Conjunctiva, cornea and sclera

INTRODUCTION

Disorders of the conjunctiva and cornea are a common cause of symptoms.The ocular

surface is regularly exposed to the external environment and subject to trauma, infection and

allergic reactions which account for the majority of diseases in these tissues. Degenerative

and structural abnormalities account for a minority of problems.

Symptoms :

Patients may complain of the following:

1 Pain and irritation. Conjunctivitis is seldom associated with anything more than mild

discomfort. Pain signifies something more serious such as corneal injury or infection.

This symptom helps differentiate conjunctivitis from corneal disease.

2 Redness. In conjunctivitis the entire conjunctival surface including that covering the

tarsal plates is involved. If the redness is localized to the limbus ciliary flush the

following should be considered:

(a) keratitis (an inflammation of the cornea);

(b) uveitis;

(c) acute glaucoma.

3 Discharge. Purulent discharge suggests a bacterial conjunctivitis. Viral conjunctivitis is

associated mainly with a watery discharge.

4 Visual loss. This occurs only when the central cornea is affected. Loss of vision is thus

an important symptom requiring urgent action.

5 Patients with corneal disease may also complain of photophobia.

Signs

The following features may be seen in conjunctival disease:

• Papillae.These are raised lesions on the upper tarsal conjunctiva, about 1 mm in

diameter with a central vascular core. They are non-specific signs of chronic

inflammation. Giant papillae, found in allergic eye disease, are formed by the

coalescence of papillae (see Fig. 7.4).

• Follicles (Fig. 7.1).These are raised, gelatinous, oval lesions about 1 mm in diameter

found usually in the lower tarsal conjunctiva and upper tarsal border, and occasionally

at the limbus. Each follicle represents a lymphoid collection with its own germinal

centre. Unlike papillae, the causes of follicles are more specific (e.g. viral and

chlamydial infections).

• Dilation of the conjunctival vasculature (termed ‘injection’).

• Subconjunctival haemorrhage, often bright red in colour because it is fully

oxygenated by the ambient air, through the conjunctiva.

Fifth stage Lec-

Dr.Nazar

Ophthalomology

28/11/2016

The features of corneal disease are different and include the following:

• Epithelial and stromal oedema may develop causing clouding of the cornea.

• Cellular infiltrate in the stroma causing focal granular white spots.

• Deposits of cells on the corneal endothelium (termed keratic precipitates or KPs,

usually lymphocytes or macrophages, see p. 92).

• Chronic keratitis may stimulate new blood vessels superficially, under the epithelium

(pannus; Fig. 7.2) or deeper in the stroma.

• Punctate Epithelial Erosions or more extensive patches of epithelial loss which are

best detected using fluorescein dye and viewed with a blue light.

CONJUNCTIVA

Inflammatory diseases of the conjunctiva

BACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS :

Patients present with:

1. redness of the eye;

2. discharge;

3. ocular irritation.

The commonest causative organisms are Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Pneumococcus and

Haemophilus. The condition is usually self-limiting although a broad spectrum antibiotic

eye drop will hasten resolution. Conjunctival swabs for culture are indicated if the condition

fails to resolve.

ANTIBIOTICS Chloramphenicol Ciprofloxacin Fusidic acid Gentamicin Neomycin

Ofloxacin Tetracycline

Ophthalmia neonatorum, which refers to any conjunctivitis that occurs in the first 28 days

of neonatal life, is a notifiable disease. Swabs for culture are mandatory. It is also important

that the cornea is examined to exclude any ulceration.

The commonest organisms are:

1. Bacterial conjunctivitis (usually Gram positive).

2. Neisseria gonorrhoea. In severe cases this can cause corneal perforation.

Penicillin given topically and systemically is used to treat the local and systemic

disease respectively.

3. Herpes simplex, which can cause corneal scarring.Topical antivirals are used to

treat the condition.

4. Chlamydia. This may be responsible for a chronic conjunctivitis and cause sight-

threatening corneal scarring.Topical tetracycline ointment and systemic

erythromycin is used is used to treat the local and systemic disease respectively.

VIRAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

This is distinguished from bacterial conjunctivitis by:

1. a watery and limited purulent discharge;

2. the presence of conjunctival follicles and enlarged pre-auricular lymph nodes;

3. there may also be lid oedema and excessive lacrimation.

The conjunctivitis is self-limiting but highly contagious. The common- est causative agent is

adenovirus and to a lesser extent Coxsackie and picornavirus. Adenoviruses can also cause a

conjunctivitis associated with the formation of a pseudomembrane across the conjunctiva.

