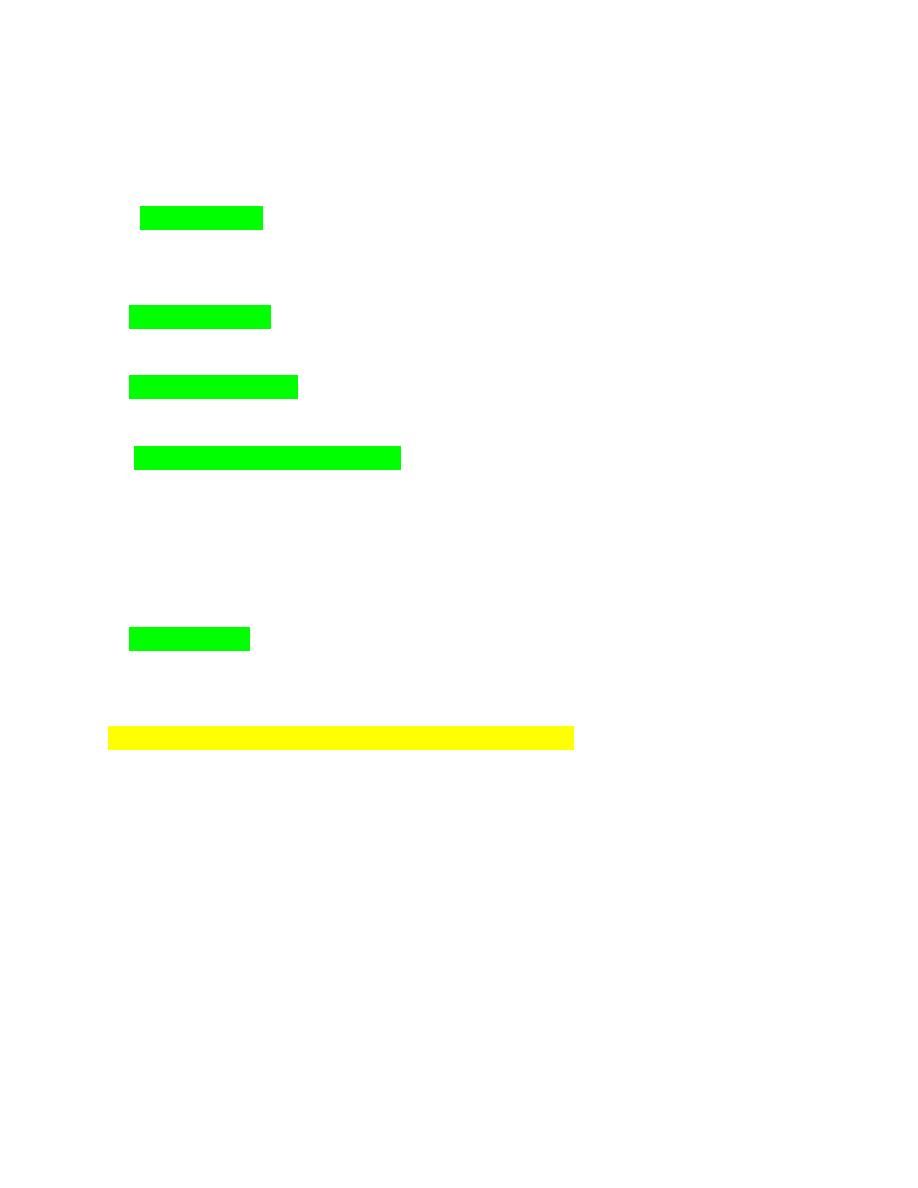

Spherocytes

1. Spherical erythrocytes that result from cell swelling and/or loss of cell

membrane are referred to as spherocytes.

2. Spherocytes lack central pallor and have smaller diameters than normal on

stained blood films (Fig. 4-50).

3. Spherical erythrocytes with slight indentations on one side may be called

stomatospherocytes

4. Spherocytes and stomatospherocytes occur most frequently in association

with immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs.

5. Other potential causes of spherocyte formation include snake

envenomations, bee stings, zinc toxicity, erythrocyte parasites,

transfusionof stored blood, and a familial dyserythropoiesis in dogs.

Spherocytes have been reported in cattle with anaplasmosis and Theileria

buffeli infection and in horses with cutaneous burns.

FIGURE 4-48 Stomatocytes

FIGURE 4-50

Spherocytes

Schistocytes

1. Erythrocyte fragments with pointed extremities are called schistocytes or

schizocytes (Fig. 4-52), and they are smaller than normal discocytes.

2. Schistocytes have also been seen in severe iron-deficiency anemia

myelofibrosis, heart failure,glomerulonephritis, hemolytic uremic syndrome,

hemophagocytic histiocytic disorders, hemangiosarcoma and

dirofilariasis in

dogs.

LeptocytesThese cells are thin, often hypochromic-appearing erythrocytes

with increased membrane-to-volume ratios. Some leptocytes appear folded

(Fig. 4-56 ).

knizocytes (Fig. 4-57) that give the impression that the erythrocyte has a

central bar of hemoglobin

FIGURE 4-52 Schistocytes

FIGURE 4-56 Leptocytes

FIGURE 4-56 knizocytes

Codocytes (target cells) (Fig. 4-58) are bell-shaped cells that exhibit a

central density or ―bull’s eye‖ in stained blood films.

