Essentials of

Clinical Periodontology

and

Periodontics

System requirement:

•

Windows XP or above

•

Power DVD player (Software)

•

Windows media player version 10.0 or above

•

Quick time player version 6.5 or above

Accompanying DVD ROM is playable only in Computer and not in DVD player.

Kindly wait for few seconds for DVD to autorun. If it does not autorun then please do the following:

•

Click on my computer

•

Click the drive labelled JAYPEE and after opening the drive, kindly double click the file Jaypee

DVD Content

Procedure on

Live Periodontal Surgery

Essentials of

Clinical Periodontology

and

Periodontics

Shantipriya Reddy

BDS MDS (Periodontia)

Professor

Dr Syamala Reddy Dental College and Hospital

Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

SECOND

EDITION

JAYPEE BROTHERS MEDICAL PUBLISHERS (P) LTD

• New Delhi • Ahmedabad • Bengaluru • Chennai • Hyderabad • Kochi • Kolkata • Lucknow • Mumbai • Nagpur

Published by

Jitendar P Vij

Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd

B-3 EMCA House, 23/23B Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi

110 002, India

Phones: +91-11-23272143, +91-11-23272703, +91-11-23282021, +91-11-23245672

Rel: +91-11-32558559, Fax: +91-11-23276490, +91-11-23245683

e-mail: jaypee@jaypeebrothers.com

Visit our website: www.jaypeebrothers.com

Branches

•

2/B, Akruti Society, Jodhpur Gam Road Satellite

Ahmedabad

380 015, Phones: +91-79-26926233, Rel: +91-79-32988717

Fax: +91-79-26927094, e-mail: ahmedabad@jaypeebrother.com

•

202 Batavia Chambers, 8 Kumara Krupa Road, Kumara Park East

Bengaluru

560 001, Phones: +91-80-22285971, +91-80-22382956, +91-80-22372664

Rel: +91-80-32714073, Fax: +91-80-22281761, e-mail: bangalore@jaypeebrothers.com

•

282 IIIrd Floor, Khaleel Shirazi Estate, Fountain Plaza, Pantheon Road

Chennai

600 008, Phones: +91-44-28193265, +91-44-28194897, Rel: +91-44-32972089

Fax: +91-44-28193231, e-mail: chennai@jaypeebrothers.com

•

4-2-1067/1-3, 1st Floor, Balaji Building, Ramkote Cross Road

Hyderabad

500 095, Phones: +91-40-66610020, +91-40-24758498, Rel:+91-40-32940929

Fax:+91-40-24758499, e-mail: hyderabad@jaypeebrother.com

•

No. 41/3098, B & B1, Kuruvi Building, St. Vincent Road

Kochi

682 018, Kerala, Phones: +91-484-4036109, +91-484-2395739, +91-484-2395740

e-mail: kochi@jaypeebrothers.com

•

1-A Indian Mirror Street, Wellington Square

Kolkata

700 013, Phones: +91-33-22651926, +91-33-22276404, +91-33-22276415

Rel: +91-33-32901926, Fax: +91-33-22656075, e-mail: kolkata@jaypeebrothers.com

•

Lekhraj Market-III, B-2, Sector-4, Faizabad Road, Indira Nagar

Lucknow

226 016, Phones: +91-0522-3040554, e-mail: lucknow@jaypeebrothers.com

•

106 Amit Industrial Estate, 61 Dr SS Rao Road, Near MGM Hospital, Parel

Mumbai

400 012, Phones: +91-22-24124863, +91-22-24104532, Rel: +91-22-32926896

Fax: +91-22-24160828, e-mail: mumbai@jaypeebrothers.com

•

“KAMALPUSHPA” 38, Reshimbag, Opp. Mohota Science College, Umred Road

Nagpur

440 009 (MS), Phone: Rel: +91-712-3245220, Fax: +91-712-2704275

e-mail: nagpur@jaypeebrothers.com

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

© 2008, Shantipriya Reddy

All rights reserved. No part of this publication and DVD ROM should be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any

form or by any means: electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the

author and the publisher.

This book has been published in good faith that the materials provided by author is original. Every effort is made to ensure

accuracy of material, but the publisher, printer and author will not be held responsible for any inadvertent error(s). In case of any

dispute, all legal matters are to be settled under Delhi jurisdiction only.

First Edition: 2006

Second Edition:

2008

ISBN 81-8448-148-9

Typeset at JPBMP typesetting unit

Printed at Ajanta Offset

Dedicated to

My late grandfather, who had believed in my abilities, it is because of

whom I chose this profession.

My grandmother, for her constant support.

My father and mother, for always being there.

My uncle for his continuous encouragement.

My husband for his unique mentorship.

My daughter and son for being so understanding

Any book requires the help and assistance of others in order to be completed successfully. In this regard, I would

like to extend special thanks to all those who had helped to accomplish this goal. First and foremost I would

like to thank my student Dr Deepti Sinha for drawing those excellent diagrams inserted in this book. Special

thanks must go to all my colleagues, postgraduate students, (Drs) Jeeth Rai, Keshav, Satish, Shabeer and Anil,

Mamatha and Sumaira, who have helped me to prepare the manuscript. I would like to extend my special thanks

to Dr Anil Kumar who helped me to collect the photographs used in this book. I am very grateful to Dr Prasad

MGS and Dr Sabna Kakarala for being so generous with their clinical photographs which helped to enhance

the overall excellence of this edition. Dr Divakaranand and Dr Rudrakshi’s helped in typing the manuscript of

this edition is greatly appreciated. My heartfelt thanks to Dr Srinivas for helping me in writing the chapter on

Oral Malodor. I would also like to thank Dr Ashwath (Smart desq navigators) for helping me with animation

photographs of various suturing techniques. The excellent co-operation of the publisher is also greatly acknowledged.

Acknowledgements

Preface to the Second Edition

I am extremely happy to present the second edition of Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics.

Three new chapters including glossary of periodontal terminology has been included in this edition. Chapters

on Host Modulation and Oral Malodor are written with same clarity and simplicity, that has been religiously

followed in the previous edition. More photographs have been included to make the student understand the

subject better.

I thank all the fellow colleagues and students who have supported me with useful suggestions while revising

the first edition. I hope to receive the same support and suggestions for the second edition also.

Shantipriya Reddy

This basic text when conceived in the year 2003 has been written in an attempt to make our understanding

of periodontal disease accessible to the undergraduate students, general practitioners and dental hygienists. The

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics is a learning textbook intended to serve the needs of several

groups of dental care professionals and is written with credibility and readability maintained at every level.

Undergraduate students especially will find it useful in integrating the concepts they have been taught in a more

elaborate way. Clarity and simplicity in language has been my objective while writing this book. The organization

of the chapters and the key points with review questions at the end of every chapter serve as a programmed-

guide for the reader.

This text can be of help for the academicians to re-think the modes of presenting information and also as

a model to test whether the students have grasped the concepts they have been taught and are able to use

them in a practical manner.

All the efforts have been made to make the text as accurate as possible and the information provided in

this text was in accordance with the standards accepted at the time of publication. In order to attain these goals,

suggestions as well as critiques from many students and clinicians have been received and utilized.

Much of the style in this textbook is compact with adequate bibliographies. The reader is advised to use them

to gain greater depth of knowledge. The way of periodontist is hard and this book will reflect the difficulty of

that path. I hope that this textbook will fulfill all the requirements and expectations of the students and practitioners

as this is a special branch of our profession. The field of periodontics remains a work in progress.

Shantipriya Reddy

Preface to the First Edition

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF PERIODONTOLOGY

Various forms of gingival and periodontal diseases have affected the human race since the dawn of history. In

the earlier historical records almost all the writings have information regarding the diseases affecting oral cavity

and majority of it is about periodontal diseases.

Early Civilizations

Summerians of 3,000 BC first practiced oral hygiene. Babylonians and Assyrians, who also have suffered from

periodontal diseases, have treated themselves using gingival massage combined with various herbal medications.

Research on embalmed bodies of the ancient Egyptians pointed out that periodontal disease was the most common

of all the diseases. Medical writings of the time Ebers Papyrus had many references to gingival diseases and also

contain various prescriptions for strengthening the teeth and gums.

The medical works of ancient India, Susruta Samhita and Charaka Samhita describe severe periodontal disease

with loose teeth and purulent discharge from the gingiva and the treatment advised was to use a stick that is

bitter for cleaning teeth.

Periodontal disease was also discussed in Ancient Chinese books. The oldest book written in 2,500 BC describes

various conditions affecting oral cavity. Gingival inflammation, periodontal abscesses and gingival ulcerations are

described in detail. They were among the earliest people to use the toothbrush to clean the teeth.

Middle Ages

The systematic therapeutic approach was not developed until the middle ages. This was a period of golden age

of Arabic science and medicine. Avicenna and Albucasis made a refined, novel approach to surgical work. Albucasis

had a clear understanding of calculus as etiology of periodontal disease and described the technique of removing

it. He had also developed a set of scalers for removing calculus. He also wrote in detail on other treatment

procedures like extraction of teeth, splinting loose teeth with gold wire, etc.

18th Century

Modern dentistry was developed in 18th century. Pierre Fauchard in 1678 who is rightly considered as Father

of Modern Dentistry designed periodontal instruments and described the technique in detail. His book “The

Surgeon Dentist” published in 1728 presented all aspects of dental practice (i.e. restorative dentistry, prosthodontics,

oral surgery, periodontics and orthodontics). Fauchard wrote in that, confections and sweets destroy the teeth

by sticking to the surfaces producing an acid. John Hunter (1728-93) known as an anatomist, surgeon and

pathologist of 18th century wrote a book entitled “The Natural History of the Human Teeth” describing the

anatomy of the teeth and their supporting structures with clear illustrations.

Prolog

Thomas Berdmore (1740-85) known as “Dentist to His Majesty” published the Treatise in the disorders and

deformities of the teeth and gums. He not only offered detailed descriptions of instrumentation but also stressed

on prevention.

19th Century

A German born dentist, Leonard Korecker in his paper Philadelphia Journal of Medicine and Physical Sciences

mentioned the need for oral hygiene by the patient, to be performed in the morning and after every meal using

an astringent powder and a toothbrush.

Levi Spear Parmly was considered the Father of Oral Hygiene and the Inventor of Dental Floss. The name

“Pyorrhea Alveolaris” was used to describe periodontal disease. John W Riggs was the first individual to limit

his practice to periodontics and was considered the first specialist in this field. Periodontitis was known as “Riggs

disease.” Several major developments took place in the second half of the 19th century starting the era called

modern medicine.

The first was the discovery of anesthesia and second scientific breakthrough was made by Louis Pasteur who

established the Germ Theory of Disease. The third scientific finding was the discovery of radiographs by Wilhelm

Roentgen.

Also the late 19th century has witnessed a proper understanding of the pathogenesis of periodontal disease

based on histopathologic studies. GV Black in 1899 gave the term gelatinous microbic plaque and described

its relationship to caries. Xenophon recognized ANUG in 4th century BC Salomon Robicsek developed a surgical

technique called gingivectomy.

20th Century

Early 20th century witnessed major changes in the treatment of periodontal disease. Gottlieb published extensive

microscopic studies of periodontal diseases in humans. It was realized that, removal of calculus and other deposits

was not enough. In addition, removal of periodontal pockets was necessary to control the disease.

Leonard Widman and Newman described flap surgery for the removal of periodontal pockets. Removal of

bone was considered essential at that time.

After World War II, the focus was on periodontal research and this led to a better understanding to the pathological,

microbiological and immunological aspects of periodontal disease.

The first workshop in periodontology was conducted in 1951. It was realized at that time, scientific methods

should be introduced in the periodontal research. Subsequent workshops conducted in periodontics has witnessed

significant scientific contributions in the field of periodontics.

JOURNALS OF PERIODONTOLOGY

The various journals of periodontology available are:

• The Journal of Periodontology by Robert. J.Genco.

• Journal of Periodontal Research by Isao Ishikawa, Jorgen Slots, Maurizio Tonetti

• Journal of Clinical Periodontology by Jan Lindhe.

• Periodontology 2000 by Jorgen Slots.

• International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry in India by Myron Nevins.

• Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology.

xiv

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

Contents

Part I: The Normal Periodontium

Chapter 1: Anatomy and Development of the Structures

of Periodontium, 3

Introduction, 3

External Anatomic Features, 3

Development of Periodontium, 4

Early Development of Cementum, 4

Later Development of Cementum, 5

Development of Junctional Epithelium, 6

Chapter 2: Biology of Periodontal Tissues, 8

Introduction, 8

The Gingiva, 8

Macroscopic Features, 8

Marginal Gingiva, 8

Gingival Sulcus, 9

Attached Gingiva, 9

Interdental Gingiva, 9

Microscopic Features, 10

Morphologic Characteristics of the Different Areas of

Gingival Epithelium, 11

Cells of the Basal Layer, 11

Stratum Spinosum, 11

Stratum Granulosum, 12

Stratum Corneum, 12

Oral Sulcular Epithelium, 12

Junctional Epithelium, 12

Epithelium-Connective Tissue Interface, 13

Supra-alveolar Connective Tissue, 14

Cells, 14

Fibers, 14

Principal Fibers, 15

Secondary Fibers, 15

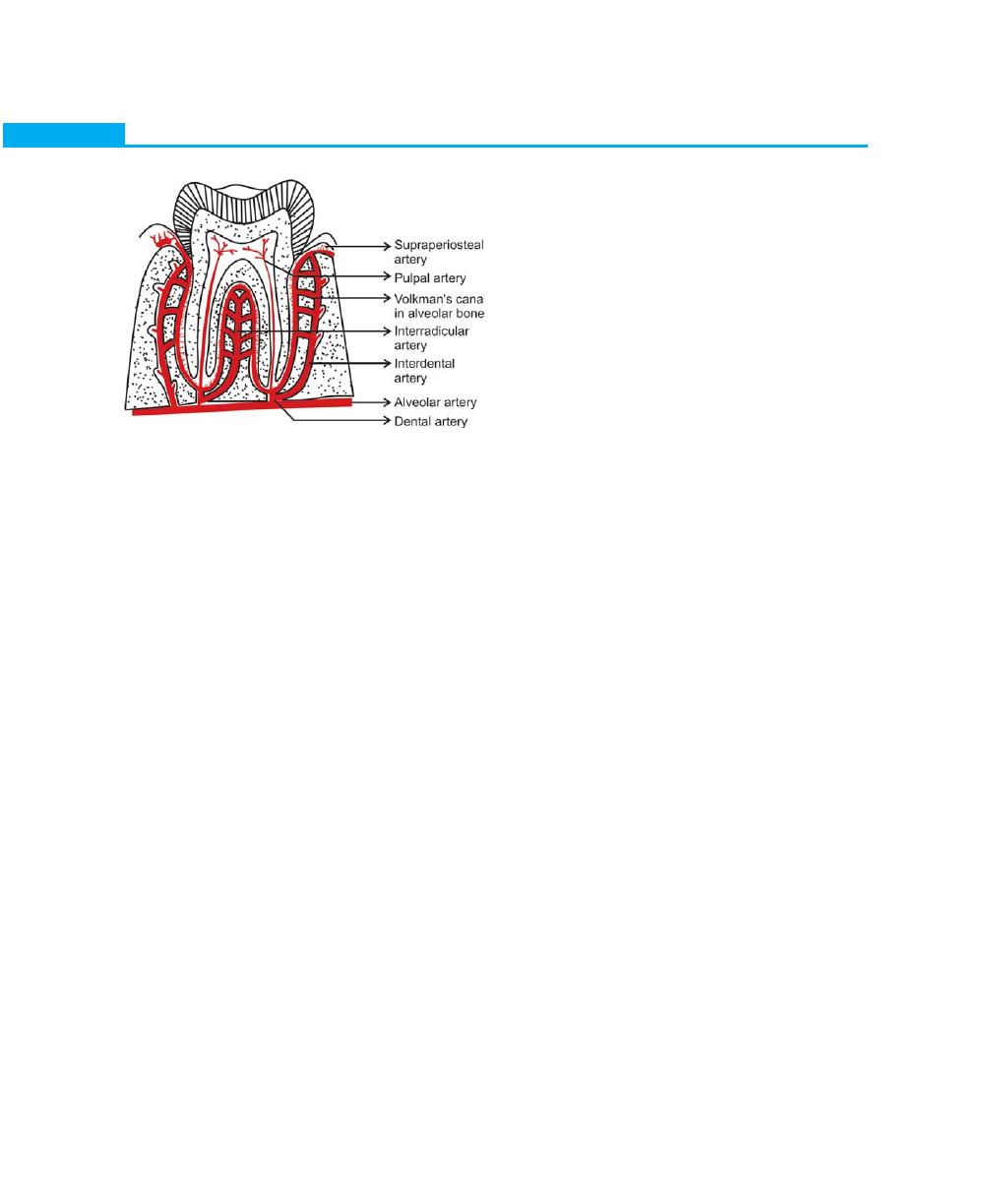

Blood Supply, Lymphatics and Nerves, 16

Periodontal Ligament, 16

Definition, 16

Structure, 16

Synthetic Cells, 17

Resorptive Cells, 17

Epithelial Cell Rests of Malassez, 17

Extracellular Components, 18

Fibers, 18

Principal Fibers, 18

Ground Substance, 19

Development of Principal Fibers, 19

Structure Present in the Connective Tissue, 20

Functions of Periodontal Ligament, 20

Clinical Considerations, 21

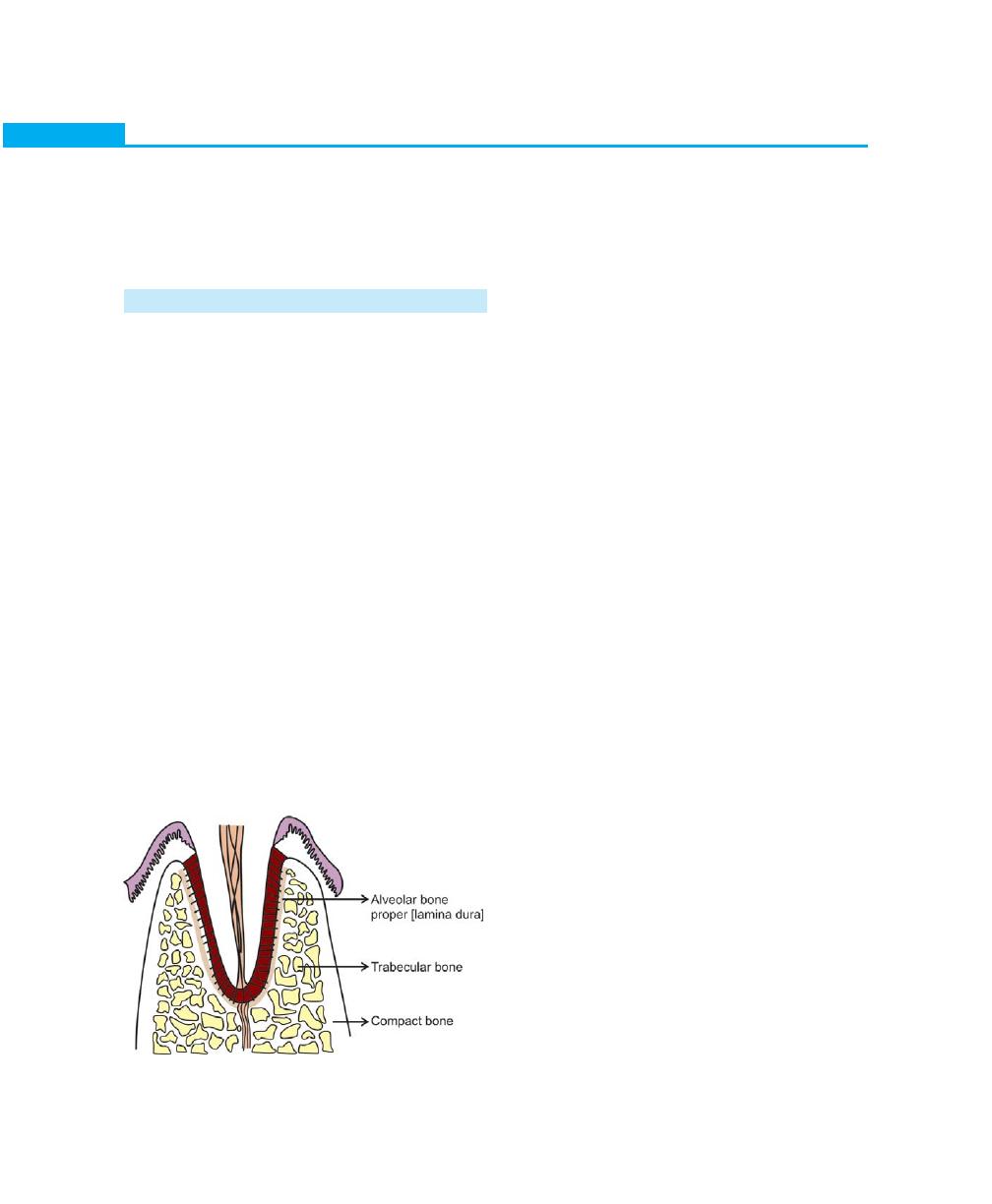

Alveolar Bone, 22

Definition, 22

Parts of Alveolar Bone, 22

Composition of Alveolar Bone, 22

Osseous Topography, 23

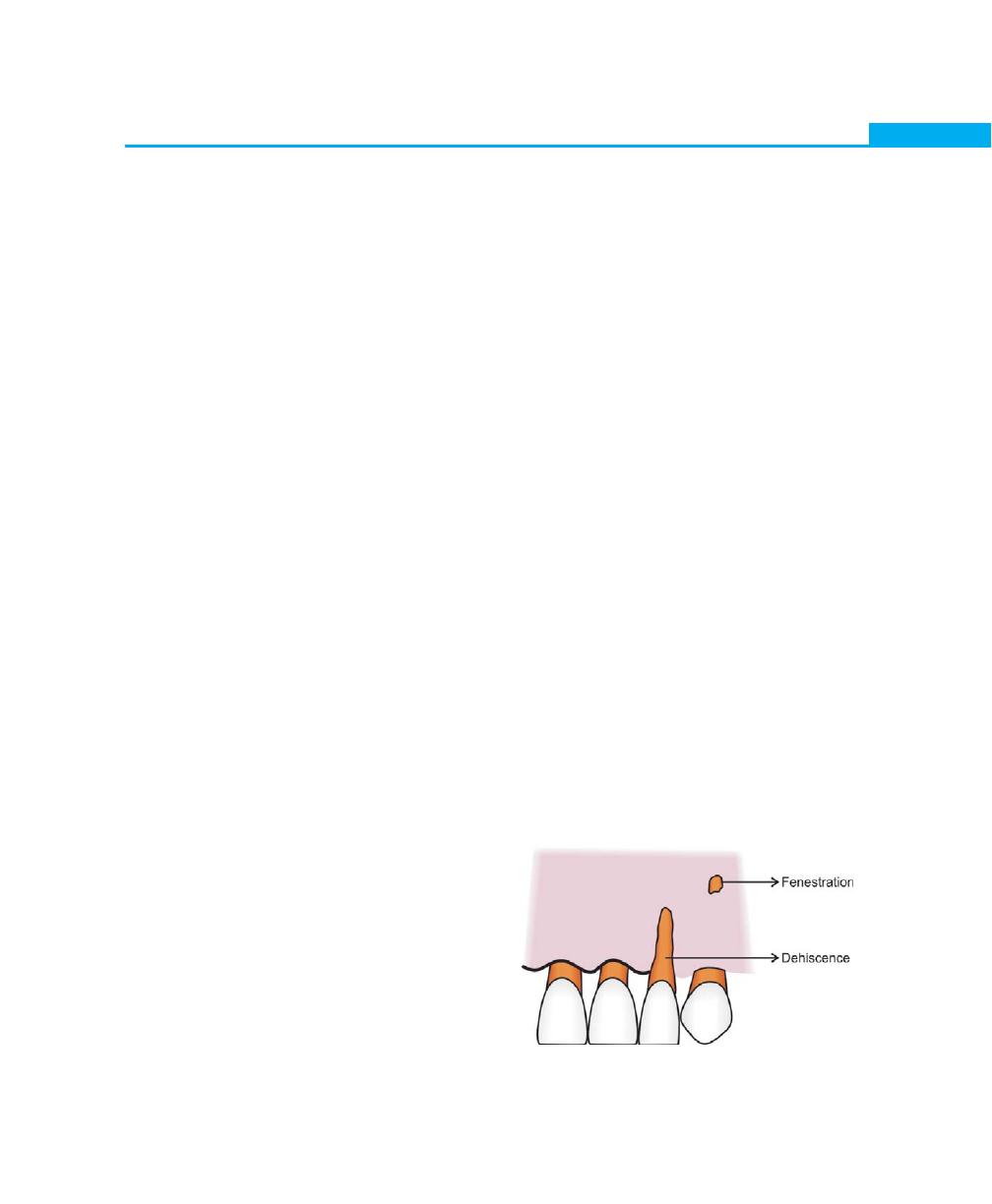

Fenestrations and Dehiscences, 23

Blood Supply to the Bone, 24

Clinical Considerations, 25

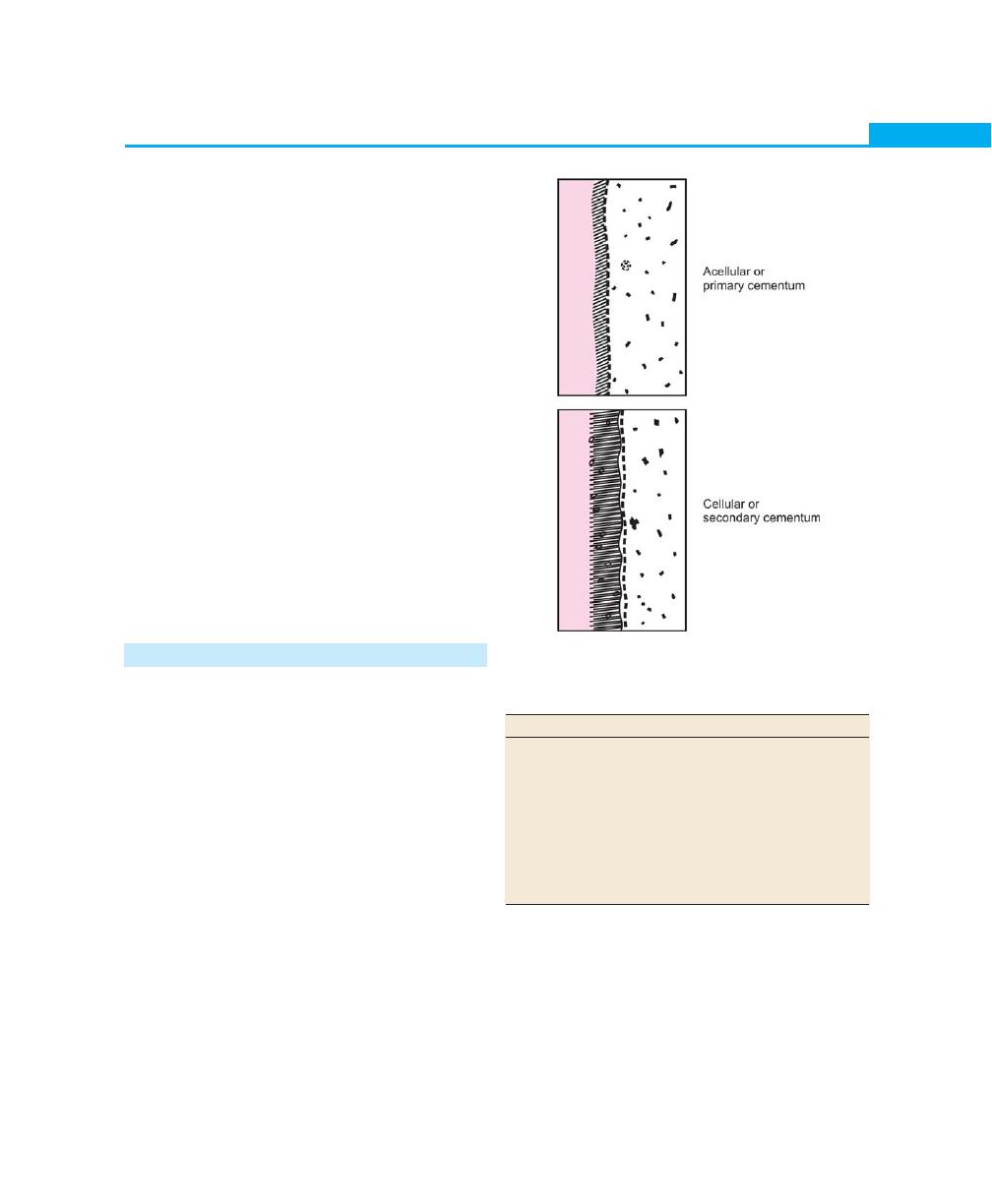

Cementum, 25

Definition, 25

Classification, 25

Functions, 26

Composition, 26

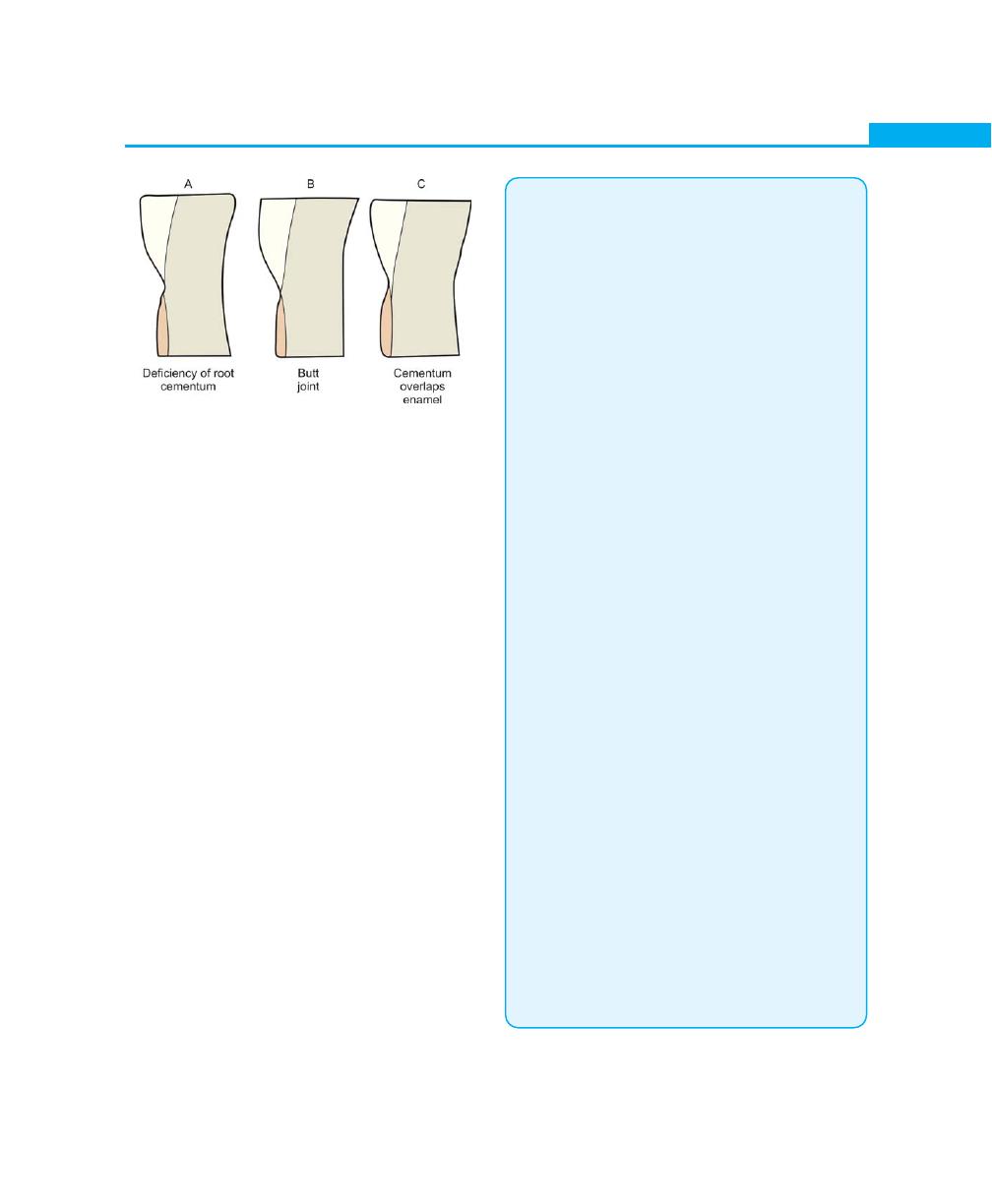

Cementoenamel Junction, 26

Cemental Resorption and Repair, 27

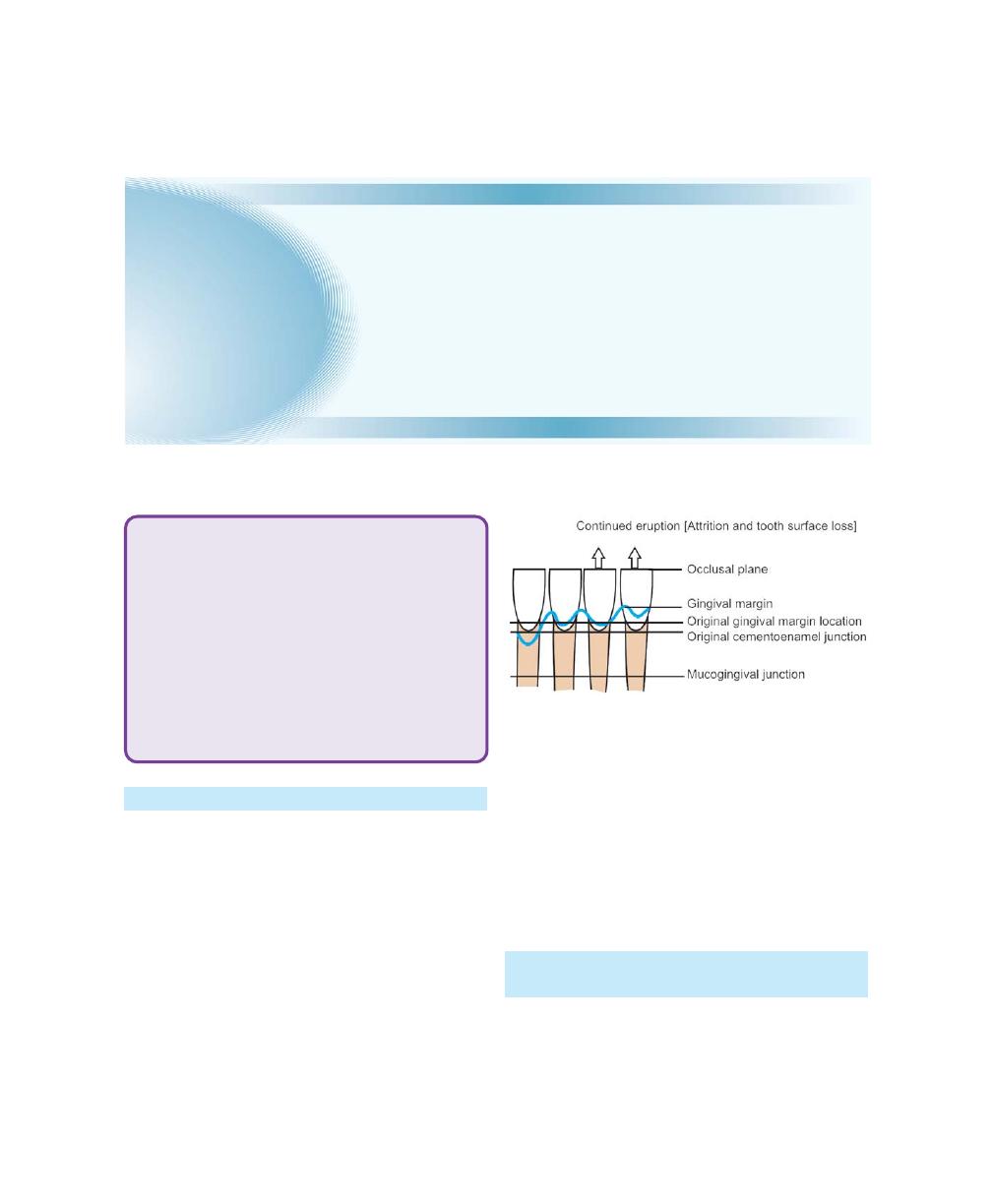

Chapter 3: Periodontal Structures in Aging Humans, 30

General Effects of Aging, 30

Skin, 30

Bone, 30

Age Changes in the Periodontium, 30

Oral Mucosa, 30

Periodontal Ligament, 31

Alveolar Bone and Cementum, 31

Bacterial Plaque and Immune Response, 31

Effects of Aging on the Progression of Periodontal Diseases, 31

Effects of Treatment on the Aging Individuals, 31

xvi

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

Part II: Classification and Epidemiology of

Periodontal Diseases

Chapter 4: Classification Systems of Periodontal

Diseases, 35

Need for Classification, 35

Current Classification Systems of Periodontal Diseases,35

World Workshop in Clinical Periodontics (1988), 35

World Workshop in Clinical Periodontics (1989), 36

Genco (1990), 36

Ranney (1993), 36

European Workshop on Periodontology (1993), 36

AAP 1999 (International Workshop of Periodontal

Disease), 37

Synopsis of Types and Characteristics of Gingival

Diseases, 38

Synopsis of Types and Characteristics of Periodontal

Diseases, 39

Chapter 5:

Epidemiology of Gingival and Periodontal

Diseases, 41

Definition, 41

Types of Epidemiologic Research, 41

Descriptive Study, 41

Analytical Study, 42

Experimental Epidemiology, 42

Index, 42

Definition, 42

Purposes and Uses of Index, 42

Characteristics of Index, 43

Various Indices Used to Assess Periodontal Problems, 43

To Assess Gingival Inflammation, 44

Papillary Marginal Attachment (PMA), 44

Gingivitis Component of Periodontal Disease, 44

Gingival Index by Loe H and Sillness J (1963), 44

Indices of Gingival Bleeding, 45

Sulcular Bleeding Index, 45

Papillary Bleeding Index, 45

Bleeding Points Index, 45

Interdental Bleeding Index, 45

Gingival Bleeding Index, 45

Indices Used to Measure Periodontal Destruction, 46

Russell’s Periodontal Index, 46

Periodontal Disease Index, 46

Extent and Severity Index, 47

Radiographic Approach, 47

The Periodontitis Severity Index, 47

Indices Used to Measure Plaque Accumulation, 47

Plaque Component of Periodontal Disease

Index, 47

Simplified Oral Hygiene Index, 48

Turesky-Gilmore-Glickman, 49

Plaque Index, 49

Modified Navy Plaque Index, 49

Plaque-free Score, 50

Papillary Bleeding on Probing, 50

Indices Used to Measure Calculus, 51

Calculus Component of Simplified Oral Hygiene

Index, 51

Probe Method of Calculus Assessment, 51

Calculus Surface Index, 51

Marginal Line Calculus Index, 51

Indices Used to Assess Treatment Needs, 51

Gingival Periodontal Index, 51

Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs,

52

Periodontal Treatment Need System, 52

Part III: Etiopathogenesis

Chapter 6:

