Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABMLecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

2016

learning-topics

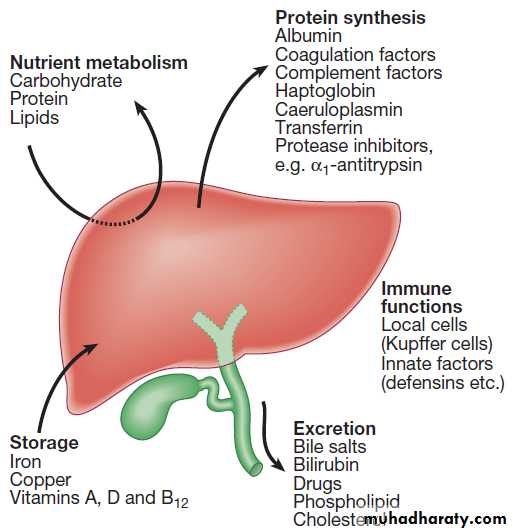

Liver andbiliary tract diseaseThe liver weighs 1.2–1.5 kg , produces 8–14 g of albumin and1–2 L of bile daily (contains bile acids (formed from cholesterol), phospholipids, bilirubin and cholesterol.

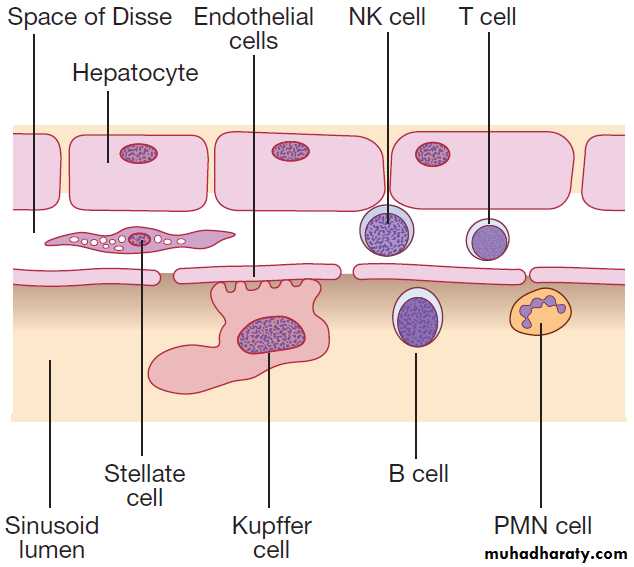

Liver cells

Hepatocytes comprise 80% of liver cells. The remaining 20% are the endothelial cells lining the sinusoids, epithelial cells lining the intrahepatic bile ducts, cells of the immune system (macrophages (Kupffer cells) and atypical lymphocytes), and non-parenchymal cells called stellate or Ito cells. Endothelial cells line the sinusoids , a network of capillary vessels that differ from other capillary beds in the body in that there is no basement membrane.

The endothelial cells have gaps between them (fenestrae) of about 0.1 micron in diameter, allowing free flow of fluid and particulate matter to the hepatocytes.

Individual hepatocytes are separated from the leaky sinusoids by the space of Disse, which contains

stellate cells that store vitamin A and play an important part in regulating liver blood flow. They may also be immunologically active and defence against pathogens. The key role of stellate cells in terms of pathology is in the development of hepatic fibrosis, the precursor of cirrhosis.

They undergo activation in response to cytokines produced following liver injury, differentiating into myofibroblasts, which are the major producers of the collagen-rich matrix that forms fibrous tissue .

Non-parenchymal liver cells. (B = B lymphocytes;

NK = natural killer cells; PMN = polymorphonuclear leucocytes;T = T lymphocytes).

Blood supply

The blood supply to the liver constitutes 25% of theresting cardiac output , receives a dual blood supply; ~20% of the blood flow is oxygen-rich blood from the hepatic artery, and 80% is nutrient-rich blood from the portal vein arising from the stomach, intestines, pancreas, and spleen.

The dual perfusion, can have important effects on the clinical expression of liver ischaemia (which typically exhibits a less dramatic pattern than ischaemia in other organs),and can raise practical challenges in liver transplant surgery.

Important liver functions.

The liver produces 8–14 g of albumin per day, and this plays a critical role in maintaining oncotic pressure in the vascular space and in the transport of small molecules like bilirubin, hormones and drugs throughout the body.Amino acids that are not required for the production of new proteins are broken down, with the amino group being

converted ultimately to urea.

• Following a meal, more than half of the glucose absorbed is taken up by the liver and stored as glycogen or converted to glycerol and fatty acids, thus preventing hyperglycaemia.

• During fasting, glycogen is broken down to release glucose (gluconeogenesis), thereby preventing

Hypoglycaemia.

• The liver plays a central role in lipid metabolism,

producing VLDL and further metabolising LDL and HDL . Dysregulation of lipid metabolism is thought to have a critical role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Lipids are now recognised to play a key part in the pathogenesis of hepatitis C, facilitating viral entry into hepatocytes.

Clotting factors

The liver produces key proteins that are involved in the

coagulation cascade. Many of these coagulation factors (II, VII, IX and X) are post- translationally modified by vitamin K-dependent enzymes, and their synthesis is impaired in VK deficiency . PT or INR , International Normalised Ratio, is therefore one of the most important clinical tools for the assessment of hepatocyte function.

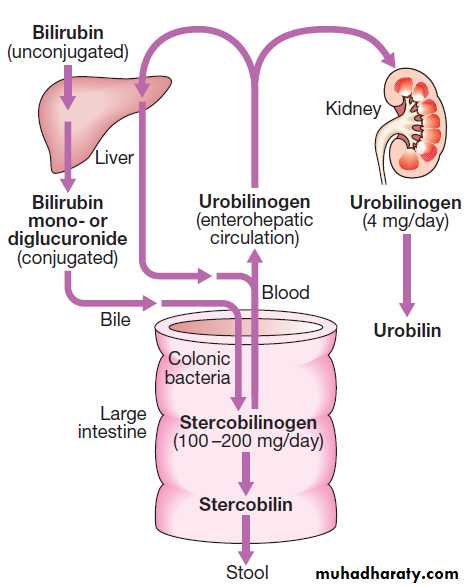

Note that the deranged PT or INR in liver disease may not directly equate to increased bleeding risk, as these tests do not capture the concurrent reduced synthesis of protein C and S anticoagulant. In general, therefore, correction of PT using blood products should be guided by clinical risk rather than the absolute value of the PT. The liver plays a central role in the metabolism of bilirubin and is responsible for the production of bile. In the blood 250–300 mg/ day of unconjugated bilirubin is produced from the catabolism of haem. Bilirubin is normally almost all unconjugated and, because it is not water-soluble, is bound to albumin and does not pass into the urine. Unconjugated bilirubin is taken by hepatocytes, conjugated in the endoplasmic reticulum by UDP-glucuronyl transferase, producing bilirubin mono- and diglucuronide.

These bilirubin conjugates are water-soluble and are exported into the bile canaliculi by specific carriers on the hepatocyte membranes. The conjugated bilirubin is excreted in the bile and passes into the duodenal lumen.

Once in the intestine, conjugated bilirubin is metabolised by colonic bacteria to form stercobilinogen, which may be further oxidised to stercobilin. Both stercobilinogen and stercobilin are then excreted in the stool, contributing to its brown colour. Biliary obstruction results in reduced stercobilinogen in the stool, and the stools become pale.

4 mg/day of stercobilinogen is absorbed from the bowel, passes through the liver, and is excreted in the urine, where it is known as urobilinogen or, following further oxidisation, urobilin.

Pathway of bilirubin excretion.

Storage of vitamins and mineralsVitamins A, D and B12 are stored by the liver in large

amounts, while others, such as vitamin K and folate, are

stored in smaller amounts and disappear rapidly if

dietary intake is reduced. The liver metabolise vitamins to more active compounds, e.g. 7-dehydrocholesterol to 25(OH) vitamin D. Also stores iron(ferritin and haemosiderin) and copper, which is excreted in bile.

Immune regulation

Approximately 9% of the normal liver is composed of

immune cells . Cells of the innate immune system include Kupffer cells derived from blood monocytes, macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells, as well as ‘classical’ B and T cells of the adaptive immune response.

The enrichment of such cells in the liver reflects the unique importance of the liver in preventing microorganisms from the gut entering the systemic circulation.

Kupffer cells constitute the largest single mass of

tissue-resident macrophages in the body and account

for 80% of the phagocytic capacity of this system. They remove aged and damaged red blood cells, bacteria, viruses, antigen–antibody complexes and endotoxin.

They also produce a wide variety of inflammatory mediators that can act locally or may be released into the systemic circulation.

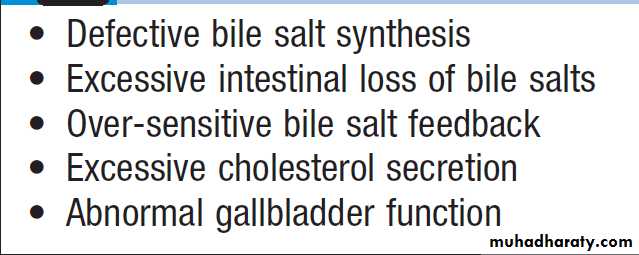

Biliary system and gallbladder

Hepatocytes provide the driving force for bile flow. Bile is secreted by hepatocytes and flows from cholangioles to the biliary canaliculi. The canaliculi join to form largerintrahepatic bile ducts, which in turn merge to form the

right and left hepatic ducts, join as they emerge from the liver to form the common hepatic duct, which becomes the common bile duct after joining the cystic duct . The common bile duct is approximately 5 cm long and

4–6 mm wide. The distal portion of the duct passes through the head of the pancreas and usually joins the pancreatic duct before entering the duodenum through the ampullary sphincter (sphincter of Oddi). The anatomy of the lower common bile duct can vary widely.

Common bile duct pressure is maintained by rhythmic

contraction and relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi; thispressure exceeds gallbladder pressure in the fasting

state, so that bile normally flows into the gallbladder,

where it is concentrated tenfold by resorption of water

and electrolytes.

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped sac typically lying

under the right hemiliver, with its fundus located anteriorly

behind the tip of the 9th costal cartilage. It concentrate, and provide a reservoir for, bile. Gallbladder tone is maintained by vagal activity, and cholecystokinin released from the duodenal mucosa during feeding causes gallbladder contraction and reduces sphincter pressure, so that bile flows into the duodenum.

INVESTIGATION OF LIVER AND HEPATOBILIARY DISEASE

• identification of the presence of liver disease

• establishing the aetiology

• understanding disease severity

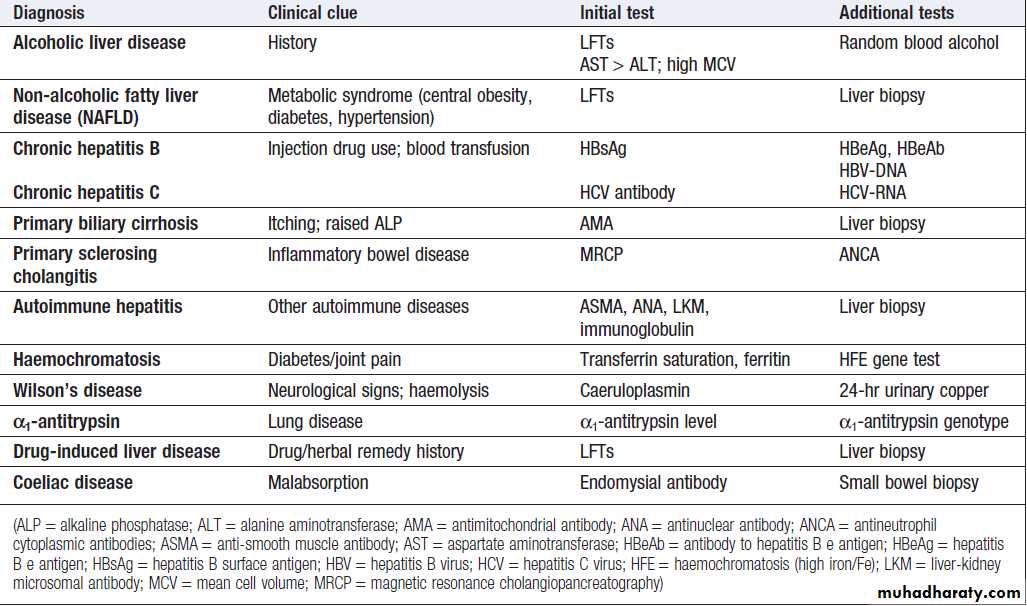

Aetiology is typically established through a combination

of history, specific blood tests and, where appropriate,

imaging and liver biopsy.

Staging of disease (in essence, the identification of

cirrhosis) is largely histological, although there is

increasing interest in non-invasive approaches, including

novel imaging modalities, serum markers of fibrosis

and the use of predictive scoring systems.

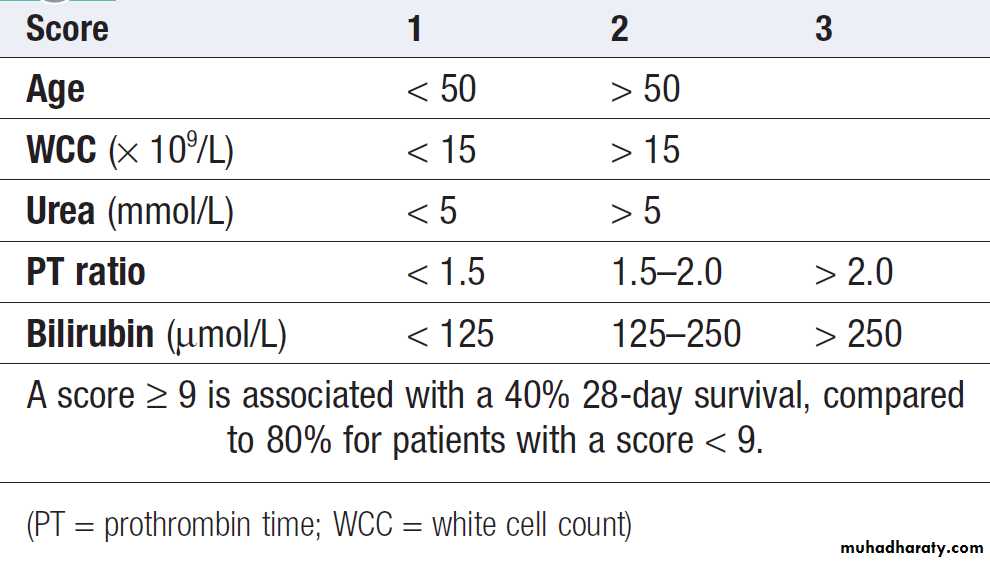

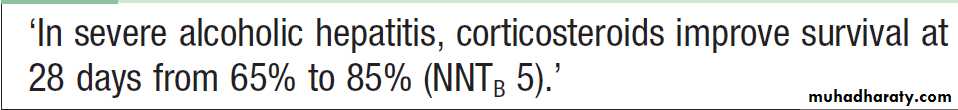

Prognostic scores: the Child–Pugh and MELD scores in

cirrhosis , the Glasgow score in alcoholic hepatitis .

Liver blood biochemistry (LFTs)

Serum bilirubin, aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase and albumin.Most analytes measured by LFTs are not truly ‘function’ tests but, given that they are released by injured hepatocytes, instead provide biochemical evidence

of liver cell damage.

Liver function per se is best assessed by the serum albumin, PT and bilirubin because of the role played by the liver in synthesis of albumin and clotting factors and in clearance of bilirubin. Serum albumin often low in liver disease, due to a change in the volume of distribution of albumin, and reduced synthesis. Since the plasma half-life of albumin is about 2 weeks, levels may be normal in acute liver failure but are reduced in chronic liver failure.

Alanine (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) are located in the the hepatocyte. Although both transaminase enzymes are widely distributed, expression of ALT outside the liver is relatively low and this enzyme is therefore considered more specific for hepatocellular damage. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) main sites of production are the liver, GIT , bone, placenta and kidney. ALP enzymes in the liver are located in cell membranes of the hepatic sinusoids and the biliary canaliculi. Accordingly, levels rise with intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary obstruction.

Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) is a microsomal

enzyme found in many cells and tissues of the body.The highest concentrations are located in the liver. The function of GGT is to transfer glutamyl groups from gamma-glutamyl peptides to other peptides and amino acids.

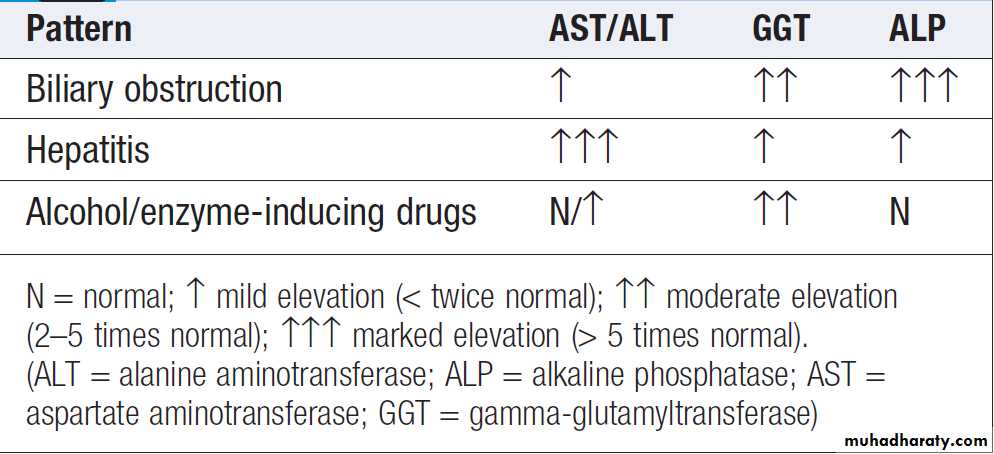

The pattern of a modest increase in aminotransferase

activity and large increases in ALP and GGT activity

favours biliary obstruction and is commonly described

as ‘cholestatic’ or ‘obstructive’ . Isolated elevation

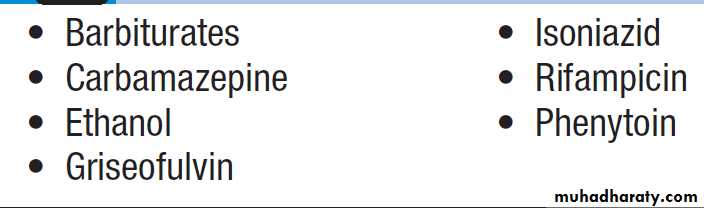

of the serum GGT is relatively common, and may

occur during ingestion of microsomal enzyme-inducing

drugs, including alcohol , but also in NAFLD.

