1

Pediatrics

Nutrition

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

www.facebook.com/ibnlatef

https://goo.gl/RpvNsl

Ibnlatef

Notes

2

Subject1:

Nutrition in clinical practice

Feeding history:

1- Breast feeding:

Way of feeding (using both right and left breast each feeding time).

Regular (at least every 3 hours) or on demand.

Any problem with feeding (large nipple, others).

2- Bottle feeding:

Way of feeding.

Way of preparation.

Type of formula use (lactose free, soy milk formula, others).

Way of sterilization of the bottle (boiling, Washing, brushing).

Number of bottles.

Number of feeding.

Regular (at least every 3 hours) or on demand.

Any problem occur after bottle feeding (diarrhea, others).

Put the bottle in freeze for cooling.

3- Mixed feeding (breast and bottle feeding).

4- Semi-solid or solid food:

At which age given.

Type.

Any problem occur after this feeding.

5- Weaning: at which age milk was taken off his diet.

Pica: Ask if the child eat soil, wood or other things (caused by iron deficiency anemia – Ca

deficiency – lead poisoning).

Nutritional requirements:

Age dependent (the younger the child the higher their energy needs per kilogram body

weight).

Generally the average term baby needs in the first year of life:

o

Fluid 100-150 ml/kg.

o

Calories 100 -120 kcal/kg.

o

Protein 1.5-2 g/kg.

o

Na 1.5 mmol/kg.

o

K 3 mmol/kg.

Premature babies may have increased needs regarding water, energy, protein, and bone

minerals to deal with their rapid growth.

3

Good nutrition is essential for:

Survival.

Physical growth.

Mental development.

Health and well-being.

Cleaning and sterilization of bottle:

First wash bottle with cold water + detergent (to remove protein - albumin).

Brush it.

Wash it by hot water (to remove lipids - carbohydrate).

Take off the tit and put the bottle in already boiling water for 10-15 min.

Put the tit for 3-5 min in the boiling water.

Then put the bottle in the refrigerator till you will use it.

Types of sterilization:

o

Boiling.

o

Steam Sterilizer.

o

Using chemicals (that are for sterilizing baby feeding equipment).

Number of bottles = number of feeds + 1.

Calories calculation for baby:

Normal baby need (100-120 kcal/kg) - preterm baby (150) - less than 6 months age (110) -

after one year (100).

Each ounce = 30 cc of water = 20 kcal.

We multiply the number of daily requirement of calories (100-120 kcal/kg) by the ideal

weight of the child.

To calculate the ideal weight you should use the chart or use the following equation ideal

weight of the infant = (age in months + 9)/2.

Then we divide it by 20 (the number of ounces that the milk spoon carry)( Ounce=20 Kcal),

the result will be the numbers that the child should feed in the day.

Example in the child ideal wt. is 5kg , 5*100 = 500 kcal/day, divided by 20, this equals

to 25 numbers, that means if the child feeds 5 times/day every bottle should contain 5

numbers.

Signs of good feeding:

1- For baby:

Urination and bowel motion start to work.

Smile and not cry.

4

Good activity.

Sleep after feeding.

2- For mother:

Disappear of pain.

Disappear of depression.

Keep her cloths clean.

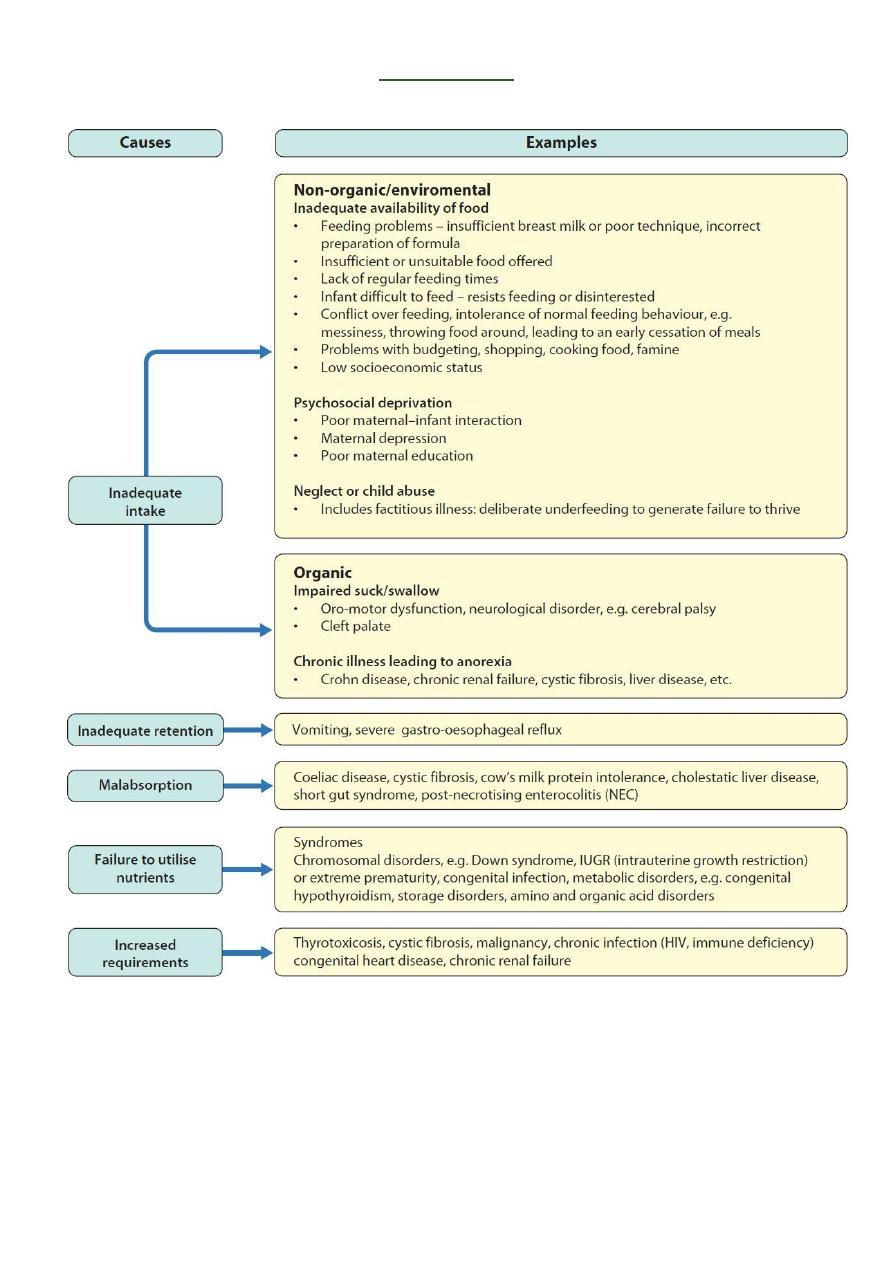

Causes of faltering growth:

1- Organic causes:

Inability to feed (cleft palate, cerebral palsy).

Increased losses (diarrhea, vomiting, GERD).

