Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABMLecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

2016

learning-topics

Sexually transmitted infectionsObservation

• Mouth• Eyes

• Joints

• Skin:

Rash of secondary syphilis

Scabies

Manifestations of HIV infection

HIV testing

It should always be standard practice to offer HIV testing as part of screening for STI (sexually transmitted infection) because the benefits of early diagnosis outweigh other considerations.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a group of

contagious conditions whose principal mode of transmissionis by intimate sexual activity involving the

moist mucous membranes of the penis, vulva, vagina,

cervix, anus, rectum, mouth and pharynx, along with

their adjacent skin surfaces. A wide range of infections

may be sexually transmitted, including syphilis, gonorrhoea, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), genital

herpes, genital warts, chlamydia and trichomoniasis.

Bacterial vaginosis and genital candidiasis are not

regarded as STIs, although they are common causes of

vaginal discharge in sexually active women.

Chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) and granuloma inguinale are usually seen in tropical countries. Hepatitis viruses A, B, C and D may be acquired sexually, as well as by other routes.

The World Health Organization estimates that 448

million curable STIs (Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydia

trachomatis, gonorrhoea and syphilis) occur world-wide

each year. In the UK in 2010, the most common treatable

STIs diagnosed were chlamydia (more than 200 000

cases) and gonorrhoea (19 000 cases). Genital warts are

the second most common complaint seen in genitourinary

medicine (GUM) departments. In addition to causing morbidity themselves, STIs may increase the risk of transmitting or acquiring HIV infection.

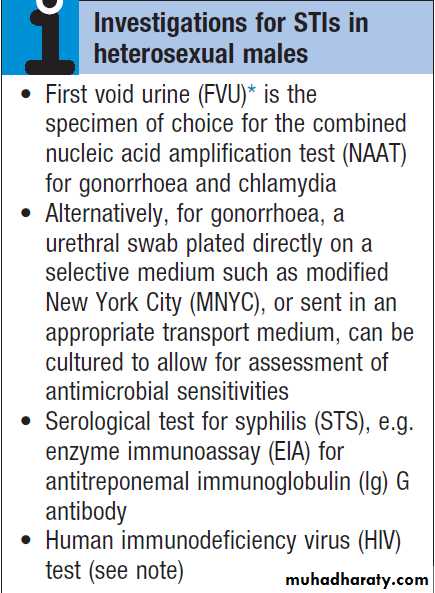

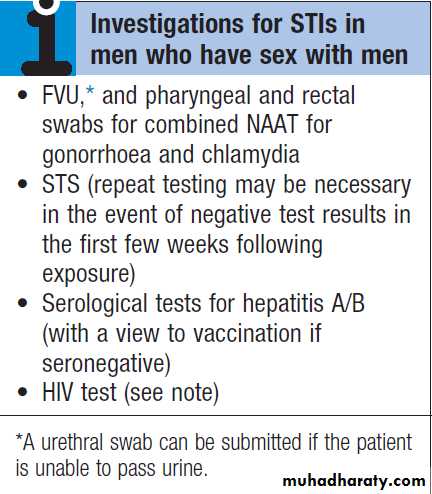

As coincident infection with more than one STI is

seen frequently, GUM clinics routinely offer a full set ofinvestigations at the patient’s first visit , regardless of the reason for attendance. In other settings, less comprehensive investigation may be appropriate.

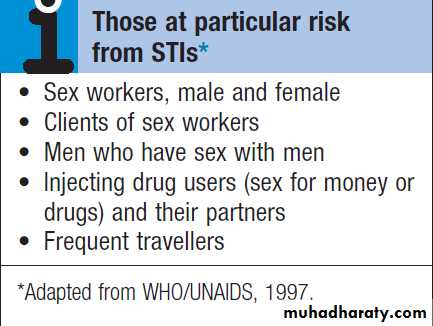

The extent of the examination largely reflects the likelihood

of HIV infection or syphilis. Most heterosexuals

in the UK are at such low risk of these infections that

routine extragenital examination is unnecessary. This is

not the case in parts of the world where HIV is endemic,

or for men who have sex with men (MSM) in the UK. In

other words, the extent of the examination is determined

by the sexual history.

How to take a sexual history

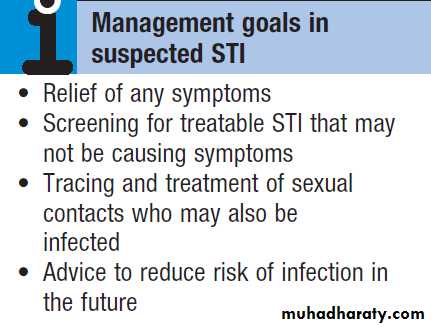

APPROACH TO PATIENTS WITH A SUSPECTED STIPatients concerned about the possible acquisition of an

STI are often anxious. Staff must be friendly, sympathetic

and reassuring; they should have the ability to put patients at ease, whilst emphasising that clinic attendance

is confidential. The history focuses on genital

symptoms, with reference to genital ulceration, rash,

irritation, pain, swelling and urinary symptoms, especially

dysuria. In men, the clinician should ask about

urethral discharge, and in women, vaginal discharge,

pelvic pain or dyspareunia. Enquiry about general

health should include menstrual and obstetric history,

cervical cytology, recent medication, especially with

antimicrobial or antiviral agents, previous STI and allergy.

Immunisation status for hepatitis A and B should be noted, as should information about recreational drug use and alcohol intake.

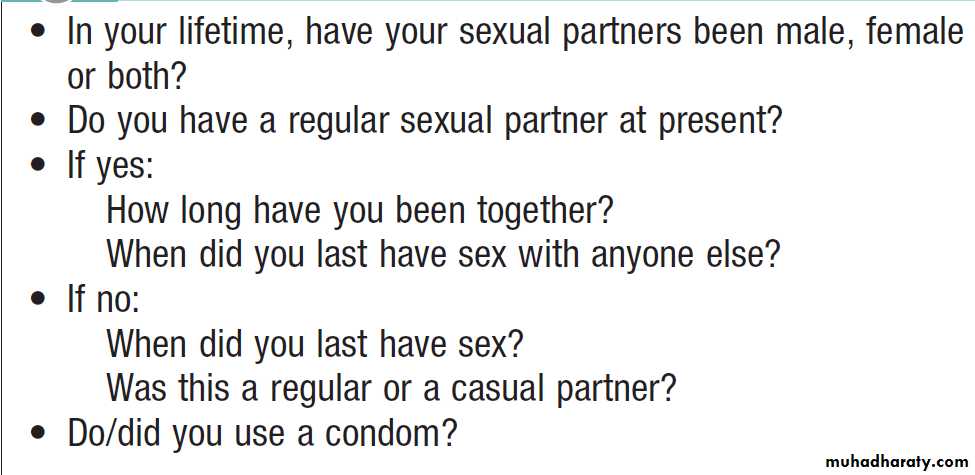

A detailed sexual history is imperative (see Box),

as this informs the clinician of the degree of risk for

certain infections, as well as specific sites that should be

sampled; for example, rectal samples should be taken

from men who have had unprotected anal sex with other

men. Sexual partners, whether male or female, and

casual or regular, should be recorded. Sexual practices

– insertive or receptive vaginal, anal, orogenital or oroanal

– should be noted, as should choice of contraception

for women, and condom use for both sexes.

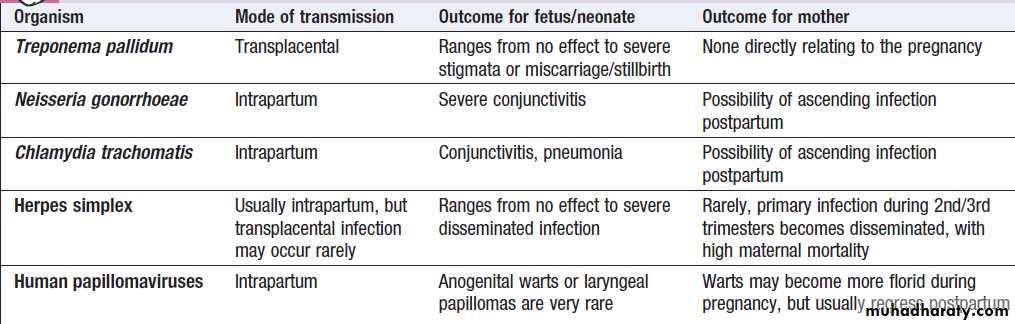

STI during pregnancy

Many STIs can be transmitted from mother to child in

pregnancy, either transplacentally or during delivery.

