1

Fifth stage

pediatrics

Lec-

Dr. Athal

9/11/2016

Pneumonia

Definition

:

• Pneumonia is an infection of the lower respiratory tract that involves the airways and

parenchyma with consolidation of the alveolar spaces.

• Lobar pneumonia describes pneumonia localized to one or more lobes of the lung.

• Bronchopneumonia refers to inflammation of the lung that is centered in the bronchioles and

leads to the production of a mucopurulent exudate that obstructs some of these small airways

and causes patchy consolidation of the adjacent lobules.

• Atypical pneumonia describes patterns typically more diffuse or interstitial than lobar

pneumonia.

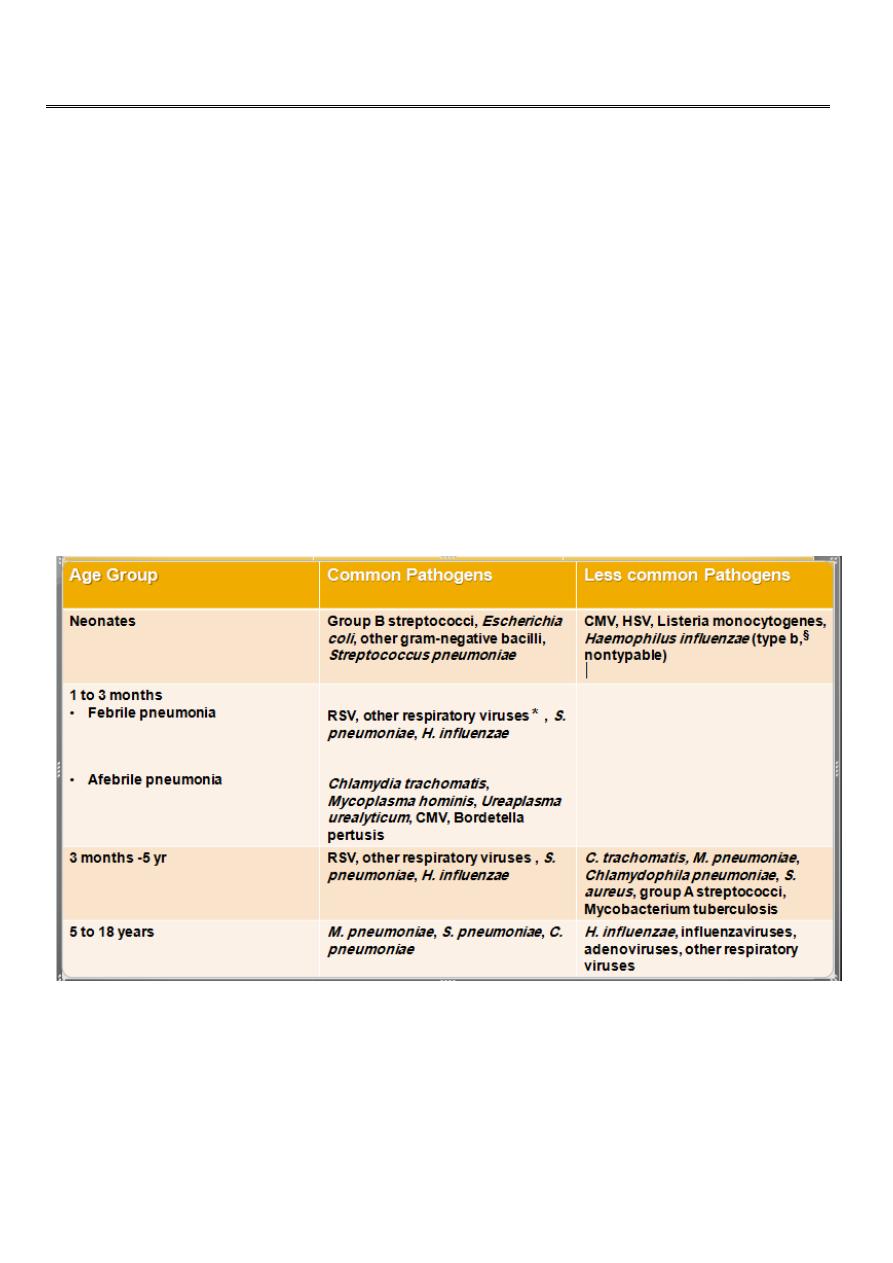

ETIOLOGY :

§

:

H. influenzae type b infection is uncommon with universal H. influenzae type b

immunization.

