1

L1

Esophagus

Lesions of the esophagus run from bland esophagitis to highly lethal cancers, yet they evoke

a similar and remarkably limited range of symptoms.

All produce dysphagia, Heartburn (retrosternal burning pain). Hematemesis (vomiting of

blood) and melena (blood in the stools) are evidence of severe inflammation, ulceration, or

laceration of the esophageal mucosa.

Massive hematemesis may reflect life- threatening rupture of esophageal varices.

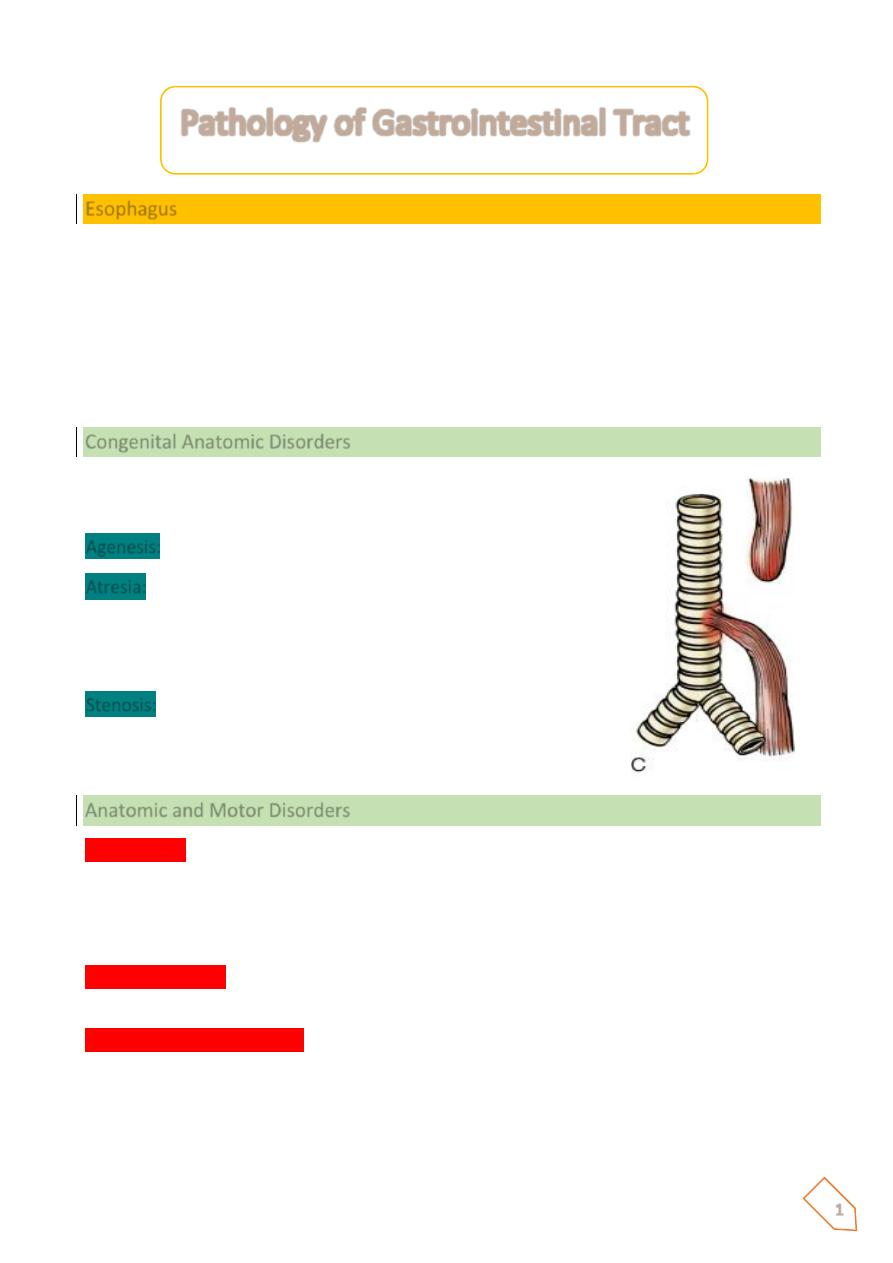

Congenital Anatomic Disorders

Present at birth with vomiting, aspiration (pneumonia, asphyxia),

and gastric distention

Agenesis:

