Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABMLecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

2016

learning-topics

Palliative care and painPRINCIPLES OF PALLIATIVE CARE

Palliative care is the active total care of patients withfar advanced, rapidly progressive and ultimately fatal

disease. Its focus is quality of life rather than cure, and

it encompasses a distinct body of knowledge and skills

that all good physicians must possess to allow them to

care effectively for patients at the end of life. In palliative

care, there is a fundamental change of emphasis in

decision-making away from a focus on prolonging life

towards decisions that balance comfort and the individual’s

wishes with treatments that might prolong life.

There is a growing recognition that the principles of, and

some specific interventions developed in the palliative

care of patients with cancer are equally applicable to

other conditions. The principles of palliative care may

therefore be applied not only to cancer but also to any

chronic disease state.

Palliative care is often seen as a means of managing

distress and symptoms in patients with cancer, where

metastatic disease has been diagnosed and death is seen

as inevitable. In other illnesses, the challenge is recognising

when patients have entered this phase of their illness, as there are fewer clear markers and the course of the illness is much more variable.

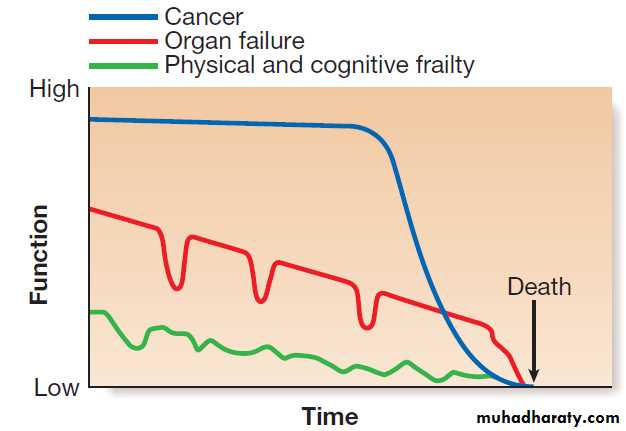

Traditionally, palliative care has been associated with

cancer because the latter is typified by a progressivedecline in function which was more predictable than

in many other diseases. This ‘rapid decline’ trajectory

is the best-recognised pattern need for palliative care and many traditional hospice services are designed to meet the needs of people on this trajectory: for example, motor neuron disease, or AIDS where ART is not available. Many chronic diseases, such as advanced COPD and intractable congestive heart failure, carry as high a burden of symptoms as cancer, as well as psychological and family distress. The ‘palliative phase’ of these illnesses may be more difficult to identify because of periods of relative stability interspersed with acute episodes of severe illness.

The challenge is that symptom management needs to be delivered at the same time as treatment for acute exacerbations. This leads to difficult decisions as to the balance between symptom relief and aggressive

management of the disease. The starting point of need for care is the point at which consideration of comfort and individual values becomes important in decision-making, often alongside management of the underlying disease. The main challenge lies in providing nursing care and ensuring that plans are agreed for the time when medical intervention is no longer beneficial. In a situation where death is inevitable and foreseeable, palliative care balances the ‘standard textbook’ approach with the wishes and values of the patient and a realistic assessment of the benefits of medical interventions.

This often results in a greater focus on comfort, symptom control and support for patient and family, and may enable withdrawal of interventions that are ineffective or burdensome.

Commonly, the outcome is less certain. In many cases, there is a substantial risk that the patient will die but there may be a small chance of improvement with further treatment. In these circumstances, it is often (but not always) correct and helpful to share this information with the patient so that better decisions can be made about further care.

The principles of palliative care are being used

increasingly in many different diseases so that death can

be managed effectively and compassionately.

Archetypal trajectories of dying.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN PALLIATIVE CAREPain

The International Association for the Study of Pain

(IASP) has defined pain as ‘an unpleasant sensory and

emotional experience associated with actual or potential

tissue damage or described in terms of such damage’. It

follows that each patient’s experience and expression of

pain are different, and that severity of pain does not

correlate with the degree of tissue damage. Effective

pain treatment facilitates recovery from injury or surgery, aids rapid recovery of function, and may minimize chronic pain and disability. Unfortunately, the delivery of effective pain relief is often impeded by factors such as poor assessment and concerns about the use of opioid analgesia.

Pain classification and mechanisms

Pain can be classified into two types:

• Nociceptive: due to direct stimulation of peripheral

nerve endings by a noxious stimulus such as

trauma, burns or ischaemia.