Periodontal Microbiology (Dental Plaque), 57

Definition, 57

Dental Plaque as a Biofilm, 57

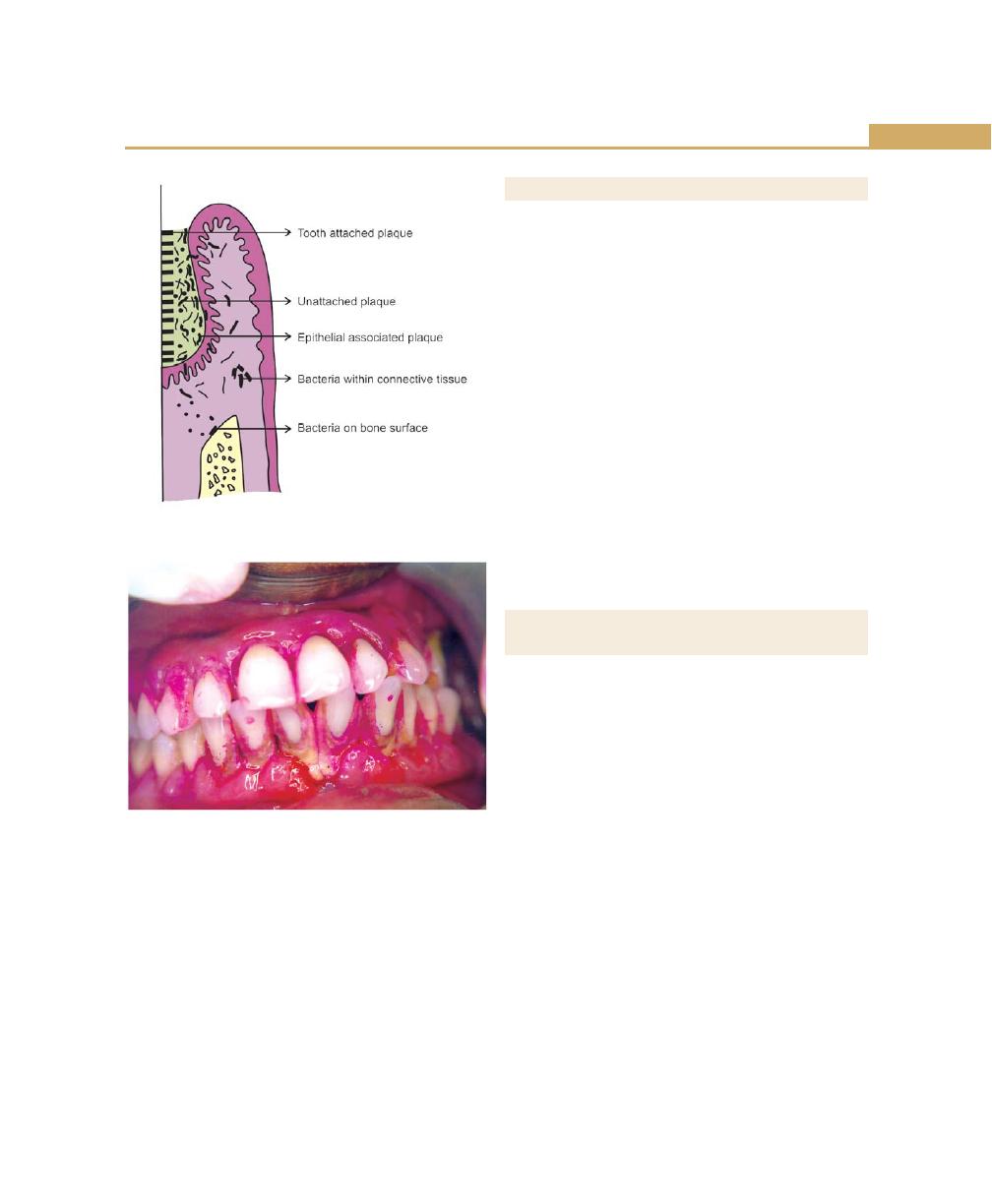

Types of Dental Plaque, 57

Supragingival Plaque, 58

Subgingival Plaque, 58

Tooth-associated Subgingival Plaque, 58

Epithelium-associated Subgingival Plaque, 58

Connective Tissue-associated Plaque, 59

Composition of Dental Plaque, 59

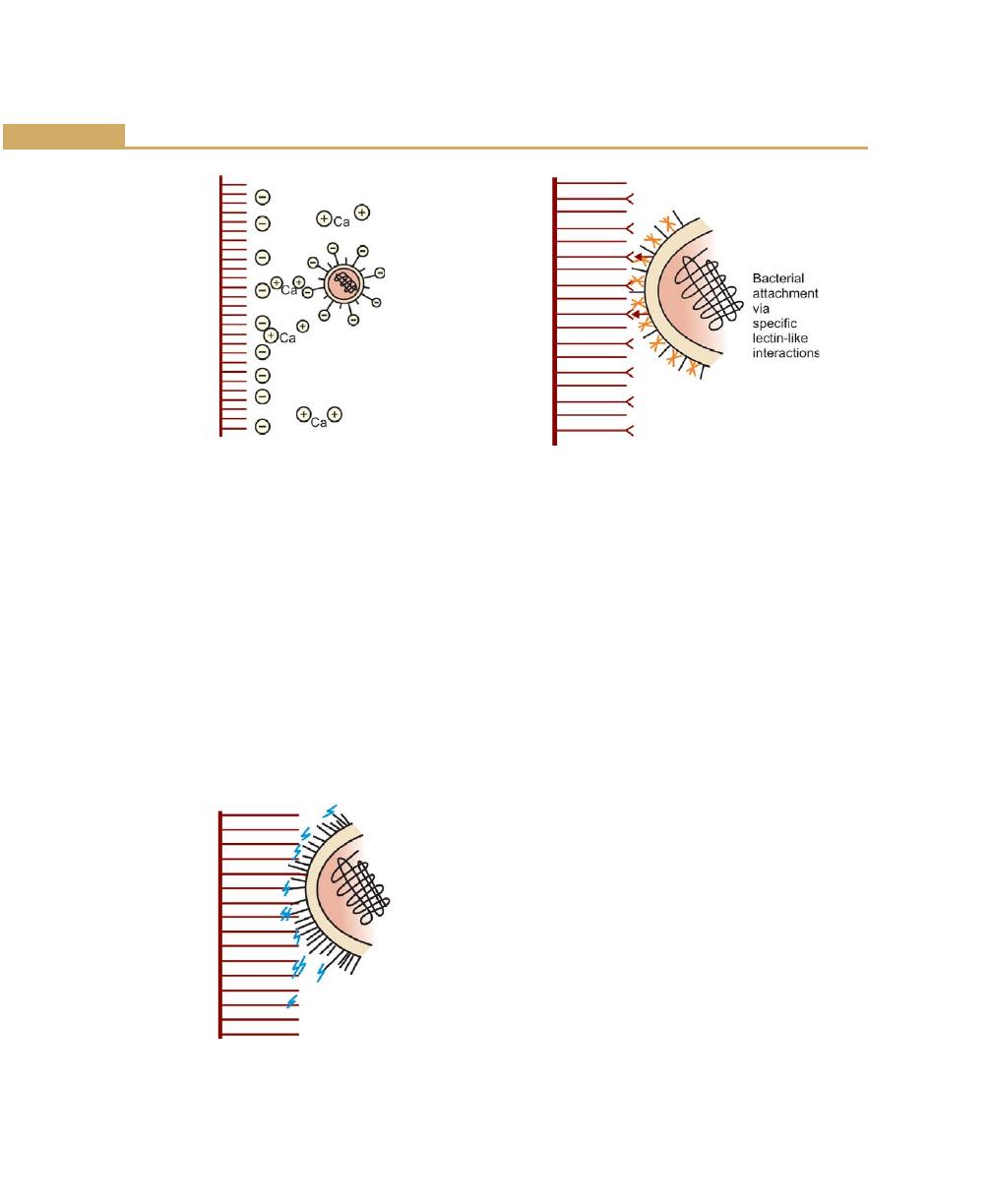

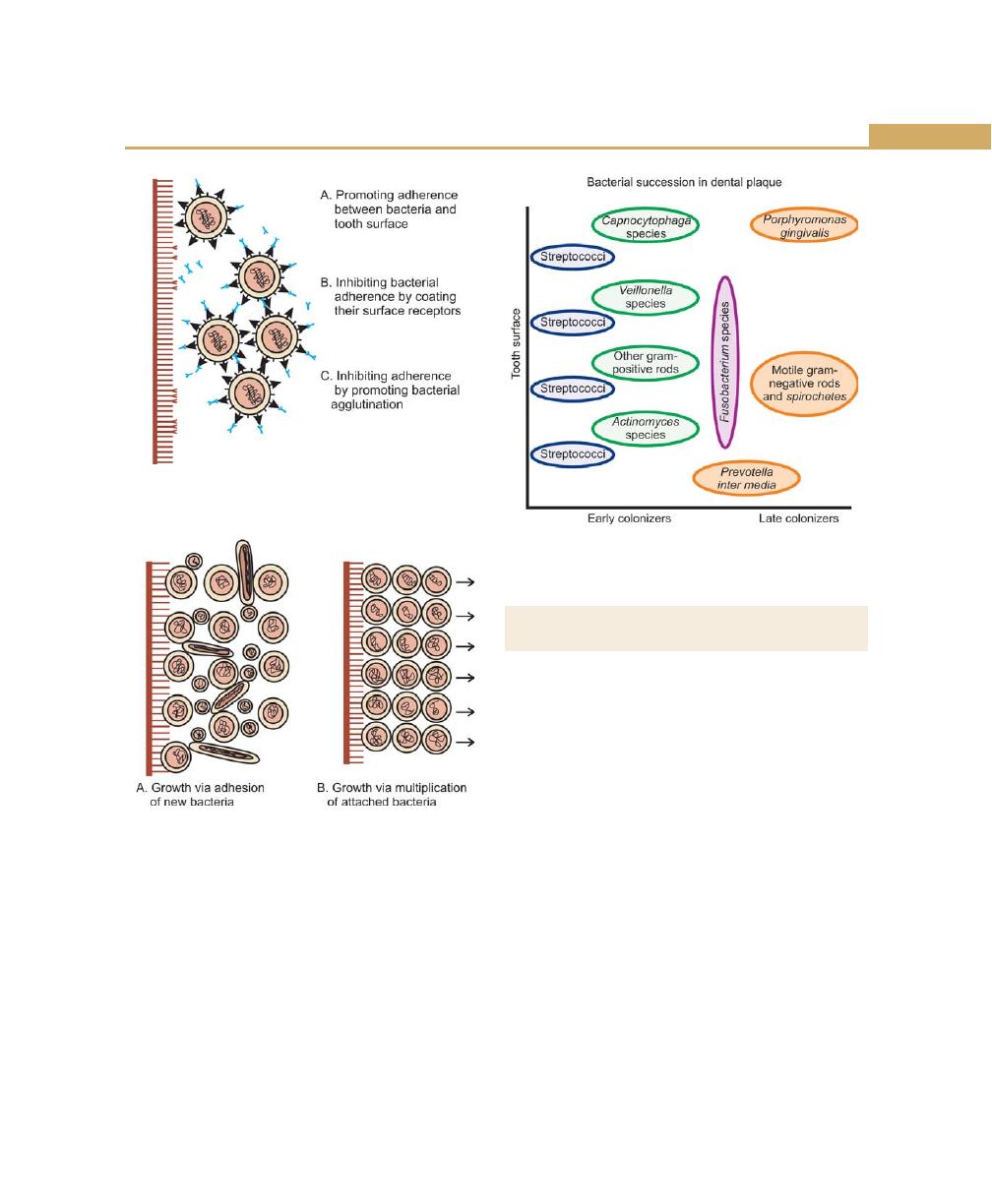

Formation/Development of Dental Plaque, 59

Structural and Microscopic Properties of Plaque, 61

Clinical Significance of Plaque, 62

Microbial Specificity of Periodontal Diseases, 62

Non-specific Plaque Hypothesis, 62

Specific Plaque Hypothesis, 62

What Makes Plaque Pathogenic, 63

Microorganisms Associated with Periodontal Diseases, 63

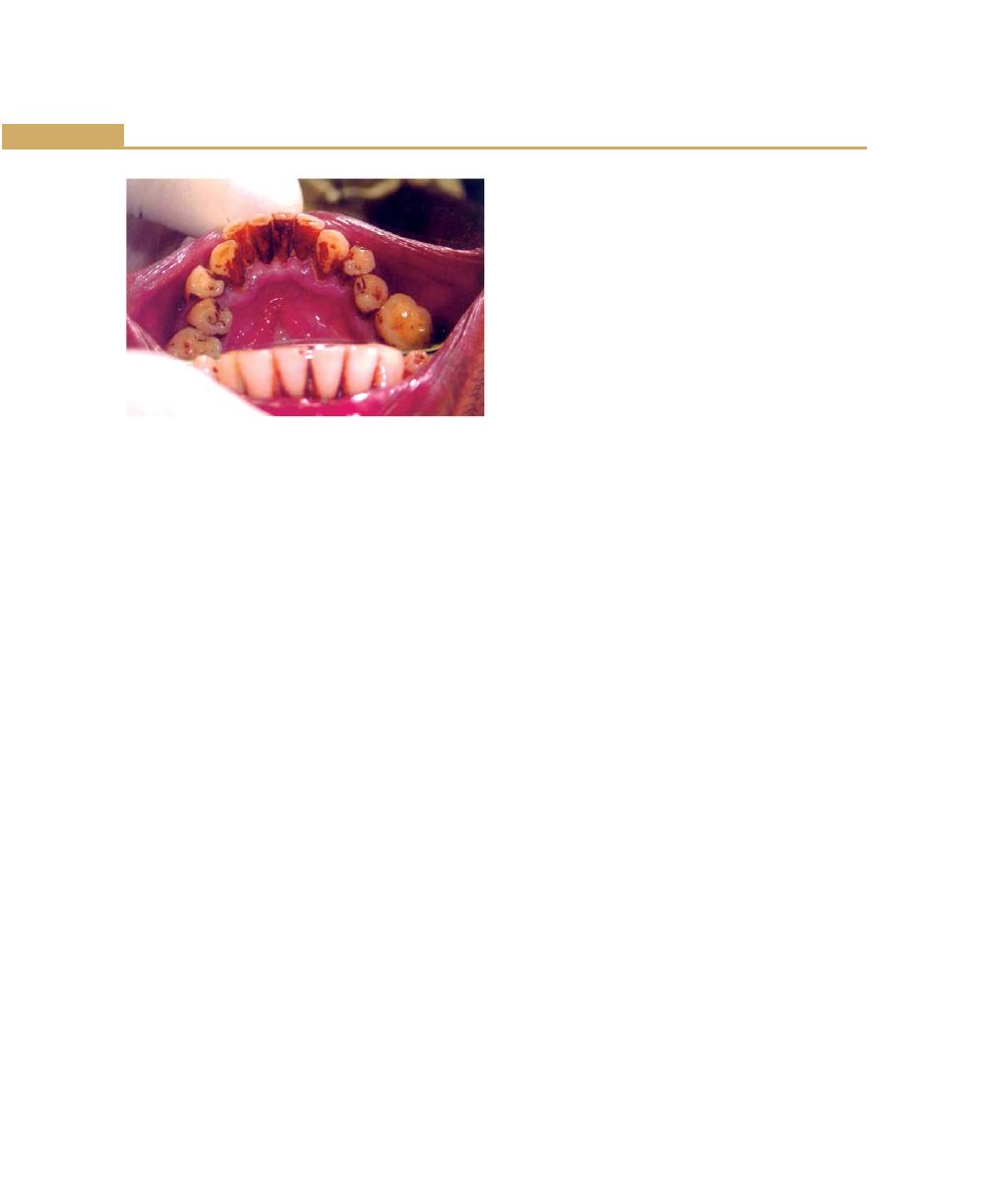

Chapter 7: Calculus and Other Etiological Factors, 66

Calculus, 66

Definition, 66

Types, 66

Supragingival Calculus, 66

Subgingival Calculus, 66

Structure, 67

Composition, 67

Difference Between Supragingival and Subgingival

Calculus, 68

Formation of Calculus, 68

Pathogenic Potential of Calculus in Periodontal

Diseases, 69

Other Contributing Etiological Factors Including Food

Impaction, 69

Iatrogenic Factors, 69

Faulty Restorations, 69

Margins of Restorations, 69

Contour of Restorations, 69

Occlusion, 70

xvii

Contents

Material, 70

Design of Removable Partial Dentures, 70

Periodontal Problems Associated with Orthodontic

Therapy, 71

Food Impaction, 71

Unreplaced Missing Teeth, 71

Malocclusion, 72

Habits, 72

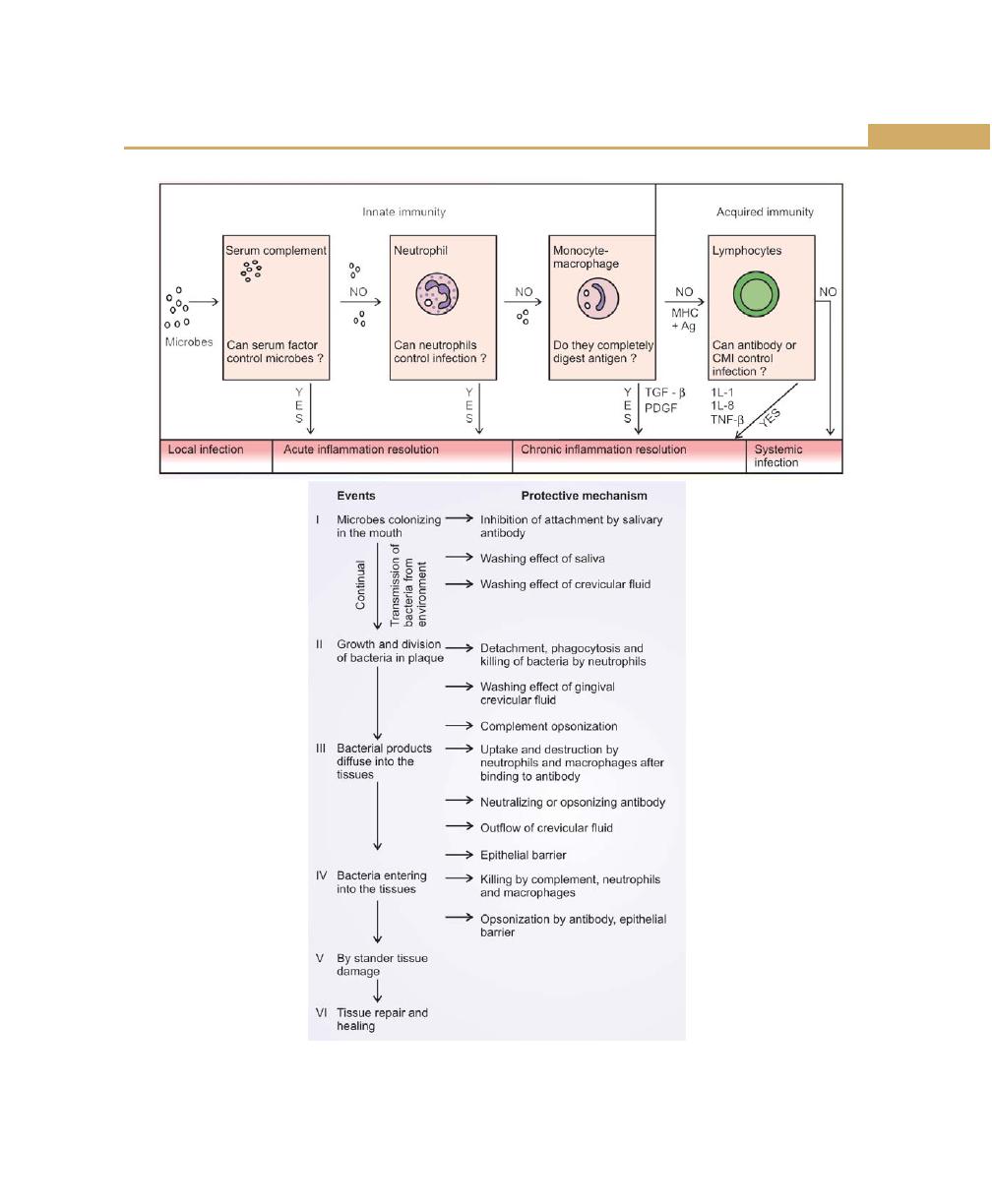

Chapter 8: Host Response: Basic Concepts, 76

Introduction, 76

Role of Saliva in the Host Defence, 76

Gingival Epithelium, 77

Gingival Crevicular Fluid, 77

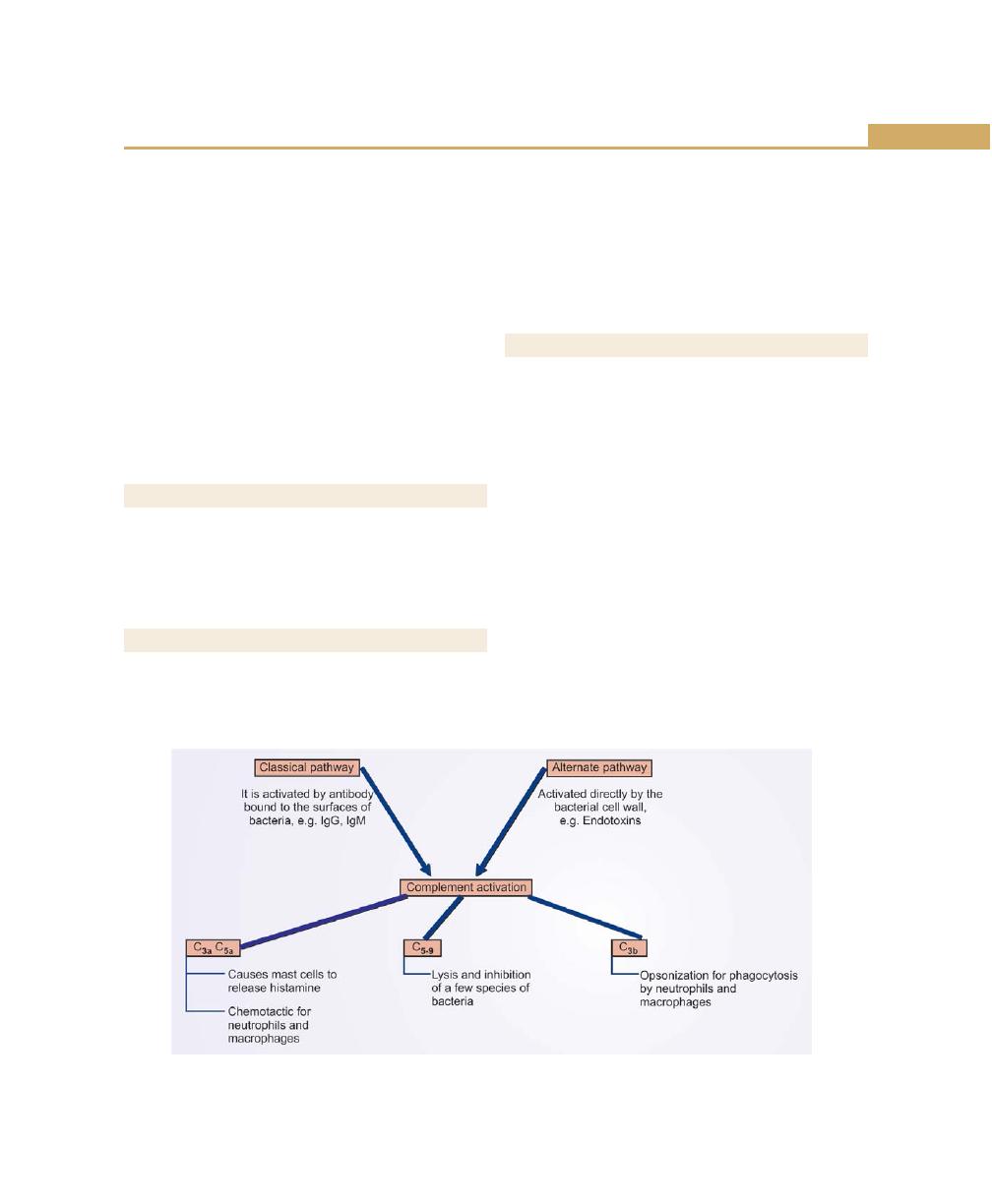

Complement, 77

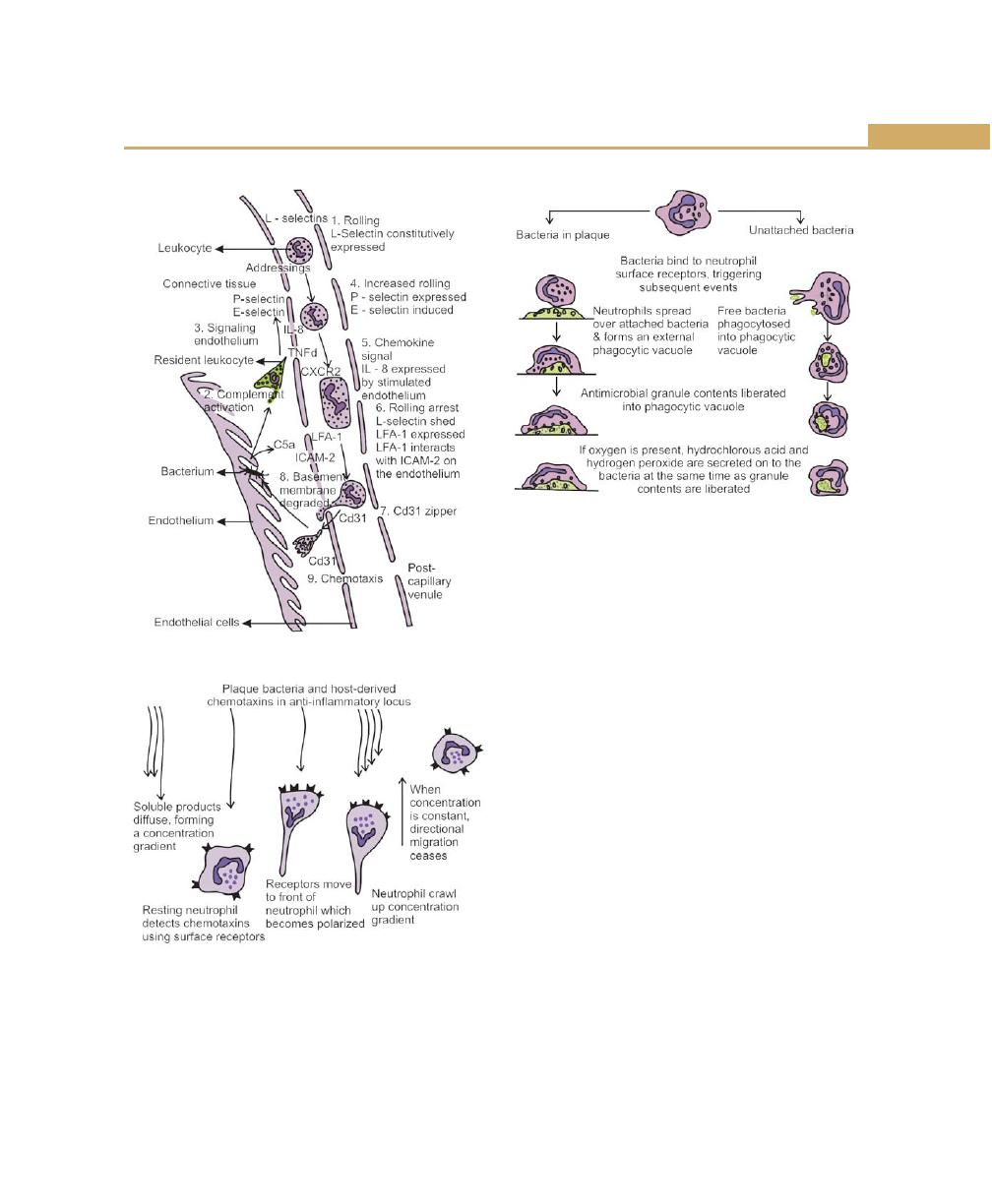

Inflammatory Cell Response, 78

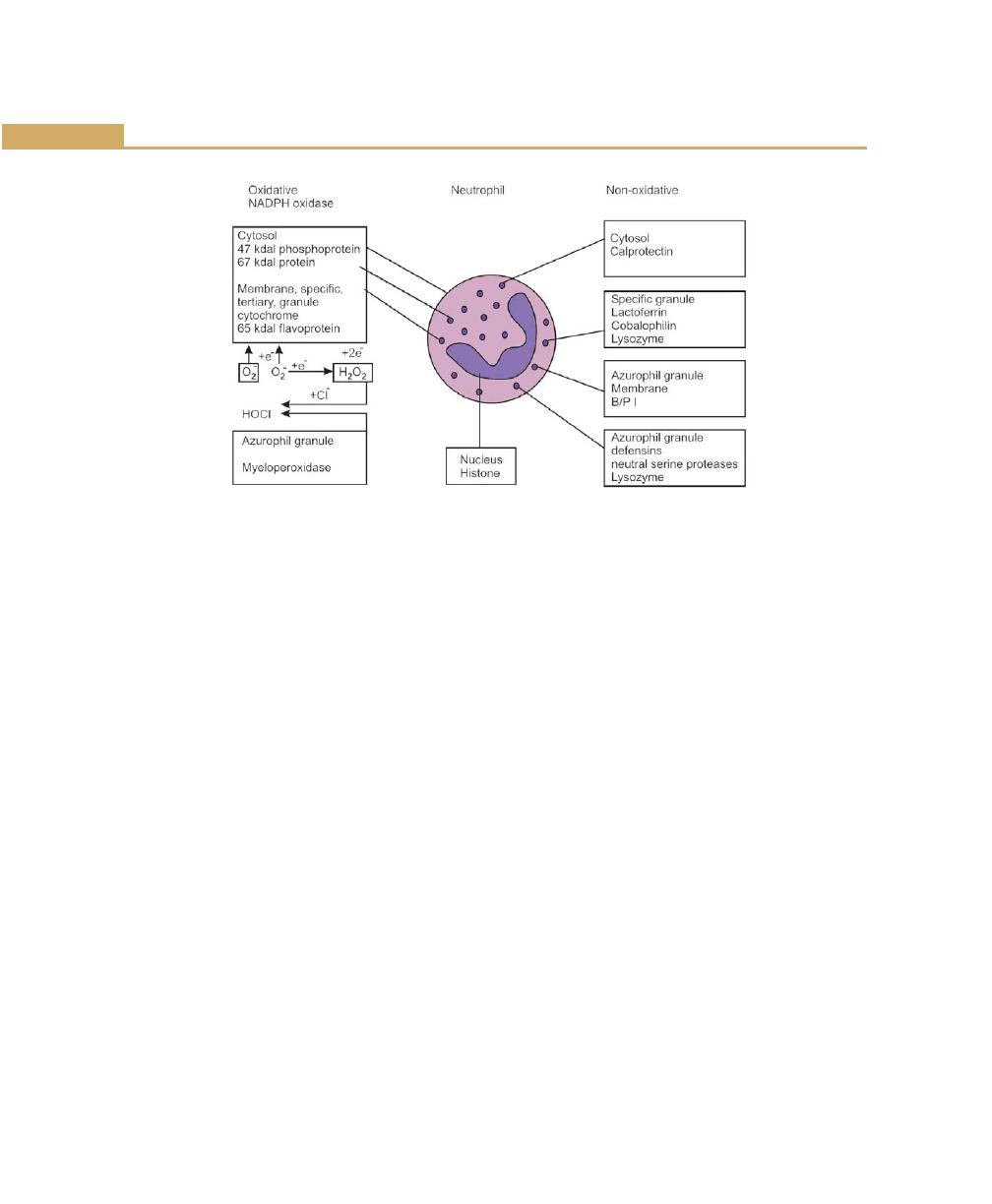

Neutrophils, 78

Neutrophil Disorder Associated with Periodontal Disease,

80

Periodontal Diseases Associated with Neutrophil

Disorders, 80

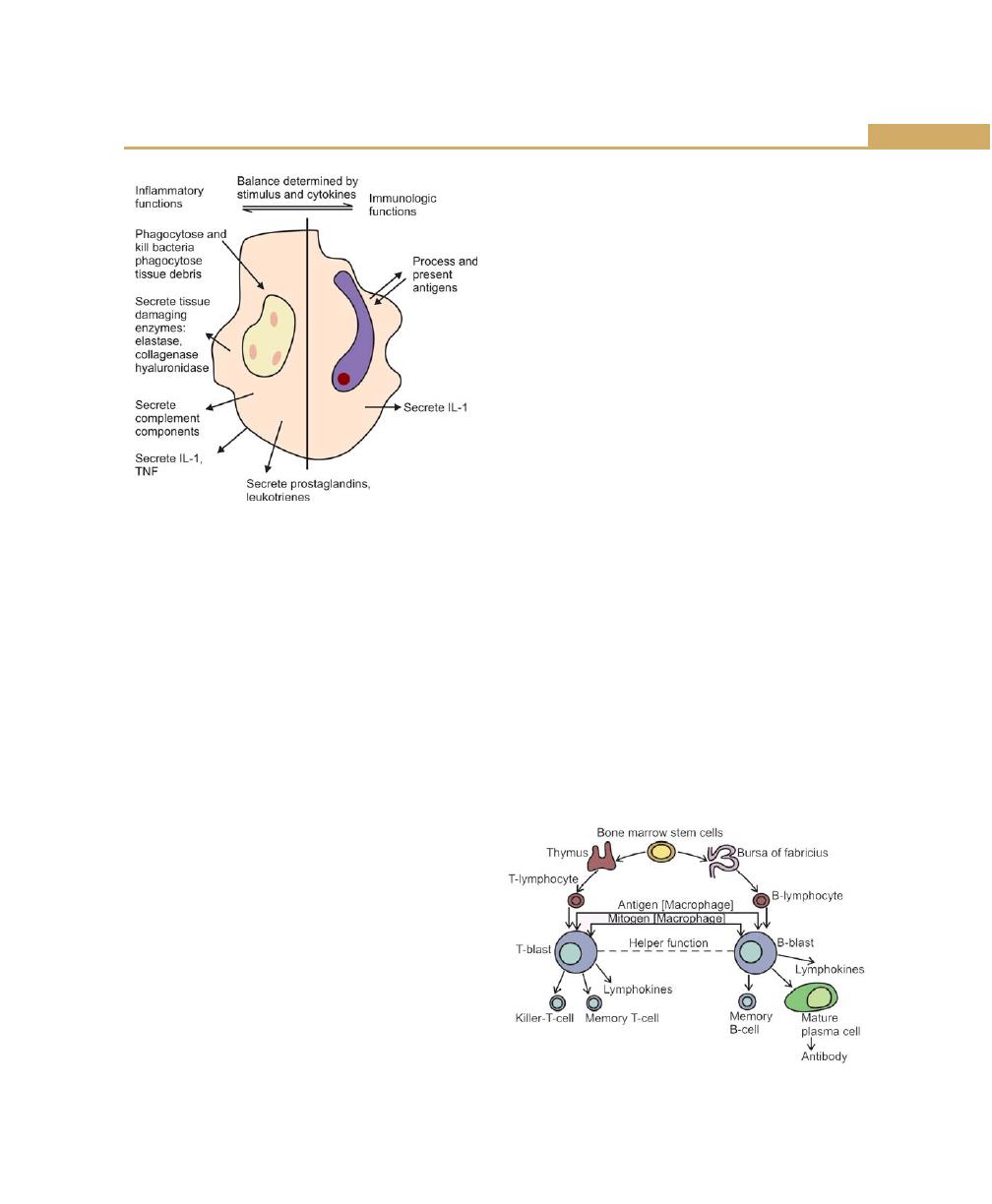

Functions of Macrophages, 81

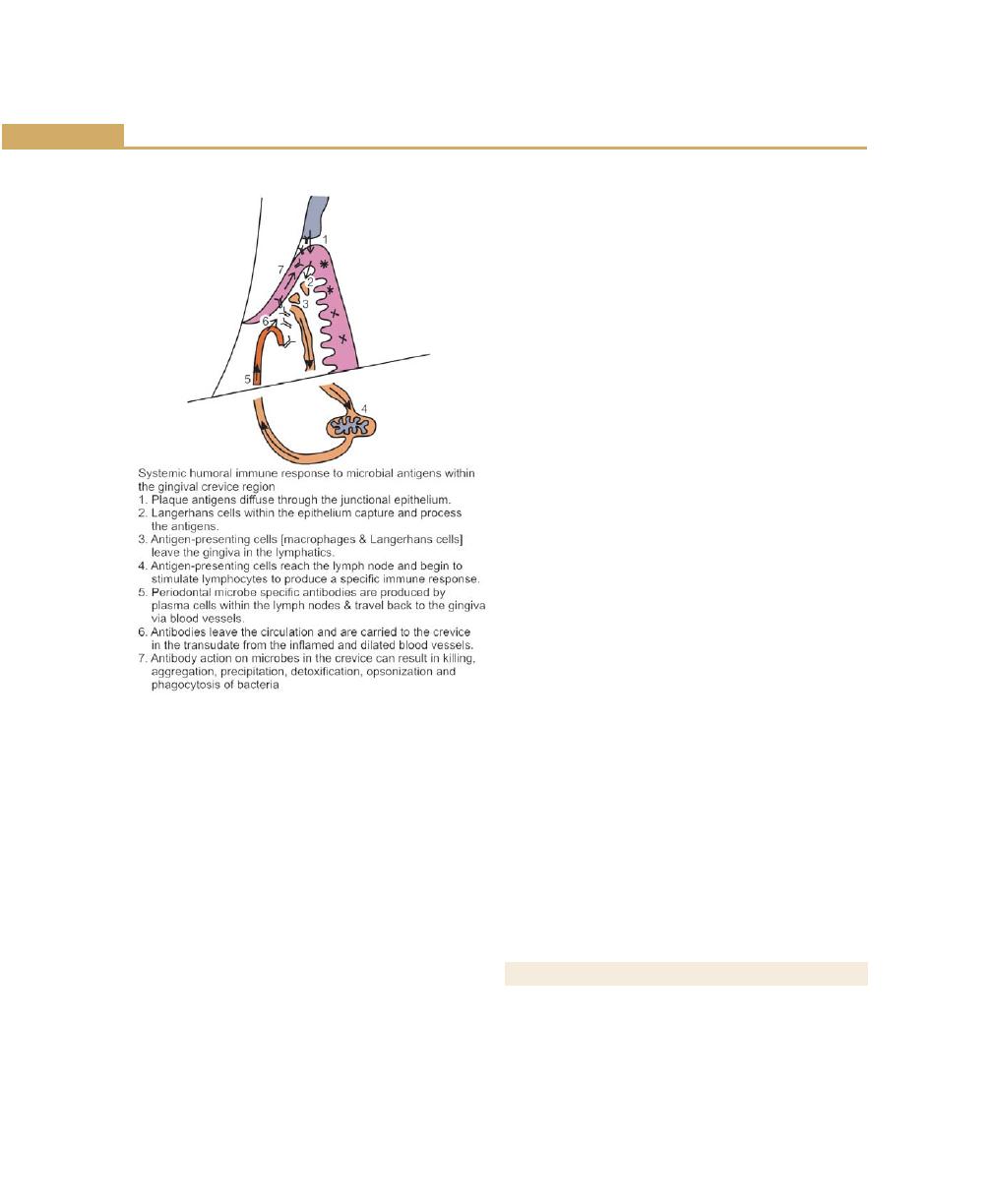

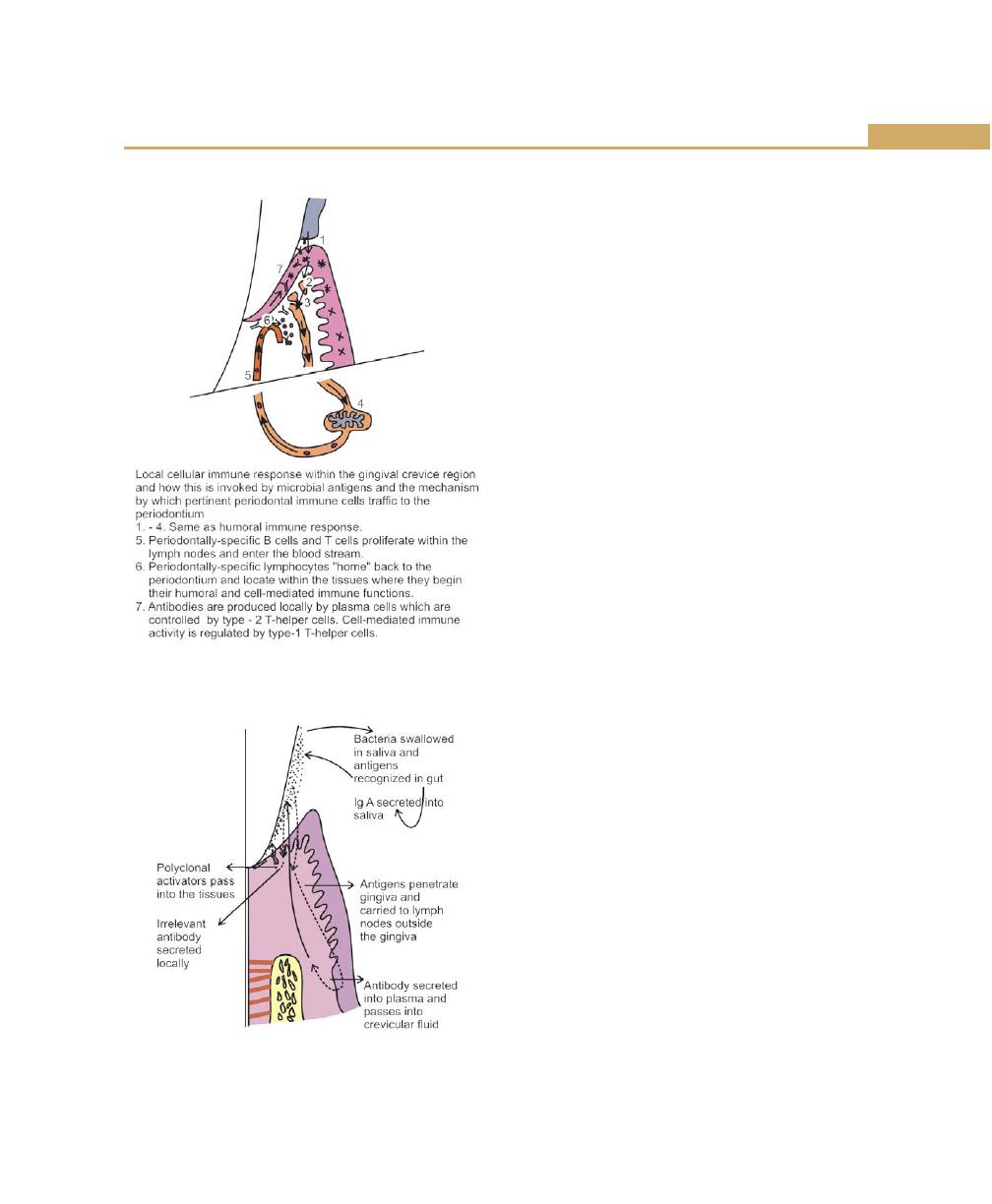

Immunological Mechanism, 82

Anaphylactic Reactions, 83

Cytotoxic Reactions, 84

Arthus Reactions, 84

Delayed Hypersensitivity, 84

Chapter 9: Trauma from Occlusion, 87

Physiologic Adaptive Capacity of the Periodontium to

Occlusal Forces, 87

Trauma from Occlusion, 87

Definition and Terminology, 87

Types, 88

Signs and Symptoms, 88

Histologic Changes, 89

Injury, 89

Repair, 89

Adaptive Remodeling, 89

Reversibility of Traumatic Lesion, 90

Effect of Increased Occlusal Forces on Pulp, 90

Role of the Trauma from Occlusion in the Progression of

Periodontal Disease, 90

Pathologic Tooth Migration, 92

Chapter 10: Role of Systemic Diseases in the Etiology

of Periodontal Diseases, 95

Introduction, 95

Dietary and Nutritional Aspects of Periodontal Disease,

95

Consistency of Diet, 95

Protein Deficiency, 96

Vitamin D Deficiency, 96

Effects of Hematological Disorders on Periodontium, 97

White Blood Cell Disorders, 97

Neutropenias, 97

Leukemia, 98

Thrombocytopenic Purpura, 99

Disorders of WBC Function, 99

Red Blood Cell Disorders, 99

Anemia, 99

Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders, 100

Diabetes mellitus, 100

Thyroid Gland, 101

Pituitary Gland, 101

Parathyroid Glands, 101

Gonads, 102

Cardiovascular Diseases, 103

Arteriosclerosis, 103

Antibody Deficiency Disorders, 103

AIDS, 103

HIV, 103

Other Systemic Diseases, 104

Bismuth Intoxication, 104

Lead Intoxication, 104

Mercury Intoxication, 104

Psychosomatic Disorders, 104

Chapter 11: Oral Malodor, 106

Introduction, 106

Classification of Halitosis, 106

Pseudo-halitosis, 106

Halitophobia, 107

Etiology, 107

Causes for Physiologic Halitosis, 107

Causes for Pathologic Halitosis, 107

Diagnosis of Halitosis, 107

Clinical Examination, 107

Measurement of Oral Malodor, 107

Organoleptic Method, 107

Gas Chromatography, 108

Halimeters, 108

BANA, 108

Chemiluminescence, 108

Treatment and Management of Oral Malodor, 108

Summary, 109

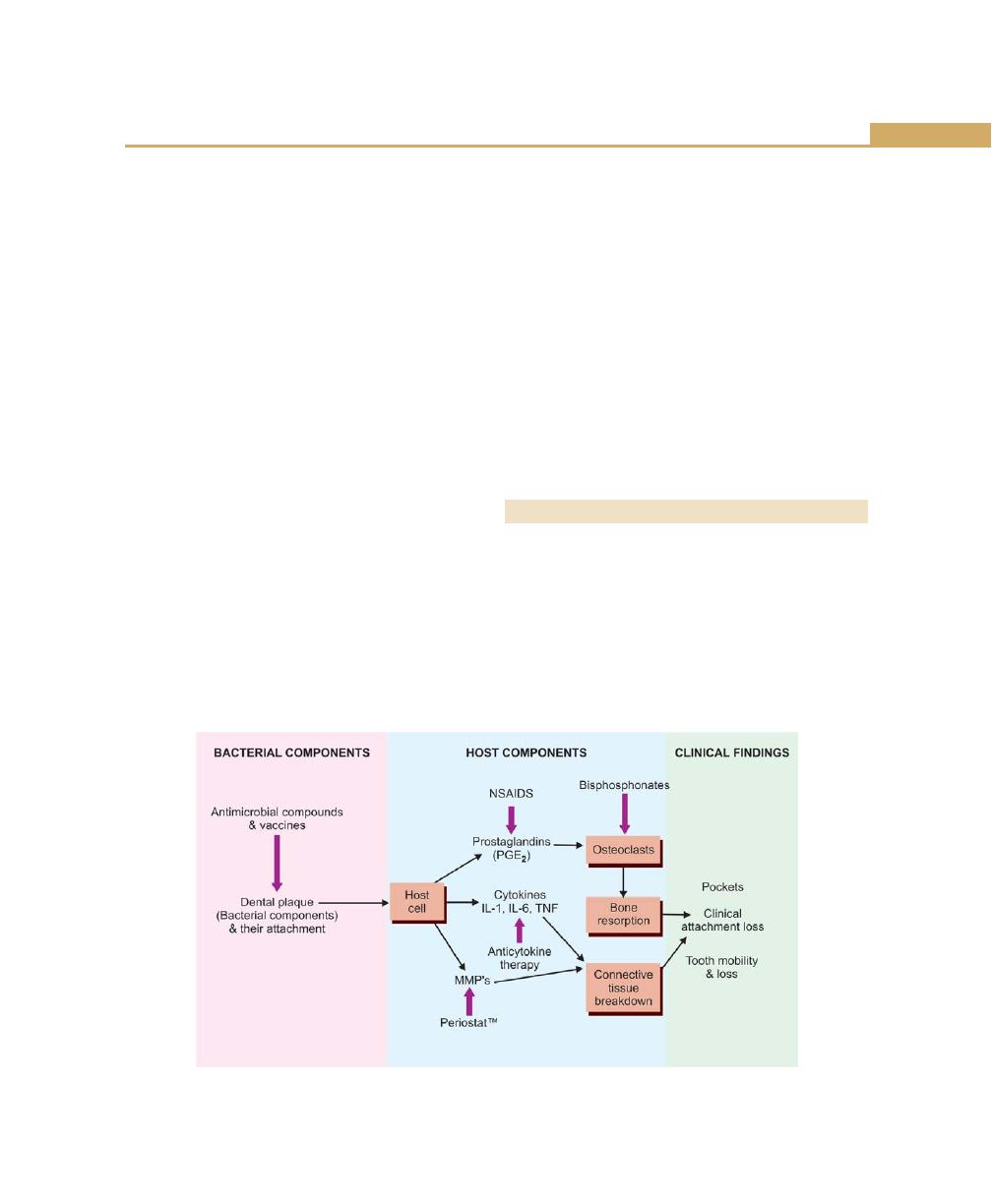

Chapter 12: Pathogenesis of Periodontal Diseases, 110

Introduction, 110

Role of Bacterial Invasion, 110

Role of Exotoxins, 110

Role of Cell Constituents, 111

Role of Enzymes, 111

Evasion of Host Responses, 111

Host Derived Bone Resorbing Agents, 112

Cytokines, 113

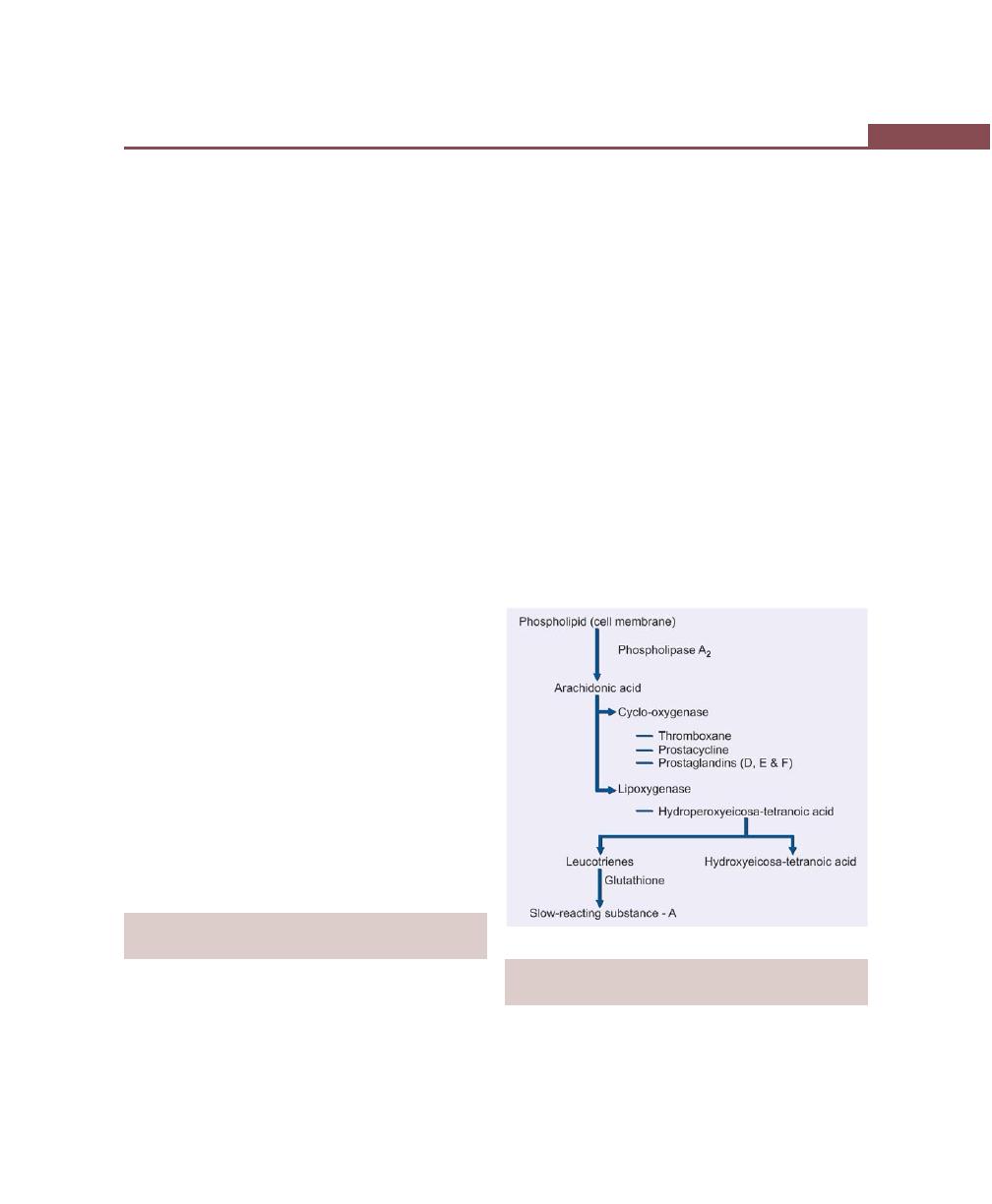

Prostaglandins, 113

Chapter 13: Periodontal Medicine, 115

Introduction, 115

Era of Focal Infection, 115

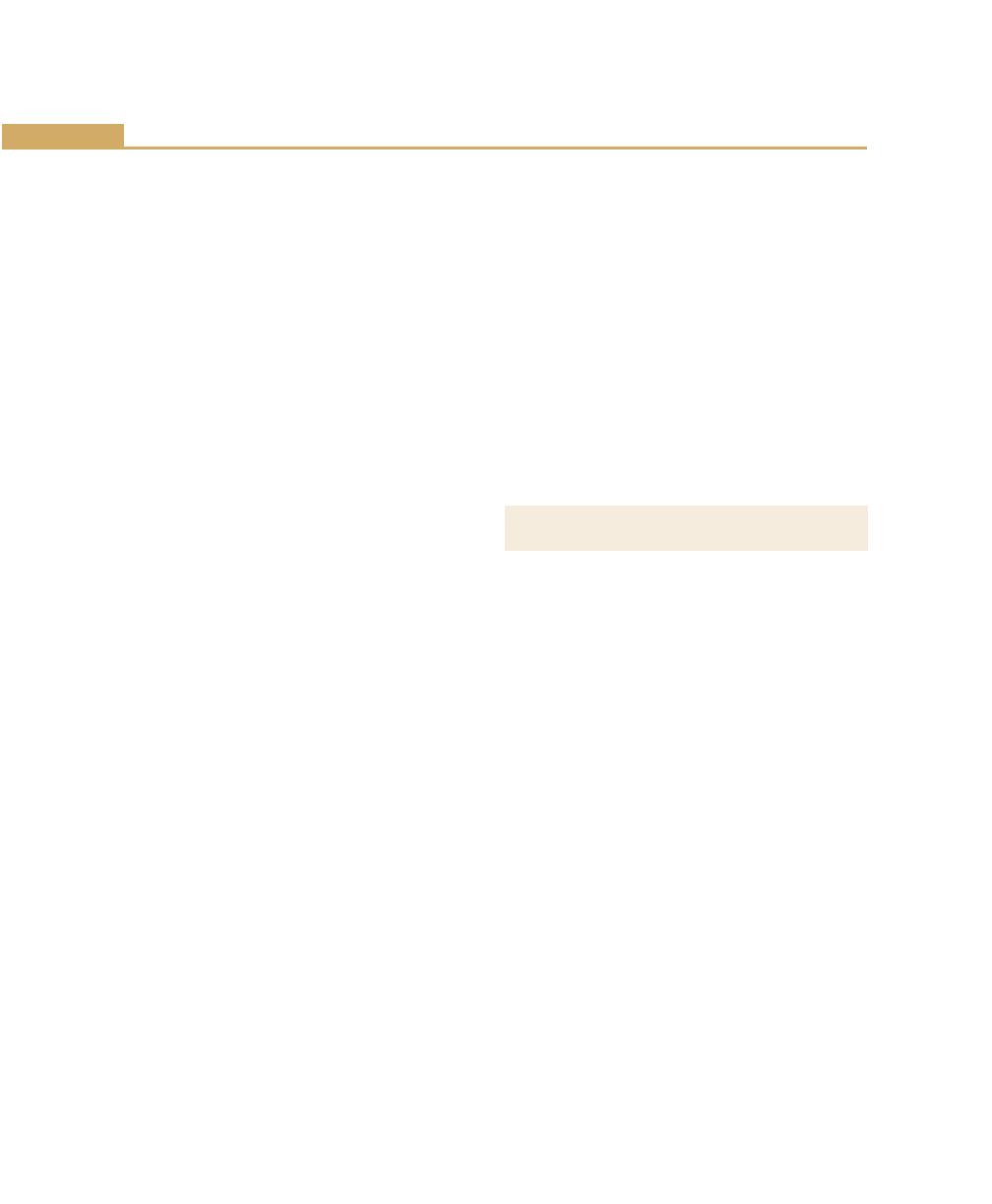

Periodontal Disease and Coronary Heart Disease/

Atherosclerosis, 116

Effect of Periodontal Infection, 117

Ischemic Heart Disease, 117

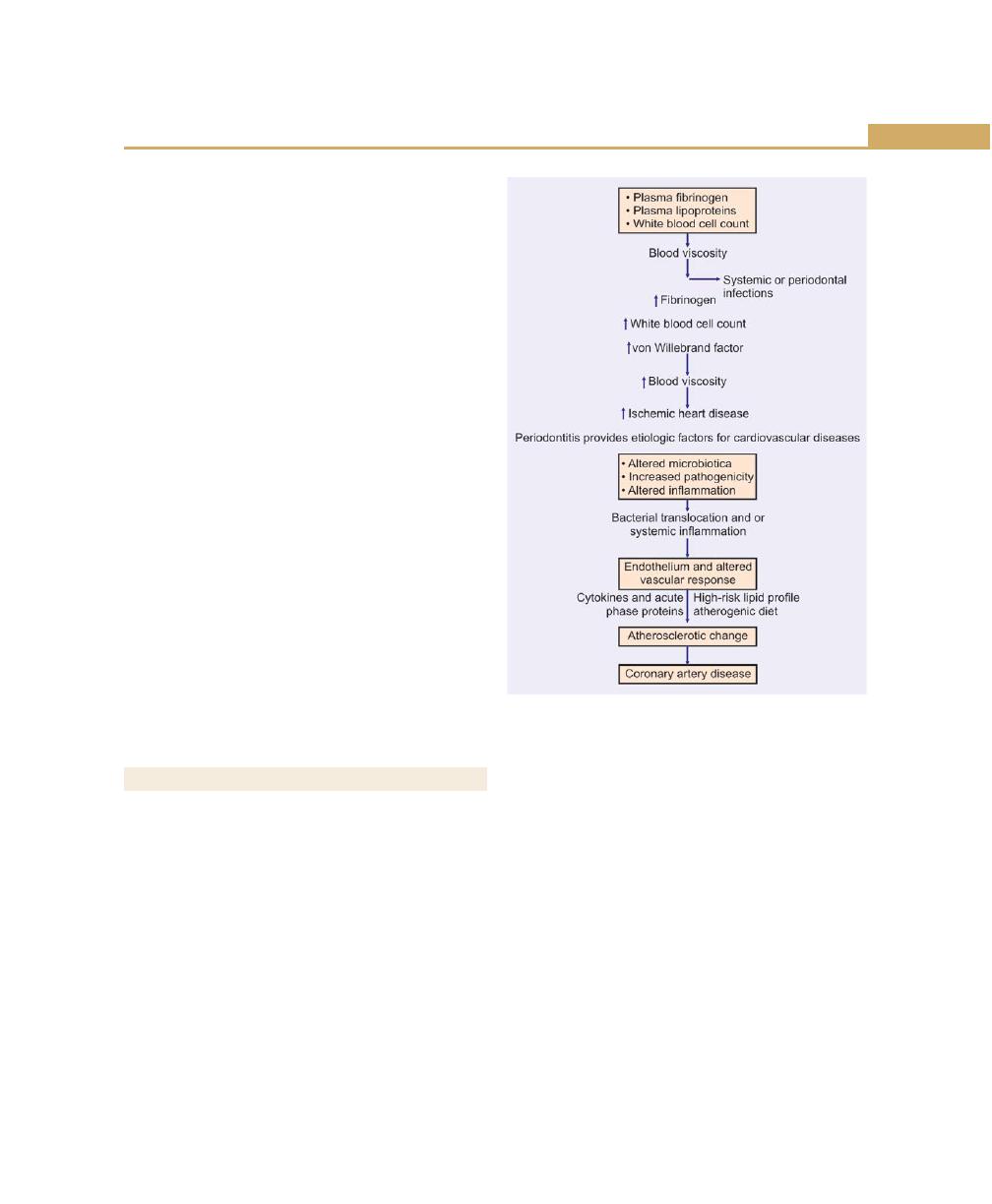

Thrombogenesis, 117

Periodontal Infection and Stroke, 118

Periodontal Disease and Diabetes Mellitus, 118

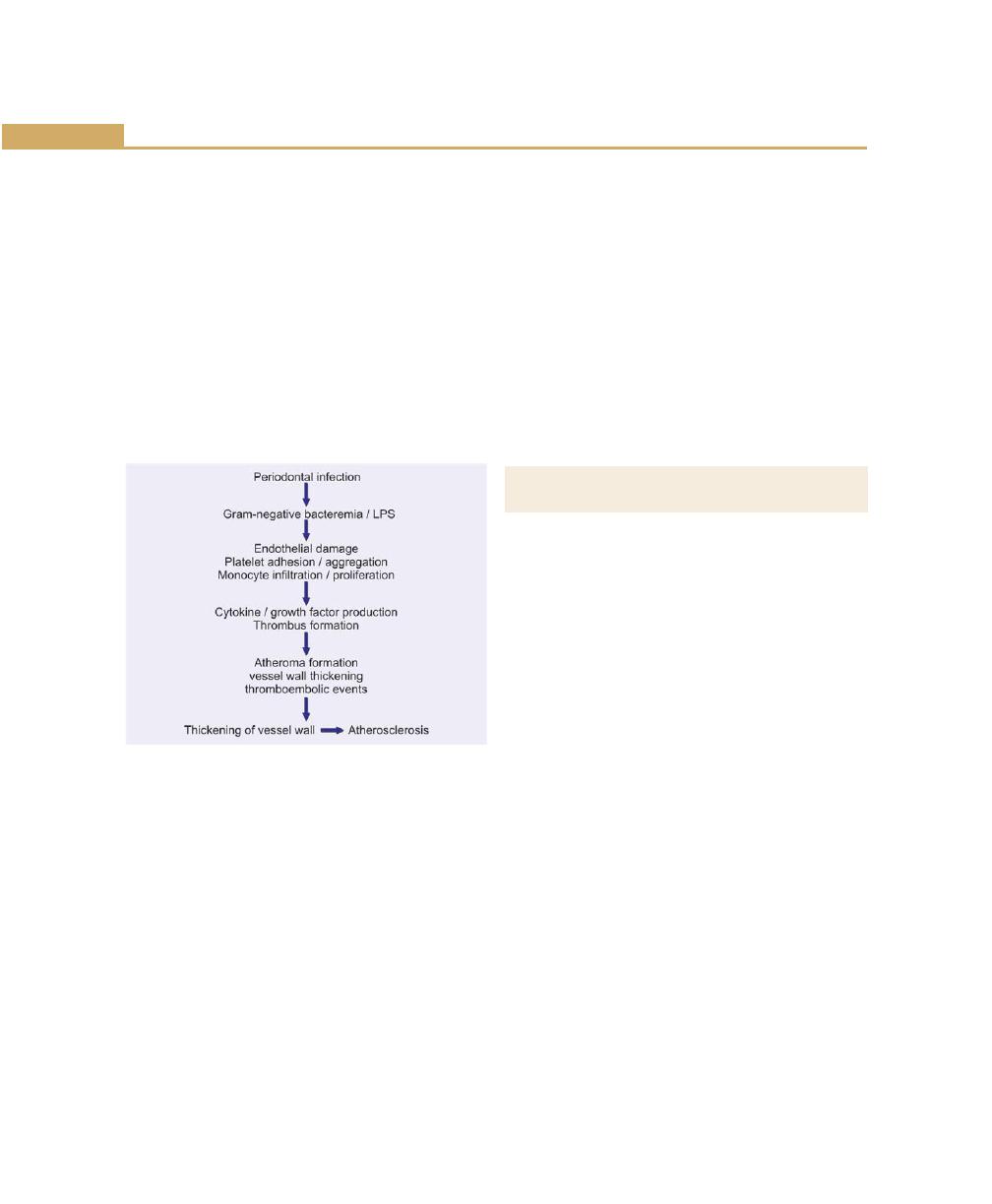

Role of Periodontitis in Pregnancy Outcome, 119

Periodontal Disease and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary

Disease, 119

Periodontal Disease and Acute Respiratory Infection, 120

Periodontal Medicine in Clinical Practice, 120

Chapter 14: Smoking and Periodontal Diseases, 122

Effect of Smoking on the Prevalence and Severity of

Periodontal Disease, 122

Effect of Smoking on the Etiology and Pathogenesis of

