Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABMLecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

2016

learning-topics

Kidney andurinary tract disease

Each kidney 11–14 cm in length in healthy adults; located retroperitoneally on either side of the aorta and IVC between the 12th thoracic and 3rd lumbar vertebra .The right is a few centimetres lower because the liver above. Both rise and descend several centimetres with respiration. The kidneys have a rich blood supply ,receive 20–25% of cardiac output , play a central role in excretion of metabolic breakdown products, including ammonia, urea and creatinine from protein, and uric acid from nucleic acids, drugs and toxins. They also regulate fluid and electrolyte balance. This is achieved by making large volumes of an ultrafiltrate of plasma (120 mL/min, 170 L/day) at the glomerulus, and selectively reabsorbing components of this ultrafiltrate at points along the nephron.

They regulate acid–base homeostasis, calcium and phosphate homeostasis, vitamin D metabolism and production of red blood cells. They are important in regulating blood pressure.

Renin is secreted from the juxtaglomerular apparatus in response to reduced afferent arteriolar pressure, stimulation of sympathetic nerves, and changes in sodium content of fluid in the distal tubule at the macula densa, and is the first step in the generation of angiotensin II and aldosterone release, which in turn regulate systemic vasoconstriction and extracellular volume. The efferent arteriole, leading from the glomerulus, supplies the distal nephron and medulla in a ‘portal’ circulation .

Under normal circumstances, more than 99% of the 170 litres of glomerular filtrate that is produced each day is reabsorbed in the tubules. The remainder passes through the collecting ducts ,drains into the renal pelvis and ureters.

Healthy kidney contain approximately 1 million nephrons.

The glomerulus comprises a tightly packed loop of capillaries supplied by an afferent arteriole and drained by an efferent arteriole. It is surrounded by a cup-shaped extension of the proximal tubule termed Bowman’s capsule, comprised of epithelial cells.

Blood that enters the glomerulus undergoes ultrafiltration

across the glomerular basement membrane (GBM),

which is formed by fusion of the basement membranes

of tubular epithelial and vascular endothelial cells .

The glomerular capillary endothelial cells contain pores (fenestrae), through which circulating molecules can pass to reach the underlying GBM.

Glomerular epithelial cells (podocytes) have multiple

long foot processes which interdigitate with those of the

adjacent epithelial cells . Mesangial cells lie in

the central region of the glomerulus. They have contractile

properties similar to those of vascular smooth muscle

cells but also have macrophage-like properties. Under normal circumstances, the glomerulus is impermeable to proteins the size of albumin (67 kDa) while proteins of 20 kDa or smaller and positively charged are filtered

freely. Very little lipid is filtered by the glomerulus.

Filtration pressure at glomerulus is normally maintained at a constant level, in the face of wide variations in systemic blood pressure and cardiac output, by alterations in muscle tone within the afferent and efferent arterioles. This is known as autoregulation. When there is a reduction in renal perfusion pressure, renin is released by juxtaglomerular apparatus, cleaves angiotensinogen to release angiotensin I, further cleaved by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) to produce angiotensin II . This restores glomerular perfusion pressure by vasoconstriction of the efferent arterioles and by inducing systemic vasoconstriction to increase blood pressure and thus renal perfusion pressure. In the longer term, angiotensin II increases plasma volume by stimulating aldosterone, which enhances sodium reabsorption by the renal tubules .

Renal tubules, loop of Henle and collecting ducts

The proximal renal tubule, loop of Henle, distal renaltubule and collecting ducts are responsible for reabsorption of water, electrolytes and other solutes, as well as regulating acid–base balance .They also play a key role in regulating calcium homeostasis by converting 25-hydroxyvitamin D to the active metabolite 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D . Fibroblast-like cells that lie in the interstitium of the renal cortex are responsible for production of erythropoietin, which in turn is required for production of red blood cells. A naemia and hypoxia increase production of erythropoietin, whereas polycythaemia and hyperoxia inhibit it.

The bladder : Sympathetic nerves arising from T10– L2 cause relaxation of the detrusor muscle and contraction of the bladder neck (α-adrenoceptors), thereby preventing release of urine from the bladder. Conversely, parasympathetic nerves arising from S2–4 stimulate detrusor contraction, promoting micturition. Afferent sensory impulses pass to the cerebral cortex, from where reflex-increased sphincter tone and suppression of detrusor contraction inhibit micturition until it is appropriate.

At approximately 75% bladder capacity, there is a desire to void. Voluntary control is now exerted over the desire to void, which disappears temporarily. These actions are coordinated by the pontine micturition centre.

The prostate gland

The prostate gland is situated at the base of the bladder,surrounding the proximal urethra. Exocrine glands within the prostate produce fluid, which comprises about 20% of the volume of ejaculated seminal fluid and is rich in zinc and proteolytic enzymes. The remainder of the ejaculate is formed in the seminal vesicles and bulbo-urethral glands, with spermatozoa arising from the testes. Smooth muscle fibres within the prostate, under sympathetic control, play a role in controlling urine flow through the bulbar urethra, and also contract at orgasm to move seminal fluid through ejaculatory ducts into the bulbar urethra (emission). Contraction of the bulbocavernosus muscle (via a spinal muscle reflex) then ejaculates the semen out of the urethra.

The penis

Blood flow into the corpus cavernosum of the penis iscontrolled by sympathetic nerves from the thoracolumbar

plexus, which maintain smooth muscle contraction.

In response to afferent input from the glans penis and

from higher centres, pelvic splanchnic parasympathetic

nerves actively relax the cavernosal smooth muscle via

neurotransmitters such as nitric oxide, acetylcholine,

vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and prostacyclin,

with consequent dilatation of the lacunar space. At the same time, draining venules are compressed, trapping blood in the lacunar space with consequent elevation of pressure and erection (tumescence) of the penis.

INVESTIGATION OF RENAL AND URINARY TRACT Glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

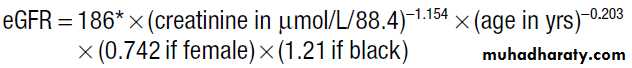

120 ± 25 mL/ min/1.73 m2. measured directly by injecting and measuring the clearance of compounds such as inulin or radiolabelled ethylenediaminetetracetic acid, which are completely filtered and not secreted or reabsorbed . Instead, GFR is usually indirectly by measuring serum creatinine, which is produced by muscle at a constant rate, is almost completely filtered, and is not reabsorbed. Although creatinine is secreted to a small degree by the proximal tubule, this is only usually significant in terms of GFR estimation in severe renal impairment. MDRD equation, accepted standard for assessing estimated GFR (eGFR).A potentially more accurate assessment of GFR can

be obtained by collection of a 24-hour urine sample andrelating serum to urinary creatinine excretion .

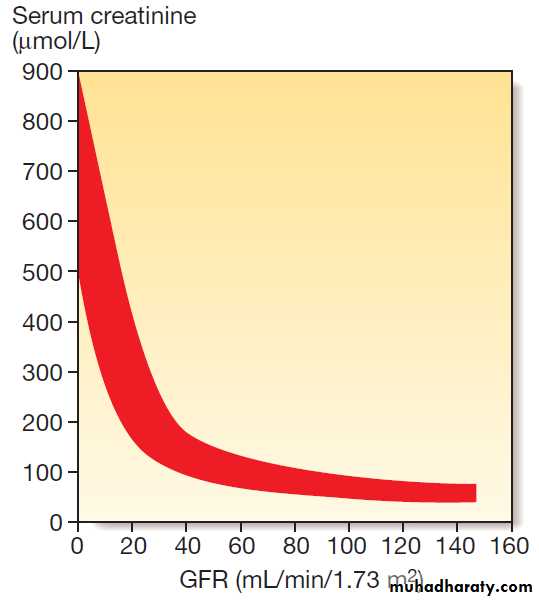

Limitations of eGFR

• least reliable at extremes of body composition (malnourished, amputees)

• Creatinine level must be stable over days; eGFR is not valid in assessing acute kidney injury

• In the elderly, who constitute the majority of those with low eGFR, there is controversy about categorising people as having CKD on the basis of eGFR alone, particularly at stage 3A, since there is little evidence of adverse outcomes when eGFR is > 50 unless there is also proteinuria

• eGFR is not valid in under-18s or during pregnancy

Serum creatinine and the glomerular filtration rate

(GFR). The inverse reciprocal relationship between GFR and serum creatinine is shown for a group of patients with renal disease. The red band indicates the range of values obtained. Note that some individuals have a GFR as low as 30–40 mL/min without serum creatinine rising outof the reference range.

Stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Urinalysis

Screening for blood, protein, glucose, ketones, nitrates and leucocytes , pH and osmolality ,can be achieved by dipstick testing .Urine microscopy can detect erythrocytes, dysmorphic erythrocytes, which suggest nephritis; red cell casts, indicative of glomerular disease; and crystals. It should be noted that calcium oxalate and urate crystals can be found in normal urine that has been left to stand. White cell casts , strongly suggestive of pyelonephritis.

Urine pH ,assessment of renal tubular acidosis . 24-hour Urine collection to measure calcium, oxalate and urate, in patients with recurrent renal stone disease . Proteinuria quantified by protein/ creatinine ratio on spot urine. Dynamic tests of tubular function, concentrating ability

Blood tests

HaematologyA normochromic normocytic anaemia is common in

CKD ,due deficiency of erythropoietin and bone marrow suppression secondary to retained toxins.Other causes of anaemia include iron deficiency from urinary tract bleeding, and haemolytic anaemia secondary to disorders such as haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

Neutrophilia and raised ESR in vasculitis or sepsis; lymphopenia and raised ESR in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); fragmented red cells in HUS and TTP.

Biochemistry

Serum levels of creatinine may be raised, reflecting reduced GFR although serum creatinine values can remain within the reference range in patients with reduced muscle mass, even when the GFR has fallen by more than 50%. Serum levels of urea are often increased in kidney disease but this analyte has limited value as a measure of GFR since levels increase with protein intake, following gastrointestinal haemorrhage and in catabolic states.Conversely, urea levels may be reduced liver failure and in malnourished, independently of renal function. Serum calcium tends to be reduced and phosphate increased in CKD, in association with high parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels caused by reduced production of 1,25(OH)2D by the kidney (secondary hyperparathyroidism).

In some patients, this may be accompanied by raised serum alkaline phosphatase levels, which are indicative of renal osteodystrophy. Raised glucose and HbA1c levels in diabetes mellitus and raised levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) in sepsis and vasculitis.

Immunology

Antinuclear antibodies, antibodies to extractable nuclear

antigens and anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies may

be detected in patients with renal disease secondary to

SLE . Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) may be detected in patients with glomerulonephritis secondary to systemic vasculitis, as may antibodies to GBM in patients with Goodpasture’s syndrome and low levels of complement in SLE, systemic vasculitis and HUS.

Imaging

Ultrasound

A valuable non-invasive technique that is indicated to assess renal size and to investigate patients who are suspected of having obstruction of the urinary tract or renal tumours, cysts or stones, to provide images of the prostate gland and bladder, and to estimate the completeness of emptying in patients with suspected bladder outflow obstruction. May show increased density of the renal cortex with loss of distinction between cortex

and medulla, which is characteristic of CKD.

Doppler can be used to study blood flow in extrarenal

and larger intrarenal vessels. High peak velocities can also occur in severe renal artery stenosis.

Computed tomography urography (CTU)

Used to evaluate cysts and mass, gives more information than IVU but entails a larger radiation dose. Contrast enhancement is particularly useful for differentiating benign from malignant lesions . CT without contrast gives clear definition of retroperitoneal anatomy regardless of obesity. Non-contrast CT of kidneys, ureters and bladder (CTKUB) is the method of choice for demonstrating stones.Computed tomography and angiography

computed tomography, following an injection of contrast medium, to obtain images of the renal vasculature. It produces high-quality images of the main renal vessels. Drawbacks include the fact that relatively large doses of contrast medium are required, which can cause renal dysfunction, and that the radiation dose is significant .

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

offers excellent resolution . It is very useful for local staging of prostate, bladder and penile cancers. MR angiography alternative to CT-angiography for imaging renal vessels.Renal arteriography

The main indication is to investigate renal artery stenosis or haemorrhage. Can often be combined with therapeutic balloon dilatation or stenting of the renal artery and can be used to occlude bleeding vessels and arteriovenous fistulae by the insertion of thin platinum wires (coils).

Intravenous urography (IVU)

Involves taking serial plain X-rays immediately before and after an intravenous injection of contrast medium. It has largely been replaced by ultrasound, CTKUB and CTU .

The disadvantages are the need for an injection, dependence on adequate renal function, and exposure to irradiation and contrast medium .

Pyelography

Direct injection of contrast medium into the collecting system from above or below. Antegrade pyelography

requires the insertion of a fine needle into the

pelvicalyceal system under ultrasound or radiographic

control. This approach is much more difficult and hazardous

in a non-obstructed kidney. In the presence of obstruction, percutaneous nephrostomy drainage can be established, and often stents can be passed through any obstruction. Retrograde pyelography can be performed by inserting catheters into the ureteric orifices at cystoscopy.

Radionuclide studies

These are functional studies requiring the injection of

gamma ray-emitting radiopharmaceuticals that are

taken up and excreted by the kidney, a process that can

be monitored by an external gamma camera, can provide valuable information about the perfusion of each kidney but is not a reliable for identifying renal artery stenosis. Renal biopsy

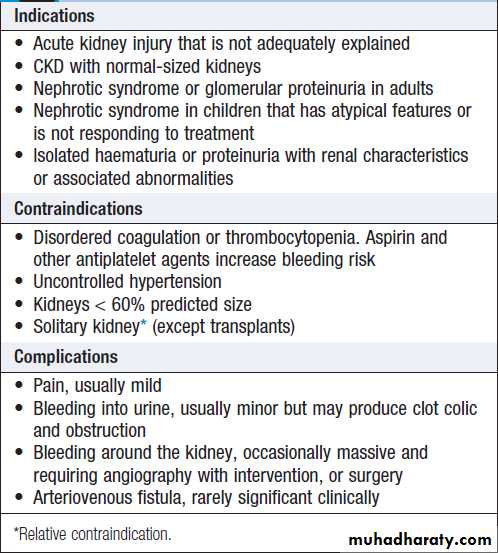

Used to establish the nature and extent of renal disease in order to judge the prognosis and need for treatment . Performed transcutaneously with ultrasound or contrast radiography guidance to ensure accurate needle placement into a renal pole. Light microscopy, electron microscopy and immunohistological assessment of the specimen may all be required.

Renal biopsy

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN RENAL AND URINARY TRACT DISEASEDysuria

Dysuria refers to painful urination, often described as

burning, scalding or stinging, and commonly accompanied

by suprapubic pain. It is often associated with frequency of micturition and a feeling of incomplete emptying of the bladder. By far the most common cause is urinary tract infection.

Other diagnoses in patients with dysuria include sexually transmitted infections and bladder stones .

