ENDOCRINE DISEASE •

10

357

• Seminomas arise from seminiferous tubules. Metastases occur via the

lymphatics, often involving the lungs. • Teratomas arise from primitive

germinal cells. They may contain cartilage, bone, muscle or fat. Well-

differentiated tumours are the least aggressive; at the other extreme,

trophoblastic teratoma is highly malignant. • Leydig cell tumours are

usually small and benign, but secrete oestrogens leading to presentation

with gynaecomastia.

Clinical features and investigations

• The common presentation is incidental discovery of a painless testicular

lump, although some complain of testicular ache. • Suspicious scrotal lumps

are imaged by USS. • Serum levels of the ‘tumour markers’

α-fetoprotein

(AFP) and

β-hCG are increased in extensive disease. • Oestradiol may be

elevated, suppressing the levels of LH, FSH and testosterone. • Accurate

staging is based on CT or MRI.

Management and prognosis

• The primary treatment is surgical orchidectomy. • Radiotherapy is the

treatment of choice for early-stage seminoma. • Teratoma confi ned to the

testes may be managed conservatively, but more advanced cancers are

treated with chemotherapy. • Follow-up is by imaging and assessment of

AFP and

β-hCG. • 5-yr survival rates are 90–95% for seminomas and

60–95% for teratomas.

THE PARATHYROID GLANDS

The four parathyroid glands lie behind the lobes of the thyroid. Parathyroid

hormone (PTH) interacts with vitamin D to control calcium metabolism.

Calcium exists in serum as 50% ionised, and 50% complexed with organic

ions and proteins. The parathyroid chief cells respond directly to changes

in calcium concentrations, secreting PTH in response to a fall in ionised

calcium. PTH promotes reabsorption of calcium from renal tubules and

bone, stimulating alkaline phosphatase and lowering plasma phosphate.

PTH also promotes renal conversion of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol to the

more potent 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, which results in increased

calcium absorption from food.

To investigate disorders of calcium metabolism, measurement of calcium,

phosphate, alkaline phosphatase and PTH should be undertaken. Most labo-

ratories measure total calcium in serum. This needs to be corrected if serum

albumin is low, by adjusting the value for calcium upwards by 0.1 mmol/l

(0.4 mg/dl) for each 5 g/l reduction in albumin below 40 g/l.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS

HYPERCALCAEMIA

Causes of hypercalcaemia are listed in Box 10.11. Primary hyperparathy-

roidism and malignant hypercalcaemia are the most common causes. Famil-

358

ENDOCRINE DISEASE •

10

ial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia (FHH) is a rare autosomal dominant

disorder in which a mutation in the calcium-sensing receptor results in

increased PTH secretion with consequent calcium retention in the renal

tubules. FHH is almost always asymptomatic and without com plication.

Unnecessary parathyroidectomy may be undertaken if FHH is misdiag-

nosed as primary hyperparathyroidism.

Clinical assessment

• Symptoms and signs of hypercalcaemia include polyuria, polydipsia, renal

colic, lethargy, anorexia, nausea, dyspepsia, peptic ulceration, constipation,

depression and impaired cognition (‘bones, stones and abdominal groans’).

• Patients with malignant hypercal caemia can have a rapid onset of symp-

toms. • Hypertension is common in hyperparathyroidism. • Parathyroid

tumours are almost never palpable. • A family history of hypercalcaemia

raises the possibility of FHH or MEN.

Investigations

•

↓Plasma phosphate and ↑alkaline phosphatase support a diagnosis of

primary hyperparathyroidism or malignancy. •

↑Plasma phosphate and

↑alkaline phosphatase accompanied by renal impairment suggest tertiary

hyperparathyroidism (p. 360). • If PTH is normal or elevated and urinary

calcium is elevated, then hyperparathyroidism is confi rmed. • Low urine

calcium excretion indicates likely FHH, confi rmed by genetic analysis of

the calcium-sensing receptor. • If PTH is low and no other cause is apparent,

then malignancy with or without bony metastases is likely. The patient

should be screened with a CXR, isotope bone scan, myeloma screen and

serum ACE (elevated in sarcoidosis). PTH-related peptide, which causes

hypercalcaemia associated with malignancy, can be measured by a specifi c

assay.

10.11 CAUSES OF HYPERCALCAEMIA

With normal/elevated (inappropriate) PTH levels

• Primary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism

•

Lithium-induced hyperparathyroidism

• Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia

With low (suppressed) PTH levels

• Malignancy (e.g. lung, breast, renal, colonic and thyroid carcinoma,

lymphoma, multiple myeloma)

•

Elevated 1,25(OH)

2

vitamin D (vitamin D intoxication, sarcoidosis, HIV)

•

Thyrotoxicosis

• Paget’s disease with immobilisation

•

Milk-alkali syndrome

•

Thiazide diuretics

•

Glucocorticoid defi ciency

ENDOCRINE DISEASE •

10

359

Management

• Treatment of severe hypercalcaemia involves rehydration with normal

saline. • Bisphosphonates (e.g. pamidronate 90 mg i.v. over 4 hrs) reduce

serum calcium for a few weeks, working maximally at 2–3 days. If the

underlying cause cannot be removed, oral bisphosphonates should be

continued. • In very ill patients, forced diuresis with furosemide, glu-

cocorticoids, calcitonin or haemodialysis may need to be employed. •

For management of hyperparathyroidism, see page 361. • FHH does not

require therapy.