Certain adenovirus serotypes also cause a troublesome punctate keratitis. Treatment for the

conjunctivitis is unnecessary unless there is a secondary bacterial infection. Patients must be

given hygiene instruction to minimize the spread of infection (e.g. using separate towels).

Treatment of keratitis is controversial. The use of topical steroids damps down symptoms

and causes corneal opacities to resolve but rebound inflammation is common when the

steroid is stopped.

CHLAMYDIAL INFECTIONS

Different serotypes of the obligate intracellular organism Chlamydia trachomatis are

responsible for two forms of ocular infections.

Inclusion keratoconjunctivitis

This is a sexually transmitted disease and may take a chronic course (up to 18 months)

unless adequately treated. Patients present with a muco- purulent follicular conjunctivitis

and develop a micropannus (superficial

peripheral corneal vascularization and scarring) associated with sub- epithelial scarring.

Urethritis or cervicitis is common. Diagnosis is confirmed by detection of chlamydial

antigens, using immunofluorescence, or by identification of typical inclusion bodies by

Giemsa staining in conjunctival swab or scrape specimens.

Inclusion conjunctivitis is treated with topical and systemic tetracycline. The patient should

be referred to a sexually transmitted diseases clinic.

Trachoma (Fig. 7.3)

This is the commonest infective cause of blindness in the world although it is uncommon

in developed countries.The housefly acts as a vector and the disease is encouraged by poor

hygiene and overcrowding in a dry, hot climate. The hallmark of the disease is

subconjunctival fibrosis caused by frequent re-infections associated with the unhygienic

conditions. Blindness may occur due to corneal scarring from recurrent keratitis and

trichiasis.

Trachoma is treated with oral or topical tetracycline or erythromycin. Azithromycin, an

alternative, requires only one application. Entropion and trichiasis require surgical

correction.

ALLERGIC CONJUNCTIVITIS

This may be divided into acute and chronic forms:

2-Acute (hayfever conjunctivitis). This is an acute IgE-mediated reaction to airborne

allergens (usually pollens). Symptoms and signs include:

(a) itchiness;

(b) conjunctival injection and swelling (chemosis);

(c) lacrimation.

2- Vernal conjunctivitis (spring catarrh) is also mediated by IgE. It oftenb affects male

children with a history of atopy. It may be present all year long. Symptoms and signs

include:

(a) itchiness;

(b) photophobia;

(c) lacrimation;

(d) papillary conjunctivitis on the upper tarsal plate (papillae may coalesce to form giant

cobblestones; Fig. 7.4);

(e) limbal follicles and white spots;

(f) ) punctate lesions on the corneal epithelium;

(g) an opaque, oval plaque which in severe disease replaces an upper zone of the corneal

epithelium.

Initial therapy is with antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers (e.g. sodium

cromoglycate; nedocromil; lodoxamide). Topical steroids are required in severe cases but

long-term use is avoided if possible because of the possibility of steroid induced

glaucoma or cataract.

Contact lens wearers may develop an allergic reaction to their lenses or to lens cleaning

materials leading to a giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) with a mucoid discharge.

Whilst this may respond to topical treatment with mast cell stabilizers it is often

necessary to stop lens wear for a period or even permanently. Some patients are unable to

continue contact lens wear due to recurrence of the symptoms.

Conjunctival degenerations

Pingueculae and pterygia are found on the interpalpebral bulbar

conjunctiva. They are thought to result from excessive exposure to the reflected or direct

ultraviolet component of sunlight. Histologically the collagen structure is altered.

Pingueculae are yellowish lesions that never impinge on the cornea. Pterygia are wing

shaped and located nasally, with the apex towards the cornea onto which they progressively

extend (Fig. 7.5). They may cause irritation and, if extensive, may encroach onto the visual

axis. They can be excised but may recur.

CONJUNCTIVAL TUMOURS

These are rare. They include:

• Squamous cell carcinoma. An irregular raised area of conjunctiva which may invade

the deeper tissues.

• Malignant melanoma. The differential diagnosis from benign pigmented lesions (for

example a naevus) may be difficult. Review is necessary to assess whether the lesion

is increasing in size. Biopsy, to achieve a definitive diagnosis, may be required.

CORNEA

Infective corneal lesions

HERPES SIMPLEX KERATITIS :

Type 1 herpes simplex (HSV) is a common and important cause of ocular disease. Type 2

which causes genital disease may occasionally cause keratitis and infantile chorioretinitis.

Primary infection by HSV1 is usually acquired early in life by close contact such as kissing.

