HematopatHology lec: 2

Normochromic Normocytic Anemia:

HEMOLYTIC ANEMIA:

Those anemias that result from an increase in the rate of red cell destruction.

Because of erythropoietic hyperplasia and anatomical extension of bone marrow, red cell

destruction may be increased several-fold before the patient becomes anemic (compensated

haemolytic disease). The normal adult marrow, after full expansion, is able to produce red cells

at 6-8 times the normal rate. It leads to a marked reticulocytosis, particularly in the more anemic

cases. Therefore, haemolytic anaemia may not be seen until the red cell lifespan is less than 30

days (the normal lifespan of RBCs is 120 days then destructed Extravascular in RES).

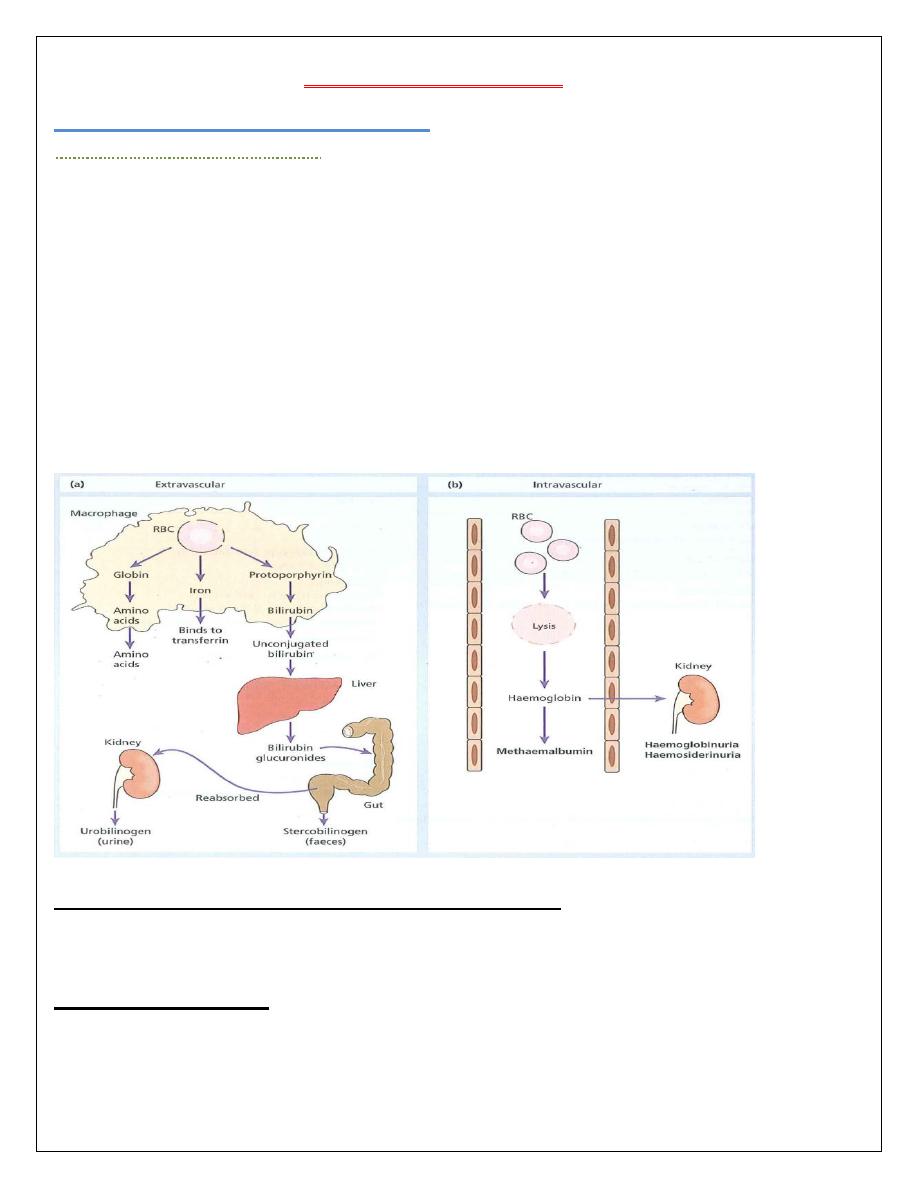

There are two main mechanisms whereby red cells are destroyed in haemolytic anaemia. There

may be excessive removal of red cells by cells of the RE system (extravascular hemolysis

EVH) or they may be broken down directly in the circulation in a process known as

(intravascular hemolysis IVH).

