1

The Vibrios

Vibrios are among the most common bacteria in surface waters worldwide.

They are curved aerobic rods and are motile, possessing a polar flagellum. V

cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 cause cholera in humans, and other vibrios may

cause skin and soft tissue infections, sepsis, or enteritis.

Vibrio cholerae

The epidemiology of cholera closely parallels the recognition of V cholerae

transmission in water and the development of sanitary water systems.

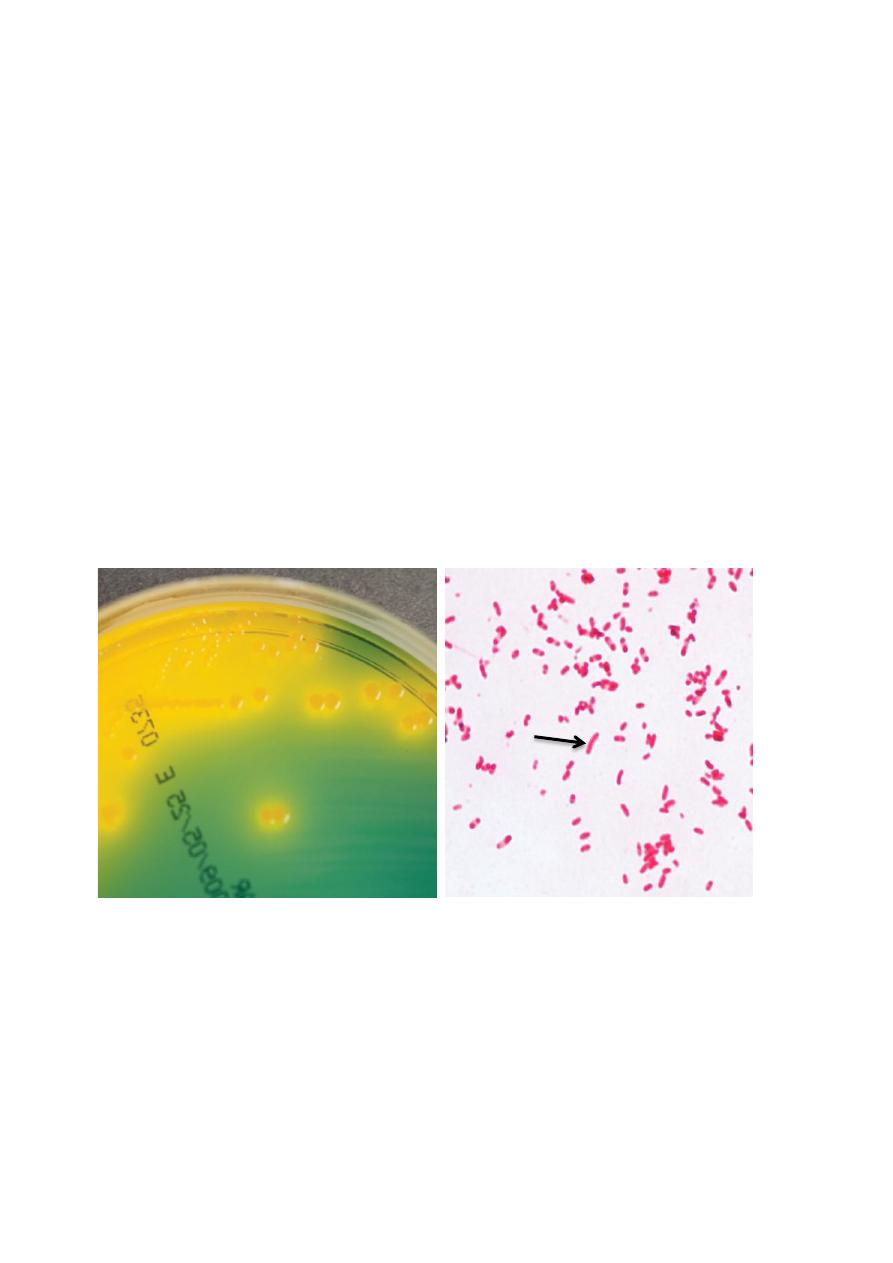

Morphology and Identification

A. Typical Organisms

Upon first isolation, V cholerae is a comma-shaped, curved rod 2–4 μm long. It

is actively motile by means of a polar flagellum. On prolonged cultivation, vibrios

may become straight rods that resemble the Gram-negative enteric bacteria.

