1

Fifth stage

Pediatrics

Lec-

Dr. Athl

22/2/2017

Nephrotic Syndrome

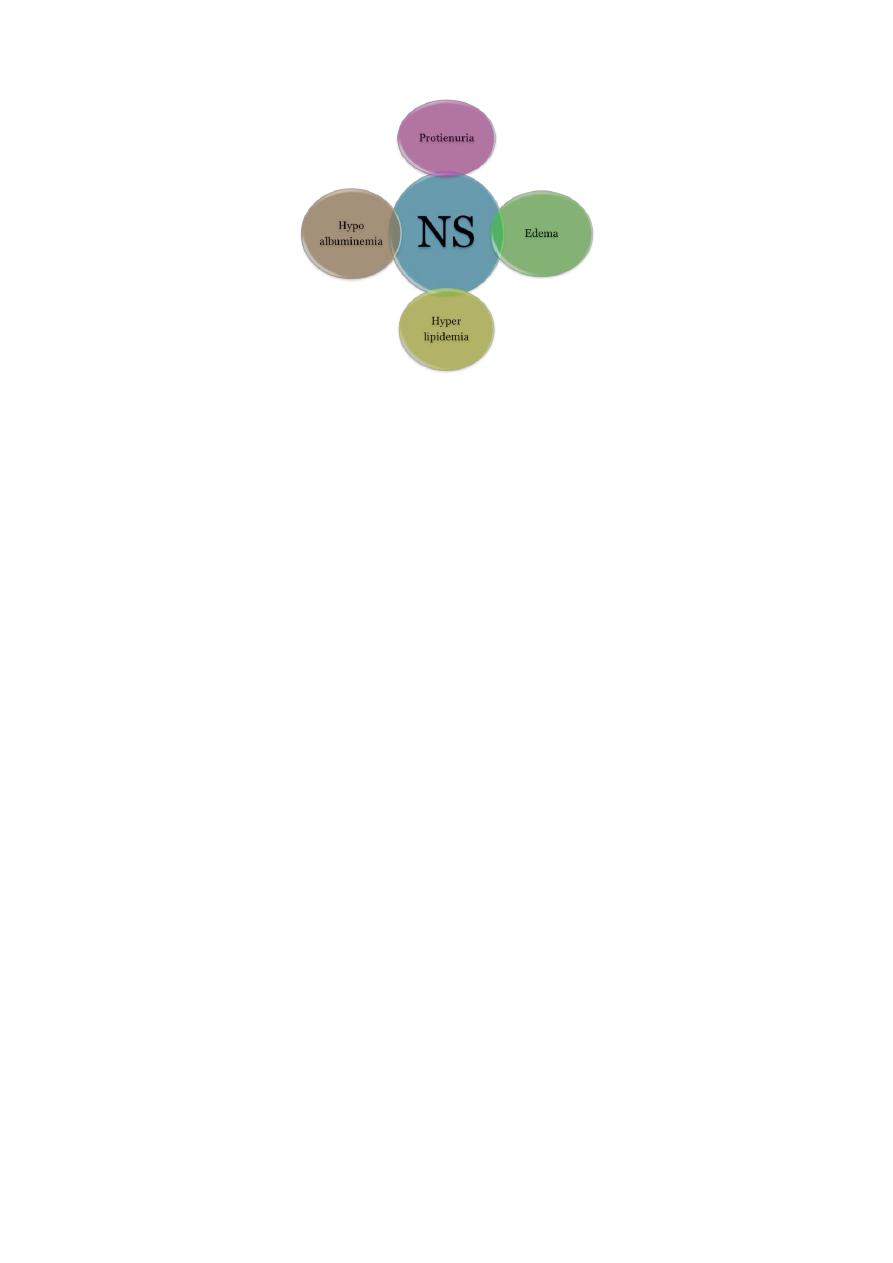

Nephrotic syndrome, is a manifestation of glomerular disease. Characterized by:

1) Heavy proteinuria (Nephrotic range proteinuria is defined protein excretion of >

40 mg/m2/hr or a first morning protein : creatinine ratio of >2-3 : 1).

2) Hypoalbuminemia(serum albumin <2.5 g/dL)

3) Edema.

4) Hyperlipidemia (serum cholesterol >250 mg/dL).

5) The annual incidence is 2-3 cases per 100,000 children per year.

Etiology :

1. Most children with nephrotic syndrome have a form of primary or idiopathic

nephrotic syndrome. Glomerular lesions associated with idiopathic nephrotic

syndrome include:

▫ minimal change disease (the most common).

▫ focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.

▫ membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

▫ membranous nephropathy.

▫ diffuse mesangial proliferation

2. Nephrotic syndrome may also be secondary to systemic diseases such as:

▫ Infections (hepatitis, HIV, malaria, toxoplasmosis)

▫ Drugs (gold, penicillamine, NSAI, Interferon)

▫ Immunologic or allergic disorders(bee sting, food allergens)

▫ Associated with malignant disease(Lymphoma & Leukemia)

3. A number of hereditary proteinuria syndromes are caused by mutations in genes

that encode critical protein components of the glomerular filtration apparatus such

as:

▫ Finnish-type congenital nephrotic syndrome

▫ Denys-Drash syndrome

2

Pathophysiology

:

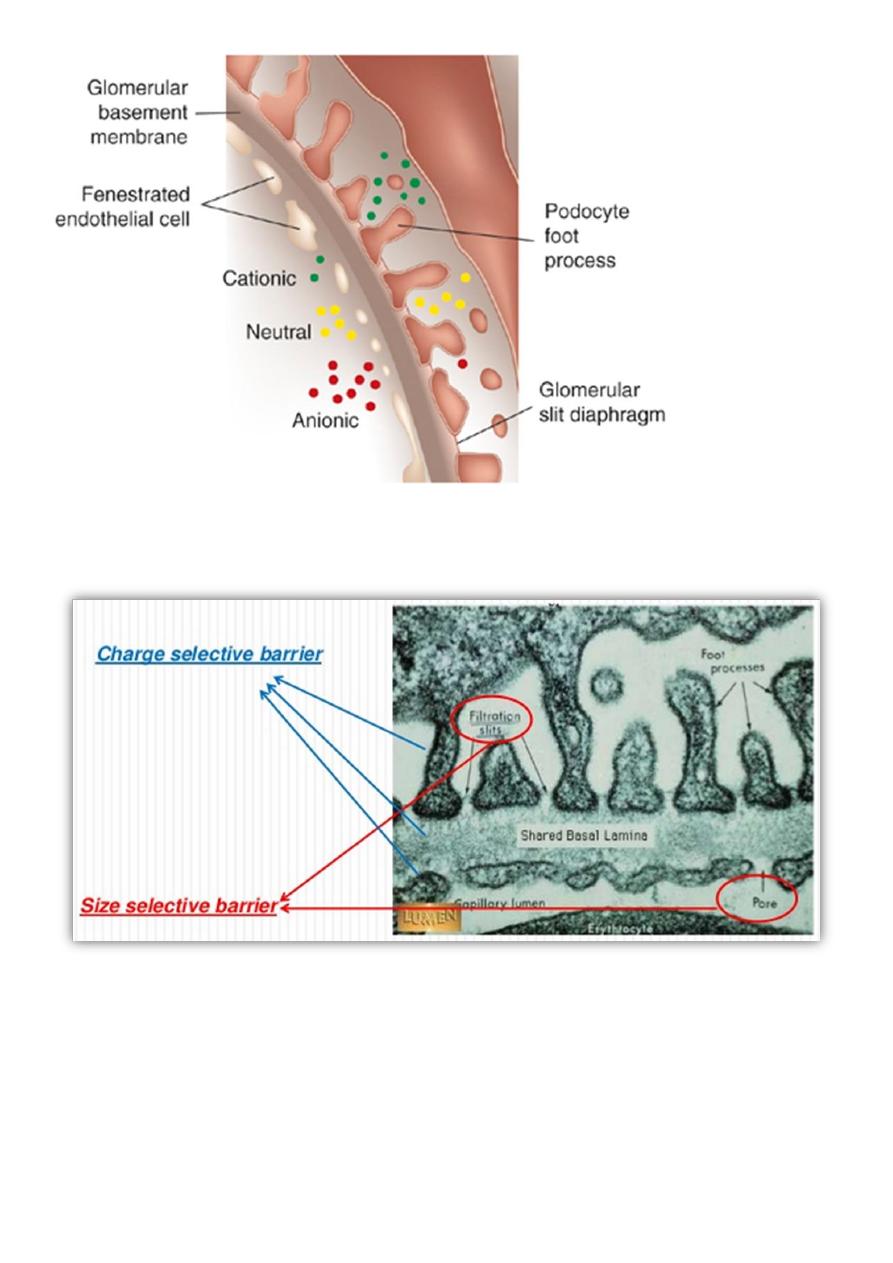

For understanding pathophysiology of NS should know the Normal Glomerular barrier &

Function.

One of the kidney’s most important functions is filtration of the blood by glomeruli,

allowing excretion of fluid and waste products, while retaining all blood cells and the

majority of blood proteins within the bloodstream.

Glomerular filter acts via two phenomenon size selectivity and charge selectivity.

