Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABMLecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

2016

learning-topics

Medical psychiatryPsychiatric disorders have traditionally been considered

as ‘mental’ rather than as ‘physical’ illnesses. This isbecause they manifest with disordered functioning in

the areas of emotion, perception, thinking and memory,

and/or have had no clearly established biological basis.

However, as research identifies abnormalities of the

brain in an increasing number of psychiatric disorders

and an important role for psychological and behavioural

factors in many medical illnesses, a clear distinction

between mental and physical illness has become increasingly questionable. We therefore refer to psychiatric disorders simply to mean those conditions traditionally regarded as the province of psychiatry.

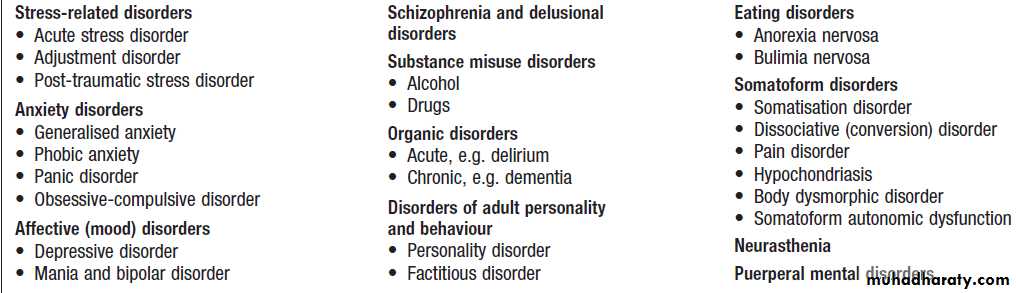

CLASSIFICATION OF PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

There are two main classifications of psychiatric disorders in current use:

• the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual (4th edition), or DSM-IV

• the World Health Organization’s International

Classification of Disease (10th edition), known as

ICD-10.

The two systems are similar; here we use the ICD-10

classification .

Classification of psychiatric disorders

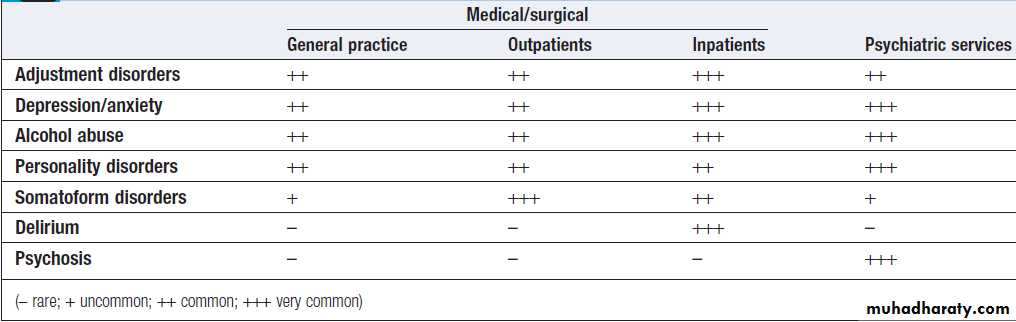

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERSPsychiatric disorders are amongst the most common of

all human illnesses. The relative frequency of each varies

with the setting (Box).

In the general population,

depression, anxiety disorders and adjustment disorders

are most common (10%) and psychosis is rare (1–2%);

In acute medical wards of general hospitals, organic disorders such as delirium (20–30%) are prevalent;

in specialist general psychiatric services, psychoses are the most common disorders.

Prevalence of psychiatric disorders by medical setting

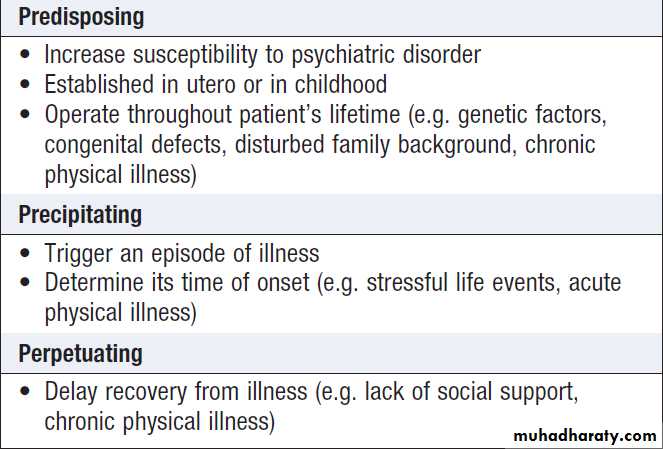

Classification of aetiological factors in

psychiatric disordersAETIOLOGY OF PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

The aetiology is multifactorial, with a combination of biological, psychological and social causes.Biological factors

Genetic

Genetic factors play a predisposing role in many psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. However, whilst some disorders such as Huntington’s disease are due to mutations in a single gene, the genetic contribution to most psychiatric disorders is polygenic in nature and mediated by the combined effects of several genetic variants, each with modest effects and modulated by environmental factors.

Brain structure and function

Brain structure is grossly normal in most psychiatricdisorders, although abnormalities may be observed

in some conditions, such as generalised atrophy in

Alzheimer’s disease and enlarged ventricles with a

slight decrease in brain size in schizophrenia. The

functioning of the brain, however, is commonly altered

with, for example, changes in neurotransmitters such

as dopamine, noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and

5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, serotonin), and differences

in activity of specific areas of the brain, as seen on functional brain scans.

Psychological and behavioural factors

Early environment

Childhood emotional deprivation or abuse, predisposes to psychiatric disorders such as depression and eating disorders.

Personality

The relationship can be difficult to assess because the development of psychiatric disorder can change a patient’s personality. However, some personality types predispose

to psychiatric disorder; for example, a depressive personality increases the risk of depression. A disordered personality may also perpetuate a psychiatric disorder. Behaviour

Predispose to the development of a disorder (e.g. excess alcohol intake leading to dependence, and dieting to anorexia) or perpetuate it.

Social and environmental factors

Social isolationThe lack of a close, confiding relationship predisposes

to some psychiatric disorders such as depression. The

reduced social support resulting from having a psychiatric

disorder may also act to perpetuate it.

Stressors

Social and environmental stressors often play an important role in precipitating psychiatric disorder in those

who are predisposed. For example, trauma in posttraumatic stress disorder, losses (such as bereavement)

in depression, and events perceived as threatening (such

as potential loss of employment) in anxiety.

DIAGNOSING PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

Differs from a standard medical assessment :• There is greater emphasis on the history.

• It includes a systematic examination of the patient’s

thinking, emotion and behaviour (mental state).

• It commonly includes the routine interviewing of an

informant (usually a relative or friend who knows

the patient), especially when the illness affects the

patient’s ability to give an accurate history.

Because of its greater complexity, a full psychiatric history (Box) and detailed mental state examination (MSE) may take an hour or more. However, a brief mental state examination, usually taking no more than a few minutes (see below), should be part of the assessment of all patients, not merely those deemed to be ‘psychiatric’.

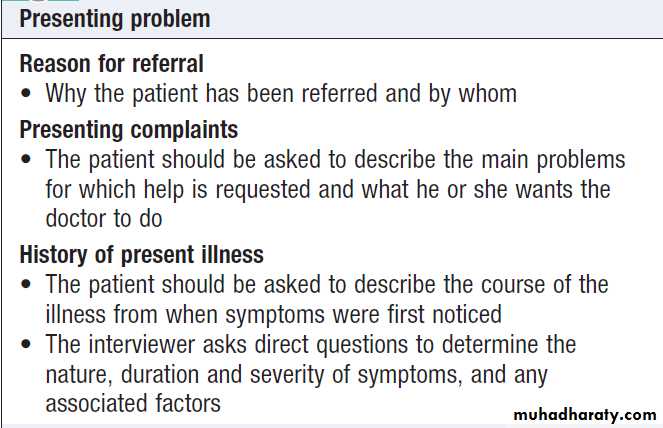

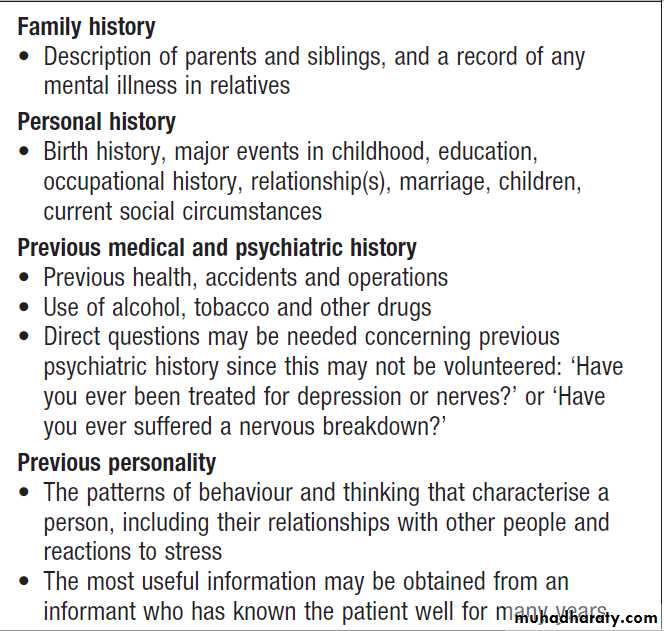

How to structure a psychiatric interview

How to structure a psychiatric interview

– cont’dPsychiatric interview

The aims of the interview are to:• establish a therapeutic relationship with the patient

• elicit the symptoms, history and background information

• examine the mental state

• provide information, reassurance and advice.

Whilst some aspects of the patient’s mental state

may be observed whilst the history is being taken, specific enquiries for important features should always be made.

Mental state examination

General appearance and behaviour

Any abnormalities of alertness or behaviour, such

as restlessness or retardation, are noted. The level of

consciousness, especially in the assessment of delirium.

Speech

Speed and fluency should be observed, including slow

(retarded) speech and word-finding difficulty.

‘Pressure of speech’ describes rapid speech that is difficult to interrupt.

Mood

Judged by facial expression, posture and movements. Patients should also be asked if they feel sad or depressed and if they lack ability to experience pleasure (anhedonia).

Are they anxious, worried or tense? Is mood elevated with excess energy and a reduced need for sleep, as in mania?

Thoughts

The content of thought can be elicited by asking ‘What

are your main concerns?’ Is thinking negative, guilty or

hopeless, suggesting depression?

Are there thoughts of self-harm?

If so, enquiry should be made about plans. Is he or she excessively worried about many things, suggesting anxiety? Does the patient think that he or she is especially powerful, important or gifted (grandiose thoughts), suggesting mania? The form of thinking may also be abnormal.

In schizophrenia, patients may display loosened associations between ideas, making it difficult to follow their train of thought. There may also be abnormalities of thought possession, when patients experience the intrusion of alien thoughts into their mind or the broadcasting of their own thoughts to other people.

Abnormal beliefs

A delusion is a false belief, out of keeping with a patient’s

cultural background, which is held with conviction

despite evidence to the contrary .

Abnormal perceptions

Illusions are abnormal perceptions of real stimuli. Hallucinations are sensory perceptions which occur in the

absence of external stimuli: for example, hearing voices when no one is present.

Cognitive function

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a useful

screening questionnaire to detect cognitive impairment.

A score of less than 24 out of 30 typically suggests cognitive impairment. A brief assessment is as follows:

• Memory. Registration of memories is tested by asking

the patient to repeat simple new information, such as a name and address, immediately after hearing it.

Short-term memory is assessed by asking him or her to repeat it after an interval of 1–2 minutes, during which time the patient’s attention should be diverted elsewhere. Long-term memory is assessed by gauging the recall of previous events.

• Concentration. Serial 7s is a test in which the patient

is asked to subtract 7 from 100 and then 7 from theanswer, and so on.

• Orientation. This is assessed by asking the patient

about place – his or her exact location; time – what

day, date, month and year it is now; and person

– details of personal identity, such as name, date of

birth, marital status and address.

• Intellectual ability. This can be gauged from the

history of the patient’s educational background and

attainments but can also be assessed during the

interview from the patient’s speech, vocabulary and

grasp of the interviewer’s questions.

Note that the degree of cognitive impairment in delirium

typically fluctuates over time, and consequently may be missed by a single assessment.

Patients’ own understanding of their symptoms (‘insight’)

Patients should be asked what they think their symptoms

are due to, and whether they warrant treatment.

