Esophagus

Dr. Nadim Nafie Ibrahim

Thoracic and Cardiovascular surgeon

F I B M S

Symptoms

Dysphagia:

Difficulty with swallowing, described as food or fluid sticking, it may occur in acute or chronic

fashion, malignancy must be ruled out.

Odynophagia:

Pain on swallowing, patient with reflux esophagitis often feel retrosternal discomfort within few

seconds of swallowing hot beverages or alcohol.

Regurgitation and reflux (heartburn)

Regurgitation refer to return of esophageal contents from above a functional or mechanical

obstruction. Reflux is the passive return of gastroduodenal contents to the mouth as part of the

symptomatology of gastroesopageal reflux disease (GERD).

Chest pain

Chest pain similar in character to angina pectoris may arise from an esophageal cause, especially

gastroesophageal reflux and motility disorders.

Investigations

Radiography:

1- plain radiography: will show some foreign bodies.

2- contrast radiography: useful investigation for demonstrating narrowing, space-occupying lesion,

anatomical distortion or abnormal motility. Video recording is useful to allow subsequent replay

and detailed analysis. Barium radiography is, however, inaccurate in the diagnosis of GERD.

3- computerised tomography ( CT scan): is an essential investigation in the assessment of

neoplasms of the esophagus.

Endoscopy:

Endoscopy is necessary for the investigation of most esophageal conditions. It is required to view

the inside of esophagus and the esophagogastric junction, to obtain a biopsy or cytology specimen,

for removal of foreign bodies and to dilate strictures. There are two types of instruments available,

the rigid esophagoscope and the flexible video endoscope.

Endosonography:

Endoscopic ultrasonography provide high detailed images of the layers of the esophageal wall and

mediastinal structures close to the esophagus.

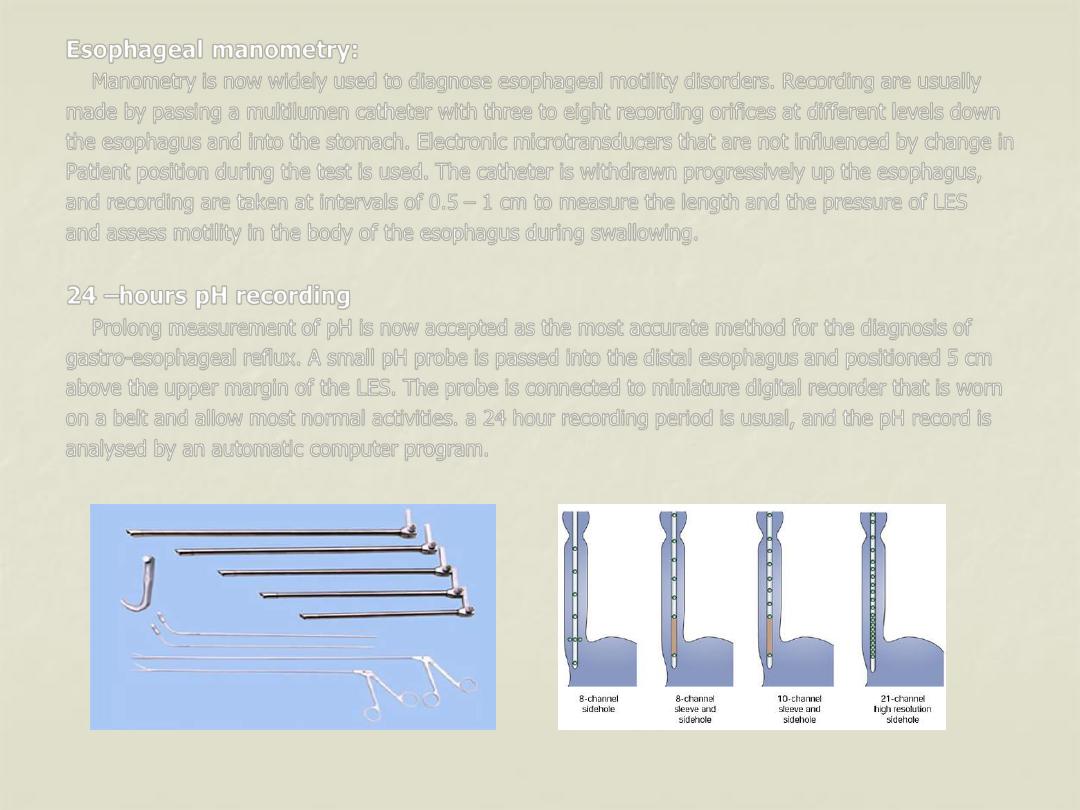

Esophageal manometry:

Manometry is now widely used to diagnose esophageal motility disorders. Recording are usually

made by passing a multilumen catheter with three to eight recording orifices at different levels down

the esophagus and into the stomach. Electronic microtransducers that are not influenced by change in

Patient position during the test is used. The catheter is withdrawn progressively up the esophagus,

and recording are taken at intervals of 0.5

– 1 cm to measure the length and the pressure of LES

and assess motility in the body of the esophagus during swallowing.