absence of esophagus. Very rare

Atresia:

failure of development of a segment of esophagus,

which is replaced by a thin non-canalized cord (absence of

lumen) with formation of upper & lower pouches; associated

with tracheo-esophageal fistula

Stenosis:

developmental defect resulting in partial obstruction or

narrowing of the esophageal lumen

Rx: Urgent medical & surgical intervention

Anatomic and Motor Disorders

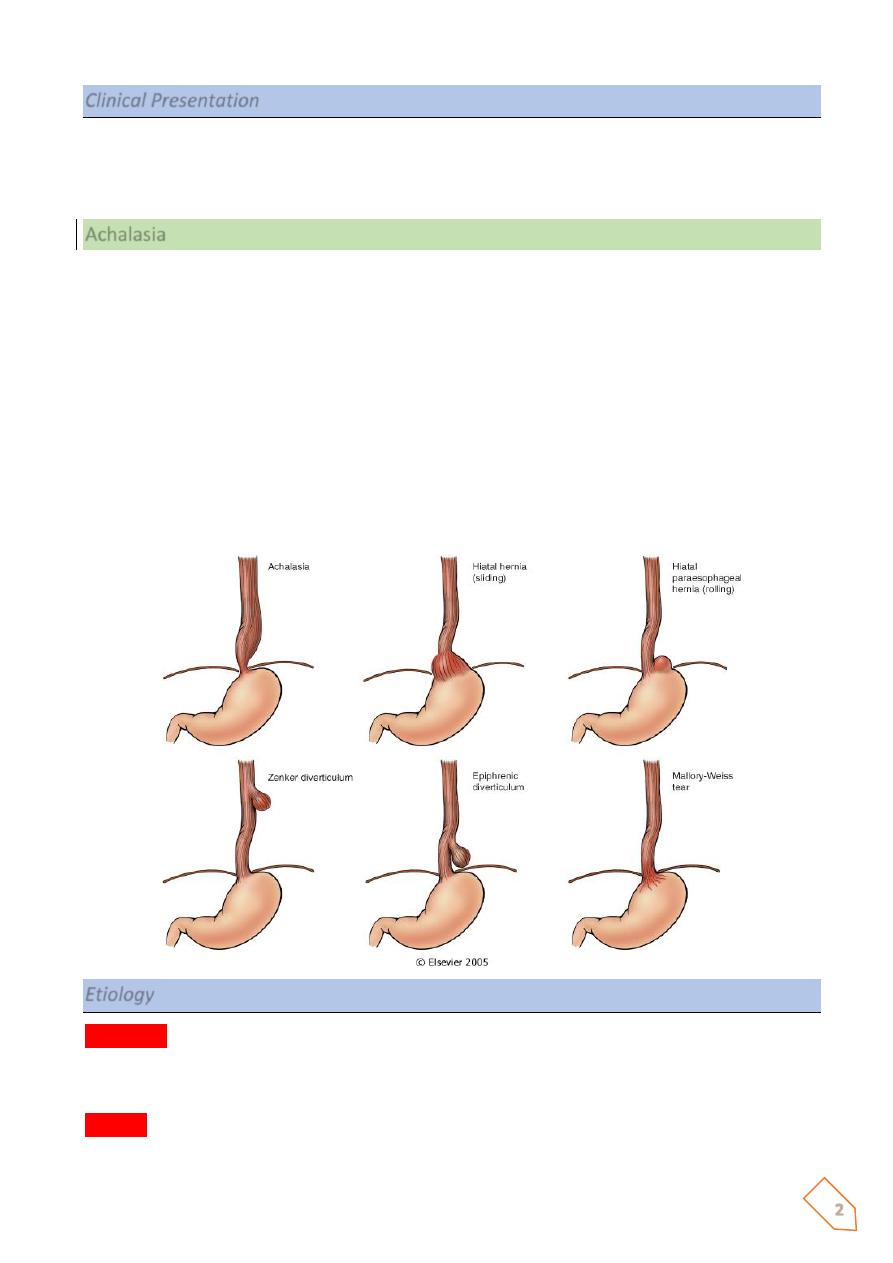

Hiatal hernia

In hiatal hernia, separation of the diaphragmatic crura and widening of the space