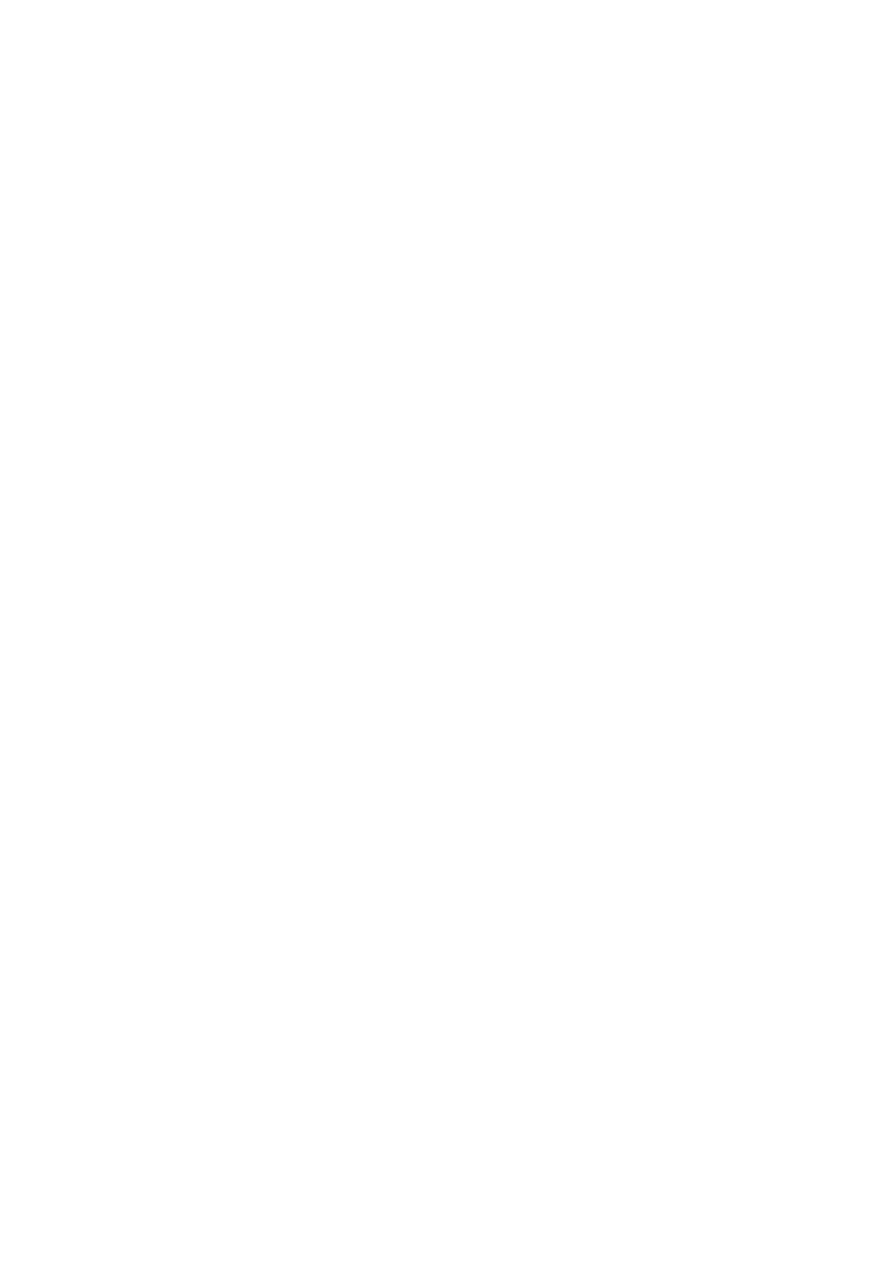

B. Culture

V cholerae produces convex, smooth, round colonies that are opaque and

granular in transmitted light. V cholera and most other vibrios grow well at 37°C