Lack of insight refers to a failure to accept that one is ill

and/or in need of treatment,

and is characteristic of acute psychosis.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN PSYCHIATRIC ILLNESS

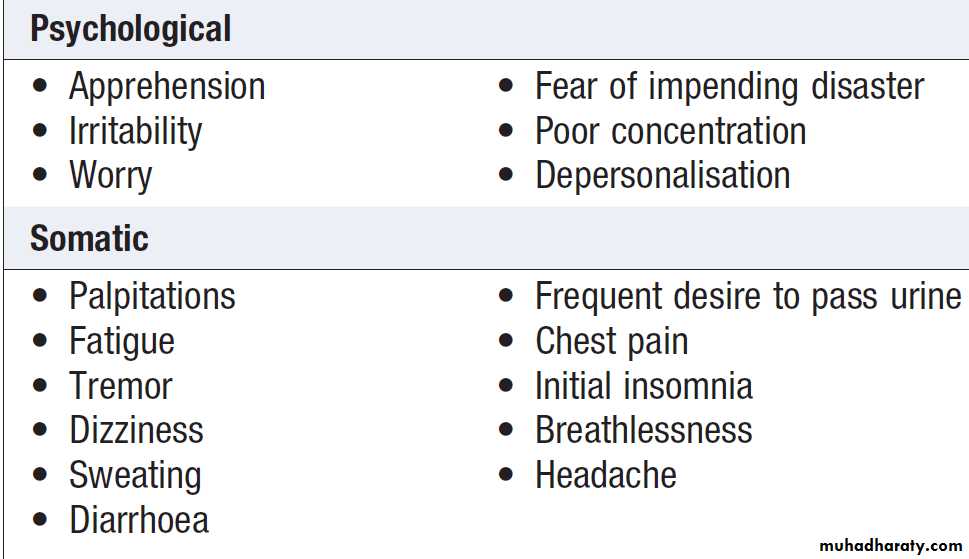

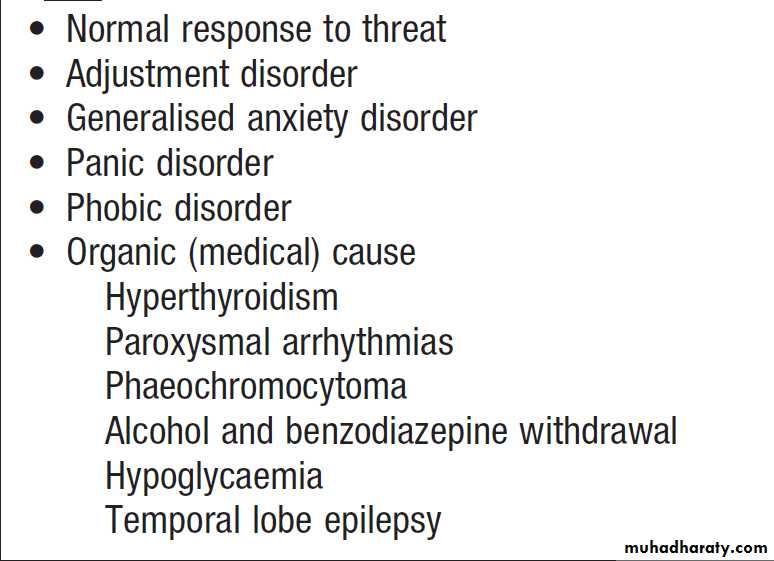

Anxiety symptomsAnxiety may be transient, persistent, episodic or limited

to specific situations. The symptoms of anxiety are both

psychological and somatic (Box). The differential

diagnosis of anxiety is shown in Box. Most anxiety

is part of a transient adjustment to stressful events:

adjustment disorders . Anxiety may occasionally be a manifestation of a medical condition such as thyrotoxicosis.

Symptoms of anxiety disorder

Differential diagnosis of anxiety

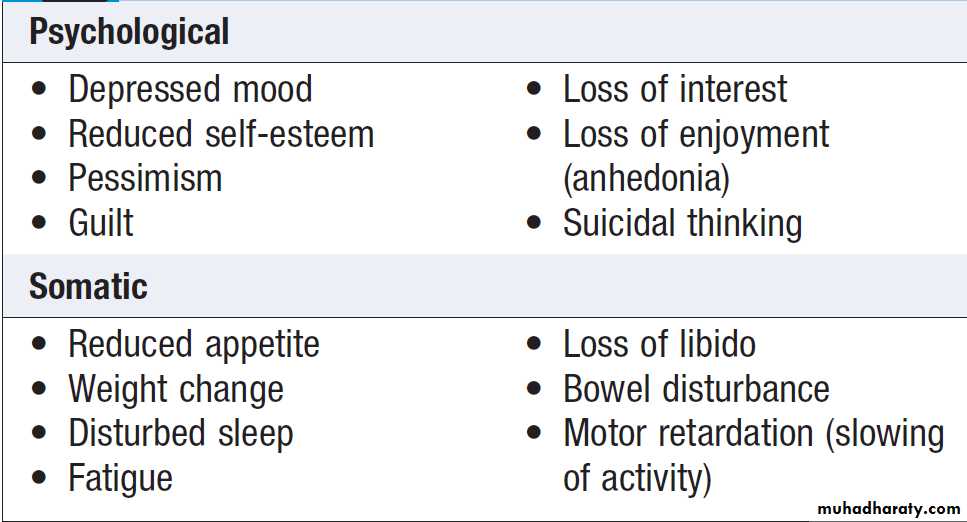

Depressed moodDepressive disorder is common, with a prevalence of

approximately 5% in the general population. Depression

is at least twice as common in the medically ill. It

is important to note that depression has physical as

well as mental symptoms (Box). The diagnosis of

depression in the medically ill, who may have physical

symptoms of disease, relies on detection of the core

psychological symptoms of low mood and anhedonia.

Symptoms of depressive disorders

Differential diagnosis

Depressive disorder must be differentiated from an

adjustment disorder with depressed mood.

Adjustment disorders are common, self-limiting reactions

to adversity, including physical illness, which are

transient and require only general support.

Depressive disorders are characterised by a more severe and persistent disturbance of mood and require specific

treatment.

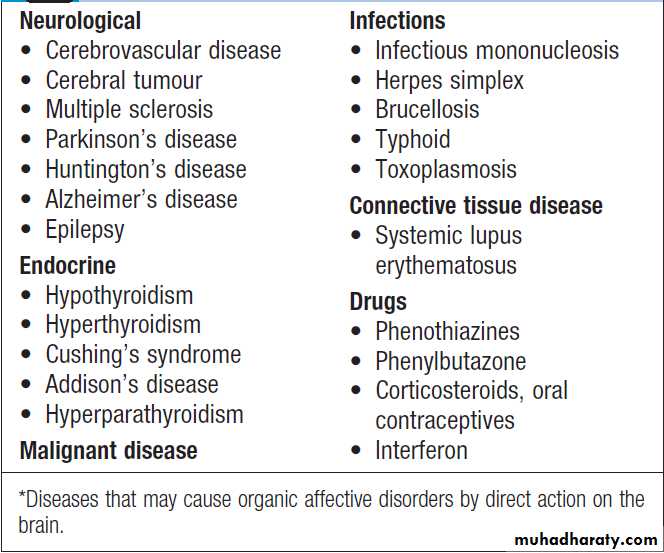

In some cases, depression may occur as a result of a direct effect of a medical condition or its treatment on the brain, when it is referred to as an ‘organic mood disorder’.

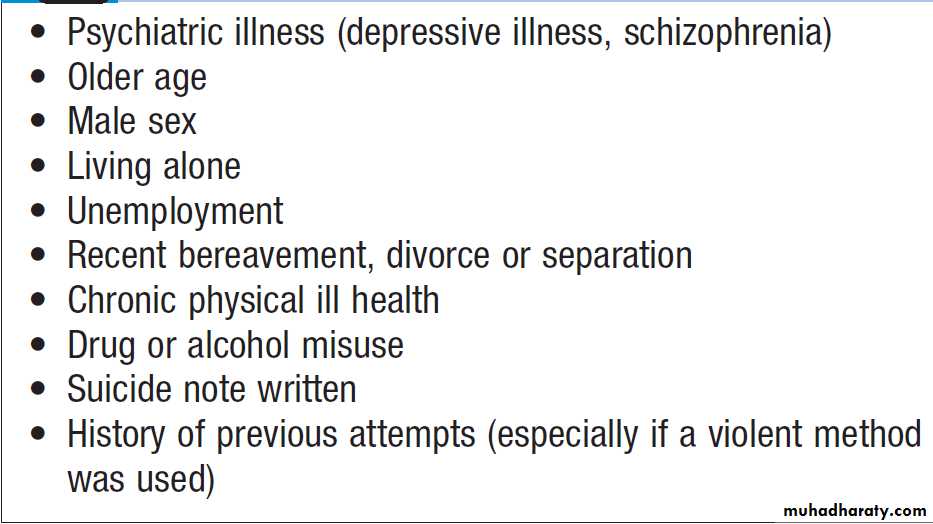

Suicide

Depression is the major risk factor for suicide. Other riskfactors are shown in Box. When depression is suspected,

tactful enquiry should always be made into suicidal

thoughts and plans.

Asking about suicide does not increase the risk of it occurring, whereas failure to enquire denies the opportunity to prevent it.

Organic mood disorders*

Risk factors for suicide

Elated moodElation, or euphoria, is the converse of depression and

is characteristic of mania. It may manifest as infectious

joviality, over-activity, lack of sleep and appetite, undue

optimism, over-talkativeness, irritability, and recklessness

in spending and sexual behaviour. When elated

mood is severe, psychotic symptoms are often evident,

such as delusions of grandeur (e.g. believing erroneously

that one is royalty). Elevated mood is much less common than depressed mood, and in medical settings

is often secondary to drug or alcohol misuse, an organic

disorder or medical treatment. Where none of these

applies, the patient may have a bipolar disorder.

Medically unexplained somatic symptoms

Patients commonly present to doctors with physicalsymptoms. Whilst these symptoms may be an expression

of a medical condition, they often are not. They

may then be referred to as ‘medically unexplained

symptoms’ (MUS). MUS are very common in patients

attending general medical outpatient clinics. Almost any

symptom can be medically unexplained, e.g.:

• pain (including back, chest, abdominal and headache)

• fatigue

• dizziness

• fits, ‘funny turns’ and feelings of weakness.

Patients with MUS may receive a medical diagnosis

of a so-called functional somatic syndrome, such as irritable

bowel syndrome (Box), and may also merit a

psychiatric diagnosis on the basis of the same symptoms.

The most frequent psychiatric diagnoses associated

with MUS are anxiety or depressive disorders.

When these are absent, a diagnosis of somatoform disorder may be appropriate.

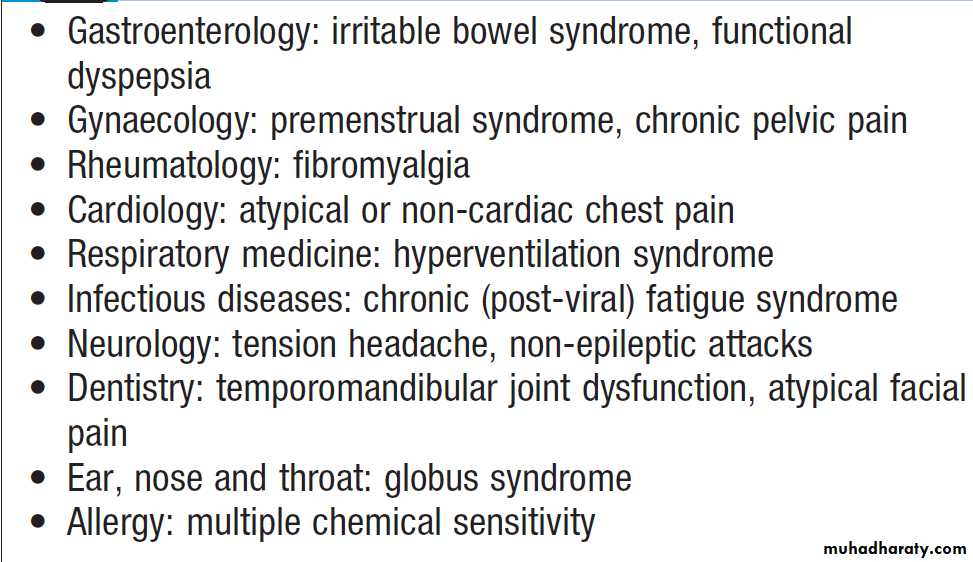

Functional somatic syndromes

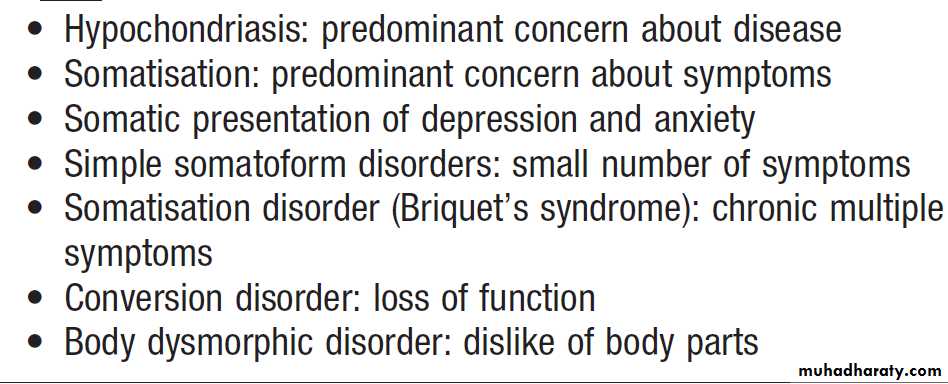

Psychiatric diagnoses for medically unexplained somatic symptoms

Differential diagnosisThe main medical differential diagnosis for MUS is from

symptoms of a medical disease. Diagnostic difficulties

are most likely with unusual presentations of common

diseases and with rare diseases. MUS are commonly an expression of depression and anxiety. A medical and

psychiatric assessment should be completed in all cases .