Periodontal Disease, 122

Microbiology, 122

Immunology, 122

Physiology, 123

Effect of Smoking on the Response to Periodontal

Therapy, 123

Effect of Smoking Cessation, 123

Chapter 15: Host Modulation in Periodontal Therapy,125

Introduction, 125

Regulation of Immune and Inflammatory Responses, 125

Excessive Production of MMP’s, 126

Role of MMP’s in Human Periodontal Diseases, 126

Production of Arachidonic Acid and Metabolites, 126

Regulation of Bone Metabolism, 127

Part IV: Periodontal Pathology

SECTION 1: GINGIVAL DISEASES

Chapter 16: Defence Mechanisms of the Gingiva, 131

Defence Mechanisms, 131

Non-specific Mechanisms, 131

Bacterial Balance, 131

Surface Integrity, 131

Surface Fluid and Enzyme, 131

Phagocytosis, 131

Inflammatory Reaction, 132

Specific Protective Mechanism, 132

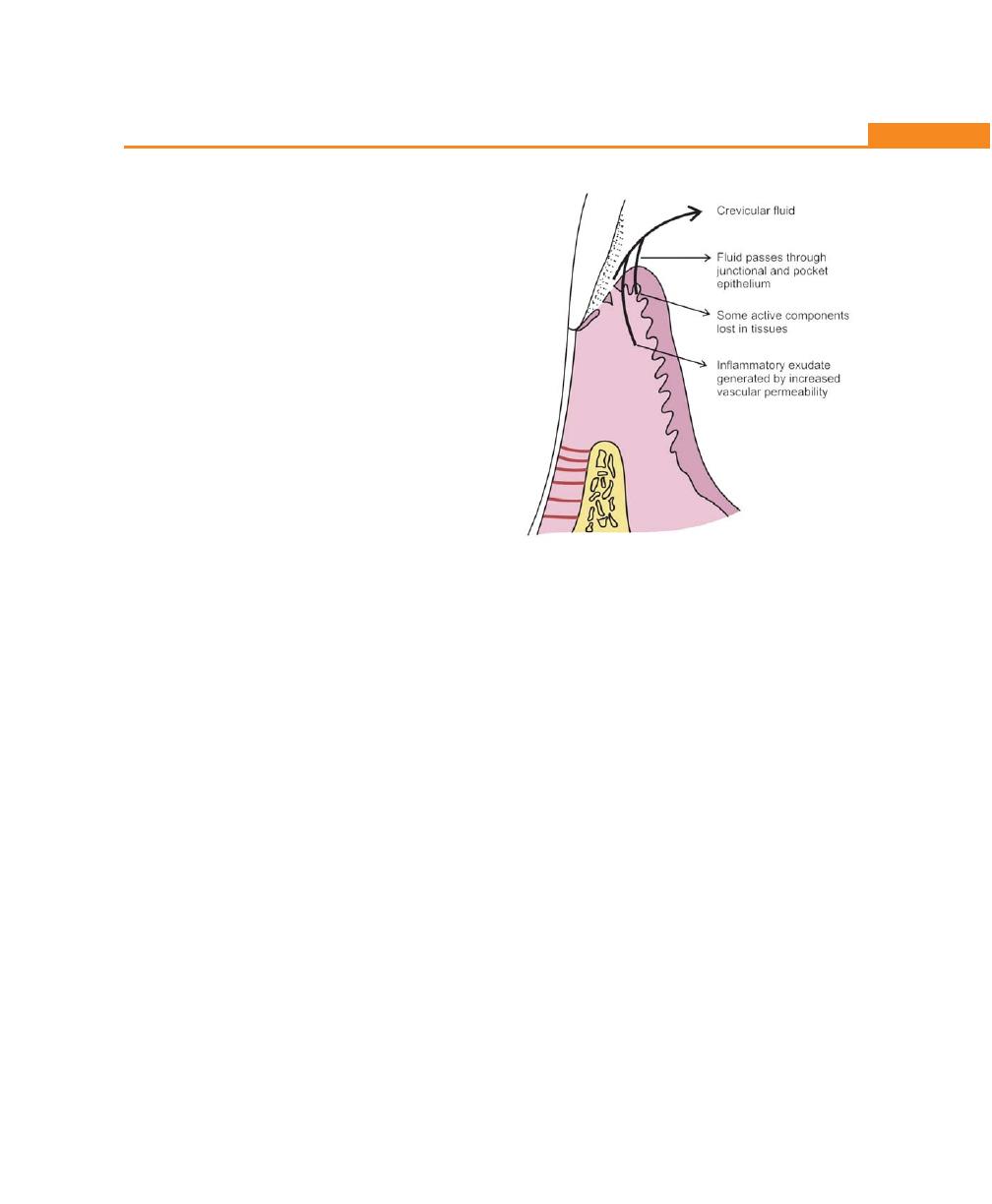

Sulcular Fluid, 132

Anatomy of Gingival Crevice, 132

Significance of Gingival Sulcus and Fluid, 133

Significance of Gingival Vasculature and

Crevicular Fluid, 133

Permeability of Sulcular and Junctional Epithelia,

133

Methods of Collection, 134

Absorbing Paper Strips, 134

Micropipettes, 134

Gingival Washings, 135

Other Methods, 135

Composition of GCF, 135

Clinical Signficance, 138

Drugs in Gingival Fluid, 138

Influence in Mechanical Stimuli, 138

Periodontal Therapy and Gingival Fluid, 139

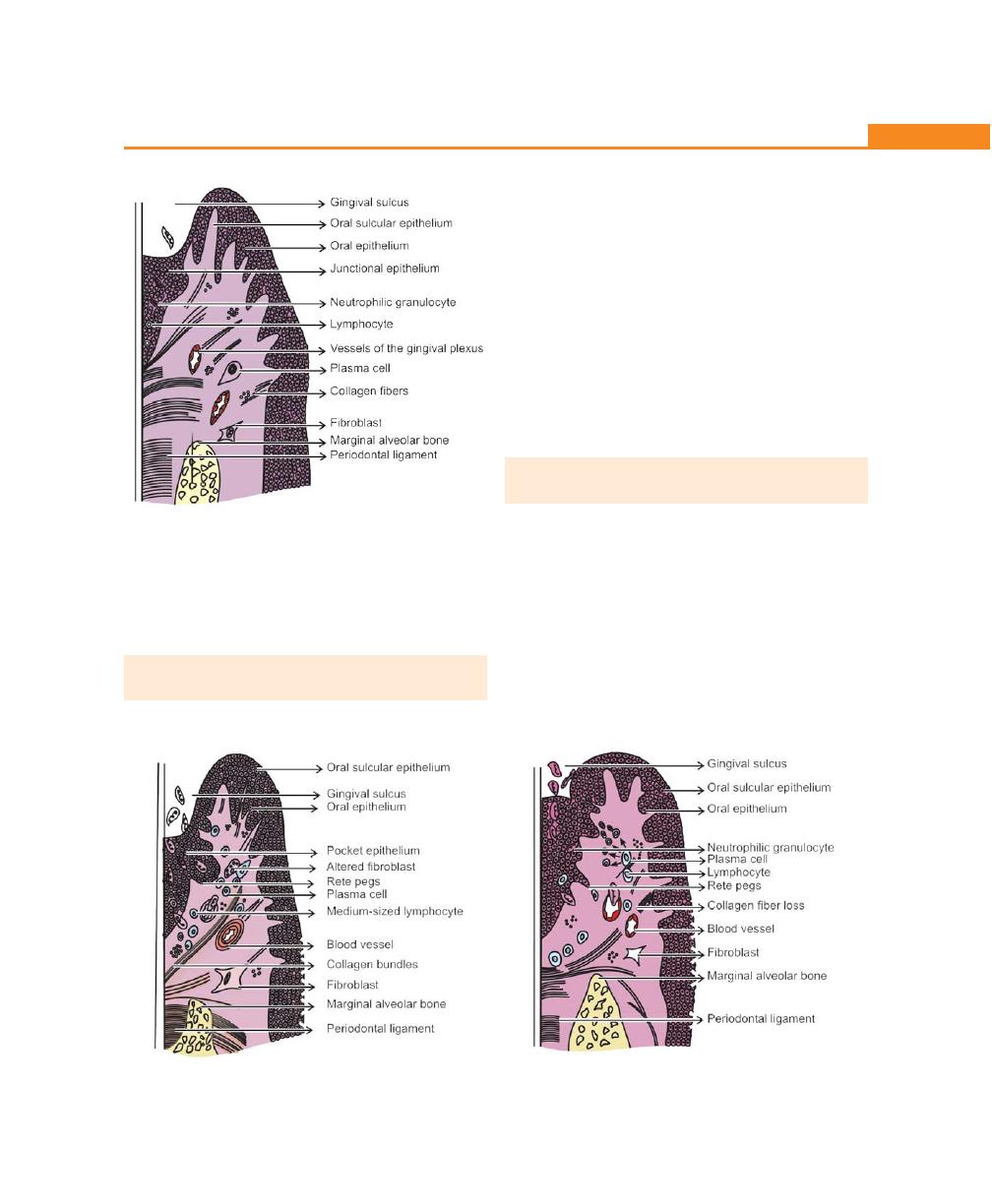

Chapter 17: Gingival Inflammation, 140

Introduction, 140

Initial Lesion, 140

Early Lesion, 141

Established Lesion, 141

Advanced Lesion, 142

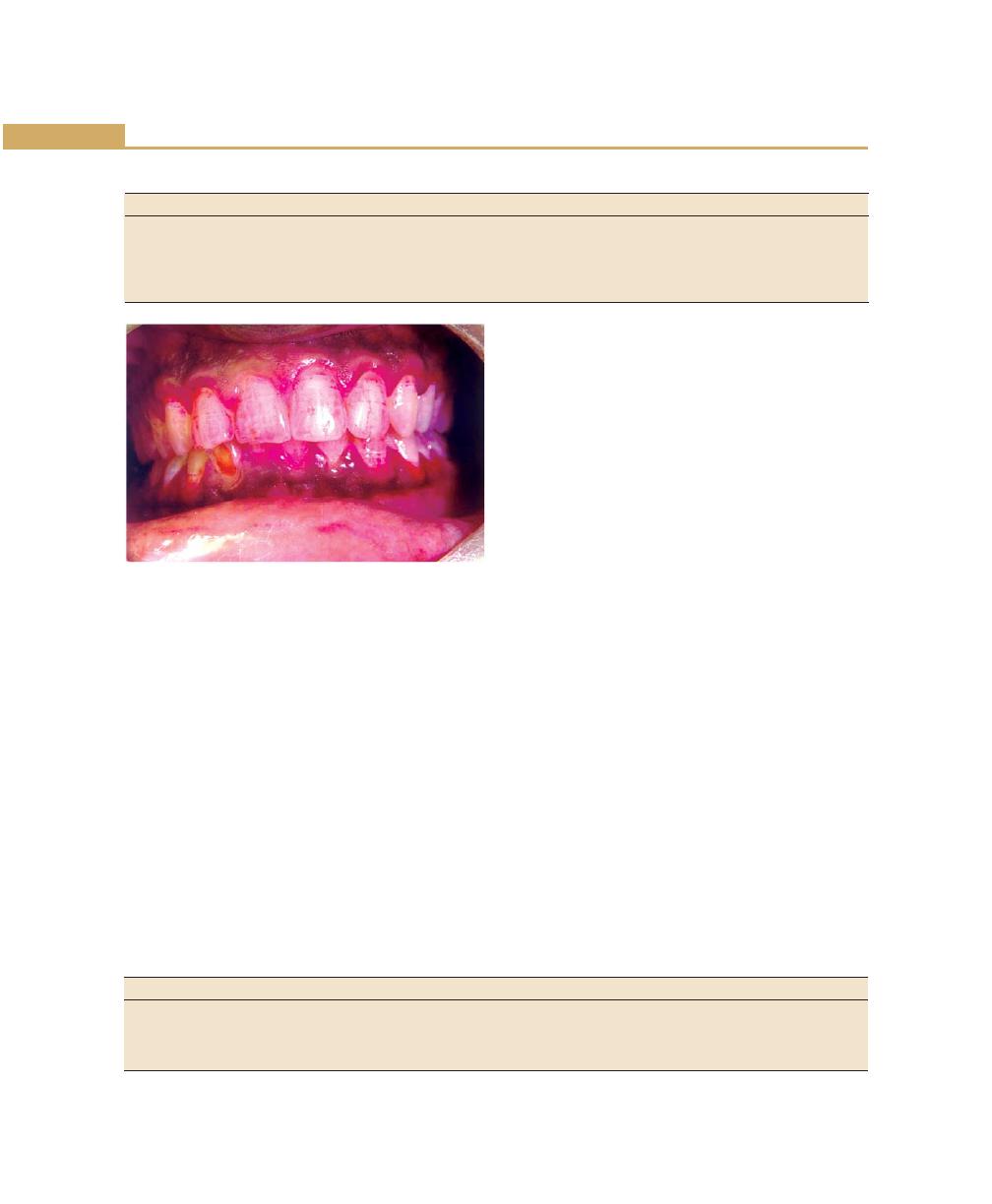

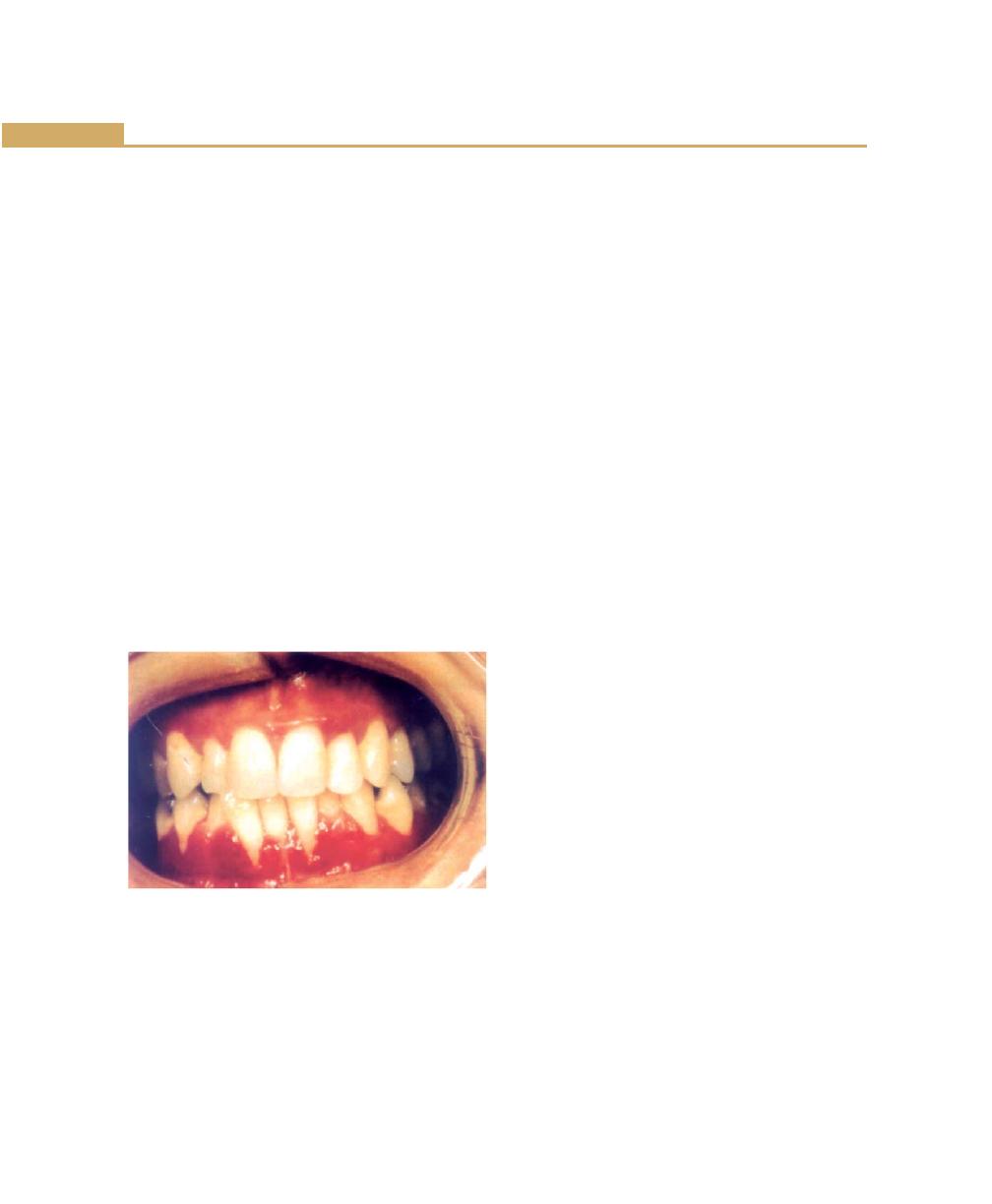

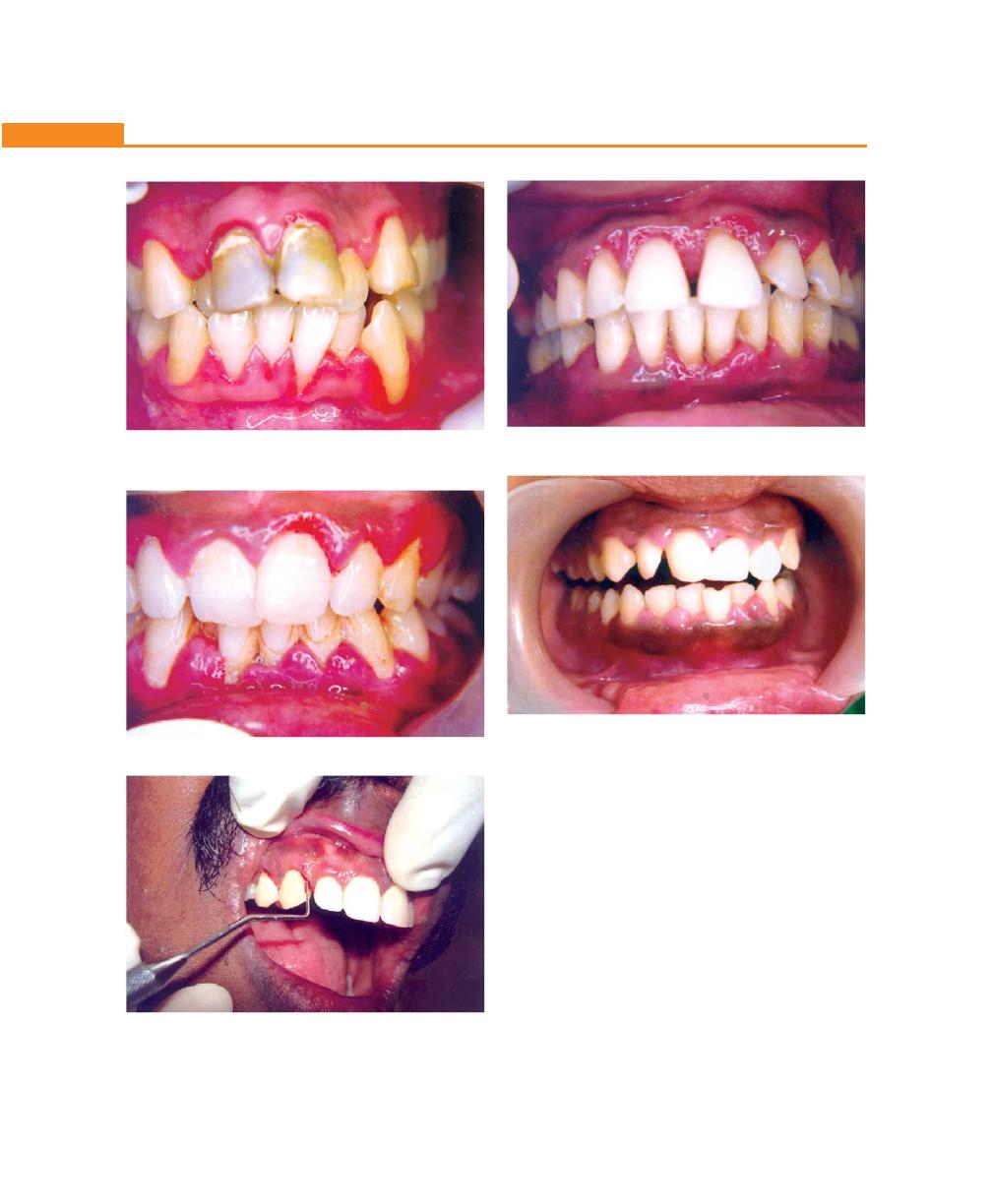

Chapter 18: Clinical Features of Gingivitis, 143

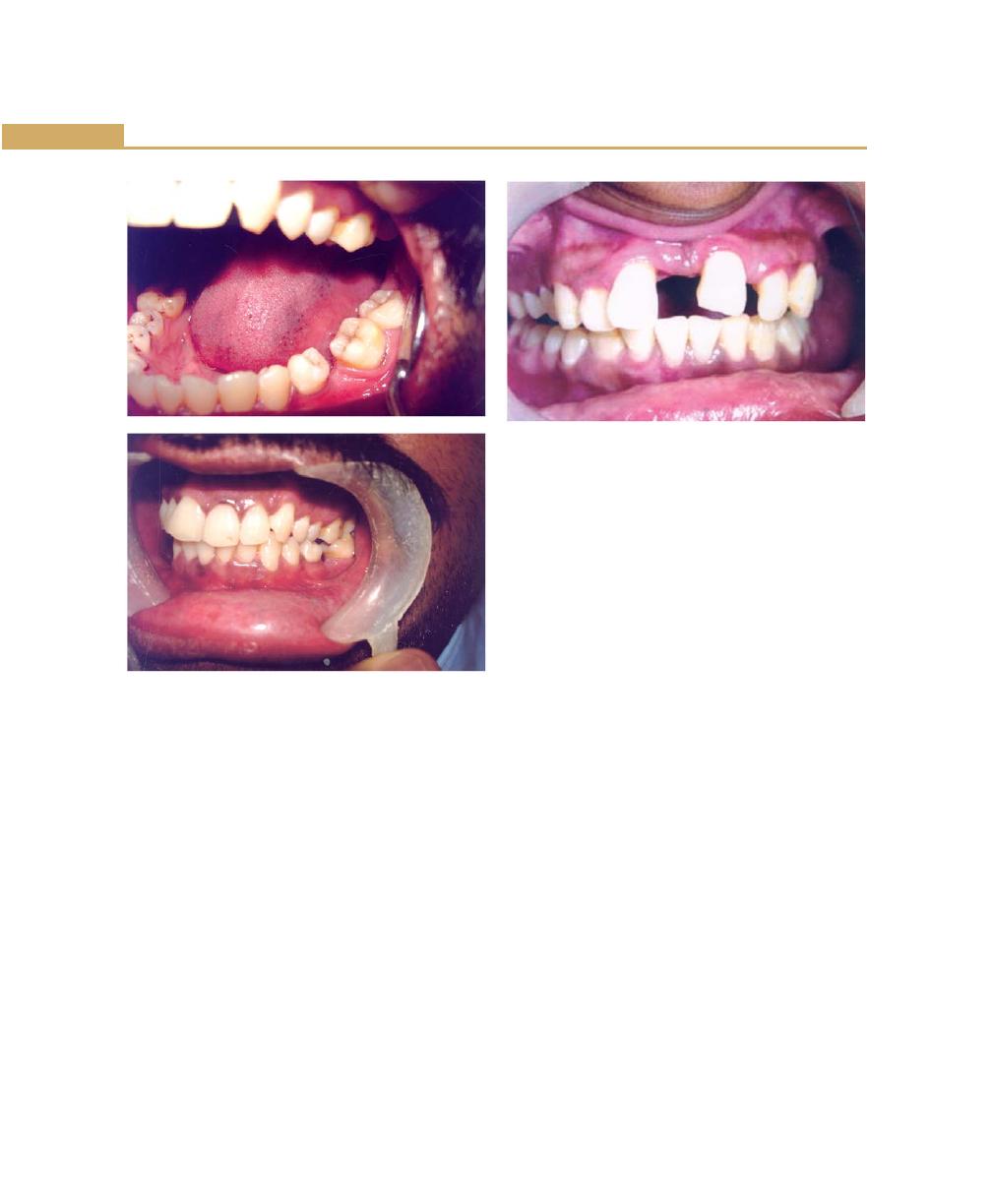

Types of Gingivitis, 143

Depending on the Course and Duration, 143

Depending on the Distribution, 143

Clinical Findings, 143

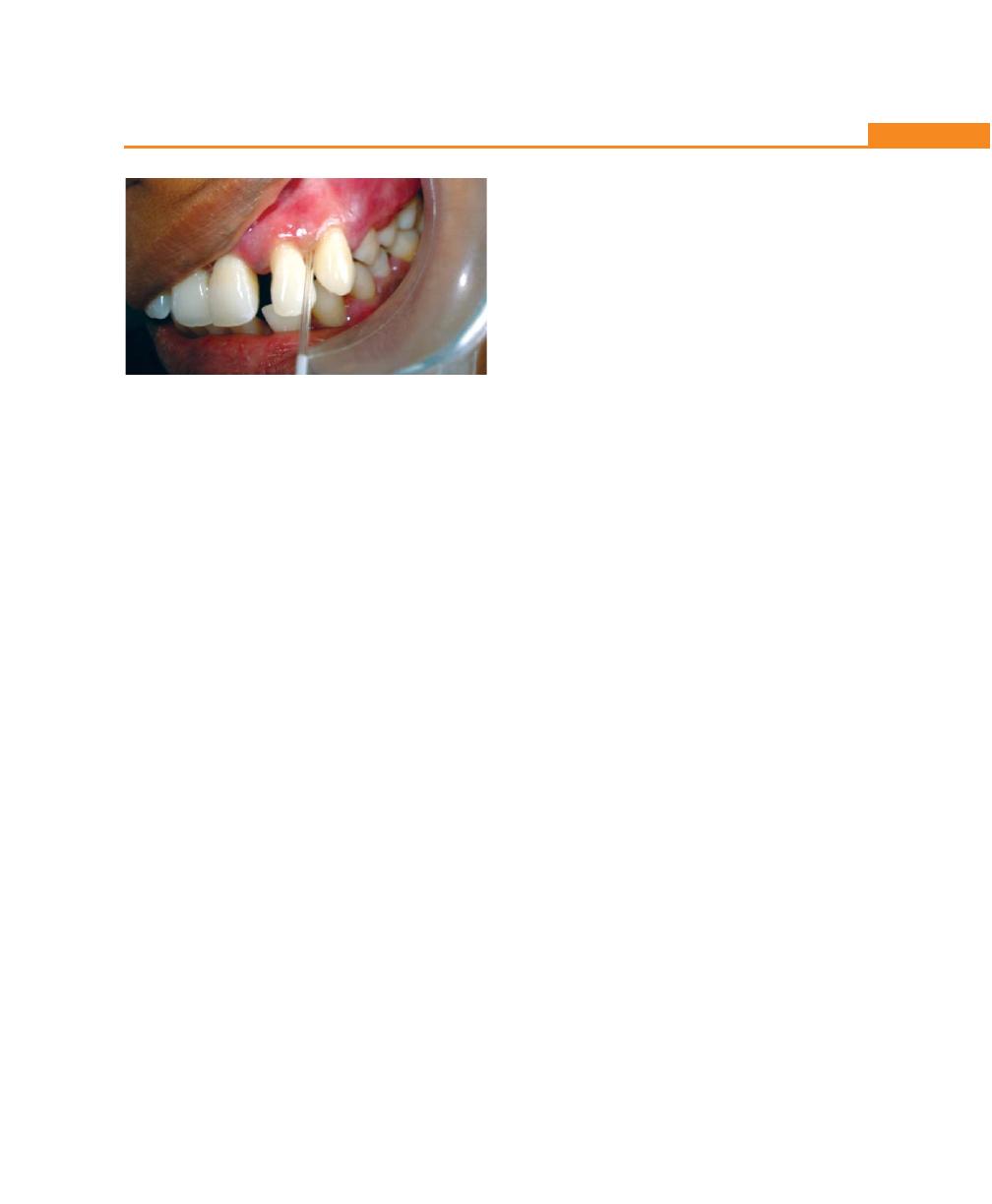

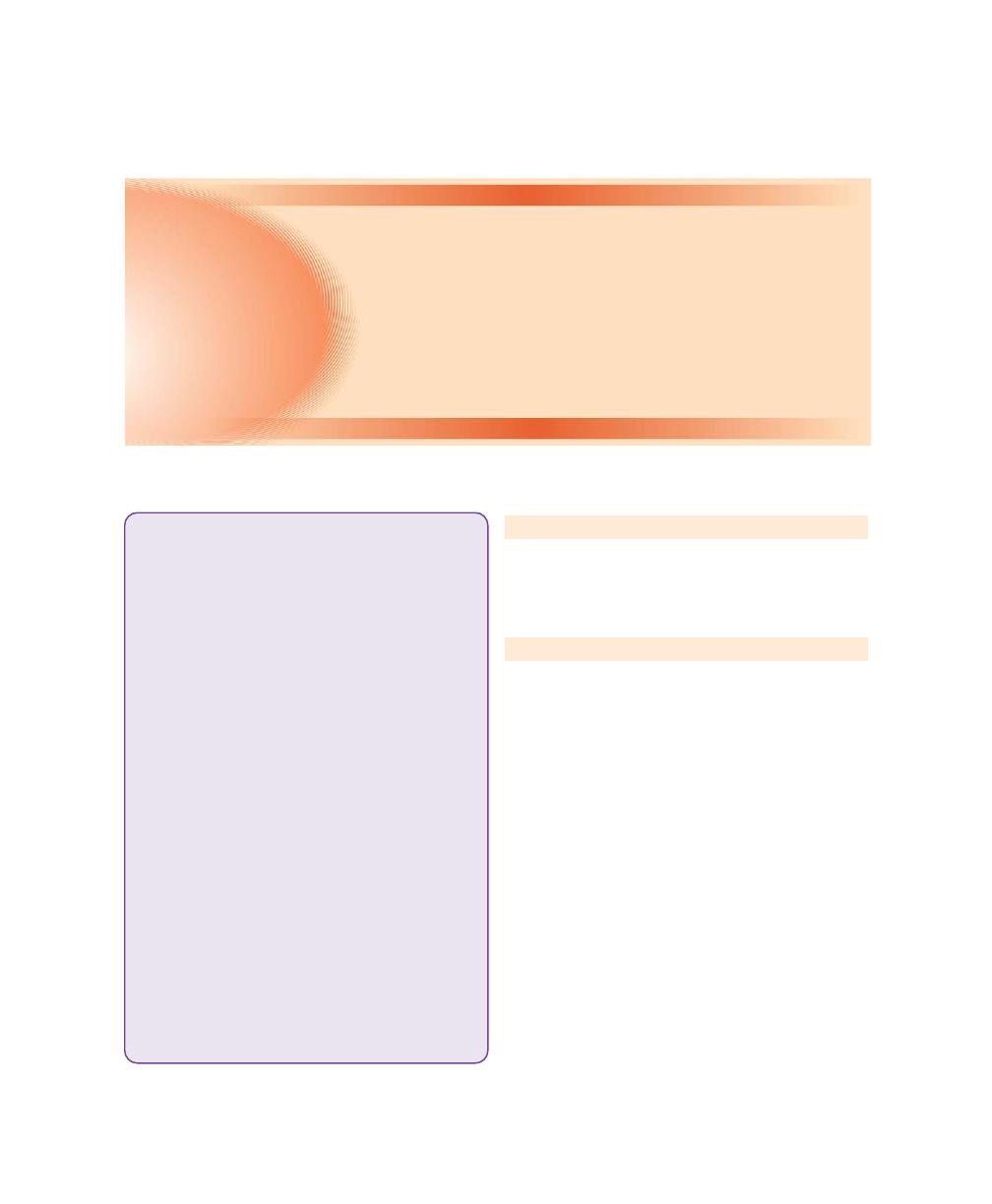

Gingival Bleeding on Probing, 144

Color Change, 147

Change in Consistency, 147

Change in Size, 147

Surface Texture, 148

Position, 148

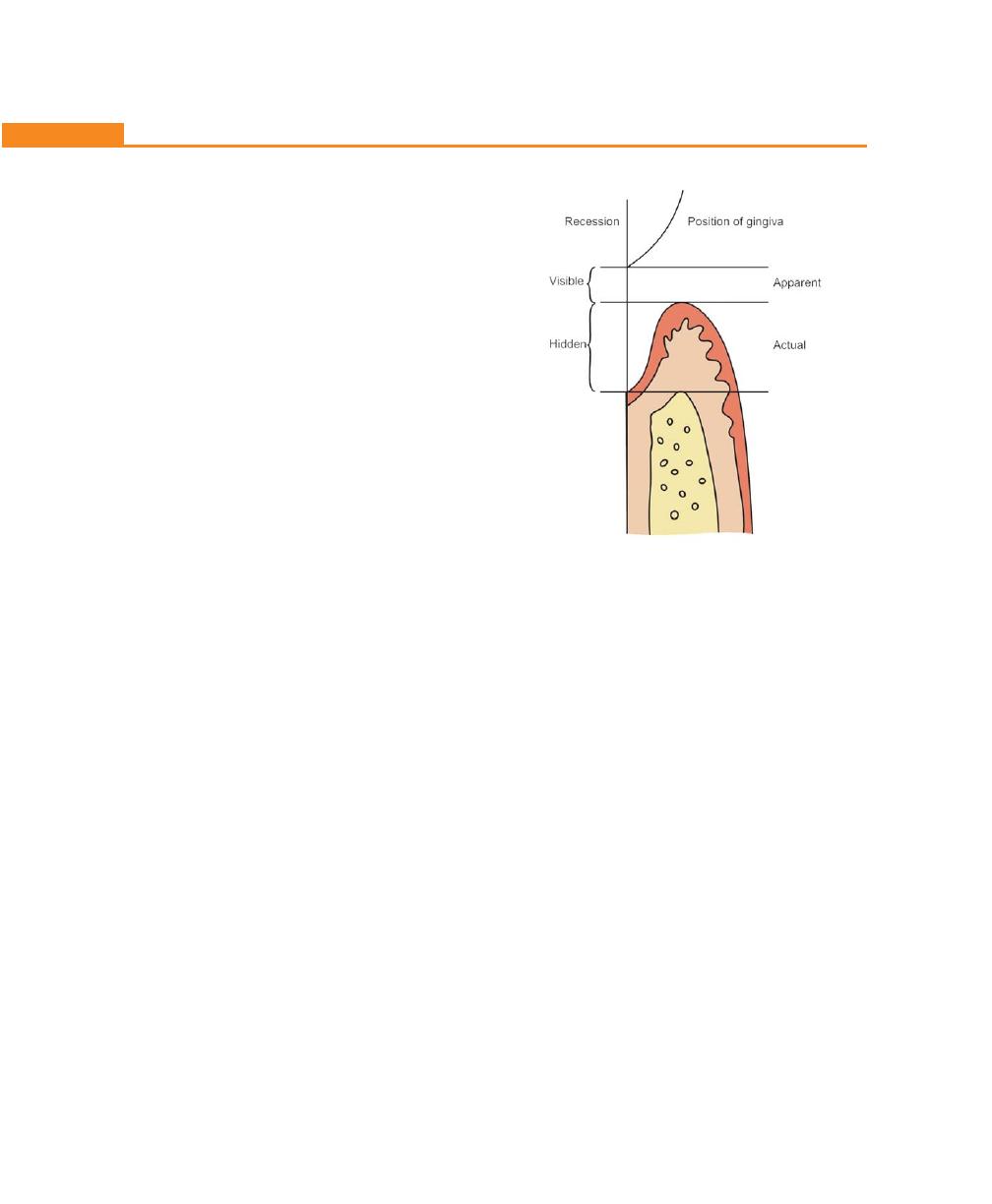

Recession, 148

Classification and Etiology, 148

Clinical Significance, 150

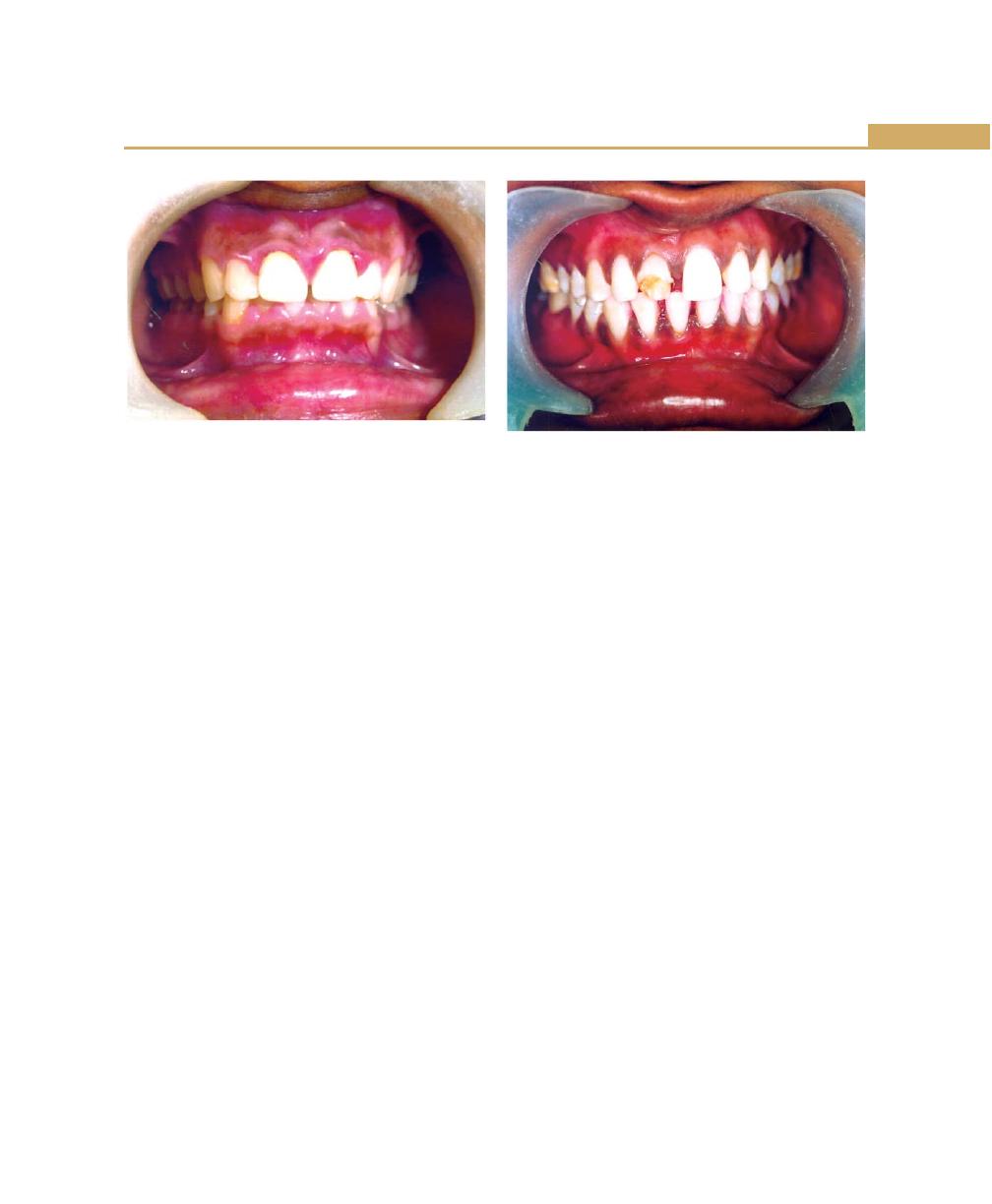

Chapter 19: Gingival Enlargements, 151

Introduction, 151

Classification, 151

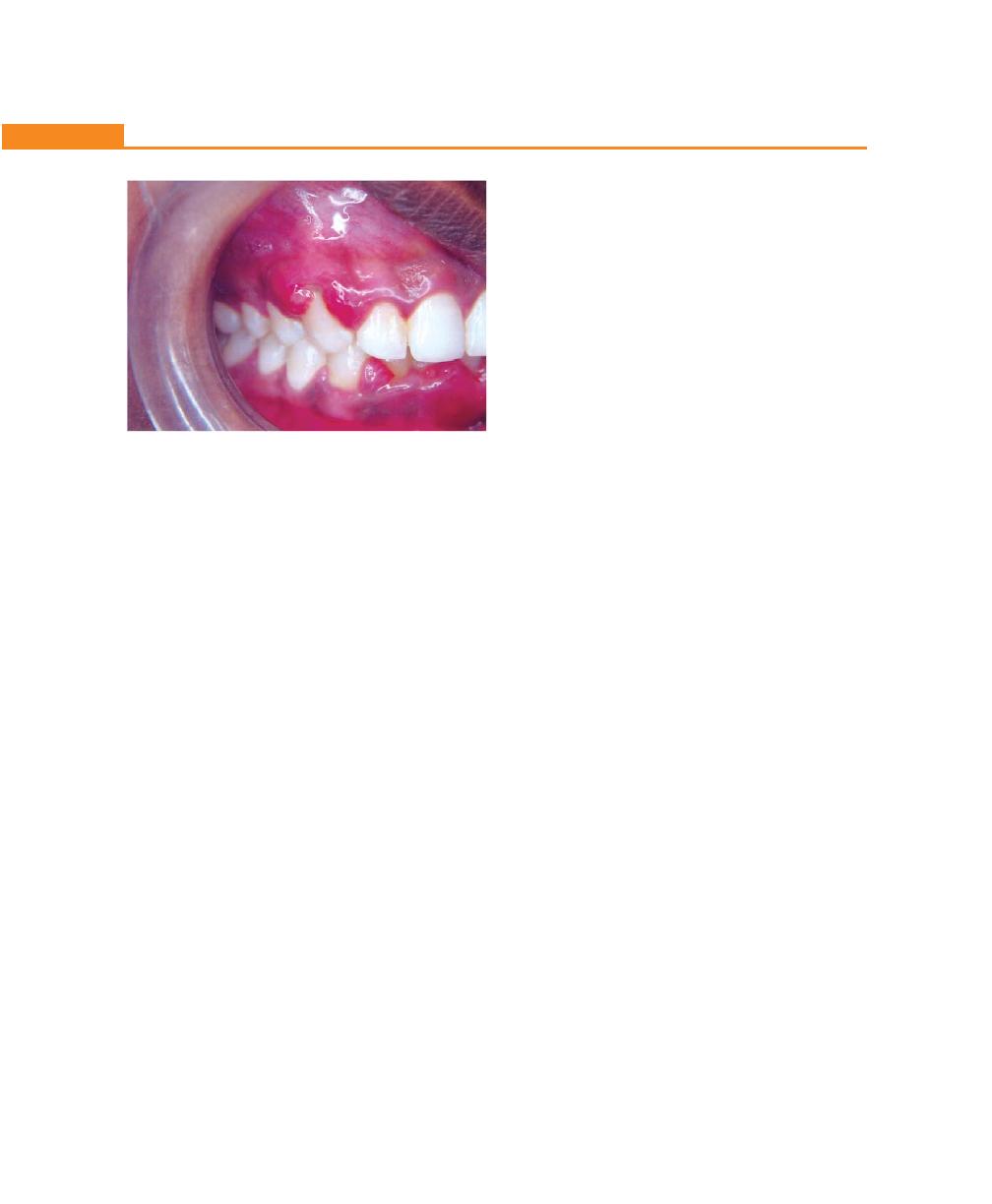

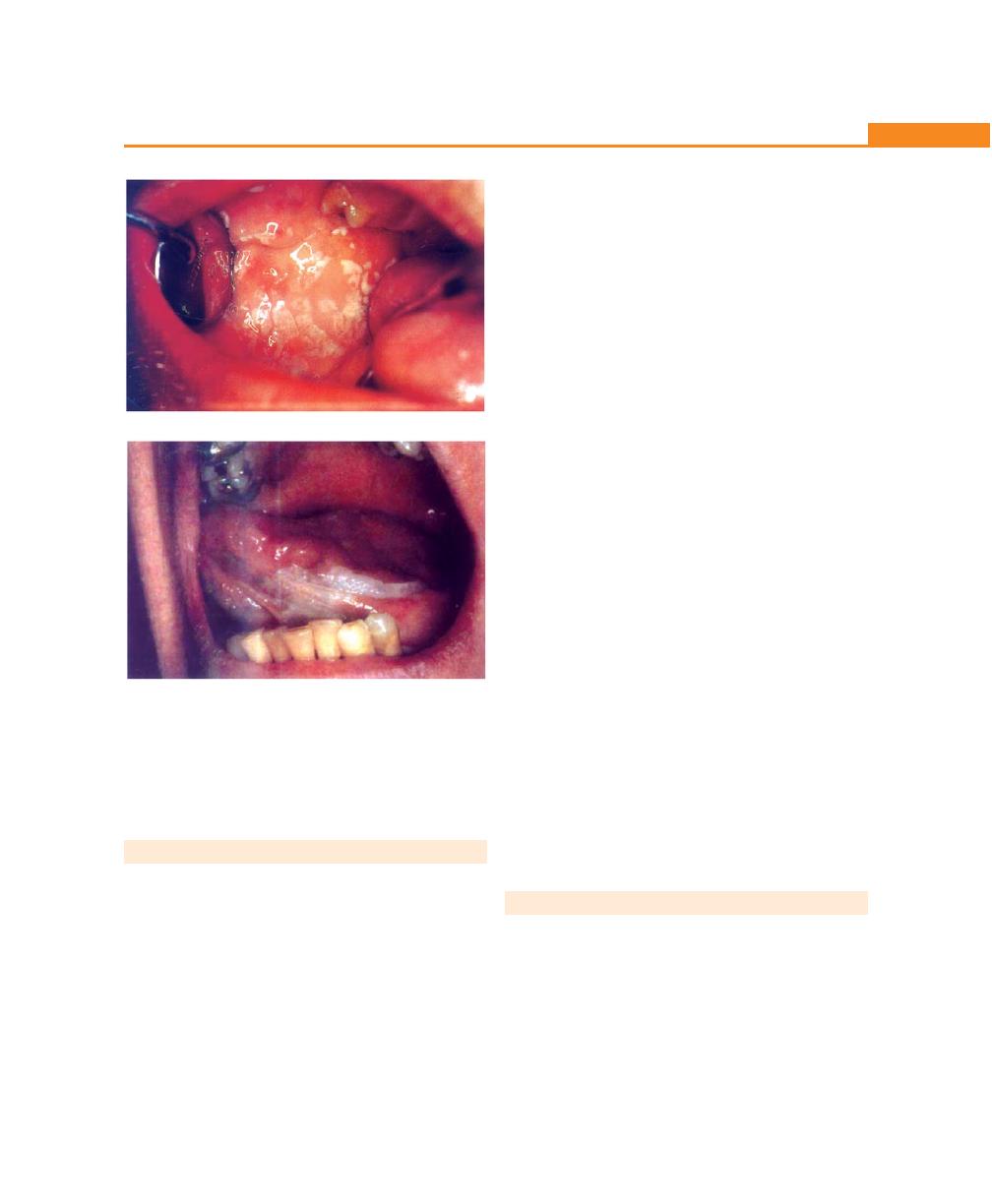

Inflammatory Enlargement, 152

Acute Inflammatory Enlargement, 152

Chronic Inflammatory Enlargement, 153

Non-inflammatory Enlargement, 154

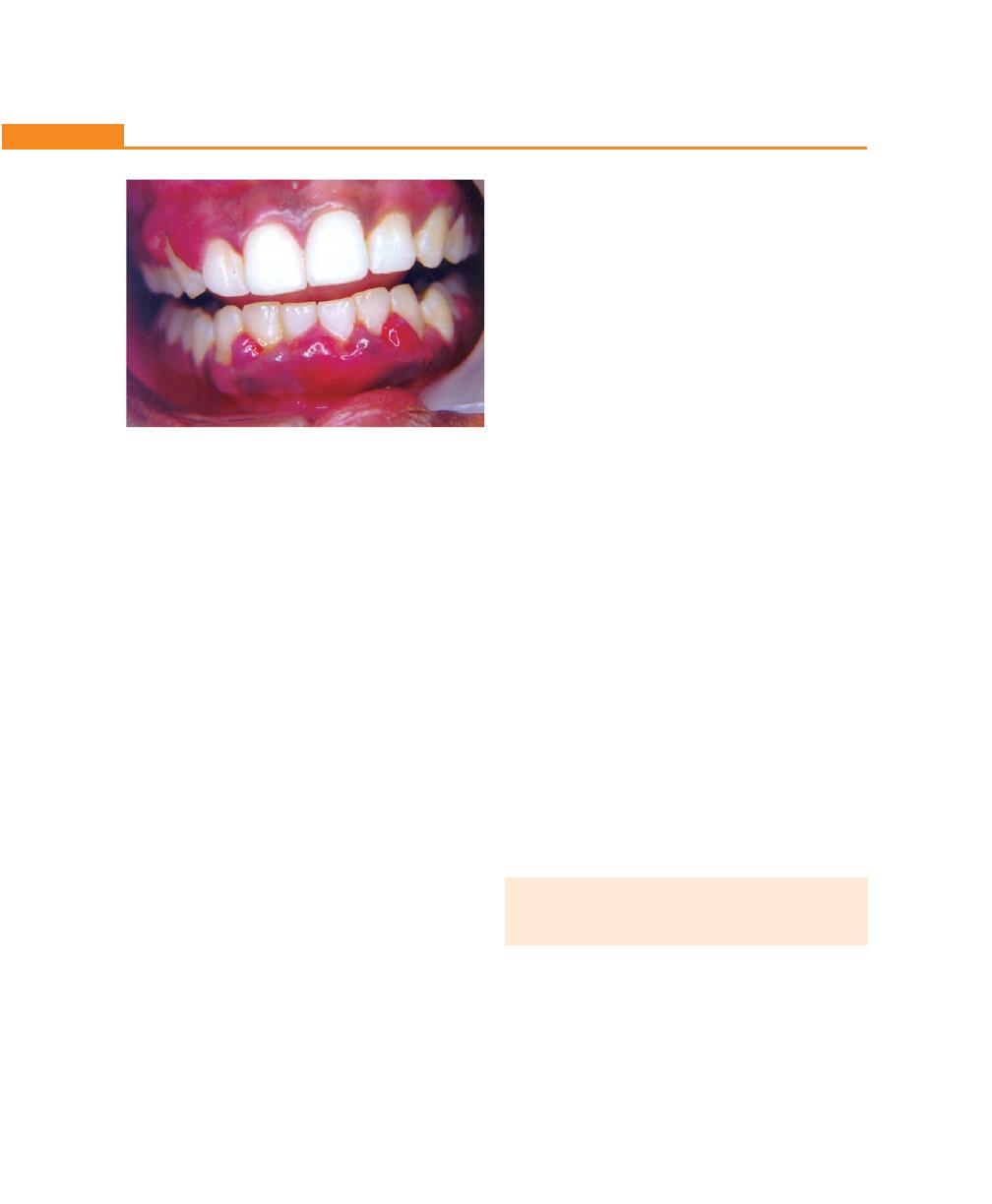

Phenytoin-induced Gingival Hyperplasia, 155

Idiopathic Gingival Fibromatosis, 157

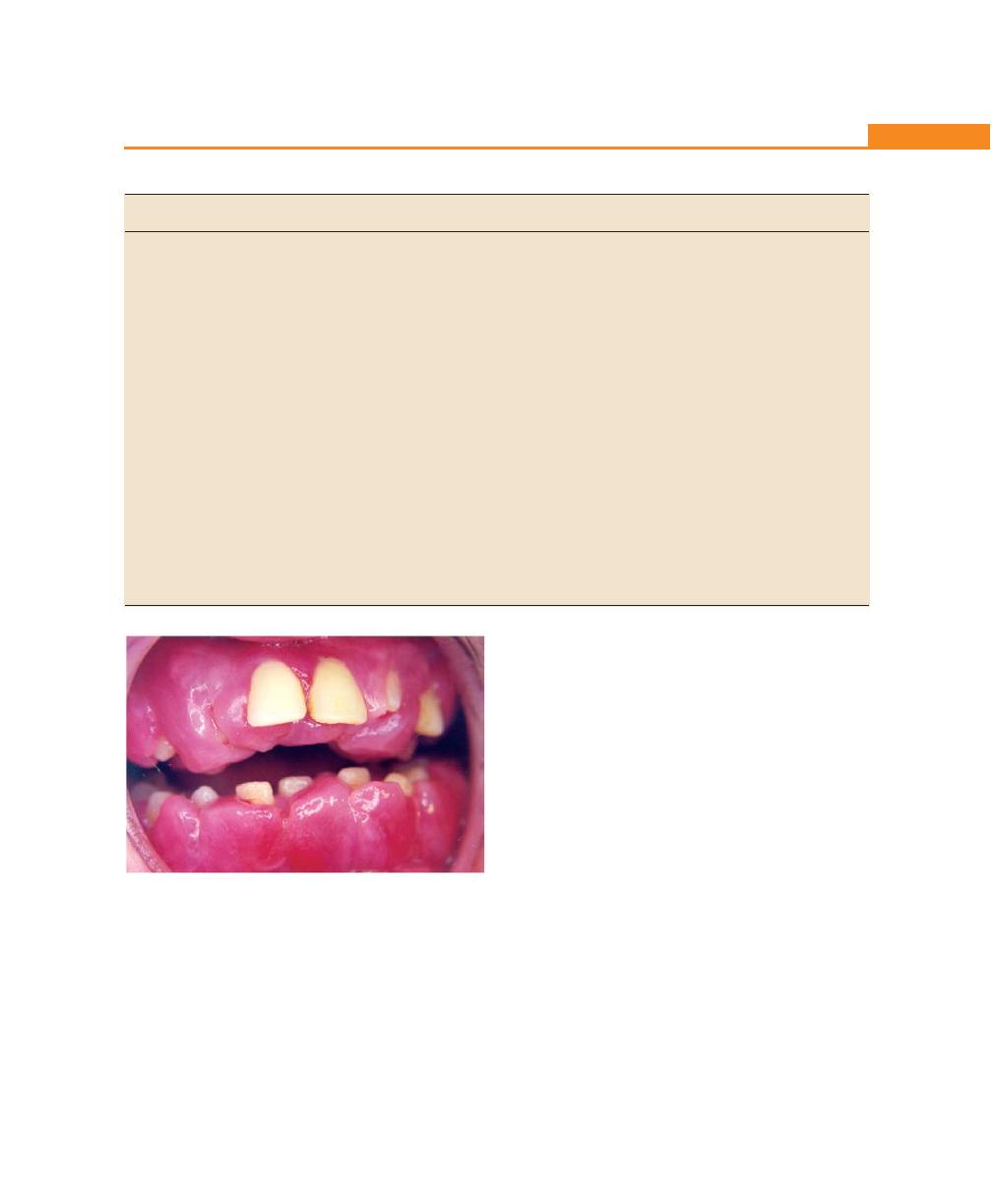

Combined Enlargement, 157

Enlargement Associated with Systemic Disease or

Condition, 159

Conditioned Enlargement, 159

Enlargement in Pregnancy, 159

Enlargement in Puberty, 160

Vitamin C Deficiency, 160

Plasma Cell Gingivitis, 161

Granuloma Pyogenicum, 161

Systemic Disease Causing Gingival Enlargement, 161

Granulomatous Diseases, 163

xviii

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

Neoplastic Enlargement, 165

Benign Tumors, 165

Malignant Tumors, 165

False Enlargement, 165

Underlying Osseous Lesions, 166

Underlying Dental Tissues, 166

Chapter 20: Acute Gingival Infections, 167

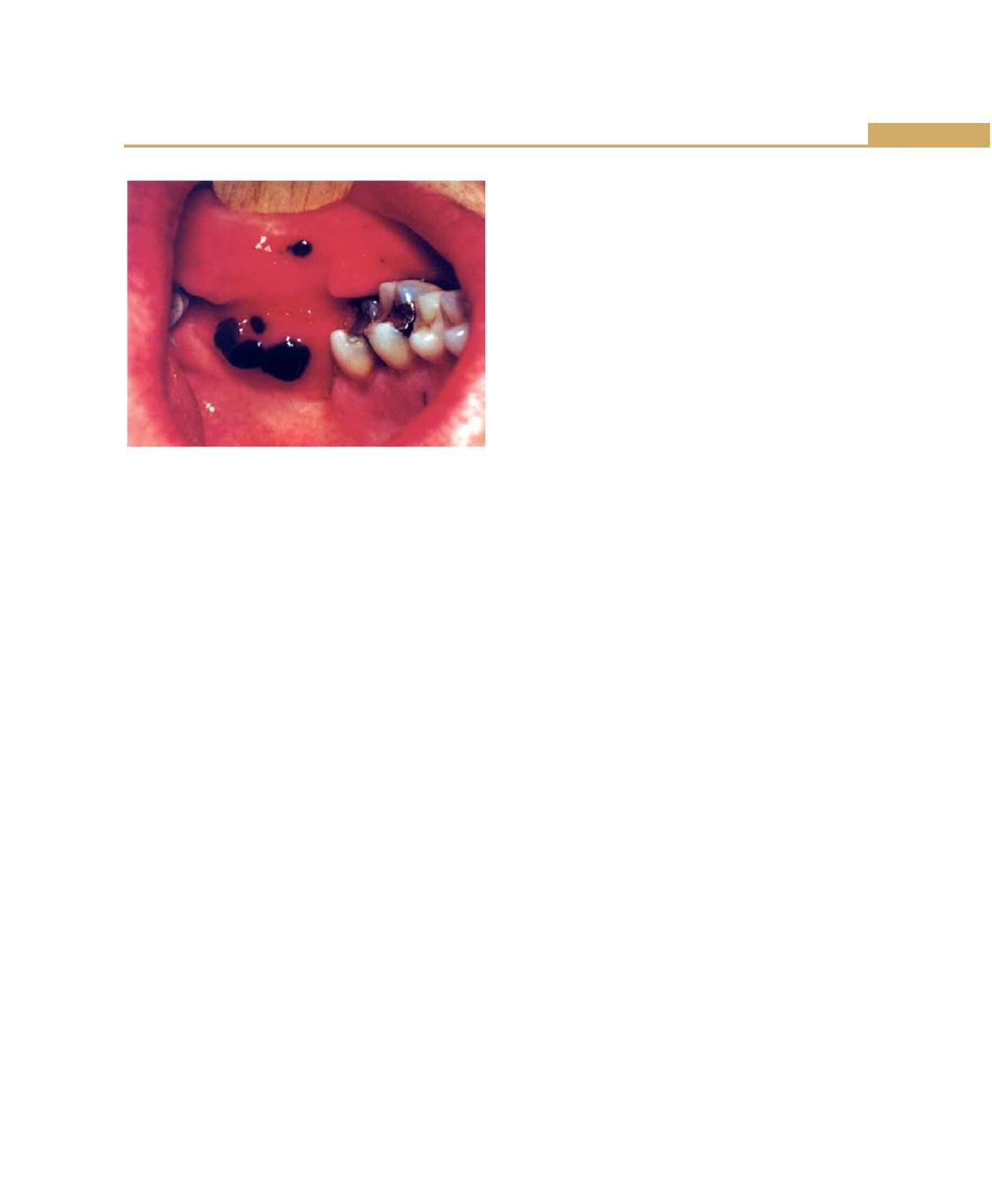

Classification of Various Acute Gingival Lesions, 167

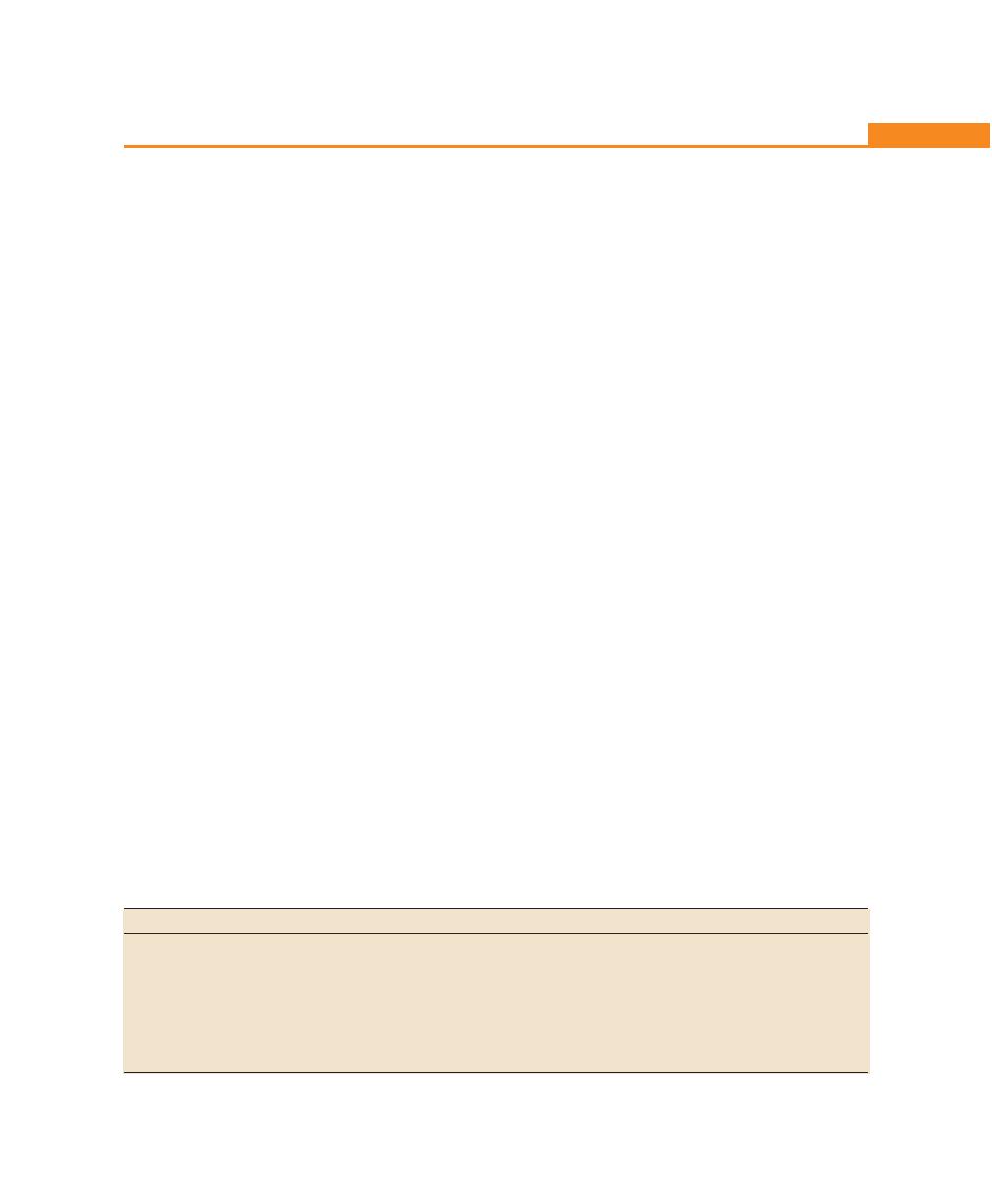

Acute Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis, 168

Terminology, 168

Clinical Features, 168

Intraoral/Extraoral Signs and Symptoms, 168

Clinical Course, 169

Etiology, 169

Histopathology, Diagnosis and Treatment, 170

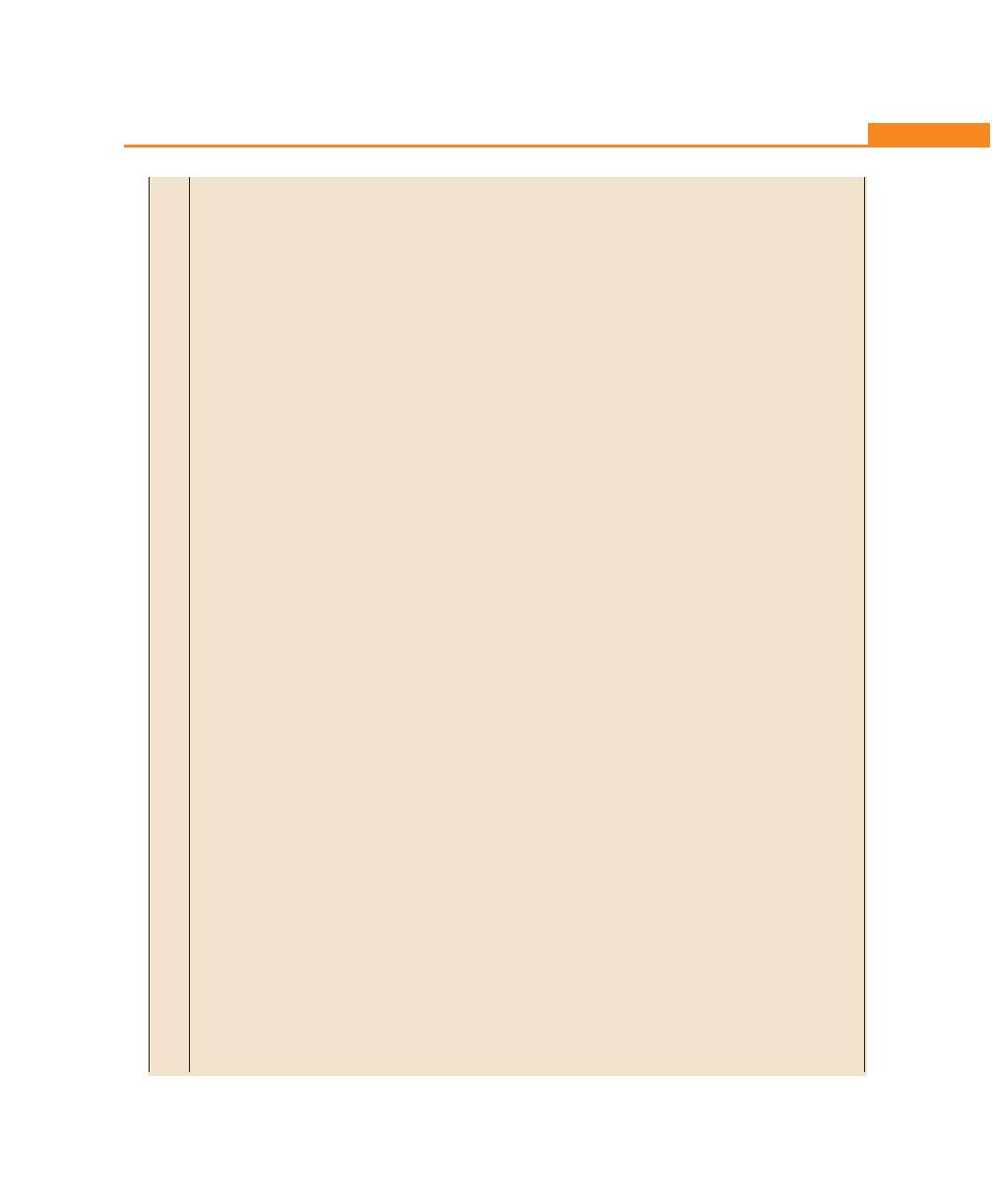

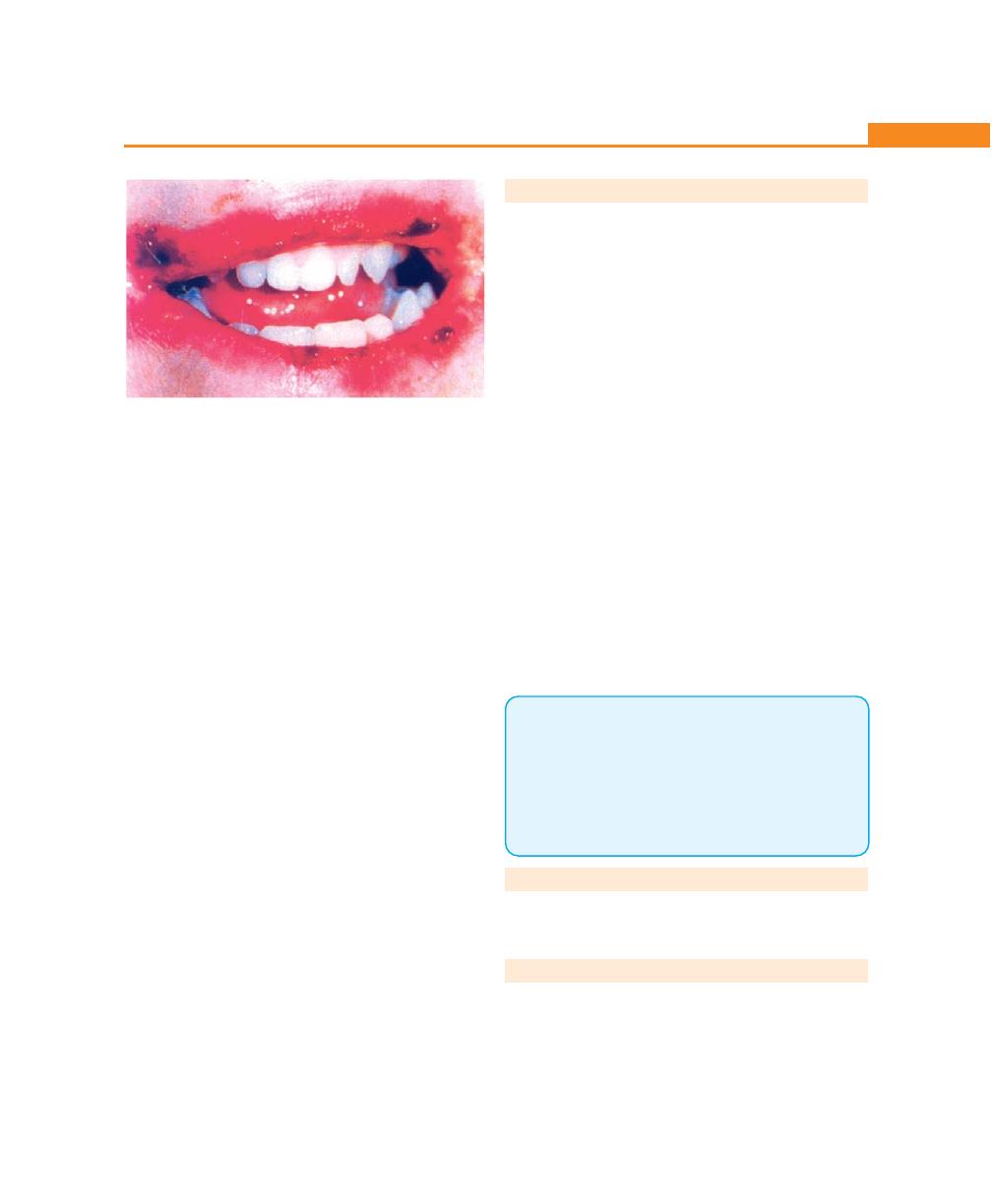

Acute Herpectic Gingivostomatitis, 172

Clinical Features, 172

Etiology, 172

History, 173

Histopathology, 173

Diagnosis, 173

Differential Diagnosis, 173

Treatment, 174

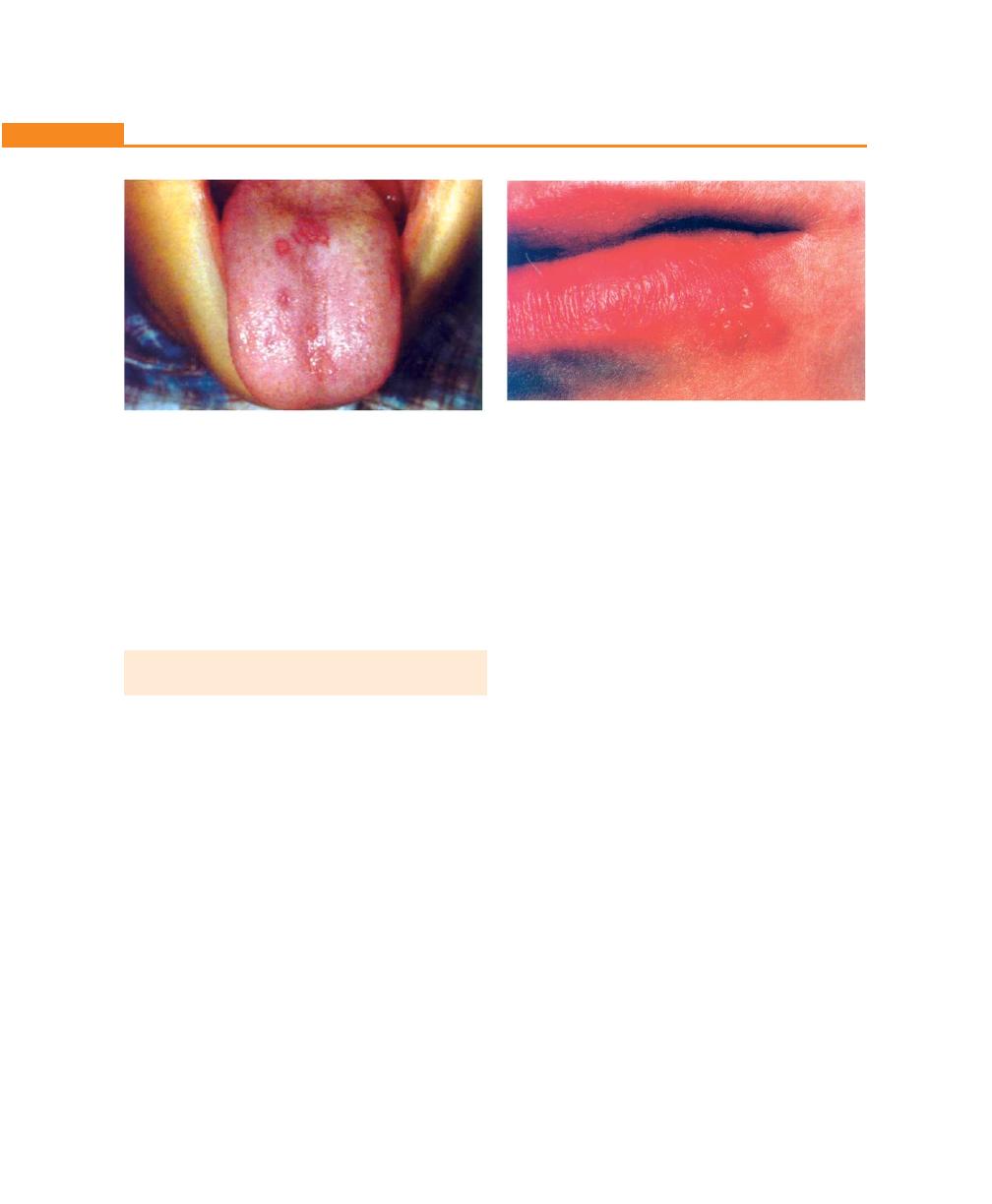

Pericoronitis, 174

Definition, 174

Types, 174

Clinical Features, 174

Complications, 175

Treatment, 175

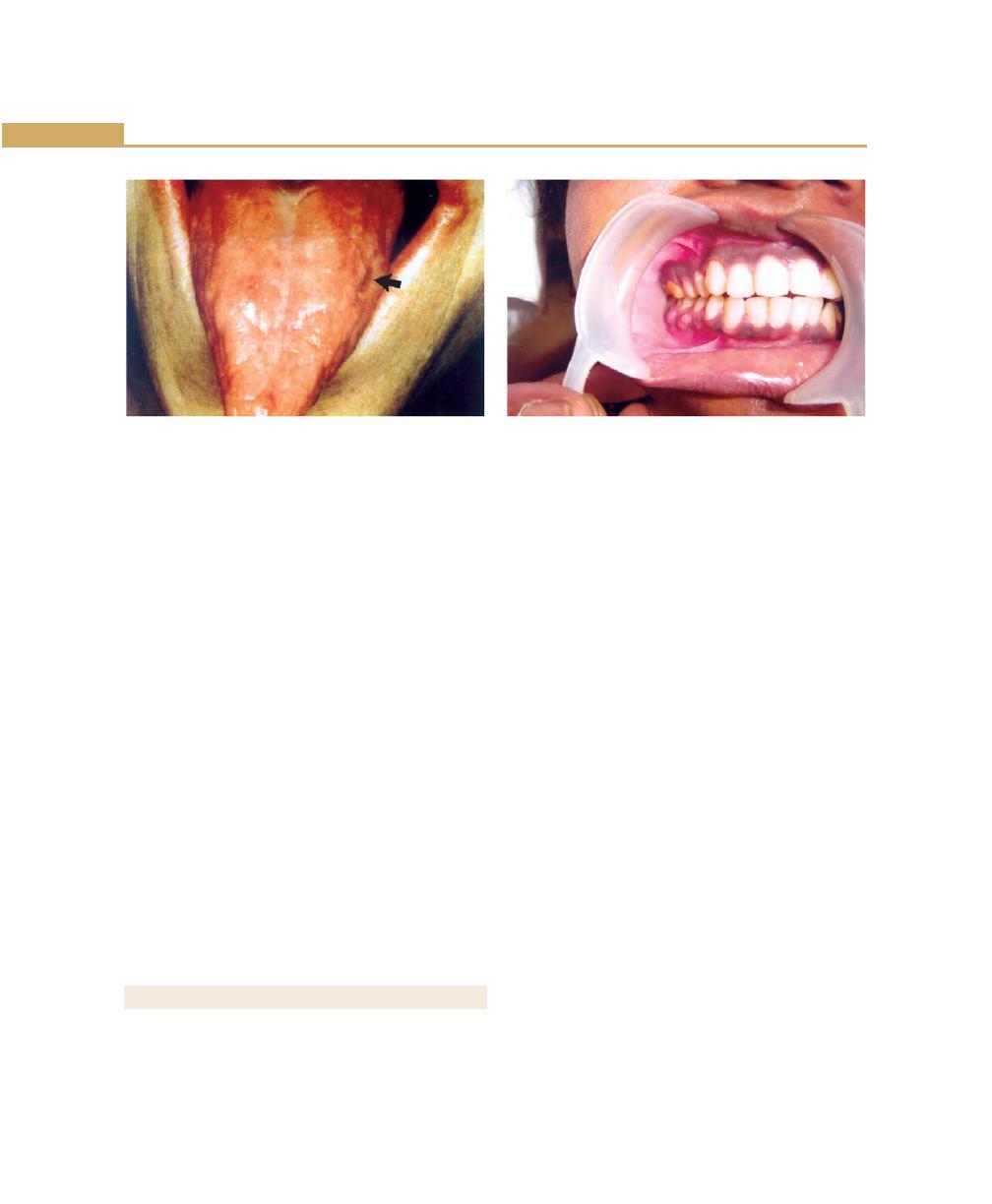

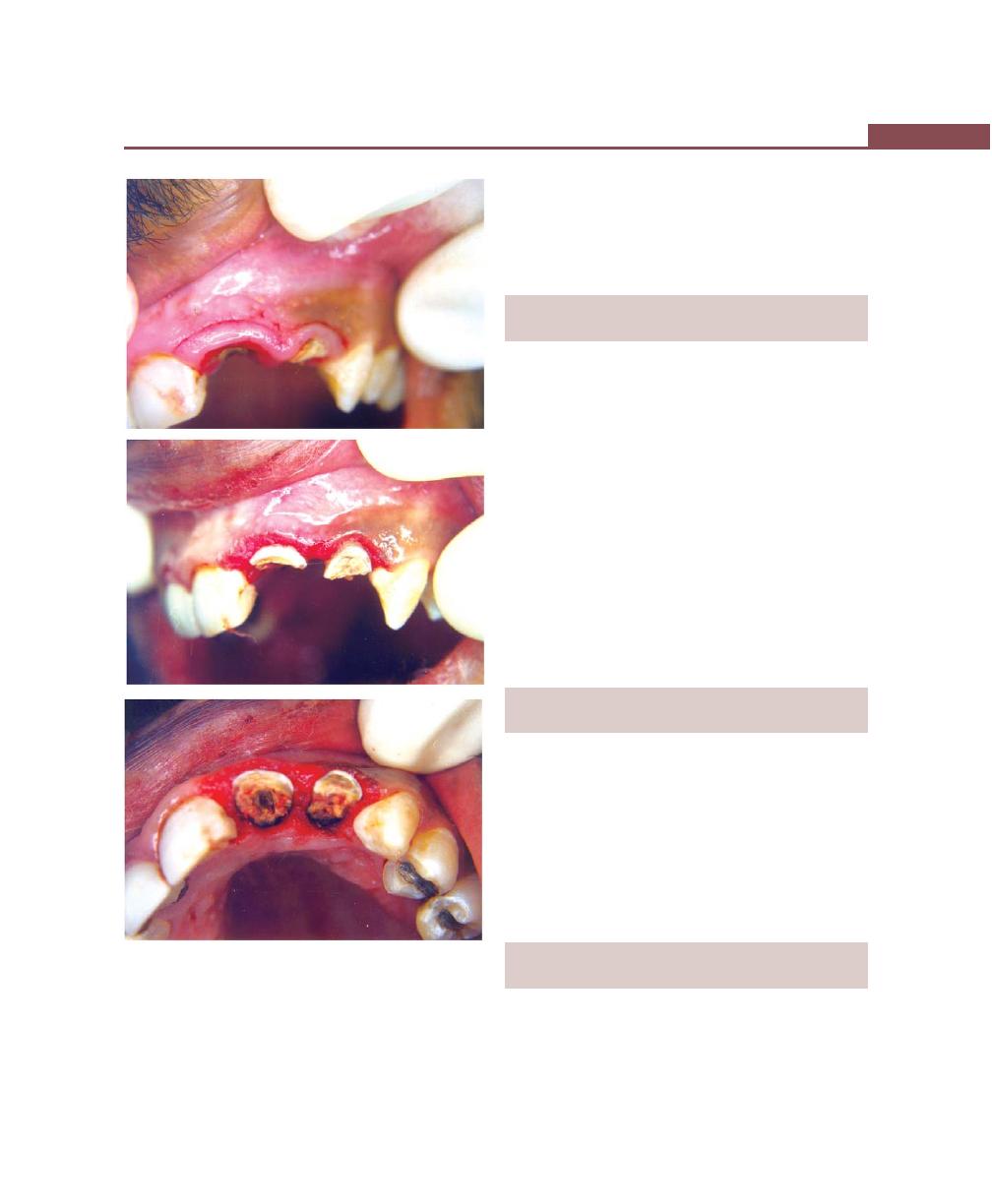

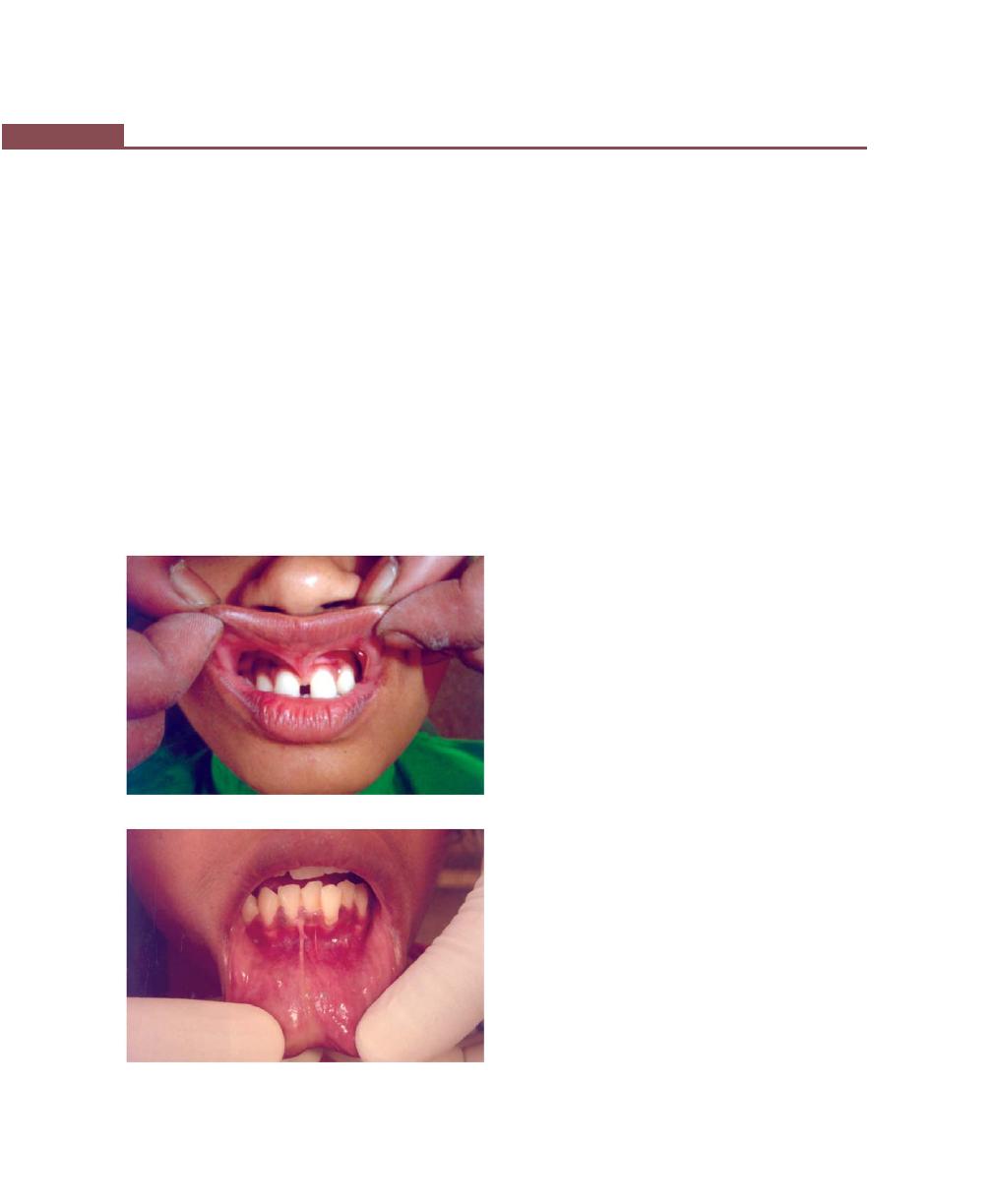

Chapter 21: Periodontal Diseases in Children and

Young Adolescents, 177

Introduction, 177

Anatomic Considerations in Children, 177

Gingiva, 177

Cementum, 177

Periodontal Ligament and Alveolar Bone, 178

Histopathology of Gingivitis in Children, 178

Microbiology of Periodontal Diseases in Children, 178

Classification of Periodontal Diseases in Children, 178

Gingival Lesions, 178

Acute Herpetic Gingivostomatitis, 178

Candidiasis, 180

Gingivitis Artefacta, 181

Localized Gingival Recession, 181

Types of Periodontitis, 181

Prepubertal Periodontitis, 181

Juvenile Periodontitis, 181

Periodontitis Associated with Syndromes, 183

Papillon-Lefévre Syndrome, 183

Ehler-Danlos Syndrome, 183

Down’s Syndrome, 183

Neutropenias, 183

Chédiak-Higashi Syndrome 183

Hypophosphatasia, 183

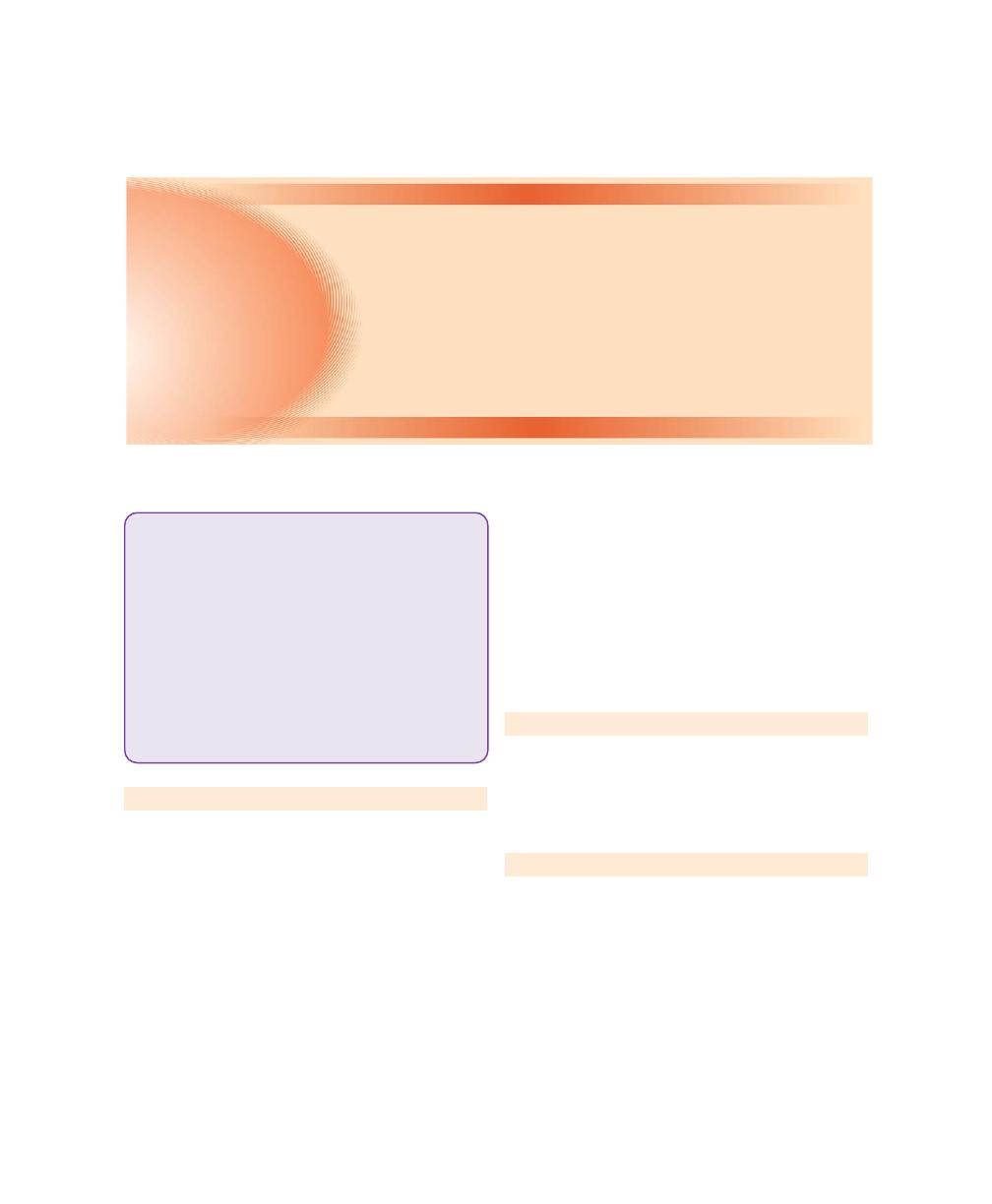

Chapter 22: Desquamative Gingivitis, 185

Introduction, 185

Diagnosis, 185

Clinical Features, 185

Mild Form, 185

Moderate Form, 186

Severe Form, 186

Histopathology, 186

Therapy, 186

Local Treatment, 186

Systemic Treatment, 188

Diseases Clinically Presenting as Desquamative

Gingivitis, 188

Lichen Planus, 188

Cicatricial Pemphigoid, 189