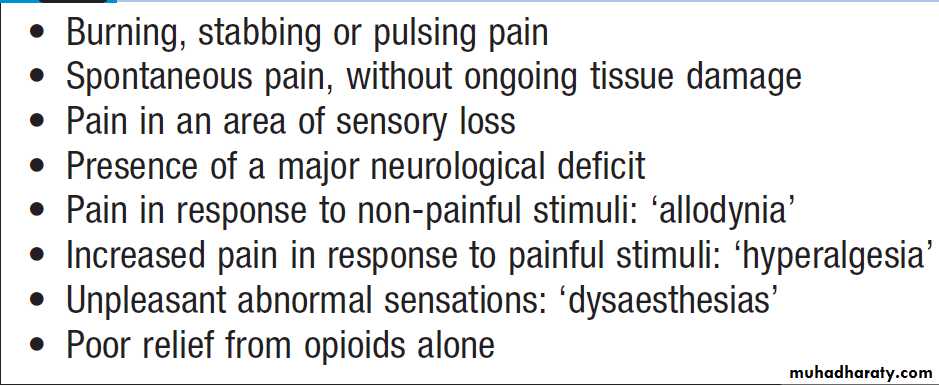

• Neuropathic: due to dysfunction of the pain

perception system within the peripheral or central

nervous system as a result of injury, disease or

surgical damage, such as continuing pain

experienced from a limb which has been amputated

(phantom limb pain). This should be identified early because it is more difficult to treat once established.

The pain perception system is not a simple hard-wired circuit of nerves connecting tissue pain receptors to the brain, but a dynamic system in which a continuing pain stimulus can cause central changes that lead to an increase in pain perception.

This plasticity (changeability) applies to all the peripheral and central components of the pain pathway.

Early and appropriate treatment of pain reduces the potential for chronic undesirable changes to develop.

Features of neuropathic pain

Assessment and measurement of pain

Accurate assessment of the patient is the first step in

providing good analgesia.

History and measurement of pain

A full pain history should be taken, to establish its

causes and the underlying diagnoses. Patients may have

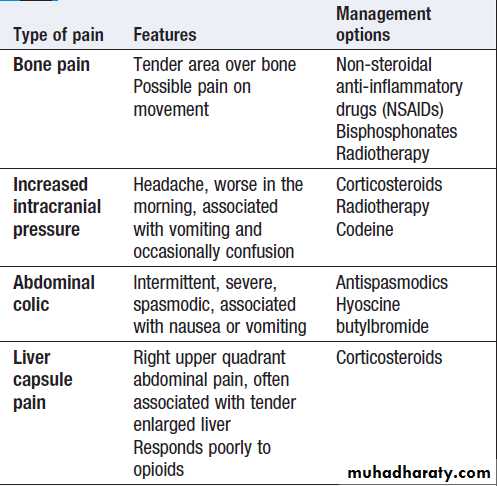

more than one pain; for example, bone and neuropathic

pain may both arise from skeletal metastases .

A diagram of the body on which the patient can mark

the pain site can be helpful.

When asked to score pain, patients consistently rate it higher than health professionals and should, if able, always be asked to rate pain themselves.

Methods include:

• Verbal rating scale. Different verbal descriptions are

used to rate pain – ’no pain’, ‘mild pain’, ‘moderate

pain’ and ‘severe pain’.

• Visual analogue scale. A question is used, such as

‘Over the past 24 hours, how would you rate your

pain, if 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain you

could imagine?’

• Behavioural rating scale. It can be particularly difficult

to decide whether a patient with cognitive

impairment is suffering pain.

A variety of measures are available which use observed behaviours, such as agitation and withdrawn posture, to assess levels of pain. Commonly used scales include Abbey and Dolorplus. Changes in behavioural rating pain

scores can indicate whether drug measures have

been successful.

Regular recording of formal pain assessment and

patient-rated pain scores improves pain management

and reduces the time taken to achieve pain control.

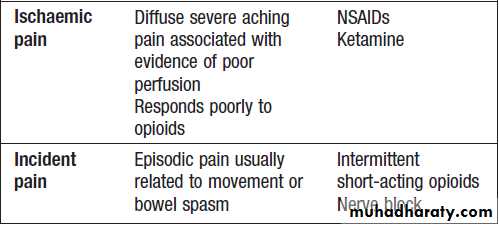

Types of pain

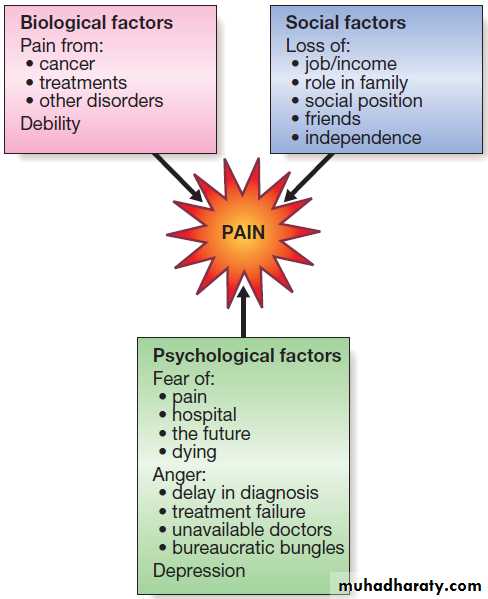

Psychological aspects of chronic painPerception of pain is influenced by many factors other

than the painful stimulus, and pain cannot therefore be

easily classified as wholly physical or psychogenic in

any individual . Patients who suffer chronic pain will be affected emotionally and, conversely, emotional distress can exacerbate physical pain .

Full assessment for symptoms of anxiety and depression is

essential to effective pain management.