EccentrocytesAn erythrocyte in which the hemoglobin is localized to part

of the cell, leaving a hemoglobin-poor area visible in the remaining part of

the cell, is termed an eccentrocyte (Figs. 4-59).

PyknocytesIrregularly spherical erythrocytes with small cytoplasmic

projections are called pyknocytes (see Figs4-60).

FIGURE 4-58 Codocytes

FIGURE 4-59

Eccentrocytes

FIGURE 4-60 pyknocyte

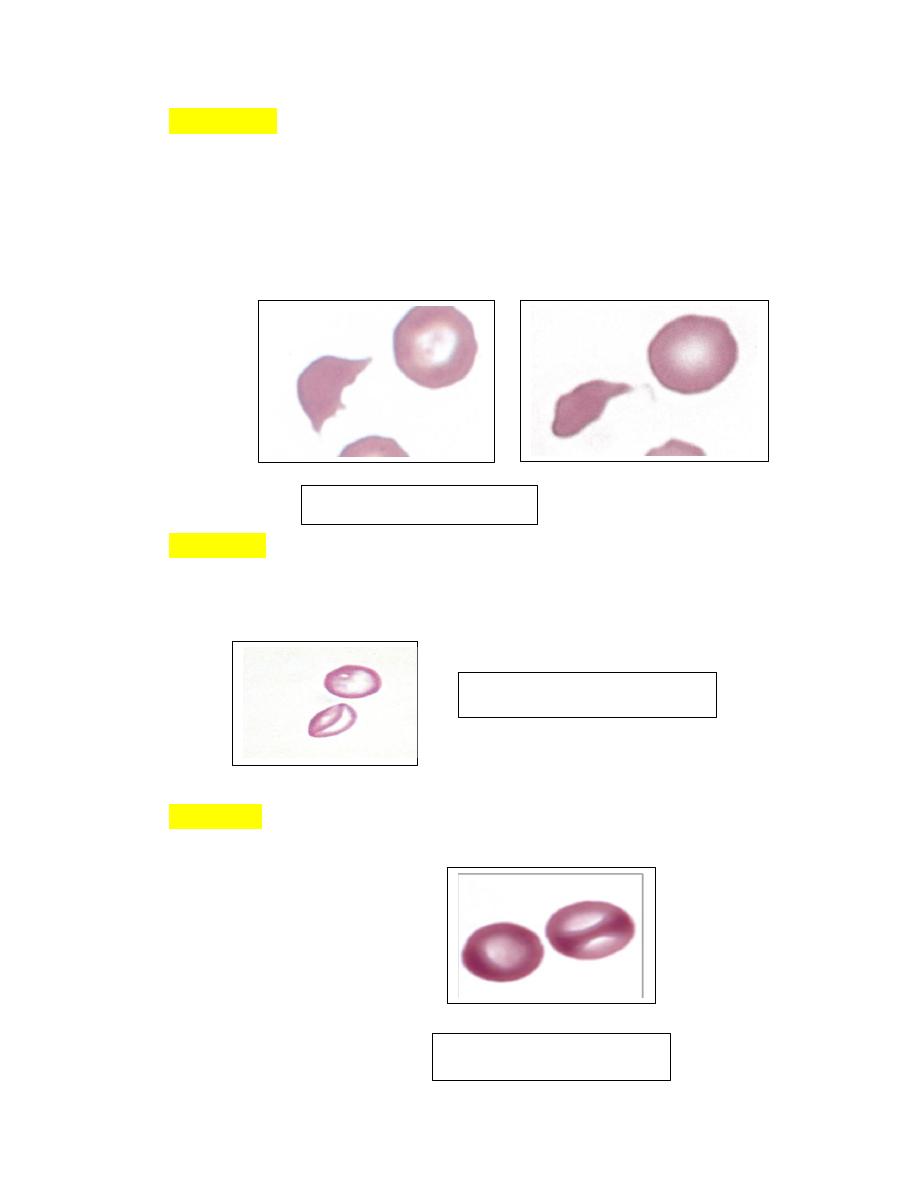

Elliptocytes (Ovalocytes)Erythrocytes from nonmammals and animals in

the Camelidae family are elliptical or oval in shape (see Fig. 4-66). They

are generally flat rather than biconcave.