Loin pain

Loin pain is often caused by musculoskeletal disease butcan be a manifestation of renal tract disease; in the latter

case, it may arise from renal stones, ureteric stones, renal

tumours, acute pyelonephritis and urinary tract obstruction.

Acute loin pain radiating anteriorly and often to

the groin is termed renal colic. When combined with

haematuria, this is typical of ureteric obstruction due to

calculi . When loin pain is precipitated by a large

fluid intake (Dietl’s crisis), upper urinary tract obstruction

caused by a congenital abnormality of the pelviureteric

junction (PUJ) is often responsible.

Oliguria/anuria

Oliguria is present when < 300 mL urine is passed per day, whereas anuria exist when < 50 mL urine is passed per Oliguria and anuria may be caused by a reduction in urine production, as in pre-renal acute kidney injury. Obstruction of the renal tract can also produce oliguria and anuria, but to do so, obstruction must be complete and occur distal to the bladder neck, be bilateral, or be unilateral on the side of a single functioning kidney. The presence of pain that is exacerbated by a fluid load suggests an acute obstruction of the renal tract .

Bladder neck obstruction is associated with lower midline abdominal discomfort due to bladder dilatation, ureteric obstruction presents as loin pain radiating to the groin.

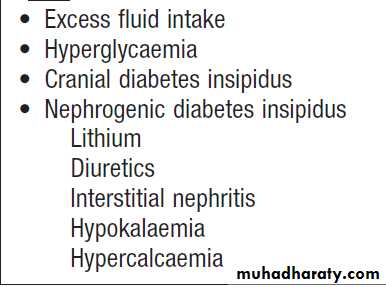

Polyuria

Defined as a urine volume in excess of 3 L/ day.Nocturia

Defined as waking up at night to void urine. It may be a consequence of polyuria , increased fluid intake or diuretic use in the late evening. Nocturia also occurs in CKD, and in prostatic enlargement when it is associated with poor stream, hesitancy, incomplete bladder emptying, terminal dribbling and urinary frequency due to partial urethral obstruction . Nocturia may also occur in sleep disturbance without functional abnormalities.

Frequency

Micturition more often than a patient’s expectations. It may be a consequence of polyuria, in patients with dysuria and prostatic diseases, when the urine volume is low.

Causes of polyuria

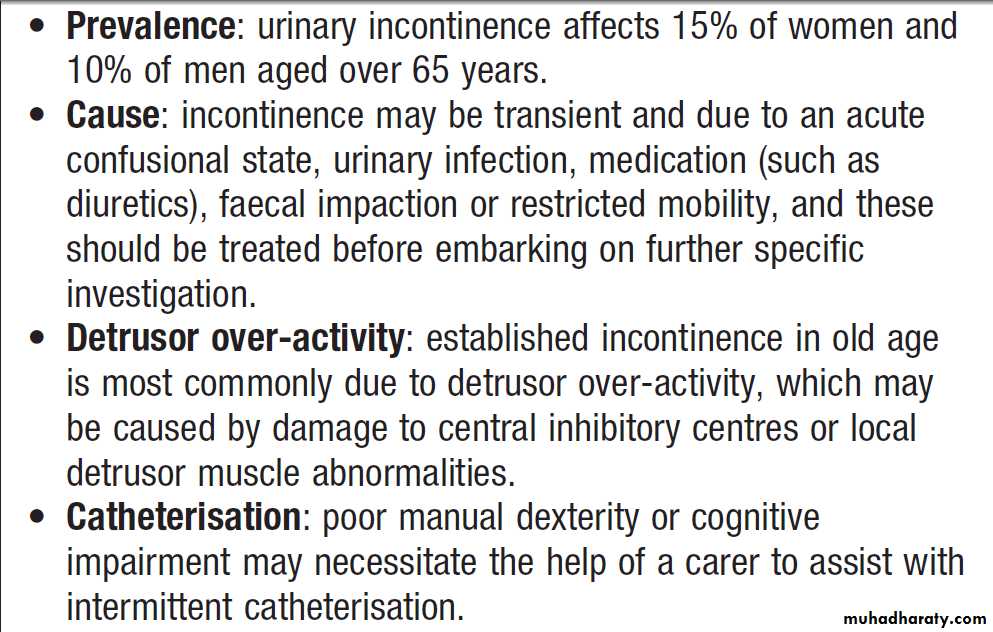

Urinary incontinenceInvoluntary leakage of urine. It may occur in patients with a normal urinary tract, as the result of dementia or poor mobility, or transiently during an acute illness or hospitalisation, especially in older people. Diuretics, alcohol and caffeine may worsen incontinence.

Stress incontinence

This occurs because passive bladder pressure exceeds

the urethral pressure, due to either poor pelvic floor

support or a weak urethral sphincter. Is very common in women and seen most frequently following childbirth.

It is rare in men and usually follows surgery to the

prostate. The presentation is with incontinence during coughing, sneezing or exertion.

Urge incontinence

This usually occurs because of detrusor overactivity,

which produces an increased bladder pressure that

overcomes the urethral sphincter. Is usually idiopathic, neurological such as spina bifida or multiple sclerosis .

It is also seen in men with lower urinary tract obstruction.

Continual incontinence

This is suggestive of a fistula, usually between the

bladder and vagina (vesicovaginal), or the ureter and vagina (ureterovaginal). It is most common following

gynaecological surgery ,gynaecological malignancy or post-radiotherapy. Continual incontinence may also

be seen in infants with congenital ectopic ureters. Occasionally, stress incontinence is so severe that the patient leaks continuously.

Overflow incontinence

This occurs with chronically overdistended bladder. It is most commonly seen with benign prostatic enlargement or bladder neck obstruction , or failure of the detrusor muscle (atonic bladder). The latter may be idiopathic but more commonly is the result of damage to the pelvic nerves, either from surgery (commonly, hysterectomy or rectal excision), trauma or infection, or from compression of the cauda equina by disc prolapse, trauma or tumour.Post-micturition dribble

This is very common in men, even in young. It is due to a small amount of urine becoming trapped in the U-bend of the bulbar urethra, which leaks out when the patient moves, pronounced with a urethral diverticulum or urethral stricture.

Incontinence in old age

Investigations

Urinalysis, culture, Ultrasound. Urine flow rates and full urodynamic assessment by cystometrography. An IVU should be performed in patients with continual incontinence. MRI is indicated when a urethral diverticulum is suspected.

Management

stress incontinence respond physiotherapy. The mainstay of treatment for urge incontinence is bladder retraining, which involves teaching patients to hold more urine voluntarily in their bladder, assisted by anticholinergic medication. Surgery may be required in patients who have severe incontinence despite conservative treatment.

The treatment of fistula, bladder obstruction is surgical. Incontinence secondary to neurological diseases

can be treated by intermittent self-catheterisation.

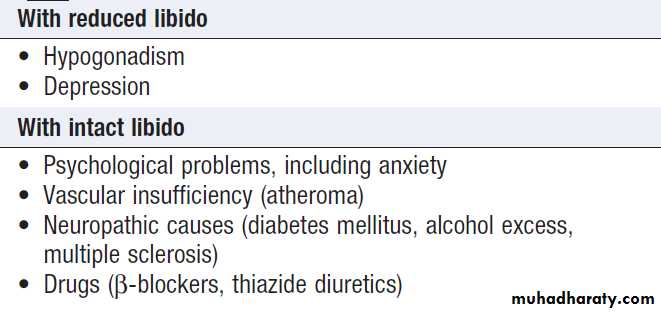

Erectile dysfunction

Vascular, neuropathic and psychological causes are mostcommon. If the patient has erections on wakening,

vascular and neuropathic causes are much less likely

and a psychological cause should be suspected.

Investigations

Glucose, prolactin, testosterone, LH and FSH. Nocturnal

tumescence monitoring (using a plethysmograph placed

around the shaft of the penis overnight) to establish

whether blood supply and nerve function are sufficient

to allow erections to occur during sleep; intracavernosal

injection of PG E1 to test the adequacy of blood supply; internal pudendal artery angiography; and tests of autonomic and peripheral sensory nerve conduction.

Causes of erectile dysfunction

ManagementFirst-line therapy is oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil, which elevate cGMP levels in the corpus cavernosum, causing vasodilatation and penile erection. Co-administration of these drugs with trinitrate, is contraindicated because of the risk of severe hypotension , intracavernosal injection or urethral administration of prostaglandin E1; vacuum devices which achieve an erection that is maintained by a tourniquet around the base of the penis; and prosthetic implants, either of a fixed rod or an inflatable reservoir.

Psychotherapy involving the patient and sexual partner

may be helpful. peripheral neuropathy and vascular disease is difficult to treat. If hypogonadism

is detected, it should be managed .

Haematuria

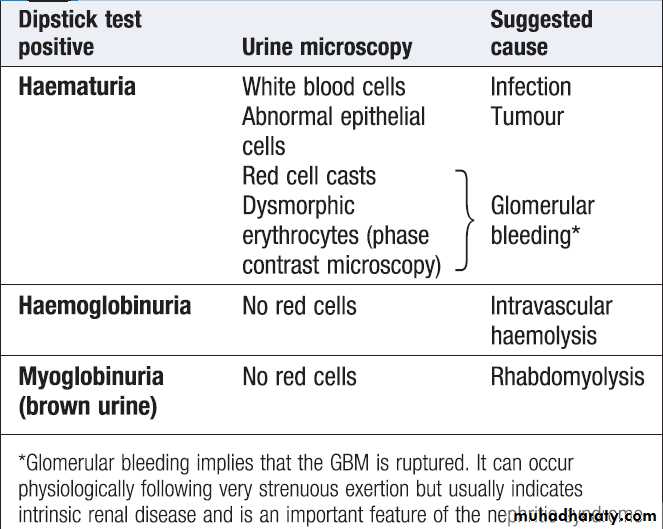

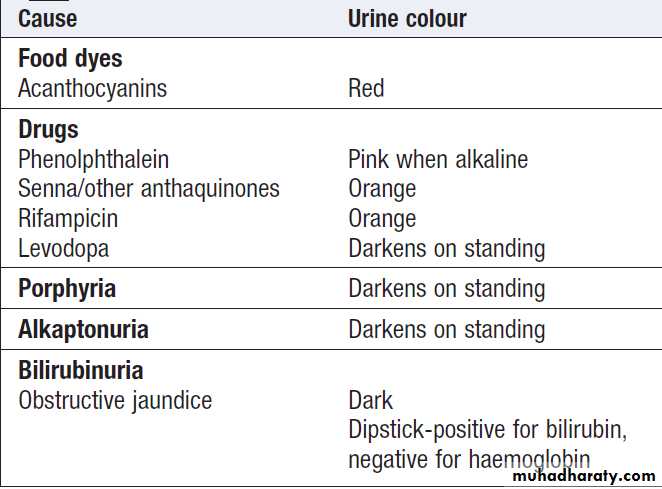

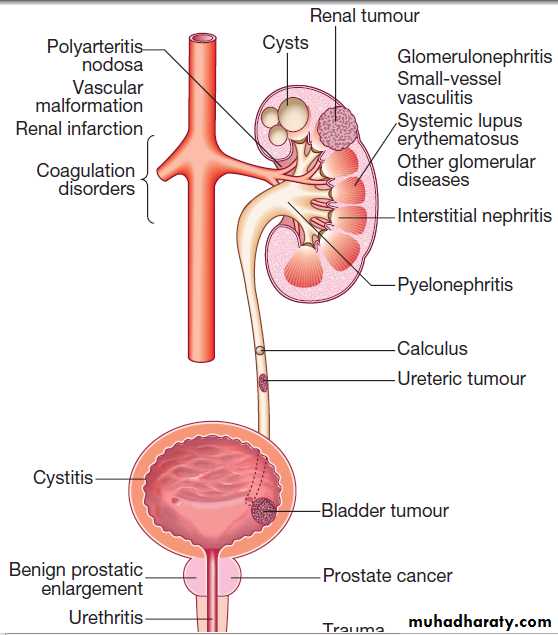

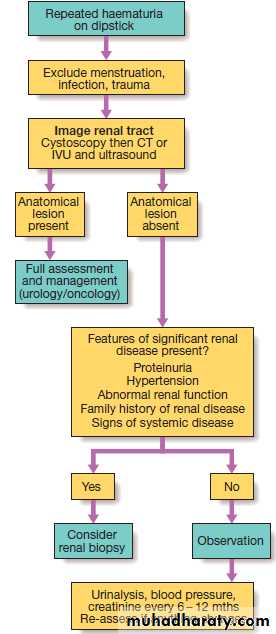

Healthy individuals may have up to 12 500 cells/mL, but the presence of macroscopic haematuria or on dipstick testing (15 000–20 000 cells/mL) is indicative of significant bleeding. First, it is important to confirm the presence of blood cells in the urine by microscopy , since dipstick tests can also be positive in the presence of free haemoglobin or myoglobin. Microscopy confirms the diagnosis ,also helpful in establishing the cause . Positive tests may also occur during menstruation, infection or strenuous exercise. In GN, one or more other features of the ‘nephritic syndrome’ may be present . Other causes are infection and stones. If haematuria occurs with proteinuria , renal biopsy may be indicated.Management should be directed at the underlying cause.

Interpretation of dipstick-positive

haematuriaDipstick-negative dark urine

Causes of haematuria

Investigation of haematuria.

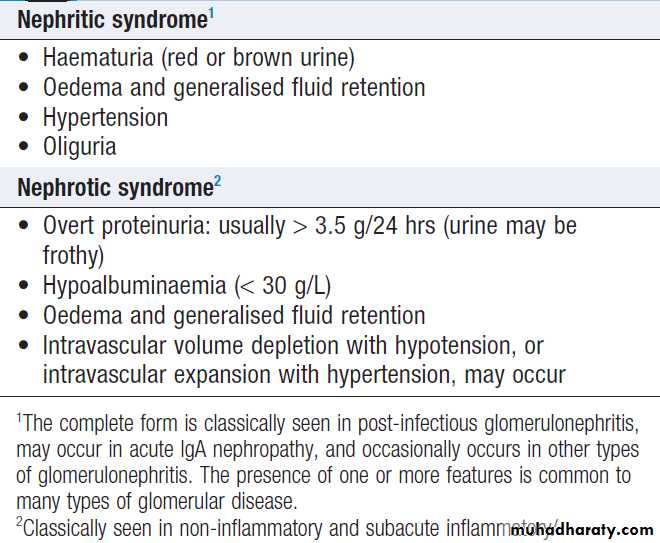

Nephritic and nephrotic syndromesProteinuria and nephrotic syndrome

Whilst moderate amounts of low-molecular-weightprotein pass through the healthy GBM, these proteins

are normally reabsorbed by receptors on tubular cells.

In healthy individuals, less than 150 mg of protein is

excreted in the urine each day. A proportion of this is Tamm–Horsfall protein, secreted by the renal tubules.

The presence of larger amounts of protein is usually

indicative of significant renal disease .

Clinical assessment

Proteinuria is usually asymptomatic and is often picked

up by urinalysis.