Examination

This should include careful assessment of the painful

area, looking for signs of neuropathic pain or bony tenderness suggestive of bone metastases. In patients with cancer, it should not be assumed that all pains are due to the cancer or its metastases.

Components of pain.

Appropriate investigationsInvestigations should be directed towards diagnosis of

an underlying cause, remembering that treatable conditions

are possible even in patients with advanced

disease. Imaging may be indicated, such as plain X-ray

for fracture or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for

spinal cord compression.

Management of pain

Many of the principles of pain management apply to anypainful condition. There are, however, distinct differences

between management of acute, chronic and palliative

pain. Acute pain post-surgery or following trauma should be controlled with medication without causing unnecessary side-effects or risk to the patient. Chronic, non-malignant pain is more difficult and it may be impossible to relieve completely. In the management of chronic pain there is a greater emphasis on non-pharmacological treatments and on enabling the patient to live with pain. Strong opioids may help chronic pain but need to be used with caution after full assessment. They are used more readily in patients with a poorer prognosis.

Two-thirds of patients with cancer experience moderate

or severe pain, and a quarter will have three or moredifferent pains. Many of these are of mixed aetiology

and 50% of pain from cancer has a neuropathic element.

Careful evaluation to identify the likely pain mechanism

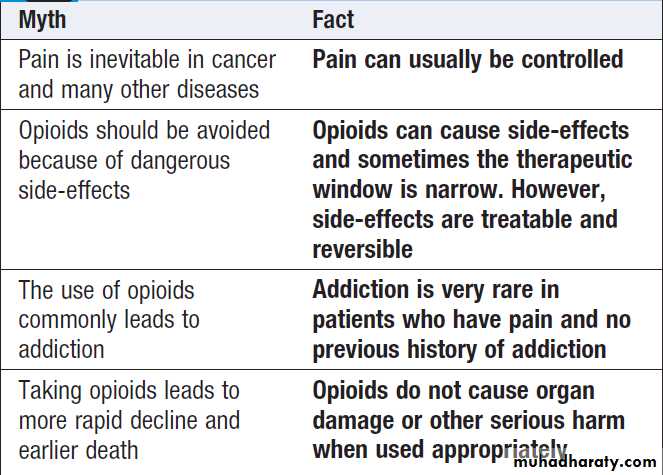

facilitates appropriate treatment . It is vital that the patient’s concerns about opioids are explored.

Patients should be reassured that, when they are used

for pain, psychological dependence and tolerance are

extremely rare.

Nearly all types of pain respond to morphine to

some degree. Some are completely opioid-responsive

but others, such as neuropathic and ischaemic pain, are

relatively unresponsive. Opioid-unresponsive or poorly

responsive pain will only be relieved by opioids at a

dose which causes significant side-effects. In these situations, effective pain relief may only be achieved with the use of adjuvant analgesics (see below).

Opioid myths

Pharmacological treatmentsNon-opioids

• Paracetamol. This is often effective for mild to

moderate pain. For severe pain, it is inadequate

alone, but is a useful and well-tolerated adjunct.

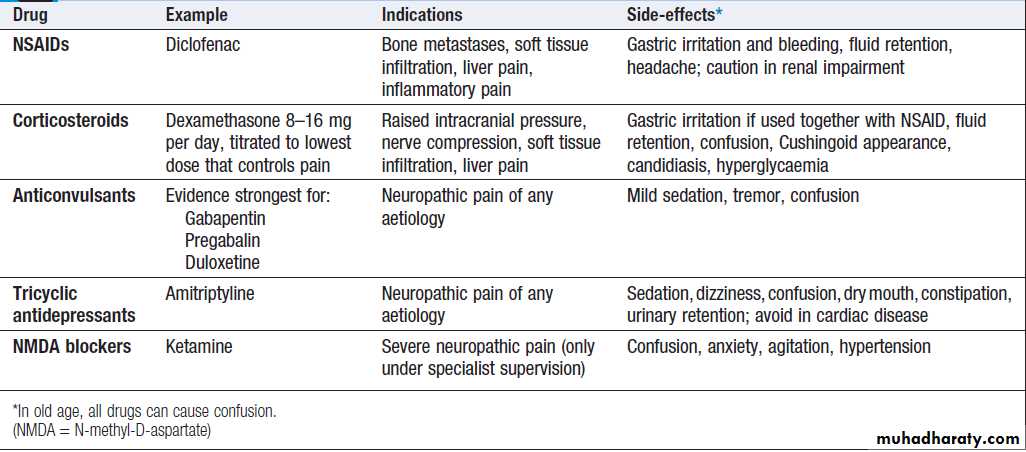

• NSAIDs. These are effective in the treatment of mild

to moderate pain, and are also useful adjuncts in

the treatment of severe pain. Adverse effects may

be serious, especially in the elderly .

Weak opioids

Codeine and dihydrocodeine are weak opioids. They

have lower analgesic efficacy than strong opioids and a ceiling dose. They are effective for mild to moderate pain.