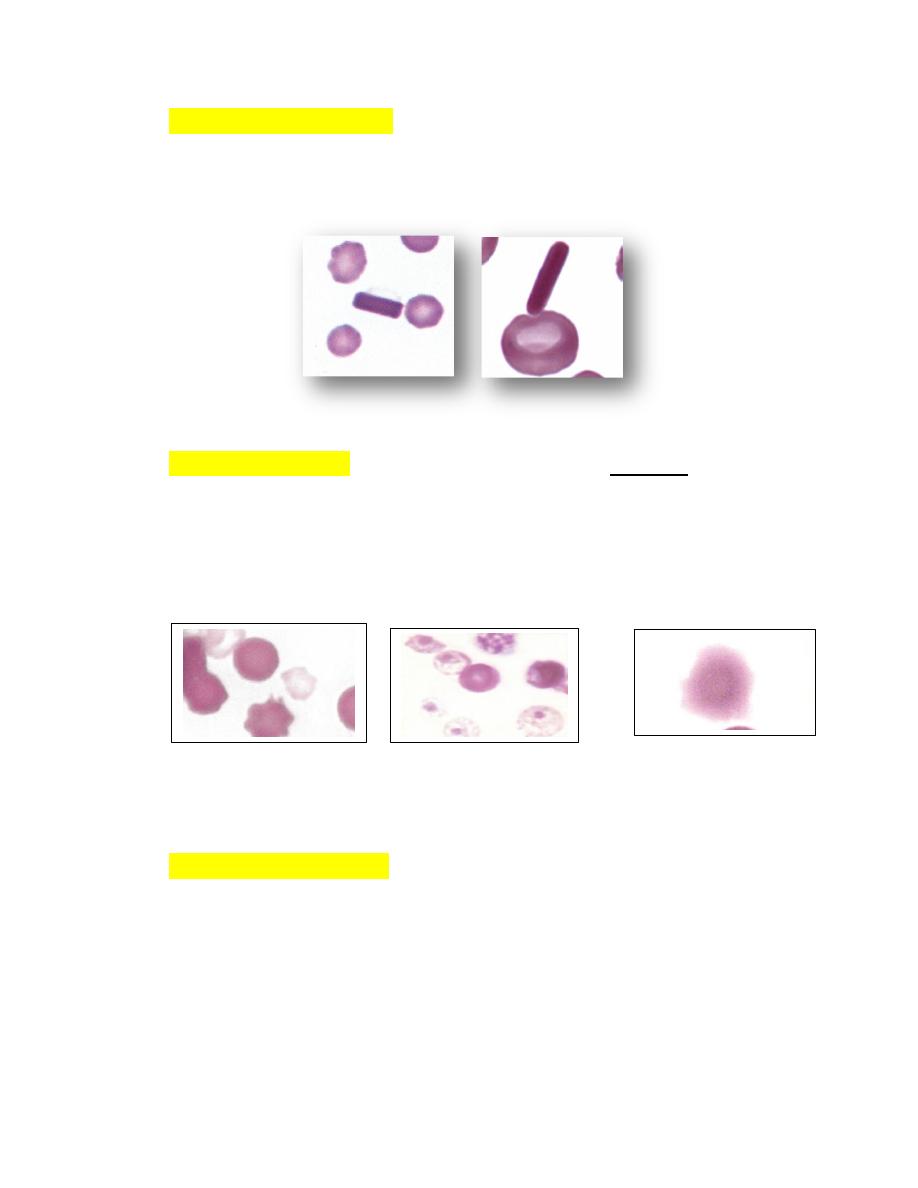

DacryocytesThese erythrocytes are teardrop-shaped with single elongated

or pointed extremities (Fig. 4-67).

Drepanocytes (Sickle Cells)These fusiform or spindle-shaped erythrocytes

were first recognized in deer blood in 1840 and in a human with sickle cell

anemia in 1910. Drepanocytes are often observed in blood from normal

deer (Figs. 4-68).

FIGURE 4-66 Elliptocytosis

FIGURE 4-67 Dacryocytes

FIGURE 4-68

Drepanocytes and

fusiform erythrocytes in a deer and

goat

Crystallized HemoglobinThe presence of large hemoglobin crystals within

erythrocytes is occasionally recognized in blood films from cats and dogs

(Fig. 4-70) and frequently in the blood of llamas and alpacas (Fig. 4-70).

FIGURE 4-70 Hemoglobin crystals in stained blood films

Lysed ErythrocytesThe presence of erythrocyte “ghosts” in peripheral

blood films indicates that the cells lysed prior to blood film preparation

(Fig. 4-72). the presence of erythrocyte ghosts indicates either recent

intravascular hemolysis or in vitro hemolysis in the blood tube after

collection.

FIGURE 4-72 Lysed erythrocytes in blood films.

Nucleated ErythrocytesRubricytes and metarubricytes (Fig. 4-75) are

seldom present in the blood of normal adult mammals, although low

numbers may occur in some normal dogs and cats. Metarubricytosis

(generally called normoblastemia in human hematology) is often seen in

blood in association with aregenerative anemia; however, their presence

does not necessarily indicate that a regenerative response is present.

FIGURE 4-75 Nucleated erythroid cells and nuclear fragmentation

INCLUSIONS OF ERYTHROCYTES

1. Howell-Jolly Bodies (Micronuclei)

These small spherical nuclear remnants form in the bone marrow following

nuclear fragmentation or rupture of the nuclear membrane, with nuclear material

left behindwhen the nucleus is expelled They have generally been called Howell-

Jolly bodies by hematologists and micronuclei by toxicologists. They may be

present in low numbers in erythrocytes of normal horses and cats. They are often

present in association with regenerative anemia or following splenectomy in other

species. Howell-Jolly bodies may be increased in animals receiving glucocorticoid

therapy. Howell-Jolly bodies, which

stain dark blue with Romanowsky-type stains

(Fig. 4-76).

FIGURE 4-76 Howell-Jolly bodies

Heinz Bodies

These inclusions are large aggregates of oxidized, precipitated hemoglobin

attached to the internal surfaces of erythrocyte membranes appearing as pale

―spots‖ within erythrocytes. In contrast to Howell-Jolly bodies, which stain dark

blue,

Heinz bodies stain red to pale pink with Romanowsky-type stains

(Fig. 4-78

A). They can also be visualized as dark refractile inclusions in new methylene blue

wet mount preparations. Heinz bodies stain lighter blue than Howell-Jolly bodies

when stained with reticulocyte stains (Brilliant crysel blue stain)

When

intravascular hemolysis occurs, they may be visible as red inclusions within

erythrocyte ghosts (Fig. 4-78 B).