Transient proteinuria can occur after vigorous exercise, during fever, in heart failure and urinary tract infection.

Orthostatic proteinuria may arise in the absence of renal disease. This occurs only during the day, in association with an upright posture, and the first morning sample is negative. Typically, less than 1 g protein per day is excreted. Orthostatic proteinuria is regarded as a benign disorder which does not require treatment.

Large amounts of protein make urine froth easily and this may be noticed by the patient.

Very large amounts can cause nephrotic syndrome,

which presents with oedema.

In adults, this predominantly affects the lower limbs but extends to the genitalia and lower abdomen

as it becomes more severe. The upper limbs and face

may be more affected on waking in the morning.

In children, ascites occurs early and oedema is often seen only in the face. Blood volume may be normal, reduced or increased. Renal sodium retention is an early and universal feature . Microalbuminuria refers to the urinary excretion of small amounts of albumin. The consistent presence of albumin in the urine is abnormal and is clinically important in identifying the very early stages of glomerular disease, as occurs in conditions like diabetic nephropathy .

Persistent microalbuminuria has also been associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular mortality but neither the mechanism of proteinuria nor an explanation for this association has been established.

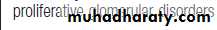

Consequences of the nephrotic syndrome and their management

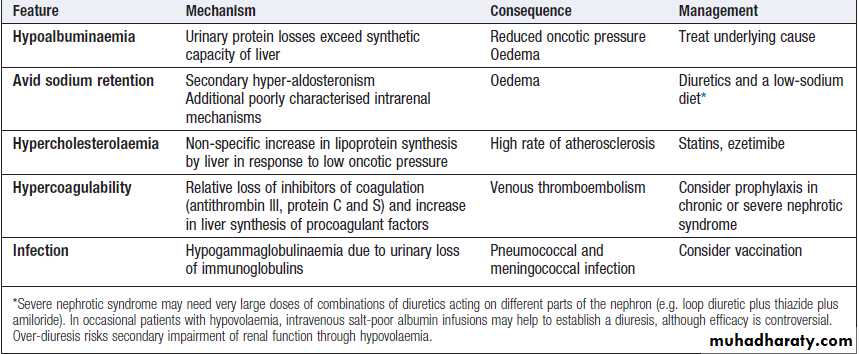

InvestigationsSince quantification by 24-hour urine collection is often inaccurate, the protein : creatinine ratio (PCR) in a spot sample of urine is preferred. It is possible to measure albumin : creatinine ratio (ACR). LMW proteins such as β2-macroglobulin may appear in the urine in >150 mg/day, Large amounts of small proteins in the urine suggest renal tubular damage (tubular proteinuria), rarely exceeds 1.5–2 g/24 hours . When >2 g protein per day is being excreted, glomerular disease is likely and renal biopsy is usually required. A notable exception is in children, when nephrotic syndrome are most commonly caused by minimal change GN and renal biopsy is not usually required unless the patient fails to respond to high-dose corticosteroid therapy.

Free immunoglobulin light chains are filtered freely at the glomerulus and can be identified as ‘Bence Jones protein’ in fresh urine samples.

Bence Jones protein is poorly identified by dipstick tests

and so specific immunodetection methods are required.

This may occur in AL amyloidosis (and in B-cell disorders, but is particularly important as a marker for

myeloma .

Management

Management of proteinuria should be directed at the

underlying cause. This may involve immunosuppressive

therapy in glomerulonephritis and supportive management

for nephrotic syndrome .

Investigation of proteinuria. (ACR = albumin : creatinine

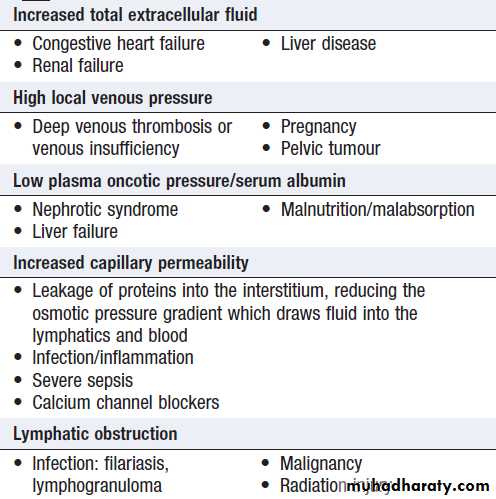

ratio; PCR = protein : creatinine ratio.)Oedema

Oedema is caused by an excessive accumulation offluid within the interstitial space. Clinically, detected by persistence of an indentation in tissue following pressure on the affected area (pitting oedema).

Non-pitting oedema is typical of lymphatic obstruction

and may also occur as the result of excessive matrix

deposition in tissues – for example, in hypothyroidism

or scleroderma . Pitting oedema tends to accumulate in the ankles during the day and improves overnight as the interstitial fluid is reabsorbed.

Clinical assessment

The ankles and lower parts of the leg are typicallyaffected first but oedema can be restricted to the sacrum

in bed-bound patients. With increasing severity, oedema

spreads to affect the upper parts of the legs, the genitalia

and abdomen. Ascites is common and often an earlier

feature in children or young adults, and in liver disease.

Pleural effusions are common and can be a feature of

generalised oedema. Facial oedema on waking is common. Features of intravascular volume depletion (tachycardia, postural hypotension) may occur when oedema is due to decreased oncotic pressure or increased capillary permeability. If oedema is localised – for example, to one ankle but not the other, then venous thrombosis, inflammation or lymphatic disease should be suspected.

Investigations

The cause of oedema is usually apparent from the

history and examination of the cardiovascular system

and abdomen. Blood should be taken for measurement

of urea and electrolytes and serum albumin, and the

urine tested for protein. Further imaging of the liver,

heart or kidneys may be indicated, based on history and

clinical examination. Where ascites or pleural effusions

occur in isolation, aspiration of fluid with measurement

of protein and glucose, and microscopy for cells, will

usually help to clarify the diagnosis in differentiating a

transudate (typical of oedema) from an exudate (more

suggestive of local pathology .

Causes of oedema

Management

Mild oedema usually responds to a thiazide or a lowdose of a loop diuretic, such as furosemide or bumetanide.

In nephrotic syndrome, renal failure and severe

cardiac failure, very large doses of diuretics, sometimes

in combination, may be required to achieve a negative

sodium and fluid balance. In resistant cases, restriction

of sodium intake and fluid intake may be required. Diuretics are not helpful in the treatment of oedema caused by venous or lymphatic obstruction or by increased capillary permeability. Specific causes of oedema, such as venous thrombosis, should be treated.

Hypertension

Hypertension is a very common feature of renal disease.Additionally, the presence of hypertension identifies a

population at risk of developing CKD and current recommendations are that patients on antihypertensive

medication should have renal function checked annually.

Control of hypertension is very important in patients with renal impairment because of its close relationship with further decline of renal function and because of the exaggerated cardiovascular risk associated with CKD.

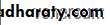

ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY (AKI)

AKI also referred to as acute renal failure, is a suddenand often reversible loss of renal function, which develops

over days or weeks and is usually accompanied by

a reduction in urine volume. Approximately 7% of all

hospitalised patients and 20% of acutely ill patients

develop signs of AKI. In AKI associated with serious infection and multiple organ failure, mortality is 50–70%. Pathophysiology

Three subtypes: ‘prerenal’,when perfusion to the kidney is reduced; ‘renal’,when the primary insult affects the kidney itself; and‘post-renal’, when there is obstruction to urine flow at any point from the tubule to the urethra .In

pre-renal AKI, the kidney becomes damaged as the

result of hypoperfusion, leading to acute tubular necrosis.

Causes of acute kidney injury

Clinical featuresall emergency admissions should have renal function, blood pressure, temperature and pulse checked on arrival and assessment for the likelihood of developing AKI. If a patient is found to have a high serum creatinine, it is important to establish whether this is an acute or acute-on-chronic or a sign of CKD. Anaemia is common in AKI and may occur as the result of blood loss, haemolysis or decreased erythropoiesis. In established AKI, there is an increased risk of bleeding and GI haemorrhage due to the uraemia. Patients with AKI need to be assessed quickly to determine the likely underlying cause. Various criteria have been proposed to classify AKI, guide treatment and provide information regarding prognosis. The most commonly used are the KDIGO and RIFLE criteria.

• Investigation of patients with established acute kidney injury

• Urea , creatinine• Compare to previous results. Chronically abnormal in CKD

• Electrolytes

• If potassium > 6 mmol/L, treat urgently

• Calcium and

• phosphate

• Low calcium and high phosphate may indicate CKD , Calcium low in

• rhabdomyolysis: measure CK, Hypercalcaemia in myeloma

• Albumin

• Low albumin in nephrotic syndrome

• Full blood count

• Clotting screen

• Anaemia may indicate CKD or myeloma , Anaemia and fragmented

• RBC on blood film with raised LDH in thrombotic microangiopathy

• Low platelets and abnormal coagulation in DIC, including in sepsis:

• take blood cultures

• C-reactive protein

• ESR is misleading in renal failure , High CRP may indicate sepsis or inflammatory disease

• Urinalysis

• Marked haematuria suggests GN , tumour of renal tract or

• bleeding disorder . Heavy proteinuria suggests glomerular disease:

• measure PCR or ACR

• Urine microscopy

• Casts or dysmorphic RBC suggest GN .WBC suggest infection

• /interstitial nephritis, Crystals in drug-induced or uric acid

• nephropathy

• Renal ultrasound

• Hydronephrosis ± enlarged bladder in UT obstruction: consider PSA.

• Small kidneys (CKD). Asymmetric kidneys in renovascular or

• developmental disease: consider renal artery imaging

Cultures , blood, urine, sputum.

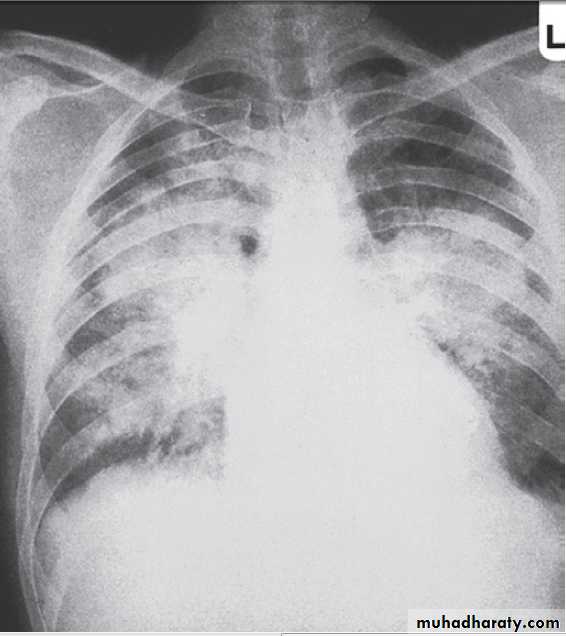

Chest X-ray Pulmonary oedema .

Globular heart in pericardial (uraemic) effusion: perform echocardiogram.

Fibrotic change in systemic inflammatory disease with lung and kidney involvement: request pulmonary function and high-resolution CT

Serology HIV and hepatitis serology is urgent if dialysis is needed

ECG If patient is > 40 yrs or has electrolyte abnormalities or risk of cardiac disease

Investigation of patients with established acute kidney injury - cont'd

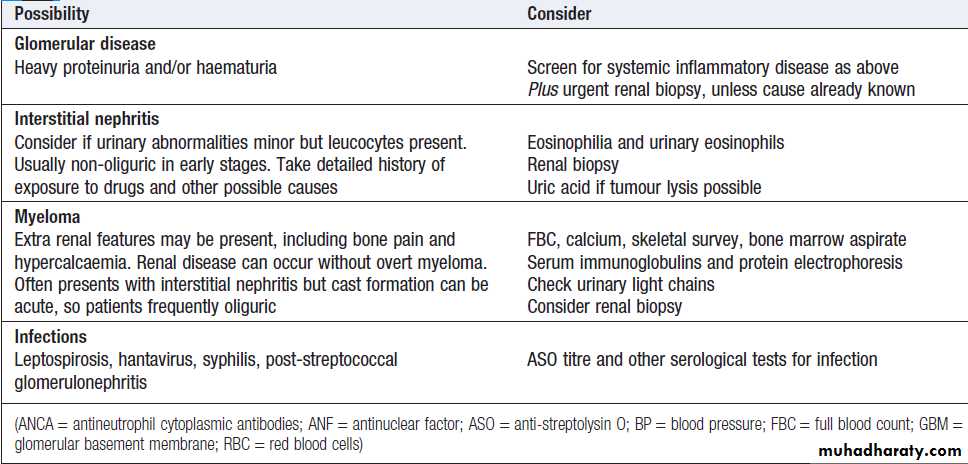

• Clinical features and investigations of specific causes of acute kidney injury

Possibility• consider

Vascular occlusion

Aorta, or renal artery to single kidney;

Pointers include missing pulses, anuria

Urgent arteriography

Doppler ultrasound

Malignant hypertension

BP very high; RBC fragments on blood

film and haemolysis

Examine optic fundi

Check previous BP readings

Scleroderma

Sclerodactyly, other features.

Autoantibodies to extractable nuclear antigens. Imaging

Systemic inflammatory disease

Multi-organ involvement, rash and

evidence of glomerular disease

Differential diagnosis includes infection,

especially endocarditis or TB.

Complement, ANCA, ANF, anti-GBM antibodies,

cryoglobulins and biopsy

Cultures, echocardiogram

Clinical features and investigations of specific causes of acute kidney injury – cont’d

• Criteria for acute kidney injury

• KDIGO (Kidney disease: improving global outcomes)• RIFLE(Risk, Injury, failure,

• loss, end-stage)

• Stage 1:

• serum creatinine increase > 1.5-1.9-fold, urine production of < 0.5 mL/kg/ hr for 6-12 hrs

• = Risk

• Stage 2:

• serum creatinine increase > 2.0-2.9-fold, urine production of < 0.5 mL/kg/ hr for ≥12 hrs

• = Injury

• Stage 3:

• serum creatinine increase> 3.0-fold, urine

• production of < 0.3 mL/kg/hr for≥24 hrs or

• absolute anuria for ≥12 hrs, or absolute serum

• creatinine > 354 µ mol /L with an acute rise of

• > 44 µ mol /L

• = Failure

• Loss: persistent AKI, or complete

• loss of kidney function for > 4 wks

• End-stage renal disease: need for RRT

• for > 3 mths

Pre-renal AKI

Patients are typically hypotensive and tachycardic with signs of poor peripheral perfusion, such as delayed capillary return. Postural hypotension (a fall in blood pressure of > 20/10 mmHg from lying to standing) are valuable signs of early hypovolaemia. The cause of the hypotension is usually obvious clinically, but concealed blood loss can occur into the gastrointestinal tract, following trauma (particularly fractures of the pelvis or femur), and into the pregnant uterus.Large volumes of intravascular fluid may also be lost into tissues after crush injuries or burns, and in severe inflammatory skin diseases or sepsis.