Bullous Pemphigoid, 189

Linear IgA Disease, 190

Dermatitis Herpetiformis, 190

Pemphigus Vulgaris, 190

Drug Reaction or Eruptions, 191

SECTION 2: PERIODONTAL DISEASES

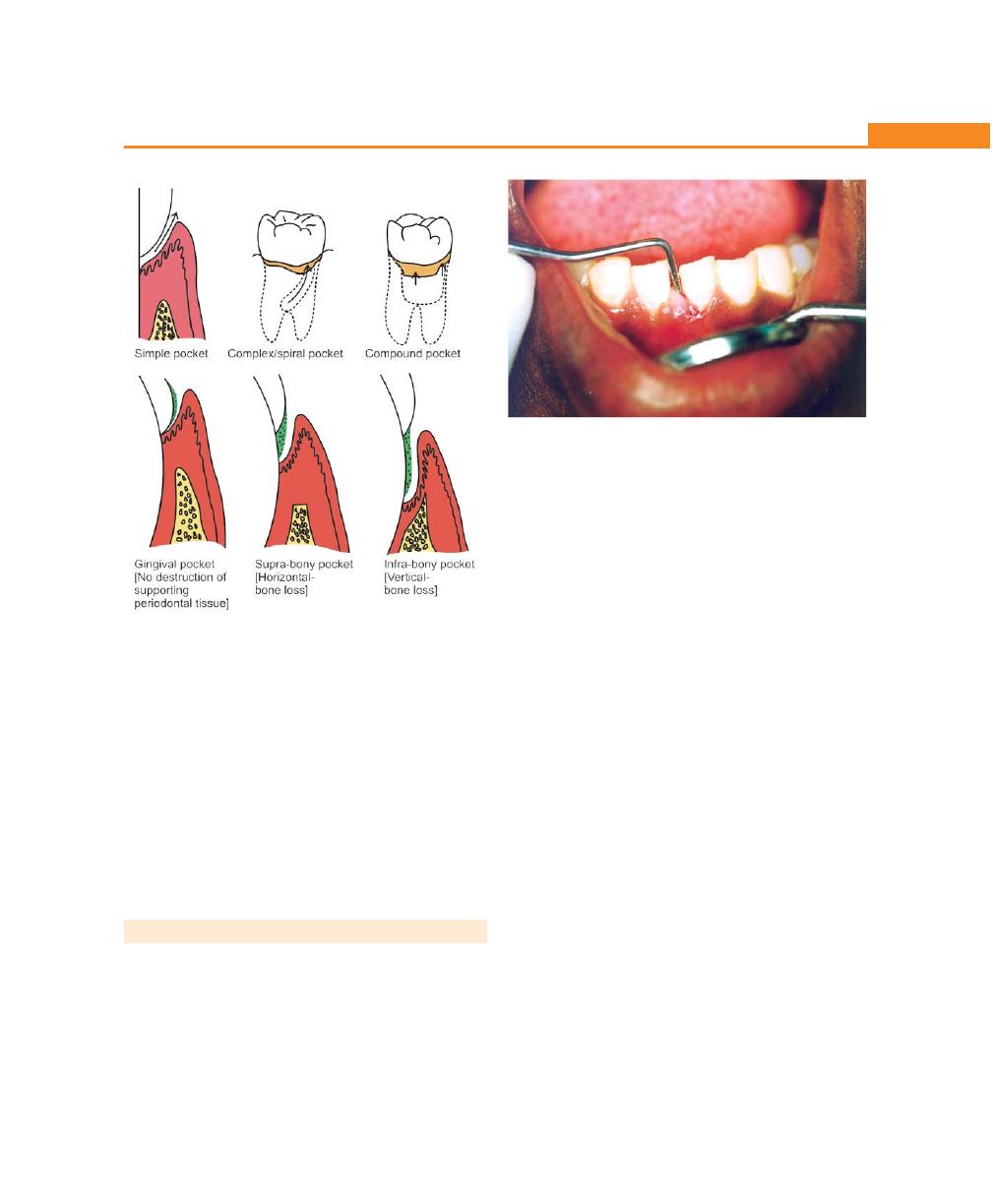

Chapter 23: The Periodontal Pocket, 192

Introduction, 192

Definition, 192

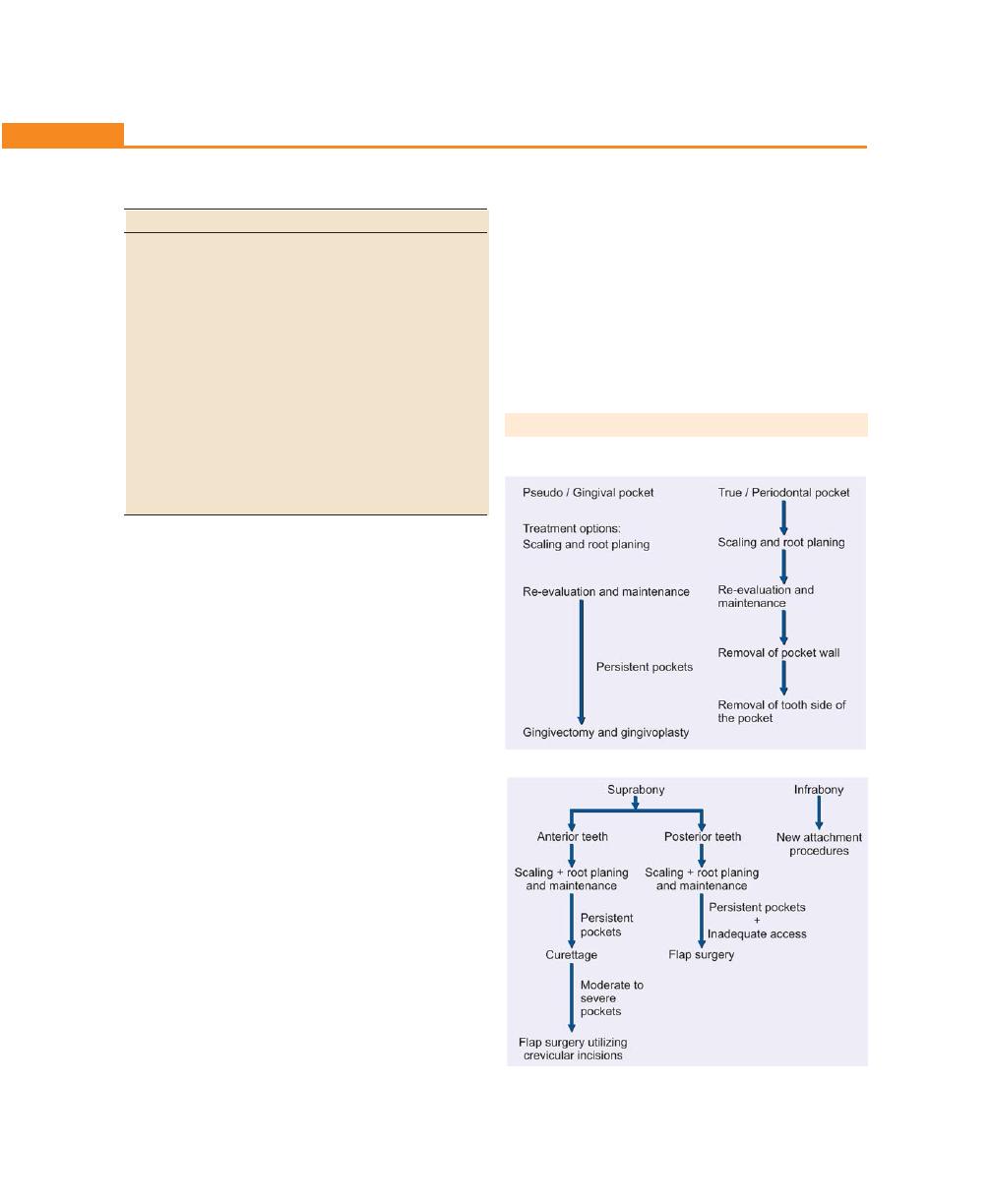

Classification of Pockets, 192

Clinical Features, 193

Signs and Symptoms, 193

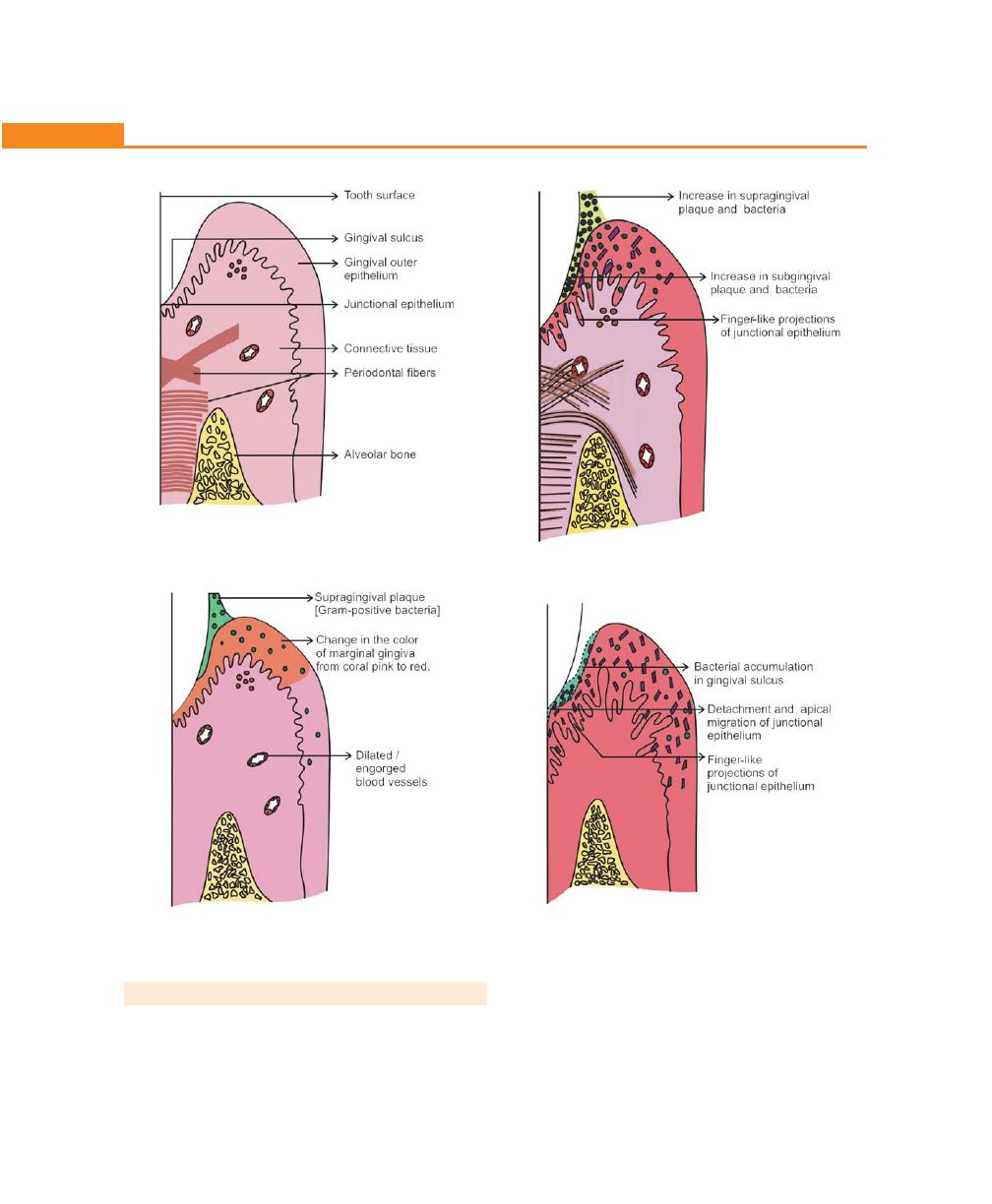

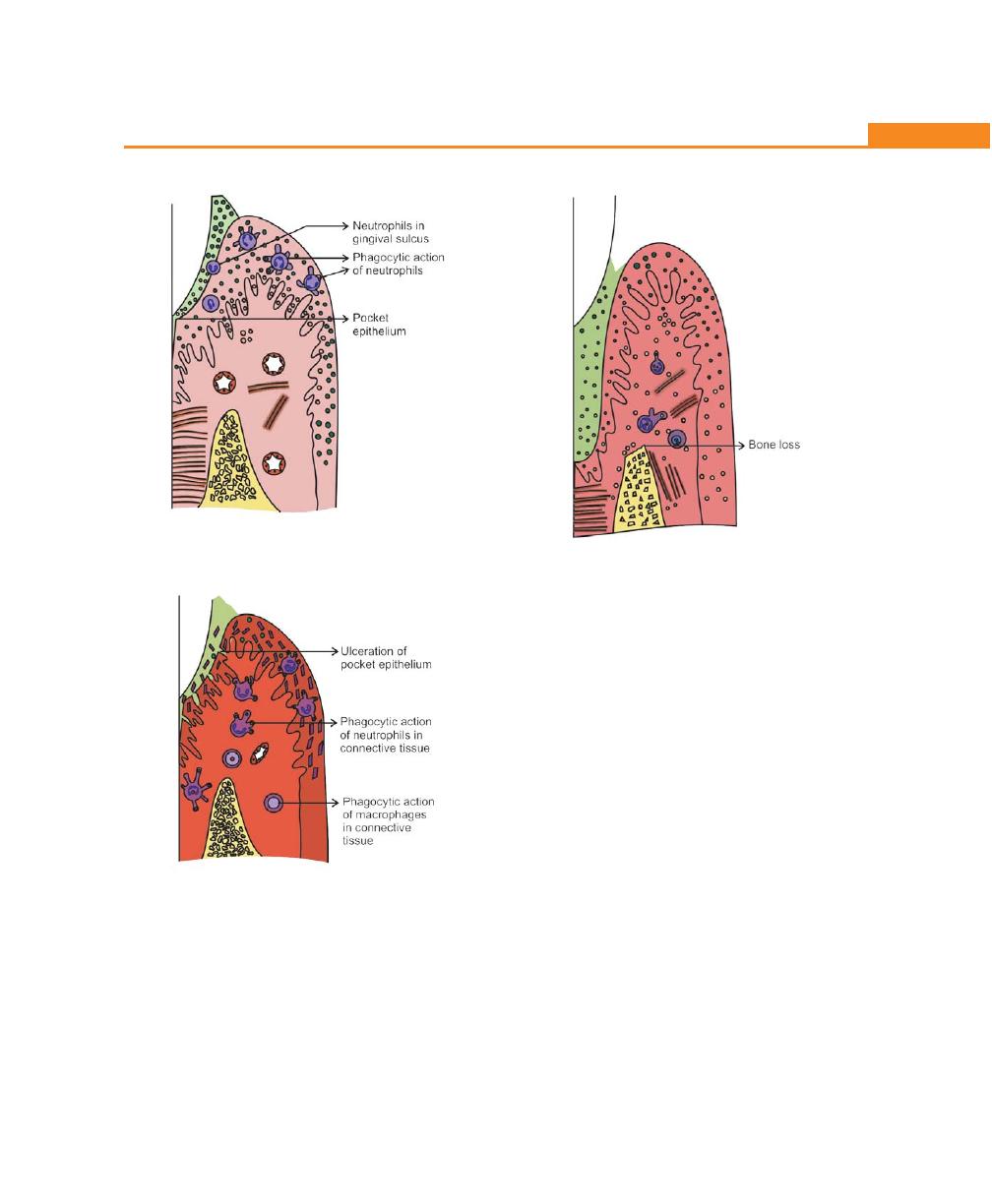

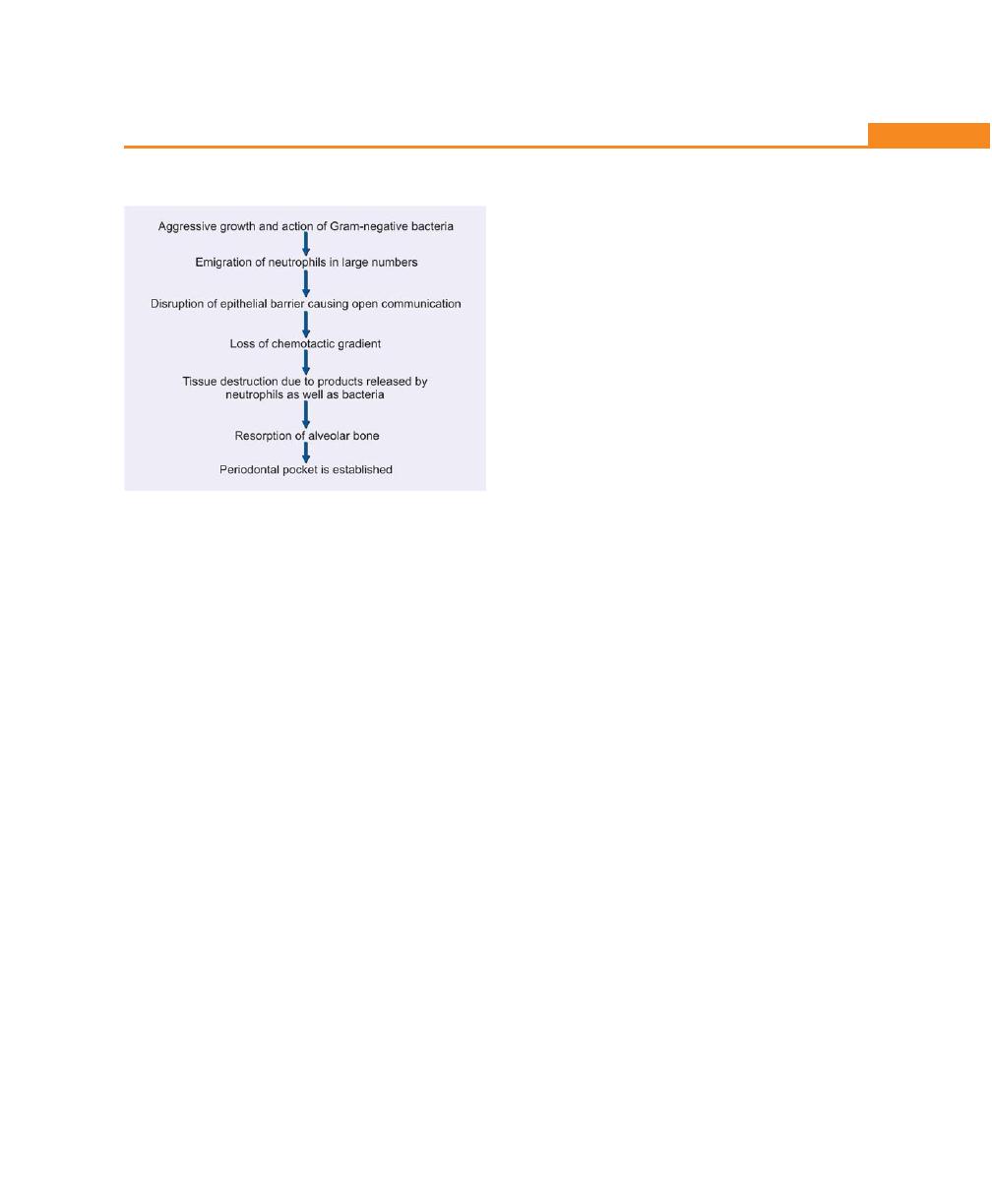

Pathogenesis, 194

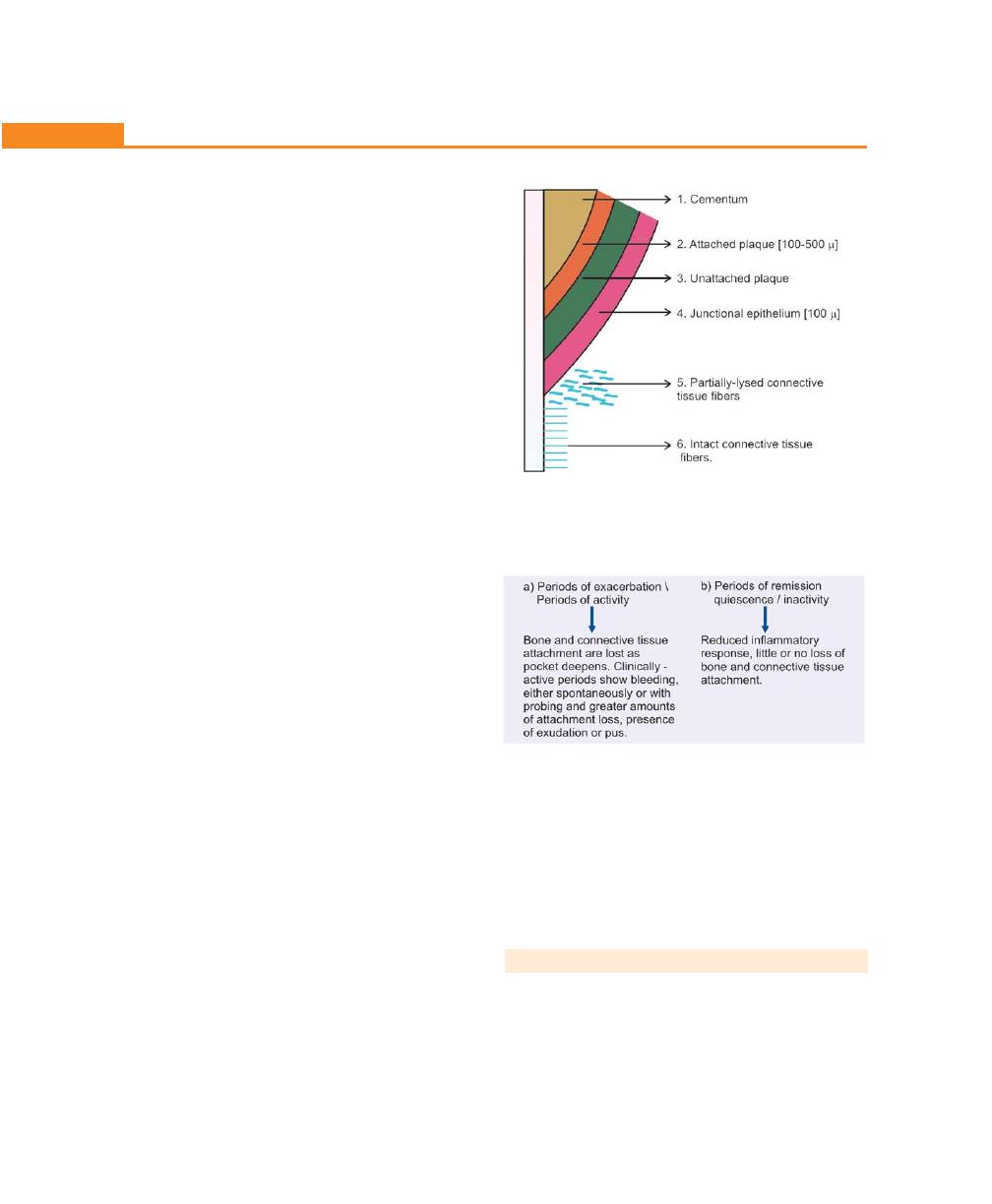

Histopathology, 197

Changes in the Soft Tissue Wall, 197

Microtopography of the Gingival Wall of the Pocket, 197

Periodontal Pocket as Healing Lesions, 197

Pocket Contents, 198

Changes in Root Surface Wall, 198

Periodontal Disease Activity, 198

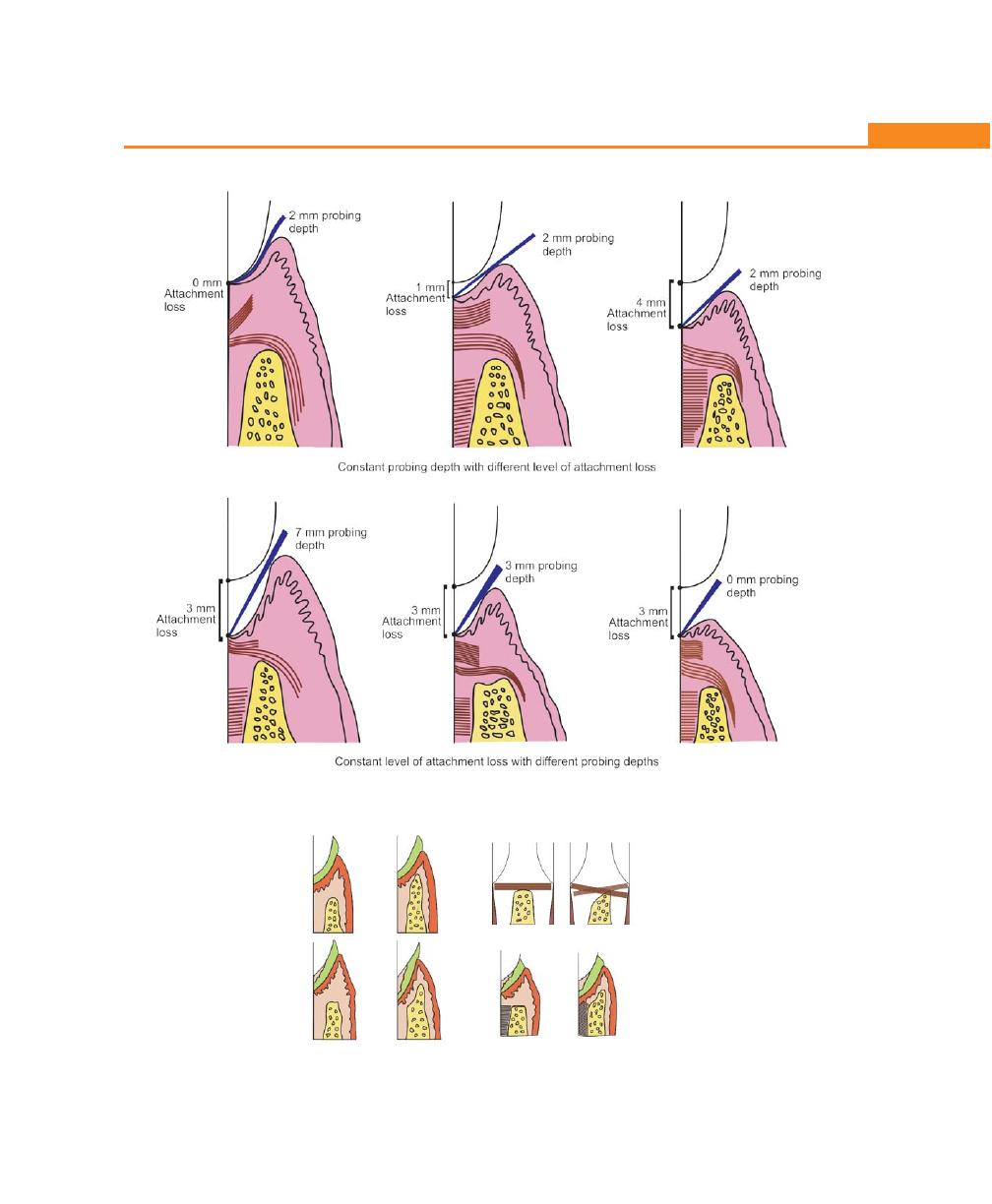

Relation of Loss of Attachment and Bone Loss to Pocket

Depth, 198

Periodontal Cyst, 198

Differences Between Suprabony and Infrabony Pocket,

200

Determination of Pocket Depth, 200

Treatment of Periodontal Pocket, 200

Chapter 24: Bone Loss and Patterns of Bone

Destruction, 202

Introduction, 202

Normal Anatomy of Alveolar Bone, 202

Mechanism of Bone Formation and Bone Destruction, 202

Local Factors, 203

Gingival Inflammation, 203

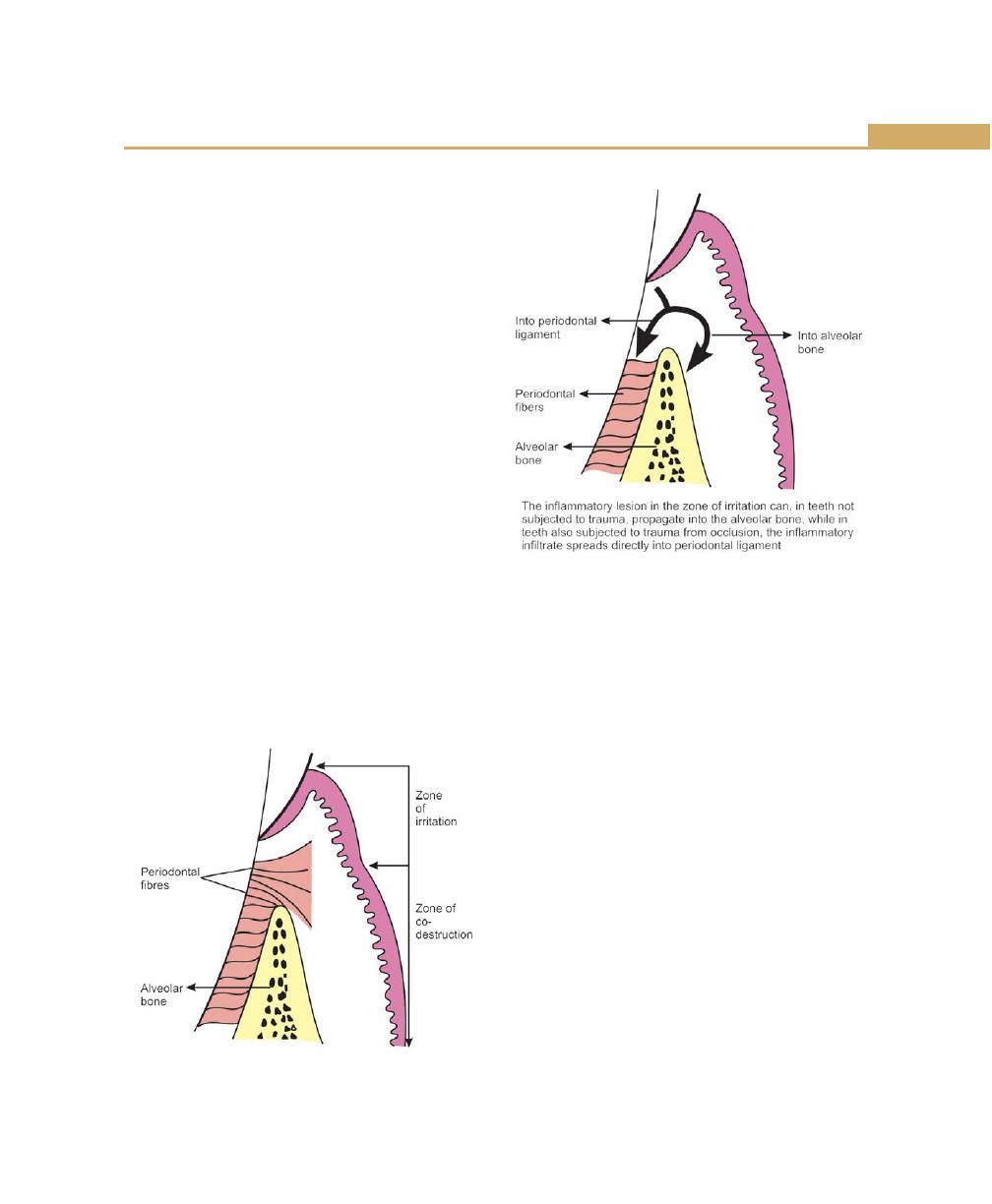

Trauma from Occlusion, 204

Systemic Factors, 204

Pharmacological Agents and Bone Resorption,

204

xix

Contents

Radius of Action, 204

Rate of Bone Loss, 204

Periods of Destruction, 204

Factors Determining Bone Morphology in Periodontal

Disease, 205

Bone Destruction Patterns in Periodontal Disease, 205

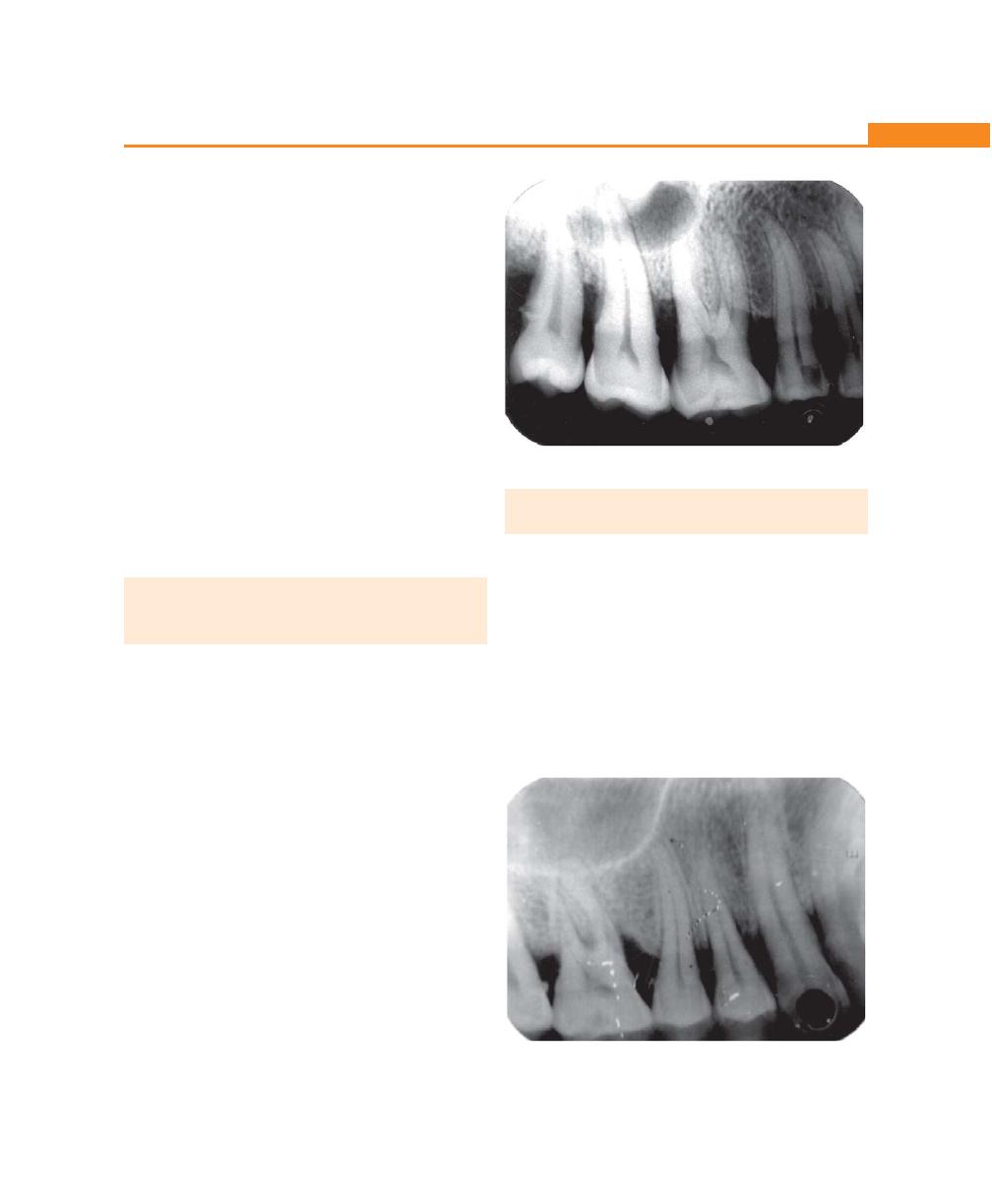

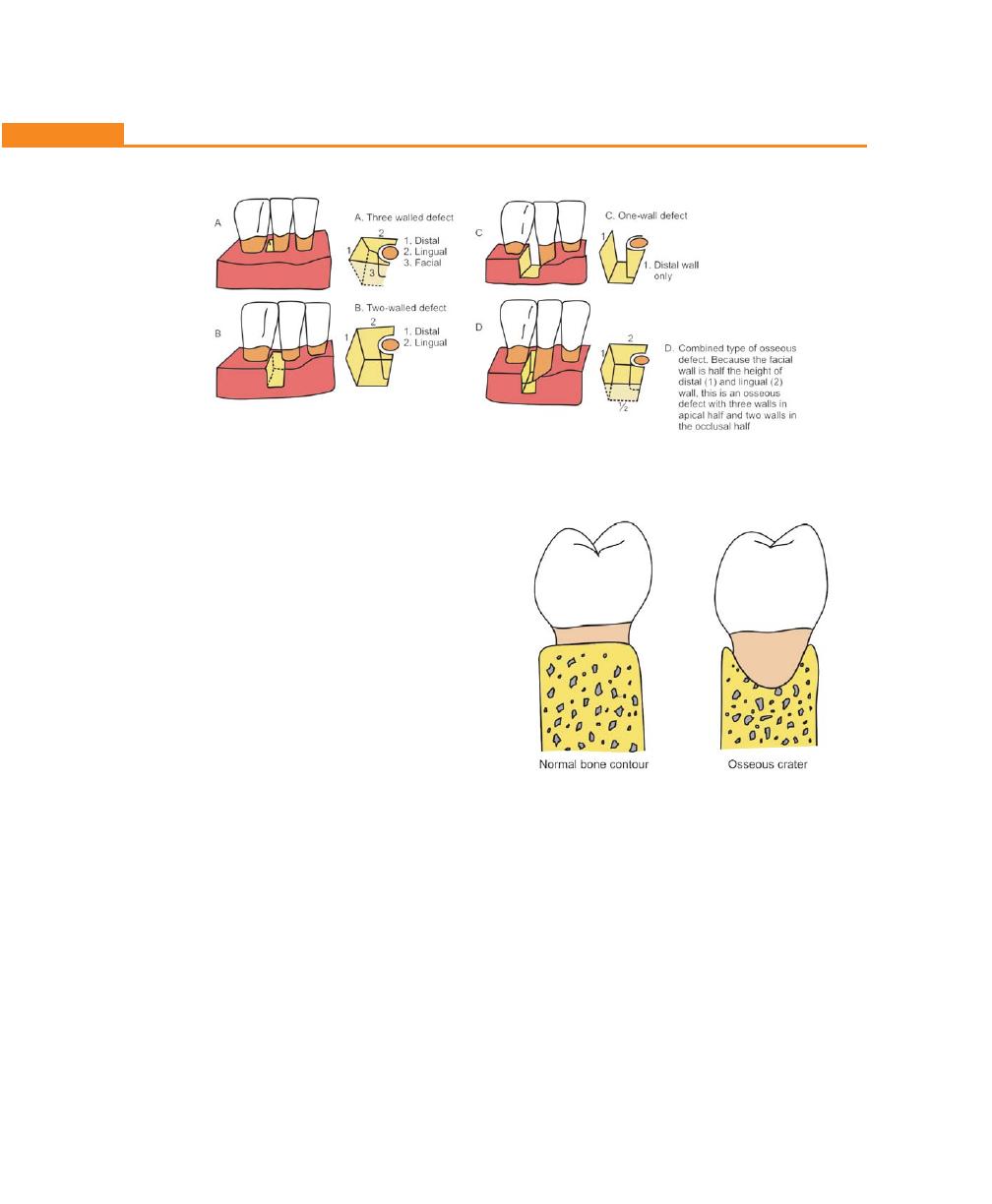

Angular Defects, 205

Osseous Craters, 206

Bulbous Bony Contours, 206

Reversed Architecture, 206

Ledges, 207

Furcation Involvements, 207

Prevalence and Distribution of Bone Defects, 207

Chapter 25: Chronic Periodontitis, 209

Introduction, 209

Definition, 209

Diagnostic Criteria, 209

Clinical Features, 209

Microbiological Features, 210

Radiographic Features, 210

Types Based on Disease Distribution and Severity, 210

Nature of Disease Progression, 211

Risk Factors for Disease, 211

General Concept for Etiology, 212

Chapter 26: Aggressive Periodontitis, 213

Introduction, 213

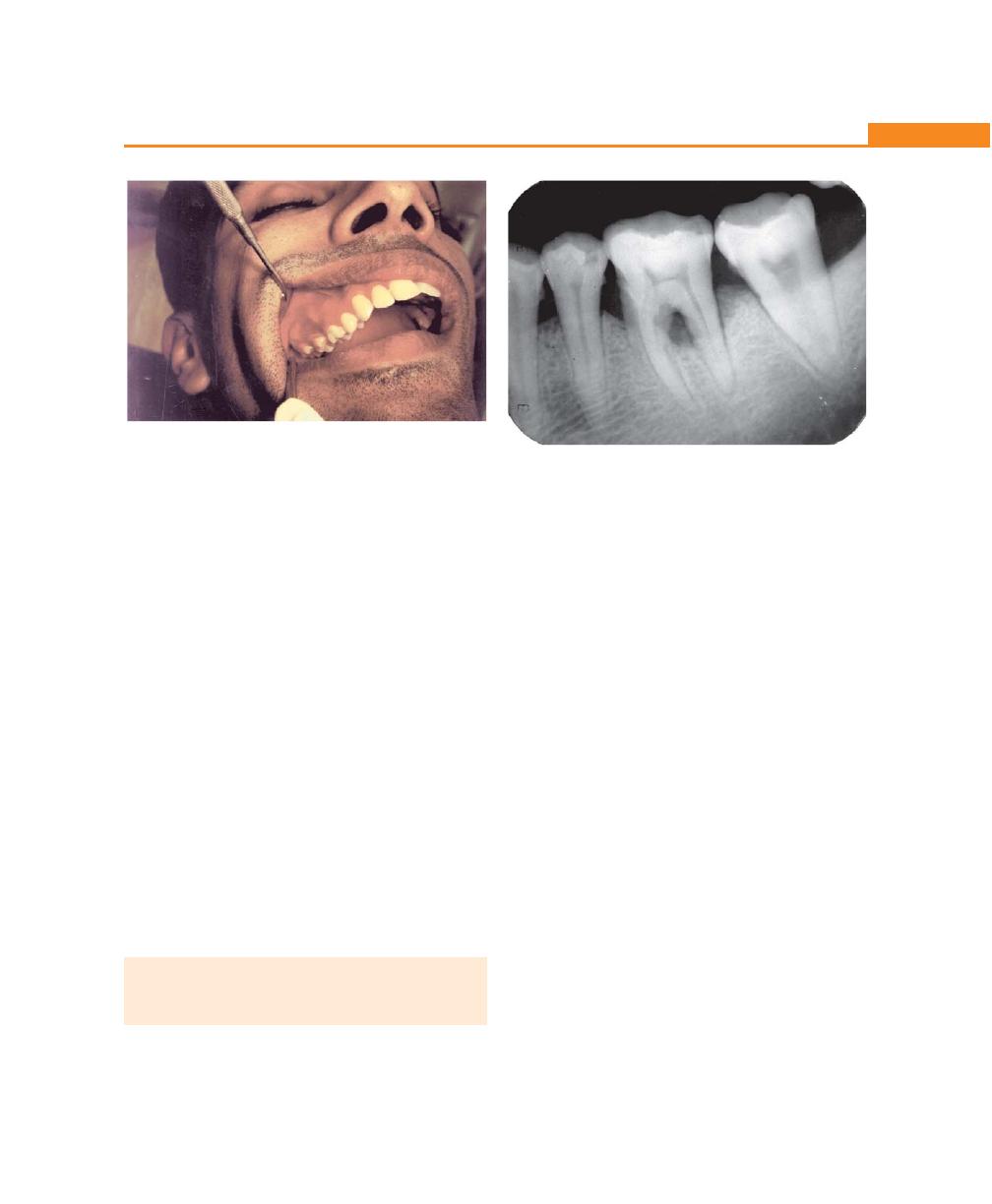

Localized Aggressive Periodontitis, 213

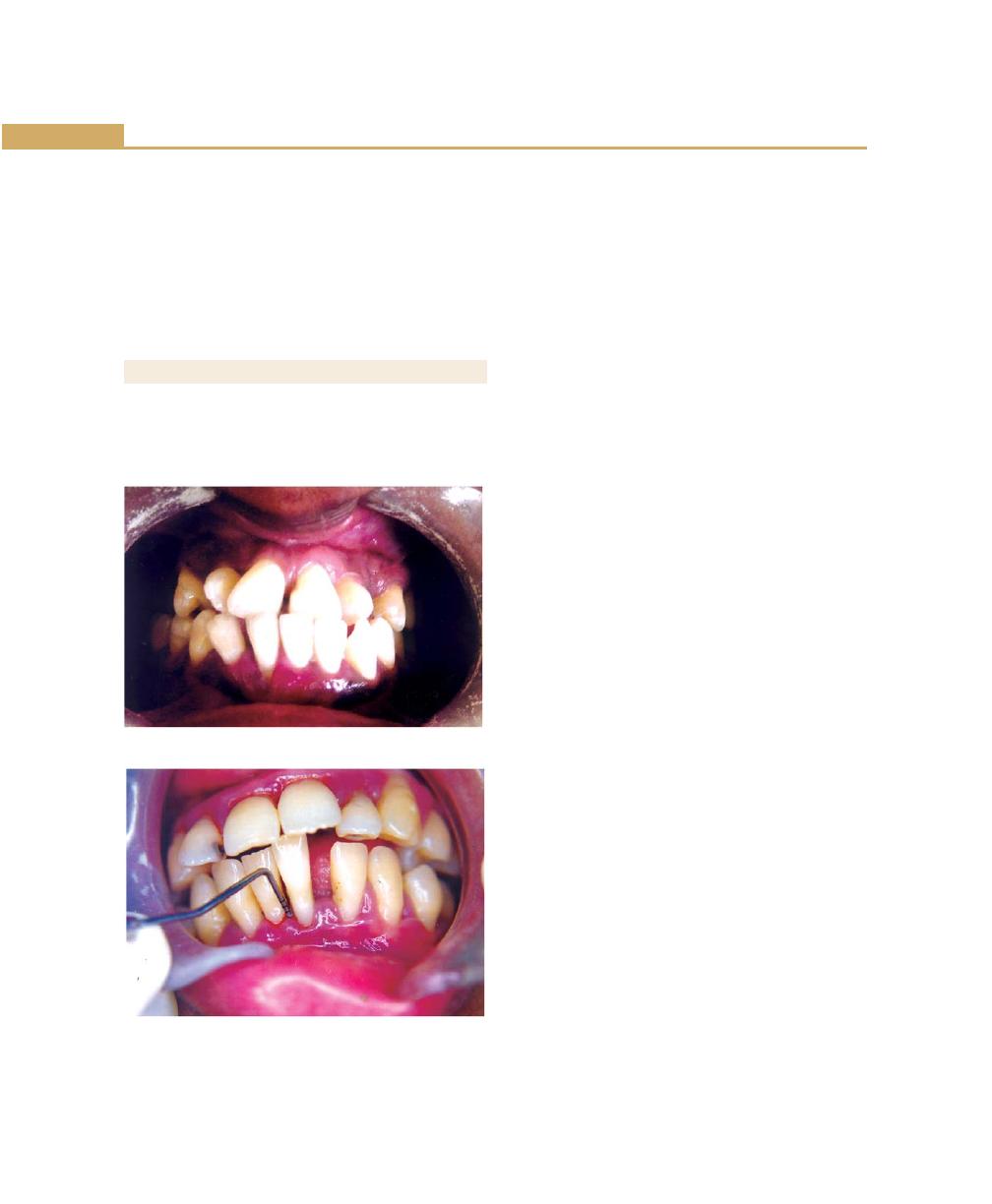

Historical Background, 213

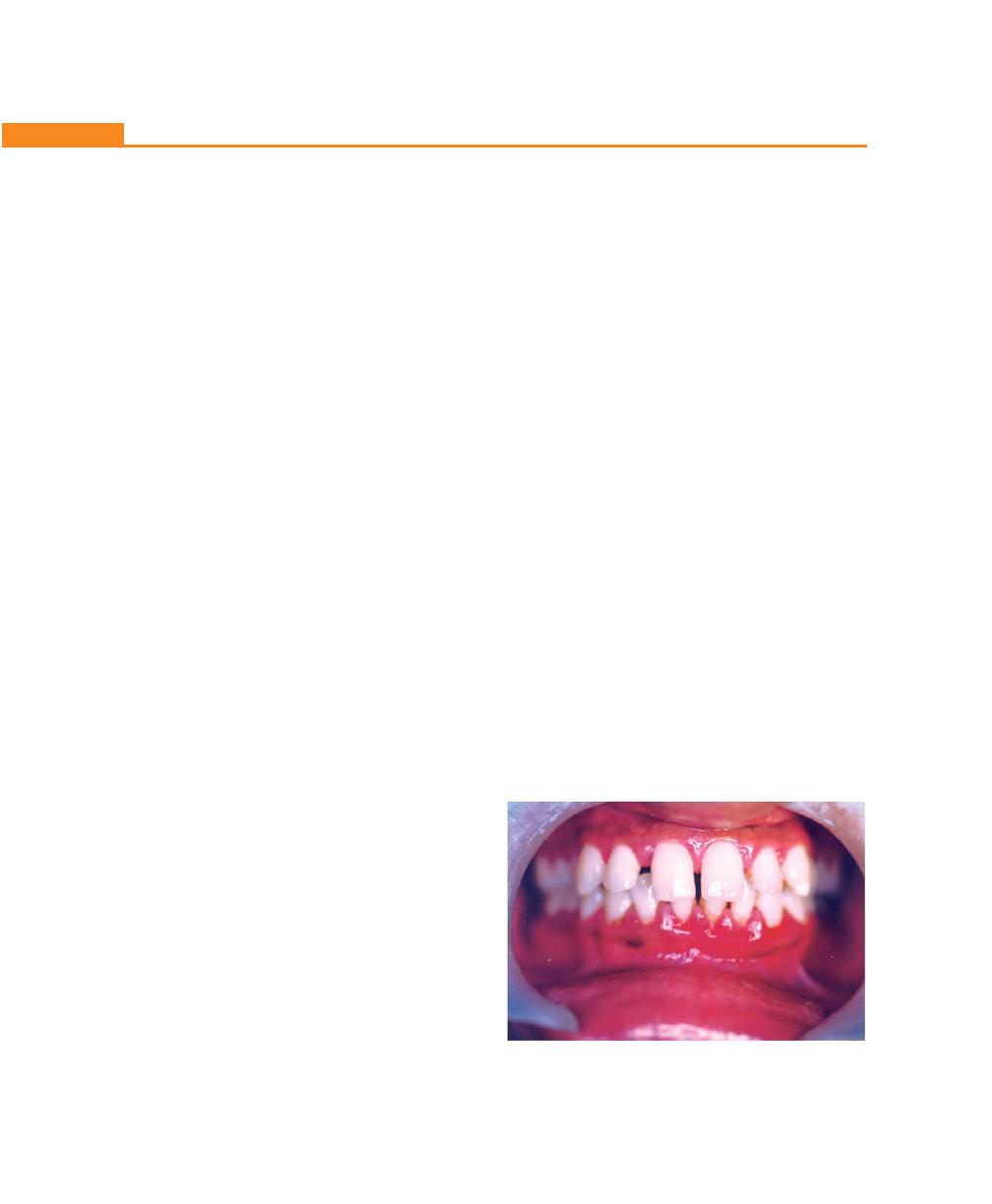

Clinical Features, 214

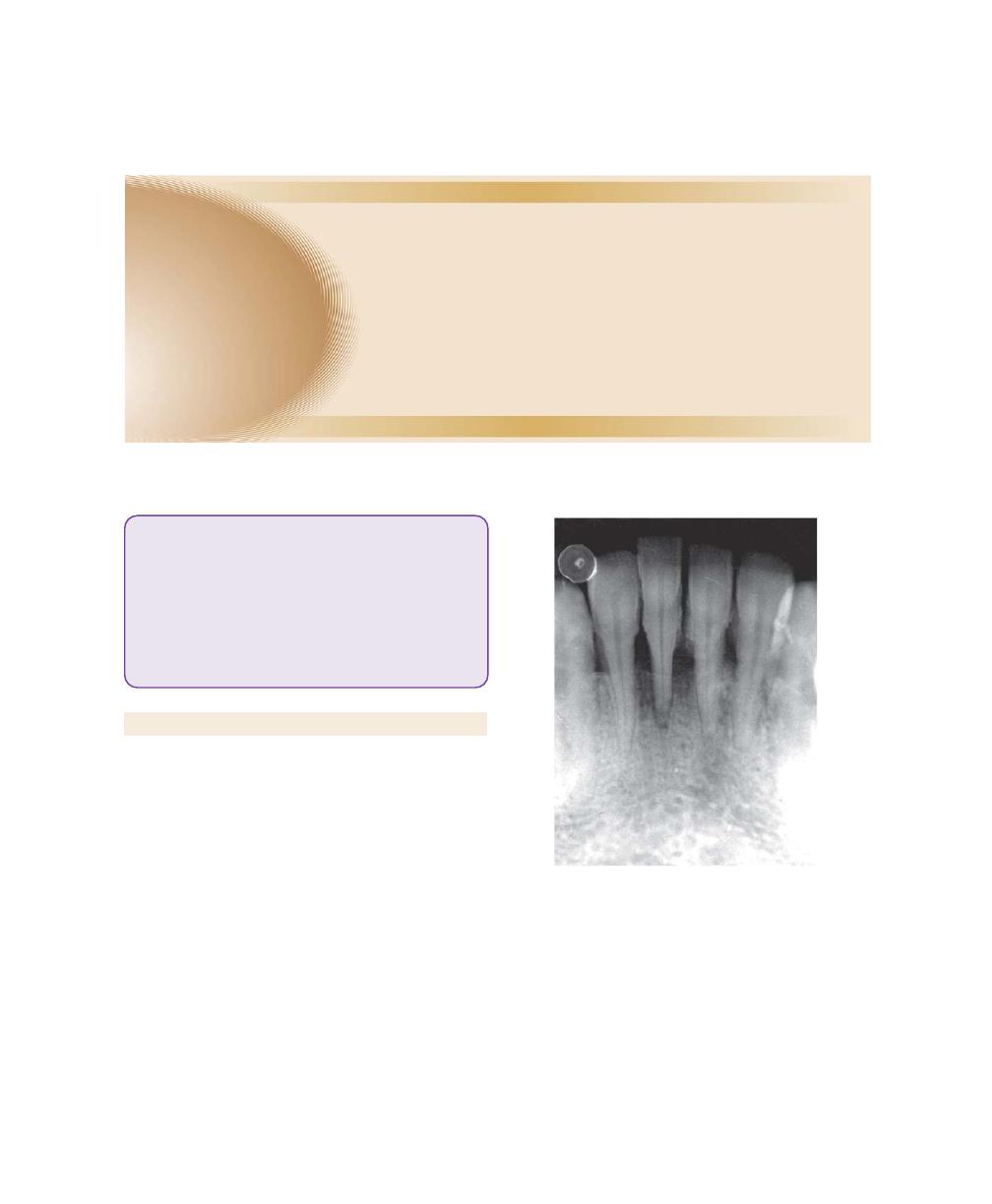

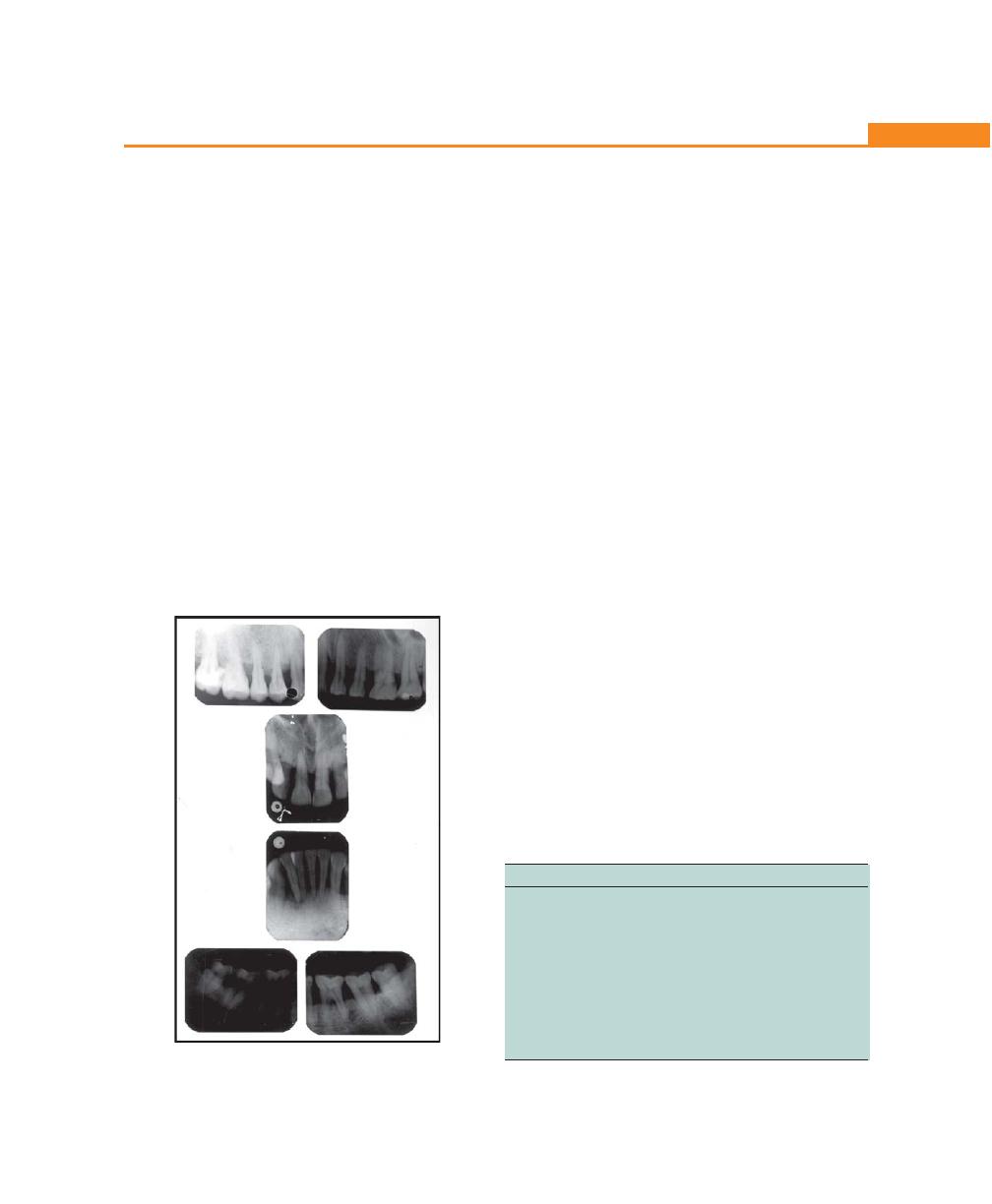

Radiographic Findings, 215

Histopathologic Features, 215

Bacteriology, 215

Immunology, 216

Treatment, 216

Generalized Aggressive Periodontitis, 216

Clinical Characteristics, 216

Radiographic Findings, 217

Risk Factors, 217

Microbiologic Factors, 217

Immunologic Factors, 217

Genetic Factors, 217

Environmental Factors, 217

Chapter 27: Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis,

Refractory Periodontitis and Periodontitis as a

Manifestation of Systemic Disease, 218

Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis (NUP), 218

Non-AIDS type, 218

AIDS associated, 219

Refractory Periodontitis, 219

Etiology, 219

Clinical Features, 219

Treatment, 220

Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Disease, 220

Papillon-Lefévre Syndrome, 220

Chédiak-Higashi Syndrome, 221

Down Syndrome, 221

Hypophosphatasia, 221

Neutropenia, 221

Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency, 221

Chapter 28: AIDS and the Periodontium, 223

HIV Opportunistic Infections, 223

Classification of Periodontal Diseases Associated with

HIV Infection, 223

Linear Gingivitis, 224

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis, 224

Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis, 224

Necrotizing Stomatitis, 224

CDC Surveillance Care Classification, 224

Most Common Oral and Periodontal Manifestations of HIV

Infection, 225

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia, 225

Oral Candidiasis, 225

Kaposi’s Sarcoma, 225

Bacillary Angiomatosis, 225

Oral Hyperpigmentation, 225

Atypical Ulcers and Delayed Healing, 225

Management, 225

Part V: Treatment of Periodontal Diseases

SECTION 1: DIAGNOSIS, PROGNOSIS AND

TREATMENT PLAN

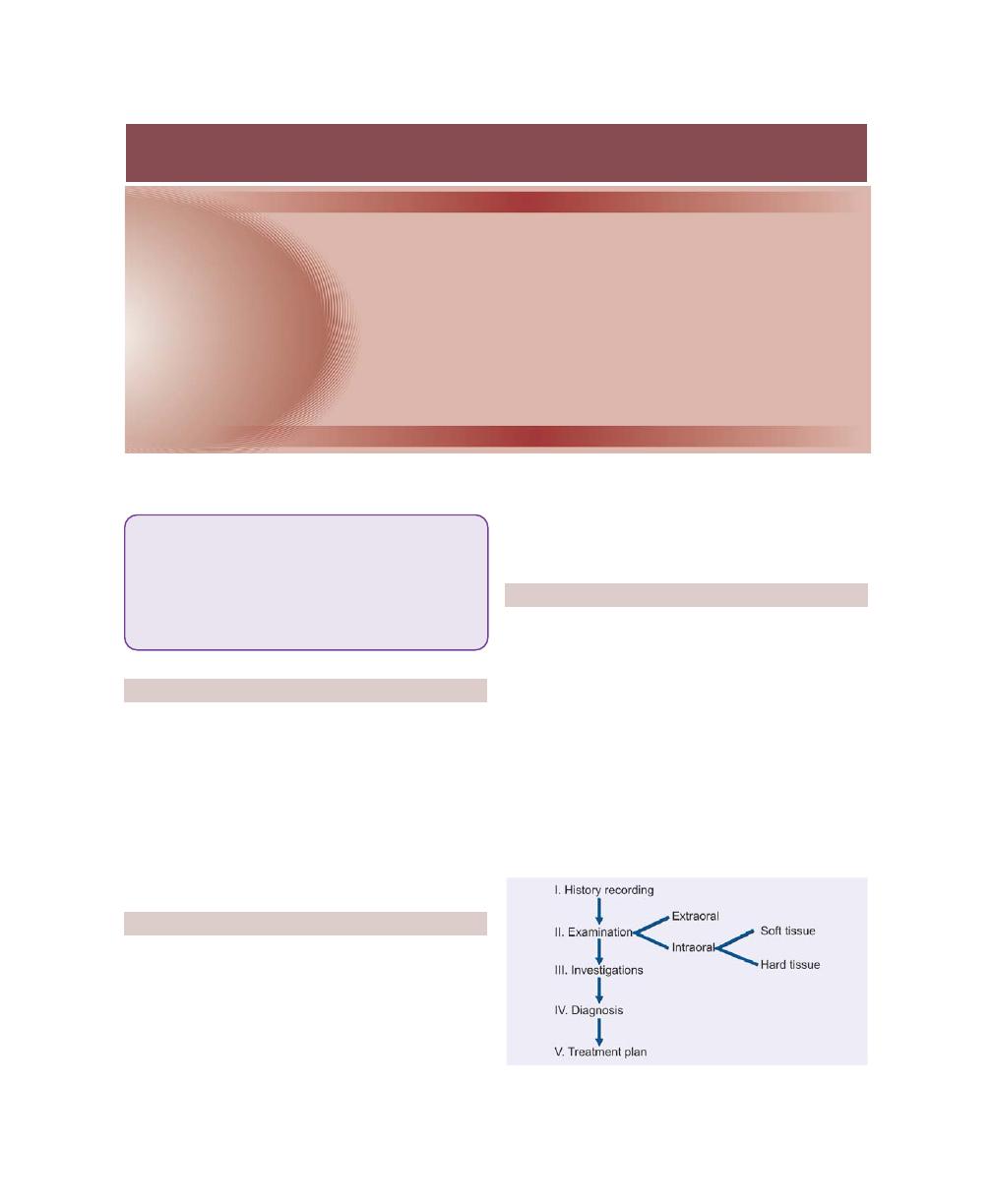

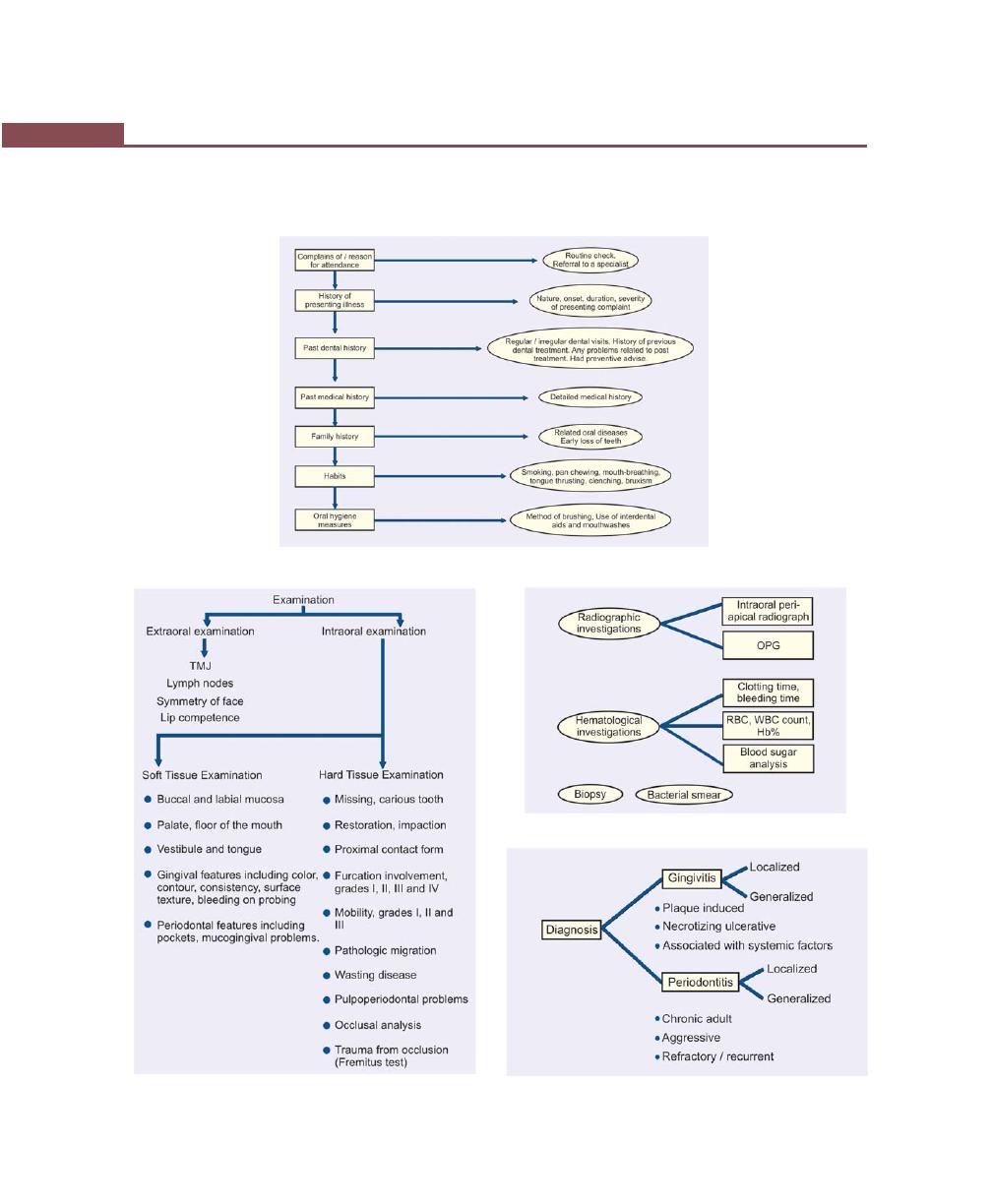

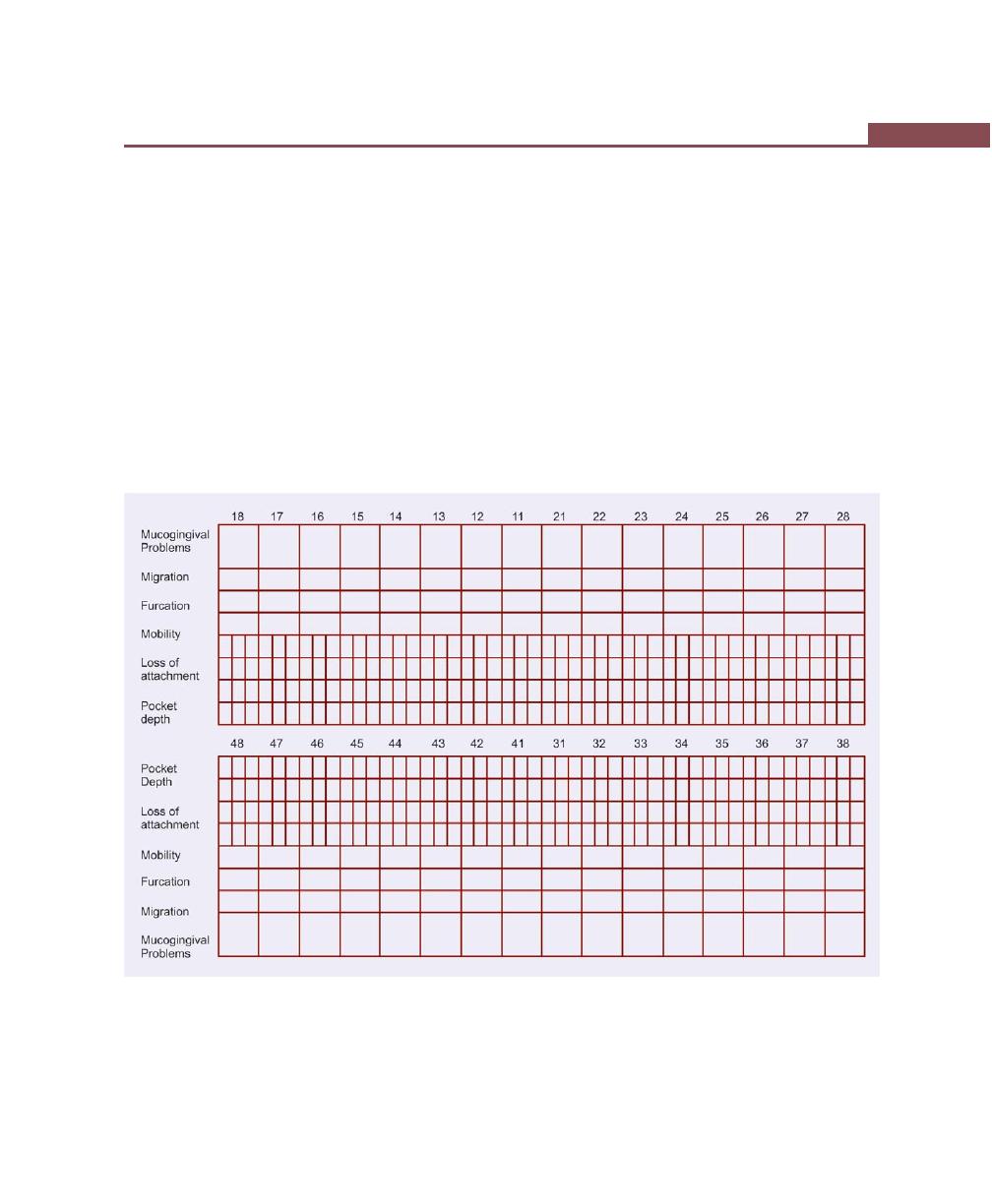

Chapter 29: Diagnosis of Periodontal Diseases, 229

Periodontal Diagnosis, 229

Principles of Diagnosis, 229

Clinical Diagnosis, 229

Stages of Diagnosis, 229

Diagnosis with Detailed Case History Recording, 230

Case History Proforma, 232

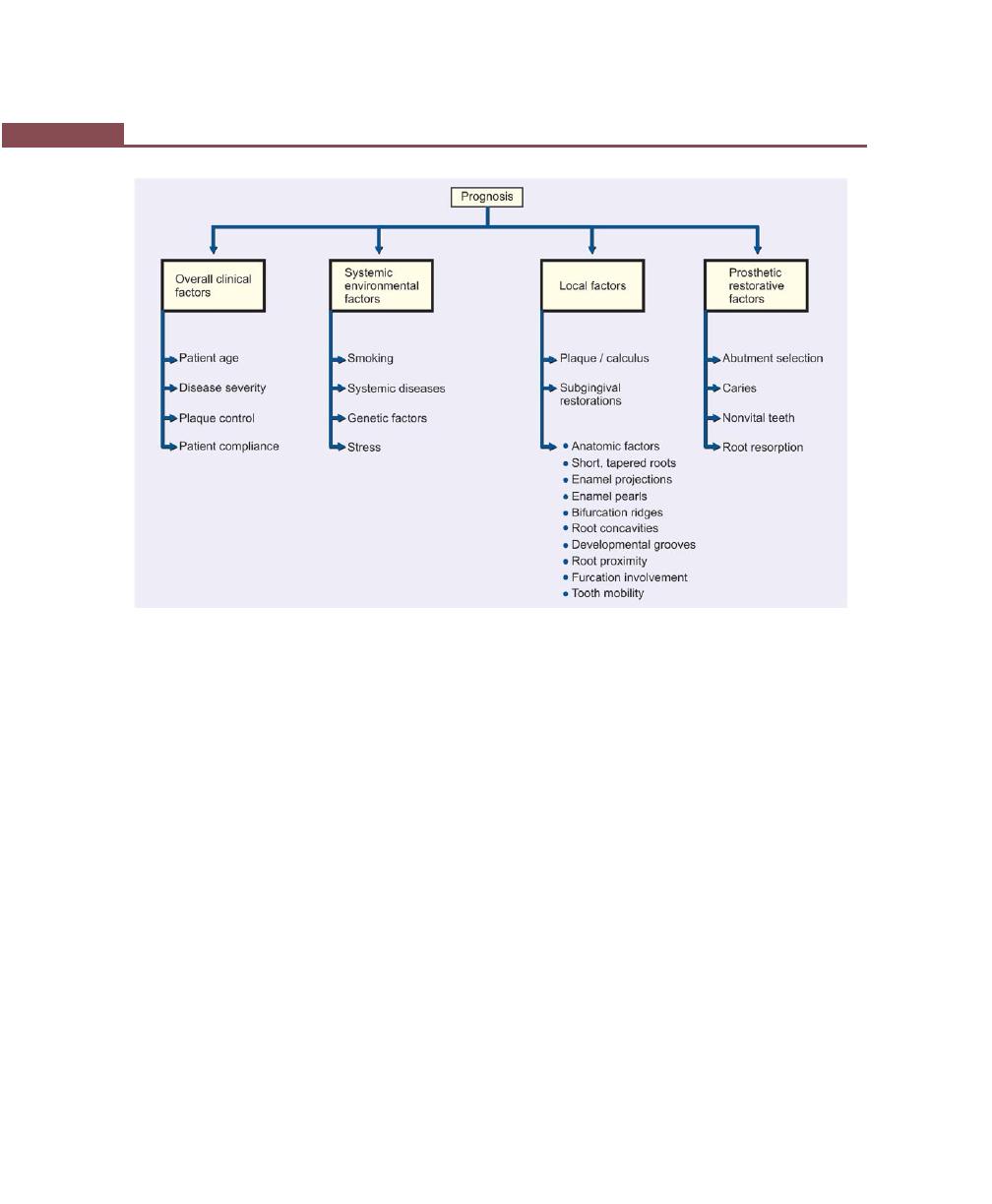

Chapter 30: Determination of Prognosis, 237

Definition of Prognosis, 237

Difference Between Prognosis and Risk, 237

Determination of Prognosis, 237

Factors for Determination of Prognosis, 238

Overall Clinical Factors, 238

Systemic/Environmental Factors, 239

Local Factors, 240

Prosthetic/restorative Factors, 241

Relationship Between Diagnosis and Prognosis, 241

Re-evaluation of Prognosis After Phase I Therapy, 243

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

xx

Chapter 31: Related Risk Factors Associated with

Periodontal Diseases, 244

Definition, 244

Risk Factors, 244

Risk Determinants, 245

Risk Indicators, 245

Risk Markers/Predictors, 245