on many kinds of media, including defined media containing mineral salts and

asparagine as sources of carbon and nitrogen. V cholera grows well on

thiosulfate-citrate-bile-sucrose (TCBS) agar, a media selective for vibrios, on

which it produces yellow colonies (sucrose fermented) that are readily visible

against the dark-green background of the agar. Vibrios are oxidase positive, which

differentiates them from enteric Gram-negative bacteria. Characteristically, vibrios

grow at a very high pH (8.5–9.5) and are rapidly killed by acid. Cultures

containing fermentable carbohydrates therefore quickly become sterile.

In areas where cholera is endemic, direct cultures of stool on selective media, such

as TCBS, and enrichment cultures in alkaline peptone water are appropriate.

Microbiology

Medical bacteriology

Dr. Zainab D. Degaim

2

However, routine stool cultures on special media such as TCBS generally are not

necessary or cost effective in areas where cholera is rare.

C. Growth Characteristics

V cholerae regularly ferments sucrose and mannose but not arabinose. A

positive oxidase test result is a key step in the preliminary identification of V

cholerae and other vibrios. Most Vibrio species are halotolerant, and NaCl often

stimulates their growth. Some vibrios are halophilic, requiring the presence of

NaCl to grow.

Antigenic Structure and Biologic Classification

Many vibrios share a single heat-labile flagellar H antigen. Antibodies to the H

antigen are probably not involved in the protection of susceptible hosts. V

cholerae has O lipopolysaccharides that confer serologic specificity. There are at

least 206 O antigen groups. V cholerae strains of O group 1 and O group 139

cause classic cholera; occasionally, non-O1/non-O139 V cholerae causes cholera-

like disease. Antibodies to the O antigens tend to protect laboratory animals

against infections with V cholerae. The V cholerae serogroup O1 antigen has

determinants that make possible further typing; the serotypes are Ogawa, Inaba,

and Hikojima. Two biotypes of epidemic V cholera have been defined, classic and

El Tor. The El Tor biotype produces a hemolysin, gives positive results on the

Voges-Proskauer test, and is resistant to polymyxin B. Molecular techniques can

also be used to type V cholerae. Typing is used for epidemiologic studies, and

tests generally are done only in reference laboratories.

V cholerae O139 is very similar to V cholerae O1 El Tor biotype. V cholerae

O139 does not produce the O1 lipopolysaccharide and does not have all the genes

necessary to make this antigen. V cholerae O139 makes a polysaccharide capsule

like other non-O1 V cholerae strains, but V cholerae O1 does not make a capsule.

Vibrio cholerae Enterotoxin

V. cholerae produce a heat-labile enterotoxin with a molecular weight (MW) of

about 84,000, consisting of subunits A (MW, 28,000) and B. Ganglioside GM1

3

serves as the mucosal receptor for subunit B, which promotes entry of subunit A

into the cell. Activation of subunit A1 yields increased levels of intracellular

cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and results in prolonged hypersecretion

of water and electrolytes. There is increased sodium-dependent chloride secretion,

and absorption of sodium and chloride by the microvilli is inhibited. Electrolyte-

rich diarrhea occurs— as much as 20–30 L/day—with resulting dehydration,

shock, acidosis, and death. The genes for V cholerae enterotoxin are on the

bacterial chromosome. Cholera enterotoxin is antigenically related to LT of

Escherichia coli and can stimulate the production of neutralizing antibodies.