Clinical features of hemolytic anemias in general:

Pallor, jaundice, splenomegaly, gallstone, skeletal abnormalities, folic acid deficiency,

iron overload with extravascular hemolysis, iron deficiency with intravascular hemolysis.

Laboratory findings:

The laboratory findings are divided into three groups:

1 Features of increased red cell breakdown:

(a) Serum bilirubin raised.

(b) Urine urinobilinogen increased.

(c) Faecal stercobilinogen increased.

2 Features of increased red cell production:

(a) Reticulocytosis.

(b) Bone marrow erythroid hyperplasia.

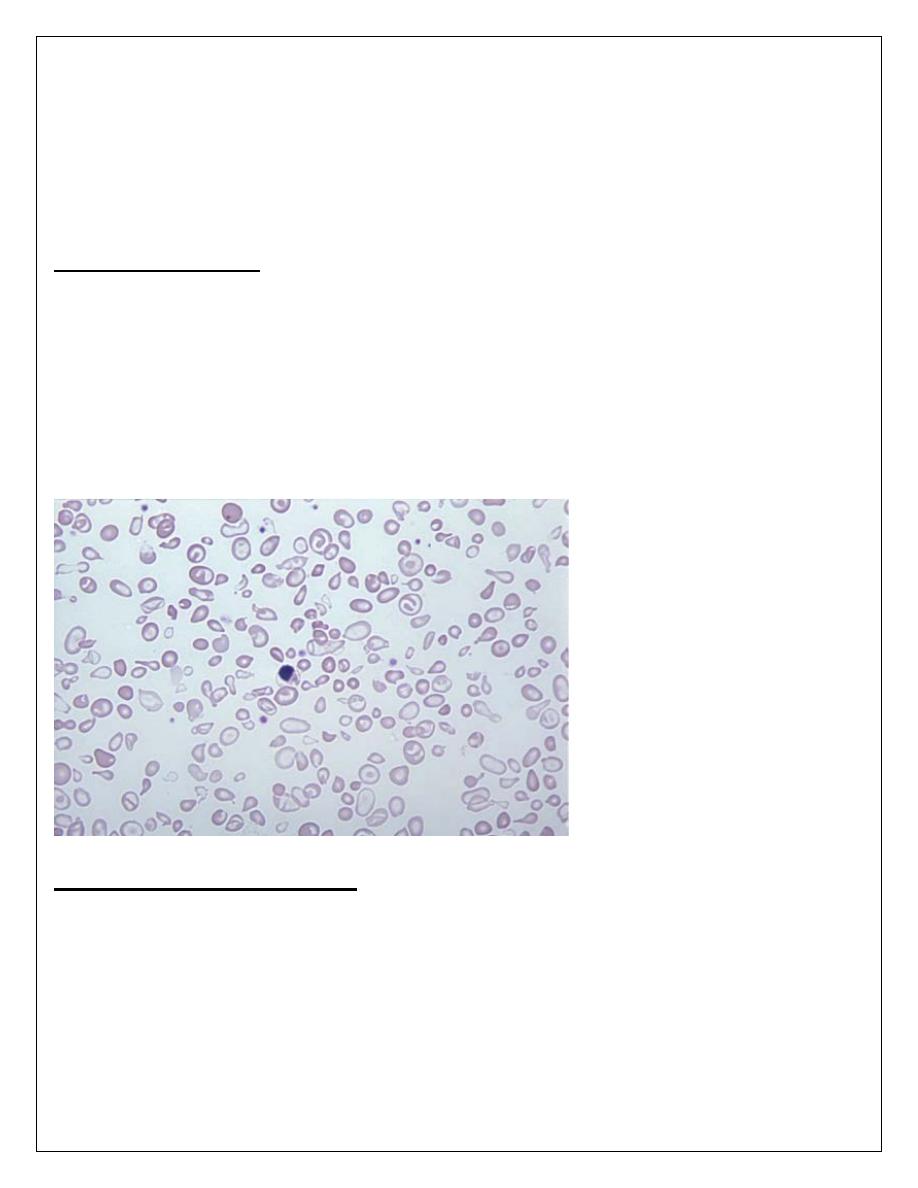

3 Damaged red cells:

Morphology (e.g.: microspherocytes, elliptocytes, fragments).