Malabsorption (cystic fibrosis, post-infective, allergic enteropathy).

Increased energy requirements (cystic fibrosis, malignancy).

Metabolic (hypothyroidism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia).

Syndromes.

2- Non-organic causes:

Insufficient breast milk or poor technique.

Maternal stress / maternal depression / psychiatric disorder.

Disturbed maternal-infant attachment.

Low socio-economic class.

Neglect.

Approach and management to faltering growth:

Recheck wright-plot weight against centile chart.

Check type and amount of feeding.

Observe feeding technique.

Assess stool.

Examine for underlying illness – appropriate investigations.

Consider admission to observe response to feeding.

Dietician involvement.

Inform general practitioner / health visitor / community nurse.

5

Subject2:

Breast feeding

Introduction:

World Health Organization (WHO) strongly advocates breast-feeding as the preferred

feeding for all infants.

The success of breast-feeding initiation and continuation depends on multiple factors,

such as education of mother, hospital breast-feeding practices and policies, routine and

timely follow-up care, and family support.

The WHO recommends exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months of life.

Six months is the recommended age for the introduction of solid foods for infants.

Breastfeeding (and/or breast milk substitutes, if used) should continue beyond the first six

months, along with appropriate types and amounts of solid foods.

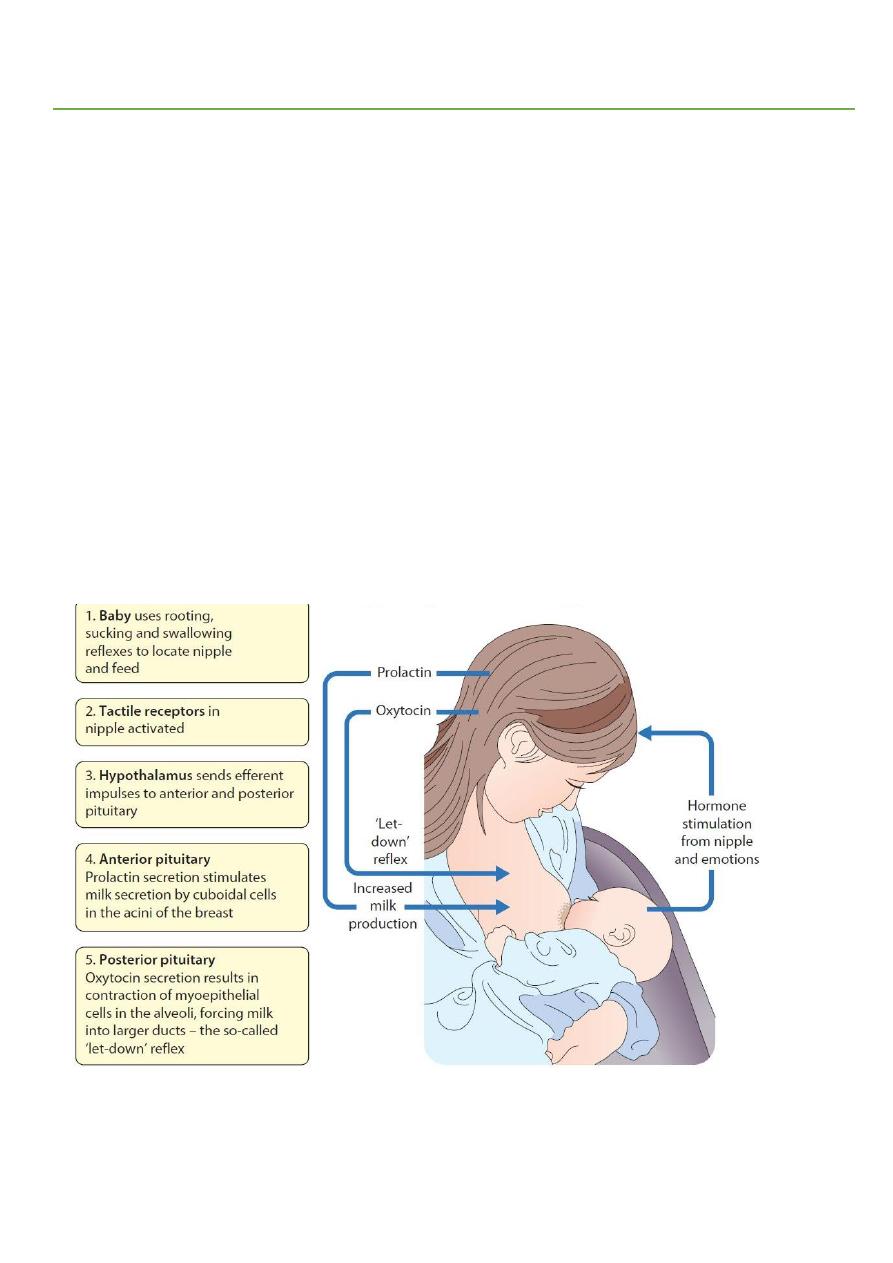

Breast milk production and secretion:

Prolactin released in response to sucking drives milk synthesis.

Oxytocin released in response to sucking stimulate the “let-down reflex”.

Physiology of breast feeding:

Colostrum:

For 2-4 days post-delivery.

Contains more sodium.

6

High in vit A and vit K.

More protein and IgA than mature milk.

Less fat and carbohydrate.

Colostrum is followed by transitional milk.

Mature breast milk is established by 4th week.