HYPOCALCAEMIA

The differential diagnosis of hypocalcaemia is shown in Box 10.12. It is

the ionised rather than total concentration which is biologically important.

The most common cause of hypocalcaemia is a low serum albumin with

normal ionised calcium concentration. Ionised calcium may be low with a

normal total serum calcium in alkalosis, e.g. hyperventilation (respiratory)

or Conn’s syndrome (metabolic).

Causes of hypoparathyroidism include:

• Parathyroid gland damage during thyroid surgery (transient hypo-

calcaemia in 10%, permanent in 1%). • Infi ltration of the glands, e.g.

haemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease. • Congenital/inherited, e.g. auto-

immune polyendocrine syndrome (APS) type I, autosomal dominant

hypoparathyroidism.

In pseudohypoparathyroidism there is tissue resistance to PTH. Clinical

features include:

• Short stature. • Short 4th metacarpals and metatarsals. • Rounded face.

• Obesity. • Calcifi cation of the basal ganglia.

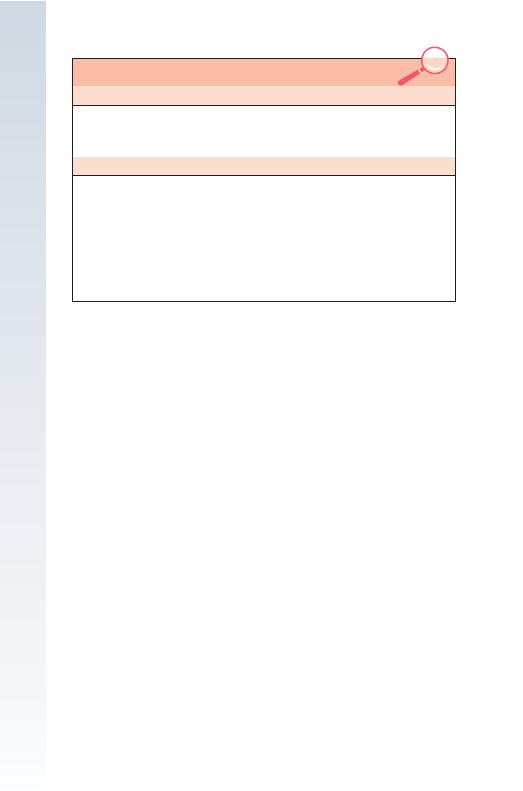

10.12 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF HYPOCALCAEMIA

Total

serum

calcium

Ionised

serum

calcium

Serum

phosphate

Serum PTH

concentration

Hypoalbuminaemia

↓

→

→

→

Alkalosis

→

↓

→

→ or ↑

Vitamin D defi ciency

↓

↓

↓

↑

Chronic renal failure

↓

↓

↑

↑

Hypoparathyroidism

↓

↓

↑

↓

Pseudohypoparathyroidism

↓

↓

↑

↑

Acute pancreatitis

↓

↓

→ or ↓

↑

Hypomagnesaemia

↓

↓

Variable

↓ or →

360

ENDOCRINE DISEASE •

10

The term ‘pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism’ describes those with these

clinical features in whom serum calcium and PTH concentrations are

normal. Due to genomic imprinting, pseudohypoparathyroidism results

from inheritance of the gene defect from the mother, but inheritance from

the father results in pseudo-pseudohypoparathyroidism.

Clinical assessment

• Low ionised calcium increases excitability of peripheral nerves. • Tetany

can occur if total serum calcium is

<2.0 mmol/l (8 mg/dl). • In children

a characteristic triad of carpopedal spasm, stridor and convulsions

occurs. Adults complain of tingling in the hands and feet and around the

mouth. • When overt signs are lacking, latent tetany may be revealed by

Trousseau’s sign (infl ation of a sphygmomanometer cuff to more than the

systolic BP causes carpal spasm) or Chvostek’s sign (tapping over the facial

nerve produces twitching of the facial muscles). • Hypocalcaemia causes

papilloedema and QT interval prolongation, predisposing to ventricular

arrhythmias. • Prolonged hypocalcaemia with hyperphosphataemia may

cause calcifi cation of the basal ganglia, epilepsy, psychosis and cataracts.

• Hypocalcaemia with hypophosphataemia (vitamin D defi ciency) causes

rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults.

Management

• To control tetany, alkalosis can be reversed by rebreathing expired air

in a bag (

↑PaCO

2

). • Injection of 20 ml of 10% calcium gluconate

slowly into a vein will raise the serum calcium concentration immediately.