‘Hepatitic’ and ‘cholestatic’/‘obstructive’

Drugs that increase gamma- glutamyltransferase

Other biochemical tests

• Hyponatraemia occurs in severe liver disease due

to increased production of antidiuretic hormone

• Serum urea may be reduced in hepatic failure,

whereas levels of urea may be increased following

gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

• When high levels of urea are accompanied by raised

bilirubin, high serum creatinine and low urinary sodium, this suggests hepatorenal failure, carries a grave prognosis.

• Significantly elevated ferritin suggests haemochromatosis. Modest rise in inflammatory disease and alcohol excess.

Haematological tests

Blood count• A normochromic normocytic anaemia may reflect

recent gastrointestinal haemorrhage, whereas chronic blood loss is characterised by a hypochromic microcytic anaemia secondary to iron deficiency. A high erythrocyte mean cell volume (macrocytosis) is associated with alcohol misuse,

but target cells in any jaundiced patient also result

in a macrocytosis.

• Leucopenia may complicate portal hypertension and

hypersplenism, whereas leucocytosis may occur with cholangitis, alcoholic hepatitis and hepatic abscesses. Atypical lymphocytes are seen in infectious mononucleosis.

• Thrombocytopenia is common in cirrhosis and is due to reduced platelet production, and increased breakdown because of hypersplenism. Thrombopoietin, required for platelet production, is produced in the liver and levels fall with worsening liver function.

Thus platelet levels are usually more depressed than white cells and haemoglobin in the presence of hypersplenism.

Thrombocytosis is unusual but may occur in those with active GI haemorrhage and, rarely,

in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Coagulation tests

The normal half-lives of the VK-dependent factors (5–72 hs), VKdeficiency, as may occur with so changes in the PT occur relatively quickly following liver damage; provide valuable prognostic information in acute and chronic liver failure. Increased PT is evidence of severe liver damage in chronic liver disease. VK does not reverse VKdeficiency if it is due to liver disease, but will correct if the cause is biliary obstruction (non-absorption of fat-soluble Vs).

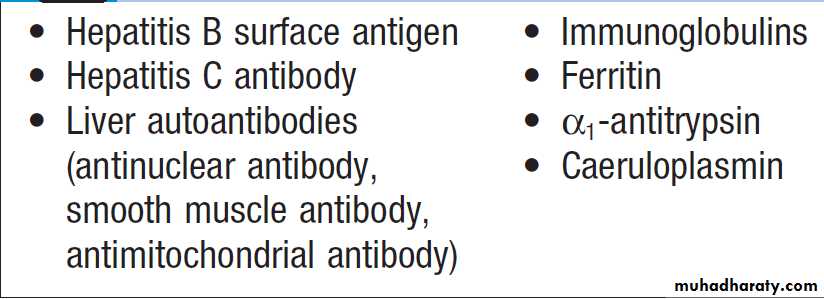

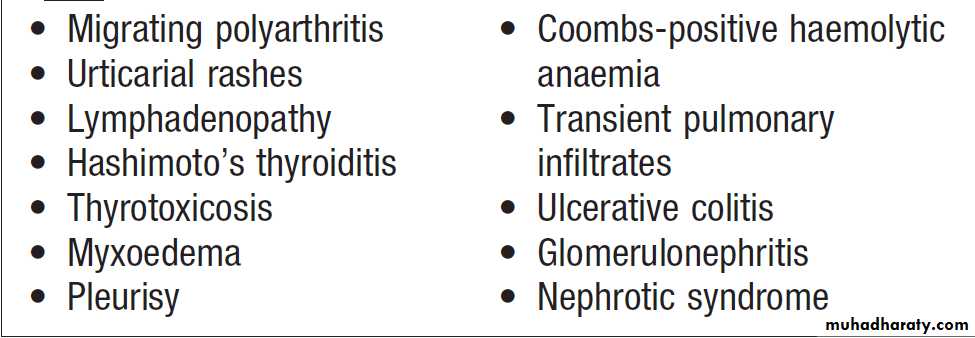

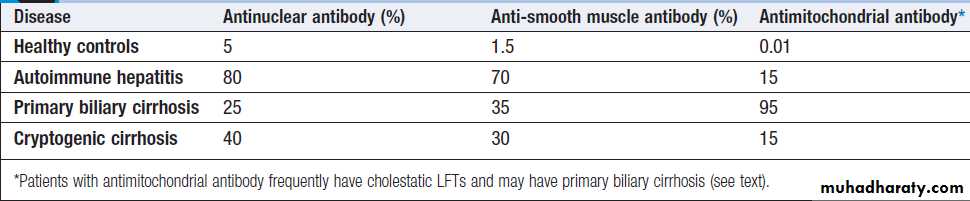

Immunological tests

The presence of liver-related autoantibodies can be suggestive of the presence of autoimmune liver disease (although false-positive results can occur in non-autoimmune inflammatory disease such as NAFLD). Elevation in overall serum immunoglobulin levels can also be suggestive of autoimmunity.

Chronic liver disease screen

How to identify the cause of LFT abnormality

ImagingSeveral imaging techniques used to determine the site and general nature of structural lesions in the liver and biliary tree. In general, however, imaging unable to identify inflammation and have poor sensitivity for liver fibrosis unless cirrhosis with portal hypertension is present.

Ultrasound

Non-invasive used as a ‘first-line’ test to identify gallstones, biliary obstruction or thrombosis in the hepatic vasculature, splenomegaly but is less effective at identifying diffuse parenchymal disease. Focal lesions, may not be detected if they are <2 cm in diameter. Doppler allows blood flow in the hepatic artery, portal vein and hepatic veins to be investigated. Endoscopic ultrasound provides high-resolution images of the pancreas, biliary tree and liver .

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

detects smaller focal lesions, especially when combined with contrast injection . MRI can also be used. Hepatic angiography is seldom used, since CT and MRI provide images of vasculature, but it still has a therapeutic role in the embolisation of vascular tumours.Cholangiography by MR cholangiopancreatography endoscopy ( MRCP) or the percutaneous approach (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, PTC). MRCP is as good as ERCP at providing images of the biliary tree but has fewer complications and is the diagnostic test of choice. Both allow therapeutic interventions, such as the insertion of biliary stents across malignant bile duct strictures. The PTC is used if it is not possible to access the bile duct endoscopically.

Histological examination

US-guided liver biopsy can confirm the severity of liver damage and provide aetiological information. Performed percutaneously with Menghini needle,through an intercostal space under local anaesthesia, or radiologically using a transjugular approach,is a relatively safe ,mortality of about 0.01%. The main complications are abdominal and/or shoulder pain, bleeding and biliary peritonitis.

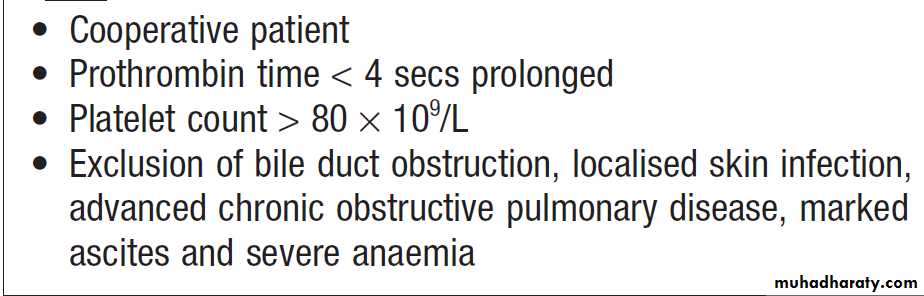

Liver biopsies can be carried out in patients with defective haemostasis if:

• the defect is corrected with fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusion

• biopsy is obtained by the transjugular route, or

• the procedure is conducted under US control and the needle track is then plugged with procoagulant material.

Conditions required for safe percutaneous liver biopsy

Non-invasive markers of hepatic fibrosisCan reduce the need for liver biopsy to assess the extent of fibrosis in some settings. Serological markers of hepatic fibrosis, such as α2-macroglobulin, haptoglobin and routine clinical biochemistry tests, are used in the Fibrotest®. The ELF® (Enhanced Liver Fibrosis) serological assay uses a combination of hyaluronic acid, procollagen peptide III (PIIINP) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1(TIMP1). An alternative to serological markers is transient elastography in which ultrasound-based shock waves are to measure liver stiffness as a surrogate for hepatic fibrosis. These tests are good at differentiating severe fibrosis from mild scarring, but is limited in its ability to detect subtle changes.

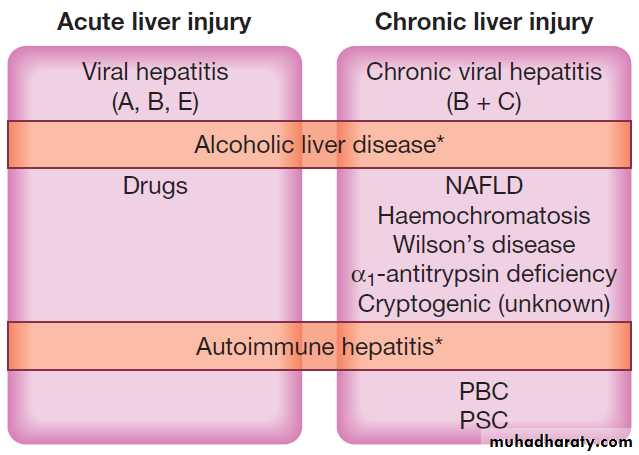

Causes of acute and chronic liver injury.

Acute liver injurymay present with non-specific symptoms of fatigue and abnormal LFTs, or with jaundice and acute liver failure.

Chronic liver injury hepatic injury,

inflammation and/or fibrosis occurring in the liver for > 6 months.

(NAFLD = non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PBC = primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC = primary sclerosing cholangitis).

Acute liver failure

Serious condition.The presentation is with progressive deterioration in liver function and mental changes progressing from confusion to coma.

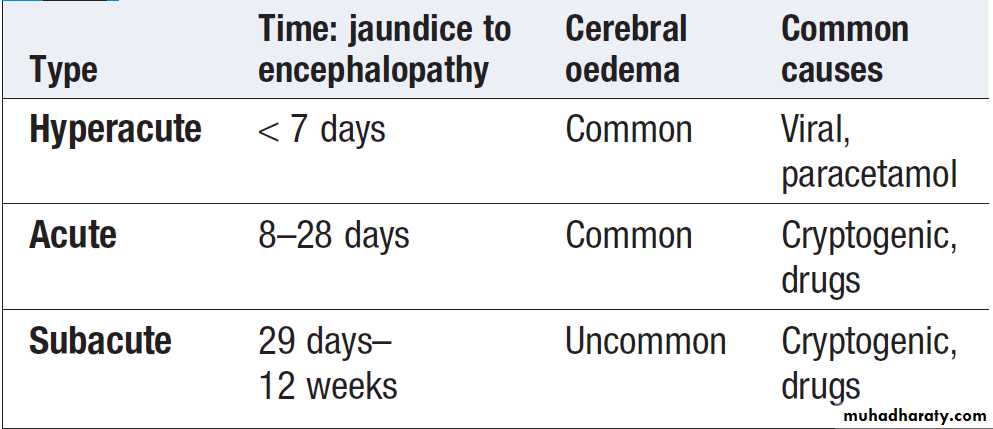

The syndrome was originally defined further as occurring within 8 weeks of onset of the precipitating illness, in the absence of evidence of preexisting liver disease. This distinguishes it from instances in which hepatic encephalopathy represents a deterioration in chronic liver disease (CLD). More recently, newer classifications have been developed divides acute liver failure into hyperacute, acute and subacute, according to the interval between onset of jaundice and encephalopathy .

Classification of acute liver failure

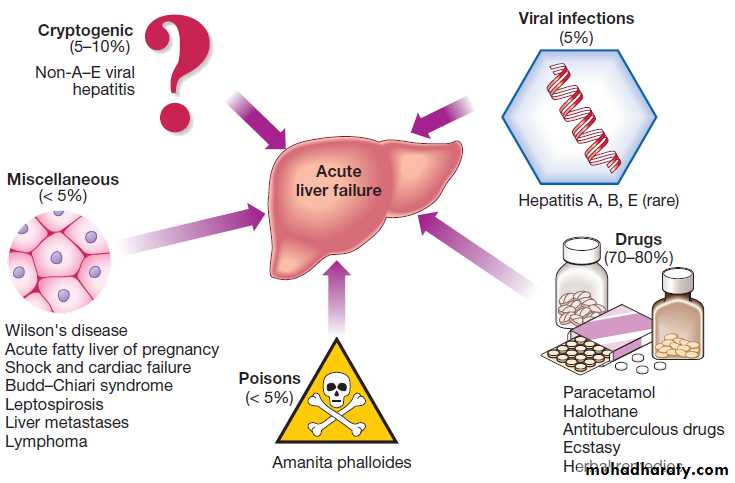

PathophysiologyAcute viral hepatitis is the most common cause worldwide,

whereas paracetamol toxicity is the most frequent cause in the UK, occasionally with other drugs, or from Amanita phalloides (mushroom) poisoning, in pregnancy, in Wilson’s disease, following shock and, rarely, in extensive malignant disease of the liver. In 10% of cases the cause of acute liver failure remains unknown and these patients are often labelled as having ‘non-A–E

viral hepatitis’ or ‘cryptogenic’ acute liver failure.

Causes of acute liver failure in the UK.

Clinical assessmenthepatic encephalopathy and/or cerebral oedema is the cardinal manifestation. The initial features are often subtle, reduced alertness and concentration, restlessness and aggression, to drowsiness and coma . Cerebral oedema may occur (increased ICP), causing abnormal pupil reaction, fixed pupils. Hypertension , bradycardia, hyperventilation, profuse sweating, focal fits or decerebrate posturing. Papilloedema rare, weakness, nausea and vomiting. Right hypochondrial discomfort. Occasionally, death occur before jaundice develops. Fetor hepaticus The liver is normal size but later becomes smaller. Hepatomegaly is unusual and, in the presence of acute ascites, suggests venous outflow obstruction (Budd– Chiari syndrome). Splenomegaly is uncommon . Ascites and oedema are late.

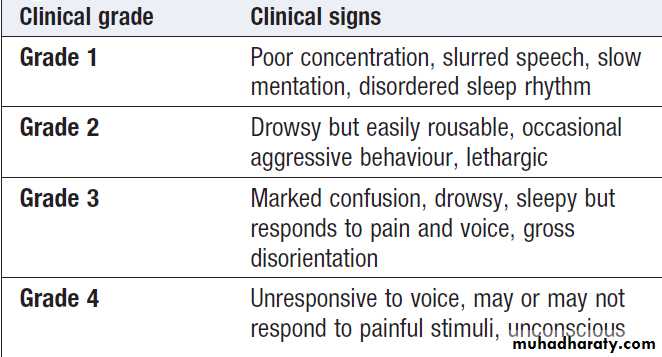

How to assess clinical grade of hepatic encephalopathy

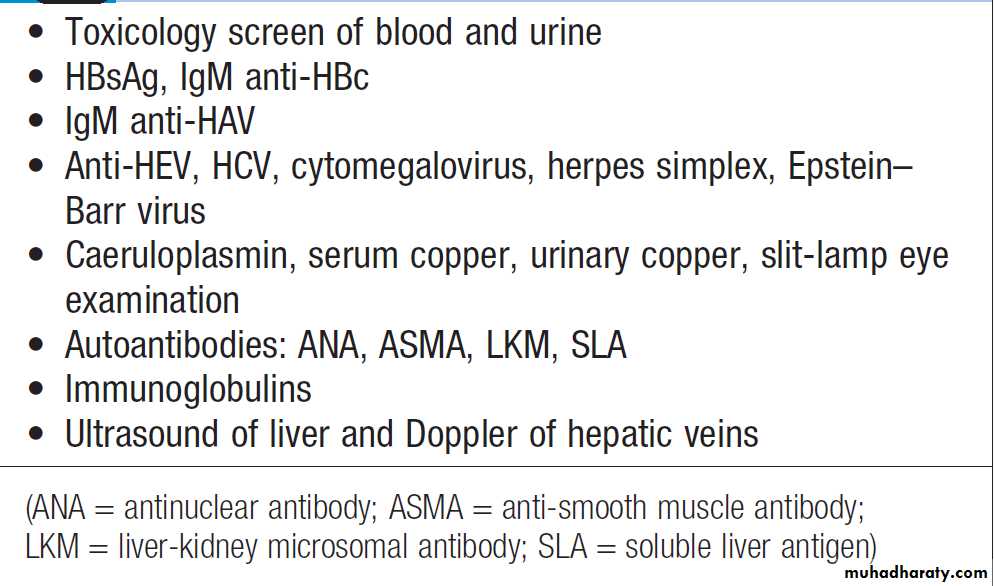

InvestigationsTo determine the cause of the liver failure and prognosis .

Hepatitis B core IgM antibody is the best screening test for acute hepatitis B infection, as liver damage is due to the immunological response to the virus, which has often been eliminated, and the test for HBsAg may be negative.

The PT rapidly prolonged and itis of greatest prognostic value and should be carried out at least twice daily. Factor V levels can be used instead of the PT to assess liver impairment. Aminotransferase is particularly high after paracetamol overdose, reaching 100–500 times normal, but falls as liver damage progresses and is not helpful in determining prognosis. Plasma albumin remains normal unless the course is prolonged. Percutaneous liver biopsy is contraindicated (severe coagulopathy).

Investigations to determine the cause of

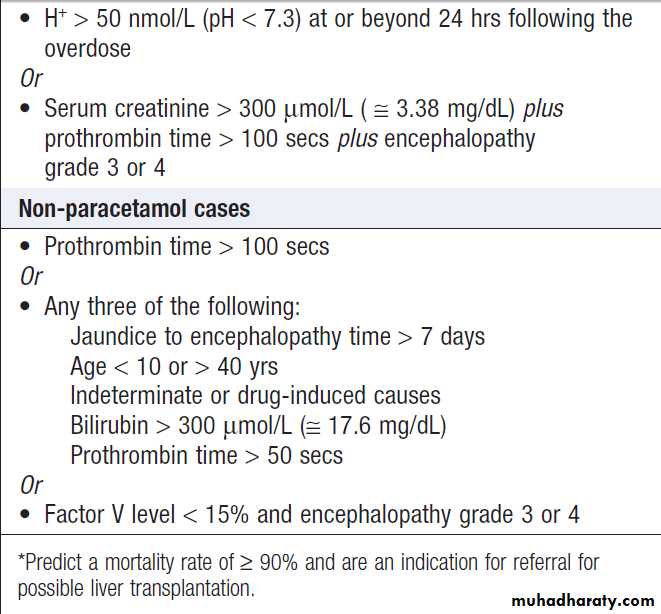

acute liver failureAdverse prognostic criteria in acute liver failure*

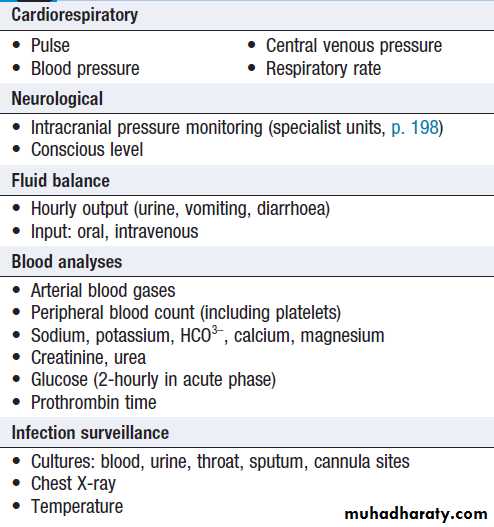

Monitoring in acute liver failure

Management

Patients with acute liver failure should be treated in ahigh-dependency or intensive care unit as soon as

progressive prolongation of the PT occurs or hepatic

encephalopathy is identified , so that prompt treatment of complications can be initiated . Conservative treatment aims to maintain life in the hope that regeneration will occur, but early transfer to a specialised transplant unit should always be considered. N- acetylcysteine may improve outcome, particularly in acute failure due to paracetamol poisoning. Liver transplantation is an increasingly important treatment option for acute liver failure. Survival following liver transplantation is improving, 1-year survival rates of about 60%.

