Collected By

P

P

r

r

o

o

f

f

.

.

D

D

r

r

.

.

S

S

a

a

m

m

i

i

h

h

H

H

.

.

A

A

r

r

s

s

a

a

l

l

a

a

n

n

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

.

.

P

P

r

r

o

o

f

f

.

.

D

D

r

r

.

.

M

M

a

a

a

a

b

b

I

I

.

.

A

A

l

l

-

-

F

F

a

a

r

r

w

w

a

a

c

c

h

h

i

i

M

M

o

o

h

h

a

a

m

m

m

m

a

a

d

d

O

O

.

.

A

A

b

b

d

d

u

u

l

l

-

-

M

M

a

a

j

j

e

e

e

e

d

d

,

,

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

L

L

e

e

c

c

t

t

u

u

r

r

e

e

r

r

O

O

m

m

a

a

r

r

K

K

h

h

.

.

A

A

l

l

-

-

H

H

a

a

n

n

k

k

a

a

w

w

e

e

,

,

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

L

L

e

e

c

c

t

t

u

u

r

r

e

e

r

r

O

O

s

s

a

a

m

m

a

a

h

h

M

M

.

.

A

A

l

l

-

-

I

I

r

r

a

a

q

q

i

i

,

,

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

L

L

e

e

c

c

t

t

u

u

r

r

e

e

r

r

M

M

o

o

d

d

r

r

e

e

k

k

a

a

M

M

.

.

A

A

L

L

-

-

H

H

a

a

s

s

a

a

n

n

,

,

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

L

L

e

e

c

c

u

u

r

r

e

e

r

r

id23041031 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com

V

V

e

e

t

t

e

e

r

r

i

i

n

n

a

a

r

r

y

y

C

C

l

l

i

i

n

n

i

i

c

c

a

a

l

l

D

D

i

i

a

a

g

g

n

n

o

o

s

s

t

t

i

i

c

c

P

P

r

r

o

o

c

c

e

e

d

d

u

u

r

r

e

e

s

s

2

2

0

0

0

0

8

8

Collected By

P

P

r

r

o

o

f

f

.

.

D

D

r

r

.

.

S

S

a

a

m

m

i

i

h

h

H

H

.

.

A

A

r

r

s

s

a

a

l

l

a

a

n

n

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

.

.

P

P

r

r

o

o

f

f

.

.

D

D

r

r

.

.

M

M

a

a

a

a

b

b

I

I

.

.

A

A

l

l

-

-

F

F

a

a

r

r

w

w

a

a

c

c

h

h

i

i

M

M

o

o

h

h

a

a

m

m

m

m

a

a

d

d

O

O

.

.

A

A

b

b

d

d

u

u

l

l

-

-

M

M

a

a

j

j

e

e

e

e

d

d

,

,

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

L

L

e

e

c

c

t

t

u

u

r

r

e

e

r

r

O

O

m

m

a

a

r

r

K

K

h

h

.

.

A

A

l

l

-

-

H

H

a

a

n

n

k

k

a

a

w

w

e

e

,

,

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

L

L

e

e

c

c

t

t

u

u

r

r

e

e

r

r

O

O

s

s

a

a

m

m

a

a

h

h

M

M

.

.

A

A

l

l

-

-

I

I

r

r

a

a

q

q

i

i

,

,

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

L

L

e

e

c

c

t

t

u

u

r

r

e

e

r

r

M

M

o

o

d

d

r

r

e

e

k

k

a

a

M

M

.

.

A

A

L

L

-

-

H

H

a

a

s

s

a

a

n

n

,

,

A

A

s

s

s

s

i

i

s

s

t

t

L

L

e

e

c

c

u

u

r

r

e

e

r

r

University of Mosul

College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Internal and Preventive Medicine

id23070765 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com

I

Preface

With knowledge growing in different scientific fields, a progress have also made in the

diagnosis of diseases. The major subjects being divided and subdivided into small fields. Such

specialization is admirable in many ways in its advantages but it does have many direct and indirect

disadvantages. Veterinary students having been taught a series of specialized subjects as separate

entities and may find it more difficult to inter-relate these subjects without being demonstrated in a

separate text.

In this text we tried to illustrate in the best way the modern techniques of diagnostic

procedures employed to differentiate diseases based on knowledge collected from most modern

sources of textbooks as well as information related to the subject from the websites. Throughout of

the text mention is made of recent commercially available products of kits used in the field of

veterinary medicine.

The text containing illustrations and many different recent techniques which can be value,

provided if they are employed in the right way at the right time and in the scientific manners. For

this purpose a basic knowledge of normal and abnormal structures, functions and why these modern

diagnostic techniques are employed, hence the students and practitioners should be aware of the

variations and errors anticipated which might occur when performing these laboratory techniques,

and logic interpretation of results is made.

It is now become believable how computer simulation has becoming sufficiently important

for having of this kinds of advances in laboratory diagnosis. However, the use of this book work

equally (might be) well in teaching laboratory procedures for academic and in fields by the

practitioners.

The primary target readership of this text is 4

th

year students in the college of veterinary

medicine, but we hope that it will be of similar benefit for the 5

th

year and post-graduate students as

well as for practitioners in the field, for its broad spectrum definitional and variety of numerous

information, examples and demonstrations contains, and hope that enough coverage of laboratory

diagnostic methods have been pursued.

Jan. 2008 Samih H. Arslan

id23091328 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com

II

Acknowledgment

This piece of work was possible to be published by the collection of scientific

laboratory diagnostic procedures based on work of many scientists and workers in this field

universally as well as staff members of this college. We hereby express our admiration to

the progress, giving the opportunity to veterinarians to learn more on the basis of recent

advances in this important science, we grateful to all. Also our thanks are due to Dean of

the college participates in make this text available for the students and practitioners. Thanks

also to our many colleagues at the department of internal and preventive medicine.

id23122843 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com

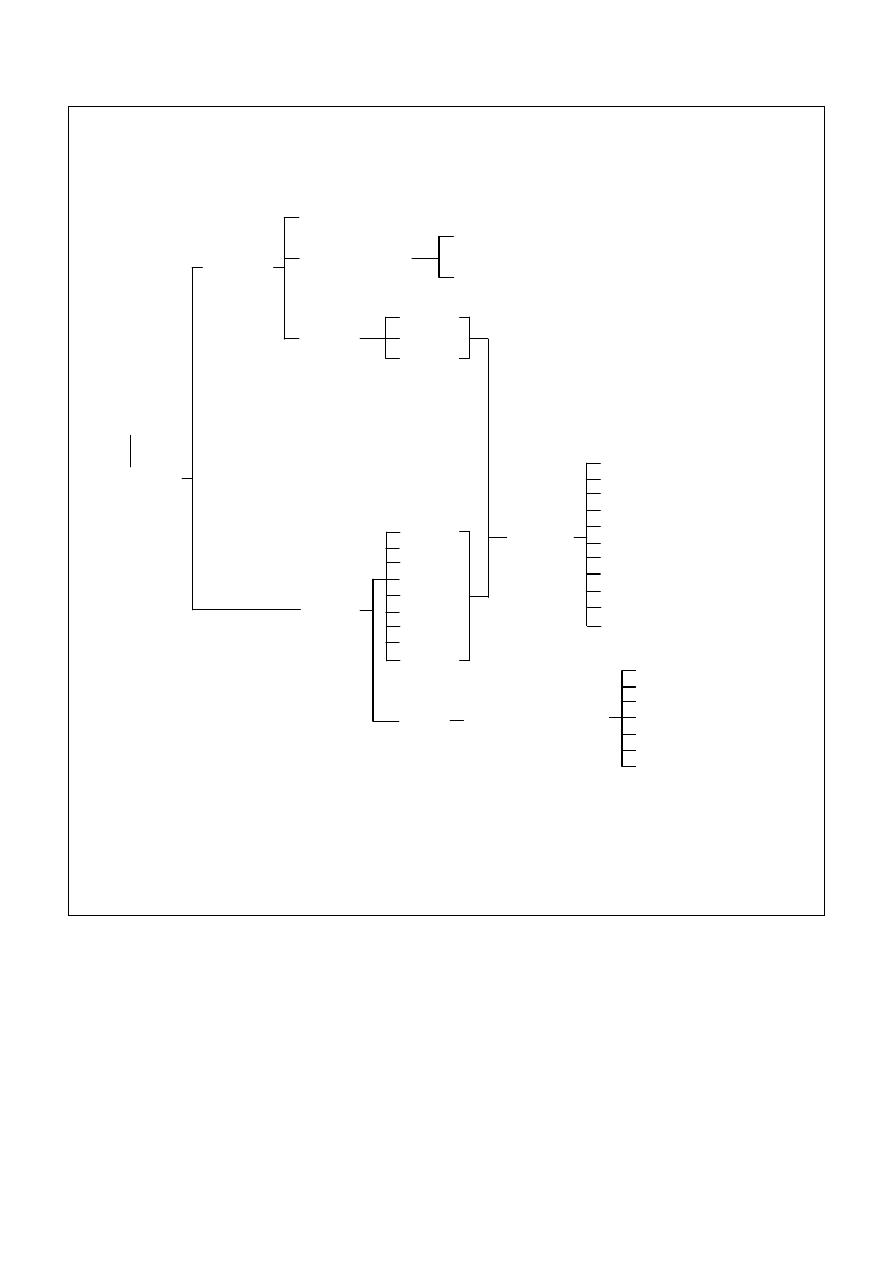

III

C

C

o

o

n

n

t

t

e

e

n

n

t

t

s

s

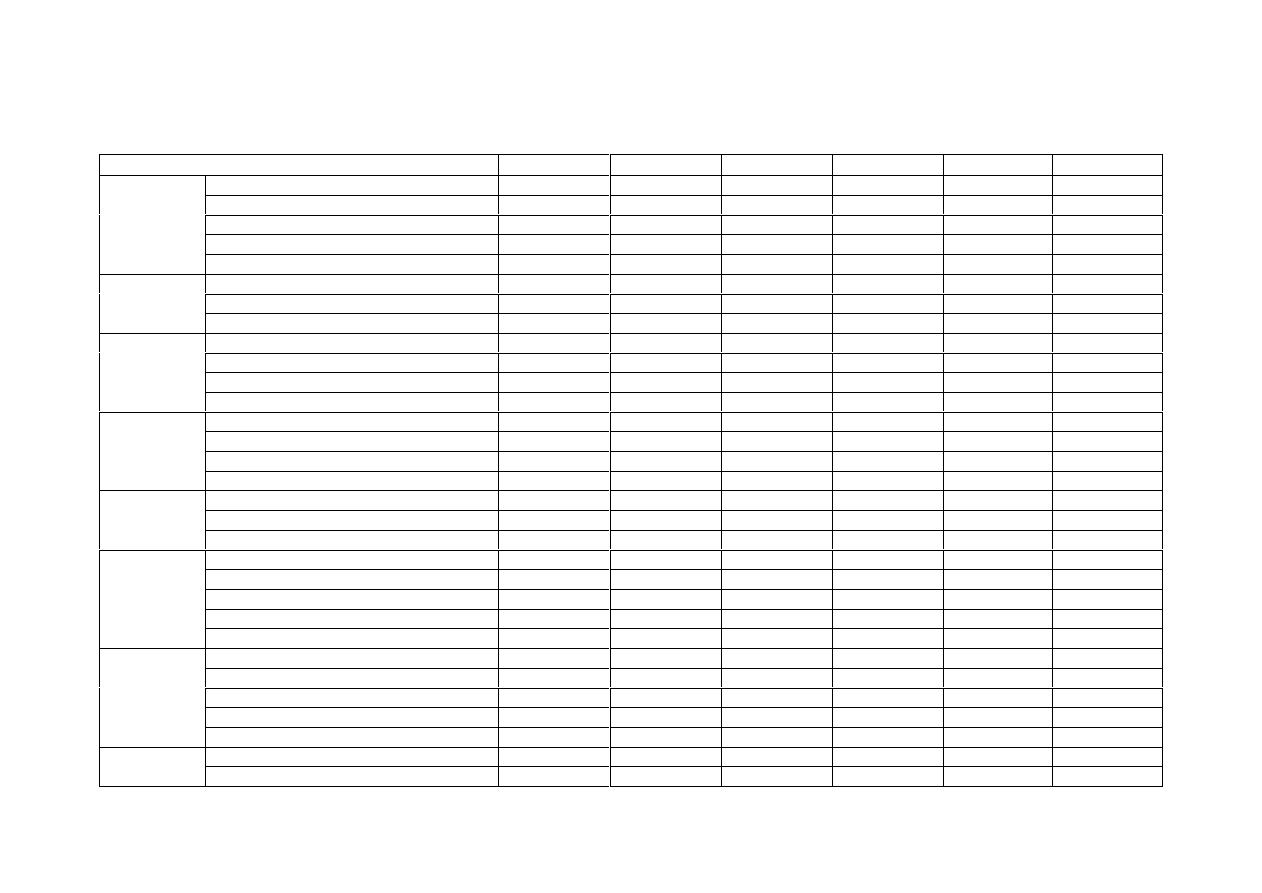

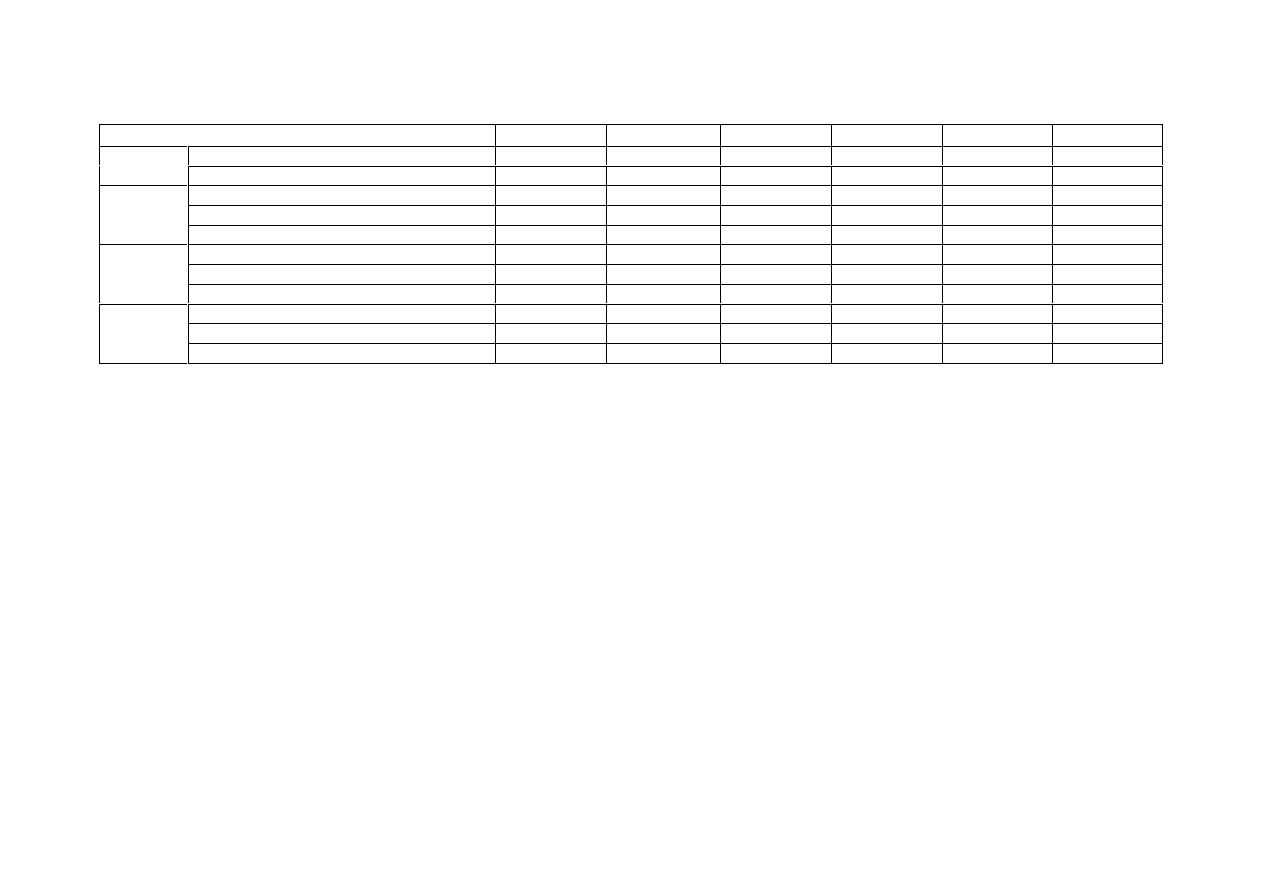

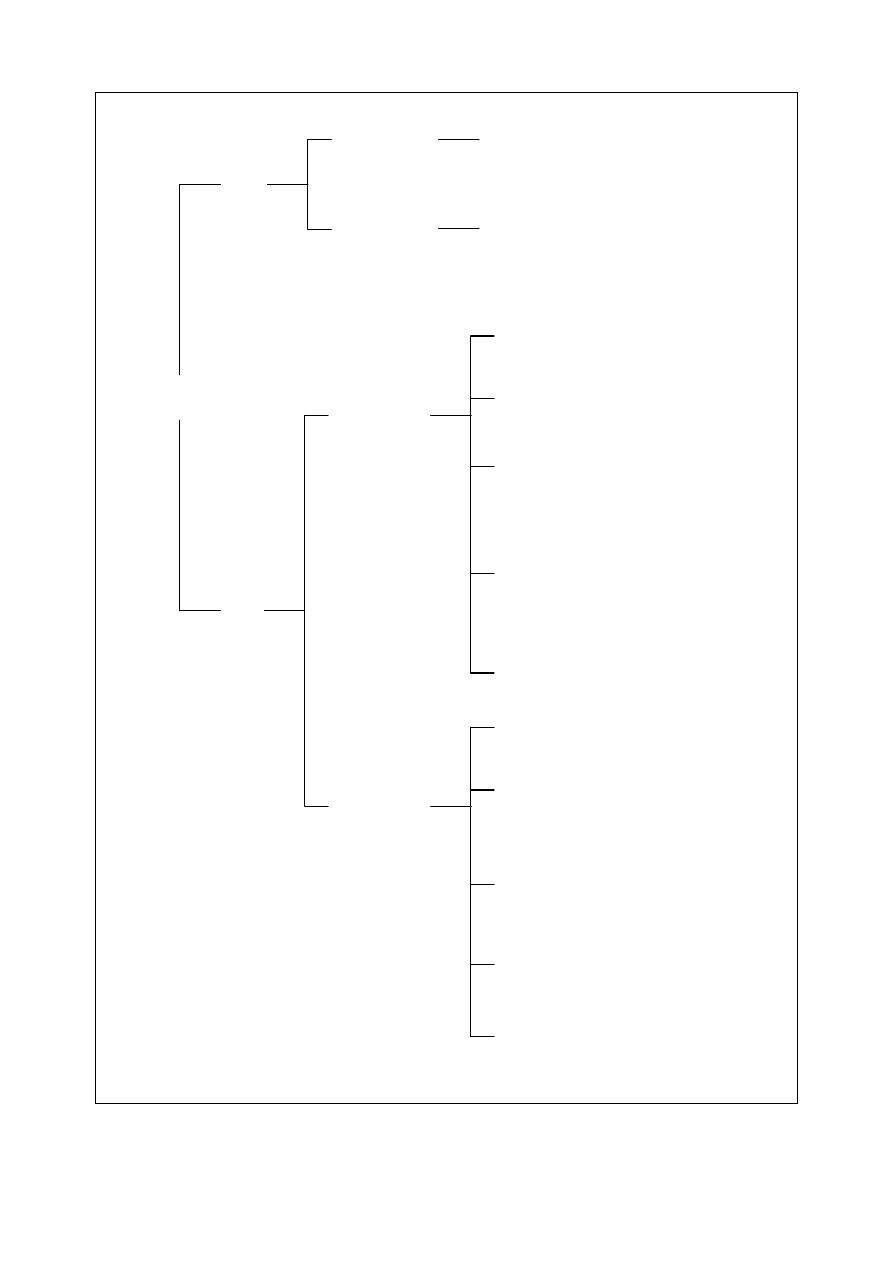

Chapter 1 … Collection of Samples ……………………………………. 1

Types of samples

………………………………………………………………………….. 1

I. Sample collected from live animals

………………………………………………… 1

1- Blood

…………………………………………………………………………… 1

2- Urine

…………………………………………………………………………….. 2

3- Feces

……………………………………………………………………………... 3

4- Milk

……………………………………………………………………………… 3

5- Genital tract and Semen

…………………………………………………………. 3

6- Abortion cases

………………………………………………………………….. 3

7- Nasal discharge, Saliva and Tears

……………………………………………….. 4

8- Eye

………………………………………………………………………………. 4

9- Skin

……………………………………………………………………………… 4

10- Body fluids

…………………………………………………………………….. 4

11- Gastric juice and Ruminal fluid

……………………………………………….. 5

12- Abscess

………………………………………………………………………. 5

II. Samples collected at post-mortem

………………………………………………… 5

III. Environmental and feed sampling

…………………………………………………. 5

Transportation of specimens

……………………………………………………………… 6

Transportation of specimens

……………………………………………………………… 6

Chapter 2 … Clinical Hematology ………………………………………. 7

Erythrocytes count

……………………………………………………………………….. 7

Leukocytes count

…………………………………………………………………………. 7

1. Total Leukocytes count (TLC)

……………………………………………………… 7

2. Differential Leukocytes count (DLC)

………………………………………………. 8

Reticulocytes count

……………………………………………………………………… 10

Thrombocytes count

……………………………………………………………………... 11

Packed Cell Volume "Hematocrit"

