HEMOSTASIS

NORMAL HEMOSTASIS

Haemostasis describes the normal process of blood clotting. It takes place via a series of

complex, tightly regulated interactions involving cellular and plasma factors.

There are five main components:

1.

Vessel wall.

2.

Platelets.

3.

Coagulation proteins.

4.

Anticoagulant proteins.

5.

Fibrinolytic system.

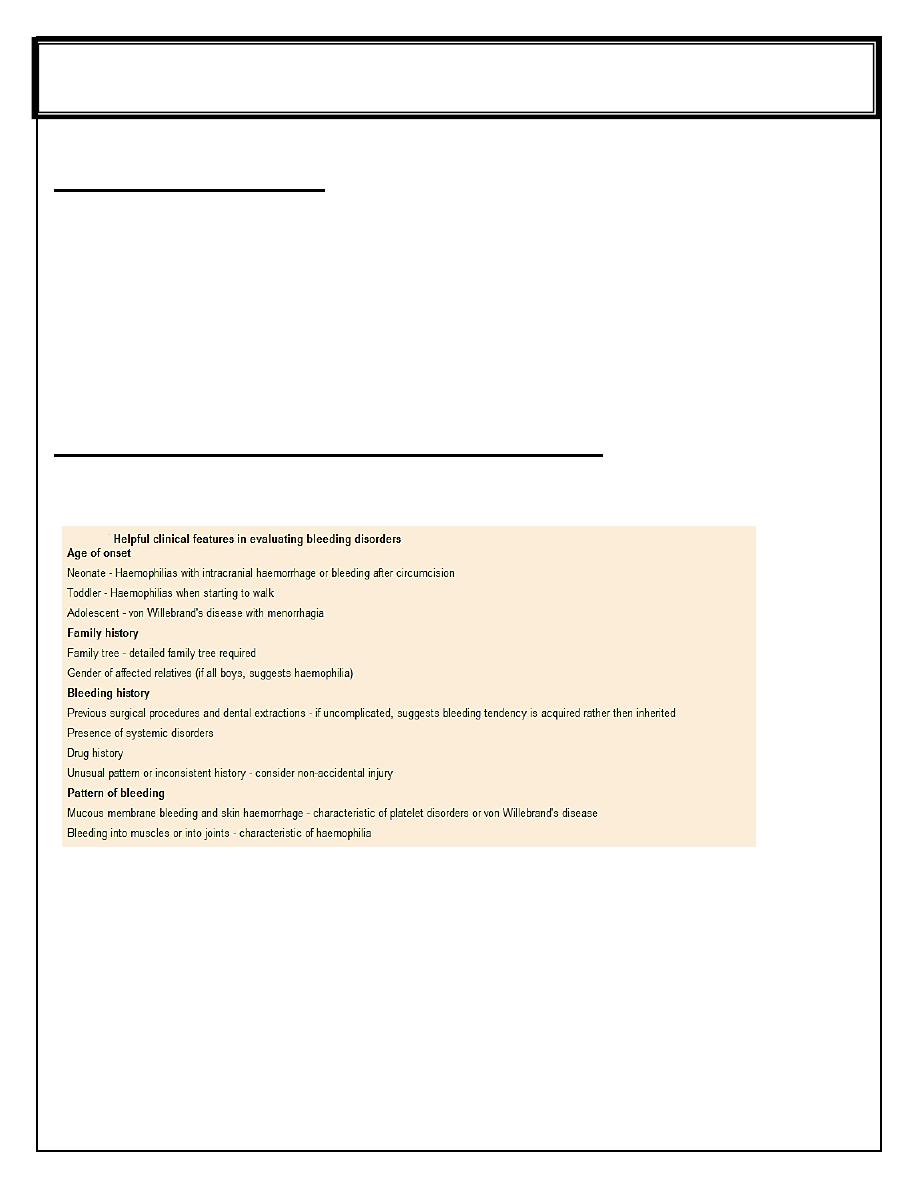

Approach to the diagnosis of bleeding disorders

The diagnostic evaluation of an infant or child for a possible bleeding disorder includes:

1.

