Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

DISEASES OF THE ESOPHAGUS

Learning objectives:

1. Review the functional anatomy and physiology of esophagus.

2. Understand the concept of Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD).

3. List the factors that associated with development of GERD.

4. Explain the clinical features of GERD.

5. List the important investigations and it’s indications in patients with GERD.

6. Review the treatment of GERD.

7. List the complications of GERD.

8. List other causes of esophagitis.

9. List the motility disorders of esophagus.

10.Describe the definition, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation of achalasia.

11.Outline the important investigations of achalasia.

12.review the treatment of achalasia.

13.List the types of esophageal carcinoma.

14.Recognized the epidemiology of esophageal carcinoma.

15.Understand the difference between squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma

of esophagus.

16.Known the clinical features of esophageal carcinoma.

17.List the important investigations of esophageal carcinoma.

18.Outline the treatment of esophageal carcinoma.

Esophagus:

• This muscular tube extends 25 cm from the cricoid cartilage to the cardiac orifice of

the stomach. It has an upper and a lower sphincter. it is lined by stratified squamous

epithelium. The muscle layers of the upper esophagus are striated skeletal muscle,

while the muscles of lower part are smooth. A peristaltic swallowing wave propels the

food bolus into the stomach.

GASTRO-ESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE:

• Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) develops when the esophageal mucosa is

exposed to gastric contents for prolonged periods of time, resulting in symptoms and,

in a proportion of cases, esophagitis.

• Gastro-esophageal reflux resulting in heartburn affects approximately 30% of the

general population.

Factors associated with the development of (GERD):

1. Obesity and dietary factors.

2. Defective oesophageal clearance.

3. Abnormal lower esophageal sphincter:

1. Reduced tone.

Page of

1

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

2. Inappropriate relaxation.

4. Hiatus hernia.

5. Delayed gastric emptying.

6. Increased intraabdominal pressure.

Hiatus hernia:

• Hiatus hernia: An anatomical abnormality in which part of the stomach protrudes up

through the diaphragm into the chest.

• Causes reflux because the pressure gradient between the abdominal and thoracic

cavities, which normally pinches the hiatus, is lost. In addition, the oblique angle

between the cardia and esophagus disappears. Many patients who have large hiatus

hernias develop reflux symptoms.

Types of hiatus hernia:

1. Sliding.

2. Rolling or paraesophageal.

Clinical features of GERD:

• Major symptoms; are heartburn and regurgitation, often provoked by bending,

straining or lying down.

• Waterbrash; which is salivation due to reflex salivary gland stimulation as acid enters

the gullet.

• Others develop odynophagia or dysphagia. A few present with atypical chest pain

which may be severe, can mimic angina and is probably due to reflux-induced

esophageal spasm.

Complications:

1. Esophagitis: A range of endoscopic findings, from mild redness to severe, bleeding

ulceration with stricture formation.

2. Barrett's esophagus: ('columnar lined oesophagus'-CLO) is a pre-malignant

glandular metaplasia of the lower esophagus, in which the normal squamous lining

is replaced by columnar mucosa of intestinal metaplasia. CLO is the major risk

factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Diagnosis of this condition requires

multiple biopsies from suspected area to detect intestinal metaplasia and/or

dysplasia. Neither potent acid suppression nor antireflux surgery will stop

progression or induce regression of CLO. Esophagectomy is widely recommended

for those with high grade dysplasia.

3. Anaemia; Iron deficiency anaemia occurs as a consequence of chronic, insidious

blood loss from long-standing esophagitis.

4. Benign esophageal stricture; Fibrous strictures develop as a consequence of long-

standing esophagitis.

Page of

2

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

5. Gastric volvulus; Occasionally a massive intra-thoracic hiatus hernia may twist

upon itself.

Investigations:

• Young patients who present with typical symptoms of gastro-esophageal reflux,

without worrying features such as dysphagia, weight loss or anaemia, can be treated

empirically without investigation.

• Is advisable if patients over 55 year old, if symptoms are atypical or if a complication

is suspected or if there is no response to empirical treatment.

• Investigations include:

1. Endoscopy is the investigation of choice. This is performed to exclude other upper

gastrointestinal diseases which can mimic gastro-esophageal reflux, and to identify

complications.

2. Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring is indicated if, despite endoscopy, the diagnosis is

unclear or surgical intervention is under consideration.

1) A slim catheter with a terminal radiotelemetry pH-sensitive probe above the

gastro-esophageal junction.

2) episodes of pain are noted and related to pH. A pH of less than 4 for more than

6-7% of the study time is diagnostic of reflux disease.

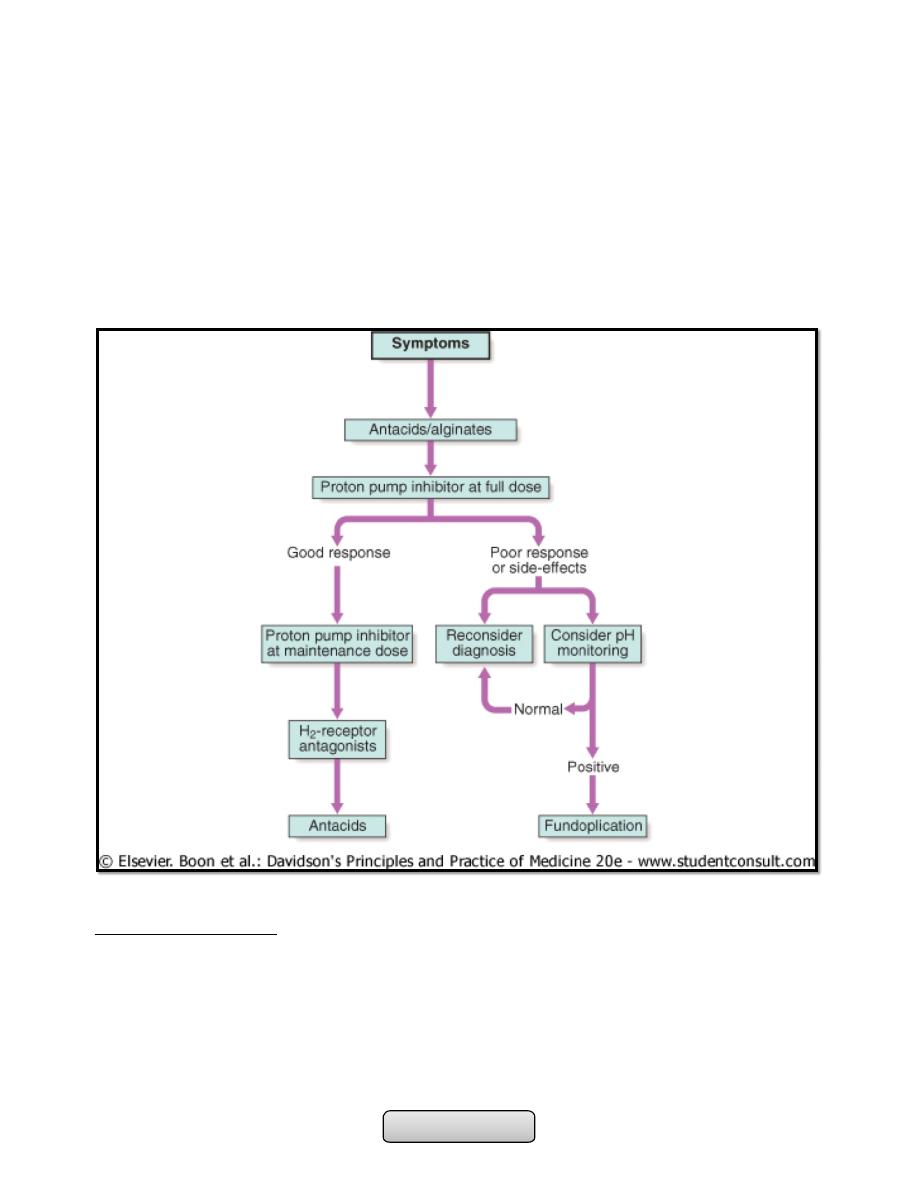

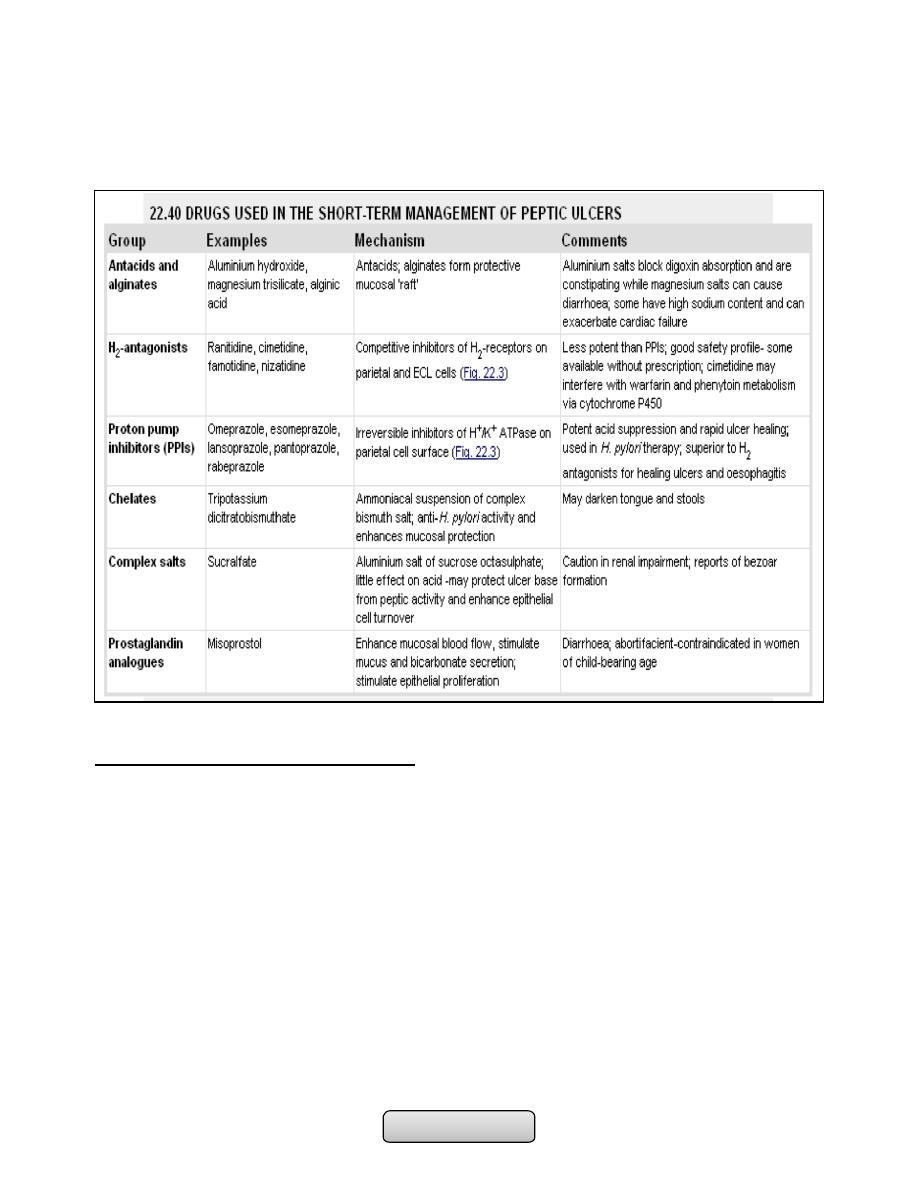

Management:

1. Lifestyle advice; including weight loss, avoidance of dietary items which the

patient finds worsen symptoms, elevation of the bed head in those who experience

nocturnal symptoms, avoidance of late meals and giving up smoking.

2. Antacids and alginates; also provide symptomatic benefit.

3. H

2

-receptor antagonist drugs; also help symptoms without healing esophagitis.

4. Proton pump inhibitors; are the treatment of choice for severe symptoms and for

complicated reflux disease.

5. Anti-reflux surgery; Patients who fail to respond to medical therapy, those who are

unwilling to take long-term proton pump inhibitors and those whose major

symptom is severe regurgitation.

OTHER CAUSES OF ESOPHAGITIS:

1. Infection; Esophageal candidiasis, Herpes simplex virus, Cytomegalovirus

(CMV) ,and HIV infection .

2. Corrosives; Strong household bleach or battery acid .

3. Drugs; Tetracyclines, potassium preparations, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs, iron sulfate, and the bisphosphonate alendronate.

• Candida esophagitis is often associated with oral thrush and tends to present with

dysphagia and only mild pain on swallowing. It has a characteristic appearance on

Page of

3

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

endoscopy, and esophageal brushings and biopsies demonstrate fungal hyphae.

Treatment with oral fluconazole is generally very effective.

• Herpes simplex virus causes multiple esophageal ulcers and presents clinically with

severe odynophagia. Acyclovir is the treatment of choice for herpes esophagitis.

• Cytomegalovirus (CMV) also causes esophageal ulceration and odynophagia. Endoscopy

usually demonstrates a single large ulcer in the distal esophagus, and biopsies often

detect viral inclusions that confirm the diagnosis. Both ganciclovir and foscarnet are

effective treatments for CMV esophagitis.

MOTILITY DISORDERS:

1. PHARYNGEAL POUCH; Incoordination of swallowing within the pharynx leads to

herniation through the cricopharyngeus muscle and formation of a pouch.

2. DIFFUSE ESOPHAGEAL SPASM

3. ACHALASIA OF THE OESOPHAGUS

4. SECONDARY CAUSES ; systemic sclerosis, Dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis and

myasthenia gravis.

Page of

4

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

PHARYNGEAL POUCH:

• Most patients are elderly and have no symptoms, although regurgitation, halitosis and

dysphagia can occur. Some notice gurgling in the throat after swallowing. A barium

swallow demonstrates the pouch and reveals incoordination of swallowing, often with

pulmonary aspiration. Endoscopy may be hazardous since the instrument may enter

and perforate the pouch. Surgical myotomy and resection of the pouch are indicated

in symptomatic patients.

Diffuse esophageal spasm:

• Episodic chest pain which may mimic angina, but is sometimes accompanied by

transient dysphagia. Some cases occur in response to gastro-esophageal reflux.

Treatment is based upon the use of proton pump inhibitor drugs when gastro-

esophageal reflux is present. Oral or sublingual nitrates or nifedipine may relieve

attacks.

ACHALASIA OF THE OESOPHAGUS:

Pathophysiology;

Achalasia is characterised by:

• A hypertonic lower esophageal sphincter: which fails to relax in response to the

swallowing wave.

• Failure of propagated esophageal contraction: leading to progressive dilatation of the

gullet.

Cause;

1. Is unknown.

2. Abnormal nitric oxide synthesis within the lower esophageal sphincter.

3. Degeneration of ganglion cells within the sphincter and the body of the esophagus

occurs.

4. Loss of the dorsal vagal nuclei within the brain stem.

5. Chagas disease.

Barium swallow findings:

• Tapered narrowing of the lower esophagus, esophageal body is dilated, aperistaltic

and food-filled.

Clinical features:

• Usually develops in middle life;

• Dysphagia develops slowly, and is initially intermittent, it is worse for solids and is

eased by drinking liquids, and by standing and moving around after eating.

• Episodes of severe chest pain due to esophageal spasm('vigorous achalasia').

• Nocturnal pulmonary aspiration develops.

• Predisposes to squamous carcinoma of the esophagus.

Investigations:

• Chest X-ray; widening of the mediastinum, aspiration pneumonia.

Page of

5

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

• A barium swallow; tapered narrowing of the lower esophagus, esophageal body is

dilated, aperistaltic and food-filled.

• Endoscopy; must always be carried out, carcinoma of the cardia can mimic the

presentation and radiological and manometric features of achalasia ('pseudo-

achalasia').

• Manometry; confirms the high-pressure, non-relaxing lower esophageal sphincter with

poor contractility of the esophageal body.

Management:

• Endoscopic Forceful pneumatic dilatation improves symptoms in 80% of patients.

Some patients require more than one dilatation, injection of botulinum toxin into the

lower esophageal sphincter.

• Surgical myotomy ('Heller's operation') with anti-reflux procedure. Proton pump

inhibitor therapy is also often necessary. Because it may be complicated by gastro-

esophageal reflux.

OESOPHAGEAL STRICTURE:

CAUSES;

1. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease

2. Webs and rings

3. Carcinoma of the esophagus or cardia

4. Extrinsic compression from bronchial carcinoma

5. Corrosive ingestion

6. Post-operative scarring following esophageal resection

7. Post-radiotherapy

8. Following long-term nasogastric intubation

CARCINOMA OF THE ESOPHAGUS:

1. Squamous cell carcinoma; rare in Western, common in Iran, parts of Africa and China,

mostly in upper 2 third of the esophagus.

• AETIOLOGICAL FACTORS;

-

Smoking.

-

Alcohol excess.

-

Chewing betel nuts or tobacco.

-

Coeliac disease.

-

Achalasia of the esophagus.

-

Post-cricoid web.

-

Post-caustic stricture.

-

Tylosis (familial hyperkeratosis of palms and soles).

2. Adenocarcinoma; In Western populations, in the lower third of the esophagus, from

Barrett's esophagus or from the cardia of the stomach.

Page of

6

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Clinical features:

• Progressive, painless dysphagia for solid foods.

• In late stages weight loss is often extreme.

• Chest pain or hoarseness suggests mediastinal invasion.

• Fistulation between the esophagus and the trachea or bronchial tree; pneumonia and

pleural effusion.

• Metastatic spread is common.

Investigations:

• Endoscopy; The investigation of choice, with cytology and biopsy.

• Barium swallow ; site and length of the stricture .

• Thoracic and abdominal CT

• Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

Management:

1. Esophageal resection; overall 5-year survival rate is 6-9%. 70% of patients have

extensive disease at presentation.

2. Neoadjuvant (pre-operative) chemotherapy with agents such as cisplatin and 5-

fluorouracil.

3. Radiotherapy; squamous carcinomas are radiosensitive.

4. Palliative treatment;

-

Relief of dysphagia and pain, laser therapy.

-

Insertion of stents.

-

Radiotherapy to shrink tumour size.

-

Nutritional support.

-

Analgesia.

………………………………………………………………………………………….

UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL HAEMORRHAGE

Learning objectives:

1. Identify upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

2. Recognize the causes of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

3. Clarify the management steps of patient with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

4. Outline the prognostic factors in patient with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

5. Identify the concept of occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage:

• Upper GI bleeding; Bleeding from GIT proximal to ligament of Teritz (band of C.T

connect the distal part of duodenum to the diaphragm).

• Is the most common gastrointestinal emergency.

Page of

7

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Clinical assessment;

1. Haematemesis; may be red with clots when bleeding is profuse, or black ('coffee

grounds') when less severe.

2. Melaena; is the term used to describe the passage of black-tarry, loose, sticky,

foul-smelling stools that containing altered blood, caused by oxidation of the iron

in hemoglobin during its passage through the colon. As little as 100 mL of blood in

the stomach can produce melena.

3. Hematochezia; The passage of bright red blood or maroon stools per rectum. Is

commonly associated with lower gastrointestinal bleeding, but may also occur

from a brisk upper GI bleed.