However, the precise role of antitoxic and antibacterial antibodies in protection

against cholera is not clear.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

Under natural conditions, V cholerae is pathogenic only for humans. A person

with normal gastric acidity may have to ingest as many as 10

10

or more V cholerae

to become infected when the vehicle is water because the organisms are

susceptible to acid. When the vehicle is food, as few as 10

2

–10

4

organisms are

necessary because of the buffering capacity of food. Any medication or condition

that decreases stomach acidity makes a person more susceptible to infection with

V cholerae. Cholera is not an invasive infection. The organisms do not reach the

bloodstream but remain within the intestinal tract. Virulent V cholerae organisms

attach to the microvilli of the brush border of epithelial cells. There they multiply

and liberate cholera toxin and perhaps mucinases and endotoxin.

Clinical Findings

About 50% of infections with classic V cholerae are asymptomatic, as are

about 75% of infections with the El Tor biotype. The incubation period is 12

hours–3 days for persons who develop symptoms, depending largely on the size of

the inoculum ingested. There is a sudden onset of nausea and vomiting and

profuse diarrhea with abdominal cramps. Stools, which resemble “rice water,”

contain mucus, epithelial cells, and large numbers of vibrios. There is rapid loss of

4

fluid and electrolytes, which leads to profound dehydration, circulatory collapse,

and anuria. The mortality rate without treatment is between 25% and 50%. The

diagnosis of a full-blown case of cholera presents no problem in the presence of an

epidemic. However, sporadic or mild cases are not readily differentiated from

other diarrheal diseases. The El Tor biotype tends to cause milder disease than the

classic biotype.

Diagnostic Laboratory Tests

A. Specimens

Specimens for culture consist of mucus flecks from stools.

B. Smears

The microscopic appearance of smears made from stool samples is not distinctive.

Dark-field or phase contrast microscopy may show the rapidly motile vibrios.

C. Culture

Growth is rapid in peptone agar, on blood agar with a pH near 9.0, or on TCBS

agar, and typical colonies can be picked in 18 hours. For enrichment, a few drops

of stool can be incubated for 6–8 hours in taurocholate peptone broth (pH, 8.0–

9.0); organisms from this culture can be stained or subcultured. Accurate

identification of vibrios, including V cholerae, using commercial systems and kit

assays is quite variable.

D. Specific Tests

V cholerae organisms are further identified by slide agglutination tests using

anti-O group 1 or group 139 antisera and by biochemical reaction patterns. The

diagnosis of cholera under field conditions has been reported to be facilitated by a

sensitive and specific immunochromatographic dipstick test.

Immunity

Gastric acid provides some protection against cholera vibrios. An attack of

cholera is followed by immunity to reinfection, but the duration and degree of

immunity are not known. In experimental animals, specific IgA antibodies occur

in the lumen of the intestine. Similar antibodies in serum develop after infection

5

but last only a few months. Vibriocidal antibodies in serum (titer ≥1:20) have been

associated with protection against colonization and disease. The presence of

antitoxin antibodies has not been associated with protection.

Treatment

The most important part of therapy consists of water and electrolyte

replacement to correct the severe dehydration and salt depletion. Many

antimicrobial agents are effective against V cholerae, but these play a secondary

role in patient management. Oral tetracycline and doxycycline tend to reduce stool

output in cholera and shorten the period of excretion of vibrios. In some endemic

areas, tetracycline resistance of V cholerae has emerged; the genes are carried by

transmissible plasmids. In children and pregnant women, alternatives to the

tetracyclines include erythromycin and furazolidine.

Colonies of Vibrio cholerae growing on thiosulfate, citrate,

bile salts, and sucrose agar. The glistening yellow colonies

are 2–3 mm in diameter and are surrounded by a diffuse

yellowing of the indicator in the agar up to 1 cm in

diameter.

Gram stain of Vibrio cholerae. Often they are

comma shaped or slightly curved (arrows) and 1 × 2 to 4

μm.