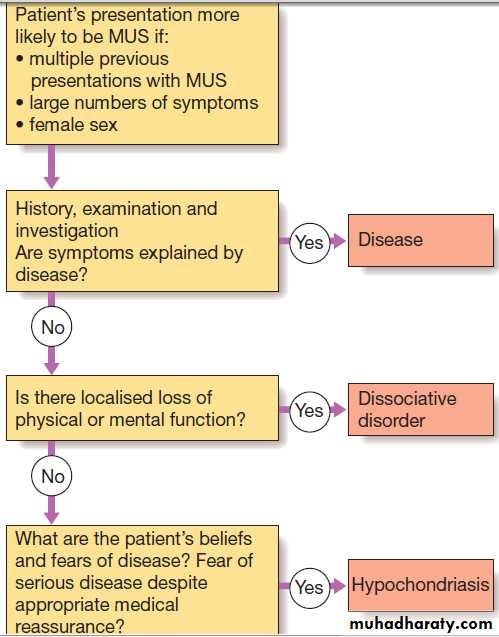

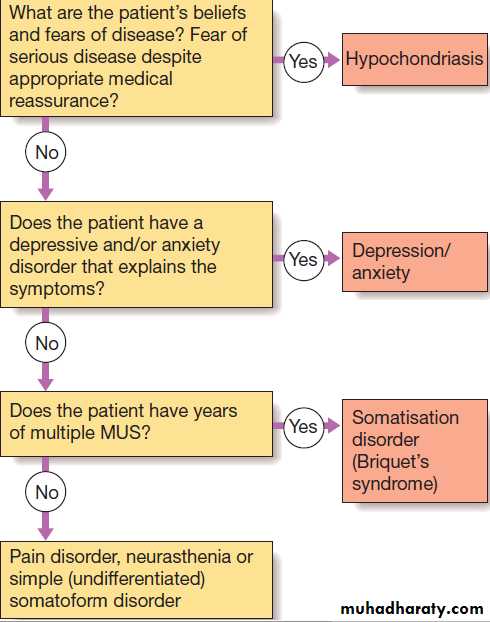

Diagnosis of medically unexplained symptoms (MUS).

Delusions and hallucinationsDelusions

Various types of delusion are identified on the basis of

their content. They may be:

• persecutory, such as a conviction that others are out

to get me

• hypochondriacal, such as an unfounded conviction

that one has cancer

• grandiose, such as a belief that one has special

powers or status

• nihilistic, e.g. ‘My head is missing’, ‘I have no

body’, ‘I am dead’.

Delusions should be differentiated from over-valued

ideas, which are strongly held but not fixed.

Hallucinations

These are perceptions without external stimuli. They

can occur in any sensory modality, most commonly

visual or auditory. Typical examples are hearing voices

when no one else is present, or seeing ‘visions’. Hallucinations have the quality of ordinary perceptions and

are perceived as originating in the external world, not

in the patient’s own mind (when they are termed

pseudo-hallucinations). Those occurring when falling

asleep (‘hypnagogic’) and on waking (‘hypnopompic’)

are not pathological. Hallucinations should be distinguished

from illusions, which are misperceptions of real external stimuli (such as mistaking a shrub for a person in poor light).

Differential diagnosis

Agitation, terror or the fear of being thought ‘mad’may make patients unable or unwilling to volunteer or

describe their abnormal beliefs or experiences. Careful

and tactful enquiry is therefore required. The nature

of hallucinations can be important diagnostically; for

example, ‘running commentary’ voices that discuss the

patient are strongly associated with schizophrenia. In

general, auditory hallucinations suggest schizophrenia,

while hallucinations in other sensory modalities, especially

vision but also taste and smell, suggest an ‘organic

psychosis’ such as delirium or temporal lobe epilepsy. Hallucinations and delusions often co-occur; if their

content is consistent with coexisting emotional symptoms,

they are described as ‘mood-congruent’.

Thus, patients with severely depressed mood may believe

themselves responsible for all the evils in the world, and

hear voices saying ‘You’re worthless. Go and kill yourself.’In this case, the diagnosis of depressive psychosis

is made on the basis of the congruence of different

phenomena (mood, delusion and hallucination). Incongruence between hallucinations, delusions and mood

suggests schizophrenia. Where hallucinations and delusions arise within disturbed consciousness and impaired cognition, the diagnosis is usually an organic disorder, most commonly delirium and/or dementia .This differential

diagnosis is made by assessing the nature, extent and

time course of any cognitive disturbances, and by investigating for underlying causes.

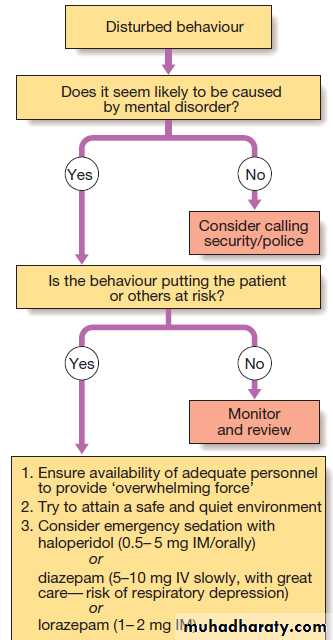

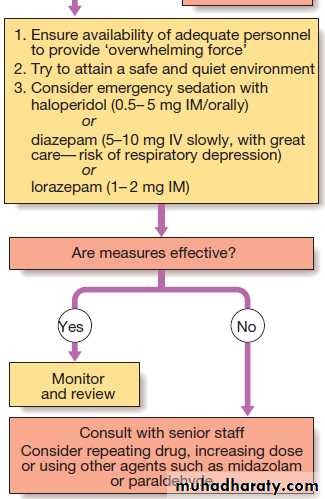

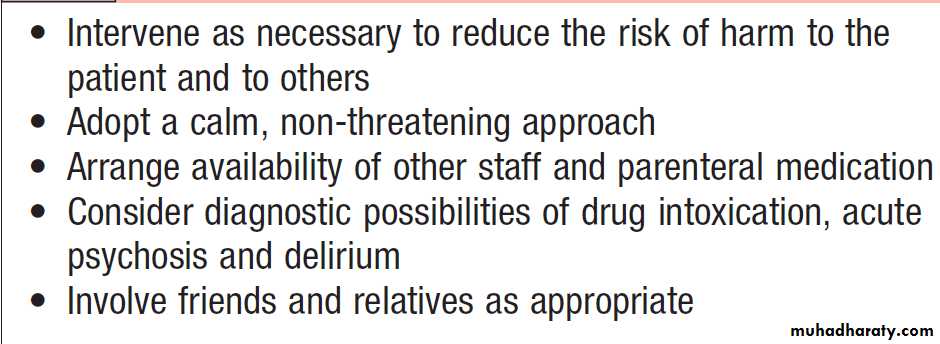

Disturbed and aggressive behaviour

Is common in general hospitals, especially in emergency departments. Most behavioural disturbance arises not from medical or psychiatric illness, but from alcohol intoxication, reaction to the situation and personality characteristics. Thekey principles of management are, first, to establish

control of the situation rapidly and thereby ensure the safety of the patient and others, and, second, to assess

the cause of the disturbance in order to remedy it. Hospital security staff and sometimes the assistance of the police may be required. In all cases, the staff approach is

important; a calm, non-threatening manner expressing

understanding of the patient’s concerns is often all that

is required to defuse potential aggression (Box).

If sedating drugs are required, antipsychotic drugs,

such as haloperidol, and benzodiazepines, such asdiazepam, are commonly used. The choice of drug, dose,

route and rate of administration will depend on the patient’s age, sex and physical health, as well as the

likely cause of the disturbed behaviour. Haloperidol can cause acute dystonias, including oculogyric crises, the benzodiazepines can precipitate respiratory depression in patients with lung disease, and encephalopathy in those with liver disease.Thus, for a frail with emphysema and delirium, sedation may be achieved with a low dose (0.5 mg) of oral haloperidol, while for a strong young man with an acute psychotic episode, at least 10 mg of IVdiazepam and a similar dose of haloperidol may be needed.

A parenterally administered anticholinergic agent, such as procyclidine, should be available to treat extrapyramidal effects arising from haloperidol, and flumazenil to reverse respiratory depression if large doses of benzodiazepines are used.

Differential diagnosis

Many factors may contribute to disturbed behaviour.

When the patient is cooperative, these are best determined at interview. Other sources of information about the patient include medical and psychiatric records, and discussion with nursing staff, family members and other

informants, including the patient’s general practitioner.

The following information should be sought:

• psychiatric, medical (neurological) andcriminal history• current psychiatric and medical treatment

• alcohol and drug misuse

• recent stressors

• the time course and accompaniments of the current

episode in terms of mood, belief and behaviour. Observation of the patient’s behaviour may also yield

useful clues.

Do they appear to be responding to hallucinations?

Are they alert or variably drowsy and confused?

Are there physical features suggestive of drug or

alcohol misuse or withdrawal?

Are there new injuries or old scars, especially on the head? Do they smell of alcohol or solvents?

Do they bear the marks of drug injection?

Are they unwashed and unkempt, suggesting a gradual development of their condition?

If the person has an acute psychiatric disorder, then

admission to a psychiatric facility may be indicated. If a

medical cause is likely, psychiatric transfer is usually

inappropriate and the patient should be managed in a

medical setting, with whatever nursing and security

support is required.

Where it is clear that there is no medical or psychiatric illness, the person should be removed from the hospital, to police custody if necessary.

Measures such as restraint, sedation, the investigation

and treatment of medical problems, and psychiatric transfer all raise legal as well as medical issues .

In most countries, including the UK, common law

confers upon doctors the right, and indeed the duty, to

intervene against a patient’s wishes in cases of acute

behavioural disturbance, if this is necessary to protect

the patient or other people. Many countries, such as the

UK, also have specific mental health legislation that may

be used to detain patients.

Acute management of disturbed behaviour.

Psychiatric emergencies

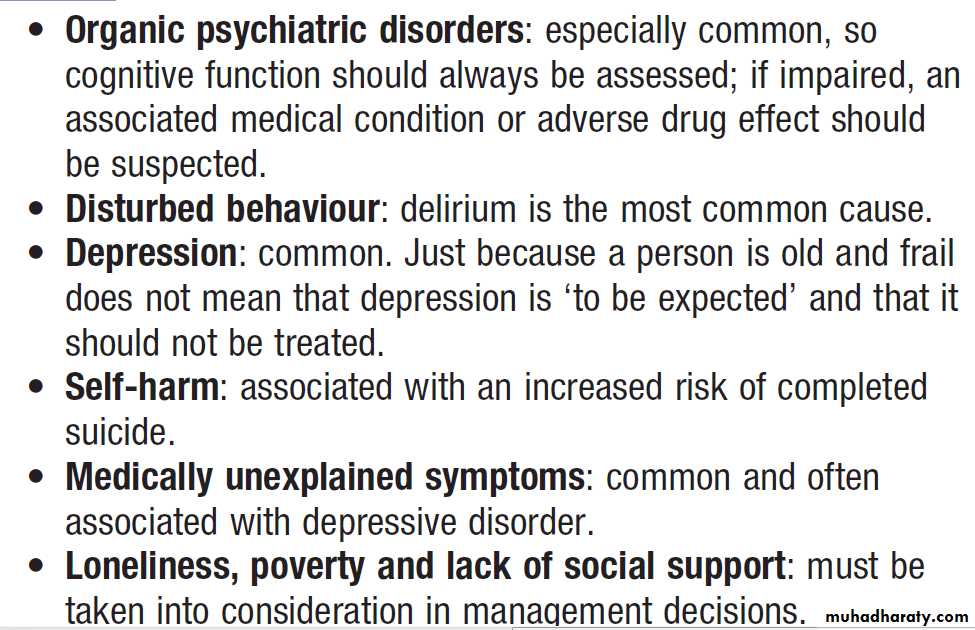

Medical psychiatry in old age

ConfusionThis is a vague term used to describe a range of primarily

cognitive problems, including disturbances in

perception, belief and behaviour. ‘Confusion’ usually

presents as a problem when it becomes clear that the

patient cannot comply with medical care; they may

repeatedly wander off the ward, pull out essential cannulae and catheters, and hit nurses. The methods of

assessment of cognitive function range from simple

screening questions to detailed psychometric testing. All

doctors should be able to undertake a brief cognitive

assessment, as outlined above.

Differential diagnosis

A history from the patient and informants is essentialto establish the time course, variability and functional

consequences of any cognitive deficit. Mental state

examination is necessary to seek evidence of associated

mood disorder, hallucinations, delusions or behavioural

abnormalities, and physical examination to identify any

relevant medical conditions.

The assessment should seek to distinguish between:

• organic disorders such as delirium, dementia, and

focal deficits secondary to brain lesions

• psychiatric disorders such as depressive pseudodementia

and dissociative disorder

• malingering

Self-harm

Self-harm (SH) is a common reason for presentation

to medical services. The term ‘attempted suicide’ is potentially misleading, as most such patients are not

unequivocally trying to kill themselves. Most cases of

SH involve overdose, of either prescribed or nonprescribed

drugs . Less common methods include

asphyxiation, drowning, hanging, jumping from a

height or in front of a moving vehicle, and the use of

firearms. Methods that carry a high chance of being fatal

are more likely to be associated with serious psychiatric

disorder. Self-cutting is common and often repetitive,

but rarely leads to contact with medical services.

The incidence of SH varies over time and between

countries. In the UK, the lifetime prevalence of suicidalideation is 15% and that of acts of SH is 4%. SH is more

common in women than men, and in young adults than

the elderly. (In contrast, completed suicide is more

common in men and the elderly (see Box).) There is

a higher incidence of self-harm among lower socioeconomic groups, particularly those living in crowded,

socially deprived urban areas. There is also an association

with alcohol misuse, child abuse, unemployment

and recently broken relationships.

Differential diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis is from accidental poisoning

and so-called ‘recreational’ overdose in drug

users. It must be remembered that SH is not a diagnosis

but a presentation, and may be associated with any psychiatric diagnosis, the most common being adjustment

disorder, substance and alcohol misuse, depressive disorder and personality disorder. In many cases, however,

no psychiatric diagnosis can be made.

