The Thyroid Gland

Dr. Haidar F. Al-Rubaye

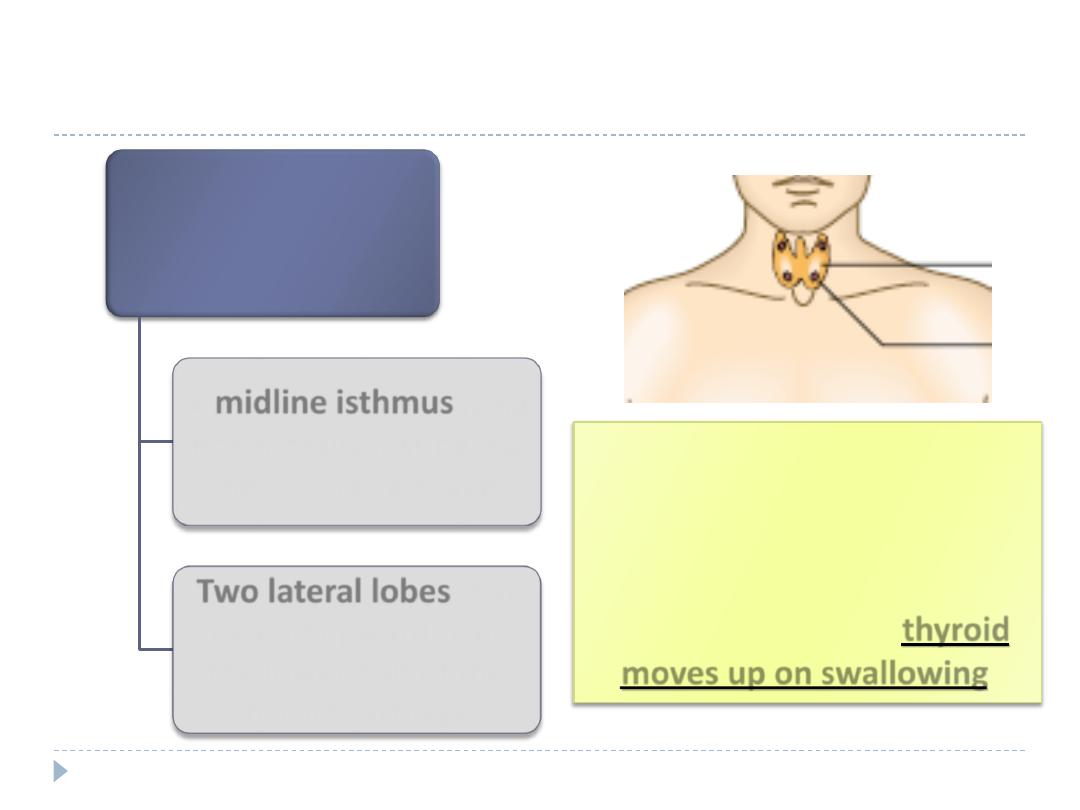

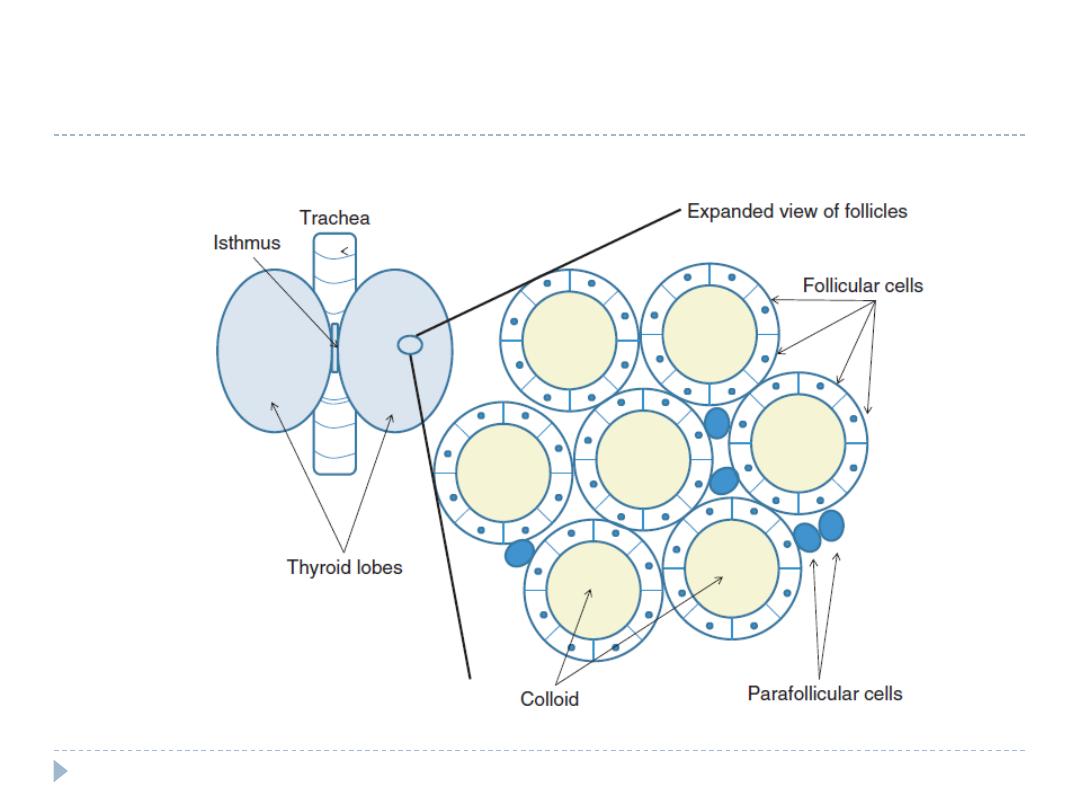

Anatomy

The thyroid

gland comprises

A

midline isthmus

lying

horizontally just below

the cricoid cartilage.

Two lateral lobes

that

extend upward over

the lower half of the

thyroid cartilage.

The gland lies deep to the

strap muscles of the neck,

enclosed in the pretracheal

fascia, which anchors it to the

trachea, so that the thyroid

moves up on swallowing.

Histology

Fibrous septa divide the gland into pseudolobules.

Pseudolobules are composed of vesicles called follicles or

acini, surrounded by a capillary network.

The follicle walls are lined by cuboidal epithelium.

The lumen is filled with a proteinaceous colloid, which

contains the unique protein thyroglobulin.

The peptide sequences of thyroxine (T 4 ) and tri-

iodothyronine (T 3 ) are synthesized and stored as a

component of thyroglobulin.