………………………………………………………. 12

Hemoglobin determination

……………………………………………………………….. 13

Erythrocytes indices

……………………………………………………………………… 13

Blood Counts by Electronic Analyzer

……………………………………………………. 13

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

……………………………………………………. 14

Hemostasis and coagulation of the blood

…………………………………………………. 14

Whole blood coagulating time

……………………………………………………………. 14

Bleeding time

…………………………………………………………………………….. 15

Chapter 3 … Bone Marrow Examination ………………………….... 17

Bone Marrow Aspiration

…………………………………………………………………. 17

Preparation of Bone Marrow Smears

….……………………………………………… 17

Preparation of Bone Marrow Sections

…………………………………………………. 18

Examination of Bone Marrow Film

……………………………………………………… 18

Cell Identification

………………………………………………………………………… 18

Chapter 4 … Clinical Biochemistry …………………………………… 21

Panel of Biochemical Analyses

…………………………………………………………. 21

Preparation of Solutions

………………………………………………………………... 21

id23145546 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com

IV

Equipments of Biochemical Analyses

…………………………………………………... 22

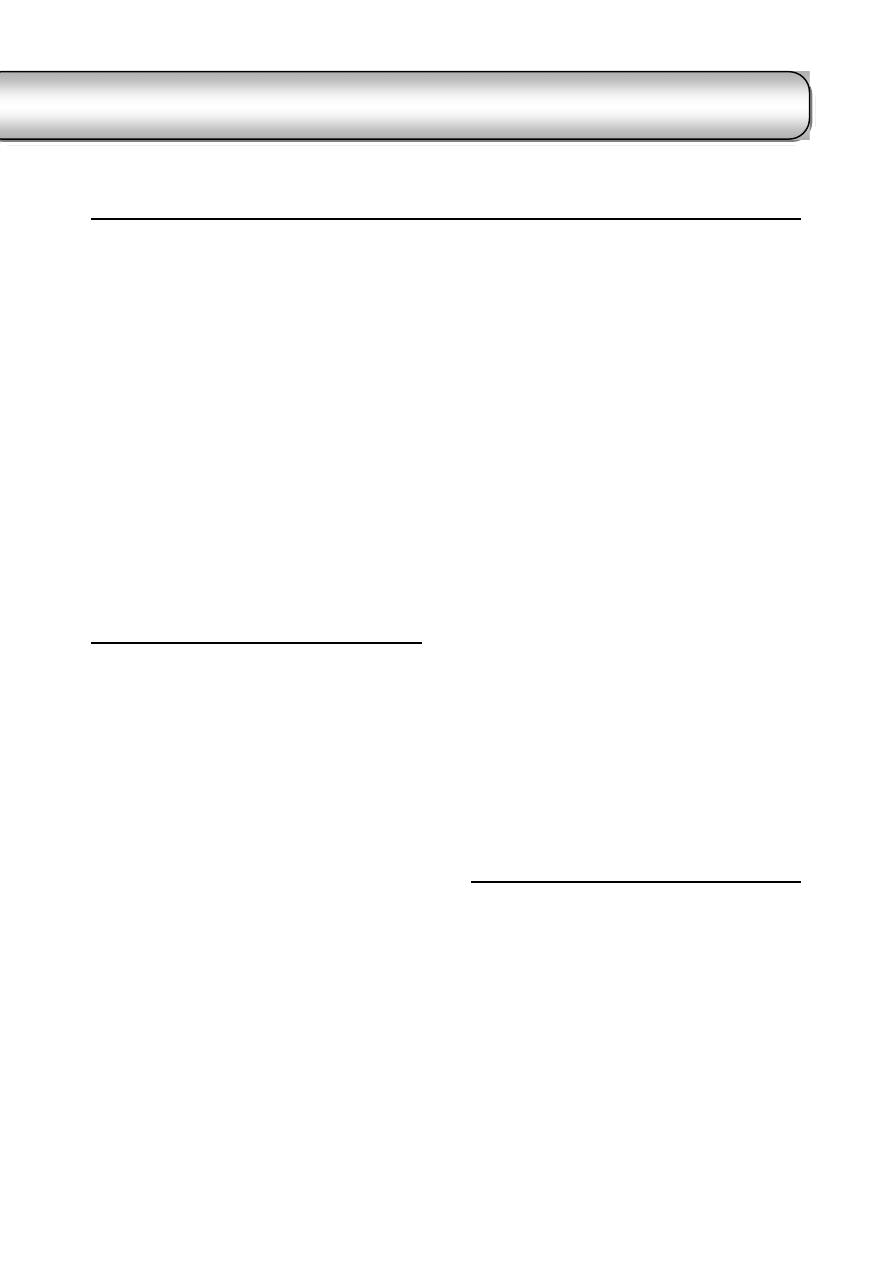

pH meter

………………………………………………………………………………. 22

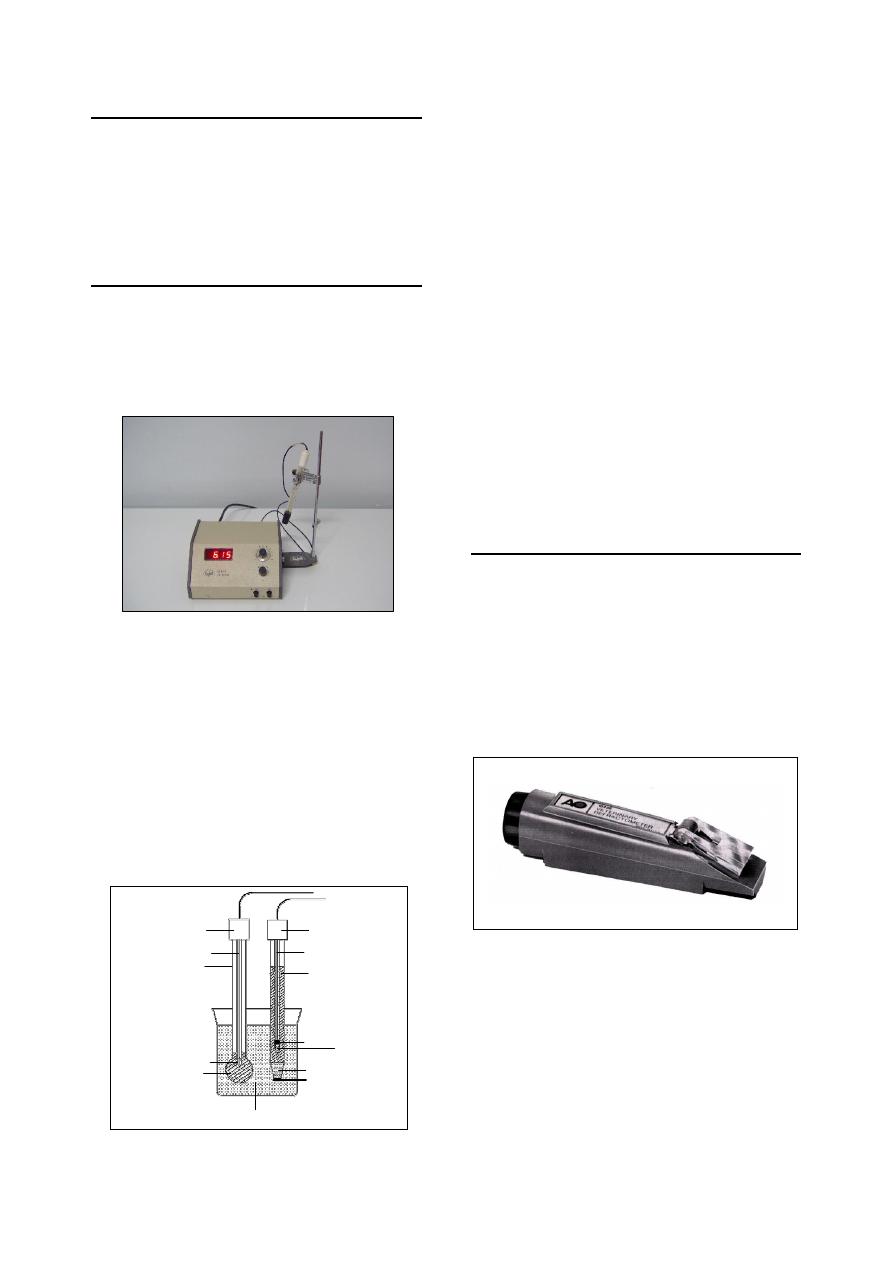

Refractometer

…………………………………………………………………………. 22

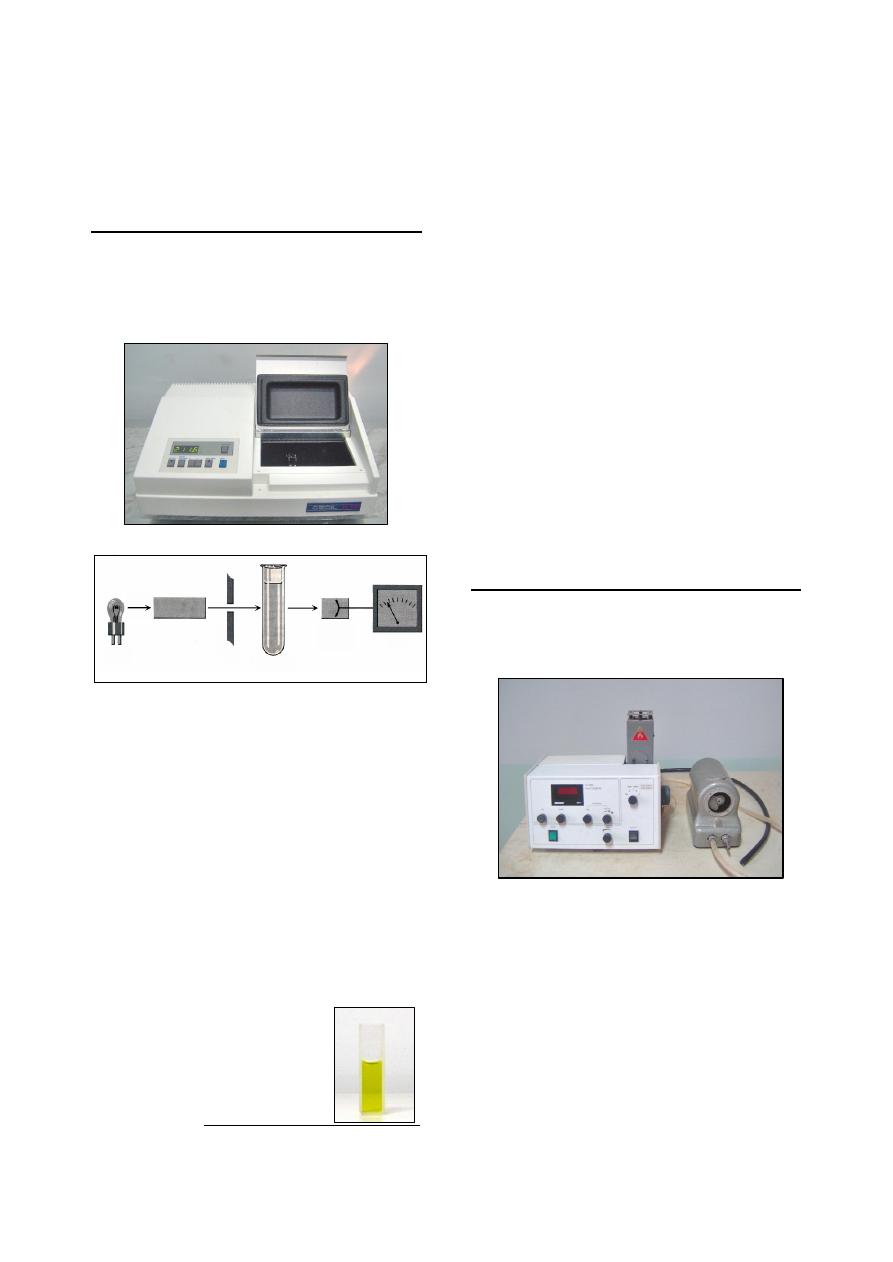

Spectrophotometer

…………………………………………………………………….. 23

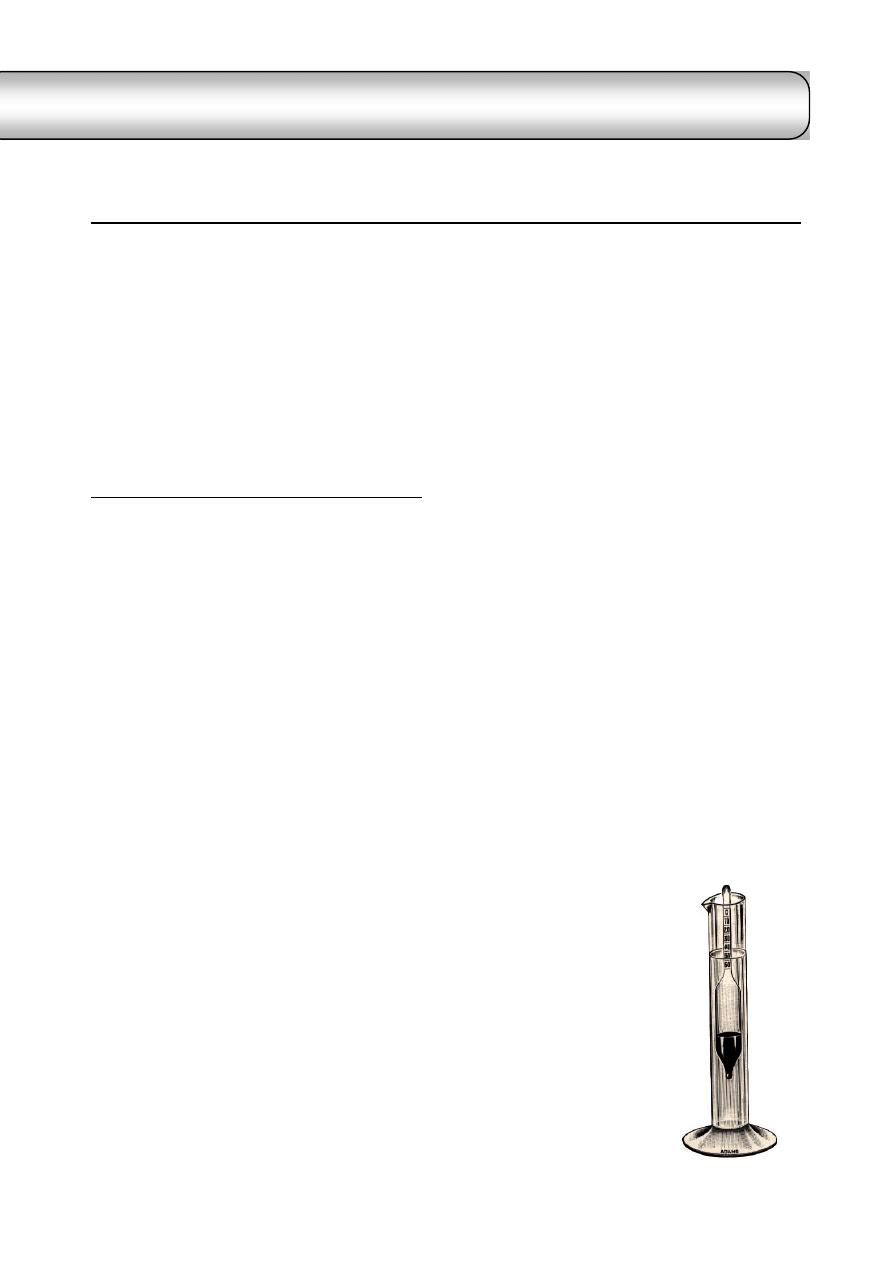

Flame photometer

……………………………………………………………………... 23

Atomic absorption spectrophotometer

………………………………………………... 24

Electrophoresis

………………………………………………………………………... 24

Enzyme linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

……………………………………… 24

VET Scan Analyzer

……….…………………………………………………………... 25

Techniques of Biochemical Analyses

………………………………………….……. 25

Tests of functional status of several organs

…………………………………………… 27

Chapter 5 … Urinalysis …………………………………………………… 29

Macroscopic Examination of the Urine

…….…………………………………………… 29

I. Physical Examination

……………………………………………………………….. 29

II. Chemical Examination

……………………………………………………………... 30

Microscopic Examination of the Urine

…….……………………………………………. 30

Component of Urinary Sediment

….…………………………………………………. 31

I. Organized Sediment

….……………………………………………………………. 31

II. Unorganized Sediment

……………………………………………………………... 31

Urine Culture

….………………………………………………………………………… 33

Kidney Function Tests

…………………………………………………………………... 33

Chapter 6 … Clinical Parasitology ……………………………………. 35

Coprological Examination

….…………………………………………………………….. 35

Macroscopic Examination

….…………………………………………………………… 35

Microscopic Examination

………………………………………………………………… 35

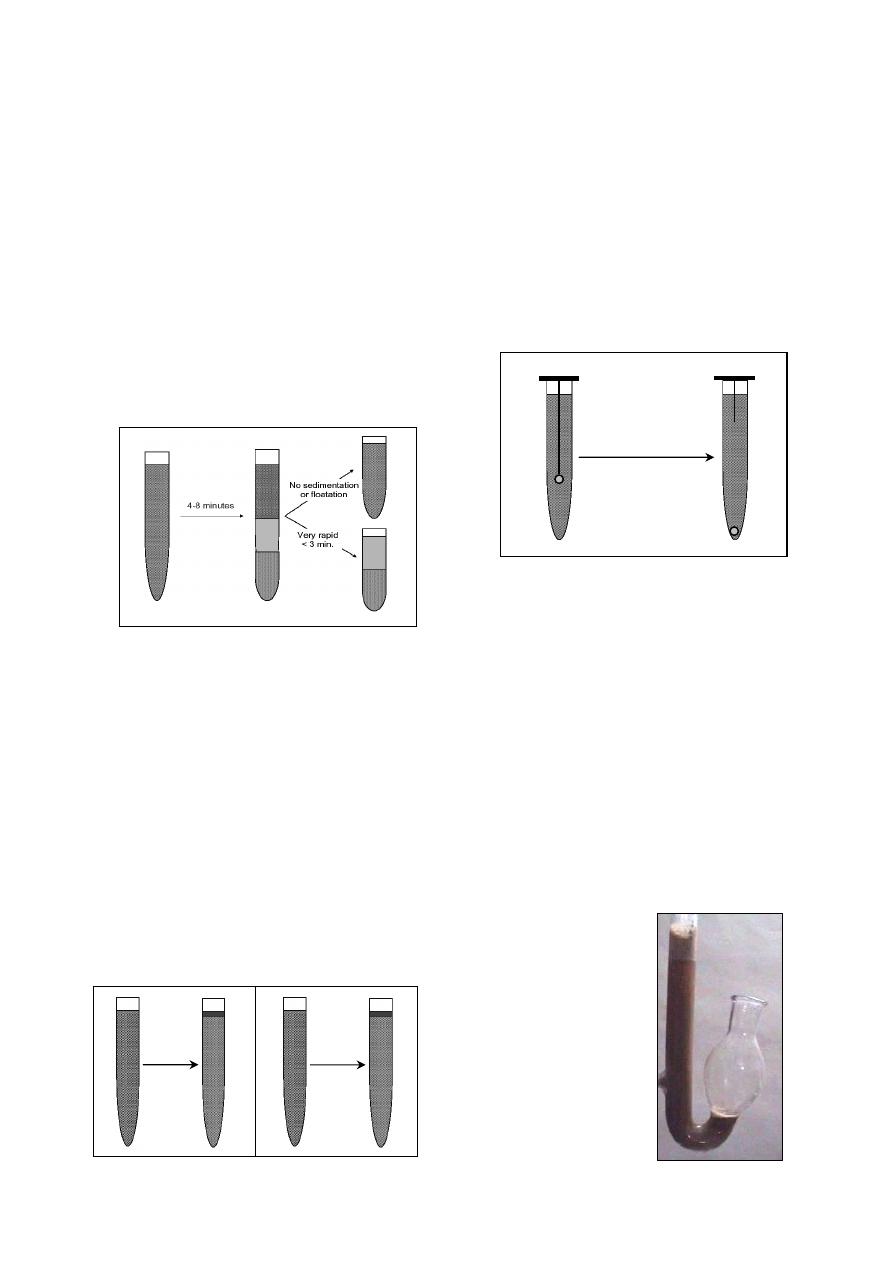

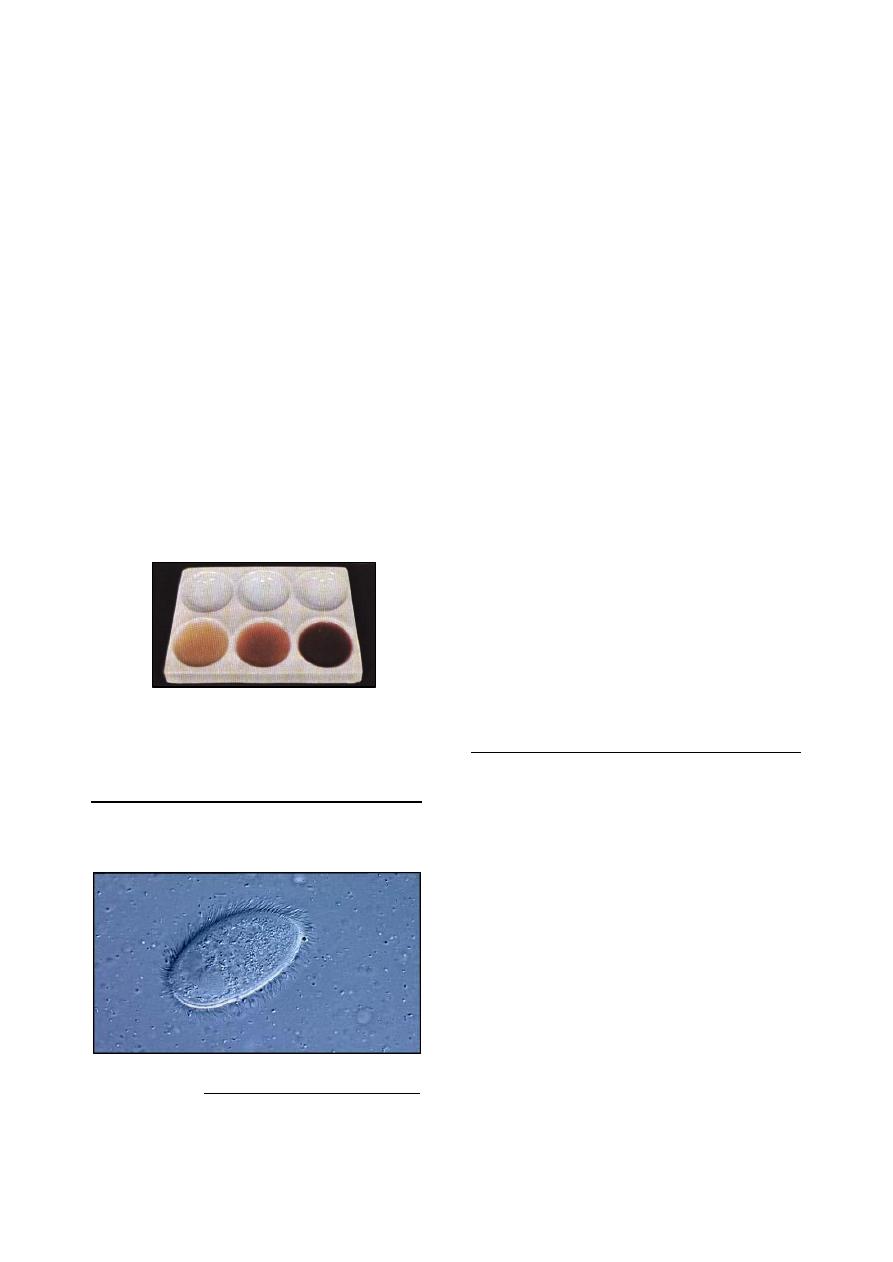

I- Qualitative Methods

………………………………………………………………… 35

II- Quantitative Methods

……………………………………………………………… 37

III- Micrometry

………………………………………………………………………... 37

Examination of Feces for Protozoa

….………………………………………………….. 38

Blood Examination

……….……………………………………………………………….. 41

Blood Protozoa

…………………………………………………………………………… 41

Babesia

………………………………………………………………………………... 41

Theileria

……………………………………………………………………………….. 41

Anaplasma

…………………………………………………………………………….. 42

Trypanosoma

………………………………………………………………………….. 42

Toxoplasma

…………………………………………………………………………… 42

Blood Nematodes

…….…………………………………………………………………. 43

Miscellaneous Parasitic Examination

….………………………………………………… 44

Parasites of the Urinary Tract

…………………………………………………………….. 44

Parasites of the Reproductive Tract

………………………………………………………. 44

Parasites of the Eye

………………………………………………………………………. 44

Diagnosis of External Parasites

….……………………………………………………….. 44

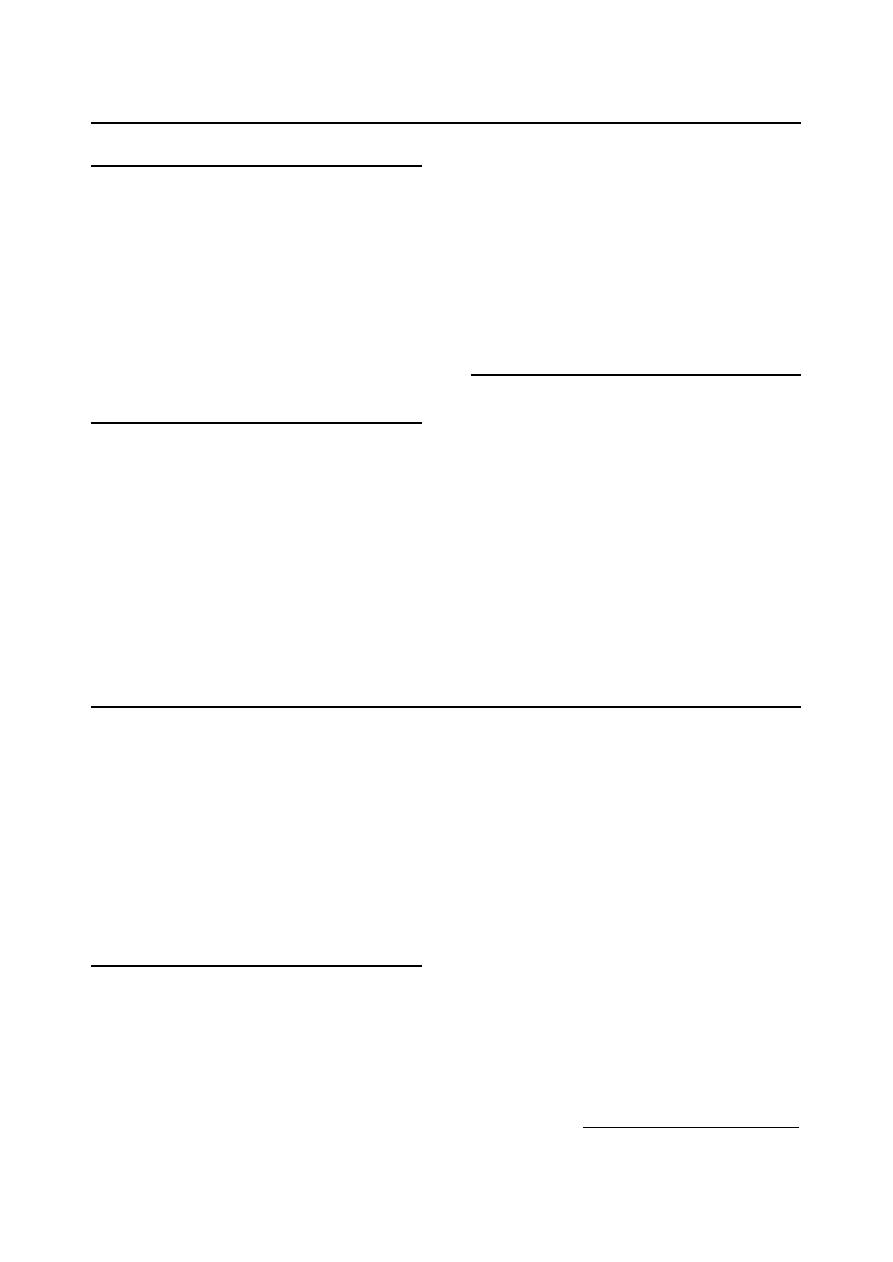

Mites

……………………………………………………………………………………… 44

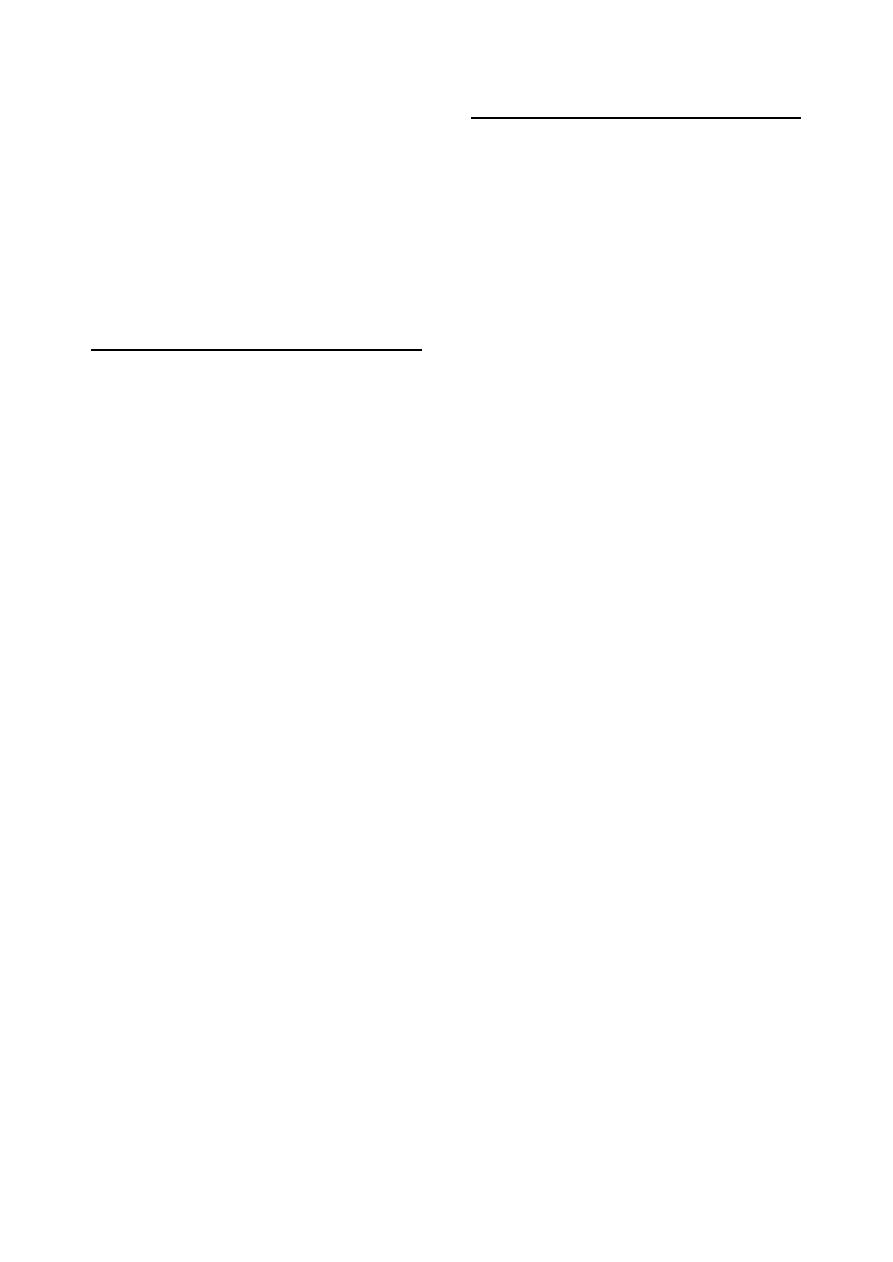

Ticks

……………………………………………………………………………………… 45

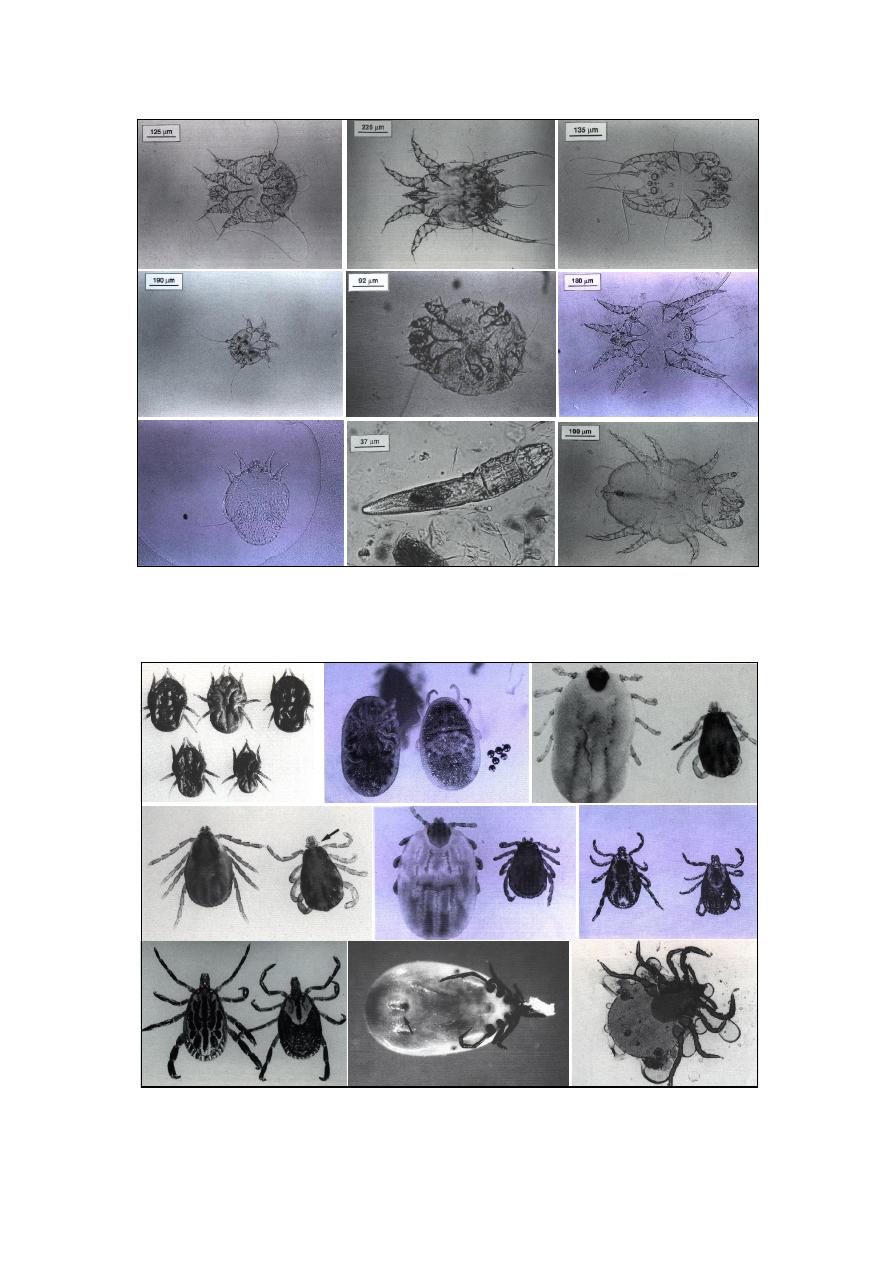

Insects

…………………………………………………………………………………….. 45

Chapter 7 … Rumen Fluid Examination …………………………….. 49

Examination of the Fluid

…….………………………………………………………….. 49

Physical Examination

……………………………………………………….……….. 49

V

Chemical Examination

………………………………………………………….…… 51

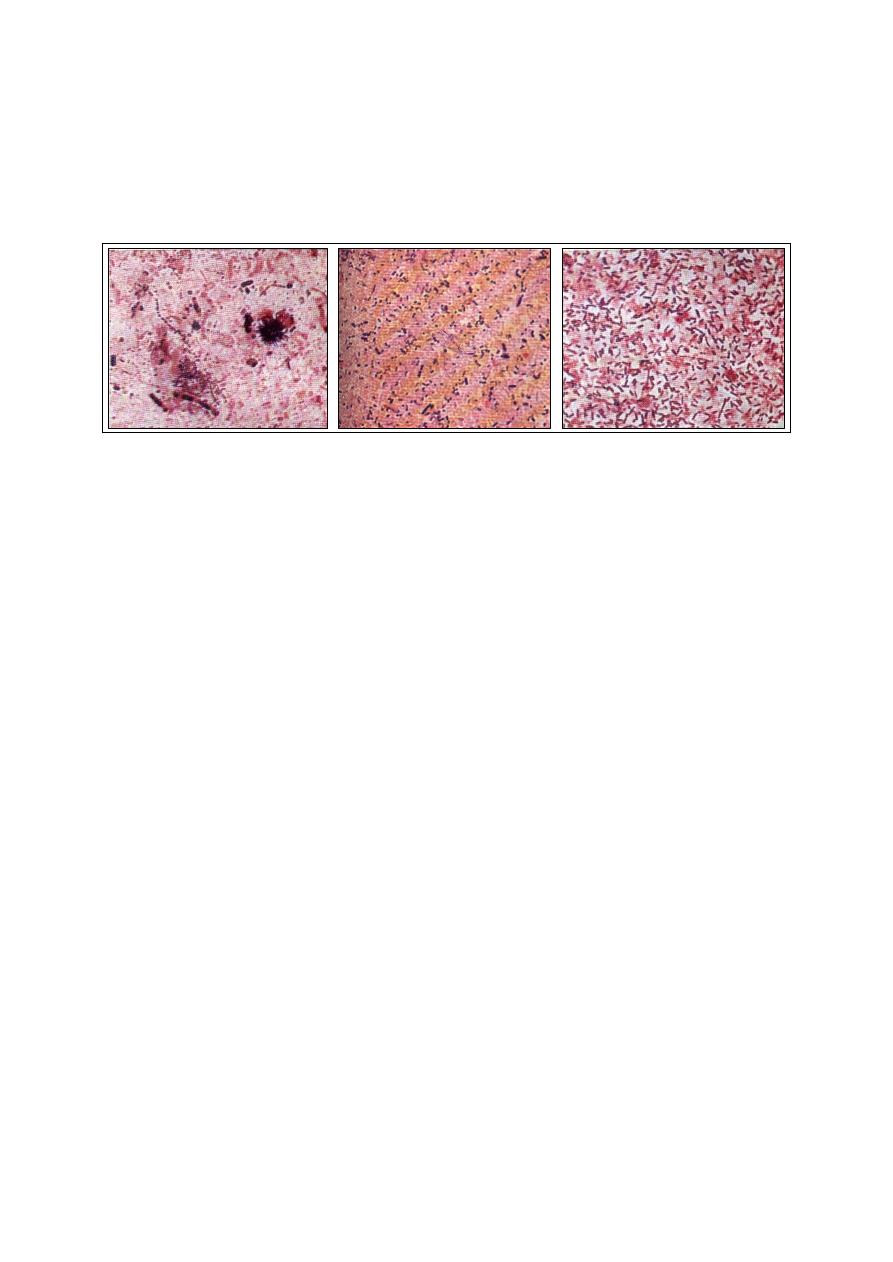

Examination of the Protozoa

……………………………………………………………... 51

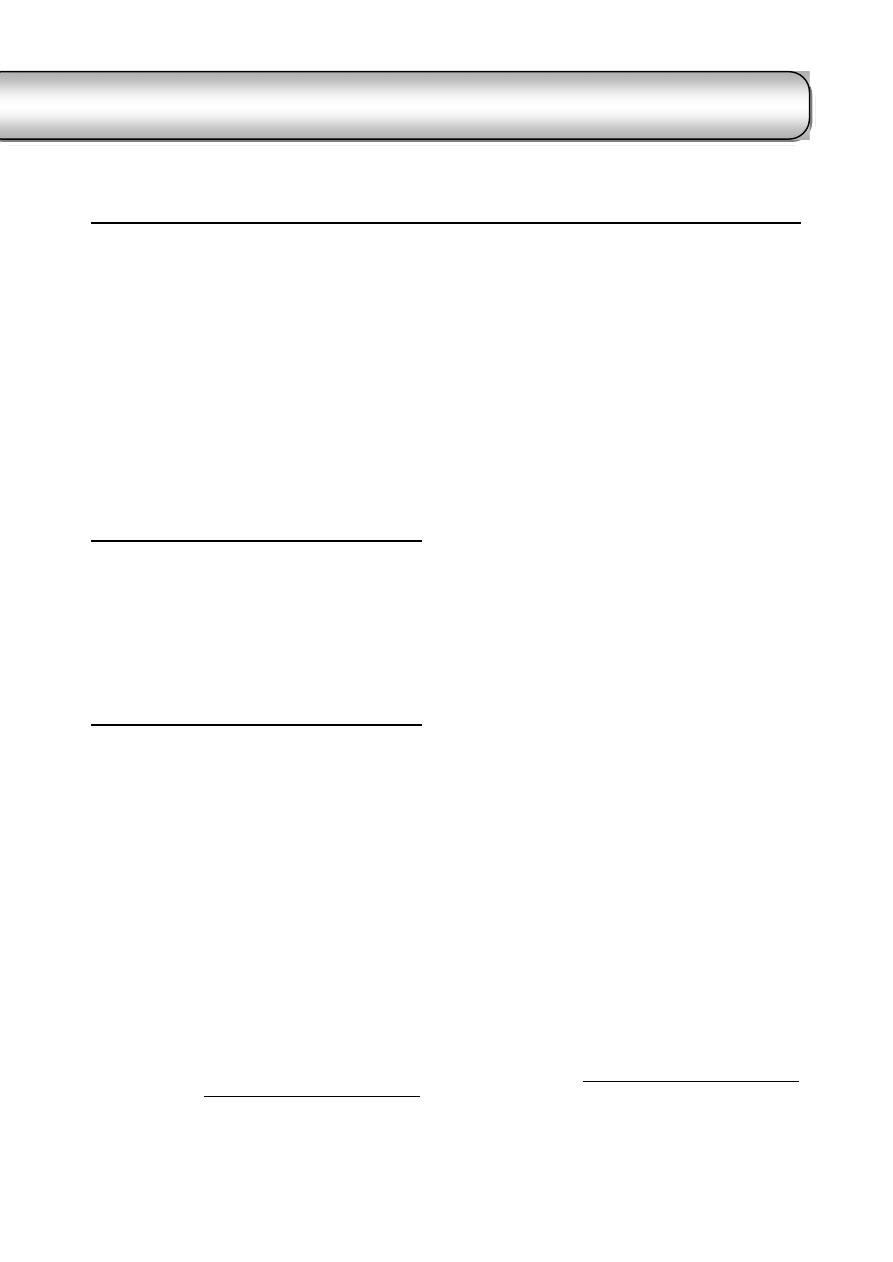

Examination of the Bacteria

………………………………………………………….…. 51

Chapter 8 … Milk Examination ……………………………………….. 53

Physical Examination (Strip-cup test)

……………………………………………….….. 53

Chemical Examination

…………….……………………………………………………. 53

Indirect Leukocyte Count

……………………………………………………………….. 54

Direct Leukocyte Count

………………………………………………………………… 55

Hotis Test

……………………………………………………………………………….. 56

Chapter 9 … Clinical Microbiology …………………………………… 57

Clinical Bacteriology

….…………………………………………………………………... 57

Methods of Bacteriological Diagnosis

……….………………………………………….. 57

1- Smears

……………………………………………………………………………… 57

2- Bacteriological Media

……………………………………………………………… 57

Preparation of Culture Media

…….……………………………………………………... 57

Inoculation of Culture Media

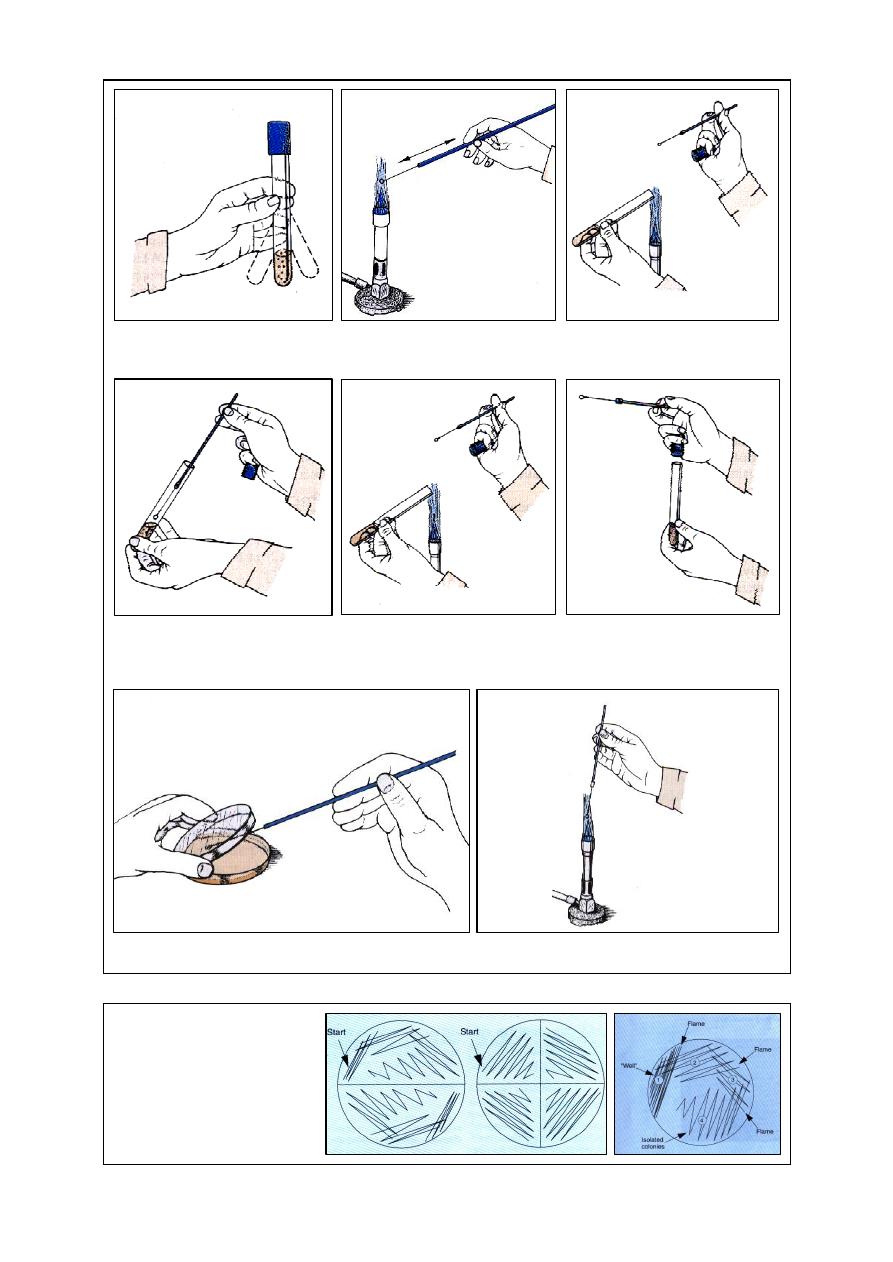

….………………………………………………………… 58

Streaking of the Plate

…….…………………………………………………………….. 58

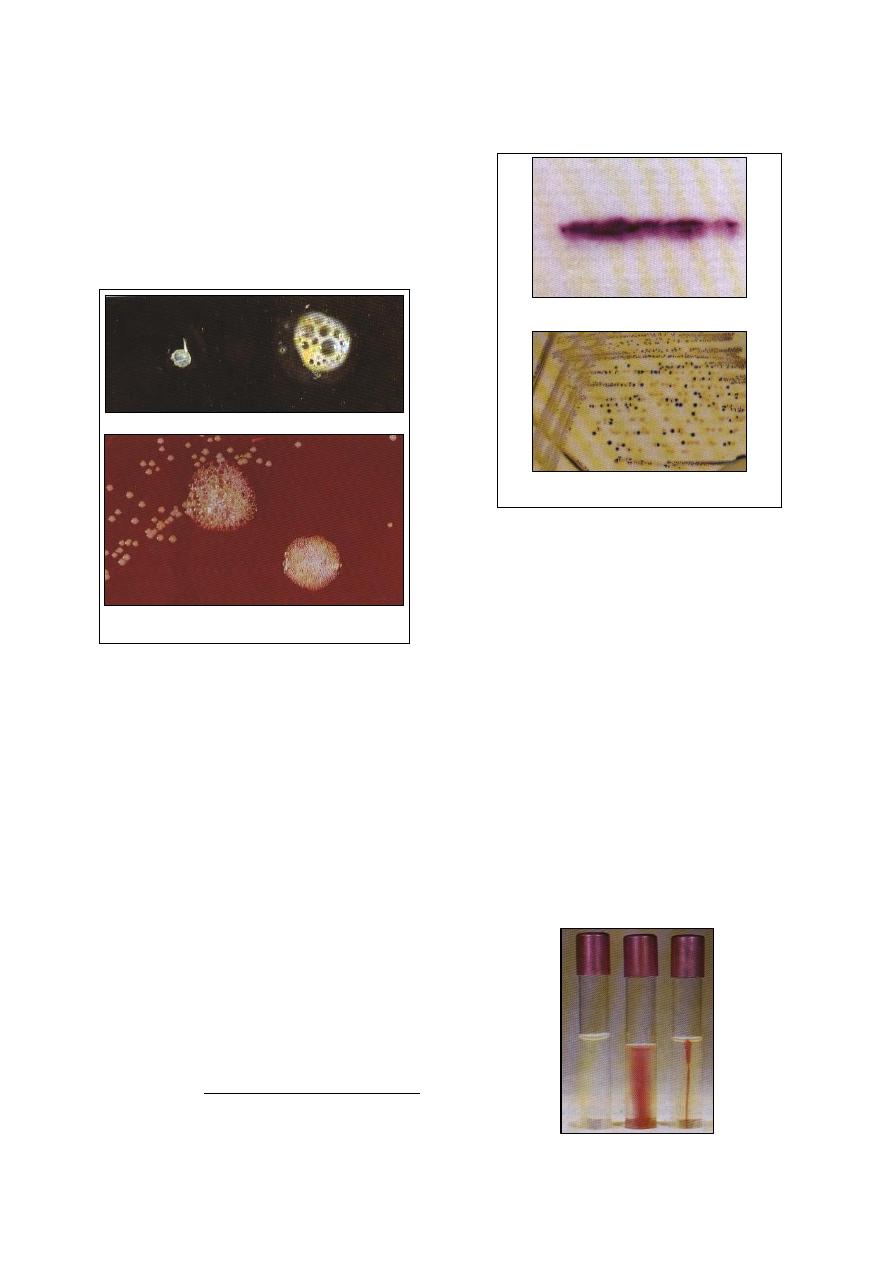

Incubation of the Plate

…….……………………………………………………………. 60

Identification of Bacteria

…….………………………………………………………….. 60

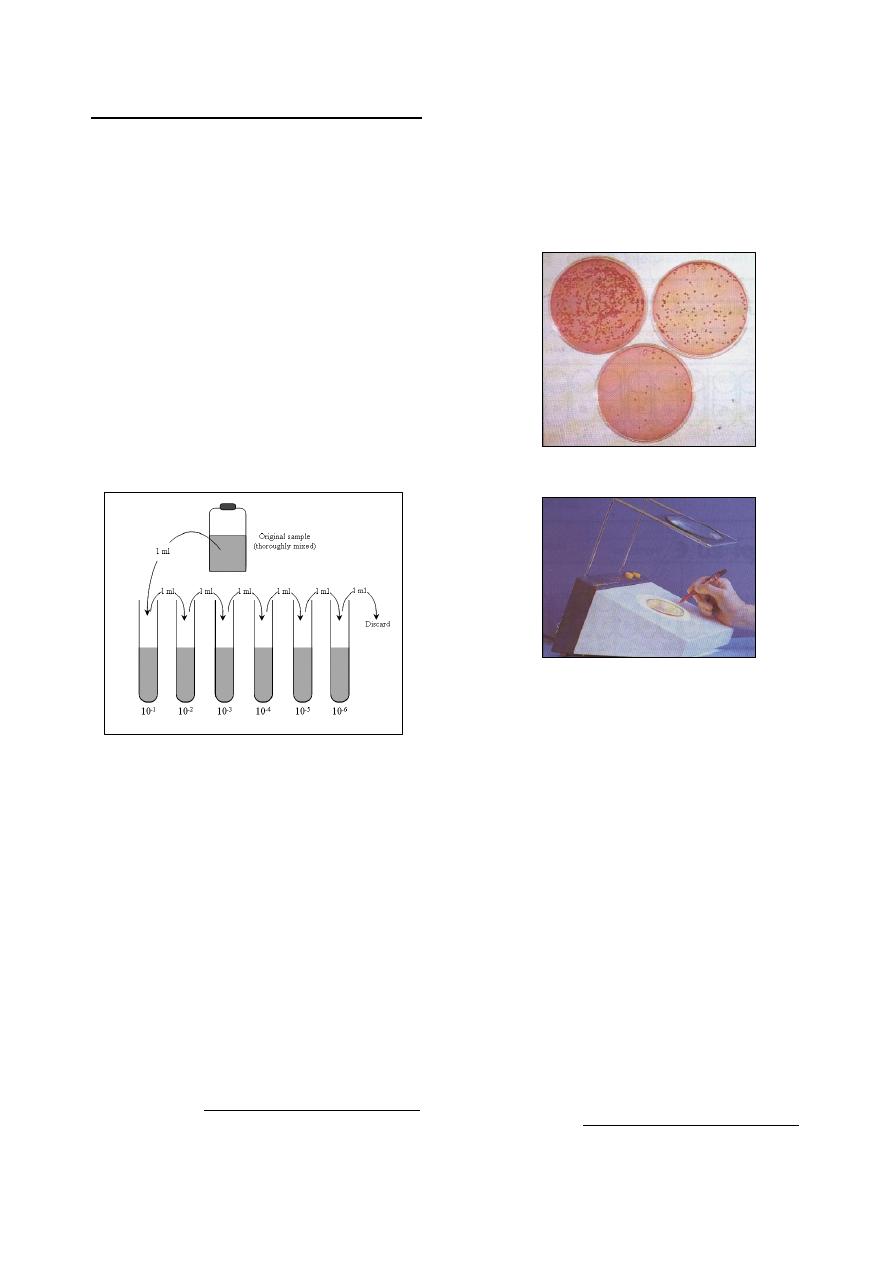

Bacterial Cell Counting Techniques

……………………………………………………... 62

Clinical Virology

……………………………………………………………………………. 63

Preparation of Clinical Specimens

……………………………………………………….. 63

Preparation of Washed Sand

……………………………………………………………. 63

Inoculation of Specimen into Susceptible Host Systems

….……………………………. 64

Preparation of Cell Culture

………………………………………………………………. 64

Virus Inoculation in Chick Embryo

…………………………………………………….. 65

Clinical Mycology

…………………………………………………………………………... 66

Direct Microscopic Examination

…………………………………………………………. 66

Isolation and Subculture of Fungi

….……………………………………………………. 67

Chapter 10 … Serology …………………………………………………… 69

Agglutination Tests

…….……………………………………………………………….. 69

Haemagglutination Test (HA)

……………………………………………………………. 70

Haemagglutination Inhibition test (HI)

…………………………………………………... 71

Agglutination-Lysis Test

……….………………………………………………………… 71

Precipitation Test

……….……………………………………………………………….. 71

Complement Fixation Test

………….…………………………………………………… 72

