Approach to Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Hemorrhage

ObjectivesOutline resuscitation and treatment strategies for acute upper Gl tract hemorrhage and hemorrhagic shock.

Be familiar with the common causes of upper Gl tract hemorrhage and their therapies.

Know the adverse prognostic factors associated with continued bleeding and increased mortality.

DEFINITION

Upper GI bleeding is defined as bleeding from a source proximal to th Ligament of TreitzCauses of Upper Gl Hemorrhage

• Nonvariceal bleeding (80%)• Portal hypertensive bleeding (20%)

Up to 30% multiple etiologies.

a proportion of cases have no endoscopically discernible cause, these cases are associated with an excellent outcome.• Nonvariceal bleeding (80%)

• Peptic ulcer disease 30-50%• Mallory-Weiss tears 15-20%

• Gastritis or duodenitis 10-15%

• Esophagitis 5-10%

• A.V. malformations 5%

• Tumors 2%

• Other 5%

• Portal hypertensive bleeding (20%):

• Gastroesophageal varices >90%

• Hypertensive portal gastropathy <5%

• Isolated gastric varices Rare

Peptic ulcer disease

Ulcer of the mucosa in / adjacent to an acid bearing area.Gastric ulcer - usually lesser curve.

Duodenal ulcer – usually first part (cap).

DU: GU = 4:1 DU, male: female = 4:1

Theories of ulcer disease pathogenesis

• No acid, no ulcer (mostly)• Smoking

• Stress

• Non-steroidal drugs (NSAID’s)

• DU - Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: multiple ulceration,unusual site, not respond to medication, hypergastinemia-gastrinoma.

• Helicobacter pylori

Presentation of bleeding peptic ulcer

Known case of peptic ulcer disease,-endoscopy, non-complianceHistory of dyspepsia.

Smoking

NSAIDS

Cardinal features:

• Epigastric pain-pointing

• Night pain

• Hunger pain

Characterized by remission and relapse course.

Treatment of peptic ulcer disease

• H. Pylori eradication (Triple therapy)

• (PPI + clarithromycin + amoxicillin)

• H2 blocker –cimitidine, rantidine

• PPI-omiprazole, lansoprazole

• Stop smoking

• Avoid aspirin +NSAID use

• (Surgery)

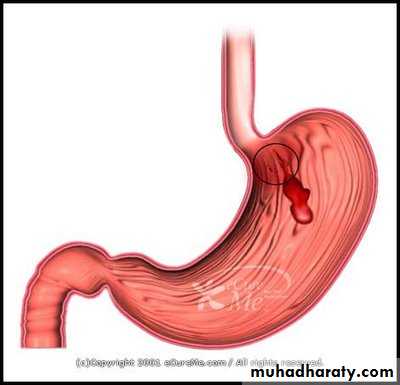

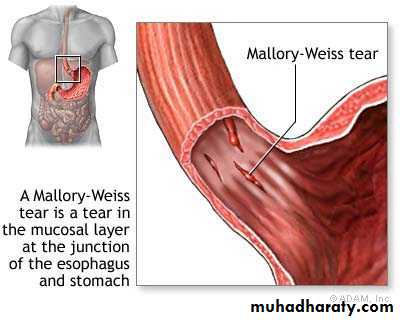

Mallory-Weiss syndrome

refers to bleeding from tears (a Mallory-Weiss tear) in the mucosa at the junction of the stomach and esophagus, usually caused by severe retching, coughing, or vomiting.Mallory-Weiss syndrome

MechanismForceful contraction of abdominal wall against an unrelaxed cardia, resulting in mucosal laceration of proximal cardia as a result of increase in intragastric pressure.

Causes: Alcoholism

The bleeding is self-limiting, mild, and amenable to supportive care and endoscopic management.

Stress gastritis:

multiple superficial erosions of entire stomach, most commonly in the body.

Stress gastritis Seen in…

• NSAID users• Sepsis

• Respiratory failure

• Hemodynamic instability

• Head injuries (Cushing ulcer)

• Burn injuries (Curling ulcer)

• Multiple trauma

Esophagitis:

Mucosal erosions frequently resulting from GERD , infections, or medications.most frequently present with occult bleeding,

Treatment: correction or avoidance of underlying causes.