Renal AKI

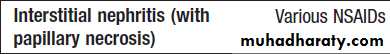

Patients with glomerulonephritis usually demonstratesignificant haematuria and proteinuria and may have clinical manifestations of an underlying disease. Immunological screen, a renal biopsy is usually required. Drug-induced (like gentamicin, omeprazole, cisplatin and amphotericin B) acute interstitial nephritis is harder to spot but should be suspected in a previously well patient if there is an acute deterioration of renal function coinciding with introduction of a drug treatment.

Post-renal AKI

Patients should be examined for evidence of bladder enlargement and should also undergo imaging with ultrasound to detect evidence of obstruction above the level of the bladder.

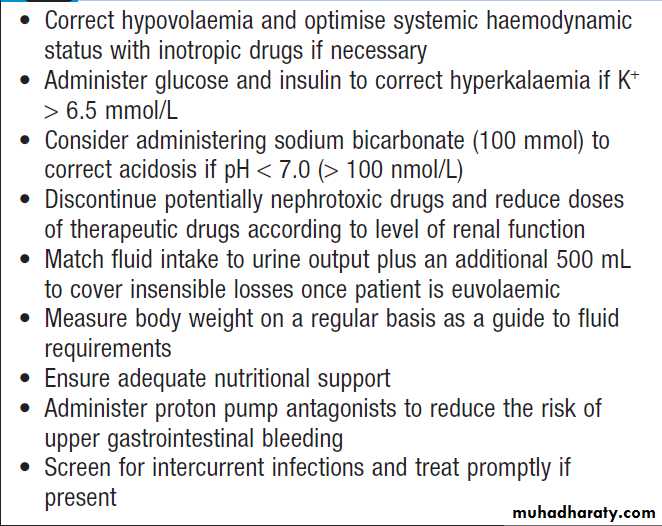

Management of acute kidney injury

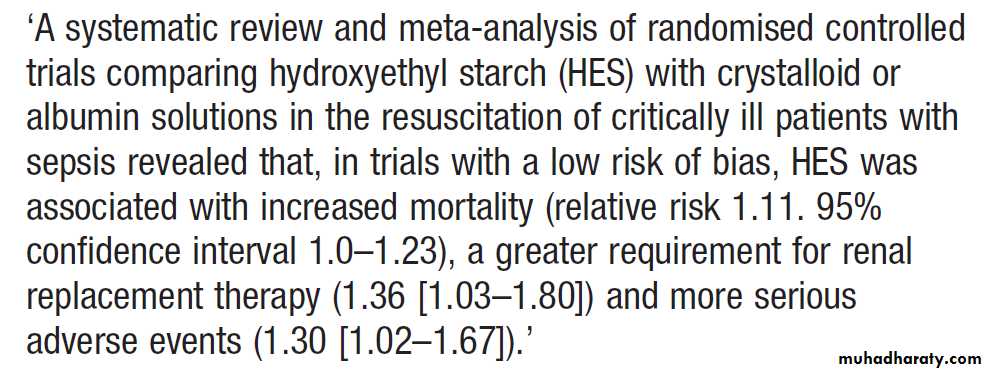

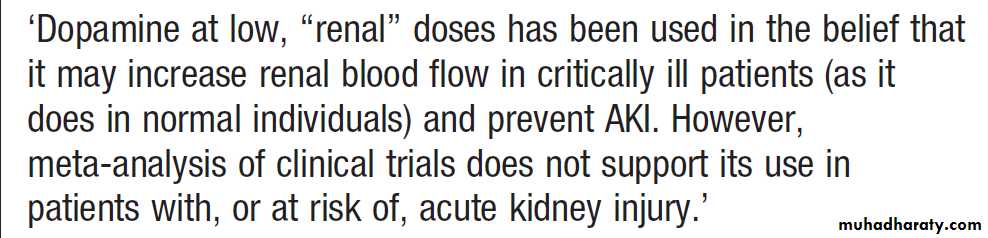

Critically ill patients may require inotropic drugs to restore an effective blood pressure but clinical trials do not support a specific role for low-dose dopamine .Colloid resuscitation fluids in the critically ill

Hyperkalaemia and acidosis

If serum K+ is > 6.5 mmol/L, should be treated immediately to prevent life-threatening arrhythmias.Metabolic acidosis develops unless prevented by loss of

hydrogen ions through vomiting or aspiration of gastric

contents. Restoration of blood volume will correct acidosis by restoring kidney function. Infusions of sodium bicarbonate (50 mL of 8.4%) may also be used, if acidosis is severe, to reduce life-threatening hyperkalaemia. Cardiopulmonary complications

Pulmonary oedema may result from the administration of excessive amounts of fluids relative to urine output and because of increased pulmonary capillary permeability. Dialysis may be required to remove excess fluid.

Temporary respiratory support may also be necessary

with CPAP or IPPV. Once initial resuscitation has been performed, fluid intake should be matched to urine output plus 500 mL to cover insensible losses, unless diarrhoea present, in which case additional fluids might be required.Electrolyte disturbances

Dilutional hyponatraemia, may occur if the patient has continued to drink freely despite oliguria or has received inappropriate amounts of intravenous dextrose. They can be avoided by paying careful attention to fluid balance. Modest hypocalcaemia is common but rarely requires treatment.

Serum phosphate levels are usually high but may fall to dangerously low levels in patients on daily or continuous dialysis or haemofiltration, necessitating replacement.

Pulmonary oedema in acute kidney injury. The appearances are indistinguishable from left ventricular failure but the heart size is usually normal. Blood pressure is often high.

Dietary measures

Adequate nutritional support should be ensured and it

is important to give sufficient amounts of energy and

adequate amounts of protein; high protein intake should

be avoided. This is particularly important in patients

with sepsis and burns who are hypercatabolic.

Infection

AKI are at substantial risk of Intercurrent infection because humoral and cellular immune mechanisms are depressed. Regular clinical examination, supplemented by microbiological investigation where appropriate, is required to diagnose infection. If infection is discovered, it should be treated promptly .

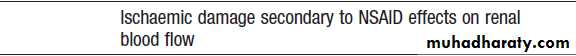

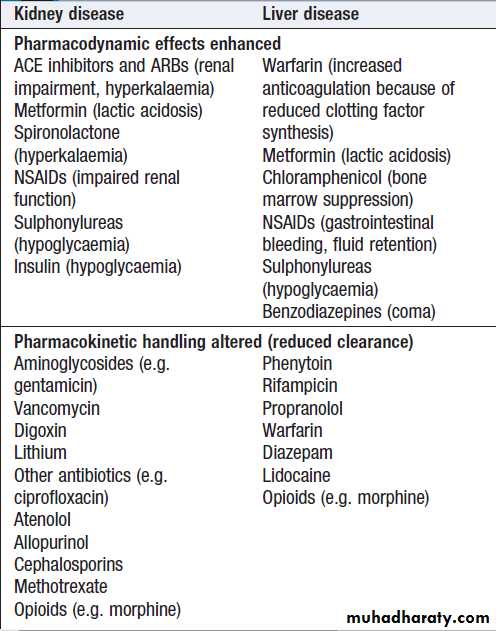

Medications

Patients with drug-induced ATN or drug-induced AIN should have the offending drug withdrawn. NSAIDs and ACE inhibitors, should be discontinued, as they may prolong AKI. H2-receptor antagonists should be given to prevent GI bleeding. Other drug treatments should be reviewed and the doses adjusted if necessary, to take account of renal function. Stop non-essential drug.Immunosuppression , plasma infusion and exchange may be required for GN .

Renal tract obstruction

In post-renal AKI, the obstruction should be relieved as

soon as possible. This may involve catheterisation in

urethral obstruction, or correction of ureteric obstruction

with a ureteric stent or percutaneous nephrostomy.

Renal replacement therapy

Conservative management can be successful in AKIwith meticulous attention to fluid balance, electrolytes and nutrition, but renal replacement therapy (RRT) may

be required in patients who are not showing signs of

recovery with these measures. Typically, the decision to

start RRT is driven by hyperkalaemia, fluid overload or

acidosis. Severe uraemia with pericarditis and neurological signs (uraemic encephalopathy) is uncommon in AKI but, when present, is a strong indication for RRT.

No specific cut-off values for serum urea or creatinine

have been identified at which RRT should be commenced,

and clinical trials of earlier versus later RRT in unselected patients with AKI have not shown differences in outcome.

Furthermore, RRT can be a risky intervention in patients with comorbidity, since it requires the placement of large intravenous catheters that may become infected and can also represent a major haemodynamic challenge in unstable patients. Accordingly, the decision to institute RRT should be made on an individual basis, taking account of the potential risks and benefits, comorbidity and other aspects of the patient’s care, including an assessment of whether early or delayed recovery is likely. The two main options for RRT in AKI are haemodialysis and high-volume haemofiltration, or the hybrid approach of haemodiafiltration.

Peritoneal dialysis is also an option if haemodialysis is

not available .

Recovery from AKI

This is usually heralded by a gradual return of urineoutput and a steady improvement in plasma biochemistry.

During recovery, there is often a diuretic phase for several days before returning to normal. This may be due in part to tubular damage and to temporary loss of the medullary concentration gradient. This gradient plays a key role in concentrating urine in the collecting duct. After a few days, urine volume falls to normal as the concentrating mechanism and tubular reabsorption are restored. During the recovery phase of AKI, it may be necessary to provide supplements of sodium chloride, sodium bicarbonate, potassium chloride and sometimes phosphate temporarily, to compensate for increased urinary losses.

Acute kidney injury in old age

Physiological change: nephrons decline in number with age and average GFR falls progressively.Creatinine: as muscle mass falls with age, less creatinine is produced each day. Serum creatinine can be misleading as a guide to renal function.

Renal tubular function: declines with age, leading to loss of urinary concentrating ability.

Drugs: increased drug prescription in older people (diuretics, ACEI and NSAIDs) may contribute to risk of AKI.

Causes: infection, renal vascular disease, prostatic obstruction, hypovolaemia and severe cardiac dysfunction .

Mortality:

rises with age, primarily because of comorbid conditions.

CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE (CKD)

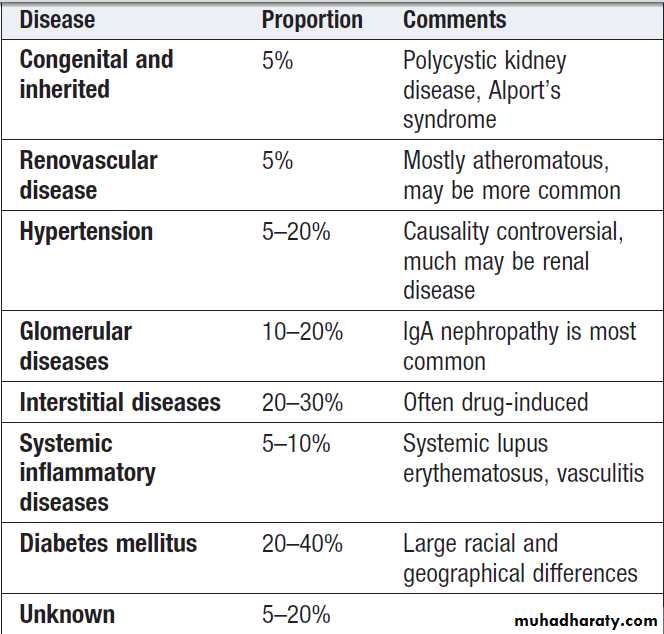

Previously termed chronic renal failure, irreversible deterioration in renal function which usually develops over a period of years . Initially, it is manifest only as a biochemical abnormality but, eventually, loss of the excretory, metabolic and endocrine functions of the kidney leads to the clinical symptoms and signs of renal failure, collectively referred to as uraemia. When death is likely without RRT (stage 5), it is called end-stage renal disease or failure (ESRD or ESRF). The great majority of stages 1–3 CKD never develop ESRD, which is fortunate. Many at a late stage have bilateral small kidneys and renal biopsy is rarely undertaken since it is more risky, less likely to provide a diagnosis because of the severity of damage, and unlikely to alter management.Common causes of end-stage renal failure

Clinical featuresThe typical presentation is with a raised urea and creatinine found during routine blood tests, frequently accompanied by hypertension, proteinuria or anaemia.

Most patients with slowly progressive disease are

asymptomatic until GFR falls < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2

(stage 4 or 5). An early symptom is nocturia, due to the loss of concentrating ability and increased osmotic load per nephron, but this is nonspecific. When GFR falls <15–20 mL/min/1.73 m2, symptoms and signs are common and can affect almost all body systems .

They typically include tiredness or breathlessness, which may, in part, be related to renal anaemia, pruritus, anorexia, weight loss, nausea and vomiting.

With further deterioration in renal function, patients may suffer hiccups, experience unusually deep respiration related to metabolic acidosis (Kussmaul’s respiration), and develop muscular twitching, fits, drowsiness and coma.

Immune dysfunction

Cellular and humoral immunity is impaired in advanced

CKD and there is increased susceptibility to infections,

the second most common cause of death in dialysis

patients, after cardiovascular disease.

Many infections are associated with access devices but some are common infections, such as pneumonia.

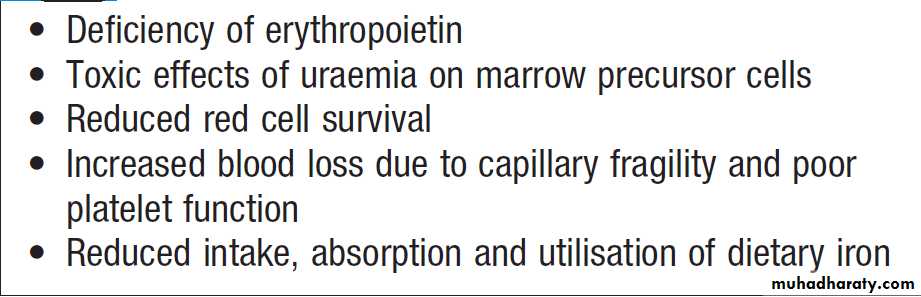

Haematological

There is an increased bleeding tendency in advancedCKD, manifests as cutaneous ecchymoses and mucosal bleeds. Platelet function is impaired and bleeding

time prolonged. Adequate dialysis partially corrects

the bleeding tendency, but these patients are at significantly increased risk of complications from all anticoagulants, including those that are required during dialysis. Anaemia is common and is due in part to reduced erythropoietin production. Haemoglobin can be as low as 50–70 g/L in CKD stage 5, although it is often less severe or absent in patients with polycystic kidney disease.

Causes of anaemia in chronic kidney disease

Electrolyte abnormalitiesCKD often develop electrolyte abnormalities , metabolic acidosis , fluid retention, sometimes leading to episodic pulmonary oedema. This is particularly associated with renal artery stenosis. Conversely, some patients with tubulo-interstitial disease can develop ‘salt-wasting’ disease and may require a high sodium and water intake, including supplements of sodium salts, to prevent fluid depletion and worsening of renal function.