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) .

………………………………………. 72

Immunofluorescence

……………………………………………………………………... 73

Chapter 11 … Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) ……………….. 75

Materials used in PCR technique

………………………………………………………… 75

Procedure of PCR technique

……………………………………………………………... 75

Appendix ……………………………………………………………………….. 79

1

C

C

h

h

a

a

p

p

t

t

e

e

r

r

1

1

C

C

o

o

l

l

l

l

e

e

c

c

t

t

i

i

o

o

n

n

o

o

f

f

S

S

a

a

m

m

p

p

l

l

e

e

s

s

Before taking samples, careful consideration

should be given to the purpose for which they

are required. This will determine the type and

number of samples needed to provide valid

results. Considerable skill and care are required

to decide on the correct samples to be sent to the

laboratory.

The samples collected should be represent the

condition being investigated and the lesions

observed.

When samples are taken from live animals,

care should be taken to avoid injury or

distress to the animal or danger to the

operator and attendants. It may be necessary

to use mechanical restraint, tranquillization or

anesthesia.

A sufficient quantity of material must be

provided to permit a thorough examination.

Sample should be obtained from the edges of

lesion and include some macroscopically

normal tissue. Microbial replication will be

most active at the lesion's edge.

For bacteriological isolation, sample should

be collected before the administration of any

form of treatment.

The risk of zoonotic disease should be kept in

mind and precautions taken to avoid human

infection.

Care should be taken to avoid environmental

contamination, or risk of spread of disease

through insects or fomites.

For obtaining specimens, select an animal

that is in advanced stages of the disease.

If the disease is a flock or herd problem,

specimens should be obtained from more than

one diseased animal which are in various

stages of illness, and also from one or two

animals that have died recently.

Identification of samples should be submitted

with each sample including complete history

as follows:

Owner's name and address.

Description of the animal including:

species, age and sex.

Duration of the condition or outbreak.

Morbidity and mortality rates.

Nature of feed including any change of

feed that has occurred.

Possibility of contact with other animals.

Clinical signs observed.

Necropsy findings.

History of treatment or vaccination.

Tentative clinical diagnosis.

Veterinarian's name, address and phone

number.

The nature of submitted sample.

Type of preservation used on specimen.

Types of samples

I. Sample collected from live animals

1-

Blood:

Blood samples may be taken for hematology

(hemograms) or for culture and/or direct

examination for bacteria, viruses, or protozoa, in

which case it is usual to use anticoagulants

.

In nearly the site of choice for taken of blood

sample in all species is the jugular vein. Other

veins provide a useful alternative to the jugular,

such as mammary vein, caudal vein (tail vein) in

standing cattle, or cephalic vein in large dogs

with short thick neck.

The blood sample is taken, as cleanly as

possible. The skin at the site of vein puncture

should be shaved and swabbed with alcohol

Anticoagulants:

1- EDTA " Ethylene Diamine Tetra Acetic Acid ":

It acts by combining with calcium. It preserve the

stainability

and

morphologic

characteristics

of

leukocytes, but it decrease PCV if EDTA is present in

excess due to cell shrinkage. It is used as:

Liquid form: 1drop of 10% sol./5ml of blood.

dry powder: 1mg of powder/1ml of blood.

2- Oxalate:

It is act by combining with calcium. It is easy to prepare

and inexpensive, but has some disadvantages.

3- Heparin:

It is act by interfering with conversion of prothrombin to

thrombin, but it is expensive and effective for only 10-12

hours.

4- Sodium fluoride:

It is not used for hematological determination, but used

for glucose estimation.

id23206265 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com

2

70%, and allowed to dry, then the blood taken

either by syringe and needle, or by needle and

vacutainer tube (Fig 1-1) and (Fig. 1-2).

Notes:

For samples that are collected with anti-

coagulant, thorough mixing is necessary as

soon as the sample has been taken, using

gentle agitation only.

It may also be necessary to make a smear of

fresh blood on a microscope slide; both thick

and thin smears may be prepared

1

.

Serum and Plasma:

Serum or plasma may be collected from

whole blood as follows:

Separation of serum:

Blood left to stand at ambient temperature

(but protected from excessive heat or cold)

for 1-2 hours until the clot begins to contract.

The clot can then be ringed round with a

sterile rod then place the tube in a refrigerator

at 4

°C for several hours or overnight.

1

Preparation of blood film will be discussed in "Chapter 2".

The sample can be centrifuged at about 1000

rpm for 10-15 minutes.

Aspire the serum with a pipette.

Avoid the tip of the pipette being pocked into

the clot, or too much suction applied near the

surface because fragments may be detached.

Separation of plasma:

Blood with anticoagulant centrifuged at about

1000 rpm for 10-15 minutes.

Aspire the plasma with a pipette.

Do not disturb the cell layer, otherwise blood

cells will be withdrawn.

Serum and plasma may be stored at 4

˚c in a

refrigerator for up to 4 days, or should be placed

into deep-freeze at (-15

˚c) to (-20˚c) until used.

2-

Urine:

Urine in the urinary bladder is normally

sterile, the urethra has microflora. Urine colleted

from animals via several methods.

(a) Manual compression of urinary bladder:

A continuous pressure should be done for

several minutes until the sphincters of the urethra

relax and urine is expelled. The bladder in small

animals

is

obtained by abdominal

palpation,

while

a gentle continuous pressure in large animals can

be applied through rectal palpation.

(b) Catheterization:

Catheterization used in female large animal.

Care must be taken to avoid contamination and

traumatic injury. The catheter should be passed

by handling it through the sterile packing mate-

rial in which it is contained, utilized sterilized

forceps, and wearing sterilized rubber gloves.

