Dr. Dlawer Abdul Hammed AL Jaff

Ph.D Pharmacology and toxicology

3/10/2016

The fourth family of receptors differs

considerably from the other three in that the

receptor is entirely intracellular and,

therefore, the ligand must diffuse into the cell

to interact with the receptor

This places constraints on the physical and

chemical properties of the ligand in that it

must have sufficient lipid solubility to be able

to move across the target cell membrane

3/10/2016

Because these receptor ligands are lipid

soluble, they are transported in the body

attached to plasma proteins, such as

albumin.

Binding of the ligand with its receptor follows

a general pattern in which the receptor

becomes activated

The activated ligandâ

€“receptor complex

migrates to the nucleus, where it binds to

specific DNA sequences, resulting in the

regulation of gene expression.

3/10/2016

The time course of activation and response of

these receptors is much longer than that of

the other mechanisms

Because gene expression and, therefore,

protein synthesis is modified, cellular

responses are not observed until considerable

time has elapsed (thirty minutes or more),

and the duration of the response (hours to

days) is much greater than that of other

receptor families

3/10/2016

Radioligand binding studies have shown that

the receptor numbers do not remain constant

but change according to circumstances.

When tissues are continuously exposed to an

agonist, the number of receptors decreases

(down-regulation)

and this may be a cause of

tachyphylaxis (loss of efficacy with frequently

repeated doses), e.g. in asthmatics who use

adrenoceptor agonist bronchodilators

excessively. Prolonged contact with an

antagonist leads to formation of new

receptors

(up-regulation).

3/10/2016

Indeed, one explanation for the worsening of

angina pectoris or cardiac ventricular

arrhythmia in some patients following abrupt

withdrawal of a (beta-adrenoceptor blocker is

that normal concentrations of circulating

catecholamines now have access to an

increased (up-regulated) population of beta-

adrenoceptors

3/10/2016

Drugs that activate receptors do so because

they resemble the natural transmitter or

hormone, and so to act for longer than the

natural substances (endogenous ligands); for

this reason

bronchodilation produced by salbutamol lasts

longer than that induced by adrenaline

3/10/2016

Antagonists (blockers) of receptors are

sufficiently similar to the natural agonist to

be 'recognised' by the receptor and to occupy

it without activating a response, thereby

preventing (blocking) the natural agonist

from exerting its effect.

Drugs that have no activating effect whatever

on the receptor are termed

pure antagonists

3/10/2016

A receptor occupied by a low efficacy agonist

is inaccessible to a subsequent dose of a high

efficacy agonist, so that, in this specific

situation, a low efficacy agonist acts as an

antagonist.

This can happen with opioids.

3/10/2016

Partial agonists. Some drugs, in addition to

blocking access of the natural agonist to the

receptor, are capable of a low degree of

activation, i.e. they have both antagonist and

agonist action. Such substances are said to

show

partial agonist activity

(PAA).

The beta- adrenoceptor antagonists pindolol

and oxprenolol have partial agonist activity

(in their case it is often called

intrinsic

sympathomimetic activity)

(ISA), while

propranolol is devoid of agonist activity, i.e. it

is a pure antagonist

3/10/2016

A patient may be as extensively '(3- blocked'

by propranolol as by pindolol, i.e. exercise

tachycardia is abolished, but the resting heart

rate is lower on propranolol; such differences

can have clinical importance.

3/10/2016

Inverse agonists.

Some substances produce effects that are

specifically opposite to those of the agonist.

The agonist action of benzodiazepines on the

benzodiazepine receptor in the CNS produces

sedation, anxiolysis, muscle relaxation and

controls convulsions; substances called

–beta

carbolines which also bind to this receptor

cause stimulation, anxiety, increased muscle

tone and convulsions; they are inverse

agonists.

3/10/2016

Receptor binding (and vice versa).

If the forces that bind drug to receptor are weak

(hydrogen bonds, van der Waals bonds,

electrostatic bonds), the binding will be easily

and rapidly reversible; if the forces involved are

strong (covalent bonds), rests on their greater

capacity to resist degradation then binding will

be effectively irreversible.

An antagonist that binds reversibly to a receptor

can by definition be displaced from the receptor

by mass action of the agonist (and vice versa). If

the concentration of agonist increases

sufficiently above that of the antagonist the

response is restored.

3/10/2016

This phenomenon is commonly seen in

clinical practice

— patients who are taking a

beta-adrenoceptor blocker, and whose low

resting heart rate can be increased by

exercise, are showing that they can raise their

sympathetic

drive

to

release

enough

noradrenaline (agonist) to diminish the

prevailing degree of receptor blockade.