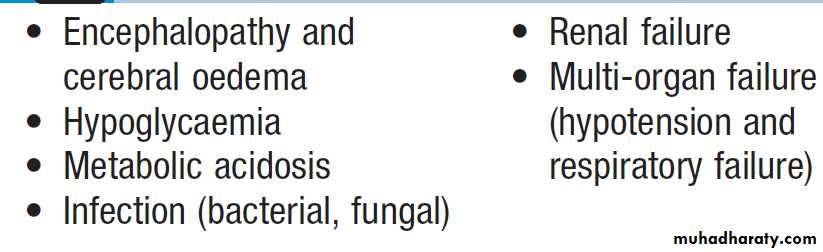

Complications of acute liver failure

Abnormal liver function testsThe prevalence has been reported to be as high as 10%. The most common abnormalities are alcoholic or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease . When LFTs are measured routinely prior to elective surgery, 3.5% are discovered to have mildly elevated transaminases. Although transient mild abnormalities may not be clinically significant, the majority of patients with persistently abnormal LFTs do have significant liver disease. Biochemical abnormalities in CLD often fluctuate over time, and therefore even mild abnormalities can indicate significant underlying disease and so warrant follow-up and investigation.

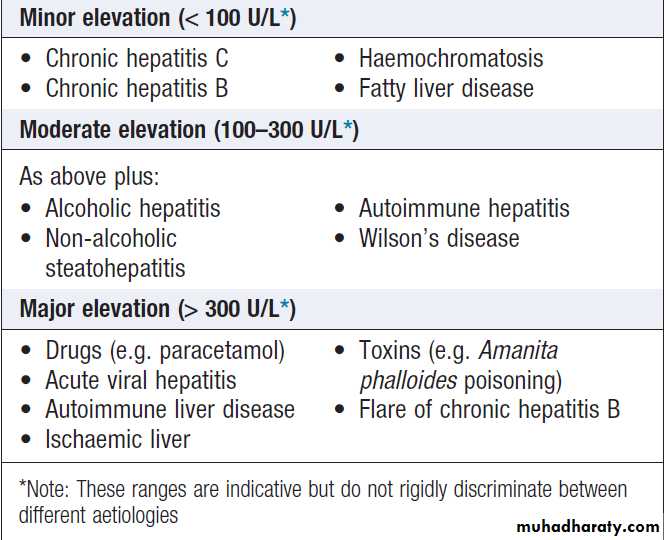

Common causes of elevated serum transaminases

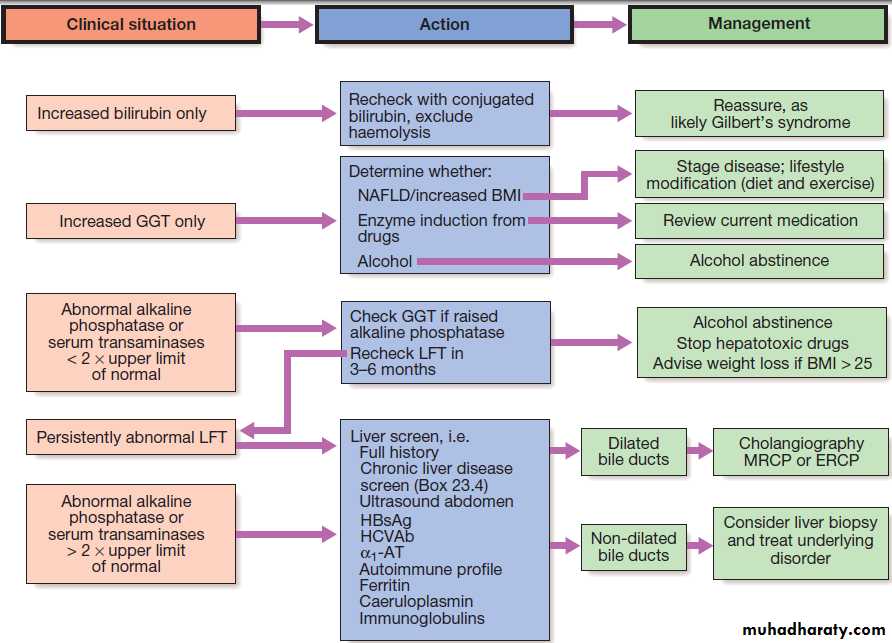

Suggested management of abnormal LFTs in asymptomatic patients. *No further investigation needed.

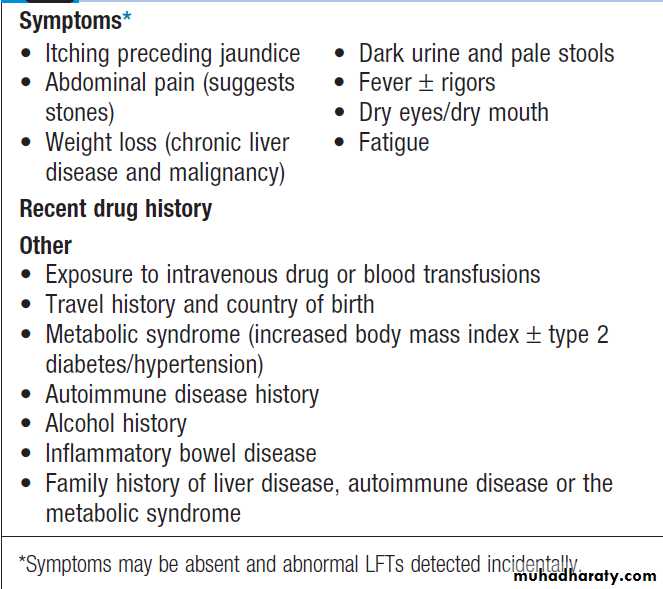

Key history points in patients with jaundice

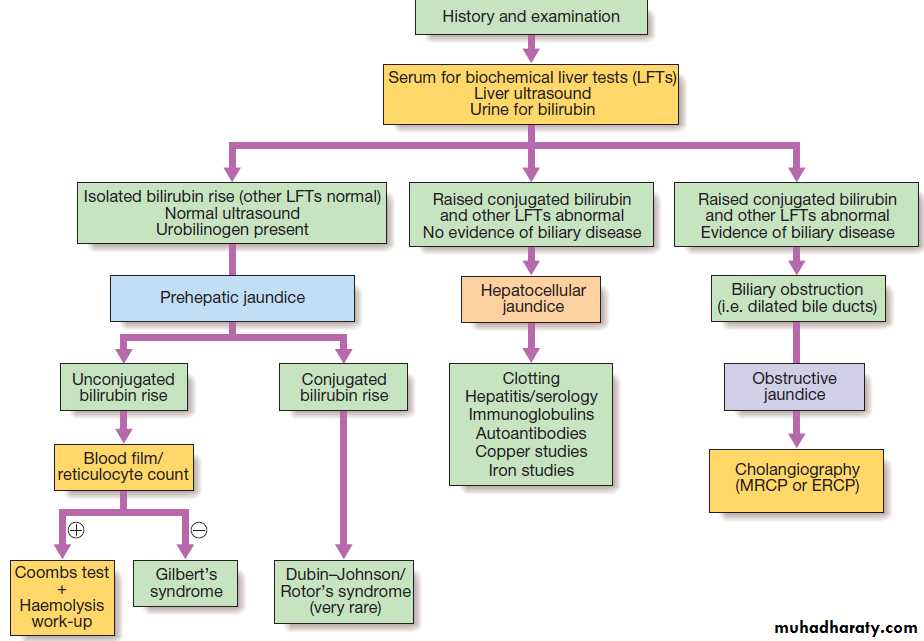

JaundiceDetectable clinically when the plasma bilirubin exceeds ~2.5 mg/ dL . It is useful to consider whether the cause pre-hepatic, hepatic or post-hepatic

Pre-hepatic jaundice

Caused either by haemolysis or congenital , and is characterised by an isolated raised bilirubin level. Jaundice due to haemolysis is usually mild because a healthy liver can excrete a bilirubin load six times greater than normal before unconjugated bilirubin accumulates in the plasma. The most common form of non- haemolytic hyperbilirubinaemia is Gilbert’s.

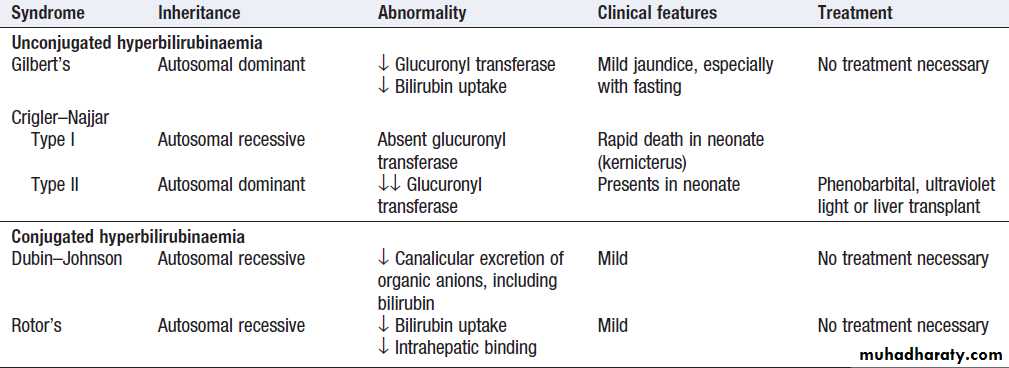

Congenital non-haemolytic hyperbilirubinaemia

Hepatocellular jaundiceResults from an inability of the liver to transport

(at any point between uptake of unconjugated bilirubin into the cells and transport of conjugated bilirubin into the canaliculi) bilirubin into the bile.

In hepatocellular , both unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin in the blood increase. Characteristically associated with increases in transaminases . Acute jaundice in the presence of an ALT of > 1000 U/L is highly suggestive of an infectious cause (e.g. hepatitis A, B), drugs (e.g. paracetamol) or hepatic ischaemia.

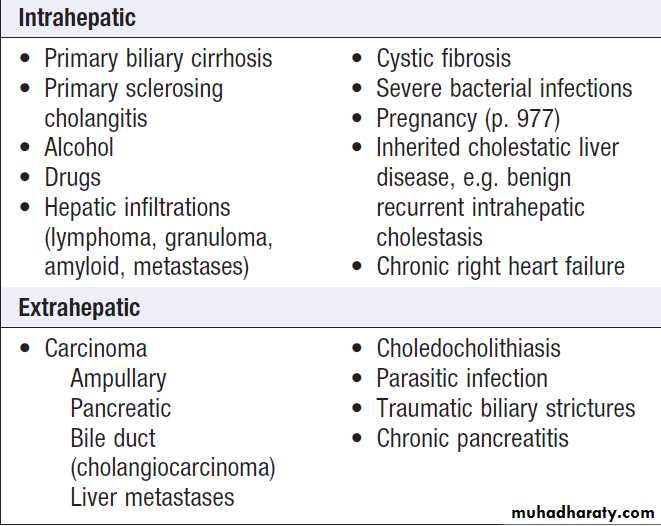

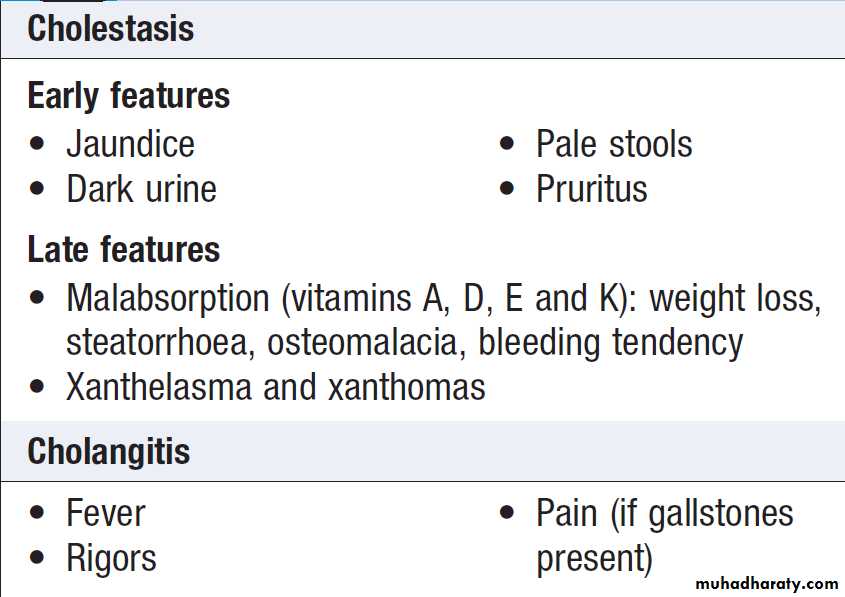

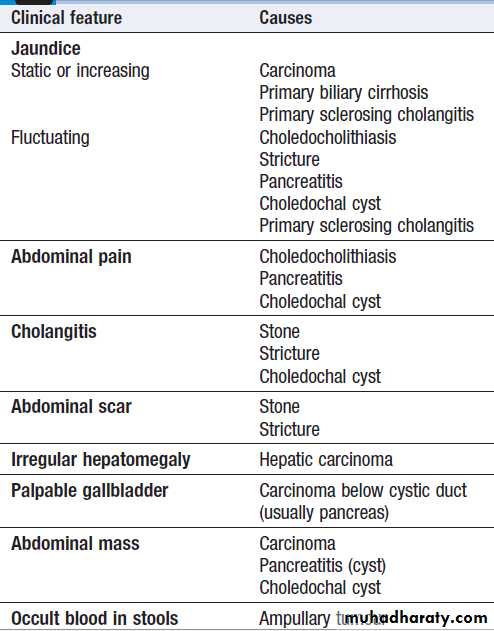

Obstructive (cholestatic) jaundice

May be caused by:

• failure of hepatocytes to initiate bile flow

• obstruction of the bile ducts or portal tracts

• obstruction of bile flow in the extrahepatic bile ducts between the porta hepatis and the papilla of Vater.

Clinical features , due to cholestasis, those due to secondary infection(cholangitis) and underlying condition. Extrahepatic biliary blockage is characteristically associated with pale stools and dark urine. Pruritus , skin excoriations may be a dominant feature.

Peripheral stigmata of chronic liver disease are absent.

If the gallbladder is palpable, the jaundice is unlikely to be caused by biliary obstruction due to gallstones, probably because a chronically inflamed stone-containing gallbladder cannot readily dilate. This is Courvoisier’s Law, and suggests that jaundice is due to a malignant biliary obstruction (e.g. pancreatic cancer).

Cholangitis is characterised by ‘Charcot’s triad’ of jaundice, right upper quadrant pain and fever.

Cholestatic jaundice is characterised by a relatively greater elevation of ALP and GGT than the aminotransferases.

Ultrasound is indicated to determine the cause .

Causes of cholestatic jaundice

Clinical features and complications of

cholestatic jaundice

*Each of the diseases listed here can give rise to almost any of the clinical

features shown, but the box indicates the most likely cause of the clinical features listed.Clinical features suggesting an underlying

cause of cholestatic jaundice*

Investigation of jaundice.