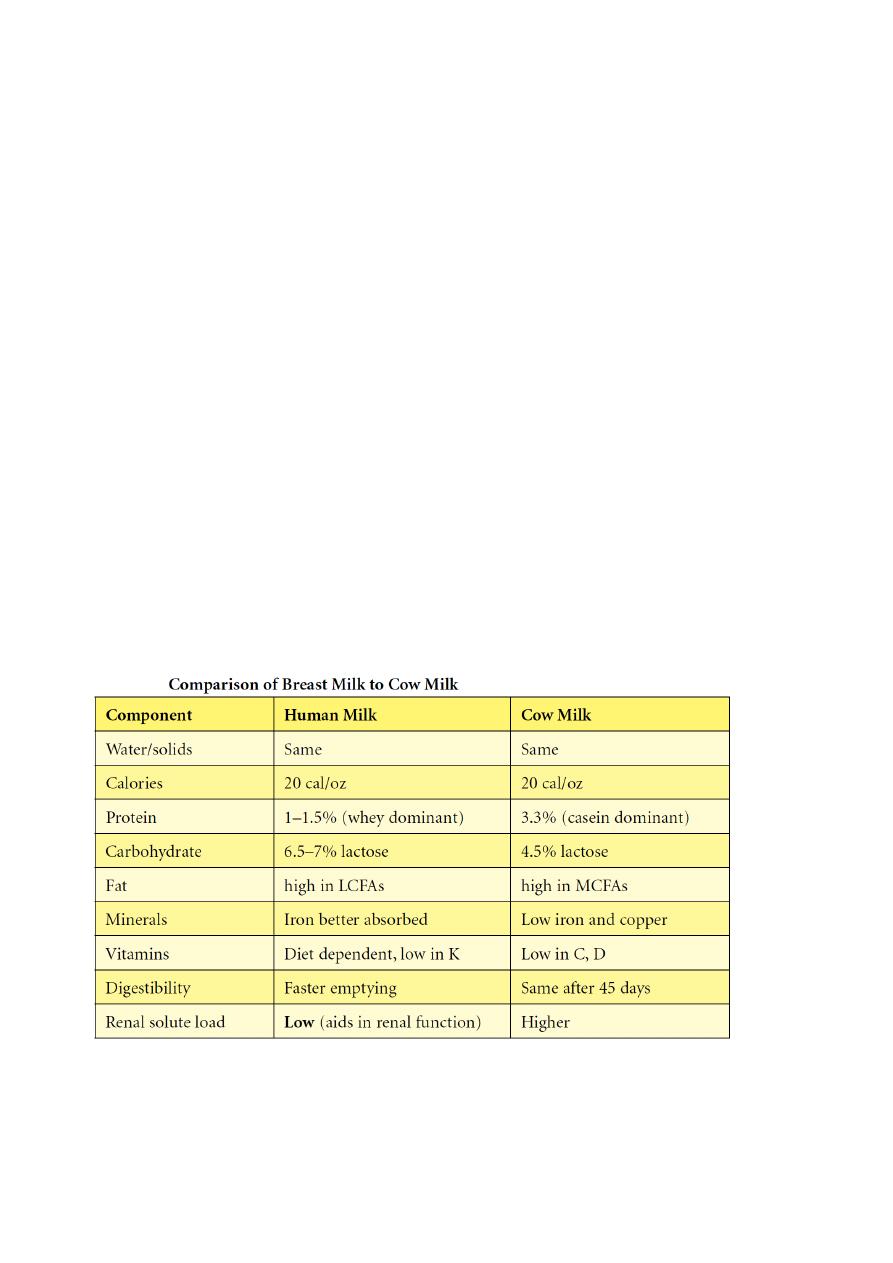

Nutritional properties:

Protein quality more easily digested curd (60 : 40 whey : casein ratio).

Lipid quality rich in oleic acid, improved digestibility and fat absorption, enhanced

lipolysis lipase.

Calcium : phosphorus ratio of 2 : 1 prevents hypocalcaemic tetany and improves

calcium absorption.

Renal solute load Low.

Iron content Bioavailable (40–50% absorption).

Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids Structural lipids; important in retinal

development.

Adequacy of milk intake:

Urine output:

o

A well-hydrated infant voids six to eight times a day.

o

Each voiding should soak, not merely moisten a diaper, urine should be colorless.

Stool:

o

By 5 to 7 days, loose yellow stools should be passed at least four times a day.

Growth:

o

Rate of weight gain provides the most objective indicator of adequate milk intake.

Let down reflex.

Contribution of Breast-feeding to Health:

Infectious and allergic disease:

o

Human milk feeding decreases the incidence and severity of diarrhea, respiratory

illnesses, otitis media, bacteremia, bacterial meningitis, and necrotizing enterocolitis.

o

Anti-infective properties: Macrophages, lymphocytes and polymorphs, Secretory IgA,

Lysozyme, Lactoferrin (an iron containing growth factor that enhances the growth of

lactobacilli which create acidic medium that inhibits the growth of E.coli.), anti-viral

agents.

o

Decreased atopic diseases and infantile colic compared to formula fed.

Breast feeding and cardiovascular health:

o

Meta-analyses have shown that breast-fed infants in industrialized countries have

lower plasma cholesterol in adult life, lower systolic blood pressure, less obese.

7

Breast feeding and neurological development:

o

There are beneficial effects of feeding preterm infants with human milk on long-term

neurodevelopment (IQ) in preterm infants.

o

Breast feeding strengthen the psychosocial mother-infant relationship.

Maternal benefits:

o

Decreased risk of postpartum hemorrhages, more rapid uterine involution.

o

Longer period of amenorrhea.

o

Decreased postpartum depression.

o

There is an association between a long lactation and a significant reduction of

hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes in the mother.

o

Cumulative lactation of more than 12 months also correlates with reduced risk of

ovarian and breast cancer.

Benefits of breast feeding:

Correct fat-protein balance.

Nutritionally complete.

Promotes healthy growth patterns.

Better jaw and tooth development.

Ensues digestibility.

Easier transition to solid food.

Enhances mother–child relationship.

Diseases protection.

Life-saving in developing countries.

Reduces the risk of gastrointestinal infection, and in preterm infants of necrotizing

enterocolitis.

Reduces risk of insulin-dependent diabetes, hypertension and obesity in later life.

Common Breastfeeding Problems:

To mother Breast tenderness, engorgement, cracked nipples.

Engorgement:

o

One of the most common causes of lactation failure.

o

Should receive prompt attention because milk supply can decrease quickly if the

breasts are not adequately emptied.

o

Applying warm or cold compresses to the breasts before nursing and hand expression

or pumping of some milk can provide relief to the mother and make the areola easier

to grasp by the infant.

Nipple tenderness:

o

Severe nipple pain and cracking usually indicate improper latch-on.

o

Proper sucking should include the areola as well.

o

Treatment include proper positioning of baby.

o

Additional measures include:

8

Exposing the nipples to air.

Applying pure lanoline emollient.

Avoiding soaps and shampoos for cleaning.

Frequent changing of nursing pads.

Nursing more frequently by proper position of the baby.

Unknown intake.

Transmission of infection Maternal CMV, hepatitis B and HIV – increases risk of

transmission to the baby.

Breast-milk jaundice Mild, self-limiting, unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, continue

breast-feeding.

Transmission of drugs Antimetabolites and some other drugs contra-indicated.

Nutrient inadequacies Breast-feeding beyond 6 months without timely introduction of

appropriate solids may lead to poor weight gain and rickets.

Potential transmission of environmental contaminants Nicotine, alcohol, caffeine.

Less flexible other family members cannot help or take part, more difficult in public

places.

Emotional upset If difficulties or lack of success can be upsetting.

Problems that may be encountered in breast fed babies:

o

Vitamin K deficiency insufficient vitamin K in breast milk to prevent hemorrhagic

disease of the newborn, supplementation is required.

o

Hypernatremia at end of first week in babies due to insufficiency.

o

Breastfeeding jaundice (in the first week) and Breast milk jaundice.

Contraindications of breast feeding:

Important: Breast feeding is not contraindicated in mastitis.

HIV (in western countries).

CMV, HSV (if lesions on breast).

HBV.

Acute maternal disease if infant does not have disease (tuberculosis, sepsis).

Breast cancer.

Substance abuse.

Galactosemia and PKU.

Drugs:

Absolute contraindications Relative contraindications

Antineoplastics Neuroleptics

Radiopharmaceuticals Sedatives

Ergot alkaloids Tranquilizers

Iodide/mercurials Metronidazole

Atropine Tetracycline

Lithium Sulfonamides

Chloramphenicol Steroids

Cyclosporine Alcohol

Nicotine

9

Weaning:

By approximately 6 months, complementary feeding of semisolid foods is suggested.