The first portion of aspired urine should be

discarded. Samples colleted by catheterization

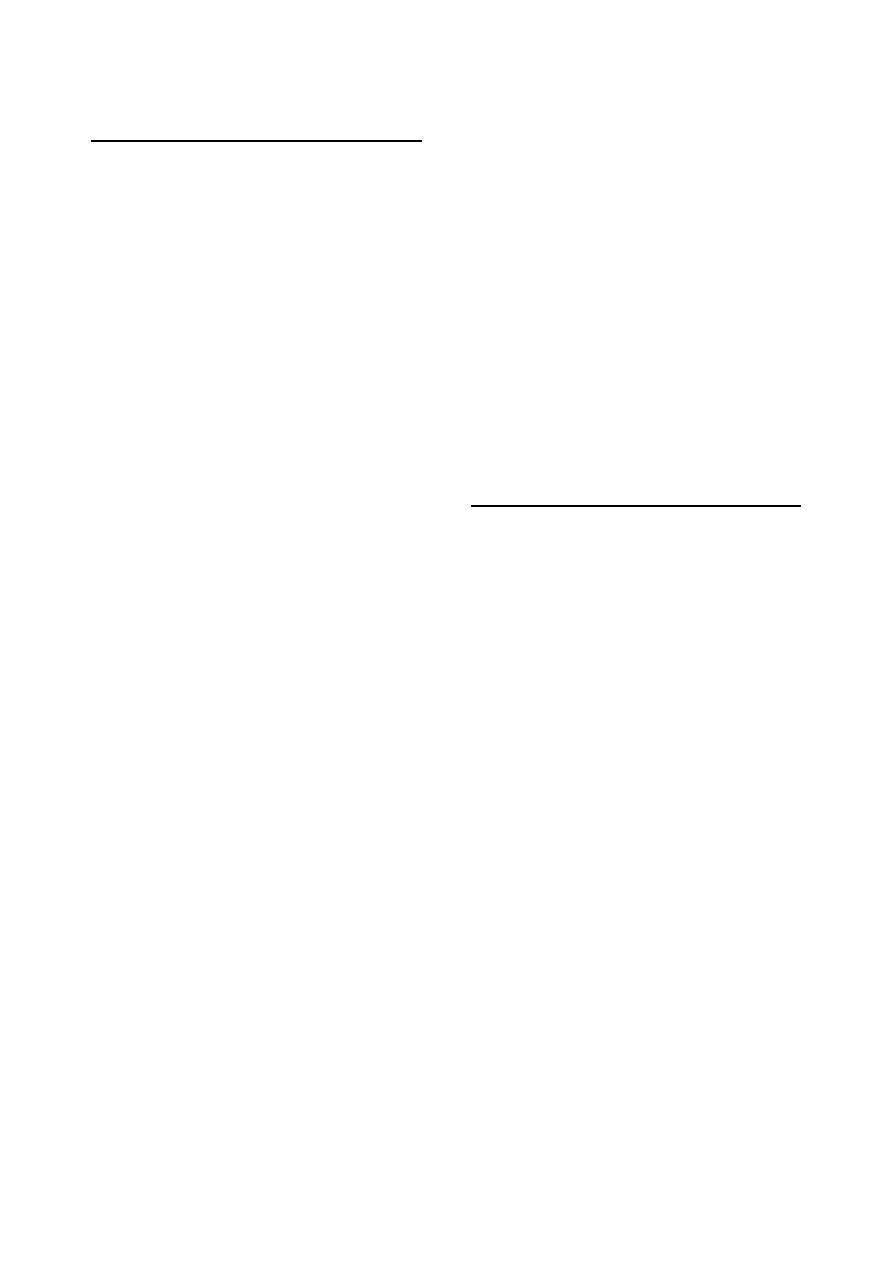

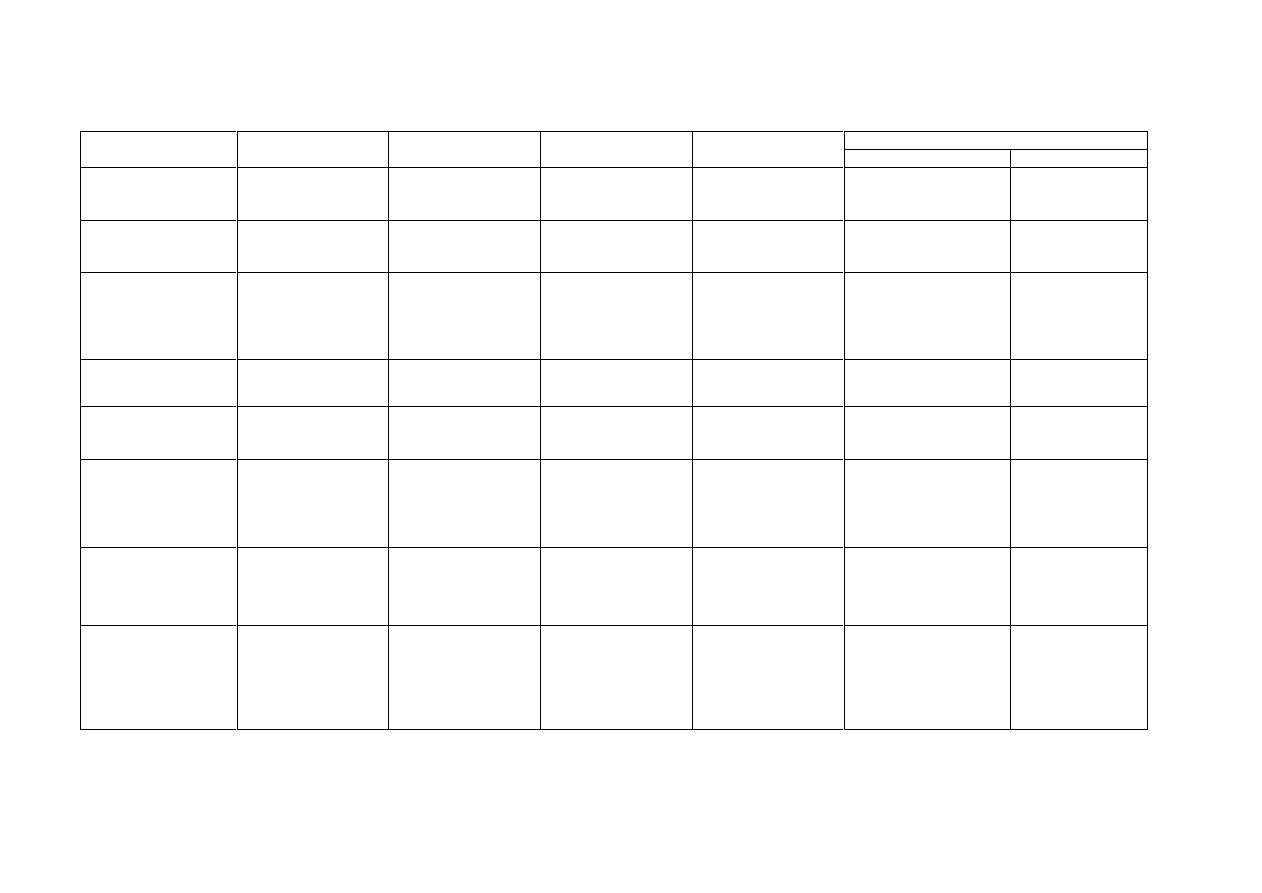

often contain a few RBCs (Fig. 1-3).

(c) Cystocentesis:

Cystocentesis indicated for bacterial culture,

and used in small animals only when the bladder

contains a sufficient volume of urine so that it is

readily palpable (Fig 1-4).

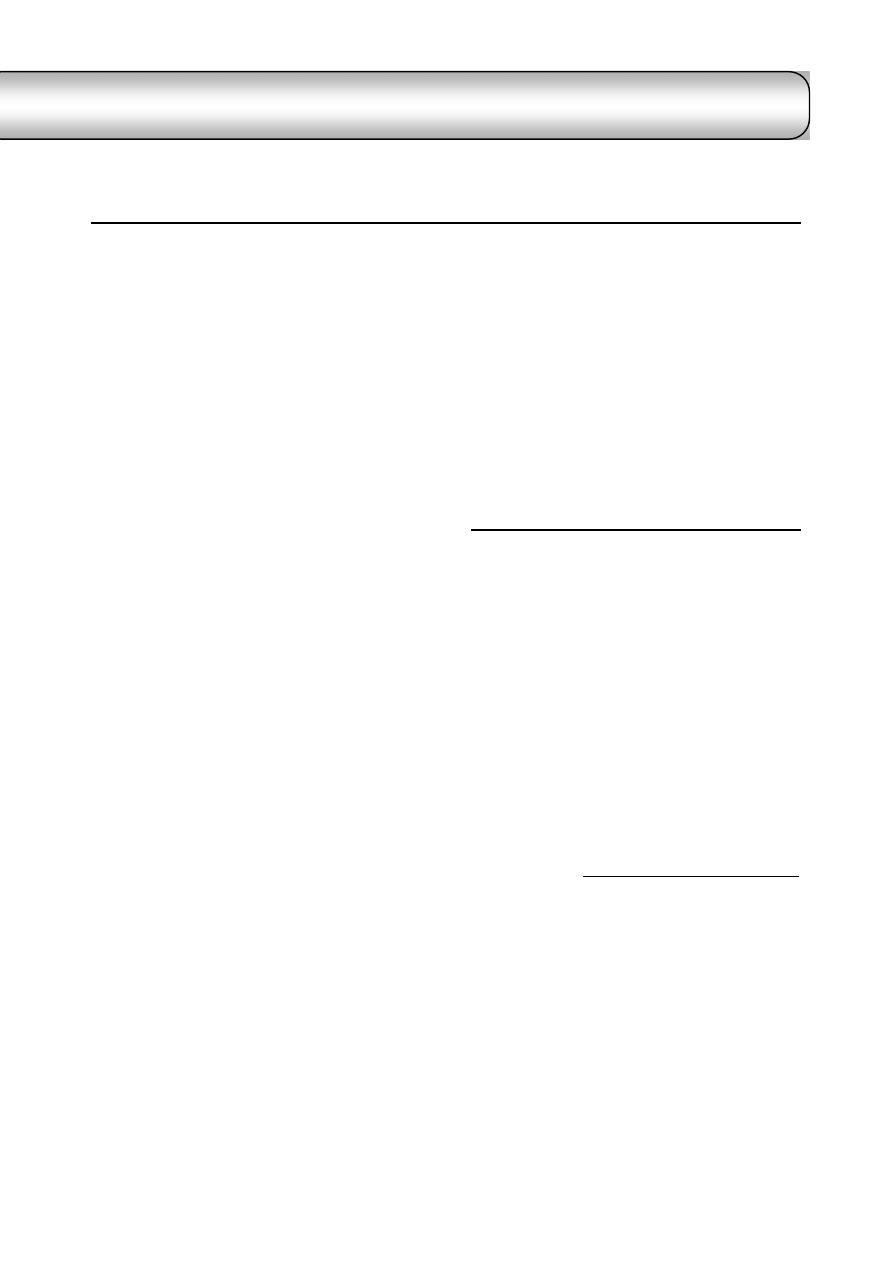

Fig. (1-1) blood sampling from the jugular vein

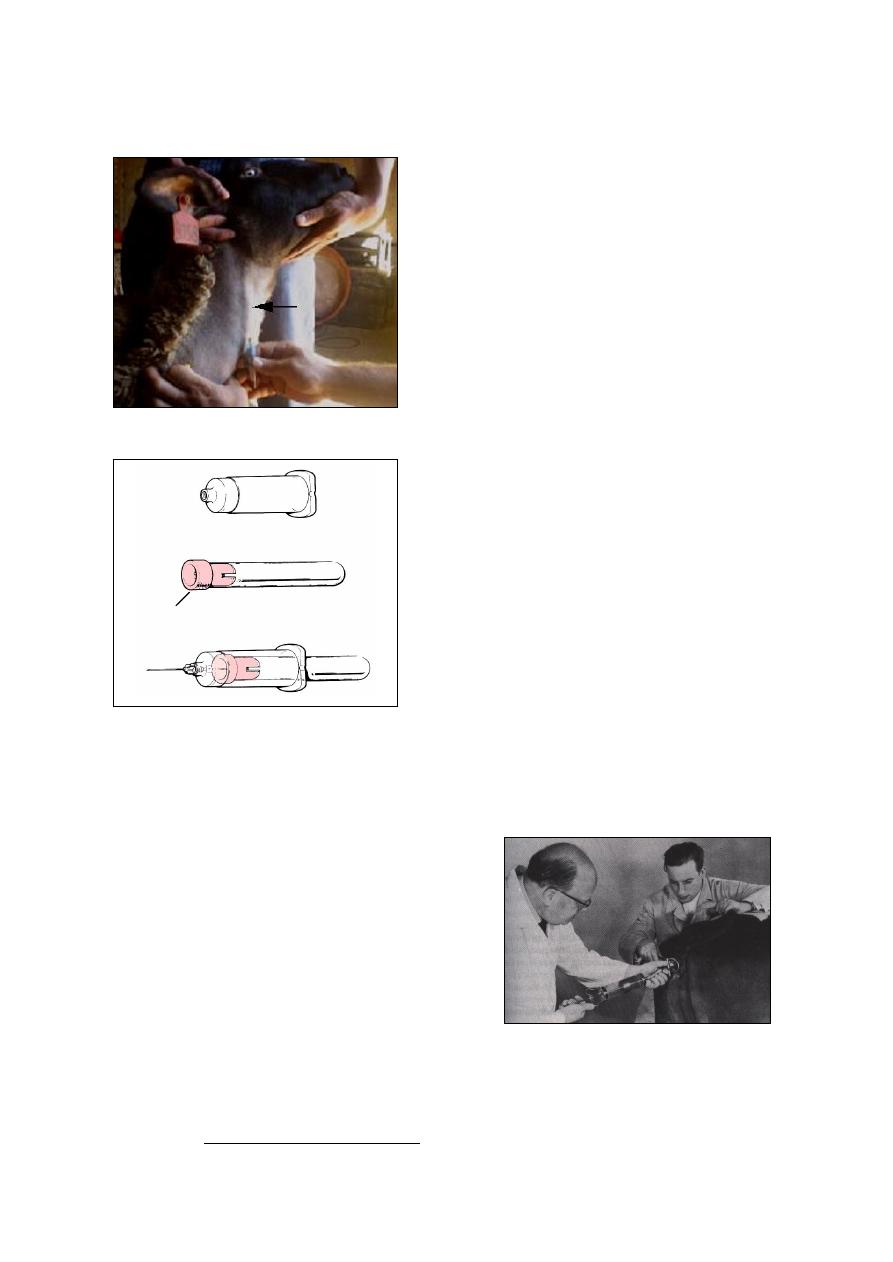

Fig. (1-2) vacutainer blood collection system

Holder

Evacuated tube

Rubber bung

Fig. (1-3) collection of urine by catheterization

3

The skin should be cleansed and prepared

aseptically.

The bladder should be held firmly.

Use a syringe and needle (1.5 by 16 gauge).

3- Feces:

At least 10 g of freshly voided feces should be

collected (Fig 1-5). Feces for parasitology should

fill the container "Screw top containers or sterile

plastic bags" and be sent to arrive at the labora-

tory within 24 hours. If transport times are likely

to be longer than 24 hours, the sample should be

sent on ice or refrigerated to prevent the hatching

of parasite eggs. Feces are best stored and

transported at 4

°C. Sterile swabs can be taken

from the rectum for bacterial examination.

4-

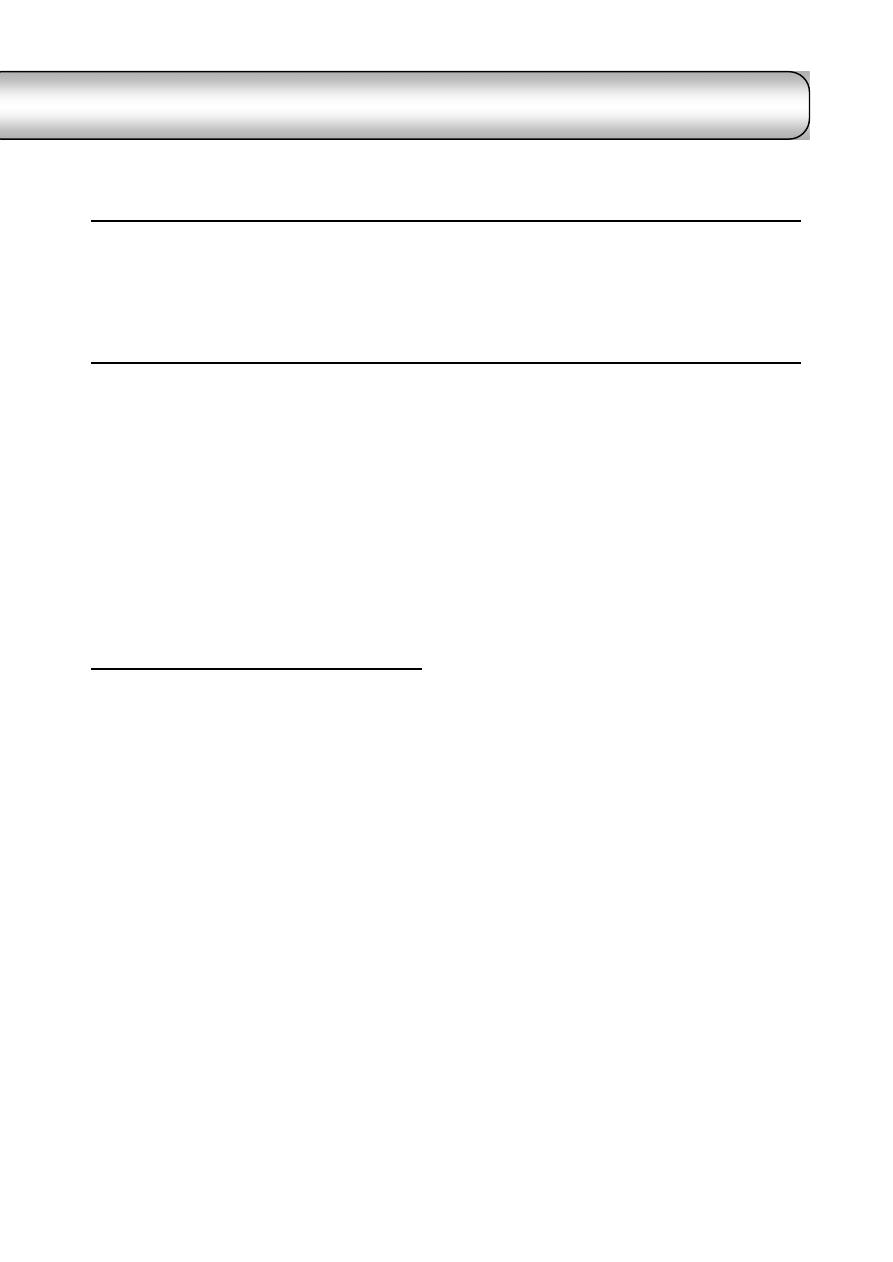

Milk:

Milk samples should be taken after cleansing

with mild soap and water, and drying the tip of

the teat. The use of antiseptics should be avoi-

ded. Initial streams of milk should be discarded

and a tube filled with the next streams (Fig 1-6).

Milk for serological tests should not have

been frozen, heated or subjected to violent

shaking. If there is going to be a delay in

submitting them to the laboratory, preservatives

can be added to milk samples that are being

collected for serological testing. Milk for

bacterial examination can be frozen.

5-

Genital tract and Semen:

Samples may be taken by vaginal or preputial

washing, or by the use of suitable swabs. The

cervix or urethra may be sampled by swabbing.

Samples of semen are best obtained using an

artificial vagina.

6- Abortion cases:

If possible, whole fetus should be submitted,

else fetal abomasal contents (in ruminants),

lung, liver and a sample of any gross lesions

in or on the fetus should be sent.

A piece of obviously affected placenta and

two or more cotyledon from aborted animals.

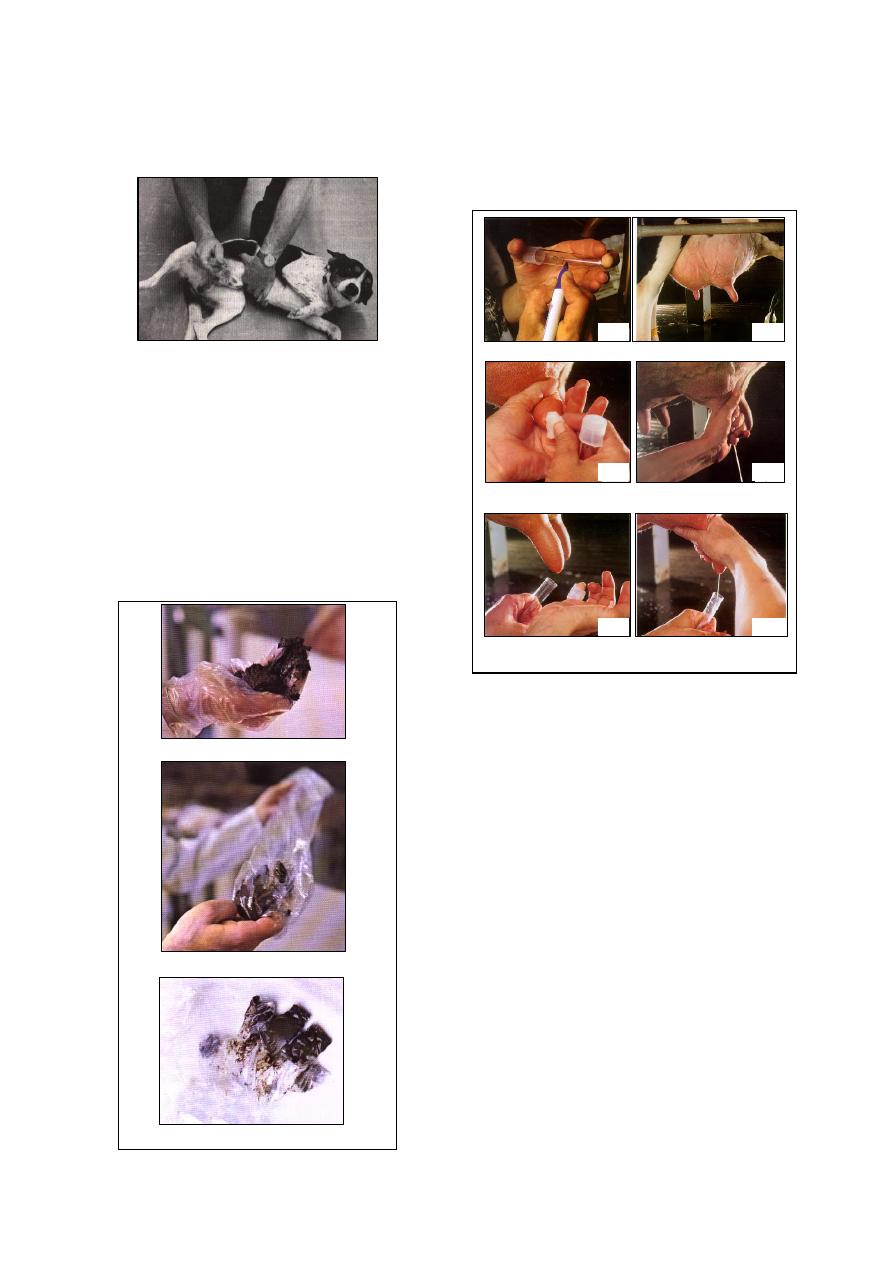

(a) the feces are taken per rectum

(b) the plastic glove is turned inside out

(c) the plastic glove is tied and labeled

Fig. (1-5) steps of feces collection

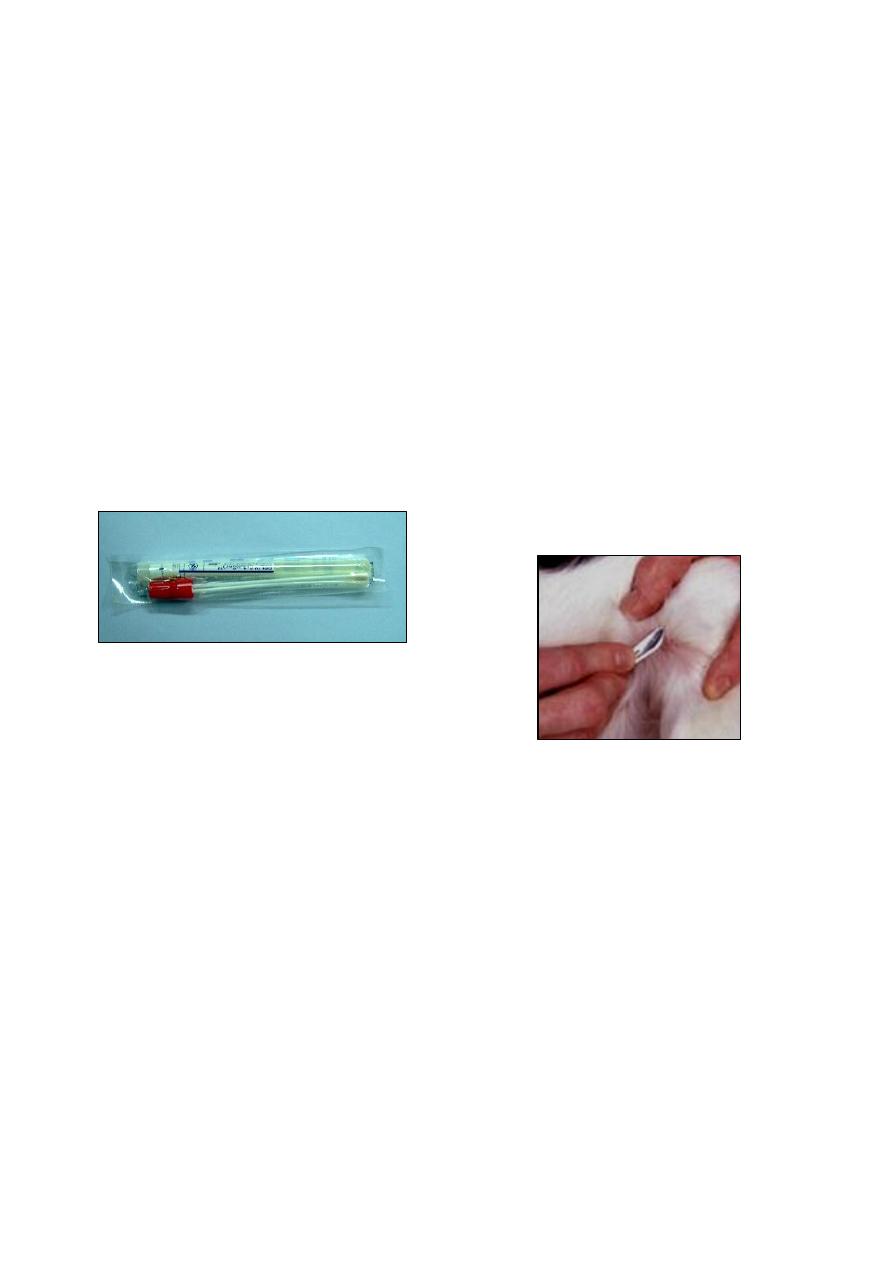

labeling of sterile tube

a

b

udder should be clean

drying the tip of the teat

c

d

remove (1-2) streams of milk

from each teat

hold the sterile tube and remove

the cap without contaminating it

e

f

hold tube at an angle to prevent

debris from entering the tube

Fig. (1-6) steps of milk collection

Fig. (1-4) collection of urine by cystocentesis

4

Uterine discharge, especially if no placenta is

available.

If there is Leptospiral abortion, 20 ml of mid-

stream urine from the dam preserved with 1.5

ml of 10% formalin should be submitted if

possible.

7-

Nasal discharge, Saliva and Tears:

Samples may be taken with cotton or gauze

swabs, preferably on wire handles as wood is

inflexible and may snap (Fig 1-7). It may be

helpful if the swab is first moistened with

transport medium. The swab should be allowed

to remain in contact with the secretions for up to

1 minute, then placed in transport medium, such

as nutrient broth, and sent to the laboratory

without delay at 4

°C.

Long protected nasopharyngeal swabs should

be used to collect samples for some suspected

viral infections. Mucopurulent nasal discharges

are rarely useful.

8-

Eye:

A sample from the conjunctiva can be taken

by holding the palpebra apart and gently

swabbing the surface.

The swab is then put into transport medium.

Scrapings may also be taken on to a

microscope slide.

Mucopurulent lacrimal discharges are rarely

useful.