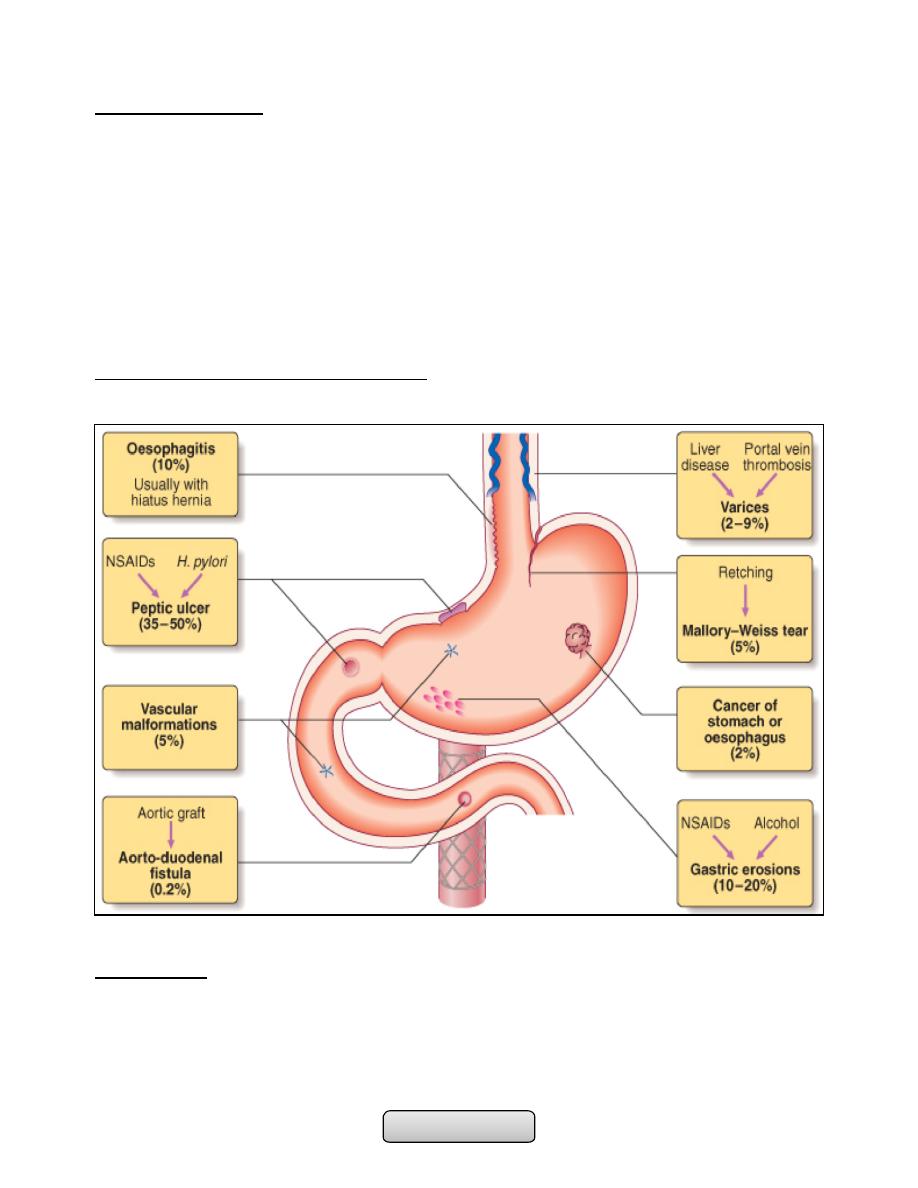

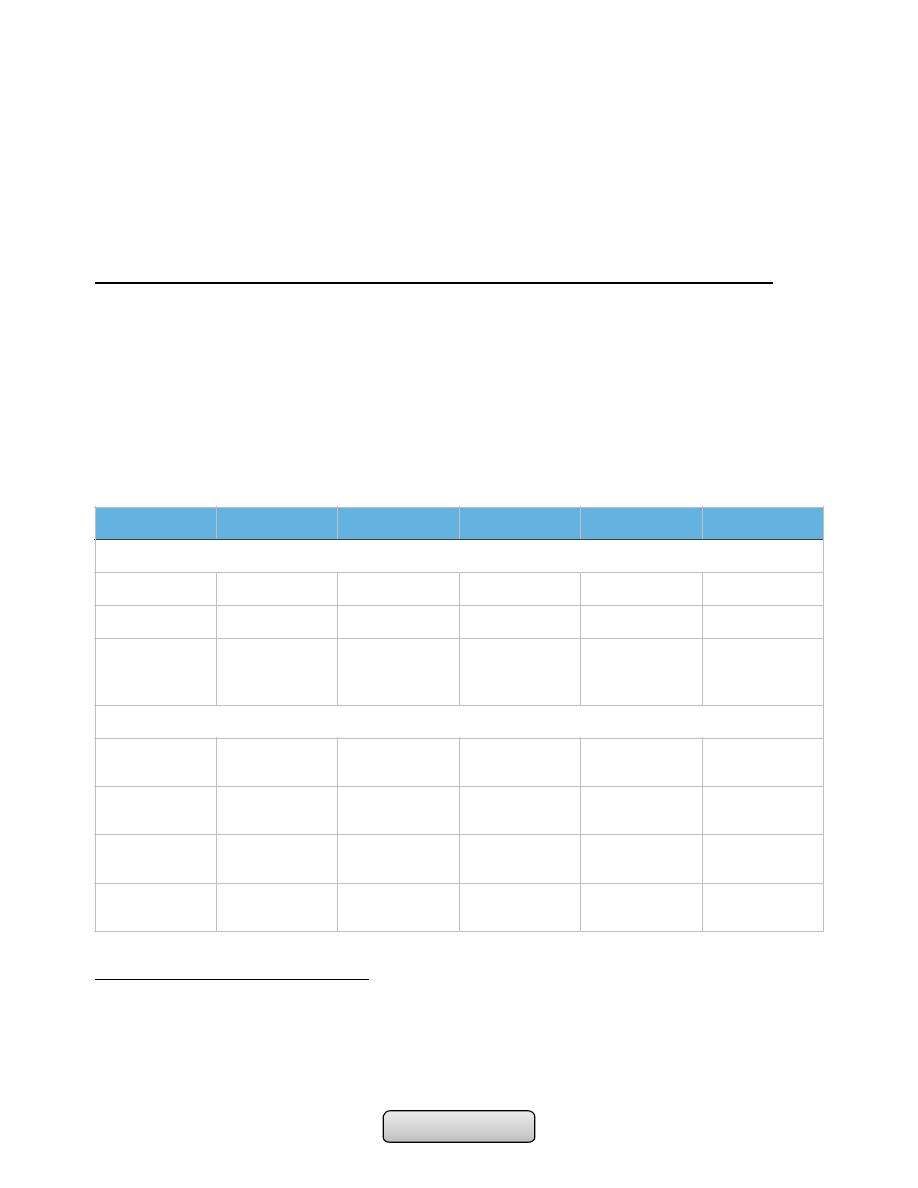

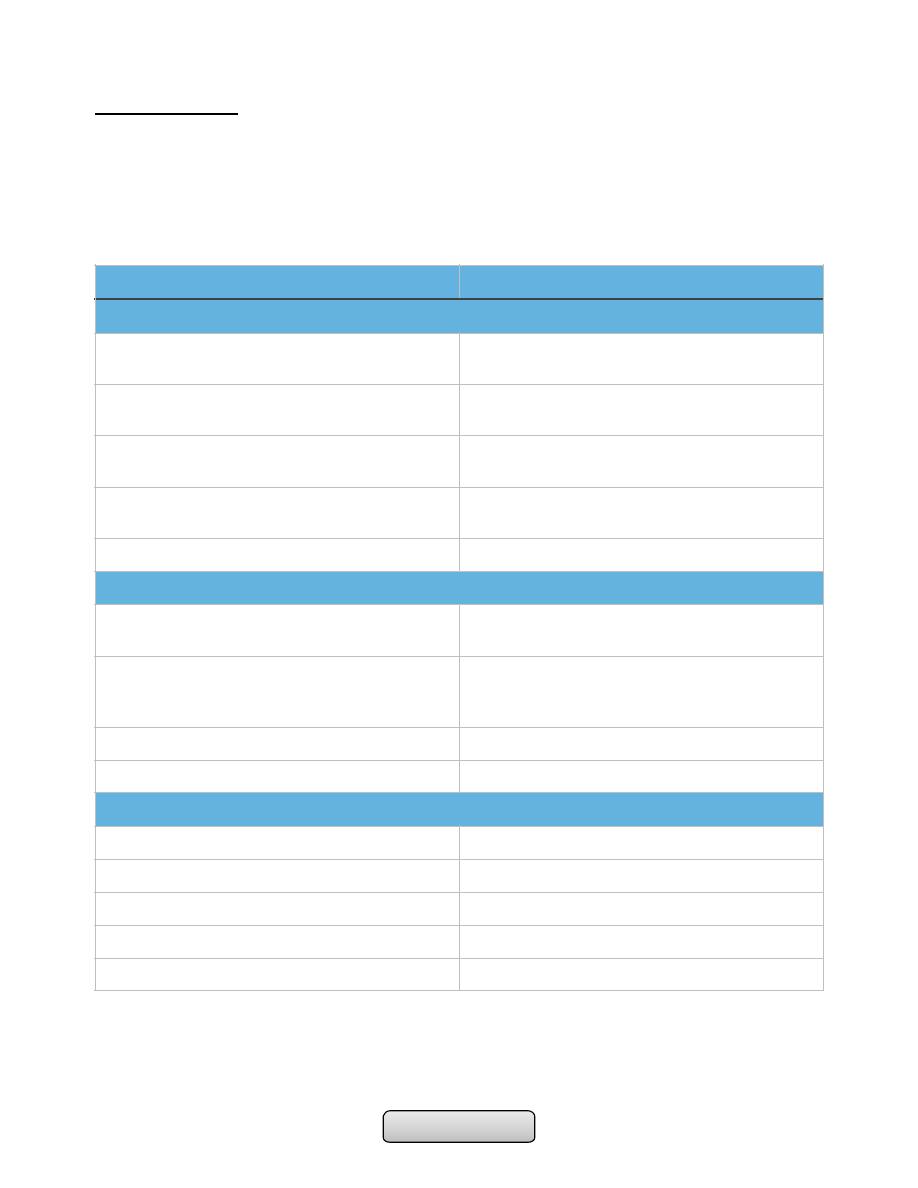

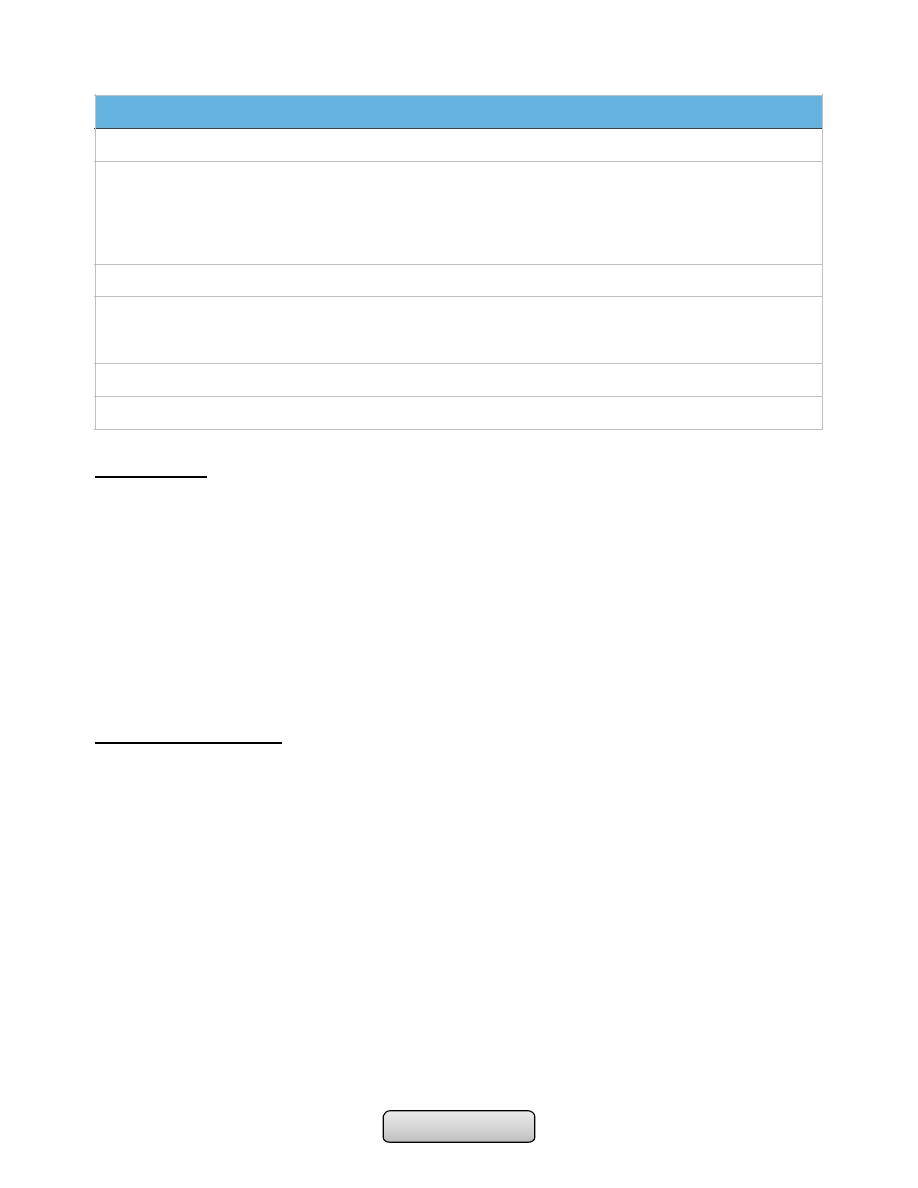

Causes of acute upper GI haemorrhage:

Management:

A. Intravenous access; Using two or at least one large-bore cannula. should be

placed in proximal large vein e. g. in antecubital fossa.

B. Initial clinical assessment;

1. Define circulatory status;

Page of

8

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

a) Systolic blood pressure drops changes positions from supine to standing

(postural hypotension); indicates lost at least 800 mL (15%) of circulating

blood volume.

b) Hypotension: tachycardia, tachypnea, and mental status; indicates that

1500 mL (30%) loss of circulating blood volume.

2. Severe bleeding ; causes tachycardia with hypotension and oliguria. The patient

is cold and sweating, and may be agitated.

3. Seek evidence of chronic liver disease; Jaundice, cutaneous stigmata,

hepatosplenomegaly and ascites may be present in decompensated liver

cirrhosis.

4. Define comorbidity; The presence of cardiorespiratory, cerebrovascular or renal

disease is important.

C. Blood tests;

1. Blood group, Rhesus and cross-matching of at least 2 units of blood; 4 units if

Systolic blood pressure drops below 100 mmHg and 6 units for active variceal

bleeding.

2. Full blood count; Chronic bleeding leads to anemia, but HB concentration may

be normal after acute bleeding.

3. Urea and electrolytes; renal failure, absorbed products of luminal blood well

be increase urea.

4. Liver function tests;

5. Prothrombin time;

D. Resuscitation; Intravenous crystalloid fluids (0.9% NS) or colloid such as (gelofusin

or Hartman's solution) are given, Blood is transfused when the patient is shocked

or HB less than 100 g per liter. NS should be avoided in patient with liver disease.

(CVP) monitoring is useful in severe bleeding.

E. Oxygen; by facemask to all patients in shock.

F. Endoscopy; after adequate resuscitation:

1. Diagnosis.

2. Endoscopic stigmata of recent haemorrhage: Spurting hemorrhage, visible

vessel or adherent clot.

a) Major stigmata of recent haemorrhage and endoscopic treatment:

(1) Active arterial spurting from a gastric ulcer. An endoscopic clip is about

to be placed on the bleeding vessel. When associated with shock, 80% of

cases will continue to bleed or rebleed.

(2) 'Visible vessel' (arrow). In reality, this is a pseudoaneurysm of the feeding

artery seen here in a pre-pyloric peptic ulcer. It carries a 50% chance of

rebleeding.

(3) Haemostasis is achieved after endoscopic clipping of the bleeding vessel

in the duodenum.

3. Endoscopic therapy.

Page of

9

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

G. Monitoring; hourly pulse, blood pressure and urine output measurements.

H. Surgical operation; urgent operation:

1. Endoscopic hemostasis fails to stop active bleeding.

2. Rebleeding; on one occasion in an elderly or frail patient, or twice in younger,

fitter patients.