3/10/2016

Increasing the dose of beta-adrenoceptor

blocker will limit or abolish exercise induced

tachycardia, showing that the degree of

blockade is enhanced as more drug becomes

available to compete with the endogenous

transmitter.

Since agonist and antagonist compete to

occupy the receptor according to the law of

mass action, this type of drug action is

termed

competitive antagonism.

3/10/2016

When

receptor-mediated

responses

are

studied either in isolated tissues or in intact

man, a graph of the logarithm of the dose

given (horizontal axis), plotted against the

response obtained (vertical axis), commonly

gives an S-shaped (sigmoid) curve, the

central part of which is a straight line.

If the measurements are repeated in the

presence of an antagonist, and the curve

obtained is parallel to the original but

displaced to the right, then antagonism is

said to be competitive and the agonist to be

surmountable.

3/10/2016

Drugs that bind

irreversibly

to receptors

include

phenoxybenzamine

(to

the

a-

adrenoceptor). Since such a drug cannot be

displaced from the receptor, increasing the

concentration of agonist does not fully

restore the response and antagonism of this

type is said to be

insurmountable

3/10/2016

The log-dose-response curves for the

agonist in the absence of and in the presence

of a noncompetitive antagonist are not

parallel. Some toxins act in this way, e.g.

bungaro toxin, a constituent of some snake

and spider venoms, binds irreversibly to the

acetylcholine receptor and is used as a tool to

study it. Restoration of the response after

irreversible binding requires elimination of

the drug from the body and synthesis of new

receptor, and for this reason the effect may

persist long after drug administration has

ceased. Irreversible agents find little place in

clinical practice

3/10/2016

Physiological (functional) antagonism

An action on the same receptor is not the only

mechanism by which one drug may oppose the effect

of another. Extreme bradycardia following overdose

of a p-adrenoceptor blocker can be relieved by

atropine which accelerates the heart by blockade of

the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic

nervous system, the cholinergic tone of which (vagal

tone) operates continuously to slow it.

Bronchoconstriction produced by histamine released

from mast cells in anaphylactic shock can be

counteracted by adrenaline (epinephrine), which

relaxes bronchial smooth muscle (P2-adrenoceptor

effect) or by theophylline. In both cases, a

pharmacological effect is overcome by a second drug

which acts by a different physiological mechanism,

i.e. there is physiological or functional antagonism.

3/10/2016

ENZYMES

Interaction between drug and enzyme is in many

respects similar to that between drug and

receptor.

Drugs may alter enzyme activity because they

resemble a natural substrate and hence compete

with it for the enzyme. For example, enalapril is

effective in hypertension because it is structurally

similar to that part of angiotensin I which is

attacked by angiotensin-converting enzyme

(ACE); by occupying the active site of the enzyme

and so inhibiting its action enalapril prevents

formation of the pressor angiotensin II.

3/10/2016

Carbidopa competes with levodopa for dopa decarboxylase and

the benefit of this combination in Parkinson's disease is reduced

metabolism of levodopa to dopamine in the blood (but not in the

brain because carbidopa does not cross the blood-brain barrier).

Ethanol prevents metabolism of methanol to its toxic metabolite,

formic acid, by competing for occupancy of the enzyme alcohol

dehydrogenase; this is the rationale for using ethanol in

methanol poisoning.

The above are examples of competitive (reversible) inhibition of

enzyme activity.

Irreversible inhibition

occurs with organophosphorus insecticides which combine

covalently with the active site of acetylcholinesterase; recovery of

cholinesterase activity depends on the formation of new enzyme.

Covalent binding of aspirin to cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibits the

enzyme in platelets for their entire lifespan because platelets

have no system for synthesising new protein and this is why low

doses of aspirin are sufficient for antiplatelet action.

3/10/2016

Continuous or repeated or administration of a

drug is often accompanied by a gradual

diminution of the effect it produces.

Tolerance is said to have been

acquired

when it

becomes necessary to increase the dose of a

drug to get an effect previously obtained with a

smaller dose

By contrast, the term

tachyphylaxis

describes the

phenomenon of progressive lessening of effect

(refractoriness) in response to frequently

administered doses it tends to develop more

rapidly than tolerance.

3/10/2016

Tolerance is readily observed with opioids

Tolerance is acquired rapidly with nitrates

used to prevent angina, possibly mediated by

the generation of oxygen free radicals from

nitric oxide

it can be avoided by removing transdermal

nitrate patches for 4-8 h, e.g. at night.

