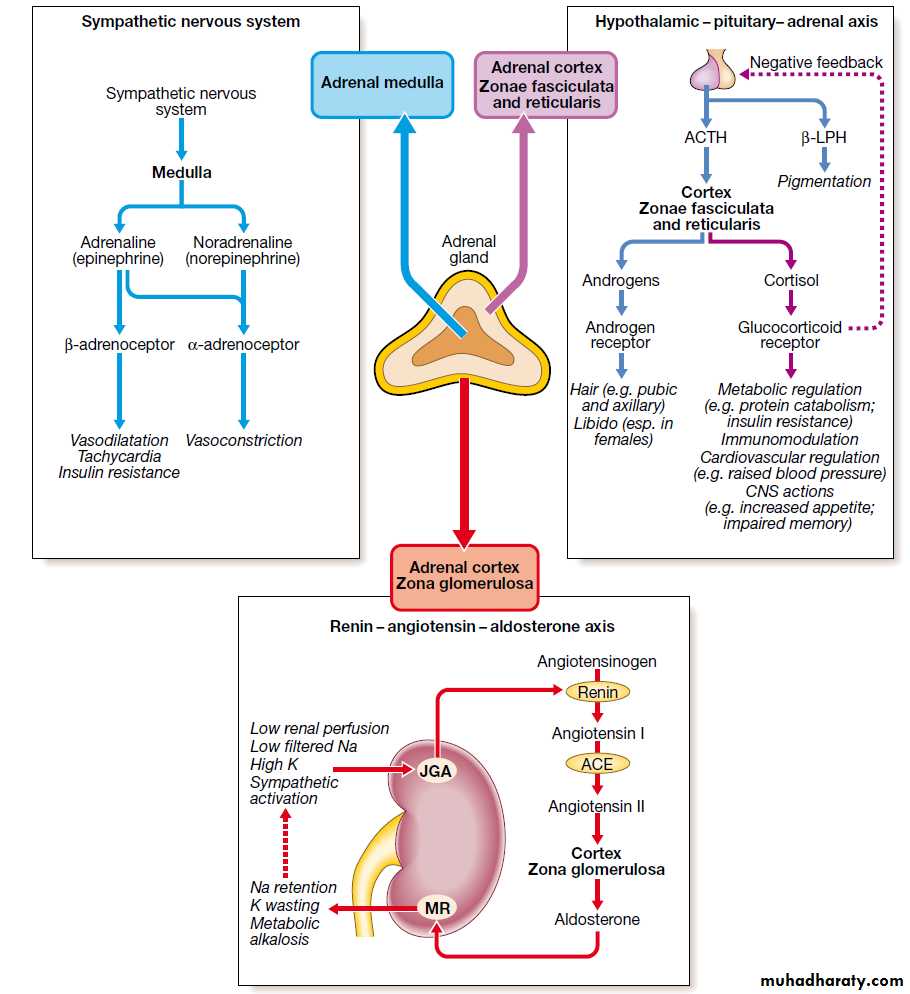

Adrenal gland

Cushing's syndrome

Cushing's syndrome is caused by excessive activation of glucocorticoid receptors.By far the most common cause is iatrogenic, due to prolonged administration of synthetic glucocorticoids such as prednisolone.

Non-iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome is rare and is often a 'spot diagnosis' made by an astute clinician.

Classification of Cushing's syndrome

Amongst endogenous causes, pituitary-dependent cortisol excess (by convention, called Cushing's disease) accounts for approximately 80% of cases.Both Cushing's disease and cortisol-secreting adrenal tumours are four times more common in women than men.

In contrast, ectopic ACTH syndrome (often due to a small-cell carcinoma of the bronchus) is more common in men.