Possible outcomes are highlighted in Box.

STI in children

The presence of an STI in a child may be indicative of

sexual abuse, although vertical transmission may explain

some presentations in the first 2 years. In an older child

and in adolescents, STI may be the result of voluntary sexual activity.

Possible outcomes of STI in pregnancy

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN MENUrethral discharge

In the UK the most important causes of urethral discharge

are gonorrhoea and chlamydia. In a significant

minority of cases, tests for both of these infections are

negative, a scenario often referred to as non-specific

urethritis (NSU). Some of these cases may be caused

by Trichomonas vaginalis, herpes simplex virus (HSV),

mycoplasmas or ureaplasmas. A small minority seem

not to have an infectious aetiology. Gonococcal urethritis usually causes symptoms within 7 days of exposure. The discharge is typically profuse and purulent.

Chlamydial urethritis has an incubation period of 1–4 weeks, and tends to result in milder symptoms than gonorrhoea; there is overlap, however, and microbiological confirmation should always be sought.

Investigations

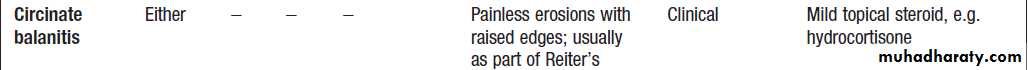

A presumptive diagnosis of urethritis can be made from a Gram-stained smear of the urethral exudate (Fig.), which will demonstrate significant numbers of polymorphonuclear leucocytes (≥ 5 per high-power field). A working diagnosis of gonococcal urethritis is made if Gram-negative intracellular diplococci (GNDC) are seen; if no GNDC are seen, a label of NSU is applied.

If microscopy is not available, urine samples and/or swabs should be taken and empirical antimicrobials prescribed.

A first-void urine (FVU) sample should be submitted for a combined nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for gonorrhoea and chlamydia; a urethral swab is an alternative if the patient cannot pass urine. When

gonorrhoea is suspected, a urethral swab should be sent

for culture and antimicrobial sensitivities of Neisseria

gonorrhoeae. Tests for other potential causes of urethritis

are not performed routinely.

A swab should also be taken from the pharynx because gonococcal infection here is not reliably eradicated by single-dose therapy.

In MSM, swabs for gonorrhoea and chlamydia should be taken from the rectum.

A Gram-stained urethral smear from a man with

gonococcal urethritis. Gram-negative diplococci are seen within polymorphonuclear leucocytes.Management

This depends on local epidemiology and the availabilityof diagnostic resources. Treatment is often presumptive,

with prescription of multiple antimicrobials to cover the

possibility of gonorrhoea and/or chlamydia. This is

likely to include a single-dose treatment for gonorrhoea,

which is desirable because it eliminates the risk of nonadherence.

The recommended agents for treating gonorrhea vary according to local antimicrobial resistance patterns . Appropriate treatment for chlamydia should also be prescribed because concurrent infection is present in up to 50% of men with gonorrhoea. Non-gonococcal, non-chlamydial urethritis is treated as for chlamydia.

Patients should be advised to avoid sexual contact

until it is confirmed that any infection has resolved and,

whenever possible, recent sexual contacts should be

traced. The task of contact tracing – also called partner

notification – is best performed by trained nurses based

in GUM clinics; it is standard practice in the UK to treat

current sexual partners of men with gonococcal or nonspecific urethritis without waiting for microbiological

confirmation.

If symptoms clear, a routine test of cure is not necessary, but patients should be re-interviewed to confirm that there was no immediate vomiting or diarrhea after treatment, that there has been no risk of reinfection, and that traceable partners have sought medical advice.

Genital itch and/or rash

Patients may present with many combinations of penile/genital symptoms, which may be acute or chronic, and

infectious or non-infectious. Box provides a guide to diagnosis.

Balanitis refers to inflammation of the glans penis, often extending to the under-surface of the prepuce, in which case it is called balanoposthitis. Tight prepuce and poor hygiene may be aggravating factors. Candidiasis is sometimes associated with immune deficiency, diabetes mellitus, and the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials, corticosteroids or antimitotic drugs. Local saline bathing is usually helpful, especially when no cause is found.

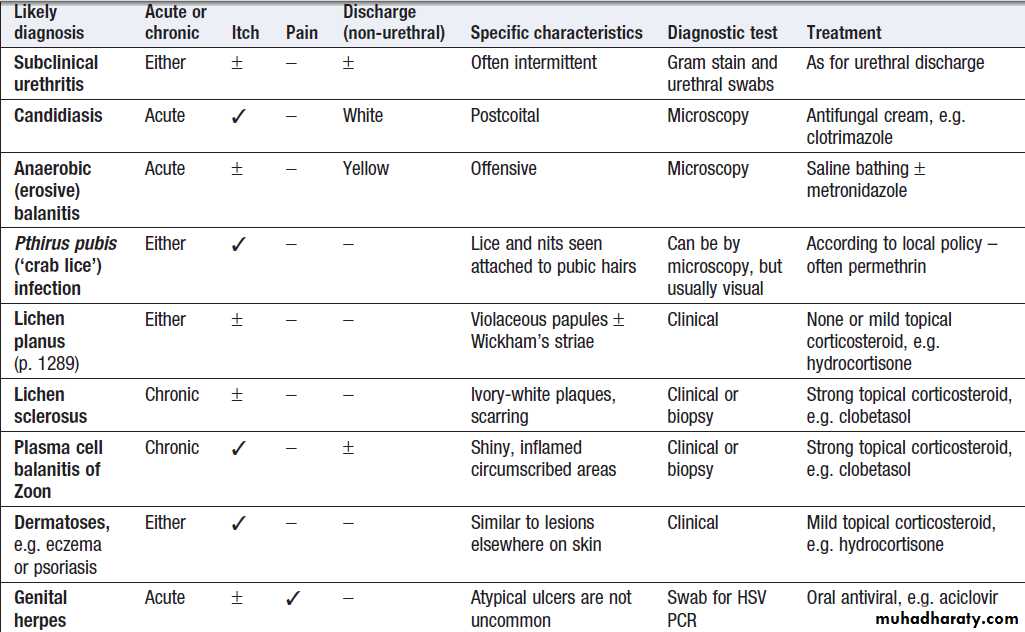

Differential diagnosis of genital itch and/or rash in men

Genital ulceration

The most common cause of ulceration is genital herpes.Classically, multiple painful ulcers affect the glans,

coronal sulcus or shaft of penis , but solitary

lesions occur rarely. Perianal ulcers may be seen in

MSM. The diagnosis is made by gently scraping material

from lesions and sending this in an appropriate transport

medium for culture or detection of HSV DNA by

polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Increasingly, laboratories

will also test for Treponema pallidum by PCR.

In the UK, the possibility of syphilis or any other

ulcerating STI is much less likely unless the patient is an

MSM and/or has had a sexual partner from a region

where tropical STIs are more common.

The classic lesion of primary syphilis (chancre) is single, painless and indurated; however, multiple lesions are seen rarely and anal chancres are often painful. Diagnosis is made in GUM clinics by dark-ground microscopy and/or PCR on a swab from a chancre, but in other settings by serological tests for syphilis .Other rare infective causes seen in the UK include varicella zoster virus and trauma with secondary infection. Inflammatory causes

include Stevens–Johnson syndrome , Behçet’s syndrome and fixed drug reactions. In older patients, malignant and pre-malignant conditions, such as squamous cell carcinoma and erythroplasia of Queyrat (intra-epidermal carcinoma), should be considered.