By this age, an exclusively breastfed infant requires additional sources of several

nutrients, including protein, iron, and zinc.

Breast milk substitutes:

Infant formulas (modified cows milk) are suitable from birth and are usually based on

cows milk (unmodified).

Whey based milks are usually first choice if not breast feeding.

Casein based milks are suggested for hungrier babies.

Follow on formulas higher iron content than cows milk.

Specialized formulas for those who are preterm or have medical conditions (lactose

fee, phenylalanine free).

Soya infant milks (Isomil, nursoy):

o

Similar to cows milk but protein derived from soya with lactose replaced with other

carbohydrates (glucose syrups).

o

Indicated in Galactosemia, lactose intolerance, cows milk allergy.

o

Soya milks contain phytoestrogens which may increase the risk of breast cancer.

o

So it should be used only when strictly indicated and no proper substitute exists.

10

Subject3:

Failure to thrive

Infants are more vulnerable to poor nutrition because of:

Poor stores of fat and protein.

Extra nutritional demands for growth.

More frequent inter-current illnesses that reduce good intake and increase nutritional

demands.

Definition:

The term ‘failure to thrive’ is used to describe suboptimal, weight gain in infants and

toddlers (malnourished infants and young children who fail to meet expected standards of

growth).

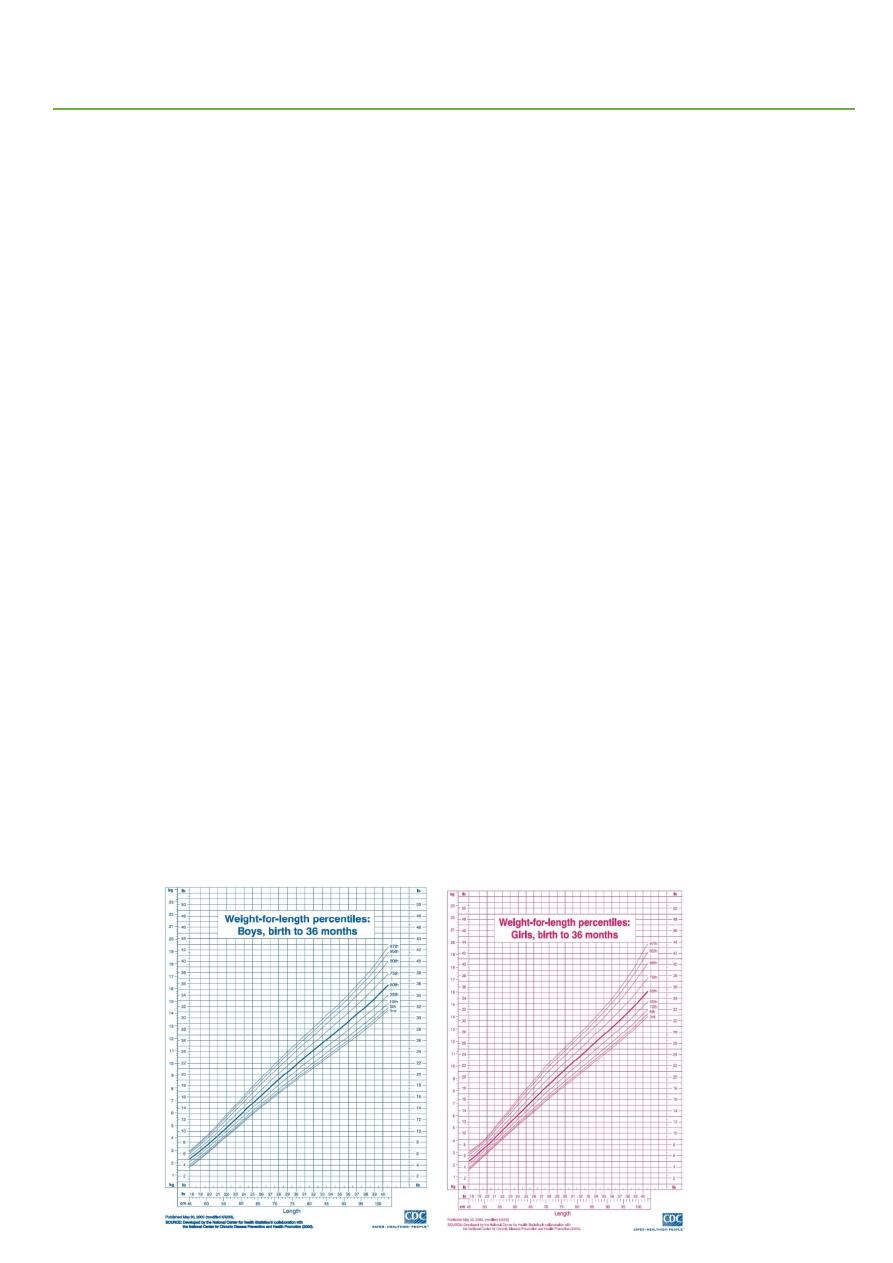

Weight that falls or remains below the 5th percentile for age.

Weight that decreases crossing two major percentile lines on the growth chart over time.

Weight that is less than 80% of the median weight for the height of the child.

Notes: repeated observations are therefore essential and are usually available from the child’s

personal child health record.

