1

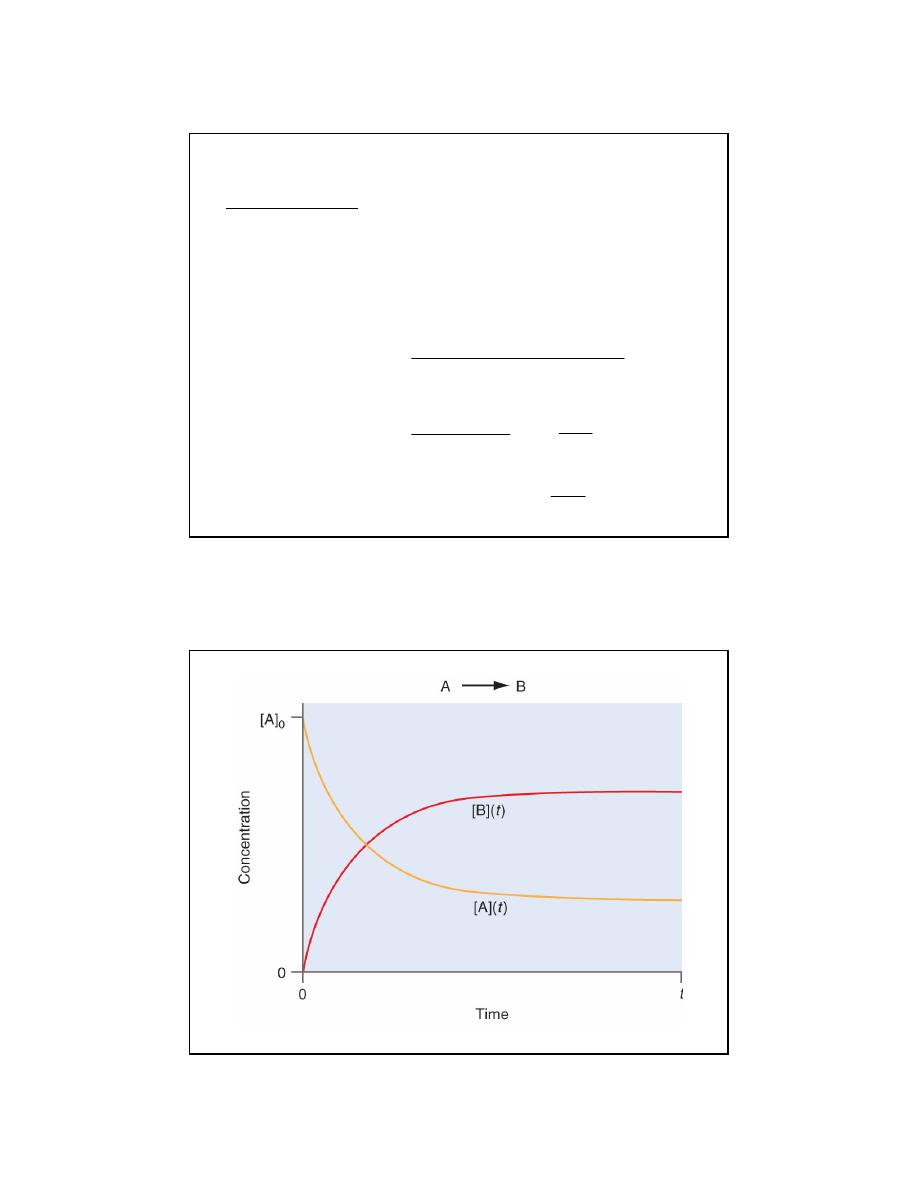

Reaction Rates:

Reaction Rate: The change in the concentration of a reactant or a

product with time (M/s).

Reactant

→ Products

A

→ B

(

)

change in number of moles of B

Average rate

change in time

moles of B

t

=

∆

=

∆

∆[A]

Rate

∆t

= −

∆[B]

∆t

=

Since reactants go away with time:

Chemical Kinetics

2

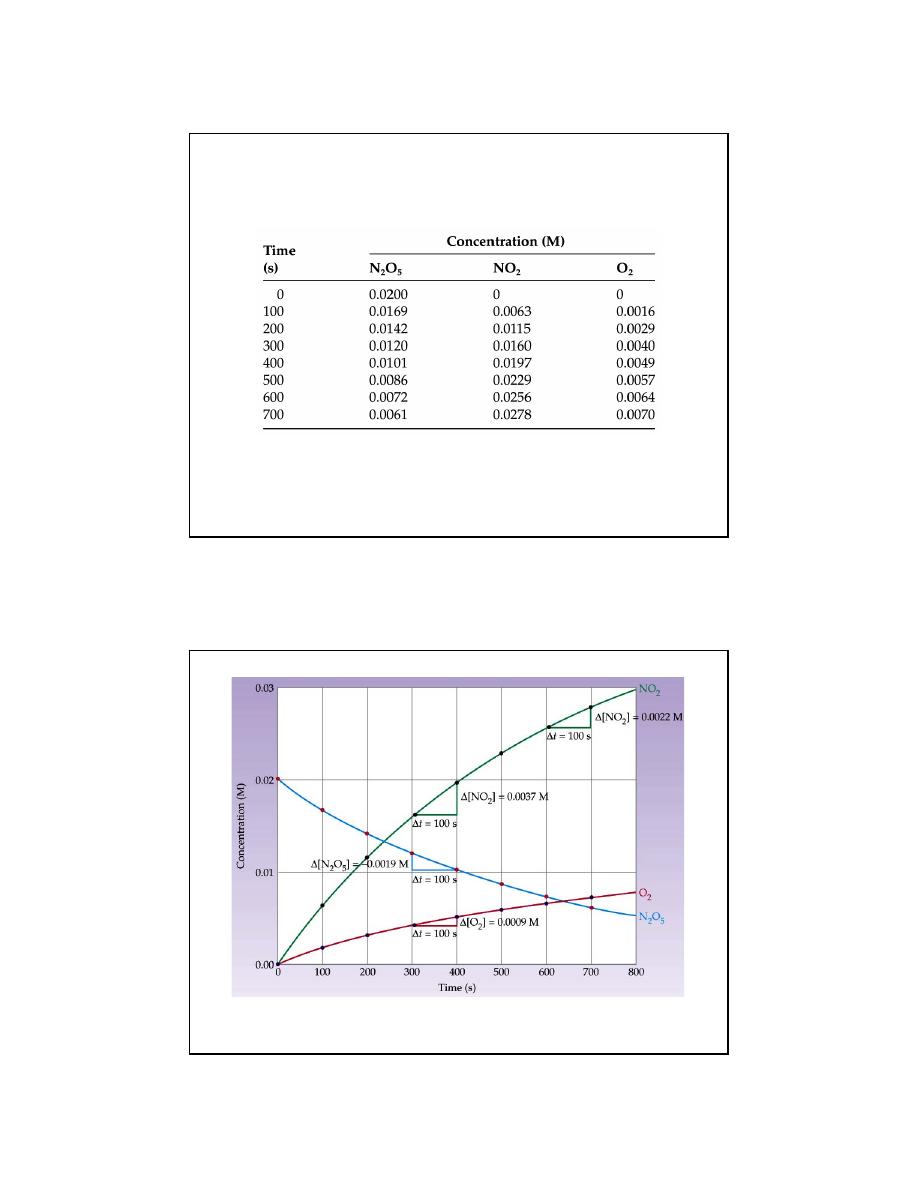

Consider the decomposition of N

2

O

5

to give NO

2

and O

2

:

2N

2

O

5

(g)

→ 4NO

2

(g) + O

2

(g)

reactants

decrease with

time

products

increase with

time

3

2N

2

O

5

(g)

→ 4NO

2

(g) + O

2

(g)

From the graph looking at t = 300 to 400 s

6

1

2

0.0009M

Rate O =

9 10 Ms

100s

−

−

= ×

5

1

2

0.0037M

Rate NO =

3.7 10 Ms

100s

−

−

=

×

5

1

2

5

0.0019M

Rate N O =

1.9 10 Ms

100s

−

−

=

×

Why do they differ?