Identifying the clinical presentation that suggest the underlying diagnosis.

2.

Initial laboratory screening tests to determine the most likely diagnosis. The most useful

initial screening tests are:

Full blood count and blood film

Prothrombin time (PT) - measures the activity of factors II, V, VII and X

Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) - measures the activity of factors II, V, VIII,

IX, X, XI and XII

If PT or APTT is prolonged, a 50: 50 mix with normal plasma will distinguish between

possible factor deficiency or presence of inhibitor

Fifth stage Lec -3

DR. ATHL HUMO

Pediatric

4/2017

Thrombin time - tests for deficiency or dysfunction of fibrinogen

Bleeding time ? Platelet function analyzer.

Quantitative fibrinogen assay

D-dimers

Biochemical screen including renal and liver function tests.

3.

Specialist investigation to characterize a deficiency or exclude important conditions that

can present with normal initial investigations, e.g. mild von Willebrand's disease, factor XIII

deficiency and platelet function disorders.

HEMOPHILIA

The commonest severe inherited coagulation disorders are haemophilia A (FVIII deficiency)

and haemophilia B (FIX deficiency). Both have X-linked recessive inheritance. Identifying

female carriers requires:

1.

A detailed family history.

2.

Analysis of coagulation factors.

3.

DNA analysis.

Prenatal diagnosis is available using DNA analysis.