Although it is usually asymptomatic, it may be associated with increased tissue catabolism and decreased protein synthesis, and may exacerbate bone disease and the rate of decline in renal function.

Endocrine function

Loss of libido at least in part, to hypogonadism as a consequence of Hyperprolactinaemia. The half-life of insulin is prolonged due to reduced tubular metabolismand there is also insulin resistance. Because of this, insulin requirements are unpredictable in diabetic.

Neurological and muscle function

Generalised myopathy may occur due to a combination

of poor nutrition, hyperparathyroidism, vitamin D deficiency and disorders of electrolyte metabolism. Muscle

cramps are common. The ‘restless leg syndrome’, patient’s legs are jumpy during the night, may be troublesome.

Both sensory and motor neuropathy can arise, presenting as paraesthesia and foot drop, respectively, they can often improve once dialysis is established.

Cardiovascular disease

The risk is substantially increased in stage 3 or worse (GFR< 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and those with microalbuminuria. LVH may occur, secondary to hypertension, and may account for the increased risk of sudden death (dysrhythmias). Pericarditis may complicate untreated or inadequately treated ESRD and cause pericardial tamponade or constrictive pericarditis. Medial vascular calcification due, in part, to the high serum phosphate levels which are present in stage 3b. Hyperphosphataemia may also contribute to the itching that arises in advanced CKD and probably contributes to the increased risk of CVD. Reflecting this fact, serum fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) levels (increase in response to serum phosphate) are an independent predictor of mortality in CKD.

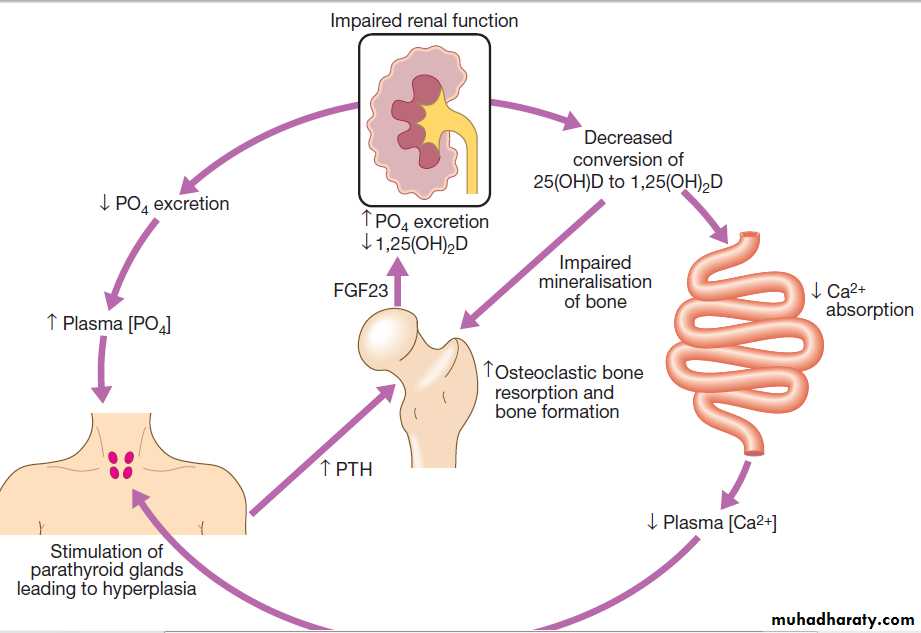

Metabolic bone disease

Disturbances of calcium and phosphate metabolism are

almost universal in advanced CKD, and various types

of metabolic bone disease may also occur, including

osteitis fibrosa cystica, osteomalacia and osteoporosis .

There is impaired conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to its active metabolite, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, due in part to renal tubular cell damage and elevated FGF23 levels. The reduced 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels impair intestinal absorption of calcium, thereby causing hypocalcaemia, which leads in turn to increased PTH production by the parathyroid glands. Serum phosphate levels also start to rise because of the reduction in GFR, leads to increased production of the hormone FGF23 from osteocytes .

The FGF23 promotes phosphate excretion, thereby compensating in part for the reduced glomerular filtration of phosphate. This homeostatic response eventually fails, and hyperphosphataemia develops. The raised phosphate complex with calcium in the extracellular space, causing ectopic calcification in blood vessels and other tissues. Patients commonly develop parathyroid gland hypertrophy secondary and in some, tertiary hyperparathyroidism supervenes, due to autonomous production of PTH; this presents with hypercalcaemia.

In osteitis fibrosa cystica, there is increased bone turnover due to the high levels of PTH, whereas low bone turnover

(adynamic bone disease) may be observed in patients

over-treated with vitamin D metabolites. Osteomalacia can occur with over-treatment of hyperphosphataemia .

Pathogenesis of renal osteodystrophy. Low 1,25(OH)2D levels cause calcium malabsorption and this, combined with high phosphate

levels, causes hypocalcaemia, which increases PTH production by the parathyroid glands. The raised level of PTH increases osteoclastic bone resorption

and bone formation. Although production of FGF23 from osteocytes also increases, promoting phosphate excretion, this is insufficient to prevent

hyperphosphataemia in advanced CKD.

Investigations

Their main aims are:• to identify the underlying cause where possible,

since this may influence the treatment

• to identify reversible factors that may worsen renal

function, such as hypertension, urinary tract obstruction, nephrotoxic drugs, and salt and water depletion

• to screen for complications of CKD, such as

anaemia and renal osteodystrophy

• to screen for cardiovascular risk factors.

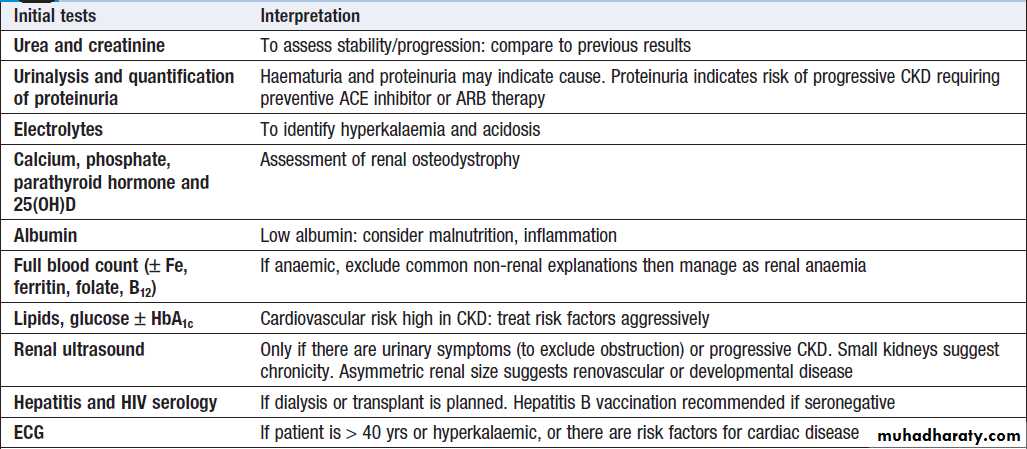

Suggested investigations in chronic kidney disease

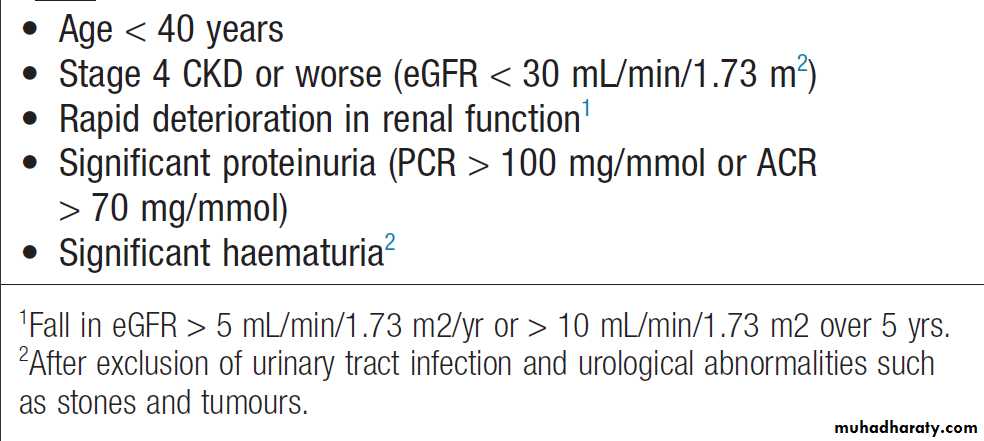

Criteria for referral of chronic kidney disease patients to a nephrologist

ManagementThe aims of management in CKD are to prevent or

slow further renal damage; to limit the adverse effects of renal impairment on the skeleton and on haematopoiesis; to treat risk factors for CVD; and to prepare for RRT .

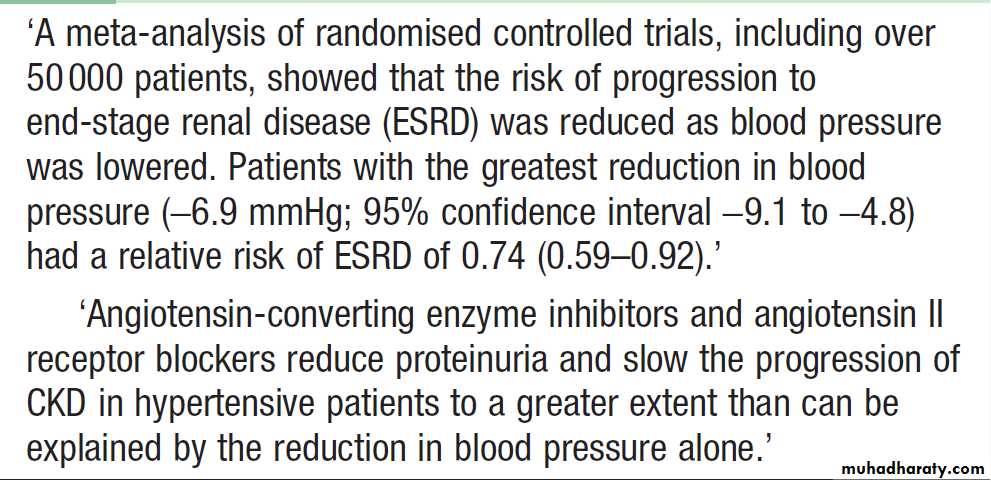

Antihypertensive therapy

Lowering of blood pressure slows the rate at which renal

function declines, independently of the agent

used and has additional benefits in lowering the risk of hypertensive heart failure, stroke and peripheral vascular disease, as well as reducing proteinuria . Various targets have been suggested, such as 130/80 mmHg for uncomplicated, and 125/75 mmHg for CKD complicated by significant proteinuria of more than 1 g/day (PCR > 100 mg/mmol or ACR > 70 mg/mmol).

Lowering blood pressure in chronic kidney disease

Reduction of proteinuria

There is a clear relationship between the degree of proteinuria and the rate of progression of renal disease, and strong evidence that reducing proteinuria reduces the

risk of progression. ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) reduce proteinuria and retard the progression of CKD . These effects are partly due to the

reduction in blood pressure but there is evidence for a

specific beneficial effect in patients with proteinuria

(PCR > 50 mg/mmol or ACR > 30 mg/mmol) and those

with incipient or overt diabetic nephropathy. In addition, ACE inhibitors have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in CKD.

Treatment with ACE inhibitors and ARBs may be

accompanied by an immediate reduction in GFR whentreatment is initiated, due to a reduction in glomerular

perfusion pressure. Treatment can be continued so long as the reduction in GFR is less than 20% and is not progressive. Accordingly ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs

should be prescribed to all patients with diabetic nephropathy and those with proteinuria, irrespective of

whether or not hypertension is present, providing that

hyperkalaemia does not occur.

Dietary and lifestyle interventions

There is experimental evidence that restricting dietaryprotein can reduce progression of CKD in animal models

but the results are less clear-cut in humans. All patients

with stage 4 and 5 CKD should be given dietetic advice

aimed at preventing excessive consumption of protein,

ensuring adequate calorific intake and limiting potassium

and phosphate intake. Severe protein restriction is

not recommended. All patients should be advised to

stop smoking, since there is evidence that this slows the

decline in renal function in addition to reducing cardiovascular risk. Exercise and weight loss may also reduce proteinuria and have beneficial effects on cardiovascular risk profile.

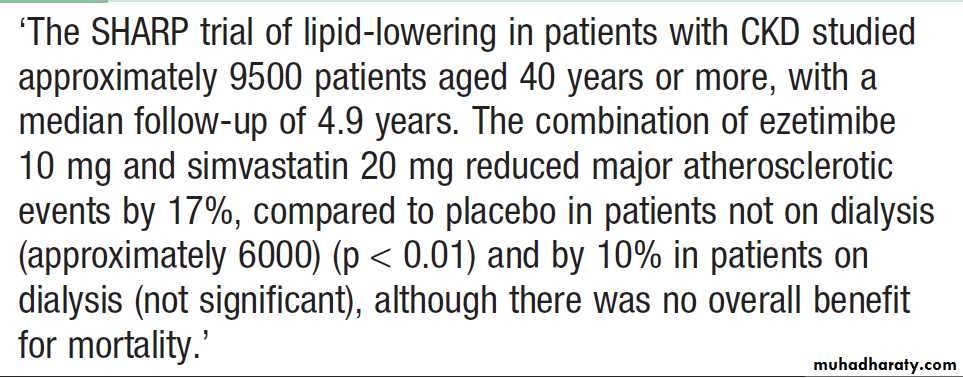

Lipid-lowering therapy

Hypercholesterolaemia is almost universal in patients

with significant proteinuria, and increased triglyceride

levels are also common in patients with CKD. Lipid

lowering has been shown to reduce vascular events in

non-dialysis CKD patients . There is some evidence that control of dyslipidaemia with statins may slow the rate of progression of renal disease.

Effects of lipid-lowering therapy in CKD

Treatment of anaemiaAnaemia is common iwith a GFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and. Recombinant human erythropoietin is effective in correcting the anaemia. Erythropoietin treatment does not influence mortality, however, and correcting haemoglobin to normal levels may carry some extra risk, including hypertension and thrombosis (including thrombosis of the arteriovenous fistulae). The target 100 and 120 g/L.

Erythropoietin is less effective in the presence of iron deficiency, active inflammation or malignancy, and with aluminium overload, which may occur in dialysis.

Maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance

Patients with evidence of fluid retention should have

dietary sodium intake limited to about 100 mmol/day,

loop diuretics may be required to treat fluid overload.

If hyperkalaemia occurs, drug therapy should be reviewed, to reduce or stop potassium-sparing diuretics, ACE inhibitors and ARBs. Correction of acidosis may be helpful, and limiting potassium intake to 70 mmol/day may be necessary. Potassium-binding resins, such as calcium resonium, may be useful in the short term.

The plasma bicarbonate should be maintained

above 22 mmol/L by giving sodium bicarbonate

supplements (starting dose of 1 g 3 times daily, increasing as required).