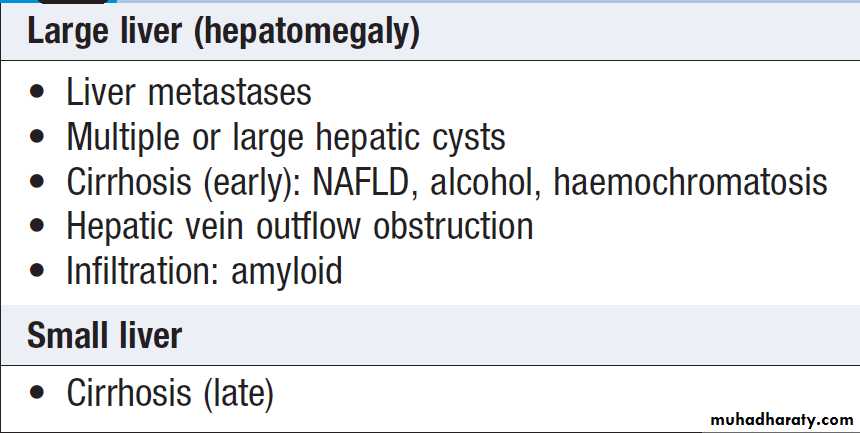

Causes of change in liver size

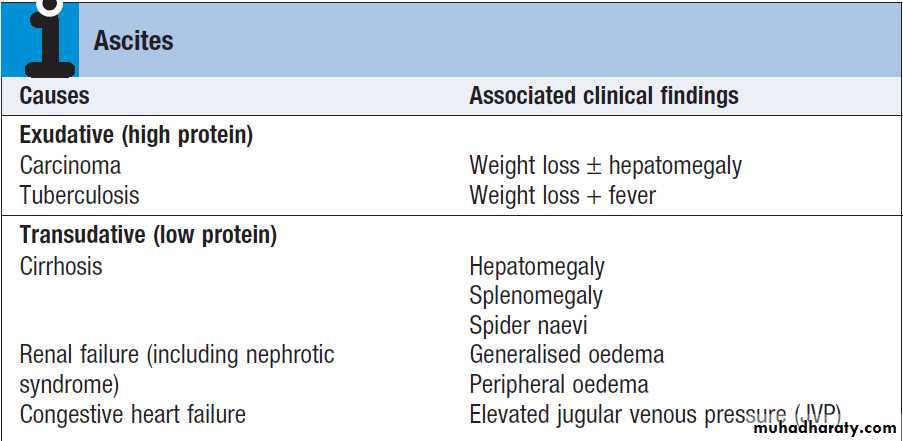

Ascites

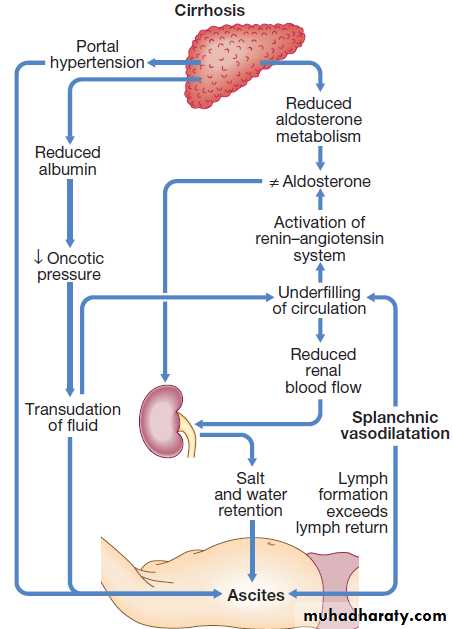

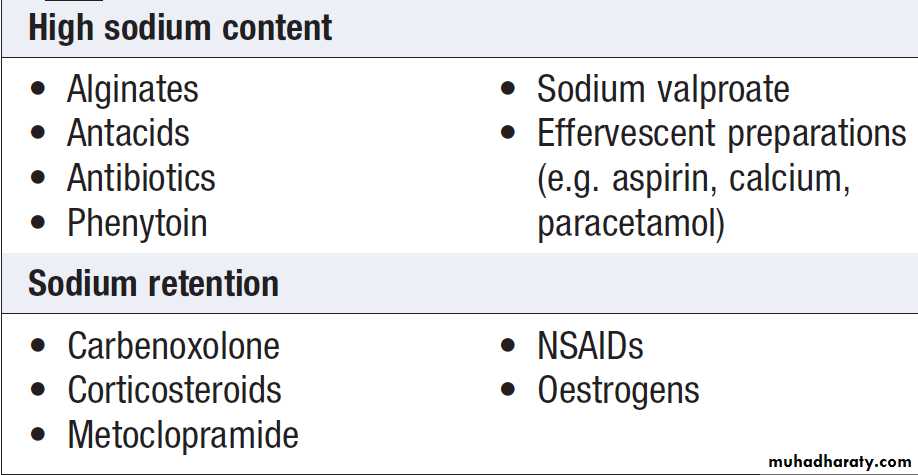

Free fluid in the peritoneal cavity, accumulations of (> 1 L) causes abdominal distension, fullness in the flanks, shifting dullness and when marked, a fluid thrill, eversion of the umbilicus, herniae, abdominal striae, and scrotal oedema. Dilated superficial abdominal veins may be seen due to portal hypertension. Splanchnic vasodilatation is thought to be the main factor leading to ascites in cirrhosis, mediated by vasodilators (mainly nitric oxide) that are released when portal hypertension causes shunting of blood into the systemic circulation. Systemic arterial pressure falls leads to activation of the RAS with secondary aldosteronism, increased sympathetic activity, increased atrial natriuretic hormone secretion and altered activity of the kallikrein–kinin system .

These systems tend to normalise arterial pressure

but produce salt and water retention. In this setting the combination of splanchnic arterial vasodilatation and portal hypertension alters intestinal capillary permeability, promoting accumulation of fluid within the peritoneum.Investigations

US is the best means of detecting ascites. Paracentesis (if necessary under ultrasonic guidance) can be used to obtain ascitic fluid for analysis.Pleural effusions are found in

about 10%, usually on the right side , most are small . Pleural effusions, particularly those on the left side, should not be assumed to be due to the ascites.

Measurement of the protein concentration and the

serum–ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) are used to distinguish a transudate from an exudate.

Pathogenesis of ascites.

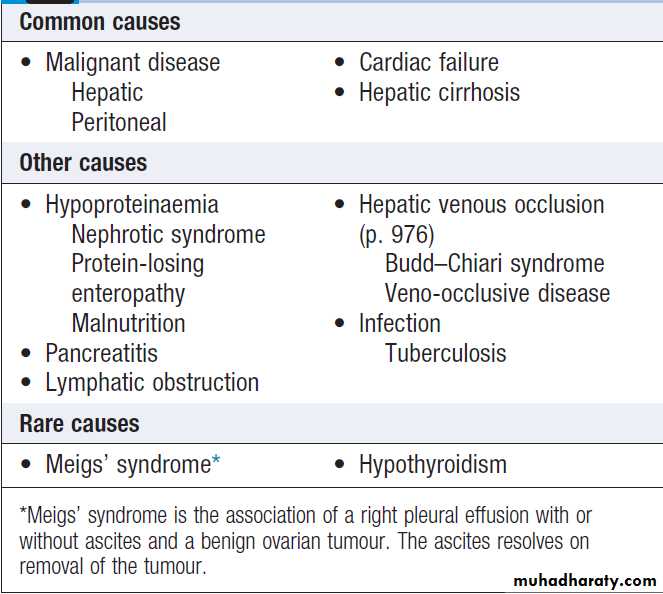

Causes of ascites

Ascitic fluid: appearance and analysis

Cirrhotic develop a transudate with a total protein concentration< 25 g/L and relatively few cells. However, in up to 30% of patients, the total protein concentration is more than 30 g/L. In these cases, it is useful to calculate the SAAG by subtracting the concentration of the ascites fluid albumin from the serum albumin. A gradient of >11 g/L is 96% predictive that ascites is due to portal hypertension. Venous outflow obstruction due to cardiac failure or hepatic venous obstruction also cause a transudate, gradient > 11 g/L but, unlike in cirrhosis, the total protein is usually > 25 g/L. Exudative ascites (ascites protein concentration > 25 g/L or a SAAG < 11 g/L) raises the possibility of infection (tuberculosis), malignancy, hepatic venous obstruction, pancreatic or hypothyroidism.Ascites amylase activity above 1000 U/L identifies pancreatic ascites, and low ascites glucose concentrations suggest malignant disease or tuberculosis.

Cytological examination may reveal malignant cells

(one-third of cirrhotic patients with a bloody tap have a

hepatocellular carcinoma). Polymorphonuclear leucocyte

counts above 250 × 106/L strongly suggest infection

(spontaneous bacterial peritonitis). Laparoscopy can be valuable in detecting peritoneal disease.

Management

Successful treatment relieves discomfort but does not

prolong life; if over-vigorous, it can produce serious disorders of fluid and electrolyte balance and precipitate

hepatic encephalopathy .

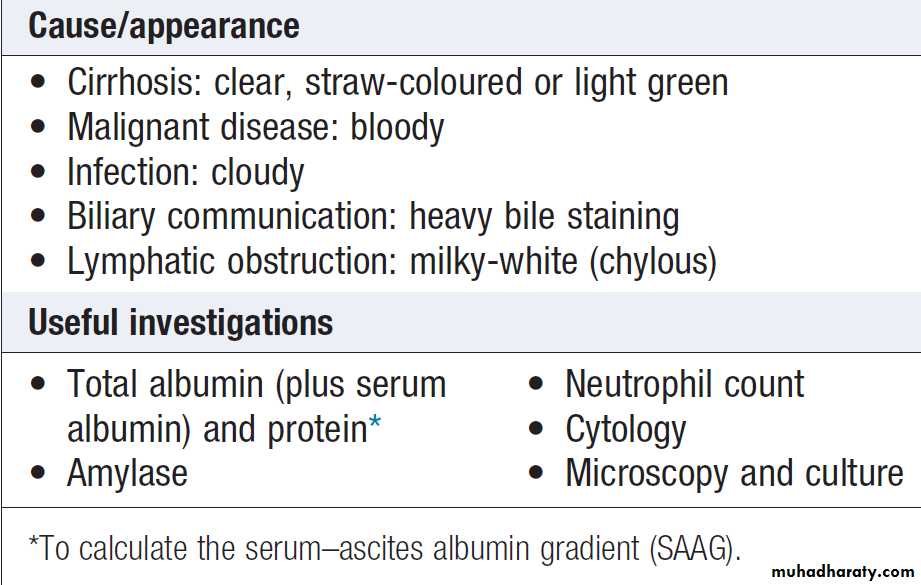

Treatment of transudative ascites is based on restricting sodium and water intake, diuretics and, if necessary, removing ascites directly by paracentesis.

Exudative ascites due to malignancy is treated with

paracentesis. During management of ascites, the patient

should be weighed regularly. Diuretics should be titrated to remove no >1 L of fluid daily, so body weight should not fall by >1 kg daily to avoid excessive fluid depletion. Sodium and water restriction

Restriction of sodium intake to 100 mmol/day (‘no added salt diet’) is usually adequate. Drugs containing relatively large amounts of sodium, and those promoting sodium retention such as NSAIDs, must be avoided .

Restriction of water intake to 1.0–1.5 L/day is necessary only if the plasma sodium falls < 125 mmol/L.

Some drugs containing relatively large amounts of sodium or causing sodium retention

Diuretics :Spironolactone (100–400 mg/day) is the first-line , it is a powerful aldosterone antagonist; it can cause painful gynaecomastia and hyperkalaemia, in which case amiloride (5–10 mg/day) can be substituted. Some also require loop diuretics. Patients who do not respond to 400 mg spironolactone and 160 mg furosemide, or unable to tolerate these doses due to hyponatraemia or renal impairment, are considered to have refractory or diuretic-resistant ascites and should be treated by other measures.Paracentesis : First-line treatment of refractory ascites is large-volume paracentesis. Paracentesis to dryness is safe, provided the circulation is supported with an IV colloid such as human albumin , 6–8 g per litre of ascites removed, Paracentesis can be used as an initial therapy or when other treatments fail.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS) can relieve resistant ascites but does not prolong life; it may be an option where the only alternative

1.is frequent, large-volume paracentesis.

2. in patients awaiting liver transplantation, but can aggravate encephalopathy in those with poor function.

Peritoneo-venous shunt

A long tube with a non-return valve running subcutaneously from the peritoneum to the internal jugular vein in the neck; it allows fluid to pass directly into the systemic circulation.

Complications, including infection, SVC thrombosis, pulmonary oedema, bleeding from oesophageal varices and DIC. limit its use.

Complications of ascites

1. Renal failure

It can be pre-renal due to vasodilatation from sepsis and/or diuretic therapy, or hepatorenal syndrome.

2. Hepatorenal syndrome

Occurs in 10% with advanced cirrhosis complicated by ascites. There are two clinical types; mediated by renal vasoconstriction.

Type 1 oliguria, a rapid rise of creatinine and a very poor prognosis .Treatment , albumin infusions with terlipressin. Haemodialysis should not be used routinely because it does not improve the outcome. Patients who survive should be considered for liver transplantation.

Type 2 occurs in patients with refractory ascites, moderate and stable increase in s creatinine, has a better prognosis.

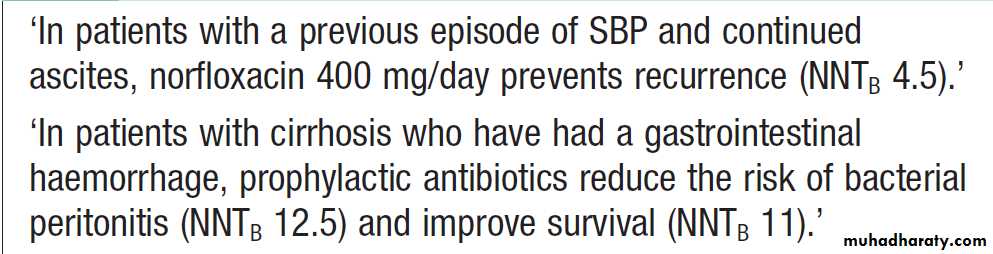

3. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

Present with abdominal pain, rebound tenderness, absent bowel sounds , fever, encephalopathy and fever. Diagnostic paracentesis may show cloudy fluid, and ascites neutrophil count above 250 × 106/L. The source of infection cannot usually be determined, but most organisms isolated are of enteric origin and Ecoli is most frequently found. Ascitic culture in blood culture gives the highest yield of organisms. SBP needs to be differentiated from other intra-abdominal emergencies. Treatment should be started immediately with broad spectrum antibiotics, such as cefotaxime or piperacillin/ tazobactam. Recurrence is common but reduced with prophylactic quinolones such as norfloxacin or ciprofloxacin .Prognosis

10–20% of patients survive 5 years from the first appearance of ascites due to cirrhosis. The prognosis is better when a treatable cause for the underlying cirrhosis is present or when a precipitating cause for ascites, such as excess salt intake, is found.Antibiotics and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

Hepatic encephalopathyA neuropsychiatric syndrome caused by liver disease.

As it progresses, confusion is followed by coma. Confusion needs to be differentiated from delirium tremens and Wernicke’s encephalopathy, and coma from subdural haematoma, which can occur in alcoholics after a fall .

Features include changes of intellect,personality, drowsiness, disorientation, slurring of speech and eventually coma. Convulsions sometimes occur. Examination usually shows a flapping tremor (asterixis), inability to perform simple mental arithmetic tasks or to draw objects such as a star (constructional apraxia), and, as the condition progresses, hyper-reflexia and bilateral extensor plantar responses.

The degree can be graded from 1 to 4.

Hepatic encephalopathy rarely causes focal neurological signs; if these are present, other causes must be sought. Fetor hepaticus, a sweet musty odour to the breath, is usually present but is more a sign of portosystemic shunting than of encephalopathy. Rarely, chronic encephalopathy gives rise to variable combinations of cerebellar dysfunction, Parkinson, spastic paraplegia and dementia.

Differential diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy

• Intracranial bleed (subdural, extradural haematoma,

• Drug or alcohol intoxication

• Delirium tremens/alcohol withdrawal

• Wernicke’s encephalopathy

• Primary psychiatric disorders

• Hypoglycaemia

• Neurological Wilson’s disease

• Post- ictal state

Pathophysiology of Hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is thought to be provoked by circulating neurotoxins that are normally metabolised by the liver. Accordingly, most affected patients have evidence of liver failure and portosystemic shunting of blood. The ‘neurotoxins’ causing encephalopathy are unknown, but they are thought to be mainly nitrogenous substances produced in the gut, at least in part by bacterial action. These substances are normally metabolised by the healthy liver and excluded from the systemic circulation. Ammonia considered an important factor. Recent interest has focused on γ- aminobutyric acid (GABA), amino acids, mercaptans and fatty acids that can act as neurotransmitters. Disruption of the blood–brain barrier may lead to cerebral oedema.Investigations

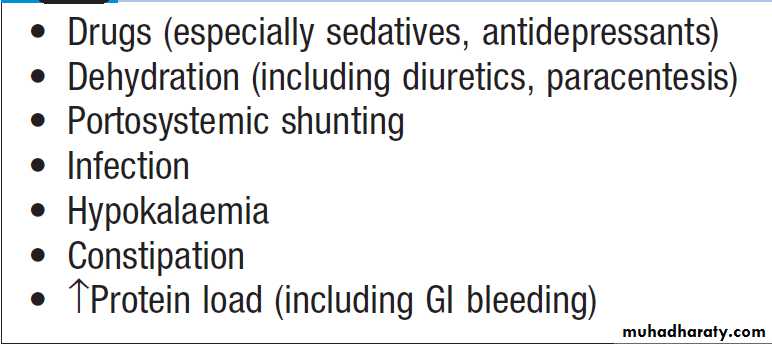

The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, electroencephalogram (EEG) shows diffuse slowing of the normal alpha waves with eventual development of delta waves. The arterial ammonia is usually increased, however, increased concentrations can occur in the absence of clinical encephalopathy, rendering this investigation of little diagnostic value.Factors precipitating hepatic encephalopathy

Management of Hepatic encephalopathyThe principles are to treat or remove precipitating causes and to suppress the production of neurotoxins by bacteria in the bowel. Dietary protein restriction is rarely needed , no longer recommended because it is unpalatable and can lead to a worsening nutritional state in already malnourished. Lactulose (15–30 mL 3 times daily) is increased until the bowels are moving twice daily. It produces an osmotic laxative effect, reduces the pH, thereby limiting colonic ammonia absorption. Rifaximin (400 mg 3 times daily) non-absorbed antibiotic that acts by reducing the bacterial content of the bowel , shown to be effective. It can be used in addition, or as an alternative to lactulose if diarrhoea becomes troublesome. Chronic or refractory encephalopathy is an indications for liver transplantation.

CIRRHOSIS

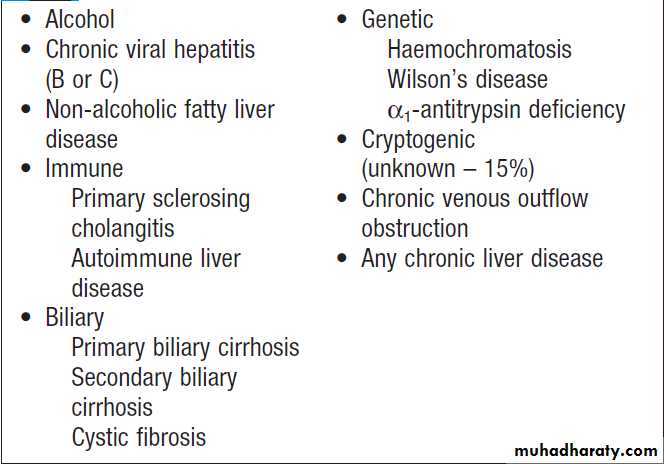

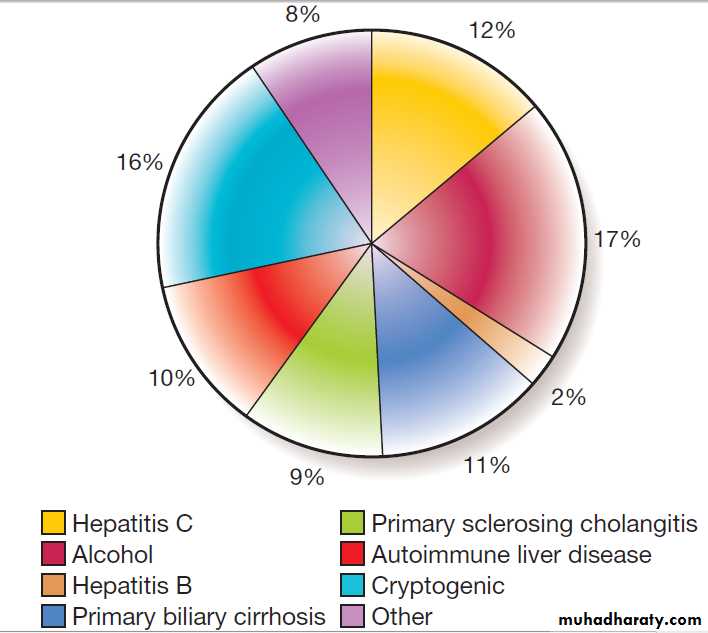

Cirrhosis is characterised by diffuse hepatic fibrosis and

nodule formation. Worldwide, the most common causes are chronic viral hepatitis, prolonged excessive alcohol consumption and NAFLD. Cirrhosis is the most common cause of portal hypertension and its complications.