Recall

:

To compare the rates one must account for the stoichiometry.

6

1

6

1

2

Rate O =

9 10 Ms

9 10 Ms

1

1

−

−

−

−

× ×

= ×

5

1

6

1

2

Rate NO =

3.7 10 Ms

9.2 10 M

1

4

s

−

−

−

−

×

×

=

×

5

1

6

1

2

5

Rate N O =

1.9 10 Ms

9.5 10

1

2

Ms

−

−

−

−

×

×

=

×

Now they

Now they

agree!

agree!

Reaction Rate and Stoichiometry

a

A +

b

B

→

c

C +

d

D

[ ]

[ ]

[ ]

[ ]

A

B

1

1

a

b

C

D

Rate

t

t

1

1

c

d

t

t

∆

∆

∆

∆

=

=

=

=

∆

∆

∆

−

∆

−

In general for the reaction:

4

The reaction rate law expression relates the rate of a reaction to

the concentrations of the reactants.

Each concentration is expressed with an order (exponent).

The rate constant converts the concentration expression into the

correct units of rate (Ms

−1

). (It also has deeper significance,

which will be discussed later)

For the general reaction:

For the general reaction:

Rate Law & Reaction Order

a

A +

b

B

→ c

C +

d

D

x

and

y

are the reactant orders

determined from experiment.

x

and

y

are NOT the

stoichiometric coefficients.

x

y

Rate = k [A] [B]

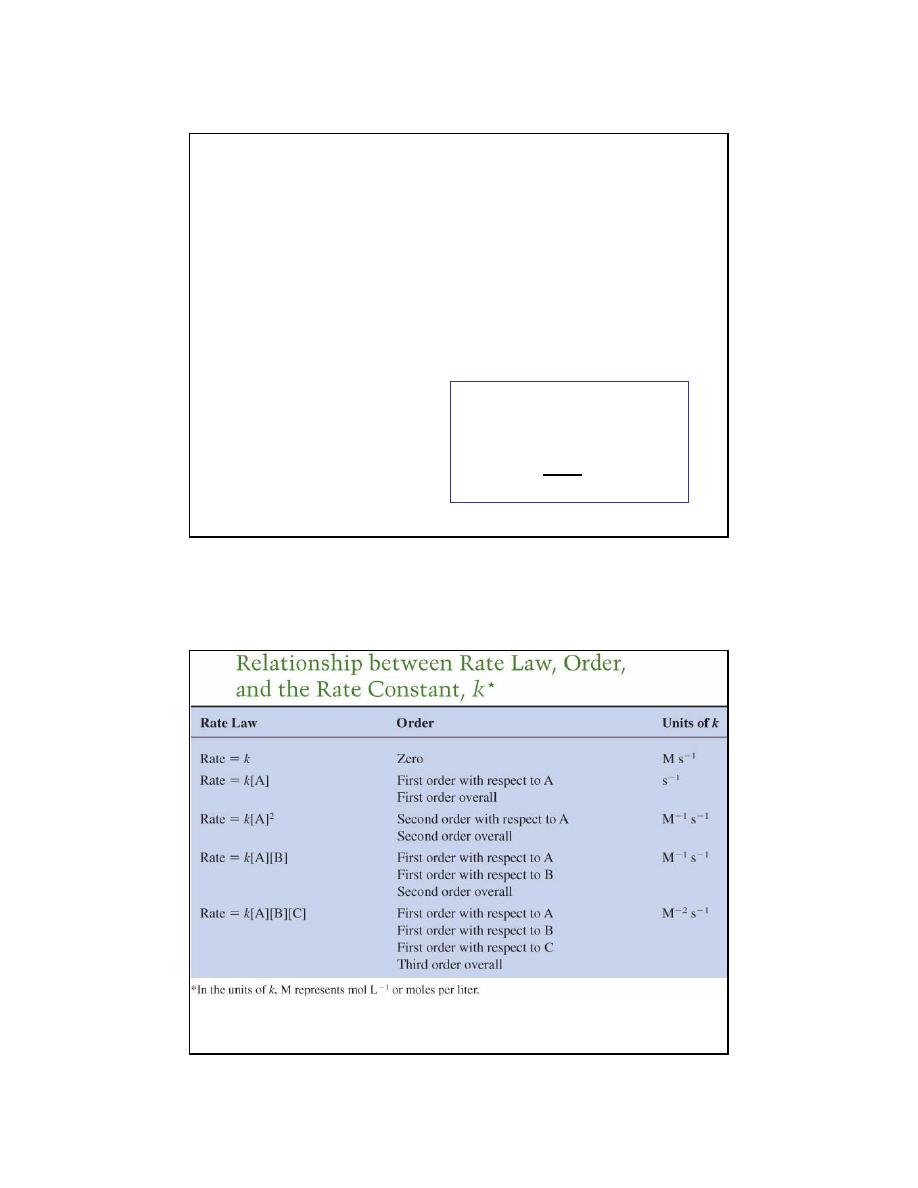

5

The Overall Order of a reaction is the sum of the individual

orders:

Rate (Ms

−1

) = k[A][B]

1/2

[C]

2

Overall order:

1 + ½ + 2 = 3.5 =

7/2

or

seven

−

halves order

note:

when the order of a reaction is 1 (first order) no

exponent is written.

Units for the rate constant:

The units of a rate constant will change depending upon the overall

order.

The units of rate are always M/s or Ms

–1

To find the units of a rate constant for a particular rate law, simply divide

the units of rate by the units of molarity in the concentration term of the

rate law.

Rate (Ms

–1

) = k[A] 1

st

order

1

1

Ms

k(units)