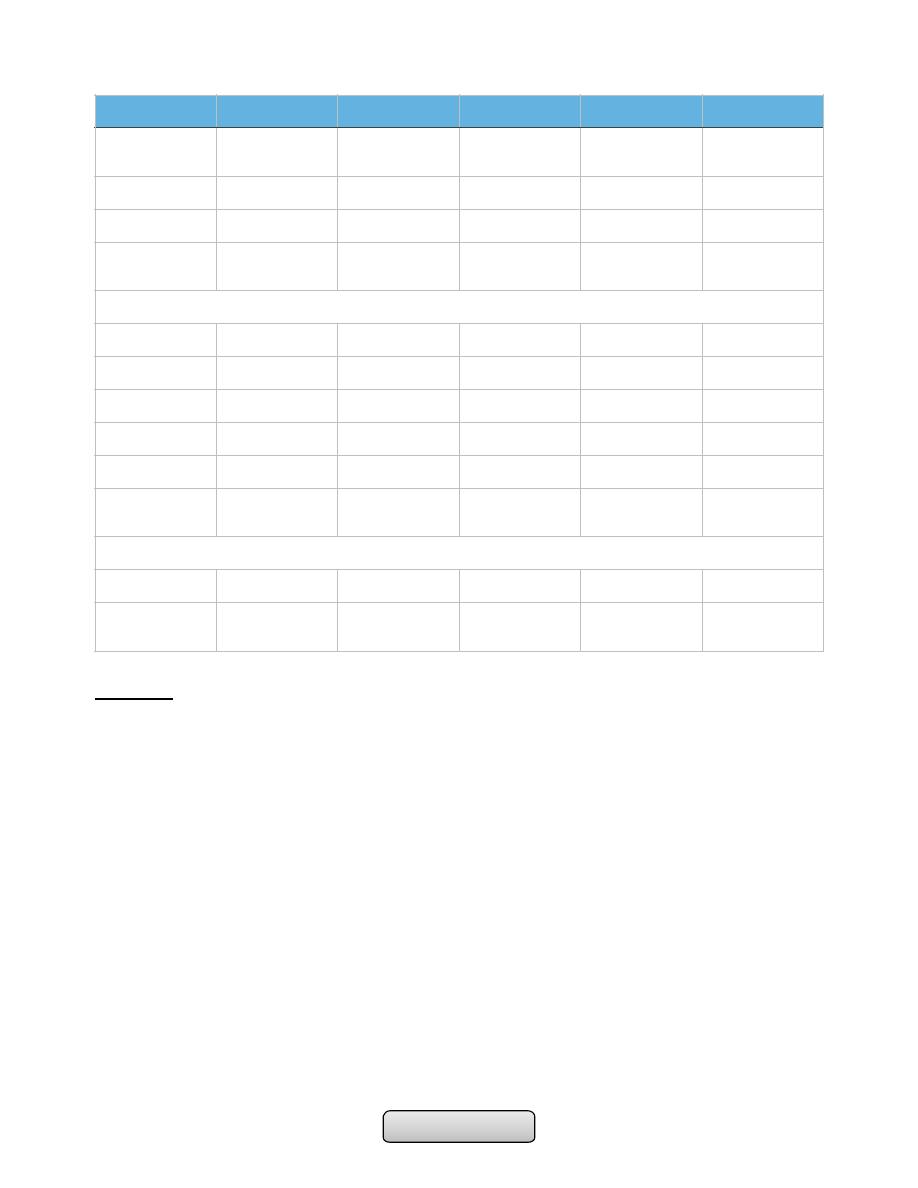

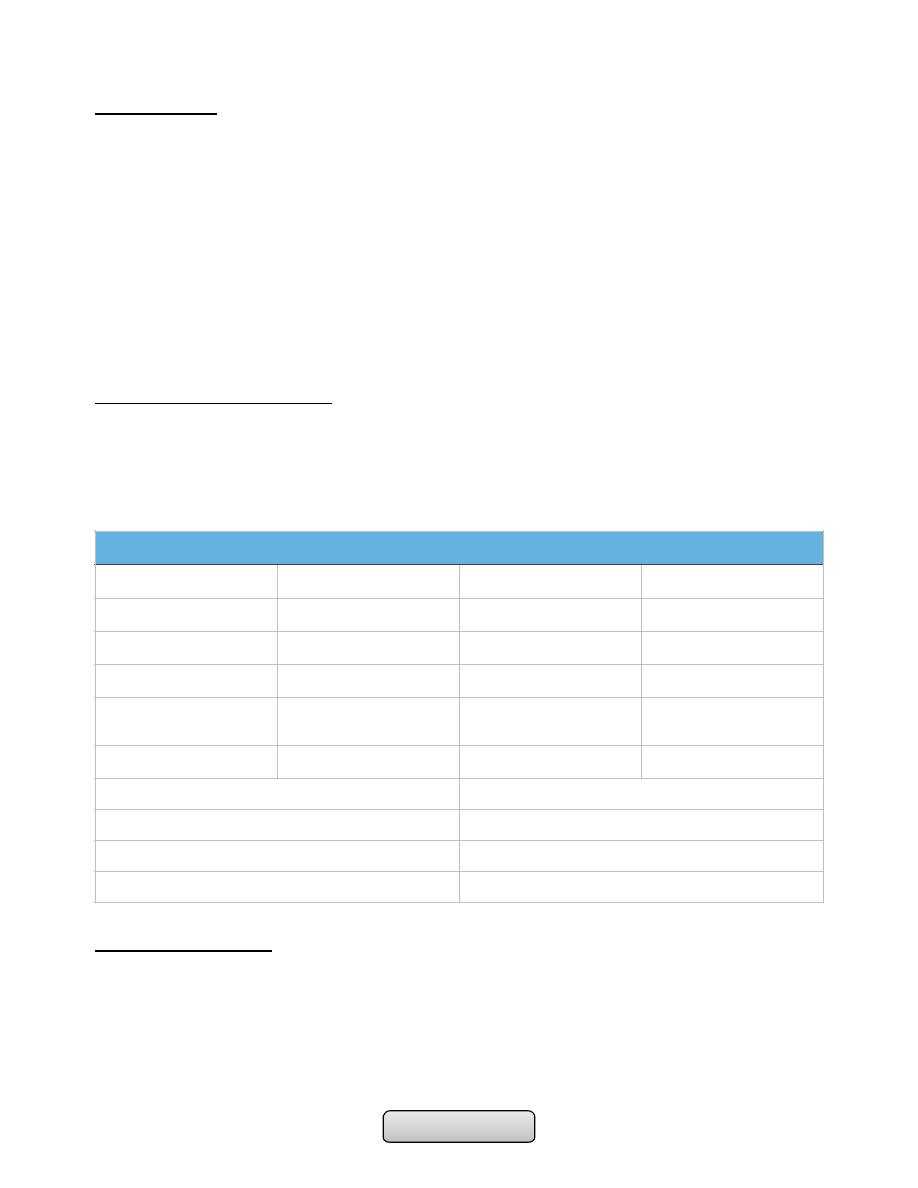

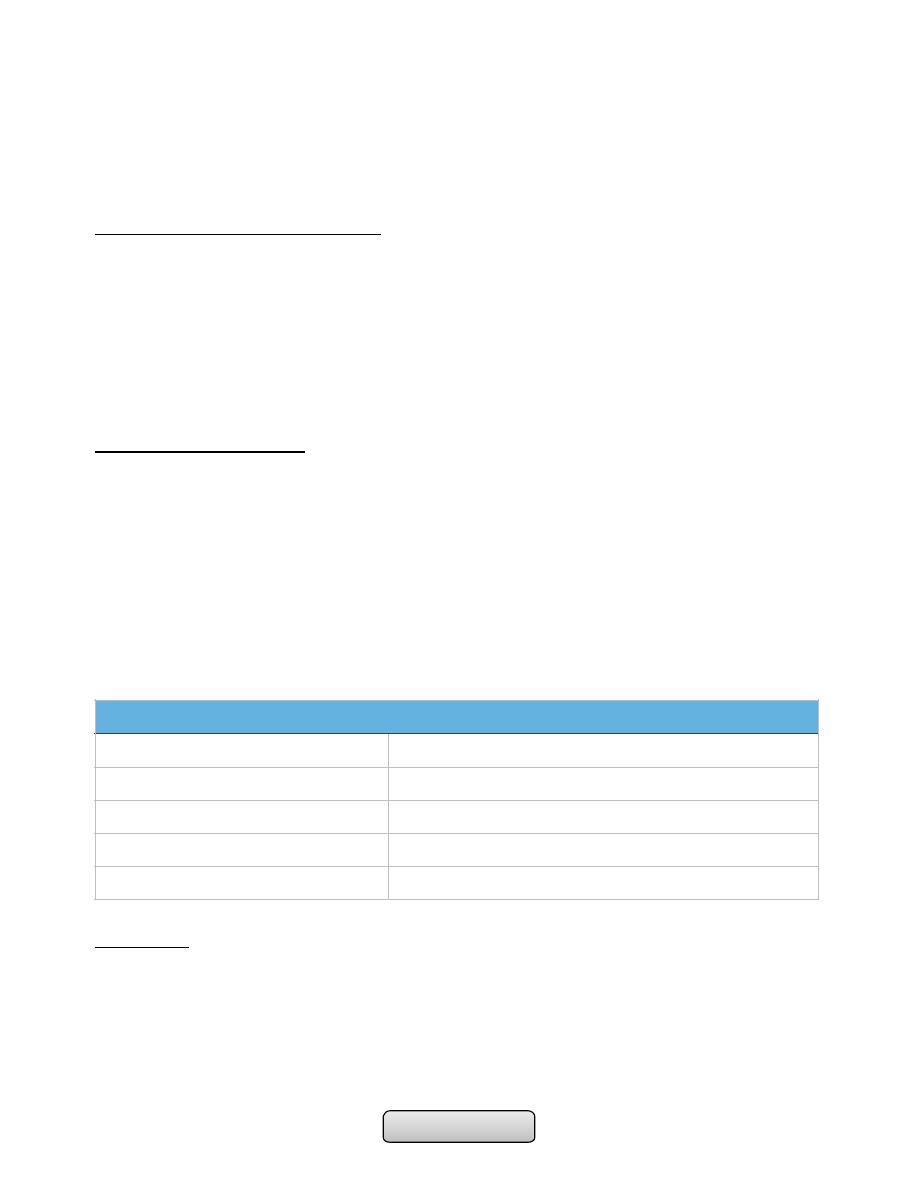

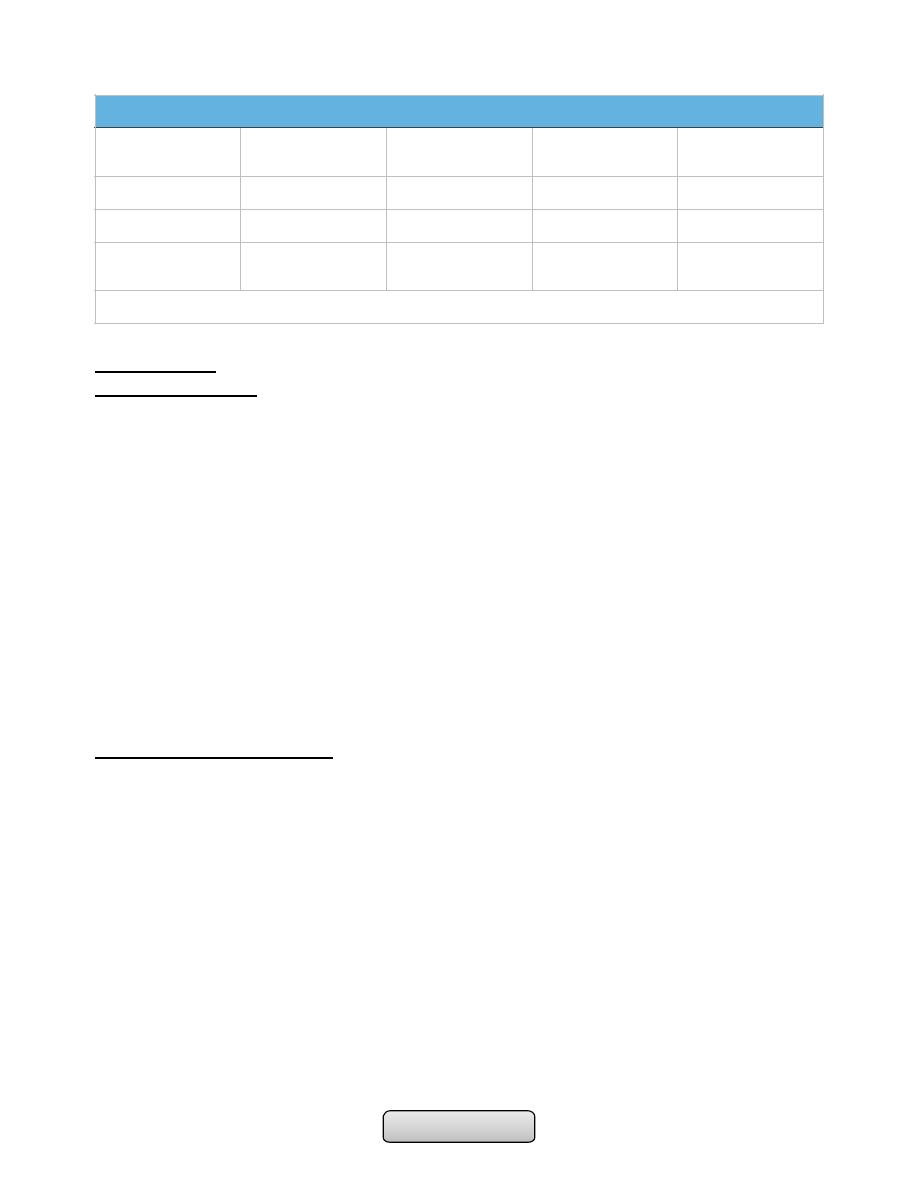

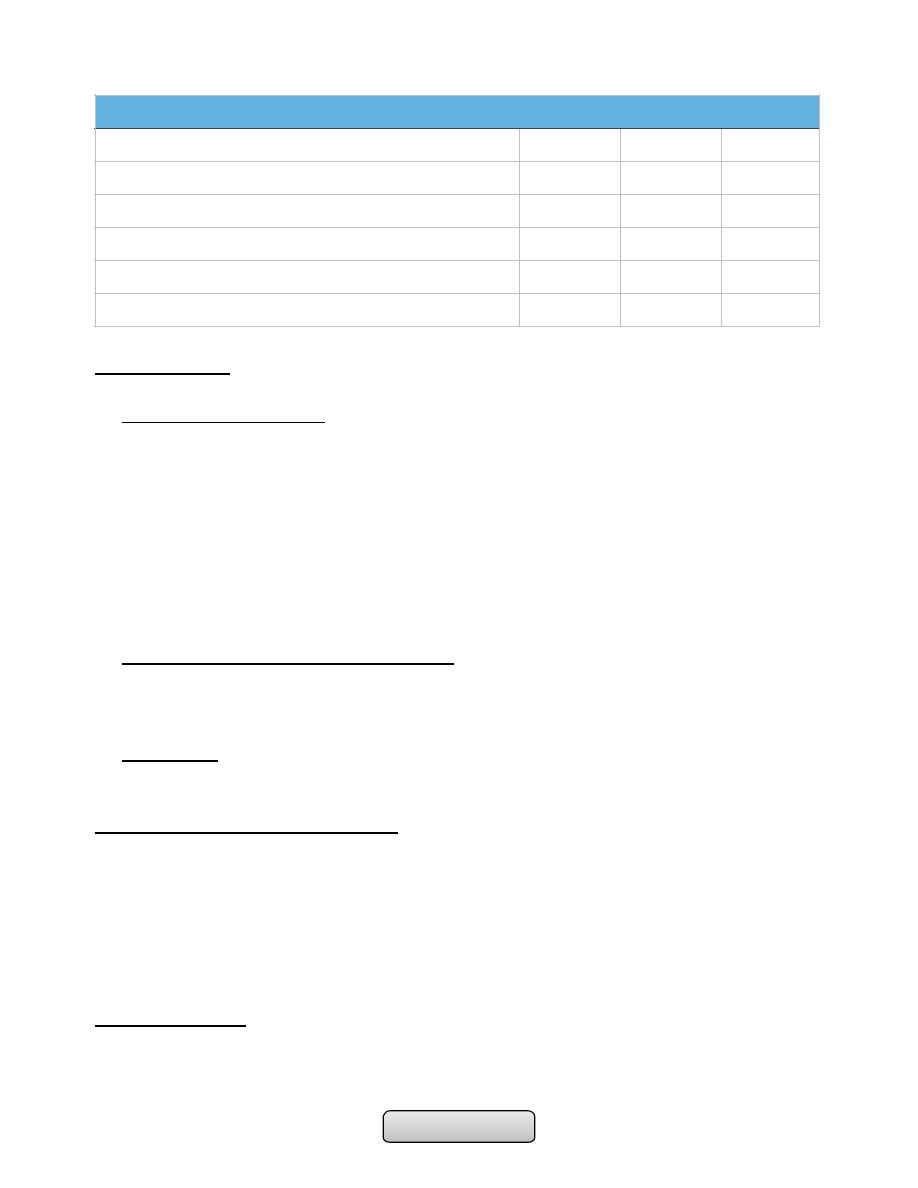

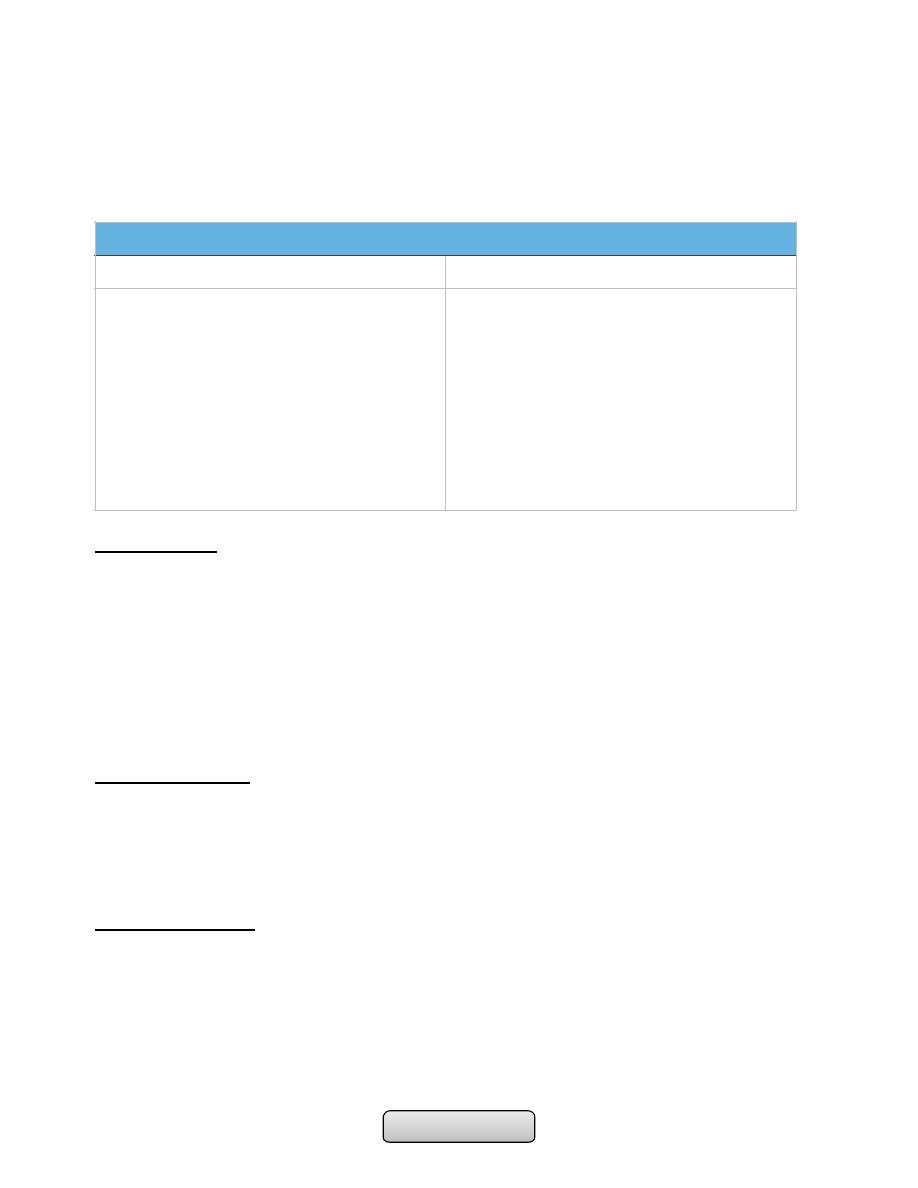

I. Prognosis; The mortality rate is depend on Rockall score for risk stratification

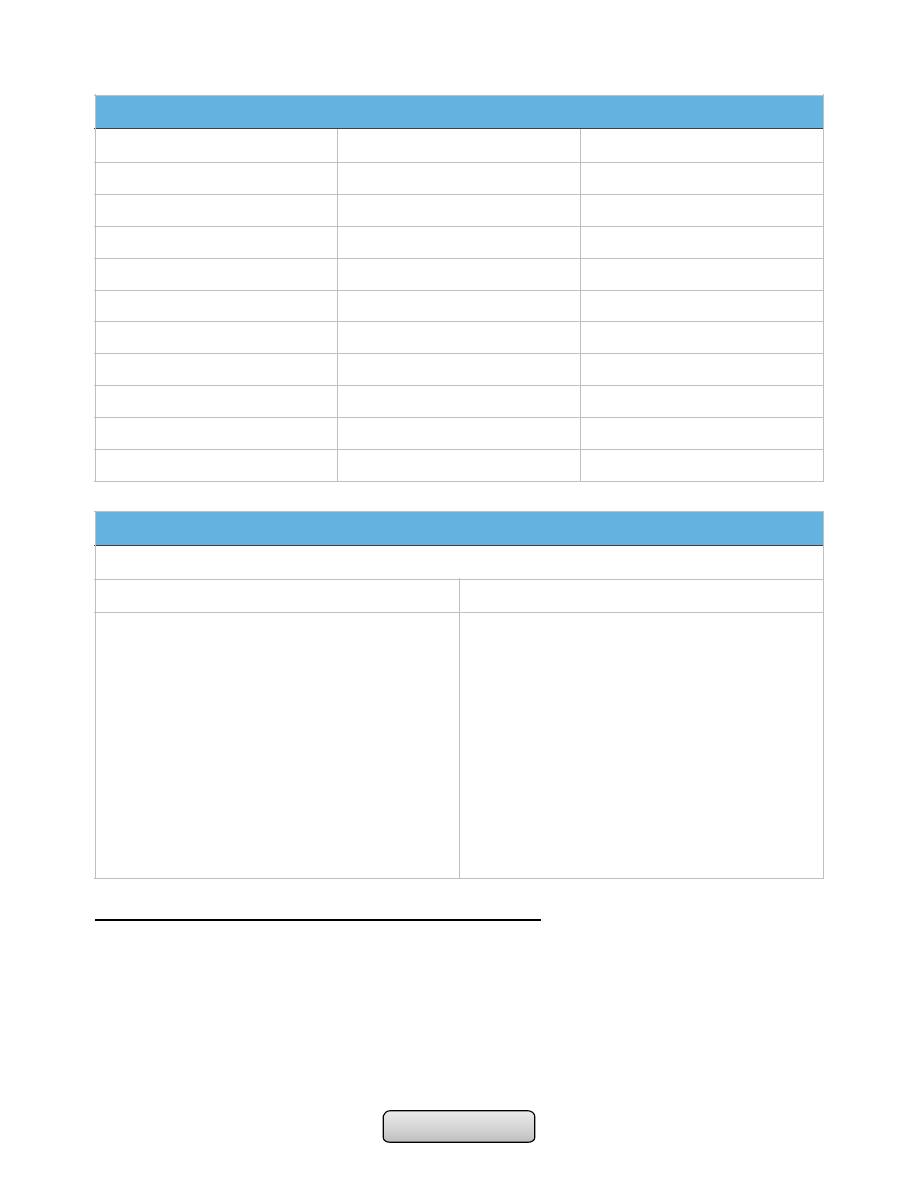

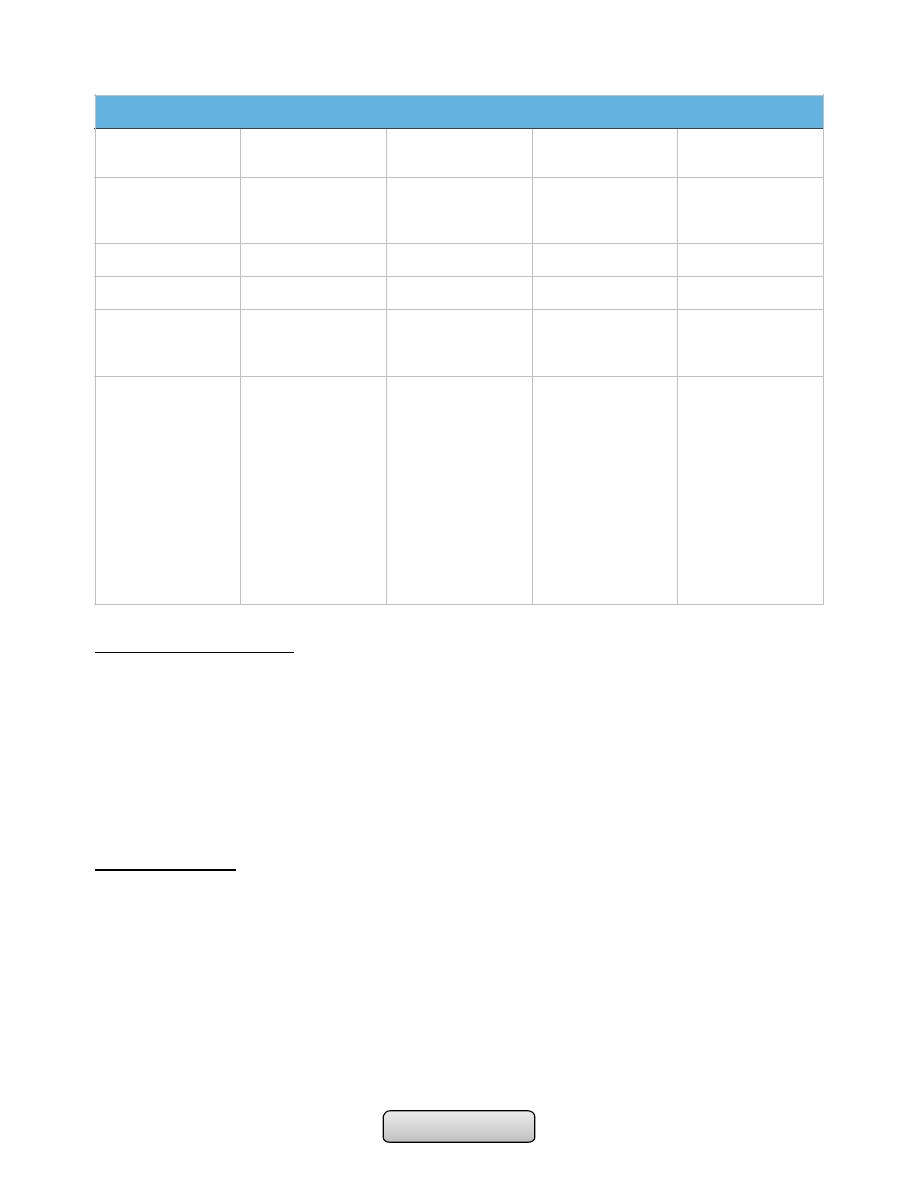

Rockall score for risk stratification in acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage:

1. Malignancy and varices have the worst prognosis.

2. These features are associated with a high risk of rebleeding. Rebleeding (fresh

haematemesis or melaena associated with shock or a fall of haemoglobin > 20 g/L

over 24 hours) is associated with a 10-fold increased risk of death.

3. An initial score can be calculated, endoscopic findings can be added later and a final

score then obtained, ranging from 0 to 11.

-

A score < 3 is associated with a good prognosis.

-

While a total score > 8 carries a high risk of mortality.

Occult gastrointestinal bleeding:

• 'Occult' means that blood or its breakdown products are present in the stool but

cannot be seen by the naked eye.

• It may reach 200 ml per day.