Esophageal variceal bleeding:

Engorged veins of the GE region, which may ulcerate and lead to massive hemorrhage; related to portal hypertension and cirrhosis.The most common cause of upper Gl tract hemorrhage in a patient with cirrhosis and portal hypertension which carries a high rate of mortality and risk of rebleeding.?PUD.

The most common cause of pediatric significant upper Gl tract hemorrhage is variceal bleeding from extrahepatic portal venous obstruction.

Dieulafoy's erosion:

Infrequent, may be missed.

aberrant submucosal artery located in the stomach.

bleeding is frequently significant and requires prompt diagnosis by endoscopy, followed by endoscopic or operative therapy.

Arteriovenous (AV) malformation:

A small mucosal lesion located along the GI tract.Bleeding is usually abrupt, but usually slow and self-limiting.

The treatment of patients with suspected upper Gl tract hemorrhage begins with an initial assessment to determine if the bleeding is acute or occult.

Acute bleeding is recognized by a history of:

• Hematemesis ,

• Coffee -ground emesis,

• Melena ,

• Bleeding per rectum(hematochezia),

occult bleeding may present with signs and symptoms associated with anemia and no clear history of blood loss.

Hematemesis: Vomiting of blood.

• Red – Fresh blood• Coffee ground –

• altered blood (acid haematin)

Differentiate from:

Haemoptysis

Bleeding from Pharynx , nasal passage

Haematochezia

10 % of upper GI bleed

Acute massive bleeding

Decrease transit time

Melaena: Black tarry offensive stools.

1) Gastric acid

2) Digestive enzymes

3) Luminal bacteria

It is a Feature of UGI bleeding

Can be seen in LGI bleeding.

At least 14 hrs in GIT

Non GI bleed – swallowing

Oral Ferous mimics melaena

OCCULT BLOOD

Presents with features of chronic blood lossSuspected in pt with iron deficiency anaemia

TEST FOR OCCULT BLOOD

COLONOSCOPY

ENDOSCOPY

ENTEROSCOPY , CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY

(--)

(--)(+)

Management of acute upper Gl tract hemorrhage

Assessment of severity of blood loss.

(1) Resuscitation, of hypovolemic shock of blood loss.

(2) Diagnosis,

(3) Treatment.

Initial assessment & resuscitation

History and physical examinationLocalization of site of bleeding

Institution of specific therapy

INITIAL ASSESSMENT & RESUSCITATIONAssess A, B, C

Severity of hemorrhage:

4 grade of hypovolaemic shock of blood loss

According to parameter:

• PR,

• BP,

• RR,

• UOP,

• CONSCIOUSNESS

Resuscitation

Two large bore IV lines-Ringer lactate

Initial lab assessment-

• Hematocrit & Hb

• Type & cross match

• Coagulation profile, platelet count

• Serum electrolytes,

• LFT

close monitoring of patient response: parameter:

Urine output-foley catheter.

Oxygen supply.

Transfusion of packed red cells

Coagulation defects corrected by FFP & platelets

• Nasogastric tube insertion following resuscitation to determine whether bleeding is active or not, upper or lower GIT bleeding.

• gastric irrigation with room-temperature water or saline until gastric aspirates are clear.

History and examination

Characteristics of bleedingTime of onset, volume and frequency

Associated symptoms: syncope, vomiting, dyspepsia,

Medications: NSAIDS, anticoagulant:Warfarin, LMW heparin

Past medical history-

peptic ulcer,

liver disease,

heart disease

Bleeding disorder

Physical examination

Examination of nose & oropharynx

Stigmata of chronic liver disease

abdomen examination:

inspection: distention , dilated veins, swelling, visible peristalsis

palpation: tenderness, hepatosplenomegaly,secondary metastasis, mass

percussion: shifting dullness ,transmitted thrill, hepatosplenomegaly,

auscultation: absent bowel sound, venous hum

• establishes a diagnosis in more than 90% .

• assesses the current activity of bleeding.• aids in directing therapy.

• predicts the risk of rebleeding.

• allows for endoscopic therapy.