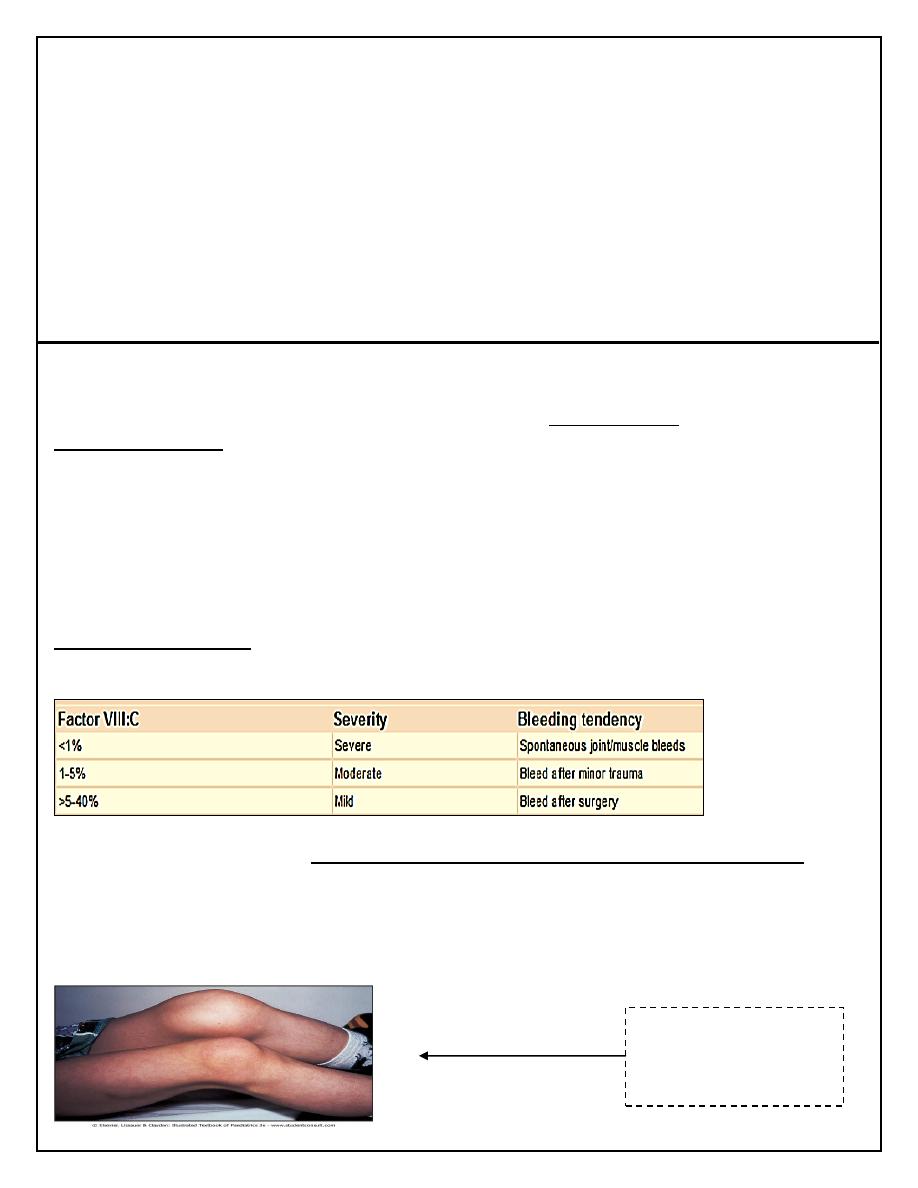

Clinical Features

The disorder is graded as severe, moderate or mild depending on the FVIII:C (or IX:C in

haemophilia B) level.

The hallmark of the disease is recurrent spontaneous bleeding into joints and muscles,

which can lead to crippling arthritis if not properly treated. Most children present towards the

end of the first year of life, when they start to crawl then walk (and fall over).

Almost 40% of cases with severe disease present in the neonatal period, particularly with

intracranial hemorrhage, bleeding post-circumcision or prolonged oozing from heel stick and

venepuncture sites. The severity remains constant within a family.

Severe arthropathy

from recurrent joint

bleeds in haemophilia

INVESTIGATIONS

1.

Prolong APTT

2.

Normal PT

3.

Quantitative assessment of factor VIII/IX concentrate

TREATMENT

1.

Recombinant FVIII concentrate for haemophilia A ( or recombinant FIX concentrate for

haemophilia B) is given by intravenous infusion whenever there is any bleeding.

2.

If recombinant products are unavailable, highly purified, virally inactivated

plasma-derived products should be used.

3.

The quantity required depends on the site and nature of the bleeding. In general, raising the

circulating level to 30% of normal is sufficient to treat minor and simple joint bleeding.

Major surgery or life-threatening bleeds require the level to be raised to 100% and then

maintained at 30-50% for up to 2 weeks to prevent secondary hemorrhage. This can only be

achieved by regular infusion of factor concentrate (usually 8- to 12-hourly for FVIII, 12- to

24-hourly for FIX, or by continuous infusion) .

4.

Dose for f VIII : desired level (%) × weight (Kg) × 0.5

Dose for f IX : desired level (%) × weight (Kg) × 1.5

5.

Desmopressin (DDAVP) may allow mild haemophilia A to be managed without the use of

blood products. It is given by infusion and stimulates endogenous release of FVIII:C and

von Willebrand factor. Adequate levels can be achieved to enable minor surgery and dental

extraction to be undertaken. DDAVP is ineffective in haemophila B.

6.

Haemophilia centers should supervise the management of children with bleeding disorders.

They provide a multidisciplinary approach with expert medical, nursing and laboratory

input. Specialised physiotherapy is needed to preserve muscle strength and avoid damage

from immobilization. Psychosocial support is an integral part of maintaining compliance.

7.

NOTE: intramuscular injections, aspirin and NSAI drugs should be avoided in all patients

with haemophilia.

8.

Home treatment is encouraged to avoid delay in treatment which increases the risk of

permanent damage, e.g. progressive arthropathy. Parents are usually taught to give

replacement therapy at home when the child is 2-3 years of age.

PROPHYLAXIS

Prophylactic FVIII/IX is given to all children with severe haemophilia to further reduce the

risk of chronic joint damage by raising the baseline level above 2%.