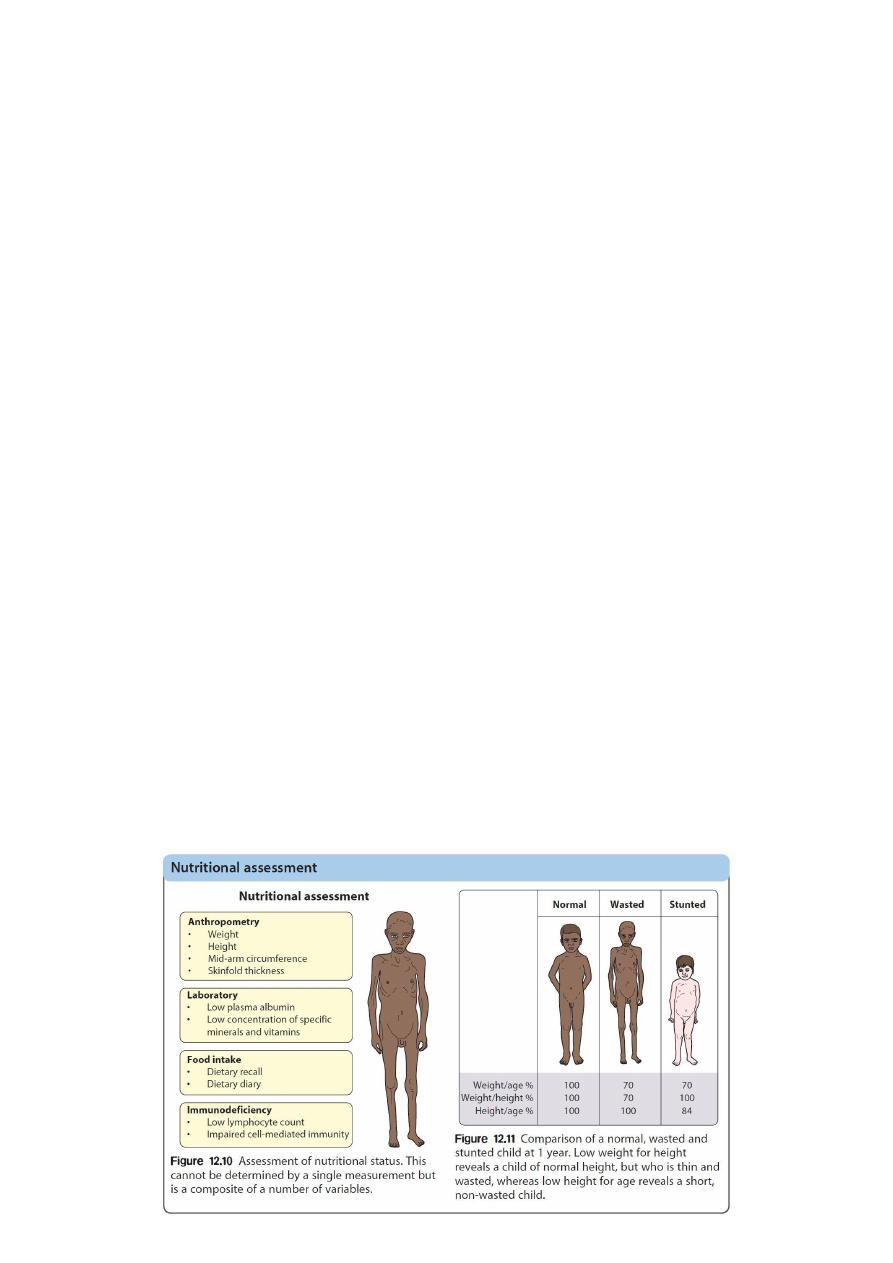

In children with FTT, malnutrition initially results in:

Wasting deficiency in weight gain.

Stunting deficiency in linear growth, generally occurs after months of malnutrition.

Head circumference generally is spared except with chronic, severe malnutrition.

Weight for height below the 5th percentile remains the single best growth chart

indicator of acute undernutrition.

Children with chronic malnutrition often have a normal weight for height because both

their weight and height are reduced.

11

Causes of FTT:

Non-organic or psychosocial FTT:

o

It is far more common than organic FTT.

o

Lack of food (poverty).

o

Lack of knowledge (poor feeding techniques, improper formula preparation, improper

mealtime environment).

o

Parental depression, emotional deprivation, child abuse or neglect.

Organic FTT:

o

Any chronic disease may lead to FTT.

o

Gastrointestinal GER, celiac disease, pyloric stenosis, cleft lip/ palate, lactose

intolerance, Hirschsprung's disease, milk protein intolerance, hepatitis, cirrhosis,

pancreatic insufficiency, biliary disease, IBD, malabsorption.

o

Renal UTI, RTA, DI, RF.

o

Cardiopulmonary Cardiac diseases leading to CHF, asthma, BPD, CF, anatomic

abnormalities of the upper airway.

o

Endocrine Hyperthyroidism, DM, adrenal insufficiency or excess, parathyroid

disorders, pituitary disorders.

o

Neurologic MR, CP, degenerative disorders, CNS tumors.

o

Infectious Parasitic or bacterial infections of the gastrointestinal tract, TB, HIV

disease.

o

Metabolic Inborn error of metabolism.

o

Genetics or Congenital Chromosomal abnormalities, congenital syndromes (fetal

alcohol syndrome), perinatal infections.

o

Miscellaneous Lead poisoning, malignancy, collagen vascular disease, recurrently

infected adenoids and tonsils.

Diagnosis of FTT:

History:

o

Prenatal and postnatal factors:

That influence growth, including the history of prenatal care, maternal illnesses

during pregnancy.

Identify fetal growth problems (IUGR), birth size (weight, length, and head

circumference).

Identify prematurity.

o

Indicators of medical diseases (review of systems): such as vomiting, diarrhea, fever,

respiratory symptoms.

o

Careful dietary history is essential:

The adequacy of the maternal milk supply or the precise preparation of formula

should be evaluated.

For older infants and young children, a detailed diet history is helpful, it is essential

to evaluate intake of solid foods and liquids.

12

Because of parental dietary beliefs, some children have inappropriately restricted

diets.

Other children with FTT drink excessive amounts of fruit juice, leading to

malabsorption or anorexia for more nutrient-dense foods.

o

Social environment: poverty, unemployment, conflict, disruptive parent-child

interactions.

Physical examination:

o

Growth chart weight, height, OFC.

o

Physical findings related to malnutrition such as dermatitis, pallor, or edema.

o

Severely malnourished children are at risk for a variety of infections.

o

Infant with FTT may exhibit thin extremities, narrow face, prominent ribs, wasted

buttocks.

o

Neglect of hygiene diaper rash, unwashed skin, untreated impetigo, uncut and dirty

fingernails, unwashed clothing.

o

Child lying on back flattened occiput with hair loss.

o

Delays in social and speech development are common.

o

Other findings avoidance of eye contact, expressionless face, hypotonia, absence of

a cuddling response.

Laboratory evaluation:

o

CBP type of anemia, WBC abnormalities (leukocytosis, neutropenia, lymphopenia).

o

Serum protein Degree of protein deficiency.

o

Blood sugar hypoglycemia.

o

Serum creatinine urea, electrolytes, acid–base status, calcium, phosphate Renal

failure, renal tubular acidosis, metabolic disorders, William syndrome.

o

Urine microscopy, culture and dipsticks Urinary tract infection, renal disease.

o

Liver function tests Liver disease, malabsorption, metabolic disorders.

o

Stool microscopy, culture and elastase Intestinal infection, parasites, elastase

decreased in pancreatic insufficiency.

o

PPD screen for TB.

o

Thyroid function tests Hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism.

o

Acute phase reactant (CRP) Inflammation.

o

Ferriaztin Iron deficiency anemia.

o

Immunoglobulins Immune deficiency.

o

IgA tissue transglutaminase antibodies coeliac disease.

o

Karyotype in girls Turner syndrome.

o

Chest X-ray and sweat test Cystic fibrosis.

Treatment of FTT:

Most children with FTT can be treated in the outpatient setting.

Hospitalization is required for:

o

Children with severe malnutrition.

13

o

Children with underlying diagnoses that require hospitalization for evaluation or

treatment.

o

Children whose safety is in danger because of maltreatment (social issues of the

family).

Nutritional management:

o

It is the cornerstone of treatment of FTT, regardless of the etiology.

o

In general, the simplest and least costly approach to dietary change is warranted.

Amount:

o

Slow gradual increment:

o

Calories can be safely started at 20% above the child recent intake.

o

If no estimate of the caloric intake is available 50-75% of the normal energy

requirement is safe.

o

Caloric intake can be increased 10-20% per day.

o

With monitoring for electrolyte imbalances, poor cardiac function, edema, feeding

intolerance.

o

If any of these occurs, further caloric increases are not made until the child's status

stabilizes.

o

The final target is to provide 100 to 120 kcal/kg based on ideal weight.