s

M

−

−

=

=

6

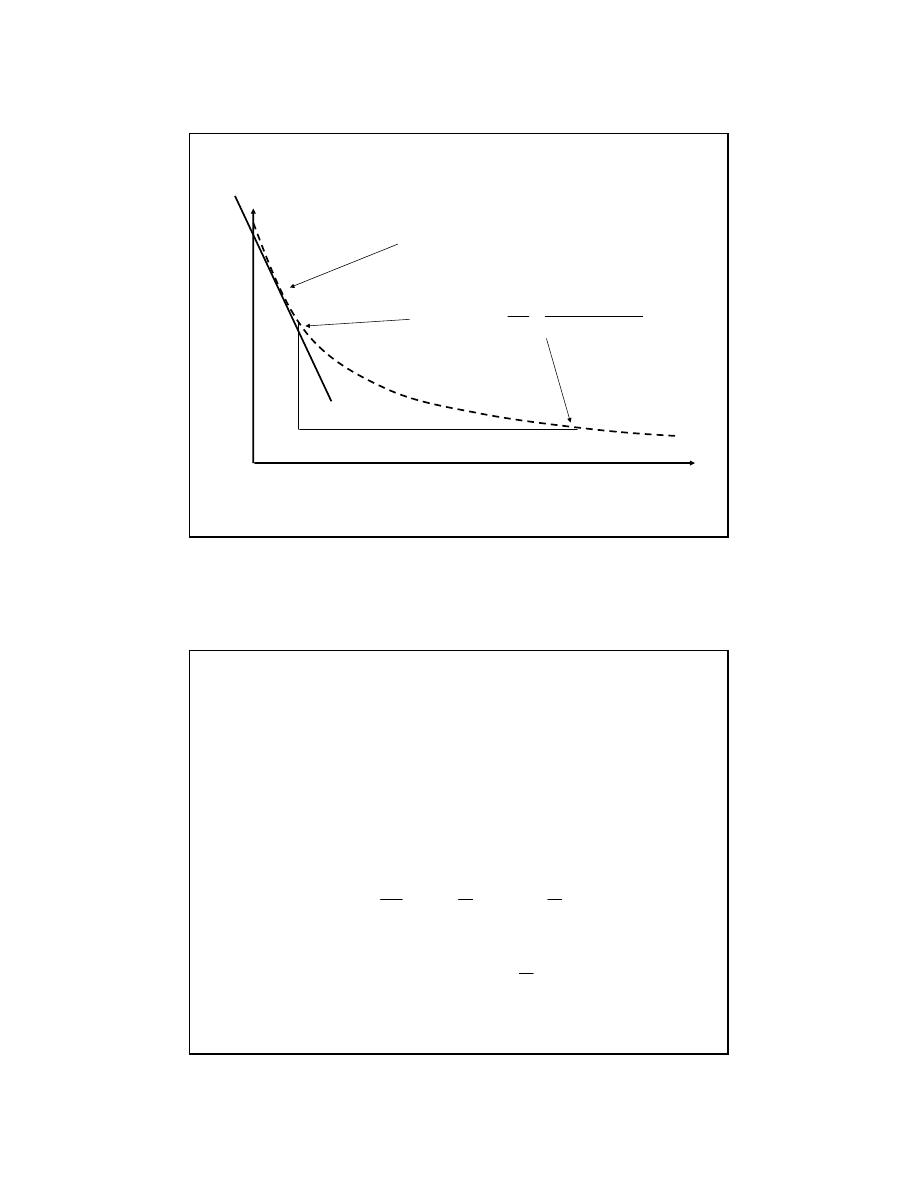

time (s)

Instantaneous rate (tangent line)

Y

[concentration]

Average Rate

X

time

∆

∆

=

∆

∆

Reaction Rates

concentration (M)

Rules of logarithms

log (1) = 0

log (10) = 1

log (100) = 2

Log (10

x

) = x

ln (1) = 0

ln (e) = 1

ln (e

x

) = x

log A

x

= xlog A

ln A

x

= xln A

x

x

x

A

A

A

log

log

x log

B

B

B

=

=

log(AB) = log A + log B

A

log

log A log B

B

=

−

7

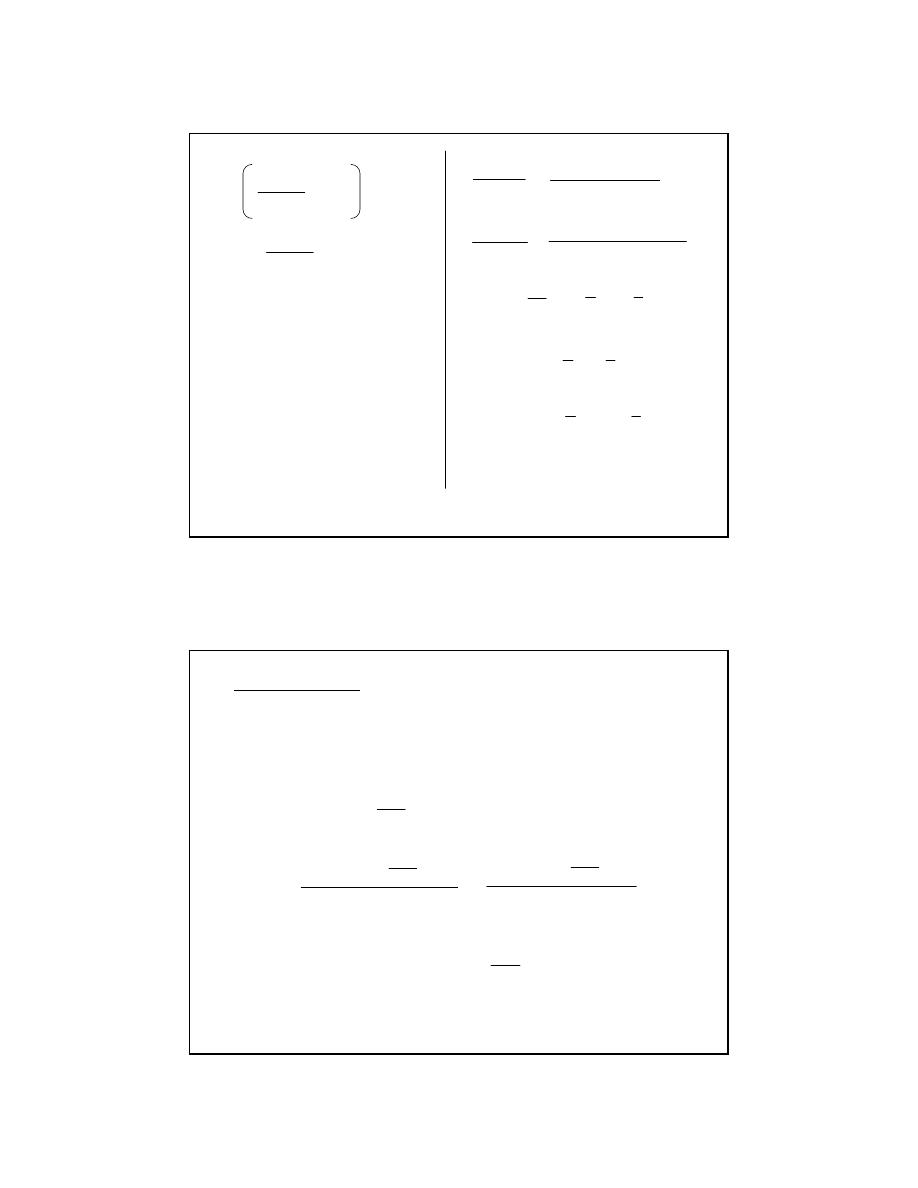

The reaction of nitric oxide with hydrogen at 1280°C is:

Determining Reaction Order: The Method of Initial Rates

2NO(g) + 2H

2

(g)

→ N

2

(g) + 2H

2

O(g)

From the following data, determine the rate law and rate constant.

0.0120

0.0200

0.0100

3

0.144

0.0300

0.0200

2

0.00600

0.0100

0.0100

1

Initial Rate

(M/min)

[H

2

]

o

(M)

[NO]

o

(M)

Run

Rate(M/min) = k [NO]

x

[H

2

]

y

The rate law for the reaction is given by:

2NO(g) + 2H

2

(g)

→ N

2

(g) + 2H

2

O(g)

Taking the ratio of the rates of runs 3 and 1 one finds:

Rate(3)

Rate(1)

=

x

y

(3)

2 (3)

x

y

(1)

2 (1)

k [NO] [H ]

k [NO] [H ]

0.0120M / min

0.00600M / min

=

x

y

x

y

k [0.0100] [0.0200]

k [0.0100] [0.0100]

y

y

[0.0200]

[0.0100]

=

2 =

y

y

[0.0200]

[0.0100]

=

y

0.0200

0.0100

8

y

0.0200

0.0100

=

2

log

y

0.0200

log

log 2

0.0100

=

( )

ylog 2

log 2

=

y = 1

Rate(1)

Rate(2)

=

x

y

(1)

2 (1)

x

y

(2)

2 (2)

k [NO] [H ]

k [NO] [H ]

0.00600

0.144

=

x

x

k [0.0100] [0.0100]

k [0.0200] [0.0300]

Now that “y” is known, we

may solve for x in a similar

manner:

1

24

=

x

1

1

2

3

×

x

1

1

2

8

=

1

1

x log

log

2

8

=

x = 3

The Rate Law is:

Rate(M/min) = k [NO]

3

[H

2

]

To find the rate constant, choose one set of data and solve:

(

) (

)

3

M

0.0120

k 0.0100M

0.0200M

min

=

(

) (

)