Clinical Risk Assessment, 246

Demographic Data, 246

Medical History, 246

Dental History, 246

Clinical Examination, 246

Chapter 32: Various Aids Including Advanced

Diagnostic Techniques, 247

Aids used in Clinical Diagnosis, 247

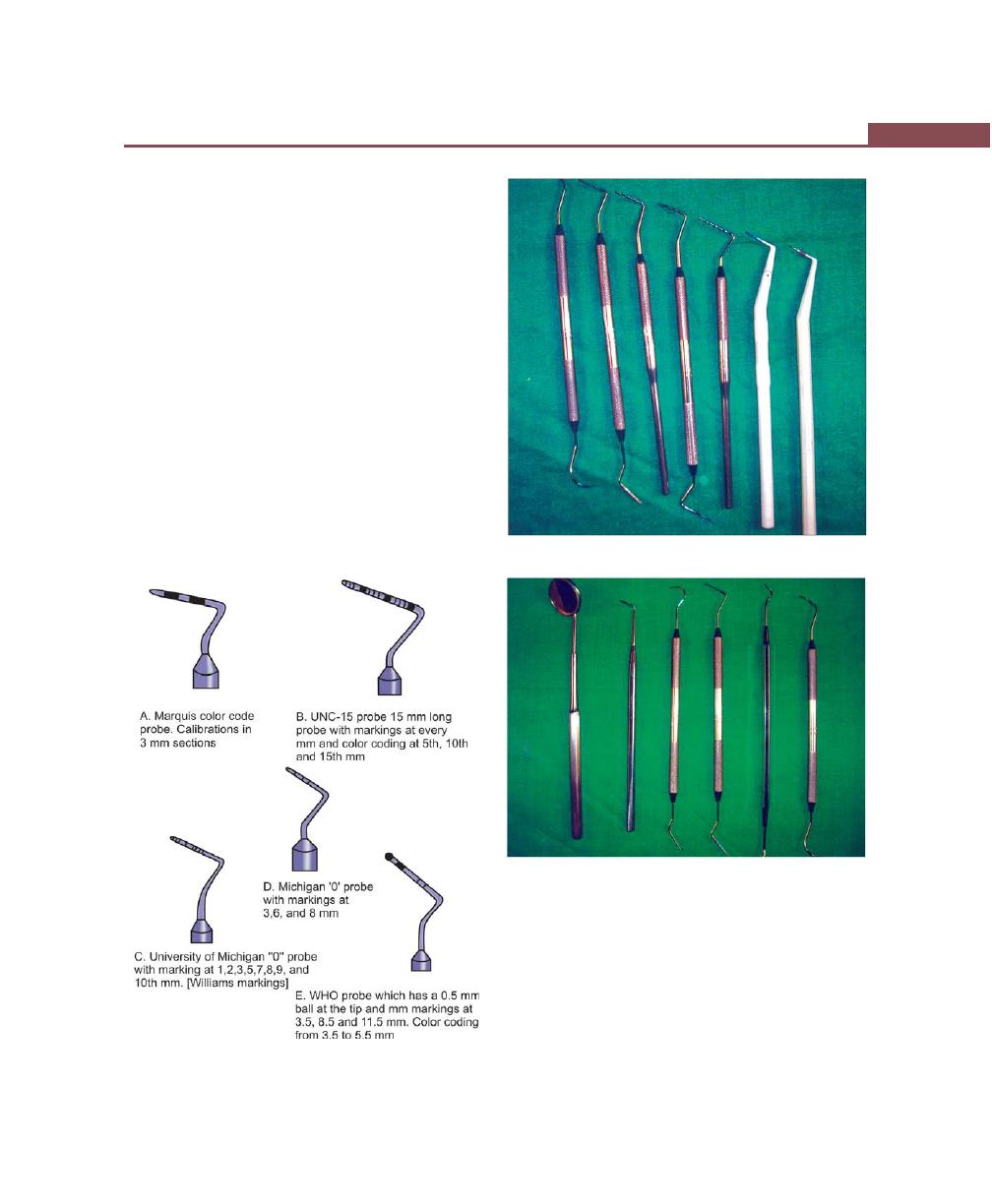

Periodontal Probes, 247

Conventional Probes, 247

PSR, 248

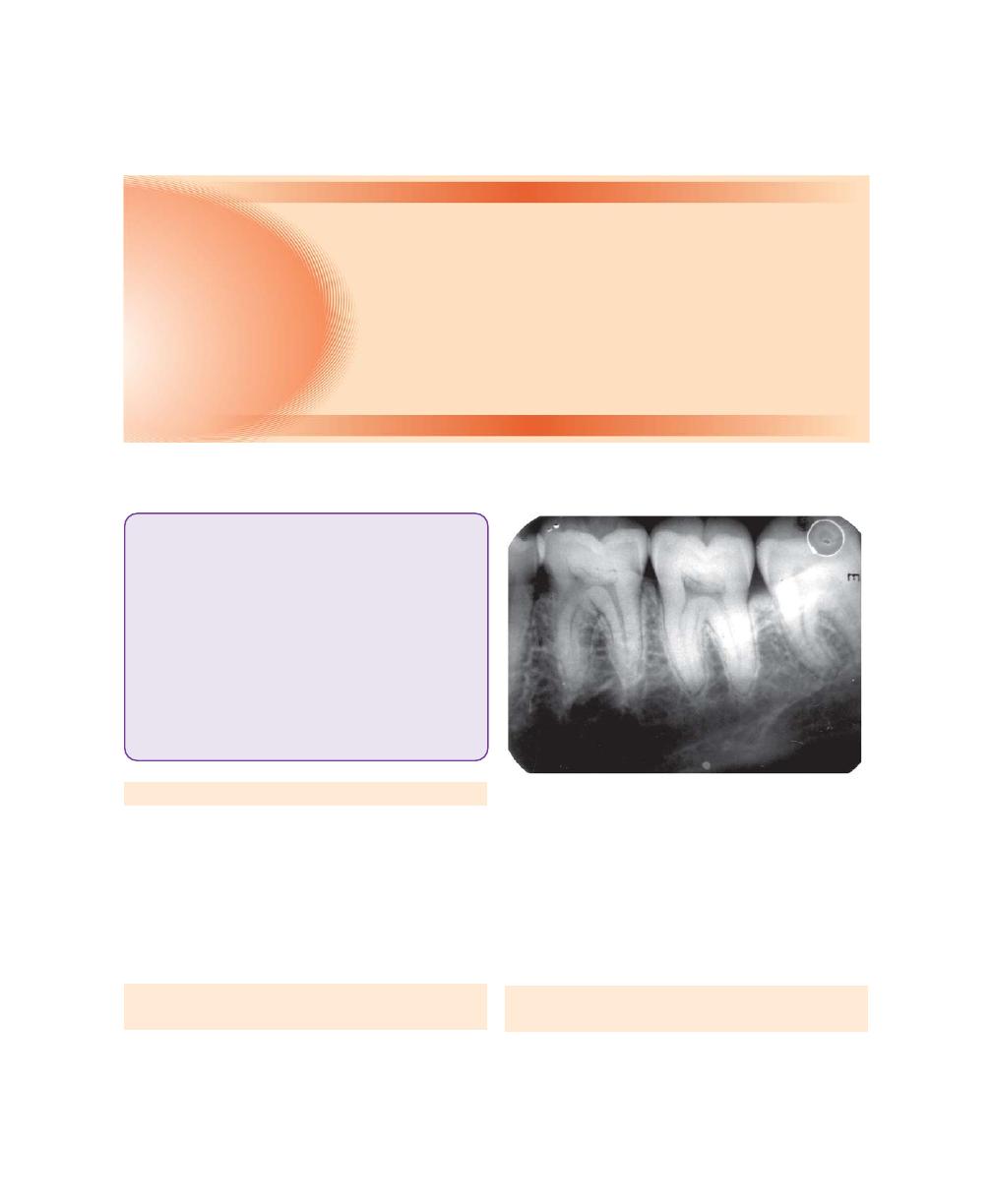

Aids used in Radiographic Diagnosis, 249

Orthopantomograph, 249

Xeroradiography, 249

Advanced Radiographic Techniques, 249

Iodine-125, 249

Photodensitometric Analysis, 250

Digital Radiography, 250

Subtraction Radiography, 250

CADIA, 250

Nuclear Medicine Bone Scan, 250

Aids in Microbiological Diagnosis, 250

Identification of Bacteria, 250

Speciation Techniques, 251

DNA Probes, 252

Aids in Immunological Diagnosis, 252

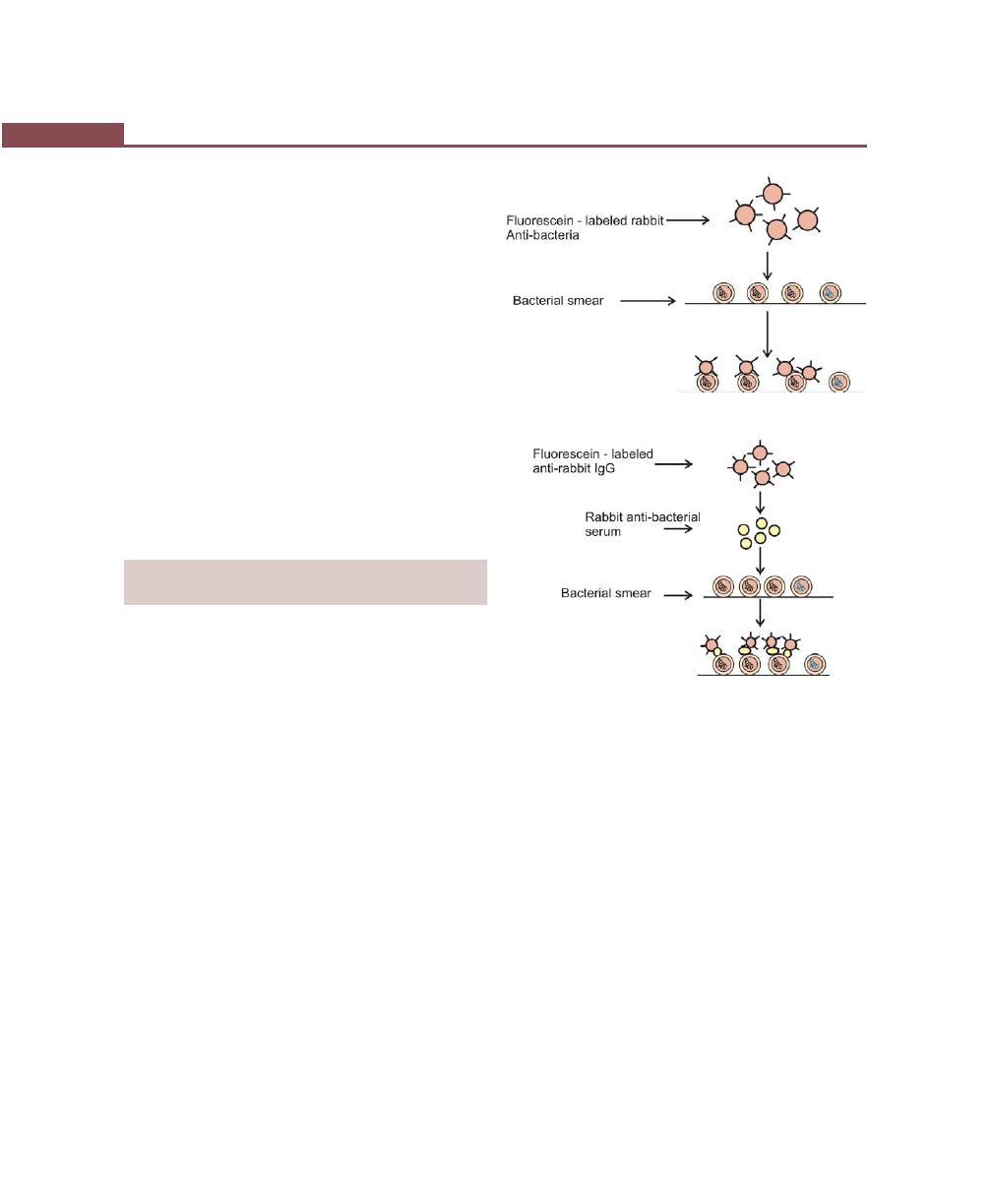

Immunofluorescence, 252

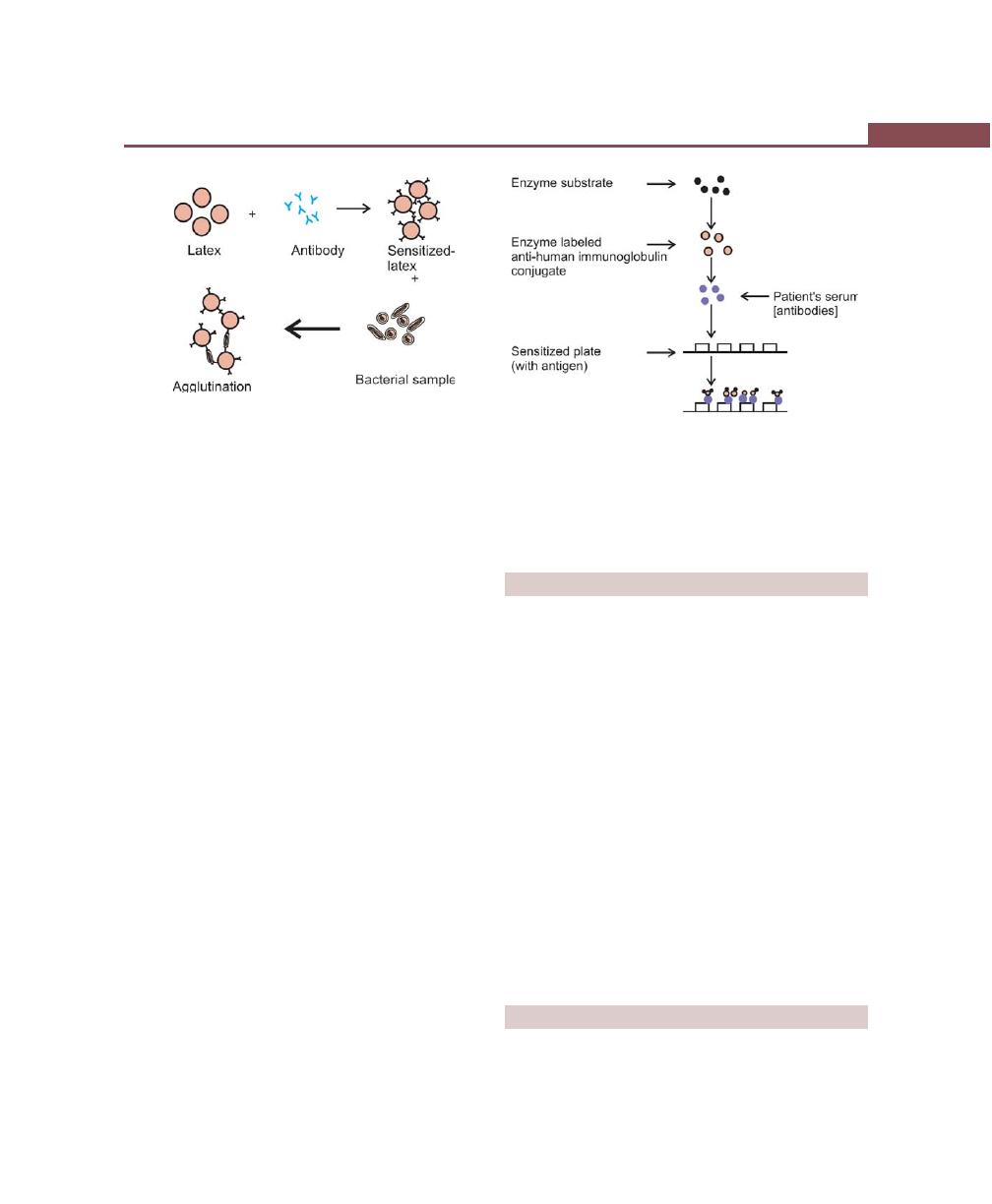

Latex Agglutination, 252

ELISA, 253

Flow Cytometry, 253

Biochemical Diagnosis, 253

Prostaglandins, 253

Collagenase, 253

Other Diagnostic Aids, 253

BANA Test, 253

FSEIA, 254

PCR, 254

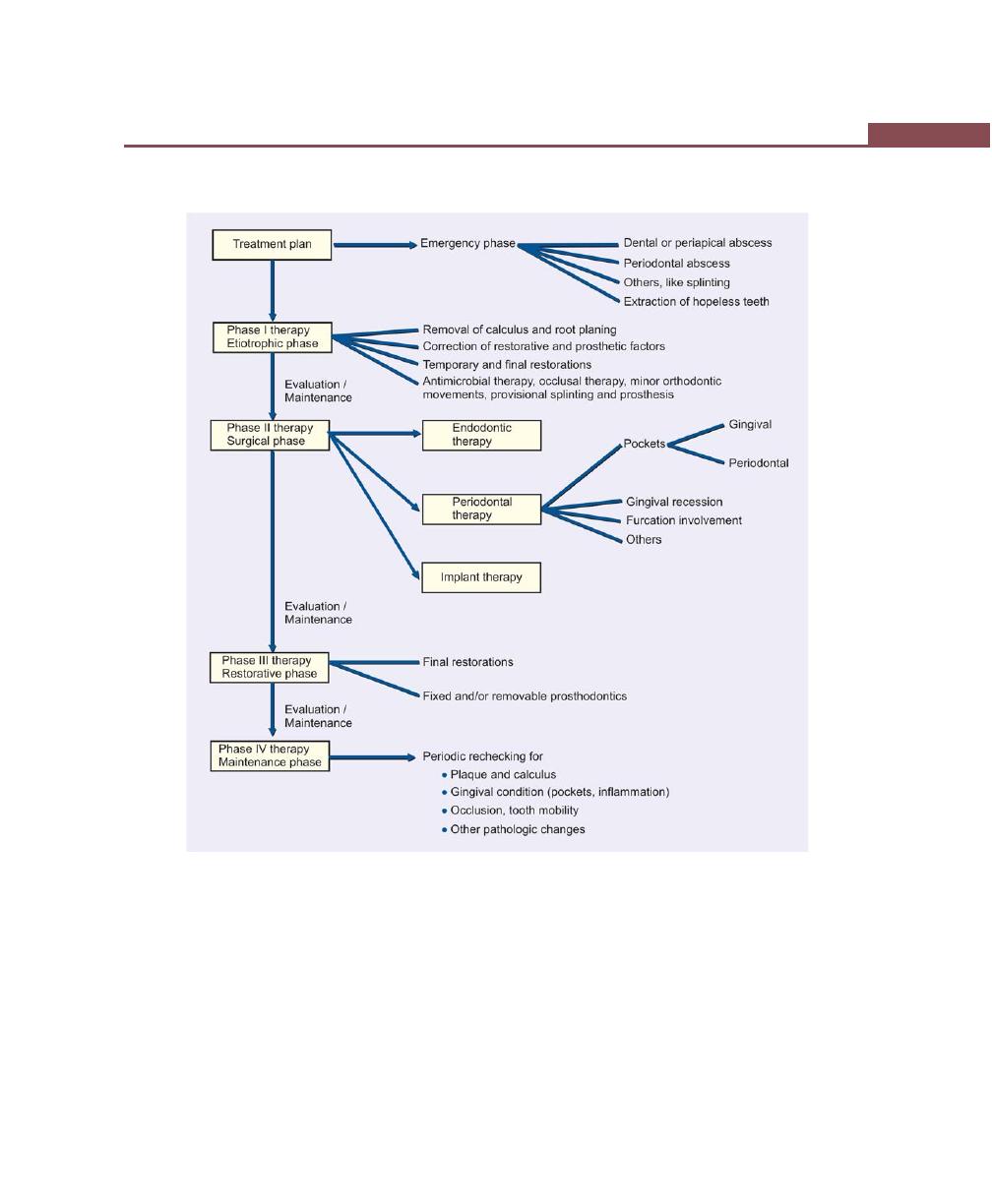

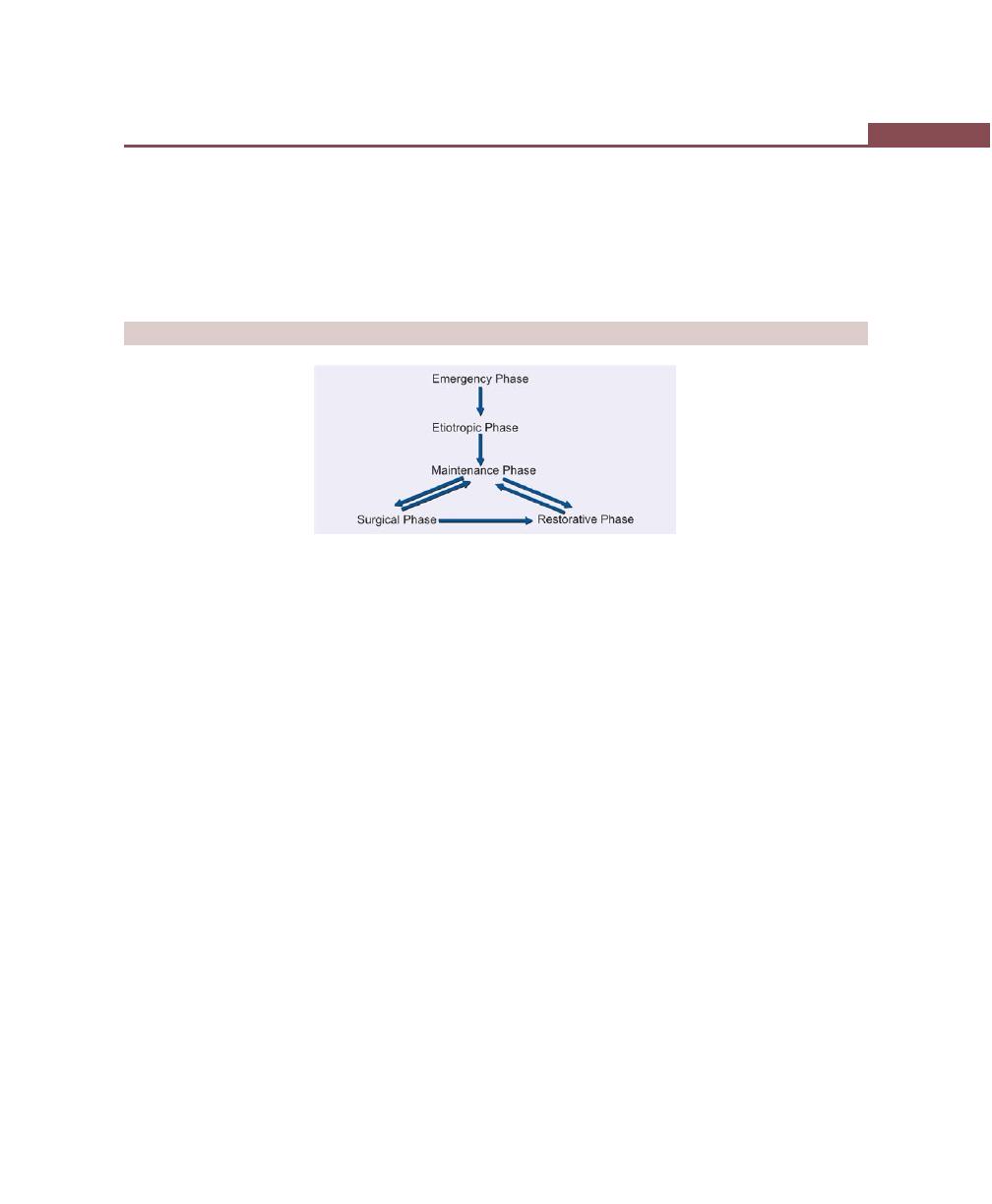

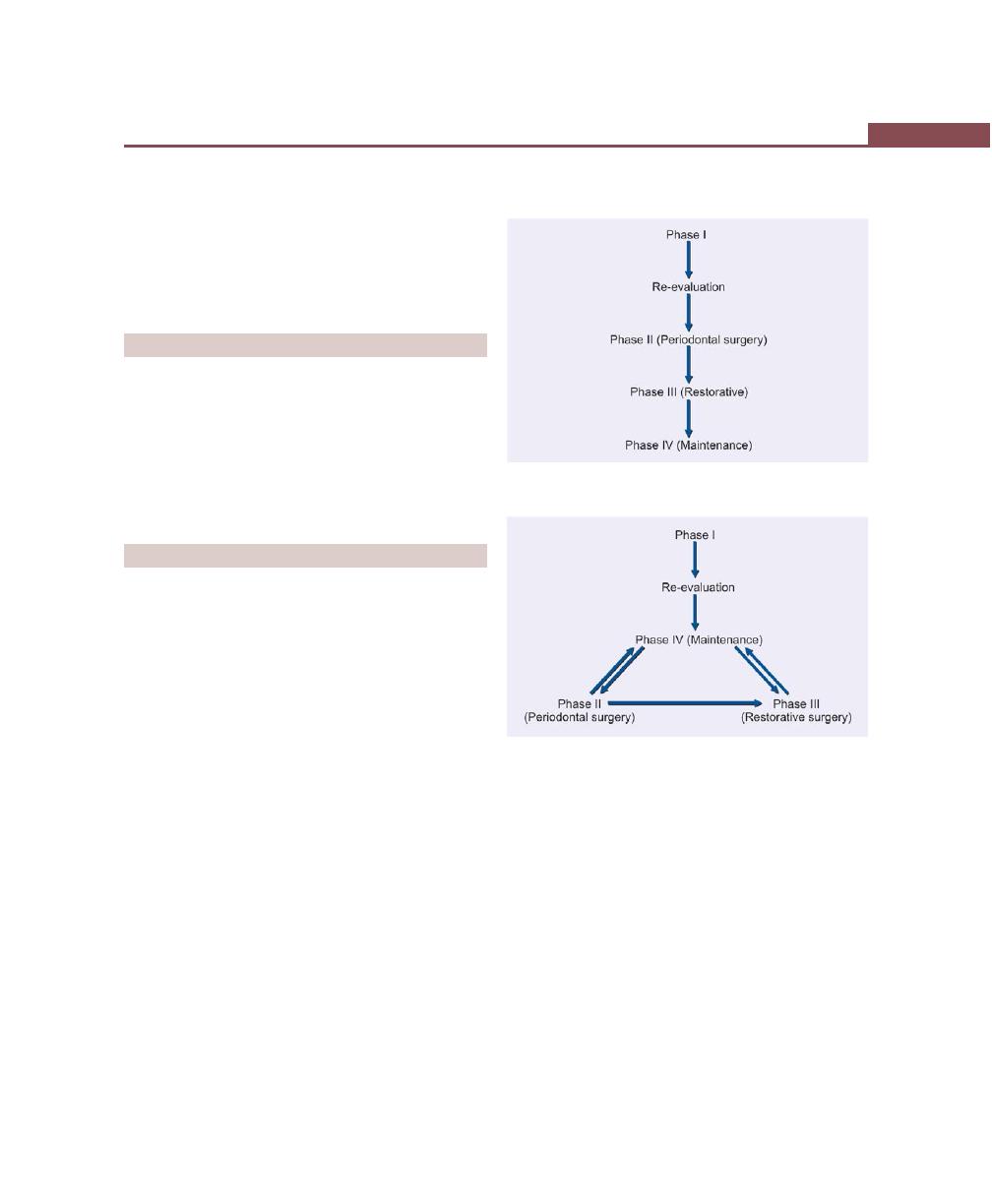

Chapter 33: Treatment Plan, 256

Introduction, 256

Sequence of Therapeutic Procedures, 256

Emergency Phase, 256

Etiotropic Phase, 256

Surgical Phase, 256

Restorative Phase, 256

Preferred Sequence of Periodontal Therapy, 257

Chapter 34: Rationale for Periodontal Treatment, 258

Objectives of Periodontal Therapy, 258

Factors which Affect Healing, 259

Local Factors, 259

Systemic Factors, 259

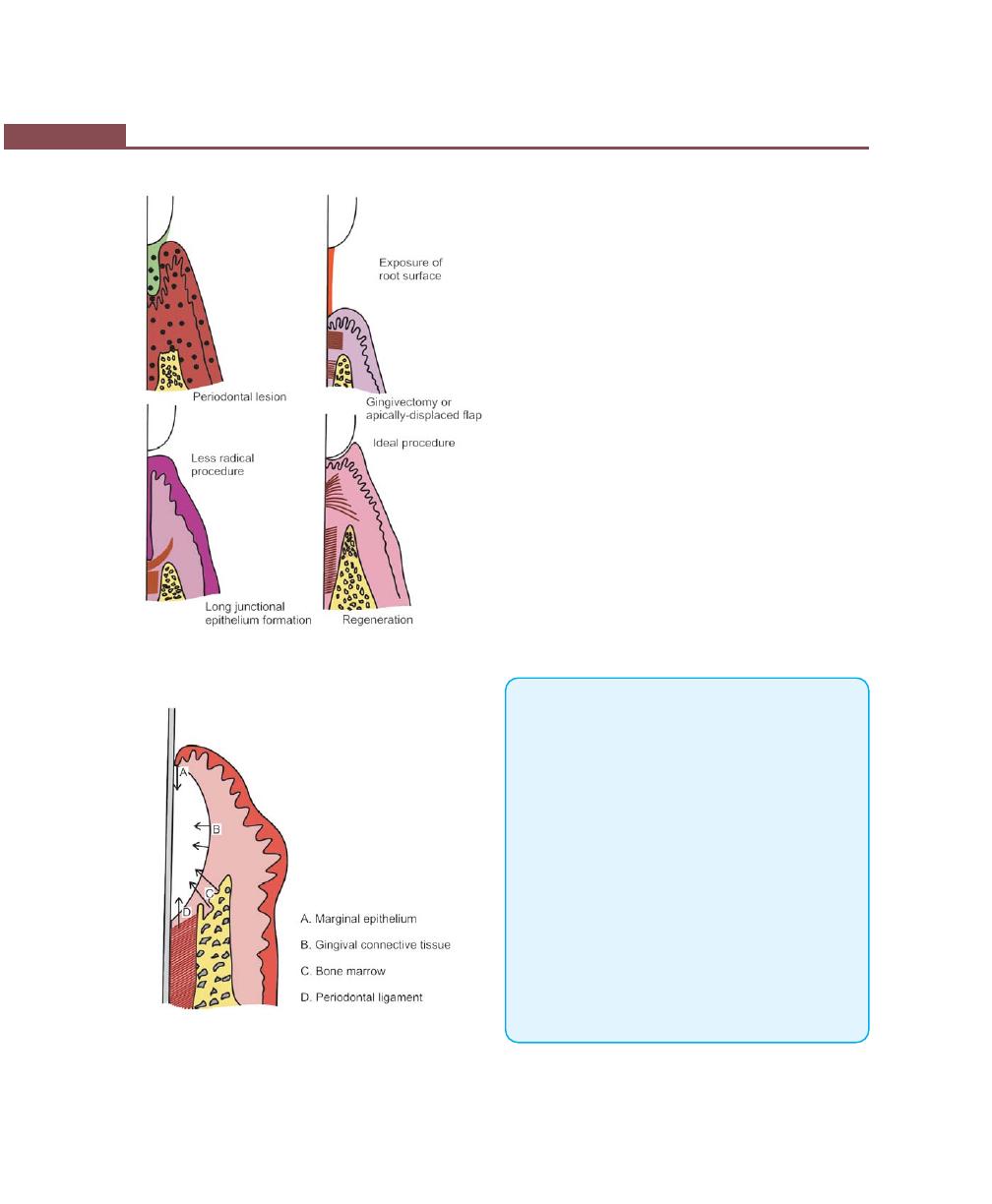

Healing After Periodontal Therapy, 259

Regeneration, 259

Repair, 259

New Attachment, 259

Reattachment, 259

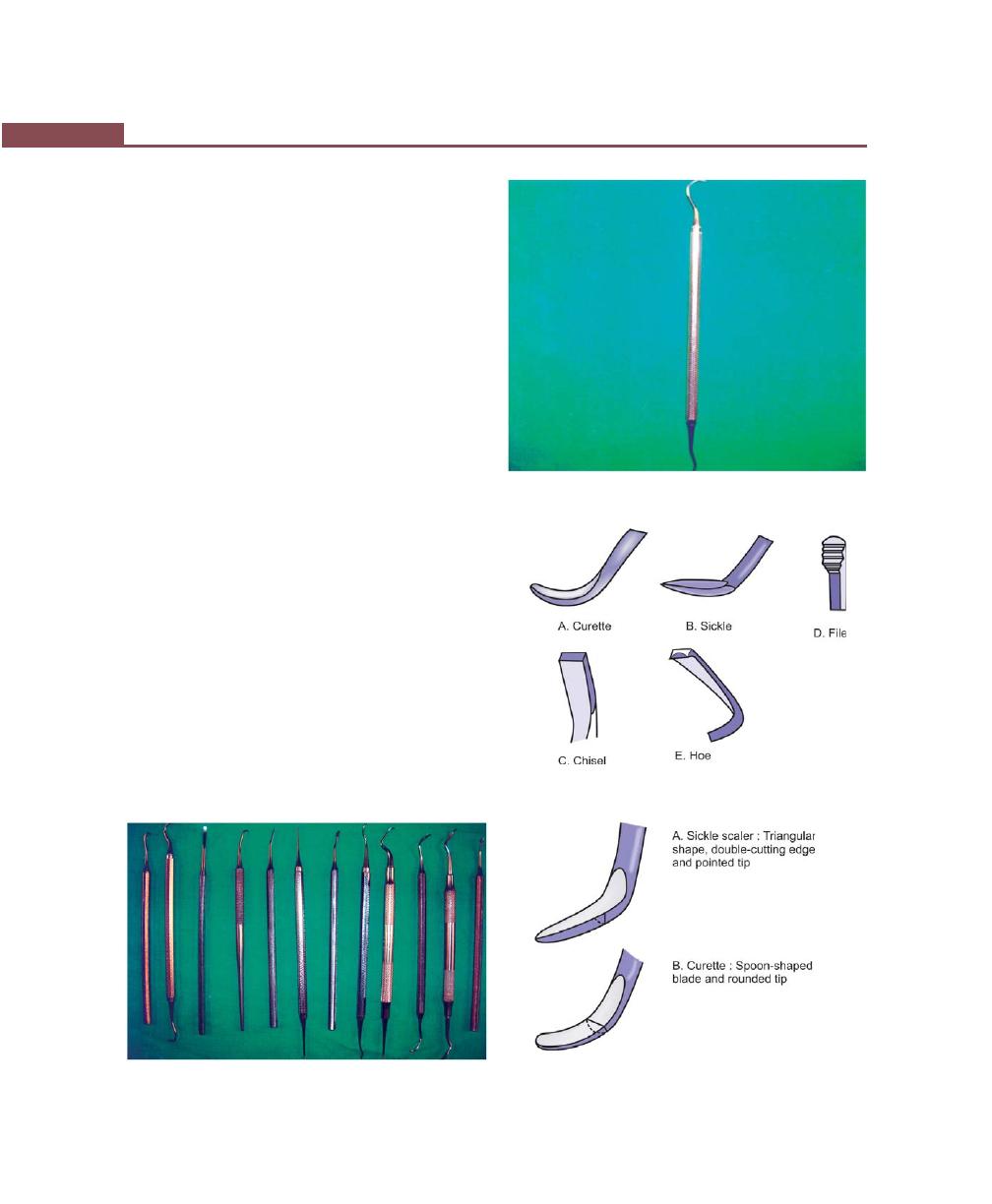

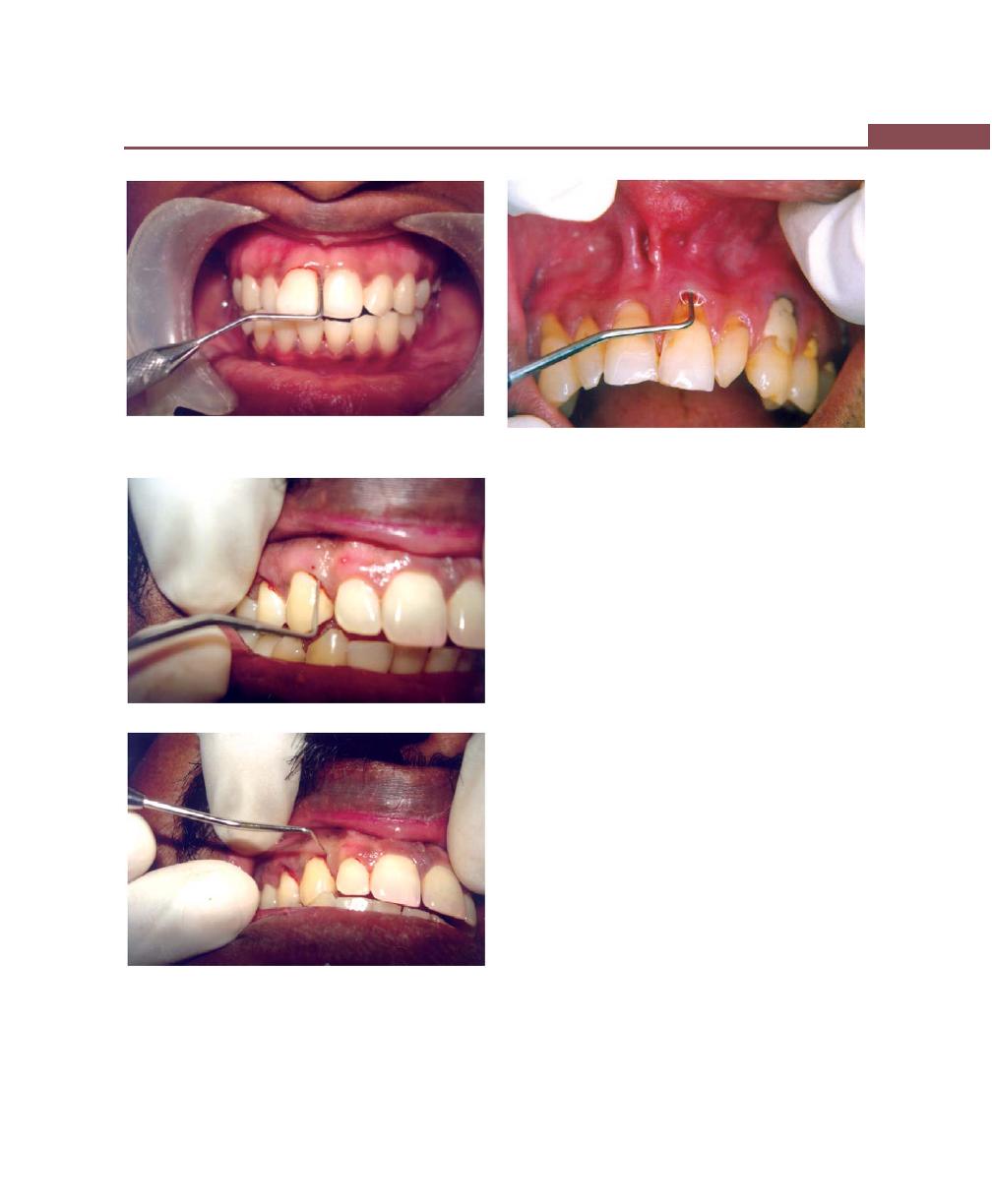

Chapter 35: Periodontal Instrumentarium, 262

Periodontal Instruments, 262

Classification of Periodontal Instruments, 262

Diagnostic Instruments, 262

Periodontal Probes, 263

Explorers, 264

Scaling and Root Planing, and Curettage Instruments,

262

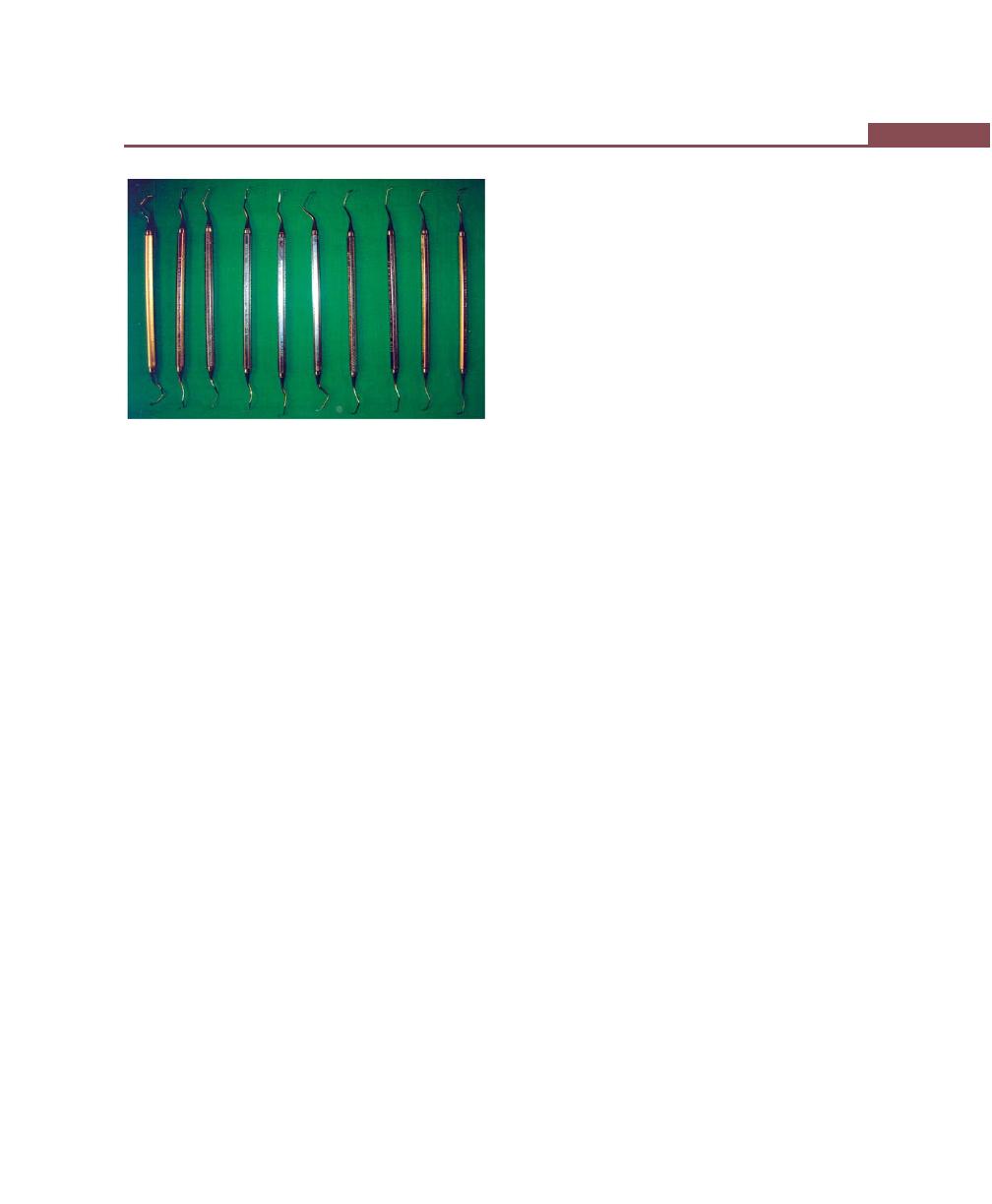

Sickle Scalers, 264

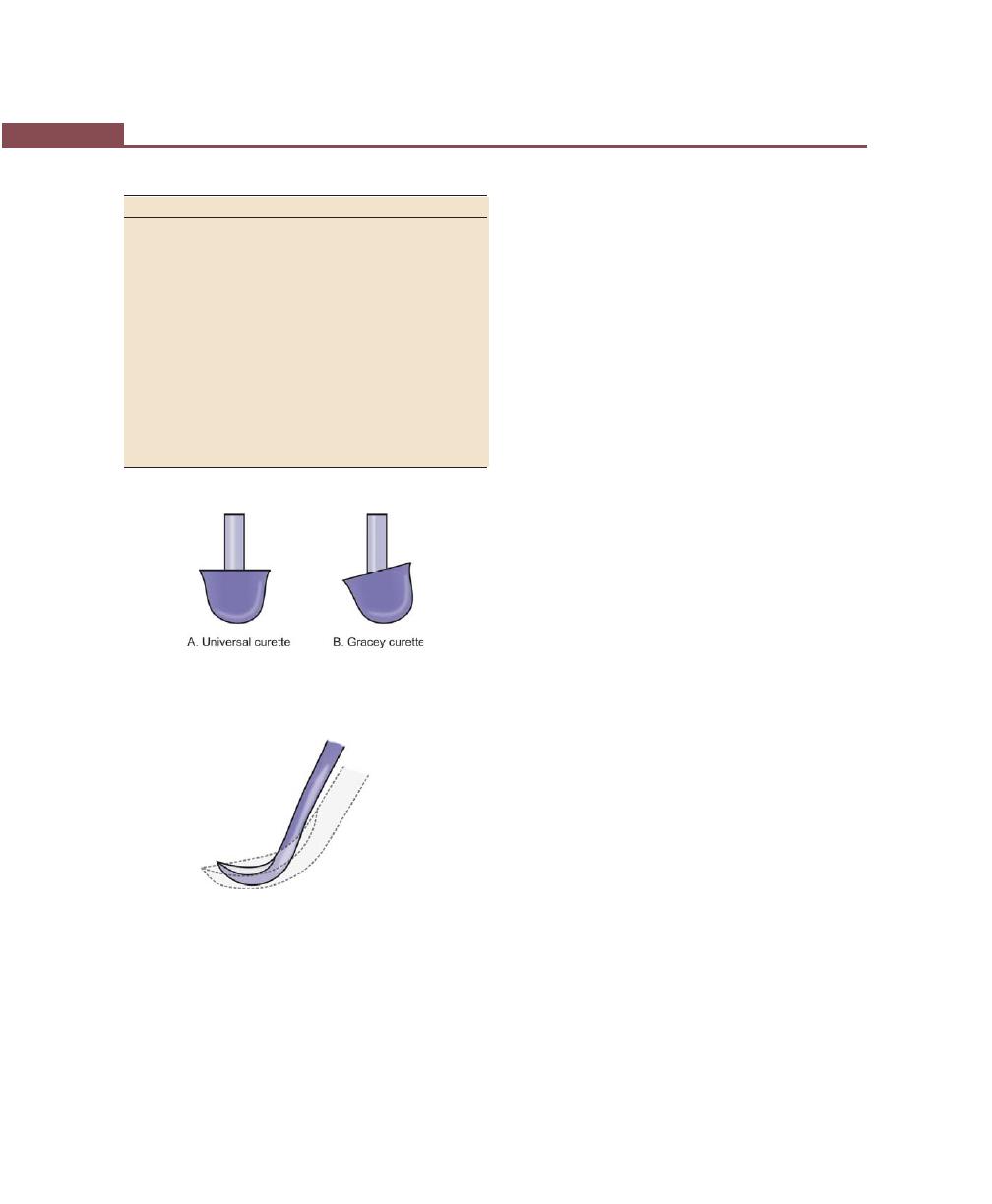

Curettes, 265

Ultrasonic Instruments, 267

Dental Endoscope, 267

Cleansing and Polishing Instruments, 267

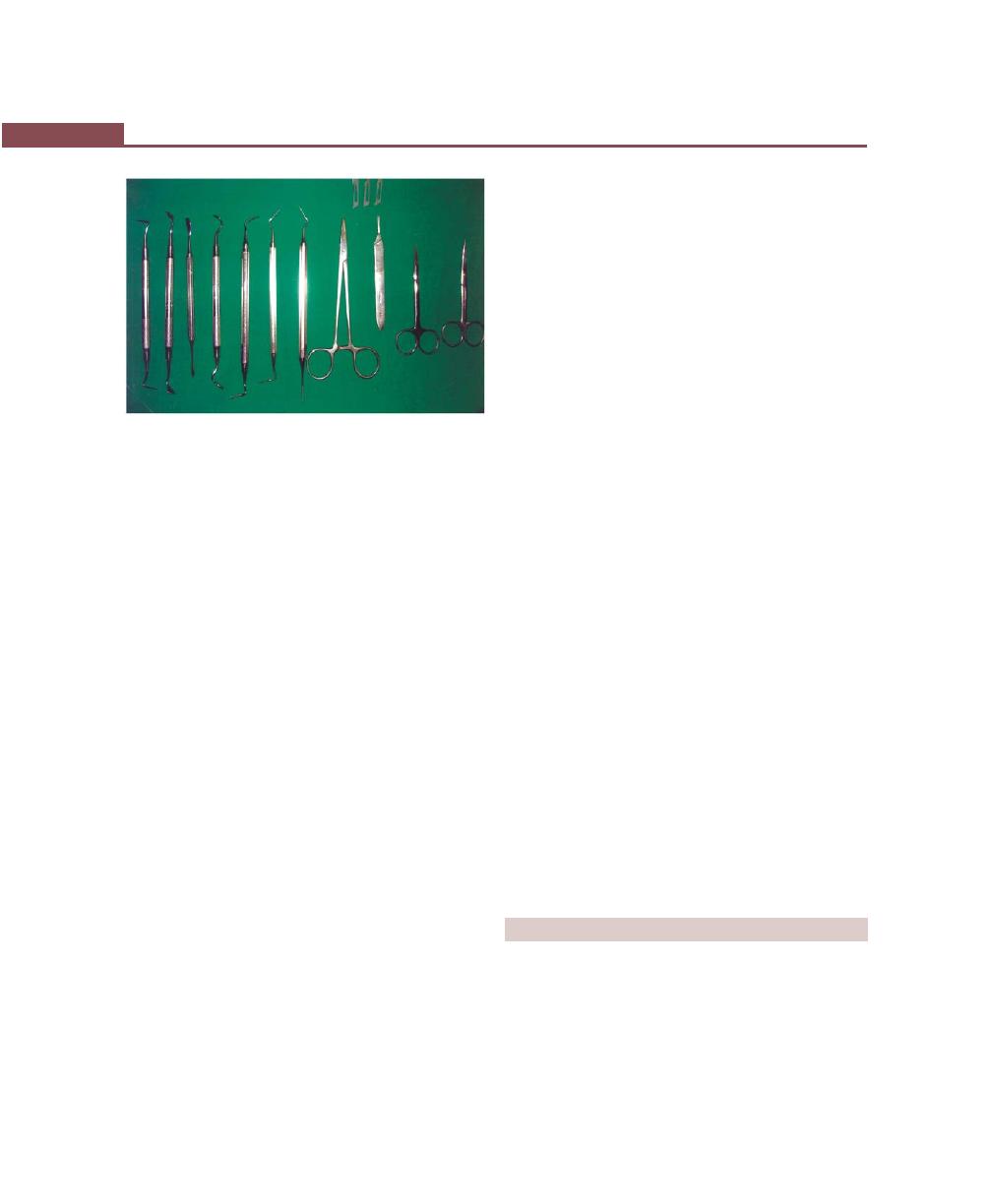

Surgical Instruments, 268

SECTION 2: PERIODONTAL THERAPY

(A) Non-Surgical Therapy

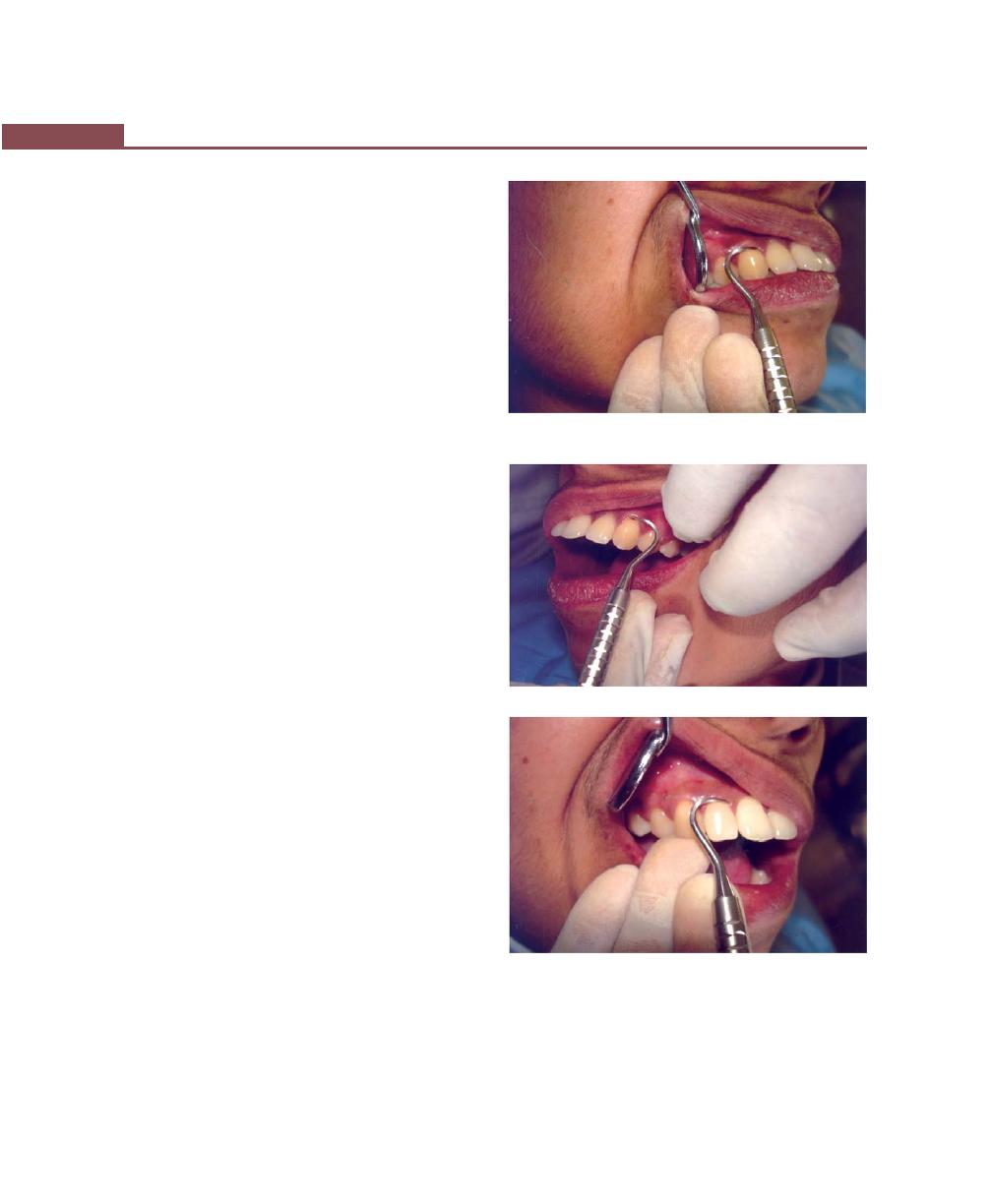

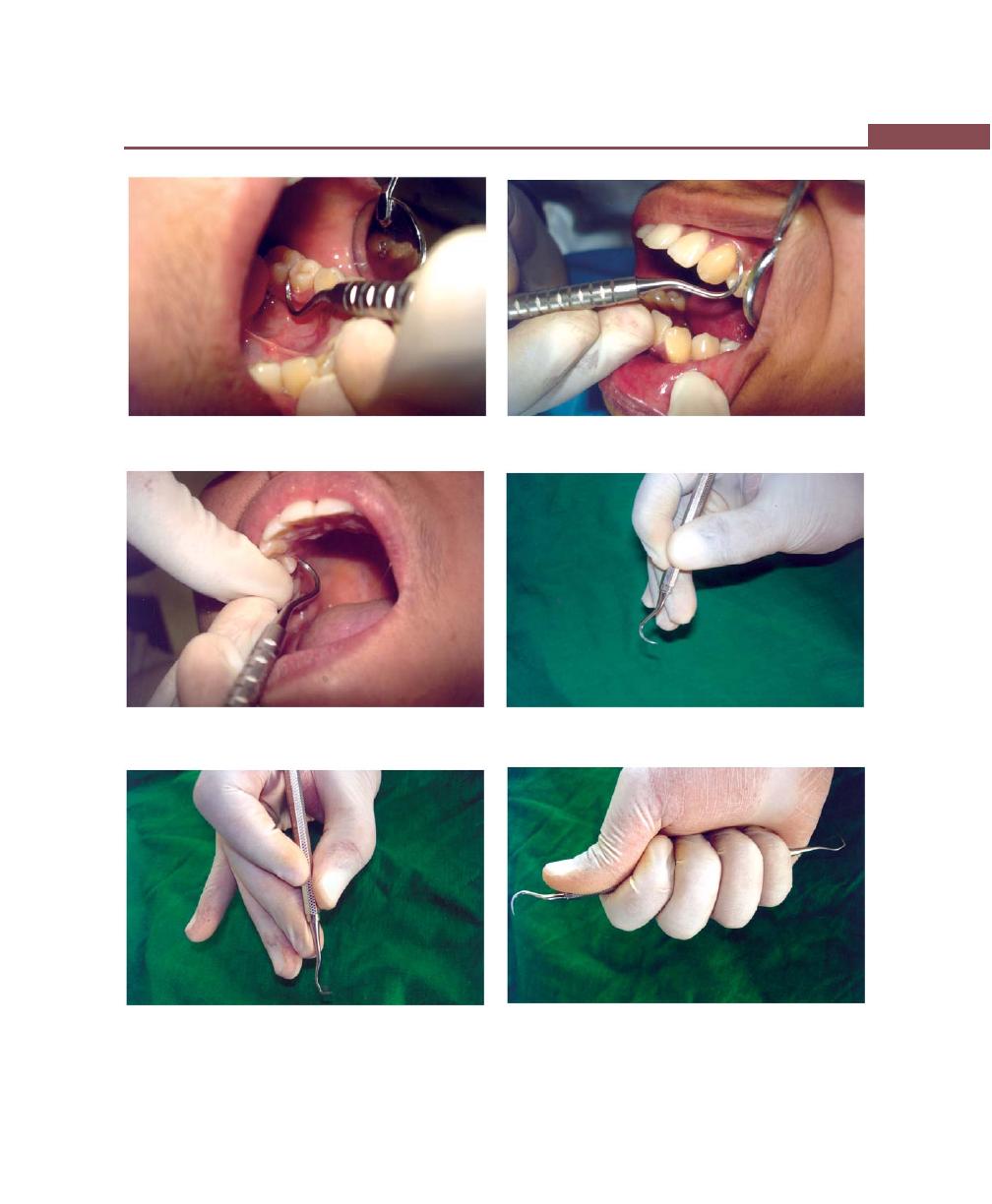

Chapter 36: Principles of Periodontal Instrumentation

including Scaling and Root Planing, 269

Introduction, 269

Accessibility, 269

Clinician Position, 269

Patient Position, 269

Visibility, Illumination and Retraction, 270

Condition of Instruments, 271

Maintaining a Clean Field, 271

Instrument Stabilization, 271

Instrument Grasp, 271

Finger Rest, 272

Instrument Activation, 273

Adaptation, 274

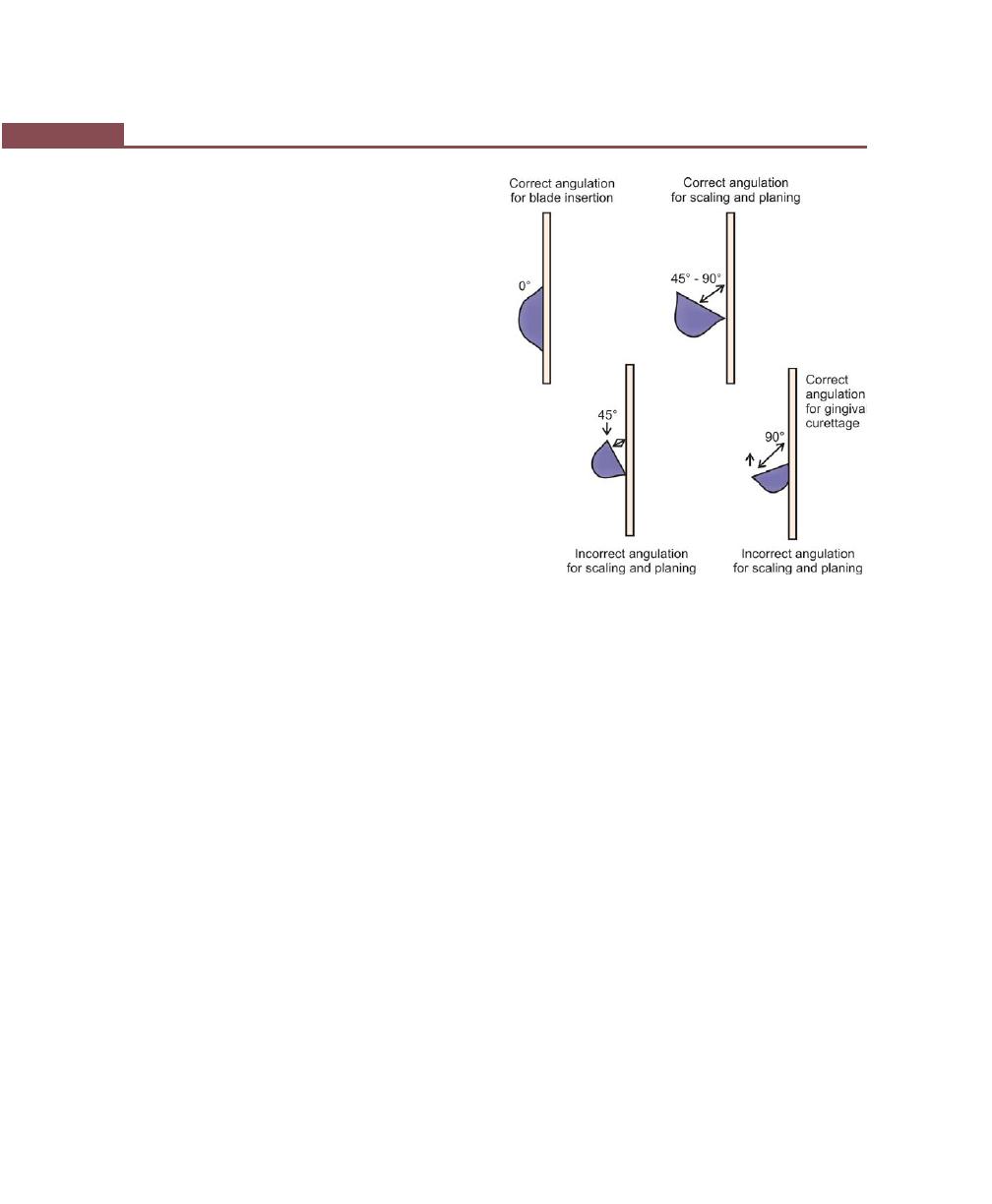

Angulation, 274

Lateral Pressure, 274

Strokes, 274

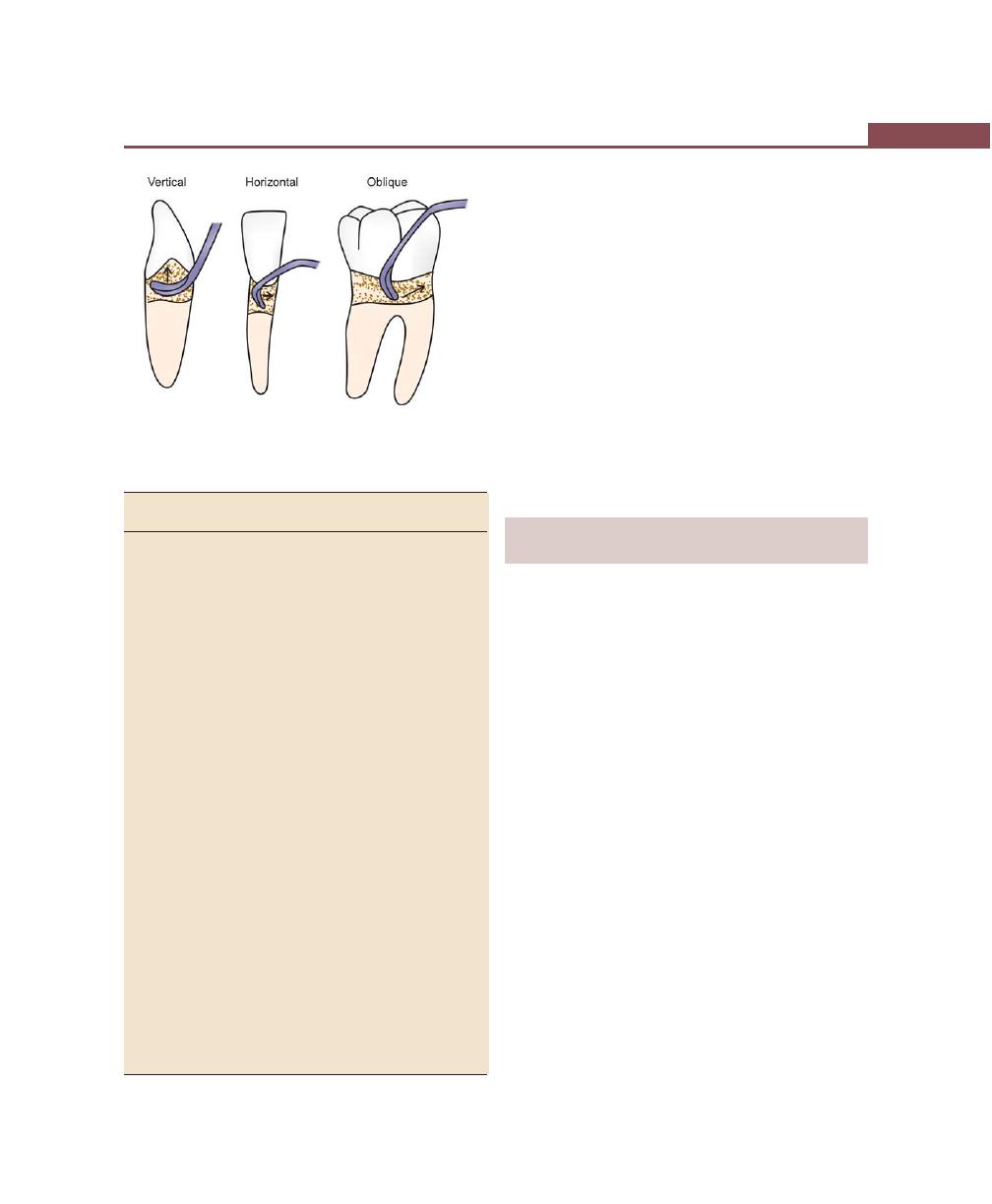

Stroke Direction, 275

Principles of Scaling and Root Planing, 275

Root Planing, 275

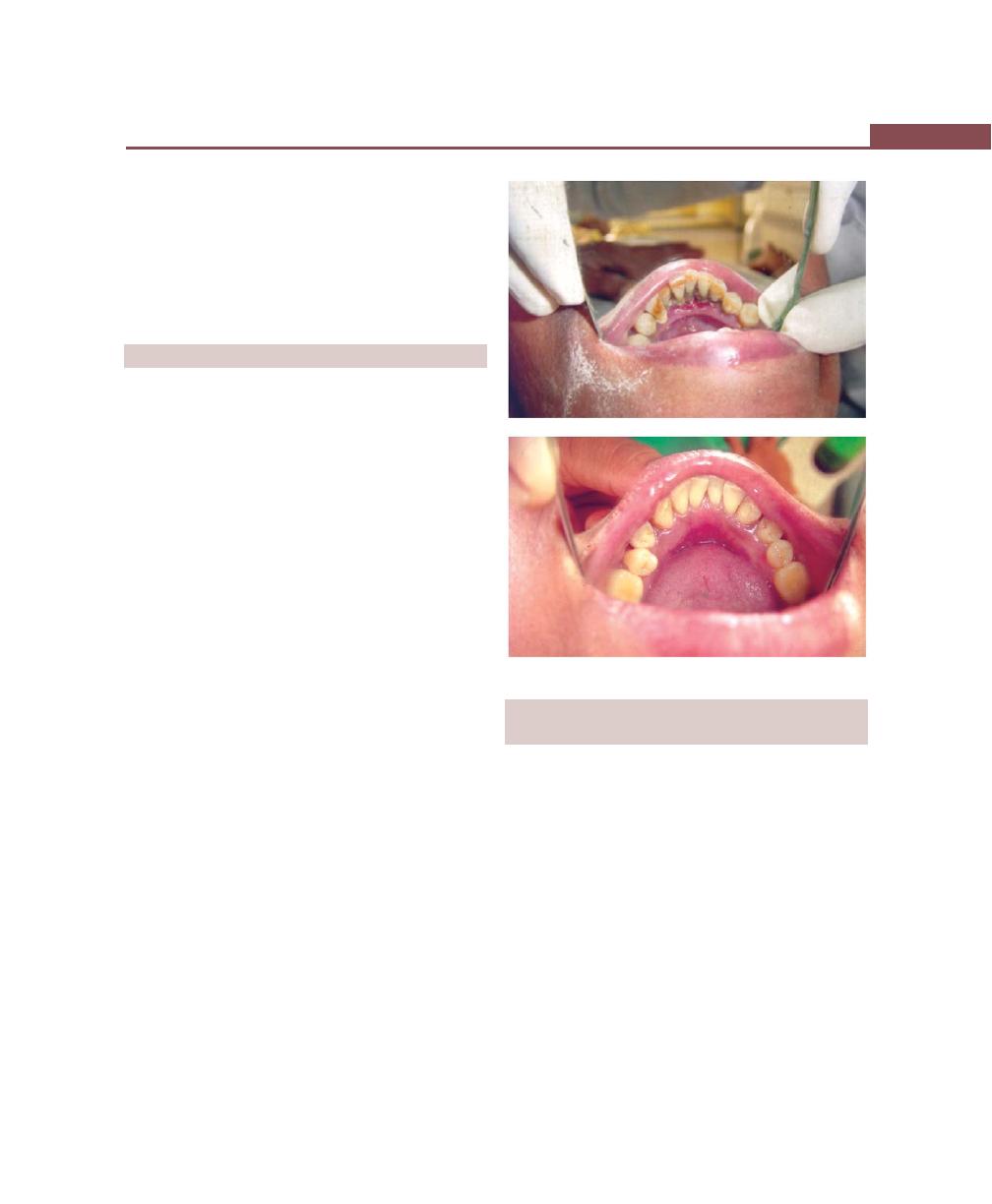

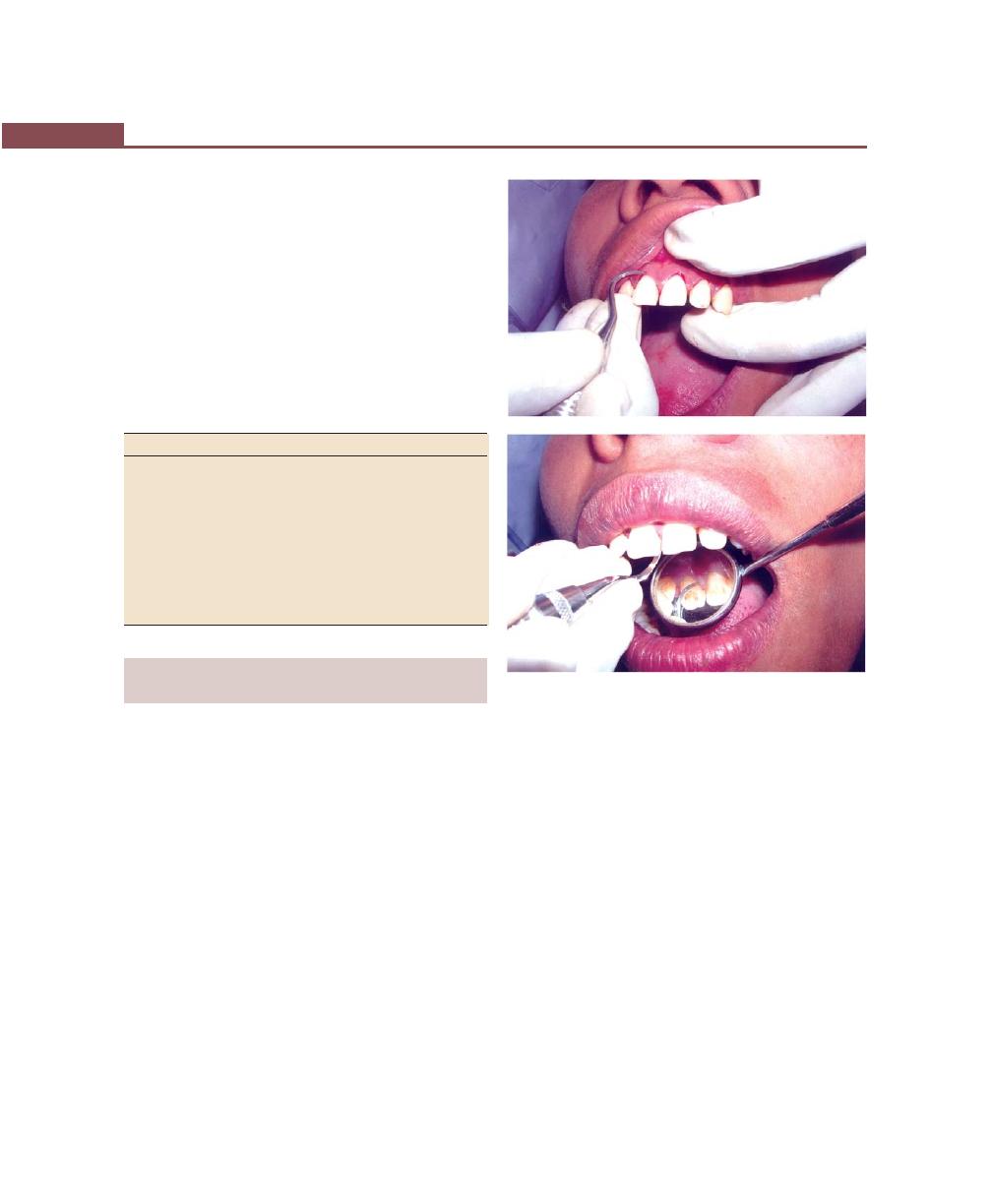

Supragingival Scaling Technique, 276

Subgingival Scaling, 276

Ultrasonic Instruments, 277

Aerosol Production, 278

xxi

Contents

Chapter 37: Plaque Control, 280

Definition, 280

Goals of Plaque Control Measures, 280

Rationale, 280

Basic Approaches for Plaque Control, 280

Mechanical Plaque Control, 280

Toothbrush, 281

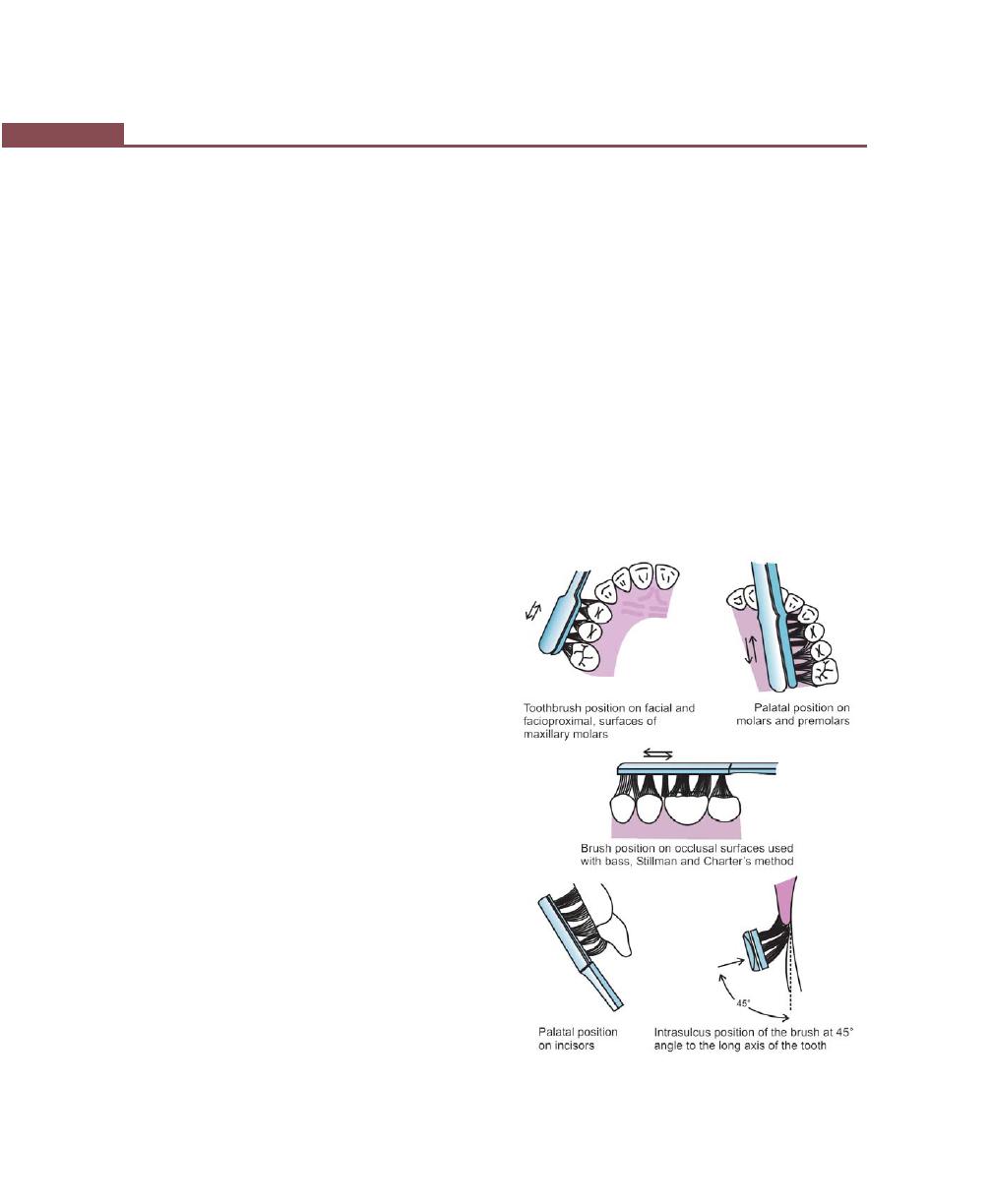

Brushing Techniques, 282

Bass Method, 282

Modified Bass Method, 283

Stillman’s Method, 283

Modified Stillman’s Method, 283

Charter’s Method, 283

Roll Method/Fones Technique, 283

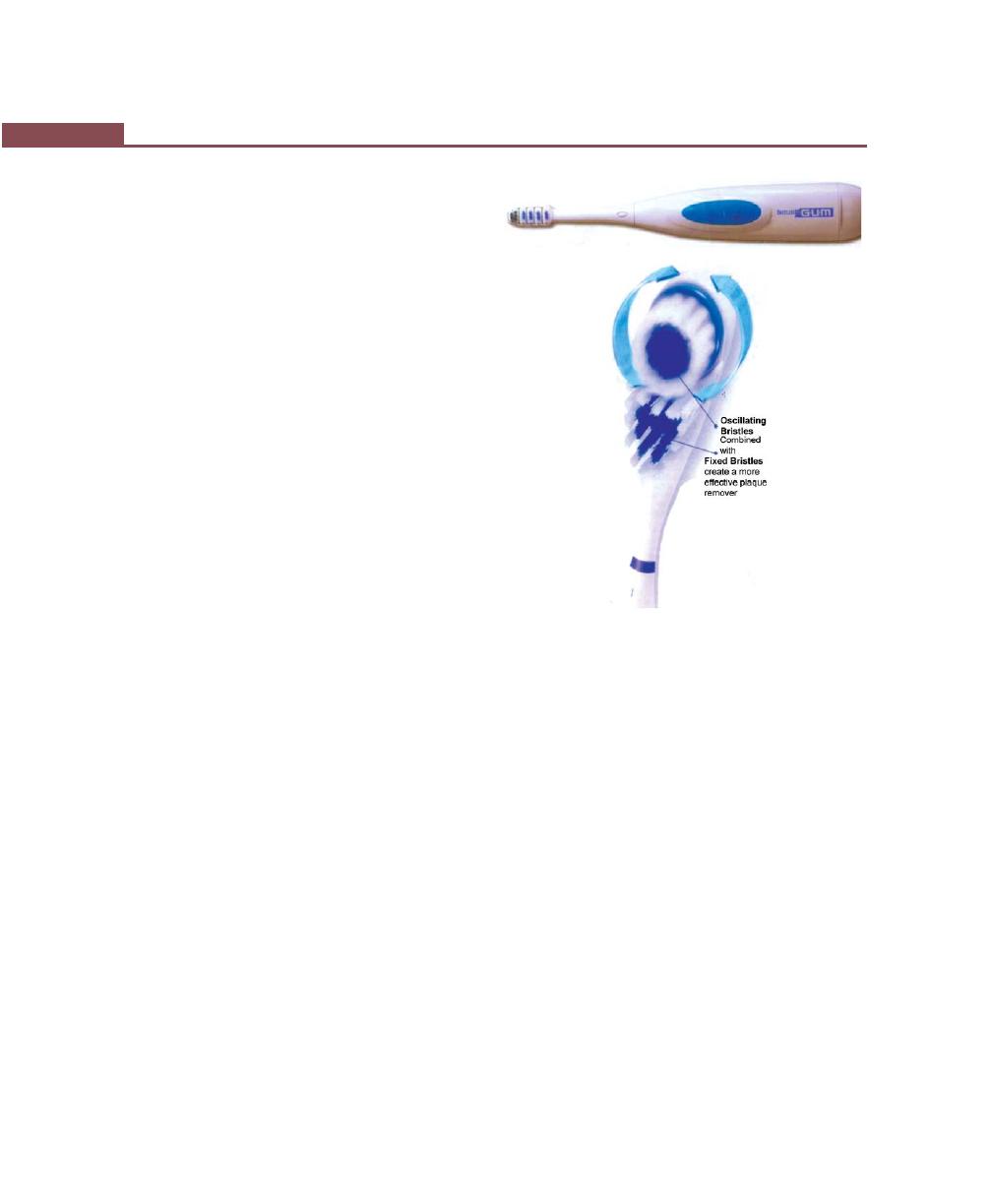

Powered Toothbrushes, 284

Dentifrices, 284

Interdental Cleaning Aids, 285

Other Aids, 286

Chemical Plaque Control, 286

Ideal Properties of a Mouthwash, 287

Classification of Antimicrobial Agents, 287

Bisbiguanides, 288

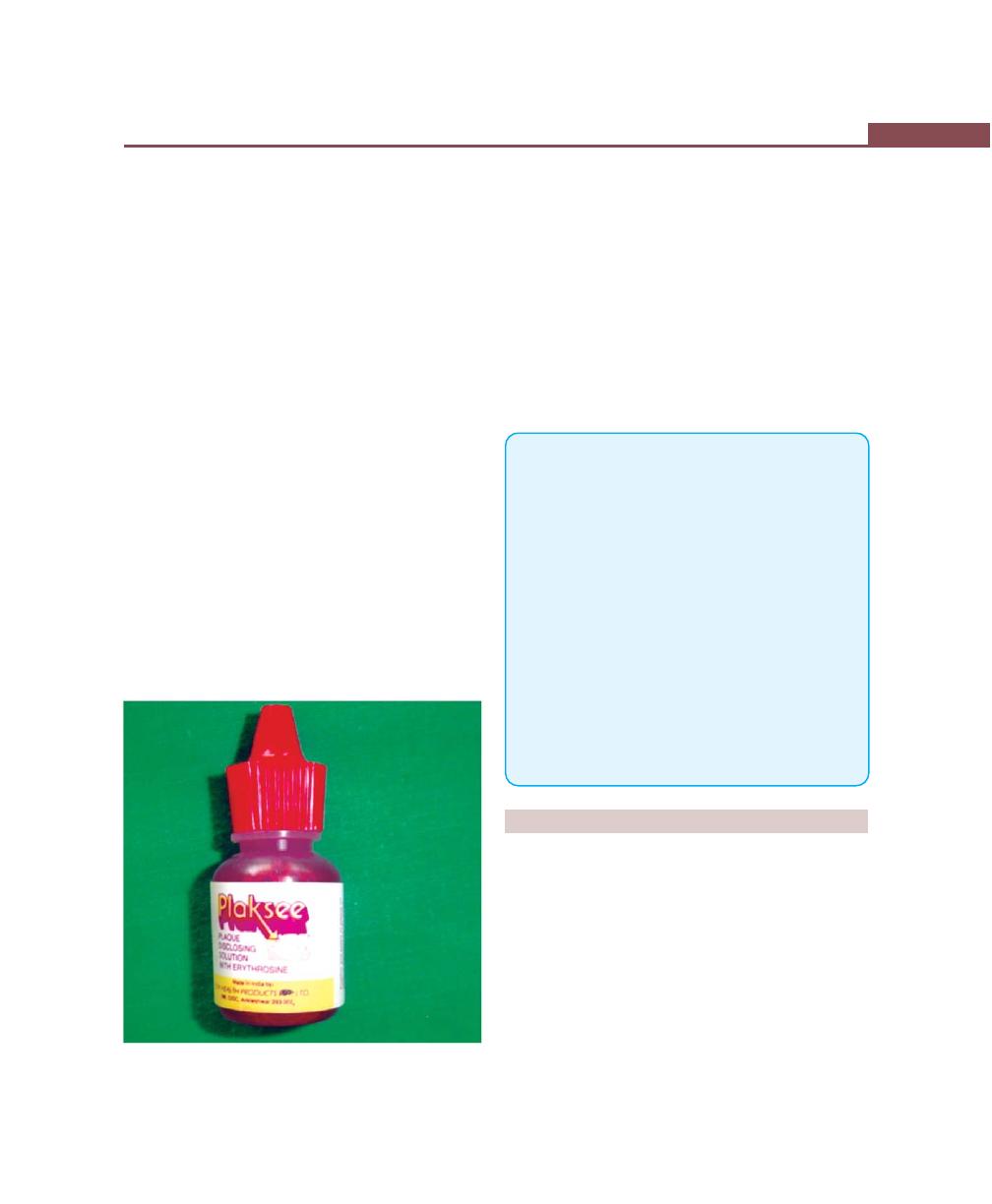

Disclosing Agents, 289

Section B: Surgical Therapy

Chapter 38: Principles of Periodontal Surgery, 291

Indications, 291

Contraindications, 291

General Principles of Surgery, 291

Patient Preparation, 292

Premedication, 292

Tissue Management, 292

Suturing Material, 292

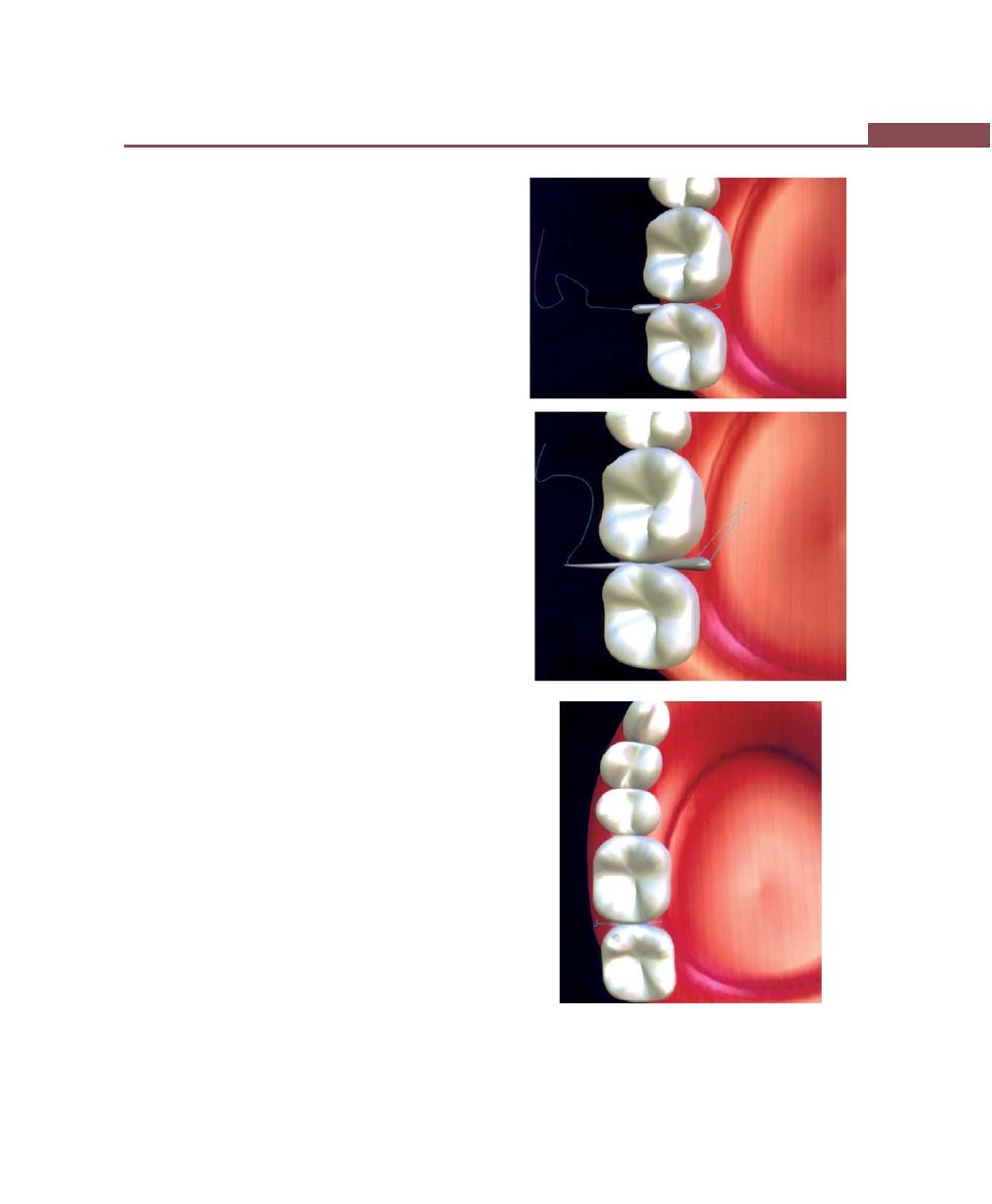

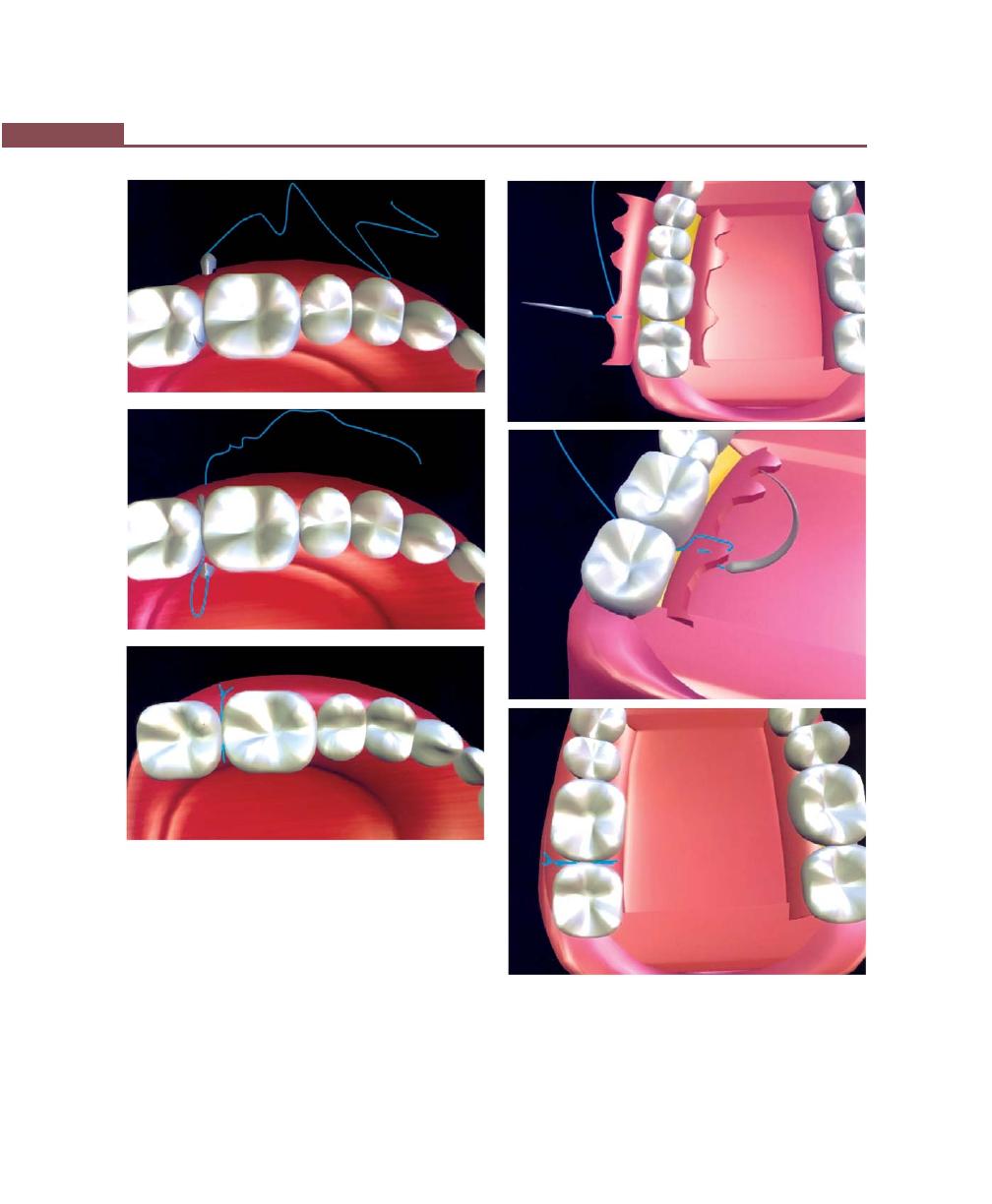

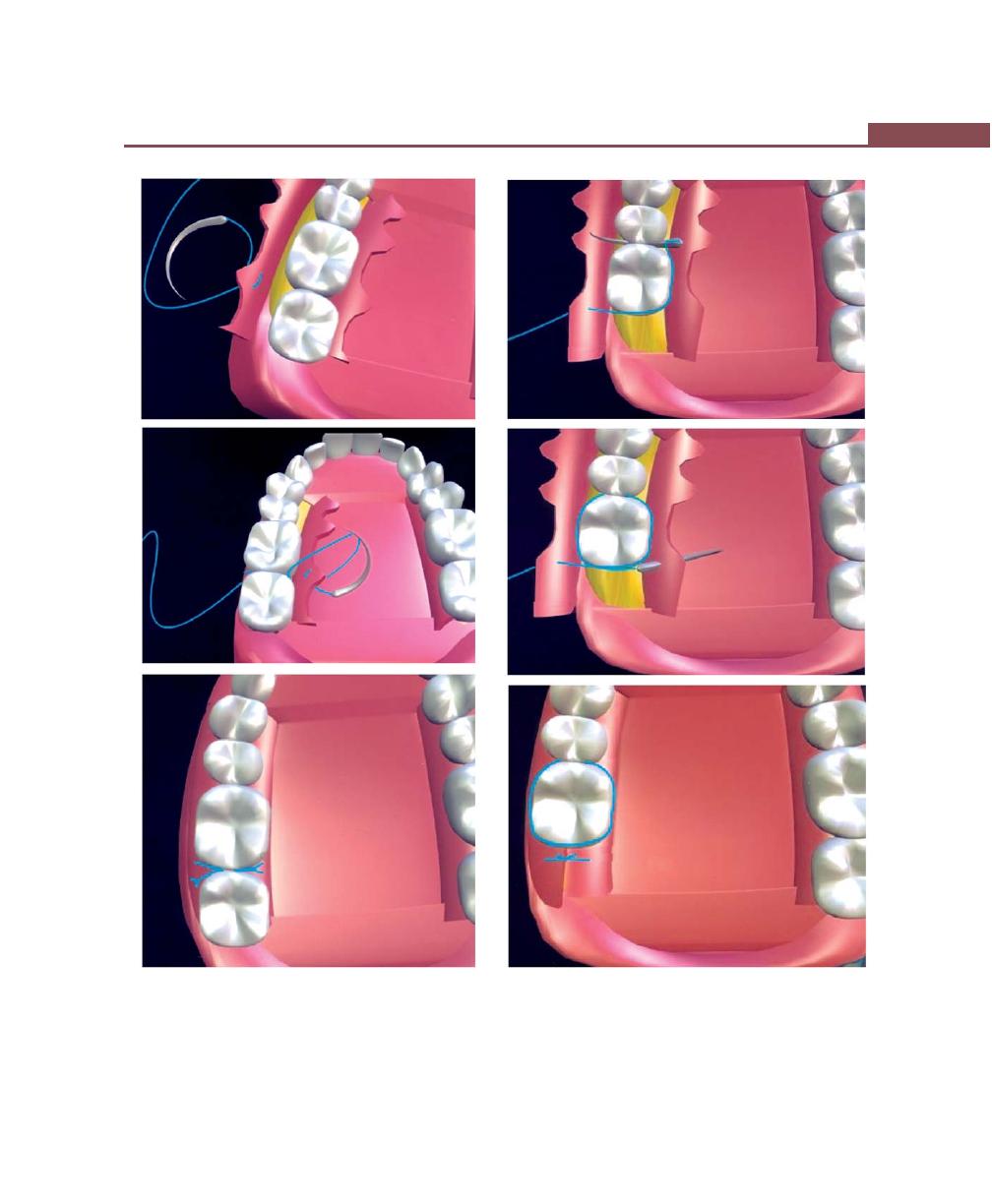

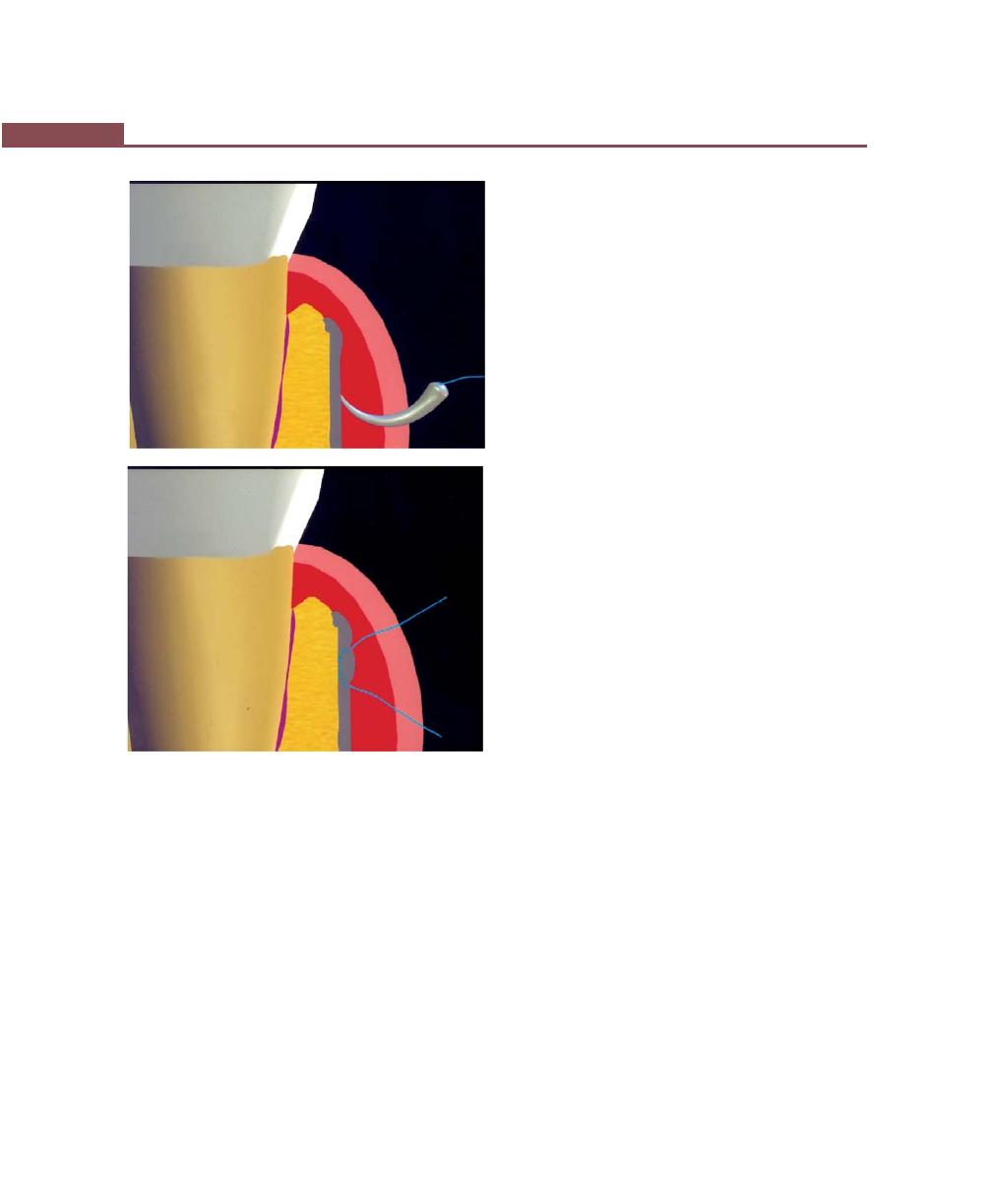

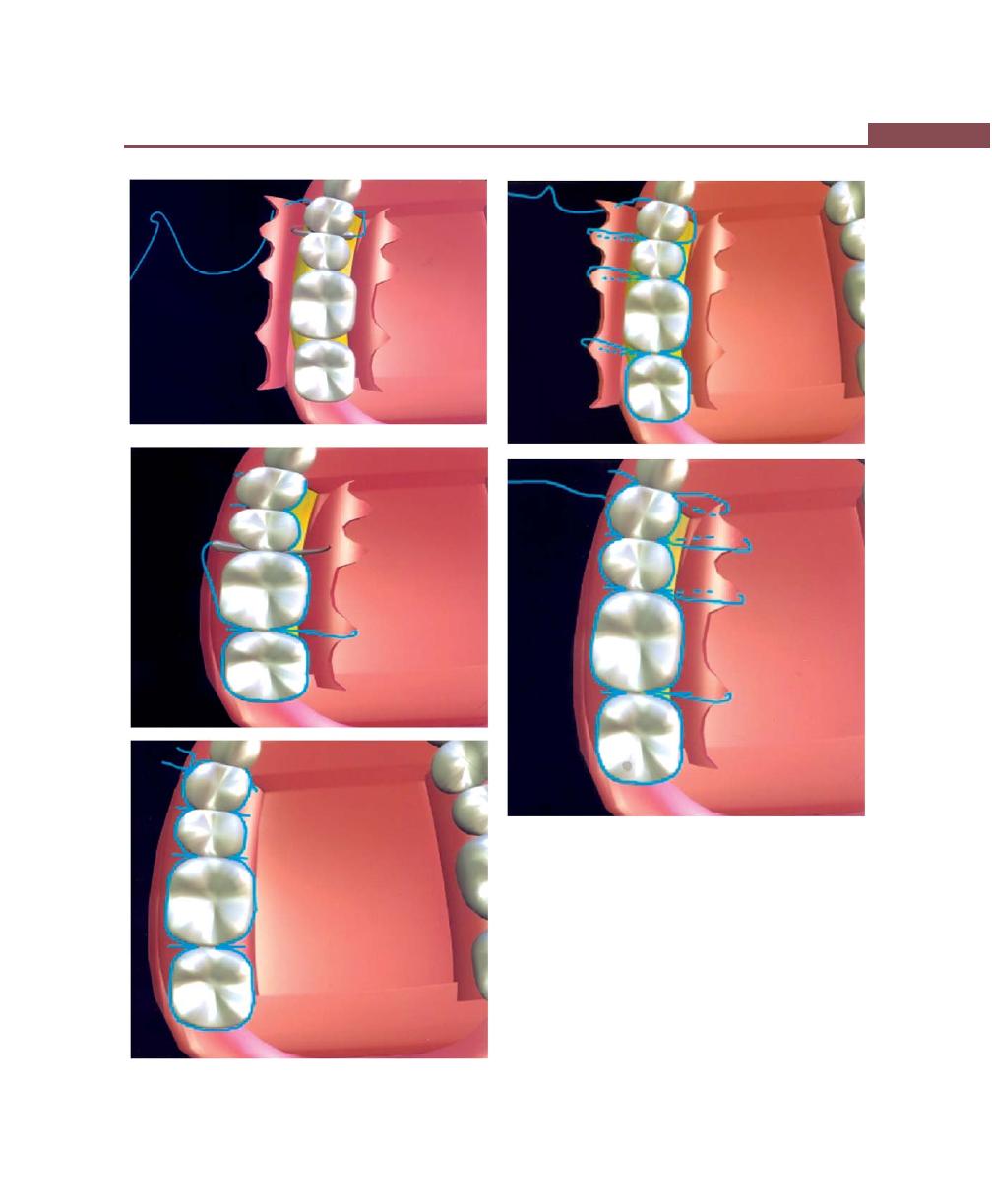

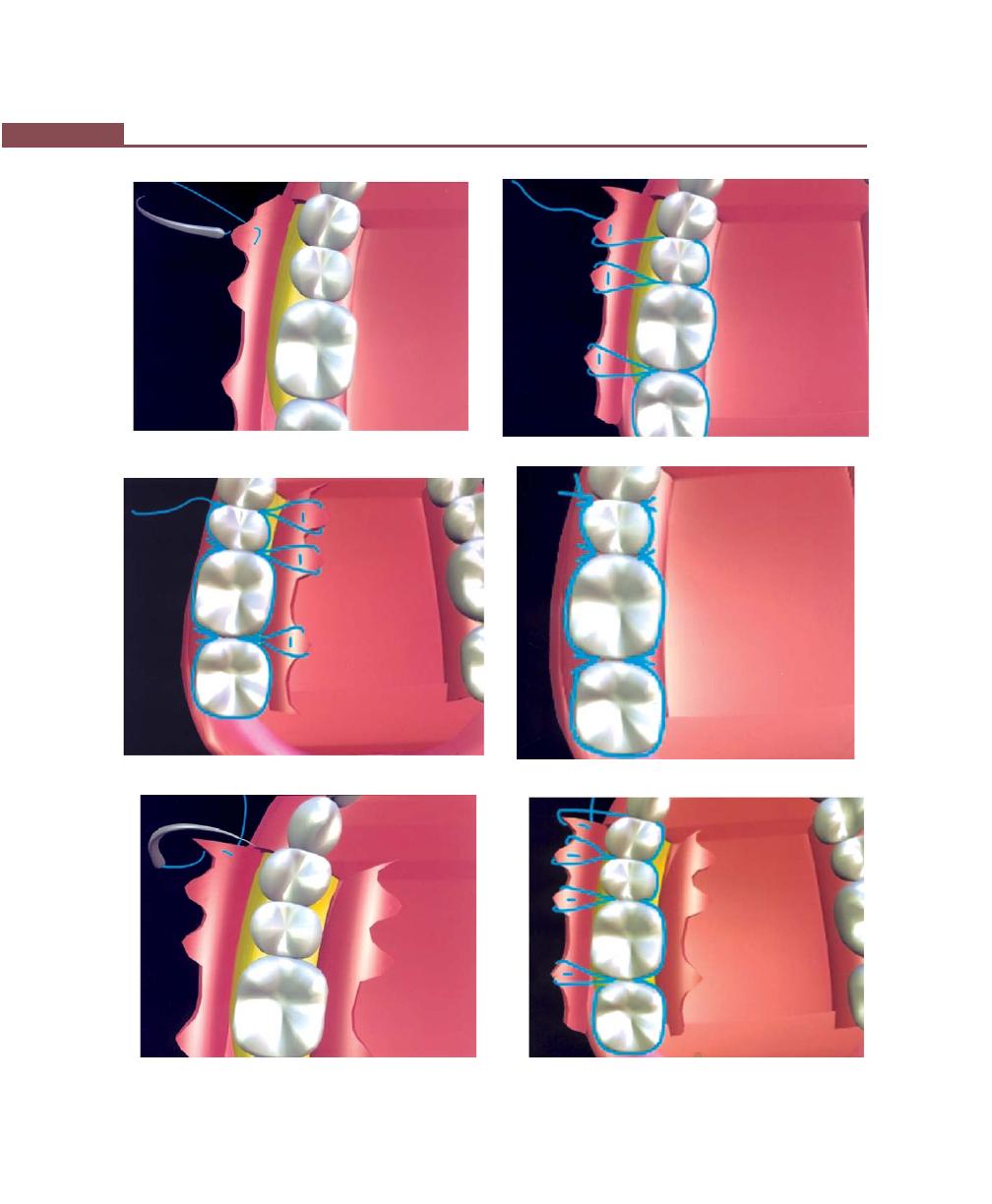

Suturing Techniques, 293

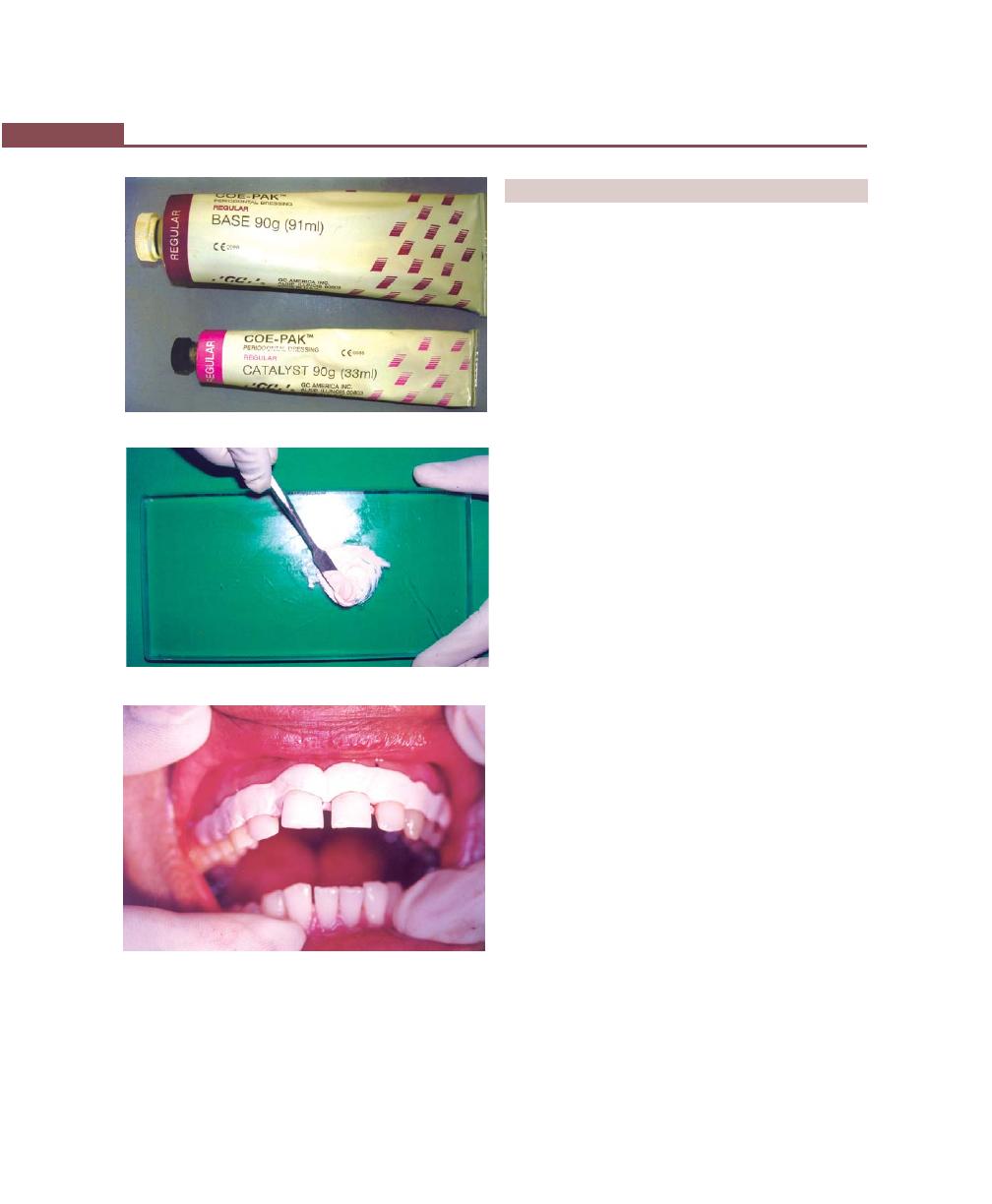

Periodontal Dressing, 293

Instructions for the Patient After Surgery, 299

Complications During Surgery, 300

Syncope, 300

Hemorrhage, 300

Complications in the First Postoperative Week, 300

Hospital Periodontal Surgery, 301

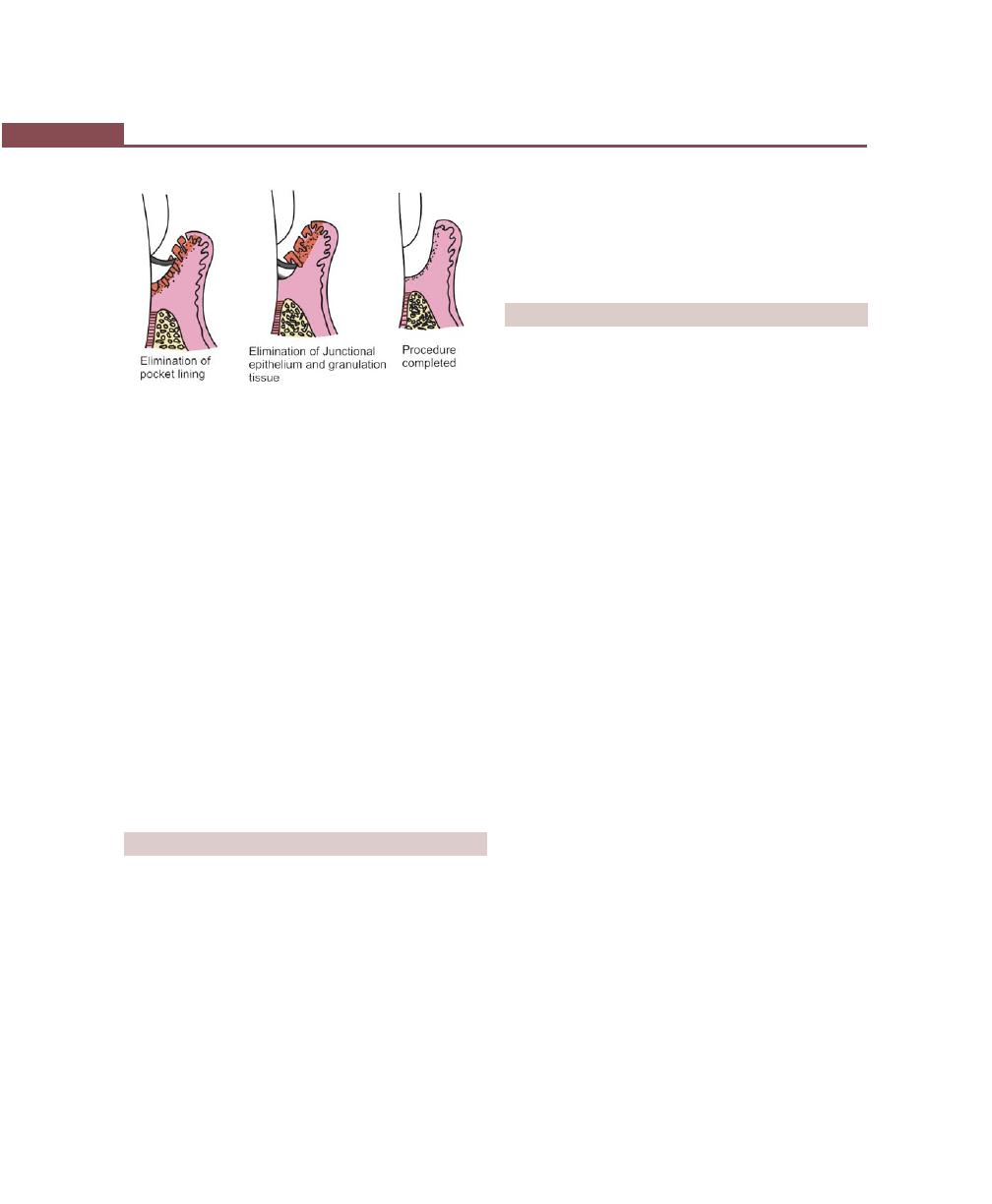

Chapter 39: Gingival Curettage, 303

Definition, 303

Types, 303

Rationale, 303

Indications, 304

Procedure, 304

Basic Technique, 304

ENAP, 304

Ultrasonic Curettage, 305

Caustic Drugs, 305

Healing After Scaling and Curettage, 305

Clinical Appearance After Scaling and Curettage, 305

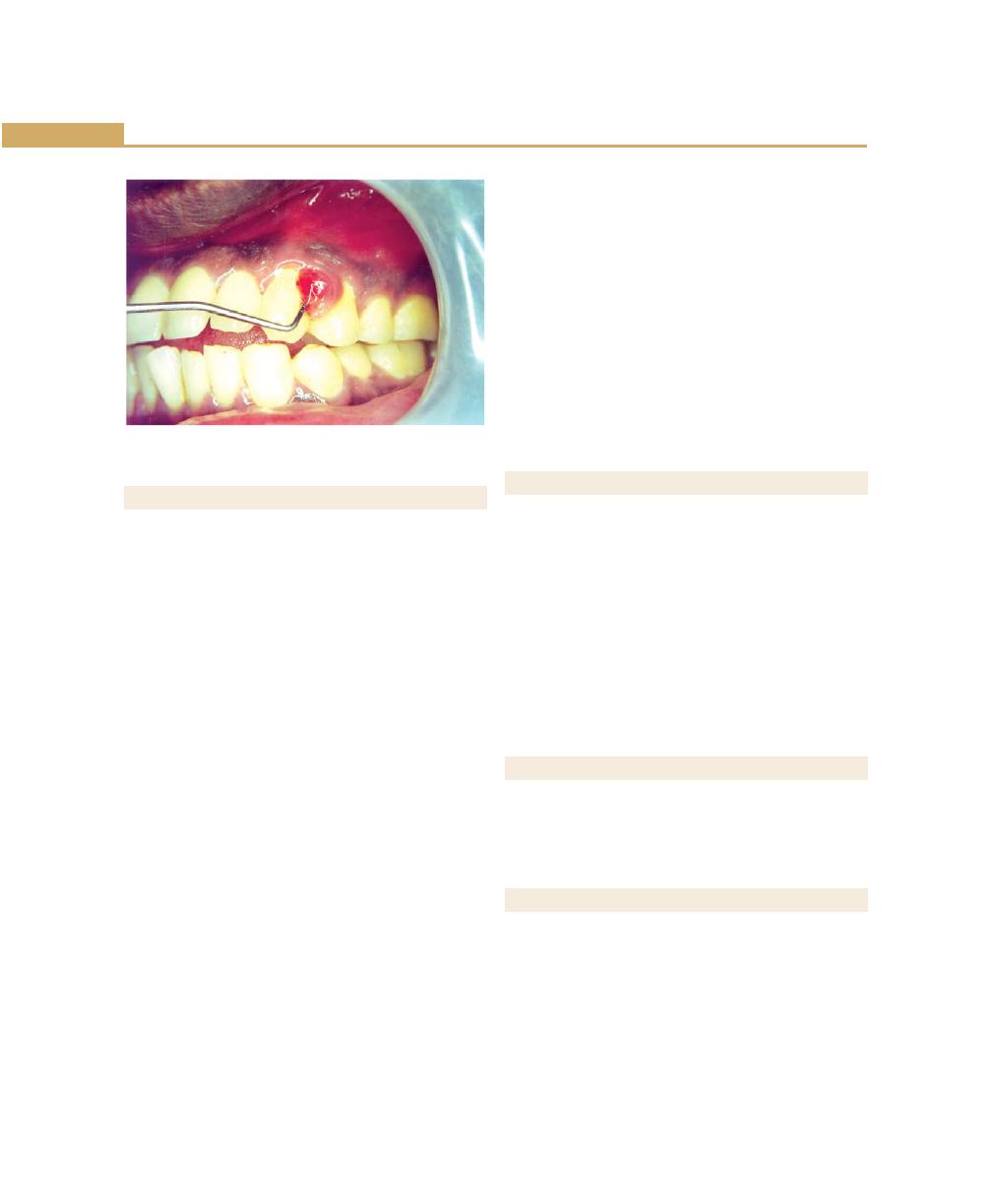

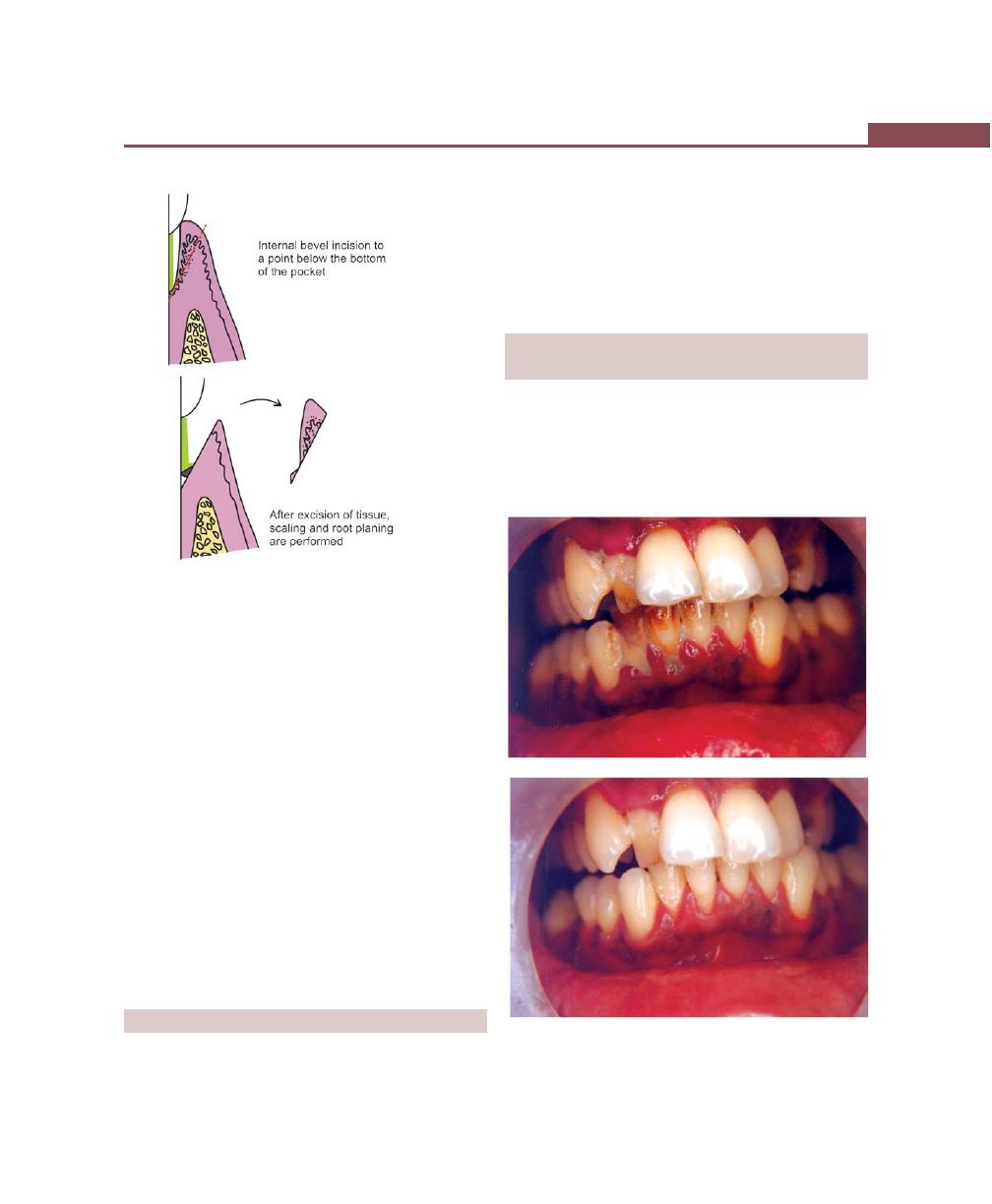

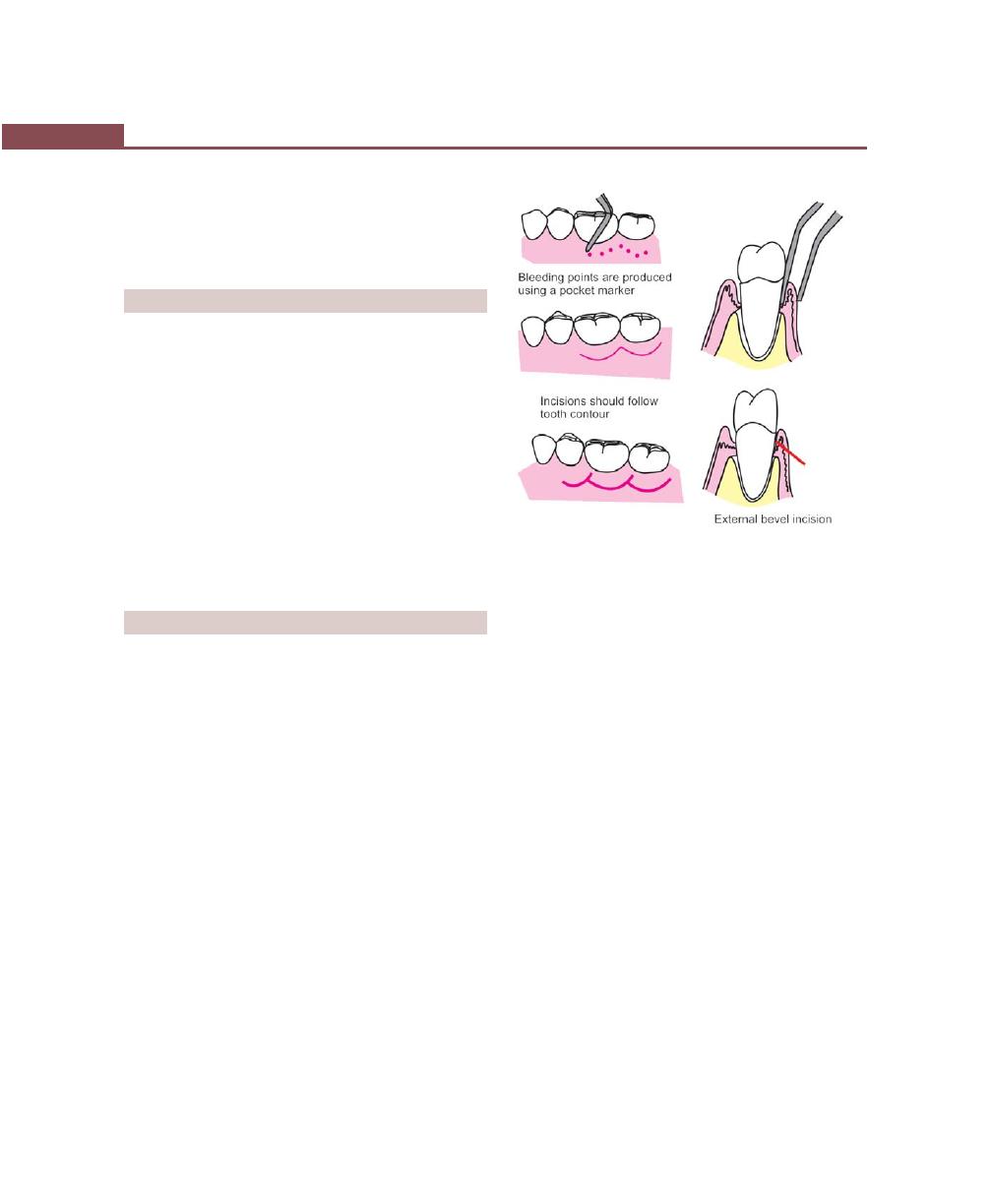

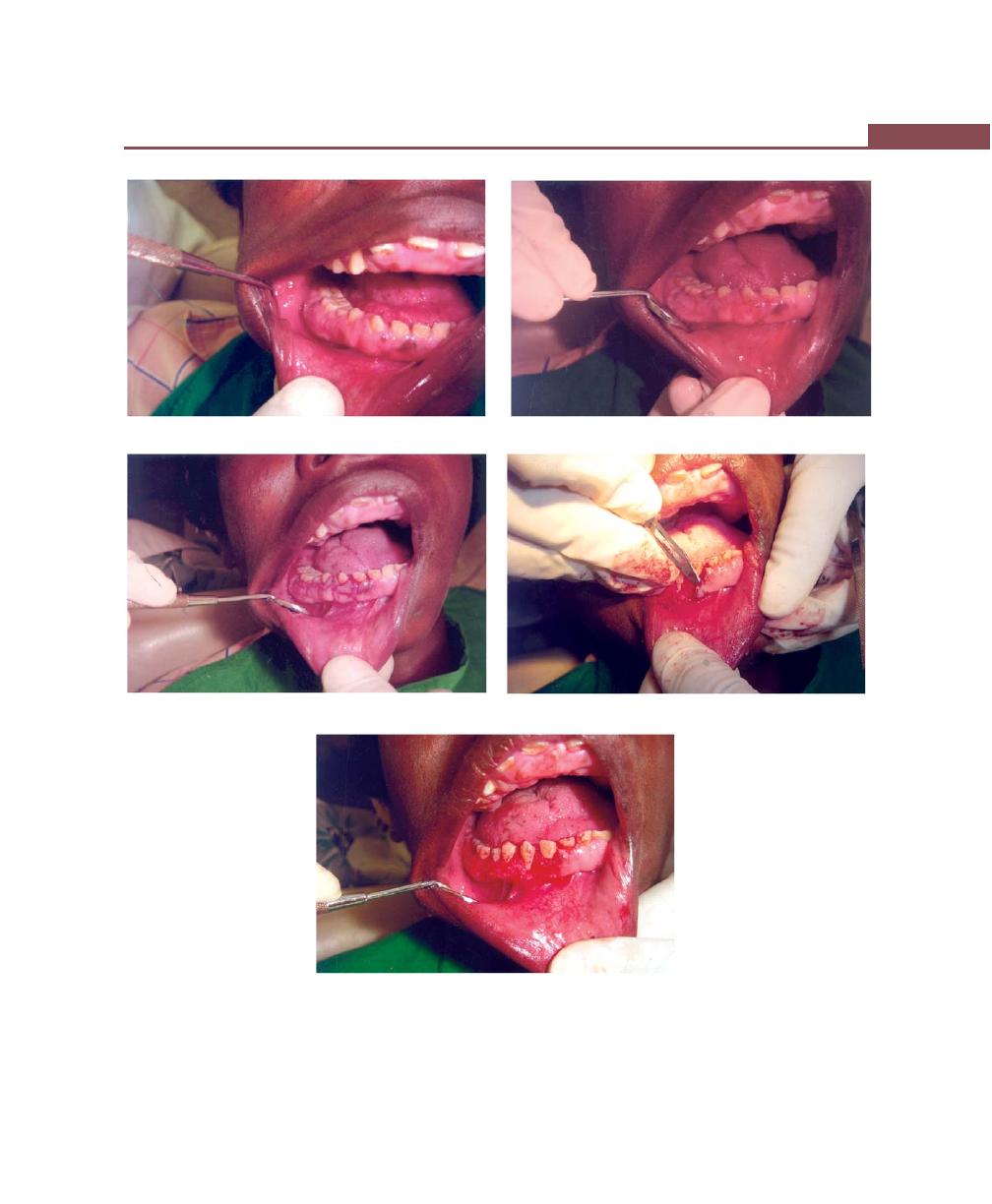

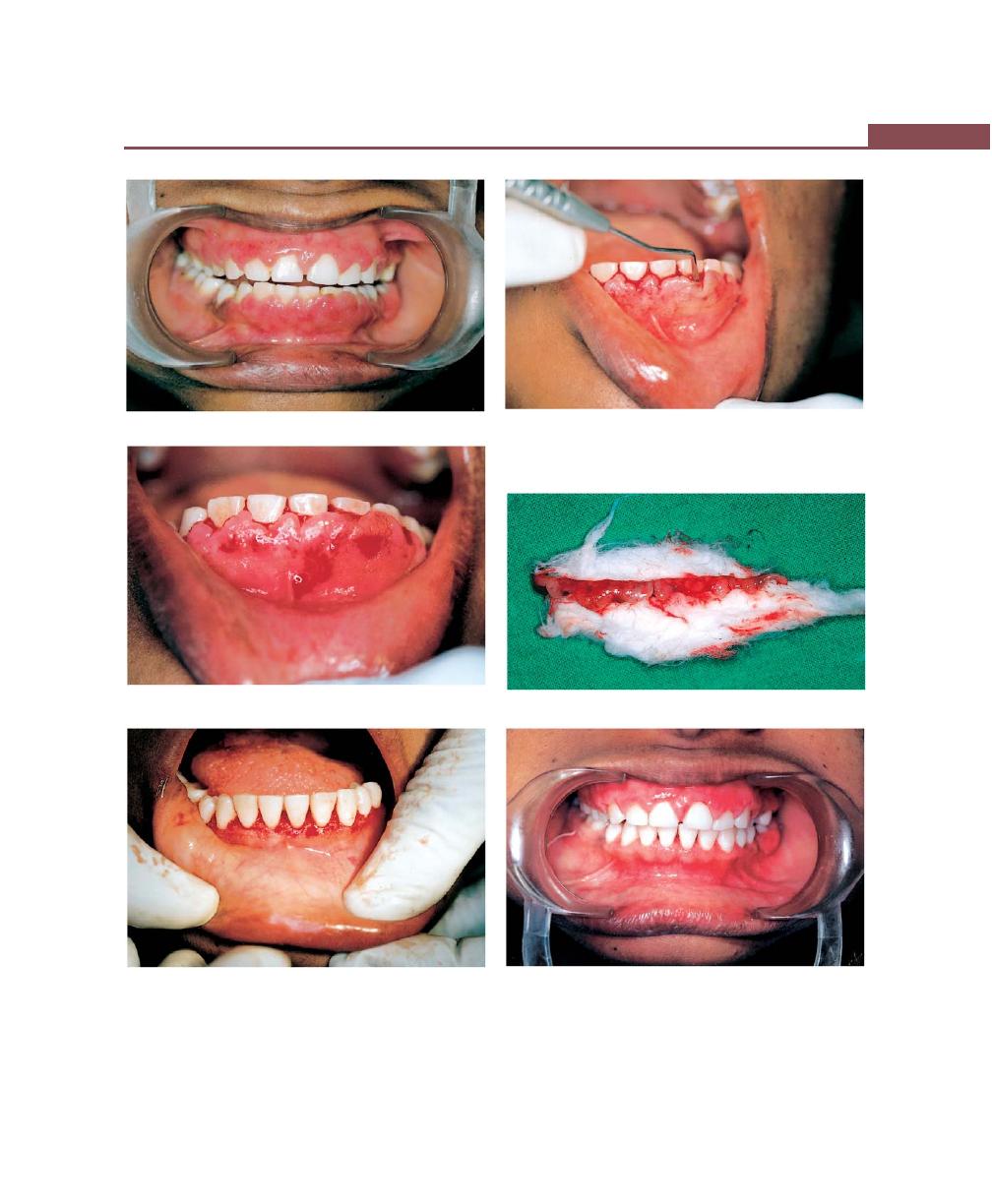