*: other respiratory viruses (parainfluenza viruses, influenzaviruses, adenoviruses, human

metapneumovirus.

2

Additional agents causes of pneumonia:

• SARS (severe acvute respiratory syndrome): due to corona virus.

• Avian influenza (bird flu): is highly contagious viral disease of poultry & other birds caused by

influenza A (H5N1). There were outbreaks among humans in South East Asia in 1997 & 2003-

2004 with high mortality rate.

• A novel influenza A (H1N1) of swine origin began circulating in 2009.

• M. pneumoniae and Chlamydophila pneumoniae are principal causes of atypical pneumonia.

Causes of pneumonia in immunocompromised persons include:

• gram-negative enteric bacteria

• mycobacteria (M. avium complex)

• fungi (aspergillosis)

• viruses (CMV)

• Pneumocystis carinii

Pneumonia in patients with cystic fibrosis usually is caused by:

• Staphylococcus aureus in infancy

• Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Burkholderia cepacia in older patients.

Risk factors for lower respiratory tract infections include:

• GERD

• Neurologic impairment (aspiration)

• Immunocompromised states.

• Anatomic abnormalities of the respiratory tract.

• Hospitalization, especially in an intensive care unit (ICU) or requiring

invasive procedures.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Fever, chills, tachypnea, cough, malaise, pleuritic chest pain, retractions, SOB &

apprehension. Apnea especially in young infant.

Examination cannot distinguish viral from bacterial pneumonia, in general:

Viral pneumonias:

are associated more often with cough, wheezing, or stridor; low

fever. Hyperexpansion cause low diaphragm or liver. Sign of consolidation diffuse.

Bacterial pneumonias:

typically are associated with higher fever, chills, cough, dyspnea,

and findings of lung consolidation localized (bronchial breathing, dull percussion, distant

breath sound & course crepitation). Poor diaphragmatic excursion may indicate large

consolidation or effusion.

3

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

WBC: in viral pneumonias is often normal or mildly elevated, with a predominance of

lymphocytes, whereas with bacterial pneumonias the WBC count is elevated

(>20,000/mm

3

) with a predominance of neutrophils.

Blood cultures are positive in 10% to 20% of bacterial pneumonia.

Viral detection: by serology or culture, but not routine.

M. pneumoniae: Mycoplasma IgM or PCR.

M. tuberculosis: is established by tuberculin skin test, and analysis of sputum or gastric

aspirates by culture or PCR.

When there is effusion or empyema, performing a thoracentesis to obtain pleural fluid

can be diagnostic and therapeutic.

The need to establish an etiologic diagnosis of pneumonia are:

• immunocompromised patients

• recurrent pneumonia

• pneumonia unresponsive to empirical therapy.

For these patients:

bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage and brush mucosal biopsy, needle aspiration of

the lung, and open lung biopsy are methods of obtaining material for microbiologic

diagnosis.