If the increased sodium intake induces hypertension or oedema, calcium carbonate (up to 3 g daily) may be used as an alternative, since this has the advantage of also binding dietary phosphate.

Renal bone disease

Treatment should be initiated with active vitamin D

metabolites (either 1-α-hydroxyvitamin D or 1,25-

dihydroxyvitamin D) in patients who are found to have

hypocalcaemia or serum PTH levels more than twice

the upper limit of normal. The dose should be adjusted

to try to reduce PTH levels to between 2 and 4 times

the upper limit of normal to avoid over-suppression of

bone turnover and adynamic bone disease, but care

must be exercised in order to avoid hypercalcaemia.

Hyperphosphataemia should be treated by dietary

restriction of foods with high phosphate content (milk,

cheese, eggs and protein-rich foods) and by the use of

phosphate-binding drugs.

Various drugs are available, including calcium carbonate, aluminium hydroxide, lanthanum carbonate and polymer-based phosphate binders such as sevelamer. The aim is to maintain serum phosphate values at 1.8 mmol/L (5.6 mg/dL) or below if possible, but many of these drugs are difficult to take and compliance may be a problem.

Parathyroidectomy may be required for the treatment

of tertiary hyperparathyroidism. An alternative is to

employ calcimimetic agents, such as cinacalcet, which

bind to the calcium-sensing receptor and reduce PTH

secretion. They have a place if parathyroidectomy is

unsuccessful or not possible.

RENAL REPLACEMENT THERAPY (RRT)

May be required on a temporary basis in patients with AKI or on a permanent basis for those with CKD secondary to the many different types of renal disease. Since the advent of long-term RRT in the 1960s, the numbers of patients with ESRD who are kept alive have increased considerably. Following initiation of dialysis in the UK, the survival is 84% at 1 year and 50% after 5 years. Comorbid conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and generalised vascular disease, also have a strong influence on mortality.

The aim of RRT is to replace the excretory functions , to maintain normal electrolyte and fluid balance. Various options available, haemodialysis, haemofiltration, haemodiafiltration, peritoneal dialysis and renal transplantation.

Preparing for renal replacement therapy

It is crucial that patients who are known to have progressive CKD are prepared well in advance for the institution of RRT. It is often possible to predict when RRT will be required from serial measurements of serum creatinine . Such patients, preparations for the initiation of RRT should be started at least 12 months before the predicted start date. Since there is no evidence that early initiation of RRT improves outcome, the overall aim is to commence RRT by the time symptoms of CKD have started to appear but before serious complications have occurred.Preparation for RRT involves providing the patient with psychological and social support for both them and their relatives from the renal multidisciplinary team, discussing the various choices of treatment.

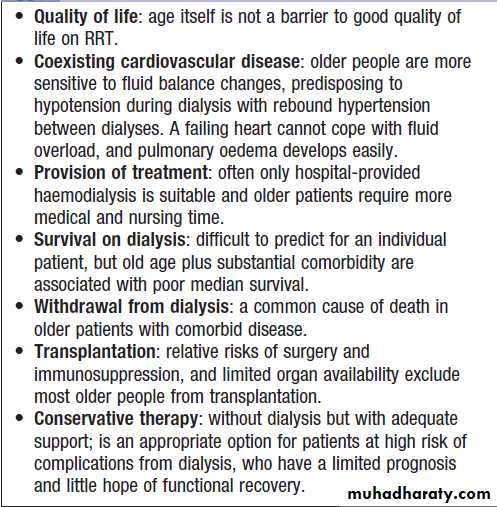

For those that decide to go ahead with RRT, there are further choices between haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis between hospital and home treatment, and on referral for renal transplantation. Conservative treatment

In older patients with multiple comorbidities, conservative

treatment of stage 5 CKD, aimed at limiting the adverse symptomatic effects of ESRD without commencing RRT, is increasingly viewed as a positive choice . Current evidence suggests that survival without dialysis can be similar or only slightly shorter than who undergo RRT, but they avoid the hospitalisation and interventions. Many of these enjoy a good quality of life for several years. It is also appropriate to discontinue dialysis, with the consent of the patient, and offer conservative therapy and palliative care when quality of life on dialysis is inadequate.

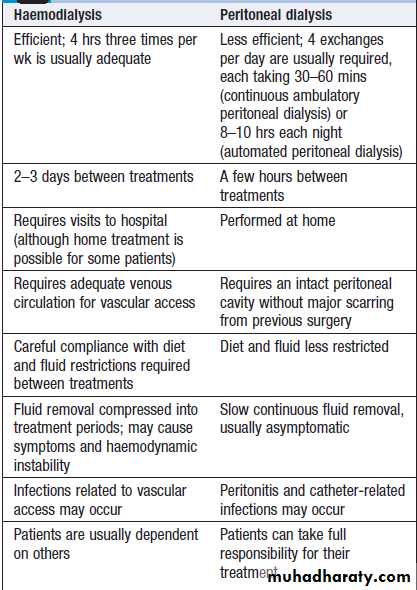

Comparison of haemodialysis and

peritoneal dialysisHaemodialysis

Is the most common form of RRT in ESRD and is also used in AKI. It involves gaining access to the circulation, either through an arteriovenous fistula, a central venous catheter or an arteriovenous shunt, such as a Scribner shunt. The patient’s blood is pumped through a haemodialyser, which allows bidirectional diffusion of solutes between blood and the dialysate across a semipermeable membrane down a concentration gradient . Haemodialysis offers the best rate of small solute clearance in AKI, but should be started gradually because of the risk of confusion and convulsions due to cerebral oedema (dialysis disequilibrium). Typically, 1–2 hours is prescribed initially but, subsequently, can be treated by 4–5 hours of on alternate daysDuring dialysis, it is standard practice to anticoagulate patients with heparin but the dose may be reduced if there is a bleeding risk. For short dialyses and in patients with abnormal clotting, it may be possible to avoid anticoagulation altogether. In AKI, dialysis is performed through a large-bore, dual-lumen catheter inserted into the femoral or internal jugular vein. Subclavian lines are avoided where possible, as thromboses will compromise the ability to form a functioning fistula in the arm if the patient fails to recover and needs chronic dialysis.

In CKD, vascular access is gained by formation of an arteriovenous fistula, in the forearm, up to a year before dialysis. After 4–6 weeks, increased pressure transmitted from the artery to the vein leading from the fistula causes

distension and thickening of the vessel wall (arterialisation).

Large-bore needles can then be inserted into the

vein to provide access for each haemodialysis treatment.Preservation of arm veins is thus very important in patients with progressive renal disease who may require haemodialysis in the future. If this access is not possible, venous or Gortex grafts may be fashioned or plastic catheters in central veins can be used for short-term access. These may be tunneled under the skin to reduce infection risk. All patients must be screened in advance for hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV, and vaccinated

against hepatitis B if they are not immune. All dialysis

units should have segregation facilities for hepatitis

B-positive patients, given its easy transmissibility.

Patients with hepatitis C and HIV are less infectious and

can be treated satisfactorily using machine segregationand standard infection control measures. Haemodialysis is usually carried out for 3–5 hours three times weekly, either at home or in an outpatient unit. The intensity and frequency of dialysis should be adjusted to achieve a reduction in urea during dialysis (urea reduction ratio) of over 65%. Most patients notice an improvement in symptoms during the first 6 weeks of treatment. Plasma urea and creatinine are lowered by each treatment but do not return to normal. More frequent dialysis and nocturnal dialysis can achieve better fluid balance and electrolyte control than standard dialysis and, in particular, better control of serum phosphate levels.

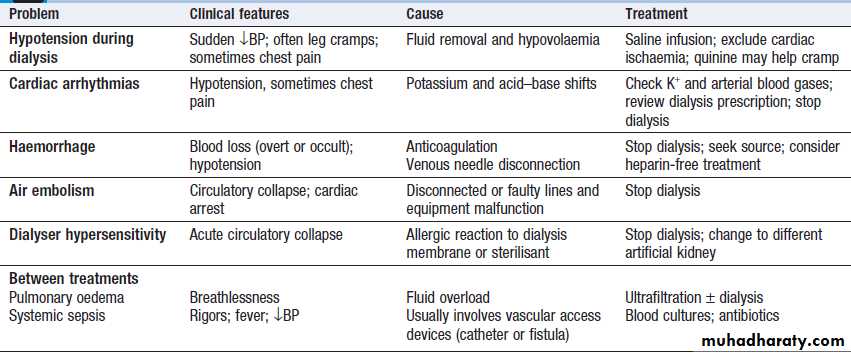

Problems with haemodialysis

HaemofiltrationPrincipally used in the treatment of AKI. Water and solutes are filtered from blood across a porous semipermeable membrane under a pressure gradient. Haemofiltration may be either intermittent or continuous, and typically 1–2 litres of filtrate is replaced per hour (equivalent to a GFR of 15–30 mL/min); higher rates of filtration may be of benefit in patients with sepsis and multi-organ failure.

Haemodiafiltration

This technique combines haemodialysis with approximately

20–30 litres of ultrafiltration (with replacement of filtrate) over a 3–5-hour treatment.

It is sometimes used in the treatment of AKI but is increasingly favoured in the treatment of CKD.

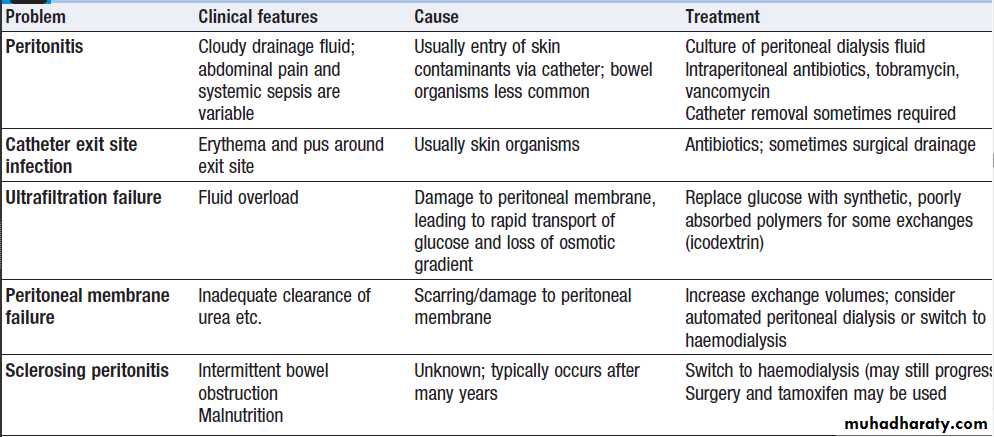

Peritoneal dialysis

Is principally used in the treatment of CKD. It requires the insertion of a permanent Silastic catheter into the peritoneal cavity .Two types are in common use. In continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), about 2 litres of sterile, isotonic dialysis fluid are introduced and left in place for approximately 4–6 hours. Metabolic waste products diffuse from peritoneal capillaries into the dialysis fluid down a concentration gradient. The fluid is then drained and fresh dialysis fluid introduced, in a continuous four-times-daily cycle.

The inflow fluid is rendered hyperosmolar by the addition of glucose or glucose polymer; this results in net removal of fluid from the patient during each cycle, due to diffusion of water from the blood through the peritoneal membrane down an osmotic gradient (ultrafiltration).

The patient is mobile and able to undertake normal daily activities. Automated peritoneal dialysis (APD) is similar to CAPD but uses a mechanical device to perform the fluid exchanges during the night, leaving the patient free, or with only a single exchange to perform, during the day.

CAPD is particularly useful in children, as a first

treatment in adults with residual renal function, and as

a treatment for elderly patients with cardiovascular

instability. The long-term use of peritoneal dialysis may

be limited by episodes of bacterial peritonitis and

damage to the peritoneal membrane, including sclerosing

peritonitis, but some patients have been treated successfully for more than 10 years.

Renal replacement therapy in old age

Problems with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis

Renal transplantation

Renal transplantation offers the best chance of long-termsurvival in ESRD, and is the most cost-effective treatment.

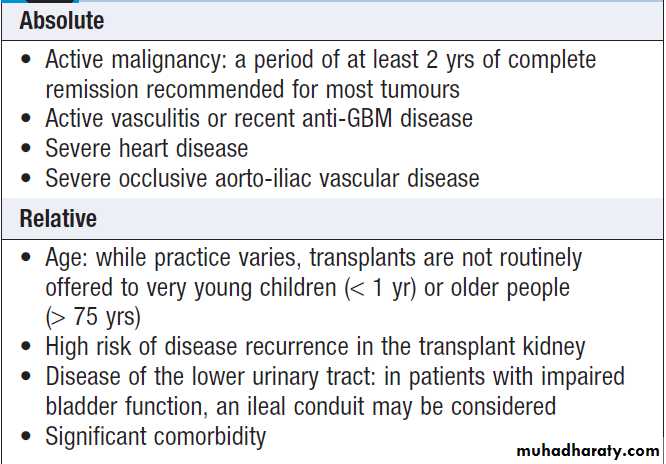

Transplantation can restore normal kidney function and correct all the metabolic abnormalities of CKD but requires long-term immunosuppression with its attendant risks . All patients with ESRD should be considered for transplantation, unless there are contraindications.

Kidney grafts may be taken from a cadaver after brain death or circulatory death or from a living donor . Compatibility of ABO blood group between donor and recipient is usually required and the degree of matching for major histocompatibility (MHC) antigens, particularly HLADR, influences the incidence of rejection.

Immediately prior to transplantation, tests should be performed for antibodies against HLA antigens and for antibodies that can bind to lymphocytes of the donor . Positive tests predict early rejection. Although some ABO- and HLA-incompatible transplants are now possible, this

involves appropriate preparation with pre-transplant

plasma exchange and/or immunosuppression, so that

recipient antibodies to the donor’s tissue are reduced to

acceptably low levels. This option is generally only available for living donor transplants because of the preparation required. During the transplant operation, the kidney is placed in the pelvis; the donor vessels are usually anastomosed to the recipient’s internal iliac artery and vein, the donor ureter anastomosed to the bladder .

The failed kidneys are usually left in place.

Peri-operative problems include:

• Fluid balance. Careful matching of input to output isrequired. Patients can be very polyuric in the initial

period after transplantation.

• Primary graft non-function.Causes include hypovolaemia, preservation injury/acute tubular necrosis during storage and transfer, other pre-existing renal damage, hyperacute rejection, vascular occlusion and urinary tract obstruction.

• Sepsis. In addition to risks of sepsis associated with

any operation, there is an increased risk due to the

uraemia and immunosuppression. Once the graft begins to function, near-normal biochemistry is usually achieved within days to weeks.

The median eGFR of patients in the UK receiving a deceased donor transplant at 1 year is 51 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Life-long immunosuppressive therapy is required to prevent rejection but needs to be more intensive in the early post-transplantation period, when the risk is highest. A common regimen is triple therapy with prednisolone; ciclosporin or tacrolimus; and azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. Sirolimus (rapamycin) is an alternative that can be introduced later. Antibodies to deplete or modulate specific lymphocyte populations are increasingly used; targeting the lymphocyte interleukin (IL)-2 receptor is particularly

effective for preventing rejection. Acute rejection is usually treated, by short courses of methylprednisolone 500 mg IV on 3 consecutive days. Other therapies, such as antilymphocyte antibodies, IV immunoglobulin and plasma exchange, can be used for episodes of acute rejection that do not respond to high dose corticosteroids.