3/10/2016

The order of reaction or process

In the body, drug molecules cross cell

membranes, are transported across cells, and

many are altered by being metabolised.

These movements and changes involve

interaction with membranes, carrier proteins

and enzymes.

The

rate

at which these movements or

changes can take place is subject to

important influences that are referred to as

the

order

of reaction or process.

3/10/2016

In biology generally, two orders of such

reactions

are

recognised

First-order

processes by which a constant

fraction

of

drug is transported/metabolised in unit time.

Zero-order processes by which a constant

amount

of drug is transported/metabolised in

unit time.

3/10/2016

In the majority of instances the rates at which

absorption, distribution, metabolism and

excretion of a drug occur are directly

proportional to its concentration in the body.

In other words, transfer of drug across a cell

membrane or formation of a metabolite is

high at high concentrations and falls in direct

proportion to be low at low concentrations

(an exponential relationship).

3/10/2016

This is because the processes follow the Law of

Mass Action, which states that the rate of

reaction is directly proportional to the active

masses of reacting substances.

In other words, at high concentrations, there are

more opportunities for crowded molecules to

interact with each other or to cross cell

membranes

than

at

low,

uncrowded

concentrations.

Processes for which rate of reaction is

proportional to concentration are

called first-

order.

In doses used clinically, most drugs are

subject to first-order processes of absorption,

distribution, metabolism and elimination. The

knowledge that a drug exhibits first-order

kinetics is useful.

3/10/2016

As the amount of drug in the body rises, any

metabolic reactions or processes that have

limited capacity become saturated. In other

words, the rate of the process reaches a

maximum amount at which it stays constant,

e.g. due to limited activity of an enzyme, and

further increase in rate is impossible despite

an increase in the dose of drug.

3/10/2016

Clearly, these are circumstances in which the

rate of reaction is no longer proportional to

dose, and processes that exhibit this type of

kinetics are described as rate-limited or

dose-dependent or zero-order or as showing

saturation

kinetics.

In

practice

enzymemediated metabolic reactions are the

most likely to show rate-limitation because

the amount of enzyme present is finite and

can become saturated.

3/10/2016

Alcohol (ethanol) is a drug whose kinetics has

considerable implications for society as well

as for the individual, as follows. Alcohol is

subject to first-order kinetics with a t1/2 of

about one hour at plasma concentrations

below 10 mg/dl [attained after drinking about

two thirds of a unit (glass) of wine or beer]

Above this concentration the main enzyme

(alcohol dehydrogenase) that converts the

alcohol into acetaldehyde approaches and

then reaches saturation, at which point

alcohol metabolism cannot proceed any

faster.

3/10/2016

Thus if the subject continues to drink, the

blood

alcohol

concentration

rises

disproportionately, for the rate of metabolism

remains the same (at about 10 ml or 8 g/h

for a 70 kg man), i.e. a constant amount is

metabolised in unit time, and alcohol shows

zero-order kinetics.

3/10/2016

Absorption

•

Enteral:

by mouth (swallowed) or by sublingual

or buccal absorption; by rectum

•

Parenteral:

by intravenous injection or infusion,

intramuscular injection, subcutaneous injection

or infusion, inhalation, topical application for

local (skin, eye, lung) or for systemic

(transdermal) effect

•

Other routes,

e.g. intrathecal, intradermal,

intranasal, intratracheal, intrapleural, are used

when appropriate.

3/10/2016

The

small intestine

is the principal site for

absorption of nutrients and it is also where

most orally administered drugs enter the

body. This part of the gut has two important

attributes, an enormous surface area due to

the intestinal villi, and an epithelium through

which fluid readily filters in response to

osmotic differences caused by the presence

of food.

3/10/2016

It follows that drug access to the small intestinal

mucosa is important and disturbed alimentary

motility can reduce absorption, i.e. if gastric

emptying is slowed by food, or intestinal transit

is accelerated by gut infection.

The colon is capable of absorbing drugs and

many sustained release formulations probably

depend on absorption there. The stomach does

not play a major role in absorbing drugs, even

those that are acidic and thus unionized and

lipid-soluble at gastric pH, because its surface

area is much smaller than that of the small

intestine and gastric emptying is speedy (t/£ 30

min).

3/10/2016

This system is illustrated by the bile salts, which

are conserved by circulating through liver,

intestine and portal blood about eight times a

day. A number of drugs form conjugates with

glucuronic acid in the liver and are excreted in

the bile. These glucuronides are too polar

(ionised) to be reabsorbed; they therefore remain

in the gut, are hydrolysed by intestinal enzymes

and bacteria, releasing the parent drug, which is

then reabsorbed and reconjugated in the liver.