Strong opioids

Immediate-release (IR) oral morphine takes about

20 minutes to have an effect and usually provides pain

relief for 4 hours. Most patients with continuous pain

should be prescribed IR oral morphine every 4 hours

initially, as this will provide continuous pain relief over

the whole 24-hour period.

Controlled-release (CR) morphine lasts for 12 or 24 hours but takes longer to provide analgesia.

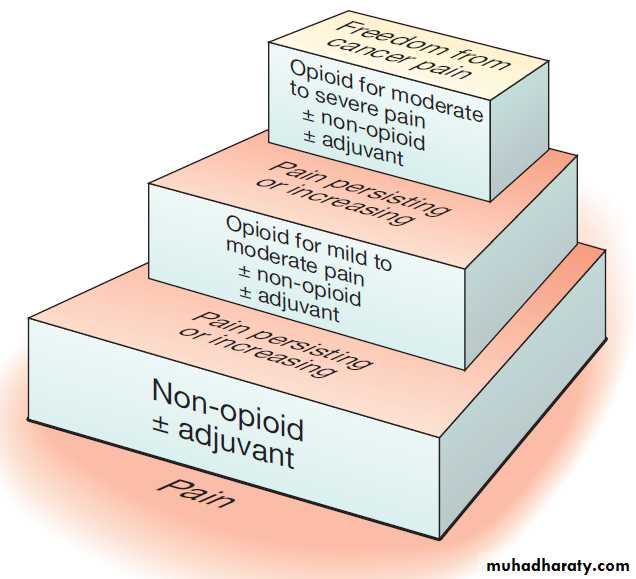

The WHO analgesic ladder

The basic principle of the WHO ladder is that analgesia which is appropriate for the degree of pain should be prescribed. If pain is severe or remains poorlycontrolled, strong opioids should be prescribed and

increased as indicated by the patient’s need for additional

analgesia (opioid titration).

A patient with mild pain is started on a non-opioid

analgesic drug, such as paracetamol 1 g 4 times daily

(step 1).

If the maximum recommended dose is not sufficient or the patient has moderate pain, a weak opioid, such as codeine 60 mg 4 times daily, should be added (step 2).

If adequate pain relief is still not achieved with the maximum recommended dosages or if the patient has severe pain, a strong opioid is substituted for the weak opioid (step 3). It is important not to move ‘sideways’ (change from one drug to another of equal potency) on a particular step of the ladder.

All patients with severe pain should receive a full trial of

strong opioids with appropriate adjuvant analgesia, as

described below.

In addition to the regular dose, an extra dose of IR

morphine should be prescribed ‘as required’ for when

the patient has pain that is not controlled by the regular

prescription (breakthrough pain).

This should be one-sixth of the total 24-hour dose of opiate. The frequency of breakthrough doses should be dictated by their efficacy and any side-effects, rather than by a fixed time interval. A patient may require breakthrough analgesia as frequently as hourly if pain is severe, but this should lead to early review of the regular prescription. The patient and/or carer should note the timing of any breakthrough doses and the reason for them. These should be reviewed daily and the regular 4-hourly dose increased for the next 24 hours on the basis of:

• frequency of and reasons for breakthrough

analgesia

• degree and acceptability of side-effects.

The regular dose should be increased by adding the

total of the breakthrough doses over the previous24 hours, unless there are significant problems with

unacceptable side-effects. When the correct dose has

been established, a CR preparation can be prescribed,

usually twice daily.

Worldwide, the most effective and appropriate route

of administration is oral, though transdermal preparations

of strong opioids (usually fentanyl) are useful in

certain situations, such as in patients with dysphagia or

those who are reluctant to take tablets on a regular basis.

Diamorphine is a highly soluble strong opioid used for

subcutaneous infusions, particularly in the last few days

of life, but is only available in certain countries.

The WHO analgesic ladder.

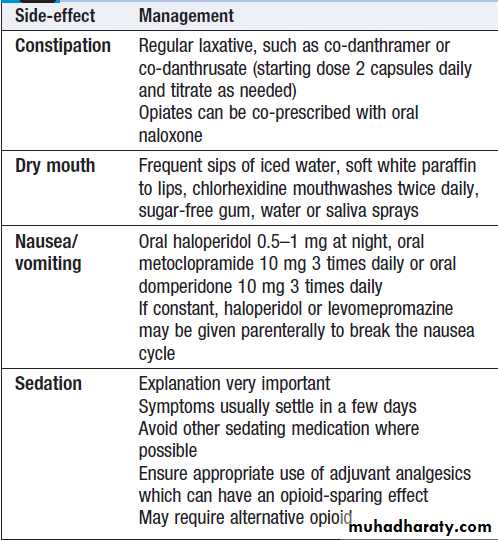

Common side-effects of opioids are shown in Box .Nausea and vomiting occur initially but usually settle after a few days. Confusion and drowsiness are dose-related and reversible. In acute dosing, respiratory depression can occur but this is rare in those on regular opioids.