It is accompanied by:

• fever;

• vesicular lid lesions;

• follicular conjunctivitis;

• pre-auricular lymphadenopathy;

• most are asymptomatic.

The cornea may not be involved although punctate epithelial damage may be seen.

Recurrent infection results from activation of the virus lying latent in the trigeminal

ganglion of the fifth cranial nerve. There may be no past clinical history. The virus travels in

the nerve to the eye. This often occurs if the patient is debilitated (e.g.. Emotional stress,

systemic illness, immunosuppression,fever, menstruation, topical or systemic steroid). It is

characterized by the appearance of dendritic ulcers on the cornea (Fig. 7.6). These usually

heal without a scar. If the stroma is also involved oedema develops causing a loss of

corneal transparency. Involvement of the stroma may lead to permanent scarring. If

corneal scarring is severe a corneal graft may be required to restore vision. Uveitis and

glaucoma may accompany the disease.

Disciform keratitis is an immunogenic reaction to herpes antigen in the stroma and presents

as stromal clouding without ulceration, often associated with iritis.

Dendritic lesions are treated with topical antivirals which typically heal within 2 weeks.

Topical steroids must not be given to patients with a dendritic ulcer since they may cause

extensive corneal ulceration (Ameboid or geographic ulcer). In patients with stromal

involvement (keratitis) steroids are used under ophthalmic supervision and with antiviral

cover.

ANTIVIRAL AGENTS Vidarabine Trifluorothymidine Aciclovir Ganciclovir

HERPES ZOSTER OPHTHALMICUS (OPHTHALMIC SHINGLES) (Fig. 7.7)

This is caused by the varicella-zoster virus which is responsible for chickenpox. The

ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is affected. Unlike herpes simplex infection

there is usually a prodromal period with the patient systemically unwell. Ocular

manifestations are usually preceded by the appearance of vesicles in the distribution of the

ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. Ocular problems are more likely if the naso-

ciliary branch of the nerve is involved (vesicles at the root of the nose).

Signs include:

• lid swelling (which may be bilateral);

• keratitis;

• iritis;

• secondary glaucoma.

Reactivation of the disease is often linked to unrelated systemic illness. Oral antiviral

treatment (e.g. aciclovir and famciclovir) is effective in reducing post-infective neuralgia

(a severe chronic pain in the area of the rash) if given within 3 days of the skin vesicles

erupting. Ocular disease may require treatment with topical antivirals and steroids.

The prognosis of herpetic eye disease has improved since antiviral treatment became

available. Both simplex and zoster cause anaesthesia of the cornea. Non-healing indolent

ulcers may be seen following simplex infection and are difficult to treat.

BACTERIAL KERATITIS

Pathogenesis

A host of bacteria may infect the cornea.

• Staphylococcus epidermidis

• Staphylococcus aureus

• Streptococcus pneumoniae

• Coliforms

• Pseudomonas

• Haemophilus

Some are found on the lid margin as part of the normal flora. The conjunctiva and cornea

are protected against infection by:

• blinking;

• washing away of debris by the flow of tears;

• entrapment of foreign particles by mucus;

• the antibacterial properties of the tears;

• the barrier function of the corneal epithelium (Neisseria gonnorrhoea

is the only organism that can penetrate the intact epithelium).

Predisposing causes of bacterial keratitis include:

• keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eye);

• a breach in the corneal epithelium (e.g. following trauma);

• contact lens wear;

• prolonged use of topical steroids.

Symptoms and signs

These include:

• pain, usually severe unless the cornea is anaesthetic;

• purulent discharge;

• ciliary injection;

• visual impairment (severe if the visual axis is involved);

• hypopyon sometimes (a mass of white cells collected in the anterior chamber; see pp.

91–92);

• a white corneal opacity which can often be seen with the naked eye (Fig. 7.8).

Treatment

Scrapes are taken from the base of the ulcer for Gram staining and culture. The patient is

then treated with intensive topical antibiotics often with dual therapy (e.g. cefuroxime

against Gram +ve bacteria and gentamicin for Gram —ve bacteria) to cover most

organisms. The use of fluoro- quinolones (e.g. Ciprofloxacin, Ofloxacin) as a

monotherapy is gaining popularity. The drops are given hourly day and night for the first

couple of days and reduced in frequency as clinical improvement occurs. In severe or

unresponsive disease the cornea may perforate. This can be treated initially with tissue

adhesives (cyano-acrylate glue) and a subsequent corneal graft. A persistent scar may

also require a corneal graft to restore vision.