between the muscular crura and the esophageal wall permits a dilated segment of the

stomach to protrude above the diaphragm. Two anatomic patterns are recognized :

1- the axial, or sliding, hernia 2- and the nonaxial, or paraesophageal, hernia.

The sliding hernia

constitutes 95% of cases; protrusion of the stomach above the diaphragm

creates a bell-shaped dilation, bounded below by the diaphragmatic narrowing

In paraesophageal hernias

, a separate portion of the stomach, usually along the greater

curvature, enters the thorax through the widened foramen.

The cause of this deranged anatomy is obscure. On the basis of radiographic studies, hiatal

hernias are reported in 1% to 20% of adult subjects, increasing in incidence with age.

Pathology of Gastrointestinal Tract

2

Clinical Presentation

Adult with progressive dysphagia to solids and eventually to all foods; heartburn or

regurgitation of gastric juices into the mouth. These symptoms result from incompetence of

the lower esophageal sphincter than from the hiatal hernia per se

Achalasia

The term achalasia means “failure to relax” and in the present context denotes incomplete

relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter in response to swallowing. This produces

functional obstruction of the esophagus, with consequent dilation of the more proximal

esophagus. Manometric studies show three major abnormalities in achalasia:

1. aperistalsis,

2. partial or incomplete relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter with swallowing, and

3. Increased resting tone of the lower esophageal sphincter.

It is now generally accepted that in primary achalasia there is loss of intrinsic inhibitory

innervation of the lower esophageal sphincter and smooth muscle segment of the esophageal

body.

Etiology

Secondary

achalasia may arise from pathologic processes that impair esophageal function.

The classic example is Chagas disease, caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, which causes

destruction of the myenteric plexus of the esophagus, duodenum, colon, and ureter.

Primary

disorder of uncertain etiology. Autoimmunity and previous viral infection have been

hypothesized but remain unproven

3

Morphology

ⱴ In primary achalasia, there is progressive dilation of esophagus above the level of the

lower esophageal sphincter.

ⱴ The wall of the esophagus may be of normal thickness, thicker than normal because of

hypertrophy of the muscularis, or markedly thinned by dilation.

ⱴ The myenteric ganglia are usually absent from the body of the esophagus -

Inflammation in the location of the esophageal myenteric plexus is pathognomonic of

the disease.

C/P: progressive dysphagia and inability to completely convey food to the stomach. Nocturnal

regurgitation and aspiration of undigested food may occur. It usually becomes manifest in

young adulthood, but it may appear in infancy or childhood.

Complication

Is the hazard of developing esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, reported to occur in about

5% of patients and typically at an earlier age than in those without achalasia.