Type:

o

According to age of the child and type of feeding.

o

Breast fed infant:

Continue breast feeding and may add cow milk or special cows’ milk based formula

(F75 or F100).

o

Bottle fed:

Increased amount of cow milk, or change to other types if indicated like:

Special cows’ milk based formula (F75 or F100)

Calorically dense formula for anorectic and picky eater, concentration of

formula can be changed from 20 cal/oz to 24 or 27 cal/oz.

Soy based (isomil) for lactose-intolerant child.

Hydrolyzed protein type (pregestemil) for cow milk protein intolerant.

Homemade (oil, butter, peanut butter, others).

o

Toddlers:

Dietary changes should include increasing the caloric density of favorite foods by

adding butter, oil, peanut butter, or other high-calorie foods.

High-calorie oral supplements that provide 30 cal/oz are often well tolerated by

toddlers.

Vitamin and mineral supplementation:

o

It is needed, especially during catch-up growth.

o

Vitamin and mineral intake in excess of the daily recommended intake is provided to

account for the increased requirements, this is frequently accomplished by giving an

age-appropriate daily multiple vitamin.

14

Causes of FTT

15

Subject4:

Malnutrition

Causes of malnutrition:

Major causes poverty – food process – dietary practices.

Consequences of health issues like gastroenteritis – chronic illness – HIV.

Diarrhea and other infections.

Parasitic infections.

Abnormal nutrient loss.

Lack of adequate breast feeding.

Degree of malnutrition:

Mild malnutrition abdominal sub-cutaneous fat is decreased.

Moderate malnutrition Thigh and buttock sub-cutaneous fat is decreased.

Severe malnutrition old face appearance.

Protein and calories deficiency:

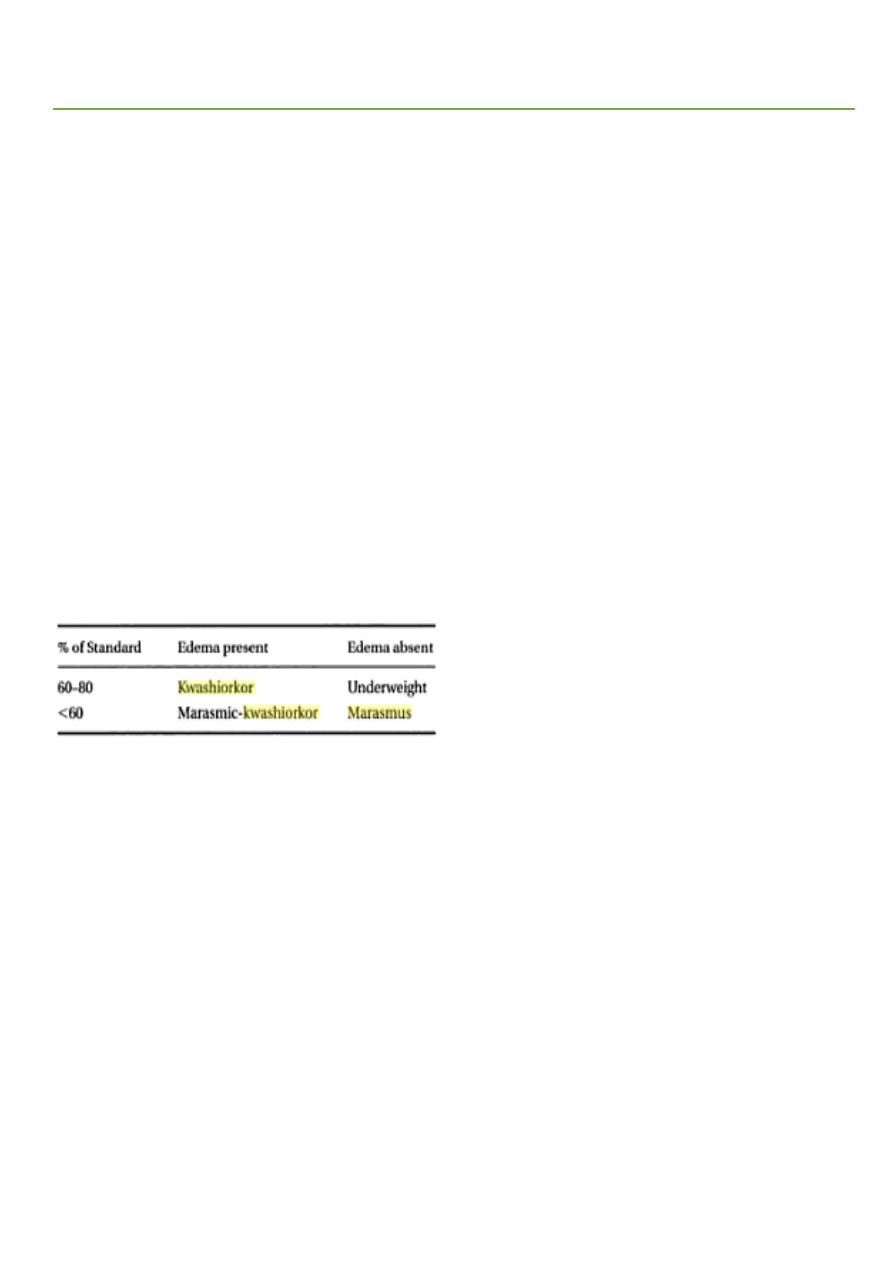

Kwashiorkor (protein deficiency) change in mod – dull patient – loss of appetite –

skin change (dermatitis) – change in skin color – thin hair – wasting – liver enlargement

- focal edema (swelling in the limbs and belly).

Marasmus (calories deficiency) good appetite – alert – low weight – severe wasting

– little or no edema – minimal subcutaneous fat – severe muscle wasting.

Marasmic-Kwashiorkor (Protein and calories deficiency) weight less than 60% of

ideal weight – edema.

Vitamins deficiency:

Vit A white spot in the eye.

Vit B1 (thiamine) beriberi "dry & wet”.

Vit B2 angular stomatitis – glossitis.

Vit B3 (Niacin) pellagra "diarrhea, dementia, dermatitis".

Vit B6 neurological change.

Vit B7 (Biotin) hypotonia, ataxia.

Vit B9 (folate) anemia.

Vit B12 Megaloblastic anemia.

Vit C gum hypertrophy.

Vit D rickets rosary – widening of wrest – developmental delay – bowing of the

lower limbs.

16

Vit E ecchymosis – petechiae.

Vit K bleeding.

Minerals deficiency:

Iron iron deficiency anemia.

Zinc acro-dermatitis in napkin area ((also occur with candidiasis and atopy like

contact dermatitis)).

General signs of malnutrition:

Face moon face (kwashiorkor) – simian face (marasmus).

Eye dry eye – pale conjunctiva – Bitot's spots (Vit A) peri-orbital edema.