ACANTHAMOEBA KERATITIS (Fig. 7.9)

This freshwater amoeba is responsible for infective keratitis. The infection is becoming

more common due to the increasing use of soft contact lenses. A painful keratitis

with prominence of the corneal nerves results. The amoeba can be isolated from the

cornea (and from the contact lens case) with a scrape and cultured on special plates

impregnated with Escherichia coli. Topical chlorhexidine, polyhexamethylene

biguanide (PHMB) and propamidine are used to treat the condition.

FUNGAL KERATITIS

more common in warmer climates. It should be considered in:

• lack of response to antibacterial therapy in corneal ulceration;

• cases of trauma with vegetable matter;

• cases associated with the prolonged use of steroids.

The corneal opacity appears fluffy and satellite lesions may be present. Liquid and

solid Sabaroud’s media are used to grow the fungi. Incubation may need to be prolonged.

Treatment requires topical antifungal drops such as pimaricin 5%.

INTERSTITIAL KERATITIS

This term is used for any keratitis that affects the corneal stroma without epithelial

involvement. Classically the most common cause was syphillis, leaving a mid stromal scar

with the outline (‘ghost’) of blood vessels seen. Corneal grafting may be required when the

opacity is marked and visual acuity reduced.

Corneal dystrophies (Fig. 7.10)

These are rare inherited disorders. They affect different layers of the cornea and often

affect corneal transparency. They may be divided into:

• Anterior dystrophies involving the epithelium. These may present with recurrent

corneal erosion.

• Stromal dystrophies presenting with visual loss. If very anterior they may cause

corneal erosion and pain.

• Posterior dystrophies which affect the endothelium and cause gradual loss of vision

due to oedema. They may also cause pain due to epithelial erosion.

Disorders of shape

KERATOCONUS

This is usually a sporadic disorder but may occasionally be inherited. Thinning of the

centre of the cornea leads to a conical corneal distortion. Vision is affected but there is no

pain. Initially the associated astigmatism can be corrected with glasses or contact lenses. In

severe cases a corneal graft may be required.