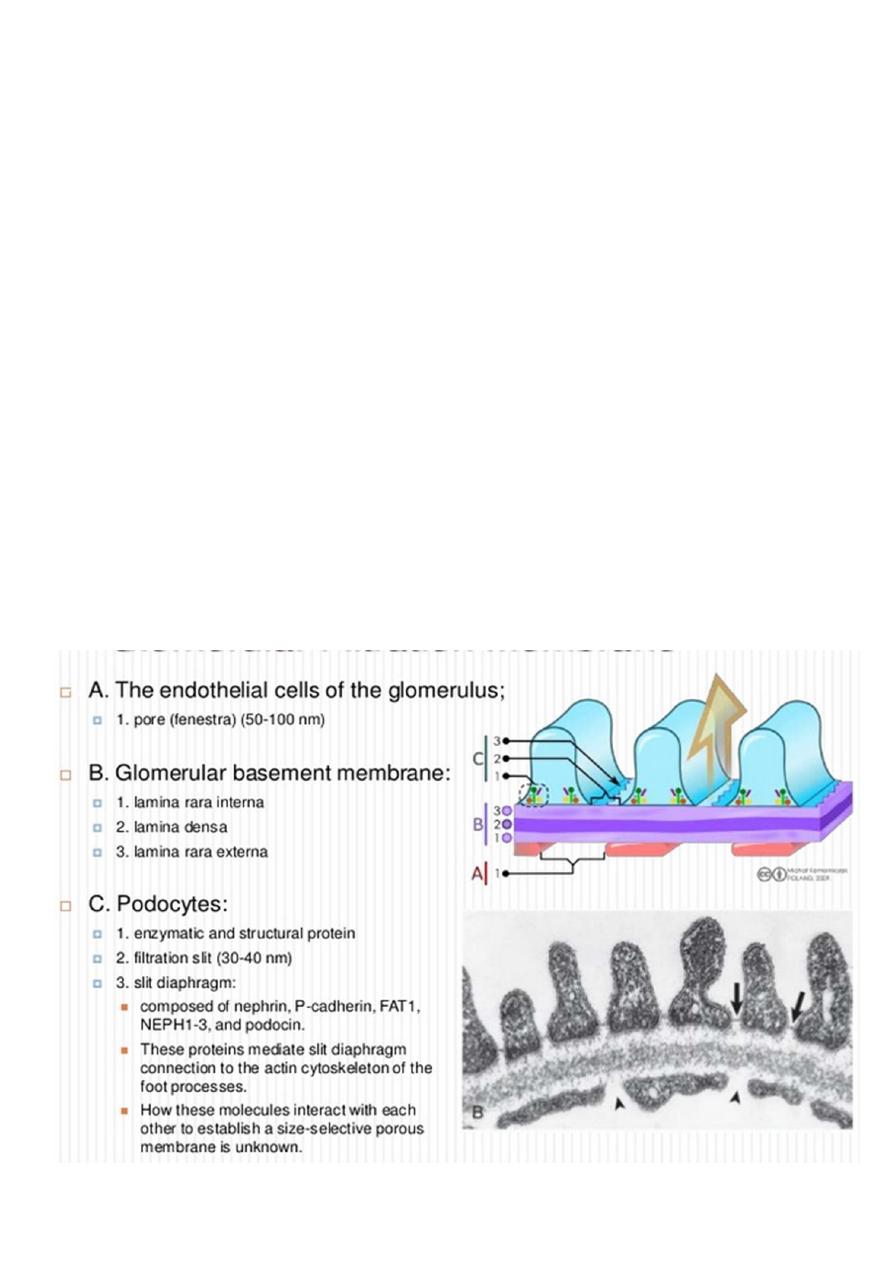

Each glomerulus is composed of numerous capillaries which have evolved to permit

ultrafiltration of the fluid that eventually forms urine. The capillary walls are

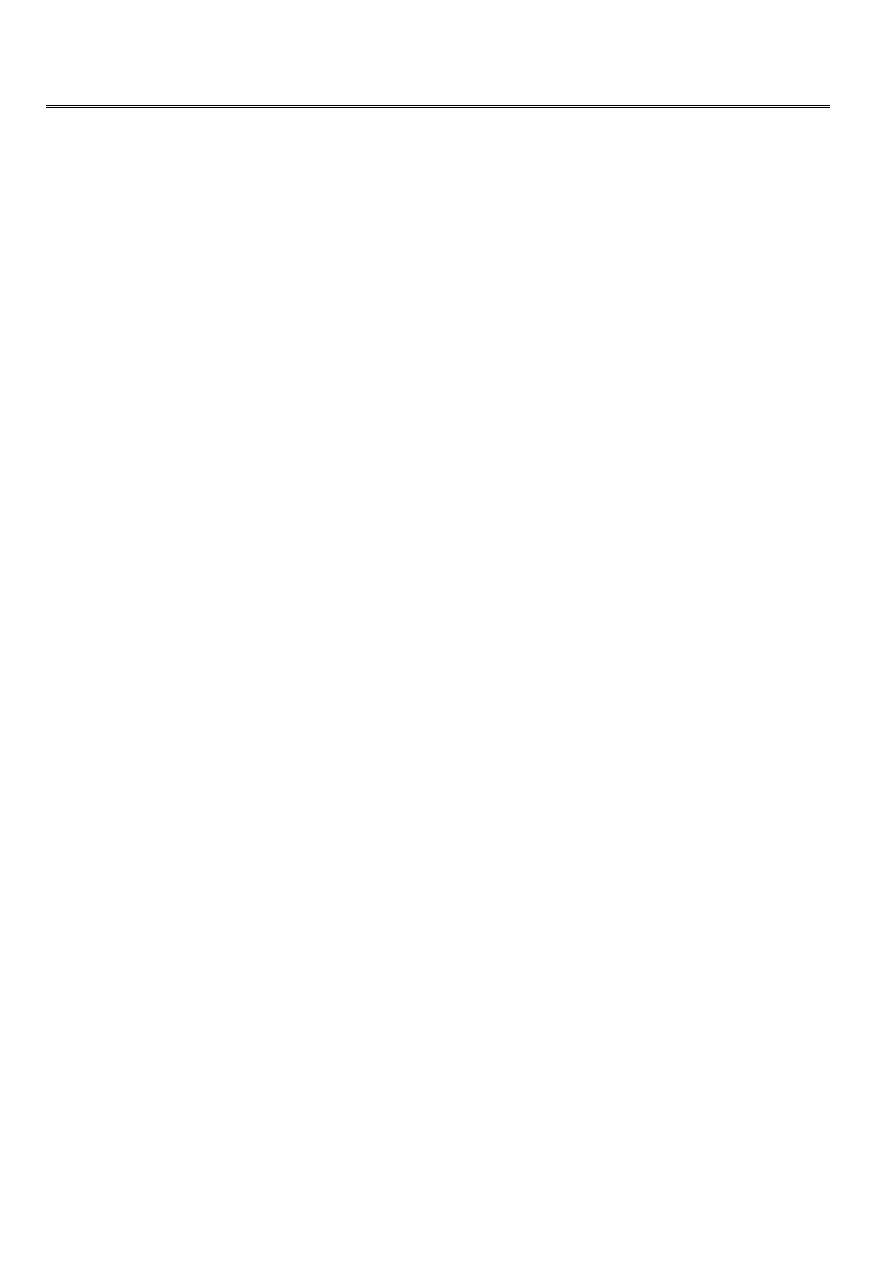

composed of :

▫ an inner endothelial cell cytoplasm, with pores known as ‘fenestrations’.

▫ GBM.