Complications of immunosuppression include infections

and malignancy .Approximately 50% of white patients develop skin malignancy by 15 years after transplantation.

The prognosis after kidney transplantation is good.

Recent UK statistics for transplants from cadaver donors

indicate 96% patient survival and 93% graft survival at

1 year, and 88% patient survival and 84% graft survival

at 5 years. Even better figures are obtained with living

donor transplantation (91% graft survival at 5 years). Advances in immunosuppression have greatly improved

results from using genetically unrelated donors .

Contraindications to renal transplantation

RENAL VASCULAR DISEASESDiseases which affect renal blood vessels may cause

renal ischaemia, leading to acute or CKD or secondary hypertension.

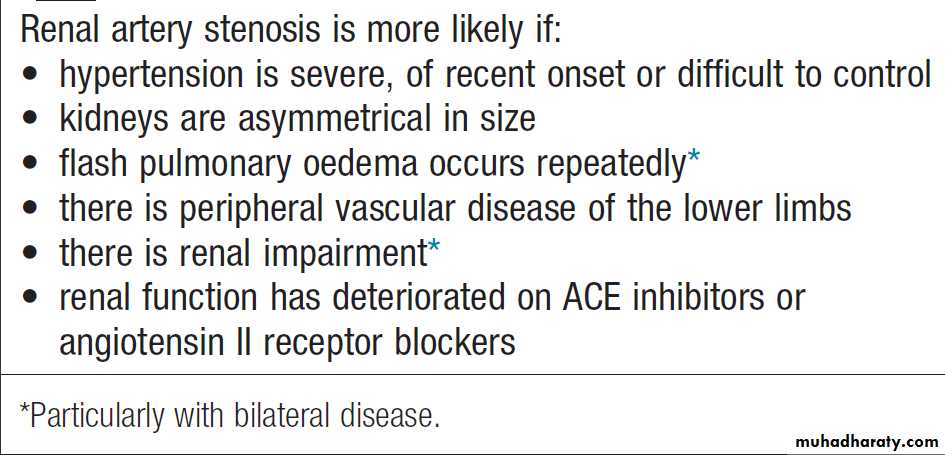

Renal artery stenosis (RAS)

Arelatively uncommon disorder, which presents clinically with hypertension, occur in about 2% of unselected patients

with hypertension but may affect up to 4% of older

patients with hypertension who have evidence of

atherosclerotic disease elsewhere. Most cases are caused by atherosclerosis but fibromuscular dysplasia of the vessel wall may be responsible in young. Rare causes : vasculitis (Takayasu’s arteritis and polyarteritis nodosa) ,

thromboembolism and aneurysms of the renal artery.

Pathophysiology

RAS results in a reduction in renal perfusion pressure, which activates the renin–angiotensin system, leading to increased circulating levels of angiotensin II. This provokes vasoconstriction and increases aldosterone production by the adrenal, causing sodium retention by the renal tubules. Significant reduction of renal blood flow occurs when there is >70% narrowing of the artery . The characteristic lesion is an ostial stenosis. As the stenosis becomes more severe, renal ischaemia leads to shrinkage of the affected kidney and may cause renal failure (ischaemic nephropathy). In young, fibromuscular dysplasia is a more likely cause. This is an uncommon of unknown cause. It is characterised by hypertrophy of the media (medial fibroplasia), which narrows the artery but rarely leads to total occlusion.

85% of patients will not develop progressive renal impairment. Unfortunately, methods of predicting which patients are at risk of progression or who will respond to treatment are still imperfect.

Clinical features

RAS can present in various ways ,including hypertension, renal failure (with bilateral disease), a deterioration in renal function when ACE inhibitors or ARBs are used, or acute pulmonary oedema. Although many patients experience a slight drop in GFR when commencing these drugs, an increase in serum creatinine of 25% or more raises the possibility of renal artery stenosis. Acute pulmonary oedema is particularly characteristic of bilateral renovascular disease.

Presentation and clinical features of renal artery stenosis

InvestigationsWhen appropriate, imaging of the renal vasculature

with either CT or MR angiography should be performed to confirm the diagnosis .

Biochemical testing may reveal impaired renal

function and an elevated plasma renin activity, sometimes

with hypokalaemia due to hyperaldosteronism.

Ultrasound may also reveal a discrepancy in size

between the two kidneys. While these investigations provide supportive information, they are insufficiently

sensitive or specific to be of value in diagnosis of renovascular disease in hypertensive patients.

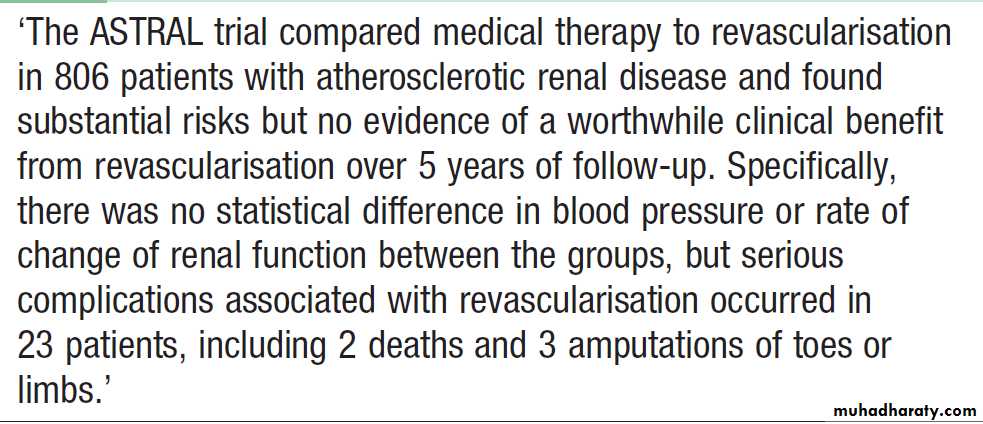

Management

The first-line management in patients with renal artery

stenosis is medical therapy with antihypertensive drugs, supplemented, where appropriate, by statins and low-dose aspirin in those with atherosclerotic disease.

Interventions to correct the vessel narrowing should be considered in young patients (age < 40) suspected of having renal artery stenosis; those in whom blood pressure cannot easily be controlled with antihypertensive; those who have a history of ‘flash’ pulmonary oedema or accelerated phase (malignant) hypertension; and those in whom renal function is deteriorating.

The most commonly used technique is angioplasty.

The best results are obtained in non-atheromatousfibromuscular dysplasia, where correction of the stenosis

has a high chance of success in improving blood

pressure and protecting renal function. Angioplasty and

stenting can sometimes be successful in atherosclerotic.

The risks of angioplasty and stenting include renal artery occlusion, renal infarction, and atheroemboli from manipulations in a severely diseased aorta.

Small vessel disease distal to the stenosis may preclude substantial functional recovery.

Stenting for renal artery stenosis

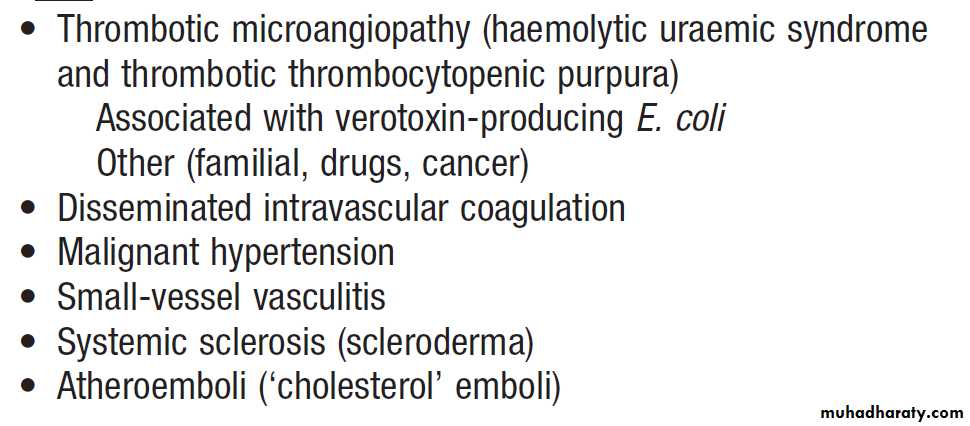

Microvascular disorders associated with

acute renal damage

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS)

Characterised by thrombotic microangiopathy that causes damage to endothelial cells of the microcirculation. This is accompanied by swelling of the endothelial cells, increasedplatelet adherence and intravascular thrombosis. There

is a marked reduction in the platelet count and anaemia,

with features of intravascular haemolysis , such as a raised unconjugated bilirubin level, raised levels of LDH and decreased circulating levels of haptoglobin. The most common cause of classical HUS is infection associated with organisms that produce enterotoxins called verotoxins: so-called diarrhea-positive HUS (D+HUS).

The organisms most commonly implicated in (D+HUS)

are enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli .

Management

Supportive care, optimizing fluid and electrolyte balance, transfusion and RRT if necessary. Infusion of fresh frozen plasma can be helpful (presumably by replacing complement components), as can plasma exchange (presumably by removing pathogenic autoantibodies). Recently, impressive results have been reported with the anti-C5 monoclonal antibody, eculizumab, which binds to C5, thereby preventing activation of the terminal complement cascade.Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

Like HUS, TTP is characterised by thrombotic microangiopathy, which causes damage to endothelial cells of the microcirculation.This leads to swelling of the endothelial cells, increased platelet adherence and intravascular thrombosis.

In contradistinction to HUS, the brain is more commonly

affected in TTP and involvement of the kidney is

usually less prominent. TTP is an autoimmune disorder

caused by antibodies against ADAMTS-13, which is involved in regulating platelet aggregation.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Occur as a complication of a range of illnesses and can be accompanied by multi-organ failure and renal failure.

Systemic sclerosis

Renal involvement is a serious complication of SS, which is more likely to occur in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (DCSS) than in limited (LCSS). The renal lesion is caused by intimal cell proliferation and luminal narrowing of intrarenal arteries and arterioles. There is intense intrarenal vasospasm and plasma renin activity is markedly elevated. Renal involvement usually presents clinically with severe hypertension, microangiopathic features and progressive oliguric renal failure (scleroderma renal crisis).

Use of ACE inhibitors to control the hypertension

has improved the 1-year survival from 20% to 75% but

about 50% of patients continue to require RRT.