Anatomy

Physiology

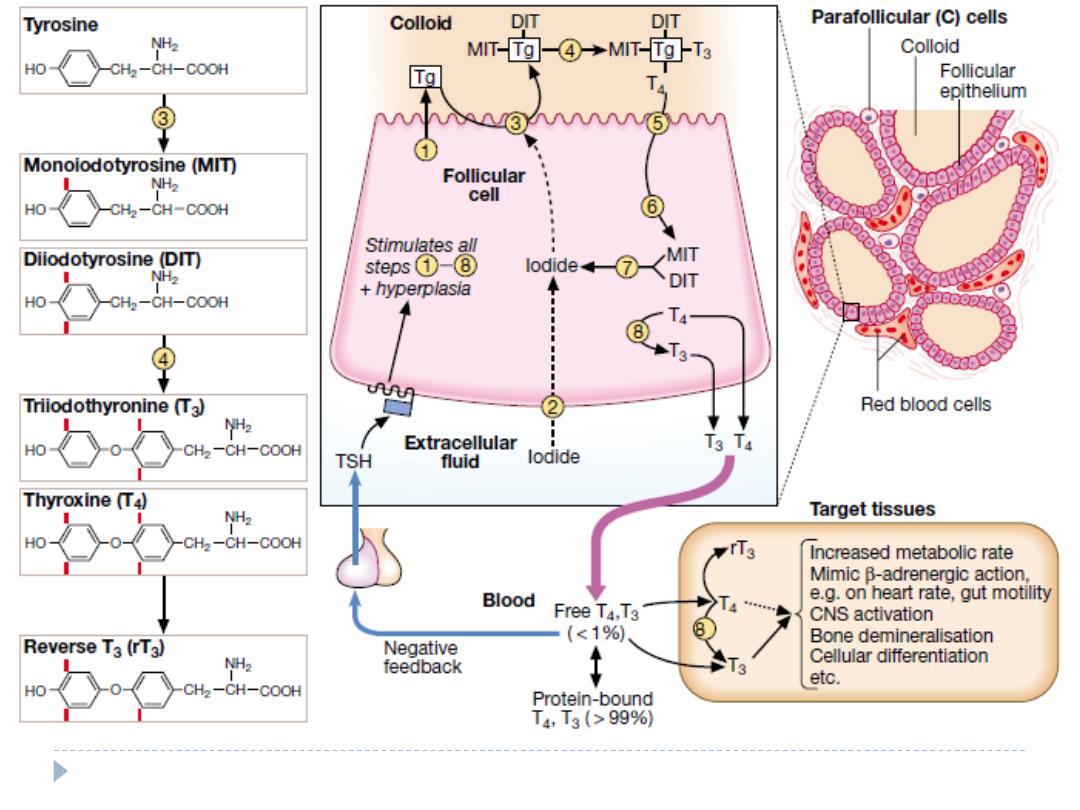

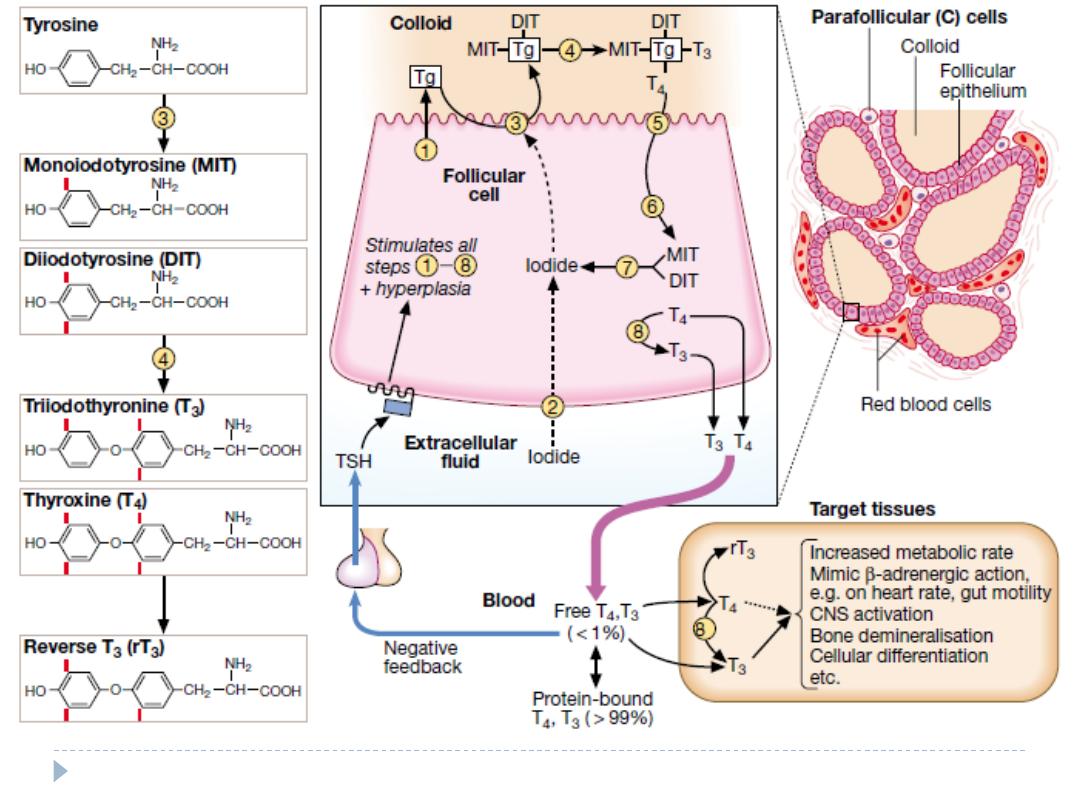

Thyroid hormone contains iodine. Iodine enters the

thyroid in the form of inorganic or ionic iodide, which is

organized by the thyroid peroxidase enzyme at the cell–

colloid interface.

Subsequent reactions result in the formation of

iodothyronines.

The thyroid is the only source of T4 . The thyroid secretes

20% of circulating T3 ; the remainder is generated in

extraglandular tissues by the conversion of T4 to T3 by

deiodinases (largely in the liver and kidneys).

Physiology

In the blood, T4 and T3 are almost entirely bound to plasma

proteins.

T4 is bound in d order of affinity to T4 -binding globulin (TBG),

transthyretin (TTR), and albumin.

T3 is bound 10–20 times less avidly by TBG and not

significantly by TTR.

Only the free or unbound hormone is available to tissues. The

metabolic state correlates more closely with the free than the

total hormone concentration in the plasma.

The relatively weak binding of T 3 accounts for its more rapid

onset and offset of action.

The concentration of free hormones does not necessarily vary

directly with that of the total hormones; e.g., while the total T

4 level rises in pregnancy, the free T 4 (FT 4 ) level remains

normal.

Classification of thyroid disease

Primary

Secondary

Hormone excess

Graves’ disease

Multinodular goitre

Adenoma

Subacute thyroiditis

TSHoma

Hormone deficiency

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

Atrophic hypothyroidism

Hypopituitarism

Hormone

hypersensitivity

Hormone resistance

Thyroid hormone resistance

syndrome

5′-monodeiodinase deficiency

Non-functioning

tumours

Differentiated carcinoma

Medullary carcinoma

Lymphoma

Thyroid Function Tests

TSH

TOTAL

T4

TOTAL

T3

FREE

T4

FREE

T3

How to interpret thyroid function test

results

TSH

• Undetected

T4

• Raised

T3

• Raised

Primary

thyrotoxicosis

TSH

• Undetected

T4

• Normal

T3

• Raised

Primary

T3-toxicosis

TSH

• Undetected

T4

• Normal

T3

• Normal

Subclinical

thyrotoxicosis

TSH

• Undetected

or low

T4

• Raised

T3

• Low, normal

or raised

Sick

euthyroidism/

non-thyroidal

illness

TSH

• Undetected

T4

• Low

T3

• Low

Secondary

hypothyroidism

/Transient

thyroiditis in

evolution

TSH

• Normal

T4

• Low

T3

• Low

Secondary

hypothyroidism

TSH

• Mildly

elevated

• 5–20 mU/L

T4

• Low

T3

• Low

Primary

hypothyroidism

/Secondary

hypothyroidism

TSH

• Elevated

• > 20 mU/L

T4

• Low

T3

• Low

Primary

hypothyroidism

TSH

• Mildly

elevated

• 5–20 mU/L

T4

• Normal

T3

• Normal

Subclinical

hypothyroidism

TSH

• Elevated

• 20–500 mU/L

T4

• Normal

T3

• Normal

Artefact

Endogenous IgG antibodies which interfere with TSH assay

TSH

• Elevated

T4

• Raised

T3

• Raised

Non-compliance with T4 replacement (Recent ‘loading’ dose)

Secondary thyrotoxicosis

Thyroid hormone resistance

Thyrotoxicosis

Thyrotoxicosis describes a constellation of clinical

features arising from elevated circulating levels of thyroid

hormone.

The most common causes are Graves’ disease,

multinodular goitre and autonomously functioning

thyroid nodules (toxic adenoma)

Thyroiditis is more common in parts of the world where

relevant viral infections occur, such as North America

Causes of thyrotoxicosis and their relative

frequencies

Cause

Frequency (%)

Graves’ disease

76

Multinodular goitre

14

Solitary thyroid adenoma

5

Thyroiditis

Subacute (de Quervain’s)

Post-partum

3

0.5

Iodide-induced

Drugs (e.g. amiodarone)

Radiographic contrast media

Iodine prophylaxis programme

1

-

-

Causes of thyrotoxicosis and their relative

frequencies

Cause

Frequency (%)