▫ external, epithelial cell (podocytes), the epithelial cells are large, with

specialized cytoplasmic extensions known as foot processes, which firmly

anchor them to the GBM. The adjacent foot processes do not come into

contact with each other and are separated by ~40 nm wide spaces known as

filtration slits. These slits are bridged by a continuous membrane-like structure

known as the slit diaphragm

3

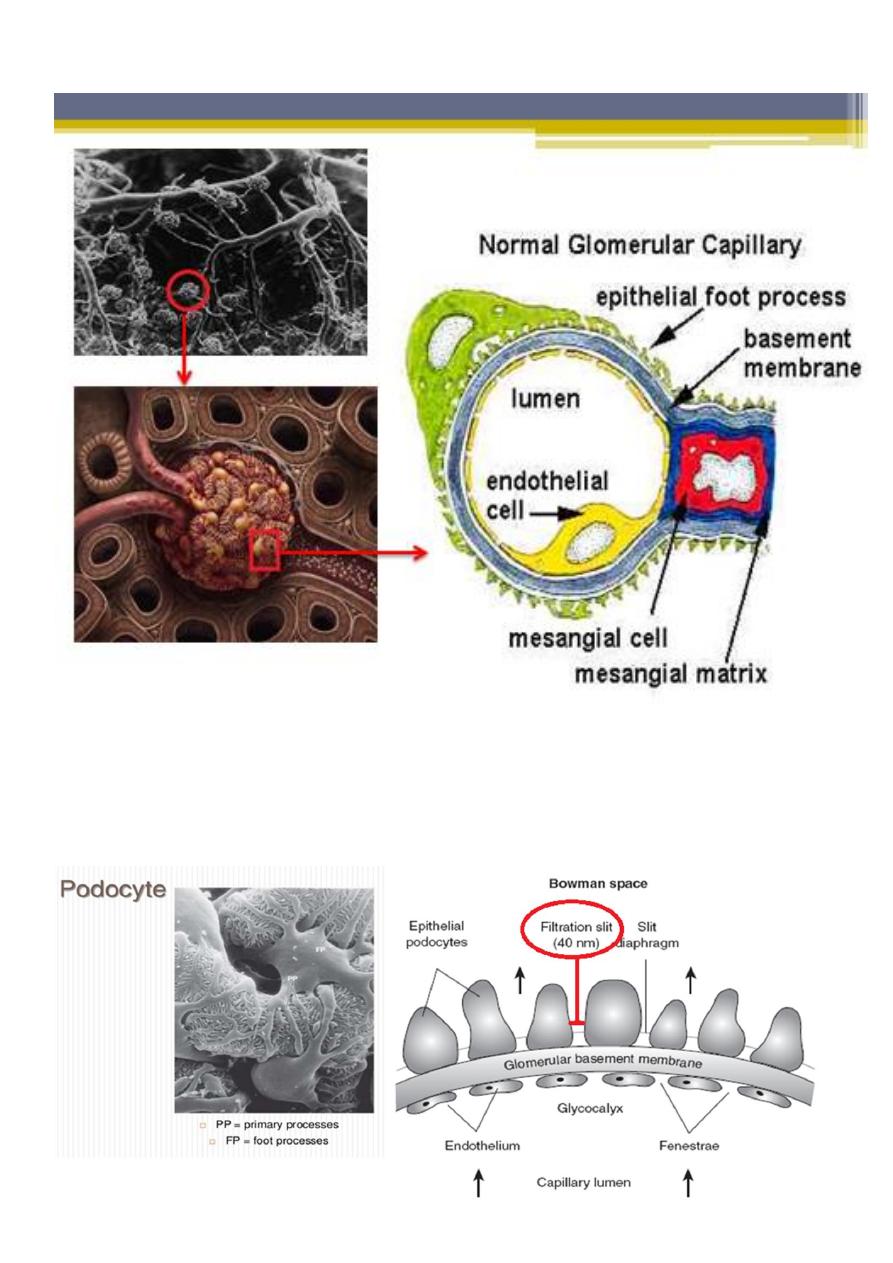

Size selectivity:

under normal conditions, molecules greater than 42 Å in diameter are unable to cross the

filtration barrier.

4

Charge selectivity:

• In addition to molecular size, molecular charge has also been shown to influence the

clearance of macromolecules from the glomerular capillary.

• Electrical charge is an important determining factor for the passage of protein

molecules through the glomerular filtration barrier. Several reports have indicated a

reduction in the negative charge of the GBM in nephrotic syndrome

• This has led to the concept that the passage of anionic molecules such as plasma

proteins is actively hindered by the anionic surface charge of the glomerular filter

• Negative charge is thought to retard filtration of anionic molecules (red) such as

albumin, facilitate filtration of cationic molecules (green), and have little impact on

neutral molecules (yellow).