In contrast to other domestic animal species, normal cats may have up to 5% Heinz

bodies within their erythrocytes. Increased numbers of Heinz bodies have been

FIGURE 4-78 A: Heinz bodies in blood from a cat appearing as pale “spots”

within erythrocytes.

FIGURE 4-78 B: Heinz bodies in blood from a cat. New methylene blue

reticulocyte stain.

seen in kittens fed fish-based diets and in cats fed commercial soft-moist diets

containing propylene glycol.

Heinz body associated with hemolytic anemia.

Basophilic Stippling

Reticulocytes usually stain as polychromatophilic erythrocytes with Romanowsky-

type blood stains owing to the presence of dispersed ribosomes and polyribosomes;

however, sometimes the ribosomes and polyribosomes aggregate together, forming

blue-staining punctate inclusions referred to as basophilic stippling (Fig. 4-

81).Diffuse basophilic stippling commonly occurs in regenerative anemia in

ruminants. It may be prominent in any species in the presence of lead poisoning.

Cabot Rings

Cabot rings are reddish purple-staining thread like loops or figure-eight structures

that are primarily found in reticulocytes in humans.

Cabot rings have been bserved

in normal camel and llama erythrocytes stained with reticulocyte stains (Fig. 4-84).

FIGURE 4-81 Diffuse and focal basophilic stippling

FIGURE 4-84 Cabot rings in erythrocytes

Cabot rings in erythrocytes

INFECTIOUS AGENTS OF ERYTHROCYTES

1. A number of infectious agents are recognized to occur in or on erythrocytes.

These include

intracellular protozoal parasites

Babesia species

Theileria species

Cytauxzoon felis)

Intracellular rickettsial organisms

(Anaplasma species)

A. Erythrocytic anaplasma

a. Anaplasma marginali and Anaplasma centrali (cattle)

b. Anaplasma ovis and Anaplasma hercei (sheep)

B. Leukocytic anaplasma

Anaplasma phagocytophilia

Ehrlichia spp.

Epicellular Mycoplasma species

c. ( Hemotrophic Mycoplasma e.g. Mycoplasma heamofelies, Mycoplasma

heamocanis, Mycoplasma hemolama, Mycoplasma wenyonii ).