3

M

0.0120

min

k

0.0100M

0.0200M

=

(

) (

)

3

4

M

0.0120

min

0.0100

0.0200 M

=

3

5

M

k 6.00 10

min

−

=

×

9

Integrated Rate Laws: time dependence of concentration

For a first order process, the

rate law can be written:

A

→ products

1

[A]

Rate(Ms )

k[A]

t

−

∆

= −

=

∆

This is the “

average rate

”

If one considers the infinitesimal changes in concentration and time the rate

law equation becomes:

1

d[A]

Rate(Ms )

k[A]

dt

−

= −

=

o

[A]

t

[A]

0

d[A]

k dt

[A]

= −

∫

∫

where [A] = [A]

o

at time t = 0

and [A] = [A] at time t = t

This is the “

instantaneous rate

”

Integrating in terms of d[A] and dt:

o

[A]

t

[A]

0

d[A]

k dt

[A]

= −

∫

∫

o

[A]

ln

kt

[A]

= −

kt

o

[A]

e

[A]

−

=

Taking the exponent to each side of the equation:

or

kt

o

[A] [A] e

−

=

Conclusion:

Conclusion:

The concentration of a reactant governed by first

order kinetics falls off from an initial concentration

exponentially with time.

10

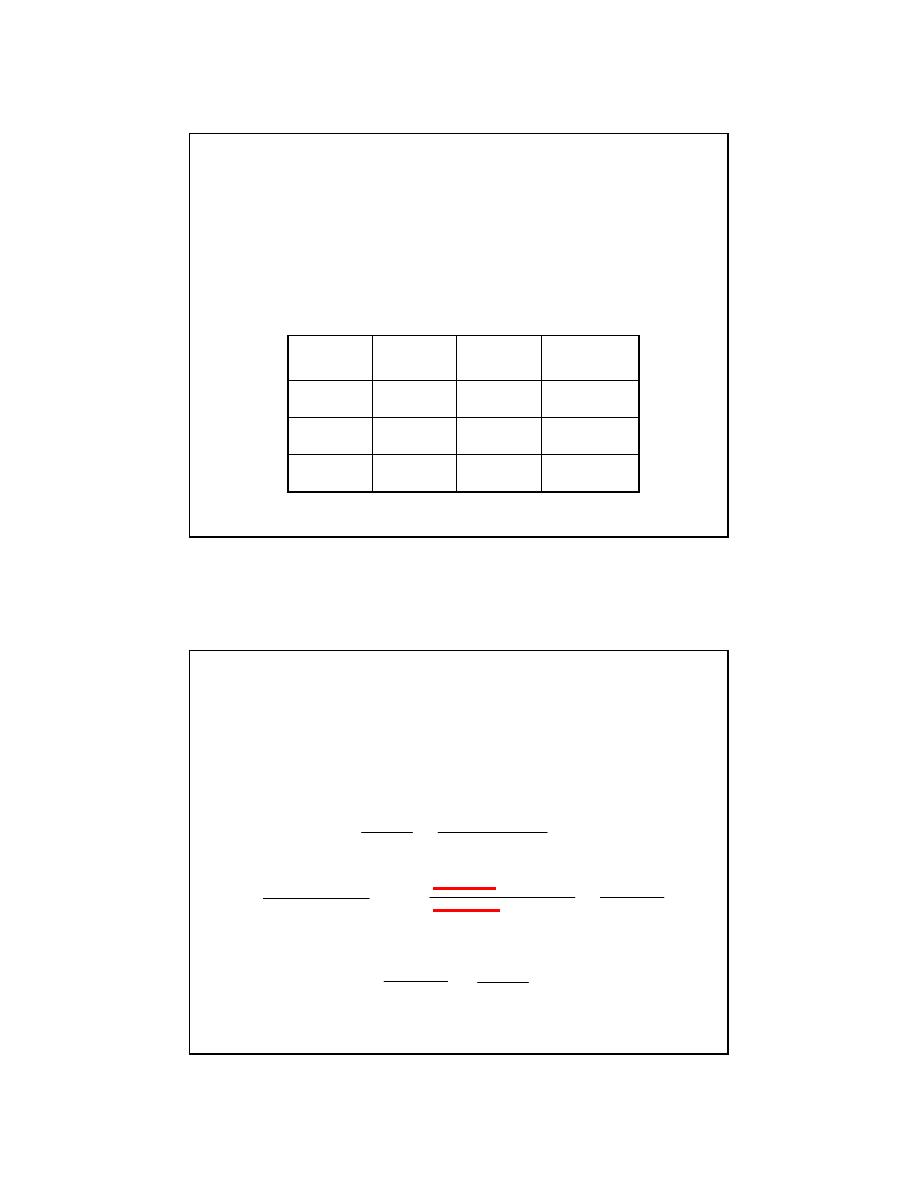

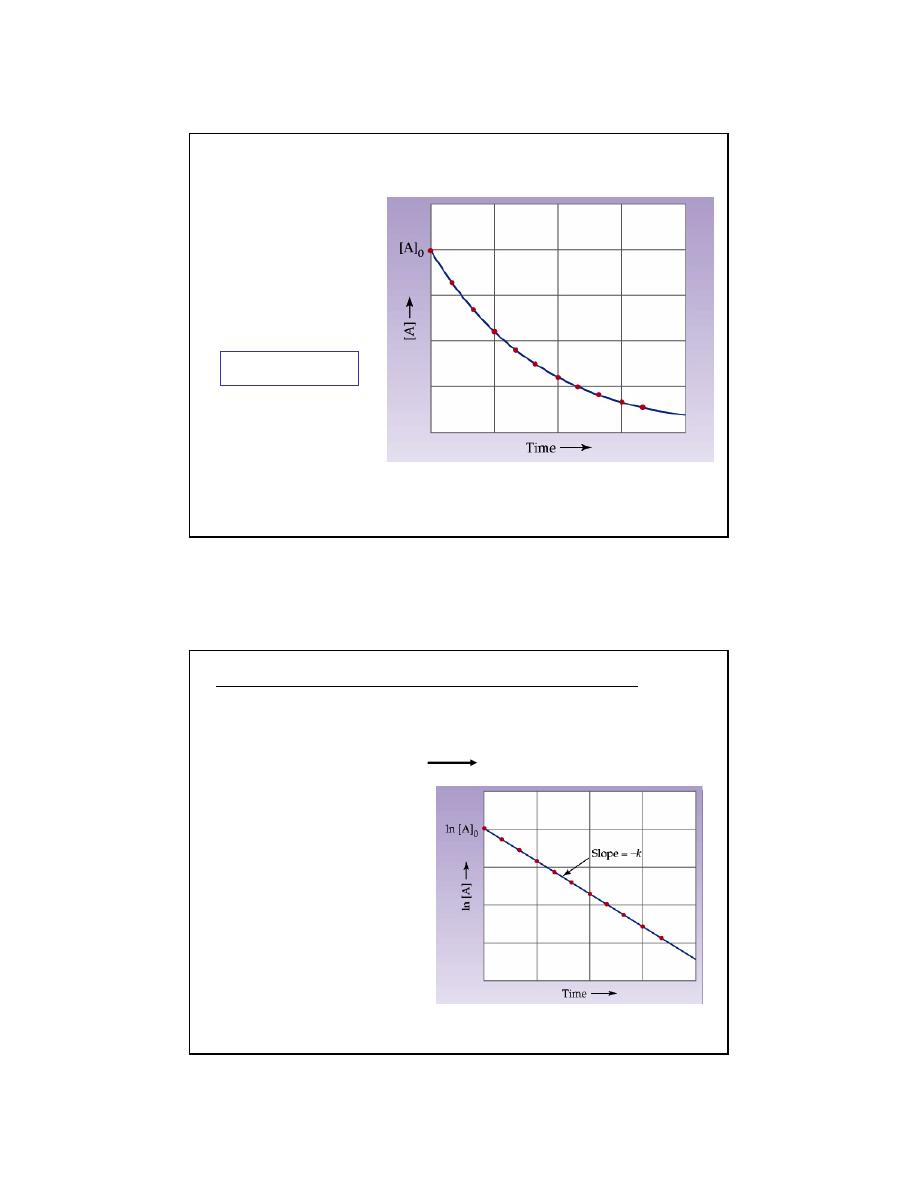

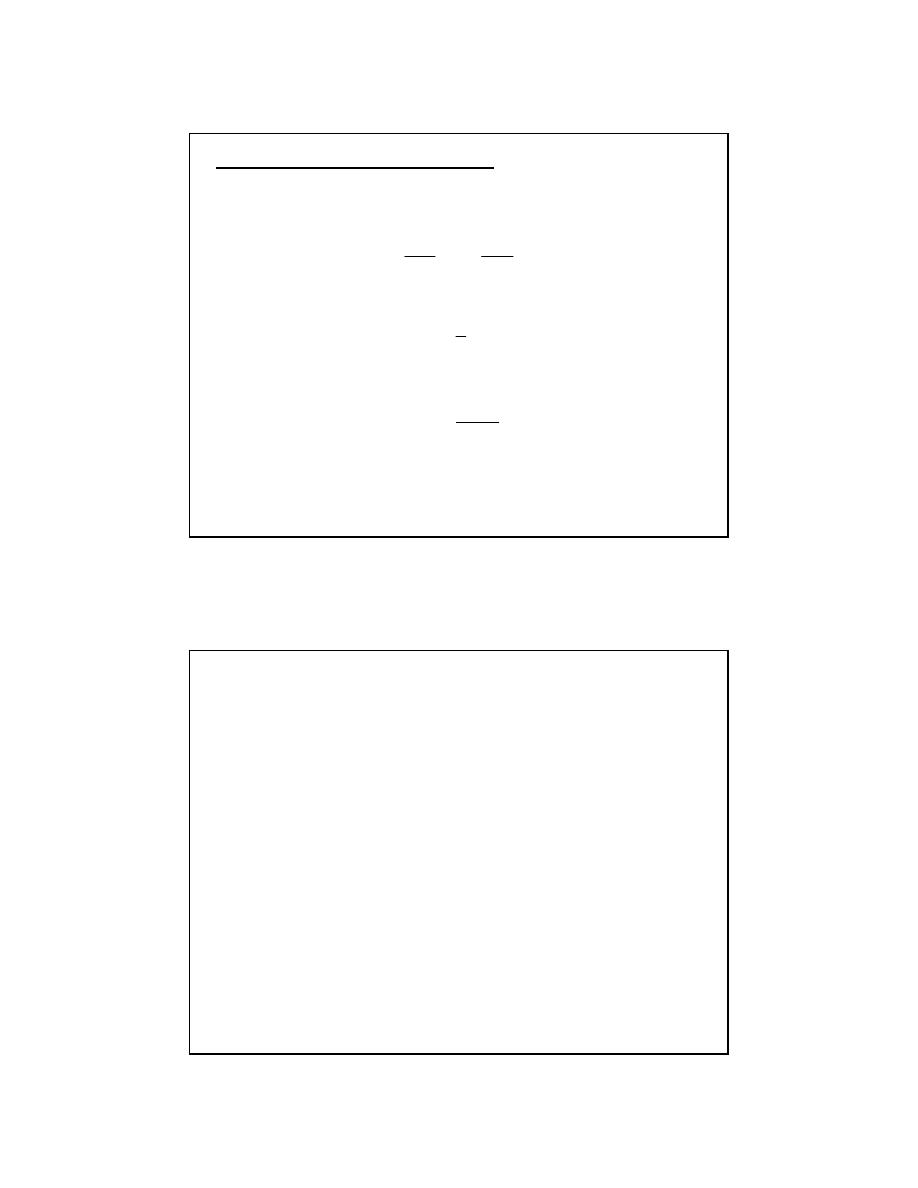

Recognizing a first order process:

AÆproducts

Whenever the conc. of a

reactant falls off

exponentially, the kinetics

follow first order.

kt

o

[A] [A] e

−

=

A plot of ln[A] versus time (t)

is a straight line with slope -k

and intercept ln[A]

o

(

)

kt

o

ln [A] [A] e

−

=

Determining the Rate constant for a first order process

Taking the log of the integrated rate law for a first order process we find:

o

ln[A] ln[A]

k t

=

− ×

11

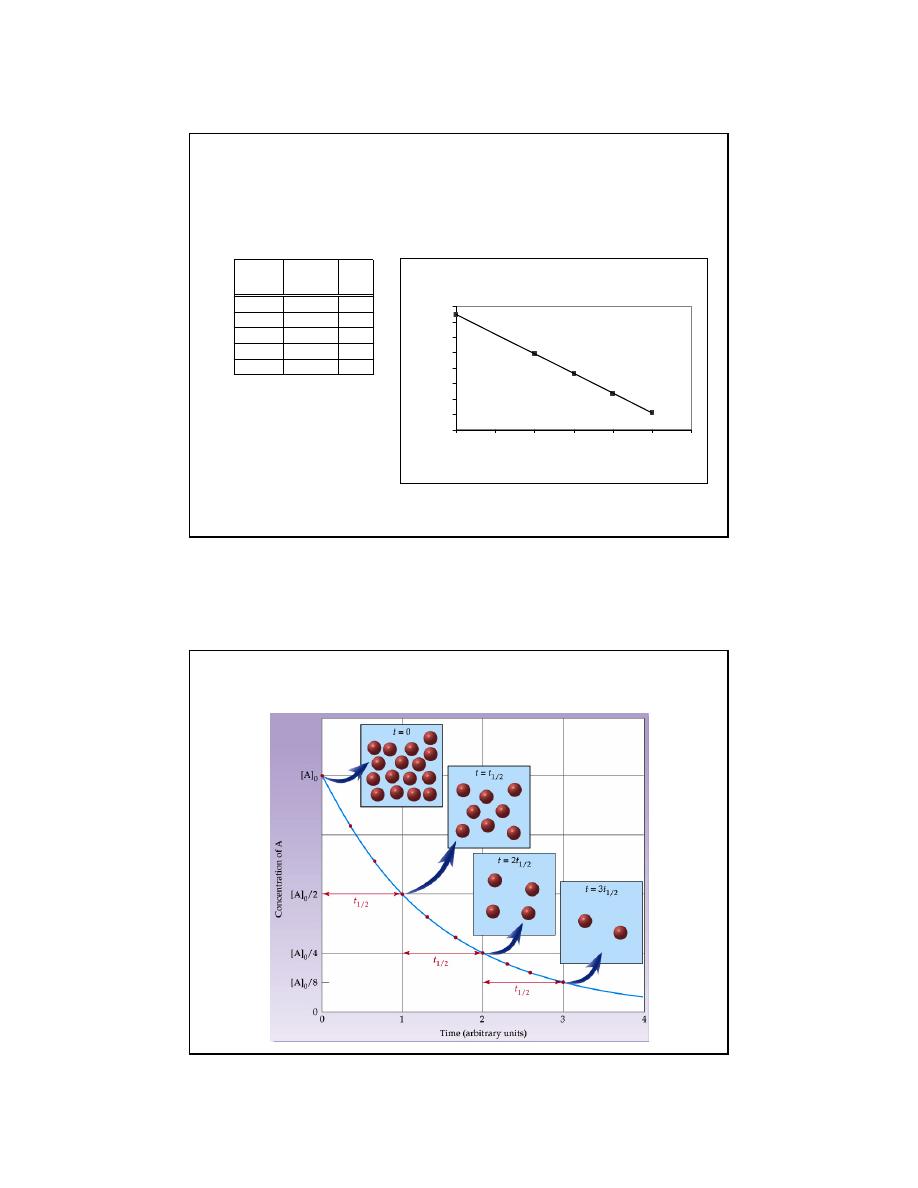

Example:

The rate of decomposition of azomethane (C

2

H

6

N

2

) was

studied by monitoring the partial pressure of the reactant as a function of

time.