Genital lumps

The most common cause of genital ‘lumps’ is warts.These are classically found in areas of friction

during sex, such as the parafrenal skin and prepuce of

the penis. Warts may also be seen in the urethral meatus,

and less commonly on the shaft or around the base of

the penis. Perianal warts are surprisingly common in

men who do not have anal sex. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum and skin tags.

Adolescent boys may confuse normal anatomical features such as coronal papillae, parafrenal glands or sebaceous glands (Fordyce spots) with warts.

Proctitis in men who have sex with men (MSM)

STIs that may cause proctitis in MSM include gonorrhoea,

chlamydia, herpes and syphilis. The substrains of Chlamydia trachomatis that cause LGV (L1–3) have been associated with outbreaks of severe proctitis in Northern Europe, including the UK. Symptoms include mucopurulent anal discharge, rectal bleeding, pain and tenesmus. Examination may show mucopus and erythema with contact bleeding . In addition to the diagnostic tests on mentioned above , a PCR test for HSV and a request for identification of the LGV substrain should be arranged if chlamydial infection is detected. MSM may also present with gastrointestinal symptoms from infection with organisms such as Entamoeba

histolytica,Shigella,Campylobacter and Cryptosporidium spp.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN WOMEN

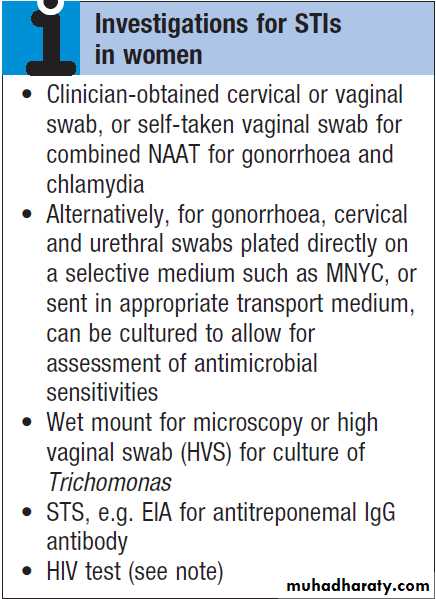

Vaginal dischargeThe natural vaginal discharge may vary considerably,

especially under differing hormonal influences such

as puberty, pregnancy or prescribed contraception. A

sudden or recent change in discharge, especially if associated with alteration of colour and/or smell, or vulval

itch/irritation, is more likely to indicate an infective

cause than a gradual or long-standing change.

Local epidemiology is particularly important when

assessing possible causes. In the UK, most cases of

vaginal discharge are not sexually transmitted, being due to either candidal infection or bacterial vaginosis (BV).

World-wide, the most common treatable STI causing vaginal discharge is trichomoniasis; other possibilities

include gonorrhoea and chlamydia. HSV may cause increased discharge, although vulval pain and dysuria are usually the predominant symptoms. Noninfective causes include retained tampons, malignancy and/or fistulae.

Speculum examination often allows a relatively accurate

diagnosis, with appropriate treatment to follow.

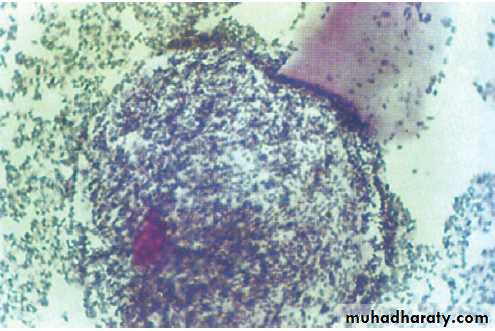

If the discharge is homogeneous and offwhite in colour, vaginal pH is greater than 4.5, and Gram stain microscopy reveals scanty or absent lactobacilli with significant numbers of Gram-variable organisms, some of which may be coating vaginal squamous cells (so-called Clue cells Fig.), the likely diagnosis is BV.

If there is vulval and vaginal erythema, the discharge is

curdy in nature, vaginal pH is less than 4.5, and Gram

stain microscopy reveals fungal spores and pseudohyphae,

the diagnosis is candidiasis. Trichomoniasis tends to cause a profuse yellow or green discharge and is usually associated with significant vulvovaginal inflammation. Diagnosis is made by observing motile flagellate protozoa on a wet-mount microscopy slide of vaginal material. If examination reveals the discharge to be cervical in origin, the possibility of chlamydial or gonococcal infection is increased and appropriate cervical or vaginal swabs should be taken . In addition, Gram stain of cervical and urethral material may reveal GNDC, allowing presumptive treatment for gonorrhoea to be given.

If gonococcal cervicitis is suspected, swabs should

also be taken from the pharynx and rectum; infectionsat these sites are not reliably eradicated by single-dose

therapy and a test of cure will therefore be required.

GUM clinics in the UK may offer sexually active

women presenting with vaginal discharge an STI screen.

In other settings, such as primary care or gynaecology,

testing for chlamydia and gonorrhoea may be

considered in young women (< 25 years old), those who

have changed partner recently, and those not using a

barrier method of contraception, even if a non-STI cause

of discharge is suspected clinically.

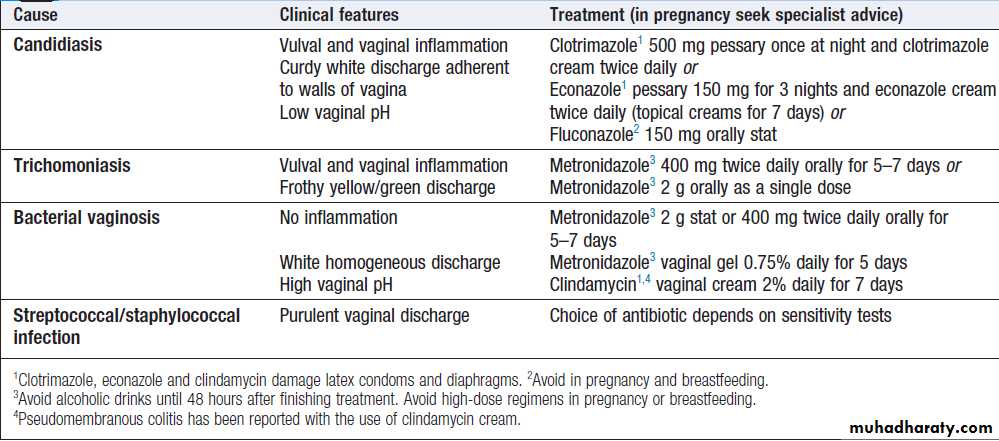

Treatment of infections causing vaginal discharge is

shown in Box.

Gram stain of a Clue cell from a patient with bacterial

vaginosis. The margin of this vaginal epithelial cell is obscured by a coating of anaerobic organisms.Infections that cause vaginal discharge

Lower abdominal painPelvic inflammatory disease (PID, infection or inflammation of the Fallopian tubes and surrounding structures) is part of the extensive differential diagnosis of lower abdominal pain in women, especially those who are sexually active. The possibility of PID is increased if, in addition to acute/subacute pain, there is dyspareunia, abnormal vaginal discharge and/or bleeding. There may also be systemic features, such as fever and malaise. On examination, lower abdominal pain is usually bilateral, and vaginal examination reveals adnexal tenderness with or without cervical excitation. Unfortunately, a definitive diagnosis can only be made by laparoscopy.

A pregnancy test should be performed (as well as the diagnostic tests above) because the differential diagnosis includes ectopic pregnancy. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, including those active against gonorrhoea and chlamydia, such as ofloxacin and metronidazole, should be prescribed if PID is suspected, along with appropriate analgesia. Delaying treatment increases the likelihood of adverse sequelae, such as abscess formation, and tubal scarring that may lead to ectopic pregnancy or infertility. Hospital

admission may be indicated for severe symptoms.

Genital ulceration

The most common cause of ulceration is genital herpes.Classically, multiple painful ulcers affect the introitus,

labia and perineum, but solitary lesions occur rarely.

Inguinal lymphadenopathy and systemic features, such

as fever and malaise, are more common than in men.