Primary prophylaxis usually begins at age 2-3 years, and is given two to three times per

week. If peripheral venous access is poor, a central venous access device may be required.

Prophylaxis has been shown to result in better joint function in adult life.

Von Willebrand Disease

Von Willebrand disease is a common AD inheritance disorder (found in 1% of the population)

caused by a deficiency of von Willebrand factor

Von Willebrand factor (vWF) has two major roles:

1.

It facilitates platelet adhesion to damaged endothelium.

2.

It acts as the carrier protein for FVIII, protecting it from inactivation and clearance.

vWD results from either a quantitative or qualitative deficiency of von Willebrand factor

(vWF). This causes defective platelet plug formation and, since vWF is a carrier protein for

FVIII, patients with vWD also are deficient in FVIII.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Bruising

Excessive, prolonged bleeding after surgery

Mucosal bleeding such as epistaxis and menorrhagia.

In contrast to haemophilia, spontaneous soft tissue bleeding such as large haematomas and

haemarthroses are rare.

INVESTIGATIONS

1.

VWF antigen (VWF:Ag), measures total amount of VWF protein present.

2.

VWF activity (VWF : Ristocetin Cofactor [Rco]), assess interaction of VWF and platelets

as mediated by ristocetin antibiotic. The rate of Ristocetin induced agglutination is related

to the concentration and functional activity of the plasma von Willebrand factor).

3.

APTT mildly prolonged.

4.

Bleeding time is prolonged.

TREATMENT

1.

Mild vWD can usually be treated with DDAVP, which causes secretion of both FVIII and

vWF into plasma.

2.

More severe types of vWD have to be treated with vWF- FVIII concentrate.

3.

Cryoprecipitate is no longer used to treat vWD as it has not undergone viral inactivation.

4.

Intramuscular injections, aspirin and NSAI drugs should be avoided in all patients with

vWD.