Variable

Score 0

Score 1

Score 2

Score 3

Score

Calculate on admission

1- Age

< 60

60-79

> 80

2- Shock

No shock

Pulse > 100

SBP < 100

3- Comorbidity

Nil major

CCF, IHD,

major

comorbidity

Renal/liver

failure

Metastatic

cancer

Calculate after endoscopy

4- Diagnosis

Mallory-Weiss

tear or normal

All other

diagnoses

GI malignancy1

5- Evidence of

bleeding

None

Blood in

stomach

Adherent clot

Visible or

spurting vessel2

Final score

(range 0-11)

Page of

10

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

• Cause iron deficiency anemia (IDA). Clinically suspected when a patient presents with

unexplained IDA.

• Any cause of GI bleeding m. b. responsible but the most important is colorectal

cancer.

• Investigations; IDA, faecal occult blood (FOB) test (Guaiac test), positive FOB test

necessitates upper and lower endoscopy.

………………………………………………………………………………………..

PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

Learning objectives:

1. Review the functional anatomy and physiology of stomach and duodenum.

2. List the factors that responsible for normal mucosal defense mechanism against

ulcer formation.

3. Understand the concept of peptic ulcer disease (PUD).

4. Review the prevalence of PUD.

5. Explaine the pathophysiology and aetiology of PUD.

6. Clarify the pathological changes of PUD.

7. Recognize the clinical features of PUD.

8. Outline the important investigations of PUD.

9. Review the treatment of PUD.

10.List the complications of PUD.

Peptic Ulcer Disease:

Functional anatomy and physiology of stomach and duodenum;

• Stomach; The stomach acts as a 'hopper', retaining and grinding food, then actively

propelling it into the upper small bowel.

• It’s divided into four regions; the cardia, the fundus, the body, and the antrum: which

end by pyloric channal.

• The gastric rugae (or gastric folds) provide the stomach to increased surface when the

food in it.

• The mucosa, is formed by a layer of columnar epithelium, with numerous

invaginations of the surface epithelium into the lamina propria, which are

called gastric pits

• The muscularis mucosae, a thin layer of smooth muscle, forms the border between

the mucosa and submucosa.

• The submucosa, immediately deep to the mucosa, provides a dense connective tissue

in which lymphocytes, plasma cells, arterioles, venules, lymphatics, and the

myenteric plexus are contained.

Page of

11

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

• The third tissue layer, the muscularis propria, is a combination of an inner oblique, a

middle circular, and an outer longitudinal smooth muscle layer.

• The serosa, a thin, transparent continuation of the visceral peritoneum.

Gastric glands:

the gastric pits branched into four or five gastric glands made up of highly specialized

epithelial cells.

1. Parietal (Oxyntic) cells, which secrete both acid and intrinsic factor. Acid is

secreted in response to the activity of the hydrogen-potassium ATPase ('proton

pump') .

2. Chief cells, which secrete pepsinogen .

3. Enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, which secrete histamine .

4. G cells, which secrete gastrin .

5. D cells, which secrete somatostatin.

6. Mucus, secreting cells.

The duodenum:

• The most proximal portion of the small intestine, forms a C-shaped loop around the

head of the pancreas and is in continuity with the pylorus proximally and the jejunum

distally.

• Angular changes in course divide the duodenum into four portions. The first part of

the duodenum is the duodenal bulb or cap.

• The submucosal Brunner's glands that produce bicarbonate-rich secretions involved in

acid neutralization.

The mucosal defense system:

1. The first line of defense is a mucus-bicarbonate layer.

2. The next line of defense is the epithelial cells, intracellular tight junctions, cells

migration, and cell proliferation and renewal.

3. Prostaglandins are important in maintaining mucosal blood flow.

PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE:

• Peptic ulcer: refers to an ulcer in the lower oesophagus, stomach or duodenum, in the

jejunum after surgical anastomosis to the stomach or, rarely, in the ileum adjacent to a

Meckel's diverticulum, which penetrate the muscularis mucosae.

• Erosions; do not penetrate it.

• Ulcer may be acute or chronic, but acute ulcer show no evidence of fibrosis.

Gastric and duodenal ulcer:

• The prevalence of peptic ulcer is decreasing in Western communities as a result of

widespread use of H. pylori eradication therapy.

Page of

12

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

• It remains high in developing countries.

• Male to female ratio for duodenal ulcer varies from 5:1 to 2:1, whilst that for gastric

ulcer is 2:1 or less.

Pathophysiology and aetiology of PUD:

I. H. pylori infection;

A. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in developed world approxim. 50% of those

over the age of 50 yrs while 90% of the adult population in developing world are

infected.

B. The vast majority of colonized people remain healthy and asymptomatic.

C. 90% of duodenal ulcer patients and 70% of gastric ulcer patients are infected with

H. pylori.

D. H. pylori: Is Gram-negative, spiral and has multiple flagella at one end which make

it motile, allowing it to burrow and live deep beneath the mucus layer closely

adherent to the epithelial surface.

E. Production of the enzyme urease, this produces ammonia from urea and raises the

pH around the bacterium. It spread by person-to-person contact via gastric

refluxate or vomit.

F. H. pylori exclusively colonises gastric-type epithelium, in duodenum in assoctation

of gastric metaplasia. In most people H. pylori causes antral gastritis --depletion

of somatostatin (from D cells)---hypergastrinaemia --- increase acid production.

G. The majority of patients remains asyptomatic, but in some patients this effect is

exaggerated, leading to duodenal ulceration. The role of H. pylori in the

pathogenesis of gastric ulcer is less clear but it probably acts by reducing gastric

mucosal resistance to attack from acid and pepsin. In approximately 1% of infected

people, H. pylori causes a pangastritis leading to gastric atrophy and

hypochlorhydria ---gastric cancer.

H. The end result of H pylori infection:

1. Gastritis.

2. PUD.

3. Gastric MALToma.

4. Gastric cancer.

II. NSAIDs;

A. NSAIDs induce ulcer by reducing mucosal resist.– decr. Prostagl.– mucos. Injury.

B. RISK FACTORS FOR NSAID-INDUCED ULCERS:

1. Age > 60 years.

2. Past history of peptic ulcer.

3. Past history of adverse event with NSAIDs.

4. Concomitant corticosteroid use.

5. High-dose or multiple NSAIDs.

Page of

13

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

6. Individual NSAID-highest with azapropazone, piroxicam, ketoprofen; lower with

ibuprofen.

III. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES);

A. Gastrin-secreting tumors, accounts for 0.1% of causes of PUD.

B. Should be considered in patients with ulcers in unusual sites (e.g., distal

duodenum or jejunum); multiple, recurrent, or complicated duodenal ulcers; or

ulcers associated with chronic diarrhea.

IV. Smoking;

A. Increased risk of GU and, to a lesser extent DU, more complications and less

healing.

Pathology of PUD:

• Duodenal Ulcers mostly in the first portion of duodenum (>95%), Ulcers are sharply

demarcated, the base of the ulcer often consists of a zone of eosinophilic necrosis

with surrounding fibrosis. Malignant DUs are extremely rare.

• GUs can represent a malignancy, benign GUs are histologically similar to DUs.

Clinical features:

• The most common characteristics of abdominal pain suggestive of PUD:

-

Chronic recurrent abdominal pain with a history of spontaneous relapse and

remission lasting for decades.

-

Localisation to the epigastrium.

-

Relationship to food.

-

Episodic occurrence.

• Epigastric pain described as a burning or gnawing discomfort, hunger pain, relieved by

antacids or food, awakes the patient from sleep ,associated with weight gain.

• Vomiting occurs in about 40%; persistent daily vomiting suggests gastric outlet

obstruction.

• In some patients --silent ulcer; anaemia from chronic undetected blood loss.

• Complications; haematemesis, or acute perforation.

• The pain pattern in GU patients may be different from that in DU patients, where

discomfort may actually be precipitated by food. Nausea and weight loss occur more

commonly in GU patients.

Investigations of PUD:

1. Endoscopy: is the preferred investigation. Gastric ulcers must always be biopsied.

2. Barium studies: DU appears as a well-demarcated crater, most often seen in the

bulb. Benign GU also appears as a discrete crater with radiating mucosal folds

originating from the ulcer margin. Ulcers >3 cm in size or associ. with a mass are

more often malignant.

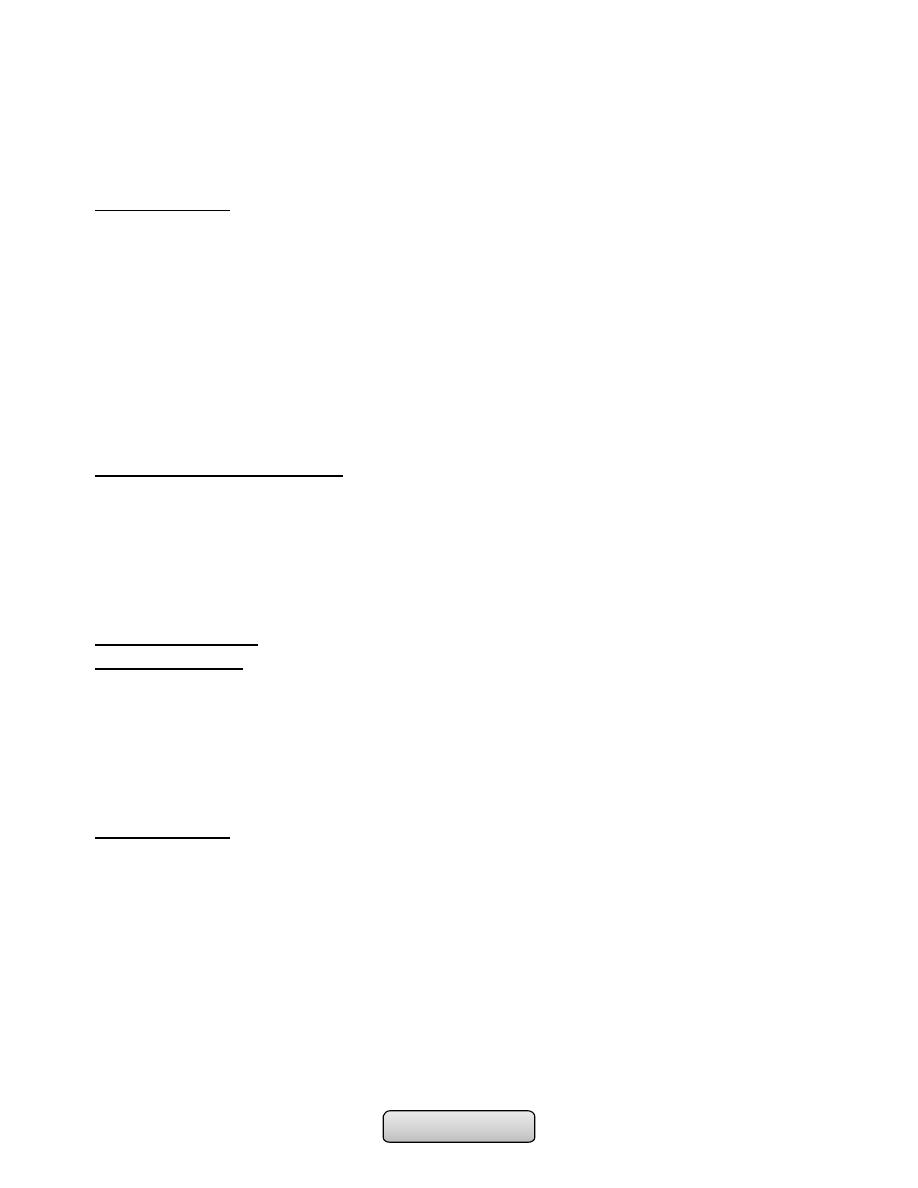

3. Tests for Detection of H. pylori infection.

Page of

14

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Management:

The aims of management are to relieve symptoms, induce healing and prevent

recurrence.

1. H. pylori eradication.

2. General measures.

3. Short-term management.

4. Maintenance treatment.

5. Surgical treatment.

Regimens for H. Pylori eradication;

• First-line therapy is a proton pump inhibitor (12-hourly), clarithromycin 500 mg 12-

hourly, and amoxicillin 1 g 12-hourly or metronidazole 400 mg 12-hourly, for 10 days.

• Second-line therapy is a proton pump inhibitor (12-hourly), bismuth 120 mg 6-hourly,

metronidazole 400 mg 12-hourly, and tetracycline 500 mg 6-hourly, for 10 days.

• General measures; Cigarette smoking, aspirin and NSAIDs should be avoided

• Short-term management; after H pylori eradication ,followed by continuous acid

suppre. drugs ( H2 RB or PPI) for 4-6 wks.

• Maintenance treatment; GU need 8-12 wks to complete healing, with repeated

endoscopy and biopsy.

• Surgical treatment;

-

Emergency; Perforation, Haemorrhage.

-

Elective; Complications, e.g. gastric outflow obstruction. Recurrent ulcer following

gastric surgery.

Refractory ulcer:

• A GU that fails to heal after 12 weeks or DU after 8 weeks of therapy should be

considered refractory.