CLASSIFICATION OF HAEMOLYTIC ANEMIAS

Inherited (usually IVH)

1. Hemoglobinopathies (thalassaemia, sickle cell disorders).

2. Enzyme deficiencies: Hexose-monophosphate shunt enzyme (G6PD)

3. Membrane defects: Hereditary spherocytosis, hereditary elliptocytosis.

Acquired (usually EVH)

1. Immune

1. Allo-immune: hemolytic transfusion reactions HTR, hemolytic disease of the newborn HDN.

1. Autoimmune: due to pathological production of warm antibodies or cold agglutinins.

3. Drug induced immune hemolysis.

2. Non-immune (mechanical damage)

1. Microangiopathic hemolysis: disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), thrombotic

thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS), vasculitis, pre-

eclampsia, mechanical heart valves (microangiopathic).

2. Infections: clostridium infections, malaria.

3. Chemical & physical: burn injury, drugs, industrial chemicals.

4. March hemoglobinuria

5. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) (intrinsic defect).

Inherited Hemolytic Anemias:

1. Disorders Of Hemoglobin (hemoglobinopathies):

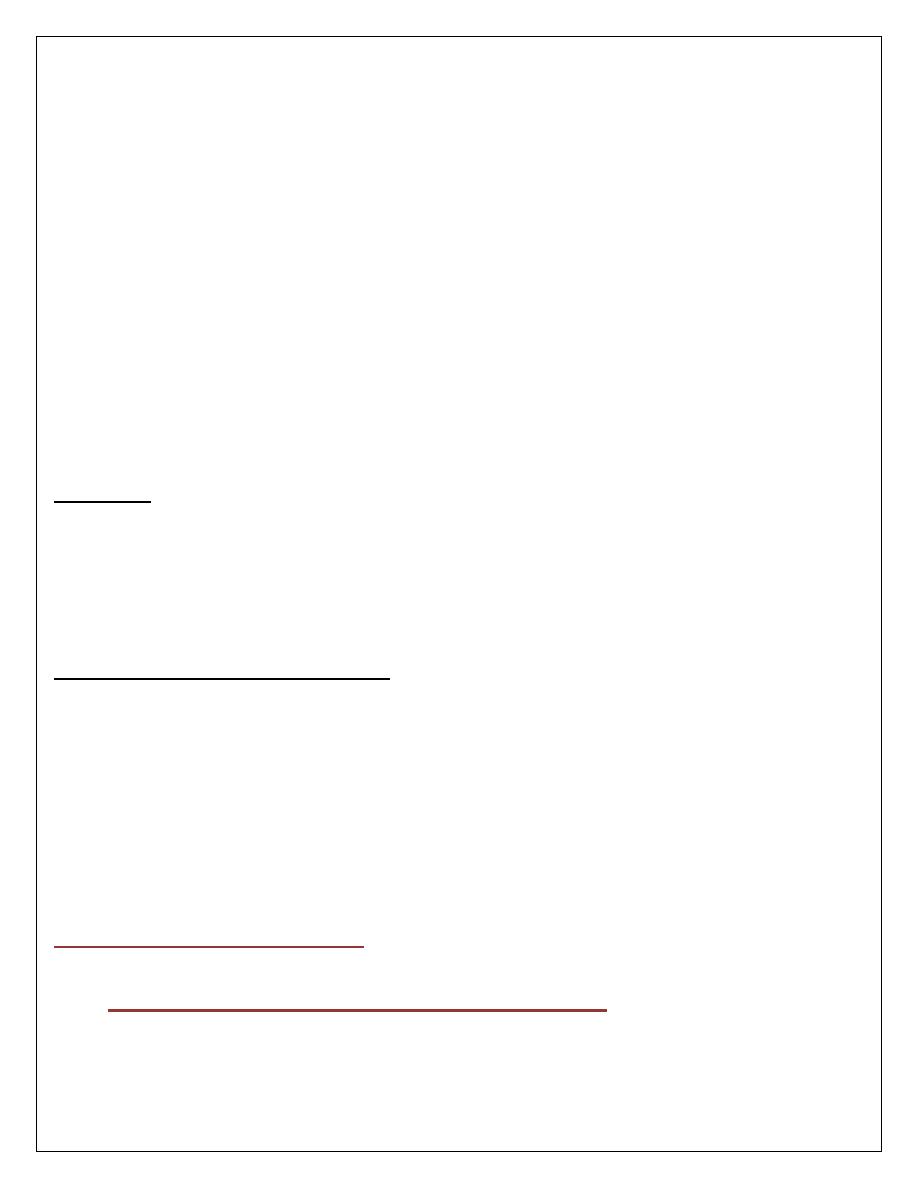

Each red cell contains approximately 640 million hemoglobin molecules. Each molecule

of normal adult hemoglobin ((Hb A the dominant hemoglobin in blood after the age of 3-6

months)) consists of four polypeptide chains (

α2β2) each with its own haem group. Normal

adult blood also contains small quantities of two other hemoglobin: Hb F and Hb A2. These

also contain

α chains, but with γ and δ chains, respectively, instead of β.

A tetramer of four globin chains each with its own haem group in a 'pocket' is then formed to

make up a hemoglobin molecule.

The structural genes for

α globin chains are located on the short arm of the 16th chromosome.

The structural genes for

β globin chains are found on the short arm of the 11th chromosome.

Mutations in the globin genes are the most prevalent monogenic disorders worldwide and affect

approximately 7% of the world's population.

Mutations in the globin genes can cause either a quantitative reduction in output from that gene

or alter the amino acid sequence of the protein produced. Quantitative

defects cause

thalassaemia whereas qualitative changes, referred to as hemoglobin variants, cause a wide

range of problems including sickle cell disease.

THALASSEMIAS:

These are a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders that result from a reduced rate of synthesis

of one or more of the hemoglobin chains (

α or β chains), transmitted by autosomal recessive

pattern of inheritance.