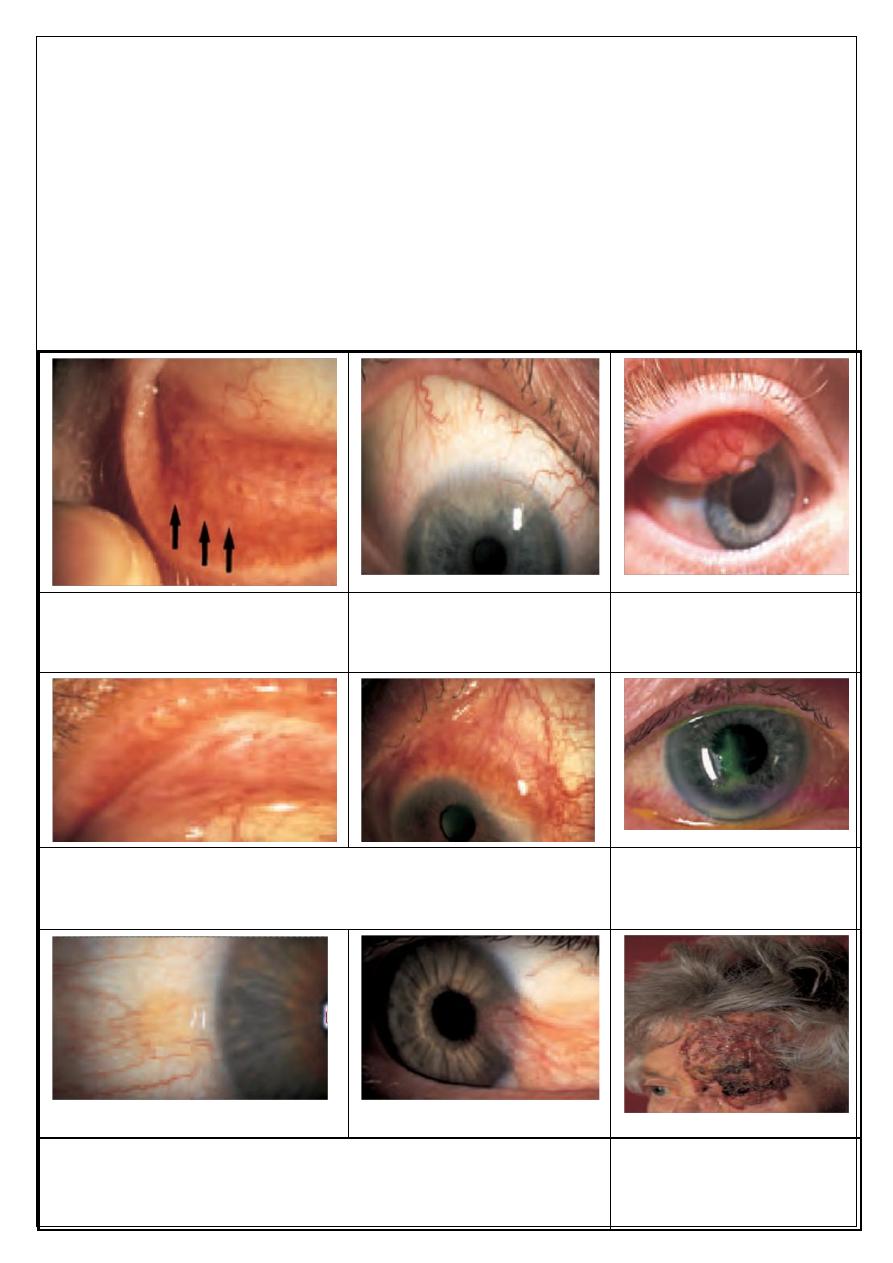

Central corneal degenerations

BAND KERATOPATHY (Fig. 7.11)

the subepithelial deposition of calcium phosphate in the exposed part of the cornea. It

is seen in eyes with chronic uveitis or glaucoma. It can also be a sign of systemic

hypercalcaemia as in hyperparathyroidism or renal failure. and may cause visual loss or

discomfort if epithelial erosions form over the band. If symptomatic it can be scraped off

aided by a chelating agent such as sodium edetate.The excimer laser can also be effective in

Degenerative Changes of Cornea

Keratoconus:

القرنية المخروطية

Progressive coning of corneal due to thinning of inf. Paracentral stroma.

Usually bilateral but may be asymmetrical

Start in teens age (puberty), more in females.

Associations:

1. Vernal catarrh

2. Atopic dermatitis

3. Down syndrome

4. Turner syndrome

5. Marfan syndrome

6. Ehler Danlos Syndrome

Present: Progressive blurring of vision (irregular myopic astigmatism & corneal opacities).

O/E:

1- Thinning & forward bowing of inf. Paracentral cornea stroma (slit lamp ex.)

2- Brownish ring (Fleischer) around the base of cone due to hemosiderin deposit.

3- Distortion of the corneal light reflection (placido disc).

4- Altered ophthalmoscopic & retinoscopic light reflexes.

5- Munson’s sign (indentation of the lower lid by the conical corneal when patient

looks downward).

6- Acute hydrops=stromal oedema due to rupture descemet membrane.

Nowadays ,it is mostly diagnosed by corneal topography examination during the pre-

oprative assessment of refractive surgery

Treatment:

1- Corneal Collagen Cross-linking, in early cases to arrest the disease

2- Glasses

3- Contact lenses (Rigid)

4- Intra-stromal corneal rings

5- Penetrating keratoplasty or Lamellar keratoplasty..in advanced cases or corneal

scarring

Peripheral corneal degenerations

CORNEAL THINNING

A rare cause of painful peripheral corneal thinning is Mooren’s ulcer, a condition

with an immune basis. Corneal thinning or melting can also be seen in collagen diseases

such as rheumatoid arthritis and Wegener’s granulomatosis. Treatment can be difficult and

both sets of disorder require systemic and topical immunosuppression. Where there is an

associated dry eye it is important to ensure adequate corneal wetting and corneal protection

(see pp. 59–60).

LIPID ARCUS

This is a peripheral white ring-shaped lipid deposit, separated from the limbus by a

clear interval. It is most often seen in normal elderly people (arcus senilis) but in young

patients it may be a sign of hyperlipidaemia. No treatment is required.

Corneal grafting (Fig. 7.12)

Donor corneal tissue can be grafted into a host cornea to restore corneal clarity or

repair a perforation. Donor corneae can be stored and are banked so that corneal grafts can

be performed on routine operating lists. The avascular host cornea provides an immune

privileged site for grafting,

with a high success rate. Tissue can be HLA-typed for grafting of vascular- ized corneae at

high risk of immune rejection although the value of this is still uncertain. The patient uses

steroid eye drops for some time after the operation to prevent graft rejection. Complications

such as astigmatism can be dealt with surgically or by suture adjustment.

GRAFT REJECTION

Any patient who has had a corneal graft and who complains of redness, pain or visual

loss must be seen urgently by an eye specialist, as this may indicate graft rejection.