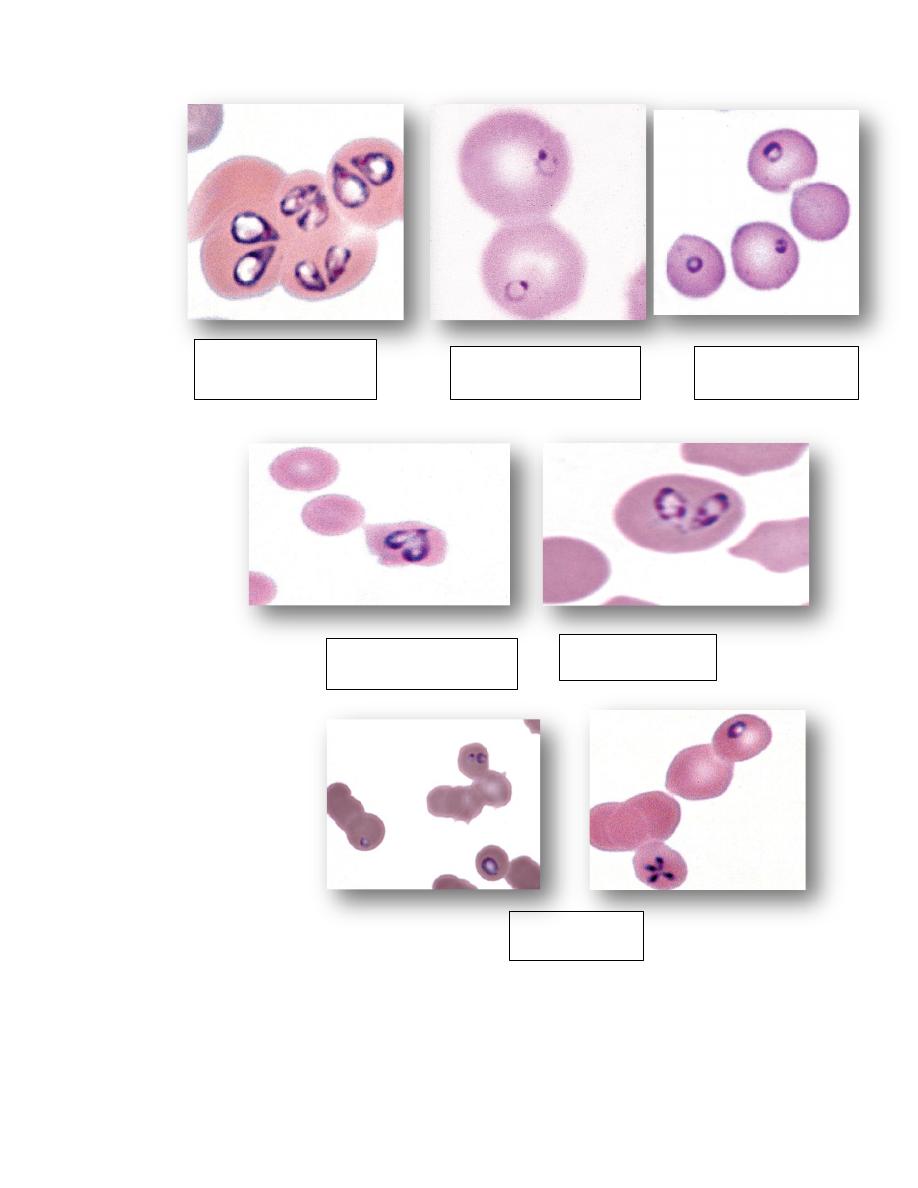

1. The erythrocyte protozoal organisms (piroplasms) of the order

Piroplasmida (Babesia species Theileria species) each have a nucleus

within their cytoplasm.

2. In contrast to Plasmodium and Haemoproteus genera, these organisms do

not form pigment in infected erythrocytes even though they also consume

hemoglobin.

3. The rickettsia and mycoplasma organisms are bacteria and therefore lack

nuclei.

4. These infectious agents generally cause mild to severe hemolytic anemia

depending on the pathogenicity of the organism and the susceptibility of the

host.