Forrest Classification

FIActive bleeding

FII a

Ulcer with visible vessel or pigmented protuberance (40 – 80%)

FII b

Ulcer with an adherent clot (20%)

FII c

Ulcer with a pigmented spot (10%)

FIII

Ulcer with clean base (rarely bleeds)

Institution of specific therapy

• Pharmacological

• Endoscopic

• Surgical modalities

Pharmacological

Antisecretory agents such as:• Histamine-2 blockers

• Proton pump inhibitors

Testing for Helicobacter pylori should be performed and if this organism is present, treatment should be initiated. Eradication of H pylori.

Any NSAID use should be discontinued.

Stop smoking,alcoholism.

Therapeutic endoscopy

Endoscopic hemostasis can be achieved through:• injection therapy.

• sclerotherapy.

• thermotherapy.

• electrocoagulation.

• cliping.

Absolute Indications of surgery

• Hemodynamic instability despite vigorous resuscitation (>6 units transfusion)

• Failure of endoscopic techniques to arrest hemorrhage

• Recurrent hemorrhage after initial stabilization (with up to two attempts at obtaining endoscopic hemostasis)

• Shock associated with recurrent hemorrhage

• Continued slow bleeding with a transfusion requirement exceeding 3 units/day

Relative Indications of surgery

• Rare blood type or difficult cross match• Refusal to transfusion

• Shock at presentation

• Advanced age

• Severe comorbid diseases

• Bleeding chronic gastric ulcer where malignancy is a possibility

For a bleeding gastric ulcer where there is a concern for possible malignancy, either gastrectomy or excision of the ulcer is indicated.

For other types of ulcers, the vessel may require ligation followed by a vagotomy procedure and pyloroplasty.

If the bleeding source cannot be identified but active bleeding is clearly occurring, patients may undergo selective angiography.

This treatment strategy can diagnose and treat bleeding in roughly 70% of patients;

arterial embolization with gel foam, metal coil springs, or a clot can be used to control bleeding.

arterial vasopressin can stop in some patients with peptic ulcer disease.

prognosis of Acute upper Gl tract Bleeding

Acute upper Gl tract Bleeding tends to be:

-self-limited in 80% .

-Continuing or recurrent in 20% and is the major contributor to mortality.

Overall mortality is 10% .

mortality with acute upper Gl tract bleedingPatient mortality increases with:

• Rebleeding ,

• Increased age,

• Patients who develop bleeding in the hospital.

A number of clinical predictors and endoscopic stigmata are associated with the increased risk of recurrent bleeding.

factors associated with increased rebleeding and mortality

CLINICAL:• Shock on admission

• Prior history of bleeding requiring transfusion ,

• Admission hemoglobin <8 g/dL

• Transfusion requirement >5 U of packed red blood cells

• Continued bleeding noted in nasogastric aspirate

• Age >60 y (increased mortality but no increase in rebleeding)

factors associated with increased rebleeding and mortality

ENDOSCOPIC:

• Visible vessel in ulcer base (50% rebleeding risk).

• Oozing of bright blood from ulcer base.

• Adherent clot at ulcer base.

• Location of ulcer (worse prognosis when located near large arteries, eg,posterior duodenal bulb or lesser curve of stomach)

Management of bleeding oesophageal varices

• Blood transfusion• Correct coagulopathy

• Oesophageal balloon tamponade (Sengstaken–Blakemoretube)

• Drug therapy (vasopressin/octreotide)

• Endoscopic sclerotherapy or banding

• Assess portal vein patency (Doppler ultrasound or CT)

• Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunts (TIPSS)

• Surgery:

• Portosystemic shunts

• Oesophageal transection

• Splenectomy and gastric devascularisation

case

A 38-year-old man presents at the emergency department with tarry stools and a feeling of light-headedness. The patient indicates that over the past 24 hours he has had several bowel movements containing tarry-colored stools and for the past 12 hours has felt light-headed.His past medical and surgical history are unremarkable. The patient complains of frequent headaches caused by work-related stress, for which he has been self-medicating with 6-8 tablets of ibuprofen a day for the past 2 weeks. He consumes two to three martinis per day and denies tobacco or illicit drug use.

On examination, his temperature is 37.0°C (98.6°F), pulse rate 105/min (supine), blood pressure 104/80, and respiratory rate 22/min. His vital signs upright are pulse 120/min and blood pressure 90/76. He is awake, cooperative, and pale. The cardiopulmonary examinations are unremarkable. His abdomen is mildly distended and mildly tender in the epigastrium. The rectal examination reveals melanotic stools but no masses in the vault.