It may also occur in prolonged biliary damage or obstruction, as is found in primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis and post-surgical biliary strictures. Persistent blockage of venous return from the liver, such as occurs in venoocclusive disease and Budd– Chiari syndrome, can also result in cirrhosis.

Variceal bleeding

Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage from gastrooesophageal varices is common in chronic liver disease.Investigation and management are discussed below.

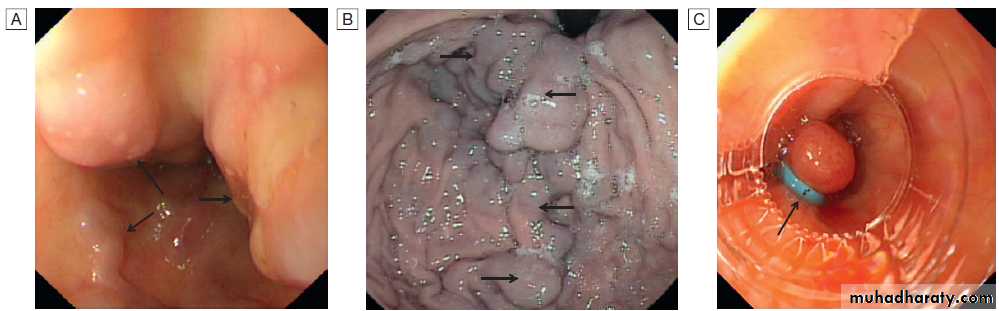

Varices: endoscopic views. A Oesophageal varices (arrows) at the lower end of the oesophagus. B Gastric varices (arrows). C Appearance of oesophageal varices following application of strangulating bands (band ligation, arrow).

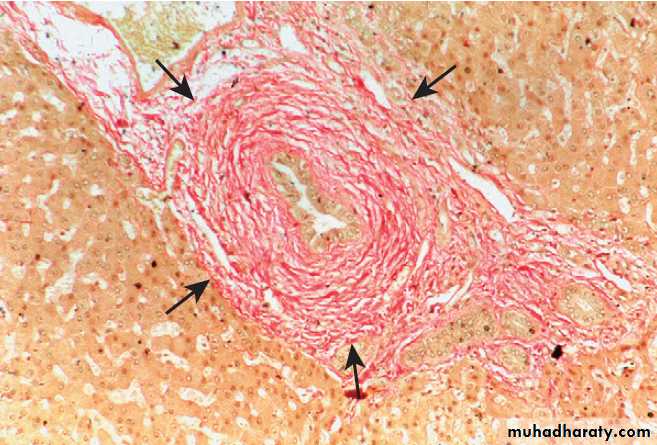

Pathophysiology

Following liver injury, stellate cells in the space of Disseare activated by cytokines produced by Kupffer cells and hepatocytes. This transforms the stellate cell into a myofibroblast-like cell, capable of producing collagen, pro-inflammatory cytokines and other mediators that promote hepatocyte damage and fibrosis .

Cirrhosis is a histological diagnosis

classified histologically into:

• Micronodular cirrhosis, nodules about 1 mm in diameter and typically seen in alcoholic cirrhosis.

• Macronodular cirrhosis, larger nodules of various sizes.

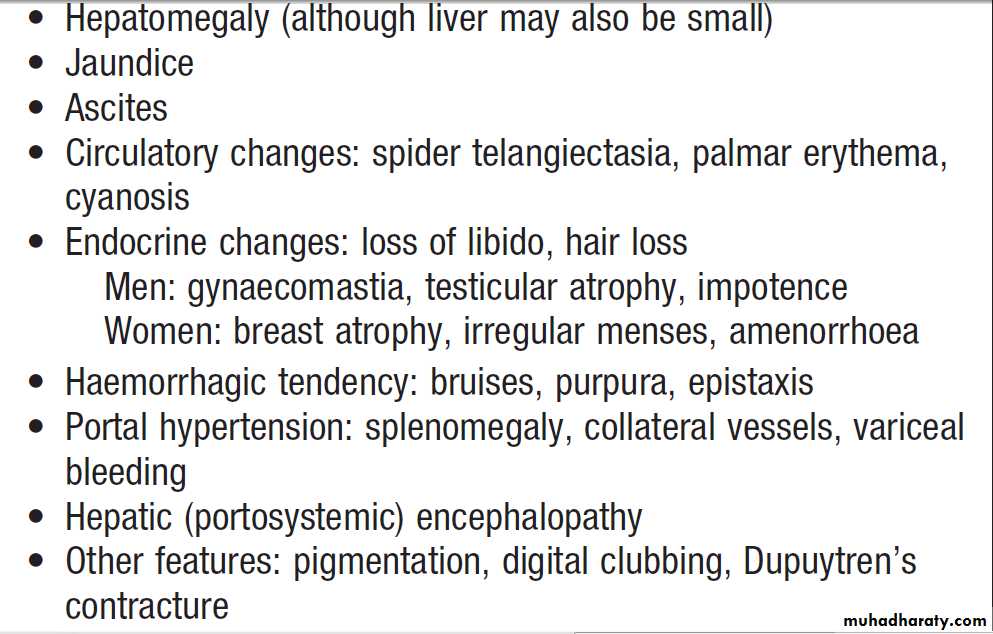

Clinical features

Some patients are asymptomatic and the diagnosis is made incidentally at ultrasound or at surgery. Others present with isolated hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, signs of portal hypertension or hepatic insufficiency. When symptoms are present, they are often non-specific and include weakness, fatigue, muscle cramps, weight loss, anorexia, nausea, vomiting and upper abdominal discomfort . Cirrhosis will occasionally present because of shortness of breath due to a large right pleural effusion, or with hepatopulmonary syndrome .Hepatomegaly is common when the cirrhosis is due

to ALD or haemochromatosis.

A reduction in liver size is especially common if the cause

is viral hepatitis or autoimmune liver disease. The liver

is often hard, irregular and non-tender. Jaundice is mild

due primarily to a failure to excrete bilirubin. Palmar erythema. Spider telangiectasias. 1 to 2 mm in diameter, and are usually found only above the nipples. Florid spider telangiectasia, gynaecomastia and parotid enlargement are most common in alcoholic cirrhosis. Pigmentation in haemochromatosis and in cirrhosis with prolonged cholestasis. Pulmonary arteriovenous shunts also develop, leading to hypoxaemia and central cyanosis. Endocrine changes are noticed more readily in men, loss of male hair distribution and testicular atrophy. Gynaecomastia is common.

Easy bruising. Splenomegaly and collateral vessel formation are features of portal hypertension, in advanced disease . Ascites also signifies advanced disease.

Nonspecific features include clubbing. Dupuytren’s contracture is traditionally regarded as a complication of cirrhosis, but the evidence for this is weak. Chronic liver failure develops when the metabolic capacity of the liver is exceeded.It is characterised by the presence of encephalopathy and/or ascites. The term ‘hepatic decompensation’ or ‘decompensated liver disease’ is often used when chronic liver failure occurs.

Other features may be present these include peripheral oedema, renal failure, jaundice, and hypoalbuminaemia and coagulation abnormalities.

Causes of cirrhosis

Clinical features of hepatic cirrhosis

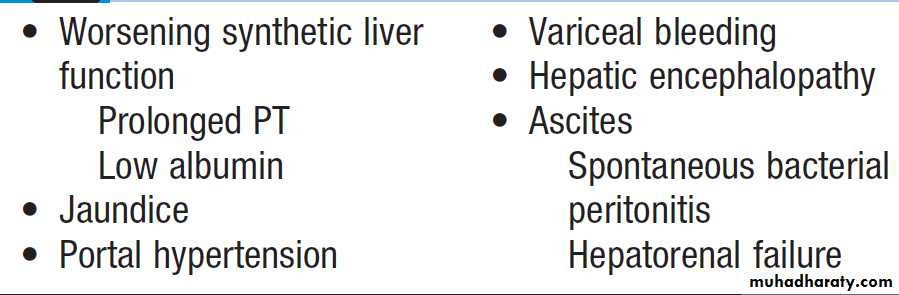

Features of chronic liver failure

Management of hepatic cirrhosis

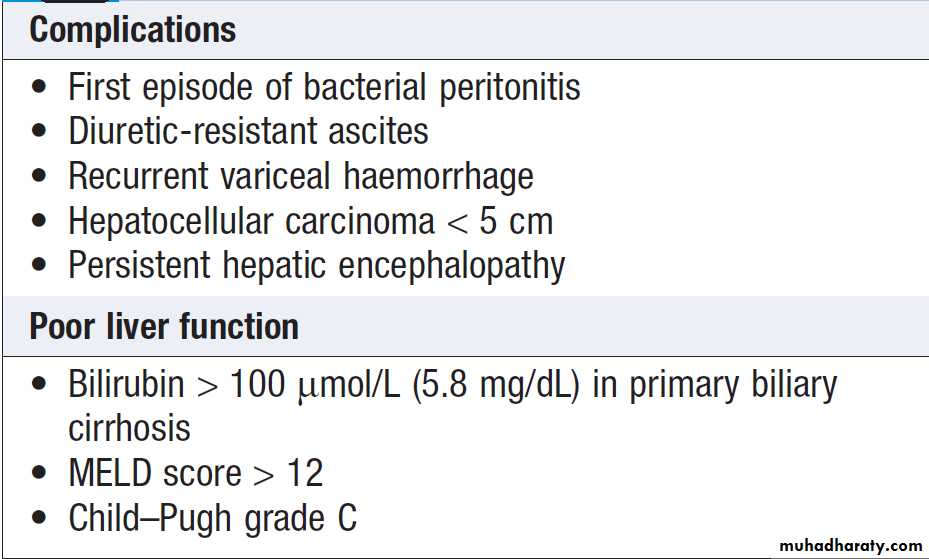

This includes treatment of the cause, maintenance of nutrition and treatment of complications, endoscopy should be performed to screen for oesophageal varices and repeated every 2 years. As cirrhosis is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), patients should be placed under regular surveillance.Chronic liver failure due to cirrhosis can also be treated by liver transplantation.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis is poor. 25% of patients survive

5 years from diagnosis but, where liver function is good, 50% survive for 5 years and 25% for up to 10 years.

The prognosis is more favourable when the underlying cause of the cirrhosis can be corrected, as in alcohol misuse, haemochromatosis or Wilson’s disease.

Deteriorating liver function, indicates a poor prognosis unless a treatable cause such as infection is found.

Increasing bilirubin, falling albumin, hyponatraemia

(< 120 mmol/L) not due to diuretic therapy, and a prolonged PT are all bad prognostic features .

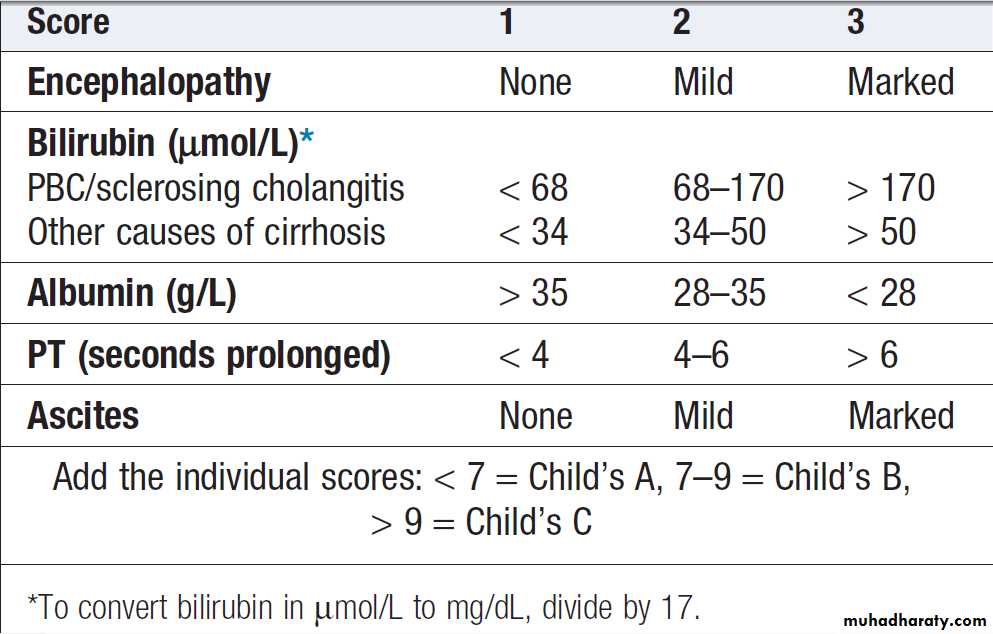

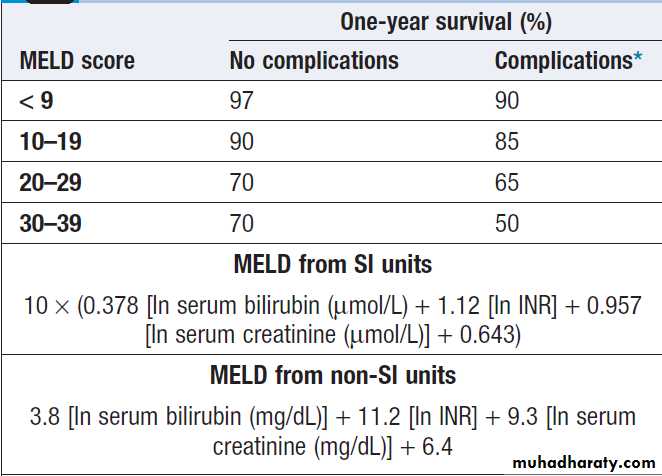

The Child–Pugh score and, more recently, the MELD (Model for End-stage Liver Disease) score can be used to assess prognosis.

Although these scores give a guide to prognosis, the course of cirrhosis can be unpredictable, as complications such as variceal bleeding may occur.

Child–Pugh classification of prognosis in cirrhosis

One-year survival rate depending on MELD score

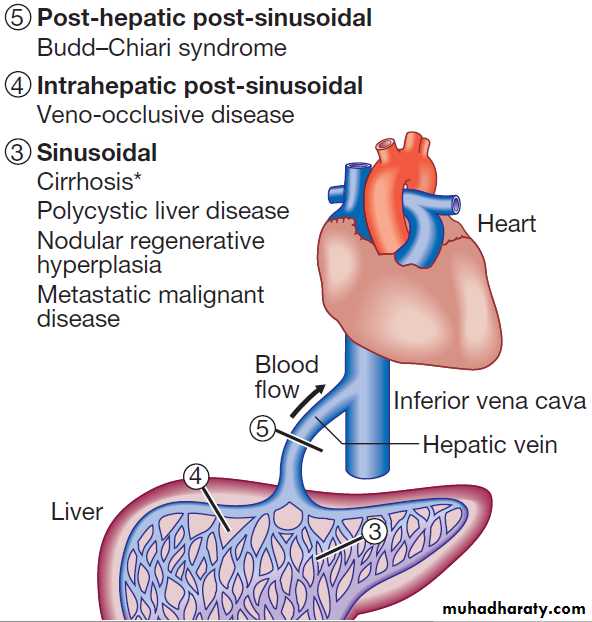

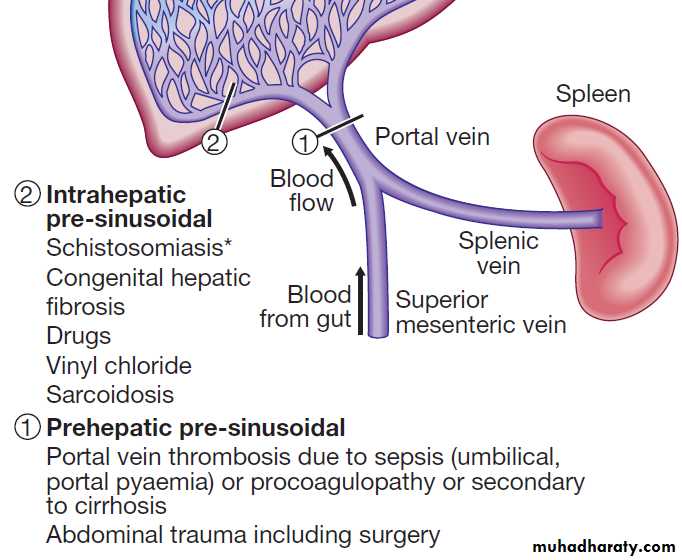

PORTAL HYPERTENSIONThis frequently complicates cirrhosis. The normal hepatic venous pressure gradient (difference between the wedged hepatic venous pressure and free hepatic venous pressure) is 5–6 mm Hg. Clinically significant portal hypertension is present when the gradient exceeds 10 mm Hg and risk of variceal bleeding increases beyond a gradient of 12 mm Hg. Causes are classified in accordance with the main sites

of obstruction. Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction is the usual source of portal hypertension in childhood and adolescence, while cirrhosis causes at least 90% of cases in adults in developed countries. Schistosomiasis is the most common cause of portal hypertension worldwide but is infrequent outside endemic areas .

Classification of portal hypertension according to site of vascular obstruction.

*Most common cause. Note that splenic vein occlusion can also follow pancreatitis, leading to gastric varices.Clinical features

The clinical features result principally from portalvenous congestion and collateral. Splenomegaly is a cardinal finding, and a diagnosis of portal hypertension is unusual when splenomegaly cannot be detected clinically or by US. The spleen is rarely enlarged >5 cm below the left costal margin. Collateral vessels may be visible on the anterior abdominal wall and occasionally several radiate from the umbilicus to form a caput medusae. Rarely, a large umbilical collateral vessel has a blood flow sufficient to give a venous hum on auscultation (Cruveilhier– Baumgarten syndrome). The most important collateral occurs in the oesophagus and stomach, and this can be a source of severe bleeding.

Rectal varices also cause bleeding and are often mistaken for haemorrhoids . Fetor hepaticus results from portosystemic shunting of mercaptans to the lungs.

Ascites occurs as a result of renal sodium retention

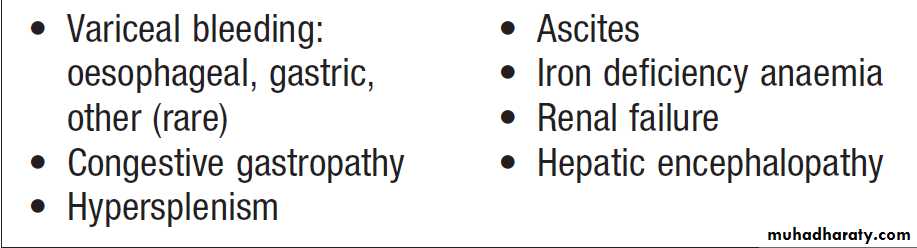

and portal hypertension .The most important consequence of portal hypertension is variceal bleeding, which commonly arises from oesophageal varices located within 3–5 cm of the gastrooesophageal junction, or from gastric varices. The size of the varices, endoscopic variceal features such as red spots and stripes, high portal pressure and liver failure are all general factors that predispose to bleeding. Drugs capable of causing mucosal erosion, such as salicylates and NSAIDs, can also precipitate bleeding.