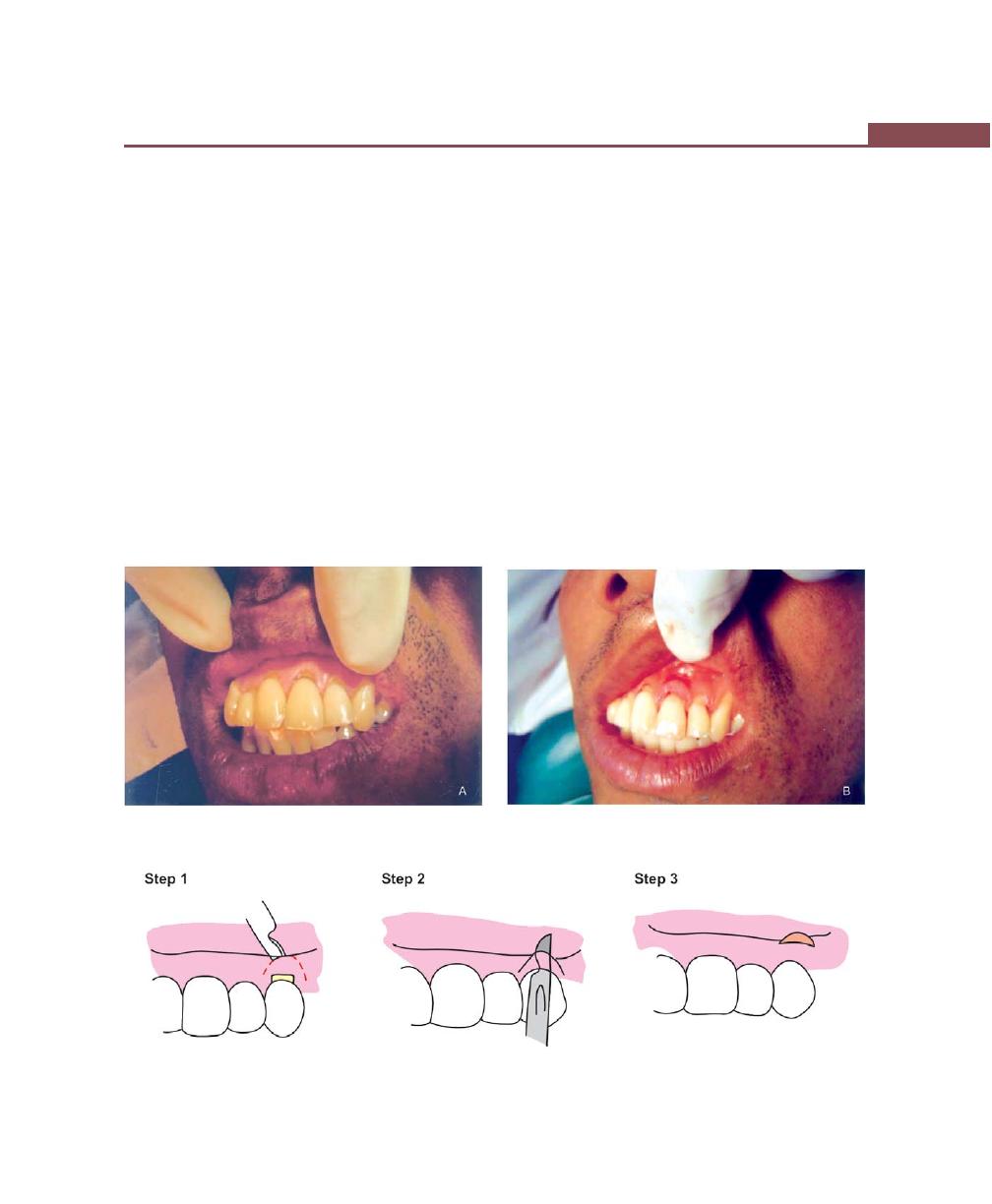

Chapter 40: Gingivectomy, 307

Introduction, 307

Definitions, 307

Pre-requisites, 307

Indications, 307

Contraindications, 308

Types of Gingivectomy, 308

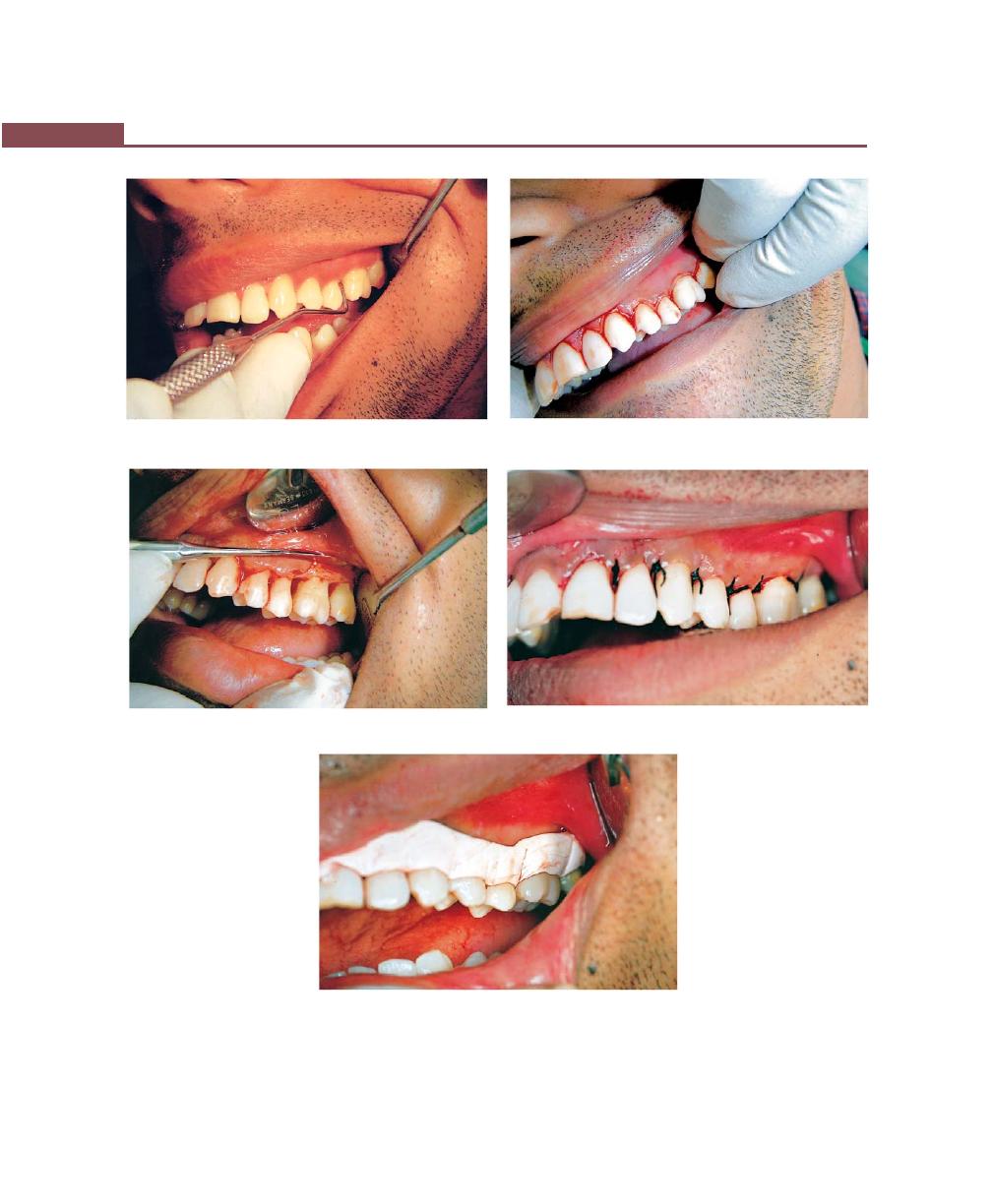

Surgical Gingivectomy, 308

Procedure for Gingivoplasty, 310

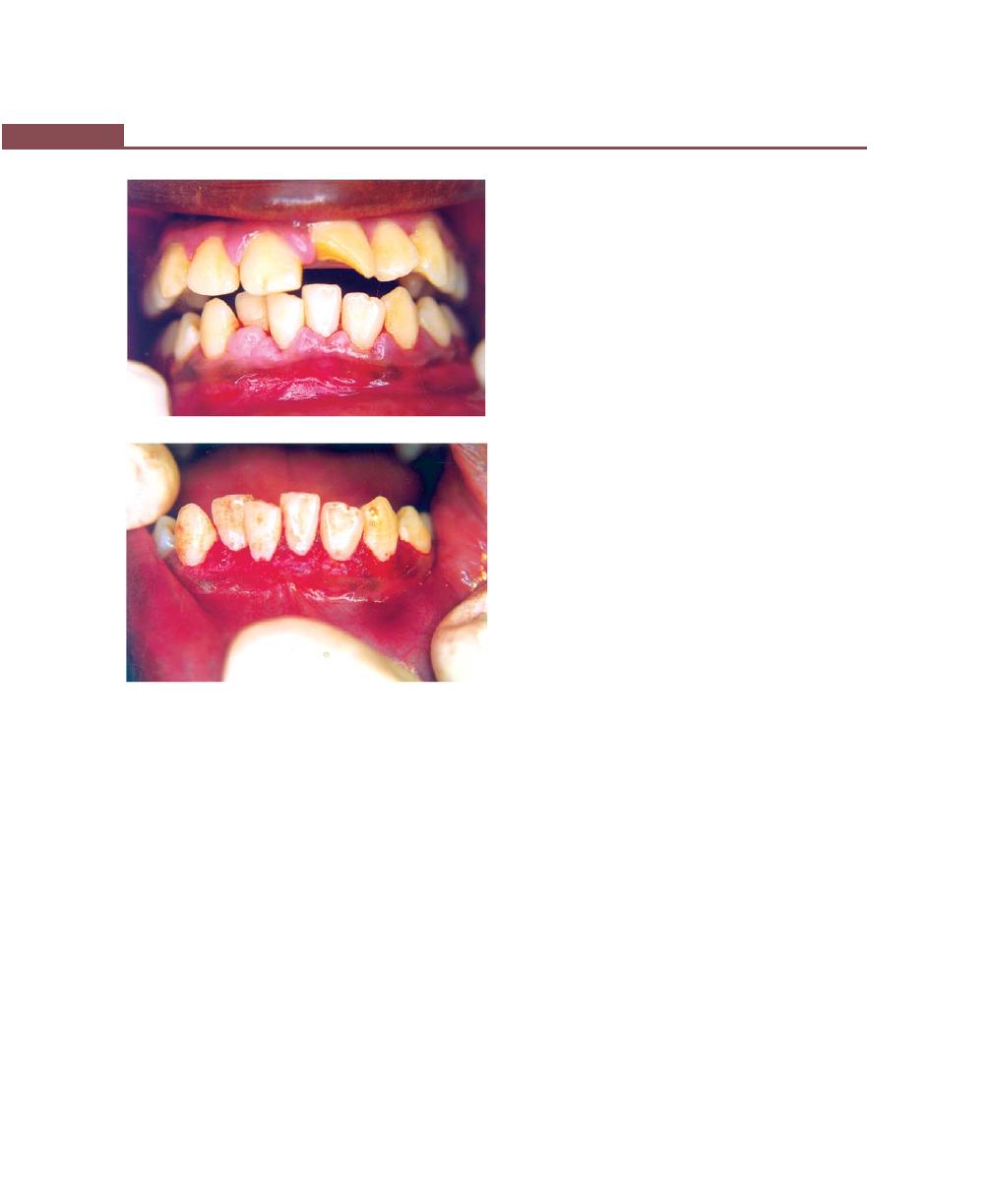

Healing After Surgical Gingivectomy, 310

Electrosurgery, 310

Laser Gingivectomy, 312

Gingivectomy by Chemosurgery, 312

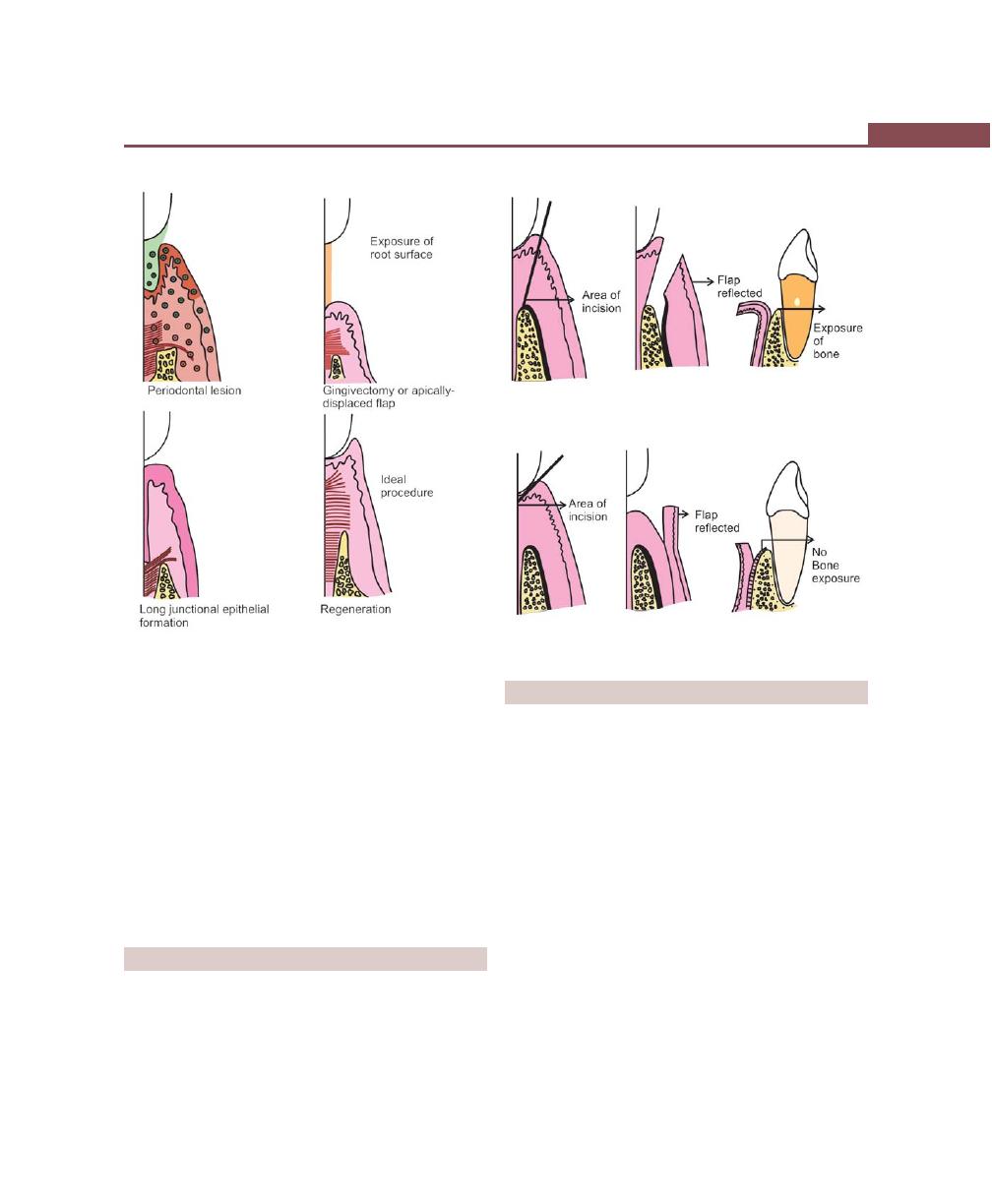

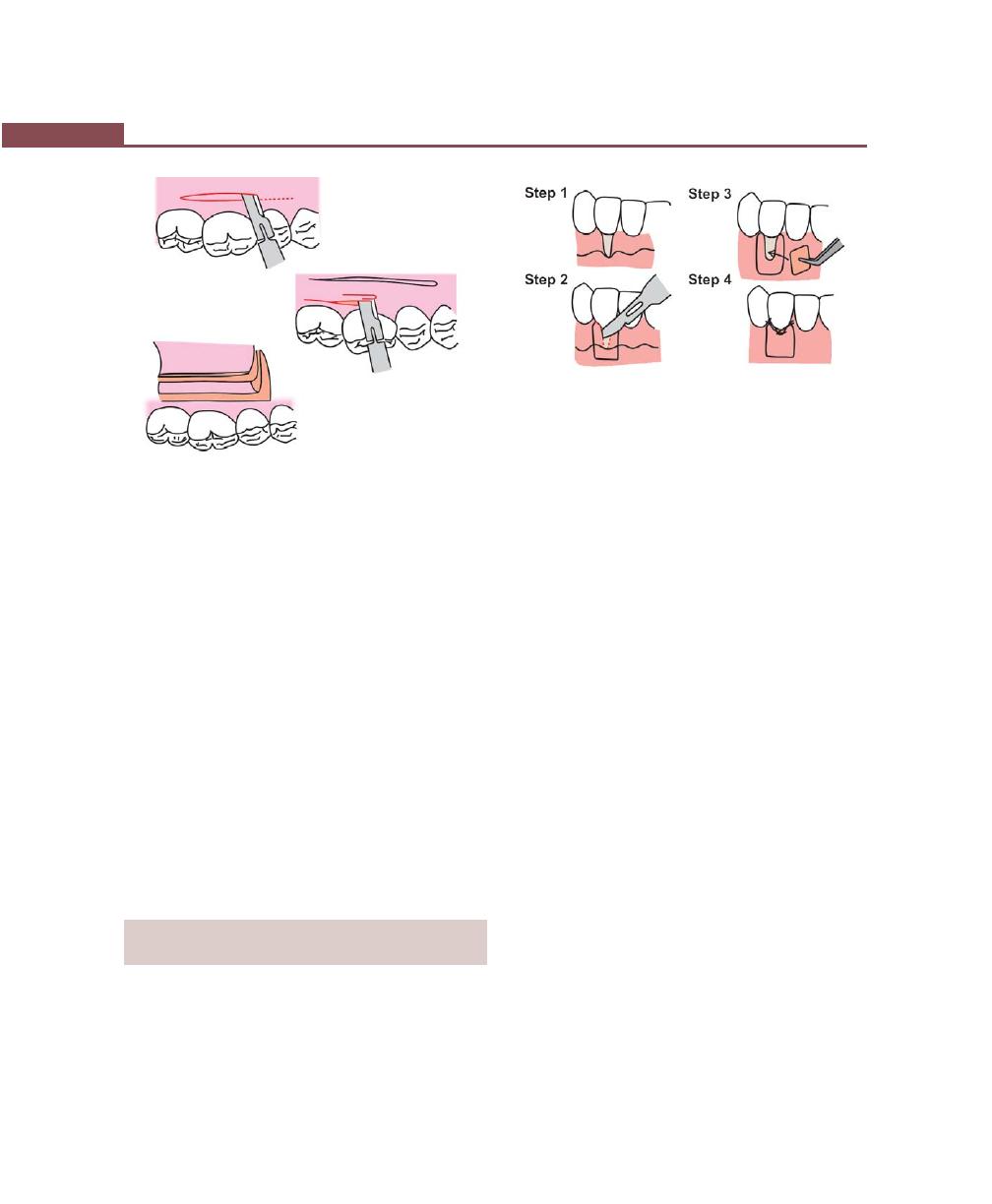

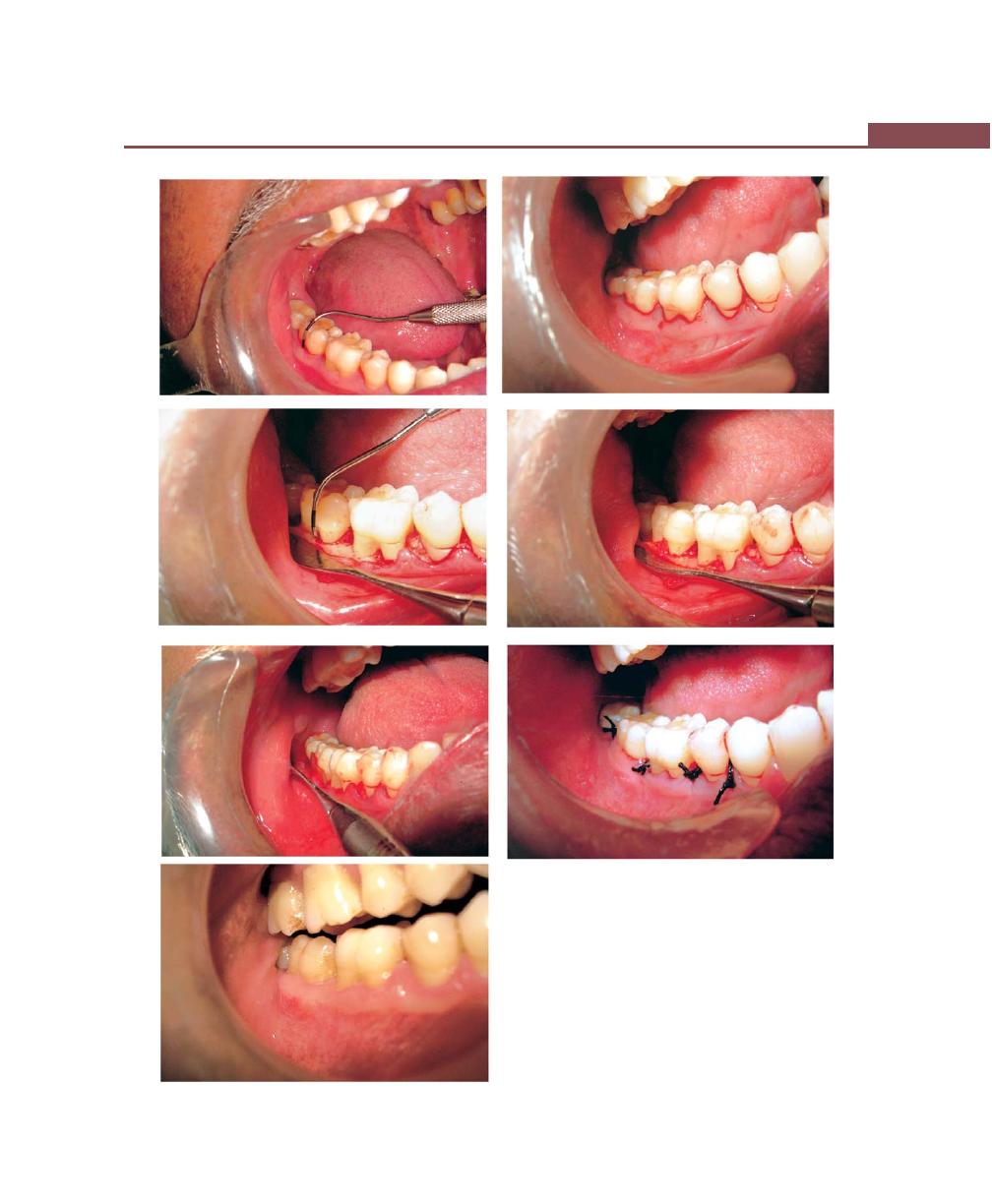

Chapter 41: Periodontal Flap, 314

Introduction, 314

Indications/Objectives of Flap Surgery, 314

Definition, 315

Classification, 315

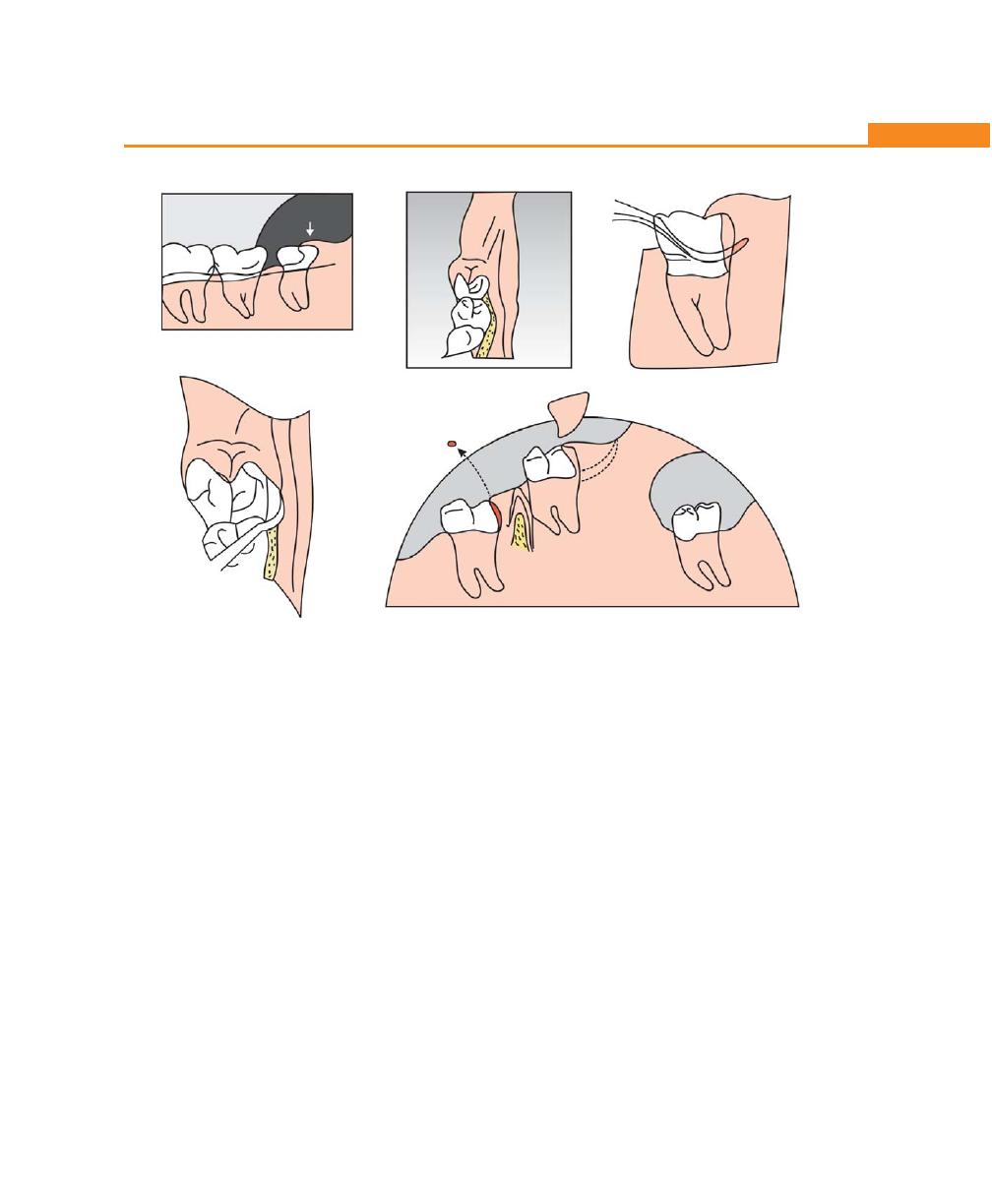

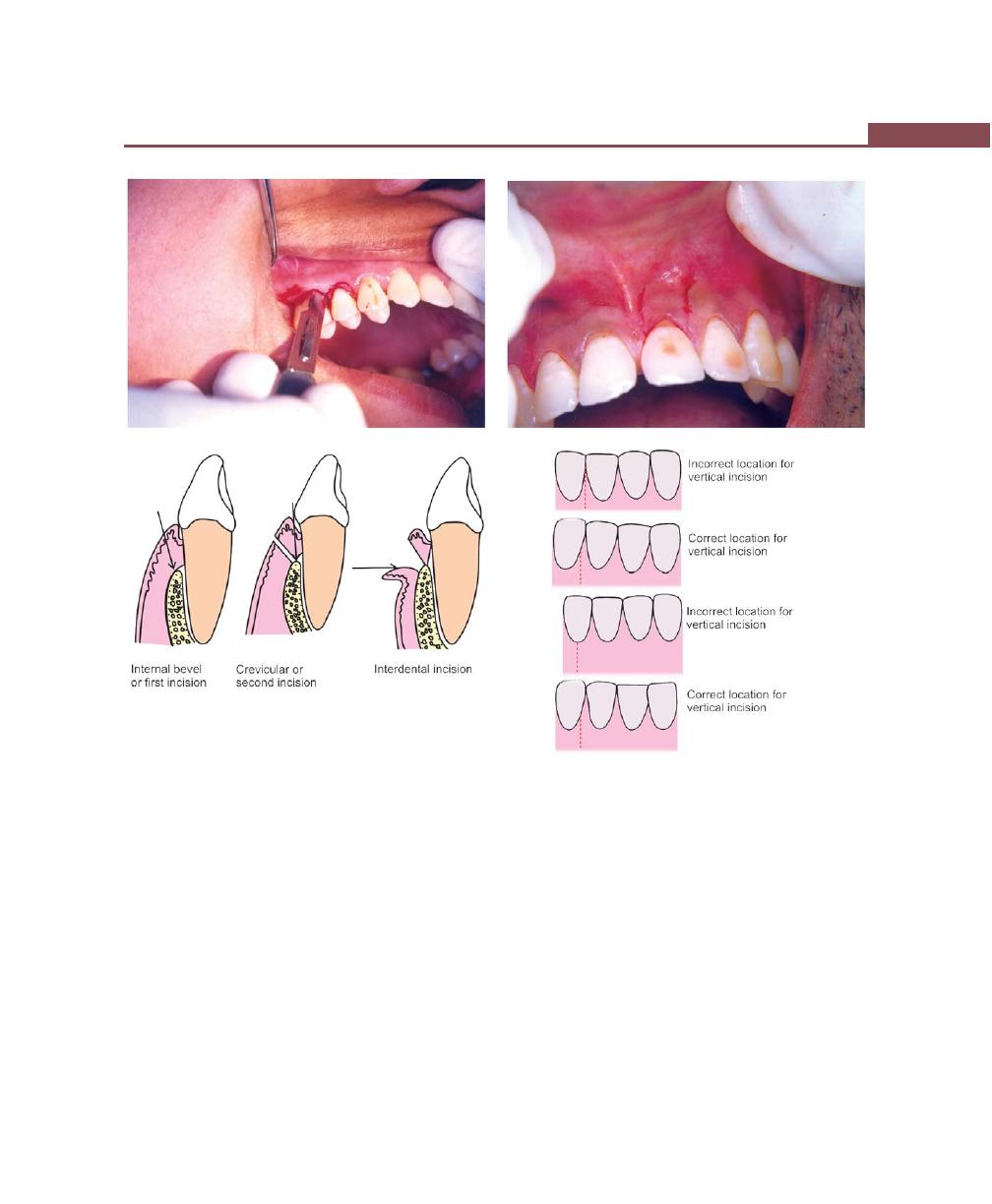

Incisions, 316

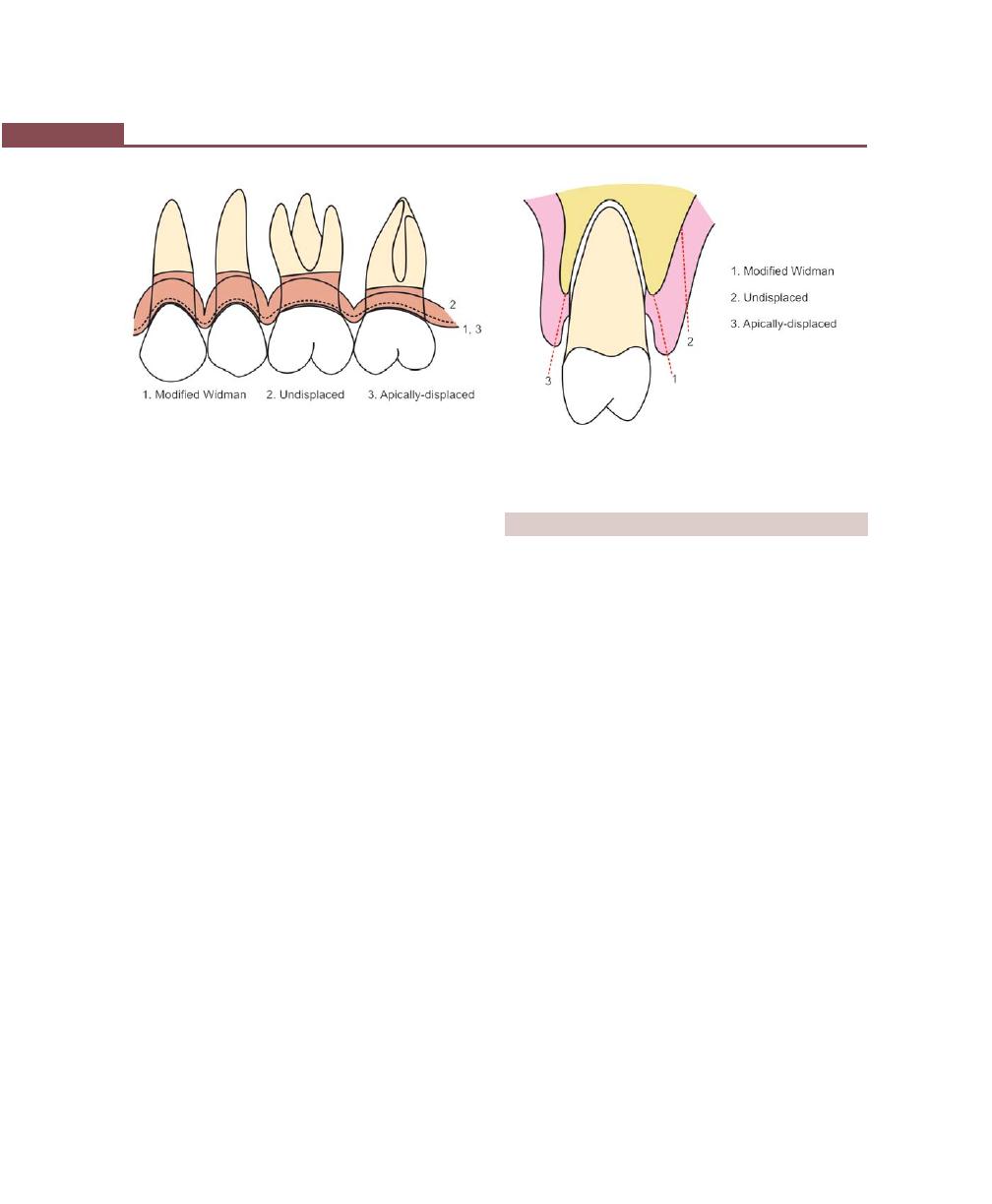

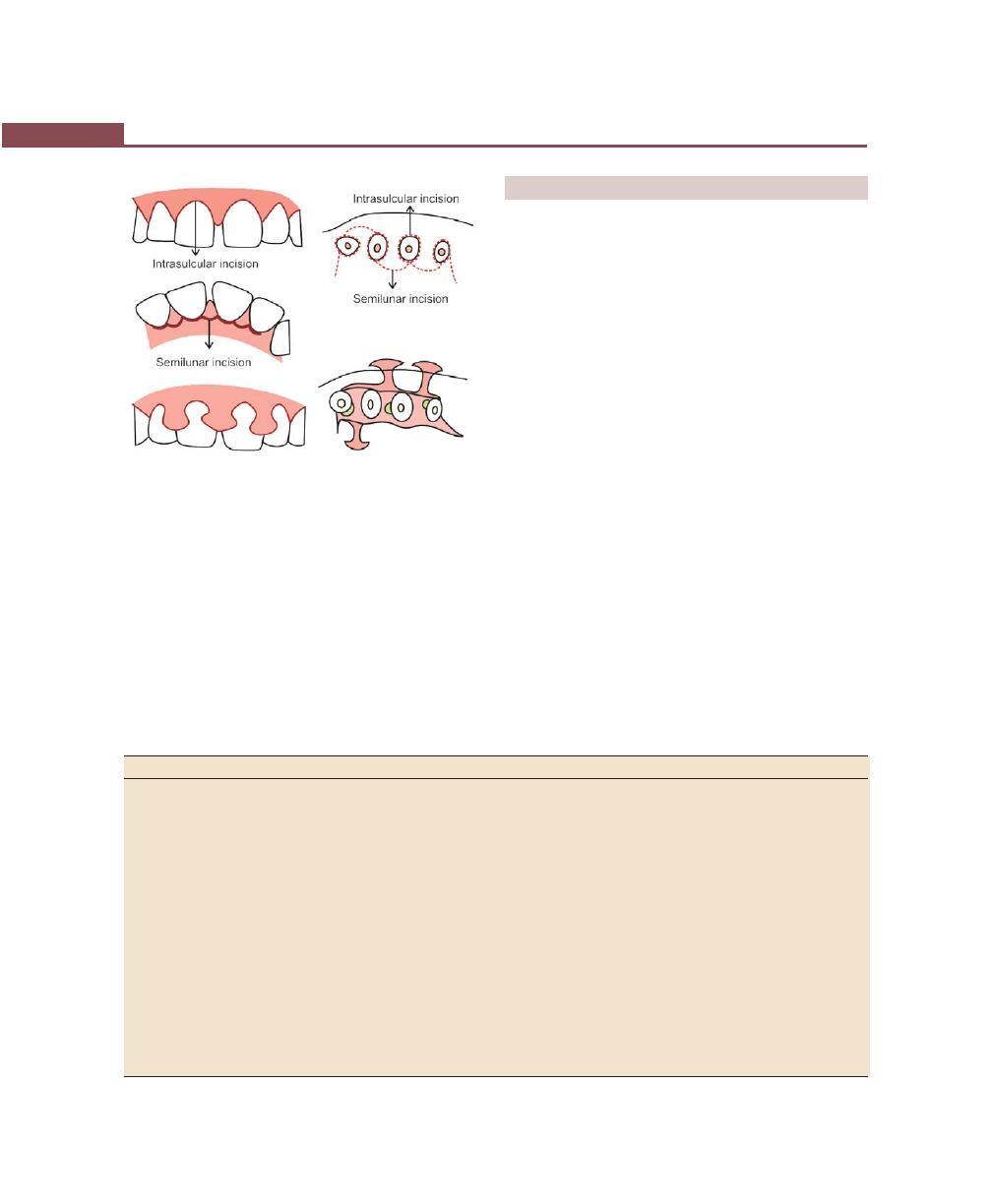

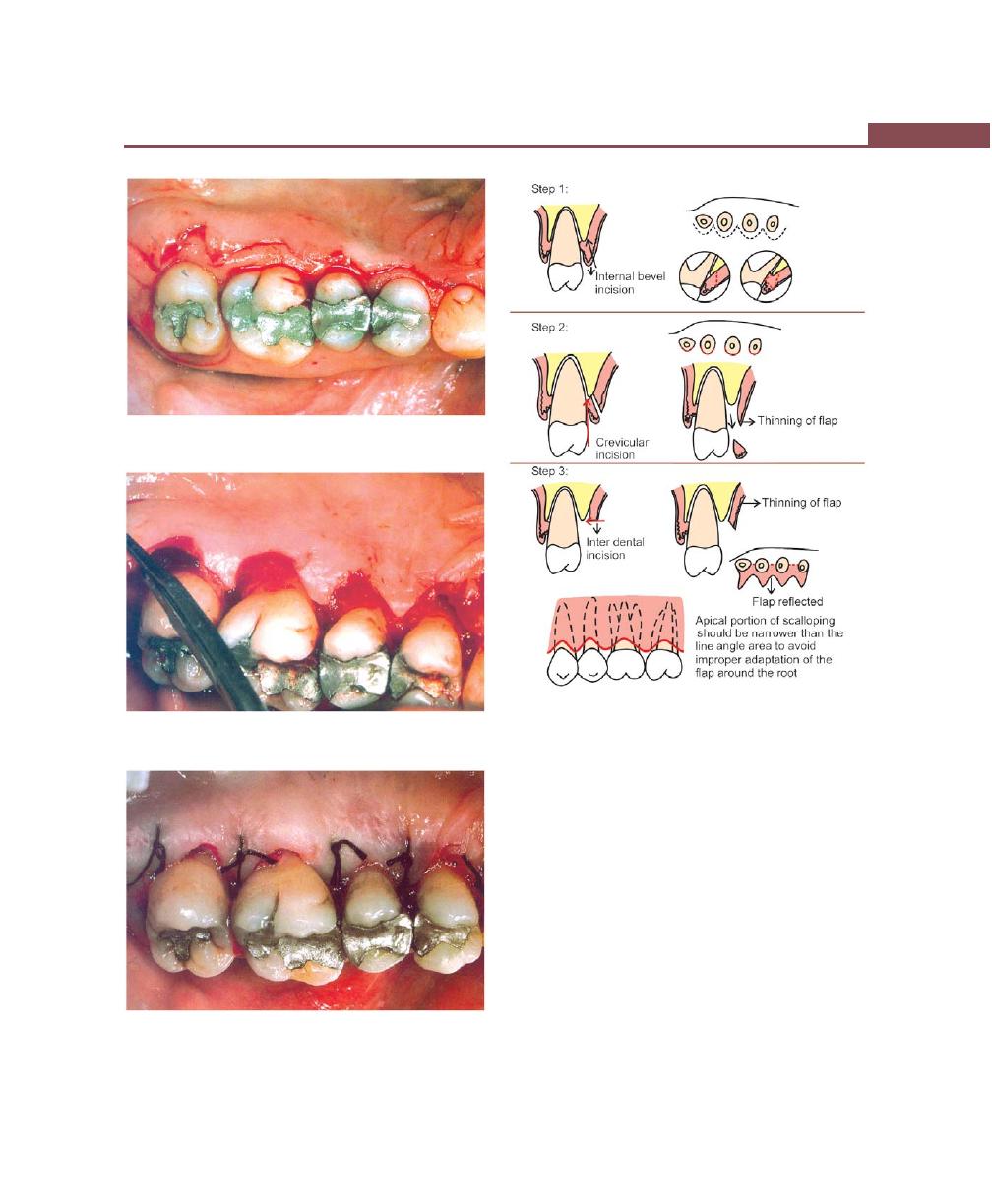

Flap Techniques for Pocket Therapy, 320

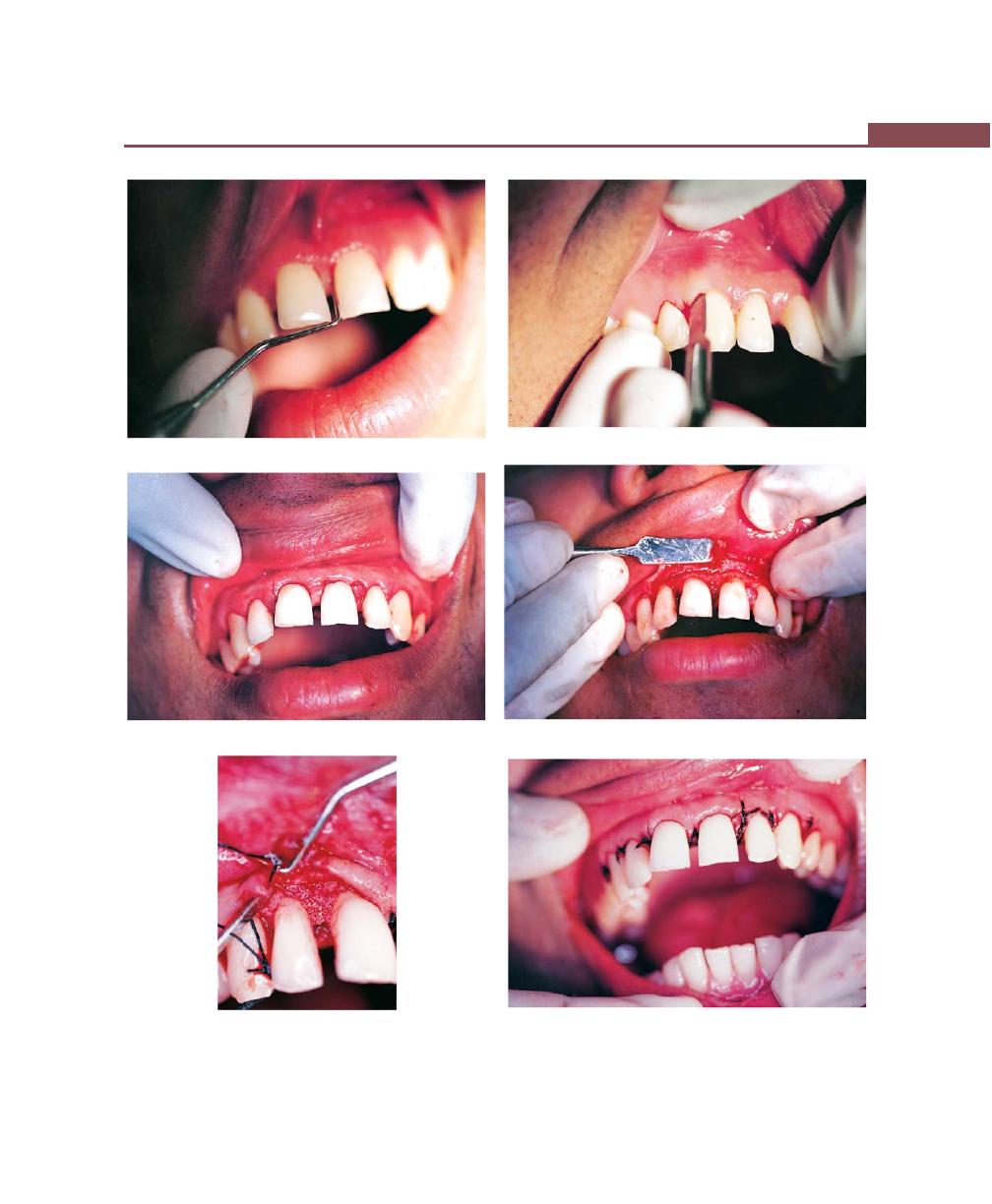

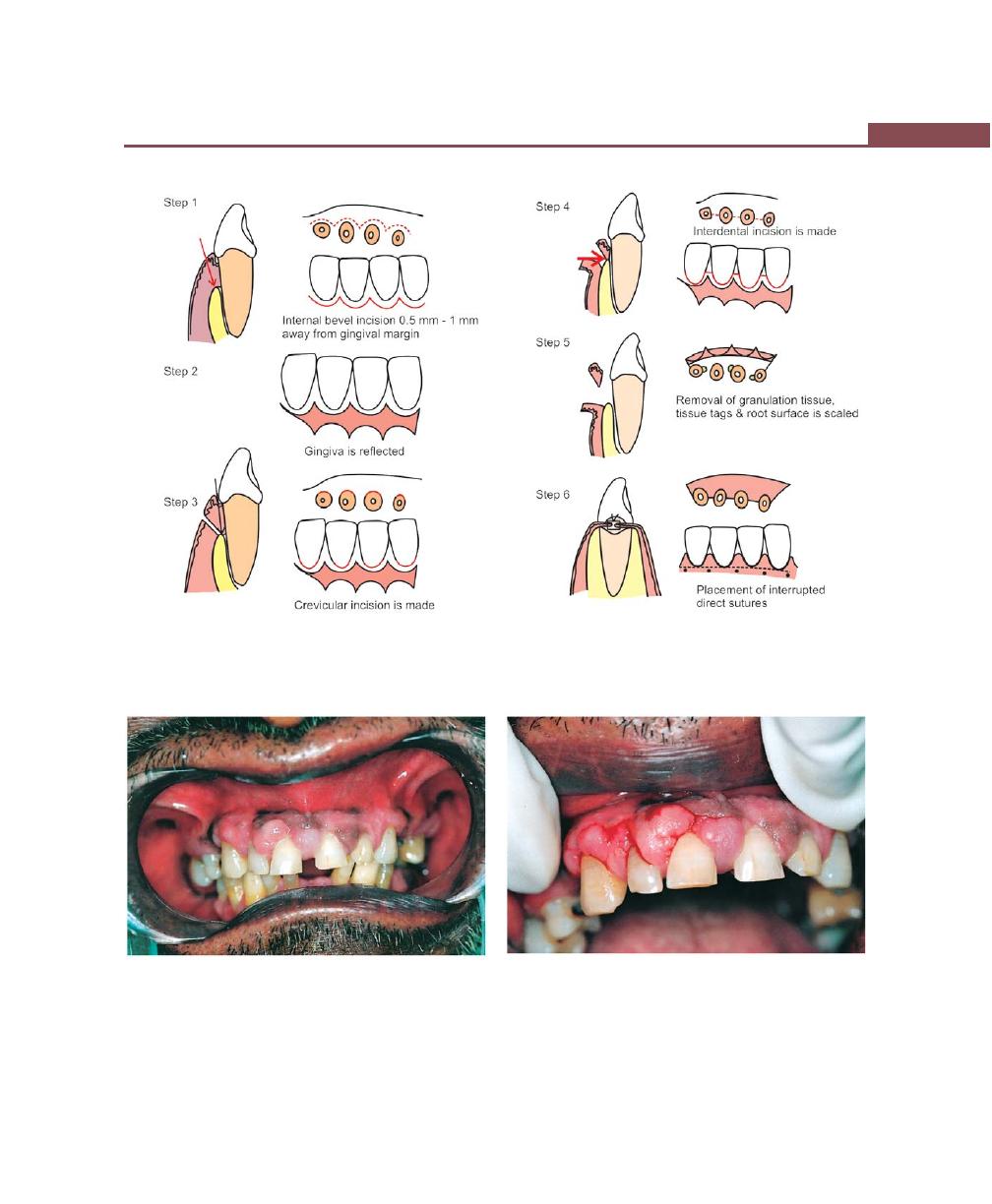

Modified Widman Flap, 320

Undisplaced Flap, 325

Palatal Flap, 326

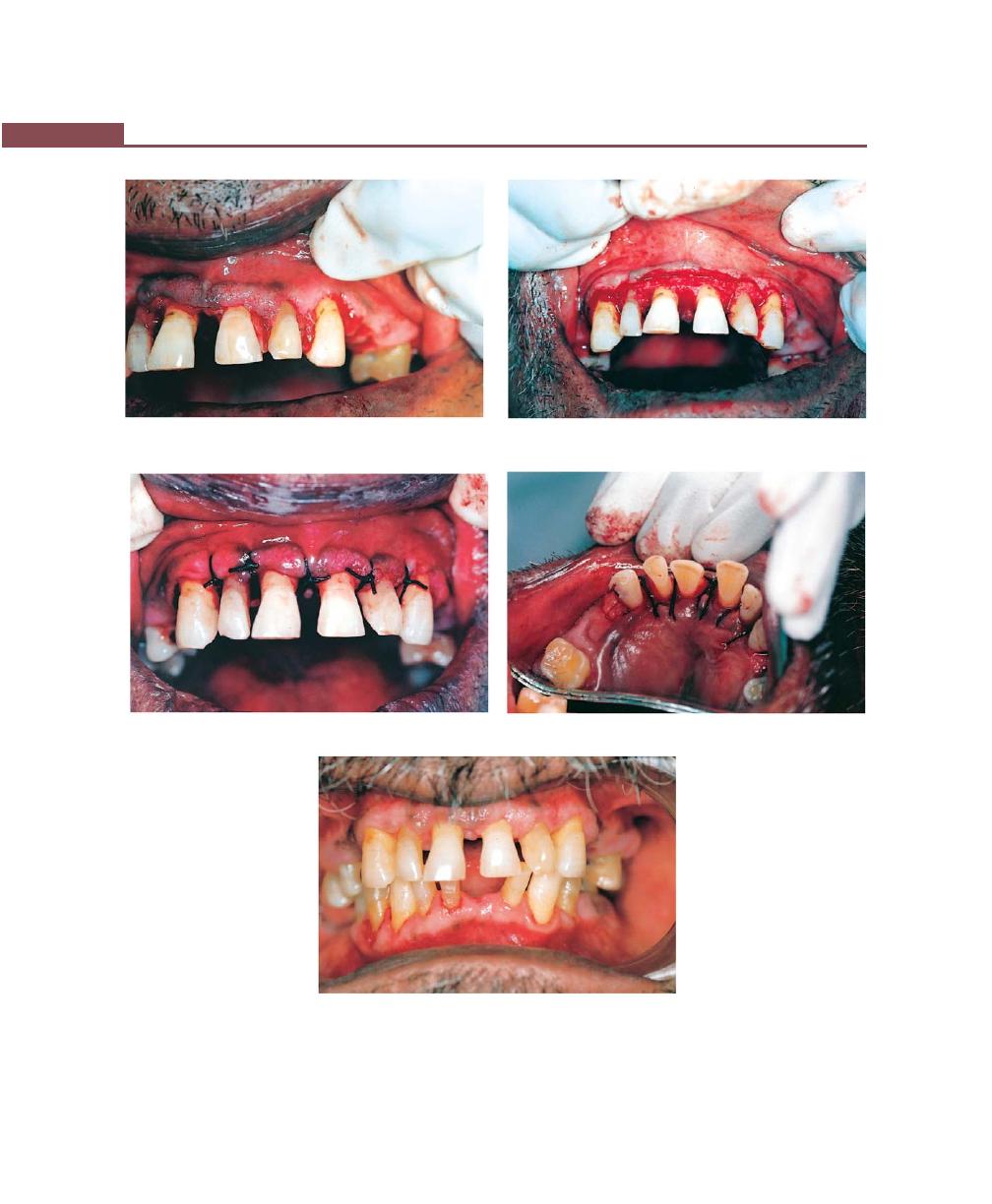

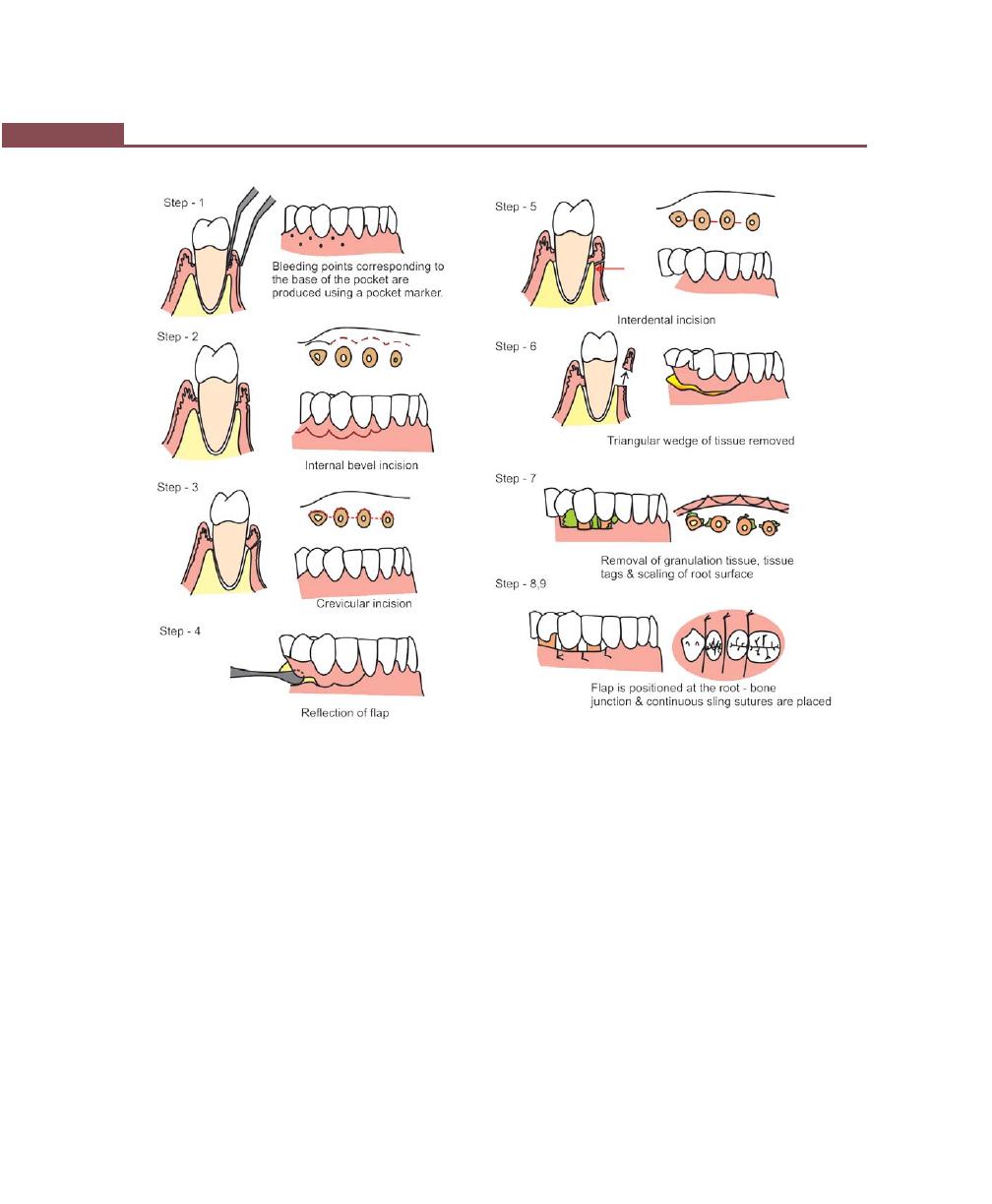

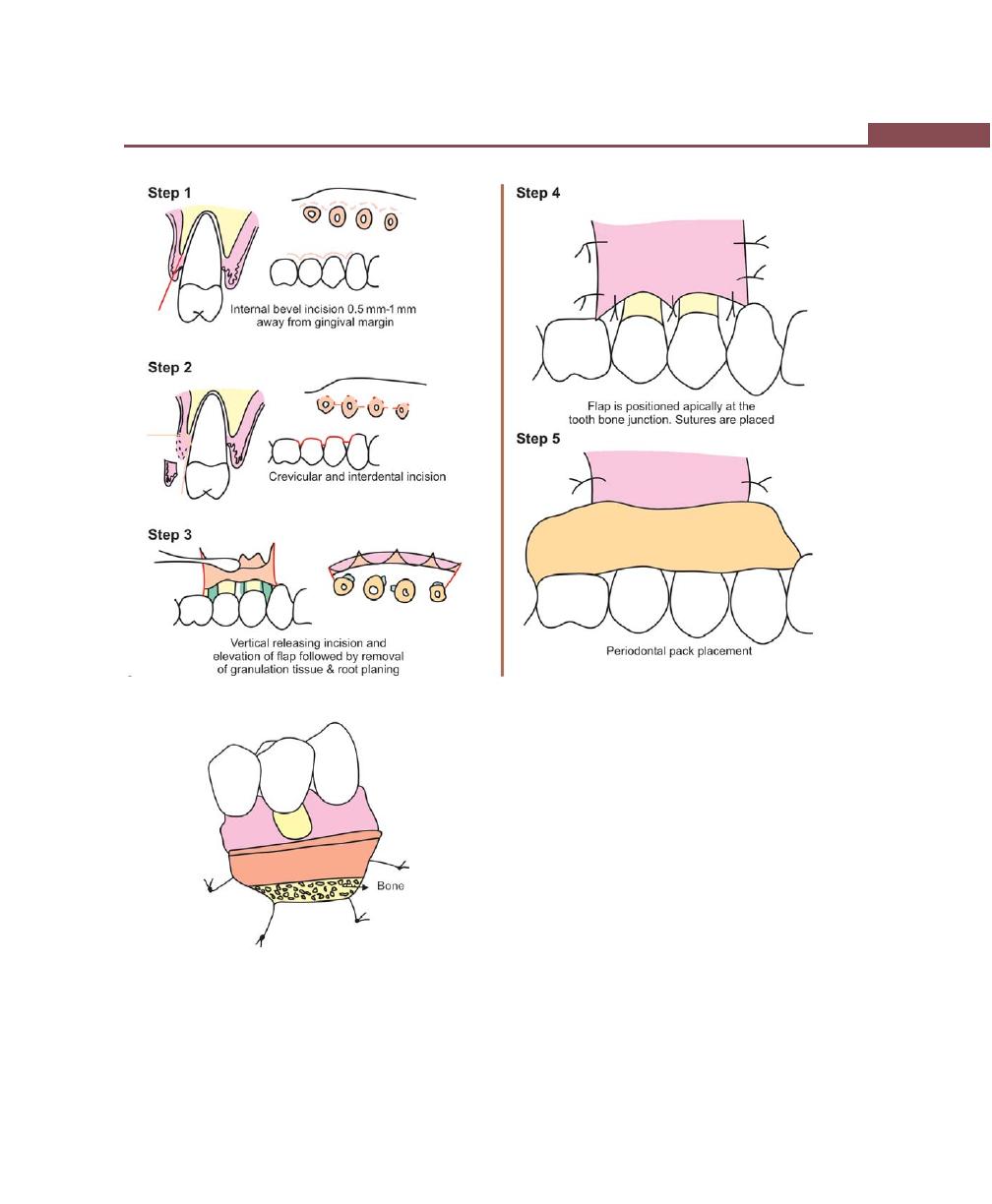

Apically-displaced Flap, 328

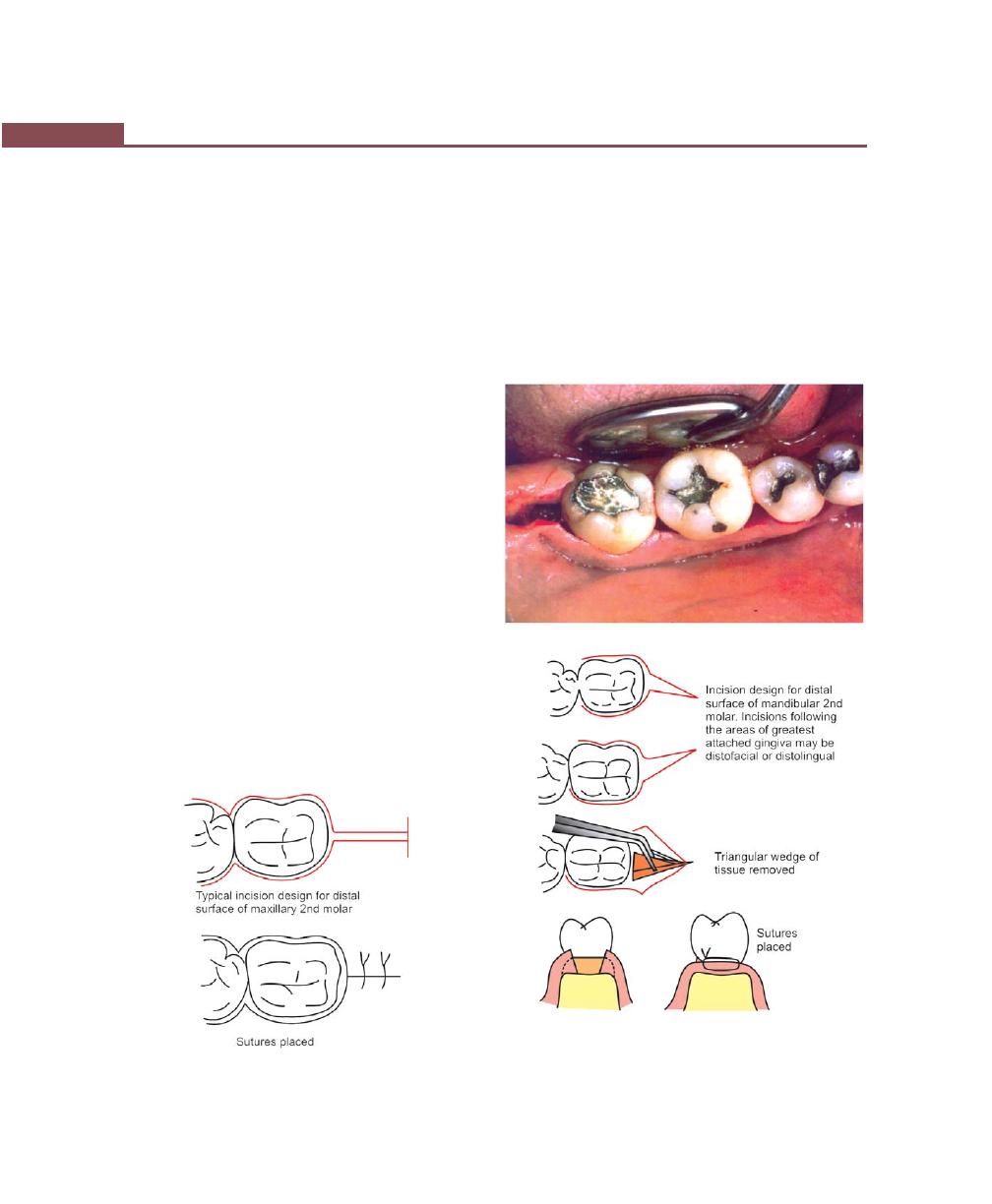

Distal Molar Surgery, 328

Healing After Flap Surgery, 329

Chapter 42: Osseous Surgery, 330

Definition, 330

Rationale, 330

Terminology, 330

Types of Osseous Surgery, 331

Resective Osseous Surgery, 331

Indications, 331

Contraindications, 331

Methods of Osseous Surgery, 332

Instruments Used, 332

Technique, 332

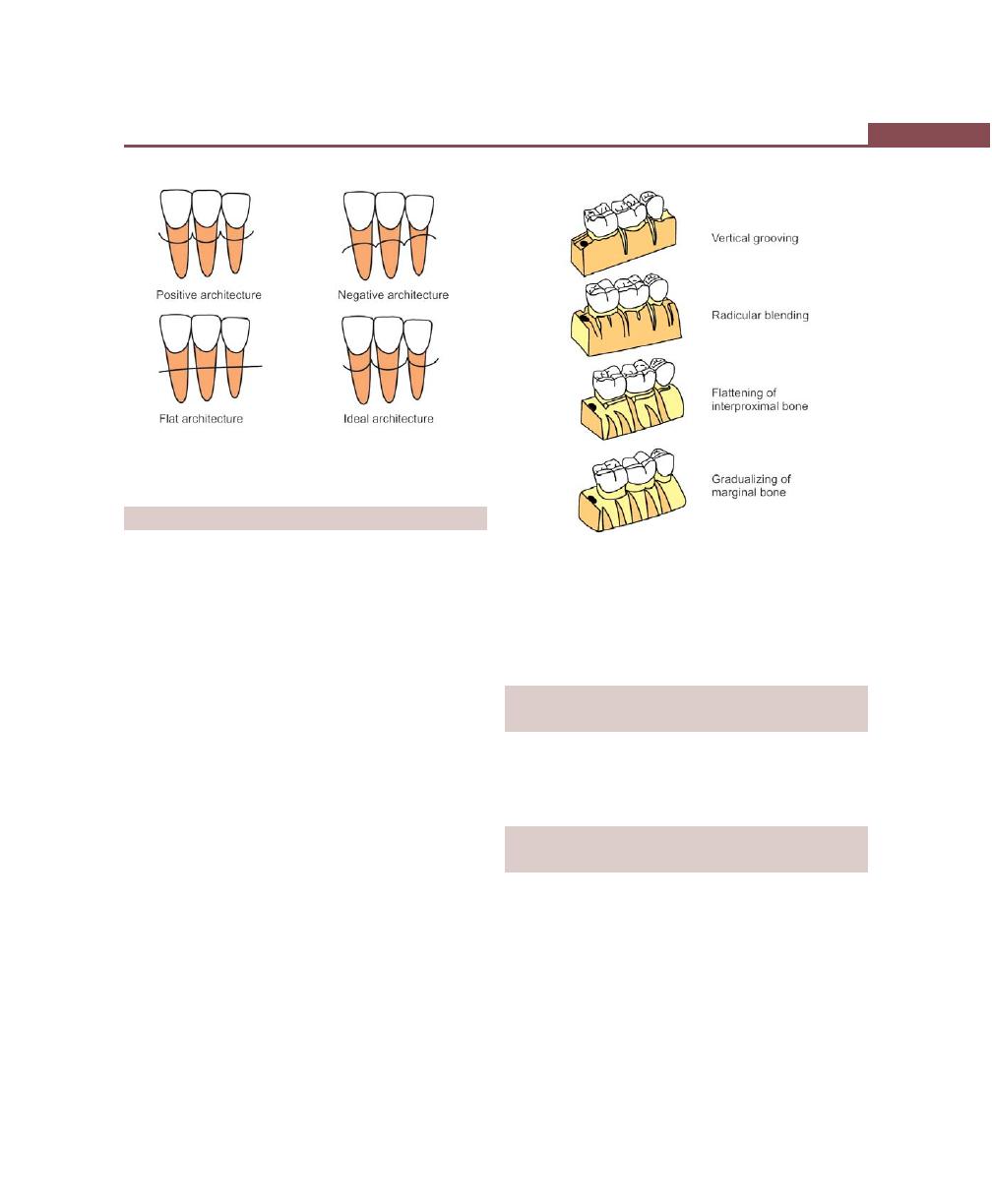

Vertical Grooving, 332

Radicular Blending, 332

Flattening of Interproximal Bone, 332

Gradualizing Marginal Bone, 332

Healing After Resective Osseous Surgery, 333

Reconstructive Osseous Surgery, 333

Evaluation of New Attachment, 333

Clinical Method, 333

Radiographic Methods, 333

Surgical Re-entry, 333

Histological Methods, 333

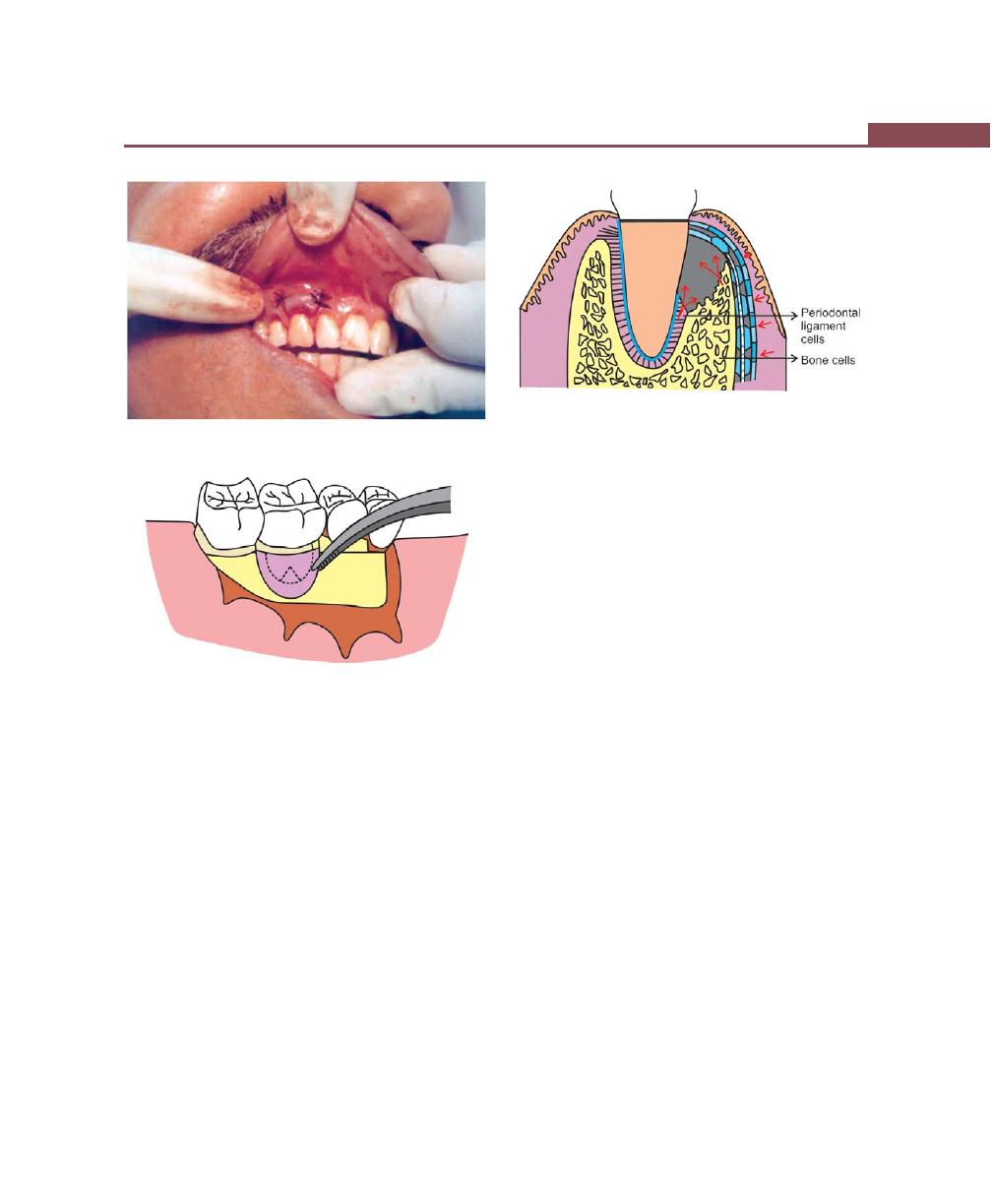

Nongraft-associated New Attachment, 334

Removal of Junctional and Pocket Epithelium, 334

Prevention of Epithelial Migration, 334

GTR, 334

Root Biomodification, 336

xxii

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

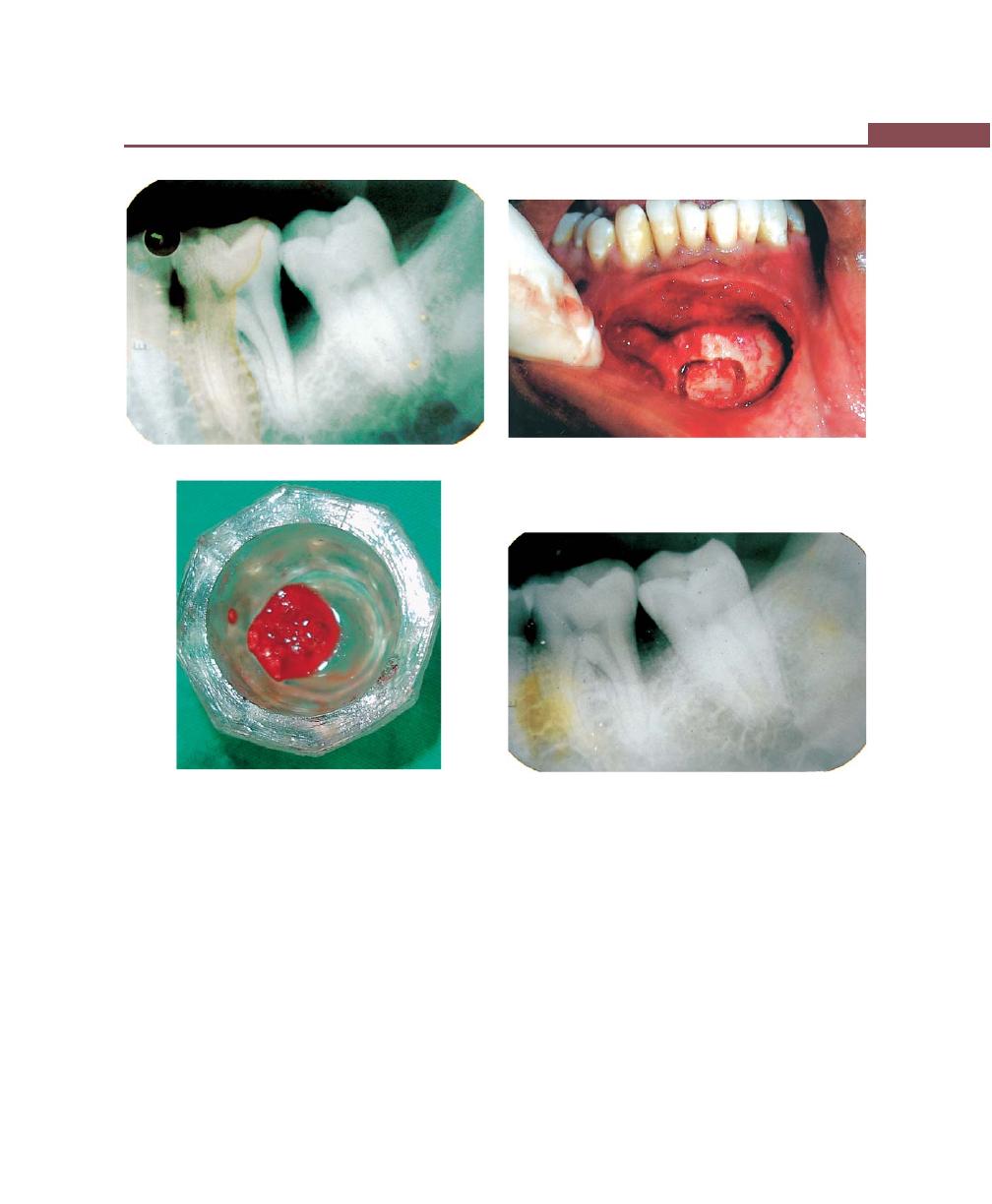

Graft-associated New Attachment, 336

Terminology, 336

Ideal Requirements of a Bone Graft Material, 337

Autografts, 337

Allografts, 338

Xenografts, 338

Alloplasts, 338

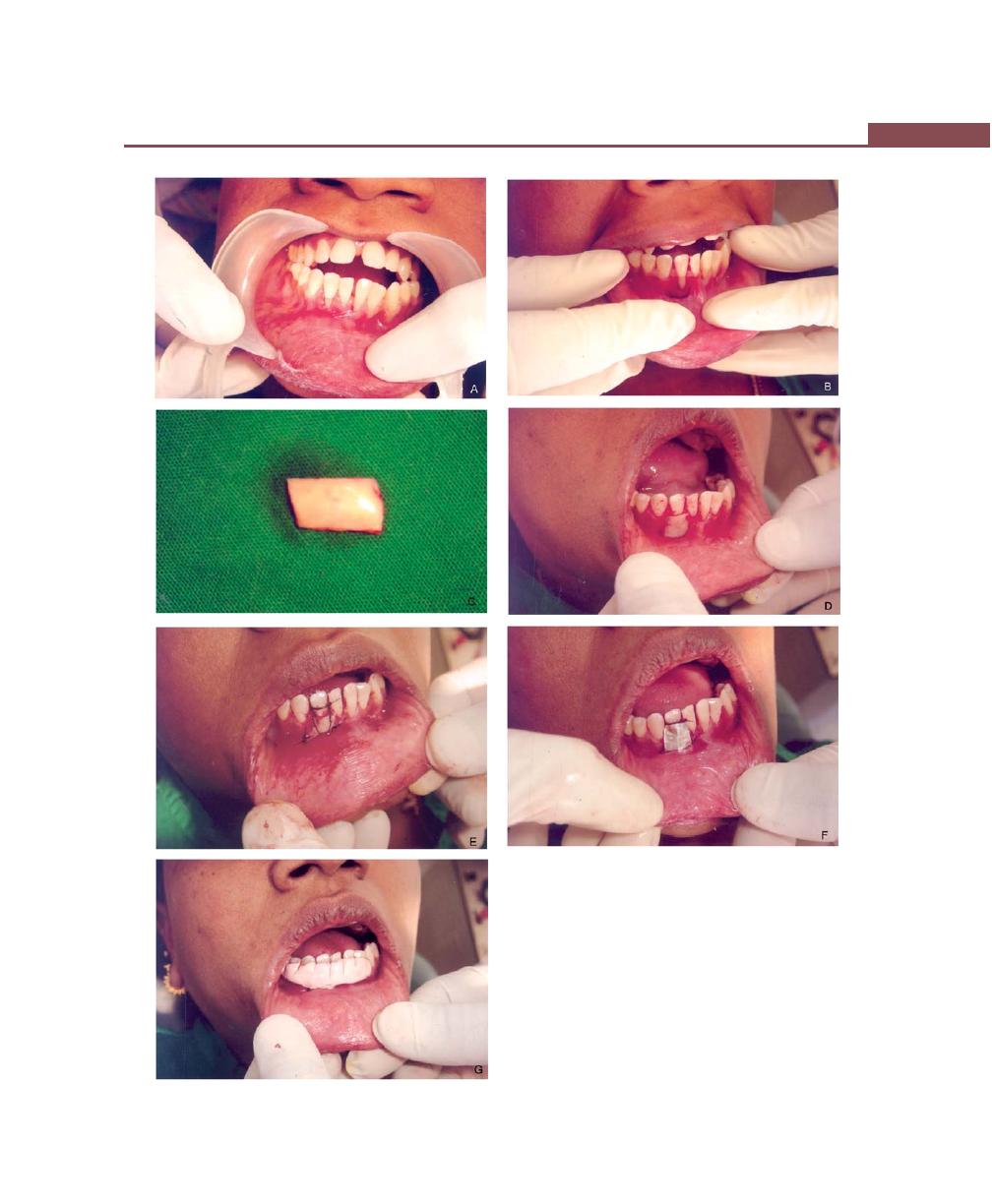

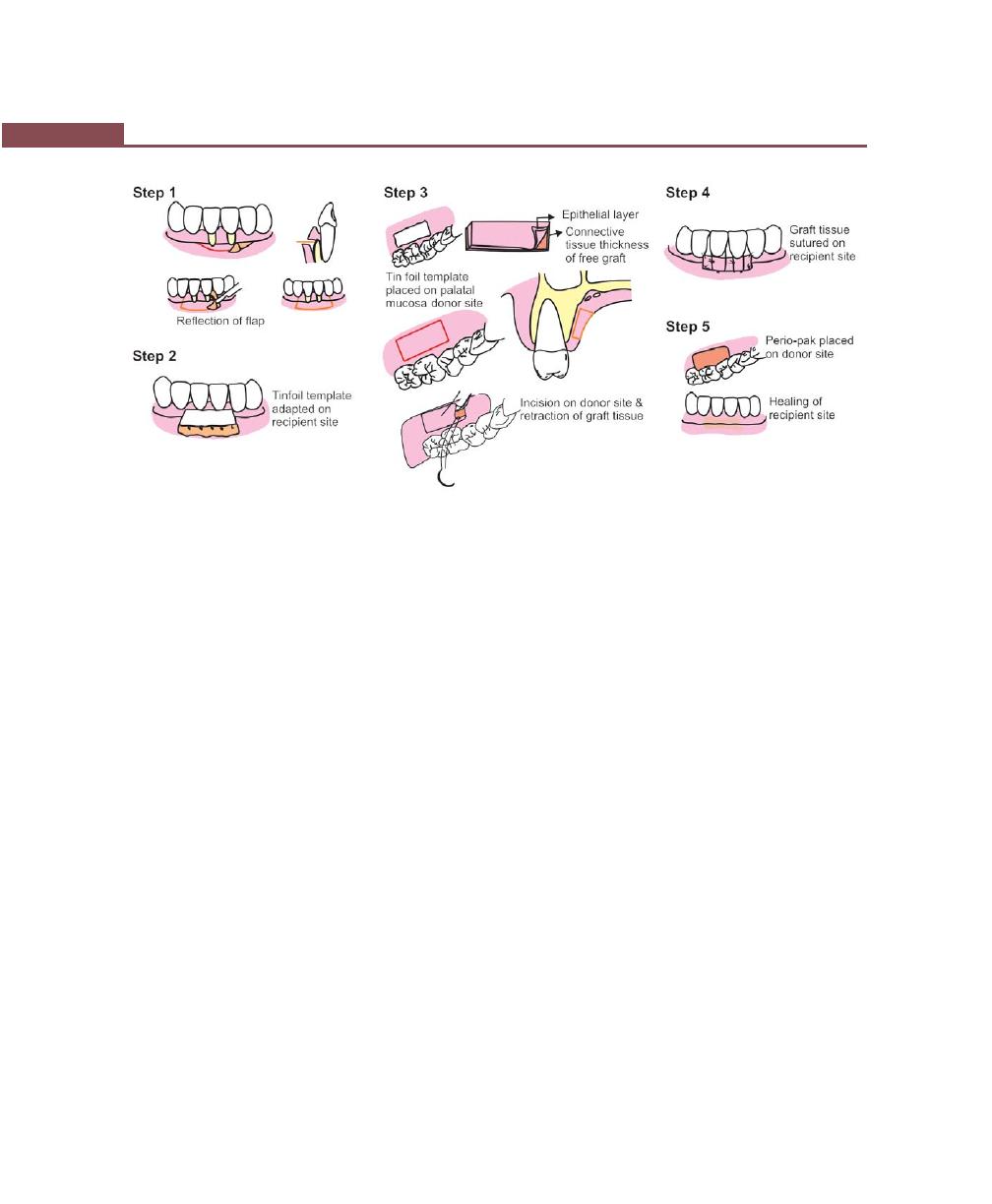

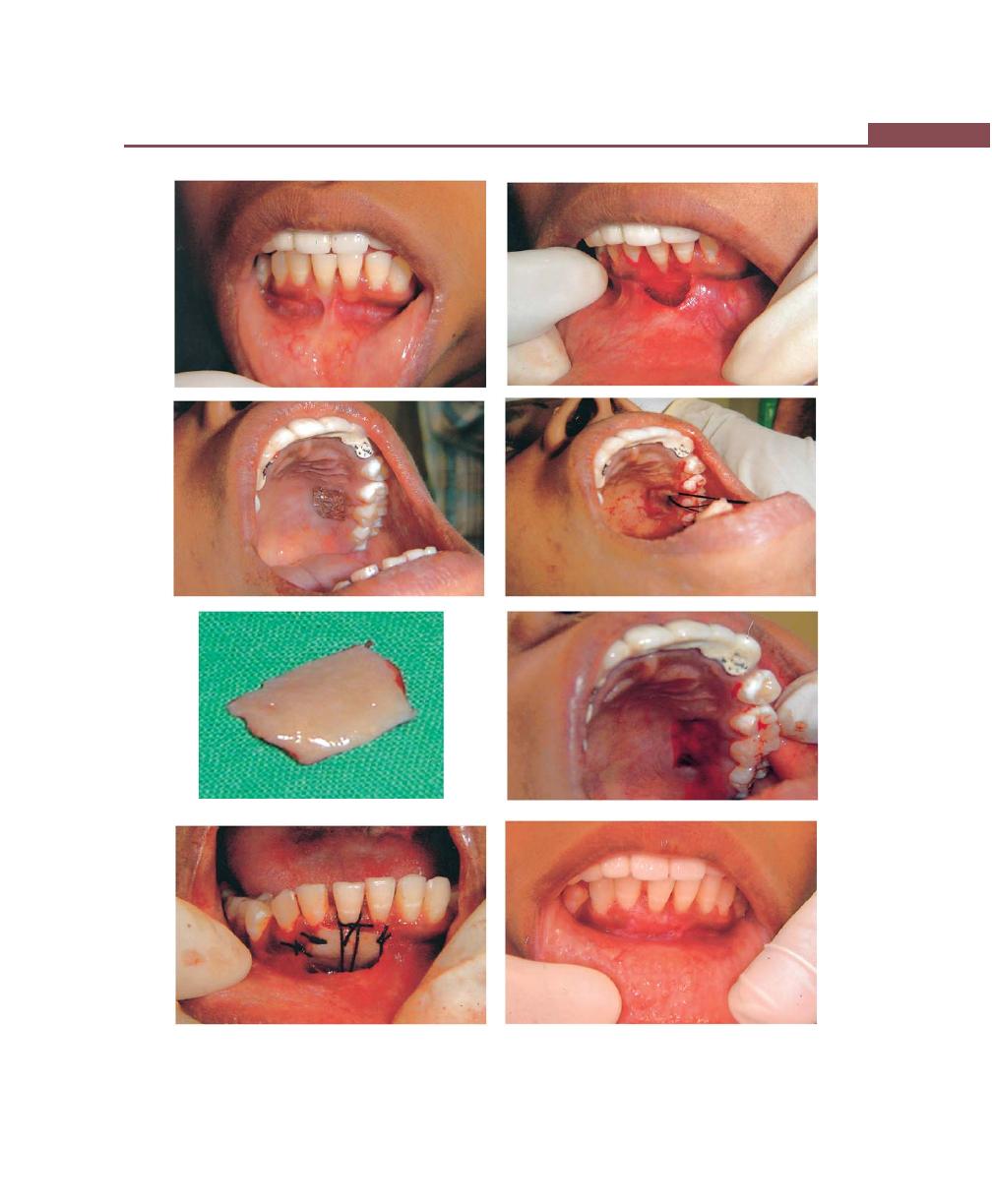

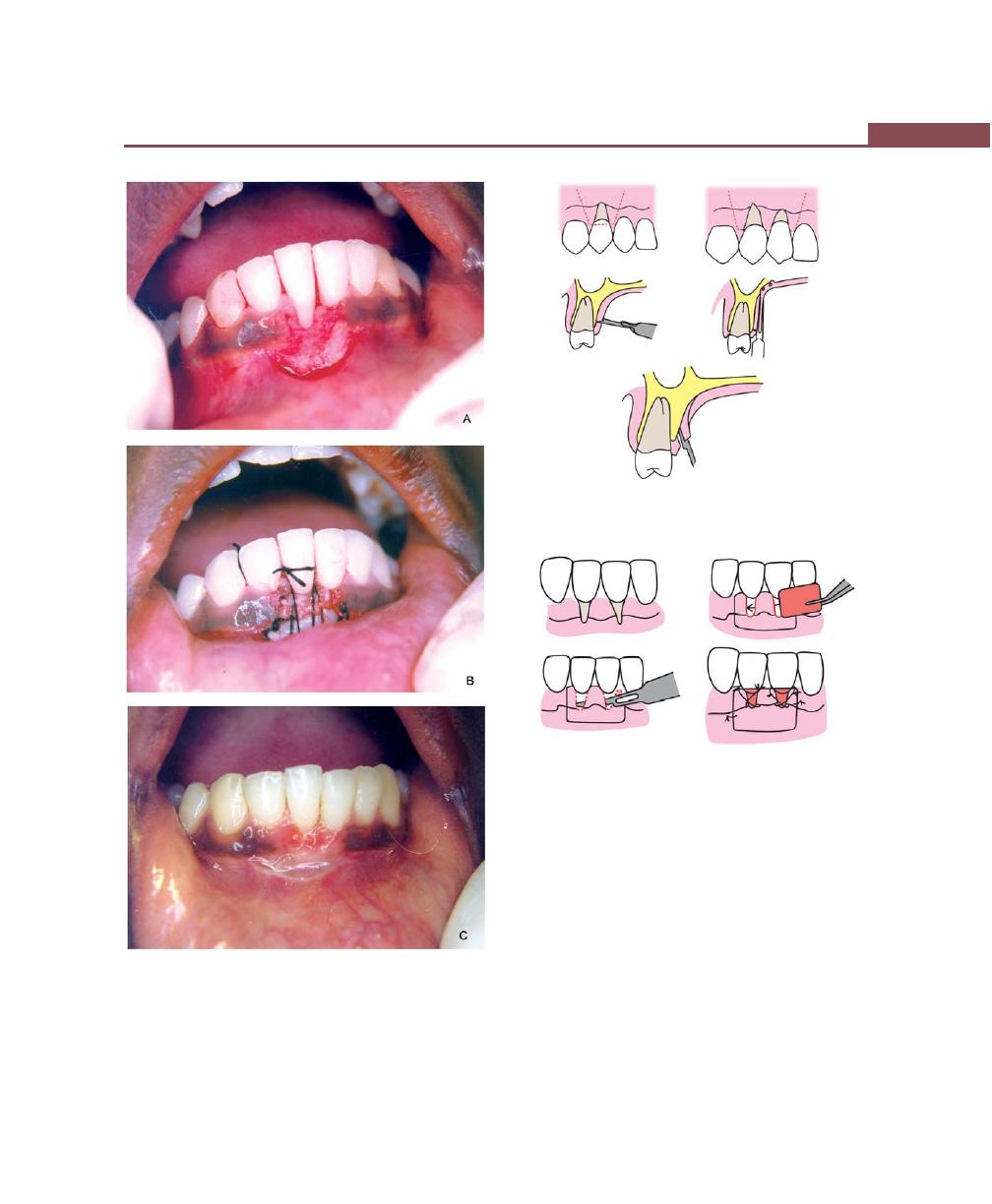

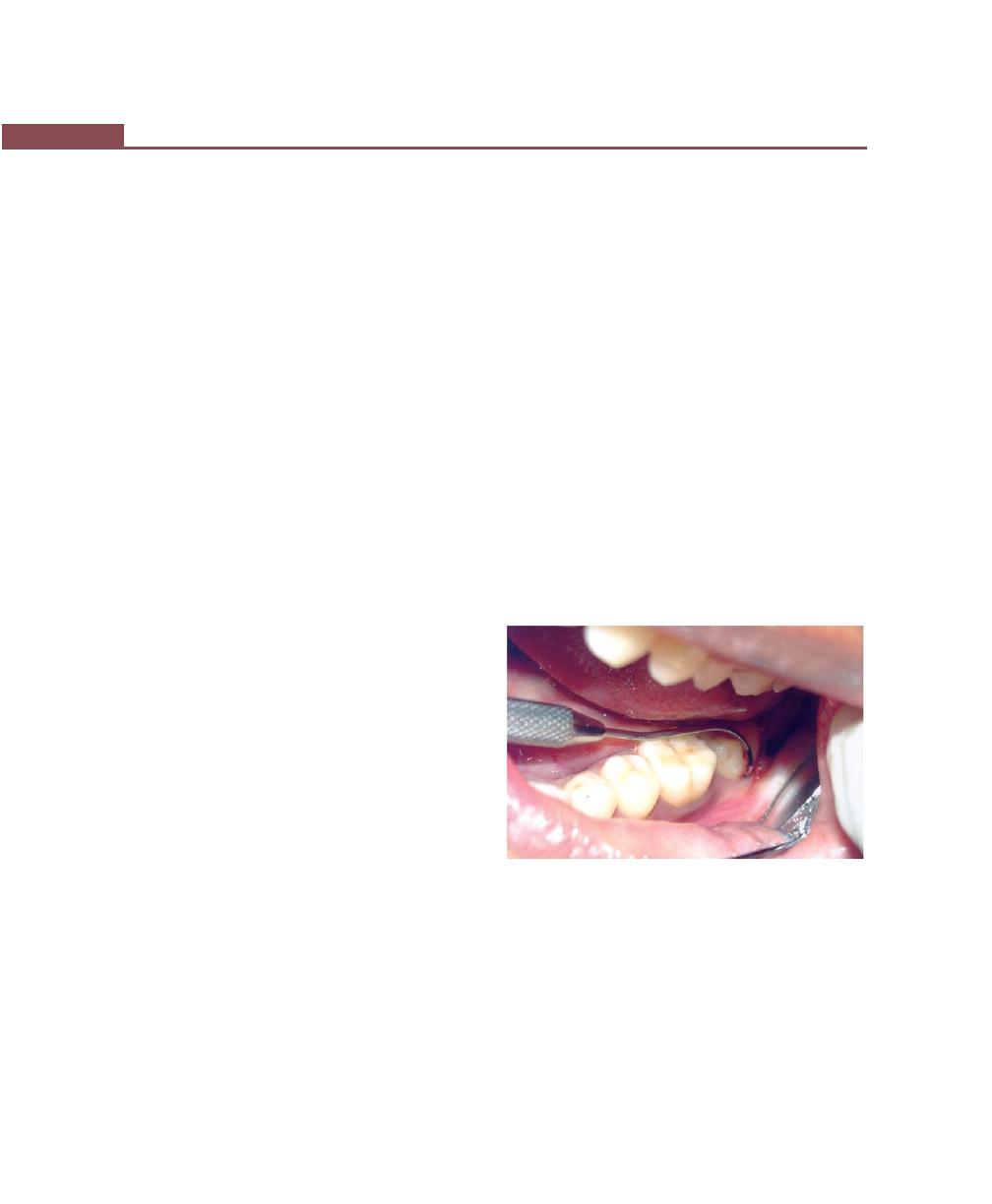

Chapter 43: Mucogingival Surgery, 341

Definition, 341

Mucogingival Problems, 341

Objectives, Indications and Contraindications of

Mucogingival Surgery, 341

Techniques to Increase the Width of Attached Gingiva, 342

Free Soft Tissue Autograft, 342

Classic Technique, 342

Variant Techniques, 344

Accordian Technique, 346

Strip Technique, 346

Connective Tissue Technique, 346

Combination Techniques, 346

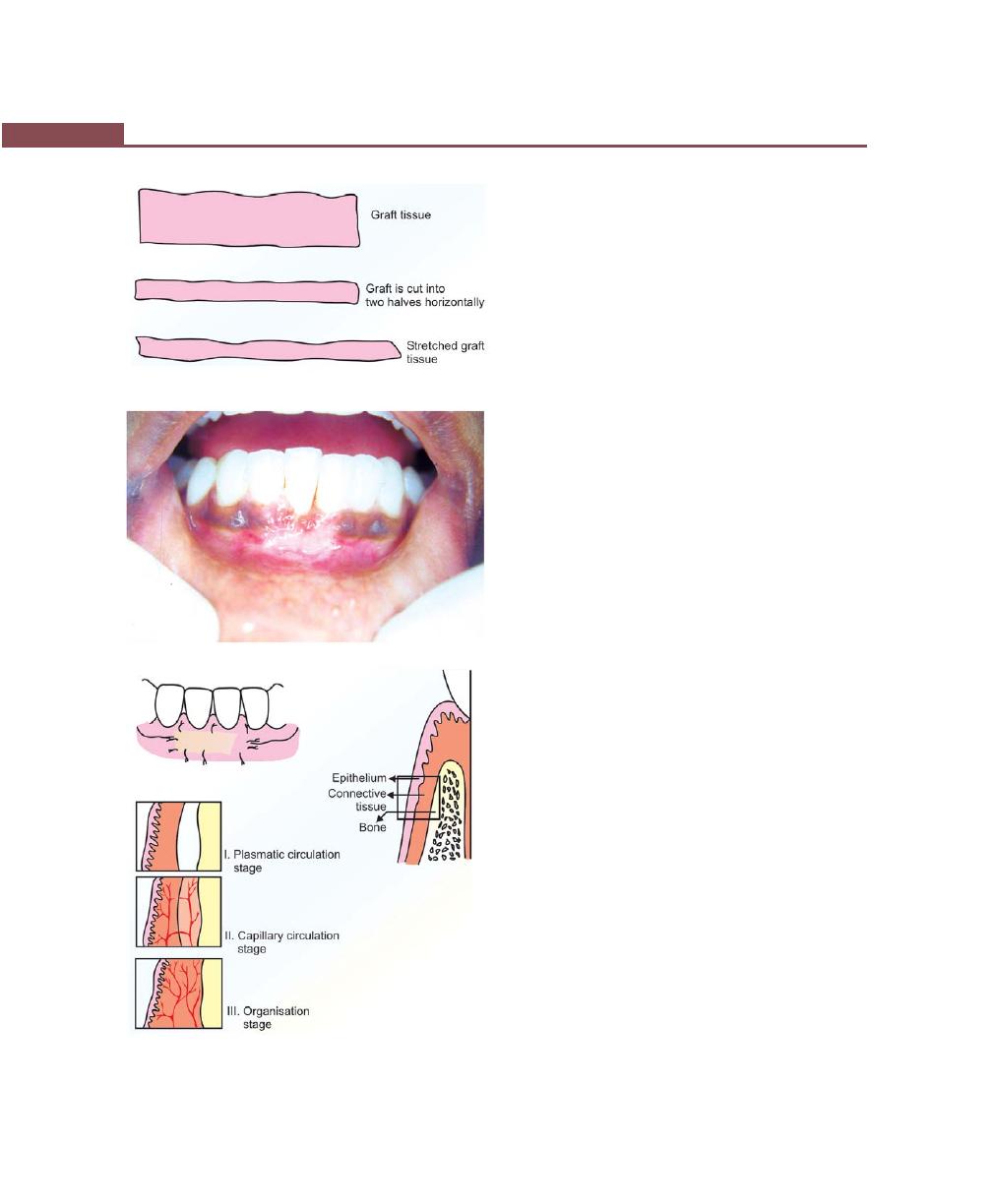

Healing of the Graft, 346

Apically-Displaced Flap, 346

Other Techniques, 348

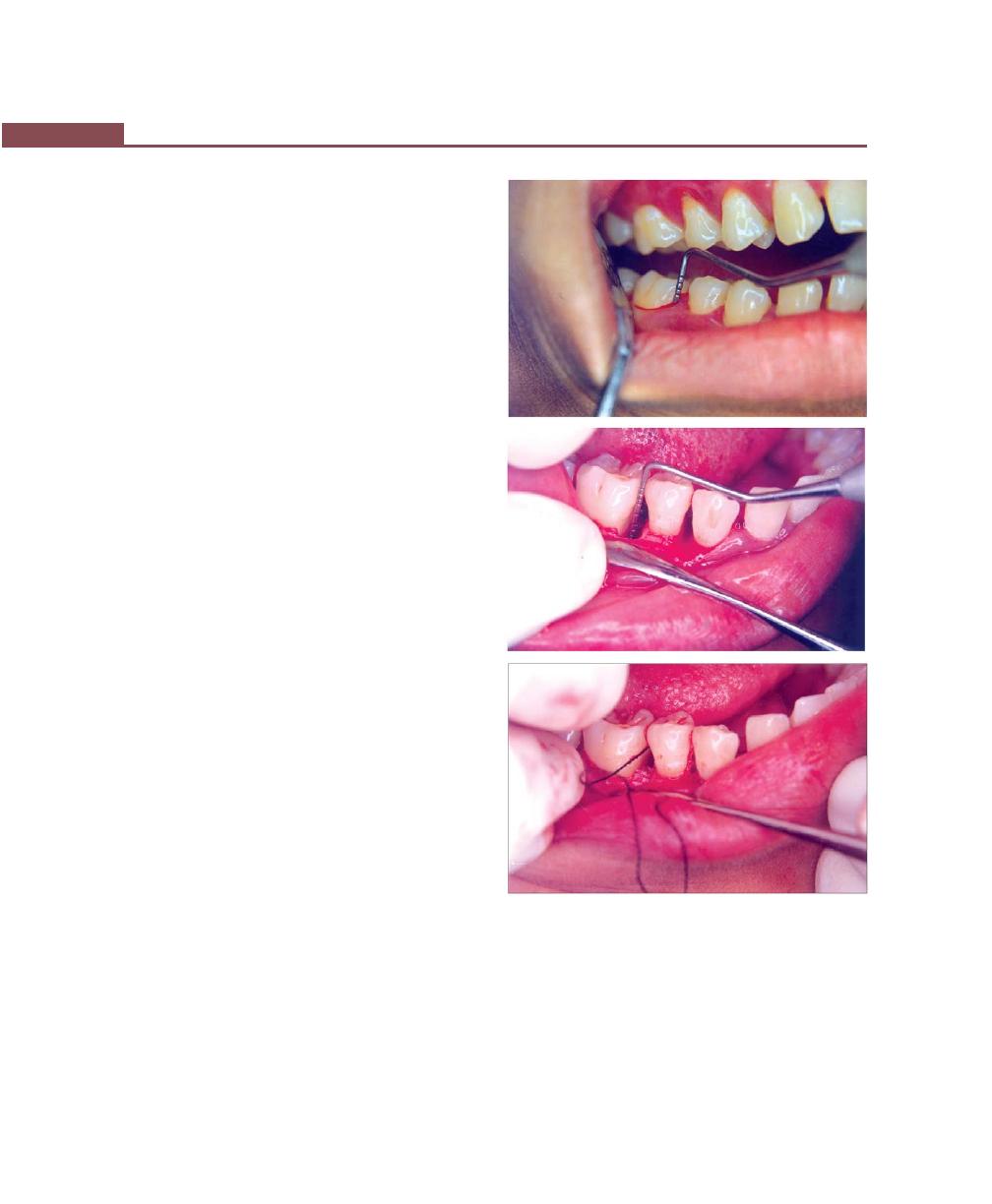

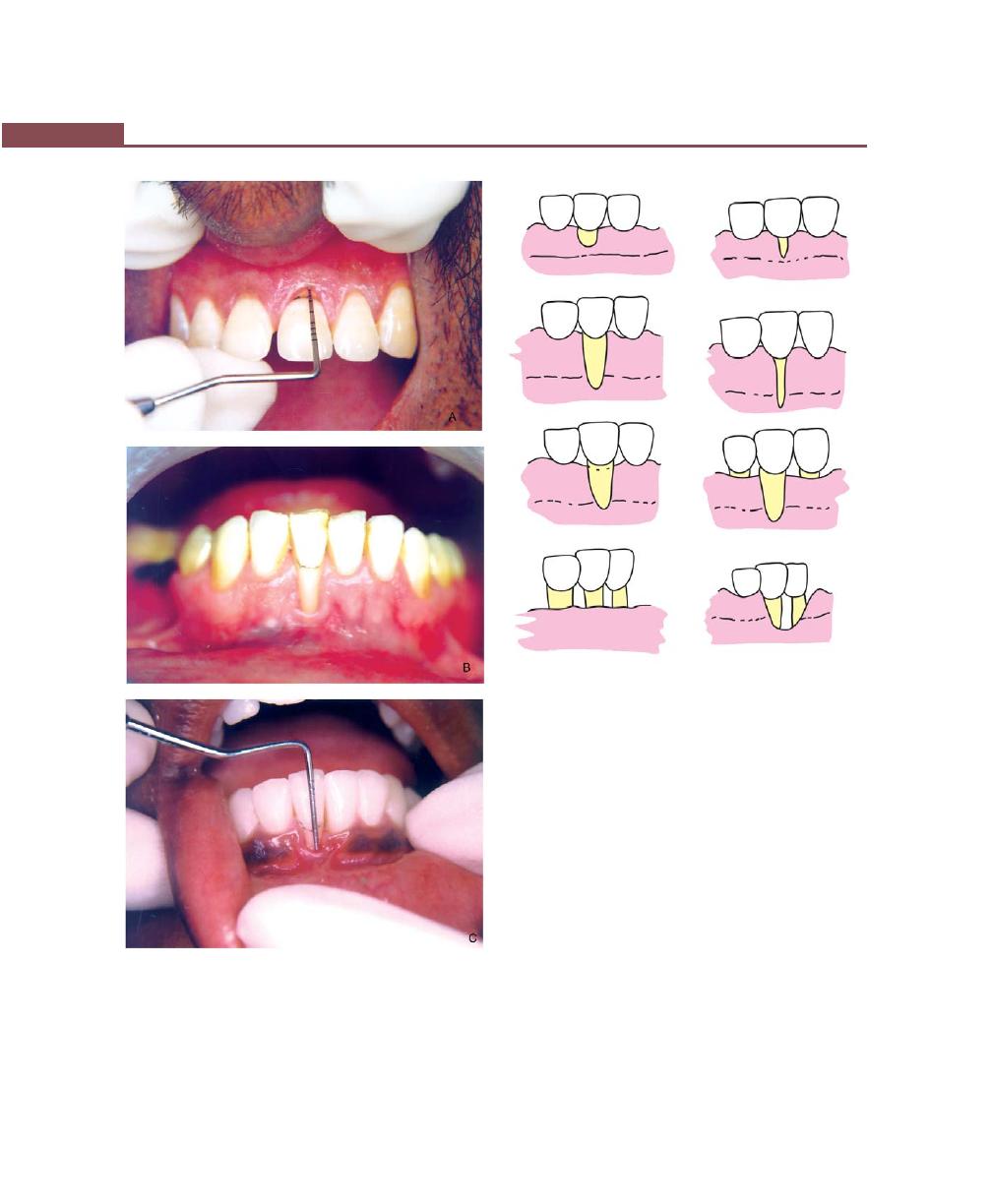

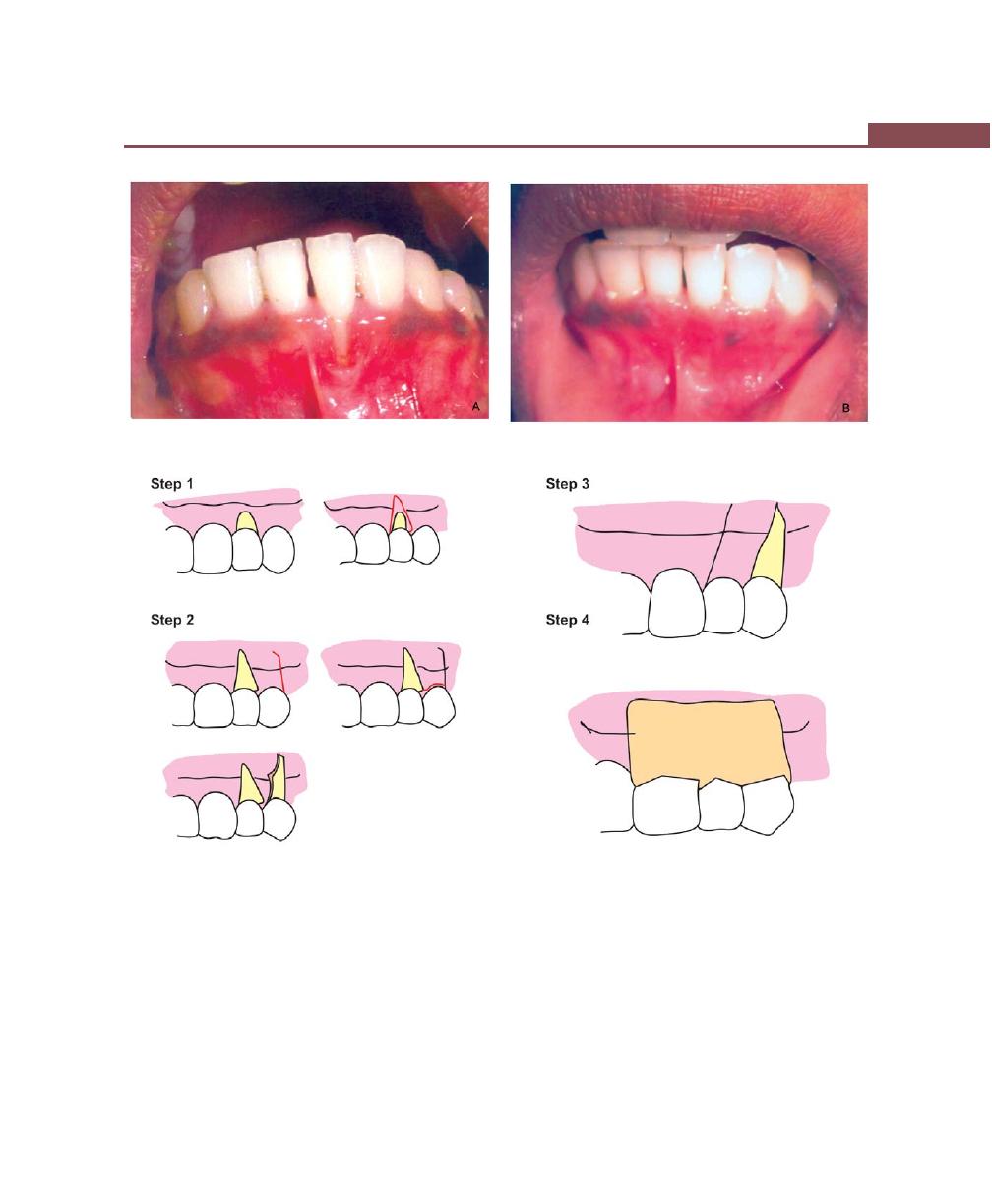

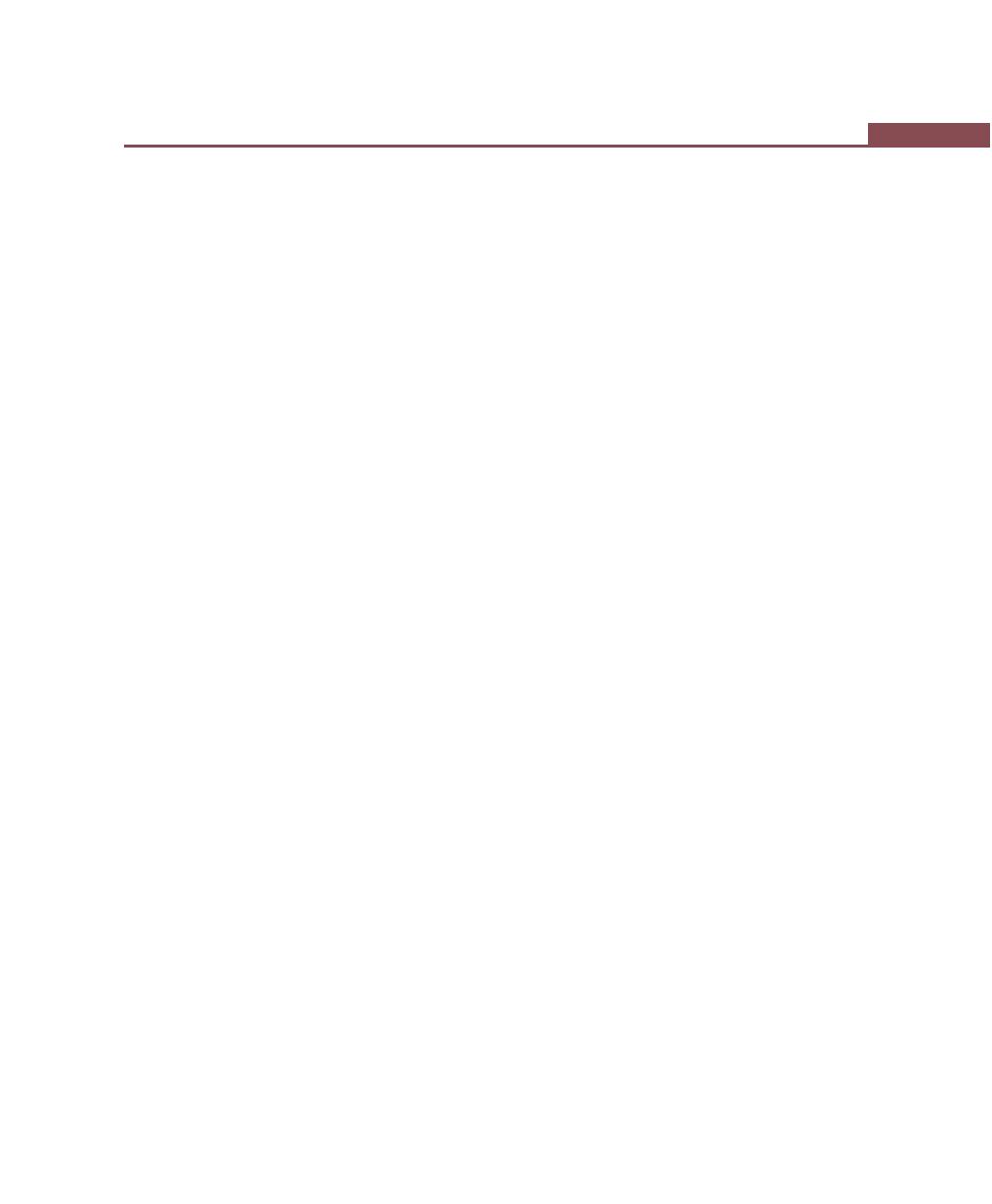

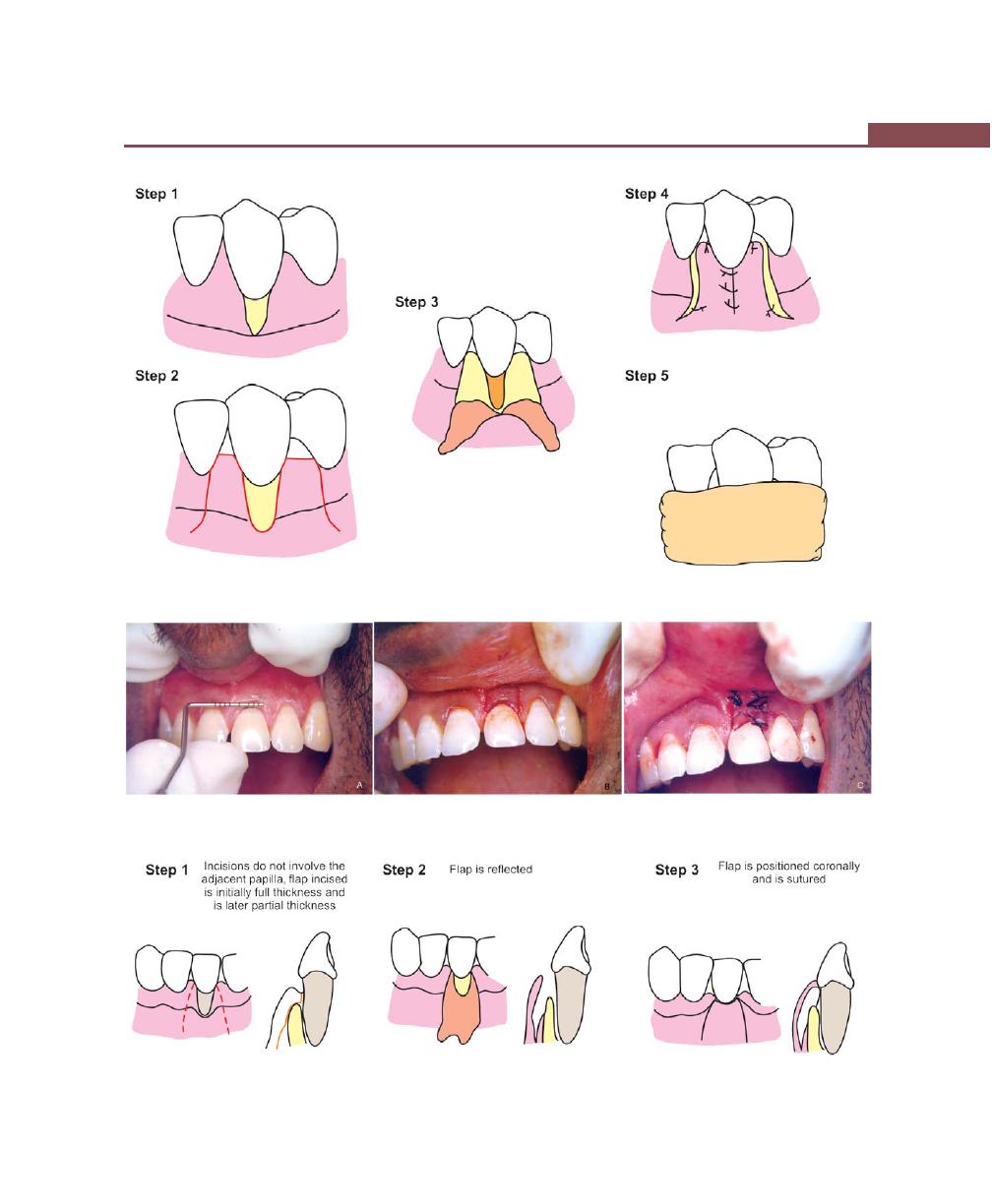

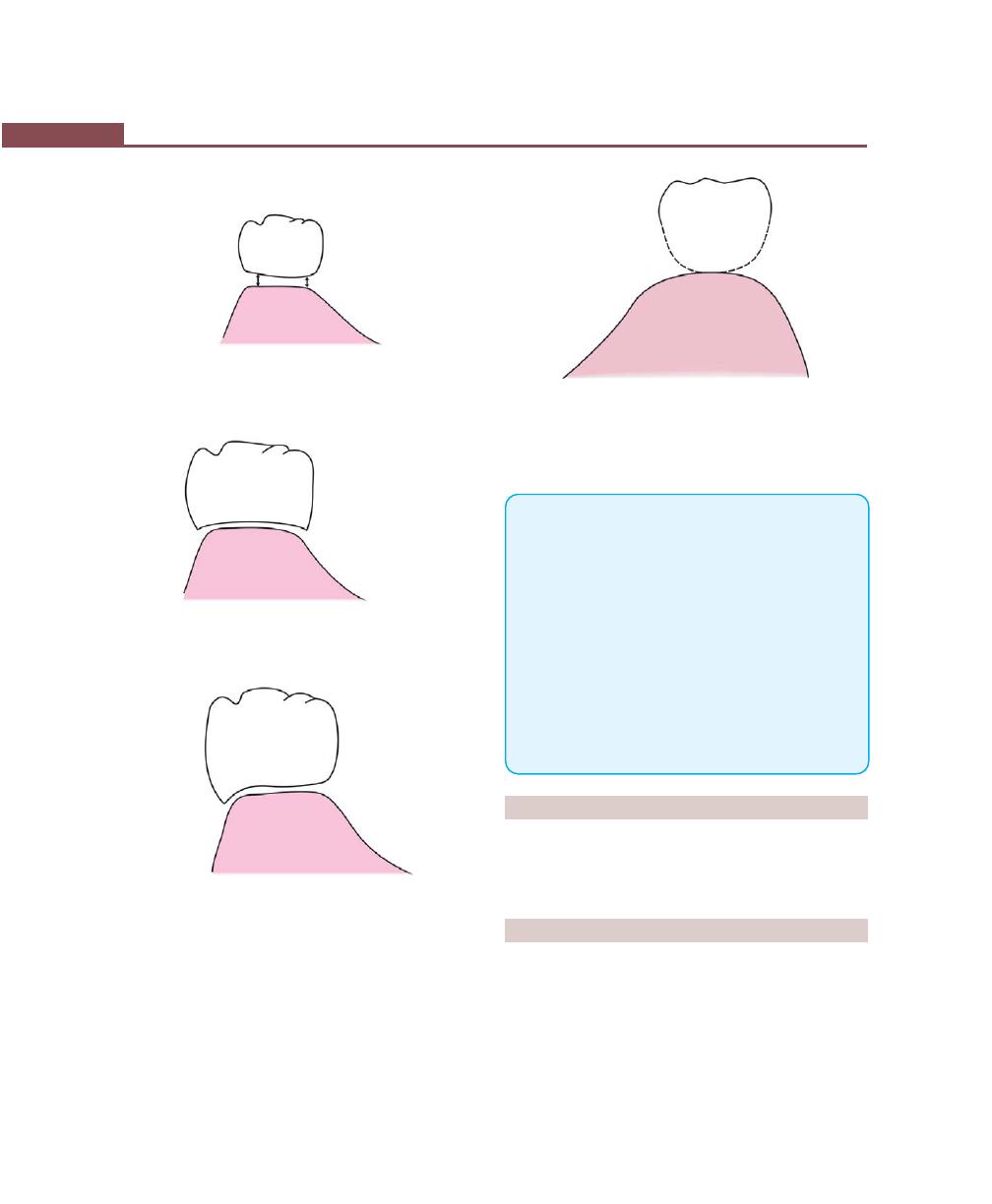

Procedures for Root Coverage, 348

Indications, 348

Classification, 349

Conventional Procedures, 351

Laterally Displaced Flap, 352

Double Papilla Flap, 353

Coronally-Repositional Flap, 353

Semilunar Flap, 357

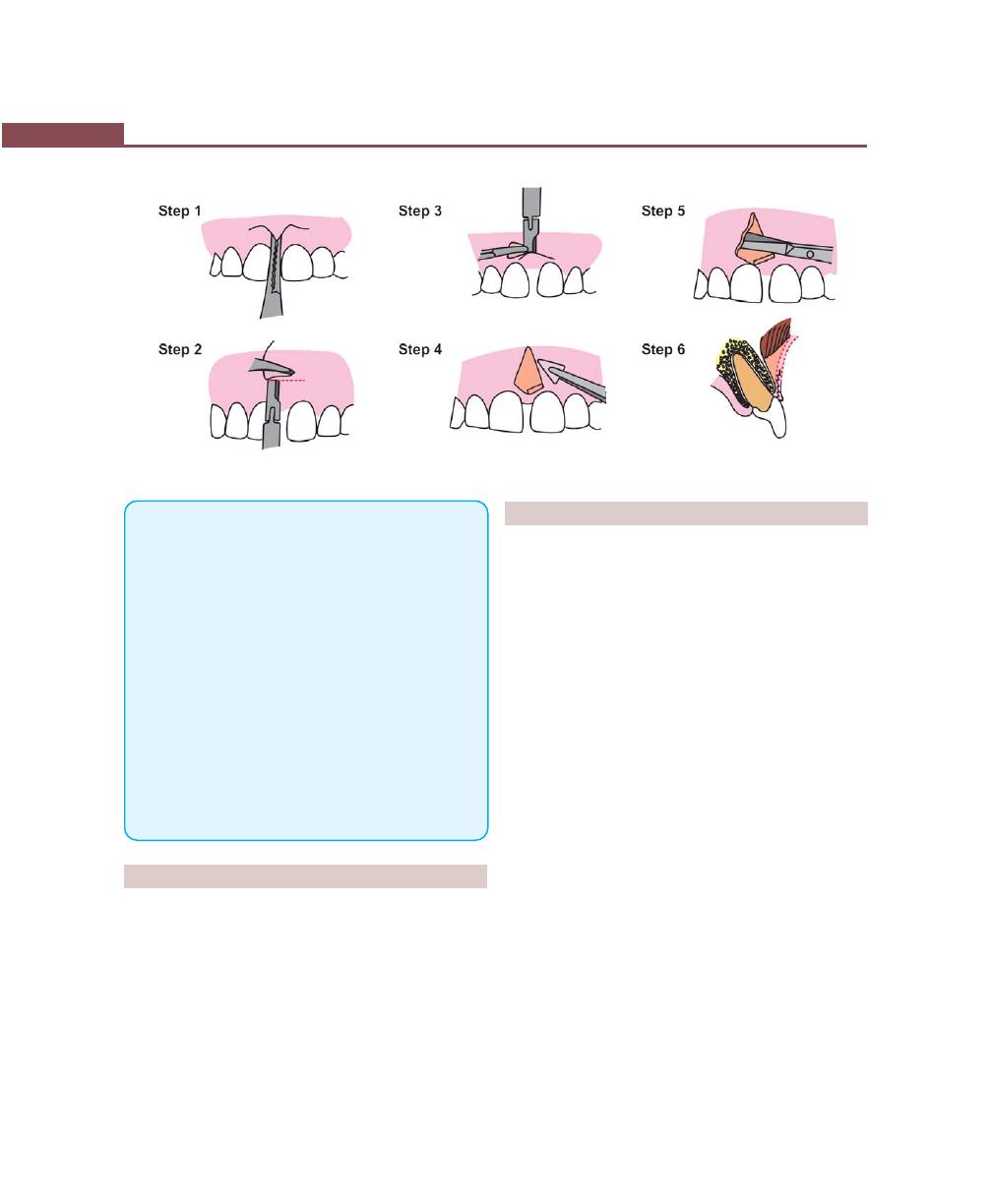

Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft, 358

Modifications, 358

Envelope Technique, 358

Langer’s Technique, 360

Pouch and Tunnel Technique, 360

Guided Tissue Regeneration Technique for Root

Coverage, 360

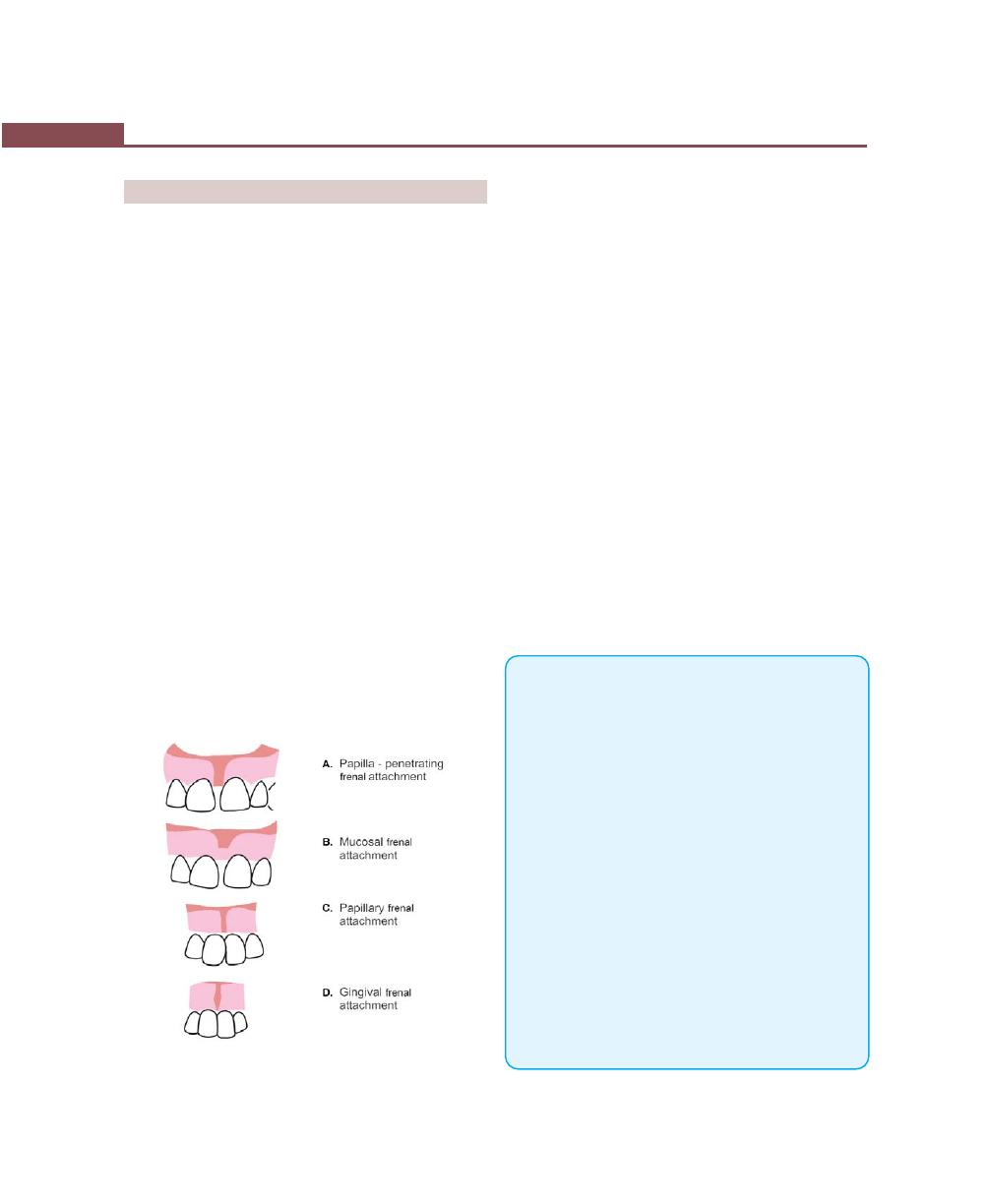

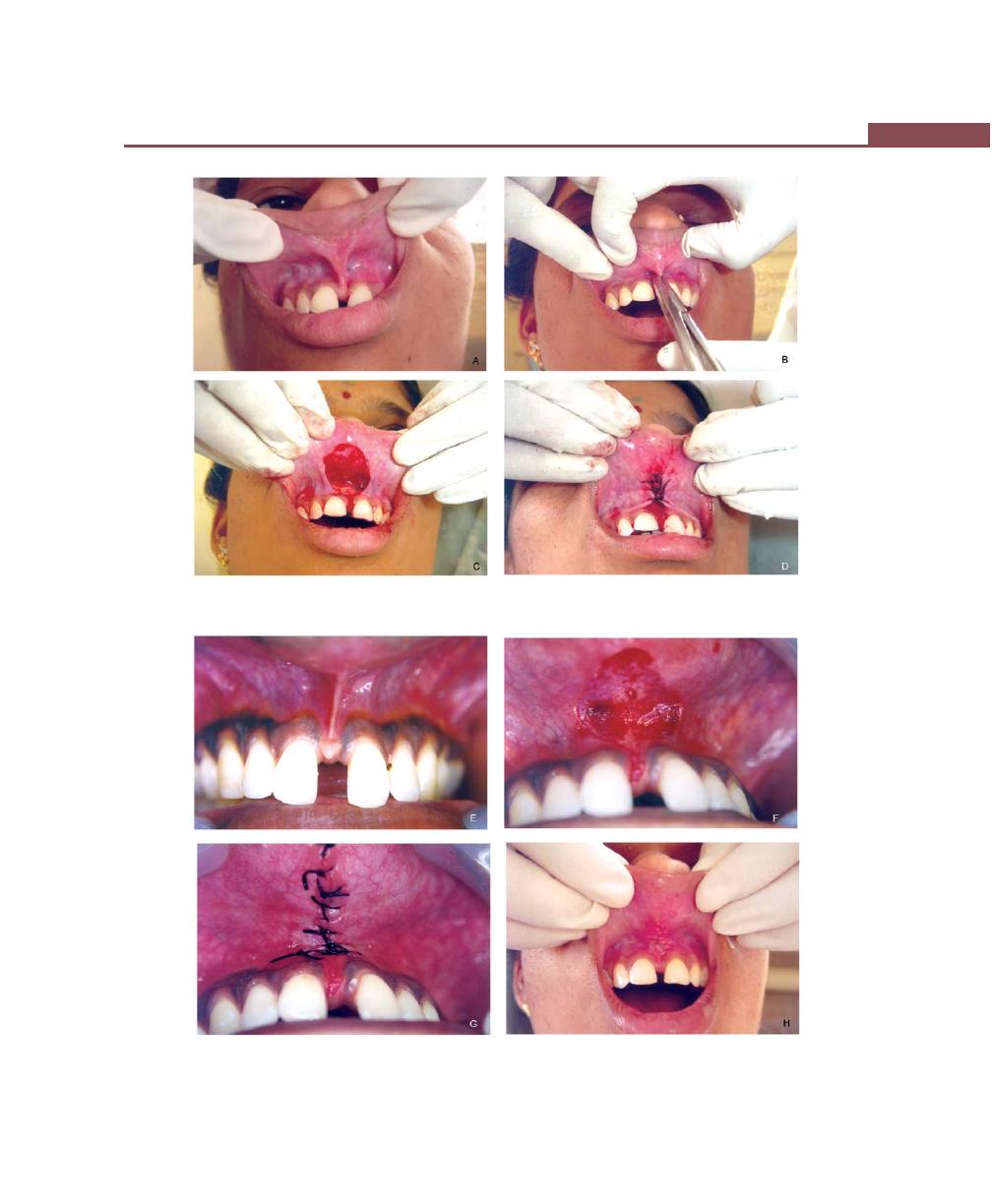

Operations for Removal of Frena, 362

Frenectomy, 362

Frenotomy, 362

Technique, 362

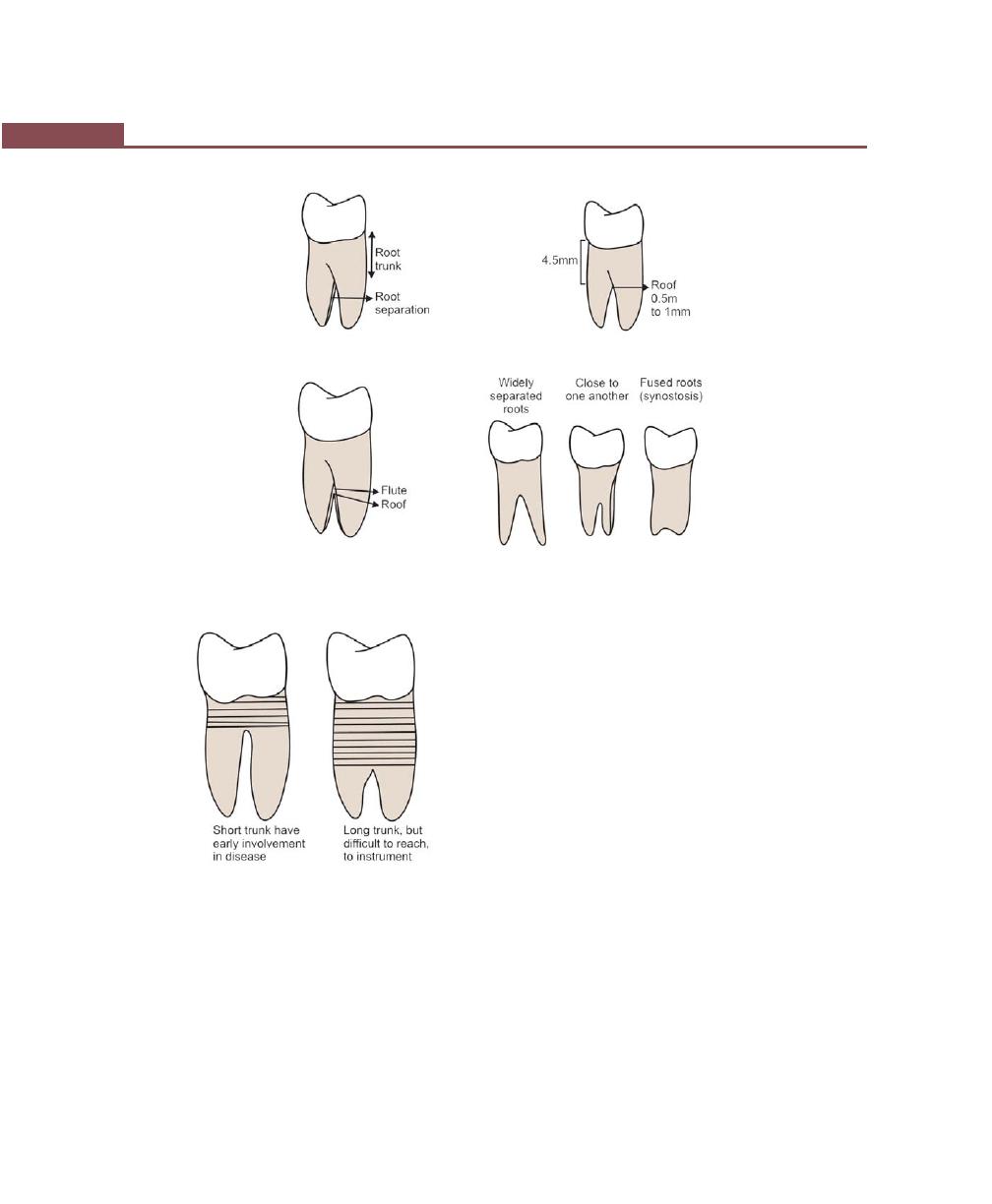

Chapter 44: Furcation Involvement and Its

Management, 365

Definition, 365

Etiology, 365

Primary Etiologic Factor, 365

Anatomic Considerations, 365

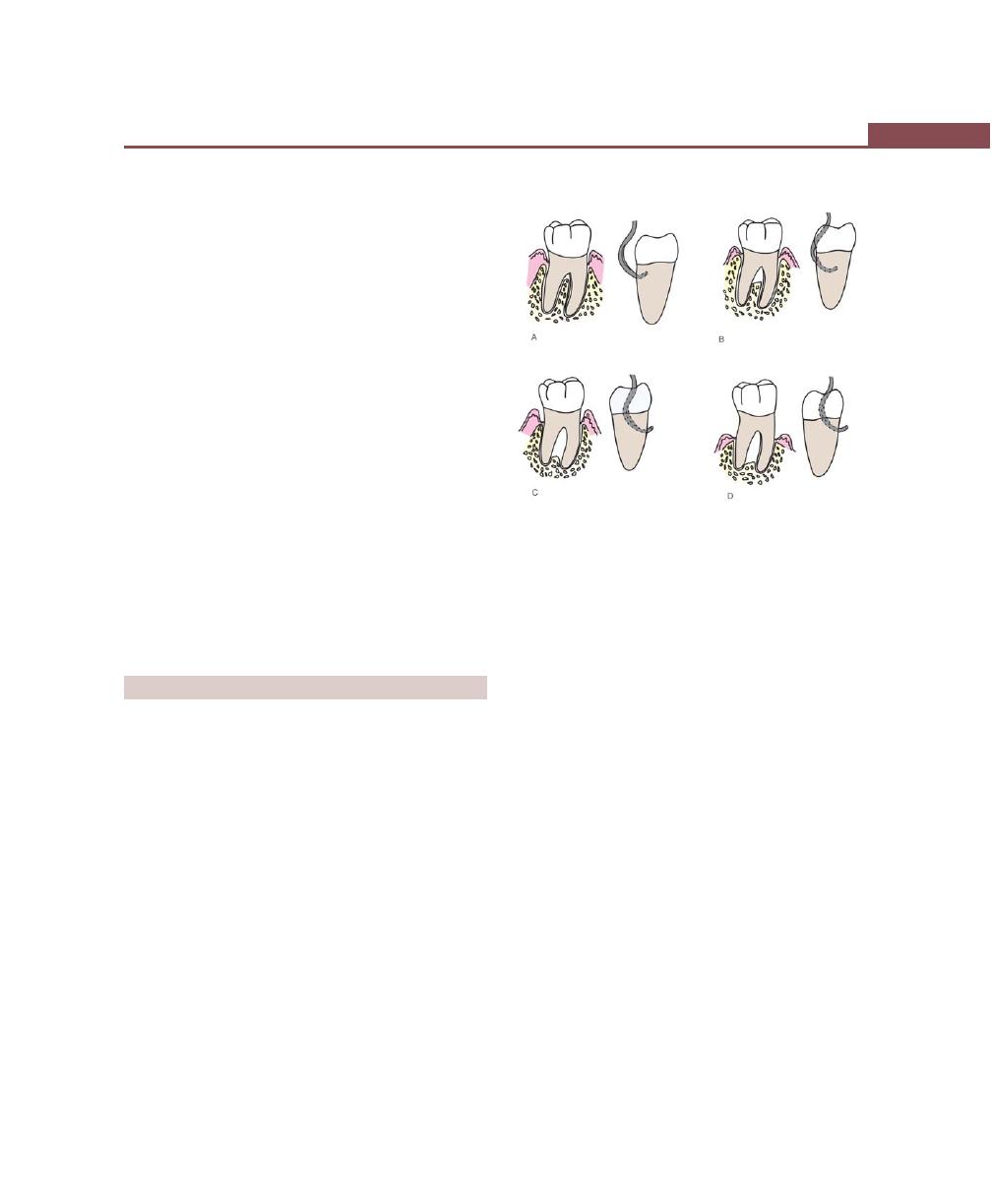

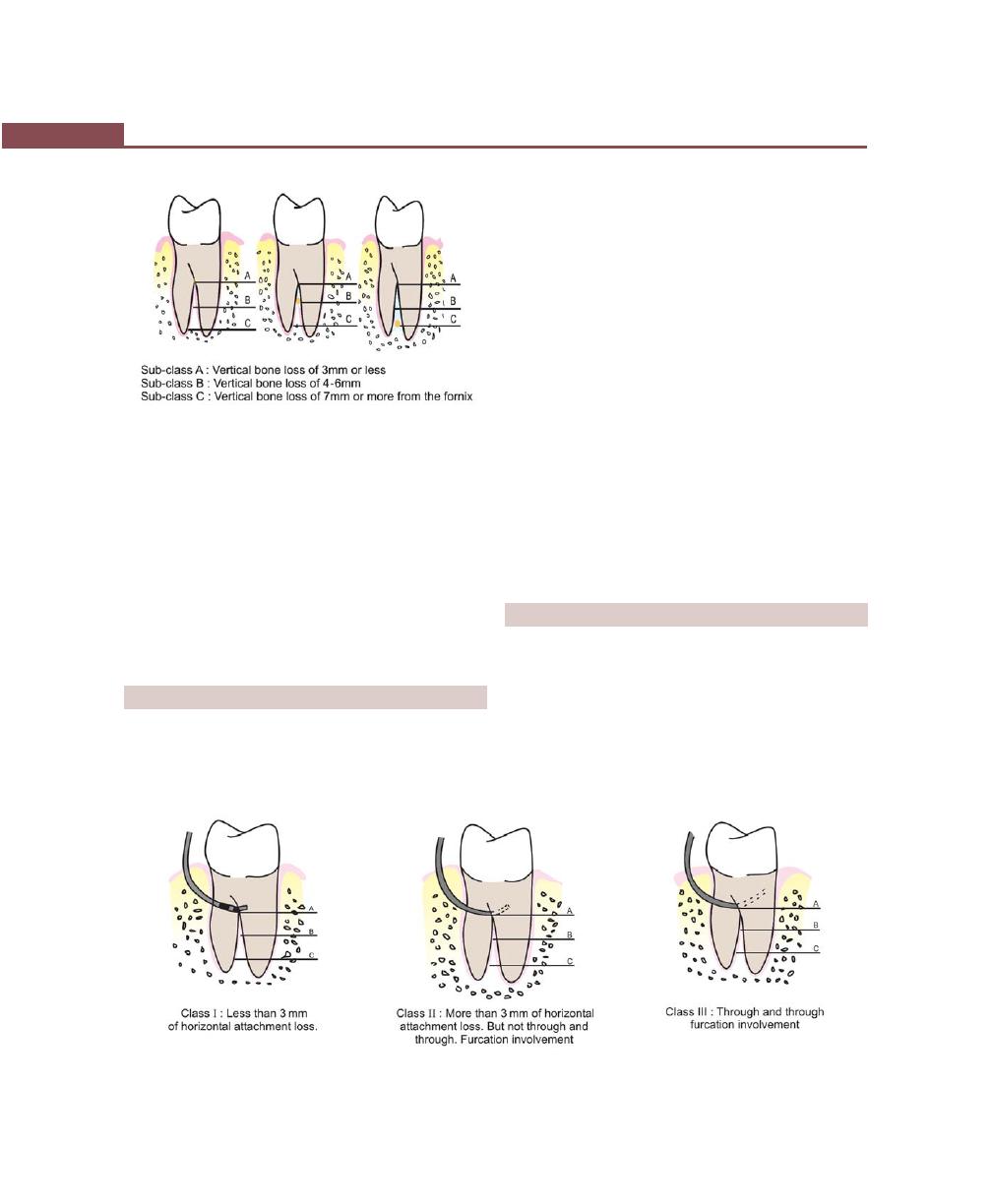

Classification, 367

Clinical Features, 368

Prognosis, 368

Treatment, 369

Traditional Treatment, 369

Reconstructive/Regenerative Treatment, 369

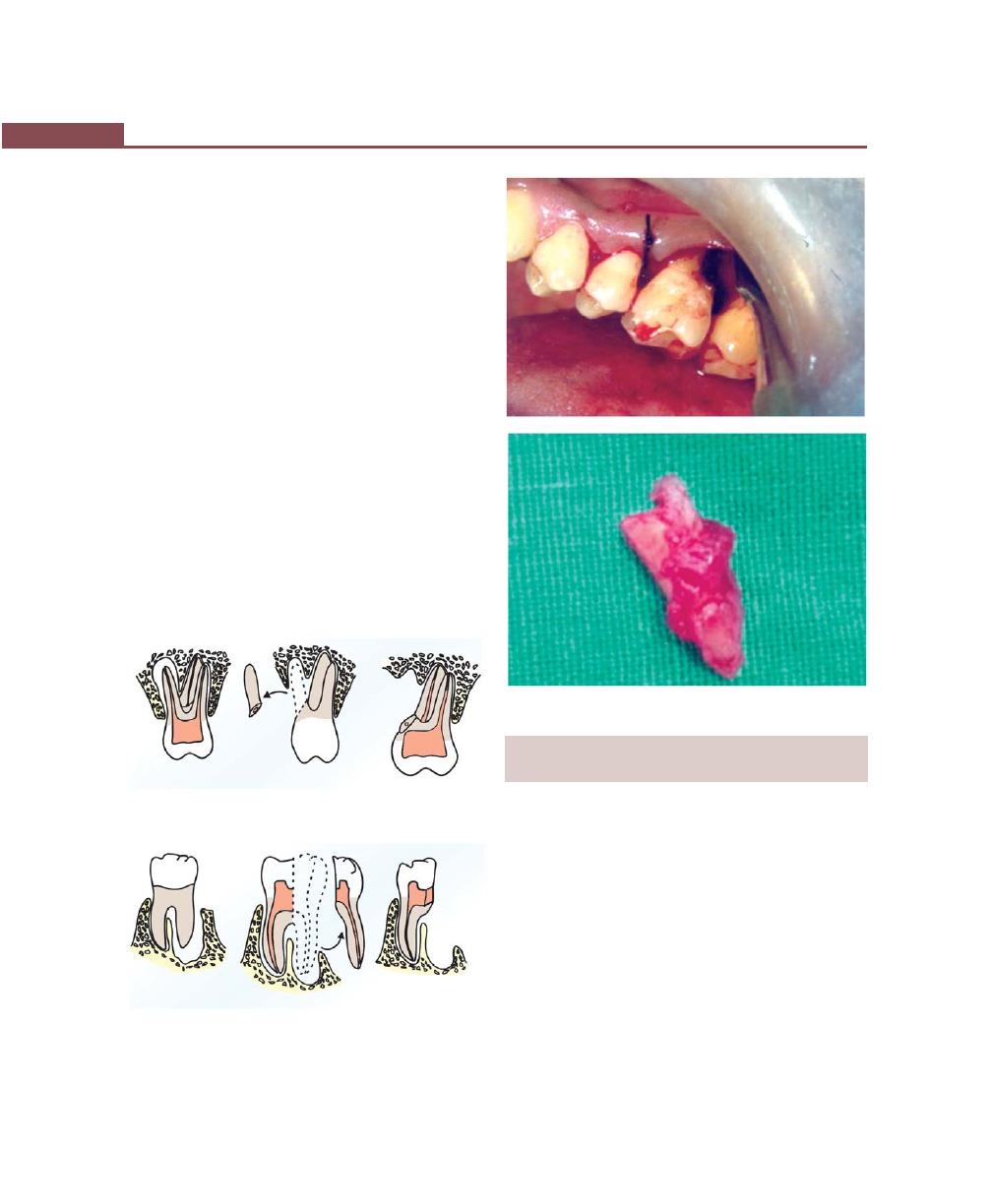

Resective Treatment, 370

Definition, 370

Indications and Contraindications, 370

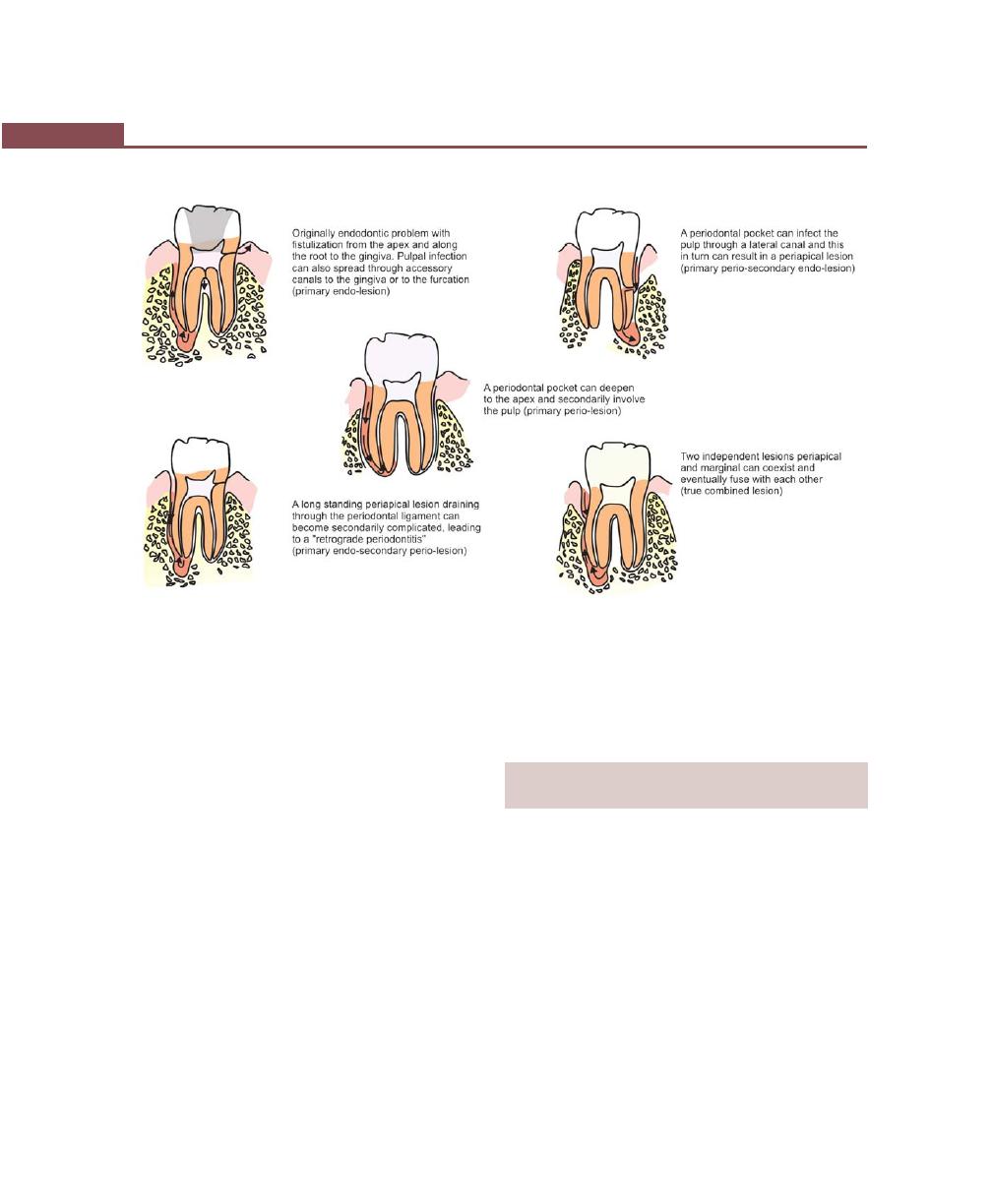

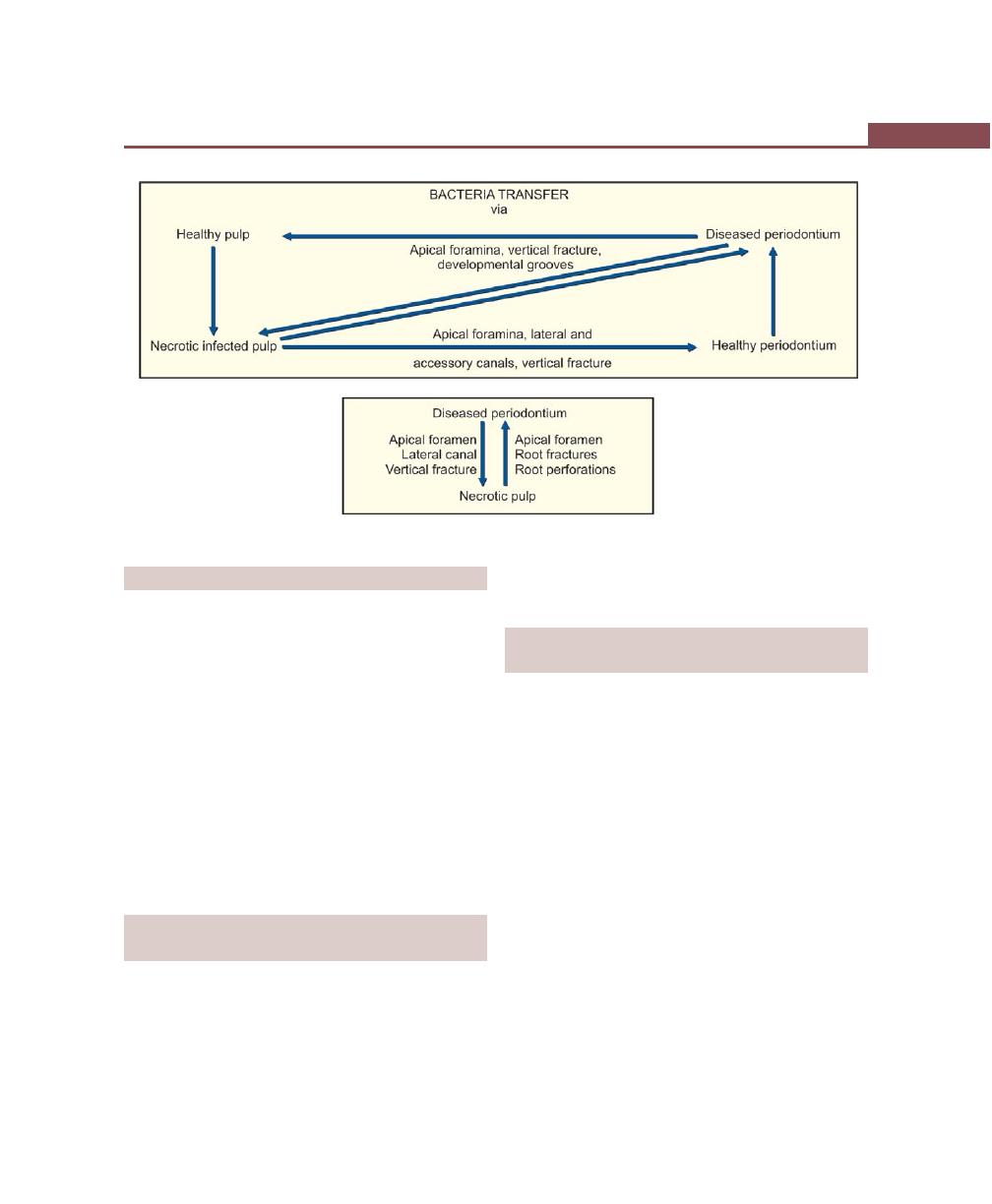

Chapter 45: Pulpoperiodontal Problems, 373

Introduction, 373

Pathways of Communication Between Pulp and

Periodontium, 373

Developmental Origin, 373

Pathological Origin, 373

Iatrogenic Origin, 373

Effects of Pulpal Disease on the Periodontium, 373

Effects of Periodontitis on the Pulp, 374

Classification of Endo-Perio Lesions, 375

Microbiological Findings of Endo-Perio Lesions, 375

Diagnosis and Treatment of Endo-Perio Lesions, 375

Chapter 46: Splints in Periodontal Therapy, 378

Definition, 378

Objectives of Splinting, 378

Classifications of Splints, 379

Various Commonly Used Splints, 379

Principles of Splinting, 379