Extrathyroidal source of thyroid

hormone

Factitious thyrotoxicosis

Struma ovarii

0.2

-

TSH-induced

TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma

Choriocarcinoma and

hydatidiform mole

0.2

-

Follicular carcinoma ± metastases 0.1

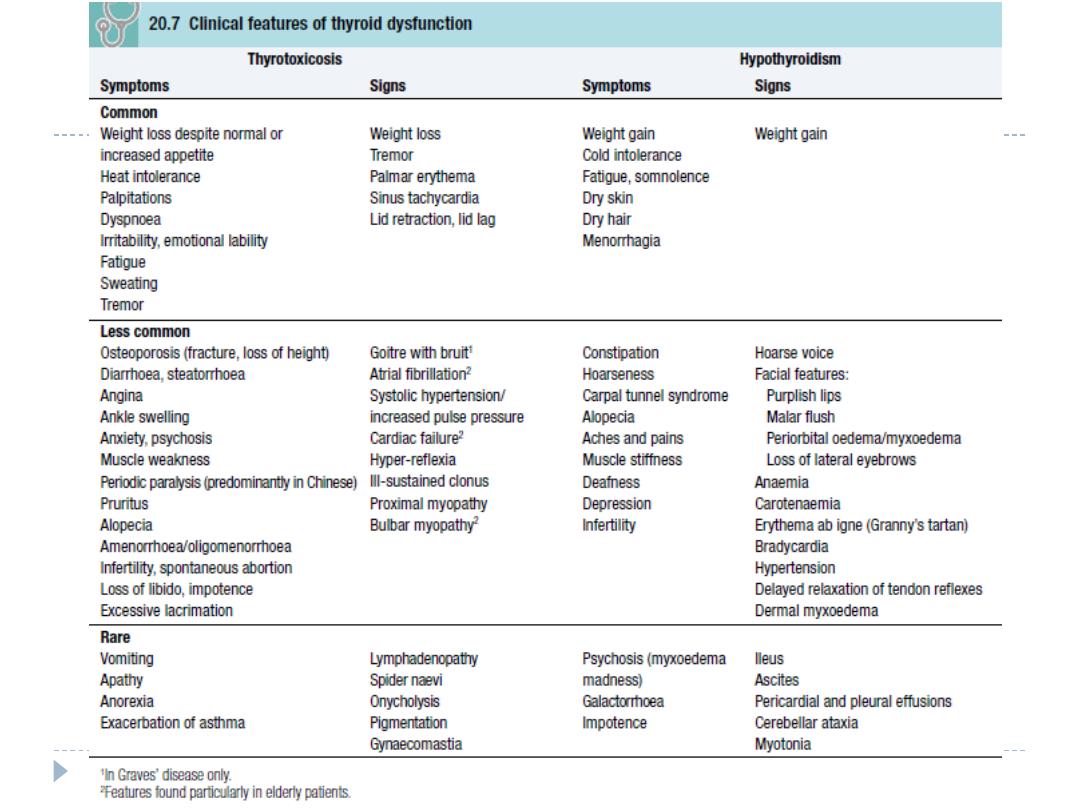

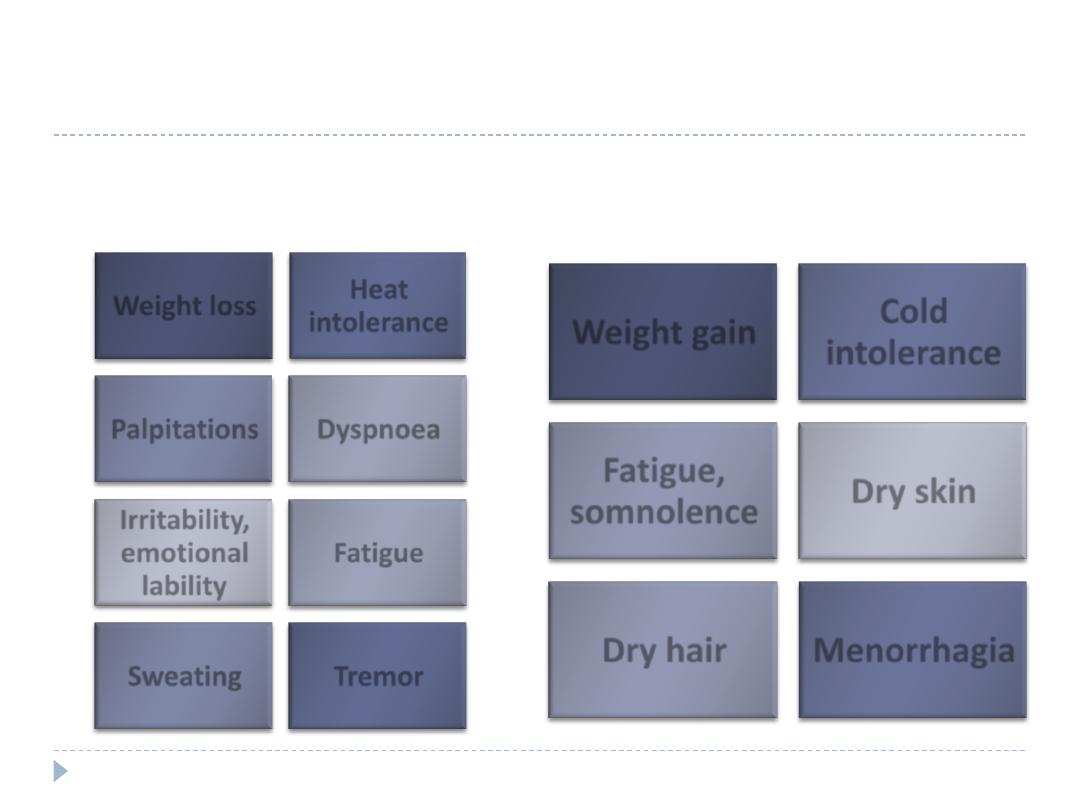

Clinical features of thyrotoxicosis & hypothyroidims-

common symptoms

Thyrotoxicosis-symptoms

Hypothyroidism-symptoms

Weight loss

Heat

intolerance

Palpitations

Dyspnoea

Irritability,

emotional

lability

Fatigue

Sweating

Tremor

Weight gain

Cold

intolerance

Fatigue,

somnolence

Dry skin

Dry hair

Menorrhagia

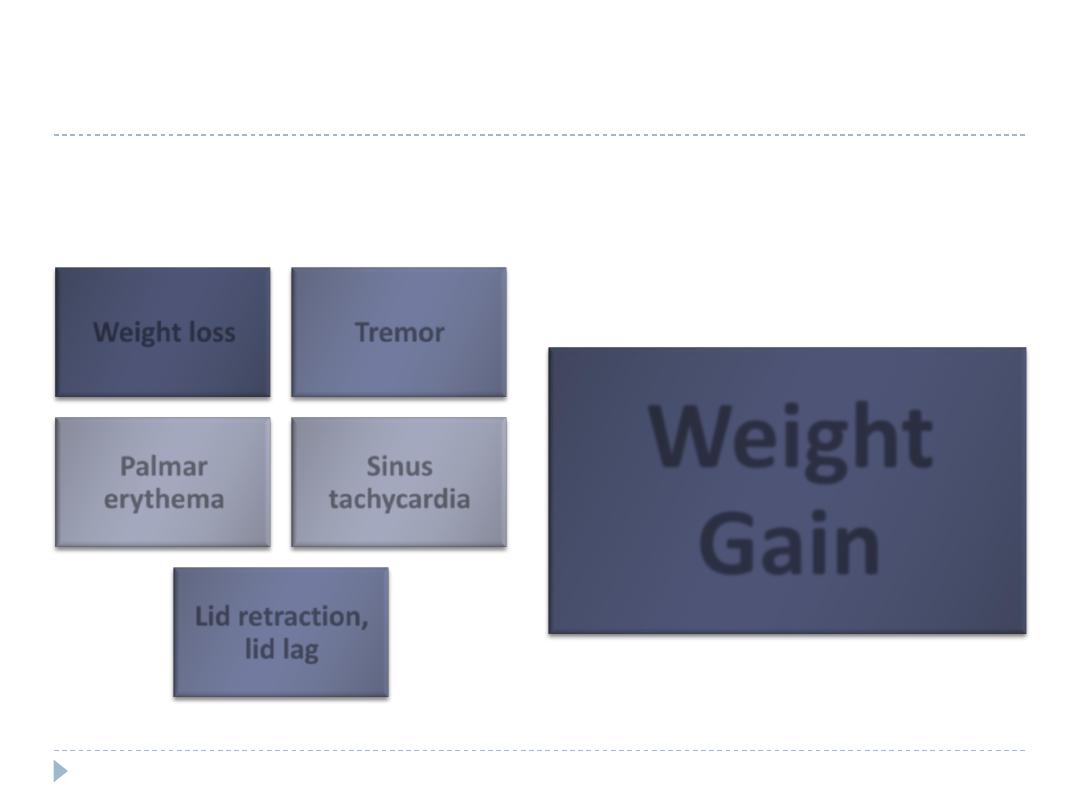

Clinical features of thyrotoxicosis & hypothyroidims-

common signs

Thyrotoxicosis-signs

Hypothyroidism-signs

Weight loss

Tremor

Palmar

erythema

Sinus

tachycardia

Lid retraction,

lid lag

Weight

Gain

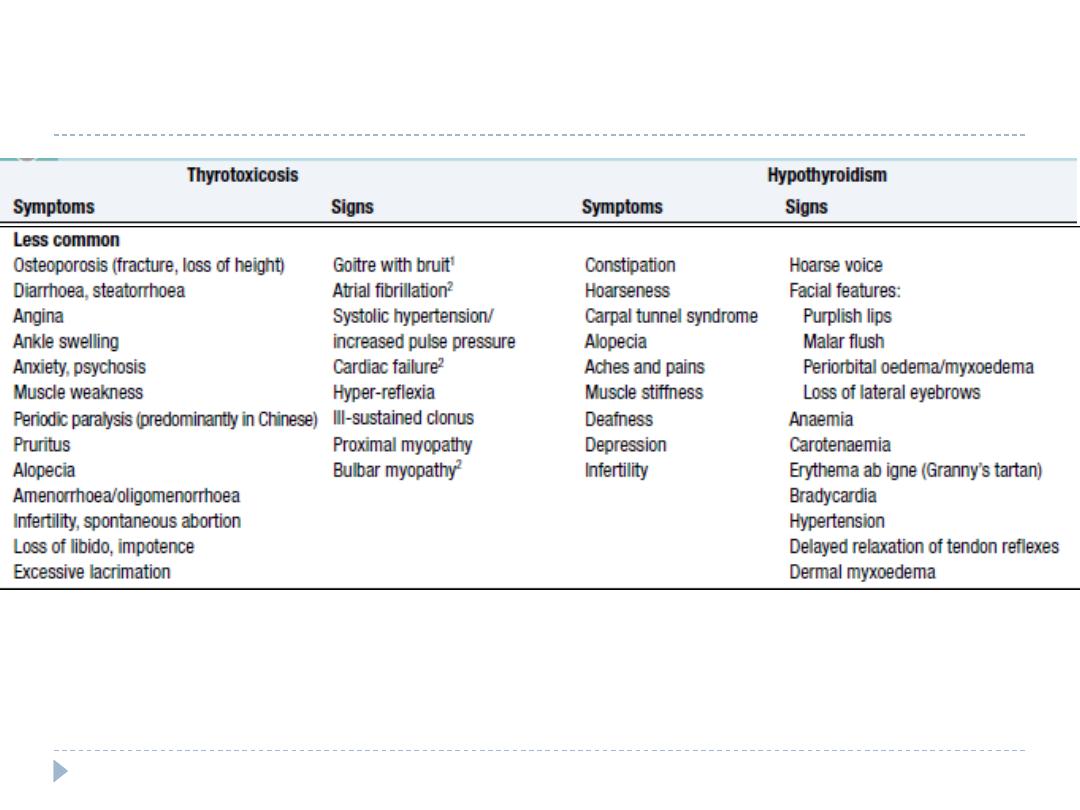

Clinical features of thyrotoxicosis & hypothyroidims-

common signs

The most common symptoms are weight loss with a

normal or increased appetite, heat intolerance,

palpitations, tremor and irritability.