Enterohepatic recycling appears to help sustain

the plasma concentration.

3/10/2016

When a drug is injected intravenously it

enters the systemic circulation and thence

gains access to the tissues and to receptors,

i.e. 100% is available to exert its therapeutic

effect. If the same quantity of the drug is

swallowed, it does not follow that the entire

amount will reach first the portal blood and

then the systemic blood, i.e. its availability for

therapeutic effect via the systemic circulation

may be less than 100%.

3/10/2016

The terms potency and efficacy are often used

imprecisely and therefore, confusingly

Potency is the amount (weight) of drug in relation to

its effect, e.g. if weight-for-weight drug A has a

greater effect than drug B, then drug A is more potent

than drug B, although the maximum therapeutic

effect obtainable may be similar with both drugs.

The diuretic effect of bumetanide 1 mg is equivalent

to frusemide 50 mg, thus bumetanide is more

potent

than frusemide but both drugs achieve about the

same maximum effect.

The difference in weight of drug that has to be

administered is of no clinical significance unless it is

great.

3/10/2016

Pharmacological efficacy

refers to the strength of response induced by

occupancy of a receptor by antagonists

(intrinsic activity).

3/10/2016

Half-Life

The half-life (

t

½

) is the time it takes for the plasma

concentration or the amount of drug in the body to

be reduced by 50%.

T ½ =0.693*Vd/CL

Clearance is the measure of the body's ability to

eliminate a drug; thus, as clearance decreases, owing

to a disease process, for example, half-life would be

expected to increase. However, this reciprocal

relationship is valid only when the disease does not

change the volume of distribution.

For example, the half-life of diazepam increases with

increasing age; however, it is not clearance that

changes as a function of age but rather the volume of

distribution. Similarly, changes in protein binding of a

drug may affect its clearance as well as its volume of

distribution, leading to unpredictable changes in

half-life as a function of disease.

3/10/2016

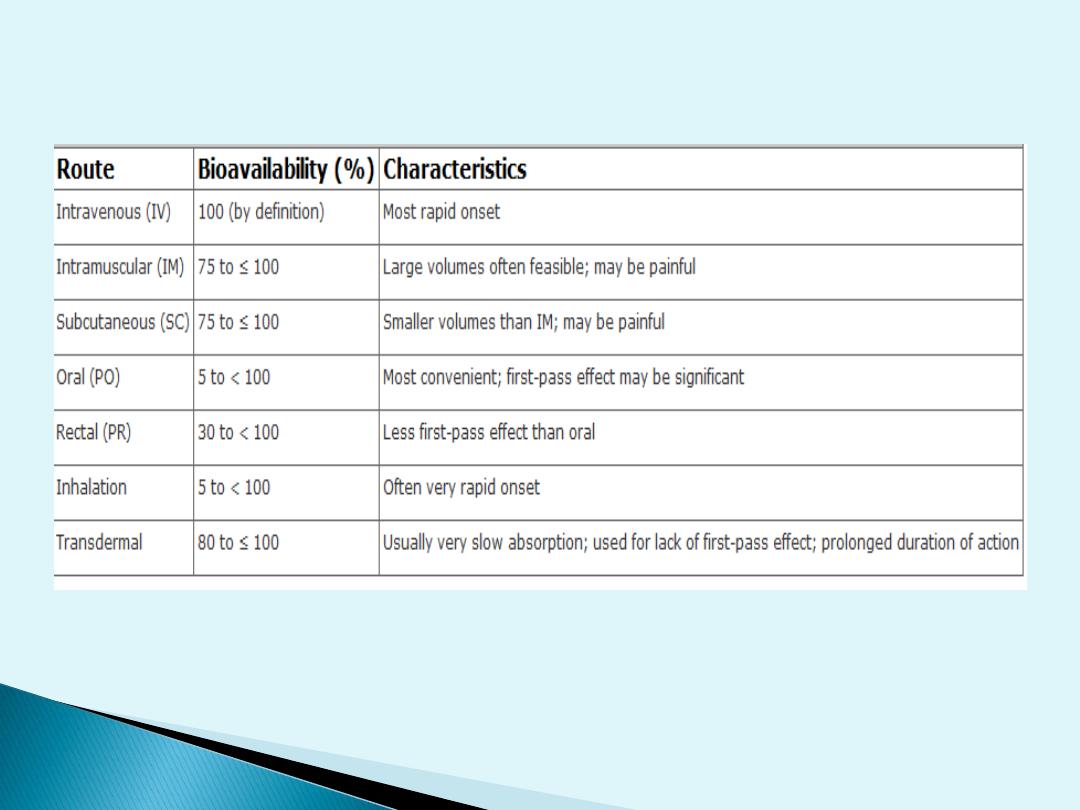

Bioavailability

Bioavailability is defined as the fraction of

unchanged drug reaching the systemic

circulation following administration by any

route.