Complications of portal hypertension

PathophysiologyIncreased portal vascular resistance leads to a gradual

reduction in the flow of portal blood to the liver and

simultaneously to the development of collateral vessels,

allowing portal blood to bypass the liver and enter the

systemic circulation directly. Portosystemic shunting

occurs, particularly in the GIT especially the distal oesophagus, stomach and rectum, in the anterior abdominal wall, and in the renal, lumbar, ovarian and testicular vasculature. Stomal varices can occur at the site of an ileostomy. As collateral vessel formation progresses, > half of the portal blood flow may be shunted directly to the systemic circulation. Increased portal flow contributes to portal hypertension.

Investigations

The diagnosis is often made clinically. Portal venous pressure measurements are rarely needed for clinical assessment or routine management, but can be used to confirm portal hypertension and to differentiate Sinusoidal and pre-sinusoidal forms.Pressure measurements are made by using a balloon catheter inserted using the transjugular route (via the inferior vena cava into a hepatic vein and then hepatic venule) to measure the wedged hepatic venous pressure (WHVP).

This is an indirect measurement of portal vein pressure.

Thrombocytopenia is common (hypersplenism), usually in the region of 100 × 109/L. Leucopenia occurs occasionally but anaemia is seldom attributed to hypersplenism; if anaemia is found, a source of bleeding should be sought. The most useful investigation is endoscopy to determine whether varices are present. Ultrasonography often shows features of portal hypertension, such as splenomegaly and collateral, and can sometimes indicate the cause, such as liver disease or portal vein thrombosis.

CT and MRI angiography can identify the extent of portal vein clot and are used to identify hepatic vein patency.

Management

Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage from gastrooesophageal varices is a common manifestation ofchronic liver disease. In the presence of portal hypertension,

the risk of a variceal bleed occurring within 2 years

varies from 7% for small varices up to 30% for large

varices. The mortality following a variceal bleed has

improved to around 15% overall but is still about 45%

in those with poor liver function (i.e. Child–Pugh C). The management of portal hypertension is largely focused on the prevention and/or control of variceal haemorrhage. However, it should be remembered that bleeding can also result from peptic ulceration, which is more common in patients with liver disease than in the general population.

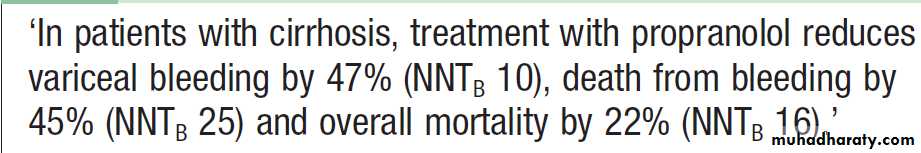

Primary prevention of variceal bleeding

If non-bleeding varices are identified at endoscopy,β-blocker , propranolol at doses that reduce the heart rate by 25% has been shown to be effective in the primary prevention of variceal bleeding (80–160 mg/day) or nadolol is effective in reducing portal venous pressure. The efficacy of β-blockers is similar to that of prophylactic banding, which may also be considered, particularly in patients that are unable to tolerate β-blocker therapy. Carvedilol, a non- cardioselective vasodilating β-blocker, is also effective.

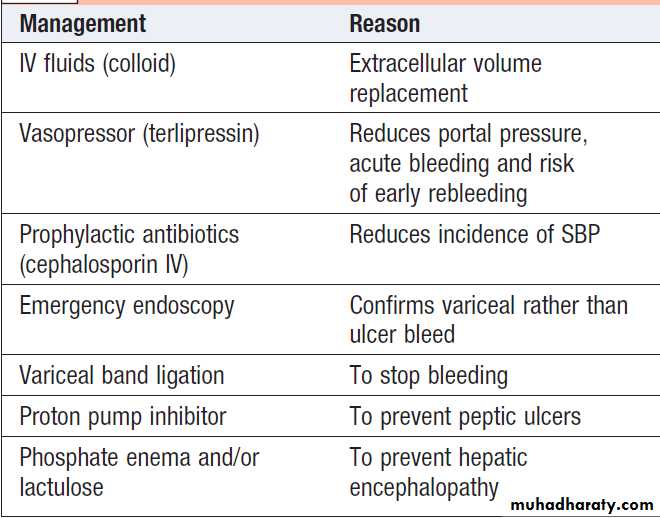

Management of acute variceal bleeding

The priority in acute bleeding is to restore the circulationwith blood and plasma, because shock reduces liver blood flow and causes further deterioration of. The source of bleeding should always be confirmed by endoscopy, because about 20% of bleeding from non- variceal lesions. All patients should receive prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as oral ciprofloxacin or intravenous cephalosporin,because sepsis is common and antibiotics has been shown to improve outcomes. The

measures used to control bleeding include vasoactive medications (e.g. terlipressin), endoscopic therapy (banding or sclerotherapy), balloon tamponade, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent

shunting (TIPSS) and, rarely, oesophageal transection.

Emergency management of bleeding

Pharmacological reduction of portal venous pressure.Terlipressin is a synthetic vasopressin analogue that, in contrast to vasopressin, can be given by intermittent injection rather than continuous infusion, reduces portal blood flow and/or intrahepatic resistance and hence reduces portal pressure. It reduces mortality in the setting of acute variceal bleeding. The dose is 2 mg IV 4 times daily until bleeding stops, and then 1 mg 4 times daily for up to 72 hours.

Caution is needed in patients with severe ischaemic heart disease or peripheral vascular disease because of the drug’s vasoconstrictor properties.

Banding ligation and sclerotherapy. This is the most

widely used initial treatment. It stops variceal bleeding in 80% of patients and can be repeated if bleeding recurs.

Band ligation involves the varices being sucked into a cap placed, allowing them to be occluded with a tight rubber band. The occluded varix subsequently sloughs with variceal obliteration. Banding is repeated every 4–6 weeks until the varices are obliterated. Regular follow-up endoscopy is required to identify and treat any recurrence. Band ligation has fewer side effects than, and has largely replaced, sclerotherapy, a technique in which varices are injected with a sclerosing agent. Banding is associated with a lower risk of oesophageal perforation or stricturing.

Prophylactic acid suppression with PPI reduces the risk of secondary bleeding from banding-induced ulceration.

Protection of the patient’s airway with endotracheal

intubation may aid the endoscopist, facilitating therapy, and significantly reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration.

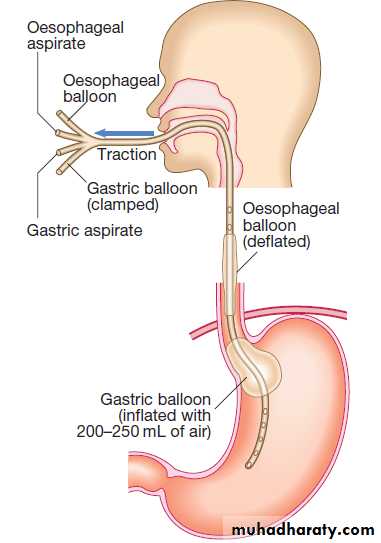

Sengstaken–Blakemore tube.

Balloon tamponade.Sengstaken–Blakemore tube possessing two balloons that exert pressure in the fundus of the stomach and in the lower oesophagus respectively . Additional lumens allow material to be aspirated from the stomach and from the oesophagus above the oesophageal balloon. This technique may be used in the event of life-threatening haemorrhage if early endoscopic therapy is not available or is unsuccessful.

The tube should be passed through the mouth and its presence in the stomach should be checked by auscultating the upper abdomen while injecting air and by radiology.

The safest technique is to inflate the balloon in the

stomach under direct endoscopic vision. Gentle traction is essential to maintain pressure on the varices. Initially, only the gastric balloon should be inflated, with 200– 250 mL of air, as this will usually control bleeding. Inflation of the gastric balloon must be stopped if the patient experiences pain because inadvertent inflation in the oesophagus can cause oesophageal rupture.

If the oesophageal balloon needs to be used because of continued bleeding, it should be deflated for about 10 minutes every 3 hours to avoid oesophageal mucosal damage. Pressure in the oesophageal balloon should be monitored with a sphygmomanometer, and should not exceed 40 mm Hg. Balloon tamponade will almost always stop variceal bleeding, but is only a bridge to more definitive therapy. Self-expanding removable oesophageal stents are a new alternative in patients with bleeding oesophageal, but not gastric, varices.

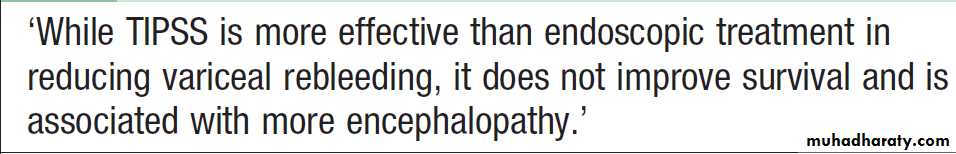

TIPSS. This technique uses a stent placed between the

portal vein and the hepatic vein within the liver to

provide a portosystemic shunt and portal pressure

It is carried out under radiological control via the internal jugular vein; prior patency of the portal vein must be determined angiographically, coagulation deficiencies may require correction with fresh frozen plasma, and antibiotic cover is provided. Successful shunt placement stops and prevents variceal bleeding.

Hepatic encephalopathy may occur following TIPSS and is managed by reducing the shunt diameter. Although associated with less rebleeding than endoscopic therapy, survival is not improved .

Portosystemic shunt surgery. prevents recurrent bleeding, carries high mortality and often leads to encephalopathy, now reserved for patients in whom other treatments have not been successful and those with good liver function.

Oesophageal transection. Rarely performed as a last resort when bleeding cannot be controlled by other means, mortality is high.

Secondary prevention of variceal bleeding

Beta-blockers are used as a secondary measure to

prevent recurrent variceal bleeding. Following successful

treatment by endoscopic therapy, patients should be

entered into an oesophageal banding programme with

repeated sessions of therapy at 1- to 2-week intervals

until the varices are obliterated. In selected individuals,

TIPSS may also be considered in this setting.

Congestive gastropathy

Long-standing portal hypertension causes chronic

gastric congestion recognisable at endoscopy as multiple

areas of punctate erythema (‘snake skin gastropathy’).

Rarely, similar lesions occur more distally in the gastrointestinal tract. These areas may become eroded,

causing bleeding from multiple sites. Acute bleeding

can occur but repeated minor bleeding causing iron deficiency anaemia is more common. Anaemia may be

prevented by oral iron supplements but repeated blood

transfusions can become necessary. Reduction of the

portal pressure using propranolol (80–160 mg/day) is

the best initial treatment. If this is ineffective, a TIPSS

procedure can be undertaken.

INFECTIONS AND THE LIVER

Viral hepatitisAll these viruses cause illnesses with similar clinical and pathological features and which are frequently anicteric

or even asymptomatic. They differ in their tendency

to cause acute and chronic infections. A non-specific prodromal illness characterised by headache, myalgia, arthralgia, nausea and abdominal discomfort usually precedes the development of jaundice by a few days to 2 weeks. Dark urine and pale stools may precede jaundice. The liver is often tender but only minimally enlarged. Occasionally, mild splenomegaly and cervical lymphadenopathy are seen. Symptoms rarely last longer than 3–6 weeks. Complications may occur but are rare.

Investigations

A hepatitic pattern of LFTs develops, with serum transaminases typically between 200 and 2000 U/L in an acute infection .The plasma bilirubin reflects the degree of liver damage. The ALP rarely exceeds twice the upperlimit of normal. Prolongation of the PT indicates the

severity of the hepatitis but rarely exceeds 25 seconds,

except in rare cases of acute liver failure. The white cell

count is usually normal with a relative lymphocytosis.

Serological tests confirm the aetiology of the infection.

Management

Most individuals do not need hospital care. Alcohol, sedatives and narcotics, which are metabolised in the

liver, should be avoided. No specific dietary modifications

are needed. Elective surgery should be avoided.

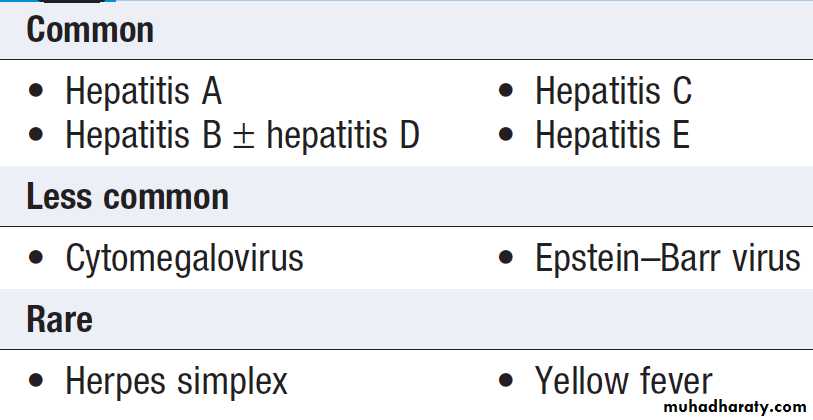

Causes of viral hepatitis

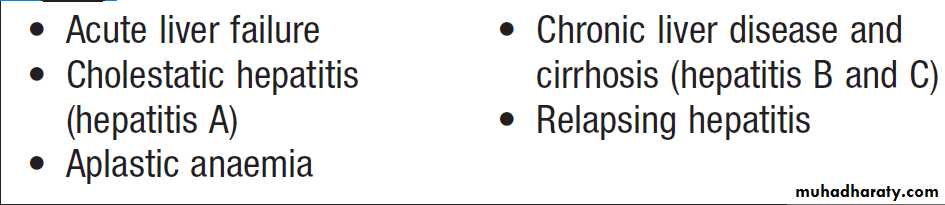

Complications of acute viral hepatitis

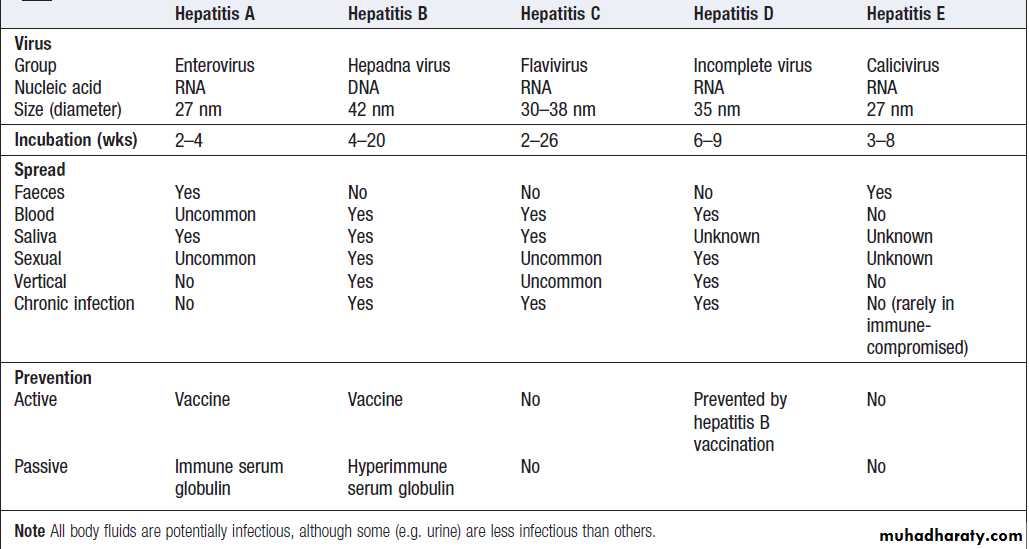

Features of the main hepatitis viruses

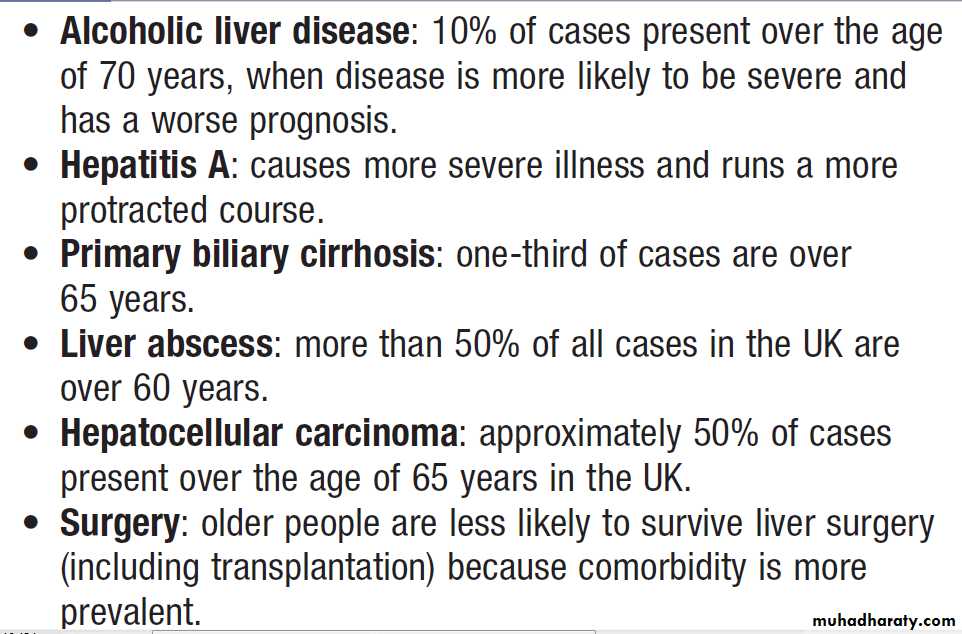

Hepatitis AHAV enterovirus is highly infectious , spread by the faecal–oral route. Infected, excrete the virus in faeces for about 2–3 weeks before the onset and further 2 weeks or so. 30% of adults will have serological evidence of past infection but give no history of jaundice. chronic carrier state does not occur. Acute liver failure is rare (0.1%) .In adults, a cholestatic phase may complicate infection

Investigations

One HAV antigen has been found , anti-HAV is important in diagnosis, as HAV present in the blood transiently during the incubation period. Excretion in the stools occurs for 7–14 days virus cannot be grown readily. Anti-HAV of the IgM and is diagnostic of an acute infection. Titres fall to low levels within about 3 months of recovery.

Anti-HAV of the IgG type is of no diagnostic value, persists for years , used as a marker of previous HAV infection. Its presence indicates immunity to HAV.