5. Distemper virus inclusions may also be seen in dog erythrocytes.

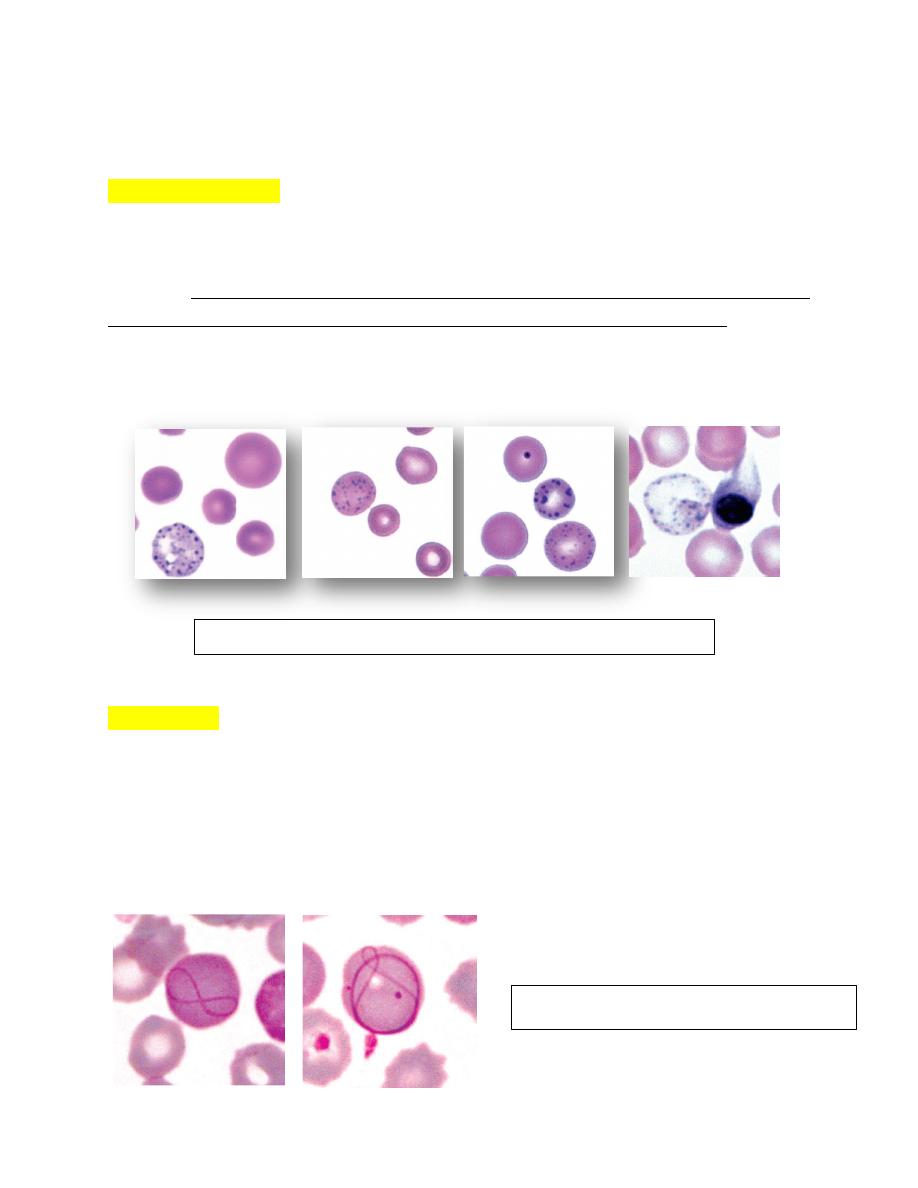

Two pear-shaped

Babesia canis

Single small Babesia

gibsoni in dog

Single Babesia felis

Babesia bigemina cow

Babesia caballi

Horse

Babesia equi

Horse

Theileria buffeli in cow

Theileria cervi in deer

Cytauxzoon felis in cat

Anaplasma marginale in cow

Anaplasma ovis in goat

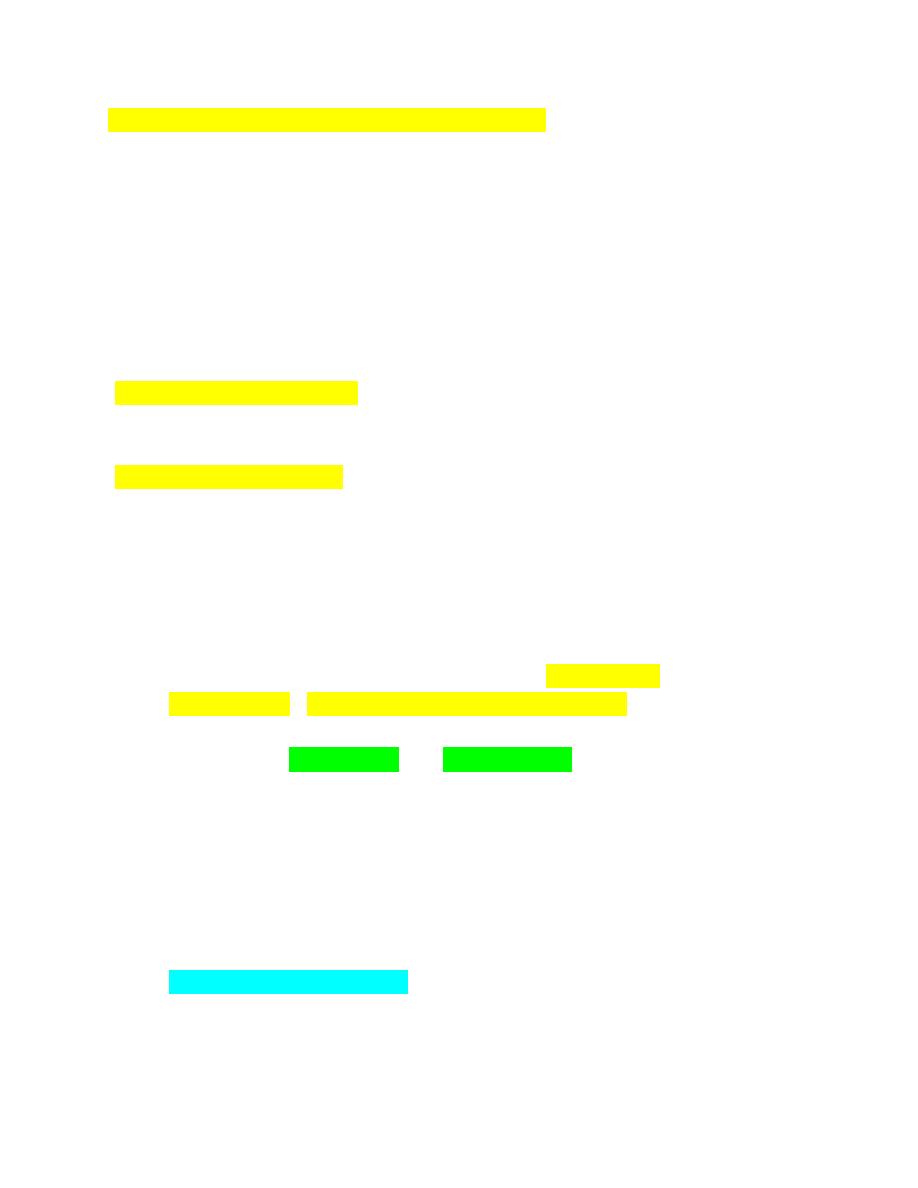

Mycoplasma haemofelis

Mycoplasma haemocanis

Mycoplasma suis

Mycoplasma ovis

Mycoplasma wenyonii

Mycoplasma haemolama

Bartonella henselae in cat

Distemper inclusions in dog

erythrocytes

Anemia and DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ANEMIA

True or absolute anemia is defined as a decrease in erythrocyte mass within

the body. HCT, hemoglobin, and RBC count values are usually below their

reference intervals.

the anemia can sometimes be masked by concomitant dehydration.

Low erythrocyte parameters may also be present in blood when the total-

body erythrocyte mass is normal (relative anemia).

This can result from overhydration resulting in erythrocyte dilution and from

splenic sequestration of erythrocytes as occurs with splenic relaxation during

anesthesia, heparin-induced erythrocyte agglutination in horses, and various

causes of splenomegaly.

Anemia is a condition, not a diagnosis. Anemia is classifiedin various ways

to assist in determining its specific cause so that effective therapy can be

given.

In addition to past history, presenting complaints, and laboratory findings,

results of other test procedures (e.g., diagnostic imaging) are important in

reaching a final diagnosis.

Anemia may occur following blood loss ( Hemorrhagic anemia), increased

erythrocyte destruction ( Hemolytic anemia), or decreased erythrocyte

production ( Aplastic anemia) .

Factors that can be useful in categorizing anemia into these broad causes

(and often into more specific causes) include:

a. reticulocyte counts, erythrocyte indices, erythrocyte morphology on stained

blood films,

b. the appearance of the plasma,

c. plasma protein concentration,

d. serum iron measurements,

e. serum bilirubin determination,

f. direct antiglobulin test,

g. and bone marrow evaluation.

Anemia may also develop as a result of the expansion ofthe vascular space

faster than the expansion of the total-body erythrocyte mass.

This hemodilution contributes to the anemia of the neonate and to the mild

anemia that develops during pregnancy in most domestic animals, the horse

being an exception.