Tachycardia, palmar erythema and lid lag are common

signs.

Not all patients have a palpable goitre, but experienced

clinicians can discriminate the diffuse soft goitre of

Graves’ disease from the irregular enlargement of a

multinodular goitre.

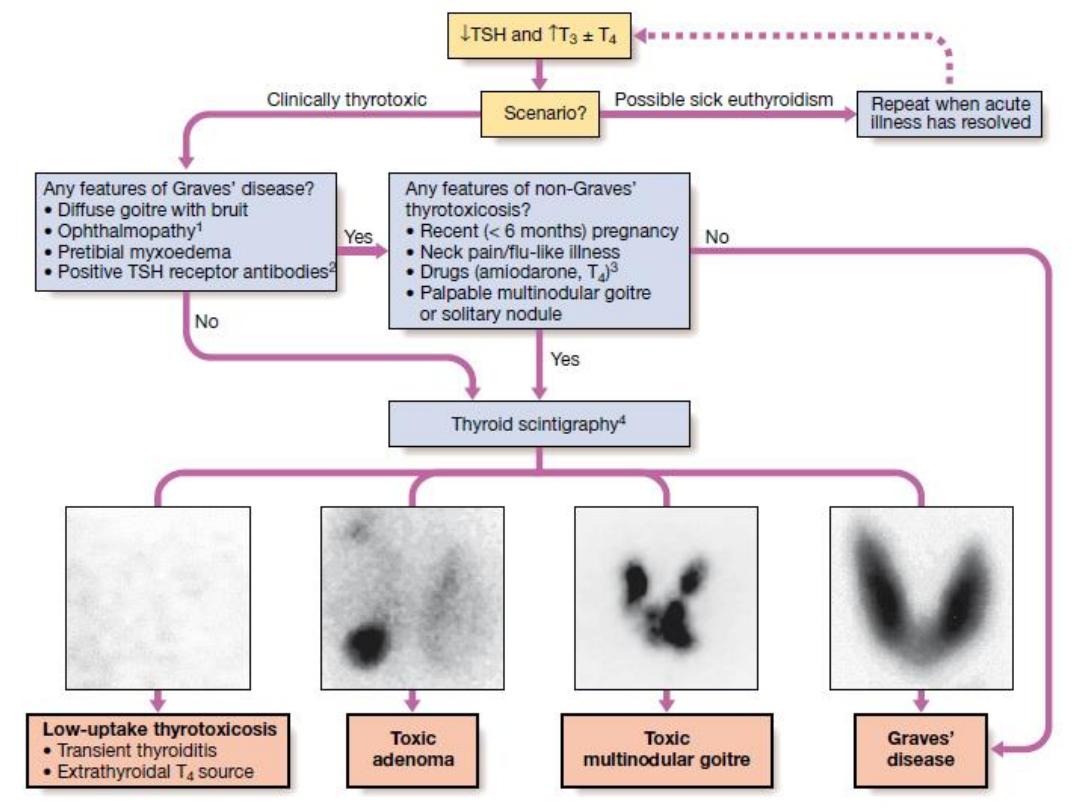

Investigation of thyrotoxicosis

The first-line investigations are serum T3, T4 and TSH.

If abnormal values are found, the tests should be repeated and

the abnormality confirmed in view of the likely need for

prolonged medical treatment or destructive therapy.

In most patients serum T3 and T4 are both elevated but T4 is in

the upper part of the normal range and T3 raised (T3 toxicosis)

in about 5%.

Serum TSH is undetectable in primary thyrotoxicosis but values

can be raised in the very rare syndrome of secondary

thyrotoxicosis caused by a TSH-producing pituitary adenoma.

↓TSH and ↑T3 ± T4

Repeat when acute

illness has resolved

Scenario?

Any features of Graves’

disease?

• Diffuse goitre with bruit

• Ophthalmopathy

• Pretibial myxoedema

• Positive TSH receptor

antibodies

Any features of non-Graves’ thyrotoxicosis?

• Recent (< 6 months) regnancy

• Neck pain/flu-like illness

• Drugs (amiodarone, T4)3

• Palpable multinodular goitre or solitary

nodule

Yes

No

Thyroid Scintigraphy

Yes

Low-uptake thyrotoxicosis

• Transient thyroiditis

• Extrathyroidal T4 source

Toxic adenoma

Toxic MNG

Graves’ disease

No

Clinically thyrotoxic

Possible sick

euthyroidism

Investigation of thyrotoxicosis

When biochemical thyrotoxicosis has been confirmed,

further investigations should be undertaken to determine

the underlying cause, including measurement of

TSH

receptor antibodies

(TRAb, elevated in Graves’ disease,

and

isotope scanning

.

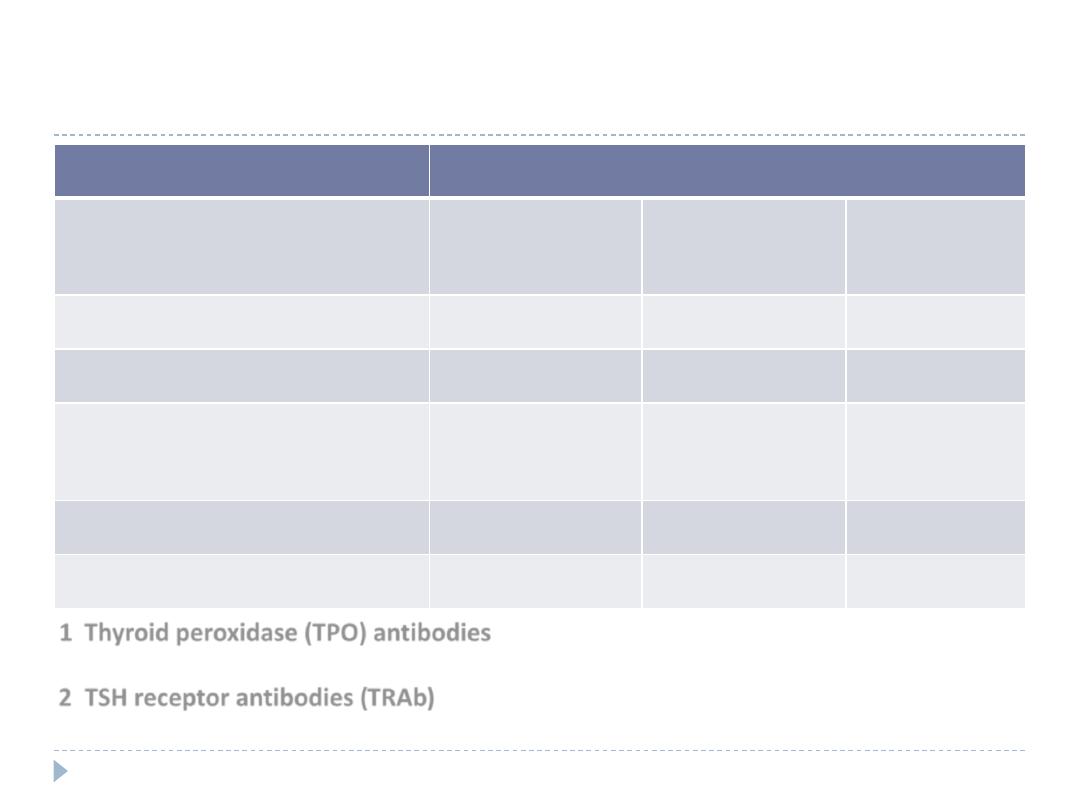

Prevalence of thyroid autoantibodies (%)

Antibodies to:

Thyroid

peroxidase

Thyroglobuli

n

TSH

receptor

Normal population

8–27

5–20

0

Graves’ disease

50–80

50–70

80–95

Autoimmune

Hypothyroidism

90–100

80–90

10–20

Multinodular goitre

∼30–40

0

0

Transient thyroiditis

∼30–40

0

0

1 Thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies

are the principal component of what was

previously measured as thyroid ‘microsomal’ antibodies.

2 TSH receptor antibodies (TRAb)

can be agonists (stimulatory, causing Graves’

thyrotoxicosis) or antagonists (‘blocking’, causing hypothyroidism).