Management :

There is no role for antiviral drugs . Infection is best prevented by improving social conditions, especially overcrowding and poor sanitation. Active immunisation with an inactivated virus vaccine, should be considered for individuals with chronic hepatitis B or C, close contacts, the elderly, those with other major disease, People travelling to endemic areas and perhaps pregnant women. Immune serum globulin (Anti-HAV) give immediate protection if given soon after exposure to the virus. Can be effective in an outbreak of hepatitis, in a school or nursery, as injection of those at risk prevents secondary spread to families.

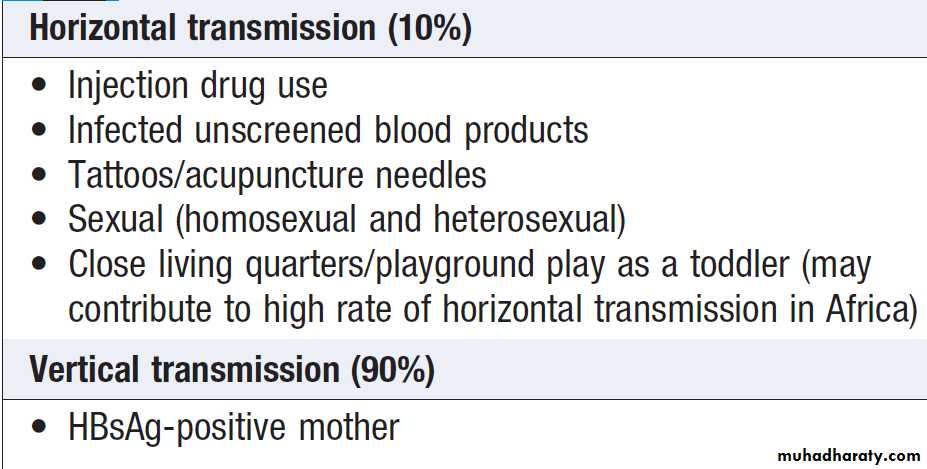

Hepatitis B

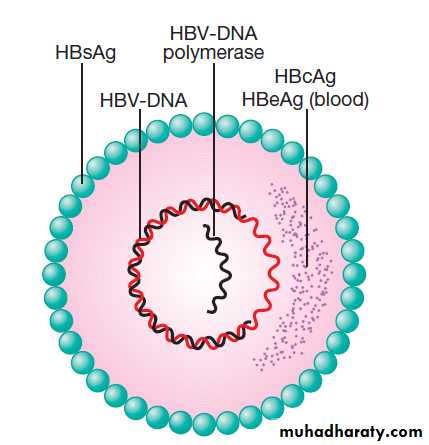

Consists of a core containing DNA and a DNA polymerase enzyme needed for virus replication. Humans are the only source of infection. Hepatitis B is one of the most common causes of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide. Approximately one-third of the world’s population have serological evidence of past or current infection. Many individuals with acute and chronic hepatitis B asymptomatic. The risk of progression to chronic disease depends on the source and timing of infection. Vertical transmission from mother to child in the perinatal period is the most common cause of infection and carries the highest risk of ongoing chronic infection .

Schematic diagram of hepatitis B virus. Hepatitis B

surface antigen (HBsAg) is a protein that makes up part of the viral envelope. Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) is a protein that makes upthe capsid or core part of the virus (found in the liver but not in blood).

Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) is part of the HBcAg that can be found in the blood and indicates infectivity.

Source of hepatitis B infection and risk of chronic infection

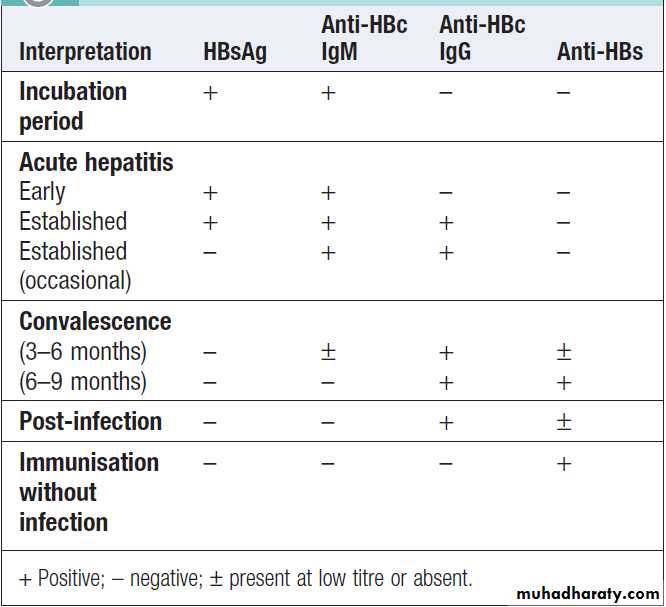

Chronic hepatitis can lead to cirrhosis or HCC, usually after decades of infection . It should be remembered that the virus is not directly cytotoxic to cells; rather it is an immune response to viral antigens displayed on infected hepatocytes that initiates liver injury.Investigations

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is an indicator of active infection. In acute liver failure from hepatitis B, the liver damage is mediated by viral clearance and so HBsAg is negative, with evidence of recent infection shown by the presence of hepatitis B core IgM.

HBsAg appears in the blood late in the incubation period, usually lasts for 3–4 weeks and persist for up to 5 months.

The persistence >6 months indicates chronic infection.

Antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs) usually appears after 3–6 months and persists for many years or permanently.

Anti-HBs implies either a previous infection, in which case anti-HBc is usually also present, or previous vaccination, in which case anti-HBc is not present.

Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). HBcAg is not found

in the blood, but antibody to it (anti- HBc) appears early in the illness and rapidly reaches a high titre, which

subsides gradually but then persists. Anti-HBc is initially

of IgM type, with IgG antibody appearing later.

Anti-HBc (IgM) can sometimes reveal an acute HBV

infection when the HBsAg has disappeared and before

anti-HBs has developed .

Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg). HBeAg is an indicator

of viral replication, it may appear only transiently at the outset followed by the production of anti-HBe. The HBeAg reflects active replication of the virus in the liver.Chronic HBV infection is marked by the presence of HBsAg and anti-HBc (IgG) in the blood.

Viral load and genotype

HBV-DNA can be measured by PCR in the blood. Viral

loads are usually >105 copies/mL in the presence of active viral replication, as indicated by the presence of e antigen. In contrast, in those with low viral replication, HBsAg- and anti-HBe-positive, viral loads are less than 105 copies/ mL.

The exception is in patients who have a mutation in the pre-core protein, which means they cannot secrete e antigen into serum. Such individuals will be anti-HBe-positive but have a high viral load and often evidence of chronic hepatitis.

They respond differently to antiviral drugs from those with

classical e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis.

Measurement of viral load is important in monitoring

antiviral therapy and identifying patients with pre-core mutants. Specific HBV genotypes (A–H) can also be identified using PCR.

How to interpret the serological tests of

acute hepatitis B virus infectionManagement of acute hepatitis B

Treatment is supportive, monitoring for acute liver failure, which occurs in <1%. There is no definitive evidence that antiviral therapy reduces the severity or duration. Full recovery occurs in 90–95% of adults . 5–10% develop a chronic infection that usually continues for life, although later recovery occasionally occurs. Infection passing from mother to child at birth leads to chronic infection in the child in 90% of cases and recovery is rare. Chronic infection is also common in immunodeficient. Recovery from acute infection occurs within 6 months. Persistence of HBeAg beyond this time indicates chronic infection.Combined HBV and HDV causes more aggressive disease.

Management of chronic hepatitis B

Treatments are still limited, as no drug is consistentlyable to eradicate hepatitis B infection completely (i.e.

render the patient HBsAg-negative).

The goals of treatment are HBeAg seroconversion, reduction in HBV-DNA and normalisation of the LFTs.

The indication for treatment

High viral load in the presence of active hepatitis(elevated transaminases and/or histological evidence)

The oral antiviral agents are more effective in reducing

viral loads in patients with e antigen-negative than in those with e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B, as the pre-treatment viral loads are lower.

Most patients with chronic hepatitis B are asymptomatic

and develop complications such as cirrhosis andhepatocellular carcinoma only after many years.

Cirrhosis develops in 15–20% of chronic HBV over 5–20 years. This proportion is higher in e antigen-positive.

Two different types of drug are used :

direct-acting nucleoside/nucleotide analogues and

pegylated interferon-alfa.

Direct-acting oral nucleoside/nucleotide are the mainstay of therapy. These act by inhibiting the reverse transcription of pre-genomic RNA to HBV-DNA by HBV-DNA polymerase , relapse is common if treatment is withdrawn.

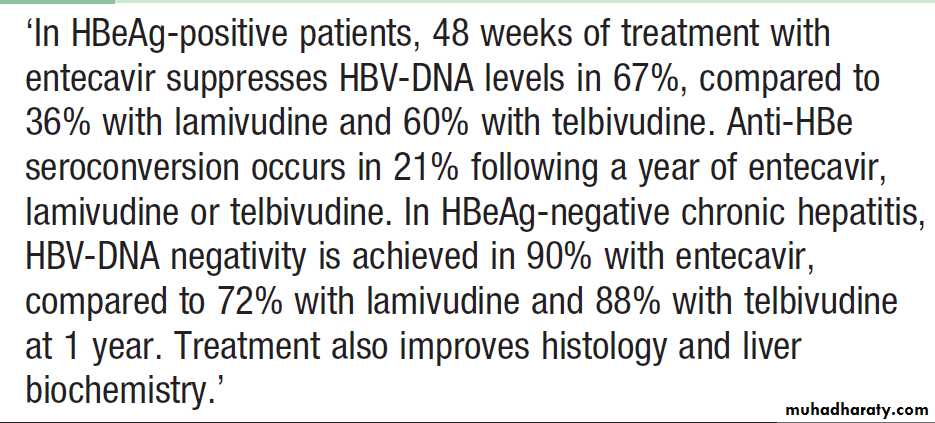

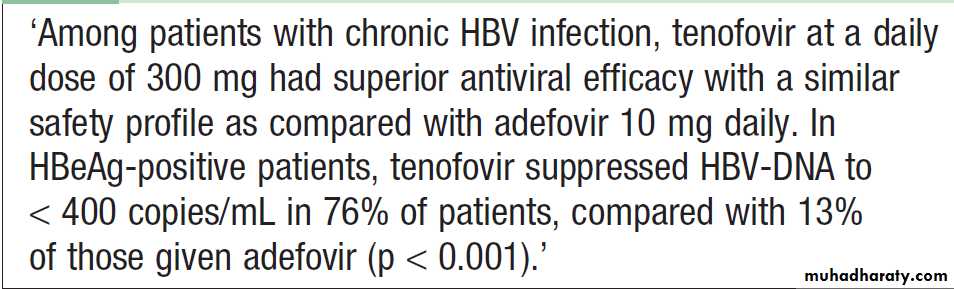

Entecavir and tenofovir are potent with a high barrier to genetic resistance, and so are first-line agents.

Antiviral resistance mutations occur in only1–2% after 3 years of entecavir drug exposure. Both drugs have anti-HIV and so their use as monotherapy is contraindicated in HIV-positive, as it may lead to HIV antiviral resistance.

Lamivudine. Although effective, long-term therapy is

often complicated by the development of HBV-DNA

polymerase mutants characterised by a rise in viral load during treatment. Telbivudine is more potent but is also susceptible to viral resistance. Adefovir is associated with development of HBV-DNA mutants lower than lamivudine.

Entecavir and telbivudine in chronic hepatitis B infection

Tenofovir for chronic hepatitis B

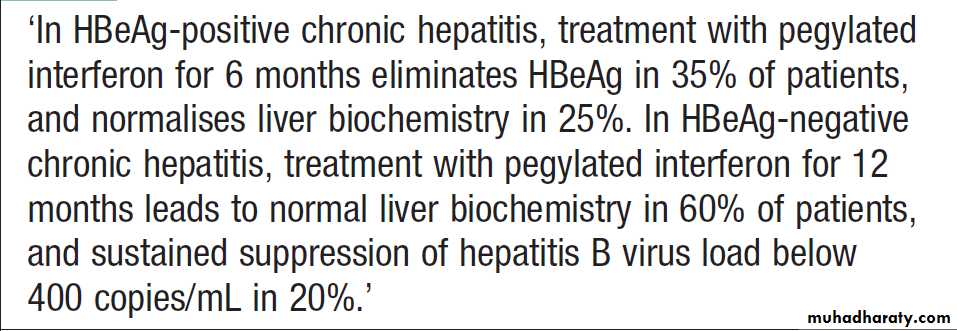

Interferon-alfaThis is most effective in patients with a low viral load ,

in whom it acts by augmenting a native immune response. In HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis, 33% lose e antigen after 4–6 months of treatment, compared to 12% of controls. Response rates are lower in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis, even with longer courses of treatment.

Interferon is contraindicated in the presence of cirrhosis, as it may cause a rise in serum transaminases and precipitate liver failure.Longer-acting pegylated interferons that can be given once weekly have been evaluated.

Side-effects are common , include fatigue, depression, irritability, bone marrow suppression and the triggering of autoimmune thyroid disease.

Liver transplantation

Historically, was contraindicated in hepatitis B because infection often recurred in the graft. However, the use of post-liver transplant prophylaxis with direct-acting antiviral agents and hepatitis B immunoglobulins has reduced the re-infection to 10% and increased 5-year survival to 80%, making transplantation an acceptable treatment option.Pegylated interferons in chronic hepatitis B infection

Prevention

Individuals are most infectious when markers of continuingviral replication, such as HBeAg, and high levels

of HBV-DNA are present in the blood. HBV-DNA can

be found in saliva, urine, semen and vaginal secretions.

The virus is about ten times more infectious than hepatitis C, which in turn is about ten times more infectious than HIV.

A recombinant hepatitis B vaccine containing HBsAg

is available (Engerix) and is capable of producing active

immunisation in 95% of normal individuals.

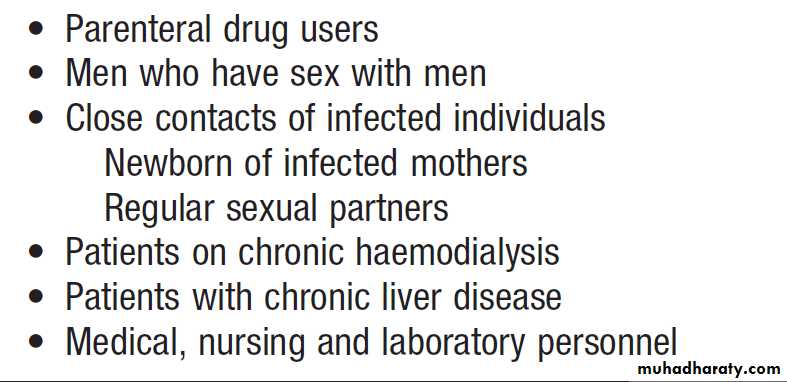

The vaccine should be offered to those at special risk of infection who are not already immune, as evidenced by anti-HBs in the blood .

The vaccine is ineffective in those already infected by HBV.

Infection can also be prevented or minimised by the intramuscular injection of hyperimmune serum globulin prepared from blood containing anti-HBs. This should be given within 24 hours, or at most a week, of exposure to infected blood in circumstances likely to cause infection (e.g. needlestick injury, contamination of cuts or mucous membranes). Vaccine can be given together with hyperimmune globulin (active–passive immunisation).Neonates born to hepatitis B-infected mothers should

be immunised at birth and given immunoglobulin. Hepatitis B serology should then be checked at 12 months of age.

At-risk groups meriting hepatitis B

vaccination in low-endemic areas

Hepatitis D (Delta virus)

RNA-defective virus that has no independent existence; it requires HBV for replication and has the same sources and modes of spread. It can simultaneously infect individuals with HBV, or can superinfect those who are already chronic carriers of HBV. Simultaneous infections give rise to acute hepatitis, which is often severe but is limited by recovery from the HBV infection. Chronic infection with HBV and HDV can also occur, and this frequently causes rapidly progressive chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. HDV has a worldwide distribution, transmission is mainly by close contact and occasionally by vertical transmission. In non-endemic areas, transmission is mainly a consequence of parenteral drug misuse.Investigations

HDV contains a single antigen to which infected individuals make an antibody (anti-HDV). Delta antigen appears in the blood only transiently, and in practice diagnosis depends on detecting anti-HDV. Simultaneous infection with HBV and HDV followed by full recovery is associated with the appearance of low titres of anti-HDV of IgM type within a few days of the onset of the illness. This antibody generally disappears within 2 months but persists in a few patients. Superinfection of patients with chronic HBV infection leads to the production of high titres of anti-HDV, initially IgM and later IgG. Such patients may then develop chronic infection with both viruses.Effective management of hepatitis B prevents hepatitis D.

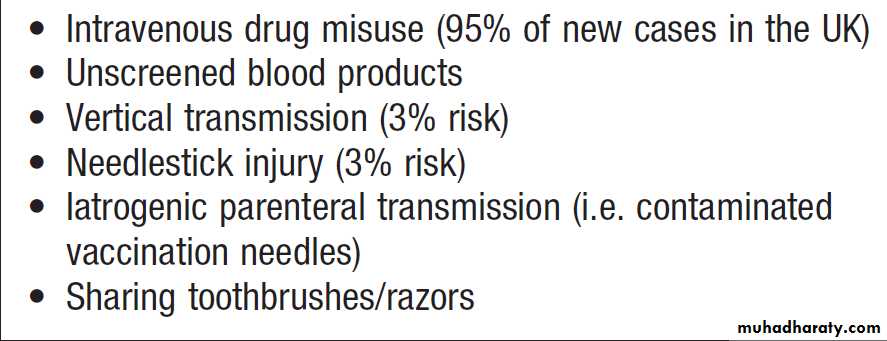

Hepatitis C

This is caused by an RNA flavivirus. Acute symptomatic infection is rare. Most individuals identified when they develop chronic liver disease. 80% of individuals exposed to the virus become chronically infected and late spontaneous viral clearance is rare. Hepatitis C infection is usually identified in asymptomatic screened because they have risk factors for infection, such as previous injecting drug use , or have incidentally abnormal liver blood tests. InvestigationsSerology and virology

The HCV protein contains several antigens that give rise

to antibodies in an infected person. Active infection is confirmed by the presence of serum hepatitis C RNA.

Anti-HCV antibodies persist in serum even after viral clearance, whether spontaneous or post-treatment.

Molecular analysis

There are six common viral genotypes. Genotype 1 is less easy to eradicate than types 2 and 3 with traditional pegylated interferon alfa/ ribavirin-based treatments.

Liver function tests

Jaundice is rare , LFTs may be normal or show fluctuating serum transaminases between 50 and 200 U/L. and only usually appears in end-stage cirrhosis.

Liver histology

biopsy is often required to stage the degree of liver

damage. The degree of inflammation and fibrosis can be scored histologically. Metavir system, which scores fibrosis from 1 to 4, the latter equating to cirrhosis.