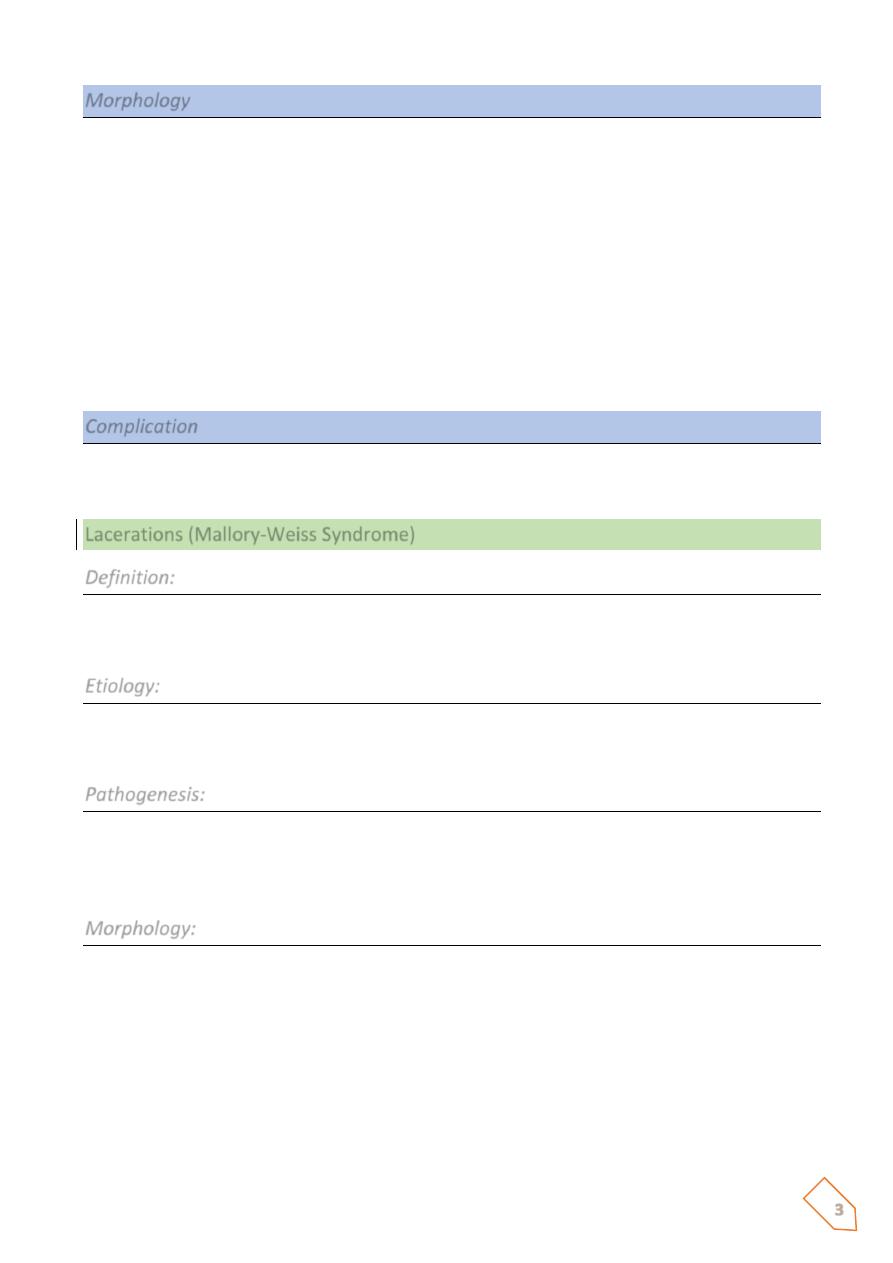

Lacerations (Mallory-Weiss Syndrome)

Definition:

Longitudinal tears in the esophagus at the esophagogastric junction are termed Mallory-

Weiss tears.

Etiology:

They are encountered in chronic alcoholics after a bout of severe retching or vomiting, but

they may also occur during acute illnesses with severe vomiting.

Pathogenesis:

May be due to inadequate relaxation of the musculature of the lower esophageal sphincter

during vomiting, with stretching and tearing of the esophagogastric junction at the moment

of propulsive expulsion of gastric contents.