The

area

under

the

blood

concentration-time curve (AUC) is a common

measure of the extent of bioavailability for a

drug given by a particular route.

For an intravenous dose of the drug,

bioavailability is assumed to be equal to

unity. For a drug administered orally,

bioavailability may be less than 100% for two

main

reasons

—incomplete

extent

of

absorption and first-pass elimination

3/10/2016

3/10/2016

EXTENT OF ABSORPTION

After oral administration, a drug may be incompletely

absorbed, eg, only 70% of a dose of digoxin reaches

the systemic circulation. This is mainly due to lack of

absorption from the gut. Other drugs are either too

hydrophilic (eg, atenolol) or too lipophilic (eg,

acyclovir) to be absorbed easily, and their low

bioavailability is also due to incomplete absorption.

If too hydrophilic, the drug cannot cross the lipid cell

membrane; if too lipophilic, the drug is not soluble

enough to cross the water layer adjacent to the cell.

Drugs may not be absorbed because of a reverse

transporter associated with P-glycoprotein.

This process actively pumps drug out of gut wall

cells back into the gut lumen. Inhibition of P-

glycoprotein and gut wall metabolism, eg, by

grapefruit juice, may be associated with substantially

increased drug absorption

3/10/2016

FIRST-PASS ELIMINATION

Following absorption across the gut wall, the

portal blood delivers the drug to the liver prior to

entry into the systemic circulation. A drug can be

metabolized in the gut wall (eg, by the CYP3A4

enzyme system) or even in the portal blood, but

most commonly it is the liver that is responsible

for metabolism before the drug reaches the

systemic circulation.

In addition, the liver can excrete the drug into

the bile. Any of these sites can contribute to this

reduction in bioavailability, and the overall

process is known as first-pass elimination. The

effect of first-pass hepatic elimination on

bioavailability is expressed as the extraction ratio

(ER):

3/10/2016

Volume of Distribution

Volume is a second fundamental parameter

that is useful in considering processes of

drug disposition. The volume of distribution

(

V

) relates the amount of drug in the body to

the concentration of drug (

C

) in the blood or

plasma depending on the fluid measured.

This volume does not necessarily refer to an

identifiable physiological volume but rather

to the fluid volume that would be required to

contain all the drug in the body at the same

concentration measured in the blood or

plasma:

3/10/2016

A drug's volume of distribution therefore

reflects the extent to which it is present in

extravascular tissues and not in the plasma.

The plasma volume of a typical 70-kg man is

3 L, blood volume is about 5.5 L, extracellular

fluid volume outside the plasma is 12 L, and

the

volume

of

total-body

water

is

approximately 42 L.

V=amount of the drug in the body /C

3/10/2016

Many drugs exhibit volumes of distribution

far in excess of these values. For example, if

500 g of the cardiac glycoside

digoxin

were

in the body of a 70-kg subject, a plasma

concentration of approximately 0.75 ng/ml

would be observed. Dividing the amount of

drug in the body by the plasma concentration

yields a volume of distribution for digoxin of

about 667 L, or a value approximately 10

times greater than the total-body volume of a

70-kg man.

3/10/2016

In fact, digoxin distributes preferentially to

muscle and adipose tissue and to its specific

receptors (Na

+

,K

+

-ATPase), leaving a very

small amount of drug in the plasma to be

measured.

For drugs that are bound extensively to

plasma proteins but that are not bound to

tissue

components,

the

volume

of

distribution will approach that of the plasma

volume because drug bound to plasma

protein is measurable in the assay of most

drugs.

3/10/2016

The volume of distribution may vary widely

depending on the relative degrees of binding

to high-affinity receptor sites, plasma and

tissue proteins, the partition coefficient of the

drug in fat, and accumulation in poorly

perfused tissues.

As might be expected, the volume of

distribution for a given drug can differ

according to patient's age, gender, body

composition, and presence of disease. Total-

body water of infants younger than 1 year of

age, for example, is 75% to 80% of body

weight, whereas that of adult males is 60%

and that of females is 55%.

3/10/2016