9-

Skin:

Skin specimens differ according to the type of

the lesions.

(a) In diseases producing vesicular lesions:

2 g of affected epithelial tissue as aseptically

as possible should be collected, and place it in

5 ml phosphate buffered glycerine or Tris-

buffered tryptose

broth virus transport media

at pH 7.6.

The vesicular fluid should be sampled where

unruptured vesicles are present; if possible,

vesicular fluid should be aspirated with a

syringe and placed in a separate sterile tube.

(b) Plucked hair or wool samples are useful for

surface-feeding mites, lice and fungal infec-

tions. Deep skin scrapings, using the edge of

a scalpel blade, are useful for burrowing

mites. Arthropod parasites can be most

effectively stored in 70% ethyl alcohol or

glycerin for shipment or long term preser-

vation. Formalin 10% will also preserve

arthropods.

(c) When mites are suspected, skin scrapings can

be collected and forwarded to the laboratory

by placing them in glycerin in a lightly sealed

vial for shipment. Vials should be packed

carefully to prevent breakage or leakage. The

following technique is used for the diagnosis

of mites:

Add several drops of mineral oil or

glycerin to the area to be scraped. The area

should be at the periphery of the

continuous lesion, not in the center of the

lesion.

Scrape with a scalpel blade the area to a

depth that blood begins to ooze from the

wound (Fig 1-8).

Transfer the bloody material that was scraped

to a microscope slide.

Add additional mineral oil and cover with a

coverslip.

Examine under low power (40x) firstly, if

nothing seen, increase the magnification.

Note:

Large amounts of hair or skin can digested in

10% KOH for 12-24 hours, and the sediment

can be examined for mites either directly after

centrifugation or the sediment can be

examined with the sugar flotation solution.

10- Body fluids (Paracentesis):

Cerebrospinal fluids (CSF), synovial fluids,

fluids of thoracic, pleural, pericardial and

abdominal cavities are aspired aseptically

with a sterile needle of proper length and

Fig. (1-8) method of making skin scraping with a

scalpel blade.

Fig. (1-7) Culture swab, collection and transport system

5

gauge, and collected in sterile screw cap

bottle without preservatives.

Samples for cellular examination, not later

than 24 hrs., could be preserved with a tube

containing EDTA, or 10% formalin, or 10%

normal saline, at a rate of (1 drop / 2-5 ml).

11- Gastric juice and Ruminal fluid:

In monogastric animals, when gastritis or a

chemical poison is suspected, sample of vomitus

should be collected.

In ruminants, ruminal fluid is aspirated

through stomach tube and suction pump in a

glass container (Fig 1-9).

12- Abscess:

Abscess must be collected before the lesion is

opened for drainage. The surface is disinfected

with 70% alcohol, a sterile needle introduce in

the abscess and the contents are withdrawn by a

syringe. The contents are evacuated in a sterile

stopper tube that is placed in a refrigerated

package.

II. Samples collected at post-mortem

Tissues may be collected for microbiological

culture, parasitology, biochemistry, histopatho-

logy and/or immuno-histochemistry, and for

detection of proteins or genome nucleic acids.

The person conducting the post-mortem

examination should have sufficient knowledge of

anatomy and pathology to select the most

promising organs and lesions for sampling.

Samples of tissue from a variety of organs

can be taken. This procedure will requires:

Knife, saw, cleaver, scalpel, forceps and

scissors, including scissors with a rounded tip

on one blade, for opening intestines.

Plentiful supply of containers appropriate to

the nature of the sample, with labels and

report forms including the date, tissue and

animal identification.

Special media may be required for transport

of samples from the field.

The operator should wear protective clothing:

overalls, washable apron, rubber gloves and

rubber boots. If potential zoonotic diseases

are being investigated, the post-mortem

examination should be conducted in a

biological safety cabinet; if this is not

possible, an efficient face mask and eye

protection should be worn.

After collection, the samples for micro-

biological examination should be refrigerated

until shipped. If shipment cannot be made

within 48 hours, the samples should be

frozen; however, prolonged storage at -20

°C

may be detrimental to virus isolation.

For histopathology, blocks of tissue not more

than 0.5 cm thick and 1-2 cm long are cut and

placed in neutral buffered 4-10% formalin,

which should be at least ten times the volume

of the tissue sample.

Because of the rapid post-mortem invasion of

the animal body by anaerobes from the

intestinal tract, samples from animals died for

more than four hours are usually unsuitable.

The considerations of Samples for anaerobic

culture are:

Bone marrow appears to be one of the last

tissue to be invaded by contaminating

bacteria, so that it is a good sample for the

diagnosis of blackleg or malignant edema.

In suspected enterotoxemia cases, at least

20 ml of the ileal contents should be

submitted for demonstration of the

specific toxin. Or a loop of ileum with

contents tied of at each ends, or the ileal

contents may be drained into a screw-

capped bottle.

Any samples must be arrived at the

laboratory as soon as possible after

collection.

III. Environmental and feed sampling

Samples may be taken to monitor hygiene or

as part of a disease enquiry. Environmental

samples are commonly taken from litter or

bedding and voided feces or urine. Swabs may

be taken from the surface of ventilation ducts,

feed troughs and drains. Samples may also be

taken from animal feed, in troughs or bulk

containers. Water may be sampled in troughs,

drinkers, header tanks or from the natural or

artificial supply.

Fig. (1-9) method of ruminal fluid collection

6

Transportation of specimens

The specimens should be forwarded to the

laboratory by the fastest method available. If

they can reach the laboratory within 48 hours,

samples should be sent refrigerated. If dry ice is

used, the additional packaging requirements

must be met. Infectious substances, which can

include diagnostic specimens, are not permitted

to be shipped as checked luggage or as carry on

luggage and must be shipped as cargo.

Packaging

The shipper should ensure that the specimens

are packaged so they arrive at the laboratory in

good condition and there is no leakage during

shipment. There are three of the national

guidelines provide explicit directions for

packaging and shipping diagnostic specimens:

(a) The packaging should consist of three

components:

1- a leak-proof primary receptacle(s).

2- a leak-proof secondary packaging.

3- an outer packaging of adequate strength for

its capacity, mass and intended use, and

having minimum dimensions of:

(100 mm

× 100 mm).

(b) For liquids, absorbent material in sufficient

quantity to absorb the entire contents must be

placed between the primary receptacle(s) and

the secondary packaging so that, during

transport, any release or leak of a liquid

substance will not reach the outer packaging

and will not compromise the integrity of the

cushioning material.

(c) When multiple fragile primary receptacles are

placed in a single secondary packaging, they

should be either individually wrapped or

separated to prevent contact between them.

References

Coles, E. H. (1986). Veterinary clinical pathology. 4

th

ed., WB Saunders Co Philadelphia, London,

Toronto.

Cruickshank, R. Duguid, J. P., Marmion, B. P. and

Swain, R. H. A. (1975). Medical microbiology.

12th ed. Edinbarch, London and New York.

Kerr, M. G. (2002). Veterinary laboratory medicine:

clinical biochemistry & hematology. 2nd ed.,

Blackwell Science.

Mitchell, B., Neary, N. and Kelly, G. Blood Sampling

in Sheep. Purdue University, Department of

Animal Sciences:

http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia

OIE. (2006). Manual of Diagnostic Tests and

Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. :

http://www.oie.int.

Rosenberger, G. (1977). Clinical Examination of

Cattle. 2

nd

ed., Verlag Paul Parey, Berlin and

Hamburg, Germany.

Sloss, M. W., Kemp, R. L. & Zajac, A. M. (1994).

Veterinary clinical parasitology. 6th ed.,

Blackwell Co, Iowa State Press.

Thienpont, D., Rochette, F. & Vanparijs, O. F. J.

(1979). Diagnosing helminthiasis through

coprological examination. Janssen Founda-

tion, Beerse, Belgium.

7

C

C

h

h

a

a

p

p

t

t

e

e

r

r

2

2

C

C

l

l

i

i

n

n

i

i

c

c

a

a

l

l

H

H

e

e

m

m

a

a

t

t

o

o

l

l

o

o

g

g

y

y

The clinician should be able to perform a

number of hematological examinations. These

include: erythrocyte count, total and differential

leukocyte counts, platelet count, packed cell

volume, hemoglobin estimation, erythrocyte

sedimentation rate and clotting time.

Erythrocytes count

Erythrocytes are counted via hemocytometer

1

which is consist of:

Thoma blood cell diluting pipettes with

plastic mouthpiece

2

.

Double cell counting chamber with Neubauer

ruling central (Fig 2-1 a, b & c) and (Fig 2-2).

Procedure of erythrocytes count:

Blood should be carefully drawn to the 0.5

mark of the pipette.

An isotonic solution such as normal saline or

Hayem's solution

3

drawn to the mark 101 and

well mixed.

Discharged onto the hemocytometer counting

chamber and allowed to settle for several

minutes. Before the areas in the chamber are

counted, the slide should be examined under

low power to check distribution of cell in the

ruled area.

Count RBCs in five squares in the center of

the counting chamber, then multiplied by

10,000. This value represents the total

number of erythrocytes per microliter.

Note: Some difficulty may be encountered in

counting the same cell twice. One method of

avoiding duplication is to count only those cells

that touch the lower and right boundaries.

1

Further to hemocytometer method, there is photoelectric

counting method, and electronic counting methods such as

coulter analyzer.

2

Note that the red corpuscles pipette is marked 0.5 and 101

in order to give blood dilution of 1 in 200, and has red

bead. The white cell pipette is marked 0.5 and 11 for

blood dilutions of 1 in 20, and has white bead.

3

Hayem's solution consist from: sodium chloride 1.0 g,

sodium sulphate 5.0 g, mercuric 0.5 g, and distilled water

200 ml.

Leukocytes count

1.

Total Leukocytes count (TLC):

Hemocytometer

4

is used for enumeration of

total leukocytes.

Carefully blood drawn to the 0.5 mark of the

pipette.

The diluting fluid (Turck's solution)

5

is then

drawn to the mark 11 and well mixed.

Discharged onto the hemocytometer counting

chamber as done in erythrocytes count.

The total number of WBCs in four squares of

larger ruled area in the corner of the counting

chamber is determined and multiplied by 50.

This value represents the total number of

leukocytes per microliter.

4

Further to hemocytometer method, there is

electronic

method, DNA viscosity technique, examination of

wet blood film stained with new methylene blue,

and from stained blood film.

5

Turck's solution consist from: glacial acetic acid 2 ml, in

100 ml of distilled water, to which has been added 1 ml of

1% aqueous solution of gentian violet. This diluting fluid

should carefully filtered prior to use to remove particles

that might be confused with leukocytes.

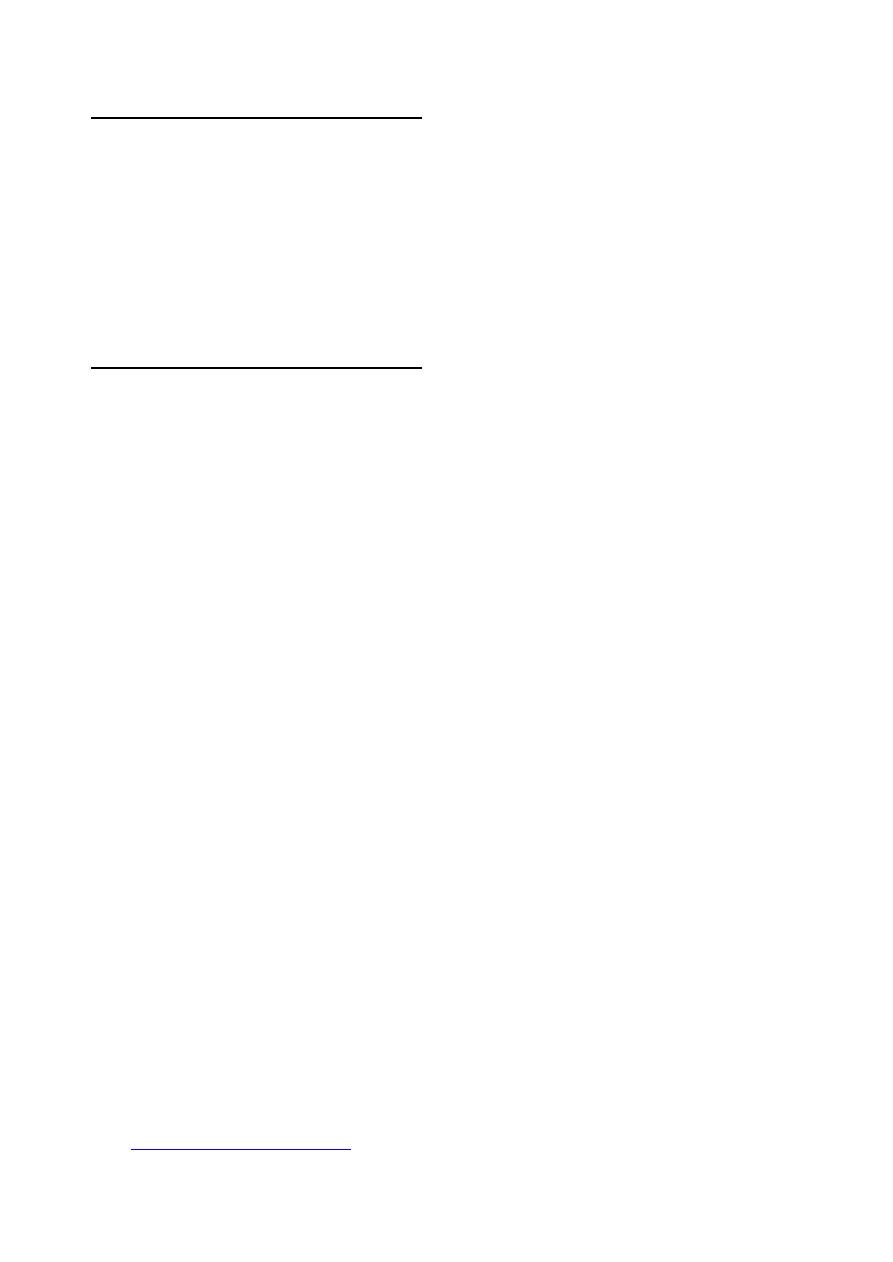

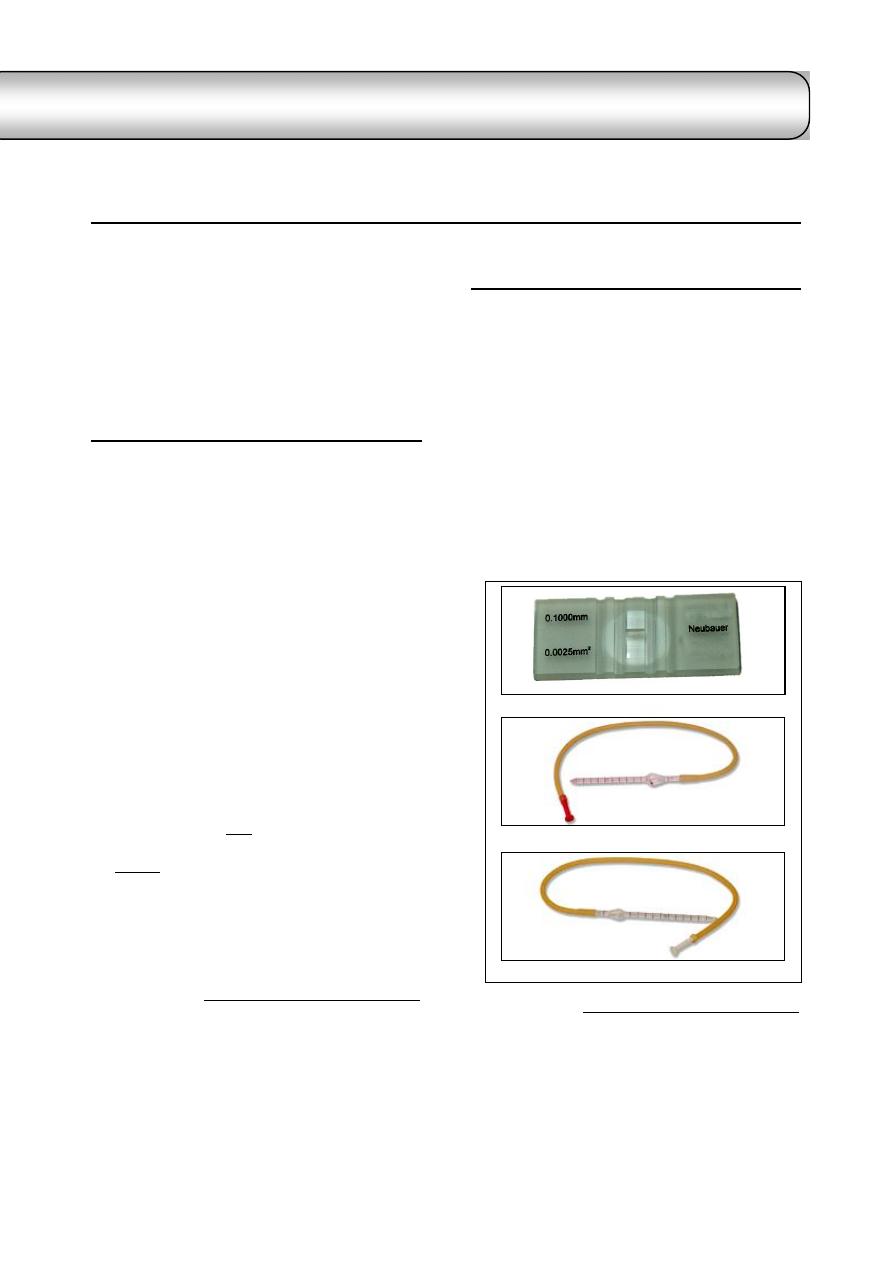

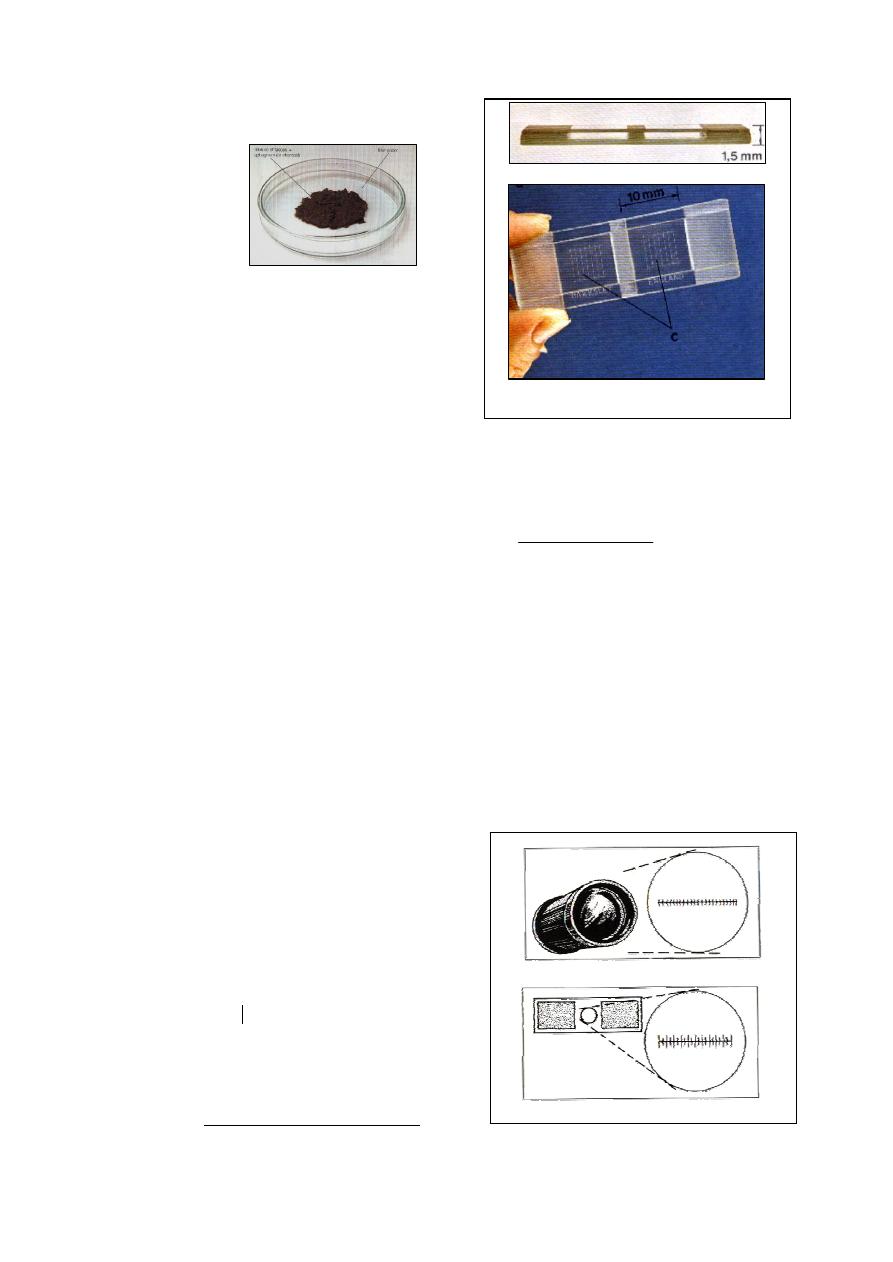

Fig. (2-1) Parts of Hemocytometer

(a) Neubauer hemocytometer slide

(b) Pipette used for erythrocyte count -has red bead-

(c) Pipette used for leukocytes count -has white bead-

id23273265 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com

8

2.

Differential Leukocytes count (DLC):

Differential leukocytes are counted by blood

film

1

. The blood film should be made from fresh

blood containing no anticoagulants (as soon as

possible after collection of the blood); otherwise,

best results are obtained if EDTA is used as the

anticoagulants

2

.

Films of blood may be prepared either on a

microscope slide or coverslip. The microscope

slide is preferable to the coverslip for routine

laboratory work, because the slides are easy to

clean and store, identify and file, while the

coverslip method is better than the microscope

slide because there are usually more suitable

fields for examination, and leukocytes are well

distributed (there are more leukocytes per field

than with slide method), and there is generally

better cell definition.

Microscope slide method:

Select good quality, clean, grease-fresh slides

.

Place a slide on a flat surface, or held by

edges between the forefinger and thumb.

1

There are other parameters can be estimated by blood film

such as erythrocytes abnormalities, platelet count, blood

protozoa. These are will discussed in the followings.

2

Bovine lymphocytes may be adversely affected within a

few hours by EDTA causing the appearance of abnormal

lymphocytes in blood films.

Place small drop of well-mixed blood near

one end of the slide by using of applicator

stick or capillary tube.

Immediately after placing blood on the slide,

place second slide "spreader" in front of the

drop of blood at an angle of approximately

30

and pull it back until it comes to contact

with the drop of blood, and the pause until the

blood spreads along the edge of the spreader

(Fig 2-3).

After the blood spreads along the edge of the

spreader, push the spreader forward smoothly

and quickly at an angle about 30

. The greater

the angle the thicker and shorter blood smear,

and the smaller the angle the thinner and

longer smear.

Dry blood film quickly by waving it in the air

.

Identify the blood film by writing in the date

and client's name, or a reference number,

along the end of smear with a pencil or the

edge of the spreader slide.

Whenever possible fix and stain blood films

immediately

3

they are prepared, otherwise fix

them in absolute methanol and then store

them in a clean box until they can be stained.

Coverslip method:

Square coverslip 22 by 22 mm of No. 1

thinness are used.

Hold a clean, dry coverslip by its edges in

one hand.

Place a small drop of blood on the center of

the coverslip.

Place a second clean, dry coverslip diagonally

on the first, forming an eight-pointed star; the

blood will immediately spread.

Grasp the top coverslip by its corners and

using a smooth motion slide the two apart

(Fig 2-4), then wave the coverslip in the air to

enhance drying.

The coverslips should be identified by

placing it in a small box with the name of the

owner or number of the case on it.

3

See the appendix for the stains and their preparation.

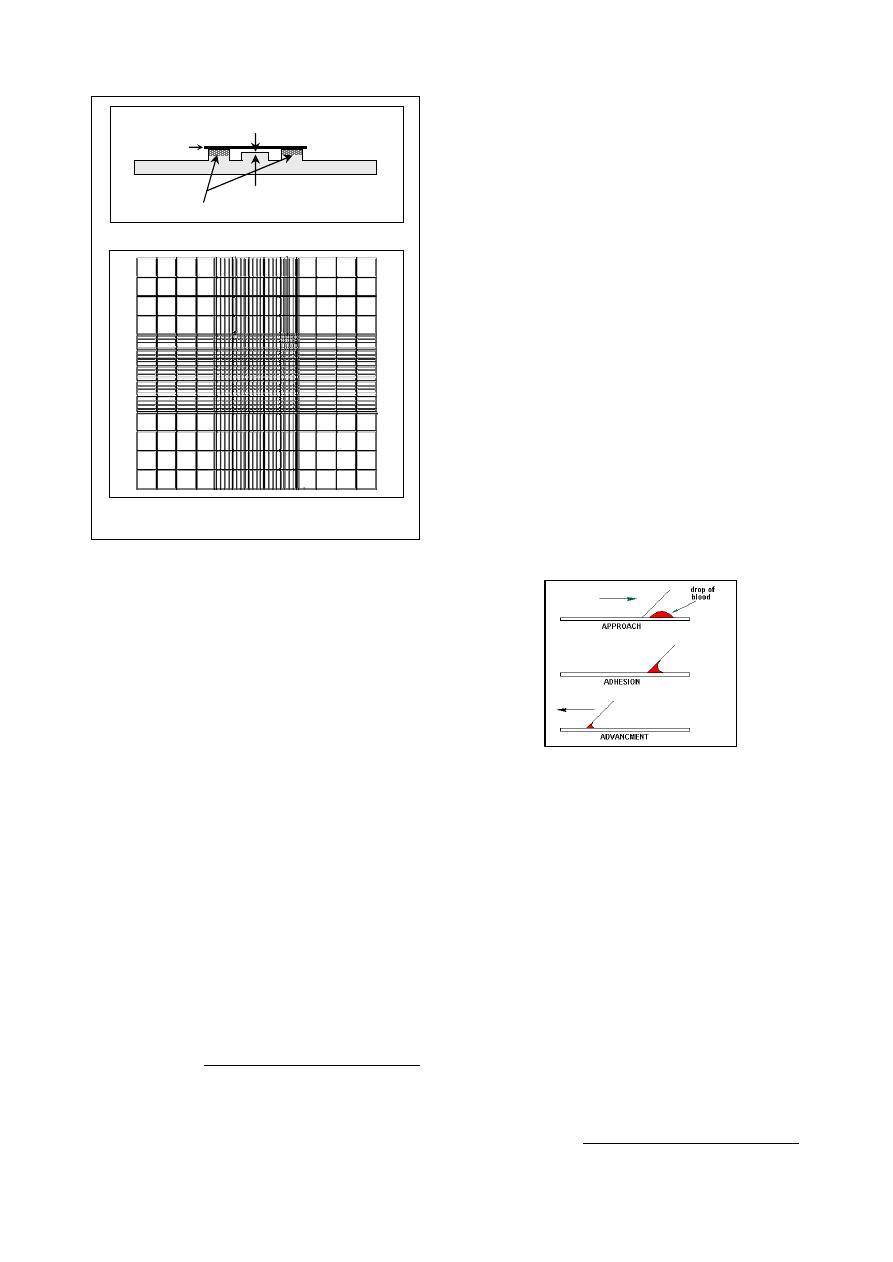

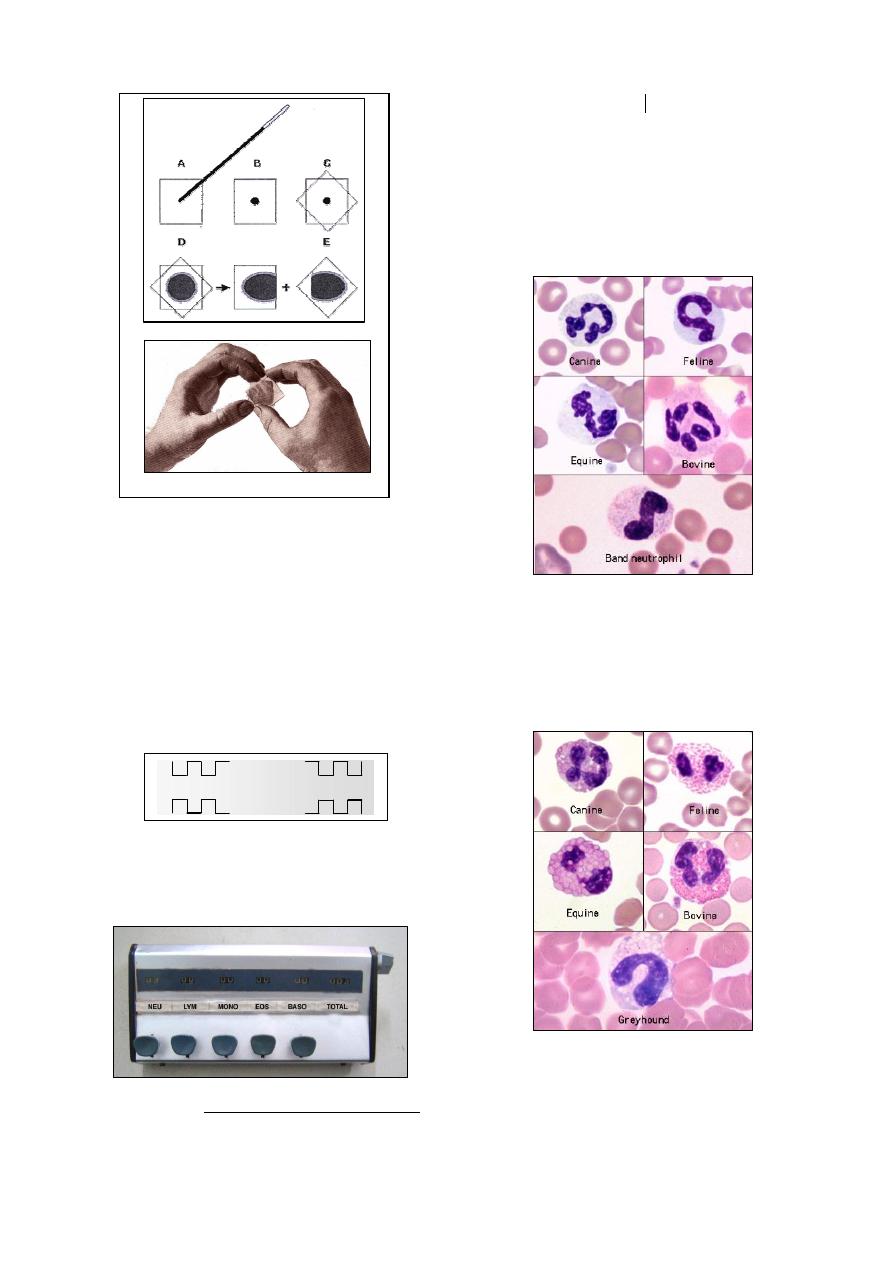

Fig. (2-3) Procedure of microscope slide method

of preparation of blood film

W

W

W

W

R

R

R

R

R

cover slip

depth of chamber = 0.1 mm

ruled platform

raised platform

(a) Cross section of hemocytometer slide and cover slip

(b) Improved Neubauer ruling. R= squares used for

RBC count, W= squares used for WBC count

Fig. (2-2) Double hemocytometer slide and Neudauer

ruling central

9

Method of differential Leukocytes count:

The examination is made with oil-immersion

objective.