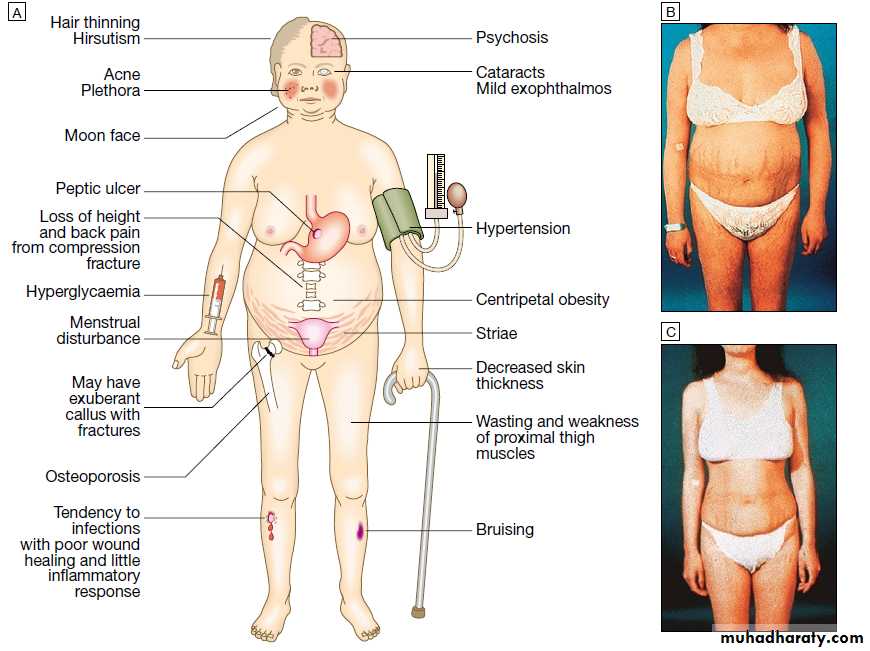

Clinical features

It is vital to exclude iatrogenic causes in all patients with Cushing's syndrome since even inhaled or topical glucocorticoids can induce the syndrome in susceptible individuals.

A careful drug history must therefore be taken before embarking on complex investigations.

Some clinical features are more common in ectopic ACTH syndrome.

Unlike pituitary tumours secreting ACTH, ectopic tumours have no residual negative feedback sensitivity to cortisol, and both ACTH and cortisol levels are usually higher than with other causes.Very high ACTH levels are associated with marked pigmentation.

Very high cortisol levels overcome the barrier of 11β-HSD2 in the kidney and cause hypokalaemic alkalosis. Hypokalaemia aggravates both myopathy and hyperglycaemia (by inhibiting insulin secretion).

When the tumour secreting ACTH is malignant, then the onset is usually rapid and may be associated with cachexia.

For these reasons, the classical features of Cushing's syndrome are less common in ectopic ACTH syndrome, and if present suggest that a less aggressive tumour (e.g. bronchial carcinoid) is responsible.

In Cushing's disease, the pituitary tumour is usually a microadenoma (< 10 mm in diameter); hence other features of a pituitary macroadenoma (hypopituitarism, visual failure or disconnection hyperprolactinaemia) are rare.