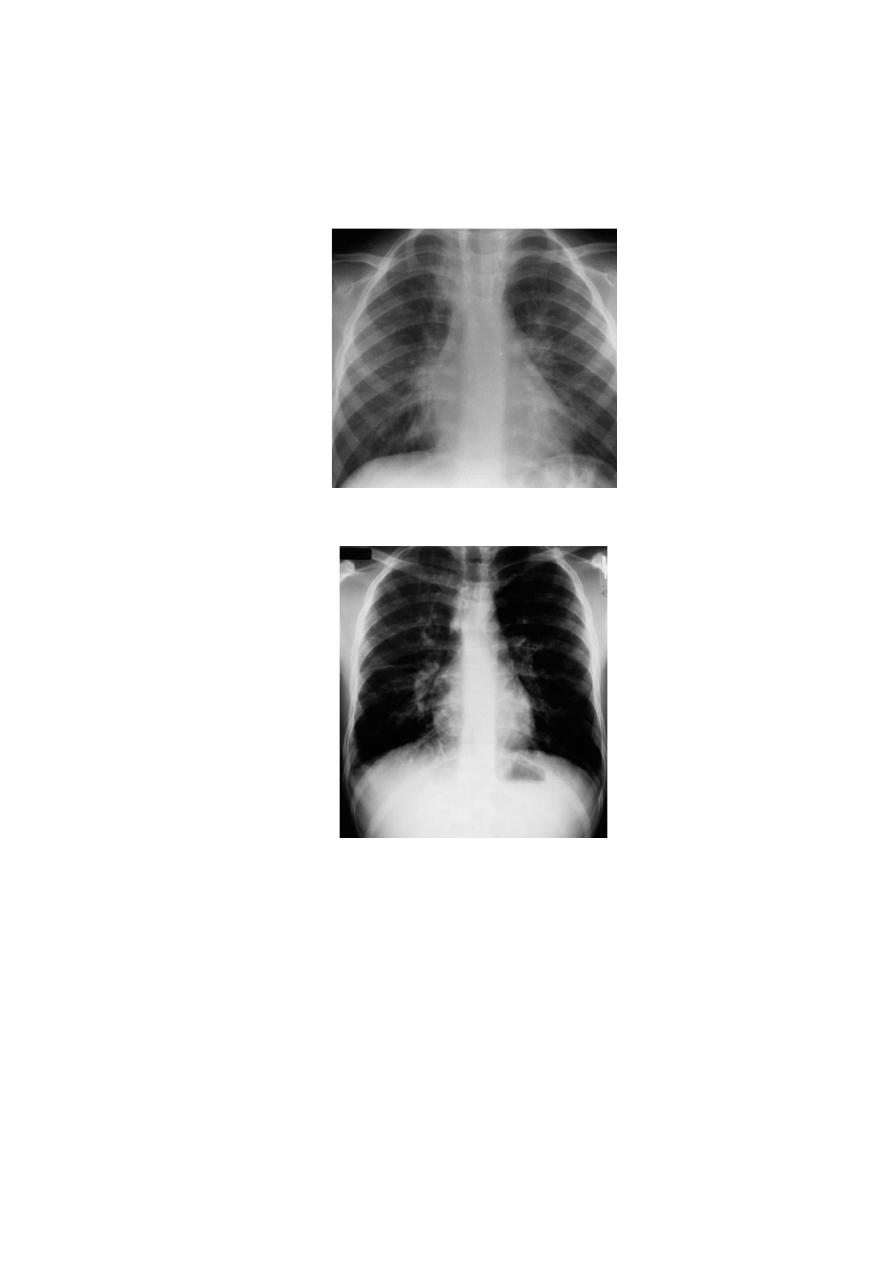

"Lobar Pneumonia"