Examination shows graft oedema, iritis and a line of activated T-cells attacking the graft

endothelium. Intensive topical steroid application in the early stages can restore graft clarity.

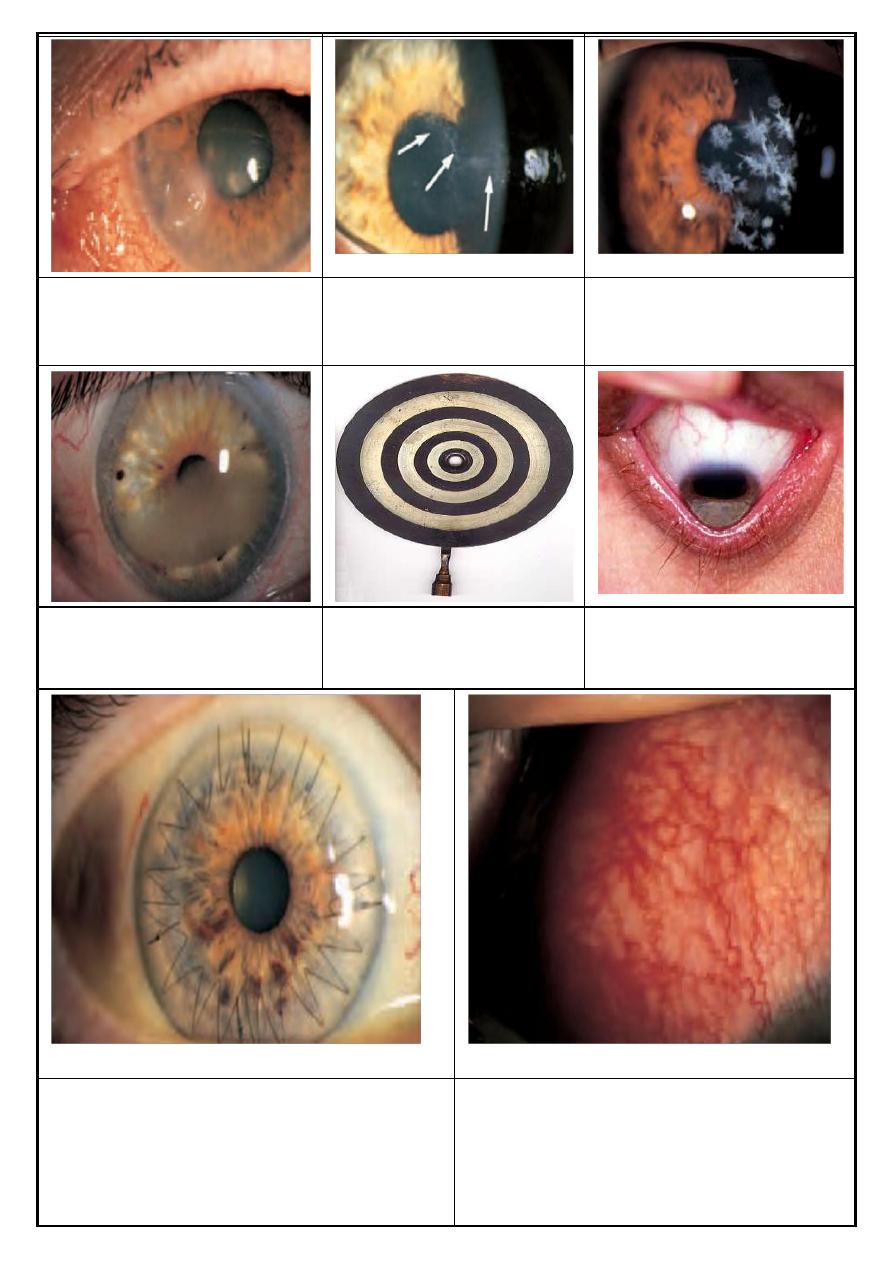

SCLERA

EPISCLERITIS

This inflammation of the superficial layer of the sclera causes mild discomfort. It is

rarely associated with systemic disease. It is usually self-limiting but as symptoms are

tiresome, topical anti-inflammatory treatment can be given. In rare, severe disease, systemic

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory treatment may be helpful.

SCLERITIS (Fig. 7.13)

This is a more severe condition than episcleritis and may be associated with the

collagen-vascular diseases, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis. It is a cause of intense

ocular pain. Both inflammatory areas and ischaemic areas of the sclera may occur.

Characteristically the affected sclera is swollen. The following may complicate the

condition:

• scleral thinning (scleromalacia), sometimes with perforation;

• keratitis;

• uveitis;

• cataract formation;

• glaucoma.