24

–hours pH recording

Prolong measurement of pH is now accepted as the most accurate method for the diagnosis of

gastro-esophageal reflux. A small pH probe is passed into the distal esophagus and positioned 5 cm

above the upper margin of the LES. The probe is connected to miniature digital recorder that is worn

on a belt and allow most normal activities. a 24 hour recording period is usual, and the pH record is

analysed by an automatic computer program.

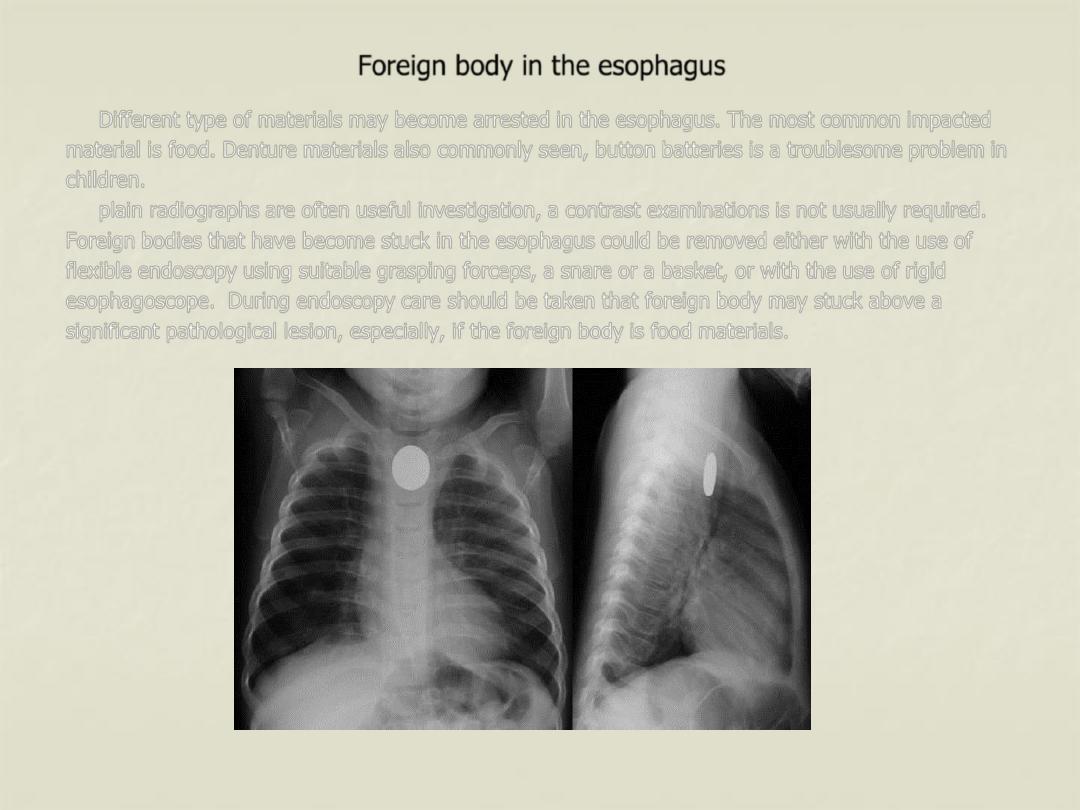

Foreign body in the esophagus

Different type of materials may become arrested in the esophagus. The most common impacted

material is food. Denture materials also commonly seen, button batteries is a troublesome problem in

children.

plain radiographs are often useful investigation, a contrast examinations is not usually required.

Foreign bodies that have become stuck in the esophagus could be removed either with the use of

flexible endoscopy using suitable grasping forceps, a snare or a basket, or with the use of rigid

esophagoscope. During endoscopy care should be taken that foreign body may stuck above a

significant pathological lesion, especially, if the foreign body is food materials.

Perforation of the esophagus

Etiology

1- Barotraumas ( spontaneous perforation, Boerhaave syndrome)

This occur usually when a person vomits against a closed glottis. The pressure in the esophagus

increases rapidly, and the esophagus burst at its weakest point in the lower third, sending stream of

material into the mediastinum and often the pleural cavity as well.