A standard procedure, such as battlement

(meander) method, should be employed in

examining blood smear for cytological

differentiation.

Count and differentiate 50 leukocytes at each

of the corner of the film

1

(Fig 2-5).

The individual cells can be tabulated in

columns on a prepared sheet of paper, or a

blood cell counter (fig 2-6).

1

The minimum number of leukocytes counted in arriving at

the differential count is 100, but if abnormal cells are

present, 200 or more cells should be enumerated.

The characteristics of l

eukocytes as follows:

1.

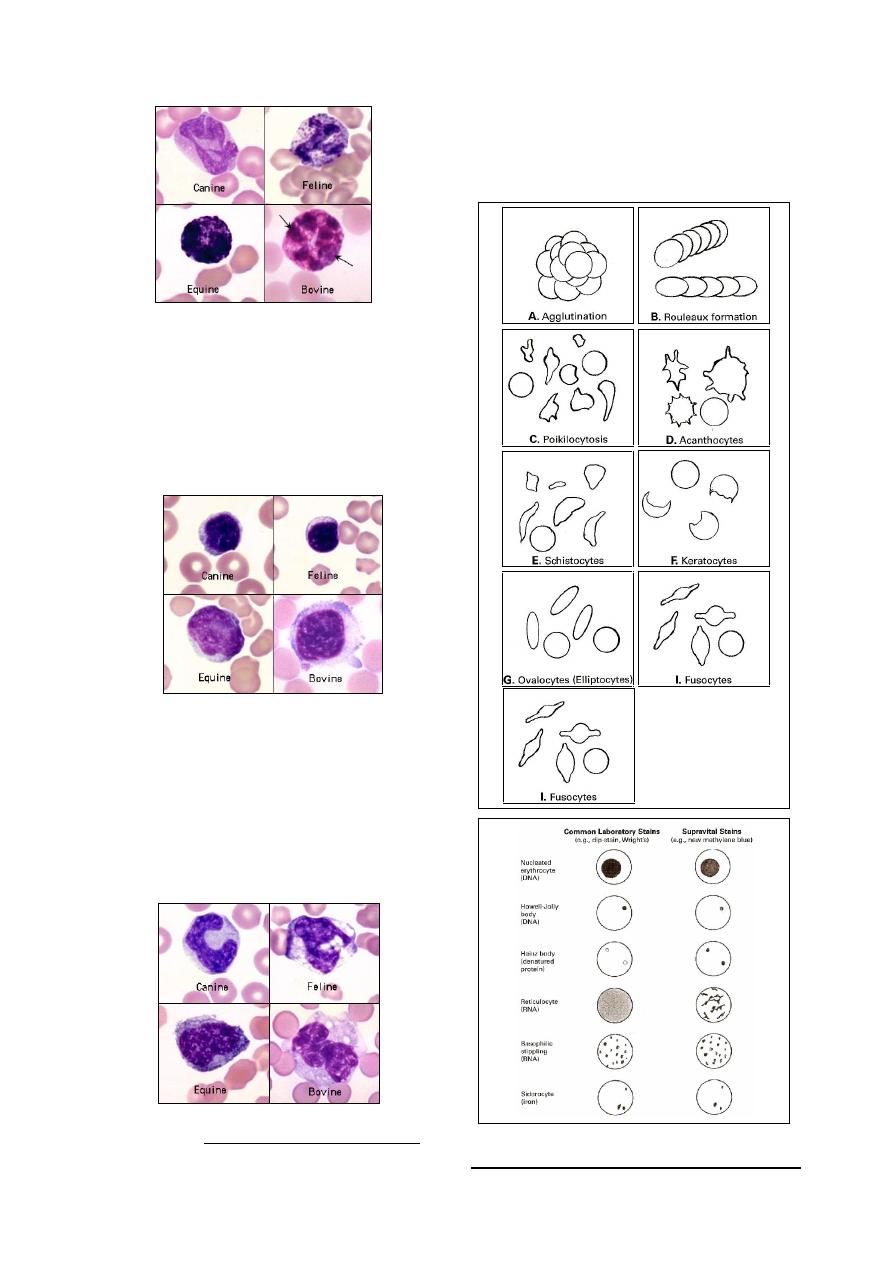

Neutrophils:

Mature cell has either mono-lobular nucleus,

or its nucleus may have up to five lobes

which are joints by thin strands. In correctly

stained blood films, they have faintly

acidophilic cytoplasm with a deeply staining

nucleus (Fig 2-7).

2.

Esinophisls:

The cell has numerous small, regularly

cellular, oranged-red granules. Nuclei of

mature cell are shorter and less segmented

than neutrophil nuclei and the cytoplasm, if

visible, is pale blue

(Fig 2-8)

.

3.

Basophisls:

Purple staining granules scattered throughout

the cytoplasm. They occur rarely in the blood

of the dog and cat (Fig 2-9).

Fig. (2-4) Procedure of coverslip method of

preparation of blood film

Fig. (2-5) Meander method of blood film examination

Fig. (2-6) blood cell counter

Fig. (2-7) Neutrophils of different animals

Fig. (2-8) Esinophils of different animals

(a) Steps of the method

(b) Technique of the method

10

4.

Lymphocytes:

They are occur in two varieties: large size,

and small size

1

(less than 10

µm in diameter).

The cell almost

circular

or slightly intended

nucleus, and a narrow peripheral zone of

blue-stained cytoplasm which may contain a

group of comparatively large, dark blue or

red (azurophilic) granules (Fig 2-10).

5.

Monocytes:

They are the largest cells in the leukocyte

series,

their

nuclei

are

more

varied

morphologically, being oval, elliptical or

horse-shoe shaped and even segmented or

presenting a folded appearance. The cyto-

plasm is faintly granular, stains distinctly

basophilic and may have a vacuolated or

foamy appearance (as in cattle) (Fig 2-11).

1

The commonest type of lymphocytes are small size.

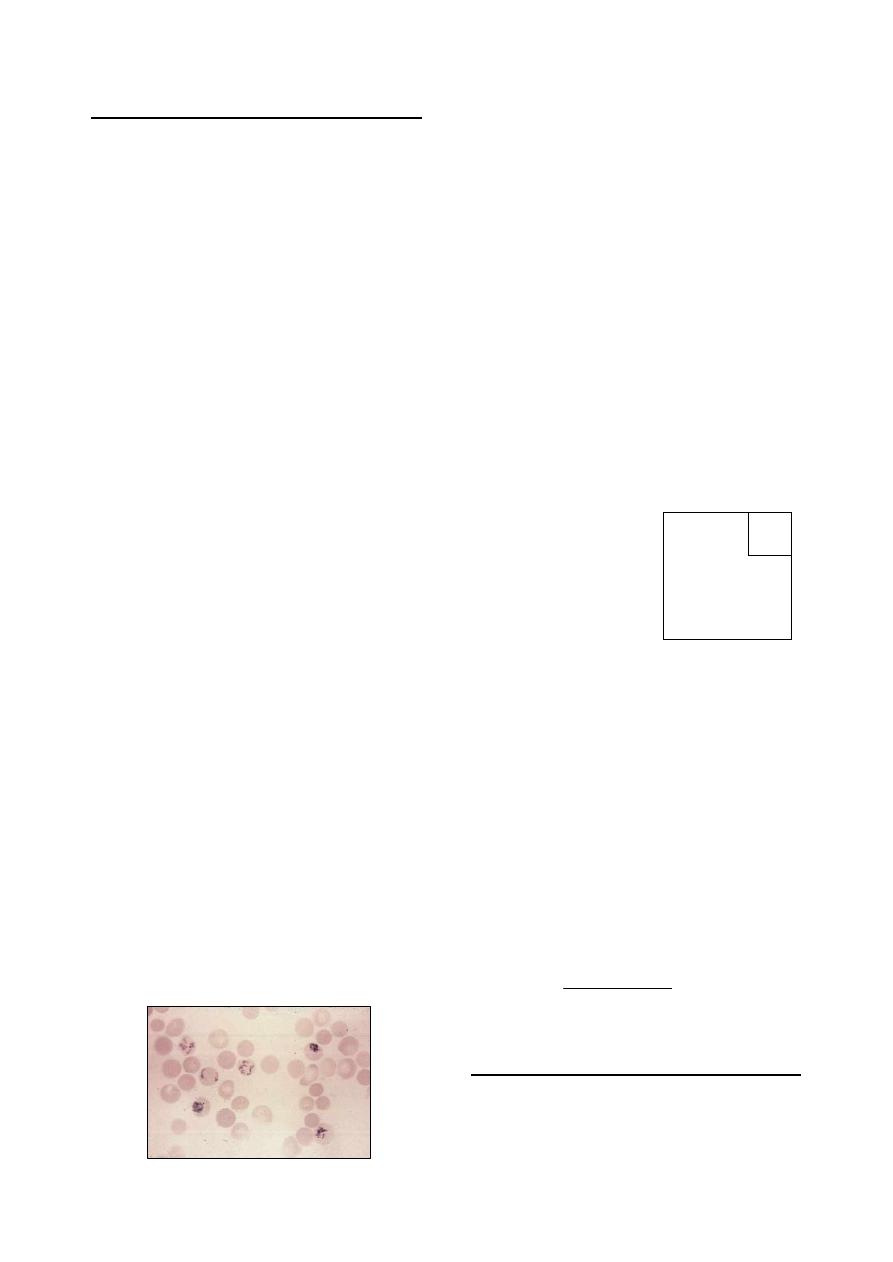

Note:

During examination of blood films for diffe-

rential leukocytes count, abnormallities in the

appearance of erythrocytes can be indicated (Fig

2-12, 2-13).

Fig. (2-9) Basophils of different animals

Fig. (2-10) Lymphocytes of different animals

Fig. (2-11) Monocytes of different animals

Fig. (2-12) Examples

of variations of the

appearance of eryth-

rocytes.

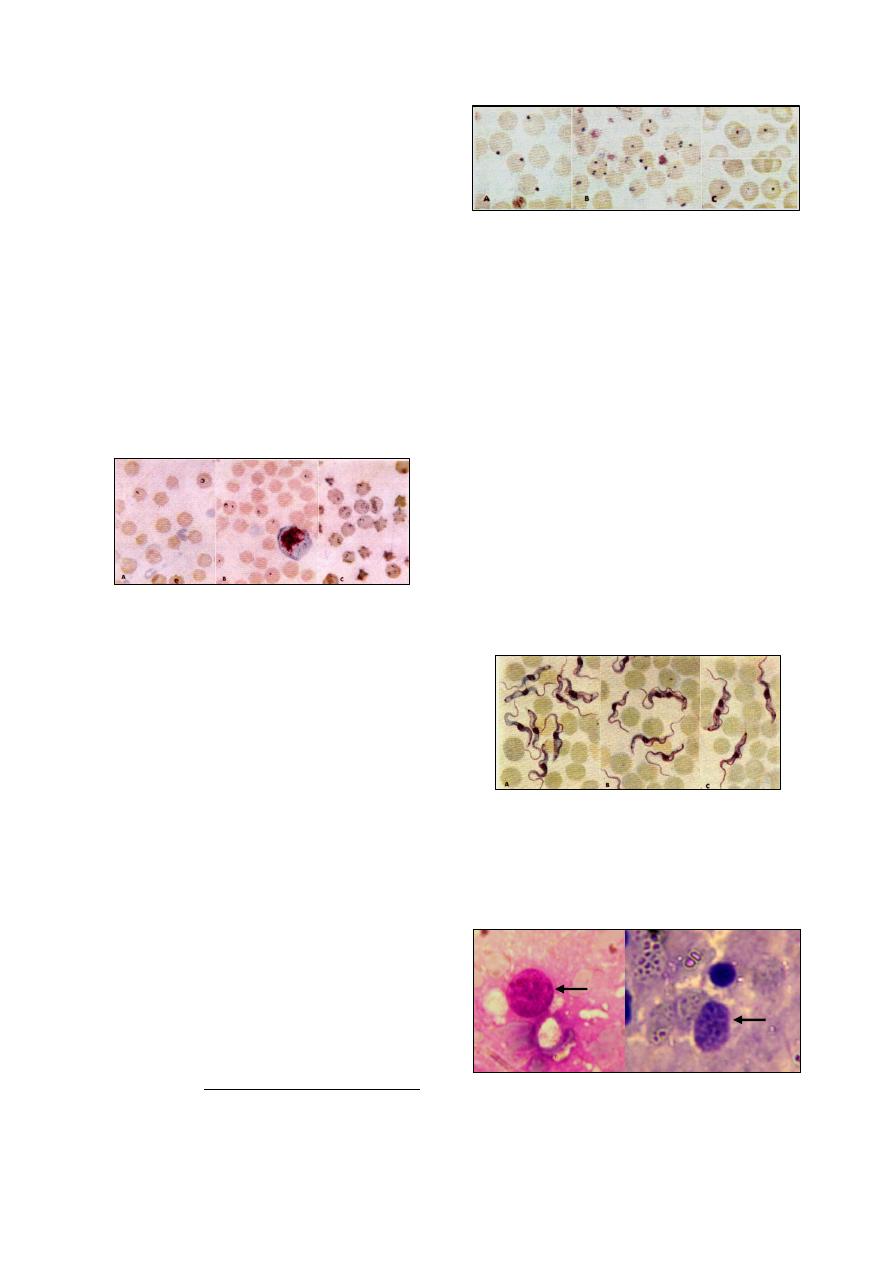

Fig. (2-13) Appearance of cellular invclusions inside

the erythrocytes, stained with different stains.

11

Reticulocytes count

Reticulocytes are juvenile red cells. They

contain remnants of ribosomes and ribonucleic

acids which were present in larger amounts in

their nucleated precursors.

Because the number of reticulocytes in the

peripheral blood is a fairly accurate reflection of

erythropoietic activity, a reticulocyte count is

one of the essential procedures in diagnostic

haematology.

The most immature reticulocytes are those

with the largest amount of precipitable ribosomal

material, whilst in the least immature only a few

dots or strands are seen.

Method for the Reticulocyte Count:

Staining solution

Reticulocytes are best demonstrated by use of

supra-vital stains. The most commonly used are

new methylene blue and brilliant cresyl blue.

1.0 gm of New methylene blue or Azure B is

dissolved in 100 ml of citrate-saline solution

(1 part 3% tri-sodium citrate to 4 parts 0.85%

saline).

1.0 gm of brilliant cresyl blue is dissolved in

100 ml of physiological saline.

After dissolving the dyes, the solution is

filtered and is then ready for use. Store at 40 C.

Staining method

Add two or three drops of stain into a tube.

Add approximately equal volume of patient's

blood. If anaemic use a larger proportion of

blood; and use a smaller proportion of blood

if polycythaemic.

Mix and leave in water bath or incubator at

37

˚C for 15-20 minutes. At the end of this

time, resuspend the red cells by gentle mixing

and make a thin film in the usual way.

When dry, the films are examined without

counter-staining.

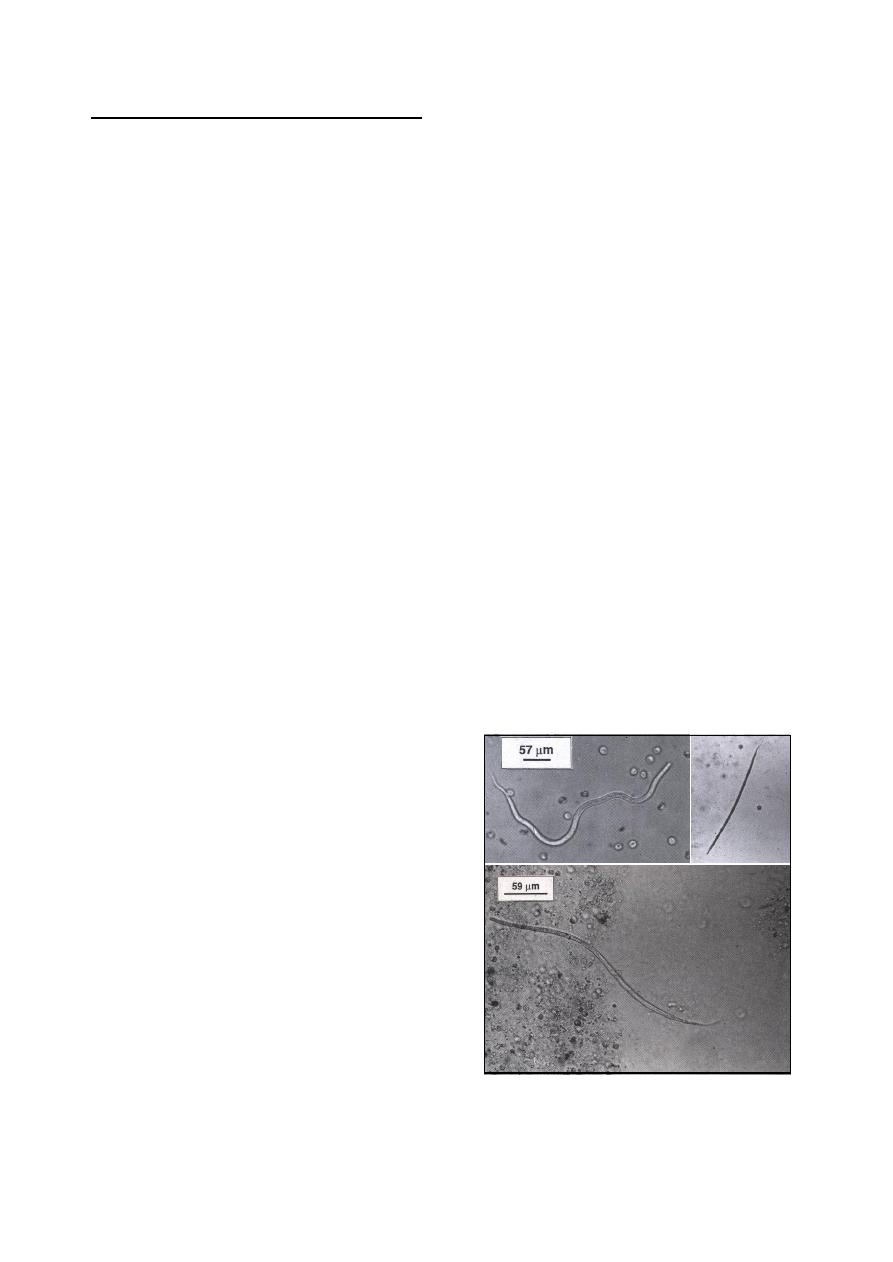

Reticulocytes stained in this manner have a

bluish stippling in the center of the cell. The

quantity of bluish staining material in any

reticulocytes may vary depending upon the

stage of maturation (Fig 2-14).

Counting

Choose an area of the field where the cells are

undistorted and the staining is good.

Using the x100 oil-immersion lens, count the

number of reticulocytes seen per 1000 red

cells.

Counting the red cells can be helped by

inserting into the eyepiece a paper or

cardboard diaphragm in the centre of which

has been cut a small square to reduce the

optical field.

An easier labour-saving method is to use a

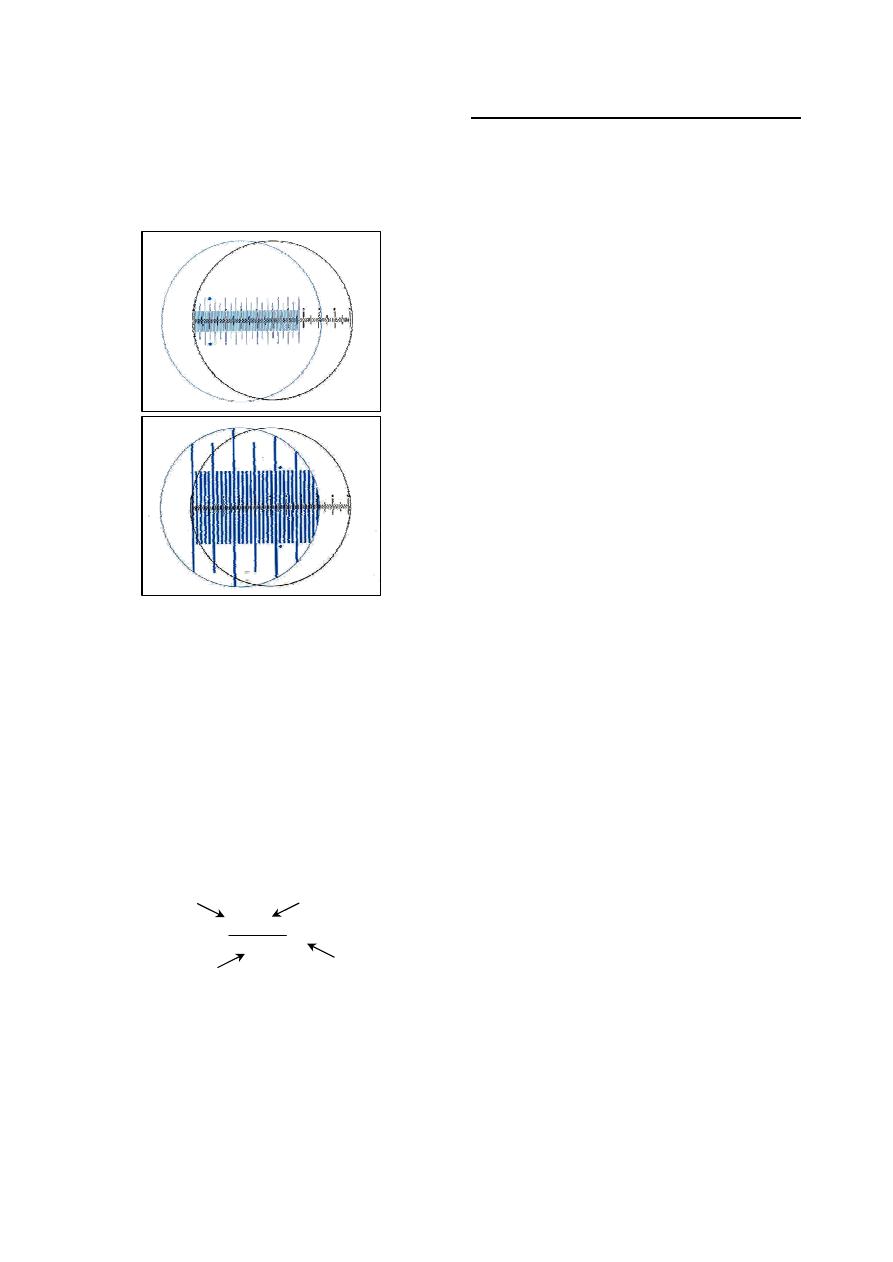

Miller squares, which inserted in the eyepiece

of the microscope. Miller square consists of a

large square inside which in one corner is a

smaller square of one-ninth the area of the

large square (Fig 2-15). Provided that the red

cells are evenly distributed, the red cells need

to be counted only in the small square as

there will be approximately nine times that

number in the complete large square.

Calculation

No. of reticulocytes in (n) fields = x

when: (n)= number of counted fields

Average number of cells in small squares = y

Total number of cells in (n) fields = 9

×y×n

Reticulocyte percentage = x / (9

×y×n)

Absolute reticulocyte count =

% Reticulocytes x RBC (x10

12

/L)

Usually more convenient to report as x10

9

/L.

As an example:

reticulocytes per 1000 red cells = 18.

the percentage of reticulocytes =

18/1000

× 100% = 1.8%

RBC = 4.5 x 10

12

/L

Absolute reticulocyte count:

Thrombocytes count

The total number of thrombocytes "platelets"

in the blood can be determined directly by

hemocytometer method, or indirectly by exami-

nation of stained blood film (Fig 2-16).

9

12

10

81

100

10

5

.

4

8

.

1

Fig. (2-14) reticulocytes stained with new methylene blue

Fig. (2-15) Miller squares.

Reticulocytes only are counted

within the boundary of the

larger square, but all RBCs are

counted within the boundary

of the smaller square.

12

1.

Hemocytometer method:

Direct counting of platelets is performed in

the same manner as for erythrocytes counting.

Blood should be carefully drawn to the 0.5 mark

of the pipette, and diluting fluid (Rees-Ecker)

1

drawn to the mark 101, well mixed and then

discharged onto the hemocytometer counting

chamber which should be placed ia a petri dish

containing a piece of moistened filter paper ad

allowed to stand for up to 20 min. Platelets

2

are

counted in the entire ruled area on each side of

the counting chamber. Multiply the number of

platelats in the ruled area by 1000 to give total

thrombocytes/

µl.