Morphology:

Tears may involve only the mucosa or may penetrate the wall. Infection of the defect may

lead to an inflammatory ulcer or to mediastinitis. Most often bleeding is not profuse and

ceases without surgical intervention, but life-threatening hematemesis may occur. Even with

severe blood loss, supportive therapy with vasoconstrictive medications, transfusions, and

sometimes balloon tamponade, is usually all that is required. Healing is usually prompt, with

minimal to no residua

4

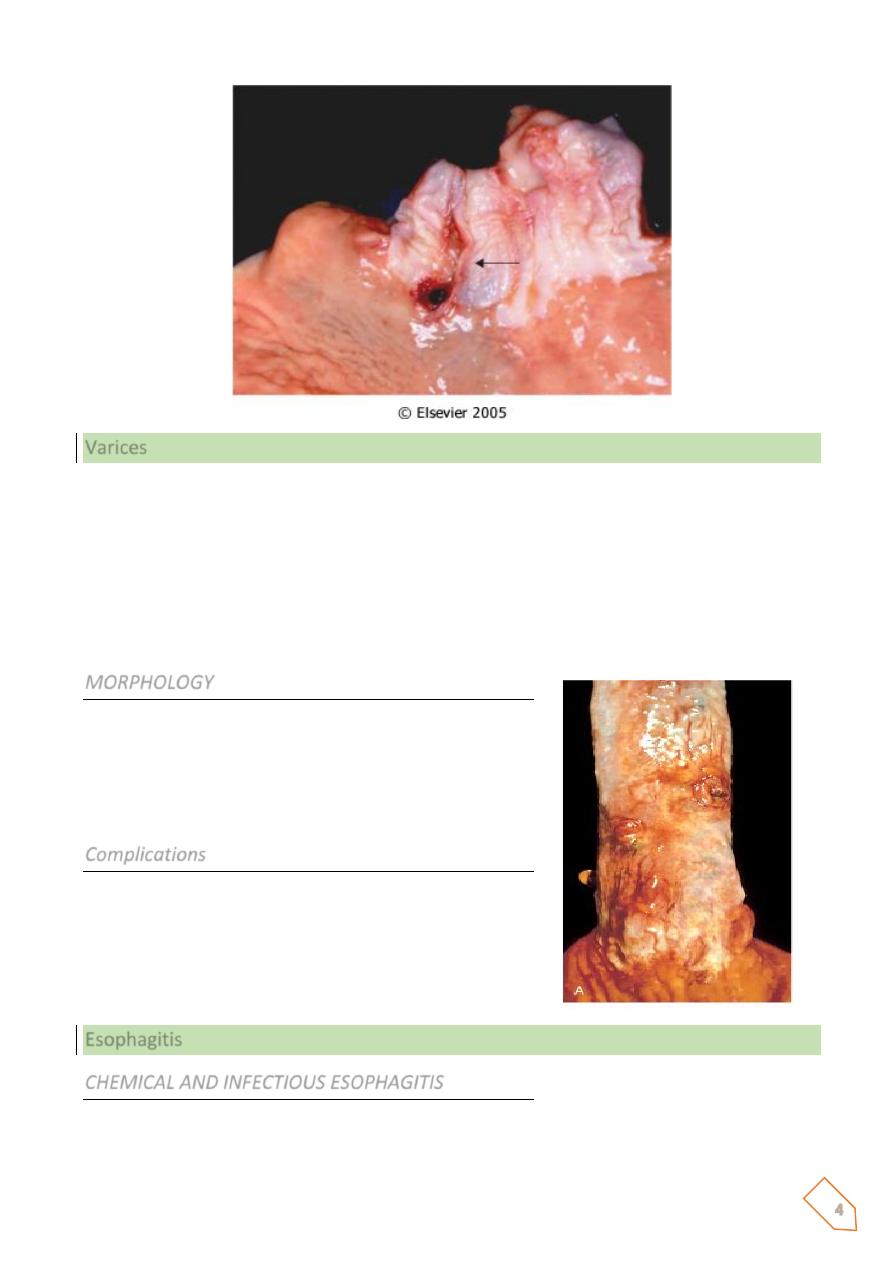

Varices

One of the few potential sites for communication between the intra-abdominal splanchnic

circulation and the systemic venous circulation is through the esophagus. When portal

Venous blood flow into the liver is impeded by cirrhosis or other causes the resultant portal

hypertension induces the formation of collateral bypass channels wherever the portal and

systemic systems communicate. The increased pressure in the esophageal plexus produces

dilated tortuous vessels called varices. They are most often associated with alcoholic

cirrhosis.