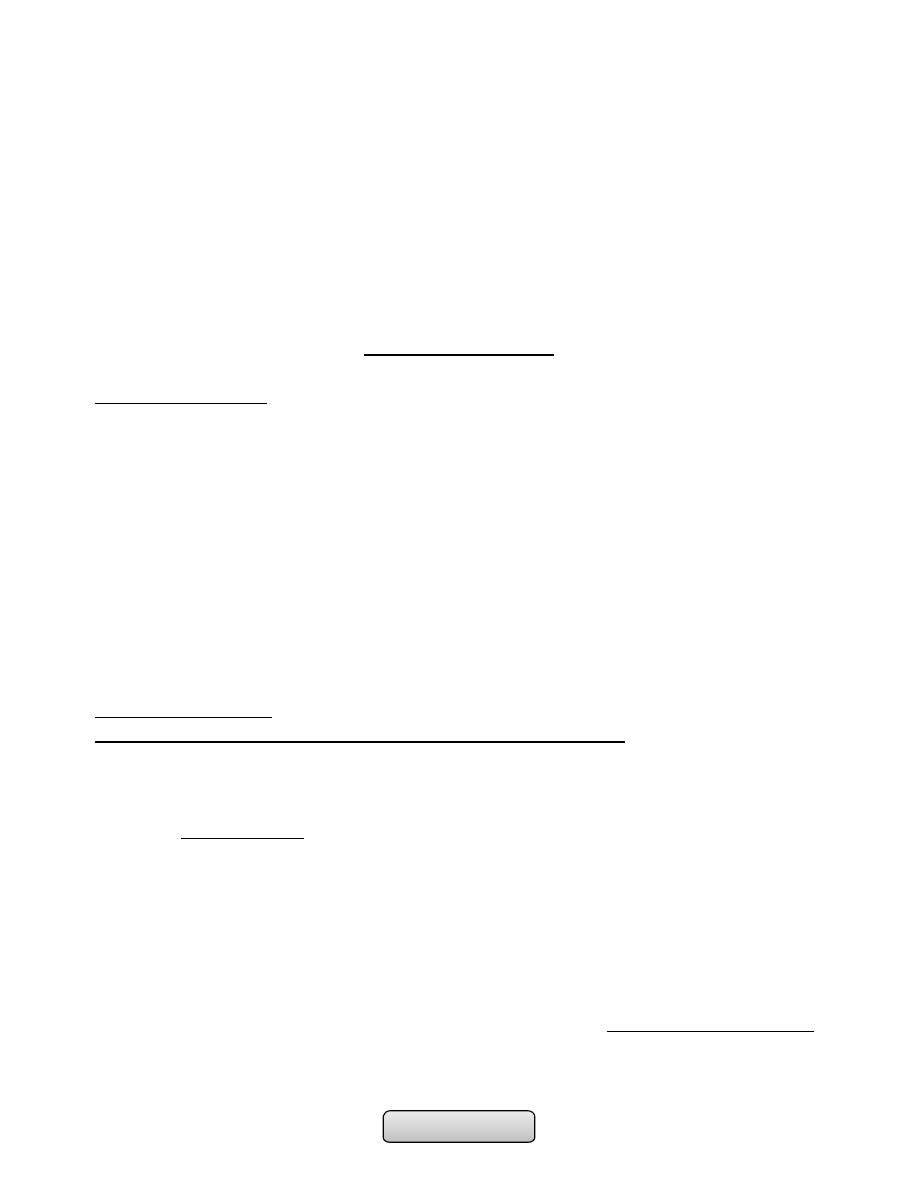

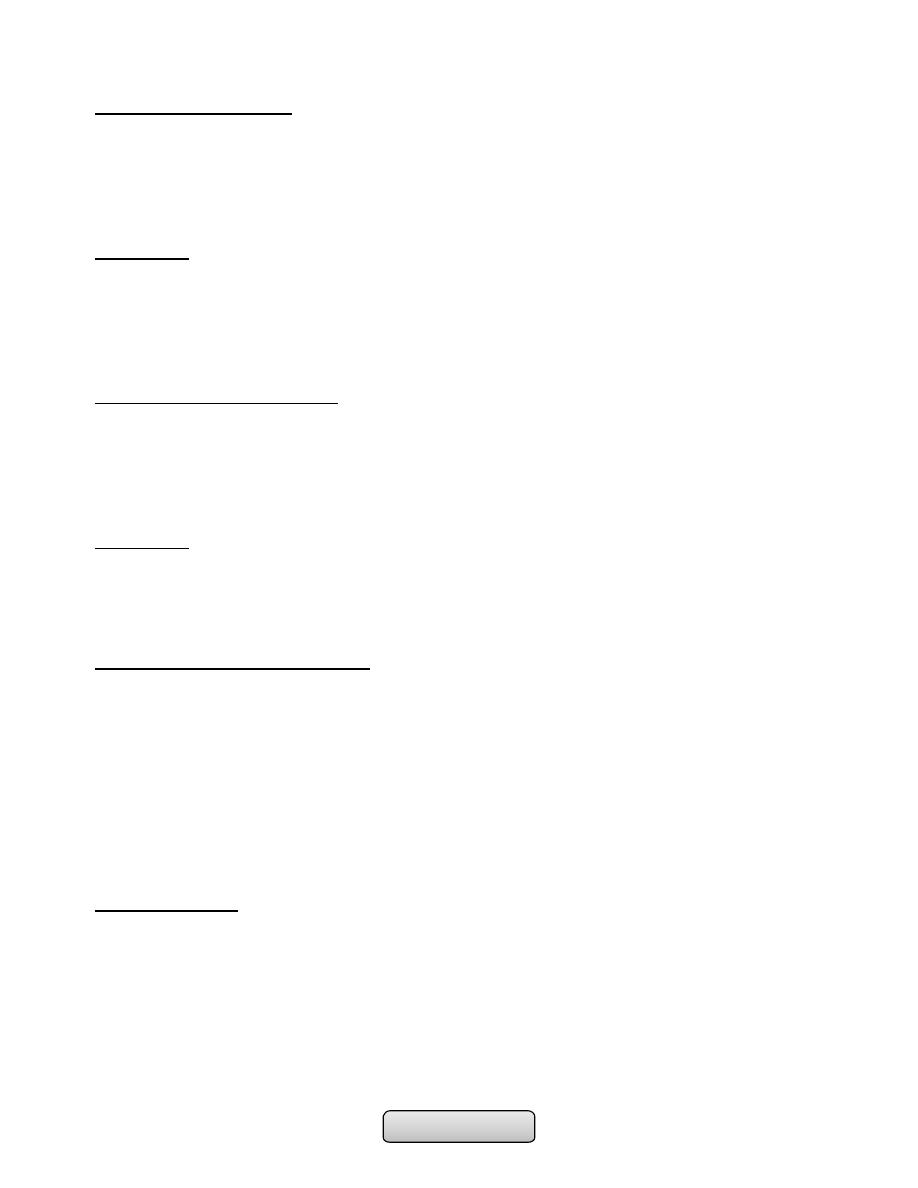

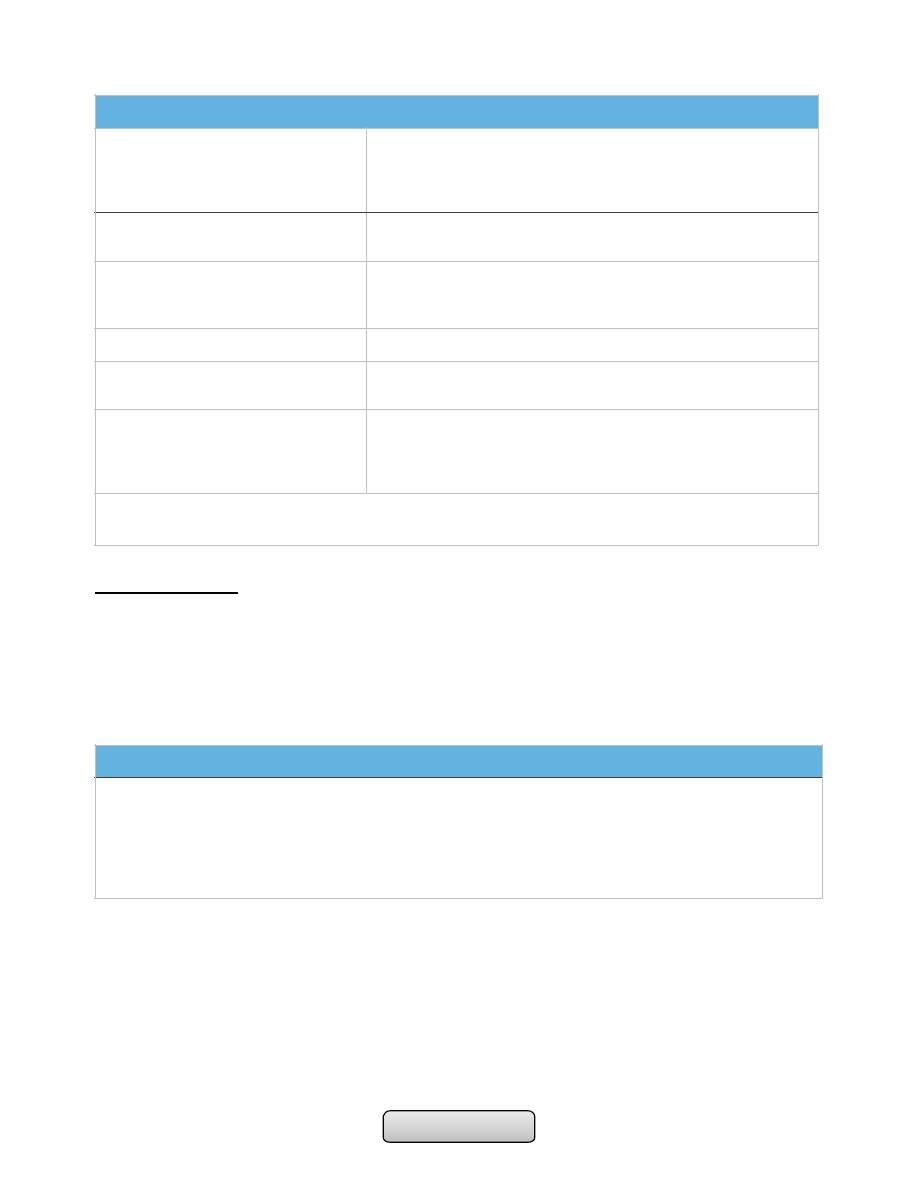

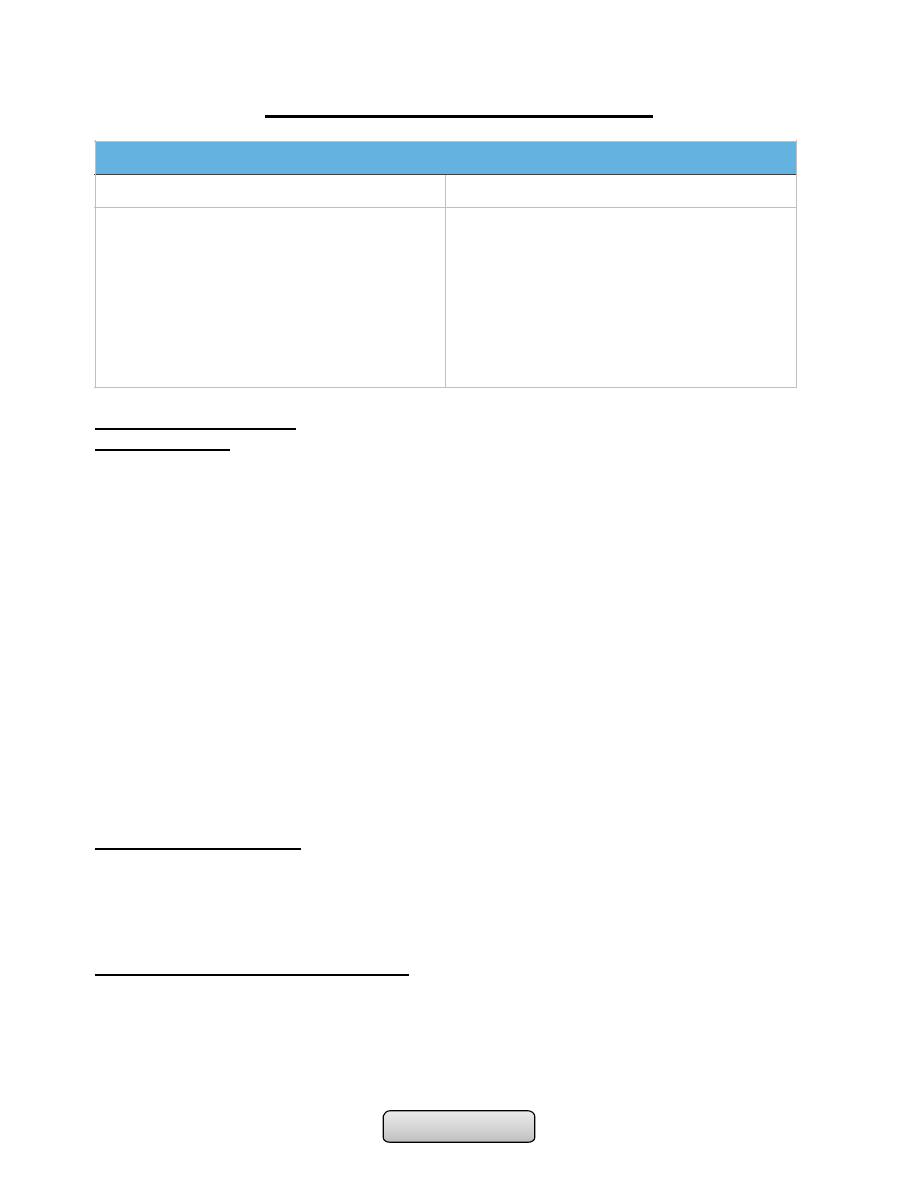

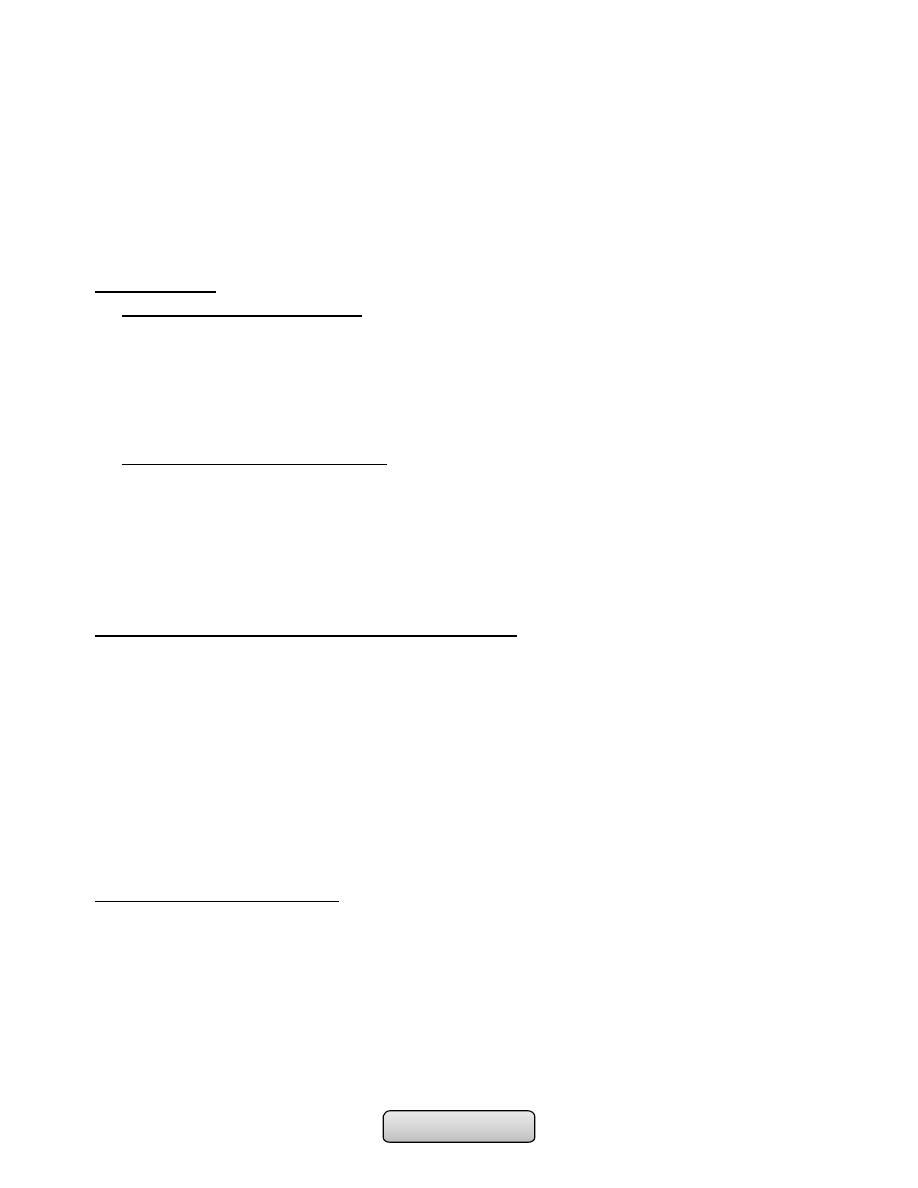

Test

Advantages

Disadvantages

NON-INVASIVE

Serology

Rapid kits available

Lacks sensiti and specif

Urea breath tests

High sensitivi and specifi

expensive

Faecal antigen test

Cheap, accurate

Acceptability

INVASIVE (ANTRAL BIOPSY)

Histology

Sensitivity and specificity

False negatives occur

Rapid urease tests

Cheap, quick, specifi.

Lack sensitivity

Microbiological culture

Gold standard'

Slow and laborious

Page of

15

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

• Common causes; poor compliance , persistent H. pylori infection, NSAID use,

cigarette smoking , GU malignancy and ZES.

Complications of peptic ulcer disease:

A. Complications of gastric resection or vagotomy:

1. Dumping.

2. Bile reflux gastritis.

3. Diarrhoea and maldigestion.

4. Weight loss.

5. Anaemia.

6. Metabolic bone disease.

7. Gastric cancer.

B. Complications of PUD it self:

1. Perforation.

2. Bleeding.

3. Gastric outlet obstruction

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Page of

16

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

TUMOURS OF THE STOMACH

Learning objectives:

1. Classify the gastric tumours.

2. Review the prevalence of gastric tumours.

3. Describe the pathophysiology, causes and risk factors of gastric tumours.

4. Explain the pathology of gastric tumours.

5. Clarify the clinical features of gastric tumours.

6. Understand the important investigations and staging of gastric tumours.

7. Explain the treatment of gastric tumours.

TUMOURS OF THE STOMACH:

1. GASTRIC CARCINOMA.

2. GASTRIC LYMPHOMA.

3. OTHER TUMOURS OF THE STOMACH; Gastrointestinal stromal cell tumours (GIST), a

variety of polyps, and gastric carcinoid tumours.

GASTRIC CARCINOMA:

• The incidence of gastric cancer in the UK has fallen markedly in recent years, It is

extremely common in China, Japan and parts of South America.

• Japanese migrants to the USA have much lower incidence in second-generation

migrants, confirming the importance of environmental factors.

• It is more common in men, after 50 years of age.

Aetiology;

1. H. pylori infection; is associated with chronic atrophic gastritis -- hypo- or

achlorhydria --- gastric cancer.

2. Diets; rich in salted, smoked or pickled foods and the consumption of nitrites and

nitrates may increase cancer risk. Diets lacking fresh fruit and vegetables as well

as vitamins C and A.

3. Smoking.

4. Alcohol.

5. Autoimmune gastritis (pernicious anaemia).

6. Adenomatous gastric polyps.

7. Previous partial gastrectomy (> 20 years).

8. Ménétrier's disease: It is a rare condition the gastric pits are elongated and

tortuous, with replacement of the parietal and chief cells by mucus-secreting

cells. As a result, the mucosal folds of the body and fundus are greatly enlarged.

Total gastrectomy specimen cut open to show giant gastric rugae and excessive

mucous secretion.

9. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer families (HDC-1 mutations).

10.Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

Page of

17

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Pathology;

• Microscopically; All tumours are adenocarcinomas arising from mucus-secreting cells:

-

either 'intestinal', arising from areas of intestinal metaplasia, more common.

-

or 'diffuse', arising from normal gastric mucosa, poorly differentiated and occur in

younger patients.

• Macroscopically; Classified as polypoid, ulcerating, fungating or diffuse a scirrhous

cancer (linitis plastica):

-

Early gastric cancer; Is defined as cancer confined to the mucosa or submucosa,

regardless of lymph node involvement often recognized in Japan due to

widespread screening.

-

Advanced gastric cancer; Over 80% of patients in the Westren present at this

stage.

• Location; 50% in the antrum, 20-30% occur in the gastric body, 20% in the cardia, or

diffuse submucosal infiltration (uncommon).

Clinical features:

• Which depend on the location, size, and growth pattern of gastric cancer.

• Early gastric cancer is usually asymptomatic.

1. Dyspepsia.

2. Dysphagia.

3. Weight loss.

4. GI bleeding; Anaemia from occult bleeding, haematemesis, and melaena.

5. Palpable epigastric mass.

6. Pylorus/cardia obstruction.

7. Perforation.

8. Metastatic spread;

1. To the supraclavicular lymph nodes (Troisier's sign).

2. To umbilicus ('Sister Joseph's nodule').

3. To ovaries (Krukenberg tumour).

4. To the perirectal pouch (Blumer shelf).

5. Liver ---Jaundice.

6. Bone --- Bone pain.

7. Peritoneum --- Ascitis.

9. Paraneoplastic syndromes;

1. Thrombophlebitis (Trousseau's sign).

2. Acanthosis nigricans (pigmented dermal lesions).

3. Membranous nephropathy.

4. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

5. Leser-Trélat sign (seborrheic keratosis).

6. Dermatomyositis.

Page of

18

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Diagnosis and staging:

• Upper GI endoscopy; Is the investigation of choice in;

-

Dyspeptic patient with 'alarm features‘

-

New onset of dyspepsia in patient >55 years

-

Dyspepsia & family h/o gastric carcinoma

• Barium meal; is a poor alternative.

• CT abdomen; show evidence of intra-abdominal spread or liver metastases.

• Laparoscopy; is required to determine whether the tumour is resectable.

Management:

1. Surgery; cure can be achieved in 90% of patients with early gastric cancer by total

gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy, which is the operation of choice.

2. Unresectable tumours; for advanced cancer:

1. Chemotherapy; using FAM (5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and mitomycin C) or ECF

(epirubicin, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil).

2. Endoscopic laser ablation for dysphagia or recurrent bleeding.

3. Carcinomas at the cardia; endoscopic dilatation, laser therapy or insertion of

expandable metallic stents.