Non-specific laboratory abnormalities in

thyroid dysfunction*

Thyrotoxicosis

• Serum enzymes

• Raised alanine aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl

transferase (GGT), and alkaline phosphatase from liver

and bone

• Raised bilirubin

• Mild hypercalcaemia

• Glycosuria: Associated diabetes mellitus, ‘Lag storage’

glycosuria

Hypothyroidism

• Serum enzymes: Raised creatine kinase, aspartate

aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

• Hypercholesterolaemia

• Anaemia: Normochromic normocytic or macrocytic

• Hyponatraemia

*These

abnormalities

are not useful in

differential

diagnosis, so the

tests should be

avoided and any

further

investigation

undertaken only

if abnormalities

persist when the

patient is

euthyroid.

Management

Definitive treatment of thyrotoxicosis depends on the

underlying cause and may include antithyroid drugs,

radioactive iodine or surgery.

A non-selective β- adrenoceptor antagonist (β-blocker),

such as propranolol (160 mg daily) or nadolol (40–80 mg

daily), will alleviate but not abolish symptoms in most

patients within 24–48 hours.

Beta-blockers should not be used for long term treatment

of thyrotoxicosis, but are extremely useful in the short

term, whilst patients are awaiting hospital consultation or

following

131

I therapy.

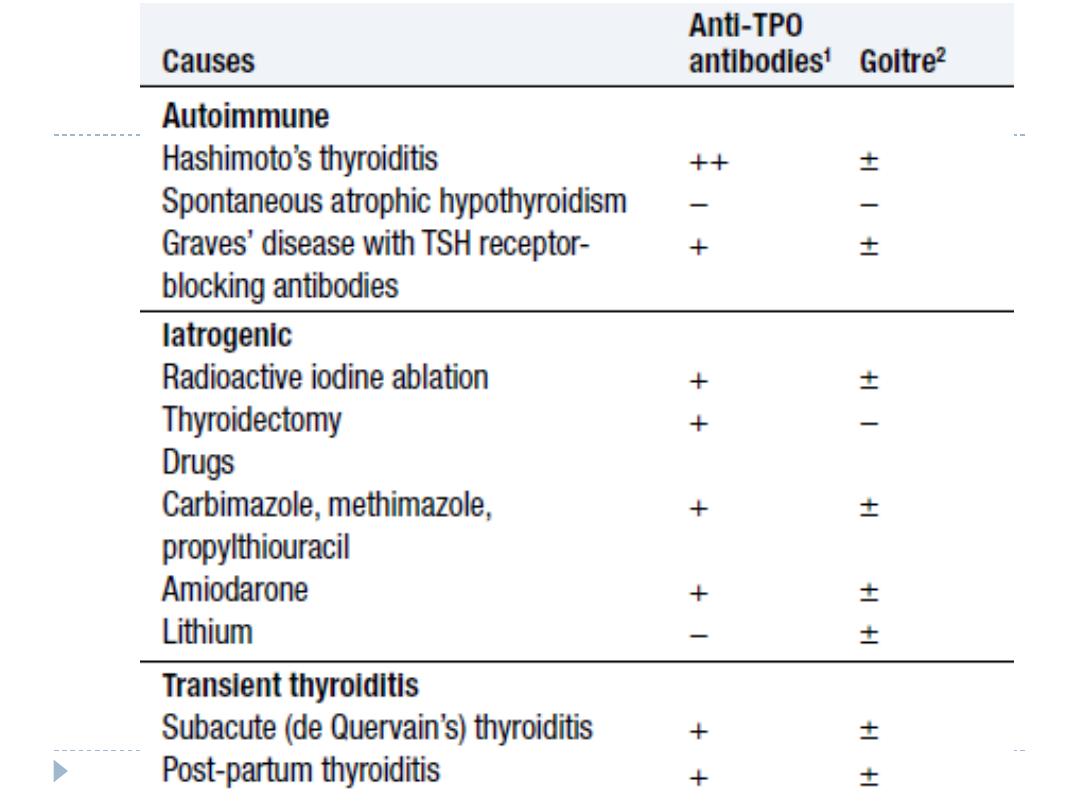

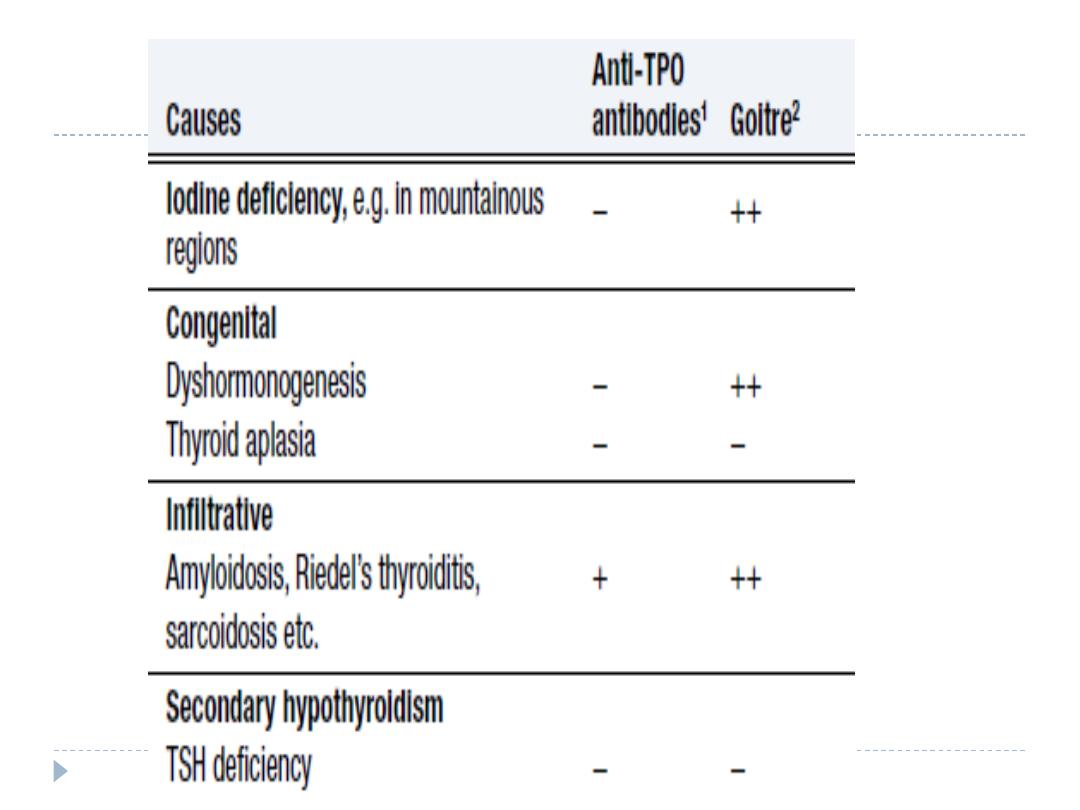

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is a common condition with various

causes but autoimmune disease (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis)

and thyroid failure following

131

I or surgical treatment of

thyrotoxicosis account for over 90% of cases, except in

areas where iodine deficiency is endemic.

Women are affected approximately six times more

frequently than men.

Clinical features

The clinical presentation depends on the duration and severity

of the hypothyroidism.

A consequence of prolonged hypothyroidism is the infiltration

of many body tissues by the mucopolysaccharides, hyaluronic

acid and chondroitin sulphate, resulting in a low-pitched voice,

poor hearing, slurred speech due to a large tongue, and

compression of the median nerve at the wrist (carpal tunnel

syndrome).

Infiltration of the dermis gives rise to non-pitting oedema

(myxoedema) which is most marked in the skin of the hands,

feet and eyelids.

The resultant periorbital puffiness is often striking and, when

combined with facial pallor due to vasoconstriction and

anaemia, or a lemon-yellow tint to the skin due to

carotenaemia, purplish lips and malar flush, the clinical

diagnosis is simple.

Most cases of hypothyroidism are not clinically obvious,

however, and a high index of suspicion needs to be maintained

so that the diagnosis is not overlooked in the middle-aged

woman complaining of non-specific symptoms such as

tiredness, weight gain, depression or carpal tunnel syndrome.