MORPHOLOGY

Varices appear primarily as tortuous dilated veins lying

primarily within the submucosa of the distal esophagus

and proximal stomach.

Varices produce no symptoms until they rupture.

Complications

Rupture of varices. The factors leading to initial rupture

of a varix are unclear: silent erosion of overlying thinned

mucosa, increased tension in progressively dilated

veins, and vomiting with increased intra-abdominal

pressure are likely to be involved.

Esophagitis

CHEMICAL AND INFECTIOUS ESOPHAGITIS

The stratified squamous mucosa of the esophagus may be damaged by a variety of irritants

including alcohol, corrosive acids or alkalis, excessively hot fluids, and heavy smoking.

5

The esophageal mucosa may also be injured when medicinal pills lodge and dissolve in the

esophagus rather than passing into the stomach intact, a condition termed pill-induced

esophagitis.

C/P:Esophagitis due to chemical injury generally only dysphagia (pain with swallowing).

Hemorrhage, stricture, or perforation may occur in severe cases.

Infectious esophagitis may occur in otherwise healthy individuals but are most frequent in

those who are debilitated or immunosuppressed as a result of disease or therapy.

REFLUX ESOPHAGITIS

GE reflux disease affects about 0.5% is of the US adult population. Dominant symptom

recurrent heartburn.

Etiology:

• Decrease efficacy of esophageal antireflux mechanisms.

• Inadequate or slowed esophageal clearance of refluxed material.

• Sliding hiatal hernia. Fat, chocolate, alcohol, smoking

• Increased gastric volume.

• Impaired reparative capacity of the esophagus mucosa by prolonged exposure to

gastric juices.

MORPHOLOGY

The anatomic Changes depend on the causative agent and on the duration and severity of

the exposure. Mild esophagitis may appear macroscopically as simple hyperemia, with

virtually no histologic abnormality. In Contrast the mucosa in severe esophagitis exhibits