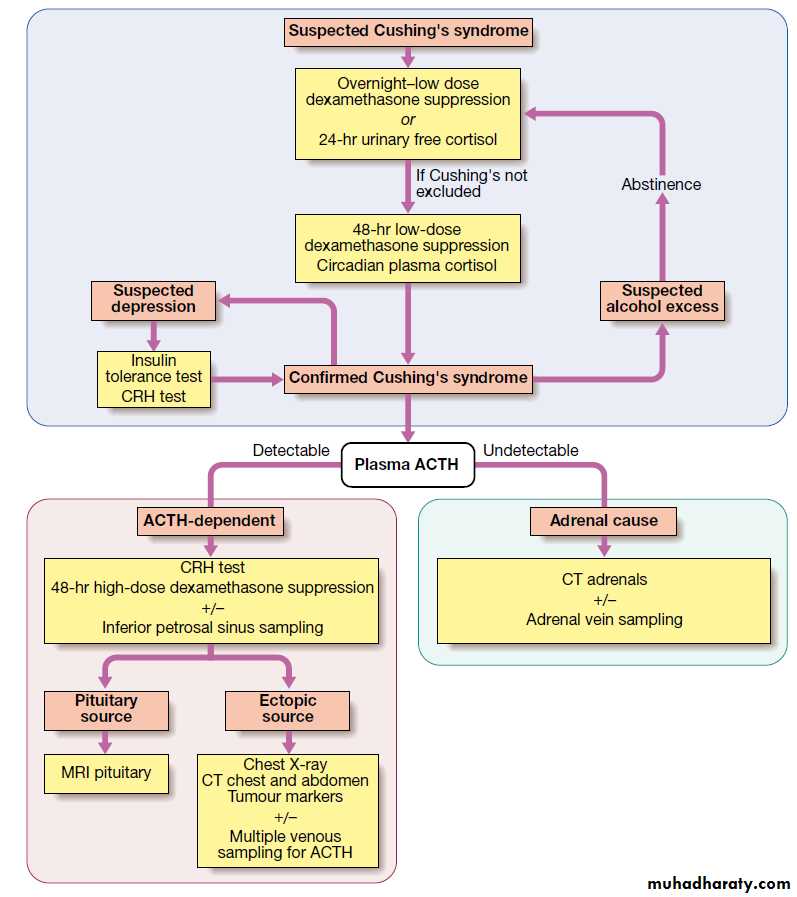

investigations

The large number of tests available for Cushing's syndrome reflects the limited specificity and sensitivity of each test in isolation.Several tests are usually combined to establish the diagnosis.

It is useful to divide investigations into

those which establish whether the patient has Cushing's syndrome,

those which are used subsequently to define the cause.

Some additional tests are useful in all cases of Cushing's syndrome, including plasma electrolytes, glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin and bone mineral density measurement.

In iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome, cortisol levels are low unless the patient is taking a corticosteroid (such as prednisolone) which cross-reacts in immunoassays with cortisol.

Establishing the presence of Cushing's syndrome

Cushing's syndrome is confirmed by the demonstration of increased secretion of cortisol (measured in plasma or urine) that fails to suppress with relatively low doses of oral dexamethasoneLoss of diurnal variation, with elevated evening plasma cortisol, is also characteristic of Cushing's syndrome, but samples are awkward to obtain.

Plasma cortisol levels are highly variable in healthy subjects and random measurement of daytime plasma cortisol is of no value in supporting or refuting the diagnosis

Dexamethasone is used for suppression testing because, unlike prednisolone, it does not cross-react in radioimmunoassays for cortisol.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis may 'escape' from suppression by dexamethasone if a more potent influence, such as psychological stress, supervenes.

Determining the underlying cause

Once the presence of Cushing's syndrome is confirmed, measurement of plasma ACTH is the key to establishing the differential diagnosis.In the presence of excess cortisol secretion, an undetectable ACTH indicates an adrenal tumour, while any detectable ACTH suggest a pituitary cause or ectopic ACTH.

Tests to discriminate pituitary from ectopic sources of ACTH rely on the fact that pituitary tumours, but not ectopic tumours, retain some features of normal regulation of ACTH secretion.

Thus, in pituitary-dependent Cushing's disease, ACTH secretion is suppressed by high-dose dexamethasone and ACTH is stimulated by corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH).

MRI detects around 70% of pituitary microadenomas secreting ACTH.

Inferior petrosal sinus sampling with measurement of ACTH may be helpful in confirming Cushing's disease if the MRI does not show a microadenoma. CT or MRI detects most adrenal tumours; adrenal carcinomas are usually large (> 5 cm) and have other features of malignancy

Management

Untreated Cushing's syndrome has a 50% 5-year mortality.Most patients are treated surgically with medical therapy given for a few weeks prior to operation.

A number of drugs are used to inhibit corticosteroid biosynthesis, including metyrapone and ketoconazole.

The dose of these agents is best titrated against 24-hour urine free cortisol.

Cushing's disease

Trans-sphenoidal surgery with selective removal of the adenoma is the treatment of choice.Experienced surgeons can identify microadenomas which were not detected by MRI and cure about 80% of patients.

If the operation is unsuccessful, then bilateral adrenalectomy is an alternative.

If bilateral adrenalectomy is used in patients with pituitary-dependent Cushing's syndrome, then there is a risk that the pituitary tumour will grow in the absence of the negative feedback suppression previously provided by elevated cortisol levels.

This can result in Nelson's syndrome, with an aggressive pituitary macroadenoma and very high ACTH levels causing pigmentation.

Nelson's syndrome can be prevented by pituitary irradiation.