Mouth Angular stomatitis – cheilitis – glossitis – parotid enlargement – spongy

bleeding gums (Vit C).

Teeth enamel mottling – delayed eruption.

Hair dull – sparse – brittle – hypo-pigmentation – flag sign – alopecia.

Skin loose and wrinkled (marasmus) – shiny and edematous (kwashiorkor) dry –

poor wound healing – erosions – hypo or hyper pigmentation.

Nail koilonychia – thin and soft nail plates – fissures or ridges.

Musculature muscles wasting (buttocks and thigh).

Skeletal deformities (Vit C, Vit D, Calcium deficiency).

Abdomen distended – hepatomegaly – fatty liver – ascites.

Cardiovascular bradycardia – hypotension – reduced cardiac output – small vessel

vasculopathy.

Neurologic global developmental delay – loss of knee and ankle reflexes – poor

memory.

Hematological pallor – petechiae – bleeding diathesis.

Behavior lethargic – apathetic.

17

Subject5:

Severe childhood undernutrition SCU

Protein energy malnutrition (PEM):

Marasmus was thought to result primarily from inadequate energy intake.

Kwashiorkor was thought to result primarily from inadequate protein intake.

Marasmic kwashiorkor has features of both disorders (wasting and edema).

Etiology:

Primary malnutrition:

o

Malnutrition resulting from inadequate food intake.

Secondary malnutrition:

o

Increased nutrient needs.

o

Decreased nutrient absorption.

o

Increased nutrient losses.

WELLCOME classification:

Marasmus:

Non-edematous SCU.

Can be defined as:

o

Emaciation with body weight below 60 % of median (50th percentile) for age.

o

Below 70% of the ideal weight for height and depleted body fat store.

Loss of muscle mass and subcutaneous fat stores is confirmed by inspection or

palpation and quantified by anthropometric measurements.

Clinical manifestations:

Growth chart criteria.

Failure to gain weight, weight loss, until emaciation results.

Mental changes irritability, listlessness, may be apathetic & weak.

18

Skin dry, thin, loses turgor and becomes wrinkled and loose as subcutaneous fat

disappears. Loss of fat from the sucking pads of the cheeks often occurs late in the

course of the disease; thus, the infant's face may retain a relatively normal appearance

compared with the rest of the body, but this, too, eventually becomes shrunken and

wizened.

Head may appear large but proportional to length.

Hair thin sparse easily pulled.

Tongue atrophy of filliform papilli, monilial stomatitis.

Muscles atrophy and resultant hypotonia.

Abdomen may be distended or flat, and the intestinal pattern may be readily

visible.

Temperature usually becomes subnormal.

Pulse slows.

Bowel motion constipation but may develop starvation diarrhea with frequent

small stool containing mucous.

Infections and parasitic infestations are common.

Kwashiorkor

Edematous SCU.

Hypoalbuminemic, edematous malnutrition may become evident from early infancy to

about 5 yr of age, usually after weaning from the breast.

Can be defined as: Body weight of the child ranges from 60-80% of expected weight for

age with edema.

Clinical manifestations:

Growth chart criteria.

Mental changes especially irritability and apathy, stupor, coma, and death.

Hair:

o

Often sparse and thin, easily plucked, appears dull brown, red, or yellow-white.

o

Nutritional repletion restores hair color, leaving a band of hair with altered

pigmentation followed by a band with normal pigmentation (flag sign).

Face facial edema result in moon facies.

Skin:

o

A relative maintenance of subcutaneous adipose tissue, skin changes are common and

may include:

o

Hyperpigmented hyperkeratosis.

o

Erythematous macular rash (pellagroid) on the trunk and extremities.

o

Darkening of the skin appears in irritated areas but not in those exposed to sunlight, a

contrast to the situation in pellagra.

19

o

In the most severe form of kwashiorkor, a superficial desquamation occurs over

pressure surfaces ("flaky paint" rash).

Edema:

o

Varies from a minor pitting of the dorsum of the foot to generalized edema with

involvement of the eyelids and scrotum.

o

Edema usually develops early; failure to gain weight may be masked by edema, which

is often present in internal organs before it can be recognized in the face and limbs.

Muscle marked atrophy of muscle mass.

Tongue and mouth Angular cheilosis, atrophy of the filiform papillae of the tongue,

and monilial stomatitis.

Abdomen may reveal an enlarged, soft liver with an indefinite edge, the abdomen is

distended, and bowel sounds tend to be hypoactive.

GIT anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea.

Other lymphatic tissue commonly is atrophic, infections and parasitic infestations.

Complications of PEM:

Infection: Malnourished children are more susceptible to infection, especially sepsis,

pneumonia, and gastroenteritis.

Because:

o

Malnutrition causes defects in host defenses.

o

Conversely, infection increases the metabolic needs of the patient and often is

associated with anorexia.

Children with FTT may suffer from a malnutrition-infection cycle, in which recurrent

infections exacerbate malnutrition, which leads to greater susceptibility to infection.

Children with FTT must be evaluated and treated promptly for infection and followed

closely.

Treatment regimens should be appropriate for the infection.

Refeeding syndrome:

With the rapid reinstitution of feeding after starvation, fluid and electrolyte

homeostasis may be lost, and the body may be unable to maintain normal serum

concentrations of vital electrolytes.

Changes in serum electrolyte concentrations and the associated complications

resulting from these changes are collectively termed refeeding syndrome.

These changes typically cause decrease in phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and

magnesium and can result in life-threatening cardiac or neurological problems.

Serum phosphate levels of ≤ 0.5 mmol/L can produce weakness, rhabdomyolysis,

neutrophil dysfunction, cardiorespiratory failure, arrhythmias, seizures, altered level of

consciousness, or sudden death.

20

Refeeding syndrome can be avoided by slow institution of nutrition for children with

severe malnutrition, close monitoring of serum electrolytes during the initial days of

feeding, and prompt replacement of depleted electrolytes.

Hypoglycemia is common after periods of severe fasting, but also may be a sign of

sepsis.

Hypothermia may signify infection or, with bradycardia, may signify a decreased

metabolic rate to conserve energy. Bradycardia and poor cardiac output predispose

the malnourished child to heart failure, which is exacerbated by acute fluid or solute

loads.

Micronutrient deficiencies also can complicate malnutrition. Vitamin A and zinc

deficiencies are common in the developing world and are an important cause of

altered immune response and increased morbidity and mortality.

Depending on the age at onset and the duration of the malnutrition, malnourished

children may have:

o

Permanent growth stunting.

o

Delayed development.

Treatment:

In general the simples and least coasty approach is recommended.

The usual approach to treatment of PEM includes three phases.

1-Stabilization phase:

o

The first relatively brief phase (1-7 days).

o

Dehydration, if present, is corrected.

o

Antibiotic therapy is initiated to control infection.

o

Because of the difficulty of estimating hydration, oral rehydration therapy is preferred.

o

If intravenous therapy is necessary, estimates of dehydration should be assessed

frequently, particularly during the first 24hr of therapy.

o

Treat or prevent hypothermia, hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalances.

o

Oral feedings are also started with specialized high-calorie formula, that can be made

with simple ingredients. The initial phase of oral treatment is with the F75 diet (75 kcal

or 315 kg/100 mL).