confluent epithelial erosions or total ulceration into the submucosa

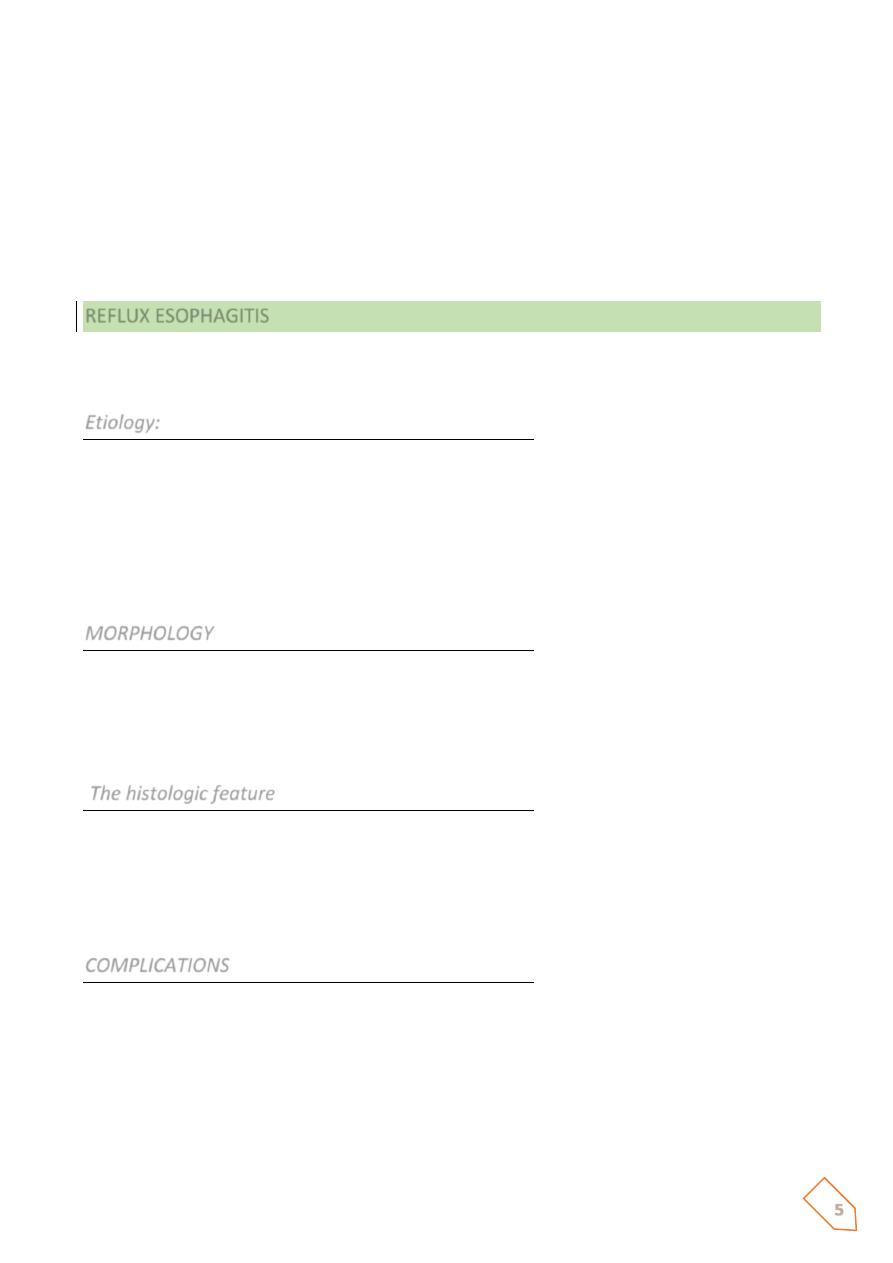

The histologic feature

Are characteristic of uncomplicated reflux esophagitis is:

1. eosinophils, with or without neutrophils, in the epithelial layer;

2. basal zone hyperplasia; and

3. elongation of lamina propria papillae

COMPLICATIONS

• BLEEDING

• STRICTURE

• BARRETT ESOPHAGUS

• PREDISPOSITION TO MALIGNANCY

6

BARRETT ESOPHAGUS

Barrett esophagus is a complication of long-standing gastroesophageal reflux, occurring in up

to 10% of patients with persistent symptomatic reflux disease, as well as in some patients

with asymptomatic reflux.

Barrret esophagus is defined as

the replacement of the normal distal stratified squamous

mucosa by metaplastic columnar epithelium containing goblet cells.

Prolonged and recurrent gastroesophageal reflux is thought to produce inflammation and

eventually ulceration of the squamous epithelial lining.

Healing occurs by in growth of stem cells and re-epithelialization. In the microenvironment of

an abnormally low pH in the distal esophagus caused by acid reflux, the cells differentiate into

columnar epithehum.

Metaplastic columnar epithelium is thought to be more resistant to injury from refluxing

gastric contents.

Barrett esophagus affects males more often than females (ratio of 4:1) and is much more

common in whites than in other races. Genetic factors are suggested by clustering in families.

Ulcer and stricture may develop as a complication of Barrett esophagus.

However, the chief clinical significance of Barrett esophagus relates to the development of

adenocarcinoma. Patients with Barrett esophagus have a 30- to 40-fold greater risk of