Adrenal tumours

Adrenal adenomas are removed by laparoscopy or a loin incision. Surgery offers the only prospect of cure for adrenocortical carcinomasEctopic ACTH syndrome

Localised tumours such as bronchial carcinoid should be removed surgically. In patients with incurable malignancy it is important to reduce the severity of the Cushing's syndrome using medical therapy (see above) or, if appropriate, bilateral adrenalectomy.Therapeutic use of glucocorticoids

The remarkable anti-inflammatory properties of glucocorticoids have led to their use in a wide variety of clinical conditions, but the hazards are significant.

Topical preparations (dermal, rectal and inhaled) can also be absorbed into the systemic circulation.

Although this rarely occurs to a sufficient degree to produce clinical features of Cushing's syndrome, it can result in significant suppression of endogenous ACTH and cortisol secretion.

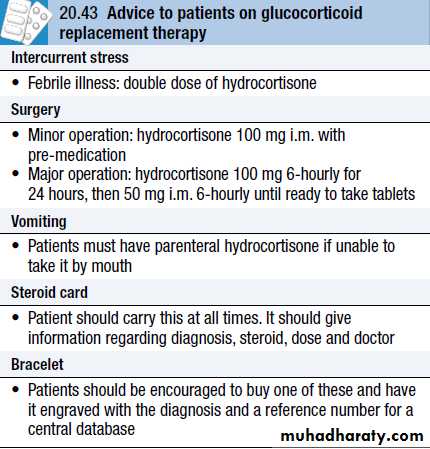

Management of glucocorticoid withdrawal

All glucocorticoid therapy, even if inhaled or applied topically, can suppress the HPA axis. In practice, this is only likely to result in a crisis due to adrenal insufficiency on withdrawal of treatment if glucocorticoids have been administered orally or systemically for longer than 3 weeks, if repeated courses have been prescribed within the previous year, or if the dose is higher than the equivalent of 7.5 mg prednisolone per day.In these circumstances, the drug, when it is no longer required for the underlying condition, must be withdrawn slowly at a rate dictated by the duration of treatment.

If glucocorticoid therapy has been prolonged, then it may take many months for the HPA axis to recover. All patients must be advised to avoid sudden drug withdrawal. They should be issued with a steroid card and/or wear an engraved bracelet

Recovery of the HPA axis is aided if there is no exogenous glucocorticoid present during the nocturnal surge in ACTH secretion.

This can be achieved by giving glucocorticoid in the morning.

Giving ACTH to stimulate adrenal recovery is of no value as the pituitary remains suppressed.

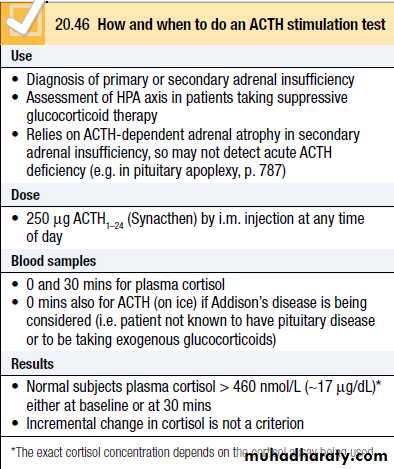

In patients who have received glucocorticoids for longer than a few weeks, it is often valuable to confirm that the HPA axis is recovering during glucocorticoid withdrawal.

Once the dose of glucocorticoid is reduced to a minimum (e.g. 4 mg prednisolone or 0.5 mg dexamethasone per day), then measure plasma cortisol at 0900 hrs before the next dose. If this is detectable, then perform an ACTH stimulation test to confirm that glucocorticoids can be withdrawn completely.

Even once glucocorticoids have been successfully withdrawn, short-term replacement therapy is often advised during significant intercurrent illness occurring in subsequent months, as the HPA axis may not be able to respond fully to severe stress.