Risk factors for the acquisition of chronic

hepatitis C infectionManagement

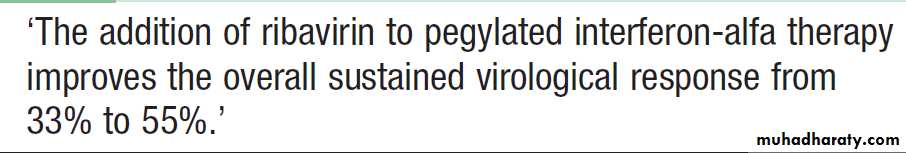

The aim of treatment is to eradicate infection. Untilrecently, the treatment of choice was dual therapy with

pegylated interferon- alfa given as a weekly subcutaneous injection, together with oral ribavirin, a synthetic nucleotide analogue .The main side-effects of ribavirin are haemolytic anaemia and teratogenicity.

Side-effects of interferon are significant and include

flu-like symptoms, irritability and depression.

Virological relapse can occur in the first 3 months after stopping treatment, and cure is defined as loss of virus from serum 6 months after completing therapy (sustained virological response, or SVR).

The length of treatment and efficacy depend on viral genotype (12 months’ treatment for genotype

1 results in a 40% SVR, whereas 6 months’ treatment

for genotype 2 or 3 leads to an SVR in > 70%). Response to treatment is better in patients who have an early virological response, as defined by negativity of HCVRNA in serum 1 month after starting therapy.

The recent availability of triple therapy with the

addition of protease inhibitors such as telaprevir and

boceprevir to standard pegylated interferon/ribavirin

has provided a significant advance in therapy, with SVR

rates for genotype 1 individuals comparable to those

previously only achieved in genotypes 2 and 3.

Liver transplantation should be considered when

complications of cirrhosis occur, such as diuretic resistant

ascites. Unfortunately, hepatitis C almost always recurs in the transplanted liver and up to 15% will develop cirrhosis in the liver graft within 5 years of transplantation.

There is no active or passive protection against HCV.

Progression from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis, 20% occurs

over 20–40 years. Risk factors for progression include

male gender, immunosuppression , prothrombotic states and heavy alcohol misuse.

Once cirrhosis is present, 2–5% per year will develop primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Once complications like ascites have arisen, the 5-year survival is around 50%.

Treatment of hepatitis C

Hepatitis EHepatitis E is caused by an RNA virus. The clinical presentation and management of hepatitis E are similar to that of hepatitis A. Disease is spread via the faecal–oral route; in most cases, it presents as a self-limiting acute hepatitis and does not usually cause chronic liver disease, although some cases have been described, usually in immunocompromised patients.

Hepatitis E differs from hepatitis A in that infection

during pregnancy is associated with the development of acute liver failure, which has a high mortality. In acute

infection, IgM antibodies to HEV are positive.

Other forms of viral hepatitis

Non-A, non-B, non-C (NANBNC) or non-A–E hepatitis .Other viruses that affect the liver, Cytomegalovirus and EBV infection. Herpes simplex is a rare cause in adults, and most of these patients are immunocompromised.

Abnormal LFTs are also common in chickenpox, measles, rubella and acute HIV infection.

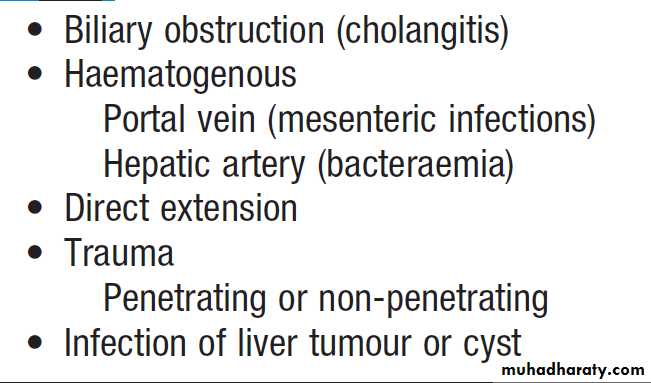

Liver abscess

Classified as pyogenic, hydatid or amoebic.

Pyogenic liver abscess

Uncommon but important because they are potentially curable, carry significant morbidity and mortality if untreated, and are easily overlooked. The mortality of liver abscesses is 20–40%.

Causes of pyogenic liver abscesses

PathophysiologyMost common in older patients and usually result from ascending infection due to biliary obstruction (cholangitis) or contiguous spread from an empyema of the gallbladder. They can also complicate dental sepsis. Abscesses complicating suppurative appendicitis now rare. Immunocompromised are particularly likely to develop liver abscesses. Single lesions are more common in the right liver; multiple abscesses are usually due to infection secondary to biliary obstruction. E coli and various streptococci, are the most common organisms; anaerobes, including streptococci and Bacteroides, can often be found when infection has been transmitted from large bowel pathology via the portal vein, and multiple organisms are present in one-third of patients.

Clinical features

Patients are generally ill with fever, and sometimesrigors and weight loss. Abdominal pain is the most

common symptom and is usually in the right upper

quadrant, sometimes with radiation to the right shoulder.

The pain may be pleuritic in nature. Tender

hepatomegaly is found in more than 50% of patients.

Mild jaundice may be present, becoming severe if large

abscesses cause biliary obstruction. Atypical presentations are common and explain the frequency with which the diagnosis is made only at postmortem. This is a particular problem in patients with gradually developing illnesses or pyrexia of unknown origin without localising features.

Investigations

Liver imaging is the most revealing investigation and

shows 90% or more of symptomatic abscesses. aspiration under ultrasound guidance confirms the diagnosis and provides pus for culture. A leucocytosis is frequently found, plasma ALP activity is usually increased, and the serum albumin is often low.

The chest X-ray may show a raised right diaphragm and lung collapse, or an effusion at the base of the right lung. Blood cultures are positive in 50–80%. Abscesses caused by gut-derived organisms require active exclusion of significant colonic pathology, such as a colonoscopy to

exclude colorectal carcinoma.

Management

This includes prolonged antibiotic therapy and drainageof the abscess. Associated biliary obstruction and cholangitis require biliary drainage (endoscopically).

Pending the results of culture of blood and pus

from the abscess, treatment should be commenced with

a combination of antibiotics such as ampicillin, gentamicin and metronidazole. Aspiration or drainage with a catheter placed in the abscess under ultrasound guidance is required if the abscess is large or if it does not respond to antibiotics. Surgical drainage is rarely undertaken, although hepatic resection may be indicated for a chronic persistent abscess or ‘pseudotumour’.

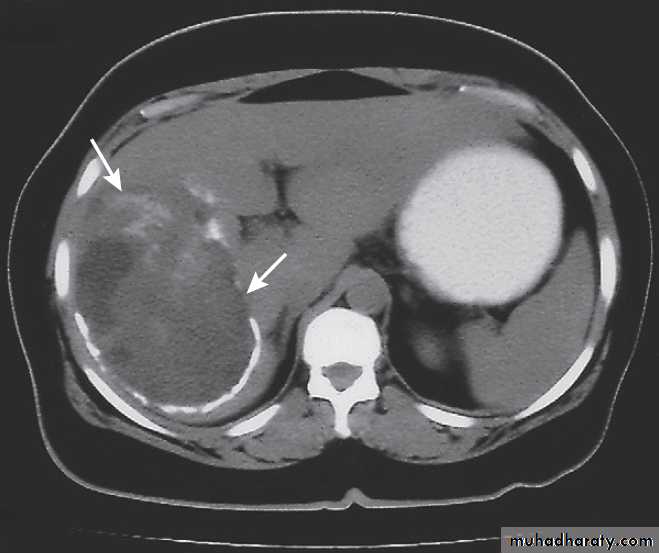

Hydatid cysts

Caused by Echinococcus granulosus infection .They have an outer layer derived from the host, an intermediate laminated layer and an inner germinal layer. They can be single or multiple. Chronic cysts become calcified. The cysts may be asymptomatic but may present with abdominal pain or a mass. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is present in 20% of cases, whilst X-rays may show calcification of the rim of the abscess. CT reliably shows the cyst(s), and Echinococcus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) has 90% sensitivity for hepatic hydatid cysts.Rupture or secondary infection of cysts can occur, and a

communication with the intrahepatic biliary tree canthen result, with associated biliary obstruction.

All patients should be treated medically with albendazole or mebendazole prior to definitive therapy. In the absence of communications with the biliary tree, treatment consists of percutaneous aspiration of the cyst followed by the injection of 100% ethanol into the cysts and then re-aspiration of the cyst contents (PAIR).

Where there is communication between the cyst and biliary system, surgical removal of the intact cyst is the preferred treatment.

Hydatid cyst of the liver on CT (arrows).

Amoebic liver abscessesCaused by Entamoeba histolytica infection .Up to 50% of cases do not have a previous history of intestinal disease. Abscesses are usually large, single and located in the right lobe; multiple abscesses may occur in advanced disease. Fever and abdominal pain or swelling are the most common symptoms. Diagnosis may depend on cyst aspiration revealing the classic anchovy sauce appearance of the cyst fluid. Analysis of serum for Entamoeba antibodies by immunoassay carries 99% sensitivity and over 90% specificity, and is more accurate than stool analysis in amoebic liver disease.

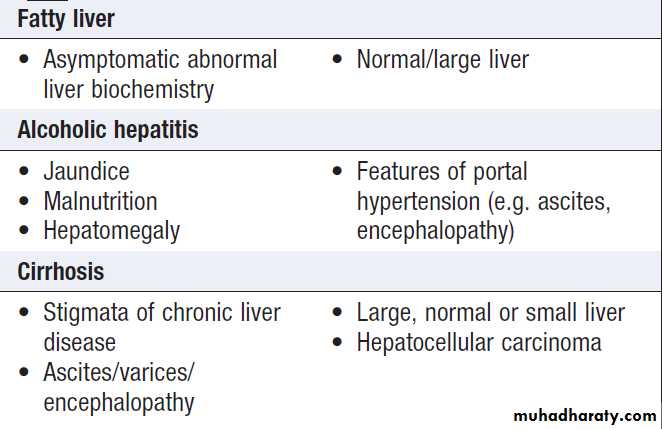

ALCOHOLIC LIVER DISEASE (ALD)

Alcohol is one of the most common causes of chronicliver disease worldwide. Patients with ALD may also have risk factors for other liver diseases (e.g. coexisting NAFLD or chronic viral hepatitis infection), and these interact to increase disease severity. A threshold of 14 units/week in women and 21 units/week in men is generally considered safe. The risk threshold for developing ALD begins at 30 g/day. 1 unit = 8gm of ethanol .

Consumption of > 80 g /day, for >5 years, is required to confer significant risk of advanced liver disease.

The average alcohol consumption of a man with cirrhosis is 160 g/day for over 8 years.

Some of the risk factors for ALD are:

• Drinking pattern. Liver damage is more likely to occur in continuous rather than intermittent or ‘binge’ drinkers, as this pattern gives the liver a chance to recover. It is therefore recommended that people should have at least two alcohol-free days each week. The type of beveragedoes not affect risk.

• Gender. The incidence is increasing in women, who have higher blood ethanol levels than men after consuming the same amount of alcohol. This may be related to the reduced volume of distribution of alcohol.

• Genetics. Alcoholism is more concordant in monozygotic than dizygotic twins.

• Nutrition. Obesity increases the incidence of liver-related mortality by over fivefold in heavy drinkers.

Ethanol itself produces 7 kcal/g (29.3 kJ/g) and many alcoholic drinks also contain sugar, which further increases the calorific value and may contribute to weight gain. Excess alcohol consumption is frequently associated with nutritional deficiencies that contribute to morbidity.

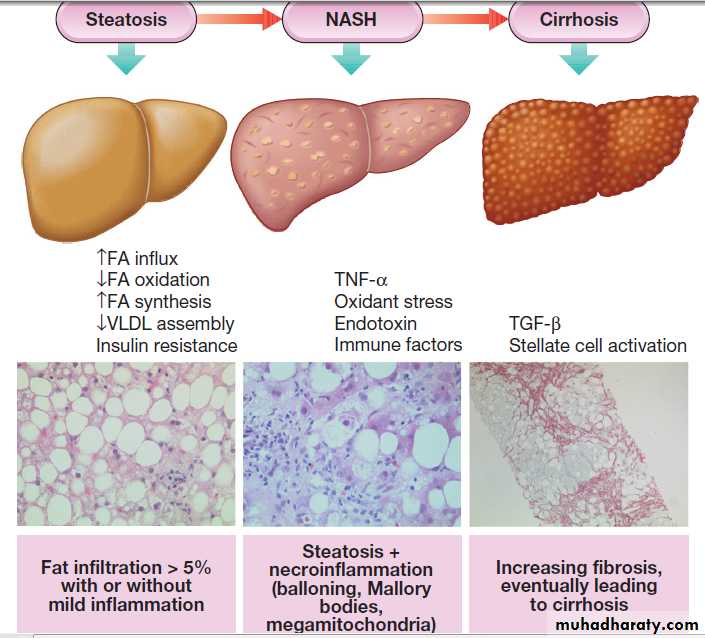

Pathophysiology

Alcohol reaches peak blood concentrations after about

20 minutes, although this may be influenced by stomach

contents. It is metabolised almost exclusively by the liver via one of two pathways .

Approximately 80% of alcohol is metabolised to

acetaldehyde by the mitochondrial enzyme, alcohol

dehydrogenase (ADH).

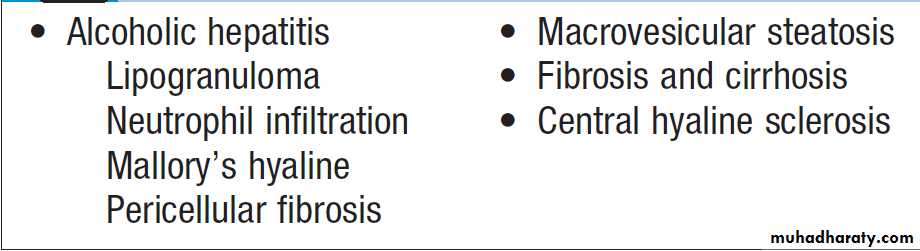

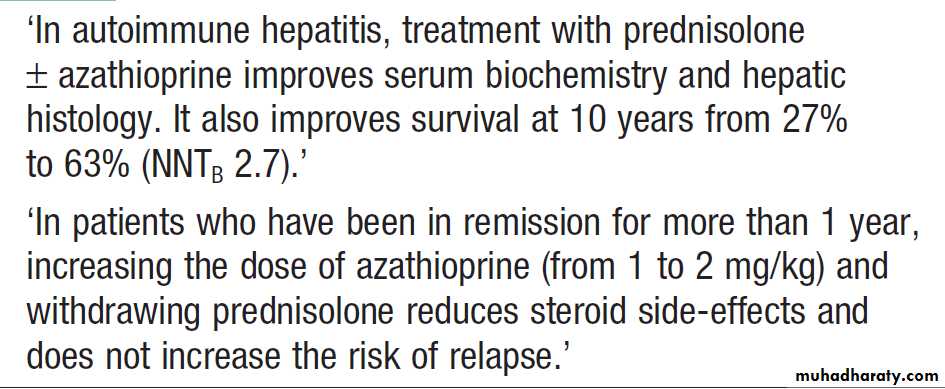

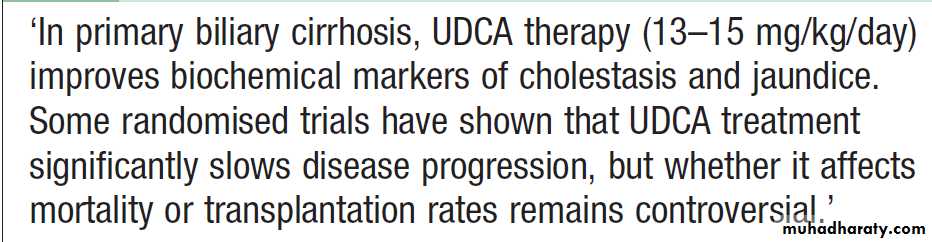

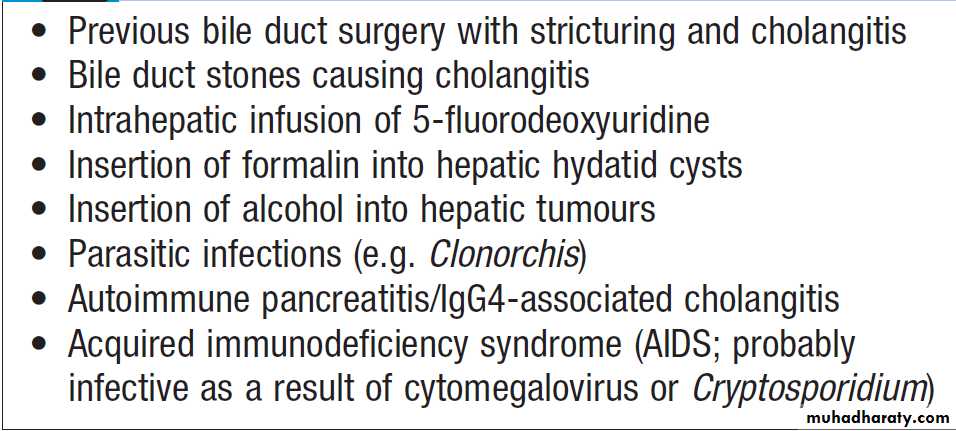

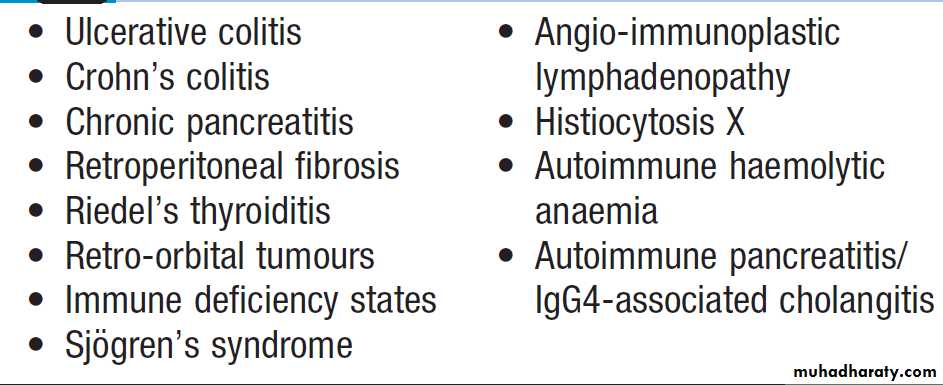

Acetaldehyde is then metabolised to acetyl-CoA and acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenase. This generates NADH from NAD (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), which changes the redox potential of the cell. Acetaldehyde activate the immune system, contributing to cell injury. The remaining 20% of alcohol is metabolised by the microsomal ethanol- oxidising system (MEOS) pathway.