Diagnosis is made by gently scraping material from

lesions and sending this in an appropriate transport

medium for culture or detection of HSV DNA by PCR.

Increasingly, laboratories will also test such samples for

Treponema pallidum by PCR. In the UK, the possibility of

any other ulcerating STI is unlikely unless the patient

has had a sexual partner from a region where tropical

STIs are more common .

Inflammatory causes include lichen sclerosus, Stevens–Johnson syndrome , Behçet’s syndrome and fixed drug reactions. In older patients, malignant and pre-malignant conditions, such as squamous cell carcinoma, should be considered.

Genital lumps

The most common cause of genital ‘lumps’ is warts.

These are classically found in areas of friction during

sex, such as the fourchette and perineum. Perianal warts

are surprisingly common in women who do not have

anal sex.

The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum,

skin tags and normal papillae or sebaceous glands.

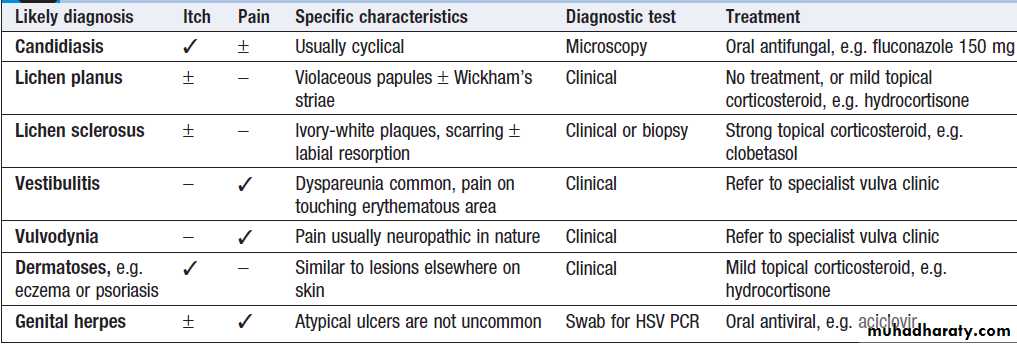

Chronic vulval pain and/or itch

Women may present with a range of chronic symptomsthat may be intermittent or continuous (Box).

Recurrent candidiasis may lead to hypersensitivity to

candidal antigens, with itch and erythema becoming

more prominent than increased discharge.

Effective treatment may require regular oral antifungals, e.g. fluconazole 150 g once every 2–4 weeks plus a combined antifungal/corticosteroid cream such as Daktacort or Canesten HC.

Chronic vulval pain and/or itch

PREVENTION OF STI

Case-findingEarly diagnosis and treatment facilitated by active case-finding will help to reduce the spread of infection by

limiting the period of infectivity; tracing and treating

sexual partners will also reduce the risk of re-infection.

Unfortunately, the majority of individuals with an STI

are asymptomatic and therefore unlikely to seek medical

attention. Improving access to diagnosis in primary care

or non-medical settings, especially through opportunistic

testing, may help.

However, the impact of medical intervention through improved access alone is likely to be small.

Changing behaviour

The prevalence of STIs is driven largely by sexual behaviour.Primary prevention encompasses efforts to delay

the onset of sexual activity and limit the number of

sexual partners thereafter. Encouraging the use of barrier

methods of contraception will also help to reduce the

risk of transmitting or acquiring STIs. This is especially

important in the setting of ‘sexual concurrency’, where

sexual relationships overlap.

Unfortunately, there is contradictory evidence as to

which (if any) interventions can reduce sexual activity.

Knowledge alone does not translate into behaviour

change, and broader issues, such as poor parental role

modelling, low self-esteem, peer group pressure in the

context of the increased sexualisation of our societies,

gender power imbalance and homophobia, all need to

be addressed. Throughout the world there is a critical

need to enable women to protect themselves from undisciplined and coercive male sexual activity.

Economic collapse and the turmoil of war regularly lead to situations where women are raped or must turn to prostitution to feed themselves and their children, and an inability to negotiate safe sex increases their risk of

acquiring STI, including HIV.

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

SyphilisSyphilis is caused by infection, through abrasions in the

skin or mucous membranes, with the spirochaete

Treponema pallidum. In adults the infection is usually

sexually acquired; however, transmission by kissing,

blood transfusion and percutaneous injury has been

reported. Transplacental infection of the fetus can occur.

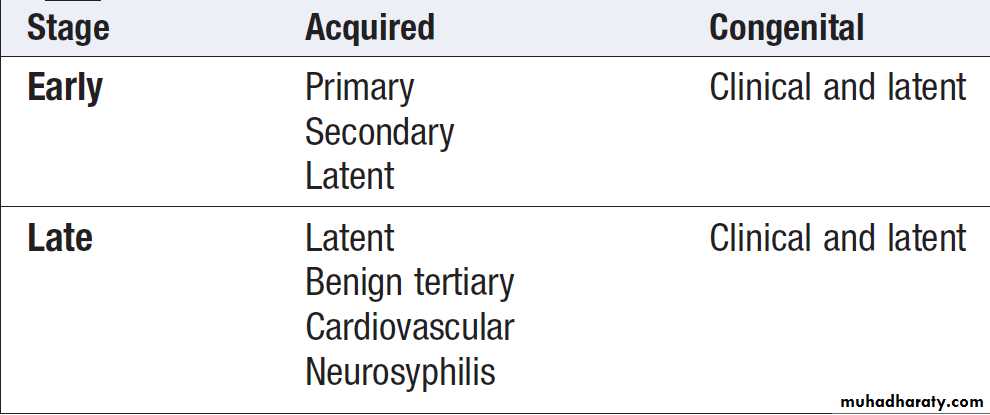

The natural history of untreated syphilis is variable.

Infection may remain latent throughout, or clinical features may develop at any time. The classification of syphilis is shown in Box.

All infected patients should be treated. Penicillin remains the drug of choice for all stages of infection.

Classification of syphilis

Acquired syphilisEarly syphilis

Primary syphilis

The incubation period is usually between 14 and 28

days, with a range of 9–90 days. The primary lesion or

chancre (Fig.) develops at the site of infection,

usually in the genital area. A dull red macule develops,

becomes papular and then erodes to form an indurated

ulcer (chancre). The draining inguinal lymph nodes

may become moderately enlarged, mobile, discrete and

rubbery. The chancre and the lymph nodes are both

painless and non-tender, unless there is concurrent or

secondary infection. Without treatment, the chancre will

resolve within 2–6 weeks to leave a thin atrophic scar.

Chancres may develop on the vaginal wall and on the

cervix. Extragenital chancres are found in about 10% ofpatients, affecting sites such as the finger, lip, tongue,

tonsil, nipple, anus or rectum. Anal chancres often

resemble fissures and may be painful.

Primary syphilis. A painless ulcer (chancre) is shown in the

coronal sulcus of the penis. This is usually associated with inguinal lymphadenopathy.Secondary syphilis

This occurs 6–8 weeks after the development of thechancre, when treponemes disseminate to produce a

multisystem disease. Constitutional features, such as

mild fever, malaise and headache, are common. Over

75% of patients present with a rash on the trunk and

limbs that may later involve the palms and soles; this is

initially macular but evolves to maculopapular or

papular forms, which are generalised, symmetrical and

non-irritable. Scales may form on the papules later. The

rash affects the trunk and proximal limbs, and characteristically involves the palms, soles and face. Lesions are red, changing to a ‘gun-metal’ grey as they resolve.

Without treatment, the rash may last for up to 12 weeks.

Condylomata lata (papules coalescing to plaques) maydevelop in warm, moist sites such as the vulva or perianal

area. Generalised non-tender lymphadenopathy is

present in over 50% of patients. Mucosal lesions, known

as mucous patches, may affect the genitalia, mouth,

pharynx or larynx and are essentially modified papules,

which become eroded. Rarely, confluence produces

characteristic ‘snail track ulcers’ in the mouth.

Other features, such as meningitis, cranial nerve palsies, anterior or posterior uveitis, hepatitis, gastritis,

glomerulonephritis or periostitis, are sometimes seen.

Neurological involvement may be more common in

HIV-positive patients.