2-Rehabilitation phase:

o

2nd phase last (2-6weeks).

o

Continued antibiotic therapy with appropriate changes if the initial combination was

not effective.

o

Diet:

Providing maintenance requirements of energy and protein along with adequate

electrolytes, trace minerals, and vitamins.

Nutritional management similar to FTT.

The rehabilitation diet is with the F100 diet (100 kcal or 420 kg/100 mL).

21

Feedings are initiated with higher frequency and smaller volumes; over time, the

frequency is reduced from 12 to 8 to 6 feedings/24 hr.

If the infant is unable to take the feedings from a cup or bottle, administration of

feedings by nasogastric tube rather than by the parenteral route is preferred.

Iron supplements are not recommended during the acute rehabilitation phase,

especially for children with kwashiorkor, for whom ferritin is often high. Additional

iron may pose an oxidative stress, and iron supplementation has been associated

with higher morbidity and mortality.

o

By the end of the second phase:

Any edema that was present has usually been mobilized.

Infections are under control.

The child is becoming more interested in his or her surroundings, and his or her

appetite is returning.

3-Final follow-up phase:

o

Which consists of feeding to cover catch-up growth as well as the provision of

emotional and sensory stimulation.

o

The child should be fed ad libitum.

o

The child should be switched gradually to a recovery diet providing up to

150kcal/kg/24hr.

o

In all phases, parental education is crucial for continued effective treatment as well as

prevention of additional episodes.

o

Time frame for the management of a child with severe malnutrition.

22

Subject6:

Obesity

Introduction:

Obesity is the most common nutritional disorder affecting children and adolescents in

the developed world.

Its importance is in its short- and long-term complications and that obese children tend

to become obese adults.

Definitions:

In children, the body mass index (BMI = weight in kg/height in metres2) is expressed as

a BMI centile in relation to age and sex-matched population.

Overweight is a BMI >91st centile, obese is a BMI >98th centile.

Very severe obesity is >3.5 standard deviations above the mean.

Extreme obesity >4 standard deviations.

For children over 12 years old overweight is BMI ≥25, obese ≥30, very severe

obesity BMI ≥35 and extreme obesity BMI ≥40 kg/m2.

Etiology:

The reasons for this marked increase in prevalence are unclear but are due to changes

in the environment and behavior relating to diet and activity.

Energy-dense foods are now widely consumed, including high-fat fast foods and

processed foods.

However, there is no conclusive evidence that obese children eat more than children

of normal weight.

Children’s energy expenditure has undoubtably decreased.

Children from low socioeconomic homes are more likely to be obese, females from the

lowest socioeconomic quintile are 2.5 times more likely to be overweight when

compared with the highest quintile.

Endogenous causes:

Overnutrition accelerates linear growth and puberty.

Obese children are therefore relatively tall and will usually be above the 50th centile

for height.

An endogenous cause, i.e. hypothyroidism and Cushing syndrome should be sought in

short, obese children, in whom height velocity is decreased as height remains static in

these conditions.

23

In children who are obese with learning disabilities, or who are dysmorphic, a

syndrome should be considered.

The commonest of these is Prader–Willi (obesity, hyperphagia, poor linear growth,

dysmorphic facial features, hypotonia and undescended testes in males).

In severely obese children under the age of 3 years, gene defects, e.g. leptin deficiency,

should be considered.

Complications of obesity:

Orthopedic slipped upper femoral epiphysis, tibia vara (bow legs), abnormal foot

structure and function.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension headaches, blurred optic disc margins.

Hypoventilation syndrome daytime somnolence, sleep apnea, snoring, hypercapnia,

heart failure.

Gallbladder disease.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Hypertension.

Abnormal blood lipids.

Increased risk of certain malignancies endometrial, breast and colonic carcinoma.

Other medical sequelae asthma, changes in left ventricular mass.

Psychological sequelae low self-esteem, teasing, depression.

Management:

Most obese children are managed in primary care.

Specialist pediatric assessment is indicated in any child with complications or if an

endogenous cause is suspected.

In the absence of evidence from randomized controlled trials, a pragmatic approach in

any individual child based on consensus criteria has to be adopted.

Treatment should be considered where the child is above the 98th centile for BMI and

the family are willing to make the necessary difficult lifestyle changes.

Weight maintenance is a more realistic goal than weight reduction and will result in a

demonstrable fall in BMI on centile chart as height increases.

It can only be achieved by sustained changes in lifestyle:

o

Healthier eating no sugar-containing juices or fizzy drinks; decrease food portion

size by 10–20%; increase protein- and non-carbohydrate containing vegetables,

discourage snacking and encourage family meals.

o

An increase in habitual physical activity to 60 min of moderate to vigorous daily

physical activity.

o

Reduce physical inactivity e.g. small screen time, during leisure time to less than an

average of 2 h per day.

24

Drug treatment and surgery:

o

Drug treatment has a part to play in children over the age of 12 who have extreme

obesity (BMI>40 kg/m2) or have a BMI>35 kg/m2 and complications of obesity.

o

It is recommended that drug treatment should only be considered after dietary,

exercise and behavioral approaches have been started.

o

Orlistat is a lipase inhibitor, which reduces the absorption of dietary fat and thus

produces steatorrhea.

o

Fat intake should be reduced to avoid the unpleasant gastrointestinal side-effects.

o

Metformin is a biguanide that increases insulin sensitivity, decreases gluconeogenesis

and decreases gastrointestinal glucose absorption.

o

If there is evidence of insulin insensitivity (Acanthosis nigricans), metformin should be

considered.

o

Orlistat may be appropriate if fat intake is high.

o

Bariatric surgery is generally not considered appropriate in children or young people

unless they have almost achieved maturity, have very severe or extreme obesity with

complications, e.g. type 2 diabetes or hypertension, and all other interventions have

failed to achieve or maintain weight loss.

o

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding is the most appropriate operation.

Prevention:

There are few randomized controlled trials and most involve complex packages of

interventions.

Interventions include decreased fat intake, increased fruit and vegetables, reduction in

time spent in front of small screens, increased physical activity, and education.

Of these, a reduction in time spent on small screens appears to be the most effective

single factor.

Main messages for patients and parents about obesity:

Incidence of obesity in children is increasing.

Obesity is a health concern in itself and also increases the risk of other serious health problems, such as high blood

pressure, diabetes and psychological distress.

An obese child tends to become an obese adult.

Obesity in children may be prevented and treated by increasing physical activity/ decreasing physical inactivity (e.g. small

screen time) and encouraging a well-balanced and healthy diet.

Lifestyle changes involve making small gradual changes to behavior.

Family support is necessary for treatment to succeed.

Generally, the aim of treatment is to help children maintain their weight (so that they can ‘grow into it’).

Most children are not obese because of an underlying medical problem but as a result of their lifestyle.

Ibnlatef

Notes

Pediatric – Nutrition