5

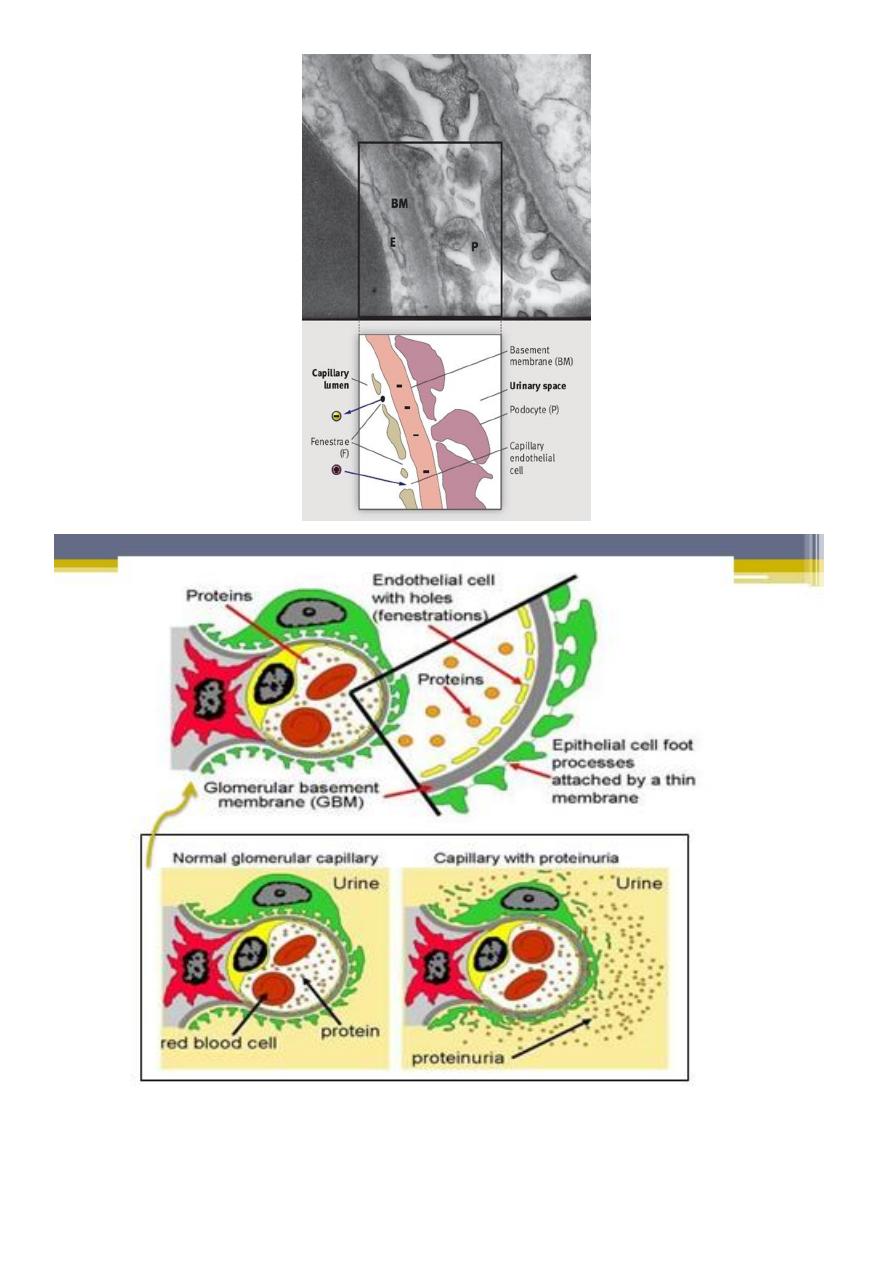

Glomerular Filtration Membrane charge & size selective barrier :

6

Pathophysiology in NS:

1. Proteinuria:

The underlying abnormality in nephrotic syndrome is an increased

permeability of the glomerular capillary wall, which leads to massive

proteinuria.

In idiopathic NS found that it is associated with complex disturbances in the

immune system, especially T cell–mediated immunity which lead to :

Extensive effacement of podocyte foot processes (the hallmark of

idiopathic nephrotic syndrome) suggests a vital role for the podocyte,

which is normally prevent passage of large molecule as albumin.

loss of the glomerular basement membrane sialoproteins, which leads to

a loss of the normal negative charge responsible for the increase in

capillary wall permeability.(normally prevent passage of anionic

molecules as albumin)

In focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, a plasma factor, probably produced by a

subset of activated lymphocytes, may be responsible for the increase in

capillary wall permeability.

Changes to capillary endothelial cells, GBM, or podocytes, which

normally filter serum protein selectively by size and charge.

Glomerular Proteinuria develops when there is alteration in either

charge selectivity and size selectivity

7

8

2. Hypoalbuminemia:

Massive proteinuria that results leads to a decline in serum proteins, especially

albumin.

3. Edema:

Although the mechanism of edema formation in nephrotic syndrome is

incompletely understood, it seems likely that in most instances, massive

urinary protein loss leads to hypoalbuminemia, which causes a decrease in

plasma oncotic pressure and transudation of fluid from the intravascular

compartment to the interstitial space. The reduction in intravascular volume

decreases renal perfusion pressure, activating the renin-angiotensin-

aldosterone system, which stimulates tubular reabsorption of sodium. The

reduced intravascular volume also stimulates the release of antidiuretic

hormone, which enhances the reabsorption of water in the collecting duct.

This theory does not apply to all patients with nephrotic syndrome because

some patients actually have increased intravascular volume with diminished

plasma levels of renin and aldosterone. Therefore, other factors, including

primary renal avidity for sodium and water, may be involved in the formation

of edema in some patients with nephrotic syndrome.

4. Hyperlipidemia:

In the nephrotic state, serum lipid levels (cholesterol, triglycerides) are elevated for 2

reasons:

Hypoalbuminemia stimulates generalized hepatic protein synthesis, including

synthesis of lipoproteins. This is also why a number of coagulation factors are

increased, increasing the risk of thrombosis.

In addition, lipid catabolism is diminished as a result of reduced plasma levels

of lipoprotein lipase related to increased urinary losses of this enzyme.

9

Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome :

Approximately 90% of children with nephrotic syndrome have idiopathic nephrotic

syndrome. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome is associated with primary glomerular disease

without evidence of a specific systemic cause.

Pathology :

Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome includes multiple histologic types:

1. minimal change disease: about 85% of total cases of nephrotic syndrome in

children, 95% are steroid responsive .

2. mesangial proliferation: 50% are steroid responsive .

3. focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: only 20% are steroid responsive, the

disease is often progressive, ultimately involving all glomeruli, and ultimately

leads to end-stage renal disease in most patients.

4. membranous nephropathy.

5. membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

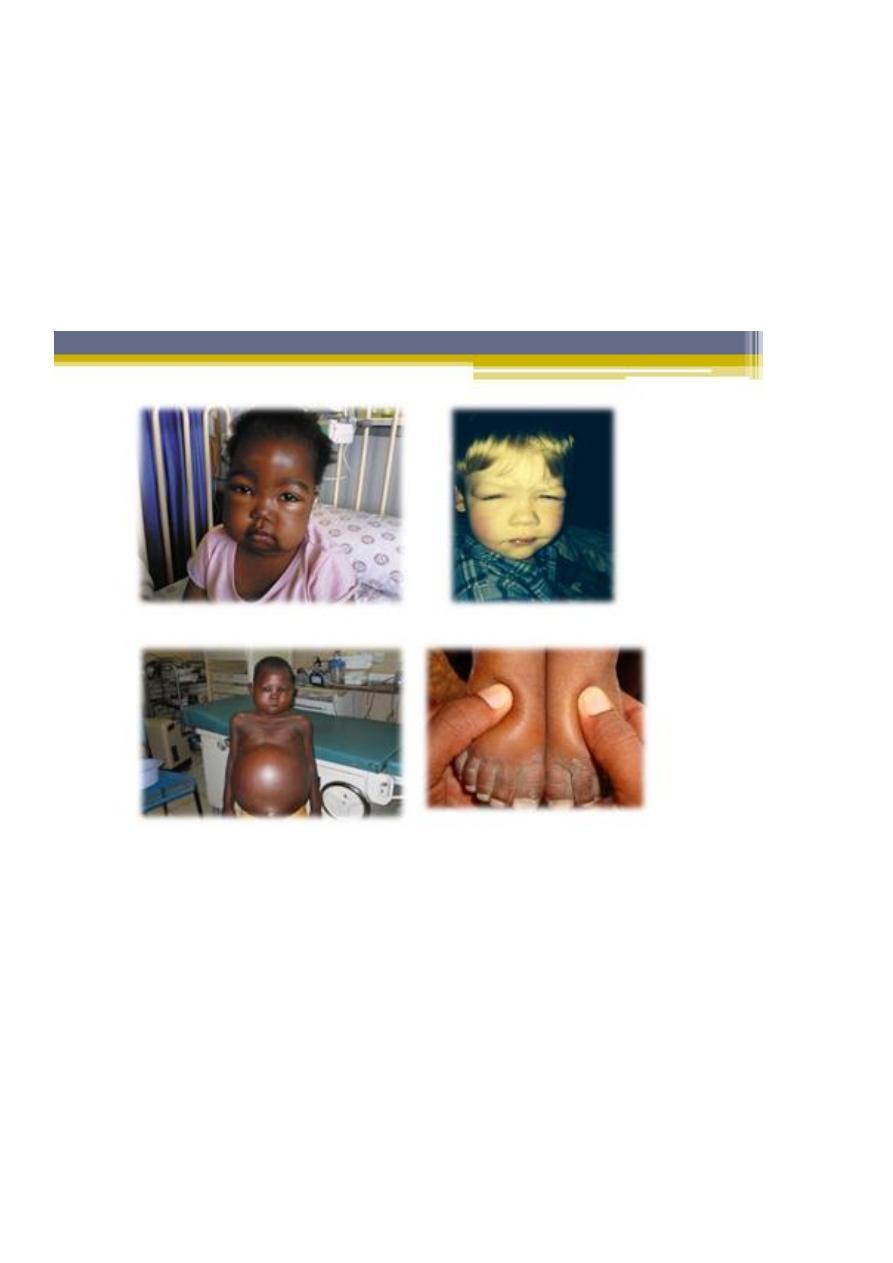

Clinical Manifestations :

1. The idiopathic nephrotic syndrome is more common in boys than in girls (2 : 1).

2. Most commonly appears between the ages of 2 and 6 yr. However, it has been

reported as early as 6 mo of age and throughout adulthood.

3. MCNS is present in 85-90% of patients <6 yr of age. In contrast, only 20-30% of

adolescents who present for the first time with nephrotic syndrome have MCNS. The

more common cause of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in this older age group is

FSGS.

4. The initial episode of INS, as well as subsequent relapses, usually follows minor

infections and, uncommonly, reactions to insect bites, bee stings, or poison ivy.

5. Children usually present with mild edema, which is initially noted around the eyes

and in the lower extremities.

6. Nephrotic syndrome can initially be misdiagnosed as an allergic disorder because of

the periorbital swelling that decreases throughout the day. With time, the edema

becomes generalized, with the development of ascites, pleural effusions, and genital

edema.

7. Anorexia, irritability, abdominal pain, and diarrhea are common. Important features

of minimal change idiopathic nephrotic syndrome are the absence of hypertension

and gross hematuria (previously termed nephritic features).

8. A diagnosis other than MCNS should be considered in:

10

▫ children <1 yr of age.

▫ a positive family history of nephrotic syndrome.

▫ presence of extrarenal findings (e.g., arthritis, rash, anemia).

▫ hypertension or pulmonary edema.

▫ acute or chronic renal insufficiency.

▫ gross hematuria.

Differential Diagnosis :

The differential diagnosis of the child with marked edema includes:

protein-losing enteropathy.

hepatic failure.

heart failure.

acute or chronic glomerulonephritis.

protein malnutrition.

11

Diagnosis :

1. Urinalysis :

Proteinuria: 3+ or 4+

Urinary protein excretion exceeds 40 mg/m2/hr.