The differential diagnosis of secondary syphilis can

be extensive, but in the context of a suspected STI,

primary HIV infection is the most important alternative

condition to consider . Non-STI conditions

that mimic the rash include psoriasis, pityriasis rosea,

scabies, allergic drug reaction, erythema multiforme and

tinea versicolor.

The clinical manifestations of secondary syphilis will

resolve without treatment but relapse may occur, usually

within the first year of infection. Thereafter, the disease

enters the phase of latency.

Latent syphilis

This phase is characterised by the presence of positivesyphilis serology or the diagnostic cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF) abnormalities of neurosyphilis in an untreated

patient with no evidence of clinical disease.

It is divided into

early latency (within 2 years of infection), when

syphilis may be transmitted sexually, and

late latency,

when the patient is no longer sexually infectious. Transmission of syphilis from a pregnant woman to her fetus, and rarely by blood transfusion, is possible for several years following infection.

Late syphilis

Late latent syphilis

This may persist for many years or for life. Without treatment, over 60% of patients might be expected to suffer little or no ill health. Coincidental prescription of antibiotics for other illnesses, such as respiratory tract or skin infections, may treat latent syphilis serendipitously.

Benign tertiary syphilis

This may develop between 3 and 10 years after infection

but is now rarely seen in the UK. Skin, mucous membranes,

bone, muscle or viscera can be involved.The characteristic feature is a chronic granulomatous lesion called a gumma, which may be single or multiple. Healing with scar may impair the function of the structure affected.

Skin lesions may take the form of nodules or ulcers, whilst subcutaneous lesions may ulcerate with a gummy discharge. Healing occurs slowly, with the formation of characteristic tissue paper scars. Mucosal lesions may occur in the mouth, pharynx, larynx or nasal septum, appearing as punched-out ulcers. Of particular importance is gummatous involvement of the tongue, healing of which may lead to leukoplakia with the attendant risk of malignant change. Gummas of the tibia, skull, clavicle and sternum have been described, as has involvement of the brain, spinal cord, liver, testis and, rarely, other organs. Resolution of active disease should follow treatment, though some tissue damage may be permanent. Paroxysmal cold

haemoglobinuria may be seen.

Cardiovascular syphilis

This may present many years after initial infection. Aortitis,which may involve the aortic valve and/or the coronary ostia, is the key feature. Clinical features include aortic incompetence, angina and aortic aneurysm. It affects the ascending , sometimes the aortic arch; aneurysm of the descending aorta is rare. Treatment with penicillin will not correct anatomical damage and surgery may be required.

Neurosyphilis

This may take years to develop. Asymptomatic infection is associated with CSF abnormalities. Meningovascular disease, tabes dorsalis and general paralysis of the insane constitute the symptomatic forms . Neurosyphilis and cardiovascular syphilis may coexist and are sometimes referred to as quaternary syphilis.

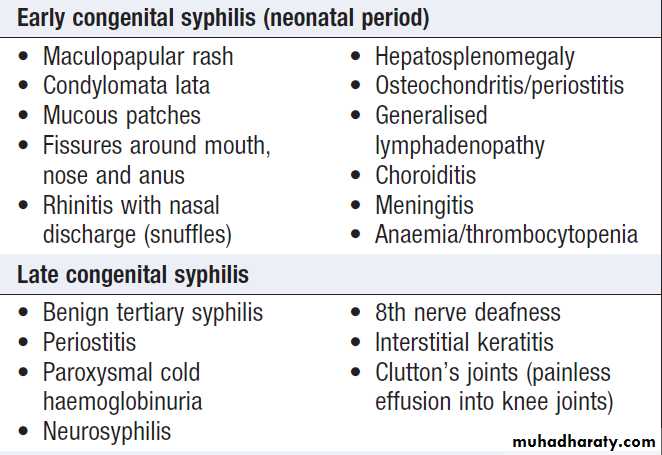

Congenital syphilis

Is rare where antenatal serological screening is practised. Antisyphilitic treatment in pregnancy treats the fetus, if infected, as well as the mother. Treponemal infection may give rise to a variety of outcomes after 4 months of gestation, when the fetus becomes immunocompetent:• miscarriage or stillbirth, prematurely or at term

• birth of a syphilitic baby (a very sick baby with

hepatosplenomegaly, bullous rash and perhaps pneumonia)

• birth of a baby who develops signs of early

congenital syphilis during the first few weeks of life

• birth of a baby with latent infection who either

remains well or develops congenital syphilis/

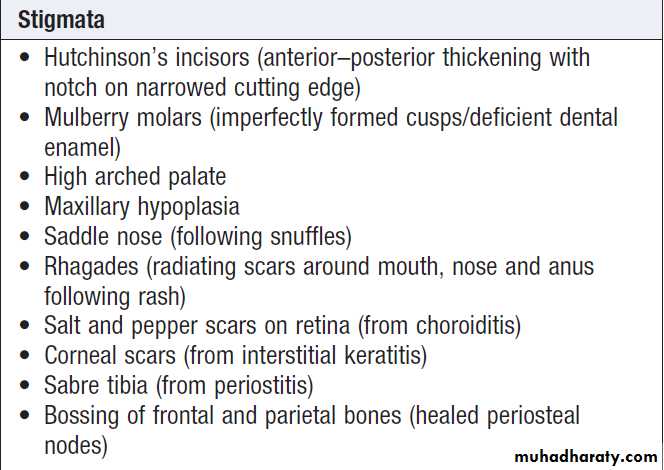

stigmata later in life (see Box).

Clinical features of congenital syphilis

Clinical features of congenital syphilis– cont’d

Investigations in adult casesTreponema pallidum may be identified in serum collected

from chancres, or from moist or eroded lesions in secondary syphilis using a dark-field microscope, a direct

fluorescent antibody test or PCR.

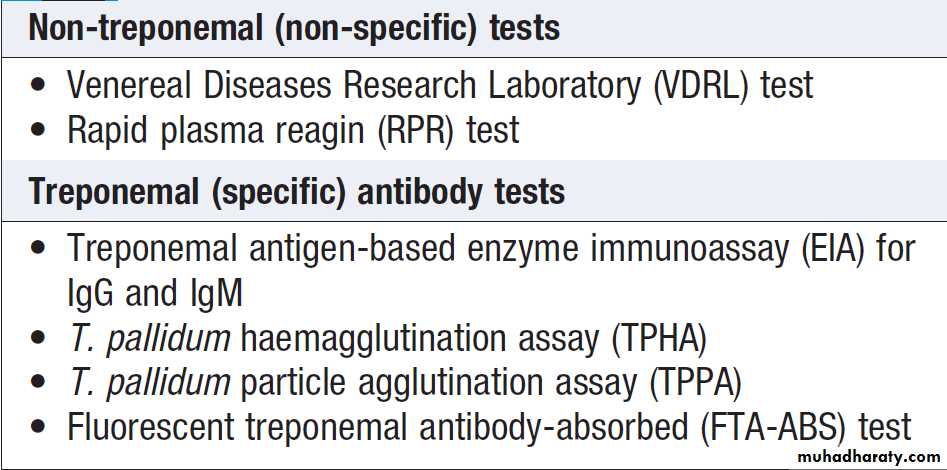

The serological tests for syphilis are listed in Box .

Many centres use treponemal EIAs for IgG and IgM

antibodies to screen for syphilis. EIA for antitreponemal

IgM becomes positive at approximately 2 weeks, whilst

non-treponemal tests become positive about 4 weeks

after primary syphilis. All positive results in asymptomatic

patients must be confirmed by repeat tests.

Biological false-positive reactions occur occasionally;

these are most commonly seen with Venereal Diseases

Research Laboratory (VDRL) or rapid plasma reagin

(RPR) tests (when treponemal tests will be negative).

Acute false-positive reactions may be associated with

infections, such as infectious mononucleosis, chickenpox

and malaria, and may also occur in pregnancy. Chronic

false-positive reactions may be associated with autoimmune diseases. False-negative results for nontreponemal tests may be found in secondary syphilis because extremely high antibody levels can prevent the

formation of the antibody–antigen lattice necessary for

the visualisation of the flocculation reaction

(prozone phenomenon).

