Lecture-2

Work of Breathing

Under resting conditions, the respiratory muscles normally perform “work” to cause

inspiration but not to cause expiration. The work of inspiration can be divided into three parts

that required: (1) to expand the lungs against the lung and chest elastic forces, called

compliance work or elastic work; (2) to overcome the viscosity of the lung and chest wall

structures, called tissue resistance work; and (3) to overcome airway resistance to movement

of air into the lungs, called airway resistance work.

●During quite breathing, 3-5% of total energy of the body is spent for respiration, while in

heavy exercise; it increases up to 50 folds.

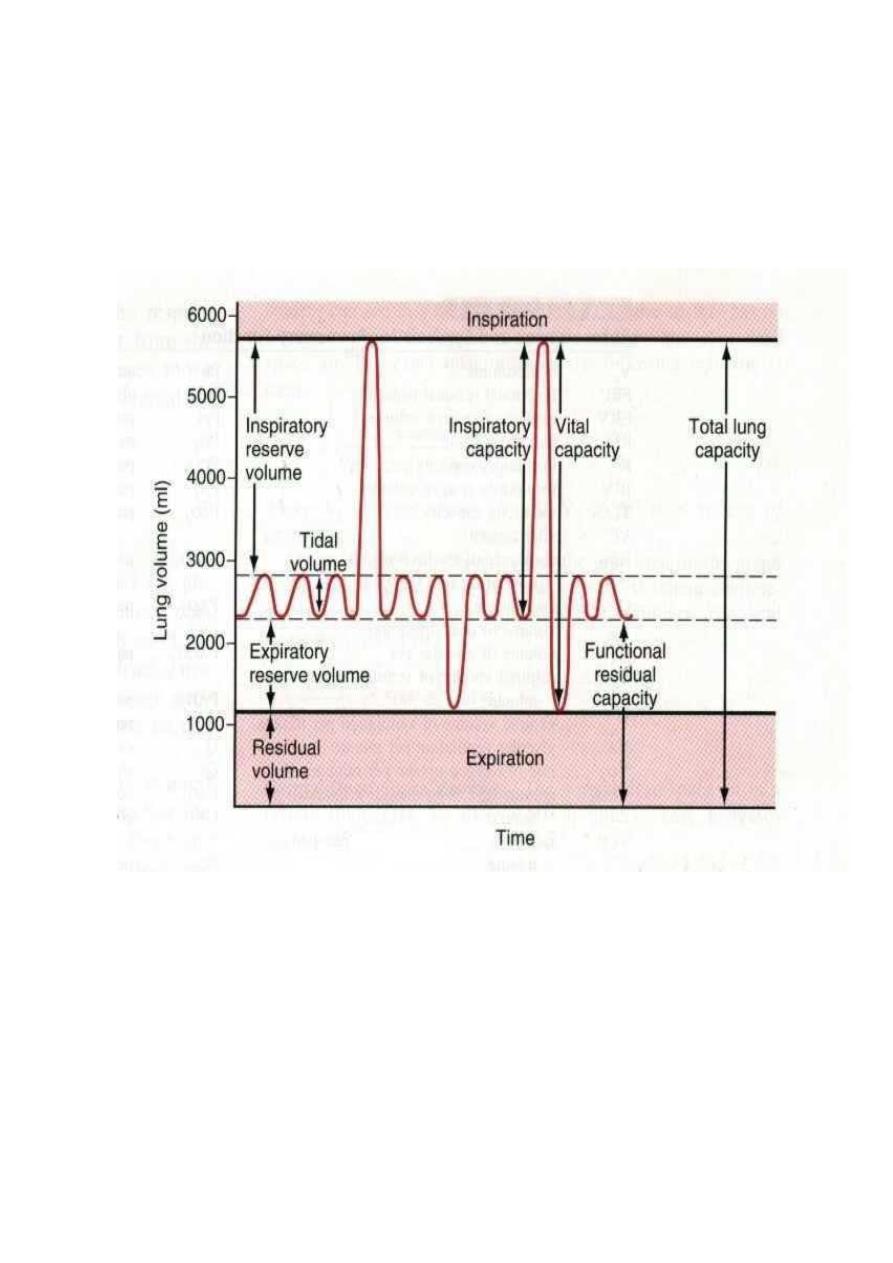

Pulmonary Volumes (fig 5)

A lung volume refers to a basic volume of the lung, the following lung volumes can be

measured directly or indirectly with a spirometer:

1. The tidal volume (VT) is the volume of air inspired or expired with each normal breath; it

amounts to about 500 ml in the adult male.