Classification of Anemia using Erythrocyte Indices

An anemia can also be classified using the MCV and MCHC values to assist

in determining its cause.

The terms used to indicate size are macrocytic (increased MCV),

normocytic (normal MCV), and microcytic (decreased MCV).

The terms used to describe MCHC values are normochromic (normal

MCHC) and hypochromic (decreased MCHC).

Anemias are not classified as hyperchromic because high MCHC values are

artifacts.

Causes of Hemolytic Anemias in Domestic Animals

1. Immune-mediated erythrocyte destruction: Primary or autoimmune

hemolytic anemia (common in dogs); neonatal isoerythrolysis (primarily

horses and cats); lupus erythematosus (primarily dogs); incompatible blood

transfusions; drugs, including penicillin (horses), cephalosporins (dogs),

levamisole (dogs), sulfonamides (horses and dogs), pirimicarb (insecticide in

dogs), and propylthiouracil (cats)

2. Erythrocyte parasites (may have an immune-mediated component): Anaplasma

spp. (ruminants), erythrocytic Mycoplasma spp. (except horses), Babesia spp.,

Cytauxzoon felis, Theileria spp. (ruminants)

3. Other infectious agents (may have an immune-mediated component): Leptospira

and Clostridium spp. (primarily ruminants and horses), FeLV (seldom hemolytic),

equine infectious anemia virus (multifactorial, also with decreased production),

Sarcocystis spp. (cattle and sheep), Trypanosoma spp. (primarily outside the

United States)

4. Chemicals and plants (most are oxidants): Onions, red maple (horses), Brassica

spp. (ruminants), lush winter rye (cattle), copper (sheep and goats), phenothiazine

(horses), acetaminophen (cats and dogs), methylene blue (cats and dogs),

benzocaine (cats and dogs), phenazopyridine (cats), methionine (cats), vitamin K

(dogs), propylene glycol (cats), naphthalene (dogs?), zinc (dogs and ruminants),

indole (experimental in cattle and horses), tryptophan (experimental in horses),

crude oil (marine birds), venoms (snakes, bees,wasps, and spiders)

5. Fragmentation: Disseminated intravascular coagulation (primarily dogs),

dirofilariasis (especially posterior vena cava syndrome) in dogs, hemangiosarcoma

(dogs), vasculitis, hemolytic uremia syndrome.

6. Hypo-osmolality: Hypotonic fluid administration, water intoxication (primarily

in cattle)

7. Hypophosphatemia: Postparturient hemoglobinuria (cattle), ketoacidotic diabetic

animals following insulin therapy (cats and dogs), hepatic lipidosis (cats).

8. Hereditary erythrocyte defects: Pyruvate kinase deficiency (dogs and cats),

phosphofructokinase deficiency (dogs), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

deficiency (horses), hereditary stomatocytosis (mild anemia in dogs),

erythropoietic porphyria (cattle and cats), , erythrocyte flavin adenine dinucleotide

deficiency in horses (methemoglobinemia and sometimes mild anemia), hereditary

spherocytosis in cattle.

9. Miscellaneous: Liver failure (horses), selenium deficiency in cattle grazing on

St. Augustine grass, postparturient hemoglobinuria in cattle not associated with

hypophosphatemia

Causes of Blood-Loss Anemias in Domestic Animals

1. Trauma: Accidents, fights, gastrointestinal foreign bodies, surgery

2. Parasites: Hookworms, fleas, blood-sucking lice, Haemonchus spp. (small

ruminants), liver flukes, Coccidia spp.

3. Coagulation disorders: Vitamin K deficiency, sweet clover (dicoumarol)

toxicity (cattle), rodenticide toxicity, bracken fern toxicity (cattle and sheep),

disseminated intravascularcoagulation, inherited coagulation factor deficiencies.

4. Platelet disorders: Thrombocytopenia and inherited platelet function defects

5. Neoplasia: Gastric tumors including carcinomas, and lymphoma; transitional

cell carcinoma and transitional cell papilloma of urogenital system; and ruptured

hemangioma, hemangiosarcoma, and adrenal gland tumors with bleeding into body

cavities and tissues

6. Gastrointestinal ulcers: Glucocorticoids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,

mast cell tumors, gastrinoma, stress, metabolic diseases (uremia, liver failure,

hypoadrenocorticism)

7. Vascular abnormalities: Arteriovenous fistula and vascular ectasia in the

gastrointestinal or urogenital tracts

8.

Phenylephrine-induced

hemorrhage:

Presumably

associated

with

hypertension in aged horses treated for nephrosplenic entrapment of the large

colon.

Anemias Resulting from Decreased Erythrocyte Production in Domestic

Animals

1. Chronic renal disease: Primarily lack of erythropoietin

2. Endocrine deficiencies: Hypothyroidism, hypoadrenocorticism,

hypopituitarism, hypoandrogenism

3. Inflammatory disease: Inflammation and neoplasia

4. Cytotoxic damage to the marrow: Bracken fern poisoning (cattle), cytotoxic

anticancer drugs, estrogen toxicity (dogs and ferrets), chloramphenicol (cats,

usually not anemic), phenylbutazone (dogs), trimethoprim-sulfadiazine (dogs),

radiation, albendazole (dogs, cats, alpacas), griseofulvin (cats), trichloroethylene

(cattle)

5. Infectious agents: Ehrlichia spp. (dogs, horses, and cats), FeLV,

nonbloodsucking trichostrongyloid parasites (ruminants), parvovirus (pups)

6. Immune-mediated: Nonregenerative anemia, selective erythroid aplasia,

continued treatment with recombinant human erythropoietin, idiopathic aplastic

anemia (?)