Indications and Contraindications of Splinting, 379

Advantages and Disadvantages of Splinting, 380

Chapter 47: Dental Implants: Periodontal

Considerations, 381

Introduction, 381

Terminology, 381

Historical Background, 382

Biological Considerations of Implants, 382

Soft Tissue Implant Interface, 382

Bone Implant Interface, 383

Biomaterials Used for Implants, 383

Classification of Implants, 383

Classification of Implant Systems, 384

Treatment Planning, 384

Clinical Assessment, 384

Absolute Requirements, 384

Indications, 384

Absolute Contraindications, 385

Intraoral Contraindications, 385

Radiographs, 385

Other Radiographic Procedures, 385

Surgical Procedures, 385

One-stage: Endosseous Implant Surgery, 385

Two-stage: Endosseous Implant Surgery, 386

Healing Following Implant Surgery, 386

Early Phase, 386

Late Stage, 386

Peri-implant Complications, 387

Types of Peri-implant Disease, 387

xxiii

Contents

Clinical Features, 387

Diagnosis, 387

Management, 387

Maintenance, 388

Chapter 48: Maintenace Phase (Supportive Periodontal

Treatment), 390

Importance of Maintenance Phase, 390

Rationale for Supportive Periodontal Therapy, 390

Causes for Recurrence of Periodontal Disease, 390

Objectives of Maintenace Phase, 391

Parts of Maintenance Phase, 391

Part-I: Examination, 391

Part-II: Treatment, 391

Part-III: Schedule Next Procedure, 391

Determination of Maintenance Recall Intervals, 392

Management of Particular Type of Recall Patients, 392

Chapter 49: Occlusal Evaluation and Therapy in the

Management of Periodontal Disease, 394

Terminology, 394

Clinical Evaluation of Occlusion, 394

Temporomandibular Disorders, 394

Intraoral Evaluation, 395

Management of Trauma from Occlusion, 395

Occlusal Therapy, 395

Chapter 50: The Role of Orthodontics as an Adjunct

to Periodontal Therapy, 396

Introduction, 396

Rationale for Orthodontic Treatment in Periodontal

Therapy, 396

Reducing Plaque Retention, 396

Improving Gingival and Osseous Form, 396

Improving Esthetics, 397

Indications and Contraindications of Orthodontic Therapy,

397

Timing of Orthodontic Procedures in Periodontal

Treatment, 397

Iatrogenic Effects Associated with Orthodontic Treatment,

397

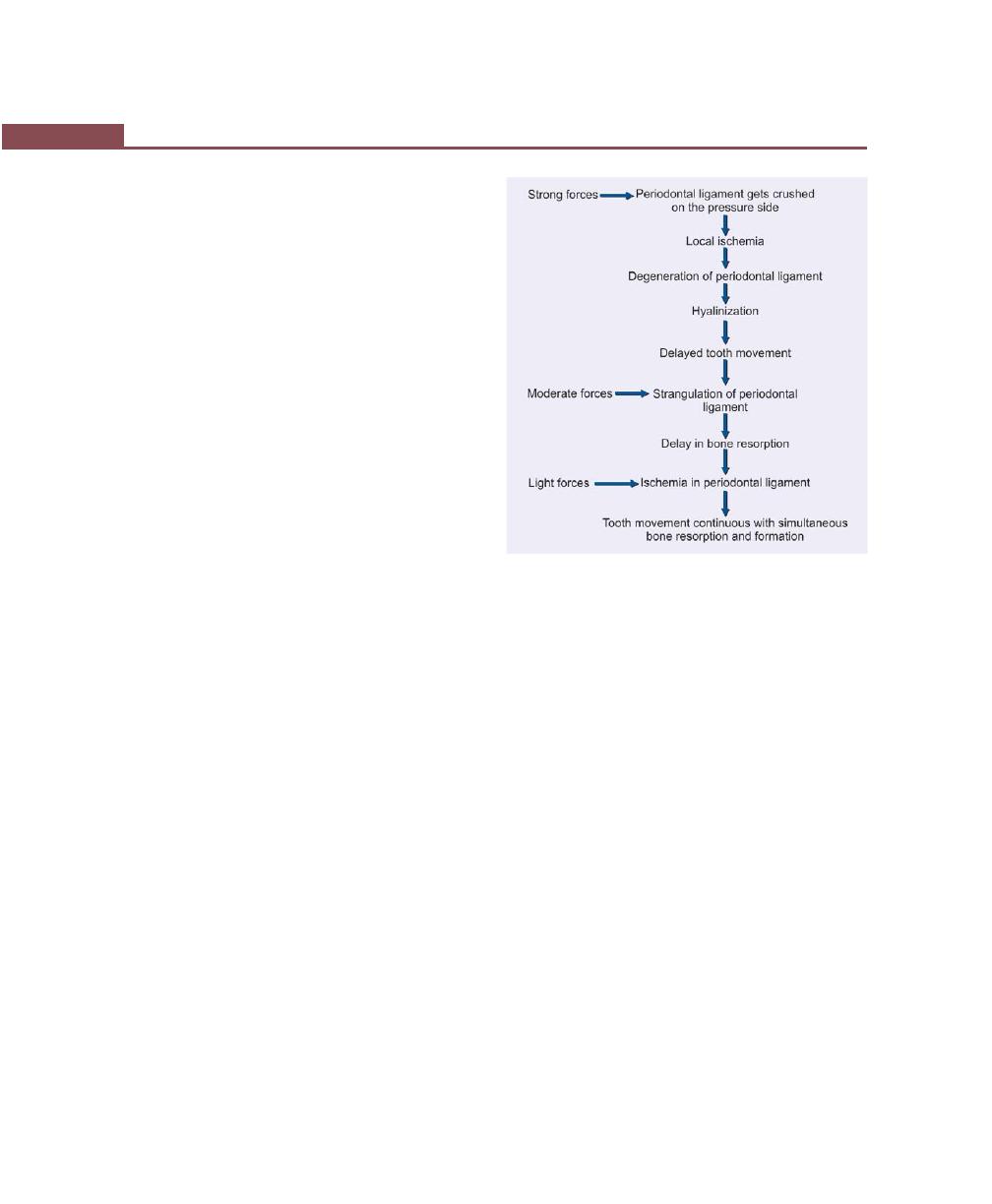

Response of Periodontal Ligament to Orthodontic Forces,

398

Chapter 51: Periodontal: Restorative Inter-relationship,

400

Margins of Restorations, 400

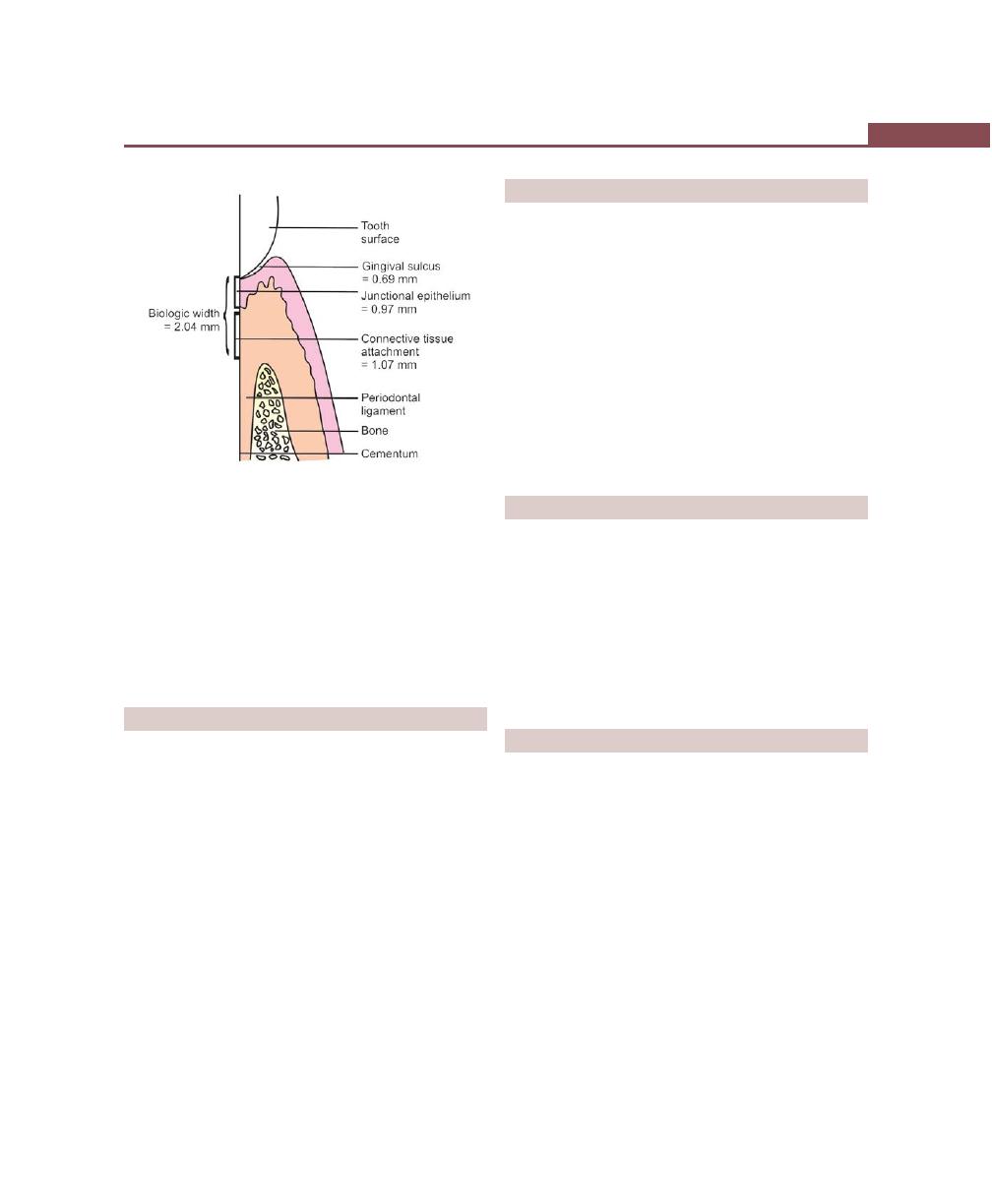

Restorative Margins Encroaching on the Biologic Width,

400

Crown Contour, 401

Hypersensitivity to Dental Materials, 401

Proximal Contact and Embrasure, 401

Pontic Design, 401

Chapter 52: Drugs Used in Periodontal Therapy, 403

Introduction, 403

Classification of Various Drugs Used in Periodontal

Therapy, 403

Depending on Antimicrobial Efficacy and

Substantivity, 403

Chemicals Used for Supragingival Plaque Control,

404

Phenols, 404

Quaternary Ammonium Compounds, 404

Antibiotics Used in Periodontal Therapy, 404

Systemic Administration of Antibiotics, 404

Local Administration of Antibiotics, 405

Tetracyclines, 405

Metronidazole, 406

Penicillins, 407

Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), 407

Mechanism of Action of NSAID, 407

Local Administration of Antibiotics and Antimicrobial

Agents, 407

Classification of Controlled-Release, 408

Methods of Delivery of Chemotherapeutic Agents, 408

Keyes Technique, 408

Root Biomodification, 408

Home Irrigation Devices, 409

Conclusion, 409

53. Questionnaire for Clinical Case Discussion, 411

Glossary, 439

Index, 465

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

xxiv

1

Anatomy and Development

of the Structures of

Periodontium

❒

❒

❒

❒

❒ EXTERNAL ANATOMIC FEATURES

❒

❒

❒

❒

❒ DEVELOPMENT OF PERIODONTIUM

• Early Development of Cementum

• Later Development of Cementum

• Development of Junctional Epithelium

INTRODUCTION

The term periodontium arises from the Greek word “Peri”

meaning around and “odont” meaning tooth, thus it

can be simply defined as the “tissues investing and

supporting the teeth”. The periodontium is composed

of the following tissues namely alveolar bone, root

cementum, periodontal ligament (supporting tissues) and

gingiva (investing tissue).

The various diseases of the periodontium are

collectively termed as Periodontal diseases. Their

treatment is referred to as Periodontal therapy. The

clinical science that deals with the periodontium in health

and disease is called Periodontology. The branch of

dentistry concerned with prevention and treatment of

periodontal disease is termed Periodontics or Periodontia.

EXTERNAL ANATOMIC FEATURES

The oral mucosa consists of three zones:

1. Masticatory mucosa: It includes the gingiva and the

covering of the hard palate.

2. Specialized mucosa: It covers the dorsum of the

tongue.

3. Lining mucosa: Is the oral mucous membrane that

lines the oral cavity. Among all the structures of the

periodontium, only the gingiva is visible clinically. The

gingiva is divided anatomically into free or marginal,

attached and interdental gingiva. The border or

groove between marginal and attached gingiva is

called as a free gingival groove, a shallow depression

on the faciogingival surface that roughly corresponds

to the base of the gingival sulcus. The junction

between the attached gingiva and alveolar mucosa

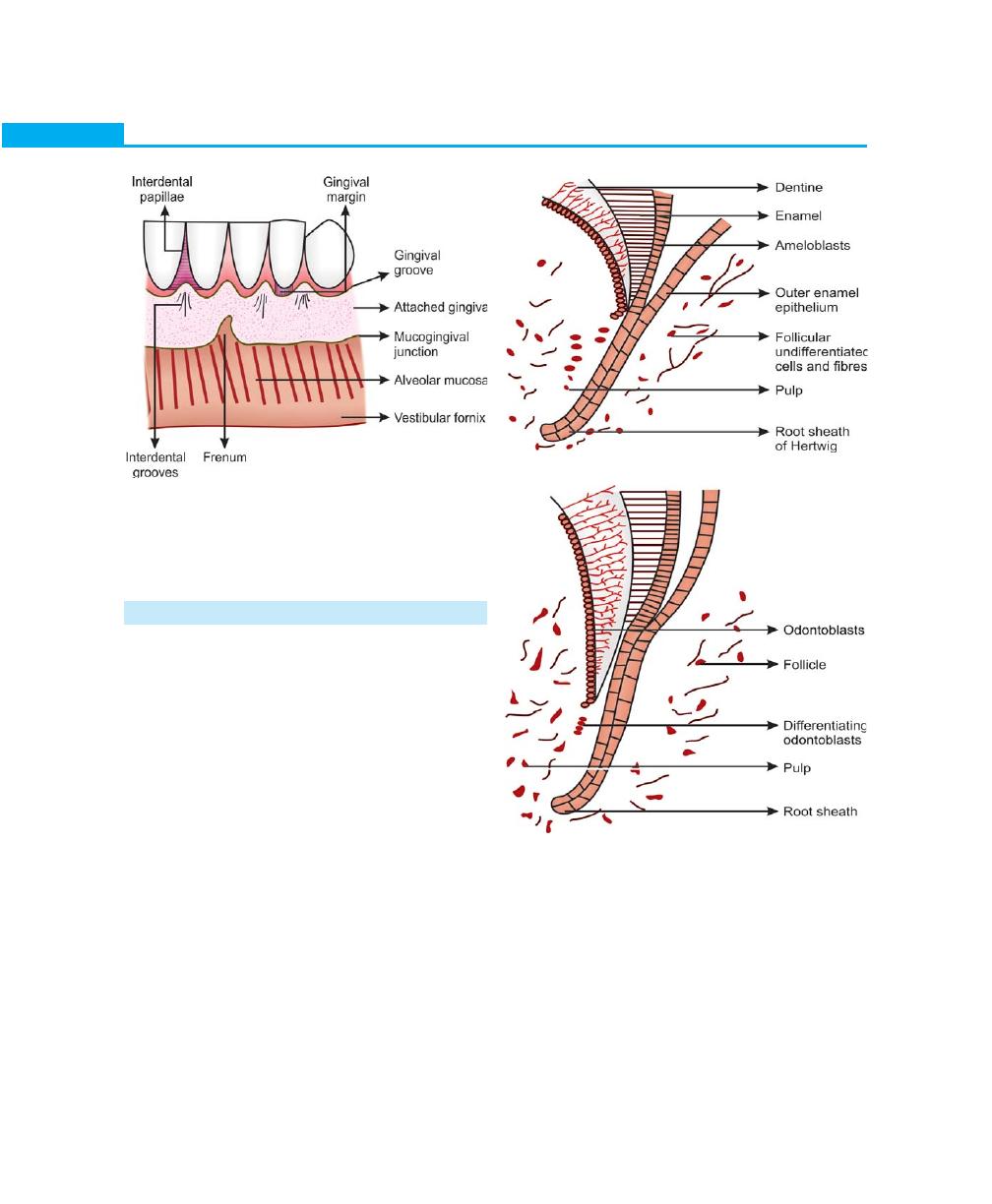

is called as mucogingival line or junction (Fig. 1.1).