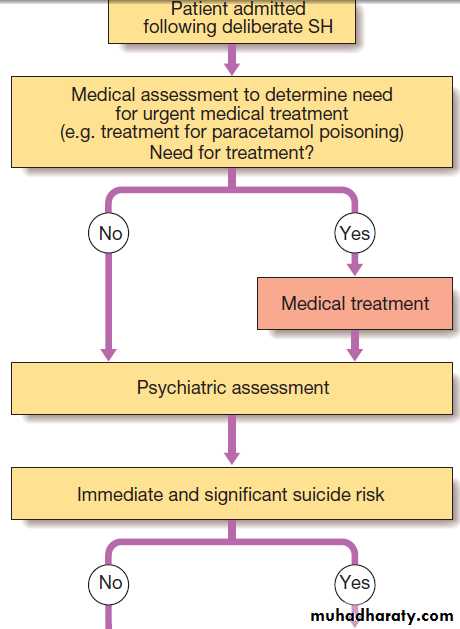

Initial management

A thorough psychiatric and social assessment shouldbe attempted in all cases (Fig.), although some

patients will discharge themselves before this can take

place. The need for psychiatric assessment should not,

however, delay urgent medical or surgical treatment,

and may need to be deferred until the patient is well

enough for interview.

The purpose of the psychiatric assessment is to:

• establish the short-term risk of suicide

• identify potentially treatable problems, whether

medical, psychiatric or social.

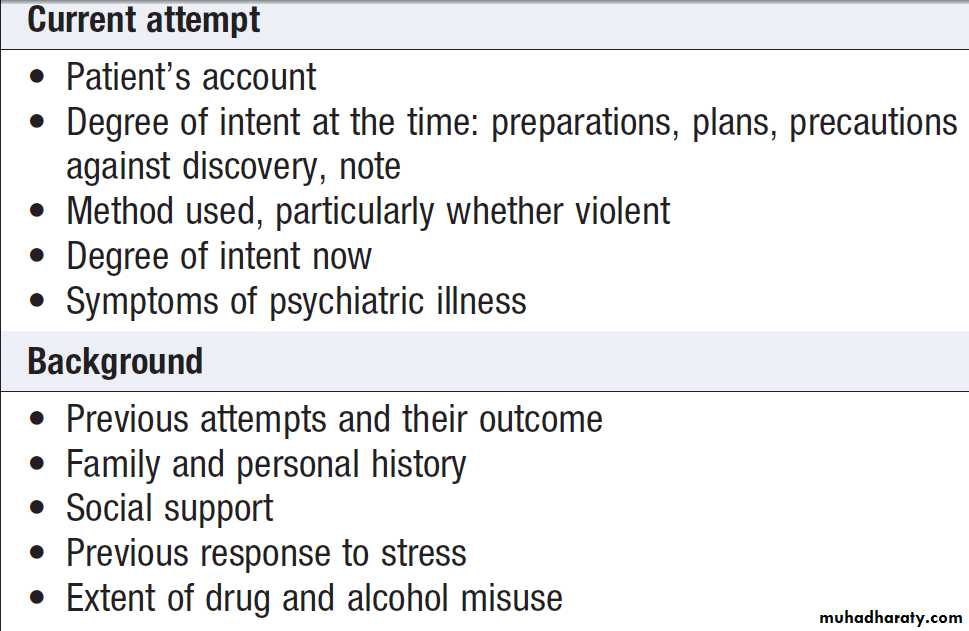

Topics to be covered when assessing a patient are

listed in Box.

Assessment of patients after self-harm

Assessment of patients admitted following self-harm (SH).

The history should include events occurring immediately before and after the act, and especially any evidence of planning. The nature and severity of any current psychiatric symptoms must be assessed, along with the personal and social supports available to the patient outside hospital.Most SH patients have depressive and anxiety symptoms

on a background of chronic social and personal difficulties and alcohol misuse but no psychiatric disorder.

They do not usually require psychotropic medication or specialised psychiatric treatment but may benefit from personal support and practical advice from a GP, social worker or community psychiatric nurse.

Admission to a psychiatric ward is necessary only for

persons who:• have an acute psychiatric disorder

• are at high risk of suicide

• need temporary respite from intolerable circumstances

• require further assessment of their mental state.

Approximately 20% of SH patients make a repeat

attempt during the following year and 1–2% kill themselves.

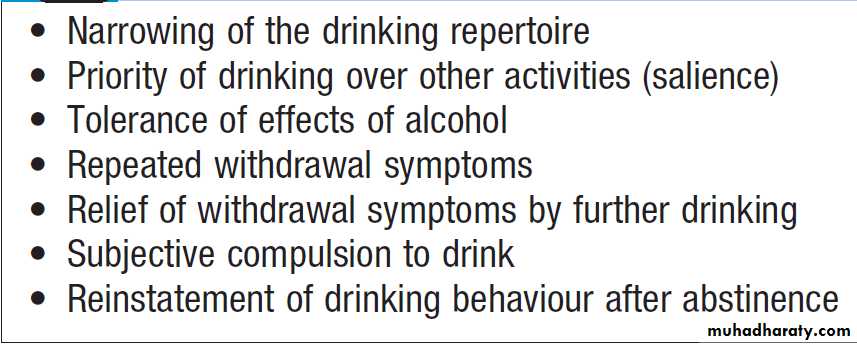

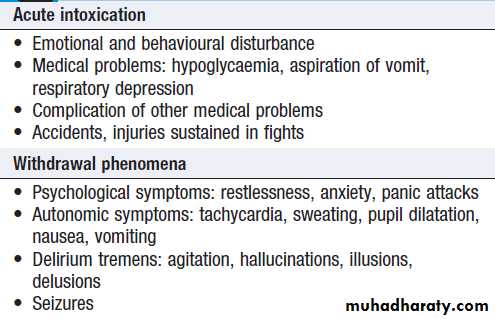

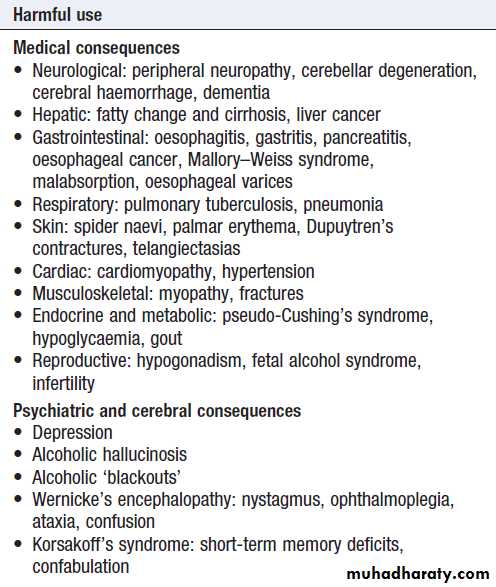

Alcohol misuse

Misuse of alcohol is a major problem worldwide. It

presents in a multitude of ways . In many cases, the link to alcohol will be all too obvious; in others, it may not be. Denial and concealment of alcohol intake are common.

In the assessment of alcohol intake, the patient should be asked to describe a typical week’s drinking, quantified in terms of units of alcohol (1 unit contains approximately 8 g alcohol and is the equivalent of half a pint of beer, a single measure of spirits or a small glass of wine). Drinking becomes hazardous at levels above 21 units weekly for men and 14 units weekly for women.

The history from the patient may need corroboration by the GP, earlier medical records and family members. The mean cell volume (MCV) and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) may be raised, but are abnormal in only half of problem drinkers; consequently, normal results on these tests do not exclude an alcohol problem.

When abnormal, these measures may be helpful in challenging denial and monitoring treatment response.

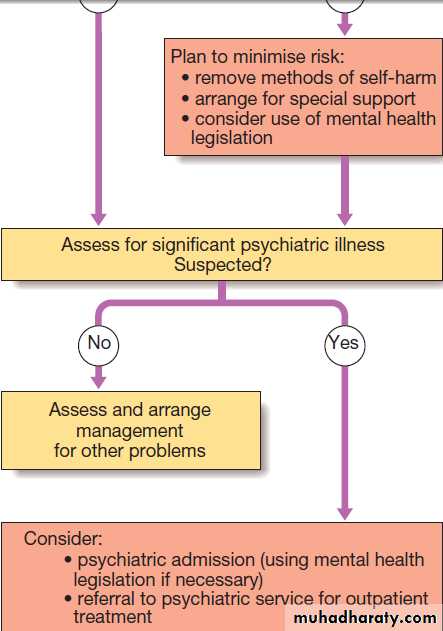

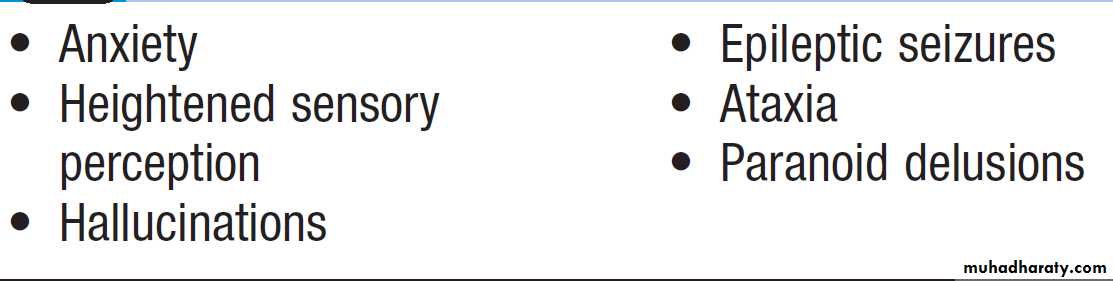

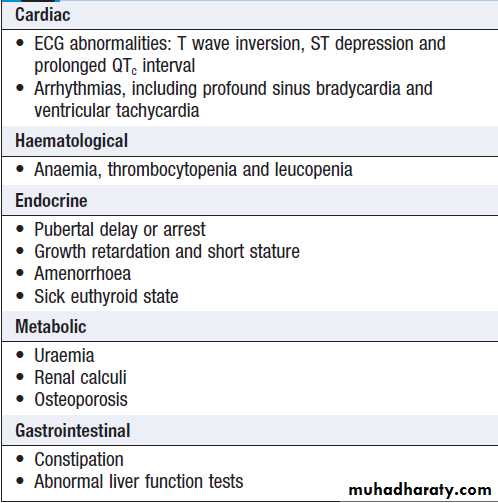

Substance misuse

The misuse of drugs of all kinds is also widespread.There are two additional sets of problems associated with drug misuse:

• problems linked with the route of administration,

such as intravenous injection

• problems arising from pressure applied to doctors

to prescribe the misused substances.

Substance misuse: additional presenting problems

Psychological factors affecting medical conditions

Psychological factors may influence the presentation,

management and outcome of medical conditions. Specific

factors are shown in Box. The most common

psychiatric diagnoses in the medically ill are anxiety and depressive disorders. Often these appear understandable as adjustments to illness and its treatment; however, if the anxiety and depression are severe and persistent, they may complicate the management of the medical condition and active management is required. Anxiety may present as an increase in somatic symptoms such as breathlessness, tremor or palpitations, or as the avoidance of medical treatment.

It is most common in those facing difficult or painful treatments, deterioration of their illness or death. Depression may manifest as increased physical symptoms such as pain or fatigue and disability, as well as with depressed mood and loss of interest and pleasure. It is most common in patients who have suffered actual or anticipated losses, such as receiving a terminal diagnosis or undergoing disfiguring surgery.

Treatment is by psychological and/or pharmacological

therapies, as described below. Care is required when

prescribing psychotropic drugs to the medically ill in

order to avoid exacerbation of the medical condition and

harmful interactions with other prescribed drugs.

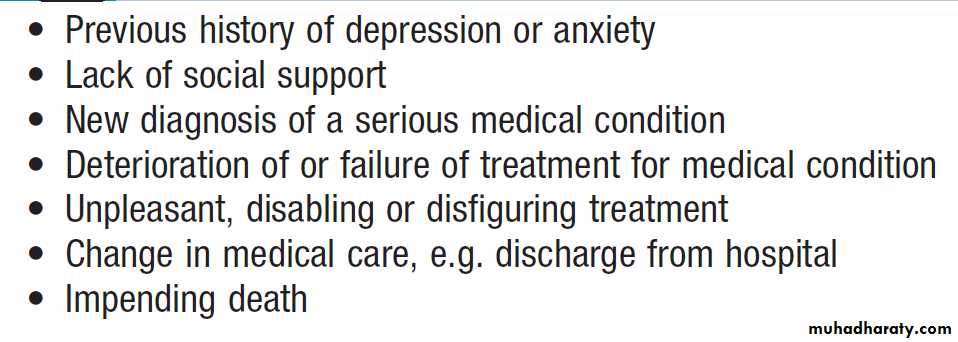

Risk factors for psychological problems associated with medical conditions

TREATING PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERSThe multifactorial origin of most psychiatric disorders

means that there are multiple potential targets for

treatment.