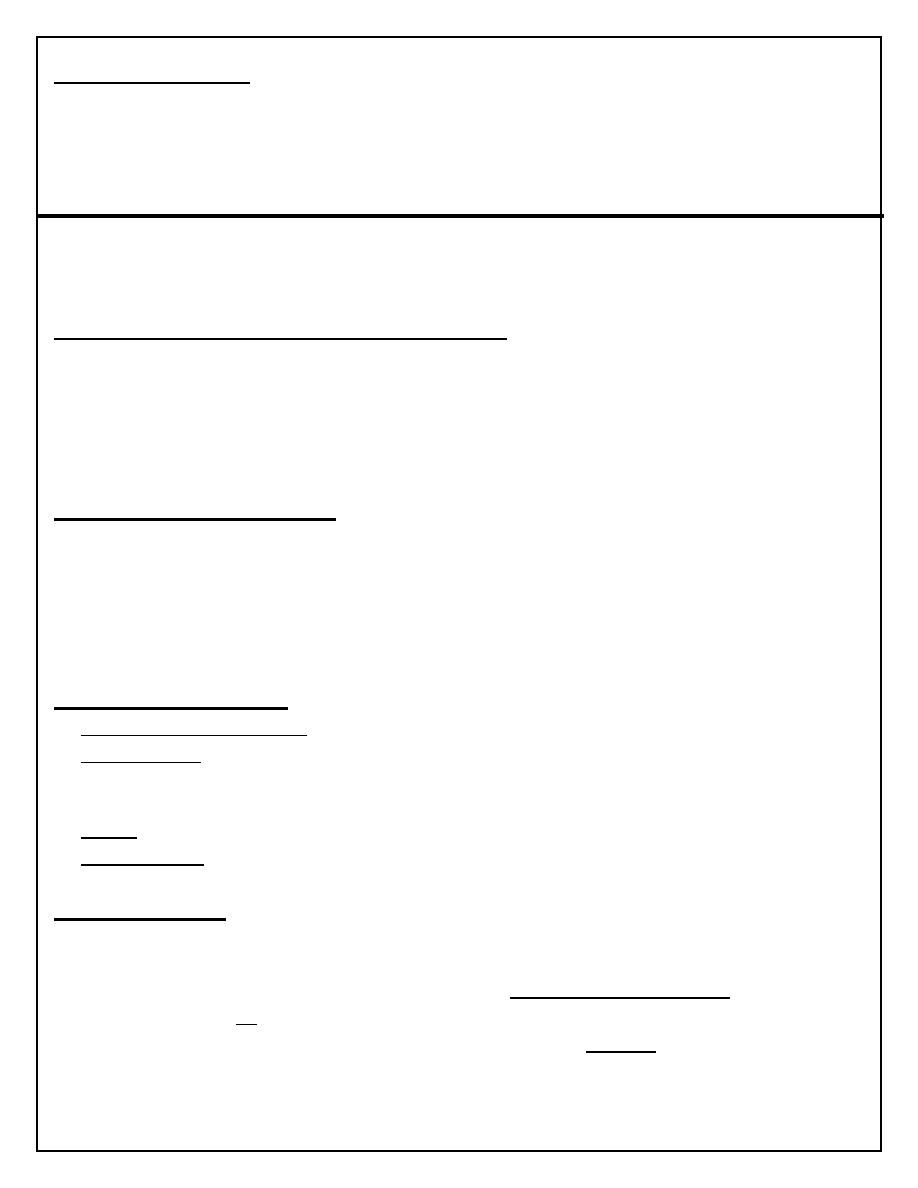

Investigations in haemophilia A & vWD

Lab

Haemophilia A

von Willebrand's disease

PT

Normal

Normal

APTT

↑↑

Normal or ↑

Factor VIII:C

↓↓

Normal or ↓

vWF Ag

Normal

↓

RiCoF (activity)

Normal

↓

vWF multimers

Normal

Variable

Acquired Disorders of Coagulation

The main acquired disorders of coagulation affecting children are those secondary to:

1.

Haemorrhagic disease of the newborn due to vitamin K deficiency.

2.

liver disease.

3.

ITP (immune thrombocytopenia).

4.

DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation).

THROMBOCYTOPENIA

Thrombocytopenia is a platelet count <150 × 10

9

/L. The risk of bleeding depends on the

level of the platelet count:

1.

Severe thrombocytopenia (platelets <20 × 10

9

/L) - risk of spontaneous bleeding.

2.

Moderate thrombocytopenia (platelets 20-50 × 10

9

/L) - at risk of excess bleeding during

operations or trauma but low risk of spontaneous bleeding.

3.

Mild thrombocytopenia (platelets 50-150 × 10

9

/L) - low risk of bleeding during operations

or trauma.

Thrombocytopenia may result in bruising, petechiae, purpura and mucosal bleeding (e.g.

epistaxis, bleeding from gums when brushing teeth). Major haemorrhage in the form of

severe gastrointestinal haemorrhage, haematuria and intracranial bleeding is much less

common.