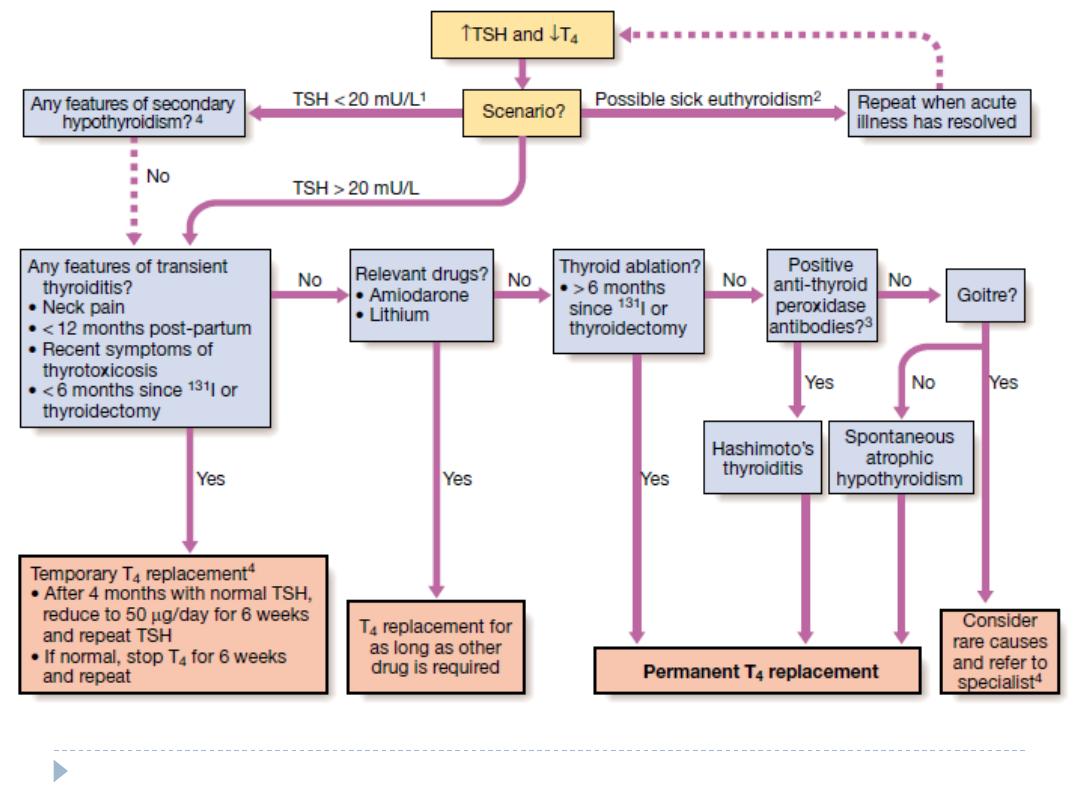

Care must be taken to identify patients with transient

hypothyroidism, in whom life-long thyroxine therapy is

inappropriate.

This is often observed during the first 6 months after subtotal

thyroidectomy or

131

I treatment of Graves’ disease, in the post-

thyrotoxic phase of subacute thyroiditis and in post-partum

thyroiditis. In these conditions thyroxine treatment is not

always necessary as the patient may be asymptomatic during

the short period of thyroid failure.

Investigations

In the vast majority of cases hypothyroidism results from

an intrinsic disorder of the thyroid gland (primary

hypothyroidism). In this situation serum T4 is low and TSH

is elevated, usually in excess of 20 mU/L.

Measurements of serum T3 are unhelpful since they do

not discriminate reliably between euthyroidism and

hypothyroidism.

The rare condition of secondary hypothyroidism is caused

by failure of TSH secretion in a patient with hypothalamic

or anterior pituitary disease. This is characterised by a

low serum T4 but TSH may be low, normal or even slightly

elevated

Management

Treatment is with thyroxine replacement. It is customary

to start with a low dose of 50 μg per day for 3 weeks,

increasing thereafter to 100 μg per day for a further 3

weeks and finally to a maintenance dose of 100–150 μg

per day.

Thyroxine has a half-life of 7 days so it should always be

taken as a single daily dose and at least 6 weeks should

pass before repeating thyroid function tests and adjusting

the dose, usually in increments of 25 μg per day.

Patients feel better within 2–3 weeks. Reduction in

weight and periorbital puffiness occurs quickly, but the

restoration of skin and hair texture and resolution of any

effusions may take 3–6 months.

The dose of thyroxine should be adjusted to maintain

serum TSH within the reference range.

To achieve this, serum T4 often needs to be in the upper part

of the normal range or even slightly raised, because the T3

required for receptor activation is derived exclusively from

conversion of T4 within the target tissues, without the usual

contribution from thyroid secretion.

Some patients remain symptomatic despite

normalisation of TSH and may wish to take extra

thyroxine which suppresses TSH values.

However, there is evidence that suppressed TSH is a risk factor

for osteoporosis and atrial fibrillation, so this approach cannot

be recommended.

It is important to measure thyroid function every 1–2

years once the dose of thyroxine is stabilised.

This encourages patient compliance with therapy and allows

adjustment for variable underlying thyroid activity and other

changes in thyroxine requirements

Thyroxine replacement in ischaemic heart disease

Hypothyroidism and ischaemic heart disease are common

conditions which often occur together.

Although angina may remain unchanged in severity or paradoxically

disappear with restoration of metabolic rate, exacerbation of

myocardial ischaemia, infarction and sudden death are recognised

complications of thyroxine replacement, even using doses as low as

25 μg per day.

In patients with known ischaemic heart disease, thyroid hormone

replacement should be introduced at low dose and increased very

slowly under specialist supervision.

It has been suggested that T3 has an advantage over T4 since T3 has

a shorter half-life and any adverse effect will reverse more quickly,

but the more distinct peak in hormone levels after each dose of T3

is a disadvantage.

Coronary artery surgery or angioplasty is required in the minority of

patients with angina who cannot tolerate full thyroxine replacement

therapy despite maximal anti-anginal therapy.

Hypothyroidism in pregnancy

Most pregnant women with primary hypothyroidism

require an increase in the dose of thyroxine of

approximately 50 μg daily to maintain normal TSH levels.

This may reflect increased metabolism of thyroxine by the

placenta and increased serum thyroxine-binding globulin

during pregnancy, resulting in an increase in the total

thyroid hormone pool to maintain the same free T4 and

T3 concentrations.

Recent research suggests that inadequate maternal T4

therapy is associated with impaired cognitive

development in their offspring. Serum TSH and free T4

should be measured during each trimester and the dose

of thyroxine adjusted to maintain a normal TSH.

Myxoedema coma

This is a rare presentation of hypothyroidism in which

there is a depressed level of consciousness, usually in an

elderly patient who appears myxoedematous.

Body temperature may be as low as 25°C, convulsions are

not uncommon and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure

and protein content are raised.

The mortality rate is 50% and survival depends upon early

recognition and treatment of hypothyroidism and other

factors contributing to the altered consciousness level,

such as phenothiazines, cardiac failure, pneumonia,

dilutional hyponatraemia and respiratory failure.

Myxoedema coma is a medical emergency and treatment must

begin before biochemical confirmation of the diagnosis.

Suspected cases should be treated with an intravenous injection of

20 μg triiodothyronine followed by further injections of 20 μg 8-

hourly until there is sustained clinical improvement. In survivors

there is a rise in body temperature within 24 hours and, after 48–72

hours, it is usually possible to switch patients on to oral thyroxine in

a dose of 50 μg daily.

Unless it is apparent that the patient has primary hypothyroidism,

the thyroid failure should also be assumed to be secondary to

hypothalamic or pituitary disease and treatment given with

hydrocortisone 100 mg i.m. 8-hourly, pending the results of T4, TSH

and cortisol measurement

Other measures include slow rewarming, cautious use of

intravenous fluids, broad-spectrum antibiotics and high-flow oxygen.

Occasionally, assisted ventilation may be necessary.

Autoimmune thyroid diseases

Thyroid diseases are amongst the most prevalent

antibody- mediated autoimmune diseases and are

associated with other organ-specific autoimmunity

Autoantibodies may produce inflammation and

destruction of thyroid tissue resulting in hypothyroidism,

goitre (in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) or sometimes even

transient thyrotoxicosis (‘Hashitoxicosis’), or they may

stimulate the TSH receptor to cause thyrotoxicosis (in

Graves’ disease).

There is overlap between these conditions, since some

patients have multiple autoantibodies.

Graves’ disease

Graves’ disease can occur at any age but is unusual before

puberty and most commonly affects women aged 30–50

years.

The most common manifestation is thyrotoxicosis with or

without a diffuse goitre.

Graves causes clinical features shown in previous lectures

Graves’ disease also causes ophthalmopathy and rarely

pretibial myxoedema

These extrathyroidal features usually occur in thyrotoxic

patients, but can occur in the absence of thyroid dysfunction.

Graves’ thyrotoxicosis-Pathophysiology

The thyrotoxicosis results from the production of IgG

antibodies directed against the TSH receptor on the thyroid

follicular cell, which stimulate thyroid hormone production

and proliferation of follicular cells, leading to goitre in the

majority of patients. These antibodies are termed thyroid-

stimulating immunoglobulins or TSH receptor antibodies

(TRAb) and can be detected in the serum of 80–95% of

patients with Graves’ disease.

The concentration of TRAb in the serum is presumed to

fluctuate to account for the natural history of Graves’

thyrotoxicosis

The thyroid failure seen in some patients may result from the

presence of blocking antibodies against the TSH receptor, and

from tissue destruction by cytotoxic antibodies and cell-

mediated immunity.

Features of Graves disease in addition to diffuse

goitre

Periorbital

oedema

Conjunctival

irritation

Exophthalmos

Diplopia

Pretibial

myxoedema

Thyroid

acropachy

A suggested trigger for the development of thyrotoxicosis

in genetically susceptible individuals may be infection

with viruses or bacteria.

Certain strains of the gut organisms Escherichia coli and

Yersinia enterocolitica possess cell membrane TSH

receptors; antibodies to these microbial antigens may

cross-react with the TSH receptors on the host thyroid

follicular cell.