• I.V. magnesium is required to correct hypocalcaemia associated

with hypomagnesaemia. • Vitamin D defi ciency, persistent hypoparathy-

roidism and pseudohypoparathyroidism are treated with oral calcium salts

and vitamin D analogues (alfacalcidol, calcitriol). • Monitoring of therapy

is required because of the risks of iatrogenic hypercalcaemia, hypercalciuria

and nephrocalcinosis.

PRIMARY HYPERPARATHYROIDISM

The three categories of hyperparathyroidism are shown in Box 10.13.

• In primary hyperparathyroidism there is autonomous secretion of PTH,

usually by a single parathyroid adenoma. • In secondary hyperparathy-

roidism there is increased PTH secretion to compensate for prolonged

hypocalcaemia, thus increasing serum calcium levels by bone resorption.

It is associated with hyperplasia of all parathyroid tissue. • In a small pro-

portion of secondary hyperparathyroidism cases, continuous stimulation of

the parathyroids results in adenoma formation and autonomous PTH secre-

tion. This is known as tertiary hyperparathyroidism.

Primary hyperparathyroidism has a prevalence of 1 in 800 and is 2–3

times more common in women; 90% of patients are over 50. It also occurs

in MEN syndromes. Clinical presentation is described under hypercalcae-

mia (p. 358).

ENDOCRINE DISEASE •

10

361

Skeletal and radiological changes include:

• Osteoporosis-reduced bone mineral density on DEXA scanning. • Osteitis

fi brosa results from increased bone resorption by osteoclasts with fi brous

replacement. It presents as bone pain, fracture and deformity.

• Chondrocalcinosis is due to deposition of calcium pyrophosphate crystals

within articular cartilage, typically the knee, leading to osteoarthritis or

acute pseudogout. • X-ray changes include subperiosteal erosions, terminal

resorption in the phalanges, ‘pepper-pot’ skull and renal calcifi cation.

Imaging to locate the adenoma or differentiate hyperplasia has tradition-

ally not been necessary, but its increasing use allows more targeted resec-

tion through a smaller incision. Localisation of parathyroid tumours may

be carried out using

99m

Tc-sestamibi scanning, USS, CT or selective neck

vein catheterisation with PTH measurements. Without imaging, >90% of

adenomas can be located at surgery.

Management

Treatment of severe hypercalcaemia is described above (p. 359). Hypercal-

caemia in primary hyperparathyroidism responds less well to glucocorti-

coids and bisphosphonates. Most patients do not require urgent surgical

treatment. However, the only long-term therapy is surgery, with excision

of an adenoma or debulking of hyperplastic glands. Part of the hyperplastic

gland can be transplanted to the forearm to allow further debulking at a

later date. Post-operative hypocalcaemia can occur while residual sup-

pressed parathyroid tissue recovers.

Surgery is indicated for patients under 50 and for those with symptoms

or complications, e.g. peptic ulceration, renal stones, renal impairment

or osteopenia. The remainder can be reviewed annually, with assess-

ment of symptoms, renal function, serum calcium and bone mineral

density.

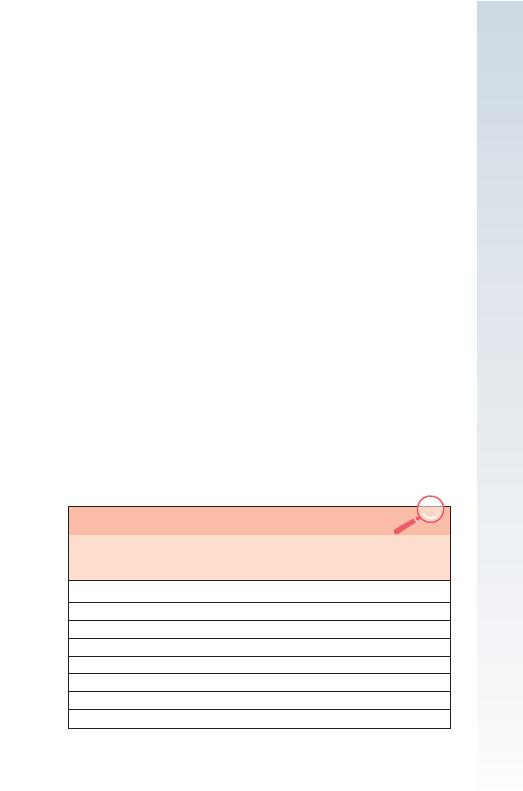

10.13 HYPERPARATHYROIDISM

Type

Serum calcium

PTH

Primary

Single adenoma (90%), multiple

adenomas (4%), nodular hyperplasia

(5%), carcinoma (1%)

Raised

Not suppressed

Secondary

Chronic renal failure, malabsorption,

osteomalacia and rickets

Low

Raised

Tertiary

Raised

Not suppressed