Determine if the data below support a first order reaction.

Calculate the rate constant for the reaction.

Time

(s)

P

(mmHg

ln (P)

0

284 5.65

100

220 5.39

150

193 5.26

200

170 5.14

250

150 5.01

Plot of lnP vs. time

y = -0.0026x + 5.6485

R

2

= 1

4.90

5.00

5.10

5.20

5.30

5.40

5.50

5.60

5.70

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

time (s)

ln

P

k = 2.6x10

-3

s

-1

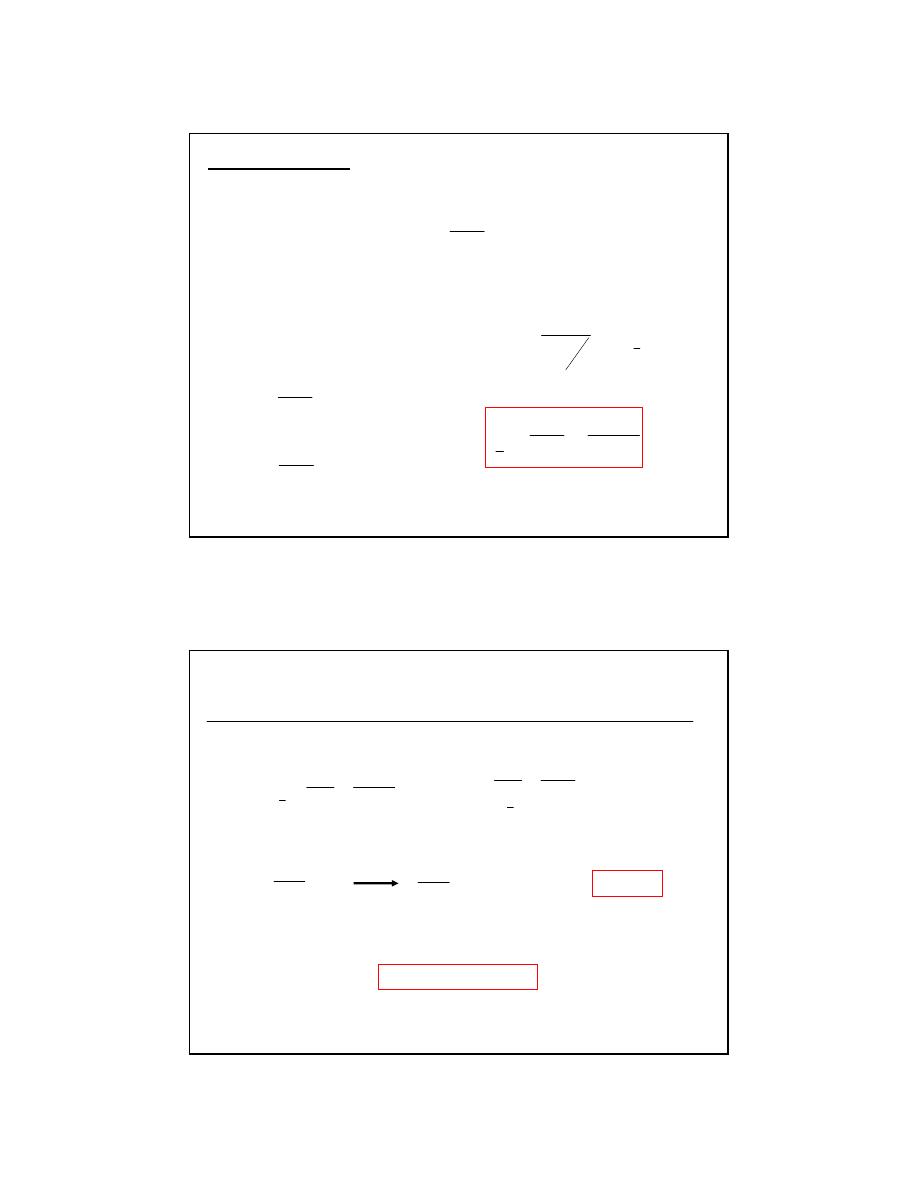

Reaction Half-Life

12

Reaction Half-life:

Half-life is the time taken for the concentration of a reactant to drop to

half its original value.

o

[A]

[A]

2

=

For a first order process the half life (

t

½

) is found mathematically from:

[ ]

[ ]

0

(1) ln A

kt ln A

= − +

[ ]

[ ]

0

(2) ln A

ln A

kt

−

= −

[ ]

0

A

(3) ln

kt

[A]

= −

[ ]

0

A

(4) ln

kt

[A]

=

[ ]

0

1

0

2

A

(5) ln

kt

[A]

2

=

1

2

ln 2

0.693

t

k

k

=

=

A certain reaction proceeds through t first order kinetics.

The half-life of the reaction is 180 s.

What percent of the initial concentration remains after 900s?

Step 1: Determine the magnitude of the rate constant, k.

1

2

ln 2

0.693

t

k

k

=

=

1

1

2

ln 2

ln 2

k

0.00385s

t

180s

−

=

=

=

kt

o

[A]

e

[A]

−

=

1

0.00385 s 900 s

o

[A]

e

[A]

−

−

×

=

= 0.0312

Using the integrated rate law, substituting in the value of k and 900s we find:

Since the ratio of [A] to [A]

0

represents the fraction of [A]

o

that remains, the

% is given by:

100

× 0.0312 = 3.12%

13

For a Second Order

Process

:

A

→ Products

Rate = k[A]

2

1

2

d[A]

Rate(Ms )

k[A]

dt

−

= −

=

Integrating as before we find:

[ ]

[ ]

0

1

1

kt

A

A

=

+

A plot of 1/[A] versus t is a straight line with slope k and intercept 1/[A]

0

For a second order reaction, a plot of ln[A] vs. t is

not linear

not linear

.

[ ]

[ ]

0

1

1

kt

A

A

=

+

Non

−

linearity indicates

that the reaction

is not first order.

Slope = k (rate constant)

14

Half-life for a second-order reaction

Unlike a first order reaction, the rate constant for a second order process

depends on and the initial concentration of a reactant.

[ ]

[ ]

t

0

1

1

kt

A

A

=

+

[ ]

[ ]

t

0

1

A

A

2

= ×

at the half–life,

Substituting and solving,

[ ]

1/ 2

0

1

t

k A

=

If [NOBr]

o

= 7.5

×

10

-3

M, how much NOBr will be left

after a reaction time of 10 minutes?

Determine the half-life of this reaction.

EXAMPLE:

The reaction

2 NOBr (g)

→ 2 NO (g) + Br

2

(g)

is a second order reaction with respect to NOBr.

k

= 0.810 M

-1

⋅

s

-1

at 10

o

C.

15

[

]

t

1

NOBr

=

[

]

[

]

t

0

1

1

kt

NOBr

NOBr

=

+

-1

-1

(0.810 M s ) (600 s)

⋅

×

3

1

7.5 10 M

−

+

×

[

]

2

-1

t

1

6.19 10 M

NOBr

=

×

[

]

3

t

NOBr

1.6 10 M

−

=

×

SOLUTION:

One can solve for the amount of NOBr after 10 minutes by

substituting the given data into the integrated rate law for a second-order

reaction.

(

Second Order

)

To determine the half-life for this reaction, we substitute the

initial concentration of NOBr and the rate constant for the

reaction into the equation for the half-life of a second-order

reaction.