4

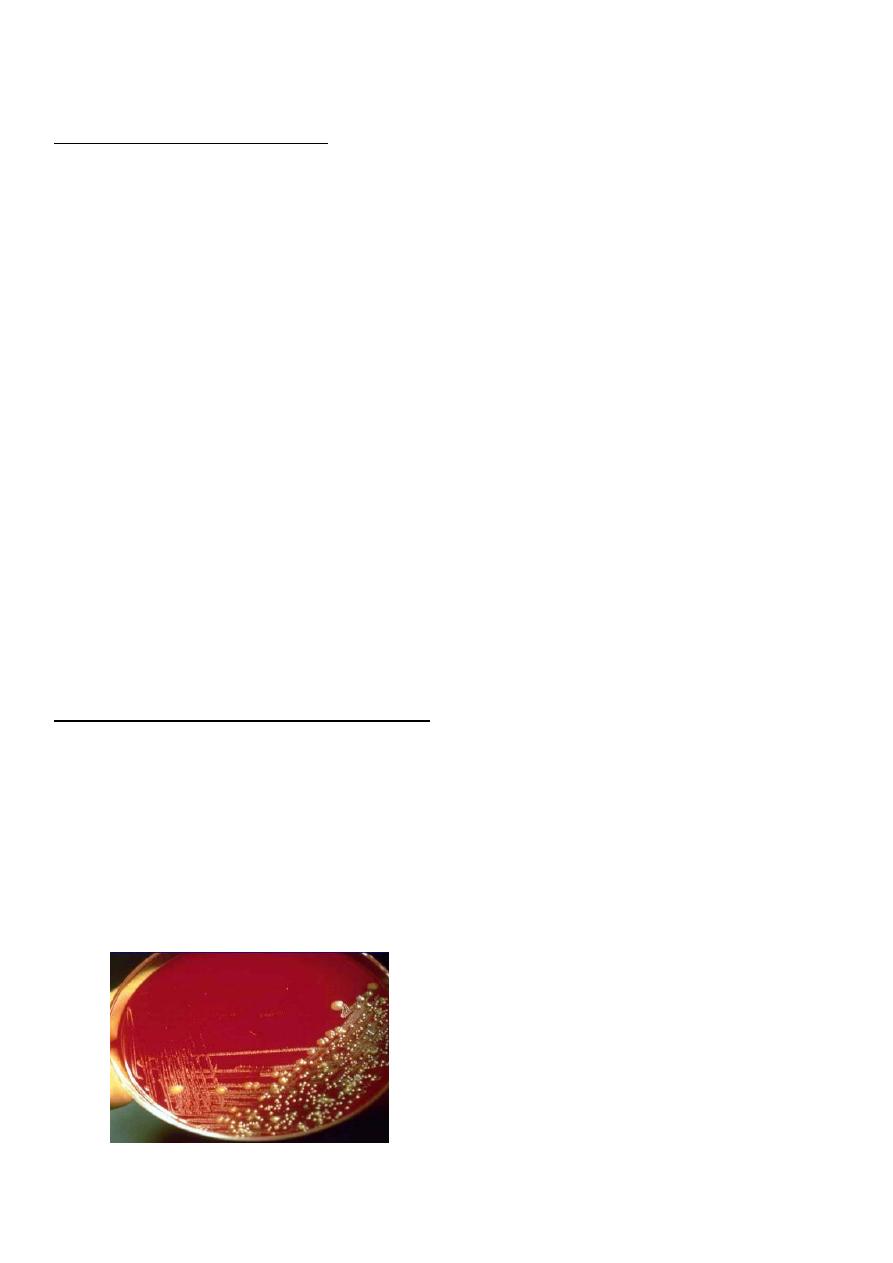

"Bronchopneumonia"

"

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection (atypical pneumonia)"

CXR:

Frontal & lateral:

-Bacterial pneumonia characteristically shows lobar consolidation, or a round

pneumonia, with pleural effusion in 10% to 30% of cases.

-Viral pneumonia characteristically shows diffuse, streaky infiltrates of

bronchopneumonia.

-Atypical pneumonia, such as with M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae, shows

increased interstitial markings or bronchopneumonia.

Decubitus

views to assess size of pleural effusions.

Ultrasound:

to assess pleural effusions.

CT:

is used to evaluate serious disease, abscesses & effusions.

5

TREATMENT

Therapy for pneumonia includes supportive and specific treatment and depends on the

degree of illness, complications, and knowledge of the infectious agent likely causing the

pneumonia.

Factors Suggesting Need for Hospitalization :

1. Age <6 months with suspected bacterial pneumonia.

2. Immunocompromised state

3. Toxic appearance

4. Severe respiratory distress

5. Requirement for supplemental oxygen

6. Dehydration

7. Vomiting

8. No response to appropriate oral antibiotic therapy.

9. Suspect pathogen with increased virulence e.g. methicillin resistant staph

aureus.

10. Noncompliant parents

Outpatients treatment: 7-10 days

Amoxicillin

Erythromycin, azithromycin, or clarithromycin if atypical pn. suspected.

Hospital treatment: 10-14 days

Usually combined antibiotic therapy according to age & suspected organism.

Neonate

: treated as sepsis

< 5 years:

Amoxicillin or ampicillin (if fully immunized for s. pneumoniae & H. influenzae type b).

Alternative: cefotaxime or ceftriaxone if not fully immunized or local pencillin resistant.

Plus clindamycin

Plus macrolide if atypical pneumonia suspected.

> 5 years:

Ampicillin Plus macrolide if atypical pneumonia suspected.

6

Treatment in the ICU: 10-14 days

Intravenous administration for inpatients except for the macrolides (erythromycin,

azithromycin, and clarithromycin), which are given orally.

< 5 years:

o Cefotaxime or ceftriaxone

o Plus nafcillin , oxacillin, clindamycin or vancomycin.

o Plus macrolide if atypical pneumonia suspected.

> 5 years:

o Cefuroxime or ceftriaxone

o Plus macrolide if atypical pneumonia suspected.

o

With or without clindamycin or vancomycin.