The normal gingiva is pink in color (salmon coral

pink) and accumulation of melanin pigmentation is

normal. The surface of the gingiva exhibits an orange

peel-like appearance referred to as stippling. In health,

the gingiva completely fills the embrasure spaces between

the teeth and is known as the interdental gingiva. In the

posterior teeth, where the contact areas between the

teeth are usually broad, the interdental gingiva consists

of two papillae, facial and lingual which are connected

by the col. The significance of col is that, it is made up

4

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

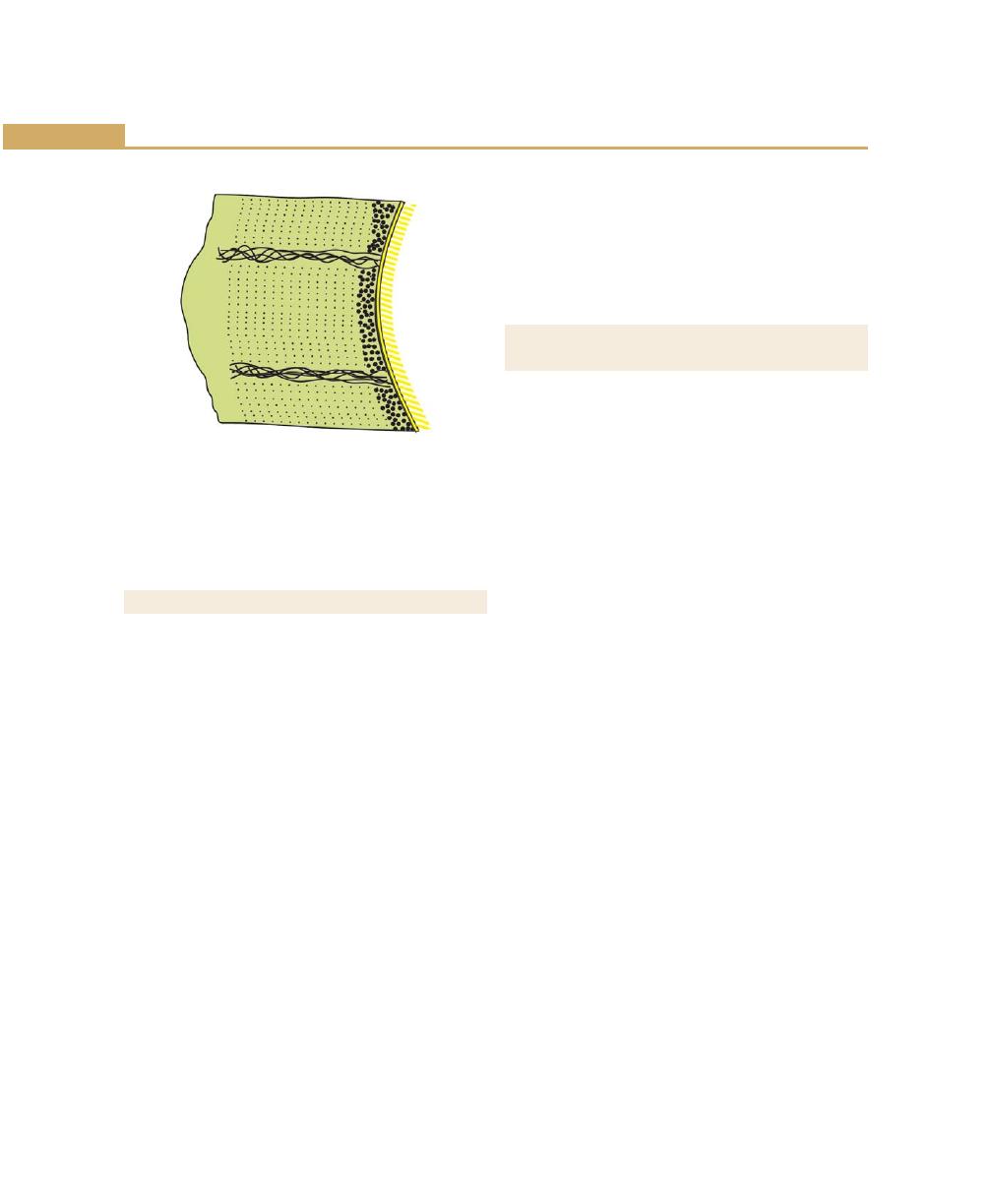

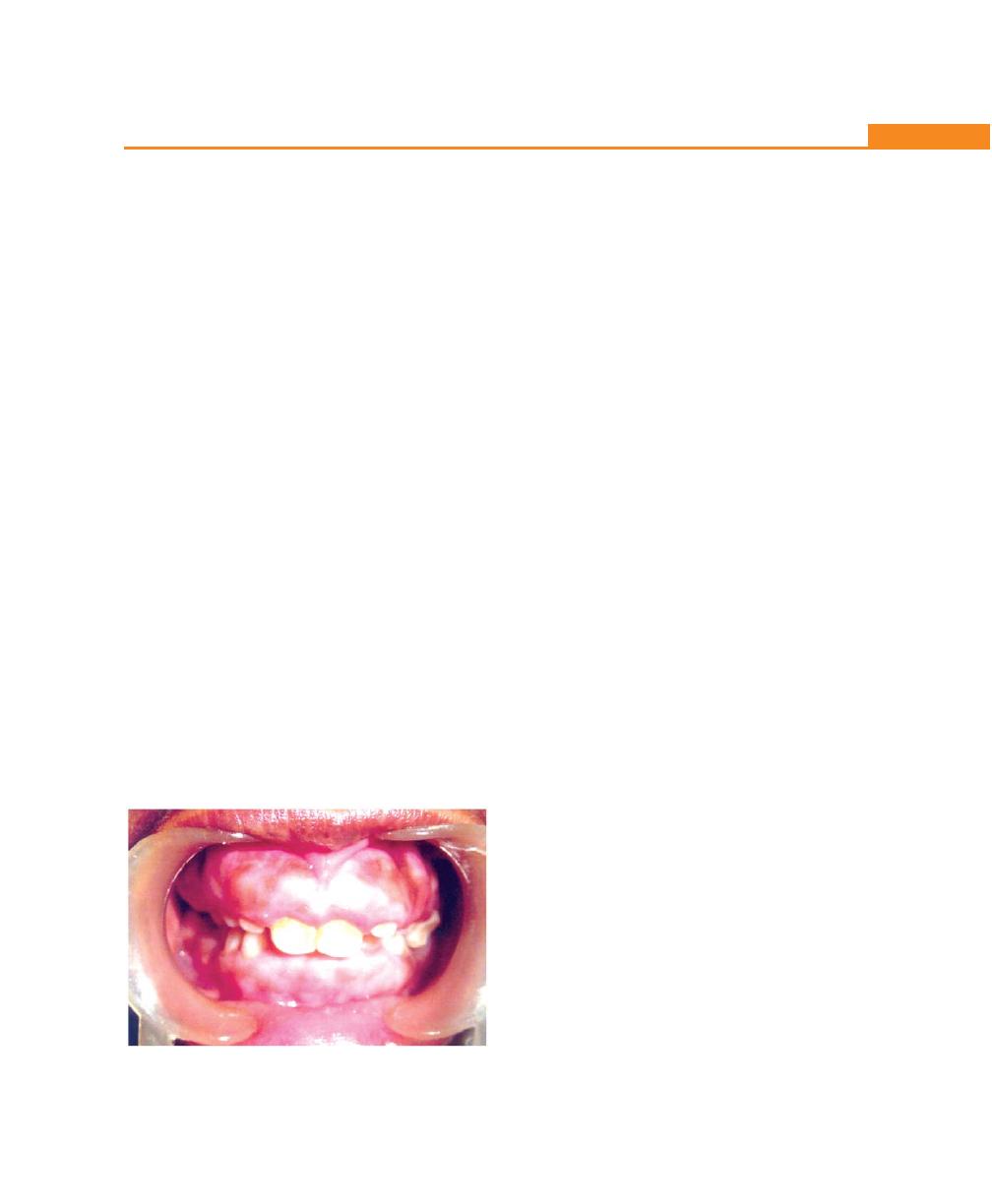

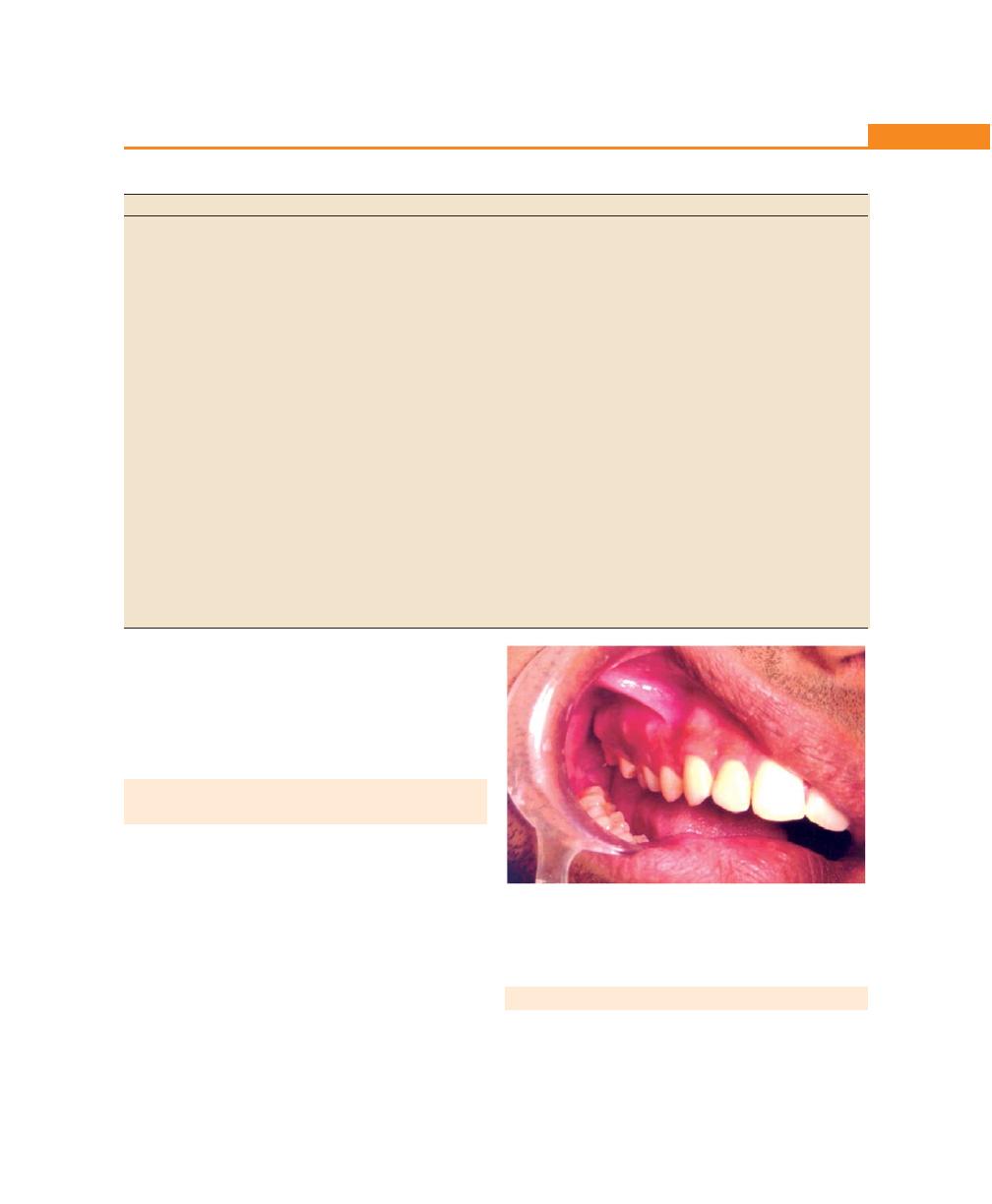

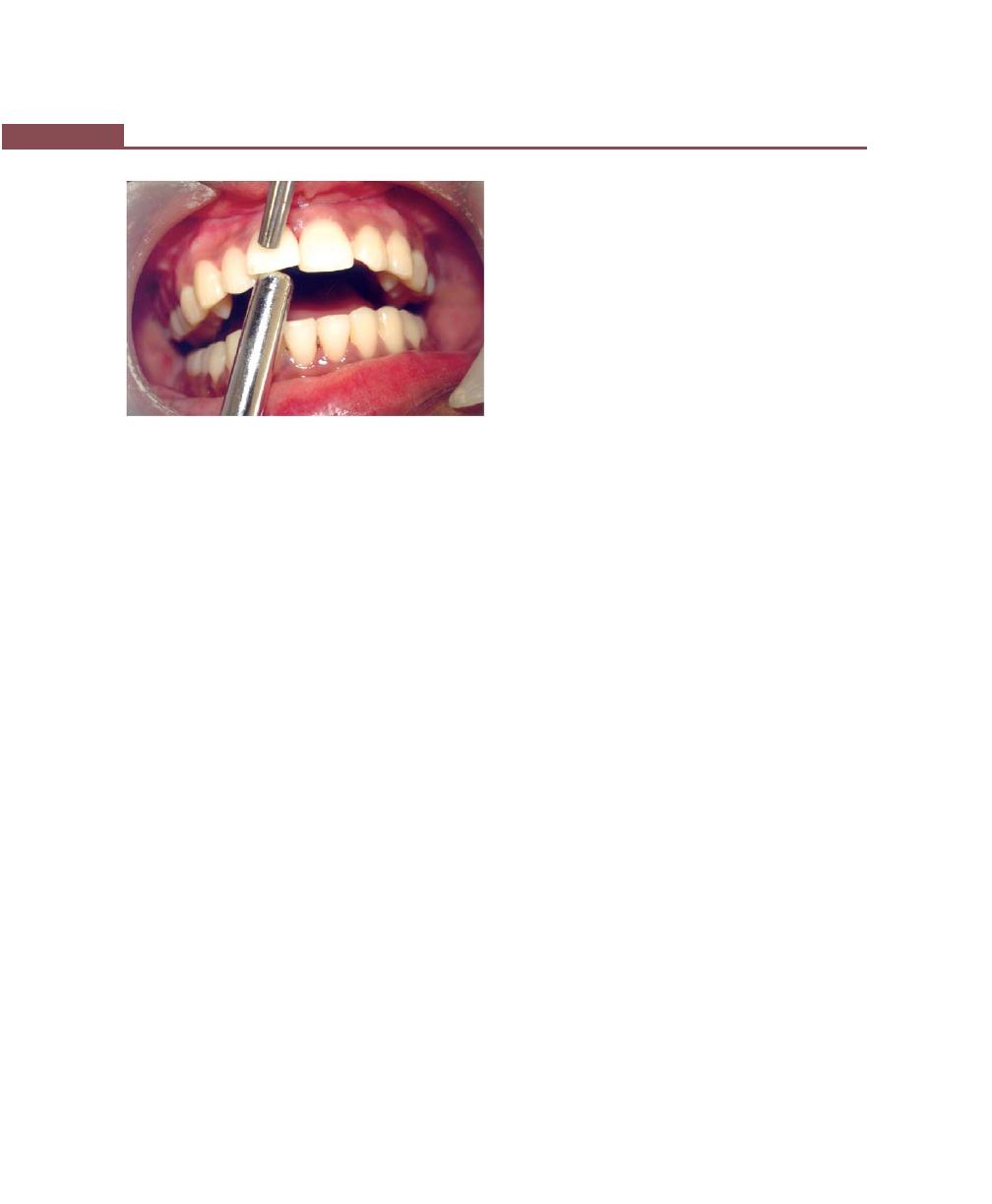

Fig. 1.1:

Surface characteristics of the clinically-

normal gingiva

Fig. 1.2:

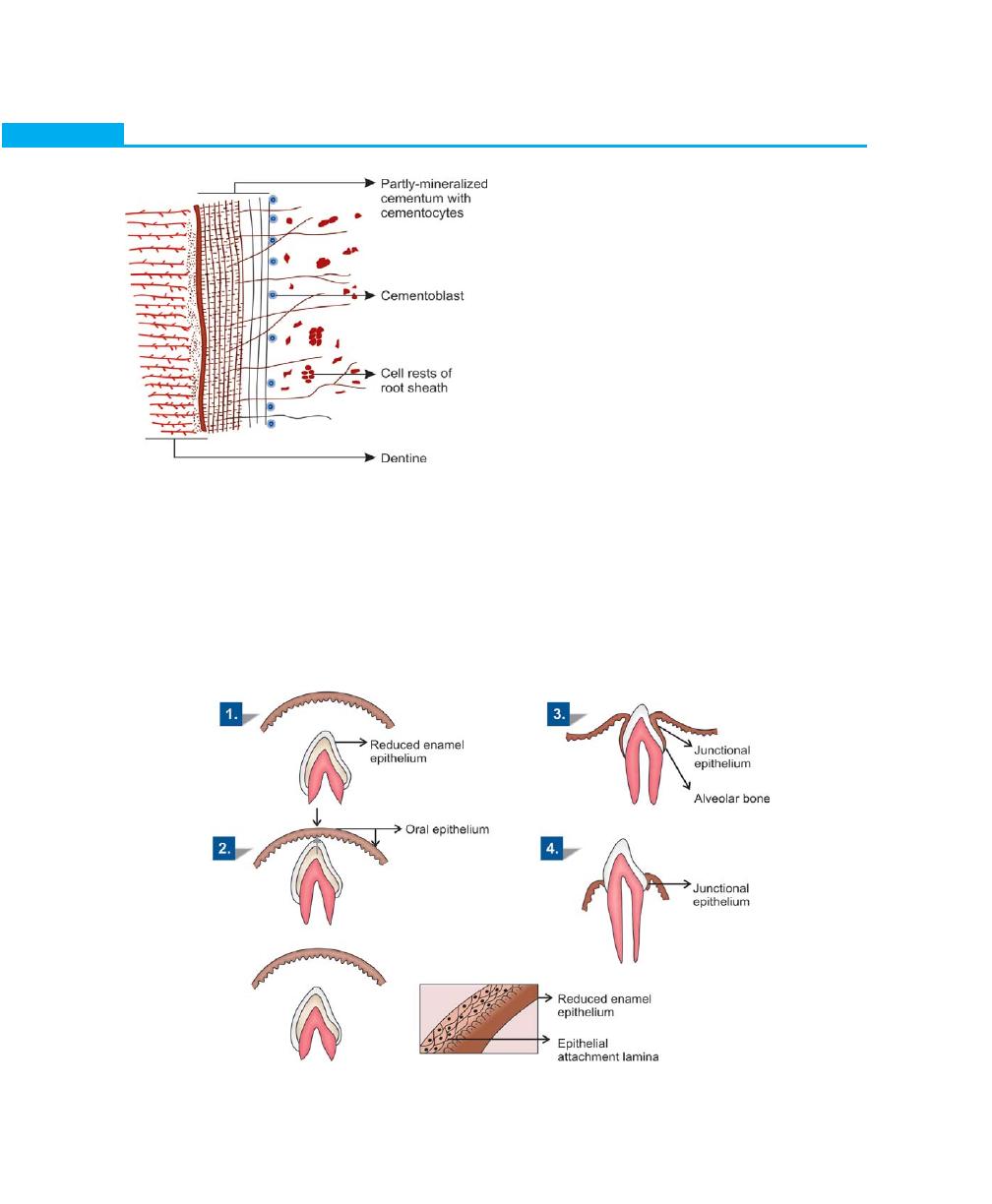

Root sheath of Hertwig

Fig. 1.3:

Proliferation of root sheath and further dentine

formation in an apical direction

of non-keratinized epithelium and hence represents the

most frequent site for initiation of disease process.

DEVELOPMENT OF PERIODONTIUM

To understand the development of periodontal tissues

one has to have a clear understanding of the root

formation. Development of cementum and roots of the

teeth starts once the formation of enamel is completed.

The outer and inner epithelia together form the epithelial

root sheath of Hertwig, which is responsible for deter-

mining the shape of the root.

Early Development of Cementum

The outer and inner epithelial layers become continuous

(without stratum intermedium or stellate reticulum) in

the area of the future cementoenamel junction and form

a two-layered sheath, which grows into the underlying

mesenchyme. The apical portion of the root sheath

remains constant whereas the coronal portion, which

is associated with dentin and cementum formation moves

in the direction of the oral cavity. The root sheath bends

horizontally at the level of future cementoenamel junction

forming the epithelial diaphragm, following which the

cervical opening becomes smaller (Figs 1.2 and 1.3).

Once the crown formation is complete the cells of

the inner enamel epithelium loose their ability to form

enamel and is called reduced enamel epithelium. They

retain the ability to induce perimesenchymal cells to

differentiate into odontoblasts and to proceed with the

formation of predentin and dentin.

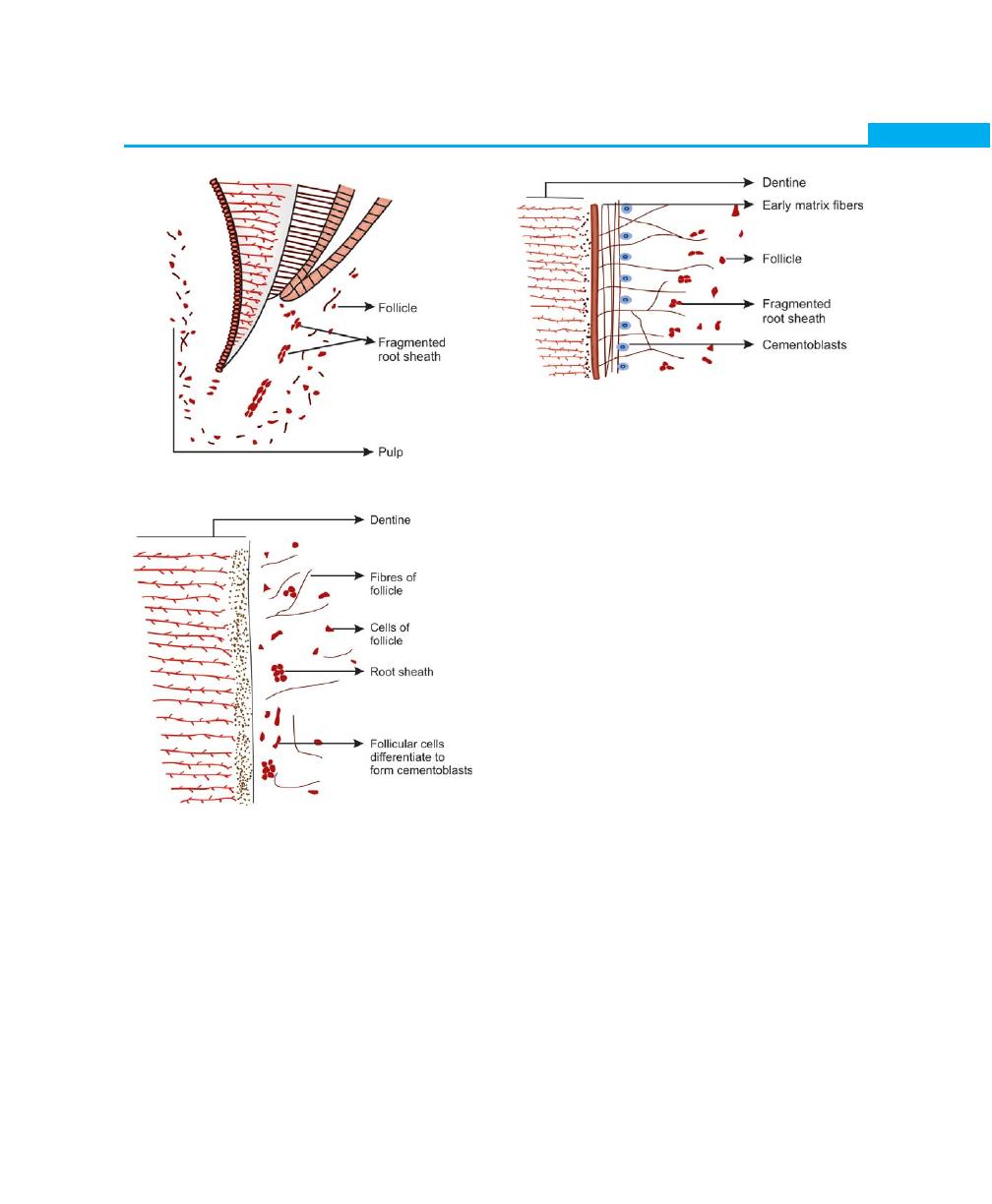

After the dentin formation is completed, certain

changes occur in the root sheath. Recent studies have

5

Anatomy and Development of the Structures of Periodontium

Fig. 1.4:

Fragmentation of root sheath

Fig. 1.5:

Follicular cells and fibres contact dentine surface

Fig. 1.6:

Early deposition of matrix

shown that, the epithelial cells of the root sheath produce

a layer on the root dentin, which is 10 /xm thick, has

a hyaline appearance and contains fine granules and

fibrils. This layer is called the hyaline layer of Hopewell

Smith or intermediate cementum. The epithelial cells of

the root sheath secrete enamel proteins such as

amehgenin or enameloids. The root sheath at this stage

becomes discontinuous and enables the surrounding

follicular mesenchyme to come in contact with the

amelogenin. These follicular cells then differentiate into

cementoblasts and deposit the organic matrix of

cementum on the root surface (Figs 1.4 and 1.5).

Later Development of Cementum

Cementoblasts are cuboidal cells that are arranged on

the outer surface of the hyaline layer. These cells are

responsible for the deposition of the organic matrix of

cementum, which consists of proteoglycan ground

substance, intrinsic collagen fibers and is followed by

subsequent mineralization of the organic matrix (Fig.

1.6).

Mineralization starts with the formation of a thin layer

called cementoid. Mineral salts are derived from the tissue

fluid containing calcium and phosphate ions and are

deposited as hydroxyapatite crystals.

The disintegrated Hertwigs root sheath slowly moves

away from the root surface and remain in the periodontal

ligament as epithelial cell rests of Malassez. The

periodontal ligament forms from the dental follicle soon

after root formation begins. Before a tooth erupts, fibers

from the follicle are incorporated in the cementum and

they lie parallel to the root surface. Once the tooth erupts,

the fibers are arranged in an oblique manner and are

regarded as the precursor of the periodontal ligament

fibers. As the cementum continues to increase in thickness,

more fibers become incorporated into the cementum

and eventually called as Sharpey’s fibers, when

periodontal ligament becomes established.

Alveolar bone forms around the periodontal ligament.

With continuous bone deposition the periodontal

6

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

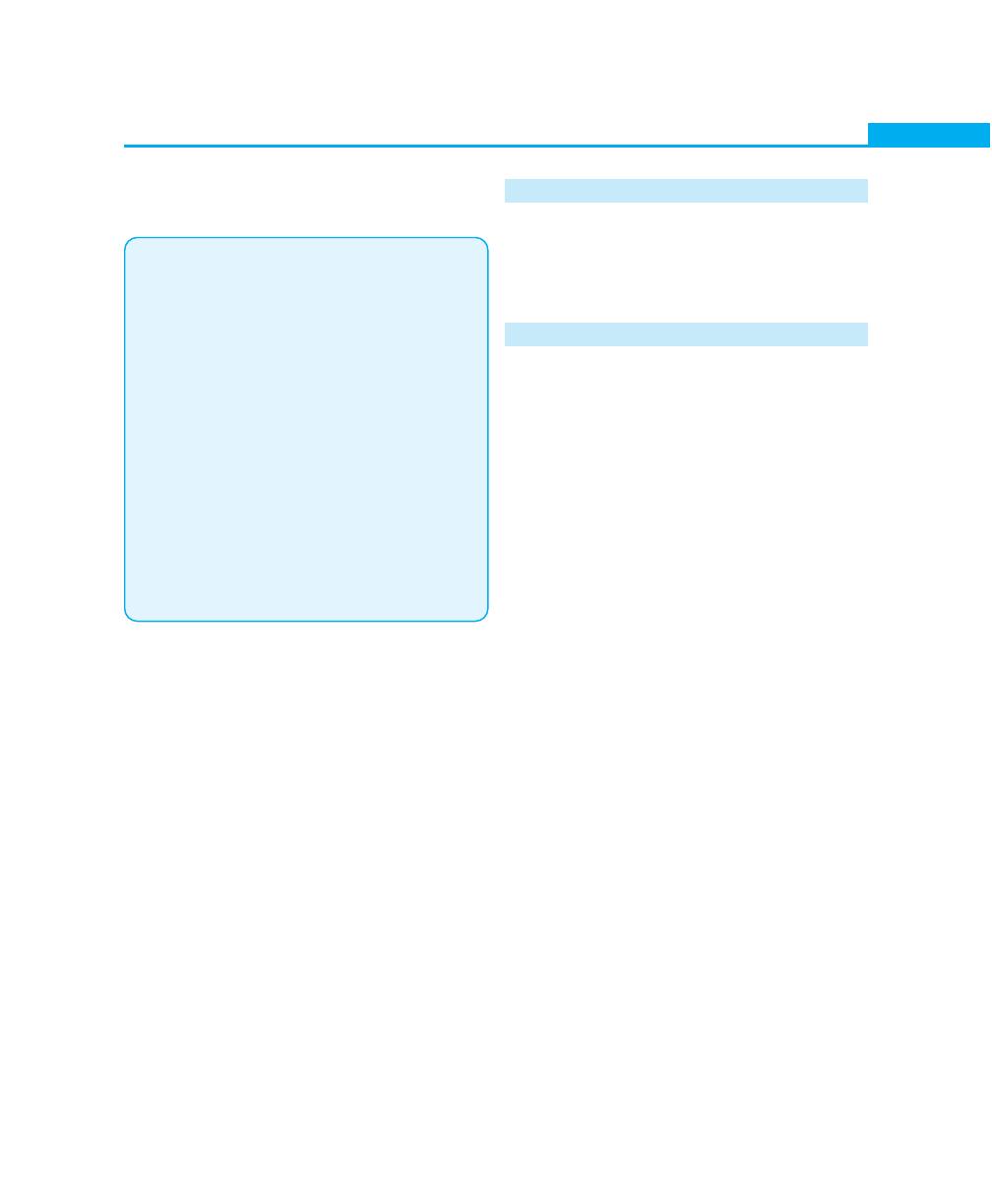

the surface of the enamel called primary enamel cuticle.

The inner enamel epithelium after laying down enamel

reduces to a few layers of flat cuboidal cells, which is

then called as reduced enamel epithelium. It covers the

entire enamel surface extending till the cemento-enamel

junction. During eruption, the tip of the tooth approaches

the oral mucosa leading to fusion of the reduced enamel

epithelium with the oral epithelium. As the crown

emerges into the oral cavity the former ameloblasts that

-are in contact with the enamel get transformed into

Junctional epithelium. Coronally the Junctional

epithelium is continuous with the oral epithelium. As the

tooth erupts, the reduced enamel epithelium grows

shorter gradually. A shallow groove, the gingival

sulcus may develop between the gingiva and the tooth

surface.

Hence, the ameloblasts pass through two phases, in

one they form enamel and in the other phase they help

in formation of primary epithelial attachment or

Junctional epithelium. When the Junctional epithelium

forms from the ameloblasts it is called primary epithelial

attachment. Junctional epithelium that forms after surgical

therapy takes its origin from the basal cells of oral

ligament space gradually becomes narrower. The alveolar

process develops during the eruption of the teeth and

cells responsible for bone formation are osteoblasts

(Fig. 1.7).

Development of Junctional Epithelium (Fig. 1.8)

When the enamel formation is complete the ameloblasts

become shorter, and they leave a thin membrane on

Fig. 1.7:

Advanced formation of cementum

Fig. 1.8:

Development of junctional epithelium

7

Anatomy and Development of the Structures of Periodontium

epithelium instead of ameloblasts. This is called secondary

epithelial attachment.

KEY POINTS TO NOTE

1. The periodontium is composed of alveolar bone, root

cementum, periodontal ligament (supporting tissue) and

gingiva (investing tissue).

2. The gingiva is the only structure of the periodontium that

is clinically visible and anatomically it can be divided into

marginal, attached and interdental gingiva.

3. The junction between the marginal and attached gingiva is

called free gingival groove, where as the junction between

the attached gingiva and alveolar mucosa is called as

mucogingival junction.

4. Once the dentin formation is completed, the root sheath

becomes discontinuous and allows the surrounding

mesenchyme to come in contact with the products of the

epithelial cells of the root sheath i.e. amelogenin. These

follicular cells then differentiate into cementoblasts,

fibroblasts and osteoblasts by which cementum, periodontal

ligament fibers and alveolar bone are deposited.

5. Fusion of the oral epithelium along with the reduced enamel

epithelium gives rise to the Junctional epithelium or epithelial

attachment.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. Define periodontology and periodontics.

2. What are the parts of periodontium?

3. Describe the development of structures of

periodontium.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. BG Jansen Van Rensburg. Oral Biology, Chapter 8.

Quintessence Publishing Co Ltd, 1995; 301-7.

2. BRR Varma, RP Nayak. Current Concepts in Periodontics,

Chapter 2. Arya Publishing, 2002; 4-8.

3. S.N.Bhasker. Orbans, Oral Histology and Embryology,

10th edition, CBSP Publishers and Distributers, New Delhi,

41-4.

4. Tencate. Oral Histology, Development, Structure and

Function, 3rd edition, Jaypee Bros. 228–43.

8

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

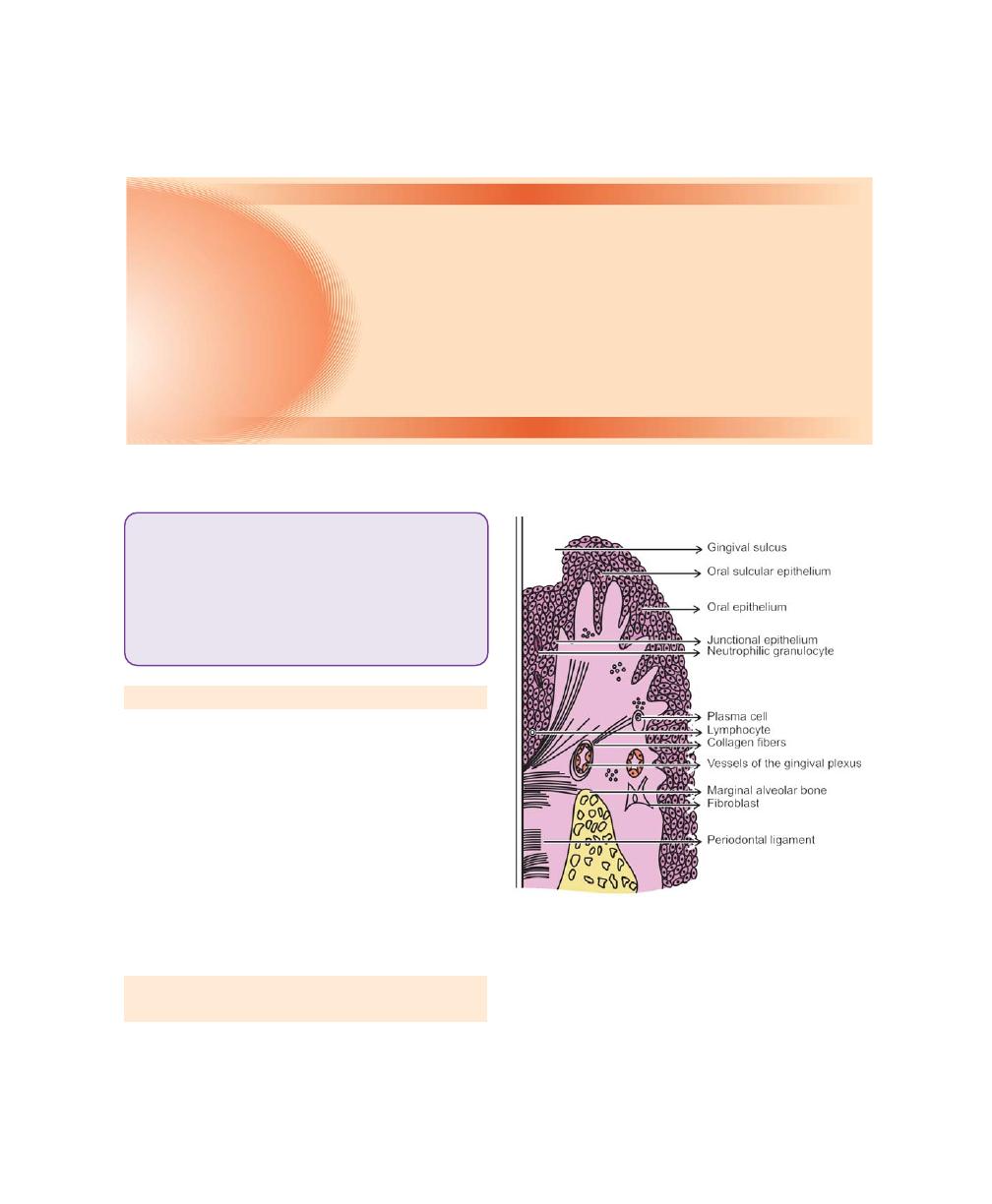

INTRODUCTION

Periodontium is the functional unit of tissues supporting

the tooth including gingiva, the periodontal ligament,

the cementum and the alveolar process. The tooth and

periodontium are together called as the dentoperiodontal

unit. The main support of the tooth is provided by the

periodontal ligament, which connects the cementum of

the root to the alveolar bone or tooth socket, into which

the root fits. The main function of the gingiva is to protect

the surrounding tissues from the oral environment.

THE GINGIVA

Macroscopic Features

The gingiva is that part of the oral mucosa (masticatory

mucosa) that covers the alveolar process of the jaws and

surrounds the necks of the teeth. Anatomically the gingiva

is divided into—marginal, attached and interdental

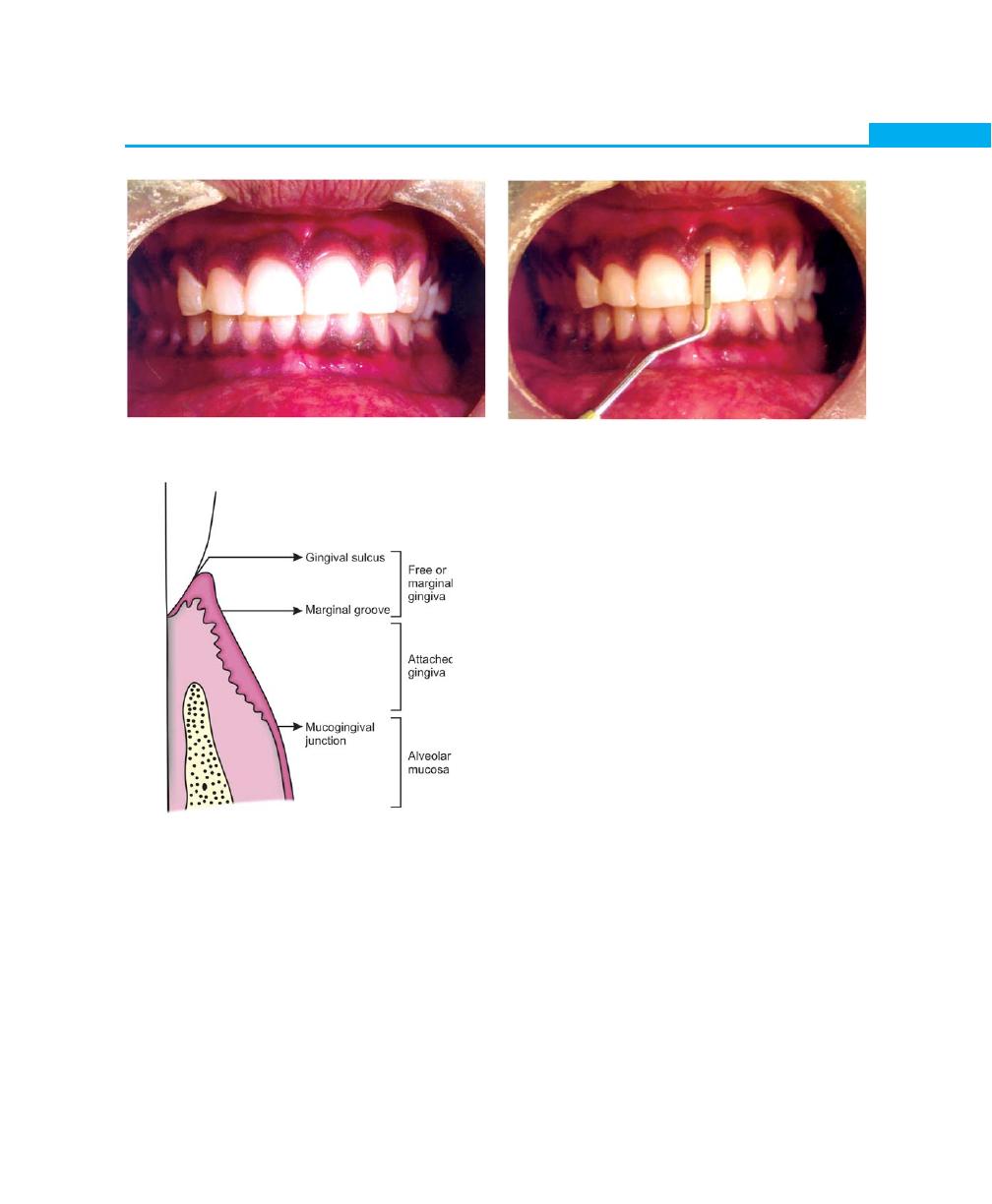

gingiva (Fig. 2.1).

Marginal Gingiva or Free Gingiva or

Unattached Gingiva

It is defined as the terminal edge or border of the gingiva

surrounding the teeth in a collar-like fashion. In some

cases it is demarcated apically by a shallow linear

depression called the “free gingival groove”. Though the

❒

❒

❒

❒

❒ THE GINGIVA

• Macroscopic Features

• Microscopic Features

❒

❒

❒

❒

❒ TOOTH-SUPPORTING STRUCTURES

❒

❒

❒

❒

❒ PERIODONTAL LIGAMENT

• Definition

• Structure

• Cellular Composition

• Extracellular Components

• Development of Principal Fibers of

Periodontal Ligament

• Structures Present in the Connective

Tissue

• Functions of Periodontal Ligament

• Clinical Considerations

❒

❒

❒

❒

❒ ALVEOLAR BONE

• Definition

• Parts of Alveolar Bone

• Composition of Alveolar Bone

• Osseous Topography

• Blood Supply to the Bone

• Clinical Considerations

❒

❒

❒

❒

❒ CEMENTUM

• Definition

• Classification

• Functions

• Composition

• Thickness of Cementum

• Cementoenamel Junction

• Cemental Resorption and Repair

2

Biology of

Periodontal Tissues

9

Biology of Periodontal Tissues

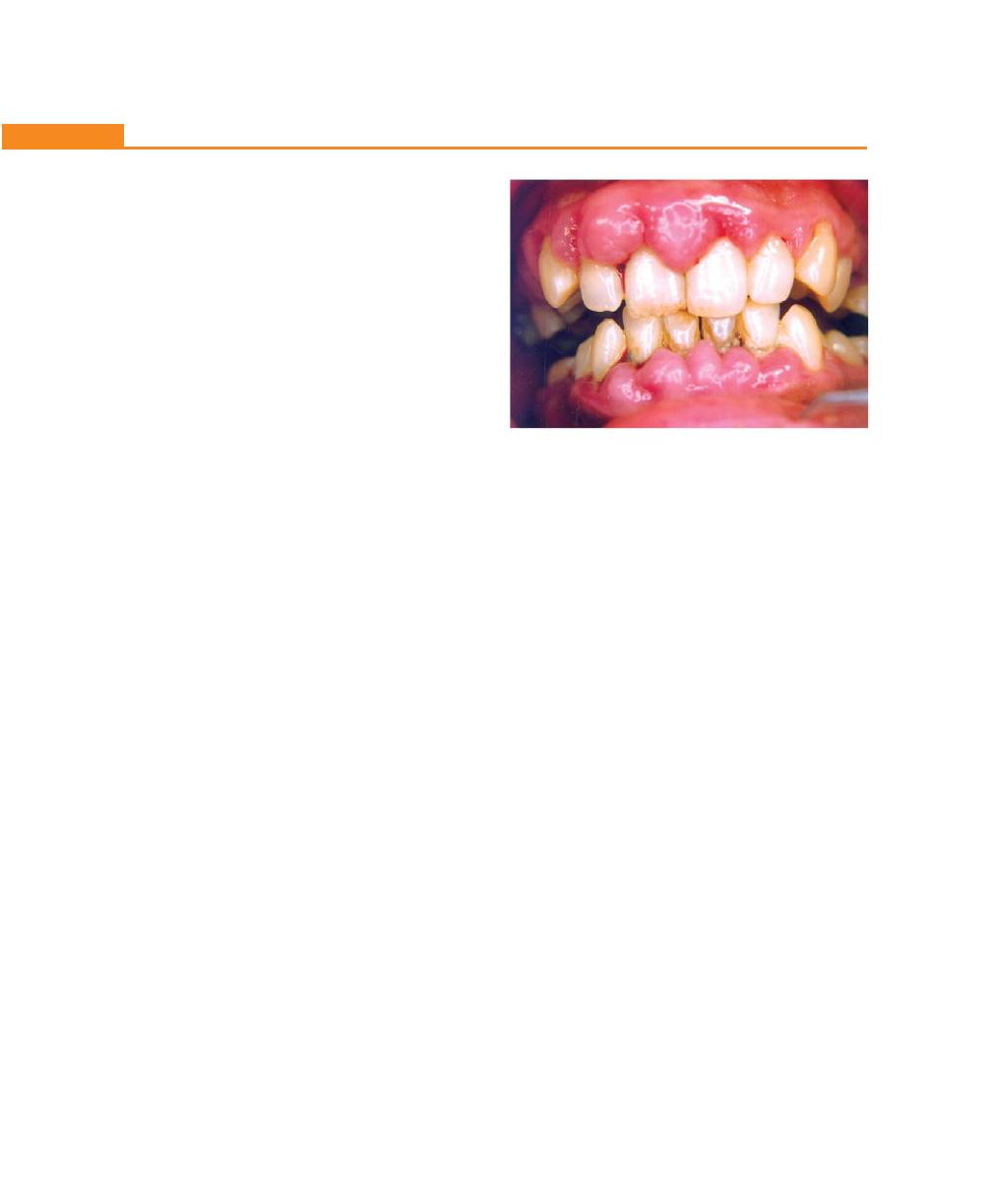

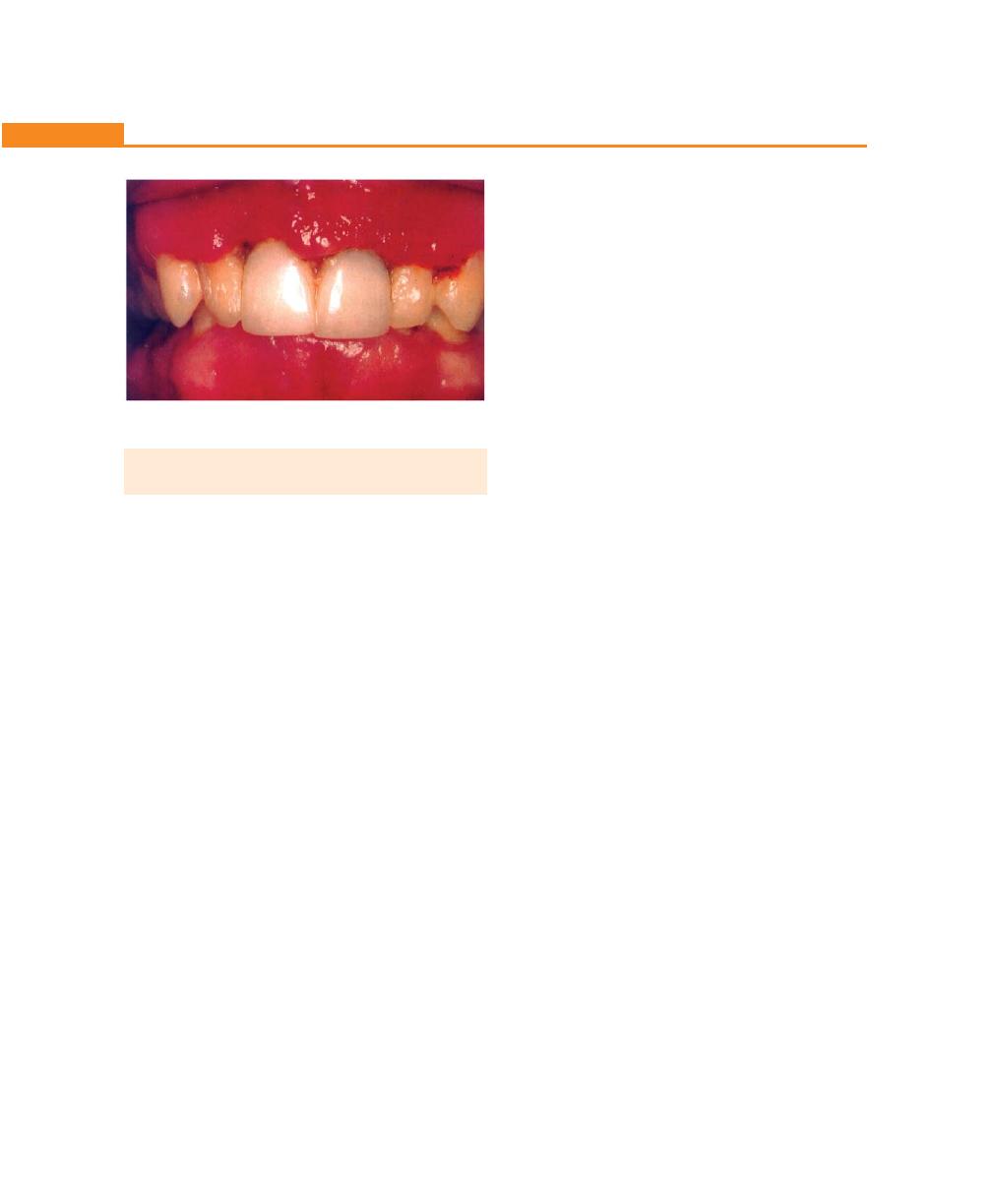

Fig. 2.1:

Normal gingiva in health

marginal gingiva is well-adapted to the tooth surface,

it is not attached to it (Fig. 2.2).

Gingival Sulcus

It is defined as the space or shallow crevice between the

tooth and the free gingiva, which extends apical to the

junctional epithelium. It is V-shaped and barely permits

the entrance of a periodontal probe. Under normal or

ideal conditions it is about 0 mm (seen only in germ

free animals). The so-called probing depth of a clinically-

Fig. 2.2:

Anatomic land marks of gingiva

Fig. 2.3:

Sulcus depth in healthy gingiva

normal gingival sulcus in humans is 2 to 3 mm

(Fig. 2.3).

Attached Gingiva

It is defined as that part of the gingiva that is firm, resilient

and tightly-bound to the underlying periosteum of the

alveolar bone. On the facial aspect it extends upto the

loose and movable alveolar mucosa, from which it is

demarcated by the mucogingival junction. The width of

attached gingiva is the distance between the mucogingival

junction and the projection on the external surface of

the bottom of the gingival sulcus or the periodontal

pocket.

It varies in different areas of the mouth, greater in

the maxilla than mandible, least width in the mandibular

first premolar area, greatest width in the maxillary incisor

region. The width of attached gingiva increases with age

and in supraerupted teeth.

Interdental Gingiva

Usually occupies the gingival embrasure. There are three

parts of interdental gingiva, facial papilla, lingual papilla

and col, which is a valley-like depression that connects

the facial and lingual papilla. The lateral borders and

tips of the interdental papilla are formed by continuation

of marginal gingiva and the intervening portion by the

attached gingiva. In the presence of diastema the

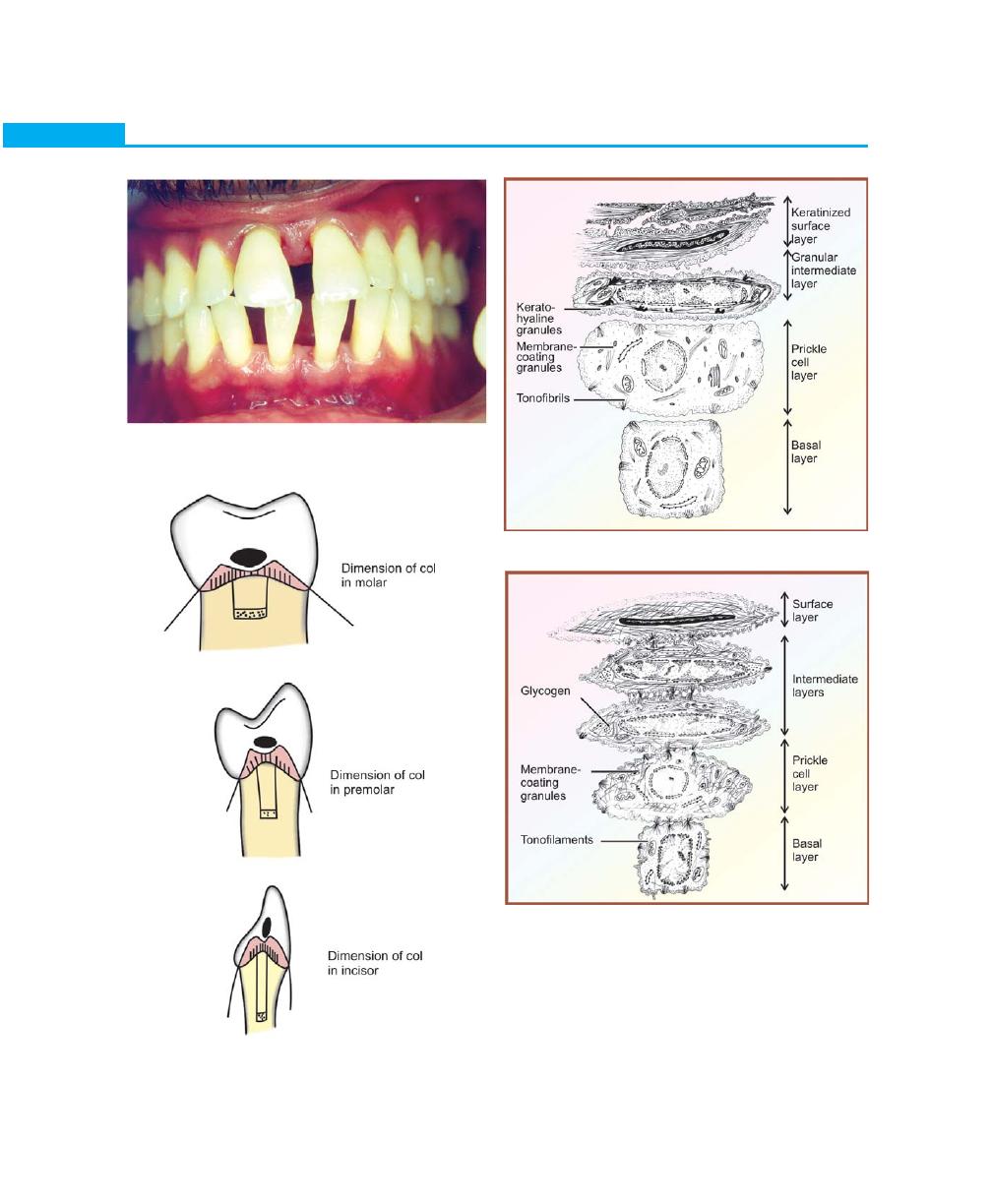

interdental papilla will be absent (Figs 2.4 and 2.5).

10

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

Fig. 2.5:

‘COL’ in various types of contacts

Fig. 2.6:

Orthokeratinized epithelium

Fig. 2.7:

Non-keratinized epithelium

Fig. 2.4:

Absence of interdental papilla in

diastema cases

Microscopic Features

The gingiva consists of a central core of connective tissue

covered by stratified squamous epithelium. Three types

of epithelium exists in the gingiva.

1. The oral or outer epithelium (Keratinized epithelium)

(Fig. 2.6).

11

Biology of Periodontal Tissues

2. The sulcular epithelium

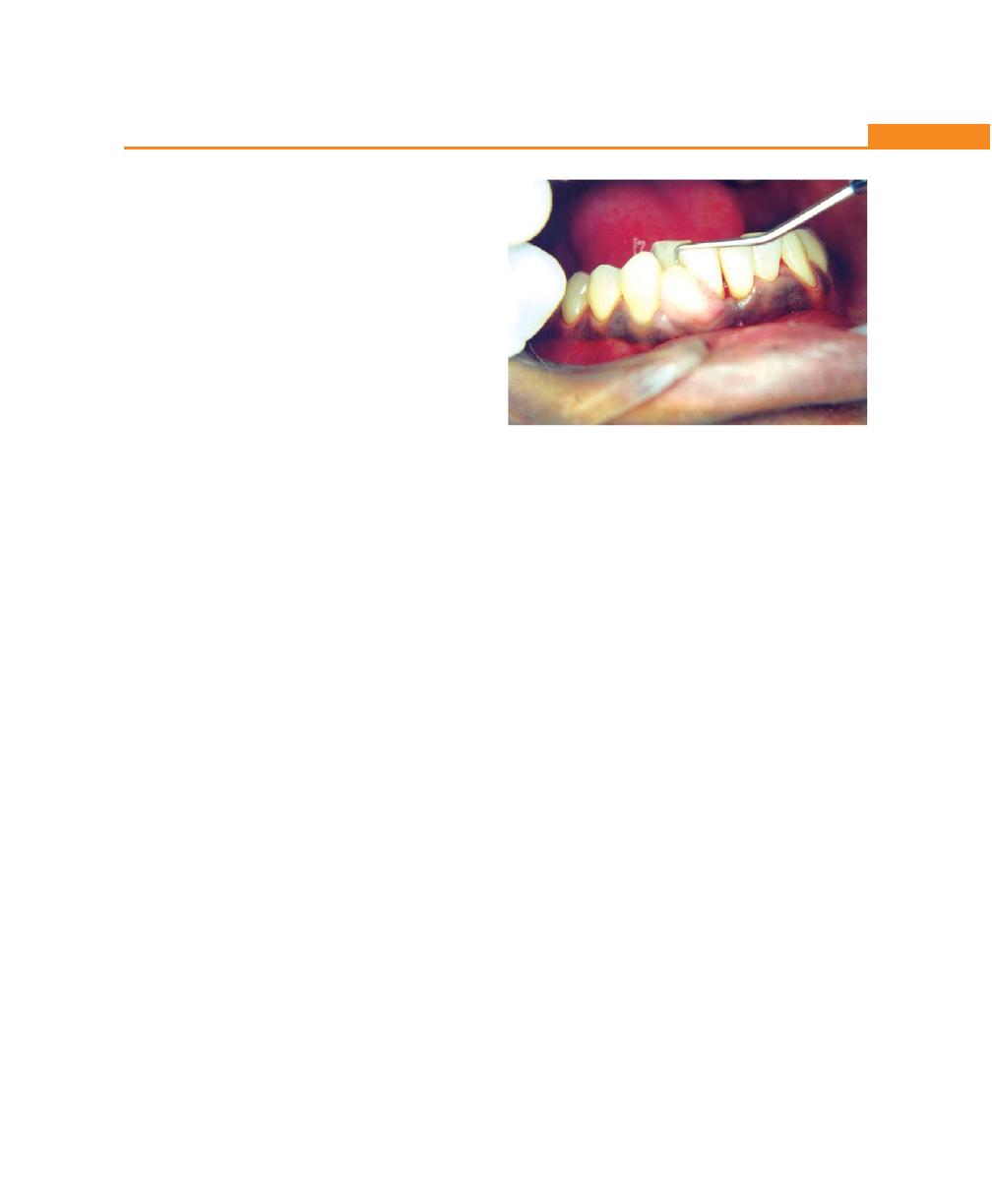

3. The junctional epithelium (non-keratinized epithe-

lium) (Fig. 2.7).

In the keratinized epithelium, the principal cell type

is the keratinocyte, which can synthesize keratin. The

process of keratinization involves a sequence of bioche-

mical and morphological events that occur in a cell as

it migrates from the basal layer towards the cell surface.

The non-keratinized epithelium contains clear cells,

which include Melanocytes, Langerhans cells, Merkel cells

and Lymphocytes.

The oral epithelium has the following cell layers:

1. Basal layer (Stratum basale or Stratum germinativum).

2. Spinous layer (Stratum spinosum).

3. Granular layer (Stratum granulosum).

4. Keratinized cell layer (Stratum corneum).

There are three distinct differences between the oral

sulcular epithelium, oral epithelium and the junctional

epithelium:

a. The size of the cells in the junctional epithelium is,

relative to the tissue volume, larger than in the oral

sulcular epithelium.

b. The intercellular space in the junctional epithelium

is, comparatively wider than in the oral epithelium.

c. Granular layer, which is seen in the oral epithelium,

is absent in sulcular and junctional epithelium.

Morphologic Characteristics of the Different

Areas of Gingival Epithelium

Oral or outer epithelium: It covers the crest and outer

surface of the marginal gingiva and the surface of the

attached gingiva. It is keratinized or parakeratinized or

combination of both. Keratinization varies in different

areas in the following order: palate (most keratinized),

gingiva, ventral aspect of the tongue and cheek (least

keratinized). The keratinized epithelium of the gingiva

consists of four layers, namely stratum basale, stratum

spinosum, stratum granulosum and stratum corneum.

The cells of the basal layer are either cylindrical

or cuboidal and are in contact with the basement

membrane. The basal cells possess the ability to divide,

it is in the basal layer that the epithelium is renewed

and therefore this is also called as stratum germinativum.

When two daughter cells have been formed by cell

division an adjacent “older” basal cell is pushed into the

spinous cell layer and starts as a keratinocyte, to traverse

the epithelium. It takes approximately one month

for a keratinocyte to reach the outer epithelial surface

where it becomes desquamated from the stratum

corneum.

The basal cells are separated from the connective

tissue by a basement membrane. In light microscopy

this membrane appears as a zone approximately 1 µm

wide and reacts positively to a PAS stain (periodic acid

Schiff stain), which indicates the presence of carbo-

hydrates (glycoproteins) in the basement membrane. In

electron micrograph, immediately beneath the basal cell,

an approximately 400 Å wide electrolucent zone can

be seen which is called lamina lucida. Beneath the lamina

lucida an electron dense zone – lamina densa is observed.

From the lamina densa so-called anchoring fibrils project

in fan-shaped fashion into the connective tissue. The

epithelial cells facing the lamina lucida contain a number

of electron dense, thicker zones called hemidesmosomes.

The hemidesmosomes are involved in the attachment

of the epithelium to the underlying basement

membrane.

Stratum spinosum consists of large cells with short

cytoplasmic processes resembling spines. Since they are

arranged at regular intervals they give the cells a prickled

appearance. The cells are attached to one another by

numerous desmosomes (pairs of hemidesmosomes),

which are located between the cytoplasmic processes of

adjacent cells.

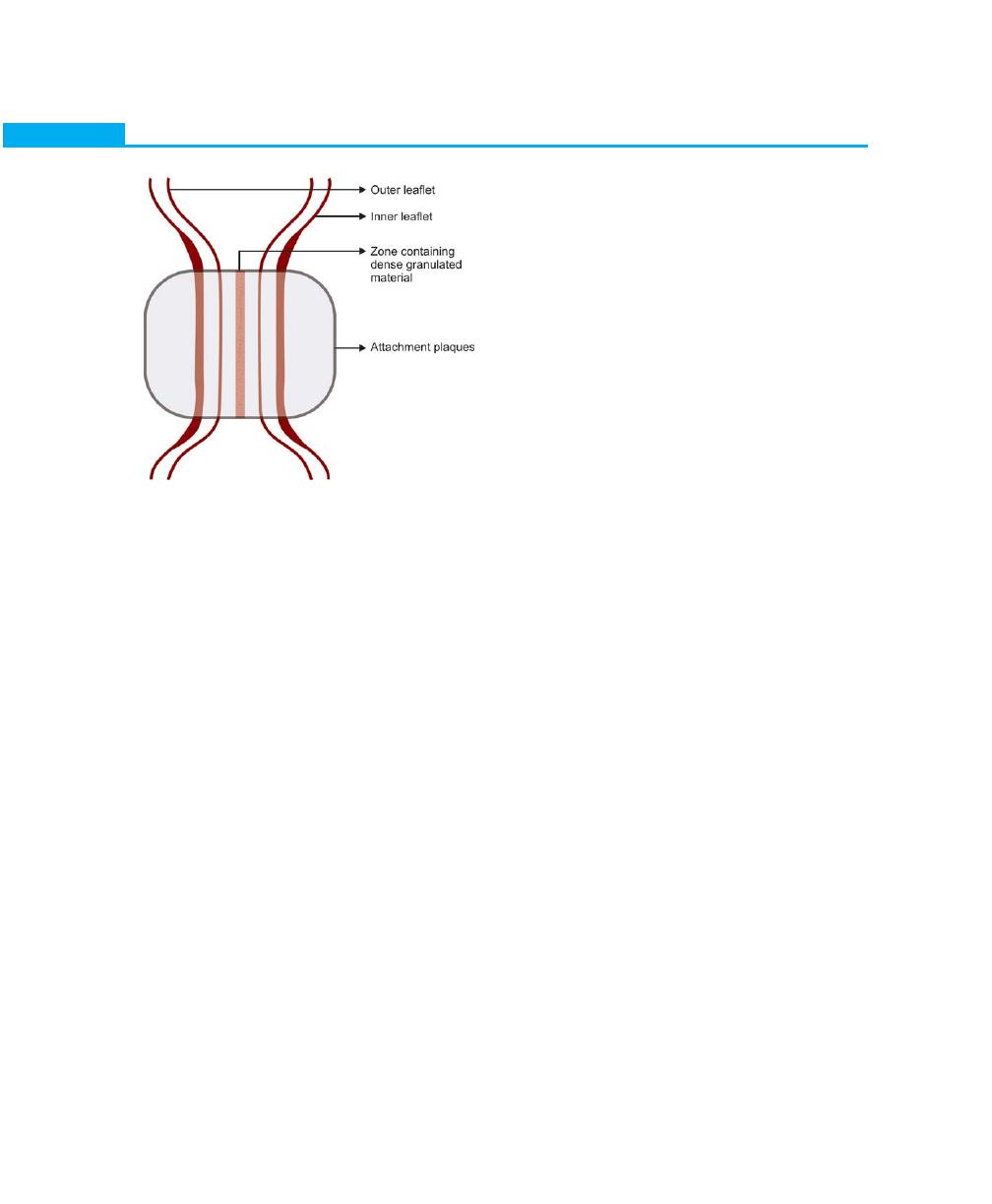

Composition of a desmosome: It consists of two adjoining

hemidesmosomes separated by a zone containing

electron dense granulated material (GM). In addition,

outer and inner leaflets of the cell (OL, IL) and the

attachment plaque (AP), represent granular and fibrillar

material in the cytoplasm (GM) (Fig. 2.8).

12

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

Stratum granulosum: Electron dense keratohyalin

bodies begin to occur, these granules are believed to

be related to the synthesis of keratin. Here, there is

conversion of cells to “acellular” structure bordered by

a cell membrane indicating keratinization of the cytoplasm

of the keratinocyte.

Stratum corneum: The cytoplasms of the cells in this

layer are filled with keratin and the entire nucleus is lost.

But in parakeratinized epithelia, the cells contain remnants

of nuclei.

Keratinization is considered as a process of diffe-

rentiation rather than degeneration. The keratinocytes

while traversing from the basal layer to the epithelial

surface undergoes certain changes.

a. From the basal layer to the granular layer both the

number of tonofilaments in the cytoplasm and the

number of desmosomes increase significantly.

b. In contrast, the number of organelles such as

mitochondria, lamellae of rough endoplasmic

reticulum and Golgi apparatus decrease.

Oral sulcular epithelium: The soft tissue wall of the

gingival sulcus is lined coronally with sulcular epithelium,

extending from the gingival margin to the junctional

epithelium. It is made up of basal and prickle cell layer.

The sulcular epithelium resembles the oral/gingival

epithelium in all respects with the exception that it does

not become fully keratinized. Although it contains

keratinocytes they do not undergo keratinization.

However, the surface cells are flattened and exhibit a

tendency towards partial keratinization in response to

physical stimulation. Normally, there are no regular

retepegs in sulcular epithelium but they form during the

inflammation of the lateral wall.

Junctional epithelium: Denotes the tissue that joins to

the tooth on one side and to the oral sulcular epithelium

and connective tissue on the other. It forms the base

of the sulcus. It has been examined in detail by several

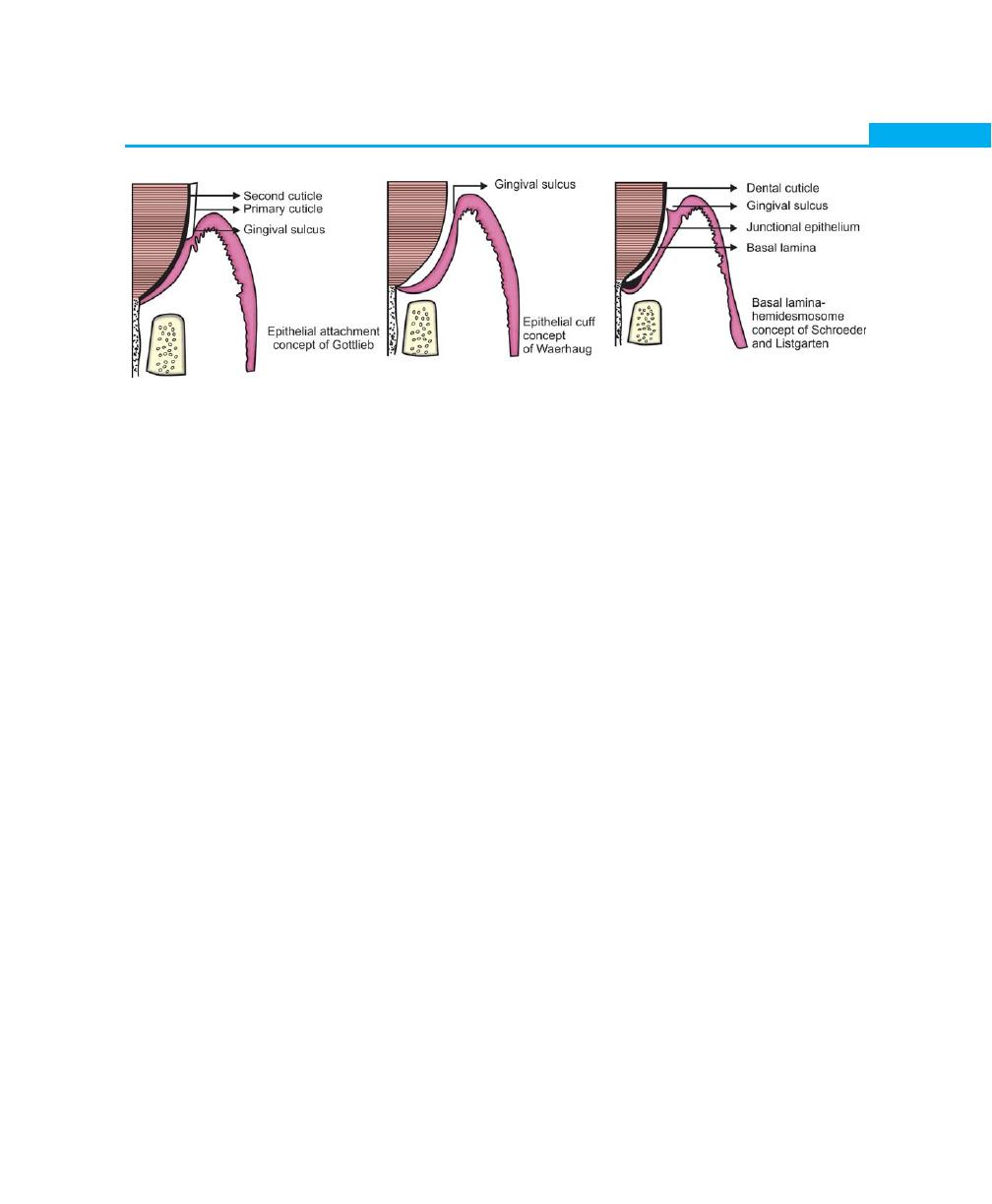

investigators, many hypothesis have been put forward

to explain the mode of attachment of the epithelium

to the tooth surface.Prior to the Gottlieb concept, it was

believed generally, that the gingival soft tissues were closely

opposed, but not organically united to the surface of

the enamel. This concept was based on the clinical finding

that the gingiva could be easily deflected from the tooth

surface during instrumentation. However, experimental

and clinical observations have led Gottlieb to the concept

that the soft tissues of the gingiva are organically united

to the enamel surface. He termed it as “epithelial

attachment”. Although it was accepted generally, the

concept did not explain how exactly junctional epithelium

attaches to the root surface (Fig. 2.9).

Waerhaugh in 1952, based on his observations

presented the concept of the “epithelial cuff, he concluded

that the gingival tissues are closely apposed, but not

organically united to the tooth surface. In 1962 Stern

showed that the attachment to the tooth surface is

through hemidesmosomes. This was supported by

extensive studies conducted by Schroeder and

Listgarten, they revealed that there is a structural

continuity between the tooth surface and epithelium.

These studies by Schroeder and Listgarten states that

the epithelium-tooth interface was observed to be similar

to the epithelium-connective tissue interface and that is

Fig. 2.8:

Composition of a desmosome

13

Biology of Periodontal Tissues

Fig. 2.9:

Concepts of epithelial attachment

by hemidesmosome and basal lamina. A basal lamina

is always interposed between epithelial cells and crown

or root surface, and the epithelial cells are united to the

basal lamina by hemidesmosomes.

The junctional epithelium is attached to the tooth

surface by internal basal lamina and to the gingival

connective tissue by an external basal lamina. The internal

basal lamina consists of a lamina densa (adjacent to the

enamel) and a lamina lucida to which hemidesmosomes

are attached. Various studies have also shown that

junctional epithelial cells are involved in the production

of laminin and play a key role in the adhesion

mechanism. The attachment of the junctional epithelium

to the tooth surface is reinforced by the gingival fibers.

Hence the junctional epithelium and gingival fibers are

considered as a functional unit, referred to as the

dentogingival unit.

General structural features of junctional epithelium: It

consists of a collar like band of stratified squamous non

keratinizing epithelium. Thickness varies from three or

four layers in early life and increases with age upto 15

to 20 layers at the base of the gingival sulcus, and only

1 or 2 cells at the most apical portion. The length of

the junctional epithelium ranges from 0.25 to 1.35 mm.

The cells are arranged into basal and suprabasal layers

and they do not have granular layer or cornified layers.

They exhibit unusual cytologic features and differ

significantly from other oral epithelia. Three zones in

junctional epithelium have been described, apical,

coronal and middle. Apical is for germination, middle

is for adhesion and coronal is permeable.

The basal cells are cuboidal or in some cases, flattened.

They contain slightly more rough endoplasmic reticulum

and lysosomal content. The content of mitochondria of

the cells as they migrate toward and along the tooth

surface decreases. Cells of the suprabasal layer especially

those adjacent to the tooth surface exhibit complex

microvillus formation and interdigitation. Junctional

epithelial cells, especially those near the base of the

gingival sulcus, appear to have phagocytic capacity.

The structural features of junctional epithelium

indicate that it is highly permeable. Leukocytes and

lymphocytes within junctional epithelium are seen even

in clinically healthy gingiva. The densities of desmosomes

that interconnect the cells are considerably less than that

of oral epithelia and represents wider intercellular

junctions.

Epithelium–Connective Tissue Interface

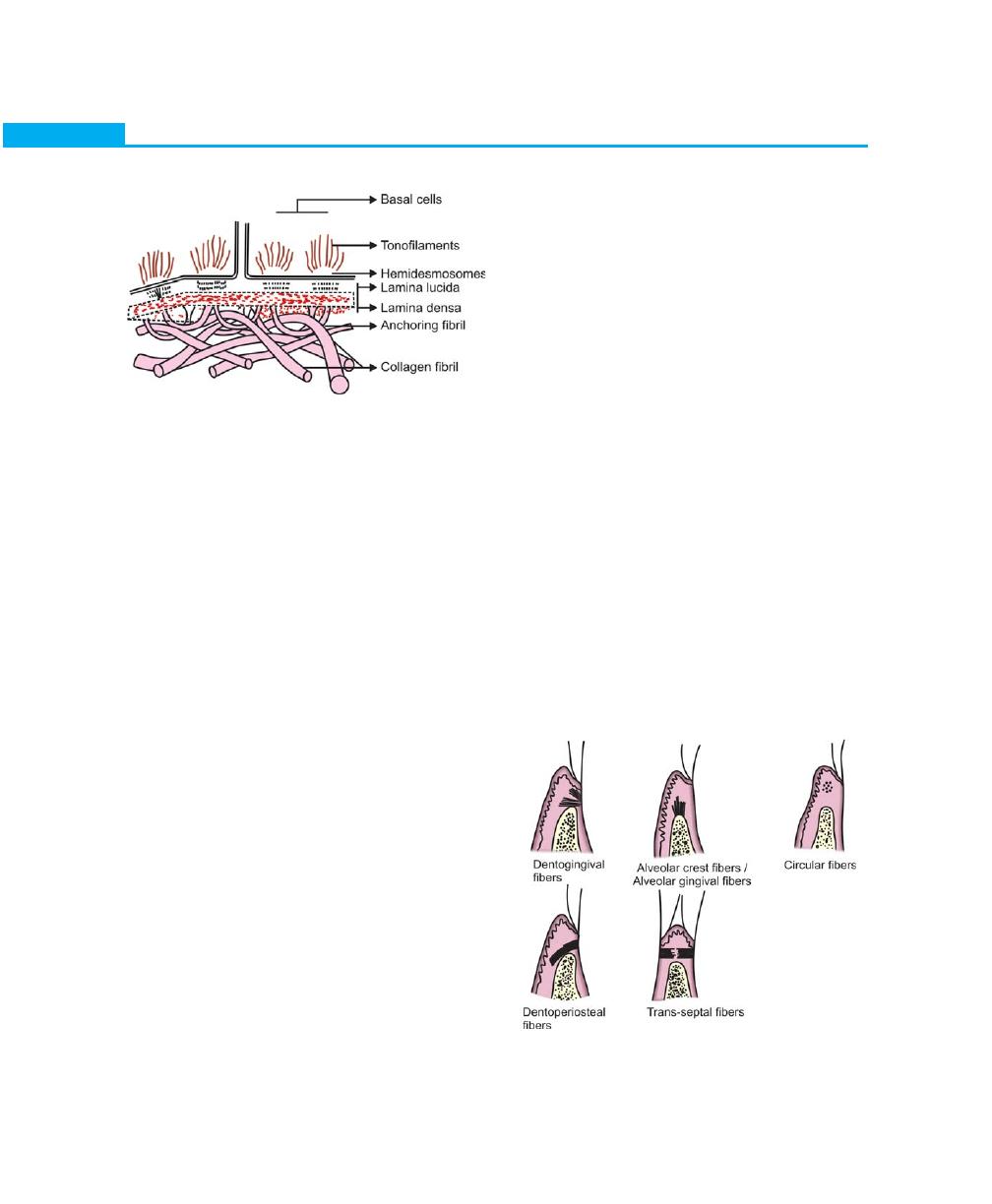

Histological sections have demonstrated that, the

retepegs of epithelial cells project deeply into the

connective tissue leading to the formation of a series of

inter- connecting epithelial ridges. Basement membrane

seems to form a continuous sheet that connects the

epithelium and connective tissue. Electron microscope

reveals a faintly fibrillar structure, called as the basal

14

Essentials of Clinical Periodontology and Periodontics

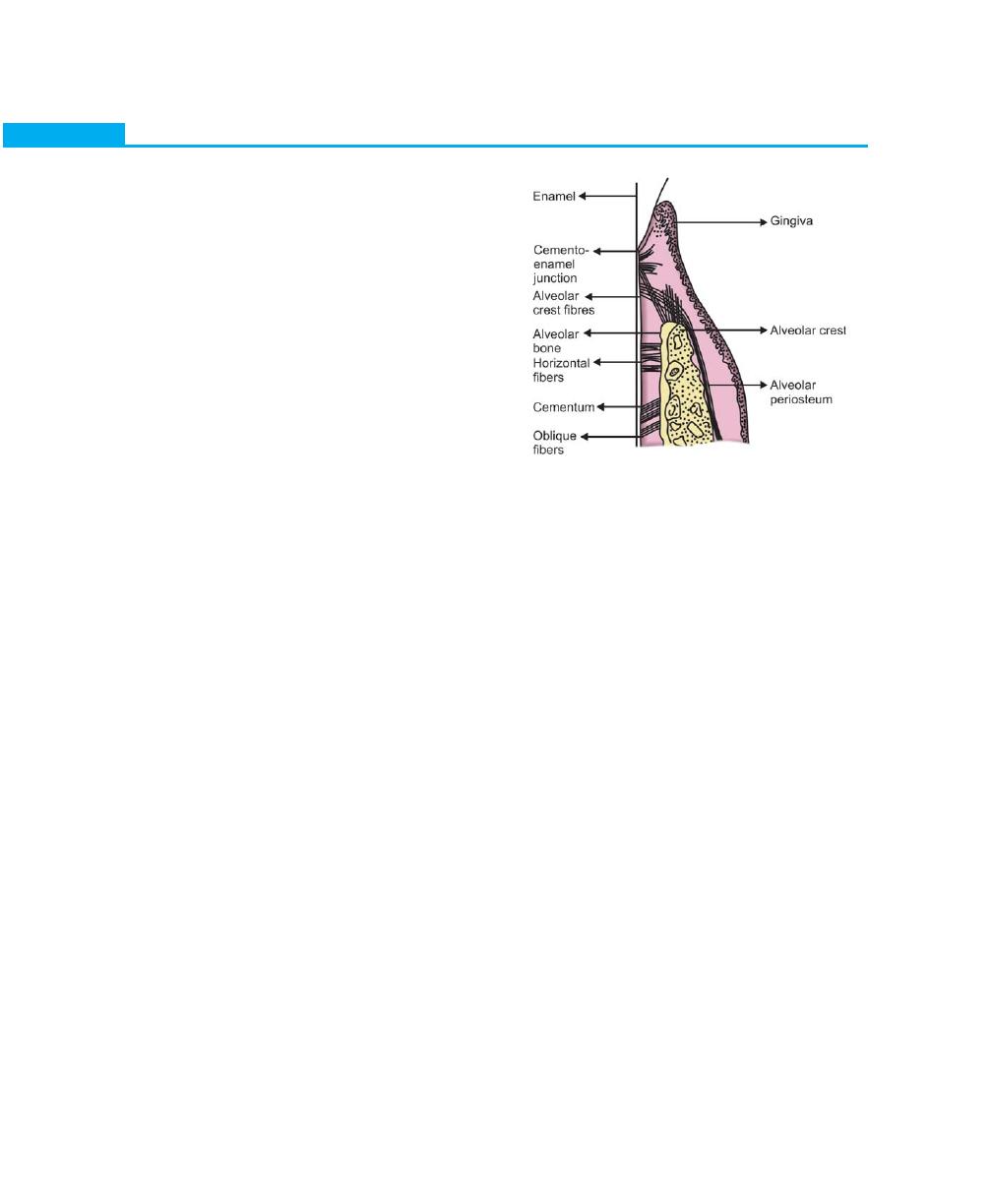

Fig. 2.11:

The principal group of fibers

lamina, which is a part of the basement membrane. This

structure has lamina lucida adjacent to the basal epithelial

cells and lamina densa towards connective tissue. Basal

lamina is produced by adjacent epithelial cells and is made

up of collagenous proteins and proteoglycans binded

together into a totally-insoluble complex. It also contains

laminin and fibronectin. Fibrils measuring 20 to 40 nm

in diameter seem to extend from the basal cells through

the basal lamina and into the lamina propria of the

connective tissue. These structures called as anchoring

fibrils are supposed to bind the basal cells, basal lamina

and connective tissue together (Fig. 2.10).

Supra-alveolar Connective Tissue

The connective tissue supporting the oral epithelium is

termed as the lamina propria and for descriptive purpose

it can be divided into two layers:

a. The superficial papillary layer—associated with the

epithelial ridges.

b. Deeper reticular layer—that lies between the papillary

layer and the underlying structures.

The term reticular here means net-like and refers to the

arrangement of collagen fibers. In the papillary layer,

the collagen fibers are thin and loosely-arranged and

many capillary loops are present. The reticular layer is

dominated by collagen arranged in thick bundles.

The lamina propria consists of cells, fibers, blood

vessels embedded in amorphous ground substances.

I. Cells: Different types of cells present are:

a. Fibroblast

b. Mast cells

c. Macrophages

d. Inflammatory cells.

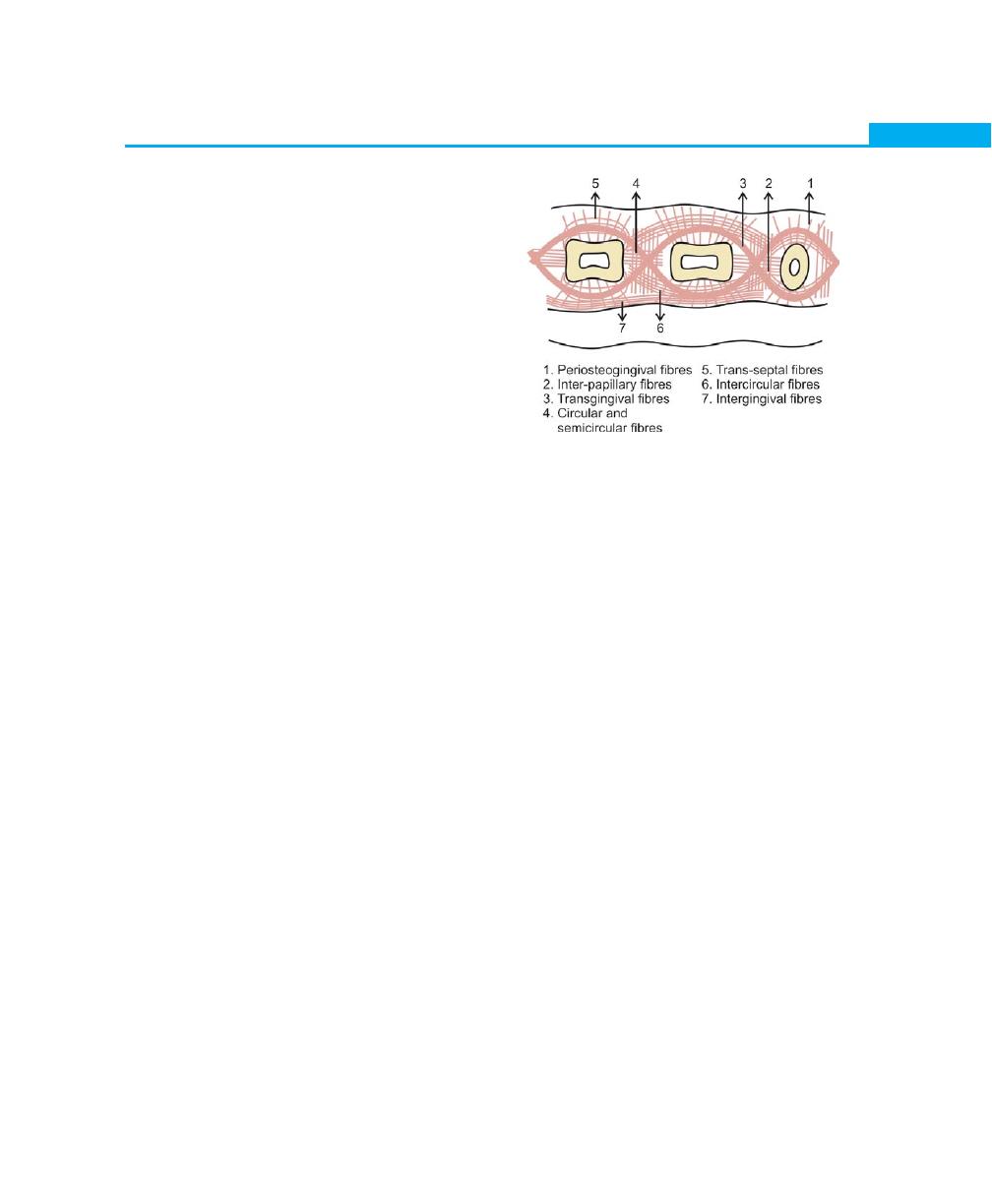

II. Fibers: The connective tissue fibers are produced by

fibroblasts and can be divided into:

a. Collagen fibers

b. Reticulin fibers

c. Oxytalan fibers

d. Elastin fibers.

Collagen type I form the bulk of the lamina propria

and provide the tensile strength to the gingival tissues.

Type II collagen is seen in the basement membrane.