7. Congenital/inherited: Foals and dogs?

8. Myelophthisis: Myeloid leukemias, lymphoid leukemias, myelodysplastic

syndromes,

multiple

myeloma,

myelofibrosis,

osteosclerosis,

metastatic

lymphomas, metastatic mast cell tumors.

ERYTHROCYTOSIS (POLYCYTHEMIA)

Erythrocytosis refers to an increase in HCT, hemoglobin, and RBC count above

the normal reference interval.

Relative Erythrocytosis

1. Splenic contraction: Excitement, exercise, pain (primarily in horses, dogs, and

cats)

2. Dehydration: Water loss, water deprivation, shock with fluid shift into tissues

Absolute Erythrocytosis

1. Primary erythrocytosis: A myeloproliferative neoplasm in adult dogs and cats

2. Familial erythrocytosis in young Jersey cattle: Etiology unknown

3. Hypoxemia with compensatory increased erythropoietin production: Chronic

lung disease, heart disease with right-to-left shunting of blood, chronic

methemoglobinemia (rare in dogs and cats)

4. Inappropriate erythropoietin production: Renal lesions (primarily tumors),

nonrenal erythropoietin secreting tumors (rare).

Evaluation of Leukocytic Disorders

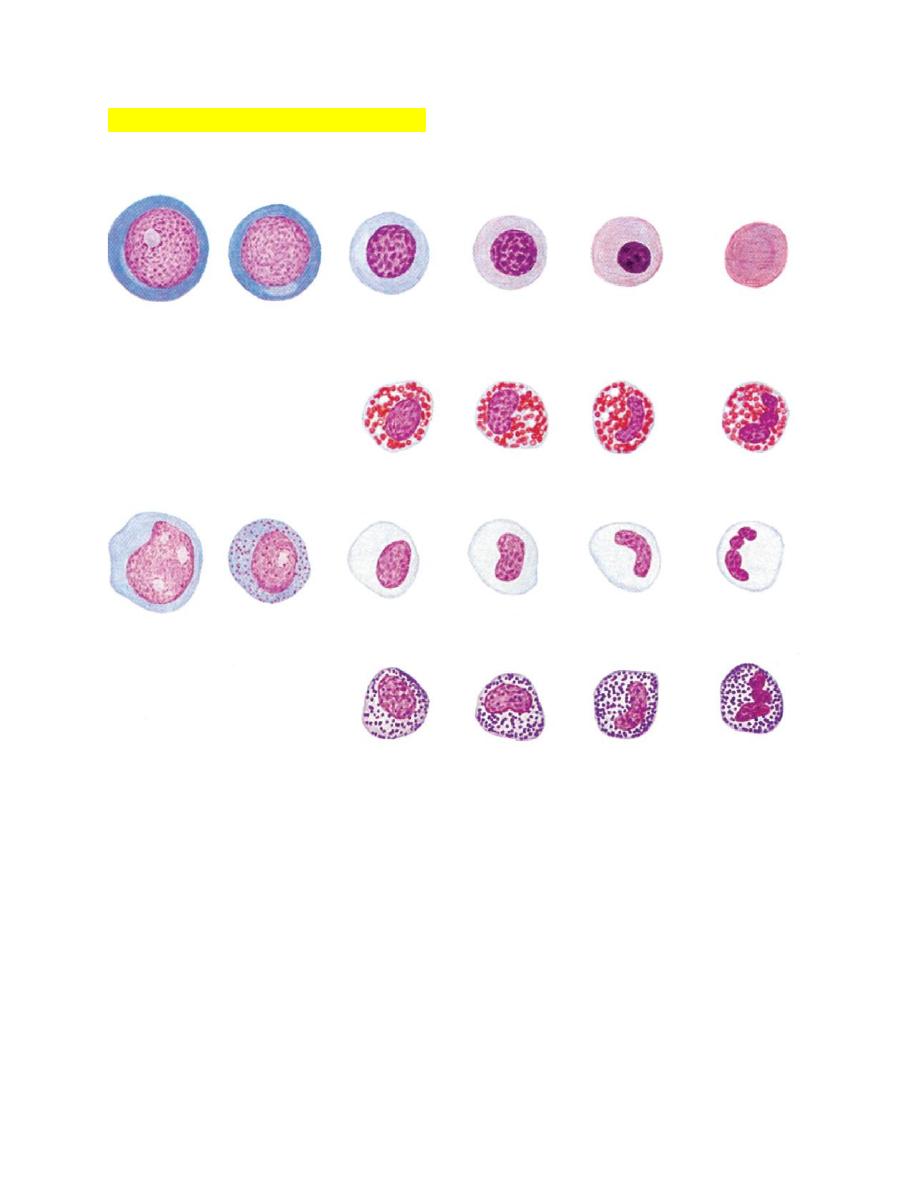

FIGURE 3-10 Maturation of canine erythroid and granulocytic cells as they

appear in Wright-Giemsa-stained bone marrow aspirate smears.