^ What is your next step?

♦ What is the best initial treatment?

Summary:

A 38-year-old man presents with signs and symptoms of acute upper gastrointestinal (Gl) tract hemorrhage.The patient's presentation suggests that he may have had significant blood loss leading to class III hemorrhagic shock.

Answer

^ Next step:The first step in the treatment of patients with upper Gl hemorrhage is intravenous fluid resuscitation.

The etiology and severity of the bleeding dictate the intensity of therapy and predict the risk of further bleeding and/or death.

^ Best initial treatment:

Prompt attention to the patient'sairway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) is mandatory for patients with acute upper Gl hemorrhage.

After attention to the ABCs, the patient is prepared for endoscopy to identify the etiology or source of the bleeding and possible endoscopic therapy to control hemorrhage.

In this patient's case, his symptoms and physiologic parameters suggest severe, acute blood loss (class III hemorrhagic shock with up to 35% total blood volume loss) and should prompt:

immediate resuscitation

with close monitoring of patient response :

• urine output,

• clinical appearance,

• blood pressure,

• heart rate,

• serial hemoglobin and hematocrit values,

• central venous pressure monitoring.

A nasogastric tube should be inserted following resuscitation to determine whether bleeding is active.

The stomach should be irrigated with room-temperature water or saline until gastric aspirates are clear.

For patients with massive upper GI tract bleeding, agitation, or impaired respiratory status, endotracheal intubation is recommended prior to endoscopy.

Laboratory studies to be obtained include:

• a complete blood count,

• liver function studies,

• prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time.

• A type and cross-match should be ordered.

Platelets or fresh-frozen plasma should be administered when thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy is identified, respectively.

Early endoscopy identifies the bleeding source in patients with active ongoing bleeding and may achieve early control of bleeding.

Given the history of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, it would be appropriate to begin empirical therapy for a presumed gastric ulcer and gastric erosions with a proton pump inhibitor prior to endoscopic confirmation.

A 55-year-old man has undergone upper endoscopy. He is told by his gastroenterologist that although this disorder may cause anemia, it is unlikely to cause acute GI hemorrhage. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

• Gastric ulcer

• Duodenal ulcer

• Gastric erosions

• Esophageal varices

• Gastric cancer

E. Gastric cancer is relatively asymptomatic until late in its course. Weight loss and anorexia are the most common symptoms with this condition. Hematemesis is unusual, but anemia from chronic occult blood loss is common.

A 32-year-old man comes to the emergency department with a history of vomiting "large amounts of bright red blood." Which of the following is the most appropriate first step in the treatment of this patient?

• Obtaining a history and performing a physical examination

• Determining hemoglobin and hematocrit levels

• Fluid resuscitation

• Inserting a nasogastric tube

• Performing urgent endoscopy

C. Fluid resuscitation is the first priority to maintain sufficient intravascular volume to perfuse vital organs.

A 65-year-old man is brought into the emergency department with acute upper GI hemorrhage. A nasogastric tube is placed with bright red fluid aspirated. After 30 minutes of saline flushes, the aspirate is clear. Which of the following is the most accurate statement regarding this patient's condition?

• He has approximately a 20% chance of rebleed.

• The mortality for his condition is much lower today than 20 years ago.

• His age is a poor prognostic factor for rebleeding.

• Mesenteric ischemia is a likely cause of his condition.

A. Approximately 20% of patients with acute upper Gl hemorrhage have continued or rebleeding episodes. The mortality has remained the same (approximately 8-10%) over the past 20 years.

A 52-year-old man with alcoholism and known cirrhosis comes into the emergency department with acute hematemesis. Bleeding esophageal varices are found during upper GI endoscopy. Which of the following is most likely to be effective treatment for this patient?

• Balloon tamponade of the esophagus

• Proton pump inhibitor

• Triple antibiotic therapy

• Misoprostol oral therapy

• Endoscopic sclerotherapy

E. Endoscopic injection of sclerosing agents directly into the varix is effective in controlling acute hemorrhage caused by variceal bleeding in approximately 90% of cases. Balloon tamponade is a therapy used infrequently for acute esophageal variceal bleeding because of its limited effectiveness in achieving sustained control of bleeding. Other therapies include vasopressin or octreotide to decrease portal pressure.