A spot urine protein: creatinine ratio exceeds 2.0.

Microscopic hematuria is present in 20%.

Serum creatinine value is usually normal, but it may be abnormally

elevated if there is diminished renal perfusion from contraction of the

intravascular volume.

2. Serum albumin level is <2.5 g/dL.

3. Serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels are elevated.

4. Serum complement levels are normal.

5. Renal biopsy: if there is atypical feature( suggest other than MCNS):

Gross hematuria.

Hypertension.

Renal insufficiency.

Hypocomplementemia.

Age <1 yr or >8 yr.

Frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome.

Steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome.

Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome .

Treatment :

1. Children with their first episode of nephrotic syndrome and mild to moderate edema

may be managed as outpatients.

2. The pathophysiology and treatment of nephrotic syndrome must be carefully

reviewed with the family to enhance understanding of their child's disease. The

child's parents must be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of the

complications of the disease and its treatment and must be taught how to use and

interpret the results of urinary dipstick testing for protein.

3. Children with nephrotic syndrome should attend school and participate in physical

activities as tolerated.

4. Low sodium diet until remission.

12

5. Oral diuretics used with cautious if needed because the risk of thromboembolic

complication.

Indication for hospitalization:

1. Initial episode may need hospitalization for teaching of parents.

2. Children with severe symptomatic edema, including:

▫ Large pleural effusions.

▫ Ascites.

▫ Severe genital edema.

▫ Infection (e.g., severe cellulitis, peritonitis)

3. Compromised renal function

4. Significant hypertension

5. Significant electrolyte abnormalities

Treatment in hospital:

1. Sodium restriction.

2. Fluid restriction may be necessary if the child is hyponatremic.

3. A swollen scrotum may be elevated with pillows to enhance fluid removal by gravity.

4. Diuresis may be augmented by the administration of loop diuretics (furosemide),

orally or intravenously, with caution.

5. IV administration of 25% albumin (0.5-1.0 g albumin/kg), as a slow infusion followed

by furosemide (1-2 mg/kg/dose IV) is sometimes necessary when a patient has

significant generalized edema with evidence of intravascular volume depletion (e.g.,

hemoconcentration). Such therapy mandates close monitoring of volume status,

blood pressure, serum electrolyte balance, and renal function. Symptomatic volume

overload, with hypertension, heart failure, and pulmonary edema is a potential

complication of parenteral albumin therapy, particularly when administered as rapid

infusions.

6. Children with typical feature suggestive MCNS, prednisone is started without need

for biopsy.

7. prednisone should be administered at a dose of 60 mg/m2/day or 2 mg/kg/day

(maximum daily dose, 60 mg) in a single daily dose for 4-6 consecutive wk.

8. An initial 6-wk course of daily steroid treatment leads to a significantly lower relapse

rate than previously recommended shorter courses of daily therapy.

9. About 80-90% of children respond to steroid therapy (clinical remission, diuresis, and

urine trace or negative for protein for 3 consecutive days) within 3 wk. The vast

majority of children who respond to prednisone therapy do so within the first 5 wk of

treatment.

13

After the initial 6-wk course, the prednisone dose should be tapered to

40 mg/m2/day given every other day as a single daily dose for at least 4 wk.

The alternate-day dose is then slowly tapered and discontinued over the next 1-2 mo.

There is evidence that both an increased dose of steroids and a prolonged duration

of therapy are important factors in reducing the risk of relapse, but the frequency of

SE is higher.

Children who continue to have proteinuria (2+ or greater) after 8 wk of steroid

therapy are considered steroid resistant, and a diagnostic renal biopsy should be

performed.

Relapse :

• Many children with nephrotic syndrome experience at least 1 relapse (3-4+

proteinuria plus edema). Although relapse rates decrease after treated with longer

initial steroid courses.

• Relapses should be treated with 60 mg/m2/day (80 mg daily max) in a single am dose

until the child enters remission (urine trace or negative for protein for 3 consecutive

days). The prednisone dose is then changed to alternate-day dosing as noted with

initial therapy, and gradually tapered over 1-2month.

• Patients who respond well to prednisone therapy but relapse ≥4 times in a 12-mo

period are termed frequent relapsers.

• A subset of patients relapse while on alternate-day steroid therapy or within 28 days

of completing a successful course of prednisone therapy. Such patients are termed

steroid dependent.

• Children who fail to respond to prednisone therapy within 8 wk of therapy are

termed steroid resistant. Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome is usually caused by

FSGS (80%), MCNS, or mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis.

Alternative therapies :

Steroid-dependent patients, frequent relapsers, and steroid-resistant patients are

candidates for alternative therapies, particularly if the child has severe corticosteroid

toxicity (cushingoid appearance, hypertension, cataracts, and/or growth failure).

Cyclophosphamide

Cyclosporine or tacrolimus

Mycophenolate

14

Levamisole

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II blockers may be

helpful as adjunct therapy to reduce proteinuria in steroid-resistant patients.

Complications :

1. Infection: is a major complication of nephrotic syndrome. Children in relapse have

increased susceptibility to bacterial infections because of:

▫ urinary losses of immunoglobulins and properdin factor B.

▫ defective cell-mediated immunity.

▫ their immunosuppressive therapy.

▫ Malnutrition.

▫ edema or ascites acting as a potential culture medium.

▫ Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a common infection. Although

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common organism causing peritonitis,

gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli may also be encountered.

Because fever & physical finding may be minimal in presence of steroid

therapy, the patient's caregivers should be counseled to seek medical

attention if the child appears ill, has a fever, or complains of persistent

abdominal pain. A high index of suspicion for bacterial peritonitis, prompt

evaluation (including cultures of blood and peritoneal fluid), and early

initiation of antibiotic therapy are critical.