COMPLICATIONS AND PROGNOSIS

• Parapneumonic effusion

• Empyema

• Lung abscess

• Pneumatocele

• Bronchiectasis

•

Bronchiolitis obliterans: due to severe adenovirus pneumonia, inflammatory process in

which the small airways are replaced by scar tissue, resulting in a reduction in lung

volume and lung compliance.

PREVENTION

• Annual influenza vaccine is recommended for all children over 6 mo.

• Universal childhood vaccination with conjugate vaccines for H influenzae type b and S.

pneumoniae.

• The severity of RSV infections can be reduced by use of palivizumab in high-risk patients.

• Reducing the duration of mechanical ventilation and administering antibiotics judiciously

reduces the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonias.

• The head of the bed should be raised to 30 to 45 degrees for intubated patients to minimize

risk of aspiration, and all suctioning equipment and saline should be sterile.

• Hand washing before and after every patient contact and use of gloves for invasive

procedures are important measures to prevent nosocomial transmission of infections.

• Hospital staff with respiratory illnesses or who are carriers of certain organisms, such as

methicillin-resistant S. aureus, should comply with infection control policies to prevent

transfer of organisms to patients.

7

• Most children recover from pneumonia rapidly and completely, although radiographic

abnormalities may take 6 to 8 weeks to return to normal.

• In a few children, pneumonia may persist longer than 1 month or may be recurrent. In such

cases, the possibility of underlying disease must be investigated further, such as:

Tuberculin skin test

sweat chloride determination for cystic fibrosis

serum Ig and IgG subclass determinations

Bronchoscopy to identify anatomic abnormalities or foreign body

Barium swallow for GERD.