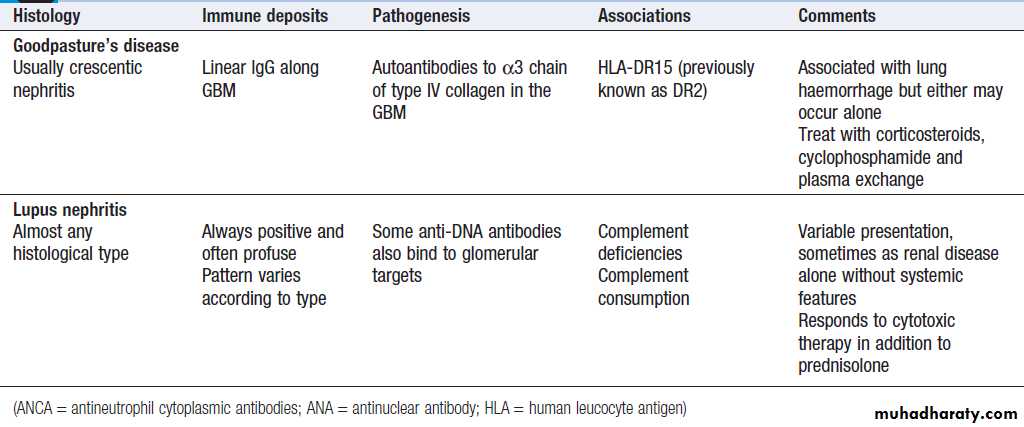

GLOMERULAR DISEASES

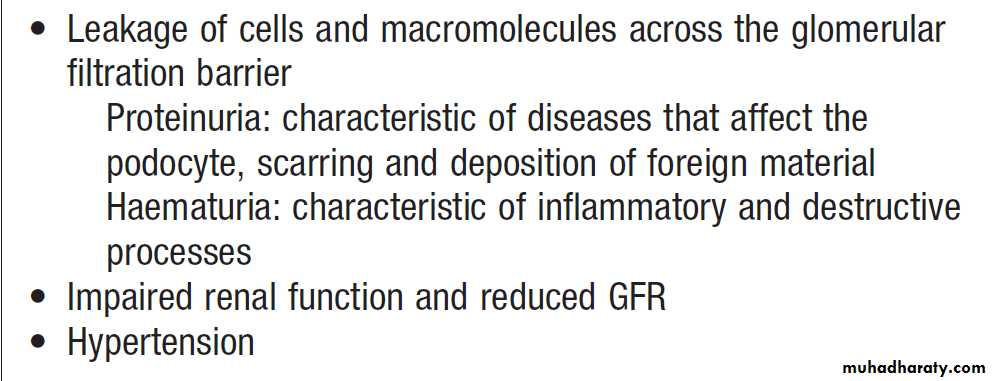

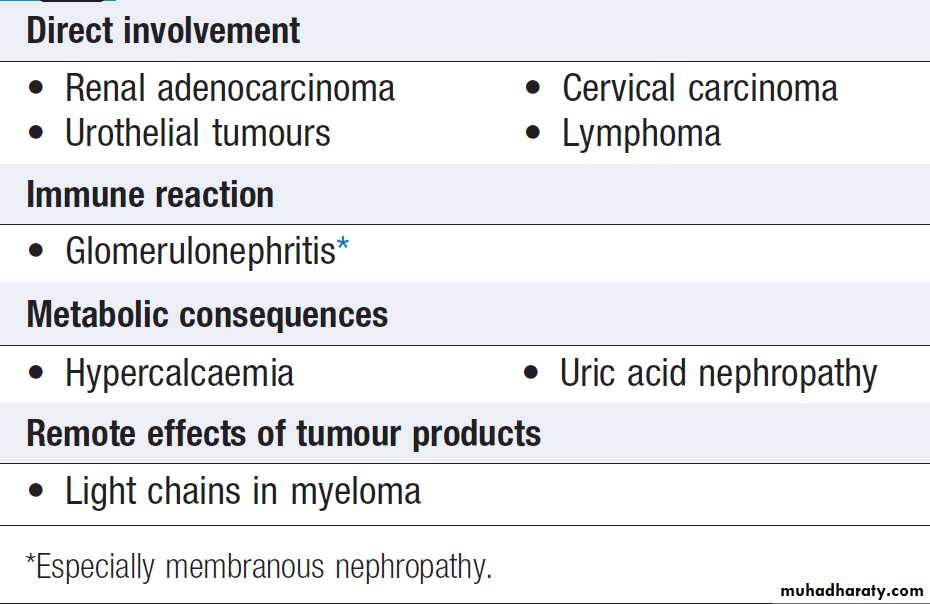

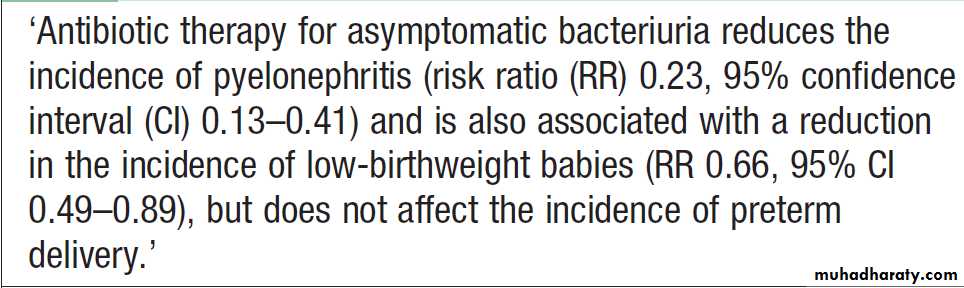

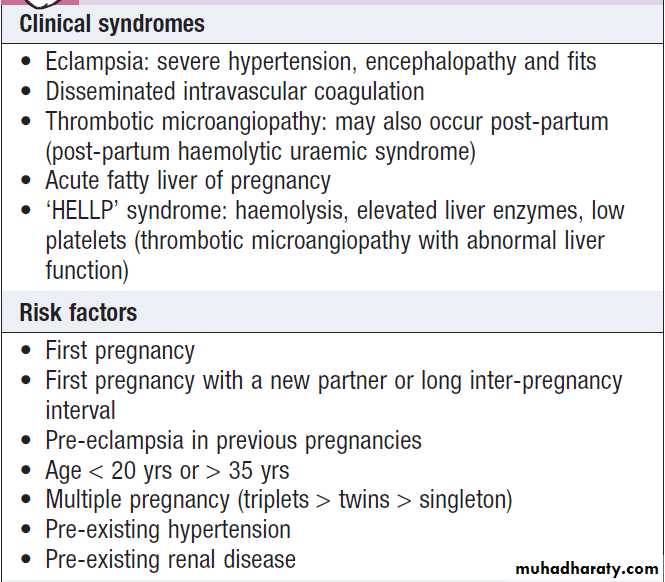

Account for a significant proportion of acute and chronic kidney disease. There are many causes of glomerular damage, including immunological injury, inherited such as Alport’s syndrome , metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus , and deposition of abnormal proteins such as amyloid in the glomeruli. Most patients do not present acutely and are asymptomatic until abnormalities are detected on routine screening of blood or urine samples.Clinical and laboratory features of glomerular injury

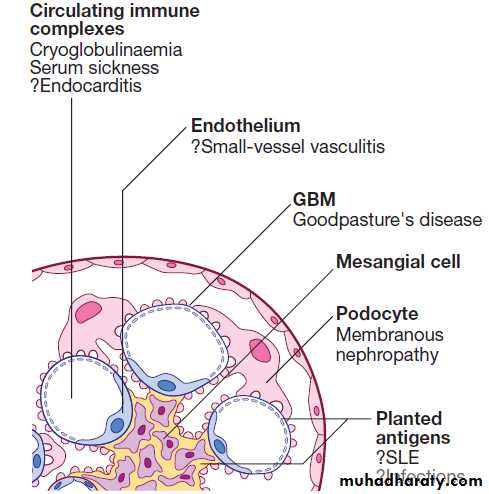

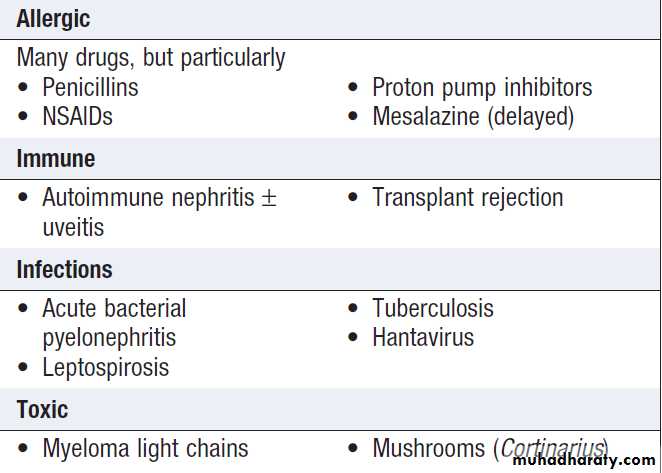

Cells of the glomerulus and targets of immunity and

autoimmunity. Antibodies and antigen–antibody (immune) complexes are described according to their site of deposition: subepithelial, between podocyte and GBM; intramembranous, within the GBM; subendothelial,between endothelial cell and GBM; and mesangial, within the mesangial matrix. (GBM = glomerular basement membrane;

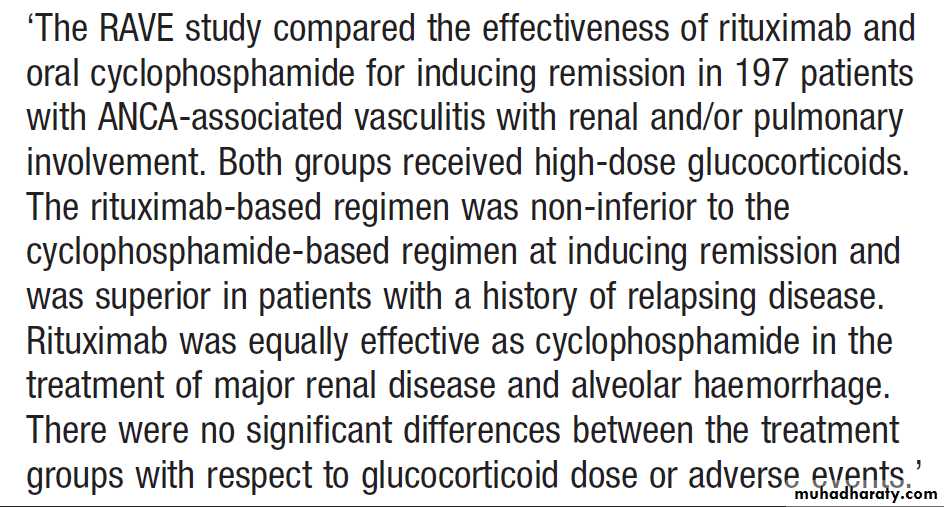

Glomerulonephritis (GN)

literally means ‘inflammation of glomeruli’. The term is used to describe all types of glomerular disease, even though some of these (such as minimal change nephropathy) are not associated with inflammation.Most types are immunologically mediated, deposition of antibody occurs in many but, frequently, the presumed mechanisms involve cellular immunity. Although deposition of circulating immune complexes was previously thought to be a common mechanism, it now seems that most deposits of immunoglobulin are formed

‘in situ’ by antibodies which complex with glomerular antigens, or with other antigens derived from viruses and bacteria that have become deposited in the glomeruli .

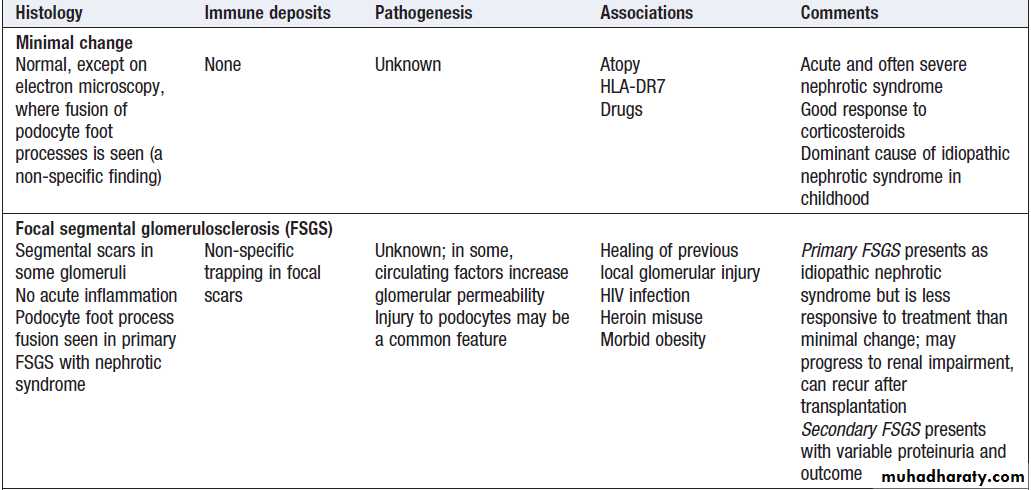

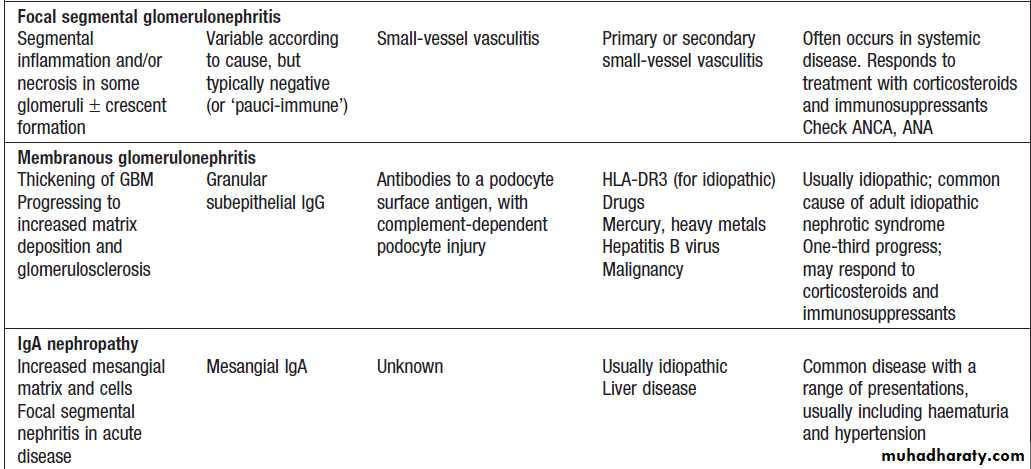

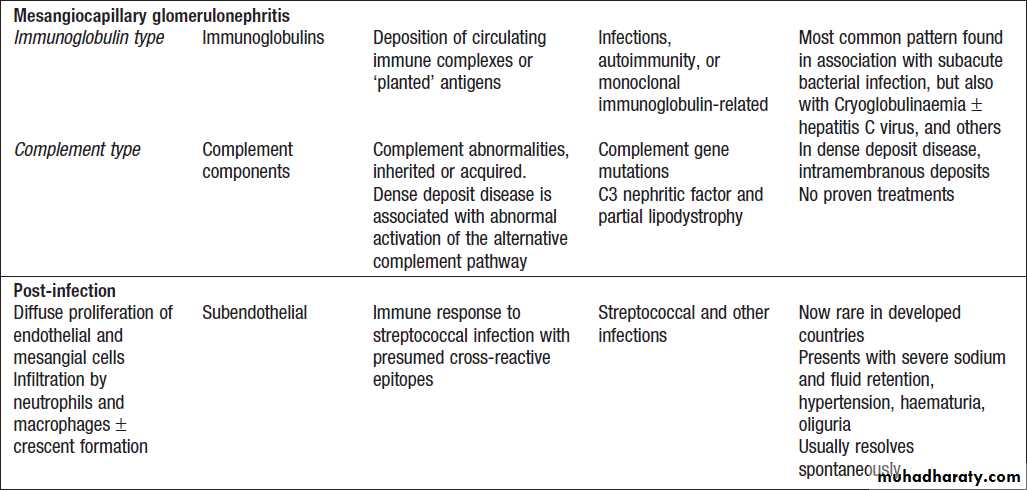

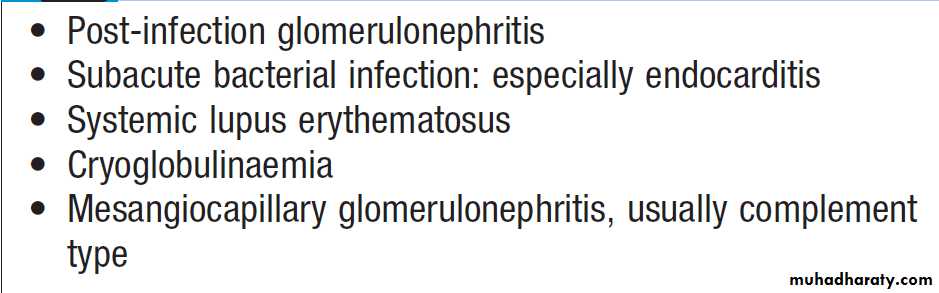

Glomerulonephritis: types, associations and causes

Glomerulonephritis: types, associations and causes'cont'd

Glomerulonephritis: types, associations and causes'cont'd

Glomerulonephritis: types, associations and causes'cont'd

Minimal change nephropathy

Minimal change disease occurs at all ages but accountsfor nephrotic syndrome in most children and about one-quarter of adults. It is caused by reversible dysfunction of podocytes. The presentation is with proteinuria or nephrotic syndrome, which typically remits with high-dose corticosteroid therapy (1 mg/kg prednisolone for 6 weeks). Some patients who respond incompletely or relapse frequently need maintenance corticosteroids, cytotoxic therapy or other agents.

Minimal change disease does not progress to CKD but

can present with problems related to the nephrotic syndrome and complications of treatment.

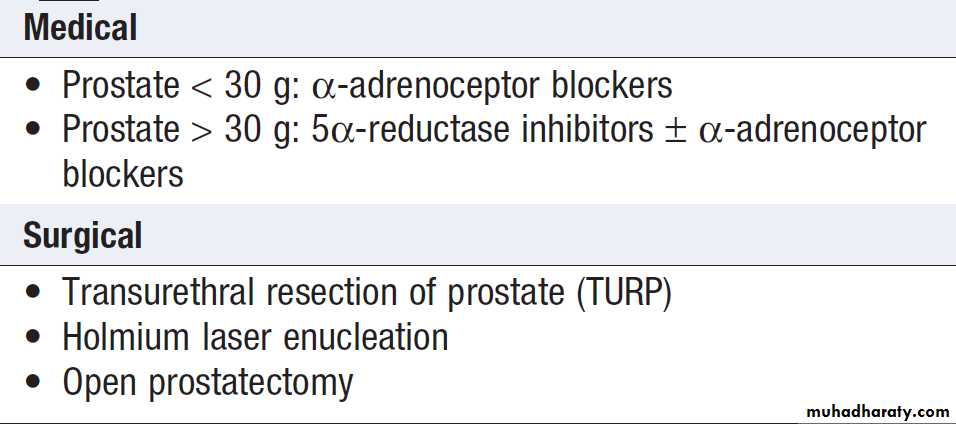

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)