Opioid toxicity

All patients will develop dose-related side-effects, such

as nausea, drowsiness, confusion or myoclonus; this is

termed opiate toxicity. The dose at which this occurs

varies from 10 to 5000 mg of morphine, depending on

the patient and the type of pain. When opiates are being

titrated, side-effects should be assessed regularly. The

earliest side-effects are often visual hallucinations (often

a sense of movement at the periphery of vision) and a

distinct myoclonic movement.

Pain should be re-assessed to ensure that appropriate adjuvants are being used.

Parenteral rehydration is often helpful to speed upexcretion of active metabolites of morphine. The dose of

opioid may need to be reduced or changed to an alternative strong opiate.

Different opioids have different side-effect profiles

in different people. If a patient develops side-effects,

switching to an alternative strong opioid may be helpful.

Options include oxycodone, transdermal fentanyl,

alfentanil, hydromorphone and occasionally methadone,

any of which may produce a better balance of

benefit against side-effects.

Fentanyl and alfentanil have no renally excreted active metabolites and may be particularly useful in patients with renal failure.

Pethidine is used in acute pain management but not

for chronic or cancer pain because of its short half-life

and ceiling dose.

It is important to be very careful when switching

opiates, as it is easy to make calculation mistakes and

prescribe too much or too little.

Opioid side-effects

Adjuvant analgesicsAn adjuvant analgesic is a drug with a primary indication

other than pain but which provides analgesia in

some painful conditions and may enhance the effect of

the primary analgesic. At each step of the WHO analgesic

ladder, an adjuvant analgesic should be considered,

the choice depending on the type of pain

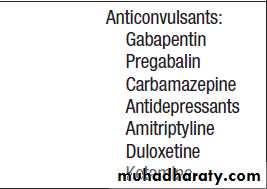

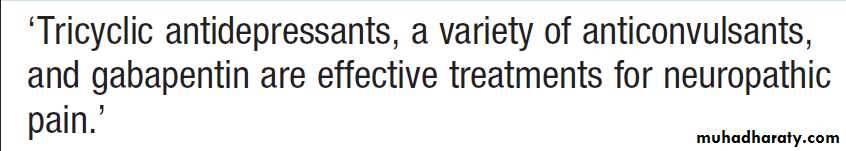

Treatment of neuropathic pain

Adjuvant analgesics

Non-pharmacological and complementary treatmentsRadiotherapy

Radiotherapy can improve pain from bone metastases

and may be considered for cancer in other sites .

Physiotherapy

This helps to alleviate pain and restore function, through

active mobilisation and specific physiotherapy techniques, such as spinal manipulation, massage, application of heat or cold, and exercise. Immediate application of cold with ice packs can reduce subsequent swelling and inflammation after a direct injury.

Psychological techniques

These include simple relaxation, hypnosis, cognitivebehavioural therapies and biofeedback ,

which train the patient to use coping strategies and

behavioural techniques. This is often more relevant in

chronic non-malignant pain than in cancer pain.

Stimulation therapies

Acupuncture has been used successfully in Eastern medicine for centuries. It causes release of endogenous analgesics (endorphins) within the spinal cord. It can be particularly effective in pain related to muscle spasm. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may have a similar mechanism of action to acupuncture and can be used in both acute and chronic pain.

Acupuncture.

Herbal medicine and homeopathyThese are widely used for pain, but often with little

evidence for efficacy . Safety regulations for these

treatments are limited, compared with conventional

drugs, and the doctor should be wary of unrecognised

side-effects which may result.

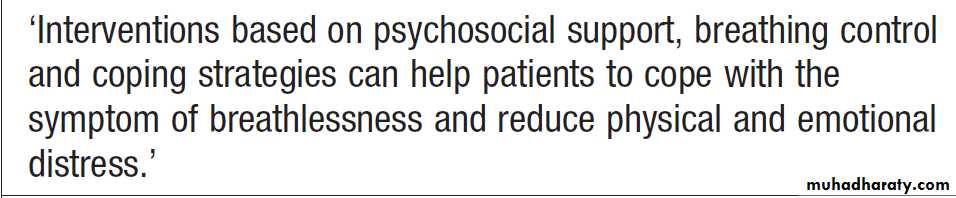

Breathlessness

The sensation of breathlessness is the result of a complex interaction between different factors at the levels of production (the pathophysiological cause), perception(the severity of breathlessness perceived by the patient)

and expression (the symptoms expressed by an individual

patient). A patient’s perception and expression of

breathlessness can be significantly improved, even if

there is no reversible ‘cause’ . Assessment and treatment should therefore be targeted at modifying these factors, particularly when there is no reversible pathophysiology.

Clearly reversible causes of breathlessness should be identified and managed, but investigation and

treatment should be appropriate to the prognosis and

stage of disease. A therapeutic trial of corticosteroids

(dexamethasone 8 mg for 5 days) and/or nebulised salbutamol may be helpful.

Breathlessness may be worsened by specific anxieties

and beliefs; these should be explored. Many people with

heart failure are concerned that exertional breathlessness

will lead to worsening of their heart condition. Patients with advanced disease have specific panic– breathlessness cycles in which breathlessness leads to panic, which leads to worsening breathlessness and worsening panic.