In benign tertiary and cardiovascular syphilis, examination of CSF should be considered because asymptomatic neurological disease may coexist. The CSF should also be examined in patients with clinical signs of neurosyphilis and in both early and late congenital

syphilis. Positive STS may be found in patients who are

being investigated for neurological disease, especially

dementia. In many instances, the serology reflects previous

infection unrelated to the presenting complaint,

especially when titres are low.

Chest X-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiogram are useful in the investigation of cardiovascular syphilis. Biopsy may be required to diagnose gumma. Endemic treponematoses, such as yaws, endemic (non-venereal) syphilis (bejel) and pinta,

are caused by treponemes that are morphologically

indistinguishable from T. pallidum and cannot be differentiated by serological tests. A VDRL or RPR test may help to elucidate the correct diagnosis because adults

with late yaws usually have low titres.

Serological tests for syphilis

Investigations in suspected congenital syphilisPassively transferred maternal antibodies from an adequately treated mother may give rise to positive serological tests in her baby. In this situation, non-treponemal tests should become negative within 3–6 months of birth.

A positive EIA test for antitreponemal IgM suggests

early congenital syphilis.

A diagnosis of congenital syphilis mandates investigation of the mother, her partner and any siblings.

Management

Penicillin is the drug of choice. Currently, a single doseof 2.4 megaunits of intramuscular benzathine penicillin

is recommended for early syphilis (< 2 years’ duration),

with three doses at weekly intervals being recommended

in late syphilis. Doxycycline is indicated for patients

allergic to penicillin, except in pregnancy (see below).

Azithromycin is a further alternative. All patients must

be followed up to ensure cure, and partner notification

is of particular importance. Resolution of clinical signs

in early syphilis with declining titres for non-treponemal

tests, usually to undetectable levels within 6 months

for primary syphilis and 12–18 months for secondary

syphilis, is an indicator of successful treatment.

Specific treponemal antibody tests may remain positive for life. In patients who have had syphilis for many years there may be little serological response following treatment.

Pregnancy

Penicillin is the treatment of choice. Erythromycin stearate can be given if there is penicillin hypersensitivity, but crosses the placenta poorly; the newborn baby must therefore be treated with a course of penicillin and consideration given to retreating the mother. Some specialists recommend penicillin desensitization for pregnant mothers so that penicillin can be given during temporary tolerance. The author has successfully prescribed ceftriaxone 250 mg IM for 10 days in this situation. Babies should be treated in hospital with the help of a paediatrician.

Treatment reactions

• Anaphylaxis. Penicillin is a common cause; on-sitefacilities should be available for management .

• Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction. This is an acute febrile

reaction that follows treatment , characterised by headache, malaise and myalgia; it resolves within 24 hours. It is common in early syphilis and rare in late syphilis. Fetal distress or premature labour can occur in pregnancy. The reaction may also cause worsening of neurological (cerebral artery occlusion) or ophthalmic (uveitis, optic neuritis) disease, myocardial ischaemia (inflammation of the coronary ostia) and laryngeal stenosis(swelling of a gumma).

Prednisolone 10–20 mg orally three times daily for 3 days is recommended to prevent the reaction in patients

with these forms of the disease; antisyphilitic treatment can be started 24 hours after introducing corticosteroids. In high-risk situations it is wise to initiate therapy in hospital.

• Procaine reaction. Fear of impending death occurs

immediately after the accidental intravenous injection of procaine penicillin and may be associated with hallucinations or fits.

Symptoms are short-lived, but verbal assurance and sometimes physical restraint are needed. The reaction can be prevented by aspiration before intramuscular

injection to ensure the needle is not in a blood vessel.

Gonorrhoea

Gonorrhoea is caused by infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and may involve columnar epithelium in thelower genital tract, rectum, pharynx and eyes. Transmission is usually the result of vaginal, anal or oral sex.

Gonococcal conjunctivitis may be caused by accidental

infection from contaminated fingers. Untreated mothers

may infect babies during delivery, resulting in ophthalmia

neonatorum (Fig.). Infection of children beyond

the neonatal period usually indicates sexual abuse.

Gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum.

Clinical featuresThe incubation period is usually 2–10 days. In men the

anterior urethra is commonly infected, causing urethral

discharge and dysuria, but symptoms are absent in about 10% of cases. Examination will usually show a

mucopurulent or purulent urethral discharge. Rectal infection in MSM is usually asymptomatic but may present with anal discomfort, discharge or rectal bleeding.

Proctoscopy may reveal either no abnormality, or clinical evidence of proctitis such as inflamed rectal mucosa and mucopus. In women, the urethra, paraurethral glands/ducts,

Bartholin’s glands/ducts or endocervical canal may be

infected. The rectum may also be involved either due to

contamination from a urogenital site or as a result of anal

sex. Occasionally, the rectum is the only site infected.

About 80% of women who have gonorrhoea are asymptomatic. There may be vaginal discharge or dysuria but these symptoms are often due to additional infections, such as chlamydia (see below), trichomoniasis or candidiasis, making full investigation essential . Lower abdominal pain, dyspareunia and intermenstrual bleeding may be indicative of PID. Clinical examination may show no abnormality, or pus may be expressed from urethra, paraurethral ducts or Bartholin’s ducts. The cervix may be inflamed, with mucopurulent discharge and contact bleeding.

Pharyngeal gonorrhoea is the result of receptive orogenital

sex and is usually symptomless.

Gonococcal conjunctivitis is an uncommon complication, presenting with purulent discharge from the eye(s), severe inflammation of the conjunctivae and oedema of the eyelids, pain and photophobia. Gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum presents similarly with purulent conjunctivitis and oedema of the eyelids. Conjunctivitis must be treated

urgently to prevent corneal damage.

Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) is seen

rarely, and typically affects women with asymptomatic

genital infection. Symptoms include arthritis of one or

more joints, pustular skin lesions and fever. Gonococcal

endocarditis has been described.

Investigations

Gram-negative diplococci may be seen on microscopy of

smears from infected sites . Pharyngeal smears are difficult to analyse due to the presence of other diplococci, so the diagnosis must be confirmed by culture or NAAT.

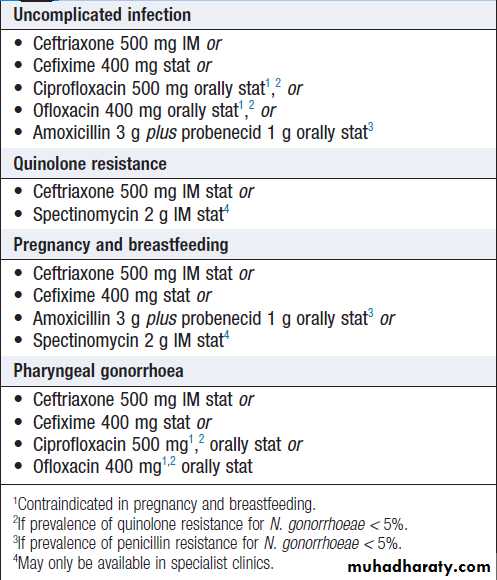

Management of adults

Emerging resistance is making it increasingly difficult

to cure gonorrhoea with a single oral dose of antimicrobials, and recommended treatment in the UK

has changed to intramuscular ceftriaxone 500 mg. The

alternatives listed in Box are less likely to be effective.

Longer courses of antibiotics are required for complicated

infection. Partner(s) of patients with gonorrhea should be seen as soon as possible.