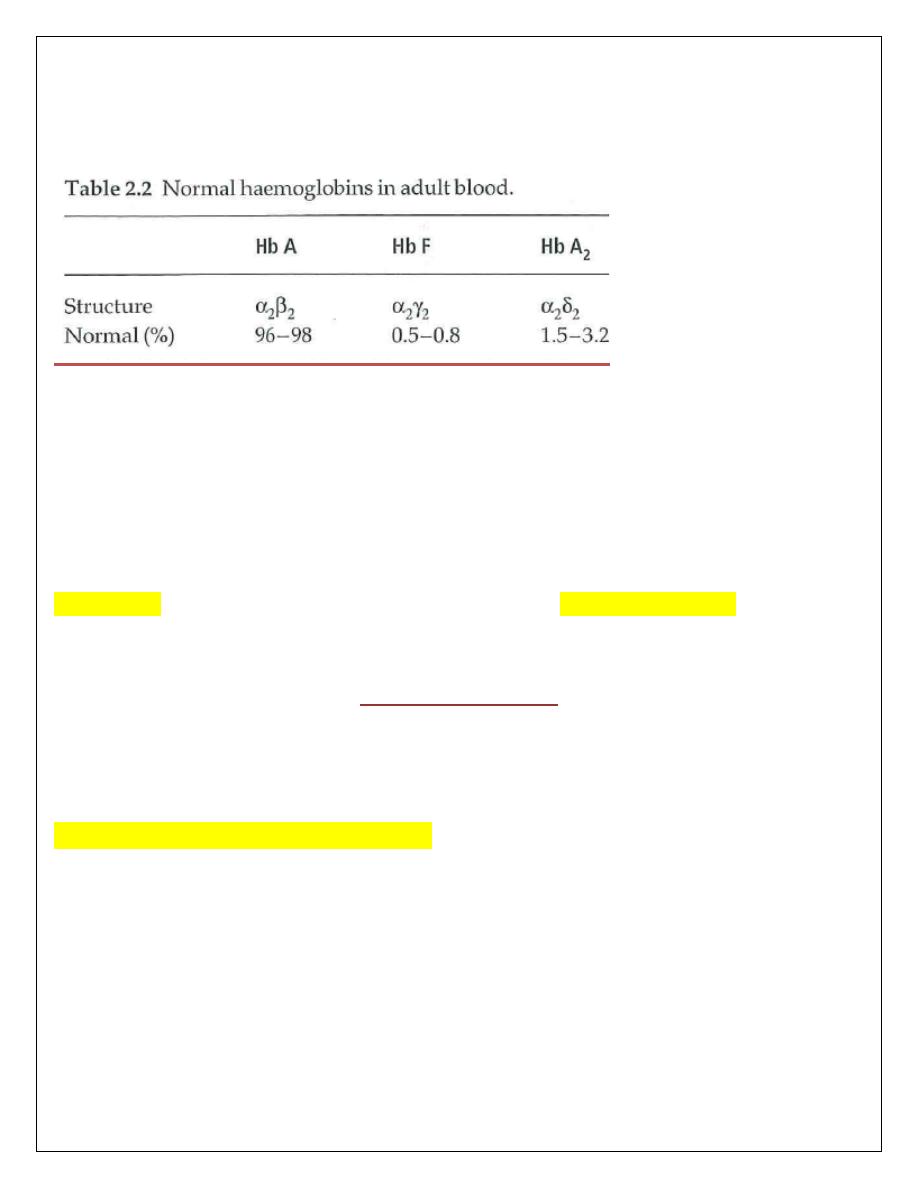

α (Alpha)Thalassaemia syndromes:

These are usually caused by gene deletions. Because there are normally four copies of the

α

globin gene, the clinical severity can be classified according to the number of genes that are

missing or inactive. Loss of all four genes completely suppresses

α chain synthesis and because

the

α chain is essential in fetal as well as in adult hemoglobin this is incompatible with life and

leads to death in utero (hydrops fetalis).

Three

α gene deletions leads to a moderately severe (hemoglobin 7-11 g/dL) microcytic,

hypochromic anemia with splenomegaly. This is known as Hb H disease because hemoglobin H

(

β4) can be detected in red cells of these patients by electrophoresis or in reticulocyte

preparations. In fetal life, Hb Barts (

β4) occurs.

The

α thalassaemia traits are caused by loss of one or two genes and are usually not associated

with anaemia, although the MCV and MCH are low and the red cell count is over 5.5 x 10

12

/L.

Haemoglobin electrophoresis is normal and

α/ β chain synthesis studies or DNA analyses are

needed to be certain of the diagnosis.

β

(Beta)Thalassaemia syndromes:

β

Thalassaemia major:

This condition occurs on average in one in four offspring if both parents are carriers of

the

β thalassaemia trait (minor). Either no β chain or small amounts are synthesized.

Excess

α chains precipitate in erythroblasts and in mature red cells causing the severe

ineffective erythropoiesis and hemolysis that are typical of this disease. The greater the

α chain excess, the more severe the anemia. Unlike α thalassaemia, the majority of

genetic lesions are point mutations rather than gene deletions.