These should be identified and explained to the patient. Many fear that they will die during one of these episodes, and explanation of the panic cycle can be very reassuring. Another frequently expressed fear is that breathlessness will continue to worsen until it is continuous and unbearable, leading to a distressing and undignified death. Reassurance should again be given that this is uncommon and can be effectively managed with opioids and benzodiazepines.

A rapidly acting benzodiazepine, such as sublingual

lorazepam, or non-drug measures, such as relaxation

techniques, may help panic–breathlessness cycles.

Attention to energy conservation (thinking clearly about

using limited energy reserves sensibly) and pacing ofactivity is also extremely helpful. Physiotherapists are

good at this and should be involved in developing an

individual plan for each patient.

Perception of breathlessness may also be improved

by night-time or regular morphine, or by regular

benzodiazepines.

Oxygen does not help breathlessness unless the patient is hypoxic. An electric fan, piped air or an open window can be as effective as oxygen in patients who are breathless but not hypoxic. The patient’s, family’s or even professional beliefs about the benefits and need for oxygen may be the main reason for its apparent efficacy in non-hypoxic patients who feel less breathless when using oxygen.

Palliative treatment of breathlessness

CoughCough can be a troubling symptom in cancer and other

illnesses such as motor neuron disease, cardiac failure

and COPD. There are many possible causes .

Management should focus on treating the underlying

condition if possible. If this fails to bring about the

desired response, antitussives, such as codeine linctus,

are sometimes effective, particularly for cough at night.

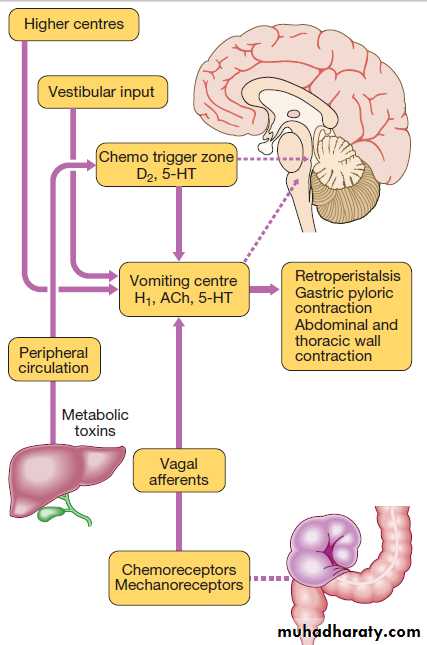

Nausea and vomiting

The presentation of nausea and vomiting differs,

depending on the underlying cause, of which there are

many .Large-volume vomiting with little nausea

is common in intestinal obstruction, whereas constant

nausea with little or no vomiting is often due to metabolic

abnormalities or drugs. Vomiting related to raised

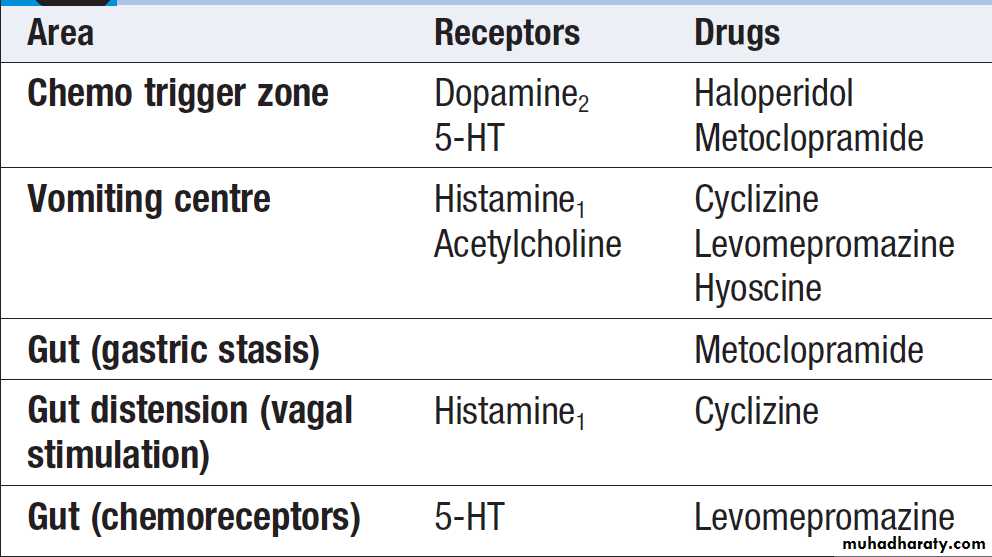

intracranial pressure is worse in the morning. Different receptors are activated, depending on the cause or causes of the nausea . For example, dopamine receptors in the chemotactic trigger zone in the fourth ventricle are stimulated by metabolic and drug causes of nausea, whereas gastric irritation stimulates histamine receptors in the vomiting centre via the vagus nerve.

Reversible causes, such as hypercalcaemia and constipation, should be treated appropriately.

Drug-induced causes should be considered and the offending drugs stopped if possible.