In regions of iodine deficiency, iodine supplementation

can precipitate thyrotoxicosis, but only in those with pre-

existing subclinical Graves’ disease. Smoking is weakly

associated with Graves’ thyrotoxicosis, but strongly linked

with the development of ophthalmopathy.

Management

Symptoms of thyrotoxicosis respond to β-blockade, but

definitive treatment requires control of thyroid hormone

secretion.

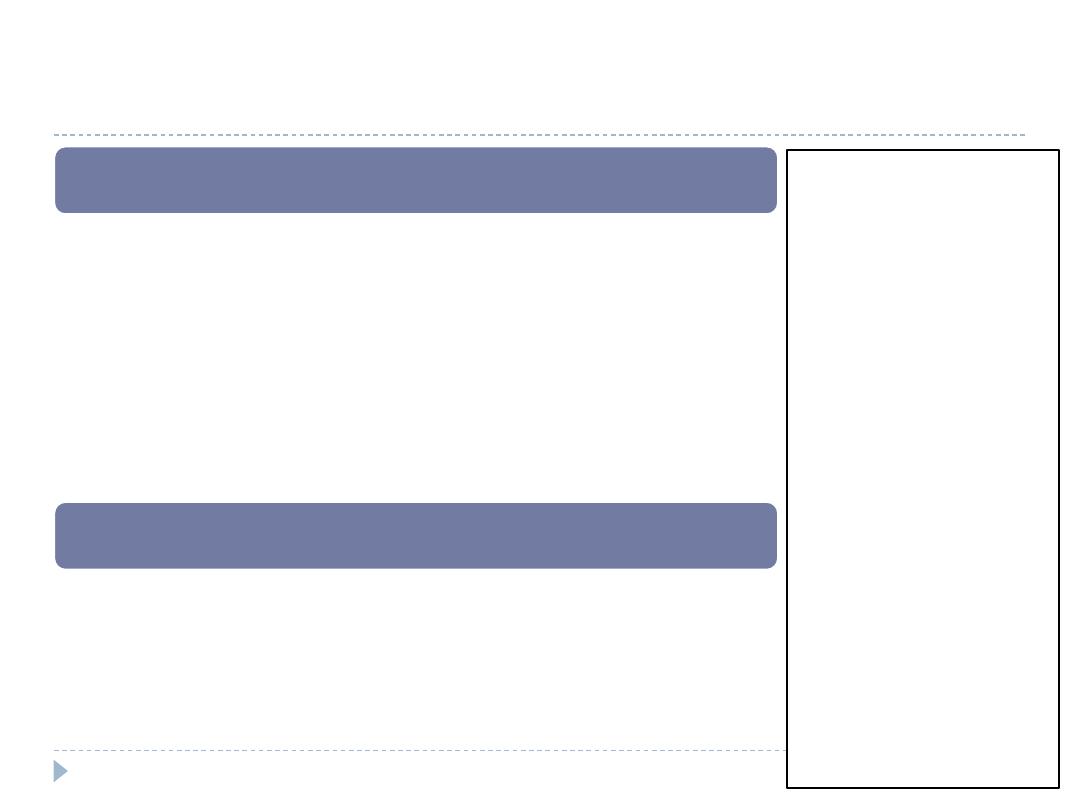

Comparison of treatments for the thyrotoxicosis of

Graves’ disease

Management

Common

indications

Contraindications

Disadvantages/

complications

Antithyroid

drugs

Subtotal

thyroidectomy

Radio-iodine

First episode

in patients

< 40 yrs

Large goitre

Poor drug compliance,

especially in young patients

Recurrent thyrotoxicosis

after course of antithyroid

drugs in young patients

First episode

in patients

< 40 yrs

Comparison of treatments for the thyrotoxicosis of

Graves’ disease

Management

Common

indications

Contraindications

Disadvantages/

complications

Antithyroid

drugs

Subtotal

thyroidectomy

Radio-iodine

Breastfeeding

(propylthiouracil

suitable)

Previous thyroid

surgery

Dependence upon

voice, e.g. opera

singer, lecturer

Pregnancy or planned pregnancy

within 6 months of treatment

Active Graves’ ophthalmopathy

Comparison of treatments for the thyrotoxicosis of

Graves’ disease

Management

Common

indications

Contraindications

Disadvantages/

complications

Antithyroid

drugs

Subtotal

thyroidectomy

Radio-iodine

Hypersensitivity rash 2%

Agranulocytosis 0.2%

> 50% relapse rate usually within 2 years of stopping drug

Hypothyroidism (∼25%)

Transient hypocalcaemia (10%)

Permanent hypoparathyroidism (1%)

Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy1 (1%)

Hypothyroidism, ∼40% in first year, 80% after 15 years

Most likely treatment to result in exacerbation of

ophthalmopathy

Thyrotoxicosis in pregnancy

The coexistence of pregnancy and thyrotoxicosis is unusual, as

anovulatory cycles are common in thyrotoxic patients and

autoimmune disease tends to remit during pregnancy, when

the maternal immune response is suppressed.

Thyroid function tests must be interpreted in the knowledge

that thyroid-binding globulin, and hence total T

4

and T

3

levels,

are increased in pregnancy and that TSH normal ranges may

be lower

A fully suppressed TSH with elevated free thyroid hormone

levels indicates thyrotoxicosis.

The thyrotoxicosis is almost always caused by Graves' disease.

Both mother and fetus must be considered, since maternal

thyroid hormones, TRAb and antithyroid drugs can all cross the

placenta to some degree, exposing the fetus to the risks of

thyrotoxicosis, iatrogenic hypothyroidism and goitre.

Thyrotoxicosis should be treated with antithyroid drugs which

cross the placenta and also treat the fetus, whose thyroid

gland is exposed to the action of maternal TRAb.

Propylthiouracil may be preferable to carbimazole since the

latter might be associated with a skin defect in the child,

known as aplasia cutis.

In order to avoid fetal hypothyroidism and goitre, it is

important to use the smallest dose of antithyroid drug

(optimally less than 150 mg propylthiouracil per day) that will

maintain maternal (and presumably fetal) free T

4

, T

3

and TSH

within their respective normal ranges.

After delivery, if antithyroid drug is required and the patient

wishes to breastfeed, then propylthiouracil is the drug of

choice, as it is excreted in the milk to a much lesser extent

than carbimazole.

If subtotal thyroidectomy is necessary because of poor

drug compliance or drug hypersensitivity, it is most safely

performed in the second trimester.

Radioactive iodine is absolutely contraindicated, as it

invariably induces fetal hypothyroidism.

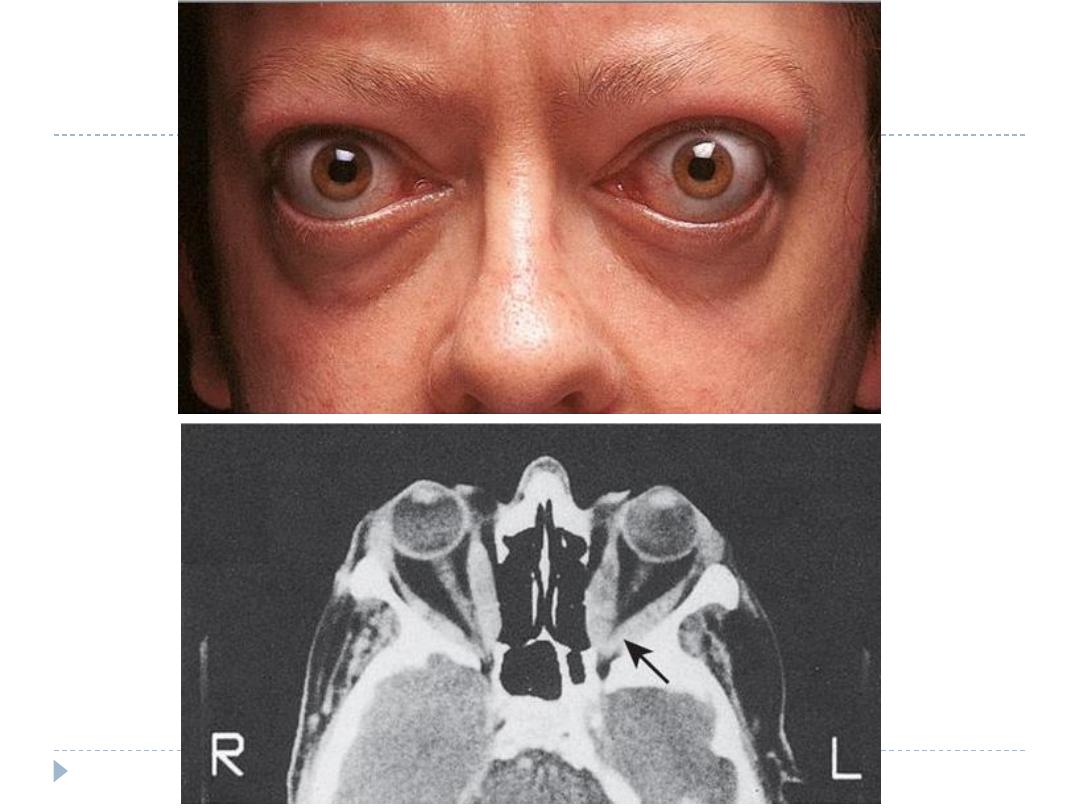

Graves' ophthalmopathy

This condition is immunologically mediated, but the autoantigen has not

been identified.