developing esophageal adenocarcinoma compared with normal populations

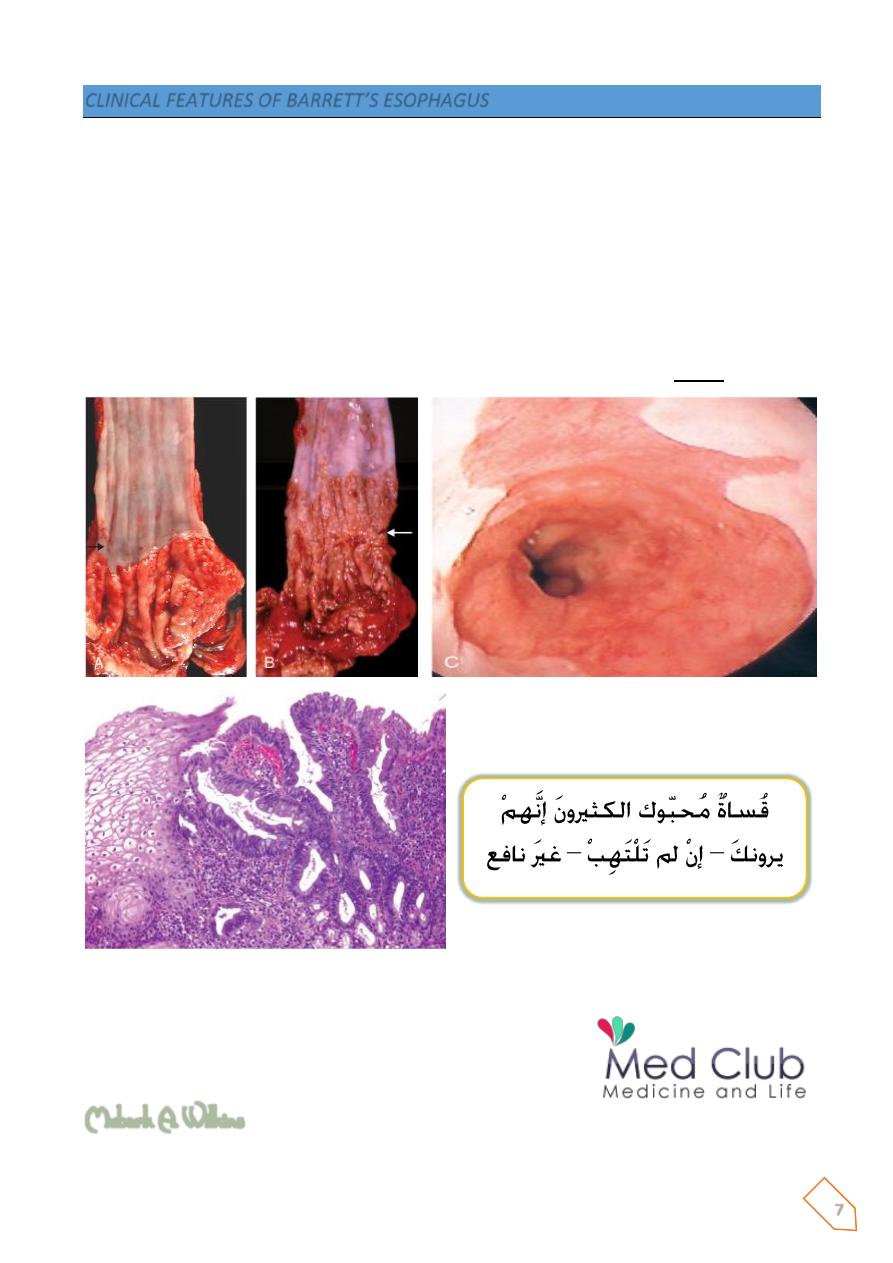

MORPHOLOGY

Barrett esophagus is apparent as a salmon-pink, velvety mucosa between the smooth, pale

pink esophageal squamous mucosa and the more light brown gastric mucosa.

Microscopically, the esophageal squamous epithelium is replaced by metaplastic columnar

epithelium.

7

CLINICAL FEATURES OF BARRETT’S ESOPHAGUS

ⱴ Clinical symptoms:

• Dysphagia, retrosternal pain, hemetemesis, melena

ⱴ Secondary complications:

• Barrett’s ulcers

• Strictures

• Dysplasia

• Adenocarcinoma: 8-10% of patients develop Ca (patients with Barrett’s

esophagus have 30-40 fold higher risk than general population)

Barrett’s esophagus is the only recognized precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma

Mubark A. Wilkins