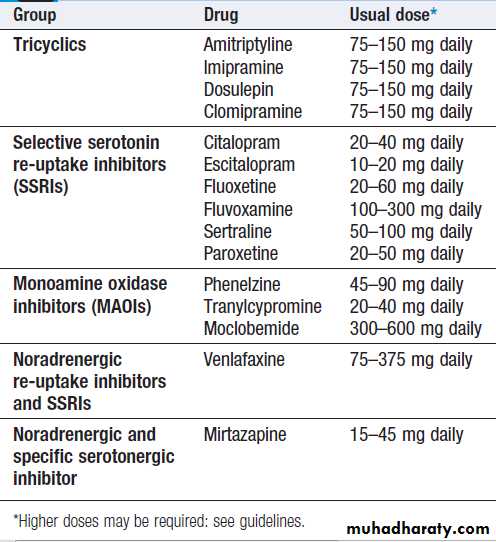

Biological treatments

These aim to relieve psychiatric disorder by modifying

brain function. The main biological treatments are

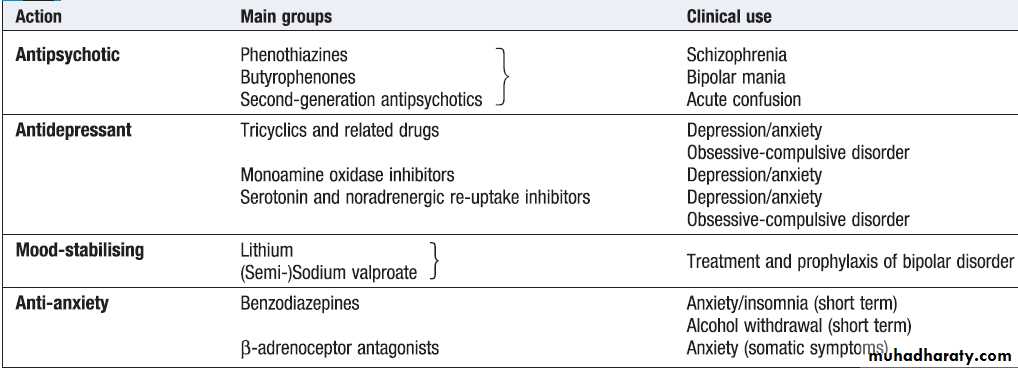

psychotropic drugs. These are widely used for various purposes; a pragmatic classification is set out in Box. It should be noted that some drugs have applications to more than one condition; for example, antidepressants are also widely used in the treatment of anxiety and chronic pain. The specific subgroups of psychotropic drugs are discussed in the sections on the appropriate disorders.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) entails producing a

convulsion by the administration of high-voltage, brief,

direct-current impulses to the head while the patient

is anaesthetised and paralysed by muscle relaxant. If

properly administered, it is remarkably safe, has few

side-effects, and is of proven efficacy for severe depressive illness. There may be amnesia for events occurring a few hours before ECT (retrograde) and after it (anterograde).

Pronounced amnesia can occur but is infrequent and difficult to distinguish from the effects of severe depression. Surgery to the brain (psychosurgery) has a very limited place and then only in the treatment of severe chronic psychiatric illness resistant to other measures.

Classification of commonly used psychotropic drugs

Psychological treatmentsThese treatments are useful in many psychiatric disorders

and also in non-psychiatric conditions. They are based on talking with patients, either individually or in groups. Sometimes discussion is supplemented by ‘homework’ or tasks to complete between treatment sessions. Psychological treatments take a number of forms based on the duration and frequency of contact, the specific techniques applied and their underlying theory.

General or supportive psychotherapy

This should be part of all medical treatment.

It involves empathic listening to the patient’s account of their symptoms and associated fears and concerns, followed by the sympathetic provision of accurate information that addresses these.

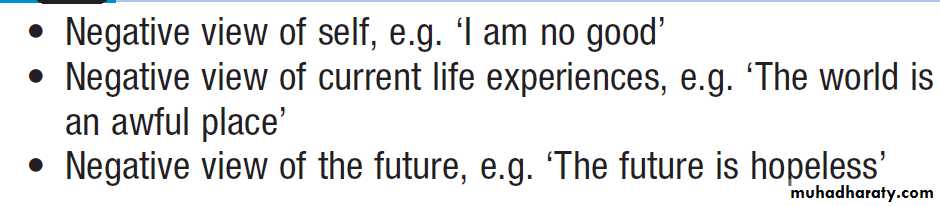

Cognitive therapy

This therapy is based on the observation that some psychiatric disorders are associated with systematic errors in the patient’s conscious thinking: for example, a tendencyto interpret events in a negative way or see them

as unduly threatening. A triad of ‘cognitive errors’ has

been described in depression (Box). Cognitive

therapy aims to help patients to identify such cognitive

errors and to learn how to challenge them. It is widely

used for depression, anxiety and eating and somatoform

disorders, and also increasingly in psychoses.

The negative cognitive triad associated with depression

Behaviour therapyThis is a practically orientated form of treatment, in

which patients are assisted in changing unhelpful

behaviour: for example, helping patients to implement

carefully graded exposure to the feared stimulus in

phobias.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)

CBT combines the methods of behaviour therapy and cognitive therapy.

It is the most widely available and extensively researched

psychological treatment.

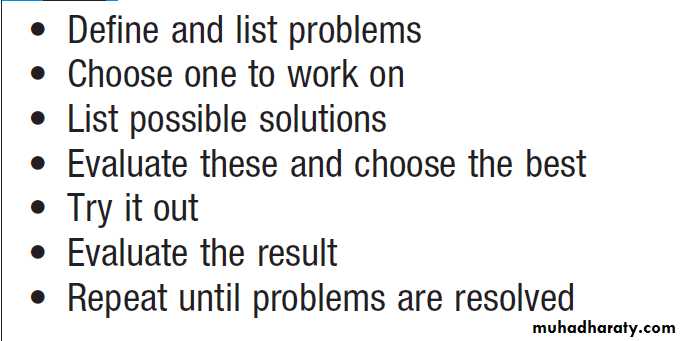

Problem-solving therapy

This is a simplified brief form of CBT, which helpspatients actively tackle problems in a structured way

(Box). It is of benefit in mild to moderate depression,

and can be delivered by non-psychiatric doctors

and nurses after appropriate training.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy

This treatment, also known as ‘interpretive psychotherapy’,

was pioneered by Freud, Jung and Klein,

amongst others. It is based upon the theory that early

life experience generates powerful but unconscious

motivations.

Psychotherapy aims to help the patient to become aware of these unconscious factors on the assumption that, once identified, their negative effects are reduced.

The relationship between therapist and patient is used as a therapeutic tool to identify issues in patients’ relationships with others, particularly parents, which may be replicated or transferred to their relationship with the therapist. Explicit discussion of this relationship (transference) is the basis for the treatment, which traditionally requires frequent sessions over a period of months or even years.

Stages of problem-solving therapy

Interpersonal psychotherapyInterpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is a specific form of

brief psychotherapy that focuses on patients’ current

interpersonal relationships and is an effective treatment

for mild to moderate depression.

Social interventions

Some adverse social factors, such as unemployment,may not be readily amenable to intervention, but others,

such as access to benefits and poor housing, may be.

Patients can be helped to address these problems themselves by being taught problem-solving.

Befrienders and day centres can reduce social isolation, benefits advisers can ensure appropriate financial assistance, and medical recommendations can be made to local housing departments to help patients obtain more appropriate accommodation.

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

Stress-related disordersAcute stress reaction

Following a stressful event such as a serious medical

diagnosis or a major accident, some people develop

a characteristic pattern of symptoms. These include

a sense of bewilderment, anxiety, anger, depression,

altered activity and withdrawal. The symptoms are transient and usually resolve completely within a few days.

Adjustment disorder

A more common psychological response to a major stressor is a less severe but more prolonged emotional reaction. The predominant symptom is usually depression and/or anxiety, which is insufficiently persistent or intense to merit a diagnosis of depressive or anxiety disorder.

There may also be anger, aggressive behavior and associated excessive alcohol use. Symptoms develop

within a month of the onset of the stress, and their duration and severity reflect the course of the underlying stressor.

Grief reactions following bereavement are a particular

type of adjustment disorder. They manifest as a brief

period of emotional numbing, followed by a period of

distress lasting several weeks, during which sorrow,

tearfulness, sleep disturbance, loss of interest and a

sense of futility are common. Perceptual distortions may

occur, including misinterpreting sounds as the dead person’s

voice. ‘Pathological grief’ describes a grief reaction

that is abnormally intense or persistent.

Management and prognosis

Ongoing contact with and support from a doctor orother who can listen, reassure, explain and advise are

often all that is needed. Most patients do not require

psychotropic medication, although benzodiazepines

reduce arousal in acute stress reactions and can aid

sleep in adjustment disorders.

Psychotherapy may be helpful for patients with abnormal grief reactions.

These conditions usually resolve with time but can develop into depressive or anxiety disorders and require treating as such.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Is a protracted response to a stressful event of an exceptionally threatening or catastrophic nature. Examples of such events include natural disasters, terrorist activity, serious accidents and witnessing violent deaths.

PTSD may also sometimes occur after distressing medical treatments.

There is usually a delay ranging from a few days to

several months between the traumatic event and the

onset of symptoms.

Typical symptoms are recurrent intrusive memories (flashbacks) of the trauma, as well as sleep disturbance, especially nightmares (usually of the traumatic event) from which the patient awakes in a state of anxiety, symptoms of autonomic arousal, emotional blunting and avoidance of situations that evoke memories of the trauma. Anxiety and depression are often associated and excessive use of alcohol or drugs frequently complicates the clinical picture.

Management and prognosis

Immediate counselling for those who have survived amajor trauma is only likely to benefit those who request

it. The main aims are to provide support, direct advice

and the opportunity for emotional catharsis. In established

PTSD, structured psychological approaches

(CBT, eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing

(EMDR), and stress management) are effective. Antidepressant drugs are moderately effective. The condition runs a fluctuating course, with most patients

recovering within 2 years. In a small proportion, the

symptoms become chronic.

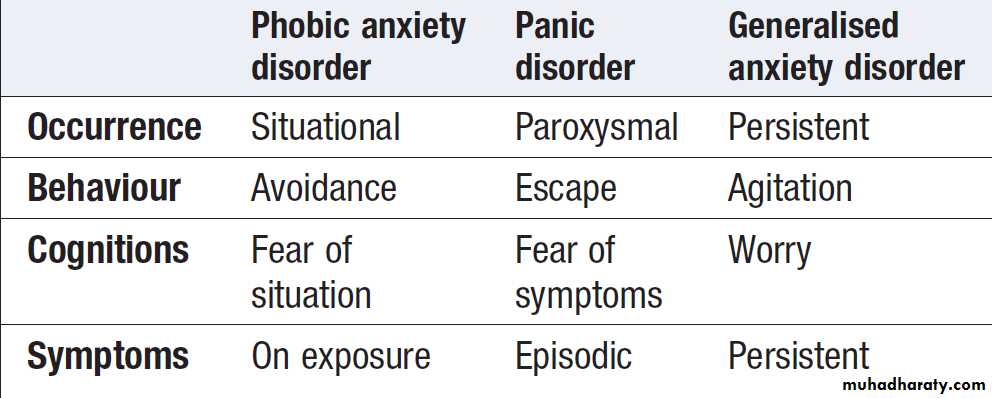

Anxiety disorders

These are characterised by the emotion of anxiety, worrisome thoughts, avoidance behaviour and the somaticsymptoms of autonomic arousal. Anxiety disorders are

divided into three main subtypes: phobic, paroxysmal

(panic) and generalised (Box).

The nature and prominence of the somatic symptoms often lead the patient to present initially to medical services. Anxiety may be stress-related and phobic anxiety may follow an unpleasant incident.

Patients with anxiety often also have depression.

Classification of anxiety disorders

Phobic anxiety disorderA phobia is an abnormal or excessive fear of an object

or situation, which leads to avoidance of it (such as

excessive fear of dying in an air crash leading to avoidance of flying).

A generalised phobia of going out alone or being in crowded places is called agoraphobia.

Phobic responses can develop to medical procedures such as venepuncture.

Panic disorder

Panic disorder describes repeated attacks of severeanxiety, which are not restricted to any particular situation

or circumstances. Somatic symptoms such as chest

pain, palpitations and paraesthesiae in lips and fingers

are common. The symptoms are in part due to involuntary

over-breathing (hyperventilation). Patients with

panic attacks often fear that they are suffering from a

serious illness such as a heart attack or stroke, and seek

emergency medical attention. Panic disorder is often

associated with agoraphobia.

Generalised anxiety disorder

This is a chronic anxiety state associated with uncontrollable worry. The associated somatic symptoms of muscle tension and bowel disturbance often lead to a medical presentation.

Management of anxiety disorders

Psychological treatment

Explanation and reassurance are essential, especially

when patients fear they have a serious medical condition.

Specific treatment may be needed. Treatments

include relaxation, graded exposure (desensitisation) to

feared situations for phobic disorders, and CBT.

Drug treatment

Antidepressants are the drugs of choice.

Benzodiazepines are useful in the short term but long-term use can lead to dependence. A β-blocker such as propranolol can help when somatic symptoms are prominent.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

Is characterised by obsessive thoughts, which are recurrent, unwanted and usually anxiety-provoking, but recognised as one’s own; and by compulsions, which are repeated acts performed to relieve the anxiety. An example is repeated hand-washing related to thoughts of contamination. The differential diagnosis is normal checking behavior and delusional beliefs about thought possession. Unlike other anxiety disorders, which are more common in

women, OCD is equally common in men and women.

Management and prognosis

OCD usually responds to some degree to antidepressantdrugs (SSRIs) and to CBT, which helps patients expose themselves to the feared thought or situation without performing the anxiety-relieving compulsions.

However, relapses are common and the condition often becomes chronic.

Mood disorders

Mood or affective disorders include:

• unipolar depression: one or more episodes of low

mood and associated symptoms

• bipolar disorder: episodes of elevated mood

interspersed with episodes of depression

• dysthymia: chronic low-grade depressed mood

without sufficient other symptoms to count as

‘clinically significant’ or ‘major’ depression.

Depression

Major depressive disorder has a prevalence of 5% in the

general population and approximately 10–20% in chronically ill medical outpatients. It is a major cause of disability and suicide.

If comorbid with a medical condition, depression magnifies disability, diminishes adherence to medical treatment and rehabilitation, and may even shorten life expectancy.