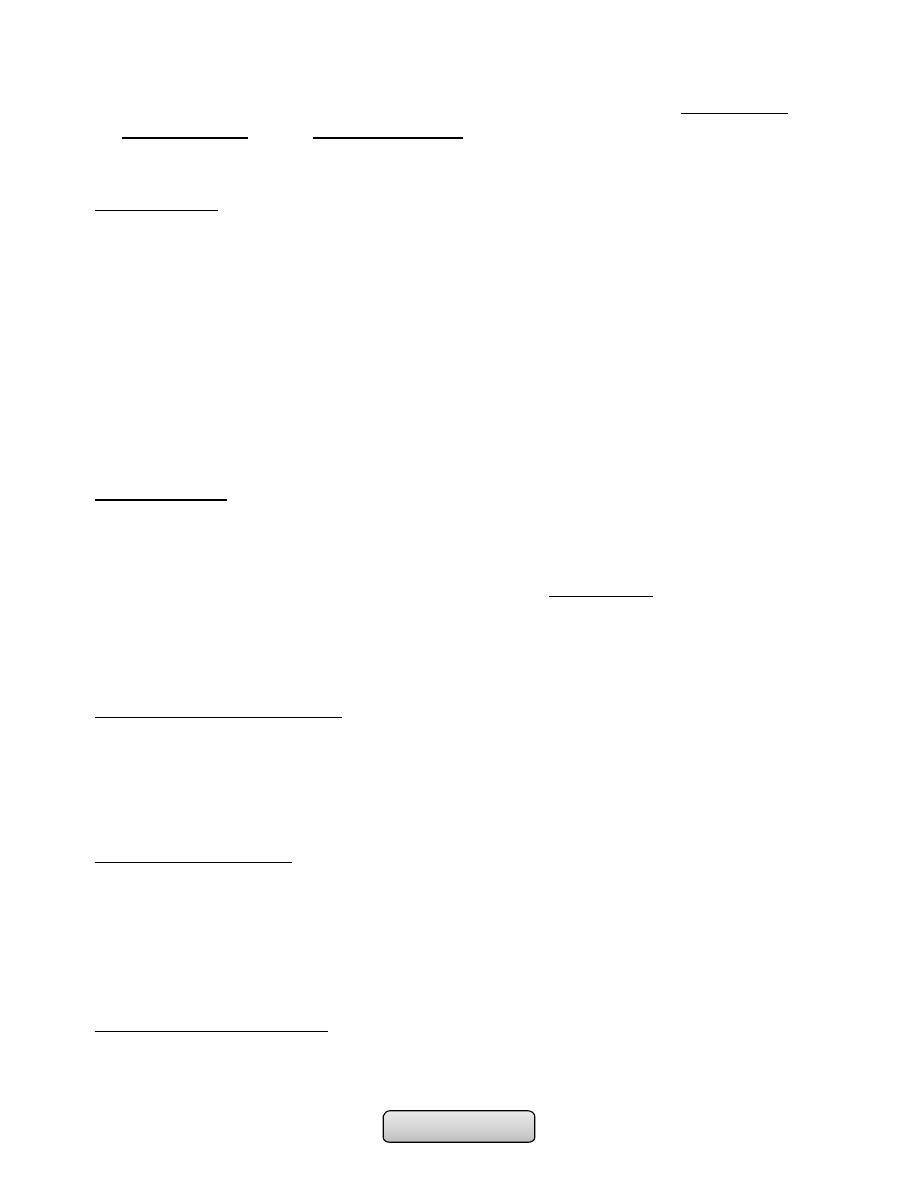

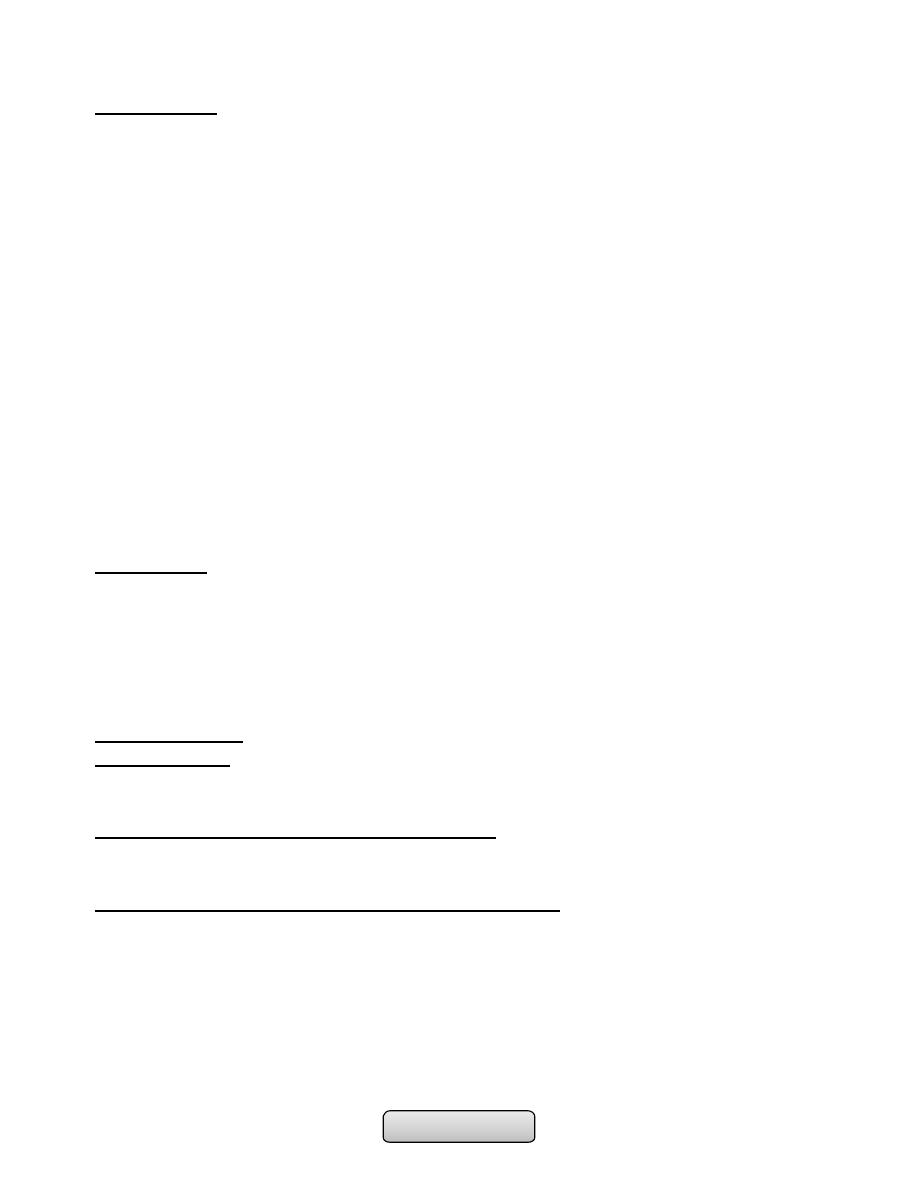

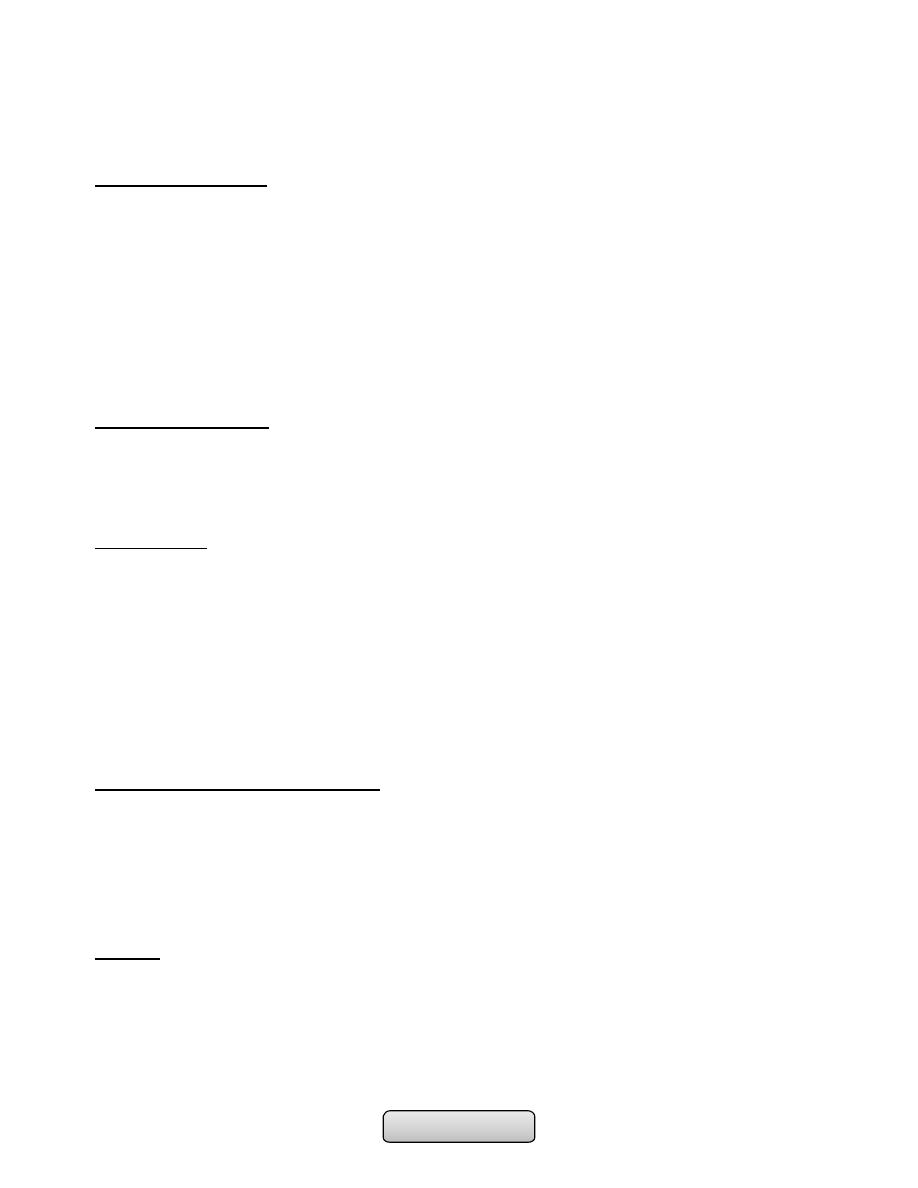

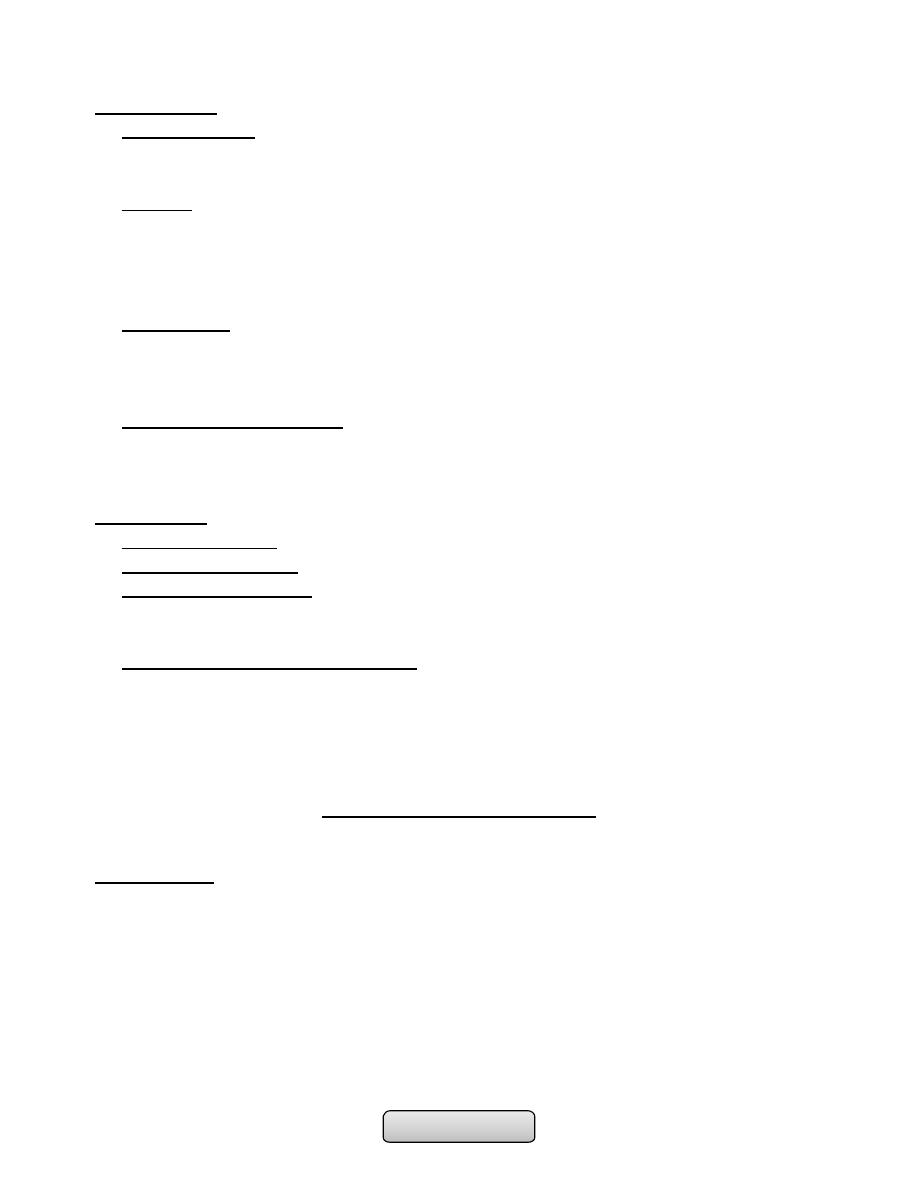

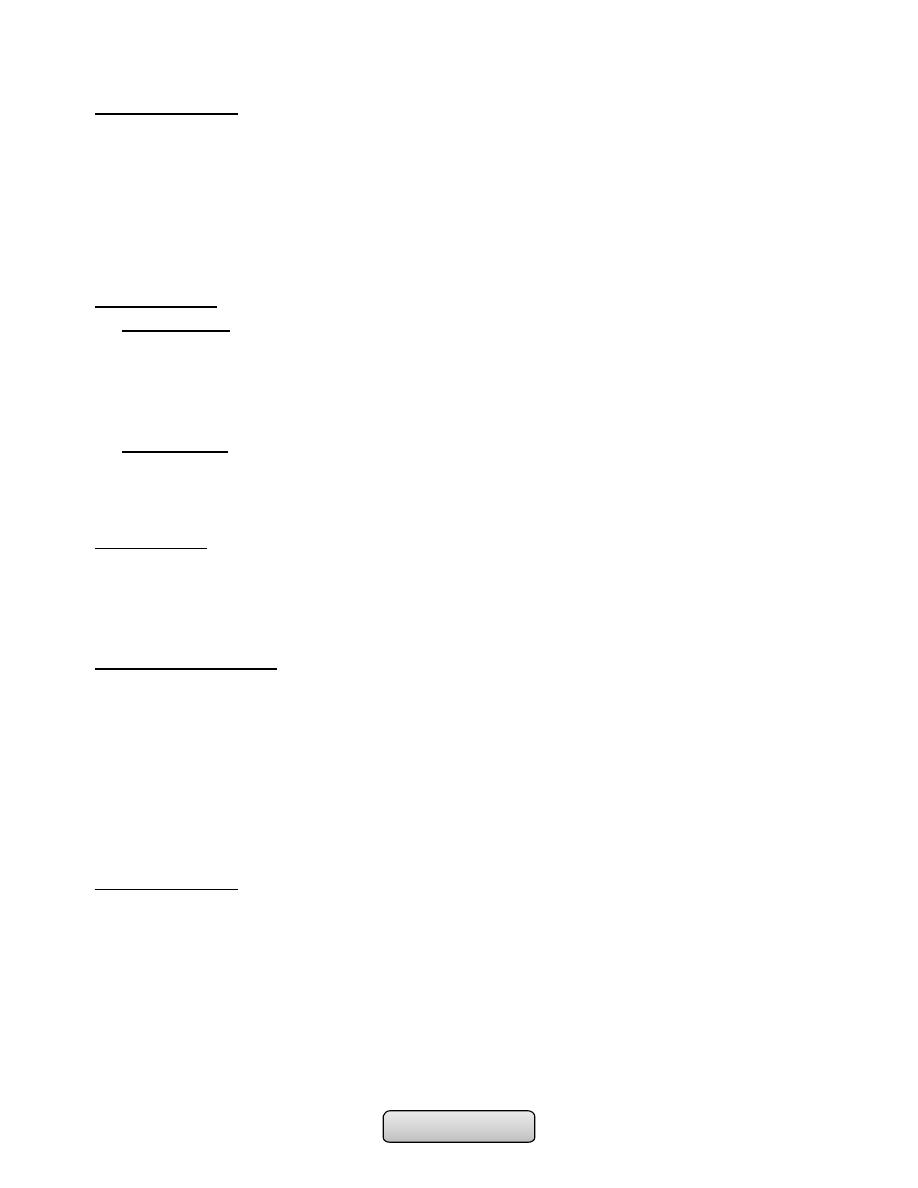

TNM staging of gastric cancer

T

Tis

Intaepithelial tumour

T1

Tumour invades submucosa

T2

Tumour invades muscularis

propria

T3

Tumour penetrates serosa

T4

Tumour invades adjacent

structures

N

N0

No regional lymph node

metastases

N1

Metastasis in 1 to 2 regional

lymph nodes

N2

Metastasis in 3 to 6 regional

lymph nodes

N3

Metastasis in 7 or more regional

lymph nodes

M

M0

No distant metastasis

M1

Distant metastasis

Page of

19

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Prognosis:

• Remains very poor, with the exception of early gastric cancer. So endoscopic screening

of patients with new-onset dyspepsia in those over the age of 55years, or those with

'alarm' features, are essential.

GASTRIC LYMPHOMA:

• Primary gastric lymphoma accounts for less than 5% of all gastric malignancies.

• The stomach is the most common site for extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL).

• Lymphoid tissue is not found in the normal stomach but lymphoid aggregates develop

in the presence of H. pylori infection.

• There are 2 types of gastric lymphoma;

1) Gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALToma); It is low-

grade lymphoma, H. pylori infection is closely associated.

2) Extranodal manifestation of high grade NHL.

• Clinical presentation; is similar to that of gastric cancer.

• Endoscopically; the tumour appears as a polypoid or ulcerating mass.

• Treatment;

-

Low-grade MALTomas consists of H. pylori eradication and close observation.

-

High-grade B-cell lymphomas are treated by a combination of chemotherapy,

surgery and radiotherapy.

• Prognosis; Depends on the type and stage of lymphoma at the time of diagnosis.

..............................................................................................................

FUNCTIONAL (NON-ULCER) DYSPEPSIA

Learning objectives:

1. Define functional dyspepsia.

2. List the causes of functional dyspepsia.

3. Review the clinical features of functional dyspepsia.

4. List the important investigations of functional dyspepsia.

5. Outline the management of functional dyspepsia.

FUNCTIONAL (NON-ULCER )DYSPEPSIA:

• Dyspepsia; is a collective symptoms thought to be originate from the upper

gastrointestinal tract, that may include pain or discomfort, bloating, feeling of

fullness with very little intake of food , feeling of early satiety, nausea, loss of

appetite or heartburn.

• Functional dyspepsia; chronic dyspepsia (more than 3 months) in the absence of

organic disease.

Page of

20

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Aetiology;

• The pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia is unclear but probably due to mucosal,

motility, psychiatric disorders or H. pylori infection.

Clinical features;

• Usually young (< 40 years) women.

• Abdominal pain associated with a variable 'dyspeptic' symptoms( nausea and bloating

after meals).

• Morning symptoms are characteristic.

• A drug history, pregnancy, and alcohol misuse should be ruled out.

Examination;

• Usually negative apart from inappropriate tenderness on abdominal palpation, no

weight loss, patients may be anxious.

• Symptoms may appear disproportionate to clinical well-being.

Investigations;

1. Endoscopy is necessary to exclude mucosal disease.

2. Testing for H. pylori infection.

3. Ultrasound scan may detect gall stones.

Management;

• Explanation of symptoms and reassurance that the risk of cancer is very low in

absence of alarm features.

• Possible psychological factors should be explored.

• Give dietary advice; stop smoking, take regular meals, limit spicy, acidic and fatty

foods may be helpful.

• Review medications that may aggravating symptoms.

Drug treatment;

1. Antacids and alginates are sometimes helpful.

2. Prokinetic drugs such as metoclopramide or domperidone -- if nausea, vomiting or

bloating is prominent.

3. H

2

-receptor antagonists or PPI -- if night pain or heartburn is troublesome.

4. The role of H. pylori eradication remains controversial. Indicated in those who are

positive results. (Testing and treating for H. pylori) used as a role.

5. Low-dose amitriptyline is sometimes of value.

6. Some patients need behavioral or other formal psychotherapy.

………………………………………………………………………………………….

Page of

21

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD):

• IBD refers to two ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease which have relapsing and

remitting course, usually extending over years, precipitated by a complex interaction

of environmental, genetic, and immunoregulatory factors.

• The diseases have many similarities and it is sometimes impossible to differentiate

between them.

• A crucial distinction is that ulcerative colitis only involves the colon, while Crohn's

disease can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus.

• In developing world Crohn's disease appears to be very rare, but ulcerative colitis

becoming more common.

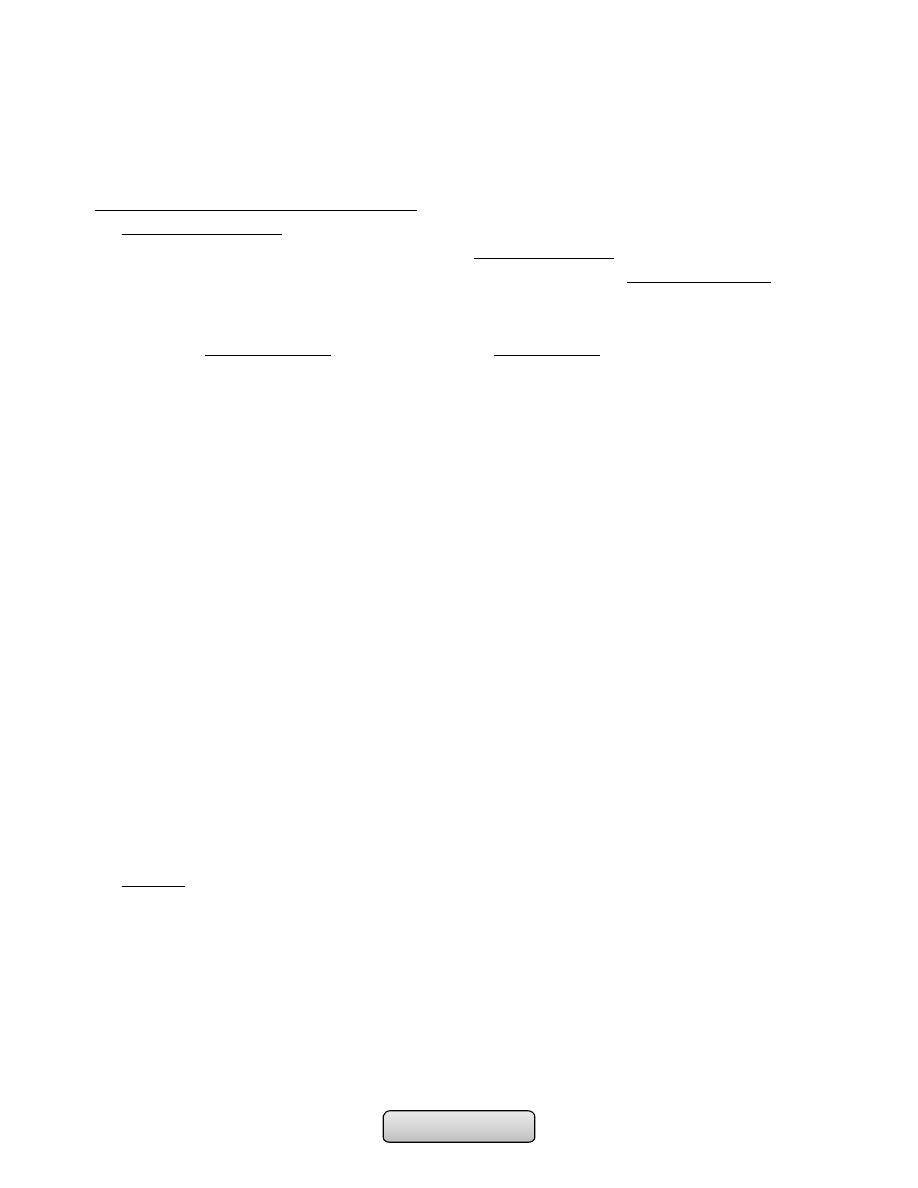

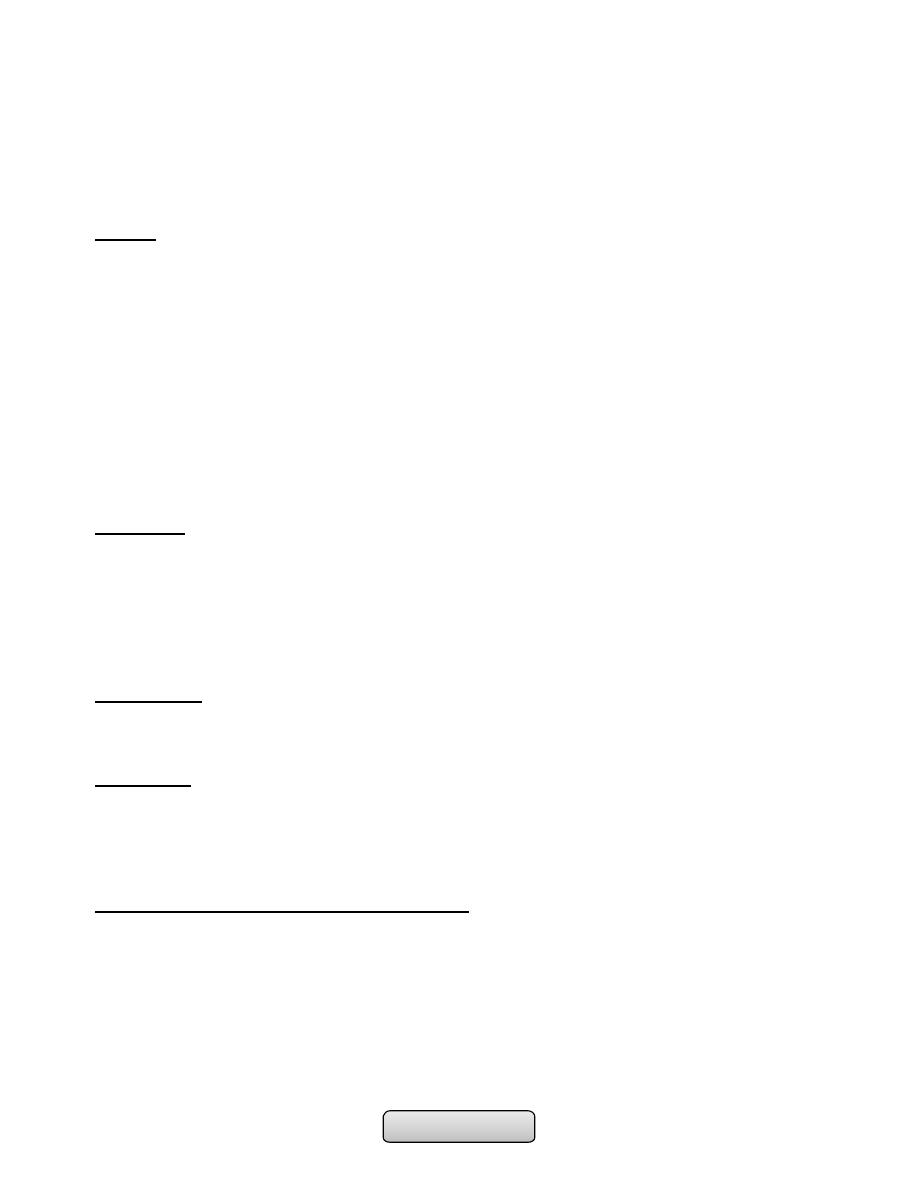

Comparison of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease

Ulcerative colitis

Crohn's disease

Age group

Any

Any

Gender

M = F

M = F

Ethnic group

Any

Any; more common in Ashkenazi Jews

Genetic factors

HLA-DR103 associated with

severe disease

CARD 15/NOD-2 mutations predispose

Risk factors

More common in non smokers.