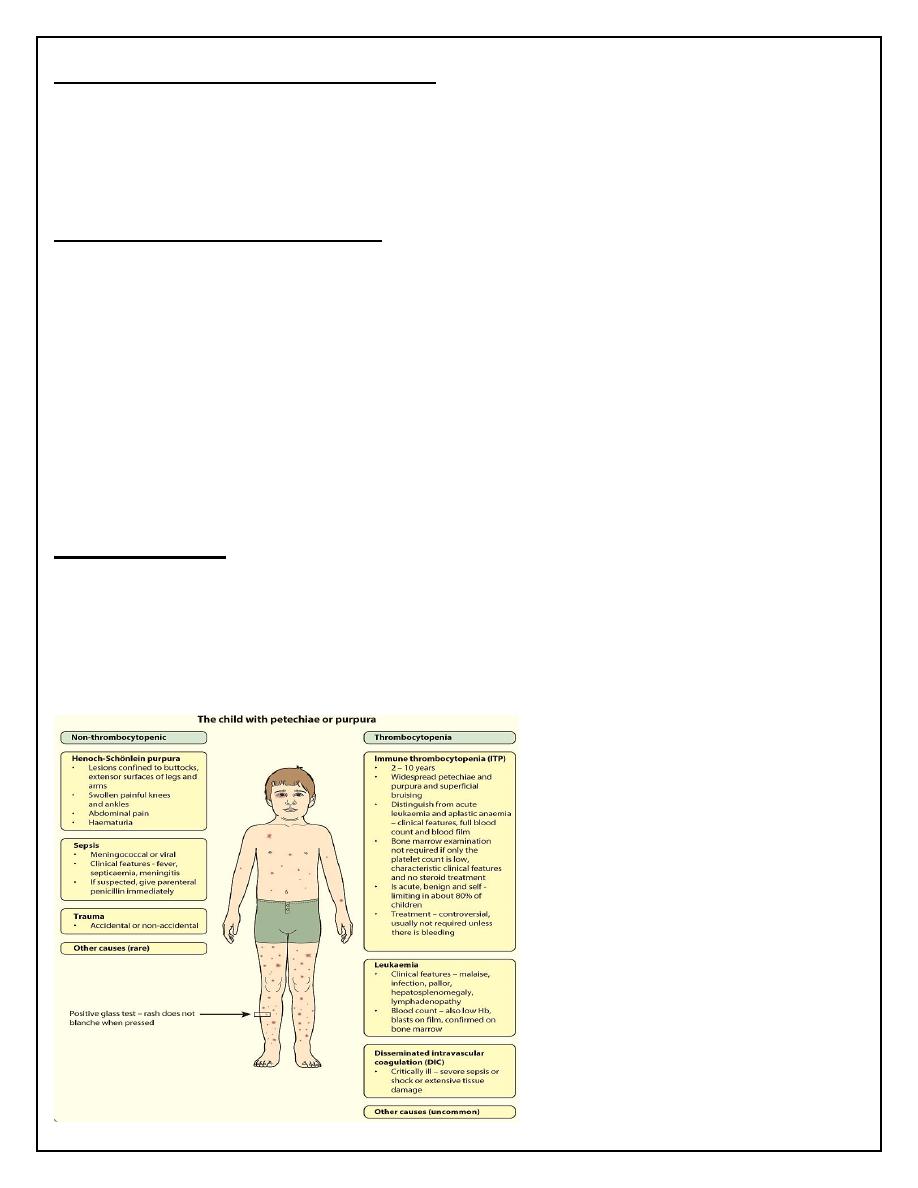

While purpura may signify thrombocytopenia, it also occurs with a normal platelet count

from platelet dysfunction and vascular disorders.

Immune Thrombocytopenia

Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura(ITP)

Childhood ITP is a common disorder that usually follows an acute viral infection. Childhood

ITP is caused by an antibody (IgG or IgM) that binds to the platelet membrane. The

condition results in Fc receptor–mediated splenic destruction of antibody-coated platelets.

Rarely, ITP may be the presenting symptom of an autoimmune disease, such as systemic

lupus erythematosus (SLE).

The reduced platelet count is accompanied by a compensatory increase of megakaryocytes in

the bone marrow.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Most children present between the ages of 2 and 10 years, with onset often 1-2 weeks after a

viral infection. Affected children develop petechiae and purpura and superficial bruising . It

can cause epistaxis and other mucosal bleeding but profuse bleeding is uncommon.

Intracranial bleeding is a serious but rare complication, occurring in 0.1-0.5%, mainly in

those with a long period of severe thrombocytopenia.

Significant adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly is unusual, and the RBC & WBC counts are

normal.

The presence of abnormal findings such as HSM, bone or joint pain, remarkable

lymphadenopathy other cytopenias, or congenital anomalies suggests other diagnoses

(leukemia, syndromes).