1/ 2

t

=

-1

1

3

1

0.810 M s (7.5 10 M)

−

−

⋅

×

160 s

=

[ ]

1/ 2

0

1

t

k A

=

16

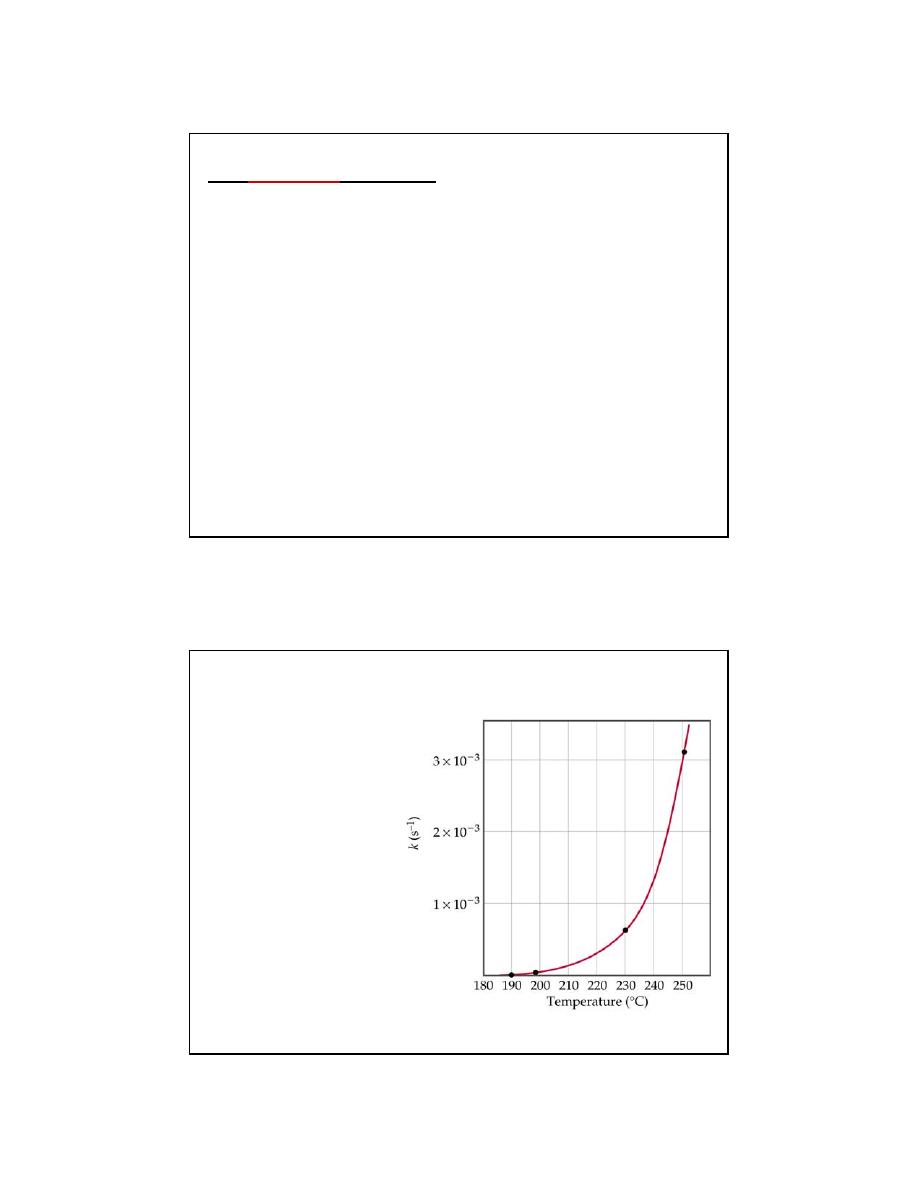

The

Arrhenius

Equation:

Temperature dependence of the Rate Constant

Most reactions speed up as temperature increases.

(

example:

food spoils when not refrigerated.)

k f (T)

=

Where “f” is some function.

The magnitude of a first order rate constant is seen to increase

exponentially with an increase in temperature.

f (T)

k(T)

e

∝

Therefore one can

Therefore one can

conclude that:

conclude that:

17

Why would k (along with the rate) increase with temperature?

Let’s go back to

Kinetic Molecular Theory

to understand…

The Collision Model:

Also, the more molecules present, the greater the probability of

collision and the faster the rate.

Thus reaction

rate

should

increase

with an increase in the

concentration of reactant molecules.

In order for molecules to react they must

collide.

Therefore, the greater the number of collisions the faster the rate.

As temperature increases, the molecules move faster and the

collision frequency increases.

Thus reaction

rate

should

increase

with an increase in temperature.

Activation Energy

(1) In order to form products, bonds must be broken in the

reactants.

(2) Bond breakage requires energy.

(3) Molecules moving too slowly, with too little kinetic energy,

don’t react when they collide.

The

Activation energy

,

E

a

, is the minimum energy required to

initiate a chemical reaction.

E

a

is specific to a particular reaction.

Arrhenius:

Molecules must posses a minimum amount of energy

to react. Why?

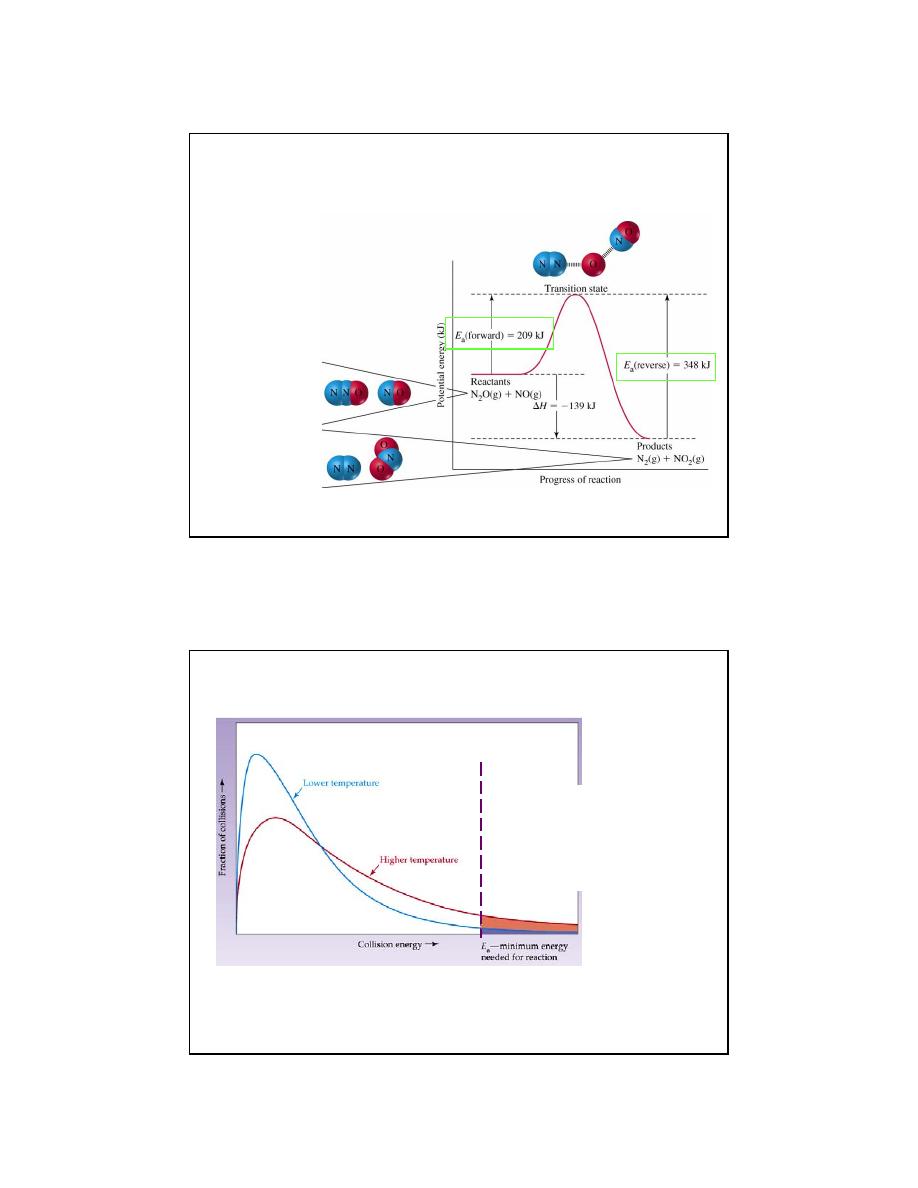

18

N

2

O(g) + O

2

(g)

→ N

2

(g) + NO

2

(g)

Consider the reaction:

The progress of a reaction

can be described by a

Reaction Coordinate

Reactants

Products

Recall for KMT that the temperature for a system of particles is

described by a distribution.