Aetiology

There is a genetic predisposition to depression, especially

when of early onset, number and identity of the genes are largely unknown but the serotonin transporter gene is a candidate. Emotional deprivation early in life also predispose to depression.Depressive episodes are often, but not always, triggered by stressful life events ,medical illnesses. Associated biologicalfactors include hypofunction of monoamine neurotransmitter systems (5-HT and noradrenaline )and abnormal hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) results in elevated cortisol levels that do not suppress with dexamethasone.

Diagnosis

Depression may be mild, moderate or severe. It may also be episodic, recurrent or chronic. It can be both a complication of a medical condition and a cause of MUS so physical examination is essential; an associated medical condition should always be considered.Management and prognosis

There is evidence that both drug and psychological

treatments work. Severe depression complicated by psychosis, dehydration or suicide risk may require ECT.

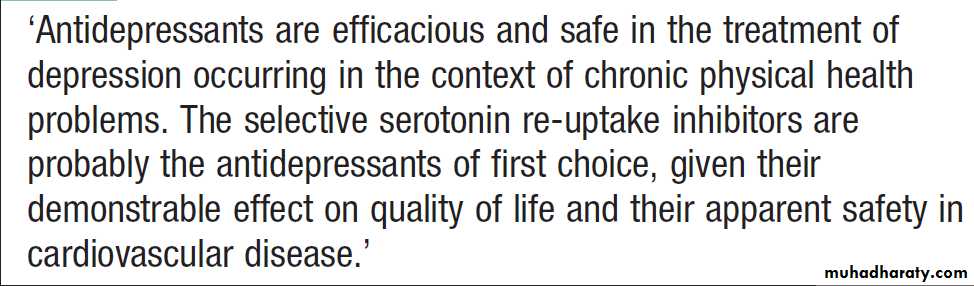

Drug treatment

Antidepressant drugs are effective in patients whose

depression is secondary to medical illness, as well as

those in whom it is the primary problem.

• Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). These agents inhibit the re-uptake of the amines noradrenaline and 5-HT at synaptic clefts. The therapeutic effect is noticeable within a week or two.

Side-effects, such as sedation, anticholinergic effects, postural hypotension, lowering of the seizure threshold and cardiotoxicity, can be troublesome during this period. TCAs may be dangerous in overdose and in people who have coexisting heart disease, glaucoma and prostatism.

• Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs). These

are less cardiotoxic and less sedative than TCAs,and have fewer anticholinergic effects. They are

safer in overdose, but can still cause headache,

nausea, anorexia and sexual dysfunction. They can

also interact with other drugs increasing serotonin

to produce ‘serotonin syndrome’. This is a rare

syndrome of neuromuscular hyperactivity, autonomic hyperactivity and agitation, and potentially seizures, hyperthermia, confusion and even death.

• Newer antidepressants. including venlafaxine, mirtazapine and duloxetine.They have slightly different modes of action and adverse effects but are generally no more effective than the agents listed above.

• Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). These drugs

increase the availability of neurotransmitters at

synaptic clefts by inhibiting metabolism of noradrenaline and 5-HT. They are now rarely prescribed in the UK, since they can cause potentially dangerous interactions with drugs such as amphetamines, and foods rich in tyramine

such as cheese and red wine. This is due to

accumulation of amines in the systemic circulation,

causing a potentially fatal hypertensive crisis.

These different classes of antidepressant have similar

efficacy and about three-quarters of patients respond totreatment. Successful treatment requires the patient to

take an appropriate dose of an effective drug for an

adequate period. For patients who do not respond, a

proportion will do so if changed to another antidepressant.

The patient’s progress must be monitored and,

after recovery, treatment should be continued for at least

6–12 months to reduce the high risk of relapse. The dose

should then be tapered off over several weeks to avoid

discontinuation symptoms.

Psychological treatments

Both CBT and interpersonal therapy are as effective as

antidepressants for mild to moderate depression. Antidepressant drugs are, however, preferred for severe

depression. Drug and psychological treatments can be

used in combination.

Over 50% of people who have had one depressive

episode and over 90% of people who have had three or

more episodes will have another. The risk of suicide in

an individual who has had a depressive disorder is ten

times greater than in the general population.

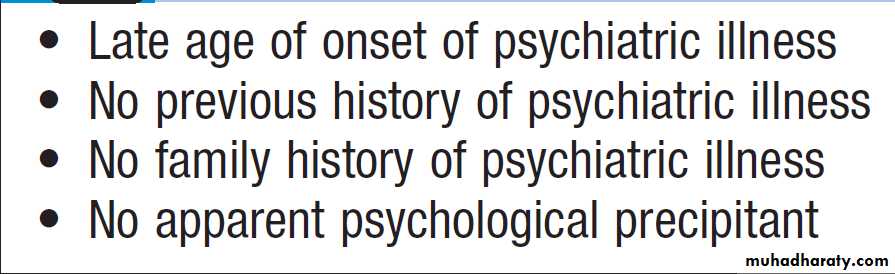

Antidepressants in the medically ill

Antidepressant drugs

Pointers to an organic cause for psychiatric disorder

Bipolar disorderBipolar disorder is an episodic disturbance with interspersed periods of depressed and elevated mood; the latter is known as hypomania when mild or short-lived, or mania when severe or chronic.The lifetime risk of

developing bipolar disorder is approximately 1–2%.

Onset is usually in the twenties, and men and women are equally affected. In DSM-IV, bipolar disorder has

been divided into two types:

• Bipolar I disorder has a clinical course characterised

by one or more manic episodes or mixed episodes.

Often individuals have also had one or more major

depressive episodes.

• Bipolar II disorder features depressive episodes that

are more frequent and more intense than manicepisodes, but there is a history of at least one

hypomanic episode.

Aetiology

Bipolar disorder is strongly heritable (approximately

70%). Relatives of patients have an increased incidence

of both bipolar and unipolar affective disorder. Life

events, such as physical illness, sleep deprivation and

medication, may play a role in triggering episodes.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on clear evidence of episodes of

depression and mania. Isolated episodes of hypomania

or mania do occur but they are usually preceded or followed by an episode of depression. Psychosis may occur in both the depressive and the manic phases, with delusions and hallucinations that are usually in keeping with

the mood disturbance. This is described as an affective

psychosis. Patients who present with symptoms of both

bipolar disorder and schizophrenia may be given a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder. A clinical picture of

recurrent depression with one or more episodes of hypomania may be referred to as type 2 bipolar disorder.

Management and prognosis

Depression should be treated as described above.However, if antidepressants are prescribed, they should

be combined with a mood-stabilising drug (see below)

to avoid ‘switching’ the patients into (hypo)mania.

Manic episodes and psychotic symptoms usually

respond well to antipsychotic drugs .

Prophylaxis to prevent recurrent episodes of depression

and mania with mood-stabilising agents is important.

The main drugs used are lithium and sodium valproate. Olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone are

increasingly used. Caution must be exercised when

stopping these drugs, as a relapse may follow.

• Lithium carbonate is the drug of choice. It is also used for acute mania, and in combination with a tricyclic as an adjuvant treatment for resistant depression. It has a narrow therapeutic range, so regular blood monitoring is required to maintain a serum level of 0.5–1.0 mmol/L. Toxic effects include nausea, vomiting, tremor and convulsions. With long-term treatment, weight gain, hypothyroidism, increased calcium and parathormone, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and renal failure can occur. Thyroid and renal function should be checked before treatment is started and regularly thereafter. Lithium may be teratogenic, and should not be prescribed during the first trimester of pregnancy.

• Sodium valproate (an anticonvulsant) and olanzapine (an antipsychotic) are both used as prophylaxis in bipolar disorder, usually as a second-line alternative to lithium. Valproate conveys a high risk of birth defects and should also not be used in women of child-bearing age. Olanzapine can cause significant weight gain. (For a list of the adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs, see Box.) The relapse rate of bipolar disorder is high, although patients may be perfectly well between episodes. After one episode the annual average risk of relapse is about 10–15%, which doubles after more than three episodes. There is a substantially increased lifetime risk of suicide of 5–10%.

Somatoform disorders

The essential feature of these disorders is that thesomatic symptoms are not explained by a medical condition (medically unexplained symptoms), nor better diagnosed as part of a depressive or anxiety disorder.

Aetiology

The cause is incompletely understood but contributory factors include depression and anxiety, the erroneous interpretation of somatic symptoms as evidence of disease, excessive concern with physical illness and a tendency to seek medical care. A family history or previous history of a particular condition may have shaped the patient’s beliefs about illness. Doctors may exacerbate the problem, either by dismissing the complaints as non-existent or by overemphasizing the possibility of disease.

Somatisation disorder

Somatisation disorder (Briquet’s syndrome) is characterisedby the occurrence of chronic multiple somatic symptoms for which there is no physical cause. Symptoms

start in early adult life and may be referred to any

part of the body. The disorder is much more common in

women. Common complaints include pain, vomiting,

nausea, headache, dizziness, menstrual irregularities

and sexual dysfunction. Patients may undergo a multitude

of negative investigations and unhelpful operations,

particularly hysterectomy and cholecystectomy.

There is no proven treatment but minimisation of iatrogenic harm from multiple investigations and attempts at medical treatment is important.

Hypochondriacal disorder

Patients with this condition, also known as health

anxiety, have a strong fear or belief that they have a

serious, often fatal, disease and that fear persists despite

appropriate medical reassurance. They are typically

highly anxious and seek many medical opinions and

investigations in futile but repeated attempts to relieve

their fears. Treatment with CBT may be helpful. The

condition may become chronic.

In a small proportion of cases, the conviction that disease is present reaches delusional intensity. The bestknown example is that of parasitic infestation (‘delusional parasitosis’), which leads patients to consult dermatologists. Antipsychotic medication may be effective in such cases.

Body dysmorphic disorder

This describes a preoccupation with bodily shape orappearance, with the belief that one is disfigured in

some way (previously known as dysmorphophobia).

People with this condition may make inappropriate

requests for cosmetic surgery. CBT or antidepressants

may be helpful.

The belief in disfigurement may sometimes be delusional, in which case antipsychotic drugs may help.

Somatoform autonomic dysfunction

This describes somatic symptoms referable to bodilyorgans that are largely under the control of the autonomic

nervous system. The most common examples

involve the cardiovascular system (‘cardiac neurosis’),

respiratory system (psychogenic hyperventilation) and

gut (psychogenic vomiting and irritable bowel syndrome).

Antidepressant drugs and CBT may be helpful.

Somatoform pain disorder

This describes severe, persistent pain that cannot be

adequately explained by a medical condition. Antidepressant drugs (especially tricyclics and dual action

drugs such as duloxetine and mirtazapine) are helpful,

as are some of the anticonvulsant drugs, particularly

carbamazepine, gabapentin and pregabalin.

CBT and multidisciplinary pain management teams are also useful.

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is also referred to asneurasthenia. It is characterised by excessive fatigue

after minimal physical or mental exertion, poor concentration, dizziness, muscular aches and sleep disturbance.

This pattern of symptoms may follow a viral infection

such as infectious mononucleosis, influenza or hepatitis.

Symptoms overlap with those of depression and anxiety.

There is good evidence that many patients improve with

carefully graded exercise and with CBT, as long as the

benefits of such treatment are carefully explained.

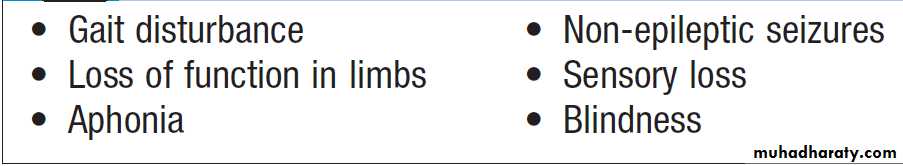

Dissociative (conversion) disorder

Dissociative disorder refers to a loss or distortion ofneurological functioning that is not fully explained by

organic disease. Psychological functions commonly

affected include conscious awareness and memory.

Physical functions affected (conversion) include changes

in sensory or motor function that may mimic lesions in

the motor or sensory nervous system (Box). The

aetiology of dissociation is unknown. There is an association

with adverse childhood experiences, including

physical and sexual abuse.

Organic disease may both facilitate dissociative mechanisms and provide a model for symptoms; thus, for example, non-epileptic seizures often occur in those with epilepsy. CBT may be of benefit.

Coexisting depression should be treated with CBT or antidepressant drugs.

Common presentations of dissociative

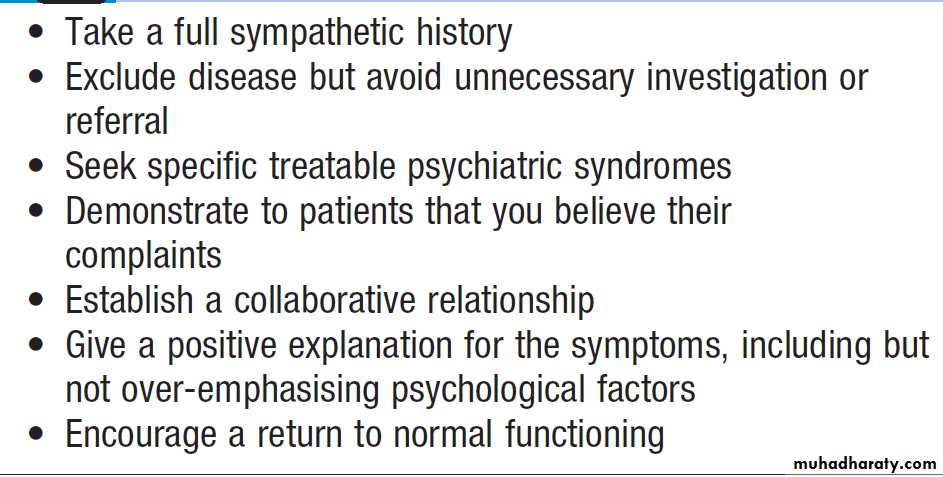

(conversion) disorderGeneral management for medically unexplained symptoms

The management of the various syndromes of medicallyunexplained complaints described above is based on

general principles (Box).