Within the orbit (and the dermis) there is cytokine-mediated proliferation

of fibroblasts which secrete hydrophilic glycosaminoglycans.

The resulting increase in interstitial fluid content, combined with a chronic

inflammatory cell infiltrate, causes marked swelling and ultimately fibrosis

of the extraocular muscles and a rise in retrobulbar pressure.

The eye is displaced forwards (proptosis, exophthalmos) and in severe

cases there is optic nerve compression.

The majority of patients require no treatment other than reassurance.

Methylcellulose eye drops and gel counter the gritty discomfort of dry

eyes, and tinted glasses or side shields attached to spectacle frames reduce

the excessive lacrimation triggered by sun or wind.

Severe inflammatory episodes are treated with glucocorticoids (e.g. daily

oral prednisolone or pulsed i.v. methylprednisolone) and sometimes orbital

irradiation.

Loss of visual acuity is an indication for urgent surgical decompression of

the orbit. In 'burnt out' disease, surgery to the eyelids and/or ocular

muscles may improve conjunctival exposure, cosmetic appearance and

diplopia.

Pretibial myedema

This infiltrative dermopathy occurs in fewer than 10% of

patients with Graves’ disease and has similar pathological

features as occur in the orbit.

It takes the form of raised pink-coloured or purplish

plaques on the anterior aspect of the leg, extending on to

the dorsum of the foot.

The lesions may be itchy and the skin may have a ‘peau

d’orange’ appearance with growth of coarse hair; less

commonly, the face and arms are affected.

Treatment is rarely required, but in severe cases topical

glucocorticoids may be helpful.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is characterised by destructive

lymphoid infiltration of the thyroid, ultimately leading to a

varying degree of fibrosis and thyroid enlargement.

There is an increased risk of thyroid lymphoma, although this

is exceedingly rare.

Many present with a small or moderately sized diffuse goitre,

which is characteristically firm or rubbery in consistency.

The goitre may be soft, however, and impossible to

differentiate from simple goitre by palpation alone.

Around 25% of patients are hypothyroid at presentation. In the

remainder, serum T4 is normal and TSH normal or raised, but

these patients are at risk of developing overt hypothyroidism

in future years.

Antithyroid peroxidase antibodies are present in the serum in

more than 90% of patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. In

those under the age of 20 years, antinuclear factor (ANF) may

also be positive.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

Levothyroxine therapy is indicated as treatment for

hypothyroidism, and also to shrink an associated goitre.

In this context, the dose of thyroxine should be sufficient

to suppress serum TSH to low but detectable levels.

Transient thyroiditis

Subacute (de Quervain’s) thyroiditis

In its classical painful form, subacute thyroiditis is a transient

inflammation of the thyroid gland occurring after infection

with Coxsackie, mumps or adenoviruses.

There is pain in the region of the thyroid that may radiate to

the angle of the jaw and the ears, and is made worse by

swallowing, coughing and movement of the neck.

The thyroid is usually palpably enlarged and tender. Systemic

upset is common.

Affected patients are usually females aged 20–40 years.

Painless transient thyroiditis can also occur after viral infection

and in patients with underlying autoimmune disease.

The condition can also be precipitated by drugs, including

interferon-α and lithium.

Irrespective of the clinical presentation, inflammation in the thyroid

gland occurs and is associated with release of colloid and stored

thyroid hormones, but also with damage to follicular cells and

impaired synthesis of new thyroid hormones.

As a result, T4 and T3 levels are raised for 4–6 weeks until the pre-

formed colloid is depleted.

Thereafter, there is usually a period of hypothyroidism of variable

severity before the follicular cells recover and normal thyroid

function is restored within 4–6 months

In the thyrotoxic phase, the iodine uptake is low, because the

damaged follicular cells are unable to trap iodine and because TSH

secretion is suppressed.

Low-titre thyroid autoantibodies appear transiently in the serum,

and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is usually raised.

High-titre autoantibodies suggest an underlying autoimmune

pathology and greater risk of recurrence and ultimate progression to

hypothyroidism.

The pain and systemic upset usually respond to simple measures

such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Occasionally, however, it may be necessary to prescribe

prednisolone 40 mg daily for 3–4 weeks.

The thyrotoxicosis is mild and treatment with a β-blocker is usually

adequate.

Antithyroid drugs are of no benefit because thyroid hormone

synthesis is impaired rather than enhanced.

Careful monitoring of thyroid function and symptoms is required so

that

levothyroxine can be prescribed temporarily in the hypothyroid

phase.

Care must be taken to identify patients presenting with

hypothyroidism who are in the later stages of a transient thyroiditis,

since they are unlikely to require life-long levothyroxine therapy

Post-partum thyroiditis

The maternal immune response, which is modified during pregnancy to

allow survival of the fetus, is enhanced after delivery and may unmask

previously unrecognised subclinical autoimmune thyroid disease.

Surveys have shown that transient biochemical disturbances of thyroid

function occur in 5–10% of women within 6 months of delivery

Those affected are likely to have anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies in the

serum in early pregnancy.

Symptoms of thyroid dysfunction are rare and there is no association

between postnatal depression and abnormal thyroid function tests.

However, symptomatic thyrotoxicosis presenting for the first time within 12

months of childbirth is likely to be due to post-partum thyroiditis and the

diagnosis is confirmed by a negligible radio-isotope uptake. The clinical

course and treatment are similar to those of painless subacute thyroiditis

Postpartum thyroiditis tends to recur after subsequent pregnancies, and

eventually patients progress over a period of years to permanent

hypothyroidism.

Iodine-associated thyroid disease

Thyroid enlargement is extremely common in certain

mountainous parts of the world, such as the Andes, the

Himalayas and central Africa, where there is dietary

iodine deficiency (endemic goitre). Most patients are

euthyroid with normal or raised TSH levels, although

hypothyroidism can occur with severe iodine deficiency.

Iodine supplementation programmes have abolished this

condition in most developed countries.

Iodine-induced thyroid dysfunction

Iodine has complex effects on thyroid function.

Very high concentrations of iodine inhibit thyroid hormone release and this

forms the rationale for iodine treatment of thyroid storm and prior to

thyroid surgery for thyrotoxicosis

Iodine administration initially enhances, but then inhibits, iodination of

tyrosine and thyroid hormone synthesis

The resulting effect of iodine on thyroid function varies according to

whether the patient has an iodine-deficient diet or underlying thyroid

disease.

In iodine-deficient parts of the world, transient thyrotoxicosis may be

precipitated by prophylactic iodinisation programmes.

In iodine-sufficient areas, thyrotoxicosis can be precipitated by

radiographic contrast medium or expectorants in individuals who have

underlying thyroid disease predisposing to thyrotoxicosis, such as

multinodular goitre or Graves’ disease in remission.

Induction of thyrotoxicosis by iodine is called the Jod–Basedow effect.

Chronic excess iodine administration can, however, result in

hypothyroidism. Increased iodine within the thyroid gland down-regulates

iodine trapping, so that uptake is low in all circumstances.

Amiodarone

The anti-arrhythmic agent amiodarone has a structure

that is analogous to that of T4 and contains huge

amounts of iodine; a 200 mg dose contains 75 mg iodine,

compared with a daily dietary requirement of just 125 µg.

Amiodarone also has a cytotoxic effect on thyroid

follicular cells and inhibits conversion of T4 to T3.

Most patients receiving amiodarone have normal thyroid

function, but up to 20% develop hypothyroidism or

thyrotoxicosis and so thyroid function should be

monitored regularly.

The ratio of T4:T3 is elevated and TSH provides the best

indicator of thyroid function.

Amiodarone

The thyrotoxicosis can be classified as either:

type I: iodine-induced excess thyroid hormone synthesis in patients with an

underlying thyroid disorder, such as nodular goitre or latent Graves’ disease

type II: thyroiditis due to a direct cytotoxic effect if amiodarone administration

results in a transient thyrotoxicosis.

Antithyroid drugs may be effective in patients with the type I form, but are

ineffective in type II thyrotoxicosis. Prednisolone is beneficial in the type II

form.

A pragmatic approach is to commence combination therapy with an

antithyroid drug and glucocorticoid in patients with significant

thyrotoxicosis.

A rapid response (within 1–2 weeks) usually indicates a type II picture and

permits withdrawal of the antithyroid therapy; a slower response suggests

a type I picture, when antithyroid drugs may be continued and

prednisolone withdrawn.

If the cardiac state allows, amiodarone should be discontinued, but it has a

long half-life (50–60 days) and so its effects are long-lasting.

To minimise the risk of type I thyrotoxicosis, thyroid function should be

measured in all patients prior to commencement of amiodarone therapy,

and amiodarone should be avoided if TSH is suppressed.

Hypothyroidism should be treated with levothyroxine,

which can be given while amiodarone is continued.