When the onset is insidious, especially in an adolescent, chronic ITP or the possibility of a

systemic illness, such as SLE, is more likely.

DIAGNOSIS

ITP is a diagnosis of exclusion, so careful attention must be paid to the:

1.

History.

2.

Clinical features.

3.

Lab finding:

CBC & blood film: ↓platelet count (normal or ↑size platelet), normal RBC & WBC count.

Bone marrow examination [shows normal granulocytic and erythrocytic series, with

characteristically normal or increased numbers of megakaryocytes], usually not done unless

there is atypical finding as :

an abnormal WBC count or differential

unexplained anemia

as well as findings on history and physical examination suggestive of a bone

marrow failure syndrome or malignancy as HSM & LAP.

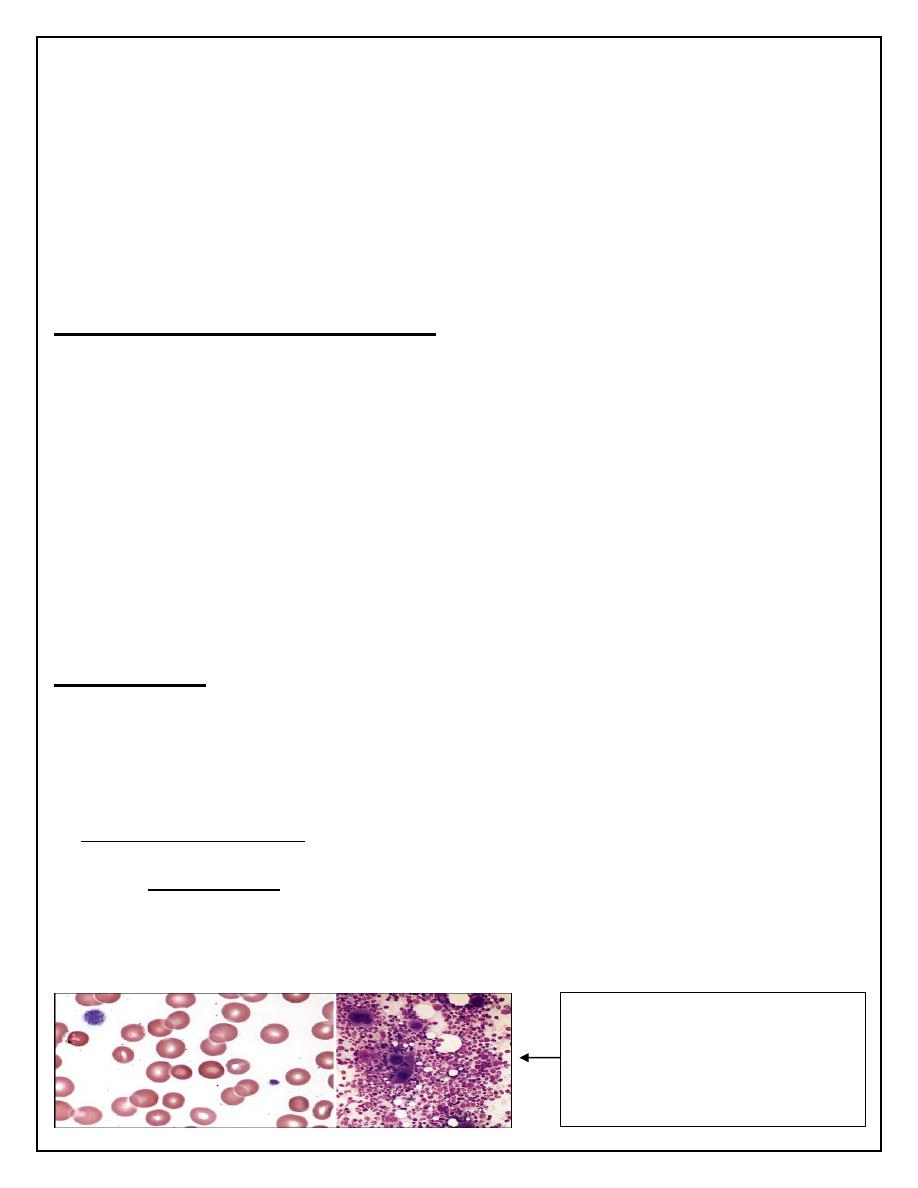

A. Blood smear (large platelets)

B. Bone marrow aspirate

(Increased numbers of

megakaryocytes, many of

which appear immature)