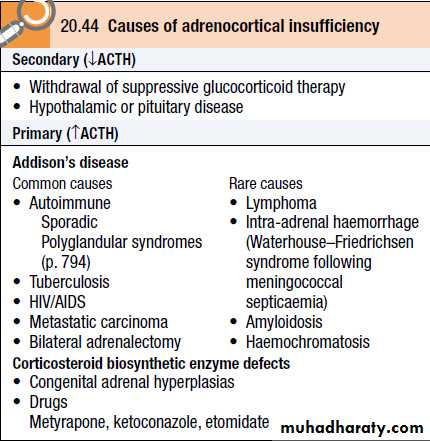

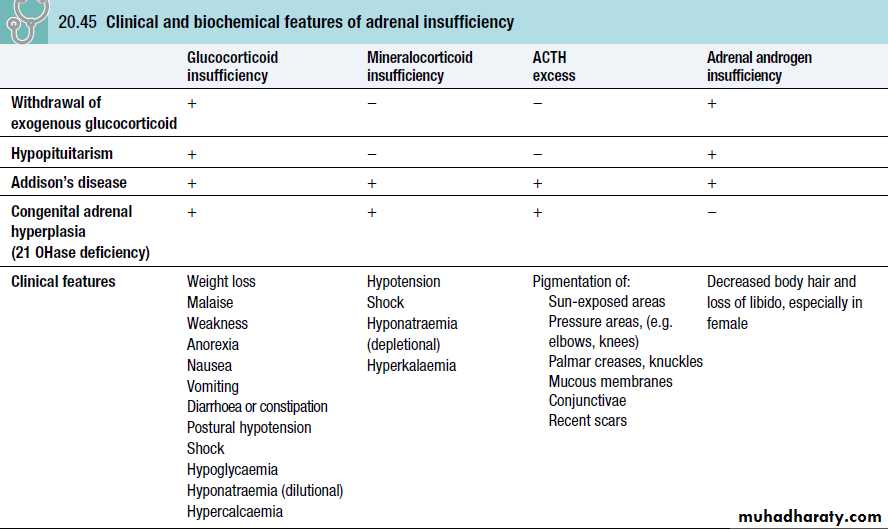

Adrenal insufficiency

Adrenal insufficiency results from inadequate secretion of cortisol and/or aldosterone.

It is potentially fatal and notoriously variable in its presentation.

A high index of suspicion is therefore required in patients with unexplained fatigue, hyponatraemia or hypotension.

The most common is ACTH deficiency (secondary adrenocortical failure), usually because of inappropriate withdrawal of chronic glucocorticoid therapy or a pituitary tumour

Congenital adrenal hyperplasias and Addison's disease (primary adrenocortical failure) are rare

Acute adrenal crises

Features of an acute adrenal crisis include:circulatory shock with severe hypotension,

hyponatraemia,

hyperkalaemia

hypoglycaemia

hypercalcaemia.

Muscle cramps, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and unexplained fever may be present.

The crisis is often precipitated by intercurrent disease, surgery or infection.

Vitiligo occurs in 10–20% of patients with autoimmune Addison’s disease

Assessment of mineralocorticoids

Mineralocorticoid secretion in patients with suspected Addison’s disease cannot be adequately assessed by electrolyte measurements since hyponatraemia occurs in both aldosterone and cortisol deficiencyHyperkalaemia is common, but not universal, in aldosterone deficiency.

Plasma renin activity and aldosterone should be measured in the supine position.

In mineralocorticoid deficiency, plasma renin activity is high, with plasma aldosterone being either low or in the lower part of the normal range

Assessment of adrenal androgens

This is not necessary in men because testosterone from the testes is the principal androgenManagement

Patients with adrenocortical insufficiency always need glucocorticoid replacement therapy and usually, but not always, mineralocorticoid.Adrenal androgen replacement for women is controversial. Other treatments depend on the underlying cause.

Glucocorticoid replacement

Hydrocortisone (cortisol) is the drug of choice.In someone who is not critically ill, hydrocortisone should be given by mouth, 15 mg on waking and 5 mg at around 1800 hrs.

The dose may need to be adjusted for the individual patient but this is subjective.

Excess weight gain usually indicates over-replacement, whilst persistent lethargy or hyperpigmentation may be due to an inadequate dose. Measurement of plasma cortisol levels isunhelpful, because the dynamic interaction between cortisol and glucocorticoid receptors is not predicted by measurements such as the maximum or minimum plasma cortisol level after each dose.

These are physiological replacement doses which should not cause Cushingoid side-effects

Mineralocorticoid replacement

Fludrocortisone (9α-fluoro-hydrocortisone) is administered in a dose 0.05–0.1 mg daily and adequacy of replacement may be assessed objectively by measurement of blood pressure, plasma electrolytes and plasma renin activity.

MINERALOCORTICOID EXCESS

MINERALOCORTICOID EXCESSIndications to test for mineralocorticoid excess in hypertensive patients include:

• Hypokalaemia.