Appendicectomy protects

More common in smokers

Anatomical distribution

Colon only; begins at anorectal

margin with variable proximal

extension

Confluent lesion

Any part of gastrointestinal tract; perianal

disease common; patchy

distribution-'skip lesions'

Extraintestinal

Common

Common

Presentation

Bloody diarrhoea

Variable; pain, diarrhoea, weight loss all

common

Histology

Inflammation limited to mucosa;

crypt distortion, cryptitis, crypt

abscesses, loss of goblet cells

Submucosal or transmural inflammation

common; deep fissuring ulcers, fistulas;

patchy changes; granulomas

Management

5-ASA; corticosteroids;

azathioprine; colectomy is curative

Corticosteroids; azathioprine;

methotrexate; biologic therapy (anti-

TNF); nutritional therapy; surgery for

complications, is not curative

Page of

22

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Ulcerative colitis;

• Inflammation invariably involves the rectum (proctitis) but can spread to involve the

sigmoid colon (proctosigmoiditis) or the whole colon (pancolitis). Inflammation is

confluent and is more severe distally.

• In long-standing pancolitis the bowel can become shortened and 'pseudopolyps'

develop which are normal or hypertrophied residual mucosa within areas of atrophy.

• Both acute and chronic inflammatory cells infiltrate the lamina propria and the crypts

('cryptitis'). Crypt abscesses are typical.

Crohn's disease;

• The most common site involved is the terminal ileum and right side of colon.

• The entire wall of the bowel is oedematous and thickened, and there are deep ulcers

which often appear as linear fissures; thus the mucosa between them is described as

'cobblestone'.

• initiate abscesses or fistulas involving the bowel, bladder, uterus, vagina and skin of

the perineum.

• Crohn's disease has a patchy distribution and the inflammatory process is interrupted

by islands of normal mucosa.

Clinical features:

Ulcerative colitis:

• The major symptom is bloody diarrhoea. The first attack is usually the most severe

and thereafter the disease is followed by relapses and remissions. Emotional stress,

intercurrent infection, gastroenteritis, antibiotics or NSAID therapy may all provoke a

relapse.

• Proctitis or Proctosigmoiditis causes rectal bleeding and mucus discharge, sometimes

accompanied by tenesmus. Constitutional symptoms do not occur.

• Extensive colitis causes bloody diarrhoea with passage of mucus. In severe cases

anorexia, malaise, weight loss and abdominal pain occur, and the patient is toxic with

fever, tachycardia and signs of peritoneal inflammation.

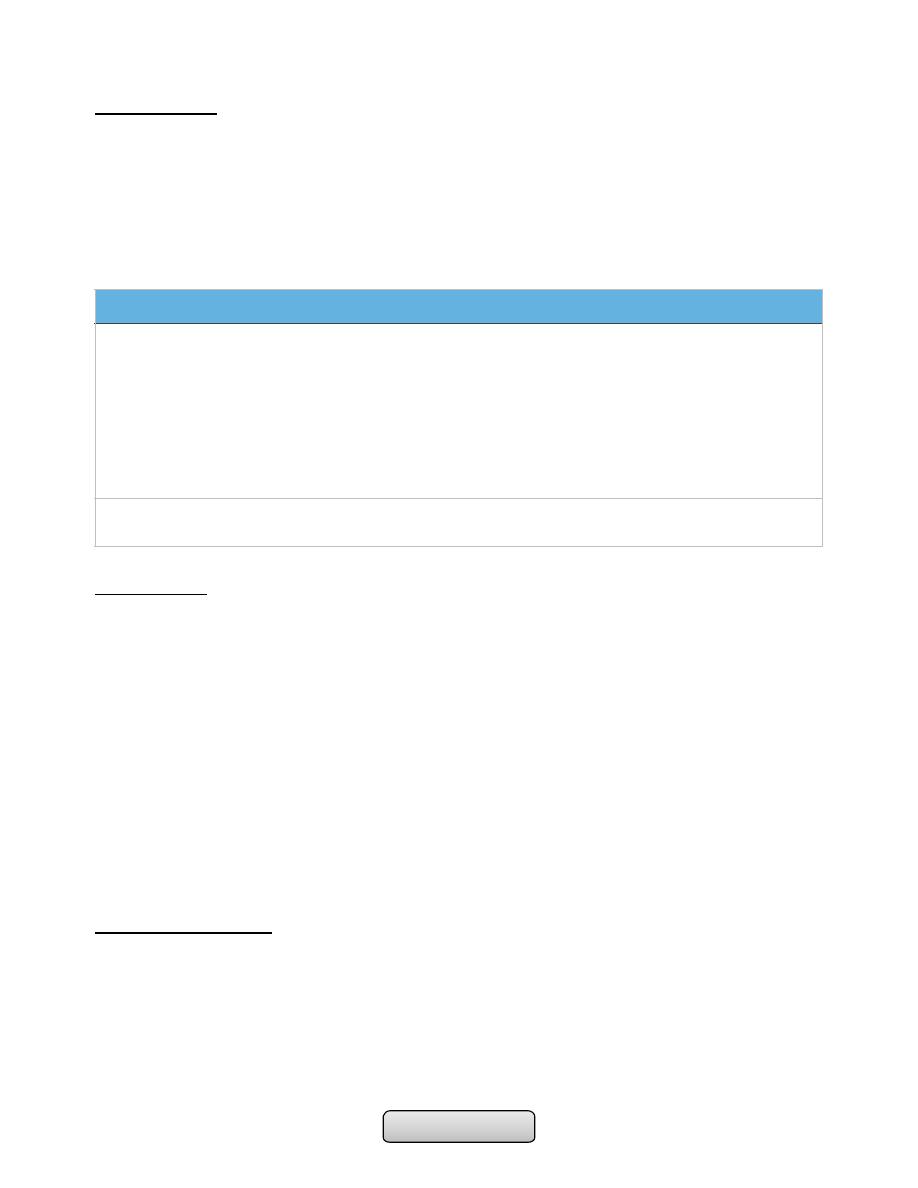

• Factors considered for disease severity assessment in ulcerative colitis

Crohn's disease:

• The major symptoms are abdominal pain, diarrhea and weight loss.

• Ileal Crohn's disease may cause subacute or even acute intestinal obstruction or

watery diarrhea.

• Crohn's colitis presents in an identical manner to ulcerative colitis, but rectal sparing

and the presence of perianal disease are features which favour a diagnosis of Crohn's

disease.

• Many patients present with symptoms of both small bowel and colonic disease

• Few have isolated perianal disease, vomiting from jejunal strictures or severe oral

ulceration.

Page of

23

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Differential diagnosis of small bowel Crohn's disease:

• Other causes of right iliac fossa mass

-

Caecal carcinoma

-

Appendix abscess

• Infection (tuberculosis, Yersinia, actinomycosis)

• Mesenteric adenitis

• Pelvic inflammatory disease

• Lymphoma

Factors considered for disease severity assessment in ulcerative colitis

Mild

Severe

Daily bowel frequency

< 4

> 6

Blood in stools

+/-

+++

Stool volume

< 200 g/24 hrs

> 400 g/24 hrs

Pulse

< 90 bpm

> 90 bpm

Temperature

Normal

> 37.8°C, 2 days out of 4

Sigmoidoscopy

Normal

Blood in lumen

Abdominal X-ray

Normal

Dilated bowel

Haemoglobin

Normal

< 100 g/L (< 10 g/dL)

ESR

Normal

> 30 mm/hr

Serum albumin

> 35 g/L (> 3.5 g/dL)

< 30 g/L (< 3 g/dL)

Differential diagnosis

Conditions which can mimic ulcerative or Crohn's colitis

Infective

Non-infective

• Bacterial:

-

Salmonella

-

Shigella

-

Campylobacter jejuni

-

E. coli O157

-

Gonococcal proctitis

-

Pseudomembranous colitis

-

Chlamydia proctitis

• Viral:

-

Herpes simplex proctitis

-

Cytomegalovirus

• Protozoal:

-

Amoebiasis

• Vascular:

-

Ischemic colitis

-

Radiation colitis

• Idiopathic:

-

Collagenous colitis, Behçet's disease

• Drugs: NSAIDs

• Neoplastic:

-

Colonic carcinoma

• Other:

-

Diverticulitis

Page of

24

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Complications:

1. Life-threatening colonic inflammation;

• This can occur in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. In the most extreme

cases the colon dilates (toxic megacolon) and bacterial toxins pass freely across the

diseased mucosa into the portal then systemic circulation.

• An abdominal X-ray should be taken daily because when the transverse colon is

dilated to more than 6 cm there is a high risk of colonic perforation, although this

complication can also occur in the absence of toxic megacolon.

2. Haemorrhage; is due to erosion of a major artery is rare but can occur in both

conditions.

3. Fistulas; These are specific to Crohn's disease. Enteroenteric, Enterovesical,

Enterovaginal fistula and Fistulation from the bowel may also cause perianal or

ischiorectal abscesses, fissures and fistulas.

4. Cancer; The risk of colon cancer is increased in patients with long-standing,

extensive, active colitis of more than 8 years' duration.

Page of

25

105

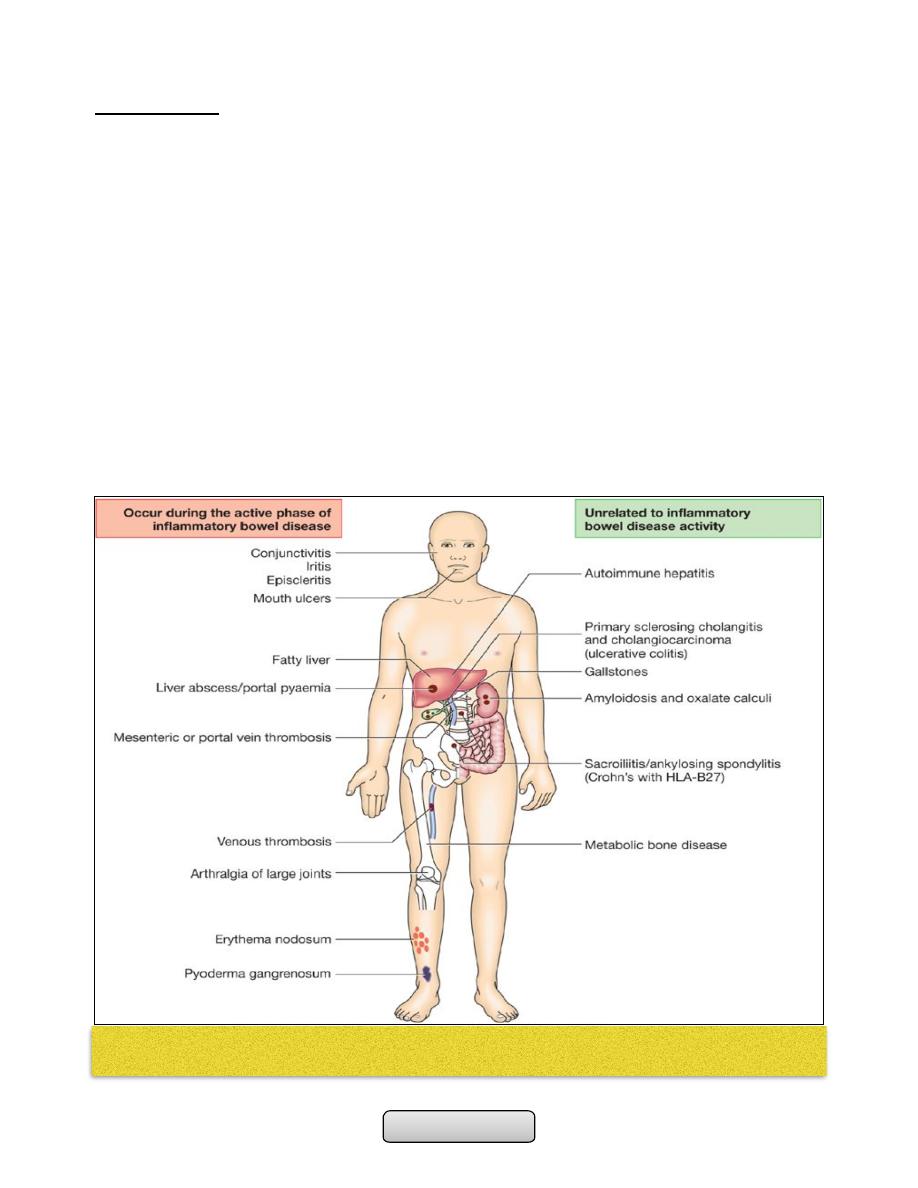

Extraintestinal complications are common in IBD and may dominate the clinical

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Investigations:

1. General; Full blood count may show anaemia resulting from bleeding or malabsorption

of iron, folic acid or vitamin B

12

.

2. Endoscopy;

• Sigmoidoscopy with biopsy is an essential investigation in all patients who present

with diarrhoea, which show loss of vascular pattern, granularity, friability and

ulceration.

• Colonoscopy may show active inflammation with pseudopolyps or a complicating

carcinoma. Biopsies should be taken to confirm the diagnosis and define disease

extent, and also to seek dysplasia in patients with long-standing colitis.

3. Radiology;

• Barium enema is a less sensitive investigation than colonoscopy in patients with colitis

and is now little used.

• Contrast studies of the small bowel can be helpful in the investigation of Crohn's

disease; affected areas are narrowed and ulcerated, and multiple strictures are

common.

• MRI scans provide comparable information without radiation exposure or risking small

bowel obstruction and are useful in delineating pelvic or perineal involvement.

Management:

The key aims of treatment are to:

• Treat acute attacks

• Prevent relapses

• Detect carcinoma at an early stage

• Select patients for surgery.

Ulcerative colitis:

Active proctitis;

• Mesalazine enemas or suppositories combined with oral mesalazine are effective first-

line therapy.

Active left-sided or extensive ulcerative colitis;

• high-dose aminosalicylates combined with topical aminosalicylate and corticosteroids

are effective. Oral prednisolone 40 mg daily is indicated for more active disease.

Severe ulcerative colitis or fulminant ulcerative colitis:

• Intravenous fluids.

• Transfusion if Hb < 100 g/L.

• I.v. methylprednisolone (60 mg daily) or hydrocortisone (400 mg daily).

• Topical and oral aminosalicylates are also used.

• Antibiotics for proven infection.

• Nutritional support.

• Subcutaneous heparin for prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism.

Page of

26

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

• Avoidance of opiates and antidiarrhoeal agents.

• Consider intravenous ciclosporin or infliximab in stable patients not responding to 3-5

days of corticosteroids.

Crohn's disease:

• Patients with active colitis or ileocolitis:

-

Are initially treated in a similar manner to those with active ulcerative colitis.

-

Aminosalicylates and corticosteroids are both effective and usually induce

remission in active ileocolitis and colitis.

• Patients with isolated ileal disease; Should be treated with;

-

Corticosteroids

-

Aminosalicylates

-

Anti-TNF antibodies; infliximab

-

Oral metronidazole

Fistulas and perianal disease;

• Metronidazole and/or ciprofloxacin are first-line therapies.

• Thiopurines are used in chronic disease.

• Infliximab and adalimumab heal enterocutaneous fistulas and perianal disease in

many patients.

• Surgical intervention:.

Surgical treatment:

Ulcerative colitis:

• Impaired quality of life: Loss of occupation or education

• Failure of medical therapy

• Fulminant colitis

• Disease complications unresponsive to medical therapy: nArthritis or Pyoderma

gangrenosum

• Colon cancer or severe dysplasia

Crohn's disease:

• Similar to those for ulcerative colitis.

• Fistulas, abscesses and perianal disease.

• Small or large bowel obstruction.

……………………………………………………………………………………………..

Page of

27

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

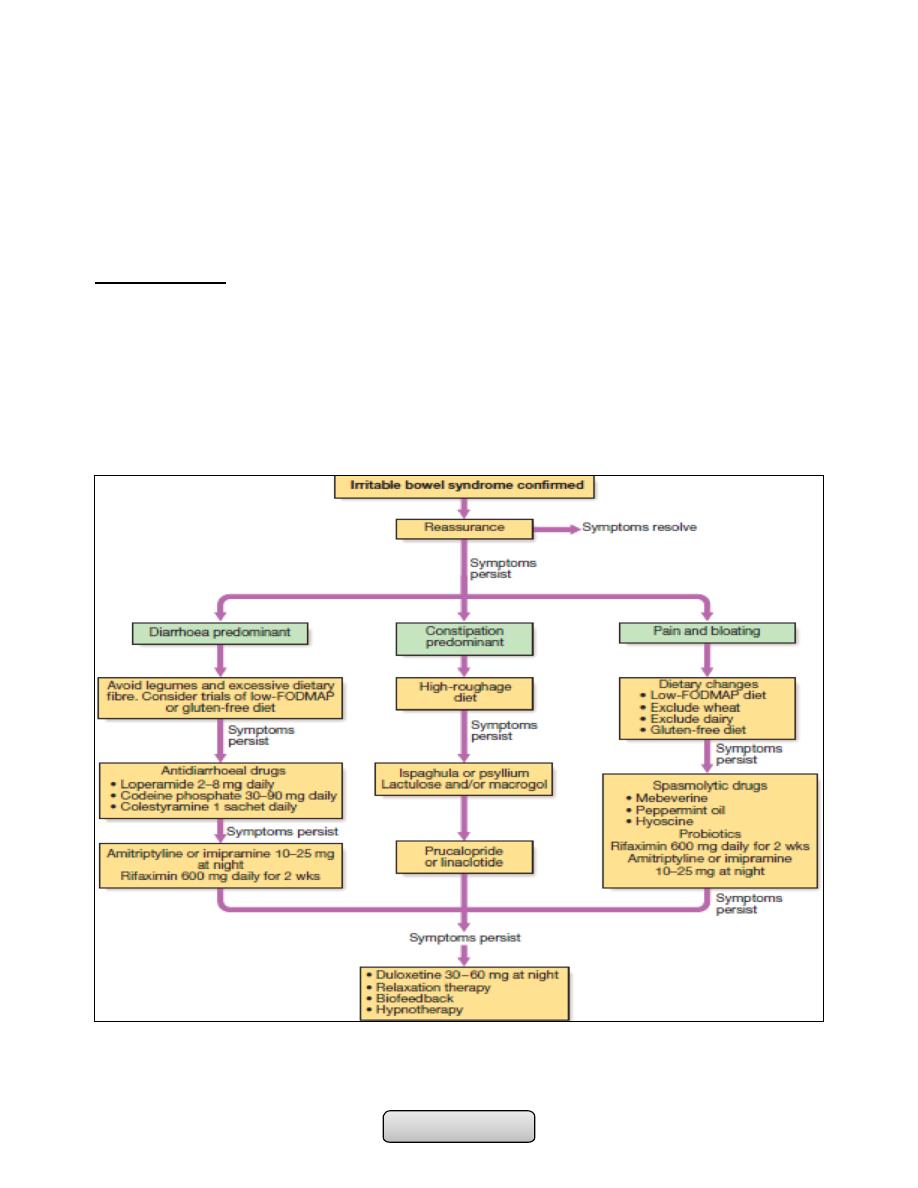

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS);

• Is a functional bowel disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain or

discomfort and altered bowel habits in the absence of structural abnormalities.

• diagnosis of the disorder is based on clinical presentation

• About 10–15% of the population are affected. Young women are affected 2–3 times

more often than men.

Pathophysiology;

The cause of IBS is incompletely understood but the following factors are thought to play

an important role;

1. Behavioural and psychosocial factors;

• Most patients do not have psychological problems but some patients have an anxiety

or depression.

2. Physiological factors;

• Relatively excessive release of 5-HT in diarrhoea-predominant IBS (D-IBS) and relative

deficiency with constipation-predominant IBS (C-IBS).

• Immune activation with raised numbers of mucosal mast cells.

3. Luminal factors;

• Alterations in intestinal bacterial contents (the gut microbiota) with small intestinal

bacterial overgrowth.

• Dietary factors are also important. Some patients have chemical food intolerances

(not allergy) to poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates (lactose, fructose and

sorbitol, among others), collectively known as FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di- and

monosaccharides, and polyols). Their fermentation in the colon leads to bloating,

pain, wind and altered bowel habit.

• Noncoeliac gluten sensitivity (negative coeliac serology and normal duodenal biopsies)

seems to be present in some IBS patients

Clinical features;

• The most common presentation is that of recurrent abdominal discomfort (Rome III

criteria). This is usually colicky or cramping in nature, felt in the lower abdomen and

relieved by defecation. Associated with abdominal bloating worsens throughout the

day.

• There is an alteration of bowel habits, patients classify as having predominantly

constipation or predominantly diarrhoea.

Diagnosis;

• Based on Rome criteria combined with the absence of alarm symptoms, with normal

investigation results (Full blood count, with or without sigmoidoscopy).

Page of

28

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Rome Ill criteria for diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome:

• Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days/mth in the last 3 months,

associated with two or more of the following:

-

Improvement with defecation.

-

Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool.

-

Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool

Alarm features:

-

Age > 50 yrs; male gender

-

Family history of colon cancer.

-

Weight loss.

-

Anaemia.

-

Nocturnal symptoms.

-

Rectal bleeding.