2- pathological perforation

Free perforation of ulcers or tumors of the esophagus into the pleural space is rare. Erosion into

adjacent structures with fistula formation is more common. Fistula into the bronchus is most common

and usually encountered in primary malignant disease of the esophagus or bronchus.

3- Penetrating injury

Penetration by knives and bullets is uncommon, even in wars, as the esophagus is relatively small

target surrounded by other vital organs.

4- foreign bodies

An object that have been left in the esophagus for several days will erode through the wall,

Perforation during removal of foreign body is more common.

5- Instrumental perforation

Instrumentation is by far the most common cause of perforation, it may follow biopsy of a

malignant tumor. Patients undergoing therapeutic endoscopy ( e.g., graduated dilatation) have a

perforation risk that is at least 10 times greater than those undergoing diagnostic endoscopy.

Symptoms

1- suspicion: in the presence of technical difficulties or interventional procedures.

2- cervical perforation may result in pain localized to neck, hoarseness, painful neck movement and

subcutaneous emphysema.

3- intrathoracic and intraabdominal perforation, are more common, giving rise to immediate symptom

and signs either during or at the end of the procedure, including chest pain, haemodynamic

instability , oxygen desaturation.

4- within the first 24 hours, there may be evidence of subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax or

hydropneumothorax.

5- delayed diagnosis beyond 24 hours, the patient will present as unexplained pyrexia, systemic

sepsis or the development of clinical fistula.

Investigations

1- careful endoscopic assessment at the end of the procedure.

2- chest x-ray.

3- contrast swallow, water soluble contrast or a dilute barium swallow.

4- CT scan can be used to replace contrast swallow or as adjunct with it.

Treatment

Perforation of the esophagus usually lead to mediastinitis. The aim of the treatment is to limit

mediastinal contamination and to prevent or deal with the infection.

Non-operative treatment aim to limit the effect of mediastinitis and provide an environment in

which healing can take place. Indications for non-operative treatment include:

1- small instrumental perforation of clean esophagus without obstruction.

2- instrumental perforation in the cervical esophagus, which are usually small.

3- thoracoabdominal perforations that are detected early before oral alimentation.

4-patients who have remained clinically stable despite delay diagnosis.

The principles of non-operative treatment include:

1- hyperalemintations preferably by an enteral rout.

2- nasogastric suction.

3- broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic.

Surgical management is indicated whenever patients:

1- unstable with sepsis and shock.

2- have evidence of heavily contaminated mediastinum, pleural space or peritoneum.

3- have widespread intrapleural or intraperitoneal extravasations of contrast media.

Interventions include:

1- placement of self-expanding stent, in frail patient unfit for major surgery with on-going luminal

obstruction (mostly due to malignancy).

2- direct repair if the perforation is recognized early (within 4-6 hours), and the extent of mediastinal

and pleural contamination is small.

3- T-tube into the esophagus along with appropriately located drain and feeding jejunostomy in the

presence of wide spread mediastinitis and pleural contamination.

Corrosive injury of the esophagus

Accidental ingestion occur in children and when corrosives are stored in bottles labeled as

beverages. Corrosives either alkalis or acids, all can cause damage to the mouth, pharynx, larynx,

esophagus and stomach. The type of the agent, its concentration and the volume ingested largely

determined the extent of damage.

Alkali cause liquefaction, saponification of fat, dehydration and thrombosis of blood vessels that

usually leads to fibrous scaring. Acids cause coagulative necrosis with eschar formation, and this

coagulant may limit penetration to deeper layers of the esophageal wall. Acids also cause more

gastric damage than alkalis because of the induction of intense pylorospasm with pooling in the

antrum.

Symptoms and signs are unreliable in predicting the severity of the injury, the widespread use of

broad-spectrum antibiotics and steroids is not supported by evidence . The key of the

management is early endoscopy to inspect the whole of the esophagus and stomach. Minor injuries

with only oedema of mucosa resolve rapidly with no late sequelae, these patients can safely be fed.

With more sever injuries, a feeding jejunostomy maybe appropriate until the patient can swallow

saliva satisfactory. Regular endoscopic examination are the best way to assess stricture development.

significant stricture formation occur in about 50 % of the patients with extensive mucosal damage.

Dilatation may be appropriate for short strictures. Esophageal resection should be differed for at least

3 months until the fibrotic phase is established. Esophageal replacement is usually required for very

long or multiple strictures. Because of associated gastric damage, colon may be used as the

replacement conduit.