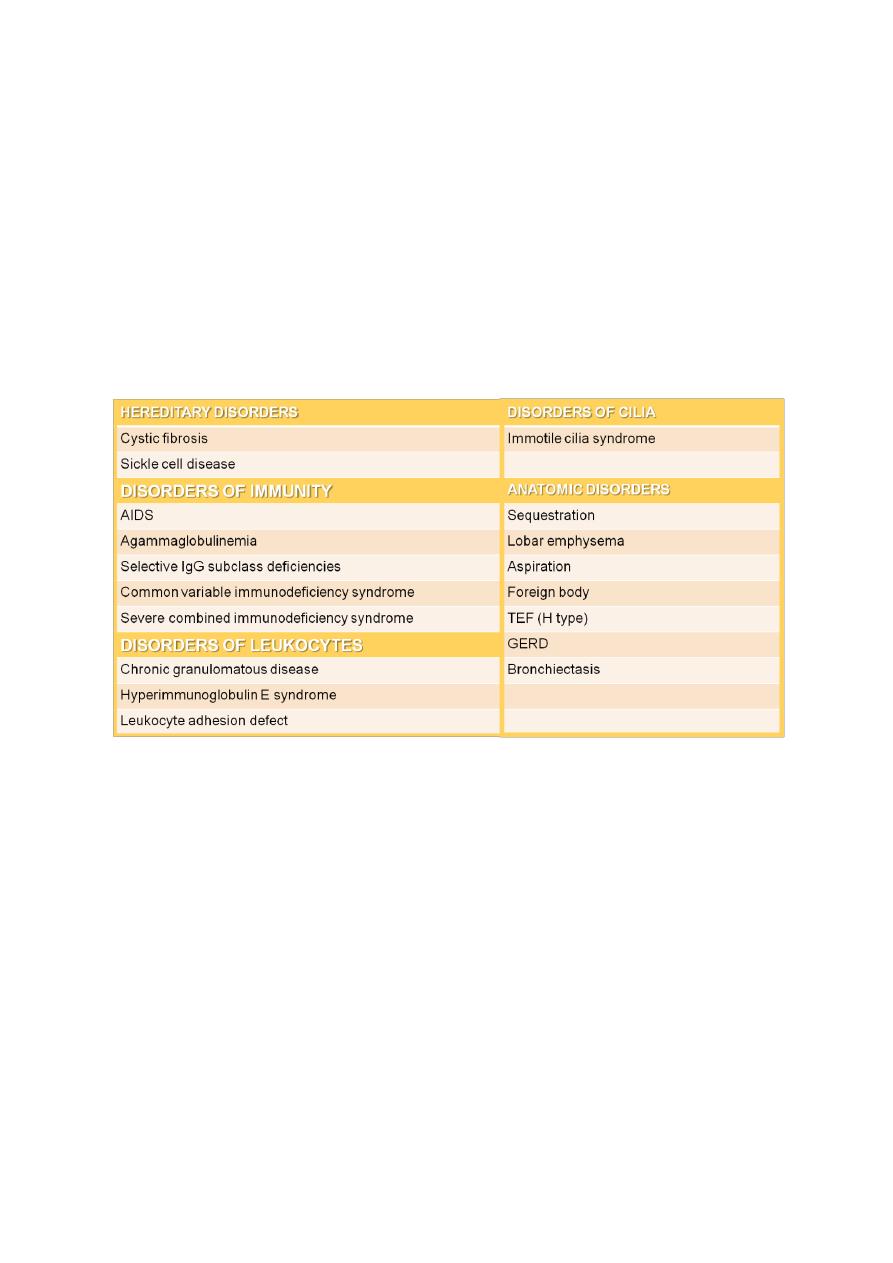

• Differential Diagnosis of Recurrent Pneumonia

PERTUSSIS

• Classic pertussis, whooping cough, is caused by B. pertussis, a gram-negative pleomorphic

bacillus with fastidious growth requirements.

• B. pertussis infect only humans and are transmitted person to person by coughing.

• The incubation period is 7-10 days. Patients are most contagious during the first 2 weeks of

cough.

• The peak age incidence of pertussis in the US is < 4 months of age-among infants too young

to be completely immunized and most likely to have the severe complications.

• Infections in adolescents have also been rising, likely due to waning immunity from previous

vaccines.

8

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The progression of the disease is divided into catarrhal, paroxysmal, and convalescent

stages.

• The catarrhal stage

: is marked by nonspecific signs (increased nasal secretions, and low-

grade fever) lasting 1 to 2 weeks.

•

The paroxysmal stage

: is the most distinctive stage of pertussis and lasts 2 to 4 weeks.

Coughing occurs in paroxysms during expiration, causing young children to lose their

breath. This pattern of coughing is needed to dislodge plugs of necrotic bronchial epithelial

tissues and thick mucus. The forceful inhalation against a narrowed glottis that follows this

paroxysm of cough produces the characteristic whoop. Post-tussive emesis is common.

•

The convalescent stage

: is marked by gradual resolution of symptoms over 1 to 2

weeks. Coughing becomes less severe, and the paroxysms and whoops slowly disappear.

Although the disease typically lasts 6 to 8 weeks, residual cough may persist for months,

especially with physical stress or respiratory irritants.

Infants

may not display the classic pertussis syndrome. The first sign in the neonate may

be episodes of

apnea.

Young infants are unlikely to have the classic whoop, more likely to

have

CNS damage as a result of hypoxia,

and more likely to have

secondary

bacterial pneumonia.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

• Isolation of B. pertussis by culture on specialized media.

• PCR

• Lymphocytosis: is present in 75% to 85% of patients but not diagnostic. WBC increase

to to more than 50,000 cells/mm

3,

consisting primarily of mature lymphocytes.

• CXR: segmental lung atelectasis. Perihilar infiltrates are common and are similar to

what is seen in viral pneumonia.