2.

Indirect method:

This method performed from a stained blood

film as that prepared for routine hematological

examination.

A count is made of platelets accompanying

RBC in the same way as for DLC.

If the TLC is known, the number of platelets

may compared with the number of WBC:

If the total RBC is known, the number of

platelets may compared with RBC number:

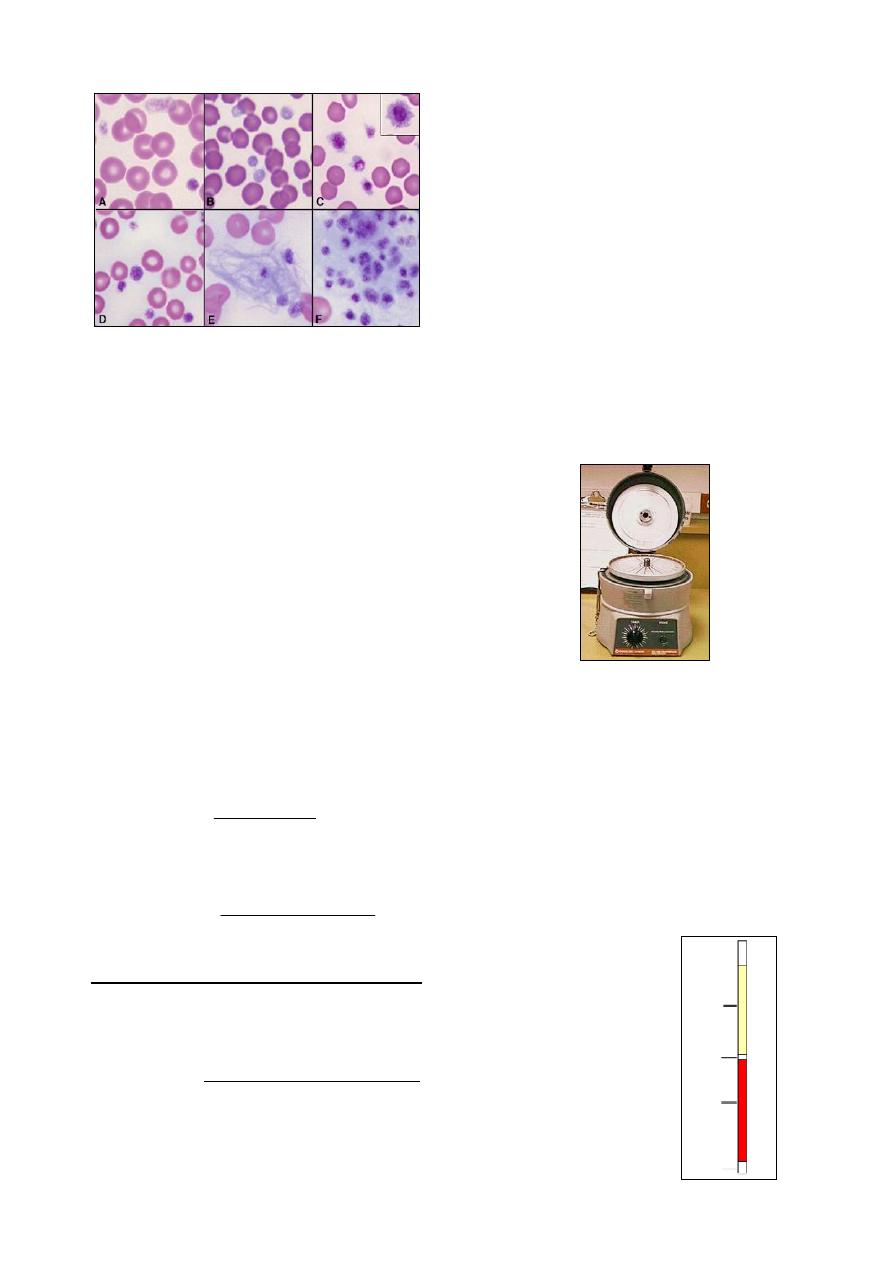

Packed Cell Volume "Hematocrit"

The packed cell volume (PCV), or hematocrit

(HCT) represents the proportion of blood

composed of red blood cells, expressed as %

(vol/vol).

1

Rees-Ecker fluid consist from: sodium citrate 3.8 g, 40%

formaldehyde 0.2 ml, brilliant cresyl blue 0.05 g, distilled

water 100 ml.

2

Platelets will appear as rod- or oval-shaped bodies,

approximately one-half the diameter of erythrocytes.

It is the quickest and most accurate measure

of the red cell component of blood. Micro-

hematocrit is the suitable method for routine use.

The procedure as follows:

Thoroughly mix the blood samples and fill

capillary

tubes

to approximately 3 quarters of

their length with the samples.

Wipe excess blood from the outside of each

tube, then seal the unfilled end of the tube

using heat or by pushing gently into the

plastic material such as Cristaseal or wax.

Make sure that the top of the clay can be

easily seen, and check that the seal has a flat

surface. Discard any tube where the upper

surface of the clay is noticeably uneven.

Place the capillary tubes in the grooves of the

base plate of the microhematocrit centrifuge

with the sealed end pointing outwards. Note

the position and identity of each tube (Fig 2-

17).

Firmly secure the inner lid of the centrifuge,

then close the outer lid. Centrifuge for five

minutes at 12000 g (but see below).

As soon as the centrifuge has stopped,

remove the tubes and stand them upright until

they are read. It is important that the cells are

not allowed to settle and that reading takes

place with the minimum of delay. If delay by

more than a few minutes is unavoidable, seal

the top of the tubes as well to avoid

evaporation of the plasma. The capillary tube

after centrifugation will be as (Fig 2-18).

count

WBC

Total

WBC

platelets

of

number

platelets

of

number

100

1000

/ l

RBC

platelets

of

number

platelets

of

number

Fig. (2-17) Microhematocrit centrifuge

Fig. (2-18) Capillary tube after

centrifugation:

(1)

Wax plug.

(2)

Packed red cells (mass

of erythrocytes).

(3)

Buffy coat (leukocytes

and thrombocytes).

(4)

Plasma.

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

- canine

- equine

- feline

- bovine

- fibrin clump

- platelet clump

Fig. (2-16) Thrombocytes of different animals

13

Read the PCV by a special reader (Fig 2-19)

as follows:

Place the bottom of RBC column (which

is just above the sealed end) on the box

line of the reader.

Move the reader until the top of the

plasma layer exactly meets upper line.

Observe a line on the reader which passes

across the top of the RBC layer.

Read the PCV from the scale at the point

where this line meets it.

Hemoglobin determination

Methods for hemoglobin determination

are many and varied

such as oxyhemoglobin

method, cyanmethaemoglobin method and direct

matching methods.

The manual methods for

determining blood hemoglobin is the acid

hematin method that use Sahli hemoglobino-

meter (Fig 2-20).

The blood is mixed with dilute hydro-chloric

acid which hemolyzes the red cells, disrupting

the integrity of the red cells' membrane and

causing the release of hemoglobin, which is

converted to a brownish-colored solution of acid

hematin. The acid hematin solution is then

compared with a color standard.

Add N/10 hydrochloric acid to the 20 mark

on the graduated tube.

Fill the pipette with the blood to the mark 20

µl, and expelling it into the acid solution,

followed by rinsing out the pipette to ensure

thorough mixing.

The tube and contents should be removed

from bright light and left until acid hematin

has developed.

Dilute the contents with distilled water until

the color matches that of the glass standard.

Erythrocytes Indices

These values are of particular importance in

determining the morphological type of anemia,

and normal erythrocyte mass or existence of

hemoconcentration.

1- Mean Corpuscular volume (MCV):

2- Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH):

3-

Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration

(MCHC):

Blood Counts by Electronic Analyzer

Many electronic counters are available.

Earlier models required the users to calibrate the

counters individually and to identify the

appropriate settings for distinguishing red cells

from leucocytes and platelets. Most modern

analyzers include measurement of RBC , WBC,

platelets, haemoglobin, packed cell volume and

absolute values (MCV, MCH and MCHC).

Coulter A

C.

T diff Analyzer

1

:

It used to analyze blood contents for

hematology during 16 seconds. It is consist from

four parts (Fig 2-21):

Probe, draw about 12

µl of blood.

Internal analyzing system with calculator and

special diluting fluid.

Digital screen.

Printer.

1

This analyzer produced by Beckman Co., USA, model

2004.

)

(

.

)

(

)

/

(

10

)

(

2

s

femtoliter

fl

mm

millions

count

RBC

Total

numbers

whole

PCV

MCV

)

(

.

)

(

)

/

(

10

)

/

(

2

picogram

pg

mm

millions

count

RBC

Total

dl

gm

Hb

MCH

dl

gm

numbers

whole

PCV

dl

gm

Hb

MCHC

/

)

(

)

(

100

)

/

(

Fig. (2-19) Microhematocrit reader

Fig. (2-20) Sahli hemoglobinometer

14

General principles:

It is act by detecting and measuring changes

in electrical resistance as follows:

when a particle, such as a cell, in a

conductive liquid passes through a small

aperture, impedes the current and causes a

measurable pulse.

The number of pulses signals the number of

particles.

The height of each pulse is proportional to the

volume of that particle.

The analyzer has a spectrophotometer to

measure Hb at wave length 525 nm.

The computer:

o

Computes Hct "PCV", MCH, MCHC,

LY#, MO#, and GR#.

o

Derives MCV and RDW from the RBC

histogram.

o

Drives MPV and Plt count from the

platelet histogram.

o

Drives LY%, MO%, and GR% from the

WBC histogram.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR)

When blood containing anticoagulant is

allowed to stand in a perpendicular tube, the

erythrocytes sink because they are heavier than

the plasma in which they are suspended. The

speed with which erythrocytes fall in the blood

of normal animals is relatively slow, but in

animals with inflammatory diseases in which

there is tissue necrosis and degeneration, speed is

increased. This alteration in suspension stability

probably results from changes that occur in the

physiochemical properties of the erythrocyte

surfaces and the plasma.

Mix the blood well and draw the sample into

clean dry Westergren tube that has a length of

about 30 cm and a bore of 2.5 mm

Place the tube into the stand, taking care that

the base is firmly positioned on the base pad

to prevent leakage.

Adjust the rack so that the tube rests in an

exactly vertical position.

Leave undisturbed for 20 minutes in horses, 1

hours in dog and cats, 24 hours in ruminants.

It is conventional to set up sedimentation

rates at room temperature (18 - 25

o

C).

At the end of the time, read the height of clear

plasma above the upper margin of the column

of sedimenting cells to the nearest millimeter

(Fig 2-22).

H

H

e

e

m

m

o

o

s

s

t

t

a

a

s

s

i

i

s

s

a

a

n

n

d

d

C

C

o

o

a

a

g

g

u

u

l

l

a

a

t

t

i

i

o

o

n

n

o

o

f

f

B

B

l

l

o

o

o

o

d

d

:

:

Whole blood coagulating time

The whole blood coagulating time (Clotting

time) can be determined by several techniques. A

simple method is the capillary tube method:

The skin is punctured, the first drop of blood

is wiped away, and the capillary tube

1

is filled

with blood noting the time when blood first

appears in the capillary tube.

1

approximately 15 cm long and 1-1.5 mm diameter is used.

Holding the tube between the thumb and

index finger of both hands.

Gently break off small pieces every 30

seconds until a strand of fibrin is seen

extending across the gap between the two

broken ends of the tube.

The interval between the appearance of blood

and the appearance of a fibrin strand is the

clotting time.

Fig. (2-21) Coulter A

C.

1 diff analyzer

Fig. (2-22) Westergren tube placed in ESR stand

15

Bleeding time

Determination of bleeding time is a simple

and sometimes useful tool for evaluation the

efficiency of the capillary-platelet aspect of

hemostasis. The technique as follows:

With the animal suitably restrained, or even

anesthetized, carefully clip an area of skin

where there are comparatively few hairs.

Wash the area thoroughly with soap and

water, and dry it.

Using a sterile disposable lancet, swiftly

make 2 small puncture wounds in the skin a

short distance apart avoiding any major blood

vessels.

Start the stop-watch. At 30 seconds intervals,

gently touch the drop of blood on each wound

with a piece of filter paper. Take care not to

touch the edge of the wound because this may

dislodge the platelet plug.

When no spot of blood appears on the filter

paper, read the time. Accept the longer of 2

times as the bleeding time.

Laboratory tests for coagulation defect

(specific techniques):

1.

coagulation time.

2.

bleeding time.

3.

platelet counting and evaluation.

4.

fibrinogen

1

.

5.

one-stage prothrombin test.

Tests for measuring intrinsic system factors:

1.

partial thromboplastin time.

2.

prothrombin consumption.

3.

thromboplastin generation test (TGT).

These tests can be determined by using

specific kits that should be added to the samples

according to the manufacturer's directions.

References

Bush, B. M. (1975). Veterinary laboratory manual.

1st ed., The Gresham Press, London.

Coles, E. H. (1986). Veterinary clinical pathology. 4

th

ed., WB Saunders Co Philadelphia, London.

Jain, N. (1986). Schalm's Veterinary Hematology. 4

rd

ed., Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, U.S.A.

Kelly, W. R. (1984). Veterinary Clinical Diagnosis.

3rd ed. Bailliere Tindall. London.

1

Fibrinogen is a plasma protein produced by the liver. It

functions in the clotting mechanism and plays a

significant role in the body's defense by moving into

extravascular spaces to assist in localization of disease

processes. Estimation of fibrinogen level have been found

useful in evaluation of the inflammatory response. In

some species, such as ruminants, fibrinogen determination

is preferred to an ESR estimation.

Meyer, D. J. & Harvey, J. W. (2004). Veterinary

laboratory medicine: interpretation & dia-

gnosis. 3rd ed., Saunders, Elsevier Inc, USA.

WHO (2006). Blood Safety and Clinical Technology:

Guidelines on Standard Operating Proce-

dures for haematology.

16

17

C

C

h

h

a

a

p

p

t

t

e

e

r

r

3

3

B

B

o

o

n

n

e

e

M

M

a

a

r

r

r

r

o

o

w

w

E

E

x

x

a

a

m

m

i

i

n

n

a

a

t

t

i

i

o

o

n

n

Examination of the bone marrow may be of

valuable diagnostic tool in the differential diag-

nosis of diseases characterized by alterations in

the peripheral blood. Such an examination is

especially indicated in diseases associated either

with a decrease or increase in cellular elements

or with appearance of abnormal cellular forms.

Bone Marrow Aspiration

Equipments needed for sterile aspiration:

Syringe (20 ml) with metal tip.

2 syringe (10 ml) with metal tip.

2-3 hemostats.

Knife handle and blades.

2 bone marrow needles, there size and length

will depend upon the species of animal, see

(Fig 3-1).

Numerous clean slides (about 20).

Different surgical equipments, and local or

general anesthesia.

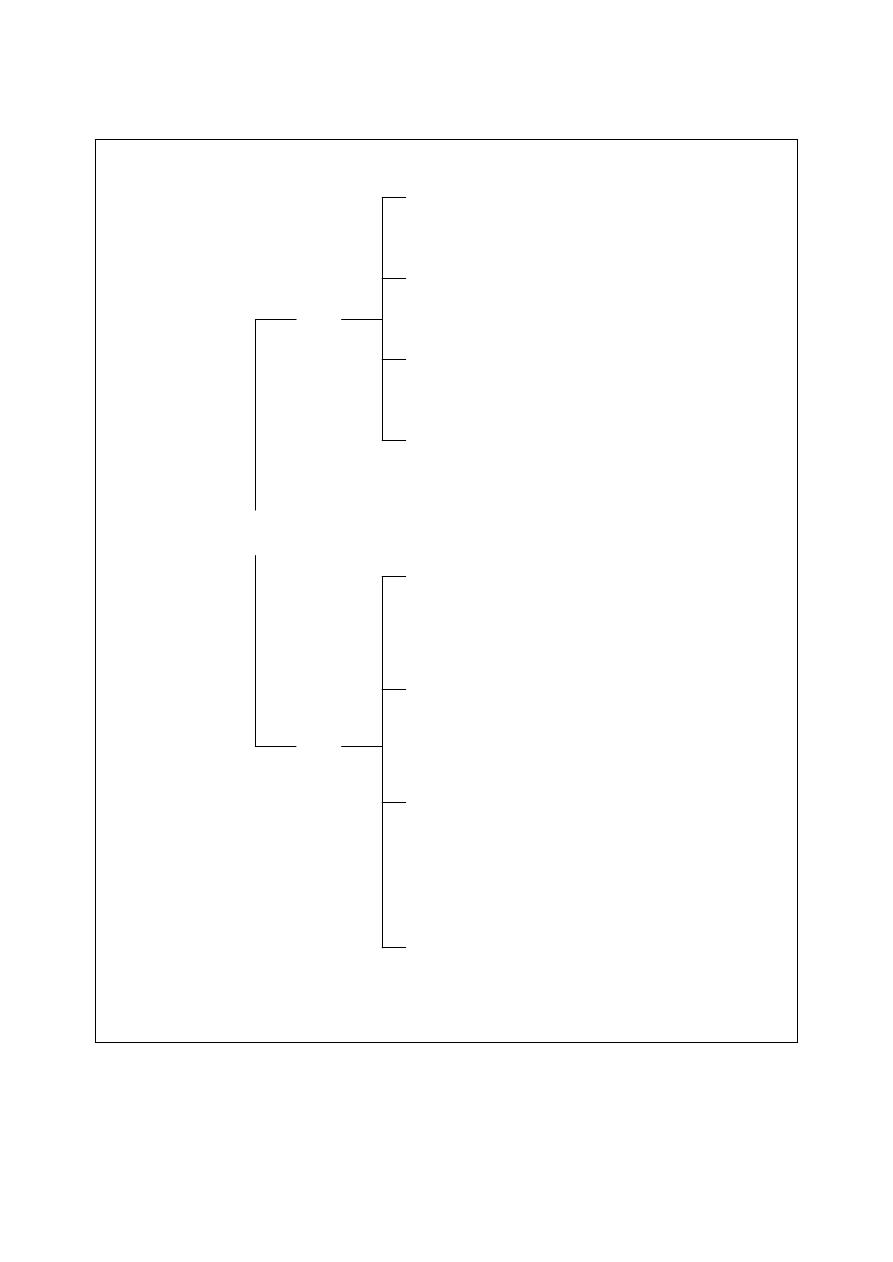

Sites used for bone marrow aspiration:

Bone marrow sample is readily obtained either

from trochanteric fossa or iliac crest. It can be

also obtained from sternum or humerus.

Steps of bone marrow aspiration:

Under general or local anesthesia and after

aseptic surgical preparation of the surface, a

short skin incision is made to facilitate penet-

ration.

A sterile aspiration needle with a stylet is

passed through the skin and muscle. When the

needle is forced into the bone by steady

pressure accompanied by rotation. When the

needle become firmly embedded,

it has usually

penetrated the medullary cavity.

A stylet is utilized to free the lumen of the

needle of tissue and bone particles, and a dry

20 ml glass syringe is fitted to the needle.

The plunger of the syringe should be pulled

out a considerable distance to establish a

vacuum and withdraw marrow fluid. Only a

small amount of fluid (0.5-1.0 ml) should be

aspirated.

As soon as fluid appears, vacuum should be

discontinued, as further negative pressure may

result in rupture of a sinusoid and contamina-

tion with peripheral blood.

Preparation of Bone Marrow Smears

As soon as possible after aspiration, prepare a

bone marrow smear similar to that used in

preparation of blood film

1

.

A few drops of marrow are placed on the end

of a slide and excess blood is aspirated back

into the syringe. If tissue fragments are aspi-

rated, a "squash" preparation is made by

placing a second slide firmly down on top of

the marrow particles and very carefully

drawing the two slides apart.

Slides should be waved in the air for rapid

drying.

Bone marrow smear stains with any good

polychrome stain, such as Wright's, Wright-

Giemsa,

or May-Gr

ünwald-Giemsa.

The smear

should be exposed to stain for a longer period

of time than is necessary for peripheral blood

smear.

1

If desired, some aspirated marrow may be placed into a

tube containing anticoagulant for later examination.

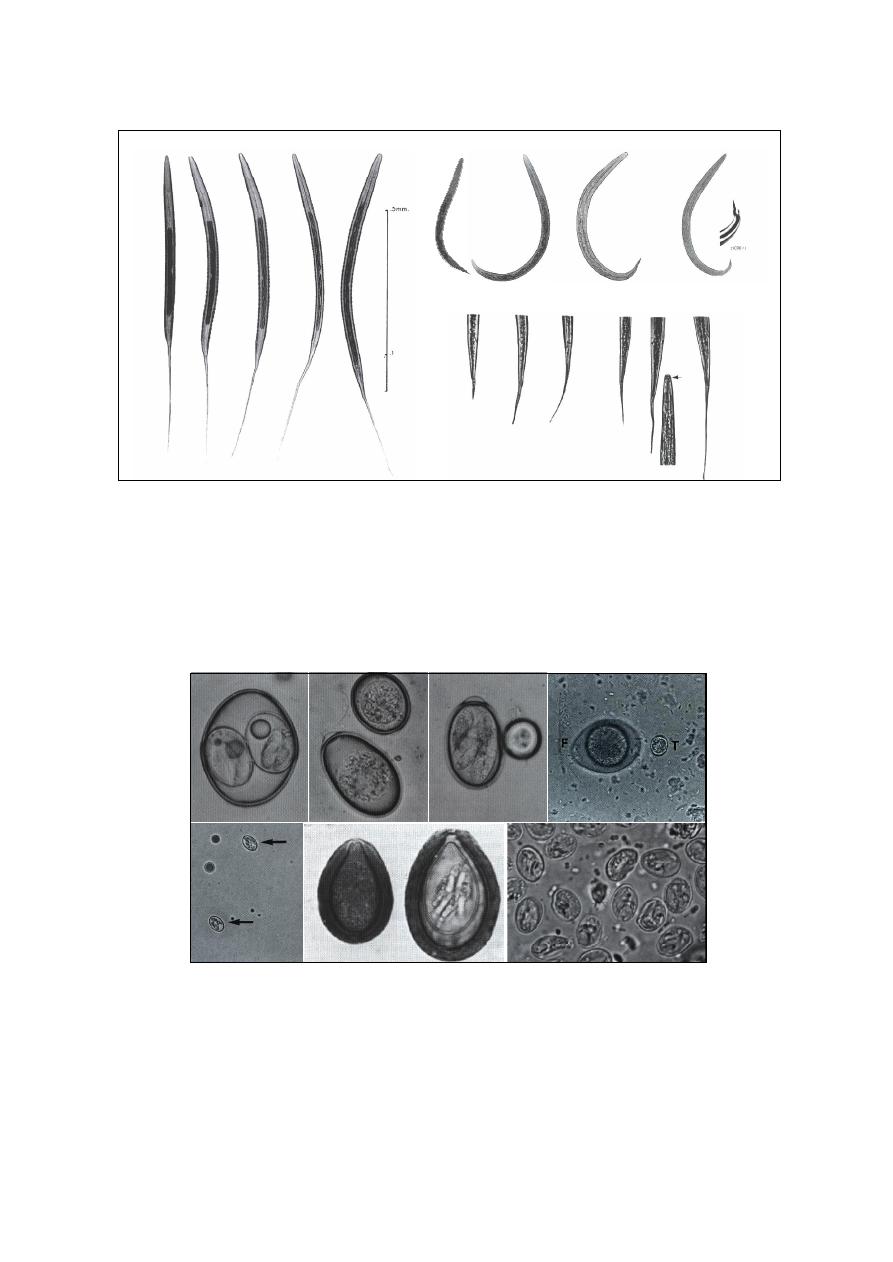

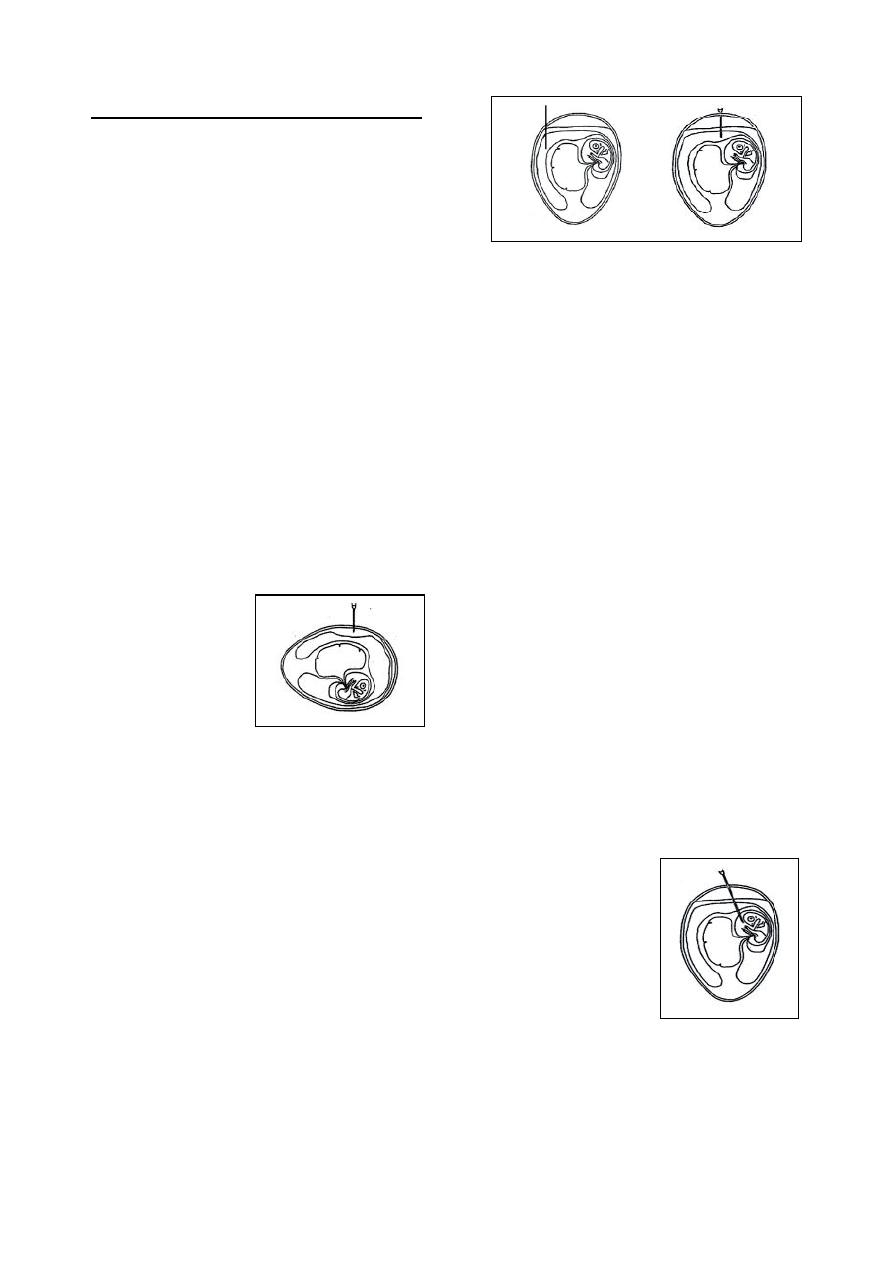

Fig. (3-1) Needles used for bone marrow collection

Fig. (3-2) Anatomical sites for bone marrow aspiration

(a) trochanteric fossa, (b) iliac crest.

(a)

(b)

id23357078 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com

18

Preparation of Bone Marrow Sections

Bone marrow sections may be also prepared

by one of the following methods:

Remove the amount of marrow required for

preparation of smears and permit the

remainder of the aspirate to clot in the syringe.

This clot is placed in a fixative for sectioning.

Collect the bone marrow in an anti-coagulant,

place it on a slide, and the excess blood is

removed from the edge of the slide with

gauze. Place the specimen in a fixative for

centrifugation and later sectioning.