Reassurance

Patients should be asked what they are most worried

about. Clearly, it may be unwise to state categorically

that the patient does not have any disease, as that is difficult to establish with certainty.

However, it can be emphasised that the probability of having a disease is low. If patients repeatedly ask for reassurance about the same health concern despite reassurance, they may have hypochondriasis.

General management principles for medically unexplained symptoms

Explanation

Patients need a positive explanation for their symptoms.It is unhelpful to say that symptoms are psychological

or ‘all in the mind’. Rather, a term such as ‘functional’

(meaning that the symptoms represent a reversible disturbance of bodily function) may be more acceptable.

When possible, it is useful to describe a plausible physiological mechanism that is linked to psychological

factors such as stress and implies that the symptoms are

reversible. For example, in irritable bowel syndrome,

psychological stress results in increased activation of the

autonomic nervous system, which leads to constriction

of smooth muscle in the gut wall, which in turn causes

pain and bowel disturbance.

Advice

This should focus on how to overcome factors perpetuatingthe symptoms: for example, by resolving stressful

social problems or by practising relaxation. The doctor

can offer to review progress, to prescribe (for example)

an antidepressant drug and, if appropriate, to refer for

physiotherapy or psychological treatments such as CBT.

The attitudes of relatives may need to be addressed if

they have adopted an over-protective role, unwittingly

reinforcing the patient’s disability.

Drug treatment

Antidepressant drugs are often helpful, even if the

patient is not depressed (Box).

Antidepressants for medically unexplained

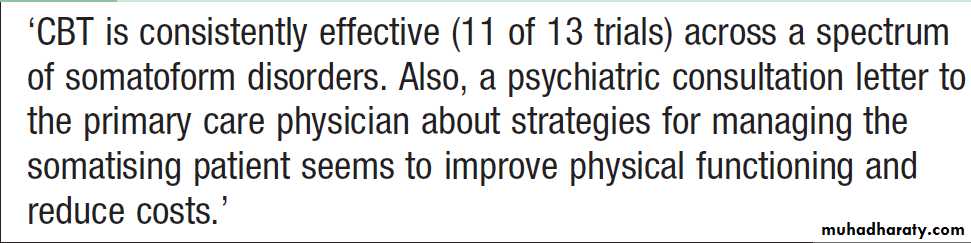

somatic symptomsPsychological treatment

There is evidence for the effectiveness of CBT (Box ).Other psychological treatments such as IPT may

also have a role.

Rehabilitation

Where there is chronic disability, particularly in dissociative

(conversion) disorder, conventional physical

rehabilitation may be the best approach.

Shared care with the GP

Ongoing planned care is required for patients with

chronic intractable symptoms, especially those of somatization disorder.

Review by the same specialist, interspersed with visits to the same GP, is probably the best way to avoid unnecessary multiple re-referral for investigation, to ensure that treatable aspects of the patient’s problems, such as depression, are actively managed, and to prevent the GP from becoming demoralised.

CBT for medically unexplained somatic symptoms

Factitious disorder and malingeringIt is important to distinguish somatoform disorders

from factitious disorder and malingering.

Factitious disorder

This describes the repeated and deliberate production

of the signs or symptoms of disease to obtain medical

care. It is uncommon. An example is the dipping of

thermometers into hot drinks to fake a fever.

The disorder feigned is usually medical but can be a psychiatric illness, with false reports of hallucinations or symptoms of depression.

Münchausen’s syndrome

This refers to a severe chronic form of factitious disorder.Patients are usually older and male, with a solitary, peripatetic lifestyle in which they travel widely, sometimes visiting several hospitals in one day.

Although the condition is rare, such patients are memorable

because they present so dramatically. The history

can be convincing enough to persuade doctors to undertake investigations or initiate treatment, including

exploratory surgery. It may be possible to trace the patient’s history and show that he has presented similarly

elsewhere, often changing name several times.

Some emergency departments hold lists of such patients.

Management is by gentle but firm confrontation with

clear evidence of the fabrication of illness, together with

an offer of psychological support. Treatment is usually

declined but recognition of the condition may help to

avoid further iatrogenic harm.

Malingering

Malingering is a description of behaviour, not a psychiatric diagnosis.It refers to the deliberate and conscious

simulation of signs of disease and disability. Patients

have motives that are clear to them but which they

conceal from doctors. Examples include the avoidance

of burdensome responsibilities (such as work or court

appearances) or the pursuit of financial gain (fraudulent

claims for benefits or compensation). Malingering can be

hard to detect at clinical assessment, but is suggested by

evasion or inconsistency in the history.

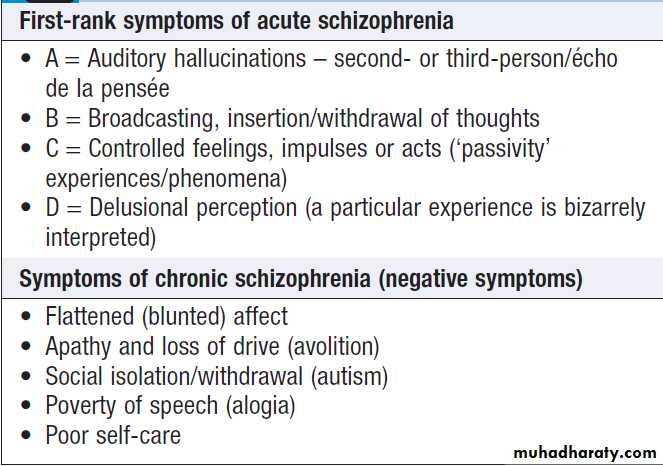

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a psychosis characterised by delusions,hallucinations and lack of insight. Acute schizophrenia

may present with disturbed behaviour, marked delusions,

hallucinations and disordered thinking, or with

insidious social withdrawal and other so-called negative

symptoms and less obvious delusions and hallucinations.

The prevalence is similar worldwide at about 1% and the disorder is more common in men. The children of one affected parent have approximately a 10% risk of developing the illness, but this rises to 50% if an identical twin is affected. The usual age of onset is the mid-twenties.

Aetiology

There is a strong genetic contribution, probably involving

many susceptibility genes, each of small effect. The

best candidates, such as disrupted in schizophrenia-1

(DISC1) and neuregulin-1 (NRG1), have supportive

linkage, association, animal model and basic neurobiological evidence. Environmental risk factors include obstetric complications and urban birth. Brain imaging techniques have identified subtle structural abnormalities, including an enlargement of the lateral ventricles and an overall decrease in brain size (by about 3% on average), with relatively greater reduction in temporal lobe volume (5–10%).

Episodes of acute schizophrenia may be precipitated by social stress and also by cannabis, which increase dopamine turnover and sensitivity.

Consequently, schizophrenia is now viewed as a neurodevelopmental disorder, caused by abnormalities of

brain development associated with genetic predisposition

and early environmental influences, but precipitated

by later triggers.

Diagnosis

Schizophrenia usually presents with an acute episodeand progresses to a chronic state. Acute schizophrenia

should be suspected in any individual with bizarre

behaviour accompanied by delusions and hallucinations

that are not due to organic brain disease or substance

misuse. The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds, with investigations used principally to rule out organic brain

disease. The characteristic clinical features are listed

in Box. Hallucinations are typically auditory, although they can occur in any sensory modality. They commonly involve voices from outside the head that talk to or about the person.

Sometimes the voices repeat the person’s thoughts.

Patients may also describe ‘passivity of thought’, experienced as disturbances in the normal privacy of thinking – for example, the delusional belief that their thoughts are being ‘withdrawn’ from them, perhaps ‘broadcast’ to others, and/or alien thoughts being ‘inserted’ into their mind. Other characteristic symptoms are delusions of control: believing that one’s emotions, impulses or acts are controlled by others. Another phenomenon is delusional perception, a delusion that arises suddenly alongside a normal perception (e.g. ‘I saw the moon and I immediately knew he was evil’).

Many other, less specific symptoms may occur, including thought disorder, as manifest by incomprehensible speech and abnormalities of movement, such as those in which the patient can become immobile or adopt awkward postures for prolonged periods (catatonia).

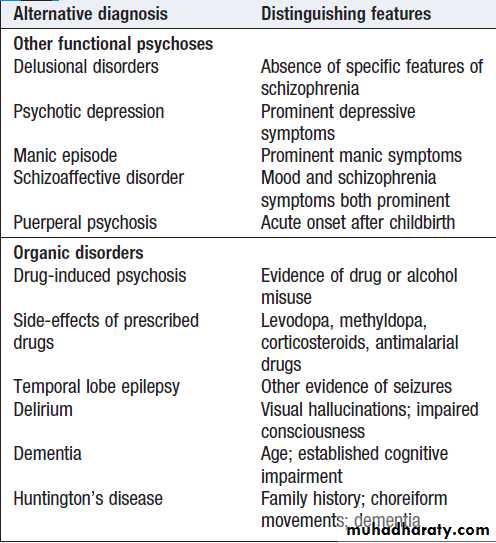

The main differential diagnosis of schizophrenia

(Box) is:

• Other functional psychoses, particularly psychotic depression and mania, in which delusions and hallucinations are congruent with a marked mood disturbance (negative in depression and grandiose in mania). If features of schizophrenia and affective disorder coexist in equal measure, a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder is made .

Schizophrenia must also be differentiated from specific delusional disorders that are not associated with the other

typical features of schizophrenia.

• Organic psychoses, including delirium, in which

there is impairment of consciousness and loss of

orientation (not found in schizophrenia), typically

with visual hallucinations, and drug misuse, the

latter particularly in young people. Schizophrenia

must also be differentiated from other organic

psychoses such as temporal lobe epilepsy, in which

olfactory and gustatory hallucinations may occur.

Many of those who experience acute schizophrenia

go on to develop a chronic state in which the acute, so-called positive symptoms resolve, or at least donot dominate the clinical picture, leaving so-called

negative symptoms that include blunt affect, apathy,

social isolation, poverty of speech and poor self-care.

Patients with chronic schizophrenia may also manifest

positive symptoms, particularly when under stress, and

it can be difficult for those who do not know the patient

to judge whether or not these are signs of an acute relapse.

Symptoms of schizophrenia

Differential diagnosis of schizophrenia

ManagementFirst-episode schizophrenia usually requires admission

to hospital because patients lack the insight that they are

ill and are unwilling to accept treatment. In some cases,

they may be at risk of harming themselves or others.

Subsequent acute relapses and chronic schizophrenia

are now usually managed in the community.

Drug treatment

Antipsychotic agents are effective against the positive

symptoms of schizophrenia in the majority of cases.

They take 2–4 weeks to be maximally effective but have

some beneficial effects shortly after administration.

Treatment is then ideally continued to prevent relapse.

In a patient with a first episode of schizophrenia, this

will usually be for 1–2 years, but in patients with multiple

episodes, treatment may be required for many years.

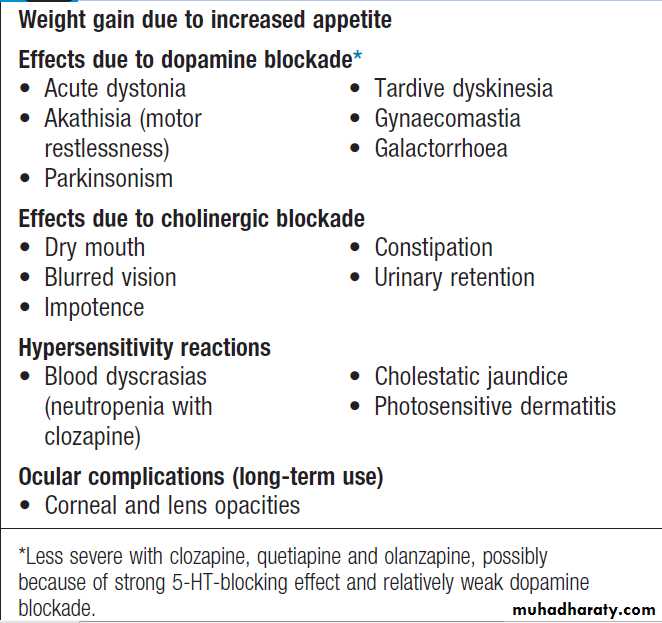

The benefits of prolonged treatment must be weighed

against the adverse effects, which include extrapyramidal

side-effects (EPSE) like acute dystonic reactions (which may require treatment with parenteral anticholinergics), akathisia, Parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia (abnormal movements, commonly of the face, over which the patient has no voluntary control). For long-term use, antipsychotic agents are often given in slow-release (depot) injected form to improve patient adherence.