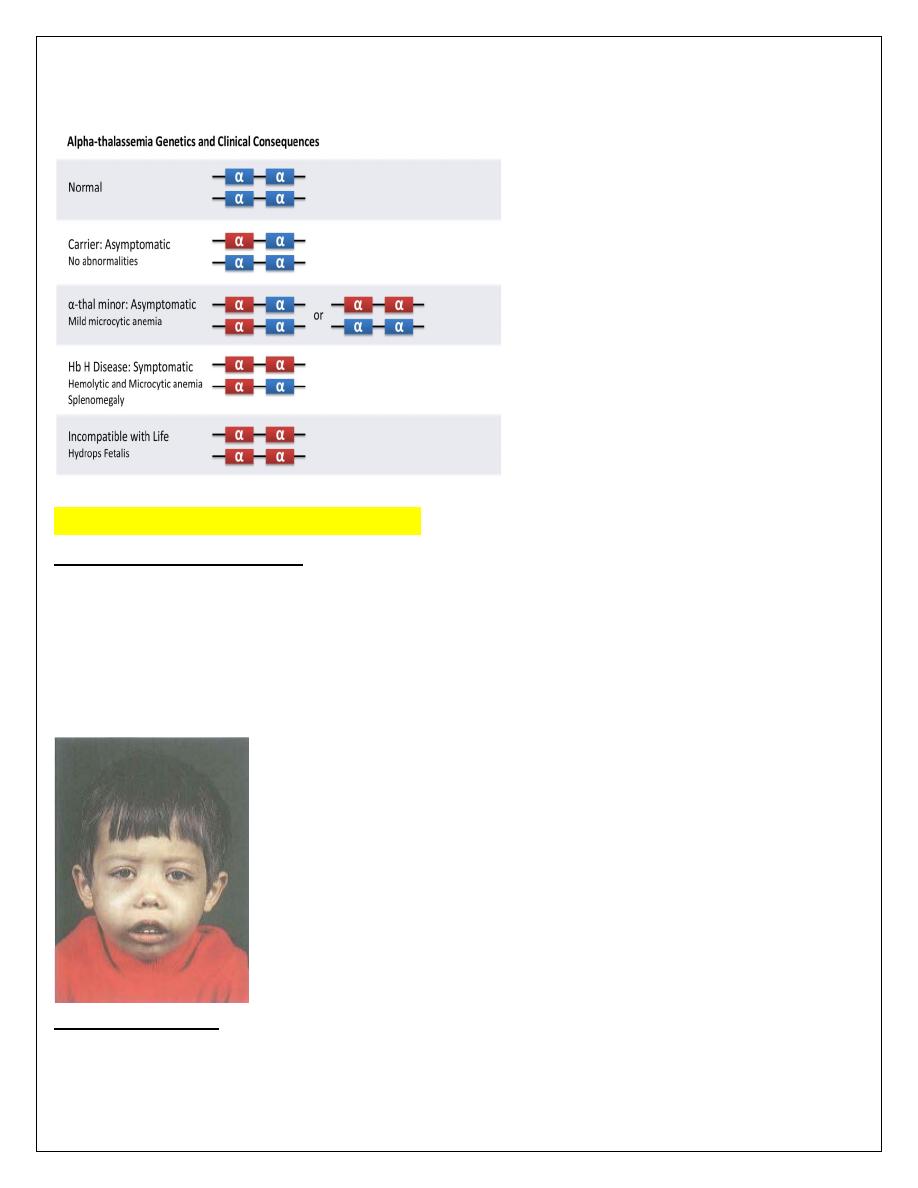

Clinical features:

1. Severe anaemia becomes apparent at 3-6 months after birth

2. Enlargement of the liver and spleen occurs as a result of excessive red cell

destruction, extramedullary haemopoiesis and later because of iron overload.

3. Expansion of bones caused by intense marrow hyperplasia leads to a thalassemic

facies.

4. The patient can be sustained by blood transfusions but iron overload caused by

repeated transfusions is inevitable unless chelation therapy is given. Each 500 mL of

transfused blood contains approximately 250 mg iron. Iron damages the liver and the

endocrine organs with failure of growth, delayed or absent puberty, diabetes mellitus,

hypothyroidism and hypoparathyroidism.

Laboratory diagnosis:

1. There is a severe hypochromic, microcytic anemia, raised reticulocyte percentage

with normoblasts, target cells' and basophilic stippling in the blood film.

2. Haemoglobin electrophoresis reveals absence or almost complete absence of Hb A

with almost all the circulating hemoglobin being Hb F. The Hb A2 percentage is

normal, low or slightly raised.

α/ β-Globin chain synthesis studies on reticulocytes show an increased α/ β ratio with

reduced or absent

β chain synthesis. DNA analysis is used to identify the defect on each

allele.

β Thalassaemia trait (minor):

This is a common, usually symptomless, abnormality characterized like

α thalassaemia trait by

a hypochromic, microcytic blood picture (MCV and MCH very low) but high red cell count

(>5.5 x 10

12

/L) and mild anaemia (hemoglobin 10-12 g/dL). It is usually more severe than

α

trait.