2. The inspiratory reserve volume (IRV) is the extra volume of air that can be inspired

over and above the normal tidal volume when the person inspires with full force; it is usually

equal to about 3000 ml.

3. The expiratory reserve volume (ERV) is the maximum extra volume of air that can be

expired by forceful expiration after the end of a normal tidal expiration; this normally

amounts to about 1100 ml.

4. The residual volume (RV) is the volume of air remaining in the lungs after the most

forceful expiration; this volume averages about 1200 ml.

Pulmonary Capacities (fig 5)

Lung capacities are the sum of two or more basic lung volumes.

1-Inspiratory Capacity (IC): the maximal volume of air that can be inspired from normal

end-expiration or VT + IRV (about 3500 ml).

2-The functional residual capacity (FRC): equals the ERV + RV. This is the amount of air

that remains in the lungs at the end of normal expiration (about 2300 ml).

3-The vital capacity: equals the IRV+ VT+ ERV. This is the maximum amount of air a

person can expel from the lungs after first filling the lungs to their maximum extent (about

4600 ml).

4. The total lung capacity is the maximum volume to which the lungs can be expanded with

the greatest possible effort (about 5800 ml); it is equal to the vital capacity plus the residual

volume.

●All pulmonary volumes and capacities are about 20 to 25 per cent less in women than in

men, and they are greater in large and athletic people than in small and asthenic people.

● Functional residual capacity cannot be determined by spirometry directly but can be

determined by using helium dilution method.

●The residual volume (RV) can be determined by subtracting expiratory reserve volume

(ERV), as measured by normal spirometry, from the FRC (RV = FRC – ERV).

●The total lung capacity (TLC) can be determined by adding the inspiratory capacity (IC)

to the FRC (TLC = FRC + IC).

●The minute respiratory volume is the total amount of new air moved into the respiratory

passages each minute; this is equal to the tidal volume times the respiratory rate per minute.

The tidal volume (500 ml) multiplied by the respiratory rate (12/min) = 6000ml/minute.

Alveolar Ventilation

It is the rate at which new air reaches the gas exchange areas of the lungs which are the

alveoli, alveolar sacs, alveolar ducts, and respiratory bronchioles.

“Dead Space” and Its Effect on Alveolar Ventilation

The dead space is the space where no gas exchange occurs and on expiration, the air in the

dead space is expired first. It is either normal or called anatomically (150 ml) which are nose,

pharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, bronchioles); or physiological dead space whereby some

alveoli are not functional because of absent or partial blood supply (normally it should be

zero).

So the total dead space is the sum of anatomical and physiological dead spaces and so

normally equals to 150 ml and this increases slightly with age.

So the alveolar ventilation per minute is the total volume of new air entering the alveoli and

adjacent gas exchange areas each minute.

The volume of alveolar ventilation per minute= respiration rate per minute*{tidal volume-

dead space volume}

12*{500-150} =12*300= 4200 ml/min.