Treatment may require high doses of systemic steroids or in severe cases cytotoxic

therapy and investigation to find any associated systemic disease.

Scleritis affecting the posterior part of the globe may cause choroidal effusions or

simulate a tumour.

• Avoid the unsupervised use of topical steroids in treating ophthalmic conditions since

complications may be serious.

• In contact lens wearers a painful red eye is serious; it may imply an infective keratitis.

• Redness, pain and reduced vision in a patient with corneal graft suggests rejection and is

an ophthalmic emergency.

Box 7.4 Key points in corneal disease.

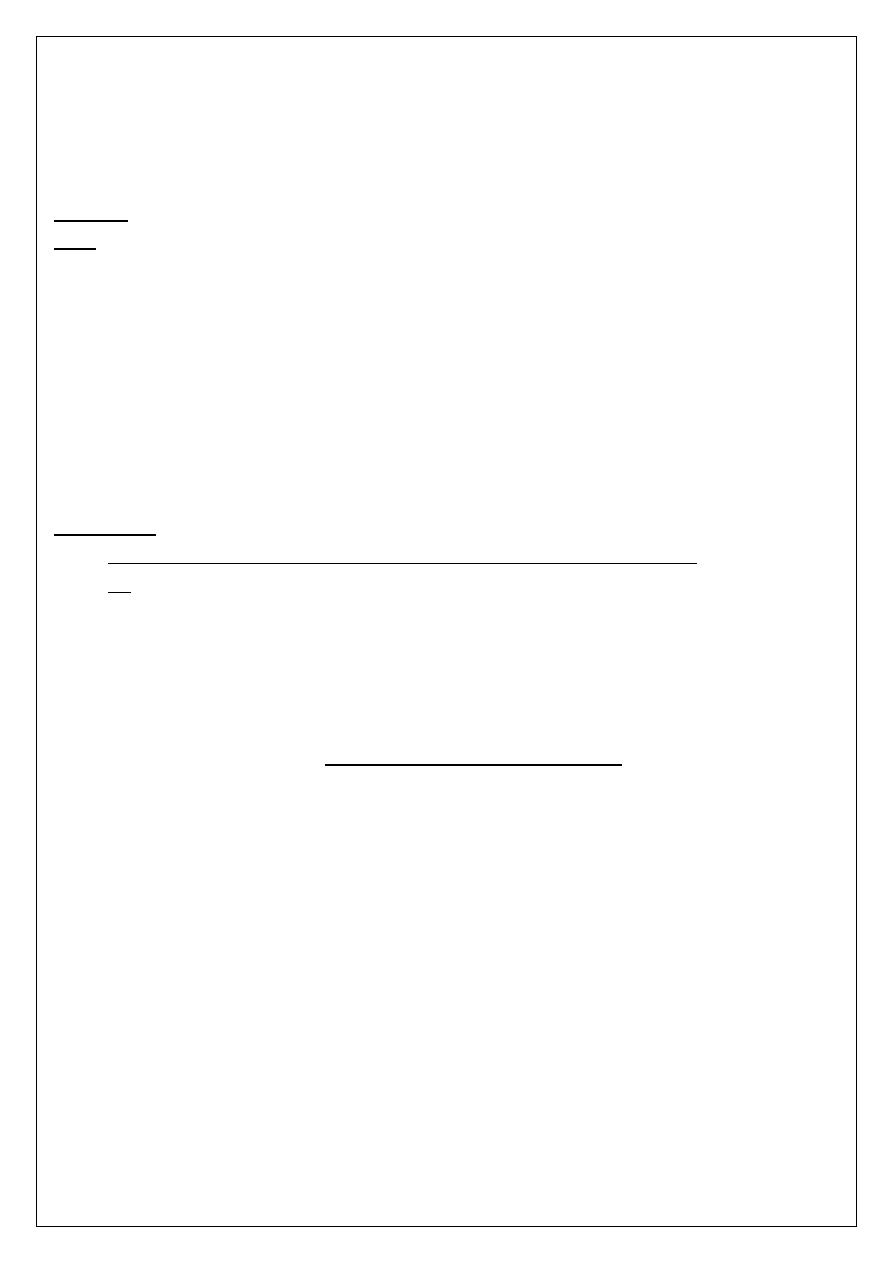

Fig.

7.1

The clinical appearance of

follicles.

Fig.

7.2

Pannus.

Fig.

7.4

The appearance of

giant (cobblestone) papillae in

vernal conjunctivitis

Fig.