At higher temps, more particles have enough energy to go over the

barrier.

E > E

a

E < E

a

Since the probability of

a molecule reacting

increases, the rate

increases.

19

Orientation factors into the equation

The orientation of a molecule during collision can have a

profound effect on whether or not a reaction occurs.

Some collisions do not lead to reaction even if there is sufficient

energy.

The Arrhenius Equation

Arhenius discovered that most reaction-rate data obeyed an equation

based on three factors:

(1) The number of collisions per unit time.

(2) The fraction of collisions that occur with the correct orientation.

(3) The fraction of the colliding molecules that have an energy

greater than or equal to E

a

.

From these observations Arrhenius developed the aptly named

Arrhenius equation

Arrhenius equation

.

20

Arrhenius equation

Arrhenius equation

a

E

RT

k Ae

−

=

Both A and E

a

are specific to a given reaction.

k

is the rate constant

E

a

is the activation energy

R

is the ideal-gas

constant (8.314 J/Kmol)

T

is the temperature in K

A

A

is known the

frequency

frequency

or

pre

pre

–

–

exponential factor

exponential factor

In addition to carrying the units of the rate constant, “A” relates to

the frequency of collisions and the orientation of a favorable

collision probability

Determining the Activation Energy

E

a

may be determined experimentally.

First take natural log of both sides of the Arrhenius equation:

a

E

RT

k Ae

−

=

ln

a

E

ln k

ln A

RT

= −

+

Golly

Golly

–

–

gee, what do we

gee, what do we

have once again…

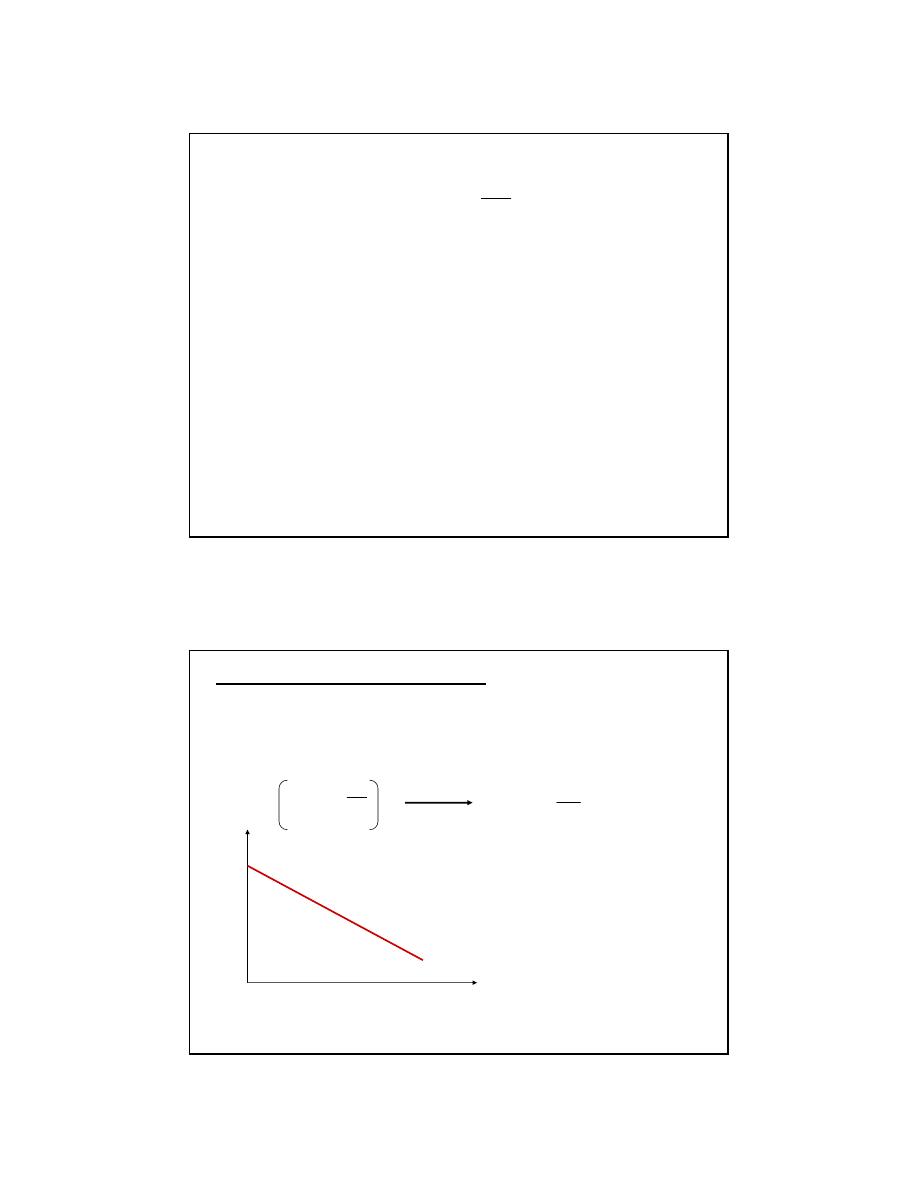

have once again…

ln k

1/T

A plot of ln k vs 1/T will

have a slope of –E

a

/R

and a y-intercept of ln A.

21

Determining the Activation Energy

a

1

1

E

ln k

ln A

RT

= −

+

a

2

2

E

ln k

ln A

RT

= −

+

2

1

ln k

ln k

−

One can determine the activation energy of a reaction by measuring

the rate constant at two temperatures:

Writing the Arrhenius equation for each temperature:

If one takes the natural log of the ratio of k

2

over k

1

we find that:

2

1

k

ln

k

=

a

2

1

1

2

E

k

1

1

ln

k

R T

T

=

−

presto!

presto!

Knowing the rate at two temps yields

the rate constant.

or

Knowing the E

a

and the rate constant

at one temp allows one to find k(T

2

)

a

1

E

ln A

RT

−

+

Substituting in the values for E

a

into the equation:

a

2

E

ln A

RT

−

+

2

1

ln k

ln k

−

=

−

Lookie

Lookie

what happens…

what happens…

22

Example:

The activation energy of a first order reaction is 50.2 kJ/mol at

25

o

C. At what temperature will the rate constant double?

2

1

k

2k

=

2

1

k

ln

k

=

1

1

2k

ln

k

ln(2)

=

a

1

2

E

1

1

R T

T

=

−

a

E

R

=

3

10 J

50.2 kJ/mol

1kJ

J

8.314

mol K

×

⋅

3

6.04 10 K

=

×

ln(2) 0.693

=

3

6.04 10 K

=

×

×

2

1

1

298K T

−

3

1

2

1

3.24 10 K

T

−

−

=

×

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

T

T

2

2

= 308 K

= 308 K

A 10

o

C change of

temperature doubles

the rate!!