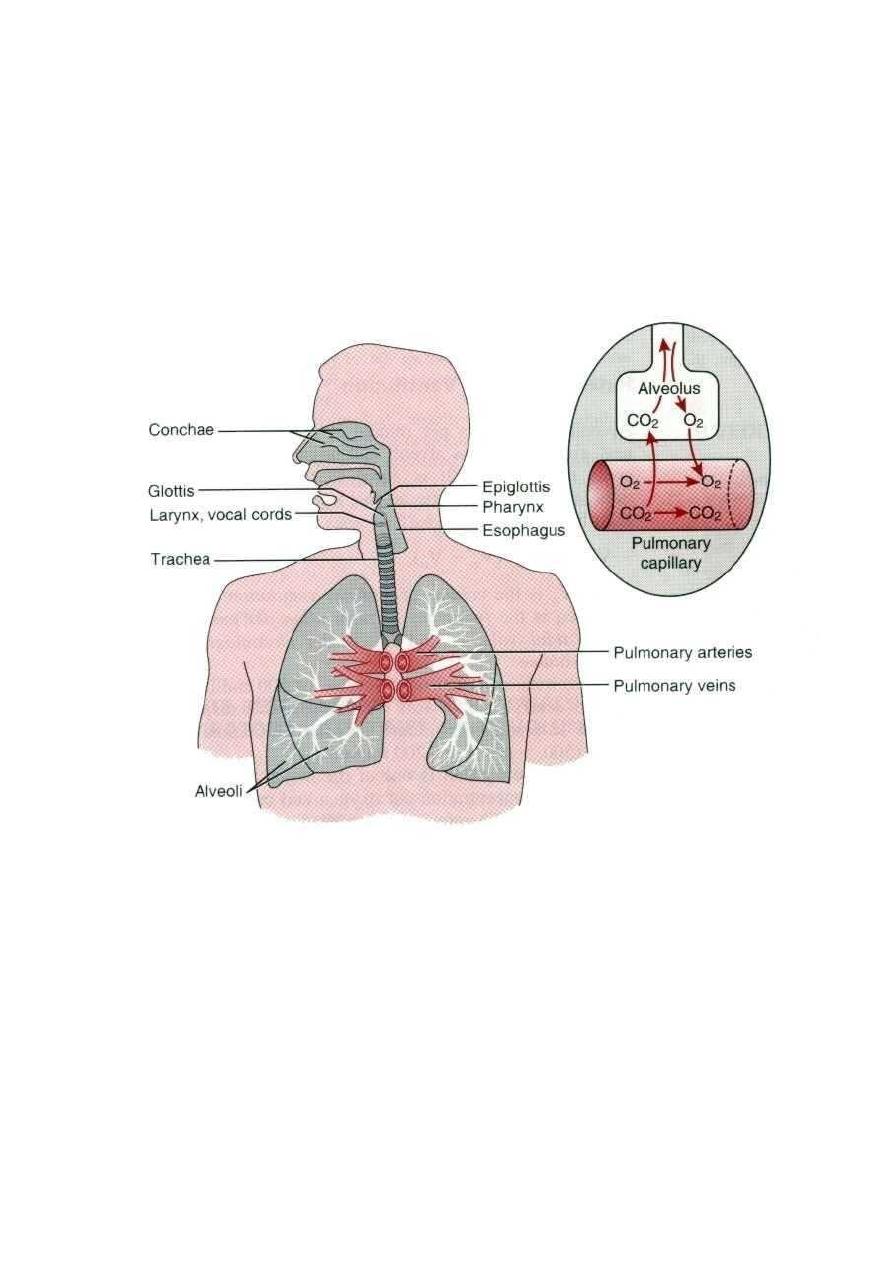

Functions of the Respiratory passageways (fig 6)

The air is distributed to the lungs by way of the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles.

To keep the trachea from collapsing there are multiple cartilage rings extend about five sixths

of the way around the trachea. In the walls of the bronchi there are less extensive curved

cartilage plates also maintain a reasonable amount of rigidity yet. These plates become

progressively less extensive in the later generations of bronchi and are gone in the

bronchioles, bronchioles kept open as alveoli due to transpulmonary pressure.

●All wall areas of the trachea and bronchi are not occupied by cartilage plates are composed

mainly of smooth muscle. Also, the walls of the bronchioles consist of smooth muscle except

the respiratory bronchiole, which are mainly pulmonary epithelium and underlying fibrous

tissue plus a few smooth muscle fibers.

Resistance to airflow in the bronchial tree: In normal quiet breathing, less than 1cm of

water pressure gradient need to cause enough airflow from the alveoli to the atmosphere.

The greatest airflow resistance occurs in the larger bronchioles (bronchi near the trachea)

than in the minute air passages of the terminal bronchioles, this due to that there are few of

these larger bronchi in comparison with terminal bronchioles through each of which only a

minute amount of air must pass, but in disease conditions the minute air passages play a

greater role in determining air way resistance because they are easily occluded.