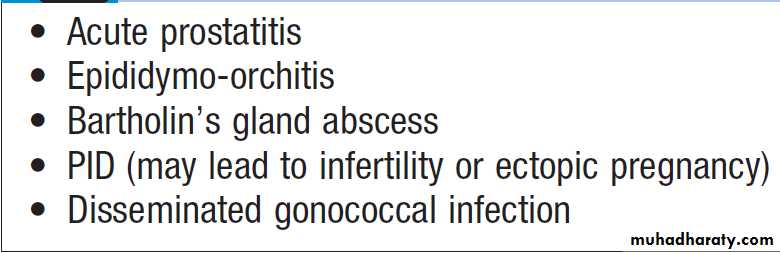

Delay in treatment may lead to complications

Treatment of uncomplicated anogenital

gonorrhoeaComplications of delayed therapy in gonorrhoea

Chlamydial infection

Chlamydial infection in menChlamydia is transmitted and presents in a similar way

to gonorrhoea; however, urethral symptoms are usually

milder and may be absent in over 50% of cases. Conjunctivitis is also milder than in gonorrhoea; pharyngitis does not occur. The incubation period varies from1 week to a few months.

Without treatment, symptoms may resolve but the patient remains infectious for several months. Complications, such as epididymoorchitis and Reiter’s syndrome, or sexually acquired reactive arthropathy (SARA), are rare.

Sexually transmitted pathogens, such as chlamydia or gonococci, are usually responsible for epididymo-orchitis in men aged less than 35 years, whereas bacteria such as Gramnegative enteric organisms are more commonly implicated in older men.

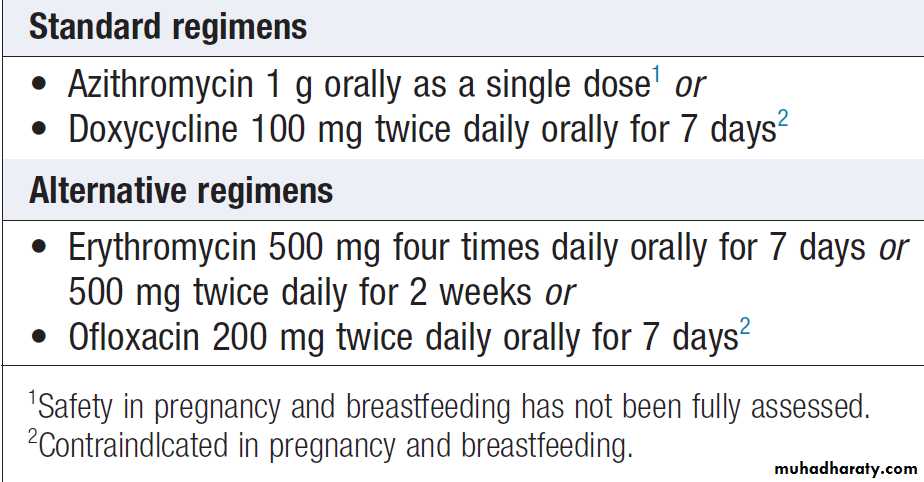

Treatments for chlamydia are listed in Box.

NSU is treated identically.

The partner(s) of men with chlamydia should be treated, even if laboratory tests for chlamydia are negative. Investigation is not mandatory but serves a useful epidemiological purpose; moreover, positive results encourage further attempts at contact-tracing.

Treatment of chlamydial infection

Chlamydial infection in womenThe cervix and urethra are commonly involved. Infection

is asymptomatic in about 80% of patients but may

cause vaginal discharge, dysuria and intermenstrual

and/or postcoital bleeding. Lower abdominal pain and

dyspareunia are features of PID. Examination may

reveal mucopurulent cervicitis, contact bleeding from

the cervix, evidence of PID or no obvious clinical signs.

Treatment options are listed in Box. The patient’s

male partner(s) should be investigated and treated.

Some infections may clear spontaneously but others

persist. PID, with the risk of tubal damage and subsequent

infertility or ectopic pregnancy, is a rare but

important long-term complication.

Other complications include perihepatitis, chronic pelvic pain, conjunctivitis and Reiter’s syndrome or SARA.

Perinatal transmission may lead to ophthalmia neonatorum and/or pneumonia in the neonate.

Other sexually transmitted bacterial infections

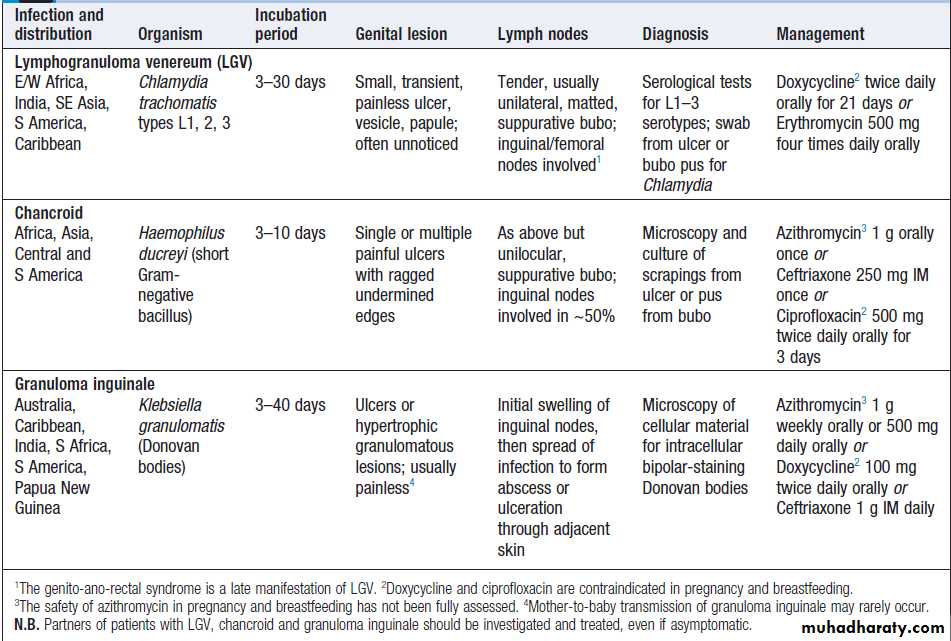

Chancroid, granuloma inguinale and LGV as causes of

genital ulcers in the tropics are described in Box .

LGV is also a cause of proctitis in MSM

Salient features of lymphogranuloma venereum, chancroid and granuloma inguinale (Donovanosis)

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED VIRAL INFECTIONS

Genital herpes simplexInfection with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or

type 2 (HSV-2) produces a wide spectrum of clinical

problems and may facilitate HIV transmission.

Infection is usually acquired sexually (vaginal, anal, orogenital or oro-anal), but perinatal transmission to the

neonate may also occur. Primary infection at the site of

HSV entry, which may be symptomatic or asymptomatic,

establishes latency in local sensory ganglia.

Recurrences, symptomatic or asymptomatic viral shedding, are a consequence of HSV reactivation. The first symptomatic episode is usually the most severe. Although HSV-1 is classically associated with orolabial herpes and HSV-2 with anogenital herpes, HSV-1 now accounts for more than 50% of anogenital infections in the UK.

Clinical features

The first symptomatic episode presents with irritable

vesicles that soon rupture to form small, tender ulcers

on the external genitalia . Lesions at other sites (e.g. urethra, vagina, cervix, perianal area, anus or rectum) may cause dysuria, urethral or vaginal discharge, or anal, perianal or rectal pain. Constitutional symptoms, such as fever, headache and malaise, are common.

Inguinal lymph nodes become enlarged and tender, and there may be nerve root pain in the 2nd and 3rd sacral dermatomes. Extragenital lesions may develop at other sites, such as the buttock, finger or eye, due to auto-inoculation.

Oropharyngeal infection may result from orogenital sex.

Complications, such as urinary retention due to autonomic

neuropathy, and aseptic meningitis, are occasionally

seen.

First episodes usually heal within 2–4 weeks without

treatment; recurrences are usually milder and of shorter

duration than the initial attack.

They occur more oftenin HSV-2 infection and their frequency tends to decrease with time.

Prodromal symptoms, such as irritation or burning at the subsequent site of recurrence, or neuralgic pains affecting buttocks, legs or hips, are commonly seen. The first symptomatic episode may be a recurrence of a previously undiagnosed primary infection. Recurrent episodes of asymptomatic viral shedding are important in the transmission of HSV.