As different classes of antiemetic drug act at different receptors, antiemetic therapy should be based on a careful assessment of the probable causes and a rational decision to use a particular class of drug. The subcutaneous route is often required initially to overcome gastric stasis and poor absorption of oral medicines.

Mechanisms of nausea.

(ACh = acetylcholine; D2 = dopamine;5-HT = 5-hydroxytryptamine, serotonin;

H1 = histamine)

Receptor site activity of antiemetic drugs

Gastrointestinal obstructionGastrointestinal obstruction is a frequent complication

of intra-abdominal cancer. Patients may have multiple

levels of obstruction and symptoms may vary greatly in

nature and severity. Surgical mortality is high in patients

with advanced disease and obstruction should normally

be managed without surgery.

The key to effective management is to address the

presenting symptoms – colic, abdominal pain, nausea,

vomiting, intestinal secretions – individually or in combination, using drugs which do not cause or worsen

other symptoms. This can be problematic when a specific

treatment worsens another symptom.

Cyclizine improves nausea and colic responds well to anticholinergic agents, such as hyoscine butylbromide, but both slow gut motility. Nausea will improve with metoclopramide, although this is contraindicated in the presence of colic because of its prokinetic effect. There is

some evidence that corticosteroids (dexamethasone

8 mg) can shorten the length of obstructive episodes.

Somatostatin analogues, such as octreotide, will reduce

intestinal secretions and therefore large-volume vomits.

Occasionally, a nasogastric tube is required to reduce

gaseous or fluid distension.

Weight loss and general weakness

Patients with cancer lose weight due to an alteration of

metabolism by the tumour known as the cancer cachexia

syndrome. NSAIDs and megestrol may be helpful in

early-stage disease but are unlikely to be effective in

advanced cancer. Corticosteroids can temporarily boost

appetite and general well-being, but may cause false

weight gain by promoting fluid retention. Their benefits

need to be weighed against the risk of side-effects.

Anxiety and depression

Depression is common in palliative care but diagnosis ismore difficult, as the physical symptoms of depression

are similar to those of advanced disease. Anxiety and

depression may still respond to treatment with a combination of drugs and psychotherapeutic approaches.

Citalopram and mirtazapine are better tolerated

in patients with advanced disease. It should not be

assumed that depression is an ‘understandable’ consequence of the patient’s situation.

Delirium and terminal agitation

Many patients become confused or agitated in the lastdays of life. It is important to identify and treat potentially

reversible causes , unless the patient is too close to death for this to be feasible. Early diagnosis and effective management of delirium are extremely important. As in other palliative situations, it may not be possible to identify and treat the underlying cause, and the focus of management may be to ensure comfort. It is important to distinguish between behavioural change due to pain and that due to delirium, as opioids will improve one and worsen the other. It is important, even in palliative care to treat delirium with antipsychotic medicines such as haloperidol rather than regard it as distress or anxiety and use benzodiazepines only.

DEATH AND DYING

Talking about and planning towards dying

There have been dramatic improvements in medical

treatment and care of patients with cancer and other

illnesses over recent years, but the inescapable fact

remains that everyone will die at some time. Planning

for death is not required for people who die suddenly

but should be actively considered in patients with

chronic diseases when the death is considered to be foreseeable or inevitable. Doctors rarely know exactly when a patient will die but we are often aware that the risk of dying is increasing and that medical interventions are unlikely to prolong life or improve function.

Many people wish their doctors to be honest about this situation to allow them time to think ahead, make plans and

address practical issues. A smaller number do not wish

to discuss future deterioration or death; this avoidance

of discussion should be respected. For doctors, it is helpful to understand an individual’s wishes and values about medical interventions at this time, as this can help guide decisions about ceilings of intervention. Some interventions will not work in patients with far advanced disease. It is useful to distinguish between those that will not work (a medical decision) and those that do not confer sufficient benefit to be worthwhile (a decision that can only be reached with a patient’s involvement and consent).

A common example of this would be decisions about not attempting cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

In general, people wish for a dignified and peaceful

death and most prefer to die at home. Families also are

grateful for the chance to prepare themselves for the

death of a relative, by timely and gentle discussion

with their doctor or other health professionals. Early

discussion and effective planning improve the chances

that an individual’s wishes will be achieved.

Diagnosing dying

When patients with cancer become bed-bound, semicomatose, unable to take tablets and only able to take

sips of water, with no reversible cause, they are likely to

be dying and many will have died within 2 days. Patients

with other conditions also reach a stage where death is

predictable and imminent.

Doctors are sometimes poor at recognising this, and should be alert to the views of other members of the multidisciplinary team. A clear decision that the patient is dying should be agreed and recorded.