A raised Hb A2 (>3.5%) confirms the diagnosis. One of the most important indications for

making the diagnosis is that it allows the possibility of prenatal counselling to patients with a

partner who also has a significant hemoglobin disorder. If both carry

β thalassaemia

trait there is a 25% risk of a

β thalassaemia major child.

Thalassaemia intermedia:

Cases of thalassaemia of moderate severity (hemoglobin 7.0-10.0 g/dL) that do not need regular

transfusions are called thalassaemia intermedia. This is a clinical syndrome which may be

caused by a variety of genetic defects.

Sickle cell anaemia

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited chronic haemolytic anaemia whose clinical

manifestations arise from the tendency of the hemoglobin (HbS or sickle hemoglobin) to

polymerize and deform red blood cells into the characteristic sickle shape.

Hb S (Hb

α

2

β

2

s

) is insoluble and forms crystals when exposed to low oxygen tension. The red

cells sickle and may block different areas of the microcirculation or large vessels cause infarcts

of various organs. The sickle

β

globin abnormality is caused by substitution of valine for

glutamic acid in position 6 in the

β

chain. It is very widespread and is found in up to one in four

West Africans, maintained at this level because of the protection against malaria that is afforded

by the carrier state(more than 200,000,000 cases throughout the world).

Sickle cell disease -Homozygous disease-(Hb SS):

Clinical features:

are of a severe haemolytic anaemia punctuated by crises. The symptoms of anaemia are

often mild in relation to the severity of the anaemia because Hb S gives up oxygen (O

2

) to

tissues relatively easily compared with Hb A.

The clinical expression of Hb SS is very variable, some patients having an almost normal life,

free of crises but others develop severe crises even as infants and may die in early childhood or

as young adults. Crises may be vaso-occlusive, visceral, aplastic or haemolytic.

Painful vasa-occlusive crises:

These are the most frequent and are precipitated by such factors as infection, acidosis,

dehydration or deoxygenation (e.g. altitude, operations, obstetric delivery, stasis of the

circulation, exposure to cold, violent exercise). Infarcts can occur in a variety of organs

including the bones, the lungs and the spleen. The most serious vaso-occlusive crisis is of the

brain or spinal cord.

Visceral sequestration crises:

These are caused by sickling within organs and pooling of blood, often with a severe

exacerbation of anaemia. The acute sickle chest syndrome is a feared complication and the most

common cause of death after puberty.

Hepatic sequestration and splenic sequestration crises may lead to severe illness

requiring exchange transfusions. Splenic sequestration is typically seen in infants and presents

with an enlarging spleen, falling hemoglobin and abdominal pain. Attacks tend to be recurrent

and splenectomy is often needed.

Aplastic crises:

These occur as a result of infection with parvovirus or from folate deficiency and are

characterized by a sudden fall in hemoglobin, usually requiring transfusion. They are

characterized by a fall in reticulocytes as well as hemoglobin.

Haemolytic crises:

These are characterized by an increased rate of hemolysis with a fall in hemoglobin but rise in

reticulocytes and usually accompany a painful crisis.