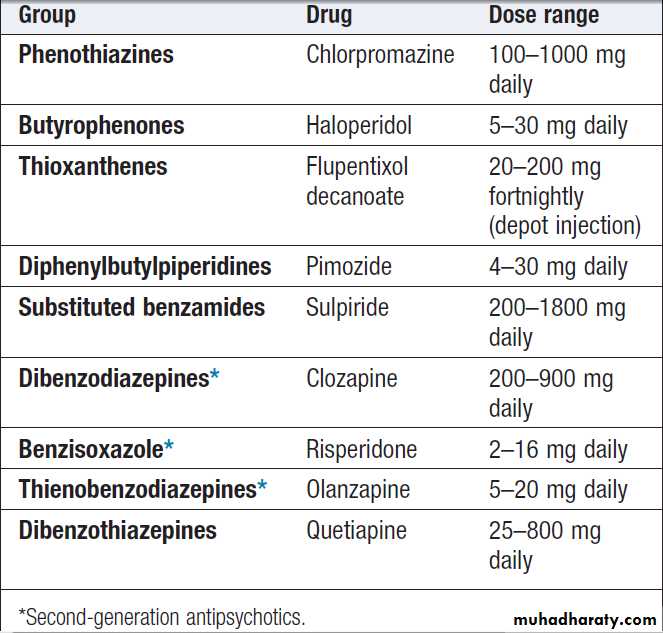

A number of antipsychotic agents are available (Box ).

These may be divided into conventional (typical,first-generation) drugs such as chlorpromazine and

haloperidol, and newer or atypical (also so-called novel

or second-generation) drugs such as clozapine. All are

believed to work by blocking D2 dopamine receptors in

the brain. Patients who have not responded to conventional

drugs may respond to newer agents, which are

also less likely to produce unwanted EPSE but do tend

to cause greater weight gain and metabolic disturbances

such as dyslipidaemia. Clozapine can also cause an

agranulocytosis and consequently requires regular monitoring of the white blood cell count, initially on a weekly basis. Details of the side-effects of antipsychotic drugs are listed in Box.

Serious adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs include:

• Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, which is a rare butserious condition. It is characterised by fever, tremor and rigidity, autonomic instability and confusion. Characteristic laboratory findings are an elevated creatinine phosphokinase and leucocytosis. Antipsychotic medication must be stopped immediately and supportive therapy provided, often in an intensive care unit. Treatment includes

ensuring hydration and reducing hyperthermia. Dantrolene sodium and bromocriptine may be helpful. Mortality is 20% untreated and 5% with treatment.

• Prolongation of the QTc interval, which may be

associated with VT, torsades de pointes and sudden death. Treatment is by stopping the drug, monitoring the ECG

and treating serious arrhythmias

Antipsychotic drugs

Side-effects of antipsychotic drugs

Psychological treatmentIncluding general support for the patient and his or her family, is now seen as an essential component of management. CBT may help patients to cope with symptoms. There is evidence that personal and/or family education, when given as part of an integrated treatment package, reduces the rate of relapse.

Social treatment

After an acute episode of schizophrenia has been controlled by drug therapy, social rehabilitation may be

required. Recurrent illness is likely to cause disruption

to patients’ relationships and their ability to manage

their accommodation and occupation; consequently,

they may need help to obtain housing and employment.

A graded return to employment and sometimes a period

of supported accommodation are required. Patients with chronic schizophrenia have particular difficulties and may need long-term, supervised accommodation.This now tends to be in sheltered or hostel accommodation in the community. Patients may also benefit from sheltered employment if they are unable to participate effectively in the labour market. Ongoing contact with a health worker allows monitoring for signs of relapse, sometimes as part of a multidisciplinary team working to agreed plans (the ‘care programme approach’). Partly because of a tendency to inactivity, smoking and a poor diet, patients with chronic schizophrenia are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and stroke, and require proactive medical as well as psychiatric care.

Prognosis

About one-quarter of those who develop an acute

Schizophrenic episode have a good outcome. One-third

develop chronic, incapacitating schizophrenia, and the

remainder largely recover after each episode but suffer

relapses. Most will not work or live independently. Prophylactic treatment with antipsychotic drugs reduces

the rate of relapse in the first 2 years after an episode of

schizophrenia from 50% to 10%.

Schizophrenia is associated with suicide, with up to 1 in 10 patients taking their own lives.

Delirium, dementia and other organic disorders

Delirium, dementia and other organic disorders couldbe considered to be medical conditions rather than psychiatric disorders, as they are a result of reduced brain

function; they are, however, included in psychiatric classifications and are sometimes misdiagnosed because

they often manifest with disturbed behaviour.

Delirium

Delirium is common in acute medical settings, especially

in the elderly and patients in high-dependency and

intensive care units.

Dementia

Dementia is a clinical syndrome characterised by a lossof previously acquired intellectual function in the

absence of impairment of arousal, and affects 5% of

those over 65 and 20% of those over 85. It is defined as

a global impairment of cognitive function, and is typically

progressive and non-reversible. Although memory

is most affected in the early stages, deficits in visuospatial

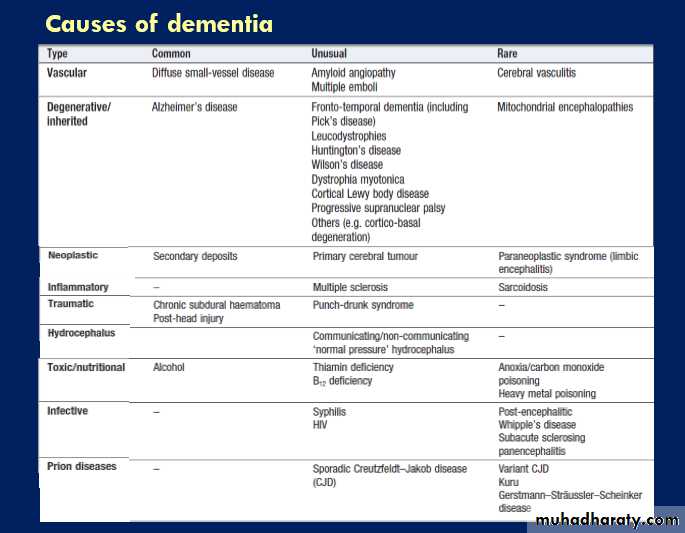

function, language ability, concentration and attention gradually become apparent. There are many causes (Box) but Alzheimer’s disease and diffuse vascular disease are the most common.

Rarer causes of dementia should be actively sought in younger patients and those with short histories.

Aetiology

Dementia may be divided into ‘cortical’ and ‘subcortical’types, depending on the clinical features. Many of the

primary degenerative diseases that cause dementia have

characteristic features that may allow a specific diagnosis

during life. Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, for example,

is usually relatively rapidly progressive (over months),

is associated with myoclonus, and demonstrates characteristic abnormalities on EEG.

The more slowly progressive dementias are more difficult to distinguish during life, but fronto-temporal dementia typically presents with focal (temporal or frontal lobe) dysfunction, and Lewy body dementia may present with visual hallucinations. The course may also help to distinguish types of dementia, as it may be gradual (as in Alzheimer’s disease) or step-wise (as in vascular dementia).

Clinical features

The usual presentation is with a disturbance of personalityor memory dysfunction. A careful history is essential and it is important to interview both the patient and a close family member. Simple bedside tests such as the MMSE are useful in assessing the nature and severity of the cognitive deficit, although a more intensive neuropsychological assessment may sometimes be required, especially if there is diagnostic uncertainty.

It is important to exclude a focal brain lesion. This is done by determining that there is cognitive disturbance in more than one area. Mental state assessment is important to seek evidence of depression, which may coexist with or occasionally cause apparent cognitive impairment.

Investigations

The aim is to seek treatable causes and to estimate prognosis.This is done using a standard set of investigations.

Imaging of the brain can exclude potentially

treatable structural lesions, such as hydrocephalus, cerebral

tumour or chronic subdural haematoma, though

the only abnormality usually seen is that of generalised

atrophy. If the initial tests are negative, more invasive

investigations, such as lumbar puncture or, rarely, brain

biopsy, may be indicated.

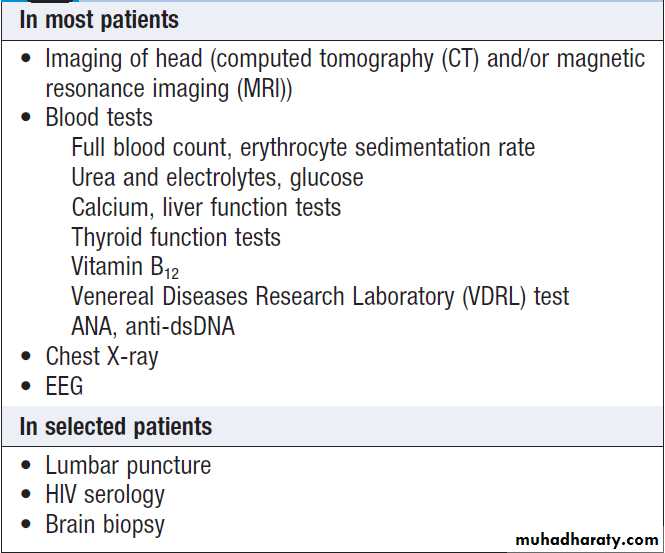

Initial investigation of dementia

ManagementThis is directed at addressing treatable causes, and providing support for patient and carers if no specific

treatment exists. If the diagnosis is Alzheimer-type

dementia, anticholinesterase inhibitors and memantine

may arrest progression for a time. Treating vascular

risk factors may slow deterioration in vascular dementia.

Psychotropic drugs may help where there is associated

disturbance of sleep, perception or mood, but

should be used with care because of an increased mortality in patients who have been treated long-term with

these agents. Sedation is not a substitute for good care

for patients and carers or, in the later stages, attentive

residential nursing care.

In the UK, incapacity and mental health legislation may be required to manage patients’ financial and domestic affairs, as well as to determine their safe placement.

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of

dementia, but is rare under the age of 45 years.

Aetiology

Genetic factors play an important role and about 15% of

cases are familial. Familial cases fall into two main

groups: early-onset disease with autosomal dominant

inheritance and a later-onset group whose inheritance

is polygenic.

Mutations in several genes have been described.

The inheritance of one of the alleles of apolipoprotein

ε (apo ε4) is associated with an increased risk of developing the disease (2–4 times higher in heterozygotes and 6–8 times in homozygotes). Its presence is,

however, neither necessary nor sufficient for the development of the disease, so screening for its presence

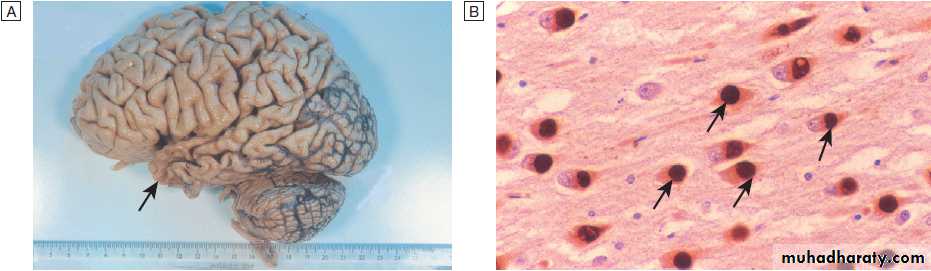

is not clinically useful. The brain in Alzheimer’s disease

is macroscopically atrophic, particularly the cerebral

cortex and hippocampus. Histologically, the disease is

characterised by the presence of senile plaques and

neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral cortex.

Histochemical staining demonstrates significant quantities of

amyloid in the plaques (Fig.), which typically stainpositive for the protein ubiquitin, involved in targeting

unwanted or damaged proteins for degradation. This

has led to the suggestion that the disease may be due

to defects in the ability of neuronal cells to degrade

unwanted proteins. Many different neurotransmitter

abnormalities have also been described. In particular,

there is impairment of cholinergic transmission, although abnormalities of noradrenaline, 5-HT, glutamate and

substance P have also been described.

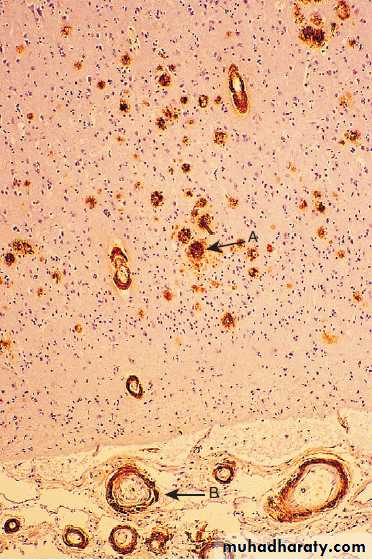

Alzheimer’s disease. Section of neocortex stained with polyclonal antibody against βA4 peptide showing amyloid deposits in

plaques in brain substance (arrow A) and in blood vessel walls (arrow B).

Clinical features

The key clinical feature is impairment of the ability toremember new information. Hence, patients present

with gradual impairment of memory, usually in association with disorders of other cortical functions.

Short and long-term memory are both affected, but

defects in the former are usually more obvious. Later in

the course of the disease, typical features include apraxia,

visuo-spatial impairment and aphasia. In the early

stages of the disease, patients may notice these problems,

but as the disease progresses it is common for patients to deny that there is anything wrong (anosognosia).

In this situation, patients are often brought to

medical attention by their carers.

Depression is commonly present. Occasionally, patients become aggressive, and the clinical features can be made acutely worse by intercurrent physical disease. Investigations and management

Investigation is aimed at excluding treatable causes

of dementia (see Box), as histological confirmation

of the diagnosis usually occurs only after death. There

is no known treatment, though anticholinesterases such

as donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine, and the

NMDA receptor antagonist, memantine, have been

shown to be of some benefit. Management consists

largely of providing a familiar environment for the

patient and support for the carers. Many patients

are depressed, and treatment with antidepressant

medication may be helpful.

Fronto-temporal dementia

This term encompasses a number of different syndromes,

including Pick’s diseases and primary progressive

aphasia. Patients may present with personality

change due to frontal lobe involvement or with language

disturbance due to temporal lobe involvement. These

diseases are much rarer than Alzheimer’s disease. Histological examination of the brain reveals argyrophilic