• Poor control of BP with conventional therapy.

• Presentation at a young age

Causes of excessive activation of mineralocorticoid receptors can be differentiated by renin and aldosterone measurement.

increased Renin and increased aldosterone (secondary hyperaldosteronism):

This is the most common cause.Enhanced renin secretion is in response to inadequate renal perfusion and hypotension, e.g. diuretic therapy, cardiac failure, liver failure or renal artery stenosis.

Very rarely, renin-secreting renal tumours cause secondary hyperaldosteronism.

Decreased Renin and increased aldosterone (primary hyperaldosteronism):

A small minority of patients with hypertension will be found to have primary hyperaldosteronism.Depending on the diagnostic criteria used, between 1 and 20% of these have an adrenal adenoma secreting aldosterone (Conn’s syndrome) and the remainder have idiopathic bilateral adrenal hyperplasia

Decreased Renin and decreased aldosterone

The mineralocorticoid receptor pathway in the distal nephron is activated, even though aldosterone levels are low. Either the receptors are activated by cortisol (ectopic ACTH syndrome) or 11-deoxycorticosterone (adrenal tumour), or post-receptor mechanisms are inappropriately activated (e.g. the epithelial sodium channel in Liddle’s syndrome).

Clinical assessment

Many patients are asymptomatic but they may have features of sodium retention or potassium loss• Sodium retention may cause oedema.

• Hypokalaemia causes muscle weakness (or even paralysis), polyuria (renal tubular damage producing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus) and occasionally tetany (associated metabolic alkalosis and low ionised calcium).

Investigations

Biochemical:Plasma electrolytes: hypokalaemia, ↑bicarbonate, sodium upper normal (primary hyperaldosteronism), hyponatraemia (secondary hyperaldosteronism: hypovolaemia stimulates antidiuretic hormone (ADH) release and high angiotensin II levels stimulate thirst). Renin and aldosterone should be measured.

Localisation

Abdominal CT/MRI can localise a Conn’s adenoma but non-functioning adrenal adenomas are present in ∼20% of patients with essential hypertension. If the scan is inconclusive, adrenal vein catheterisation with measurement of aldosterone may be helpful.

Management

• Spironolactone, an aldosterone antagonist, treats both hypokalaemia and hypertension due to mineralocorticoid excess (up to 400 mg daily).• Spironolactone can be changed to amiloride (10–40 mg/day) or eplerenone if gynaecomastia develops (∼20%).

• In patients with Conn’s adenoma, pre-operative therapy to normalise whole-body electrolyte balance should be undertaken before unilateral adrenalectomy.

• Postoperatively, hypertension remains in as many as 70% of cases.

PHAEOCHROMOCYTOMA

This is a rare tumour of chromaffi n tissue which is responsible for < 0.1% of cases of hypertension. There is useful rule of ten:∼10% are malignant

∼10% are extra-adrenal

10% are familial

Clinical features

These can be paroxysmal and include:

• Hypertension (with postural hypotension).

• Palpitations.

• Pallor.

• Sweating.

• Headache.

• Anxiety (with fear of death).

• Abdominal pain.

• Glucose intolerance.

Some patients present with a complication of hypertension, e.g. stroke. There may be features of familial syndromes, e.g. neurofi bromatosis, von Hippel–Lindau syndrome and MEN type 2.

Investigations

Excessive secretion of catecholamines can be confirmed by measuring them in serum (adrenaline/epinephrine, noradrenaline/norepinephrine and dopamine) and their metabolites in urine (e.g. vanillyl-mandelic acid, VMA; conjugated metanephrine and normetanephrine).False-negative results may be obtained due to intermittent catecholamine secretion.

• Phaeochromocytomas are identified by abdominal CT/MRI.

• To localise extra-adrenal tumours, scintigraphy using meta-iodobenzyl guanidine (MIBG) is used.

Management

Medical therapy is required pre-operatively, preferably for a minimum of 6 wks.The non-competitive α-antagonist phenoxybenzamine (10–20 mg orally 6–8-hourly) is used with a β-blocker (e.g. propranolol) or combined α- and β-antagonist (e.g. labetalol).

β-antagonists must not be given before the α-antagonist as this may cause a paradoxical rise in BP.