Nerve stimulation

“Sympathetic” Dilation of the Bronchioles: Direct control of the bronchioles by

sympathetic nerve fibers is weak. However, the bronchial tree is exposed to norepinephrine

and epinephrine released into the blood by sympathetic stimulation of the adrenal gland

medullae. Both these hormones especially epinephrine, because of its greater stimulation of

beta-adrenergic receptors—cause dilation of the bronchial tree.

Parasympathetic Constriction of the Bronchioles:

A few parasympathetic nerve fibers derived from the vagus nerves penetrate the lung

parenchyma secrete acetylcholine which causes mild to moderate constriction of the

bronchioles.

●Sometimes the parasympathetic nerves are also activated by reflexes that originate in the

lungs. This initiated by noxious gases, dust, cigarette smoke, or bronchial infection leading to

irritate the epithelial membrane of the respiratory passageways and constrict them.

Local secretory factors often cause bronchiolar constriction: Several substances formed

in the lungs themselves are causing bronchiolar constriction as histamine and slow reactive

substance of anaphylaxis. Both of these are released in the lung tissues by mast cells during

allergic reactions, especially those caused by pollen in the air causing the airway obstruction

that occurs in allergic asthma.

The role of Mucus and Cilia Lining the Respiratory Passageways

All the respiratory passages, from the nose to the terminal bronchioles, are kept moist by a

layer of mucus that coats the entire surface. The mucus is secreted partly by individual

mucous goblet cells in the epithelial lining of the passages and partly by small submucosal

glands. In addition to keeping the surfaces moist, the mucus traps small particles out of the

inspired air and preventing them reaching the alveoli.

The mucus itself is removed from the passages in the following manner: The entire surface

of the respiratory passages, both in the nose and in the lower passages down as far as the

terminal bronchioles, is lined with ciliated epithelium, and the cilia in the lungs moving

upward toward the pharynx. While the cilia in the nose move downward. This continual

moving cause the mucus and its entrapping particles are either swallowed or coughed to the

exterior.

Cough Reflex

The bronchi and trachea are so sensitive to light touch send afferent nerve impulses pass

through the vagus nerves to the medulla of the brain, then automatically causing the

following effect.

First, up to 2.5 L of air are rapidly inspired.

Second, the epiglottis closes, and the vocal cords shut tightly to entrap the air within the

lungs.

Third, the abdominal muscles contract forcefully, pushing against the diaphragm while other

expiratory muscles, such as the internal intercostals, also contract forcefully. Consequently,

the pressure in the lungs rises rapidly to as much as 100 mm Hg or more.

Fourth, the vocal cords and the epiglottis suddenly open widely, so that airs under this high

pressure in the lungs blow up outward.

Indeed, sometimes this air is expelled at velocities ranging from 75 to 100 miles per hour.

The noncartilaginous parts of bronchi and trachea invaginate inward during cough, so that

the exploding air actually passes through bronchial and tracheal slits.

Sneeze Reflex

The initiating stimulus of the sneeze reflex is irritation in the nasal passageways, the afferent

impulses pass in the fifth cranial nerve to the medulla, where the reflex is triggered. A series

of reactions similar to those for the cough reflex takes place; however, the uvula is

depressed, so that large amounts of air pass rapidly through the nose, thus helping to clear the

nasal passages of foreign matter.

Normal Respiratory Functions of the Nose

As air passes through the nose, three normal respiratory functions are performed by the nasal

cavities:

(1) The air is warmed by the extensive surfaces of the conchae and septum.

(2) The air is almost completely humidified even before it passes beyond the nose.

(3) The air is partially filtered by the hairs at the entrance to the nostrils.

Vocalization

Speech involves not only the respiratory system but also (1) specific speech nervous control

centers in the cerebral cortex (2) respiratory control centers of the brain; and (3) the

articulation and resonance structures of the mouth and nasal cavities. Speech is composed of

two mechanical functions: (1) phonation, which is achieved by the larynx, and (2)

articulation, which is achieved by the structures of the mouth.

Fig-5 Diagram showing respiratory excursions during normal breathing and during maximal

inspiration and maximal expiration

Fig -6 Respiratory passages