Management

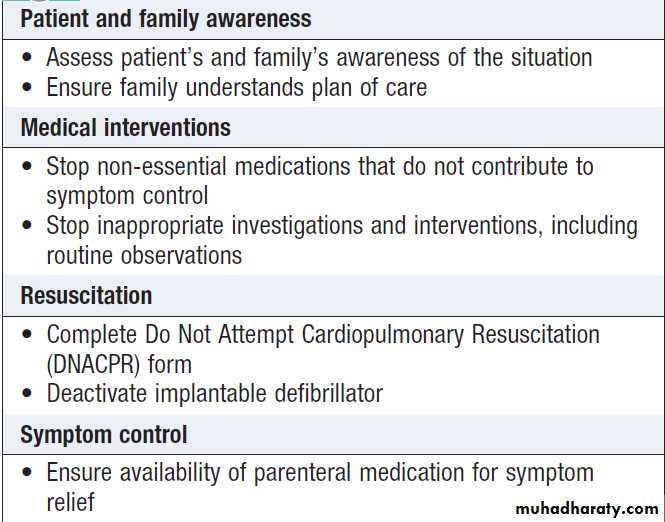

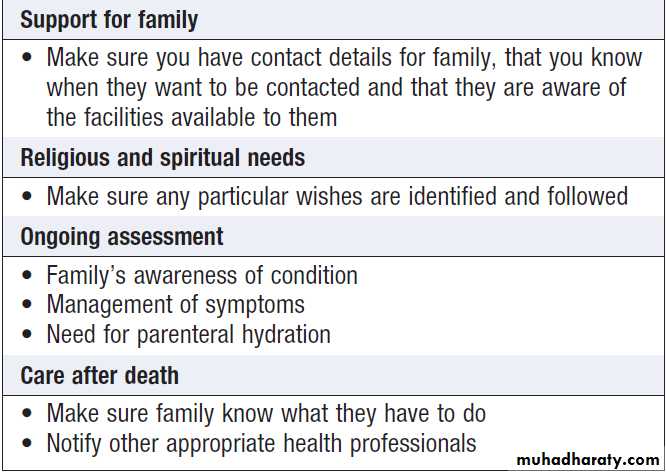

Once the conclusion has been reached that a patient isgoing to die in the next few days, there is a significant shift in management . Symptom control, relief of distress and care for the family become the most important elements of care. Medication and investigation are only justifiable if they contribute to these ends.

When patients can no longer drink because they are

dying, intravenous fluids are usually not necessary and

may cause worsening of bronchial secretions. Medicines

should always be prescribed for the relief of symptoms.

For example, morphine or diamorphine may be used

to control pain, levomepromazine to control nausea,haloperidol to treat confusion, diazepam or midazolam

to treat distress, and hyoscine hydrobromide to reduce

respiratory secretions. Side-effects, such as drowsiness,

may be acceptable if the principal aim of relieving distress

is achieved. It is important to discuss and agree the

aims of care with the patient’s family.

How to manage a patient who is dying

How to manage a patient who is dying – cont’d

Ethical issues at the end of lifeIn Europe, between 25 and 50% of all deaths are associated with some form of decision which may affect the

length of a patient’s life. The most common form of decision

involves withdrawing or withholding further treatment:

for example, not treating a chest infection in a patient who is clearly dying from advanced cancer. It is important to have a framework for considering such decisions (such as the four ethical principles: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice), which balances degrees of importance when there is conflict:

for example, when a patient wishes to receive treatment

which a doctor believes will be ineffective or which may

cause harm.

A decision has to be taken as to which principle is most important: whether it is better to respect a patient’s wishes, even if it causes harm, or to reduce the risk of harm but not accede to those wishes.

A futile treatment is one which has no chance of

achieving worthwhile benefit: that is, the treatment

cannot achieve a result that the patient would consider,

now or in the future, to be worthwhile.

Doctors are not required to institute futile treatments, such as resuscitation, in the event of cardiac arrest in a patient with terminal cancer.

Incapacity and advance directives

Patients’ wishes are very important in Western medical

ethics, although other cultures emphasise the views of

the family. If a patient is unable to express his or her

view because of communication or cognitive impairment,

that person lacks ‘capacity’. In order to decide

what the patient would have wished, as much information

as possible should be gained about any previously

expressed wishes, along with the views of relatives and

other health professionals.

An advance directive is a previously recorded, written document of a patient’s wishes.

It should carry the same weight in decision-making as a patient’s contemporaneously expressed wishes, but may not be sufficiently specific to be used in a particular clinicalsituation. The legal framework for decision-making

varies in different countries.

Hydration

Deciding whether to give intravenous fluids can be difficult when a patient is very unwell and the prognosis is uncertain.If a patient is clearly dying and has a prognosis

of a few days, rehydration may cause harm by

increasing bronchial secretions, and will not benefit

the patient by prolonging life.

A patient with a major stroke, who is unable to swallow but expected to survive the event, will develop renal impairment and thirst if not given fluids and should be hydrated. Each decision should be individual and discussed with the patient’s family.

Euthanasia

In the UK and Europe, between 3 and 6% of dying

patients ask a doctor to end their life. Many of these

requests are transient; some are associated with poor

control of physical symptoms or a depressive illness. All

expressions of a wish to die are an opportunity to help

the patient discuss and address unresolved issues and

problems.

Reversible causes, such as pain or depression, should

be treated. Sometimes, patients may choose to discontinue

life-prolonging treatments, such as diuretics or

anticoagulation, following discussion and the provision

of adequate alternative symptom control.