………………………………………………………………………………………………

Page of

29

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

COLORECTAL CANCER

COLORECTAL CANCER:

• Colorectal cancer is the second most common internal malignancy and the second

leading cause of cancer deaths in Western countries (Lung is the first). But it is

relatively rare in the developing world. Why?

• It becomes increasingly common over the age of 50.

Aetiology:

Both genetic and environmental factors are important in colorectal carcinogenesis:

I. Genetic factors:

A. Accumulation of multiple genetic mutations.

B. Hereditary syndromes (autosomal dominant inheritance):

1. Nonpolyposis syndrome (Lynch syndrome).

2. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

II. Environmental factors;

A. Dietary factors are believed to be most important:

1. Increased risk:

a) Red meat.

b) Saturated animal fat.

2. Decreased risk.

a) Dietary fibre.

b) Fruit and Vegetables.

c) Calcium.

d) Folic acid.

e) Omega-3 fatty acids.

B. Non-dietary risk factors in colorectal cancer:

1. Medical conditions:

2. Colorectal adenomas.

3. Long-standing extensive ulcerative colitis or Crohn's colitis.

4. Ureterosigmoidostomy.

5. Acromegaly.

6. Pelvic radiotherapy.

C. Others:

1. Obesity and sedentary lifestyle.

2. Smoking.

3. Alcohol (weak association).

4. Cholecystectomy (effect of bile acids in right colon).

5. Type 2 diabetes (hyperinsulinaemia).

6. Streptococcus Bovis Bacteremia in individuals who develop endocarditis may

have a possible risk.

Page of

30

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Risk factors for malignant change in colonic polyps:

1. Large size (> 2 cm)

2. Multiple polyps

3. Dysplastic polyp

Pathology:

• Most tumours arise from malignant transformation of a benign adenomatous polyp.

• Over 65% occur in the rectosigmoid

• Macroscopically, the majority of cancers are either polypoid and 'fungating', or

annular and constricting.

• Spread occurs through the bowel wall.

• Rectal cancers may invade the pelvic viscera and side walls.

• Lymphatic invasion is common at presentation, as is spread through both portal and

systemic circulations to reach the liver and, less commonly, the lungs.

Clinical features:

• Symptoms vary depending on the site of the carcinoma

• In tumours of the left colon, fresh rectal bleeding is common and obstruction occurs

early.

• Tumours of the right colon present with anaemia from occult bleeding, or altered

bowel habit, but obstruction is a late feature.

• Colicky lower abdominal pain is present in two-thirds of patients and rectal bleeding

occurs in 50%.

• A minority present with features of either obstruction or perforation, leading to

peritonitis, localized abscess or fistula formation.

• 10 and 20% of all patients present solely with iron deficiency anaemia or weight loss.

On examination:

• Signs of anaemia

• Low rectal tumours may be palpable on digital examination.

• If disease has spread to the abdomen, there may be a palpable mass, ascites, bowel

obstruction or hepatomegaly.

• Metastatic spread to the pelvic region may become evident as bladder dysfunction,

sciatic nerve pain, and vaginal discharge or bleeding.

• Lesions that have spread to the lung or bone marrow can remain silent until very

advanced disease is present.

Investigations:

• Double-contrast air-barium enema revealing tumor as filling defect or stricture with

apple-core appearance. If the test is positive colonoscopy should be undergo.

Page of

31

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

• Colonoscopy is the investigation of choice because it is more sensitive and specific

than barium enema. lesions can be biopsied and polyps removed.

• CT colography ('virtual colonoscopy') is a sensitive non-invasive technique for

diagnosing tumors and polyps greater than 1 cm that can be used if colonoscopy is

incomplete or high-risk.

• CT is valuable for detecting hepatic metastases and the extent of tumor spread.

• A proportion of patients have raised serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

concentrations but this is variable and so of little use in diagnosis. Measurements of

CEA are valuable, however, during follow-up and can help to detect early recurrence.

Management:

• Surgery;

-

The tumour is removed, along with adequate resection margins and pericolic

lymph nodes.

-

Post-operatively, patients should undergo colonoscopy after 6-12 months and

periodically thereafter to search for local recurrence

-

Two-thirds of patients have lymph node or distant spread (Dukes stage C) at

presentation and are, therefore, beyond cure with surgery alone.

• Adjuvant therapy;

-

5-fluorouracil and folinic acid (to reduce toxicity) for 6 months improves both

disease-free and overall survival in patients with Dukes C colon cancer by around

4-13%.

• Radiotherapy;

-

Pre-operative radiotherapy can be given to patients with large, fixed rectal

cancers to 'down-stage' the tumour, making it resectable and reducing local

recurrence.

-

Dukes C and some Dukes B rectal cancers are given post-operative radiotherapy to

reduce the risk of local recurrence if operative resection margins are involved.

• Palliative treatment:

-

Surgical resection to treat obstruction, bleeding or pain.

-

Palliative chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid improves survival.

-

Pelvic radiotherapy is sometimes useful for distressing rectal symptoms such as

pain, bleeding or severe tenesmus

-

Endoscopic laser therapy or insertion of an expandable metal stent can be used to

relieve obstruction.

Prevention and screening:

1. Chemoprevention; The most promising agents at present are aspirin, calcium and folic

acid.

2. Secondary prevention (screening):

Page of

32

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

• Faecal occult blood (FOB) testing; In the USA, annual FOB screening is recommended

after the age of 50 years.

• Flexible sigmoidoscopy ; In the USA every 5 years in all persons over the age of 50.

• Colonoscopy; Remains the gold standard but requires expertise, is expensive and

carries risks; many countries lack the resources to offer this form of screening. In the

USA every 10 yr.

• Screening by molecular genetic analysis is an exciting prospect but is not yet

available.

• Faecal occult blood test (Guaiac test): In the presence of heme and a hydrogen

peroxide developer guaiac acid is oxidized producing a blue color.

……………………………………………………………………………………………

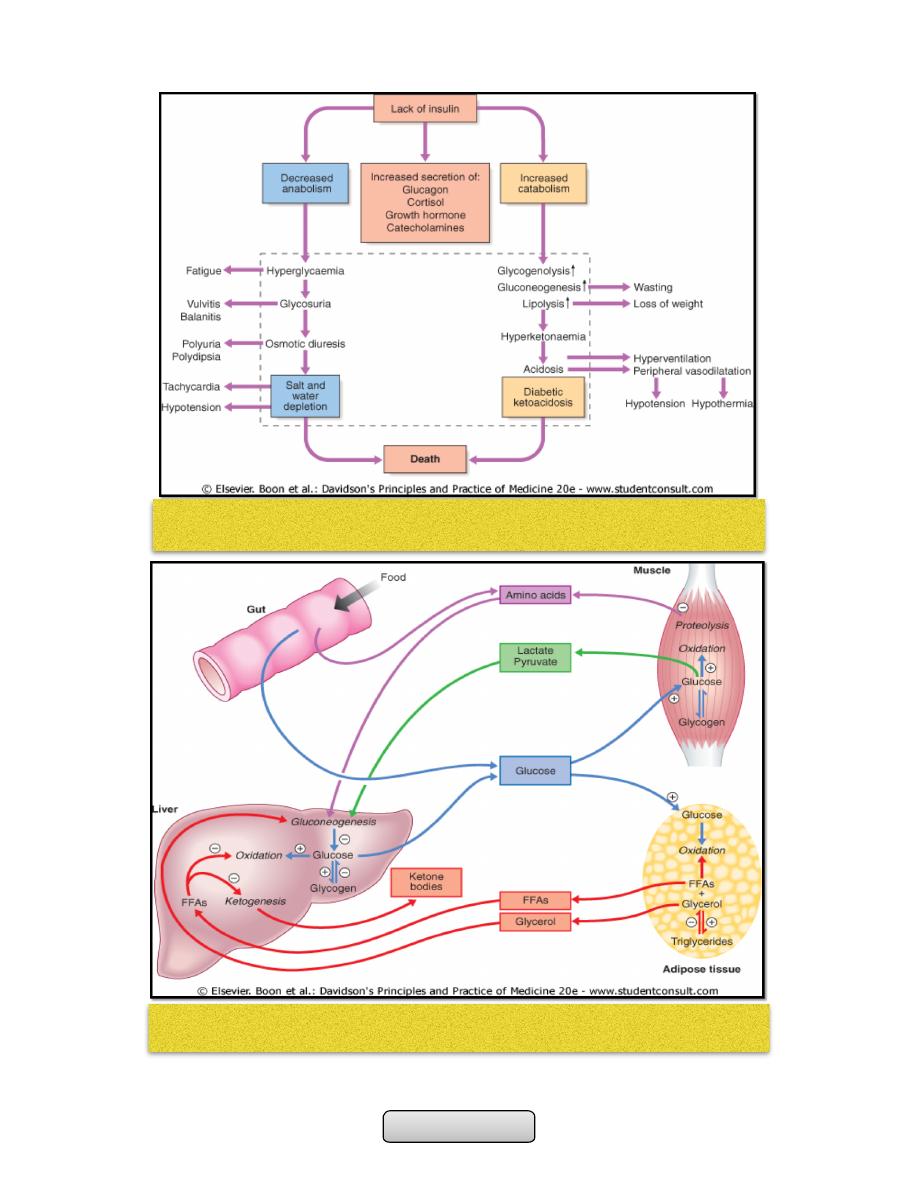

ACUTE AND CHRONIC HEPATITIS

Acute hepatitis:

• Hepatitis; is clinicopathologic conditions due to liver damage by viral, toxic,

metabolic, pharmacologic, or immune-mediated attack.

• Acute hepatitis; inflammation of liver lasting less than 6 months.

• Fate: Either complete resolution or rapid progression to fulminant hepatitis and acute

liver failure or slowly progress to chronic hepatitis.

Causes of Acute Hepatitis:

1. Viral Hepatitis; Hepatitis A virus, Hepatitis B virus Hepatitis C virus, Hepatitis D

virus ("delta agent") and Hepatitis E virus.

Other: Epstein-Barr virus Cytomegalovirus.

2. Alcohol.

3. Toxins; Amanita phalloides mushroom poisoning and Herbal preparations.

4. Drugs; Acetaminophen, Isoniazid, Halothane Phenytoin, Ketoconazole.

5. Other; Autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson's disease.

Acute Viral Hepatitis:

• This is a common cause of jaundice.

Page of

33

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Serology:

• Hepatitis A:

-

Anti-HAV of IgM type, indicating a primary immune response, is already present in

the blood at the onset of the clinical illness and is diagnostic of an acute HAV

infection.

• Hepatitis B:

-

Acute infection the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs Ag) is a reliable marker of HBV

infection

-

Anti-HBs Ab usually appears after about 3-6 months and persists for many years or

perhaps permanently

-

The hepatitis B core antigen (HBc Ag) is not found in the blood, but antibody to it

(anti-HBc) appears early in the illness and rapidly reaches a high titre which then

subsides gradually but persists. Anti-HBc is initially of IgM type while IgG antibody

appearing later.

-

The hepatitis B e antigen (Hbe Ag) appears only transiently at the onset of the

illness and is followed by the production of antibody (anti-HBe). The Hbe Ag

reflects active replication of the virus in the liver.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis E

Group

Enterovirus

picornavirus

Hepadna

Flavivirus

Incomplete

virus

Calicivirus

Nucleic acid

RNA

DNA

RNA

RNA

RNA

Size (diameter) 27 nm

42 nm

30-38 nm

35 nm

27 nm

Incubation

(weeks)

2-4

4-20

2-26

6-9

3-8

Spread

Faeces

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

Blood

Uncommon

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Saliva

Yes

Yes

Yes

?

?

Sexual

Uncommon

Yes

Uncommon

Yes

?

Vertical

No

Yes

Uncommon

Yes

No

Chronic

infection

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Prevention

Active

Vaccine

Vaccine

No

Prevented by

No

Passive

Immune serum

globulin

Hyperimmune

serum globulin

No

Hepatitis B

vaccination

No

Page of

34

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

-

The persistence of HBs Ag for longer than 6 months indicates chronic infection.

-

Chronic HBV infection is marked by the presence of HBs Ag and anti-HBc (IgG) in

the blood.

-

HBV-DNA can be measured by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the blood. Viral

loads are usually in excess of 105 copies/ml in the presence of active viral

replication.

• Hepatitis D:

-

HDV contains a single antigen to which infected individuals make an antibody

(anti-HDV) initially IgM and later IgG.

• Hepatitis C:

-

Eighty per cent of individuals exposed to the virus will become chronically infected

-

hepatitis C RNA can be identified in the blood as early as 2-4 weeks after

infection.

-

Active infection is confirmed by the presence of serum hepatitis C RNA in anyone

who is antibody positive.

Clinical features of viral hepatitis:

1. Prodromal phase;

• Which last for several days and characterized by malaise, fatigue, anorexia, nausea,

vomiting, myalgia, headache, and mild fever.

• Arthritis and urticaria (serum sickness) due to immune complex deposition, may be

present in 5 to 10% of cases of acute hepatitis B and C.

• Taste and smell alteration.

2. Icteric phase;

• Jaundice appear after few days to 2 weeks.

• Dark urine and pale stools.

• Improvement in the patient's well-being.

• Splenomegaly is found in about one-fifth of patients.

• Anicteric phase; Symptoms without jaundice.

• Laboratory;

-

Aminotransferases (ALT & AST) serum levels rise to greater than 20- 100 fold

normal.

-

An elevated serum bilirubin (>2.5 to 3.0 mg/dL) or higher than 20 mg/dL.

-

Serum alkaline phosphatase when it rise to more three times of normal levels

indicate cholestatic hepatitis.

-

Prolongation of the prothrombin time in sever hepatitis.

-

Serological tests confirm the aetiology of the infection.

3. Recovery phase; Gradual resolution of symptoms and laboratory values.

Complications:

1. Cholestatic hepatitis.

Page of

35

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

2. Acute liver failure.

3. Chronic hepatitis.

4. Aplastic anemia.

5. Relapsing hepatitis.

Management:

1. Supportive treatment;

• Rest.

• Maintenance of hydration and adequate dietary intake.

• Alcohol should be avoided.

• Hospitalization if severe nausea and vomiting or deterioration of liver function.

• Drugs such as sedatives and narcotics should be avoided.

• Elective surgery should be avoided.

• Acute hepatitis C; α-interferon may decrease the risk of chronicity.

• Vitamin K indicated if prolonged cholestasis.

2. Liver transplantation;

• Very rarely indicated, when the patient developed acute liver failure.

Chronic Hepatitis:

• Defined as a hepatic inflammatory process lasting more than 6 months.

Causes of Chronic Hepatitis;

1. Viral Hepatitis; B, C and Hepatitis B with superimposed hepatitis D.

2. Alcoholic hepatitis.

3. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

4. Drugs and Toxins; Methyldopa, Nitrofurantoin, Amiodarone, Captopril,

Propylthiouracil.

5. Autoimmune

6. Genetic and Metabolic Disorders; Wilson's disease, and α

1

-Antitrypsin deficiency.

Classification:

A. Initial classification; which depend on histopathology only;

1. Chronic persistent hepatitis; inflammatory activity confined to portal areas --

good prognosis.

2. Chronic lobular hepatitis; inflammatory activity and necrosis scattered

throughout the lobule -- good prognosis.

3. Chronic active hepatitis; inflammation that spilled into the adjacent lobule

associated with necrosis and fibrosis, which progress to cirrhosis and liver

failure.

B. Recent classification; which depend on;

1. Etiologic agent

Page of

36

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

2. Grade of injury (numbers and location of inflammatory cells)

3. Stage of disease (degree and location of fibrosis)

Chronic hepatitis B:

• Route of transmission and risk of chronic infection

• Horizontal transmission (10%); Injection drug use, infected unscreened blood

products, tattoos/acupuncture needles, sexual.

• Vertical transmission (90%); From HBs Ag positive mother.

Clinical features:

• Asymptomatic, fatigue, jaundice, malaise and anorexia, may progress to liver failure.

• Extrahepatic features; Arthralgias and arthritis, glomerulonephritis, and vasculitis ,

due to immune complexes deposition.

Invx;

• Aminotransferases elevated. HBs Ag +ve, HBe Ag +ve, and anti-HBc IgG Ab +ve.

Treatment:

• Indication for treatment; High viral load, elevated serum transaminases and/or

histological evidence of inflammation.

-

Alfa-interferon or longer-acting pegylated interferons; that augmenting immune

response.

-

Lamivudine; Nucleoside analogue which inhibits DNA polymerase and suppresses

HBV-DNA levels.

-

Adefovir; Nucleotide analogue which inhibits HBV-DNA polymerase.

• Liver transplantation.

Chronic Hepatitis D;

• Chronic hepatitis B plus D has similar clinical and laboratory features to those seen in

chronic hepatitis B alone– but more severe chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis.

• Preventing hepatitis B effectively prevents hepatitis D.

• Anti-HDV IgG titer is high.

Chronic Hepatitis C:

• 75% will become chronically infected.

Clinical features;

• Similar to chronic hepatitis B, fatigue common, but jaundice is rare.

• Extrahepatic features; Essential mixed cryoglobulinemia , Sjögren's syndrome, lichen

planus, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

• Progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Page of

37

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Invx;

• Presence of serum hepatitis C RNA in anyone who is antibody-positive.

• Liver histology degree of liver fibrosis

Treatment;

• Pegylated α-interferon together with oral ribavirin, a synthetic nucleotide analogue.

• Liver transplantation:

Alcoholic hepatitis:

• Alcohol is one of the most common causes of chronic liver disease (ALD) worldwide

• A unit of alcohol contains 8 g of ethanol. Consumption of more than 80 g/day, for

more than 5 years, is required to confer significant risk of advanced liver disease

Risk factors for ALD are:

• Drinking pattern; liver damage is more likely to occur in continuous rather than

intermittent or ‘binge’ drinkers, Gender; more in women, Genetics, Nutrition; more

in obese

Pathophysiology;

• 80% of alcohol is metabolised to acetaldehyde that activate the immune system,

contributing to cell injury. 20% of alcohol is metabolised by Cytochrome CYP2E1 lead

to hepatotoxicity from low doses of paracetamol.

C/F;

• Jaundice, malnutrition, hepatomegaly or features of portal hypertension (e.g.

ascites,encephalopathy)

Investigations;

• AST elevated to higher degree than ALT , GGT also elevated, increase s. bilirubin,

macrocytosis in the absence of anaemia, PT increase and albumin decrease in sever

liver dysfunction, liver biopsy to show extent of liver damage

Management;

• Cessation of alcohol consumption

• Good nutrition is very important

• Corticosteroids have a value in the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis

• Pentoxifylline, which has a weak anti-TNF action, may be beneficial in severe

alcoholic hepatitis.

• Liver transplantation have a good prognosis if the patient remains abstinent from

alcohol.

Page of

38

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis:

• Most common in persons who are overweight, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.

Clinical features;

Asymptomatic; As abnormal LFTs.

Complication;

Cirrhosis, variceal haemorrhage or hepatocellular carcinoma.

U/S; liver will appear bright.

Liver biopsy; fat deposition is usually macrovesicular, neutrophil infiltration and fibrosis.

Treatment;

• Weight reduction

• Vitamin E (as an antioxidant)

• Lipid-lowering agents, particularly gemfibrozil.

• Drugs that improve insulin resistance like metformin.

Autoimmune hepatitis:

• Is a liver disease of unknown aetiology

• Association with other autoimmune diseases

• Hypergammaglobulinaemia and autoantibodies

• Young women

• Insidious, with fatigue, anorexia, jaundice, fever, arthralgia, and vitiligo.

• Spider naevi ,hepatosplenomegaly, 'cushingoid' face with acne, hirsutism and pink

cutaneous striae.

Investigations;

• Antinuclear antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibody and antimicrosomal antibodies

(anti-LKM) are positive. Increase IgG level.

Treatment;

• With corticosteroids, Azathioprine for maintenance.

GENETIC AND METABOLIC HEPATITIS:

• Wilson's disease and α

1

-antitrypsin deficiency

• Before the age of 35 years

• Family history of liver disease

Wilson's disease:

• Wilson's disease is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder of copper metabolism that is

caused by a variety of mutations in the gene ATP7B on chromosome 13. Total body

copper is increased, with excess copper deposited in, and causing damage to, several

organs.

• Hepatic disease occurs predominantly in childhood and early adolescence.

Page of

39

105

Internal Medicine: 4

th

Stage TUCOM Dr.Hassan

• Neurological damage causes basal ganglion syndromes and dementia which tends to

present in later adolescence.

• Others include renal tubular damage and osteoporosis.

• Kayser-Fleischer rings the most important single clinical clue to the diagnosis and can

be seen in 60% of adults.

• Diagnosis and treatment:

-

Low serum caeruloplasmin is the best single laboratory clue to the diagnosis. high

free serum copper concentration. high urine copper excretion of greater than 0.6

µmol/24 hrs and a very high hepatic copper content

-

The copper-binding agent penicillamine is the drug of choice.

Alpha

1

-antitrypsin deficiency:

• Alpha

1

-antitrypsin (α

1

-AT) is a serine protease inhibitor (Pi) produced by the liver. It’s

gen located on chromosome 14. which described as medium (M), slow (S), and very

slow (Z). Homozygous individuals (PiZZ) have low plasma α

1

-AT concentrations, these

forms cannot be secreted into the blood by liver cells because it is polymerised within

the endoplasmic reticulum of the hepatocyte, that leads to hepatic and pulmonary

disease.

• Liver disease includes chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis in adults, and in the long term