9

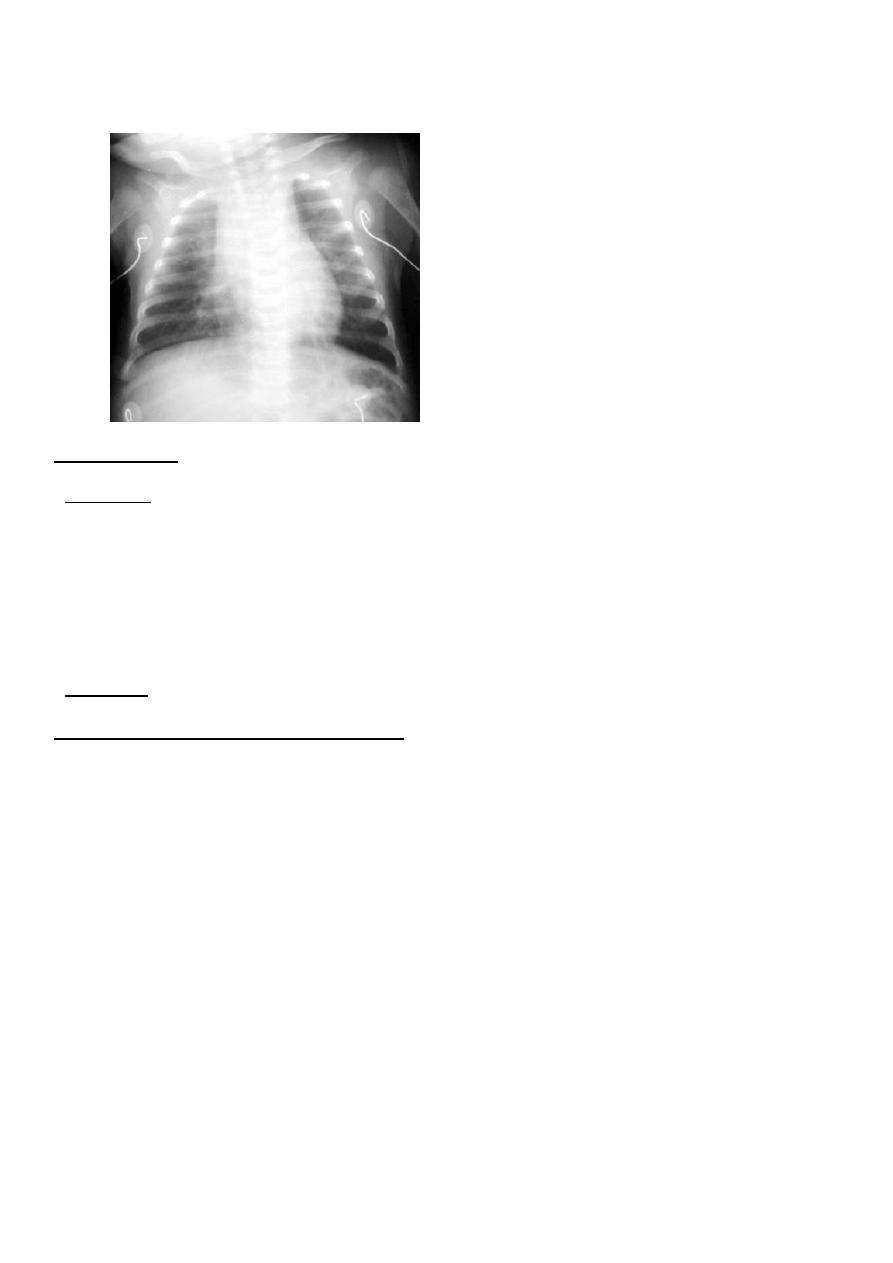

"shaggy heart" on CXR in a patient with Bordetella pertussis pneumonia.

TREATMENT

• Macrolide are recommended for children under 1 month of age. Azithromycin should be

used in neonates due to the association of erythromycin treatment and the development

of pyloric stenosis.

• Early treatment eradicates nasopharyngeal carriage of organisms within 3 to 4 days and

lessens the severity of symptoms.

• Treatment in the paroxysmal stage does not alter the course of illness but decrease the

potential for spread to others.

• TMP-SMZ is an alternative therapy among children >2mo, but this remains unproved.

COMPLICATIONS AND PROGNOSIS

Major complications are most common among infants and young children and include:

1. Hypoxia

2. Apnea

3. Pneumonia (caused by B. pertussis itself or resulting from secondary bacterial infection)

4. Atelectasis may develop secondary to mucous plugs.

5. The force of the paroxysm may produce pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, or

interstitial or subcutaneous emphysema; epistaxis; hernias; and retinal and

subconjunctival hemorrhages.

6. Otitis media and sinusitis may occur.

7. Seizures

8. Encephalopathy

9. Malnutrition.

10. Most children do well with complete healing of the respiratory epithelium and have

normal pulmonary function after recovery. Young children can die from pertussis and

are more likely to be hospitalized than older children. Most permanent disability is a

result of encephalopathy.

11

PREVENTION

Active immunity is induced with acellular pertussis components given in

combination with the tetanus and diphtheria toxoids (DTaP ).

Macrolides are effective in preventing secondary cases in contacts exposed to

pertussis.

Under immunized close contacts under 7 years of age should receive a booster

dose of DTaP (unless a booster dose has been given within the preceding 3 years),

where as those 7-10 years of age should receive Tdap.

All close contacts should receive prophylactic antibiotic for 5 days (azithromycin)

or 7 to 14 days (clarythromcin or erythromycin)