▫ Sepsis.

▫ Pneumonia.

▫ Cellulitis.

▫ Urinary tract infections.

2. Thromboembolic events:

▫ The incidence of this complication in children is 2-5%.

▫ Both arterial and venous thromboses may be seen, including renal vein

thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, sagittal sinus thrombosis, and thrombosis of

indwelling arterial and venous catheters.

▫ The risk of thrombosis is related to:

Increased prothrombotic factors (fibrinogen, thrombocytosis,

hemoconcentration, relative immobilization).

15

Decreased fibrinolytic factors (urinary losses of antithrombin III, proteins

C and S).

▫ Prophylactic anticoagulation is not recommended in children unless a previous

thromboembolic event has occurred.

▫ To minimize the risk of thromboembolic complications, aggressive use of

diuretics and the use of indwelling catheters should be avoided if possible.

Prognosis :

Steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome:

Most children with steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome have repeated

relapses, which generally decrease in frequency as the child grows older.

Although there is no proven way to predict an individual child's course,

children who respond rapidly to steroids and those who have no relapses

during the first 6 mo after diagnosis are likely to follow an infrequently

relapsing course.

It is important to indicate to the family that the child with steroid-responsive

nephrotic syndrome is unlikely to develop chronic kidney disease, that the

disease is rarely hereditary, and that the child (in the absence of prolonged

cyclophosphamide therapy) will remain fertile.

To minimize the psychologic effects of the condition and its therapy, children

with idiopathic nephritic syndrome should not be considered chronically ill and

should participate in all age-appropriate childhood activities and maintain an

unrestricted diet when in remission.

Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome:

Children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, most often caused by

FSGS, generally have a much poorer prognosis.

These children develop progressive renal insufficiency, ultimately leading to

end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation.

Recurrent nephrotic syndrome develops in 30-50% of transplant recipients

with FSGS.

16

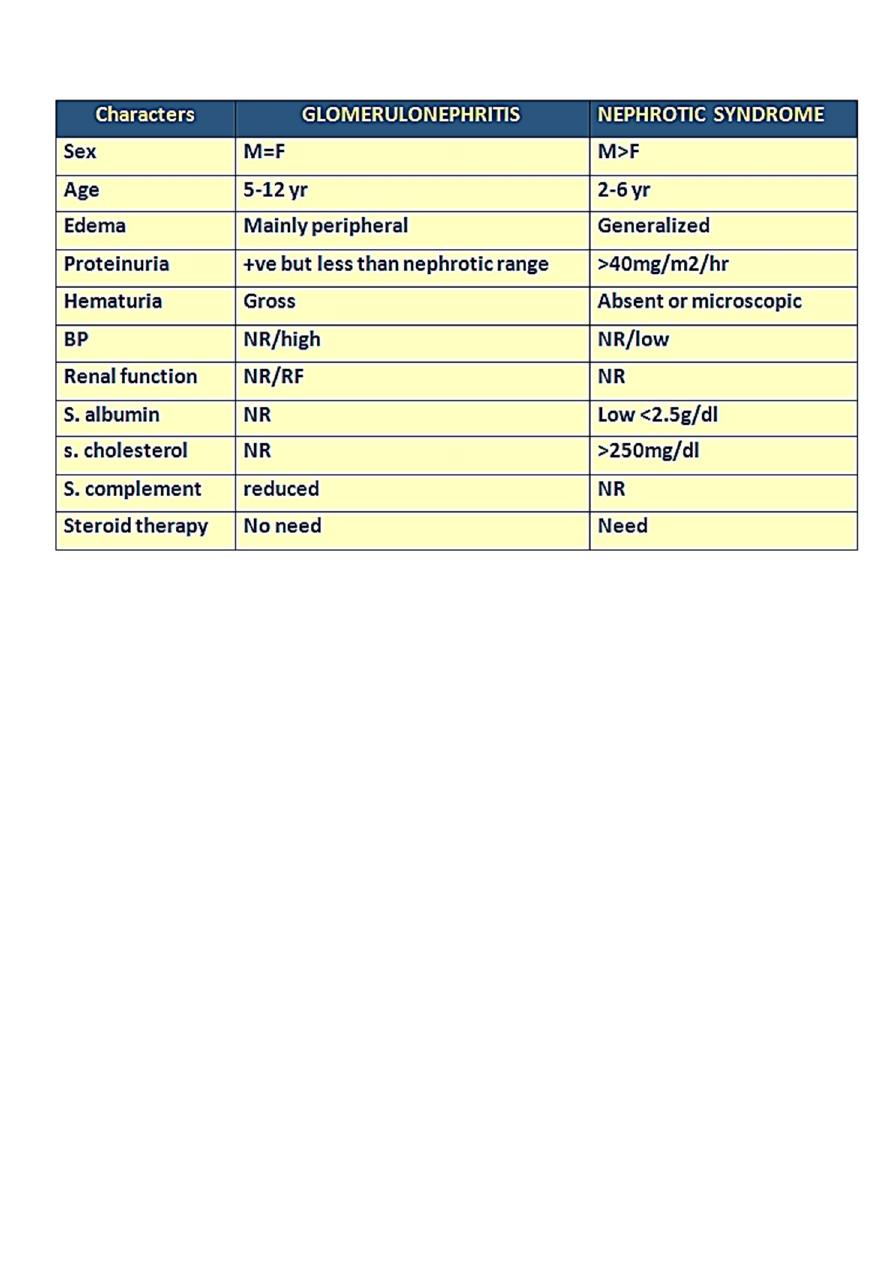

The difference between APGN & NS :