7.3

Scarring of (

a

) the upper lid (everted) and (

b

) the cornea in

trachoma.

Fig.

7.5

The clinical appearance of: (

a

) a pingueculum; (

b

) a pterygium.

Fig.

7.6

A dendritic ulcer seen

in herpes simplex infection.

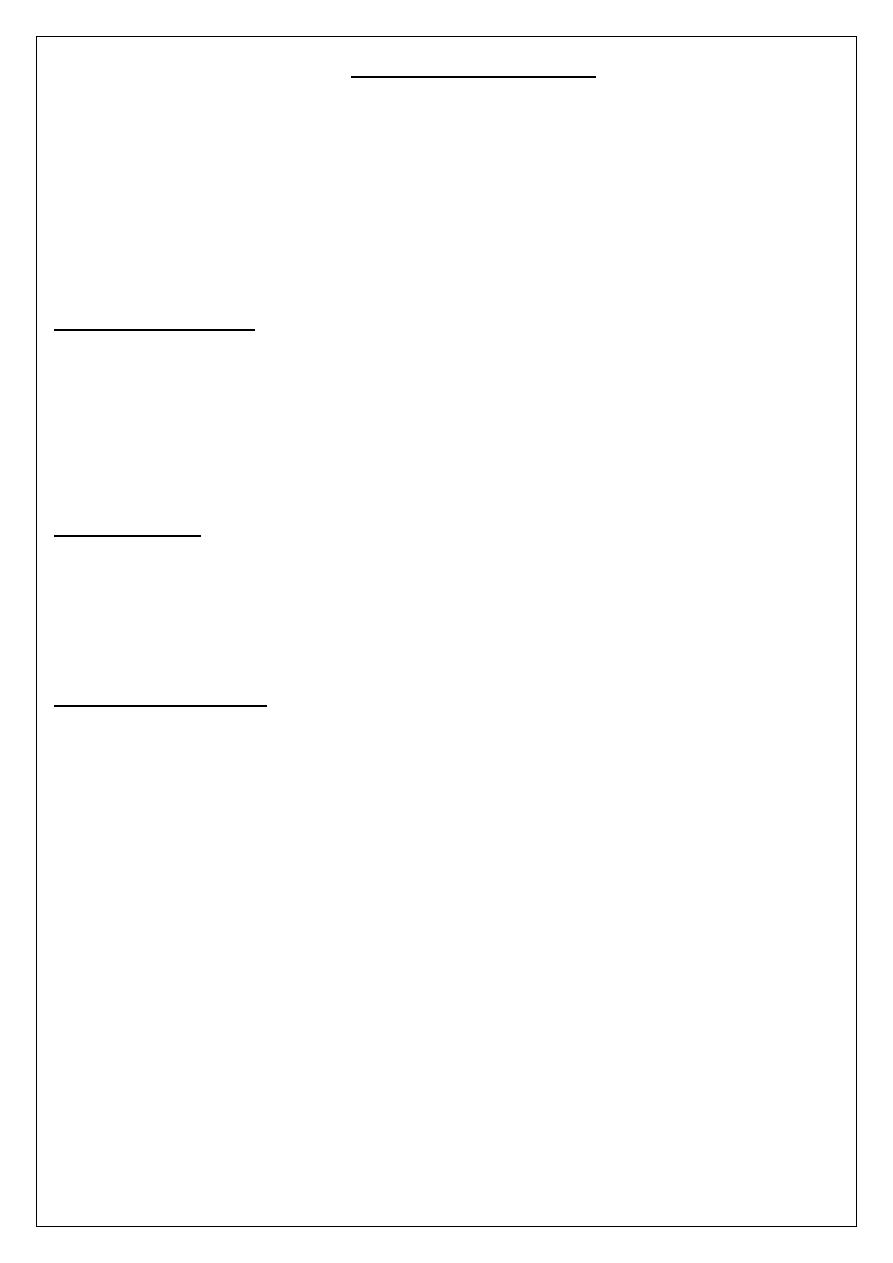

Fig.

7.7

The clinical appearance

of herpes zoster ophthalmicus

.

Fig.

7.8

Clinical appearance of a

corneal ulcer.

Fig.

7.9

The clinical appearance

of acanthamoeba keratitis. Arrows

indicate neurokeratitis.

Fig.

7.10

Example of a corneal

dystrophy (granular dystrophy).

Fig.

7.11

Placido disc

Munson’s sign

.

7.12

A corneal graft, nFigote the interrupted and the

continuous sutures at the interface between graft and

host.

Fig.

7.13

The appearance of scleritis.