Examination of Bone Marrow Film

In general, there are two ways in which a

marrow film is examined:

Entails scanning the slide under the low power

of the microscope, then under the high dry

objective, and finally under oil immersion

magnification. This method give the operator

possibility to formulate impressions concern-

ing the number and distribution of cells.

Entails making a differential count and calcu-

lating the percentage of each cell type. A

minimum of 500 cells should be examined,

and it is preferable to count 1000 cells.

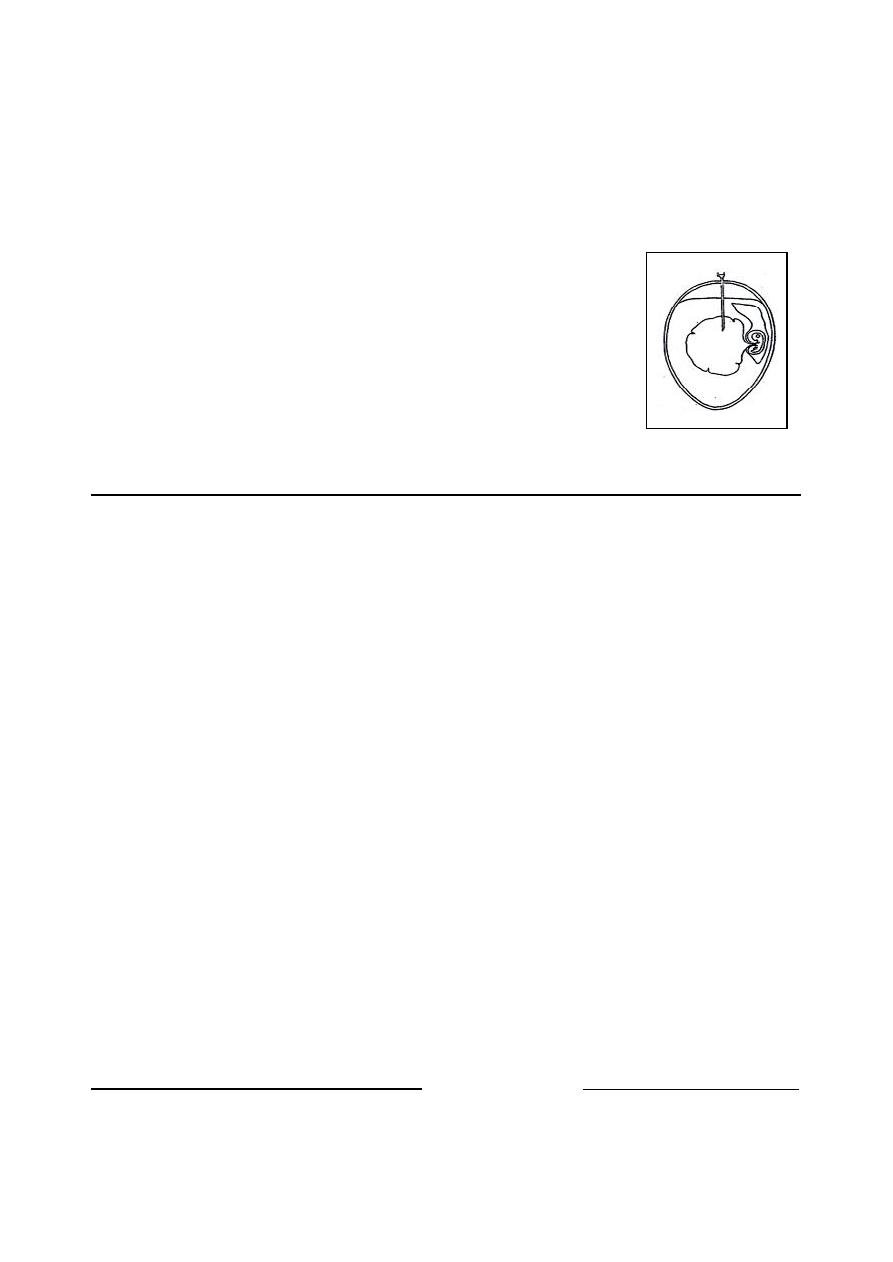

The cellularity of the smear can be evaluated

using low power magnification. Older animals

have more fat, while younger animals have less

fat (Fig 3-3).

Cell Identification:

All cells that develop in bone marrow alter

morphologically as they progress from primitive

to mature types. Primitive cells are usually larger

than mature cells, and the nuclei of these young

cells are relatively large in relation to the amount

of cytoplasm.

Erythrocytes series:

The developmental stages (from immature to

mature) of the erythrocytes are:

rubriblast

→ prorubricyte → rubricyte (from

basophilic

→ polychromatophilic → normo-

chromic)

→ metarubricyte → reticulocyte →

erythrocyte.

Leukocytes series:

(1) Granulocytic series:

The developmental stages (from immature to

mature) of the granulocytes are:

myeloblast

→ progranulocyte → myelocyte →

metamyelocyte

→ band cell → segmented

granulocyte.

(2) Lymphocytic series:

Lymphocytes are formed in lymphoid tissues

in many parts of the body, and a few them are

formed in the marrow. The developmental stages

(from immature to mature) of the lymphocytes

are:

lymphoblast

→ prolymphocyte → lymphocyte.

(3) Monocytic series:

Young forms of monocytes, particularly

monoblasts, may be difficult to differentiate

from other immature cells in marrow.

Other cells:

There are other cells may be found in marrow

smear, these are: reticulum cells, plasma cells,

tissue esinophils, tissue basophils, osteoblasts,

osteoclasts.

Myeloid to Erythroid Ratio (M:E):

The most significant information available

following bone marrow examination is the ratio

of myeloid to erythroid cells (M:E). This ratio is

calculated by dividing the number of all granulo-

cytic cells (myeloid) of bone marrow by the total

number of nucleated erythroid cells.

Interpretation of the M:E ratio can be made

only in relationship to the total leukocyte count

of peripheral blood.

The M:E ratio increases when there is:

o

Increase in granulocyte production.

o

Erythroid hypoplasia.

The M:E ratio decreases when there is:

o

decrease in granulocyte production.

o

Erythroid hyperplasia.

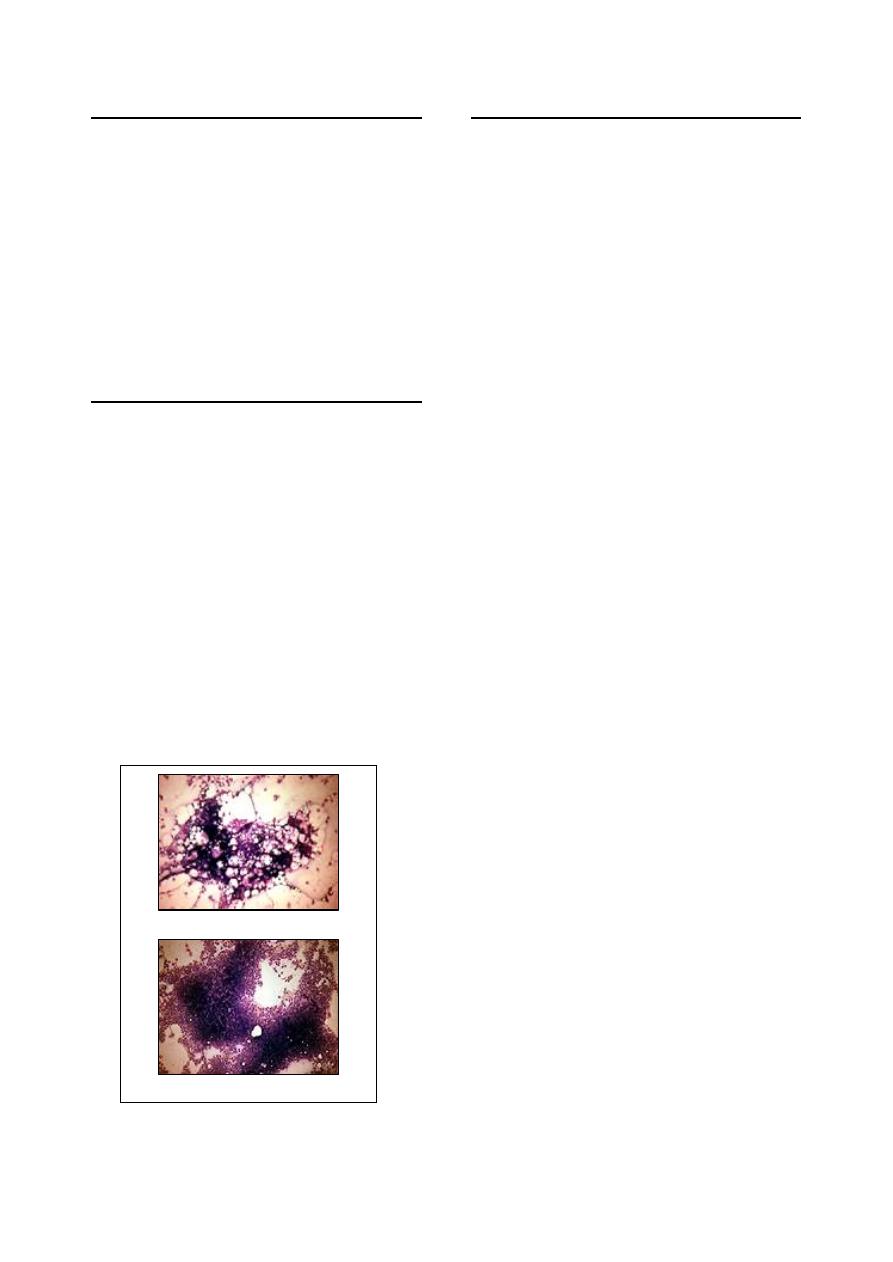

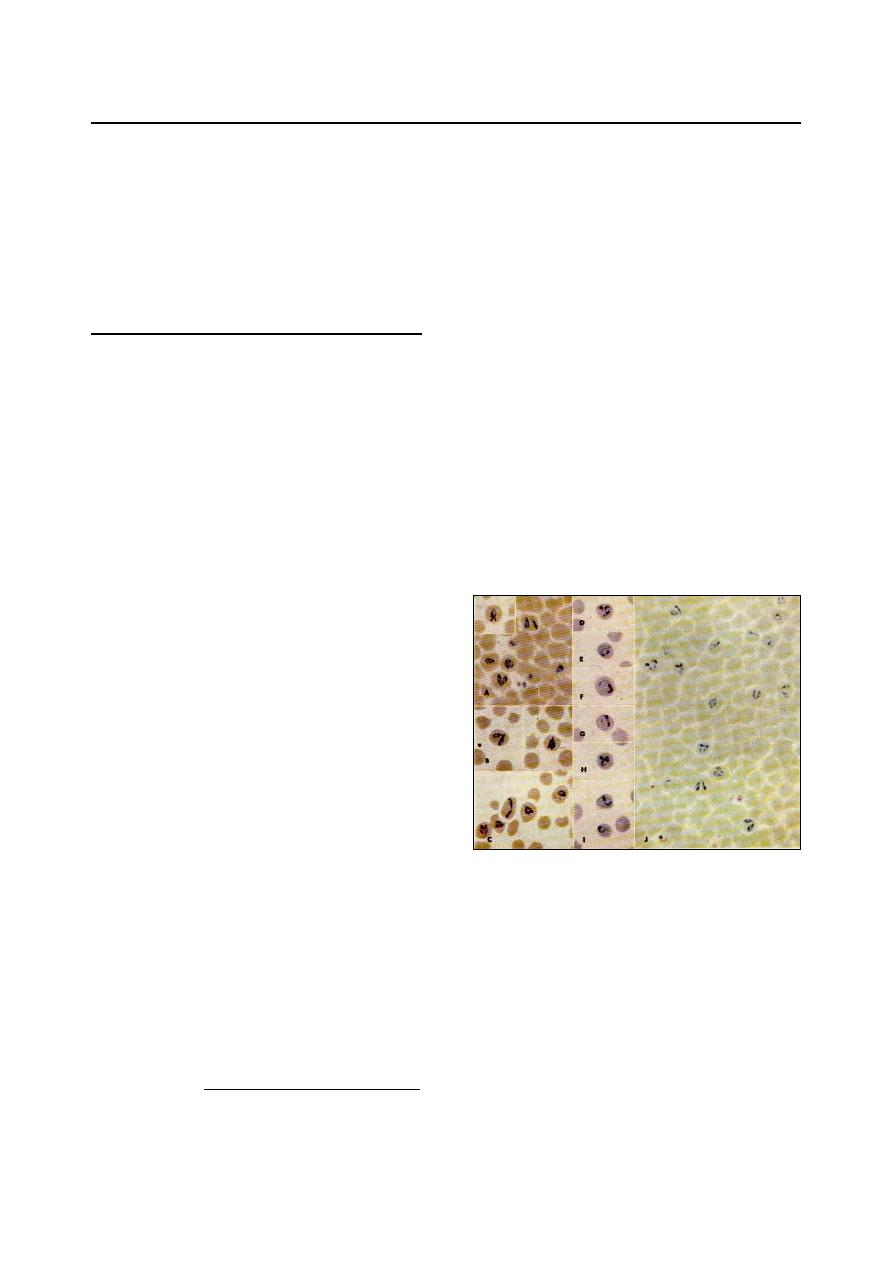

Fig. (3-3) Cellularity of the bone marrow smear

(a) hypocellular

(b) hypercellular.

19

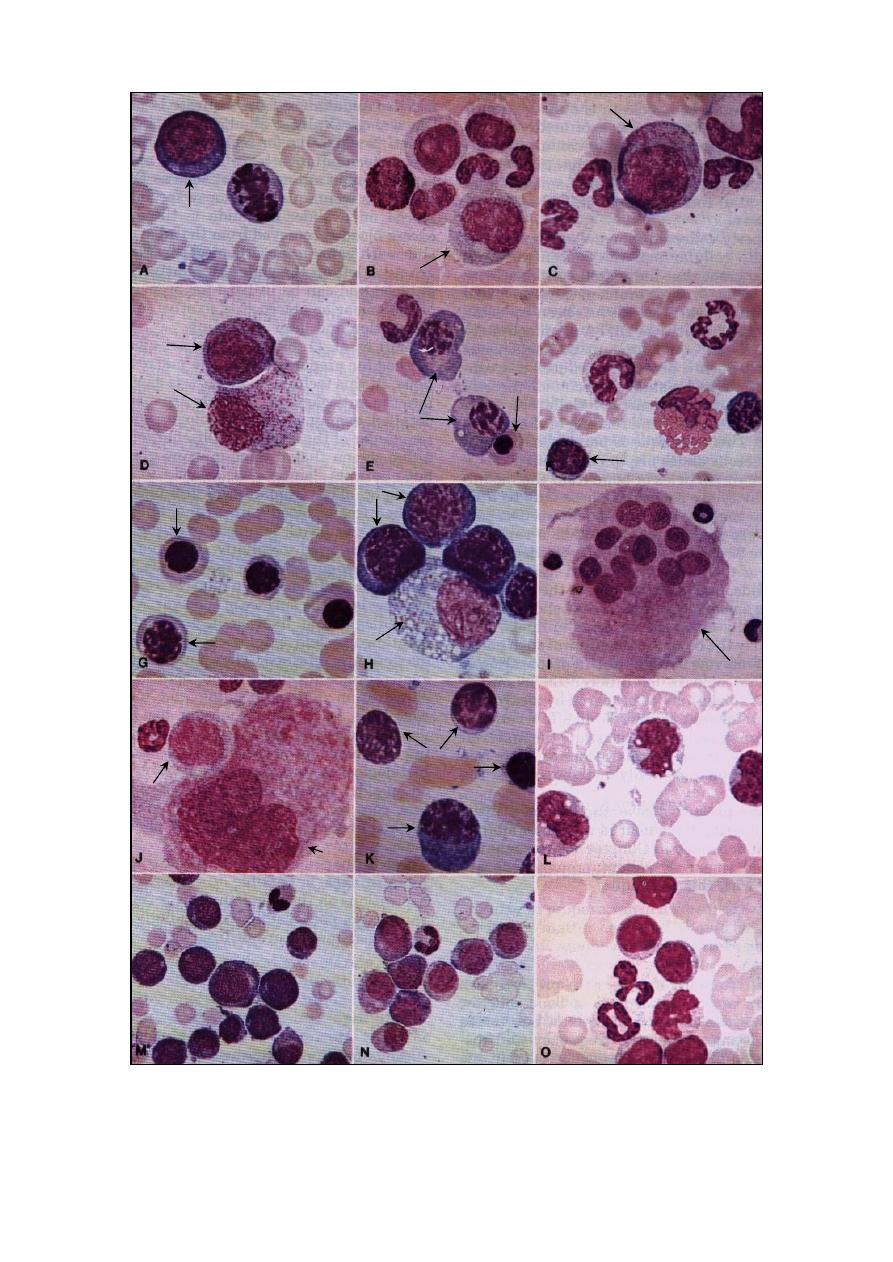

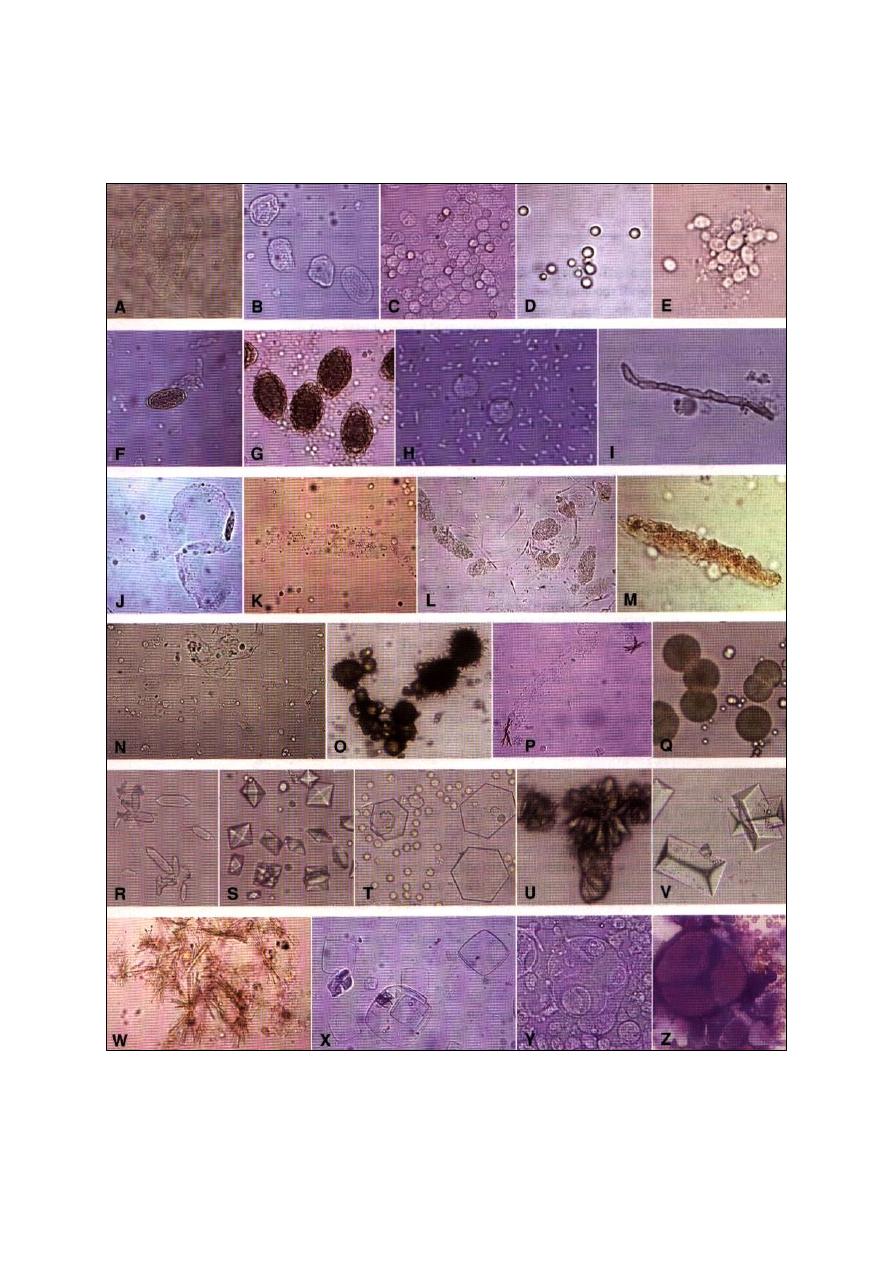

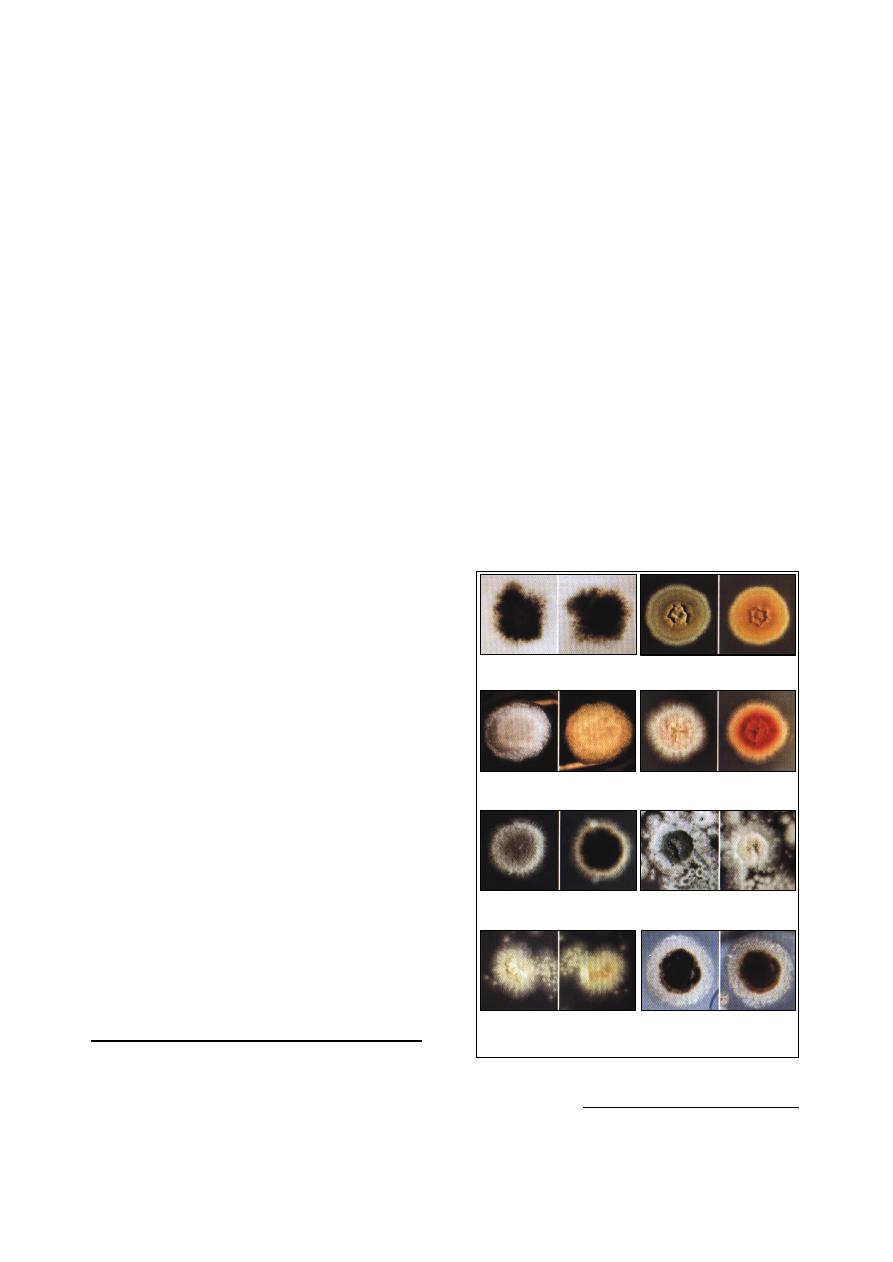

Fig. (3-4) Different cells of the bone marrow smear. A- blast cell (500x), B- neutrophilic myelocyte (500x), C- progranulocytes (500x),

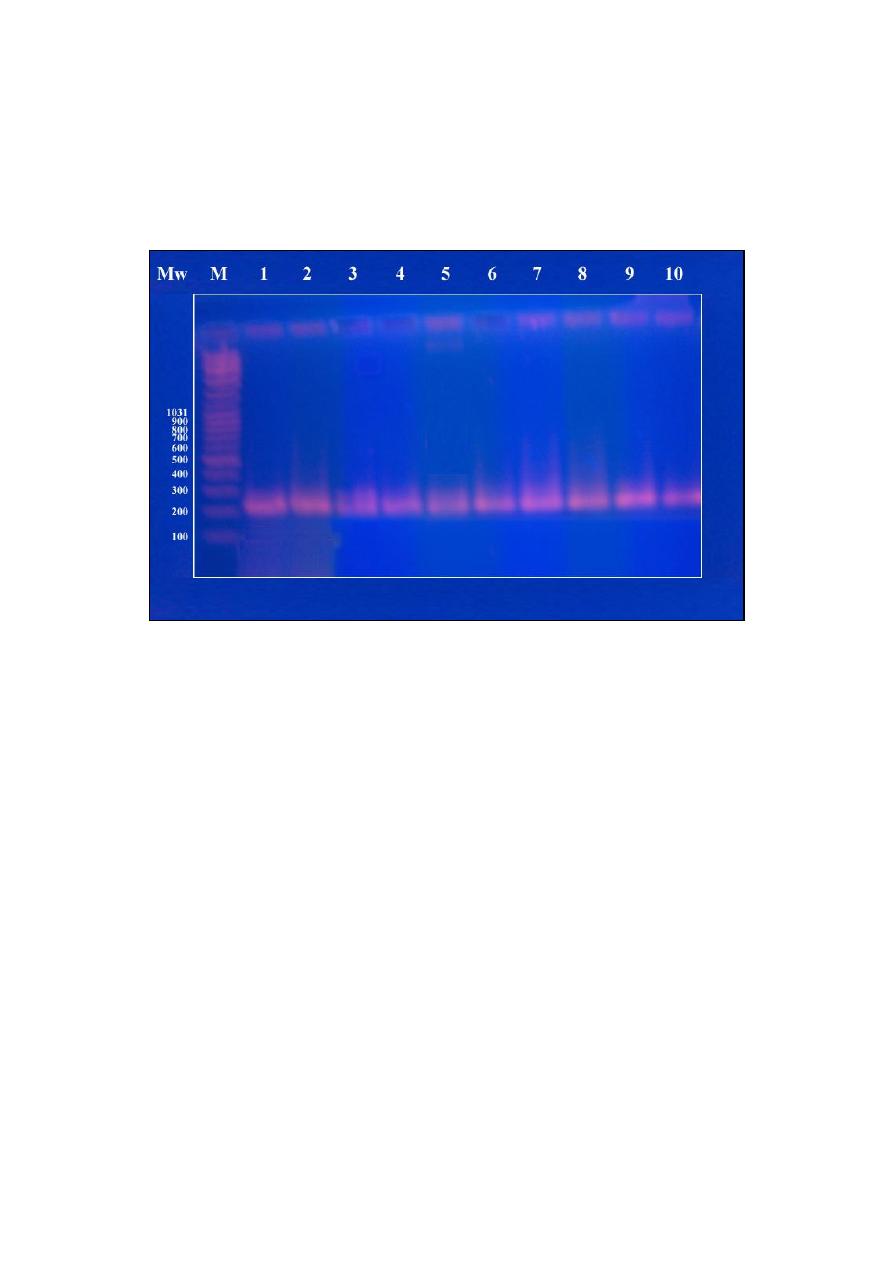

D- 1: early progranulocytes, 2: granular histiocytes (500x), E- 1: plasma cell, 2: metarubricyte (500x), F- rubricyte (500x), G- 1:meta-