Diagnosis

Swabs are taken from vesicular fluid or ulcers for detection

of DNA by PCR, or tissue culture and typing as either HSV-1 or 2. Electron microscopy of such material will only give a presumptive diagnosis, as herpes group viruses appear similar. Type-specific antibody tests are available but are not sufficiently accurate for general use.

Management

First episode

The following 5-day oral regimens are all recommended

and should be started within 5 days of the beginning of

the episode, or whilst lesions are still forming:

• aciclovir 200 mg five times daily

• famciclovir 250 mg three times daily

• valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily.

Analgesia may be required and saline bathing can be

soothing. Treatment may be continued for longer than 5

days if new lesions develop. Occasionally, intravenous therapy may be indicated if oral therapy is poorly tolerate or aseptic meningitis occurs.

Catheterisation via the suprapubic route is advisable

for urinary retention due to autonomic neuropathybecause the transurethral route may introduce HSV into

the bladder.

Recurrent genital herpes

Symptomatic recurrences are usually mild and may

require no specific treatment other than saline bathing.

For more severe episodes, patient-initiated treatment at

onset, with one of the following 5-day oral regimens,

should reduce the duration of the recurrence:

• aciclovir 200 mg five times daily

• famciclovir 125–250 mg twice daily

• valaciclovir 500 mg twice daily.

In a few patients, treatment started at the onset of

prodromal symptoms may abort recurrence.

Suppressive therapy may be required for patients

with frequent recurrences, especially if these occur at

intervals of less than 4 weeks. Treatment should be

given for a minimum of 1 year before stopping to assess

recurrence rate. About 20% of patients will experience

reduced attack rates thereafter, but for those whose

recurrences remain unchanged, resumption of suppressive

therapy is justified. Aciclovir 400 mg twice daily is

most commonly prescribed.

Management in pregnancy

If her partner is known to be infected with HSV, a pregnantwoman with no previous anogenital herpes should

be advised to protect herself during sexual intercourse

because the risk of disseminated infection is increased

in pregnancy. Consistent condom use during pregnancy

may reduce transmission of HSV. Genital herpes

acquired during the first or second trimester of pregnancy

is treated with aciclovir as clinically indicated.

Although aciclovir is not licensed for use in pregnancy

in the UK, there is considerable clinical evidence to support its safety. Third-trimester acquisition of infection has been associated with life-threatening haematogenous dissemination and should be treated with aciclovir.

Vaginal delivery should be routine in women who

are symptomless in late pregnancy. Caesarean section is

sometimes considered if there is a recurrence at the

beginning of labour, although the risk of neonatal herpes

through vaginal transmission is very low.

Caesarean section is often recommended if primary infection occurs after 34 weeks because the risk of viral shedding is very high in labour.

Human papillomavirus and anogenital warts

Human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA typing has demonstrated over 90 genotypes , of which HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16 and HPV-18 most commonly infect the genital tract through sexual transmission. It is important to differentiate between the benign genotypes (HPV-6 and 11) that cause anogenital warts, and genotypes such as16 and 18 that are associated with dysplastic conditions and cancers of the genital tract but are not a cause of benign warts.

All genotypes usually result in subclinical infection of the genital tract rather than clinically obvious lesions affecting penis, vulva, vagina, cervix, perineum or anus.

Clinical features

Anogenital warts caused by HPV may be single or multiple, exophytic, papular or flat. Perianal warts , whilst being more commonly found in MSM, are alsofound in heterosexual men and in women. Rarely, a

giant condyloma (Buschke–Lِwenstein tumour) develops

with local tissue destruction. Atypical warts should

be biopsied. In pregnancy, warts may dramatically

increase in size and number, making treatment difficult.

Rarely, they are large enough to obstruct labour and,in this case, delivery by Caesarean section will be required. Rarely, perinatal transmission of HPV leads to anogenital warts, or possibly laryngeal papillomas, in the neonate.

Management

The use of condoms can help prevent the transmission

of HPV to non-infected partners, but HPV may affect

parts of the genital area not protected by condoms. Vaccination against HPV infection has been introduced and

is in routine use in several countries. There are two types

of vaccine:

• A bivalent vaccine (Cervarix®) offers protection

against HPV types 16 and 18, which account for

approximately 75% of cervical cancers in the UK.

• A quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil®) offers additional

protection against HPV types 6 and 11, which

account for over 90% of genital warts.

Both types of vaccine have been shown to be highly

effective in the prevention of cervical intra-epithelialneoplasia in young women, and the quadrivalent vaccine

has also been shown to be highly effective in protecting

against HPV-associated genital warts (Box). It is

currently recommended that HPV vaccination should be

administered prior to the onset of sexual activity, typically

at age 11–13, in a course of three injections. In the

UK, only girls are offered vaccination, and it should be

noted that this approach will not protect HPV transmission

for MSM. As neither vaccine protects against all

oncogenic types of HPV, cervical screening programmes

will still be necessary.

A variety of treatments are available for established

disease, including the following:

• Podophyllotoxin, 0.5% solution or 0.15% cream

(contraindicated in pregnancy), applied twice daily

for 3 days, followed by 4 days’ rest, for up to 4 weeks is suitable for home treatment of external warts.

• Imiquimod cream (contraindicated in pregnancy),

applied 3 times weekly (and washed off after 6–10

hours) for up to 16 weeks, is also suitable for home

treatment of external warts.

• Cryotherapy using liquid nitrogen to freeze warty

tissue is suitable for external and internal warts but

often requires repeated clinic visits.

• Hyfrecation – electrofulguration that causes superficial charring – is suitable for external and internal warts. Hyfrecation results in smoke plume which contains HPV DNA and has the potential to cause respiratory infection in the operator/patient.

Masks should be worn during the procedure and adequate extraction of fumes should be provided.

• Surgical removal. Refractory warts, especially

pedunculated perianal lesions, may be excised

under local or general anaesthesia.

HPV vaccination and precancerous cervical

intra-epithelial neoplasia

Molluscum contagiosum

Infection by molluscum contagiosum virus, both sexualand non-sexual, produces flesh-coloured umbilicated

hemispherical papules usually up to 5 mm in diameter

after an incubation period of 3–12 weeks . Larger lesions may be seen in HIV infection . Lesions are often multiple and, once established in an individual, may spread by auto-inoculation. They are found on the genitalia, lower abdomen and upper thighs when sexually acquired. Facial lesions are highly suggestive of underlying HIV infection. Diagnosis is made on clinical grounds and by expression of the central core, in which the typical pox-like viral particles can be seen on electron microscopy (differentiating molluscum contagiosum from genital warts).

Typically, lesions persist for an average of 2 years before spontaneous resolution occurs.

Treatment regimens are therefore cosmetic; they include cryotherapy, hyfrecation, topical applications of 0.15% podophyllotoxin cream (contraindicated in pregnancy) or expression of the central core.

Viral hepatitis

The hepatitis viruses A–D may be sexually transmitted:• Hepatitis A (HAV). Insertive oro-anal sex, insertive

digital sex, insertive anal sex and multiple sexual partners have been linked with HAV transmission in MSM. HAV transmission in heterosexual men and women is also possible through oro-anal sex.

• Hepatitis B (HBV). Insertive oro-anal sex, anal sex and multiple sexual partners are linked with HBV infection in MSM. Heterosexual transmission of HBV is well documented and commercial sex workers are at particular risk.

Hepatitis D (HDV) may also be sexually transmitted.

• Hepatitis C (HCV). Sexual transmission of HCV is

well documented in MSM, but less so in heterosexuals. Sexual transmission is less efficient than for HBV.The sexual partner(s) of patients with HAV and HBV

should be seen as soon as possible and offered immunization where appropriate. Patients with HAV should

abstain from all forms of unprotected sex until noninfectious. Those with HBV should likewise abstain

from unprotected sex until they are non-infectious or

until their partners have been vaccinated successfully.

No active or passive immunisation is available for protection against HCV but the consistent use of condoms

is likely to protect susceptible partners.

Active immunization against HAV and HBV should be offered to susceptible people at risk of infection.

Many STI clinics offer HAV immunisation to MSM along with routine HBV immunisation; a combined HAV and HBV vaccine is available.