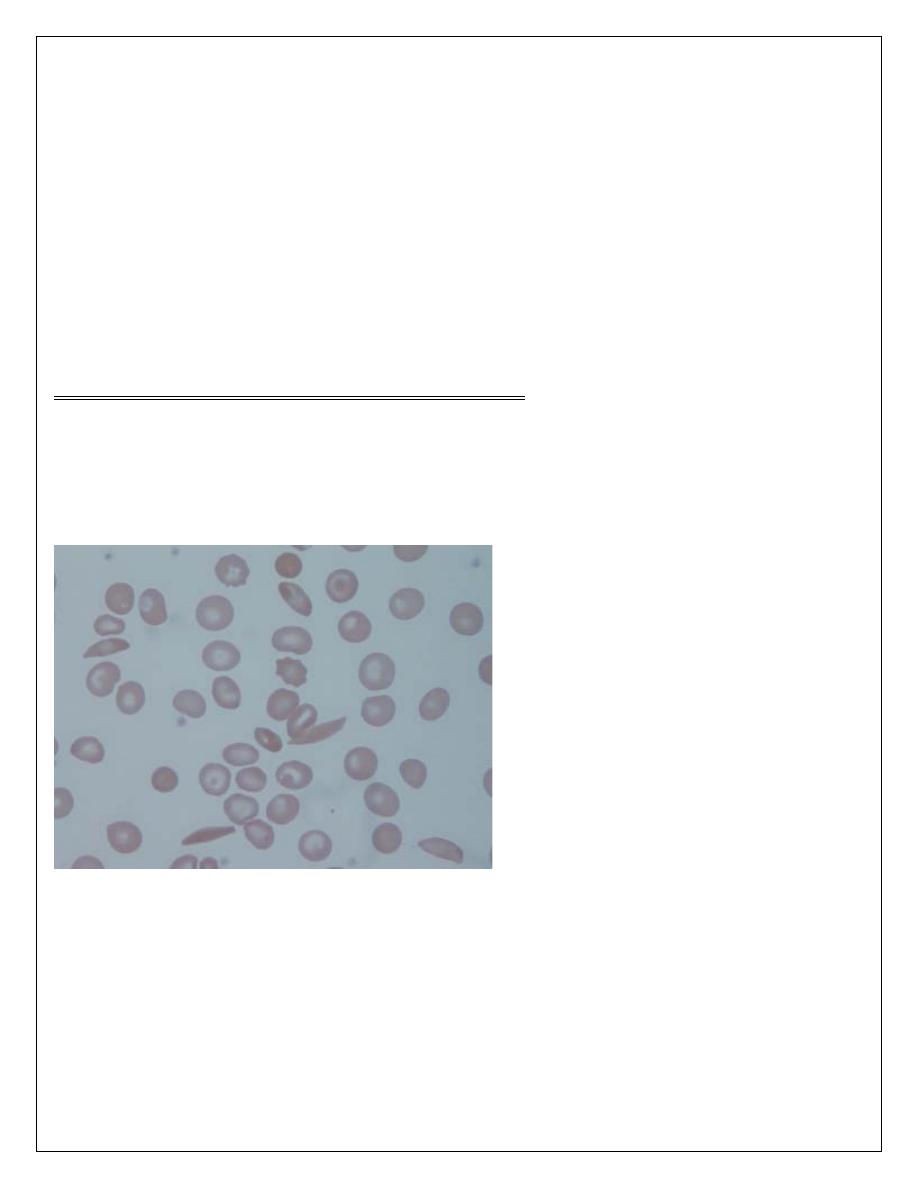

Laboratory findings

1. The hemoglobin is usually (6-9 g/dL) low in comparison to symptoms of anaemia.

2. Sickle cells and target cells occur in the blood. Features of splenic atrophy (e.g. Howell-Jolly

bodies) may also be present.

3. Screening tests for sickling are positive when the blood is deoxygenated.

• sickling test: induction of sickling by incubation of the red cells with a reducing agent.

• sickle solubility test by using reducing agent , HbS precipitates causing a cloudy solution.

4. Haemoglobin electrophoresis: in HbSS, no Hb A is detected. The amount of Hb F is

variable and is usually 2-20 %, larger amounts are normally associated with a milder disorder.

Sickle cell trait -Heterozygous disease-(Hb AS):

This is a benign condition associated with normal growth and life expectancy with no anaemia

and normal appearance of red cells on a blood film.

Hematuria is the most common symptom and is thought to be caused by minor infarcts of the

renal papillae. Hb S varies from 25 to 45% of the total hemoglobin. Care must be taken with

anesthesia, pregnancy and at high altitudes.

ﺍﻟﺪﻛﺘﻮﺭﺍﻻﺧﺘﺼﺎﺹ

ﻋﻠﻲ ﻋﺒﻴﺪ ﺍﺑﺮﺍﻫﻴﻢ ﺍﻟﺨﻔﺎﺟﻲ

ﺩﻛﺘﻮﺭﺍﺓ ) ﺑﻮﺭﺩ ( ﺍﻣﺮﺍ

ﺽ ﺍﻟﺪﻡ

M.B.Ch.B. F.I.C.M.S