TREATMENT

In about 80% of children, the disease is acute, benign and self-limiting, usually remitting

spontaneously within 6-8 weeks. Most children can be managed at home and do not require

hospital admission.

The American Society of Hematology Guidelines:

1.

No therapy, except to increase platelet count > 20.

2.

Prednisone 1-4mg/kg/day, short course until plat >20.

3.

IVIG: 1g/kg single dose for 2 days (downregulating Fc-mediated phagocytosis of

antibody-coated platelets.

4.

Intravenous anti-D therapy: for Rh-positive patients at a dose of 50-75 μg/kg for 2-3 days

(induces mild hemolytic anemia. RBC-antibody complexes bind to macrophage Fc receptors

and interfere with platelet destruction)

5.

Splenectomy:

Acute ITP with ICH & life-threatening bleeding not respond to platelet

transfusion & other therapy.

Child ≥ 4 years with severe chronic ITP, not respond to other therapy.

Chronic ITP

In 20% of children the platelet count remains low for 6-12 months after diagnosis; this is

known as chronic ITP.

No treatment is given unless there is major bleeding, treatment is mainly supportive, the

child should avoid contact sports but be encouraged to continue normal activities, including

schooling.

Splenectomy may benefit patient with significant bleeding, but has significant morbidity and

may be unsuccessful in up to 25% of cases.

Rituximab, has been used to treat chronic ITP.

Thrombopoiesis stimulator, romiplastin and eltrombopag are encouraging for treating

chronic ITP.

If ITP in a child becomes chronic, regular screening for SLE should be performed, as the

thrombocytopenia may predate the development of autoantibodies.

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

DIC describes a disorder characterised by coagulation pathway activation leading to diffuse

fibrin deposition in the microvasculature and consumption of coagulation factors and platelets.

This altered balance of hemostasis usually caused by life-threatening severe systemic disease

associated with hypoxia, acidosis, tissue necrosis, shock, and/or endothelial damage.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Bleeding frequently first occurs from sites of venipuncture or surgical incision.

The skin may show petechiae and ecchymoses.

Tissue necrosis as infarction of large areas of skin, subcutaneous tissue, or kidneys.

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

LABORATORY FINDINGS

No single test reliably diagnoses DIC. However, DIC should be suspected when the following

abnormalities coexist:

1.

Thrombocytopenia.

2.

Prolonged PT (prothrombin time).

3.

Prolonged APTT.

4.

Low fibrinogen.

5.

Raised fibrinogen degradation products and D-dimers.

6.

Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia.

7.

There is also usually a marked reduction in the naturally occurring anticoagulants, protein C,

S and antithrombin.

TREATMENT

1.

Treat underlying cause.

2.

Supportive:

correcting hypoxia, acidosis and poor perfusion.

replace depleted blood-clotting factors, platelets, and anticoagulant proteins by transfusion.

3.

Heparin may be used to treat significant arterial or venous thrombotic disease unless sites of

life-threatening bleeding coexist.

THROMBOSIS

Thrombosis is uncommon in children. It may be due to an:

1.

Inherited disorder:

protein C deficiency

protein S deficiency

antithrombin deficiency.

2.

Acquired secondary to another underlying illness or its treatment:

catheter-related thrombosis.

DIC.

polycythaemia (e.g. due to congenital heart disease).

malignancy .

SLE.

All children with thrombosis should be screened for inherited or acquired predisposing

disorders.